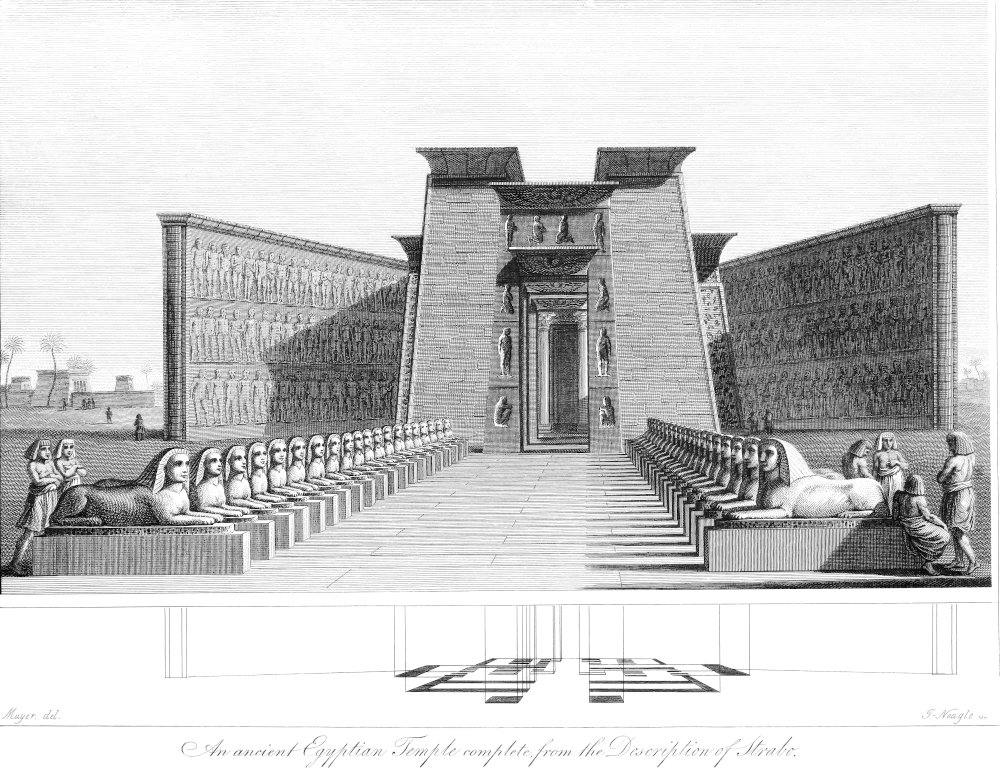

| L-Mayer. del. | J-Neagle Sct. |

An ancient Egyptian Temple complete, from the Description of Strabo.

Title: Travels in Africa, Egypt, and Syria, from the year 1792 to 1798

Author: William George Browne

Release date: December 18, 2023 [eBook #72452]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Cadell junior and W. Davies

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRAVELS

IN

AFRICA, &c.

| L-Mayer. del. | J-Neagle Sct. |

An ancient Egyptian Temple complete, from the Description of Strabo.

By W. G. BROWNE.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR T.

CADELL JUNIOR AND W. DAVIES, STRAND; AND

T. N. LONGMAN AND O. REES, PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1799.

![[Decoration]](images/decor.jpg)

IF the desire of literary fame were the chief motive for submitting to public notice the following sheets, the writer is not so far blinded by self-love, as not to be conscious of having failed of his object. The simple narrative of a journey is perhaps as little a proper source of reputation for elegance of composition, as a journey of the kind described is in itself of the pleasures of sense. But the present, from various circumstances, comprehends so small a portion of what might be expected from the observations of several years, that he has been often disposed to give it a different title.

The retrospect on the events of his life which are briefly mentioned in the ensuing pages, offers him a[vi] mixed sensation. The hopes with which he undertook the voyage, even without being very sanguine, contrasted with the disappointment with which he now sits down to relate its occurrences, allow him little satisfaction from what has been executed. He feels, however, some confidence of not experiencing severe censure when his design shall be understood. The work is not offered as elaborate or perfect. The account of Dar-Fûr fills up a vacancy in the geography of Africa; and of a country so little known, the information obtained should not be estimated by its quantity, but by its authenticity. Sitting in a chamber in Kahira or Tripoli, it is easy to give a plausible account of Northern Africa, from Sennaar and Gondar to Tombuctoo and Fez. It would not be difficult even to sanction it by the authority of the Jelabs. These people are never at a loss whatever question is asked them, and if they know not the name of the place inquired for, they recollect some other place of a name a little resembling it in sound, and describe what they never heard of by what they know. With regard to manners they are as little to be relied on. Ask but a leading[vii] question, and all the miracles of antiquity, of dogheaded nations, and men with tails, will be described, with their situation, habits, and pastimes.

But their descriptions, when given without the smallest appearance of interested views, if verified on the spot, are constantly found defective or erroneous.

The writer is aware, that when the length of the time he passed in Dar-Fûr is considered, the short account here given will appear, to persons accustomed to the busy scenes of Europe, but very imperfectly to fill up the void. Confiding, however, that those of more reflection and experience in travelling, will be better pleased with a short and clear narrative of what really happened, than by frivolous anecdotes or remarks, inserted merely to swell the size of the volume, he has contented himself with extracting from his journal the principal occurrences during his residence there, and giving them the connection required; at the same time omitting nothing that could any way contribute to throw light on[viii] the state of the country, or character of the inhabitants.

A more creative imagination would have drawn more animated pictures; a mind more disposed to observation would have collected more facts and incidents; and a more vigorous intellect would have converted those facts and incidents into materials of more interesting and more striking investigation. The descriptions would have been more impressive, and the deductions more profound.

The present work has the merit of being composed from observations made in the places and on the subjects described. But the praise of fidelity, the only one to which the writer lays claim, cannot be received till another shall have traced his footsteps.

With respect to Egypt a greater number of persons may be found who are qualified to decide, and there is not the same reason for suspension of judgment.

[ix]Without pretending to any extraordinary sources of information, the writer hopes, that what is here said will afford some little satisfaction to those who wish for the latest information concerning that country. He arrogates not to himself the praise of augmenting greatly the sum of knowlege already to be found in books; but very widely dispersed, and within the reach of comparatively few persons.

Innumerable books have been written on Egypt, but none of them, in our language, can pretend to a popular plan. Those of Pococke and Norden are most known to ourselves—valuable works for all that concerns the antiquities, and they are by no means superseded. The form and price, however, at this time keep them out of the hands of the greater number.

Niebuhr’s writings require not an additional testimony of their value; but the professed object of his voyage was Arabia; and the account of Egypt is only incidental.

[x]Volney and Savary are in the public hands, and no attempt shall be made to influence its judgment of their works. The talents of the former are well known; but he saw the East with no favourable eye; and his manner in speaking of Egypt will be found materially different from that here adopted.

Of Syria the Author could expect to say little that is new, after the numberless descriptions which have already been published, and he has accordingly used great rapidity in his narrative.

In Kahira, the sources of information are few and scanty. A traveller may remain there many months, without finding his ideas of the country, or its inhabitants, much more clear or precise.

The Europeans, there immured as prisoners, may be reasonably excused for hastening their commercial advantages, and, whenever unengaged by that object, for amusing themselves in trying to forget the place in which their ill fortune has obliged them to reside. Those who are found there, with every[xi] disposition to accommodate strangers, and receiving them always with complacency and kindness, are yet, with few exceptions, not of the order of men most able to generalize their ideas, and avail themselves to the utmost of the information which accident throws in their way.

The Greeks, whose inquisitive turn, and more intimate connexion with the people at large and with the government, make them more familiar with characters and occurrences, rarely represent things as they really are, but as they feel them, or would have them to be. Where their report is not entirely imaginary, their portraits are like those of Lely, all adorned with nicely-combed locks and a fringed neckcloth. They mark no character, but as it appears to their prejudices; give no history that is not interlarded with their own fables; and describe no place but in the vague and superficial manner that satisfies their own ignorance.

The Copts who, it might be supposed, would be accurately informed of all that relates to the government[xii] and history of the country, have no sentiment of antient glory, and are wholly immersed in gain or pleasure.

Settled in the composure of ignorance, they cannot conceive the motive of minute inquiries; and timid and reserved, they fear to discover even what they know.

The more liberal among the Mohammedan ecclesiastics, may be safely consulted for what concerns literature and the laws, and some few of them are communicative; but in general they despise strangers, and do not readily answer questions not of the most ordinary occurrence. On the whole, the most intelligent and communicative among the people of Kahira are the Mohammedan merchants, of a certain rank, who have visited various parts of the empire, and who have learned to think that all wisdom is not confined to one country or one race of men; and who having been led to mix, first by necessity and then by choice, with various nations, preserve their attachment to their own persuasion, without[xiii] thinking all the rest of mankind dogs and accursed.

The general design of the Writer, as will be seen in the sequel, was of such a nature, that, without being extremely sanguine, he might have hoped to execute a considerable part of it. His prospects the first year were darkened by an unexpected disappointment on his arrival at Assûan; concerning which he may say, without any disposition to complaint, that he felt it severely. Another winter furnished him with a little more information and more experience: but still, as he afterwards unfortunately discovered, by no means all that was necessary to his purpose.

He might have appeared in Dar-Fûr as a Mohammedan, if he had known that the character was necessary to his personal security, or to his unrestrained passage; but, from the accounts he received in Kahira, among the people of Soûdan no violent animosity was exhibited against Christians. The character of the converts to Mohammedism, among[xiv] the black nations, was, according to the general voice of the Egyptians who travelled among them, mild and tolerant. A disposition so generally acknowleged, that the more zealous among the latter are little scrupulous in honouring them with the appellation of Caffre. His surprise therefore was not inconsiderable at finding, on his arrival, that an unbeliever in the infallibility of the Korân was more openly persecuted, and more frequently insulted, than in Kahira itself.

The information received, previously to his departure in 1793, taught the writer to expect, from having chosen the route of what is called the Soudân Caravan, the choice of a free passage to Sennaar, which would, without much doubt, have secured him an entrance into Habbesh, under the conduct of the Fungni, who trade there: for the Fûrian monarch, had his favour not been withdrawn in consequence of false insinuations, would readily have accorded a safe-conduct through Kordofân, which was all that circumstances required. The being removed a few weeks journey too far to the Westward, was no objection, when he reflected on the[xv] confusion then reigning at Sennaar, and that in proportion as the road he took was indirect, the less suspicion would be entertained of him as a Frank, the greater experience he must acquire among the people of the interior, and the more easily he might be suffered to pass as a mere trader.

He had been taught, that the expeditions in quest of slaves, undertaken by the people of Fûr and its neighbourhood, extended often forty or more days to the Southward. This, at the lowest computation, gave a distance of five degrees on a meridian, and the single hope of penetrating so much farther Southward than any preceding traveller, was worth an effort to realize. He owns, he did not then foresee all the inconveniences of being exposed, on the one hand, to the band of plunderers whom he was to accompany, and on the other, to the just resentment of the wretched victims whom they were to enthral. Perhaps those very evils were magnified greatly beyond their real value by the Fûrians to whom he applied, and who were predetermined not to allow him to pass.

[xvi]Another inducement to this route was, that part of it was represented to lie along the banks of the Bahr-el-abiad, which he had always conceived to be the true Nile, and which apparently no European had ever seen. To have traced it to its source was rather to be wished than expected; but he promised himself to reach a part of it near enough to that source, to enable him to determine in what latitude and direction it was likely to exist. It is unnecessary to observe, that, had either of these objects been realized, much interesting matter must have occurred in the course of the route. He could not in the sequel discover that the armed expeditions of the Fûrians extend to any high reaches of the Bahr-el-abiad.

Another object, perhaps in the eyes of some the most important of the three, was to pass to one or more of the extended and populous empires to the Westward. Africa, to the North of the Niger, as is certified from the late discoveries, is almost universally Mohammedan; and to have been well received among one of the nations of that description,[xvii] would have been a strong presumption in favour of future efforts. He expected in that road to have seen part of the Niger, and even though he had been strictly restrained to the direct road from Dar-Fûr through Bernou and thence to Fezzan and Tripoli, an opportunity must have offered of verifying several important geographical positions, and observing many facts worthy remembrance relative to commerce and general manners; or, if those designs had entirely failed, at least of marking a rough outline of the route, and facilitating the progress of some future traveller.

So fixed was his intention of executing some one of these plans, that near three years of suffering were unable to abate his resolution; and the pain he endured at being ultimately compelled to relinquish them, had induced him to neglect the only opportunity that was likely to offer of personal deliverance, till the destitution of the means of living roused him from his lethargy; and the ridicule of his Mohammedan friends, who, fatalists as they are, yield to circumstances, instructed him that to[xviii] despair was weakness and not fortitude; and that the frail offspring of hope, nursed by credulity, and not by prudence, marks the morbid temperament of the mind that conceived it.

The following papers would perhaps have been something less imperfect, if what was originally committed to writing had been altogether within the reach of the writer, when he began to prepare them for publication. Two accidents, however, both equally unforeseen, rendered abortive his hope of compensating in some measure for the general failure in his design, by greater exactness and detail as to the particulars of what he had actually seen.

The losses he had sustained in Soudân, were not very important, comprising only some specimens of minerals, vegetables, and other cumbrous materials, which he designed to have brought with him. On his arrival in Kahira, he thought it would be an impediment, in his journey through Syria, to transport all he possessed thither, and therefore caused the greater part of his baggage to be sent to Alexandria;[xix] among which were copies of such papers as he thought least unfit for the use of a third person. In the number he regrets a register of the caravans which had arrived in Kahira from Fûr since the year of Hejira 1150, containing an account of their numbers, and many other curious particulars; copied from a book belonging to the shech of the slave-market in Kahira.

A kind of general itinerary, in the hand-writing of a Jelab of his acquaintance, containing the roads of Eastern Africa.

A vocabulary of the Fûrian language, compiled by himself.

Some remarks on natural history.

List of names of places both in Egypt and Fûr, written by an Arab.

The detail of particulars relating to the time and manner of his observations in Astronomy, with other remarks tending to illustrate the geography of his route.

To return to a few considerations on the present intercourse between Egypt and Abyssinia.

[xx]Towards the close of the year 1796, I was told by the Coptic patriarch, that for the preceding nine years or more, no communication had taken place between Egypt and Abyssinia. Two men pretending to be priests of that country, came in 1793 to Kahira, but it was afterwards discovered that they were either not Abyssins, or fugitives, and without authority or commission. The interception of their intercourse by land might be caused by the unsettled state of Sennaar and Nubia. Slaves from Abyssinia are usually brought by the Red Sea from Mâsuah to Jidda, and many of them are sold in Mecca, though but few reach Kahira by way of Cossîr and Suez. Gold sometimes comes to market by the same route, and the Abyssins are thence supplied with such foreign commodities as they stand in need of.

To the slaves of Habbesh no very marked preference is shewn in Egypt. They are more beautiful than those of Soudân; but the price of the two kinds, cæteris paribus, is nearly the same.

[xxi]A priest of the Propaganda, a native of Egypt, and consequently possessing every advantage of language and local knowlege, during my absence to the Southward, had endeavoured to penetrate into Abyssinia. Having reached Sennaar, he was dissuaded by the people of that city from attempting to proceed. Unmindful of their representations he prosecuted his journey, but was assassinated between Sennaar and Teawa.

The Propagandists had a single missionary, a native of Habbesh, at Gondar, and styled Bishop of Adel, but concealing himself under the exterior of a physician. In 1796, the order at Kahira told me that they had received no authentic intelligence concerning him during several years preceding.

At Suez, March 1793, I met an Armenian merchant, who had formerly traded to Abyssinia, and seemed a man of intelligence. He told me that he was at Gondâr while Bruce was there, and that Yakûb was universally talked of with praise. This[xxii] merchant narrated of his own accord the story of shooting a wax-candle through seven shields; but when I asked him if Bruce had been at the Abyssinian source of the Nile, he affirmed that he never was there. He observed that Bruce had been appointed governor of Râs-el-Fîl, a province in which Arabic is spoken. My informer added, that the Abyssins were a gross ignorant people, and often ate raw flesh.

In Dar-Fûr a Bergoo merchant, named Hadji Hamâd, who had long resided in Sennaar, and was in Bruce’s party from Gondar to Sennaar, said that Yakûb had been highly favoured in the Abyssinian court, and lived splendidly. He was often observing the stars, &c. Both my informers agreed that he had been governor of Râs-el-Fîl; and both, that he had never visited the Abyssinian source of the Nile, esteemed the real one in that ignorant country.

An Englishman under the name of Robarts came to Alexandria in 1788, and after a short stay proceeded[xxiii] to Kahira. His intention was, it is said, to have penetrated into Abyssinia by way of Massuah. While at Kahira he applied repeatedly to the Coptic Patriarch for a letter from him to the head of the Abyssin church; with which the latter, under various pretences, constantly refused to furnish him. He continued at Kahira several months, and afterwards found his way to Moccha. Repeated attempts were made by him to execute his projected voyage to the opposite territory, but all without success. The persons from whom I received this information, and who, as would seem, derived it from his own authority, assured me that he had encountered almost insurmountable obstacles, and been obliged to submit even to personal indignities. They allowed too that this gentleman was far from being unqualified for the enterprize, in judgment, experience, or physical force. The same persons acquainted me that he had afterwards advanced to the Mogul peninsula, and had accompanied the British troops, during two campaigns, against the usurper of Mysore, in various parts of the peninsula. He even returned to Alexandria after the treaty of Seringapatam;[xxiv] and at that place, being attacked by an acute disease, breathed his last in the Franciscan convent there established. More authentic and interesting materials respecting this traveller, may possibly have reached this country. Yet I thought it not improper to mention these few particulars, which may tend to illustrate the nature of a voyage to Abyssinia.

The errors in African geography are numerous, and proceed from various causes. Among those causes, however, are particularly to be enumerated,

That the same province has often one name in the language of that province, and another in Arabic. Of the places called indiscriminately Fertît by the Arabs, each little district has an appropriate name.

Again, the name of a small province is occasionally taken for a large one, and vice versâ. Bahr is applied to a great lake, as well as to a river. Dar is a kingdom, and is sometimes applied to a village, and often to a district.

[xxv]Fûr seems to be an Arabic name, signifying in that tongue a Deer; and, it may be conjectured, has been applied to that people in the same sense as Towshân, a hare, is by the Turks to the natives of the Greek islands—from the rapidity of their flight before the Mohammedan conquerors.

Nothing can well be more vague than the use of the word Soudan or Sûdan. Among the Egyptians and Arabs Ber-es-Soudan is the place where the caravans arrive, when they reach the first habitable part of Dar-Fûr: but that country seems its eastern extremity; for I never heard it applied to Kordofân or Sennaar. It is used equally in Dar-Fûr to express the country to the West; but on the whole seems ordinarily applied to signify that part of the land of the blacks nearest Egypt.

An innovation as to the orthography of some proper names, it is supposed, will not appear affected or improper, when the reason is explained; as Kahira, Damiatt, Rashîd, for Cairo, Damietta, Rosetto. It is of some use in appellatives to approximate to the pronunciation of the natives, and there[xxvi] can be as little reason for receiving Arabic names through the medium of the Italian, as for adopting the French way of writing Greek ones, as Denys for Dionysius, and Tite-Live for Titus Livius. Kahira and Rashîd have each of them their proper meaning in Arabic.—In Italian they have no meaning. The only rule observed has been, to bring back proper names to the original pronunciation, as far as might be done without obscurity.

Where a circumflex has been put over a vowel it is to denote its length, or something exotic in the enunciation. An approach to systematic regularity would have been attempted in expressing Arabic words by Roman letters, but the author freely owns that no rule, at once general in its use and simple and easy enough to be remembered, has yet occurred to him. He has therefore added the original word, wherever it could in any degree tend to illustration or precision.

The word Turk is never applied to signify a professor of Mohammedism, an indefinite mode of designation, that occasions perpetual confusion in[xxvii] speaking of the affairs of the East. The design was, to confine that term to the natives of Europe and Asia Minor. Arab is applied equally to the inhabitants of Syria, Egypt, and the coast of Barbary, as well as to those of Arabia Proper, whether villagers or wanderers. The wandering tribes are however more frequently marked by the terms Bedouin and Muggrebin.

The orthography of the word Calif conveys no idea of the strong guttural letter with which it commences; it is therefore here written Chalîf, or more properly Chalifé. He is no stranger to the Turkish word Bek or Beg; but as those whose enunciation of that language is esteemed most correct, but faintly articulate the consonant which terminates it, he has retained the common orthography Bey. In general, the original language is esteemed the criterion of spelling; and if the same word be occasionally spelled in two different ways, it is only because they are both equally near to that original.

[xxviii]Weights and Measures.

Jewels, Gold, and Silver.

Measure of Cloth, &c.

| CHAP. I. | |

| ALEXANDRIA. | |

| Antient walls and ruins — The two ports — Reservoirs — Vegetation — Antiquities — Population — Government — Commerce — Manufactures — Anecdote of recent history. | Page 1 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| SIWA. | |

| Attempt to penetrate to the Temple of Jupiter Ammon — Route and provisions — Animals of the desert — Occurrences on the road — Description of Siwa — Antient edifice — Intercourse with other countries — Produce and manners — Attempt to penetrate farther into the desert — Return. | 14 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| FROM ALEXANDRIA TO RASHID. | |

| Abu-kîr — Fertility of the country — Description of Rashîd — Journey to Terané — Fué, Deîrut, and Demenhûr. | 30 |

| [xxx]CHAP. IV. | |

| TERANE AND THE NATRON LAKES. | |

| Government of Terané — Carlo Rossetti — The trade in natrôn — Manners — Journey to the Lakes — Observations there — Remarks on natrôn — Coptic convents and MSS. — Proceed to Kahira. | 36 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| KAHIRA. | |

| Topography — Government of Kahira and of Egypt — Pasha and Beys — Mamlûks — Birth, education, dress, arms, pay — Estimate of their military skill — Power and revenue of the Beys — The Chalige — The NILE — Mosques, baths, and okals — Houses — Manners and customs — Classes of people — Account of the Copts. | 45 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| KAHIRA. | |

| Commerce — Manufactures — Mint — Castle and well — Misr-el-Attîké and antient mosque — Antient Babylon — Fostat and Bûlak — Jizé — Tomb of Shafei — Pleasure-boats — Charmers of serpents — Magic — Dancing girls — Amusements of Ramadân — Coffee-houses — Price of provisions — Recent history of Egypt — Account of the present Beys. | 74 |

| [xxxi]CHAP. VII. | |

| KAHIRA. | |

| Brief abstract of the history of Africa in general, and Egypt in particular, under the domination of the Arabs. | 93 |

| CHAP. VIII. | |

| UPPER EGYPT. | |

| Design to penetrate into Habbesh or Abyssinia — Voyage on the Nile — Description of Assiût — General course of the Nile — Caverns — Kaw — Achmîm — Painted caverns — Jirjé or Girgi — Dendera — Antient temple — Kous — Topography of Upper Egypt — El-wah-el-Ghîrbi — Situation of the Oasis parva. | 120 |

| CHAP. IX. | |

| UPPER EGYPT. | |

| Thebes — Site and antiquities — Painted caverns — Their discovery and plan — Manners of the people of Thebes — Isna — Fugitive Beys — Antiquities — Rain — Assûan or Syené — Obstacles to farther progress — Return to Ghenné. | 134 |

| [xxxii]CHAP. X. | |

| JOURNEY TO COSSÎR ON THE RED SEA. | |

| Inducements and danger — Route — Account of Cossîr — Commerce — Return by another route — Granite rocks, and antient road — Marble quarries — Pretended canal — Earthen ware of Ghenné — Murder of two Greeks, and subsequent report of the Author’s death. | 143 |

| CHAP. XI. | |

| OCCURRENCES AT KAHIRA. | |

| Arrival of the Pasha — Death of Hassan Bey — Decline of the French factory in Kahira — Expulsion of the Maronite Christians from the Custom-house — Riot among the Galiongîs — Obstructions of the canal of Menûf — Supply of fish in the pools of Kahira — Expedition of Achmet Aga, &c. | 151 |

| CHAP. XII. | |

| ANTIENT EGYPTIANS. | |

| Their persons, complexion, &c. | 159 |

| CHAP. XIII. | |

| JOURNEY TO FEIUME. | |

| Tamieh — Canals — Feiume — Roses — Lake Mœris — Oasis parva — Pyramids — of Hawara — of Dashûr — of Sakarra — of Jizé,[xxxiii] or the Great Pyramids — Antient Memphis — Egyptian capitals. | 167 |

| CHAP. XIV. | |

| JOURNEY TO SINAI. | |

| Route — Suez — Ships and ship-building — Trade — Scarcity of water — Remains of the antient canal — Tûr — Mountains of red granite — Description of Sinai — Eastern gulf of the Red Sea — Return to Kahira. | 175 |

| CHAP. XV. | |

| JOURNEY TO DAR-FÛR, | |

| A KINGDOM IN THE INTERIOR OF AFRICA. | |

| Design to penetrate into the interior of Africa — Difficulties — Caravan from Soûdan or Dar-Fûr — Preparations — Departure from Assiût — Journey to El-wah — Mountains — Desert — Charjé in El-wah — Bulak — Beirîs — Mughes — Desert of Sheb — Desert of Selimé — Leghéa — Natrôn spring — Difficulties — Enter the kingdom of Fûr — Sweini — Detention — Representations to the Melek — Residence — New difficulties — Villany of Agent — Sultan’s letter — Enmity of the people against Franks — El-Fasher — Illness — Conversations with the Melek Misellim — Relapse — Robbery — Cobbé — Manners — Return to El-Fasher — The Melek Ibrahim — Amusements — Incidents — Audience of the Sultan Abd-el-rachmân-el-Rashîd — His personal character — Ceremonies of the Court. | 180 |

| [xxxiv]CHAP. XVI. | |

| DAR-FÛR. | |

| Residence with the Melek Mûsa — Dissimulation of the Arabs — Incidents — Return to Cobbé — Endeavours to proceed farther into Africa — Constrained to exercise medicine — Festival — Punishment of Conspirators — Art of the Sultan — Atrocious conduct of my Kahirine servant — At length an opportunity of departure is offered, after a constrained residence in Dar-Fûr of nearly three years. | 216 |

| CHAP. XVII. | |

| DAR-FÛR. | |

| Topography of Dar-Fûr, with some account of its various inhabitants. | 234 |

| CHAP. XVIII. | |

| DAR-FÛR. | |

| On the mode of travelling in Africa — Seasons in Dar-Fûr — Animals — Quadrupeds — Birds — Reptiles and insects — Metals and minerals — Plants. | 246 |

| [xxxv]CHAP. XIX. | |

| DAR-FÛR. | |

| Government — History — Agriculture — Population — Building — Manners, Customs, &c. | 276 |

| CHAP. XX. | |

| DAR-FÛR. | |

| Miscellaneous remarks on Dar-Fûr, and the adjacent countries. | 305 |

| CHAP. XXI. | |

| MEDICAL OBSERVATIONS. | |

| Psoropthalmia — Plague — Small-pox — Guinea worm — Scrophula — Syphilis — Bile — Tenia — Hernia — Hydrocele — Hemorrhoides and fistula — Apoplexy — Umbilical ruptures — Accouchemens — Hydrophobia — Phlebotomy — Remedies — Remarks — Circumcision — Excision. | 314 |

| CHAP. XXII. | |

| FINAL DEPARTURE FROM KAHIRA, AND JOURNEY TO JERUSALEM. | |

| Voyage down the Nile to Damiatt — Vegetation — Papyrus — Commerce — Cruelty of the Mamlûk government — Voyage to Yaffé[xxxvi] — Description of Yaffé — Rama — Jerusalem — Mendicants — Tombs of the kings — Bethlehem — Agriculture — Naplosa — Samaria — Mount Tabor. | 351 |

| CHAP. XXIII. | |

| GALILEE — ACCA. | |

| Improvements by Jezzâr — Trade — Taxes — White Promontory, and River Leontes — Tyre — Seide — Earthquake — Kesrawan — Syrian wines — Beirût — Anchorage — Provisions — River Adonis — Antûra — Harrîse — Tripoli — Ladakia — Journey to Aleppo, or Haleb. | 366 |

| CHAP. XXIV. | |

| OBSERVATIONS AT HALEB. | |

| Sherîfs and Janizaries — Manufactures and commerce — Quarries — Price of provisions — New sect — Journey to Antioch — Description of antient Seleucia — Return to Haleb. | 384 |

| CHAP. XXV. | |

| JOURNEY TO DAMASCUS. | |

| Entrance of the Hadjîs — Topography of Damascus — Trade and manufactures — Population — Observations on the depopulation of the East — Government and manners of Damascus — Charitable foundations — Anecdotes of recent history — Taxes — Price of provisions — Sacred caravan. | 394 |

| [xxxvii]CHAP. XXVI. | |

| Journey from Damascus to Balbec — Syriac language — Balbec — Recent discoveries — Zahhlé — Printing-office — Houses of Damascus — Return to Aleppo. | 405 |

| CHAP. XXVII. | |

| Journey from Aleppo towards Constantinople — Route — Aintâb — Mount Taurus — Bostan — Inhabitants, their manners and dress — Kaisarîa — Angora — Walls and antiquities — Angora goats — Manufactures — Topography — Journey to Ismît — Topography — General remarks concerning Anatolia or Asia Minor. | 410 |

| CHAP. XXVIII. | |

| Observations at Constantinople — Paswân Oglo — Character of the present Sultan — State of learning — Public libraries — Turkish taste — Coals — Greek printing-house — Navy — Return to England. | 419 |

| CHAP. XXIX. | |

| Comparative view of life and happiness in the East and in Europe. | 425 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

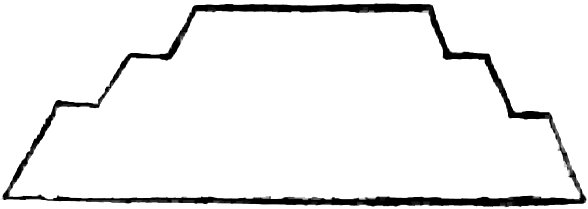

| No. I. | Illustration of Maps | Page 445 |

| II. | Itineraries | 451 |

| III. | Meteorological Table | 473 |

| IV. | Remarks on the works of Savary and Volney | 481 |

| V. | Remarks on the recent French accounts of Egypt | 486 |

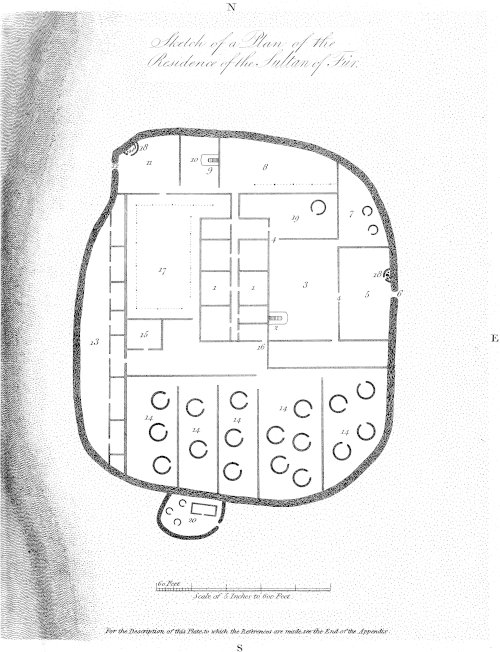

| VI. | Explanation of the plate facing page 286 | 495 |

| An ancient Egyptian Temple complete, from the Description of Strabo. | Frontispiece |

| Map of the route of the Soudan Caravan | to face page 180 |

| Map of Darfur | to face page 284 |

| Sketch of a Plan of the Residence of the Sultan of Fûr. | to face page 286 |

[1]TRAVELS

IN

AFRICA,

EGYPT, AND SYRIA.

ALEXANDRIA.

Antient Walls and Ruins — The two Ports — Reservoirs — Vegetation — Antiquities — Population — Government — Commerce — Manufactures — Anecdote of recent History.

THE transit from the coasts of Britain to those of Egypt was marked by nothing that can interest or amuse, unless it be the contrast between the phenomena of winter on the former, with those which strike the view on approaching the latter. A sea voyage is always tedious, except to the merchant and the mariner; and therefore, though our’s was attended with every favourable circumstance, and occupied no more than twenty-six days, there is scarcely any thing relative to it that can afford entertainment in the recital. I arrived in Egypt on the 10th of January 1792.

[2]Alexandria now exhibits very few marks, by which it could be recognized as one of the principal monuments of the magnificence of the conqueror of Asia, the emporium of the east, and the chosen theatre of the far-sought luxuries of the Roman Triumvir, and the Egyptian queen. Its decay doubtless has been gradual; but fifteen centuries, during which it has been progressive, have evinced its antient opulence by the slowness of its fall.

The present walls are of Saracenic structure, and therefore can determine nothing with respect to the antient dimensions of the city[1]. They are lofty, being in some places more than forty feet in height, and apparently no where so little as twenty. But, though substantial and flanked with towers, they could offer no resistance, unless it were against the Mamlûk cavalry, which alone the inhabitants fear, and accordingly keep them in some repair. They also furnish a sufficient security against the Bedouins, who live part of the year on the banks of the canal, and often plunder the cattle in the neighbourhood. The few flocks and herds, which are destined to supply the wants of the city, are pastured on the herbage, of which the vicinity of the canal favours the growth, and generally brought in at night, when the two gates are shut; as they also are whenever it is known that hostile tribes are encamped near them.

[3]These Saracenic walls present nothing curious, except some ruinous towers: and the only remain of the antient city worth notice is a colonnade, near the gate leading to Rashîd, of which, however, only a few columns remain; and what is called the amphitheatre on the south east, a rising ground, whence is a fine view of the city and port. Of the singular suburb styled Necropolis, or “The City of the Dead,” no remain exists.

It cannot be supposed that the antient city should have occupied only the small space contained within the present inclosure. The pristine wall was certainly far more extensive than the present: yet even of this only an inconsiderable portion between the two ports is now filled with habitations.—What remains is laid out in gardens, which supply such fruits and vegetables as are suited to the climate and soil, and the natives are most accustomed to use for food; or left waste, and serving as a receptacle for offal and rubbish; being in part rendered unfit for culture by the ruins which cover the surface to a considerable depth. For, though it be not now possible to determine the antient boundaries of the city, or to assign with precision the site of its more remarkable edifices, these vestiges of former magnificence yet remain. Heaps of rubbish are on all sides visible, whence every shower of rain, not to mention the industry of the natives in digging, discovers pieces of precious marble, and sometimes antient coins, and fragments of sculpture.

The harbour on the east, styled, I know not why, the new port, which in all appearance could never have been a very good one, from the rocky nature of the bottom, has the farther[4] disadvantage of partaking in the agitation of the sea when certain winds prevail. The European vessels which frequent it are, however, enabled, with some precautions, to lie at anchor securely, to the number of about twenty. They are confined to this small space, which bears no proportion to the whole extent of the harbour, by the shallowness of the water, which seems in some degree the effect of great quantities of ballast, that from time to time have been discharged within its limits. The Government pays no regard to this practice, which yet in the end must render the port useless. It is currently reported in the place, and many marks yet exist to give credibility to that report, as well as the design of Norden, which so represents it, that the water, within the memory of persons now living, reached the gate of the old custom-house; which I now find removed many fathoms from the water’s edge. So that it would seem the sea is retiring, and that nature, rather than any weaker agent, has effected the change. The old port, allotted to the Mohammedans, is spacious, though somewhat of less extent than the other. There is throughout a depth of five or six fathom; and in many places more: the anchorage is generally secure.

The city extends along a part of the isthmus and the peninsula; at the eastern extremity of which is situated a fort, where it would seem may formerly have stood the Pharos. This fort is now ruinous, and is joined with the continent by a mole built of stone, and in which are wrought arches, to weaken the effect of the water. It has been sheltered by a wall on the west side, now also ruinous. The houses, which are chiefly masonry,[5] are commonly of more than one story, and well adapted to the mode of living among the inhabitants. Though rain occasionally fall in the autumn, a flat roof is found to answer every purpose of security from the weather, and accordingly it is the general form of the dwelling-houses.

Of the deep and capacious reservoirs, which preserved the water of the Nile during the annual subsidence of that river, and of which there was probably a series, continued from one to the other extremity of the city, not more than seven remain fit for use. From these the citizens are at this time supplied; and, as they are some way removed from the inhabited quarter, a few of the poorer class obtain a subsistence by drawing the water, and carrying it on camels from house to house; and for each camel’s load they receive four or five paras, about twopence. The roofs of these cisterns or reservoirs are supported by massy timber. They have probably been thus constructed at the beginning, as it is difficult to suppose that the modern Alexandrians should entirely have changed so essential a part, and have chosen to substitute wood for stone, in a place where the former is extremely scarce, and the other very abundant.

The elevation of the city above the level of the sea is small; and it seems very difficult to render it capable of offering any formidable resistance to an external enemy.

The soil, wherever a vegetable mould is discoverable, is light, and favourable to any kind of culture; but it has apparently been brought there for the purpose, as the natural soil seems[6] wholly unfit for cultivation, being throughout either sand or stone. The orange and lemon are found in the gardens here, but not in great quantities. The dates are good, though not of the most esteemed kind. Yet they are found the most profitable article that the owner of the ground can cultivate. And accordingly these trees, with which the gardens are filled, not only relieve the eye from the dry whiteness of buildings, and the sandy soil; but well repay the owners for the trouble required to manage them, and for the space they occupy to the exclusion of almost every thing else. The greater number of esculent herbs, or roots, that are common among us, may be raised here, without any other difficulty than that of watering. The fruit trees that I have remarked as peculiar to the place, are the nebbek (Paliurus Athenæi) and the kishné (Cassia Keshta,) the latter of which is also found in the West Indies. The former bears a small fruit like the cherry in size, and having a stone of the same kind; but very different in colour and flavour, which more resemble those of the apple.

The chief monuments of antiquity remaining in any degree perfect, are the column, usually but improperly termed of Pompey[2], and the obelisk. On the former, not even so much of the inscription as Pococke copied is now to be distinguished. There is also a sarcophagus or chest of serpentine marble in the great mosque, which is used for a cistern. It is of the same kind with that so minutely described by Niebuhr, at Kallaat el Kabsh in Kahira, and seems to be almost as rich in hieroglyphics. It[7] has the additional advantage of being entire, and little if at all injured by time. It is said, that one of those who farmed the customs some years since, on retiring from Egypt, had negociated for the removal of this precious monument of antiquity, on board of an European vessel, with the intention of carrying it as a present to the Emperor of Germany. On the night when it was to be embarked, however, the secret being disclosed, the citizens clamorously insisted that the property of the mosque was inviolable. The projected removal was accordingly relinquished, and the chest has ever since been watched with uncommon vigilance, so that it is now difficult for an European even to obtain a sight of it; which must be my excuse for not having been more minute in my description of a monument that seems not to have been particularly observed by former travellers.

The population consists of Mohammedans of various nations; Greeks in considerable number, who have a church and convent, containing only three or four religious, but agreeably situated on the highest ground among the gardens; Armenians, who have also a church; and a few Jews, who have their synagogue. The whole, perhaps, may not amount to less than twenty thousand souls[3]; which, however, the length of my residence there did not enable me to decide. The Franciscans of Terra Santa have a church and monastery, in which reside three or four of their order. The habitations of the European consuls[8] and merchants are all near together, east of the city and close to the sea. They associate with each other, dress and live as in Europe, and, unless by their mutual animosities, are perfectly undisturbed. It is true, indeed, that the natives bear no very good character for their behaviour to strangers, but, I believe, when incivility has been experienced, it has generally first been provoked: and the natives are, perhaps, at least as often the dupes of the Frank merchants, as the latter are of the native brokers and factors, whom their commercial concerns oblige them to employ. The command of the fort, and of the few troops which are in the city, is vested in a Sardar, who is sometimes a Cashef, sometimes an inferior officer of the Beys. The internal government is in the hands of the citizens. The chief magistrate is the Cadi, an Arab, who receives his appointment from Constantinople; the others are, the Shechs of the four sects, and the Imâms of the two principal mosques. Here it may be observed, once for all, that the municipal magistrates in the east are always of the sacerdotal order.

The revenues of Alexandria, under the Ptolemies, are stated at 12,500 talents, which at 193l. 15s. the talent, is little less than two millions and an half sterling. At this time it is thought that they do not exceed four thousand five hundred purses, or 225,000l.

The commerce of Alexandria is more considerable than that of Damiatt. All exports to Europe, or imports from thence, are made at the former. The whole of the timber for house or ship building is brought from Candia, or the Archipelago. The[9] copper, manufactured or rough, of which the consumption is large, from Constantinople. Coffee and rice, raw leather, &c. are exported to that and other places. The transit of all these keeps the inhabitants in that state of activity to which they are eminently disposed; and if various causes operate unavoidably to fetter and stagnate commerce, it cannot be said that they are in fault. The navigation from Alexandria to Rashîd is conducted in small vessels of from fifteen to fifty tons burthen, which deposit their goods at Rashîd, whence they are embarked in boats of another form, and conveyed to Kahira.

Among the articles of native produce, considerable quantities of which are taken by the Frank merchants in return for the goods of their respective countries, are saffranon, Carthamus tinctorius, which is cultivated in Egypt; and senna, which chiefly comes by way of Suez: but some portion of which is also produced in Nubia, and near the first Cataract.

The consumption of broad cloth in Egypt used to be about eight hundred bales; but it was greatly decreased when I left the country, owing to the war in Europe, which prevented a proper supply. The consequent high price constrained many to have recourse to the native manufactures. Red coral is imported from Leghorn, glass beads, &c. from Venice.

The Alexandrians are remarkable for the facility with which they acquire different languages. But their own Arabic is impure, being mingled with Turkish and other dialects.

[10]Among the characteristic features of the people of this city, it is deserving of notice that they preserve the ancient character of perseverance and acuteness, especially ascribed to them by the historian of the Alexandrian war[4]. For example, suppose they wish to divide an antique column of three or four feet diameter, into two parts, for the purpose of securing the foundations of the houses near the shore from the encroachments of the sea, they make a line not more than half an inch deep, for the space of one twelfth of the circumference, then inserting two pieces of tempered steel, not larger than a dollar, at the extremities of the line, they drive a wedge in the midst. At the same time, small pieces of steel, like the former, are fixed at equal distances round the column, to the number of five or six, by means of small hammers, which strike quick, but with no violence. Thus the piece is cut off regular, and in a very short space of time.

Glass for lamps and phials is made at Alexandria, both green and white. They use natron in the manufacture instead of barilla: and the low beaches of the Egyptian coast afford plenty of excellent sand.

A dispute has lately arisen between the Alexandrians and the government, which originated in the conduct of the Syrian Christian, who has the management of the customs here. The people of Alexandria, it is to be remarked, are not among the most obedient and tractable subjects of the Mamlûk government;[11] and their situation, together with other circumstances, has favoured them in their opposition to public orders. The present Beys, especially, they affect to consider as rebels against the authority of the Porte. Thus mutually jealous, each party is constantly on the watch to profit by any oversight of the other: the Beys, in order to put the Alexandrians in the same unqualified subjection, with respect to them, as the rest of the Egyptians are; and the Alexandrians to perpetuate that qualified dependence, or imperfect autocracy, in which, by subterfuge and fertility of expedient, they have hitherto maintained themselves.

Affairs were in this state when an order came from Murad Bey, who had the jurisdiction of this district, to shut up the public warehouses, or okals, where commerce is chiefly carried on. A Cashef was sent to see it executed, but unaccompanied by any military force: he had also orders to arrest, and bring with him to Kahira, the person of Shech Mohammed el Missiri, one of the chief Mullas who had always been active in promoting opposition to the measures of the Beys; and who is remarkable, as I am informed, for eloquence both persuasive and deliberative. The greater part of the inhabitants assembled in the principal mosque, and came to the resolution of obliging the Cashef to quit the city. They also determined on sending away the superintendant of the customs, who by frauds of every kind had rendered himself hateful to them, and against whom unavailing complaints had already repeatedly been made to the Bey. Some of the body were deputed to inform both parties, that they must leave the city before night, under pain of death.[12] But the impatience of the people was too great to wait for night, and they were compelled to depart instantly, the Cashef by land, and the Christian by sea.

Orders were given to repair the walls, plant cannon, and put every thing in a state of defence. Shech Mohammed advised the citizens to divide themselves into districts; which being complied with, it was resolved that every man should provide himself with arms, who should be able to purchase them; and that those who could not should be armed at the public expence. At the end of about a month, notice was brought that two Cashefs were on their way, with a body of troops, to punish the inhabitants for their contumacious behaviour. When their arrival at Rashîd was known, the Alexandrians sent them word, that if they came without hostile intentions, they would be peaceably received: but if it were their design to have recourse to violent measures, the whole force of the city would be opposed to their entrance. One of these Cashefs afterwards proved to be the same who had before been sent back. The other was a man of the first rank, having formerly filled the office of Yenktchery Aga. They were in fact unattended, except by the domestics of this latter, perhaps in all two hundred men, chiefly on foot. The Cashef declared he had no view but to certify that the minds of the citizens were not alienated from the government, nor their intentions hostile to it; which from the news, that they were putting themselves in a state of defence, Murad Bey had been led to imagine. Yet he recommended it to them, in proof of their pacific disposition, to depute three or four of the chief citizens to Kahira, who might have an opportunity of informing[13] the Beys concerning such grievances as they should have found reason to represent, and might pave the way to a future good understanding.

This was not complied with, and the Cashef remained without proposing any alternative. After fourteen or fifteen days he left Alexandria, with a present of very small value from the citizens, and some trifles given him, in respect to the character he bore, by the European merchants. So ended this great turmoil, which I have mentioned perhaps at too great length; but which throws some light on the situation and character of the late government.

JOURNEY TO SIWA.

Attempt to penetrate to the Temple of Jupiter Ammon — Route and Provisions — Animals of the Desert — Occurrences on the Road — Description of Siwa — Antient Edifice — Intercourse with other Countries — Produce and Manners — Attempt to penetrate farther into the Desert — Return.

The information I had obtained in Alexandria having induced me to resolve on attempting to explore the vestiges of the Temple of Jupiter Ammon from that place, I procured a proper person as interpreter, and made the necessary arrangements with some Arabs, who are employed in transporting through the desert, dates and other articles, between Siwa (a small town to the westward) and Alexandria, to convey my baggage and provisions, and to procure for me a secure passage among the other tribes of Arabs, who feed their flocks at this season in the vicinity of the coast. In this I was much assisted by Mr. Baldwin, who readily entered into my views, and used all the means in his power to promote their success.

When the Arabs had finished the business on which they came to the city, and had fixed on an hour, as they thought, auspicious to travellers, they made ready for departure; and on[15] Friday, 24th February 1792, we left Alexandria. The inclinations of my conductors were in unison with mine, in the choice of a route; for they preferred that nearest the sea, for the sake of forage for their camels, which abounds more there than in the direct road; and I preferred it, as being the same that Alexander had chosen for the march of his army.

We travelled the first day only about eight miles[5], in which space several foundations of buildings are discoverable; but so imperfect are the remains, that it is not possible to say whether they were antient or modern, or to what purpose they might have been applied. From that time till Sunday, 4th March, our route lay along the coast, and we were never long together out of sight of the sea. The coast is plain; and after having left the neighbourhood of Alexandria, where it is rocky, the soil is generally smooth and sandy. Many spots of verdure, particularly at this season, relieve the eye from the effect of general barrenness: and though the vegetation be very inconsiderable, the greater part of it consisting only of different kinds of the grasswort, or kali, it offers a seasonable relief to the suffering camel. For our horses we were obliged to carry a constant supply of barley and cut straw.

There are several kinds of preserved meat prepared among the orientals for long journies. They obviate the inconveniency of salt provision by using clarified butter. The kind most used is called mishli, and will keep good for many years. It is brought from Western Barbary to Kahira.

[16]In the places where we generally rested are found the jerboa, the tortoise, the lizard, and some serpents, but not in great number. There is also an immense quantity of snails attached to the thorny plants on which the camels feed. These the Arabs frequently eat. Very few birds were visible in this quarter, except of the marine kind. One of our party killed a small hawk, which was the only one I saw. Near the few springs of water are found wild rabbits, which in Arabic they distinguish by the same name as the hare, (ارنب) and the track of the antelope and the ostrich are frequently discoverable. We passed no day without being incommoded with frequent showers; and generally a cold wind from north-west and north-west by north. Several small parties of Bedouins, who were feeding a few goats, sheep, and asses, were encamped in the road, and in the vicinity of the lake Mareotis, now dry. Such of them as were the friends of our conductor received us with every mark of hospitality and kindness; and regaled us with milk, dates, and bread newly baked. One party, indeed, became contentious for a present, or tribute on passing; but being in no condition to enforce their demand, it was after a time relinquished.

On Sunday the 4th, having travelled about six hours, we came to a well where was a copious supply of water; and having given the camels time to drink, we left the coast, and proceeded in a south-west direction. From Alexandria to this well, the time employed in motion was seventy-five hours and an half, or nearly so. Thence to Siwa, there being little or no water, we were obliged to use all possible diligence in[17] the route. Our arrival there happened on Friday the 9th, at eight in the evening. The space of time we were actually travelling from the coast, was sixty two hours and a quarter. The road from the shore inward to Siwa is perfectly barren, consisting wholly of rocks and sand, among which talc is found in great abundance. On Wednesday the 7th, at night, we had reached a small village called قارة ام الصغير Karet-am-el Sogheir: it is a miserable place, the buildings being chiefly of clay; and the people remarkably poor and dirty. It afforded the seasonable relief of fresh water, a small quantity of mutton, (for the Shech el Bellad was kind enough to kill a sheep, in return for some trifling presents which were made him,) and wood to dress pilau, from which we had been obliged to abstain since leaving the coast. This village is independent, and its environs afford nothing but dates, in which even the camels and asses of this quarter are accustomed to find their nourishment.

For about a mile and an half from Karet-am-el Sogheir the country is sprinkled with date trees, and some water is found. After which it again becomes perfectly desert, consisting of the same mountains of sand and barren rock, as before remarked, for the space of about five hours travelling. Then we were employed for more than eight hours in passing an extensive plain of barren sand, which was succeeded by other low hills and rocks. I observed, through a large portion of the road, that the surface of the earth is perfectly covered with salt.

We at length came to Siwa, which answers the description given of the Oases, as being a small fertile spot, surrounded on[18] all sides by desert land. It was about half an hour from the time of our entrance on this territory, by a path surrounded with date trees, that we came to the town, which gives name to the district. We dismounted, and seated ourselves, as is usual for strangers in this country, on a misjed, or place used for prayer, adjoining the tomb of a Marabût, or holy person. In a short time the chiefs came to congratulate us on our arrival, with the grave but simple ceremony that is in general use among the Arabs. They then conducted us to an apartment, which, though not very commodious, was the best they were provided with; and after a short interval, a large dish of rice and some boiled meat were brought; the Shechs attending while the company was served, which consisted of my interpreter, our conductor, two other Bedouins our companions, and myself.

I should here mention that my attendants, finding reason to fear that the reception of a Frank, as such, would not be very favourable, had thought proper to make me pass for a Mamlûk. Not having had any intimation of this till it was too late, and unable as I then was to converse in Arabic, it was almost impossible to remain undiscovered. Our arrival happening before the evening prayer, when the people of the place disposed themselves to devotion, in the observance of which they are very rigorous, it was remarked that I did not join. This alone was sufficient to create suspicions, and the next morning my interpreter was obliged to explain. The Shechs seemed surprised at a Christian having penetrated thus far, with some expence and difficulty, and apparently without having any urgent business to transact. But all, except one of them, were disposed to conciliation;[19] inclined thereto, no doubt, by a present of some useful articles that had been brought for them. This one was, with the herd of the people, violently exasperated at the insolence of an unbeliever, in personating and wearing the dress of a Mohammedan. At first they insisted on my instant return, or immediate conversion to the true faith; and threatened to assault the house, if compliance with these terms should be refused. After much altercation, and loud vociferations, the more moderate gained so far by their remonstrances, that it was permitted I should remain there two or three days to rest. But so little were the chiefs able to keep peace, that during the two days ensuing, whenever I quitted my apartment, it was only to be assailed with stones, and a torrent of abusive language. The time that had been allowed me to rest operated favourably for my interest, at least with the chiefs, though the populace continued somewhat intractable. For the former were contented on the fourth day to permit me to walk, and observe what was remarkable in the place.

We left our apartment at day-break, before any great number of people was assembled; and having taken with me such instruments as I was provided with, we passed along some shady paths, between the gardens, till at the distance of about two miles we arrived at what they called the ruins, or birbé. I was greatly surprised at finding myself near a building of undoubted antiquity, and, though small, in every view worthy of remark. It was a single apartment, built of massy stones, of the same kind as those of which the pyramids consist; and covered originally with six large and solid blocks, that reach from one wall[20] to the other. The length I found thirty-two feet in the clear; the height about eighteen, the width fifteen. A gate, situated at one extremity, forms the principal entrance; and two doors, also near that extremity, open opposite to each other. The other end is quite ruinous; but, judging from circumstances, it may be imagined that the building has never been much larger than it now is. There is no appearance of any other edifice having been attached to it, and the less so as there are remains of sculpture on the exterior of the walls. In the interior are three rows of emblematical figures, apparently designed to represent a procession: and the space between them is filled with hieroglyphic characters, properly so called. The soffit is also adorned in the same manner, but one of the stones which formed it is fallen within, and breaks the connection. The other five remain entire. The sculpture is sufficiently distinguishable; and even the colours in some places remain. The soil around seems to indicate that other buildings have once existed near the place; the materials of which either time has levelled with the soil, or the natives have applied to other purposes. I observed, indeed, some hewn stones wrought in the walls of the modern buildings, but was unable to identify them by any marks of sculpture.

It was mentioned to me that there were many other ruins near; but after walking for some time where they were described to be, and observing that they pointed out as ruins what were in fact only rough stones, apparently detached from the rock, I returned fatigued and dissatisfied. The Shechs had provided for us a dinner in a garden, where we were unmolested[21] by intruders; and the sun being then near the meridian, I took the opportunity of observing its altitude by means of an artificial horizon. They who are best versed in these matters will be far from thinking this the most accurate method of determining the latitude. But the result was not materially different, though in the sequel I repeated my observation. It gave N. L. 29° 12′, and a fraction:—the long. E. F. 44° 54′.

The following day I was led to some apartments cut in the rock, which had the appearance of places of sepulture. They are without ornament or inscription, but have been hewn with some labour. They appear all to have been opened; and now contain nothing that can with certainty point out the use to which they may have been originally applied. Yet there are many parts of human sculls, and other bones, with fragments of skin, and even of hair, attached to them. All these have undergone the action of fire: but whether they are the remains of bodies, reposited there by a people in the habit of burning the dead, or whether they have been burned, in this their detached state, by the present inhabitants, it must now be difficult to affirm. Yet the size of the catacombs would induce the belief that they were designed for bodies in an unmutilated state; the proportions being, length twelve feet, width six, height about six. The number of these caverns may amount to thirty, or more.

Having found a monument so evidently Egyptian in this remote quarter, I had the greater hope of meeting with something more considerable by going farther; or of being able to[22] gain some information from the natives, or the Arabs, that would fix exactly the position of the remains, if any such there were, of the far-famed Temple of Jupiter Ammon. The people of Siwa have communications equally with Egypt and Fezzan, and the wandering Arabs pass the desert in all directions, in their visits to that small territory, where they are furnished at a cheaper rate with many articles of food than they can be in the towns of Egypt. They pass thither from Elwah, from Feium, and the district of Thebes, from Fezzan, from Tripoli, from Kahira, and from Alexandria. It seemed therefore unlikely that any considerable ruins should exist within three or four days of Siwa, and unknown to them; still less so that they should be ignorant of any fertile spot, where might be found water, fruits, and other acceptable refreshments.

I therefore, by means of my interpreter, whom I had always found honest in his report, and attentive to my wishes, collected three of the Shechs who had shewn themselves most friendly to us, with my conductor, and two other Arabs who happened to be there. They entered freely into conversation about the roads, and described what was known to them of Elwah, Fezzan, and other places. But in the direction laid down for the site of the temple, they declared themselves ignorant of any such remains. I inquired for a place of the name of Santrieh, but of this too they professed their ignorance. Then, said I, if you know of no place by the name I have mentioned, and of no ruins in the direction or at the distance described, do you know of no ruins whatever farther to the westward or south-west? Yes, said one of them, there is a place called Araschié,[23] where are ruins, but you cannot go to them, for it is surrounded by water, and there are no boats. He then entered into an enchanted history of this place; and concluded with dissuading me from going there. I soon found, from the description, that Araschié was not the Oasis of Ammon, but conceiving it something gained to pass farther west, and that possibly some object might eventually offer itself that would lead to farther discovery, I determined, if it were possible, to proceed thither.

For this purpose we were obliged to use all possible secrecy, as the Siwese were bent on opposing our farther progress. An agreement was therefore made with two persons of the poorer class of the natives, for a few zecchins, that they should conduct us to Araschié; and if what we sought for was not there found, that they should, on leaving it, proceed with us to the first watering-place that they knew directly to the southward. The remainder of the time I stayed at Siwa was employed in combating the difficulties that were raised about our departure; and it was not till Monday, 12th March, that we were enabled to commence our journey west.

The Oasis which contains the town Siwa, is about six miles long, and four and a half or five wide. A large proportion of this space is filled with date trees; but there are also pomegranates, figs, and olives, apricots and plantains; and the gardens are remarkable flourishing. They cultivate a considerable quantity of rice, which, however, is of a reddish hue, and different from that of the Delta. The remainder of the cultivable land furnishes wheat enough for the consumption of the[24] inhabitants. Water, both salt and fresh, abounds; but the springs which furnish the latter are most of them tepid; and such is the nature of the water, air, and other circumstances, that strangers are often affected with agues and malignant fevers. One of those springs, which rises near the building described, is observed by the natives to be sometimes cold and sometimes warm.

I had been incommoded by the cold in the way, but in the town I found the heat oppressive, though thus early in the season. The government is in the hands of four or five Shechs, three of whom in my time were brothers, which induced me to suppose that their dignity was hereditary; but the information I received rather imported that, ostensibly, the maxim detur digniori was observed in the election, though, in fact, the party each was able to form among the people, was the real cause of his advancement. These parties, as well as the Shechs, are continually opposed to each other, which renders it difficult to carry any measure of public utility. The Shechs perform the office of Cadi, and have the administration of justice entirely in their own hands. But though external respect is shewn them, they have not that preponderating influence that is required for the preservation of public order. On the slightest grounds arms are taken up; and the hostile families fire on each other in the street, and from the houses. I observed many individuals who bore the marks of these intestine wars on their bodies and limbs. Perhaps too it is to the debility of the executive power that we are to attribute some crimes, that seem almost exclusively to belong to a different state of society. While I was there, a newly[25] born infant was found murdered, having been thrown from the top of a house. I understood that these accidents were not unfrequent. It would seem an indirect proof of libertinism in the women, which, however, no other circumstance led me to suppose. Inquiry was instituted, but no means offering to identify the perpetrator of the crime, the matter was dropped. The complexion of the people is generally darker than that of the Egyptians. Their dialect is also different. They are not in the habitual use either of coffee or tobacco. Their sect is that of Malik. The dress of the lower class is very simple, they being almost naked: among those whose costume was discernible, it approaches nearer to that of the Arabs of the desert, than of the Egyptians or Moors. Their clothing consists of a shirt of white cotton, with large sleeves, and reaching to the feet; a red Tunisine cap, without a turban; and shoes of the same colour. In warm weather they commonly cast on the shoulder a blue and white cloth, called in Egypt melayé; and in winter they are defended from the cold by an ihhram, or blanket. The list of their household furniture is very short; some earthen ware made by themselves, and a few mats, form the chief part of it, none but the richer order being possessed of copper utensils. They occasionally purchase a few slaves from the Murzouk caravan. The remainder of their wants is supplied from Kahira or Alexandria, whither their dates are transported, both in a dry state, and beaten into a mass, which when good in some degree resembles a sweet meat. They eat no large quantity of animal food; and bread of the kind known to us is uncommon. Flat cakes, without leaven, kneaded, and then half baked, form part of their nourishment. The remainder consists of thin[26] sheets of paste, fried in the oil of the palm tree, rice, milk, dates, &c. They drink in great quantities the liquor extracted from the date tree, which they term date-tree water, though it have often, in the state they drink it, the power of inebriating. Their domestic animals are, the hairy sheep and goat of Egypt, the ass, and a very small number of oxen and camels. The women are veiled, as in Egypt. After the rains the ground in the neighbourhood of Siwa is covered with salt for many weeks.

Having left our temporary residence, we proceeded, myself and my interpreter on horseback, our original conductor on foot, and the two men we had hired each on an ass: but we had not gone far, before one of the latter told us that it would be necessary to return, as the people of the town were in pursuit of us, and would not permit us to go and disinter the treasures of Araschié.

We nevertheless continued our journey for two days, without any particular molestation; in constant alarm indeed, from the pretended vicinity of hostile tribes, but without actually seeing any. At the end of that time we arrived at the place described to us. It is not far from the plain of Gegabib[6]. I found it an island, in the middle of a small lake of salt water, which contained misshapen rocks in abundance, but nothing that I could positively decide to be ruins; nor indeed was it very likely that any such should be found there, the spot being entirely destitute of trees and fresh water. Yet I had the[27] curiosity to approach nearer to these imaginary ruins; and accordingly forced my horse into the lake. He, from fatigue and weakness, or original inability to swim, soon found himself entangled, and could not keep his head above water. I fell with him, and was unable immediately to detach myself: at length, when I found myself again on dry ground, the circumstances I was under prevented me from making further observation on this island and lake.

After having visited this place, we continued our journey south, according to the agreement made with our guides, but found the pursuit equally fruitless. After having, at the end of the third day, arrived in lat. 28. 40. or nearly so, we became much distressed for water. We remained a whole night in suspense concerning our destiny, when at length a supply of this necessary refreshment was found. Not having, however, discovered any thing that bore the least resemblance to the object of our search, we were obliged to think of returning, as well from the importunity of the Arabs, as from our own fatigue and unpleasant sensations. We did so, and having fallen into the strait road from Siwa to Alexandria, we arrived at the latter place, without any new occurrence, on Monday, 2d April 1792.

I had been much indisposed with a fever and dysentery, apparently caused by drinking brackish water; and for the latter part of the time was utterly incapable of making observations, having been obliged to continue prostrate on a camel.

[28]After leaving Siwa to go to Araschié, at about six miles from the former, we passed a small building of the Doric order, apparently designed for a temple. There either has been no inscription on it, or it is now obliterated. But the proportions are those of the best age of architecture, though the materials are ordinary, being only a calcareous stone, full of marine spoils.

The ruin at Siwa resembles too exactly those of the Upper Egypt, to leave a doubt that it was erected and adorned by the same intelligent race of men. The figures of Isis and Anubis are conspicuous among the sculptures; and the proportions are those of the Egyptian temples, though in miniature. The rocks, which I saw in the neighbourhood, being of a sandy stone, bear so little resemblance to that which is employed in this fabric, that I am inclined to believe the materials cannot have been prepared on the spot. The people of Siwa seem to have no tradition concerning this edifice, nor to attribute to it any quality, but that of concealing treasures, and being the haunt of demons.

The distance between Siwa and Derna, on the coast, is said to be thirteen or fourteen days journey; from Siwa to Kahira, twelve days; and the same from Siwa to Charjé, the principal village of Elwah.

Since the above was written, an opinion has been communicated to me, that Siwa is the Siropum mentioned by Ptolemy, and that the building described was probably coëval with the Temple of Jupiter Ammon, and a dependency thereon[7]. The[29] discovery of that celebrated fane, therefore, yet remains to reward the toil of the adventurous, or to baffle the research of the inquisitive. It may still survive the lapse of ages, yet remain unknown to the Arabs, who traverse the wide expanse of the desert; but such a circumstance is scarcely probable. It may be completely overwhelmed in the sand; but this is hardly within the compass of belief.

FROM ALEXANDRIA TO RASHID.

Abu-kîr — Fertility of the Country — Description of Rashîd — Journey to Terané — Fué — Deîrut and Demenhûr.

After a month, passed in recovering from the effects of the journey to the westward, I prepared for leaving Alexandria. For many days boats could not pass to Rashîd from the contrary winds, and I constantly preferred going by land, as affording the means of more frequent and interesting observation. Reports were spread, of the road being infested by Bedouins; but I chose rather to encounter a slight danger, than omit seeing what might offer of the country. Accordingly, on the 1st of May, I commenced my journey to Rashîd. We were near four hours in reaching the village called ابوقير Abu-kîr, on horseback.

The road, for about two miles after leaving the gate of Rashîd, is marked by many vestiges of buildings, but nothing worth observing. There are also many date trees scattered round in the neighbourhood of the canal, and vegetation enough to serve for food for the small flocks of the city. About two miles from Abu-kîr are the ruins of a town, close to the sea, and a part of them under water. There are also some remains[31] of columns. This is what has been remarked as the Taposiris parva of antiquity. Abu-kîr is a village, consisting of few inhabitants. There is near it, however, a small port, and on the point of land which forms it, a fortress, but of little strength. A Tsorbashi resides there, with a few soldiers. He collects a toll from those who pass the ferry near it. It is a place of no trade, and vessels that frequent it come there chiefly for the purpose of avoiding bad weather. We were eight hours and a half in reaching Rashîd, exclusively of the time taken up in crossing two ferries. The latter part of the road, from the seaside to Rashîd, has been all marked with short columns of burned brick, at certain distances from each other.

The beauty and fertility of the country round Rashîd deserves all the praise that has been given it. The eye is not, indeed, gratified with the romantic views, flowing lines, the mixture of plain and mountain, nor that universal verdure that is to be observed on the banks of the Rhine or the Danube. But his taste is poor who would reduce all kinds of picturesque beauty to one criterion. To me, after being wearied with the sandy dryness of the barren district to the west, the vegetable soil of Rashîd, filled with every production necessary for the sustenance, or flattering to the luxury of man, the rice fields covering the superficies with verdure, the orange groves exhaling aromatic odours, the date trees formed into an umbrageous roof over the head; shall I say the mosques and the tombs, which, though wholly incompatible with the rules of architecture, yet grave and simple in the structure, are adapted to fill the mind with pleasing ideas; and above all, the unruffled[32] weight of waters of the majestic Nile, reluctantly descending to the sea, where its own vast tide, after pervading and fertilizing so long a tract, is to be lost in the general mass: these objects filled me with ideas, which, if not great or sublime, were certainly among the most soothing and tranquil that have ever affected my mind.