Title: Mysteries of the missing

Author: Edward H. Smith

Release date: May 26, 2024 [eBook #73706]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: The Dial Press

Credits: Demian Katz and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University.)

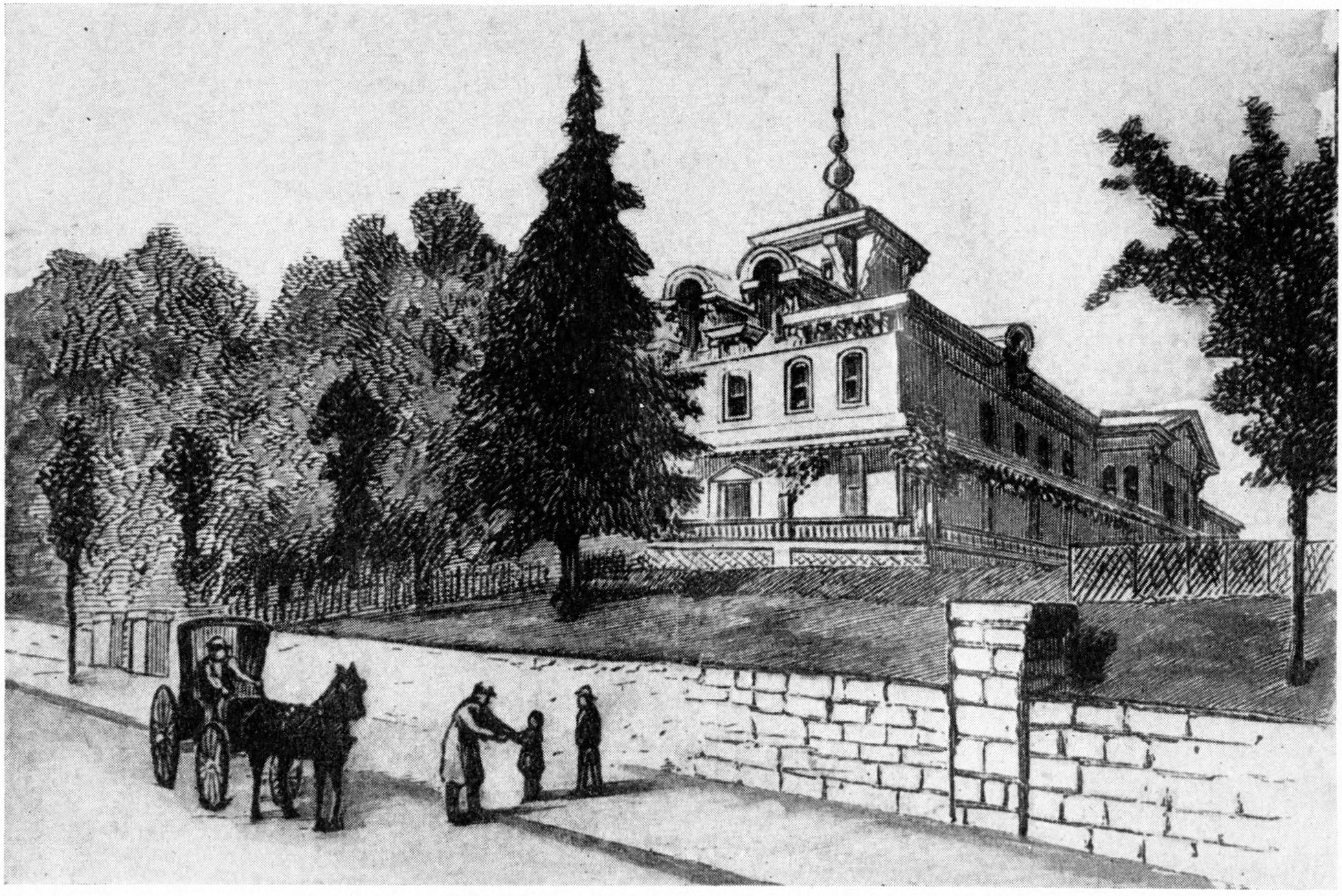

~~ SCENE OF THE ABDUCTION OF CHARLIE ROSS ~~

The Ross house, Washington Lane, Germantown, Pa.

From a sketch by W. P. Snyder

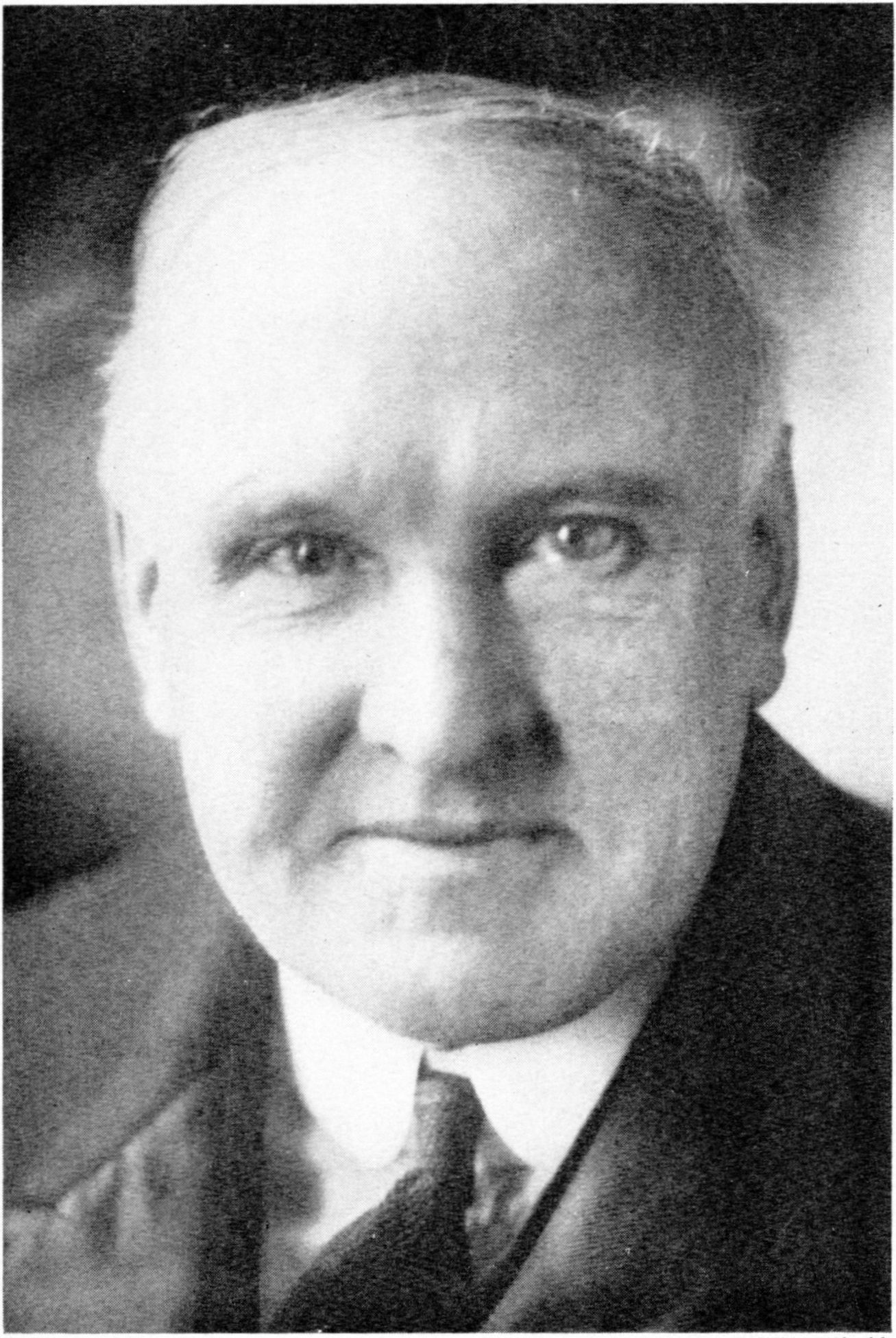

By EDWARD H. SMITH

Author of “Famous Poison Mysteries,” etc.

LINCOLN MAC VEAGH

THE DIAL PRESS

NEW YORK · MCMXXVII

Copyright, 1924, by

Street and Smith Corporation

Copyright, 1927, by

The Dial Press, Inc.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE VAIL-BALLOU PRESS, INC., BINGHAMTON, N. Y.

To

JOSEPH A. FAUROT

A GREAT FINDER OF WANTED MEN

—Laus Veneris.

“... but whosoever of them ate the lotus’ honeyed fruit wished to bring tidings back no more and never to leave the place; there with the lotus eaters they desired to stay, to feed on lotus and forget the homeward way.”

The Odyssey, Book IX.

The Lotophagi are gone from the Libyan strand and the Sirens from their Campanian isle, but still the sons of men go forth to strangeness and forgetfulness. What fruit or song it is that calls them out and binds them in absence, we must try to read from their history, their psyche and the chemistry of their wandering souls. Some urgent whip of that divine vice, our curiosity, drives us to the exploration and will not relent until we discover whether they have been devoured by the Polyphemus of crime, bestialized by some profane Circe or simply made drunk with the Lethe of change and remoteness.

The unreturning adventurer—the man whose destiny is hid in doubt—has tormented the imagination in every century. In life the lost comrade wakes a more poignant curiosity than the returning Odysseus. What of the true Smerdis and the false? Was it the great Aeneas the Etruscans slew, and where does Merlin lie? Did Attila die of apoplexy in the arms of Hilda or shall we believe the elder Eddas, the Nibelungen and Volsunga sagas or the Teutonic legends of later times? Was it the genuine Dmitri who was murdered in the Kremlin, and what of the two other pseudo-Dmitris? What became of Dandhu Panth after he fled into Nepal in 1859; did he perish soon or is there truth in the tale of the finger burial of Nana Sahib? And was it Quantrill who died at Louisville of his wounds after Captain Terrill’s siege of the barn at Bloomfield?

These enigmas are more lasting and irritating than any other minor facet of history, and the patient searching of scholars seems but to add to the popular confusion and to the charm of our doubts. Even where research seems to arrive at positive results, the general will cling to their puzzlement, for a romantic mystery is always sweeter than a sordid fact.

Even in the modern world, so closely organized, so completely explored and so prodigiously policed, those enigmas continue to pile up. In our day it is an axiom that nothing is harder to lose sight of than a ship at sea or a man on land. This sounds, at first blush, like a paradox. It ought, surely, to be easy to scrape the name from a vessel, change her gear and peculiarities a little, paint a fresh word upon her side and so conceal her. Simpler still, why can’t any man, not too conspicuous or individual, step out of the crowd, alter the cut of his hair and clothes, assume another name and immediately be draped in a fresh ego? Does it not take a huge annual expenditure for ship registry and all sorts of marine policing on the one side, and an even greater sum for the land police, on the other, to prevent such things? Truly enough, and it is the police power of the earth, backed by certain plain or obscure motivations in mankind, that makes it next to impossible for a ship or a man to drop out of sight, as the phrase goes.

Leaving aside the ships, which are a small part of our argument, we may note that, for all the difficulty, thousands of human beings try to vanish every year. Plainly there are many circumstances, many crises in the lives of men, women and children, that make a complete detachment and forgottenness desirable, nay, imperative. Yet, of the twenty-five thousand persons reported missing to the police of the City of New York every year, to take an instance, only a few remain permanently undiscovered. Most are mere stayouts or young runaways and are returned to their inquiring relatives within a few hours or days. Others are deserting spouses—husbands who have wearied or wives who have found new loves. These sometimes lead long chases before they are reported and identified, at which time the police have no more to do with the matter unless there is action from the domestic courts. A number are suicides, whose bodies soon or late rise from the city-engirdling waters and are, almost without fail, identified by the marvelously efficient police detectives in charge of the morgues. Some are pretended amnesics and a few are true ones. But in the end the police of the cities clear up nearly all these cases. For instance, in the year 1924, the New York police department had on its books only one male and one female uncleared case originating in the year of 1918, or six years earlier. At the same time there were four male and six female cases dating from 1919, three male and one female cases that had originated in 1920, no male and three female cases that originated in 1921, three male and two female cases of the date of 1922, but in 1924 there were still pending, as the police say, twenty-eight male and sixty-three female cases of the year preceding, 1923.

The point here is that only one man and one woman could stay hid from the searching eyes of the law as long as six years. Evidently the business of vanishing presents some formidable difficulties.

However, it is not even these solitary absentees that engage our interest most sharply, for usually we know why they went and have some indication that they are alive and merely skulking. There is another and far rarer genus of the family of the missing, however, that does strike hard upon that explosive chemical of human curiosity. Here we have those few and detached inexplicable affairs that neither astuteness nor diligence, time nor patience, frenzy nor faith can penetrate—the true romances, the genuine mysteries of vanishment. A man goes forth to his habitual labor and between hours he is gone from all that knew him, all that was familiar. There is a gap in the environment and many lives are affected, nearly or remotely. No one knows the why or where or how of his going and all the power of men and materials is hopelessly expended. Years pass and these tales of puzzlement become legends. They are then things to brood about before the fire, when the moving mind is touched by the inner mysteriousness of life.

Again, there are those strange instances of the theft of human beings by human beings—kidnappings, in the usual term. Nothing except a natural cataclysm is so excitant of mass terror as the first suggestion that there are child-stealers abroad. What fevers and rages of the public temper may result from such crimes will be seen from some of what follows. The most celebrated instance is, of course, the affair of Charlie Ross of Philadelphia, which carries us back more than half a century. We have here the classic American kidnapping case, already a tradition, rich in all the elements that make the perfect abduction tale.

This terror of the thief of children is, to be sure, as old as the races. From the Phoenicians who stole babes to feed to their bloody divinities, the Minoans who raped the youth of Greece for their bull-fights, and the priests of many lands who demanded maidens to satisfy the wrath of their gods and the lust of their flesh, down to the European Gypsies, who sometimes steal, or are said to steal, children for bridal gifts, we have this dread vein running through the body of our history. We need, accordingly, no going back into our phylogeny or biology, to understand the frenzy of the mother when the shadow of the kidnapper passes over her cote. The women of Normandy are said still to whisper with trembling the name of Gilles de Rais (or Retz), that bold marshal of France and comrade in arms of Jeanne d’Arc, who seems to have been a stealer and killer of children, instead of the original of Perrault’s Bluebeard, as many believe. What terror other kidnappers have sent into the hearts of parents will be seen from the text.

This volume is not intended as a handbook of mysteries, for such works exist in numbers. The author has limited himself to problems of disappearance and cases of kidnapping, thereby excluding many twice-told wonders—the wandering Ahasuerus, the Flying Dutchman, Prince Charles Edward, the Dauphin, Gosselin’s Femme sans nom, the changeling of Louis Philippe and the Crown Prince Rudolf and the affair at Mayerling.

Neither have I attempted any technical exploration of the conduct and motives of vanishers and kidnappers. It must be sufficiently clear that a man unpursued who flees and hides is out of tune with his environment, ill adjusted, nervously unwell. Nor need we accent again the fact that all criminals, kidnappers included, are creatures of disease or defect.

A general bibliography will be found at the end of the book. The information to be had from these volumes has been liberally supported and amplified from the files of contemporary newspapers in the countries and cities where these dramas of doubt were played. The records of legal trials have been consulted in instances where trials took place and I have talked with the accessible officials having knowledge of the cases or persons here treated.

E. H. S.

New York, August, 1927.

THE CHARLIE ROSS ENIGMA

Late on the afternoon of the twenty-seventh of June, 1874, two men in a shabby-covered buggy stopped their horse under the venerable elms of Washington Lane in Germantown, that sleepy suburb of Philadelphia, with its grave-faced revolutionary houses and its air of lavendered maturity. All about these intruders was historic ground. Near at hand was the Chew House, where Lord Howe repulsed Washington and his tattered command in their famous encounter. Yonder stood the old Morris Mansion, where the British commander stood cursing the fog, while his troops retreated from the surprise attack. Here the impetuous Agnew fell before a backwoods rifleman, and there Mad Anthony Wayne was forced to decamp by the fire of his confused left. Not far away the first American Bible had been printed, and that ruinous house on the ridge had once been the American Capitol. The whole region was a hive of memories.

Strangely enough, the men in the buggy gave no sign of interest in all these things. Instead, they devoted their attention to the two young sons of a grocer who happened to be playing among the bushes on their father’s property. The children were gradually attracted to confidence by the strangers, who offered them sweets and asked them who they were, where their parents were staying, how old they might be, and how they might like to go riding.

The older boy, just past his sixth birth anniversary, tried to respond manfully, as his parents had taught him. He said that he was Walter Ross, and that his companion was his brother, Charlie, aged four. His mother, he related, had gone to Atlantic City with her older daughters, and his father was busy at the store in the business section of the settlement. Yes, that big, white house on the knoll behind them was where they lived. All this and a good deal more the little boy prattled off to his inquisitors, but when it came to getting into their buggy he demurred. The men got pieces of candy from their pockets, filled the hands of both children, and drove away.

When the father of the boys came home a little later, he found his sons busy with their candy, and he was told where they had got it. He smiled and felt that the two men in the buggy must be very fond of children. Not the least suspicion crossed his mind. Yet this harmless incident of that forgotten summer afternoon was the prelude to the most famous of American abduction cases and the introduction to one of the abiding mysteries of disappearance. What followed with fatal swiftness came soon to be a matter of almost worldwide notoriousness—a case of kidnapping that stands firm in popular memory after the confusions of fifty-odd years.

On the afternoon of July 1, the strangers came again. This time they had no difficulty in getting the children into their wagon.[1] Saying that they were going to buy fire crackers for the approaching Fourth of July, they carried the little boys to the corner of Palmer and Richmond Streets, Philadelphia, where Walter Ross was given a silver quarter and told to go into a shop and buy what he wanted. At the end of five or ten minutes the boy emerged to find his brother, his benefactors and their buggy gone.

[1] Walter Ross, then 7 years old, testified at the Westervelt trial, the following year, that he had seen the men twice before, but this seems unlikely.

Little Walter Ross, abandoned eight miles from his home in the toils of a strange city, stood on the curb and gave childish vent to his feelings. The sight of the boy with his hands full of fireworks and his eyes full of tears, soon attracted passers-by. A man named Peacock finally took charge of the youngster and got from him the name and address of his father. At about eight o’clock that evening he arrived at the Ross dwelling and delivered the child, to find that the younger boy had not been brought home, and that the father was out visiting the police stations in quest of his sons.

In spite of the obvious facts, the idea of kidnapping was not immediately conceived, and it even got a hostile reception when the circumstances forced its entertainment. The father of the missing Charlie was Christian K. Ross, a Philadelphia retail grocer who was popularly supposed to be wealthy, and was in fact the owner of a prosperous business at Third and Market streets, and master of a competence. His flourishing trade, the big house in which he lived with his wife and seven children, and the fine grounds about his home naturally caused many to believe that he was a man of large means. In view of these facts alone the theory of abduction should have been considered at once. Again, Walter Ross recited the details of his adventure with the men in a faithful and detailed way, telling enough about the talk and manner of the men to indicate criminal intent. Moreover, Mr. Ross was aware of the previous visit of the strangers. Finally, the manœuver of deserting the older boy and disappearing with his brother should have been sufficiently suggestive for the most lethargic policeman. Nevertheless, the Philadelphia officials took the skeptical position. Their early activities expressed themselves in the following advertisement, which I take from the Philadelphia Ledger of July 3:

“Lost, on July 1st, a small boy, about four years of age, light complexion, and light curly hair. A suitable reward will be paid on his return to E. L. Joyce, Central Station, corner of Fifth and Chestnut streets.”

The advertisement was worded in this fashion to conceal the fact of the child’s vanishment from his mother, who was not called from her summer resort until some days later.

The police were, however, not long allowed to rest on their comfortable assumption that the boy had been lost. On the fifth, Mr. Ross received a letter which had been dated and posted on the day before in Philadelphia. It stated that Charlie Ross was in the custody of the writer, that he was well and safe, that it was useless to look for him through the police, and that the father would hear more in a few days. The note was scrawled by some one who was trying to conceal his natural handwriting and any literate attainments he may have possessed. Punctuation and capitals were almost absent, and the commonest words were so crazily misspelled as to betray purposiveness. The unfortunate father was addressed as “Mr. Ros,” a formal appellation which was later contracted to “Ros.” This missive and some of those that followed were signed “John.”

Even this communication did not mean much to the police, though they had not, at that early stage of the mystery, the troublesome flood of crank letters to plead as an excuse for their disbelief. As a matter of fact, this first letter came before there had been anything but the briefest and most conservative announcements in the newspapers, and it should have been apparent to any one that there was nothing fraudulent about it. Yet the police officials dawdled. A second message from the mysterious John wakened them at last to action.

On the morning of July 7, Mr. Ross received a longer communication, unquestionably from the writer of the first, in which he was told that his appeal to the detectives would be vain. He must meet the terms of the ransom, twenty thousand dollars, or he would be the murderer of his own child. The writer declared that no power in the universe would discover the boy, or restore him to his father, without payment of the money, and he added that if the father sent detectives too near the hiding place of the boy he would thereby be sealing the doom of his son. The letter closed with most terrifying threats. The kidnappers were frankly out to get money, and they would have it, either from Ross or from others. If he failed to yield, his child would be slain as an example to others, so that they would act more wisely when their children were taken. Ross would see his child either alive or dead. If he paid, the boy would be brought back alive; if not, his father would behold his corpse. Ross’ willingness to come to terms must be signified by the insertion of these words into the Ledger: “Ros, we be willing to negotiate.”

Such an epistle blew away all doubts, and the Charlie Ross terror burst upon Philadelphia and surrounding communities the following morning in full virulence. The police surrounded the city, guarded every out-going road, searched the trains and boats, went through all the craft lying in the rivers, spread the dragnet for all the known criminals in town and immediately began a house-to-house search, an almost unprecedented proceeding in a republic. The newspapers grew more inflammatory with every fresh edition. At once the mad pack of anonymous letter writers took up the cry, writing to the police and to the unfortunate parents, who were forced to read with an anxious eye whatever came to their door, a most insulting and disheartening array of fulminations which caused the collapse of the already overburdened mother.

In the fever which attacked the city any child was likely to be seized and dragged, with its nurse or parent, to the nearest police station, there to answer the suspicion of being Charlie Ross. Mothers with golden-haired boys of the approximate age of Charlie resorted to Christian Ross in an unending stream, demanding that he give them written attestation of the fact that their children were not his, and the poor beladen man actually wrote hundreds of such testimonials. The madness of the public went to the absurdest lengths. Children twice the age and size of the kidnapped boy were dragged before the officials by unbalanced busybodies. Little boys with black hair were apprehended by the score at the demand of citizens who pleaded that they might be the missing boy, with his blond curls dyed. Little girls were brought before the scornful police, and some of the self-appointed seekers for the missing boy had to be driven from the station houses with threats and blows.

Following the command of the child snatchers with literal fidelity, Mr. Ross had published in the Ledger the words I have quoted. The result was a third epistle from the robbers. It recognized his reply, but made no definite proposition and gave no further orders, save the command that he reply in the Ledger, stating whether or not he was ready to pay the twenty thousand dollars. On the other hand, the letter continued the ferocious threats of the earlier communication, laughed at the police efforts as “children’s play,” and asked whether “Ros” cared more for money or his son. In this letter was the same labored effort to appear densely unlettered. One new note was added. The writer asked whether Mr. Ross was “willen to pay the four thousand pounds for the ransom of yu child.” Either the writer was, or wanted to seem, a Briton, used to speaking of money in British terms. This pretension was continued in some of the later letters and led eventually to a search for the missing boy in England.

In his extremity and natural inexperience, Mr. Ross relied absolutely on the police and put himself into their hands. He asked how he was to reply to the third letter and was told that he should pretend to acquiesce in the demand of the abductors, meantime actually holding them off and relying on the detectives to find the boy. But this subterfuge was quickly recognized by the abductors, with the result that a warning letter came to Mr. Ross at the end of a few days. He was told that he was pursuing the course of folly, that the detectives could not help him, and that he must choose at once between his money and the life of his child.

Ross was advised by some friends and neighbors to yield to the demands of the extortioners, and several men of means offered him loans or gifts of such funds as he was not able to raise himself. Accordingly he signified his intention of arriving at a bargain, and the mysterious John wrote him two or three well-veiled letters which were intended to test his good faith. At this point the father and the abductors seemed about to agree, when the officials again intervened and caused the grocer to change his mood. He declared in an advertisement that he would not compound a felony by paying money for the return of his child. But this stand had hardly been taken when Mrs. Ross’ pitiful anxiety caused another change of front.

Unquestionably this vacillation had a harmful effect in more than one direction. Its most serious consequence was that it gave the abductors the impression that they were dealing with a man who did not know his own mind, could not be relied upon to keep his promises, and was obviously in the control of the officers. Accordingly they moved with supercaution and began to impose impossible conditions. By this time they had written the parents of their prisoner at least a dozen letters, each containing more terrifying threats than its antecedents. To look this correspondence over at this late day is to see the nervousness of the abductors, slowly mounting to the point of extreme danger to the child. But Mr. Ross failed to see the peril, or was overpersuaded by official opinion.

At this crucial point in the negotiations the blunder of all blunders was made. Philadelphia was tremulous with excitement. The police of every American city were looking for the apparition of the boy or his kidnappers. Officials in the chief British and Continental ports were watching arriving ships for the fugitives, and millions of newspaper readers were following the case in eager suspense. Naturally the police and the other officials of Philadelphia felt that the eyes of the world were upon them. They quite humanly decided on a course calculated to bring them celebrity in case of success and ample justification in case of failure. In other words, they made the gesture typical of baffled officialdom, without respect to the safety of the missing child or the real interests of its parents. At a meeting presided over by the mayor, attended by leading citizens and advised by the chiefs of the police, a reward of twenty thousand dollars, to match the amount of ransom demanded, was subscribed and advertised. The terms called for “evidence leading to the capture and conviction of the abductors of Charlie Ross and the safe return of the child,” conditions which may be cynically viewed as incongruous. The following day the chief of police announced that his men, should they participate in the successful coup, would claim no part of the reward.

All this was intended, to be sure, as an inducement to informers, the hope being, apparently, that some one inside the kidnapping conspiracy would be bribed into revelations. But the actual result was quite the opposite. A sudden hush fell upon the writer of the letters. Also, there were no more communications in the Ledger. A week passed without further word, and the parents of the boy were thrown into utter hopelessness. Finally another letter came, this time from New York, whereas all previous notes had been mailed in Philadelphia. It was clear that the offer of a high reward had led the abductors to leave the city, and their letter showed that they had slipped away with their prisoner, in spite of the vaunted precautions.

The next note from the criminals warned Ross in terms of impressive finality that he must at once abandon the detectives and come to terms. He signified his intention of complying by inserting an advertisement in the New York Herald, as directed by the abductors. They wrote him that they would shortly inform him of the manner in which the money was to be paid over. Finally the telling note came. It commanded Mr. Ross to procure twenty thousand dollars in bank notes of small denomination. These he was to place in a leather traveling bag, which was to be painted white so that it might be visible at night. With this bag of money, Ross was to board the midnight train for New York on the night of July 30-31 and stand on the rear platform, ready to toss the bag to the track. As soon as he should see a bright light and a white flag being waved, he was to let go the money, but the train was not to stop until the next station was reached. In case these conditions were fully and faithfully met, the child would be restored, safe and sound, within a few hours.

Ross, after consultation with the police, decided to temporize once more. He got the white painted bag, as commanded, and took the midnight train, prepared to change to a Hudson River train in New York and continue his journey to Albany, as the abductors had further instructed. But there was no money in the valise. Instead, it contained a letter in which Ross said that he could not pay until he saw the child before him. He insisted that the exchange be made simultaneously and suggested that communication through the newspapers was not satisfactory, since it was public and betrayed all plans to the police. Some closer and secret way of communicating must be devised, he wrote.

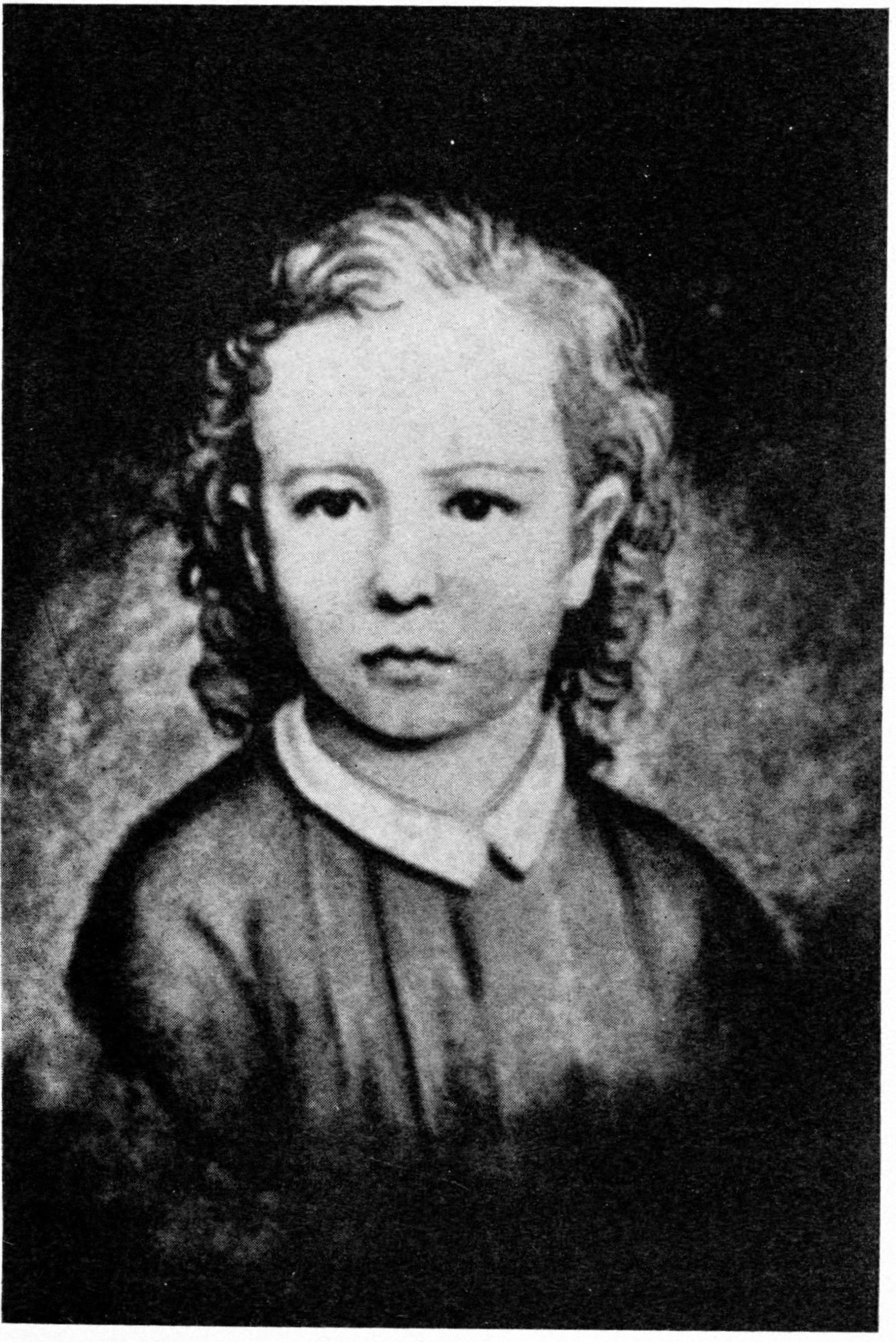

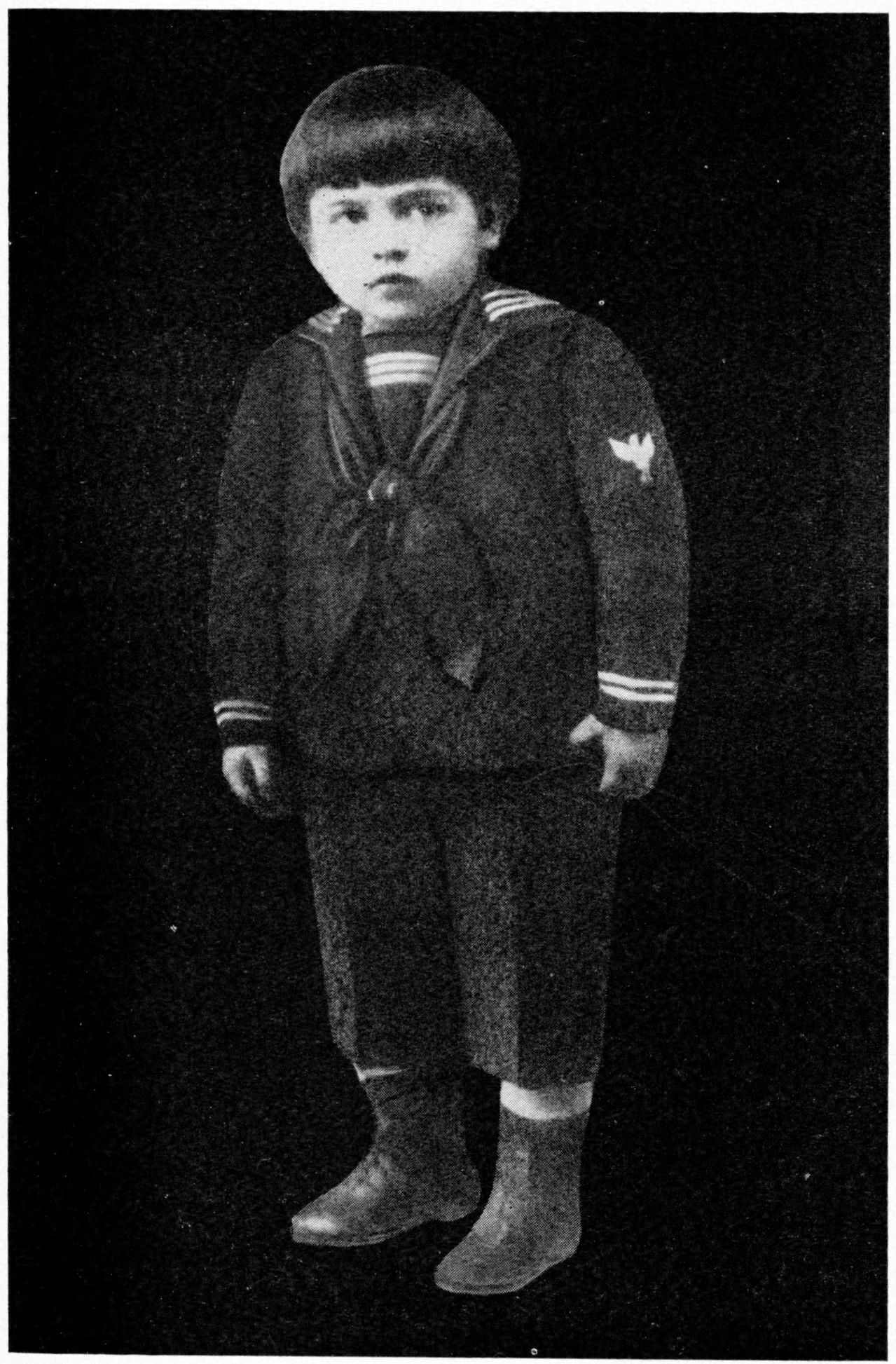

~~ CHARLIE ROSS ~~

So Mr. Ross set out with a police escort. He rode to New York on the rear platform of one train and to Albany on another. But the agent of the kidnappers did not appear, and Ross returned to Philadelphia crestfallen, only to find that a false newspaper report had caused the plan to miscarry. One of the papers had announced that Ross was going West to follow up a clew. The kidnappers had seen this and decided that their man was not going to make the trip to New York and Albany. Consequently there was no one along the track to receive the valise. Perhaps it was just as well. The abductors would have laughed at the empty police dodge of suggesting a closer and secret method of communication—for the purpose of betraying the malefactors, of course.

From this point on, Ross and the abductors continued to argue, through the New York Herald, the question of simultaneous exchange of the boy and money. Ross naturally took the position that he could not risk being imposed on by men who perhaps did not have the child at all. The robbers, on their side, contended that they could not see any safe way of making a synchronous exchange. So the negotiations dragged along.

The New York police entered the case on August 2, when Chief Walling sent to Philadelphia for the letters received by Mr. Ross from the abductors. They were taken to New York by Captain Heins of the Philadelphia police, and “Chief Walling’s informant identified the writing as that of William Mosher, alias Johnson.”

In order to draw the line between fact and fable as clearly as possible at this point, I quote from official police sources, namely, “Celebrated Criminal Cases of America,” by Thomas S. Duke, captain of police, San Francisco, published in 1910. Captain Duke says that his facts have been “verified with the assistance of police officials throughout the country.” He continues with respect to the Ross case:

“The informant then stated that in April, 1874—the year in question—Mosher and Joseph Douglas, alias Clark, endeavored to persuade him to participate in the kidnapping of one of the Vanderbilt children, while the child was playing on the lawn surrounding the family residence at Throgsneck, Long Island. (Evidently a confusion.) The child was to be held until a ransom of fifty thousand dollars was obtained, and the informant’s part of the plot would be to take the child on a small launch and keep it in seclusion until the money was received, but he declined to enter into the conspiracy.”

With all due respect to the police and to official versions, this report smells strongly of fabrication after the fact, as we shall see. It is, however, true that the New York police had some sort of information early in August, and it may even be true that they had suspicions of Mosher and were on the lookout for him. A history of subsequent events will give the surest light on this disputed point.

The negotiations between Ross and the abductors continued in a desultory fashion, without any attempt to deliver the child or get the ransom, until toward the middle of November. At this time the kidnappers arranged a meeting in the Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York. Mr. Ross’ agents were to be there with the twenty thousand dollars in a package. A messenger was to call for this some time during the day. His approach and departure had been carefully planned. In case he was watched or followed, he would not find the abductors on his return, and the child would be killed. Only good faith could succeed. Mr. Ross was to insert in the New York Herald a personal reading, “Saul of Tarsus, Fifth Avenue Hotel—instant.” This would indicate his decision to pay the money and signify the day he would be at the hotel.

Accordingly the father of the missing boy had the advertisement published, saying that he would be at the hotel with the money “Wednesday, eighteenth, all day.” Ross’ brother and nephew kept the tryst, but no messenger came for the money, and the last hope of the family seemed broken.

The Rosses had long since given up the detectives and recognized the futility of police promises. The father of the boy had, in his distraction, even voiced some uncomplimentary sentiments pertaining to the guardians of the law, with the result that the unhappy man was subjected to taunt and insult and the questioning of his motives. Resort was, accordingly, had to the Pinkerton detectives, who evidently counseled Mr. Ross to act in secret. In any event, the appointment at the Fifth Avenue Hotel was the last of its kind to be made, though Ross and the abductors seemed to have been in contact at later dates. Whatever the precise facts may be on this point, five months had soon gone by without the recovery of the boy, or the apprehension of the kidnappers, while search was apparently being made in many countries. If, as claimed, Chief Walling of the New York police had direct information bearing on the identity of the abductors the first week in August, he managed a veritable feat of inefficiency, for he and his men failed, in four months, to find a widely known criminal who was afterward shown to have been in and about New York all of that time. Not the police, but a stroke of destiny, intervened to break the impasse.

On the stormy night of December 14-15, 1874, burglars entered the summer home of Charles H. Van Brunt, presiding justice of the appellate division of the New York supreme court. This mansion stood overlooking New York Bay from the fashionable Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn. The villa was then unoccupied, but in the course of the preceding summer Justice Van Brunt had installed a burglar alarm system which connected with a gong in the home of his brother, J. Holmes Van Brunt, about two hundred yards distant from the jurist’s hot weather residence. Holmes Van Brunt occupied his house the year around. He was at home on the night in question, and the sounding of the gong brought him out of bed. He sent his son out to reconnoiter, and the young man came back with the report that there was a light moving in his uncle’s place.

Holmes Van Brunt summoned two hired men from their quarters, armed them with revolvers or shotguns and went out to trap the intruders. The house of Justice Van Brunt was surrounded by the four men, who waited for the burglars to emerge. After half an hour two figures were seen to issue from the cellar door and were challenged. They answered by opening fire. The first was wounded by Holmes Van Brunt. The second ran around the house, only to be intercepted by young Van Brunt and shot down, dying instantly.

When the Van Brunts and their servants gathered about the wounded man, who was lying on the sodden ground in the agony of death, he signified that he wished to make a statement. An umbrella was held over him to keep off the driving rain, and he said, in gasping sentences, that he was Joseph Douglas, and that his companion was William Mosher. He understood he was dying and therefore wished to tell the truth. He and Mosher had stolen Charlie Ross to make money. He did not know where the child was, but Mosher could tell. Mr. Van Brunt told him that Mosher was dead, and the body of the other burglar was carried over and exhibited to the dying man. Douglas then gasped that the child would be returned safely in a few days. On hearing one of the party express doubt about his story, Douglas is said to have remarked:

“Chief Walling knows all about us and was after us, and now he has us.”

Douglas died there on the lawn, with the rain drenching his tortured body. Both he and Mosher were identified from the police records by officers who had known them and by relatives. Walter Ross and a man who had seen the kidnappers driving through the streets of Germantown with the two boys, were taken to New York. The brother of the kidnapped child, though he was purposely kept in the dark as to his mission, immediately recognized the dead men in the morgue as the abductors, saying that Douglas was the one who gave the candy, and that Mosher had driven the horse. This identification was confirmed by the other witness.

The return of the stolen boy was, therefore, anxiously and hourly expected. But he had not arrived at the end of a week, and the police officials immediately moved in new directions.

Mosher had married the sister of William Westervelt, of New York, a former police officer, who was later convicted of complicity in the abduction. Westervelt and Mrs. Mosher were apprehended. The one-time policeman made a rambling statement containing little information, but his sister admitted that she had been privy to the matter of the kidnapping. She had known for several months, she said, that her husband had kidnapped Charlie Ross, but she had not been consulted in his planning, and did not know where he had kept the child hidden, and was unable to give any information.

Mrs. Mosher went on to say that she believed the child to be alive and stated her reasons. She did not believe her husband, burglar and kidnapper though he was, capable of injuring a child. He had four of his own and had always been a good father. The poverty of his family had driven him to the abduction. Also, Mrs. Mosher related, she had pleaded with her husband to return the stolen boy to his parents, saying that it was cruel to hold him longer, that there seemed to be little chance of collecting the ransom safely, and that the danger to the abductors was becoming greater every day. This conversation, she said, had taken place only a few days before the Van Brunt burglary and Mosher’s death. Accordingly, since Mosher had then agreed that the child should be sent home, she felt sure it was still living.

But Charlie Ross never came back. The death of his abductors only intensified the quest for the boy. Detectives were sent to Europe, to Mexico, to the Pacific coast, and to various other places, whither false clews pointed. The parents advertised far and wide. Mr. Ross himself, in the course of the next few years, made hundreds of journeys to look at suspected children in all parts of the United States. He spent, according to his own account, more than sixty thousand dollars on these hopeful, but vain, pilgrimages. Each new search resulted as had all the others. At last, after more than twenty years of seeking, Christian K. Ross gave up in despair, saying he felt sure the boy must be dead.

For some time after the kidnappers had been killed and identified, a large part of the American public suspected that Westervelt or Mrs. Mosher, or some one connected with them, was detaining the missing child for fear of arrest and prosecution in case of its return home. The theory was that Charlie Ross was old enough to observe, remember and talk. He might, if released, give information that would lead to the imprisonment of Mosher’s and Douglas’ confederates. Accordingly, steps were taken to get the child back at any compromise. The Pennsylvania legislature passed an act, in February, 1875, which fixed the penalty for abducting or detaining a child at twenty-five years’ imprisonment, but the new law contained a proviso that any person or persons delivering a stolen child to the nearest sheriff on or before the twenty-fifth day of March, 1875, should be immune from any punishment. At the same time Mr. Ross offered a cash reward of five thousand dollars, payable on delivery of the child, and no questions asked. He named more than half a dozen responsible firms at whose places of business the child might be left for identification, announcing that all these business houses were prepared to pay the reward on the spot, and guaranteeing that those bringing in the boy would not be detained.

All this was in vain, and the conclusion had at last to be reached that the boy was beyond human powers of restoration.

To tell what seems to have been the truth—though it was suspected at the time—the New York police had fairly reliable information on Mosher and Douglas soon after the crime. Chief Walling appears, though he never openly said so, to have been informed by a brother of Mosher’s who was on bad terms with the kidnapper. Not long afterwards he had Westervelt brought in for questioning. That worthy had been dismissed from the New York police force a few months earlier for neglect of duty or shielding a policy room. His sister was Bill Mosher’s (the suspected man’s) wife and it was known that Westervelt had been in Philadelphia about the time of the abduction of Charlie Ross. He was trying, by every device, to get himself reinstated as a policeman, and Walling held out to him the double bait of renewed employment and the whole of the twenty thousand dollars of reward offered for the return of the boy and the capture of the kidnappers.

Here a monumental piece of inefficiency and stupidity seems to have been committed, for though Westervelt visited the chief of police no fewer than twenty times, he was never trailed to his scores of appointments with his brother-in-law and the other abductor. Neither did the astute guardians of the law get wind of the fact that Mosher and Douglas were in and about New York most of the time. They failed to find out that Westervelt and probably one of the others had been seen with the little Ross boy in their hands. Indeed, they failed to make the least progress in the case, though they had definite information concerning the names of the kidnappers, both of them experienced criminals with long records. It might be hard to discover a more dreadful piece of police bluffing and blundering. First the Philadelphia and then the New York forces gave the poorest possible advice, made the most egregious boasts and promises and then proceeded to show the most incredible stupidity and lack of organization. A later prosecutor summed it all up when he said the police had been, at least, honest.

But, after Mosher and Douglas had been killed at Judge Van Brunt’s house and Douglas had made his dying statements, it was easy to lure Westervelt to Philadelphia, arrest him, charge him with aiding the kidnappers and his wife with having been an accessory. Walter Ross had identified Mosher and Douglas as the men who had been in the buggy but had never seen Westervelt. A neighboring merchant appeared, however, and picked him out as the man who had spent half an hour in his shop a few weeks after the kidnapping, asking many questions about the Rosses, especially as to their financial position and the rumor that Christian K. Ross was bankrupt. Another man had seen him about Bay Ridge the day before Mosher and Douglas broke into the Van Brunt house and were killed. A woman appeared who had seen Westervelt riding on a Brooklyn horse-car with a child like Charlie Ross. In short, it was soon reasonably clear that the one-time New York policeman had conspired with his brother-in-law and the other man to seize the boy and get the ransom. Westervelt’s motives were rancor at being caught at his tricks and dismissed and financial necessity, for he was almost in want after his discharge. Apparently, he had assisted in the preparations for the kidnapping, had the boy in his charge for a time and used his standing as a former officer to hoodwink the New York police. He had also had to do with some of the ransom letters.

On August 30, 1875, Westervelt was brought to trial in the Court of Quarter Sessions, Philadelphia, Judge Elcock presiding. Theodore V. Burgin and George J. Berger, the two men who had helped the Van Brunts waylay and kill the two burglars, testified as to Douglas’ dying story. The witnesses above mentioned told their versions of what they had heard and observed. A porter in Stromberg’s Tavern, a drinking resort at 74 Mott Street, then not yet overrun by the Celestial hordes, testified that Westervelt was often at the Tavern drinking and consulting with Mosher and Douglas, that he had boasted he could name the kidnappers and that he had arranged for secret signals to reveal the presence of the two confederates now dead. Chief Walling also testified against the man. The jury returned a verdict of guilty on three counts of the indictment, reaching its decision on September 20, after long deliberation. On October 9, Judge Elcock sentenced the disgraced policeman to serve seven years in solitary confinement at labor, in the Eastern Penitentiary.

Westervelt took his medicine. Never did he admit that the decision against him was just, confess that he had taken any part in the kidnapping or yield the least hint as to the fate of the unfortunate little boy.

Nothing can touch the heart more than the fearful vigil of the parents in such a case. In his book, Christian K. Ross recites, without improper emotion, that, not counting the cases looked into for him by the Pinkertons, he personally or through others investigated two hundred and seventy-three children reported to be the lost Charlie. In every case there was a mistake or a deception. Some of the lads put forward were old enough to have been conventional uncles to him.

In the following decades many strange rumors were bruited, many false trails followed to their empty endings, and many spurious or unbalanced claimants investigated and exposed. The Charlie Ross fever did not die down for a full generation, and even to-day mothers in the outlying States frighten their children into obedience with the name and rumor of this stolen boy. He has become a fearful tradition, a figure of pathos and terror for the generations.

As recently as June 5 of the current year, the Los Angeles Times, a journal staid to reaction, printed long and credulous sticks of type to the effect that John W. Brown, ill in the General Hospital of Los Angeles, was really the long lost Charlie Ross. The evil rogue “confessed” that he had remained silent for fifty years in order to “guard the honor of my mother” and said he had been kidnapped by his “foster-father, William Henry Brown,” for revenge when Mrs. Ross “declined to have anything further to do with him.”

Comment upon such caddism can be clinical only. The fact that the wretch who uttered it was sick and dying alone explains the fevered hallucination.

As an old newspaper man, I know that any kind of an item suggesting the discovery of Charlie Ross is always good copy and will be telegraphed about the country from end to end, and printed at greater or lesser length. If the thing has the least aura of credibility about it, Sunday features will follow, remarkable mainly for their inaccuracies. In other words, that sad little boy of Washington Lane long since became a classic to the American press.

At the end of more than fifty years the commentator can hazard no safer opinion on the probable fate of Charlie Ross than did his contemporaries. The popular theories then were that he had died of grief and privation, that Mosher had drowned him in New York Bay when he felt the police were near at hand, or that he had been adopted by some distant family and taught to forget his home and parents. Of these hollow guesses, the reader may take his choice now as then.

“SEVERED FROM THE RACE”

Headless horsemen and other strange ghostly figures march nightly on the beach at Nag’s Head. For more than two years these shades and spectres have been seen and Coast Guardsman Steve Basnight has been trying vainly to convince his fellows. They have laughed upon him with sepulchral laughter, as though the dead enjoyed their mirth. They have chided him as a seer of visions, a mad hallucinant.

But now there are others who have seen and fled. Mrs. Alice Grice, passing the lonely sands in her motor, had trouble with the engine and saw or thought she saw a man standing there, brooding across the waters. She called to him and he, as one shaken from some immortal reverie, moved slowly off, turning not, nor seeming quite to walk, but floating into the fog, silent and serene.

Some scoffers have suggested that these be but smugglers or rum runners, enlarged in the spume by the eyes of terror. But that cannot be so, for the coast guard is staunch and active. This is no ordinary visitor, no thing of flesh and blood. This is some grieved and restless spirit, risen through a transcendence of his grave and come to haunt this wild and forlorn region.

George Midgett, long a scoffer, has seen this uncharnelled being most closely and accurately. It is a tall, great man, clad in purest white, strolling along the beach in the full moonlight, which is no clearer than the sad and dreaming face.

It is Aaron Burr. And he is seeking his lost daughter, whose wrecked ship is believed by many to have been driven ashore at this point.

So much for the lasting charm of doubt, since I take my substance here, and most of my mystery, from the New York World of June 9, 1927, contained in a dispatch from Manteo, N. C., bearing the date of the previous day—one hundred and fifteen years after the happening.

But if we see Aaron Burr ghostwalking in the moonlight as once he trod in the tortured flesh at the Battery, looking out upon those bitter waters that denied him hope, or if we believe, with many writers, that he fell upon his knees and cried out, “By this blow I am severed from the human race!” we are still not much nearer to the pathos or the mystery of that old incident in 1812, when Theodosia Burr set out for New York by sea and never reached it.

“By and by,” says Parton in his “The Life and Times of Aaron Burr,” “some idle tales were started in the newspapers, that the Patriot had been captured by pirates and all on board murdered except Theodosia, who was carried on shore as a captive.”

Idle tales they may have been, but their vitality has outlived the pathetic facts. Indeed, unless probability be false and romance true, “the most brilliant woman of her day in America” perished at sea a little more than a hundred and fifteen years ago, caught off the Virginia Capes in a hurricane that scattered the British war fleet and crushed the “miserable little pilot boat” that was trying to bear her to New York. In that more than a century of intervening time, however, a tradition of doubt has clouded itself about the quietus of Aaron Burr’s celebrated daughter which puts her story immovably upon the roster of the great mysteries of disappearance. The various accounts of piratical atrocities connected with her death may be fanciful or even studiedly fictive, but even this realization does nothing to dispel the fog.

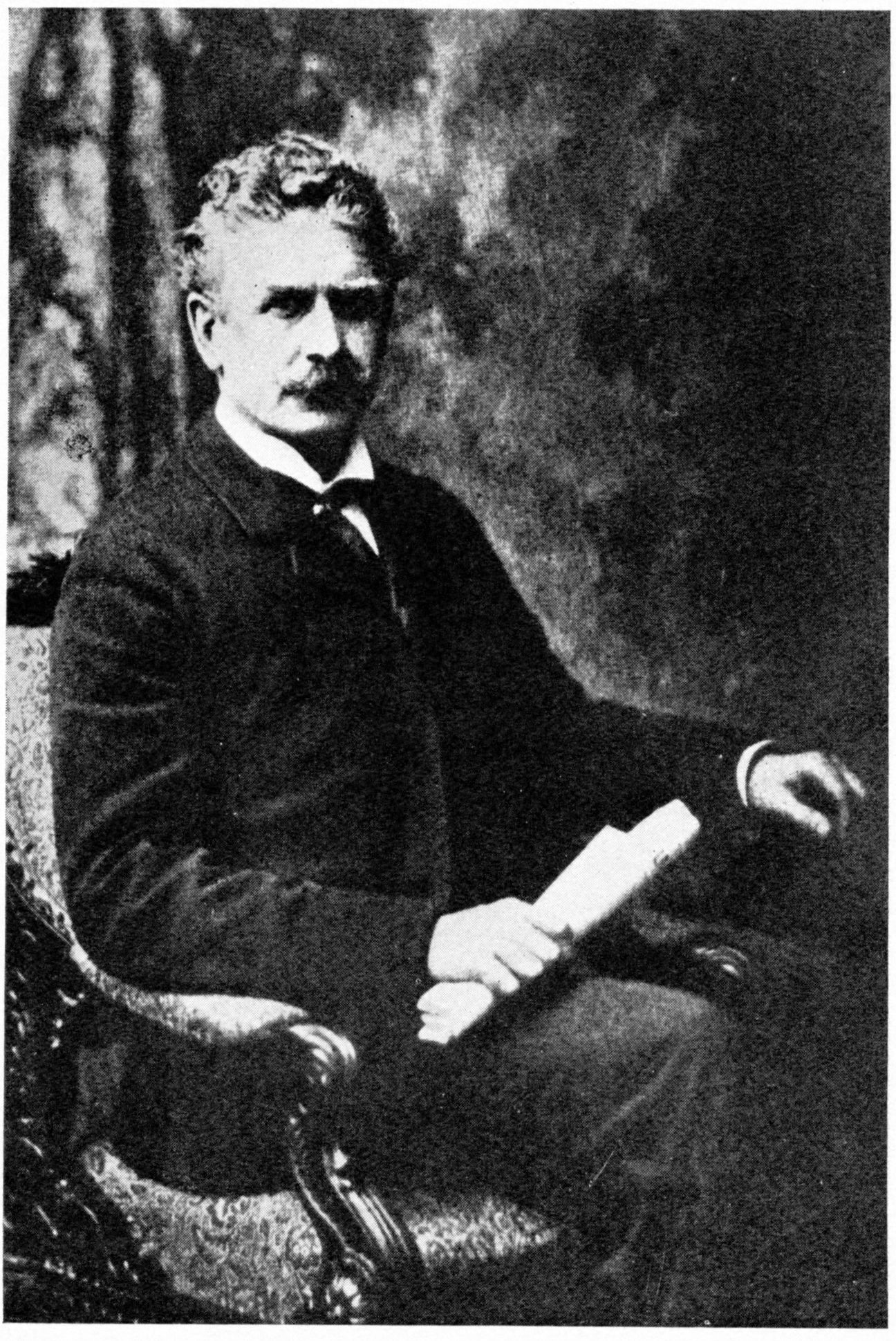

Theodosia Burr was born in New York in 1783 and educated under the unflagging solicitude and careful personal direction of her distinguished father, who wanted her to be, as he testifies in his letters, the equal of any woman on earth. To this enlightened training the precious girl responded with notable spirit and intellectual acquisitiveness, mastering French as a child and becoming proficient in Latin and Greek before she was adolescent. At fourteen, her mother having died some years earlier, she was already mistress of the house of the New York senator and a figure in the best political society of the times. As a slip of a girl she played hostess to Volney, Talleyrand, Jerome Bonaparte and numberless other notables, and bore, in addition to her repute as a bluestocking, the name of a most beautiful and charming young woman. Something of her quality may be read from her numerous extant letters, two of which are quoted below.

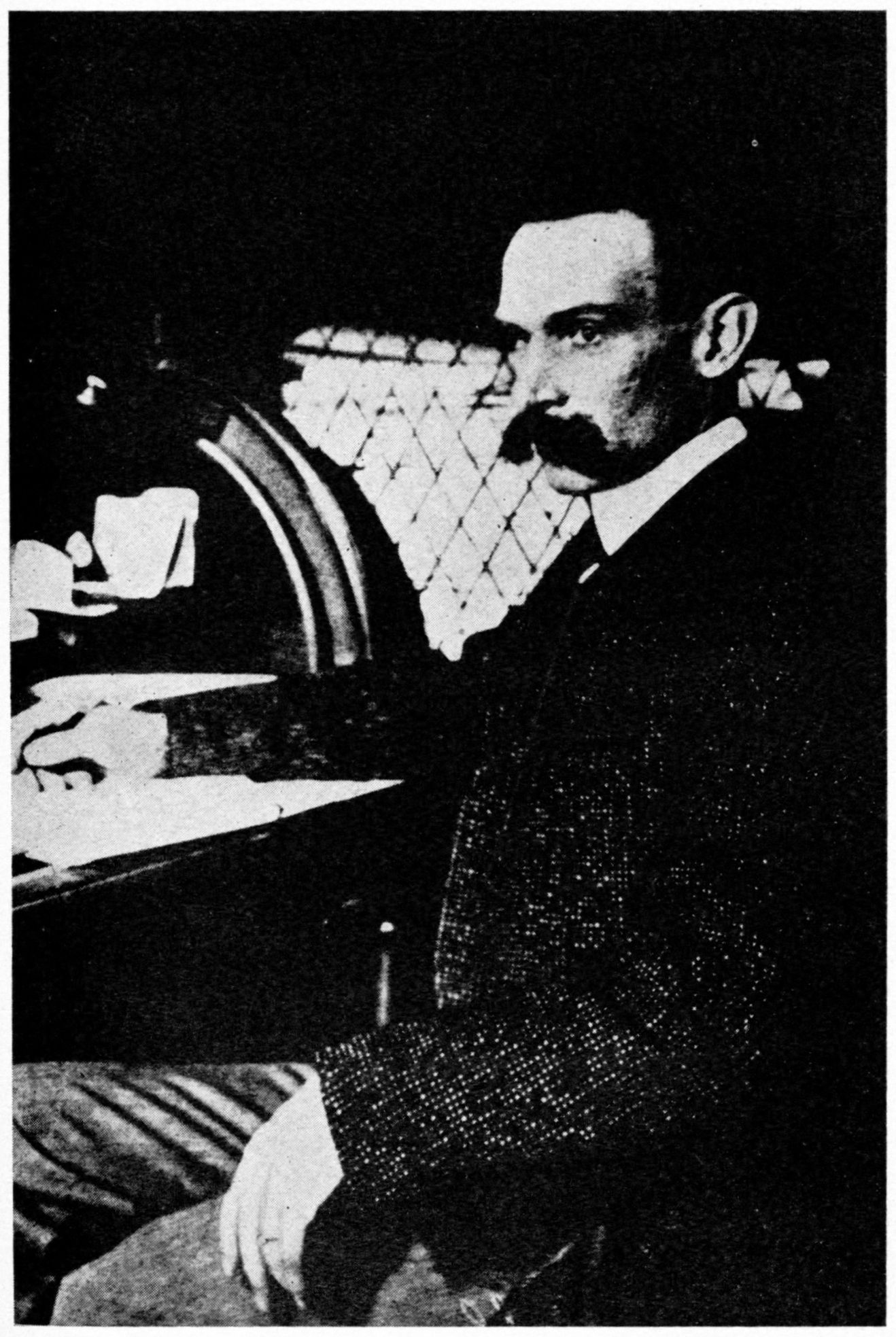

In 1801, just after her father had received the famous tied vote for the Presidency and declined to enter into the conspiracy which aimed to prefer him to Jefferson, recipient of the popular majority, Theodosia Burr was married to Joseph Alston, a young Carolina lawyer and planter who later became governor of his state. Thus, about the time her father was being installed as Vice-President, his happy and adoring daughter, his friend and confidante to the end, was making her twenty days’ journey to her new home in South Carolina, where her husband owned a residence in Charleston and several rice plantations in the northern part of the state.

At the time of the famous duel with Hamilton, in 1804, Burr was still Vice-President, still one of the chief political figures and at the very height of his popularity and fortune, an elevation from which that unfortunate encounter began his dislodgment. Theodosia was in the South with her husband at the time and knew nothing either of the challenge or of the duel itself until weeks after Hamilton was dead.

Of the merits of the Burr-Hamilton controversy or the right and wrong of either man’s conduct little need be said here. As time goes on it becomes more and more apparent that Burr in no way exceeded becoming conduct or violated the gentlemanly code as then practised. Hamilton had been his persistent and by no means always honorable enemy. He had attacked and not infrequently belied his opponent, thwarting him where he could politically and even resorting to the use of his personal connections for the private humiliation of his foe. The answer in 1804 to such tactics was the challenge. Burr gave it and insisted on satisfaction. Hamilton met him on the heights at Weehawken, across the Hudson from New York, and fell mortally wounded at the first exchange, dying thirty-one hours later.

It is evident from a reading of the newspapers of the time and from the celebrated sermon on Hamilton’s death delivered by Dr. Nott, later president of Union College, that duelling was then so common that there existed “a preponderance of opinion in favor of it,” and that the spot at which Hamilton fell was so much in use for affairs of honor that Dr. Nott apostrophized it as “ye tragic shores of Hoboken, crimsoned with the richest blood, I tremble at the crimes you record against us, the annual register of murders which you keep and send up to God!” Nevertheless, the town was shocked by the death of Hamilton, and Burr’s enemies seized the moment to circulate all manner of absurd calumnies which gained general credence and served to undo the victorious antagonist.

It was reported that Hamilton had not fired at all, a story which was refuted by his powder-stained empty pistol. Next it was charged that Burr had coldly shot his opponent down after he had fired into the air. The fact seems to be that Hamilton discharged his weapon a fraction of a second after Burr, just as he was struck by his adversary’s ball. Hamilton’s bullet cut a twig over Burr’s head. The many yarns to the general effect that Burr was a dead shot and had practised secretly for months before he sent the challenge seem also to belong to the realm of fiction. Burr was never an expert with fire-arms, but he was courageous, collected and determined. He had every right to believe, from Hamilton’s past conduct, that his opponent would show him no mercy on the field. Both men were soldiers and acquainted with the code and with the use of weapons.

But Hamilton’s friends were numerous, powerful and bitter. They left nothing undone that might bring upon Burr the fullest measure of public and private reprehension. The results of their campaign were peculiar, inasmuch as Burr lost his influence in the states which had formerly been the seat of his power and gained a high popularity in the comparatively weak new western states, where Hamilton and the Federalist leaders were regarded with hostility. At the expiration of his term of office Burr found himself politically dead and practically exiled by the charges of murder which had been lodged against him both in New York and New Jersey.

The duel and its consequences marked the beginning of the Burr misfortunes. Undoubtedly the ostracism which greeted him after his retirement from office was the immediate fact which moved him to undertake his famous enterprise against the West and Mexico, an adventure that resulted in his trial for treason. The fact that he was acquitted, even with the weight of the government and the personal influence of President Jefferson, his onetime friend, thrown against him, did not save him from still further popular dislike, and he was at length forced to leave the country. It was in the course of this exile in Europe that Theodosia wrote him the well known letter from which I quote an illuminating extract:

“I witness your extraordinary fortitude with new wonder at every new misfortune. Often, after reflecting on this subject, you appear to me so superior, so elevated above other men; I contemplate you with such a strange mixture of humility, admiration, reverence, love and pride, that very little superstition would be necessary to make me worship you as a superior being; such enthusiasm does your character excite in me. When I afterwards revert to myself, how insignificant my best qualities appear. My vanity would be greater if I had not been placed so near you; and yet my pride is our relationship. I had rather not live than not be the daughter of such a man.”

Burr remained abroad for four years, trying vainly to interest the British government and then Napoleon in various schemes of privateering. The net result of his activities in England was an order to leave the country. Nor did Burr fare any better in France. Napoleon simply refused to receive him and the American’s past acquaintance with and hospitable treatment of the emperor’s brother, once king of Westphalia, failed to avail him. Consequently, Burr slipped back into the United States in 1812, quite like a thief in the night, not certain what reception he might get and even fearful lest Hamilton’s wildest partisans might actually undertake to throw him into jail and try him for the shooting of their chief. The reception he got was hostile and suspicious enough, but there was no attempt to proceed legally.

Theodosia, who had never ceased to work in her father’s interest, writing to everyone she knew and beseeching all those who had been her friends in the days of Burr’s ascendancy, in an effort to clear the way for his return to his native land, was overjoyed at the homecoming of her parent and expressed her pleasure in various charmingly written letters, wherein she promised herself the excitement of a trip to New York as soon as arrangements could be made.

But the Burr cup of misfortune was not yet full. That summer Theodosia’s only child, Aaron Burr Alston, sickened and died in his twelfth year, leaving the mother prostrated and the grandfather, who had doted on the boy, supervised his education and centered all his hopes upon him, bereft of his composure and optimism, possibly for the first time in his varied and tempestuous life. Mrs. Alston’s letters at this time deserve at least quotation:

“A few miserable days past, my dear father, and your late letters would have gladdened my soul; and even now I rejoice in their contents as much as it is possible for me to rejoice at anything; but there is no more joy for me; the world is a blank. I have lost my boy. My child is gone for ever. He expired on the thirtieth of June. My head is not sufficiently collected to say any thing further. May Heaven, by other blessings, make you some amends for the noble grandson you have lost.”

And again:

“Whichever way I turn the same anguish still assails me. You talk of consolation. Ah! you know not what you have lost. I think Omnipotence could give me no equivalent for my boy; no, none—none.”

This was the woman who set out a few months later, sadly emaciated and very weak, to join her father in New York, hoping that she might gain strength and hope again from the burdened but undaunted man who never yet had failed her.

The second war with England was in progress. Theodosia’s husband was governor of South Carolina, general of the state militia and active in the field. He could not leave his post. Accordingly, the plan of making the trip overland in her own coach was abandoned and Mrs. Alston decided to set sail in the Patriot, a small schooner which had put into Charleston after a privateering enterprise. Parton says that “she was commanded by an experienced captain and had for a sailing master an old New York pilot, noted for his skill and courage. The vessel was famous for her sailing qualities and it was confidently expected she would perform the voyage to New York in five or six days.” On the other hand, Burr himself referred to the ship bitterly as “the miserable little pilot boat.”

Whatever the precise facts, the Patriot was made ready and Theodosia went aboard with her maid and a personal physician, whom Burr had sent south from New York to attend his daughter on the voyage. The guns of the Patriot had been dismounted and stored below. To give her further ballast and to defray the expenses of the trip, Governor Alston filled the hold with tierces of rice from his plantations. The captain carried a letter from Governor Alston addressed to the commander of the British fleet, which was lying off the Capes, explaining the painful circumstances under which the little schooner was voyaging and requesting safe passage to New York. Thus occupied, the Patriot put out from Charleston on the afternoon of December 30th and crossed the bar on the following morning. Here fact ends and conjecture begins.

When, after the elapse of a week, the Patriot had not reached New York, Burr began to worry and to make inquiries, but nothing was to be discovered. He could not even be sure until the arrival of his son-in-law’s letter, that Theodosia had set sail. Even then, he hoped there might be some mistake. When a second letter from the South made it plain that she had gone on the Patriot, Burr still did not abandon hope and we see the picture of this sorely punished man walking every day from his law office in Nassau street to the fashionable promenade at the Battery, where he strolled up and down, oblivious to the hostile or impertinent glances of the vulgar, staring out toward the Narrows—in vain.

The poor little schooner was never seen again nor did any member of her crew reach safety and send word of her end. In due time came the report of the hurricane off Cape Hatteras, three days after the departure of the Patriot. Later still it was found that the storm had been of sufficient power to scatter the British fleet and send other vessels to the bottom. In all probability the craft which bore Theodosia had foundered with all hands.

Naturally, every other possibility came to be considered. It was at first believed that the Patriot might have been taken by a British man-of-war and held on account of her previous activities. Before this could be disproved it was suggested that the schooner might readily have been attacked by pirates, since her guns were stored below decks, and Mrs. Alston taken prisoner. Since there were still a few buccaneers in Southern waters, who sporadically took advantage of the preoccupation of the maritime powers with their wars, this theory of Theodosia Alston’s disappearance gained many adherents, chiefly among the romantics, it is true. But the possibility of such a thing was also seriously considered by the husband and for a time by the father, who hoped the unfortunate woman might have been taken to one of the lesser West Indies by some not unfeeling corsair. Surely, she would soon or late make her escape and win her way back to her dear ones. In the end Burr rejected this idea, too.

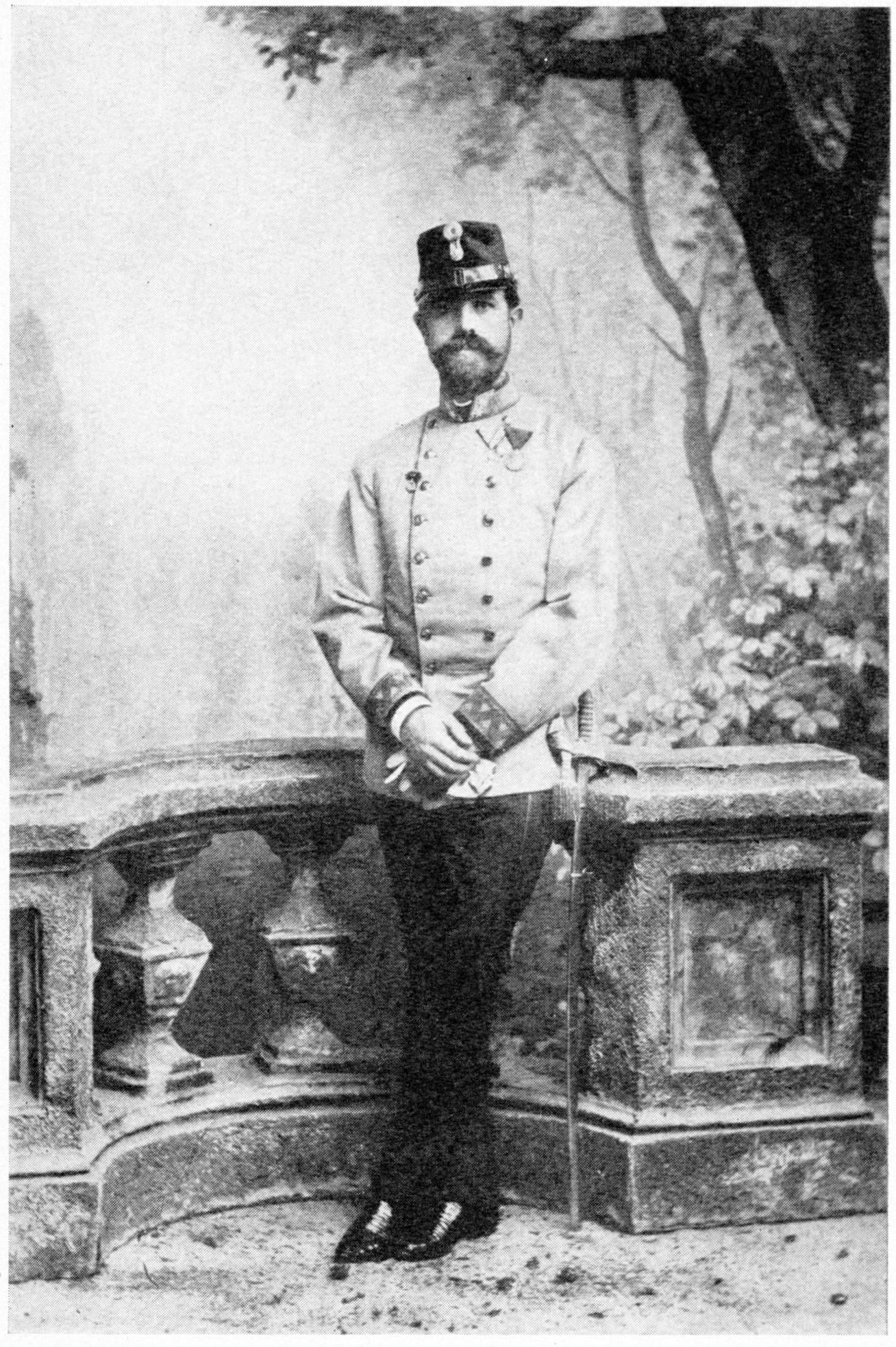

~~ THEODOSIA BURR ~~

“No, no,” he said to a friend who revived the fable of the pirates, “she is indeed dead. Were she alive all the prisons in the world could not keep her from her father.”

But the mystery persisted and so the rumors and stories would not down. For a number of years after 1813 the newspapers contained, from time to time, reports from various parts of the world, generally to the effect that a beautiful and cultured woman had been seen aboard a ship supposed to be manned by pirates, that such a woman had been found in a colony of sea refugees in some vaguely described West Indian or South American retreat, or that a woman of English or American characteristics was being detained in an island prison, whither she had been consigned along with a captured piratical crew. The woman was always, by inference at least, Theodosia Burr.

Nor were the persevering Burr calumniators idle, a circumstance which seems to testify to the fear his enemies must have had of this strange and greatly mistaken man. Theodosia Burr had been seen in Europe in company with a British naval officer who was paying her marked attentions; she had been located on an island off Panama, where she was living in contentment as the wife of a buccaneer; she was known to be in Mexico with a new husband who had first been her captor, then her lover and now was in the southern Republic trying to revive Burr’s dream of empire.

The death of Governor Alston in 1816 caused a fresh crop of the old stories to blossom forth and the long deferred demise of Aaron Burr in 1836 released a still more formidable crop of rumors, fables and speculations. It was not until Burr had passed into the grave that there appeared on the American scene a type of romantic who made the next fifty years delightful. He was the old reformed pirate who desecrated his exit into eternity with a Theodosia Burr yarn. The great celebrity of the woman in her lifetime, the tragic fame of her father and the circumstances of her death naturally conspired to promote this kind of aberrant activity in many idle or unsettled minds. The result was that “pirates” who had been present at the capture of the Patriot in the first days of 1813 began to appear in many parts of the country and even in England, where they told, usually on their deathbeds, the most engaging and conflicting tales. It took, as I have remarked, half a century for all of them to die off.

The accounts given by these various confessors differed in details only. All agreed that the Patriot had been captured by sea rovers off the Carolina coast and that the entire crew had been forced to walk the plank or been cut down by the pirates. Thus the fabulists accounted for the fact that nothing had ever been heard from any of Mrs. Alston’s shipmates. Nearly all accounts agreed that Theodosia had been carried captive to an unnamed island where she had first been a rebellious prisoner but later the docile and devoted mate of the pirate chief. A few of the relators gave their narratives the spice of novelty by insisting that she, too, had been made to walk the plank into the heaving sea, after she had witnessed all her shipmates consigned to the same fate. The names of the pirate ships and pirate captains supposed to have caught the Patriot and disposed of Theodosia Burr Alston ranged through all the lists of shipping. No two dying corsairs ever agreed on this point.

Forty years after the disappearance of Mrs. Alston this typical yarn appeared in the Pennsylvania Enquirer:

“An item of news just now going the rounds relates that a sailor, who died in Texas, confessed on his death bed that he was one of the crew of mutineers who, some forty years ago, took possession of a brig on its passage from Charleston to New York and caused all the officers and passengers to walk the gang plank. For forty years the wretched man had carried about the dreadful secret and died at last in an agony of despair.

“What gives the story additional interest is the fact that the vessel referred to is the one in which Mrs. Theodosia Alston, the beloved daughter of Aaron Burr, took passage for New York, for the purpose of meeting her parent in the darkest days of his existence, and which, never having been heard of, was supposed to have been foundered at sea.

“The dying sailor professed to remember her well and said she was the last who perished, and that he never forgot her look of despair as she took the last step from the fatal plank. On reading this account, I regarded it as fiction; but on conversing with an officer of the navy he assured me of its probable truth and stated that on one of his passages home several years ago, his vessel brought two pirates in irons who were subsequently executed at Norfolk for recent offenses, and who, before their execution, confessed that they had been members of the same crew and had participated in the murder of Mrs. Alston and her companions.

“Whatever opinion may be entertained of the father, the memory of the daughter must be revered as one of the loveliest and most excellent of American woman, and the revelation of her untimely fate can only serve to invest that memory with a more tender and melancholy interest.”

Despite the crudities of most of those yarns and their obvious conflict with known facts, the public took the dying confessions seriously and the editors of Sunday supplements printed them with a gay air of credence and a sad attempt at seriousness. Whatever else was accomplished by this complicity with a most unashamed and unregenerate band of downright liars, the pirate legend came to be disseminated in every civilized country and there was gradually built up the great false tradition which hedges the name and fame of Theodosia Burr. She has even appeared in novels, American, British and Continental, in the shape of a mysterious queen of freebooters.

The celebrity of her case came to be such that it was in time seized upon by the art fakers—perhaps an inevitable step toward genuine famosity. Several authentic likenesses of Theodosia Burr are extant, notably the painting by John Vanderlyn in the Corcoran Gallery, Washington. Vanderlyn was the young painter of Kingston, N. Y., whom Burr discovered, apprenticed to Gilbert Stuart and sent to Paris for study. He painted the landing of Columbus scene in the rotunda of the Capitol. But the work of Vanderlyn and others neither restrained nor satisfied the freebooters of the arts. On the other hand, the pirate tales inspired them to profitable activity.

In the nineties of the last century the New York newspapers contained accounts of a painting of Theodosia Burr which had been found in an old seashore cottage near Kitty Hawk, N. C., the settlement afterwards made famous by the gliding experiments of the brothers Wright, and the scene of their first successful airplane flights. The printed accounts said that this picture had been found on an old schooner which had been wrecked off the coast many years before and various inconclusive and roundabout devices were employed for identifying it as a likeness of the lost mistress of Richmond Hill.

Later, in 1913, a similar story came into most florid publicity in New York and elsewhere. It was, apparently, given out by one of the prominent Fifth Avenue art dealers. A woman client, it was said, had become interested in the traditional picture of Theodosia Burr, recovered from a wrecked vessel on the coast of North Carolina. Accordingly, the art dealer had undertaken a search for the missing work of art and had at length recovered it, together with a most fascinating history.

In 1869 Dr. W. G. Pool, a physician of Elizabeth City, N. C., spent the summer at Nag’s Head, a resort on the outer barrier of sand which protects the North Carolina coast about fifty miles north of Cape Hatteras. While there he was called to visit an aged woman who lived in an ancient cabin about two miles out of the town. His ministrations served to recover her health and she expressed the wish to pay him in some way other than with money, of which useful commodity she had none. The good doctor had noticed, with considerable curiosity, a most beautiful oil painting of a “beautiful, proud and intelligent lady of high social standing.” He immediately coveted this picture and asked his patient for it, since she wanted to give him something in return for his leechcraft. She not only gave him the portrait but she told him how she had come by it. Many years before, when she was still a girl, the old woman’s admirer and subsequent first husband had, with some others, come upon the wreck of a pilot boat, which had stranded with all sails set, the rudder tied and breakfast served but undisturbed in the cabin. The pilot boat was empty and several trunks had been broken open, their contents being scattered about. Among the salvaged goods was this portrait, which had fallen to the lot of the old woman’s swain and come through him to her.

From this old woman and Dr. Pool, the picture had passed to others without ever having left Elizabeth City. There the enterprising dealer had found it in the possession of a substantial widow, and she had consented to part with it. The rest of the story—the essentials—was to be surmised. The wrecked pilot boat was, to be sure, the Patriot, the date of its stranding agreed with the beclouded incidents of January, 1813, and the “intelligent lady of high social standing” was none other than Theodosia Burr.

It is unfortunate that the reproductions of this marvelous and romantic work do not show the least resemblance to the known portrait of Theodosia, and it is also lamentable to find that the art dealer, in his sweet account of his find, fell into all the vulgar misconceptions and blunders as regards his subject and the tales of her demise. But, while both these portrait yarns may be dismissed without further attention, they have undoubtedly served to keep the old and enchanting story before modern eyes.

In the light of analysis the prosaic explanation of the Theodosia Burr case seems to be the acceptable one. The boat on which she embarked was small and frail. At the very time it must have been passing the treacherous region of Cape Hatteras, there was a storm of sufficient violence to scatter the heavy British frigates and ships of the line. The fate of a little schooner in such weather is almost a matter for assurance. Yet of certainty there can be none. The famous daughter of the traditional American villain—the devil incarnate to all the melancholy crew of hypocritical pulpiteers and propagandists—went down to sea in her cockleshell and returned no more. Eleven decades have lighted no candle in the darkness that engulfed her.

THE VANISHED ARCHDUKE

One of the most engrossing of modern mysteries is that which hides the final destination of Archduke Johann Salvator of Austria, better known to a generation of newspaper readers as John Orth. In the dawn of July 13, 1890, the bark Santa Margarita,[2] flying the flag of an Austrian merchantman, though her owner and skipper was none other than this wandering scion of the imperial Hapsburgs, set sail from Ensenada, on the southern shore of the great estuary of the Plata, below Buenos Aires, and forthwith vanished from the earth. With her went Johann Salvator, his variety-girl wife and a crew of twenty-six. Though search has been made in every thinkable port, through the distant archipelagoes of the Pacific, in ten thousand outcast towns, and though emissaries have visited all the fabled refuges of missing men, from time to time, over a period of nearly forty years, no sight of any one connected with the lost ship has ever been got, and no man knows with certainty what fate befell her and her princely master.

[2] Sometimes written Sainte Marguerite.

The enigma of his passing is not the only circumstance of curious doubt and romantic coloration that hedges the career of this imperial adventurer. His story, from the beginning, is one marked with dramatic incidents. As much of it as bears upon the final episode will have to be related.

The Archduke Johann Salvator was born at Florence on the twenty-fifth day of November, 1852, the youngest son of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany, and Maria Antonia of the Two Sicilies. He was, accordingly, a second cousin of the late Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary. At the baptismal font young Johann received enough names to carry any man blissfully through life, his full array having been Johann Nepomuk Salvator Marie Josef Jean Ferdinand Balthazar Louis Gonzaga Peter Alexander Zenobius Antonin.

Archduke Johann was still a child when the Italian revolutionists drove out his father and later united Tuscany to the growing kingdom of Victor Emanuel. So the hero of this account was reared in Austria and educated for the army. Commissioned as a stripling, he rose rapidly in rank for reasons quite other than his family connections. The young prince was endowed with a good mind and notable for independence of thought. He felt, as he expressed it, that he ought to earn his pay, an opinion which led to indefatigable military studies and some well-intentioned, but ill-advised writings. First, the young archduke discovered what he considered faults in the artillery, and he wrote a brochure on the subject. The older heads didn’t like it and had him disciplined. Later on, Johann made a study of military organization and wrote a well-known pamphlet called “Education or Drill,” wherein he attacked the old method of training soldiers as automatons and advised the mental development of the rank and file, in line with policies now generally adopted. But such advanced ideas struck the military masters of fifty years ago as bits of heresy and anarchy. Archduke Johann was disciplined by removal from the army and the withdrawal of his commission. At thirty-five he had reached next to the highest possible rank and been cashiered from it. This in 1887.

Johann Salvator had, however, been much more than a progressive soldier man. He was an accomplished musician, composer of popular waltzes, an oratorio and the operetta “Les Assassins.” He was an historian and publicist, of eminent official standing at least, having collaborated with Crown Prince Rudolf in the widely distributed work, “The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Word and Picture,” which was published in 1886. He was also a distinguished investigator of psychic phenomena, his library on this subject having been the most complete in Europe—a fact suggestive of something abnormal.

Personally the man was both handsome and charming. He was, in spite of imperial rank and military habitude, democratic, simple, friendly, and unaffected. He liked to live the life of a gentleman, with diverse interests in life, now playing the gallant in Vienna—to the high world of the court and the half world of the theater by turns; again retiring to his library and his studies, sometimes vegetating at his country estates and working on his farms. Official trammels and the rigid etiquette of the ancient court seemed to irk him. Still, he seems to have suffered keen chagrin over his dismissal from the army.

Johann Salvator had, from adolescence, been a close personal friend of the Austrian crown prince. This intimacy had extended even to participation in some of the personal and sentimental escapades for which the ill-starred Rudolf was remarkable. Apparently the two men hardly held an opinion apart, and it was accepted that, with the death of the aging emperor and the accession of his son, Johann Salvator would be a most powerful personage.

Suddenly, in 1889, all these high hopes and promises came to earth. After some rumblings and rumorings at Schoenbrunn, it was announced that Johann Salvator had petitioned the emperor for permission to resign all rank and title, sever his official connection with the royal house, and even give up his knighthood in the Order of the Golden Fleece. The petitioner also asked for the right to call himself Johann Orth, after the estate and castle on the Gmündensee, which was the favorite abode of the prince and of his aged mother. All these requests were officially granted and confirmed by the emperor, and so the man John Orth came into being.

The first of the two Orth mysteries lies concealed behind the official records of this strange resignation from rank and honor. Even to-day, after Orth has been missing for a whole generation, after all those who might have been concerned in keeping secret the motives and measures of those times have been gathered to the dust, and after the empire itself has been dissolved into its defeated components, the facts in the matter cannot be stated with any confidence. There are two principal versions of the affair, and both will have to be given so that the reader may make his own choice. The popular or romantic account deserves to be considered first.