Title: Miles Lawson

or, the Yews

Author: Mrs. W. Reynolds Lloyd

Release date: January 17, 2024 [eBook #72740]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Ira Bradley & Co, 1896

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

OR,

THE YEWS.

BY THE AUTHOR OF

"HOW TO SEE THE ENGLISH LAKES," ETC.

"Therefore, although it be a history

Homely and rude, I will relate the same,

For the delight of a few natural hearts."

WORDSWORTH.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY IRA BRADLEY & CO.

162 WASHINGTON STREET.

CONTENTS.

Chapter VI. The Mountain Echoes

MILES LAWSON;

OR,

THE YEWS.

THE HOMESTEAD.

"The lonely cottage in the guardian nook,

Hath stirred then deeply—with its own dear brook,

Its own small pasture—almost its own sky."

WORDSWORTH.

BENEATH the crags which overhang one of the deep mountain valleys of Westmoreland, there nestles an old farm-house, whose low, irregular roof, deep stone porch, and large round chimneys, make it a type of its class. Its windows are low, wide, and mullioned; and on the sunny side, next the small garden, they are quite embowered by an ancient jasmine, an old-fashioned cabbage rose, and a broad sheet of ivy, whose twisted stems are as large as those of a good-sized tree, and whose long, clinging arms clasp the walls nearly all round the building, festooning and fringing even the great round chimneys. Those chimneys are almost as large as little lime-kilns; but the smoke, which curls up in gentle volumes, is of that pure blue tint which betokens it to be the breath of a peat fire. The house is beautifully white—whitewashed afresh by loving hands at every Whitsuntide Scrow. *

* The great annual house-cleaning of the north.

But the glory of the homestead consists in its two enormous yew trees, a pair of sombre giants, which are so old that they never seem to grow older. They became stiff, twisted and furrowed with age, so many centuries ago, that a few generations time, a few odd scores of years here and there, are nothing to them now—a mere trifle that is not worth noticing. And so there they stretch their huge branches towards each other, across the flagged path which leads straight up from the garden wicket to the pointed porch, making a dim twilight of their own, even at mid-day.

There is a rustic seat encircling the trunk of one of the brother yew trees. Ah! That is Miles's work. Miles, the oldest son of the house, cut those billets and branches out of the little copse-wood at the entrance of the glen, and made them into a seat for his sister Alice to rest on, when she is sewing in the golden light of the summer evenings. There is a cluster of larches, as well as a spreading oak and a sycamore, grouped about the farm buildings; but the place borrows its name from none of these, and for three hundred years it has been known as "The Yews." A slab of stone, let into the wall of the house, just above the porch, bears the date 1559.

Pass through that deep stone porch, and you enter the farm kitchen, a long room, whose low, raftered ceiling is made lower still by the rack which is stretched across it, on which rest flitches of smoked bacon, and a large assortment of dried herbs and simples; for Mrs. Lawson is famed through the dales for her herb teas and febrifuges. She is known, too, for better things than these; for the perfume of her humble piety spreads like an atmosphere around her, though her daily cup has long been seasoned with the bitter herbs of affliction. She does not complain of these distasteful draughts, but declares that they are the best of medicines, the very things to strengthen and purify the soul's health.

"If they were not good for me, I shouldn't have them. My Saviour knows what a bitter cup is; and he wouldn't hand it to me unless he saw I wanted it."

Watch her as she sits in her rocking chair, which is softly cushioned with little diamonds of patchwork. That many-colored patchwork is a mosaic representing her whole life. She has often expounded the story from those little pictured memorials. This lilac spot ("pop," she calls it) is a relic of her first short frock: the pink square is the only survivor of the dress she wore on her first visit to Kendal—to her a wonderful metropolis, which she thought could be like nothing less than Jerusalem itself, "beautiful for situation, on the sides of the north." Ah! That "innocent" chintz was her wedding gown. Her Miles chose it himself, and he had been a good husband to her, "walking in his house with a perfect heart," and trying to bring up his children "in the nurture and admonition of the Lord."

Whenever Mrs. Lawson spoke on serious subjects, she dropped unconsciously into the language of Scripture: for she had been a close student of only one book; and after Miles was taken from her, that book had been the household lamp which had lightened the darkness that had fallen upon The Yews. She has that old family Bible on her lap now, as she sits beside the large open hearth; and the look of settled repose on her brow is a fine commentary on the words which she is now reading: "In quietness and confidence shall be your strength." Now her eye is following her daughter Alice's lively motions, as she sees her through the open door of the cottage parlor, where she is dusting the furniture.

That room has a delightful old-world look; it is panelled all round with black oak, cracked and worm-eaten, but still shining. The mantel-piece is of carved dark oak likewise; and faces, hideous as masks, there display their long-lived rage or changeless smiles. Opposite the fire-place is an ancient chest, with the name "MILES LAWESON, 1562," cut on it in high relief, and the motto, "FEARE GOD, AND WORKE RYTEOUSNESSE," runs along on a ribbon-like scroll, which binds together a pair of stiff trees, like gooseberry bushes, but which are evidently designed to represent the goodly Yews. This, then, is the muniment room of the Lawson family.

They were not of gentle birth; but they have been a race of sturdy, free-born yeomen, "statesmen" * of the dales, watching jealously over the integrity of their fell-side acres, and of their few green meadows beside the stream: and in every generation since 1562, has there been a young "Miles Lawson of the Yews" to transmit the memory of him of the old oak chest.

* "Estatesmen:" Small freeholders, whose little properties often

remain in the same family, from generation to generation, for centuries.

This sombre-looking parlor is Alice's quiet world of romance; it is her "chamber of imagery." For here her young mind, stimulated by the antique features which surrounds her, loves to picture the scenes and people of former days.

The chief source whence she draws her genealogical groupings of Lawsons (of whom she firmly believes the hideous faces on the mantle-piece to be faithful portraits), is the fine historical memory of Mark Wilson, the itinerating schoolmaster of the dales. Mark is expected to-day at the Yews, to take up his residence there for the next month, in the course of his regular routine journey from homestead to homestead. * He is the orphan son of the old curate of one of the neighboring dales, who could leave him from his spare pittance little besides his moderate store of learning and his thinly furnished bookshelves. But with this important legacy Mark felt himself, and was universally acknowledged to be, the learned man of the district. Pardon him his little weaknesses, for Mark is a good, honest, true-hearted lad, though his gait is a shade too measured, and the fountain of his learning a little too apt to overflow. Pardon him these fertilizing inundations; for he considers the land around to be marvellously dry and thirsty, and he thinks he is commissioned to do the bountiful work of the Nile when it overflows its banks and refreshes the waiting gardens and meadows of Egypt.

* This is the plan pursued in the more remote dales, where the

population is very thinly scattered.

Before Alice had finished polishing her household motto, and rubbing up her ungainly family portraits, the latch of the wicket gate is heard, and she hastily looks out of the window. "Master Wilson is come, mother, books and all!"

The said books distend the old leather bag on the shoulders of the young man who enters, far more than do the few quaint articles of his slender wardrobe. If this be all he includes under the portentous name of "luggage," life is a tolerably simple thing, after all.

"Peace be unto this house," says Mark, solemnly, as he bends his tall thin figure under the low porch: and he looks like a true son of peace himself, as he pronounces his accustomed benediction, though his broad and high forehead is not without some lines which belong rather to the autumnal ploughing than to the spring-tide of life. But no one who ever saw the steady light of his fine clear eye could doubt that in him the words had been fulfilled, "They looked unto him [their Lord] and were lightened; and their faces were not ashamed."

Alice received him with great deference, and a certain distant timidity; for she herself has been Master Wilson's pupil, as well as Miles and her younger brother Mat. He gives her a grave nod, and passes on to the widow's easy chair.

"Winter has been here since I saw you, Mrs. Lawson. How did you bear up under the cold? Has the rheumatism been a little quieter?" This was spoken in a voice of such singular sweetness and power, that if one had caught its accents in the midst of the crush of one of the principal streets of London, one would have been impelled to look round and search out the speaker.

"Nae, nae, Mark," said the widow, "the rheumatism hasn't been quiet—far awa' from that. But God hasn't forgotten the old woman; and when he giveth quietness, who then can make trouble?"

"You have got hold of the true medicine, Mrs. Lawson; better than any herb tea which you can concoct."

"Nae!" said the widow, in a rather controversial tone. "They all help! It's the three P's that does it, say I—Prayer, Patience, and Pennyroyal."

"Well, well," replies the schoolmaster; "give me the first two and you may keep the third. But where's my scholar, Mat?"

"Mat was off to the Scar after the sheep, hours ago," said Alice.

"He had better get them to the lower fells before long, I'm thinking," said his mother, turning towards the window, and looking at the sky; "there's a snow-storm in yon clouds above Rowter Fell—though 'tis over late in the season for snow."

"If I read the signs aright," said the schoolmaster, "we shall have a quiet life hereaway, blocked in by a deep fall of snow. A fine time for Mat and his learning. Perhaps we shall get Miles, too, to go over some of the old ground and refresh his memory. Is Miles at home?"

"Miles has been a good deal out lately—more than I like," said his mother, as, a cloud of care gathered upon her calm forehead, just like that which was veiling the fine brow of Rowter Fell at the same moment.

"I think he must be taking to mining work, up on the 'Old Man,'" * said Alice; "he goes that way so very often."

* "Coniston Old Man," the name of a mountain.

"Does not he tell you what he is about, when he leaves you?" inquired Mark, anxiously.

"Nae, nae; not so very often now," was the mother's reply; "young men like to think they are their own masters. He says he doesn't like to be watched and followed about."

"He always used to like me to set him off as far as the top of Green Gap in all weathers," said Alice, mournfully; "but he thinks I can't keep up with him now, he says, and yet I can run all the way there and back faster than old Chance."

"Does Chance go with his master?"

"No; he will not let him go either, though the dear old fellow whines after him."

"There is some mystery here," thought the schoolmaster. "Heaven grant that the widow's son, the son of many prayers, may not be turning at last into the 'broad path.'"

"Perhaps it's only Bella Hartley, after all," exclaimed Alice, with a sudden flush of illumination.

"Nae, I fear not," the widow replied. "Bella is a good girl, and he needn't be ashamed to visit her; he knows he would have his mother's blessing upon the head of that any day," though her brimming eyes, as she looked round tenderly on the old place, showed how much it would cost her to leave the ancestral Yews, and abdicate her quiet throne in favor of a youthful successor.

At this moment came in Mat from the fells with a flushed face; and pulling down his open forehead by the front curl, by way of bow, he stood, cap in hand, evidently with something to say.

"Well, Mat, my man," said his teacher in his kindest tone, "what cheer from the fells?"

"We've brought the sheep all down to the lower fells, because there's snow in the cloud over Rowter."

"Did Miles help you?"

"Nae; 'twas Chance and I. But Chance did it all. I'm sure he saw the storm coming, he looked so all around, and sniffed, and began at the sheep before I set him. But there are two men yon, who want Miles."

"What like are the men?" asked the widow uneasily. "And what do they want of Miles?"

"They said he was bound to meet them in the Gap, and he didn't come, so they want to know if he is in the house."

"Did you bid them in, Mat? I would as lief know who my son's friends may be."

"They said they would bide without and speak with him there."

The widow shook her head and exchanged an anxious look with Mark Wilson, who left the room immediately.

The two strangers, sullen, ill-favored men, one of whom never looked you full in the face, but was always glancing anywhere rather than straight before him, did not appear to wish for a parley with the schoolmaster, the clear daylight of whose countenance was in perfect keeping with the uprightness of his character, and the unbending texture of his principles.

"What is your will, friends?"

"We only want Miles Lawson. Is he in or off?"

"I cannot say. May I ask your business with him?"

"No. 'Twas only for a talk with him. He wasn't in the Gap, where he should have met us, for we are naught but friends: as he wasn't there, we came on. That's all."

The speaker looked a miner, and his companion might have been a broom-maker; but they were ungainly, unhappy-looking men; the one, bold and defiant, the other sinister and cunning.

"Well!" said the miner, after a pause. "If you can't tell us anything, we are off again. Come along, Jack."

"Stop!" cried Mark, hastily. "Is there no message for Miles Lawson? Nothing about the business which brings you here?"

"No," said the man, rudely; "catch us telling you."

And laughing loudly, they walked off at a quick pace.

Mark was still standing under the yew trees, thinking over this suspicious affair, when he heard a step and a whistle, and Miles himself appeared, lounging along with his hands in his pockets. He started, and flushed crimson, when he recognized the old friend and master who had not only taught him all that he knew of book-learning in his many migratory visits, but who had earnestly endeavored to counteract the faults of his character by instilling good, sound Bible principles. The younger man's face was a strikingly fine one as to outline and feature; but there was a look of uncertainty and hesitation, a wandering, restless expression about the eye, which gave the impression that principles were beginning to give way to mere impulses, healthy feeling to heartless selfishness; a critical moment in a young man's history.

"Well Miles, dear old fellow, I'm glad you are come home. There's a storm abroad, and we shall have a rare time for the books. I have brought a history of England, and a book about the stars."

Miles held out his hand; but it was not with his old eager cordiality: no hearty welcome to the old Yews was given or felt; and after an awkward silence, he turned round and said in a constrained voice, "I am sorry I shall not be at home for awhile. I have business that takes me away."

Mark Wilson turned the full power of his piercing eye upon his face, and was grieved to see that his friend's eye fell under the searching survey. "I am sorry too, I am sure. I thought we should have had some capital times of reading and talk in the long evenings, when the mother has got her knitting and her Bible, and Mat is learning to write, and Alice is listening with her eyes as much as her ears. I confess I am very sorry, Miles, unless you have some object in hand on which you can ask God's blessing, and your mother's prayers, just as freely as if you were sitting in your father's own seat in his own old place."

The young man winced painfully at this, and then, recovering himself with a bluster, (the usual recourse of a bad cause), exclaimed, "I declare, I am treated like a child. I am watched and questioned, and doubted, as if I was not old enough to take care of myself: and mind, I am not a little fool of a schoolboy any longer, Mark Wilson, I say."

Mark's powerful eyes were still fastened on his old friend, so that the voice, which began boldly enough, died off into a pitiful shake before the sentence was finished. He saw his advantage and quietly said, "You know he is the fool who says in his heart, 'There is no God:' and it is really and practically to say this, if we act as if we had not his all-seeing eye constantly upon us. You never need tell me what you are about, if you go to God and tell him. You know I don't want your confidence, Miles, if you can give it to God in prayer, and to your widowed mother in grateful love. But a man is known by the company he keeps." This was said in so significant a tone that it was Miles' turn now a look of searching inquiry; and he read something in Mark's face which evidently startled and troubled him.

"What do you know about my friends? What do you mean by the company I keep?"

Mark lifted up his heart in silent prayer and then replied, "I will just leave this little word with you, my brother, 'If sinners entice thee, consent thou not.'"

"Well," said Miles, after musing for a long season, in which, strong symptoms of the inward conflict between the two principles of good and of evil were visible on his changing countenance; "well, I do believe you are my true friend, Mark, after all; and I wish I had never sought others."

The poor fellow wrung the hand of his old master, while a rushing tide of feeling rose within him until it left a moisture even in his softened eyes. Mark pressed his hand in return, in wise silence; and the two reconciled friends entered the farm kitchen together. Neither knew that during this painful conversation, one, feeble in body but strong in faith, had been earnestly wrestling for a blessing; and that even young Alice had stolen into the old oak parlor, and slipping down on her knees, in a dark corner, had offered up the clear, pure gems of a sister's tears. The mother looked up through her misty spectacles, and saw, as the young men crossed the threshold, that the prayer of faith had gained the victory, at least for this time.

"Mother, we'll have a regular jolly evening, as Mark is come. He shall not say a word about his old books; we're going to have a holiday. Where's Alice? Alice give us your best riddle-cakes, and Mat shall bring out some of his whitest honey. Let us have some broiled ham, too; and then we'll crack * to heart's content."

* "Crack" signifies chat in Westmoreland parlance, as well as in

Scotland.

This was spoken with an uneasy effort to be cheerful, which did not deceive any one of the party. But they were rejoiced to have the truant son of the ancient house, the representative of an honored father—glad to have him safely amongst them, on any terms. And so a grand fire was built up on the hearth on scientific principles, by Alice's skilled hands, peat laid against peat, and log resting on log, until the crackling and sputtering were prodigious. The whole long, low room was brilliantly illuminated; the jets of reflected flame danced upon the shining old oak; a great toasting and buttering of cakes began; the frying-pan added its characteristic hearth-song to the general chorus of household music, which was in truth more cheering than melodious; a coarse table-cloth of snow-like whiteness was spread; horn-handled knives and forks were arranged like rays about the round-table; and a great homemade cheese took its respectable stand in the centre.

The mother's calm eyes watched Alice's movements with loving approval; other eyes followed her, too, but she took little heed, until Miles broke out with the words—sincere, genuine words this time—

"Well, it is a pleasure to have such a warm home, and a nice handy little sister to make one comfortable on a cold winter evening."

She looked full at her brother with a sparkling smile; but her eyes presently brimmed over at the recollection of how rarely of late that brother had chosen to be "made comfortable" beside his own warm hearth-stone. He saw what was in her mind; for Alice's was a face as truthful in reflecting all her meanings, as the little tarns and broader lakes which enamel her mountain land, to mirror the blue skies or the solemn stars of heaven, and to give back the bending of a reed or the waving of a fern:

"Heaven's height and home's deep valley,

Much of earth, but more of heaven."

Miles read the thoughts which were reflected on his sister's simple, open countenance; his own flushed at the silent expostulation; and turning hastily to the schoolmaster, he led him off into talk about the months which had passed since the last round of scholastic visits. "How are the folk up at Scarf Beck?"

"Oh, they are very well; the sons are fine likely lads, and Bella is a clever winsome girl. They have got a deal of learning, out of my mouth amongst them. Fine scholars they will be, the best in the round, except you, Miles, and little Mat here. At least, you have been my prime scholar, and Mat promises fair. I wish you would keep it up. It is a fine thing to have a good home-pursuit, something to keep the hearth bright besides the peat and the logs."

"There are no books to be had," said Miles evasively; "one can't read the spelling book over and over again. It's weary work, that."

"Weary, indeed; but if you will only give me an order, I can get a capital assortment of good sound healthy books for you. I can easily fill those little shelves above the oak chest: nay, I declare that you and I will knock up some more. It will be grand in-door work for us, now that we are in for a snow-storm. I have some small literary taste, and I am not without a literary connection—that is, amongst the booksellers of Kendal," said the simple young pedant, drawing himself up and looking round upon his admiring friends.

This was poor Mark's weak point; and it was every now and then "cropping out," as miners would say; though every revealing of his inner man always showed fine veins of pure ore, as well as a little of the lighter rubbish, which slightly, very slightly, overlaid it. In truth, Mark's object in this talk was to revive in his favorite old pupil the taste for intellectual improvement, which, in earlier days, he had succeeded in implanting in him. He had a very exalted view of the duties of Christian friendship. He felt that those duties had to deal with the whole moral, intellectual, and spiritual being; and for the treatment of each of these divisions of that mysterious being, he had his list of simples, and febrifuges, and strengthening drinks, just as dear mother Lawson, there, in her patchwork cushioned easy chair, had for the many ails of the other great division—the physical.

They were dear and close friends, the aged Christian and the young. The one supplied the deeper teachings of long experience, the other brought to her the energy of the young believer who had not spent the strength of his days for naught, nor wasted his substance in the service of a wasteful world. The one could speak of the many days of the years of her pilgrimage, wherein her God had led her about in the wilderness, to humble her, to prove her, and to know what was in her heart; the other told of the sweetness of his first love for Christ and of the joy of his espousals. The one spoke of the fiery trials of temptation or of the heated furnace of affliction; the other told of triumphant conflict and of the hope which maketh not ashamed. The one spoke thankfully of the "peace which passeth all understanding;" the other, of "joy in the Holy Ghost." But they were one in all the great truths of the gospel; both felt that they were sinners, lost, undone, and bankrupt, but for the pardoning mercy of God in Christ, the redeeming love of the Saviour, the sanctifying power of the in-dwelling Spirit. Both knew that they had no title to the favor of God but through the finished work of Jesus, and no fitness for his presence except through the work of the Spirit in their hearts. Thus were they "one in Christ;" and if the angel believer were sustained by a deeper faith, the younger was animated by a more lively hope; while the third great grace of the Spirit, love, equally overflowed the heart of each.

It was beautiful to see them communing together, whenever the fixed routine of his circuit brought the young man to "The Yews;" and Alice used to look and listen until she felt that it was indeed good to be there. There was a secret work going on in her own young heart; but it was as yet wholly hidden, except by its gentle fruits; for she had not yet found the courage to speak of what God had done for her soul. The time for the confession of the lips was not yet come, though the season for the evidence of the life was already begun. Love was her characteristic: love, deep and true to Him who had first loved her; love to her widowed mother; love to her father's memory; tender love to each brother, though in the one there had lately been so much to disappoint and chill; love for all the world, and even for every living thing about her; and love, (shall it be told?) love strong and pure, though timid and unconfessed, for the teacher, who was to her the very ideal of every thing that was noble and true.

Mark was not so much older than his young friends as his stability of character and superior endowments might have led one to suppose. He was but twenty-five years of age when he came for his month's teaching to the Yews. Miles was twenty; Alice about eighteen; young Mat fourteen. But Mark Wilson, had always been ahead of everybody in the whole compass of the dales, excepting the neighboring clergyman, who treated him with much kindness, and looked upon him as a fellow-worker; so that his position was a really influential one. He had been "round schoolmaster" ever since he was a grave, thoughtful, intelligent youth of eighteen; and ever since that time, the consistency Christian character had been unimpeached.

The Yews was not entirely a solitary house. There was a little dwelling close at hand which was occupied by the old laborer, Geordie Garthwaite, whose attachment to the soil was little less binding than that of the Lawson family themselves; and under this roof the more shifting population of farm servants, who were generally changed at every fresh "hiring day," that is once in six months, was housed and fed. They commonly all lived under one roof: but Mrs. Lawson had a decided preference for family completeness and household quiet; and so the two strong lads, who aided in the work of the farm, always obeyed Old Geordie's blowing of the cow's horn which summoned them in to breakfast, dinner, supper and bed, if they were ploughing the Beck meadows or herding the kine and the sheep on the Gap Fells.

Dear old Chance knew the jocund meaning of that most dismal blast as well as Johnny and Jamie, and was sure to be home before them, unless he were out on picket duty; at which seasons, he pricked his ears and whined with a gentle resignation, and yet with a lofty sense of duty, which were quite edifying to witness. He won his undignified name of "Chance," by scratching and whining at the kitchen door of the farm-house late on a bitter winter's night long ago; and when the door was opened, there was such a footsore and emaciated creature looking pitifully in little Alice's face, with such a pair of tenderly mournful eyes, that she brought him in immediately, burst into a flood of sympathizing tears, and on her knees before the fire gave him all her own porridge with her own spoon. He looked as if he would much rather have helped himself out of the bowl; but he evidently appreciated the tenderness of her touch, and submitted with an awkward grace to the ministrations of the spoon. This was years ago; but the noble fellow, (a great black dog with a white tip to his tail, and a slight touch of tan over each eye and on each foot,) had maintained his position on that warm hearth ever since the night of tears and the spoon.

For some weeks, he seemed uneasy in his mind, and not quite sure that he had done what was right, for he searched the face of every stranger he met, and made a visit of inquiry to every homestead in the district. Miles drew the conclusion from this conduct, that he had lost his master, perhaps a Scotch drover, who had probably taken the coach at Ambleside, and so had accidentally thrown his faithful servant hopelessly off the scent.

Whatever may have been the previous story of his life, Chance, as he was now called, instantly turned into a fresh course of duty, and adopted the interests of his benefactors as if he had been attached to them all his days. At first, he much preferred the society of the cows to that of the sheep, evidently from his old drover habits; but finding that he made himself much more important by herding the black-nosed sheep and checking their ranging propensities, he very wisely turned his attention to that especial branch of his new duties, and soon became accomplished sheep dog, reading his masters meanings from a simple wave of the hand, and fulfilling his commissions with beautiful fidelity.

There was a younger dog, one on whom Chance evidently looked down as a mere ignorant lad, whose playful vagaries were to be tolerated rather than countenanced. This was "Laddie," a handsome brindled dog, with a magnificent white plumy tail. He was a native-born dalesman, and had a fine eye and ear for a shepherd calling. The two worked when they were out on duty, as if they had but one mind, doing everything in concert, and vying with each other in the most literal fulfilment of their master's wishes; but when off work, the two creatures were as different as youth and age, the one brimming over with extravagant frolic, the other, sober, sedate and dignified. When either of them caught the sound of Alice's step, and clear ringing voice, or could succeed in licking their aged mistress's hand, the look of affection which beamed out of their fine, expressive eyes, was the same in each.

A leading character in the community was old Ann, the wife of old Geordie. She managed to live an active life, although bent almost double by long-standing rheumatism. It was marvellous how she could maintain her equilibrium, with that extraordinary gait and figure. But she was cheery old woman, kind to all dumb creatures and dearly beloved by them in return. It was a picture to see her sallying forth from her door-way, her blue bed-gown tied round her waist by her blue linsey apron, which was almost always full of potato skins or bran, or corn, for one class or another of the subjects in her little kingdom; while a blue serge petticoat completed her uniform. Winter or summer she never wore a bonnet. It was rumored she possessed one of extraordinary dimensions, date unknown, in a corner of a huge chest, which was supposed to contain other superfluities. But it never appeared. The little church was too far off for old Ann to join the scattered congregation, bent and infirm as she was; and so on Sundays, a clean cap was put on, and she sat with her suffering mistress in the farm kitchen, while the sweet old lady read in her own peculiar Westmoreland intonation, the solemn narratives of the Old Testament and the precious teachings of the New. The widow, though helplessly bound to her easy chair, had always a very earnest and feeling prayer to pour, forth into the listening ear of Almighty Love, before the little service was concluded; and then the aged women shook hands, while the one said "God bless thee, Ann," and the other said "God bless thee, mistress."

But to return to the large "following" which always attended the clump, clump, of old Ann's heavy wooden and iron-shod clogs, * wherever she went in the farm premises. First there were the turkeys, the turkey-cock being a formidable fellow, the martinet of the yard, who hectored and domineered over everybody and everything, with the single exception of old Ann, towards whom he was as gentle as a dove.

* The shoes of the country: they are soled with wood, and then shod

with iron, and make a prodigious noise.

Then there were the guinea-fowls picking daintily about, with round backs, and refined, not to say affected gait; while every evening there was enacted that little scene which is so peculiarly their own—the cock bird always flying to the top of the highest chimney and there shouting, "Come back! Come back!" as if he were recalling lost companions. Next there were the geese, which used to walk out into the meadows that bordered upon the beck * in long Indian file, the most experienced and responsible gander leading the way, a trustworthy young one bringing up the rear: comparatively uninteresting creatures they were, save for their self-sacrificing love of their young, in whose defence, if attacked by strange dogs, they would lay down their lives.

* The local name for "stream."

Then there were ducks without end, and cocks and hens innumerable, quaking, crowing, cackling, screaming about the desirable contents of old Ann's linsey apron, and besetting her wherever she turned.

She treated them all as dear friends, talked incessantly to them, in return for their vociferous addresses. "Coom, lad, coom along with thee this gait. Well, lile * lassie! Get awa', wilt thoo?" Thou hast a kindly heart, old Ann. Thou would'st not willingly hurt a single thing: and when a violent end has to be put to the happy little lives of thy many pets, it costs thy loving nature more than thou would'st like to tell. Those who have studied the ways of the feathered creatures, as thou hast done, know that there are fine distinctions of character, and beautiful adaptations of that mysterious instinct which is the gift of their kind Creator, that the careless and indifferent observer has never discovered or even suspected.

* "Lile" is almost invariably used for "little" in the country

districts of Westmoreland.

They are alluded to here, not for the sake of crowding the canvas with pictures of animal life, but in order to cultivate a loving interest in the happiness of the living things around our daily path. They are, many of them, helpless in themselves, and entirely dependent on our good will. By all means, let there be as much innocent happiness as there can be in this selfish world. Let consideration for the comfort of animals, as long as their poor lives last, (and this life, remember, is their little all,) be a regular part of the home-training of children; and then the beautiful world we live in would not be such a scene of oppression and wrong as it is.

CONSCIENCE.

"Would'st draw a bow at a venture? Then see

thou to it, that the point of thy arrow be dipped in

love, and its winged shaft in prayer."

Before supper was over at the Yews, Chance and Laddie were heard barking vehemently without. This vociferous demonstration was made whenever any stranger appeared on the premises, but was not warlike in its meaning; it was only intended as a notification that there was somebody come, who ought to be attended to.

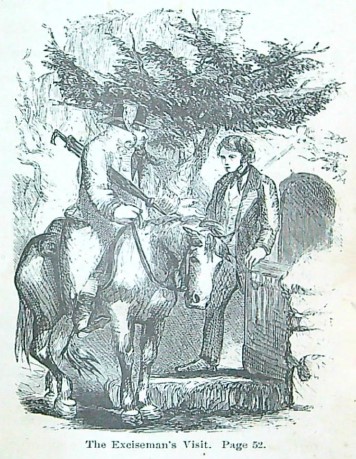

The somebody on this occasion was an old exciseman, Mr. Knibb, who itinerated though the dales almost as punctually as the schoolmaster, but who was not nearly so popular a personage. And yet when his old white mare, Madam, was comfortably housed in the stable, and the drab top-coat was hung up in the kitchen, Mr. Knibb could make himself very pleasant company beside the hearth, or at the simple table of the farm-houses within his round: for it was he who brought the greatest amount of intelligence respecting the doings of the great wide world on the other side of the barrier mountains; and he generally had in his pocket a Kendal newspaper, not more than ten days or a fortnight old.

Mr. Knibb, therefore, helped to keep up the circulation of ideas within his circuit; and a great flood-tide of news overflowed the valleys and rose up to the homesteads on the steep hill-sides whenever he made his periodical appearances. Old Madam was so thoroughly aware of her master's communicative habits, that she used to make a full stop whenever she met a grown person in winding lane or rocky pathway; and if left to her own devices, she would allow her master just ten minutes for every "crack;" at the expiration of which social interval, she would prick her ear and slowly jog on again. Boys and girls neither she nor her master thought it worth while to enlighten, but trotted past them with contemptuous indifference.

Somehow or other, Mr. Knibb's visit on the present occasion was not acceptable to the young master of the Yews. Nobody looked exactly pleased when the old gentleman's well-known whistle was heard without, because it was a rather uncongenial interruption to the new-born happiness of the household group; but Miles looked both displeased and discomposed. He started—turned pale—flushed deep red—and then hastily rose and went to the door as if to bid the visitor welcome: but this movement seemed less like an impulse of hospitality than a mask for his unaccountable confusion. In truth, Miles was strangely moved.

These symptoms of perturbed feeling were not lost upon the young schoolmaster, whose calling had cultivated that keen perception of character and that skill in reading the symbolic language of manner, look, and tone, with which he had been originally gifted. The old lady—and lady she might fairly be called, because, in spite of provincial accent and mountain phrase, she was one of nature's own aristocracy, and one of religion's own gentlewomen—the old lady bestowed a kindly and courteous greeting on the guest, who in his turn advanced to her chair, and gave her that horizontal shake of the hand, (swinging cheerily like a pendulum from side to side) which is supposed to express cordiality.

The Exciseman's Visit.

Mr. Knibb soon formed a member of the group round the circular table, which was drawn near the widow's rocking chair. A solemn grace, not a ceremonial form, but a heart-felt giving of thanks, was spoken from that same presidential chair; and then the sharp clatter of knife and fork began in earnest. Much too earnest was the business in hand, in its earlier stages, to admit of any table-talk; but when the healthy intercourse between good appetites and good fare had begun a little to relax, Mr. Knibb opened the sluices of conversation.

"Madam and I could scarce make our way up the valley, the wind was so strong, and as keen as a razor, right in our faces. Besides, the snow was driving full against us; and if the good old mare hadn't known every foot of the way, we might have got into a deep drift, and stayed there until you and Chance had dug us out, Mat."

"You had better have stopped away for the night, and not got into the dale at all," said Miles.

"Nay," replied the old gentleman, "Madam knows good quarters as well as her master: besides, I have a little job in hand, and I don't rightly know how it will turn out yet. I shall want your help in it, Miles Lawson."

"What is afoot now, then?" said the young "statesman," hastily.

"Why, I'm half on and half off a pretty good scent this time—something out of the common run—and scent lies strong upon the heather. We shall run down some sort of game, I'm thinking, before another nightfall; unless this unfortunate snow-storm throws us off the tracks."

Miles rose and poked the peat fire violently, sending showers of sparks careering about the hearth, some of which alighted on his mother's white apron. Alice and Mat and the schoolmaster were all up in a moment, the two former crushing out the threatening danger with their eager hands, while the zealous young philosopher fluttered the poor old lady yet more by solemnly pouring a whole jug of milk into her lap.

"Heigh, then! The lad is daft for sure," cried the gasping widow. "He has drowned out the fire, but he will bring on the rheumatism, like enough."

Mark was much abashed by the evident unpopularity of his attempt to lead the fire brigade; but larger interests soon engrossed his thoughts; for his attention was speedily riveted by the strange perturbation of Miles' countenance and manner, while Mr. Knibb went on with his talk.

"I want you good folks to help me in a queer sort of job, for sure. I cannot fairly see through it; but I have got hold of information (no matter how) that there's a deal of spirits drunk in some of the miners' cottages round the Old Man; and I have tracked some of it into several of the farm-houses in my district. Now, where it comes from is the question."

"Surely there cannot be anything like smuggling going on in my valleys?" said the honest young schoolmaster, opening his large blue eyes with wonder.

"Well, I will let you into one or two facts, Mr. Wilson, and then you may reason upon them, like a philosopher as you are."

"Like a Christian, as I would rather be," said Mark, parenthetically.

"Very well; like a Christian, as I am sure you are. I found a strong smell of whisky in one or two of the homesteads that I visited rather out of course; for Madam was tired, and I couldn't find in my heart to give her the whip—we've jogged on too long together for that; and so, as I said, I was rather out of time all through the round; and I found some of the lads saucy and quarrelsome. I knew what had made them so, for I saw by their ways that something stronger than the malt had got into their hot heads. However, I took it quietly and said nothing. But in coming along a little mountain road up out of yon dale and down into the next, I saw a cart ahead of me, with two men. When we came alongside, Madam pulled up as usual for a crack. But one of the men, with a lot of brooms on his back, said, 'Hush! or you'll waken the poor old mother in the cart.' 'What's to do with the old mother?' said I. 'She's had a stroke,' said he, and we are taking her as soft as we can over to the workhouse at Milnthorpe.' And so seeing the poor body lying all of a heap in the cart amongst the heather brooms, I just said, 'Poor soul and went my ways. But I'm thinking they were too many for old George Knibb; for Bella Hartley tells me that she came sharply upon them just after, in a turn of the lane, and saw them bargaining with some potters, who had another cart with them; and all of a sudden, they tossed the 'old women' out upon the ground, and she fell abroad into nothing but a bundle of clothes with an old bonnet upon the top of it."

Mr. Knibb here laughed heartily at his story; but everybody else looked startled, except Miles, who over-acted his part by violent bursts of explosive laughter.

The schoolmaster watched him with pain; and then said quietly, "After all, there is no fun in sin."

"Sin?" said Miles, looking fiercely at him, "I am not laughing at sin; it was only a capital joke—capital."

"It will be no joke to those men if I can catch them," resumed the exciseman; "but I am very much obliged to them for putting me on the true scent."

"The scent lies no further than the cart, however," remarked Miles; "and there's naught to prove there was anything but brooms in that, as far as I see."

"Stop a bit, my good friend; Bella Hartley's bright eyes made out more than that. She saw great heavy jars taken out from under the heather, and exchanged with the potters for empty ones; and then, from the other side of the wall, she watched them dressing up the 'old woman' again, and heard them calling her a 'witch,' because she was mounted on a broom, forsooth. And then, I hear, they took the road to the Old Man."

"And what are you minded to do now then?" asked the young farmer, in an oft hand manner.

"Why, of course, I am for following it up as best I can. It's my clear duty to do that. I must try the mountain and about; for though we are not in Ireland, I have a strong suspicion that I shall find an illicit still, hid away in some nook or crevice."

The young man turned white—so white that even Alice's unsuspicious mind read something painful and alarming in his face. She looked appealingly at Mark while his eye rested compassionately on her anxious brow. She turned from him to her mother, and saw that her thin hands were clasped tight together, as they always were when the mother's heart within her was working with fear and wrestling in the hidden might of prayer. Her eyes were fixed upon her wayward son, but they were lambent with the holy light of love.

"It is growing over late for any more talk," said she, gently, "and seems to me that the best thing we can do will be to have our chapter and our little bit prayer. Mark Wilson, thou wilt take the book;" and her trembling finger pointed at the great family Bible on the little oak table beside her.

Mark silently took his place before the book, asking in his heart that God the Spirit would guide him "rightly to divide the word of truth," would "take of the things of Christ; and show them unto them;" would send home the teaching until it should be "as a nail in a sure place." He opened upon that precious story which has been the turning point in the downward path of so many thousands of sinners, who are now rejoicing saints in their Father's house above.

"And he said, a certain man had two sons." Mark's was a voice of wondrous power, and as sweet as it was strong; but never had it sounded more thrilling than when it read how the young man waywardly demanded the portion of goods that fell to him, and went away into a far country to waste his substance with riotous living; never more mournful than when it told of the great famine that arose when he had spent all, and how he began to be in want; never more touching in its chastened gladness than when the story told how the young man "came to himself" in the depth of his utter desolation, and said, "I will arise and go to my father;" but never had it swelled so triumphantly to the higher notes of joy, as when it told that the father "saw him when he was yet a great way off;" but here the clear voice trembled, shook, fell; and then kneeling down, Mark Wilson turned the rest into a prayer.

He prayed and said, "Father, I have sinned against heaven and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son:" he prayed and asked that the robe, the seamless robe of the Redeemer's righteousness, might be brought forth and put on each returning prodigal; that the ring of covenant love might be placed on the trembling hand of repentance; that the wounded feet of the weary wanderer might be shod afresh to walk in the ways of holiness, until they became even "beautiful upon the mountains," as bearers of "good tidings of great joy." Then Mark Wilson paused again, and his voice changed from the pleading accents of prayer to the full hymn-notes of praise, while he repeated the words of the reconciled father, "For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found."

No one stirred—but there was a sound as of a wind sobbing in the branches of the shaken trees, and there were drops falling, as of a gracious rain on the mown grass. It was Alice who was sobbing, but so gently that she knew not it could be heard—it was Miles whose strong limbs were trembling with over-mastering emotion, and whose tears were falling fast as rain. The widowed mother had retired into that inner chamber of the heart where the believing soul communes with her Lord; and there she was interceding, as Moses interceded for the rebellious children of his people:—

"Oh, he hath sinned a great sin; yet now, if thou wilt forgive his sin—"

Old Mr. Knibb had quietly submitted to the turn which things had taken, though he was altogether unenlightened as to the true cause of the emotion which was prevailing around him. But the old man's thoughts had gone back into some almost forgotten haunts of memory, and the handmaid, who, with lantern in hand, was lighting him through those dim and crooked bye-paths of the past, was none other than conscience. Yes, conscience, a rather sleepy inmate of the old man's "house of life," had been suddenly aroused from her long lethargy, and, her lantern, which had gone out, was suddenly lighted up afresh from the clear lamp of the word. And he was seeing some turns in his past road as he had never seen them before, and wish, nay, longing, that the crooked had been made straight, and the broad had been narrow, never mind how narrow, so that it might not have brought him to the hard parched land of his dry old age.

Look! the old man is weeping—weeping softly and tenderly as a little child. Perhaps there may be a beam of Divine love shining on those tears which the old man is wiping away with the back of his hard thin hand. Sometimes, very late in the evening there is a light—light enough to show the cross of Christ, though the eye maybe dim and the natural strength abated, and it be very late in the day to bring the offering of a contrite heart into the house of the Lord. But he has taken his candle and gone to his chamber; and there we will leave him alone with God.

The party round the hearth now broke up and withdrew to their several rooms, after exchanging a scarcely audible "good night." But when Miles, who had lingered behind the guests, stooped to kiss his mother, he seemed struck with her sunk and worn look; and instead of allowing Mat and Alice to push her chair into the little chamber opening out of the kitchen, which she always occupied with Alice as her companion, in order to avoid the stairs, he gently, very gently, put his strong arms around, her shrunk frame and carried her into her room. This was so like one of the little thoughtful acts of former days, that the old lady, when he had placed her in the chair by her bedside, laid her shaking hand upon his thick brown curls and solemnly pronounced the Old Testament blessing: "'The Lord bless thee, and keep thee: The Lord make his face to shine upon thee and be gracious unto thee: The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace,' my son!"

"Amen," said Miles, in a choking voice, as he again kissed his mother, and rushed to his own little chamber. He closed the door and flung himself upon his knees in an agony of remorse.

"Ah!" muttered he, in the bitterness of his spirit. "I see how it is now. It is the first wrong step that leads one off the road. I thought I was the strong man that could stand in his strength. I thought my training was so good, and my principles so firm that I could afford to look, temptation in the face. I thought 'twas only weak people that yielded, and it was not needful for such as I to keep out of harm's way. And then thought it was well to see what life is, that it would only give one experience and strength to look a little into what the rest of the world were about. And I made acquaintance with young men who said there was no spirit in the dull sort of life I was living, ordered about by a sick mother, and led blindfold by a silly little sister, and a 'prig of a preaching schoolmaster, that carried his head above all his betters in the whole country side.' At first I only laughed, for I knew well enough they were mistaken."

"Ah! I see now, plain as sunlight, that when a young man laughs at evil insinuations, the devil is sure to be laughing too: the one laugh is only the echo of the other. Then came the Ambleside fair, and that nasty little booth with the play going on in it. I shook my head at the things that were acted there and at the still worse things that were hinted at. Ah, those vile hints! They are a deal worse than saying the full meanings right out, because that would have shocked, and the other just amuses and leads one's curiosity on further still. Yes, at first I shook my head, but before it was over I laughed; and that laugh again was an echo from beneath. I don't rightly know what followed; because when I came out from the booth I was so thirsty that I went into the tap to take one glass—only just one, no more, on any account, before going home."

"Bella! Bella! And thou had'st begged me in thy own sweet way, begged and prayed me not to cross the threshold of temptation. But I vowed in my heart that I would only take that one glass of needful refreshment—yes, refreshment I called it—and in I went. Miner Jack was there, and Tim o' the Brooms presently came in, and told capital stories, until we roared with fun. I am sure I don't know what followed—only, those two tempters saw me home as far as the dale, talking very large about speculations, and good safe investments for a young man's money, remunerative labor, and grinding laws, that 'twas a spirited young fellow's duty to break through, because they were unrighteous legislation. I thought them brave, noble fellows, fool as I was. They have been constantly at me ever since that fatal night, alluring me into their deadly ways until they have got me wholly in their power, bound hand and foot. Father of the prodigal! Father, I have sinned against heaven and in thy sight: I am no more worthy to be called thy son. I know I am a very great way off; but oh, canst not thou see me even here, and have compassion and come to meet me?"

Just at this very moment, and a critical moment it was—for that young man's soul was hovering over the dim confines betwixt life and death—a low whistle was heard without.

The young man started to his feet with a spring, clasping his hands, and crying with an exceeding bitter cry, "Hast thou found me, O mine enemy?"

Yes, truly; his hard task-master had come to look after the bond-slave who at that moment was meditating desertion from his side. It was not probable that Satan would give up his own, without another effort to retain him. It is not safe for the sinner to say, "Ah, I can turn, repent, and live, whenever I choose: all in good time. Sin is not quite so pleasant as I thought it would be; and so, on the whole, I think I had better go home and lead a new life."

Poor Miles Lawson! The strong man armed "thinks he shall be able to keep thee a little longer in peace;" let us wait, and see whether "a stronger than he shall come upon him and overcome him, and take from him all his armour wherein he trusteth, and divide his spoils."

Again the low whistle is heard, and this time it sounds just beneath his window. How was it that Chance and Laddie did not begin to bark until the first whistle was heard? It must have been the snow that muffled the tread of that stealthy foot. They are barking furiously now! But Miles, flinging open the casement, bids them be still; and unwillingly they drop into sullen silence, broken at times by a low, protesting growl.

"Send away your dogs, or I'll finish them right out," said the voice uneasily from below.

"Be off; Chance, I say—away with thee, Laddie," said their poor master from the chamber window. Laddie obeyed, and disappeared; Chance withdrew a few yards, and then sat down determinately on the cold white snow. They thought he was gone, and the voices renewed their parley.

"You have got the old fox in there. Now that he has run to earth, I say keep him there."

"I can't keep him here, unless the snow stops the hole for you," was the troubled reply.

"What are you at by saying for us? It is just as much for yourself. You are in it full as deep as we. I would lame his old mare, but the stable door is locked, and the dogs are about."

"He came unbidden, and he shall leave unhindered," said Miles firmly.

"Yes; and you think to be his guide. You are going to try your mean hand at the informer's trade; for it is always the chief rogue that turns king's evidence," said Tim o' the Brooms, with an insulting sneer.

"I'm going to do naught of the kind," said Miles, "but the old man shall go his own gait. He has always been a friend of the family, like—my dead father's friend; and nothing shall harm him."

"Very well, as you like," was the cool reply: "then the stock must be shifted before morning; that's all."

"Stay, where will you be putting it? I will know that," cried Miles.

"Oh, it's all ready planned. We've got a safe hiding in view. The scent will be hard up at somebody else's door. 'Twill be a good joke, too, to catch the psalm-singers up at Scarf Beck in a trap. But that's your concern, not mine."

"I'll not have that done, whatever else may be," cried Miles, with burning cheek and clenched fist. "I'd sooner die than any of them should be harmed. There shall not a breath stir against any one belonging to—to—the folk up at Scarf Beck."

The man sneered offensively, and said, "I know how the land lies well enough. But if you don't bring your cart tonight, and help us to shift right off, 'over sands,' * we'll move all the whisky jars into the old barn at Scarf Beck; and we'll see if anybody will believe the Hartley lads when they swear they didn't put them there." So saying, Tim o' the Brooms glided noiselessly away over the snow.

* Across Morecambe Bay.

THE SNOW-DRIFT.

"A snow-feathered pillow,

On snow-drifted bed;

As foam on the billow,

So white was it spread."

Miles leaned on the windowsill, and thought long and anxiously. The snow, continued to fall, soft and silent. The deep stillness of the night was oppressive in its solemn weight. Even the dreary night-wind seemed to hold its breath for awe; but all this while, each downy snowflake that fluttered to the ground took its place slowly and surely beside its sister-flake, quietly laying the foundations of one of those heavy and long-standing falls which sometimes re-assert their dominion over the mountain land, even after spring has begun to awaken the sleeping life of the earth.

The soul of Miles Lawson was in the darkness of desertion and dismay. He thought that every moment there was a fresh loop added to the great net which Satan was forming around him; he almost fancied he could see him netting, netting on, plying his mesh and his supple cords, the while he laughed at his misery. "He got my will first; and now he has bound my limbs, so that I cannot work when I would. This is thick darkness—no light and no hope. And all this while I am losing precious time; all this while those men, who are too strong and too cunning for me, are laying their dreadful traps and snares at Bella's very door. I can't endure that. Anything rather than that. I will go directly to Scarf Beck, and give them warning; informer or no informer, spy or no spy, traitor or not, I will go and save Bella and those harmless lads from wrong."

He tried to open the window again, but it would scarcely stir, for it was so banked up with snow. "Darkness, deathly darkness, and deep, treacherous snow!" muttered the miserable young man. Suddenly there was a rent in the black pall of clouds, which parted on either hand, and the full moon looked serenely down upon the white world beneath.

Miles clasped his hands: "Oh, Father of the repentant prodigal! If thou canst part the thick clouds like that, and give light, wilt thou not give me light in my soul, and show me the way I should go?" He repeated over to himself "the way—the way," when suddenly there darted into his bewildered mind the luminous words, "I am the way, the truth; and the life. No man cometh unto the Father, but by me."

Miles crept to his bedside, and dropped down on his knees in the very place where he used to pray his little prayers when he was yet a little child; and, like a little child, he clasped his hands, and prayed the simple prayers of his childhood. He even remembered every word of the hymn with which his mother used to sing him to sleep, and he repeated that too. Miles continued long on his knees, and when he gently rose and went to the window, it was not with the "exceeding bitter cry" with which he had last sprung to his feet, but with the words, whispered as if he could "scarce believe for joy and wonder":

"Hast thou indeed found me, O my Saviour?"

The moon was now shining steadily upon the scene, and the snow had ceased falling; but it lay so deep upon all around, that the usual tracks were obliterated.

"Nevertheless I must go," said he, firmly, in answer to the remonstrances of thought; "Bella must be saved at any cost from this wicked wrong; and I must tell these men that I have done with them forever, but that I will not inform against them if they will only give up the bad line they are in, and leave the neighborhood."

He opened the door, and listened: all was quiet, except that the clock ticked on the stairs in its own measured way, and he started when it struck three, as he glided past it with shoeless feet. He found his black-and-white shepherd's plaid wrapper hanging on the pin in the kitchen, and he threw it around him in the approved mountain fashion, whereby it forms a good protection for chest and shoulders, while sufficient freedom is left for the arms. He then put on a stout pair of boots, drew on his warm worsted gloves, tied Alice's "comforter" round his neck, and taking his stout staff, opened the door.

The porch was floored with snow: the walk was a shining sheet of white: Alice's pet plants were buried, or else feathered into white and drooping plumes: the brother yews were bending under masses of snow: the little wicket stood like bars of alabaster before him; and rather than break the shining spell, he vaulted lightly over it.

He passed through the farm-yard, and his favorite young horse whinnied when he heard his master's step, muffled thought it was by the deadening snows. Laddie sprang to his side, but was waved off; Chance did not appear, yet all the while he was watching and lurking about behind corners, and under walls; for he had settled it in his faithful mind that go he would, whatever orders he received to the contrary. He did not like the look of the man who had been whistling and whispering under the window, and he did not like the snow; and therefore if danger were abroad, wherever his master was, there would his faithful servant be.

Miles was quite unconscious of this mute resolve, and of its answering movements, but plodded heavily on along the white lane, and across the white fields in the well-known direction of Green Gap. As he approached the narrow gateway into the glen, he found that the snow forced through the narrow pass by the driving wind of the previous evening, had been whirled about in wild eddies, and had then settled into fantastic wreaths, or gathered into smooth and sloping banks, as the accidents of the ground or the impulse of the gale had determined. Onward, however, he forced his way, until he was startled to see that, in the very jaws of the Gap white walls rose above his head, here eight, then ten, now twelve feet high, sometimes smooth as Parian marble; at others, crested like a breaking wave. What if that curling and foaming billow should suddenly bend, break, and engulf him? What if the treacherous wind should blow a blast against that mountain surge, and shiver it into showers of frozen spray? He stops and looks up. The moon is shining coldly upon the glistening crags; and there, gleaming through the Gap, rises the Old Man, with a white sheet thrown over his lofty forehead, enwrapping his broad shoulders, and lying in glittering folds about his feet.

The scene was magnificent in its wintry grandeur; but it was appalling to the young man's mind. How was he to force his lonely way up the gorge to Scarf Beck? He clasped his cold hands and breathed a prayer for guidance; "Leave me not, neither forsake me; show me the way in which thou would'st have me to walk, outwardly as well as inwardly, through the snows and through the snares. Guide me by thine eye: uphold me with thy hand. I look unto thee to save me, for thou art my God." These, and other little fragments of broken prayer, little snatches of precious psalms, little bits of remembered teachings, came thrilling through his bewildered mind.

And still he struggled on. Oh, the weariness and the weight! the weariness of dragging his limbs out of the deepening snows, the weight of the aching limbs as he plunged them into fresh wreaths and took the soundings of new depths.

Is he in the right path? He looks round, but he is growing dizzy: his eyes must be dazzled by the moonshine on the glittering snows: it is sickening, that changeless glare. He wishes the moon would go behind the cloud to relieve his giddy brain for one brief space, only that would leave him in darkness.

On, then he must go. He should be beside the beck by this time, Scarf Beck, Bella's beloved stream. Ah, that thought rouses him from his sleepy languor. He listens: he catches a muffled sound—how unlike its usual living gladness; how thick its voice compared with its wonted clear cadences, or with its loud tumultuous brawl when once it is angry. It must be half choked with snows and dulled with intruding ice. Ah, the weariness and the weight! He must rest, must sleep away his sickening giddiness, just for a little moment, before he struggles and labors onward. He is reeling, rambling towards that smooth bed, that soft pillow, those fringed curtains, those white and winding sheets. Stay, Miles, it is the cold white bed of death.

Now Chance, this is thy moment. Thou hast been laboring on after thy unconscious master without a word to encourage thee, without a sign to teach thee thy duty: thou hast dragged thy weary way a few yards behind him, not daring to show thy self for fear of being driven back as usual, Now, then, at last, thy time come. The noble dog plunges forward, all tired as he is, and jumps to lick his failing master's hand.

"What is it? Chance, my poor, poor fellow, art thou come to help thy master? Thanks, thanks, Chance," murmured he in a dull, dreary voice. But the kind tone, the evident acceptance of his poor presence, the hand laid upon his great black head, all this was payment enough, and over payment to old Chance, and he is happy.

Encouraged by his dog's companionship, Miles struggles on a few yards further. But his spasmodic efforts cannot hold out much longer. Once more, he reels, staggers, sinks into a deep drift. And there we leave him to sleep out his leaden sleep, which that melancholy bark of the old dog, and that most piteous whining have no power to awaken.

THE SEARCH.

"Take we heed to all our foot-prints;

Tell-tales are they, where we go.

Let them bear no evil witness

On the sand, or on the snow;

On the mould, or on the clay,

Or life's dusty, thronged highway."

THE family at The Yews are sleeping rather longer than usual on the morning at which we are now arrived. Sleep had been a late guest at the pillows of several of the household, for anxious thoughts had kept the earlier watches of the night with them, "holding their eyes waking." At last Mat was up, and out with Geordie and the farm lads, looking after the sheep. Laddie was at hand in readiness to help; but Chance failed to obey the whistle which generally brought him in a moment, eager for his work.

"What's to do with the old dog, that he doesn't come at call?" said Geordie Garthwaite; "I heard both the dogs barking terribly fierce in the night; but Chance is no where this morning. Is the young master at home, I wonder?"

"Yes," said Mat, "so far as I know. He was in last night. But he's lying late this morning;" and away they went to dig out some of their sheep, which had been buried in the drifts of the night.

"Miles dear," shouted Alice at her brother's door—"Miles, come to breakfast."

No answer.

She opened the door and he was not there. There was the bed just as her own careful hands had left the sheet neatly turned down, and the pillow round and smooth. The casement was not quite closed, and there was a little bank of snow lying on the windowsill.

A single glance showed her all this, and she rushed down to the kitchen in consternation "Oh, Mark! he isn't there; and his bed is all untouched. He must have gone out—and oh I think of the snow."

"Gone?" exclaimed Mark, with terror in his face, "and such a night!"

He ran up stairs to Miles's room to try to collect evidences of what had occurred; but he could gain nothing here. Then the place where hung the hats and plaids was examined; and Miles's hat and plaid were gone; his boots were gone too, and his mountain staff.

"He has taken his 'comforter,'" sobbed Alice, "mine that he liked so much; and the gloves that I knitted."

"Has he?" said Mark, with a brightening face, "then he wasn't desperate; he wouldn't have done things so orderly, unless he were cool and clear. There is hope in that, dear Alice;" and he took her hand tenderly. "I will go and seek him; and thou must trust me, as thou would'st a brother."

"I will," was her firm reply; but when she saw him silently making ready to set forth, her heart misgave her; and going up to him, she said pleadingly, "Will you not tell me where you are going, and what you will do?"

"Going to call Geordie and the lads, and then search the road to the Old Man."

Alice shuddered; and quietly laying her cold hand on his arm, said, "Mark, you must let me go with you. I cannot stay behind."

"And leave the mother in her desolation, Alice? Besides," he added in a low voice, as he rushed out through the porch, "how could I bear to risk my all?"

Poor Alice! She knew only too well how great was her stake, too. But every wandering thought was called home to assist in the dreaded duty of breaking Miles' mysterious disappearance to the widowed mother.

There was no wringing of hands, no tearing of hair, no wild burst of passionate grief; but there was a look of inexpressible anguish which seemed to make her ten years older at one stroke; and there were just these few words, "I had best be alone, Alice, dear; but bring me my book; for I am thinking I shall want every promise I can find, and every prayer I can pray."

Alice silently crossed the door, and left her to the prayer of faith.

In the meantime, Mark was far on his way to the Green Gap, striding onward in eager haste, and Geordie and the lads plodded after, looking anxiously for tracks as they went. But some fresh snow had fallen in the early morning, obliterating the footmarks which had been left, first by Tim o' the Brooms, and then by Miles and his mute companion.

"I see nothing but smooth snows," shouted Mark to the group behind him.

"Well, Master Wilson, I seem to see sores in the snow, which have healed over, like. They'll serve for the length of a man's stride well enough, too. Look ye here."

And here and there slight signs of disturbance were just visible, though only the eye of a shepherd, who had often tracked his lost sheep in the fields and fells of snow, could have detected them.

Now they have reached the Gap, and they look with inward misgivings at the snowy battlements by which it was defended—rampart, curtain, and fosse. However, borne by their strong limbs and helped by their strong staves, and impelled by their strong motive, the bold young men and the brave old man forced their way through.

On the further side of the barrier there were two mountain roads branching off from that which they had been following, the one leading up the gorge to Scarf Beck Farm, the other winding up the side of the Old Man. The party stop to consider. Mark Wilson thinks he has grounds for the belief that his friend would take the way of the mountain; but as his suspicions are vague, founded only upon the hints and half-revealings of the previous day, which he had painfully put together, he could give his companions no reason for the course which he intended to pursue.

"Seems to me," said Geordie Garthwaite, "that young master is kind, like, to Scarf Beck Bella—and so, like enough, he's gone there. That's an old man's mind upon it."

"No," said Mark, "I must search the mountain's side before I go home."

"Then it's my belief," replied Geordie, "that we shall never get home at all, if we do the like of that. There's snow enough in places to bury us all, like sheep. But, stay! What's this, again?"

And sure enough there were undeniable footmarks plodding up the path which led to the old workings of a deserted mine, high up on the mountainside.

Geordie stooped down and examined. "It's a man's foot, however, turning up here; and the prints are part filled again with new snow, looser and softer than the old. So it's done since evening, when there was the great fall. We'll try the mountain, master."

But those tracks, all the while, were but the tracks of Tim o' the Brooms.

Poor Chance! Thou dost not know how near is help, and how it is already turning away and leaving thee in thy distress. And yet thy poor unenlightened instinct is doing wonders of self-sacrificing devotion, and of beautiful, tender skill. Thou halt dug away the snow which had closed over thy unconscious master; thou hast licked his pale forehead; licked his livid face over and over again; licked his stiffening wrists: takes his hand in thy mouth in thy agonized efforts to rouse him from his strange, cold sleep; and then, lying down close to his side, thou hast moaned and whined to the winds. If there be a heart yet beating feebly within that rigid form, it is because thy anxious efforts have not suffered the last faint glow of animal heat to die out.

The little band of searchers is now working its way wearily up the steep. It was well that the old shepherd knew the path in past times, or they would have been inevitably lost. They are too much engrossed, by their life and death engagement, to see how glorious in its wintry majesty is the scene above, beneath, and around; the shining crest of the mountain, each broad white shoulder, and every descending line, sharply cut against the dark blue sky; the lake beneath as blue as the deep sapphire above, each headland projected in silvery curves into the lake, pencilled with the feathery outlines of snow-laden branches, or heavily fringed and embroidered with the dull dark green of the pines. The crags, where they were too precipitous to afford a resting-place to the snows, on ledge or in hollow, looked out stern and bald from the prevailing drapery; and here and there a fleecy cloud had floated down to hold some mysterious parley with a mountain-top, for the time confounding all distinction between earth and sky.

"What can that little line of thread be, up there in the hollow of the crag?" asked Mark Wilson. "It cannot be a shred of mist, can it? It looks strangely like smoke." They all looked up; and there was, sure enough, a slender line of blue smoke curling upward from a dark crevice of the rock.

"Smoke, heather smoke, and none other, unless I am blinded with the snow," was Geordie's reply. "It's uncommon strange, that. Come, my lads, we will find out who has lighted a heather fire up on the heights like that, and what for it is."

Mark made no reply, but strode and clambered on. He had his own painful theory whereby to account for the phenomenon. They were now at the foot of the crag, when first one man's head, and then another, was seen peering down over the rocks. The heads instantly disappeared again; and presently, after, the curling line of blue smoke disappeared also; but the old shepherd's practised eye had already carefully taken its bearings and noted its way-marks.

"Up this way, lads; we will soon see what sort of bird has been building its nest in such a queer hole as that."

"It is the nest of foul birds of prey, and we must net them, if we can," remarked the schoolmaster, gloomily.

"Ay, ay, net them, master; and carry off the nest egg," said the shepherd with a knowing smile.

"Have they got guns up there, I wonder?" said one of the farm lads, in a hesitating voice. "I can't say as though I much like the sport."

"Come on," cried the schoolmaster, "we are doing our duty, and that is enough for brave Englishmen."

Scarcely had he spoken when a bullet whistled sharply past his head, and splintered a projecting point of rock close behind him.

"Now, then, I am strong to do my duty," said Mark, "for they are murderers in their hearts, though God has spared me."

Another bullet whizzed by.

"This will not do at all," said old Geordie, quietly; "now, then, my lads, make a rush for your dear lives."

The old man planted his iron-shod shepherd's staff on the rock, and sprang up with the agility of a native-born cragsman; for he had robbed many a raven's nest, and eagle's eyrie, in his distant youth, and had won the shepherd's prize for the feat. At this instant, a man rushed down the craggy path and sprang away like a goat from rock to rock.

"There goes Miner Jack," cried one of the lads.

But another figure which had been stealing round a buttress of the mountain fortress, suddenly leaped out upon Mark Wilson with a yell of hatred, and grappling with him, rolled heavily down the steep.

"Save the master, save him," shouted old Geordie from above.

The young men rushed down after the yet rolling figures, and contrived to stop them in their headlong course. It was but just in time; a yard or two more and they would have bounded together down a precipice which was masked by snow, and been dashed in pieces at the foot. Tim o' the Brooms instantly shook himself free from the lads, writhing from their grasp like a slippery serpent, as he was, glided rapidly down the path, and disappeared.

"Now for the hawk's nest, without the old birds," said Geordie.

They climbed to the entrance of an old working of the deserted mine—an "adit," the Cornish miners would have called it—and looking in, they were half-stifled by the smoke of an expiring heather fire, and by the stupefying fumes of distilling whiskey.

Mark's eye eagerly searched the cave for an expected object, but that object, to his inexpressible relief, he found not.