CANONGATE TOLBOOTH.

Title: Domestic annals of Scotland

from the revolution to the rebellion of 1745

Author: Robert Chambers

Release date: November 29, 2023 [eBook #72262]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Susan Skinner, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

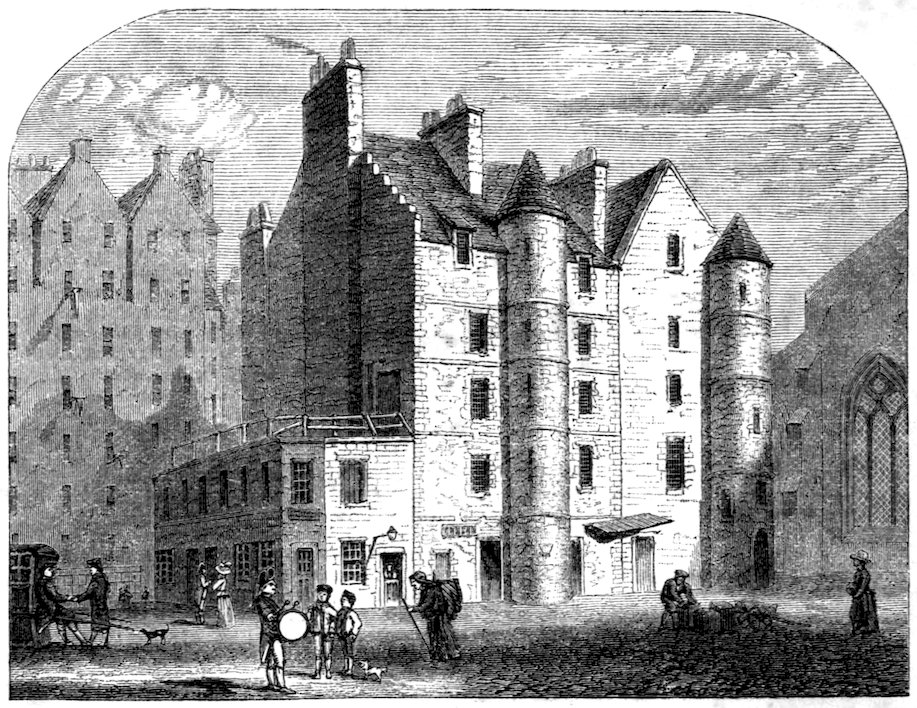

CANONGATE TOLBOOTH.

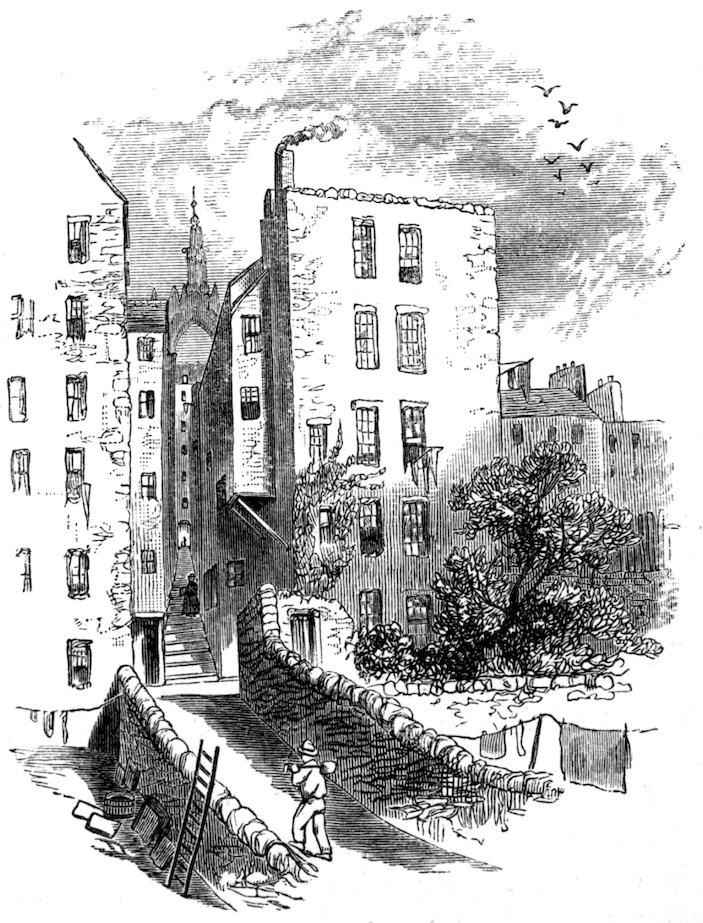

Bargarran House.

The Domestic Annals of Scotland from the Reformation to the Revolution having experienced a favourable reception from the public, I have been induced to add a volume containing similar details with regard to the ensuing half-century. This is in many respects an interesting period of the history of Scotland. It is essentially a time of transition—transition from harsh and despotic to constitutional government; from religious intolerance and severity of manners to milder views and the love of elegance and amusement; from pride, idleness, and poverty, to industrious courses and the development of the natural resources of the country. At the same time, the tendency to the wreaking out of the wilder passions of the individual is found gradually giving place to respect for law. We see, as it were, the dawn of our present social state, streaked with the lingering romance of earlier ages. On these considerations, I am hopeful that the present volume will be pronounced in no respect a falling off in contrast with the former two.

It will be found that the plan and manner of treatment pursued in the two earlier volumes are followed here. My object has still been to trace the moral and economic progress of Scotland through the medium of domestic incidents—whatever of the national life is overlooked in ordinary history; allowing the tale in every case to be told as much as possible in contemporary language. It is a plan necessarily subordinating the author to his subject, almost to the extent of neutralising all opinion and sentiment on his part; yet, feeling the value of the self-painting words of these dead and gone generations—so quaint, so unstudied, so true—so corrective in their genuineness of the glozing idolatries which are apt to arise among descendants and party representatives—I become easily reconciled to the restricted character of the task. If the present and future generations shall be in any measure enabled by these volumes to draw from the errors and misjudgments of the past a lesson as to what is really honourable and profitable for a people, the tenuis labor will not have been undergone in vain.

Edinburgh, January 1861.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| REIGN OF WILLIAM AND MARY: 1689–1694, | 1 |

| REIGN OF WILLIAM III.: 1695–1702, | 107 |

| REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE: 1702–1714, | 257 |

| REIGN OF GEORGE I.: 1714–1727, | 389 |

| REIGN OF GEORGE II.: 1727–1748, | 535 |

| APPENDIX, | 619 |

| INDEX, | 627 |

| Frontispiece—CANONGATE TOLBOOTH, EDINBURGH. | |

| Vignette—BARGARRAN HOUSE. | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| THE BASS, | 106 |

| AFRICAN COMPANY’S HOUSE AT BRISTO PORT, EDINBURGH, | 123 |

| PORTRAIT OF DR PITCAIRN, | 224 |

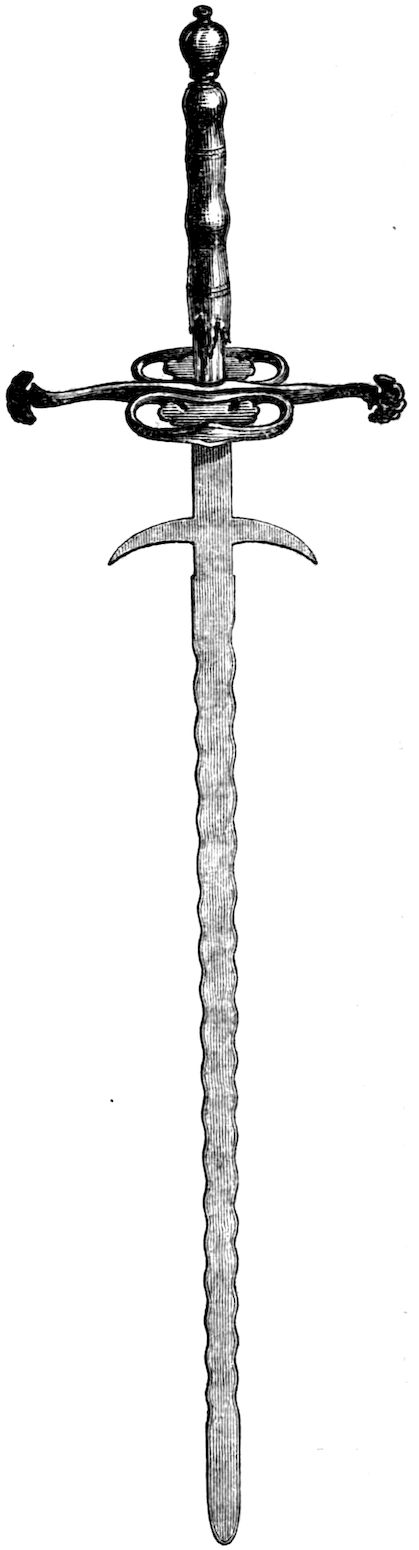

| MACPHERSON’S SWORD, | 234 |

| HOUSE OF LORD ADVOCATE STEUART, | 256 |

| DRESSES OF THE PEOPLE OF SCOTLAND, 1676, | 270 |

| BARGARRAN COAT OF ARMS, | 511 |

| LADY PLAYING ON SPINET, | 574 |

| OLD TOLBOOTH, EDINBURGH, | 638 |

Our narrative takes up the political story of Scotland at the crisis of the Revolution, when, King James having fled in terror to France, his nephew and daughter, the Prince and Princess of Orange, were proclaimed king and queen as William and Mary, and when the Episcopacy established at the Restoration, after a struggling and unhonoured existence of twenty-eight years, gave way to the present more popular Presbyterian Church. It has been seen how the populace of the west rabbled out the alien clergy established among them; how, notwithstanding the gallant insurrection of my Lord Dundee in the Highlands, and the holding out of Edinburgh Castle by the Duke of Gordon, the new government quickly gained an ascendency. It was a great change for Scotland. Men who had lately been in danger of their lives for conscience’ sake, or starving in foreign lands, were now at the head of affairs—the Earl of Melville, Secretary of State; Crawford, President of Parliament; Argyle restored to title and lands, and a privy-councillor; Dalrymple of Stair, Hume of Marchmont, Steuart of Goodtrees, and many other exiles, come back from Holland to resume prominent positions in the public service at home—while the instruments of the late unhappy government were either captives under suspicion, or living terror-struck at their country-houses. Common sort of people, who had last year been skulking in mosses from Claverhouse’s dragoons, were now marshalled in a regiment, and planted as a watch on the Perth and Forfar gentry. There were new figures in the Privy Council, and none of them ecclesiastical. There was a wholly new set of senators on the bench of the Court of Session. It looked like the sudden shift of scenes in a pantomime, rather than a series of ordinary occurrences.

2Almost as a necessary consequence of the Revolution, a war with France commenced in May 1689. Part of the operations took place in Ireland, where James II., assisted with troops by King Louis, and supported by the Catholic population, continued to exercise sovereignty till his defeat at the Boyne (July 1, 1690). The subjugation of Ireland to the new government was not completed till the surrender of Limerick and other fortified places by treaty (October 3, 1691). Long before this time, the Jacobite movement in Scotland had come to a close by the dispersion of the Highlanders at Cromdale (April 1690). A fortress and garrison were then planted at Inverlochy (Fort William), in order to keep the ill-affected clans Cameron, Macdonald, and others, in check. At the same time, the Earl of Breadalbane was intrusted with the sum of twelve thousand pounds, with which he undertook to purchase the pacification of the Highlands. In 1691, there were still some chiefs in rebellion, and a threat was held out that they would be visited with the utmost severities if they did not take the oaths to the government before the 1st of January next. This led to the massacre of the Macdonalds of Glencoe (February 13, 1692), an affair which has left a sad shade upon the memory of King William.

In Scotland, it gradually became apparent that, though the late changes had diffused a general sense of relief, and put state control more in accordance with the feelings of the bulk of the people, there was a large enough exception to embarrass and endanger the new order of things. There certainly was a much larger minority favourable to Episcopacy than was at first supposed; whole provinces in the north, and a majority of the upper classes everywhere, continued to adhere to it. A very large portion of the nobility and gentry maintained an attachment to the ex-king, or, like the bishops, scrupled to break old oaths in order to take new. Even amongst those who had assisted in the Revolution, there were some who, either from disappointment of personal ambition, or a recovery from temporary fears, soon became its enemies. Feelings of a very natural kind assisted in keeping alive the interest of King James. It was by a nephew (and son-in-law) and a daughter that he had been displaced. A frightful calumny had assisted in his downfall. According to the ideas of that age, in losing a crown he had been deprived of a birthright. If he had been guilty of some illegal doings, there might be some consideration for his age. Anyhow, his infant son was innocent; why punish him for the acts of his father? These considerations fully appear as giving point and strength to the Jacobite feeling which soon began to take a definite form in the country. The government was thus forced into severities, which again acted to its disadvantage; and thus it happened that, for some years after the deliverance of Scotland from arbitrary power, we have to contemplate a style of administration in 3which arbitrary power and all its abuses were not a little conspicuous.

In the very first session of the parliament (summer of 1689), there was a formidable opposition to the government, headed chiefly by politicians who had been disappointed of places. The discontents of these persons ripened early next year into a plot for the restoration of the ex-king. It gives a sad view of human consistency, that a leading conspirator was Sir James Montgomery of Skelmorley, who was one of the three commissioners sent by the Convention in spring to offer the crown to William and Mary. The affair ended in Montgomery, the Earl of Annandale, and Lord Ross, informing against each other, in order to escape punishment. Montgomery had to flee to the continent, where he soon after died in poverty. The offences of the rest were overlooked.

Amongst the events of this period, the ecclesiastical proceedings bear a prominent place—efforts of statesmen for moderate measures in the General Assembly—debates on church-patronage and oaths of allegiance—tramplings out of old and rebellious Episcopacy; but the details must be sought for elsewhere.[1] During 1693, there were great alarms about invasion from France, and the forcible restoration of the deposed king; and some considerable severities were consequently practised on disaffected persons. By the death of the queen (December 28, 1694), William was left in the position of sole monarch of these realms.

The first emotions of the multitude on attaining confidence that the Prince of Orange would be able to maintain his ground, and that the reigning monarch would be brought low, that the Protestant religion would be safe, and that perhaps there would be good times again for those who loved the Presbyterian cause, were, of course, very enthusiastic. So early as the close of November, the populace of Edinburgh began to call out ‘No pope, No papist,’ as they walked the streets, even when passing places where guards were stationed. The students, too, whose pope-burning enthusiasm had been sternly dealt with eight years back, now broke out of all bounds, and had a merry cremation of the pontiff’s effigy at the cross, ending with its being ‘blown up with art four stories high.’ This, however, was looked upon as a hasty 4|1688.|business, wanting in the proper solemnity; so, two days after, they went to the law-court in the Parliament Close, and there subjected his Holiness to a mock-trial, and condemned him to be burned ceremoniously on Christmas Day, doubtless meaning by the selection of the time to pass an additional slight upon the religion over which they were now triumphing.

On the appointed day, the students had a solemn muster to execute the sentence. Arranged in bands according to their standing, each band with a captain, they marched, sword in hand, to the cross, preceded by the janitor of the college, carrying the mace, and having a band of hautbois also before them. There, in presence of the magistrates and some of the Privy Council, they solemnly burned the effigy, while a huge multitude looked on delighted.[2]

There were similar doings in other parts of the country; but I select only those of one place, as a specimen of the whole, and sufficient to shew the feeling of the time.

A Protestant town-council being elected at Aberdeen, the boys of the Marischal College resolved to celebrate the occasion with a burlesque Pope’s Procession. They first thought proper to write to the new magistrates, protesting that their design was not ‘tumultuary,’ neither did they intend to ‘injure the persons or goods of any.’ The ceremonial reminds us slightly of some of the scenes in Lyndsay’s Satire of the Three Estates. Starting from the college-gate at four in the afternoon, there first went a company of men carrying links, six abreast; next, the janitor of the college, with the college-mace, preceding six judges in scarlet robes. Next marched four fifers playing; then, in succession, four priests, four Jesuits, four popish bishops, and four cardinals, all in their robes; then a Jesuit in embroidered robes, carrying a great cross. Last came the pope, carried in his state-chair, in scarlet robes lined with ermine, his triple crown on his head, and his keys on his arm; distributing pardons and indulgences as he moved along.

Being arrived at the market-cross, the pope placed himself on a theatre, where a dialogue took place between him and a cardinal, expressing the pretensions commonly attributed to the head of the Catholic Church, and announcing a doom to all heretics. In the midst of the conference, Father Peter, the ex-king’s confessor, entered with a letter understood to convey intelligence of the late 5|1689.| disastrous changes in London; whereupon his holiness fell into a swoon, and the devil came forward, as to help him. The programme anticipates that this would be hailed as a merry sight by the people. But better remained. The pope, on recovering, began to vomit ‘plots, daggers, indulgences, and the blood of martyrs,’ the devil holding his head all the time. The devil then tried in rhyme to comfort him, proposing that he should take refuge with the king of France; to which, however, he professed great aversion, as derogatory to his dignity; whereupon the devil appeared to lose patience, and attempted to throw his friend into the fire. But this he was prevented from doing by the entry of one ordering that the pope should be subjected to a regular trial.

The pontiff was then arraigned before the judges as guilty of high treason against Omnipotence, in as far as he had usurped many of its privileges, besides advancing many blasphemous doctrines. ‘The court adduced sufficient proofs by the canons of the church, bulls, pardons, and indulgences, lying in process;’ and he was therefore pronounced guilty, and ordered to be immediately taken to the public place of execution, and burned to ashes, his blood to be attainted, and his honours to be blotted out of all records. The procession was then formed once more, and the sentence was read from the cross; after which ‘his holiness was taken away from the theatre, and the sentence put in execution against him. During the time of his burning, the spectators were entertained with fireworks and some other divertisements.

‘After all was ended, the Trinity Church bell—which was the only church in Scotland taken from the Protestants and given to the papists, wherein they actually had their service—was rung all the night.’[3]

Patrick Walker relates,[4] with great relish, the close of the political existence of the unhappy episcopate of Scotland, amidst the tumults attending the sitting of the Convention at Edinburgh, during the process of settling the crown on William and Mary. For a day or two after this representative body sat down, several bishops attended, as a part of the parliamentary constitution of the country, and by turns took the duty of saying prayers. The last who did so, the Bishop of Dunkeld, spoke pathetically of the 6|1689.| exiled king as the man for whom they had often watered their couches, and thus provoked from the impetuous Montgomery of Skelmorley a jest at their expense which will not bear repetition. They were ‘put out with disdain and contempt,’ while some of the members expressed a wish that the ‘honest lads’ knew of it, ‘for then they would not win away with hale gowns.’ And so Patrick goes on with the triumph of a vulgar mind, describing how they ‘gathered together with pale faces, and stood in a cloud in the Parliament Close. James Wilson, Robert Neilson, Francis Hislop, and myself were standing close by them. Francis Hislop with force thrust Robert Neilson upon them; their heads went hard upon one another. But there being so many enemies in the city, fretting and gnashing their teeth, waiting for an occasion to raise a mob, where undoubtedly blood would have been shed; and we having laid down conclusions among ourselves to guard against giving the least occasion to all mobs; kept us from tearing off their gowns.

‘Their graceless graces went quickly off; and neither bishop nor curate was seen in the streets; this was a surprising change not to be forgotten. Some of us would have been rejoiced more than in great sums, to see these bishops sent legally down the Bow, that they might have found the weight of their tails in a tow, to dry their hose-soles, that they might know what hanging was; they having been active for themselves, and the main instigators to all the mischiefs, cruelties, and bloodshed of that time, wherein the streets of Edinburgh, and other places of the land, did run with the innocent, precious, dear blood of the Lord’s people.’

A more chivalric adversary might have, after all, found something to admire in these poor prelates, who permitted themselves to be so degraded, purely in consequence of their reverence for an oath, while many good Presbyterians were making little of such scruples. On the other hand, a more enlightened bench of bishops might have seen that the political status which they now forfeited had all along been a worldly distinction working against the success of spiritual objects, and might thus have had some comfortable re-assurances for the future, as they ‘stood in a cloud in the Parliament Close,’ to receive the concussion of Robert Neilson pushed on by Francis Hislop.

Since Christmas of the past year, there had been constant mob-action against the Episcopal clergy, especially in the western shires, about three hundred having been rudely expelled or forced to 7|1689.| flee for safety of their lives. On the rebound of such a spring, nothing else was to be expected; perhaps there is even some force in the defence usually put forward for the zealous Presbyterians on this occasion, that their violences towards those obnoxious functionaries were less than might have been expected. I do not therefore deem it necessary to go into ‘the Case of the present Afflicted Clergy,’[5] or to call attention to the similar case of the faithful professors of the Edinburgh University, expelled by a commission in the autumn of 1690. There is, however, one anecdote exemplifying Christian feeling on this occasion, which it must be pleasant to all to keep in green remembrance. ‘The last Episcopal clergyman of the parish of Glenorchy, Mr David Lindsay, was ordered to surrender his charge to a Presbyterian minister then appointed by the Duke [Earl] of Argyle. When the new clergyman reached the parish to take possession of his living, not an individual would speak to him [public feeling on the change of church being here different] except Mr Lindsay, who received him kindly. On Sunday, the new clergyman went to church, accompanied by his predecessor. The whole population of the district were assembled, but they would not enter the church. No person spoke to the new minister, nor was there the least noise or violence till he attempted to enter the church, when he was surrounded by twelve men fully armed, who told him he must accompany them; and, disregarding all Mr Lindsay’s prayers and entreaties, they ordered the piper to play the march of death, and marched away the minister to the confines of the parish. Here they made him swear on the Bible that he would never return, or attempt to disturb Mr Lindsay. He kept his oath. The synod of Argyle were highly incensed at this violation of their authority; but seeing that the people were fully determined to resist, no further attempt was made, and Mr Lindsay lived thirty years afterwards, and died Episcopal minister of Glenorchy, loved and revered by his flock.’[6]

A little incident connected with the accession of King William and Queen Mary was reported to Wodrow as ‘beyond all question.’ When the magistrates of Jedburgh were met at their market-cross to proclaim the new sovereigns, and drink their healths, a Jacobite chanced to pass by. A bailie asked him if he 8|1689.| would drink the king’s health; to which he answered no, but he was willing to take a glass of the wine. They handed him a little round glass full of wine; and he said: ‘As surely as this glass will break, I drink confusion to him, and the restoration of our sovereign and his heir;’ then threw away the glass, which alighted on the tolbooth stair, and rolled down unbroken. The bailie ran and picked up the glass, took them all to witness how it was quite whole, and then dropping some wax into the bottom, impressed his seal upon it, as an authentication of what he deemed little less than a miracle.

Mr William Veitch happening to relate this incident in Edinburgh, it came to the ears of the king and queen’s commissioner, the Earl of Crawford, who immediately took measures for obtaining the glass from Jedburgh, and ‘sent it up with ane attested account to King William.’[7]

The sitting of the Convention brought out a great amount of volunteer zeal, in behalf of the Revolution, amongst those extreme Presbyterians of the west who had been the greatest sufferers under the old government. They thought it but right—while the Highlanders were rising for James in the north—that they should take up arms for William in the south. The movement centered at the village of Douglas in Lanarkshire, where the representative of the great House of that name was now devoted to the Protestant interest. On the day noted, a vast crowd of people assembled on a holm or meadow near the village, where a number of their favourite preachers addressed them in succession with suitable exhortations, and for the purpose of clearing away certain scruples which were felt regarding the lawfulness of their appearing otherwise than under an avowed prosecution of the great objects of the Solemn League and Covenant.

After some difficulties on these and similar points, a regiment was actually constituted on the 14th of May, and nowhere out of Scotland perhaps could a corps have been formed under such unique regulations. They declared that they appeared for the preservation of the Protestant religion, and for ‘the work of reformation in Scotland, in opposition to popery, prelacy, and arbitrary power.’ They stipulated that their officers should exclusively be men such as ‘in conscience’ they could submit to. A minister was appointed for the regiment, and an elder nominated 9|1689.| for each company, so that the whole should be under precisely the same religious and moral discipline as a parish, according to the standards of the church. A close and constant correspondence with the ‘United Societies’—the Carbonari of the late evil times—was settled upon. A Bible was a part of the furniture of every private’s knapsack—a regulation then quite singular. Great care was taken in the selection of officers, the young Earl of Angus, son of the Marquis of Douglas, being appointed colonel; while the second command was given to William Cleland, a man of poetical genius and ardent soldierly character, who had appeared for God’s cause at Bothwell-brig. It is impossible to read the accounts that are given of this Cameronian Regiment, as it was called, without sympathising with the earnestness of purpose, the conscientious scrupulosity, and the heroic feelings of self-devotion, under which it was established, and seeing in these demonstrations something of what is highest and best in the Scottish character.

It is not therefore surprising to learn that in August, when posted at Dunkeld, it made a most gallant and successful resistance to three or four times the number of Highlanders, then fresh from their victory at Killiecrankie; though, on this occasion, it lost its heroic lieutenant-colonel. Afterwards being called to serve abroad, it distinguished itself on many occasions; but, unluckily, the pope being concerned in the league for which King William had taken up arms, the United Societies from that time withdrew their countenance from the regiment. The Cameronians became the 26th Foot in the British army, and, long after they had ceased to be recruited among the zealous in Scotland, and ceased to exemplify Presbyterian in addition to military discipline, they continued to be singular in the matter of the Bible in the knapsack.[8]

There had been for some time in Scotland a considerable number of French Protestants, for whom the charity of the nation had been called forth. To these was now added a multitude of poor Irish of the same faith, refugees from the cruel wars going on in their own country, and many of whom were women, children, and infirm persons. Slender as the resources of Scotland usually were, and sore pressed upon at present by the exactions necessary for supporting the new government, a collection was going on in behalf of the refugee Irish. It was 10|1689.| now, however, represented, that many in the western counties were in such want, that they could not wait till the collection was finished; and so the Lords of the Privy Council ordered that the sums gathered in those counties be immediately distributed in fair proportions between the French and Irish, and enjoining the distributors ‘to take special care that such of those poor Protestants as stays in the remote places of those taxable bounds and districts be duly and timeously supplied.’ Seventy pounds in all was distributed.

Five days before this, we hear of John Adamson confined in Burntisland tolbooth as a papist, and humanely liberated, that he might be enabled to depart from the kingdom.[9]

This morning, being Sunday, the royal orders for the appointment of fifteen new men to be Lords of Session reached Edinburgh, all of them being, of course, persons notedly well affected to the new order of things. Considering the veneration professed for the day by zealous Presbyterians in Scotland, and how high stood the character of the Earl of Crawford for a religious life, one is rather surprised to find one of the new judges (Crossrig) bluntly telling that that earl ‘sent for me in the morning, and intimated to me that I was named for one of them.’ He adds a curious fact. ‘It seems the business had got wind, and was talked some days before, for Mr James Nasmyth, advocate, who was then concerned for the Faculty’s Library, spoke to me to pay the five hundred merks I had given bond for when I entered advocate; which I paid. It may be he thought it would not be so decent to crave me after I was preferred to the bench.’[10]

It is incidental to liberating and reforming parties that they seldom escape having somewhat to falsify their own professions. The Declaration of the Estates containing the celebrated Claim of Right (April 1689) asserted that ‘the imprisoning of persons, without expressing the reasons thereof, and delaying to put them to trial, is contrary to law.’ It also pronounced as equally illegal ‘the using of torture without evidence in ordinary crimes.’ Very good as a party condemnation of the late government, or as a declaration of general principles; but, for a time, nothing more.

One of the first acts of the new government was for the ‘securing of suspect persons.’ It could not but be vexing to 11|1689.| the men who had delivered their country ‘from thraldom and poperie, and the pernicious inconveniences of ane absolute power,’ when they found themselves—doubtless under a full sense of the necessity of the case—probably as much so as their predecessors had ever felt—ordering something like half the nobility and gentry of the country, and many people of inferior rank, into ward, there to lie without trial—and in at least one notorious case, had to resort to torture to extort confession; thus imitating those very proceedings of the late government which they themselves had condemned.

All through the summer of 1689, the register of the Privy Council is crammed with petitions from the imprisoned, calling for some degree of relief from the miseries they were subjected to in the Edinburgh Tolbooth, Stirling Castle, Blackness Castle, and other places of confinement, to which they had been consigned, generally without intimation of a cause. The numbers in the Edinburgh Tolbooth were particularly great, insomuch that one who remembers, as the author does, its narrow gloomy interior, gets the idea of their being packed in it much like the inmates of an emigrant ship.

Men of the highest rank were consigned to this frightful place. We find the Earl of Balcarres petitioning (May 30) for release from it on the plea that his health was suffering, ‘being always, when at liberty, accustomed to exercise [his lordship was a great walker];’ and, moreover, he had given security ‘not to escape or do anything in prejudice of the government.’ The Council ordained that he should be ‘brought from the Tolbooth to his own lodging in James Hamilton’s house over forgainst the Cross of Edinburgh,’ he giving his parole of honour ‘not to go out of his lodgings, nor keep correspondence with any persons in prejudice or disturbance of the present government.’ With the like humanity, Lord Lovat was allowed to live with his relative the Marquis of Athole in Holyroodhouse, but under surveillance of a sentinel.

Sir Robert Grierson of Lagg—who, having been an active servant of the late government in some of its worst work, is the subject of high popular disrepute as a persecutor—was seized in his own house by Lord Kenmure, and taken to the jail of Kirkcudbright—thence afterwards to the Edinburgh Tolbooth. He seems to have been liberated about the end of August, on giving security for peaceable behaviour.

The most marked and hated instrument of King James was 12|1689.| certainly the Chancellor Earl of Perth. He had taken an early opportunity of trying to escape from the country, so soon as he learned that the king himself had fled. It would have been better for all parties if his lordship had succeeded in getting away; but some officious Kirkcaldy boatmen had pursued his vessel, and brought him back; and after he had undergone many contumelies, the government consigned him to close imprisonment in Stirling Castle, ‘without the use of pen, ink, or paper,’ and with only one servant, who was to remain close prisoner with him. Another high officer of the late government, John Paterson, Archbishop of Glasgow, was placed in close prison in Edinburgh Castle, and not till after many months, allowed even to converse with his friends: nor does he appear to have been released till January 1693.

Among the multitude of the incarcerated was an ingenious foreigner, who for some years had been endeavouring to carve a subsistence out of Scotland, with more or less success. We have heard of Peter Bruce before[11] as constructing a harbour, as patentee for a home-manufacture of playing-cards, and as the conductor of the king’s Catholic printing-house at Holyrood. It ought likewise to have been noted as a favourable fact in his history, that the first system of water-supply for Edinburgh—by a three-inch pipe from the lands of Comiston—was effected by this clever Flandrian. At the upbreak of the old government in December, Bruce’s printing-office was destroyed by the mob, and his person laid hold of. We now (June 1689) learn, by a petition from him to the Privy Council, that he had been enduring ‘with great patience and silence seven months’ imprisonment, for no other cause or crime but the coming of one Nicolas Droomer, skipper at Newport, to the petitioner’s house, which Droomer was likewise on misinformation imprisoned in this place, but is released therefra four weeks ago,’ He adds that he looks on his imprisonment to be ‘but ane evil recompense for all the good offices of his art, has been performed by him not only within the town of Edinburgh, but in several places of the kingdom, to which he was invited from Flanders. He, being a stranger, yet can make it appear [he] has lost by the rabble upwards of twenty thousand merks of writs and papers, besides the destruction done to his house and family, all being robbed, pillaged, and plundered from him, and not so much as a shirt left him or his wife.’ He 13|1689.| thinks ‘such barbarous usage has scarce been heard [of]; whereby, and through his imprisonment, he is so out of credit, that himself was like to starve in prison, [and] his family at home in the same condition.’ Peter’s petition for his freedom was acceded to, on his granting security to the extent of fifty pounds for peaceable behaviour under the present government.

Another sufferer was a man of the like desert—namely, John Slezer, the military engineer, to whom we owe that curious work the Theatrum Scotiæ. The Convention was at first disposed to put him into his former employment as a commander of the artillery; but he hesitated about taking the proper oath, and in March a warrant was issued for securing him ‘untill he find caution not to return to the Castle [then held out for King James].’[12] He informed the Council (June 3) that for some weeks he had been a close prisoner in the Canongate Tolbooth by their order, till now, his private affairs urgently requiring his presence in England, he was obliged to crave his liberation, which, ‘conceiving that he knew himself to be of a disposition peaceable and regular,’ he thought they well might grant. They did liberate him, and at the same time furnished him with a pass to go southward.

One of the petitioning prisoners, Captain Henry Bruce, states that he had been in durance for nine months, merely because, when the rabble attacked Holyroodhouse, he obeyed the orders of his superior officer for defending it. That superior officer himself, Captain John Wallace, was in prison on the same account. He presented a petition to the Council—February 5, 1691—setting forth how he had been a captive for upwards of a year, though, in defending Holyrood from the rabble, he had acted in obedience to express orders from the Privy Council of the day, and might have been tried by court-martial and shot if he had not done as he did. He craved liberation on condition of self-banishment. The Council ordered their solicitor to prosecute him; and on a reclamation from him, this order was repeated. In the ensuing November, however, we find Wallace still languishing in prison, and his health decaying—although, as he sets forth in a petition, ‘by the 13th act of the Estates of this kingdom, the imprisoning persons without expressing the reasons, and delaying to put them to a trial, is utterly and directly contrary to the known statutes, laws, and freedoms of this kingdom.’ He was not 14|1689.| subjected to trial till August 6, 1692, when he had been nearly four years a prisoner. The laborious proceedings, extending over several days, and occupying many wearisome pages of the Justiciary Record, shew the anxiety of the Revolution government to be revenged on this gallant adversary; but the trial ended in a triumphant acquittal.

Several men and women were imprisoned in the Tolbooth for giving signals to the garrison holding out the Castle. One Alexander Ormiston petitioned for his liberation as innocent of the charge. He had merely wiped his eyes, which were sore from infancy, with his napkin, as he passed along the Grassmarket; and this had been interpreted into his giving a signal. After a confinement of twelve days, Alexander obtained his liberation, ‘free of house-dues.’

John Lothian petitioned, August 19, for liberation, having been incarcerated on the 8th of July. He declared himself unconscious of anything that ‘could have deserved his being denied the common liberty of a subject,’ A most malignant fever had now broken out in the Tolbooth, whereof one prisoner died last night, and on all hands there were others infected beyond hope of recovery. He, being reduced to great weakness by his long confinement, was apprehensive of falling a victim. John Rattray, on the ensuing day, sent a like petition, stating that he had lain six weeks ‘in close prison, in a most horrible and starving condition, for want of meat, drink, air, and bedding,’ A wife and large family of small children were equally destitute at home, and likely to starve, ‘he not having ane groat to maintain either himself or them.’ Lothian was liberated, but the wretched Rattray was only transferred to ‘open prison’—that is, a part of the jail where he was accessible to his family and to visitors.

Amongst the multitude of political prisoners was one James Johnstone, who had been put there two years before, without anything being laid to his charge. The new government had ordered his liberation in June, but without paying up the aliment due to him; consequently, he could not discharge his prison-dues; and for this the Goodman—so the head-officer of the jail was styled—had detained him. He was reduced to the most miserable condition, often did not break bread for four or five days, and really had no dependence but on the charity of the other scarcely less miserable people around him. The Council seem to have felt ashamed that a friend of their own should have been allowed to lie nine months in jail after the Revolution; so they ordered 15|1689.| his immediate dismissal, with payment of aliment for four hundred and two days in arrear.[13]

Christopher Cornwell, servitor to Thomas Dunbar, stated to the Privy Council, March 19, 1690, that he had been in the Edinburgh Tolbooth since June last with his master, ‘where he has lived upon credit given him by the maid who had the charge of the provisions within the prison, and she being unable as well as unwilling to furnish him any more that entertainment, mean as it was, his condition hardly can be expressed, nor could he avoid starving.’ He was liberated upon his parole.

David Buchanan, who had been clerk to Lord Dundee’s regiment, was seized in coming northward, with some meal believed to be the property of his master, and he was thrown in among the crowd of the Tolbooth. For weeks he petitioned in vain for release.

The Privy Council, on the 13th May 1690, expressed anxiety about the prisoners; but it was not regarding their health or comfort. They sent a committee to consider how best the Tolbooth might be made secure—for there had been an escape from the Canongate jail—and for this purpose it was decreed that close prisoners should be confined within the inner rooms; that the shutters towards the north should be nightly locked, to prevent communications with the houses in that direction; and that ‘there should be a centinel all the daytime at the head of the iron ravell stair at the Chancellary Chamber, lest letters and other things may be tolled up.’[14]

The chief of the clan Mackintosh, usually called the Laird of Mackintosh, claimed rights of property over the lands of Keppoch, Glenroy, and Glenspean, in Inverness-shire, ‘worth five thousand merks of yearly rent’—a district interesting to modern men of science, on account of the singular impress left upon it by the hand of nature in the form of water-laid terraces, commonly called the Parallel Roads of Glenroy, but then known only as the haunt of a wild race of Macdonalds, against whom common processes of law were of no avail. Mackintosh—whose descendant is now the peaceable landlord of a peaceable tenantry in this 16|1689.| country—had in 1681 obtained letters of fire and sword as a last desperate remedy against Macdonald of Keppoch and others; but no good had come of it.

In the year of the Revolution, these letters had been renewed, and about the time when Seymour and Russell were inviting over the Prince of Orange for the rescue of Protestantism and liberty, Mackintosh was leading a thousand of his people from Badenoch into Glenspean, in order to wreak the vengeance of the law upon his refractory tenants. He was joined by a detachment of government troops under Captain Mackenzie of Suddy; but Keppoch, who is described by a contemporary as ‘a gentleman of good understanding, and of great cunning,’ was not dismayed. With five hundred men, he attacked the Mackintosh on the brae above Inverroy, less than half a mile from his own house, and gained a sanguinary victory. The captain of the regular troops and some other persons were killed; the Laird of Mackintosh was taken prisoner, and not liberated till he had made a formal renunciation of his claims; two hundred horses and a great quantity of other spoil fell into the hands of the victors.[15] The Revolution, happening soon after, caused little notice to be taken of this affair, which is spoken of as the last clan-battle in the Highlands.

Now that Whiggery was triumphing in Edinburgh, it pleased Keppoch to rank himself among those chiefs of clans who were resolved to stand out for King James. Dundee reckoned upon his assistance; but when he went north in spring, he found this ‘gentleman of good understanding’ laying siege to Inverness with nine hundred men, in order to extort from its burghers at the point of the sword some moneys he thought they owed him. The northern capital—a little oasis of civilisation and hearty Protestantism in the midst of, or at least close juxtaposition to, the Highlands—was in the greatest excitement and terror lest Keppoch should rush in and plunder it. There were preachings at the cross to animate the inhabitants in their resolutions of defence; and a collision seemed imminent. At length the chieftain consented, for two thousand dollars, to retire. It is alleged that Dundee was shocked and angry at the proceedings of this important partisan, but unable or unwilling to do more than expostulate with him. Keppoch by and by joined him in earnest with his following, while Mackintosh held off in a state of indecision.

17This gave occasion for a transaction of private war, forming really a notable part of the Scottish insurrection for King James, though it has been scarcely noticed in history. It was when Dundee, in the course of his marching and countermarching that summer, chanced to come within a few miles of Mackintosh’s house of Dunachtan, on Speyside, that Keppoch bethought him of the opportunity it afforded for the gratification of his vengeful feelings. He communicated not with his commander. He took no counsel of any one; he slipped away with his followers unobserved, and, stooping like an eagle on the unfortunate Mackintosh, burned his mansion, and ravaged his lands, destroying and carrying away property afterwards set forth as of the value of two thousand four hundred and sixty-six pounds sterling.

This independent way of acting was highly characteristic of Dundee’s followers; but he found it exceedingly inconvenient. Being informed of the facts, he told Keppoch, in presence of his other officers, that ‘he would much rather choose to serve as a common soldier among disciplined troops, than command such men as he; that though he had committed these outrages in revenge of his own private quarrel, it would be generally believed he had acted by authority; that since he was resolved to do what he pleased, without any regard to command and the public good, he begged that he would immediately be gone with his men, that he might not hereafter have an opportunity of affronting the general at his pleasure, or of making him and the better-disposed troops a cover to his robberies. Keppoch, who did not expect so severe a rebuke, humbly begged his lordship’s pardon, and told him that he would not have abused Mackintosh so, if he had not thought him an enemy to the king as well as to himself; that he was heartily sorry for what was past; but since that could not be amended, he solemnly promised a submissive obedience for the future.’[16]

The preceding was not a solitary instance of private clan-warfare, carried on under cover of Dundee’s insurrection. Amongst his notable followers were the Camerons, headed by their sagacious chief, Sir Ewen of Locheil, who was now well advanced in years, though he lived for thirty more. A few of this clan having been hanged by the followers of the Laird of Grant—a chief strong in the Whig cause—it was deemed right 18|1689.| that a revenge should be taken in Glen Urquhart. ‘They presumed that their general would not be displeased, in the circumstances he was then in, if they could supply him with a drove of cattle from the enemy’s country.’ Marching off without leave, they found the Grants in Glen Urquhart prepared to receive them; but before the attack, a Macdonald came forward, telling that he was settled amongst the Grants, and claiming, on that account, that none of the people should be injured. They told him that, if he was a true Macdonald, he ought to be with his chief, serving his king and country in Dundee’s army; they could not, on his account, consent to allow the death of their clansmen to remain unavenged. The man returned dejected to his friends, the Grants, and the Camerons made the attack, gaining an easy victory, and bearing off a large spoil to the army in Lochaber.

Dundee consented to overlook this wild episode, on account of the supplies it brought him; but there was another person grievously offended. The Macdonald who lived among the Grants was one of those who fell in the late skirmish. By all the customs of Highland feeling, this was an event for the notice of his chief Glengarry, who was one of the magnates in Dundee’s army. Glengarry appeared to resent the man’s death highly, and soon presented himself before the general, with a demand for satisfaction on Locheil and the Camerons. ‘Surprised at the oddness of the thing, his lordship asked what manner of satisfaction he wanted; “for,” said he, “I believe it would puzzle the ablest judges to fix upon it, even upon the supposition that they were in the wrong;” and added, that “if there was any injury done, it was to him, as general of the king’s troops, in so far as they had acted without commission.” Glengarry answered that they had equally injured and affronted both, and that therefore they ought to be punished, in order to deter others from following their example.’ To this Dundee replied with further excuses, still expressing his inability to see what offence had been done to Glengarry, and remarking, that ‘if such an accident is a just ground for raising a disturbance in our small army, we shall not dare to engage the king’s enemies, lest there may chance to be some of your name and following among them who may happen to be killed.’ Glengarry continued to bluster, threatening to take vengeance with his own hand; but in reality he was too much a man of the general world to be himself under the influence of these Highland feelings—he only wished to appear before his people as eager to avenge 19|1689.| what they felt to be a just offence. The affair, therefore, fell asleep.[17]

The Earl of Balcarres, having failed to satisfy the government about his peaceable intentions, was put under restraint in Edinburgh Castle, which was now in the hands of the government. There, he must have waited with great anxiety for news of his friend Lord Dundee.

‘After the battle of Killiecrankie, where fell the last hope of James in the Viscount of Dundee, the ghost of that hero is said to have appeared about daybreak to his confidential friend, Lord Balcarres, then confined to Edinburgh Castle. The spectre, drawing aside the curtain of the bed, looked very steadfastly upon the earl, after which it moved towards the mantel-piece, remained there for some time in a leaning posture, and then walked out of the chamber without uttering one word. Lord Balcarres, in great surprise, though not suspecting that which he saw to be an apparition, called out repeatedly to his friend to stop, but received no answer, and subsequently learned that at the very moment this shadow stood before him, Dundee had breathed his last near the field of Killiecrankie.’[18]

On the news of the defeat of the government troops, his lordship had some visits from beings more substantial, but perhaps equally pale of countenance. In his Memoirs, he tells us of the consternation of the new councillors. ‘Some were for retiring to England, others to the western shires of Scotland ... they considered whether to set at liberty all the prisoners, or make them more close; the last was resolved, and we were all locked up and debarred from seeing our friends, but never had so many visits from our enemies, all making apologies for what was past, protesting they always wished us well, as we should see whenever they had an opportunity.’

Lord Balcarres was liberated on the 4th of March 1690, on giving caution for peaceable behaviour, the danger of Jacobite reaction being by that time abated.

A poor young woman belonging to a northern county, wandering southwards in search of a truant lover, like a heroine of one of the old ballads, found herself reduced to the last extremity of distress 20|1689.| when a few miles south of Peebles. Bewildered and desperate, she threw her babe into the Haystown Burn, and began to wander back towards her own country. A couple of the inhabitants of Peebles, fishing in the burn, soon found the body of the infant, and, a search being made, the wretched mother was discovered at a place called Jedderfield, brought into town, and put in confinement, as a suspected murderess. The magistrates of the burgh applied to the sheriff, John Balfour of Kailzie, to have the supposed culprit taken off their hands, and tried; but he refused to interfere, owing to ‘the present surcease of justice’ in the country. Consequently, the magistrates were ‘necessitate to cause persons constantly guard the murderer, the prison not being strong enough to secure her.’ On their petition, the Privy Council allowed the Peebles authorities to send Margaret Craig, with a guard, to Edinburgh, and ordained her to be received into the Tolbooth of Leith, till she be processed for the murder.[19]

This miserable young woman must have lain in prison three years, for she was tried by the Court of Justiciary in June 1692, and condemned to be hanged.[20]

There is something interesting in the early difficulties of so valuable an institution as the Post-office. John Graham had been appointed postmaster-general for Scotland in 1674, with a salary of a thousand pounds Scots (£83, 6s. 8d. sterling), and had set about his duty with great spirit. He had travelled to many towns for the purpose of establishing local offices, thus incurring expenses far beyond what his salary could repay. He had been obliged on this account to encroach on money belonging to his wife; also to incur some considerable debts; nor had he ever been able to obtain any relief, or even the full payment of his salary from the late state-officers. He was now dead, and his widow came before the Privy Council with a petition setting forth how she had been left penniless by her husband through his liberality towards a public object. It was ordained that Mrs Graham should get payment of all debts due by provincial offices to her husband, and have the income of the general office till Martinmas next.

It is to be feared that Mrs Graham did not profit much by this order, as on the subsequent 19th of October we find her complaining that William Mean of the Edinburgh letter-office, and others, 21|1689.| had refused to pay her the arrears declared to be due to her; wherefore the order was renewed.

The general post-mastership was at this time put upon a different footing, being sold by roup, July 24, 1689, to John Blair, apothecary in Edinburgh, he undertaking to carry on the entire business on various rates of charge for letters, and to pay the government five thousand one hundred merks (about £255 sterling) yearly, for seven years. The rates were, for single letters to Dumfries, Glasgow, and Ayr, Dundee, Perth, Kelso, and Jedburgh, two shillings; to Carlisle, Portpatrick, Aberdeen, and Dunkeld, three shillings; to Kirkcudbright and Inverness, four shillings, all Scots money.

In October of this year, the above-mentioned William Mean was sent with a macer to the Tolbooth for keeping up letters sent from Ireland ‘untill payment of the letters were paid to him, albeit the postage were satisfied in England, and that he had sent back packets to London which were directed for Ireland.’ Also, ‘notwithstanding the former order of Council appointing him to deliver in to them any letters directed for James Graham, vintner, he had kept up the same these eight or ten days, and had never acquainted any member of Council therewith.’ He was liberated two days after, on caution for reappearance under 500 merks. It may be surmised that William Mean was disposed to take advantage of some regulations of his office in order to give trouble to the existing government.

In the course of 1690, besides a deliberate robbery of the post-boy on the road between Cockburnspath and Haddington (see under August 16th of that year), the fact of the bag frequently coming with the seals broken, is adverted to in angry terms by the Privy Council. An edict for the use of official seals and the careful preservation of these was passed; nevertheless, we soon after hear of the bag or box coming once more into Edinburgh with the seals broken, Mrs Gibb, the post-mistress at the Canongate post,[21] sent for, Mrs Mean of the letter-office also called up, and much turmoil and fume for a while, but no sort of decisive step taken in consequence. It is to be observed that the post from the English to the Scottish capital was at this time carried on horseback with a fair degree of speed. English parliamentary proceedings of Saturday are noted to be in the hands of the Edinburgh public on the ensuing Thursday.[22]

22Alexander Irvine of Drum, the representative of a distinguished historical family in Aberdeenshire, was unfortunately weak both in mind and body, although it is related that he could play well on the viol, and had picked up the then popular political tune of Lullibullero in the course of a few days. Under sanction of the Privy Council, Dr David Mitchell of Edinburgh undertook to keep him in his house in a style befitting his quality, and with the care required by his weakly condition, and for this purpose hired some additional rooms, and made other necessary furnishings and preparations. The laird came to him at the close of July, but before the end of August, Marjory Forbes had induced the laird to own her as his wife, and it became necessary that Drum should leave his medical protector. A petition being presented by Dr Mitchell for payment of board and recompense for charges thus needlessly incurred, he was allowed by the Lords £500 Scots, or £41, 13s. 4d. sterling, over and above twenty pieces he had received for a professional visit paid to the laird’s Aberdeenshire castle, to arrange for his migration to Edinburgh.[23]

James Broich, skipper of Dundee, was proceeding in his scout to Norway with a small parcel of goods, and a thousand pounds Scots wherewith to buy a larger vessel. In mid-sea he fell in with a French privateer, who, after seizing cargo and money, having no spare hands to leave on board, proceeded to cut holes in the vessel, in order to sink her, proposing to put the unfortunate crew to their boat, in which case they must have perished, ‘there being then a great stress.’ By the prayers and tears of the skipper and his people, the privateer was at length induced to let them go in their vessel, but not without first obtaining a bond from Broich, undertaking to remit six hundred guelders to Dunkirk by a particular day. As a guarantee for this payment, the rover detained and carried off the skipper’s son, telling him he would hear no good of him if the money should fail to be forthcoming.

Poor Broich got safe home, where his case excited much commiseration, more particularly as he had suffered from shipwreck and capture four times before in the course of his professional life. He was penniless, and unable to support his family; his son, also—‘the stay and staff of his old age’—had a wife and small children of his own left desolate. Here was a little 23|1689.| domestic tragedy very naturally arising out of the wars of the Grand Monarque! Beginning in the council-room of Versailles, such was the way they told upon humble industrial life in the port of Dundee in Scotland. It was considered, too, that the son was in ‘as bad circumstances, in being a prisoner to the French king, as if he were a slave to the Turks.’

On the petition of Broich, the Privy Council ordained a voluntary contribution to be made for his relief in Edinburgh, Leith, Borrowstounness, and Queensferry, and in the counties of Fife and Forfar.

In a contemporary case, that of a crew of Grangepans, carried by a privateer to Dunkirk, and confined in Rochefort, it is stated that they were each allowed half a sous per diem for subsistence, and were daily expecting to be sent to the galleys.[24]

It was now acknowledged of the glass-work at Leith, that it was carried on successfully in making green bottles and ‘chemistry and apothecary glasses.’ It produced its wares ‘in greater quantity in four months than was ever vended in the kingdom in a year, and at as low rates as any corresponding articles from London or Newcastle.’ The Privy Council therefore gave it the privileges of a manufactory, and forbade introduction of foreign bottles, only providing that the Leith work should not charge more than half-a-crown a dozen.

The magistrates of Edinburgh were ordered to put William Mitchell upon the Tron, ‘and cause the hangman nail his lug [ear] thereto,’ on Wednesday the 4th instant, between eleven and twelve in the forenoon, with a paper on his breast, bearing ‘that he stands there for the insolencies committed by him on the Guards, and for words of reflection uttered by him against the present government.’[25]

A large flock of mere-swine (porpoises?) having entered the Firth of Forth, as often happens, and a considerable number having come ashore, as seldom happens, at Cramond, the tenants of Sir John Inglis, proprietor of the lands there, fell upon them with all possible activity, and slew twenty-three, constituting a prize of no inconsiderable value. After fastening the animals with ropes, so as to prevent their being carried out to sea—for the 24|1690.| scene of slaughter was half a mile in upon a flat sandy beach—the captors sold them for their own behoof to Robert Douglas, soapboiler in Leith, fully concluding that they had a perfect right to do so, seeing that mere-swine are not royal fish, and neither had they been cast in dead, in which case, as wrack, I presume, they would have belonged to the landlord.

The greater part of the spoil had been barrelled and transported to Leith—part of the price paid, too, to the captors—when John Wilkie, surveyor there, applied to the Privy Council for a warrant to take the mere-swine into his possession and dispose of them for the benefit of such persons as they should be found to belong to. He accordingly seized upon the barrels, and disposed of several of them at eleven pounds four shillings per barrel, Douglas protesting loudly against his procedure. On a petition, representing how the animals had been killed and secured, Wilkie was ordained to pay over the money to Douglas, deducting only his reasonable charges.

A few hot-headed Perthshire Jacobites, including [George] Graham of Inchbrakie, David Oliphant of Culteuchar, and George Graham of Pitcairns, with two others designed as ensigns, met to-day at the village of Dunning, with some other officers of the government troops, and, getting drink, began to utter various insolencies. They drank the health of King James, ‘without calling him the late king,’ and further proceeded to press the same toast upon the government officers. One of these, Ludovick Grant, quarter-master of Lord Rollo’s troop, was prudentially retiring from this dangerous society, when Ensign Mowat cocked a pistol at him, saying: ‘Do you not see that some of us are King William’s officers as well as you, and why will ye not drink the health as well as we?’ Grant having asked him what he meant by that, Inchbrakie took the pistol, and fired it up the chimney—which seems to have been the only prudential proceeding of the day. The party continued drinking and brawling at the place, till James Hamilton, cornet of Rollo’s troop, came with a party to seize them, when, drawing their swords, they beat back the king’s officer, and were not without great difficulty taken into custody. Even now, so far from being repentant, Inchbrakie ‘called for a dishful of aqua vitæ or brandy, and drank King James’s health,’ saying ‘they were all knaves and rascals that would refuse it.’ He said ‘he hoped the guise would turn,’ when Lord Rollo would not be able to keep Scotland, and he would get 25|1690.| Duncrub [Lord Rollo’s house and estate] to himself. His fury against the soldiers extended so far, that he called for powder and ball to shoot the sentinels placed over him, and ‘broke Alexander Ross’s face with ane pint-stoup.’ Even when borne along as prisoners to Perth, and imprisoned there, these furious gentlemen continued railing at Lord Rollo and his troop, avowing and justifying all they had done at Dunning.

The offenders, being brought before the Privy Council, gave in defences, which their counsel, Sir David Thores, advocated with such rash insolency that he was sent away to prison. The culprits were punished by fines and imprisonment. We find them with great difficulty clearing themselves out of jail six months after.[26]

In religious contentions, there is a cowardice in the strongest ascendency parties which makes them restlessly cruel towards insignificant minorities. The Roman Catholics in Scotland had never since the Reformation been more than a handful of people; but they had constantly been treated with all the jealous severity due to a great and threatening sect. Even now, when they were cast lower than at any former time, through the dismal failure of King James to raise them, there was no abatement of their troubles.

It was at this time a great inconveniency to any one to be a Catholic. As a specimen—Alexander Fraser of Kinnaries, on the outbreak of the Revolution, to obviate any suspicion that might arise about his affection to the new government, came to Inverness, and put himself under the view of the garrison there. Fears being nevertheless entertained regarding him, he was sent to prison. Liberated by General Mackay upon bail, he remained peaceably in Inverness till December last, when he was sent to Edinburgh, and there placed under restraint, not to move above a mile from town. |Mar. 2.| He now represented the hardship he thus suffered, ‘his fortune being very small, and the most of his living being only by his own labouring and industry.’ ‘His staying here,’ he added, ‘any space longer must of necessity tend to his own and his family’s utter ruin.’ With difficulty, the Lords were induced to liberate him under caution.

Mr David Fairfoul, a priest confined in prison at Inverness, only regained his liberty by an extraordinary accident. James Sinclair of Freswick, a Caithness gentleman, had chanced a 26|1690.| twelvemonth before to be taken prisoner by a French privateer, as he was voyaging from his northern home to Edinburgh. Having made his case known to the Scottish Privy Council, he was relieved in exchange for Mr Fairfoul (June 5, 1690).

About the end of the year, we find a considerable number of Catholics under government handling. Steven Maxwell, who had been one of the two masters in the Catholic college at Holyroodhouse, lay in durance at Blackness. John Abercrombie, ‘a trafficker,’ and a number of other priests recently collected out of the Highlands, were immured in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh. Another, named Mr Robert Davidson, of whom it was admitted that ‘his opinion and deportment always inclined to sobriety and moderation, shewing kindness and charity to all in distress, even of different persuasions, and that he made it no part of his business to meddle in any affairs, but to live peaceably in his native country for his health’s sake,’ had been put into Leith jail, with permission to go forth for two hours a day, under caution to the amount of fifty pounds, lest his health should suffer.

At this very time, a fast was under order of the General Assembly, with sanction of the government, with a reference to the consequences of the late oppressive government, citing, among other things, ‘the sad persecutions of many for their conscience towards God.’[27]

It was declared in the legislature that there were ‘frequent murders of innocent infants, whose mothers do conceal their pregnancy, and do not call for necessary assistance in the birth.’ It was therefore statute, that women acting in this secretive manner, and whose babes were dead or missing, should be held as guilty of murder, and punished accordingly.[28] That is to say, society, by treating indiscretions with a puritanic severity, tempted women into concealments of a dangerous kind, and then punished the crimes which itself had produced, and this upon merely negative evidence.

Terrible as this act was, it did not wholly avail to make women brave the severity of that social punishment which stood on the other side. It is understood to have had many victims. In January 1705, no fewer than four young women were in the Tolbooth of Aberdeen at once for concealing pregnancy and 27|1690.| parturition, and all in a state of such poverty that the authorities had to maintain them. On the 23d July 1706, the Privy Council dealt with a petition from Bessie Muckieson, who had been two years ‘incarcerat’ in the Edinburgh Tolbooth on account of the death of a child born by her, of which Robert Bogie in Kennieston, in Fife, was the father. She had not concealed her pregnancy, but the infant being born in secret, and found dead, she was tried under the act.

At her trial she had made ingenuous confession of her offence, while affirming that the child had not been ‘wronged,’ and she protested that even the concealment of the birth was ‘through the treacherous dealing and abominable counsel of the said Robert Bogie.’ ‘Seeing she was a poor miserable object, and ane ignorant wretch destitute of friends, throwing herself at their Lordships’ footstool for pity and accustomed clemency’—petitioning that her just sentence might be changed into banishment, ‘that she might be a living monument of a true penitent for her abominable guilt’—the Lords looked relentingly on the case, and adjudged Bessie to pass forth of the kingdom for the remainder of her life.[29]

It was seldom that such leniency was shewn. In March 1709, a woman named Christian Adam was executed at Edinburgh for the imputed crime of child-murder, and on the ensuing 6th of April, two others suffered at the same place on the same account. In all these three cases, occurring within four weeks of each other, the women had allowed their pregnancy and labour to pass without letting their condition be known, or calling for the needful assistance, Adam acting thus at the entreaty of her lover, ‘a gentleman,’ who said it would ruin him if she should declare her state. Another, named Bessie Turnbull, had been entirely successful in concealing all that happened; but the consciousness of having killed her infant haunted her, till she came voluntarily forward, and gave herself up. At the scaffold, Adam ‘gave the ministers much satisfaction;’ Margaret Inglis ‘did not give full satisfaction to the ministers;’ Turnbull ‘seemed more affected than her comrade, but not so much as could be wished.’[30]

Our old acquaintance, Captain John Slezer, turns up at this time in an unexpected way. Three or four months before, he 28|1690.| had obtained a commission as captain of artillery from their majesties, and now he was about to leave Edinburgh on duty; but, lo, John Hamilton, wright, burgess of Edinburgh, ‘out of a disaffection to their majesties and the present government,’ gave orders to George Gilchrist, messenger, to put in execution letters of caption against the captain, for a debt due by him, ‘albeit he [Slezer] the night before offered him satisfaction of the first end of the money.’ The Council, ‘understanding that the same has been done out of a design to retard their majesties’ service, called for Hamilton, and, in terms of the late act of parliament, desired him to take the oath of allegiance and assurance, which he refused to do.’ They therefore ordained him to be committed prisoner to the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, and ‘declares Captain Slezer to be at liberty to prosecute his majesty’s service.’ The debtor and creditor might thus be said to have changed places: one can imagine what jests there would be about the case among the Cavalier wits in the Laigh Coffee-house—how it would be adduced as an example of that vindication of the laws which the Revolution professed to have in view—how it would be thought in itself a very good little Revolution, and well worthy of a place in the child’s toy picture of The World Turned Upside Down.

After a six weeks’ imprisonment, Hamilton came before the Council with professions of peaceable inclination to the present government, and pleaded that he was valetudinary with gravel, much increased by reason of his confinement, ‘and, being a tradesman, his employment, which is the mean of his subsistence, is altogether neglected by his continuing a prisoner,’ and he might be utterly ruined in body, family, and estate, if not relieved. Therefore the Lords very kindly liberated this delinquent creditor, he giving caution to live inoffensively in future, and reappear if called upon.

We find a similar case a few years onward. Captain William Baillie of Colonel Buchan’s regiment was debtor to Walter Chiesley, merchant in Edinburgh, to the extent of three thousand merks, for satisfaction of which he had assigned his estate, with power to uplift the rents. He was engaged in Edinburgh on the recruiting service, when Chiesley, out of malice, as was insinuated, towards the government of which Baillie was the commissioned servant, had him apprehended on caption for the debt, and put into the Tolbooth of Edinburgh. Thus, as his petition to the Privy Council runs (February 7, 1693), ‘he is rendered incapable of executing that important duty he is upon, which will many 29|1690.| ways prejudice their majesties’ service;’ for, ‘if such practices be allowed, and are unpunished, there should not ane officer in their majesties’ forces that owes a sixpence dare adventure to come to any mercat-town, either to make their recruits or perform other duty.’ For these good reasons, Baillie craved that not only he be immediately liberated, but Walter Chiesley be censured ‘for so unwarrantable ane act, to the terror of others to do the like.’

The Council recommended the Court of Session to expede a suspension, and put at liberty the debtor; but they seem to have felt that it would be too much to pass a censure on the merchant for trying to recover what was justly owing to him.

But for our seeing creditors treated in this manner for the conveniency of the government, it would be startling to find that the old plan of the supersedere, of which we have seen some examples in the time of James VI., was still thought not unfit to be resorted to by that régime which had lately redeemed the national liberties.

James Bayne, wright in Edinburgh—the same rich citizen whose daughter’s clandestine nuptials with Andrew Devoe, the posture-master, made some noise a few years back[31]—had executed the carpentry-work of Holyroodhouse; but, like Balunkin in the ballad, ‘payment gat he nane.’ To pay for timber and workmen’s wages, he incurred debts to the amount of thirty-five thousand merks (about £1944 sterling), which soon increased as arrears of interest went on, till now, after an interval of several years, he was in such a position, that, supposing he were paid his just dues, and discharged his debts, there would not remain to him ‘one sixpence’ of that good stock with which he commenced the undertaking.

At the recommendation of ‘his late majesty [Charles II.?],’ the Lords of the Treasury had considered the case, and found upwards of £2000 sterling to be due to James Bayne, ‘besides the two thousand pounds sterling for defalcations and losses, which they did not fully consider,’ and they consequently ‘recommended him to the Lords of Session for a suspension against his creditors, ay, and while the money due to him by the king were paid.’ This he obtained; ‘but at present no regard is had to it.’ Recently, to satisfy some of his most urgent creditors, the Lords of the Treasury gave him an order 30|1690.| for £500 upon their receiver, Maxwell of Kirkconnel; but no funds were forthcoming. His creditors then fell upon him with great rigour, and Thomas Burnet, merchant in Edinburgh, from whom he had been a borrower for the works at the palace, had now put him in jail, where he lay without means to support himself and his family.

Bayne craved from the Privy Council that the two thousand pounds already admitted might as soon as possible be paid to him, and that, meanwhile, he should be liberated, and receive a protection from his creditors, ‘whereby authority will appear in its justice, the petitioner’s creditors be paid, and no tradesman discouraged to meddle in public works for the advancement of what is proper for the government to have done.’ The Privy Council considered the petition, and recommended the Lords of Session ‘to expede ane suspension and charge to put to liberty’ in favour of James Bayne, on his granting a disposition of his effects in favour of his creditors.[32]

It was, after all, fitting that the government which interfered, for its own conveniency, to save its servants from the payment of their just debts, should stave off the payment of their own, by similar interpositions of arbitrary power.

The ‘happie revolution’ had not made any essential change in the habits of those Highlanders who lived on the border of the low countries. It was still customary for them to make periodical descents upon Morayland, Angus, the Stormont, Strathearn, and the Lennox, for ‘spreaths’ of cattle and other goods.

Sir Robert Murray of Abercairney, having lands in Glenalmond and thereabouts, employed six men, half of whom were Macgregors, as a watch or guard for the property of his tenants. These men, coming one day to the market of Monzie, were informed that a predatory party had gone down into the low country, and ‘fearing that they might, in their return, come through Sir Robert’s lands, and take away ane hership from his tenants,’ they lost no time in getting the land, over which they were likely to pass, cleared of bestial. They were refreshing themselves after their toil at the kirk-town of Monzie, when the caterans came past with their booty. Enraged at finding the ground cleared, the robbers seized the six men, and carried them away as prisoners.

A few days after, having regained their liberty, they were 31|1690.| apprehended by Lord Rollo, on a suspicion of having been accomplices of the robbers, by whom it appeared his lordship’s tenants had suffered considerably; and they were immediately dragged off to Edinburgh, and put into the Canongate jail. There they lay for two months, ‘in a very starving condition, and to the ruin of their poor families at home;’ when at length, Lord Rollo having failed to make good anything against them, and Sir Robert Murray having undertaken for their appearance if called upon, they were allowed to go home, with an order to the governor of Drummond Castle for the restoration of their arms.

On the 22d January 1691, Lord Rollo represented to the Privy Council that ‘in the harvest last, the Highland robbers came down and plundered his ground, and because of his seeking redress according to law, they threaten his tenants with ane other depredation, and affrights them so as they are like to leave the petitioner’s lands, and cast them waste.’[33] The matter was remitted to the Commander of the Forces.[34]

32Andrew Cockburn, the post-boy[35] who carried the packet or letter-bag on that part of the great line of communication which lies between Cockburnspath and Haddington, had this day reached a point in his journey between the Alms-house and Hedderwick Muir, when he was assailed by two gentlemen in masks; one of them ‘mounted on a blue-gray horse, wearing a stone-gray coat with brown silk buttons;’ the other ‘riding on a white horse, having a white English gray cloak coat with wrought silver thread buttons.’ Holding pistols to his breast, they threatened to kill him if he did not instantly deliver up ‘the packet, black box, and by-bag’ which he carried; and he had no choice but to yield. They then bound him, and, leaving him tied by the foot to his horse, rode off with their spoil to Garlton House near Haddington.

As the packet contained government communications besides the correspondence of private individuals, this was a crime of a very high nature, albeit we may well believe it was committed on political impulse only. Suspicion seems immediately to have alighted on James Seton, youngest son of the Viscount Kingston, and John Seton, brother of Sir George Seton of Garlton; and Sir Robert Sinclair, the sheriff of the county, immediately sought for these young gentlemen at their father’s and brother’s houses, but found them not. With great hardihood, they came to Sir Robert’s house next morning, to inquire as innocent men why they were searched for; when Sir Robert, after a short examination in presence of the post-boy, saw fit to have them disarmed and sent off to Haddington. It was Sunday, and Bailie Lauder, to whose house they came with their escort, was about to go to church. If the worthy bailie is to be believed, he thought their going to the sheriff’s a great presumption of their innocence. He admitted, too, that Lord Kingston had come and spoken to him that morning.[36] Anyhow, he concluded that it might be enough in the meantime if he afforded them a room in his house, secured 33|1690.| their horses in his stable, and left them under charge of two of the town-officers. Unluckily, however, he required the town-officers, as usual, to walk before him and his brother-magistrates to church; which, it is obvious, interfered very considerably with their efficiency as a guard over the two gentlemen. While things were in this posture, Messrs Seton took the prudent course of making their escape. As soon as the bailie heard of it, he left church, and took horse after them with some neighbours, but he did not succeed in overtaking them.