Title: The Isle of Retribution

Author: Edison Marshall

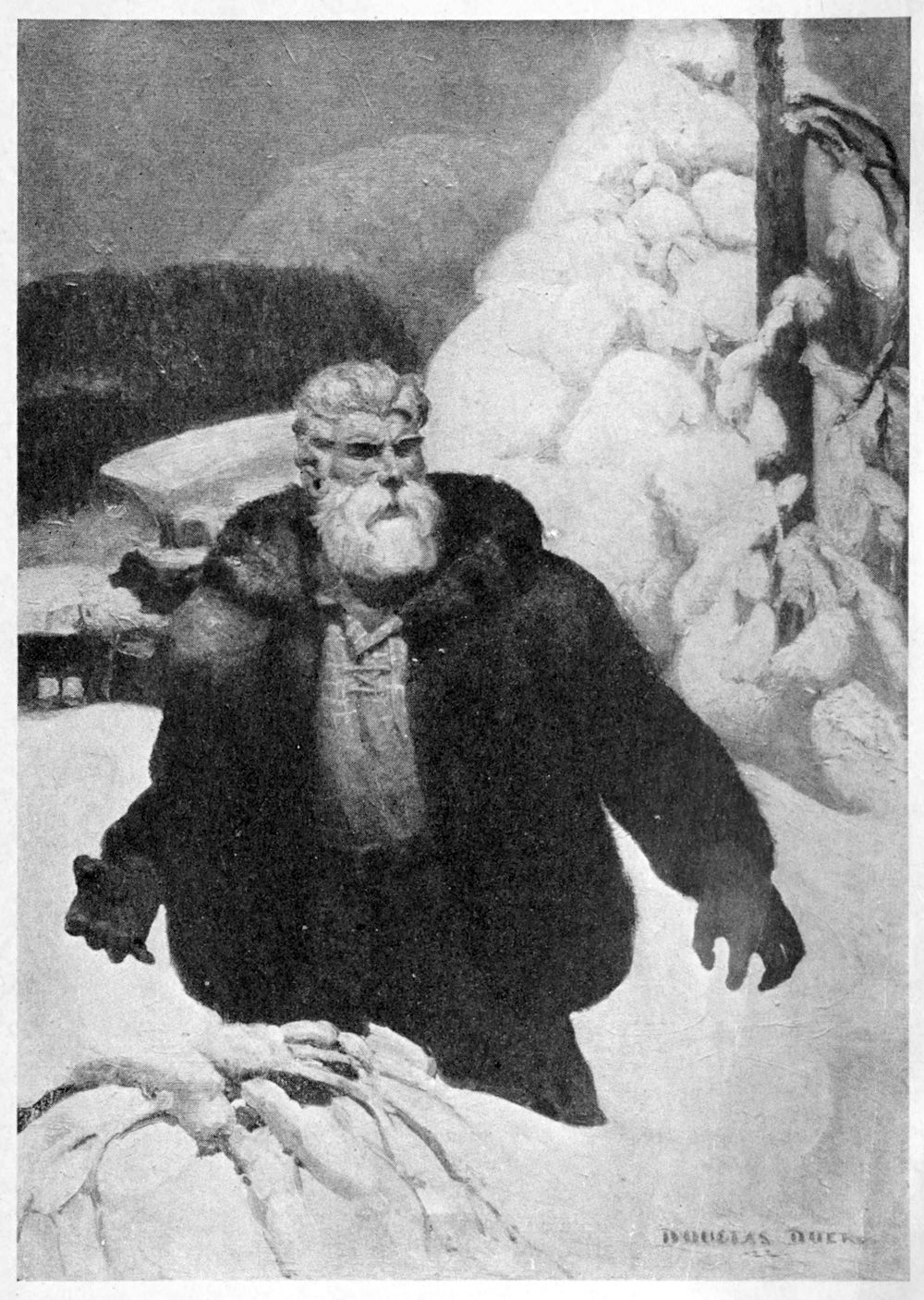

Illustrator: Douglas Duer

Release date: September 30, 2022 [eBook #69070]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Little, Brown and Company

Credits: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net from page images generously made available by the Internet Archive

When he caught sight of the fugitives, they were already out of effective pistol range.

FRONTISPIECE. See page 308.

THE ISLE OF

RETRIBUTION

BY

EDISON MARSHALL

WITH FRONTISPIECE BY

DOUGLAS DUER

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1923

Copyright, 1923,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

Published February, 1923

Printed in the United States of America

The Isle of Retribution

The manifold powers of circumstance were in conspiracy against Ned Cornet this late August afternoon. No detail was important in itself. It had been drizzling slowly and mournfully, but drizzle is not uncommon in Seattle. Ned Cornet had been passing the time pleasantly in the Totem Club, on Fourth Street, doing nothing in particular, nothing exceedingly bad or good or even unusually diverting; but such was quite a customary practice with him. Finally, Cornet’s special friend, Rodney Coburn, had just returned from one of his hundred sojourns in far places,—this time from an especially attractive salmon stream in Canada.

The two young men had met in Coburn’s room at the Totem Club, and the steward had gone thither with tall glasses and ice. Coburn had not returned empty-handed from Canada. Besides pleasant memories of singing reels and throbbing rods and of salmon that raced like wild sea horses down the riffles, he had brought that which was much less healthful,—various dark bottles of time-honored liquors. Partly in celebration of his return, and partly because of the superior quality of the goods that had accompanied him, his friend Ned raised his afternoon limit from two powerful pre-dinner cocktails to no less than four richly amber whiskies-and-sodas. Thus their meeting was auspicious, and on leaving the club, about seven, it came about that Ned Cornet met the rain.

It was not enough to bother him. He didn’t even think about it. It was only a lazy, smoky drizzle that deepened the shadows of falling twilight and blurred the lights in the street. Ned Cornet had a fire within that more or less occupied his thoughts. He didn’t notice the rain, and he quite failed to observe the quick pulsation of the powerful engine in his roadster that might otherwise have warned him that he had long since passed the absolute limit that tolerant traffic officers could permit in the way of speed.

Cornet was not really drunk. His stomach was fortified, by some years of experience, against an amount somewhere in the region of a half-pint of the most powerful spirits,—sufficient poison to kill stone dead a good percentage of the lower animals. Being a higher animal Ned held his liquor surprisingly well. He was somewhat exhilarated, faintly flushed; his eyes had a sparkle as of broken glass, and he felt distinctly warm and friendly toward all the hurrying thousands on the street, but his motor centers were not in the least impaired. Under stress, and by inhaling sharply, he could deceive his own mother into thinking that he had not had a drink. Nevertheless a pleasant recklessness was upon him, and he couldn’t take the trouble to observe such stupid things as traffic laws and rain-wet pavements.

But it came about that this exhilaration was not to endure long. In a space of time so short that it resembled some half-glimpsed incident in a dream, Ned found himself, still at his wheel, the car crosswise in the street and the front wheels almost touching the curb, a terrible and ghastly sobriety upon him. Something had happened. He had gone into a perilous skid at the corner of Fourth and Madison, the car had slid sickeningly out of his control, and at the wrong instant a dark shape, all too plainly another automobile, had lurched out of the murk of the rain. There had been no sense of violent shock. All things had slid easily, the sound at his fender was slow and gentle, and people, in the fading light, had slow, peculiar expressions on their faces. Then a great fear, like a sharp point, pricked him and he sprang from his seat in one powerful leap.

Ned Cornet had had automobiles at his command long before it was safe for him to have his hands on them. When cold sober he drove rather too fast, none too carefully, but had an almost incredible mastery over his car. He knew how to pick his wheel tracks over bumpy roads, and he knew the exact curve that a car could take with safety in rounding a corner. Even now, in the crisis that had just been, he had handled his car like the veteran he was. The wonder was not that he had hit the other car, but rather, considering the speed with which he had come, that it should continue to remain before his sight, but little damaged, instead of being shattered into kindling and dust. His instincts had responded rather well. It was a somewhat significant thing, to waken hope in the breast of an otherwise despairing father, that in that stress and terror he had kept his head, he had handled his brakes and wheel in the only way that would be of any possible good, and almost by miracle had avoided a smashing crash that could have easily killed him and every occupant in the colliding car. Nevertheless it was not yet time to receive congratulations from spectators. There had been serious consequences enough. He was suddenly face to face with the fact that in his haste to get home for dinner he had very likely obliterated a human life.

There was a curious, huddled heap on the dim pavement, just beyond the small car he had struck. It was a girl; she lay very still, and the face half covered by the arm seemed very white and lifeless. And blasted by a terror such as was never known in all his wasted years, Ned leaped, raced, and fell to his knees at her side.

It seemed to him that the soft noise of the crash was not yet dead in the air. It was as if he had made the intervening distance in one leap. In that same little second his brain encompassed limitless areas,—terror, remorse, certain vivid vistas of his past life, the whiteness of the eyelids and the limpness of the little arms, and the startled faces of the spectators who were hurrying toward him. His mental mechanism, dulled before by drink, was keyed to such a degree that the full scope of the accident went home to him in an instant.

The car he had struck was one of the thousands of “jitneys” of which he had so often spoken with contempt. The girl was a shopgirl or factory worker, on her way home. Shaken with horror, but still swift and strong from the stimulus of the crisis, he lifted her head and shoulders in his arms.

It was a dark second in the life of this care-free, self-indulgent son of wealth as he stared into the white, blank, thin face before him. He was closer to the Darkness that men know as Death than he had ever been before,—so close that some of its shadow went into his own eyes, and made them look like odd black holes in his white skin, quite different from the vivid orbs that Rodney Coburn had seen over the tall glasses an hour before. For once, Ned Cornet was face to face with stern reality. And he waited, stricken with despair, for that face to give some sign of life.

It was all the matter of a second. The people who had seen the accident and the remaining passengers of the “jitney” had not yet reached his side. But for all that, the little instant of waiting contained more of the stuff of life than all the rest of Ned Cornet’s time on earth. Then the girl smiled in his face.

“I’m not hurt,” he heard her say, seemingly in answer to some senseless query of his. She shook her head at the same time, and she smiled as she did it. “I know what I’m saying,” she went on. “I’m not hurt—one—bit!”

A great elation and enthusiasm went over the little crowd that was gathering around her. There could be no doubt but that she told the truth. Her voice had the full ring of one whose nerves are absolutely unimpaired. Evidently she had received but the slightest blow from one of the cars when its momentum was all but spent. And now, with the aid of a dozen outstretching hands, she was on her feet.

The little drama, as if hurled in an instant from the void, was already done. Tragedy had been averted; it was merely one of the thousands of unimportant smash-ups that occur in a great city every year. Some of the spectators were already moving on. In just a moment, before half a dozen more words could be said, other cars were swinging by, and a policeman was on the scene asking questions and jotting down license numbers. Just for a moment he paused at Ned’s elbow.

“Your name and address, please?” he asked coldly.

Ned whirled, turning his eyes from the girl’s face for the first time. “Ned Cornet,” he answered. And he gave his father’s address on Queen Anne Hill.

“Show up before Judge Rossman in the morning,” he ordered. “The jitney there will send their bills to you. I’d advise you to pay ’em.”

“I’ll pay ’em,” Ned agreed. “I’ll throw in an extra twenty to pay for their loss of time.”

“This young lady says she ain’t hurt,” the policeman went on. “It certainly is no credit to you that she ain’t. There is plenty of witnesses here if she wants to make a suit.”

“I’ll give this young lady complete satisfaction,” Ned promised. He turned to her in easy friendliness, a queer little crooked smile, winning and astonishingly juvenile, appearing at his mouth. “Now let’s get in my car. I’ll take you home—and we can talk this over.”

They pushed together through the little circle of the curious, he helped her courteously into the big, easy seat of his roadster, and in a moment they were threading their way through the early evening traffic.

“Good Lord,” the man breathed. “I wouldn’t have blamed that mob if they had lynched me. Where do we go?”

She directed him out Madison, into a district of humble, modest, but respectable residences. “It’s lucky you came along—I don’t often get a ride clear to my door.”

“Lucky! I want to say if it wasn’t for all the luck in the world you’d be going to the hospital instead. I’m taking all the blame for that smash back there—I got off mighty lucky. Now let’s settle about the dress—and a few other things. First—you’re sure you’re not hurt?”

He was a little surprised at the gay, girlish smile about her lips. “Not a particle. It would be nice if I could go to the hospital two weeks or so, just to rest—but I haven’t the conscience to do it. I’m not even scratched—just pushed over in the street. And I’m afraid I can’t even charge you for the dress. I’ve always had too much conscience, Mr. Cornet.”

“Of course I’m going to pay——”

“The dress cost only about twenty dollars—at a sale. And it doesn’t seem to be even damaged. Of course it will have to be cleaned. To save you the embarrassment I see growing in your face, I’ll gladly send the bill to you if you like——”

In the bright street light he looked up, studying her face. He had never really observed it before. Before he had watched it for a sign of life that was only the antithesis of death, but now he found himself regarding it from another viewpoint. Her slender, pretty face was wholly in keeping with her humor, her honesty, her instinctive good manners. If she were a factory worker, hard toil had not in the least coarsened or hardened her. Her skin had a healthy freshness, pink like the marvelous pink of certain spring wild flowers, and she had delicate girlish features that wholly suited his appraising eye.

She was one of those girls who have worlds of hair to spend lavishly in setting off piquant faces. It must have been dark brown; at least it looked so in the street light. Below was a clear, girlish brow, with never a line except the friendly ones of companionship and humor. Her eyes seemed to be deeply blue, good-natured, childishly happy, amazingly clear and luminous, a perfect index to her mood. Now they were smiling, partly with delight in the ride and in the luxury of the car, partly from the sheer joy of the adventure. Ned rather wished that the light was better. He’d like to have given them further study.

She had a pretty nose, and full, almost sensuous lips that curled easily and softly as she smiled. Then there was a delectable glimpse of the little hollow of a slender throat, at the collar of her dress.

Ned found himself staring, and he didn’t know just why. He was no stranger to women’s beauty; some degree of it was the rule rather than the exception in the circle in which he moved; but some way this before him now was beauty of a different kind. It was warm, and it went down inside of him and touched some particular mood and fancy that had never manifested itself before. He had seen such beauty, now and again, in children—young girls with the freshness of a spring flower, just emerging into the bloom of first womanhood, and not yet old enough for him to meet in a social way—but it had never occurred to him that it could linger past the “flapper” age. This girl in his car was in her early twenties—over, rather than under—of medium height, with the slender strength of an expert swimmer, yet her beauty was that of a child.

He couldn’t tell, at first, in just what her beauty lay. Other girls had fresh skins, bright eyes, smiling lips and masses of dark, lustrous hair,—and some of them even had the simplicity of good manners. Ned had a quick, sure mind, and for a moment he mused over his wheel as he tried to puzzle it out.

In all probability it lay in the soft, girlish lines about her lips and eyes. Curiously there was not the slightest hardness about them. Some way, this girl had missed a certain hardening process that most of his own girl friends had undergone; the life of the twentieth century, in a city of more than three hundred thousand, had left her unscathed. There were only tenderness and girlish sweetness in the lines, not sophistication, not self-love, not recklessness or selfishness that he had some way come to expect.

But soon after this Ned Cornet caught himself with a whispered oath. He was positively maudlin! The excitement, the near approach to tragedy, the influence of the liquor manifesting itself once more in his veins were making him stare and think like a silly fool. The girl was a particularly attractive shopgirl or factory worker, strong and athletic for all her appealing slenderness, doubtless pretty enough to waken considerable interest in certain of his friends who went in for that sort of thing, but he, Ned Cornet, had other interests. The gaze he bent upon her was suddenly indifferent.

They were almost at their destination now, and he did not see the sudden decline of her mood in response to his dying interest. Sensitive as a flower to sunlight, she realized in a moment that a barrier of caste had dropped down between them. She was silent the rest of the way.

“Would you mind telling me what you do—in the way of work, I mean?” he asked her, at her door. “My father has a business that employs many girls. There might be a chance——”

“I can do almost anything with a needle, thank you,” she told him with perfect frankness. “Fitting, hemstitching, embroidery—I could name a dozen other things.”

“We employ dozens of seamstresses and fitters. I suppose I can reach you here—after work-hours. I’ll keep you in mind.”

An instant later he had bidden her good night and driven away, little dreaming that, through the glass pane of the door, her lustrous blue eyes had followed the red spark that was his tail-light till it disappeared in the deepening gloom.

Ned Cornet kept well within the speed laws on his way back to his father’s beautiful home on Queen Anne Hill. He was none too well pleased with himself, and his thoughts were busy. There would be some sort of a scene with Godfrey Cornet, the gray man whose self-amassed wealth would ultimately settle for the damages to the “jitney” and the affront to the municipality,—perhaps only a frown, a moment’s coldness about the lips, but a scene nevertheless. He looked forward to it with great displeasure.

It was a curious thing that lately he had begun to feel vague embarrassment and discomfiture in his father’s presence. He had been finding it a comfort to avoid him, to go to his club on the evenings his father spent at home, and especially to shun intimate conversation with him. Ned didn’t know just why this was true; perhaps he had never paused to think about it before. He simply felt more at ease away from his father, more free to go his own way. Some way, the very look on the gray face was a reproach.

No one could look at Godfrey Cornet and doubt that he was the veteran of many wars. The battles he had fought had been those of economic stress, but they had scarred him none the less. His face was written over, like an ancient scroll, with deep, dark lines, and every one marked him as the fighter he was.

Every one of his fine features told the same story. His mouth was hard and grim, but it could smile with the kindest, most boyish pleasure on occasion. His nose was like an eagle’s beak, his face was lean with never a sagging muscle, his eyes, coal black, had each bright points as of blades of steel. People always wondered at his trim, erect form, giving little sign of his advanced years. He still looked hard as an athlete; and so he was. He had never permitted “vile luxury’s contagion” to corrupt his tissues. For all the luxury with which he had surrounded his wife and son, he himself had always lived frugally: simple food, sufficient exercise, the most personal and detailed contact with his great business. He had fought upward from utter poverty to the presidency and ownership of one of the greatest fur houses of his country, partly through the exercise of the principle of absolute business integrity, mostly through the sheer dynamic force of the man. His competitors knew him as a fair but remorseless fighter; but his fame carried far beyond the confines of his resident city. Bearded trappers, running their lines through the desolate wastes of the North, were used to seeing him come venturing up their gray rivers in the spring, fur-clad and wind-tanned,—finding his relaxation and keeping fit by personally attending to the buying of some of his furs. Thus it was hard for a soft man to feel easy in his presence.

Ned Cornet wished that he didn’t have to face him to-night. The interview, probably short, certainly courteous, would leave him a vague discomfort and discontent that could only be alleviated by further drinks, many of them and strong. But there was nothing to do but face it. Dependence was a hard lot; unlike such men as Rodney Coburn and Rex Nard, Ned had no great income-yielding capital in his own name. He was somewhat downcast and sullen as he entered the cheerfully lighted hallway of his father’s house.

In the soft light it was immediately evident that he was his father’s son, yet there were certain marked differences between them. Warrior blood had some way failed to come down to Ned. For all his stalwart body, he gave no particular image of strength. There was noticeable extra weight at his abdomen and in the flesh of his neck, and there was also an undeniable flabbiness of his facial muscles.

Godfrey Cornet’s hands and face were peculiarly trim and hard and brown, but in the bright light and under careful scrutiny, his son’s showed somewhat sallow. To a casual observer he showed unmistakable signs of an easy life and luxurious surroundings; but the mark of prolonged dissipation was not immediately evident. Perhaps the little triangles on either side of his irises were not the hard, bluish-white they should be; possibly there was the faintest beginning of a network of fine, red lines just below the swollen flesh sacks beneath his eyes. The eyes themselves were black and vivid, not unlike his father’s; he had a straight, good nose, a rather crooked, friendly mouth, and the curly brown hair of a child. As yet there was no real viciousness in his face. There was amiable weakness, truly, but plenty of friendly boyishness and good will.

He took his place at the stately table so gravely and quietly that his parent’s interest was at once wakened. His father smiled quietly at him across the board.

“Well, Ned,” he asked at last. “What is it to-day?”

“Nothing very much. A very close call, though, to real tragedy. I might as well tell you about it, as likely enough it’ll be in the papers to-morrow. I went into a bad skid at Fourth and Madison, hit a jitney, and before we got quite stopped managed to knock a girl over on the pavement. Didn’t hurt her a particle. But there’s a hundred dollars’ damage to the jit—and a pretty severe scare for your young son.”

As he talked, his eyes met those of his father, almost as if he were afraid to look away. The older man made little comment. He went on with his dessert, and soon the talk veered to other matters.

There hadn’t been any kind of a scene, after all. It was true that his father looked rather drawn and tired,—more so than usual. Perhaps difficult problems had come up to-day at the store. His voice had a peculiar, subdued, quiet note that wasn’t quite familiar. Ned felt a somber heaviness in the air.

He did not excuse himself and hurry away as he had hoped to do. He seemed to feel that to make such an offer would precipitate some impending issue that he had no desire to meet. His father’s thoughts were busy; both his wife and his son missed the usual absorbingly interesting discourse that was a tradition at the Cornet table. The older man finished his coffee, slowly lighted a long, sleek cigar, and for a moment rested with elbows on the table.

“Well, Ned, I suppose I might as well get this off my chest,” he began at last. “Now is as auspicious a time as any. You say you got a good scare to-day. I’m hoping that it put you in a mood so that at least you can give me a good hearing.”

The man spoke rather humbly. The air was electric when he paused. Ned leaned forward.

“It wasn’t anything—that accident to-day,” he answered in a tone of annoyance. “It could have happened to any one on slippery pavements. But that’s ridiculous—about a good hearing. I hope I always have heard everything you wanted to tell me, sir.”

“You’ve been a very attentive son.” Godfrey Cornet paused again. “The trouble, I’m afraid, is that I haven’t been a very attentive father. I’ve attended to my business—and little else—and now I’m paying the piper.

“Please bear with me. It was only a little accident, as you say. The trouble of it is that it points the way that things are going. It could very easily have been a terrible accident—a dead girl under your speeding wheels, a charge of manslaughter instead of the good joke of being arrested for speeding, a term in the penitentiary instead of a fine. Ned, if you had killed the girl it would have been fully right and just for you to spend a good many of the best years of your life behind prison walls. I ask myself whether or not I would bring my influence to bear, in that case, to keep you from going there. I’m ashamed to say that I would.

“You may wonder about that. I would know, in my heart, that you should go there. I am not sure but that you should go there now, as it is. But I would also know that I have been criminal too—criminally neglectful, slothful, avoiding my obligations—just as much as you have been neglectful and slothful and avoiding your obligations toward the other residents of this city when, half-intoxicated, you drove your car at a breakneck pace through the city streets. I can’t accuse you without also accusing myself. Therefore I would try to keep you out of prison. In doing that, I would see in myself further proof of my old weakness—a weak desire to spare you when the prison might make a man of you.”

Ned recoiled at the words, but his father threw him a quick smile. “That cuts a little, doesn’t it? I can’t help it. Ned, your mother and I have always loved you too well. I suppose it is one of the curses of this age—that ease and softness have made us a hysterical, sentimental people, and we love our children not wisely, but too well. I’ve sheltered you, instead of exposing you to the world. The war did not stiffen you—doubtless because you were one of the millions that never reached the front.”

Ned leaned forward. “That wasn’t my fault,” he said with fire. “You know that wasn’t my fault.”

“I know it wasn’t. The fact remains that you lost out. Let me go on. I’ve made it easy for you, always, instead of bitter hard as I should have done. I’ve surrounded you with luxury instead of hardship. You’ve never done an honest day’s toil on earth. You don’t know what it is to sweat, to be so tired you can’t stand, to wonder where the next meal is coming from, to know what a hard and bitter thing life is!

“A girl, thrown on the pavement. A working girl, you said—probably homely, certainly not your idea of a girl. Perhaps, in your heart, you think it wouldn’t have much mattered if you had killed her, except for the awkwardness to you. She was just one of thousands. You, my son, are Ned Cornet—one of our city’s most exalted social set, one of our fashionable young clubmen.”

His tone had changed to one of unspeakable bitterness. Ned leaned forward in appeal. “That isn’t true,” he said sharply. “I’m not a damned snob!”

“Perhaps not. I’m not sure that I know what a snob is. I’ve never met one—only men who have pretended to be snobs to hide their fear of me. Let me say, though, Ned—whatever her lot, no matter how menial her toil, your life could be spared much easier than hers. It would be better that you should be snuffed out than that she should lose one of her working hands. Likely you felt superior to her as you drove her home; in reality you were infinitely inferior. She has gone much farther than you have. She knows more of life; she is harder and better and truer and worth more to this dark world in which we live. The world could ill afford to lose her, a fighter, a worker. It would be better off to lose you—a shirker, a slacker!

“I’m not accusing you. God knows the blame is on my own head. For my part I sprang from the world of toil—never do I go out into that society in which you move but that I thank God for the bitter toil I knew in youth. The reason is that it has put me infinitely above them. Such soft friends as you have wither before my eyes, knowing well that they can not meet me on even grounds; or else they take refuge in an air of conceit, a pretense of caste, that deceives themselves no more than it deceives me. They talk behind my back of my humble origin—fearfully clothing their own nakedness with the garments of worthy, fighting men who have preceded them—and yet their most exalted gates open before my knock. They dare not shut their doors to me. They treat me with the respect that is born of fear.

“That toil, that hard schooling, has made me what I am and given me the highest degree possible of human happiness. I find a satisfaction in living; I am able to hold my head up among men. I have health, the adoring love of a wonderful woman; I give service to the world. I can see old age coming upon me without regret, without vain tears for what might have been, without fear for whatever fate lies beyond. I am schooled for that fate, Ned. I’ve got strength to meet it. My spirit will not be buffeted willy-nilly in those winds that blow between the worlds. I am a man, I’ve done man’s work, and I can hold my place with other men in the great trials to come.

“What those tests are, I do not know. Personally I lean toward an older theology, one mostly outworn now, one cast away by weak men because they are afraid to believe in it. It is not for me to say that Dante foresaw falsely. The only thing I can not believe is the legend over the door—‘Abandon Hope, ye who enter here.’ There is no gateway here or hereafter that can shut out Hope. I believe that no matter how terrible the punishment that lies within those gates, however hard the school, there is a way through and out at last.

“Hell is not the dream of a religious fanatic, Ned. I believe in it just as surely as I believe in a heaven. There must be some school, some bitter, dreadful training camp for those who leave this world unfitted to go on to a higher, better world. Lately souls have been going there in ever-increasing numbers. Let softness and self-indulgence and luxury continue to degenerate this nation, and all travel will be in that direction. My hope is yet, the urge behind all that I’m saying to you to-night, is that you may take some other way.”

His black eyes gleamed over the board. For the moment, he might have been some prophet of old, preaching the Word to the hosts of Israel. The long dining room was deathly still as he paused. Realizing that the intensity of his feeling was wakening the somber poetry within him, revealing his inmost, secret nature, he steadied himself, watching the upcurling smoke of his cigar. When he spoke again his voice and words were wholly commonplace.

“There is no force in heaven or earth so strong as moral force,” he said. “In the end, nothing can stand against it. If it dies in this land, Lord help us—because we will be unable to help ourselves. We can then no longer drive the heathen from our walls. With it, we are great—without it we are a race of weaklings. And with luxury and ease upon us, it seems to me I see it manifested ever less and less.

“Ned, there’s one thing to bring it back—and that is hardship. I mean by hardship all that is opposite to ease: self-restraint instead of license; service instead of self-love; devotion to a cause of right rather than to pleasure; most of all, hard work instead of ease. I’ve heard it said, as a thing to be deplored, that shirt sleeves go to shirt sleeves every three generations. Thank God it is so. There is nothing like shirt sleeves, Ned, to make a man—and hard-working, bunching muscles under them. And through my own weakness I’ve let those fine muscles of yours grow flabby and soft.

“Your mother and I have a lot to answer for. Both of us were busy, I with my business, she with her household cares and social duties, and it was easier to give you what you wanted than to refuse you things for your own good. It was easier to let you go soft than to provide hardship for you. It was pleasanter to give in than to hold out—and we loved you too much to put you through what we should have put you through. We excused you your early excesses. All young men did it, we told each other—you were merely sowing your wild oats. Then I found, too late, that I could not interest you in work—in business. You had always played, and you didn’t want to stop playing. And your games weren’t entirely harmless.

“This thing we’ve talked over before. I’ve never been firm. I’ve let you grow to man’s years—twenty-nine, I believe—and still be a child in experience. The work you do around my business could be done by a seventeen-year-old boy. You don’t know what it means to keep a business day. You come when you like and go when you like. In your folly you are no longer careful of the rights of other, better people—or you wouldn’t have driven as you did to-day. You can no longer be bright and attractive at dinner except under the stimulation of cocktails—nothing really vicious yet, but pointing to the way things are going. Ned, I want to make a man of you.”

He paused again, and their eyes met over the table. All too plainly the elder Cornet saw that his appeal had failed to go home. His son was smiling grimly, his eyes sardonic, unmistakable contempt in the curl of his lips. Whether he was angry or not the gray man opposite could not tell. He hoped so in his heart—that Ned had not sunk so low that he could no longer know the stirring urge of manly anger. A great depression drew nigh and enfolded him.

“This isn’t a theater,” was the calloused reply at last. “You are not delivering a lecture to America’s school children! Strangely, I feel quite able to take care of myself.”

“I only wish that I could feel so too.”

“You must think I’m a child—to try to scare me with threats of hell fire. Father, I didn’t realize that you had this streak of puritanism in you.”

His father made no reply at first. Ned’s bitter smile had seemingly passed to his own lips. “I suppose there’s no use of going on,” he said.

“By all means go on, since you are so warmed up to your subject,” Ned answered coldly. “I wouldn’t like to deprive you of the pleasure. You had something on your mind: what is it?”

“It was a real opportunity for you—a chance to show the stuff you’re made of. It wasn’t much, truly—perhaps I have taken the whole thing too seriously. Ned, I wonder if you like excitement.”

“Do I? You know how I love polo——”

“You love to watch! The point is, do you like excitement well enough to take a slight risk of your life for it? Do you care enough about success, on your own hook, to go through snow and ice to win it? A chance came to-day to make from fifty to a hundred thousand dollars for this firm; all it takes is a little nerve, a little endurance of hardship, a little love of adventure. I hoped to interest you in it—by so doing to get you started along the way that leads to manhood and self-respect. You carry this off successfully, and it’s bound to give you ambition to tackle even harder deals. It means contact with men, a whole world of valuable experience, and a world of fun to boot. It wouldn’t appeal to some of your cheap friends—but heaven knows, if you don’t take it up, I’m going to do it myself.”

“Go ahead, shoot!” Ned urged. He smiled wanly, almost superciliously at the enthusiasm that had overswept his father’s face. The old man’s eyes were gleaming like black diamonds.

It was a curious thing, this love of adventure and trial and achievement! The old man was half-mad, immersed in the Sunday-school sentiments of a dead and moth-eaten generation, yet it was marvelous the joy that he got out of living! He was one of an older generation, or he would never anticipate pleasure in projects that incurred hardship, work, responsibility, the silences of the waste places such as he knew on his annual fur-buying expeditions. His sense of pleasure was weird; yet he was consistent, to say the least. Now he was wildly elated from merely thinking about his great scheme,—doubtless some stupid plan to add further prestige to the great fur house of Godfrey Cornet. Ned himself could not find such happiness in twice the number of drinks that were his usual wont.

“It’s simply this,” his father went on, barely able to curb his enthusiasm. “To-day I met Leo Schaffner at lunch, and in our talk he gave me what I consider a real business inspiration. He tells me, in his various jobbing houses, he has several thousand silk and velvet gowns and coats and wraps left on his hands in the financial depression that immediately followed the war. He was cussing his luck because he didn’t know what to do with them. Of course they were part of the surplus that helped glut the markets when hard times made people stop buying—stock that was manufactured during the booming days of the war. He told me that this finery was made of the most beautiful silks and velvets, but all of it was a good three seasons out of style. He offered me the lot of two thousand for—I’m ashamed to tell you how much.”

“Almost nothing!” his son prompted him.

“Yes. Almost nothing. And I took him up.”

His son leaned back, keenly interested for the first time. “Good Lord, why? You can’t go into business selling out-of-date women’s clothes!”

“Can’t, eh? Son, while he was talking to me, it occurred to me all at once that the least of those gowns, the poorest one in the lot, was worth at least a marten skin! Think of it! A marten skin, from Northern Canada and Alaska, returned the trapper around sixty dollars in 1920. Now let me get down to brass tacks.

“It’s true I don’t intend to sell any of those hairy old white trappers any women’s silk gowns. But this was what I was going to have you do: first you were to hire a good auxiliary schooner—a strong, sturdy, seaworthy two-masted craft such as is used in northern trading. You’d fit that craft out with a few weeks’ supplies and fill the hold with a couple of thousand of those gowns. You’d need two or three men to run the launch—I believe the usual crew is a pilot, a first and second engineer, and a cook—and you’d have to have a seamstress to do fitting and make minor alterations. Then you’d start up for Bering Sea.

“You may not know it, but along the coast of Alaska, and throughout the islands of Bering Sea there are hundreds of little, scattered tribes of Indians, all of them trappers of the finest, high-priced furs. Nor do their women dress in furs and skins altogether, either, as popular legend would have you believe. Through their hot, long summer days they wear dresses like American women, and the gayer and prettier the dresses, the better they like ’em. To my knowledge, no one has ever fed them silk—simply because silk was too high—but being women, red or white, they’d simply go crazy over it.

“The other factor in the combination is that the Intrepid, due to the unsettled fur market, failed to do any extensive buying on her last annual trading trip through the islands, and as a result practically all the Indians have their full catch on hand. The Intrepid is the only trader through the particular chain of islands I have in mind—the Skopin group, north and east of the Aleutian chain—and she’s not counting on going up again till spring. Then she’ll reap a rich harvest—unless you get there first.

“The Skopin Islands are charted—any that are inhabited at all—easy to find, easy to get to with a seaworthy launch. Every one of those Indians you’ll find there will buy a dress for his squaw or his daughter to show off in, during the summer, and pay for it with a fine piece of fur. For some of the brighter, richer gowns I haven’t any doubt but that you could get blue and silver fox. As I say, the worst of ’em is worth at least a single marten. Considering your lack of space, I’d limit you to marten, blue and silver fox, fisher and mink, and perhaps such other freak furs as would bring a high price—no white fox or muskrat or beaver, perhaps not even ermine and land otter. Ply along from island to island, starting north and working south and west clear out among the Aleuts, to keep out of the way of the winter, showing your dresses at the Indian villages and trading them for furs!

“This is August. I’m already arranging for a license. You’d have to get going in a week. Hit as far north as you want—the farther you go the better you will do—and then work south. Making a big chain that cuts off the currents and the tides, the Skopin group is surrounded by an unbroken ice sheet in midwinter, so you have to count on rounding the Aleutian Peninsula into Pacific waters some time in November. If you wait much longer you’re apt not to get out before spring.

“That’s the whole story. The cargo of furs you should bring out should be worth close to a hundred thousand. Expenses won’t be fifteen thousand in all. It would mean work; dealing with a bunch of crafty redskins isn’t play for boys! Maybe there’d be cold and rough weather, for Bering Sea deserves no man’s trust. But it would be the finest sport in the world, an opportunity to take Alaskan bear and tundra caribou—plenty of adventure and excitement and tremendous profits to boot. It would be a man’s job, Ned—but you’d get a kick out of it you never got out of a booze party in your life. And we split the profits seventy-five—twenty-five—the lion’s share to you.”

He waited, to watch Ned’s face. The young man seemed to be musing. “I could use fifty thousand, pretty neat,” he observed at last.

“Yes—and don’t forget the fun you’d have.”

“But good Lord, think of it. Three months away from Second Avenue.”

“The finest three months of your life—worth all the rest of your stupid, silly past time put together.”

Almost trembling in his eagerness, the old man waited for his son’s reply. The latter took out a cigarette, lighted it, and gazed meditatively through the smoke. “Fifty thousand!” he whispered greedily. “And I suppose I could stand the hardship.”

Then he looked up, faintly smiling. “I’ll go, if Lenore will let me,” he pronounced at last.

The exact moment that her name was on Ned’s lips, Lenore Hardenworth herself, in her apartment in a region of fashionable apartments eight blocks from the Cornet home, was also wondering at the perverse ways of parents. It was strange how their selfish interests could disarrange one’s happiest plans. All in all, Lenore was in a wretched mood, savagely angry at the world in general and her mother in particular.

They had had a rather unpleasant half-hour over their cigarettes. Mrs. Hardenworth had been obdurate; Lenore’s prettiest pouts and most winsome ways hadn’t moved her a particle. The former knew all such little wiles; time was when she had practiced them herself with consummate art, and she was not likely to be taken in with them in her old age! Seeing that these were fruitless, her daughter had taken the more desperate stand of anger, always her last resort in getting what she wanted, but to-night it some way failed in the desired effect. There had been almost, if not quite, a scene between these two handsome women under the chandelier’s gleam—and the results, from Lenore’s point of view, had been absolutely nil. Mrs. Hardenworth had calmly stood her ground.

It was the way of the old, Lenore reflected, to give too much of their thought and interest to their own fancied ills. Not even a daughter’s brilliant career could stand between. And who would have guessed that the “nervousness” her mother had complained of so long, pandered to by a fashionable quack and nursed like a baby by the woman herself, should ever lead to such disquieting results. The doctor had recommended a sea voyage to the woman, and the old fool had taken him at his word.

It was not that Lenore felt she could not spare, for some months, her mother’s guiding influence. It was merely that sea voyages cost money, and money, at that particular time, was scarce and growing scarcer about the Hardenworth apartment. Lenore needed all that was available for her own fall and winter gowns, a mink or marten coat to take the place of her near-seal cloak, and for such entertaining as would be needed to hold her place in her own set. Seemingly the only course that remained was to move forward the date of her marriage to Ned, at present set for the following spring.

She dried her eyes, powdered her nose; and for all the late storm made a bewitching picture as she tripped to the door in answer to her fiancé’s knock. Lenore Hardenworth was in all probability the most beautiful girl in her own stylish set and one of the most handsome women in her native city. She was really well known, remembered long and in many places, for her hair. It was simply shimmering gold, and it framed a face of flowerlike beauty,—an even-featured, oval face, softly tinted and daintily piquant. Hers was not a particularly warm beauty, yet it never failed to win a second glance. She had fine, firm lips, a delicate throat, and she had picked up an attractive way of half-dropping firm, white lids over her gray, langourous eyes.

No one could wonder that Lenore Hardenworth was a social success. Besides her beauty of face, the grace of a slender but well-muscled form, she unquestionably had a great deal of ambition and spirit. She was well schooled in the tricks of her trade: charming and ingratiating with her girl friends, sweet and deeply respectful to the old, and striking a fine balance between recklessness and demureness with available men. It can be said for Lenore that she wasted no time with men who were not eligible, in every sense of the word. Lenore had her way to make in this world of trial and stress.

Long ago Ned had chosen her from among her girl friends as the most worthy of his courtship,—a girl who could rule over his house, who loved the life that he lived, whose personal appeal was the greatest. Best of all, she was the product of his own time: a modern girl in every sense of the word. The puritanism he deplored in his own parents was conspicuously absent in her. She smoked with the ease and satisfaction of a man; she held her liquor like a veteran; and of prudery she would never be accused. Not that she was ever rough or crude. Indeed there was a finesse about her harmless little immoralities that made them, to him, wholly adorable and charming. She was always among the first to learn the new dances, and no matter what their murky origin—whether the Barbary Coast or some sordid tenderloin of a great Eastern city—she seemed to be able to dance them without ever conveying the image of vulgarity. Her idea of pleasure ran along with his. Life, at her side, offered only the most delectable vistas.

Besides, the man loved her. His devotion was such that it was the subject of considerable amusement among the more sophisticated of their set. He’d take the egg, rather than the horse-and-buggy, they told each other, and to those inured in the newest slang, the meaning was simply that Lenore, rather than Ned, would be head of their house. The reason, they explained wisely, was that it spelled disaster to give too much of one’s self to a wife these days. Such devotion put a man at a disadvantage. The woman, sure of her husband, would be speedily bored and soon find other interests. Of course Lenore loved him too, but she kept herself better in hand. For all his modern viewpoint, it was to be doubted that Ned had got completely away from the influence of a dead and moth-eaten generation. Possibly some little vestige of his parent’s puritanism prevailed in him still!

Ned came in soberly, kissed the girl’s inviting lips, then sat beside her on the big divan. Studying his grave face, she waited for him to speak.

“Bad news,” he said at last.

She caught her breath in a quick gasp. It was a curious thing, indicating, perhaps, a more devout interest in him than her friends gave her credit for, that a sudden sense of dismay seemed to sweep over her. Yet surely no great disaster had befallen. There was no cause to fear that some one of the mighty arms on which they leaned for happiness—the great fur house of Cornet, for instance—had weakened and fallen. Some of the warm color paled in her face.

“What is it?” She spoke almost breathlessly, and he turned toward her with wakened interest.

“Nothing very important,” he told her casually. “I’m afraid I startled you with my lugubrious tones. I’ve got to go away for three months.”

She stared a moment in silence, and a warm flush, higher and more angry than that which had just faded, returned to her cheeks. Just for an instant there was a vague, almost imperceptible hardening of the little lines about her beautiful eyes.

“Ned! You can’t! After all our plans. I won’t hear of it——”

“Wait, dearest!” the man pleaded. “Of course I won’t go if you say not——”

“Of course I say not——”

“But it’s a real opportunity—to make forty or fifty thousand. Wait till I tell you about it, anyway.”

He told her simply: the exact plan that his father had proposed. Her interest quickened as he talked. She had a proper respect for wealth, and the idea of the large profits went home speedily and surely to her imagination, shutting out for the moment all other aspects of the affair. And soon she found herself sitting erect, listening keenly to his every word.

The idea of trading obsolete gowns for beautiful furs was particularly attractive to her. “I’ve got some old things I could spare,” she told him eagerly. “Why couldn’t you take those with you and trade them to some old squaw for furs?”

“I could! I don’t see why I shouldn’t bring you back some beauties.”

Her eyes were suddenly lustful. “I’d like some silver fox—and enough sable for a great wrap. Oh, Ned—do you think you could get them for me?”

His face seemed rather drawn and mirthless as he returned her stare. It had been too complete a victory. It can be said for the man that he had come with the idea of persuading Lenore to let him go, to let him leave her arms for the sake of the advantages to be accrued from the expedition, but at least he wanted her to show some regret. He didn’t entirely relish her sudden, unbounded enthusiasm, and the avaricious gleam in her eyes depressed and estranged him.

But Lenore made no response to his darkened mood. Sensitive as she usually was, she seemed untouched by it, wholly unaware of his displeasure. She was thinking of silver fox, and the thought was as fascinating as that of gold to a miser. And now her mind was reaching farther, moving in a greater orbit, and for the moment she sat almost breathless. Suddenly she turned to him with shining eyes.

“Ned, what kind of a trip will this be?” she asked him.

He was more held by the undertone of excitement in her voice than by the question itself. “What is it?” he asked. “What do you mean——?”

“I mean—will it be a hard trip—one of danger and discomfort?”

“I don’t think so. I’m going to get a comfortable yacht—it will be a launch, of course, but a big, comfortable one—have a good cook and pleasant surroundings. You know, traveling by water has got any other method skinned. In fact, it ought to be as comfortable as staying at a club, not to mention the sport in hunting, and so on. I don’t intend to go too far or too long—your little Ned doesn’t like discomfort any too well to deliberately hunt it up. I can make it just as easy a trip as I want. It’s all in my hands—hiring crew, schooner, itinerary, and everything. Of course, father told a wild story about cold and hardship and danger, but I don’t believe there’s a thing in it.”

“I don’t either. It makes me laugh, those wild and woolly stories about the North! It’s just about as wild as Ballard! Edith Courtney went clear to Juneau and back on a boat not long ago and didn’t have a single adventure—except with a handsome young big-game hunter in the cabin.”

“But Juneau—is just the beginning of Alaska!”

“I don’t care. This hardship they talk about is all poppycock, and you know it—and the danger too. To hear your father talk, and some of the others of the older generation, you’d think they had been through the infernal regions! They didn’t have the sporting instincts that’ve been developed in the last generation, Ned. Any one of our friends would go through what they went through and not even bother to tell about it. I tell you this generation is better and stronger than any one that preceded it, and their stories of privation and danger are just a scream! I’m no more afraid of the North than I am of you.”

She paused, and he stared at her blankly. He knew perfectly well that some brilliant idea had occurred to her: he was simply waiting for her to tell it. She moved nearer and slipped her hand between his.

“Ned, I’ve a wonderful plan,” she told him. “There’s no reason why we should be separated for three months. You say the hiring of the launch, itinerary, and everything is in your hands. Why not take mother and me with you?”

“My dear——”

“Why not? Tell me that! The doctor has just recommended her a sea trip. Where could she get a better one? Of course you’d have to get a big, comfortable launch——”

“I intended to get that, anyway.” Slowly the light that shone in her face stole into his. “Are you a good sailor——?”

“It just happens that neither mother nor I know what sea-sickness means. Otherwise, I’m afraid we wouldn’t find very much pleasure in the trip. You remember the time, in Rex Nard’s yacht, off Columbia River bar? But won’t you be in the inside passage, anyway?”

“The inside passage doesn’t go across the Bay of Alaska—but father says it’s all quiet water among the islands we’ll trade at, in Bering Sea. It freezes over tight in winter, so it must be quiet.” He paused, drinking in the advantages of the plan. They would be together; that point alone was inducement enough for him. By one stroke an arduous, unpleasant business venture could be turned into a pleasure trip, an excursion on a private yacht over the wintry waters of the North. It was true that Lenore’s point of view was slightly different, but her enthusiasm was no less than his. The plan was a perfect answer to the problem of her mother’s sea trip and the inevitable expense involved. She knew her mother’s thrifty disposition; she would be only too glad to take her voyage as the guest of her daughter’s fiancé. And both of them could robe themselves in such furs as had never been seen on Second Avenue before.

“Take you—I should say I will take you—and your mother, too,” he was exclaiming with the utmost enthusiasm and delight. “Lenore, it will be a regular party—a joy-ride such as we never took before.”

For a moment they were silent, lost in their own musings. The wind off the Sound signaled to them at the windows—rattling faintly like ghost hands stretched with infinite difficulty from some dim, far-off Hereafter. It had lately blown from Bering Sea, and perhaps it had a message for them. Perhaps it had heard the scornful words they had spoken of the North—of the strange, gray, forgotten world over which it had lately swept—but there was no need to tell them that they lied. A few days more would find them venturing northward, and they could find out for themselves. But perhaps the wind had a note of grim, sardonic laughter as it sped on in its ceaseless journey.

Ned planned to rise early, but sleep was heavy upon him when he tried to waken. It was after ten when he had finished breakfast and was ready to begin active preparations for the excursion. His first work, of course, was to see about hiring a launch.

Ten minutes’ ride took him to the office of his friend, Rex Nard, vice-president of a great marine-outfitting establishment, and five minutes’ conversation with this gentleman told him all he wanted to know. Yes, as it happened Nard knew of a corking craft that was at that moment in need of a charterer, possibly just the thing that Cornet wanted. The only difficulty, Nard explained, was that it was probably a much better schooner than was needed for casual excursions into northern waters.

“This particular craft was built for a scientific expedition sent out by one of the great museums,” Nard explained. “It isn’t just a fisherman’s scow. She has a nifty galley and a snug little dining saloon, and two foxy little staterooms for extra toney passengers. Quite an up-stage little boat. Comfortable as any yacht you ever saw.”

“Staunch and seaworthy?”

“Man, this big-spectacled outfit that had it built took it clear into the Arctic Sea—after walrus and polar bear and narwhal and musk ox; and she’s built right. I’d cross the Pacific in her any day. Her present owners bought her with the idea of putting her into coastal service, both passengers and freight, between various of the little far northern towns, but the general exodus out of portions of Alaska has left her temporarily without a job.”

“How about cargo space?”

“I don’t know exactly—but it was big enough for several tons of walrus and musk ox skeletons, so it ought to suit you.”

“What do you think I could get her for?”

“I don’t think—I know. I was talking to her owner yesterday noon. You can get her for ninety days for five thousand dollars—seventy-five per for a shorter time. That includes the services of four men, licensed pilot, first and second engineer, and a nigger cook; and gas and oil for the motor.”

Ned stood up, his black eyes sparkling with elation, and put on his hat. “Where do I find her?”

“Hunt up Ole Knutsen, at this address.” Nard wrote an instant on a strip of paper. “The name of the craft is the Charon.”

“The Charon! My heavens, wasn’t he the old boy who piloted the lost souls across the river Styx? If I were a bit superstitious——”

“You’d be afraid you were headed straight for the infernal regions, eh? It does seem to be tempting providence to ride in a boat with such a name. Fortunately the average man Knutsen hires for his crew doesn’t know Charon from Adam. Seamen, my boy, are the most superstitious crowd on earth. No one can follow the sea and not be superstitious—don’t ask me why. It gets to them, some way, inside.”

“Sorry I can’t stay to hear a lecture on the subject.” Ned turned toward the door. “Now for Mr. Knutsen.”

Ned drove to the designated address, found the owner of the craft, and executed a charter after ten minutes of conversation. Knutsen was a big, good-natured man with a goodly share of Norse blood that had paled his eyes and hair. Together they drew up the list of supplies.

“Of course, we might put in some of dis stuff at nordern ports,” Knutsen told him in the unmistakable accent of the Norse. “You’d save money, though, by getting it here.”

“All except one item—last but not least,” Ned assured him. “I’ve got to stop at Vancouver.”

“Canadian territory, eh——?”

“Canadian whisky. Six cases of imperial quarts. We’ll be gone a long time, and a sailor needs his grog.”

At which the only comment was made after the door had closed and the aristocratic fur trader had gone his way. The Norseman sat a long time looking into the ashes of his pipe. “Six cases—by Yiminy!” he commented, with good cheer. “If his Pop want to make money out of dis deal he better go himself!”

There was really very little else for Ned to do. The silk gowns and wraps that were to be his principal article of trade would not be received for a few days at least; and seemingly he had arranged for everything. He started leisurely back toward his father’s office.

But yes, there was one thing more. His father had said that his staff must include a fitter,—a woman who could ply the needle and make minor alterations in the gowns. For a moment he mused on the pleasant possibility that Lenore and her mother could hold up that end of the undertaking. It would give them something to do, an interest in the venture; it would save the cost of hiring a seamstress. But at once he laughed at himself for the thought. He could imagine the frigid, caste-proud Mrs. Hardenworth in the rôle of seamstress! In the first place she likely didn’t know one end of a needle from another. If in some humble days agone she had known how to sew, she was not the type that would care to admit it now. He had to recognize this fact, even though she were his sweetheart’s mother. Nor would she be likely to take kindly to the suggestion. The belligerence with which she had always found it necessary to support her assumption of caste would manifest itself only too promptly should he suggest that she become a needlewoman, even on a lark. Such larks appealed to neither Mrs. Hardenworth nor her daughter. And neither of them would care for such intimate relations with the squaws, native of far northern villages. The two passengers could scarcely be induced to speak to such as these, much less fit their dresses. No, he might as well plan on taking one of his father’s fitters.

And at this point in his thoughts he paused, startled. Later, when the idea that had come to him had lost its novelty, he still wondered about that strange little start that seemed to go all over him. It was some time before he could convince himself of the real explanation—that, though seamstress she was, on a plane as far different from his own Lenore as night was from day, the friendliness and particularly the good sportsmanship of his last night’s victim had wakened real gratitude and friendship for her. He felt really gracious toward her, and since it was necessary that the expedition include a seamstress, it would not be bad at all to have her along. She had shown the best of taste on the way home after the accident, and certainly she would offend Lenore’s and his own sensibilities less than the average of his father’s employees.

He knew where he could procure some one to do the fitting. Had not Bess Gilbert, when he had left her at her door the previous evening, told him that she knew all manner of needlecraft? Her well-modeled, athletic, though slender form could endure such hardships as the work involved; and she had the temperament exactly needed: adventurous, uncomplaining, courageous. He turned at once out Madison where Bess lived.

She was at work at that hour, a gray, sweet-faced woman told him, but he was given directions where he might find her. Ten minutes later he was talking to the young lady herself.

Wholly without warmth, just like the matter of business that it was, he told her his plan and offered her the position. It was for ninety days, he said, and owing to the nature of the work, irregular hours and more or less hardship, her pay would be twice that which she received in the city. Would she care to go?

She looked up at him with blue eyes smiling,—a smile that crept down to her lips for all that she tried to repel it. She looked straight into Ned’s eyes as she answered him simply, candidly, quite like a social equal instead of a lowly employee. And there was a lilt in her voice that caught Ned’s attention in spite of himself.

“I haven’t had many opportunities for ocean travel,” she told him—and whether or not she was laughing at him Ned Cornet couldn’t have sworn! Her tone was certainly suspiciously merry. “Mr. Cornet, I’ll be glad enough to accompany your party, any time you say.”

It was a jesting, hilarious crowd that gathered one sunlit morning to watch the departure of the Charon. Rodney Coburn was there, and Rex Nard, various matrons who were members of Mrs. Hardenworth’s bridge club, and an outer and inner ring of satellites that gyrated around such social suns as Ned and Lenore. Every one was very happy, and no one seemed to take the expedition seriously. The idea of Ned Cornet, he of the curly brown hair, in the rôle of fur trader in the frozen wastes of the North appealed to his friends as being irresistibly comic. The nearest approach to seriousness was Coburn’s envy.

“I’d like to be in your shoes,” he told Ned. “Just think—a chance to take a tundra caribou, a Kodiac bear, and maybe a polar bear and a walrus—all in one swoop! I’ll have to hand over my laurels as a big-game hunter when you get back, old boy!”

“Lewis and Clark, Godspeed!” Ted Wynham, known among certain disillusioned newspaper men as “the court jester”, announced melodramatically from a snubbing block. “In token of our esteem and good wishes, we wish to present you with this magic key to success and happiness.” He held out a small bundle, the size of a jack-knife, carefully wrapped. “You are going North, my children! You, Marco Polo”—he bowed handsomely to Ned—“and you, our lady of the snows,”—addressing Lenore—“and last but not least, the chaperone”—bowing still lower to Mrs. Hardenworth, a big, handsome woman with iron-gray hair and large, even features—“will find full use for the enclosed magic key in the wintry, barbarous, but blessed lands of the North. Gentleman and ladies, you are not venturing into a desert. Indeed, it is a land flowing with milk and honey. And this little watch charm, first aid to all explorers, the friend of all dauntless travelers such as yourselves, explorers’ delight, in fact, will come in mighty handy! Accept it, with our compliments!”

He handed the package to Ned, and a great laugh went up when he revealed its contents. It contained a gold-mounted silver cork-screw!

Both Lenore and her mother seemed in a wonderful mood. The ninety-day journey on those far-stretching sunlit waters seemed to promise only happiness for them. Mrs. Hardenworth was getting her sea trip, and under the most pleasant conditions. There would also, it seemed, be certain chances for material advantages, none of which she intended to overlook. In her trunk she had various of her own gowns—some of them slightly worn, it was true; some of them stained and a trifle musty—yet suddenly immensely valuable in her eyes. She had intended to give them to the first charity that would condescend to accept them, but now she didn’t even trust her own daughter with them. Somewhere in those lost and desolate islands of the North she intended trading them for silver fox! Ned had chest upon chest of gowns to trade; surely she would get a chance to work in her own. Her daughter looked forward to the same profitable enterprise, and besides, she had the anticipation of three wonderful, happy months’ companionship with the man of her choice.

They had dressed according to their idea of the occasion. Lenore wore a beautifully tailored middy suit that was highly appropriate for summer seas, but was nothing like the garb that Esquimo women wear in the fall journeys in the Oomiacs. Mrs. Hardenworth had a smart tailored suit of small black and white check, a small hat and a beautiful gray veil. Both of them carried winter coats, and both were fitted out with binoculars, cameras, and suchlike oceanic paraphernalia. Knutsen, of course, supposed that their really heavy clothes, great mackinaws and slickers and leather-lined woolens, such as are sometimes needed on Bering Sea, were in the trunks he had helped to stow below. In this regard the blond seaman, helmsman and owner of the craft, had made a slight mistake. In a desire for a wealth of silver fox to wear home both trunks had been filled with discarded gowns to the exclusion of almost everything else.

Ned, in a smart yachting costume, had done rather better by himself. He had talked with Coburn in regard to the outfit, and his duffle bag contained most of the essentials for such a journey. And Bess’s big, plain bag was packed full of the warmest clothes she possessed.

Bess did not stand among the happy circle of Ned’s friends. Her mother and sister had come down to the dock to bid her good-by, and they seemed to be having a very happy little time among themselves. Bess herself was childishly happy in the anticipation of the adventure. Hard would blow the wind that could chill her, and mighty the wilderness power that could break her spirit!

The captain was almost ready to start the launch. McNab, the chief engineer, was testing his engines; Forest, his assistant, stood on the deck; and the negro cook stood grinning at the window of the galley. But presently there was an abrupt cessation of the babble of voices in the group surrounding Ned.

Only Ted Wynham’s voice was left, trailing on at the high pitch he invariably used in trying to make himself heard in a noisy crowd. It sounded oddly loud, now that the laughter had ceased. Ted paused in the middle of a word, startled by the silence, and a secret sense of vague embarrassment swept all his listeners. A tall man was pushing through the crowd, politely asking right of way, his black eyes peering under silver brows. For some inexplicable reason the sound of frolic died before his penetrating gaze.

But the groups caught themselves at once. They must not show fear of this stalwart, aged man with his prophet’s eyes. They spoke to him, wishing him good day, and he returned their bows with faultless courtesy. An instant later he stood before his son.

“Mother couldn’t get down,” Godfrey Cornet said simply. “She sent her love and good wishes. A good trip, Ned—but not too good a trip.”

“Why not—too good a trip?”

“A little snow, a little cold—maybe a charging Kodiac bear—fine medicine for the spirit, Ned. Good luck!”

He gave his hand, then turned to extend good wishes to Mrs. Hardenworth and Lenore. He seemed to have a queer, hesitant manner when he addressed the latter, as if he had planned to give some further, more personal message, but now was reconsidering it. Then the little group about him suddenly saw his face grow vivid.

“Where’s Miss Gilbert——?”

The group looked from one to another. As always, they were paying the keenest attention to his every word; but they could not remember hearing this name before. “Miss Gilbert?” his son echoed blankly. “Oh, you mean the seamstress——”

“Of course—the other member of your party.”

“She’s right there, talking to her mother.”

A battery of eyes was suddenly turned on the girl. Seemingly she had been merely part of the landscape before, unnoticed except by such clandestine gaze as Ted Wynham bent upon her; but in an instant, because Godfrey Cornet had known her name, she became a personage of at least some small measure of importance. Without knowing why she did it, Mrs. Hardenworth drew herself up to her full height.

Cornet walked courteously to the girl’s side and extended his hand. “Good luck to you, and a pleasant journey,” he said, smiling down on her. “And, Miss Gilbert, I wonder if I could give you a charge——”

“I’ll do my best—anything you ask——”

“I want you to look after my son Ned. He’s never been away from the comforts of civilization before—and if a button came off, he’d never know how to put it on. Don’t let him come to grief, Miss Gilbert. I’m wholly serious—I know what the North is. Don’t let him take too great a risk. Watch out for his health. There’s nothing in this world like a woman’s care.”

There was no ring of laughter behind him. No one liked to take the chance that he was jesting, and no one could get away from the uncomfortable feeling that he might be in earnest. Bess’s reply was entirely grave.

“I’ll remember all you told me,” she told him simply.

“Thank you—and a pleasant voyage.”

Even now the adventurers were getting aboard. Mrs. Hardenworth was handing her bag to Knutsen—she had mistaken him for a cabin boy—with instructions to carry it carefully and put it in her stateroom; Lenore was bidding a joyous farewell to some of her more intimate friends. The engine roared, the water churned beneath the propeller, the pilot called some order in a strident voice. The boat moved easily from the dock.

Swiftly it sped out into the Sound. A great shout was raised from the dock, hands waved, farewell words blew over the sunlit waters. But there was one of the four seafarers on the deck who seemed neither to hear nor to see. He stood silent, a profundity of thought upon him never experienced before.

He was wondering at the reality of the clamor on the shore. How many were there in the farewell party who after a few weeks would even remember his existence? If the blond man at the wheel were in reality Charon, piloting him to some fabled underworld from which he could never return, how quickly he would be forgotten, how soon they would fail to speak his name! He felt peculiarly depressed, inwardly baffled, deeply perplexed.

Were all his associations this same fraud? Was there nothing real or genuine in all the fabric of his life? As he stood erect, gazing out over the shimmering waters, Lenore suddenly gazed at him in amazement.

For the moment there was a striking resemblance to his father about his lips and in the unfathomable blackness of his eyes. Her own reaction was a violent start, a swift feeling of apprehension that she could not analyze or explain. Her instincts were sure and true: she must not let this side of him gain the ascendency. Her very being seemed to depend on that.

But swiftly she called him from his preoccupation. She had something to show him, she said,—a parting gift that Ted Wynham had left in her stateroom. It was a dark bottle of a famous whisky, and it would suffice their needs, he had said, until they should reach Vancouver.

Mrs. Hardenworth had made it a point to go immediately to her stateroom, but at once she reappeared on deck. She seemed a trifle more erect, her gray eyes singularly wide open.

“Ned, dear, I wonder if that fellow made a mistake when he pointed out my stateroom,” she began rather stiffly. “I want to be sure I’ve got the right one that you meant for me——”

“It’s the one to the right,” Ned answered, somewhat unhappily. He followed her along the deck, indicating the room she and her daughter were to occupy. “Did you think he was slipping something over on you, taking a better one himself?”

“I didn’t know. You can’t ever tell about such men, Ned; you know that very well. Of course, if it is the one you intended for me, I’m only too delighted with it——”

“It’s really the best on the ship. It’s not a big craft, you know; space is limited. I’m sorry it’s so small and dark, and I suppose you’ve already missed the running water. I do hope it won’t be too uncomfortable. Of course, you can have the one on the other side, but it’s really inferior to this——”

“That’s the only other one? Ned, I want you to have the best one——”

“I’m sorry to say I’m not going to have any. Miss Gilbert has to have the other. But there’s a corking berth in the pilot house I’m going to occupy.”

“I’d never let Miss Gilbert have it!” The woman’s eyes flashed. “I wouldn’t hear of it—you putting yourself out for your servant. Why can’t she occupy the berth in the pilot house——”

“I don’t mind at all. Really I don’t. The girl couldn’t be expected to sleep where there are men on watch all night.”

“It’s a shame, just the same. Here she is going to have one of the two best staterooms all to herself.”

At once she returned to her room; but the little scene was not without results. In the first place it implanted a feeling of injury in Ned, whose habits of mind made him singularly open to suggestion; and in the second it left Mrs. Hardenworth with a distinct prejudice against Bess. She was in a decided ill-humor until tea time, when she again joined Ned and Lenore on the deck.

She was not able to resist the contagion of their own high spirits, and soon she was joining in their chat. Everything made for happiness to-day. The air was cool and bracing, the blue waters glittered in the sun, a quartering wind filled the sails of the Charon, and with the help of the auxiliary engines whisked her rollicking northward. None of the three could resist a growing elation, a holiday mood such as had lately come but rarely and which was wholly worth celebrating. Soon Ned excused himself, but reappeared at once with Ted Wynham’s parting gift.

“It’s a rare day,” he announced solemnly.

“And heavens! We haven’t christened the ship!” Lenore added drolly.

“Children, children! Not yet a day out! But you mustn’t overdo it, either of you!” Mrs. Hardenworth shook her finger to caution them. “Now, Ned, have the colored man bring three glasses and water. I’d prefer ginger ale with mine if you don’t mind—I’m dreadfully old-fashioned in that regard.”

A moment later all three had watered their liquor to their taste, and were nodding the first “here’s how!” Then they talked quietly, enjoying the first stir of the stimulant in their veins.

Through the glass window of the cabin whence she had gone to read a novel Bess watched that first imbibing with lively interest. It was her first opportunity to observe her social superiors in their moments of relaxation, and she didn’t quite know what to make of it. It was not that she was wholly unfamiliar with drinking on the part of women. She had known unfortunate girls, now and again, who had been brought to desolation by this very thing, but she had always associated it with squalor and brutality rather than culture and luxury. And she was particularly impressed with the casual way these two beautiful women took down their staggering doses.

They didn’t seem to know what whisky was. They drank it like so much water. Evidently they had little respect for the demon that dwells in such poisoned waters,—a respect that in her, because of her greater knowledge of life, was an innate fear. They were like children playing with matches. She felt at first an instinct to warn them, to tell them in that direction lay all that was terrible and deadly, but instantly she knew that such a course would only make her ridiculous in their eyes.

But Bess needn’t have felt surprise. Their attitude was only reflective of the recklessness that had come to be the dominant spirit of her age,—at least among those classes from whom, because of their culture and sophistication, the nation could otherwise look for its finest ideals. She saw them take a second drink, and later, ostensibly hidden from Mrs. Hardenworth’s eyes, Ned and Lenore have a sma’ wee one together, around the corner of the pilot house.

With that third drink the little gathering on the deck began to have the proportions of a “party.” Of course, no one was drunk. Mrs. Hardenworth was an old spartan at holding her liquor; Lenore and Ned were merely stimulated and talkative.

The older woman concealed the bottle in her stateroom, but the effects of what had already been consumed did not at once pass away. Their recklessness increased: it became manifest, to some small degree, in speech. Once or twice Ned’s quips were a shade off-color, but always rollicking laughter was the response: once Mrs. Hardenworth, half without thinking, turned a phrase in such a way that a questionable inference could hardly be avoided.

“Why, mama!” Lenore exclaimed, in mock amazement. “Thank heaven you’ve got the grace to blush.”

“You wicked old woman,” Ned followed up with pretended gravity. “What if our little needlewoman had heard you!”

In reality Bess Gilbert had overheard the remark, as well as some of Ned’s quips that had preceded it, and had been almost unable to believe her ears. It was not that she was particularly ingenuous or innocent. As an employee in a great factory she had a knowledge of life beyond any that these two tenderly bred women could have hoped to gain. But always before she had associated such speech with ill-bred and vulgar people with whom she would not permit herself to associate, never with those who in their attitude and thought presumed to be infinitely her superior.

She was not lacking in good sense; so she gave no sign of having heard. She wondered, however, just how she would have received such sallies had she been properly a member of their party. Wholly independent, with a world of moral courage to support her convictions, she could not have joined in the laughter that followed, even to avoid being conspicuous. It would have been a situation of real embarrassment to her.

The conclusion that she came to was that her three months’ journey on board the Charon would be beset with many complications.