Title: The greatest story in the world, period 2 (of 3)

The further story of the Old World up to the discovery of the New

Author: Horace G. Hutchinson

Release date: November 21, 2024 [eBook #74771]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John Murray

Credits: Al Haines

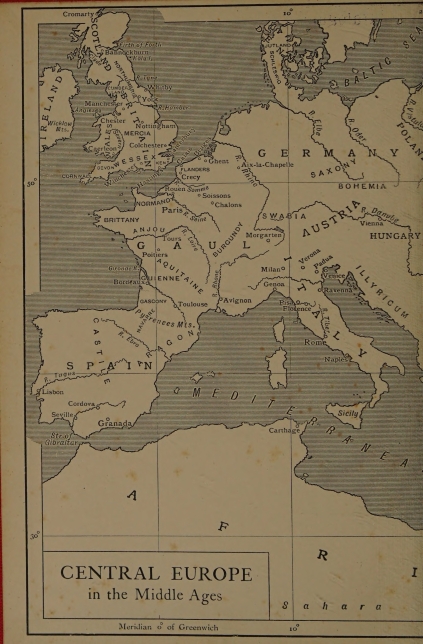

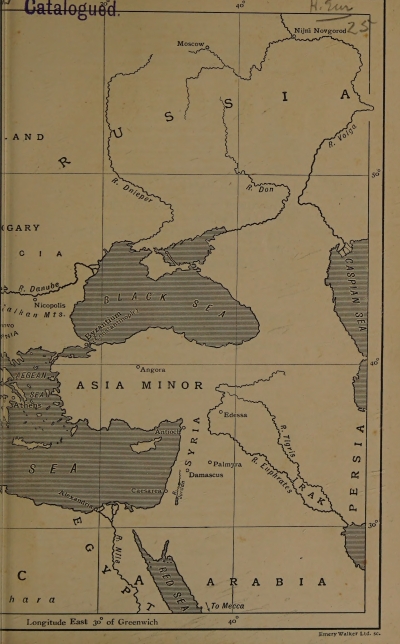

Map: CENTRAL EUROPE in the Middle Ages (left half)

Map: CENTRAL EUROPE in the Middle Ages (right half)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

THE GREATEST STORY IN THE WORLD, PERIOD I

NATURE'S MOODS AND TENSES

WHEN LIFE WAS NEW

THE FORTNIGHTLY CLUB

EDITED BY

THE PRIVATE DIARIES OF THE RT. HON. SIR A. WEST

WARRIORS AND STATESMEN

From the Literary Gleanings of the late EARL BRASSEY

All rights reserved

THE GREATEST STORY

IN THE WORLD

PERIOD II

The Further Story of the Old World up to the Discovery

of the New

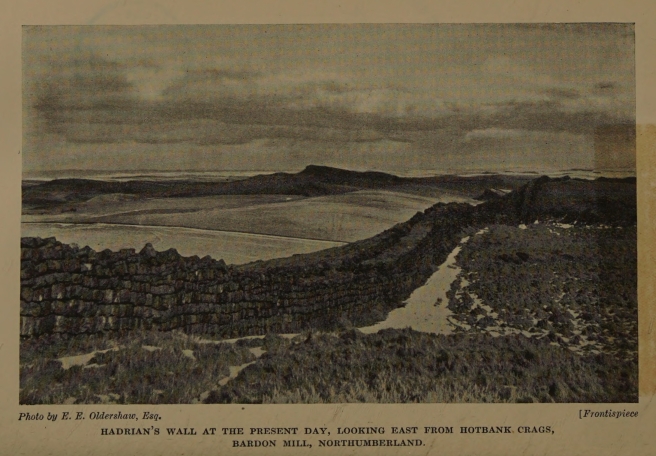

HADRIAN'S WALL AT THE PRESENT DAY, LOOKING EAST FROM HOTBANK CRAGS,

BARDON MILL, NORTHUMBERLAND. Photo by E. E. Oldershaw, Esq.

PERIOD II

The Further Story of the Old World up to the

Discovery of the New

BY HORACE G. HUTCHINSON

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

FIRST PUBLISHED ... 1924

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES.

I have taken up our "Greatest Story" from the point at which we dropped it at the end of the first volume; that is about the year A.D. 100, when the Roman Empire was a solidly established institution.

Throughout that first volume our own land of Britain scarcely had a place. In the latter part of the period—A.D. 100 to A.D. 1500—which this second volume covers, men of Britain played a great role. For centuries, kings of England were rulers of large domains on the Continent of Europe also, and at one time their Continental territories were more extensive and richer than their insular possessions. The world story thus becomes, in some measure, England's also. Moreover, when there have seemed to be two or more ways open for the telling of the story, I have always tried to adopt what I may call the English way, the way which seemed likely to bring it most warmly and intimately home to English hearts and minds. Thus, for example, when the course of history brought us to the point at which we were to consider the manner of life of those Gothic or Germanic tribes which came flooding in from the eastern side of the Rhine, I have chosen, for a type of their lives in general, what we partly know and partly surmise of those lives as they were lived in our own island. Again, where I have endeavoured to give an idea of the manner in which the Northmen, the sea-rovers, made their settlements, I have taken their incursions on England as a type {x} of the rest. In both instances it would have been equally possible to tell the story of some of the people of Charlemagne's great empire and the Continental settlements of the Northmen as typical examples, but the other appeared to me the way far more likely to make the picture real and the story appealing to the eye of an Anglo-Saxon reader.

The period is one of dissolution, in the first place, as the Roman Empire broke to pieces under its own dissensions and the inroads of the barbarians. The break-up was followed by a certain reconstruction under the later empire of Charlemagne. But this again was followed by a second dissolution, less complete than the former. The feudal system then plays its temporary part as a means of holding society together in some sort of cohesion. And finally we see the kings asserting the central authority in their kingdoms more and more at the cost of the local authority of the feudal lords.

Throughout these centuries of successive change there is one power which works all the while to prevent humanity from falling back into a state of barbarism and complete lawlessness—the power of the Church exercised through the person of the Pope and of his officials who covered Christendom. The Crusades, with all that they brought of good and ill, are an episode in the story's course.

By the end of the period the Moor has finally been expelled from the south-western corner of the scene, but the Turk has established himself largely on its eastern side.

The year A.D. 1500 brings the story down to the dawn of a new day, when the darkness of the Middle Ages shall be dispelled by the light which is spreading out from Italy to illuminate Europe. We are at the point when the new story of America in the West and the very ancient stories of India and China in the {xi} East are just about to be brought in and woven up with our own story. But they have not been brought in yet.

In this second volume I have followed the plan adopted for the first—avoiding, as far as possible, names and dates that are not of the highest importance, for the sake of simplification and in order to give their true value to those which are the most important. Only the large outlines are laid down, so that the reader may know, when he comes to the study of any one particular section of history, the place which that section occupies in relation to the whole.

I have again aimed at telling the narrative in very simple language; but in this second volume I have tried to adapt it for scholars perhaps a year or so older than those for whom the first was specially written. I have made this slight difference presuming that the scholar was likely to read the earlier part of the story first and then to pass on to this latter.

And once more, as in the Preface to Period I, I have to thank Mr. R. B. Lattimer for much valuable correction and advice.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. Britain

II. The Camps of the Legions

III. The Barbarian at the Walls

IV. The Division of the Empire

V. The Barbarian breaking through

VI. How Britain became England

VII. The Passing of the Barbarian

VIII. The Pope

IX. How England became Christian

X. The Saracens

XI. The Franks and the Feudal System

XII. How the People Lived

XIII. How the People Lived—continued

XIV. The Settlements Of The Sea-Rovers

XV. The Crusades

XVI. The Slavs in Eastern Europe

XVII. Normans and Angevins

XVIII. The Strength and the Weakness of Rome

XIX. The Moslems in Spain

XX. The Plantagenets in France and England

XXI. England, France, and Burgundy

XXII. The Teuton and the Slav

XXIII. The Turks in Europe

XXIV. The New Dawn

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Hadrian's Wall To-Day .... Frontispiece

Stonehenge

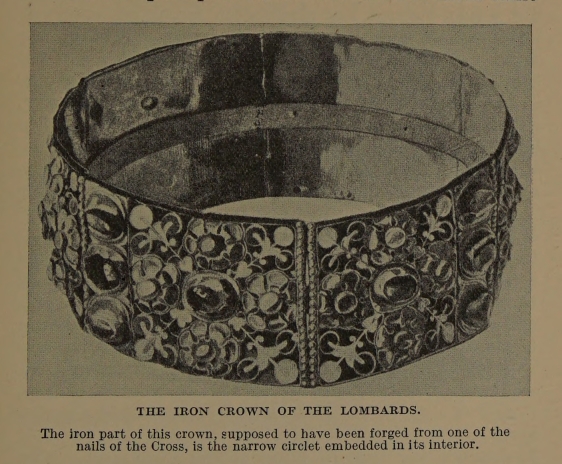

The Iron Crown of the Lombards

Rome and St. Peter's

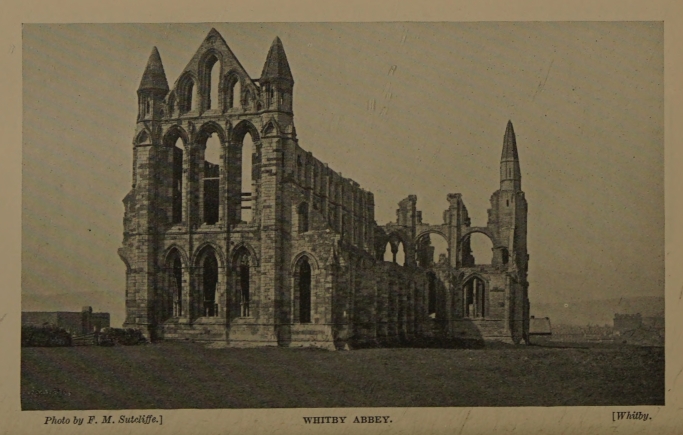

Whitby Abbey

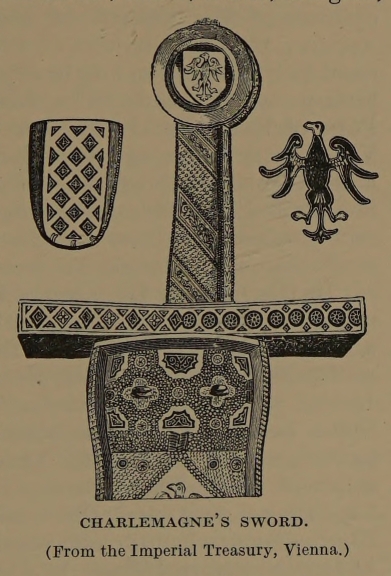

Charlemagne's Sword

Canterbury

An Anglo-Saxon Mansion

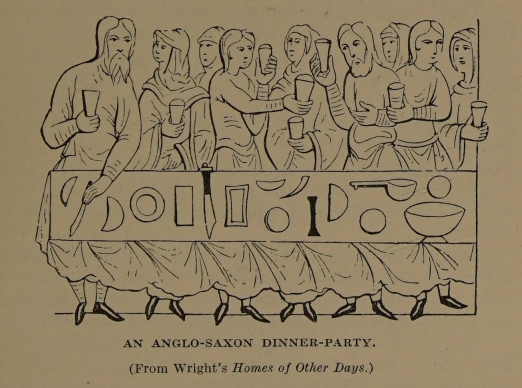

An Anglo-Saxon Dinner Party

A Viking Ship

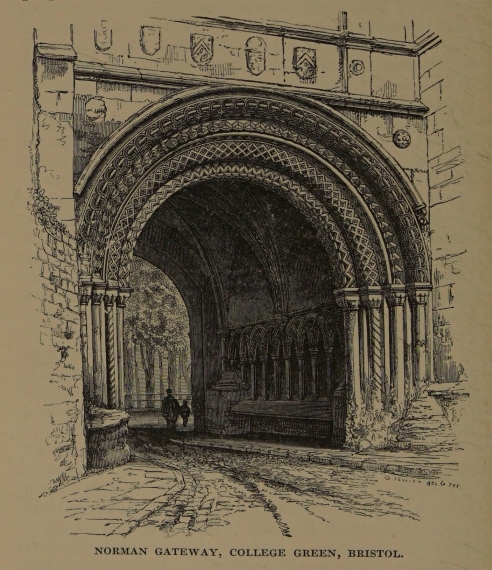

Norman Gateway

A Crusader

A Knight Templar

A Norman Household

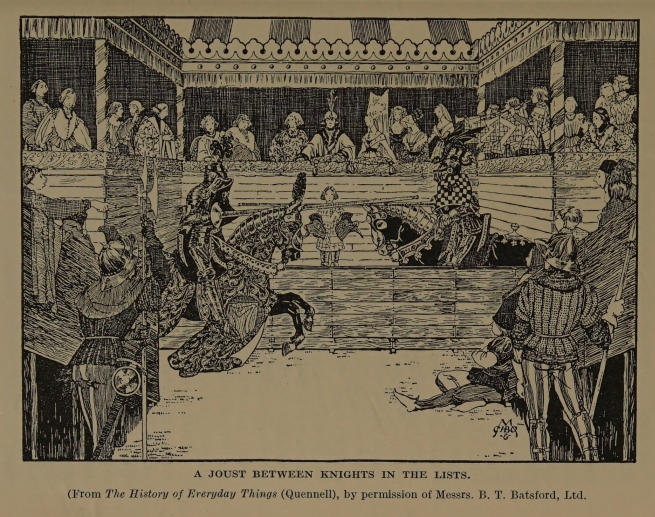

A Joust between Knights

Cœur-de-Lion's Prison

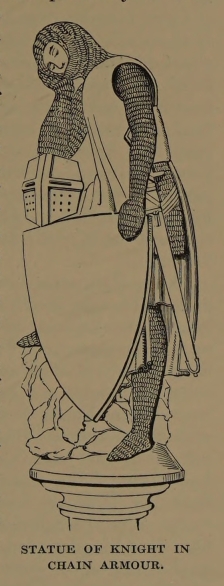

Knight in Chain Armour

The Giralda, Seville

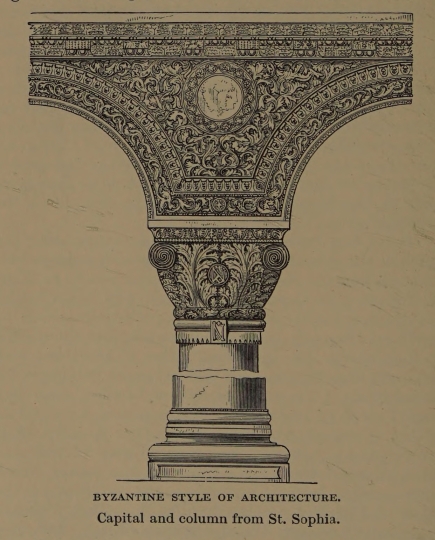

Byzantine Architecture

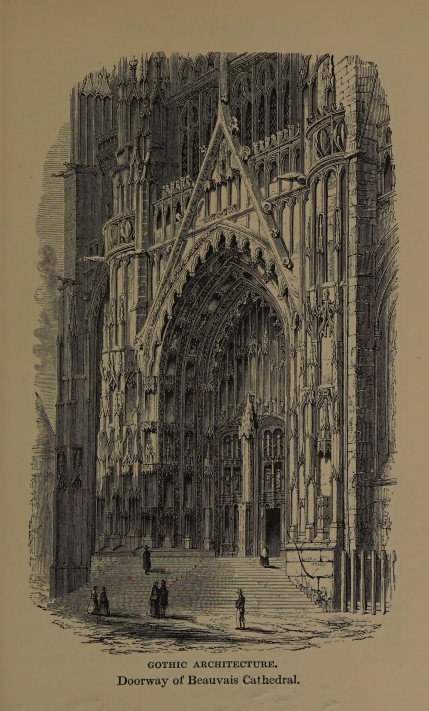

Gothic Architecture

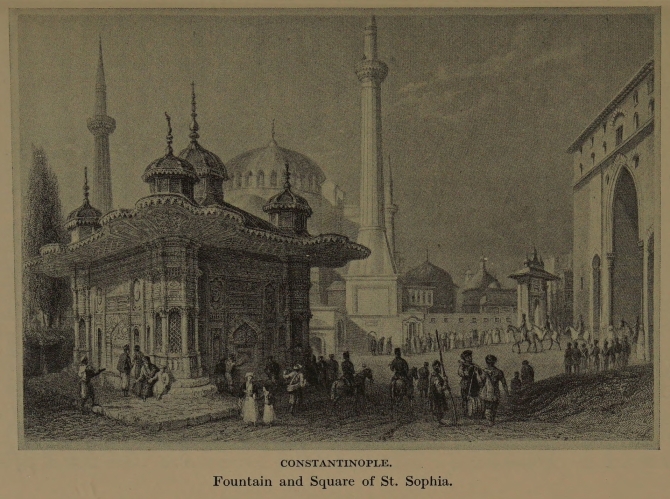

Constantinople

Genoa

Columbus

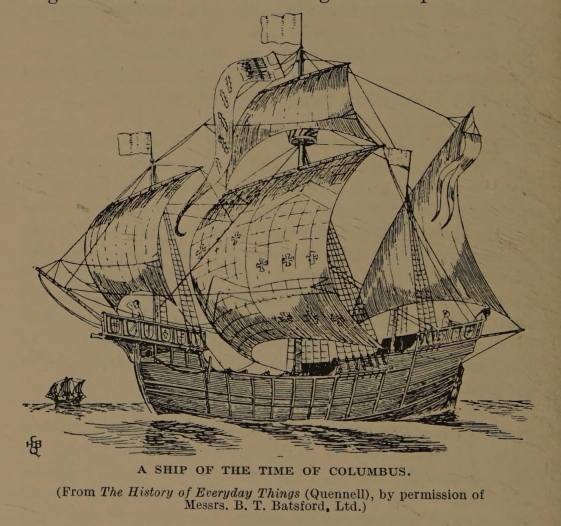

Ship of Columbus' Time

THE GREATEST STORY IN THE WORLD

In the first volume of this Greatest Story in the World we saw how man lived upon the earth from the earliest times at which we know anything about him. We followed the story down to about the year A.D. 100 when the different threads of the story came together into one hand—the mighty hand of Rome and of the firmly established Roman Empire. The whole world, or what the people of that time regarded as the whole of the world that mattered, was controlled by the Roman hand. This second volume will be mainly the story of what happened when the grasp of that hand weakened, and allowed the threads to fall apart again.

Rome had driven its fine roads, which you may imagine going out, from the imperial city as their centre, like the spokes of a great wheel, to the farthest ends of the Empire. And you should notice a peculiarity about those spokes—those roads—that they always went straight. It did not matter how high a hill they came to, nor how deep a {2} valley—unless the hill or the vale side were impossibly steep, the road never turned. It did not go round the hill: it went over the top of it and down the other side.

I suggest to you that you should take notice of this straight going of the roads, partly because the fact of their straightness is interesting in itself and also because it is so like the way in which the Romans, who made those roads, acted in all their doings. They went straight ahead and would not be turned aside or stopped by any obstacles. Their roads, of which we are still able to trace portions, are signs of their character as a nation.

Posting along these roads they had a fine system of mounted messengers, one messenger, at a post say twenty miles out of Rome, taking up, with a fresh horse, the message which another had brought out from the city, and so on—perhaps as far as Byzantium (the name of Constantinople had not yet been thought of) eastward, as far as the coasts of Gaul, from which men could look across to the cliffs of Britain, northward. They were roads along which armies would march, trade would be carried, government officials, with all their train of slaves and servants, would go to their appointed places in the provinces, carrying with them Roman ideas of discipline and obedience, Greek arts and thought and, possibly, and more and more as time went on, the new religion of Christianity.

At the northern cliffs of what we now call France the road would come to an end—of necessity, because there the sea began. But, once across the narrow sea which we call the Channel, the road building would begin again, if the Romans were intending to make any long stay in the country. The first time that the Roman legions came they were led by Julius Cæsar about 50 years B.C. Probably that wise general and statesman did not think that the cost of making Britain a part of the Roman Empire was worth paying, at {3} that time. His legions had plenty to do in keeping the tribes of Gaul in order. He established no Roman authority in Britain, but sailed back to the Continent, and the Romans seem to have paid no attention whatever to Britain for nearly a hundred years.

Claudius in Britain

And on this second occasion of their coming there is no doubt that they came intending to stay. It was about A.D. 50, or a little sooner, that Claudius, the emperor, himself with the legions, appeared in Britain and easily made himself master of most of the southern and all the south-eastern part of the island.

We must try to get a picture in our minds of the state of Britain at that time, and realise how the people lived and what kind of people they were.

Perhaps the first thing to realise about them is that they were not English at all. This name English, if it was used in those days at all, was the name of a tribe that lived across the North Sea on what we now call Sleswig. North of them lived a tribe called the Jutes, on that Jutland from which the great sea-fight takes its name, and south of them a tribe called Saxons. All were of the same race, originally, and all came conquering to Britain—but not just yet.

When Julius Cæsar, and also when Claudius, nearly a century later, came to Britain it was inhabited by a people from whom it had its name, the Brythons. It is believed that they were not the original inhabitants of the island, but that they had come from some part of that great nursery of the human family, the east of Germany and Poland and the west and south of Russia. There had been at least two great westward migrations of an ancient race called Celts from that nursery, before the time of the Romans coming to Britain. All over the western world and as far south as Byzantium itself these Celts penetrated, and, coming from the east, it is noticeable that they maintained themselves against later invaders most strongly in {4} the farthest west—in Spain, in Brittany, in Cornwall, Wales, Ireland and the West of Scotland.

The Brythons

The earlier immigration of Celts into Britain had taken place in what is called the Bronze Age, when man had learnt to make weapons and tools and ornaments of bronze, but had not yet learnt the use of iron. These Bronze Age Celts were called Goidels. But the people after whom the island was named, the Brythons, came in the Iron Age; and it was them that Cæsar and all the later-coming Romans found in possession.

So much has been written about the ancient Britons dyeing themselves blue with "woad" and so on that we are inclined to regard them as far more rude and savage than they were. They seem to have lived in huts made of stone and turf and partly excavated in the ground and to have been hunters, and, in a very simple way, farmers. Some of their houses were built on oak piles driven into the soft ground of the marshes. They lived in small communities, or tribes, often fighting against each other, and with a head-man over each tribe. But besides these communities scattered over the country, there had already been established towns where markets, for buying and selling, were held. This, at all events, would be a tolerably correct picture of the south and east of Britain, where there was a close connection, across the narrow Channel, with Gaul and the Roman influences. Cæsar's Romans found the Brythons buying and selling with gold coins and iron bars serving them for money.

I say that this is a tolerably true picture of the south and east, particularly because it is in those parts that an invader, whether he came for peaceful trading or for warlike aggression, would find it the most easy to establish himself. If we look for a moment at the geography of our country we shall see that this must have been so.

For one thing, they are the parts which lie nearest to Gaul and the rest of the Continent from which the invader would be likely to come. And then you will see that the south and east, say as far north as the Humber and as far west as the Severn, are, in spite of certain high ridges of downs and hills, by far the more level, generally, and less broken. They were easier to traverse. We have to imagine all the country far more densely wooded than it is now, and all the river valleys far more marshy. In consequence of the marshy softness of the lower ground, we find that the old tracks generally went along the uplands, wherever that was possible.

Colchester, in Essex, was the chief city of Britain when the first serious Roman invasion came, and under Claudius the legions crossed the Thames, took Colchester and mastered all the south-east of Britain. Wherever the Romans came, it was their custom to make military roads if they had any intention of settling in the country. Julius Cæsar's expedition we have to regard as little more than one of discovery—to see what the island was like, and whether its products would pay the Empire for the cost of conquest. His decision must have been that it was worth the cost, because we know that several of the emperors had designs for making the conquest, but, busy as they were elsewhere, nothing was done to achieve it until Claudius came to the throne in Rome.

The produce that the Romans found, which induced them to think that the island was worth conquering, was chiefly mineral; tin, lead and iron, with a little gold; and later Britain grew corn for the Empire.

The Brythons seem to have been stubborn fighters. They had horses and chariots, with blades, like scythes, sticking out from the sides of the chariots. But it seems that they had little discipline and little idea of forming themselves into any order when they went {6} into battle. They could have had no real chance against the experience and skill, to say nothing of the better arms, of the Roman soldiers.

So, after the establishment of the Roman authority in the south, the penetration of the island by the legions went on. They penetrated as far north as Cromarty, and as far west as Anglesey, but they never really subdued either the far north, where the people called Picts then lived, or the broken and hilly countries in the west, which the Celtic Brythons still occupied. Under one of the generals, Agricola, whose campaigns are described by the Roman historian, Tacitus, we find that a line of forts was established across the narrowest part of Scotland, from the Clyde to the Forth. But under the Emperor Hadrian, who reigned from 117 to 138, the great effort of the Empire was to establish certain limits, or boundaries, which it would be able to hold against all attacks from beyond those boundaries. During his reign the Empire gave up some of its conquered territory in Asia. Hadrian erected a line of palisades, or strong wooden walls, along the boundary line of the Empire between the Rhine and the Danube, and in Britain he threw up a wall, a long way south of the Clyde and Forth, from the Solway to the mouth of the Tyne. Evidently, however, this obstacle was not effective in keeping out the Pict, for twenty years later we find his successor, Antoninus Pius, building a second wall from Forth to Clyde, for the better security of the frontier.

It never was any part of the Empire's plan to drive out the native people from lands that it subdued. What it wanted of these people was that they should stay where they were and follow their own customs and provide the necessities and the luxuries of life for their conquerors. The Romans were what we should call a very practical nation. Roman laws, of course, had to prevail in the lands so conquered, but otherwise it does not seem that there was much upsetting of the national habits of the people. But the influence of the conquerors, their way of thought, their discipline and so on, of course worked among the conquered, and the natives of the provinces so became Romanised, as it is called.

In order to understand and to follow the course of this greatest of all stories we ought to try to form a picture in our minds of the world at this time, say from A.D. 100 to 200.

There is the Roman Empire; and that is all the world that seemed to matter to those who were the great actors in the story at that time. We have to regard that Empire as shut in, walled off. The sea, from the mouth of the Rhine to the coast of Africa, is the boundary north and west. There is a strip of Empire in Africa reaching to Egypt, between the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara desert, and all that strip is protected by a line of forts against incursions {8} from any Ethiopians from the desert. There is Egypt itself. Then there is so much of Asia Minor as from time to time was held as Roman. It included Syria, at all events, but the boundary here was more often changed perhaps than elsewhere, though it did not in many parts remain quite fixed. So we come up to the Black Sea, and to the mouth of the Danube. The Danube, during most of the time that the Empire lasted, formed a boundary line, though the province of Dacia was for a while held beyond it. And we know that there were palisades—a wooden wall—drawn along from the Danube to the Rhine.

That completes the enclosure, with Britain lying apart like a kind of crumb, crumbled off the big loaf.

Roman "citizens"

Thus there is this great Empire, fenced within walls and other limits, such as the limits that the sea makes; and at certain places outside the wall there are people looking over—outsiders, whom the Romans called "barbarians," men who said "bar bar," that is to say, who were unintelligible, when they tried to talk. The Brythons themselves were barbarians, of course, to the Romans. So were the Gauls, whom Julius Cæsar conquered in the land that is now France. So were the Iberians, who were the people that the Romans found in Spain. Thus there were many barbarians within the boundaries, as well as outside. But as time went on these natives of the different regions within the Empire became "Romanised." Roman modes of law and of the governing of cities made their way all over the Empire. What we should call "municipal life," that is to say the management of towns by "municipal" authorities, like our mayors and councillors, came into fashion. The natives became more like their Roman conquerors in their thoughts and in their ways of life. Natives and Romans made marriages, and the children of these marriages hardly would know what to call themselves—whether {9} Romans or Gauls. In the early days of Rome, when it was a Republic, the privileges of a Roman citizen were very important. The "citizen" alone had the right to a vote for the election of the officials by whom he and the whole Republic and its dependencies were to be governed. But this right of voting was given more and more freely as the years went on and as other parts of the Empire increased in importance. To all the free men—all who were not slaves—of certain states that had loyally helped Rome when she was hard pressed by her enemies, the right was given first; then to all Italian free men; and soon it was extended widely through the Empire. We notice how St. Paul, at Cæsarea, claimed his right, as a free man of the Empire, to make appeal to the Emperor himself at Rome, and how that right could not be disallowed.

Now one of the rights that "citizenship" had carried with it in the early days was the right, and the duty, of being called up for military service in defence of the Empire and to fight its foes. The "legion" about which we hear so much in this great story, first came into existence in this way. It was a collection (the word "legion" itself is a form of the last two syllables of col-"lection") of the citizens to fight for their city.

As the Republic grew and began to take possession of more and more lands far away from its centre, there was need of armies of quite a different kind from this. The citizens of the first legion went on military service, when called upon; but they looked forward to going back to their farms, or whatever their business was, as soon as the fighting was over. The increasing power of the Republic and the increase of the territory and peoples over which it ruled, made it necessary that the government at Rome should have an army, or several armies, ready to take the field when required. {10} And thus a Roman "standing army," as we should call it, came into existence; its soldiers were men who had no other business than soldiery; the military life was their profession, by which they earned their livelihood.

But the name of legion was still used, although it was used for something very different from that to which the name had been given at first. It grew to be used for what we might call "a division," of an army. The number of soldiers in a legion differed slightly from time to time, but for the most part it was about 6,000, nearly all foot-soldiers. They were heavily armed, with heavy throwing spears, short, double-edged swords and long thrusting spears. Their general way of battle was to discharge the throwing spears in a volley and then to charge in and destroy the enemy, already sorely vexed by the heavy javelins, with the short swords.

The legions, as we have seen already, might be moved hither and thither to any point of the great Empire where their services were needed. While the Empire was being created, and the nations were being subdued, there was frequent occasion for this movement of large bodies of troops; but you must realise that we have now come to a point in the story at which the Empire—especially under the wise Emperor Hadrian—is concerned more with making good the conquests it has already won, than in adding to them. The boundaries, the limits, have been set, as we have just been tracing them—or somewhat like that. The Romans are within the boundaries; the barbarians are without. And wherever the barbarians are there is need of one or other of the legions, acting as a kind of police, to see that no one breaks through the wall.

The result of that is that the legions are not required to move about so much as they were when the Empire {11} was being won. Now that it is won, they are set here and there, like watch dogs, along the boundaries. The positions which they occupy become permanent camps. The legionaries are allowed to marry and to live outside the actual confines of the camp.

The Legions in Britain

I think this then may give us some general idea of the picture that we should carry in our minds of the Roman Empire—which is almost as much as to say, of the world—at this point in the story, about A.D. 200. There are in all twenty-five legions. In Britain itself there were three, one at Chester, one at York, one at Caerleon. Now the number of troops in a legion was commonly, as we have seen, 6,000, but twenty-five of these legions did not nearly represent the total army of the Roman Empire, because to each of the legions was attached at least an equal number of auxiliaries, light-armed troops. Thus the establishment of a legion in any district meant a huge increase of population, a very large castrum or camp, from which we get the names of such places as Man-chester, Dor-chester, and Chester itself—Chester being a modification of the Roman word castrum. Besides the auxiliaries, who were light-armed foot-soldiers, there were a few mounted troops attached to each legion, but the chief of the fighting was supposed to be done by the legionaries, or soldiers of the legions. Just as we saw that among the Greeks the hoplites, the heavy-armed soldiers of the phalanx, were considered to form the strength of the army, so it was with the heavy-armed legionaries of the Romans.

The tradition was still kept up, that the legionaries should be men who had the privileges of free citizens of Rome, while the auxiliaries were taken from a lower class of the people who had not these privileges. But we have seen that this privilege was given to more and more as time went on, so that Roman citizenship ceased to be as valuable as it once was, because it {12} had become more common. Recruits to the legions were taken from the natives of the conquered lands. Moreover, since the legionaries in these settled camps were allowed to marry, their sons were naturally disposed to become soldiers, like their fathers, when they grew up.

Legions independent

The effect of all this was to make the legions very closely attached to the places in which their permanent camps were pitched. The camps became home to them. They no longer looked to Rome as their home; and by degrees they ceased to look to Rome as the centre at which what we should call their Headquarter Staff resided. They became more and more independent of Rome. If an attack came, or was threatened, from the barbarians beyond the limits which they had to guard, they dealt with the threat or the attack. They were not obliged to send back to Rome for their instructions.

Realise then, for it is of much importance in the development of the great story, the increasing independence of the legions in their large camps, when once these camps had been established as permanent settlements. We left the story, at the end of the first volume, at a point where its threads had been gathered together in the great hand of the Roman Empire. This second volume is largely occupied with the disruption and pulling apart of those threads out of that hand; and the reason why the hand was obliged to relax its grasp and so allow the threads to be torn apart again is twofold. One part of the reason is this independence of the "far flung" legions, which became less and less attentive and obedient to orders from the centre at Rome. Another part of the reason is that the barbarians beyond the limits began knocking at the walls harder and harder and finally broke through.

What is so interesting to see in this story is not {13} only the events that happened, but also (and perhaps more interesting still) the explanation why they happened as they did. I have tried to make clear how it was that the armies of the Empire grew to be almost independent of any orders coming from the centre, and how that independence partly explained the break-up of the Empire.

I must now try to make clear to you why it was that the barbarians knocked as they did at the walls and finally broke through them and so completed the disruption of the power of Rome.

For a whole hundred years now, that is from A.D. 200 to 300, this greatest story in the world is really made up of a succession of small stories, each almost exactly the same as the last. They are stories about the "barbarian," at some point or other of the boundaries of the Empire, trying to break through, here and there succeeding in making a breach in the wall, and penetrating into the Empire, but again and again being thrust back, so that the old boundaries, as established by Hadrian, were on the whole tolerably well maintained all through this hundred years.

The first serious break in the wall was made by a tribe called the Franks, from the east side of the Rhine, breaking through the boundary between the Empire and Germany. There was at least one other tribe in alliance with the Franks in this invasion, but it is the Franks of whom we should, I think, take notice particularly, because here we find them for the first time in what the Romans called Gaul, and in what is now called, from these very Franks, or from their descendants, France.

The Gallic Empire

But they did not remain long in Gaul at that time. They were driven out by the legions. And the legions in that province had to do the work of driving them out without getting any help from Rome. The result of that was that these legions, finding that they had to rely on themselves, thought that they might as well have a government of their own. They {15} chose an "emperor" for themselves, a "Gallic Empire" was founded—the Empire of Gaul—and it was obeyed even across the Pyrenees, in Spain, and across the Channel, in Britain. This so-called Gallic Empire had an existence of about thirty years, after which it was overthrown and the Empire of Rome was re-established over Gaul.

The story was almost exactly repeated in other parts of the Empire. The Goths, a tribe perhaps of the same race and origin as the Franks, and of similar habits, but living not so far towards the north, broke in across the Danube. They were a very formidable force, and overran the Balkans. They defeated a Roman army, under the Emperor Decius himself, and Decius was killed in the battle. We must not allow ourselves to be misled by the term "barbarian," applied by the Romans to all these peoples, and to think of them as mere savages. These Goths had possessions on the Black Sea and they are said to have sent out, during this century, a fleet estimated at 500 ships which made incursions along the coasts of Asia Minor and Greece as formidable as any that the Vikings, later on, made further north. They actually stormed and pillaged such cities as Corinth and Athens.

Further east the Persians came pressing in upon the Empire. They were defeated and driven back by the Syrian dux Orientis, duke of the East, as he was called. He was no more than a high official, appointed by Rome, but after this success against the Persians he proclaimed himself as an independent prince, the Prince of Palmyra. Zenobia, his widow, who succeeded him in his real power, though a young son was the successor to his title, maintained the independence of Palmyra, and even conquered Egypt, but again there happened that which we have seen more than once in the course of the great story—the {16} enemies of Rome prevail against her for a while, until she is provoked to put forth her full strength against them; but, once she is roused to strenuous action, they go down before her. Zenobia was defeated and brought in triumph to Rome about twenty-four years before the end of the century, and in A.D. 300 the Roman Empire stood within its bounds not greatly changed from its bounds of a hundred years before. There was, however, a real, if not a very visible, difference: the "barbarians," although for the time thrust back, had probably learnt that the Roman power was not quite invincible; and the legions guarding the frontiers had learnt that they had to rely on their own forces, without assistance from the central headquarters at Rome, for repelling the barbarians, and therefore felt less disposed to look on Rome as their master.

The barbarians

The condition of the Empire within its frontiers was far less prosperous at the close than it had been at the beginning of the century. We saw how the Greek thought and culture had been carried along the Roman roads to the far boundaries of the Empire. But although the barbarian armies were still kept outside those boundaries, a great many of the barbarians had come to settle within the Empire and had been taken into the legions. No doubt some of them learned the arts and the wisdom and the civilisation which the Romans had learnt from the Greeks, but on the other hand they prevented the spreading of these good lessons throughout the world. If they became somewhat "Romanised," the Roman Empire at the same time became somewhat "barbarised," by their coming in. Moreover Gaul, as we have seen, had been the scene of war, and so, too, parts of Italy itself, Greece, the Balkans, as we should call the district now, Asia Minor and Egypt. There was scarcely a corner of the Empire in which the Pax {17} Romana, had not been broken. Therefore the fields were waste, the population diminished, the towns were partially abandoned, trade was nearly at a standstill. Disease and lack of food followed in the train of war.

Thus, although the boundaries of the Empire stood in the year A.D. 300 much as they had stood a hundred years before, the Empire within had grown far weaker. If the barbarian should break through again, as it was most likely that he would, there would not be the old strength to repel him. But, before we come to the actual breaking-through point, we would do well to consider a question which I expect will have come to your minds: What sort of people, of what race, and of what habits of life were these barbarians, so-called, and what was the reason why they kept on thus trying to break in upon the Empire?

We get our first knowledge of the way of life of these barbarians from the great Roman historian Tacitus; and his account is especially interesting to us, who are English, because it is the account of the way in which those people lived who were our own ancestors. For the very name of English or Englishmen, we may take it, was not known in the Britain of that day, nor for some time after A.D. 300. There were English, as we have noted, in Sleswig, and to north and south of them were Jutes and Saxons. The three were closely allied in race and in language, and the Romans, because they came into touch with the Saxons chiefly, the most southern of the tribes, called them all Saxon. It seems, however, that among themselves they commonly used the word English, which strictly was the name of the nation or tribe in the middle, to include all three tribes. All were Englishmen, but the Jutes and Saxons were distinct, though allied, tribes within the English description.

The barbarians that Tacitus writes of lived to the south and east of these, on the eastern side of the Rhine, but what he has to say about them we may take to apply to those forefathers of our own, because, just as the name English included Jutes and Saxons, so too the English and many others, such as the Goths and the Franks, were all to be included under a name of wider meaning still. All were related. All spoke a language which had evidently come from the same original source, though different tribes had learnt to speak rather differently because they had lived far apart from each other for a great many years. All had very similar customs and ways of life, and the same religion. Christianity had not yet come to them.

Tacitus on the Goths

What Tacitus tells us is that all these allied nations were made up of people living the life of farmers. They liked to live separately from each other, in families apart. Their farm would consist of as much plough land as the head of the family and his sons and daughters could work and keep in good order, and as much pasture land as his cattle required. These farmers would be established in the midst of the great forests which covered all the land. They would be either in natural glades in these forests or in clearances made by the people themselves.

Each family lived by itself on its farm; but within a certain region there would be a collection of these farms, not far apart from each other; and this gathering of farms would form a tribe, or a division within a tribe, by itself, apart from any other tribe. And immediately surrounding each tribal group it seems as if the forest was always left in its natural state, so that there was a wide strip, or "mark"—a word we find later in the form of the "march" and the "marches"—between one and the other. This strip was always dangerous to traverse. It was the home {19} of wild beasts. Moreover the farmers imagined it to be the home of evil spirits of many kinds which might lead men astray and destroy them. And it was necessary, if a man did have the courage and fortune to make his way safely through this terrible belt of forest, that he should sound his horn loudly as he passed the further side of it and came into the farmed land of one of another tribe. If he did not give notice of his coming by this horn-blowing, he was to be suspected as an enemy, and was liable to be killed without further inquiry.

Thus, you see, these communities were made up of men owning their own land. They were free-holders, as we should say. And, because they owned land, they had the rights of free-holders, or free men. The right, really, was the right of self-government. For although they lived so much apart from each other, and were, as Tacitus tells us, very much attached to their independent way of living, yet they had intercourse together. To the Roman historian, accustomed to the crowded cities of Italy, their solitary way of living would naturally seem extraordinary, and very likely it was not quite so solitary as his description would make us think. They had, at all events, their government, their laws and customs, and had, as it appears, perfect liberty for arranging all these for themselves.

They used to meet from time to time, probably at a set time once a year, in a certain place, generally a hill, to which a certain sacredness was ascribed on that account, and there they would hold courts of law, to settle disputes brought before them, and would impose sentences, and discuss matters of interest to the tribe generally. Every free-man, every free-holder of land, had a right to be there and to give his vote. The man who had no land had no vote; he had no rights. So it was held a dreadful thing in {20} those days to be a "land-less" man. These free-holders were called "ceorls" (in later English, "churls"), and "ceorl" really means "man"; as if to imply that those who had not the right which the possession of land gave were hardly men at all. And of the "ceorls" there were some larger proprietors, who were called "eorls" (later "earls"). From that word too we get the "eorldermen" (or eldermen), who sometimes deliberated apart at the meetings and were greatly considered, as men of position and wisdom. But they had no rights over the "ceorls," except such as the "ceorls" voted to them and might take back again by vote.

If any man deemed himself injured by another he could bring his case before the court, and if he made it good the court would award him compensation for the injury done him in the form of some cattle, or other valuable property to be given over to him by the man that did him the injury. The amount of the compensation it would be part of the work of the court of law to settle when it was assembled at the "mote hill" or place where the eldermen of the tribe gathered for the purpose.

But, you may say, that is all very well for the man who had suffered an injury that was not fatal. You could compensate him, perhaps. But how about a man that had been killed? You could not very well compensate him.

You could not. All you could do in a case like this would be to make the killer give compensation, in form of a heavy fine of cattle or goods, to the wife and family of the murdered man. But that would not be enough: the killer must be personally punished too, probably with death.

And then you may say that, if he was to be punished with death, it would not much matter to him how many of his cattle or how much of his goods were {21} taken from him and given to the family of the man he had killed.

The Gothic family

It would not—to him personally; but it would matter to his wife and family. They would be the poorer by the amount of the fine that was paid. And it is thought likely that it was in this way that the custom grew of looking upon the family of a person who had suffered wrong as the people who were to be compensated for the wrong, rather than the sufferer himself; and also of looking upon the family of the man who had done the wrong as the people who should make the compensation, rather than the wrong-doer himself.

The result of that was to make each person in the family look upon every other person of the same family as one whose acts might make a great deal of difference to him. The whole family had to suffer when any of its members did wrong: the whole family had a claim against a person who had wronged one of its members.

So they had this sentiment, that all the members of a family were dependent each on the acts of the other, and that they must suffer together when wrong was done; but in other ways they were very independent people.

They seem to have been generally tall and big, both men and women. They had light hair, which even the men allowed to grow long, so as to fall on their shoulders, blue eyes and fair complexions.

That is a general description which may serve for all the tribes of the barbarians which came knocking on the northern and eastern walls of the Empire in Europe all the way down from Sleswig, where the Saxons were, to the lands occupied by the Goths, some of whom lived as far east as the shores of the Black Sea, where they had formed, as we have seen, a large fleet. It is possible for a general account like this to serve for the many different tribes and nations {22} into which the barbarians on this boundary of the Empire were split up, because they were all of one race originally, rather as we of Great Britain and most of the Americans are of the Anglo-Saxon race, although we are now of different nations.

All these peoples, of whom it is convenient to speak by the Roman term of barbarians, were of the great family of mankind that is called the Indo-European—that is the more general name, including them all, of which I wrote a few pages back. It is given that name, because some of the family went south, into India, and some west, into Europe, out of some region in the north and east, which seems to have been a great hive or nursery of mankind out of which we came swarming south and west.

This hive seems to have had its home perhaps in the west of Russia; but little is known about it. Probably it would be more right to speak of many hives, scattered over a large region, than of one. But we may know that the scattered members of the family—those in India and those in Europe—are related by the similarity of some of the most common words, or parts of words, in the languages of India and of those lands of which the European members of the family got possession.

Besides its troubles from the threats of these barbarians on its north-west borders, the Empire, as we have seen, had its troubles through most of this century from Persians and others on the south-east; and I now want to ask you to notice an effect of these troubles and threats of trouble on the Empire itself, for it was an effect which made a very great difference to the story. This effect was the dividing up of the one Empire into two, with a Western Empire, as of old, having its seat of government at Rome; but also with an Eastern Empire having its centre of government at Byzantium, as Constantinople was then called.

The causes that led to the dividing up of the Empire are easily understood. What is far less easy to understand is how Rome ruled the world, as the world then was known, so long as she did. Remember this: at that time you could only travel, and you could only send a message, as fast as a horse could gallop, if it was by land that you went or sent; and only as fast as a ship—a ship with a very simple and primitive way of setting the sails—could be urged through the water by sailing or by rowing, if your going was by sea. For practical purposes of getting news or of moving troops, the world of the Romans of that date, say from Egypt to Britain at its furthest points, was a very great deal larger than the whole of the globe is to us to-day. If you can understand it in that sense, their Empire was very much larger, much less under the eye and the direction of the centre of government, than the whole British Empire to-day. And we find that large enough. The Romans had the further trouble, which we have not, that the leaders of the legions in the provinces, when they had repelled the barbarians, sometimes claimed to be independent of the central authority, as we saw both in Gaul and in Asia Minor.

So the wonder really is, not that Rome should at length fail to govern all this Empire from one centre, but that she should have succeeded in doing so at all, {24} and for so long. From causes which I have spoken of already, the home government was not as strong as it had been; and as the power at the centre grew less the pressure of the barbarians on the boundaries grew more. Especially it became convenient to have a centre of government nearer the boundary on the south-east, where the eastern barbarians were constantly making their attacks and where a great leader of the army, if he checked the attack, might become too strong for the authority of Rome to control unless it put forth all its force. A solution of the trouble was attempted by the Emperor Diocletian, who came to the imperial throne in 284. What he did was to appoint a colleague for himself to whom he gave his own title of Augustus, though he also retained the title for himself. There were, therefore, two Augusti. And besides the Augusti, he appointed two leaders of armies in the provinces to bear the title of Cæsar. Thus there were two Cæsars and two Augusti. The Empire and its armies were portioned out between these four great persons. Diocletian himself had the command of the army of Syria. His colleague, the other Augustus, commanded the armies of Italy and of Africa. One of the Cæsars had the armies guarding the Rhine, and the other the armies guarding the Danube boundary.

In this way were the Empire and its defending forces divided up. The Cæsars were considered to be in an inferior position to the Augusti, and as between the Augusti themselves Diocletian was supposed to to be the superior of the other. We may think it likely that the Emperor, in making these appointments, did little more than give his formal approval to arrangements that already existed, in fact. Very probably these important persons would have been able to make themselves practically independent of the Emperor, even if he had not given them these {25} offices, and very likely they were the more ready to pay him some show of deference because he had given them his approval.

There is one point about the arrangement to which I would call your attention, and that is that Diocletian, who claimed to be the superior of them all, assumed, for his own command, the army of Syria, of the East. You will perceive what that seems to indicate—that the Romans had begun to look upon the Eastern side of the Empire as more important than the Western. As early as the year 300, or even earlier, this was their view.

In Diocletian's time we find that any claim of power by the people, the democracy, was entirely given up. The government was an autocracy; though there might be more than one autocrat. There was no longer any value in being a citizen of Rome. Rome and Italy had no privileges above the rest of the Empire. They were administered and taxed in the same way as all the provinces.

Constantine the Great

This formal division of authority under Diocletian did not long answer the purpose for which he designed it, and he and his fellow "Augustus" abdicated in 305, and for nearly twenty years there was continual fighting between rival "Emperors" elected by the different armies. For a time, but for a time only, peace within the Empire was gained under Constantine I.—Constantine the Great, as he was deservedly called. He deserves that distinguishing title if only for two acts of his reign which made a very great impression on the story of the world: he accepted the Christian religion as the recognised religion of the Empire, and he built the City of Constantine—Constantinople—to be the new capital of the Empire, the new centre.

He died, however, in 337, and immediately the fighting between rival Emperors was resumed. It {26} was nearly thirty years before the world had any peace from these rivalries. At length Valentinian is proclaimed Emperor by his soldiers, and he appoints, as his colleague and fellow "Augustus," his own brother Valens. To Valens he gives the title of Emperor of the East, with the capital of that Eastern Empire at Constantinople. For himself he takes the Empire of the West, with its capital still at Rome. It appears that the independence of the two Empires is complete. Their boundaries are defined, the limit of the Eastern Empire being drawn so far to the west as to include Macedonia and Greece.

Of all the Indo-European tribes or nations the most powerful, the most numerous and that which occupied the largest territory, was the great nation of the Goths. They may have come down from Scandinavia—from Norway and Sweden. There are some evidences which make that likely, but the evidence is not very clear. They owned the country along the boundary of the Roman Empire from the Danube to the Vistula.

The Huns

And behind all these tribes of Indo-Europeans settled for the most part in what we now call Germany and Austria—behind them, that is to say to the north and east, in the region of that great hive or nursery of mankind which seems to have been somewhere in the north of Asia—there was another nation, not belonging to the Indo-European family, not speaking a language that resembled theirs, not made up of persons at all like these Indo-Europeans in appearance. The Indo-Europeans, whom it will perhaps be more convenient to call Germans, because they lived in the countries now occupied by Germans and Austrians—these German tribesmen were tall and fair. This other nation, to the eastward, was of small dark men. They were called Huns.

You may remember that antiquaries—men learned {27} in ancient history—tell us that man, in his progress to civilisation, has passed through two rather distinct stages—the hunting stage and the pastoral stage—and through them came to a third stage, the agricultural, when he settled down to grow crops. The German tribes were already in this third stage, at the point which our story has reached, but the Huns were in the second stage only; they wandered, with their flocks and herds.

This nation of little dark men seems, by their language and by other evidences, as if it must have been related to the Finns, of Finland. The evidences, however, are not very clear; but what is tolerably clear is that they were a numerous and a warlike race of little dark men, and that they kept up a constant pressure, from the north and east, upon the Goths and other German tribes; especially on the more eastern Goths, called Ostrogoths.

And very often it seems to have been that pressure of the Huns from the North and East that made the Germans try and try again to break through the boundary of the Roman Empire and work their way towards the west. The first of these breaks through, however, which had any success, was in a southward, rather than a westward direction. It was a break through of the Goths towards Constantinople, and it was very formidable indeed.

When Diocletian appointed a colleague for himself, a second "Augustus," he, as we saw, took the Eastern command for himself and gave the Western to the colleague. When Valentinian finally divided the Empire between himself and his brother Valens, he took the West and gave the East to his brother. It is possible that he may have foreseen something of the trouble that was soon to come on that eastern side. Within three years of his accession to the throne of Constantinople Valens was called upon to lead his legions to {28} repel a great incursion of the Goths. He met them at Adrianople and suffered a terrible defeat. He himself was killed in the battle. The barbarians pressed on. They were at the walls of Constantinople.

Barbarian tribes

A hundred years before this, Goths, crossing the Danube, had fought and conquered Roman legions and had killed an Emperor, namely Decius, who is notorious for his cruel persecution of the Christians known in history as "the Decian persecutions." The Goths had at this time been checked by further Roman forces that were brought against them, but it was then that the Empire lost the province of Dacia, which lay north and east of the Danube, and the Danube thereafter became the boundary.

Now the children of these Goths, rather more than a hundred years later, were across the Danube again, had again conquered the legions and again a Roman Emperor had been slain by them in battle. Constantine had himself been forced to fight the Goths in Thrace, and, when building his new capital, had encircled it with defensive walls. It was well for his successors that he did so. The Gothic army was held before the walls. A large number of their nation had already crossed the Danube and had been admitted as peaceful settlers within the bounds of the Empire. It is certain that Gothic invaders from north of the Danube would find many friends, for the Goths already settled in the Empire were dissatisfied with their treatment by the Romans. And even in the Roman legions that they defeated there would be many of their countrymen, for the recruiting of barbarians among the legionaries had been going on for more than one century. Theodosius the Great, who had succeeded Valens, killed by the Goths, as Emperor of the East, made a treaty with the conquerors, which was faithfully observed until the death of Theodosius in 395. But then the Goths {29} threw off the yoke which the treaty had put upon their necks.

It was fortunate indeed for the Empire that the Persians were no longer a danger on the eastern boundary. A peace with that nation had been arranged in 364, and was not broken for nearly 150 years.

The Goths were divided into several different tribes, not always at peace with each other; and especially into Visigoths and Ostrogoths—that is Western Goths and Eastern. They were so completely divided by the end of the fourth century that the Ostrogoths had fallen under the domination of the Huns, while the Visigoths, further westward, were independent of that fierce and strange people.

But even these Western Goths felt the pressure, pushing them westward, of the Hun, though not so directly. They had the Ostrogoths in between, and sometimes we actually find the Ostrogoths, with the Huns, fighting against the Visigoths. Thus intermixed was the fighting.

And you should know too that although the Romans still called these nations barbarians, many barbarians had come to high honour and great power in one or other of the Roman cities. The division between Roman and barbarian was not nearly so distinct and sharp as the word "barbarian" suggests to us. It was not possible that there should be much idea of inequality between them, seeing that the barbarian could hold such high honour in the chief places of the Empire.

You will see now what the story told in the first few chapters of this volume is, for the most part, about. It is about the efforts of the Empire—on the whole, the successful efforts of the Empire—to keep itself intact within its walls and to keep the barbarians out. The pressure of those barbarians without, together with the weakened state of the Empire itself, has led to the division of the Eastern from the Western Empire. And that is the story up to close on the year 400.

After that year 400, or a few years before, the story changes. It is no longer about the efforts of the Empire to keep the barbarian out. The barbarian is triumphantly breaking through; and it is with that break through, and with all that happened to the Empire, as a consequence, that the story has now to deal.

We shall think it curious, as we follow it, to note how the different tribes of the barbarians seem as if they acted together, in concert with each other, from the northern extremity of the Empire's boundary right down to where we saw those Visigoths permitted to settle south of the Danube. They seem to have pressed in from the east, within the space of very few years, along the whole of that boundary.

Probably it was by no pre-concerted arrangement, that is to say not following any already arranged {31} plan, that they pressed in along that boundary nearly all at the same time. Probably what happened was that all of them were feeling a pressure from the Huns, their neighbours on the east: so that they were all ready to move. Then, when one tribe heard of the success of another in moving west, the tribe that heard this news would be encouraged to attempt a westward push on its own account. That push would be all the more likely to succeed because the Roman legions were busy trying to stop those that had moved westward already.

British legions re-called

To what extent they acted together in order to help each other we do not know—probably with very little idea of giving each other this help, for often when they encountered each other in the course of the westward move, they actually fought amongst themselves. What we do know—and it is a fact that made a great difference to the story of our own islands—is that within a very short time the Empire found its legions so hard beset on the Continent of Europe that it recalled the three legions that had been holding Britain. This happened in 407.

I have already, I think, mentioned the names of all those Indo-European or Germanic tribes that occupy chief place in the story with the exception of the Vandals. These Vandals had their home somewhere between the Oder and the Vistula, in modern Prussia, and they travelled further than any of the rest, actually going down through Spain, across into Africa, turning eastward again and working their way along the north coast of Africa, establishing themselves at Carthage, equipping a great fleet there and crossing over and taking Rome itself by assault from the sea—a very wonderful story indeed.

But the first people to move in this great irruption, or break in, of the barbarians into the Empire were those most southern, the Visigoths. They pressed {32} along, not southward this time but westward, into Gaul.

We always have to bear in mind that these movements of the tribes westward were not like the marches of an army only, but rather like the migrations of a whole people. It was land, land to settle on and to live in without vexation from Huns and other enemies, that they came to seek; and they brought with them their wives and children and live stock, to settle them down on the newly won land. It seems to have been the custom of all these tribes to take to themselves one-third of the land that they conquered, leaving the conquered people two-thirds—a far more generous proceeding than we should have expected from them. But we have seen something of their institutions and courts of law. Although called "barbarians," they were far from being what we should term savages. They had, however, very little idea of learning or arts or science. The Greek thought had not penetrated among them, although many of them had by this time become Christian. They were not nearly so advanced in civilisation as the Romans, and their conquest of all Western Europe checked the progress of civilisation and threw all mankind backward into ways of life and of thought that probably the Romans and Greeks never expected man to return to.

It was under pressure of their own kinsmen, the Ostrogoths, acting with their superior lords, the Huns, that the Visigoths at this time invaded Gaul and pushed into the north of Italy and down into Greece. They had become Christians. A large number of monks came with the armies and, in their religious zeal, destroyed many beautiful temples of the pagan gods in Greece and elsewhere.

The westward advance of the Goths was not continuous. It met with checks from the legions, but {33} again and again they came on, like waves of the sea, returning after retreating. In 402 they were driven back, but in a later invasion they came three times, in three successive years, up to the walls of Rome itself: that is, in 408, 409, and 410; and some time in these years it seems that a large force of the Ostrogoths joined their kinsmen of the Western Goths in this Italian invasion. These Eastern Goths were still pagans. In 410 the Goths actually entered and sacked Rome. The effect of this was that the Empire was compelled, if it was to survive at all, to make some terms of peace with the invaders, even if the terms meant that it had to give up a large territory to them. This is precisely what happened. Within a few years after the sack of Rome the Goths had established themselves in the south of Gaul and pushed down over the Pyrenees into Spain. Their Spanish conquests at this time were given back to the Roman Empire, though some of the Goths remained in Spain, but by way of compensation Rome recognised what was known as the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse. This Visigothic territory reached right across to the Atlantic Ocean and as far north as the River Loire.

The Vandals

But now we ought to take a look at what was happening a little further north again, for this pressing through of the Germanic barbarians went on, as I have said, all along the eastern boundary. Just as the Goths had come flooding in from across the Danube, so too came the Vandals from across the Rhine. This happened in 406 or 407; and it was in 407 that the Empire, harassed by all these incursions from the east, was obliged to withdraw its legions from Britain.

We have seen something already of a tribe or nation called Franks, that had passed into Northern Gaul some years before this and had been repelled by the Romans. But some of them stayed within the Empire's bounds on terms of friendship with the {34} Romans, and when the Vandals appeared in Gaul these Franks met them in a great battle wherein the Vandals are said to have lost two thousand killed—a very large number, considering the comparatively small armies of the time. The effect of this beating seems, curiously enough, to have been, not to send them back, as we should expect, to the north-east, whence they came. Instead of that we find them going onward, south-west, and two years later crossing the Pyrenees into Spain. They fought there with the Visigoths and other German tribes that had found their way there before them, and in the end—that is to say, after twenty or more years—had taken possession of that southern part of Spain, which is called Andalusia.

And then a very strange thing happened, and they undertook an extraordinary adventure, which we have already just glanced at.

Vandals in Africa

A stretch of the northern coast of Africa, along the south of the Mediterranean Sea, belonged to the Western Roman Empire. It ran from the Straits of Gibraltar eastward to the boundary of the province of Egypt which was part of the Eastern Empire. All this strip was put under the command of a Roman official who had the title of Count of Africa.

Just at this time the Count of Africa had given offence to the Imperial authority, and, in his fear of what the offended majesty of Rome might do to him, he invited the Vandals to come across the straits to his assistance. They came—probably in larger numbers than he had reckoned on. Eighty thousand of them, in all, including the women and children, are said to have come. The Count of Africa quickly repented of what he had done. He patched up his quarrel with the Emperor, and then set to work to turn out these guests and helpers that he had invited. But they were by no means so ready to go as they had {35} been to come. They fought to remain, and so successfully that within two years of their landing in Africa they had possession of all the Roman territory along that shore with the exception of three cities, of which Carthage was the chief. At this time Carthage was estimated as the most important city, after Rome and Constantinople, in the Empire. And a few years later again, the Vandal king, breaking a treaty which he had made with Rome, attacked and took Carthage itself; and so, once again, this city, which had been the source of such deadly peril to the Empire in the days of Hannibal, fell into an enemy's hands; and it was for nearly a hundred years held in those hands.

Thus, to the year 440 or so, we may trace the extraordinary fortunes of this people to their zenith—their highest point. There, for the moment, we leave them.

Now a great part of the reason why the Vandals in Spain were so very ready to respond to the invitation of the Count of Africa was that the Visigoths with some allied tribes were pressing upon them there very much more severely than was pleasant. Spain is a country, as you should know, very much cut up and divided by mountain ranges, so that it was difficult for any conqueror to conquer the whole of the country, because those who were defeated could retreat into the mountainous places from which it was hard to hunt them out. You will find this happening again and again in the story of what we now call Spain. It is not certain, but it seems likely, that the people called Basques, living along the Pyrenees, are descendants of those Celts whom we saw moving westward and settling as Brythons in Britain and in Brittany. If that is so, they have maintained their language and their national character to this day, in spite of the many conquerors that have, at one time {36} or other in the great story, had possession of the greater part of Spain.

I write sometimes of "Spain" and sometimes of "Italy," and so forth, because it seems the natural and easy way of indicating the lands which we now speak of by those names; but they were not so known at the time of which I am telling you. And I would warn you against a mistake into which we are only too ready to fall—the mistake of supposing that this Spain and this Italy, for example, have certain natural boundaries—that there is any particular reason, apart from the arrangements, the treaties and so on, which nations, in the course of the story, have made with each other, why they should have the bounds which are set to them to-day. It is true that these arrangements about the territory allotted to each are determined in some measure by the natural features, as we call them—by mountain ranges and by big rivers—but if it were not for these arrangements there is no reason in nature why the countries should be divided out among mankind as they are, and the divisions are continually being changed all through the story.

Now the Visigoths, as soon as they were free of the Vandals, extended their Kingdom of Toulouse, as it was called, towards the west until they were masters of nearly all Spain; but that was not until, in conjunction with the Romans, they had attended to another business further north—that is to the invasion of Gaul by Attila, King of the Huns. That Hunnish invasion was checked and pushed back by a great battle fought near Chalons in 451; and, curiously enough, it was almost exactly at the same place that the advance of the Eastern power, the Germans, was checked and repelled in the Great War of a few years ago. In this battle against the Huns, which was one of the battles that has made a great difference in the {37} story of the world, there were fighting together, Romans, Visigoths and also Franks.

The Franks

The Franks, as we saw before, were perhaps the first of the Germanic tribes to break through the Roman wall. But on that first incursion they were repulsed and made a treaty with the Empire. Then they came again in the year 429 and, though defeated once, gradually fought their way south beyond the Somme River, and eventually right down to the Loire. South of that region they fought as allies of the Romans as late as 460.

The battle at, or near, Chalons counted for a great deal in our story. The Huns were a far more savage and uncultured people than any of the former invading tribes, and it really was a battle fought on behalf of civilisation, as civilisation was then understood, between the Romans, Goths, and Franks on the one side and the Huns and savagery on the other. And with these Huns were some of the Ostrogoths, whom we thus find fighting against their own kinsmen. One of the results of the battle was that the Ostrogoths now shook off the yoke of the Huns and became again an independent people.

And not only was the battle of Chalons a battle on behalf of civilisation; it was a battle on behalf of Christianity too, for the Huns—probably one and all—and the Ostrogoths, for the most part, were pagans, and the Goths and Franks and Romans nearly all Christians.

Therefore you see that Romans and barbarians had come together and made common cause, as we say, by the middle of the fifth century. Let us see what was happening in Britain in the meantime, now that the Roman soldiers had been withdrawn from it.

We might naturally expect to find that as soon as the conquering Romans left our island, the native Brythons would rejoice in their freedom and in getting rid of their masters. They had, indeed, made an attempt, under their Queen Boadicea, to free themselves while the legions still were there, but the attempt had failed. The good discipline and fighting qualities of the Romans had been too much for them.

So, for a short while after the Roman soldiers went, they may have rejoiced in their freedom; but they did not rejoice long. You remember those walls that the Romans built across the island, and what their purpose was. It was to help keep out the Picts and Caledonians, those wild tribes that lived in what we call the Highlands of Scotland. We should regard these walls, not as insurmountable barriers, but merely as aids to defence, connecting camps and forts established at intervals along them. And within a very short time of the withdrawal of the Roman garrison, or guards, the Picts were over the wall and constantly harrying and robbing and killing the Britons.

Now the story goes that the Britons, worn by the perpetual inroads of the Northerners, invited to their assistance certain princes of the Saxon people—the people, you will remember, who lived in Sleswig. There were Jutes in the North of that country—in Jutland—then Angli, as the Romans called them, {39} that is English, in the middle, and Saxons in the south. But both Angli and Saxons were names used to cover all those people. The names were used rather inexactly.

The Anglo-Saxons

These Anglo-Saxons—let us call them so, for that will include both the covering names—were great sea-farers, rovers, pirates. They went on marauding expeditions in their ships just as the Phœnicians had gone marauding long before and just as the Northmen, the Vikings, went a little later. It may be they were invited by the Britons; it may be they came without invitation, as their pirate fleet went down along the east coast of Britain. If they were invited, the result was very much like the result of the invitation which we saw that the Count of Africa gave to the Vandals. The Vandals came and helped him; but then they helped themselves also so liberally that they drove him out of his own possessions. The Anglo-Saxons did just the same by the Britons. They helped them: they drove back the Caledonians: but then they stayed: they drove out the Britons: they established themselves in the island: they changed Britain, the land of the Britons, into England, the land of the Angles.

At least, they made that change over much of the island. We have noted its geography in an earlier chapter, and saw that the east and the south are less mountainous and therefore less strong for defence against an invader, than the west and north. So it was all down the East of England and along the southern part that the Anglo-Saxons settled. The Britons went back into the hills of Devon and Cornwall, of Wales and of Cumberland.

We have to picture to ourselves all the eastern and southern shores of Britain and the western coast of the Continent of Europe as very liable to the attack of one or other of the sea-rovers at this time, and, as a consequence of different tribes of these rovers arriving {40} in strength in different parts of our island, we find it divided into three different main kingdoms—in the north the kingdom of Northumbria, which reached up as far as the Firth of Forth; in the south the kingdom of Wessex, or the West Saxons; and between the two the kingdom of Marcia, or Mercia, which meant, originally, the kingdom of the Marches—of the "mark" or boundary between the English and the Britons.

The Briton had become Romanised—that is to say had adopted Roman ways of thought and living, and had lived under Roman law, while the legions were there. Of course, since the legions formed permanent encampments—practically towns—as we have seen, all the Romans and the Roman influence did not leave when the soldiers and the governors, appointed by Rome, went. The Britons had the Roman way of talking of these English as "barbarians"—men outside the pale.

Then these barbarians came in, just as they had come into Gaul, and conquered. But, for reasons that are not easily seen, they treated the conquered people, the Britons, with far more severity than the Continental conquerors showed. Perhaps they were of a fiercer race. Whatever the reason, they came killing, exterminating the natives; and, whereas in Gaul and other provinces that the Germans conquered, the Roman methods of law and all the Roman customs were allowed to go on, in Britain the Anglo-Saxons did away with all the Roman institutions and manners. They brought in their own ways and their own religion.

They were pagans, and the native Britons had become Christian. Perhaps that, in part, is why they treated the Britons so badly. But we have to be on our guard about believing quite all that is told us of their cruelty; because the only people who have told us about it, who wrote the history of the time {41} and of the doings of the conquerors, were clerics, clerks of the holy orders, monks of a Christian monastery.

Druids

Britain had been Christian, because the Romans had introduced Christianity and established it in the stead of the old Druid religion of which the great stone circle at Stonehenge remains as a monument. But England was now pagan, and followed the religion of the North, whose gods were Woden, or Odin, the god of battles, who gives us our name for one of the days of the week—Woden's day, or Wednesday, and Thor, the god of the hammer, the great smith, like Vulcan in the religion which the Romans took from Greece. From Thor we get our Thursday. And Freia, the goddess who was supposed to be the wife of Odin, gives us our Friday. Tuesday is the day of the god Tiw.

![STONEHENGE. The Druidical circle, from the air, at the present day. R. R. Edwards.] [Salisbury.](images/img-041.jpg)

STONEHENGE.

The Druidical circle, from the air, at the present day.

R. R. Edwards. Salisbury.

By way of completing the story of our weekdays—Sunday, of course, is the day of the Sun; Monday, of the Moon. And Saturday—and you {42} should note this, because it shows what a mixture our language is of words taken from the Saxon on the one side and from the Latin, the Roman, on the other—Saturday is the day of Saturn, one of the Roman gods adopted from the Greek.

For more than a century England remained pagan. It was not till very nearly A.D. 600 that any attempt was made to bring in Christianity again. That attempt was made in the south-eastern corner of England, just where the Anglo-Saxon pagans themselves had landed, and quite near our present chief cathedral town of Canterbury. But the revival of Christianity in England did not really come that way. The northern kingdoms in England were too strong for any influence from the southern kingdom to prevail, Christianity was reintroduced into England from Ireland, whither the Saxons had never come to destroy it. It came by way of an island, Iona, off the west coast of Scotland, and so across to the Holy Island, off the coast of Northumberland.

Then arose great fighting between the heathen, under Penda, King of Mercia and of the "Middle English," as you will read of their being called, and Christians under Oswi, King of Northumbria. Oswi utterly defeated Penda in A.D. 655 and from that victory followed the establishment of Christianity as the accepted religion over the British islands.

All this story of England under the rule of the Anglo-Saxons is separate and quite apart, for very many years, from the rest of the great story, which is, at this time, chiefly concerned with the destruction by the barbarians of the Western Roman Empire. It will come very closely into the great story again before many centuries are past, and you will see that it is closely involved in it by the time we reach the end of this volume; but until 600 or so, England is rather out of the main current of European history.