Title: Fighting King George

Author: John T. McIntyre

Illustrator: J. A. Graeber

Release date: April 3, 2022 [eBook #67765]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Penn Publishing Company, 1905

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Library of Congress)

TWO FIGURES BOUNDED UPON

THE WALLS

by

John T McIntyre

Illustrated

by

J A Graeber

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

M C M V

Copyright 1905 by The Penn Publishing Company

| I | How Fort Johnson Fell | 7 |

| II | How Tom Deering Made a Name | 31 |

| III | How the British Ships Ran From Charleston Harbor | 57 |

| IV | How Two Men Buried a Chest of Gold | 84 |

| V | How Tom Joined Marion’s Brigade | 101 |

| VI | How Francis Marion Heard Good News From Williamsburg | 123 |

| VII | How Tom Deering Fought With Gates at Camden | 140 |

| VIII | How Tom Braved the Tories | 148 |

| IX | How Tom Deering Held the Staircase | 174 |

| X | How Marion’s Men Lay in Ambush and What Came of It | 200 |

| XI | How Tom Met With a Blindfold Adventure | 213 |

| XII | How Tom Took Part in a Mysterious Consultation | 245 |

| XIII | How the Unexpected Happened on Christmas Eve | 261[4] |

| XIV | How the British Lost Some Prisoners | 283 |

| XV | How Tom Deering Fought His First Fight Upon the Sea | 306 |

| XVI | How Tom Deering Served With General Greene | 322 |

| XVII | How a Traitor to His Country was Taken and Lost | 337 |

| XVIII | How Tom Deering Rode With Washington at Yorktown | 350 |

| PAGE | |

| Two Figures Bounded Upon the Walls | Frontispiece |

| Marion Took the Packet | 62 |

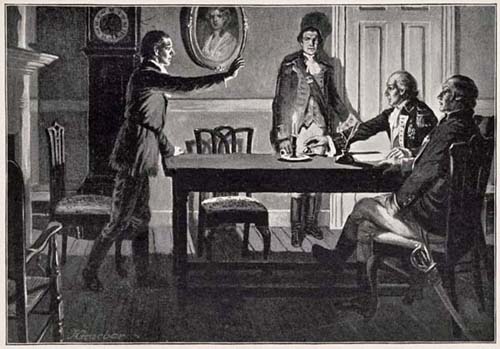

| “They Are Rare Good Lads, All of Them,” Spoke the Burgess | 134 |

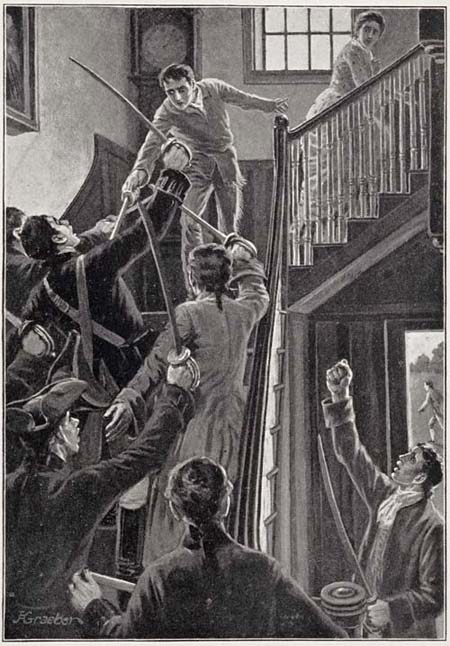

| Step by Step He was Beaten Back | 194 |

| “This Gentleman,” Said Cornwallis, “Will Introduce You” | 252 |

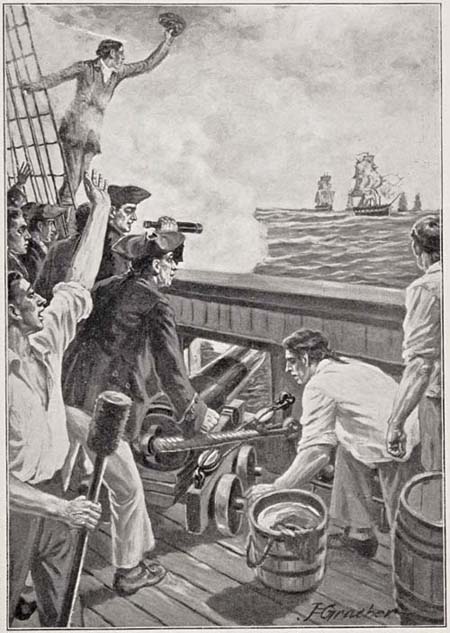

| “Well Aimed,” Praised Mr. Johnson | 316 |

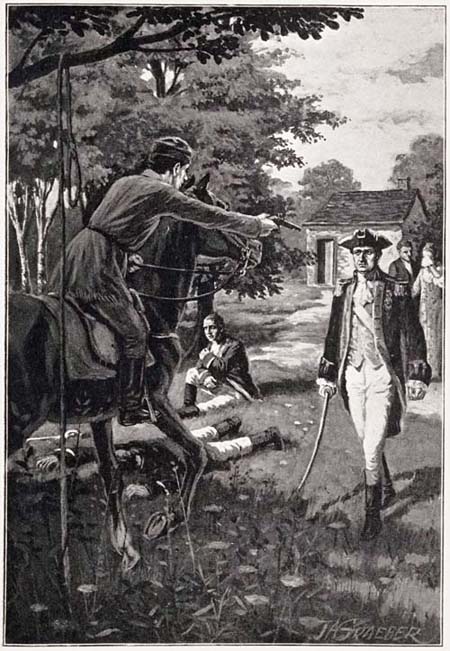

| The Officer Sprang Forward | 344 |

[6]

Fighting King George

“The wind’s changing again, Cole,” said Tom Deering, as he threw his rudder handle to leeward in order that the sheet might catch the full benefit of the breeze.

The person to whom he spoke was a negro, young in years but of colossal size; as he sat amidships in the skiff, with the sheet rope in his hand, his sleeveless shirt showing his mighty arms bare to the shoulder, he resembled a statue of Hercules, cut out of black marble. Tom Deering was about sixteen, and the son of a rich planter, just below Charleston; he was a tall, strongly built boy for his years, but beside the giant negro slave he looked like an infant. Cole had been born[8] upon Tom’s father’s plantation and was about five years the elder; the two were inseparable; where Tom went the huge black followed him like a shadow.

When he had the sail drawing nicely, Tom continued:

“I wonder, Cole, how all this is going to end?”

Cole shook his woolly head and grinned; then suddenly his face changed and he held up one hand as though bidding his young master to listen.

From across the bright stretch of water between them and the shore came a drum beat; the evening sun slanted down upon the white crests and upon the meadow-lands below the city. No one was in sight, but the hollow rub-a-dub of the drum continued. Seeing his master had caught the sound Cole turned and silently pointed out into the bay.

Two armed vessels, flying the British flag, were standing on and off Sullivan’s Island. From where he sat in the stern of the skiff,[9] Tom’s keen eyes noticed that an unusual air of alertness hung about the vessels; and the wind now and then carried toward them the sound of an officer’s command sharply spoken through a trumpet.

“It’s the Tamar and the Cherokee,” said Tom. “They’ve been lying in Rebellion Roads for the last couple of days. When I saw them up anchor an hour ago I thought something was going to happen, and I was right. Perhaps Colonel Moultrie is going to strike a blow for liberty and South Carolina at last.”

It was the fourteenth of September, in the year 1775. Because of the oppressive acts of the mother country, the British colonies in North America had risen in protest. But their words had been mocked and jeered at by King George and his counselors; and the heavy burdens of the afflicted colonies were only added to. This was more than a spirited people could stand; so from words the colonists proceeded to deeds; in the April before[10] the first shot of the Revolution had been fired at Lexington; and now South Carolina was about to follow the glorious example of her sister state in New England.

If the people of Boston had a “tea party” in Massachusetts Bay, so had the residents of Charleston one in the Cooper river. The public armory of the town was broken open during one dark night and eight hundred stand of arms, two hundred cutlasses, besides cartouches, flints and other material of war were seized by the patriots. Another party possessed itself of the powder at a town near by; while still another emptied Cochran’s magazine.

An army of two thousand infantry and four hundred horse had been raised by the colony. This force was divided into three bodies; the second regiment was placed under the command of Colonel Moultrie, a gallant Indian fighter who had served with credit in the campaigns against the Cherokee nation.

The tap of the drum from the town came to[11] the boys’ ears every little while; the wind was blowing freshly and the sail of the heavy skiff bellied to it, causing her bow to cut through the water at a great rate.

“We’ll soon be on the ground, Cole,” said Tom, peering under the boom to see how far they were away from their usual mooring-place when they sailed up to Charleston. “If it’s Colonel Moultrie’s men being summoned together for service perhaps the hour is at hand when you can settle your account with those who treated you so inhumanly.”

The giant held up one great arm, its huge muscles standing out in knots; the fist clinched and was shaken at Fort Johnson, on James Island, whose guns grinned wickedly across the calm water and whose sentries could be seen pacing backward and forward on the bastions. There was an expression of hate in the face of the slave; he turned to Tom, a strange sound coming from his throat, the forefinger of his left hand pointing to his open mouth. Tom reached forward and[12] pressed Cole’s hand and his dark eyes glowed as he swept his glance toward the British flag which flowed from the tall staff at Fort Johnson.

Cole, by a horrible act of brutality, had been rendered dumb!

A year before, during one of the spasmodic outbreaks of indignation which had become so frequent, the authorities had occasion to suspect Tom Deering’s father of some act against the government.

A party of dragoons were sent to his plantation to secure evidence against him; the leader of this party was a young and arrogant lieutenant, noted for his cruelty even to his own men. The colossal size of Cole at once attracted the officer’s attention when the slaves were summoned to testify against their master.

“We’ll have this fellow out,” cried he, pointing to Cole. “He’s the one that will tell us what we want to hear. He knows; I can see it in his face.”

[13]In vain Cole protested his ignorance of anything his master had done.

“You know, you black hound,” thundered the dragoon. “Tie him up, men; we’ll make him talk fast enough.”

Cole was bound to a cottonwood-tree in front of his master’s door; he continued to protest that he knew nothing, but in vain. The elder Deering and Tom were detained by a sergeant and a file of men inside the house and consequently had no knowledge of what was going forward without.

They heard the angry voice of the young lieutenant raised now and then in a shower of horrible oaths, apparently urging his men to the commission of something which they were reluctant to do. At length a dreadful scream sounded—a sharp, agonizing cry that caused the planter and his son to turn pale and stare at one another with eyes filled with horror. Then the sergeant and his file were hurriedly called from the house; as they were mounting in the yard, Tom and his[14] father rushed out; Cole hung limp against the ropes that bound him to the tree, covered with blood. As the hoofs of the dragoons’ chargers grew faint down the road, it was discovered what had occurred. Wild with rage at what he considered Cole’s defiance the brutal officer had had the slave’s jaws pried open, and had cut his tongue with the point of his sabre.

The great strength of the giant negro and his superb condition carried him through the effects of this barbarous act; in a remarkably short time he had recovered; but he was deprived of speech forever; it was only in gestures such as that which he had made against Fort Johnson that he could convey the longing that filled him, to come to hand-grips with those who had treated him so inhumanly.

They had reached the wharf and were running in alongside; Cole loosed the halyard and lowered the sail. While he was furling it, he stopped suddenly, and by his gestures,[15] which Tom could read very plainly, he called the attention of his companion to a strange stillness on the river.

Tom gazed up and down the stream for a moment and his eyes snapped.

“All the shipping has dropped down the river,” cried he. “That can only mean one thing! Colonel Moultrie is about to attack——”

“Belay there, nevvy,” growled a rough voice, almost in his ear. “Not quite so slack with the jaw tackle.”

“Uncle Dick,” exclaimed Tom, in surprise.

“Yes, it’s the old sea-horse,” responded the owner of the voice, from above them on the wharf.

“You frightened me,” laughed Tom, as he climbed up over the wharf log.

“My frightening you, nevvy,” said the other, “will be nothing to the scare you’ll get if any of Governor Campbell’s spying swabs heard what you were just now going to say.”

[16]Uncle Dick, or as the world knew him, Capt. Richard Deering of the schooner Defence, nodded in a friendly fashion to Cole, who grinned back, from his seat in the bow of the skiff. The captain of the Defence was a sturdy-looking man of about fifty, with his long, gray hair gathered in a cue, sailor-fashion; his weather-tanned face was smoothly shaven; he wore a round, glazed hat, a short pilot coat with metal buttons and long leather boots.

“What is going on, Uncle Dick?” asked Tom, seating himself at the old salt’s side. “I heard a drum beat while we were sailing in the shallows below the town and noticed the Cherokee and the Tamar standing up and down, with all hands ready.”

Captain Deering spat carefully over the wharf log into the water; and then looked up and down the river.

“There is going to be something happen on this river to-night,” said he, “that in the days to come they’ll write in their history books.[17] See all them boats pulled up on the sand, above there?”

There was a long line of galleys and barges and other heavy boats lying half out of the water, under guard of some half dozen men.

“Behind them trees, further up,” continued Captain Deering, “is the whole of Colonel Moultrie’s command—or, at least, all of them as can be got together at short notice.”

“Then it is coming at last,” breathed Tom, his eyes aglow. “South Carolina is to strike for her liberty as those in the north struck, months ago.”

“She is,” cried Captain Deering, catching some of his nephew’s enthusiasm. “Blow my tarry tops, lad, we can’t let those Lexington fellows beat us in the cause. The first shot out of the locker is to be the capture of Fort Johnson; I know, for I collected the boats up there; the attacking party is going to cross the river in them. Those chaps keeping watch are from the crew of the Defence.”

“When is the affair to begin?” asked[18] Tom, hardly able to keep still, so excited was he.

“As soon as it is dark enough to conceal the approach of the boats. There don’t seem to be any unusual goings-on in the fort, so I don’t think they suspect anything; but them two war craft, down in the roads, look bad; they must have had news from somewhere.”

Scarcely had the old sailor ceased speaking when there came a sudden rattle of hoofs; turning they saw a party of scarlet-coated dragoons wheel around a corner and, at a sharp gallop, proceed up the river road. A tall, burly man rode in the midst of them; his red face was angry and fierce looking, and he carried one hand upon his sword in a manner that told his thoughts as plainly as words.

“It’s Lord William Campbell, the new governor!” exclaimed Tom, with a gasp, “and they are on their way to the place where Moultrie’s men are assembled.”

The captain of the Defence arose to his feet.

[19]“There is likely to be trouble,” remarked he. “You climb back into your boat, nevvy, and make sail for the plantation.”

“Not I!” Tom Deering drew himself up proudly. “If there is anything to be done, I am going to help.”

Uncle Dick looked at him sharply for a moment; then he uttered a short laugh, that had a satisfied ring in it.

“Good lad!” cried he. “Blow my tarry old hulk, but there never was a Deering yet that wasn’t always on hand when wanted.” He clapped the boy proudly on the back as he spoke. “Well, come along; we’ve got no time to lose; the breeze is fresh and straight up the river. What kind of a sailer is that craft of yours?”

“There is not a better in these waters for the sort of wind that’s blowing now.”

They clambered into the skiff; Cole shoved the boat clear of the wharf and hauled up the sail. A few strokes of the paddle brought her out into the stream, Uncle Dick threw[20] her into the wind, and away she raced up the river.

The dragoons could still be seen proceeding at their sharp pace along the river road; the black, lowering figure still rode in the midst of them, his hand still upon the hilt of his sword.

“It’s good,” said Tom, “that there is a ridge between the road and the river, just above there; otherwise they’d see the boats, and maybe would try to scatter them and so break up the attempt on the fort.”

Captain Deering smiled.

“Moultrie is nearer than you think for, nevvy,” said he. “A whistle from one of my fellows there on shore would bring a hundred men to the boats in five minutes.” The skiff turned a wooded headland at this moment. “Look there; what did I tell you?”

Upon a smooth piece of ground, which the trees had hidden until they rounded the headland, was gathered the slender force of South Carolina; an awkward-looking body of men,[21] poorly armed, and with a total lack of soldierly appearance. They were mostly planters, woodsmen and artisans who had volunteered for service to their country, without hope of pay. They wore their ordinary dress, though here and there there was an attempt at military smartness; their weapons were fowling-pieces, cutlasses, axes and the plunder of the town arsenal. They were drawn up in order and their officers were putting them through a drill.

The distance by water to this point was much shorter than by road; the skiff had lowered its sail and run its nose up on the sand before the dragoons reached the spot. Captain Deering was just about to hail the militia when there was a flash of red from amidst the green of the trees and Lord Campbell and his company came into view. So sudden was their appearance that the untrained militia would have been thrown into confusion at the bare sight of them had it not been for the sharp commands of their officers.[22] They dressed ranks at the word and wheeled to face the dragoons. The latter had their weapons ready as they lined up on the verge of the woods; Lord Campbell, his face still dark with anger, rode forward toward a small group of officers who stood apart within easy hearing distance of where Tom stood at the water’s edge.

“What body of men is this?” demanded the governor.

An officer of commanding appearance stepped forward.

“It is the authorized force of the colony of South Carolina,” said he.

“Authorized!” Lord Campbell’s eyes blazed. “Authorized by whom?”

“By the Provincial Congress,” returned the officer.

“There is no power in the colony to collect armed bodies of men save my own—under the authority of the king. I command you all in the name of King George to lay down your arms and disperse!”

[23]His angry glance swept along the gathered patriots before him; his burly frame was quivering with rage at the idea to their daring to assemble in defiance of his power and that of his royal master. But there was no movement to obey; he paused for a moment, and then in a voice choking with passion he inquired of the officers:

“Which of you is Mr. Moultrie?”

The question was greeted with dead silence. The governor’s face lit up with triumph; their leader was afraid to proclaim himself; it would be an easy task to put them down.

“I have had information,” cried he fiercely, “that this insurrection is under the leadership of a Mr. Moultrie. Let him stand forth.”

A small, dark officer of infantry stepped forward.

“In this command,” said he, “I will venture to say that there is no Mr. Moultrie. But,” he paused and looked the wrathful governor in the eye with great coolness, “there is, however, a Colonel Moultrie.”

[24]“Ah!” Lord Campbell stared at the speaker with a bitter sneer. “Then will Colonel Moultrie have the goodness to step forward?”

The officer who had answered him in the first instance, advanced, a quiet smile upon his handsome face.

“Colonel Moultrie,” blazed forth the angry king’s man, not giving the other a chance to speak, “do you or do you not intend to disperse this gathering?”

“It is not in my power,” answered Colonel Moultrie.

“Do you not command them?”

“I do; under the Council of Safety.”

“Bah!” The governor’s teeth snapped in a fury of rage at this. “That is all one hears these days—the Provincial Congress, the Committee General, the Council of Safety. I know nothing and care nothing for these rebels against the king and their usurped authority. I recognize none but you in this matter. You are here at the head of an[25] armed force, in open rebellion; and I call upon you to lay down your arms and unconditionally surrender yourself, in the king’s name. Refuse and you must take the consequence of your folly.”

Tom Deering, with a thrill at his heart, saw the small, dark officer, who had spoken so coolly to Lord Campbell, step back and give a command to his company in a low voice. The line of the militia closed in a resolved fashion and the ducking guns were held in instant readiness for use. Lord Campbell saw it, also; and he saw the determined faces of those before him; a glance at his own slender company showed him that smart and soldier-like though they were, they were not a match for the assembled patriots. He turned to Colonel Moultrie, who still stood quietly watching him.

“You refuse?”

“Can you doubt it?”

Without a word the governor wheeled his horse and rode back to his men; another[26] moment and they were going down the river road at the same sharp gallop with which they had arrived.

Dusk had thrown its shadows across the waters of the river; the lights at Fort Johnson began to twinkle. Colonel Moultrie and his officers consulted together. The sharp businesslike departure of Lord Campbell and his men was not at all to their liking. In a few moments they had summoned Captain Deering, of the Defence, and after a few questions the latter turned and beckoned to Tom.

“Captain Deering,” said Colonel Moultrie, smilingly, “tells us that you are a patriot and a native son of the colony.”

“I am both, sir,” answered Tom, gravely.

“Good! You saw the Cherokee and Tamar under sail in Rebellion Roads a while ago, I understand.”

“I did, sir,” said the boy.

“Did they seem as though they intended to ascend the river?”

“No, sir.” Tom answered the question[27] quickly enough; then the actions of the two vessels came back to him, and he added, a light breaking upon him: “But they seemed as though they’d like to; it was just as though they were waiting for a signal.”

“And that,” cried Colonel Moultrie, “is just exactly what they are waiting for. And Lord Campbell is now on his way to give it. Gentlemen,” turning to his officers, “we must cross the river and make the attempt upon the fort at once; otherwise we will have two war vessels scattering cannon shot among us in our passage.”

The orders were quickly given; the patriot force was soon at the water’s edge, embarking in the boats which Captain Deering had collected. Small as their numbers were, the boats were too few to accommodate them, and a good quarter were forced to remain behind. The attacking party had pushed off and was already pulling toward the fort through the quickly gathering darkness, when the small, dark officer who had spoken so coolly to Lord[28] Campbell, came hurrying along. He had been making a disposition of the companies remaining behind and now seemed destined to be left also. He dashed out waist deep in the river in an effort to catch the last galley, but too late. At that moment Tom Deering’s skiff passed slowly by; there was room for another, and Tom called eagerly:

“Climb in, captain. We’re going, too; and we’ll land you there ahead of any of them.”

With a hasty word of thanks the officer scrambled into the boat and took up a position in the bow, from which point he could see all that was going forward.

This was Tom Deering’s first meeting with Francis Marion, afterward to become the great partisan chief of the Revolution and be known to the world as the Swamp-Fox.

Within an hour the attacking party had arrived at James Island and deployed in the darkness before the walls. Marion had sprung ashore as soon as the prow of the skiff grated[29] upon the sand; Tom and Cole were left alone, for they had touched at a point slightly further down than Colonel Moultrie’s men.

“I’m glad Uncle Dick did not cross in our skiff,” said Tom to Cole, as they drew the boat up on the sand. “Now we can look into things on our own account.”

While the militia was arranging, front and rear, for the attack, the boy and his companion were stealing through the bush that grew thickly about the walls of the fort, and wondering at the silence within. It required a half hour for Moultrie to get everything in readiness; and at last, just as he was about to give the word for the attack to begin, two figures bounded upon the walls from inside the fort; one was a handsome youth of seventeen; the other was a giant negro slave. Each waved a blazing torch above his head exultantly.

“Colonel Moultrie,” cried Tom Deering, “the place belongs to you. The British have fled to their ships.”

[30]It was true; the creaking of blocks and the dark loom of a mainsail showed them a vessel scudding down the river. Fort Johnson had fallen without firing a shot.

Tom Deering and Monsieur Victor St. Mar, late of the French army, lowered the small swords and stood panting and smiling at each other, in the orchard one afternoon, not long afterward.

“You grow proficient,” said St. Mar in very good English, considering that he had been in the colonies but a few years, “your guard is excellent and your thrust, monsieur, is growing formidable.”

Praise from the French soldier was praise indeed, for he had been a master of the sword in the regiments of King Louis, among which were the greatest swordsmen in the world. He had paused for a time at Charleston on his way from New Orleans to Philadelphia; and during his stay he taught the use of his favorite weapon to the young men of the city.[32] Tom was the youngest and most apt of his pupils; the youth’s strength, length of arm and sureness of eye made him a natural swordsman. At the French soldier’s praise he flushed with pleasure.

“I am glad, monsieur,” said he, as he wiped his brow, “that you think I am progressing. I like the practice of sword play.”

“The rapier,” said the Frenchman, “is a grand weapon—a gentleman’s weapon. I have taught many persons, and have studied the use of the cutlass, the broadsword, the pike, bayonet and dagger; but the rapier is the king of them all; with three feet of bright steel in his hand the master of the sword should fear the attack of nothing that breathes.”

He began buckling the long, slender weapons into their leather case, but paused and looked up at Tom, seriously.

“Study—practice steadily—experiment. That is the way to become a master. You have the material in you for a swordsman;[33] but you must see to the defence—the parry—the guard. You Americans, I find, think the attack is everything. But it is not so. Study the guard. Some day you may meet a foe who has a thrust which you have never seen before. If you have not the parry to meet it your skill in attack will be like that.”

He snapped his fingers and puffed out his cheeks; then he buckled up his sword-case and took his leave with many bows.

Tom Deering had long been a good horseman, a dead-shot with rifle or pistol; but sword-practice was new to him and he threw himself into the art with all the ardor of his seventeen years. Trouble was brewing between the king and his colonies, that was evident, and he was anxious to prepare himself for the struggle, for he had firmly made up his mind that, should the dark cloud of war that he saw gathering burst, he would be one of the first to offer himself for service.

For the capture of Fort Johnson was not immediately followed by open war, as all had[34] expected. For some reason the British did not make any movement. Lord Campbell, the governor, had fled to the Tamar, which still lay in the harbor along with the Cherokee, but, except for sending his secretary to protest he took no steps. The patriots still had a lingering hope that all might yet be well; there were many that clung to the belief that a reconciliation might yet be effected between king and colonies. The proceedings of the people of Charleston still wore, however loosely, a pacific aspect. Though actively preparing for war, they still spoke the language of loyalty, still dealt in vague assurances of devotion to the crown.

But Tom Deering was wide awake; he had a brain and he used it. The hesitation of the colonists would not last long he felt confident; and when they once cast it aside the storm would come in earnest—the sword would be drawn to be sheathed no more until the struggle was lost or won.

After St. Mar, the sword-master, had taken[35] his departure, Tom took his customary afternoon plunge into the river, after which he was ready for a visit which he had planned. Cole brought his best horse, a powerful, intelligent looking chestnut with strong lines of speed and bottom, around to the front of the house and Tom vaulted lightly into the saddle. Cole mounted another horse, a great bay, and followed his youthful master, as was his custom. There were not many horses upon the Deering plantation capable of supporting the great weight of the giant slave for any length of time and still make speed. But the bay carried him as though he were a feather, hour after hour, sometimes, and never showed more than ordinary weariness.

Tom’s father, a tall, dignified gentleman, with the appearance more of a scholar than a planter, and bearing scarcely any resemblance to his brother, the skipper of the schooner Defence, met them on the road near the house.

“Are you going up to the city?” asked he, drawing rein.

[36]“No, sir,” replied his son. “I’m going over to the Harwood plantation. I have not been there for some weeks.”

“You have not been there, I suppose, since the taking of Fort Johnson?”

“No, sir.”

Mr. Deering looked grave. Jasper Harwood, who owned the large plantations some eight miles from them, was his half-brother, and he knew his real character better than Tom.

“I will not forbid you to go,” said the father. “But it will be just as well if you’d stay away.”

Tom looked surprised.

“Why, father, what do you mean?”

Mr. Deering laughed.

“After the part you took in the little affair of the night of the fourteenth of September,” said he, “I don’t think your presence will be very welcome upon the Harwood plantation. I hardly think Jasper Harwood looks upon the matter from the same point of view as you, Tom.”

[37]“Do you mean that he is a king’s man, sir,” exclaimed Tom.

“I’m sure of it,” answered his father.

“I can’t bring myself to believe it, father. He is, perhaps, like a great many others just now, reluctant to prove disloyal, but when the real time comes to act, I think you will find him as staunch for the Provincial Congress as any of us.”

Mr. Deering laughed at his son’s earnestness.

“Well, my boy, I trust you’re right, but I don’t think so. Jasper Harwood is a Tory, and will hardly take the trouble to hide it from you. So, you will not be kept long in suspense, if you are going there.”

From the time he left his father and struck across the fields and swamps toward the Harwood place, Tom was deep in thought. Perhaps his father was right. He knew that Jasper Harwood was a harsh, arrogant man, with a violent temper and a great respect for the crown; but that he would let the latter[38] blind him to the blessings of liberty, and turn his hand and tongue against his neighbors and friends was more than Tom, boy like, could realize.

“But even if the master of the plantation himself is a king’s man, there are others there who are not,” mused the boy as he loped along, followed by Cole on the big bay. “Mark will prove true to the colony, I know. And then, there is Laura! Every throb of her heart is of indignation against British oppression. I am confident of that.”

He was still deep in thought, and they were ascending a narrow road that led to the Harwood house before Tom realized it. Suddenly Cole uttered his strange cry and touched his horse with the spur. In a moment he was beside Tom, one hand upon his shoulder, and the other pointing to a small clump of trees by the roadside near the house. A half dozen horses were tied there, and from their trappings Tom knew them to be the mounts of the king’s dragoons. A like visit[39] to their own plantation was still vivid in his mind; its horrible result to Cole caused all sorts of dreadful fears to crowd into his mind, and with beating heart he urged his steed forward at a gallop and threw himself from its back before the door. The sound of the galloping hoofs coming up the graveled path caused a rush to the doors and windows; among a group of red-coated dragoon officers, at the top of the high stone steps leading to the door, Tom recognized the planter, Jasper Harwood. Far from being in any peril, he seemed to be very well content, having a long churchwarden pipe in his hand, and the jovial looks upon the officers’ faces caused the boy to banish his fears for his half-uncle’s safety, at least.

There seemed to be a perfect understanding between the planter and the dragoons, but as he recognized Tom, Harwood’s flush deepened into one of anger.

“Ha, Master Deering, is it?” cried he,[40] loudly. “I thought it was a troop of horse from the way you came charging up the path.”

Tom passed the bridle over his arm, and leaning against the chestnut’s shoulder he stood looking up at the group upon the high steps of the mansion.

“I am very sorry that I startled you,” he said.

At this the dragoons burst into a roar of laughter.

“He’s sorry he startled us,” bellowed one, his face purple with glee. “By the Lord Harry, but that’s good! A snip of a boy startle a lot of king’s officers.”

Once more the laughter rang out. Tom looked at them composedly enough for a time; but suddenly his face paled, his mouth set, and an angry light began to gather in his eyes. He looked about for Cole; but the giant negro was not to be seen; and, after assuring himself of this the lad breathed a sigh of relief. For, among the officers at Jasper Harwood’s door, he recognized the lieutenant[41] whose brutality had deprived Cole of his speech. The sight of the ruffian filled him with indignation; but he knew that it would hardly do to give vent to it at this time, so he held his peace.

“This young blade is a friend of yours, Mr. Harwood, I suppose,” spoke this officer, his voice thick and husky.

“He is from a neighboring plantation,” answered Harwood, scowling at Tom, darkly.

“Let’s have him in,” cried another. “He seems to be an excellent horseman; let’s see if he’s equally good at other things. Introduce us, I beg of you, to the youth who is good enough to fear that he startled us,” and once more they roared.

“That will, perhaps, follow in good time, gentlemen. Meanwhile, don’t let the table be idle; keep your knives and forks. I’ll join you in a few moments.”

At this hint the dragoons disappeared into the mansion, and Harwood was left alone with Tom.

[42]“So,” said the planter, after a pause, during which his eyes had been searching Tom’s face, “you’ve come, have you?”

“Yes, sir,” answered the lad, wondering what the expression upon the man’s face meant. “I thought I’d ride over and see you all.”

“I had not thought,” sneered the Tory, “that you would have the courage to face me after what you have done.”

Tom drew himself up proudly.

“I have done nothing of which I am ashamed,” said he, quietly.

“Do you dare stand there and tell me that? Do you tell me to my face that you are not ashamed?”

“Anything that I have done I would do again,” declared the boy, boldly.

“Oh, I see,” the planter’s sneer returned. “You are saturated with the radical teachings of the mob yonder there in the city. And with your head full of their accursed doctrines you have dared to raise your hand against the king.”

[43]“I have dared to raise my hand against a tyrant,” cried Tom, forgetting caution in his ardor for the cause. “If King George does not know how to govern a free people it’s high time he was learning.”

The Tory’s face grew dark with wrath; but before he could speak, a boy, who seemed a few years Tom’s senior, stepped through the doorway.

“Just a moment, father,” said he. “Don’t speak while you are angry; it will only create ill blood between relatives, and that should not be.”

This was Mark Harwood, the planter’s only son; he was a thick-set youth with a far from prepossessing face, and a sly manner. His father looked at him for a moment, in surprise; he must have seen something in the glance which was directed secretly at him, for he held his peace, though the anger did not die out of his face.

Mark Harwood descended the steps, with outstretched hand.

[44]“Tom,” said he, with great cordiality in his voice, but a lurking look of craft in his eyes that the other did not like, “I’m very glad to see you.”

Tom took the offered hand.

“Thank you,” said he. “You are very good, Mark.”

“Not at all. But tie up your horse and come in; we must have you join us; as you have seen, we are entertaining some friends, rare good fellows who will be glad to meet you.”

“Thank you, Mark, but I think I had best be riding homeward.”

“I cannot permit that!” Mark took him by the shoulder in a very friendly fashion and continued, earnestly: “If we were to allow you to go now there would always be a feeling of estrangement between us; you would feel that you were not welcome here, and we should feel that we had, in an angry moment, offended you. Come, don’t let us have a mere matter of politics step in between us.”

“I’ll not, Mark.” Tom gripped the other’s[45] hand warmly. Then he turned to the planter. “If in a moment of heat, Mr. Harwood,” he continued, “I answered you unbecomingly, I beg your pardon.”

“Say nothing more about it,” said Harwood. Tom tied his horse under the window, as he expected to remain but a few moments; he did not catch the looks that passed between father and son as he did so; if he had he would not, probably, have crossed their doorsill with so light a heart. As he followed them through the wide hallway, which ran directly through the middle of the house and contained an immense fireplace capable of accommodating great back logs that would last for weeks in the coldest winter, Tom happened to glance in at a partly open doorway. He caught sight of a beckoning finger; without hesitation he stepped aside, pushed open the door and entered. In a moment he was eagerly pounced upon by a dark-eyed girl of about his own age, or perhaps a year or so older.

[46]“Oh, Tom,” she cried, “I am so glad to see you.”

“I thought I’d have to go away without catching a glimpse of you, Laura,” he returned. “And it was to see you, more than anything else, that I came.”

She laughed and looked pleased.

“I’m flattered, sir, I’m sure,” she said. Then her manner changed suddenly. “I wanted you to come, Tom, ever so much, so you could tell me the news of Colonel Moultrie’s taking of Fort Johnson. Uncle Jasper heard that you were there; that you were the very first over the walls.”

“Yes, I was there,” said Tom, proudly, “but Cole was first over the wall; I was second, because he reached down and pulled me over after him.”

Laura Thornton clapped her hands delightedly.

“Oh, you’re so brave, Tom; I wish I was a boy, then I, too, could do something for the cause. But they’re all Tories here—uncle,[47] Cousin Mark and all; I dare not say a word of what I think about that hateful old King George!”

“I call that too bad,” said Tom, warmly. “A person should always be allowed to say what he thinks.”

“That’s what I say, too, but I’m afraid of Uncle Jasper, Tom; he’s so violent when he’s angry. Oh, if I could only break out on him as you did awhile ago! I stood at the window and heard it all. You were so splendid, Tom; you were not in the least bit afraid of him, were you?”

“Well, I should hope not,” said Tom.

“But don’t trust him, Tom,” she whispered, as though fearful of being overheard. “Don’t trust him or Mark, either; they both hate you, and just now I heard them talking to one of the officers whom they are entertaining; they are going to——”

Here she was interrupted by her uncle’s harsh voice, calling:

[48]“Tom! Tom Deering, I say, where have you gotten to!”

A heavy foot sounded upon the bare, polished floor of the hall, coming toward the door of the room in which they were standing.

“He’s coming,” said Tom.

“I must tell you about the despatch,” said Laura, hurriedly, catching Tom by the arm.

“The despatch?” said he, looking at her wonderingly.

“Lieutenant Cheyne is to ride with it after dark to a point below the city; there will be a boat’s crew awaiting to carry him aboard one of the king’s ships. Oh, Tom, they intend to-morrow night to bombard Charleston!”

Tom’s face paled.

“Are you sure?” he demanded.

“I heard it from their own lips. Oh, Tom, Tom, what will the poor people do if the despatch reaches Lord Campbell’s hands?”

“It shall not reach them,” said Tom, firmly.[49] “I’ll give my life, if need be, to prevent it.”

At this moment the door was pushed rudely open and Jasper Harwood strode into the apartment.

“Ha!” said he, angrily. “I find you here, do I! I’ve been bawling all over the place for you.”

“I saw Laura, sir,” said Tom, “and just paused for a moment to speak to her.”

“Well,” growled he, not seeming to relish this explanation in the least, “now that you have spoken with her, suppose you come into the dining-hall and not keep my guests waiting for you.”

Tom pressed Laura’s hands in hurried thanks; his glowing eyes told her how grateful he was for the information which she had just given him. In it he saw a chance to serve his country and make a name for himself at the same time.

The planter led him through the hall, into the room in which his dragoon guests were[50] assembled. The table contained some bottles; and, as though by chance, the sword of each dragoon lay near him ready to hand.

“Ah!” said Mark Harwood, as Tom entered, at the planter’s heels. “Here you are at last!”

There was something like a sneer in his tone as he said this; the officers seemed to see a hidden meaning in them, for they laughed boisterously and hammered the table with their glasses. They made room, however, for the boy at the head of the table, as though anxious to do him honor. Cheyne, the lieutenant who had tortured Cole so barbarously, slapped him familiarly upon the shoulder.

“Now, fall to, youngster. You’re a pretty sprout of a king’s man, and a king’s man should never shirk.”

“In these times of rebellion,” said Mark Harwood reaching forward and filling a goblet, which stood upon the table before Tom, “good, loyal subjects are rare. So[51] let us treat them well when they visit us.”

Tom Deering flashed the young Tory a rapid glance.

“Come, take your glass, my lad,” cried Cheyne.

“Yes, yes!” shouted the others, holding their own bumpers aloft, and laughing expectantly.

“Pardon, gentlemen,” said the soft voice of Mark Harwood. “I was about to propose a toast!”

“A toast! A toast!” The dragoons sprang to their feet as one man, glasses in hand. Tom knew by the sudden malice of his Tory cousin’s look that it was for this that he had been invited into the dining-hall. Something was about to occur—something by which he was to be humiliated before these British soldiers. But with flashing eyes he, too, arose and faced the Tory. Mark raised his glass.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “I give you the king.”

“The king!” they shouted and were about[52] to drain their goblets when Cheyne stayed them.

“One moment,” requested he. “Our young friend here does not seem disposed to honor the toast.”

Angry looks came from all sides. The sly, oily voice of Mark Harwood reached Tom’s ears.

“You mistake, gentlemen,” said Mark. “Of course he will join us.”

By his look Mark was daring Tom to refuse; like a flash the latter saw the plan and his cheeks flushed with resentment. The young Tory thought he would be afraid to refuse. In the glance that Tom had darted about the room a few moments before he saw Laura, unnoticed, standing with frightened face in the doorway; come what may he would not be humiliated before her, above all others.

“The toast!” cried the dragoons, eagerly, all their eyes fixed upon him with threatening looks.

[53]“Very well, gentlemen.” Tom quietly put down the glass and took up a goblet of water. “I will drink a toast with you.”

“Of course he will,” laughed Jasper Harwood, his hard face glowing with triumph at what he took to be an exhibition of cowardice.

“I never had the slightest doubt of it,” sneered Mark.

“Yes, gentlemen, I will give you a toast that any honest man can drink.” He looked about at the expectant British officers and then at the sneering Tories; his voice was steady, his hand never trembled. “I give you the Provincial Congress!” Amid dead silence he lifted the cool water to his lips and took a sip; then he threw the glass into the middle of the table, where it smashed into a hundred pieces, as he shouted, “Down with the king!”

The dragoons grasped their sabres, but he was through the door, out at a window and upon his horse’s back before they could act. They crowded through the front door and ran[54] along the path toward the place where their horses were; but Tom was already out upon the road waving his hat at them defiantly. Wheeling his fleet steed he dashed down the narrow road, then suddenly pulled up with a cry of delight. Almost directly in his path was Cole, a wide grin upon his ebony face; upon a long rope he had the dragoons’ horses, and at the word was ready to make off with them. The British officers discovered their loss almost at the same moment, and they ran down the rough road, brandishing their sabres and shouting a volley of most dreadful threats.

“We’ll take them along with us, Cole,” said Tom, laughing. “Lord Campbell can get another supply, but Colonel Moultrie would appreciate them very much.”

So, despite the threats that rang in his ears, Tom Deering rode gaily away behind his first capture from the enemy. Seeing that he had no intention of surrendering their mounts, the dragoons soon gave up the chase and[55] returned in no very sweet tempers to the mansion of their Tory host.

Late that night, Lieutenant Gordon Cheyne, of Tarleton’s Dragoons, rode slowly, upon a borrowed horse, along a deserted road in the neighborhood of Charleston. Suddenly, as he turned a bend, and just at a place where the woods grew thick upon each side of the road, a horseman rode into his path and presented a pistol at his head.

“Stand!” ordered the newcomer.

“What do you want?” demanded the lieutenant, pulling up suddenly.

“Your despatches.”

Cheyne started, and his hand crept toward his holster.

“Make no movement toward a weapon,” said the horseman. “Give me the despatches, and give me them quickly.”

With a cry Cheyne drew a packet from his breast and threw it at the horseman. The[56] latter caught it deftly and stuffed it into his boot leg.

“Now,” said he, “about face and return to those who sent you.” The officer of dragoons wheeled and set off, in a fury, down the road. “And tell them,” called the horseman after him, “that the Provincial Congress has a thousand eyes.”

On the 9th of November, which was but a few days previous to Tom Deering’s adventure with the British, the Provincial Congress of South Carolina resolved “by every military operation to oppose the passage of any British armament”; and this order was issued to the commandant at Fort Johnson, Colonel Moultrie. The fort itself was strengthened, more men were enlisted, and bills of credit were issued. The blow for which all had been waiting seemed now about to be struck; the redcoats and patriots were about to grapple in that fierce struggle which was to last eight long years and set a continent free.

Colonel Moultrie had taken up his headquarters at Haddrill’s Point, which was being[58] fortified; it was here that the training of his men was going forward, and the place had the appearance of quite a formidable camp.

The eastern sky was beginning to gray under the hand of approaching morning, when the sentinel on guard at the upper road caught the sound of flying hoofs rapidly approaching him. His musket quickly came around and he stood ready to receive friend or foe.

“Halt!” he cried.

The galloping horse was pulled up so quickly as to almost throw him back upon his haunches.

“Who goes there?” demanded the sentry.

“A friend,” came the voice of Tom Deering.

“Advance, friend, with the countersign.”

Tom walked his snorting horse forward.

“I have not received the countersign,” said he. “But I have urgent business with Colonel Moultrie, and must see him at once.”

“Against orders,” said the sentry. “I’ll[59] call out the sergeant of the guard, though, and leave him to settle it with you.”

In a few moments the sergeant had presented himself. Tom was led forward into the light of a camp-fire, where the sergeant carefully questioned him.

“I can answer no questions,” said the boy, “unless asked by Colonel Moultrie or——”

“Captain Marion, perhaps,” said a voice behind him.

Tom turned quickly; within a foot of him was the small, dark officer with the aquiline nose and the burning black eyes, whom he had carried across the river in his skiff on the night when Fort Johnson was taken.

Francis Marion was, at this time, past his fortieth year. He had been a planter, his only previous military experience having been in the war with the Cherokees some years before; in this he had gained some fame as a leader of a “forlorn hope” at the battle of Etchoee, in which the Carolinians had defeated the French and Indians. Then[60] he had been a lieutenant in the regiment of Middleton. Colonel Moultrie, who was in command of the patriot forces, had been captain of the company in which Marion served at that time.

“So,” said Marion, “you would like to see Colonel Moultrie, would you, my lad?”

Tom, holding the bridle of his horse with one hand, raised the other in salute.

“Yes, captain,” answered he promptly.

“Well,” said Marion, “I owe you something for your service that night on the river.” He laughed lightly. “You see, I have not forgotten it; nor have I forgotten the fact that you, single handed and alone, captured a fortified position.”

Captain Marion was pleased to regard Tom’s errand lightly, it seemed; a boy must always prove that his doings are worth the consideration of his elders. In spite of the fact that he recognized in Tom Deering no ordinary lad, Marion could not accept his word that his business with Colonel Moultrie[61] was not some hair brained freak. Tom saw all this in the dark, smiling face of the soldier before him; and he recognized the fact that he must come down to plain dealing and take him into the matter before he could hope to see the colonel.

“Captain Marion,” said Tom, with a glance at the sergeant and his file of listening men, “can I have a word in private with you?”

Still smiling, Marion led the boy a little way apart, but well out of earshot.

“Now,” said he, “tell me all about it.”

“Would you consider it a serious matter,” asked Tom, looking him candidly in the eye, “if the British ships came up and bombarded the city in the night?”

Marion’s face grew grave, and he glanced keenly at the boy’s intent face, an alert look stealing into his eyes.

“I would consider it very serious,” said he, in reply, his voice sober and low.

“There is to be such an attack to-night,” said Tom. He drew the captured despatches[62] from his boot leg, and held them out. “This packet I took from an officer of Tarleton’s dragoons two hours ago, some distance below here.”

“Have you examined them?”

“I have, in order to make sure that I was not at fault. I did not wish to come here with nothing to substantiate my statement.”

Marion took the packet and glanced hurriedly through the papers. After a moment’s examination he said, quietly:

“Come with me.”

Within a quarter of an hour a dozen officers were gathered in Colonel Moultrie’s cabin in the center of the encampment. The captured papers were before them; Tom Deering stood at the table answering the questions with which they plied him.

“This attempt seems mere madness,” said Colonel Moultrie, at length. “How do they hope to get their vessels past the fortified points without danger of being destroyed?”

MARION TOOK THE PACKET

This seemed to be the general opinion of[63] the council; but Marion, who happened to glance at Tom at that moment, saw an eager light in his eyes.

“Speak out, lad,” said he, kindly. “If you have anything to say upon this question I have no doubt but that Colonel Moultrie will be glad to hear it.”

“Of course,” said the colonel. “You have done us too great a service already, my boy, for us to refuse to listen to you.”

“I just wanted to say, sir,” exclaimed Tom, eagerly, “that the British ships can get up to the city, and without the slightest danger to themselves.”

The colonel looked startled.

“You are sure of what you say?” he demanded.

“I am positive. They can come up by way of Hog-Island channel.”

“But that is not deep enough for their heavy vessels,” cried an officer.

“At high water,” said Tom Deering, calmly, “there is water enough to float the largest[64] ship in their fleet, providing they have a man at the wheel who knows the course. I have come through the channel many a time with my uncle, Captain Deering, of the schooner Defence.”

This information set the council in a state of great excitement; Tom was thanked over and over for what he had done.

“You have, without doubt,” said Colonel Moultrie, “saved us from making a fatal mistake.”

Before the sun was three hours high a plan of action had been formulated and was in progress of execution. Captain Deering was summoned in hot haste from his schooner, which lay in the river, and ordered to cover and protect a party detailed to sink a number of stone-laden hulks in the narrow Hog-Island channel. The Defence, some weeks before, had been fitted up with carronades and a long thirty pounder cannon, and she was just the ready, quick-sailing craft for the work.

[65]By early afternoon the hulks were being floated into the channel, the Defence hovering about them like a great bird watching over its young. The work had scarcely begun, however, when the British lookouts discovered it, and the Tamar bore down upon the hulks, firing from her bow guns as she came. The Cherokee was only a little behind her sister craft in promptness of action, and opened with her lighter guns, also. The Defence answered with her carronades, but their range was not great enough, and she did but little damage; the guns from Fort Johnson opened; a few shots were effective; but the firing was discontinued as soon as the British war-ships showed signs of hesitation. Meanwhile the alarm was beat at Charleston, where the troops stood to their arms. But the time was not yet; the Tamar and Cherokee, seeing that they could not frighten the blockading party off, went about and retreated beyond range.

From this time on the local patriots began[66] to proceed vigorously. Ships were impressed and armed like the Defence, and they were badly needed, for the British in the harbor became more and more troublesome. Captain Thornborough, the officer in command of them, began to seize all vessels within his reach, entering or coming out of the port.

Of the newly-gathered fleet of the Americans Captain Deering was placed in charge. Heavy artillery was mounted on Haddrill’s Point and the work of fortification at the same place was hurriedly completed. A new fort was raised on Jones’ Island and another one begun on Sullivan’s Island, some distance below the city; the volunteers were constantly coming in, swelling the ranks of the patriots both ashore and afloat. Among these latter was Tom Deering’s father; the planter armed a small sloop and manned it with a crew of slaves, who gladly offered to follow him against the British.

But Tom, to his father’s surprise, refused to join him.

[67]“Is it possible, Tom,” demanded he, sternly, on the morning upon which he formally took charge of the sloop as an officer of the colony, “that you have suddenly grown faint-hearted?”

“Faint-hearted! I!” Tom looked at his father reproachfully. “You don’t think that, father, surely! Have I not done some service, already, for the cause of liberty?—not much, of course, but still, enough to prove that I am ready to go to any length against oppression.”

“You have done some things,” said Mr. Deering, his eyes alight with pride, “that have made me thank the good God who had given me such a son. But,” and his face grew grave once more, “it seems strange that you will not enter the service of the colony, now that she needs you.”

“I have thought the matter over very carefully,” answered Tom, “and have concluded that I shall be better as I am.”

“Tom!” his father’s face grew white. “What do you mean?”

[68]“If I enlist,” returned Tom, “I shall be forced to march in the ranks and obey orders. If I remain free, I can do as I will; and by so doing I can render much more effective service. Those despatches which I captured are not the only ones that will be carried through the outlying districts under the cover of night; there is information to be gained of the enemy’s movements and plans, by one who knows the roads, the cane-brakes and swamps, and has the courage to dare the British dragoons. This is the work that I have laid out for myself, father, in this fight. And this is the work, I think, that I can best do.”

“Tom!” The planter clasped his hand and threw one arm about him; “forgive me for what I have said. I might have known, my lad—I might have known.”

The whole of the long winter and spring passed; the British had all retreated to their ships; while the colonists were deeply absorbed in preparations for the defence of the[69] city. Inland, parties of loyalists, or Tories, had risen and were slaying and burning, but their ravages were confined to a small district as yet. Jasper Harwood, Tom’s half-uncle, and his son Mark, were at the head of a band of these partisans, and they were carrying terror wherever they went. Moultrie sent small parties in pursuit, now and then; but these only served to check the outrages for a space; when the patriots once more returned to the city the slaying and burnings were at once renewed.

Tom did splendid service against these desperate bands. In company with Cole, his giant servant, he penetrated very frequently into their districts, and often gained information that saved both lives and property. During this time, Marion, now a major, was in command of the depot of supplies at Dorchester and it was with his small force that Tom was most frequently in touch. In this way he came to realize the genius and resolution of this small, kindly man with the burning,[70] deep-set, black eyes; for at no time was he unready to spring into the saddle and dash at the head of his men to the rescue of some imperiled section; at no time was his invention at fault for a plan of onset or ambush.

But the constant rumors of the coming of a strong fleet to reinforce the Cherokee and Tamar caused Marion to ask for a change of post to Charleston, where he would be more actively engaged. This was granted him; he was once more appointed to the Second Regiment under Colonel Moultrie and stationed at Fort Sullivan, on the island of that name which stands at the entrance to Charleston harbor and within point-blank shot of the channel. Tom, during the long months at Dorchester had become devoted to Marion and this, together with the expectation of a battle, caused him to follow him to Fort Sullivan—or Fort Moultrie as it was then called, in honor of its commandant.

Tom helped to build the fort; for when he arrived there it was scarcely more than an[71] outline. It was constructed of palmetto logs, a simple square, with a bastion at each angle, sufficient to cover a thousand men. The logs were laid one upon another in parallel rows, at a distance of sixteen feet, bound together with heavier timbers which were dovetailed and bolted into the logs. The work of constructing this fort was a good preparatory lesson for the great conflict that was to follow. Tom grew brown and tough and sinewy with the long days of labor in the sun; the wonderful strength of Cole, the dumb-slave, was a constant source of astonishment to both officers and men; to the amazement of all he would lift, unaided, a great piece of massy timber to crown an embrasure and set it in place, or, when horses were scarce, go down on the beach and drag the ponderous tree trunks from the water. At sight of the open-eyed astonishment of those about him he would throw back his head, his white teeth shining in two even rows, and laugh with the perfect glee of a child.

[72]In spite of the incessant labor of the soldiers the fort was still unfinished when the recently arrived and powerful British fleet appeared before its walls. Colonel Moultrie’s force consisted of four hundred and thirty-five men, rank and file, comprising four hundred and thirteen of the Second Regiment, and twenty-two of the Fourth Artillery. The fort at this time mounted thirty-one guns; nine were French twenty-sixes; six, English eighteens; the remainder were twelve and nine pounders.

The day before the British hove in sight, Tom Deering was witness to an exciting scene which took place between General Charles Lee, whom the Continental Congress at Philadelphia had recently sent to take command of the Army of the South, and Colonel Moultrie. The two officers were standing upon a bastion, looking seaward; Tom and Cole were bolting some timbers together, near at hand.

“It is madness to attempt a defence of this[73] point,” said General Lee. “The fleet is even now in the roadstead and the works, here, are far from being finished.”

“I disagree with you, general,” returned Colonel Moultrie.

“But, Colonel Moultrie,” cried General Lee, not seeming to relish having his opinion so candidly opposed, “how are you going to defend yourself?”

“With the guns of the fort,” said the colonel; “and the brave men who will be behind them.”

“All very well, my dear sir, if it were Frenchmen or Spaniards who manned the attacking fleet; but they are British ships, sir! British ships, and sailed by British tars!”

General Charles Lee had been trained in the English army, and he had, perhaps, naturally enough, an overweening respect for the prowess of an English fleet. It is fortunate that this feeling of awe was not shared by Colonel Moultrie and his men.

“Let them once get within range of my[74] heavy guns,” said the colonel, “and it will make no difference as to what nation they belong. We shall make them run from Charleston harbor, just the same.”

“Your fort presents, at present, little more than a front to the sea,” protested General Lee. “Once let them get into the position for enfilading and you cannot maintain your position.”

“I will risk it,” said Colonel Moultrie. His officers were with him in this; and Lee’s authority was not great enough to force them to evacuate their position against their will.

On the 20th day of June, 1776, the British ships of war, nine in number, and consisting of two vessels of fifty guns, five of twenty-eight, one of twenty-six, and a small bomb-vessel, sailed up the harbor under the able command of Sir Peter Parker. They drew abreast of the fort, let go their anchors with springs upon their cables, and began a terrible bombardment. They strove, after a time, to gain a position for the destructive enfilading[75] fire which General Lee so feared; but the Defence, the Tartar sloop, commanded by Tom’s father, and several other small vessels, came down boldly and maintained such a stubborn resistance, that Sir Peter quickly displayed signals ordering the attempt to be abandoned.

Fort Moultrie at the beginning of the fight had but five thousand pounds of powder; this small supply had to be used with great care.

“Not a shot must be wasted,” cried Colonel Moultrie; “every one must do execution. Let each officer in command of a gun aim it in person.”

This command was obeyed, and its results were frightfully fatal to the British and their ships. In the battle the Bristol, Sir Peter’s flag-ship, lost forty killed and wounded; Sir Peter himself lost one of his arms; the Experiment, another fifty gun vessel, lost about twice as many. The fire of the fort was directed mainly at the heavy craft. Tom Deering, as he toiled with rammer and sponge at[76] one of the French twenty-six pounders, of which Marion had charge, heard that little officer constantly call to his brother gunners:

“Look to the Commodore—look to the heavy ships; they can do us most damage!”

In the heat of the action the Acteon, one of the smaller of the enemy’s ships, being hard pressed by the Defence and Tartar, ran aground and immediately took fire. At this point the British Commodore would have been forced to strike his colors, or be destroyed, but suddenly the powder ran out and the fire of the fort slackened and finally ceased altogether.

Struck with astonishment at this the British also ceased their fire, thinking the fort had been abandoned.

“We must secure ammunition,” cried Colonel Moultrie, his face ashen. Here was victory all but in his grasp, and to have to give it up would be almost fatal in its effect upon his men.

“The schooner Defence has a large supply,”[77] said Marion, to his commander, as he wiped the black powder stains from his face.

“But she is nowhere in sight,” said Moultrie, sweeping the harbor with his glass.

Tom stepped forward, his hand at the salute.

“Well,” demanded the colonel.

“I saw the Defence chased into Stone Gap Creek awhile ago,” stated the lad eagerly. “She is safe, though, for see,” and he pointed shoreward, “there are her topmasts above the trees.”

“Good,” exclaimed Marion, his face lighting up.

“But how can we reach her? The enemy’s vessels will not allow her to come out,” said the colonel.

“We can go to her,” ventured Tom, hesitatingly, for it seemed presumptuous for him to offer a suggestion to his commander. “The Tartar is lying under the guns of the fort. We could reach the Defence in her. The[78] British could not follow us up the creek; they draw too much water.”

The ammunition that remained on board the Tartar, save a few rounds, Tom’s father gladly gave up to Colonel Moultrie, and a few guns resumed service from the fort, but firing slowly. Under mainsail and jib the gallant little sloop then stood out, in the teeth of the British, heading for the creek where the Defence was lying. Major Marion, Tom Deering and Cole stood upon her deck, watching a brig-of-war which had just started to head them off.

“She’s a fast sailer,” said Mr. Deering, a shade passing over his face, after he had watched the quality of their pursuer for a few moments.

“Do you think she can overhaul us?” asked Major Marion.

“There is no question about it,” returned the planter, “if she is given time enough. But the distance to the creek is short; we may reach there. Then, with the help of the[79] Defence, we can fight her off on the return run.”

The Tartar had arrived within hailing distance of the mouth of the creek, when the brig suddenly discharged a lucky shot from a long bow gun that splintered the sloop’s mast and left her lying a helpless hulk upon the waters.

“It’s all over,” said Marion, quietly.

“The boat remains,” said Mr. Deering. “Quick. You have still time to gain the Defence.”

“And you, father?” said Tom.

“I remain with the sloop,” answered the planter.

“But you will be taken prisoner!”

“I will not leave my crew,” said his father, firmly. “There is not room for us all in the single yawl.”

“Then I will remain, also,” said Tom.

“You will join Major Marion in the boat,” commanded the planter, evenly. “Carolina has need of all her youth. It would be[80] a needless sacrifice for you to throw yourself into the hands of her enemies.”

Despite the boy’s protests, his father remained firm; so with a heavy heart Tom climbed into the boat with Marion. Cole would have remained behind with his master; but the planter, who recognized the great attachment of the giant black to his son, and saw how valuable he would be during these dangerous times, promptly ordered him, also, into the yawl.

They were just pulling into Stone Gap when a small boat with an armed crew left the British brig and pulled for the wrecked Tartar. So it happened that Roger Deering was one of the first prisoners of war taken in Carolina.

Apparently the British skipper did not realize the significance of the sloop’s errand; for after taking her crew from her she set fire to the hull and sailed back to rejoin the other vessels in the line of battle.

An hour later the Defence crept out of[81] Stone Gap Creek and headed for Fort Moultrie. She was a swift sailer, and the old salt who commanded her knew how to make her do her best. So, in spite of pursuit and flying shot, she anchored under the guns of the fort and quickly transferred her powder. The British, during the protracted lull in the fort’s fire, had drawn closer; but now, under the brisk and accurate cannonade they withdrew again to their first position. The fight then continued, hotter than ever; shortly afterward the fort received another supply of powder from the city, which did much to encourage the defenders.

The cheers, however, that greeted the arrival of the ammunition had scarcely died away when a distant roar of voices raised in exultation came from the British fleet.

“Look; the flag,” cried some one.

A solid shot from one of the flag-ship’s heavy guns had carried away the flag and it fell, fluttering like a wounded bird, outside the walls of the fort. In an instant Tom[82] Deering, who was once more helping to serve the gun, threw his rammer to Cole and leaped upon the wall. A storm of canister swept about him and a hundred voices shouted for him to return; but, without hesitation he leaped to the sandy beach below, between the ramparts and the enemy, seized the fallen colors, stuffed them into his bosom and then with the help of the mighty, outstretched arm of Cole, scrambled back inside.

Again the flag was run up to the top of the staff, by means of fresh halyards; the sight of it seemed to give the colonists renewed courage, for they turned to the conflict with a resolution that was unconquerable. The British ships were fast becoming mere wrecks, so seeing that a continuation of the combat would be mere folly, the signal flags were flown at the masthead of Commodore Parker’s vessel to cease firing. Ten minutes afterward a fleet of ships, with sails hanging from the rigging in shot-rent rags, and with hulls battered, leaking and[83] torn with canister, ran out of Charleston harbor in disorder.

“They carry your father with them, a prisoner,” said Major Marion, to Tom Deering, as they leaned, watching, upon a hot gun.

“But they shall not keep him,” cried the lad, “to die in their prison hulks! He shall be free! I am only a boy; but the whole British navy shall not keep me from him. It may be a month, a year, or even more, but he shall be free in spite of all the fleets and armies they can send!”

The battle of Fort Moultrie was of immense importance to all the confederated states. It happened before the Declaration of Independence was passed at Philadelphia. Because of the slowness of travel in those days the news did not become known in the capital city and other points of the north for a month or more afterward; but it served to strengthen the patriots in their cause, and that went for much in that dark hour of doubt.

For three years the British made no further attempt to invade Carolina.

During this time Tom Deering saw service against the Cherokees and Tories; but the greater part of his time was devoted to trying to find his father. He and Cole used every means in their power to find where the planter had been taken; more than once they[85] assumed the characters of loyalists, when they saw a British ship standing in near shore, and with a boat-load of fresh vegetables they would pull or sail out to her under pretence of desiring to sell the things to the officers. But all their questioning upon these and other occasions went for nothing; no trace was to be had of his father. But Tom was not disheartened; the finding of his father was to be his task, and he persisted in it day after day, week after week; wherever there promised to be a shred of information, there he rode, sailed or walked. But not once in the entire three years did he gain a single clue.

Then, suddenly, came the surprise of General Howe at Savannah; the Americans were dispersed and the city fell into the hands of the British. Ten thousand picked troops under Sir Henry Clinton sailed from New York upon Charleston, bringing a train of heavy artillery. Six weeks after the city was invested it fell, and four thousand men were[86] taken prisoners; the command of the British then was given to Lord Cornwallis, and at once the entire colony began to feel the gross abuse of power and wanton tyrannies with which that officer soiled his name.

Tom Deering, between his marches in the Cherokee and Tory countries had found much time to attend to the plantation. Nothing had been heard of his father since the day the boat’s crew of the brig-of-war took him from the wrecked sloop, so the whole care of the extensive estate now fell upon the boy.

Tom’s mother had died when he was but a child, and he had no brothers or sisters. The only relatives he knew of, in the wide world, other than Captain Deering were the Harwoods, and these, of course, he never saw, as they had not ventured into the neighborhood of Charleston since once taking arms against their neighbors. Tom was now a stalwart, bronzed youth of about nineteen; hard riding had developed him wonderfully in body and constant danger had given him that calm,[87] steady, tried courage that is a soldier’s best gift.

The Deering mansion was crowded with many objects of value in the way of plate, pictures and antique carvings, of which his father had been a tireless collector. Upon looking over the books of the plantation one day, Tom discovered that there was also about four thousand pounds in gold in the house, his father having drawn all his money out of the banks at the first sign of trouble between the colony and Great Britain. This was a very large sum and its possession troubled the boy not a little. The money was locked up in a heavy oaken chest in his father’s private room; and when the news reached him that Sir Henry Clinton was in the outer roadstead, he set about finding a hiding-place for it, his judgment telling him that the city was in danger.

He and Cole opened the chest one night; the broad gold pieces, mostly Spanish, were tied up in stout bags.

[88]“If the enemy storm and demolish Fort Moultrie,” said Tom, as he looked reflectively at the bags, “they will be very keen after hard money to pay off their men and obtain fresh supplies. So they would not hesitate a moment in seizing upon this if they chanced upon it.”

The hiding-place must be a secret known only to themselves; the slaves upon the plantation could be trusted to the last one; but if the dragoons of Tarleton suspected the presence of treasure upon the place, they would terrorize the negroes by threats of torture and compel them to tell where it was hidden.

Some distance from the house, in the middle of an orchard, was an old well, the waters of which were used in dry weather to keep the young trees in good condition. As a small boy Tom had often lowered himself into its dark depths in a spirit of exploration; and now, as he cast his mind about for a safe place to conceal the gold, the well occurred to him.

[89]“I have it, Cole,” exclaimed he, cheerfully. “The old well in the orchard is the place; about half-way down, a large stone fell out a long time ago, and behind the bed where the stone lay we can dig out a hole large enough to contain all the money.”

Cole nodded delightedly; in his opinion it was just the thing. So out they went, at a side door at the upper end of the house to prepare the hiding-place. Cole carried a long rope, for Tom decided not to trust his weight to the well rope, which was old and very likely rotten; they also had a masked lantern, a short iron bar and a small spade.

“We must be careful and not be seen,” said Tom, as they picked their way through the garden. “The Tories are drawing in close, at the expectation of a British victory; and if one of them saw us prowling about in the darkness he would suspect something at once.”

They reached the well in a very few minutes, and he at once set to work to descend.[90] Cole formed a sling at one end of the rope and passed it about Tom’s body. The boy had the masked lantern fastened to his belt; the spade and bar were lying upon the low curb of the well; he was just about to swing himself down into the black hole when suddenly there came a low, sullen shock as of distant thunder, followed by another and another. The eyes of the boy and the giant went instantly in the direction of the harbor; a flare of light ran along the sky, and immediately vanished.

“The British!” said Tom. “That was their big guns that spoke; and they are firing rockets, too. They mean to attack the fort in the darkness. We are none too soon, Cole; for there is no knowing what will happen now.”

Cole’s strong arms lowered him slowly into the well, and he soon found the place he sought. A large and almost square stone had fallen out and behind where it had lain in the lining of the shaft the earth could be seen.[91] Tom carefully pried out some few other and smaller stones with the bar; these he passed up to Cole, after which he set to work with the spade to dig an aperture sufficiently large to hold the sacks of gold.

As he worked he could hear the steady growl of the distant guns; above his head he could see but a small, round spot in the sky through the shaft of the well; and every little while this small, round spot would be lit up by a sudden glare of rockets sent hissing into the heavens as signals to the captains of the attacking fleet.

In about half an hour Tom’s task was completed. Cole was signaled and hauled him out of the well.

“Now,” said Tom, “let’s get the bags down. It will be daybreak, almost, when we finish with this matter; and we want to be done with it before any of the hands are stirring.”

When they reached Mr. Deering’s office, Tom was about to open the chest once more and take the bags out for transportation to the[92] orchard. But a gesture from Cole stopped him. With an ease that made even Tom’s eyes open in wonder, and the lad was accustomed to Cole’s exhibitions of tremendous strength, the giant slave hoisted the chest upon his back, and motioned to his master to go before him and open the doors. It was a dead weight and sufficient to crush an ordinary man; but Cole carried it downstairs, through the wide hall, out into the garden, and thence to the orchard, where he lowered it to the ground with scarcely a labored breath.

“Cole,” said Tom Deering in astonishment, “I believe you are a second cousin to an elephant! You’re growing stronger every day!”

The great slave grinned; he took a childish pleasure in his enormous power, and it made him happy when notice was taken of it by Tom, or his father. The sacks were now taken out of the chest, and once more the lad was swung down into the well, carrying[93] several of them in his arms. Quite a number of trips were necessary before the gold was all stored in the hollow behind the stones.

“Now,” said Tom, “we must block up the opening. It will not do to allow it to remain as it is.”

Some lime was procured from a barrel in the negro quarters, slacked and quickly mixed with sand and water.

“It’s not very good mortar,” remarked Tom, “but it will have to answer, as it’s the best we can do.”