Title: The fort in the wilderness

or, The soldier boys of the Indian trails

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Illustrator: A. B. Shute

Release date: August 15, 2023 [eBook #71411]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co

Credits: David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

OR

THE SOLDIER BOYS OF THE INDIAN TRAILS

BY EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of "With Washington in the West,"

"Larry the

Wanderer,"

"American Boys' Life of William

McKinley,"

"Old Glory Series,"

"Pan-American

Series," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY A. B. SHUTE

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Published September, 1905.

Copyright, 1905, by Lothrop, Lee and Shepard Company

All rights reserved

The Fort in the Wilderness

Norwood Press

Berwick and Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

"The Fort in the Wilderness" is a complete tale in itself, but forms the fifth volume in a line known under the general title of "Colonial Series."

When I began this series I had in mind to pen not more than three volumes, embracing colonial times during the fourth intercolonial war, when Canada, and the territory lying between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi, were wrested from the domination of France. The first volume, entitled "With Washington in the West," told of the disastrous Braddock campaign against Fort Duquesne; the second, called "Marching on Niagara," related the particulars of General Forbes's expedition against Fort Duquesne, and also the advance of Generals Prideaux and Johnson against Fort Niagara; while the third volume, "At the Fall of Montreal," took our youthful heroes down the mighty St. Lawrence, to fight under General Wolfe and to witness the conclusion of a struggle which had lasted for years and had been bloody in the extreme.

After this war the Colonists hoped for peace, but this was not to be. The Indians were enraged to see the English occupying territory which they considered their own, and soon, led by the wily and resourceful Pontiac, they entered into a conspiracy to fall upon all the frontier forts and settlements simultaneously and massacre all who dared oppose them. There was a demand that I relate something of these times to my youthful readers, and in the fourth volume of the series, called "On the Trail of Pontiac," I told of what was done by Indians and whites during the years 1761 and 1762, when the great conspiracy was slowly drawing to a head and more than one small settlement was wiped out in the crudest manner imaginable.

Early in the year 1763 Chief Pontiac considered the time ripe to strike, and in the present volume are related the particulars of the siege of Detroit, the attack upon Fort Pitt, and the uprisings at numerous other points, followed by the advance of Colonel Bouquet against the red men, the memorable battle of Bushy Run, and other contests, by which the Indians were forced to give up a struggle they at last realized was hopeless. In this volume the Morris boys do their duty as of old, helping to make this grand country of ours what it is to-day.

In writing this volume the author has tried to be as accurate, historically, as possible. May the reading of the work prove an inspiration to all who have the good of our land at heart.

Edward Stratemeyer.

July 15, 1905.

| I. | Out in the Forest |

| II. | Facing a Big Bear |

| II. | In Camp with Old Friends |

| VV. | A Tramp through the Snow |

| V. | A Letter of Interest |

| VI. | The Trading-post on the Ohio |

| VII. | Henry's Strange Discovery |

| VIII. | Surrounded by the Indians |

| IX. | The Attack on the Trading-post |

| X. | Jean Bevoir Appears |

| XI. | The Flight from the Post |

| XII. | White Buffalo's Peril |

| XIII. | Sugar Making, and Hunting |

| XIV. | The Beginning of the Uprising |

| XV. | At Fort Cumberland |

| XVI. | Up the Ohio |

| XVII. | The Arrival at Fort Pitt |

| XVIII. | Something Concerning the Twins |

| XIX. | In Which Barringford is Made Prisoner |

| XX. | Deep in the Wilderness |

| XXI. | At Fort Detroit |

| XXII. | The Attack on Fort Detroit |

| XXIII. | In the Wilderness Once More |

| XXIV. | Lost |

| XXV. | The Attack on Fort Pitt |

| XXVI. | The Missing Children |

| XXVII. | In the Ranks Once More |

| XXVIII. | The Battle of Bushy Run |

| XXIX. | Dave among the Indians |

| XXX. | Escape and Flight |

| XXI. | The Last Fight—Conclusion |

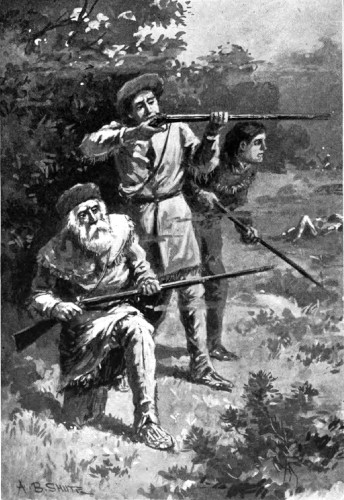

"There's your chance, Rodney. You can't miss him if you are careful."

"I'll do my best, Dave. But you must remember I haven't had as much experience at hunting as you and Henry," answered Rodney Morris, as he examined his long rifle, to see that the flintlock and the priming were in proper condition for use. "Hadn't I better try to get a little closer?"

"Just a little, but don't wait too long, or that deer will get away from you," returned Dave Morris. "Remember, the wind is blowing almost toward him, and if he scents us he'll be off like a streak."

"Perhaps you had better do the shooting, Dave. If I miss him——"

"Never mind, Rodney. Do the best you can. You've got to get into practice sooner or later, and you might as well begin right now."

"But you were the one to see the deer first."

"And you saw the tracks in the snow. Go ahead. I'm sure you can bring him down if you are careful," urged Dave Morris.

"You stand ready to give him a second shot, if I miss," answered Rodney, and then moved off through the snow, with his cousin at his heels. The two young hunters were in the depths of a Virginia forest, and had crossed the tracks of a deer but a short while before. The animal was now in sight, stripping the bark from a young tree several hundred feet away.

Such a shot as now presented itself would have been easy for Dave Morris, but with Rodney it was different. The latter had been a cripple for several years, and had had scant opportunity for going out after game. His eye was not as trained as that of his younger cousin, nor was his nerve as steady.

"Make for the clump of hemlocks," whispered Dave. "You ought to get a fine shot from there."

Rodney did as directed, and in a few seconds more was in a position to draw an excellent "bead" on the deer, that was feeding as peacefully as ever.

It must be admitted that Rodney's hand trembled slightly as he raised his long rifle and gazed along the shining barrel. There was a brief pause, during which Dave also brought up his weapon. Bang! went Rodney's piece, and up into the air leaped the deer, shot through the shoulder.

"Good!" shouted Dave. "You've got him, Rodney."

"I—I don't know about that," was the quick reply. "See, he is trying to run away."

"I'll finish him, but he's your game," was Dave's answer, and an instant later his own weapon spoke out, and the deer leaped once more, and then fell dead in its tracks.

Hurrying up, the young hunters surveyed the haul with interest. The deer was of good size, but rather lean, for the winter had been severe, and food was scarce.

"I'm glad we got him," said Rodney, with a quiet smile. "Mother was wishing for fresh venison only yesterday. He's not as fat as he might be, but that can't be helped. Do you think there are any more around?"

"If there were, they ran off at the shots," answered Dave. He walked a few feet away. "See here, Rodney!"

"What is it?"

"The track of a bear, unless I am greatly mistaken."

"A bear!"

"Yes, and the track isn't very old either."

"Let us go after him, Dave!" cried his cousin. "I'd give almost anything to bring down a bear. It would give us so much meat,—and the skin would come in handy, too."

"I'm willing. But we must be careful. A bear at this time of year is an ugly creature to tackle. Don't you remember how old Bard Donaldson was chewed up by one last winter? And how that old she-bear tackled Nat Striker in his own dooryard the first year I went to the war?"

"Of course, I remember. But a fellow on the hunt must take some chances. I'll wager you and Henry have taken many chances when out."

"That is true, and we got into more than one tight hole, too. But I'm willing to go after his bearship as soon as we've reloaded. Let us throw the deer into a crotch of a tree, so the wolves can't get at him. Those wolves are getting pretty bold lately," added Dave.

The game was soon hoisted to a place of temporary safety, and then each of the young hunters inspected his rifle with care, and reloaded the weapon. This done, they began to follow up the tracks of the bear, with eyes on the alert for the first sign of the creature. While they are on this trail, let me introduce them more specifically than has already been done.

Dave Morris was the only son of James Morris, a trapper and fur trader, who, when at home, lived at Will's Creek, Virginia, close to where the town of Cumberland now stands. Dave's father was a widower, and the pair made their home with Mr. Morris's brother Joseph, whose household consisted of his wife Lucy, his son Rodney, already mentioned, Henry, a sturdy youth of about Dave's age, and little Nell, a girl of tender years, dear to the hearts of all.

James Morris was a natural trader, and when his wife died he left Dave in charge of his brother, and drifted to what was then called the West, or "Western Countries," where he established a trading-post on the Kinotah, a small stream of water flowing into the Ohio River. This was at the time when George Washington, our first President, was a young surveyor, and in the first volume of this series, entitled, "With Washington in the West," I related how Dave worked for Washington, and later on became a soldier, to fight under General Braddock and under Washington during the ill-fated expedition against Fort Duquesne, afterwards called Fort Pitt, and located where the great manufacturing city of Pittsburg stands.

The colonial war between England and France had now become a certainty, and with the repulse of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne, the French, aided by the Indians, sought to drive out every English settler and trader in the north and west. As a consequence, James Morris's trading-post was attacked, and he was made a prisoner. During the conflict Dave was also captured, but both were rescued from the enemy by the clever work of Sam Barringford, a frontiersman well known to them, aided by White Buffalo, a friendly Indian.

Thinking that the English settlers would have their hands full fighting the French, the Indians became very bold, and plundered many settlements, and not infrequently massacred the inhabitants. In some cases children were carried off into captivity, and this was what happened to little Nell Morris, much to the horror of all her relatives.

Aroused to the situation at last, strong forces were sent against the enemy, and in the second volume of the series, entitled "Marching on Niagara," I related how Fort Duquesne was finally captured, and what was done to bring about the surrender of Fort Niagara, a French stronghold on the Great Lakes. In this campaign Dave Morris and his cousin Henry took an active part, accompanied by old Sam Barringford, and when the fighting was over, succeeded in rescuing little Nell, who was found in the custody of some Indians under the command of rascally French trader named Jean Bevoir, who had caused the Morrises a great deal of trouble in the past.

The fall of Fort Niagara and of Fort Duquesne put the English once more in possession of all the territory lying between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. But the terrible war was not yet at an end, and in the third volume of this series, entitled "At the Fall of Montreal," I related how Dave and Henry continued to do their duty as young soldiers, fighting under the heroic General Wolfe and others, until the bloody struggle came to an end, and Canada passed into the hands of England.

The home-coming of the young soldiers had been a time of great rejoicing. Everybody was glad that the long-drawn war was at an end, and the boys and Sam Barringford, who had continued to fight with them, had to tell their stories over and over again.

"I sincerely trust you never have to go to war again," Mrs. Morris had said. "This constant turmoil and butchery is enough to drive one insane."

"And it has cost our Colonies a tremendous sum," added her husband. "I do not know if we can ever pay the debt."

"Now the war is at an end, I am going back to the West," James Morris had said. The old trading-post had been burned down, but he was willing to go to the labor and expense of building another, knowing well that fur trading in the immediate future was to become exceedingly profitable. He departed, taking with him Dave and Henry, as well as old Sam Barringford, and some other trappers, and White Buffalo, with his handful of faithful Delawares.

The hope for peace at this time was a vain one. The war was at an end so far as France was concerned, but the Indians who had favored the French were not satisfied, and led by the wily chief Pontiac and other leaders, they soon joined in a conspiracy, which had for its object a simultaneous attack on all the forts and settlements of the English frontier. What effect this Indian war had upon the Morrises, and the new trading-post, is told in part in the fourth volume of this series, entitled "On the Trail of Pontiac." The fighting was exceedingly bitter, and on more than one occasion it looked as if the whites would be totally exterminated. Dave was captured by the red men, and then fell into the hands of the rascally Jean Bevoir. But his father, Barringford, White Buffalo, and some others, came up in the nick of time and saved him, and Jean Bevoir was seriously wounded, and had to ride away at a break-neck speed to save his life. In the meantime, a part of the plot of Pontiac and his followers was exposed, and the Indians had to withdraw for the time being, to rearrange their bloodthirsty plans. Thus far Pontiac had been fighting for two years; he now resolved that the third year of the conflict should witness the total subjugation or annihilation of the English on the frontier. He laid his plans with greater secrecy than ever; and what the outcome was will be told in the pages which follow.

"He's a crafty one, an' he means business," was the comment of old Sam Barringford. "Ye have got to watch him with both eyes an' ears open."

"My white brother speaks the truth," was what White Buffalo said. "Pontiac is as a fox for slyness, a wolf for plunder, and a buffalo for strength. More than that, he is of the great magicians, and his word is a command to thousands." Even though the others had scoffed at Pontiac's powers as a so-called magician, White Buffalo, in common with all other red men, still believed in his power of magic.

The capture of Dave had occurred while he, Barringford, and White Buffalo, were on the way to Will's Creek. After being rescued, the youth and his friends had continued the journey, arriving finally at the homestead in safety. James Morris had returned to the trading-post, and his nephew Henry remained with him.

It was a clear, cold day in early January. The snow covered the ground to an average depth of eight inches, but many spots had been swept clear by the high winds, while other places were buried under huge drifts.

Dave and his cousin Rodney had left the Morris homestead early in the morning, to be gone all that day, and possibly the next also. The stock of fresh meat at the cabin was running low, and as Joseph Morris was away from home on business, it fell to the lot of Dave and Rodney to replenish the larder. It was now well along toward the middle of the afternoon, but previous to discovering the deer they had brought down only two rabbits and a wild turkey.

"That is next to nothing," Dave had said. "Why, we can eat all of the bag at one meal." The bringing down of the deer made him feel better, and the prospect of laying low a bear filled him with enthusiasm. As my old readers know, he was not such a hunter as his cousin Henry, who often went out just for the sport of it, but he loved to bring in meat that he knew was needed.

"I'd like to be as good a shot as Henry is," remarked Rodney, as he trudged along by his cousin's side. "I can tell you, he's a wonder. Sam Barringford says so, and he ought to know."

"Henry takes to it naturally," answered Dave. "But you needn't to worry, Rodney,—you shoot better now than many of the settlers do. Look at Brown, and Katley, and Jabbs. They can't hit a thing, although they have tried often enough. Since you've got around again you have done wonderfully well."

"I suppose Henry is doing some tall hunting out around the trading-post these days."

"More than likely—if the Indians will allow it." Dave's face grew sober for a moment. "I wish I was sure that everything was all right at the post."

"Don't you imagine it is?" came quickly from the young man who had been a cripple.

"I don't know what to think—we haven't heard from them in so long. I don't like to talk of these things at home—they only worry Aunt Lucy and the rest. But it's queer father didn't send us some sort of a message around New Year's."

"I was talking to Sam Barringford a few days ago about Pontiac. Sam feels almost certain that Pontiac won't rest until he has one grand fight, and either wins or gets whipped."

"Pontiac is certainly a masterful man—his authority over the different tribes is simply wonderful. When I met him, I could see at once that he wasn't a fellow who would allow himself to be dictated to. Every one of the other chiefs had to bow to him—they couldn't help themselves."

"They are afraid of his magic."

"Perhaps, but some of the other big chiefs must know his so-called magic is simply humbug. No, he's a natural born leader, and they can't help but follow him."

Rodney gave a long-drawn sigh. "Beats all how much fighting we have been having of late year's," he said. "First it was with the French, now it is with the redskins. It seems to me we never will be settled. For two years the crops haven't amounted to anything, because we couldn't attend to them and fight the redskins too. I wish we could have peace."

"You don't wish it any more than I do, Rodney. Look at all Henry and I had to go through with,—when we were in the army. They talk about the glories of a soldier's life. I think there was more hard work than glory."

"Really?" Rodney glanced at his cousin in an odd way, and smiled. "You say that, but I'll wager a shilling that if war came again you'd be one of the first to march against the enemy."

"Perhaps so. It would depend on what the war was about. I've got no use for a fellow who stays at home when his duty is at the front—especially if he's a young man, and hasn't a family depending upon him."

"Well, I agree with you on that, and I should certainly have joined the army myself if I hadn't been so crippled. As you say, if—What's the matter?"

"Wait a minute, and stop talking," answered Dave in a whisper. "These tracks look pretty fresh to me, and if that's so, that bear can't be very far off."

They had covered a good half mile since bringing down the deer. The trail led up to the top of a small hill, covered with a stunted growth of ash and pines, with here and there a dense clump of bushes. On the other side of the hill was a series of rocks, leading down into a small ravine, where, in the summer time, flowed a tiny brook, but which was now partly filled with ice and snow. A stiff wind was blowing, and it pierced them through and through when they gained the summit of the rise.

"Phew! this is cold!" murmured Rodney, who had spent many winters by the fireside in his easy chair. "I suppose you don't mind it, but it cuts me like a knife."

"Come, we'll get behind yonder rocks," answered Dave. "Don't make any noise after this."

"Do you see the bear?"

"Not yet. But I feel certain he can't be far away. Such rocks as these are just the place for a bear's den. We don't want to—Hark!"

Dave broke off, as a distant rifle shot reached their ears. Thus was quickly followed by another, and then all became as quiet as before.

"What do you make of that?" questioned Rodney.

"Somebody else must be out hunting in this vicinity."

"You don't suppose there are Indians around?"

"No,—all the Indians have gone northward for the present, so Lieutenant Plawood was telling me yesterday. They were ordered by the commandant at Fort Cumberland to keep their distance, and they promised to do so."

"An Indian won't hesitate to break his promise if he feels like it."

"That is true; but they are not on the war-path just now. It's too cold for them."

Both of the young hunters now became silent, and after a survey of the bear tracks before them, proceeded along a ridge of rocks overlooking the ravine. Presently they came to a space where the wind had swept the rocks clear of snow, and here the trail appeared to come to an end.

"This looks as if we were stumped," whispered Rodney.

"I'm pretty certain his bearship went off in that direction," answered Dave, pointing with his hand. "Let us climb down——"

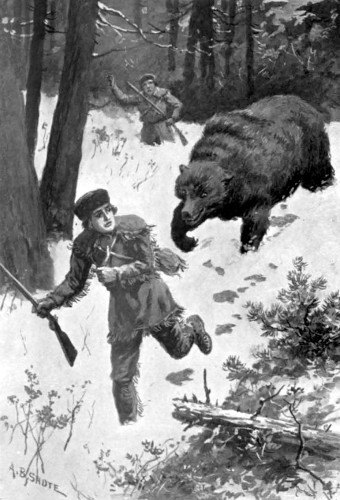

Dave got no further, for at that instant the bear burst upon their gaze, leaping suddenly from behind a point of rock not five rods away. He was a big, shaggy beast, with a pair of eyes which were just then looking their wildest. One of his ears was gone, and the blood was flowing from a wound in his neck.

"There he is!" shouted Rodney, and taking hasty aim, he pulled the trigger of his rifle. The bullet hit the bear in the hindquarters, inflicting a deep but by no means serious wound. The discharge of the weapon was followed by a snarl of pain and rage, and then the wounded beast leaped out on the rocks directly in front of the two young hunters.

It was a chance not to be missed, and as the bear arose on his hind legs, Dave took aim directly for his heart. Down came the hammer of the flintlock, but, alas! the weapon failed to go off.

"Shoot! Why don't you shoot?" yelled Rodney, trying his best to reload.

"My flint is cracked," answered Dave. "Confound the luck!" He took aim again and pulled the trigger as before, but now the bear was crouching down on the rocks, and the bullet merely cut a furrow along his shaggy side. Then came a perfect roar of rage, and the big beast leaped from rock to rock and came directly for the hunters.

"Give him another, Rodney!" sang out Dave.

"I haven't got my priming ready!" gasped the young man.

"Then run for it! Run, or he'll have you down!"

On coming closer the bear had turned from Dave to Rodney, and was now within a dozen feet of the former cripple. Rodney started to run, and seeing a high rock some feet away, leaped for it, slipped, and rolled down into the gully. The bear watched him in evident amazement, and as he disappeared in the snow, turned once more toward Dave.

The young hunter was trying to reload with all speed. But his rifle was of the old-fashioned English pattern of 1755, and to load and prime it in a hurry was next to impossible. As the bear came on he backed away, until, reaching a hollow which was covered over with drifted snow, he, too, went down and out of sight exactly as his cousin had done.

Such sudden disappearances were evidently a new experience for the bear, for he stood stock still, gazing first at the gully and then at the hollow, as if wondering which of his human enemies would be the first to reappear.

As fortune would have it, Rodney was the first to emerge from the snow, puffing and spluttering. He had his rifle still in hand, but the weapon was not ready for use, and the bear seemed to know it. With a snarl, the beast hurled himself down in front of the former cripple. But his leap was a trifle short, and Rodney, with quick presence of mind, rolled out of the way. Then the young hunter uttered a loud shout for assistance.

Dave, coming up out of the hollow, heard the shout. Close at hand was a small rock, and catching it up he hurled it at the bear, taking the beast in the back of the head. Again the bear snarled, and now turned once more.

"Look out!" screamed Rodney. "He's coming for you. Run! run!"

"Look out!" screamed Rodney, "He's coming for you. Run! Run!"

Dave did run, over the rocks, and then toward a clump of low-branched trees. Once in the trees he felt he would have time to reload and give the bear a shot that might finish him. But there was ice on the slope, and suddenly he slipped upon this, fell sprawling, and then rolled over and over into another hollow. Strange as it may seem, the bear slipped likewise, and came down almost within arm's length of the youth he was after.

"Get away from here!" gasped Dave, as soon as he could speak, and grasping his rifle by the barrel, he made a wild pass at the bear. This caused the beast to tumble back for a moment. Then the young hunter started to roll away, but the bear was on the alert, and in a twinkling he made two leaps, and came down fairly and squarely on the youth.

It was only the softness of the snow beneath him that saved Dave from serious injury. As the bear came down on the young hunter both sank so deeply that Dave was buried completely from sight. The beast ripped the sleeve of his hunting jacket, but that was all.

By this time Rodney was coming up once more. He managed to reload, and taking a somewhat unsteady aim, he let drive, and struck bruin in the left side. The wound caused the bear to utter a grunt of pain, and scramble up beside where Dave lay.

"Jump, Dave!" cried Rodney. "Jump for your life!" But Dave did not hear him, for the reason that his ears were completely filled with snow.

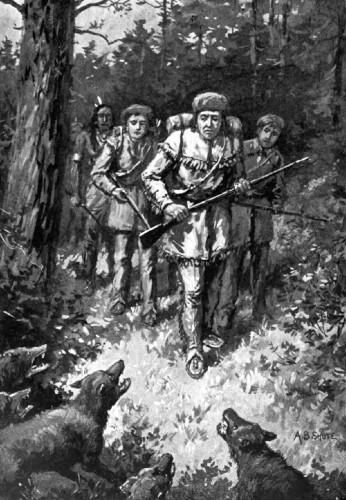

At this critical moment something occurred which filled Rodney with satisfaction. Forth from the forest came two men, one a tall, bronzed frontiersman, dressed in a thick hunting shirt and a coonskin cap, and the other a somewhat aged Indian of the Delaware tribe. Both were armed, and each carried several rabbits and turkeys in his game bag.

"Sam Barringford! And White Buffalo!" ejaculated the former cripple. "Hurry up! The bear has Dave in the snow, and is going to maul him."

"Not ef I know it!" sang out the old frontiersman addressed, and he brought around his long rifle with a movement so quick it could scarcely be followed. Several long leaps took him to the very side of the beast. Bang! went his weapon, and the bullet entering the creature's ear, passed directly through the brain. This shot was followed almost instantly by one from White Buffalo, which took the bear in the eye, and with a shudder the beast sank down, gave a quiver or two, and remained still forever.

"Good for you, Sam," said Rodney, when it was over. "That was a prime shot. And yours was good, too, White Buffalo."

"White Buffalo's shot was not needed," answered the Indian, simply. "But White Buffalo could not stand by and see his friend Dave in such great danger. The bear was big and powerful. There are times when one shot is not enough for a big bear."

"It's the same that we hit afore," came from Sam Barringford. "He is a sockdolager, an' no error. We tried our prettiest to bring him down, but he got away from us."

By this time Dave was climbing out of the snow as best he could. As he cleared his face, he gazed in astonishment at the newcomers, and then at the bear.

"Did you—did you kill him?" he questioned.

"Reckon as how we did, Dave," answered Sam Barringford, with a broad grin. "Sorry if you didn't want it done, lad."

"Didn't want it done? Oh, Sam, I'm thankful you came up."

"White Buffalo gave him the one in the eye, and I soused it into his ear. Arfter thet he kinder lost interest in livin'," added the old frontiersman.

"Then I must thank you, too, for my escape," said Dave, going up to the Indian. "How are you?" and he shook hands.

"How? how?" returned White Buffalo. "Glad Dave not killed. He was big bear."

"I've never seen a larger around these parts," returned the young hunter. "Have you, Sam?"

"Never, lad. Dock Fisher once got one about as big, but he wasn't so heavy, to my way o' thinkin'. White Buffalo an' I spotted this chap three hours ago, and clipped him, but he got away—as you found out."

"He was hurt just enough to be ugly," came from Rodney. "I'm thankful he is out of it," and he gave a deep sigh of relief.

"We have been looking for you for over a week," went on Dave to the old frontiersman. "I thought you'd go out hunting with us."

"I've been over to Fort Bedford—thought I could larn something about them twins—but I couldn't," answered Sam Barringford. "Struck White Buffalo at the fort, an' we decided to do a little hunting between us, an' bring the quarry to your place. Have ye had any luck?"

"Yes, we got some rabbits, and turkeys, and one deer."

"Good enough! Rodney, how do you like bein' out?"

"I like it very much."

"My brother Rodney is getting strong," said White Buffalo, with as much of a smile as he ever exhibited. "It is well, and White Buffalo's heart is glad."

"And what is the news from among the Indians, White Buffalo?" asked Rodney.

At this question the Indian looked grave, and for a moment he turned his face away. As my old readers know, White Buffalo was a chief of the Delawares, but during the war with France, and the Indian uprisings, he had been at variance with the majority of his tribe, only a handful supporting him when he sided with the English. The others had fought with the French, and under Pontiac, and where they were now the old Delaware chief did not know.

"Those who are now in authority tell not their secrets to such an aged man as myself," answered White Buffalo. "Because White Buffalo would not fight against his friends, they call him a squaw, and say his heart has turned to water."

"Don't you care, you did what was right—and those Indians will find out so, sooner or later," answered Dave, quickly.

"White Buffalo tells me that the redskins are a-holdin' many secret meetin's," came from Sam Barringford. "Pontiac is stirrin' 'em up. Thet Injun expects to do big things next season, mark my words."

"Pontiac is still as powerful as ever," continued White Buffalo. "It has reached White Buffalo's ears that he has called a special council, whereat the red men for many miles around can tell of the wrongs which have been done them. When they meet, Pontiac will fill them with words of fire and of blood, and the war-hatchet will be dug up once more."

"Our soldiers ought to stop that pow-wowing," said Rodney. "It seems to me it is time somebody put his foot down heavily."

"The whole trouble is, that it costs money to carry on a war against anybody," said the old frontiersman. "The Colonies are poor, and England is carrying a whopping big debt. I heard 'em talkin' about it over to Greenway Court."

"Were you there?" cried Dave.

"Yes, an' saw a lot o' your old friend, includin' the Washingtons," was the frontiersman's reply. "They sent their regards to you."

"I'd love to visit the Court," murmured Dave.

The young hunter had had one sleeve of his hunting jacket ripped open by the bear, but had suffered no serious bruises, for which he was thankful. It was decided to haul the dead bear from the hollow and then place him on a drag made of a tree bough, and all hands would help in dragging him to the Morris homestead.

"He ain't goin' to be no easy load," was Barringford's comment.

"Better a heavy load of game than no game at all," said White Buffalo, sagely.

"Remember, we have that deer too," put in Rodney. "We'll have to put him on top of the bear."

"In that case we can't reach the house to-night," said the frontiersman. "It's too late to travel nine miles with sech a load."

"Well, let us go where we left the deer. It will make a pretty fair sort of camping place," returned Dave.

Like the true woodsman that he was, Barringford carried a sharp hatchet and a strong hunting knife, and soon had a suitable bough chopped and trimmed. Then all set to work to haul the bear out of the hollow and tied him on the drag. It was hard labor and made them perspire freely regardless of the cold. A stout cord was tied to the front of the drag and the four proceeded to haul their load through and over the snow as best they could.

"I don't believe it's as cold as it was," remarked Dave, as they trudged along. "Or else this work is making me warm."

"It's moderatin' fer another fall o' snow," answered Sam Barringford. "I was calculatin' we'd git it by noon to-day."

"More snow come to-night," said White Buffalo.

"I wish it wouldn't come until after we get home," said Rodney. "This load is bad enough as it is."

It took the best part of two hours to reach the spot where the deer had been left. As they came closer a mournful howl rent the air.

"Wolves!" cried Dave. "I knew they'd be after that meat."

"Yes, but they are running away," answered Rodney. "They are not hungry enough to show fight," and he was right, as the hunters came into view the wolves lost no time in slinking out of sight, nor did they show themselves again.

"A fine deer," said White Buffalo, on inspecting the game. "Mistress Morris will be glad to get such good meat at such a season."

"Here is the spot I thought of for a camp," said Dave. "Is it all right, Sam?"

"It is, lad; and we can knock together a shelter in no time. I'll cut the branches and you and Rodney can do the building, while White Buffalo starts up the fire. Bein' as I haven't had anything to eat sence sunrise I've got an amazin' holler vacancy in my interior, which same needs attention."

"You shall have your choice of bear steak or venison cutlets," cried Dave.

"And I'll cook it just the way you like it," added Rodney, whose life at home had made him an excellent cook. "We brought a little coffee along, too, and some bread."

"Good!" shouted the old frontiersman. "An' with our tobacco, we'll feast like kings; won't we, White Buffalo?"

"I hope you aren't going to eat the tobacco," said Dave, with a twinkle in his eye.

"Now, don't go for to poke fun at an old man, Dave. Ye know what I'm a-drivin' at. Here's another for ye!" And Barringford threw down a big bough directly on the young hunter's head. "Got to keep ye down somehow, ye know," he added.

It was astonishing how quickly they had a cozy shelter of boughs and brushwood constructed. In the meantime the Indian lit the fire and the pot Dave carried with ice and snow, so that they might have boiling water for their coffee. All voted in favor of a thick, juicy bear steak, and Barringford cut it from the game without injuring the hide—for in those days, as now, a bear robe was worth considerable money.

When the smell of the broiling steak filled the air, all gathered around the fire in anticipation of the well-earned feast. The young hunters were as hungry as the older men, but Rodney insisted upon helping Barringford and White Buffalo first, while Dave gave each a drink of the steaming coffee and a chunk of the bread. In those primitive days there was no style to the meal, and instead of knives and forks those gathered around used their fingers, and one small coffee bowl, with a wide top and a narrow bottom, had to serve for all.

"This is prime, and no mistake," said Dave, after masticating a particularly sweet bit of the bear meat. "It seems to taste twice as good out here as it does at home."

"Which proves that fresh air is a good sauce," answered Sam Barringford. "Now, I'd rather eat out o' doors any day than under a roof—thet is, onless it's stormin' putty hard."

The meal finished, the old frontiersman and the Indian sat down for a quiet smoke, while the two young hunters gathered some additional firewood, for use during the night and for breakfast. The day's outing had made Dave tired, and he was glad, at eight o'clock, to turn in. The others soon after followed his example, and it was not long before all were sleeping soundly.

In the morning White Buffalo was the first to awaken, and without arousing the others, he started up the fire and put on some water to boil. It was snowing and the new fall covered the old snow by several inches.

"Phew! this is quite a storm!" cried Barringford, as he peered from the shelter. "An' comin' down more yet, too," he added, with a look at the dark sky.

"I hope we don't get snow-bound," was Rodney's comment, as he started to boil what was left of the coffee. "We're not situated for anything of that sort—unless we want to live on bear meat and venison."

"Be thankful we've got the meat, an' rabbits an' turkeys," said the old frontiersman. "It's a heap sight better nor to be snow-bound with nuthin' at all."

For breakfast they fixed up a pair of the rabbits, and these went very well with the remainder of the coffee and the bread. The snow kept coming down steadily, so they ate the meal under the protection of the shelter. The wind had died down utterly, consequently it was not nearly as cold as it had been.

"Do you think we ought to start for home in such a snow-storm as this?" questioned Dave. "If it comes down any heavier we might lose our way."

"Humph! this ain't nuthin' to the snow-storm I got caught in the winter I found them twins," said Sam Barringford. "I don't want none like thet again, not me! We can get git home in this, right enough."

The storm the old frontiersman referred to had occurred two years before. It had been little short of a blizzard, and while out in the worst of it Barringford had come to a spot where a man and a horse lay dead and partly devoured by the wolves. A bundle rested in a tree near by, and much to the old frontiersman's amazement it contained two baby boys, in all probability twins, by their close resemblance to each other. With the bundle clasped to his breast the old hunter had tried to fight his way through the blizzard to the Morris homestead, three miles away. He had almost reached it when he found himself exhausted, and had been rescued by James Morris and his brother Joseph. At the cabin, the twins had been cared for by Mrs. Morris. Nothing could be learned concerning their identity, or the identity of the man found dead beside them, and they had at last been adopted by Barringford, who was an old bachelor, and who called them Tom and Artie, after two of his uncles. We shall learn more of these twins as our story proceeds.

About eleven o'clock there was a slight lull and Barringford announced that they had better start without further delay. The others were willing, and in a short space of time the camping spot was left behind, and they were crossing the first of the hills which separated them from the Morris homestead.

"This is the sort of storm to keep up for several days," observed Rodney, and he was right, the fall of snow lasted for forty-eight hours longer and made all the roads in that vicinity impassable for the time being.

It was nightfall when they reached the Morris homestead, standing as my old readers know, in the midst of a rather large clearing. It was a rude but comfortable cabin, long, low, and narrow, with the back roof sloping down to a kitchen porch. There were four fair-sized rooms, all on the ground floor, and above them a loft used occasionally for a sleeping room, and stored with seeds and with supplies for the winter. Not far from the house was a rude shelter of logs and sods for the cattle, back of which, in the summer time, flowed a gurgling brook of the clearest spring water.

As they approached the cabin Dave and Rodney set up a loud shout. This brought Joseph Morris from the cattle shed, and likewise brought Mrs. Morris, little Nell, and the twins to the doorway of the homestead.

"Hullo! back again, eh?" sang out Joseph Morris. "Good enough. And Sam and White Buffalo, too. Glad to see you once more."

"I didn't know you expected to be back from town so soon, father," answered Rodney.

"I had an accident that made me cut my trip short," answered Joseph Morris. He limped forward. "Bess got frightened at a wildcat and threw me over her head. In coming down my foot struck a sharp rock, and I gave my ankle a bad twist."

"That's too bad," said Dave. "I hope the wildcat didn't trouble you."

"I didn't give him a chance. I had my old Spanish pistol with me, and I blazed away at such a close range that I about blew the wildcat's head off. I had a time getting home, I can tell you. Bess wouldn't come near the dead cat, so I had to hobble after her the best I could for several rods."

"Ye had better keep off the foot for a few days," put in Sam Barringford. "A twisted ankle ain't nuthin' to fool with."

"I'm going to rest—now the boys are home again. But I couldn't let my wife look after the cattle in such a storm as this," returned Joseph Morris. He gazed at the drag and the various game bags. "A deer and a bear, and rabbits and turkeys! You've had luck, that is certain."

"Yes, and a narrow escape in the bargain," answered Rodney.

The two young hunters passed toward the house, leaving the men to talk the matter over between them. As they approached the twins set up a cry of welcome and little Nell joined in.

"Uncle Davey tummin'!" cried one twin.

"Uncle Roddy tummin'!" echoed the other twin.

"Did you get a deer?" asked Nell, eagerly. She was a sweet-faced girl, with dancing eyes, and curly hair that hung far down over her shoulders.

"Oh, Nell, you mustn't expect a deer every time," remonstrated her mother. "I am glad to see you back, boys. I see you got some rabbits and turkeys," and she gave each a warm smile.

"Yes, and we got the deer, too," added Rodney, with a touch of pride in his tone. "But Dave is to be thanked for that."

"Nonsense," cried the youth mentioned. "Rodney had as much to do with bringing him down as I did. But we got more than that, Aunt Lucy—that is, the whole crowd did. Sam Barringford and White Buffalo are with us. They stopped at the shed to talk to Uncle Joe."

"And what more did you get?" questioned little Nell, eagerly.

"A bear—a great big bear—one of the biggest ever shot around here."

"You don't say so!" exclaimed Mrs. Morris, while Nell shrank back, as if half expecting bruin would come after her. "That was certainly luck. I'm glad the bear didn't get you."

"He came close to it," said Dave, and after kicking the snow from his feet, he entered the living room of the cabin and told his story, while Rodney did the same. The latter was rather winded from his long tramp through the snow and glad to sink down in his old chair by the open fireplace and rest. Dave hung up the guns and powder horns, and placed the small game in a pantry, and by that time the older men came up to the door.

"That certainty is a big bear," was Mrs. Morris's comment.

"Oh, I'm almost afraid to go near him," said Nell, with a shudder. "Think of being out in the woods all alone and meeting such a creature!" And she shuddered again.

The twins, however, were not so fearful, and both ran out in wild delight and climbed directly on top of the game. Sam Barringford caught up first one and then the other and gave each a squeeze and a kiss, which made them crow loudly.

"Nice Uncle Sam!" said each. "Love Uncle Sam!" And then he gave them another kiss. In his way, the old frontiersman was as fond of the children as if they were his own flesh and blood.

"White Buffalo did not bring his little lady any pappoose this time," said the Indian, when Nell greeted him.

"Never mind, I've got the other doll yet," answered Nell, and brought it forth, dressed in a gown she had just been making. "Isn't it grand, White Buffalo?" The old Indian chief had presented her with this doll of his own making two years before.

"White Buffalo bring this for his little lady," and slowly and cautiously he brought forth from under his heavy winter blanket several strings of highly ornamental beads.

"Oh, how beautiful! How very, very beautiful!" screamed Nell, gazing at the beads with wide-open eyes. "Oh, White Buffalo, are they really for me, really and truly?"

"Yes. They belonged to White Buffalo's little cousin. But she is dead and so are all of her folks, and so now they are to go to my little lady, if she will have them."

"This is kind of you, White Buffalo," said Mrs. Morris. "As Nell says, they are very beautiful."

"Then let her wear them, let her wear them always," returned the old Indian chief, gravely. "Always," he added. His words meant much, as we shall learn later.

As late as it was, Sam Barringford set to work to skin the bear, while Dave performed the same operation on the deer. Then the carcasses were hung up in the cold pantry, where they would be safe from molestation by any wild beasts that might be prowling around. In the meanwhile Mrs. Morris bustled about, preparing a hot supper for all.

Within the cabin, it was a picturesque and comfortable scene. The walls were of rude logs plastered with clay to keep out the wind. The fireplace was large and in it burned a back log six feet long and a foot in diameter, and also several other smaller sticks. Over the fire hung several pots and kettles, and on a spit a good-sized piece of meat was broiling.

The furnishings of this little room were plain, for the first cabin of the Morrises, that containing so many heirlooms of both families, had been burned down by the Indians. There was a long table, without a cloth, several chairs, and two good-sized benches, often called puncheon benches, for they were made of split logs, smoothed off on the upper side and held up by four props, or legs. There was also a shelf, containing the family Bible, several books, and a few gazettes and "almanacks." Back of the door was a loaded rifle, and a shotgun rested on a pair of elk antlers not far away. In one corner stood a spinning wheel, which Mrs. Morris used whenever she had time to do so. A rude wooden box hanging close to the fireplace contained a few knives, forks, spoons, and kindred things, and another shelf contained some plates and bowls.

When the meal was ready, the boys and men washed, and all sat down at the table. Joseph Morris said grace, and the food was passed around, so that each might take whatever he wanted. Only White Buffalo waited to be served by Mrs. Morris, and during the repast the Delaware said not a word, nor did he open his mouth until after a "pipe of peace" had been passed around by Mr. Morris, to himself and Sam Barringford.

"White Buffalo has been well received, his heart is glad," said the old Indian to Mrs. Morris. This was all he ever said after dining at the cabin, but his words had the ring of truth in them.

The meal over, all gathered around the fire, to talk over matters in general, and to tell of their various experiences. Rodney was glad to rest and retired early. Joseph Morris had to admit that his twisted ankle hurt him not a little, and he bathed it with some liniment and bound it up. When all of the others had withdrawn, Sam Barringford and White Buffalo made themselves comfortable on the cabin floor before the cheerful blaze. Outside the snow came down as thickly as ever, and occasionally the rising wind swept mournfully through the tree branches. As Dave turned over on his rude but comfortable couch, he was glad he was home again and not out in the trackless forest with its many perils.

One snow-storm succeeded another during the following two weeks, so hunting was out of the question for Sam Barringford and White Buffalo. The former amused himself with the twins, while the Indian either sat by the fire smoking, or made toys out of wood for Nell. Occasionally the Delaware would tell stories of great hunts or great fights with rival tribes, and the little miss never tired of listening to his tales.

"White Buffalo is the best Indian that ever was," declared Nell to her mother. "Oh, he is just—just beautiful!"

"He certainly is good-hearted," answered Mrs. Morris. "Would that all the red men were the same," and she heaved a deep sigh, as she remembered the many perils of the past.

Instead of getting better Joseph Morris's twisted ankle seemed to grow worse and for the time being he had to keep off his feet. It was not a serious hurt, but he was afraid that it might become so if he attempted to use the member.

"You had better take it easy, Uncle Joe," said Dave. "I can do the outside work well enough."

"And I'll do my share," added Rodney, and between them they looked after the cattle, brought in the wood and water, and did what they could to keep the snow from the door.

In those days the Morris homestead was as completely isolated as if it had been located a hundred miles from any settlement. The nearest neighbor lived a quarter of a mile away, and only seventeen families resided within a radius of two miles. The majority of the roads were mere trails, used alike by human beings and wild animals. There were but few bridges over the streams, so that in traveling much fording had to be done. Each cabin had a small clearing around it, but otherwise the primeval forest stretched for miles upon all sides. At times, especially in winter, the wild animals would become particularly bold, and wolves had often appeared, trying to get at the meat hung up in the pantry, and once a half-starved doe had come to the door to be fed.

On account of the wars, Dave had lost considerable schooling, and a part of each winter day was given over to studying, in which Rodney joined. The main studies were reading, spelling, writing, and arithmetic. There were no copybooks and but little paper, so much of the writing was done on smooth birch-bark, with pens made of turkey quills. There was one general "History of the Old World and the New, Containing a Complete Account of All Civilized Nations," a thin volume, printed in large type and containing several curious maps and equally curious engravings. This was also used as a text-book, and it was not long before Dave almost knew the volume by heart.

"The author doesn't know as much of the great West as we do," said Dave one day, to his uncle. "See, he hasn't located a single fort or settlement west of Winchester. All the rest is to him 'The Unexplored Western Countries,' said to be overrun with ferocious wild beasts and Indians who are cannibals."

"Some day the great West will be explored," answered Joseph Morris. "But it will take years and years to do it. Our troubles with the Indians must first be settled."

"Do you think the Indians will ever be at perfect peace with us, Uncle Joe?"

"Not until we have conquered them. We must show them that we are masters. It is a mistake to let some of them believe that we want to be friendly just because that is the proper thing. Many Indians take that as a sign that we are afraid of them."

"White Buffalo doesn't look at it in that light."

"White Buffalo is an exception to the rule. He has lived among the whites for many years and he understands us. But the wild red men of the forest can never understand us, nor can we understand them, for our ways of living are so different. It's not in the nature of an Indian to be at peace all the time. He loves to hunt, and if he can't hunt wild animals, he hunts his rival red men, or us whites."

"Thet's exactly it," said Sam Barringford, who sat by, cleaning and oiling his rifle. "Barrin' a few like White Buffalo the critters ain't more'n half human, to my way o' thinkin'. Look at the way they sculp folks, an' burn 'em at the stake, an' sech. It's enough to make one sick a-thinkin' on it."

"But some of the lawless trappers are almost as bad," replied Rodney. "They do fearful things when they are in the humor for it."

"It's the liquor, Rodney," answered the old frontiersman. "Put liquor into a hot-tempered man an' ye make a fiend o' him. Those fellers see the redskins do things, an' then they want to go the red varmints one better, an' there ye are."

"Oh, I know that rum has caused a whole lot of trouble in this world," answered Rodney. "For my part, I'd like to see the manufacture and sale of the stuff stopped."

"Won't never see that, lad—too many folks a-makin' money out o' the traffic. Besides, ef they did try to stop it some would be makin' it on the sly, an' drinkin' it, too."

"If the red men would only turn to farming all might go well," said Joseph Morris, thoughtfully. "But they seem to hate work in the fields. An Indian would rather hunt all day for a single turkey, or fish all day for a single trout, than gather a bushel of corn if it was given to him. Even White Buffalo won't work the ground if he can help it."

At last the snowstorms seemed at an end, and one day Dave, Rodney, and White Buffalo went out to hunt. The red man had his bows and arrows with him, and showed them how easy it was to bring down some birds on the wing without disturbing the other game that was near. No large game was discovered, but the three returned to the cabin loaded down with half a dozen small animals and twenty-six birds of various kinds. They also laid low two foxes, and the skins were given to Mrs. Morris for a muff.

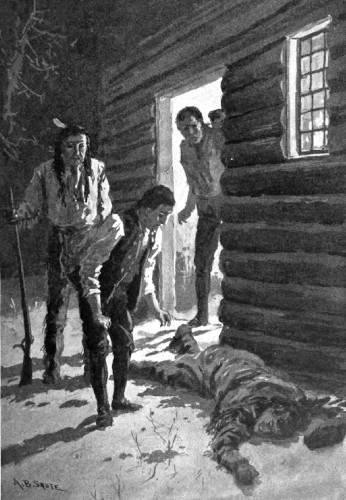

One night Dave and Rodney were on the point of retiring when there came a loud knock on the side of the cabin. Mrs. Morris, Nell, and the twins had already gone to sleep, and the others were dozing near the fire.

"What's that?" exclaimed Dave, and by instinct he leaped for the gun behind the door. Seeing this, Rodney reached for the weapon resting on the elk antlers.

The knock was repeated. It came from the side of the cabin where there was no door. Joseph Morris roused up sleepily.

"Did you let something fall, boys?" he asked.

"No," answered Rodney. "Somebody is knocking on the side of the house."

Awakened by this declaration, Joseph Morris sprang up, and so did Sam Barringford and White Buffalo. Again came the knock.

"Who is there?" demanded Joseph Morris, loudly.

"A friend! Let me in!" was the low answer.

"Who are you?"

"Ira Sanderson."

"Ira Sanderson!" ejaculated Dave. "Oh, he must bring news from the trading-post!" He ran towards the door and started to open it.

"Wait—it may be a ruse," said his uncle, stopping him. "Sanderson, are you alone?" he called out.

"Ye—yes. Let me in. I—I am hurt."

No more was said. Opening the door cautiously, Joseph Morris stepped outside, followed by Dave and the others. At first they could see nobody, but presently discovered the form of a man lying in a heap in the snow, close to the wall of the cabin. The man was limp and almost unconscious, and they had to carry him inside, where he was placed on the floor in front of the fire and given stimulants.

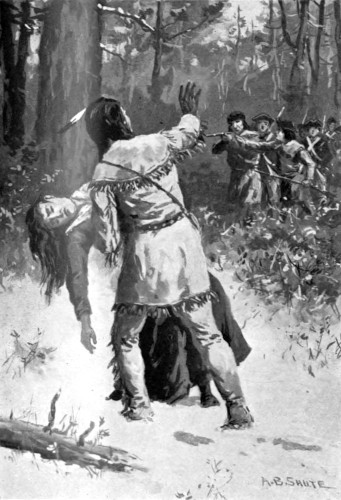

They presently discovered the form of a man lying in a heap in the snow.

As my old readers know, Ira Sanderson was a hunter and trapper well known in that vicinity. He had accompanied James Morris on more than one expedition to the west, and had once taken charge of the trading-post during Mr. Morris's absence.

"Father must have sent him with news," said Dave. "Is he shot, or what is the matter?"

It was soon ascertained that Sanderson had been struck in the side by an arrow. The wound had been bound up in a rude way, but the loss of blood had so weakened the hunter that he could no longer stand up. It was a good hour before he felt strong enough to speak and then he said only a few words.

"I left the trading-post four weeks ago," he said. "Got captured by the redskins. They carried me up the Monongahela, an' were goin' to burn me at the stake, but I gave 'em the slip. Then comin' from Fort Pitt I got plugged in the side, as you see. But I kept on, until I got in sight of the cabin, when all my strength seemed to leave me."

"Is everybody safe at the trading-post?" asked Dave, eagerly.

"Safe so far, Dave. But there ain't no tellin' how long it will last. I—I—I'll tell you all about it when—when I'm stronger. Here is a—a letter your father—writ——" He pointed to his breast and then fainted.

While the others worked over the wounded messenger, Dave brought forth the letter mentioned and perused it, not once but several times. It was written in James Morris's characteristic style, and ran, in part, as follows:

"You will be glad to learn that so far the season has been a very good one. I have made a bargain with some French as well as English and Indian trappers for their furs, and they are bringing in all that I can handle. A few of the Frenchmen tried to get the best of me, but I showed them that I knew my business and since that time they have not bothered me. They now realize that the French cause in the Colonies is hopelessly lost.

"One of the French trappers used to be a personal friend of that rascal, Jean Bevoir. He says Bevoir is recovering from his wounds, and expects to go back to trading himself in the near future. I do not care what he does, so long as he does not molest us again. But if he tries any of his underhand work I am going to do my best to put him in the hands of the authorities, for he richly deserves a long term of imprisonment for his past misdeeds.

"Pontiac's failure to unite all the Indian tribes in a war against us last year and the year before, has caused some of the Wyandottes and Delawares to desert him. But the others seem to stick to him still, and I am afraid they are plotting greater mischief than ever. One trapper told me that the Indians up at the Lakes are very restless, and hold a great many pow-wows and war talks. Yesterday I had three strange Indians here, Ottawas, and I did not like their manner in the least. They took careful note of how the post was laid out, and asked one of the men if we had any extra guns on hand. I half believe they were spies, but as I could not prove it, I had to let them go.

"Henry wants to be remembered to all at home. He is well and has had some great success at hunting. He fixed up a trap last week and on Saturday night brought in the most ferocious wolverine ever seen in these parts.

"Since penning the above, I have just come from interviewing two other strange Indians. They did a little trading, but spent most of their time in looking over the trading-post. They wished to know what I wanted for four good guns, but told them I had no firearms to sell. This angered them, and they went off muttering to themselves. I must say I did not like their looks at all.

"Ira Sanderson is to start with this letter to-morrow. He can give you more details than I can write. I am anxious to hear from you, for I know the Indians must be as restless around Fort Cumberland as they are here."

Leaving Ira Sanderson to recover and tell his story to those at the Morris homestead, let us journey westward and learn for ourselves what had occurred at James Morris's trading-post during the months in which Dave had been absent.

The new trading-post, built on the bank of the Ohio River after the first post, located on the Kinotah, twenty miles away, had been destroyed, was a substantial affair of heavy logs. The main building now consisted of four rooms, and not far away was a storehouse of two rooms, to which was attached a horse stable of fair size. The post was built on a tiny bluff overlooking the broad Ohio, and close at hand was a small brook backed up by rocks. A strong palisade of sharpened logs driven into the soil ran around a portion of the grounds which was not protected by the water, and here was located a heavy pair of gates, ten feet wide, secured by two strong crossbars. At convenient distances loopholes were cut in the palisade, to be used for shooting purposes in case of an attack.

On all sides of the trading-post the forest stretched for miles, broken only by the river and smaller streams, with here and there a tiny waterfall or a lake. In some spots the wilderness of trees and underbrush was so dense that to cut a path through was next to impossible. For miles and miles the only settlements were those of the Indians, who wandered from place to place, as their fancy pleased them. And this was but a hundred and forty odd years ago. To-day this same section of our country contains numerous towns and cities, the river counts its hundreds of steamboats, and the luxurious railroad trains dash by well cultivated farms. Truly the progress of our country has been marvelous.

For several weeks after Dave was rescued from the Indians, and left to continue his journey eastward, matters moved along smoothly at the trading-post. Henry missed his cousin greatly, for the two young soldiers had been like brothers since childhood. But he did not complain, for he knew that his Uncle James must feel equally lonely.

Every day the hunters and trappers who made the post their stopping-place came and went. Some were kind and considerate enough, but others were brutal, and a few wished to carouse and fight, something which Mr. Morris would not tolerate. A great many had been to the war and found it difficult to settle down after so much fighting.

"The war spirit gets into a fellow's veins," said one old trapper to Henry. "It seems so quiet with nothing going on."

"I know the feeling," answered Henry. "I was in the war myself."

"So Tony Jadwin was telling me, Henry; he said you saw lots of fighting, too, you an' your cousin Dave."

"We did—more than I want to see again."

"The Injuns ain't done makin' trouble, Henry."

"I believe you," answered the youth, seriously.

It was the next day that the three strange Indians put in an appearance, as described in James Morris's letter. Henry saw them, and he and his uncle talked the matter over after the red men had departed.

"They certainty did act suspicious," declared the youth. "And they were wicked-looking customers, too."

"I shall notify Jadwin to keep a sharp lookout in the future," answered James Morris. Tony Jadwin was now his right-hand man at the post, a hunter and trapper as well known as Sanderson and Sam Barringford.

Following this visit came the visit of the two other Indians. They caught Henry cleaning up several guns and pistols, and this made them speak of buying some firearms.

"They were actually angry because we wouldn't sell to them," said Henry. "Uncle James, they certainly mean mischief."

"Just my notion, Henry. But they can't do much single-handed."

"Don't you think there are other Indians around?"

"Jadwin hasn't seen any—I mean any that are strange. Those Delawares who train with White Buffalo are here, but I don't fear them."

"Have you any idea what has become of Pontiac?"

"A French trapper told me yesterday that Pontiac is reported to be in the vicinity of Fort Detroit. They say he has some sort of a home on an island in the Detroit River."

"If he was down here he'd be certain to make trouble."

"Pontiac isn't thinking of us just now, Henry. I believe he is plotting to attack the big forts. He'll leave the under chiefs to attack the little posts and the settlements."

For several days after Sanderson's departure for the east, matters ran along smoothly at the trading-post. Only a few well-known Indians came in, to exchange furs for other commodities. These Indians reported having seen some Ottawas on the Ohio, moving to the northward.

"Perhaps they have left the vicinity," said James Morris, and breathed a short sigh of relief. He had seen so much of excitement he wanted no more of it.

On the following day Henry went out to do some fishing. He had with him a strong pike pole and also the necessary lines and bait. He traveled a short distance down the river, and finding a spot that suited him, cut a circular hole in the ice with his pike pole and then started to fish.

It was a clear, cold day, and as the fish did not bite very lively the youth occasionally walked around to keep his blood in circulation. Once he walked a short distance up the shore, to look around a bend, and there to his surprise saw six Indians, hurrying into the depths of the wilderness with a heavy bundle among them.

"Can they be going to our post?" he asked himself. "If so, they are taking a roundabout way of getting there."

He watched the Indians out of sight and then returned to his fishing. But he had lost interest in the spoil, and soon wound up his lines and hurried back to the post, where he told his uncle of what he had seen.

"Six Indians, and all strainers, eh?" said James Morris. "If they are coming here they ought to arrive soon."

He hurried out and made his preparations to receive them. At the post at the time were Tony Jadwin and three other frontiersmen—all the others, and the friendly Indians, being out hunting or trapping. James Morris called the crowd together.

"They may be friendly, but we must take no chances," he said. "Load your guns and keep on guard."

These orders had been given so many times before, that the men knew exactly what was expected of them. Jadwin took his station at the stockade gates, and the others lounged around, each with his gun and a pistol ready for instant use, should any shooting be necessary.

But the Indians did not come, and by nightfall the temporary alarm was over. One of the frontiersmen began to poke fun at Henry and said he "reckoned as how" the youth had made a mistake.

"No, I didn't make a mistake," answered Henry. "I saw them as plain as day. Perhaps they were going to some other post."

"If so, they have a long tramp before them," returned the frontiersmen. "No other post nigh to thirty miles from here." This was true.

On the following day two friendly Indians reported seeing a fine herd of deer a short distance down the river. This interested those at the fort, and two of the men went off shortly after noon to see if they could bring down some of the game. Henry wanted to go along, but Mr. Morris demurred.

"I would rather have you here," he said to his nephew. "With those men gone we may need you. You can go some other time."

Henry saw the wisdom of his uncle's reasoning and so contented himself by working around the post, taking care of some hides which had recently come in, and in exercising one of the horses. Henry loved a good horse almost as much as he loved hunting, and he spent a full hour in the saddle.

"Rides as ef he was born to it," remarked Jadwin, who was looking on. "Just see him stick when the horse makes that sharp turn!"

"Henry is an out-door young man if ever there was one," answered James Morris. "And my Dave is about of the same nature," he added.

The winter sun was almost setting when two Indians appeared at the stockade gates. They were strangers and set up a cry for admission.

"What do you want?" demanded James Morris, as he appeared at the top of a small ladder, gun in hand.

"Want to sell skins," grunted one of the red men, a dirty individual with particularly repulsive features.

The Indians had a big bundle on a drag, and each carried his bow and arrows on his back. Seeing this, James Morris called to the others in the post to be on guard, and then descended the ladder and opened one of the gates.

"Where do you come from?" he asked, as the Indians came in, dragging their big bundle.

"Come from the south," was the answer. "Two moons of hard hunting," and the Indian pointed to the bundle, meaning that the latter contained the results of a two months' hunting tour. "Make trade to-morrow," he continued.

"To-morrow?" queried James Morris. "Don't you want to trade now?"

"No. Black Ear not here. Black Ear own some skins. He come to-morrow, den all trade."

"You mean that some of the skins belong to Black Ear?"

"Yes."

"And he will be here to-morrow?"

"Yes."

"All right then, you come in to-morrow and trade. You can't stay here overnight. I don't allow that sort of thing any more."

"Indians no want to stay. But want leave big bundle skins. Heavy bundle, Indians tired. Put bundle in dare," and the red man pointed to the storehouse.

"All right, you can put the bundle in there if you wish," answered James Morris, carelessly.

"Bundle safe dare?"

"Yes."

"No touch bundle—Black Ear say wait—he angry if touch bundle skins."

"I shan't touch 'em, so don't worry," answered the owner of the post. "Come on," and he showed the Indians where they might deposit the big bundle. It was placed in a corner of the storehouse, and then, with a sharp look around the post, the strangers prepared to depart.

"Give Indians rum?" said the one who could speak English.

"I haven't any rum."

"Give Indians a little tobacco."

"I'll do that," said James Morris, and handed over a fair-sized pouch full. For this the red men seemed to be very grateful, and hurried away, saying that they would come back with Black Ear in the morning and do their trading.

"Very well," said Mr. Morris. "I'll do the best I can by you."

He followed the red men to the gates, and after they were gone barred the barriers as carefully as before. The Indians did not look back, but plunged at once into the depths of the forest. When they were out of sight of the post one Indian looked suggestively at his companion.

"Think you did the white trader suspect?" asked one, in his native tongue.

"He suspected nothing," was the reply. "The plan was too well laid."

"We must hurry and tell Rain Cloud and let him gather the others. At the cry of the whip-poor-will we must stand ready to fall upon the post and kill all who are stationed there."

"Uncle Jim, I didn't like the looks of those Indians at all," said Henry, after the red men were out of sight.

"Oh, they didn't seem to be anything out of the ordinary," answered James Morris. "They've got a pretty big bundle of skins with 'em."

"Perhaps they stole the skins. To me they looked like Indians who couldn't be trusted."

"I'll question them closely when they come in again, Henry. I certainly want no stolen skins, in trade or otherwise."

"Did you ever see those redskins before?"

"I believe I saw one of them last year, but where I can't remember. They were about as dirty as any around here," added the trader. "I wouldn't let them sleep here even if I knew it to be safe. I'd have the place alive with vermin."

"It's queer how some of them hate a bath, especially in cold weather," said the youth, with a laugh. "Perhaps they think the dirt helps to keep 'em warm."

The night was cold and clear. There was no moon, but the stars shone brightly, so it was not as dark as it might otherwise have been. Only a faint breeze was blowing, not sufficient to move the stark tree branches of the great wilderness which surrounded the lonely post.

Ever since the last uprising of the Indians, Mr. Morris had made it a point to have somebody on guard during the night. All the trappers who remained at the post knew that such duty was expected of them, and that they were doing it as much for their own protection as for the good of others. Guard duty began at six in the evening and ended at six in the morning, and the twelve hours were divided equally among whoever happened to be at the post during that period of time.

Tony Jadwin was the first to do guard duty that evening, and it was arranged that Henry should be the one to relieve him. But though free from duty, Henry was not disposed to lie down, and he wandered around, from the stable to the general living room.

"Why don't you go to sleep, Henry?" asked his uncle. "You'll be tired out when it comes your turn to go on guard."

"I don't feel a bit like sleeping, Uncle Jim. I'm as wide awake as an owl."

"Better lie down, anyway. It's a good night for sleeping."

"I can't get those Indians out of my mind," went on the youth.

To this James Morris did not answer, and presently Henry left the main building of the post and walked back to the stable, to get a pair of gloves which he had forgotten.

As he passed the horses one of the animals gave an uncertain snort, as of fear. The youth stopped by his side and patted him.

"What is it, Nelson?" he asked softly.

But the horse could not answer and merely rubbed his nose against Henry's face. The youth patted him again and then passed on, secured the gloves, and prepare to leave the stable.

"Guess I'll take a look at that bundle of skins," he said to himself. "It won't do any harm to turn it over and see what it looks like."

Henry's experience as a hunter and trapper had given him a good idea of the value of hides and furs, and James Morris often appealed to him when in doubt over a certain skin that was offered in trade. He had seen a peculiar looking skin sticking from the end of the bundle and he wondered what it was and if it was of great value.

On his journey to the stable, the youth had carried a lantern,—a big, old-fashioned affair,—and this was still in his hand. Coming to the storeroom door he flashed the rays of the light inside.

What he saw caused him to start back in amazement, and for the moment he could not believe the evidence of his senses. The bundle was moving!

Henry stared for several seconds and as he did this he saw the hand of an Indian come forth from the bundle and clutch at one of the thin rawhides which held the skins together. Then he discovered that the foot of an Indian was sticking out of the other end of the bundle.

The perils of the wilderness, and of army life, had taught Henry to act quickly in case of an emergency, and setting down the lantern, he drew his hunting knife and rushed forward.

"Stop right where you are, you skunk!" he cried. "Don't dare to move another inch, or I'll stick you with this!" And as he uttered the words he let the point of the sharp hunting knife fall on the back of the Indian's hand.

There was a disappointed grunt from inside the bundle, and the hand was pulled back several inches. Henry had caught the rascal inside in the very act of liberating himself.

Stepping to the storehouse doorway the youth blew upon a whistle he carried. It was the signal that something was wrong, and in a moment Tony Jadwin came running to the spot.

"What's up, Henry?" he cried.

"I've got a prisoner. Collared him bound hand and foot too," and the youth had to smile at his own little joke.

"A prisoner? Where?" quickly asked James Morris, who was behind Jadwin.

"Here, in the bundle, Uncle Jim. I knew all along that those Indians couldn't be trusted."

"In the bundle—what do you mean?"

"There's a redskin in this bundle. I caught him in the very act of trying to get out."

"It must be a plot to capture the post!" ejaculated James Morris. "Jadwin, get back to the stockade at once, and fire on the first redskin who shows himself!"

"Shall I go, too?" asked Henry.

"Yes. I'll take care of this rascal, and then I'll join you," answered the trader.

Waiting to hear no more, the youth ran for the main building of the trading-post and secured his rifle, and also an extra rifle and a pistol. Tony Jadwin was equally armed, and each ran for a corner of the inclosure.

"We'll have some hot work cut out for us, if an attack comes," said the old trapper. "Reckon as how that redskin meant to kill us while we slept, or throw open the gates on the sly."

"You're right, Tony. I wish the rest of the men were back. Wouldn't it be a good idea to fire a signal for them?"

"It ain't likely they are in sound o' a gun, lad."

No more was said, and each took his place at the palisade and gazed through one loophole and another anxiously. All was quiet outside and not a single human being was in sight.

A quarter of an hour passed, and then James Morris joined his nephew, carrying several loaded guns and pistols.

"Well?" he questioned, laconically.

"Haven't seen anybody yet," answered Henry.

"I tied that rascal up good and hard," said the trader.

"What did he have to say for himself?"

"He tried to worm out of it by saying he was drunk yesterday and his friends must have tied him in the bundle for fun while he was sleeping. He professes to be friendly and says he will fight the others for playing such a trick on him."

"Do you believe such a yarn, Uncle Jim?"

"No, and I told him so. If any of those redskins appear don't let them get too close."

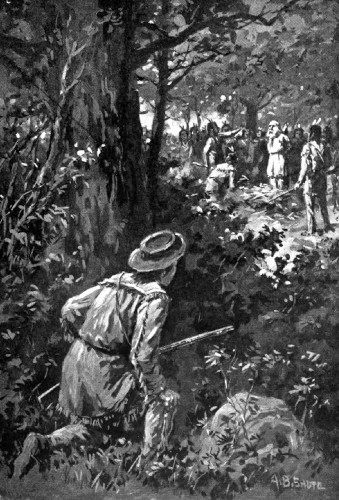

James Morris went off, to interview Tony Jadwin. He was gone but a minute when Henry saw something dark moving cautiously along a mass of brushwood down near the brook.

"An Indian, I'll wager a shilling," he murmured to himself, and raised his rifle. "More than likely he is waiting for a signal from the rascal we caught." And in this surmise the youth was correct.

The Indian outside passed behind some trees and was followed by a second red man and presently a third. Henry gave a low whistle, which brought his uncle to the spot once more.

"Saw three of 'em," said he. "They are back of yonder trees. It is too dark to get much of a look at 'em."

"Tony saw two," answered the trader. "Henry, I am afraid we are in for it," he continued, seriously. "Had you not found that rascal in the bundle we might have all been murdered by this time."

"I wish there was some way of letting the others know how we are surrounded."

"There is no way just now. One of us might try to go out toward sunrise—if we can keep them off that long. I presume they are waiting anxiously to hear from the fellow we have captured."

"To be sure. I think—There is another, and he is coming pretty close!" added Henry, excitedly.

"Wait—I'll talk to him. There is no use of our keeping silent any longer," said James Morris. He raised his voice. "Hold, there!" he shouted. "What do the red men want around this post at this hour of the night?"

The Indian addressed was evidently taken by surprise, for he stood stock still for fully a minute before replying.

"Who calls to Rain Cloud?" he asked at last.

"I call, the owner of this place," answered the trader. "This is no hour for coming here, and Rain Cloud knows it."

"Rain Cloud would speak to his white brother," said the Indian, smoothly.

"What about?" and there was a peculiar sharpness in James Morris' voice as he spoke.