MARTHA WASHINGTON.

FROM AN UNFINISHED PORTRAIT BY GILBERT STUART. ENGRAVED FOR

ST. NICHOLAS BY W. B. CLOSSON.

MARTHA WASHINGTON.

FROM AN UNFINISHED PORTRAIT BY GILBERT STUART. ENGRAVED FOR

ST. NICHOLAS BY W. B. CLOSSON.

Vol. XIII. October, 1886. No. 12.

[Copyright, 1886, by The CENTURY CO.]

By Edith M. Thomas.

It is astonishing how short a time it takes for very wonderful things to happen. It had taken only a few minutes, apparently, to change all the fortunes of the little boy dangling his red legs from the high stool in Mr. Hobbs’s store, and to transform him from a small boy, living the simplest life in a quiet street, into an English nobleman, the heir to an earldom and magnificent wealth. It had taken only a few minutes, apparently, to change him from an English nobleman into a penniless little impostor, with no right to any of the splendors he had been enjoying. And, surprising as it may appear, it did not take nearly so long a time as one might have expected, to alter the face of everything again and to give back to him all that he had been in danger of losing.

It took the less time because, after all, the woman who had called herself Lady Fauntleroy was not nearly so clever as she was wicked; and when she had been closely pressed by Mr. Havisham’s questions about her marriage and her boy, she had made one or two blunders which had caused suspicion to be awakened; and then she had lost her presence of mind and her temper, and in her excitement and anger had betrayed herself still further. All the mistakes she made were about her child. There seemed no doubt that she had been married to Bevis, Lord Fauntleroy, and had quarreled with him and had been paid to keep away from him; but Mr. Havisham found out that her story of the boy’s being born in a certain part of London was false; and just when they all were in the midst of the commotion caused by this discovery, there came the letter from the young lawyer in New York, and Mr. Hobbs’s letters also.

What an evening it was when those letters arrived, and when Mr. Havisham and the Earl sat and talked their plans over in the library!

“After my first three meetings with her,” said Mr. Havisham, “I began to suspect her strongly. It appeared to me that the child was older than she said he was, and she made a slip in speaking of the date of his birth and then tried to patch the matter up. The story these letters bring fits in with several of my suspicions. Our best plan will be to cable at once for these two Tiptons,—say nothing about them to her,—and suddenly confront her with them when she is not expecting it. She is only a very clumsy plotter, after all. My opinion is that she will be frightened out of her wits, and will betray herself on the spot.”

And that was what actually happened. She was told nothing, and Mr. Havisham kept her from suspecting anything by continuing to have interviews with her, in which he assured her he was investigating her statements; and she really began to feel so secure that her spirits rose immensely and she began to be as insolent as might have been expected.

But one fine morning, as she sat in her sitting-room at the inn called “The Dorincourt Arms,” making some very fine plans for herself, Mr. Havisham was announced; and when he entered, he was followed by no less than three persons—one was a sharp-faced boy and one was a big young man and the third was the Earl of Dorincourt.

She sprang to her feet and actually uttered a cry of terror. It broke from her before she had time to check it. She had thought of these newcomers as being thousands of miles away, when she had ever thought of them at all, which she had scarcely done for years. She had never expected to see them again. It must be confessed that Dick grinned a little when he saw her.

“Hello, Minna!” he said.

The big young man—who was Ben—stood still a minute and looked at her.

“Do you know her?” Mr. Havisham asked, glancing from one to the other.

“Yes,” said Ben. “I know her and she knows me.” And he turned his back on her and went and stood looking out of the window, as if the sight of her was hateful to him, as indeed it was. Then the woman, seeing herself so baffled and exposed, lost all control over herself and flew into such a rage as Ben and Dick had often seen her in before. Dick grinned a trifle more as he watched her and heard the names she called them all and the violent threats she made, but Ben did not turn to look at her.

“I can swear to her in any court,” he said to Mr. Havisham, “and I can bring a dozen others who will. Her father is a respectable sort of man, though he’s low down in the world. Her mother was just like herself. She’s dead, but he’s alive, and he’s honest enough to be ashamed of her. He’ll tell you who she is, and whether she married me or not.”

Then he clenched his hand suddenly and turned on her.

“Where’s the child?” he demanded. “He’s going with me! He is done with you, and so am I!”

And just as he finished saying the words, the door leading into the bedroom opened a little, and the boy, probably attracted by the sound of the loud voices, looked in. He was not a handsome boy, but he had rather a nice face, and he was quite like Ben, his father, as any one could see, and there was the three-cornered scar on his chin.

Ben walked up to him and took his hand, and his own was trembling.

“Yes,” he said, “I could swear to him too. Tom,” he said to the little fellow, “I’m your father; I’ve come to take you away. Where’s your hat?”

The boy pointed to where it lay on a chair. It evidently rather pleased him to hear that he was going away. He had been so accustomed to queer experiences that it did not surprise him to be told by a stranger that he was his father. He objected so much to the woman who had come a few months before to the place where he had lived since his babyhood, and who had suddenly announced that she was his mother, that he was quite ready for a change. Ben took up the hat and marched to the door.

“If you want me again,” he said to Mr. Havisham, “you know where to find me.”

He walked out of the room, holding the child’s hand and not looking at the woman once. She was fairly raving with fury, and the Earl was calmly gazing at her through his eyeglasses, which he had quietly placed upon his aristocratic, eagle nose.

“Come, come, my young woman,” said Mr. Havisham. “This won’t do at all. If you don’t want to be locked up, you really must behave yourself.”

And there was something so very business-like in his tones that, probably feeling that the safest thing she could do would be to get out of the way, she gave him one savage look and dashed past him into the next room and slammed the door.

“We shall have no more trouble with her,” said Mr. Havisham.

And he was right; for that very night she left the Dorincourt Arms and took the train to London, and was seen no more.

When the Earl left the room after the interview, he went at once to his carriage.

“To Court Lodge,” he said to Thomas.

“To Court Lodge,” said Thomas to the coachman as he mounted the box; “an’ you may depend on it, things is taking a uniggspected turn.”

When the carriage stopped at Court Lodge, Cedric was in the drawing-room with his mother.

The Earl came in without being announced. He looked an inch or so taller, and a great many years younger. His deep eyes flashed.

“Where,” he said, “is Lord Fauntleroy?”

Mrs. Errol came forward, a flush rising to her cheek.

“Is it Lord Fauntleroy?” she asked. “Is it, indeed!”

The Earl put out his hand and grasped hers.

“Yes,” he answered, “it is.”

Then he put his other hand on Cedric’s shoulder.

“Fauntleroy,” he said in his unceremonious, authoritative way, “ask your mother when she will come to us at the Castle.”

Fauntleroy flung his arms around his mother’s neck.

“To live with us!” he cried. “To live with us always!”

The Earl looked at Mrs. Errol, and Mrs. Errol looked at the Earl. His lordship was entirely in earnest. He had made up his mind to waste no time in arranging this matter. He had begun to think it would suit him to make friends with his heir’s mother.

“Are you quite sure you want me?” said Mrs. Errol, with her soft, pretty smile.

“Quite sure,” he said bluntly. “We have always wanted you, but we were not exactly aware of it. We hope you will come.”

Ben took his boy and went back to his cattle ranch in California, and he returned under very comfortable circumstances. Just before his going, Mr. Havisham had an interview with him in which the lawyer told him that the Earl of Dorincourt wished to do something for the boy who might have turned out to be Lord Fauntleroy, and so he had decided that it would be a good plan to invest in a cattle ranch of his own, and put Ben in charge of it on terms which would make it pay him very well, and which would lay a foundation for his son’s future. And so when Ben went away, he went as the prospective master of a ranch which would be almost as good as his own, and might easily become his own in time, as indeed it did in the course of a few years; and Tom, the boy, grew up on it into a fine young man and was devotedly fond of his father; and they were so successful and happy that Ben used to say that Tom made up to him for all the troubles he had ever had.

But Dick and Mr. Hobbs—who had actually come over with the others to see that things were properly looked after—did not return for some time. It had been decided at the outset that the Earl would provide for Dick, and would see that he received a solid education; and Mr. Hobbs had decided that as he himself had left a reliable substitute in charge of his store, he could afford to wait to see the festivities, which were to celebrate Lord Fauntleroy’s eighth birthday. All the tenantry were invited, and there were to be feasting and dancing and games in the park, and bonfires and fireworks in the evening.

“‘ARE YOU QUITE SURE YOU WANT ME?’ SAID MRS. ERROL.”

“Just like the Fourth of July!” said Lord Fauntleroy. “It seems a pity my birthday wasn’t on the Fourth, doesn’t it? For then we could keep them both together.”

It must be confessed that at first the Earl and Mr. Hobbs were not as intimate as it might have been hoped they would become, in the interests of the British aristocracy. The fact was that the Earl had known very few grocery-men, and Mr. Hobbs had not had many very close acquaintances who were earls; and so in their rare interviews conversation did not flourish. It must also be owned that Mr. Hobbs had been rather overwhelmed by the splendors Fauntleroy felt it his duty to show him.

The entrance gate and the stone lions and the avenue impressed Mr. Hobbs somewhat at the beginning, and when he saw the Castle, and the flower-gardens, and the hot-houses, and the terraces, and the peacocks, and the dungeon, and the armor, and the great staircase, and the stables, and the liveried servants, he really was[887] quite bewildered. But it was the picture gallery which seemed to be the finishing stroke.

“Somethin’ in the manner of a museum?” he said to Fauntleroy, when he was led into the great, beautiful room.

“N—no—!” said Fauntleroy, rather doubtfully. “I don’t think it’s a museum. My grandfather says these are my ancestors.”

“Your aunt’s sisters!” ejaculated Mr. Hobbs. “All of ’em? Your great-uncle, he must have had a family! Did he raise ’em all?”

And he sank into a seat and looked around him with quite an agitated countenance, until with the greatest difficulty Lord Fauntleroy managed to explain that the walls were not lined entirely with the portraits of the progeny of his great-uncle.

He found it necessary, in fact, to call in the assistance of Mrs. Mellon, who knew all about the pictures, and could tell who painted them and when, and who added romantic stories of the lords and ladies who were the originals. When Mr. Hobbs once understood, and had heard some of these stories, he was very much fascinated and liked the picture gallery almost better than anything else; and he would often walk over from the village where he staid at the Dorincourt Arms, and would spend half an hour or so wandering about the gallery, staring at the painted ladies and gentlemen who also stared at him, and shaking his head nearly all the time.

“And they was all earls!” he would say, “er pretty nigh it! An’ he’s goin’ to be one of ’em, an’ own it all!”

Privately he was not nearly so much disgusted with earls and their mode of life as he had expected to be, and it is to be doubted whether his strictly republican principles were not shaken a little by a closer acquaintance with castles and ancestors and all the rest of it. At any rate, one day he uttered a very remarkable and unexpected sentiment:

“I wouldn’t have minded bein’ one of ’em myself!” he said—which was really a great concession.

What a grand day it was when little Lord Fauntleroy’s birthday arrived, and how his young lordship enjoyed it! How beautiful the park looked, filled with the thronging people dressed in their gayest and best, and with the flags flying from the tents and the top of the Castle! Nobody had staid away who could possibly come, because everybody was really glad that little Lord Fauntleroy was to be little Lord Fauntleroy still, and some day was to be the master of everything. Every one wanted to have a look at him, and at his pretty, kind mother, who had made so many friends. And positively every one liked the Earl rather better, and felt more amiably toward him because the little boy loved and trusted him so, and because, also, he had now made friends with and behaved respectfully to his heir’s mother. It was said that he was even beginning to be fond of her, too, and that between his young lordship and his young lordship’s mother, the Earl might be changed in time into quite a well-behaved old nobleman, and everybody might be happier and better off.

“‘MY GRANDFATHER SAYS THESE ARE MY ANCESTORS,’ SAID FAUNTLEROY.”

What scores and scores of people there were under the trees, and in the tents, and on the lawns! Farmers and farmers’ wives in their Sunday suits and bonnets and shawls; girls and their sweethearts; children frolicking and chasing about; and old dames in red cloaks gossiping together. At the Castle, there were ladies and gentlemen who had come to see the fun, and to congratulate the Earl, and to meet Mrs. Errol. Lady Lorredaile and Sir Harry were there, and Sir Thomas Asshe and his daughters, and Mr. Havisham, of course, and[888] then beautiful Miss Vivian Herbert, with the loveliest white gown and lace parasol, and a circle of gentlemen to take care of her—though she evidently liked Fauntleroy better than all of them put together. And when he saw her and ran to her and put his arm around her neck, she put her arms around him, too, and kissed him as warmly as if he had been her own favorite little brother, and she said:

“Dear little Lord Fauntleroy! dear little boy! I am so glad! I am so glad!”

And afterward she walked about the grounds with him, and let him show her everything. And when he took her to where Mr. Hobbs and Dick were, and said to her, “This is my old, old friend Mr. Hobbs, Miss Herbert, and this is my other old friend Dick. I told them how pretty you were, and I told them they should see you if you came to my birthday,”—she shook hands with them both, and stood and talked to them in her prettiest way, asking them about America and their voyage and their life since they had been in England; while Fauntleroy stood by, looking up at her with adoring eyes, and his cheeks quite flushed with delight because he saw that Mr. Hobbs and Dick liked her so much.

“Well,” said Dick solemnly, afterward, “she’s the daisiest gal I ever saw! She’s—well, she’s just a daisy, that’s what she is, ’n no mistake!”

Everybody looked after her as she passed, and every one looked after little Lord Fauntleroy. And the sun shone and the flags fluttered and the games were played and the dances danced, and as the gayeties went on and the joyous afternoon passed, his little lordship was simply radiantly happy.

The whole world seemed beautiful to him.

There was some one else who was happy, too,—an old man, who, though he had been rich and noble all his life, had not often been very honestly happy. Perhaps, indeed, I shall tell you that I think it was because he was rather better than he had been that he was rather happier. He had not, indeed, suddenly become as good as Fauntleroy thought him; but, at least, he had begun to love something, and he had several times found a sort of pleasure in doing the kind things which the innocent, kind little heart of a child had suggested,—and that was a beginning. And every day he had been more pleased with his son’s wife. It was true, as the people said, that he was beginning to like her too. He liked to hear her sweet voice and to see her sweet face; and as he sat in his armchair, he used to watch her and listen as she talked to her boy; and he heard loving, gentle words which were new to him, and he began to see why the little fellow who had lived in a New York side street and known grocery-men and made friends with boot-blacks, was still so well-bred and manly a little fellow that he made no one ashamed of him, even when fortune changed him into the heir to an English earldom, living in an English castle.

It was really a very simple thing, after all,—it was only that he had lived near a kind and gentle heart, and had been taught to think kind thoughts always and to care for others. It is a very little thing, perhaps, but it is the best thing of all. He knew nothing of earls and castles; he was quite ignorant of all grand and splendid things; but he was always lovable because he was simple and loving. To be so is like being born a king.

As the old Earl of Dorincourt looked at him that day, moving about the park among the people, talking to those he knew and making his ready little bow when any one greeted him, entertaining his friends Dick and Mr. Hobbs, or standing near his mother or Miss Herbert listening to their conversation, the old nobleman was very well satisfied with him. And he had never been better satisfied than he was when they went down to the biggest tent, where the more important tenants of the Dorincourt estate were sitting down to the grand collation of the day.

They were drinking toasts; and, after they had drunk the health of the Earl, with much more enthusiasm than his name had ever been greeted with before, they proposed the health of “Little Lord Fauntleroy.” And if there had ever been any doubt at all as to whether his lordship was popular or not, it would have been settled that instant. Such a clamor of voices, and such a rattle of glasses and applause! They had begun to like him so much, those warm-hearted people, that they forgot to feel any restraint before the ladies and gentlemen from the castle, who had come to see them. They made quite a decent uproar, and one or two motherly women looked tenderly at the little fellow where he stood, with his mother on one side and the Earl on the other, and grew quite moist about the eyes, and said to one another:

“God bless him, the pretty little dear!”

Little Lord Fauntleroy was delighted. He stood and smiled, and made bows, and flushed rosy red with pleasure up to the roots of his bright hair.

“Is it because they like me, Dearest?” he said to his mother. “Is it, Dearest? I’m so glad!”

And then the Earl put his hand on the child’s shoulder and said to him:

“Fauntleroy, say to them that you thank them for their kindness.”

Fauntleroy gave a glance up at him and then at his mother.

LORD FAUNTLEROY MAKES A SPEECH TO THE TENANTS.

“Must I!” he asked just a trifle shyly, and she smiled, and so did Miss Herbert, and they both nodded. And so he made a little step forward, and everybody looked at him—such a beautiful, innocent little fellow he was, too, with his brave trustful face!—and he spoke as loudly as he could, his childish voice ringing out quite clear and strong.

“I’m ever so much obliged to you!” he said, “and—I hope you’ll enjoy my birthday—because I’ve enjoyed it so much—and—I’m very glad I’m going to be an earl—I didn’t think at first I should like it, but now I do—and I love this place so, and I think it is beautiful—and—and—and when I am an earl, I am going to try to be as good as my grandfather.”

And amid the shouts and clamor of applause, he stepped back with a little sigh of relief, and put his hand into the Earl’s and stood close to him, smiling and leaning against his side.

And that would be the very end of my story; but I must add one curious piece of information, which is that Mr. Hobbs became so fascinated with high life and was so reluctant to leave his[890] young friend that he actually sold his corner store in New York, and settled in the English village of Erlesboro, where he opened a shop which was patronized by the Castle and consequently was a great success. And though he and the Earl never became very intimate, if you will believe me, that man Hobbs became in time more aristocratic than his lordship himself, and he read the Court news every morning, and followed all the doings of the House of Lords! And about ten years after, when Dick, who had finished his education and was going to visit his brother in California, asked the good grocer if he did not wish to return to America, he shook his head seriously.

“Not to live there,” he said. “Not to live there; I want to be near him, an’ sort o’ look after him. It’s a good enough country for them that’s young an’ stirrin’—but there’s faults in it. There’s not an auntsister among ’em—nor a earl!”

THE END.

By Susan Hartley.

One bright spring morning, two boys were walking out into the open country, near the little village of Cowes, on the Isle of Wight. Each lad carried under his arm a miniature cutter. It was the day of the great race between the Sea Mew and the Prince Albert, the reputations of which, as winning cruisers, had been earned in many a hard-fought battle on the pond then in sight. A number of boys were already at the shore, and their boats, beating up and down the lake, gave it a very animated appearance. As Ralph and Dick approached, bringing the champion cutters, all the competitors moved to the head of the lake, and soon the signal for the race was given. The Sea Mew and the Prince Albert got off first; then came the smaller boats; while following up the race, some in a skiff and some along shore, the boys shouted and cheered the imaginary skippers of the various crafts, who, it must be confessed, sailed them in a rather curious way. As the Prince Albert rounded the stake on the homestretch, a queer personage came aboard. The boys were allowed to put their crafts about, and Ralph had waded out and was just about to stop his boat, when it came in collision with a floating mass of leaves that threw it up into the wind. From the wrecked leaves nimbly darted the only survivor, a large spider, so alarmed at the catastrophe that it reached the crosstrees of the Prince Albert before it even looked about it.

“The Prince has been boarded by a shipwrecked crew!” shouted Ralph, giving the mast a rap that sent the spider to the topmast-head.

“Let him stay,” said Dick, picking up the leaves that now floated by. “You ran him down, and now you must take him ashore, or we’ll treat you as they did the man in America who was tarred and feathered and carried in a cart.”

So the spider was taken back by the cutter to the starting-point, and it must have brought good luck to the cutter, for the Prince Albert came in ahead and won the “cup,” as the boys called the old-fashioned blue soup-tureen, ornamented with figures of Neptune and dolphins. And within this receptacle the shipwrecked spider was carefully placed after the race was over.

“Here’s his craft!” said Dick. “Let’s put it in some water and see if he’ll take to it again.”

So the “cup” was filled and the layer of leaves thrown in, when the spider, without a moment’s hesitation, leaped into the water from the side of the tureen—or “cup”—and soon clambered upon the leaves, much to the amusement of the young yachtsmen, who had gathered around to see what it would do.

In this manner, Dick and Ralph carried the spider home to Dick’s father, who told the boys, much to their astonishment, that it was a ship-building spider.

“Examine the leaves more closely,” he said. “Don’t you find that the bunch has not been accidentally caught together, but that the leaves have been drawn carefully one over another, and fastened together by silken cords, forming a perfect boat?”

THE SPIDER AND HIS CRAFT.

The boys soon saw that this was indeed the fact, and, much interested, they started out next day, determined to become better acquainted with these nimble little boatmen. They were amply repaid for their trouble; for they had not gone far when Dick cried:

“Here is one, Ralph!” In a little bay, Dick had discovered a small bunch of leaves whirling around and around, and lying closely upon it a large and handsome spider that might easily have been the First Lord of the Admiralty of the Spider-Queen’s navy. Around its brown body was a band, or sash, of rich orange color barred in a curious manner; while a double row of white spots upon the under side, Ralph said,[892] represented its rank. Its legs were a light red—and altogether its outward coloring made up a very fanciful and appropriate uniform.

But I grieve to say that the spider was really a pirate of the boldest and most cruel type. Finding that the circular motion was caused by the peculiar way in which the turned-up tip of a leaf caught the breeze, Ralph gave the craft a start, and away it went before the wind, the red-legged skipper lying low for plunder.

Near the head of the pond several members of the Dolomedes fimbriatus family (for this is their scientific name) were found, and the boys came upon one fellow in the very act of starting out on a voyage.

By lying upon the bank and keeping very still, the lads finally gained possession of many secrets of this cunning ship-builder. At first the spider seemed to be looking for something in the grass near the water’s edge; finally he seized upon a dead leaf, which he dragged down a slight decline, where the boys now saw several other leaves collected. By deft movements of his long legs, the leaf was lifted and tucked in between the others—the builder lashing them together by silken cords which he spun, and fastened them by a simple pressure of his body against the leaf. This leaf being satisfactorily placed, another was brought, and the same process repeated, the creature running rapidly about, passing silken cords over the entire mass, and now and then raising himself up and down, as if testing the strength of his craft. The vessel gradually grew in size until it was an inch and a half thick and four inches across, when it seemed to satisfy its owner.

THE SPIDER BUILDING HIS BOAT.

The spider now ran down to the water several times, returning every time thoroughly to inspect the vessel; finally, taking the craft in his strong mandibles, or jaws, he drew it several inches toward the water. Then, resting for a moment, he took it a second time by the side and drew it fairly to the water’s edge. Once there, he took a last hold, the leafy ship glided clear of the shore, and the gay launcher, leaping aboard with surprising skill, sailed out into the stream.

But the launch was not even yet a success. A spear of grass growing from the water became entangled in the silken cables, and stopped the fairy craft. The spider rushed at the obstruction, seized it in his mandibles, and, to the astonishment of the watchers, walked down it into the water. Soon he re-appeared and again scrambled aboard. But as he now seemed to be greatly agitated and disturbed, the boys here interfered, and cast off the raft for him, whereupon the skipper settled down as if completely satisfied. If they touched him with a blade of grass, he darted into the water and clung to the under side, coming out when[893] the danger was over. Soon an unfortunate fly alighted near the raft, when the pirate, instead of rowing his boat alongside, actually dashed into the water to secure his victim, swimming back to the raft to devour it at his leisure. The last the boys saw of the spider, he had jumped again at something that rippled the water; but he never returned. Possibly a self-satisfied young frog that soon hopped upon the bank could have explained the absence of the skipper of the now deserted craft.

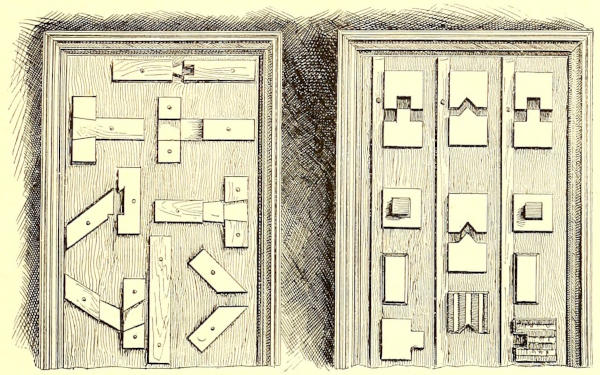

Thoroughly interested, the boys repeatedly watched the spiders, and studied their manners and their labors. They found also another spider, which, although it did not make a raft, had no fear of the water, and frequently went fishing; while Dick’s father told them of still another that lived under water by carrying down bubbles of air with it. Its home, too, might be called a queer diving-bell, as may be seen from the illustration.

THE SPIDER THAT LIVES UNDER WATER.

There are certain ants that show quite as much intelligence as the spider, and the “driver ants” not only build boats, but launch them, too; only, these boats are formed of their own bodies. They are called “drivers,” because of their ferocity. Nothing can stand before the attacks of these little creatures. Large pythons have been killed by them in a single night,[894] while chickens, lizards, and other animals in Western Africa flee from them in terror. To protect themselves from the heat they erect arches under which numerous armies of them pass in safety. Sometimes the arch is made of grass and earth gummed together by some secretion, and again it is formed by the bodies of the larger ants, which hold themselves together by their strong nippers, while the workers pass under them.

THE DRIVER ANTS FORMED INTO A FLOATING BALL.

At certain times of the year, freshets overflow the country inhabited by the “drivers,” and it is then that these ants go to sea. The rain comes suddenly, and the walls of their houses are broken in by the flood, but instead of coming to the surface in scattered hundreds and being swept off to destruction, out of the ruins rises a black ball that rides safely on the water and drifts away. At the first warning of danger, the little creatures rush together, and form a solid ball of ants, the weaker in the center; often this ball is larger than a common base-ball, and in this way they float about until they lodge against some tree, upon the branches of which they are soon safe and sound. And from this resting-place they escape by their curious bridges, a description of which was given in “Jack-in-the-Pulpit,” in St. Nicholas for July, 1881.

THE GREBE AND HER FLOATING NEST.

One would scarcely look for ship-builders among birds, so many of which are boats in themselves, going either upon or under the water; but in the curious family of grebes, one branch of which produces the beautiful feathers so coveted by ladies, there is one kind that forms a nest which is a veritable ark. Instinctively these birds seek the low boggy marshes to build their nests. But there they are in continual danger from the high tides that often cover the marshes, or from the drift-wood which washes in, or from many other accidents. So the ingenious grebe, looking like a[895] clerk with feathery pens behind her ear, constructs a nest that will rise and fall with the tides, and can be moved from place to place. The boat is first built of rushes and grass; this is then packed with moss, and lined and relined until it is perfectly water-tight; and in this the eggs are laid. The home either is anchored to tufts of grass, or drifts, perhaps, here and there, though always guided by the mother-skipper, as she stands by the helm in all kinds of weather. We have seen that the spider is completely at the mercy of the wind, but the grebe propels her boat along. If the young are half grown, they readily take to the water; but if they are just hatched, the mother, at the approach of danger, steps upon one side of the boat, and uses one of her webbed feet as an oar to paddle away from the enemy into one of the innumerable inlets or lanes in the marsh, where she is almost sure to escape.

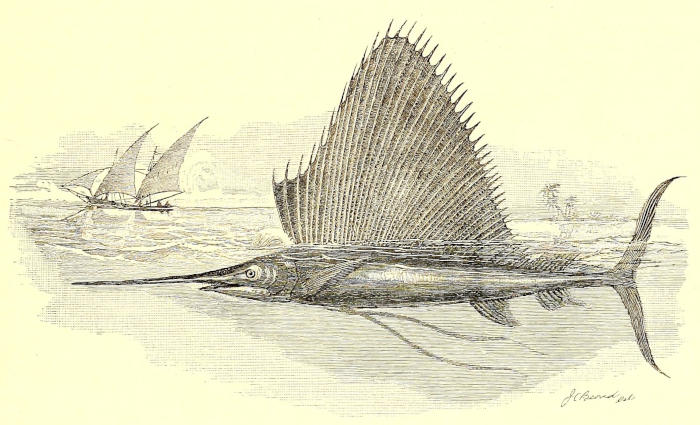

THE SAILOR-FISH OF THE INDIAN OCEAN.

In the warm waters of the Indian Ocean a strange mariner is found that has given rise to many curious tales among the natives of the coast thereabout. They tell of a wonderful sail often seen in the calm seasons preceding the terrible hurricanes that course over those waters. Not a breath then disturbs the water, the sea rises and falls like a vast sheet of glass; suddenly the sail appears, glistening with rich purple and golden hues, and seemingly driven along by a mighty wind. On it comes, quivering and sparkling, as if bedecked with gems, but only to disappear as if by magic. Many travelers had heard with unbelief this strange tale; but one day the phantom craft actually appeared to the crew of an Indian steamer, and as it passed by under the stern of the vessel, the queer “sail” was seen to belong to a gigantic sword-fish, now known as the sailor-fish. The sail was really an enormously developed dorsal fin that was over ten feet high, and was richly colored with blue and iridescent tints; and as the fish swam along on or near the surface of the water, this great fin naturally waved to and fro, so that, from a distance, it could easily be mistaken for a curious sail.

Some of these fishes attain a length of over twenty feet, and have large, crescent-shaped tails and long, sword-like snouts, capable of doing great damage.

In the Mediterranean Sea, a sword-fish is found that also has a high fin, but it does not equal the great sword-fish of the Indian Ocean.

December came and went, and although the girls had agreed to postpone their accustomed giving of gifts to one another until spring, when they hoped to present trophies of the winter’s warfare, the season was otherwise filled with the usual gayety.

Our heroines had not in the least relaxed their interest in the world in general, because of their interest in their own worlds in particular, and had not “cut loose,” as Nan at first had threatened. But, as their lives began to have more of purpose in them, their tastes changed somewhat, so that gradually the most “frothy” of their society friends drifted away unregretted, while new people, whom they had “found out,” as Evelyn phrased it, one by one slipped into the vacant places.

So it was that with less frequent but more spirited contact with society, the winter months flew away, and when the first rays of June sunshine streamed through the glass roof into “Cathy’s kingdom,” the most joyous sight they fell upon was the happy face of the proud mistress, as she went about among the radiant blooms and verdure, cutting her choicest buds for Evelyn’s luncheon, to be given that day in honor of Nan’s return and the reunion of the “jolly four.”

When the girls met in the Ferrises’ dining-room, and surveyed Evelyn’s beautiful table arrangements, they were more than usually jolly, and as that sweet young housekeeper had taken much pride in her festive board, she was deeply gratified by their exclamations of approval.

They pirouetted around and around it, admiring everything, beginning with the artistic lunch-cloth, embroidered by the same fingers which had laid a handful of Cathy’s flowers across each napkin; and they would have proceeded to scrutinize each separate detail, had not Bert seized upon a card bearing her name, attached to a cunning basket, which, in its turn, was tied with a gorgeous bow to one of the chairs. This discovery stimulated research on the part of the others, and immediately each guest was “pouncing,” as Bert said, on her own particular basket.

Nan was the first to investigate the contents. “Bonbons!” she shouted. “What richness! After luncheon, let’s toast these marsh-mallows on the ends of hat-pins over a lamp!—But who is the giver?”

Diving among the sweets for a clew, Cathy succeeded in finding a card which bore the inscription: “From the cook. Warranted pure.”

“You didn’t make ’em, Evelyn?” exclaimed Bert, popping a chocolate-cream into her mouth.

“Yes, I did,” laughed Evelyn, “and it’s as easy!—But see here!” and she held aloft a tawny yellow vase, with a flight of butterflies, in all rich hues, encircling the top.

“Waiting for the flowers with which I hope soon to be able to fill them,” Cathy said, as the girls looked radiantly at her work, and Bert hugged one of Pompeiian red, with dull blue butterflies, while Nan suggested the “divine” effect that scarlet nasturtiums would make with the yellow butterflies and the peacock-blue background of hers.

In the meanwhile, Bert, making further search under the fringe of the table-cloth, brought to view a fascinating cabinet. “With a place for a plaque, a place for a jug, and a place for my jar!” she shouted; while Cathy added, as she lovingly surveyed hers, “Yes, and a place for secrets behind the cunning little door!”

“Don’t, girls!” protested Nan, as they heaped thanks upon her. “You needn’t worry; they are not mahogany, nothing but pine, and a cheap carpenter made them, and I stained and polished them myself, so they cost hardly anything.”

“Oh, now, Nan, if you have been to New York and do up your hair in a new way, you can’t get me to believe that!” said Bert decidedly; while Evelyn asked sarcastically, “And did you also design them, Nannie?”

“Of course! What am I studying for, if I can’t design a simple shelf?” cried her sister.

The girls opened their eyes wide, but Nan averted another avalanche of praise by producing the last article on her chair. She gave a deep sigh of satisfaction as she comprehended that Bert had bestowed upon her a set of photographs of the most famous pictures in the world; while Cathy sat down and gloated over her “Goethe Gallery,” and Evelyn smiled into the faces of her favorite authors.

“I beg pardon, Bert,” said Nan, “for the vulgarity of admiring the setting as much as the gem,—but, girls, will you just observe the magnificence of these Japanese leather portfolios?”

The girls observed with joy, and Evelyn said:

“Considering how smart we have already shown ourselves to be, I venture to inquire, dear Bert, if[897] you took the photographs yourself, or only tanned the leather?”

“Neither,” laughed Bert; “I only earned them with my inky fingers, so they are the first real presents I ever gave! And now let us sit down and admire one another.”

“You would be more sensible to admire my bouillon,” suggested Evelyn, as she ordered in the cups containing the first course.

So the merriment went on, through all the changes of Evelyn’s dainty banquet, while the girls compared notes on their various experiences.

“BERT SEIZED UPON A BASKET TIED TO ONE OF THE CHAIRS.”

“Let us add up, subtract, and get our totals, both financially and spiritually,” said Bert. “Who’ll begin?—Ah, what delicious chicken croquettes these are, Evelyn!—Come, Nan! You are responsible for the whole social and moral revolution, you know; so lead off with your account.”

“Nonsense,” replied that young woman; “if I hadn’t begun it, one of you would have fired our noble hearts,—for we should have died of inanition if we had lolled in the lap of luxury another week. So as you, Bert, scrambled down to the ground first, you should begin the reports. How is your exchequer?”

“Low, very low; but my spirits are not, and what matters it therefore, so long as I’m happy?” answered the confidential clerk. “No, money isn’t everything, for I have a gain far better. I feel genuine; I respect Miss Me; and, best of all, I have found my father. So, Nannie dear, I thank you sincerely, for I never was so happy in my life. So much for my grand total, with a large deficit of ennui.”

There was a general clicking of spoons in the after-dinner coffee-cups by way of applause, as Bert finished; and she at once demanded that Nan should next be heard.

The young artist responded promptly:

“Well, we all are happy, I hope,—because, thank goodness, it is no longer the chief object of our lives to be so;—that is one of the valuable lessons I have learned as I sat, day after day, at table between fat Miss Lee and thin Miss Jennings. I have been dreadfully discouraged at times, but I used to have worse ‘blues’ when I was only trying to amuse myself. I have had a happy winter; and even if I never sell a design (I hope to sell at least one next year), I never shall regret the experiment I have made; for the feeling of self-reliance is better than a bag of gold to your friend Nan!”

“But how about the fun you were bent on having?” mildly inquired Cathy.

“Oh, I’ve had a delightful time! Girls with a purpose are twice as interesting as those without; and as most of us were impecunious, we had numberless gay little three-cent larks. Ha, I can tell you there was no lack of fun!” and Nan laughed at certain merry remembrances. “But now, Cathy,” she resumed, “I pine to know all about that famous greenhouse.”

“Green-houses,” replied the young florist, with dignity. “All flowers can’t grow in the same temperature, my dear.”

“Oh,—I want to know!” drawled Nan. “But are you dreadfully in debt? And do things really sprout?”

“Sprout!” exclaimed Evelyn. “You would think so, Nan, if you had seen the big basket of yellow pansies she sent to old Mrs. Burk on the anniversary of her wedding-day! But Cathy will never roll in wealth; she gives all her flowers away. She ought to hang out a sign with the words ‘Flower Mission’ on it.” And Evelyn gave her friend a loving glance.

“Never mind,” retorted Cathy, blushing a little. “Our crusade was not so much to earn money as for the right to be happy, each in her own way; and since I have repaid what Fred loaned me, I can give away my very own things if I wish to, especially as they are usually in the good company of jellies and other lovely delicacies from Evelyn’s larder,” she added. “But don’t be disturbed, my dears, about my generosity; I shall charge you opulent creatures a good round dollar for every bud you get of me.—And now, Evelyn, it’s your turn; but your luncheon has been more eloquent than words——”

“No, no!” broke in Nan, with sudden mournfulness; “Evelyn has been an egregious failure, so far as her family is concerned; she has struck for higher wages——”

But a look from her sister warned Nan not to go further, while Cathy burst out:

“Oh, Evelyn, let me tell!”

“No,” she said, with an odd expression of mingled pride and timidity on her face. “I will tell it myself; why shouldn’t I? Besides, all but Bert know of it already, and I’m sure she suspects.”

“Are you really?” wildly demanded Bert, inconsequently except to the feminine mind.

“Yes, really!” answered Evelyn with shining eyes and flushed cheeks, while Nan groaned:

“Oh, Bert, woe is me! To think that I aided and abetted in this miserable business by encouraging Cathy to become independent, and so allowed her brother Fred to engage my sister for a wife!”

“You gave me a sister!” cried Cathy, as she tipped over her chair in an excited rush at Evelyn, whom she clasped in her arms, crying a little for joy, although her brother had partly prepared her for the glad news,—while Bert exclaimed heartily:

“You have my blessing, Evelyn dear!—And are there any more secrets to be divulged? Nan, you are in the designing business. Is there any decorative youth in view?”

“Not for me!” laughed Nan. “But, Bert, where has all your money gone? I expected you to ask me to accompany you and some delightful chaperon to Europe this summer, at your expense.”

“Oh, I frittered my funds away!” she cried. “Come, come; let us toast the marsh-mallows. Light the droplight, Evelyn. Where are the hat-pins?”

“Now, Bert,” said Evelyn, seriously, “I have found out your secret, and I’m going to tell——” But Bert had escaped and was flying upstairs, while Evelyn continued: “She has given a library to the working-girls’ association, and all that the world knows is that it came from ‘a girl who is thankful to have found out how much better work is than idleness.’ That’s what Bert has done with her money!”

THE END.

By Bessie Chandler.

The Fair Rosamond, sloop yacht, N. Y. Y. C., lay at anchor off the east shore of Cape Cod Bay, her polished brasswork and white hull glittering like gold and silver in the morning sunlight. No one was visible on board, forward or aft, until presently a youthful form showed itself above the cabin hatch, halting there a moment to survey the scene, and then stepping forth in full view upon the deck. This was Jasper. The noticeable things about Jasper were his homely, freckled face, his slim, ungainly figure, and his intensely solemn air. One would have thought, to look at him, that he was the most sober person in the world, whereas, in point of fact, he was never known to be serious two minutes at a time, and was forever making fun. He stood there for several moments, his hands in the pockets of his yachting jacket, yawning lazily and looking forward along the deck.

“Well,” he at length observed, “this is a hilarious state of things, I must say! I wonder when those men are coming?” Suddenly he assumed an attitude of declamation, and, raising his head and throwing out his right hand by way of gesture, he exclaimed:

These lines, not altogether inappropriate so far as they went, were interrupted here by some one coming up softly from behind and seizing the speaker by the collar. He quickly freed himself, however, and turning about, with hand still extended, finished his verse in good order:

Captain Fred laughed.

“So here you are,” said he, “come up like a whale to spout.”

“A very good joke, my dear brother,” replied Jasper. “I’ll tell you a better, though.”

“What’s that?” asked Captain Fred.

“Your merry men have not appeared yet.”

“What!” exclaimed the captain, scowling and looking forward.

Owing to a serious disagreement between the yacht’s foremast hands, Captain Fred had summarily discharged them all, and sent his sailing-master to Provincetown to pick up a new crew. It was now the third day that he had been absent on this errand; and Captain Fred had counted upon his arrival, with the four sailor men, by an early train that morning. “This is dreadfully annoying!” he declared.

Jasper began quoting again.

Jasper had a talent for quotations, as the reader will presently perceive. But again he was cut off by an arrival on deck, this time that of three young ladies and a small boy. These were Captain Fred’s pretty young wife, his niece Ethel, her intimate friend Kitty, and little Fred,—the last sometimes known as Frederick the Little, as distinguished from his uncle, Captain Frederick the Great. The girls looked wonderfully fresh and pretty, considering they had just made their toilet in a seven by nine state-room. Kitty was Ethel’s school friend, and had only been with them a few days. She was a bright, vivacious young person, however, and had already made herself quite at home on board. It was she who spoke up now.

“What is the matter, Captain Fred?” cried she. “Are the tea-kettle halliards foul again, this morning?” This was in allusion to a joke of Jasper’s, the first morning she had been on board.

“The matter is,” said Captain Fred, looking as pleasant as he could, “that our crew has[900] not yet arrived; and we may have to lie here a day or two longer.”

At breakfast, Captain Fred announced that he was going ashore. Something must be done at once about a crew. He should run down to Provincetown himself, and should not return until the afternoon at the earliest. Meanwhile, they must get along as best they could. The yacht was in a perfectly safe position; the steward (the only man left on board) was an entirely competent and trustworthy person; and the sailing-master himself would be back, without fail, before night. “And since I am without a crew,” Captain Fred concluded, “I think that you young people will have to man my gig for me.”

ON BOARD THE YACHT, “FAIR ROSAMOND.”

This proposal was agreed to, willingly enough; and a few minutes later, the gig being brought alongside, Jasper called “Giglers away!” and they all got in, Ethel and Kitty at the oars (they were accustomed to rowing together), Freddy in the bow, and Captain Fred and Jasper in the stern-sheets. Mrs. Fred preferred to remain on board and read. They pulled directly inshore. The village and railroad station were some distance below, but much nearer by land than by water. “Good-bye, all!” said Captain Fred as he jumped ashore. “Take good care of yourselves. And, Jasper, do try to behave yourself for one day.” Then he waved his “gripsack” and was gone.

They rowed along, not caring to land,—for the shore everywhere had the genuine Cape aspect, barren and unattractive,—but finding it pleasure enough to float upon the bosom of the sparkling blue water, now drifting idly, now pulling themselves here and there as the fancy seized them. They chatted and laughed and shouted, growing even boisterous by and by, Freddy and the two girls getting into a regular romp at last in the forward part of the boat. Jasper (who was not strong) sat looking down upon this with an air of elderly indulgence. It was one of Jasper’s delights to give himself patriarchal airs. Although just Ethel’s age, sixteen, he was, like Captain Fred, uncle to both her and Freddy,—a relationship which had, by courtesy, been extended to Kitty during her stay with them, though that young lady had professed herself quite indifferent to the honor,—and he loved to talk of his “avuncular responsibilities.”

“Ah, children,” he now declared, “it does your poor old uncle good to see you enjoying yourselves in this way.

“Jasper,” asked Kitty, flushed with exercise and suddenly resting on her oar, “can you sing?”

“Sing!” Jasper looked at her as though he thought her crazy. “My dear niece, what can you be thinking of? I could no more sing than I could—raise a pair of side-whiskers.” He gave his cheek a melancholy tap.

“Oh, yes, you can!” said Kitty. “You can sing something,—can’t you? Some old song or other.”

“Some old song?” Jasper shook his head. “No,” said he,

“Pshaw!” cried Kitty, who evidently had some object in view. “I am sure you can sing something,—and you must. Don’t you know ‘Hail Columbia,’ or ‘Home, Sweet Home,’ or ‘Bonnie Doon’?”

“I know ‘Old Grimes,’” said Jasper.

“‘Old Grimes’? Well let me hear it.”

So Jasper began to sing, to a tolerably correct air but in a voice which was far from musical, the song “Old Grimes is Dead.” He grew somewhat in love with his own performance as he proceeded, and gave the “old gray coat” such a thorough “buttoning down before” in the chorus, that Kitty grew impatient.

“Why, to be sure!” she interrupted. “That air is the same as ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ and will do perfectly.” Then she turned to Freddy: “Now, Freddy, what can you sing?”

“Oh, I say,” protested Jasper, “you’re not going to make Freddy exhibit himself, too?

Kitty inexorably repeated her question; and Freddy, showing no disposition to plead his tender years as an excuse, declared that he could sing “’Way down upon the Suwanee River,” and he freely opened his mouth and delivered himself of a verse of the song indicated, in proof of his assertion.

“That will do capitally,” pronounced Miss Kitty. “And, Ethel, you can take ‘Ben Bolt,’ say, and I will take ‘Home, Sweet Home.’ The simpler and more familiar the tunes the better. And now I’ll tell you what I wish you to do. It’s ever so much fun! We tried it one day, up at Lenox, and we got into a perfect gale over it. It’s just this: Whatever any one of us has to say, no matter what it is and without any exception, we must sing it instead of saying it, every one using the tune assigned him or her. Do you understand?

She calmly illustrated her meaning to the tune of “Home, Sweet Home.”

“Of course,” she added, “it’s perfectly ridiculous. But that’s the fun of it, you know.”

They all fell in with the scheme at once, though Jasper proposed to improve it a little.

“Wouldn’t it be well,” he suggested, “to prescribe some penalty or forfeit in case anybody forgets, and talks instead of singing? Suppose, for instance, we agree, each of us, to pay ten cents every time we break the rule, all money so obtained to be devoted to some charitable object.”

“I consent to that,” said Ethel, quite approving.

“And I, too!” cried Kitty. “It will make us all the more particular.”

“Well, then, I don’t!” shouted Freddy, rising up, very red in the face. “It’s all very well for you people who have allowances. But I’m not as rich as the Pennsylvania Railroad Company myself.”

“Well, youngster,” said Jasper, “we’ll only charge you five cents when you break over.”

To this Freddy assented.

“And, of course,” Jasper continued, “we’ll have to make the agreement for a certain length of time—two hours, say. Will that do? Very well,”—looking at his watch,—“it is distinctly understood then that from this moment—it is now half-past eleven—for two whole hours we shall sing everything we have to say, every one to the tune agreed on, and that we shall pay the sum of ten cents for every violation of this rule,—with the exception of Freddy, who is to pay five cents.—Each, upon honor, agrees to this solemn compact.”

He looked about, and all gravely nodded assent.

“All right,” said Jasper. Then, to the familiar strains of “Auld Acquaintance,” without the slightest hesitation he sang these lines, giving his words the proper rhyme and rhythm almost unconsciously:

Four young people, full of frolic, found it easy to laugh at this, as well as at a number of similar outbursts on the part of the others, equally ridiculous if somewhat less elaborate. And the fun went on for some minutes. Nevertheless, it must be confessed that Miss Kitty’s plan, promising as it had seemed, did not turn out quite so well as she had expected. Admirably adapted, as no doubt it was, to a picnic party, where all sorts of people would be constantly moved to say all sorts of things, it was found not to work at all well among four persons of about the same age, in an[902] open boat, where there was no especial necessity for saying anything. Somehow or other, after a little, the singing began to grow less funny, and presently everybody appeared to have discovered that it was easier to keep still than to express one’s self, and so a grim silence fell upon the boat. Freddy played with the water alongside; the girls bent to their oars; and Jasper attended to his steering. And, bound as they were by their absurd agreement, it is to be feared that the crew of the gig would have had a dreary time of it for the next two hours, but for an idea that suddenly suggested itself to Jasper’s fertile mind.

All at once the coxswain gave the helm a turn; and then the boat’s keel was heard grating softly upon the sand. The others looked around in surprise. The boat was close inshore, and the next moment it brought up with a gentle bump against the bank. A short distance away a railroad crossing could be seen, and, just beyond it, a red house. Jasper rose to his feet, and sang:

“I’m ready, for one,” cried Freddy, jumping ashore at once, painter in hand.

“Ahem!” uttered Jasper loudly.

And Master Frederick, looking up, found a finger warningly pointed in his direction, and realized that he had broken the rule. Jasper solemnly took out his note-book and made an entry. Next he leaped ashore himself and stood waiting to help the girls, who, after a moment’s hesitation, also stepped ashore. Then, the boat being made fast to a convenient post, they all started leisurely up the bank.

They soon came to a road which led them directly across the railroad and toward the red house. This house was a small, one-story cottage, very humble, but with the thrifty Cape Cod look, having a bright garden in front and a neat walk, bordered with curious shells, running down to the gate. Jasper, catching sight of a well near the side door, was about to make an excuse for turning in, when Kitty forestalled him.

“Oh,” sang she, her spirits already revived by the change from sea to shore, “Be it ever so humble, I must have some water.”

They went in, therefore, and Jasper was about to let down the bucket, which worked by some modern arrangement, when a woman came running out with a glass.

“Here, here!” she cried shrilly. “We don’t ’low strangers to meddle with that well! I’ll draw it for you, if you please.” And she put Jasper one side, carefully letting down the bucket, and then breathlessly drawing it up. “You gave me quite a turn, I declare!” she observed as she handed Ethel the glass. “I thought you were that sewin’-machine man when I first heard ye. He said he sh’d come to-day.”

She eyed them curiously. She was a spare, energetic-looking woman, with a pinched face and small bright eyes. She seemed rather puzzled when no one spoke, though the two girls and Freddy bowed their thanks profusely as they finished drinking. Her bewilderment may well have grown to wonder as she beheld Jasper, with one hand still extended after handing back the glass and the other laid dramatically upon his heart, open his mouth and begin to sing, to the air of “Auld Lang Syne,” familiar in Cape Cod homes as everywhere else in the world,

The combined exigencies of the tune and the effort to adapt the quotation to it, left the singer, attitude and all, hanging, so to speak, at the end of a high note; and the effect was supremely ludicrous. Jasper’s comrades could not restrain their laughter.

The woman regarded him for an instant with a look of amazement; but people on the Cape have a way of keeping their feelings to themselves, and she quickly recovered her self-possession.

“Humph!” said she, glancing keenly from Jasper to the rest. “Where do you folks come from, anyway?”

“We came,” Jasper answered, still true to “Auld Acquaintance,”

He broke a little on the last line and finished rather lamely.

“Humph!” the woman dryly repeated. “You’ve come to a dangerous place, then. P’r’aps you may not be aware that ’twas only right down here a bit that Cap’n Cook was killed.”

Here Kitty, delighted to see her scheme displaying at last some of the qualities she had claimed for it, took it upon herself to answer, clasping her hands in horror at the announcement made:

Her rhythm was not quite as smooth as Jasper’s; but she was true to her air, and the rhyme at the end fairly surprised herself.

“Well,” the woman answered seriously, “we gen’rally call it the Cape. Though they do say,” she added, “that they’re tryin’ hard to make an island of it, up to Sandwich.” This was a reference, no doubt, to the famous Cape Cod Canal. Then, still looking her visitors over and trying to make them out, “Do they all sing their words,” she inquired, “in the country you come from?”

Kitty was about to reply again; but at this instant a diversion occurred. Master Freddy, moved to exploration on his own account, had strayed away to the kitchen door, and, peeping within it, his eye had fallen upon a huge dish, full of freshly made crullers, resting upon the table. Utterly ravished by the sight, he had given vent to a prolonged “Oh!” and then, mindful of forfeits, but quite compelled to utter himself, he, too, began to sing, and the well worn notes of the “Suwanee River” rose rapturously to the breeze:

“Sakes alive!” exclaimed the woman, looking around. “That reminds me. There’re my crullers all this time. I must run. Come in, won’t ye? Come in an’ try ’em.”

Ethel being the only one inclined to hold back, and she being of a yielding nature, they all followed the woman indoors, and were ushered presently into a little sitting-room next the kitchen. It was a poorly furnished, but neat and pleasant apartment, with snow-white curtains, worn haircloth furniture, and a parlor organ, and with a sewing machine in one corner. Freddy came in after the rest, a huge ring of a cruller firmly grasped in one hand, and another of more elongated proportions thrust deeply down his throat. The woman followed immediately with the dish, and her cordially repeated invitation to “try ’em” was gladly accepted. Jasper possessed himself of a magnificent specimen, and loudly sang the praises of itself and donor, pleasing himself immensely by an ingenious combination of “try ’em” and “fry ’em.” Ethel glanced at him reproachfully, feeling a pang of shame that he should persist in his joking in the face of this kindly hospitality. But Jasper was not to be stopped at such a time. Nor did Kitty seem disposed to be prudent. She was, as she herself might have expressed it, gradually working up to “concert pitch”; and she and Jasper, evidently, were having a much better time with their singing than they had while they were in the boat. Kitty also sought to celebrate in song the virtues of the crullers, even venturing upon a little parody wherein “sweet crullers” was substituted for “sweet home,” and “crumble” for “humble,” which, absolutely nonsensical as it may have been, caused Jasper to go off in fits of laughter and clap his hand upon his knee and cry “capital!” in utter violation of his vow. And then Freddy sang, too, and even Ethel sang; and they all got to laughing harder and harder, with that absurd, unreasonable laughter that laughs at almost anything, and that the more it laughs, the more it will laugh, until by and by it grows to be quite uncontrollable. All of which, the writer is aware, was exceedingly silly and ridiculous on the part of these young people whom he has introduced to the reader; but he begs the latter to remember that they were only boys and girls after all, and that they were really a little beside themselves that morning, and that, at any rate, no single one of them meant a particle of real harm by it. The only person who preserved her countenance was their hostess. That problem of a woman went in and out among them, never so much as smiling at anything that was said or done, watching them closely with her small, sharp eyes, always seeming to be “making them out,” but letting no sign of any conclusion to which she might have come find its way into her face.

At length Ethel, thinking to quiet things, glanced toward the organ and asked respectfully (though to music, of course) if she might “try the instrument.”

“Oh!” replied the woman, following Edith’s glance, and with an odd, scared look coming into her face as she did so, “I couldn’t let ye touch that, Miss; indeed, I couldn’t. Why, ’taint mine, yet; an’ I don’t know now as ’t ever will be.” Then she interrupted herself with an air of deep chagrin. “Why, you mean the melodyun, don’t ye? I thought all the while you meant the sewin’-machine. How stupid! Seem’s if I can’t think o’ anythin’ lately but that sewing-machine. It’s nigh worritted my life out. You see, I bought it last winter of an agent, an’ agreed to pay ten dollars a month for it till ’twas paid for. But, somehow or ruther, Silas hasn’t earned anythin’ to speak of, sence he came back from Georges Banks, an’ things ha’ gone hard; an’ now the time is up, an’ there’s twenty-seven dollars still due. I’ve scraped up twenty, here and there, but I’m lackin’ seven, yet. The man’s comin’ to-day to take the machine, an’ I’ve got to lose all I’ve paid him. That was the bargain. But,”—she hesitated and her thin lip quivered,—“I vow it’s too bad! An’ I don’t believe the law would allow it.”

At this instant, as it happened, a step and a heavy rap were heard at the outer door. The woman started.

“There he is now!” she exclaimed. “I know his knock’s well ’s I do the minister’s or the doctor’s. ’Xcuse me a minute.” And, with lips shut tight, she left the room. Then the occupants of the sitting-room heard a man’s voice roughly explaining that he could not take the machine to-day, but that he should be along again to-morrow and should certainly take it then if the money was not ready. The woman seemed to have very little to say in reply; and presently, having dismissed her unwelcome caller, she came back into the sitting-room.

“About that melodyun, Miss,” she resumed at once with an absent air; “you’d be welcome to play on it, but Salome’s gone over to Hyannis for a visit, an’ she accidentally took the key off with her in her rettycule. Salome’s my daughter,” she added, with a touch of motherly pride. “She’s took lessons. If she was here, she’d play for ye!”

What a mischievous spirit it was that prompted Kitty to break forth, in accents as tenderly regretful as any ever attained in the singing of “Sweet Home” itself!—

She wondered herself, the next moment, what had possessed her, realizing that in thus turning the absent daughter’s name to ridicule, she was doing a distinctly rude and unkind thing. She started up, sincerely meaning to apologize. But the woman had turned away, seeming not to have noticed it; and Kitty sank back in her chair again.

The woman had noticed, however, and there was a faint flush on her cheek and a resentful glitter in her eye as she stood at the table, pretending to look for something in her work-basket, and for several moments speaking not a word. Suddenly, with an air of decision, she turned and walked straight out to the kitchen, going to a back door that was there and opening it. Then they heard her calling somebody in her shrill, far-reaching voice:

“Silas! Si—las! Silas!”

Silas—whom all understood to be the woman’s husband—must have been close at hand, for almost immediately a man’s voice sounded without, and then the two were heard talking together in low tones inside the kitchen. The next moment they appeared at the sitting-room door.

The woman, when they entered the room, was preparing to throw a shawl about her shoulders. But nobody, at that moment, thought very much about her. Her visitors were too much struck by the appearance of the remarkable individual who attended her. He was a man of immense physical proportions, more than six feet high, and correspondingly broad. His short, stubby hair was of a dull red color, as were also the thick, wiry whiskers that covered his face. His skin, where it could be seen, was deeply burned. One of his eyes was closed and sightless. He was dressed in a big green baize jacket, oil trousers, and “fish boots.” In his hand he carried a short, heavy clam hoe. Altogether he was a formidable-looking person. The two girls uttered a little cry of dismay when they saw him; Jasper himself looked troubled, and Freddy fixed upon him a look of fascinated horror. Freddy was thoroughly familiar with the story of Polyphemus (Jasper had told it to him many times), and his one thought now was that that awful monster stood before him.

“Silas,” said the woman sharply, turning toward him as she pinned her shawl, “here’s some people. I don’t know who they air, nor where they come from; but I do know that they’re stark, starin’ crazy, every one of ’em. They can’t do anythin’ but sing an’ laugh. I’m afraid of ’em; an’ I’m goin’ to run down to Squire Baker’s an’ have him send up a constable, an’ have ’em taken care of. They ought to be put in the mad-house. I want you to stay here an’ keep guard over ’em till I come back.”

And with that, before Jasper and the rest had at all grasped the meaning of her words or comprehended her intention, she was gone.

The giant, who was left behind, reached over to draw to him a large rocking-chair that stood near by and sat down before the door, not saying a word. Freddy felt quite certain now that he was Polyphemus—Polyphemus, with his terrible single eye, sitting at the door of his cave and keeping guard over Ulysses and his band. As for the rest, they knew not what to do or say. What did it all mean? What strange people these they had come among,—the woman who took them for lunatics, and that grim creature at the door? Could the woman really have believed them crazy? She had said so. And her manner from the first, as they now recalled it, suspicious and uneasy, seemed to say so too. And, indeed, it was hardly to be wondered at, considering their absurd actions. What then would come of it? Would the constable, when he came, think they were crazy too?—and the magistrate? Cape Cod people, they had always heard, were queer people. The situation seemed really serious. They looked at each other soberly, not speaking yet, but all thinking some such thoughts as these.

But Jasper, as the man of the party, felt that it behooved him to do something at once. He got up from his chair and advanced, with as determined a bearing as he could assume, in the direction of their keeper. Ethel turned pale.

“Oh, Jasper!” she murmured. “What are you going to do? Please don’t go near him.”

“No,” Kitty whispered, equally alarmed; “pray don’t. Let us wait quietly till the constable comes. It will be all right then.” No one of them thought any longer of maintaining their agreement as to singing, which, indeed, had been quite driven out of their minds.

“Pooh!” answered Jasper with lofty valor, “I’m only going to request our monumental friend here to move one side a little so that we can pass out. It’s time we were going.” Then, as the person alluded to paid no attention, he addressed him directly. “If you please, my friend, we’d like to pass out.”

“‘I WANT YOU TO KEEP GUARD OVER ’EM TILL I COME BACK,’ SAID THE WOMAN.”

The other shook his head,—calmly and quietly enough. It was not anything the man did, nor indeed anything he said, when he came to speak, that was so terrible, after all; it was simply his forbidding face and his gigantic figure.

“I’m very sorry,” said he in a voice so deep and sepulchral one might well have fancied it was supplied to him somehow from the cellar below, “very sorry indeed. But the fact is ye can’t be allowed to go,—not till Malviny comes back.”

“Look here, now,” observed Jasper, straightening up and trying to look terrible himself.

“Wall, I’m lookin’ here.” The man calmly regarded him with his single eye.

“Do you know who we are?” Jasper continued.

The giant shook his head again. “Hevn’t the slightest idee. Couldn’t no more say who ye air ’n I could say who’ll be keepin’ Highland Light in the year nineteen hundred ’n eighty-six. Malviny says ye’re a passel o’ crazytics, an’ that’s all I want to know about ye. I never go behind what Malviny says. She’ll be back with the cunstable presently, an’ they’ll settle your case. Meanwhile, here you’ll hev to stay till they come.”

He leaned back in his chair and began rocking to and fro, resting his clam hoe across his knees.

“But see here,” persisted Jasper; “that is all nonsense, you know, about our being crazy. We——”

“Hi! hi!” interrupted the giant, stopping his chair. “What’s that ye say? Be keerful, young man. Be keerful!” He lifted his ponderous fore-finger and slowly waved it back and forth with an air of solemn warning. “Don’t you ventur’ fur to dare fur to assertify that anything Malviny says is nonsense! She allus knows what she’s talkin’ about. If she says you’re crazy, crazy you be,—an’ ye can’t help yourselves.”

“But I say——” poor Jasper once again began.

“Now, be keerful, young man. Be keerful!” The awful finger again cleft the air.

“Oh!” cried Jasper, stamping his foot in impotent rage. “This is intolerable! You’ve not a particle of right to keep us here. Move one side, I say, and let us pass.”

He advanced a step and threateningly confronted his enemy.

But the latter remained perfectly unmoved, save that again he gravely shook his head.

“Not till Malviny comes,” was his imperturbable answer. “Not till Malviny comes.”

And Jasper, brave as any lad, but well aware in his heart that he would no more think of actually attacking that gigantic adversary than of throwing himself upon an advancing locomotive, yielded to the renewed entreaties of Ethel and Kitty, and sullenly returned to his seat.

Then for many minutes—just how many, no one knew—there was perfect silence in the house,—or silence the perfection of which was only marred by the ticking of the little Waterbury clock on the kitchen mantel. The prisoners sat there in a dazed, despairing sort of mood, their eyes most of the time bent upon the floor, content to wait without further motion the issue of events.

All at once, from the watcher’s direction, there came a sound, loud, clear, sonorous, unmistakable—the sound of a human snore. They all looked up surprised, and a single glance at the mammoth form in the doorway assured them of the fact which the sound had intimated. Their keeper slept.

Jasper, with a swift gesture of caution to his comrades, sat and watched the sleeper for a moment, to be sure that it was so; then he rose to his feet. The time for action had undoubtedly arrived. He glanced about the room, marking its ways of egress. The windows were open, but not far enough, and it would not do to risk the noise of opening them farther. There were four doors in the room, besides that leading to the kitchen, all closed. Jasper passed three of these by as admitting without doubt to bedrooms or cupboards, and turned to the fourth. This opened, as he had expected, into a little front hall; and there, right at hand, was the outer door. Jasper’s heart sank as he saw that the key was gone; but he tried the door, and lo! to his surprise, it was not locked at all. Here then was freedom at last, in their very grasp! “Come! Come!” he whispered, beckoning eagerly to his companions. And then, like a captain who must be last to quit the wreck, he stood holding open the door for the others to pass through.

Freddy came first, painfully tiptoeing his way, and scarcely able even now to remove his glance from the fearful being across the room. Then Kitty glided out and Ethel followed, and the three stood safely outside. Jasper lingered a moment, latch in hand, glancing back at the grim sentinel in the rocking-chair. The man still sat there, his head thrown back and his dreadful eye fast closed, wrapped apparently in profoundest slumber. Jasper felt all his old assurance coming back. He kissed his hand to the sleeper.

“Good-bye, my dear guardian, good-bye!” he cried, half aloud.

But what meant that movement on the part of the sleeper? Jasper stared. The huge frame was certainly shaking in its chair. Could it be that the man was laughing in his sleep? The lad did not stop to ponder the question, but closed the door behind him and hurried after the rest.

At the crossing, they came suddenly upon Mrs. Malviny. Jasper made her a bow.

“May I ask,” he inquired, “if you saw Squire Baker?”

“Yes,” answered she gloomily; “I saw him. He says it’s no use. Unless I pay the money, the man can take the machine. I can’t—But sho! There I am again. You mean did I see him about the constable? Well, no; I didn’t.” She looked at them now with a humorous twinkle in her eye. “The fact is, that was one o’ my jokes. You seemed to be havin’ a good deal o’ fun at my expense, up to the house, an’ so I thought I’d have a little at yours. I hope ye didn’t have any trouble with Silas. He’s the best-natered man in the world,—wouldn’t harm a toad-fish. If he would, I’d set him after that sewin’-machine man! There’s Silas at the front gate now! What’s he laughin’ at, I wonder? Well, good-day! If anybody in your country asks after us Cape folks, you tell ’em we aint all fools down here. We don’t live on fish for nothin’.”

“Well!” uttered Jasper, gazing after her a moment with an air of profound admiration, and then looking down at himself in equally deep disgust. “If we haven’t been most beautifully and artistically circumvented this time, I should like to know the reason why! I feel as cheap as an eighty-cent dollar.”

“We certainly have had a good fright!” declared Kitty.

“It seems to me,” observed Ethel seriously, “that this ought to be a lesson to us not to turn everything and everybody to ridicule quite so freely in the future.”

“Yes,” cried Freddy. “And how about all that money you three will have to pay for talking all this while, instead of singing?”

“Sure enough!” said Kitty.

“I’ll tell you what we’ll do,” suggested Ethel. “We will let ourselves off, once for all, for seven dollars; and we’ll make up that sum and send it to Mrs. Malviny to complete the twenty-seven dollars she owes her sewing-machine man.”

“Done!” shouted Jasper with enthusiasm.

And done it was, that very night.

Of all the sharp-toothed and vindictive little animals that prey upon their comrades and sometimes do service for man, none is sharper or more vindictive than the weasel—a bright-eyed little beast, with a coat of golden-brown fur and a clean white shirt-front. It somewhat resembles the rat, and also the squirrel; but it is, really, the deadly enemy of both.

And of all the hateful reptiles that crawl and coil and sting, there are few more venomous and hateful than is the little olive-brown snake known as the adder—a rattlesnake without rattles, and the untiring foe to mice and birds and moles, thus also occasionally proving of service to man.

Both the weasel, which belongs to the family known as the mustelidæ, or mouse-eaters, and the adder, which belongs to the viperidæ, or viper family, are, as you see, agreed upon one thing—a liking for mice for dinner. And they are just as heartily united upon another subject—their hatred of each other.

So when, as in the above picture, weasel and adder meet in the way, there is certain to be a duel to the death.

The weasel is a spry and fiery-tempered little animal; the adder is treacherous and equally hot-headed. And although, as the rule, the weasel is worsted in such encounters, sometimes the coils of the adder squirm and droop and stiffen as, with one quick snap, the sharp teeth of the weasel seize and break the mottled neck of the snake.