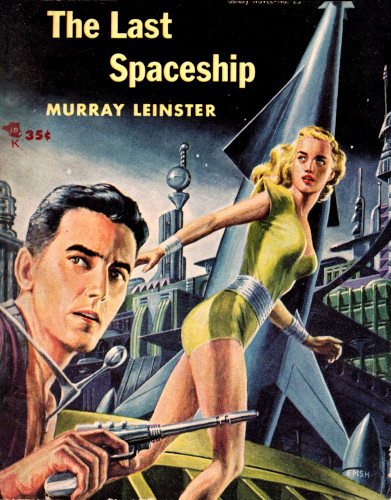

Title: The last space ship

Author: Murray Leinster

Release date: January 31, 2023 [eBook #69916]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Galaxy Publishing Corp, 1949

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

A Breathtaking Power Packed Full Length Novel

GALAXY PUBLISHING CORP.

421 HUDSON STREET

NEW YORK 14, N. Y.

GALAXY Science Fiction Novels, selected by the editors of

GALAXY Science Fiction Magazine, are the choice of science

fiction novels both original and reprint.

GALAXY Science Fiction Novel No. 25

35c a copy. Six Novel Subscriptions $2.00

Copyright 1949 by Will F. Jenkins

Reprinted by arrangement with the publishers,

FREDERICK FELL, INC.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

by

THE GUINN COMPANY, INC.

NEW YORK 14, N. Y.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

| 1 | Victim of Tyrants |

| 2 | Break for Freedom |

| 3 | Rays of Destruction |

| 4 | Outcasts of Space |

| 5 | Super-Science |

| 6 | Haven at Last |

| 1 | Empires in the Making |

| 2 | The Deadly Beams |

| 3 | Contact! |

| 4 | Encounter in the Void |

| 5 | The Needed Fuel |

| 6 | Man-Made Meteor |

| 7 | Ready for Action |

| 8 | Pitched Battle |

| 9 | Homecoming |

| 1 | Damaged Transmitter |

| 2 | Enemy Sabotage |

| 3 | Dangerous Trip |

| 4 | Despots Take Over |

| 5 | Industrial World |

| 6 | Vanished World |

| 7 | One Chance in a Million |

| 8 | Dark Barrier |

| 9 | Gadget of Hope |

Kim Rendell stood by the propped-up Starshine in the transport hall of the primary museum on Alphin III. He regarded a placard under the space-ship with a grim and entirely mirthless amusement. He was unshaven and hollow-cheeked. He was even ragged. He was a pariah because he had tried to strike at the very foundation of civilization. He stood beside the hundred-foot, tapering hull, his appearance marking him as a blocked man. And he re-read the loan-placard within the railing about the exhibit:

Citizens, be grateful to Kim Rendell, who shares with you the pleasure of contemplating this heirloom.

This is a space-ship, like those which for ten thousand years were the only means of travel between planets and solar systems. Even after matter-transmitters were devised, space-ships continued to be used for exploration for many years. Since exploration of the Galaxy has been completed and all useful planets colonized and equipped with matter-transmitters, space-ships are no longer in use.

This very vessel, however, was used by Sten Rendell when the first human colonists came in it to Alphin III, bringing with them the matter-transmitter which enabled civilization to enter upon and occupy the planet on which you stand.

This ship is private property, lent to the people of Alphin III by Kim Rendell, great-grandson of Sten Rendell.

Kim Rendell read it again. He was haggard and hungry. He had been guilty of the most horrifying crime imaginable to a man of his time. But the law would not, of course, allow him or any other man to be coerced by any violence or threat to his personal liberty.

Freedom was the law on Alphin III, a wryly humorous law. No man could be punished. No man could have any violence offered him. Theoretically, the individual was free as men had never been free before in all of human history. Despite Kim's crime, this space-ship still belonged to him and it could not be taken from him.

Yet he was hungry, and he would remain hungry. He was shabby and he would grow shabbier. This was the only roof on Alphin III which would shelter him, and this solely because the law would not permit any man to be excluded from his rightful possessions.

A lector came up to him and bowed politely.

"Citizen," he said apologetically, "may I speak to you?"

"Why not?" asked Kim grimly. "I am not proud."

The lector said uncomfortably:

"I see that you are in difficulty. Your clothes are threadbare." Then he added with unhappy courtesy, "You are a criminal, are you not?"

"I am blocked," said Kim in a hard voice. "I was advised by the Prime Board to leave Alphin Three for my own benefit. I refused. They put on the first block. Automatically, after that, the other blocks came on one each day. I have not eaten for three days. I suppose you would call me a criminal."

"I sympathize deeply," the lector answered unhappily. "I hope that soon you will concede the wisdom of the advised action and be civilized again. But may I ask how you entered the museum? The third block prevents entrance to all places of study."

Kim pointed to the loan-card.

"I am Kim Rendell," he said drily. "The law does not allow me to be prevented access to my own property. I insisted on my right to visit this ship, and the Disciplinary Circuit for this building had to be turned off at the door so I could enter." He shivered. "It is very cold out-of-doors today, and I could not enter any other building."

The lector looked relieved.

"I am glad to know these things," he said gratefully. "Thank you." He glanced at Kim with a sort of fluttered curiosity. "It is most interesting to meet a criminal. What was your crime?"

Kim looked at him under scowling brows.

"I tried to nullify the Disciplinary Circuit."

The lector blinked at him, fascinated, then walked hastily away as if frightened. Kim Rendell stooped under the railing and approached the Starshine.

The entrance-port was open, and a flush ladder led up to it. Kim, hollow-cheeked and ragged and defiant, climbed the steps and entered. The entry-port gave upon a vestibule which Kim knew from his grandfather's tables to be an airlock. Kim's grandfather had once gone off into space in the Starshine with his father. It was, possibly, the last space-flight ever made.

For a hundred years, now, the ship had been a museum-piece, open to public inspection. But parts had been sealed off as uninstructive. Kim broke the seals. This was his property, but if he had not already been a criminal under block, the breaking of the seals would have made him one. At least, it would have had to be explained to a lector who, at discretion, could accept the explanation or refer it to a second-degree counsellor.

The counsellor might deplore the matter and dismiss it, or suggest corrective self-discipline.

If the seal-breaker did not accept the suggestion the matter would go to a social board whose suggestion, in turn, could be rejected. But when it reached the Prime Board—and any matter from the breaking of a seal to mass murder would go there if suggested self-discipline was refused—there was no more nonsense.

Kim's case had reached the Prime Board instantly, and he had been advised to leave Alphin III for his own good. His crime was monstrous, but he had ironically refused exile.

Now he was under block. His psychogram had been placed in the Disciplinary Circuit.[1]

[1] Disciplinary Circuit: The principal instrument of government during the so-called Era of Perfection in the First Galaxy. In early ages, all the functions of government were performed by human beings in person. The Electric Chair (q.v.) was possibly the first mechanical device to perform a governmental act, that of the execution of criminals.

The Disciplinary Circuit was a device based upon the discovery of the psychographic patterns of human beings, which permitted the exact identification of any person passing through a neuronic field of the type IX2H.... A development which permitted the induction of alternative electric currents in any identified person, made the Disciplinary Circuit possible.... It was first used in prisons, permitting much less supervision of prisoners (See Prisons and Prisoners) with equal security.

Later, because it allowed of an enormous reduction in the personnel of government, all citizens were psychographed. Circuits were set up in all cities of the First Galaxy. When a broadcast adaptation became possible, the system was complete. Every citizen was liable to discipline at any time.

No offender could hide from government. Wherever he might be, he was subject to punishment focused upon him because of his completely individual psychographic pattern.... Worship of efficiency and the obvious reduction in taxes (See Taxes) at first obscured the possibilities of tyranny inherent in such a governmental system....

[See (1) Era of Perfection, (2) Revolts, (3) Ades, (4) First Galaxy, Reconquest of. For typical developments of government based upon the Disciplinary Circuit, see articles on Sirius VIII, Algol II, Norten V and the almost unbelievable but authenticated history of government on Voorten II.]

Encyclopaedia of History, Vol. XXIV. Cosmopolis, 2nd Galaxy.

On the first day he was blocked from the customary complete outfit of new garments, clean, sterile, and of his own choice. These garments normally arrived by his bedside in the carrier which took away the old ones to be converted back to raw material for the garment machines.

On the second day he could enter no place of public recreation. An attempt to pass the door of any sport-field, theatre, or concert stadium caused the Disciplinary Circuit to act. His body began to tingle. He could turn back then. If he persisted, the tingling became more severe. If he was obstinate, it became agony, which continued until he turned back.

On the third day he found it impossible to enter any place of study or labor. The fourth day blocked him from any place where food or drink was served. On the fifth day his own quarters were barred to him.

After seven days the city and the planet would be barred. Anywhere he went, his body would tingle, gently in the morning, more and more strongly as the day wore on, until the torment became unbearable. Then he would go to the matter-transmitter, name his chosen place of exile, and walk off the planet which was Alphin III.

But it happened that Kim was a matter-transmitter technician. It happened that he knew that the Disciplinary Circuit was tied in to the matter-transmitter, and blocked men were not sent to destinations of their own choosing.

Blocked men automatically went to Ades. And they did not come back. Ever.

Behind the sealed-off parts of the space-ship, Kim searched hungrily and worked desperately, not for food, of course. He had determined to attempt the impossible. He had accomplished only the first step toward it when he felt an infinitesimal tingling all over his body. He stood rigid for a second, and then smiled grimly. He closed the casing of the catalyzer he had examined and worked on.

"Just in time," he said. "The merciless brutes!"

He moved from the catalyzer. A moment later he heard footsteps. Someone came up the flush ladder and into the space-ship. Kim Rendell turned his head. Then he bent over the fuel-register, which amazingly showed the tanks to be almost one-twelfth full of fuel, and stood motionless.

The footsteps moved here and there. Presently they came cautiously to the engine-room. Kim did not stir. A man made an indescribable sound of satisfaction. Kim, not moving even his eyes, saw that it was the lector who had spoken to him outside the ship. He did not address Kim now. With a quite extraordinary air of someone about to pick up an inanimate object, the lector laid hands upon Kim to lift him off his feet.

"Citizen!" Kim said severely. "What does this mean?"

The lector gasped. He fell back. His mouth dropped open and his face went white.

"I—I thought you were paralyzed."

"I do not care what you thought," Kim said. "It is against the law for any citizen to lay violent hands upon another."

By an effort the lector babbler regained his self-control.

"You—you.... The Circuit failed to work!"

"You reported that I had entered this ship," Kim said drily. "There is some uneasiness about what I do, because of my crime. So the Circuit was applied to paralyze me, and you were ordered to bring me quietly to the matter-transmitter. As you observe, it is not practical. Go back and report it."

The lector said something incoherent, turned and fled. Kim followed him leisurely to the entry-port. He turned the hand-power wheels which put a barrier across the entrance. He went back to his examination of the ship. The first part of the impossible had been achieved, but there was much more, too much more, which must be done. He worked feverishly.

His grandfather had told him many tales of the Starshine. She had made voyages of as long as two years in emptiness, at full acceleration, during which she had covered four hundred light-years of space, had purified her air, and fed her crew. Her tanks could hold fuel for six years' drive at full acceleration and her food-synthesizers, primitive as they were by modern standards, could yet produce some four hundred foodstuffs from the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and traces of other elements into which almost any organic raw material could be resolved.

She was, in fact, one of the last and most useful space-ships ever constructed at the last space-ship yard in existence. She was almost certainly the last ever to be used. But she was only a museum-piece now and her switches were opened and her control-cables severed lest visitors to the museum injure her. But Kim's grandfather had lectured him at great length upon her qualities. The old gentleman had had an elderly man's distaste for modern perfectionism.

Kim threw switches here and there. He spliced cables wherever he found them cut. He was hungry and he was gaunt, and he worked with a bitter anticipation of failure. He had been in the museum for almost an hour, and in the ship for half of that, when voices called politely through the barrier-grille.

"Citizen Kim Rendell, may we enter?"

He made sure it was safe, then opened the way.

"Enter and welcome, citizens," he said ironically, in the prescribed formula. But his hands were clenched and he was all ready to fight for his life.

Slowly the Prime Board of Alphin III filed up the flush ladder and into the cabin of the Starshine. There was Malby, who looked like an elderly sheep. There was Ponter, who rather resembled an immature frog. There was Shimlo, who did not look like anything but an advanced case of benevolent imbecility, and Burt, who at least looked intelligent and whom Kim Rendell hated with a corrosive hatred.

"Greeting, citizen," Malby said. Even his voice had a bleating quality. "Despite your crime, we have broken all precedent to come and reason with you. You are not mad, yet you act like a madman."

Kim grinned savagely at him.

"Come, now! I found a material that changes a man's psychogram, so he's immune to the Disciplinary Circuit. I was immune to discipline. So you four had me seized and my little amulet taken away from me. And then you sealed up every other bit of that material on the planet. Not so?"

"Naturally," Burt said pleasantly. "The Disciplinary Circuit is the basis of civilization nowadays. All discipline and hence all civilization would cease if the Circuit were nullified. Naturally, you must be disposed of."

"But carefully, so if there is anyone who shares my secret, he'll be betrayed by trying to help me!" said Kim. "And quietly, too, so those amiable sheep, my fellow-citizens, won't suspect there's anything wrong. They don't realize that they're slaves. They don't know of your pleasure-palaces on the other side of the planet. They don't realize that, when you take a fancy to a woman and she's blocked in her quarters until she's hysterical with fear and loneliness, you advise her to take psychological treatments which make her a submissive inmate of the harems you keep there. They don't know what happens to men you put under block for being too inquisitive about those women and who enter the matter-transmitter for exile."

Burt looked mildly inquiring. "What does happen to them?"

"Ades!" Kim said furiously. "They go to the transmitter and name their chosen place of exile, and the transmitter-clerk dutifully pushes the proper buttons, but the Circuit takes over. They go to Ades! And no man has ever come back."

There was a sudden tension in the air. Burt looked at his fellows. Shimlo was the picture of benevolent indignation, but his eyes were ugly. Ponter opened his mouth and closed it absurdly, looking more than ever like a frog.

"This is monstrous!" Malby bleated. "This is monstrous!"

Burt held up his hand.

"How did you get this strange idea?" he asked.

"I'm a matter-transmitter technician, fourth grade," Kim said coldly. "I worked on the transmitter when it gave trouble. I found the Disciplinary Circuit tie-in. I traced it. So I knew there was something wrong about all personal freedom on Alphin III and I started to look for more things wrong. I found them. I started to do something about them. Then I got caught."

Burt nodded.

"So!" he said thoughtfully. "We underestimated you, Kim Rendell. It is much pleasanter to rule Alphin Three as beloved citizens than as admitted tyrants. There are times when we have to protect ourselves. Naturally, we would rather not show our hands. It is clear that you must be sent into exile. Frankly, to Ades—whatever it may be like there. Apparently you did not have any friends."

"I dared not trust any of the sheep you rule," Kim said angrily. "But I did know there was more hafnium on this ship. I didn't dare come at first, or you'd have guessed. But after I'd starved a bit and was convincingly cold, I risked the venture. You guessed my intention too late. I can defy you again, even if you did take away my first protection from the Circuit. You know that?"

Burt nodded again.

"Of course," he admitted. "Yet we do not want a scandal. We will make a bargain within limits. You must be disposed of, but we will promise that you can go wherever you choose via the matter-transmitter."

"Your word's no good," Kim snapped.

"You will starve," Burt said mildly. "Of course you can seal yourself in the ship, but we will have lectors, special lectors, waiting for you when you come out again."

Kim scowled. "Yes?" he said. "I've been here half an hour. The ship's circuits were cut, but I've put the communicator back in working order. I can broadcast over the entire planet, telling the truth. I won't destroy your power, but I'll make your slaves begin to realize what they are. Sooner or later, one of them will kill you."

Malby bleated. It was not necessarily panic, but there are some minds to whom public admiration is necessary. Such persons will commit any crime to get admiration which they crave with a passionate desire. Burt held up his hand again.

"But why tell us?" he asked pleasantly. "Why didn't you simply broadcast what you've learned? Possibly it was because you wished to bargain with us first? You have terms?"

Kim ground his teeth.

"That's right," he said. "There is a girl, Dona Brett. She was to marry me, but one of you saw her, I think you, Burt. She is now blocked in her quarters to grow hysterical and terrified. It was on account of her that I acted too soon, and got caught. I want her here."

Burt considered without perceptible emotion.

"She is quite pretty, but there are others," he said in his detached way. "If we send her, you will not broadcast?"

"I'll kill her and myself," Kim said. "It's apparently the only service I can do her. Get out, now. It will take your best technician at least forty minutes to make a scrambler which will keep me from broadcasting. I'll give you twenty minutes to get her to me. I'll talk to all the planet if she isn't here."

Burt shrugged.

"Almost, I overestimated you," he said mildly. "I thought you had an actual plan. Very well. She will come. But if I were you, I would not delay my suicide."

Burt's eyes gleamed for an instant. Then he went out, followed by the others. Kim worked the controls which sealed the ship. He got feverishly to work again.

From time to time he stared desperately out of the vision-ports, and then resumed his labors. His task seemingly was an impossible one. The Starshine had been made into a mere museum exhibit. It was complete, but Kim's knowledge was inadequate and his time far too short.

Eighteen minutes passed before he saw Dona. She stood quietly beside the railing outside the space-ship, alone and quite pale. He opened the outer airlock door. She came up. He closed the outer door and opened the inner. She faced him. She was deathly white. As she saw him, hollow-cheeked and bitter, she managed to smile.

"My poor Kim! What did they do to you?"

"Blocked me!" Kim cried. "Took away my hafnium gadget and put me on the Circuit. They locked up every scrap of hafnium on the planet behind an all-citizen block. They just didn't know that it was used in space-ships in the fuel-catalyzers. I've found enough to make the two of us safe, though. Here!" He thrust a scrap of metal into her hand. "Hold it tightly. It has to touch your skin."

She caught her breath.

"I was blocked in my quarters, and I couldn't come out," she told him unsteadily. "I was going crazy with terror, because you'd told me what it might mean. I tried—so hard—to break through. But flesh and blood can't face the Circuit. I hadn't any reason to hope that you'd be able to do anything, but I did hope."

"I told them I'd kill both of us," he said fiercely. "Maybe I shall! But if I can only find the right cable, we'll have a chance!"

Suddenly, every muscle in his body went rigid and a screaming torment filled him. It lasted for part of a second. His face went gray. He wetted his lips.

"Burt!" he said thickly. "He had a psychometer under his robe. They came here, and he knew my psychogram was changed by the hafnium I'd found, so while they talked he stole the new pattern. It's taken them this long to get it ready for the Circuit. Now they're putting it in."

With a sudden, convulsive jerk, he went rigid once more. His muscles stood out in great knots. He was paralyzed, with every nerve and sinew in his body tensed to tetanic rigor. Agony filled him with an exquisite torment. It was the Disciplinary Circuit. It was those waves broadcast, focused upon him at full power. They would have found him anywhere upon the planet. And their torment was unspeakable.

Dona sobbed suddenly.

"Kim!" she cried desperately. "I know you can hear me! Listen! They must have me on the Circuit too, only what you gave me has thrown it off. They expect to hold us paralyzed while they cut in with torches and take us. But they mustn't! So I'm going to give you the thing you gave me. If it changed my pattern, it will change yours again, to something they can't guess at." She sobbed again. "Please, Kim! Don't give it back. Go ahead and do what you planned, whatever it is. And if you don't win out, please kill me before you give up. Please! I don't want to be conditioned to do whatever they want in their pleasure-palaces."

She took the tiny sliver of metal in her shaking fingers. She pushed aside the flesh of her hand to put it in his grip. Courageously she released it.

The agonized paralysis left Kim Rendell. But now Dona was a pitiful figure of agony.

Kim groaned. Rage filled him. His anguish and fury was so terrible that he would have destroyed the whole planet, had he been able. But he could not permit her gift, which she had given at the price of such torment, to go without reward. He must struggle on to save them both, even though now he had no hope.

He sprang to the control-board. He stabbed at buttons almost at random, hoping for a response. He'd tried to get the ship into some sort of operating condition, but now there was no time. Frenziedly he attempted to find some combination of controls which would make something, anything happen. He slipped the second bit of hafnium into his mouth to have both hands free. In desperation he ripped the control-board panel loose. He saw clipped wires everywhere behind it. Seizing the dangling ends, he struck them fiercely together. A lurid blue spark leaped. He cried out in triumph, and the morsel of metal Dona had sacrificed to him dropped from his lips.

His muscles contorted and agony filled him.

There was a roaring noise. The Starshine bucked violently. There were crashes and there was a feeling of intolerable weight which he could feel, despite his agony. The ship reeled crazily. It smashed through a wall. It battered into a roof. It spun like a mad thing and went skyward tail-first with Kim Rendell in frozen, helpless torment, holding two cables together with muscles utterly beyond his control.

It went up toward empty space, in which no other vessel was navigating anywhere.

Eventually the "Starshine," alone in space as no other space-ship had been alone in twenty thousand years, behaved like a sentient thing. At first, of course, her actions were frenzied, almost insane, as if the Disciplinary Circuit waves which made Dona a statue of agony and kept Kim frozen with contorted muscles could affect the space-ship too.

Wildly the little vessel went upward through air which screamed as it parted for her passage. She yawed and swayed and ludicrously plunged backwards. The screaming of the air rose to a shriek, and then to a high thin whistle, and then ceased altogether. Finally she was free of the air of Alphin III.

After this she really made speed, backing away from the planet. Her meteor-detectors had been turned on in one of Kim's random splicings, and when current reached them they reported a monstrous obstruction in her path and shunted in the meteor-repelling beams. The obstacle was the planet itself, and the beams tried to push it away. Naturally, they pushed the ship itself away, out into the huge chasm of interplanetary space.

It kept up for a long time, too, because Kim was paralyzed by the broadcast waves. They were kept focused upon him by the psychographic locator. So long as those waves of the Disciplinary Circuit came up through the ionosphere, Kim's spasmodically contracted muscles kept together the two cables which had started everything. But the Starshine backed away at four gravities acceleration, faster and ever faster, and ordinary psychographic locators are not designed for use beyond planetary distances.

Ultimately the tormenting radio-beam lessened from sheer distance. At last the influence broke off suddenly and Kim's hands on the leads dropped away. The beam fumbled back to contact, and wavered away again, and presently was only a tingling sensation probing for a target the locators could no longer keep lined up.

Then the Starshine seemed to lose her frenzy and become merely a derelict. She sped on, giving no sign of life for a time. Then her vision-ports glowed abruptly. Kim Rendell, working desperately against time and with the chill of outer space creeping into the ship's unpowered hull, had found a severed cable which supplied light and heat.

An hour later still, the ship steadied in her motion. He had traced down the gyros' power-lead and set them to work.

Two hours later yet the Starshine paused in her flight. Her long, pointed nose turned about. A new element of motion entered the picture she made. She changed course.

At last, as if having her drive finally in operation gave her something of purposefulness, the slim space-ship ceased to look frenzied or frowsy or bemused, and swam through space with a serene competence, like something very much alive and knowing exactly what she was about.

She came to rest upon the almost but not quite airless bulk of Alphin II some thirty hours after her escape from Alphin III. Kim was desperately hungry. But for the lesser gravity of the smaller inner planet, which was responsible for its thinned-out atmosphere, he might have staggered as he walked. Certainly a normal space-suit would have been a heavy burden for a man who had starved for days. Dona, also, looked pale and worn-out when she took from him the things he brought back through the airlock.

They put the great masses of spongy, woody stuff in the synthesizer. It was organic matter. Some of it, perhaps, could have been consumed as food in its original state. But the synthesizer received it, and hummed and buzzed quietly to itself, and presently the man and woman ate. The synthesizer was not the equivalent of those magnificently complex food-machines which in public dining-halls provide almost every dish the gourmets have ever invented from raw materials. But it did make a palatable meal from the tasteless vegetation of the small planet.

Kim said quietly, when they had finished eating, "Now we'll find out for certain what Burt intends to do about us." He grimaced. "He's dangerously intelligent. He underestimated me before. He may consider us dead, or he may overestimate us. I think he'll play it safe. I would, in his place."

"What does that mean?" Dona asked wistfully. "We will be able to go to some other planet, won't we, Kim? As if we'd gone in the matter-transmitter in a perfectly normal fashion? Simply to take up residence on another world?"

Kim shook his head. "I'm beginning to doubt it," he said slowly. "The discovery that with a bit of hafnium a man can change his psychographic pattern is high explosive. If the Disciplinary Circuit can't pick him out as an individual, any man can defy any government which depends on the Circuit. Which means that no government is safe. I've got to remove you for the sake of the government everywhere in the Galaxy."

"But they can't touch us here," said Dona. "We're safe now."

Kim shook his head.

"No. I was too hungry to think, before. We're not safe. I've got to work like the devil. Do you remember your Galactic History? Remember what the Disciplinary Circuit was built up to? Remember the Last War? It's not only the space-ships which went into museums. I'm suddenly scared stiff."

He stood up and abruptly began to put on the space-suit again. His face had become haggard.

"In the Last War there were no battles, only massacres," he said curtly as he snapped buckles. "There was no victory. They used a beam which was a stepped-up version of the Disciplinary Circuit. They called it a fighting-beam, then, and they thought they could fight with it. But they couldn't. It simply made war impossible. So ultimately they hooded over the projectors of the fighting-beams, and most of them probably fell to rust. But there are some in the museums. If Burt and the others want to play safe, they'll haul those projectors out of the museum and hook them up to find and kill us. And there's no question but that they can do it."

He stepped into the airlock and closed the door, still fumbling with the last adjustments to his space-suit.

Dona was puzzled by his gloomy forebodings. She heard the outer door open. As she stood there bewildered, she heard him bringing more raw food-stuff to the airlock with a feverish haste. He made two trips, three, and four.

She found herself screaming shrilly because of an agony already past.

It had been a bare flash of pain. It was gone in the fraction of a second, in the fraction of a millisecond. But it was such pain! It was the anguish of the Disciplinary Circuit a thousand times multiplied. It was such torment as the ancients tried vainly to picture as the lot of damned souls in hell. Had it lasted, any living creature would have died of sheer suffering.

But it flashed into being, and was gone, and Dona had cried out in a strangled voice. She was filled with a horrible weakness from the one instant of anguish, and she felt stark panic lest it come again.

The outer airlock door slammed shut. The inner opened. Kim came staggering within. He did not strip off the space-suit. He ran clumsily toward the now-repaired control-panel, his face contorted.

"Lie down flat!" he shouted as he opened his face-plate. "I'm taking off."

The Starshine roared from the almost-barren world which was an inferior planet of the sun Alphin, not worth colonization by men. Acceleration built up and built up and built up to the very limit of what the human body could stand.

After twenty minutes, it dropped from four gravities to one.

"Dona!" Kim called hoarsely.

She answered faintly.

"They've got the ancient projectors hooked up," he said as hoarsely as before. "They're searching for us. We were so far away that the beam flashed past. It won't record finding us for minutes, as it'll take time for the response to get back. That's what will save us, but they're bound to touch us occasionally until we get out of range."

The Starshine swung about in space. The brutal acceleration began again, at an angle to the former line of motion.

Ten minutes later there was another moment of intolerable pain. Every nerve in their bodies jumped in a tetanic convulsion. Had it continued, their muscles would have torn loose from their bones and their hearts would have burst from the violence of the fearful contraction. The Starshine would have gone on senselessly as a speeding coffin. But again the searing torment lasted for only the fraction of a second.

Back on Alphin III, great projectors swept across the sky. They were ancient devices, those projectors. They were quaint, even primitive in appearance. But a thousand years before they had been the final word in armament. They represented an attack against which there was no defense. A defense which could not be breached. Those machines had ended wars.

They poured forth tight beams of the same wave-frequencies and forms of which the Disciplinary Circuit was a more ancient development still. But where the Circuit was an exquisitely sensitive device for the exquisitely graduated torment of individuals, these beams were murderers of men. They were not tuned to the psychographic patterns of single persons, but coarsely, in irresistible strength, to all living matter containing given amino-chain molecules. In short, to all men.

And they had made the Last War the last. There had been one battle in that war. It had taken place near Canis Major, where there had been forty thousand warships of space lined up in hostile array. The two fleets were almost equally matched in numbers, and both possessed the fighting beams. They hurtled toward each other, the beams stabbing out ahead. They interpenetrated each other and went on, blindly.

It was a hundred years before the last of the run-away derelicts blundered to destruction or was picked up by other space-ships which then still roved the space-ways. Because there was no defense against the fighting-beams, which were aimed by electronic devices, a ship did not cease to fight when its crew was dead. And every crew had died when a fighting-beam lingered briefly on their ship. There was not one single survivor of the Battle of Canis Major. The fleets plunged at each other, and every living thing in both fleets had perished instantly. Thereafter the empty ships fought on as robots against all other ships. So there were no more wars.

For two hundred years after that battle, the planets of the Galaxy continued to mount their projectors and keep their detector-screens out. But war had defeated itself. There could be no victories, but only joint suicides. There could be no conquests, because even a depopulated planet's projectors would still destroy all life in any approaching space-ship for as many years as the projectors were powered for. But in time, more especially after matter-transmitters had made space-craft useless, they were forgotten. All but those which went into museums for the instruction of the young.

These resuscitated weapons were now at work to find and kill Kim and Dona. In a sense it was like trying to kill flies with a sixteen-inch gun. The difficulties of aiming were extreme. To set up a detector-field and neutralize it would take time and skill which were not available.

So the beams swept through great arcs, with operators watching for signs of contact. It was long minutes after the first contact before the instruments on the projectors recorded it, because the news could only go back at the speed of light. Then the projectors had to retrace their path, and the Starshine had moved. The beams had to fumble blindly for the fugitives, and they told of each touch, but only after it occurred. And Kim struggled to make his course unpredictable.

In ten hours the beam struck four times only, because Kim changed course and acceleration so fiercely and so frequently that a contact could only be a matter of chance.

Then for a long time there was no touch at all. In two days Alphin, the sun, had dwindled until it was merely the brightest of the stars, with a barely perceptible disk. On the third day the beam found them yet again, and Dona burst into hysterical sobs. But it was not really bad, this time. There is a limit to the distance to which a tight beam can be held together in space, by technicians who have no space-experience and instinctive know-how.

Within hours after this fifth contact, Kim Rendell found the last key break in the control-cables of the ship, and was able to throw on the overdrive, by which the Starshine fled from Alphin at two hundred times the speed of light. Then, of course, they were safe. Even had the beam of agony been trained directly upon the ship, it could not have overtaken them.

But Dona was a bundle of shrinking nerves when it was over, and Kim raged as he looked at her scared eyes.

"I know," she said unsteadily, when he had her in the control-room to look at the cosmos as it appeared at faster-than-light speed. "I know I'm silly, Kim. It can't hurt us any more. We're going to another solar system entirely. They won't know anything about us. We're all right. Quite all right. But I'm just all in little pieces."

With somber brow, Kim stared at the vision-plates about him. The Universe as seen at two hundred light-speeds was not a reassuring sight. All stars behind had vanished. All those on either hand were dimmed to near-invisibility. Ahead, where the very nose of the space-ship pointed, there were specks of light in a recognizable star-pattern, but the colors and the magnitudes were incredible.

"We're heading now for Cetis Alpha," Kim said slowly, after a long time. "It's the next nearest solar system. Our fuel-tanks are one-twelfth full. We have power to travel a distance of fifty light-years, no more, and it would take us three months to cover that. Cetis Alpha is seven light-years away, or it was."

"We're going to settle on one of the planets there?" Dona asked hopefully. "What are they like, Kim?"

"You might look them up in the Pilot," Kim said, rather glumly. "There are six inhabited ones."

"You sound worried," she said. "What is it?"

"I'm wondering," Kim admitted. "If Burt and the Prime Board should send word ahead of us by matter-transmitter, to these six planets and all the other inhabited planets within fifty or a hundred light-years, it would be awkward for us. Transmission by matter-transmitter is instantaneous, and it wouldn't take too long for the governments on the Cetis Alpha planets to set up detectors and remount the projectors which could kill us. Burt would call us very dangerous criminals. He'd say we were so dangerous we had better be killed before we land." He paused, and added, "He's right."

"I don't see why they should do anything so cruel."

"We've struck at the foundation of government," Kim said savagely. "On Alphin Three there's a pretense that all men are free, and we know it's a lie. But on the other planets they don't even pretend. On Loré Four they have a king. On Markab Two the citizens wear collars of metal—slave-collars—and members of the aristocracy have the right to murder social inferiors at pleasure. On Andrometa Nine the Disciplinary Circuit, and so the government, is in the hands of a blood-thirsty lunatic. The Circuit backs all governments alike, the supposedly free and the frankly despotic governments impartially. We're a danger to all of them. Even a decent government, if there is one, would dread having its citizens able to defy the Circuit. Yet in ten words I can tell how to nullify the one instrument on which all government is based. Once that knowledge gets loose, nothing can suppress it."

Dona sighed.

"I was hoping we could go some place where we would be safe," she said. "Isn't there any such place?"

Kim's laugh was bitter.

"I wonder if there's any place where we can be free," he said. "I planned big, Dona, but it didn't work out. There wasn't another man on Alphin Three who wanted to be free as much as I did. I'd about decided that just the two of us would put on protectors and journey from one planet to another in search of freedom. But then Burt saw you, and you were locked up so you'd go frantic with fear and loneliness. Later they'd have given you a psychological conditioning to cure you of terror, and sent you away to Burt's pleasure-palace."

"Why didn't you take me away before Burt saw me?" she asked. "Why did you wait?"

Kim groaned. "Because I wasn't ready. When I realized the danger, I tried to get you, and I was caught. They found out what I had and everything became hopeless. They put me on block to see if anyone would try to befriend me, but I hadn't any friends. I didn't know anyone else who wouldn't have been frightened if I'd told him he was a slave. I threatened the Prime Board with a broadcast, but I'm afraid nobody would have believed me."

"It all happened because of me," Dona said. "Forget what I said about wanting to be safe, Kim. I don't care any more, not if I'm with you."

Kim scowled at the weird pattern of strangely-colored stars upon the vision-plate.

"We're using a lot of our fuel in trying for Cetis Alpha's planets. I'd like to—well—have a marriage ceremony."

Despite her anxiety, Dona burst out laughing.

"It's about time, you big lug!" she cried. "I was beginning to lose hope."

Kim laughed too. "All right. I'll see if it can be managed. But if warnings have been sent ahead of us, marriage may be difficult."

Like a silver arrow, the "Starshine" continued to bore on through a weird, synthetic Universe, two hundred times faster than light. In the space-ship Kim worked angrily, making desperate attempts to devise a method of nullifying the non-individualized fighting beams with which—now that he was in free space in a space-ship—any attempt to land upon an inhabited planet might be frustrated.

In the end he constructed two small wristlets, one for himself and one for Dona to wear. If tuned waves of the Circuit struck them, the wristlets might nullify them. But if the fighting-beams struck, that would be another story.

Twelve days after turning on the overdrive, which by changing the constants of space about the space-ship, made two hundred light-speeds possible, Kim turned it off. He had previously assured himself that Dona was wearing the little gadget he had built. As he snapped off the overdrive field, the look of the Universe changed with a startling suddenness. Stars leaped into being on every side, amazingly bright and astoundingly varicolored. Cetis Alpha loomed almost dead ahead, a glaring globe of fire with enormous streamers streaming out on every side.

There were planets, too. As the Starshine jogged on at a normal interplanetary—rather than interstellar—speed, Dona focused the electron telescope upon the nearest. It was a great, round disk, with polar ice-caps and extraordinarily interconnected seas, so that there were innumerable small continents distributed everywhere. Green vegetation showed, and patches of cloud, and when Dona turned the magnification up to its very peak, they were certain that they saw the pattern of a magnificent metropolis.

She looked at it hungrily. Kim regarded it steadily. They did not speak for a long time.

"It would be nice there," Dona said longingly, at last. "Do you think we can land, Kim?"

"We're going to try," he told her.

But they didn't. They were forty million miles away when a sudden overwhelming anguish smote them both. All the Universe ceased to be....

Six weeks later, Kim Rendell eased the Starshine to a landing on the solitary satellite of the red dwarf sun Phanis. It was about four thousand miles in diameter. Its atmosphere was about one-fourth the density needed to support human life. Such vegetation as it possessed was stunted and lichenous. The terrain was tumbled and upheaved, with raw rock showing in great masses which had apparently solidified in a condition of frenzied turmoil. It had been examined and dismissed as useless for human colonization many centuries since. That was why Kim and Dona could land upon it.

They had spent half their store of fuel in the desperate effort to find a planet on which they could land.

Their attempt to approach Cetis Alpha VI had been the exact type of all their fruitless efforts. They came in for a landing, and while yet millions of miles out, recently reinstalled detector-screens searched them out. Newly stepped-up long distance psychographic finders had identified the Starshine as containing living human beings. Then projectors, taken out of museums, had hurled at them the deadly pain-beams which had made war futile a thousand years before. They might have died within one second, from the bursting of their hearts and the convulsive rupture of every muscular anchorage to every bone, except for one thing.

Kim's contrived wristlets had saved them. The wristlets, plus a relay on a set of controls to throw the Starshine into overdrive travel through space. The wristlets contained a morsel of hafnium, so that any previous psychographic record of them as individuals would no longer check with the psychogram a searchbeam would encounter. But also, on the first instant of convulsive contraction of muscles beneath the wristlets, they emitted a frantic, tiny signal. That signal kicked over the control-relay. The Starshine flung itself into overdrive escape, faster than light, faster than the pain-beams could follow.

They had suffered, of course. Horribly. But the pain-beams could not play upon them or more than the tenth of a millisecond before the Starshine vanished into faster-than-light escape. They had tried each of the six planets of Cetis Alpha. They had gone rather desperately to Cetis Gamma, with four inhabited planets, and Sorene, with three. Then the inroads on their scant fuel-supply and their dwindling store of vegetation from Alphin II made them accept defeat. The massed volumes of the Galactic Pilot for this sector, age-yellowed, brittle volumes now, had told them of vegetation on the useless planet of the dwarf star Phanis. They came to it. Kim was stunned and bitter. And they landed.

After the ship had settled down in a weird valley with fantastic overhanging cliffs and a frozen small waterfall nearby, the two of them went outside. They wore space-suits, of course, because of the extreme thinness of the air.

"I suppose we can call this home, now," Kim said bitterly.

It was night. The sky was cloudless, and all the stars of the Galaxy looked down upon them as they stood in the biting cold. His voice went by space-phone to the helmet of Dona, by his side.

"I guess I can stand it if you can, Kim," she said quietly.

"We've got fuel for six weeks' drive," he said ironically. "That means we can go to any place within twenty-five light-years. We've tried every solar system in that range. They're all warned against us. They all had their projectors in operation. We couldn't land. And we'd have starved unless we got to some new material for the synthesizer. This was the only place we could land on. So we have to stand it, if we stand anything."

Dona was silent for a little while.

"We've got each other, Kim," she said slowly.

"For a limited time," he said. "If we use our fuel only for heat and to run the synthesizer for food, it will probably last several years. But ultimately it will run out and we'll die."

"Are you sorry you threw away everything for me, Kim?" asked Dona. "I'm not sorry I'm with you. I'd rather be with you for a little while and then die. Certainly death is better than what I faced."

Kim made a furious gesture.

"It's recognized, everywhere, that the population of a planet has the right to make all the laws of that planet. We are the population here. We could be married by our own act. But suppose we had children? When our fuel gives out they'd die with us. I think we'd go mad anticipating that. We can't even have each other. We're imprisoned here as they used to imprison criminals. For life. We can have no hope. There is nothing we can work at. We can't even try to do anything."

He clenched his hands inside his space-gloves. Dona looked at him.

"Are you going to give up, Kim?"

"Give up what?" Then he said bitterly, "No, Dona. I'm going to find some excuse for hoping. Some lie I can tell myself. But I'll know I'm simply trying to deceive myself."

There was a long silence. Hopelessness. Futility.

"I've been thinking, Kim," Dona said softly, at last. "There are three hundred million inhabited planets. There are trillions and quintillions of people in the Galaxy. If they knew about us, some of them at least would want to help us. There are some, probably, who'd hope we could help them. If we were to think of a new approach to the problem we face, and reach the people who would want to help us, it might mean eventual rescue."

"Signals travel at the speed of light," Kim said. "We'd be dead long before even a tight-beam signal could reach another star-cluster, if there were anybody there to receive or act on it. But there aren't any space-ships except the Starshine. It was the last ship used in the Galaxy."

Dona said stoutly:

"We've been regarding our predicament as if it were unique, as if nobody else in the Universe wanted to be free. As if there was only one problem—ours! I heard a story once, Kim. It was about a man who had to carry a certain particular grain of dust to another place. A silly story, of course. But this was the top grain in a dust-pile. The man tried to find something that would pick up the one grain of dust, and something that would hold it quite safe. But he couldn't solve the problem. There wasn't any box that would hold a single grain of dust. He couldn't even pick up a solitary dust-grain. And how could he carry it if he couldn't pick it up?"

"That's a fable," Kim said, harshly. "There's a moral?"

Dona smiled. "Yes," she said. "There is. He picked up the dust-grain. With a shovel. He picked up a lot of others, too, but that didn't matter. And he could find a box to hold a hundred thousand dust-grains, when he couldn't find a box to hold one."

Kim was silent. Dona nodded and smiled at him.

"If you want a new way to think, how about thinking not just of us and our problem, but the problem of all the people like us who have gone into revolt?" she said. "How about all the people who've been sent to Ades? How about all those who will go in years to come? I don't know the answer, Kim, but it's another way to think. Since we've failed to solve a little problem by itself, suppose we look at it as part of a big one? It's a new approach, anyhow."

There was silence. The bright, many-colored stars overhead moved perceptibly toward what would be called the west by age-old custom. Weird shapes of frozen rock loomed above the space-ship, and the starlight glimmered up on thin hoarfrost which settled everywhere upon this small planet in the dark hours.

Kim stirred suddenly, and was still again. Dona continued to watch him. She could not see his face, but it seemed to her that he stood straighter, somehow. Then, suddenly, he spoke gruffly.

"Let's go back in the ship," he said. "Space-suits are admirable inventions, Dona, but they have limitations. I can't kiss you through a space-helmet."

He did not wait until they were out of the airlock, and she clung to him. Then he grinned for the first time in many days.

"My dear," he said contentedly. "Not only are you the best-looking female I ever saw, but you've got brains. Now watch me!"

"What are you going to do?" she asked breathlessly.

"Too much to waste time talking about it," he told her. "Want to help? Look up Ades in the Pilot. I had completely forgotten I was a matter-transmitter technician."

He kissed her again, exuberantly, and strode for the Starshine record-room, shedding the parts of his space-suit as he went. He pulled down the microfilm reels covering the ship's construction and zestfully set to work to review them, making notes and sketches from time to time. The reels, of course, contained not only the complete working drawings of the entire ship, showing every bolt and rivet, but also every moving part in stereoscopic relationship to its fellows, with full data so that no possible breakdown could take place without full information being available for its repair.

Dona watched him furtively as she began the tedious task of hunting through the Galactic Pilot of this sector, two-hundred-odd volumes, for even a stray reference to the planet Ades.

Ultimately she did find Ades mentioned. Not in the bound volumes of the Pilot, but in the microfilm abbreviated Galactic Directory. Ades rated just three lines of type—its space-coördinates, the spectral type of its sun, a climate-atmosphere symbol which indicated that three-fourths of its surface experienced sub-Arctic conditions, and the memo:

"Its borderline habitability caused it to be chosen as a penal colony at a very early date. Landing upon it is forbidden under all circumstances. A patrol-ship is on guard."

The memorandum was quaint, now that no space-line had operated in five centuries, no exploring ship in nearly two, and the Space Patrol itself had been disbanded three hundred years since.

"Mmmm!" Kim said. "If we need it, not too bad. People could survive on Ades. People probably have. And they won't be sheep, anyhow."

"How far away is it?" Dona asked uneasily. "We have enough fuel for twenty-five light-years' travel, you said."

"Ades is just about halfway across the Galaxy," he told her. "We couldn't really get started there if our tanks were full. The only way to reach it is by matter-transmitter."

But he did not look disheartened. Dona watch his face.

"It's ruled out. What did you hope from it, Kim?"

"A wedding," he said, and grinned. "But it isn't ruled out, Dona. Nothing's ruled out, if an idea you gave me works. Your story about the dust-grain hit my mind just right. I was trying to figure out how to travel a hundred light-years on twenty-five light-years' fuel, even though the Prime Board may have sent warnings three times that far. But if you can't solve a little problem, make it a big one and tackle that. That's what your story meant. It's a nice trick!"

Dona was puzzled by what Kim had said. She stared at him, wide-eyed, trying to figure out his meaning. For a moment or two he made no attempt to explain. He just stood there, grinning at her.

"Listen, Dona," he said, finally. "Why did they stop making space-ships?"

"Matter-transmitters are quicker and space-ships aren't needed any more."

"Right!" Kim said. "But why was the Starshine used by my revered great-grandfather to bring the first colonists to Alphin Three?"

"Because—well—because you have to have a receiver for a matter-transmitter, and you have to carry it. Alphin Three was almost the last planet in the Galaxy to be colonized, wasn't it?"

"Yes. Why do you have to carry a receiver? No, don't bother. But do answer this one. If two places are both too far to get to, what's the difference?"

"Why, none."

"Oh, there's a lot!" he told her. "The next star-cluster is too far away for the Starshine with her present drive and fuel. To the next galaxy is no farther. But when I stopped trying to think of ways to stretch our fuel, and started trying to think of a way to get to the next galaxy, I got it."

She stared.

"Are we going there to live?" she said submissively. But her eyes were sparkling with mirth.

He kissed her exuberantly.

"My dear, I wouldn't put anything past the two of us together. But let me show you how it works."

He spread out the drawings he had made from the construction-records while she searched the Pilot. He expounded their meaning enthusiastically and she listened and made admiring comments, but it is rather doubtful if she really understood. She was too much occupied with the happy knowledge that he was again confident and hopeful.

But the idea was not particularly complicated. Every fact was familiar enough. Space-ships, in the old days, and the Starshine, in this, were able to exceed the speed of light by enclosing themselves in an overdrive field, which was space so stressed that in it the velocity of light was enormously increased. Therefore the inertia of matter, its resistance to acceleration, or its mass, was reduced by the same factor, y.

The kinetic energy of a moving space-ship, of course, had to remain the same when an overdrive field was formed about it. Thus when its inertia was decreased by the field, its velocity had to increase. Mathematically, the relationship of mass to velocity with a given quantity of kinetic energy is, for normal space, MV=E. In an overdrive field, where the factor y enters, the equation is M/y, yV=E. The value of y is such that speeds up to two hundred times that of light result from a space-ship at normal interplanetary speed going into an overdrive field.

A matter-transmitter field, as everyone knows now, simply raises the value of y to infinity. The formula then becomes M/infinity, infinity V=E. The mass is divided by infinity and the velocity multiplied by infinity. The velocity, in a planet-to-planet transmitter, is always directly toward the receiver to which the transmitter is tuned.

In theory, then, a man who enters such a transmitter passes through empty space unprotected, but his exposure is so exceedingly brief—across the whole First Galaxy transit was estimated to require .0001 second—that not one molecule of the air surrounding him has time to escape into emptiness.

Thus the one device is simply an extension of the principle of the other. A matter-transmitter is merely an enormously developed overdrive-field generator with a tuning device attached. But until this moment, apparently it had not happened that a matter-transmitter technician was in a predicament where the only way out was to put those facts together. Kim was such a technician, and on the Starshine he had probably the only overdrive field generator of space-ship pattern still in working order in the Universe.

"All I've got to do is to add two stages of coupling and rewind the exciter-secondary," he told her zestfully. "Doing it by hand may take a week. Then the Starshine will be a matter-transmitter which will transmit itself! The toughest part of the whole job will be the distance-gauge. And I've got that."

Worshipfully, Dona looked up at him. She probably hoped that he would kiss her again, but he mistook it for interest.

He explained at length. There could be, of course, no measure of distance traveled in emptiness. Astrogation has always been a matter of dead reckoning plus direct observation. But at such immeasurably high speeds there could be no direct observation. At matter-transmitter speeds, no manual control could stop a ship in motion within any given galaxy!

So Kim had planned a photo-gauge, which would throw off the transmitter-field when a specific amount of radiation had reached it. At thousands of light-speeds, the radiation impinging on the bow of a ship, would equal in seconds the normal reception of years. When a specific total of radiation had struck it, a relay would cut off the drive field. Among other features, such a control would make it impossible for a speeding ship to venture too close to a sun.

Kim set joyously to work to make three changes in the overdrive circuit, and to build a radiation-operated relay.

Outside the space-ship the sky turned deep-purple. Presently the dull-red sun arose, and the white hoarfrost melted and glistened wetly, and most of it evaporated in a thin white mist. The frozen waterfall dripped and dripped, and presently flowed freely. The lichenous plants rippled and stirred in the thin chill winds that blew over the small planet, and even animals appeared, stupid and sluggish things, which lived upon the lichens.

Hours passed. The dull-red sun sank low and vanished. The little waterfall flowed more and more slowly, and at last ceased altogether. The sky became a deep dense black and multitudes of stars shone down on the grounded space-ship.

It was a small, starved world, this planet, swinging in lonely isolation around a burned-out sun. About it lay the Galaxy in which were three hundred million inhabited worlds, circling brighter, hotter, much more splendid stars. But the starveling little planet was the only place in all the Galaxy, save one, where no Disciplinary Circuit held the human race in slavery.

Nothing happened visibly upon the planet during many days. There were nights in which the hoarfrost glistened whitely, and days in which the frozen waterfall thawed and splashed valiantly. The sluggish, stupid animals ignored the space-ship. It was motionless and they took it for a rock. Only twice did its two occupants emerge, to gather the vegetation which was raw material for their food-synthesizer. On the second expedition, Kim seized upon an animal to add to the larder, but its helpless futile struggles somehow disgusted him. He let it go.

"I prefer test-tube meat," he said distastefully. "We've food enough anyhow for a long, long time. At worst we can always come back for more."

They went into the ship and stored the vegetable matter in the synthesizer-bins. They returned, then, to the control-room.

"I think it's right," Kim said soberly, as he took the seat before the control-panel. "But nobody ever knows. Maybe we have a space-ship now which makes matter-transmitters absurd. Maybe we've something we can't control at all, which will land us hundreds of millions of light-years away, so that we'll never be able to find even this galaxy again."

"Maybe we might have something which will simply kill us instantly," Dona said quietly. "That's right, isn't it?"

He nodded.

"When I push this button we find out."

She put her hand over his. She bent over and kissed him. Then she pressed down his finger on the control-stud.

Incredible, glaring light burst into the viewports, blinding them. Relays clicked loudly. Alarms rang stridently. The Starshine bucked frantically, and the vision-screens flared with a searing light before the light-control reacted....

There was a sun in view to the left. It was a blue-white giant which even at a distance which reduced its disk to the size of a water-drop, gave off a blistering heat. To the right, within a matter of a very few millions of miles, there was a cloud-veiled planet.

"At least we traveled," Kim said. "And a long way, too. Cosmography's hardly a living science since exploration stopped, but that star surely wasn't in the cluster we came from."

He cut off the alarms and the meteor-repeller beams which strove to sheer the Starshine away from the planet, as they had once driven it backward away from Alphin III. He touched a stud which activated the relay which would turn on overdrive should a fighting-beam touch its human occupants.

He waited, expectant, tense. The space-ship was no more than ten million miles from the surface of the cloud-wreathed world. If there were an alarm-system at work, the detectors on the planet should be setting up a terrific clamor, now, and a fighter-beam should be stabbing out at any instant to destroy the two occupants of the Starshine. Kim found himself almost cringing from anticipation of the unspeakable agony which only an instant's exposure to a pain-beam involved.

But nothing happened. They watched the clouds. Dona trained the electron telescope upon them. They were not continuous. There were rifts through which solidity could be glimpsed, sometimes clearly, and sometimes as through mist.

She put in an infra-red filter and stepped up the illumination. The surface of the planet came into view on the telescope-screen. They saw cities. They saw patches of vegetation of unvarying texture, which could only be cultivated areas providing raw material for the food-synthesizers. They saw one city of truly colossal size.

"We'll go in on planetary drive," Kim said quietly. "We must have gone beyond news of us, or they'd have stabbed at us before now. But we'll be careful. I think we'd better sneak in on the night-side. We'll turn on the communicator, by the way. We may get some idea of the identity of this sun."

He put the little ship into a power-orbit, slanting steeply inward in a curve which would make contact with the planet's atmosphere just beyond the sunset line. He watched the hull-thermometers for their indications.

They touched air very high up, and went down and down, fumbling and cautious. The vision-screens were blank for a long time, but the instruments told of solidity two hundred miles below, then one hundred, then fifty, twenty-five, ten—

Suddenly the communicator-speaker spoke in a gabble of confusing voices. Dona tuned it down to one. All the Galaxy spoke the same language, of course, but this dialect was strangely accented. Presently they grew accustomed and could understand.

"We all take pride in the perfection of our life," the voice said unctuously. "Ten thousand years ago perfection was attained upon this planet, and it is for us to maintain that perfection. Unquestioningly, we obey our rulers, because obedience is a part of perfection. Sometimes our rulers give us orders which, to all appearances, are severe. It is not always easy to obey. But the more difficult obedience may be, the more necessary it is for perfection. The Disciplinary Circuit is a reminder of that need as it touches us once each day to spur us to perfection. The destruction of a family, even to first and second cousins, for the disobedience of a single member, is necessary that every seed of imperfection shall be eliminated from our life."

Kim and Dona looked at each other. Dona turned to another of the voices.

"People of Uvan!" The tones were harsh and arrogant. "I am your new lord. These are your orders. Your taxes are increased by one-tenth. I require absolute obedience not only to myself, but to my guards. If any man, woman or child shall so much as think a protest against my lightest command, he or she shall writhe in agony in a public place until death comes, and it will not come quickly! Before my guards you will kneel. Before my personal attendants you will prostrate yourselves, not daring to lift your eyes. That is all for the present."

Dona cut it off quickly. A dry, crisp voice came in on a higher wave-length.

"This is Matix speaking. You will arrange at once to procure from Khamil Four a shipment of fighting animals for the Lord Sohn's festival four days hence. Fliers will arrive at the matter-transmitter to take them on board tomorrow afternoon two hours before sunset. Lord Sohn was most pleased with the gheets in the last shipment. They do not fight well against men, but against women they are fairly deadly. In addition—"

"Somehow, I don't think we'll land, Dona," Kim said very quietly. "But turn back to the first voice."

Her hand shook, but she obeyed. The unctuous voice had somehow the air of ending its speech.

"Before going on, I repeat we are grateful for the perfection of our way of life, and we resolve firmly that so long as our planet shall circle Altair, in no wise will we depart from it."

Kim turned the nose of the Starshine upward. The stars of the Galaxy seemed strangely bright and monstrously indifferent. The little space-ship drove back into the heavens.

After a pause, Kim turned to Dona.

"Look up Altair," he said. "We came a very long way indeed."

There was silence save for the rustling of the index-volume as Dona searched for Altair in the sun-index. Presently she read off the space-coördinates. Kim calculated, ruefully.

"That wasn't space-travel," he said drily. "That was matter-transmission. The Starshine is a matter-transmitter, Dona, transmitting itself and us. I wasn't aware of any interval between the time I pressed the stud and the time the altered field shut off. But we came almost a quarter across the Galaxy."

"It was—horrible," Dona said, shivering. "I thought Alphin Three was bad, but the tyranny here is ghastly."

"Alphin Three is a new planet," Kim told her grimly. "This one below us is old. Alphin Three has been occupied for barely two hundred years. Its people have relatively the vigor and the sturdy independence of pioneers, and still they're sheep! We're in an older part of the Galaxy now and the race back here has grown old and stupid and cruel. And I imagine it's ready to die."

He bent forward and made a careful adjustment of the light-operated distance-gauge. He cut it down enormously.

"We'll try it again," he said. He pressed the stud....

An increasing sense of futility and depression crept over Kim and Dona during the next few days.

They visited four solar systems, separated by distances which would have seemed unthinkable before the alteration of the overdrive.

There was no longer any sensation of travel, because no distance required any appreciable period of time. Once, indeed, Kim commented curtly on the danger that would exist if they went too close to the Galaxy's edge. With only the amount of received light to work the cut-out switch, under other circumstances they might have plunged completely out of the Galaxy and to unimaginable distances before the switch could have acted.

"I'm going to have to put a limiting device of some sort on this thing," he observed. "With a limiting device, the transmitter-drive can't stay on longer than a few micro-seconds. If we don't, we might find ourselves lost from our own Galaxy and unable to find it again. Not that it would seem to matter so much."

His skepticism seemed justified. The Starshine was the only vessel now plying among the stars. It had been of the last and best type, though by no means the largest, ever constructed, and by three small changes in its overdrive mechanism Kim had made it into something of which other men had never dreamed.

For the first time in the history of the human race, other galaxies were open to the exploration and the colonization of men. It was probably possible for the cosmos itself to be circumnavigated in the Starshine. But its crew of two humans could find no planet of their own race on which they dared to land.

They approached Voorten II, and found a great planet seemingly empty of human beings. There were roads and cities, but the roads were empty and the cities full of human skeletons. Kim and Dona saw only three living beings of human form, and they were skin and bones and shook clenched fists and gibbered at the slim space-craft as it hovered overhead. The Starshine soared away.

It hovered over Makab VI, and there were towers which had been power-houses rusting into ruin, and human beings naked and chained, pulling ploughs while other human beings flourished whips behind them. The great metropolis where the matter-transmitter should have been was ruins. Unquestionably the matter-transmitter here had been destroyed and the planet was cut off from the rest of civilization.

They came fearfully to rest above the planet center upon Moteh VII and saw decay. The people reveled in the streets, but listlessly, and the communicator brought only barbarous, sensual music and howled songs of a beastliness that was impossible to describe.

The vessel actually touched ground upon Xanin V. Kim and Dona actually talked to two citizens. But those folk were blank-faced and dull. Yet what they told Kim and Dona, apathetically, in response to questioning, was so disheartening that Dona impulsively offered to take them away. But the two citizens were frightened at the idea. They fled when Dona would have urged them.

Out in clear space again, on interplanetary drive, Kim looked at Dona with brooding eyes.

"It looks as if we can't find a home, Dona," he said quietly. "The human race is finished. We completed a job, we humans. We conquered a galaxy and we occupied it, and the job was done. Then we went downhill. You and I, we came from the newest planet of all, and we didn't fit. We're criminals there. But the older planets, like these, are indescribably horrible." He stopped, and asked wryly, "What shall we do, Dona? I'd have liked a wedding ceremony. But what are we going to do?"

Dona smiled at him.

"There's one place yet. The Prime Board called us criminals. Let's look up the criminals on Ades. Maybe—and it's just possible—people who have mustered energy and independence enough to commit political crimes would be bearable. If we don't find anything there, why, we'll go to another galaxy, choose a planet and settle down. And I promise I won't be sorry, Kim!"

Kim made his computations and swung the Starshine carefully. He was able to center the course of the space-ship with absolute precision upon the sun around which Ades circled slowly in lonely majesty. He pressed the matter-transmission stud, and the alarm-bells rang stridently, and there was the sun and the planet Ades barely half a million miles from their starting-point.

It was not a large planet, and there was much ice and snow. The electron telescope showed no monster cities, either, but there were settlements of a size that could be picked out. Kim sent the Starshine toward it.

"Of course, I'm only head of this small city," said the man with the bearskin hat. "And my powers are limited here, but I think we'll find plenty to join us. I'll go, of course, if you'll take me."

Kim nodded in an odd grim satisfaction.

"We'll set up matter-transmitters," he suggested. "Then there'll be complete and continuous communication with this planet from the start."

"Right," said the man with the bearskin hat. He added candidly: "We've brains on Ades, my friend. We've got every technical device the rest of the Galaxy has, except the Disciplinary Circuit, and we won't allow that! If this is a scheme of some damned despot to add another planet to his empire, it won't work. There are three empires already started, you know, all taken by matter-transmitter. But that won't work here!"

"If you build the transmitters yourselves, you'll know there's nothing tricky about the circuits," Kim said. "My offer is to take a transmitter and an exploring party to the next nearest galaxy and pick out a planet there to start on. Ades isn't ideal."

"No," agreed the man with the bearskin hat. "It's too cold, and we're overcrowded. There are twenty million of us and more keep coming out of the transmitter every day. The Galaxy seems to be combing out all its brains and sending them all here. We're short of minerals, though—metals, especially. So we'll pick some good sound planets to start on over in a second galaxy. Hm! Come to the communicator and we'll talk to the other men we need to reach."

They went out of the small building which was the center of government of the quite small city. There was nothing impressive about it, anywhere. It was not even systematically planned. Each citizen, it appeared, had built as he chose. Each seemed to dress as he pleased, too.

To Kim and to Dona there was a startling novelty in the faces they saw about them. On Alphin III almost everybody had looked alike. At any rate their faces had worn the same expression of bovine contentment.

On other planets contentment had not been the prevailing sentiment. On some, despair had seemed to be universal.

But these people, these criminals, were individuals. Their manner was not the elaborate, cringing politeness of Alphin III. It was free and natural.

The communicator-station was rough and ready. It was not a work of art, but a building put up by people who needed a building and built one for that purpose only. The vision-screens lighted up one by one and faces appeared, as variegated as the costumes beneath them. They had a common look for aliveness which was heartening to Kim.

The conference lasted for a long time. There was enthusiasm, and there was reserve. The Starshine would carry a matter-transmitter to the next galaxy and open a way for migration of the criminals of Ades to a new island universe for conquest.

Kim would turn over the construction-records of the space-ship so that others could be built. He would give the details of the matter-transmitter alteration. No space-ships had been attempted by the inhabitants of Ades, because fighting-beams would soon have been mounted on useful planets, against them, and all useful planets contained only enemies.

"What do you want?" asked a figure in one vision-plate. "We don't do things for nothing, here, and we don't take things without paying for them, either."

"Dona and I want only a place to live and a people to live among who are free," Kim answered sharply.

"You've got that," the man in the bearskin hat said. "All right? We'll all call public meetings and confirm these arrangements?"

The heads of other cities nodded.

"We'll pass on the news to other cities at once," another man said. He was one of those who had nodded. "Everybody will wish to come in on it, of course. If not now, then later."

"Wait!" Kim said suddenly. "How about the planets around us? Are we going to leave them enslaved?"

"Nobody can free a slave," a whiskered man in a vision-plate said drily. "We could only release prisoners. In time we may have to take them over, I suppose, but on the planet I come from there aren't a dozen men who'd know how to be free if we emancipated them. They don't want to be free. They're satisfied as they are. If any of them want to be free, they'll be sent here, eventually."

"I am reluctant to desert them," Kim answered slowly.