Title: Hearts of Oak

A story of Nelson and the Navy

Author: Gordon Stables

Release date: April 28, 2025 [eBook #75979]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John F. Shaw and Co, 1893

Credits: Al Haines

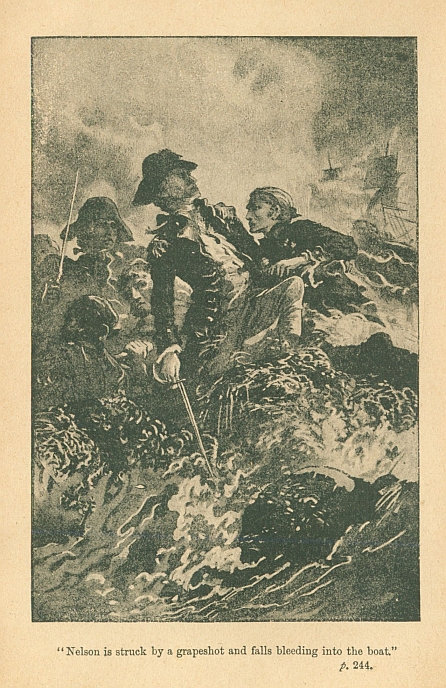

"Nelson is struck by a grapeshot and falls bleeding into the boat." p 244.

A STORY OF

Nelson and the Navy.

By

GORDON STABLES, M.D., C.M.

(Surgeon Royal Navy),

AUTHOR OF "FROM SQUIRE TO SQUATTER;"

"IN THE DASHING DAYS OF OLD;" "EXILES OF FORTUNE;"

"ENGLAND, HOME, AND BEAUTY;"

ETC. ETC.

"'Hearts of oak!' our captain cried; when each gun

From its adamantine lips

Spread a death-shade round the ships

Like the hurricane eclipse

Of the sun." CAMPBELL.

NEW EDITION.

LONDON:

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO.,

48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME.

HEARTS OF OAK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . By Dr. GORDON-STABLES. FOR ENGLAND, HOME, AND BEAUTY . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. EXILES OF FORTUNE . . . . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. IN SEARCH OF FORTUNE . . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. TWO SAILOR LADS . . . . . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. IN THE DASHING DAYS OF OLD . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. FACING FEARFUL ODDS . . . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. GRAHAM'S VICTORY . . . . . . . . . . . . G. STEBBING. THE TWO CASTAWAYS . . . . . . . . . . . . LADY F. DIXIE. HONOURS DIVIDED . . . . . . . . . . . . . W. C. METCALFE. ON TO THE RESCUE . . . . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. BEL-MARJORY. A Tale of Conquest . . . . L. T. MEADE. EUSTACE MARCHMONT . . . . . . . . . . . . E. EVERETT-GREEN. A TRUE GENTLEWOMAN . . . . . . . . . . . EMMA MARSHALL. THE END CROWNS ALL. A Story of Life . . EMMA MARSHALL. BISHOP'S CRANWORTH . . . . . . . . . . . EMMA MARSHALL. FIGHTING FOR FREEDOM . . . . . . . . . . ANDREW REED. CITY SNOWDROPS . . . . . . . . . . . . . M. E. WINCHESTER. COUNTESS MAUD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . EMILY S. HOLT. HER HUSBAND'S HOME. A Tale . . . . . . . E. EVERETT-GREEN. IDA VANE. A Tale of the Restoration . . ANDREW REED. ONE SNOWY NIGHT . . . . . . . . . . . . . EMILY S. HOLT. FOR HONOUR NOT HONOURS . . . . . . . . . Dr. GORDON-STABLES. WINNING AN EMPIRE . . . . . . . . . . . . G. STEBBING. A REAL HERO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . G. STEBBING. A TANGLED WEB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . EMILY S. HOLT. DOROTHY'S STORY . . . . . . . . . . . . . L. T. MEADE. BEATING THE RECORD . . . . . . . . . . . G. STEBBING. BRITAIN'S QUEEN . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. PAUL. THE FOSTER-SISTERS . . . . . . . . . . . L. E. GUERNSEY. A KNIGHT OF TO-DAY . . . . . . . . . . . L. T. MEADE. NEVER GIVE IN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . G. STEBBING. EDGAR NELTHORPE . . . . . . . . . . . . . ANDREW REED. MARION SCATTERTHWAITE . . . . . . . . . . M. SYMINGTON.

LONDON: JOHN F. SHAW & CO., 48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

PREFACE.

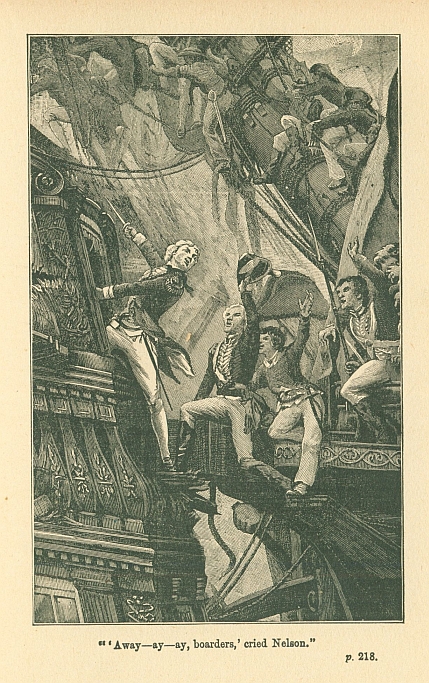

I have no need, I trust, to apologise for the introduction of the name and chief exploits of so great a naval hero as Horatio Nelson into this story of sea life. It is due to my readers as well as myself, however, to state that it is a tale of the sea, and not intended as a life of Nelson. Nevertheless I have endeavoured throughout to paint his character to the life by a series of tableaux vivants, which I humbly hope will not be found altogether ineffective.

With the exception of the calm and peaceful days that Nelson spent at the old parsonage of Burnham-Thorpe, I have dealt solely with his doings and deeds afloat, and from the time he joined the grand old service until the day of his death on board the Victory the sword is seldom out of his hand. My Nelson is Nelson on the quarter-deck. With Nelson at Court, whether at home or abroad, I have nothing whatever to say. The young fellows for whom I write, I know well, infinitely prefer the sailor's cutlass to a lady's fan.

And Nelson is notably a boy's hero; so good, so gentle, and yet withal so brave! And never during all his career was his mind so overwhelmed with his own cares on shipboard, as to preclude him from interesting himself in what pertained to his junior officers, with a tenderness too that was almost fatherly. Another trait in his character that must cause every true boy to look upon Nelson as a hero, was his love of duty and justice.

Says Alison, "He was gifted too by nature with undaunted courage, with indomitable resolution, and undecaying energy. He possessed also the eagle glance, the quick determination, and coolness in danger, that constitute the rarest qualities in a consummate commander."

I pray heaven that in our next naval war—and it cannot be very long ere this rages over the seas—our country may be in possession of a few admirals who shall emulate the dash and elan of our great and mighty Nelson.

* * * * *

Descending to my lesser heroes, young Lord Raventree, and Tom Bure, they are neither greater nor less than any true-hearted British boy may be, who has the honour to draw dirk or sword in the dashing days of warfare which most assuredly are before us.

Descending to still humbler heroes, it will do the reader no harm to know that poor Uncle Bob, and his honest and gentle old brother Dan, have had their counterparts in real life.

So, too, has the faithful collie dog Meg, with all her gentle, winning ways, who so cheered the last sad days of her helpless invalid master.

May we not love even a dog for the possession of virtues higher far than many mortals can lay claim to?

GORDON STABLES.

TWYFORD, BERKS,

March, 1892.

Dedication.

TO

FRANK SMITH, ESQ.,

JOURNALIST, ETC.,

A FRIEND WHOM I HAVE NEVER YET SEEN,

BUT WHO SO VERY OFTEN

CHEERS ME WITH BRIGHT AND WITTY LETTERS,

Himself a Heart of Oak,

THIS BOOK

IS DEDICATED WITH EVERY KINDLY WISH

BY

THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

Book I.

IN PEACE AND AT HOME.

CHAPTER

I. Poor Uncle Bob

II. The Wreck on the Gorton Sands

III. "I see it all," He said; "I see it all"

IV. Uncle Bob tells Tom's story

V. A Mountain Wave comes swelling o'er the Sands

VI. Summer Morning on a Norfolk Broad

VII. The Launch of the "Queen of the Broads"

VIII. "Stay at Home, my Lad, and plant Cabbages"

IX. Horatio Nelson's Earlier Days

X. "I will be a Hero, and trusting to Providence brave every Danger"

XI. "There's a Storm brewing, and you'll be in it, Tom"

XII. "Dan will ne'er be Dan again," they said

Book II

WILD WAR'S BLAST.

I. Tom's Baptism of Blood

II. How Tom Bure joined the Service

III. In the Gunroom Mess—The Great War Game

IV. Were there really Tears in Nelson's Eyes?

V. The glorious old "Agamemnon"

VI. A Duel to the Death

VII. The Battle of St. Vincent

VIII. Life in Nelson's Ship

IX. Bombarding Cadiz—A madcap Expedition

X. A Dark Night's Work

XI. A Happy Home-coming

Book III.

IN HONOUR'S CAUSE.

I. A Gipsy's Warning

II. The Fight on Blackmuir Marsh

III. "Volunteers" for the Navy—The Burning of the "Highflyer"

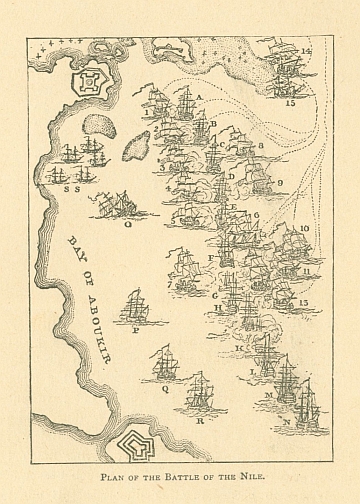

IV. The Search for the French Fleet—At Last

V. The Battle of the Nile—Horrors of the Cockpit—Nelson Wounded

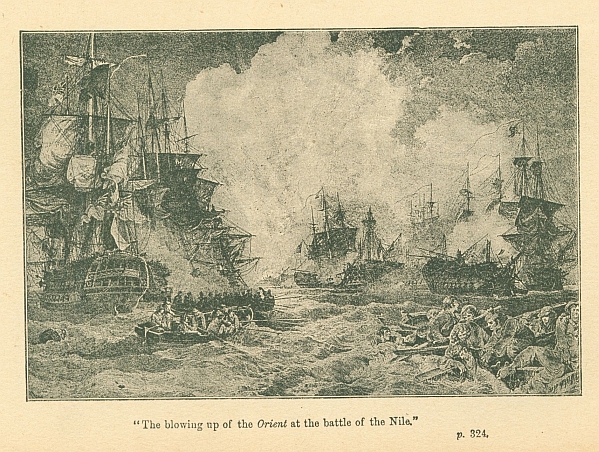

VI. The Burning of the "Orient"—A Heart of Oak

VII. Face to Face with the Danish Ships

VIII. A "Glorious Day's Renown"

IX. Nelson's Last Days and Hours

X. "Jack, I Feel there is Something Wanting in my Life"

HEARTS OF OAK

"Happy Britain! matchless isle,

Whose natives, like the sturdy oak,

Secure in inborn force, may smile

And mock the tempest's heaviest stroke.

"If roused in war, shall dreadful move

Britannia's vengeance on her foes; to prove,

Where'er again her banners are unfurled,

The dread and envy of the wond'ring world."—DIBDIN.

"I wonder what makes Tom so late?" said Uncle Bob to himself, as he opened his eyes and looked around him. "Why," he added, "it is precious nearly three bells in the second dog-watch, as sure as I'm a living sailor. Living! Well, there isn't a deal of life about me, for the matter of that; but I'm right about the time. The shadow of yonder poplar tree just touches my toes at four bells, and it doesn't want a yard of doing so now. I must have been dozing a bit, too. It is a drowsy kind of an evening anyhow. But it was that blackbird in the cherry-tree that set me off, and maybe the hum o' the bees round their hives yonder, and the whispering of the wind in the old cedar must have helped a bit. Heigho!"

Poor Uncle Bob yawned a little, then listened.

"Made sure I heard Tom singing just then," continued the invalid half aloud, "but I dare say it was the sea-gulls. They're coming inland to-night, and I'm no seaman if it doesn't blow big guns before morning."

Uncle Bob talked to himself for the best of reasons: there was no one else to talk to. For little Ruth, his niece, was helping her mother in the house, and Daniel, his brother, had gone to the Hall with a boat. No chance of Dan being home early to-night, for the boat required the heaviest cart for its conveyance, and the mare had gone a bit lame lately.

To have looked at Uncle Bob's face as he lay there in his cot, which had been wheeled out under the shade of the trees on the daisied grass, no one would have taken him for an invalid. His rather handsome face, with its short brown beard and well-chiselled features was placid and contented, nay, even happy and hopeful-looking.

O, yes, Uncle Bob had not ceased to hope. For seven long years and over, day after day, whenever the sun shone, or it was dry weather, that cot upon wheels had been hauled out of doors, where it is now in this sweet May evening, by the sturdy and kindly hands of Brother Dan. Yet if the boat-shed close by had taken fire, poor Uncle Bob could not have lifted hand or foot to save himself from destruction. The paralysis from which this seaman suffered had been accidental. It was this, probably, that gave him hopefulness and made his sad life in a measure bearable. And in certain states of the weather, strange to say, Uncle Bob could move his fingers.

Dr. Downs used to call as he passed by to talk with him for a few minutes, and never failed to tell Uncle Bob that as he wasn't an old man by any means, time might work wonders.

Mr. Curtiss, the curate, a kindly-hearted young fellow from Yorkshire, often dropped round, and would sit and talk to the invalid for a whole hour at a time. Nor did he ever leave without some words of consolation that, to say the least, were well-meant. Bob had very much to be thankful for, the curate would say; he wasn't in pain of any sort; he had his appetite and the use of his eyes and ears, and everybody loved him and was good to him.

Uncle Bob being a sailor, the curate thought it was his duty to always introduce an allegorical ship of some kind in his conversation with the stricken mariner. Besides, wasn't Mr. Curtiss himself somewhat of an authority on nautical matters? Hadn't he been down to the sea in ships—well no, not quite that, but he had made one long and dangerous voyage from Great Yarmouth to London in a herring yawl, which enabled him to talk with some degree of confidence about "green seas," "contrary winds," "luff tackle, main sheets and shrouds," and all the rest of it. Mr. Curtiss meant well therefore, and he never left the invalid without leaving him something nice to think about, without, in fact, leaving him better in mind, if not in body, than he had found him. But after all said and done it isn't everyone who could have lain in a cot all these years so peacefully as Uncle Bob had done.

Brother Dan, you must know, reader, was a boat-builder—not of pair-oared gigs or outriggers, or any of the beautiful dashing boats you see on the Thames and other rivers—Dan's speciality was cobbles, or good, honest, strongly-built, broad-beamed boats, on which you could float on the lovely waters of the Norfolk lakes, and at times step a mast and hoist a bit of sail, without much danger of turning turtle, so long as you sat to windward. Ay, and you might venture a long way out to sea too in one of Dan's boats, and if you kept your weather eye lifting now and then, and your hand on the main sheet, you could crack on very prettily indeed through a lumpy sea-way.

And Brother Dan's house was just over the way yonder, across a little rustic private bridge that brought you here to this half lawn, half paddock, but wholly pleasant and tree-shaded spot, where Bob's cot was safely moored under the shade of the cedar. After you passed the bridge you had to turn sharp round to the right, and on through the garden by a well-kept gravel path, before you came to the porch of Dan's old-fashioned, but comfortable, Norfolk cottage.

Lying out here all by himself, one might have said that Bob looked a little lonesome this evening. And perhaps he was, for with the exception of the blackbird that seemed to be singing to the invalid, and to him alone, he had no companion. Now and then the bleating of sheep in the distance, the low contented moan of cows, or the barking of a dog fell on his ear, and in a small lake almost close by his cot, and over which the shadows of some giant poplars were thrown, half-wild ducks played at hide and seek among the tall reeds, while occasionally a fish leapt up and made rippling rings on the surface of the water, but that was about all of life that was at present indicated.

In fine weather it was cheerful enough for Uncle Bob here, because Dan worked close beside him in the boat-shed, into which he could wheel the cot if a shower threatened. And Brother Dan with his rosy face and his square paper cap, hammering at a boat, or making the white curly shavings fly from his plane was a very cheerful figure indeed.

Over and above all this, Dan's property—he always called it his own property—was situated on high ground, or what is called high ground in this part of the world, for Norfolk is not Switzerland; so that from between the trees Bob could catch glimpses of the far-off country side, at which he never tired looking. For it takes very little indeed to create interest in the mind of the confirmed invalid. The trees in front of him were mostly tall and weirdly Scottish pines, whose brown pillar-like stems hardly obstructed the view. So Bob could feast his eyes on green fields, where sheep and cattle sheltered themselves from the sun's rays under the spreading elms; on an ancient gray-stone hall that rose boldly above a cloudland of foliage; on an archery lawn near it; on the shimmer of a silvery lake or broad, and on the flashing waters of a winding reed-bordered stream. Among the woods to the right and left of the centre of this picture was here and there a touch of red among the greenery of the trees, representing the tiled roofs of farm-houses or cottages. All combined did not make much of a picture perhaps, but it was nevertheless a very peaceful and very pleasant one.

Gazing dreamily at it, Uncle Bob had almost gone to sleep again, when the voice of a young girl raised in song, awoke him thoroughly, and looking up he saw Ruth herself, right on the centre of the rustic bridge, waving a handful of wild flowers towards him. In front of her bounded a beautiful black and tan collie dog.

"Dear old Meg!" said Uncle Bob, as the animal put her fore paws almost on his pillow and licked his ear. "Been away for hours I'll wager, haven't you now, Meg, ranging over the hills and fields and chasing the squire's rabbits?"

The collie leant her cheek against her master's breast, in that inexpressibly pretty way that such dogs have of showing pity and affection combined.

"Hullo! Ruth, my little sweetheart, you look as fresh and lovely as the figure head of the old Queen Bess in a new coat of paint. Come and kiss your old uncle, you rogue. Now I've been picturing you to myself with your sleeves rolled up, washing plates and things in the kitchen; 'stead o' that you've been gathering wild flowers."

"Hullo! Ruth, you look as fresh and lovely as the figurehead of the old Queen Bess."

"All for you, Uncle Bob. Look at the buttercups and the ox-lips, and oh, uncle, just smell those red ragged Robins. See I've tied the posie with grass, and I'll lay them on your breast so you can scent them."

She patted her uncle's brow, and added, "I've wetted both my feet trying to get a yellow iris, so I shall run and change my stockings, and get supper ready 'gainst father and Tom comes home. Ta, ta, uncle. Meg will stop here, so you won't feel lonely."

Ruth was a fresh-complexion, pretty girl of sweet thirteen, with shy dark eyes, blithesome face and a lithesome figure. Mr. Curtiss, the curate, had said more than once, than only to see Ruth going singing about at her work of a morning made him feel good all day.

Uncle Bob was naturally very fond of his little niece, but between our two selves, reader, he was fonder far of Tom; for when the boy was not away at school, or scouring the woods and hills with Meg, he was the invalid's constant companion.

"Tom won't be long now, Meg, will he?" said Uncle Bob when Ruth had disappeared. "Ha! you're cocking your ears, old lady. D'ye hear young master?" Meg emitted just one half-hysterical bark of joy and jumped down.

Her sharp ears had caught the sound of the boy's footsteps on the road not far off, so away she bounded.

A few minutes after, young Tom himself, red and dusty with running, his eyes sparkling with joyous health and excitement, appeared upon the scene.

Instead, however, of coming quietly up behind Uncle Bob, and kissing his brow—for the lad was almost girlish in the affection he displayed for the helpless invalid—Tom stood at the foot of the cot, a Times newspaper over his head, and shouting—

"Hip, hip, hooray—ay!

"Hip, hip, hooray—ay—ay!"

"Whatever ails you, sonny? Where have you been to, and what have you got?"

"Why The Times, Uncle Bob. I walked all the way to the Hall, round by the broad, to borrow it, after my tutor told me the news. 'Cause why, uncle, 'cause I knew you'd like to read the news with your own old-fashioned eyes. Oh! glorious news, I can tell you. That is what Mr. Curtiss called it. The French are going to fight again, at least he thinks so. Won't it be glorious? won't it be fun? After supper Uncle Bob, after supper—oh, not now. It is too good to be scamped and hurried over; besides, I'm so hungry. And, poor uncle, so must you be. But there! I haven't told you all the news. The most glorious part of it is to come. I went to the Hall, you know. Well, I saw Lady Colemore, and she sent the footman into the garden with me to see I should eat as many strawberries as I could hold, and to-morrow, little Bertha Colemore and her maid are going to bring you a great big, big basketful all to yourself, and I'm to feed you with them, and not eat one."

Then Tom laughed so merrily, that he was forced to lie down on the grass and roll, and Meg was by no means slow to follow his example.

Uncle Bob laughed too, though there wasn't anything very special to laugh about, but the sight of happiness in others always pleased Bob.

"Look here, you young rascal," said Uncle Bob at last.

"That's me," cried Tom, springing up.

He stood at attention, after touching his cap.

"Away aloft, young sir, and have a look round the horizon. Take the glass, sir."

"Ay, ay, sir," said Tom. "Away aloft it is!"

And next moment he was swarming up the rigging with all the agility of a practised sailor.

Up and up and up, hand over hand, till his head touches the bottom of the crow's-nest, then he enters it from below and settles himself to have a good look round through the glass.

Now in case this last sentence should seem enigmatical to the reader I must explain. The crow's nest was a hugely large and strong barrel, that had been hoisted up into one of the poplar trees, and firmly secured at a distance of forty feet above board, that is above the level of the lawn. The tree, which was a very beautiful one, with one strong trunk which reached a height of five-and-twenty-feet, then bifurcated into two that tapered skywards for fully fifty feet more, grew almost in the water of the little lake, and strong ratlines or rigging, similar to that on a ship, led upwards to the nest. Above this nest was a kind of Jacob's ladder, up which Tom could swarm for twenty feet higher and seat himself on what he and Bob called the top-gallant cross-trees.

From near the bottom of the nest hung a stout rope, and up this Tom could climb when he chose, or come down by the run.

This out-look or crow's nest was one of the pleasures of poor Uncle Bob's lonesome life. It was a pleasure even to look at it when Tom wasn't there, but when the lad did come home—and his arrival was one of the chief events of the day with Bob—hardly had he exchanged greetings with uncle ere the order was, "Away aloft, lad!" Then standing in the cosy nest, or seated high up on the cross-trees, Tom would keep the invalid informed, for half-an-hour at a time, or even a whole hour sometimes, of all that was going on at sea.

"Now then, lad," shouted Bob, "is the brig still there?"

"How hard the lot for sailors cast,

That they should roam

For years, to perish thus at last

In sight of home."—DIBDIN.

"Yes, sir; and she has dropped anchor at the tail of the Gorton Sands."

"Her skipper's mad," cried Bob; "as mad as a March hare. Why it's coming on to blow big guns from the south-east, or soon will be, and if he doesn't trip it and be off, there won't be a stick of him left together by moon-set. Don't look at him, Tom, he's no sailor."

"Five yawls, sir, tacking through Hewett's Channel. Foremost has got into the blue, filled, and is running north away."

"Thank you, Tom. Fishermen, I suppose."

"There's a three-masted ship, sir, coming straight in from the east, under all sail. But there isn't above a capful of wind."

"Did you say a ship, Tom? Now, be careful."

"Yes, sir; I'll look again. Now she's gone about, and I can see she's a barque."

"Bravo, Tom! But mind you this, lad, I've seen a man had down from aloft and receive four dozen at the grating, for just such a trifling mistake as that."

"Now," continued Tom, "I can just raise the topga'nt sails of a ship far away north. It is a ship right enough, sir. Appears to be on the la'board tack, and standing over for the French coast."

"Fiddlesticks, Tom! She'll be about in half-an-hour."

"Why, sir," cried Tom presently, "four of the fishermen are crowding all sail to the nor'ard, but the fifth——"

"Yes, Tom. What's the matter?"

"She's luffed, and hugging the Gortons!"

"See anything strange about her, Tom?"

"Never saw a yawl so deep in the water before. She can't be going fishing, uncle. I see something else, sir, now."

"Well, Tom?"

"But what are you whistling for, Uncle Bob?"

"I'm whistling for the wind, lad."

"Oh, you needn't, sir! That—that—strange craft is bringing it up with her. But I can't quite make her out. She is long and low, not big; and carries a press of fore-and-aft sail on two thin masts."

"That isn't a very lucid nor very seaman-like description, Tom," cried Bob, laughing. "Has she any top-masts?"

"Ye—es, but——"

"But what?"

"But I can hardly see them. She seems in a hurry, but doesn't carry topsails. She puzzles me."

"Ah, lad, she's playing a game! She's the d——l in disguise, Tom."

"Oh, uncle, if Ruth heard you!"

"That's what shore folks call these craft, Tom. Now the brig must see the strange sail. What are they doing?"

"Why, they're signalling to the yawl, I think."

At this moment the trees caught the wind. The cedar rattled its great limbs as if in proud defiance of any blast that could blow. The pine trees waved their dark heads like the plumes on a Highlander's bonnet. The elm trees rustled, then roared, and the tapering poplars bent like fishing-rods before the force of the breeze.

Uncle Bob laughed aloud.

"Hold firm there, lad," he shouted. His long illness had not weakened his voice. "Don't get emptied out. I knew that I could bring the wind by whistling."

"It is only a squall, I suppose, Uncle Bob?"

"That's all; but there's another to follow, and one or two more to follow that. Then it'll settle down for a dirty night and blow a sneezer. Look at the blackhead gulls going shrieking round your head, Tom."

"But now, lad, tell me what's doing at sea. How does the sea itself look, Tom?"

"Waves all flecked with froth, sir."

"With foam, Tom."

"Yes, foam I mean."

"Well, Tom, say so, else I'll have you down, sir, and introduce you to the gunner's daughter. Liken the waves to white-maned horses if you please, but not to quarts o' beer with good heads on them."

Tom was very busy up in the nest for the next few minutes. There was some little difficulty in holding the telescope steady, owing to the breeze, and Bob noticed that first he would direct it east and by south, then south-east, then east by north.

"Oh, Uncle Bob," cried Tom at last, talking excitedly, "I do wish you could come up here for a few minutes."

"Ah! lad, I wish I could. I'd give my left eye for that pleasure."

"Oh, I'm so sorry! I forgot you couldn't walk."

"Never mind. What's doing, my boy?"

"Why, sir, they've all gone mad."

"The brig was mad before, else she wouldn't have got so close to the Gorton bank. What is she doing now?"

"Shaking loose her sails. And she's getting up anchor to be off."

"And the yawl, the deep one, uncle, has put right about, and is driving north after the fishermen. Wind's gone two points more to the south'ard now."

"I notice that, lad. It's only the play o' the squall. What about the d——l in disguise, Tom?"

"She's mad too. Instead of taking in sail she has hoisted her topsails, and she's heeling over till she looks like a paper kite, or a kite's wake."

"How's her head?"

"She's close hauled, sir, and bearing down towards the brig."

"And the brig?"

"Just ready, sir. Going off on the sta'board tack."

"Close work, won't it be, Tom?"

"At least, I think she is——. Oh-h-h, uncle!"

"What is it, Tom? Speak, boy; tell me, quick."

"Why, she has——yes, Uncle Bob, she has missed stays, and is driving on to the Corton sands. Oh, it's awful, awful!"

A pause of some minutes.

"Now she has struck. Down go the masts, and the seas are leaping over her like wild hyenas."

"Heaven help the poor ship," said Uncle Bob. "What a lubber of a skipper. I told him, Tom—I told him—at least, I told you. I don't know exactly what I'm saying, Tom. But what's the yawl doing?"

"Carrying on, sir, heading right away north. But it's getting so dark, what with the rising clouds and the dusk, that——."

"You're sure, Tom, the yawl is cracking on?"

"Sure, sir."

"The dastard, not to help her consort."

Tom looked down from aloft.

"The wind caught the last word, Uncle Bob," he shouted. "I didn't."

"I said 'consort,' Tom," cried Bob. "You don't understand the drama that's being enacted before your eyes. Tom, it's a tragedy now. That brig is or was a smuggler. They're not so likely to suspect lubberly brigs of playing that game. The yawl was coming down with a cargo to her. See, Tom. And the d——l in disguise is a government sloop."

"I understand now. But, sir, I can just see that a boat has been lowered from her, and is making straight for the wreck with a bit of sail set."

"Bravo! bravo! I hope they'll save the men. The skipper deserves to be choked in the Gorton sands. Now, lad, come below. Here is Ruth, just heaving in sight at the other side of the bridge. Ah! Ruth, lass, there is terrible news. The brig we talked about in the morning has gone on shore on the tail of the Gorton bank. Heaven help them, little sweetheart; but I fear by this time it is a sad case."

Ruth put the end of her apron up to her eyes as if to shut out the terrible vision of breaking spars and timbers, rolling surf, and waves more than houses high.

"Come, Ruth," said Tom, touching the girl on the shoulder, "let us wheel Uncle Bob home over the bridge. There is no time to lose."

"Why what does the boy mean?" said Uncle Bob.

"Wait, uncle, till you're in the house, and I'll tell you. Come, Ruth, you pull and I'll shove. Heave-o-ee. There she goes. A little more to sta'board, Ruth. That's it. Now then, steady as you go; a long pull and a strong pull. Ruth, you're a beauty. What a capital sailor's wife you'll make!"

Talking thus, with Bob smiling in spite of himself, in spite of the tragedy he knew was at that moment being enacted on the Gorton sands, Tom and Ruth speedily wheeled the invalid's cot towards and right into his own wing of the cottage.

If ever a helpless man had a kind and thoughtful brother that man was Uncle Bob. The whole aim and object of Daniel Brundell's life, indeed, seemed to be to make the lad—as he often called Bob—happy and snug; and in this good work he had a most faithful helpmeet in his wife. As regards inventing invalids' comforts, I do believe that such a man as Dan would in our days make his fortune. Let us follow the cot on wheels for instance. Not into the house by the main doorway was it taken, for it could not have been turned, but into what was called 'Uncle's wing,' the door of which, although surrounded by a rustic jasmine-covered porch, opened straight into the room. Once inside, the cot was wheeled broadside on to a small bed of the same height, a block and tackle were attached to the upper or hammock portion of Bob's cot, both at the head and at the feet, Ruth hoisted one end and Mrs. Brundell the other, and lo! in ten seconds uncle was raised and swung easily and carefully on to his bed.

Then the cot was wheeled out to a dry shed till it should again be required; the invalid's head and shoulders were raised, and he was snug and happy for the evening. As a rule Tom fed the poor fellow, but to-night the lad had something else on his mind.

"I'm going to drink a pint of milk," he said, "and put some bread and cheese in my pocket to eat by the way, then run all the road to Lunton Cave, and get Ashley's yawl under way to go round Gorton. They'll meet the navy boat, won't they, uncle?"

"Why, boy," said Bob, "as soon as the navy boat saves whom she can off the brig she'll stand off for the sloop, and be picked up."

"That she won't, uncle. I saw what you didn't."

"Well, boy?"

"Just before I came down I had another look, and could see that the Government craft had filled sail, and was standing right away north in pursuit of the yawl. So, of course, her boat will run in shore and try to land at Gorton, or head away for the north pier at Gorleston. Am I right, uncle?"

"Why, lad, I'm proud o' you! My own bringing up too. Right? Yes; an admiral of the fleet couldn't be righter. Well, God speed you, Tom. Strikes me, though, that the disguised sloop has all her work cut out if she means to overhaul that yawl. They'll slip their cargo over the bows without being seen, and the lighter she is the faster she'll fly. Besides in the dark and storm——"

"Not so dark, though, uncle. There's a big round moon peeping up already. But, good-bye, uncle, mother, and Ruth—I'm off."

And away he went, and certainly very little grass grew under his feet ere he reached the fisherman's cave.

Ashley was there himself, and his two sons also, and Davies, a Welsh fisherman, who lived at the cave. The yawl too was all ready in a little artificial harbour the men had dug close to the cave in which they lived.

Tom soon told his story, and the men were in no way loth to try their luck at piloting, as they phrased it.

"But," said Ashley, "it'll be a dirty night, and we'll have to work every inch o' the way to windward. Never mind, boys, it's to save precious life!"

"Yes, yes," said Davies, "and doubtless we will have the king's money too, into the bargain, Mr. Ashley."

Old Ashley looked at the man and laughed.

"Take care," he said, "you don't have to take the king's money in a way you'd little relish, now you've married a nice young wife."

Ashley's sons laughed, and the Welshman was silent. The owner of the yawl went up the steps to the door of the cave, which by-the-way had once been a smuggler's den, but was now a comfortably-furnished house, high above the sea-level, except during very high tides.

"You're surely not going fishing to-night!" cried Mrs. Ashley, a tall, lanky woman, as brown as a gipsy.

"What if I were, good wife?" answered the old man gruffly. "Haven't I been out on many a dirtier? See to it that you have plenty of hot water, and some supper. We're expecting company."

"Maggie," he added, addressing a young and pretty woman, "you help mother. There's been a wreck on the Gorton, and we're going to bear a hand in saving life."

"All right, daddy," said Mrs. Davies.

He beckoned to her, and she followed him out.

"Is the brick cave safe?" he asked.

"Yes, daddy," she answered, surprise and alarm depicted on her face. "But——are they friends?"

"No, not quite. Revenue."

Maggie nodded and smiled, and went indoors.

In a few minutes more the sail—all that could be carried—was hoisted, and the yawl rushing out into the mist and darkness of a squall, the spray dashing inward over the bows, while the cutwater, rising and falling, struck angrily at each advancing wave.

The Fairy yawl was a handy little craft, and, sub rosâ, had been found handy in many ways as well as in fishing. The Ashleys used to boast openly in Yarmouth harbour, that in the Fairy they could go anywhere and do anything, high water or low, blow or fine. And everybody admitted that the Fairy's crew were just as daring as they looked.

It really wasn't all for the sake of gain, however, that the Fairy was now braving the dangers of this ugly night, nor had Ashley anything at all to do with the brig that had gone on shore. The old man really had a good heart of his own, and he could not have borne the thoughts of men drowning or clinging to the hull of a wreck without his doing his best to save them.

"I don't think you should have come, boy," he said kindly to Tom. "Here, get inside this spare oilskin, or bury yourself in the cuddy."

"Thank you, Mr. Ashley," said Tom, putting on the oilskin and an old sou'wester, "but I like to look about me."

The sky soon cleared, and the moon was now well above the horizon, and as they bore away on the sta'board tack everything around seemed as bright as day. Indeed to Tom the cliffs on the shore they were soon approaching looked most dangerously near.

But to old Ashley at the helm all was plain sailing. He could read the sea around here, and the wild sand banks, and rock or cliff and cloud, as one reads a book.

"Be good, be honest, serve a friend,

Are maxims well enough;

Who swabs his brows at other's woe

That tar's for me your sort;

His vessel right ahead shall go

To find a joyful port."—DIBDIN.

No yacht ever sailed more closely to the wind than did the Fairy. She needed all her powers to-night however to beat to windward, and indeed there must have been times, while the squalls were at their worst, when she was hardly holding her own.

Old Ashley, with his bronzed and wrinkled face, was the very image of an ancient mariner. His wet oilskin and sou'-wester glittered yellow in the moonlight, his wet face glimmered red, his eyes positively shone at times, despite the fact that they were almost hidden by his bunchy eyebrows. Many and many a gale of wind the old man had stared into, his eyes seemed formed indeed to face the tempest and the spray from dashing waves.

As he lay there snugly curled up in his oilskins, the boy, young though he was—but little over ten—could not help admiring the old man's coolness and courage, nor the way he steered.

His sons, and Davies too, sat grimly staring ahead and watching the sea, but ready to spring to sheet or tackle at the first word of command.

They had been out nearly an hour and a half, and in that time had hardly made two miles of southing. Hardly anyone had spoken all this time, certainly there had been no attempt at conversation, but now just as the moon escaped from behind a great grey snowy-edged cloud, Davies half rose, and pointing ahead and to windward shouted:

"I was see her! I was see the boat! Look you quick, Mr. Ashley!"

Luckily the wind had gone down between the squalls, when they drove near the boat, a voice from which came loudly calling for assistance. It was answered by Ashley himself.

The sloop's boat had her mast carried away; she was swamped, and, loaded as she was, would soon have gone down.

Ashley passed her with a cheering word or two, put his yawl prettily round, lowered his mainsail, and driving down under his jibs ashiver, and little after sail, laid the boat aboard in the neatest way imaginable.

With some further skilful management everybody was got on board, with the exception of two left to bale, and the boat was taken in tow.

It was a lieutenant of the Royal Navy who came on board with his men and prisoners—five only had been saved off the brig—about a third of her crew. The officer was in undress uniform, but armed with sword and pistols, and he was proceeding to thank old Ashley, when that ancient mariner gruffly told him to "flop down out o' the way, else how could he steer."

The lieutenant said no more. But presently the yawl drew in near the shore, for she had been positively flying before the wind.

"Stand by," roared Ashley, "to lower away."

So quickly did the Fairy come round, that the proud lieutenant found himself down to leeward with his sword between his feet, and his cap in the sea. Next minute the yawl was in harbour.

"'Scuse me," said Ashley, "if I talked a bit rough. We aren't much used to king's officers here away. What, lost your cap? Here, take mine."

The ancient mariner pulled his own sou'-wester off as he spoke and clapped it unceremoniously on the lieutenant's head, almost extinguishing him. But the officer laughed right merrily, again thanked Ashley, and then gave orders to his men to form a guard round the prisoners, who had already begun to cast sheep's eyes towards the cliffs, as if they'd like to be off.

"Come, sir," said old Ashley, "follow me up the steps, and all your merry men. What's your name, captain?"

"Merryweather, at your service, my good fellow."

They had just entered the lower and outer cave, a large room with a rough deal table and wooden benches, but well lighted with whale-oil lamps. Old Ashley turned to his guest, and laughingly edged the brim of the sou'-wester off his brow, exposing the whole features of a sun-bronzed but pleasant face, slightly disfigured, or, let us say, rendered all the more interesting, by a white scar there over brow and cheek.

"Did you say Merryweather? Well, 'scuse me, but durn me if ye look the least little bit like a merry-weather sailor. Got that cut across your figure-head by fallin' on a foot-stool in church, eh?"

And Ashley laughed at his own joke till the cave rang again.

Meanwhile the sailors and their prisoners crowded in sans ceremonie.

"Sit down there, lads," said Ashley; "you'll all have bite and sup before long. Captain Merryweather, this way, sir, please."

Up another staircase, through a short passage and into another cave, far better furnished and more brilliantly lighted than the last. Here, May though the month was, a fire of peats and wood burned on a low hearth, and Ashley pointed to a chair near it and bade his guest sit down.

A table stood near, and presently Mrs. Davies bustled in and laid the supper, the captain rising and bowing to her most gallantly. A huge dish of potatoes boiled in their skins, and a great joint of beef, the steam from which went curling to the cave's roof.

Ashley went to the door, and shouted down to the under cave. "Below there, sons! see that those poor fellows have plenty o' bread and fish and beer. Tom Brundell, what are you doin' down there? Come up here, quick."

Tom entered shyly, and threw down his hat.

"There, captain," cried Ashley, "that's the chap you have to thank for savin' your life."

Tom turned as red as a beet at first, but in five minutes he was perfectly at ease, and thought this officer was by far and away the most pleasant gentleman he had ever met in his life.

But it really was love at first sight with both of them, and Merryweather was soon laughing right heartily at Tom's description of the poplar tree rigged like a ship's mast, and the crow's-nest and cross-trees and all the rest of it.

"And whose idea was it, my boy?"

"Poor Uncle Bob's, sir. At least, he isn't my uncle, sir, but he brought me home with father from Jamaica, where I was born. Father was drowned, you know, sir—at least not quite drowned, because he lived some time after—and Uncle Bob's brother Dan, my daddy, you know, reared me. He and old mother, who isn't mother exactly——"

"Stop, stop, boy! Why I am getting mixed, or you are getting mixed, or—— Oh, I know how it is! Mr. Ashley, that rum of yours, that you say has never paid duty, has gone to my noddle. Now, Tom, my brave lad, will you begin again?"

Ashley laughed right pleasantly now.

"Why," he said, "that little birkie has a story to tell, or there's a story to tell about him. It's too long though; besides, here is Mrs. Davies and my old woman waiting."

"I beg a thousand pardons," said Merryweather, jumping up and drawing a chair towards the table. "What a pleasant home you have, Mrs. Ashley!"

"Handy enough at times," said the old lady.

Mrs. Davies trod on her toes under the table.

"Mother means," said old Ashley, "that it is a good habitation in fine weather; but when the sea takes charge o' the downstairs, and sobs and sighs against the door here, why it ain't quite so cheery. Now heave round with the beef. The 'taties grew over your head on the cliff-top, and, as I said afore, the rum never paid duty. Fine thing to tell a king's officer. Ha! ha!"

"Now Tom, birkie, fill the captain's glass."

But though this story dates back to the old drinking days, Merryweather was a very abstemious officer. He was very much pleased, however, with his strange surroundings, and after supper sat long in the easy chair, smoking and listening to stories of the time when this had really been a smuggler's cave.

"But now," said Merryweather at last, "I must go to my boat and try to snatch a few hours' sleep. The little Porcupine may be back to-morrow, and then——"

"Back to-morrow, eh?" said old Ashley, laughing. "No, sir, not if she means crackin' on after the Dorothy yawl."

"Yes, and my mate'll have her too," said the lieutenant.

"Oh, sir!" said Tom, blushing at his own boldness, "do come home with me. Father and mother have a nice little spare room, and——"

"Why, Tom, you said your father was drowned? But come, my lad, I'll go with you, if it isn't too far."

"Only about a mile, sir, and I'll be up and down to the crow's nest all the morning, and will see the Porcupine ten miles away."

"I'll go, lad."

In another minute the ancient mariner had conducted his guest by a private staircase to the breezy cliff-top. Merryweather shook hands, and off went Tom and he together.

When they reached home, Meg came joyfully barking to meet them, and there was the wagon in the yard, and Tom could hear the mare stumping her lame foot in the stable; so he knew that daddy had come.

There was a light in Uncle Bob's window, and it occurred to the boy that he might as well take Lieutenant Merryweather in here first. So he began to sing, which was the invariable signal to Uncle Bob that announced his arrival.

Tom opened the door a little way and peeped in. "May I come in, Uncle Bob, and bring—a friend?"

"Come in, you young rascal. Wager two-pence you've got one o' the crew o' the d——l in disguise with you."

So in walked Tom.

And in marched the officer.

But certainly the boy was not prepared for what followed. Uncle Bob had turned his eyes towards the door, but they positively seemed to grow as large and round as saucers when they alighted on the sun-browned features of Lieutenant Merryweather. Nor did the latter appear one whit less surprised than Uncle Bob. But he recovered himself sooner.

"What!" he cried, "can it be possible? My old shipmate, Bob Brundell, that sailed with me for years in the old Turtle, and was in my own watch? Wonders will never cease. Why I heard you were drowned ever so long ago. Wonders never do cease; but tip us your nipper, for auld lang syne."

Then Uncle Bob's face fell, and tears sprung to his eyes, aye, and trickled over his face.

"Ah! sir," he said mournfully, "poor Bob is on his beam ends, and couldn't move a toe if the ship was on fire."

"Oh, this is inexpressibly sad," said Merryweather. patting his old shipmate's cheek. "But there is hope, isn't there? Ah! here comes your elder brother. I knew him at once from you, Bob. How d' ye do, sir? Glad to make the acquaintance of my old friend's brother. How glad I am to see you both!"

"Tom," cried Uncle Bob, "bring my pipe and light it for me. Sit you down, mate. Well, you were mate you know in the dear old days, though now you're lieutenant. Sit down, brother Dan. Thank you, Tom. I do believe the young rascal'll soon learn to smoke just with lighting my pipe. What's the time, youngster?"

"Just gone one bell in the middle watch," said Tom seriously, after consulting an old silver turnip that he pulled with an air of manliness out of his fob.

"Going to be a sailor, my boy?" said the lieutenant, putting his hand on Tom's head.

Uncle Bob answered for him.

"Why, old shipmate," he said, "he's almost a sailor already. And he was born in the service."

"Oh, by the way," cried Merryweather, "I must hear the lad's story. It's mixed up with yours I know, Bob. One bell in the middle watch is no time at all, so heave round with your yarn."

"I'll heave round," said Bob; "but brother Dan's mixed up in it too, so he'll have to put a hand to the wheel as well. Light your pipe, Dan. Ah! if you only knew what a dear old brother Dan is to me, Mr. Merryweather——."

"Hush, hush," cried Dan.

But Merryweather stretched out his white, soft hand, and squeezed the rough, red fist that Dan put in it. "I can see it all," he said. "I can see it all. Now, Bob, it is you to begin the story."

"If to engage they give the word,

To quarters all repair;

While splintered masts go by the board,

And shots sing through the air."—DIBDIN.

"Mr. Merryweather," Uncle Bob began, "it's many years since the old Turtle was re-commissioned out at Bermuda, and you and I parted."

"That it is, Bob. Ten, if a dog-watch."

"And you stopped in the tub, as we used to call her, and I went out to join the Billy Ruffian at Jamaica. Now, mate—for mate I will call you, though you're a bold lieutenant now—take a hold o' young Tom there, and turn him round to the light. Focus the little chap right, and see if he doesn't put you in mind o' someone you know."

Lieutenant Merryweather did as he was told.

"Why not Miss Raymond, surely? Yet indeed he does. The dark eyes, the small mouth and nose, and all complete. Come, Bob, I shall listen with more marked attention to this yarn of yours, now."

"Well, first and foremost, it must be pipe down hammocks as far as young Tom is concerned," Bob began.

"I'll turn in at once, Uncle Bob," said Tom.

So he bade good-night to all hands and trotted off.

"Did you say ten years, mate, since you and I parted? Why it's going on for a round dozen. Let me see, I'm two-and-thirty, and you can't want a deal of thirty."

"Worse luck, Bob, and only lieutenant yet. Should have been promoted long ago. Don't think me on the swagger, Bob, if I say that my services have been meritorious enough since I saw the last of you. But I've seen youngster after youngster promoted over my head. More interest, Bob; more interest!"

"Well, Mr. Merryweather, you were a jolly young waterman anyhow when I left you in Bermuda. And it was about this very Miss Raymond you fought the duel on the very morning after the ball—aye, and winged your soldier too."

"So it was, Bob, and I remember how sleepy I was. But I resolved not to take life; so instead of firing at the major, I took aim at a bunch of bananas that hung on a tree some yards to his right."

"Yes," said Bob, laughing, "and that was why you hit the major. If you'd aimed at the major you'd have hit the bananas. Plucky little fellow, though, he was, for even when the surgeon was probing his arm with his pipe-cleaner he apologised to you most handsomely. Think I see him yet, reclining in his second's arms on the grass, and you standing forenenst him, stem on, and taking all the honour and glory of that shot. 'Sir! It was a pretty shot,' cried the major, 'and I owe you my life. A man who could rip open his opponent's pistol arm so neatly as that could have put his bullet through the bridge of his nose and spoiled his beauty for life. Excuse my left hand, sir, but I want to grasp the fist of a brave and generous gentleman.'

"'I don't believe in taking life, major,' you drawled out, 'when it can be avoided, and so——'

"'And so you wing your men. Bravo! I shall remember that, and sir, you must dine with me as soon's I'm out of the doctor's hands.'"

"Did you dine with him, Mr. Merryweather?"

"I did, Bob, and he proved a brick; but then the bone of contention, pretty Miss Raymond, had disappeared. I' faith, Bob, I did fall in love with that girl, head over heels, and if she'd asked me to cut the buttons off my coat, and pitch them at the admiral's head, I'd have done it. But heave round, Bob."

"Well, mate, Miss Raymond came to Jamaica with her father the colonel. There were some disturbances in the bush, and Commander Bure was sent on shore with a party of bluejackets to support the soldiers. Why these Joeys were behaving about as silly as silly could be, marching through the country with drums and pipes, to attack an enemy that killed them right and left from behind the scrub and the bush, but never showed a head. We altered all that, we took the enemy in the rear, we never piped, and we never drummed, but we killed 'em by the score, and the prisoners we hung like herrings on the trees. It was wild work, but it had to be done."

"Well, mate, Bure, our good commander, was a very active gentleman, he would push on, and he would show himself at times when he didn't ought to; so he got downed, ay, and would have been scuppered too, if I and my mates hadn't rushed in and drove the butchers off."

"Where did you drive them to, Bob?"

"Made flies' meat o' them, sir. But the commander swore I'd saved his life, and he would make me his servant, and have me always about him on shore or afloat; and when he got engaged to Miss Raymond, why, mate, it was me that carried all the billy-doos back and fore, you know. Sometimes I'd be ashore and off again twice in every watch. Well, Mr. Merryweather, what with all the billing and cooing and billy-doo-ing the commander and she got spliced at last. Ah! that was a spree, I can tell you. And a sweet bonnie bride the charming lady looked!"

"Hush, hush, Bob; you're opening old sores."

"Well, mate, the commander was nearly always on shore after this, and our old captain—O'Hare was his name—told Bure one day straight to his face that marriage made muffs of men, and spoiled 'em for the service."

"It was pretty nearly ten months after my good commander's marriage that we hove up anchor and went off east to look out for some flighty Frenchees, that were playin' fast and loose with our merchant ships that scorned to go in convoys. I never saw anything in my life, mate, so affecting-like as the parting atween the commander and his young wife—she in tears and clinging to him, and he——, well, it doesn't do to say that a sailor pipes his eyes, but la! sir, I was glad when it was all over and our boat was speedin' away towards the ship.

"For six mortal months we kept our weather eyes open looking for the Frenchee's cruisers, and then we came up with two. And—why they must between the pair of them have carried twice our number of guns.

"We crowded all sail, mate, put her dead afore the wind, and the race began. We were running away though, and however the Frenchees didn't see through the caper is more than I can tell. In less than half an hour there was three-quarters of a mile betwixt the foremost Frenchee and her consort. So we got ready for action without making any extra fuss about it. Then we wore ship, and the captain of that foremost frigate must have begun to scratch his head. Seems to me, Mr. Merryweather, he knew just as much about navy tactics as a cow does about chess. Presently she put about though, with signals flying to her consort—signals of distress we called them. When near enough we sent a round shot or two roaring through her rigging, but if the Frenchee thought our game was to be a stand-off fight he was miserably mistaken. Under one pretence or another, and always firing another shot or two, we got far enough to windward to bear down on her with a beam wind. Why we were near enough to shave her stern almost when we raked her. I think her wheel and steersman must have been blown up to the moon. Down went her mast, and before the confusion was over we had tacked and filled, and come up on her port quarter. Our master laid the Ruffian aboard as prettily as you please, and next minute we were on the Frenchman's decks.

"It was hammer and tongs for a good five minutes, then, on a blood-stained battle-deck, a smiling and bowing French officer gave up his sword to our bold Commander Bure.

"O'Hare complimented him when he returned on board. 'Marriage,' he said, 'may make muffs of some men, but it hasn't taken the heart of oak out of you, Bure.'

"I must make a long story short, Mr. Merryweather, for it's two bells if it's a tick. Almost the first man to board us when we got back to Kingston harbour was Colonel Raymond himself. I knew the moment I saw him that poor Mary, as my commander called her, was dead. But I'll never forget the state of utter collapse—the doctor called it that—I found Bure in when I entered his cabin.

"'Oh, Bob, Bob,' he cried, 'My poor Mary! my poor Mary!'

"He was weeping like a school-girl, the self-same hero that had received the French commander's blood-stained sword.

"For months Bure never laughed or smiled. His chief pleasure and delight was to go on shore and play with or talk to his baby boy.

"Well, mate, we stuck together all the commission, and did a bit o' fighting too whenever we had the chance. To tell you the truth, after poor Mrs. Bure had been dead about two years, there were only just two situations in which you might have said the commander was happy—one was when little Tom was brought on board by his nurse, and the other when Bure had a sword in his hand, and was boarding a frog-eating Frenchee.

"But it was in a boat action that my dear commander received a shot that, for the time being, seemed to have clean knocked the life out of him, and—I do think even now—was the beginning of the end. He lay in hospital on shore for a long time, three months I think, and it wasn't till the end of that time that the doctors found the bullet. The beggarly thing had entered his shoulder in front, and instead o' lodging there as a respectable bullet ought, it must go on a cruise on its own hook, and was finally fished out of the poor fellow's side.

"'Bob,' he said to me one day, sometime after this, 'they are going to send me home with a batch of invalids in convoy. I'm not sorry for my little lad's sake, but, mind you, I don't think I'm going to weather this illness.'

"I tried to laugh away his fears, but he stopped me.

"'Belay that, Bob!' he said, or words to that effect, 'and listen. I like you, Bob, because you're a good, faithful fellow.'

"I felt ashamed like when he told me that, and maybe he noticed it, for he spoke up.

"'Oh, yes, you have been faithful to me, Bob, and you love my little chap Tom. Well, Bob, I'm not saying that I can't weather this, the doctor says I may; but just for the present, imagine that you're listening to the words of a dying man. You're like myself, Bob, a Norfolk man, and, singularly enough, you come from the very coast where relations of mine have estates that might—mind you, Bob, I only say might—eventually belong to my little fellow. But—are you listening, Bob?'

"'That I am, heartily, sir,' I replied.

"'Well, Bob, my cousin, who owned these estates, is dead, only a month ago. He leaves behind him a son some years older than Tom, and a baby daughter. Now this baby daughter doesn't count, the son is the owner, and the mother, who loves me, Bob, about as a much as a Frenchman loves red-hot shot, holds the estates in his behalf. I hear the lad is sickly, and if anything happened to him I'd come in, if alive, and if dead, my little Tom. If there was no little Tom, Bob, the estates would pass to her ladyship's male relations, second cousins of mine and hers, for there has been marrying and inter-marrying, Bob.'

"'Well, sir?'

"'Well, Bob, you see that box?'

"'Yes, sir.'

"'Look to that, Bob, if I should die. Take it with you to your brother's house when you go there. If your brother is half as good as you, Bob——'

"'He's twice as good, sir,' I cried.

"'You and he will take it to my Yarmouth bankers, and they will keep it safe for Tom.'

"He held out his hand—a thin white one it was—and I gave him mine with a heave O! and a hearty O! and the compact was made.

"'About little Tom, here,' he said after a pause. 'I don't want him to be a sailor you know, but if he wants to be—why he must be.'

"'And his friends and relations, sir?' I made bold to ask.

"The commander laughed bitterly.

"'Friends, he has none,' he replied, 'except his father, you Bob, and perhaps your brother.'

"'Well, sir,' I said, 'I hope it won't come to that.'

"'Hush! Bob, hush!' he said, 'It is our duty in this world to be always prepared for the unseen.'

"Well, Mr. Merryweather, I thought my poor commander was much better after this. So indeed he told me. 'I've relieved my mind, Bob,' he said, 'and the doctors have relieved my body.'"

"After this he would chat with me for an hour at a time, about the quiet and happy life he meant to lead on shore with his little son. How they would shoot and fish on the broads throughout all the long summer days, and how they'd live in a pretty little cottage in the land o' poppies, all surrounded by gardens and shrubberies, and how he himself would attend to the boy's education, and try to make a man of him, fit to take his place in the battle of life, whether that battle was to be fought on shore or on the deep blue sea.

"Our voyage home in convoy was a long but not very eventful one. It was long because the fleet o' merchantmen guarded by the convoys was a very big one, and some kept dropping behind, or getting lost, and as there was always, or nearly always, a Frenchman or two hovering like hawks about us, we had to be cautious I can tell you.

"But long before we reached the Downs little Tom had received his baptism o' the briny, there wasn't a doubt about it. He was the pet of the ship, he was dressed like a little tar, and looked it all over. I only wonder he never tumbled overboard, for I've seen the young nipper half-way up to the maintop, and nobody near him.

"One day he told his father on the quarter-deck that he was going to be 'a sailor man, and nuffin else, and fight the Flenchman for his king and country O!'

"I daresay some of the blue-jackets had piped this into him, but his father looked about to where I was standing laughing—I couldn't help it—and said, 'Ah, Bob, I'm afraid it's born in him.'

"'I'm afraid so too,' I said, and his father kind o' sighed, but didn't say any more.

"We got into the Downs at last safe and sound, and lay there wind-bound for a fortnight. But at last we got just the breeze we were waiting for, and slipped away past the North Foreland, and in a day or so more our ship was safe in dock.

"I wrote to brother Dan here, and told him my master and myself would start for Yarmouth within a week in the saucy Polly Ann.

"But there, now, Dan will tell you the rest, but just stick my pipe in my mouth first, Dan.'"

Dan cleared his throat, lit Bob's pipe, and sat down near his bed to hold it for the poor helpless fellow, while he himself continued the yarn.

"His form was of the manliest beauty,

His heart was kind and soft;

Faithful below he did his duty,

But now he's gone aloft."—DIBDIN.

"When I heard," said Dan Brundell, "that there was a brig ashore on the tail of the Gorton Sands, I had no more notion that it was Bob's Polly Ann than I have o' what the weather will be this day month. I'd been down with some oars Gorton ways, and I met old Ashley while returning.

"Would I volunteer, he said, to go in the Fairy; one of his sons was from home, and we might, he said, pick up a bit o' salvage, as well as flotsom.

"'She's hard and fast now,' he says, 'but is bound to break up.'

"So I thought too, when I embarked, for it was blowing 56-pounders, and a heavy sea tearing in from the east. It was the heavy, tearing sea that did it. 'Fore we had got well abreast o' the Gorton Tail, we could see in the bright moonlight the dark hull o' the brig, both masts snapped short off, lifting and falling in the jaws of the foaming seas like a creature in agony.

"'She can't stand it for half-an-hour," said Ashley; 'and what's more, Dan, we can't get anyw'eres near her. There'll be widows a-weeping to-morrow mornin', mate, at old Yarmouth docks.'

"But what we saw next astonished Ashley himself, though, man and boy, he'd been on the water all his life. It was a mountain sea coming swelling over the sands and swallowing everything up before it, and lo! sir, in a minute more, there was the dark hull of that brig being borne bodily toward us.'

"What happened after this I can't well describe, bein' as how I'm slow o' speech like, but in half-an-hour all the beach for a mile and more, was strewn wi' wreck, and many a body was washed in on the surf and left dead, or for dead, on the sands. But lawk! sir, you could have knocked me down with a sledge-hammer when, on turning over one of these bodies, I found it was poor Bob yonder, and no one else."

"He had a small deed-box alongside him, with a piece o' manilla round it. He had come ashore with this. I didn't doubt that, even then.

"At first I thought him dead. But he soon opened his eyes and spoke.

"'Haul me high and dry,' he said, 'high and dry, dear brother, for I can't move. It isn't drowned I am at all. It's a stroke, Dan; a stroke."

"This was a sad sort of a meeting 'twixt two brothers that had always loved each other same as Bob and me has, and for the life of me I couldn't have spoken then, no, never a word. I tried to swallow back my grief and tears, as it were, and lifted the lad right up in my arms, and carried him away beyond the reach o' the raging surf, and there I laid him down. I knelt beside him there in the pale moonlight. I cared for nothing nor nobody just then, but only Bob. I noticed though, that his eyes and head were turned wistful-like towards the boiling sea.

"'Dan,' he said, 'bring the box and put it close by me. Thanks, dear Dan; you were always good. Now go at once, Dan, and look for Captain Bure and his little boy.' It wasn't long either 'fore I found 'em. The poor little tot of a chap with long, silken hair, and bonnie black eyes, was weeping and wailing over his father.

"'Oh, sailor man,' he said to me, 'poor pa! poor pa! He's deaded! he's deaded!'

"'No, no, my little man,' I answered. 'Your father isn't dead.' So I hurried away and got the gentlemen into the cave. Gentle and simple, dead and maimed and living, they all lay there, with the cold moonbeams glinting in through the doorway, and struggling like wi' the yellow rays of the whale oil lamp.

"In two hours' time the doctor had come, and we—the living ones—began to gain hope and courage.

"The good man did all he could for everybody, and next day Captain Bure, with his little boy Tom—yes, Tom that has just gone to turn in—and poor Bob, were fetched in the boat waggon to our cottage here. The captain was soon able to get about, but Bob lay quiet enough, and never yet has he lifted hand or foot.

"But it wasn't a stroke, the doctor said, not of the 'pplexy, anyhow. 'More likely,' he said, 'it's been a stroke with a floating spar, and the neck is injured right smart.'

"Well, sir, it would have done your heart good to have seen how kind and attentive the captain was to Bob. 'He's been my nurse many's the time,' he said, 'and now, Mr. Dan, it's my turn.'

"But all the time I could see as plain's I see the moon shining on the curtains yonder, that the poor captain himself would soon be under the daisies and grass."

"One morning, says the gentleman to me smiling-like, 'I'm going to charter your boat-waggon to-day, Dan, if you'll come with me to Yarmouth, and young Tom'll stop with Bob till we return.'

"It was a lovely day, sir, with the birds all singing as if their hearts were swelling with the joy that was in them, and their feelings had to find vent somewhere in song, or in lofty flight. So we drove round by the big hill on the broad.

"I could see the captain meant to make a day of it, and so I drove slow.

"When I came near the hall and the pretty grounds and the swaying trees and rookeries and things, he told me to drive slower still, that he might enjoy every thing, and all the beauties of nature around him. But la! sir, I was surprised to see him so white and pale like. At last he said, 'Drive on now, Dan as fast ye like.' He was still white and ghastly-like, though, so I jumped down at a pub and got a tot of rum. I took a sip myself, more for fashion sake like, and made him swallow the rest.

"He was better all day after that; but I remember he laughed once or twice as he told me his feet were so cold. 'Seems funny,' he said, 'on so fine a day.'

"I didn't answer much. I knew well there wasn't a deal of fun in it.

"We had that deed-box with us, and we went into the bank. We left the box there, and had a long talk with the banker. Leastways, Captain Bure had.

"Then he turned to me, and laughed again.

"'My good Dan,' he said, 'if the cold of my feet gets higher up and goes round the heart——'

"The tears sprang to my silly eyes, sir.

"'Oh, sir!' I cried, 'don't talk so, it grieves me to hear it.'

"'There are times,' he said, 'when men must talk straight. Now, I've known your brother so long, Dan, and heard so much about you, that I want you to be a father to little Tom—if——'

"'I know, sir!' I cried. 'Don't repeat it. My wife and I have neither chick nor child savin' little Ruth. We'll see to Tom.'

"He clasped my hand.

"'Mr. Mackay,' he said, 'has full instructions, and enough money of mine to give Tom bite and sup, and a good education. Come, Dan, and we'll buy some comforts for poor Bob.'

* * * * *

"I am not sure," continued Dan, after a pause, "if that isn't all the story."

"Not quite," said Mr. Merryweather. "There is the death of Captain Bure, you know."

"Ah, sir, we won't speak of that. It happened soon; and he lies in a quiet corner of the great churchyard at Yarmouth. Little Tom and I go there one Sunday every month to put flowers upon the grave."

The honest boat-builder ceased talking and lit his pipe.

"Dear droll little Tom," he added a moment after, "he does say such queer things. Maybe other folks wouldn't notice 'em, but I do. 'It's only pa's body that lies here, you know, daddy,' he said to me two Sundays ago, 'his soul has gone up to the clouds to live, hasn't it?'

"I didn't speak for a minute, I was thinkin' o' the words of that song, sir—

'For though his body's under hatches,

His soul has gone aloft.'

"The little chap sat down beside the grave and arranged the flowers, then smoothed all the long grass out straight as if it had been hair. He took my hand after that, and we walked quietly and silently away.

"'Pa,' he said afterwards, 'is only afraid I'll be drowned if I go to sea. But I think he'll be pleased when I am a sailor all the same.'

"No, Tom never looks upon his father as really dead, you know.

"Mr. Curtiss is our curate, and he is Tom's tutor, though Bob there teaches him a lot, and has pretty nearly made a sailor of him already. And I'm sure I cannot blame poor Bob——for——"

Dan paused now, and held up his forefinger warningly, while his eyes rested on his brother's face. He took the pipe away and shifted the light, for the invalid was fast asleep. Then he went silently away on tip-toe, and Mr. Merryweather followed him, with just one good-night glance at the sleeping form of his old shipmate, Bob.

"The coot was swimming in the reedy pond,

Beside the water-hen so soon affrighted;

And in the weedy moat the heron, fond

Of solitude, alighted.

"The moping heron, motionless and stiff,

That on a stone as silently and stilly

Stood, an apparent sentinel, as if

To guard the water lily."—TOM HOOD.

Our little hero, Tom, was early astir next morning. In fact he was up with the lark. High up, too; for his first act, after sluicing his sleepy face in a bucket of water, and drying off with a rough brown towel, was to swarm up into the crow's nest and have a look around.

The morning was bright and clear, and the beach was swarming with country people; but there was no sign of the government vessel or of the yawl she had gone in pursuit of. Not content with scanning the horizon from the crow's nest, Tom must needs climb up as high as the cross-trees, and take observations from that coign of vantage.

The wind had gone down to the gentlest breeze, but a heavy sea still rolled over the sands, and broke in white surging waves upon the beach. From where he stood, or rather hung, Tom could easily hear the boom or roar of each mountain breaker, keeping up a kind of deep bass to the screaming of the sea birds that floated near him.

The sun had only just risen, and was flooding the ocean with a strange yellow light, while bars of silvery and crimson clouds lay parallel with the horizon, even far away to the west.

It was indeed a lovely morning, one to make a person feel as light and happy as the birds that sang in every bush or thicket. But nevertheless a wave of sadness passed over the boy's heart as he thought of the drowned men who lay so quiet and still upon the sands out yonder, and of their friends and relations who were left to mourn.

It somehow seemed to Tom unnatural that so much of sorrow should mingle with the gladsomeness of this sunny summer's day. He had yet to learn that all the world and all our lives are made up of light and shade, and that even in the midst of life we are in death.

But as he walked homeward now over the rustic bridge, he checked the song that rose to his lips. He would not sing, with dead men lying unburied on the sands of Yare.

* * * * *

It seemed to Tom that this morning would take a long, long time to pass by. He got his books, and went with Meg to the little summer-house by the lake, and tried hard to settle down to the tasks Mr. Curtiss, his kindly tutor, had set him to perform. But all in vain; so he left the books on the garden seat, putting a stone over them lest a spiteful puff of wind might blow the leaves about. Then "Come on, Meg," he cried, "we'll go for a row."

"Wouff—ff," barked Meg, and away they went.

For a boy of his years Tom was wonderfully well developed, and when he stripped off his jacket and rolled up his sleeves, the white forearm he showed seemed as hard and round as the backstay of a gun-brig.

Meg sat forward in the bows of the little boat, with her forelegs leaning over the gunwale that she might bark at the fish and the birds, and make brave pretence that she meant to jump over and catch them.

By-and-by Tom came to a winding worm of a stream or lead that he had some difficulty in navigating his craft through, but he managed at last, and soon found himself afloat in one of the most beautiful of all the Norfolk broads.

The lake was a deep one, and not only plentifully encircled with tall, reedy bulrushes, but in many places lined with "wild woods thickening green," and banks whereon grew the most lovely of wild flowers. Tom paused often that he might inhale the early-morning perfume of these wildlings of nature, and watch the movements of the numerous birds that had their homes on this peaceful broad.

And not a bird is there among them all that seems very much afraid of the boy in his little boat or of Meg either. Perhaps the birds know Tom, for wild creatures are very observant, and know too that neither he nor that gentle-faced collie will do them any harm. Indeed Meg has dropped her bonnie head upon her paws, and appears to have gone fast asleep.

The sky above is very blue, albeit a fleece-white cloud is floating here and there, and the waters of this still lake are very dark, yet clear. How richly, softly green is the foliage on yon cloudland of trees, how tender the tints of verdure on the rustling, whispering reeds. Look at the pink on that flowering rush, to which a reed-warbler is clinging as it sings its low, sweet lilt. Only for a few moments does it cling there, however. It is far too busy to spend all the morning in song, for the pretty thing has a grass hammock of a nest swung between some reeds close to the bank. No boy in the neighbourhood knows where that nest is save Tom, and he won't touch it, but he marvels while he admires the freak of nature that has almost surrounded the birdie's hammock with the bells of the pink convolvulus.

Hark! there is a nightingale trilling its heaven-taught song in a thicket not many yards away. How sharp and clear is every note, and yet how pathetic and mournful are the lower ones! But presently the bird ceases to sing, for he too has a mate sitting close at the foot of a bush in a nest so artfully disguised as hardly to be discerned, and this little mate needs her breakfast of succulent slugs and beetles.

"Cheeky—cheeky—chee—chee—chee," sings the sedge bird, who has far too much to say, and instead of listening reverently to the song of the nightingale, the thrush, or the blackbird, must needs put his oar in and throw harmony quite out of joint. But there are many other birds that do the same, for each and all sing for their own mates only.

Very quietly now glides Tom's little boat; very still the boy sits too, fascinated as it would seem by the beauty of his surroundings, and as if afraid to disturb the privacy of the lovely feathered creatures whose home he has invaded.

He almost holds his breath as a pair of dark-plumaged coots with white brows go quietly sailing past ahead of him, gazing at him with their expressive beads of eyes, but ready to start off at the slightest movement on his part. A little way farther on are a family of charming water-hens, that go paddling and nodding on across the deep dark water, so intent on their own business that hardly do they notice the slowly-gliding boat.

But Meg lifts her head to look about her and take her bearings, and off scurry the coots; the water-hens too take alarm, and in a moment more all have sought the shelter of the whispering reeds.

More birds take the alarm here and there among the sedges; and in the water there is plashing and whirring and diving, while, uttering a sound that is partly a croak and partly a cry, a great heron, that had previously been standing as still as a statue on the edge of a bank, goes sailing away high in air.

Tom lies on his oars now, and in a few minutes peace and repose is once more restored to the reed-bound brood.

"Meg," says Tom quietly, "you just go to sleep there please, or at least pretend to."

Meg shuts one eye and gives one little wag of her tail, and the boat forges slowly ahead. Tom pulls more in towards the edge now, where the flat round leaves of the water lilies are floating, with flowers snow-white or brilliant yellow just appearing, where the flowering ash blooms prettily, and the orange iris shows against the fresh green of young reeds.

Though it is very early in the morning, the sun is gaining power, and busy among the gnats and midges that dance over the water and over the whispering reeds, filling the air with their dreamy humming, flit and fly the swallows and martins. They even touch the surface at times, long enough to drink or have a little bath, then off and away again, like chips of lightning with the sunlight on their wings.

Tom lands at last among soft green moss, among many a budding alder, many a silvery drooping, dwarf birch-tree, and many a feathery fern. He warns Meg that she is not to follow, but only lie and watch, while he goes wading over the marsh. Oh, what beauty and loveliness on every side! Oh, what a wealth of wild flowers! Yonder is a bush of yellow furze, and a rose-linnet's nest is there. The cosy wee mother sits still on the eggs even when Tom peeps in under her scented golden roof-tree, but the cock-bird that erst sang so sweetly on that bush of sallow changes his notes to a peevish cry of alarm.

Not a nest of any kind of bird that Tom does not know where to seek and find; the titlark's and skylark's near tussocks; the yellow bunting's in the low, close thorn or bank; the sedge-bird's, with its warm wee eggs and even nests of snipe, and coot, and teal—all are known to him, but all are sacred.

The boy spends fully an hour roaming around here; but, getting very hungry, he begins to retrace his steps at last, yet not before he has culled a bouquet of the choicest wild flowers, the flowers that uncle Bob loves best.