Title: In the hollow of His hand

Author: Hesba Stretton

Illustrator: Walter Jenks Morgan

Release date: July 31, 2025 [eBook #76597]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Religious Tract Society, 1897

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

HE LAID HIS HAND ON HER HEART.

BY

HESBA STRETTON

AUTHOR OF

"JESSICA'S FIRST PRAYER," "ALONE IN LONDON,"

"BEDE'S CHARITY," ETC., ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

PREFACE

THE most extraordinary and inexplicable phase of Christianity is the

persecution of Christians by Christians. Persecution is absolutely

opposed to the nature and teaching of the Lord, who said to His

disciples, when they desired to call down fire from heaven on the

Samaritans who refused them hospitality, "Ye know not what manner of

spirit ye are of. For the Son of Man is not come to destroy men's

lives, but to save them."

In my former story, "The Highway of Sorrow," I attempted to set forth

the religious principles of the Stundist men, and their steadfast

courage in maintaining them. I have received a letter from Russia

saying that this narrative "is true to fact." "In the Hollow of His

Hand" endeavours to show the bitter sufferings of women and children in

the storm of persecution now raging in Russia. The latest suggestion

made for the complete stamping out of Stundism is that all children

should be taken from their Stundist parents and brought up in the

Orthodox Church. When this was done, in the Middle Ages, to the Jews

in Spain, many parents adopted the awful alternative of slaying their

children.

In writing both stories I have drawn largely from two sources. One

is a pamphlet, called "The Stundists: the Story of a Great Religious

Revolt," published in 1893 by James Clarke & Co. The other is a most

valuable work, entitled "Siberia and the Exile System," by George

Kennan, from whose volumes I have drawn many of the details of the

protracted journey to Eastern Siberia. Both of these stories are

sorrowful, but they are true. And I would earnestly ask my readers to

ponder over the words of our Lord, "Blessed are ye, when men shall

revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against

you falsely, for My sake. 'Rejoice,' and be 'exceeding glad:' for great

is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which

were before you."

This blessing the Stundists realise.

HESBA STRETTON.

1897.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

XXIV. THE EXILES' BEGGING SONG

XXVIII. THE SEED OF THE CHURCH

IN THE HOLLOW OF HIS HAND

THE SCOTCH COVENANTERS

"BEHOLD, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves."

The boy who was reading in a clear, low voice, though with a foreign accent, felt the pressure of his mother's feeble hands, and lifted up his eyes to her white and placid face. He was kneeling beside her bed, and she pushed back the thick curls of his brown hair, and looked with a very tender gaze into his frank, boyish face.

"That's true, my laddie," she said; "true for you, but not for me. He calls me home, but He sends your father and you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves. Ah! The Lord Jesus knew; and He knows now. Never think He's away, and not minding your troubles. You'll go back to your father, when I'm gone home—not to Knishi, never again to Knishi. Oh, if I'd only known, I'd have gone home to heaven from there!"

The feeble, gasping voice ceased for a minute or two. But the mother's eyes still rested fondly and anxiously on her boy.

"And, oh, my Michael," she said, "be wise! Don't anger the neighbours more than you can help. You're only a boy yet, and they'll leave you alone if you keep quiet. Be 'harmless as doves,' says our Lord."

"But you wouldn't have me a coward, mother," answered the boy somewhat hotly.

"Me, Michael? Me?" she cried, a faint colour flushing her pallid face. "No, no! Weren't my ain forebears among the Covenanters? Both on father's and mother's sides! Didn't they suffer the loss o' all things—eh! and die for conscience' sake? Nay, Michael, I'd send you to death, if need be, for the truth. But it's hard to think of young little ones having to suffer cruelly because their parents must act according to their conscience. Oh, my Michael! And my little Velia!"

She sank back on her pillows with closed eyelids, through which the tears were slowing oozing. Michael did not go on with his reading. They were both thinking of the last twelve months, when Catherine Ivanoff had left her Russian home to try if her native air in Scotland would restore her health. Michael had accompanied her, being old enough to be a help and comfort to her during the long voyage from Odessa to Glasgow, and through her sojourn among her own kinsfolk. It had been on the whole a happy year, filled at first with delusive hopes. But all hope was gone now. She would never be able to bear the voyage and the inland journey homewards.

Her brother's house, where she lay dying, was a small Scotch farm, not unlike the homestead she had left in Russia. She lay still, thinking longingly of it now. The thick walls of dried mud, with their deep window-sills; the large house-place, with its oak table, and oak benches standing along the walls, which she had kept beautifully polished; the huge stove, which seemed to fill half the room; and the great barns and stables built round the fold-yard. Oh, if she had only been there now!—dying in the little bedroom which opened out of the roomy house-place, where she could watch her husband going to and fro, and have her little Velia in her sight. Her house in Knishi had been the best in the village, almost equal to the church-house; and she had cherished a secret pride in it. The garden on the eastern side was even better than the priest's garden, for her husband as well as herself took great pleasure in it. It was already near the end of February; and the snow would be melting, and the buds swelling on the fruit-trees, and the earliest flowers pushing their first shoots through the moist earth. Oh, how happy she and her husband had been in Knishi!

It was eight years since they had gone there, with their two young children, to rent a farm belonging to her husband's cousin, Paul Rodenko, who had been exiled to Siberia for holding fast to his Stundist faith. A sharp outbreak of persecution had taken place, during which three of the leading Stundists had been imprisoned—one of them dying in prison. And the mother of Paul Rodenko had fallen a martyr to the uncurbed violence of a mob. There had been some official inquiries into the cause of her death. And though no one was punished, the peasants, after their wild excess of savagery, were ashamed of the crime.

Since then the Stundists had been unmolested, left very much to themselves, and practically cut off from all village intercourse. Alexis Ivanoff was their presbyter; and though they had no stated hour or place of worship, it was well-known they maintained their own religious views.

Alexis Ivanoff's letters to his wife told her that this tranquil state of affairs showed signs of coming to an end. Although there was a good and kind-hearted priest, Father Cyril, appointed in the place of the old Batoushka, who had fomented the persecution eight years ago, there were symptoms of hard times coming for the Stundists. The Starosta, who was the chief layman in the village, was a fierce bigot and a churlish miser; and it lay in his power to injure those whom he disliked. Already Alexis had been compelled to pay sundry fines for himself and his poorer fellow Stundists; and the exactions were increasing. It was no use appealing to any court of law against these unjust and vexatious taxes; were they not Stundists? But he hoped the oppression would be confined to monetary forfeits.

"I would send Velia to you out of the way," he wrote, "if I thought

Okhrim would do more than tax us unjustly. But he is fond of money, and

will be content to fleece us; when the sheep are slain, there is no

more to be gained. Velia is the treasure I value most—my only earthly

joy, now you and Michael are away. Yet, if the Lord required it, you

and I would give up our children, precious as they are. My Catherine,

this life is only a journey, and a short one at the longest. What

matters it if we come to the end soon, or travel on a little longer? If

we walk in smooth paths or rough ones? Let us work while it is called

to-day; 'the night cometh when no man can work.' And at nightfall we go

home and rest with our beloved ones."

This was his last letter. It lay under her pillow.

Michael had risen from his knees beside his mother, and gone to the little lattice window, through which he could see the distant mountains still capped with snow. Below the house lay a pleasant valley, which had been the resort of the Covenanters in times long gone by, when they must needs worship God in secret. In the room below, on one side of the wide, old open hearth, there was a little closet four feet square, cunningly contrived behind the wainscot, where many a time godly men had hidden whilst their persecutors searched the homely farmstead for them, or sat round the fire cursing their fruitless efforts. The whole place and neighbourhood were full of legends of the Covenanters, and Michael had heard of them, and listened to them with avidity, for the last twelve months.

He was longing to be home again with his father and Velia, especially now when there was a threatening of renewed oppression. He loved his fatherland, Russia, with a boy's hot patriotism. He had fretted inwardly at his long exile, though he fancied he had concealed his home-sickness successfully from his mother. It would soon be over now, and the tears fell fast down his cheeks. For it was only when his beloved mother passed through the gates of death, already opening slowly before her, that he could be free to hasten away home.

"Michael!" cried his mother in a strong and happy voice.

He sprang towards her.

She had half-raised herself in bed, and her face was full of radiant gladness, such as he had never seen before.

"I'm dying! And it's beautiful!" she said. "Tell your father death is beautiful! And I'm not alone—no, not alone!"

THE RUSSIAN STUNDISTS

THREE weeks later Michael set out on his return home in a vessel sailing from Glasgow to Odessa. Sandy Gordon, his uncle, accompanied him to Glasgow, loath to part with the boy who had become very dear to his Scotch kindred. They urged him to stay with them, but he could not bear the thought of it. His home-sickness had greatly increased since his mother's death, and he had an intense longing to be once more in his own country, to cross the limitless steppes, and taste again the spring breezes full of the scent of flowers. He pined for the familiar sound of his own language, and the songs in which his people delighted. And underneath this natural love of his own country lay a boy's desire to share with his father and sister any perils which might be hanging over them.

"No, Uncle Sandy," he said, with his arms round Sandy Gordon's neck, and his brown head resting on his uncle's grizzled hair, "no! I'm a Russian, and I ought to live in my own country, and help my own people."

"And if they send your father to Siberia, my laddie," said Sandy Gordon, "as they did his cousin Paul Rodenko, what will you and Velia do then?"

"We'll do what father says," answered Michael; "if he goes, I shall want to go too. But there is little Velia! Father must settle for us. She's a tender little thing is Velia."

"My lad," said Sandy earnestly, "remember there's always a home for you and Velia here with us. For Catherine's sake—and your own sake, Michael—you'll be welcome. And there's one of your own kin in Odessa, a well-to-do man, dealing in corn, John Gordon by name. In any trouble think of him, my boy; and he'll help you, for he has the means and the will."

Sandy Gordon gave Michael a letter addressed to his kinsman in Odessa, to be delivered between leaving the port and reaching the railway station of the line which was to carry him to about fifty miles from Knishi, the village where his home had been since his early childhood, and where his father was to meet him. It seemed to him an almost intolerable interruption to stay some hours in Odessa, but the elderly merchant was pleased with the boy, and with the news he brought from Scotland. He promised to be ready with any help he could give, if the troubles anticipated by Alexis Ivanoff should break out.

The short spring-tide of Russia was in its fullest beauty when Michael reached the railway station, where his father was to meet him with a telega, and the old mare whom he had so often fed. The past winter with its bitter winds was already forgotten, and the scorching heat of summer lurked still in the future. The boy's heart was torn with conflicting emotions. His mother's death still filled it with profound grief, but the joy of coming home again to his father and Velia was as strong as his sorrow. He had felt no fatigue from his long and tedious journey, and though his heart leaped at the sound of the Russian tongue spoken by all about him, he had sat almost speechless, and absorbed in memories, during the many hours since he had left Odessa.

His father was standing by the telega, outside the barrier, a tall, strong, middle-aged man, with a grave and handsome face, and a dignified carriage, very unlike the uncouth and rough aspect of most Russian farmers. He had the look of a leader among men. Michael recognised it for the first time, and he felt a new sensation of pride in him. When he left home a year before, he did not understand all his father was as a man. But in Scotland, having his mind filled with stories of the unconquerable courage of the Covenanters, who defied the power of king and soldiers when they sought to interfere with freedom of conscience, he discovered that his father was such a man as they had been. Now he saw it with his eyes.

He threw himself into his father's arms, and felt his kisses mingled with hot tears falling from his father's eyes. The thought of the lost wife and mother, who had been buried so far away from them, was in both of their minds. Silently they got into the telega, and drove away from the noisy crowd gathered about the station.

Everything about him seemed so new, yet so familiar to Michael, that he felt that it must be a dream, one of those many dreams of Russia that had haunted his sleep whilst he had been in Scotland. His father sitting silent beside him, the noisy creaking of the cart-wheels, which might be heard half a mile off, the jolting over the rough road, the slow jog-trot of the old mare—were these real? Or would he awake by and by, and find himself gazing out down the gentle valley under his window at his uncle's farmhouse?

Presently there was nothing to be seen around them but leagues upon leagues of apparently level land, with an unbroken horizon lying low, like the sky-line at sea. Wherever the ground could be cultivated, a brilliant yet delicate green carpeted the rich brown soil, showing the young corn, which would soon be waving under the summer sun. In the untilled portions of the plain, innumerable flowers were in blossom, and butterflies and bees fluttered in clouds above them. The cry of the curlew that loves lonely places followed them mile after mile. Not a barn or a dwelling was visible in all the vast expanse. The father and son drove on in almost unbroken silence, only speaking a word or two now and then. There was so much to say that they knew not where to begin. At length a soft, gentle breeze just touched Michael's cheek, which seemed to him as if his mother had kissed it.

"Father," he said, looking up into the sad yet serene face beside him, "my mother told me to tell you death is beautiful! And her face said it too; it was full of gladness. Yes, until we laid her in the coffin."

"Thank God!" said Alexis Ivanoff, lifting up his eyes to the cloudless sky above them. "I praise Thee, O Lord, that Thou halt taken her away from the troubles to come. She was too tender to bear them. We men, Michael, can bear hardness as soldiers of our Lord Christ, but when we think of our women and children—it is that which breaks our hearts."

The boy's whole frame thrilled with delight as his father uttered the words, "We men." Then he was no longer to be considered a child; this was a summons to enter the ranks of manhood. He was ready to obey the call, and eager to endure hardships. Yet, as if he were already a man, the moment of delight was quickly followed by a sharp sense of dread piercing him, as he recollected Velia, his little sister, who must share whatever sorrows and perils befell them. How was it he had never experienced this vague terror before? Was it because he was almost a man?

"But could not God save us?" he asked after a while.

"What do you mean by being saved?" inquired his father.

Michael did not answer immediately. He meant that God should give them the freedom of conscience, and liberty to worship as they believed best, for which the Scotch Covenanters had fought so long and so stubbornly. But he knew the tenets of the Stundists forbade all resistance by force, and taught simple submission to authority in everything, except coercion in religious matters. Moreover, he had seen too much of life in Scotland to be able to convince himself that the Scotch, as a people, were saved. Had he not seen drunkenness there as bad as in Russia? Were there not lying and dishonesty and quarrelling, and all the long list of sins which he ran through in his mind?

"I cannot tell what I mean," he said at last.

"Christ came to save us from our sins," answered his father, "not from sorrow. 'In the world ye shall have tribulation,' He said; and the history of His people has been the same through all generations, and in all countries. The Church has always been built on the graves of the martyrs. As we beat out the grain from the straw with our flails, stroke after stroke, so will the world smite us. But God will gather His corn into His granary; not one grain lost, only the chaff left. The flail is the world, my son, but God's hand holds it."

"Are they beginning the persecution, father?" asked Michael.

"It has never ceased," answered Alexis, "but now it is growing hotter. Okhrim has been made Starosta in Savely's room, and there is not a harder or more cruel man in all Knishi. Father Cyril can do little to control him. He is a saint and a Christian, our Batoushka, but Okhrim is his enemy. Khariton Kondraty was taken to Kovylsk, and thrown into prison there last week. I expect to be the next. But he leaves me alone, because I pay every fine he imposes; and the farm is not mine, I only pay rent for it. It belongs to Paul Rodenko, who was exiled years ago. Old Karpo will take care it is not confiscated, because it will go to his daughter, Paul's wife, if he dies first. Still, the hour must come for me at last."

Silence fell upon them again. Michael had a vivid idea of what persecution meant in Knishi. Instead of the fairy tales and ballads which other children heard from their elders, he had listened all through his childhood to stories of martyrs—martyrs in Scotland, and martyrs in his own country. Even the dear home in which they dwelt had been the scene of martyrdom; and the bench on which they sat beside the stove had been the deathbed of Paul Rodenko's mother. But hitherto he had thought of persecution as a thing of the past, or far-off in other villages; now it stood face to face with him.

Yet life was very pleasant for the time being. He drew in deep breaths of the sweet, fresh air of the spring, and looked up into the clear blue of the sky, and gazed across the vast, sea-like plain. His heart beat high with the mere joy of living. Courage and hope and an unquestioning faith in his father filled his mind. Whatever troubles might be coming, surely he could bear them as his forefathers among the heathery mountains of Scotland had borne theirs. When he came to think of it, only a small number of the Covenanters had actually perished; most of them won through, and secured freedom for themselves, and their children after them. It would be the same with the Stundists in Holy Russia.

They were five days travelling homewards; for Alexis seized this opportunity for visiting the scattered bands of Stundists, already becoming terrified and disorganised by the increasing severity of the persecution. Alexis was not only the deacon of the little church at Knishi; he was also the presbyter of a wide district containing a number of churches. He was in constant communication with the Stundist exiles and prisoners, and managed the funds by which they were helped and the most distressed members of the sect were maintained. He had therefore much business to transact, and much comfort and information to give. Compared with most of the other presbyters and deacons, he was both a rich and educated man; for he had travelled in other lands, and his wife had possessed a small income, safely invested in Scotland.

In every village they met with terror and sorrow. Spies abounded, and it had become impossible to hold regular meetings. Alexis dared not address the assembled congregations, as he had been wont to do. In two or three places tales so terrible were told him that he would not let Michael hear them. But everywhere he preached non-resistance, not only from policy, but from obedience to the direction of our Lord—"But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil." If they could not conquer by obeying the commands of Jesus Christ, they must perish.

In some villages, he found that the more timid among the Stundists were going back to the Orthodox Church, and these were more to be dreaded than the spies. But in all the little bands, there were some who were ready to go into exile, or even, if need be, to die for conscience' sake. These were all poor working men and women, like the carpenters and fishermen who were our Lord's earliest disciples. Alexis saw them in secret, and encouraged them. To suffer for Christ was to reign with Him. There were light afflictions but for a moment on one hand; a more exceeding and eternal weight of glory on the other!

AT HOME

THE last night was spent at Kovylsk. This place was the chief town of the province. Here the governor lived. Here also was the dwelling of the archbishop. The law courts, the consistory, and the jail were here. Civil law and ecclesiastical law held their high courts in Kovylsk. Alexis was very busy, but also very cautious in this town of the governor and archbishop.

They took up their quarters in the abode of Markovin, a secret disciple, more timid than Nicodemus, but a very useful friend to the Stundists. He was in abject terror all the time a Stundist was under his roof, but he never refused to shelter them. Alexis and Michael left their telega and horse at a little inn quite at the other side of the town, and did not go near him till dusk.

Markovin had means of succouring the men in prison, of receiving news from them, and of smuggling in letters to them. One of the warders who was favourably inclined towards Stundism came occasionally to his house, bringing information about them. He had been several years in the prison wards, and was trusted greatly by the authorities, as he seemed always a stupid but well-principled man. His name was Pafnutitch, and he had formerly been a soldier. He happened to look in whilst Alexis and Michael were in Markovin's room.

"Look here!" he said, after giving them all the news he could. "There's poor Kondraty would give his ears to have a sight of one of you. I daren't take you, Alexis, but if Michael didn't mind running a little bit of a risk, just put his head for a moment in the jaws of the lion, I'd pass him in—ay! and out again, unless we were very unlucky. Let him bring a bag o' tools with him, and I'll say he's my sister's son learning to be a carpenter. What do you say?"

"I'm ready!" cried Michael, springing eagerly to his feet.

"No! No! No!" exclaimed Markovin, in terrified accents. "Not from my house. Not from here!"

"Not now," said Alexis quietly. "It would be useless. We have no important news yet to send to Kondraty. But another time, Pafnutitch, I may send Michael to you."

It was the first call upon his courage and sympathy, and Michael rejoiced to feel that he had not for a moment hesitated to answer it; no cowardice or indifference had made him fail.

It was evening when Alexis and Michael drove slowly, with their tired horse, along the grass-grown village street of Knishi. Each cottage, built of wood or mud, stood at the back of fold-yards large or small, according to the number of sheep or cattle possessed by the owner. Only on the eastern side of the dwellings were any doors or windows to be seen, for the Oukrainian houses are built always to face the east. But though on one side of the road, the inmates looked out through their doors and windows to see who was passing, as they heard the creaking of the telega wheels, not one gave them a smile or a word of welcome. On the other side, some of the people, curious to know who was coming, peeped round the corner of the huts, but they, too, only stared and frowned.

Michael felt a lump in his throat, and tears burning under his eyelids. It was not in this way he had dreamed of coming home. He had been absent only a year, and he knew all their names, and recollected their faces. Some of the women had kissed him when he went away; and the children had followed them as far as the barrier, calling farewell after them as long as they were in sight. But now the boys, his playfellows, slouched away, as if they were ashamed or afraid to recognise him, or stood and stared at him with unconcealed animosity in their manner. This was not what he had looked forward to.

In his trunk lying at the bottom of the telega were a number of little keepsakes, which he had bought with great pleasure in Scotland. He had often thought of how he should go round the village, from house to house, giving them away, and telling strange tales of his voyage and his sojourn in a foreign country. He had all the strong desire of a traveller to narrate his adventures. He had not even forgotten his enemies, Father Vasili, the Batoushka, and his wife, but now Father Vasili was dead, and only the Matoushka was left. Was it possible that nobody would accept his keepsakes?

Presently they were past Knishi, and on the road to Ostron, half a mile farther on, where their home was. Michael could no longer bear the wearied jog-trot of the old mare. He sprang from the telega with a shout, and ran eagerly towards the farmstead. Yes! There it was! The very home which had haunted his dreams, by night and day, during all his long absence.

The front was in shadow, for it was evening, but the setting sun shone slantwise on the barns and stables, and made golden tracks down each side of the fold-yard. The buds on the lilac trees at the corner of the house stood out against the low light. In the doorway stood Paraska, her usually sad face kindled into a look of glad welcome; and on the turf seat by her, outside the door, was Velia, her long pretty hair pushed back from her eyes and forehead. With a loud cry of delight, she flew across the yard and threw herself into his open arms.

"Never go away again, brother!" she cried. "Never leave little Velia again!"

For a few moments Michael was silent, gazing with dreamy eyes at the open doorway. For it seemed to him that just within the shadow, behind Paraska, he saw dimly a vague form, like his mother, with such a smile upon her face as had lingered there to the last, when they closed her coffin. Was it possible she was there to take a share in the joy of the home-coming? He clasped Velia more closely to him, and kissed her tenderly. When he lifted up his head again, the vision had vanished.

Paraska, too, was gone. She threw her apron over her head, and ran away to the little room that had been made for her in a corner of the granary. She was the wife of Demyan, a Stundist, who had been sentenced to exile at the same time as Paul Rodenko, to whom the farm at Ostron belonged. He was now living at Irkutsk, in Eastern Siberia, thousands of miles away. When he went away, she had chosen to stay behind with her two babies, who were too young to bear the privations and perils of the long journey, made chiefly on foot. But when her children were four and five years of age, they had been taken from her by the Church authorities, to be brought up in the Orthodox faith, and she had never been able to find out where they were. Catherine Ivanoff had taken the broken-hearted mother, penniless and friendless, and almost maddened, into their house, and treated her as an old and cherished friend. But the forlorn woman was a prey to grief, and went through her daily life almost speechlessly.

"Let us run after Paraska and speak to her," said Velia.

Up the rude ladder and across the granary floor they ran to Paraska's little room, but so piteous were the sobs and cries they heard beyond the closed door, that they crept quietly away again.

Yet, in spite of all, that evening was a very happy one. Alexis sat by the great stove, for it was still cool at night, with Velia on his knee, and his right arm round his son. Michael had much to tell them, and they had a thousand questions to ask. They did not avoid talking of the mother, whom they spoke of not as one dead and lost to them, but only as having reached the end of a journey, and entered the heavenly home before them.

To Michael and Velia, if not to Alexis himself, heaven was as real as if it had been another land on the face of this earth. They seemed to know as much about it as they did of Siberia, or the Transcaucasus, whither so many of the Stundists had been banished, and where they might go themselves some day. Only there was this difference: they had no doubt of going to heaven, and they were not sure of going to Siberia.

ESTRANGED FRIENDS

MICHAEL was resolved not to let the coldness of his old friends and comrades separate him from them. True, they looked upon him as a heretic, but he had been that before he went to Scotland—that was no new thing. Of course, there was his chief friend, Kondraty's son, Sergio, a heretic like himself, whose friendship was as close and dear as ever. But Michael had been on good terms with all the village boys, and he knew they would listen with delight to the story of his travels, nee, would go into a rapture of joy over the treasures he had brought home. There were at least a dozen pocket knives, which his Uncle Sandy had bought to be given away among the lads of Knishi. He was eager to renew the good understanding and comradeship which had been broken off a year ago.

Then there were the packets of needles for the women, and the dolls for the little girls. Such needles and dolls had never been seen in Knishi; surely they would open every door and every heart to him. There was Marina's little girl, Velia's chief playfellow. He had brought an English doll for her precisely like Velia's. Yarina had been great friends with his mother, and he had a memento to give to her, sent by Catherine herself.

The first morning after his home-coming, he filled his pockets with his presents, and giving one doll to Velia, bade her take the other one in her arms. He started off joyously to Knishi, but as he was turning down the road leading to Yarina's farm, Velia drew him back.

"We must not go there," she said, with a sob.

"Why not?" asked Michael.

"Okhrim is Starosta now," she answered, "and he says I mustn't play with Sofia any more. He is her grandfather, you know. Unless I cross myself, and bow to the icons," she added, looking up to him with eyes full of tears.

"You must not do that," said Michael, his bright boyish face clouding suddenly.

"Oh no!" replied the little girl. "But oh, I miss Sofia so!"

The tears were rolling down her cheeks, but a moment afterwards Velia looked up again with a smile.

"But I shan't mind now," she continued, clasping Michael's hand with all her might; "I have my own big brother now."

"Does nobody play with you, my Velia?" he asked.

"Only the other Stundist children," she said; "and they don't let us go to school now. Father Cyril would let us go, but Father Vasili got an order, just before he died, to say the Stundist children must not go to Orthodox schools if they did not go to church. Father Cyril cannot get it altered."

"I'll go and see Sergius," cried Michael, "and you must give Sofia's doll to little Clava."

"Little Clava will love it," said Velia, "but oh, I am so sorry for Sofia. We must never let her know it was brought all the way from Scotland for her, and given away to another girl."

The house belonging to Khariton Kondraty, the father of Michael's chief friend, Sergius, was much smaller and poorer than the farmhouse where Alexis lived. It lay a little way apart from the village, and near to the steppe, a part of it so thickly carpeted with flowers that not a blade of grass or an inch of soil could be seen. Long rows of beehives lay under a hedge, which sheltered them from the north wind. Khariton Kondraty had taken up the business of Loukyan, an old deacon who had died from ill-usage in prison at the last outbreak of persecution in Knishi. He maintained himself and his family chiefly by the sale of honey and wax, and since he had been imprisoned in Kovylsk, his son Sergius, a boy about the same age as Michael, and his daughter Marfa, a girl of twelve, had proved themselves quite capable of managing the bees, and tilling the small plot of ground belonging to their father.

The whole family welcomed Michael with delighted cries of welcome. Marfa alone could not his speak, but her eyes filled with tears. Sergius clasped his friend in his arms; and little Clava jumped about for joy, with her English doll in her arms. Tatiania, Kondraty's wife, kissed him as fondly as if he had been her own son. No welcome could have been warmer, and Michael's spirits rose again.

"Let us go and look at the hives, Serge," he said.

He wanted to get Sergius alone, to inquire about the school and the exclusion of the Stundist children from all the pursuits and games of the Orthodox children. It was too true. The Orthodox parents forbade their children to have any intercourse with the heretics. They were in fact excommunicated. This had caused bitter, though perhaps short-lived grief in many households in the village; for the friendships of children are often very close and tender. Yarina's little girl, Sofia, had been made quite ill by her separation from Velia and little Clava. But the Stundist children were getting no teaching except what their parents could give in their very few leisure moments.

"Then I will keep school myself for our own children," said Michael.

He soon found out that the boys of the village were more than willing to listen to his traveller's tales, and accept his presents, if they could do so in secret. But this Alexis would not allow. Michael himself saw the risk and the folly of any clandestine intercourse; for Okhrim, the Starosta, was on the lookout keenly for some pretext for fresh fines and oppressions.

IN THE FOREST

MICHAEL began his school, protected and encouraged by Father Cyril, the Batoushka, though the Starosta did his best to put a stop to it. Father Cyril had been appointed to the Orthodox Church in Knishi, on the death of Father Vasili, with the idea that his holiness of life and sweetness of nature would bring back the straying Stundists to the Orthodox faith. He was loyally attached to the Greek Church, and never having been in close contact with the Stundists before, he had come to this parish with high hopes of soon rooting out the pestilent heresy by conciliatory measures and telling arguments. He found the unlettered peasants very open to conciliation, but their arguments, taken simply and solely from the New Testament, he could not often combat, and could never overthrow. In the meanwhile he had conceived a great respect and a real friendship for Alexis Ivanoff.

Alexis had had more than a village education. He had lived some years in Moscow, and availed himself eagerly of every opportunity for acquiring knowledge. His wife, Catherine, had been no ordinary woman; she had always been a true helpmate and companion to him. He had learned English from her, and possessed many English books. He had translated the best English hymns into Russian verse, which were printed and widely circulated.

Father Cyril was greatly interested in this heretical household—the well-read, intelligent farmer, the manly yet boyish son, and his pretty, sweet-tempered little girl. The sad, broken-hearted Paraska, mourning for her children, also aroused his deepest sympathy. The farmstead was a model to the village. Whenever Father Cyril passed it, and saw the clean fold-yard, the comfortable house, with its shining windows, and the flowers blossoming round it, he sighed to think he could not point it out as a pattern to his idle and drunken parishioners without giving great offence to the Orthodox people. He could not even go as often as he would like to visit Alexis Ivanoff.

Michael's school for the Stundist children prospered; he proved to be a very good teacher. There was no doubt he was doing better than the village schoolmistress, who took no real interest in her work. The Stundist children, who were obliged to pass through Knishi to reach Ostron were often assailed with threats and bad language and occasionally with missiles from the Orthodox children. For the spirit of persecution is easily aroused, but very difficult to suppress.

The summer was nearly over, and the harvest was gathered in, an abundant harvest, which filled every barn to overflowing. Michael gave himself and his little school a holiday that they might spend a whole day in the forest, which lay to the east of Ostron. Paraska made a large supply of pasties, some of which were filled with boiled cabbage, and others with fruit; and she baked a quantity of bread and cakes; for there were quite a dozen children to go besides Michael and Velia, and Sergius and Marfa, who came as guests, being too old and too busy to attend the school. They kept this expedition a profound secret, lest the Orthodox children should follow to the forest and spoil their holiday.

There was no road, only a foot track to the forest; and between it and the steppe lay a deep ravine, crossed by a rude bridge of the trunk of a tree, which had fallen across the chasm generations ago. Some of the oldest trees in it had been left untouched for centuries, and as the timber belonged to the Government, it was left to grow very wild and untrimmed, though the village was often in dire need of fuel. There was a great tangle of brushwood; and it had the reputation of being haunted in some parts of its dark and moist thickets. Only the most daring spirits among the Knishi boys would venture into its glades. But the Stundist children were at home there. For during the last few years, many a secret meeting for worship had been held in a deserted hut some distance within it.

It was a lovely day in September. The sun was still hot, but there were sweet, warm gusts of wind, which tossed the leafy branches to and fro, and brought with it the sweet perfume of wild flowers and the pungent scent of herbs. There were many open spaces where the sun had dried the moist earth, and where the children could play safely. They played till the little ones were tired, and then they turned their steps towards the deserted hut, to eat their dinner.

It had been a charcoal-burner's hut, but for many years no peasant had consented to work there, so near was it to a fatally-haunted spot. It stood in a dense thicket, with no beaten track to it; for the Stundists were careful not to tread down a path which might betray their meeting-place. A few rough trunks of trees formed some benches for the congregation to sit upon, and a large log set on end served as a table for the preacher to stand at, and lay his Bible and hymnbook on. The children sat here and ate their dinner with a subdued gaiety even more enjoyable than the boisterous play outside. They sang a grace before the meal began.

"Let us hold a meeting," Sergius proposed, when dinner was over, "and Michael shall be our deacon."

"Yes, yes!" cried all the children, clapping their hands.

A few hymn-books were concealed in a hole in the thatched roof. These were quickly brought out, and Michael took his place behind the preacher's log, whilst his congregation seated themselves with smiling faces on the benches.

"My little brothers and sisters," he began, "we can sing a hymn, but I don't think it would be right for me to pray. I am too young to do that out loud, and for you to listen to me. I might say something I ought not to say; and you would perhaps be thinking of me, not of God. But I'll talk to you, after we have sung 'Oh, happy band of pilgrims!'"

THE CHILDREN'S SERVICE

THE children's voices rang out in clear, sweet, and harmonious tones; for the Oukrainians are a musical people, and fond of choral singing. Only now and then a shrill note, sounding like a cry of triumph, broke the harmony. It was little Clava, who had not yet learned how to modulate her voice; and Sergius would have checked her, only Michael gave him a sign to let the child sing on.

"And now," he said, when the favourite hymn was finished, "I am going to tell you about the children in Scotland, whose fathers and mothers were like the Stundists. They were called the Covenanters, and the king wanted to make them say they believed what they didn't believe, and worship God in the churches; and they couldn't, for conscience' sake—just like our fathers and mothers. All they wanted was to be left alone to worship God, and obey Him, in the way they believed to be right. Then the king said they were rebels, and, he sent his soldiers to compel them to do as he wished, or to put them to death. Then the Covenanters said they were ready to die, but they could never, never disobey God. So the men had to flee away, and hide in the steppes and the mountains. Now, their steppes are not like ours, all open, and plain to see across, but they are full of rocks and woods and hollows, where they could hide easily. They suffered dreadfully from hunger and cold and ragged clothing; and the soldiers hunted them down, and some of them they caught and shot like wild beasts; and others they sent to prison; and they hanged many of them. What for? Because they obeyed God rather than man.

"But the women, of course, stayed at home with the children; and sometimes the poor men would steal in to see them, and to get a little good food and warmth. Then the spies told the soldiers—they were traitors, those spies were—and the soldiers came; and all the men and women fled away into the woods, and left the children alone in the houses. Oh, you may be sure they could hardly bear to do it but everybody thought, 'The soldiers have children of their own, and they will not hurt our little ones.'

"Then the troopers came on great black battle-horses, with swords and guns; and they searched one house after another, and could find no one but little children—boys and girls no older than Velia. For big boys like Serge and me had gone off to the woods and caves with the grown-up people, because they knew the soldiers would have no mercy on them.

"Well, when nobody was found, the captain was very angry. In a great rage he had all the children gathered together, and asked them where their fathers and mothers were. Do you think the children told the captain?"

Michael paused to take breath, and Clava's shrill little voice cried out, "No!"

"No, my little Clava," continued Michael, "and you would never tell, if father or mother were hiding. Then the captain set them all in a row, with a row of soldiers opposite to them with their guns ready to shoot them, and bade them kneel down to be killed. So they knelt down, and the oldest little girl, like Velia, said to the others, 'It will not hurt much, and then we shall be in heaven!'

"The captain told them to say their prayers, but the little girl said they did not know how to pray aloud, though they could sing a hymn. And the children began to sing a hymn they all knew, and the soldiers turned away, and rode off on their battle-horses, telling the captain they were ready to fight with men but not with children, and before the hymn was finished they were all out of sight."

"Ah!" sighed the children, drawing a long breath.

"That was about two hundred years ago," Michael went on, "in Scotland; and in the very house I lived in there was a little secret closet in the chimney corner, as if it was close to one of our stoves. One night the father was warming himself at the fire, when they heard the soldiers coming, and he slipped into the secret closet, and the mother ran and got into bed, and only a girl like Marfa was left clearing up the house. There was a good fire on the hearth, so the soldiers felt sure somebody was there, and they searched up and down, and then they asked the girl where her father was, but of course she would not tell. So they said they would flog her, and she ran out of doors as quickly as she could run. They followed her, thinking she was running to her father.

"But I will tell you why she ran out into the fold-yard. She said to herself, 'Father will hear if they flog me in the house, and he will come out and be killed.'

"And they did flog her, but she stuffed her apron in her mouth, lest she should scream out. And at last, the soldiers were ashamed. One of them said she was a brave lassie! She was my grandfather's grandmother, and they talk about her to this day, so brave she was.

"But it does not always end as well as that. There is poor Paraska; you know how both her children have been taken away from her. Well that may happen to us—not to big boys and girls like Serge and Marfa and me, they will treat us like grown-up people—but you little ones! Oh, if any of you are taken away from your own fathers and mothers, you must never forget them, and what they taught you. You must be true to God and them. If we die for it, we must be true. We cannot bow down to icons, or pray to anyone but God. Never! Never! Death is not dreadful if we love God. It only takes a few minutes to die. Then we are safe for ever with our Lord Jesus Christ. You will remember?"

"Yes, yes!" they all cried.

"It helps me to think often that our Lord was once just like me," continued Michael; "a boy as old as me, working with His father, and living at home; just my age—"

Clava's little brown hand was lifted up to interrupt him; she had an important question to ask.

"Was He ever just as little as me?" she said.

"Exactly as little as you, my Clava," answered Michael; "six years old only, and His mother took care of Him, just like your mother; and, oh, He made her so happy, for He was never naughty! Well, whenever we are tempted, we must try to think what He would have done in our place. Remember our Lord Jesus died a martyr, and we must be ready to follow Him. It is not grown-up people only who are martyrs!"

FATHER CYRIL

AT that moment, whilst Michael was still speaking, the doorway of the hut was darkened by a man's figure standing between them and the green light of the forest. The children huddled into a corner, like frightened lambs; whilst Michael and Sergius stood out boldly in front of them. The hearts of both of the boys were filled with trouble and dismay. It was Father Cyril, the Batoushka, who had discovered their retreat.

"Are you afraid of me, my children?" he asked in a gentle voice, as he sat down on one of the logs, and stretched out his arms towards the startled group. "Come to me, Velia; and little Clava, I have a sweetmeat for you. Come and sit on my knee. Shake hands with me, Michael and Sergius. I heard you singing some little time ago, and after some trouble, I found out where you were hidden."

"Batoushka," said Michael, stammering and hesitating, "this old hut is a secret."

"Not from me now," answered Father Cyril, "but don't be alarmed, my boys, I respect your fathers, and I will not betray you or your people."

Michael stood aside, and pushed Velia and Clava towards the village priest. He took Clava on his knee, and put his arm round Velia; whilst the rest of the children drew near him, attracted by his kind and benign aspect. His pale, thoughtful face was that of a youngish man, though his uncut hair, parted in the middle, and hanging on his shoulders, and his long beard, gave him a venerable appearance. There was a half smile on his lips and in his eyes, in spite of the sadness with which he regarded this childish band of heretics, already eager for martyrdom. He knew better than they did the perils and sorrows drawing nearer every day. The resolute, manly bearing of Michael, the more timid yet firm manner of Sergius, the tender delicacy of Velia, and the clinging weakness of little Clava, appealed irresistibly to his pity. He felt as the Lord may have felt when they brought young children to Him for His blessing, if He foresaw that these little ones must pass through the fires of persecution. Father Cyril knew that these helpless children were doomed to swiftly coming sorrows; and his heart ached, and tears came into his eyes, as he laid his hand on Clava's head and gave her a silent benediction.

"My children," he said, "I see you seldom, but none the less I feel as if you belonged to me. You are in my parish, and the Church has appointed me to be your Batoushka. I would give all I have—yes, and lay down my life—to bring you, and all your people, back to the Church you have forsaken. Yes, Michael, I know that cannot be at present. The Church must be purified and reformed, but we too are Christians. I would have no man dare to sign himself with the sign of the cross, without truly recollecting the cross of Christ. No man should put an icon into his house, except as a reminder of the constant presence of God, before whose sight, he could not commit a wrong deed, and in whose hearing he could not utter an evil word. The symbols must only represent truths, or they are worse than useless. There will come a time—but the end is very far-off."

Father Cyril paused, with a break in his voice like the sob of a wearied runner. Velia pressed closer to him, and leaned her head against him as if he had been her father. The hearts of the children were touched, and they drew still nearer to him, clustering about his feet. Michael's eyes were fastened upon the Batoushka's agitated face.

"Oh, I wish we could belong to you!" he cried. "But we cannot! We cannot!"

"But we can pray together, my children," said Father Cyril.

Kneeling down in the midst of the children, under the roof of the deserted hut, where alone the proscribed Stundists dared to worship, the Batoushka offered a simple prayer, intelligible even to little Clava, that God would be with them in the troublous times that were coming, and save them from all evil, especially the sin of disobeying His voice when He spoke through their conscience.

When they rose from their knees, he kissed each one of them on the forehead; and they bent their heads as he pronounced a priestly benediction upon them. The Batoushka and the band of childish heretics were very near to each other at that moment.

Father Cyril walked slowly homewards through the thickly-grown forest. He felt sure that he could win the people back to Orthodoxy but for the persecution they were always encountering. He had no faith in coercive measures. Besides, he acknowledged sadly and reluctantly that a vast accumulation of superstitious rites and beliefs was suffocating the Church. He had never been so conscious of it as since he had lived in this remote country parish, where none of the spirit of town life breathed over the stagnant waters.

When at last he came in sight of the church-house, he saw his wife—the young Matoushka, as the villagers called her—standing at the door, looking out anxiously for his return. She held in her hand a large official-looking packet, which she raised above her head as he came in sight.

"From the consistory," she called out, "with the archbishop's seal. Oh, I am so curious!"

Father Cyril hastened in, and opened the document and read in unbroken silence, whilst his wife waited impatiently for news. He sank down on a seat, and covered his face with his hands.

"Oh, my dearest one!" she cried. "Tell me what is the matter quickly."

"A cruel thing," he groaned, "a cruel thing; and I must do it."

"What is it?" she asked again breathlessly.

"An order from the consistory," he answered, "that I must take all Stundist children between two and ten years of age from their parents, and place them in Orthodox families; their maintenance to be paid for by fines levied on their heretic fathers. Think of it, dear wife—think of our own little ones. Ah! Those monks who have neither wife nor children do not know how cruel they are!"

The Matoushka burst into a passion of tears, when Father Cyril told her with a broken voice and a face of profound pity.

"I'd rather see my children in their coffins," she sobbed, "than lose them in such a cruel way. Poor Tatiania! Her husband in prison, and little Clava to be taken from her. It will break her heart! And Velia Alexovna! How old is she, Cyril?"

"Not ten yet," he answered. "Oh, it is frightful, and absolutely useless! We shall never win them back if the authorities adopt measures like these. Would to God I could disregard the order!"

"Cannot you put it off, and go to see the archbishop?" she asked.

"No," he replied; "the Starosta has got an order from the police in Kovylsk to assist me in carrying out the order. Okhrim will rejoice over it; he hates the Stundists with all his heart, and so does the old Matoushka. Oh, they are at the bottom of all this!"

Father Cyril could not sleep that night, his brain was too much worried with vexatious and perplexing questions. How should he break the terrible tidings to the Stundist families? How could he bear the heartrending scenes he would be obliged to witness—himself the unwilling messenger of the cruel sentence? And what homes could he choose for the children, whom he must provide for as carefully and kindly as possible? They must be homes with which the sober, cleanly, and religious parents might be moderately content. He awoke his wife to ask her if she would be willing to take Velia and Clava into their own home, to live with their own children, and she answered drowsily, "Yes, yes, beloved!" Surely no objection could be made to this step. A priest's house was an Orthodox house.

Then there was Yarina, the richest woman in Knishi, with only one little girl. True she was Okhrim's daughter-in-law, but she was a widow for the second time, and quite independent of her husband's father. She was regular at church; though she was not as devout as the old Matoushka, Father Vasili's widow, who never missed a church service. He would not place a child with the old Matoushka—her temper was bad, and she was too miserly—a child would lead a terrible life with her.

Well, he must do the best he could for all of them. They would be under his own eye; and he would see each child every day in the village school, which of course they would now be expected to attend. Poor Michael! His little class would be scattered.

One clause of the order hurt Father Cyril's tender soul more than the others. The parents were not permitted to hold any kind of intercourse with their children unless they returned to the Orthodox faith. Ah! What daily agony there would be both for parents and children! It would have been almost better—more merciful—to have removed the little ones altogether out of sight. Yet, after all, would there not be some consolation to the mothers to see their children, even from afar?

A CRUEL BLOW

THE children who had been spending the day in the forest went home at sunset, wearied but very happy. They parted with one another after they had crossed the rough bridge, and Michael and Velia went on hand in hand towards Ostron. Michael felt his heart strongly attracted by Father Cyril. If all priests were like him, he thought, there would be no persecution. And why should not people think differently about religion, as they did about everything else? The Stundists accepted the teaching of the New Testament literally. The Orthodox people added symbols and ceremonies and the traditions of the Church to it. He could not see that it made the New Testament any more binding. If the Lord gave a command, His followers must obey it.

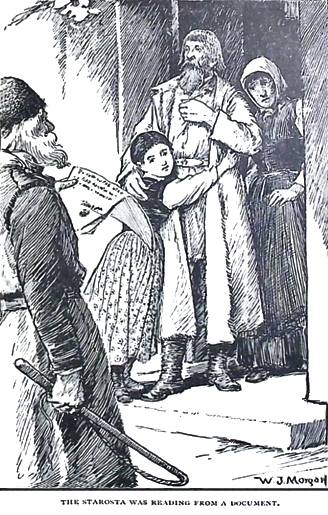

As Michael and Velia turned into the fold-yard, they heard a loud harsh voice speaking on the other side of the house. They hurried round the corner, and saw Okhrim, the Starosta, who was reading with some difficulty from a large official document. He had not entered the house; and Alexis stood listening, whilst Paraska could be seen partly concealed by the door which she held ajar.

THE STAROSTA WAS READING FROM A DOCUMENT.

Michael and Velia drew near just as Okhrim, with a spiteful smile on his harsh face, read the plainly-worded order that the Starosta was to aid the parish priest in removing all children of Stundist parents, between the ages of two and ten years, and placing them in Orthodox families, where they would be brought up in the Orthodox faith. A wild frenzied shriek from Paraska rang through the quiet evening air; and Velia, who understood the slowly-uttered order, uttered a cry of terror, and flinging herself into her father's arms, clung closely to him, as if no power on earth could tear her from the shelter of his breast.

"Oh, my God!" cried Alexis. "What can I do?"

"Do?" repeated Okhrim contemptuously. "Why, become a good Christian, and go to church and pay the Church dues. Ay! And drink vodka as other Christians do. I believe you Stundists are the greatest fools living. The child is to be brought up Orthodox, and if you won't do it, somebody else must. I'll take her myself, and if fair means won't 'tice her to church, there is always this."

He cracked his whip, which he always flourished in his hand, and was not reluctant to use it on anybody he dared to tyrannise over. Alexis felt Velia tremble violently in his arms.

"O Father," he cried, "if it be possible, save us from this hour!"

"There you go," said Okhrim, with a sneer and a laugh, "as if God Almighty could hear you amid all His angels and archangels singing and chanting, to say nothing of the blessed saints. If I were in your plight, I'd pray humbly to one of the smallest saints, and get him to speak to those higher up; and maybe it might reach at last the ear of the Mother of God. Not that she'd do anything for a cursed Stundist. Besides, she'd never interfere with our archbishop and the consistory."

"Can we do nothing, father?" cried Michael.

"I must think," said Alexis, turning to him with an expression of almost hopeless anguish; "we have no power, no influence. Oh, if I had only sent Velia to Scotland with you, she would have been safe! But there are other fathers and other mothers. Oh, my God! Help us to bear it!"

For once in his life Okhrim's conscience stung him, and he turned away, slowly passing out of sight.

Alexis carried Velia into the house, and Paraska locked and barred the door, as if she could shut out the coming trouble.

It was a sleepless night for Alexis, as well as for Father Cyril. The thought crossed his mind that he would have time to carry Michael and Velia to Odessa, and get his wife's kinsman there to send them away to Scotland. But a step like this would only precipitate and intensify the storm ready to burst, not only upon himself but upon hundreds of fellow Stundists in the district. There were other parents, even in Knishi, who would have the same most heavy cross laid upon them. They were not only to be bereft of their children, but they knew those children would be brought up in tenets which they themselves renounced with such fervour that they were willing to sacrifice everything rather than profess to believe them. No, he could not save Velia in that way.

Then he thought pitifully of Tatiania, whose husband, Khariton Kondraty, had been in jail for nine months. She too would now have to give up little Clava, her youngest child, the pet and darling of the house. Poor Tatiania! Could she stand fast in her faith, so severely tried? Could any of the mothers refrain from going back to the Orthodox Church, if by doing so they could keep their little ones? Ah! This was the sharpest weapon of all in the Orthodox armoury. "Give me the children," the Church demanded, "and the mothers will follow."

Then Father Cyril was so good and kind and persuasive; so different from Father Vasili, who had been an idle, self-indulgent, and arrogant parish priest. It would make it much easier for the women to go back to the Orthodox Church. By slow degrees they would relapse into the old condition of superstitious observances, and the lamp of truth would be extinguished in Knishi, as it had been in other places.

But below every other thought there rang through his soul the cry, "Oh, Velia, my little child! Would to God we could die together, my child and I!"

The morning came, and a wretched circle assembled at breakfast. Michael and Velia had both slept, but their eyes were red, as if they had wept themselves to sleep and awoke with tears again. Paraska was heavy-eyed, and completely dumb. They were lingering together, as if they could not bear to separate, even for an hour, when Father Cyril appeared at the door.

"Ah, Okhrim has been before me!" he exclaimed. "I ought to have come last night. My poor Alexis! But the order is not to be executed before Sunday that the people may have time to make their submission, and be reconciled to the Church. Those parents who come to confession will keep their children, on condition that they bring them up as Orthodox Christians."

"We shall see who can bear the severest temptations," said Alexis, with a sad smile.

"But I will start off to Kovylsk at once if you can drive me," said Father Cyril; "and I will ask for an interview with the archbishop. Come, Alexis; I am a father too. I feel for you. I can guess the terror little Velia feels, poor lamb."

He sat down on the bench, and took the trembling little girl into his arms. The tears rolled slowly down his cheeks. He felt great shame in the errand forced upon him. This terrible order, which he was called upon to execute, seemed to him a monstrous attack upon a parent's rights—those primal rights which existed before the Church was founded. He sat in silence for some minutes, until he could command his voice. From time to time, he stroked Velia's hair and patted her cheek. And the child nestled close to him, much comforted.

"We must bestir ourselves, and do the best we can," he said, almost stammering.

"And leave the result to God," added Alexis. "But how can I quit my little daughter just now?"

"Let her go and play with my little ones," answered Father Cyril; "the Matoushka will be like a mother to her. We will put her down at the church-house; for we must tell my wife we shall be away for one or two nights."

ORTHODOX REASONING

AS they drove across the steppe, in the two-wheeled cart without springs, at the slow, monotonous trot of the old mare, Father Cyril had a better opportunity than he had ever had before of a prolonged discussion with Alexis Ivanoff on the tenets and history of their young sect. He was filled with surprise and admiration. The absolute simplicity and truthfulness of the farmer, united as it was with mental strength and a close grasp of his subject, astonished the Batoushka. Alexis was not logical; he had had no training in a theological seminary, like Father Cyril. He argued as the fishermen of Galilee would have argued. But his convictions were as strong as theirs, who had seen the Lord with their eyes, and heard Him with their ears. Father Cyril could not help admitting that the worship of the Stundists was far more in accordance with that of the apostolic age than the ornate, multitudinous, and magnificent ceremonies of the Orthodox Church. He owned that the peasants, in their ignorance, did worship the icons with idolatry. Yet in fundamental Christian doctrines, he and Alexis were one. They prayed to the same Father in heaven; they believed in the same Lord; they studied the same Holy Scriptures. There was real spiritual communion between them, as they slowly crossed the brown autumnal steppe, now lying under a thin veil of mist, which hid the horizon, and enclosed them in a soft circle of mellowed light.

They reached Kovylsk too late to go to the consistory that night. But quite early in the morning Father Cyril presented himself at the gate, and inquired for Father Paissy, who was known throughout the diocese as the archbishop's right hand. They had been at the theological seminary together, where they had been on friendly terms, but they had seen nothing of one another since Father Paissy had elected to enter the order of the monastical clergy, who take vows of celibacy, and who alone can be raised to the higher ranks of the Russian priesthood. He was already a powerful personage. He was a small, sharp-featured man, with a soft voice, and a perpetual smile on his thin lips.

"Father Cyril, parish priest of Knishi?" he said interrogatively, without condescending to recognise him as his former comrade. "Ah! You have a troublesome flock. Heresy runs like an infectious disease among them. We must stamp it out—stamp it out effectually."

"I come in the hope of seeing the archbishop," said Father Cyril.

"He is in Moscow," interrupted Father Paissy, "but I can act in his stead."

It was a great blow to Father Cyril; for the archbishop never refused him an interview, and he had placed great hopes on his indulgence. It is easier to prevent a thing being done than to get it undone. There was no sign of indulgence in the hard face opposite him.

"I came to intercede for my poor parishioners," he said gently, "those unhappy parents who are to be deprived of their young children. Some of them are scarcely out of their mothers' arms, and still require a mother's care in childish maladies. Only a mother's patience is strong enough to bear them through the first seven years. A child's heart is capable of great sorrows, and its spirit is quickly broken if it is sent among strangers, and separated from all it has known from its birth."

"Ah!" said Father Paissy, with a deep breath, which sounded almost like a sigh.

Father Cyril went on, encouraged.

"The unfortunate people who have left our holy Church," he continued, "are most affectionate parents. It is their universal practice to treat their little ones with the utmost tenderness. They look upon their children as entrusted to their care by God Himself. True, that may be an error, but it is their belief. The children never hear uncivil words; they never see a drunken person in their homes. Think, your reverence, what it must be to children so carefully reared to be distributed among the houses of peasants who are ignorant and degraded by vodka-drinking. There would be great difficulty in finding suitable homes for them with our Orthodox peasants."

"You seem to think very highly of your heretics," said Father Paissy in a scoffing tone.

Father Cyril felt that he had forgotten himself.

"I grieve over their heresy night and day," he answered earnestly; "it makes my life in Knishi a burden to me. I never had this trouble to encounter before. But oh, believe me, harsh measures will never bring them back to us, above all, not such a measure as this! Every father, every mother worthy of the name, will cry out against it. I assure your reverence, I was gaining some influence over them; I have seen two or three steal in at the church door to listen to my sermons. Let me plead their cause to you. Do you, with your powerful influence, get this terrible order rescinded. The Stundists will bless you, and it will add greatly to my influence in the parish."

"Do you forget the children's immortal souls?" asked Father Paissy. "Is their salvation of no moment?"

"Alas!" cried Father Cyril. "If salvation means to be saved from sin, I must confess that these poor straying heretics have advanced farther along the path of salvation than our superstitious, half-pagan Orthodox peasants. I am striving my utmost to teach and raise them, but only a parish priest can know how deeply they are sunk in degradation and drunkenness."

"I can do nothing for you," said Father Paissy in a chilling voice; "the consistory has issued the order, and it must remain as it is. It must also be obeyed promptly, Father Cyril."

The Batoushka felt his heart sink within him, as he looked at the set and stubborn face before him, with its cruel smile still playing about its lips. Neither this man nor the archbishop could understand what a father's love was, and they had no knowledge of a child's nature. His chief hope was gone, but another was left to him.

"I may place the children as I please," he asked, "provided I settle them in Orthodox families? Some houses are much better than others."

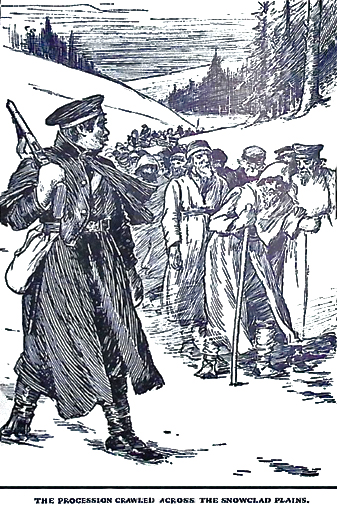

"Just as you like—just as you like," said Father Paissy impatiently; "only let me warn you, Father Cyril, no indulgence to the heretics! We intend to weed them out, root and branch. Our long-suffering is at an end. Church or Siberia! Church or Caucasus! They must choose between them."

Alexis was waiting at the entrance to the consistory when Father Cyril came out. He had been to see two or three friends in Kovylsk, who had sympathised with him deeply, but gave him no hope that the order would be rescinded. It had been sent to many other villages besides Knishi, and there was lamentation and bitter weeping in them all: "Rachel weeping for her children refused to be comforted."

"Yet, 'Thus saith the Lord,'" said Alexis, "'Refrain thy voice from weeping, and thine eyes from tears: for thy work shall be rewarded, saith the Lord; and they shall come again from the land of the enemy. And there is hope in thine end, saith the Lord, that thy children shall come again to their own border.' Send that message to the churches, and bid them trust the Lord to keep His promises."

He knew the moment he caught sight of Father Cyril's downcast face that he had failed in his mission. But Alexis had regained his habitual courage and resignation. He said to himself, "'He that loveth son or daughter more than Me is not worthy of Me.'" Hard words! But they were the words of his crucified Lord.

They scarcely spoke to one another until they were some distance out of Kovylsk, and could no longer see the glittering domes of its numerous churches. Then Father Cyril owned his bitter disappointment. "It will break my heart," he said.

"The soul is stronger than the heart," replied Alexis. "Now I submit myself to God's will, and leave my little child in His hands. He loves her better than I can; yes, He loves her with an infinite and everlasting love."

"Velia and little Clava shall come to me," said Father Cyril.

Alexis dropped the reins and turned to him, as if he had not heard clearly what was said.

"My wife and I have settled that," Father Cyril went on, with tears in his eyes; "they shall be to us the same as our own children."

"Oh, you good man!" interrupted Alexis. "Oh, how can I thank you? What can I do for you? Oh, if all Batoushkas were like you!"

"I would take them all if I could," said Father Cyril, "but I will find the best houses I can for every one of them. Yarina will take two, I am sure. Then there are seven or eight more. The worst part of the order is that the parents are to have no intercourse whatever with the children, and not in any way to interfere with their training. But they will live in the same village, and see them from time to time, though at a distance. They will know they are all under my protection, and they can always come to the church-house and hear from me, or the Matoushka, of their welfare. Oh, I will do my best for them."

"You will teach them no false religion," said Alexis.

"Oh, as for religion," replied Father Cyril, "they must come to church, and be brought up to observe the Orthodox rites and accept the Orthodox doctrines. There is no way to escape that, but, Alexis Ivanoff, there is salvation to be found in every Church."

The telega stopped at the church-house after nightfall. Father Cyril called to Alexis to come to look through the uncurtained window. There, on a rug near the stove, sat Velia, with Father Cyril's two little daughters, one on each side of her. The children's heads were close together, and their faces shone in the lamplight. They were laughing merrily, and the Matoushka was laughing too.

"God bless them!" cried Father Cyril, as he grasped Alexis Ivanoff's hand.

"God bless you!" replied Alexis.

MOTHERS AND CHILDREN

BUT to get little Clava away from her mother, Tatiania, was a hard task, almost an impossible one. The other parents recognised the absolute impossibility of evading the order of the consistory, and they listened submissively to the arrangements made for their children by the Batoushka, who was supported by Alexis Ivanoff. But Tatiania would listen to no reasoning or persuasion. Her husband had been in prison for nine months, and but for Sergius and Marfa, who had done all the work on their land, and with their beehives, the family would have fallen into dire poverty. They were, of course, much poorer than they had been in former years. But she would not give up her darling, she declared—no, not if the archbishop himself came to take her away. The Matoushka came to entreat her to trust little Clava to her, but in vain.

"Oh, foolish woman!" cried Paraska to her. "You'd know where she was, and how kind they were to her, and you'd see her in the street, and watch her growing up and changing into a girl. And I shouldn't know my boys now if I saw them. They were babies when they took them from me eight years ago, and now—! No, I'd pass them in the road and not know them for my own sons."

It was not until a letter came from Khariton Kondraty, written in his prison cell in Kovylsk, bidding his wife give up the child, that Tatiania yielded, and little Clava went to the church-house, where Velia was already settled.

Profound grief, underneath which lay a presentiment of still heavier calamities, if that were possible, took possession of the little community of Stundists. Every house had lost one or two of its children. Several of the mothers, with their hungry love for their little ones, could not keep aloof from the village church, where alone they could see them and be for a short time under the same roof. Paraska told them they were highly favoured; she did not even know if her boys were living. Alexis Ivanoff in his great pity did not reproach the women for their stolen attendances at the parish church. Velia had returned to him for two or three days before he was compelled to resign her to the care of Father Cyril and the sweet-tempered Matoushka. They had been days of unutterable anguish, the Gethsemane of his soul. After this sacrifice to his faith, no trial could be too bitter.

The old Matoushka, Father Vasili's widow, took care that a report of the return of the heretic mothers to the Orthodox Church should reach Father Paissy's ears. He heard it with a smile of self-satisfaction. At last, then, he had discovered a way of dealing with the Stundists of the diocese.

Michael's spirit in those days was hot and mutinous within him. Not so much on account of Velia, whom he could visit frequently, but for the sake of his father and little Clava's mother, who could hold no intercourse with their children, and who were visibly aged by their grief. Why could not the Stundists do as the Scottish Covenanters had done before them, set up the standard of revolt, and defend themselves until the right cause triumphed? Why should not they strike a blow for freedom—at any rate, for freedom to serve and worship God according to their conscience? Alexis listened to his boy with a melancholy smile.

"First of all," he answered, "because we remember that our Lord suffered His enemies to take Him and crucify Him, though He might have had a legion of angels to take vengeance on them. He said to Simon Peter, 'Put up thy sword into its place: for all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.' 'The cup that My Father hath given Me, shall not I drink it?' Yes, Lord, we must drink the cup that Thou givest us! Cannot God save us, if that be best for us and for our country?"

"Yes," replied the boy.

"That is the chief point," pursued Alexis, "but to revolt would be utter madness. It would mean our extermination. Scotland is a small country, and the Covenanters could easily band together. Besides, the people were mostly in their favour. But Russia is vast, and the people are our enemies, and will be as long as superstition and drink have the upper hand. Here in Knishi, with nearly a hundred parishioners—that is, heads of families—only nine of us are Stundists. Our nearest sister church is in Kovylsk, a day's journey from us; there are some thousands of inhabitants, and not more than a hundred brethren who are quite sound in the faith. Our little churches are feeble in themselves, and lie miles apart. Truly, if we took the sword, we should quickly perish with the sword. We could not combine for resistance; we can only do so for mutual sympathy and help. No, my boy, it is God's will, and we must submit to it."

The Russian people, like all Eastern nations, are fatalists; and Alexis Ivanoff was not without this strain in his temperament. There is an element of peace in it, but not much element of progress. Boy as he was, Michael chafed against it with all the love of freedom, and a desire to strike a blow for it, which he had inherited from his Scottish ancestors. God's will was ever for the right, and this persecution was wrong.