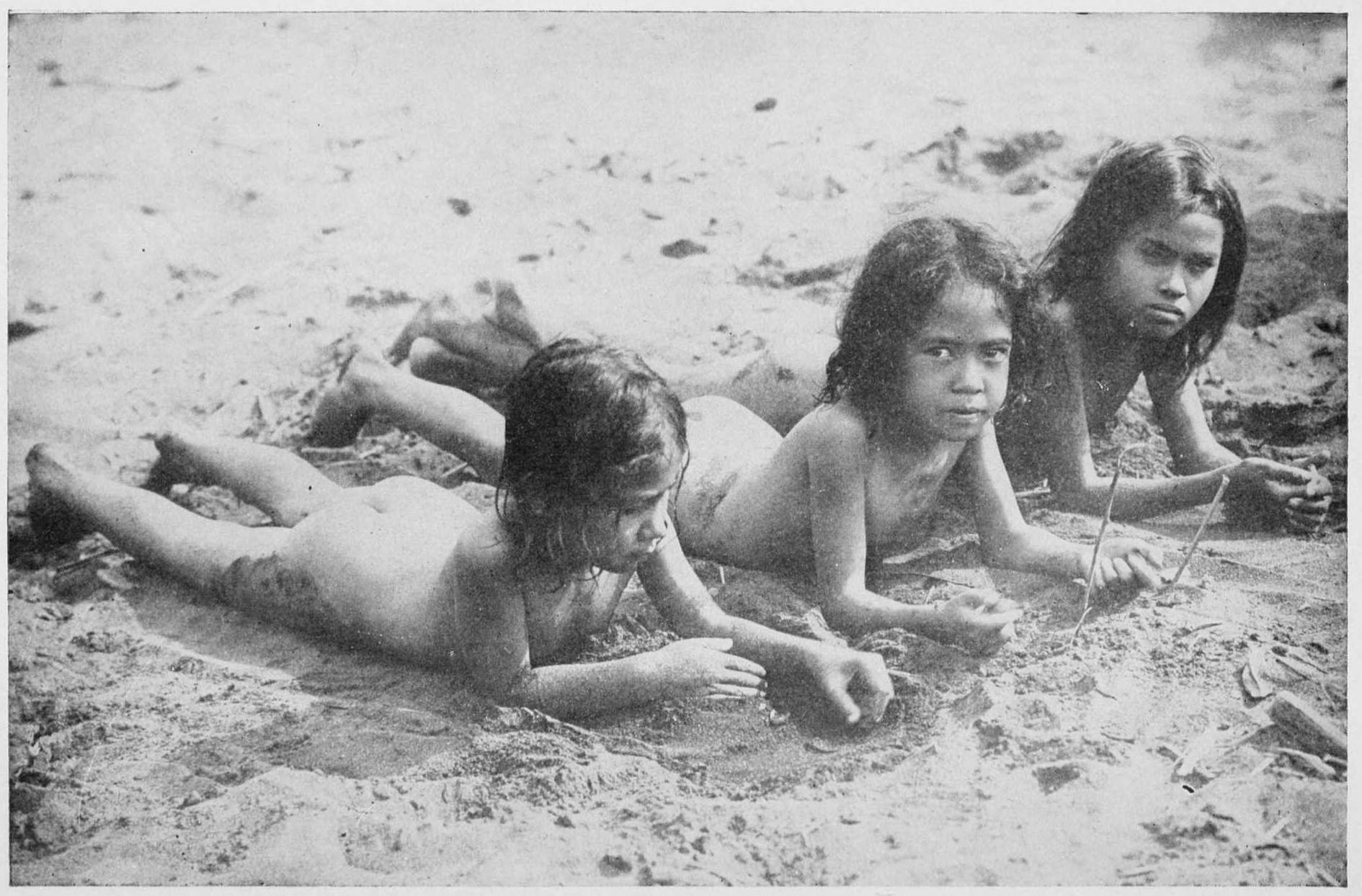

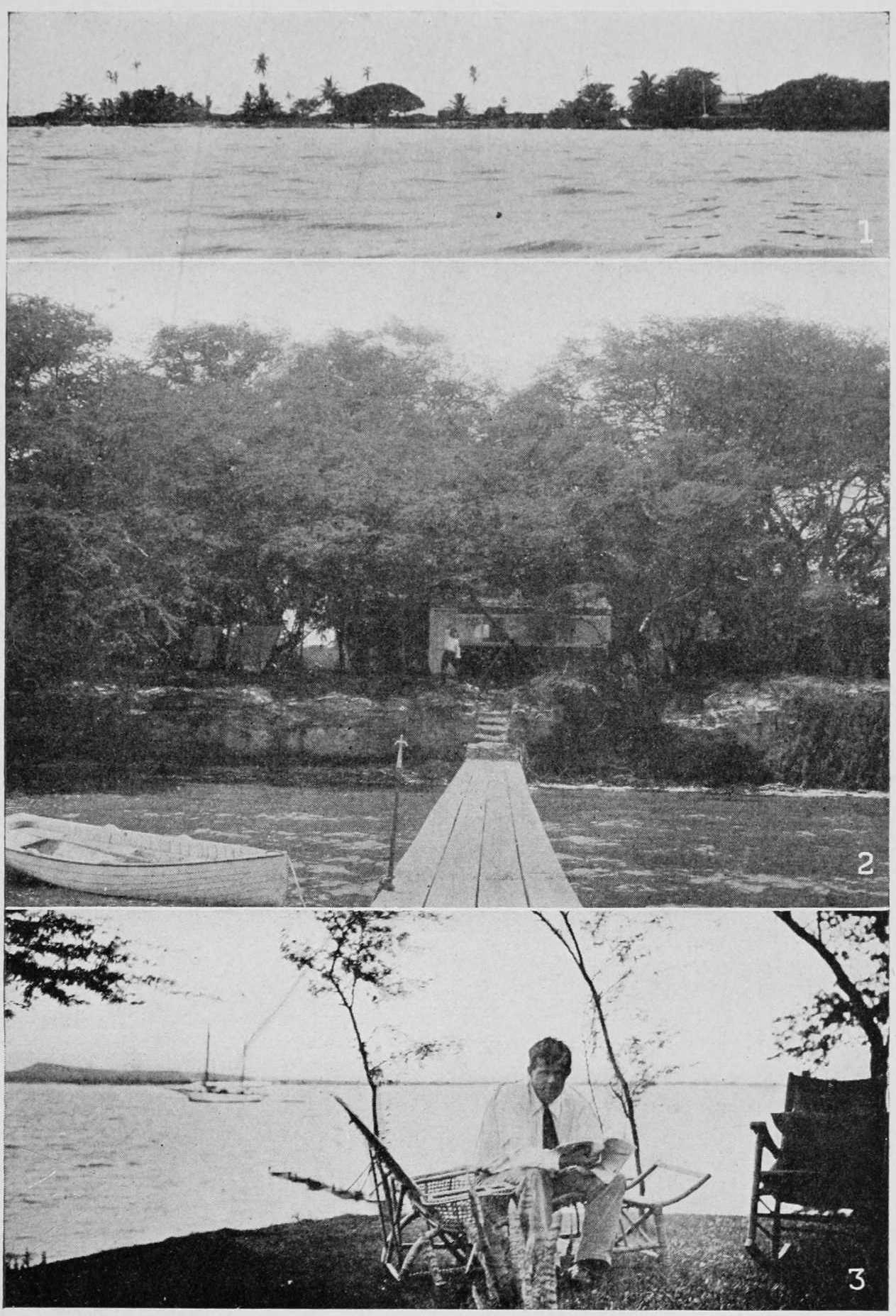

Young Hawaii

Title: Our Hawaii

(Islands and islanders)

Author: Charmian London

Contributor: Jack London

Release date: May 25, 2024 [eBook #73699]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: The MacMillan Company, 1917

Credits: Sean, an independent e-book maker in Canada (ttd ali at yahoo com)

Transcriber’s notes:

1. This text is based on the Internet Archive scan with the identifier “ourhawaiiislands00lond”.

2. Variant spellings and hyphenations are retained throughout; only a few simple printing errors have been remedied.

3. All illustrations are full-page in the original.

4. The book lacks a clear layout in its use of major headings. All headings and thought breaks (horizontal rules) have been retained as printed (centered or right-aligned). Footnotes are gathered at the end of sections.

Young Hawaii

OUR HAWAII

(Islands and Islanders)

BY

CHARMIAN LONDON

(Mrs. Jack London)

AUTHOR OF “THE LOG OF THE SNARK”

“THE BOOK OF JACK LONDON”

New and Revised Edition

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1922

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Copyright, 1917 and 1922,

By CHARMIAN K. LONDON

Set up and Electrotyped. Published December, 1917

New and Revised Edition; February, 1922

FERRIS PRINTING COMPANY

NEW YORK CITY

TO MY HAWAII

This book was originally part of the jottings I kept during a two years’ cruise of Jack London and myself in the forty-five-foot ketch Snark into the fabulous South Seas, by way of the Hawaiian Islands. The seafaring portion of my notes was published in 1915 as “The Log of the Snark.” The record of five months spent in the Paradise of the Pacific, Hawaii, I made into another book, “Our Hawaii,” issued in 1917.

The present volume is a revision of the other, from which I have eliminated the bulk of personal memoirs, by now incorporated into my “Book of Jack London,” a thoroughgoing biography. I have substituted more detail concerning the Territory of Hawaii, and endeavored to bring my subject up to date. Also, instead of making an independent work out of Jack London’s three articles, written in 1916, entitled, “My Hawaiian Aloha,” I am making them a part of my book, placing them first, because of their peculiar value with regard to vital points of view on Hawaii. These articles, published in 1916 in The Cosmopolitan Magazine, were pronounced by one citizen of Honolulu, eminent under more than two forms of government in the troublous past of the Group, as of a worth to Hawaii not to be estimated in gold and silver.

“They don’t know what they’ve got!” Jack London said of the American public, when, in the Snark, he made Hawaii his first port of call, and threw himself into the manifold beauty and wonder of this territory of Uncle Sam. And “They don’t know what they’ve got,” he repeated to each new unscrolling of its wonder and beauty during those months of enjoyment and study of land and people. On his fourth visit, after the breaking out of the Great War, he amended: “Because they have no other place to go, they are just beginning to realize what they’ve got.”

The knowledge of the average American is woefully scant concerning this islands possession, and woefully he distorts its very name, in conversation and song, into something like Haw-way’-ah. To an adept in the musical language there are fine nuances in the vowelly word; but simple Hah-wy’-ee serves well.

What does the average middle-aged American know of the amazing history of this amazing “native” people who vote as American citizens and sit in the seats of government? The name Hawaii calls to memory vague dots on a map of the Pacific Ocean, bearing a vaguely gastronomic caption that in no wise reminds him of the Earl of Sandwich, Lord of the British Admiralty, and patron of the intrepid discoverer, Captain Cook, whose valiant bones even now rest on the Kona Coast. Savage, remote, alluring, adventurous, are the impressions. Few have grasped the fact that that pure Polynesian, Kamehameha I, the Charlemagne of Hawaii, deserves to rank as one of the most remarkable figures of all time for his revolutionary genius, unaided by outland influences. Dying in 1819, little more than a year before the first missionaries sailed from Boston, he had fought his way to the consolidation under one government of the group of eight islands, ended feudal monarchy, abolished idolatry, and all unknowing made land and inhabitants ripe for Christian civilization and exploitation.

Of the many whom I have questioned, only one ever heard that, even previous to the discovery of gold in California and the starting of our forbears over the Plains by ox-team or across the Isthmus of Panama, early settlers in California were sending their children to the excellent missionary schools of these isles of inconsequential name. Also they imported their wheat from the same “savage” strand.

In this my journal, covering those few months spent a decade ago in Hawaii, concluding with a resume of experiences there in 1915, 1916, 1919 and 1920, I have tried to limn a picture of the charm of the Hawaiian Islander as he was, and of his becoming, together with the enchantment of his lofty isles and their abundant hospitality.

Men will continue to sorrow because circumstances may hold them from exploring the South Pacific; meantime they neglect the romance and loveliness that is close at hand, less than a week’s voyage from the mainland.

Charmian London.

Jack London Ranch,

Glen Ellen, California.

1921.

| Young Hawaii | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

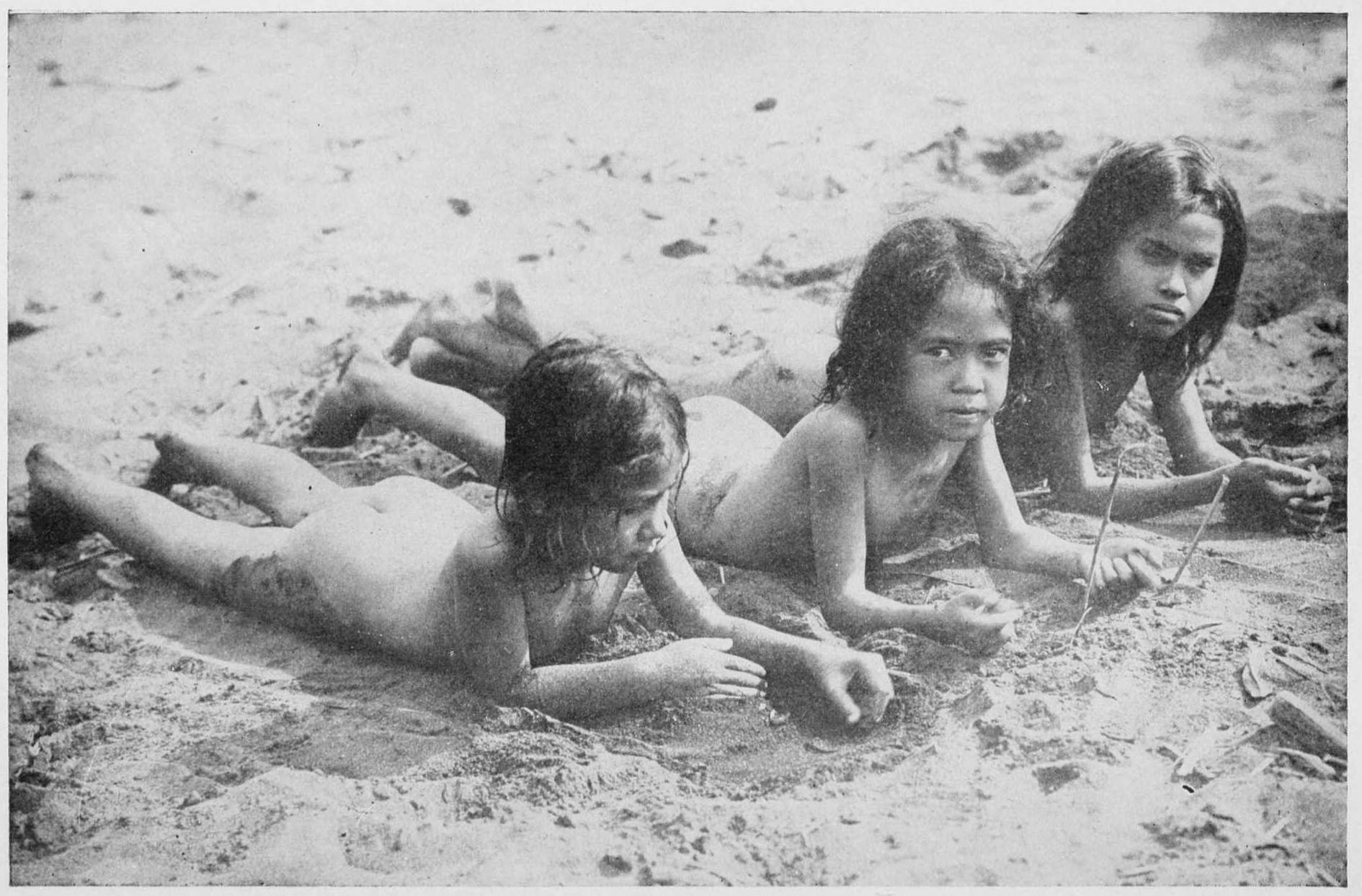

| Map: Hawaii. | 1 |

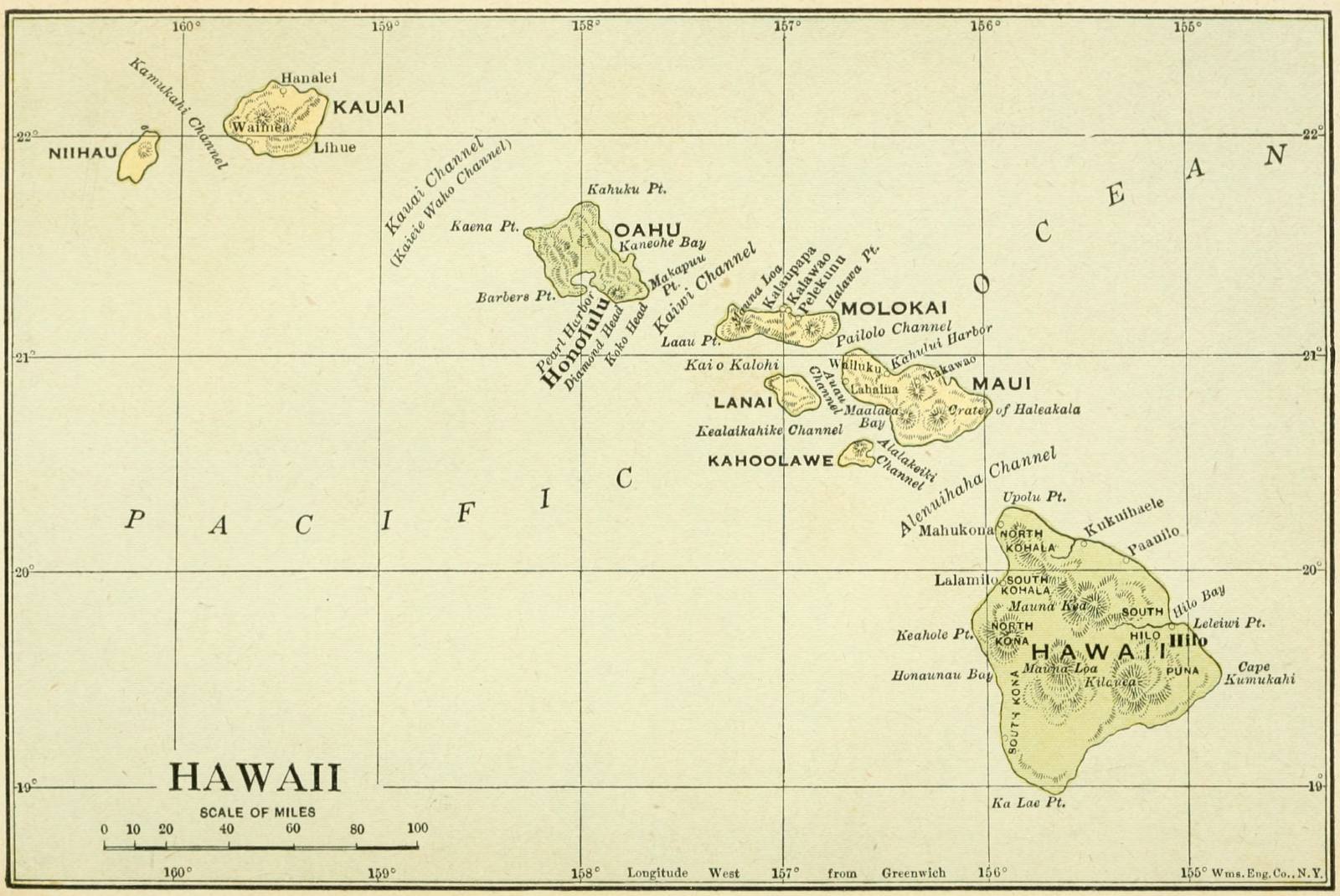

| (1) The Peninsula. (2) The Bungalow. (3) The Snark, and the Owner Ashore. | 24 |

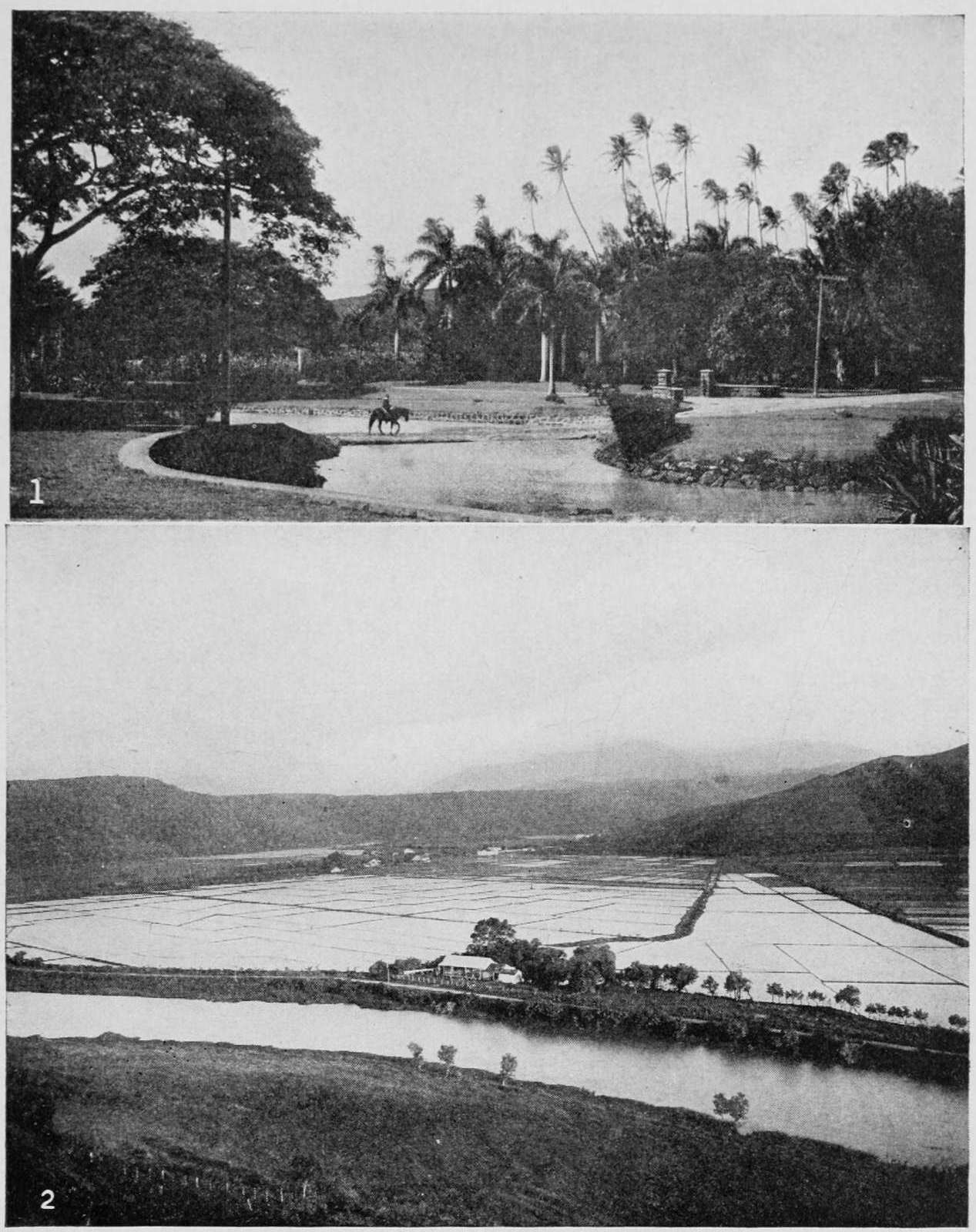

| (1) Damon Gardens, Honolulu. (2) Rice Fields on Kauai. | 50 |

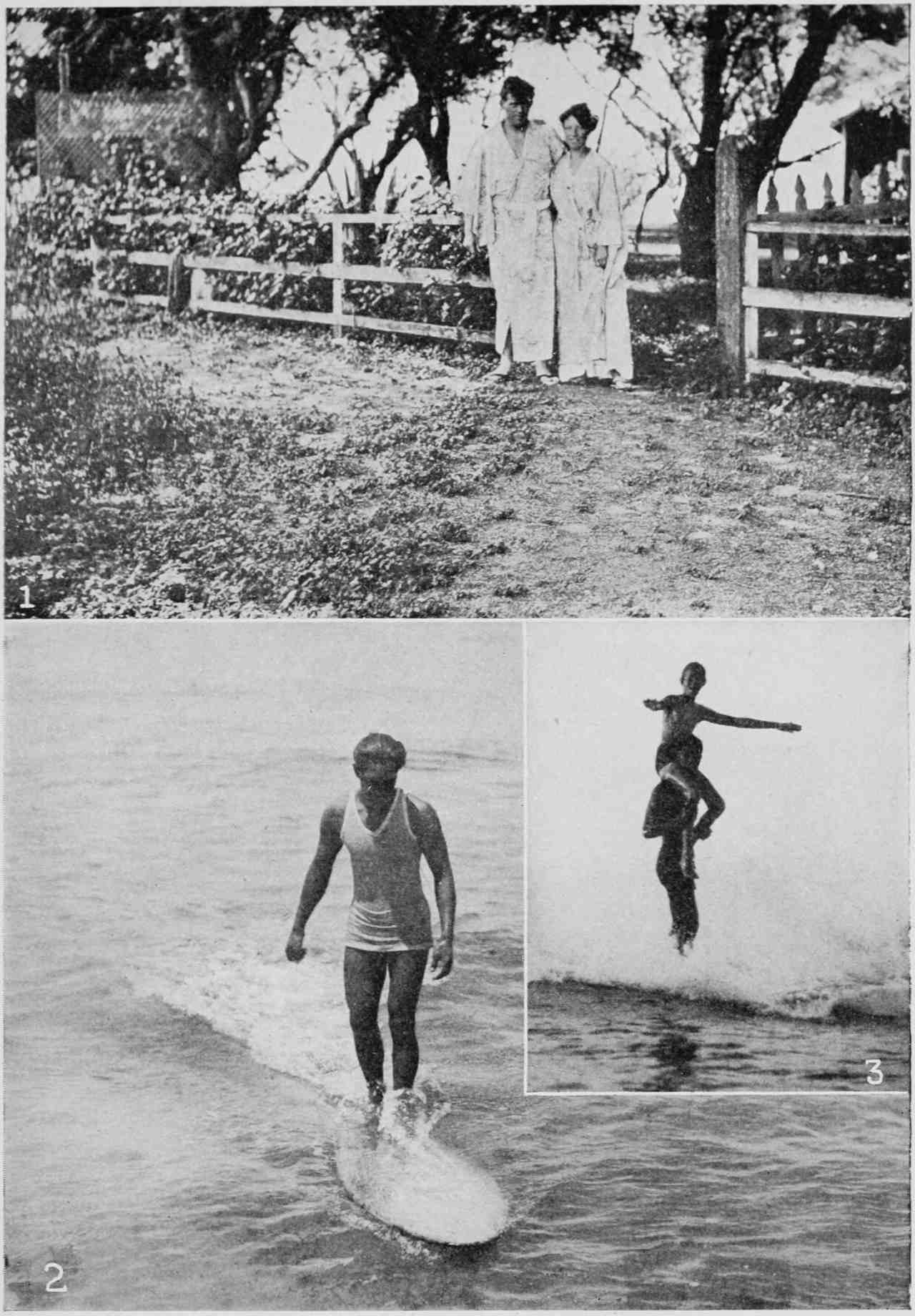

| (1) Working Garb in Elysium. (2) Duke Kahanamoku, 1915. | 74 |

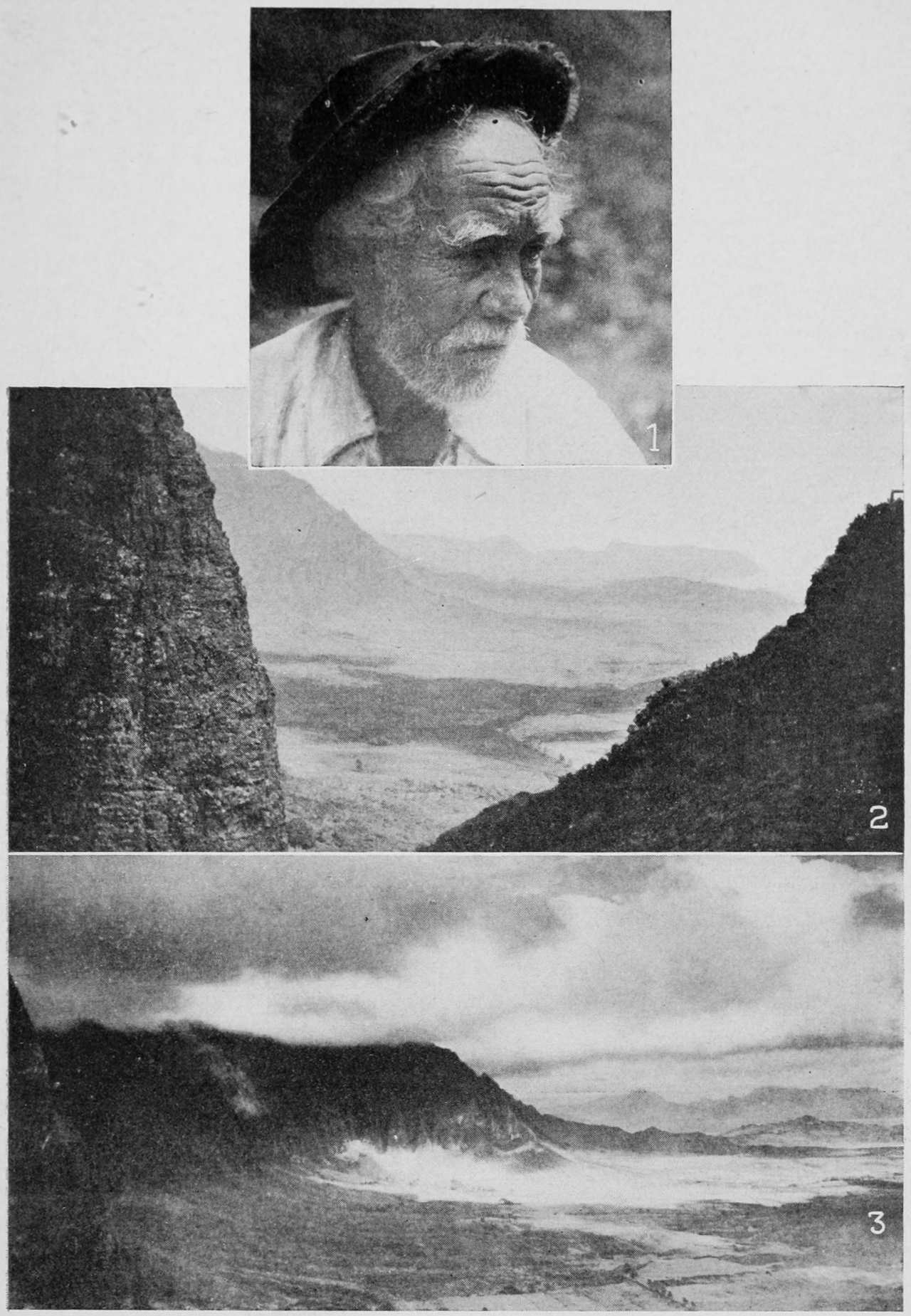

| (1) Old Hawaiian. (2) The Sudden Vision. (3) The Mirrored Mountains. (Painting by Hitchcock) | 96 |

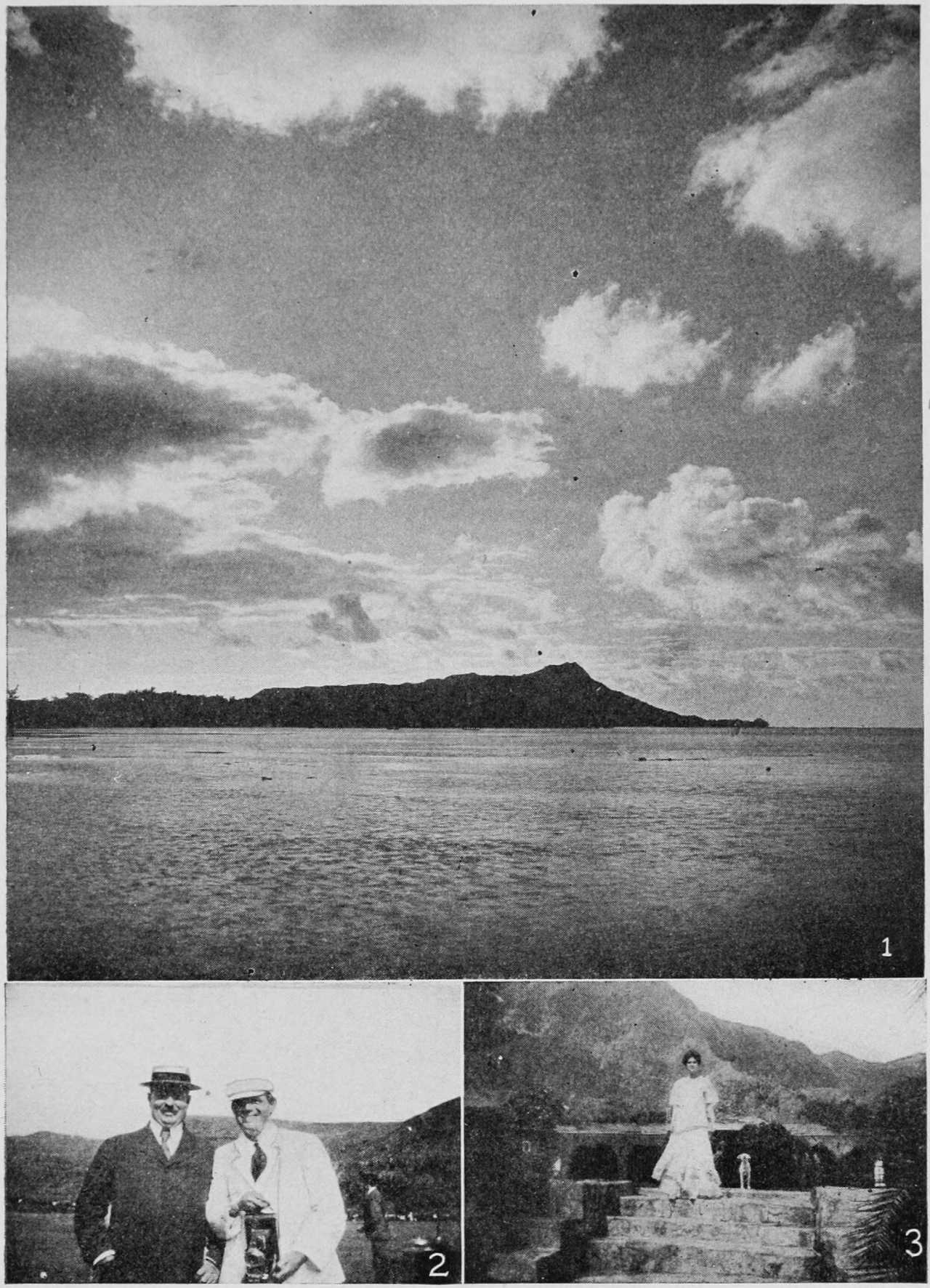

| (1) Diamond Head. (2) A Pair of Jacks—Atkinson and London. (3) Ahiumanu. | 116 |

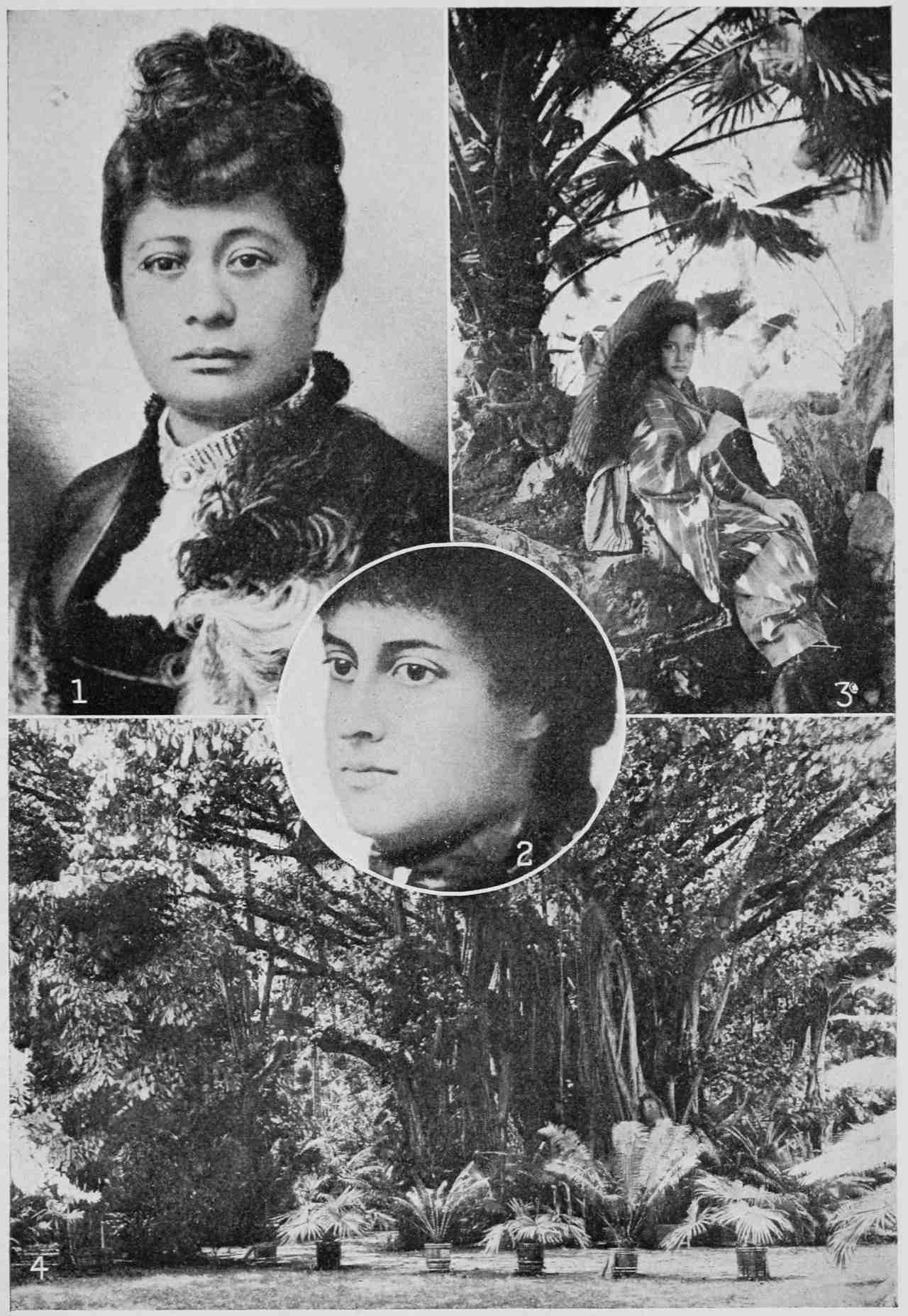

| (1) Princess Likelike (Mrs. Cleghorn). (2) Princess Victoria Kaiulani. (3) Kaiulani at Ainahau. (4) “Kaiulani’s Banyan.” | 138 |

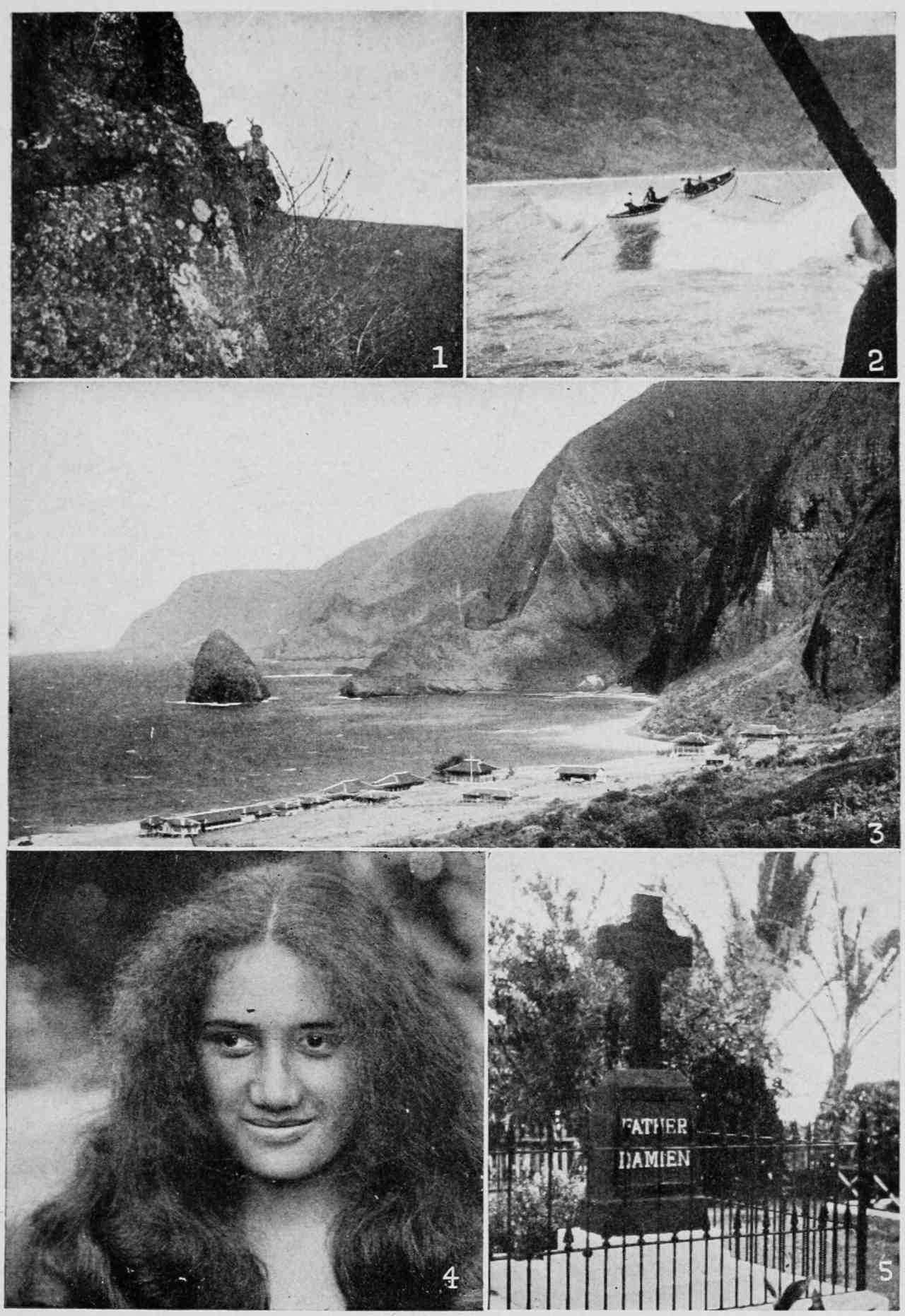

| (1) Landing at Kalaupapa, 1907. (2) The Forbidden Pali Trail, 1907. (3) Coast of Molokai—Federal Leprosarium on Shore. (4) American-Hawaiian. (5) Father Damien’s Grave, 1907. | 162 |

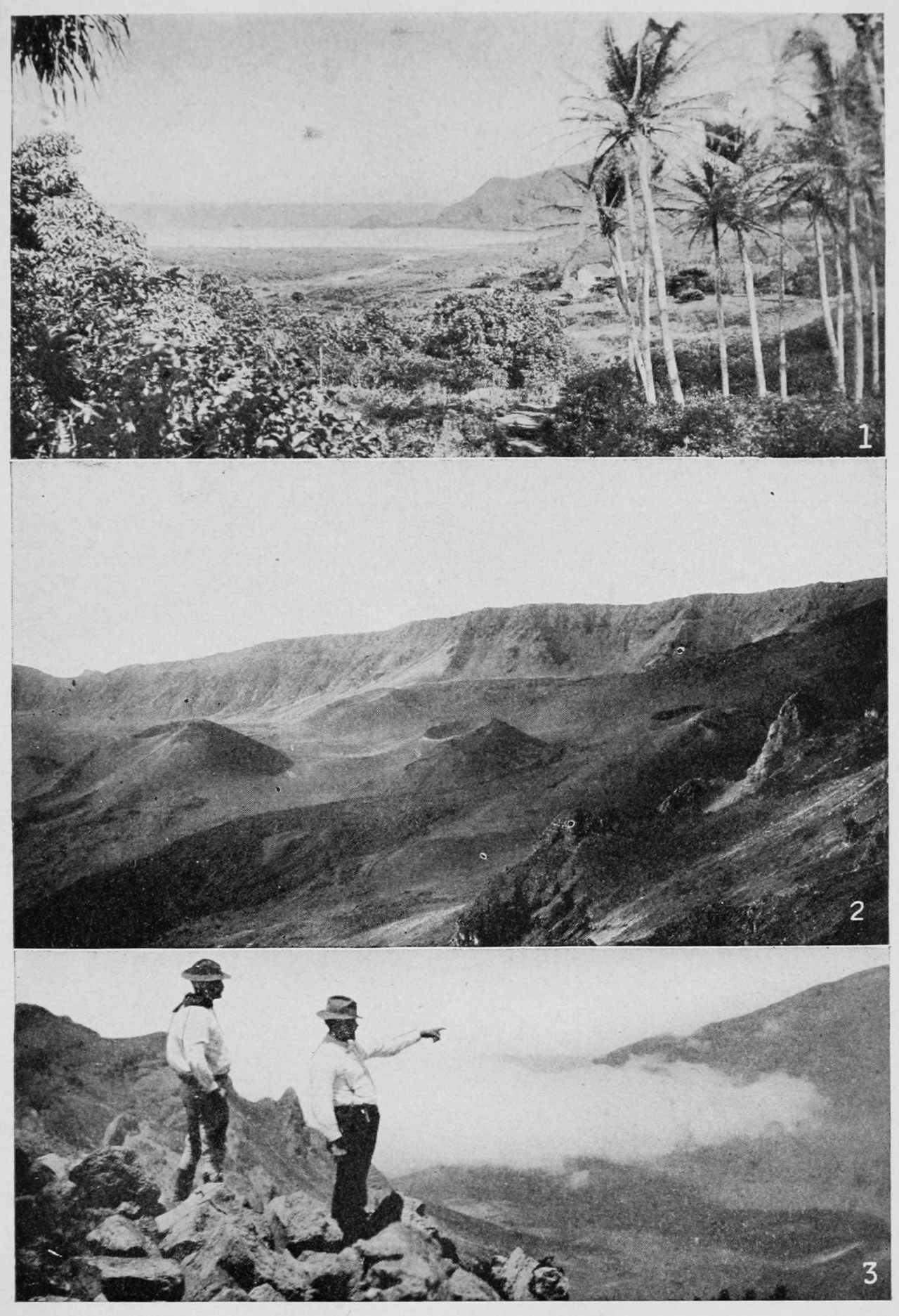

| (1) Hana. (2) The Ruin of Haleakala. (3) Von and Kakina. | 184 |

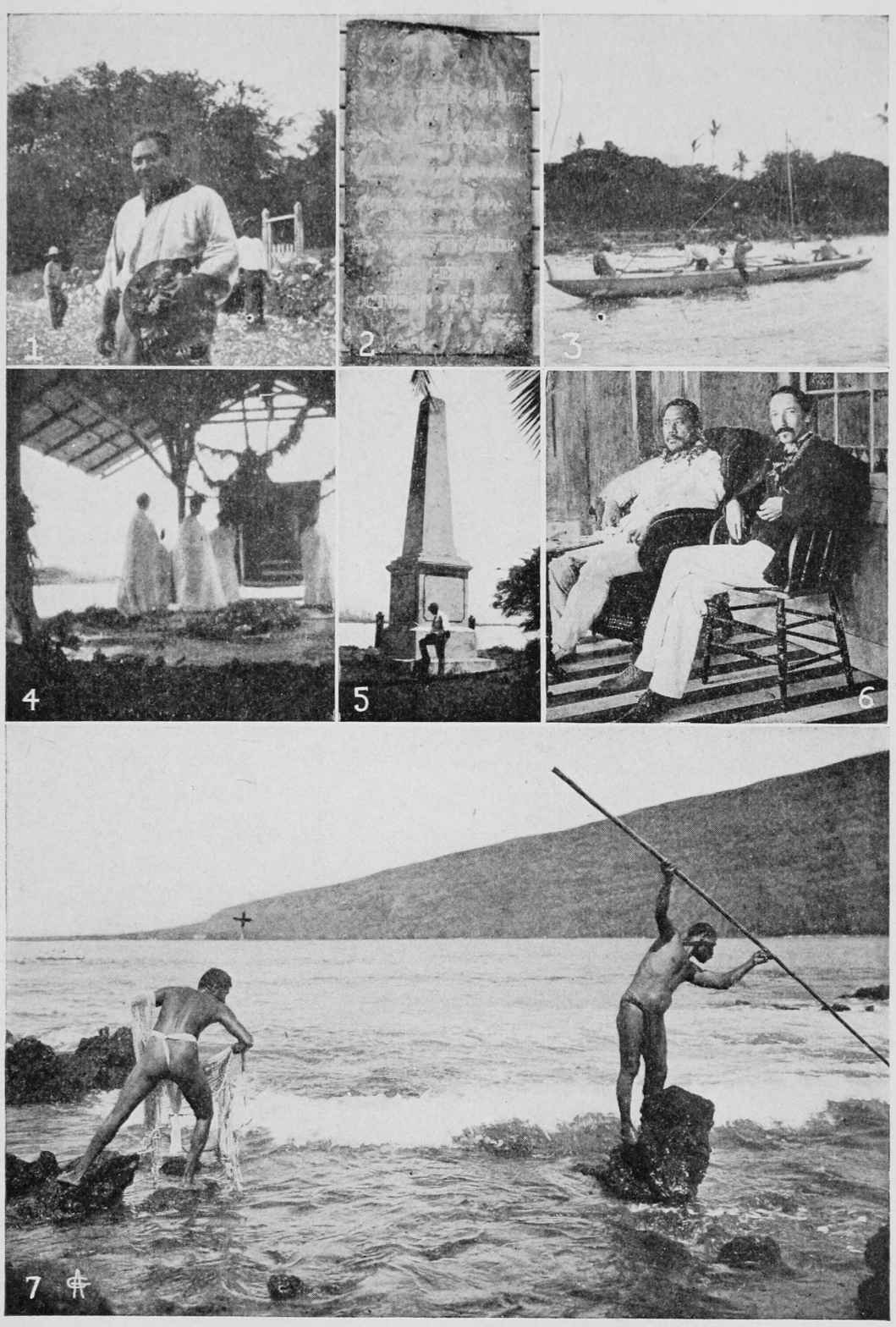

| (1) Prince Cupid. (2) Original “Monument.” (3) The Prince’s Canoe. (4) At Keauhou, Preparing the Feast. (5) Jack at Cook Monument. (6) King Kalakaua and Robert Louis Stevenson. (7) Kealakekua Bay—Captain Cook Monument at +. | 202 |

| (1) Where the Queen Composed “Aloha Oe.” (2) A Hair-raising Bridge on the Ditch Trail. (3) A Characteristic Mountain Trail in Hawaii. | 224 |

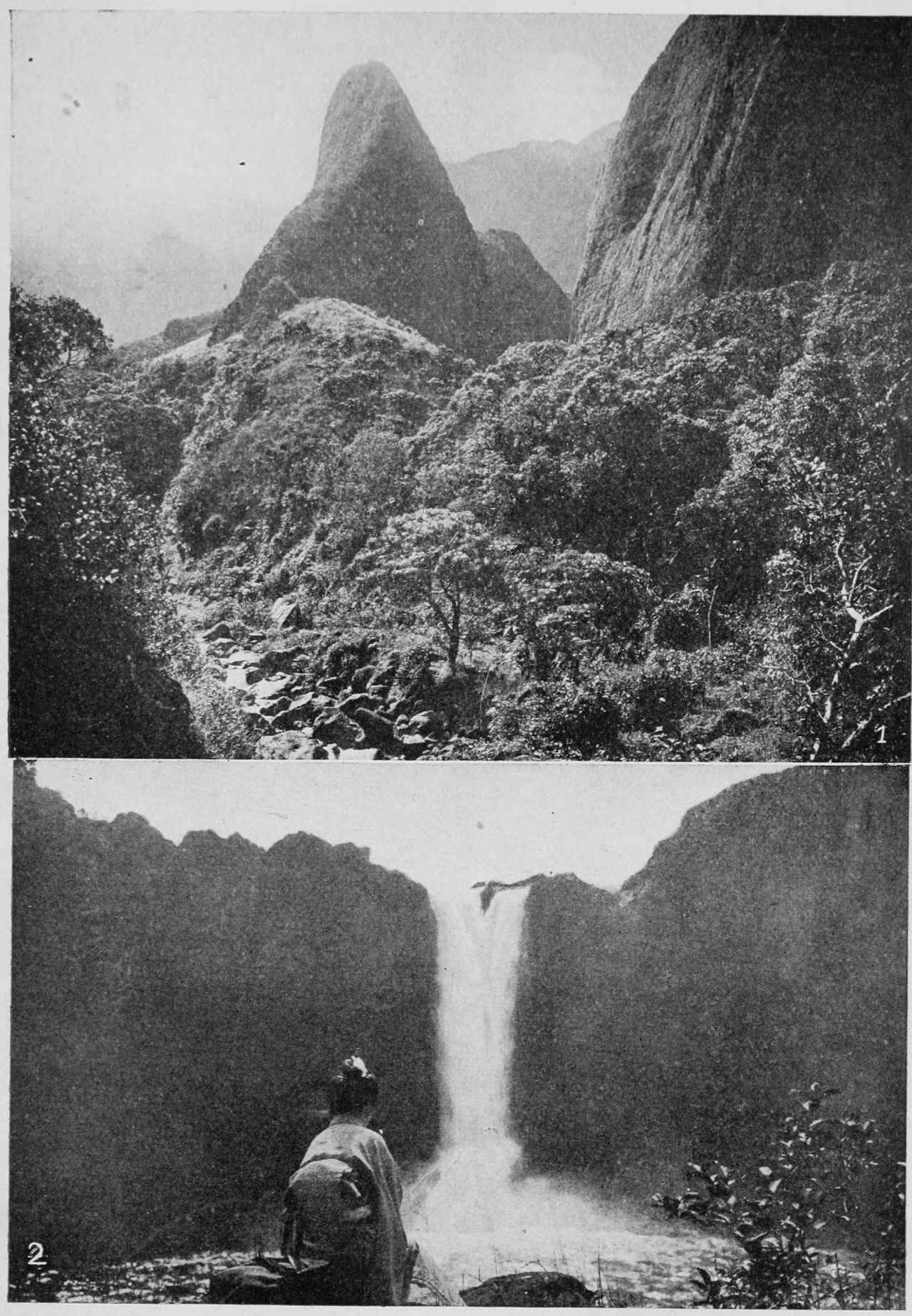

| (1) Iao Valley, Island of Maui. (2) Rainbow Falls, Hawaii. | 246 |

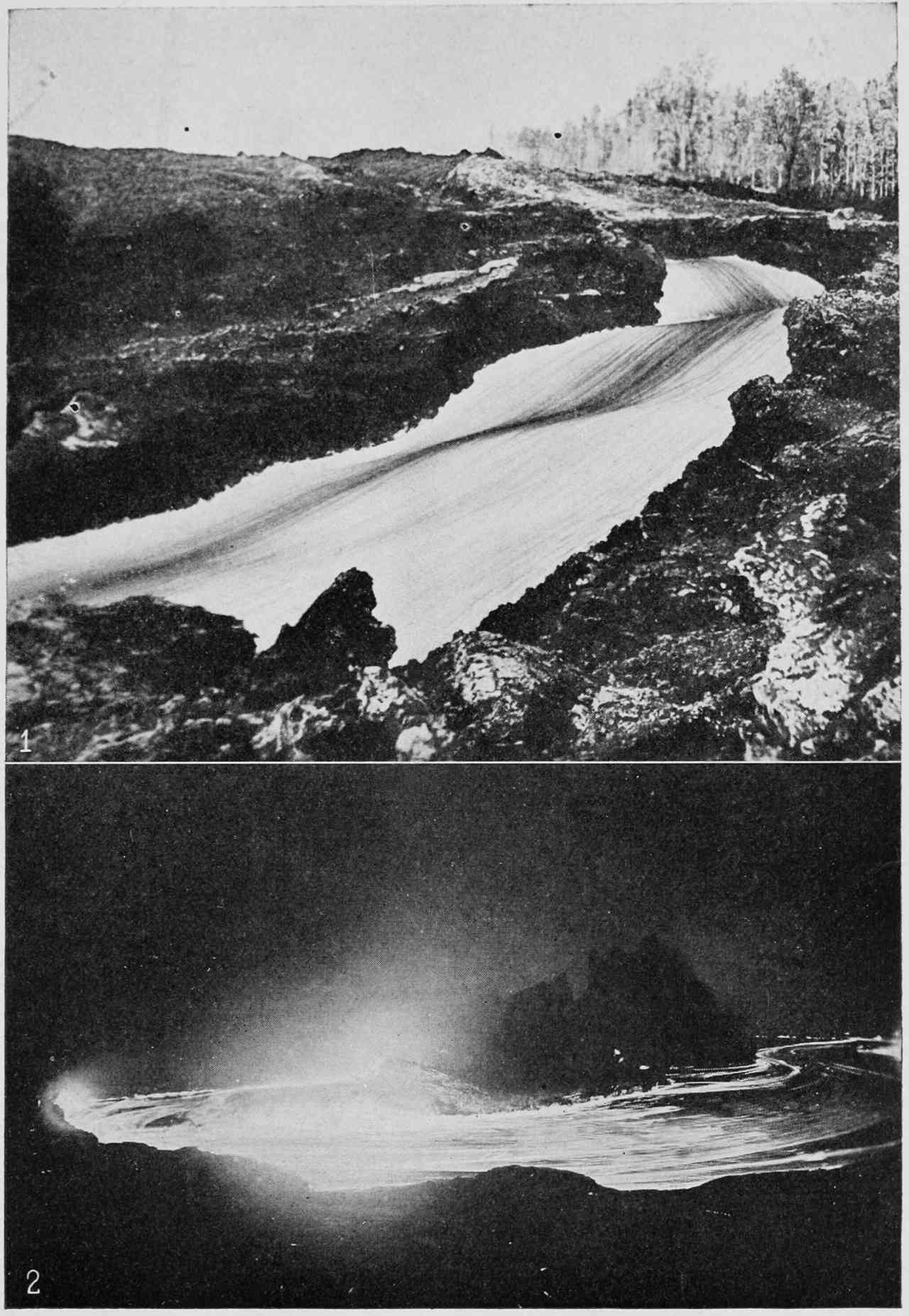

| (1) Alika Lava Flow, 1919. (2) Pit of Halemaumau. | 272 |

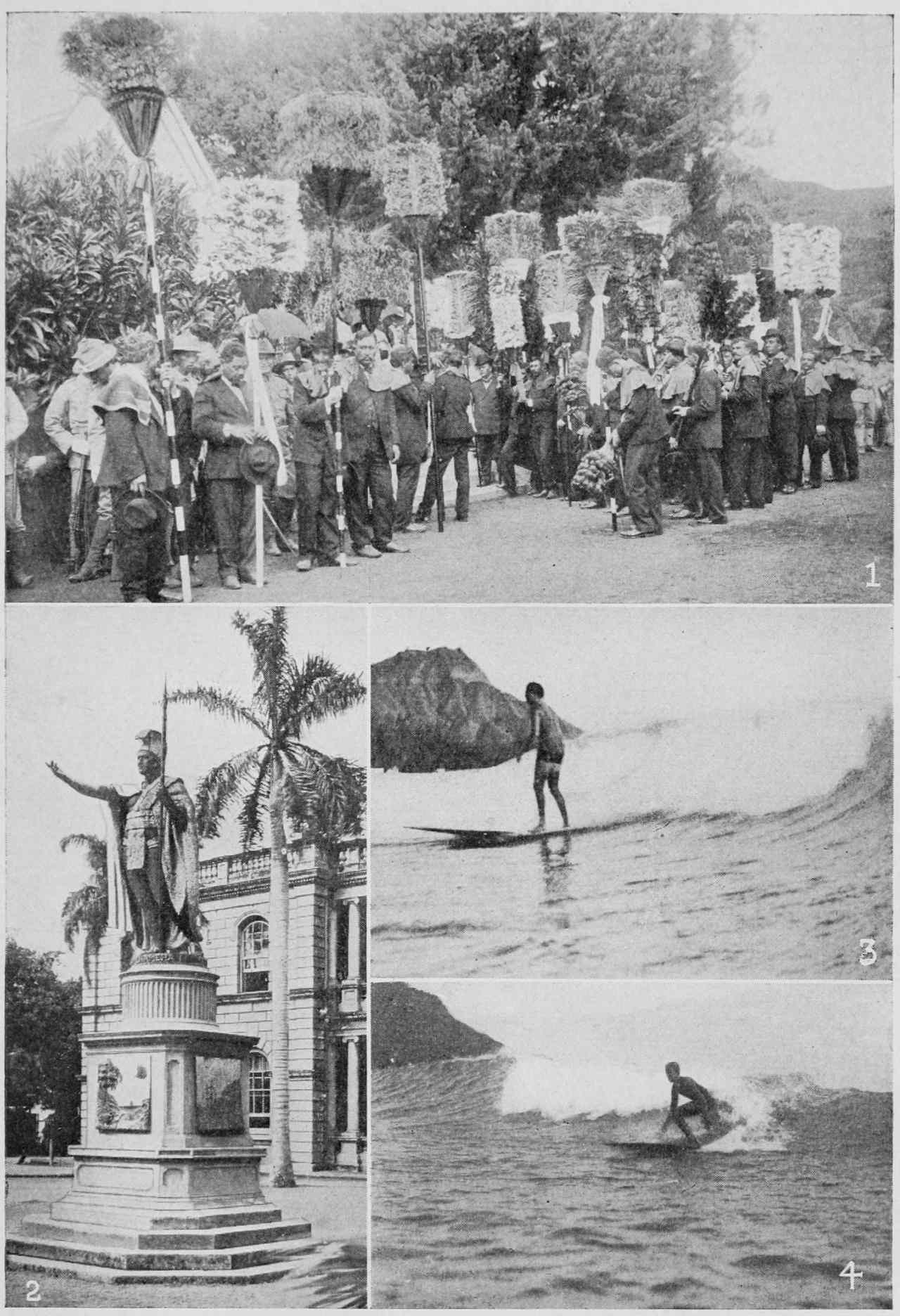

| (1) Kahilis at Funeral of Prince David Kawananakoa. (2) Kamehameha the Great. (3) and (4) Sports of Kings. | 294 |

| (1) Jack and Charmian London, Waikiki. (2) A Race Around Oahu. (3) Sailor Jack Aboard the Hawaii. (4) Pa’-u-Rider. | 316 |

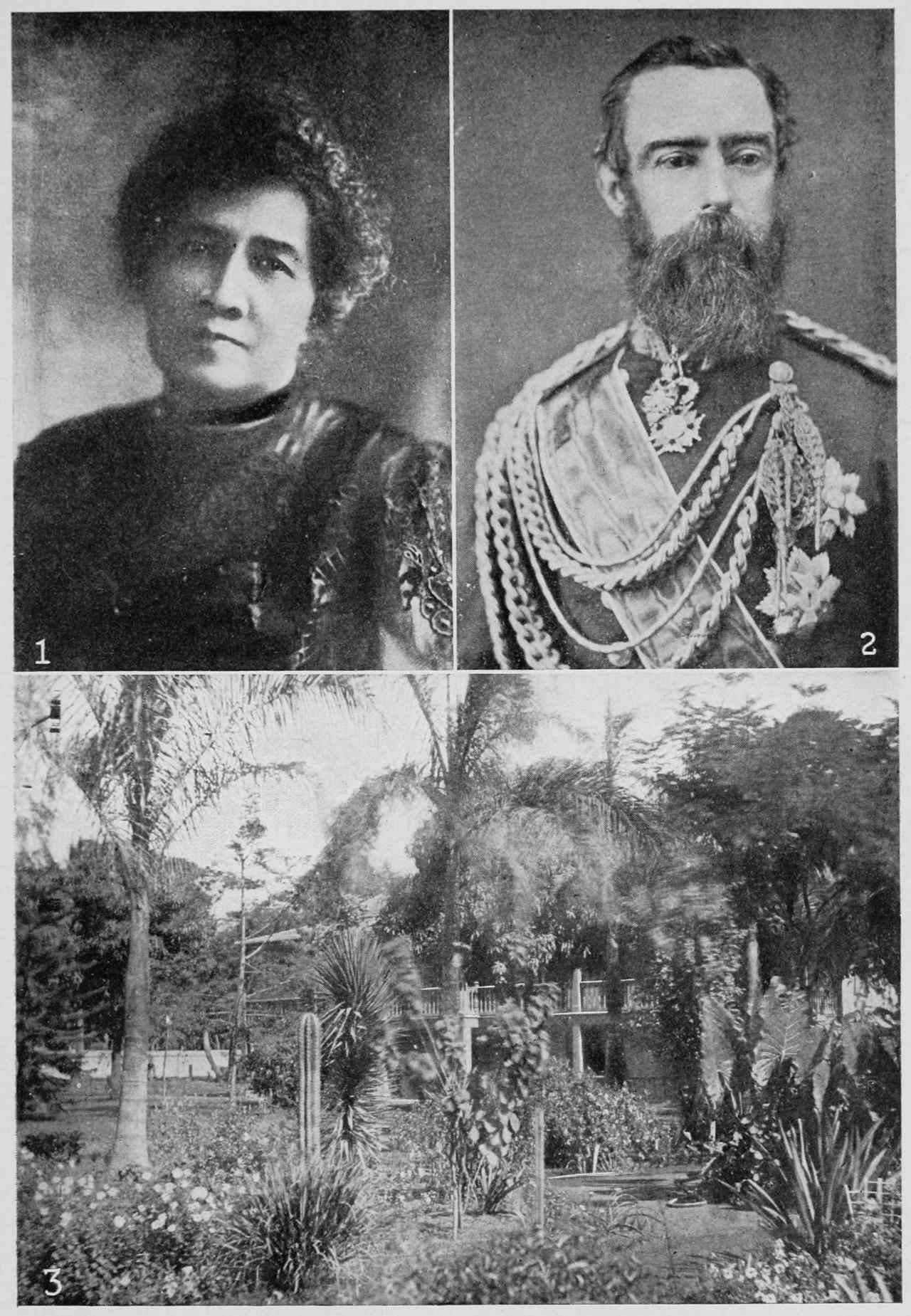

| (1) Queen Lydia Kamakaeha Liliuokalani. (2) Governor John Owen Dominis, the Queen’s Consort. (3) A Honolulu Garden—Residence of Queen Emma. | 336 |

Once upon a time, only the other day, when jovial King Kalakaua established a record for the kings of earth and time, there entered into his Polynesian brain as merry a scheme of international intrigue as ever might have altered the destiny of races and places. The time was 1881; the place of the intrigue, the palace of the Mikado at Tokio. The record must not be omitted, for it was none other than that for the first time in the history of kings and of the world a reigning sovereign, in his own royal person, put a girdle around the earth.

The intrigue? It was certainly as international as any international intrigue could be. Also, it was equally as dark, while it was precisely in alignment with the future conflicting courses of empires. Manifest destiny was more than incidentally concerned. When the manifest destinies of two dynamic races move on ancient and immemorial lines toward each other from east to west and west to east along the same parallels of latitude, there is an inevitable point on the earth’s surface where they will collide. In this case, the races were the Anglo-Saxon (represented by the Americans), and the Mongolian (represented by the Japanese). The place was Hawaii, the lovely and lovable, beloved of countless many as “Hawaii Nei.”

Kalakaua, despite his merriness, foresaw clearly, either that the United States would absorb Hawaii, or that, allied by closest marital ties to the royal house of the Rising Sun, Hawaii could be a brother kingdom in an empire. That he saw clearly, the situation to-day attests. Hawaii Nei is a territory of the United States. There are more Japanese resident in Hawaii at the present time than are resident other nationalities, not even excepting the native Hawaiians.

The figures are eloquent. In round numbers, there are twenty-five thousand pure Hawaiians, twenty-five thousand various Caucasians, twenty-three thousand Portuguese, twenty-one thousand Chinese, fifteen thousand Filipinos, a sprinkling of many other breeds, an amazing complexity of intermingled breeds, and ninety thousand Japanese. And, most amazingly eloquent of all statistics are those of the race purity of the Japanese mating. In the year 1914, the Registrar General is authority for the statements that one American male and one Spanish male respectively married Japanese females, that one Japanese male married a Hapa-Haole, or Caucasian-Hawaiian female, and that three Japanese males married pure Hawaiian females. When it comes to an innate antipathy toward mongrelization, the dominant national in Hawaii, the Japanese, proves himself more jealously exclusive by far than any other national. Omitting the records of all the other nationals which go to make up the amazing mongrelization of races in this smelting pot of the races, let the record of pure-blood Americans be cited. In the same year of 1914, the Registrar General reports that of American males who intermingled their breed and seed with alien races, eleven married pure Hawaiians, twenty-five married Caucasian-Hawaiians, three married pure Chinese, four married Chinese-Hawaiians, and one married a pure Japanese. To sum the same thing up with a cross bearing: in the same year 1914, of over eighteen hundred Japanese women who married, only two married outside their race; of over eight hundred pure Caucasian women who married, over two hundred intermingled their breed and seed with races alien to their own. Reduced to decimals, of the females who went over the fence of race to secure fathers for their children, .25 of pure Caucasian women were guilty; .0014 of Japanese women were guilty—in vulgar fraction, one out of four[1] Caucasian women; one out of one thousand Japanese women.

King Kalakaua, at the time he germinated his idea, was the royal guest of the Mikado in a special palace which was all his to lodge in, along with his suite. But Kalakaua was resolved upon an international intrigue which was, to say the least, ethnologically ticklish; while his suite consisted of two Americans, one, Colonel C. H. Judd, his Chamberlain, the other, Mr. William N. Armstrong, his Attorney-General. They represented one of the race manifest destinies, and he knew it would never do for them to know what he had up his kingly sleeve. So, on this day in 1881, he gave them the royal slip, sneaked out of the palace the back way, and hied him to the Mikado’s palace.

All of which, between kings, is a very outré thing to do. But what was mere etiquette between kings?—Kalakaua reasoned. Besides, Kalakaua was a main-traveled sovereign and a very cosmopolitan through contact with all sorts and conditions of men at the feasting board under the ringing grass-thatched roof of the royal canoe house at Honolulu, while the Mikado had never been off his tight little island. Of course, the Mikado was surprised at this unannounced and entirely unceremonious afternoon call. But not for nothing was he the Son of Heaven, equipped with all the perfection of gentleness that belongs to a much longer than a nine-hundred-years-old name. To his dying day Kalakaua never dreamed of the faux pas he committed that day in 1881.

He went directly to the point, exposited the manifest destinies moving from east to west and west to east, and proposed no less than that an imperial prince of the Mikado’s line should espouse the Princess Kaiulani of Hawaii. He assured this delicate, hot-house culture of a man whose civilization was already a dim and distant achievement at the time Kalakaua’s forebears were on the perilous and savage Polynesian canoe-drift over the Pacific ere ever they came to colonize Hawaii—this pallid palace flower of a monarch did he assure that the Princess Kaiulani was some princess. And in this Kalakaua made no mistake. She was all that he could say of her, and more. Not alone was she the most refined and peach-blow blossom of a woman that Hawaii had ever produced, to whom connoisseurs of beauty and of spirit like Robert Louis Stevenson had bowed knee and head and presented with poems and pearls; but she was Kalakaua’s own niece and heir to the throne of Hawaii. Thus, the Americans, moving westward would be compelled to stop on the far shore of the Pacific; while Hawaii, taken under Japan’s wing, would become the easterly outpost of Japan.

Kalakaua died without knowing how clearly he foresaw the trend of events. To-day the United States possesses Hawaii, which, in turn, is populated by more Japanese than by any other nationality. Practically every second person in the island is a Japanese, and the Japanese are breeding true to pure race lines while all the others are cross-breeding to an extent that would be a scandal on any stock farm.

Fortunately for the United States, the Mikado reflected. Because he reflected, Hawaii to-day is not a naval base for Japan and a menace to the United States. The haoles, or whites, overthrew the Hawaiian Monarchy, formed the Dole Republic, and shortly thereafter brought their loot in under the sheltering folds of the Stars and Stripes. There is little use to balk at the word “loot.” The white man is the born looter. And just as the North American Indian was looted of his continent by the white man, so was the Hawaiian looted by the white men of his islands. Such things be. They are morally indefensible. As facts they are irrefragable—as irrefragable as the facts that water drowns, that frost bites, and that fire incinerates.

And let this particular haole who writes these lines here and now subscribe his joy and gladness in the Hawaiian loot. Of all places of beauty and joy under the sun—but there, I was born in California, which is no mean place in itself, and it would be more meet to let some of the talking be done by the Hawaii-born, both Polynesian and haole. First of all, the Hawaii-born, unlike the Californian, does not talk big. “When you come down to the Islands you must visit us,” he will say; “we’ll give you a good time.” That’s all. No swank. Just like an invitation to dinner. And after the visit is accomplished you will confess to yourself that you never knew before what a good time was, and that for the first time you have learned the full alphabet of hospitality. There is nothing like it. The Hawaii-born won’t tell you about it. He just does it.

Said Ellis, nearly a century ago, in his Polynesian Researches: “On the arrival of strangers, every man endeavored to obtain one as a friend and carry him off to his own habitation, where he is treated with the greatest kindness by the inhabitants of the district; they place him on a high seat and feed him with abundance of the finest food.”

Such was Captain Cook’s experience when he discovered Hawaii, and despite what happened to him because of his abuse of so fine hospitality, the same hospitality has persisted in the Hawaiians of this day. Oh, please make no mistake. No longer, as he lands, will the latest beach-comber, whaleship deserter, or tourist, be carried up among the palms by an enthusiastic and loving population and be placed in the high seat. When, in a single week to-day, a dozen steamships land thousands of tourists, the impossibility of such lavishness of hospitality is understandable. It can’t be done.

But—the old hospitality holds. Come with your invitations, or letters of introduction, and you will find yourself immediately instated in the high seat of abundance. Or, come uninvited, without credentials, merely stay a real, decent while, and yourself be “good,” and make good the good in you—but, oh, softly, and gently, and sweetly, and manly, and womanly—and you will slowly steal into the Hawaiian heart, which is all of softness, and gentleness, and sweetness, and manliness, and womanliness, and one day, to your own vast surprise, you will find yourself seated in a high place of hospitableness than which there is none higher on this earth’s surface. You will have loved your way there, and you will find it the abode of love.

Nor is that all. Since I, as an attestant, am doing the talking, let me be forgiven my first-person intrusions. Detesting the tourist route, as a matter of private whim or quirk of temperament, nevertheless I have crossed the tourist route in many places over the world and know thoroughly what I am talking about. And I can and do aver, that, in this year 1916, I know of no place where the unheralded and uncredentialed tourist, if he is anything of anything in himself, so quickly finds himself among friends as here in Hawaii. Let me add: I know of no people in any place who have been stung more frequently and deeply by chance visitors than have the people of Hawaii. Yet the old heart and hale (house) hospitality holds. The Hawaii-born is like the leopard; spotted for good or ill, neither can change his spots.

Why, only last evening I was talking with an Hawaii matron—how shall I say?—one of the first ladies. Her and her husband’s trip to Japan for Cherry Blossom Time was canceled for a year. Why? She had received a wireless from a steamer which had already sailed from San Francisco, from a girl friend, a new bride, who was coming to partake of a generally extended hospitality of several years before. “But why give up your own good time?” I said; “turn your house and servants over to the young couple and you go on your own trip just the same.” “But that would never do,” said she. That was all. She had no thought of house and servants. She had once offered her hospitality. She must be there, on the spot, in heart and hale and person. And she, island-born, had always traveled east to the States and to Europe, while this was her first and long anticipated journey west to the Orient. But that she should be remiss in the traditional and trained and innate hospitality of Hawaii was unthinkable. Of course she would remain. What else could she do?

Oh, what’s the use? I was going to make the Hawaii-born talk. They won’t. They can’t. I shall have to go on and do all the talking myself. They are poor boosters. They even try to boost, on occasion; but the latest steamship and railroad publicity agent from the mainland will give them cards and spades and talk all around them when it comes to describing what Hawaii so beautifully and charmingly is. Take surf-boarding, for instance. A California real estate agent, with that one asset, could make the burnt, barren heart of Sahara into an oasis for kings. Not only did the Hawaii-born not talk about it, but they forgot about it. Just as the sport was at its dying gasp, along came one, Alexander Ford, from the mainland. And he talked. Surf-boarding was the sport of sports. There was nothing like it anywhere else in the world. They ought to be ashamed for letting it languish. It was one of the Island’s assets, a drawing card for travelers that would fill their hotels and bring them many permanent residents, etc., etc.

He continued to talk, and the Hawaii-born smiled. “What are you going to do about it?” they said, when he button-holed them into corners. “This is just talk, you know, just a line of talk.”

“I’m not going to do anything except talk,” Ford replied. “It’s you fellows who’ve got to do the doing.”

And all was as he said. And all of which I know for myself, at first hand, for I lived on Waikiki Beach at the time in a tent where stands the Outrigger Club to-day—twelve hundred members, with hundreds more on the waiting list, and with what seems like half a mile of surf-board lockers.

“Oh, yes,—there’s fishing in the Islands,” has been the customary manner of the Hawaii-born’s talk, when on the mainland or in Europe. “Come down some time and we’ll take you fishing.”—Just the same casual dinner sort of an invitation to take pot luck. And, if encouraged, he will go on and describe with antiquarian detail, how, in the good old days, the natives wove baskets and twisted fish lines that lasted a century from the fibers of a plant that grew only in the spray of the waterfall; or cleared the surface of the water with a spread of the oil of the kukui nut and caught squid with bright cowrie shells tied fast on the end of a string; or, fathoms deep, in the caves of the coral-cliffs, encountered the octopus and bit him to death with their teeth in the soft bone between his eyes above his parrot-beak.

Meanwhile these are the glad young days of new-fangled ways of fish-catching in which the Hawaii-born’s auditor is interested; and meanwhile, from Nova Scotia to Florida and across the Gulf sea shore to the coast of California, a thousand railroads, steamship lines, promotion committees, boards of trade, and real estate agents are booming the tarpon and the tuna that may occasionally be caught in their adjacent waters.

And all the time, though the world is just coming to learn of it, the one unchallengeable paradise for big-game-fishing is Hawaii. First of all, there are the fish. And they are all the year round, in amazing variety and profusion. The United States Fish Commission, without completing the task, has already described 447 distinct species, exclusive of the big, deep-sea game-fish. It is a matter of taking any day and any choice, from harpooning sharks to shooting flying-fish—like quail—with shotguns, or taking a stab at a whale, or trapping a lobster. One can fish with barbless hooks and a six-pound sinker at the end of a drop-line off Molokai in forty fathoms of water and catch at a single session, a miscellany as generous as to include: the six to eight pound moelua, the fifteen pound upakapaka, the ten-pound lehe, the kawelea which is first cousin to the “barricoot,” the hapuupuu, the awaa, and say, maybe, the toothsome and gamy kahala mokulaie. And the bait one will use on his forty-fathom line will be the fish called the opelu, which, in turn, is caught with a bait of crushed pumpkin.

But let not the light-tackle sportsman be dismayed by the foregoing description of such crass, gross ways of catching unthinkable and unpronounceable fish. Let him take a six ounce tip and a nine-thread line and essay one of Hawaii’s black sea bass. They catch them here weighing over six hundred pounds, and they certainly do run bigger than do those in the kelp beds off Southern California. Does the light-tackle man want tarpon? He will find them here as gamy and as large as in Florida, and they will leap in the air—ware slack!—like range mustangs to fling the hook clear.

Nor has the tale begun. Of the barracuda, Hawaiian waters boast twenty species, sharp-toothed, voracious, running to a fathom and even more in length, and, unlike the Florida barracuda, traveling in schools. There are the albacore and the dolphin—no mean fish for light tackle; to say nothing of the ocean bonita and the California bonita. There is the ulua pound for pound the gamest salt-water fish that ever tried a rod; and there is the ono, half way a swordfish, called by the ancient Hawaiians the father of the mackerel. Also, there is the swordfish, at which light-tackle men have never been known to sneer—after they had once hooked one. The swordfish of Hawaii, known by its immemorial native name of a’u, averages from three to four hundred pounds, although they have been caught between six and seven hundred pounds, sporting swords five feet and more in length. And not least are those two cousins of the amber jack of Florida, the yellow tail and the amber fish, named by Holder as the fish of Southern California par excellence and by him described for their beauty and desperateness in putting up a fight.

And the tuna must not be omitted, or, at any rate, the thunnus thynnus, the thunnus alalonsa, and the thunnus macrapterus, so called by the scientists, but known by the Hawaiians under the generic name of ahi, and, by light-tackle men as the leaping tuna, the long-fin tuna, and the yellow-fin tuna. In the past two months, Messrs. Jump, Burnham and Morris, from the mainland, seem to have broken every world record in the tuna line. They had to come to Hawaii to do it, but, once here, they did it easily, even if Morris did break a few ribs in the doing of it. Just the other day, on their last trip, Mr. Jump landed a sixty-seven pound yellow-fin on a nine-thread line, and Mr. Morris similarly a fifty-five pound one. The record for Catalina is fifty-one pounds. Pshaw! Let this writer from California talk big, after the manner of his home state, and still keep within the truth. A yellow-fin tuna, recently landed out of Hawaiian waters and sold on the Honolulu market, weighed two hundred and eighty-seven pounds.

|

Statistics compiled in 1921 by the Bishop Museum, of Honolulu, show that one out of every six women of Caucasian birth in the Territory of Hawaii marries a Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian; and other figures prove that a large percentage of part-Hawaiian women marry either Hawaiians or part-Hawaiians. Still another large proportion marries Caucasians or Chinese. Further, the figures illustrate that the new stock is better able to withstand disease and is, in that sense, more vigorous than its Hawaiian ancestors, as well as more prolific. It is the creation of a new race, strong, virile, and productive; while the pure-blooded Hawaiians steadily decrease in numbers. |

Hawaii is the home of shanghaied men and women, and of the descendants of shanghaied men and women. They never intended to be here at all. Very rarely, since the first whites came, has one, with the deliberate plan of coming to remain, remained. Somehow, the love of the Islands, like the love of a woman, just happens. One cannot determine in advance to love a particular woman, nor can one so determine to love Hawaii. One sees, and one loves or does not love. With Hawaii it seems always to be love at first sight. Those for whom the Islands were made, or who were made for the Islands, are swept off their feet in the first moments of meeting, embrace, and are embraced.

I remember a dear friend who resolved to come to Hawaii and make it his home forever. He packed up his wife, all his belongings including his garden hose and rake and hoe, said “Goodbye, proud California,” and departed. Now he was a poet, with an eye and soul for beauty, and it was only to be expected that he would lose his heart to Hawaii as Mark Twain and Stevenson and Stoddard had before him. So he came, with his wife and garden hose and rake and hoe. Heaven alone knows what preconceptions he must have entertained. But the fact remains that he found naught of beauty and charm and delight. His stay in Hawaii, brief as it was, was a hideous nightmare. In no time he was back in California. To this day he speaks with plaintive bitterness of his experience, although he never mentions what became of his garden hose and rake and hoe. Surely the soil could not have proved niggardly to him!

Otherwise was it with Mark Twain, who wrote of Hawaii long after his visit: “No alien land in all the world has any deep, strong charm for me but that one; no other land could so longingly and beseechingly haunt me sleeping and waking, through half a lifetime, as that one has done. Other things leave me, but it abides; other things change, but it remains the same. For me its balmy airs are always blowing, its summer seas flashing in the sun; the pulsing of its surf-beat is in my ears; I can see its garlanded crags, its leaping cascades, its plumy palms drowsing by the shore, its remote summits floating like islands above the cloudrack; I can feel the spirit of its woodland solitudes; I can hear the plash of its brooks; in my nostrils still lives the breath of flowers that perished twenty years ago.”

One reads of the first Chief Justice under the Kamehamehas, that he was on his way around the Horn to Oregon when he was persuaded to remain in Hawaii. Truly, Hawaii is a woman beautiful and vastly more persuasive and seductive than her sister sirens of the sea.

The sailor boy, Archibald Scott Cleghorn, had no intention of leaving his ship; but he looked upon the Princess Likelike, the Princess Likelike looked on him, and he remained to become the father of the Princess Kaiulani and to dignify a place of honor through long years. He was not the first sailor boy to leave his ship, nor the last. One of the recent ones, whom I know well, arrived several years ago on a yacht in a yacht race from the mainland. So brief was his permitted vacation from his bank cashiership that he had planned to return by fast steamer. He is still here. The outlook is that his children and his grand-children after him will be here.

Another erstwhile bank cashier is Louis von Tempsky, the son of the last British officer killed in the Maori War. His New Zealand bank gave him a year’s vacation. The one place he wanted to see above all others was California. He departed. His ship stopped at Hawaii. It was the same old story. The ship sailed on without him. His New Zealand bank never saw him again, and many years passed ere ever he saw California. But she had no charms for him. And to-day, his sons and daughters about him, he looks down on half a world and all of Maui from the rolling grasslands of the Haleakala Ranch.

There were the Gays and Robinsons. Scotch pioneers over the world in the good old days when families were large and patriarchial, they had settled in New Zealand. After a time they decided to migrate to British Columbia. Among their possessions was a full-rigged ship, of which one of their sons was master. Like my poet friend from California, they packed all their property on board. But in place of his garden hose and rake and hoe, they took their plows and harrows and all their agricultural machinery. Also, they took their horses and their cattle and their sheep. When they arrived in British Columbia they would be in shape to settle immediately, break the soil, and not miss a harvest. But the ship, as was the custom in the sailing-ship days, stopped at Hawaii for water and fruit and vegetables. The Gays and Robinsons are still here, or, rather, their venerable children, and younger grandchildren and great grandchildren; for Hawaii, like the Princess Likelike, put her arms around them, and it was love at first sight. They took up land on Kauai and Niihau, the ninety-seven square miles of the latter remaining intact in their possession to this day.

I doubt that not even the missionaries, wind jamming around the Horn from New England a century ago, had the remotest thought of living out all their days in Hawaii. This is not the way of missionaries over the world. They have always gone forth to far places with the resolve to devote their lives to the glory of God and the redemption of the heathen, but with the determination, at the end of it all, to return to spend their declining years in their own country. But Hawaii can seduce missionaries just as readily as she can seduce sailor boys and bank cashiers, and this particular lot of missionaries was so enamored of her charms that they did not return when old age came upon them. Their bones lie here in the land they came to love better than their own; and they, and their sons and daughters after them, have been, and are, powerful forces in the development of Hawaii.

In missionary annals, such unanimous and eager adoption of a new land is unique. Yet another thing, equally unique in missionary history, must be noted in passing. Never did missionaries, the very first, go out to rescue a heathen land from its idols, and on arrival find it already rescued, self-rescued, while they were on the journey. In 1819, all Hawaii was groaning under the harsh rule of the ancient idols, whose mouthpieces were the priests and whose utterances were the frightfully cruel and unjust taboos. In 1819, the first missionaries assembled in Boston and sailed away on the long voyage around the Horn. In 1819, the Hawaiians, of themselves, without counsel or suggestion, over-threw their idols and abolished the taboos. In 1820, the missionaries completed their long voyage and landed in Hawaii to find a country and a people without gods and without religion, ready and ripe for instruction.

But to return. Hawaii is the home of shanghaied men and women, who were induced to remain, not by a blow with a club over the head or a doped bottle of whisky, but by love. Hawaii and the Hawaiians are a land and a people loving and lovable. By their language may ye know them, and in what other land save this one is the commonest form of greeting, not “Good day,” nor “How d’ye do,” but “Love?” That greeting is Aloha—love, I love you, my love to you. Good day—what is it more than an impersonal remark about the weather? How do you do—it is personal in a merely casual interrogative sort of a way. But Aloha! It is a positive affirmation of the warmth of one’s own heart-giving. My love to you! I love you! Aloha!

Well, then, try to imagine a land that is as lovely and loving as such a people. Hawaii is all of this. Not strictly tropical, but sub-tropical, rather, in the heel of the Northeast Trades (which is a very wine of wind), with altitudes rising from palm-fronded coral beaches to snow-capped summits fourteen thousand feet in the air; there was never so much climate gathered together in one place on earth. The custom of the dwellers is as it was of old time, only better, namely: to have a town house, a seaside house, and a mountain house. All three homes, by automobile, can be within half an hour’s run of one another; yet, in difference of climate and scenery, they are the equivalent of a house on Fifth Avenue or the Riverside Drive, of an Adirondack camp, and of a Florida winter bungalow, plus a twelve-months’ cycle of seasons crammed into each and every day.

Let me try to make this clearer. The New York dweller must wait till summer for the Adirondacks, till winter for the Florida beach. But in Hawaii, say on the island of Oahu, the Honolulu dweller can decide each day what climate and what season he desires to spend the day in. It is his to pick and choose. Yes, and further: he may awake in his Adirondacks, lunch and shop and go to the club in his city, spend his afternoon and dine at his Palm Beach, and return to sleep in the shrewd coolness of his Adirondack camp.

And what is true of Oahu, is true of all the other large islands of the group. Climate and season are to be had for the picking and choosing, with countless surprising variations thrown in for good measure. Suppose one be an invalid, seeking an invalid’s climate. A night’s run from Honolulu on a steamer will land him on the leeward coast of the big Island of Hawaii. There, amongst the coffee on the slopes of Kona, a thousand feet above Kailua and the wrinkled sea, he will find the perfect invalid-climate. It is the land of the morning calm, the afternoon shower, and the evening tranquility. Harsh winds never blow. Once in a year or two a stiff wind of twenty-four to forty-eight hours will blow from the south. This is the Kona wind. Otherwise there is no wind, at least no air-draughts of sufficient force to be so dignified. They are not even breezes. They are air-fans, alternating by day and by night between the sea and the land. Under the sun, the land warms and draws to it the mild sea air. In the night, the land radiating its heat more quickly, the sea remains the warmer and draws to it the mountain air faintly drenched with the perfume of flowers.

Such is the climate of Kona, where nobody ever dreams of looking at a thermometer, where each afternoon there falls a refreshing spring shower, and where neither frost nor sunstroke has ever been known. All of which is made possible by the towering bulks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Beyond them, on the windward slopes of the Big Island, along the Hamakua Coast, the trade wind will as often as not be blustering at forty miles an hour. Should an Oregon web-foot become homesick for the habitual wet of his native clime, he will find easement and a soaking on the windward coasts of Hawaii and Maui, from Hilo in the south with its average annual rainfall of one hundred and fifty inches to the Nahiku country to the north beyond Hana which has known a downpour of four hundred and twenty inches in a single twelve-month. In the matter of rain it is again pick and choose—from two hundred inches to twenty, or five, or one. Nay, further, forty miles away from the Nahiku, on the leeward slopes of the House of the Sun, which is the mightiest extinct volcano in the world, rain may not fall once in a dozen years, cattle live their lives without ever seeing a puddle and horses brought from that region shy at running water or try to eat it with their teeth.

One can multiply the foregoing examples indefinitely, and to the proposition that never was so much climate gathered together in one place, can be added that never was so much landscape gathered together in one place. The diversification is endless, from the lava shores of South Puna to the barking sands of Kauai. On every island break-neck mountain climbing abounds. One can shiver above timber-line on the snow-caps of Mauna Kea or Mauna Loa, swelter under the banyan at sleepy old Lahaina, swim in clear ocean water that effervesces like champagne on ten thousand beaches, or sleep under blankets every night in the upland pastures of the great cattle ranges and awaken each morning to the song of sky-larks and the crisp, snappy air of spring. But never, never, go where he will in Hawaii Nei, will he experience a hurricane, a tornado, a blizzard, a fog, or ninety degrees in the shade. Such discomforts are meteorologically impossible, so the meteorologists affirm. When Hawaii was named the Paradise of the Pacific, it was inadequately named. The rest of the Seven Seas and the islands in the midst thereof should have been included along with the Pacific. “See Naples and die”—they spell it differently here: see Hawaii and live.

Nor is Hawaii niggardly toward the sportsman. Good hunting abounds. As I write these lines on Puuwaawaa Ranch, from every side arises the love-call of the quail, which are breaking up their coveys as the mating proceeds. They are California quail, yet never in California have I seen quail as thick as here. Yesterday I saw more doves—variously called turtle doves and mourning doves—than I ever saw before in any single day of my life. Day before yesterday I was out with the cowboys roping wild pig in the pastures.

Of birds, in addition to quail and doves, in place and season may be hunted wild duck, wild turkey, rice birds, Chinese and Japanese pheasants, pea fowl, guinea fowl, wild chicken (which is a mongrel cross of the indigenous moa and the haole chicken), and, not least, the delicious golden plover fat and recuperated after its long flight from Alaska and the arctic shores. Then there are the spotted deer of Molokai. Increasing from several introduced pair, they so flourished in their new habitat that they threatened the pastures and forests, and some years ago the government was compelled to employ professional hunters to reduce their numbers. Of course there is pig-sticking, and for real hunting few things can out-thrill the roping, after cowboy fashion, of the wild bulls of the upper ranges. Also are there to be had wild goats, wild sheep—yes, and wild dogs, running in packs and dragging down calves and cows, that may even prove perilous to the solitary hunter. And as for adventure and exploration, among many things, one can tackle Rabbit Island, inaccessible to all but the most intrepid and most fortunate, or seek for the secret and taboo burial places of the ancient kings.

Indeed, Hawaii is a loving land. Just as it welcomed the spotted deer to the near destruction of its forests, so has it welcomed many other inimical aliens to its shores. In the United States, in greenhouses and old fashioned gardens, grows a potted flowering shrub called lantana, which originally came from South America; in India dwells a very noisy and quarrelsome bird known as the mynah. Both were introduced into Hawaii, the bird to feed upon the cutworm of a certain moth called spodoptera mauritia; the flower to gladden with old associations the heart of a flower-loving missionary. But the land loved the lantana. From a small plant that grew in a pot with its small, velvet flowers of richest tones of orange, yellow, and rose, the lantana took to itself feet and walked out of the pot into the missionary’s garden. Here it flourished and increased mightily in size and constitution. From over the garden wall came the love-call of all Hawaii, and the lantana responded to the call, climbed over the wall, and went a-roving and a-loving in the wild woods.

And just as the lantana had taken to itself feet, by the seduction of the seeds in its aromatic blue-black berries, it added to itself the wings of the mynah, who distributed its seed over every island in the group. Like the creatures Mr. Wells writes of who ate of the food of the gods and became giants, so the lantana. From a delicate, hand-manicured, potted plant of the greenhouse, it shot up into a tough and belligerent swashbuckler from one to three fathoms tall, that marched in serried ranks over the landscape, crushing beneath it and choking to death all the sweet native grasses, shrubs, and flowers. In the lower forests it became jungle. In the open it became jungle, only more so. It was practically impenetrable to man. It filled and blotted out the pastures by tens of thousands of acres. The cattlemen wailed and vainly fought with it. It grew faster and spread faster than they could grub it out.

Like the invading whites who dispossessed the native Hawaiians of their land, so did the lantana to the native vegetation. Nay, it did worse. It threatened to dispossess the whites of the land they had won. And battle royal was on. Unable to cope directly with it, the whites called in the aid of the hosts of mercenaries. They sent out their agents to recruit armies from the insect world and from the world of micro-organisms. Of these doughty warriors let the name of but one, as a sample, be given—crenastobombycia lantenella. Prominent among these recruits were the lantana seed-fly, the lantana plume-moth, the lantana butterfly, the lantana leaf-miner, the lantana leaf-bug, the lantana gall-fly. Quite by accident the Maui blight or scale was enlisted.

Some of these predacious enemies of the lantana ate and sucked and sapped. Others made incubators out of the stems, tunneled and undermined the flower clusters, hatched maggots in the hearts of the seeds, or coated the leaves with suffocating fungoid growths. Thus simultaneously attacked in front and rear and flank, above and below, inside and out, the all-conquering swashbuckler recoiled. To-day the battle is almost over, and what remains of the lantana is putting up a sickly and losing fight. Unfortunately, one of the mercenaries has mutinied. This is the accidentally introduced Maui blight, which is now waging unholy war upon garden flowers and ornamental plants, and against which some other army of mercenaries must be turned.

Hawaii has been most generous in her hospitality, most promiscuous in her loving. Her welcome has been impartial. To her warm heart she has enfolded all manner of hurtful, stinging things, including some humans. Mosquitos, centipedes and rats made the long voyages, landed, and have flourished ever since. There was none of these here before the haole came. So, also, were introduced measles, smallpox, and many similar germ afflictions of man. The elder generations lived and loved and fought and went down into the pit with their war weapons and flower garlands laid under their heads, unvexed by whooping cough, and mumps, and influenza. Some alien good, and much of alien ill, has Hawaii embraced and loved. Yet to this day no snake, poisonous or otherwise, exists in her forests and jungles; while the centipede is not deadly, its bite being scarcely more discomforting than the sting of a bee or wasp. Some snakes did arrive, once. A showman brought them for exhibition. In passing quarantine they had to be fumigated. By some mischance they were all suffocated, and it is whispered that the quarantine officials might have more to say of that mischance than appeared in their official report.

And, oh, there is the mongoose. Originally introduced from India via Jamaica to wage war on that earlier introduction, the rat, which was destroying the sugar cane plantations, the mongoose multiplied beyond all guestly bounds and followed the lantana into the plains and forests. And in the plains and forests it has well nigh destroyed many of the indigenous species of ground-nesting birds, made serious inroads on the ground-nesting imported birds, and compelled all raisers of domestic fowls to build mongoose-proof chicken yards. In the meantime the rats have changed their nesting habits and taken to the trees. Some of the pessimistic farmers even aver that, like the haole chickens which went wild in the woods and crossed with the moa, the mongoose has climbed the trees, made friends with and mated with the rats, and has produced a permanent hybrid of omnivorous appetite that eats sugar cane, birds’ eggs, and farmyard chickens indiscriminately and voraciously. But further deponent sayeth not.

Hawaii is a great experimental laboratory, not merely in agriculture, but in ethnology and sociology. Remote in the heart of the Pacific, more hospitable to all forms of life than any other land, it has received an immigration of alien vegetable, insect, animal and human life more varied and giving rise to more complicated problems than any other land has received. And right intelligently and whole-heartedly have the people of Hawaii taken hold of these problems and striven to wrestle them to solution.

A melting pot or a smelting pot is what Hawaii is. In a single school, at one time I have observed scholars of as many as twenty-three different nationalities and mixed nationalities. First of all is the original Hawaiian stock of pure Polynesian. These were the people whom Captain Cook discovered, the first pioneers who voyaged in double canoes from the South Pacific and colonized Hawaii at what is estimated from their traditions as some fifteen hundred years ago. Next, from Captain Cook’s time to this day, has drifted in the haole, or Caucasian—Yankee, Scotch, Irish, English, Welsh, French, German, Scandinavian—every Caucasian country of Europe, and every Caucasian colony of the world has contributed its quota. And not least to be reckoned with, are the deliberate importations of unskilled labor for the purpose of working the sugar plantations. First of these was a heavy wave of Chinese coolies. But the Chinese Exclusion Act put a stop to their coming. In the same way, King Sugar has introduced definite migrations of Japanese, Koreans, Russians, Portuguese, Spanish, Porto Ricans, and Filipinos. With the exception of the Japanese, who are jealously exclusive in the matter of race, all these other races insist and persist in intermarrying, and the situation here should afford much valuable data for the ethnologist.

Of the original Hawaiians one thing is certain. They are doomed to extinction. Year by year the total number of the pure Hawaiians decreases. Marrying with the other races as they do, they could persist as hybrids, if—if fresh effusions of them came in from outside sources equivalent to such continued effusions as do come in of the other races. But no effusions of Polynesian come in nor have ever come in. Steadily, since Captain Cook’s time, they have faded away. To-day, the representatives of practically all the old chief-stocks and royal-stocks are half-whites, three-quarter whites, and seven-eighths whites. And they, and their children, continue to marry whites, or seven-eighths and three-quarters whites like themselves, so that the Hawaiian strain grows thinner and thinner against the day when it will vanish in thin air. All of which is a pity, for the world can ill afford to lose so splendid and lovable a race.

And yet, in this period of world war wherein the United States finds it necessary to prepare against foes that may at any time launch against it out of the heart of civilization, little Hawaii, with its hotch potch of races, is making a better demonstration than the United States.

The National Guard has been so thoroughly reorganized, livened up, and recruited that it makes a showing second to none on the Mainland, while, in proportion to population, it has more of this volunteer soldiery than any of the forty-eight states and territories in the United States. In addition to the mixed companies, there are entire companies of Hawaiians, Portuguese, Chinese (Hawaii-born), and Filipinos; and the reviewing stand sits up and takes notice when it casts its eyes over them and over the regulars.

(1) The Peninsula. (2) The Hobron Bungalow. (3) The Snark, and the owner ashore.

No better opportunity could be found for observing this medley of all the human world than that afforded by the Mid-Pacific Carnival last February when the population turned out and held festival for a week. Nowhere within the territory of the United States could so exotic a spectacle be witnessed. And unforgettable were the flower-garlanded Hawaiians, the women pa’u riders on their lively steeds with flowing costumes that swept the ground, toddling Japanese boys and girls, lantern processions straight out of old Japan, colossal dragons from the Flowery Empire, and Chinese school girls, parading two by two in long winding columns, bare-headed, their demure black braids down their backs, slimly graceful in the white costumes of their foremothers. At the same time, while the streets stormed with confetti and serpentines tossed by the laughing races of all the world, in the throne room of the old palace (now the Executive Building) was occurring an event as bizarre in its own way and equally impressive. Here, side by side, the two high representatives of the old order and the new held reception. Seated, was the aged Queen Liliuokalani, the last reigning sovereign of Hawaii; standing beside her was Lucius E. Pinkham, New England born, the Governor of Hawaii. A quarter of a century before, his brothers had dispossessed her of her kingdom; and quite a feather was it in his cap for him to have her beside him that night, for it was the first time in that quarter of a century that any one had succeeded in winning her from her seclusion to enter the throne-room. And about them, among brilliantly uniformed army and navy officers from generals and admirals down, moved judges and senators, sugar kings and captains of industry, the economic and political rulers of Hawaii, and many of them, they and their women, intermingled descendants of the old chief stocks and of the old missionary and merchant pioneers.

And what more meet than that in Hawaii, the true Aloha-land which has welcomed and loved all wayfarers from all other lands, that the Pan-Pacific movement should have originated. This had its inception in the mind of Mr. Alexander Hume Ford—he of Outrigger Club fame who resurrected the sports of surf-boarding and surf-canoeing at Waikiki. Hands-Around-the-Pacific, he calls the movement; and already these friendly hands are reaching out and clasping all the way from British Columbia to Panama, from New Zealand to Australia and Oceanica, and on to Java, the Philippines, China and Japan, and around and back again to Hawaii, the Cross-Roads of the Pacific and the logical heart and home and center of the movement.

Hawaii is a Paradise—and I can never cease proclaiming it; but I must append one word of qualification: Hawaii is a paradise for the well-to-do. It is not a paradise for the unskilled laborer from the mainland, nor for the person without capital from the mainland. The one great industry of the islands is sugar. The unskilled labor for the plantations is already here. Also, the white unskilled laborer, with a higher standard of living, cannot compete with coolie labor, and, further, the white laborer cannot and will not work in the canefields.

For the person without capital, dreaming to start on a shoestring and become a capitalist, Hawaii is the last place in the world. It must be remembered that Hawaii is very old... comparatively. When California was a huge cattle ranch for hides and tallow (the meat being left where it was skinned), Hawaii was publishing newspapers and boasting schools of higher learning. During the early years of the gold rush, before the soil of California was scratched with a plow, Hawaii kept a fleet of ships busy carrying her wheat, and flour, and potatoes to California, while California was sending her children down to Hawaii to be educated. The shoestring days are past. The land and industries of Hawaii are owned by old families and large corporations, and Hawaii is only so large.

But the homesteader may object, saying that he has read the reports of the millions of acres of government land in Hawaii which are his for the homesteading. But he must remember that the vastly larger portion of this government land is naked lava rock and not worth ten cents a square mile to a homesteader, and that much of the remaining land, while rich in soil values, is worthless because it is without water. The small portion of good government land is leased by the plantations. Of course, when these leases expire, they may be homesteaded. It has been done in the past. But such homesteaders, after making good their titles, almost invariably sell out their holdings in fee simple to the plantations. There is a reason for it. There are various reasons for it.

Even the skilled laborer is needed only in small, definite numbers. Perhaps I cannot do better than quote the warning circulated by the Hawaiian Promotion Committee: “No American is advised to come here in search of employment unless he has some definite work in prospect, or means enough to maintain himself for some months and to launch into some enterprise. Clerical positions are well filled; common labor is largely performed by Japanese or native Hawaiians, and the ranks of skilled labor are also well supplied.”

For be it understood that Hawaii is patriarchal rather than democratic. Economically it is owned and operated in a fashion that is a combination of twentieth century, machine-civilization methods and of medieval feudal methods. Its rich lands, devoted to sugar, are farmed not merely as scientifically as any land is farmed anywhere in the world, but, if anything, more scientifically. The last word in machinery is vocal here, the last word in fertilizing and agronomy, and the last word in scientific expertness. In the employ of the Planters’ Association is a corps of scientific investigators who wage unceasing war on the insect and vegetable pests and who are on the travel in the remotest parts of the world recruiting and shipping to Hawaii insect and micro-organic allies for the war.

The Sugar Planters’ Association and the several sugar factors or financial agencies control sugar, and, since sugar is king, control the destiny and welfare of the Islands. And they are able to do this, under the peculiar conditions that obtain, far more efficiently than could it be done by the population of Hawaii were it a democratic commonwealth, which it essentially is not. Much of the stock in these corporations is owned in small lots by members of the small business and professional classes. The larger blocks are held by families who, earlier in the game, ran their small plantations for themselves, but who learned that they could not do it so well and so profitably as the corporations, which, with centralized management, could hire far better brains for the entire operation of the industry, from planting to marketing, than was possessed by the heads of the families. As a result, absentee ownership or landlordship has come about. Finding the work done better for them than they could do it themselves, they prefer to live in their Honolulu and seaside and mountain homes, to travel much, and to develop a cosmopolitanism and culture that never misses shocking the traveler or newcomer with surprise. All of which makes this class in Hawaii as cosmopolitan as any class to be found the world over. Of course, there are notable exceptions to this practice of absentee landlordism, and such men run their own plantations and corporations and are active as sugar factors and in the management of the Planters’ Association.

Yet will I dare to assert that no owning class on the mainland is so conscious of its social responsibility as is this owning class of Hawaii, and especially that portion of it which has descended out of the old missionary stock. Its charities, missions, social settlements, kindergartens, schools, hospitals, homes, and other philanthropic enterprises are many; its activities are unceasing; and some of its members contribute from twenty-five to fifty per cent of their incomes to the work for the general good.

But all the foregoing, it must be remembered, is not democratic nor communal, but is distinctly feudal. The coolie and peasant labor possesses no vote, while Hawaii is after all only a territory, its governor appointed by the President of the United States, its one delegate sitting in Congress at Washington but denied the right to vote in that body. Under such conditions, it is patent that the small class of large land-owners finds it not too difficult to control the small vote in local politics. Some of the large land-owners are Hawaiian or part Hawaiian, as are practically all the smaller land-owners. And these and the land-holding whites are knit together by a common interest, by social equality, and, in many cases, by the closer bonds of affection and blood relationship.

Interesting, even menacing, problems loom large for Hawaii in the not distant future. Let but one of these be considered, namely, the Japanese and citizenship. Granting that no Japanese immigrant can ever become naturalized, nevertheless remains the irrefragable law and fact that every male Japanese, Hawaii-born, by his birth is automatically a citizen of the United States. Since practically every other person in all Hawaii is Japanese, it is merely a matter of time when the Hawaii-born Japanese vote will not only be larger than any other Hawaiian vote, but will be practically equal to all other votes combined. When such time comes, it looks as if the Japanese will have the dominant say in local politics. If Hawaii should get statehood, a Japanese governor of the State of Hawaii would be not merely probable but very possible.

One feasible way out of the foregoing predicament would be never to strive for statehood but to accept a commission government, said commission to be appointed by the federal government. Yet would remain the question of control in local politics. The Japanese do not fuse any more than do they marry out of their race. The total vote other than Japanese is split into the two old parties. The Japanese would constitute a solid Japanese party capable of out-voting either the Republican or Democratic parties. In the meantime the Hawaii-born Japanese population grows and grows. In passing it may be significantly noted that while the Chinese, Filipinos, and Portuguese flock enthusiastically into the National Guard, the Japanese do not.

But a truce to far troubles. This is my Hawaiian aloha—my love for Hawaii; and I cannot finish it without stating a dear hope for a degree of honor that may some day be mine before I die. I have had several degrees in the past of which I am well proud. When I had barely turned sixteen I was named Prince of the Oyster Pirates by my fellow pirates. Since they were all men-grown and a hard-bitten lot, and since the term was applied in anything but derision, my lad’s pride in it was justly great. Not long after, another mighty degree was given me by a shipping commissioner in San Francisco, who signed me on the ship’s articles as A.B. Think of it! Able-bodied! I was not a landlubber, nor an ordinary seaman, but an A.B.! An able-bodied seaman before the mast! No higher could one go—before the mast. And in those youthful days of romance and adventure I would rather have been an able-bodied seaman before the mast than a captain aft of it.

When I went over Chilcoot Pass in the first Klondike Rush, I was called a chechaquo. That was equivalent to new-comer, greenhorn, tenderfoot, short horn, or new chum, and as such I looked reverently up to the men who were sour-doughs. It was a custom of the country to call an old-timer a sour-dough. A sourdough was a man who had seen the Yukon freeze and break, traveled under the midnight sun, and been in the country long enough to get over the frivolities of baking powder and yeast in the making of bread and to content himself with bread raised from sour-dough.

I am very proud of my sour-dough degree. A few years ago I received another degree. It was in the West South Pacific. A kinky-headed, asymmetrical, apelike, head-hunting cannibal climbed out of his canoe and over the rail and gave it to me. He wore no clothes—positively no covering whatever. On his chest, from around his neck, was suspended a broken, white China plate. Through a hole in one ear was thrust a short clap pipe. Through divers holes in the other ear were thrust a freshly severed pig’s tail and several rifle cartridges. A bone bodkin four inches long was shoved through the dividing wall of his nose. And he addressed me as “Skipper.” Owner and master I was, the only navigator on board, without even a man I could trust to stand a mate’s watch; but it was the first time I had been called Skipper, and I was mighty proud of it.

I’d rather possess these several degrees of able seaman, sour-dough, and skipper than all university degrees from Bachelor of Arts to Doctor of Philosophy. They mean more to me, and I am prouder of them. But there is yet one degree I should like to receive, than which there is no other in the wide world for which I have so great a desire. It is Kamaaina.

Kamaaina is Hawaiian. It contains five vowels, which, with the three consonants, compose five syllables. No syllable is accented, all syllables are pronounced, the vowels having precisely the same values as the Italian vowels. Kamaaina means not exactly old-timer or pioneer. Its original meaning is “a child of the soil,” “one who is indigenous.” But its meaning has changed, so that it stands to-day for “one who belongs”—to Hawaii, of course. It is not merely a degree of time or length of residence. It applies to the heart and the spirit. A man may live in Hawaii for twenty years and yet not be recognized as a kamaaina. He has remained alien in heart warmth and spirit understanding.

Nor can one assume this degree for oneself. Any man who has seen the seasons around in Alaska automatically becomes a sour-dough and can be the first so to designate himself. But here in Hawaii kamaaina must be given to one. He must be so named by the ones who do belong and who are best fitted to judge whether or not he belongs. Kamaaina is the proudest accolade I know that any people can lay with the love-warm steel of its approval on an alien’s back.

Pshaw! Were it a matter of time, I could almost be reckoned a kamaaina myself. Nearly a quarter of a century ago—to be precise, twenty-four years ago—I first saw these fair islands rise out of the sea. I have been back here numerous times. As the years pass, I return with increasing frequency and for longer stays. Of the past eighteen months I have spent twelve here.

Some day, some one of Hawaii may slap me on the shoulder and say, “Hello, old kamaaina.” And some other day I may chance to overhear some one else of Hawaii speaking of me and saying, “Oh, he’s a kamaaina.” And this may grow and grow until I am generally so spoken of and until I may at last say of myself: “I am a kamaaina. I belong.” And this is my Hawaiian Aloha:

Aloha nui oe, Hawaii Nei!

Jack London.

Puuwaawaa Ranch, Hawaii,

April 19, 1916.

Pearl Harbor, Oahu,

Territory of Hawaii,

Tuesday, May 21.

Come tread with me a little space of Paradise. Many pleasant acres have I trod hitherto, but never an acre like this. It is so beautiful and restful and green. Green upon green. With blue-depthed shadows imposed from green-depthed foliage of great trees upon thick deep lawn that cushions underfoot. Bare foot. For one somehow dissociates the idea of footwear with an acre of Elysium. It is one of the paradisal blessings of this new Sweet Home of ours that we may blissfully pace it unshod, and for the most part unobserved.

The street is a mere white, meandering, coral-powdered by-way; no thing less inquisitive than the birds abides in the adjoining garden, where a rustic dwelling shows but vaguely amidst a riot of foliage; and on our southern boundary is a tropic tangle of uninhabited wildwood, fronting upon a native fishpond—an elongated bit of bay inclosed by a low wall of masonry of such antiquity that no tradition of Hawaii can place its origin.

Bayward the outlook is a shadowy coral reef, swept by tepid pea-green tides; and to its outer rim extends a slender wooden jetty, at the end of which our ship’s boat can lie even at low tide.

An eighth of a mile beyond in the rippling chrysoprase flood of Pearl Harbor, “Dream Harbor” Jack loves to call it, swings our Boat of Dreams, our little Snark, anchored in the first port of call on her mission of pure golden adventure—a gallant foolishness, perhaps, but if we be fools, let us be gallant ones. Whenever my eyes come to rest on her shining shape, I feel them growing big with visions of the coming years on her deck; and then, remembering vivid incidents of the voyage, drift back to the present with a pleased sense of several laps of adventure already run. Not the least of these is mere living in a shady nook of Paradise where one’s eyes must quest twice in the green gloom among the big trees to discover, near the waterside, the habitation—a very small, very rustic, very simple brown bungalow of three rooms.

Already, in swimming suits, we have ventured the reef at high tide, with unbounded delight in the sun-washed liquid silk. Our goal for to-morrow is the yacht, as there is scant danger from man-eating sharks in this sheltered harbor.

Beyond the Snark, across this arm of the sea, over low green volcanic hills lying southeast between Pearl Lochs and Honolulu, one is just able to glimpse the rosy bulk of Diamond Head, trembling in the fervent sunlight. To the north, over vast rice fields and upland plantations, shrug the rugged, riven Koolau Mountains, their heads lost in heavy cloud masses that everlastingly roll and shift above these tropic ranges.

Pearl Harbor embraces some twelve square miles, divided naturally into three lochs, or arms, by two peninsulas, on the eastern of which lies the village dignified by the suggestive name of Pearl City. Trust me for having already gleaned the information that the locality has been these many years filched of its jewels.

On the southeastern extremity of our particular “neck of the woods,” stray a few suburban homes of Honolulans, of which ours is one. Tochigi, Nipponese and poet-browed cabin boy of the Snark, is to live ashore with us and resume his erstwhile household service, while the rest of the yacht’s complement will retain their accommodations aboard. In these protected waters, the boat lies at least as steady as a house on wheels, as she swings to ebb and flow.

Strangely content are we in the unwonted tranquillity of motion and sound, lacking wish to venture afield, even to Honolulu, about twelve miles distant by the railroad. Enough just to rest and rest, and gaze around upon the beautiful, long-desired world of island. Scarcely can we glance athwart the apple-green water but there curves a span of rainbow between our eyes and the far hills, and like as not a double-span, with promise of a triple-bow; while frequent warm showers delicately veil the land’s vivid emerald with all melting tints of opal.

Very florid, all this, you will smile—a bit overdone, perhaps? Gird at my word-storms if you will. Then consider ... and take ship for this “fleet of islands” in the western ocean. It isn’t real; it can’t be—too sweet it is, the round twenty-four hours. Here but the one night and day, already we grope for new forms of expression, as will you an you follow the sinking sun.

The heat is not oppressive, even though the season is close to summer. But one must realize that Hawaii is only subtropical. To be precise, the group of eight inhabited islands occupies a central position in the North Pacific, and lies just within the northern tropic. For the benefit of any sailor who may run and read, Jack says I might as well be still more explicit, and record that the Snark, now anchored about 2000 sea miles southwest of her native shore, lies between 18° 54′ and 22° 15′ north latitude, and between 154° 50′ and 160° 30′ of longitude west of Greenwich. These islands are blessed with a lower temperature than any other country in the same latitude. The reasons are simple enough—the prevailing “orderly trades” that blow over a large extent of the ocean, and the ocean itself that is cooled by the return current from the region of Bering Straits. Pleasantly warm though we found the waters of Pearl Harbor this bright morning, yet are they less warm by ten degrees than the waters of other regions in similar latitudes.

And now, to go back a little and recount how we came to rest in this fair haven—Fair Haven, in passing, was the name bestowed upon Honolulu Harbor by one of her discoverers, Captain Brown, when, in 1794, in his schooner Jackal, accompanied by Captain Gordon in the sloop Prince Lee Boo, he entered the bay, and mixed in local affairs by selling arms and ammunition to King Kalanikupule of Oahu, who was resisting an invasion from the sovereign of the island of Maui, Kaeo. Right near us here, at Kalauao on the way to Honolulu, a red battle was waged, in which Kalanikupule, assisted by Captain Brown and his men, overthrew the powerful enemy. Poor Captain Brown was born unlucky, it would seem. Firing a salute the next day from the Jackal, in honor of the victory, a wad from his guns went wild and killed Captain Kendrick, who was quietly dining aboard his own vessel, the Lady Washington. The blameless skipper’s funeral, being of a different sort from the native ceremony, was looked upon by the Hawaiians as an act of sorcery to induce the death of Captain Brown. Kalanikupule paid the latter four hundred hogs for his assistance in the struggle with the vanquished Kaeo, and Brown, after the sailing of the Lady Washington for China, put his men to salting down the valuable pork at Kaihikapu, an ancient salt pond between Pearl Harbor and Honolulu.

One day while the Jackal’s mate, Mr. Lamport, and the sailors were gathering salt, Kamohomoho, uncle of Oahu’s king, boarded the Prince Lee Boo and the Jackal, and more than made good the “act of sorcery” by dispatching poor Brown as well as Gordon, imprisoning those of the crews not employed ashore. Lamport and his men were captured, but their lives spared. The gratitude of the royal family for favors rendered had been outbalanced by ambition for a modern navy with which to attack Kamehameha the Great on the “Big Island,” Hawaii. On the voyage, however, the white seamen regained possession of the vessels, sent the natives ashore in their own canoes which were being towed, and lost no time following the Lady Washington to the Orient.

I become lost in the history of the men who blazed our trail to these romantic isles, forgetting that this is the chronicle of a more modern adventure, and return to this idyllic resting spot after the tumult of our first traverse on the bit of boat yonder.

And yet, casting back over those twenty-six days of ceaseless tossing, we are aware only of pleasure in the memory of every happening, disagreeable and agreeable alike. In fact the last week aboard was so cozy and homelike that more than often we caught ourselves regretting the imminent termination of the cruise. Even at this moment of writing, despite blissful surroundings, did I not know that the Snark’s dear adventure were but just begun, I should be robbed indeed, so in love am I with sea and Snark:

“For the wind and waterways have stamped me with their seal.”

We picked up a good slant of wind to make Honolulu yesterday morning—an immeasurable relief after the worrisome calm of the night before, during which we had taken our turns at the idle wheel and scanned the contrary compass with all emotions of anxiety; while the helpless yacht swung on every arc of the circle, with no slightest fan of air to fill her limp sails that flapped ponderously in the glassy offshore heave. Never shall I forget my own tense double-watch of four hours, straining eye and ear toward the all-too-nigh coral reefs off Koko Head, with Makapuu Point light blinking to the northeast. But when a dart of sun through a decklight woke me from brief sleep, we were spanking along smartly in a cobalt sea threshed white on every rushing wave, with the green and gold island of Oahu shifting its scenery like a sliding screen as we swept past tawny Diamond Head and palm-dotted Waikiki toward Honolulu Harbor. After an oddly fishless voyage of four weeks from San Francisco (called by the natives Kapalakiko—pronounced Kah-pah-lah-ke-ko), we were joyously excited over a school of big porpoises, “puffing-pigs,” intent as any flock of barnyard fowl to cross our fleeing forefoot. Undignified haste was their only resemblance to domestic poultry, for in general movement they were more like sportive colts hurdling in pasture with snort and puff—sleek sides glistening blue black in the brilliant sunlight.

To our land-eager eyes, the beautiful old city was the surpassing picture of her pictures, when, still outside, we came abreast of her wharves—the water front with ships and steamers moored beside the long sheds, and behind, the Pompeian-red Punch Bowl, so often described by early voyagers; the suburban heights of Tantalus; the purple-deep rifts of valleys and gorges; and the green-and-violet needled peaks upthrusting through dense dark cloud rack.

Barely had we finished Martin’s eggless breakfast, when a government launch frothed alongside, and the engineer’s cheery “Want a line, Jack—eh?” sounded classic assurance of Hawaii’s far-famed grace of hospitality. Despite my sanguine temperament, I had been conscious of a premonition that something unfortunate would happen upon our arrival, probably due to the impression left by the hasty ship chandler of San Francisco, who unjustly libeled the Snark in Oak land and delayed our sailing; so this gracious “Want a line, Jack?” was music to my ears. You see, Jack London is not infrequently arrested, or nearly arrested, for one reason or another, whenever he sets his merry foot upon foreign soil (I have disquieting memories of Cuba, Japan, and Korea); and Hawaii seems like foreign soil, albeit annexed by the Stars and Stripes.

The morning paper, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, preceded Immigration Inspector and Customs Inspector over the rail, and they laughingly pointed to a conspicuously leaded item that the Snark was supposed to be lost with all on board—bright tidings already cabled to California and read by our horrified families and friends! We cannot help wishing we were early enough here to be handed the very first English newspaper published at Honolulu, in 1836—the Sandwich Islands Gazette. And two years before that, the Hawaiian sheets, Kumu Hawaii and Lama Hawaii, were the initial newspapers in the Pacific Ocean.

Speed is not the object of our junketing in the Seven Seas; but if we of the Snark had known any hurt vanity about the length of our passage, it would have been amply offset by a report the inspectors made of the big bark Edward May, arriving six days before, which beat our tardy record but forty-eight hours, after an equally uneventful voyage.

Meanwhile the pilot had come aboard, a line was passed for’ard to the launch, and we now ripped and zipped over a billowy swell to meet the port physician, whose snowy launch could be seen putting out from a wharf. That dignitary, once on deck, scanned our clean bill of health, asked a few routine questions—one of which was whether we carried any rats or snakes; and all three officials pronounced us free to enter the port of Honolulu. Whereupon Jack stated that we were bound for Pearl Lochs, to take possession of a cottage lent us by a friend. We were then told that the wharves of Honolulu were lined with her citizens, waiting to garland us in welcome; but too impelling behind our eyes was the fancied picture of the promised retreat by the still waters of Pearl Lochs, so we thanked our kind visitors, secured a launch, and towed resolutely past the hospitable city.

“It does seem a darned shame,” Jack mused regretfully. “But what can we do with all our plans made for Pearl Harbor?” “And anyway,” he added, “I don’t want the general public to see a boat of mine sail, looking as if she’s been half-built and then half-wrecked, the way this one does.... I’ve got some pride.”

Then all attention was claimed by the beauty of our westward way to the harbor entrance, as we skirted a broad shoreward reef where green breakers burst into fountains of tourmaline and turquoise, shot through with javelins of sun gold, and the air was filled with rainbow mist. Our boat slipped along in a world compounded of the very ravishment of suffused colors—land and sea, it was all of a piece; while off to the southeastern horizon ocean and sky merged in silvery azure, softly gloomed by shadowy shapes of other Promised Islands.