Title: The retreat of the ten thousand

Author: C. Witt

Xenophon

Author of introduction, etc.: Henry Graham Dakyns

Translator: Frances Younghusband

Release date: October 17, 2023 [eBook #71894]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1896

Credits: Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them. A larger, higher-resolution copy of the map may be seen by clicking (Larger) beneath it.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

WORKS BY FRANCES YOUNGHUSBAND.

THE STORY OF OUR LORD. Told in Simple Language for Children. With 25 Illustrations in Wood, from Pictures by the Old Masters, and numerous Ornamental Borders, Initial Letters, &c. from Longmans’ Illustrated New Testament. Crown 8vo. 2s. 6d. cloth plain, 3s. 6d. cloth extra, gilt edges.

THE STORY OF GENESIS, Being Part I. of The Story of the Bible. Crown 8vo. 2s. 6d.

THE STORY OF THE EXODUS. Being Part II. of The Story of the Bible. With a Map and 29 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 2s. 6d.

WORKS BY PROFESSOR C. WITT.

Head Master of the Altstadt Gymnasium, Königsberg.

Translated into English by Frances Younghusband.

MYTHS OF HELLAS. With a Preface by A. Sidgwick, M.A. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

THE TROJAN WAR. With a Preface by the Rev. W. G. Rutherford, M.A., Head Master of Westminster School. Fcp. 8vo. 2s.

THE WANDERINGS OF ULYSSES. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

THE RETREAT OF THE TEN THOUSAND. With a Preface by H. G. Dakyns, M.A., Translator of ‘The Works of Xenophon.’ Containing numerous Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

THE ROUTE of the TEN THOUSAND.

THE RETREAT

OF

THE TEN THOUSAND

BY

PROFESSOR C. WITT

HEAD MASTER OF THE ALTSTADT GYMNASIUM AT KÖNIGSBERG

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY

FRANCES YOUNGHUSBAND

Translator of ‘Myths of Hellas’

WITH A PREFACE BY H. G. DAKYNS, M.A.

Translator of ‘The Works of Xenophon’

THIRD EDITION

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

LONDON, NEW YORK, AND BOMBAY

1896

All rights reserved

Miss Younghusband kindly insists that I should write a preface to her new volume, and I cannot refuse. It contains a translation by her hand from the German of Professor C. Witt’s version of the Retreat of the Ten Thousand.

Such a book ought, I think, no less than its predecessors The Myths of Hellas, The Tale of Troy, and The Wanderings of Ulysses, to become a favourite with those youthful readers, to whom it is primarily addressed. Indeed, considering the nature of the history, older persons may perhaps find an interest in it.

The original Greek narrative, on which Professor Witt has based his version, is, of course, the well-known Anabasis of Xenophon, which is one of the most fascinating books in the world. And I agree with the translator in hoping that some of those who read the story for the first time in English will be led to study Greek sufficiently to read it again and again in the language of Xenophon himself.

vi

That remarkable personage, who in spite of his Spartan leanings was a thorough Athenian at heart—found himself on a sudden called upon to play the part of a leader: and played it to perfection. But if he deserved well of his countrymen and fellow soldiers by his service in the field, he has deserved still better of all later generations by the vigour, not of his sword, but of his pen.

Perhaps we owe it to his Socratic training that whilst the memories were still fresh he sat down to describe the exploits of the Ten Thousand in a style admirably suited to the narrative; and produced a masterpiece. I do not think there is a dull page in the book.

The incidents, albeit they took place in the broad noonday of Grecian history, are as thrilling as any tale told by the poets in the divine dawn of the highly gifted Hellenic race. The men themselves who play so noble a part are evidently true descendants of the Homeric heroes. If they have fits of black despondency—the cloud is soon dispelled when there is need for action, and by a sense of their own dignity. The spirit of their forefathers, who fought and won at Marathon and Salamis and Platææ, has entered into them. They enter the lists of battle with the same gaiety. They confront death with similar equanimity. Buoyancy is the distinctive note of the Anabasis.

vii

But there is another side to the matter. These Xenophontine soldiers are also true enfants du siècle. They bear the impress of their own half century markedly: and it was an age not by any means entirely heroic. It had its painful and prosaic side.

‘Nothing,’ a famous Frenchman, M. Henri Taine, has remarked in one of his essays entitled Xénophon, ‘is more singular than this Greek army—which is a kind of roving commonwealth, deliberating and acting, fighting and voting: an epitome of Athens set adrift in the centre of Asia: there are the same sacrifices, the same assemblies, the same party strifes, the same outbursts of violence; to-day at peace and to-morrow at war; now on land and again on shipboard; every successive incident serves but to evoke the energy and awaken the poetry latent in their souls.’

How does this happen? It is due, I think, to the Ten Thousand to admit: It was so, because in spite of personal defects they were true to themselves. ‘The Greeks,’ as the aged Egyptian priest exclaimed to Solon, in another context, ‘are always children.’

This something childlike—this glory had not as yet in the year 400 B.C. faded into the light of common day. But as M. Taine adds concerning the writing itself, ‘The beauty of style transcends even the interest of the story,’ and we may well imagine that a less capableviii writer than Xenophon (Sophænetus for instance) would have robbed the narrative and the actors alike of half their splendour.

And what of Xenophon himself? There is much to be said on that topic. But it is ‘another story.’ In this he must speak for himself.

H. G. Dakyns.

ix

In translating Professor Witt’s version of the Retreat of the Ten Thousand, I have ventured to divide the chapters, and also to re-arrange in some cases the grouping of sentences and paragraphs, for the sake of greater clearness. The figures given for numbers, distances and sums of money, are the same as in Mr. Dakyns’ translation of the works of Xenophon. Here and there too I have modified or omitted or added a phrase, as for instance in substituting, on the first page, Alfred the Great for Karl der Grosse, as an example more familiar to English readers; and in adding to the description of Persepolis one or two details to explain the illustrations. But in the main I have endeavoured to reproduce accurately Professor Witt’s text in simple English, without either addition or omission.

The illustrations are mostly taken (by permission) from MM. Perrot and Chipiez’s ‘Histoire de l’Art dans l’Antiquité.’ Some few are from Baumeister’s Dictionary.x The two views are from photographs kindly lent for the purpose by Mr. Cecil Smith, of the British Museum.

I am glad to take the opportunity of expressing my very grateful thanks to Mr. Dakyns for his kindness in forwarding this attempt to interest English children in the writings of an author to whom he has himself given so many hours of sympathetic study. And I hope that many readers of this little book may be stimulated to the effort of studying for themselves the works of the great historian in the original Greek.

Frances Younghusband.

xi

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Great King | 1 |

| II. | The Persian Empire | 7 |

| III. | Hellas | 13 |

| IV. | The Rival Brothers | 15 |

| V. | Preparations | 21 |

| VI. | On the March | 27 |

| VII. | The Princess Epyaxa | 32 |

| VIII. | Clearchus | 38 |

| IX. | Negotiations at Tarsus | 42 |

| X. | From Tarsus to Myriandus | 49 |

| XI. | The Crossing of the Euphrates | 53 |

| XII. | In the Desert | 57 |

| XIII. | The Treachery of Orontes | 62 |

| XIV. | The King approaches | 65 |

| XV. | Before the Battle | 71 |

| XVI. | The Battle of Cunaxa | 75 |

| XVII. | The Treaty with Ariæus | 81 |

| XVIII. | The Treaty with the Great King | 86 |

| XIX. | The Defection of Ariæus | 93xii |

| XX. | A Conference with Tissaphernes | 96 |

| XXI. | The Treachery of Tissaphernes | 100 |

| XXII. | Xenophon | 105 |

| XXIII. | Election of Officers | 110 |

| XXIV. | Xenophon addresses the Troops | 114 |

| XXV. | Annoyed by Mithridates | 119 |

| XXVI. | Harassed by Tissaphernes | 124 |

| XXVII. | The last of Tissaphernes | 129 |

| XXVIII. | The River or the Mountains? | 134 |

| XXIX. | The Carduchians | 137 |

| XXX. | Seizing a Pass | 141 |

| XXXI. | A long Day’s Fighting | 147 |

| XXXII. | The Crossing of the Kentrites | 151 |

| XXXIII. | The Satrap Tiribazus | 157 |

| XXXIV. | An Armenian Winter | 162 |

| XXXV. | Armenian Villages | 167 |

| XXXVI. | The Taochians | 171 |

| XXXVII. | The Sea! the Sea! | 177 |

| XXXVIII. | The Macronians and the Colchians | 181 |

| XXXIX. | The Games at Trebizond | 185 |

| XL. | The After-life of Xenophon | 189 |

xiii

| PLATES | |

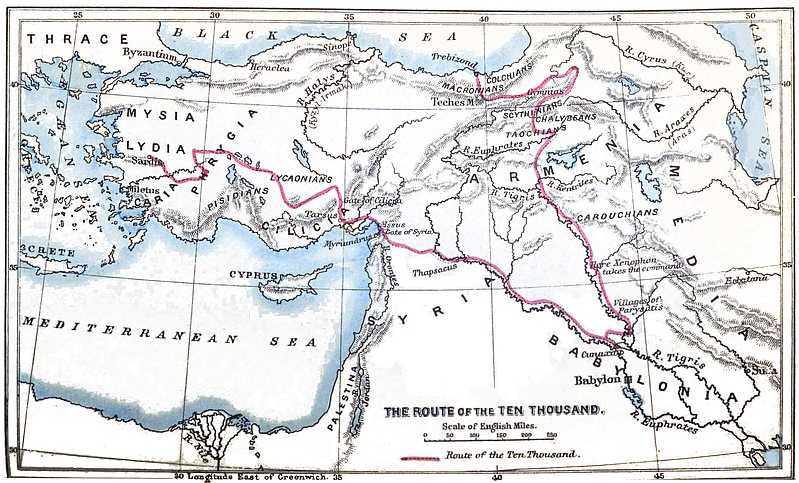

| Route of the Ten Thousand Frontispiece | |

| To face page | |

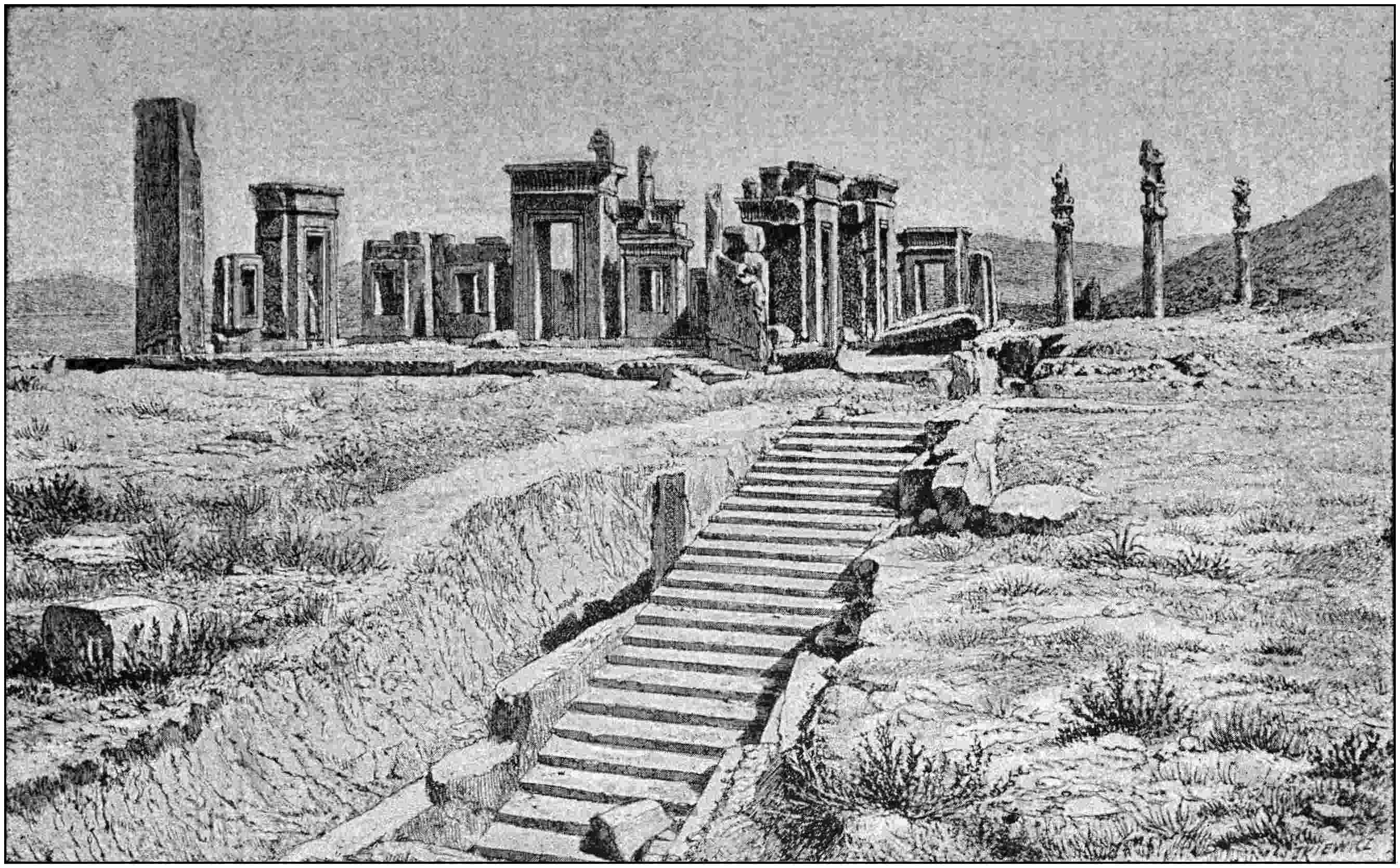

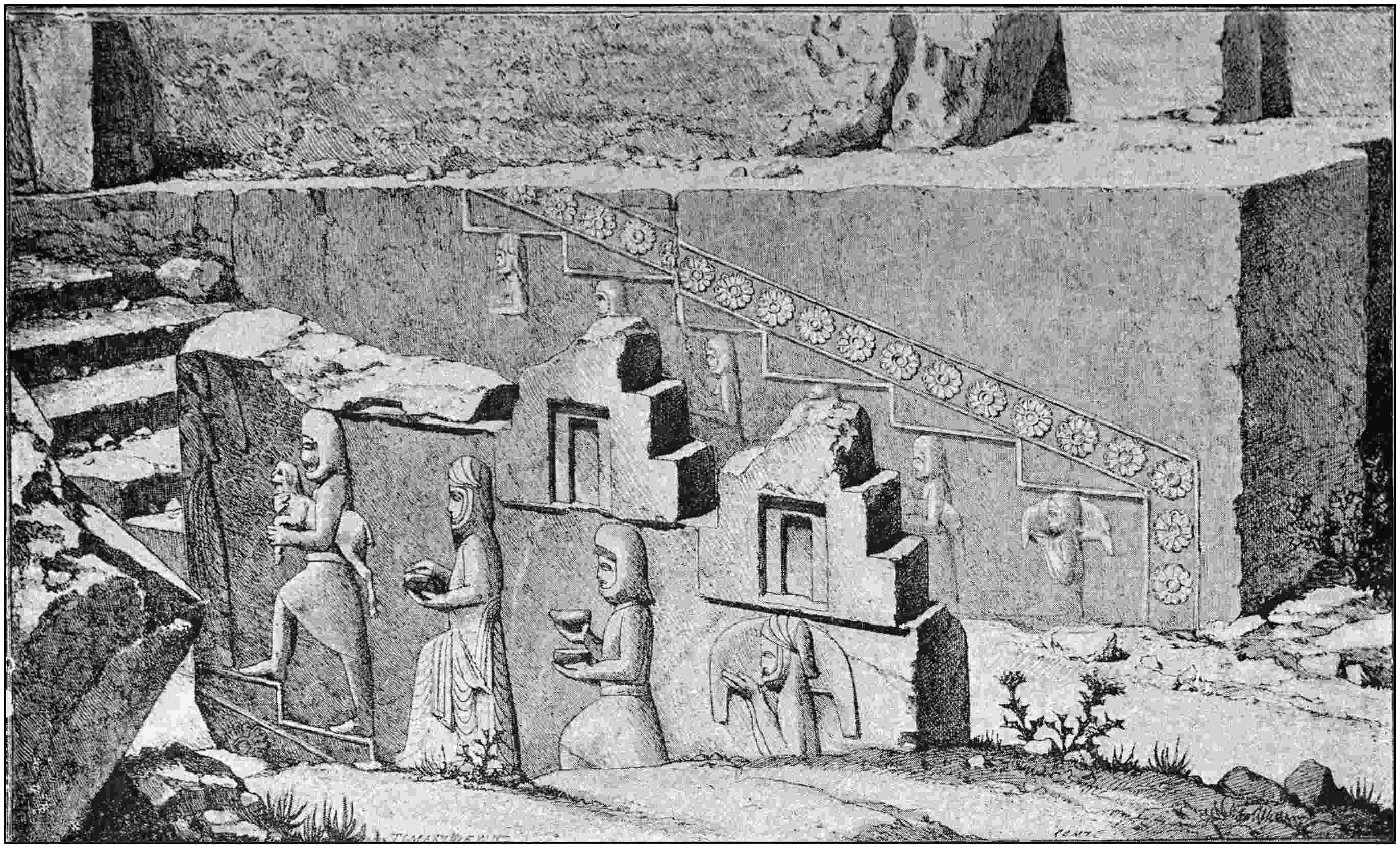

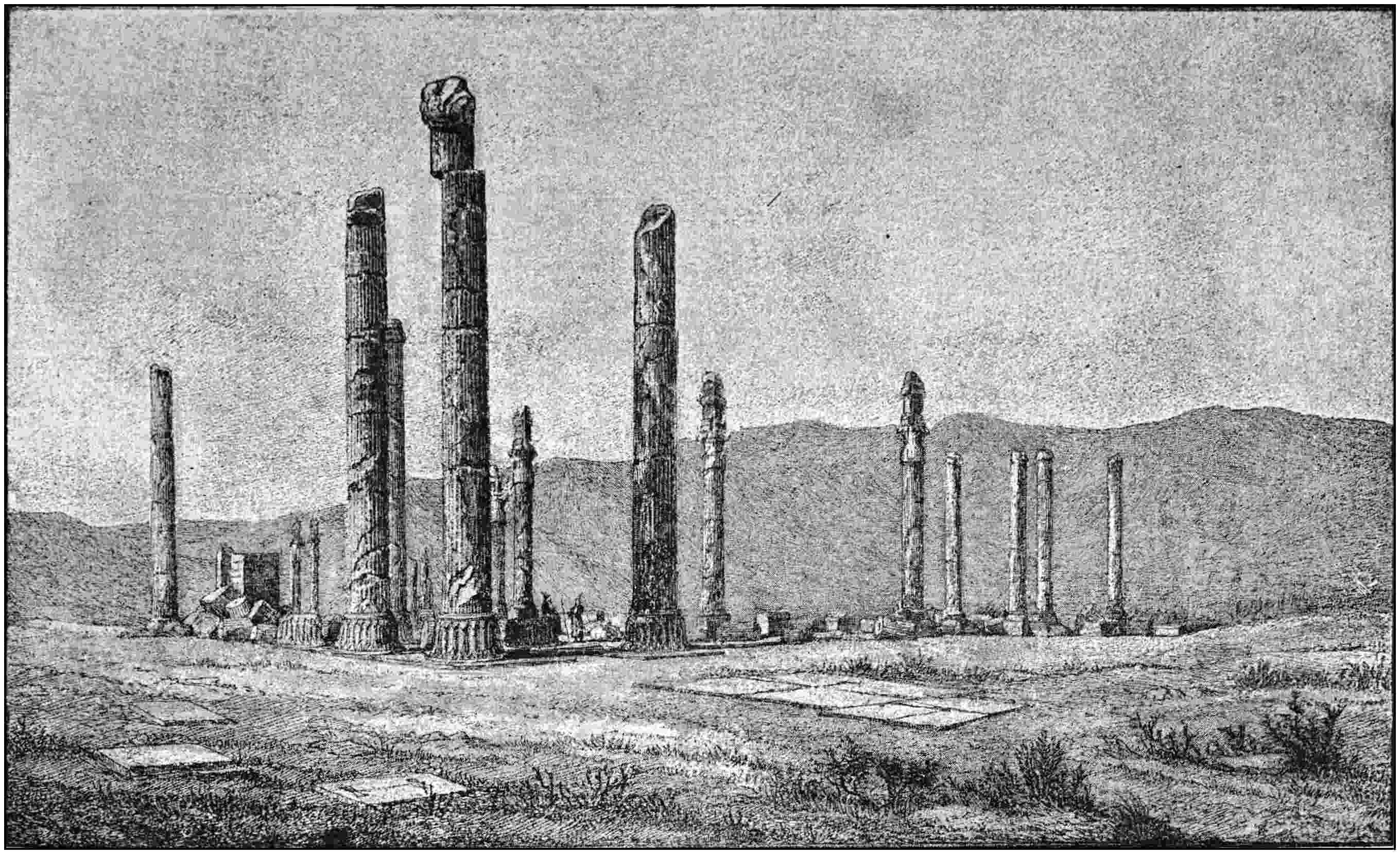

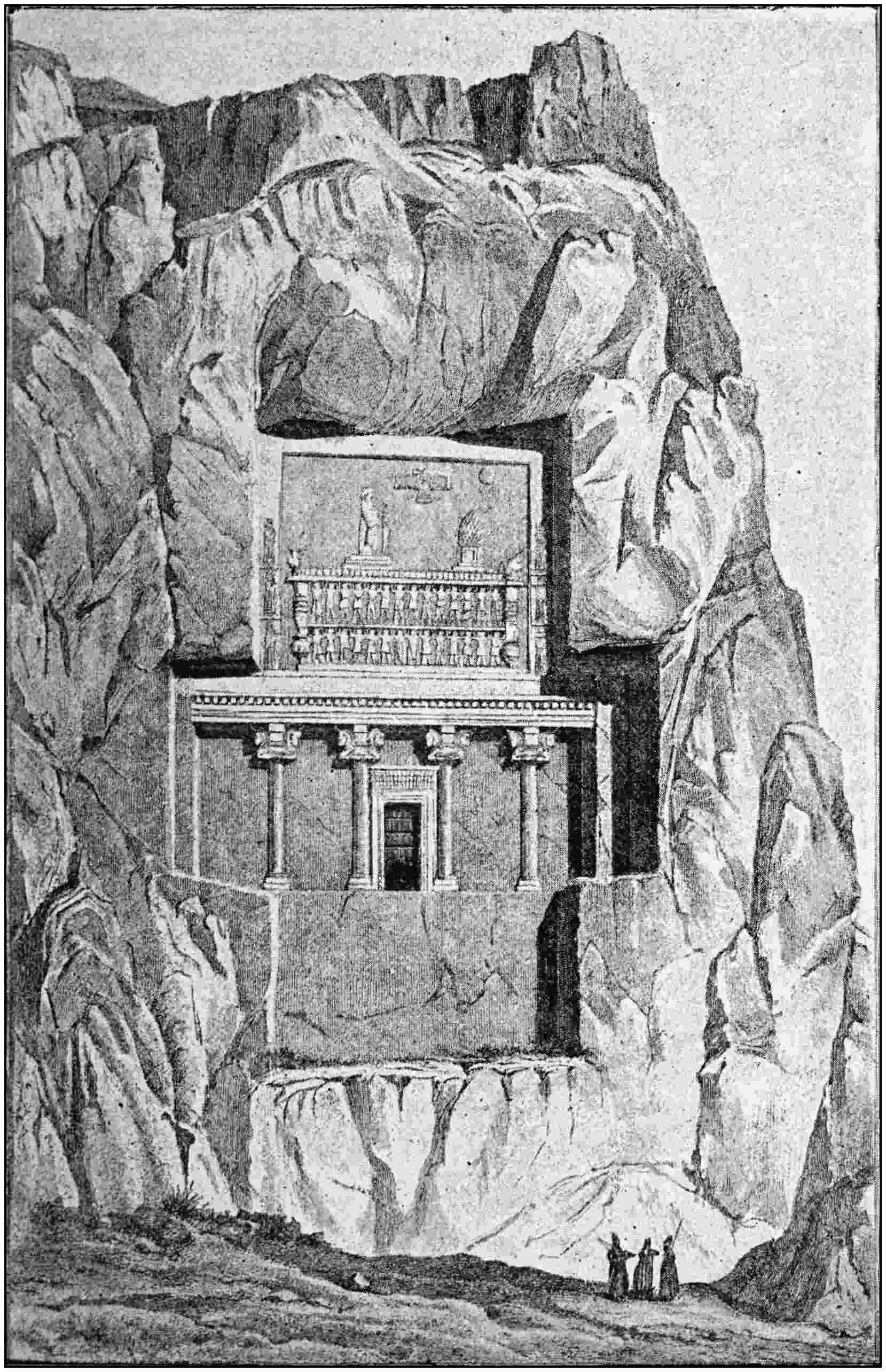

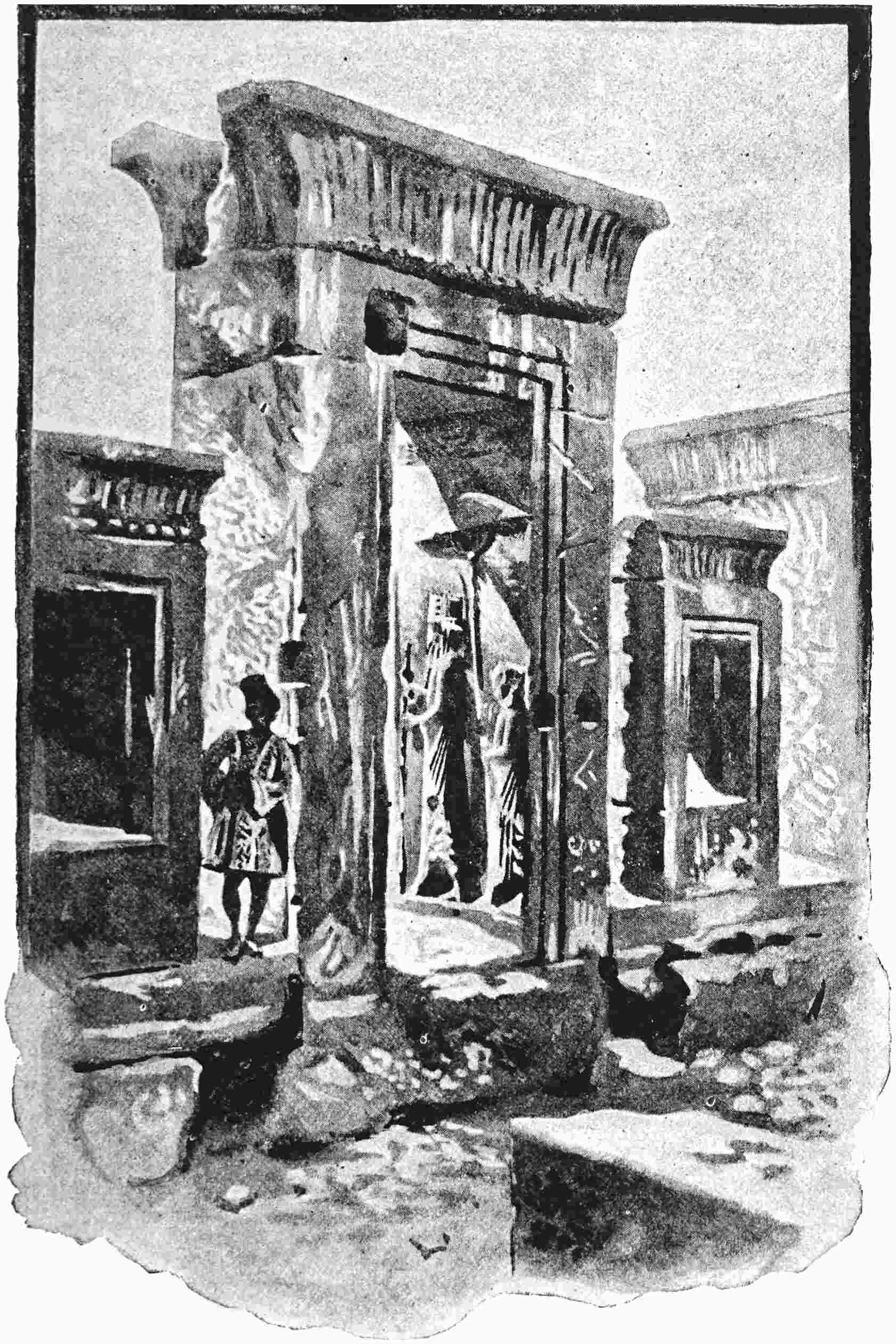

| Ruins of the Palace of Persepolis | 2 |

| Ruins of Persepolis: Balustrade of Great Staircase | 26 |

| Hall of the Hundred Columns at Persepolis—Restored | 38 |

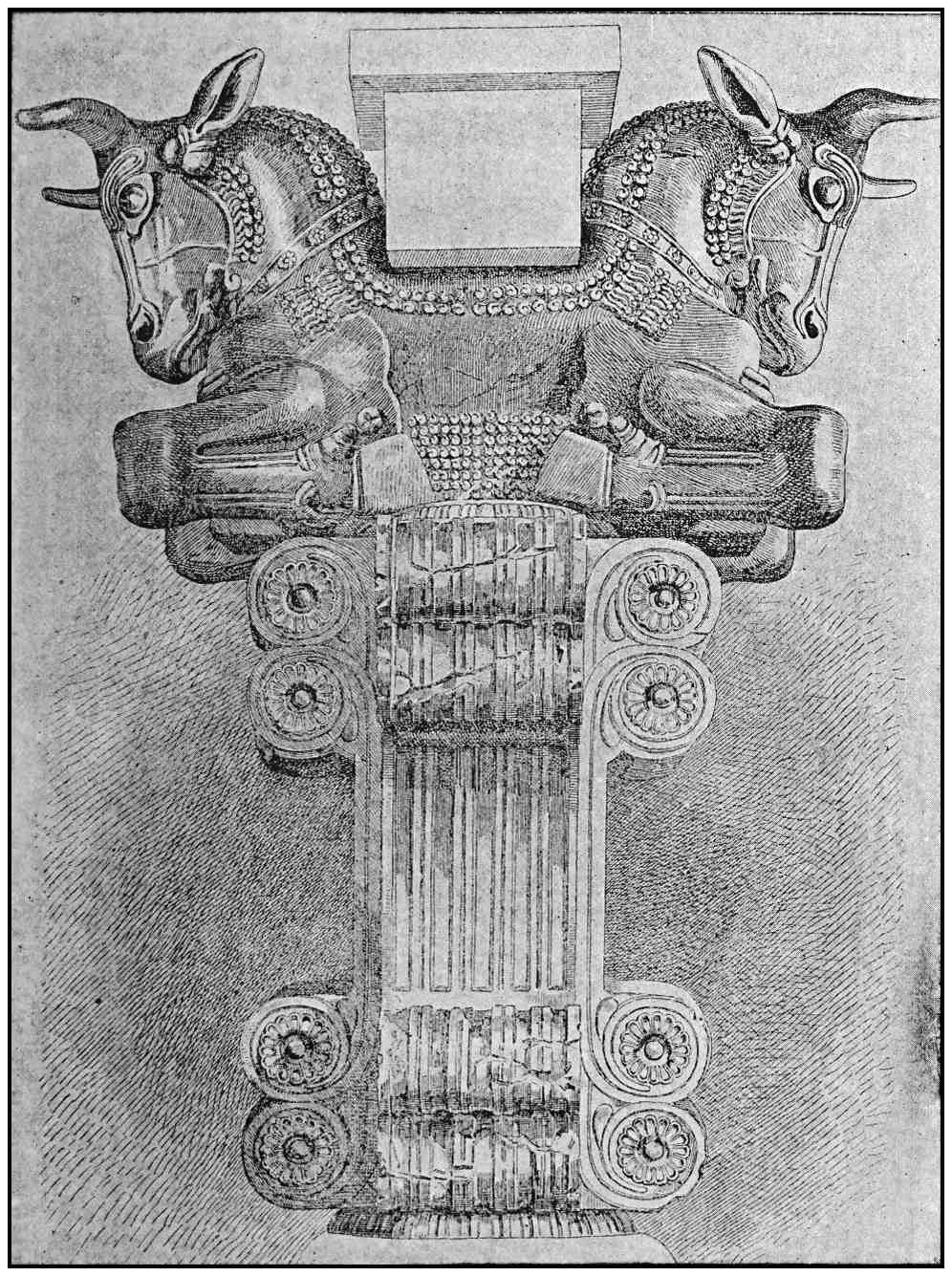

| Pillar from Hall of the Hundred Columns | 62 |

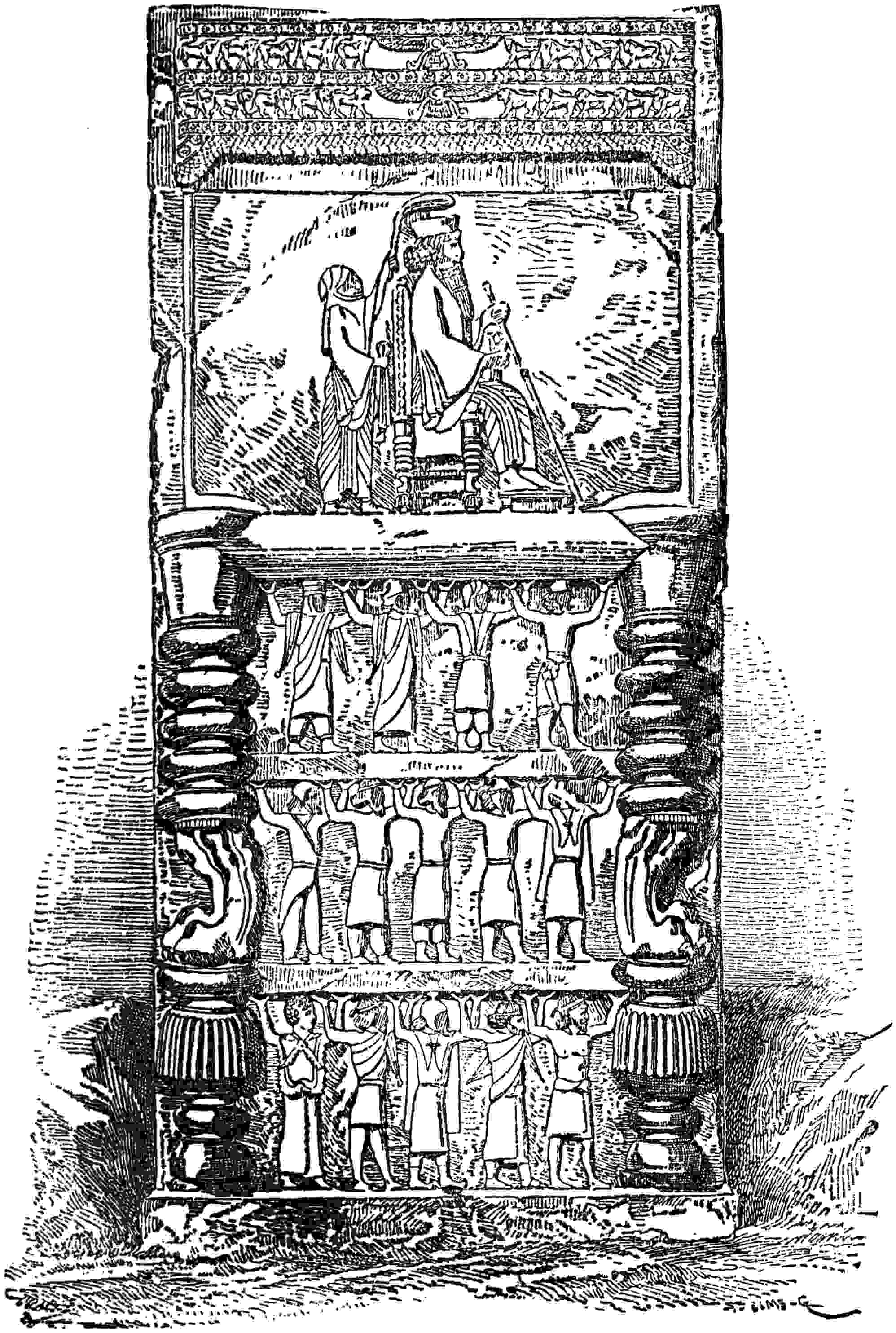

| Tomb of Darius I. near Persepolis | 80 |

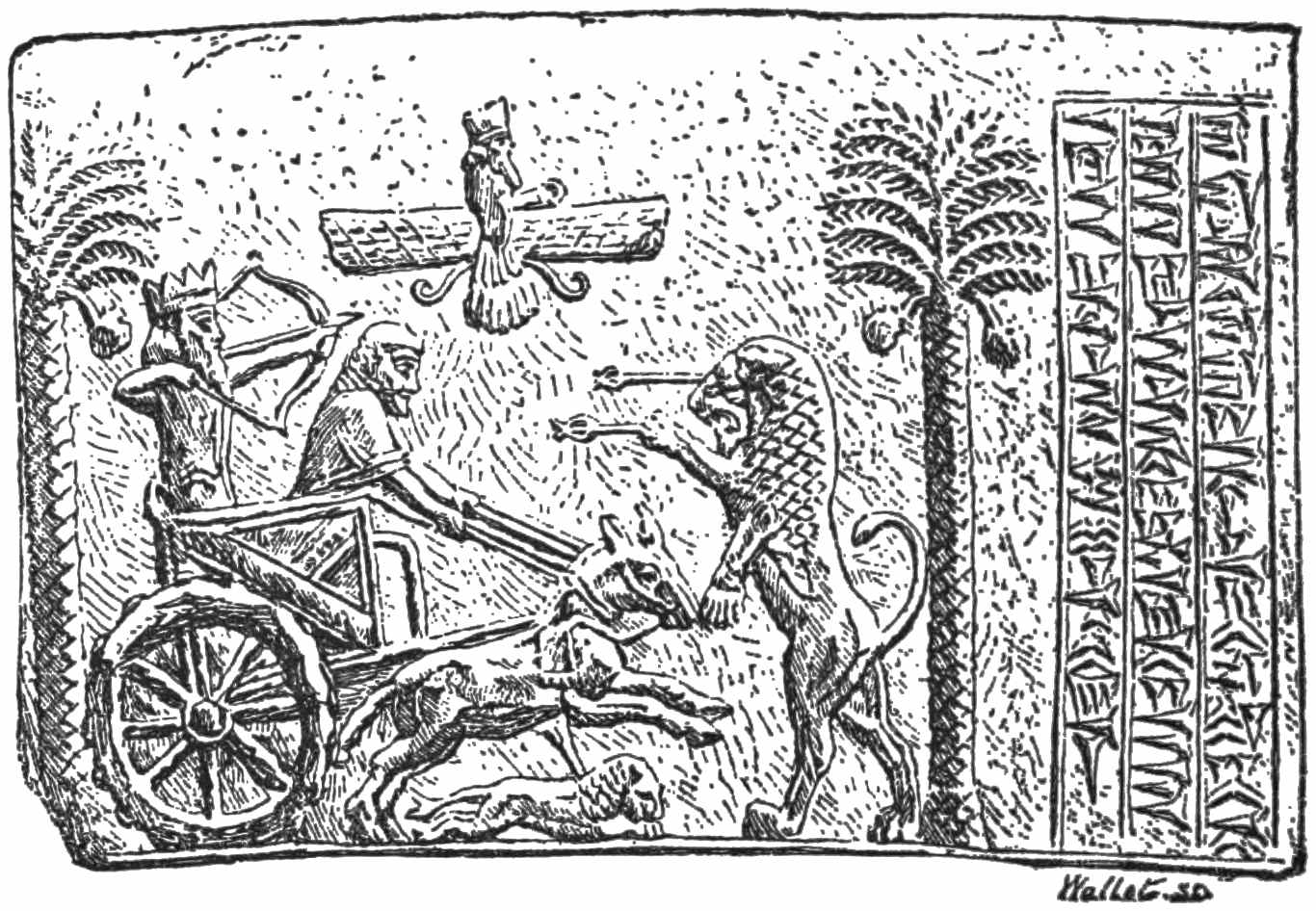

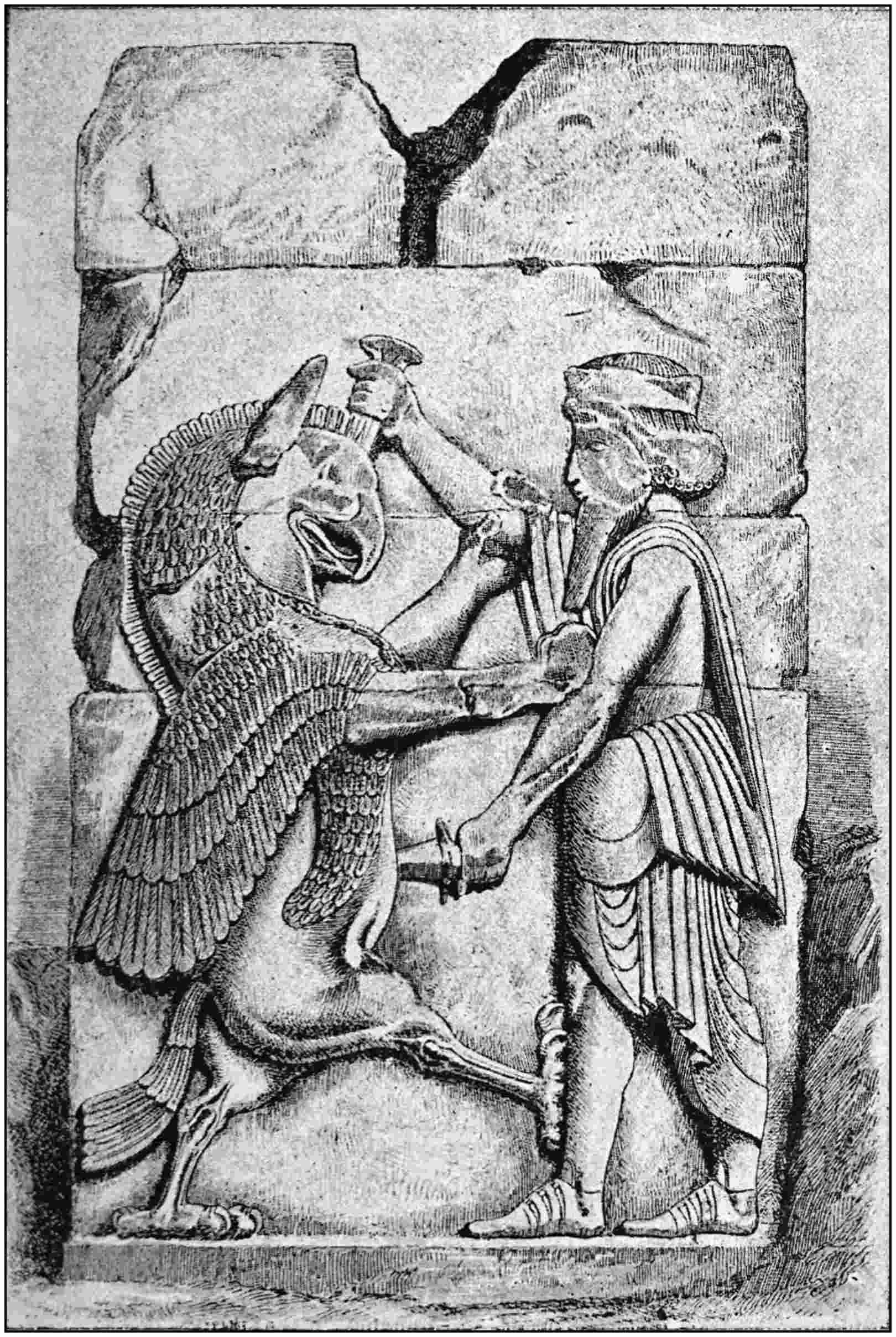

| The Great King fighting with a Monster | 88 |

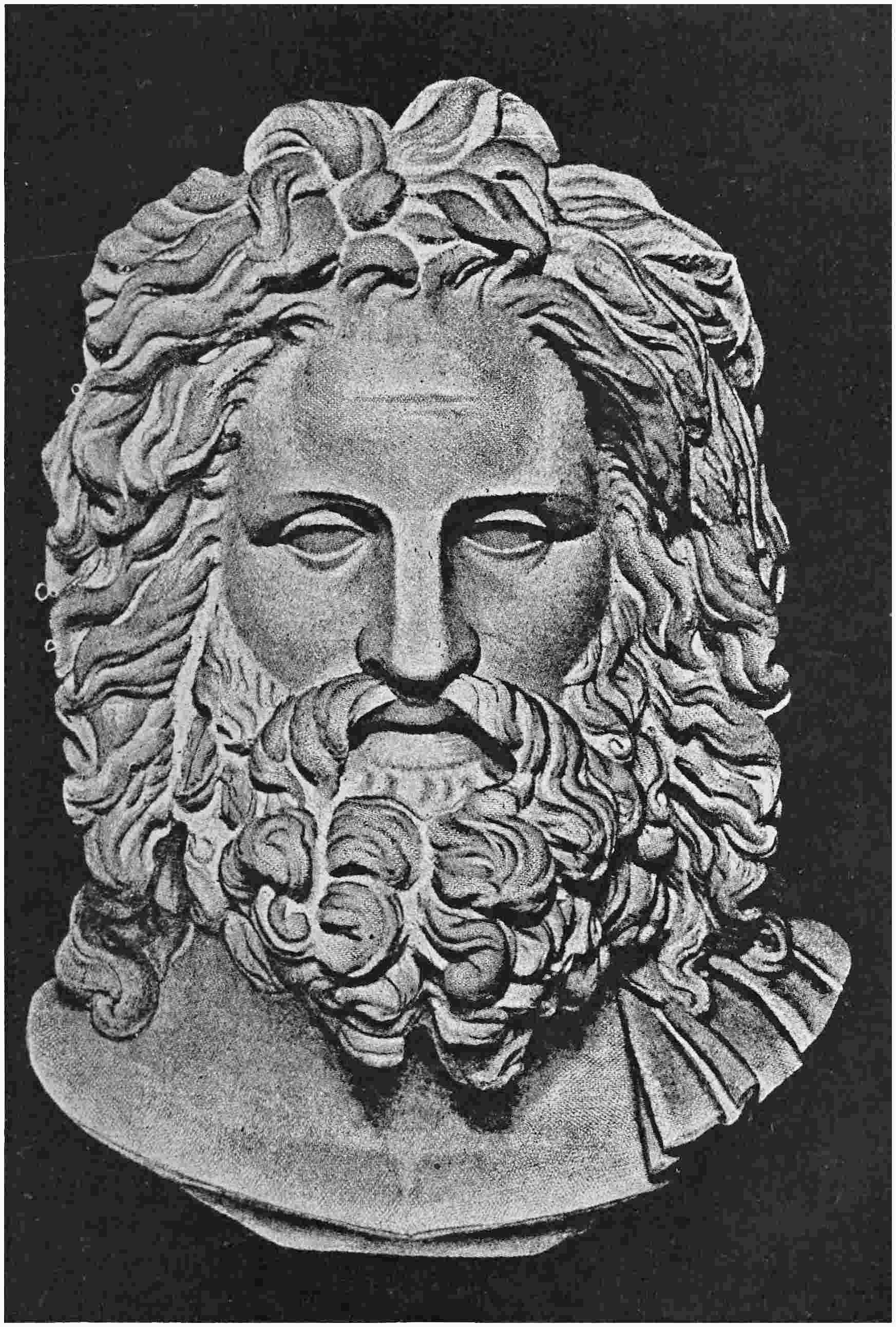

| Zeus | 114 |

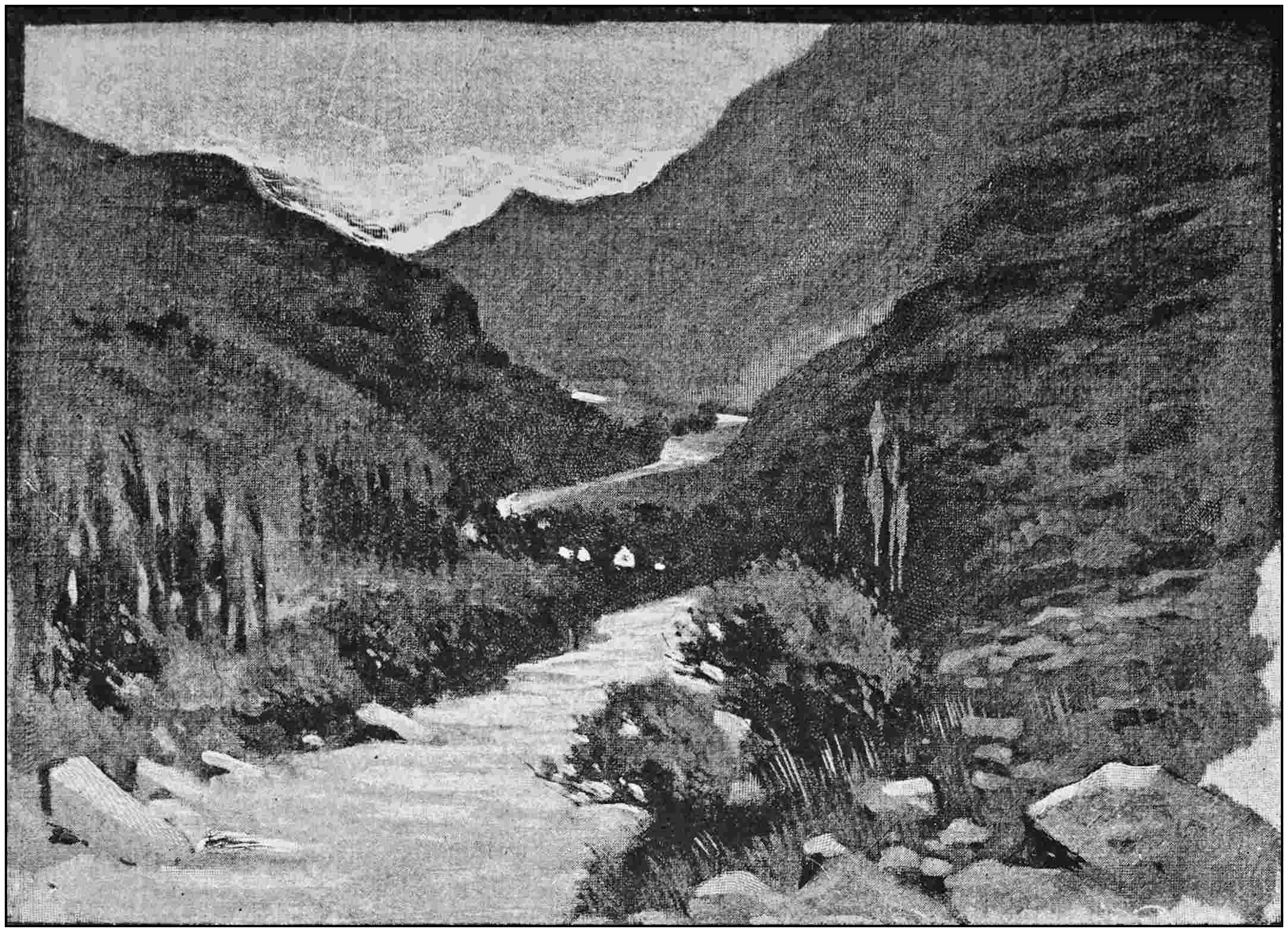

| The Hill Country East of the Tigris | 126 |

| Among the Carduchian Mountains | 142 |

| Ruins of Persepolis: Gate of Xerxes | 168 |

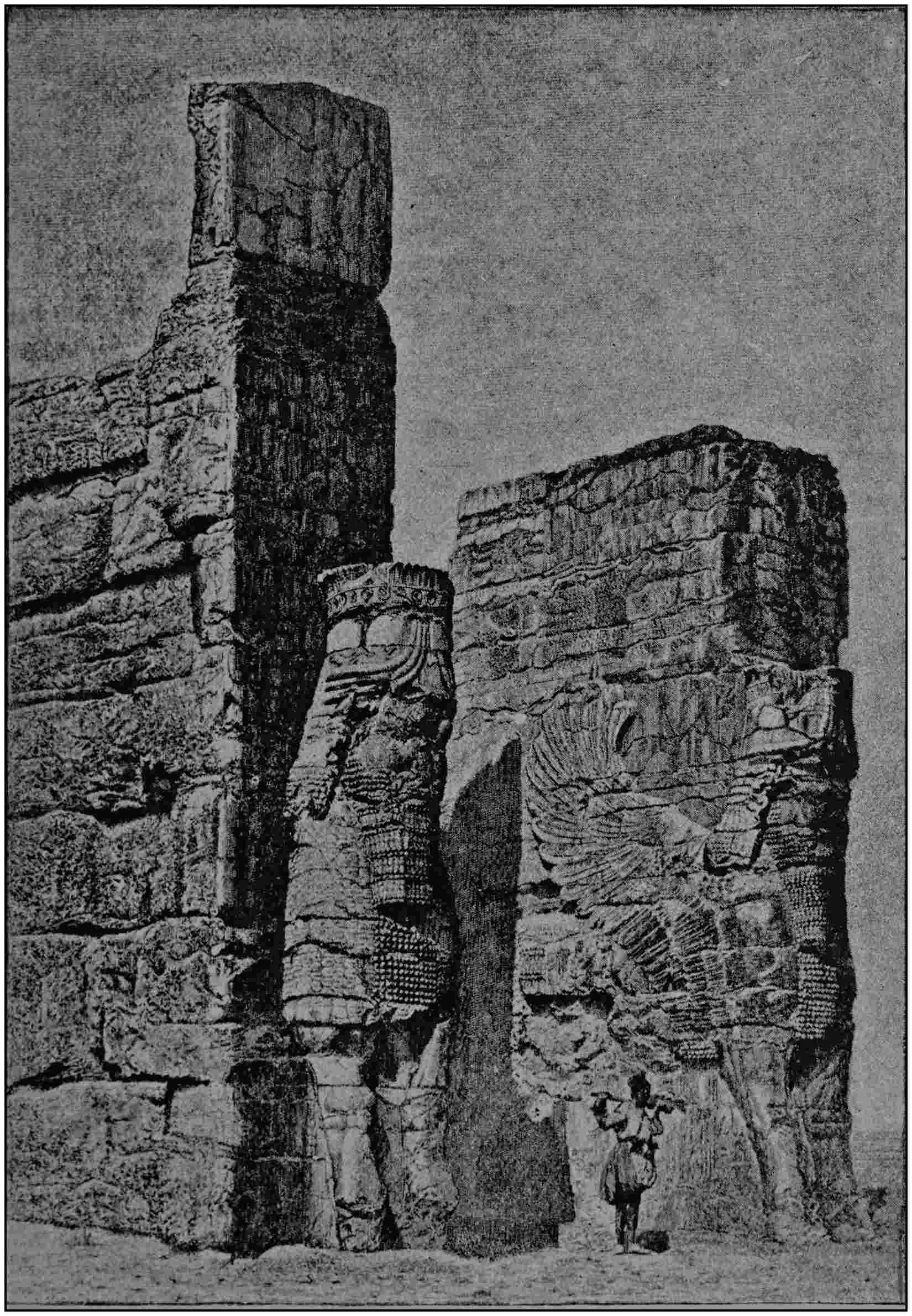

| Ruins of Persepolis: Gateway with Winged Bulls | 180 |

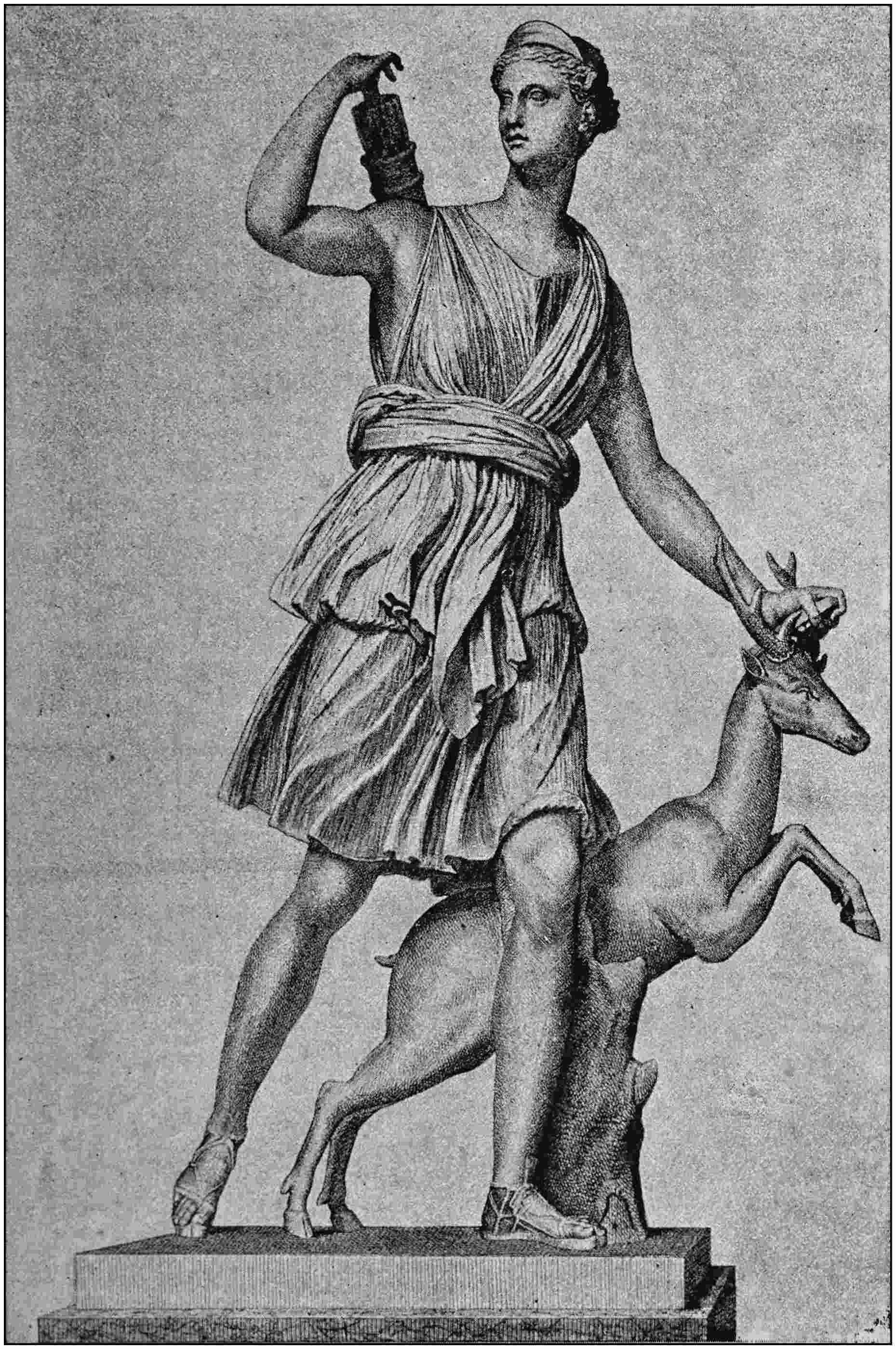

| Artemis | 190xiv |

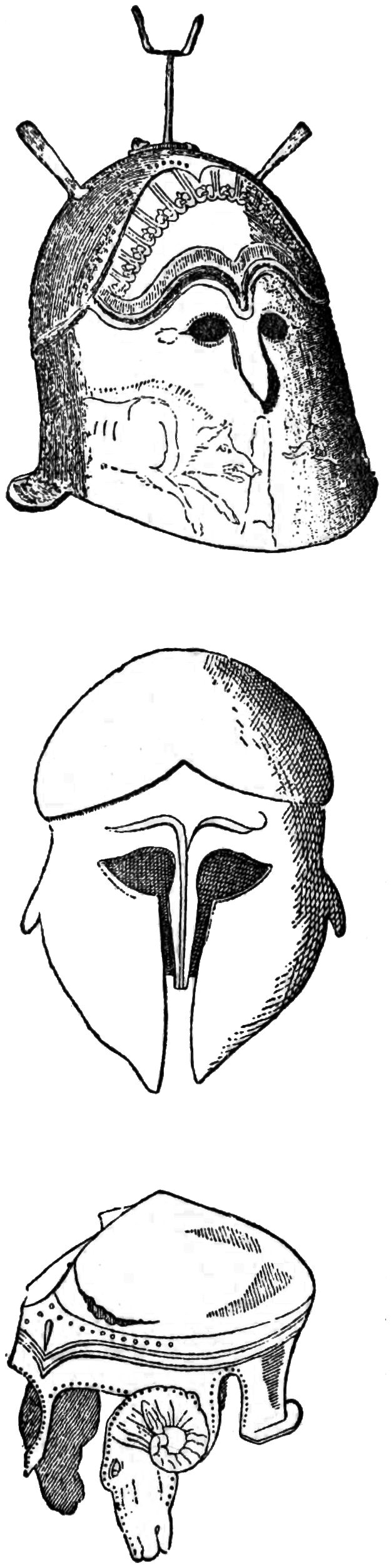

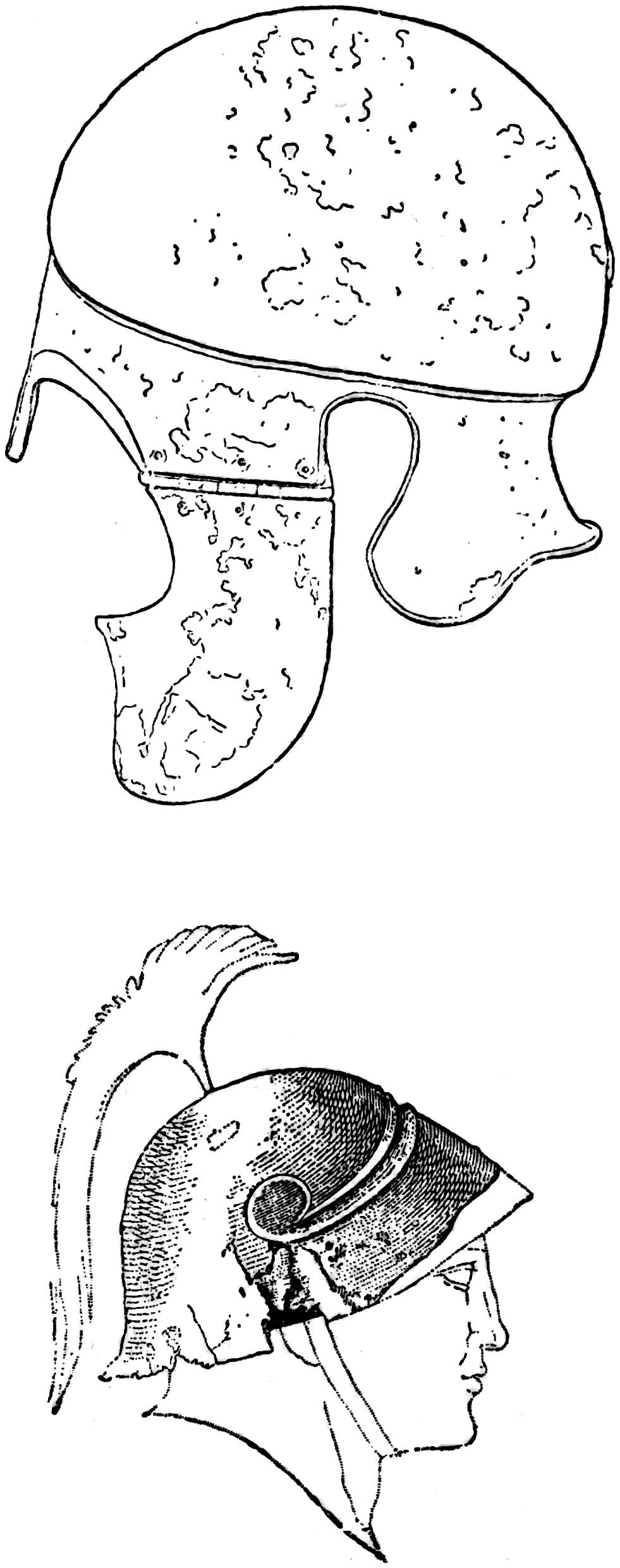

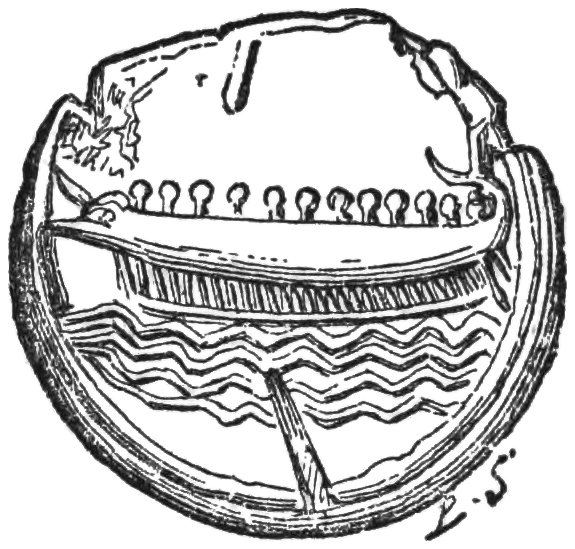

| WOODCUTS IN TEXT | |

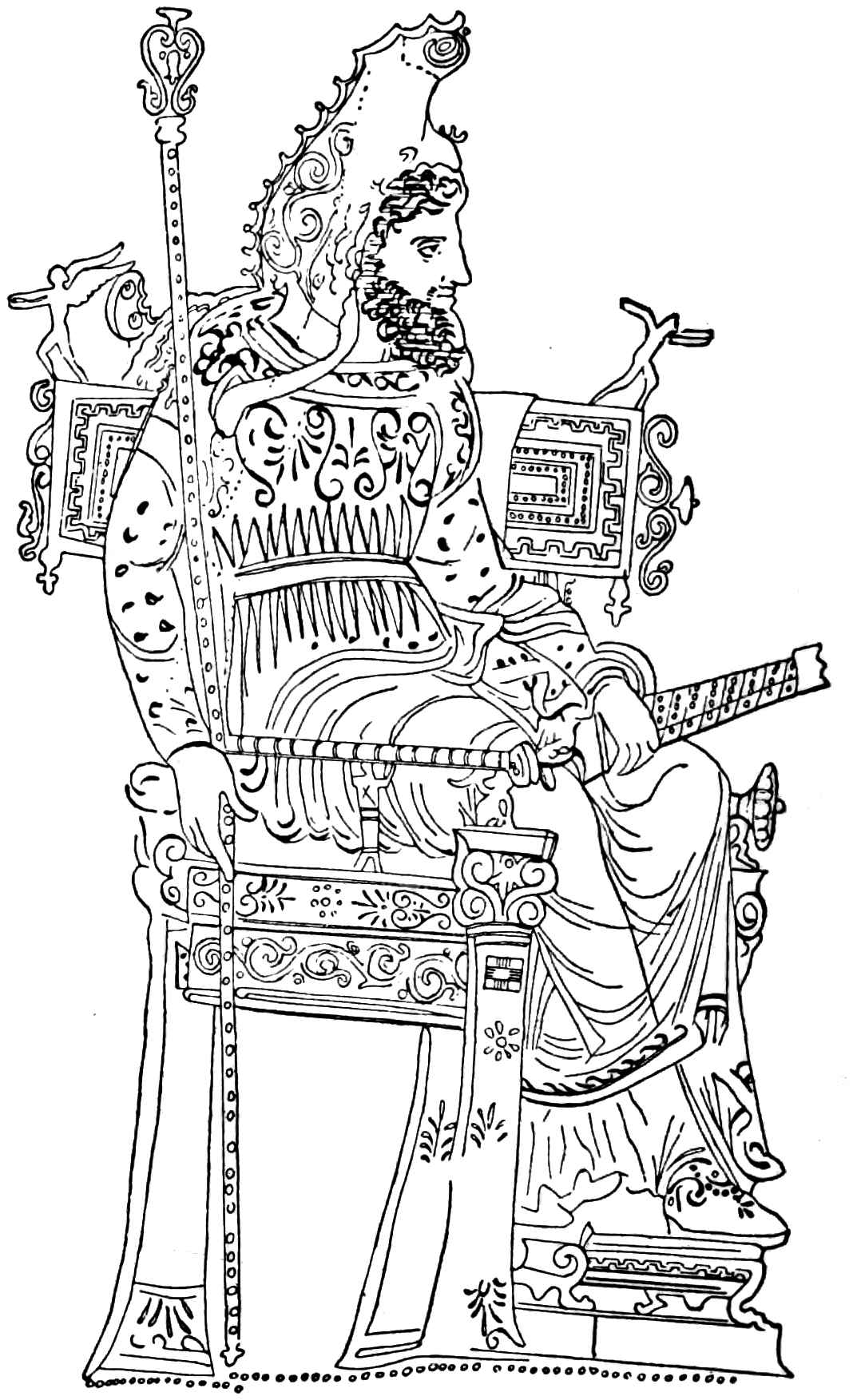

| The Great King in Gala Dress | 4 |

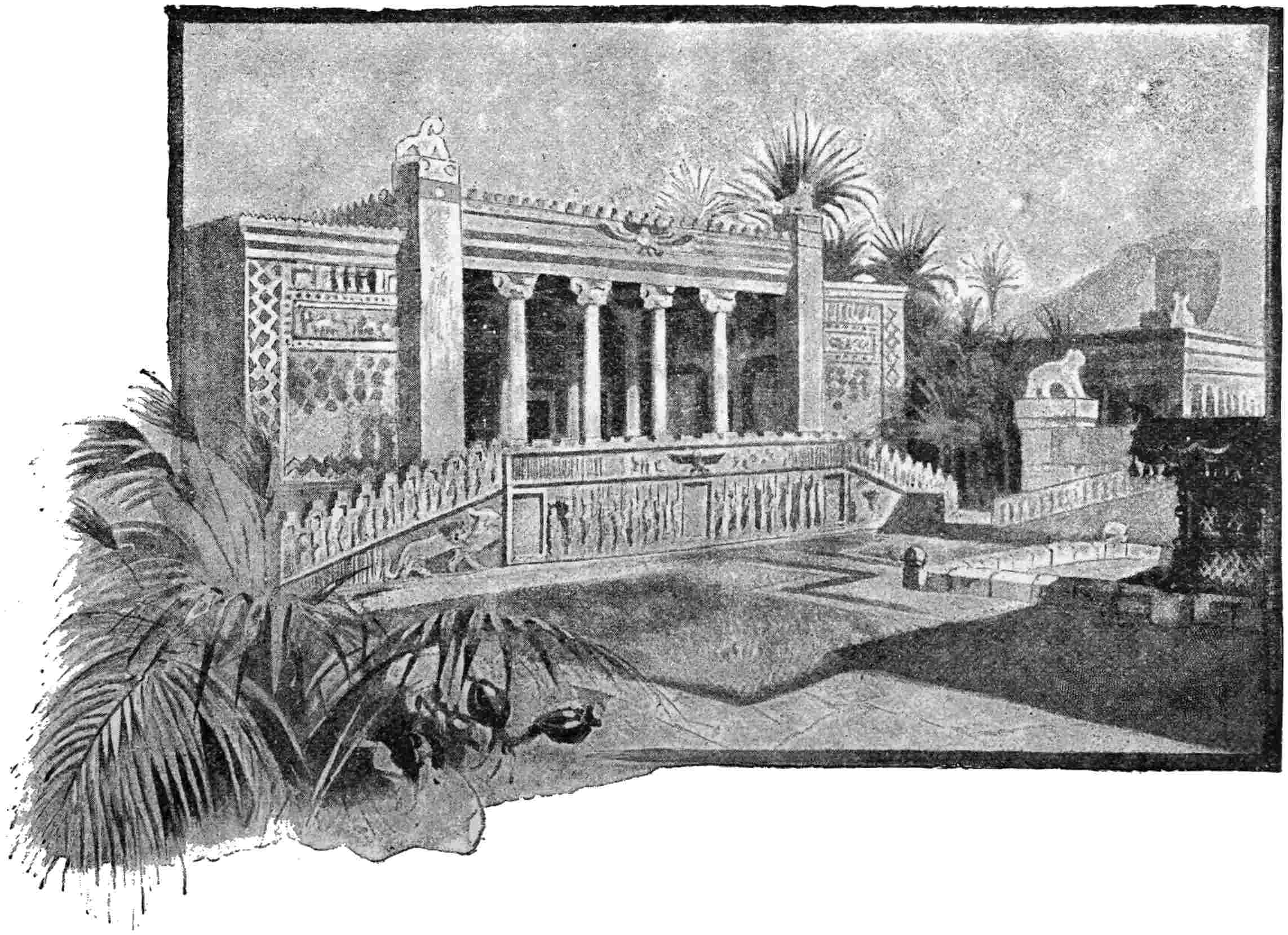

| Front of the Palace of Persepolis | 14 |

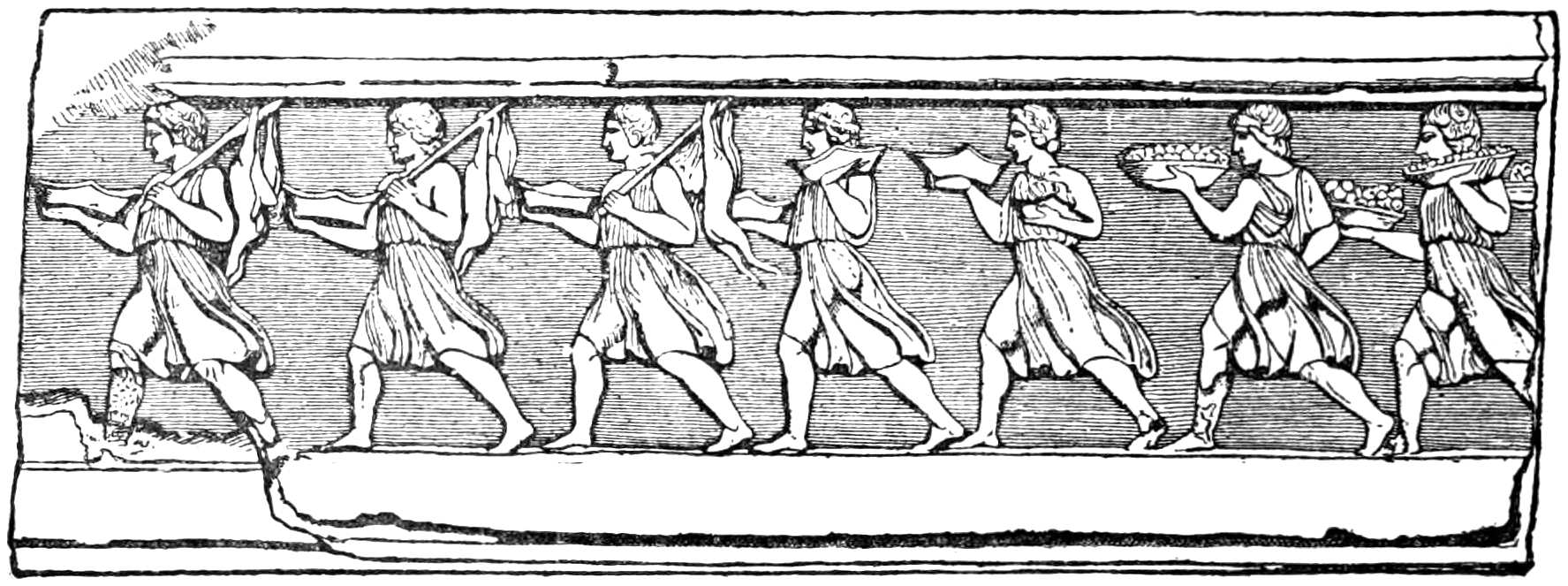

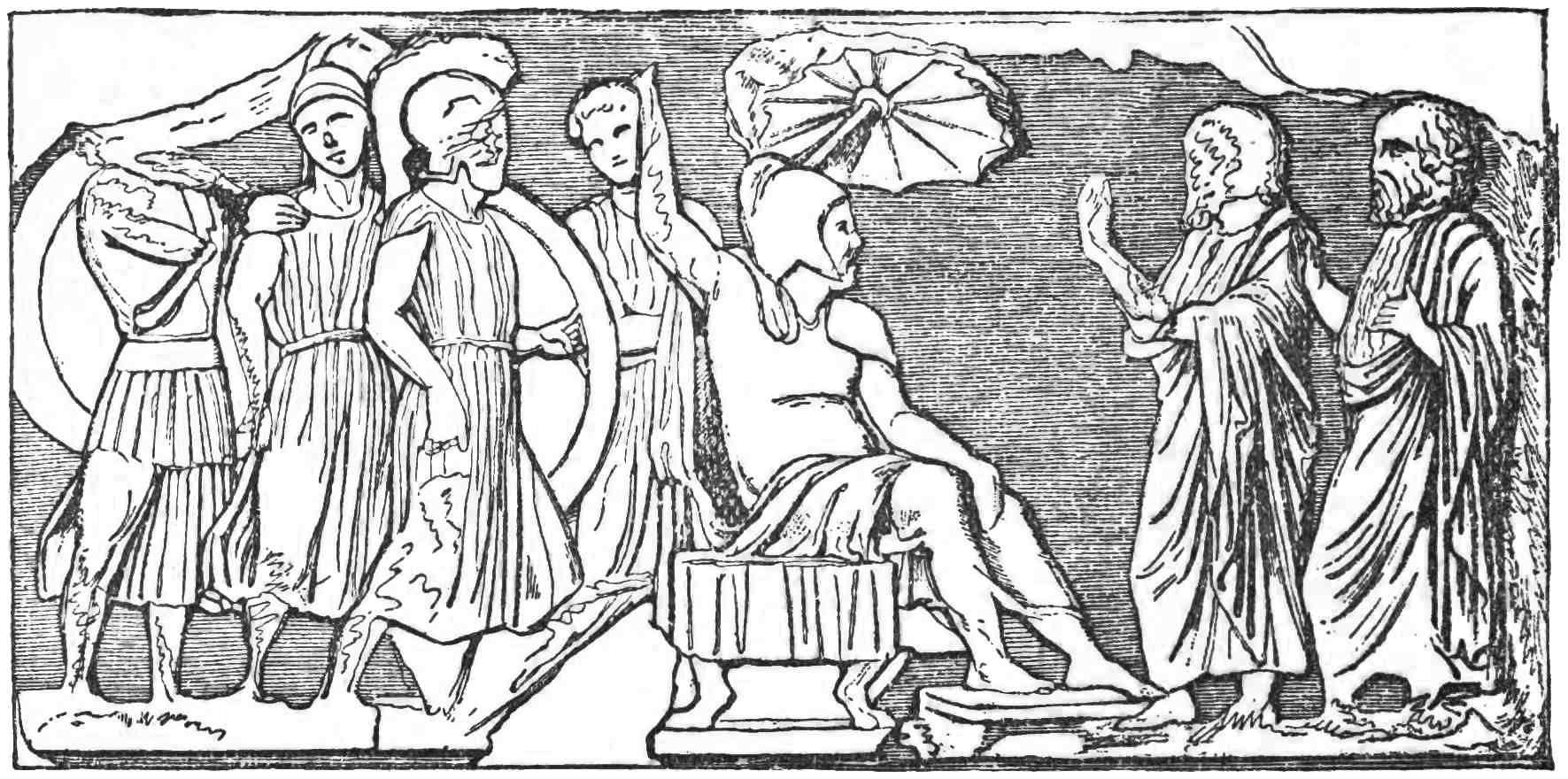

| Bringing Presents to a Satrap | 16 |

| A Bear Hunt | 17 |

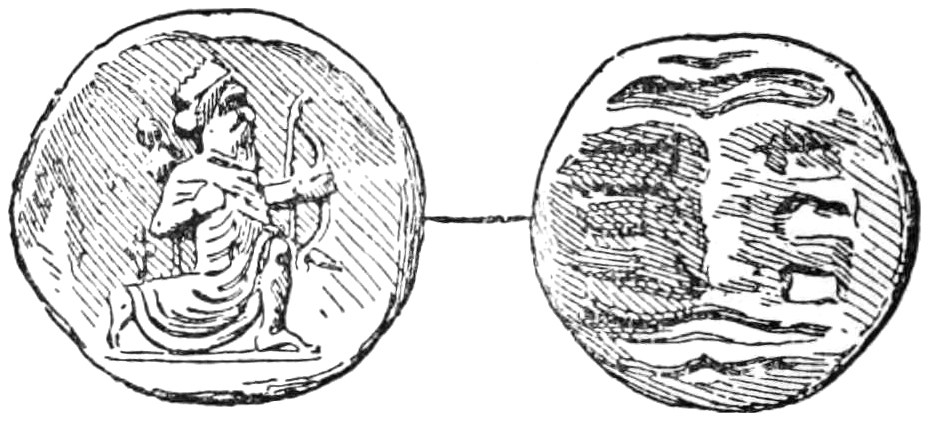

| A Gold Daric | 24 |

| Athenian Helmets | 28, 34 |

| Persian Galley | 36 |

| Ruins of Persepolis: Hall of the Hundred Columns | 47 |

| The Great King hunting | 66 |

| The Great King on his Throne, supported by the Subject Nations | 73 |

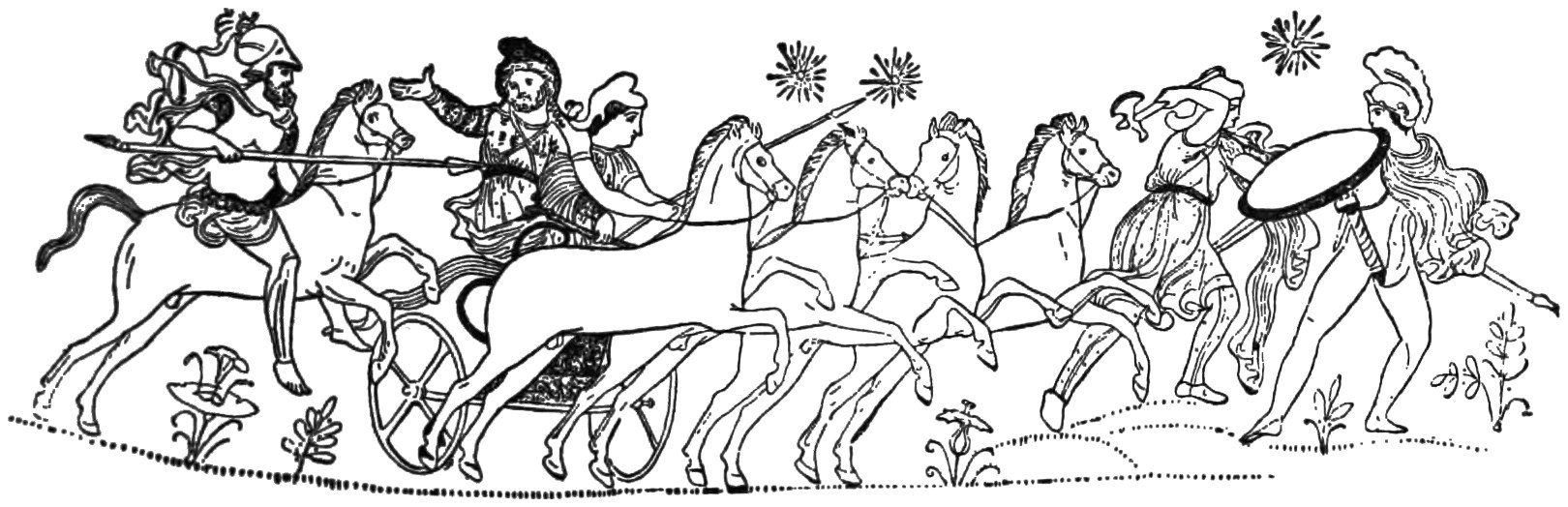

| A Fight between Hellenes and Barbarians | 77 |

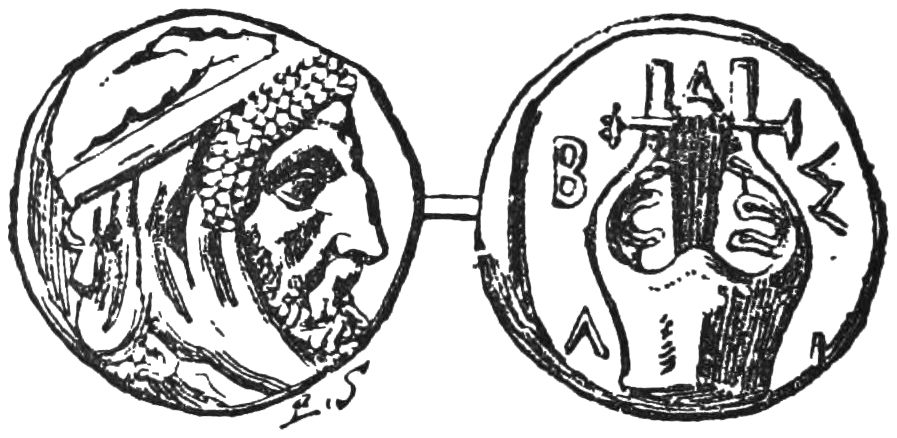

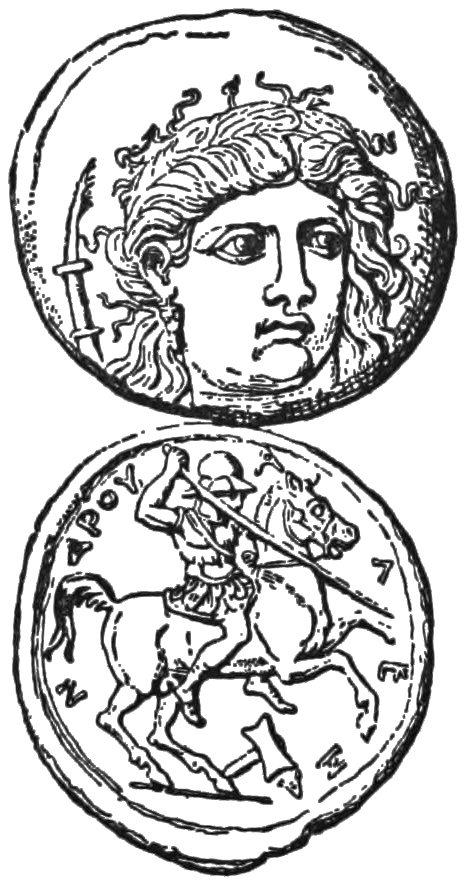

| Coin of a Satrap, probably Tissaphernes | 90 |

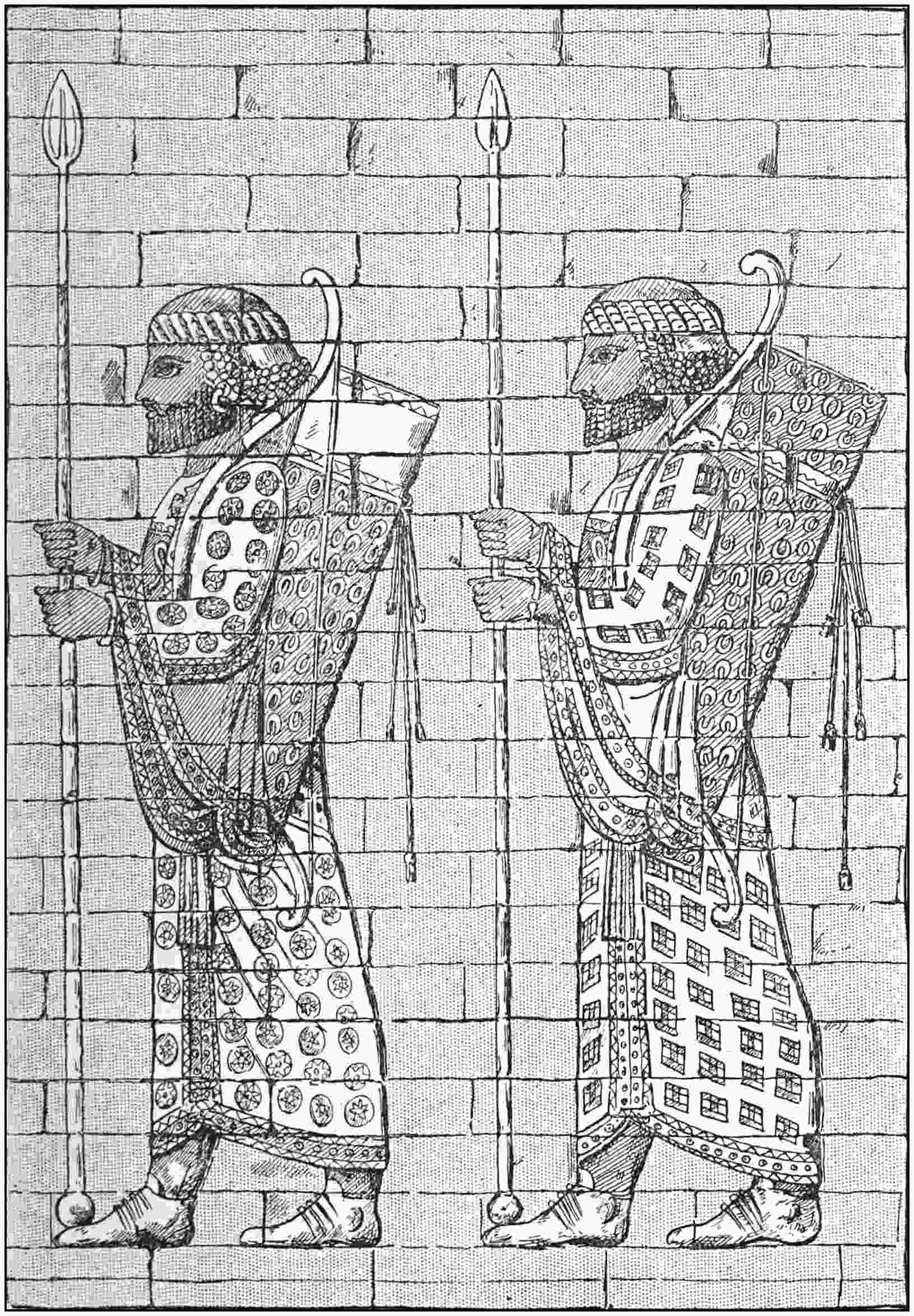

| Archers of the Royal Body-guard | 103 |

| Hellene Horseman: Coin of Alexander of Pheræ | 122 |

| Hoplite singing the Pæan | 155 |

| A Satrap receiving Deputies | 158 |

1

From time to time, in the course of the world’s history, the title of Great has been given to some monarch who has distinguished himself, either by the splendour of his victories, or by the value of his services to his fellowmen. We speak, for example, of Alexander the Great, and amongst English kings, of Alfred the Great.

There was however one empire, that of Persia, in which the title of Great carried with it no distinction, for in this country every king was called the Great King, not because it was supposed that his nature was more noble or his actions more splendid than those of other men, but because he was lord of a vast empire, greater than had ever yet been seen upon the face of the earth.

The Persian empire had been founded about a hundred and fifty years before the time of this story, by Cyrus the Great, who, having succeeded by inheritance2 to the double throne of Persia and Media, had conquered many of the surrounding nations. The kings who came after him extended their sway farther and farther, until at last, in the time of Darius I., there were no less than fifty-six countries subject to the Great King of Persia.

The Great King was looked upon as little less than a god. Every one who entered his presence threw himself flat upon the ground, as if in the presence of a divine being. It was supposed that a mere subject must of necessity be struck to the earth with sudden blindness on meeting the dazzling rays of such exalted majesty.

The court of the Great King was on a scale of the utmost splendour. His chief residence was the city of Susa, but in the hot season he preferred the city of Ecbatana, which was higher and cooler, and he also stayed occasionally at Babylon and at Persepolis. At each of these places there was an immense palace, adorned with every conceivable magnificence, and from the discoveries recently made among the ruins of Persepolis we can form some idea of what the palace of the Great King of Persia must have been like.

The palace of Persepolis stood upon a terrace above the rest of the city, and all round it were houses of a simpler kind, used for lodging the soldiers and the civil and military officers who were attached to the King’s person, and who ate daily at his expense. There must, in all, have been about fifteen thousand of them, including the ten thousand soldiers of the royal body-guard.1

The gate of the palace was approached by two superb3 flights of marble stairs, which joined in front of the entrance, and were so wide that ten horsemen could ride abreast up each side.2 Within the gate was a square building with a front of more than two hundred feet.3 The entrance-hall was a magnificent room, with a roof supported by a hundred pillars of richly carved stone,4 and on either side of it were other rooms with beautiful pillars. In all directions lovely colours and ornaments of gold and silver met the eye. The walls were covered with gigantic sculptures, representing the Great Kings Darius I. and Xerxes, who had built the palace, with attendants, both in time of peace, and at war with monsters and wild beasts.5 Together with the sculptures were inscriptions which can be read even now. This is a translation of the beginning of one of them: ‘I am Darius, the Great King, the King of kings, the King of these many countries.’ Among the sculptures is one that represents Darius seated on his throne, with a slave standing behind him, holding in his hand a fan with which to keep off the flies. The mouth of the slave is covered with a bandage, for it would have been considered a profanation to allow the air breathed by so august a sovereign to be polluted by the breath of a slave.6 Another sculpture represents an audience given to an ambassador, who, for the same reason, holds his hand before his mouth in the presence of the King.

THE GREAT KING IN GALA DRESS.

(From the Darius Vase at Naples.)

When the Great King gave an audience he sat upon a golden throne with a canopy above him which was held in its place by four slender pillars of gold4 adorned with precious stones. The whole effect was so dazzling that it would be hard to imagine anything more splendid, even in a fairy tale. On these occasions, and on all feast days, the King appeared in a purple robe, with a magnificent mantle of the same purple colour, richly embroidered. Round his waist was a golden girdle, and from it there hung a golden sabre, glittering with precious stones. On his head was the5 tiara, a sort of pointed cap worn by the Persians. Only the King might wear his tiara standing upright, all subjects were obliged to press down the point, or arrange the cap in some other way. The colour of the royal tiara was blue and white, and it was encircled with a golden crown. The full value of the gala costume was reckoned at nearly 300,000l. of our money.

It was only on rare occasions that the King walked, and then only within the precincts of the palace; on these occasions carpets were spread before him, on which no foot but his might tread. When he rode beyond the palace, the right of helping him into his saddle was bestowed as a mark of great distinction upon one of the most highly-favoured lords of the empire. More frequently, however, the King preferred to drive in his chariot, and at these times the road he intended to take was specially cleansed, and strewn with myrtle as if for a festival, and filled with clouds of incense. It was lined, moreover, with armed men on both sides; and guards with whips prevented any approach to the royal chariot. If a distant journey had to be undertaken, no less than twelve hundred camels and a whole multitude of chariots, waggons and other means of transport were required to convey the Great King, his countless attendants, and his endless baggage.

At a distance of about two miles from Persepolis was a great pile of marble rock, and here Darius I. caused his tomb to be made whilst he was yet alive. So steep and inaccessible was the cliff that the only way of placing the body in the tomb prepared for it was by raising it from below with ropes. Afterwards three other royal6 tombs were hewn out of the same rock, and three more in another, not far off.7

All Persians were allowed to have many wives, and the Great King had often a very large number; Darius, for example, had three hundred and sixty—almost as many as there are days in the year. Yet only one of these was the Queen; all the rest were so far beneath her that, when she approached, they had to bow themselves to the ground before her.

Like all Persians, the King only ate once a day, but the meal lasted a very long time. He sat at the centre of the table, upon a divan framed in gold and covered with rich hangings. At his right hand was the Queen-Mother; at his left, the Queen-Consort. The princes and intimate friends of the King, who were called his ‘table-companions,’ usually took their meal in an adjoining room. On feast days, however, they were permitted to dine in the royal presence, and on these occasions, seats made of cushions or carpets were placed for them upon the floor.

The power of the Great King was bounded by no law; from his will there was no appeal. He was a despot in the strictest sense of the word, and his subjects were all alike his slaves, from the lowest to the highest, not even excepting his nearest relations. In the whole world there was only one person whom he was required to treat with any kind of respect; this was his mother.

7

Under the vigorous rule of Darius I. the empire of Persia had attained its utmost limits; at that time fifty-six subject countries offered tribute to the Great King. But from this moment it gradually declined in power and in extent. For the wisest head and the strongest arm it would have been no easy task to govern such a dominion, and the successors of Darius were neither wise nor strong.

Neither was the Persian nation what it had been in the time of the great Cyrus, when even the nobles were simple in their habits, and when every Persian made it his pride to ride well, to shoot well, and always to speak the truth. Now, nobles and people alike had become luxurious and pleasure-loving, caring for nothing but to increase their own power and wealth, no matter at what cost to the subject nations.

The empire was unwieldy in size, and moreover it lacked any real bond of union. The various nations of which it was composed differed in language, in manners, and in habits of life. Each province was interested in its own local affairs, but was profoundly indifferent to the fate of the empire at large; and in time of war the soldiers were so little inclined to risk their lives for a8 monarch of whom they knew nothing that they only fought under compulsion, and often had to be driven with whips to face the enemy.

In order to provide for the government of the empire, it was subdivided into provinces, and each province, or group of two or more provinces, was placed under the charge of one of the great lords. It was the duty of these governors—or Satraps, as they were called—to act as the representative of the sovereign, to maintain law and order, and to take care that the people had no opportunity of revolting from their subjection to the Great King.

The power of the satraps was practically absolute, and a thoroughly disloyal Satrap could even go so far as to seize some favourable opportunity to detach his province from the empire and make himself an independent sovereign. The King was, indeed, accustomed to make a journey of inspection every year into one or other of his provinces, but in each province such visits were of rare occurrence, and a Satrap who wished to seek his own advantage, instead of studying the interests of the King and of the empire, had every opportunity of doing so. ‘The empire is large,’ he might well say to himself, ‘and the King is far away.’

With a view to checking such tendencies on the part of the Satraps, the Persian nobles were trained in habits of implicit obedience and subjection to the sovereign, and were kept in constant fear of being ruined by some report of treason or misgovernment on their part which should reach the ears of the King. Upon the smallest suspicion, and without any sort of trial, a man who was accused of plotting treason against the9 King might be removed from his post, and either openly or secretly put to death. A story is told of Darius I., who was one of the best of the Great Kings, that once, when he was about to engage in an expedition against the Scythians, a Persian noble prostrated himself before him, and craved as a boon that of his three sons he might be allowed to keep one at home with him. The King answered that he should keep them all at home, and gave command to put them to death immediately.

In a similar manner the people were crushed by severe and cruel laws, just as wild animals are cowed by ill-treatment and want of food. As conquered nations they were not expected to have any attachment to the King, or any interest in the welfare of the empire, and although now and again services rendered to the King would be rewarded by overwhelming favours, yet the means chiefly relied upon for securing good behaviour was the certainty that every offence would meet with prompt and barbarous punishment. Not only criminals, but even persons merely suspected of having committed crimes, were put to death in the most horrible manner. Some were crushed between stones, others were torn limb from limb, and others, again, suffered painful imprisonment in troughs. For merely trifling offences they were cruelly mutilated.

There is a Persian proverb that ‘the King has many eyes and ears.’ In every state the king must have means of knowing through his trusted officers, who see and hear for him, what is going on among the people. But in Persia the arrangements for obtaining information of this kind were reduced to a science. Satraps10 and people alike were constantly watched by a body of spies, and so secretly was this done that it was not even known who were the officers employed. A favourite device of the spies was to feign a friendship for the person whose actions they wished to report, and a man might be arrested and executed without once suspecting the false friend who had given information of his real or imaginary guilt. Sometimes the spy would denounce an innocent man for no other reason than to bring himself into notice as active in the King’s service.

Another plan was to take note of every one who passed along the roads which led from the various Residences of the Great King to the other principal towns of the empire. These roads were commanded by fortresses where officers were stationed whose duty it was to enquire of every wayfarer whither he was going and on what errand, and any messenger carrying a letter was obliged to give it up for inspection. This was intended to check the free passage of suspicious persons, and to prevent the sending of letters not approved by the government; but it must often have been easy to find means of evading the King’s officers.

In order that the King might be informed as quickly as possible of any risings or disturbances in the provinces, a very complete system of postal communication had been arranged. Besides the fortresses, there were stations all along the roads, at intervals of about fifteen miles apart, where the traveller could find shelter for the night. Here the swiftest horses and horsemen were always waiting in readiness to carry on the post at full gallop without a moment’s delay, whether in burning11 sun or blinding snow: and thus there came to be a saying that ‘the Persian post-riders fly faster than the cranes.’ A messenger sent from Susa to Sardis, traveling at the ordinary speed, would take a hundred days to reach his destination; but by means of the King’s posts a letter could be conveyed in six or seven days and nights. It must not be supposed, however, that ordinary letters were carried so fast. The King’s posts were entirely reserved for the King’s business, and by this means he had the advantage of getting news from the provinces and sending back his commands before any one else knew what was going on.

But, in spite of all these precautions, the King, like his subjects, lived in constant fear. He never showed himself to the people, except surrounded by his ten thousand guards. If he gave an audience, the person admitted to the royal presence was compelled, on pain of death, to present himself dressed in a robe with long sleeves falling over the hands, so that he should not be able to use his hands against his sovereign. If he entertained guests at his table, those among them who were considered the most faithful were placed at his right hand, and the less trusted at his left, because, in case of need, he would be better able to defend himself with the right hand than with the left. Each dish that was set before him was first tasted by an officer in the royal presence, lest there should be poison in the food, and in like manner, the cup-bearer always drank first from the cup that he handed.

Under such a system of mutual fear and distrust, the seeds of ruin and decay were sown throughout the Persian empire, and each succeeding century saw it12 tottering more helplessly towards its final overthrow. But from without everything appeared fair and prosperous, and up to the very last, the Great Kings were careful to maintain all the pomp and splendour of imperial power.

13

Beyond the great Persian Empire, on the other side of the Hellespont, was the little country of Hellas, or Greece. The Hellenes, or Greeks, as they are often called, were a race of men who had for centuries trained themselves in the art of noble thinking and noble living, and they looked down with some scorn on their less cultivated neighbours, to whom they gave, one and all, the name of Barbarians.

In many respects Hellas was a complete contrast to Persia. The country was a very small one, and it was further divided into a number of tiny states, each with a free government of its own, and independent of all the rest. To the Hellene citizen, the one supreme necessity of life was freedom, and consequently in almost all the states the government was in the hands of men chosen by the people. Now and again a monarchy would be established in one or other of the states, but it never lasted long, and in their horror of tyrants, the Hellenes were apt to overlook the advantages of a firm, stable government.

It is true that in Hellas there were many slaves, but they formed a class apart and were in no sense citizens. The citizens themselves were free, and the Hellenes were convinced that honour, courage, and high-mindedness can only flourish among free men. It was14 their greatest pride to recall the battles fought by their countrymen in former days against the Barbarians of Persia, when, although outnumbered by ten to one, a handful of free men had put to flight a host of slaves.

FRONT OF THE PALACE OF PERSEPOLIS.

See p. 3.

15

About the year 423 before Christ, the throne of Persia was occupied by a King, named Darius II. His Queen, the beautiful Parysatis, had borne him thirteen children, but most of them had died young, and only two sons were now alive, between whose ages there was a difference of no less than thirty years. The elder was called Artaxerxes; the younger, Cyrus. Parysatis was not an impartial mother. She loved Cyrus far better than Artaxerxes, and desired nothing more ardently than that he should succeed to the throne after the death of Darius, rather than his elder brother.

The Queen was beautiful, and wise and clever, and she had great influence over her husband, and seldom failed in persuading him to do as she wished. She hoped therefore to induce the King to name Cyrus as his successor, especially as there was much that could be urged in favour of her plan.

It was certainly true that the throne of Persia descended, as a rule, from the father to his first-born son, but there was nothing to prevent an elder son being passed over in favour of a younger, and such a course was not without precedent. In the present case, an excuse might be found in the fact that the birth of16 Artaxerxes had taken place before his father came to the throne, whereas Cyrus had been ‘born in the purple,’ and moreover bore the honoured name of the greatest of Persian sovereigns.

But a much stronger argument was the difference in character between the two men. Artaxerxes was weak and indolent, and lived constantly at the King’s court, hating exertion of any kind. Cyrus, on the contrary, was active and energetic, and had already given striking proofs of ability, both as a soldier and ruler of men, for at the age of eighteen, he had been appointed satrap of the provinces of Lydia, Greater Phrygia and Cappadocia.

Cyrus had many friends. He was a man just after the Persian heart,—a bold rider, an unrivalled archer and spear-thrower, and a passionate lover of the chase, especially when it was dangerous. He also excited the admiration of the Persians by his power of drinking an enormous quantity of wine without becoming intoxicated. This was looked upon as a sign of manliness, and a great distinction.

In the pleasant and peaceful occupation of gardening,17 Cyrus also took great delight. This charming pursuit had been raised almost to the rank of a religious duty by Zoroaster, the founder of the Persian religion, who had taught his disciples that when occupied in the planting and tending of trees useful to man, they were engaged in a good action, well-pleasing to God; and in consequence of this precept, almost every palace stood in the centre of a large park or tract of enclosed land, covered with beautiful old trees.

The palace of Cyrus stood in such a park, called by the Persians a ‘paradise.’ Here he might often be seen, attending to the trees with the utmost diligence. Here too was a convenient hunting-ground, ready to his hand, for the forest was full of wild animals who found abundant pasture in its pleasant glades. One day when Cyrus was out hunting he was attacked by a she-bear, who dragged him from his horse, and gave him several wounds before he could kill her. One of his companions came to his help, and for this service Cyrus rewarded him in so princely a manner as to make him an envied man.

As a friend, Cyrus was always generous and open-handed, and he delighted in making small presents as well as great. According to an old custom, every18 subject who came to his court brought with him gifts, and these Cyrus always accepted, but not for himself; he took them in order that he might divide them among his friends.

Sometimes, at a banquet, if he observed that the wine set before him was better than usual, he would send away part of it to one of his friends with some such message as this: ‘Drink this good wine to-day with your dearest friend.’ Or perhaps the gift would consist of half a goose or part of a loaf of bread, which would be taken to the friend with the message, ‘Cyrus has enjoyed this, and desires that you should taste it also.’

If he gave a promise, or entered into an agreement, it was certain that he would keep his word. A friendship once formed he ever afterwards regarded as sacred. Any one who did him a service, whether in war or in peace, was rewarded tenfold. At the same time, any one who offended or injured him might expect the most savage retaliation. He is said to have once prayed to the gods to grant that he might live until he had repaid all his friends and all his enemies.

As a governor, Cyrus was strictly and sternly just. Well-doers were encouraged and rewarded, but evil-doers met with immediate punishment; and as a warning to others, criminals who had been deprived of hands, legs or eyes, were exposed to view in the most frequented streets. In the whole empire there were no provinces in which natives and strangers alike were so secure from robbery and murder as in those governed by Cyrus.

Meanwhile the Great King Darius II. felt his end approaching, and as he wished to have both his sons19 beside his death-bed, he sent for Cyrus to come to Susa. On receiving the message, the young prince set out at once for the King’s court, accompanied by Tissaphernes, the satrap of a neighbouring province, whom he looked upon as one of his friends. He took with him also a body-guard of three hundred Hellenes, who had entered his service.

Cyrus was full of hope that the influence of his mother, and the favour with which he was regarded by the Persians generally, would cause his father to bequeath the throne to him, and not to Artaxerxes. If the choice of their future sovereign had been left to the people, they would probably have chosen Cyrus. But in Persia, the naming of the successor was the right of the reigning king, and the hopes of Cyrus were doomed to disappointment. On his death-bed, Darius named, not his younger, but his elder son; and the upright tiara, encircled with the golden crown, passed to Artaxerxes.

Cyrus was vexed and angry at the failure of his hopes, and probably took little pains to conceal his feelings, for he was of a very passionate nature. However this may have been, Tissaphernes, whose friendship for him had been merely feigned, went to the new King and told him that his brother had made up his mind to have him murdered.

The beginning of a new reign had often in Persia been signalled by bloody deeds, and the murder of a brother was by no means an unheard-of crime. Artaxerxes was therefore ready enough to believe the accusation, and immediately gave orders for his brother’s arrest, for he was resolved to defeat his ambitious20 schemes by the most effectual of all methods, namely by putting him to death.

Cyrus had many friends at the court, but there was not one who dared to come forward in his behalf, except his mother, Queen Parysatis. She indeed was ready to risk everything in order to save her favourite son, and being also the mother of the Great King, with a sacred claim upon his love and respect, she succeeded at last, after endless entreaties, in shaking his resolution and inducing him to pardon Cyrus.

Artaxerxes was far from being a great man, but he was at least easy-going and good-natured, and now his mother so far prevailed upon him, that he not only set Cyrus at liberty, but also reinstated him in his former dignities, and allowed him to depart to his own province.

Cyrus returned therefore to his Residence at Sardis, full of bitterness and disappointment. It is not known whether or not he had really plotted the murder of his brother. The story may very possibly have been invented by Tissaphernes through envy of Cyrus, and in the hope of succeeding to the government of his provinces.

This much however is at least certain, that after having been treated as guilty of high treason, and condemned to death in consequence, Cyrus had but one object in life, and that to further this object, he did not hesitate to employ the power entrusted to him for a very different purpose. From this time forward his whole mind was set upon obtaining by conquest the throne of Persia.

21

It was no small enterprise upon which the mind of Cyrus was now bent, and at first sight it might well have been pronounced altogether hopeless. How could a mere governor of a province hope to unseat from his throne the Great King with all the resources of the empire at his command? At the most, Cyrus could only reckon upon some 100,000 soldiers, whereas Artaxerxes was able to bring more than a million of men into the field.

On the other hand however, it might be urged that the Great King could not at once assemble his whole force. So immense were the distances in this huge empire, that a whole year of preparation would be required, in order to bring up the army to its full strength. And Cyrus intended, if possible, to take his brother by surprise. He believed moreover that his disadvantage in point of numbers would be more than counterbalanced by the infinitely superior quality of at least a part of his army.

It was from among the Hellenes that he hoped to enlist such troops as could not fail to ensure his success. Some years before this, he had visited Hellas as his father’s ambassador at the time of the Peloponnesian22 war, and had observed the unusual talent displayed by the Hellenes for military enterprise. He had made many friends among them, whose friendship he still retained, and he was anxious to induce as many Hellene soldiers as possible to enter his service.

The Hellenes had always been fond of adventure, and just at this time there were numbers of them willing and eager to engage themselves to a foreign master who promised good wages, especially when this master was a prince well known to be generous and open-handed, and above all, a lover of Hellas and the Hellenes. During the long Peloponnesian war they had become accustomed to an unsettled, adventurous camp-life, and now that the war was over, they did not care to return to peaceful pursuits.

But Cyrus could not, without betraying his plans, begin openly to enlist foreign troops. It was necessary to find a pretext for employing them, and in this he was helped by fortune. For several hundred years there had been established along the west coast of Asia, numerous flourishing colonies of Ionian Hellenes. At first, and for a long time, they were free states, but they had been conquered at last by the Persians, and now they formed part of the Persian empire, and were included in the satrapy of Tissaphernes.

Most fortunately however for Cyrus it happened that just at this time the Ionian cities rebelled, not against the Great King, but against Tissaphernes, and begged Cyrus to take them under his protection. To this he gladly agreed, for it gave him a pretext for declaring war against Tissaphernes, and supplied a cloak with which to cover the preparations he was making23 for his great enterprise. Accordingly he sent word to the Ionian cities that their garrisons should be strengthened by the addition of Hellene soldiers, which he proceeded to levy for the purpose. He also raised troops for the relief of Miletus, one of the largest of the cities, and the only one left in the hands of Tissaphernes, who had received the news of the intended revolt in time to enable him to take prompt measures for suppressing it. He had removed the garrison, put to death the leaders of the opposition, and banished all suspected persons. These banished inhabitants had come to Cyrus, and in answer to their entreaties, he agreed to besiege Miletus both by land and water.

It may seem strange that one satrap should have been able to wage war against another, whilst all the time both continued to be subjects of the Great King. But in point of fact, such rivalries between neighbouring satraps were rather encouraged than otherwise by the Great Kings, who lived in constant fear lest one or other of the great lords should take it into his head to make himself an independent sovereign, and consequently felt more secure when they were occupied in quarrelling among themselves. In this case moreover, the royal revenue suffered no loss through the revolt of the Ionian cities, for Cyrus took care to forward the tribute which they were required to send to Susa, just as regularly as it had before been sent by Tissaphernes.

Other opportunities also offered themselves to Cyrus for increasing the number of Hellene soldiers in his pay. About this time he received a visit from a Spartan named Clearchus, whose acquaintance he had made during the Peloponnesian war, and of whose ability as24 a military commander he had the highest opinion. Clearchus had come to him with a request on behalf of the cities of the Hellespont, who were at war with their barbarous neighbours, the Thracians, and could not hold their own against them without help. He wished to aid his countrymen by raising an army for their defence, and asked Cyrus to grant him for this purpose a sum of 10,000 darics.8 The request was a large one, but it was at once granted by Cyrus.

8 A daric was a gold coin, first issued by King Darius I, and called after him—worth about a guinea.

Shortly afterwards there came to him a Hellene from Thessaly, with a similar request. In his country, the party of which he was leader found itself hard pushed by the opposing faction, and he also desired to raise an army by means of which he and his friends might again have the upper hand. He asked Cyrus to let him have as much money as would enable him to hire 2,000 men for three months. ‘I will give you gold enough,’ said Cyrus, ‘to hire 4,000 men for six months, on condition that you prolong the quarrel with your enemies until I send for you.’

Other requests of a similar kind were also granted by Cyrus, always with an intimation that he might require the troops later on for his own service. And25 thus he secretly collected a force of Hellenes which he kept employed in other undertakings, but ready to come to him when he should want them.

Meanwhile he was careful not to neglect any means of improving the Barbarian soldiers of his provinces, and this could be done openly, for it was part of his duty as satrap to practise the troops in all kinds of military exercises calculated to increase their efficiency.

All this time the Great King was constantly sending spies to Sardis to find out what his brother was doing, but on their return the spies invariably reported that they had seen nothing that could be regarded as suspicious. The fact was that Cyrus knew so well how to make himself agreeable to the spies, that although they reached Sardis as the friends of the King, they always became, before leaving it, the friends of Cyrus.

Every step that he took was weighed by Cyrus with the utmost caution; every difficulty that was likely to present itself on the road to Susa was considered carefully and deliberately, in order to ascertain the best means of overcoming it. No feeling of impatience was allowed to urge him on to any rash or premature action.

At last, three years after his return from the court, he judged that the preparations were sufficiently advanced, and that the time had come when he might venture to call in the companies of Hellene mercenaries from their various services, and also assemble his Persian troops.

Even now however he took care not to disclose the real object of the campaign. For had he announced his intention of marching against Susa, the Great King26 would have been at once put upon his guard, and moreover he had every reason to fear that the Hellenes would refuse to enter upon the expedition, if they knew how desperate was the venture, and how far it would lead them from their homes. By means of his posts the King could hear in less than a week of what was doing at Sardis, but an army could not march from thence to Susa in less than six months.

For these reasons Cyrus announced that the expedition was to be directed against the marauding tribes of Pisidia, who had often made raids upon the neighbouring provinces, and laid them waste. These tribes must, he said, be exterminated, in order to maintain the safety of the empire.

But there was one whose sharp eyes had followed all the doings of Cyrus with the close watchfulness of hatred, and who saw clearly through the veil with which he sought to conceal his real purpose. This was his neighbour, Tissaphernes. When he heard of the great host gathered together for the expedition against the Pisidians, Tissaphernes felt certain that Cyrus was aiming at nothing short of the throne of Persia; and taking with him a troop of five hundred cavalry, he set off at full speed for Susa, that he might be the first to warn the King of the approaching danger.

RUINS OF PERSEPOLIS: BALUSTRADE OF GREAT STAIRCASE.

27

It was about the ninth day of March in the year 401 B.C., that the army of Cyrus began to set forward. Cyrus was commander-in-chief of the whole army, but the two divisions were kept entirely separate, each under its own officers. The Asiatic troops, who numbered 100,000, were under the command of Ariæus, one of the most distinguished of the Persian supporters of Cyrus. The Hellene force, which consisted of 13,000 men, and was afterwards increased by another thousand, was composed of a number of different companies, each commanded by the general who had raised it, and smaller or larger according to his success in getting recruits. Under the generals were captains, who each had command of a hundred men, and whose numbers consequently varied in each company with the number of the soldiers.

Of the Persian troops, the most brilliant and useful were the cavalry. The Persians had long been famous for their skill and activity as horsemen; they were also excellent archers, and could draw their long bows at full gallop with as accurate an aim as if they were standing still and undisturbed on solid ground.

Among the Hellenes, on the contrary, the most28 useful, and at the same time the most numerous, were the Hoplites, or heavy infantry. There were no cavalry, and in the whole army only forty mounted men, nearly all of whom were officers.

The hoplites wore a helmet, breast-plate and greaves of iron, and carried an oval shield of ox-hide, overlaid with metal, which protected them from the mouth to the ankles. On its inner side the shield had a handle for holding it, and a strap wide enough for a shoulder-belt was attached to it at each end, so that it could be carried over the back. This was the usual way of carrying it on the march, when the enemy was known to be in the neighbourhood so that it was necessary to have the shield at hand, but not when the soldiers were engaged in actual fighting. For weapons of attack, they carried a spear measuring from seven to eight feet in length, made of strong wood with a solid iron point, and a short sword, or curved sabre. None but fine strong men could enter the ranks of the hoplites, for the full weight of the armour and29 weapons that they had to carry was no less than seventy pounds.

The light infantry were armed quite differently. They had but one weapon of defence, a shield which was only two feet in length; besides this they had little to carry but their clothes, for they were practically a troop of foot cavalry, and it was necessary that they should be very active, and able both to advance and retreat with extreme rapidity. According to their weapons of attack, they were subdivided into troops of lancers, archers and slingers. The lancers carried several light javelins, from three to four feet in length, the archers carried bows and arrows, and the slingers carried slings, with which they hurled stones or leaden bullets at the enemy.

And now the great host is well on its way. Try to imagine the dense, suffocating clouds of dust that must have been raised by the progress of such an army! Supposing the troops to have marched ten abreast, leaving one pace between each rank, the Barbarian army would have formed a procession more than three miles long, and the Hellene army would have covered about a third of a mile more. Besides this, there was the long train of baggage-wagons, the great droves of animals brought for slaughter, the numberless beasts of burden, and the crowds of people who in some capacity or other followed the army, but did not march in the ranks.

Even in the Hellene army, which in comparison with the Barbarian force was but scantily provided with camp-followers, there were great numbers of slaves whose duty it was to pitch the tents, to prepare30 the food, and to attend generally to the comfort of the troops. The tents and utensils were packed with the other luggage in wagons which the slaves drove, or piled on the backs of transport animals which the slaves led. Many of the Hellene officers moreover, and even some of the private soldiers, had brought their own slaves to wait upon them and to carry their heavy shields and helmets when there was no likelihood of their being attacked on the march. Behind these came a number of provision-dealers and other merchants, who brought goods of all kinds to sell to the troops, and who were always ready to buy from them any spoil that they might have an opportunity of taking. Still further in the rear were trumpeters, heralds, sacrificing priests, soothsayers and surgeons.

But the Hellene camp-followers were outnumbered a hundred times by the followers of the Barbarian army. For in addition to the other slaves, the luxurious Persian lords had brought with them their cooks, their bakers, and all manner of personal attendants, besides enormous tents in which to house the many members of their households who accompanied them to the war. The complete length of the procession formed by the army and its retinue was nothing short of six miles.

This immense multitude, great enough to people a good-sized town, required every day to be fed, either by buying such provisions as could be obtained on the spot, when the country through which they were marching was fruitful and well-peopled, or, when the country was waste and desolate, by falling back upon the stores which they had brought with them. These31 stores they were careful to renew whenever there was an opportunity of doing so.

In the Barbarian army, the officers were entrusted with the duty of providing food for the troops, and seeing that each man received every day his due portion of bread, meat and wine. In the Hellene army, the men catered for themselves, for their pay was given them in money instead of food.

The ordinary pay of a Hellene soldier was one daric a month, or about twenty-one shillings of our money, and out of this he was expected to provide his own weapons. The captains received twice as much as the private soldiers, and the generals four times as much. To us such a sum appears a very miserable pittance, but it must be remembered that in those days the value of money was far greater than it is now. Moreover all alike, whether officers or privates, might count upon a good share of booty from the enemy’s country.

32

The Hellenes had now been for some considerable time in the service of Cyrus, and hitherto he had not failed to pay them punctually every month. But the enormous expenses incurred in starting the expedition had for the moment completely drained his treasury, and now, two months after the departure from Sardis, he was still unable to give them any money, although their pay was by this time three months in arrear. It was a painful and embarrassing situation, and he felt it the more keenly because he had always been accustomed to give to those whom he employed more, rather than less, than he had promised them.

For a time the soldiers had been content to wait, for they had mostly some money of their own to fall back upon. But gradually their savings were becoming exhausted, and they were obliged to remind Cyrus of his debt. At first they did this modestly, but as time went on, they became more and more persistent, and now whole bands of them were constantly gathered round his tent, clamouring for their pay.

From this unpleasant position Cyrus was rescued by help that came to him from an unexpected quarter. Just at this time he received a visit from the Princess33 Epyaxa, wife of Prince Syennesis, who was the ruler of Cilicia, a province of the Persian empire included in the satrapy of Cyrus.

The princess had made a long journey in order to meet Cyrus at this point, and she had not come empty-handed. The large sum of money that she brought with her could not have arrived at a more welcome moment, and it was sufficient to enable Cyrus to distribute four months’ pay to the Hellene soldiers, and yet reserve a considerable sum for the next time of necessity.

Cyrus was now approaching the province of Cilicia, and for some days Epyaxa accompanied his march. One day she expressed a wish that he would draw up his whole army before her, so that she might see it at its full strength.

Accordingly, when they came to some open country suitable for the purpose, Cyrus proceeded to gratify her wish, and ordered the troops to be drawn up in battle array, that he might review them in the company of the princess. Side by side they passed along the ranks, the princess in a woman’s chariot shaded by curtains that could be drawn close or opened wide at pleasure, Cyrus in a man’s chariot.

First they reviewed the Barbarian army with its endless ranks of cavalry and foot-soldiers. Then they came to the Hellene troops, who were stationed opposite. In point of numbers the Hellenes could not compare with the Barbarians, but their appearance was far more imposing, so noble and spirited was their bearing, so proud and firm their step. They were dressed in purple tunics, with brass greaves and helmets, and34 carried bright, polished shields that glittered in the sunshine.

After having driven slowly past them, Cyrus sent word to beg that the hoplites would advance, as if they were in battle, and about to charge. In answer to his request, the trumpeters gave a signal, and on hearing it, the hoplites covered themselves with their great shields, and lowered their long, powerful spears as if they saw the enemy before them. Then the war cry was sounded forth, and the hoplites began to advance, marching faster and faster, until their pace was like a whirlwind, carrying everything before it. The Barbarians were seized35 with panic, for the charge had every appearance of being in earnest; the princess sprang from her chariot and ran away as fast as she was able; the merchants left their wares, and, like the rest, sought refuge in flight; and meanwhile the Hellenes returned, laughing, to their tents.

When the princess had recovered from her fright, she could not sufficiently praise the gallant bearing of the Hellene troops, and as for Cyrus, his heart bounded with joy at the thought of the impression they would make upon his enemies when they should confront them in the field of battle.

Soon after this, the army reached the country of the Lycaonians, who were no less notorious than the Pisidians for their constant raids upon the territory of their neighbours. Cyrus desired the Hellenes to plunder their country, and thus gained a double advantage. On the one hand he was able to punish the robbers, and on the other, he could in this way provide some spoil for his Hellene troops,—an arrangement with which they were entirely satisfied.

The army was now within a few days’ march of Cilicia, and the princess returned to her home by a short route, under the escort of a company of Hellene soldiers, while the main part of the army followed by a longer but easier way.

Cyrus was prepared to find Prince Syennesis less disposed than his wife to receive him with open arms. As a subject of Artaxerxes the Great King, it would be his duty to prevent Cyrus the rebel from advancing through his country. This he could easily do, for the entrance to Cilicia was by a road so steep and narrow36 that a very small number of men could hold it against an army of invaders.

But the difficulty had been foreseen, and before leaving Sardis, Cyrus had fitted out a fleet which had followed him round the coast of Asia Minor, and was now in readiness to land soldiers on the further side of the mountains, so that they might fall upon the enemy in the rear.

It happened however that the presence of the fleet was sufficient, and that it was not necessary to land the soldiers. The prince had indeed taken possession of the heights commanding the road by which Cyrus must enter, but when he found that not only were the mountains behind him occupied by the Hellene soldiers who had accompanied his wife to her home, but that moreover the troops who were preparing to disembark from the fleet would also be in his rear, he abandoned all idea of defending it. And thus Cyrus was able to pass over the mountains unhindered, and enter the city of Tarsus without further difficulty.

Cyrus now invited the prince to visit him as a friend. But Syennesis answered, ‘I have never put myself into the power of one who was more powerful than myself, and I will not do so now.’

The princess however persuaded him to trust to the honour of Cyrus, and he finally accepted the invitation. Like his wife, he took with him a considerable sum of money to assist the rebel, and in return, Cyrus presented37 him with the usual gifts offered by the Persians to persons of distinction,—a horse with a golden bridle, a sword with a golden sheath, a ring, armlets, and a robe of honour. So little could the Great King rely upon the loyalty of his subjects!

In deciding to make his peace with Cyrus, the Cilician prince had probably considered what would be the course best calculated to forward his own interests. By occupying the mountains for a few days, he had made a display of loyalty to the Great King; and having done this, he was anxious on the other hand to secure the favour of Cyrus also, in case he should be the conqueror.

38

For twenty days the army halted at Tarsus. It seemed indeed, at one time, that at this point the expedition would break down altogether. For the Hellene troops, on whom Cyrus based all his hopes of conquest, became restive and dissatisfied. They had been engaged to punish the Pisidian marauders, but had now passed the country of the Pisidians, and were naturally beginning to ask themselves what was the real object of the expedition. Their suspicions were increased moreover by the opposition of the Cilician prince. His resistance had certainly been of the feeblest, but still he had made an attempt to stop their passage through his mountains, and had thus declared himself the enemy of Cyrus. What reason could he have had for taking such a course, were it not that he had received instructions from the Great King to bar the passage of Cyrus, because he was a rebel and was advancing to unseat him from his throne?

HALL OF THE HUNDRED COLUMNS AT PERSEPOLIS—RESTORED.

The Hellenes now discovered for the first time that they were intended to march on for hundreds of miles into the very heart of the Persian empire, and then risk their lives in battle against the Great King, of whose boundless resources they had often heard. For such a39 mad enterprise as this, they had not been engaged, they said, and they would never have agreed to enter upon it. For, putting aside the extreme length of the march to Susa, how could they expect that in case the hopes of Cyrus should be doomed to disappointment, it would be possible for them, a mere handful of strangers in an unknown country, to break through the ranks of the enemy, and make their way back to their own land?

The Hellene mercenaries were no mere collection of soldiers of fortune, picked up anywhere, and ready to undertake any service. On the contrary, they were, for the most part, respectable citizens of Hellas, who had taken service under Cyrus, with the expectation of soon returning to their families laden with spoil.

Every day their murmurs became louder, as their suspicions received additional confirmation, and at Tarsus they made a formal protest, declaring to the officers who had enlisted them, that they were betrayed, and that nothing would induce them to go a step farther.

Almost all the officers were of the same mind, but there was one who thought otherwise. This was Clearchus the Spartan, a man who had received from Cyrus many favours, and who was anxious to prove his gratitude by doing his utmost to forward the prince’s wishes. To Cyrus the ultimate decision of the Hellene troops was of the gravest consequence; in his mind there was no question that the success of his plans depended on his being able to reckon upon their help.

Clearchus was at this time about fifty years of age. He possessed the entire confidence of Cyrus, and was40 in fact the only person who had been told from the first the real, though secret, object of the expedition.

He was a man born to be a soldier. A quiet, easy life in his native land was an existence altogether without charm for him; war, with all its dangers and hardships, was his natural element, and into this favourite pursuit he threw all the energy of his character. He personally supervised the provisioning of his men, and this was only one instance of the extreme care with which he attended to every detail. Nothing that could contribute to the efficiency of his company was too insignificant for his notice.

He had nearly all the qualifications of a great general, but in one respect he failed signally. For whilst he could always command the admiration and respect of his men, he was quite incapable of gaining their affection. He had not indeed any desire to do so, for he believed in discipline, and in nothing else. His orders were strict and severe, and he required instant obedience to the most minute particular. He was accustomed to say that an army without discipline was utterly worthless, and that soldiers should fear their officers more than they feared the enemy. Yet although he was so careful to exact obedience from others, he himself was but a poor hand at rendering obedience.9

The soldiers under the command of Clearchus never saw him unbend. His face was always stern, his brow contracted, his eye restless. He punished his men constantly, and severely, and often in moments of passion did things that he afterwards sincerely regretted. The41 consequence was that when there was no immediate danger impending, his men were often tempted to leave him and take service under a less strict officer. But in any time of danger or difficulty, the soldiers would follow Clearchus more readily than any one else, for they had unbounded belief in his ability as a general.

Nothing ever disturbed his presence of mind. However threatening the danger, he always met it with perfect calm and self-possession. At such times the stern, unbending face of Clearchus seemed to his men a tower of strength, the sight of his coolness and insensibility to fear inspired them with courage, and they felt an enthusiasm for their general, in which for the moment something like affection was added to respect.

42

When first the soldiers of his company declared their intention of marching no farther, Clearchus refused to listen to them. He thought he had sufficient influence over them to compel them to do as he wished, but in this he was mistaken. For when he sternly ordered them to continue the march, and placed himself at their head to lead them on whether they would or no, they took up stones to throw at him, and if he had not quickly made his escape, they would have stoned him to death.

It was clear that any attempt to enforce discipline would be of no avail in such a case as this, but for all that, Clearchus did not intend to be beaten. He knew how to manœuvre as well as how to fight, and had no difficulty in finding ways and means to gain his end.

After allowing a little time for the excitement of the soldiers to subside, he sent to summon them to a meeting. They were at first disinclined to go, but they said to one another, ‘We may as well hear what it is that he wants us to do. But no matter what he says, we will be firm, and hold to our decision.’

When they came to the meeting, they found Clearchus so changed that they would hardly have recognised43 him. Instead of the stern officer with angry brow and flashing eyes, there stood before them a silent, downcast man, who wept like a child. Never had they seen him so deeply moved.

At last he began to speak in a low agitated voice. ‘Comrades,’ he said, ‘be not surprised that I am grieved at your decision. I have every cause to be grateful to Cyrus, who has been to me the best of friends, and for this reason it was my earnest hope that with your assistance I might be able to repay his kindness by helping him in his present undertaking. But you are not willing, and it shall never be said of me that I took the part of a Barbarian against my own countrymen. I declare therefore that I will follow you, for to me you are country, friends, comrades. Without you I can neither help a friend nor harm an enemy.’

On hearing these words, the soldiers felt perfectly satisfied, and at once made peace with their general. Moreover two thousand men, belonging to two other companies, left the generals under whom they had enlisted, in order to join the company of Clearchus. For they believed that having once said that he would not march against the Great King, Clearchus would hold to his resolution whatever happened, whereas it seemed very possible that the other officers might be won over by Cyrus, notwithstanding their present protests.

When Cyrus heard what had passed at the meeting, he was vexed and disappointed, and sent a messenger to summon Clearchus to his presence. Clearchus however refused to go, and took care that the soldiers44 should know of his refusal, but sent word secretly to Cyrus that he hoped all would yet be well.

Several more days went by, and then Clearchus again summoned the soldiers to a meeting. This time any one was allowed to attend, whether he belonged to the company of Clearchus or not, so that there was a very large gathering. Clearchus was the first to speak.

‘Comrades,’ he said, ‘we have now broken with Cyrus. We are no longer his mercenaries, and he is no longer our paymaster. Naturally he is angry with us for deserting him, and as for me, I dare not show myself in his presence, for although he is the best of friends, he is at the same time a relentless enemy, and his power is great. We shall do well therefore to lose no time in considering how we may return in safety, and above all, how it will be possible, without the help of Cyrus, to obtain food for the march. Let whosoever will, now speak his mind.’

First one man and then another rose to speak, some saying what occurred to them at the moment, and others according to instructions previously received. For Clearchus had made his own preparations for the meeting, and had prompted several of the soldiers as to what they should say. Some were to speak in favour of returning home at once, and others were to raise difficulties.

After some of the other soldiers had spoken, one of the men who had been prompted by Clearchus, rose and began to urge with great eagerness an immediate return home, as if it were the easiest thing in the world.

‘To begin with,’ he said, ‘we must lay in a store45 of provisions, and then ask Cyrus to give us ships to take us home by sea from Tarsus. Or, if he refuses that, we must ask him to supply us with a guide, who knows the country, to take us back by land. We must act promptly moreover, lest the people of the country treat us as enemies and come out against us.’

This speech was received with great applause. But immediately another of those who had been previously told what to say, rose to reply.

‘All that you have just heard,’ he said, ‘is utter nonsense. How can we expect to get food, when the only market is in the camp of the Barbarians? Do you suppose that after we have broken with Cyrus, he is likely to be so pleasant and obliging as to allow us to take provisions out of his camp for our journey? And the ships that he has brought here for his own use, is it likely that he will part with them in order that we may get home comfortably?

‘Then as regards the guide, is it to be expected that he will grant a guide to us, who by our desertion will be doing him the greatest injury and crossing all his plans? Even if he were to supply us with ships, I, for one, should expect the ships to be sunk in mid-sea in order that we might be drowned, or if he gave us a guide, I should fear that the guide would lead us into some place where we could not fail to perish.

‘This plan will never do. I propose instead that we nominate certain persons to go with Clearchus to Cyrus, and ask him what it is exactly that he wants of us. If he proposes some such enterprise as those on which our countrymen have been employed before, then let us follow him. If on the other hand it appears likely that46 his plans will involve us in great toils and dangers, we must ask him either to give us good reasons for advancing, or else consent to our going back. Then we shall either accompany him as friends, or else be allowed to return in peace.’

This speech made the desired impression, for the Hellenes could not but see that there was far more sense in the apprehensions of the last speaker than in the hopeful view of the man who had preceded him, and accordingly, when the proposal to send a deputation to Cyrus was put to the meeting, a great show of hands was raised in favour of it. The members of the deputation were therefore chosen at once, and sent away on their errand.

Cyrus granted the messengers an interview, and agreed to answer their questions. He made no mention of attacking the Pisidians, still less of marching against the Great King, but spoke of an enemy of his, a powerful satrap named Abrocamas, who lived on the banks of the Euphrates at a distance of twelve days’ march from Tarsus. It was for the purpose of fighting this satrap, he said, that he wanted the help of the Hellenes, for Abrocamas had a great army under his command. If he held his ground, he should be punished; but if on the other hand he should save himself by flight, then in that case, it would be necessary to consider further what would have to be done.

RUINS OF PERSEPOLIS: HALL OF THE HUNDRED COLUMNS

With this answer the messengers returned to their comrades, and the Hellenes declared themselves ready to remain in the service of Cyrus, on condition that he would increase their pay. To this he readily consented, and promised that instead of receiving every month one48 daric as before,10 the private soldiers should in future have a daric and a half. In like proportion, the captains were to have three darics instead of two, and the generals six darics instead of four.

The Hellenes were in the position of a man whose path lies through a bog. After he has advanced some little way, he begins to consider whether it would not be better to turn back, but finding that this is just as difficult as to go forward, he thinks it a pity to waste the effort he has already made, and decides to continue.

So to the Hellenes it seemed that to return promised to be no less dangerous than to advance. The more clear-sighted were by this time perfectly aware that whatever Cyrus might say, or refrain from saying, his ultimate design was to proclaim war against the Great King. But the great mass of the soldiers, although they knew in their hearts that this was his real intention, preferred not to think too much about it, and persisted in hoping that after all it might turn out to be something else.

49

After twenty days’ halt at Tarsus, the army again set out on its march, and in five days came to the last city in Cilicia. The next province through which they would have to pass was that of Syria, and here the entrance was even more carefully guarded than had been the approach to Cilicia.

Between the two provinces were two fortresses, called the Gates of Cilicia and Syria. They were at about six hundred yards apart, and stood one behind the other on each side of a little river which flowed from the mountains into the sea, and formed the boundary between the two provinces. The mountains at this place approached so close to the sea that the walls of the fortresses stretched the whole distance, and the only passage was through gates which opened to admit friends, but remained fast shut when enemies approached. The fortresses were quite impregnable, if defended, and it was said that Abrocamas had taken the field against Cyrus with 300,000 men, reinforced moreover by 400 Hellenes who were in the service of the Great King.

But Cyrus had long ago foreseen this difficulty as he had foreseen that of entering Cilicia, and had provided50 against it in the same way. He had desired the fleet to follow him from Tarsus, and had arranged that it should land two divisions of troops on the coast of Syria, one in the space between the river and the Syrian fortress, the other on the further side of it, so that the fortresses might be attacked on both sides at the same time.

As before however, it proved unnecessary to carry out the plan. For when Abrocamas heard that Cyrus had made his way through Cilicia, and found moreover that his Hellenes were leaving him to join their countrymen, he turned and fled, never stopping until the waters of the Euphrates were rolling behind him. The only harm that he did to Cyrus was to burn the ferry-boats employed for crossing the Euphrates, after making use of them himself.

The cowardly satrap remembered the saying that ‘discretion is the better part of valour,’ and following the example of the Cilician prince, he took care so to manage matters, that in the quarrel between the two brothers, he should have done something to help both sides. If the Great King should conquer, he could urge that he had burnt the boats and guarded the walls for a time. If, on the other hand, Cyrus should prevail, he could say that he had given way at his approach, and had yielded him free passage. He afterwards carried out this policy by bringing an army to the aid of the Great King five days after the decisive battle between the two brothers had been fought, with a plausible excuse for not having been able to arrive sooner.

A day’s march along the Syrian coast brought the troops to Myriandus, a populous sea-port of Phenicia,51 where an active trade brought many merchant-vessels to anchor in the bay. Here the army rested for seven days, and during this time two of the Hellene officers, Xenias and Pasion by name, hired a ship, and sailed away home in it with the greater part of their possessions.

These were the two officers from whom 2,000 soldiers had deserted at Tarsus in order to take service under Clearchus. They had expected that Cyrus would compel the deserters to return to them, but knowing that they would serve much better under the general of their own choice, he had allowed them to remain with Clearchus. In consequence of this, the two officers were so much annoyed that they determined to abandon the expedition.

When their flight became known, the soldiers all expected that Cyrus would send some ships of war in pursuit of them, and that having been overtaken and brought back, they would be severely punished. But in this they were mistaken, for instead of acting in any such way, Cyrus called together the remaining Hellene officers, and addressed them in an altogether different strain.

‘Xenias and Pasion,’ he said, ‘have deserted, but they are still in my power. I am fully informed as to the route they have taken, and my ships are swifter than theirs. But for all that, I will not pursue them. No one shall be able to say of me that I know how to make use of a man as long as he is with me, but that when he wishes to leave me, I lay hands upon him and seize his goods. Let them go. They will have to confess that they have treated me worse than I have treated52 them. I might detain their wives and children who have been left at home under my protection, but they shall not be deprived of them. This shall be their reward for the services they have rendered hitherto.’

This proof of high-mindedness increased the respect of all the Hellenes for Cyrus.

53

From this point, the route by which the army was to march left the coast and struck inland. The fleet could therefore be of no further service, and Cyrus accordingly sent it home from Myriandus.

It was now the hot season, which in Syria is infinitely more trying than anything that is ever experienced in our northern climates. And as the troops were marching southwards, the heat continued to increase in intensity with every day’s march.

To the Hellenes, everything in these tropical regions was new and strange; the vegetation, the animals, the people, the customs, the ways of thinking, all were very different from anything to which they were accustomed at home. One day they came to a river swarming with great fish. These were worshipped as gods by the people of the country, who would have thought it a great crime to catch them. In the same place there were large flocks of pigeons, which were also considered sacred, and any one who dared to kill or even to catch one of them, would have been severely punished.

Towards the end of August the army reached the large and flourishing city of Thapsacus, on the Euphrates. Here Cyrus called together the Hellene54 officers, and told them plainly that he was marching towards Babylon to make war upon the Great King, and that they must communicate this information to the soldiers under them, and persuade them to follow him as before.

The news was received by the men, not indeed with surprise, for they had long had their misgivings, but with considerable irritation, and many of them cried out that nothing would induce them to go any farther.

Their anger was directed, not so much against Cyrus, as against their own officers, whom they accused of having known from the first what was intended, and they said that by keeping the matter secret, the officers had involved them in an undertaking which, so far at all events, appeared absolutely hopeless.

A few days’ consideration however was sufficient to make them realise their position. What could they do? Ever since leaving Tarsus they had been marching farther and farther away from their homes, and the reasons which had then decided them to cast in their lot with Cyrus were now even more urgent than before.