Title: The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (December 1912)

Contributor: Various

Release date: March 20, 2022 [eBook #67663]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Century Co

Credits: Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from December, 1912. The table of contents, based on the index from the November issue, has been added by the transcriber.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the corresponding article.

Christmas Number

THE CENTURY

ILLUSTRATED

MONTHLY

MAGAZINE

THE CENTURY CO UNION SQUARE NEW YORK

FRANK H. SCOTT, PRESIDENT, WILLIAM

W. ELLSWORTH, VICE-PRESIDENT

AND SECRETARY, DONALD SCOTT,

TREASURER, UNION

SQUARE, NEW

YORK.

(Title Registered U. S. Pat. Off.)

Copyright, 1912, by The Century Co.]

[Entered at N.Y. Post Office as Second Class Mail Matter

HE highest expression of beauty and charm combined with utility and worthiness will be found in any gift bearing the Berkey & Gay shopmark.

The pieces to furnish a bedroom, library or dining room would constitute a wonderful remembrance, but our dealers can show you many single pieces which, while reasonably priced, still make gifts which will always be cherished. In making a present of Berkey & Gay furniture you can say: “This is

For Your Children’s Heirlooms

THE Berkey & Gay shopmark means as much on furniture as “Sterling” on fine silver. It is not a label and is more than a trademark. It is inlaid—a permanent part of the piece, and we put it there as our guaranty of value and worthiness.

With the displays on their floors in connection with our portfolio of direct photogravures, our dealers enable you to choose from our entire line. In addition to these, our special gift pieces in “novelty” furniture have an individual appeal.

OUR de luxe book, “Character in Furniture” gives an interesting and informative account of the origin of period furniture. It is illustrated in color from oil paintings by Rene Vincent. We will mail a copy to you direct for fifteen two-cent stamps. And, as a help to you in your making of gifts, we will gladly mail you our special new book entitled “Entertaining Your Guests,” which is descriptive of single pieces that are particularly appropriate.

Berkey & Gay Furniture Co.

174 Monroe Ave., Grand Rapids, Michigan

[Pg 162]

[Pg 163]

Copyright, 1912, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

| PAGE | ||

| AFTER-DINNER STORIES. | ||

| A Reminiscence of Marion Crawford. | Baddeley Boardman | 319 |

| AFTER-THE-WAR, SERIES, THE CENTURY’S. | ||

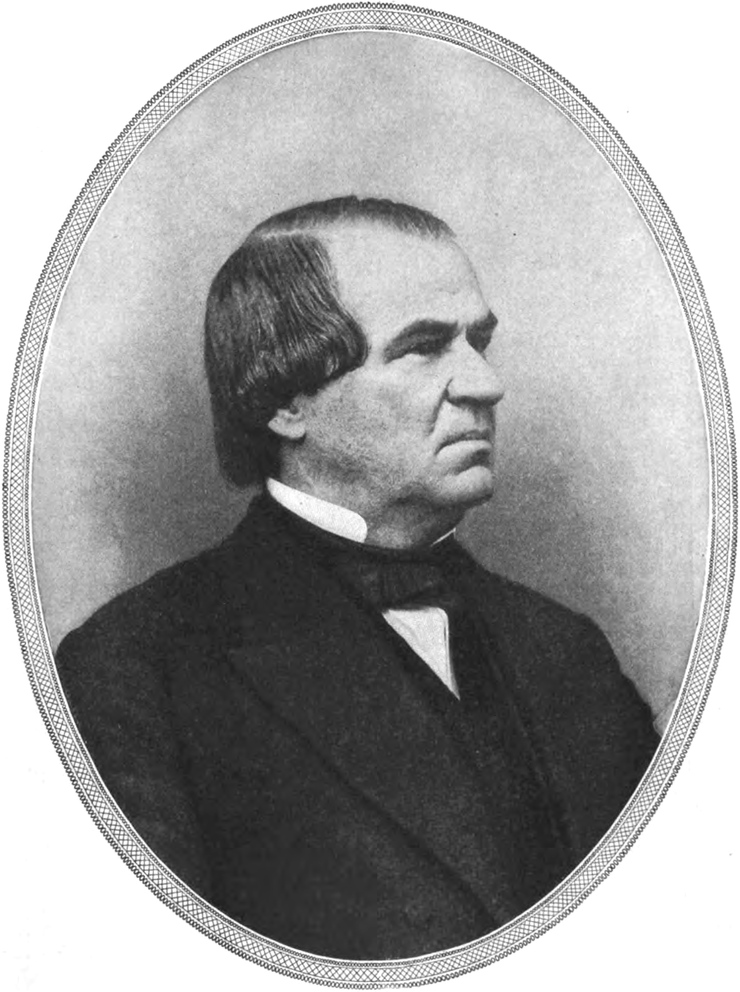

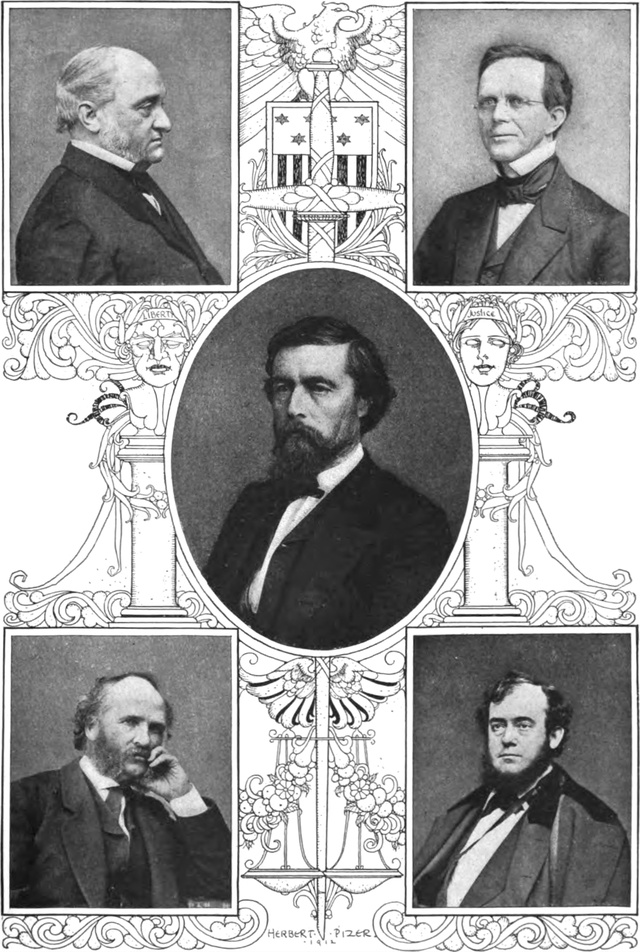

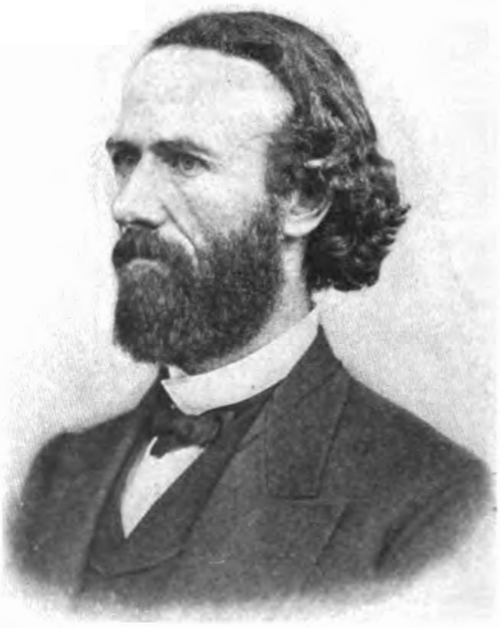

| The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson. | ||

| I. The Causes of Impeachment | Harrison Gray Otis | 187 |

| II. Emancipation and Impeachment | John B. Henderson | 196 |

| Portraits, and drawing by Jay Hambidge. | ||

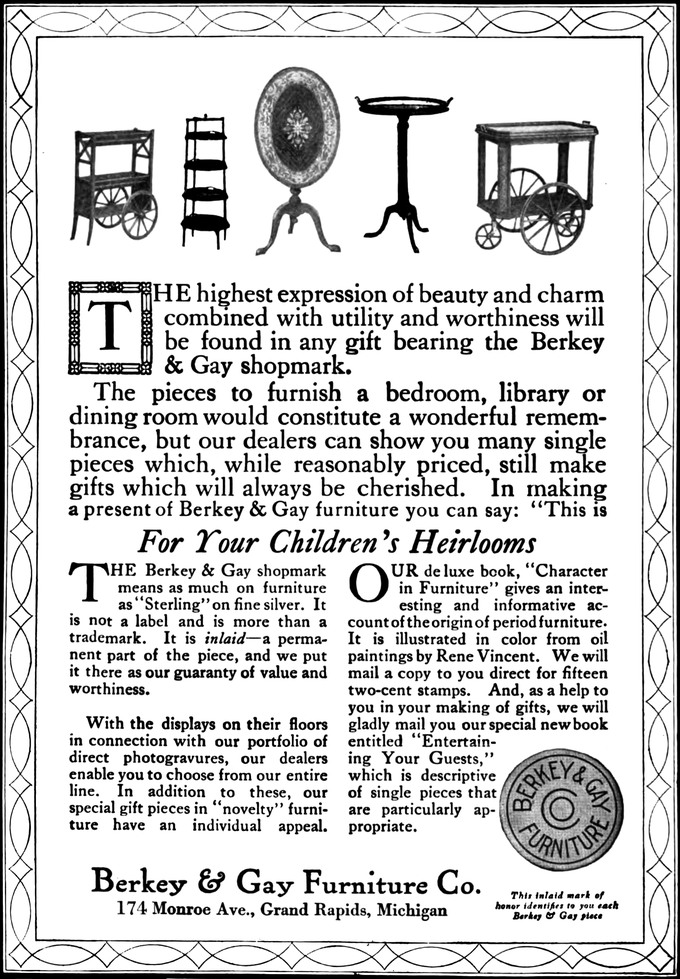

| ARTIST SERIES, AMERICAN, THE CENTURY’S | ||

| Mary Greene Blumenschein: Idleness | 162 | |

| Printed in color. | ||

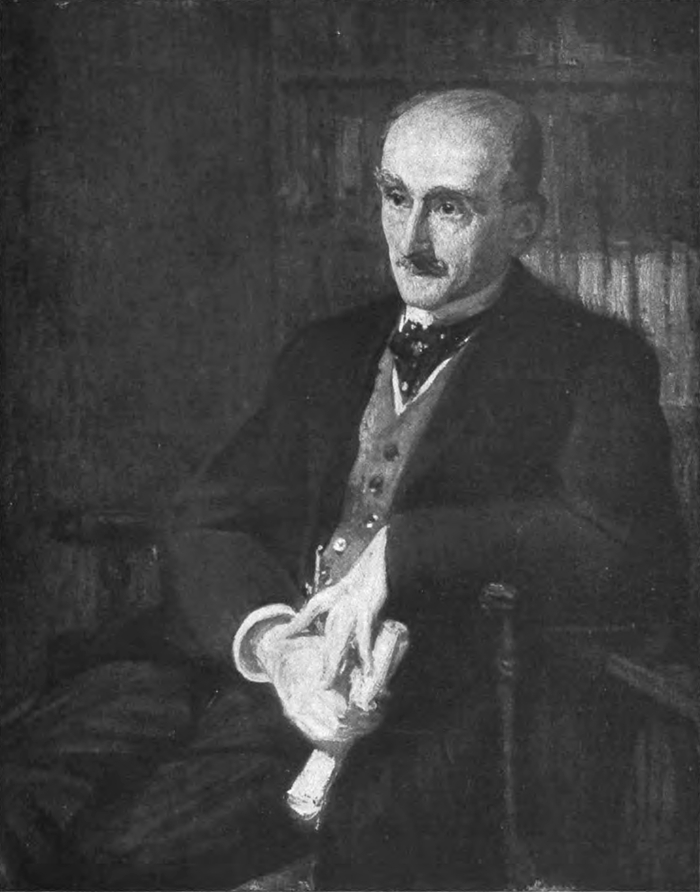

| BERGSON, HENRI | Alvan F. Sanborn | 172 |

| Portrait by Jacques Blanche. | ||

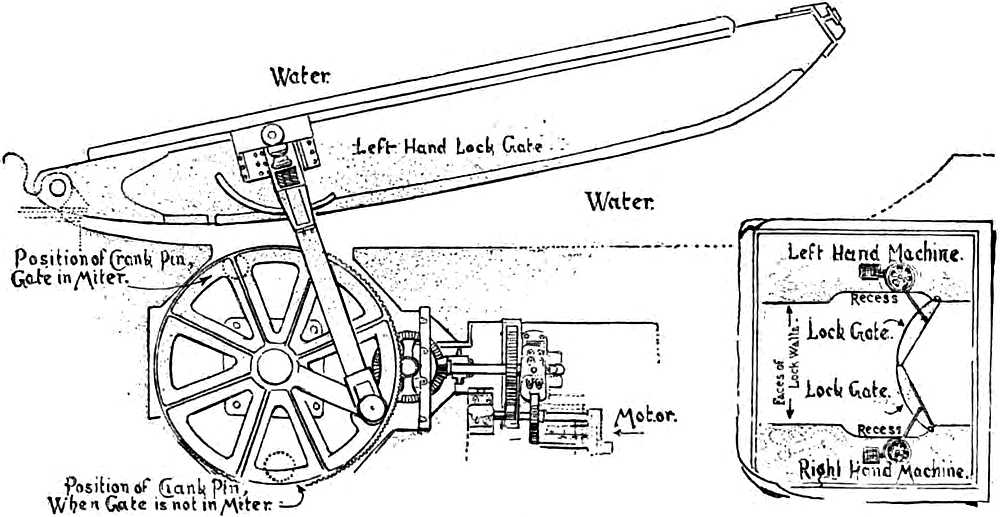

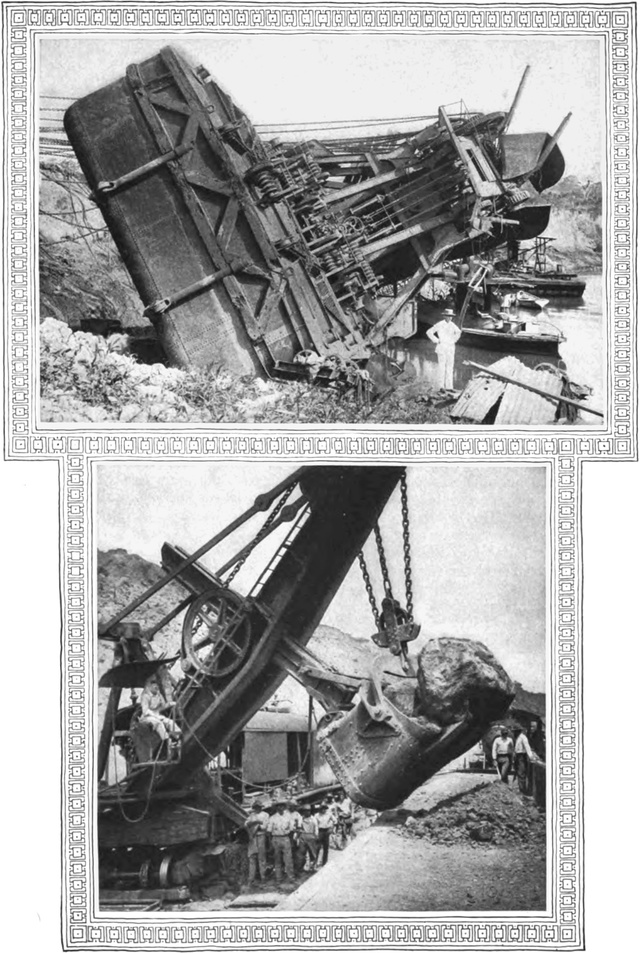

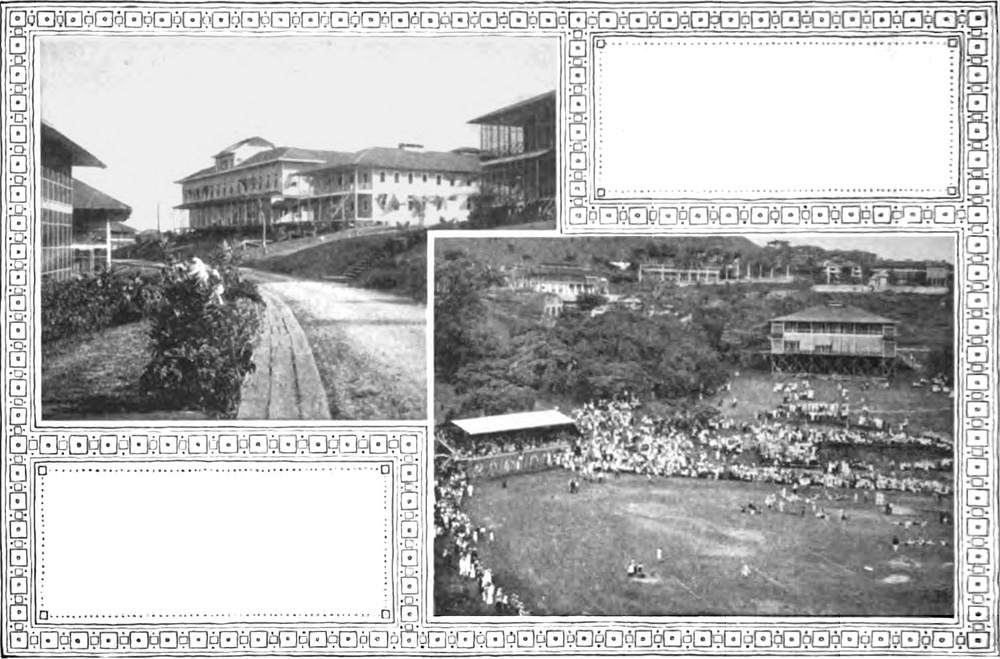

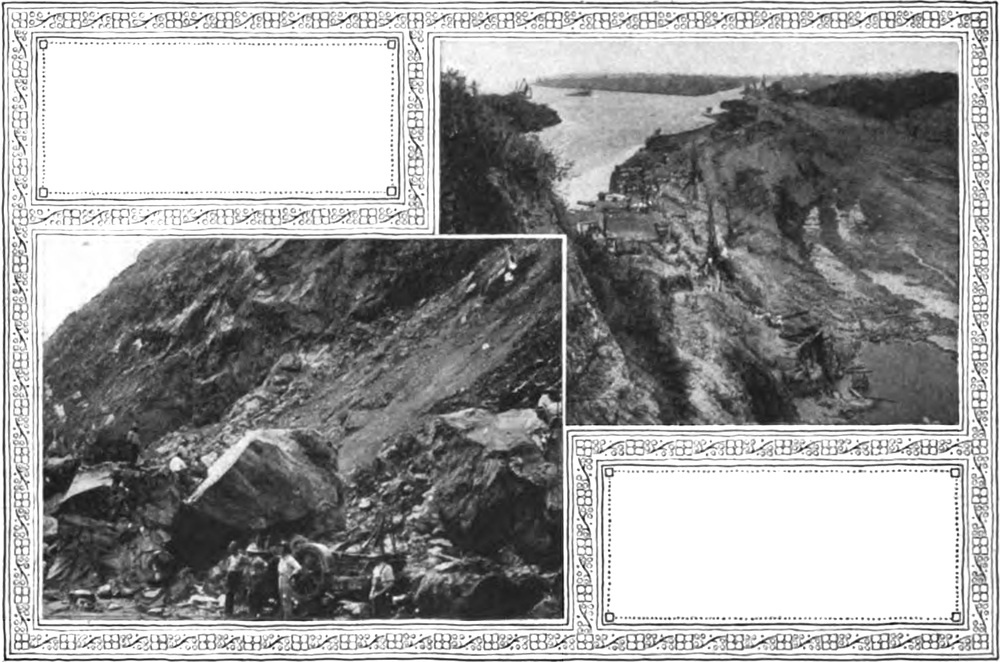

| BIG JOB, THE, THE END OF | Farnham Bishop | 271 |

| Pictures from photographs, map, and diagram. | ||

| CHILDREN’S, THE, UNCENSORED READING | Editorial | 312 |

| CHRISTMAS EMMY, JANE’S | Julia B. Tenney | 319 |

| CHRISTMAS FÊTE, A, IN CALIFORNIA | Louise Herrick Wall | 319 |

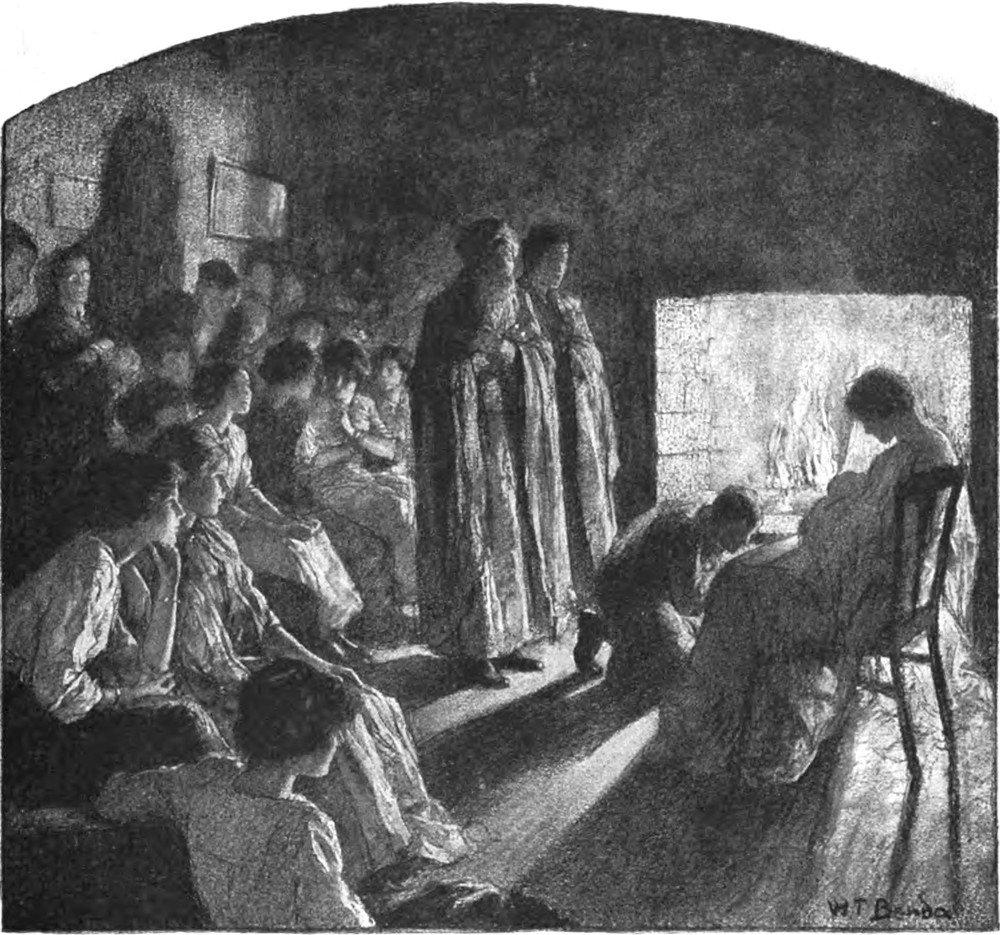

| Pictures by W. T. Benda. | ||

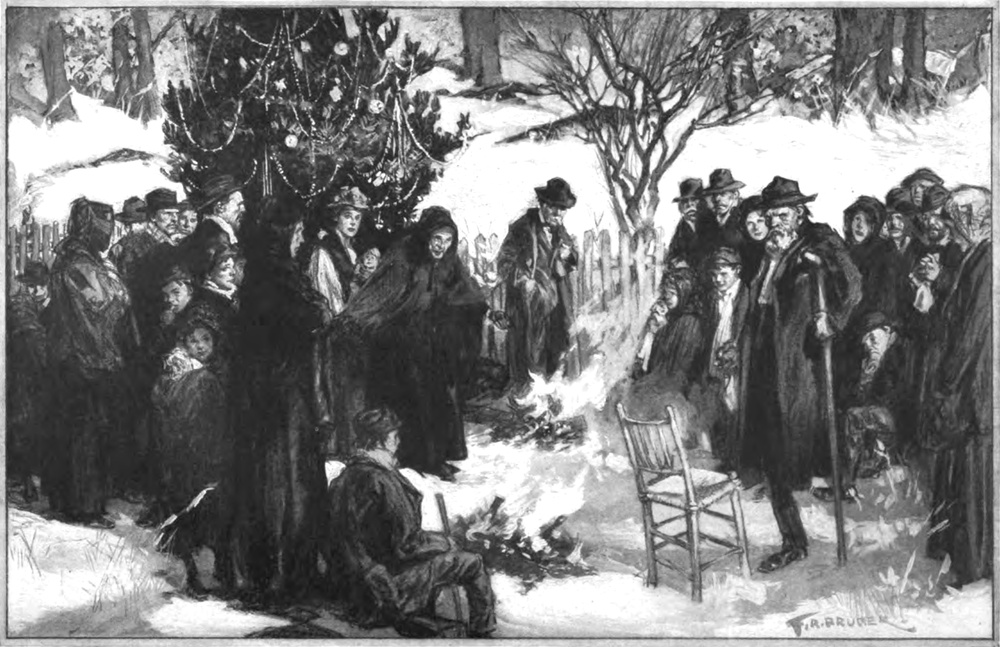

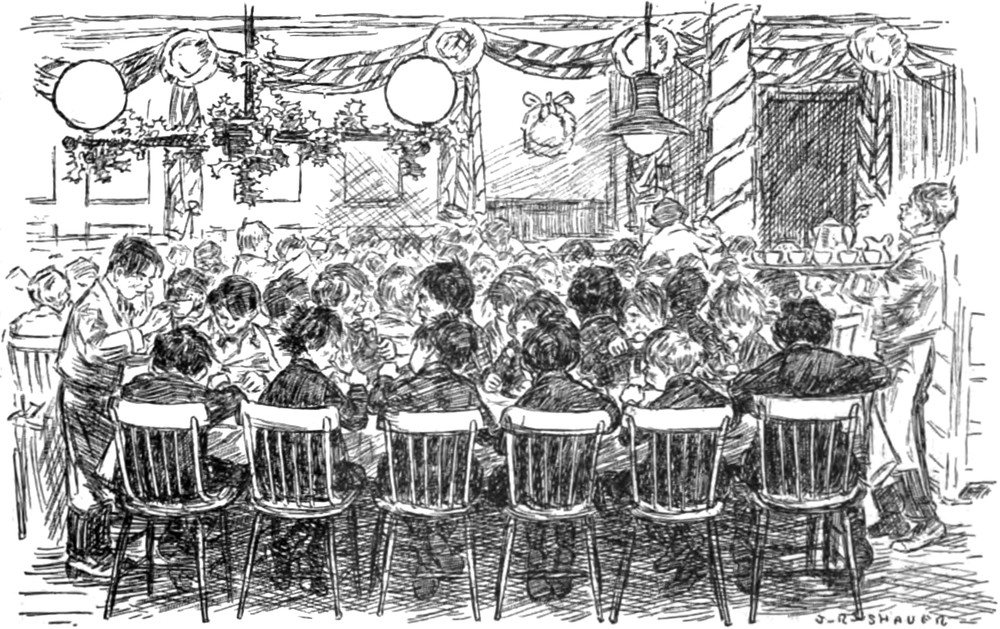

| CHRISTMAS TREE, THE, ON CLINCH | Lucy Furman | 163 |

| Pictures by F. R. Gruger. | ||

| COLE’S (TIMOTHY) ENGRAVINGS OF MASTERPIECES IN FRENCH GALLERIES | ||

| Lady Mildmay. By Hoppner | 225 | |

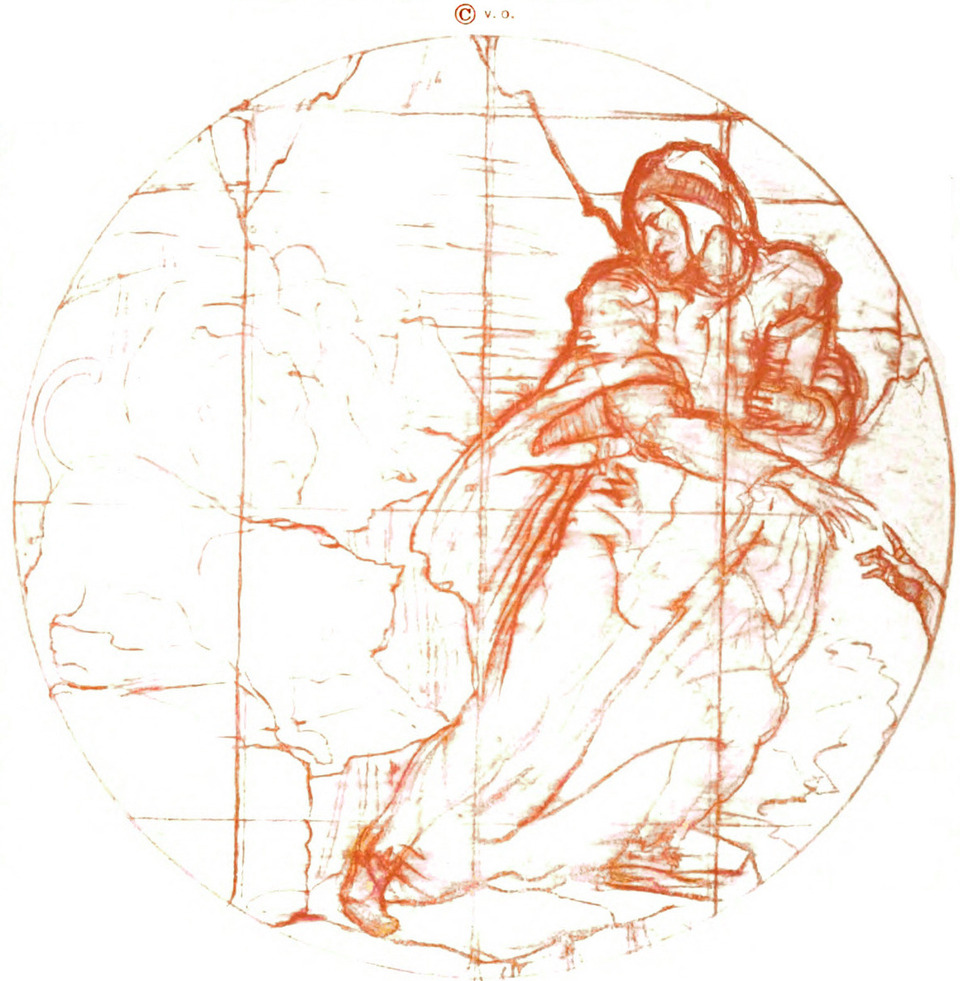

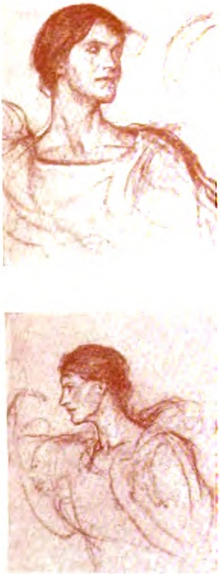

| DANTE’S DIVINE COMEDY. Red chalk drawings | Violet Oakley | 239 |

| FRATERNITIES IN WOMENS’S COLLEGES | ||

| Exclusiveness among College Women | Edith Rickert | 227 |

| GIVING AWAY THE NATION’S PROPERTY | Editorial | 315 |

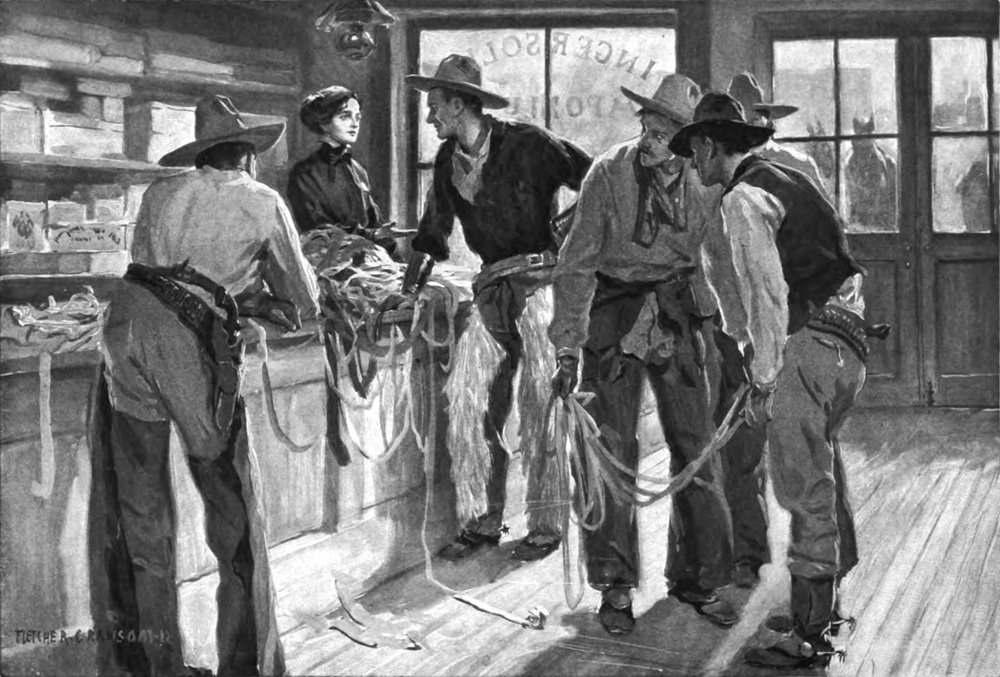

| “HOLY CALM,” THE WOOING OF | Marion Hamilton Carter | 218 |

| Picture by Fletcher C. Ransom. | ||

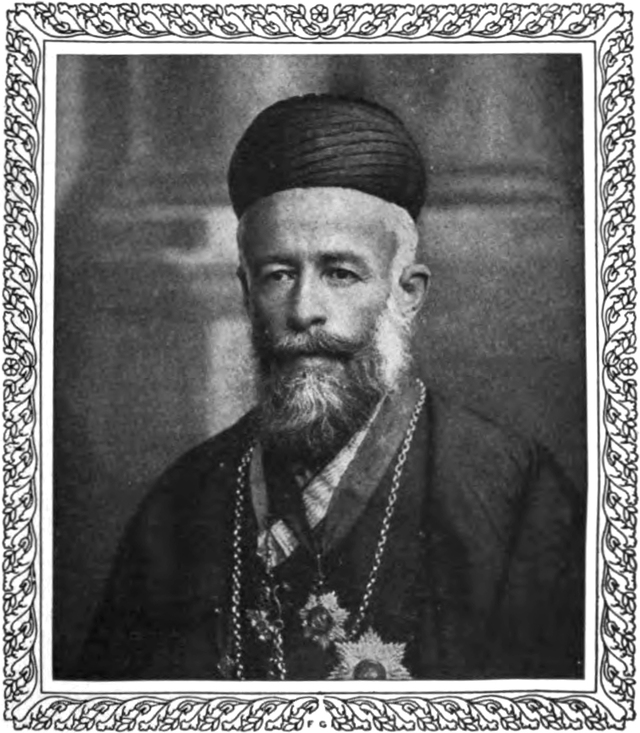

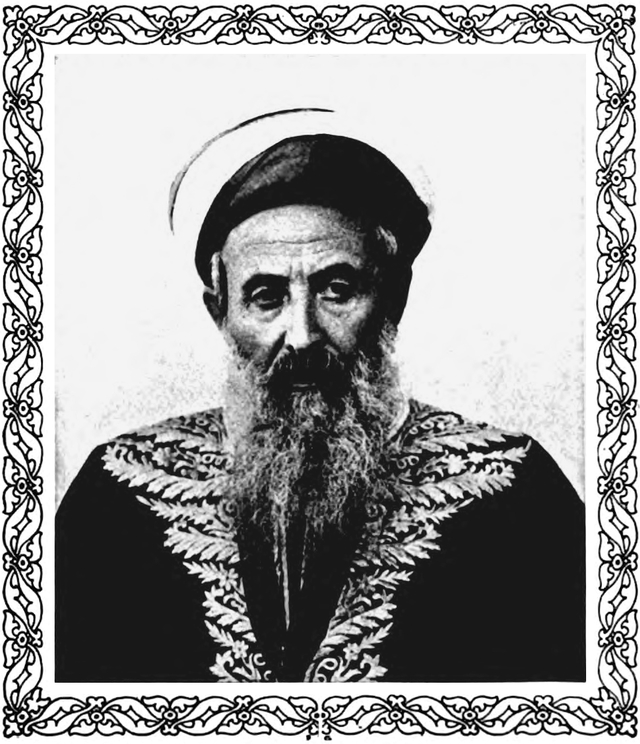

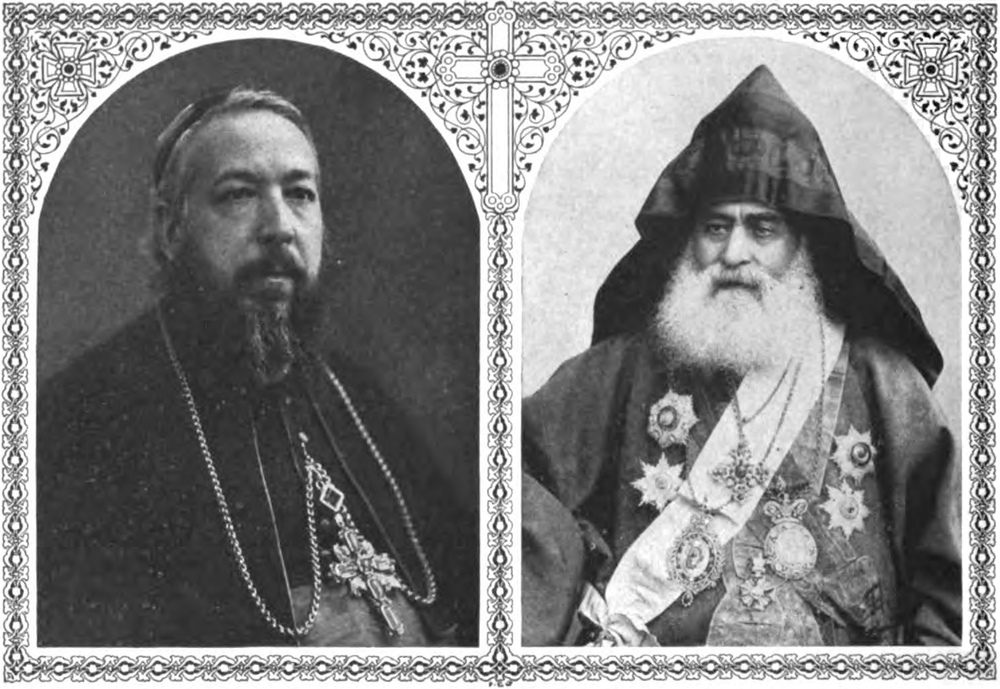

| JERUSALEM, LORDS SPIRITUAL IN | Thomas E. Green | 289 |

| MAGIC CASEMENTS, ON | Vida D. Scudder | 316 |

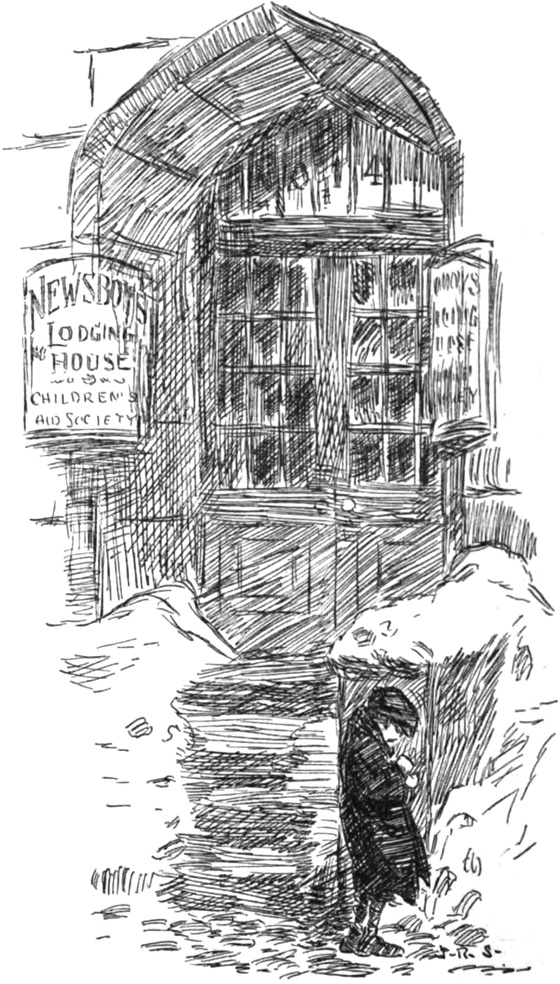

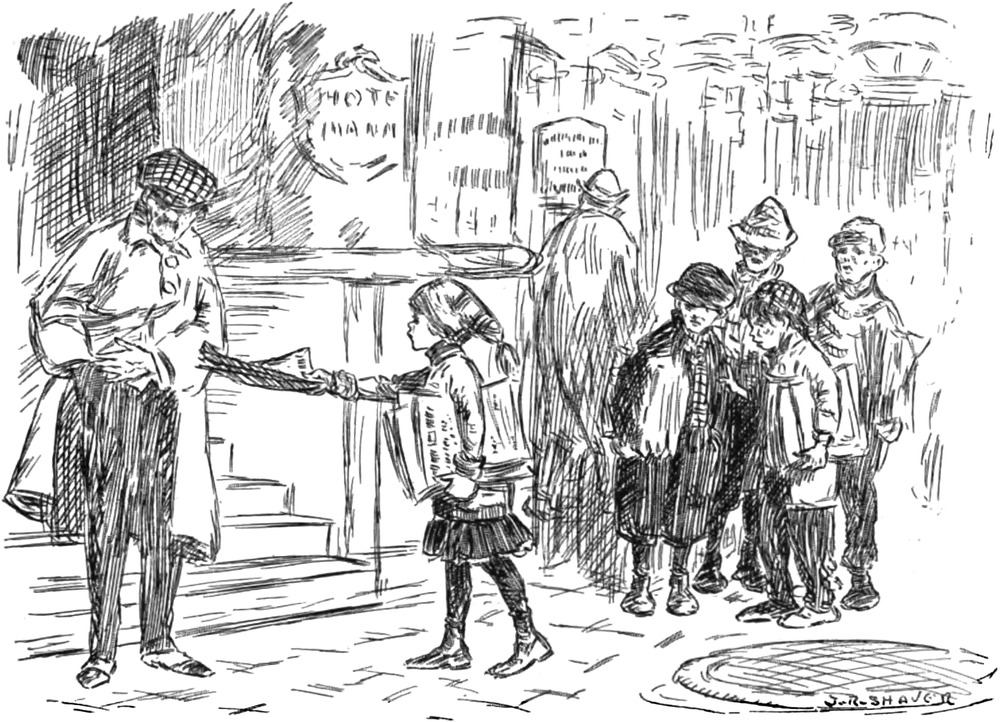

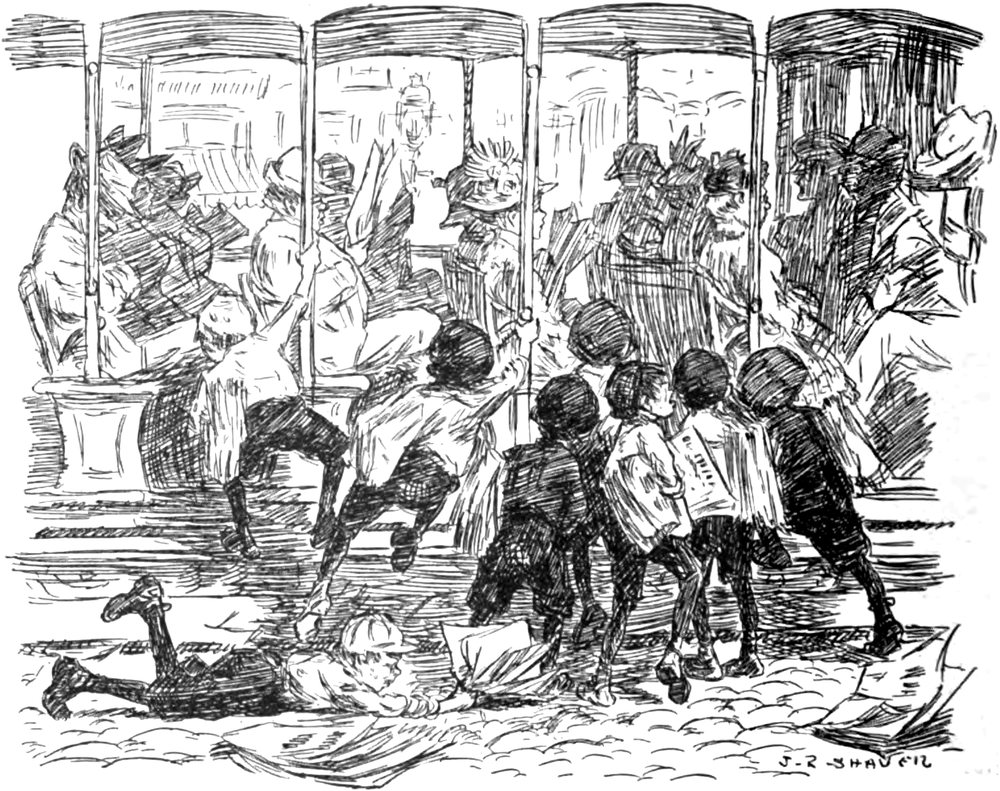

| NEWSBOY, THE NEW YORK | Jacob A. Riis | 247 |

| Pictures by J. R. Shaver. | ||

| NOËL, LITTLE, THE MIRACLE OF | Virginia Yeaman Remnitz | 182 |

| Pictures by W. T. Benda and Joseph Clement Coll. | ||

| SIREN OF THE AIR, THE | Allan Updegraff | 283 |

| Picture by W. M. Berger. | ||

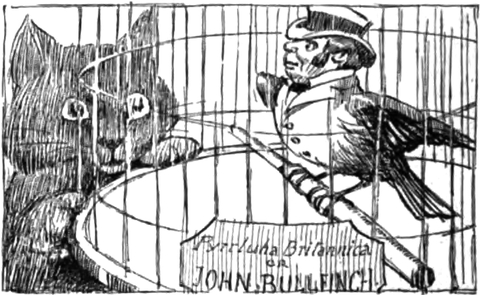

| SOCIALISM, ENGLISH, THE SET-BACK TO | Gilbert K. Chesterton | 236 |

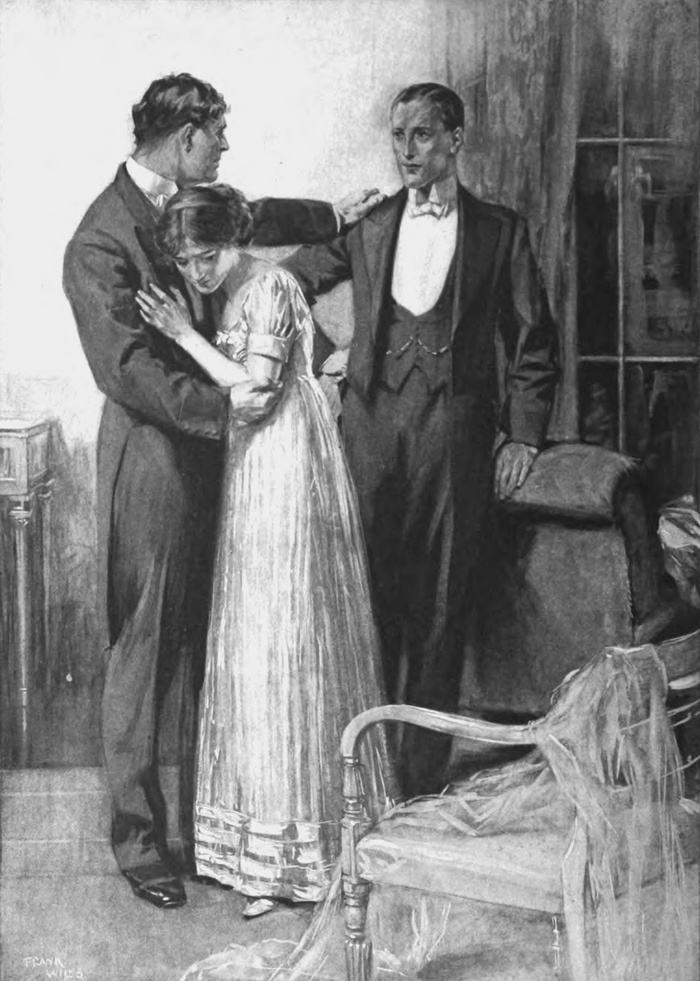

| STELLA MARIS | William J. Locke | 259 |

| Pictures by Frank Wiles. | ||

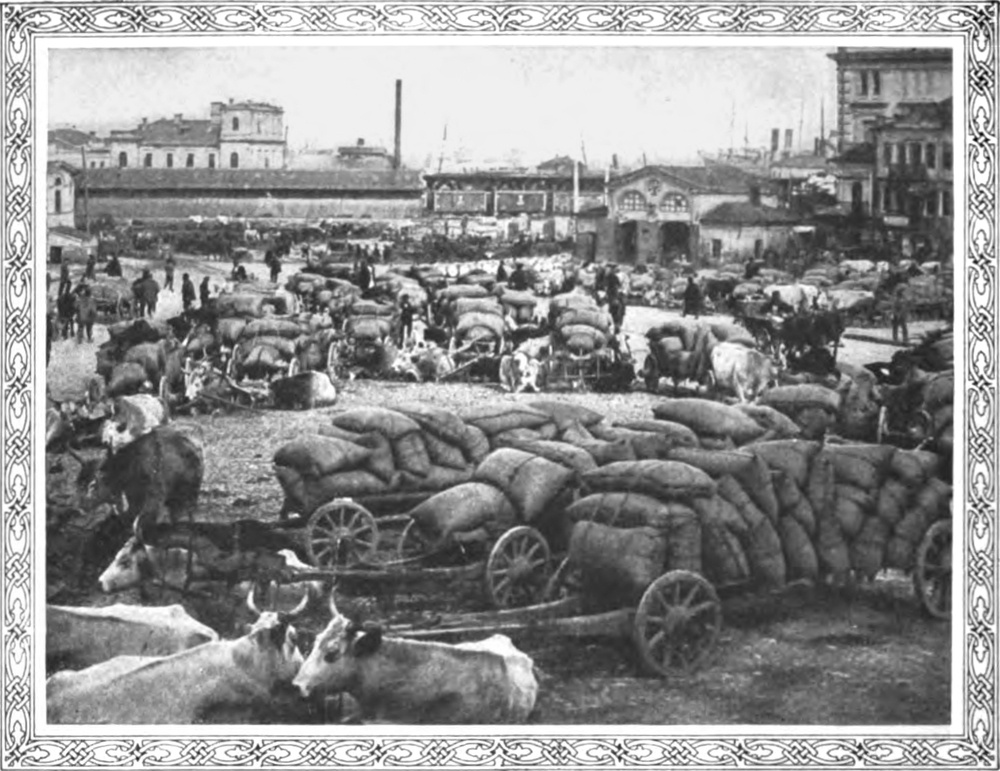

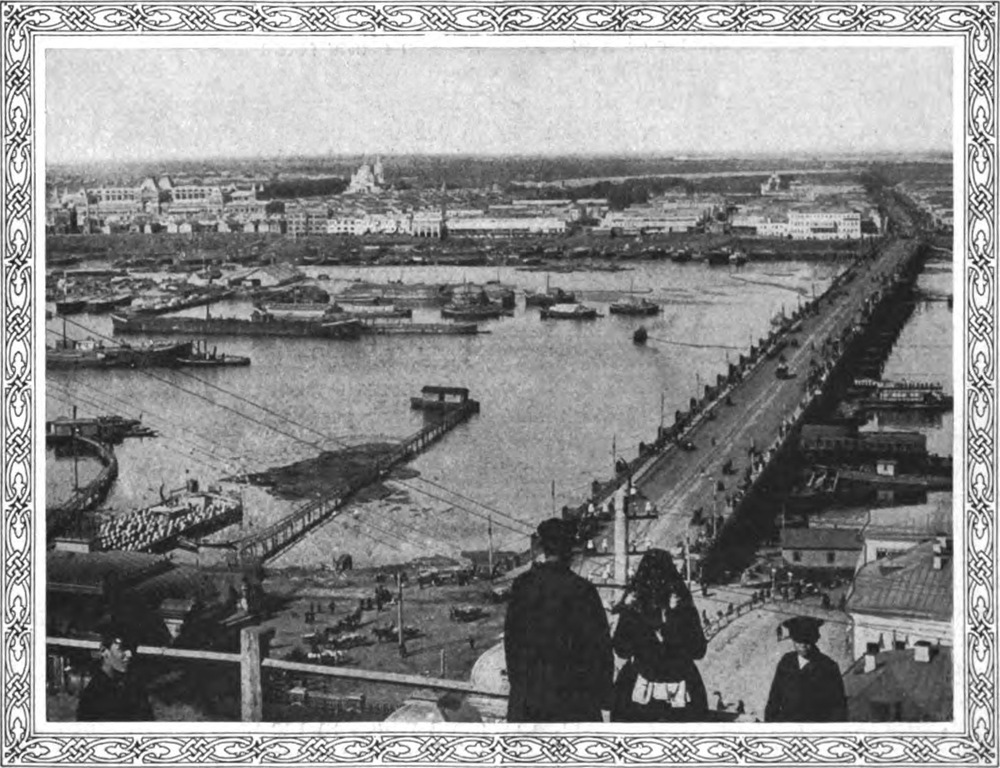

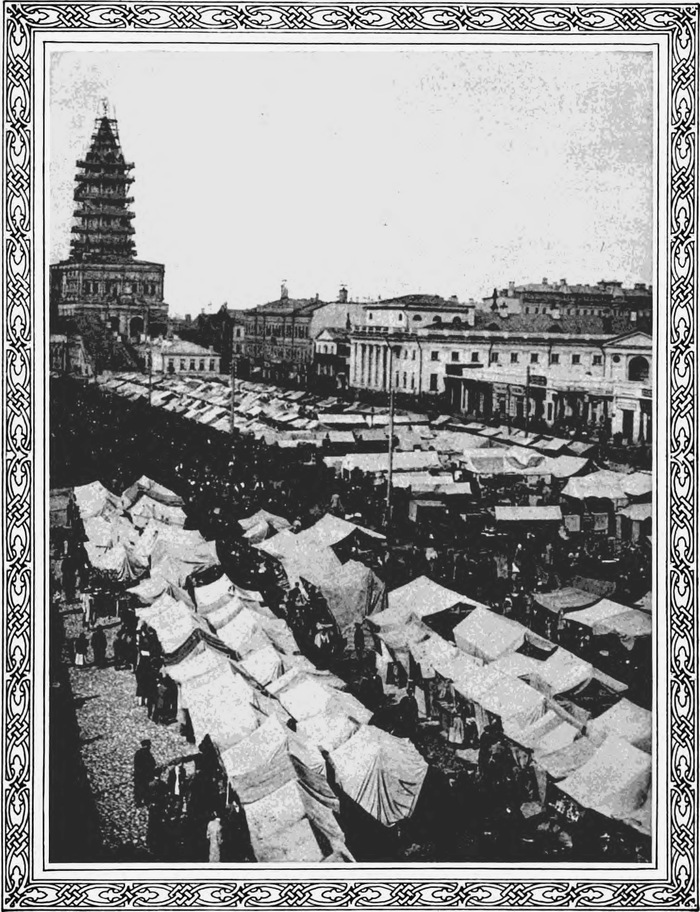

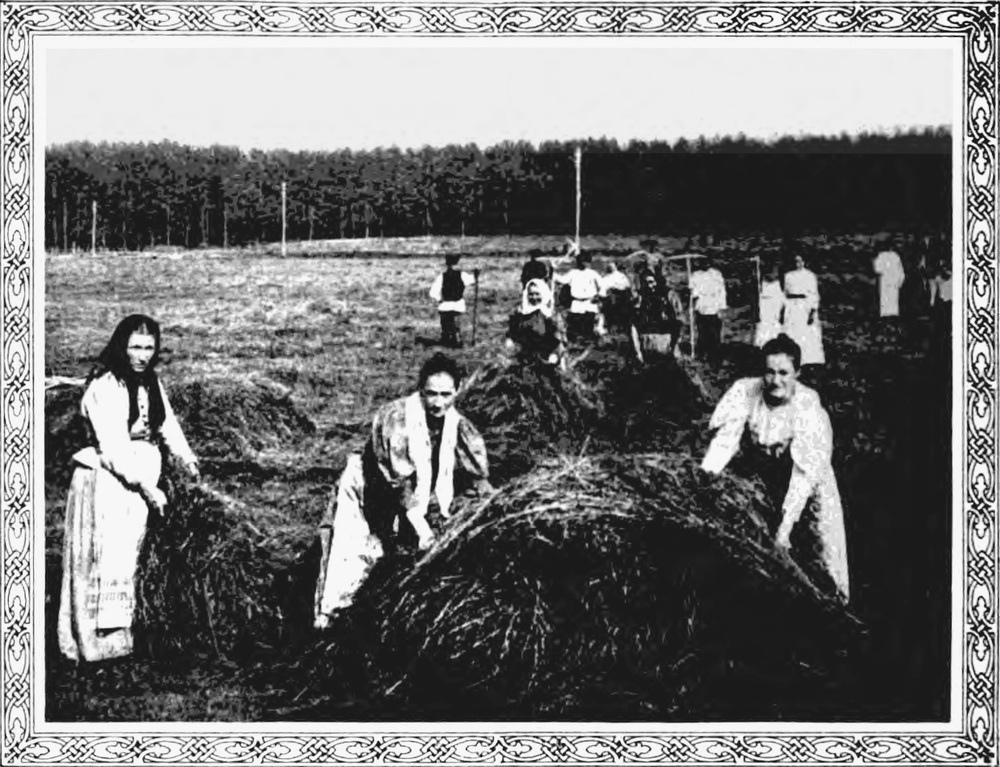

| TRADE OF THE WORLD PAPERS, THE | James Davenport Whelpley | |

| XIV. The Trade of Russia | 296 | |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| VOTING, NEW ANXIETIES ABOUT | Editorial | 311 |

| WAR AND ARBITRATION, A CRISTMAS THOUGHT ON | Editorial | 314 |

|

VERSE

|

||

| DREAMS DENIED, THE | Marion Couthouy Smith | 217 |

| GLORY SHALL FOLLOW GLORY | Charles Hanson Towne | 288 |

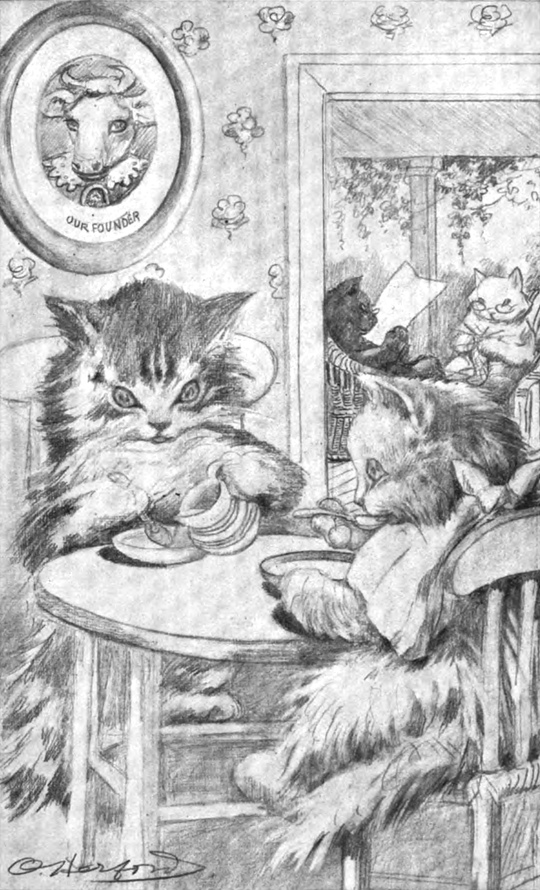

| LIMERICKS | ||

| Text and pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| XIX. The Filcanthropic Cow | 321 | |

| XX. Tact | 322 | |

| PITILESSNESS OF DESIRE, THE | Shaemas O’Sheel | 235 |

| PROVENCE, CHRISTMAS ECHOES FROM | Edith M. Thomas | 177 |

| Pictures by Charles S. Chapman. | ||

| THOUGHTS, DECEMBER TWENTY-FOURTH | Deems Taylor | 319 |

(DOINGS ON PERILOUS)

BY LUCY FURMAN

Author of “Mothering on Perilous,” etc.

WITH PICTURES BY BERNARD B. DE MONVEL

ONE Saturday morning in October the head-workers and some of the teachers of the Settlement School on Perilous were unpacking barrels and boxes on the front porch of the “big house,” a wagon having come in from the railroad the previous day. Christine Potter, the newest and youngest teacher, looked up from a box of books to see an odd procession approaching along the road. A yellow mare, bearing a small woman with an infant in arms, and a tiny child behind, was followed by a half-grown mule colt, on which rode three little girls, while a small yellow colt trotted sedately in the rear. At the school gate the party halted. The yellow colt flung his four legs in as many directions and began to frisk about his mother; the riders dismounted and came up the walk.

The woman came straight to the heads, her eager face beaming under the black sunbonnet, inevitable badge of the married woman.

“Don’t you know me?” she inquired—“little Anne Goodloe that was, from the head of Clinch? Don’t you mind the summer, ten year’ gone, you sot up a tent over there, and I holp you with the singing and gatherings?”

Yes, indeed, the heads remembered, and gave Anne a hearty welcome, asking a volley of questions about her family. But these she cut short.

“Women,” she said, “all that will keep. Let me first get off my mind what I come for. Before I lose another minute I crave to enter these young uns of mine on the highroad to l’arning in this here fine school. I have heared you write ’em down in a book, and take as they come; and many’s the time I have woke with a nightmare, dreaming my offsprings was writ down too late to get a show. I want you to put ’em down immediate’. Phœbe, Ellen, Minervy, Lukeanna, stand forth!”

The four small girls drew up in line before[Pg 164] their mother, their blue sunbonnets forming an exact stairway.

“Six, four and a half, three, and going on two is their ages,” continued Anne, “and my man-child here, too—John Jeems, four month’,—don’t pass over him.”

One of the heads wrote down the names and ages; then she inquired:

“And the last name—your married name?”

Anne watched their faces expectantly as she replied:

“Talbert.”

“Talbert!” they exclaimed in one astonished voice.

“I allowed it would take your breath to hear that John Goodloe’s daughter had married Jeems Talbert’s son,” Anne said, smiling.

“When we were over on Clinch the Goodloes and Talberts were mortal enemies. There was constant trouble between them, and not a Talbert would ever come inside our tent simply because it was on Goodloe land.”

“Yes,” said Anne; “forty year’ they have been at war—ever since Paw and Jeems fell out over a gal, and shot each other all up.”

Christine had gathered the sunbonnets, and placed a chair for Anne, who now sat down, smoothed and recoiled her abundant yellow hair, and proceeded to give her man-child his dinner, the little girls ranging themselves silently on a bench, still in step formation, and gazing about them with big eyes and bobbing pigtails.

“There was some little shooting going on when we were there,” continued the heads, “and five years previous the two eldest sons had killed each other in an engagement.”

“Yes,” replied Anne; “that was a mighty sorry time when the boys on both sides got sizable enough to take up their paps’ war—a sorry time it was for both Goodloes and Talberts.” She sighed deeply.

“Doubtless they made peace later, or you would not have married a Talbert?”

“No, they hain’t never made peace; but there never was no war betwixt me and Luke. We was the youngest on both sides, and I allus did think Luke was the prettiest boy that ever rid a nag. When we would be out hunting the cows, I never regretted when I met up with him, though of course we wouldn’t speak or let on to[Pg 165] see. But one day when we had passed in the road unseeing that a-way, we both turned back to look. Luke he blushed, and I laughed. ‘Goodloes hain’t pizen,’ I says. ‘Neither is Talberts,’ he says; and from that time we would stop and pass a few words when there wa’n’t nobody in sight. ’T wa’n’t long before I knowed he was the onliest boy I would ever marry, and him the same of me. Of course I never told nobody but granny, and she holp us off; she allus did contend that Goodloes and Talberts never ought to be nothing but friends, paw and Jeems having been raised like own brothers.

“Well, maybe you think there wa’n’t a general commotion when me and Luke run off. Paw and Jeems b’iled and raged scandalous, for men lamed and maimed up like them, and it looked like the war would be fit all over ag’in. Luke had took his logging money and bought a piece of ground from his paw right j’ining ours, and raised a house on it, so we had a roof over our heads; but nary a foot did a Goodloe or a Talbert set in it, or so much as look our way in passing, for over a year. But me and Luke we never seed no slights, and allus spoke civil and cheerful to all we met, and in time they begun to drap in, first one side and then t’other. Then when my young uns come along, paw he would sa’nter down now and then to see ’em, and finally Jeems he stumped up on his crutch a time or two, which pleased me a sight, and I had hopes of their meeting peaceable and maybe patching up the war, like granny says she knows they pine to in their hearts, now they are both widows, and getting along in years, and lonesome. But when my man-child come, what did I do but spile everything by naming him John Jeems, atter both; sence which I hain’t had a glimp’ of neither.

“But though the feeling keeps up, there hain’t been to say no active warfare betwixt paw and Jeems sence Luke and me married, and no bad shootings amongst the sons and sons-in-law, like there used to be at Christmas and election-time. Four year’ gone, a five-month district school started up two mile’ down Clinch from us, and both Goodloe and Talbert young uns has been a-going, and has got acquainted and friendly, which has sort of swaged down their payrents; so you might say the war is ended with everybody now but Jeems and paw.

“I been a-going to that district school myself sence it took up. From the time you women was over on Clinch I got me a big hankering for l’arning. Jeems Talbert had sont Luke away to school two term’, and when we was married, to see him read and write and figure, and me not able to tell a from izzard, went ag’in the grain terrible. No Goodloe don’t like to be outdone by a Talbert. So when the school started, though I were a’ old married woman of nineteen, I gathered up my young uns and lit in for l’arning, riding back and forth to school on Cindy and her mule colt. Luke he made cradles for the babes to lay in at school, and the scholars holp me mind ’em, and they never give a’ hour’s trouble. Minervy here she started on the road to knowledge at five days old,—time was precious, and I couldn’t stay away,—and now at three she knows all her a b c’s. And I am able to read and write and figure as good as Luke, and can read every word of that Testament you give me, and hain’t neglected my cooking or spinning or weaving neither.”

Having made sure that Anne would remain to dinner, the heads resumed their work, leaving Christine to entertain the guest. The interesting fact was soon established that the two were almost of an age, both being twenty-three, with birthdays in August.

“Just as good as twins,” exclaimed Anne, delightedly. Then she sighed, and looked wistfully at Christine’s girlish face. “But you that fair and tender you don’t look sixteen,” she said, “and me a’ old woman!” Later she asked, “When a woman don’t marry at fourteen or fifteen or anyhow sixteen, how does she put in her time? What is there for her to do?”

“Many girls put in their time as I did,” replied Christine. “After finishing school, I spent four years in college, then I traveled in Europe for a year, then my father said I knew little more than an infant about actual life, and ought to do some real work for a while to find out; so I came here, where I hope I am learning.”

When the dinner bell rang, Christine found great pleasure in taking Anne to the table and in watching her eager scrutiny of room, children, manners, service.

At two o’clock Anne announced that[Pg 167] she must depart, as it would be necessary to reach the half-way stop-over place, nine miles distant, by night.

“My young uns sets a nag uncommon’ well, from such constant practice going to school,” she said; “but I consider nine mile’ is about enough for ’em to travel in a day. And now,” she continued, flashing a smile at Christine, “being as we’re twins, I do hope you will use your endeavors to make me a visit before long. Seems like I have a mighty near feeling for you.”

A sudden thought came to Christine.

“Would you like me to come over and have my Christmas tree at your house?” she asked. “Father has promised that I may have one.”

“I don’t rightly know what a Christmas tree is,” said Anne, “but I will be proud to have you any time or season.”

Christine explained that a Christmas tree is simply a small evergreen tree on which at Christmas time presents and candy are hung for the children.

“I should like to have the tree at your house, and invite all the children, and older people, too, in the neighborhood,” she said.

“I can answer for the young uns turning out if there’s pretties and rarities to see,” said Anne; “but the grown-ups is different. There hain’t nobody but Goodloes and Talberts on the head of Clinch, and I misdoubt if they’ll gather under one roof. But I’ll do my best, and give ’em all a’ invite.”

Letters passed between the two later, Anne sending the names and ages of the children of the neighborhood, Christine giving directions for making strings of popcorn and holly-berries for the adornment of the tree.

BEFORE day on Christmas morning, Christine, accompanied by Howard Cleves, a big boy from the school, set forth for the head of Clinch, the great “pokes” of Christmas things slung across the saddles standing out like panniers from the sides of the two nags. As they wound up the mountain-side above Perilous Creek, the whole east awoke and flushed with joy in memory of the day.

The eighteen miles were long and difficult and lonely; the mountains folded in and out, dazzling white where they caught the sunlight, deep blue in the shadows. Occasionally in a hollow or beside a frozen stream appeared a small log-house, tight-shut against the cold, the only sign of life or cheer the thin column of smoke rising straight from its chimney. Once or twice the travelers met parties of young men and boys riding with jugs and pistols, doing their utmost to celebrate the day, but always suddenly quiet at sight of Christine.

About half-past one they drew up before Luke Talbert’s house on Clinch, and Anne, Luke, and the four little girls gave Christine the warmest of welcomes. After being thawed and fed, she glanced about the two rooms of the house with some surprise and disappointment.

“I see you haven’t put up the tree yet,” she said.

Anne looked puzzled.

“Hain’t put the tree up?” she repeated. “Why, it’s already up—up and growing back here in the gyarden.” She led the way to the back porch. There, beyond the tall palings of riven oak, in the very center of the small, sloping garden, its delicate branches garlanded with snowy popcorn and scarlet berries, was a splendid young hemlock, apparently rejoicing in its vigor and beauty and in the sacred use to which it was being put.

Christine was dumb for an instant.

“Hain’t it right?” Anne inquired anxiously.

“Yes, beautiful, the loveliest I ever saw,” answered Christine. “Usually people cut down the Christmas tree and set it up in the house; but how much more appropriate to have it living and growing!”

“It was such a pretty little tree I wouldn’t let Luke cut it when we cleared the land,” said Anne; “I told him I would plant my gyarden round it. Granny she allus liked it, too. She come down yesterday and holp me cap corn and string berries. She’s powerful keen to see the doings to-day, and aims to fetch paw along if she can.”

Two fires were already burning, one to the right, one to the left of the tree, and large piles of wood stood beside them in the snow. “Luke allowed the folks would freeze to death if we never fixed to warm ’em abundant’,” Anne explained.

Then Christine and Anne and Luke[Pg 168] and Howard set to work to fasten on Christmas bells, tinsel, bags of candy, dolls, and lighter gifts, climbing up on chairs when necessary. The oranges and heavier things were stacked below the tree. There was no need to take out the candles, with the glorious sunshine streaming all around.

“I warned the young uns not to show their faces before three,” said Anne, “but they are that wild I look for ’em any minute.” She had scarcely spoken the words before a dozen small excited faces peered through the palings. Picking up a stick of wood, Anne sallied forth. “Shoo, you feisty young uns, you!” she cried, “get along into that house there! Anybody that shows a face outside till called don’t get nary single pretty.”

Before she could return to the tree again, another crowd of children had collected at the palings, and the rout had to be repeated.

“And I see ’em a-coming as far as eye can reach,” she reported, “up Clinch and down Clinch, Talberts and Goodloes, both young and old. Of course I knowed the young would turn out, but the older ones wouldn’t make no promise, though I could see they was terrible curious to behold a Christmas tree. They’ll be mad as hops over being shut up that a-way; but they had no business to come so soon. And I hain’t aiming to take no chances on their raising a quarrel, neither: I’m locking Goodloes in one house and Talberts in t’ other, with the door fastened between.”

From this time Anne was busily occupied meeting visitors and diverting them to the two “houses” (rooms). Once a little old lady who had just dismounted from behind a gaunt, grizzled man dodged past Anne and ran into the garden. “I am just bound to see how it looks,” she said. “Oh, hain’t it a sight for cherubim!” She stood in an ecstasy of delight, hands clasped, withered little face shining within the quilted woolen sunbonnet, small body all alertness beneath the heavy homespun shawl.

“Now, Granny, you get right back in that house there with paw,” admonished Anne. “You have brung him thus far; but if he sees any Talberts, or gets wind of a whole passel being locked up in t’ other house, you know he’ll be off like a shot.”

Granny turned sorrowfully away.

“That’s p’int’ly true,” she admitted, hastening into the Goodloe room after her tall, stoop-shouldered son.

For a few minutes longer the sky seemed to rain Goodloes and Talberts. Both rooms must have been filled to bursting. Then, just as the tree was completed, and Anne was about to call out the guests, there was a last arrival. A heavy-set man, with a crutch under one arm, rode slowly into the yard, peering carefully about the house and over the palings as he came.

“My Lord! Luke, if there hain’t your paw!” cried Anne, breathlessly. “I made sure he wouldn’t come. Help him down and bring him right here, and don’t let on there’s any Goodloes in fifty mile’!” She placed a chair by the left-hand fire, and hither, on his crutch, Jeems Talbert was piloted, all the time gazing in fascination upon the tree.

The next instant garden gate and house doors were flung open, and the guests streamed out, young and old with eyes glued to the dazzling tree. Last of all came granny, her arm in that of her son, John Goodloe, whose one remaining eye was so intently fixed upon the tree that he had almost reached it before he saw his blood-enemy, Jeems Talbert, rise on his crutch not five feet distant, surprise and rage in his eyes. Both men stiffened and glared; the hand of each instinctively moved toward his hip-pocket; a gasp ran through the crowd. Granny’s cracked old voice rang out sharply:

“John, Jeems, hain’t you got no manners? Do you aim to spile the woman’s Christmas tree?”

The appeal to chivalry had its effect. Still glaring, the two enemies backed away, each to a fire.

The general uneasiness and apprehension abated somewhat when Christine stepped out in front of the tree, Anne’s Testament in her hand, and began to read, in her earnest, tender voice, the story of the first Christmas. As she proceeded, there was absolute silence. Not a person whispered, not a child stirred, not a baby winked. Faces became rapt, astonished, awed. The white, everlasting hills themselves appeared to hearken. “And Joseph also went up ... to Bethlehem ... to be taxed with Mary his espoused wife.... And she brought forth her firstborn[Pg 169] son, ... and laid him in a manger.... There were in this same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them, ... and the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.... And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.”

Christine and Howard lifted up their voices in “Hark the Herald Angels Sing,” then, beginning with the youngest,—there was one infant even newer than John Jeems, a Goodloe baby of three weeks,—Anne and Luke read off the names and handed out the gifts. To children who had not seen a store doll or toy before, the simple things were marvels indeed. For every girl, little or big, there was a doll; for every boy, a toy of some kind; every person received an orange and a tarleton bag of candy; every family a large Christmas-bell. And at the last, at Anne’s suggestion, the smaller bells and ornaments and tinsel were stripped from the tree, in order that no one should go away without a “pretty.” For granny there was a handsome Bible, none the less joyfully received that she could not read a word of it. But even as she clasped it, her eyes wandered to the dolls.

“Who would ever believe there was such pretty poppets in all this world!” she exclaimed, hearing which, Christine laid the prettiest poppet of all in her arms. At this, three or four other old ladies crowded about granny in such voluble delight that Christine was glad she had enough dolls left over to present to them.

Nor, in the general largess, was the “stranger within the gates” forgotten. The tree held for Christine a fine pair of mittens from granny, a most beautiful woven coverlet from Anne, and a rosy apple each from Phœbe, Ellen, Minervy, Lukeanna, and John Jeems.

The scene was indeed a happy one. Absorbed in the joy of their offspring, and in their own gratified love of the beautiful, Goodloes and Talberts mingled freely, and melted into friendliness and cordiality. John Goodloe and Jeems Talbert alone stood apart, each by his fire, eying gloomily his orange and poke of candy.

Suddenly granny, laying her “pretty poppet” in Christine’s arms, stepped forward in front of the tree and raised a hand for silence.

“Friends, Talberts and Goodloes,” she began, in a wavering old voice which took on strength as she proceeded, “we find ourselves gathered to-day in onlooked-for and, I may say, onpossible fashion, refreshing our mortal eyes with the sight of this here wonderly tree, and our immortal sperrits with the good tidings the fotch-on woman has just read us out of the Book. I never heared just that particular scripture read before, or if so I never kotch its full meaning. Of course I knowed Christ had come to earth ’way back yander in old, ancient days some time or ’nother; but I never heared tell of his coming to all men. From what the preachers said, I got the idee he just come for to snatch a few elect favor-rites out of the hell to which all the rest of us was predestinated, whether or no; and consequent’, I never tuck no great interest in him, or felt particular’ grateful. Even if I had had the assurance of being one of the elect myself, which I never, I still would have worried a sight over them which was bound to be lost, not seeing no justice, let alone mercy, in it.

“But now comes the woman, and reads out of the scripture that the angels theirselves laid down and declared that unto all men was borned a Saviour, that the tidings of joy was for all. Which, though it takes me by surprise, is the very best and most welcomest news that ever fell upon my years. Yes, glory to God! all men,—not only the elect, not only the upright, but the very low-downest and dog-meanest, the vilest and needingest and most predestinated, is all took in. Now that’s the kind of a Saviour my heart has allus called for; that’s the kind I have laid awake of nights longing to hear tell of; and now at last the news has come, ’pears like my bosom will bu’st with the joy I hain’t able to utter.

“And that hain’t the only good tidings we have heared this notable day. That selfsame angel, and a multitude more, sang together in that Christmas sky, ‘Peace on earth, good-will toward men.’ O[Pg 170] friends and chillens, words indeed fails me when I try to tell what powerful good news that is to me. For if ever a woman has craved peace and pursued it, if ever a woman has had her fill of bloodshed and warfare, and her heart tore and stobbed by violence and contention, I am that woman. Yes, for forty year’ I hain’t opened my eyes a single morning without fear of what the day might bring forth; my soul and body has been wore to a frazzle by anxiousness and tribulation. All you Talberts and Goodloes under the shadow of my voice know well what I mean, for all of you has staggered under the same burden. Yes, I’ll be bound there hain’t one here but has had his ’nough of war and strife, and is ready to welcome the good Christmas news to-day, and forgit whether he’s a Goodloe or a Talbert.

“Not a one, that is, but two. Surveying all around and about me, I don’t behold but two faces here that hain’t decked out, like the love-lie tree, with Christmas joy and peace. John Goodloe and Jeems Talbert is onliest humans in all this gathering that wears gloom and darkness on their countenance.

“John and Jeems, I am minded to speak out my full thought to you two boys here and now, if I die for it. I’m a-going to unbottle my mind and feelings, now I got you together, which God knows hain’t likely to happen ag’in. And I aim to speak to you, Jeems, just as free as to my son John, for the time was when you was every grain as dear to me as a son, and I never knowed no difference betwixt the two of you. Yes, when your pore young maw died at your birth, and you was left a leetle, pindling, motherless babe, not scarce able to cry, it was me, your nighest neighbor, that tuck you in and keered for you, that worked over you and prayed over you, tryin’ to keep life in your puny leetle body. Many’s the hour you and John have laid in my arms together, him a-sucking one breast and you t’other; and if the milk run short, he was the one that done without, being a week older and a sight stronger than you. And I would set, looking on you both, not able to tell which I loved the best. For him I had love, but for you both love and pity. Yes, I loved you pine-blank as good as John; I may say you was both my firstborns. And when your paw got him a new woman, it was with weeping and wailing and rebelling that I give you up; I reckon I’ll never git over the hurt of it. But even atter that, having fell into the hands of a step-maw, you was allus a-running back to me; my house was home to you; you knowed where to find understanding of your leetle troubles, sympathy for your hurts, and comfort for your stummick. I allow you hain’t forgot them batches of gingercake I used to keep cooked up for you and John?”

Jeems made no reply; but he swallowed perceptibly, and the hand on his crutch twitched nervously.

“You and John,” continued granny, “was allus together in your boy-time in all your pranks and antics; when I whupped one, I knowed it was safe to whup t’ other, and I done it glad’ and generous’, for your future profit. And as you begun, you kep’ on. In your teens, if one sneezed, t’ other kotch his breath. And finally when you got up to be tall, pretty boys, sprouting mustaches and dashing around on nags, you was just as onseparable, doing all your rambling and drinking and gallivanting together, even down to falling in love with the same gal. Yes, that ’ere pretty leetle jade, Nance Bolling, I can see her now,—these store-poppets reminds me pine-blank of her,—just as beautiful, just as empty-headed and hollow-hearted. Well, Nance she left nothing undone to agg you both on, and foment jealousy and hate in your hearts, and then, when she had you plumb beside yourselves, she sot you to fight it out. You fit it out, to that extent Jeems has gone through life on a crutch, and John with one eye and one lung; and while you was laid up with your wounds, Nance upped and run off with another boy, God help him! But did that restore you to your nateral senses and feelings? Did you rise up clothed in your right mind and ashamed of your conduct? Far from it! You riz up b’iling with rage, thirsting for blood, black in the face with that fierce hate which springs only from the root of love. You that had once lived closer than brothers, sot in to layway and ambush and kill, and to rid the earth of one another. You will both bear me out in saying it hain’t the fault of neither that t’ other draws the breath of life to-day.

“And even when you had both forgot Nance time out of mind, and tuck you[Pg 171] two of as nice women as the wind ever blowed on, you still cherished deadly hatred in your hearts, and handed it down to your innocent offsprings as they come along, so that as they growed up they holp you in your devilment, and there was war betwixt every man and boy that bore the name of Goodloe and Talbert, shootings every Christmas and election, and battles and ambushings at odd times, till I allow there hain’t a man here that hain’t got a lot of scars to show. And the worst come fifteen years gone, when your two oldest, as likely and handsome a pair as ever drawed breath, and with young wives and babes depending on them, fit the terriblest battle of all, and fell both with six bullets in ’em, stone-dead. Yes, having nothing ag’in’ each other, they died, a living sacrifice to the hatred in your hearts. Jeems, John, it was a costly price to pay. I seed John, and heared of Jeems, aging twenty-year’ in a week. The fight was right smart took out of both of you, though the pride wa’n’t; you continued to go about with hate in your eyes and guns in your pockets.

“John and Jeems, you know it’s the truth I’m a-laying down when I say it is pride, and naught but pride, that stands betwixt you now at this present time. You know well you hain’t neither of you forgot, or can forget, them fair early days when you was nigher than brothers, and never had a thought you couldn’t share, and that it is them very ricollections that has give’ such a keen edge to your hate. You know well that, being sixty year’ old now, and considable past your youth, and widows at that, with many of your acquaintance’ drapped off and gone, you would both injoy fine having a boyhood friend and brother to set by the fire and talk old times with. I know myself how lonesome it is to git old and outlive everybody.

“Jeems and John, the message comes to you this bright Christmas day straight from the tongue of angels, ‘Peace and good-will’; no more hate, no more pride, no more projeckin’ and devilment, but ‘Peace on earth, good-will toward men.’ I charge you both, boys, hearken to the words, put by your stubbornness, tromple on your pride; for Christ’s sake and your old mother’s, be j’ined together ag’in in brotherly love!”

The two grizzled, scarred men were staring across the intervening space now into each other’s eyes, fixedly, painfully, awfully, as though they saw ghosts. Suddenly the hand of Jeems dropped to his hip-pocket, he drew forth his revolver, and flung it far up on the mountain-side. John’s pistol rose almost simultaneously in the opposite direction. Then, with working faces, the two advanced and silently clasped hands.

Weeping and shouting, little granny caught the big men to the shrunken bosom from which they had once drawn life. Goodloes fell on the necks of Talberts; men embraced and wrung hands solemnly, women wept hysterically on one another’s shoulders, children cried, not knowing why; Anne and Luke shed happy tears on the face of little John Jeems between them.

After a long while granny released the two men from her clasp, held them at arms’-length a moment, looking at them hungrily and joyously, and then laid a hand on the arm of each.

“Come along home now, boys,” she said; “it’s a-gitting on late, and I allow you’ll both injoy a good batch of gingercake for supper.”

[Pg 172]

PRONOUNCED “THE FOREMOST THINKER OF FRANCE”

HIS PERSONALITY, HIS PHILOSOPHY, AND HIS INFLUENCE[1]

BY ALVAN F. SANBORN

IF the generation now coming to the front in France is healthy and vigorous physically, mentally, and morally, and proud of its health and vigor, if it is confident, expectant, full of energy and will, impatient for action and fit to act, if it dares to be happy, if it will have none of the pessimism of Schopenhauer or of the nihilism of Renan; if it is, in a word, a generation of young young men, whereas the generation that preceded it was a generation of old young men, melancholy, morbid, dilettante, neurasthenic, and proud of its melancholia, morbidness, dilettantism, and neurasthenia,—and such is generally admitted to be the case,—certainly not the least of the numerous and varied influences that have combined to bring about this radical transformation is the inspiriting message of Henri Bergson.

In the early years of the twelfth century, at the base of the Tower of Clovis, on the summit of the Montagne Ste.-Geneviève in Paris, a scholar in the habit of a monk, Pierre Abélard, proclaimed under the open sky “the rights of the earth, the right of the reason to reason” in discourses which Michelet characterizes as “the veritable point of departure of the first Renaissance for France and for Europe.” The élite of the then civilized world—two popes, twenty cardinals, fifty bishops, “all the orders,” Romans, Germans, Englishmen, Italians, Spaniards, Flemings—flocked thither to listen to the great innovator. He was silenced by the dogmatists of the period, but he left behind him an idea which “became more and more the fixed idea of the Renaissance, namely, ‘wisdom is not wisdom if it confines itself to logic, if it does not add thereto erudition, all human knowledge.’”

Five hundred years later, on this same Montagne Ste.-Geneviève, René Descartes demolished scholasticism and founded modern psychology. Persecuted by the Sorbonne, as was nearly every other expounder of new doctrines at that time, he nevertheless created a veritable furor among the bluestockings of the magnificent court of Louis XIV. His “vortexes” and “fluted matter,” his “three elements” and his “innate metaphysical ideas,” were the small talk of the précieuses; snobbishness for the most part, of course, but it is one of the redeeming features of snobbishness that it sometimes bestows its plaudits and its patronage upon genuine merit.

At the present time the philosopher Henri Bergson is assailing, in his turn, another scholasticism—the scholasticism of science. At the Collège de France, the consummation and the coronation of the various schools of the Montagne Ste.-Geneviève, he is creating a flutter in the dove-cotes of bluestockingdom such as no pure philosopher has created there since the time of Descartes. Indeed, Bergson has become so fashionable that soon, as some one facetiously observed regarding Francis of Assisi after the appearance of Sabatier’s fascinating biography of that saint, “they will be wearing him upon bonnets,” another instance of snobbishness adoring actual achievement.

The biggest amphitheater the Collège de France can provide is quite too small for M. Bergson’s would-be auditors. Long before the lecture-hour, the seats and the steps of the aisles, which can be made to serve as seats, are preëmpted by patient waiters of both sexes, of varying ages, sorts, conditions, and all nationalities. The standing-room fills up rapidly also, while about the doors are enacted scenes vaguely reminiscent of those that occur daily at the City Hall terminal of the Brooklyn Bridge during the rush hours, in which the gentle, but not always mannerly,[Pg 173] sex does rather more than its share of pushing, tugging, elbowing, and treading upon toes, in virtue, no doubt, of its superior zeal for knowledge.

When the lecture begins, the sitters, and such of the standers as are lucky enough to have their arms free, scribble furiously in their note-books, the hapless strugglers at the doors and in the vestibule crane their necks in a futile attempt to catch a glimpse of the platform through the rifts in the monstrous feminine headgear now in fashion, and all alike, those who neither see, hear, nor comprehend, as well as those who do, promptly take on the rapt, superior expression of initiates—the expression that used to characterize the audiences at “Pelléas and Mélisande” when Debussyism was in its infancy.

The lecturer is short of stature, spare, an almost perfect ascetic type, somewhat, gray and slightly bald. He has slender hands, tapering fingers, a weasel-shaped head, heavy eyebrows, a close-cropped mustache grayer than the hair, and “liquid and profound eyes that suggest mysterious molten metals in the stars.” He is correctly, even fastidiously, but not foppishly, dressed. He speaks slowly and distinctly, but easily, with engaging indifference to his notes and without any effort at oratory, his nearest approaches to gestures being abruptly arrested semispasmodic workings of the hands, periodical inclinations of the head, and an occasional deepening and darkening of the eyes. It is as though sheer intellect, abstract intellect, were endowed with the power of speech. There is not the slightest trace in M. Bergson’s manner of the overweening vanity that too often mars the public appearances of world celebrities, nor is there a scrap of the unlovely pedantry and arid officialism against the prevalence of which at the Sorbonne a considerable portion of cultivated France recently rose in revolt. On the contrary, he is constantly referred to in university circles as “the lark,” partly perhaps because he offers a certain physical resemblance to that ungarish creature; but mainly because there is a touch of lyricism in all his utterances, even his most trenchant analyses. He presents his views progressively and with a modest tentativeness which makes his auditors feel that they are assisting at the birth of a system rather than listening to the exposition of a perfected one. They seem to see the lecturer suffer and create, as the symbolical pelican of ecclesiastical tradition pierces her flank for the wherewithal to feed her young. Indeed, the regular attendants follow the stages of the creative process as eagerly and impatiently as though they were the instalments of an absorbing novel.

How far Henri Bergson’s extraordinary vogue is due to the substance and how far to the form of his thought is not easy to determine, since either alone amply suffices to account for it. His philosophy is a rehabilitation, to employ untechnical language, of God and the soul. It is a reconciliation “in a harmony felt by the heart of terms irreconcilable, perhaps, by the intellect,” of science and metaphysics with religion, of knowledge with life, of law with conduct, of liberty with authority, of the ideals of the Occident with the ideals of the Orient, of the present with the past and with the future. According to M. Bergson, the universe, which is incessant mobility, perpetual, continuous flux, is acquiring a constantly swelling volume of free creative activity, and the inner life of each and every person in the universe is absolutely original. “Life is really creation. It is not a fabrication determined by the idea of an end to be realized; it is an impetus, an initiative, an effort to make matter produce something which it would not produce of itself.” We know reality by living it. We may act freely, and in so acting we experience creation.

M. Bergson’s philosophy is a vindication of intuition, the faculty upon which the poets, the Shelleys and the Keatses, the Villons and the Verlaines, have always depended for their knowledge of themselves, of the universe, and of their relations to the universe. We who are not poets are the deluded victims, says M. Bergson in effect, of our reasoning faculty, which is constantly playing hob with us. We should submit to the authority of intuition, for to do a thing without reason, even against reason, may in certain cases be to act from the best of reasons. This does not mean that reason should be despised or discarded, as some of the philosopher’s overzealous followers are prone to proclaim,—even the great poet must resort to it in expressing the conceptions[Pg 174] his intuition gives him,—but rather that reason is a highly useful subordinate of intuition, bearing much the same relation thereto that the housemaid bears to the housewife, the mason or carpenter to the architect, the private soldier to the strategist. In short, M. Bergson’s attitude toward reason is essentially that of the immortal seers. It recalls Pascal’s “The heart has its reasons which reason knoweth not,” Joubert’s “It is easy to know God if you do not attempt to define Him,” Emerson’s “With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do,” and Browning’s “Others may reason and welcome, ’t is we musicians know.”

Our William James pronounced every page of Henri Bergson to be “like the breath of morning and the song of birds.” M. Bergson’s style, though delightfully free from affectation, is not so simple and direct as these comparisons imply. They suggest admirably its freshness, melodiousness, graciousness, and grace, but they fail to suggest the exquisite subtlety which is its most distinctive trait. They may be given a fair approach to adequacy, however, by substituting for “the morning,” a morning of luminous haze such as Corot loved to paint, and for “the song of birds,” the cuckoo’s “wandering voice.” As soft, tenuous, filmy, fluid as mist or wreathing smoke, it is as precise, not to say geometrical, in design as the spider’s gossamer web, and is equally iridescent. The critic who characterized it as Arachnean, therefore, was most happily inspired, though his purpose in doing so was, if I remember right, to hold it up to derision. No living writer, not even Maurice Maeterlinck, surpasses Henri Bergson in evoking, in projecting, in visualizing, so to speak, those subconscious activities of the soul which are commonly esteemed unanalyzable and, great poetry, possibly, apart, unutterable. He “forces language to express things for which language was not intended.” With impalpable pigments and ghostly brushes he paints upon imaginary canvases veritable landscapes of the soul. We do not go to pure philosophers for esthetic sensations,—no one ever frequented Kant, for instance, for his style,—and in general we enjoy or do not enjoy them according as they do or do not succeed in convincing us. Henri Bergson is a striking exception to this rule. We read[Pg 175] Bergson, as we read Plato, out of sheer infatuation with his verbal artistry, and we should continue to read him ecstatically if he should undertake to prove that the moon was made of green cheese.

Such as he is in the lecture-room, such as he is in his books, unassuming, unpedantic, gracious, well-poised, subtle, tactful, alert, resourceful, stimulating, such Henri Bergson is in his every-day existence. In his case, and to an unusual degree, the style is the man. An easy talker, ever ready to speak freely upon all subjects,—his personal affairs, work, and politics excepted,—he nevertheless goes little into society, not because he dislikes social functions, but because he cannot contrive to make the necessary leisure. He resides about midway between the Seine and the Bois de Boulogne, in an umbrageous and incredibly tranquil corner of the Auteuil quarter, where he is well nigh as secure from the hustle and bustle of Paris as he would be in a provincial village; and he spends his summers in Switzerland at St.-Cergue, almost ten miles from the nearest railway station, in a modest two-story villa, surrounded by meadows and evergreen woods, the front windows and veranda of which afford ravishing views of Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc. Winter and summer alike, six in the morning finds him installed at his desk, and from that moment until he retires for the night he allows himself virtually no respite save that which is afforded by an occasional varying of occupations.

Though so little of a Parisian in the sense in which the word is currently employed, M. Bergson is one of the relatively few famous Frenchmen who possess a clear title to that distinction. He was born in Paris on the eighteenth of October, 1859. From nine to eighteen he attended as a day student the Lycée Condorcet (then Lycée Bonaparte), in the Opéra quarter, an institution founded in 1803 under the consulship of the First Napoleon, which numbers among its illustrious alumni Dumas fils, De Banville, the Goncourts, Eugène Sue, and Hippolyte Taine. Less precocious than Pascal, who at sixteen wrote a treatise on conic sections that excited the admiration of Descartes, and who is said to have rediscovered at twelve the first propositions of Euclid, young Bergson was nevertheless sufficiently[Pg 176] advanced at eighteen to produce in the concours général of the Paris lycées a mathematical solution which was accorded the unusual honor of being published in full in the “Annales Mathématiques,” and which, if I mistake not, exempted him from the obligation of military service. From the Lycée Condorcet he went to the Ecole Normale Supérieure, matriculating in the section of letters, which he had chosen over the section of sciences after not a little hesitation and misgiving, for he was at that time an ardent disciple of Herbert Spencer and[Pg 177] dreamed of perfecting Spencerianism. While at the Ecole Normale he came under the joint influence of Félix Ravaisson, harmonizer of the Greek spirituality of the intelligence and the Christian spirituality of the will and of the heart, and Emile Boutroux, author of a memorable assault upon the then dominant determinism entitled “De la contingence des lois de la nature,” and now President of the Institut de France, who speedily freed him from his Spencerian obsession and turned him in the direction he has since followed. Obliged, after his graduation from the Ecole Normale to submit, like the majority of its graduates, to a period of banishment from Paris, he taught philosophy for two years at the Lycée of Angers, in the province of Anjou, and for five years at the Lycée of Clermont-Ferrand, in the province of Auvergne. During his stay at Clermont, he delivered a number of lectures in the university of that city, and wrote the work “L’essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience,” which revealed him as an original thinker and as a redoubtable antagonist of determinism. At Clermont he also mapped out his life-work (studies, researches, and publications), calculating carefully the time to be allotted to each subject, and thus far he has not only succeeded in executing his program to the letter, but he has been able to permit himself such interludes as a course of lectures on Plotinus, his essay on laughter, a lecturing sojourn at Oxford, and the projected visit to the United States.

His “stage” in the provinces over, he taught first in the Collège Rollin and then in the Lycée Henri IV, located upon the very spot where Abélard held his open-air classes. While connected with the latter institution, he published “Matière et mémoire,” and it is thanks, no doubt, to the sensation this work created in the university world that he was called in 1897 to an assistant professorship in the Ecole Normale, and, in 1900, to his present professorship at the Collège de France.

Teaching, for Henri Bergson, is not a makeshift, but a veritable sacrament. His former pupils are virtually unanimous in[Pg 178] testifying to his conscientiousness and zeal, as well as to his magnetic qualities as a teacher. Not a few of them, become teachers in their turn, call upon him often for counsel and guidance, which he invariably bestows gladly, however preoccupied and harassed by his formidable undertakings he may be at the time. And this is not the least of the reasons why a goodly proportion of the younger professors of philosophy in the French lycées and collèges of France proclaim themselves Bergsonians. Furthermore, the young men who have attended his classes or his lectures or who have come under the less direct, but only a shade less potent, spell of his writings, seem to be possessed with a passion for “living things”—for “doing things,” we would say in America—as distinguished from analyzing things.

Bergson has been hailed as “the inaugurator of a new era in philosophy,” “the foremost thinker of France,” “the most original and significant figure in the philosophical field of Europe,” “the sole philosopher of the first rank France has had since Descartes and Europe since Kant,” “the restorer of psychology,” “the modern Heraclitus,” “the Darwin or the Newton of philosophy,” “the Wells of philosophy, adventurous inventor of a new machine for exploring the world.” And his system has been characterized as “a new principle for the integral renovation of philosophy,” “the matrix of all future systems,” “the ruin of Marxism,” “the annihilation of materialism.”

Whether all of these appraisals be just or none of them be just, whether Bergsonism be sound or unsound, enduring or ephemeral, time, the supreme winnower, will of course determine. In the meanwhile it is perfectly safe to affirm that Bergson is a peculiarly fine and rich personality, an admirable example of the consecrated scholar, a consummate literary artist, a genuine prose poet, a keen psychologist, an observer of life, and one of the most suggestive and stimulating of contemporaneous thinkers; and this, even though his philosophy may ultimately share the fate of the greatest of its predecessors, is enough to make the glory of one man.

[1] Professor Bergson is about to visit the United States, and will deliver a series of lectures at Columbia University in January.

[Pg 179]

(Cache-Fiò)

I

II

III

Edith M. Thomas

[2] The Christmas chimes, so called from the confection of that season.

[Pg 180]

Seventeenth

Century—

Edith M. Thomas

[Pg 181]

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Edith M. Thomas

[Pg 182]

BY VIRGINIA YEAMAN REMNITZ]

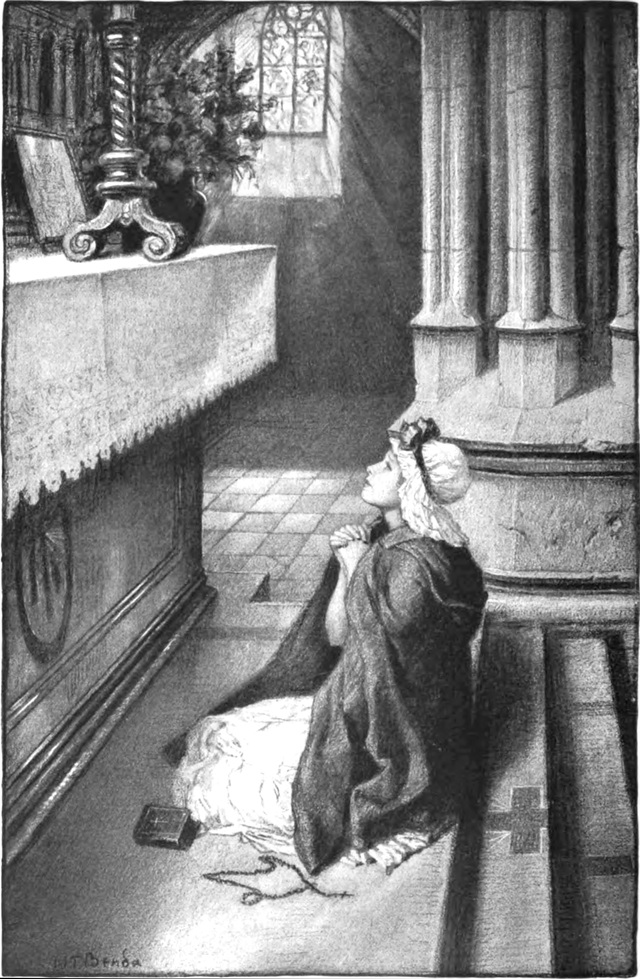

Drawn by Joseph Clement Coll

LIZETTE AMBOISE sat beside the window making lace. The lovely line of her profile caught the light; the clear white of cap and kerchief enriched the olive of her skin. Seen thus from within the room, she was so beautiful that the old eyes of Pierre’s mother brightened as they looked at her.

Pierre himself was working in the woolen mills at Lisieux. Soon after he went his house had caught fire, and Lizette, rushing through the flames, had led his mother out to safety. Since then the old woman had remembered only in flashes.

So there she sat in Lizette’s cottage, her eyes brightening as they rested on the girl. But all at once they clouded; she had remembered.

“If it was as it used to be,” she broke out in a quavering voice, “you might be restored for Pierre’s coming home.”

At the words Lizette turned, and the old woman began to cry.

“For him to come back at Christmas,” she wailed, “to see that!”

The girl looked quickly away. The rich olive of her cheek had faded to a dead pallor; her hands lay idle in her lap. “For him to come back to see that!” She used to rejoice in Pierre’s love of beauty. He was different from the other young men of the village, who cared more for a woman’s strength than for her face, and who looked always at the earth they tilled and never at the sky. Pierre could be keen and shrewd as any other Norman peasant; but Lizette knew his dreams, his delight in beauty, the thoughts he hid from his neighbors.

Once Lizette had said to him:

“Perhaps I can serve you as well making my lace as though I were strong to work in the fields.”

And Pierre, his dark eyes glowing, had answered:

“It is not your service I want, my Lizette. I want only to have you near me, to be able to look into your face.”

The words had pleased her when he spoke them; now they stabbed her to the heart. And so did these lines of the letter Pierre had written after he heard from the curé about the burning of his house, and how Lizette had saved his mother: “My beautiful, brave Lizette! How shall I wait to see you! Your face is always before me.”

“Mère Bernay,”—Lizette had turned again to the old woman,—“listen to me, Mère Bernay. What did you mean when you said I could be restored for Pierre’s return if it was as it used to be?”

“By a miracle of Little Noël. You would make the nine-days’ prayer before Christmas mass. Many are the cures were made so at our church in the old days. But that was long ago; they are made no more.”

The miracles of Little Noël! Lizette had heard of them ever since she was a child, but they had seemed merely a tradition. Suppose—her eyes widened and she drew her breath in quickly.

If the miracles had ceased, it must be because the faith of the people had died. Had not the curé often bewailed the worldliness of the times, the love of pleasure that had replaced piety? If she had faith, if she prayed with her whole heart,[Pg 183] it might be that a miracle of Little Noël would be wrought even now for her!

It was only two weeks before Christmas. Soon she could begin the nine days of special fasting and prayer; and there was time before that for preparation. Lizette rose, took down her long cloak, bent over Pierre’s mother, kissed her withered cheeks, and then went out into the golden light of the sunset.

She pulled the hood of her cloak far over her face, and walked rapidly. She saw no one until Mère Fouchard came to her door, calling shrilly to the little Henri. Mère Fouchard stopped shrilling when she saw Lizette.

“How the girl keeps the hood over her face!” she said to herself. And then, “Does she think she can hide it thus from Pierre Bernay when he comes back!”

She called a greeting, hoping Lizette would turn; but she was disappointed. The girl answered without looking around.

The church was in the middle of the wood in which the village was built. In Normandy these little villages try to hide themselves among the trees; but the gleam of their white-walled cottages betrays them.

When Lizette reached the church, twilight was gathering, and the branches of the trees wove delicate traceries against a sky of pale amethyst and rose. The old stone church, with its square tower, made a picture amid that setting which Lizette was quick to note. Pierre had taught her to see such things.

But she noted also, and with a sorrow she had never felt before, the dilapidated condition of the church. In the days when the miracles of Little Noël made the village famous, it had been different. Then, as Lizette knew, not a crumbling bit of mortar had gone untended or a candlestick unpolished. And the women of the village had woven finest cloth for the altars, and bordered them with lace of their own making. Lizette resolved that she would begin such an altar-cloth on the morrow.

Now she pushed the door open and looked shrinkingly about. There was only stillness and peace within, and the Virgin with the Child in her arms. It seemed she was waiting for Lizette. With a little sob, swept by a wave of emotion that laid bare all her heart, the girl went forward and fell on her knees, throwing back the hood from her head.

Her face was now revealed, as though for the pitiful eyes of the Virgin to see. On one side it was the beautiful face Pierre Bernay hungered for day and night: on the other it was furrowed across by the crimson scars the fire had made.

The starry eyes, upraised, overflowed with tears; the lips quivered in their supplications: “Grant to me faith, that a miracle of Little Noël may be wrought upon me! Have pity upon me and restore me for Pierre’s return!”

How often she had pictured that return—the leap of her lover’s eyes to her face, their horrified turning away; for she had begged the curé to write no hint of her disfigurement. She would have no pretense, she who had throbbed and glowed under the long caress of Pierre’s gaze. If he could not bear to look upon her, she must know it. It would be better than finding out little by little. If it should be as she feared, she would go away. She had a cousin who worked on a farm in the rich country to the east. Perhaps she could find the place; it did not much matter.

Suddenly Lizette realized that these thoughts were intruding themselves upon her devotions; that fear and foreboding were driving out the faith she longed for. She began to pray again, and little by little her heart grew still within her. It was as though a light broke softly and grew; there was no room left for fear.

In the church, meantime, the dusk had been gathering. Lizette, when she rose to her feet, could just see the face of the Child. It was in honor of his birthday the cures had been made; for the sake of the little Jesus, who had come to heal the sicknesses and sorrows of all the world.

For some minutes Lizette stood there. Then she remembered the Mère Bernay, sitting all alone, with the fire dying on the hearth; and she hurried away. But the crushing weight was gone from her heart. She walked with light steps, and looked up at the stars, which were beginning to come out in the sky.

Every day now Lizette prayed in the church, but no one who saw her pass guessed at what was in her heart. It may be, however, that Pierre’s mother knew;[Pg 184] she knew many things that no one ever told her. Sometimes when Lizette came in with that light on her face the old woman would look at her with eyes which seemed to understand.

When the time came for her to make the nine-days’ prayer, Lizette went to her devotions both morning and evening, and so absorbed was she that the fire often died on the hearth, and Pierre’s mother shivered as she sat beside it. But it was on the last day of her waiting that the girl knelt longest in the little church. When she came again it would be for the midnight mass; she hardly dared to think further than that. The old fear seemed to be hovering near, threatening to seize her. She sought shelter from it in her prayers: she even tried to forget a certain resolve she had made, lest it argue lack of faith. This resolve was that Pierre’s eyes should be the first to rest upon her after the midnight mass. She would neither look in her glass nor touch her face with her fingers. His eyes, and his alone, should tell her whether the miracle had been performed.

Pierre had written again, saying that he would come early on Christmas morning. In a few hours he would be on his way, walking from Lisieux to a little inn where he slept. But long before dawn he would start again, and be with her soon after the sun was up. She was glad that Mère Bernay lay in bed until late. She wished to watch for Pierre alone.

That evening she told the old woman that they would eat the réveillon before mass. “You would be too weary if you waited for my return,” she said; but the true reason lay in her resolve that Pierre should be the first to see her face after the midnight mass.

The réveillon may be spread either before or after that mass. Lizette brought out the roasted chestnuts soaked in wine and the little cakes. Her heart was suddenly light and gay. She made Mère Bernay put her shoes on the hearth, ready for gifts; then Lizette put one of her own beside them, and next to that she put the other of the pair for her lover.

The gifts were in readiness; the cottage wore a festive air. Branches of laurel and pine were fastened over the fireplace, and the vessels of copper and brass twinkled in the light of the yule log. Père Fouchard had brought the log in that morning. He was as kind as his wife was shrewish.

When the feast was eaten and Pierre’s mother was in bed, Lizette made herself ready to go to the church. With greater care than ever she hid her face in the hood of her cloak; then she lighted her lantern and stepped out into a white mist, which seemed to open to receive her. The frosty road crackled beneath her feet, and the branches of the trees waved ghostly arms on each side.

The mist was like a delicate veil, entwining everything. Lizette knew that the little procession of village folk had already passed on its way to the church. She had heard them singing a few minutes before as they went; but she had not wished to join them.

Now that she was on her way, she realized that her gaiety had deserted her, that she felt frightened. But she must not be frightened; she must have faith. It was faith that would make the miracle possible.

So Lizette came to the church after the others, and slipped into a dim corner. Nevertheless, several saw her and peered curiously. Among these was Mère Fouchard. Like all the rest, she had heard that Pierre Bernay returned on the morrow.

Lizette scarcely heard the hymns or the sermon. She sat like one tranced, waiting. Her rosary slipped through her fingers, and her pale lips moved. She tried to think of the words of the prayers, and she tried not to see Pierre’s eyes as they leaped to her face. Beyond her meeting with Pierre everything was a blank.

The mass was over, and Lizette was on her way home. The others had lingered to sing the Christmas carols and to exchange greetings; but Lizette had slipped out quickly, and went alone through the fog. She held her cloak tight about her with both hands. At first it had been all she could do not to touch her face, but that temptation had passed. She did not even think of it; she knew she would wait for Pierre’s coming.

But the reaction after the long strain had set in. She felt a great weariness; she would have liked to creep away into the wood and cry like a little child. But she stumbled on through the fog, came to the cottage, and lay down on her bed.

[Pg 185]

Then it was morning, and the mist was lifting and drifting away. It drifted away in trailing veils, clinging to everything it passed. But Lizette looked at the mist only a few moments; she had to make herself ready for Pierre’s coming.

She watched for him from the window where she sat when she made her lace, and the mist rose as though to let her see as far down the road as possible. She could not have said whether she believed herself healed. There was a sort of blankness in her head. Yet she knew she was suffering supreme suspense. Now and again the anguish of it pierced through the blankness; but it was only for a moment, or she could not have borne it.

Then a figure came into sight at the farthest point of the road she could see. She rose instantly; she knew it was Pierre. His tall figure, his eager gait—how often she had seen him coming thus to the cottage! But now her heart seemed to stop, and she felt she would never get to the door; never put on her cloak, and pull her hood over her head. She held the hood tight about her face as she went.

When Pierre saw her coming he stood perfectly still, his head lifted up. It was as though his very longing, the piercing delight of her nearness, had fixed him there. And Lizette, her knees trembling beneath her, went on toward him. Then stopping suddenly, she lifted her hands and threw back the hood from her face.

Ah, the leap of Pierre’s eyes! But before Lizette’s there came a swimming blackness; the earth seemed to rise up and the trees to rush past her. She tried to speak, she tried to see; then the deadly struggling ceased.

She found herself in Pierre’s arms. His eyes were on her face. Their love enveloped her and drew her close—closer than ever before. It was like something in which she lost herself. She lay still, looking up at him.

“Lizette,” he whispered brokenly. He put his face down against hers. “My brave, beautiful Lizette!”

Tears sprang to her eyes; an incredible happiness flooded her being.

“It is the miracle of Little Noël,” she whispered.

Pierre paid no heed. He seemed not to care about her meaning; he cared only for her. Raising her to her feet, he supported her with his arm. He gazed in her face as though his hunger for it could never be appeased; and at last he put one hand beneath her chin and turned her head gently to one side.

“This is the Lizette I left,” he said—“the Lizette whose beautiful face made me forget her soul. I loved her as a man loves a woman when both are young.”

He stopped, and then he turned Lizette’s face so that his eyes rested upon the side which had been burned.

“And this—” He broke off; when he could speak again, his voice had a hushed, exquisite note—“and this,” he said, “is the Lizette I never knew. It is the wonderful, beautiful soul of Lizette. When we are old and our bodies have changed, still I shall always see your brave, tender, beautiful soul.”

But Lizette, with a low cry, had pushed him from her. She put a hand to her face.

“The burns!” she gasped. “I feel the burns!”

Pierre seized her hands in his. He drew her to him, kissing the scars again and again.

“My Lizette,” he whispered, “I did not know before what love was—this love of soul and body!”

And Lizette, raising her head, clasped her hands together.

“It is the miracle of Little Noël,” she said.

[Pg 186]

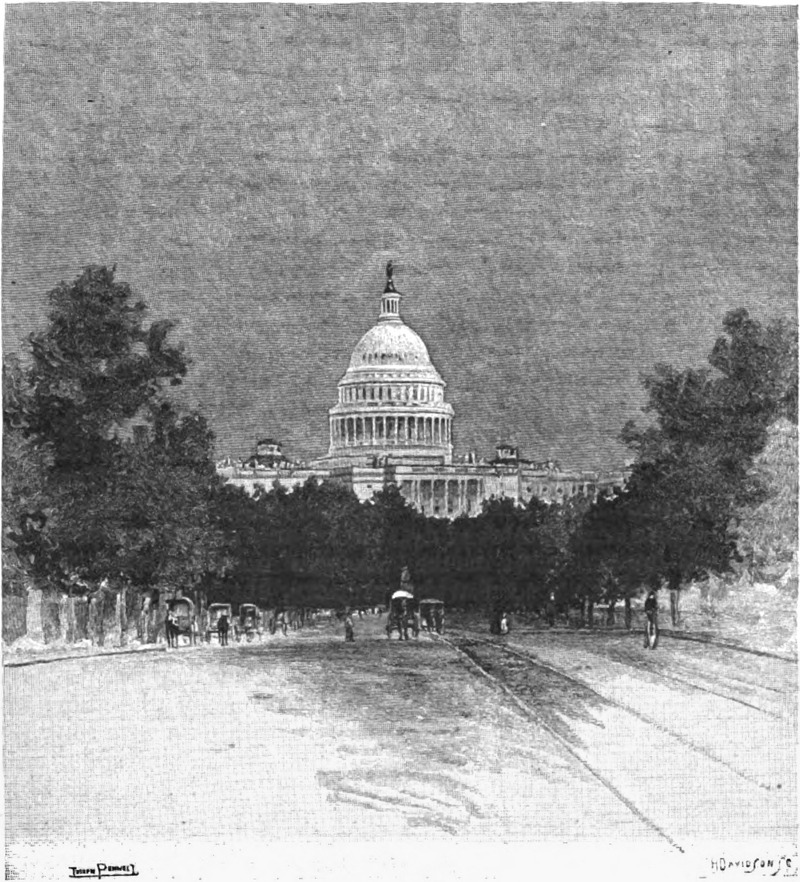

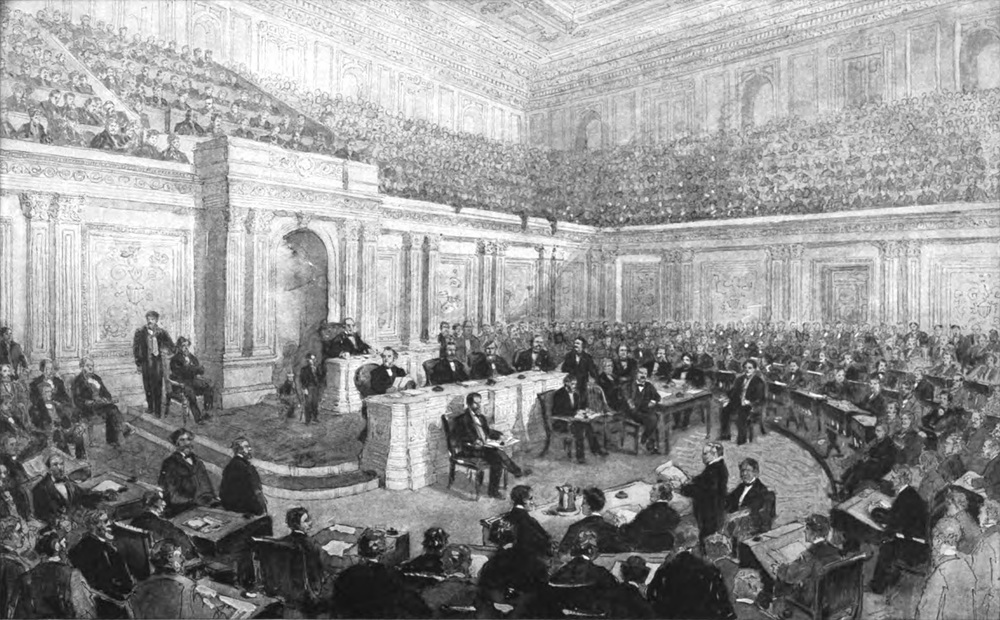

INTRODUCTION

No period of our history better repays perusal by thoughtful readers and good citizens than the political happenings of the three years following the Civil War, culminating in the attempt to “recall” President Johnson. But the subject is so vast that no magazine article can more than suggest its outlines, or sketch the personalities involved in the first efforts to reëstablish civil order in the South.

Probably no actor in that series of passionate events could write of them without some bias; nor would any picture be quite true without the perspective due to individual experience.

Considered in the large, the long fight between Congress and President Johnson must be regarded as a wrestling of political forces, a struggle for major influence in reconstruction, between the executive and legislative branches of the Government.

In the Civil War the Democratic party, which for many years had been dominated by the slave-holding interests of the South, had been dethroned by the new Republican party, which, however, could not have achieved its purpose to save the Union and abolish slavery without the aid of the large body of War Democrats who had been rallied to the support of Lincoln by his defeated rival, Senator Douglas.

At the end of the war, the Republican party was dominated by its Radical wing, whose extreme aims were almost as offensive to the War Democrats as to their old allies of the South; and the latter were not slow to grasp at the political advantage of a reunion which promised Democratic control of the National Government.

A fourth great factor in the war had been the Union men of the South, formerly Democrats, of whom Andrew Johnson had been the forceful leader. It was this prominence which dictated his nomination for Vice-President in 1864. When, at the close of the war, by the assassination of Lincoln he became President, his utterances gave the Republicans hope that as a convert his zeal would equal if not exceed that of the Radicals in their purpose to subject the South to a period of political probation. But it was soon manifest that he would steer the course of conciliation which Lincoln, before the end of battle, had already charted and begun. The tendency of Johnson’s policy was to draw to him men imbued with the old Democratic sentiment. In a little while, the Republican leaders perceived that as soon as the Democrats of the South should be allowed to vote they would unite with the Democrats of the North, and thus Republican ascendancy might come to a sudden end, and some of the results achieved by battle might be reversed at the ballot-box.

[Pg 187]

The black man had been freed, and, to protect him against the political power of his former masters, the Republicans decided to give him the ballot. This, it was expected, would also offset Democratic votes in the South, and help to perpetuate Republican rule. President Johnson had championed emancipation, but was opposed to immediate Negro suffrage. In the minds of the Radicals that attitude not only stamped him as a traitor to the party which elected him, but also incited an obstinate South. When the efforts to thwart the President by obstructive laws had failed, the Radicals sought to remove him by impeachment.

Each side had abundant legal and moral grounds for its actions, and each believed that the other was reaching for selfish political advantage. Outbreaks of lawlessness in the South, peculiar to the extraordinary conditions, and chargeable to both sides, convinced each that its worst fears were justified.

In the pages which follow, the main motives for impeachment are sketched by General Otis, who fought through the Civil War as a Union soldier, then entered the long political contest as a militant journalist, and finally resumed his place by the flag in the war with Spain. A more conservative view is taken by General Henderson, a War Democrat high in Lincoln’s confidence, and a slaveholder who yet proposed the final edict of freedom in the Senate. He is the only survivor of the seven Republican senators who thwarted impeachment, ex-Senator George F. Edmunds, of Vermont, being the only other surviving member of the court. Out of his personal recollection General Henderson describes his intercourse with Lincoln in securing emancipation, and his part in the impeachment fiasco.

Papers to follow, in the January CENTURY, will include an account of the impeachment trial, largely based on the President’s notes and letters, and an anecdotal sketch of Andrew Johnson, one of the most peculiar characters in American history.

In subsequent papers, after an interval, the later aspects of “Reconstruction” will be treated from the Southern point of view.—THE EDITOR.

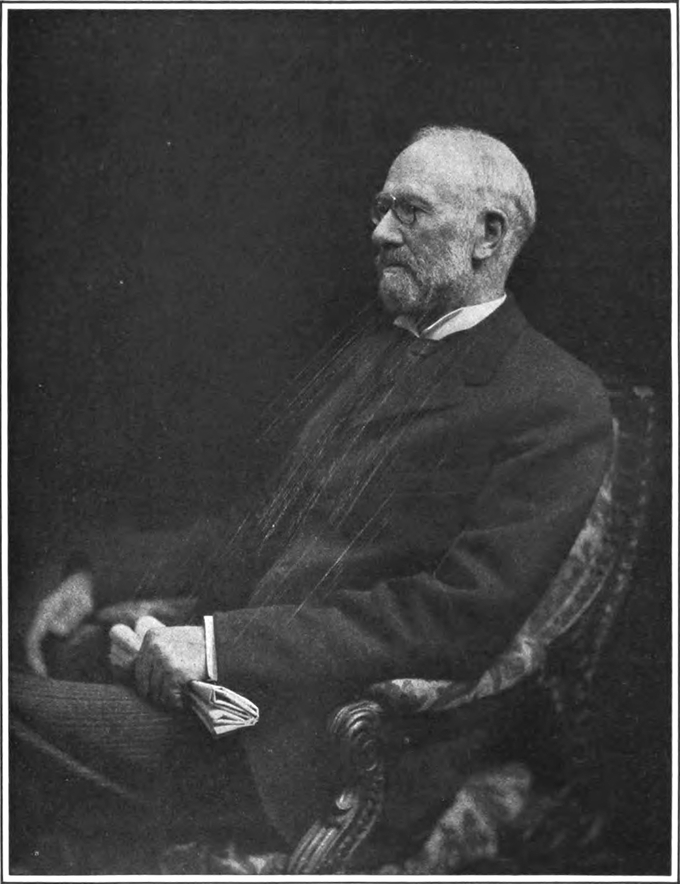

BY HARRISON GRAY OTIS

Editor of the “Los Angeles Times”; veteran of the war for the Union; Brevet Major-General in the war with Spain

THE War of the Rebellion was the offspring of a desire on the part of the South to secure exemption from laws that its people believed would be enacted by a great Northern party, following the election of Abraham Lincoln, and which would put an end to the extension of slavery, and menace its safety in the States where it existed. In vain Republican statesmen protested that slavery would not be interfered with south of the Potomac. Behind Lincoln and Seward the South beheld Garrison and Lovejoy and Phillips. It was the belief of Davis and Breckinridge and Benjamin and Toombs that to exclude slavery from Kansas and Nebraska would be to sound the prelude of its abolition in Virginia and the Carolinas, and that those who commended the raid of John Brown and indorsed Helper’s “Impending Crisis” would sooner or later dominate the Republican party and commit it to universal abolition of the system of servile labor, upon the perpetuation of which depended the industrial life of the South.

It was believed by Southern publicists that the Dred Scott decision would be[Pg 188] reversed by a reorganized Supreme Court, and that a Republican Congress would enact laws denying the slaveholders the right to carry their slaves into the territories, and to be protected there by Federal power. As a matter of fact, slave labor could not have been employed profitably in the corn-fields of Kansas and Nebraska, and the cotton States had no slaves to spare. As was wittily said by Charles Francis Adams, “The South seceded because she couldn’t get protection for a thing she hadn’t got, in a place where she didn’t want it.”

In the months between the election and inauguration of Lincoln, during which the Southern Confederacy was organized, members of the Thirty-sixth Congress made futile efforts to avert the coming struggle. Senator Mason of Virginia sneeringly characterized the Crittenden compromise resolutions as “a bread pill.” Senator Douglas rejoined that “hypochondriacs were sometimes best cured of imaginary disorders by the use of bread pills.” Compromise was impossible. The South was determined on separation. Her press and her orators cherished the delusion that Northern men would not fight to preserve the Union. They fired the Southern heart and precipitated the cotton States into a revolution.

The uprising in the North that followed the assault on Sumter amazed the South and astonished the world; but it was not until nearly two years after Sumter that the nation became fully aroused to a sense of its power, its duty, and its destiny. The Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln struck swift and sure at the cause of the war, which was the Southern determination to perpetuate slavery. It enlisted the sympathies of Christian civilization. By the late summer of 1864 it became apparent that the sacrifices, the generalship, and the desperate valor of the Confederates could not much longer hold out against the superiority of the Union forces in numbers and arms, and the financial resources of the Federal government. The one hope of the Confederacy was that, at the ensuing election, the people of the loyal States might decree to end the contest. But the soul went out of the Confederacy on the sixth of November, 1864, when the ballots cast for Abraham Lincoln settled the issue of continuing the war for the Union. Victory succeeded victory, until the old banner, hallowed by the new motive, floated over every Southern stronghold.

MANY of the volunteer troops had been authorized by the laws of their respective States to vote in the field for President of the United States. In the case of my command, this voting was done in the Shenandoah Valley on November 6, about a fortnight after the famous battle of Cedar Creek, the scene of “Sheridan’s Ride.” My brigade was then on the march from Cedar Creek to Martinsburg as guard to a long supply-train. The usual practice on infantry marches was to march fifty minutes and rest ten minutes. Our troops availed themselves of the opportunity offered by these ten-minute rests to go to the polls and cast their ballots. Polling-places had been provided in every regimental line, proper election blanks supplied by the State, and the voting was done not “early and often,” but with honesty and a fair degree of regularity. In my own regiment the care of the rolls fell to me and my associate election judges, who had charge of the polling throughout the day. A bullet through the leg, received in the battle of Kernstown three months before, had deprived me of my full “hiking” powers, compelling me to resort to the “hurricane-deck” of a mule for transportation throughout the march; but I “arrived” all right, and on the following day, in the midst of a snow-storm, I was able to collect the rolls, certify to the results, and officially transmit the papers to the Ohio Secretary of State. The votes cast were almost entirely for Abraham Lincoln’s reëlection, General George B. McClellan, his Democratic, anti-war opponent, securing scarcely more than a “look in” at the hands of this steadfast Ohio brigade. McClellan fared little better at the hands of those Ohio volunteers than had Clement L. Vallandigham when he was a candidate for governor of the Buckeye State.