Title: A Gringo in Mañana-Land

Author: Harry L. Foster

Release date: January 19, 2022 [eBook #67200]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Dodd, Mead and Company

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

HARRY L. FOSTER

Author of

“The Adventures of a Tropical Tramp,”

“A Beachcomber in the Orient,” etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM

PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1924

Copyright, 1924,

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. BY

The Quinn & Boden Company

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

RAHWAY NEW JERSEY

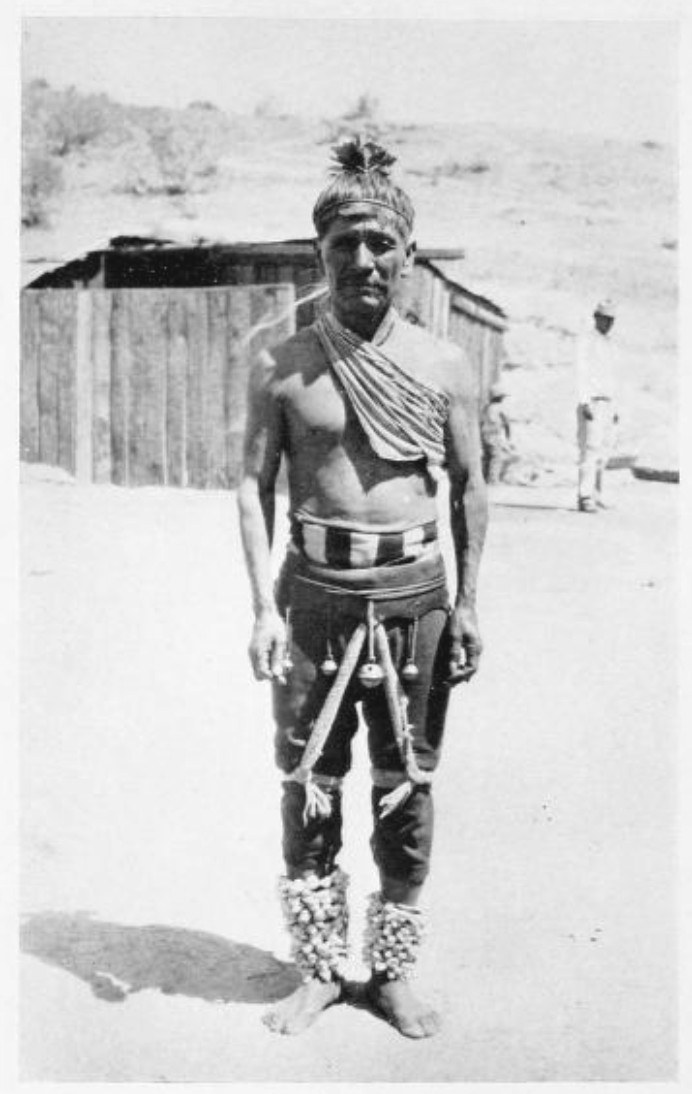

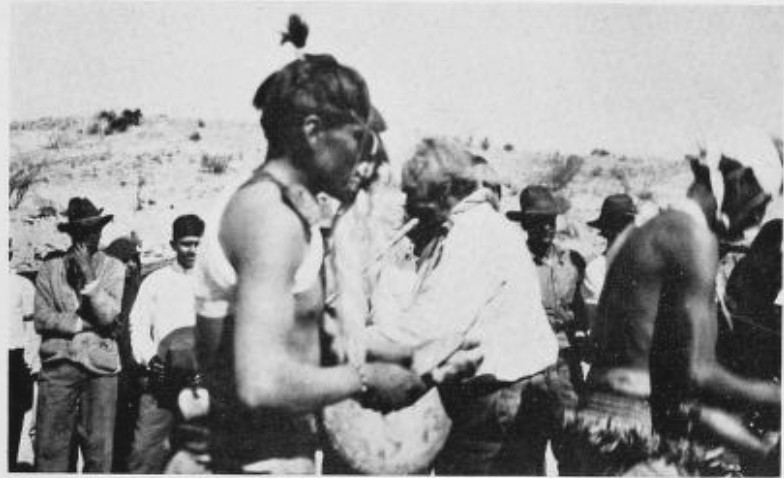

A CHIEFTAIN DRESSED FOR THE EASTER CEREMONY OF THE YAQUI INDIANS

The term “gringo”—a word of vague origin, once applied with contempt to the American in Mexico—is now used throughout Latin America, without its former opprobrium, to describe any foreigner.

The Spanish “mañana”—literally “to-morrow”—is extremely popular south of the Rio Grande, where, in phrases suggesting postponement, it enables the inhabitant to solve many of life’s most perplexing problems.

This book covers various random wanderings in Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. It deals with a romance or two, a revolution or so, and a hodge-podge of personal experience. The incidents of the earlier chapters precede, while those of the later ones follow, the author’s vagabond journeys recorded in “The Adventures of a Tropical Tramp,” and “A Beachcomber in the Orient.”

The chapter on the Yaqui Indians is published with the permission of the editor of “The Open Road.” The photographs of the Guatemalan revolution were taken by Roy Neil Bunstine, of Guatemala City.

| CHAPTER I | On the Border |

| CHAPTER II | Bandits! |

| CHAPTER III | In Sleepy Hermosillo |

| CHAPTER IV | Among the Yaqui Indians |

| CHAPTER V | Down the West Coast |

| CHAPTER VI | Those Dark-eyed Señoritas! |

| CHAPTER VII | In the Days of Carranza |

| CHAPTER VIII | The Mexican Capital |

| CHAPTER IX | Intermission |

| CHAPTER X | The Land of the Indian Vamps |

| CHAPTER XI | Those Chronic Insurrections! |

| CHAPTER XII | Up and Down Guatemala |

| CHAPTER XIII | In Sunny Salvador |

| CHAPTER XIV | The Revolution in Honduras |

| CHAPTER XV | Where Marines Make Presidents |

| CHAPTER XVI | A Long, Long Way to Costa Rica |

| CHAPTER XVII | Adios! |

| Transcriber’s Notes |

It was my original plan to ride from Arizona to Panama by automobile.

In fact, I even went so far as to purchase the automobile. It had been newly painted, and the second-hand dealer assured me that no car in all the border country had a greater reputation.

This proved to be the truth. The first stranger I met grinned at my new prize with an air of pleased recognition.

“Well! Well!” he exclaimed. “Do you own it now?”

So did the second stranger, and the third. I had acquired not only an automobile, but a definite standing in the community. People who had hitherto passed me without a glance now smiled at me. There was even some discussion of organizing a club, of which I was to be the president, my term of office to continue until I could sell the car to some one else.

When I announced that I meant to drive to Panama—down through Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and any other republics which I might discover along the way—every one who heard of the idea offered encouragement:

“You’ve got the right car for that trip, my boy. Since you’ll find no roads down there, you’ll need a companion to walk ahead and chop down the cactus or level off the mountains, and if you step hard on the gas, you’ll just about be able to keep up with him.”

I suspected that there was an element of insincerity in this encouragement.

I was rather young, however, at the time of that first venture at foreign travel. It was only a few months after the Armistice, and I felt disinclined to return to cub-reporting on a daily newspaper. I elected myself to the loftier-sounding profession of Free-Lance Newspaper Correspondent. I purchased a palm-beach suit and an automatic pistol. I was going south into the land of romance—of tropical moons glimpsed through whispering palm-trees—of tinkling guitars echoing through Moorish patios—of black-eyed señoritas and red-nosed soldiers of fortune—of all the many things beyond the ken of mere cub-reporters.

Despite the encouragement, I tacked my banner to the back of my car, and set out upon a round of farewells.

My departure was very dramatic.

Men shook hands with an air of finality. Two or three girls kissed me good-by with conventional little pecks that seemed to say, “I’ll never see the poor devil again, so I may as well waste some osculation on him.”

I had made the entire circuit, until there remained only a couple of village school-marms, who happened—most unfortunately—to live on top of the highest hill in town. Half-way to the summit, I perceived that my car was never destined to climb that hill. It slackened speed. It stopped. It commenced to roll backward. I was forced to throw it into reverse, just as the school-marms appeared in their doorway. The situation was humiliating. I became slightly flustered. I meant to step on the brake, but I stepped on the gas.

Wherefore, after some one had picked me out of the débris, I started southward by train.

I crossed the border at daybreak.

In the manner of a Gringo who first passes the Mexican frontier, I walked cautiously, glancing behind me from time to time, anticipating hostility, if not actual violence.

In the dusk of early morning the low, flat-roofed adobe city of Nogales assumed all the forbidding qualities of the fictional Mexico. But the leisurely immigration official was polite. The customs’ inspector waved me through all formalities with one graceful gesture. No one knifed me in the back. And somewhere ahead, beyond the dim line of railway coaches, an engineer tolled his bell. The train, as though to shatter all foreign misconceptions of the country, was about to depart on scheduled time!

Somewhat surprised, I made a rush for the ticket window.

A native gentleman was there before me. He also was buying passage, but since he was personally acquainted with the agent, it behooved him—according to the dictates of Spanish etiquette—to converse pleasantly for the next half hour.

“And your señora?”

“Gracias! Gracias! She enjoys the perfect health! And your own most estimable señora?”

“Also salubrious, thanks to God!”

“I am gratified! Profoundly gratified! And the little ones? When last I had the pleasure to see you, the chiquitita was suffering from—”

The engineer blew his whistle. A conductor called, “Vamonos!” I jumped up and down with Gringo impatience. The Mexican gentleman gave no indication of haste. The engineer might be so rude as to depart without him, but he would not be hurried into any omission of the proper courtesies. His dialogue was closing, it is true, but closing elaborately, still according to the dictates of Spanish etiquette, in a handshake through the ticket window, in an expression of mutual esteem and admiration, in eloquent wishes to be remembered to everybody in Hermosillo—enumerated by name until it sounded like a census—in another handshake, and finally in a long-repeated series of “Adios!” and “Que le vaya bien!”

What mattered it if all the passengers missed the train? Would there not be another one to-morrow? This, despite the railway schedule, was the land of “Mañana.”

On his first day in Mexico, the American froths over each delay. In time he learns to accept it with fatalistic calm.

As it happened, the dialogue ceased at the right moment. Every one caught the train. Another polite Mexican gentleman cleared a seat for me, and I settled myself just as Nogales disappeared in a cloud of dust, wondering why any train should start at such an unearthly hour of the morning.

The reason soon became obvious. The time-table had been so arranged in order that the engineer could maintain a comfortable speed of six miles an hour, stop with characteristic Mexican sociability at each group of mud huts along the way, linger there indefinitely as though fearful of giving offense by too abrupt a departure, and still be able to reach his destination—about a hundred miles distant—before dark.

In those days—the last days of the Carranza régime—trains did not venture to run at night, and certainly not across the Yaqui desert. It was a forbidding country—an endless expanse of brownish sand relieved only by scraggly mesquite. Torrents from a long-past rainy season had seamed it with innumerable gullies, but a semi-tropic sun had left them dry and parched, and the gnarled greasewood upon their banks drooped brown and leafless. Even the mountains along the horizon were gray and bleak and barren save for an occasional giant cactus that loomed in skeleton relief against a hot sky.

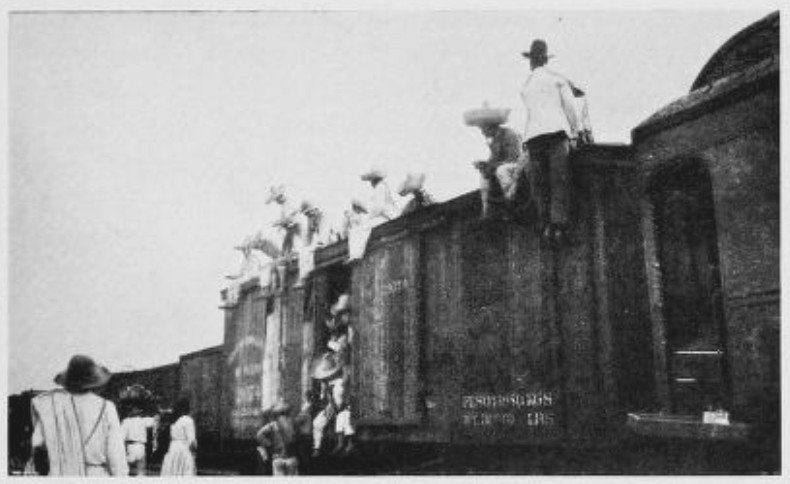

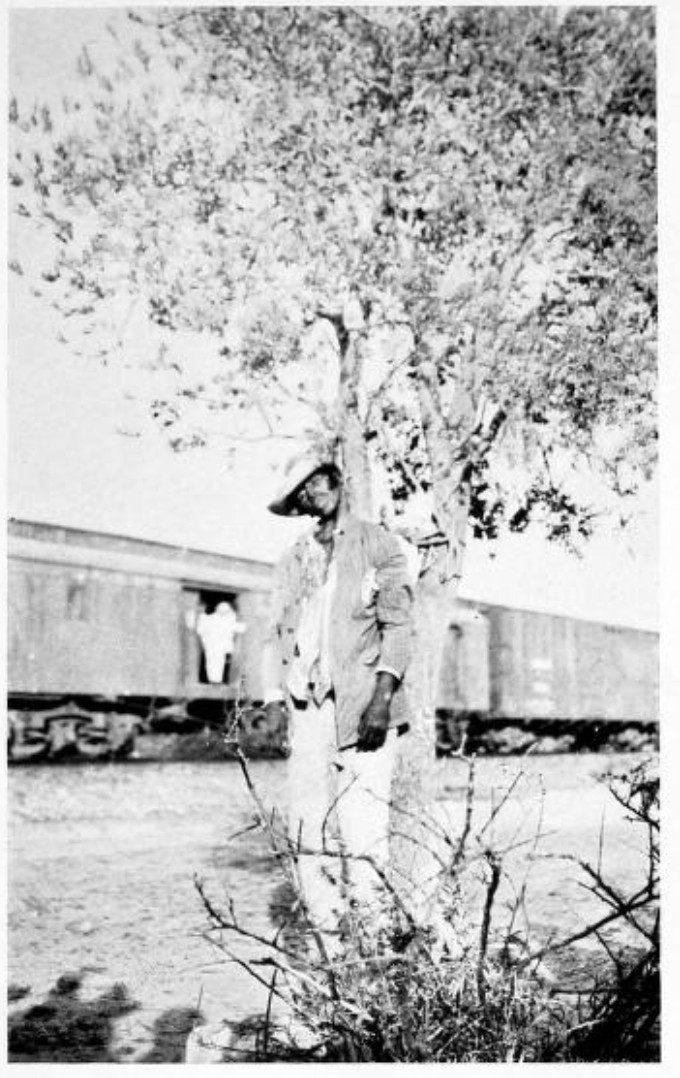

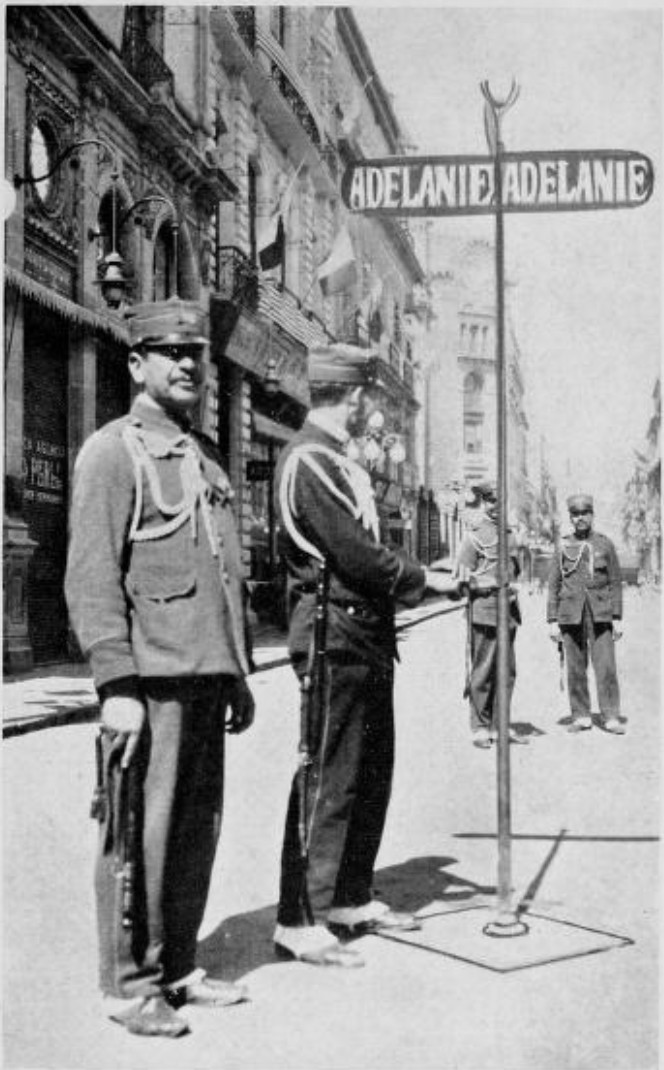

IN THOSE DAYS TRAINS DID NOT VENTURE TO RUN AT NIGHT ACROSS

THE SONORA DESERT

This was the State of Sonora, one of the richest in Mexico, but its wealth—like the wealth of all Mexico—was not apparent to the eye of the tourist. The villages at which we stopped were but groups of low adobe hovels. The dogs that slunk about each habitation, being of the Mexican hairless breed, were strangely in harmony with the desert itself. And the peons—dark-faced semi-Indians, mostly barefoot, and clad in tattered rags—seemed to have no occupation except that of frying a few beans and selling them to railway passengers.

At each infrequent station they were awaiting us. Aged beggars stumbled along the side of the coach, led by tiny children, to plead in whining voices for “un centavito”—“a little penny”—“for the love of God!” Women with bedraggled shawls over the head scurried from window to window, offering strange edibles for sale—baskets of cactus fruit resembling fresh figs—frijoles wrapped in pan-cake-like tortillas of cornmeal—legs of chicken floating in a yellow grease—while the passengers leaned from the car to bargain with them.

“What? Fifteen centavos for that stuff? Carramba!”

“Ten cents then?”

“No!”

“How much will you give?”

Both parties seemed to enjoy this play of wits, and when, with a Gringo’s disinclination to haggle, I bought anything at the price first stated, the venders seemed a trifle disappointed. Everybody bought something at each stopping-place, and ate constantly between stations, as though eager to consume the purchases in time to repeat the bargaining at the next town. The journey became a picnic, and there was a child-like quality about the Mexicans that made it strangely resemble a Sunday-school outing at home.

Although an escort of Carranzista soldiers occupied a freight car ahead as a precaution against the bandits which infested Mexico in those days, the passengers appeared blandly unconcerned.

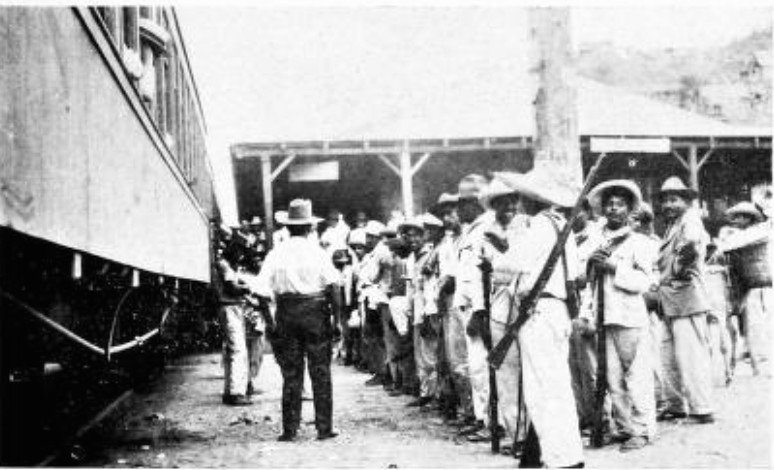

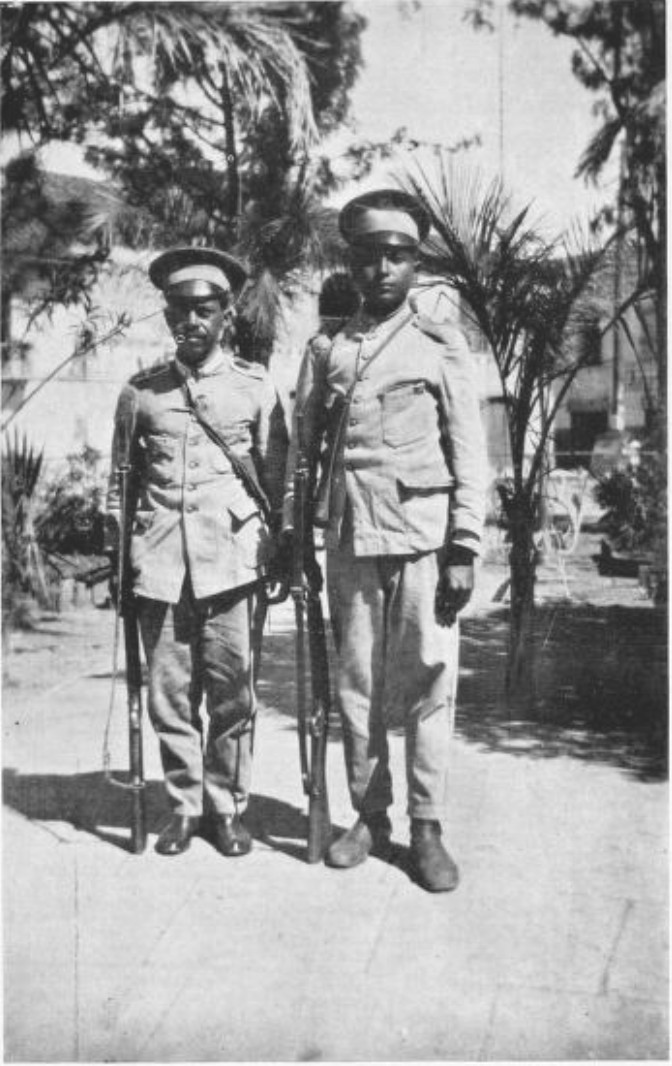

AN ESCORT OF SOLDIERS OCCUPIED A FREIGHT CAR AHEAD AS A

PRECAUTION AGAINST BANDITS

Each removed his coat, and lighted a cigarette. From the car wall a notice screamed the Spanish equivalent of “No Smoking,” but the conductor, stumbling into the coach over a family of peons who had crowded in from the second-class compartment, merely paused to glance at the smokers, and to borrow a light himself. Every one, with the friendliness for which the Latin-American is unsurpassed, engaged his neighbor in conversation. The portly gentleman who had cleared a seat for me inquired the object of my visit to Mexico, and listened politely while I slaughtered his language. The conductor bowed and thanked me for my ticket. When the peon children in the aisle pointed at me and whispered, “Gringo,” their mother ceased feeding a baby to “Shush!” them, their father kicked them surreptitiously with a loose-flapping sandal, and both parents smiled in response to my amused grin.

There was something pleasant and carefree about this Mexico that proved infectious. Atop the freight cars ahead, the escort of federal troops laid aside their Mausers, removed their criss-crossed cartridge-belts, and settled themselves for a siesta. As the desert sun rose higher, inducing a spirit of coma, the passengers also settled themselves for a nap. The babble of the morning gave place to silence—to silence broken only by the fretting cry of an infant and the steady click of the wheels as we crawled southward, hour after hour, through the empty wastes of mesquite.

And then, as always in Mexico, the unexpected happened.

The silence was punctured by the staccato roar of a machine-gun!

In an instant all was confusion.

Whether or not the shooting came from the Carranzista escort or from some gang of bandits hidden in the brush, no one waited to ascertain. Not a person screamed. Yet, as though trained by previous experience, every one ducked beneath the level of the windows, the women sheltering their children, the men whipping out their long, pearl-handled revolvers. The only man who showed any sign of agitation was my portly friend. His immense purple sombrero had tumbled over the back-rest onto another seat, and he was frantic until he recovered it.

After the first roar of the machine-gun, all was quiet. The fatalistic calm of the Mexicans served only to heighten the suspense. The train had stopped. When, a few months earlier, Yaqui Indians had raided another express on this same line, the guard had cut loose with the engine, leaving the passengers to their Fate—a Fate somewhat gruesomely advertised by a few scraps of rotted clothing half-embedded in the desert sand. The thought that history had repeated itself was uppermost in my mind, and the peon on the floor beside me voiced it also, in a fatalistic muttering of:

“Dios! They have left us! We are so good as dead!”

We waited grimly—waited interminably. With a crash, the door opened. A dozen revolvers covered the man who entered. A dozen fingers tightened upon a trigger. But it was only the conductor.

“No hay cuidado, señores,” he said pleasantly. “The escort was shooting at a jack-rabbit.”

The passengers sat up again, laughing at one another, talking with excited gestures as they described their sensations, enjoying one another’s chagrin, all of them as noisy and happy as children upon a picnic. They bought more frijoles, and the feast recommenced, lasting until mid-afternoon, when we pulled into Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora.

A swarm of porters rushed upon us, holding up tin license-tags as they screamed for our patronage. Hotel runners leaped aboard the car and scrambled along the aisle, presenting us with cards and reciting rapidly the superior merits of their respective hostelries, meanwhile arguing with rival agents and assuring us that the other fellow’s beds were alive with vermin, that the other fellow’s food was rank poison, and that the other fellow’s servants would at least rob us, if they did not commit actual homicide.

I fought my way through them to the platform, where another battle-scene was being enacted.

Mexican friends were meeting Mexican friends. To force a passage was a sheer impossibility. Two of them, recognizing each other, promptly went into a clinch, embracing one another, slapping one another upon the back, and venting their joy in loud gurgles of ecstasy, meanwhile blocking up the entire platform.

Restraining Gringo impatience once more, I stood and laughed at them. In so many cases the extravagant greetings savored of insincerity. One noticed a flabbiness in the handclasps, a formality in the hugs, an affectation in the shouts of “Ay! My friend! How happy I am to see you!” Yet in many cases, the demonstrations were real—so real that they brought a peculiar little gulp into one’s throat, even while one laughed.

Be they sincere or insincere, I already liked these crazy Mexicans.

A little brown cochero pounced upon me and took me aboard a dilapidated hack drawn by two mournful-looking quadrupeds.

“Hotel Americano?” he inquired.

“No. Hotel distinctly Mejicano.”

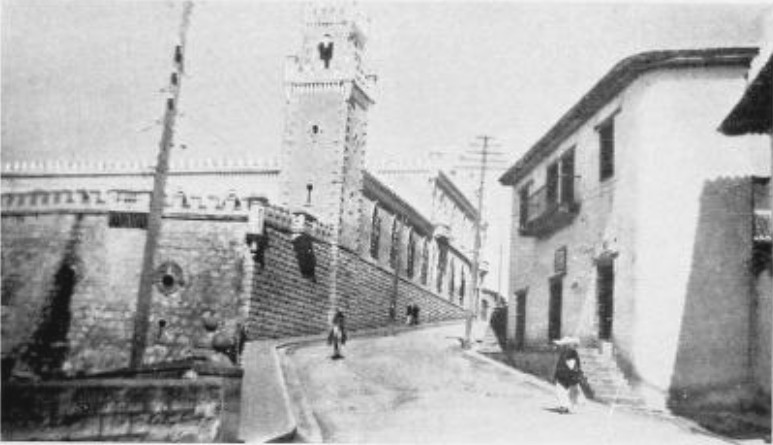

He whipped up his horses, and we jogged away through narrow streets lined with the massive, fortress-like walls of Moorish dwellings, past a tiny palm-grown plaza fronted by an old white cathedral, to stop finally before a one-story structure whose stucco was cracked and scarred, and dented with the bullet holes of innumerable revolutions.

The proprietor himself, a dignified gentleman in black, advanced to meet me. Were there rooms? Why not, señor? Whereupon he seated himself before an immense ledger, to pore over it with knitted brows, stopping now and then to stare vacantly skyward in the manner of one who solves a puzzle or composes an epic poem.

“Number sixteen,” he finally announced.

“Occupied,” said a servant.

Another period of intellectual absorption.

“Number four.”

There being no expostulation, a search ensued for the key. It developed that Room Number Four was opened by Key Number Seven, which—in conformity to some system altogether baffling to a Gringo—was usually kept on Peg Number Thirteen, but had been misplaced by some careless servant. The little proprietor waved both hands in the air.

“What mozos!” he exclaimed. “No sense of orderliness whatsoever!”

A prolonged search resulted, however, in its discovery, and the proprietor himself led the way back through a succession of patios, or interior gardens, the front ones embellished with orange trees, and the rear ones with rubbish barrels, to Room Number Four, from which the lock had long ago been broken.

It was a large apartment, with brick floor. It contained a canvas cot, a wobbly chair, and an aged bureau distinguished for its sticky drawers, an air of lost grandeur, and a burnt-wood effect achieved by the cigarette butts of many generations of guests. The bare walls were ornamented only by a placard, containing a set of rules—printed in wholesale quantities for whatever hotels craved the enhanced dignity of elaborate regulations—proclaiming, among other things, that occupants must comport themselves with strict morality.

“One of our very choicest rooms, señor,” smiled the proprietor, as he withdrew. “It has a window.”

A window did improve it.

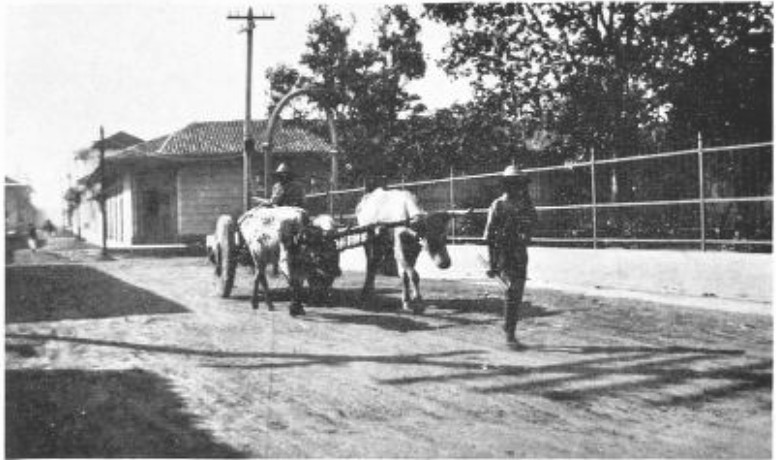

From the narrow street outside came the soft voices of peons, the sing-song call of a lottery-ticket vender, the tread of sandaled feet, the clatter of hoofs from a passing burro train laden with bullion from distant mines, the guttural protesting cry of the drivers, all in the exotic symphony of a foreign land.

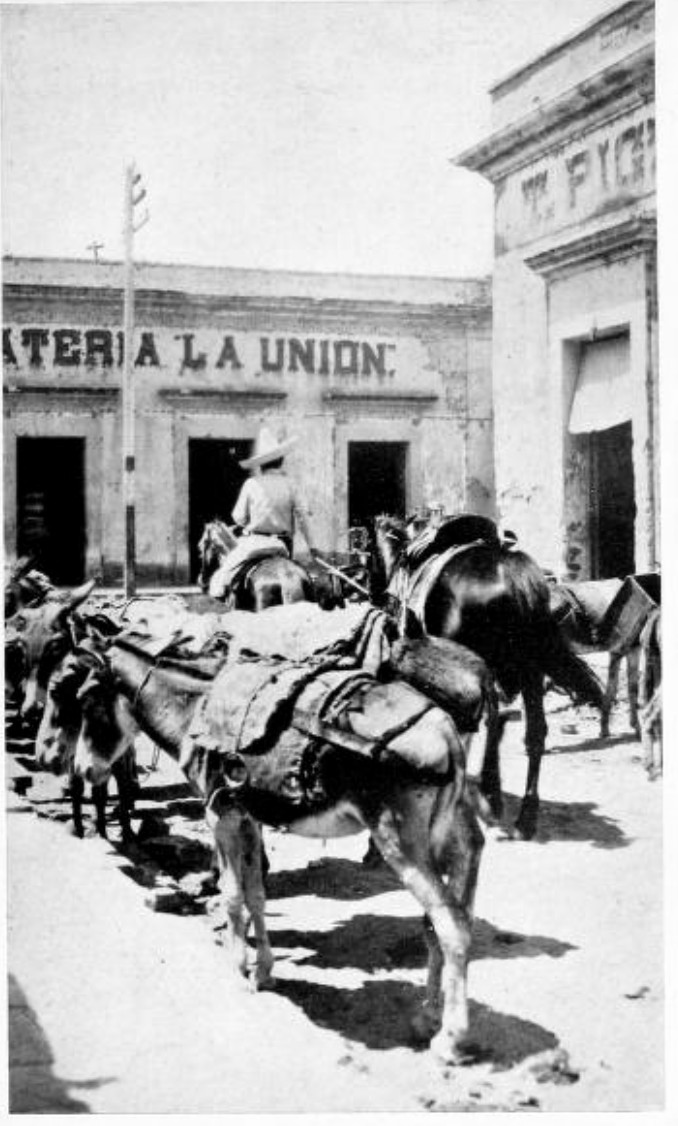

A BURRO TRAIN LADEN WITH BULLION FROM THE MINES

Yet there was a calm, subdued note about the chorus. In Mexico, a newly arrived Gringo expected melodrama. It was disconcerting to find only peace.

An Indian maiden, straight as an arrow, swung past with the flat-footed stride of the shoeless classes, balancing an earthenware jar upon her dark head. A fat old lady cantered by upon a tiny donkey, perched precariously upon the extreme stern. A little brown runt of a man staggered past under a gigantic wooden table. Another staggered past under the influence of alcohol. Women on their way to market stopped to offer me their wares. Did I wish to buy a chicken or a watermelon? Would I care for a bouquet of yucca lilies? Or an umbrella? If not an umbrella, a second-hand guitar?

“No?” They seemed surprised and disappointed. But they smiled politely. “Gracias just the same, señor! Adios!”

An ice cream vender made his rounds with a slap of leather sandals, balancing atop his sombrero a dripping freezer. He stopped before a patron to dish the slushy mixture into a cracked glass, pushing it off the spoon with a dirty finger, and licking the spoon clean before he dropped it back into the can. From one pocket he produced bottles and poured coloring matter over the concoction—scarlet, green, and purple. Then he swung his burden aloft, and continued on his way, chanting, “I carry snow! I carry snow!”

Even the cries of a peddler were soft and gentle here. I was about to turn from the window, when around the corner came a strange procession of mournful men and wailing women, led by three coffins balanced, like every other species of baggage in this country, upon the heads of peons. Mexico was Mexico after all! Here was evidence of melodrama! Excitedly I hailed the proprietor.

“A bandit attack, señor? No, indeed. José Santos Dominguez had a christening at his house last night. Purely a family affair, señor! Nothing more.”

After the dusty railway journey I craved a bath.

From a doorway across the patio a legend beckoned with the inscription of “Baños.” I called an Indian servant-maid, pointed at the legend, struggled with Spanish, and finally secured a towel. The bath-room door, like that of my room, had long ago lost its lock. Searching among the several tin cans which littered one corner, I found a stick which evidently was used for propping against the door by such bathers as desired privacy. Having undressed, I leaped jubilantly into the huge, old-fashioned tub, and turned on the water. There was no water. Poking modest head and shoulders around the edge of the door, I looked for the maid. She eventually made her appearance, as servants will, even in Mexico, and regarded me suspiciously from a safe distance.

“No, señor, there is no water. You asked for a towel. You did not mention that you wished also a bath.”

“Well, for the love of Mike, when—”

“Mañana, señor. Always in the morning there is water.”

And so, after supper and a stroll in the plaza, I retired, still coated with Sonora desert, to my room. There was some difficulty in locating the electric button, since another careless mozo had backed the bureau against it. There was also some difficulty in arranging the mosquito net over my bed. It hung from the ceiling by a slender cord which immediately broke in the pulley. I piled a chair on top of a cot, climbed up and mended the string, climbed down and lowered the net to the proper height, unfolded it, and discovered that it was full of gaping holes through which not only a mosquito but possibly a small ostrich could have flown with comfort and security. Finally, beginning to feel that the charm of Mexico had been vastly overrated by previous writers, I retired, prepared to fight mosquitos, and discovered that there were no mosquitos in Hermosillo.

In the morning, rejuvenated and reënergized, I again waylaid the Indian servant-maid.

“Ah!” she exclaimed, as though it were a new idea. “The señor wishes a bath? Why not? Momentito! Momentito!”

“Momentito” is Spanish for “Keep your shirt on!” or “Don’t raise hell about it!” or more literally “In the tiny fraction of a moment!” It suggests to the native mind a lightning-like speed, even more than does “Mañana.”

And eventually I did get the bath. There was some delay while the water was heated, and more delay while the maid carried it, a kettleful at a time, from the kitchen to the bath-room, but the last kettle was ready by the time the rest had cooled, and I finally emerged refreshed, to discover again that in Mexico the unexpected always happens.

When I pulled out the old sock used as a stopper, the water ran out upon the bath-room floor, and disappeared down a gutter, carrying with it the shoes I had left beside the tub.

But Hermosillo possessed a charm which even a Mexican bath could not destroy.

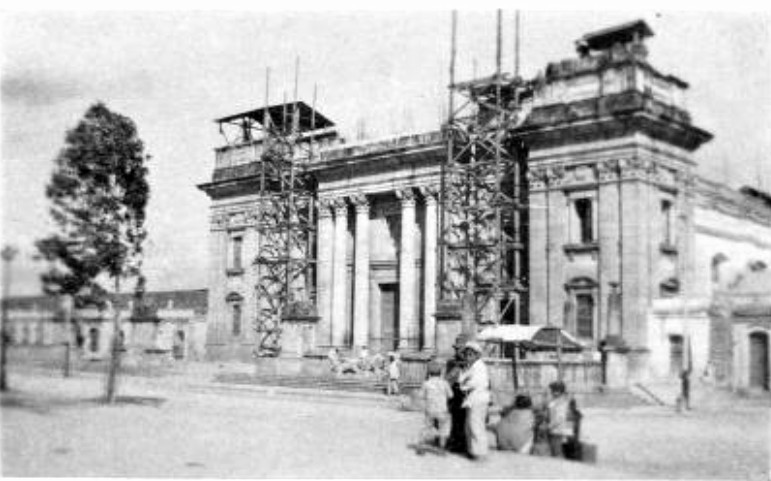

It was a sleepy little city, typically Mexican, basking beneath a warm blue sky. It stood in a fertile oasis of the desert, and all about it were groves of orange trees. Its massive-walled buildings had once been painted a violent red or green or yellow, but time and weather had softened the barbaric colors until now they suggested the tints of some old Italian masterpiece. And although ancient bullet holes scarred its dwellings, there hung over the Moorish streets to-day a restful atmosphere of tranquillity.

At noon the merchants closed their shops, and every one indulged in the national siesta. The only exception was an American—a quiet, determined-looking man—who kept walking up and down the hotel patio with quick, nervous tread.

“Somebody just down from the States?” I asked the proprietor.

“No, señor. He is the manager of mines in the Yaqui country. One of his trucks is missing, and he fears lest Indians have attacked it.”

Such a contingency, in sleepy Hermosillo, sounded quite absurd. It was the most peaceful-appearing town in all the world. As the siesta hour drew to a close, the señoritas commenced to show themselves, dressed and powdered for their evening stroll in the plaza. They were dainty, feminine creatures, not always pretty, yet invariably with a gentle womanliness that gave them charm. Upon the streets they passed a man with modestly downcast head. Behind the bars of a window and emboldened by a sense of security, they favored him with a roguish smile from the depths of languorous dark eyes, and sometimes with a softly murmured, “Adios!”

I drifted toward the plaza, wondering how a Free-Lance Newspaper Correspondent were to earn a living in any country so outwardly unexciting as Mexico, and dropped disgustedly into a bench beside another young American.

He was a rosy-cheeked, cherubic-appearing lad. He wore horn-rimmed spectacles, and his neatly-plastered hair was parted in the middle. Like myself, he was dressed in a newly purchased palm-beach suit. His name was Eustace. He, too, was just out of the army. He had enlisted, he explained, in the hope that he might live down a reputation as a model youth. And the War Department had given him a tame job on the Mexican border, cleaning out the cages of the signal-corps pigeons. Wherefore he was now journeying into foreign fields in the hope of satisfying himself with some mild form of adventure.

Very solemnly we shook hands.

“I couldn’t quite go back to cub-reporting,” he explained. “So I decided to become a free-lance newspaper correspondent.”

Even more solemnly we shook hands again. Since neither of us actually expected that any editor would publish what we sent him, we formed a partnership upon the spot. The Expedition had a new recruit. And together we mourned the disappointing peacefulness of Hermosillo.

Evening descended upon the plaza. A circle of lights appeared around the rickety little bandstand. An orchestra played. The señoritas strolled past us, arm in arm, while stately Dons and solemn Doñas maintained a watchful chaperonage from the benches. The night deepened. The cathedral clock struck ten. Dons, Doñas, and señoritas disappeared in the direction of home. The gendarmes alone remained. Each muffled his throat as a precaution against night air, and each set a lantern in the center of a street crossing. From all sides came the sound of iron bars sliding into place behind heavy doors. Hermosillo was going to bed.

As we, also, turned homeward, our footsteps rang loudly through the silent streets. A policeman unmuffled his throat and bade us “Good night.” Then he produced a tin whistle and blew a melancholy little toot, to inform the policeman on the next corner that he was still awake. From gendarme to gendarme the signal passed, the plaintive wail seeming to say, “All’s well.”

A beggar huddled in a doorway hid his cigarette beneath his ragged blanket at our approach, and held out his hand. A lone wayfarer, lingering upon the sidewalk before a window, turned to glance at us, and to bid us “Adios.” Through the bars a girl’s radiant face shone out of the darkness. Then the man’s voice trailed after us, singing very softly to the throbbing of a guitar. A moon peeped over the edge of the low flat roofs—a very aged and battered-looking moon, with a greenish tinge like that of the old silver bells in Hermosillo’s ancient cathedral—a moon which, like the city below it, suggested that it once had known troublous days, yet was now at perfect peace.

This was a delightful land, but to a pair of Free-Lance Newspaper Correspondents—

As we entered the wide-arched portals of the hotel, the telephone struck a jarring note. The American mining man, still pacing nervously up and down the patio, leaped to the receiver.

“Laughlin speaking! What news? Did they—? Shot them both? White and Garcia both? Get the troops out! I’ll be there in just—”

In an instant Eustace and I were at his elbow.

Ours was the newspaperman’s unsentimental eagerness, which might have hailed the burning of an orphan asylum with its four hundred helpless inmates as splendid front-page copy. Here was murder! This was Mexico! Viva Mexico! Here was our first story!

“No time to talk!” snapped Laughlin. “I’ll send John Luy for you in the morning. He’ll take you to La Colorada, in the Yaqui country itself. You’ll get the dope there!”

And he vanished down the street. We stood at the hotel gate, a little startled, gazing out into the night. The moon smiled down over low, flat roofs, and a man’s voice drifted to us, singing very softly to the throbbing of a guitar, and the plaintive note of a gendarme’s whistle seemed to say, “All’s well.”

John Luy met us in an elderly Buick early the next morning.

He was a stocky man in khaki and corduroy, a man of fifty or sixty, with slightly gray hair, and the keen, friendly eyes of the Westerner. He was a trifle deaf from listening to so many revolutions, and questions had to be repeated.

“Heh? Oh, the holes in the wind-shield? They’re only bullet holes.”

He motioned us into the back seat, grasped the wheel, and drove us out through the suburbs of Hermosillo into the open desert. The road was nothing more than the track of cars which had crossed the plains before us. Sometimes it led through wide expanses of dull reddish sand; sometimes the cactus and mesquite grew in thorny forests up to the very edge of the narrow trail.

It was a country alive with all the creeping, crawling things that supply local color for magazine fiction. Swift brown lizards shot from our path, starting apparently at full speed, and zigzagging through the yucca like tiny streaks of lightning. Chipmunks and ground squirrels dived into their burrows at our approach. A rattler lifted its head, hissed a warning, and retired with leisurely dignity. Jack-rabbits popped up from nowhere in particular and scampered into the brush, laying their ears flat against the head, running a dozen steps and finally bouncing away in a series of long, frantic leaps. Chaparral cocks, locally known as road-runners, sped along the trail before us, keeping about fifty feet ahead of the car, wiggling their tails in mocking challenge, slackening their pace whenever we slackened ours, speeding whenever we speeded, and shooting away into the mesquite in a low, jumping flight as John stepped on the gas.

Now and then we passed a mound of rocks surmounted by a crude wooden cross, and once we saw the wreck of what had been another automobile.

“Heh?” asked John. “Oh! Graves. People shot by Yaqui Indians. Oh, yes, quite a few of them. Quite a few.”

He gave the wheel a twist, and we plunged down a steep slope into a deep, sandy river-bed. The car lumbered through it, sinking to the hubs. In the very center it came to an abrupt stop. John picked up a rifle.

“One of you lads take the gun and lay out in the brush. This is the kind of place where White got his.”

Eustace seized the weapon, and crawled into the cactus, while I worked savagely to dig the wheels from their two-foot layer of soft, beach-like sand. John, puffing complacently at his corn-cob pipe, tried the self-starter again and again without success, meanwhile giving me the details of White’s murder:

“It was an arroyo exactly like this one. Exactly like this one. He come around a bend in his truck, and hit the waterhole, and was plowing through it when a dozen Mausers blazed out’n the cactus. Three bullets hit him square in the head. Maybe Garcia, his mechanic, got it on the first volley, too. You couldn’t be sure—so the fellows said over the telephone. The Yaquis had cut him up and shoved sticks through him ’til his own mother couldn’t’ve recognized him. Dig the sand away from that other wheel, will you?”

I breathed more freely half an hour later, when we climbed the farther bank of the river-course, and rattled on again, through ever-thickening forests of cactus, to the low adobe city of La Colorada.

John showed us a nondescript mud dwelling that passed for a hotel, and we presently sallied therefrom, with paper and pencil, fully convinced that the pleasantest method of securing copy would be that of sitting on the village hitching post and listening to the experiences of some one else.

There were half a dozen other Americans in La Colorada. It had once been the home of gold mines from which heavily-guarded mule trains carried away a hundred and eight millions of dollars in bullion, but revolutionists had destroyed the machinery during the turbulent years that led up to the Carranza régime, and the town now served only as a depot for the big motor trucks which ran through hostile Yaqui country to mines farther in the interior. The half dozen Americans were the drivers of these trucks. The eldest of them was under thirty, but most of them had knocked about the far corners of the earth since childhood, and all of them surveyed with undisguised contempt the little thirty-two-caliber automatics we carried.

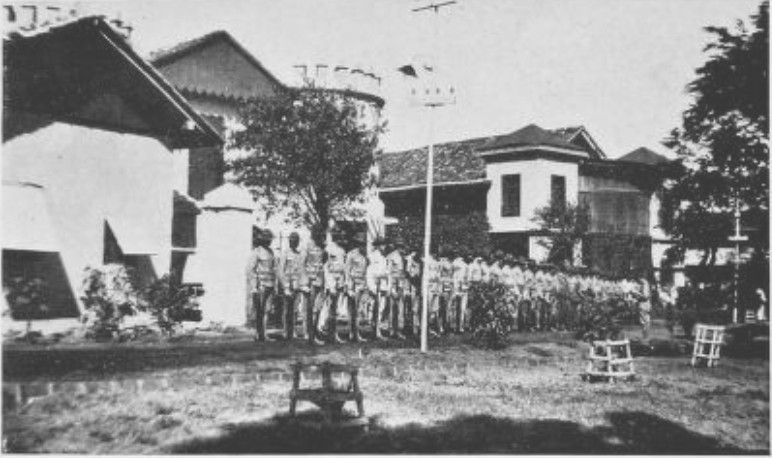

LA COLORADA, ONCE THE HOME OF GOLD MINES, NOW SERVED ONLY AS

A DEPOT FOR TRUCKS THAT CROSSED THE DESERT

“If you was to shoot me with one of them things, and I was ever to find it out,” said Dugan, a lad of twenty, “I’d be downright peeved about it.”

Dugan stood over six feet in height. His jaw resembled the Rock of Gibraltar, and his hair suggested Vesuvius in eruption. His favorite literature, I suspected, was the biography of Jesse James. He carried a forty-four in a soft-leather holster cut wide to facilitate a quick draw. His great ambition was to “shoot up” a saloon, and since there was no bar-room in La Colorada, he had recently compromised upon the local drug-stores, and had blazed holes through the pharmacist’s castor-oil bottles.

All of these youths had encountered the Yaquis. One showed us a dozen bullet-dents in his truck, mementos of a brush with Indians on his last trip. Another had been captured, stripped of his clothing, and chased naked back to town. But of the latest incident—the murder of White and Garcia—they could give us little information. W. E. Laughlin was supposed to have an understanding with the Yaqui chiefs whereby his property and his employees were protected.

“He pays ’em so much a year to leave him alone. He’s never had any trouble before this. A year ago one of his drivers was shot—Al Farrel—but it wasn’t Yaquis. It was a gang of Mexican soldiers. They robbed the truck and blamed it on the Indians, and went scouting all over the country pretending to chase the guys that did it. Maybe the same thing has happened again.”

“That’s about it,” echoed another. “The Yaquis hold us up, but it’s the Greasers they’ve got it in for. We get off light—usually. They just rob us. When they catch a Mex, they rip his clothes off and chuck him into the cactus, or cut the soles off his feet and make him dance on the hot sand.”

But the others disagreed. It was merely border tradition that the Yaquis treated Americans better than Mexicans. There was the case of Otto, the draft-dodger, who came to La Colorada to avoid the war, only to be caught by the Indians and tortured to death. There was the story of One-Legged Joe, who went prospecting just outside of town, and of whom nothing was found except the wooden leg, charred with fire. And there was the tragedy of Pedro Lehr, who left his ranch near Hermosillo for a few hours, and returned to find his entire family slain, with the exception of a sixteen-year-old daughter whom the Yaquis had carried away with them.

Pleased at our eager interest, the truck-drivers warmed toward us. Only Dugan remained aloof, grinning a trifle contemptuously. Eustace turned to him:

“What can you tell us?”

“What do you want to know?”

“Well, for a starter, how do you feel when you ride through hostile Indian country on a truckload of dynamite?”

Dugan spat eloquently upon the ground. Then he pointed toward two loaded trucks that stood in the road before us.

“MacFarlane over there is going out to a mine to-morrow. If you want to know how it feels, go along with him. He’s carrying six hundred pounds of dynamite.”

Since he put it that way, we sought out MacFarlane.

He was a tall, lean-faced man—one of the quiet, self-possessed, determined-looking mine superintendents usually encountered in Mexico. He was about to make a week’s trip to El Progresso mine, sixty miles farther in the interior. He would be glad to take us along.

And at dawn the following day, we rode out of La Colorada in one of MacFarlane’s trucks. We sat upon a miscellaneous assortment of machinery, provisions, and blasting powder, with a crew of twenty hired gunmen, each of whom wore several hundred yards of cartridge belt draped around his waist and criss-crossed over his shoulders in the approved Mexican style.

The desert seemed a trifle more forbidding than the one we had crossed the day before. When we were in the open our gunmen laughed and chatted together; when we approached the forests of yucca and mesquite, I noticed that they grew silent and watchful. But no sound came from the vast expanse of wasteland except the peaceful song of the locusts.

At rare intervals we passed a native village—a cluster of mud hovels surrounding an aged white church—and our advent created a sensation. A host of mongrel dogs but slightly removed from the coyote stage hailed us with furious yelps. Children raced barefoot beside the trucks to get a better view of us. Half-naked Indian women, pounding clothes upon the flat rocks beside a shallow brook, ceased their work to stare at us. Even the adult male population, reclining against the shady side of the adobe dwellings, sat up to look at us.

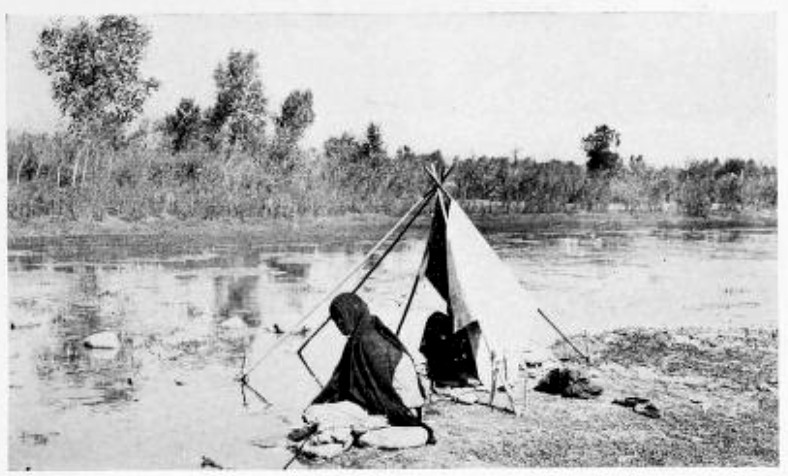

INDIAN WOMEN, POUNDING CLOTHES UPON THE ROCKS BESIDE A

SHALLOW BROOK, CEASED THEIR WORK TO STARE

There was something in these tiny hamlets that recalled pictures of the Holy Land. Civilization had changed but little here since the days of the Aztecs, and despite the excitement caused by our passage, there was an air of sleepiness about the whole place which suggested another continent, a million miles farther from Broadway. So perfect was the scene that I resented the sight of a Standard Oil tin used as a water-jar, and felt distinctly offended when I heard the click of a Singer sewing machine issuing from a tiny, cactus-roofed hut.

The natives here showed little Spanish ancestry. Their features were purely Indian. A few, by their prominent cheek-bones and dark complexion, suggested a trace of Yaqui blood, but most of them were of other tribes, and all carried arms as a precaution against Yaqui raids. Every one wore a large knife, and in an open-air barber shop one native with a six-shooter on his belt was shaving another who held a rifle across his knees. All of them greeted us with the cry:

“Have you met any Yaquis?”

The day passed without incident, however, and nightfall brought us to our first stopping-place, the village of Matape, another cluster of mud hovels surrounding an ancient white church.

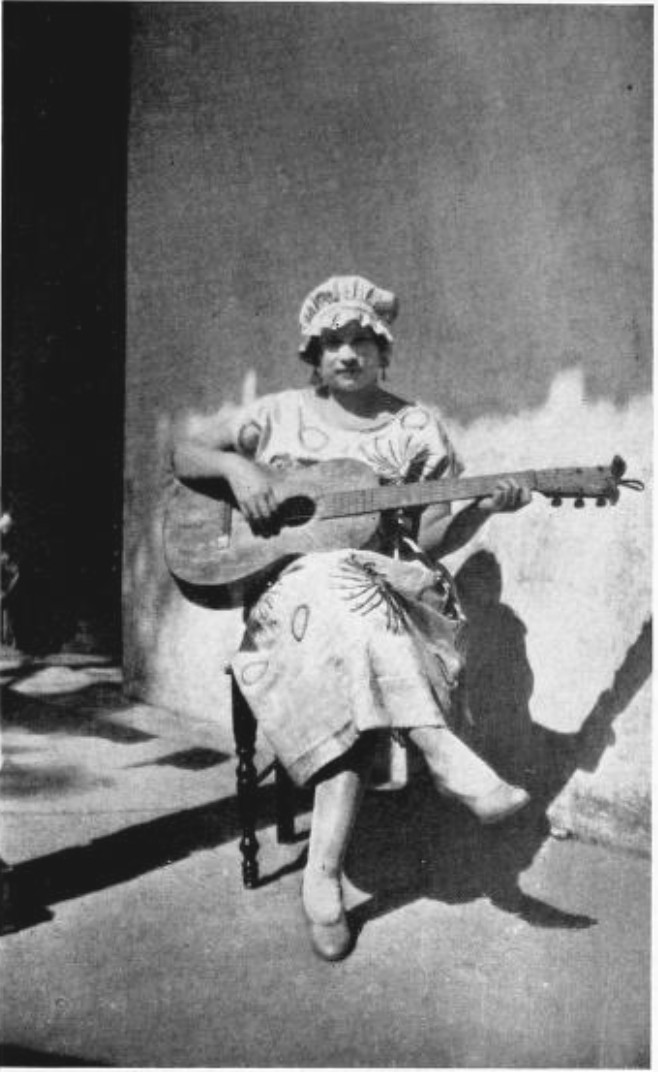

A buxom Indian woman, who operated a hotel on those rare occasions when visitors came to town, served us frijoles and tortillas—beans and cornmeal pancakes—and produced from its hiding place a bottle of fiery mescal. Later, when we had consumed the meal by the light of a flickering oil lamp, her daughter joined us with a guitar, and while MacFarlane watched his gunmen to see that no one kept the bottle too long inverted over his black moustachios, the girl sang to us. Still later, after she herself had sampled the potent Mexican liquor, she danced. She was rather comely, in a stolid Indian way, but she was much too heavy and graceless for complete success as a danseuse, even after two swigs of such inspiring stuff as mescal. The gunmen, however, found it highly diverting. They pushed back their chairs to clear a stage for her, and watched her with the pleased expression which a Mexican always wears when looking at a woman. The guitar twanged a weird, savage melody; the dim light from the swinging lantern shone upon a sea of dark faces, and reflected from a score of gleaming eyes; in the center of the crowded room the girl danced awkwardly, her bare feet pounding monotonously upon the mud floor.

As she finally sank, flushed and panting, upon a bench, her mother favored us with a toothless grin:

“For one hundred dollars gold I sell her!”

Eustace shook his head.

“She’s scarcely an essential part of a newspaper correspondent’s equipment.”

“Seventy-five!” persisted the woman.

“That’s a special rate,” exclaimed MacFarlane. “She lacks one ear. They say her last husband bit it off before chasing her home with a club. Of course, you can’t believe everything you hear. But you’d better turn in. To-morrow we travel on muleback.”

The trucks were to continue, with the guard, by the longer road to the mine. MacFarlane and ourselves, with two of the gunmen, were to ride over the mountains. The bridle trail led through questionable territory, but it was shorter.

Neither Eustace nor I had ever ridden a mule before. Both of us had read Western fiction, and had noted that the hero not only loved his steed, but left nearly everything to the animal’s good judgment, and that the noble beast, appreciating and reciprocating his master’s affection and trust, invariably anticipated his every wish, and carried the hero out of every conceivable difficulty.

We had just discussed the matter, and had determined to encourage the same fond relationship with our prospective mounts, when MacFarlane rode up to the hotel with the five most woebegone-looking specimens of quadrupeds that we had ever seen.

“Cut a good big stick,” he advised.

Two minutes after mounting, I welcomed the suggestion. It seemed inhuman to beat anything so small as that mule, but the animal appeared not to mind it in the least. The moment I ceased whaling him, he assumed that this was where I wished to stop. His one virtue was that no matter how often he stumbled on the edge of a precipice, he never fell over.

“When you come to a tight place,” warned MacFarlane, “let the mule use his own judgment.”

And there were plenty of tight places. Hour after hour the path twisted through narrow ravines, along deep water-courses strewn with bowlders, down sandy embankments where the animals slid like toboggans, around narrow cliffs, and up sharp inclines where they fairly leaped from rock to rock. It was a gloriously desolate country, hideous perhaps, yet awesome in its ugly grandeur. Mountains reared themselves above the trail, covered sometimes with huge candelabra cactus, but usually bare and towering skyward like the battlements of a gigantic fortress. So fascinating was the whole panorama that four of us rode across a valley a full mile in length before we discovered that Eustace had disappeared.

MacFarlane stopped abruptly.

“Good Lord! I told him to keep close to us! Four months ago one of my men dropped behind, and they nabbed him so quietly we never heard a sound!”

He was off his mule in an instant, and leading the way on foot, revolver in hand, while I followed at his heels, both of us crouching behind bowlders as we hurried back along the path we had traversed. Turning a bend, we found Eustace sitting on his mule at the top of a sandy decline, complacently smoking a cigar.

“What the devil are you doing?” snapped MacFarlane.

“Tight place,” said Eustace. “I’m letting the mule use his own judgment.”

“Hell!” growled MacFarlane. “The mule’s gone to sleep!”

And throughout the day he lectured us upon the fallacies of the S.P.C.A. spirit as applied to Mexican mules, all the way to Suaqui de Batuc, another mud-village at the junction of the Yaqui and Moctezuma Rivers, where we were to spend another night.

There was no hotel in this town, but we found lodgings with an Indian family. A woman brought us the inevitable frijoles and tortillas, gave us water to drink which tasted as though it had been inhabited by frogs, and ushered us to one large bed which undoubtedly was inhabited by everything except frogs. The name of the town, I learned, when translated from the Indian, meant something which could be printed only in French. As I scratched myself to sleep, I reflected upon the appropriateness of the name. I had just succeeded in closing my eyes when a volley of pistol shots sounded outside the window. Eustace and I bumped heads in a frantic dive to locate the automatics beneath our pillow.

“Don’t worry,” said MacFarlane. “It’s a gang of drunks. This is a Saint’s Day, and the faithful are celebrating.”

In the morning, before continuing the journey, I set out to secure a few photographs.

“Ask permission before you snap a native,” the mining man warned me. “Some of them are superstitious—have an idea that they’ll die within a year if you take their picture. They killed the last photographer that tried it.”

So I took special pains to ask permission. Invariably they said, “No!” Some appeared to regard the camera as a new species of machine-gun. Even those who knew what it was were reticent about posing. The more picturesque the native, and the more I wished his picture, the more resolutely he said, “NO!”

Strolling some distance from town, I finally discovered an aged squaw who looked as though she might die within a year even though her photograph were not taken. But her “NO!” was not merely in capital letters but in type larger than the largest in a Hearst newspaper. Still, I could not resist that picture. She was standing in the center of the shallow river, filling deer-skin water-sacks and loading them upon the back of a moth-eaten little burro. But since the sun shone directly in my lens, I had to pass her. And the moment I unslung my camera, she started to walk upstream directly into the light. The faster I walked, the faster she walked. I broke into a trot, and she broke into a trot, dragging the burro after her, and splashing water over the two of us. I felt a trifle undignified, but I had determined to have that picture, and I increased my pace to a run. Thereupon she gathered her skirts about her waist and sprinted like an intercollegiate champion.

From the village behind us came a series of war-whoops. I looked back to see the entire population joining in the chase. Suddenly I realized that my behavior was undignified. Some fifty angry natives were rushing toward me, waving in the air an assortment of weapons that might have delighted a collector of antiques, but which at the moment gave me no cause whatsoever for rejoicing. I stopped and faced them, trying vainly to explain my conduct in my inadequate Spanish, while they shook their fists, and waved knives in the air, and jabbered furiously.

Eustace came to my rescue. Two years and eight sweethearts upon the border had given him a fluent command of the language.

“They’ve misjudged your intentions,” he chuckled, after he had calmed the mob. “I’ve explained it all. This old geezer with the four whiskers on his chin is her man, and he says he’ll let you take her picture for two pesos. I suppose he’s tired of her, and doesn’t care whether she croaks or not.”

But the squaw evidently valued her life at more than two pesos. For she gathered up her skirts once more, and fled away down the river, dragging the burro behind her.

It was but a few hours’ ride from Suaqui to El Progresso Mine. It lay in the center of a ragged, bowl-shaped valley in the heart of the mountains, some ninety miles from the railroad—a group of gaping shafts beside a stone blockhouse, with a village of thatched laborers’ quarters straggling along a sandy, cactus-hedged street.

Some half dozen American bosses occupied the blockhouse. The native workmen numbered about two hundred, most of them Pimas and mestizos, or mixed-breeds.

“Don’t shoot at any rattlesnakes,” MacFarlane warned us, “or you’ll see everybody dropping work and running for headquarters to resist attack.”

The mine itself had never been threatened by the Yaquis, but on several occasions they had attempted to ambush the provision trucks. Like most of the mines in Mexico, El Progresso was not the sort where one had merely to walk out with a pick and chop large pieces of silver off a convenient mountain side; before a single speck of mineral could be extracted, it had been necessary to transport across the desert a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of machinery; every bit of it had been brought over the long trail on truck or muleback, and the journey of every train had meant the possibility of a fight with Indians.

The Yaquis of Sonora are closely related to the Apaches of our own border country. From the earliest coming of the white man, they have resented the invasion of their domain. The Spaniards were never able to conquer them. Porfirio Diaz, who pacified all the rest of Mexico, could never make the Yaquis recognize the sovereignty of the Mexican government over their territory. He sent expedition after expedition against them, depleted their ranks by constant warfare, and took thousands of prisoners whom he shipped to far-off Yucatan to labor as virtual slaves upon the henequin plantations. But the atrocities of the Diaz soldiers merely aggravated the Indians’ hatred of their would-be rulers.

From time to time, in more recent years, groups of Yaquis have made their peace with the Mexican authorities. Many of them, known as “manzos” in distinction from the “bravos” in the hills, are to be found in every Sonoran village and even in Arizona. As soldiers, they are the bravest in Mexico, and as laborers the most industrious. But they were never especially friendly to Carranza, and in his era, although some served in the federal army, they frequently did so in order to obtain arms or ammunition for their own use. Soldiers one day, they were apt to be bandits the next.

Although the Yaquis had first declared war upon the invading white man with every possible justification, they had been forced, through years of constant retreat into the unfertile recesses of the desert, to prey upon the invaders for a living. Although their original grievance had been against the Mexican, bandits can not be choosers. And the miners at El Progresso were always on the watch.

“It’s a bad time just now,” one man explained. “They all get together for a big hullabaloo every Easter, and drink a lot of mescal, and get so enthusiastic that they start out for a few more scalps.”

I had witnessed the Easter ceremony of the Yaqui Indians before leaving the border.

Strange as it may sound, the Yaqui is a Christian. Years ago the Spanish missionaries, the greatest adventurers in all history, penetrated the Sonora desert where warriors feared to tread, and finding themselves unable to converse with the Indians, enacted their message in sign language. To-day, at Easter time, the Yaquis reënact the same story, distorted by their own barbaric conception of it until it is but a semi-savage burlesque upon the Passion Play.

In the manzo settlement at Nogales, the Christ was represented by a cheap rag doll, garbed in brilliantly colored draperies, and cradled in a wicker basket beneath a thatched roof. The ceremonies lasted from Good Friday until after Easter Sunday, and during that time the Indians neither ate nor slept, refreshing themselves only with mescal.

The native conception of the life of Christ was that of a continual warfare with Judas. To make the odds harder for Him, they had six assistant Judases, selected—I was told—from the young braves who had committed the most sins during the current year.

THE CHRIST WAS REPRESENTED BY A CHEAP RAG DOLL CRADLED IN

A WICKER BASKET

“We have several,” explained an intelligent old Indian, “because my people could not respect a Savior who allowed himself to be licked by any one man.”

The Judases appeared in startling devil masks, and for three days they capered before the Infant, contorting their semi-naked bodies, howling like fiends, poking Him with sticks, spitting upon Him, kissing Him in mockery, and challenging Him to come out and fight. About the cradle the women of the tribe sat cross-legged upon the ground, wailing a strange Indian hymn that rose and fell in plaintive minor key. A tomtom pounded monotonously. Night descended, and the fires threw weird, fantastic shadows upon the reddened mountain sides. Hour after hour, and day after day, the barbaric orgy continued, until on Easter Sunday the tribe rose in defense of the Christ, seized the Judases and carried them to the fire, where they pretended to burn them. Afterwards, they carried the image of the Savior in mournful procession to a little grave behind the village. It was a ridiculous travesty upon religion, yet one could not laugh. There was a solemnity in the faces of these people, as they followed the rag doll to its burial place. Many of the women were weeping. The men bared their heads, and there was true reverence in the dark, savage eyes. The capering of the devil-dancers had been ludicrous, yet now I found myself strangely impressed. And, anyhow, it is inadvisable to laugh at religious fanatics—especially if they happen to be Yaqui Indians.

FOR THREE DAYS THE INDIANS NEITHER ATE NOR SLEPT, REFRESHING

THEMSELVES ONLY WITH MESCAL

The same ceremony is practiced, with variations in ritual, by the bravos in the hills.

Frequently, as the miner had suggested, it serves as a get-together for the Spring raiding season. Spring is harvest-time in southern Sonora, and an ideal time for the Yaquis to sweep down from the mountains and pillage the valleys which the Mexicans have taken from them. In the days of Carranza, the Indians not only invaded the rural districts, but carried their raids to the very outskirts of Guaymas and Hermosillo.

Word came to us at El Progresso that a band of the Indians was operating not far away. They had attacked several of the neighboring villages, and had visited the Gavilan Mine, another American concern in our district, where they had done the miners no bodily harm, but had left them without clothing or provisions.

“When we start back to-morrow, we’ll travel by night,” decided MacFarlane. “The Yaquis are superstitious about the crosses along the trail. The ghosts of the murdered men are supposed to be out for revenge after dark. That’s the safest time to travel.”

We left at sunset, a little party of five.

As we rode silently toward the vague mountains ahead, their peaks became a magic crimson that deepened slowly to purple against a silver sky. We passed Suaqui, where the rivers gleamed like shining ribbons in the last faint twilight. Then the swift desert night was upon us, and we were riding into a deep pass, where the air grew strangely chill.

I can recall every minute of that long night. Perhaps the mule could see the path. I couldn’t. Now and then, as we ascended, I caught a momentary glimpse of the rider ahead, looming abnormally large against the sky. Usually I listened to the crunch of hoofs upon the gravel, and followed close behind. One had the sensation of being about to enter a tunnel into which the other riders had disappeared. When the faint moonlight seeped down into the pass, it converted each cactus into the semblance of a crouching Yaqui. And despite MacFarlane’s assertion that night travel was comparatively safe, neither he nor the others were taking chances. The howl of a coyote or the cooing of a dove brought every revolver out of its holster, for these noises, although common enough in the mountains, are sometimes used by the Indians as signals. Once, when something trailed us for half a mile through the brush, we all rode half-turned in the saddle, covering the spot where the twigs crackled. It was probably some animal—perhaps a mountain lion—following us out of curiosity, but we watched it, lest it prove a bandit.

Hour after hour we rode in silence through the black defiles. We knew whether we were ascending or descending only from the slant of the mule’s back. The nervous strain seemed to affect even the animals. When we paused at a mountain stream to water them, my own beast suddenly lashed at me with his heels, and bolted. I chased him several hundred yards up the ragged bed of the water-course, stumbling over slippery stones, and splashing into the pools until I finally captured him, both of us making enough noise—it seemed to me—to awaken any Yaqui within a mile.

And within a mile, we turned a bend, and found ourselves in the very center of an encampment! A score of camp-fires, dwindled to smoldering red ashes, lined the trail, and about them, as though they were the spokes of a wheel, a group of men were sleeping with feet toward the blaze, in Yaqui fashion, each man with a rifle beside him. Not a sentry had stopped us. Even as I realized where we were, I found that my mule was stepping over the recumbent figures.

One of the men awoke, yawned, and raised himself on an elbow to stare at us.

“Who are you?” demanded MacFarlane in Spanish.

“Federal soldiers,” and the man composed himself for another nap.

We rode into Matape at dawn, and a truck carried us back to La Colorada. Dugan offered his hand.

“I done you an injustice, pardners. I thought you’d be scared.”

Eustace and I, exchanging confidences in private, agreed that Dugan had done neither of us an injustice, but we kept this to ourselves.

John Luy, driving us back to Hermosillo in his Buick, seemed highly amused about the whole affair. He chuckled to himself for a long time before he spoke:

“It’s funny! Mack don’t usually make that ride at night. He did it to give you guys a thrill, and I suspect he got a thrill himself. Laughlin’s been investigating that last murder, you know. It was Yaquis that done it, but a bunch of Yaquis serving as federal soldiers. Lucky they were asleep without sentries last night when you fellows rode through.”

On the train that carried me southward from Hermosillo I met “The General.”

He was young—scarcely out of his teens—slender, mild-mannered, almost feminine in voice and appearance. His large, dark eyes were shaded with long, girlish lashes. One felt startled when, upon more intimate acquaintance, he confided that he was an ex-bandit.

His rank, in reality, was only that of teniente, than which one could not be much lower in a Mexican army, but it pleased him so much when I first addressed him as “General” that I continued the practice.

Our meeting was accidental. Eustace and I, still traveling together, found him in a double-seat, with his handbags spread over whatever space he did not fill himself. As we paused before him, he looked up in surprise, apparently feeling that the railway had not made proper provision for so many passengers.

“Pardon, General, but is this bench reserved?”

He smiled. He removed his baggage most graciously. Within half an hour he had announced himself our humble servant, and was planning gay parties for us at the several stopping-places ahead. He knew all the girls along the West Coast, he said, both respectable and otherwise. He would see that we enjoyed the trip. He would be our guide and mentor in things Mexican. And when we reached Mazatlán—the southern terminus of the road, some three or four days distant—his house would be our house. We should attend his wedding, which was to be celebrated immediately upon his arrival, and if we remained long enough, we should be the godfathers to his first child.

And although he impressed me as somewhat too lavish in his promises, he proved an entertaining companion on the long journey—a journey through a monotonous continuation of the Sonora desert, with stop-overs at cities which, with minor variations, were replicas of Hermosillo—at Guaymas, San Blas, and Culiacán—cities pleasant and interesting, yet never so interesting to me as my first Mexican friend, the little General.

The young teniente was typical in many ways not only of the Mexicans, but of most of the Latin-Americans.

He lived completely in the present, with scarcely a thought of the morrow. For him tempus did not fugit, save very rarely, and even then there was sure to be more tempus afterward.

He had unlimited time for friendliness and politeness. In his friendliness he was prone to those professions of love which to the Anglo-Saxon mind savor of hypocrisy; in his politeness he was inclined toward phraseology that suggested figurative language; yet if this were hypocrisy, it was tempered with self-deception, and the phraseology was intended frankly as figurative language.

If he sometimes lacked veracity, it was because his code of etiquette called not for the truth, but for some statement that would give more satisfaction than the truth. Seldom thinking beyond the immediate present, he apparently did not reflect that an ultimate discovery of reality might bring disappointment greater than the original satisfaction.

One encounters this mental habit everywhere in Latin America. If one inquires of a fellow-passenger whether he is nearing his destination, he invariably is assured that he is, although a half-day’s journey may confront him. If one asks a hotel servant whether laundry may be washed before to-morrow night, he invariably learns that it may, although the servant knows perfectly well that the laundress will not call until the day after to-morrow.

In Guaymas, our first stopping-place, the General was to meet us in the Plaza at three o’clock to take us to visit his uncle. At about five, we bumped into him accidentally upon the street.

“Amigos!” he cried delightedly, enfolding each of us in a Latin embrace. “So glad I am to see you! I wish to take you to visit my uncle.”

“You were going to do that at three.”

“So I was! So I was! I was on my way to the plaza, but I met a friend, and we had two or three drinks of tequila, and I forgot all about it!”

He spoke not in apology. He merely offered what he considered a satisfactory explanation. To him, as to most Mexicans, an engagement was merely a tentative agreement, to prove binding only in the event that neither party forget it or happen to be doing something else at the appointed hour. He was delightfully free from any troublesome sense of obligation. While an Anglo-Saxon would rise each morning, taking mental inventory of the many things to be done during the next sixteen hours, the Mexican solved life’s problems by merely reflecting, “Here’s another pleasant day!”

Having met us upon the street, the General promptly forgot the date he had made with some one else, and took us to call upon his uncle. His uncle was not at home.

The Mexican is by nature impractical. When he makes a promise, he usually means it. Afterwards he discovers that he has promised something which he can not fulfill.

“To-night,” said the General, “I shall arrange a dance in your honor.”

And this time, he did meet us at the appointed hour—or soon thereafter. He had with him the musicians, two barefooted peons with mandolin and guitar, and we started again for his uncle’s residence. Everything was ready for the dance except that the uncle had not been informed that he was to be the host, or that any such affair was to transpire.

The General, however, was determined that we should have a good time. We were duly presented to a middle-class family of a dozen or more individuals, all eager to be friendly, but all a trifle embarrassed. The musicians played some dance that had long since faded from popularity north of the border—it was either “Smiles” or “Hindustan,” which are still the rage in Mexico—and the General made the rounds in search of a partner. In turn he offered his arm to each of his cousins—three rather shy little olive-faced girls of thirteen, fourteen, and fifteen—while each in turn pleaded:

“I don’t know how to dance. I wish I did.”

He finally discovered a stout, middle-aged lady who professed some slight knowledge of terpsichore, and marched with her thrice about the room, as is the fashion in Latin America. Then he seized her manfully, and sped away in a two-step. The lady, taken seemingly by surprise, did not move, and the little General came to a sliding stop. Still determined, he recovered his balance, and sped away in the other direction, with the same result. There was then a discussion as to whether this were a waltz or not. That question being settled by the musicians, who said it was a polka, both parties danced in the same direction, until they had made a couple of flying rounds, when they stopped, and the General offered his partner to me. It was somewhat reminiscent of putting out the ash-barrels on Monday morning, but the lady was willing, and for the next three hours Eustace and I and the General took turns whirling her over the adobe floor.

“A little excitement like that,” said the General, as we finally took our departure, “breaks the monotony of life.”

As I came to know the Mexicans better, I discovered that such an evening, although it impressed a Gringo as a trifle boresome, was quite an event in middle-class Mexican existence.

The Latin-American had an amazing knack of not being bored. This, too, was a product of his mental habit of living wholly in the present. He never suffered from the Anglo-Saxon sense of a waste of time; he was never afflicted with reflections about countless other ways of spending his evening.

He could sit every night in the same plaza, looking at the same faces. He could meet the same friends day after day, and be just as pleased to see them, and ask them the same questions about their many relatives, and part with the same elaborate courtesies. He could listen hour after hour with the same enjoyment to the same pieces of music that the village band had played for the past ten years. And he could talk with the same neighbors about exactly the same things again and again, and never lose his enthusiasm either as speaker or listener.

After supper, at the hotels along the way, proprietor and guests would bring their chairs to the sidewalk, where they could see the passers-by, and would remain there for hours, chatting with tremendous zest about nothing at all. Inconsequential remarks, which Americans of equal intelligence might consider unworthy either of utterance or audience, would be offered for popular consideration with emphatic statement, and received almost with applause. I recall the declaration of a young señorita to the effect that she considered a bath very refreshing. This bit of wisdom, which elsewhere in the world might have been accepted as trite and obvious, brought every member of the circle into enthusiastic agreement. It was quite as though she had advanced a startling new theory, which had long been hovering vaguely in the minds of the others, but which they now heard propounded for the first time. It stimulated cries of “Yes, indeed!” or “You have spoken most truly!” and the discussion lasted for half an hour.

With Mexican kindliness, they always included me in the conversation, although I spoke their language abominably. Had a foreigner murdered English as I murdered Spanish, I should not have had the patience to listen to him. Yet they listened avidly, knitting their brows sometimes in their effort to guess the meaning. If they smiled, their smiles were kindly. They were pleased that the foreigner should try to learn their language. If they disliked Americans in general, they were quickly ready to like any individual American who would meet them half-way. And the moment he showed a willingness to adopt their own elaborate courtesy, they described him as muy simpatico—an expression that means infinitely more than our nearest equivalent of “very sympathetic”—and hailed him as “paisano”—“fellow-countryman.” And they would promise him anything.

If at first impression, the elaborate Spanish politeness seems boresome, it gradually seeps its way into the soul of the average visitor so insidiously that within two weeks he finds himself resenting the rudeness of Americans more recently arrived than himself.

I met one on the train that took me out of Guaymas.

He was trying to tell the conductor that this passenger coach would have been condemned long ago in the good old U.S.A. Since the official did not understand English, even when shouted, the newcomer was growing a trifle peeved. He turned disgustedly to Eustace and myself:

“Damn these spigs, anyway! How do they expect anybody to come down here and do business with them when they can’t talk like other people?”

He seemed out of place in Mexico. He belonged essentially to the smoking compartment of an American Pullman, where his counterpart can invariably be found with thumbs beneath suspender straps, telling the world about the big deals which his type seems always to have “just pulled off between trains in Detroit.”

In Mexico, he admitted failure. He was selling soap—“the best grade of pure white bath soap on the market.” But buyers were too ignorant to converse with him in his language, and they showed a ridiculous inclination to purchase the brilliant scarlet soaps turned out by a German firm that catered to the native love of bright color.

“If I’d known what they were like,” he said, speaking loudly, “I’d have laid in a side-line of perfume and bug powder.”

We suggested that some of the passengers might understand English.

“What the hell do I care? Let ’em hear it. It’ll do ’em good. Let the dirty greasers know what we Americans think of ’em! Say, I’m glad I met you fellows. I’ve been lonesome for somebody from God’s country.”

He attached himself to us, and stuck like a leech. At Culiacán, where we stopped over for a day, he made the discovery that “whiskey” was the same in Spanish as in English. After imbibing freely in a little saloon kept by an elderly lady whose manners were those of royalty, he propped his feet on the table and expectorated with impressive accuracy at a picture of the Madonna that hung on the wall.

We dragged him out, and led him toward the hotel.

“What do I care about her?” he growled. “Damned spig! Let ’er call a policeman. I’ll lick ten Mexican policemen!”

At the hotel, after we had persuaded him not to hit the General, he favored our friend with another discourse on the relative prowess of Americans and “Greasers.”

“Any time we get good and ready, we’ll come down here and take this rotten republic and make a decent place out of it! We’ll clean up your spig army in two weeks! All you guys can do is knife people in the back! When you have a war, you point your rifles around the corner of a building and pull the trigger without lookin’ where you shoot! Any good Yank can lick ten of you—ten of you—with one arm tied behind his back!”

The General’s face darkened. I watched him, rather hoping that the slender little Mexican would proceed to mop up the floor with the valiant soap-salesman. Beneath his politeness, I knew, there was a sensitive, proud nature quick to resent an insult. Yet so ingrained were his traditions of courtesy that—even while a tigerish gleam in his eyes betrayed his wrath—he merely smiled.

“The señor,” he said, “is feeling very lively to-night.”

As he walked away, we feared that he had no further use for gringos, but on the following morning, as we sat in the plaza, the General came up to embrace us with more than his usual ardor. He was feeling “very lively” himself. He announced that he had been up all night, and that he was now ready to wander over to the shady side of town to call upon a few of the “girls.”

When we suggested that it was too early in the day, and advocated rest rather than recreation, he was agreeable, as always. He was even tractable. He would allow us to lead him back to the hotel; at the door he would embrace us again, promising to go straight to bed; fifteen minutes later he would come strolling up to us in the plaza, falling upon our necks as though it were our first meeting, and repeating his suggestion about calling upon the girls.

“How about your fiancée in Mazatlán?” Eustace inquired.

He shrugged his shoulders.

“But she is in Mazatlán! And I am in Culiacán!”

“Don’t you love her?”

“Love her! Ah, señor, who would not love her! So good, so pure, so true, so beautiful, so like an angel in Heaven! For two whole years I have dreamed of her! Throughout the two years that I was Villista in Chihuahua!

“Listen, señor. Two years ago I left Mazatlán. She promised that she would marry me. But I was penniless, señor. And in Mexico, the man must buy his bride’s trousseau. I was mechanic, and I went to Sonora to work in the mines. I was in the village of San Pedro when the Villistas came through. Some youths from the town fired upon the rear-guard, killing Villa’s cousin. And Villa ordered that every man in San Pedro should die in punishment. They herded me with the others in the public square, and took us out, twenty at a time, to the church wall, where our youths were slaughtered with pistol and machine-gun. But they spared me, for I was mechanic, and Villa had use for mechanic.

“Of course, I became Villista. Who, señor, would not? And I fought Carranza with the others. Why not? Who was Carranza but a general more fortunate than Villa, who captured Mexico City, and made himself president? I fought with Villa all through Chihuahua. Yes, I helped to fire upon Columbus, in your own New Mexico, but I liked Americans, and I fired in the air. I would have come home, but I had no money for the journey. There came a day when we took Juarez. I was lieutenant then. I captured a building with my men. It was gambling house. There was gold upon the tables, and I filled my pockets. Why not, señor? Some one else would have taken it. I ran away from the Villistas. I rode four hundred miles—four hundred miles, señor—through the mountains and across the Yaqui desert.”

Unconsciously he struck a dramatic pose.

“Would I have done that, señor, if I did not love the girl?”

Then he climbed into a coach, and rode away toward a questionable destination with a gay little wave of his hand.

I was inclined to doubt the General’s story.

He was manifestly a poseur. He possessed, among other qualities, an inordinate desire to attract attention. He knew, for instance, that he was handsome, and would spend hours combing his dark hair, or powdering his face. He loved to be stared at by the young girls in the plaza. He basked in admiration and reveled in adulation or flattery.

His vanity manifested itself also in a desire to be photographed. If I wished to snap a landscape or a street scene, Eustace had almost to hold him, lest he arrange himself artistically in the immediate foreground. Upon his return from the red light district that morning, he announced that he had promised its inmates to bring us there with our camera for a group picture.

He led us to the outskirts of town to a region where several slatternly brown females sat upon the curb in negligée, smoking cheap cigars, and introduced us in a speech which seemed more elaborate than such an informal occasion required. The ladies, surprised as Mexicans always are when some one keeps an agreement, begged that we wait while they beautified themselves, and we waited for over an hour. They appeared eventually, in silk finery, with an eighth of an inch of powder laid upon a facial coating of glycerine.

Then ensued the difficulties that confront every photographer in Latin America. They protested against venturing into the sunlight. Sunlight would ruin the complexion! When, in response to explanations, they did step out from the shade, they kept raising their hands to shelter their faces. And finally, when we had them properly grouped with the General in the center, some one exclaimed that she must be holding her doll, and while she searched for the doll, the group broke up and scurried out of the sunlight.

At length, the picture being taken, they all clamored to see it at once. To my statement that it had to be developed by a photographer, they listened with suspicion. Their familiarity with the itinerant tin-type man had bred a distrust of my slow methods. Yet they, with the politeness that extends in Latin America even to the underworld, did not voice the suspicion. And when, in the afternoon, we returned with what we considered an excellent picture, they rushed excitedly to view it.

There was a disappointed silence. They did not intend to be rude, but their grief escaped them.

“I’m not smiling!”

“My face came out dark!”

My camera, being a Gringo camera, had insulted them by its blunt frankness. But they tried to conceal their disappointment. They thanked us profusely. And they carried away the film, to destroy it as soon as our backs were turned.

“You were very foolish,” said the General afterwards. “You did not have to take a real picture. You should have pointed the camera and clicked something else. It would have pleased them.”

Strangely enough, the more hypocrisy one discovered in the little General, the more one liked him.

It was a hypocrisy leavened by kindliness and humor. And to him, as to other Latin-Americans, it was not hypocrisy at all, for his was a code of life wherein our Anglo-Saxon standards were completely inverted.

Each race has developed its own ideas as to what is important in human conduct. The Anglo-Saxon, being by nature blunt and frank, regards truth as a supreme virtue. When he discovers something wrong, he sets about correcting it. The Latin-American, being by nature suave and courteous, regards truth as an irritating and offensive bad habit. When he discovers something wrong, he politely ignores it.