CANTO IX

THE hue, which coward dread on my pale cheeks

Imprinted, when I saw my guide turn back,

Chas'd that from his which newly they had worn,

And inwardly restrain'd it. He, as one

Who listens, stood attentive: for his eye

Not far could lead him through the sable air,

And the thick-gath'ring cloud. "It yet behooves

We win this fight"—thus he began—"if not—

Such aid to us is offer'd.—Oh, how long

Me seems it, ere the promis'd help arrive!"

I noted, how the sequel of his words

Clok'd their beginning; for the last he spake

Agreed not with the first. But not the less

My fear was at his saying; sith I drew

To import worse perchance, than that he held,

His mutilated speech. "Doth ever any

Into this rueful concave's extreme depth

Descend, out of the first degree, whose pain

Is deprivation merely of sweet hope?"

Thus I inquiring. "Rarely," he replied,

"It chances, that among us any makes

This journey, which I wend. Erewhile 'tis true

Once came I here beneath, conjur'd by fell

Erictho, sorceress, who compell'd the shades

Back to their bodies. No long space my flesh

Was naked of me, when within these walls

She made me enter, to draw forth a spirit

From out of Judas' circle. Lowest place

Is that of all, obscurest, and remov'd

Farthest from heav'n's all-circling orb. The road

Full well I know: thou therefore rest secure.

That lake, the noisome stench exhaling, round

The city' of grief encompasses, which now

We may not enter without rage." Yet more

He added: but I hold it not in mind,

For that mine eye toward the lofty tower

Had drawn me wholly, to its burning top.

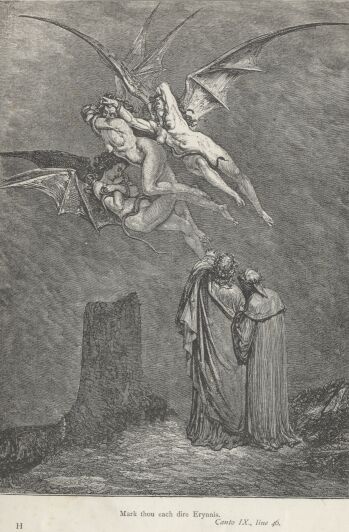

Where in an instant I beheld uprisen

At once three hellish furies stain'd with blood:

In limb and motion feminine they seem'd;

Around them greenest hydras twisting roll'd

Their volumes; adders and cerastes crept

Instead of hair, and their fierce temples bound.

He knowing well the miserable hags

Who tend the queen of endless woe, thus spake:

"Mark thou each dire Erinnys. To the left

This is Megaera; on the right hand she,

Who wails, Alecto; and Tisiphone

I' th' midst." This said, in silence he remain'd

Their breast they each one clawing tore; themselves

Smote with their palms, and such shrill clamour rais'd,

That to the bard I clung, suspicion-bound.

"Hasten Medusa: so to adamant

Him shall we change;" all looking down exclaim'd.

"E'en when by Theseus' might assail'd, we took

No ill revenge." "Turn thyself round, and keep

Thy count'nance hid; for if the Gorgon dire

Be shown, and thou shouldst view it, thy return

Upwards would be for ever lost." This said,

Himself my gentle master turn'd me round,

Nor trusted he my hands, but with his own

He also hid me. Ye of intellect

Sound and entire, mark well the lore conceal'd

Under close texture of the mystic strain!

And now there came o'er the perturbed waves

Loud-crashing, terrible, a sound that made

Either shore tremble, as if of a wind

Impetuous, from conflicting vapours sprung,

That 'gainst some forest driving all its might,

Plucks off the branches, beats them down and hurls

Afar; then onward passing proudly sweeps

Its whirlwind rage, while beasts and shepherds fly.

Mine eyes he loos'd, and spake: "And now direct

Thy visual nerve along that ancient foam,

There, thickest where the smoke ascends." As frogs

Before their foe the serpent, through the wave

Ply swiftly all, till at the ground each one

Lies on a heap; more than a thousand spirits

Destroy'd, so saw I fleeing before one

Who pass'd with unwet feet the Stygian sound.

He, from his face removing the gross air,

Oft his left hand forth stretch'd, and seem'd alone

By that annoyance wearied. I perceiv'd

That he was sent from heav'n, and to my guide

Turn'd me, who signal made that I should stand

Quiet, and bend to him. Ah me! how full

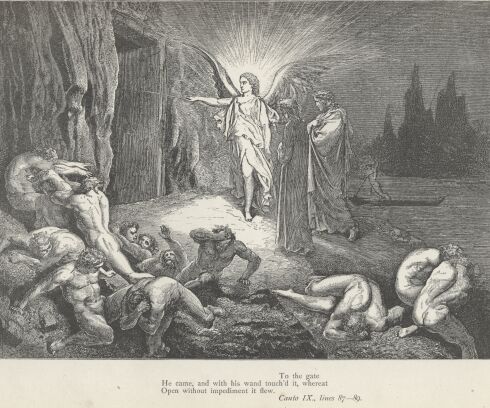

Of noble anger seem'd he! To the gate

He came, and with his wand touch'd it, whereat

Open without impediment it flew.

"Outcasts of heav'n! O abject race and scorn'd!"

Began he on the horrid grunsel standing,

"Whence doth this wild excess of insolence

Lodge in you? wherefore kick you 'gainst that will

Ne'er frustrate of its end, and which so oft

Hath laid on you enforcement of your pangs?

What profits at the fays to but the horn?

Your Cerberus, if ye remember, hence

Bears still, peel'd of their hair, his throat and maw."

This said, he turn'd back o'er the filthy way,

And syllable to us spake none, but wore

The semblance of a man by other care

Beset, and keenly press'd, than thought of him

Who in his presence stands. Then we our steps

Toward that territory mov'd, secure

After the hallow'd words. We unoppos'd

There enter'd; and my mind eager to learn

What state a fortress like to that might hold,

I soon as enter'd throw mine eye around,

And see on every part wide-stretching space

Replete with bitter pain and torment ill.

As where Rhone stagnates on the plains of Arles,

Or as at Pola, near Quarnaro's gulf,

That closes Italy and laves her bounds,

The place is all thick spread with sepulchres;

So was it here, save what in horror here

Excell'd: for 'midst the graves were scattered flames,

Wherewith intensely all throughout they burn'd,

That iron for no craft there hotter needs.

Their lids all hung suspended, and beneath

From them forth issu'd lamentable moans,

Such as the sad and tortur'd well might raise.

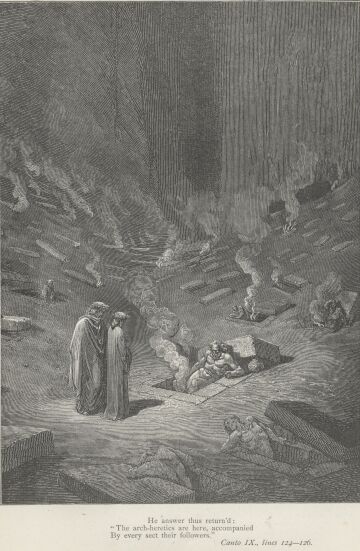

I thus: "Master! say who are these, interr'd

Within these vaults, of whom distinct we hear

The dolorous sighs?" He answer thus return'd:

"The arch-heretics are here, accompanied

By every sect their followers; and much more,

Than thou believest, tombs are freighted: like

With like is buried; and the monuments

Are different in degrees of heat." This said,

He to the right hand turning, on we pass'd

Betwixt the afflicted and the ramparts high.

CANTO X

NOW by a secret pathway we proceed,

Between the walls, that hem the region round,

And the tormented souls: my master first,

I close behind his steps. "Virtue supreme!"

I thus began; "who through these ample orbs

In circuit lead'st me, even as thou will'st,

Speak thou, and satisfy my wish. May those,

Who lie within these sepulchres, be seen?

Already all the lids are rais'd, and none

O'er them keeps watch." He thus in answer spake

"They shall be closed all, what-time they here

From Josaphat return'd shall come, and bring

Their bodies, which above they now have left.

The cemetery on this part obtain

With Epicurus all his followers,

Who with the body make the spirit die.

Here therefore satisfaction shall be soon

Both to the question ask'd, and to the wish,

Which thou conceal'st in silence." I replied:

"I keep not, guide belov'd! from thee my heart

Secreted, but to shun vain length of words,

A lesson erewhile taught me by thyself."

"O Tuscan! thou who through the city of fire

Alive art passing, so discreet of speech!

Here please thee stay awhile. Thy utterance

Declares the place of thy nativity

To be that noble land, with which perchance

I too severely dealt." Sudden that sound

Forth issu'd from a vault, whereat in fear

I somewhat closer to my leader's side

Approaching, he thus spake: "What dost thou? Turn.

Lo, Farinata, there! who hath himself

Uplifted: from his girdle upwards all

Expos'd behold him." On his face was mine

Already fix'd; his breast and forehead there

Erecting, seem'd as in high scorn he held

E'en hell. Between the sepulchres to him

My guide thrust me with fearless hands and prompt,

This warning added: "See thy words be clear!"

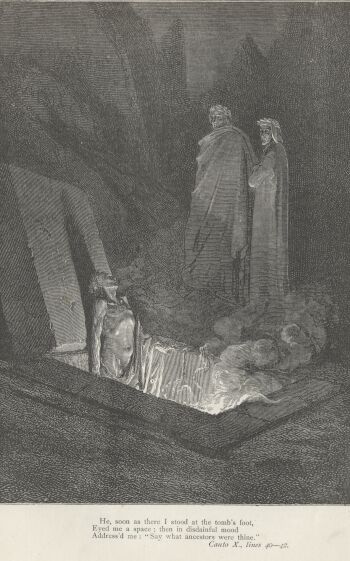

He, soon as there I stood at the tomb's foot,

Ey'd me a space, then in disdainful mood

Address'd me: "Say, what ancestors were thine?"

I, willing to obey him, straight reveal'd

The whole, nor kept back aught: whence he, his brow

Somewhat uplifting, cried: "Fiercely were they

Adverse to me, my party, and the blood

From whence I sprang: twice therefore I abroad

Scatter'd them." "Though driv'n out, yet they each time

From all parts," answer'd I, "return'd; an art

Which yours have shown, they are not skill'd to learn."

Then, peering forth from the unclosed jaw,

Rose from his side a shade, high as the chin,

Leaning, methought, upon its knees uprais'd.

It look'd around, as eager to explore

If there were other with me; but perceiving

That fond imagination quench'd, with tears

Thus spake: "If thou through this blind prison go'st.

Led by thy lofty genius and profound,

Where is my son? and wherefore not with thee?"

I straight replied: "Not of myself I come,

By him, who there expects me, through this clime

Conducted, whom perchance Guido thy son

Had in contempt." Already had his words

And mode of punishment read me his name,

Whence I so fully answer'd. He at once

Exclaim'd, up starting, "How! said'st thou he HAD?

No longer lives he? Strikes not on his eye

The blessed daylight?" Then of some delay

I made ere my reply aware, down fell

Supine, not after forth appear'd he more.

Meanwhile the other, great of soul, near whom

I yet was station'd, chang'd not count'nance stern,

Nor mov'd the neck, nor bent his ribbed side.

"And if," continuing the first discourse,

"They in this art," he cried, "small skill have shown,

That doth torment me more e'en than this bed.

But not yet fifty times shall be relum'd

Her aspect, who reigns here Queen of this realm,

Ere thou shalt know the full weight of that art.

So to the pleasant world mayst thou return,

As thou shalt tell me, why in all their laws,

Against my kin this people is so fell?"

"The slaughter and great havoc," I replied,

"That colour'd Arbia's flood with crimson stain—

To these impute, that in our hallow'd dome

Such orisons ascend." Sighing he shook

The head, then thus resum'd: "In that affray

I stood not singly, nor without just cause

Assuredly should with the rest have stirr'd;

But singly there I stood, when by consent

Of all, Florence had to the ground been raz'd,

The one who openly forbad the deed."

"So may thy lineage find at last repose,"

I thus adjur'd him, "as thou solve this knot,

Which now involves my mind. If right I hear,

Ye seem to view beforehand, that which time

Leads with him, of the present uninform'd."

"We view, as one who hath an evil sight,"

He answer'd, "plainly, objects far remote:

So much of his large spendour yet imparts

The' Almighty Ruler; but when they approach

Or actually exist, our intellect

Then wholly fails, nor of your human state

Except what others bring us know we aught.

Hence therefore mayst thou understand, that all

Our knowledge in that instant shall expire,

When on futurity the portals close."

Then conscious of my fault, and by remorse

Smitten, I added thus: "Now shalt thou say

To him there fallen, that his offspring still

Is to the living join'd; and bid him know,

That if from answer silent I abstain'd,

'Twas that my thought was occupied intent

Upon that error, which thy help hath solv'd."

But now my master summoning me back

I heard, and with more eager haste besought

The spirit to inform me, who with him

Partook his lot. He answer thus return'd:

"More than a thousand with me here are laid

Within is Frederick, second of that name,

And the Lord Cardinal, and of the rest

I speak not." He, this said, from sight withdrew.

But I my steps towards the ancient bard

Reverting, ruminated on the words

Betokening me such ill. Onward he mov'd,

And thus in going question'd: "Whence the' amaze

That holds thy senses wrapt?" I satisfied

The' inquiry, and the sage enjoin'd me straight:

"Let thy safe memory store what thou hast heard

To thee importing harm; and note thou this,"

With his rais'd finger bidding me take heed,

"When thou shalt stand before her gracious beam,

Whose bright eye all surveys, she of thy life

The future tenour will to thee unfold."

Forthwith he to the left hand turn'd his feet:

We left the wall, and tow'rds the middle space

Went by a path, that to a valley strikes;

Which e'en thus high exhal'd its noisome steam.

CANTO XI

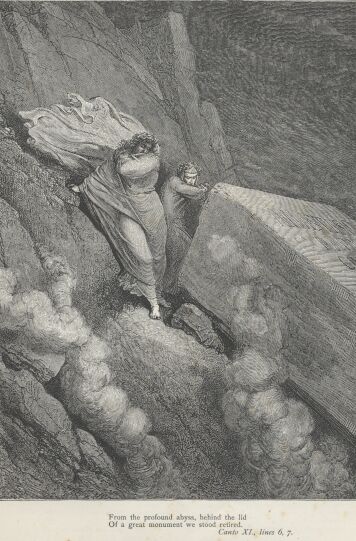

UPON the utmost verge of a high bank,

By craggy rocks environ'd round, we came,

Where woes beneath more cruel yet were stow'd:

And here to shun the horrible excess

Of fetid exhalation, upward cast

From the profound abyss, behind the lid

Of a great monument we stood retir'd,

Whereon this scroll I mark'd: "I have in charge

Pope Anastasius, whom Photinus drew

From the right path.—Ere our descent behooves

We make delay, that somewhat first the sense,

To the dire breath accustom'd, afterward

Regard it not." My master thus; to whom

Answering I spake: "Some compensation find

That the time past not wholly lost." He then:

"Lo! how my thoughts e'en to thy wishes tend!

My son! within these rocks," he thus began,

"Are three close circles in gradation plac'd,

As these which now thou leav'st. Each one is full

Of spirits accurs'd; but that the sight alone

Hereafter may suffice thee, listen how

And for what cause in durance they abide.

"Of all malicious act abhorr'd in heaven,

The end is injury; and all such end

Either by force or fraud works other's woe

But fraud, because of man peculiar evil,

To God is more displeasing; and beneath

The fraudulent are therefore doom'd to' endure

Severer pang. The violent occupy

All the first circle; and because to force

Three persons are obnoxious, in three rounds

Hach within other sep'rate is it fram'd.

To God, his neighbour, and himself, by man

Force may be offer'd; to himself I say

And his possessions, as thou soon shalt hear

At full. Death, violent death, and painful wounds

Upon his neighbour he inflicts; and wastes

By devastation, pillage, and the flames,

His substance. Slayers, and each one that smites

In malice, plund'rers, and all robbers, hence

The torment undergo of the first round

In different herds. Man can do violence

To himself and his own blessings: and for this

He in the second round must aye deplore

With unavailing penitence his crime,

Whoe'er deprives himself of life and light,

In reckless lavishment his talent wastes,

And sorrows there where he should dwell in joy.

To God may force be offer'd, in the heart

Denying and blaspheming his high power,

And nature with her kindly law contemning.

And thence the inmost round marks with its seal

Sodom and Cahors, and all such as speak

Contemptuously' of the Godhead in their hearts.

"Fraud, that in every conscience leaves a sting,

May be by man employ'd on one, whose trust

He wins, or on another who withholds

Strict confidence. Seems as the latter way

Broke but the bond of love which Nature makes.

Whence in the second circle have their nest

Dissimulation, witchcraft, flatteries,

Theft, falsehood, simony, all who seduce

To lust, or set their honesty at pawn,

With such vile scum as these. The other way

Forgets both Nature's general love, and that

Which thereto added afterwards gives birth

To special faith. Whence in the lesser circle,

Point of the universe, dread seat of Dis,

The traitor is eternally consum'd."

I thus: "Instructor, clearly thy discourse

Proceeds, distinguishing the hideous chasm

And its inhabitants with skill exact.

But tell me this: they of the dull, fat pool,

Whom the rain beats, or whom the tempest drives,

Or who with tongues so fierce conflicting meet,

Wherefore within the city fire-illum'd

Are not these punish'd, if God's wrath be on them?

And if it be not, wherefore in such guise

Are they condemned?" He answer thus return'd:

"Wherefore in dotage wanders thus thy mind,

Not so accustom'd? or what other thoughts

Possess it? Dwell not in thy memory

The words, wherein thy ethic page describes

Three dispositions adverse to Heav'n's will,

Incont'nence, malice, and mad brutishness,

And how incontinence the least offends

God, and least guilt incurs? If well thou note

This judgment, and remember who they are,

Without these walls to vain repentance doom'd,

Thou shalt discern why they apart are plac'd

From these fell spirits, and less wreakful pours

Justice divine on them its vengeance down."

"O Sun! who healest all imperfect sight,

Thou so content'st me, when thou solv'st my doubt,

That ignorance not less than knowledge charms.

Yet somewhat turn thee back," I in these words

Continu'd, "where thou saidst, that usury

Offends celestial Goodness; and this knot

Perplex'd unravel." He thus made reply:

"Philosophy, to an attentive ear,

Clearly points out, not in one part alone,

How imitative nature takes her course

From the celestial mind and from its art:

And where her laws the Stagyrite unfolds,

Not many leaves scann'd o'er, observing well

Thou shalt discover, that your art on her

Obsequious follows, as the learner treads

In his instructor's step, so that your art

Deserves the name of second in descent

From God. These two, if thou recall to mind

Creation's holy book, from the beginning

Were the right source of life and excellence

To human kind. But in another path

The usurer walks; and Nature in herself

And in her follower thus he sets at nought,

Placing elsewhere his hope. But follow now

My steps on forward journey bent; for now

The Pisces play with undulating glance

Along the' horizon, and the Wain lies all

O'er the north-west; and onward there a space

Is our steep passage down the rocky height."

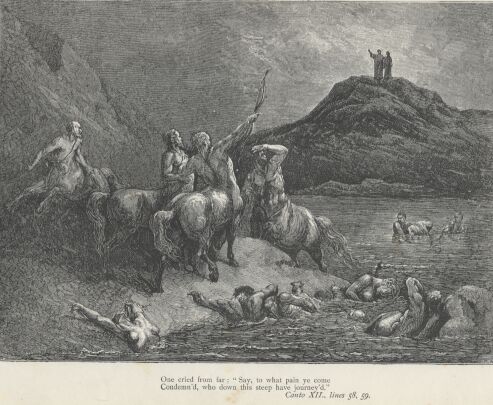

CANTO XII

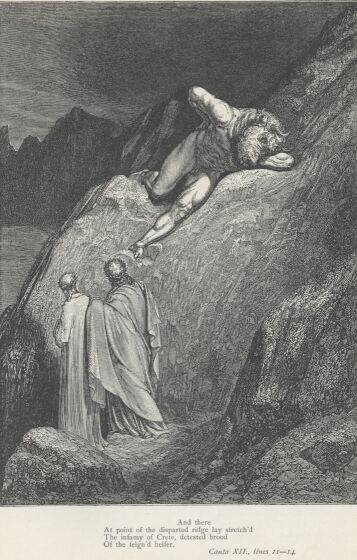

THE place where to descend the precipice

We came, was rough as Alp, and on its verge

Such object lay, as every eye would shun.

As is that ruin, which Adice's stream

On this side Trento struck, should'ring the wave,

Or loos'd by earthquake or for lack of prop;

For from the mountain's summit, whence it mov'd

To the low level, so the headlong rock

Is shiver'd, that some passage it might give

To him who from above would pass; e'en such

Into the chasm was that descent: and there

At point of the disparted ridge lay stretch'd

The infamy of Crete, detested brood

Of the feign'd heifer: and at sight of us

It gnaw'd itself, as one with rage distract.

To him my guide exclaim'd: "Perchance thou deem'st

The King of Athens here, who, in the world

Above, thy death contriv'd. Monster! avaunt!

He comes not tutor'd by thy sister's art,

But to behold your torments is he come."

Like to a bull, that with impetuous spring

Darts, at the moment when the fatal blow

Hath struck him, but unable to proceed

Plunges on either side; so saw I plunge

The Minotaur; whereat the sage exclaim'd:

"Run to the passage! while he storms, 't is well

That thou descend." Thus down our road we took

Through those dilapidated crags, that oft

Mov'd underneath my feet, to weight like theirs

Unus'd. I pond'ring went, and thus he spake:

"Perhaps thy thoughts are of this ruin'd steep,

Guarded by the brute violence, which I

Have vanquish'd now. Know then, that when I erst

Hither descended to the nether hell,

This rock was not yet fallen. But past doubt

(If well I mark) not long ere He arrived,

Who carried off from Dis the mighty spoil

Of the highest circle, then through all its bounds

Such trembling seiz'd the deep concave and foul,

I thought the universe was thrill'd with love,

Whereby, there are who deem, the world hath oft

Been into chaos turn'd: and in that point,

Here, and elsewhere, that old rock toppled down.

But fix thine eyes beneath: the river of blood

Approaches, in the which all those are steep'd,

Who have by violence injur'd." O blind lust!

O foolish wrath! who so dost goad us on

In the brief life, and in the eternal then

Thus miserably o'erwhelm us. I beheld

An ample foss, that in a bow was bent,

As circling all the plain; for so my guide

Had told. Between it and the rampart's base

On trail ran Centaurs, with keen arrows arm'd,

As to the chase they on the earth were wont.

At seeing us descend they each one stood;

And issuing from the troop, three sped with bows

And missile weapons chosen first; of whom

One cried from far: "Say to what pain ye come

Condemn'd, who down this steep have journied? Speak

From whence ye stand, or else the bow I draw."

To whom my guide: "Our answer shall be made

To Chiron, there, when nearer him we come.

Ill was thy mind, thus ever quick and rash."

Then me he touch'd, and spake: "Nessus is this,

Who for the fair Deianira died,

And wrought himself revenge for his own fate.

He in the midst, that on his breast looks down,

Is the great Chiron who Achilles nurs'd;

That other Pholus, prone to wrath." Around

The foss these go by thousands, aiming shafts

At whatsoever spirit dares emerge

From out the blood, more than his guilt allows.

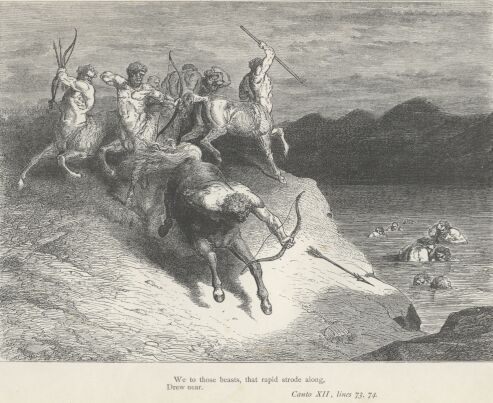

We to those beasts, that rapid strode along,

Drew near, when Chiron took an arrow forth,

And with the notch push'd back his shaggy beard

To the cheek-bone, then his great mouth to view

Exposing, to his fellows thus exclaim'd:

"Are ye aware, that he who comes behind

Moves what he touches? The feet of the dead

Are not so wont." My trusty guide, who now

Stood near his breast, where the two natures join,

Thus made reply: "He is indeed alive,

And solitary so must needs by me

Be shown the gloomy vale, thereto induc'd

By strict necessity, not by delight.

She left her joyful harpings in the sky,

Who this new office to my care consign'd.

He is no robber, no dark spirit I.

But by that virtue, which empowers my step

To treat so wild a path, grant us, I pray,

One of thy band, whom we may trust secure,

Who to the ford may lead us, and convey

Across, him mounted on his back; for he

Is not a spirit that may walk the air."

Then on his right breast turning, Chiron thus

To Nessus spake: "Return, and be their guide.

And if ye chance to cross another troop,

Command them keep aloof." Onward we mov'd,

The faithful escort by our side, along

The border of the crimson-seething flood,

Whence from those steep'd within loud shrieks arose.

Some there I mark'd, as high as to their brow

Immers'd, of whom the mighty Centaur thus:

"These are the souls of tyrants, who were given

To blood and rapine. Here they wail aloud

Their merciless wrongs. Here Alexander dwells,

And Dionysius fell, who many a year

Of woe wrought for fair Sicily. That brow

Whereon the hair so jetty clust'ring hangs,

Is Azzolino; that with flaxen locks

Obizzo' of Este, in the world destroy'd

By his foul step-son." To the bard rever'd

I turned me round, and thus he spake; "Let him

Be to thee now first leader, me but next

To him in rank." Then farther on a space

The Centaur paus'd, near some, who at the throat

Were extant from the wave; and showing us

A spirit by itself apart retir'd,

Exclaim'd: "He in God's bosom smote the heart,

Which yet is honour'd on the bank of Thames."

A race I next espied, who held the head,

And even all the bust above the stream.

'Midst these I many a face remember'd well.

Thus shallow more and more the blood became,

So that at last it but imbru'd the feet;

And there our passage lay athwart the foss.

"As ever on this side the boiling wave

Thou seest diminishing," the Centaur said,

"So on the other, be thou well assur'd,

It lower still and lower sinks its bed,

Till in that part it reuniting join,

Where 't is the lot of tyranny to mourn.

There Heav'n's stern justice lays chastising hand

On Attila, who was the scourge of earth,

On Sextus, and on Pyrrhus, and extracts

Tears ever by the seething flood unlock'd

From the Rinieri, of Corneto this,

Pazzo the other nam'd, who fill'd the ways

With violence and war." This said, he turn'd,

And quitting us, alone repass'd the ford.

|