Title: Host and Guest

a book about dinners, dinner-giving, wines, and desserts

Author: A. V. Kirwan

Release date: April 2, 2023 [eBook #70445]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Bell & Daldy, 1864

Credits: MWS, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

HOST AND GUEST.

HOST AND GUEST.

BY A. V. KIRWAN,

OF THE MIDDLE TEMPLE, ESQ.

LONDON:

BELL AND DALDY, YORK STREET,

COVENT GARDEN.

[v]

There is no want of cookery books in the principal languages of Europe, and least of all in the English language, in which, even in our own generation, several hundreds have been compiled and published. This volume, however, is not a cookery book, nor what the French call a dispensaire. It is a household book on the subject of Dinners, Desserts, Wines, Liqueurs, and on foods in general; and is the result of reading, observation, and a great deal of experience in foreign countries. I have been myself, during a life now nearly prolonged to threescore years, a diner out of some magnitude, and, as far as my means allowed, a giver of dinners; and have often when younger and less experienced, felt the want, and have heard my friends express their sense of the want, of some work of the kind now first presented, so far as I am aware, in an English dress.

[vi]

Born in a country house—a messuage producing, to use a legal phrase, within the curtilage, beef, mutton, fruits, and vegetables—I have ventured to speak of the choice and quality of these good things from an early and practical acquaintance with the subject. So much needs to be said on a matter on which all are eloquent, though few agreeable—I mean self. It is necessary to state that it is not from reading, but actual practical experience, that I have learned all about the farm, the garden, and the poultry-yard.

There are several works of a cognate character to this in Latin and French, and some in Italian and Spanish. But these are scarce, costly, old, and obsolete. Few are acquainted with the treatises of Nonnius, Taillevant, cook to Charles VII., Champier, physician to Francis I., Bélon, Patin, Charles Etienne, Lémery, La Varenne, Schookius, Le Grand, De Serres, and L’Etoile, some of them written in indifferent Latin, and others in old French. I have extracted from these works a good deal curious, and something valuable in the choice and preparation of foods. I have endeavoured to show how the traditions of cookery have occasionally survived codes and constitutions, and how these traditions have been, in turn, occasionally set aside and overturned by[vii] some new culinary fashion. The work presented to the reader is therefore, in certain parts, historical, anecdotical, gossipping, and somewhat discursive; but the main object of the author has been to induce well informed and sensible people in England to adopt all that is good in the excellent cookery, and agreeable and social life of our neighbours of France, without in any wise abandoning the best of our British customs, or the simplicity of our substantial food.

It is not for the author to say in how far he has succeeded. That he leaves to the judgment, and they are a great majority, of those who criticise in a fair and candid spirit. All, however, who affect to criticise are not candid; but it may be said of a critic who deliberately misrepresents a work, that he is unworthy of his vocation, and as heinously criminal as the man who in social or commercial life gives a false character of a servant, or a false warranty of goods or merchandise.

73, Gloucester Place, Portman Square, W.

March 1, 1864.

[ix]

CHAPTER I.—Ancient and Mediæval Cookery compared with the Cookery of the last Half Century.

Garum—Pilau seasoned with garum, 2. The Feast of Trimalchio in Petronius, 2. Macrobius’s description of a supper given by Lentulus, 2. Hedge hogs, raw oysters, and asparagus, and purple shell-fish, 2. Panes picences, 2. Greeks and Romans children in preparation of viands, 3. Carème’s opinion, 3. Cookery a practical art, 3. Characteristics of ancient and modern cookery, 4. The Monks, 4. Spanish cookery book of Ruberto de Nola, 4. Leo X., Raphael, Guido, Baccio, Bandinelli, and John of Bologna, 5. Italian wars under Charles VIII. and Louis XII., 5. Cookery under Henry III. became Italian, 6. Cookery under Henry IV., 6. The cabaret, 7. Maître queux cuisiniers porte-chapes, 7. First regular cookery book in France printed in 1692, 7. The “Dons de Comus,” 9. Preface written by Father Brumoy, 9. Brumoy’s comparison between ancient and modern cookery, 10. Idea of a perfect cook, 10. “Lettre d’un Pâtissier Anglais,” 11. Mrs. Rundell, 12. “La Science du Maître d’Hôtel Cuisinier,” 12. Carème, 13. Molière, 13. St. Evremond, 14. Lavardin, 15. The Regent Orleans, 15. The Duchess of Berri, 15. Filets de volaille à la Bellevue, 16. Poulets à la Villeroy, 16. Chartreuse à la Mauconseil, 16. Vol au vent à la Nesle, 16. Poularde à la Montmorency, 16. Louis XV., 17. Marquis de Béchamel, 18. Marshals Richelieu and Duras, Duke of La Vallière, the Marquis de Brancas, and Count de Tessé, 18. Consumption of pheasants in the kitchens of the Prince de Condé, 18. Louis XVI., 19. His enormous appetite, 19. Effects of Revolution on cookery, 19. Cardinal Caraffa, 20. Montaigne, 20. Restaurants, 21. Suppers of Madame du Deffand, 22. Dinners of D’Holbach, 22. Pic-nics of Crawford of Auchinames, 22. The epicure Barras, 23. Danton’s love of morels, 23. Barras’ love of button mushrooms, 23. Napoleon’s dinners, 23. M. de Bausset, M. de Cussy, Cambacères, Talleyrand, 25. The “Almanach des Gourmands,” 26. Purge your cooks, 28. Frog dressing at Riom, 28. Veal of Pontoise, 29. Gastaldy and the salmon, 29. Flesh killed by electricity, 30. Asses’ flesh, 30. White grease of the fig-pecker, 31. Beauvilliers, 31. Brillat Savarin, 31. Consumption of turkeys, 32. The Archbishop of Bordeaux and truffled turkeys, 33. The “Cuisinière Bourgeoise,” 33. Fauche Borel, 33. “Cuisinier Royal,” 33. Shakespeare, Age of Elizabeth, 34. Age of Anne, Wycherly, Vanbrugh, Congreve, Pope, 34. Foote’s farce, 35. Bills of fare in Pope’s day, 36. The “Queen’s Closet Opened,” 36. The “Treasure of Hidden Secrets,” 37. The “Gentleman’s Companion;” Dr. Hill, “Mrs. Glasse,” 37. The “Connoisseur,” 39. White’s, Pontacs’, Dolly’s and Horsman’s, 39. The “Art of Cookery,” by a lady, 39. The “Epicure’s Almanack,” 40. The “Cook and Confectioner’s Dictionary,” 40. Mrs. Dalgairns, 40. Scott’s “Dictionary of Cookery,” Kitchener’s “Cook’s Oracle,” 41. The “Housekeeper’s Oracle,” 41. Ude, 42. Walker’s “Original,” 42. “Domestic Cookery,” by a lady, 45. Carème, 47. Turtle soup, 48. Cookery of England and France, 50.

CHAPTER II.—On Modern Cookery and Cookery Books.

The object of sensible people should be to adopt all that is good in the cookery of France, 61. French potages and purées, 61. The gigot à l’ail aux haricots, 62. The filet de bœuf, 62. Vatel, La Chapelle, Grimod de la Reynière, Beauvilliers, Ude, Laguipierre, Carème, and Plumeret, 65.

CHAPTER III.—On Dinners and Dinner-giving.

Jules Janin, 66. Dr. Johnson, 66. Sydney Smith, 67. Apicius, 67. Nonnius, 67. Lémery, 68. Dr. Lister, 68. Dr. Kitchener, 68. Drs. Pereira and Lankester, 68. London dinners, 69. The finer cuisine bourgeoise of Paris, 69. The majority of Frenchmen thrifty, 70. Bankers’ and financiers’ dinners, 70. French punctuality, 72. The London season, 73. Difference between grand dinners in England and France, 74. Pretentious and costly rivalry in dinners, 76. Hints to dinner-givers, 78. Number of a company, 79. Expensive cookery, 81. The pot-au-feu, 82. Carème’s consommés, 82. French sauces, 82. Soles à la Normande, 82. Omelette aux fines herbes, 82. Choice of company, 84. Italian cookery, ices, and confectionery, 85. Spanish and German cookery, 85. Dutch cookery, 88. Dutch eel soup, 88. Flushing soup, 88. Russian cookery, 89. Turkish and Indian cookery, 89.

CHAPTER IV.—On Laying out a Table.

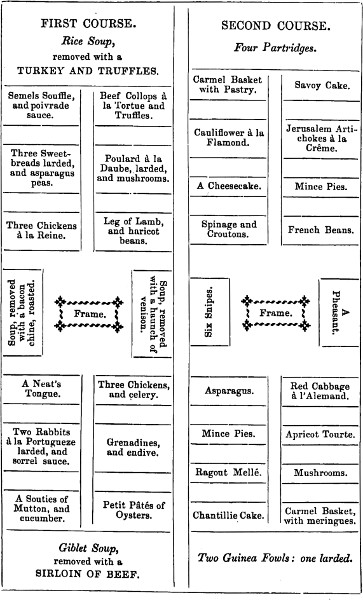

Dinners à la Russe, 91. Two and three courses, 94, 95. The dessert, 97. Memorandum as to dinners, 97.

CHAPTER V.—How to Choose Fish, Flesh, Fowl, and Game.

Salmon in and out of season, 98. How to choose various fish, 98–109. How to choose venison, 109. Mutton, 111. Lamb, veal, and pork, 112, 113. Bacon and hams, 114, 115. Poultry, game, eggs, cheese, and butter, 115–122.

CHAPTER VI.—On Soups and Broths.

Grand bouillon, 124. Rules for making nourishing broth, 125. How to make a stock-pot, 126. Celery to flavour soup, 129. Broth, 130. The great English soups and broths, 131. Carème and turtle soup, 133. Stocks for white soup, 133. French soups, 134. Purée à la Reine, des carottes au riz, de lapins, à la Chantilly, &c., 134. Soup for winter and spring months, 135.

CHAPTER VII.—How to Clean and Boil Fish.

To clean cod-fish, 137. Pilchards, mackerel, and plaice, 138. Red mullets, skate, and ling, 139. On boiling fish, 143, 144.

CHAPTER VIII.—On Fish.

Fish naturally most voracious, 145. As a diet wholesome and palatable, 146. Fish rarely served as an entrée in England, 146. Various ways of serving turbot in France, 146–7. Turbot of Mediterranean, 148. Sturgeon, 148. Caviare, 149. French modes of dressing sturgeon, 149. Modes of dressing sturgeon in England, 149. Sturgeon à la Napoleon, according to Carème, 150. American sturgeon soup, 150. Salmon, 151. French mode of dressing salmon, 151. Nonnius on salmon, 152. Cod-fish, 152. Galen on haddock, 152. Nonnius and Pliny on haddock, 152. The sole, 153. French modes of dressing, 153. Red mullet, 154. Red mullet en caisse, and à la Cardinale, 154. John Dory and lamprey, 154. Quin, the actor, 154. Receipts for dressing lamprey, 155. The Reformation and fish diet, 155. Carème on lenten diet and Murat’s kitchen, 155. Fish dinners in Paris, 157. Dinner at the Rocher de Cancale, 1828, 157. Wine at 14 frs. and 25 frs. the bottle, 158–9.

CHAPTER IX.—The Roast.

Definition of roast, 160. Rôtisseries, 161. Rôtisseurs, 161. The traiteur, 161. The cuisinier traiteur, 161. The maître cuisiniers, 162. The art of roasting, 162. The best joint for roasting, 163. Doing to a turn, 164. Good roasters rarer than good cooks, 164. Great and little roast, 164. English, roasting, 165. Our game finer than the French, 165. Swift’s lines on mutton, 166. Rules for roasting pork, lamb, veal, and poultry, 167. Table of time for roasting, 169.

CHAPTER X.—Boiling.

Rule as to boiling, 170. Advantage of slow boiling, 172. Time required to boil poultry, 173. Frying, 173.

CHAPTER XI.—Poultry.

Definition of poultry, 174. Requisites in a poultry yard, 174. Best modes of feeding and cramming poultry, 175. Wholesomeness of poultry, 175. Lémery on fowls and capons, 176–7. How the fine flavour is given to the poularde du Mans, 178. The barn-door fowl described by Berchoux, 179. Roast and boiled fowl and turkey, 180. Ways of serving fowls and turkeys in France, 180. Entrées of fowl in France, 180–1. Schools of cookery, 181. Christmas consumption of turkeys in England and France, 181. Truffles with turkey, 181. Chaptal on fowls, 182. Pros and cons for a dinde aux truffes, 182. Were turkeys known to the ancients? 183. Madame de Sévigné on capons, 183. The crammer of fowls an officer of the royal household, 184. Blackbirds and thrushes, 184.

CHAPTER XII.—Game and Pastry.

Definition of game, 186. Keeper and taker of pheasants, 186. Swanherd, 186. 17 Hen. VIII., falconry, 187. Cookery Book of Taillevant, cook to Charles VII.; receipts for dressing herons, 187. Vultures, eagles, and falcons, eaten three centuries ago, 188. Game in Spain, partridges à la Medina Cœli, 189. Sautés, filets, and recondite modes of dressing game in France, 190. Filets and cutlets of hare and rabbit, 191. Pastry and cold entrées, 191. Carème on pastry, 192. Suggestions as to patties and pastry, 193. Pâtisserie, 194. Larks of Pithiviers, 194. Partridges of Perigueux, 194. Poulardes of Angers, 194. Foies gras of Versailles, 194. Foies d’oies of Strasbourg and Toulouse, 194. The Chancellor de l’Hôpital on petits pâtés, 194.

CHAPTER XIII.—Cheese and Salads.

Soft and rich cheeses the best, 196. Stilton and Gruyère, 196. Best English cheeses, 196. Best cheeses in France, 198. Roquefort, 198. Gruyère, 198. Italian cheeses introduced into France in the reign of Charles VIII., 199.

CHAPTER XIV.—On Salad.

John Evelyn “On Salets,” 202. Fournitures of salads, 202. Chicorée, 203. Winter salads, 203. Roman or Coss lettuce, 204. Hotchpotch salads, 204. Salade à l’italienne, 204. Carème’s salade de poulets à la Reine, 204. Wine vinegar to be used for salads, 206. Chaptal’s receipt for dressing salad, 206. Sydney Smith’s ditto, 206–7. Spanish proverb as to salad, 207. D’Albignac a famous salad-dresser, 208. Eleven salads of the time of Champier, 210–11. Dr. Roques’ salad of asparagus, 211. Quickness with which asparagus may be cooked, 211. Napoleon’s salad of haricots de soissons, 212.

CHAPTER XV.—The Dessert.

Carème’s opinion of dessert, 213. La Chapelle’s opinion of dessert, 214. Forced cherries sent from Poitevins, in 1560, to Paris, 215. La Quintinié, head gardener of Louis XIV., served strawberries in March, peas in April, and figs in June, 215. Preserved pines at dessert in Paris, in 1694, 215. Italian liqueur prepared from the pine, 215. Dates, 216. Tunisian dates the best, 216. Oranges, 216. Fondness of Louis XIV. for, 216. Portuguese oranges, 217. Sweet citron, carried by ladies, to produce red lips, 217. Figs common at dessert in France 270 years ago, 217. Fig-trees placed in wooden boxes by the gardener of Louis XIV., 218. Figs at Worthing and Hampton Court, 218. Pomegranates, 218. Chestnuts, 219. Madame de Sévigné on chestnuts, 219. Cherries, 220. Apricots, 220. The reine claude, or greengage, 221. The peaches of Corbeil, of Troyes and, Dauphiné, 222. Pêches de vigne, 223. Abricots en plein vent, 223. The New-town pippin, 223. Golden pippin, 223. The paradis de Provence, 223. The capendu, 223. Pears and their different species, 224. Gooseberries, 224–5. The chasselas of Fontainbleau, and other grapes, 225. Strawberries and their varieties, 226. Trois mendiants, 227. Olives of Provence and Languedoc, 227. Gingerbread, 228. The drageoir, 229. Brandied fruits and compotes, 229. Brillat Savarin on the dessert, 230. Melon eaten with bouilli, 231. Madame de Sévigné on melons, 232.

CHAPTER XVI.—On Ices.

Ices, 233. Turks had glacières in 1553, 233. Henry III. first introduced ice, 233.

CHAPTER XVII.—Coffee.

Coffee, 235. Drank in Paris in 1657, 235. Praises of coffee by Rousseau, Buffon, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Delille, and Lebrun, 236. The retreat from Russia and coffee, 237. Twining’s coffee, 238. Brillat Savarin on pounded and ground coffee, 238. The best coffee in Paris, though the finest qualities in the London market, 240. Modes of making coffee, 241–3. Coffee sweetmeats, 242. Dr. Roques’ café à la creme frappé de glace, 243. Coffee should be hot, clear, and strong, 244. Tea, 244.

CHAPTER XVIII.—On different Liqueurs, Ratafias, and Elixirs, taken after Coffee.

Liqueurs, 245. Alkermes and rossolis, 245. Liqueurs of Batavia’, Jamaica, Martinique, and Montpelier, 246. Ratafias; absinthe, noyau, and curaçoa, 246. Eau d’or and eau de vie de Dantzic, 247. Patin on rossolis, 248. Madame Théanges and liqueurs, 248. La fenouillette and other lawful liqueurs, 249. Liqueurs of Montpelier and Lorraine, 249. Lémery on black currant ratafia, 250. Liqueurs of French West Indies, 251. L’huile de Venus, 252. Cinnamon water, crême de girofle, curaçoa, usquebaugh, &c., 253. Eau cordiale of Colladon, 254. Eau de vie d’Andaye, 254. Eau divine, cordiale du chasseur nuptiale, 257. Anisette and absinthe, 257. Cherry bounce, rum and pine-apple shrub, 257. Petit lait de Henri IV., l’eau des braves, l’huile de Vénus, le parfait amour, l’eau virginale, &c., 259. Adulterations of liqueurs, 260. German liqueurs; Pomeranzen, Wackholder, Kummel, &c., 260–61. Jean de Milan on liqueurs, 262. Famous cities for liqueurs in France, 262.

CHAPTER XIX.—Ale, Beer, Cider, and Perry.

Bass’s, Allsopp’s, and Guinness’s ale and stout, 263. Cider, its origin and history, 264. Cocky Gee, 265. Perry and hydromel, 266. Different kinds of beer, 267. The zythus and curmi of the Egyptians, 267. Fifteen hundred years ago the Parisians commenced with beer, and finished with wine, 268. The descent from wine to beer in France, 270. The French beer called godale, 271. The beer of Cambrai, of Bavaria, of Berlin, and of Brussels, 272. Beer should be light, brisk, and sparkling, 273. Forty brewers in Paris 120 years ago, 273. Seventy years ago but twenty-three, of whom Santerre the most celebrated, 273. Epitaph on Santerre, 273. English and Scotch brewers flocked to Paris at the peace in 1815, 273. In seasons of dearth Paris brewers forbidden to make beer, 274.

CHAPTER XX.—On Wines, Ancient and Modern.

Lord Bacon, Bacci, Barry, Redding, Shaw, and Denman on wines, 275, 276. Hippocrates on vinous mixtures, 276. Plato and Homer’s praises of wine, 277. Virgil, Pliny, and Columella on wines, 278. The Setine wine commended by Martial, Juvenal, and Silius Italiens, 278. Sand, powdered marble, and salt water added to ancient wines, 279. Cato’s receipt for artificial Chian and Falernian, 279. The Cæcuban, 280. The Falernian, 280. Galen and Martial on Falernian, 280. Virgil on the vinum Rhæticum, 281. The lighter wines of the Roman territory, 281. The earliest Greek wines, 281. The Thrasian and Cretan wines, 282. Greeks familiar with Asiatic and African wines, 282. Greeks drank wine diluted with water, 282. Athenæus on the πεντε και δυο, 283. The Greeks had casks, 283. Gauls knew the use of wine six centuries before Christianity was introduced, 283. Athenæus calls the wine of Marseilles good, 286. The Allobroges mixed pitch with wine, 286. Dioscorides says pitch is a necessary ingredient in Gaulish wine, 286. Secret as to the Bordelais wine, 287. The Marseillaise boiled their wine, 287. Horace and Tibullus on the smoking of wine, 288. Baccius on the wines of Alsace, 288. Domitian publishes an order for rooting up one half of the vines in some provinces, and for destroying them in others, 289. This order abrogated by Probus, 289. The Roman legions spread in Gaul employed in replanting the vine, 289. The Salique law, and law of the Visigoths, as to the cutting of the vine and stealing grapes, 290. Vine property regarded as sacred, 290. Tribute decreed by Chilperic, 290. Massacre of the officer who was to levy the tribute, 290. Passion for the culture of the vine among French kings, 290. Wine-presses and utensils for making wine in all the palaces, 290. Charlemagne and his Capitularies, 290. The Louvre enclosed vineyards within its precincts, 290. “La Bataille des Vins,” a fabliau of the thirteenth century, 291. Philip Augustus had vineyards in many districts of France, 291. Wines of Guyenne sold in Flanders and England, 291. Matthew Paris, on the sale of Gascony wine in England, 292. Froissart on the number of merchantmen that arrived at Bordeaux from England, A.D. 1372, 292. Champier as to the consumption of French wine and corn in England, 292. Charles IX. proscribed the vine in 1566, 292. His ordonnance respecting it, 293. In 1577 Henry III. modifies this ordonnance, 293. Louis XV, in 1731, forbade any new plantation of vines, 293. Origin of the expression, vendre à pot, 293. Adulterations 1800 years ago as frequent as now, 294. The ancients understood the maturing of wines, 294. Customs survive forms of polity and government, 294. Identity of the amphoræ to vessels in present use at Asti, Montepulciano, and Montefiascone, 295. Use of casks unknown to Greeks and Romans, 295. Romans employed glass, but a rude glass, 296. Invention of casks due to the Gauls, 296. Ordonnance of Charlemagne as to employment of barrels, 297. The άβαξ or abacus, 297. Misquotation of Barry as to abaci, 297. The ancients had servants like our butlers, 297. Business of the οἱνοπτης, 298. The cup-bearer and pourer out of wine, 298. Cicero’s description of a supper, &c., 298–9. Deep drinkers of a congius or gallon, 299. Cooling of wine by snow not a modern invention, 299. Pliny ascribes it to Nero, 299. Drinking of healths to absent friends, 299. Extract from Henderson as to the manner of pledging friends and drinking healths, 300. Analogy between the French and Greeks as to mixing wine and water, 300. The vin d’entremets; the wine for oysters and roast meat, 300. The coup-d’avant and du milieu, 300. The coup du milieu, according to the “Manuel des Amphitryons,” 301. Wormwood, Jamaica rum, or old cognac used for it, 301. Practice at Bordeaux in this respect, 301. The coup-d’avant used in Russia, Sweden, and Germany, 302. The coup-d’apres, what, 302. Wine used for it, 302. Wine cellars of the ancients, 303. Precautions as to cellar, 303. Women forbidden to enter the cellars of the ancients, 303. Principles of the ancients as to cellars, 303. An ante-cellar advisable, 304. Salt used in cellars, 305. The ancients more effectually preserved their wines than the moderns, 305. Wine better tasted in quarts than in pints, 305. Ancient rules for site of cellars, and on time for tasting and racking, still sanctioned by practice, 305. Wine of middle age best and most grateful, 305. Fancy prices paid for old wines, 306. No one obliged to drink on compulsion among the ancients, 306. Irish practice, 306. Some ancient sages great bibbers, but unexcited, 306. Cyrus a larger drinker than Artaxerxes, and therefore, in his own thinking, worthier of the crown, 306. Darius’s capacity of drinking, 307. Hippocrates rarely directs water, but almost invariably wine mixed with water, 307. Cornaro before and after a new vintage, 307. His plan of preserving his health, 308. Effect of fresh sugar-canes on mules, 308. Pitching ancient and modern wines, 308. Monster puncheons in Latium and Germany, 309–10. The French constructed their wine-vats in brick or stone, 310. Pierre de Blois’s denunciation of the luxury of the twelfth century, 310. Repast of Philippe de Valois and his leathern bottles, 311. Wine supplied by a miracle, 311. The tanners of Amiens obliged to furnish the bishop with two leathern bottles, 312. The derivation of the word bottle, 312. The name afterwards applied to decanters, 312. Charles VI., according to Froissart, was supplied with wine out of leathern bottles, 312. Gregory of Tours speaks of the wines of Maçon, Orleans, Cahors, and Dijon, 313. Wines of Rheims and Marne mentioned in a letter of Pandulus, 313. Henry I. and the wine of Rébréchien, 313. Louis le Jeune and the wine of Orleans, 313. Wines of Auxerre, Beaune, &c., 314. Wine of Chabli, Epernai, Rheims, &c., 314. The popes drank Beaune at Avignon, 314. The queen of Louis XII. sent Beaune to the ambassadors of the Emperor Maximilian at Blois, 314. Caprice in the estimate of wine, 315. Wine of Romanée Conti, 315. Wine of Mantes carried to Persia uninjured, 316. Burgundy and Champagne in the fifteenth century, 316. Leo X., Charles V., Francis I., and Henry VIII., had vineyards in Champagne, 316. Erasmus and Burgundy wine, 316. Champier on the excellence of French wines, 317. Rabelais vaunts Auxerre wine, 317. Canteperdrix wine, 317. This wine sent to Rome for the pope, 317. Canteperdrix wine now known as the vin de Beaucaire, 317. Favourite beverage of Henry IV., 318. Paumier on the colours of wine, 318. Wines of Château Thierry gout producing, 319. Gout does not come from Champagne, 319. Baccius on the wines of France, 319–20. Paumier on the wines of Paris, 320. Liebaut and Patin on wines, 320. The vin de Condrieux, 321. The manner of making Orleans wines, 321. Boileau on the wine of Orleans, 322. Vin de Grave, mentioned in 1550, 322. Why the wine is called Grave, 323. The Haut-Brion, 323. Hermitage, 323. Hermitage of Lord Castlereagh, afterwards Marquis of Londonderry, 323. Hermitage divided into five classes, 323. Prices of Hermitage, 324. How the Burgundy wines got their reputation, 325. The vin de Tonnerre, 325. The Abbé de Marolles’ list of Burgundy wines, 325. The wine of Olivotte, 326. The vin de Chablis for oysters, 326. Vin de Pouilly and Bucellas good with oysters, 326. Difficulty of transporting Burgundy, 327. Extent of Burgundy vineyards, 328. Arthur Young on the vineyards, 328. Mr. James Busby on the Burgundy vineyards, 329. Clos Vougeot, 329. The late notorious Ouvrard, 330. Père Perignon and the wines of Hautvilliers, 330. Sparkling Burgundy and Moselle, 330. The vin de Nuits, 330. The St. George, Meursalt, and Mont Rachet, 331. Volnay the finest wine in Barry’s time, 331. The vin de Beaune, 331. The vin de Pomard, 332. Chambertin the wine of Napoleon, 332. The Romanée Conti, 333. The Maçon and Beaujolais wines, 334. Maçon a wholesome wine, 335. Adulterated at Paris, 335. Burgundy not to be iced, 335. Burgundy at the roast, 336. Champagne wine, 337. Dispute, in the time of Louis XIV., between the Burgundy doctor and the Champenois, 337. Fagon forbid the use of Champagne to Louis XIV., 337. Opinion of the faculty of the town of Rheims, 337. Colbert, a Champenois, but he did not give renown to the wines, 338. Francis I., Leo. X., Charles V., and Henry VIII. had vineyards at Aï, 338. Volnay drank at the coronation of Sobieski, 338. Beaune served at Venice to the senators after the conquest of the Morea, 338. St. Evremond on Champagne wine, 338. Champagne used in putrid fevers, 339. Millions of worthless Champagne sold at two francs and three francs the bottle, 340. Dr. Henderson on Champagne, 340. The briskest Champagne not the best, 340. Crêmants and demi-mousseux wines, 341. Sillery Champagne, 341. Vin de la Maréchale, 342. The rich, dry Sillery, 342. Champagne not a vin de garde, 342. Old Champagne, 343. Jaquesson’s cellars, 343. Champagne always improved by ice, 343. Jullien on the high price of the vins mousseux, 344. How to obtain a first-rate Champagne, 345. Hundreds of thousands of bottles of Champagne at the docks are not worth the duty, 345. When the bottling of Champagne begins, 345. Vins grand mousseux, 346. Precautions in packing Champagne for exportation, 346. Champagne for India and America packed in salt, 346. Burgundies so packed preserve their qualities, 347. Claret, 347. Château Margaux and Château Lafitte, 348. Monton and Léoville, 348. Kirwan and Château d’Issau, 348. St. Julien, Béchevelle and St. Pierre, 348. Great management in Bordeaux cellars, 349. Brandy ought to be put in in very small quantities, 349. Extract from Davies’ work on colouring Claret, 350. A freer exchange of the vinous wealth of France with England desirable, 351. Difference in price between first and inferior wines, 352. Mixture of Benicarlo and other wines with claret, 353. The age of wine at Bordeaux counted par feuilles, 353. What Barry wrote ninety years ago on Claret wines, 353. Names of the proprietors of vineyards and factors, 110 years ago, 354. Irish Claret and Irish wine merchants, 355. The Bordeaux wines celebrated in the days of Ausonius, 355. A great proportion of the wine drank as Claret is vin ordinaire, 355. Definition of the word Claret, 356. The Côte Rôti, 356–7. Hermitage and its division into five classes, 357. White Hermitage of the late Lord Castlereagh, 357. Hermitage of the late Marquis of Wellesley, 358. The cost of wine cultivation in France immense, 359. The German wines, their general character and durability, 359. Price of Rüdesheim, 359. In Barry’s day the best old Hock sold at 50l. the auhm, 360. Marcobrunner, Rüdesheimer and Niersteiner, 360. Julius Hospitalis and Liesteinwein wines, 360. Spanish wines, 360–1. Cellars and stock of Gordon and Co. of Cadiz, 361. Amontillado, 361. Port and Madeira, 362. The Italian wines, 362. The wines of Hungary, 362. The Greek wines over-rated, 363. The Constantia wine of the Cape, 363. The Russian Champagne, 363. The New South Wales wines, 363. New vintages, 364. Advice as to purchase and stock of wines, 365. Good and low-priced wine a myth, 366. Prices of wines at sales in Edinburgh and Dublin, 366. Prices of Amontillado, Montilla, and Manzinilla, 366. Fabulous prices given for old Ports and Sherries, 366. First-rate Clarets rising in price, 367. Burgundies, 367. Dietetic qualités of wine, 367. The best Burgundies and Champagnes, 368. The best Bordeaux wines, 368. Red Constantin and Frontignan, 369. Consumption of Champagne doubled in England since 1848, 369.

CHAPTER XXI.—The Cellar for Wines.

The cellar for wines, 370. Requisites of a wine-cellar, 370. Lighter wines require a colder cellar than strong, 371.

APPENDIX.

Luxuries of the table in France and England in mediæval and modern times, 373. Menu of a dinner given by Mathieu Molé, in 1652, 375. Menu of a supper of the Regent Orleans, 376. Menu of a supper of Louis XV., 377. Carte dinatoire of the citizen General Barras, 378. Menu of the family Buonaparte at the Tuileries on Samedi Saint, 1811, 379. Bill of fare of the first dinner of Louis XVIII. at Compiègne, 380. Bill of fare of a dinner given by the Emperor Alexander on 11th September, 1815, 382. Bill of fare of the first diplomatic dinner of the Duke of Wellington in 1815, 383. Menu of a royal banquet given at the Tuileries by Louis XVIII. on Twelfth-day, 1820, 384. Bill of fare, 385. Luxuries in the days of Queen Mary, 385. Common Council’s regulation as to dinners, 385. Regulations for the aldermen, sheriffs, and city corporation, 386. City venison feasts in time of Elizabeth, 386. Letter of the Lord Mayor and aldermen to Lord Burleigh, 386. The reign of Queen Anne the golden age of cookery, 386. Dr. King’s “Art of Cookery,” 386. Sir John Hill, M.D., 386. The great Lord Chesterfield, 386. La Chapelle his cook, 386. Cookery book of La Chapelle, 386. Lord Chesterfield sitting on a chair outside Chesterfield House, 387. Bill of fare of official dinner of Lord Chesterfield, 387. Bill of fare of a supper of Lord Chesterfield, 389. The French emigrants in London, 390. Entertainments given to the French royal family by the Marquis of Buckingham and Earl of Moira, 390. Reception of the Count de Lille at Stowe, 390. Stowe, a scene of great festivity in 1805 and 1808, 390. Bill of fare of Christmas-dinner in 1808, given by the Duke of Buckingham to Louis XVIII, 391. The Prince Regent’s love of French cookery, 392. Bill of fare for the coronation banquet of George IV, 392. Bill of fare for a private dinner given at the Pavilion, Brighton, in 1817, 393. Bills of fare for dinners in January, April, May, and June, also for a dinner in plain English fashion, 395. Anthony Carème, 396. Mr. Wm. Hall’s panegyric on Carème, 398. Autobiography of Carème, 399 to 406. Fête given at the Elysée for the marriage of Prince Jerome, 406. New invention of Carème, 407. Aphorisms, thoughts, and maxims of Carème, 407. Death of Carème in 1835 or 1836, 409. Carème bestowed fine names on his soups, 409, Carème on maigre sauces, 409.

[xix]

Atelets.—Small silver skewers.

Au naturel.—Plainly done.

Bain Marie.—A warm-water bath; to be purchased at the ironmonger’s.

Barber.—To cover with slices of lard.

Blanc.—A rich broth or gravy, in which the French cook palates, lamb’s head, and many other things. It is made thus: A pound of beef kidney fat, minced, put on with a sliced carrot, an onion stuck with two cloves, parsley, green onions, slices of lemon without the peel or seeds, or, if much is wanted, two pounds of fat and two lemons. When the fat is a good deal melted, put in water made briny with salt; and when done, keep the blanc for use.

Blanchir.—To blanch by giving some boils in water.

Bourguignote.—A ragoût of truffles.

Braise.—A manner of stewing meat which greatly improves the taste by preventing any sensible evaporation.

Braisière.—Braising-pan—a copper vessel tinned, deep and long, with two handles, the lid concave on the outside, that fire may be put in it.

Brider.—To truss up a fowl or anything else with a needle and pack-thread, or tape.

Buisson.—A method of piling up pastry to a point.

Bundle or Bunch.—Made with parsley and green onions,—when seasoned, bay leaves, two bunches of thyme, a bit of sweet basil, two cloves, and six leaves of mace are added.

Capilotade.—A common hash of poultry.

Cassis.—That part which is attached to the tail end of a loin of veal: in beef, the same part is called the rump.

Civet.—A hash of game or wild fowl.

Compiegne.—A French sweet yeast cake, with fruit, &c., &c.

[xx]

Compote.—A fine mixed ragoût to garnish white poultry, &c.; also a method of stewing fruit for dessert.

Compotier.—A dish amongst the dessert service appropriated to the use of the compote.

Couronne (en).—To serve any prescribed articles on a dish in the form of a crown.

Court ou Short.—To reduce a sauce very thick.

Croustades.—Fried crusts of bread.

Cuisson.—The manner in which meat, vegetables, pastry, or sugar is dressed. It means also the broth or ragoût in which meat or fish has been dressed.

Cullis or Coulis.—The gravy or juice of meat. A strong consommé.

Dessert, entrée de.—Dish made of preceding day’s remains.

Dorer.—To brush pastry, &c., with yolk of egg well beaten.

Dorure.—Yolks of eggs well beaten.

Entre côte de Bœuf.—This is the portion of the animal which lies under the long ribs, or those thick slices of delicate meat which may be got from between them.

Entrées.—A name given to dishes served in the first course with the fish dishes.

Entremets—is the second course, which comes between the roast meat and the dessert.

Escalopes.—Small pieces of meat cut in the form of some kind of coin.

Fagot—is a bunch of parsley (the size varies of course), a bay leaf, and a sprig of thyme, tied up closely. When anything beyond this is required it is specified in the article.

Farce.—This word is used in speaking of chopped meat, fish, or herbs, with which poultry and other things are stuffed.

Feuilletage.—Puff-paste.

Filets Mignons.—Inside small fillets.

Financière.—An expensive, highly flavoured, mixed ragoût.

Glacer (to glaze).—To reduce a sauce by means of ebullition to a consistency equal to that of ice. Well made glaze adheres firmly to the meat.

Godiveau.—A common veal forcemeat.

Gras (au).—This signifies that the article specified is dressed with meat gravy.

Gratiner.—To crisp and obtain a grilled taste.

Grosses pièces de Fonds.—There are in cookery two very distinct kinds of grosses pièces: the first comprehends substantial[xxi] pieces for removes, &c.; the other pièces montées, or ornaments; by pièces de fonds is implied all dishes in pastry that, form one entire dish, whether from its composition, or from its particular appearance; as for example cold pies, Savoy cakes, brioches, Babas, gâteaux de Compiègne, &c.; whilst the pièces montées, or ornamental pastries, are more numerous.

Hors d’œuvres.—Small dishes served with the first course.

Larding-pin.—An utensil by means of which meat, &c., is larded.

Lardoire (larder).—An instrument of wood or steel for larding meat.

Lardons.—The pieces into which bacon and other things are cut, for the purpose of larding meat, &c., &c.

To Lard is when you put the bacon through the meat. Things larded do not glaze well. Everything larded on the top or surface is called piqué.

Madeleines.—Cakes made of the same composition as pound-cakes.

Mariner.—Is said of meat or fish when put in oil or vinegar, with strong herbs, to preserve it.

Mark.—To prepare meat to be dressed in a stew-pan.

Mask.—To cover a dish with a ragoût or something of the sort.

Nourir—is to put in more ham, bacon, butter, &c.

Noix de Veau.—The leg of veal is divided into three distinct fleshy parts, besides the middle bone; the larger part, to which the udder is attached, is called the noix, the flat part under it sous noix, and the side part, contre noix, &c. The petites noix are in the side of the shoulder of veal.

Paillasse.—A grill over hot cinders.

Pain de beurre.—An ounce, or an ounce and a half of butter, made in the shape of a roll.

Panner.—To sprinkle meat or fish which is dressed on the gridiron with crumbs of bread dipped in butter and eggs.

Panures.—Everything that is rolled in, or stewed with bread crumbs.

Parer—is freeing the meat of nerves, skin, and all unnecessary fat.

Paupiettes.—Slices of meat, rather broad, to be rolled up.

Piqué—is to lard with a needle game, fowls, and other meats.

Poëlé.—Almost the same operation as braising, the only difference is, that what is poëlé must be underdone; whereas a braise must be done through.

[xxii]

Puit.—A well, or the void left in the middle, when anything is dished round as a crown.

A Purée of onions, turnips, mushrooms, &c., is a pulpy mash, or sauce of the vegetable specified, thinned with boiling cream or gravy.

Quenelles.—Meat minced or potted, as quenelles of meat, game, fowls, and fish.

Roux.—This is an indispensable article in cookery, and serves to thicken sauces; the brown is for sauces of the same colour, and the colour must be obtained by slow degrees, otherwise the flour will burn and give it a bitter taste, and the sauces become spotted with black.

Reduce.—To boil a soup down to a jelly, or till it becomes rich and thick.

Sabotière.—A pewter or tin vessel, in which are placed the moulds containing the substance to be frozen.

Sasser.—To stir and work a sauce with a spoon.

Sauce tournée and velouté are not the same, nor has the latter name been substituted by the moderns for the former. Sauce tournée is an unfinished sauce; it is of itself a basis for many other white sauces, but it is in no instance served alone as a sauce with any entrée or entremets. Velouté is served with hashes of chickens, veal, boudins à la reine, émincés, and entrées of quenelles, &c.

Sautez—is to mix or unite all the parts of a ragoût, by shaking it about.

Singez.—To dust flour from the dredging-box, which is afterwards to be moistened in order to be dressed.

Tamis (Tammy).—An instrument to strain broth and sauces.

Tendrons (veal)—are found near the extremity of the ribs.

Tourner.—To stir a sauce; also to pare and cut roots, vegetables, &c., neatly.

Tourte.—A puff-paste pie.

Vanner.—To work a sauce well up with a spoon, by lifting it up and letting it fall.

[1]

The traditions of classic cookery may be said to be nearly effaced; but sufficient remains recorded to afford grounds for comparison, and he must be prejudiced who hesitates for an instant to award the palm to the moderns. An impartial person need but to glance over the ten books left us under the name of Apicius,[1] to come to the conclusion of the ingenious Jean le Clerc, who says that “the work contains receipts for extraordinary dishes and strange ragouts, which would ruin the stomach, and burn up the blood.” One of the most nauseous of the condiments which entered into the Roman ragouts was the garum, by some supposed to be the expressed brine of the anchovy: while others contend it was an acrid decoction of the mackerel. This abominable sauce has now been[2] banished Christendom, yet has found a refuge in the congenial cookery of “our most ancient ally,” the Turk. Travellers who have visited Turkey and Constantinople, will recur, as I do, with no pleasurable sensations to the pilau seasoned with this acrid and ill-savoured preparation.

Though the feast of Trimalchio, so graphically told in the pages of Petronius, is somewhat overcharged, and too Asiatic in style and taste to be true to the letter, yet it gives an idea of the domestic economy of the Romans, and supports the opinion as to the superiority of modern cookery; but if more positive evidence were wanting in support of these views, it might be found in a passage of Macrobius, the description of a supper given by Lentulus. For the first course, says the officer of the household of Theodosius, there were sea hedge hogs, raw oysters, and asparagus; for the second, a fat fowl, with another plate of oysters and shell fish, several species of dates, fig-peckers, roebuck, and wild boar, fowls encrusted with paste, and the purple shell fish, then esteemed so great a delicacy. The third course was composed of a wild boar’s head, of ducks, of a compôte of river birds, of leverets, roast fowl, and Ancona cakes, called panes picences, which must have somewhat resembled Yorkshire pudding. There is one secret, however, which we may well desire to learn from the Romans, namely, the manner of preserving oysters alive, in any journey however long or however distant. The[3] possession of this secret is the more extraordinary, as it is well known that a shower of rain will kill oysters subjected to its influence, or the smallest grain of quick lime destroy their vitality.[2] It will be seen from what I have stated, that epicurism is an ancient vice; but all the French authorities, nevertheless, agree in thinking that the Greeks and Romans, notwithstanding their luxury and civilization, were mere children in the preparation of their viands. The reason of this, says Carème, is, that they sacrificed too much to sugars, fruits and flowers, and that they had not the colonial spices and learned sauces of mediæval and modern cookery. It is true that the “officers of the mouth” of Lucullus and Pompey were possessed of secrets to stimulate the jaded appetite, and give tone to the debilitated stomach: but notwithstanding all their profusion, I am inclined to think that Carème and the corps of French cooks are right in their disparaging observations touching ancient cookery.

Cookery is eminently an experimental and a practical art. Each day, while it adds to our experience, increases also our knowledge, and as we have come long after the Romans, and have had the benefit of their experience, it is no marvel that we should have greatly surpassed them. The characteristic of ancient cookery was profusion; the characteristic of[4] modern is delicacy and refinement. In the fifth century all trace of the Roman cookery had already disappeared. The barbarians from afar had savoured the scent of the Roman ragouts. The eternal city was invested, and her kitchen destroyed. The consecutive incursions of hordes of barbarous tribes and nations had put out at once the light of science and the fire of cookery. Darkness was now abroad, and the “glory” of the culinary art was, for a time, “extinguished,” but, happily, not for ever. “Lorsque il n’y a plus de cuisine dans le monde, il n’y a plus de lettres, il n’y a plus d’unité sociale,” says the enlightened and ingenious Carème.

But the darkness of the world was not of long duration. The monks—the much-abused and much mistaken monks—fanned the embers of a nascent literature, and cherished the flame of a new cookery. The free cities of Italy, Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Florence, the common mothers of poetry, painting, sculpture, and architecture, contemporaneously revived the gastronomic taste. The Mediterranean and the Adriatic offered their fish, and the taste for table luxuries extended itself to the maritime towns and other cities of the Peninsula, to Cadiz, to Barcelona, to St. Sebastian, and to Seville.

Spain had the high honour of having furnished the first cookery book in any modern tongue. It is entitled—“Libro de Cozina, compuesto por Ruberto de Nola.” I also possess an edition of the “Arte de[5] Cocina compuesto por Francisco Martinez Montiño,” printed in Madrid in 1623, and presented by His Royal Highness the late Duke of Sussex to Lady Augusta Murray. This work is exceedingly rare. The cookery professed at this epoch was no longer an imitation of the Greek or Roman kitchen, or of the insipid dishes and thick sauces of the Byzantine cooks. It was a new and improved and extended science. It recognised the palate, stomach, and digestion of man. The opulent nobles of Italy, the rich merchant princes, charged with the affairs and commissions of Europe and Asia, the heads of the church—bishops, cardinals, and popes, now cultivated and encouraged the culinary art. Arts, letters, and cookery revived together, and among the gourmands of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, some of the most celebrated pontiffs and artists of the time may be named, as Leo X., Raphael, Guido, Baccio Bandinelli, and John of Bologna. Raphael, the divine Raphael, did not think it beneath him to design plates and dishes for his great patron the most holy father. While Italy had made this progress, France, the nurse of modern, if not the mother of mediæval cooks, was in a state of barbarism, from which she was raised by the Italian wars under Charles VIII. and Louis XII. The Gauls learned a more refined cookery at the siege of Naples, as the Cossacks did some hundreds of years later in the Champs Elysées of Paris. Here ends the parallel, however; for while the people of France,[6] like most apt pupils, surpassed their masters, we have yet to wait for the least glimmering of culinary art at Moscow, Kieff or Novogorod, or even at that fag end of Finland (which is not Russia) called St. Petersburgh. An attempt was made a couple of years ago by Mr. Money to get up a sensation in favour of Russian cookery, but the attempt was a failure.

It was under Henry III., about 1580, that the delicacies of the Italian tables were introduced at Paris. The sister arts of design and drawing were now called into requisition to decorate dishes and dinner-tables. How great was the progress in the short space of 150 years, may be inferred from an edict of Charles VI., which forbad to his liege subjects a dinner consisting of more than two dishes with the soup: “Nemo audeat dare præter duo fercula cum potagio.” At this period the dinner hour was ten o’clock in the morning, while the supper was served at four. The social, friendly, and agreeable humour of Henry IV., in a succeeding reign, contributed to the spread of a more kindly spirit, and a better cookery. This monarch was eminently of a frank and cordial nature, and his personal qualities contributed to the security of his throne, to his successes both in negotiation and war, and to the social comforts and material prosperity of his subjects. His benevolent wish that every peasant in his dominions might have a fowl in the pot for his Sunday dinner, discloses a warm and[7] affectionate heart, and was not lost on a nation combining the greatest share of intellect with sensuality. The cabaret then was what the café is now, and was the rendezvous of marquis and chevalier, and people of condition. Men learned to pursue the pleasures and enjoyments of life in the cabaret, and their wants become multiplied, and their desires extended. It was Henry IV. who first permitted the traiteurs to form a community, with the title of “Maître queux cuisiniers porte-chapes,” in 1599.

The first regular cookery book published in France was, I believe, printed at Rouen in 1692, the very year in which Sir George Rooke struck so signal and successful a blow against the marine of our neighbours. It was the production of the Sieur de la Varranne, esquire of the kitchen of M. d’Uxelles. It is dedicated to MM. Louis Châlon du Bled, Marquis d’Uxelles and of Cormartin. The first sentence of the dedication is a curiosity in its way, and sufficiently indicates the immense distance which feudalism then interposed between an esquire of the kitchen and a French marquis and lieutenant-general, holding the rank of governor of the citadel of Châlons-sur-Saone. “Monseigneur,” says the book, “bien que ma condition ne me rende pas capable d’un cœur heroïque, elle me donne cependant assez de ressentiment pour ne pas oublier mon devoir. J’ai trouvé dans votre maison, par un emploi de dix ans entiers, le secret d’apprester delicatement les viandes.” The preface is not less[8] curious than the dedication. The author begins by stating that, as it is the first book of the kind which has been published, he hopes it will not be found altogether useless. A number of books, says he, have been published containing remedies and cures at small cost; but no book has yet been printed with a view of preserving and maintaining the health in a good state, and a perfect disposition, teaching how to separate the ill quantity of viands by good and diversified seasonings, which tend only to give substantial nourishment, being well dressed. These are things conformable to the appetite, which regulate corpulency, and ought to be no less considered, &c. He expatiates on the thousand-and-one vegetables and other “victual,” which people know not how to dress with honour and contentment (“avec honneur et contentement”), and then exclaims that, as France has borne off the bell from all other nations in courtesy and bienséance, it is only right and proper that she should be no less esteemed for her polite and delicate manner of living (“pour la façon de vivre honneste et delicate”). Many of the receipts are curious, and some of them useful. The frequency with which he introduces capers into his cookery, an article for which we are indebted to Barbary, and rarely introduced into the cookery of modern France, except in sauces for turbot and salmon, and in a few entrées, liaisons, and ragouts, is extraordinary.

La Varranne, after having given hundreds of other[9] receipts, consoles himself, at the conclusion of his labours, with the reflection, “That as all other books, as well ancient as modern, were composed for the aliment of the mind, it was but just that the body should be a little considered,” and therefore it was, says he, that I meddled with a subject so necessary to its conservation. Enjoy, then, my receipts, dear reader, he exclaims, “Jouissez en, cher lecteur, pendant que je m’étudierai à vous exposer en vente quelque chose qui méritera vos emplois plus relevez et plus solides.”

The first edition of that remarkable cookery book, the “Dons de Comus,” appeared about 1740, and is in every respect a superior work to the droll production just mentioned. It was composed by M. Marin, cook of the Duchesse de Chaulnes. The very learned and ingenious preface, signed de Querlon, is by Father Brumoy, the Jesuit, the translator of the “Théâtre des Grecs.” An Italian author calls a preface the sauce of a book, “La Salsa del Libro;” and certainly never was there a more piquant and spicy sauce than that of the erudite Father. He has brought ancient and modern literature to bear on the matter in hand. Not content with citing orators, poets and historians, he has also summoned the doctors, in the persons of the Frenchman Hecquet and the Englishman Cheyne. His comparison between ancient and modern cookery is ingenious.

“Modern cookery,” says he, “established on the foundations of the ancient, possesses more variety,[10] simplicity and cleanliness, with infinitely less of labour and elaboration, and it is withal more sçavante. The ancient cuisine was complicated and full of details. But the modern cuisine is a perfect system of chemistry. The science of the cook consists in decomposing, in rendering easy of digestion, in quintessencing (so to speak) the viands, in extracting from them light and nourishing juices, and in so mixing them together, that no one flavour shall predominate, but that all shall be harmonised and blended. This is the high aim and great effort of art. The harmony which strikes the eye in a picture should in a sauce cause in the palate as agreeable a sensation.” There is nothing new under the sun. A friend has recently lent me a copy of St. Augustine, in which is the very same thought, “Omina pulchritudinis formæ unitas est,” says the learned father. The following is Father Brumoy’s idea of a perfect cook: “A perfect cook should exactly understand the properties of the substances he employs, that he may correct or render more perfect (corriger ou perfectionner) such aliments as nature presents in a raw state. He should have a sound head (la tête saine), a sure taste, and a delicate palate, that he may cleverly combine the ingredients. Seasoning is the rock of indifferent cooks (l’écueil des médiocres ouvriers). A cook should have a ready hand to operate promptly and should assiduously study the palate of his master, wholly conforming his own[11] thereto.”[3] All this is excellent in its way. It is rare to find history, metaphysics and chemistry, the tone of a man of the world, the taste of an erudite classic, and the talent of a really good cook, so happily blended. Father Brumoy is the very opposite of that Greek cook, of whom Pausanias makes mention, whom all the world praised for his running, but whom no one praised for his ragouts: for in the three volumes now before me there are a variety of admirable receipts, which have made the stock in trade of many cookery books more vaunted and better known than Father Brumoy’s.

The “Dons de Comus” was followed by a spruce little satire, intituled “Lettre d’un Patissier Anglais au nouveau cuisinier Français,” in which the soi-disant pastry-cook deals some hard blows to the Jesuit.

In the “Dons de Comus” there had been much dissertation about quintessences, and the giving the largest portion of nutriment in the smallest possible compass. Hereupon the “Patissier Anglais” says, “Thus the more the nourishment of the body shall be subtilised and alembicated, the more will the qualities of the mind be rarefied and quintessenced too. From these principles, demonstrated in your work, great advantage may be reaped in all educational establishments. Children lose an infinity of time in learning the dead languages, and other trash of that[12] kind, whereas, henceforward, it will only be necessary, according to your system, to give them an alimentary education, proper for the state for which they are destined. For example: for a young lad destined to live in the atmosphere of a court, whipped cream and calves’ trotters should be procured; for a sprig of fashion, linnets’ heads, quintessences of May bugs, butterfly broth, and other light trifles. For a lawyer, destined to the chicanery of the Palais or who would shine at the bar, sauces of mustard and vinegar and other condiments of a bitter and pungent nature would be required.” Appended to the “Patissier Anglais” was “Le Cuisinier Gascon,” an excellent and valuable little work, now extremely scarce. There are many admirable receipts in this little volume, to which Mrs. Rundell was deeply indebted. She has borrowed largely from it without acknowledgment.

“La Science du Maître d’Hôtel Cuisinier” was the next published in point of chronological order. This was an attempt to render cookery the handmaid of medicine, and had great success. The plan, though not new in the conception, for the germ of it may be found in Terence, “Coquina medicinæ famulatrix est,”[4] was undoubtedly so in the execution; and the associated booksellers reaped a profitable harvest.

The cookery of France at this epoch, and indeed[13] from the time of Louis XIV., was distinguished by luxury and sumptuousness, but, according to Carème, was wanting in “delicate sensualism.” They ate well, indeed, at the court, says the professor of the culinary art, but the rich citizens, the men of letters, the artists, “were only in the course of learning to dine, drink, and laugh with convenance. Vatel, of whom so much has been said,” says Carème, “had only a mind deeply intent on his subject, you but see in him the conscientious man of duty and etiquette. His death astonishes but does not melt you (sa mort frappe mais ne touche pas), for he had not reached the highest elevation of his art.” You cannot think, you who read these lines, that any one of our cooks of the present day, brought up by Carème, could ever fall into his faults. For whatever may happen, a cook, like a commander, and, indeed, like the great masters of the art, Laguipière and Carème, “should always have splendid and imposing reserves.”

This dictum of Carème must be taken, like many of his dishes and sauces, cum grano salis. Molière lived and wrote at this period; and though it would be unfair not to concede that he was greatly in advance of his age, and, like Shakspeare, seemed to be universally informed, and by intuition, yet on the other hand there is scarcely a better description of a gourmand than is to be found in the “Bourgeois Gentilhomme,” act iv. sc. 1. The language of the art, too, is as much superior to the jargon of professional[14] cooks, as Paques is (the pun was inevitable) to Carème. But here is the passage in extenso, from which all may judge:—“Si Damis s’en étoit mêlé, tout seroit dans les règles; il y auroit par-tout de l’élégance et de l’érudition, et il ne manqueroit pas de vous exagérer lui-même toutes les pièces du repas qu’il vous donneroit, et de vous faire tomber d’accord de sa haute capacité dans la science des tous morceaux; de vous parler d’un pain de rive à bizeau doré, relevé de croûte par-tout, croquant tendrement sous la dent; d’un vin à seve velouté, armé d’un vert qui n’est point trop commandant; d’un carré du mouton gourmandé de persil; d’une longe de veau de rivière, longue, blanche, délicate, et qui, sous les dents, est une vraie pâte d’amande; de perdrix relevées, d’un fumet surprenant; et pour son opéra, d’une soupe á bouillon perlé, soutenue d’un jeune gros dindon, cantonnée de pigeonneaux, et couronnée d’oignons blancs, mariés avec la chicorée.”[5] It should also be observed that St. Evremond, a man of letters as well as a soldier and a gentleman, rendered himself celebrated even in 1654, for the exquisiteness of his taste in cookery, and that the coterie in which he lived were equally famous for their good cheer. The dinners of the Commandeur de Souvré, of the Comte d’Oloure, and of the Marquis de Bois Dauphin, were celebrated for equal refinement and delicacy. Lavardin, Bishop of[15] Mans, in speaking of the clique, says, “Ils ne sauroient manger que du veau de rivière: il faut que leurs perdrix viennent d’Auverge: que leurs lapins soit de la Roche Guyon.”[6] The same thought may be found in the fifth Satire of Juvenal, though somewhat differently expressed.

With the qualifying restrictions previously made, it may fairly be admitted that it is not to the Grand Monarque, but to the Regent Orleans, that the French of the present day owe the exquisite cuisine of the eighteenth century. The Pain à la d’Orleans was the invention of the regent himself; the filets de lapereau à la Berri were invented by his abandoned daughter, the Duchess de Berri, who plunged into every sensual excess, and whose motto was “Courte et bonne.” Her suppers were the best, and, it must be added, the most profligate in Paris.

As the Duchess de Berri, the daughter of the regent, was gourmande as well as galante, she is deified by the race of cooks and epicures, one of whom says that the alimentary art owes to her fertile genius a great number of receipts. Nor was she the only female who distinguished herself at this era in cookery, for it became à-la-mode to be the creator of a plat.[16] The filets de volaille à la Bellevue were invented by the Marquise de Pompadour, in the château of Bellevue, for the petits soupers of the king. The poulets à la Villeroy owe their birth to the Maréchale de Luxembourg, then Duchess of Villeroy, one of the most sensual “gourmandes” of the court of Louis XV. The Chartreuse à la Mauconseil has been transmitted to us by the Marquise de Mauconseil, celebrated alike by her taste and her gallantries. The vol au vent à la Nesle proceeded from the fertile brain of the Marquis de Nesle, who refused the peerage to remain premier marquis of France, and the poularde à la Montmorency was the production of the duke of that name. Filets de veau à la Montgolfier, are so named because they are of the shape of balloons. The petites bouchées à la reine owe their origin to Maria Leczinska, wife of Louis XV., whose devotions, however self-denying in other respects, never prevented her from relishing a good dinner. All the entrées bearing the name of Bayonnaises were invented by the Maréchal Duke de Richelieu. The perdreaux à la Montglas acknowledge as their father a worthy magistrate of Montpelier, whilst the cailles à la Mirepoix were imagined by the marechal of that name, who in gourmandise, but in gourmandise only, rivalled the Marechal de Luxembourg; and last, though not least, the cotelettes à la Maintenon were the favourite dish of that frigid piece of pompous and demure hypocrisy, Madame de Maintenon herself.

[17]

It may be concluded, that the regency and the reign of Louis XV. were among the grand epochs of French cookery. The long peace which followed the treaty of Utrecht, the large fortunes made by the tribe of financiers, who, in ruining the state, enriched themselves—the tranquil and voluptuous life of a monarch who gave himself more concern about his personal pleasures and enjoyments than his royal renown—the character of the courtiers and public men of the day—all contributed to stamp an intensely sensual character on the age of Louis XV. A taste for English equipages and horses was now introduced, and our puddings and beef-steaks were also imitated. The example of the regent was refined on and extended in this reign. The petits soupers of the king were cited as models of delicacy and gourmandise. The kitchen in France, as in all the world over, requires “the cankers of a calm world and a long peace,” to sustain and support it; while the troubles of the League and the Fronde, the temperament of Louis XIV., and the despotic and tempestuous character of Richelieu, interfered with its progress in former reigns. There were great cooks as well as great captains in the reign of Louis XIV., notwithstanding the disparaging remarks which Carème casts on the memory of Vatel; but a witty author maintains that the only ineffaceable and immortal reputation of that time handed down to us in cookery, is that of the Marquis de Bechamel, who[18] introduced into the sauce for turbot and cod fish an infusion of cream. The Bechamel de turbot et de cabillaud still maintain their popularity, though kings, dynasties, and empires have fallen, and half the globe has been revolutionized.

In the royal kitchen of Louis XVI., the art as an art declined; but the sacred fire of cookery (to use the inflated language of some of the craft) was preserved in many old houses, as, for instance, in the establishments of Marshals Richelieu and Duras, the Duke of La Vallière, the Marquis de Brancas, the Count de Tessé, and some others, who equalled in the delicacy of their tables the elegant sumptuosity of the reign of Louis XV. The excesses of some of the French nobility of this day would now appear incredible. One hundred and twenty pheasants were, at this period, weekly consumed in the kitchens of the Prince de Condé; and the Duke de Penthievre, in going to preside over the estates of Burgundy, was preceded by one hundred and fifty-two hommes de bouche! Can any, after this, wonder at the excesses of the Revolution? The unexpected death of Louis XV. (says a gourmand of the succeeding reign, and who survived the Revolution and the Consulate) struck a mortal blow at cookery. His successor, young and vigorous, ate with more voracity than delicacy, and did not pride himself on (the words are untranslateable) a “grand finesse de gout”—an exquisite delicacy of taste in the choice[19] of his food. Large joints of butchers’ meat, and dishes essentially nutritive, represented his ideas of good living. His enormous appetite contented itself in satisfying hunger; learned efforts were not necessary to stimulate its vast cravings.

The French Revolution at length broke forth, and the historians of the kitchen speak with mournfulness of its effect on the science, which Montaigne quaintly calls l’art de la gueule. The kitchens of the faubourg of St. Germain and the Chaussée d’Antin no longer smoked, the perfumes of truffles were exhaled and vanished, the great and noble of the land were obliged to fly for their lives, and too often to dine with Duke Humphrey, or at best to dine frugally and sparingly. The financiers, who aped the luxuries and mimicked the extravagance of the court, were all ruined or denounced. The stoic’s fare—the radish and the egg, the Jus nigrum of the severe Spartans, and the black bread of the Germans of the middle ages, scarcely fit food for horses, were now revived. For three long years this spare Spartan régime continued. Had the Goths and Vandals gone on a little longer, says a witty epicure, who survived the Revolution, the receipt for a fricassee of chicken had been infallibly lost. The markets were no longer supplied. Beef, mutton, ham, and veal, had disappeared; as to fish, it was preposterous to think of it.[7] Not a good turbot, or salmon, or sturgeon,[20] says Grimod, appeared during the Revolution. Fowls and game had become a “sick epicure’s dream,” not a solid reality. Nor were these miseries confined to Paris alone. “You might go into a country market,” says the same author, “with a ream of assignats in your hand, and not be able to buy a sack of flour.” A return to a gold currency produced a visible alteration in the Res Cibaria. The louis and five-franc pieces again peopled the markets with a populace of poultry and partridges. Cooks again began to talk in the language which the Italian maître d’hôtel of Cardinal Caraffa addressed to the pleasant and witty Montaigne, language which the laughing author has imperishably recorded in those inimitable volumes, which will be read and admired so long as the French language and literature endure. “Il m’a fait un discours de cette science de gueule avec une gravité et contenance magistrale, comme s’il m’eust parlé de quelque grand poinct de theologie. Il m’a dechiffré une difference d’appetits; la police de ses sauces; les qualités des ingredients et leurs effects, les differences des salades. Après cela il est entré sur l’ordre de service plein de belles et importantes considerations, et tout cela enflé de riches et magnifiques paroles; et celles mêmes qu’on employe à traiter du gouvernement d’un empire.”

The oxen of Auvergne and Normandy were now again marched slowly and gravely up from the provinces to be slaughtered in Paris. The sheep of[21] Beauvais, of Cotentin and the Ardennes, were again, as under the old régime, cut up into cutlets, and the cooks soon appeared. Instead of serving as chefs de cuisine, butlers, intendants, and maîtres d’hôtel, they now were called citoyens, pensionnaires, and rentiers; for there were no grands seigneurs to employ them. For a while there was some inconvenience, but a Frenchman sooner accommodates himself to circumstances than any other human being, and such of the cuisiniers as had saved somewhat from the shipwreck of the Revolution formed eating-houses, taverns, and restaurants. These establishments have since become the temples of good cheer and gourmandise, in which wandering Englishmen spend and have spent millions upon millions of money; but it is an historical fact known to few, that the greater number of these restaurants owe their origin to the Revolution.[8]

The complete overthrow of the French kitchen, the work of three centuries, might have been[22] effected at this season, had not its traditions been preserved. Happily there were Acolytes and Neophytes sufficient in existence, says one of the historians, to catch and perpetuate the scientific savour of the ancient “flesh pots.” In such a loss as this, weightier interests had been imperilled than mere cookery. More than half the intelligence, and nearly all of the French agreeability of the past age, had been in a great degree promoted by the French cuisine. The cook of the Condés and the Soubises contributed in no mean degree to give a zest and a vivacity to the dinners at which Montesquieu, Voltaire, Diderot, Helvetius, D’Alembert, Duclos, and Vauvenargues so often met; and this remark applies, in a great degree, to the suppers of Madame du Deffand, the dinners of the Baron D’Holbach, and the dinners, suppers, and pic-nics of the agreeable Crawford of Auchinames, whose “Tableau of French Literature” is not sufficiently known nor read in our day. It was at these social réunions that French conversation, then indeed a style parlé became animated and improved by the exquisite cheer which the “cunning hand” of the cook provided. A few hours of delightful, easy, unrestrained conversation between polite and well-informed men, did more to advance the progress of the human mind than the labours of a wilderness of speculative bookmaking academies. The solution of many great and grave questions—the propagation of new and enlarged[23] views, the production of ingenious essays and instructive memoirs, are all owing to that elegant and agreeable body of men and women, kept together in a main degree by the exquisite attraction of petits soupers and luxurious dinners.

From the moment of the Executive Directory, 1795, to the period of the 18th Brumaire, all the historians among; the great cooks admit that their illustrious art was under the greatest obligations to Barras, that well-born tribune of the people, of whose family it was said, “noble comme les Barras, aussi anciens que les rochers de Provence.” Whether as Commissary of the government at Toulon—at whose siege, by the way, he first became acquainted with Bonaparte—or as Director, or as residing as a private gentleman at his château of Grosbois, Barras always exhibited those epicurean tastes which were either natural to him, or which he had acquired from a residence at the French settlement of Pondicherry.

During the most ferocious periods of the Revolution, there were but two splendid exceptions to the self-denying ordinances of the time. That desperate demagogue Danton loved and copiously indulged himself in morels, and is recorded to have given dinners at 400 francs a head; and Barras, when in the Directory, had his button mushrooms conveyed to him en poste from the Bouches du Rhone.

Napoleon, who may be said to have succeeded to power at the epoch of the 18th Brumaire, is falsely[24] represented as an enemy of the pleasures of the table. It is true, a love of good cheer was not a dominant passion with him; he did not exhibit the crapulous gluttony of an over-fed sensualist, but he was not insensible to the pleasures of good eating. M. de Bausset,[9] the prefect of the Imperial palace, has handed down in his most interesting work some of the Emperor’s ordinary bills of fare. They are distinguished by simplicity and moderation, but there is also a pervading suitableness and taste very significant of the man, and of the nation over which he “reigned and governed.”

M. de Cussy, also attached to the kitchen and household of the Emperor, and who obtained from his patron, or assumed, the title of Marquis de Cussy, has also left us interesting details on the subject. One day at breakfast, says he (this was some time after his marriage), Napoleon, after having eaten, with his habitual haste, a wing of a chicken à la Tartare, turned towards M. de Cussy (who was always present at the Emperor’s meals), and the following dialogue took place between them: “The deuce! I have always hitherto found chicken-meat flat and insipid, but this is excellent.” “Sire, if your[25] Majesty would permit, I would desire to have the honour of serving a fowl every day in a different fashion.” “What! M. de Cussy, you are then master of 365 different ways of dressing fowl?” “Yes, Sire, and perhaps your Majesty, after a trial, would take a pleasure à la science gastronomique. All great men have encouraged that science, and, without citing to your Majesty the example of the great Frederick, who had a special cook for each favourite dish, I might invoke, in support of my assertion, all the great names immortalized by glory.” “Well, then, M. de Cussy,” replied the Emperor, “we shall put your abilities to the test.” The case might be left to a jury of gourmands on this evidence, and the Emperor would be convicted, if not of gourmandise, at least of friandises. Who will, however, deny the gourmandise of his arch-chancellor, Cambacères, or of his minister of foreign affairs, Talleyrand? “The first clouds of smoke” (says Ude) “which announced the resurrection of cookery, appeared from the kitchen of a quondam bishop.” Napoleon himself was in the habit of saying that more fortunate treaties, more happy arrangements and reconciliations were due to the cook of Cambacères than to the crowds of diplomatic nonentities who thronged the ante-chambers of the Tuileries. On one occasion the town of Geneva sent to the arch-chancellor a monster trout, together with the sauce, the expense of which was verified by the[26] Cour des Comptes as amounting to 6000 francs, or 240l. of our money.

A rare epoch in the history of cookery was the publication of the first number of the “Almanach des Gourmands,” which appeared in the beginning of the year 1803, and which the late Duke of York called the most delightful book that was ever printed. The sale of this work was prodigious. 22,000 copies of the four first years were speedily disposed of, and the work subsequently went through new editions. As the book is very scarce everywhere, and not to be found in England, I may be pardoned for dwelling on it. Gastronomy became the fashion of that day. Every one spoke on the subject; many wrote on it. Cookery passed from the kitchen to the shop, from the shop to the counting-house, from the counting-house to the studies of lawyers and physicians; thence to the salons and cabinets of ladies and statesmen. The object of life, according, at least, to our simple English notions, seemed reversed: people in England eat to live; in France, they appeared to live only to eat. This was in consonance with French character and practice.

To return, however, to the “Almanach des Gourmands.” Each volume contained an almanac for the year in which it was published, and a species of nutritive itinerary of the different traiteurs, rotisseurs, restaurateurs, pork-men, poulterers, butchers, bakers, provision, sauce, and spice shops, milkmen, oilmen,[27] &c. Nor were the cafés, limonadiers, glaciers, nor wine and liqueur merchants neglected; for ample and amusing accounts of almost all the principal magasins de comestibles are given. The volumes are generally written in a playful, humorous style, and occasionally indicate originality and research. The first four numbers are by far the best, though there are passages in the seventh, eighth, and ninth equal to anything which appeared in the preceding numbers. The author and editor was Grimod de la Reyniere. His father, a fermier général was choked, in 1754, by attempting to swallow rather too voraciously a slice of a pâté de foies gras. The son inherited the hereditary passion for the pleasures of the table, joined to a sprightly yet quaint humour, which rendered him a general favourite. It must be admitted, that while he inspired a taste for cookery, he ennobled its language.

As a specimen of his manner, take a short extract from the second volume, under the head of the health of cooks. “The finger of a good cook should alternate perpetually between the stewpan and his mouth, and it is only thus in tasting every moment his ragouts, that he can hit upon the precise medium. His palate should therefore have an extreme delicacy, and be in some sort virgin, in order that the slightest trifle may stimulate it, and thus forewarn him of its faults. But the continual odour of ovens—the necessity under which a cook lies to drink often, and sometimes[28] of bad wine, the vapour of charcoal, the accumulation of bile, and many other things, each and all contribute to interfere with his organs of sense, and most quickly to derange and alter his sense of taste. His palate becomes indurated; he has no longer that tact, that finesse, that exquisite sensibility, on which depends susceptibility of taste. His palate at length becomes case-hardened. The only means of restoring to him that flower which he has lost (cette fleur qu’il a perdue), and recruiting his strength, his suppleness, and his delicatesse, is to purge him, despite of any resistance he may be induced to make; for there are cooks deaf to the voice of glory, who see no need to take physic when they are in health. Oh, ye then who wish to enjoy at your daily board delicate and recherché fare, cause your cooks to be purged frequently (faites purger souvent vos cuisiniers), for there is no other means to accomplish your wishes.”

In another volume, published in 1806, the author says that in Riom, in Auvergne, there was an innkeeper named Simon, who had a special talent for dressing frogs. The process of feeding and dressing them is given in detail, admirably and graphically told, but at far too great a length to extract. “What proves the goodness of the dish, and the impossibility of counterfeiting it,” says Grimod, “is, that the author has gained 200,000 francs at this art, though he gives you for 24 sous a dish containing three dozen of frogs.”

The three “Frères Provenceaux,” we learn in the[29] same volume, were even thus early renowned for Provençal ragouts, and, above all, for their Brandades de Merluche; and the veal of Pontoise was then, as now, fed on cream and biscuits, and carried to Paris in carriages made expressly for the purpose. It is in this year’s almanac also that the author speaks of the death of a celebrated gourmand and friend of his, Doctor Gastaldy, physician to the late Duke of Cumberland. The last dinner which he partook of was on Wednesday, the 20th December, at Cardinal Belloy’s, Archbishop of Paris, where, having eaten three times of the belly part of the salmon, he died of the effects of this invincible gluttony. The doctor would have gone to the salmon a fourth time, but that the prelate “tenderly upbraided him for his imprudence, and ordered the desired dish to be removed” (le reprit tendrement de son imprudence, et fit enlever ce sujet de convoitise). But alas, it was too late—the gulosity of Gastaldy caused his death, and he was hastily buried the day after his demise. Let this be a warning to priests in high places, whether Protestant, Popish, or Presbyterian, as to helping their guests too often to the richest part of a salmon.

In one of the volumes there is a long chapter on the opening of oysters, from which the concluding portion is extracted.

“It is not until the oyster is detached from the under shell that it ceases to live. The real lovers of oysters (such, for example, as the late M. Grimod de[30] Verneuil), won’t allow the oyster-women to open their fish, reserving to themselves the important privilege of performing this operation on their own plate, in order that they may have the pleasure of swallowing this interesting fish alive.”