Title: Travels into Bokhara (Volume 3 of 3)

Author: Sir Alexander Burnes

Release date: September 26, 2021 [eBook #66386]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Henry Flower and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

[i]

VOL. III.

[ii]

London:

Printed by A. Spottiswoode,

New-Street-Square.

[iii]

TRAVELS

INTO

BOKHARA;

BEING THE ACCOUNT OF

A JOURNEY FROM INDIA TO CABOOL, TARTARY, AND PERSIA;

ALSO, NARRATIVE OF

A VOYAGE ON THE INDUS,

FROM THE SEA TO LAHORE,

WITH PRESENTS FROM THE KING OF GREAT BRITAIN;

PERFORMED UNDER THE ORDERS OF THE SUPREME GOVERNMENT

OF INDIA, IN THE YEARS 1831, 1832, AND 1833.

BY

LIEUT. ALEXR BURNES, F.R.S.

OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S SERVICE;

AST POLITICAL RESIDENT IN CUTCH, AND LATE ON A MISSION TO

THE COURT OF LAHORE.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

MDCCCXXXIV.

[v]

THIS

THIRD VOLUME

OF

TRAVELS INTO BOKHARA,

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE RIVER INDUS,

IS INSCRIBED TO

THE MEMORY OF THE LATE

MAJOR-GENERAL SIR JOHN MALCOLM, G.C.B.

&c. &c. &c.

IN GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE,

BY

THE AUTHOR.

[vii]

NARRATIVE

OF A

VOYAGE BY THE RIVER INDUS,

FROM THE SEA TO

THE COURT OF LAHORE IN THE PUNJAB,

WITH PRESENTS FROM THE KING OF GREAT BRITAIN;

COMPRISING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE MISSION,

AND A

MEMOIR OF THE RIVER INDUS,

WITH CURSORY REMARKS ON THE REMAINS OF ANTIQUITY NEAR THAT

CLASSICAL AND CELEBRATED STREAM.

[ix]

I was employed as an officer of the Quartermaster-general’s department, for several years, in the province of Cutch. In the course of enquiries into its geography and history, I visited the eastern mouth of the Indus, to which the country adjoins, as well as that singular tract called the “Run,” into which that river flows. The extension of our knowledge in that quarter served only to excite further curiosity, in which I was stimulated by Lieut-General Sir Thomas Bradford, then Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay army. That officer directed his views, in a most enlightened manner, to the acquisition of every information regarding a frontier so important to Britain as that of north-western India. Encouraged by such approbation, for which I am deeply grateful, I volunteered my services,[x] in the year 1829, to traverse the deserts between India and the Indus, and finally, endeavour to descend that river to the sea. Such a journey involved matters of political moment; but the government of Bombay was then held by an individual distinguished above all others, by zeal in the cause of Asiatic geography and literature. Sir John Malcolm despatched me at once, in prosecution of the design, and was pleased to remove me to the political branch of the service, observing, that I should be then invested “with influence with the rulers, through whose country I travelled, that would tend greatly to allay that jealousy and alarm, which might impede, if they did not arrest, the progress of my enquiries.”

In the year 1830, I entered the desert, accompanied by Lieut. James Holland, of the Quartermaster-general’s department, an officer ably qualified to assist me. After reaching Jaysulmeer, we were overtaken by an express from the Supreme Government of India, desiring us to return, since at that time “it was deemed[xi] inexpedient to incur the hazard of exciting the alarm and jealousy of the rulers of Sinde, and other foreign states, by the prosecution of the design.” This disappointment, then most acutely felt, was dissipated in the following year, by the arrival of presents from the King of Great Britain for the ruler of Lahore, coupled, at the same time, with the desire that such an opportunity for acquiring correct information of the Indus should not be overlooked. The following work contains the narrative of that mission, which I conducted by the Indus to Lahore. The information which I collected, relative to Jaysulmeer and the countries on the N. W. frontier of India, has just been published in the Transactions of the Royal Geographical Society of London.

London, June 7. 1834.

[xiii]

| Page | |

| Introduction | ix |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Arrival of presents from the King of England—Information on the Indus desired—Suggestions for procuring it—Appointed to conduct the Mission to Lahore—Departure from Cutch—Ability of the Navigators—Arrival in the Indus—Phenomena—Scenes of Alexander’s Campaigns—Ebb and flow of the Tides—Correctness of Quintus Curtius—Visited by the Authorities—Forced out of the Country—Correspondence—Return to the Indus—Imminent Danger—Starved out of the Country—Third Voyage to the Indus—Land in Sinde—Negotiations—Advance on Tatta—Sindian Policy and Reasoning—Successful Negotiations | 1 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Tatta described—Hinglaj, a famous Pilgrimage—Return to the Sea-coast—Notions of the People—Alexander’s Journey—Embarkation on the River—Anecdote—Strictness of Religious Observances—Pulla Fish—Arrival at Hydrabad—Welcome of the Rulers—Presentation at Court—Sindian Meanness—Audience of Leave—Scenery near the Capital | 30[xiv] |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Departure from Hydrabad—Sehwun—Crew of the Boats—A Sindian Song—Sehwun described—Reasons for supposing it to be the Territory of the Sindomanni—Pilgrimage—High Antiquity of the Castle of Sehwun—Congratulations from the Ruler of Khyrpoor—Address that Personage—Character of the People—The Indus—Visited by the Vizier of Sinde—Arrival at Khyrpoor—Audience with the Chief—Character of the Sindian Rulers—Arrival at Bukkur—Amusing Predictions—Anecdote of an Afghan—Mihmandar—Alore described—Supposition of its being the Kingdom of Musicanus | 51 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| Quit Bukkur—Curiosity of the People—Reach the Frontiers of Sinde—Farewell Letters—Creditable Behaviour in our Escort—Fish Diet—Costume—Enter Bhawul Khan’s Country—Quit the Indus at Mittun—Effects of this River on the Climate—Enter the Chenab or Acesines—Incident at Ooch—Arrival of Bhawul Khan—Interview with him—Merchants of Bhawulpoor—History of Ooch—Visited by Bhawul Khan—Mountains—Pass the Sutlege—Peculiarity in the Water of two Rivers—Simplicity of the Mihmandar—Enter Runjeet Sing’s Country—Honourable Reception—Exhibition of the Dray-horses—Orders of the Court | 81 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Voyage in the Country of the Seiks—Shoojuabad—Mooltan; its Antiquity—Probably the Capital of the Malli—Public Buildings—Religious Intolerance—Climate—Phenomena—Date-trees; Traditions of their introduction—Quit Mooltan—Peloo Shrub[xv]—Arrangements for our Advance to Lahore—Alexander the Great—Enter the Ravee, or Hydräotes—Tolumba—Visit the Hydaspes—Description of its confluence with the Chenab—Probable identity of a Modern Tribe with the Cathæi—Ruins of Shorkote—Valuable Bactrian Coin found at it—Birds and Reptiles—Heat—Ruins of Harappa—A Tiger Hunt—Seik Courage—Intelligence of the Mihmandar—Letter and Deputation from Lahore—Seik Females | 108 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Enter Lahore—Presentation to Runjeet Sing—Delivery of the Presents—Copy of a Letter from the King of England—Stud—Hall of Audience—Military Spectacle—Conversations of Runjeet Sing—Amazons—French Officers—City of Lahore—Tomb of Juhangeer—Shalimar of Shah Jehan—Horse Artillery Review—Character of Runjeet Sing—Audience of Leave—Superb Jewels—Dresses of Honour—Runjeet Sing’s Letter to the King—Quit Lahore—Umritsir; its Temples—Reach the Beas, or Hyphasis—Fête of a Seik Chieftain—Reach the Sutlege—Antiquities of the Punjab—Arrival at Lodiana—Exiled Kings of Cabool—Visit them—Journey to the Himalaya Mountains—Interview with the Governor-general—Acknowledgments of his Lordship | 148 |

| MEMOIR ON THE INDUS AND ITS TRIBUTARY RIVERS IN THE PUNJAB. | |

| Notice regarding the Map of the Indus | 193 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| A general view of the Indus | 199[xvi] |

| CHAP. II. | |

| A comparison of the Indus and Ganges—Propriety of the comparison—Size of the Ganges—Of the Indus—Compared—Slope of the Indus—Conclusions from it—Tides in both Rivers | 203 |

| CHAP. III. ON SINDE. |

|

| Extent of the Country—Chiefs and Revenue—Power and Conquests—Military Strength—Connection with Persia—External Policy—Internal State—Hydrabad Family—Khyrpoor Family—Meerpoor Family—Condition of the People—Population | 212 |

| CHAP. IV. ON THE MOUTHS OF THE INDUS. |

|

| Division of the Indus into two great branches below Tatta—Sata—Buggar—Delta; its extent—Dangers in navigating it—Eleven Mouths of the Indus—The Pittee—Pieteeanee, Jooa, Reechel, Hujamree—Khedywaree, Gora, or Wanyanee—Khaeer, Mull, Seer—Koree, or Eastern Mouth—Advantage of these to Sinde—Coast of Sinde—Tides of the Indus—Curachee Seaport—Boats of the Indus; Dingees and Doondees—Indus adapted for Steam-vessels—Military remarks on the River | 228 |

| CHAP. V. ON THE DELTA OF THE INDUS. |

|

| Inundation of the Delta—Extent—Neglected State—Towns—Population—Jokea Tribe—Fisheries—Animals—Productions—Climate | 249[xvii] |

| CHAP. VI. THE INDUS FROM TATTA TO HYDRABAD. |

|

| Sand-banks—Course of the River—Towns—Country Supplies—Trade—Means of improving it—Boats; their Deficiency | 255 |

| CHAP. VII. THE INDUS FROM HYDRABAD TO SEHWUN. |

|

| Course and Depth—Fulailee River—Current—Importance of this Part of the River—Crossing the Indus—Navigation of it—Towns—Sehwun—Mountains of Lukkee | 260 |

| CHAP. VIII. THE INDUS FROM SEHWUN TO BUKKUR. |

|

| Position of Bukkur—Fertility of the Country—Current—Eastern Bank of the Indus—Western Bank—Fortress of Bukkur—Roree and Sukkur—Alore; its Antiquity—Khyrpoor and Larkhanu—Productions of the Soil | 267 |

| CHAP. IX. THE INDUS FROM BUKKUR, TILL JOINED BY THE PUNJAB RIVERS. |

|

| Breadth and Depth—Boats—Country—Shikarpoor and Subzul—Swell of the Indus—Tribes on the River | 275[xviii] |

| CHAP. X. THE INDUS FROM MITTUN TO ATTOK. |

|

| Description of the River—Dera Ghazee Khan—Line of Commerce—Military Expeditions; why they avoided the Indus—Bridging the Indus | 281 |

| CHAP. XI. THE CHENAB, OR ACESINES, JOINED BY THE SUTLEGE, OR HESUDRUS. |

|

| Chenab—Junction—Banks of the Chenab—Ooch; its Productions | 286 |

| CHAP. XII. ON BHAWUL KHAN’S COUNTRY. |

|

| Limits—Nature of the Country—Its Power and Importance—Daoodpootras; their Descent—The reigning Family—Trade of Bhawulpoor | 290 |

| CHAP. XIII. THE PUNJAB. |

|

| Extent of Runjeet Sing’s Country—Changes in the Seik Government—Probable Consequences of the Ruler’s Death—His Policy—Sirdars—Revenues of the Punjab—Military Resources and Strength—Cities | 295 |

| CHAP. XIV. THE CHENAB, OR ACESINES, JOINED BY THE RAVEE, OR HYDRAÖTES. |

|

| Chenab Described—Boats on it—Crossing the River—Province of Mooltan | 300[xix] |

| CHAP. XV. THE RAVEE, OR HYDRAÖTES, BELOW LAHORE. |

|

| The Ravee—Its tortuous Course and difficult Navigation—Towns—Lahore—Umritsir Toolumba | 305 |

| CHAP. XVI. A MEMOIR ON THE EASTERN BRANCH OF THE INDUS, AND THE RUN OF CUTCH. |

|

| Cutch; its Position—Alterations in its Western Coast, from an Earthquake—Damming of the Eastern Branch of the Indus—Injuries thereby—Dreadful Earthquake of 1819—Effects of it—Raises a natural Mound—Overflow of the Indus in 1826—its Effects on the Eastern Branch described—Opinions—Subsequent Alterations of the Indus—Run of Cutch described—Mirage—Traditions regarding the Run—Corroboration of them—Effects of the Earthquake on the Run—Flooding of the Run—Configuration of the Run Borders—Run, supposed to have been an Inland Sea—Note in corroboration of the Opinion—Note on Sindree | 309 |

[1]

NARRATIVE.

In the year 1830, a ship arrived at Bombay, with a present of five horses from the King of Great Britain to Maharaja Runjeet Sing, the Seik Chieftain at Lahore, accompanied by a letter of friendship from his majesty’s minister[1] to that prince. At the recommendation of Major-General Sir John Malcolm, then governor of Bombay, I had the honour of being nominated by the Supreme Government of India to proceed on a mission to the Seik capital, with these presents, by way of the river Indus. I held at that time a political situation in Cutch, the only portion of the British dominions in India which borders on the Indus.

The authorities, both in England and India, contemplated that much information of a political and geographical nature might be acquired in such a journey. The knowledge which we possessed of the Indus was vague and unsatis[2]factory, and the only accounts of a great portion of its course were drawn from Arrian, Curtius, and the other historians of Alexander’s expedition. Sir John Malcolm thus minuted in the records of government, in August, 1830:—

“The navigation of the Indus is important in every point of view; yet we have no information that can be depended upon on this subject, except of about seventy miles from Tatta to Hyderabad. Of the present state of the Delta we have native accounts, and the only facts which can be deduced are, that the different streams of the river below Tatta, often change their channels, and that the sands of all are constantly shifting; but, notwithstanding these difficulties, boats of a small draft of water can always go up the principal of them. With regard to the Indus above Hyderabad, there can be no doubt of its being, as it has been for more than two thousand years, navigable far up.”

In addition therefore to the complimentary mission on which I was to be employed, I had my attention most specially directed to the acquisition of full and complete information regarding the Indus. This was a matter of no easy accomplishment, as the Ameers, or rulers of Sinde, had ever evinced the utmost jealousy of Europeans, and none of the missions which[3] visited the country had been permitted to proceed beyond their capital of Hyderabad. The river Indus, likewise, in its course to the ocean, traverses the territories of many lawless and barbarous tribes, from whom both opposition and insult might be dreaded. On these matters much valuable advice was derived from Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Pottinger, political resident in Cutch, and well known to the world for his adventurous travels in Beloochistan. He suggested that it might allay the fears of the Sinde government, if a large carriage were sent with the horses, since the size and bulk of it would render it obvious that the mission could then only proceed by water. This judicious proposal was immediately adopted by government; nor was it in this case alone that the experience of Colonel Pottinger availed me, as it will be seen that he evinced the most unwearied zeal throughout the difficulties which presented themselves, and contributed, in a great degree, to the ultimate success of the undertaking.

That a better colour might also be given to my deputation by a route so unfrequented, I was made the bearer of presents to the Ameers of Sinde, and at the same time charged with communications of a political nature to them. These referred to some excesses committed by their subjects on the British frontier; but I was in[4]formed that neither that, nor any other negotiation, was to detain me in my way to Lahore. The authorities in England had desired that a suitable escort might accompany the party; but though the design was not free from some degree of danger, it was evident that no party of any moderate detail could afford the necessary protection. I preferred, therefore, the absence of any of our troops, and resolved to trust to the people of the country; believing that, through their means, I might form a link of communication with the inhabitants. Sir John Malcolm observed, in his letter to the Governor General, that “the guard will be people of the country he visits, and those familiar with it. Lieut. Burnes prefers such, on the justest grounds, to any others; finding they facilitate his progress, while they disarm that jealousy which the appearance of any of our troops excites.” Nor were my sentiments erroneous; since a guard of wild Beloochees protected us in Sinde, and allayed suspicion.

When these preliminary arrangements had been completed, I received my final instructions in a secret letter from the chief secretary at Bombay. I was informed that “the depth of water in the Indus, the direction and breadth of the stream, its facilities for steam navigation, the supply of fuel on its banks, and the con[5]dition of the princes and people who possess the country bordering on it, are all points of the highest interest to government; but your own knowledge and reflection will suggest to you various other particulars, in which full information is highly desirable; and the slow progress of the boats up the Indus will, it is hoped, give you every opportunity to pursue your researches.” I was supplied with all the requisite surveying instruments, and desired to draw bills on honour for my expenses. In a spirit also purely characteristic of the distinguished individual who then held the government, I received the thanks of Sir John Malcolm for my previous services; had my attention drawn to the confidence now reposed in me; and was informed that my knowledge of the neighbouring countries and the character of their inhabitants, with the local impressions by which I was certain to be aided, gave me advantages which no other individual enjoyed, and had led to my selection; nor could I but be stimulated by the manner in which Sir John Malcolm addressed the Governor General of India:—“I shall be very confident of any plan Lieut. Burnes undertakes in this quarter of India; provided a latitude is given him to act as circumstances may dictate, I dare pledge myself that the public interests will be[6] promoted. Having had my attention much directed, and not without success, during more than thirty years, to the exploring and surveying countries in Asia, I have gained some experience, not only in the qualities and habits of the individuals by whom such enterprises can be undertaken, but of the pretexts and appearances necessary to give them success.” A young active and intelligent officer, Ensign J. D. Leckie, of the 22d Regiment N.I., was also nominated to accompany me; a surveyor, a native doctor, and suitable establishments of servants were likewise entertained.

We sailed from Mandivee in Cutch with a fleet of five native boats, on the morning of the 21st of January, 1831. On the day succeeding our departure, we had cleared the Gulf of Cutch. The danger in navigating it has been exaggerated. The eddies and dirty appearance of the sea, which boils up and bubbles like an effervescing draught, present a frightful aspect to a stranger, but the natives traverse it at all seasons. It is tolerably free from rocks, and the Cutch shore is sandy with little surf, and presents inducements for vessels in distress to run in upon the land. We passed a boat of fifty tons, which had escaped shipwreck, with a very valuable cargo from Mozambique, the preceding year, by this expedient.

[7]

Among the timid navigators of the East, the mariner of Cutch is truly adventurous; he voyages to Arabia, the Red Sea, and the coast of Zanguebar in Africa, bravely stretching out on the ocean after quitting his native shore. The “moallim” or pilot determines his position by an altitude at noon or by the stars at night, with a rude quadrant. Coarse charts depict to him the bearings of his destination, and, by long-tried seamanship, he weathers, in an undecked boat with a huge lateen sail, the dangers and tornadoes of the Indian Ocean. This use of the quadrant was taught by a native of Cutch, who made a voyage to Holland in the middle of last century, and returned, “in a green old age,” to enlighten his country with the arts and sciences of Europe. The most substantial advantages introduced by this improver of his country were the arts of navigating and naval architecture, in which the inhabitants of Cutch excel. For a trifling reward, a Cutch mariner will put to sea in the rainy season, and the adventurous feeling is encouraged by the Hindoo merchants of Mandivee, an enterprising and speculating body of men.

On the evening of the 24th we had cleared the Gulf of Cutch, and anchored in the mouth of the Koree, the eastern, though forsaken, branch of the Indus, which separates Sinde from[8] Cutch. The Koree leads to Lueput, and is the largest of all the mouths of the river, having become a branch of the sea as the fresh water has been turned from its channel. There are many spots on its banks hallowed in the estimation of the people. Cotasir and Narainseer are places of pilgrimage to the Hindoo, and stand upon it and the western promontory of Cutch. Opposite them lies the cupola of Rao Kanoje, beneath which there rests a saint, revered by the Mahommedans. To defraud this personage of frankincense, grain, oil, and money, in navigating the Koree, would entail, it is superstitiously believed, certain shipwreck. In the reverence we recognise the dangers and fear of the mariner. There is a great contrast between the shores of Sinde and Cutch; the one is flat and depressed, nearly to a level with the sea, while the hills of Cutch rise in wild and volcanic cones, which meet the eye long after the coast has faded from the view. We gladly exchanged this grandeur for the dull monotony of the shores of Sinde, unvaried, as it is, by any other signs of vegetation than stunted shrubs, whose domain is invaded by each succeeding tide.

We followed the Sinde coast for four or five days, passing all the mouths of the Indus, eleven in number, the principal of which we entered and examined, without even the observation of the[9] inhabitants. There was little indication of our being near the estuary of so great a river, for the water was only fresh a mile off shore from the Gora, or largest mouth of the Indus; and the junction of the river water with that of the sea was formed without violence, and might be now and then discovered by a small streak of foam and a gentle ripple. The number and subdivision of the branches diminish, no doubt, the velocity as well as the volume of the Indus; but it would be supposed that so vast a river would exercise an influence in the sea far from its embouchure; and, I believe, this is really the case in the months of July and August, during the inundation. The waters of the Indus are so loaded with mud and clay, as to discolour the sea for about three miles from the land. Opposite its different mouths numberless brown specks are to be seen, called “pit” by the natives. I found them, on examination, to be round globules, filled with water, and easily burst. When placed on a plate, they were about the size of a shilling, and covered by a brown skin. These specks are considered by the pilots to denote the presence of fresh water among the salt; for they believe them to be detached from the sand banks, by the meeting of the sea and the river. They give a particularly dirty and oily appearance to the water.

[10]

At night-fall on the 28th, we cast anchor in the western mouth of the Indus, called the Pittee. The coast of Sinde is not distinguishable a league from the shore. There is not a tree to be seen, though the mirage sometimes magnifies the stunted shrubs of the Delta, and gives them a tall and verdant appearance; a delusion that vanishes with a nearer approach. From our anchorage, a white fortified tomb, in the Bay of Curachee, was visible north-west of us; and beyond it lay a rocky range of black mountains, called Hala, the Irus of Nearchus. I here read from Arrian and Quintus Curtius the passages of this memorable scene in Alexander’s expedition, the mouth from which his admiral, Nearchus, took his departure from Sinde. The river did not exceed 500 yards in width, instead of the 200 stadia (furlongs) of Arrian, and the twelve miles, which more modern accounts had assigned to it, on the authority of the natives. But there was still some resemblance to the Greek author; for the hills over Curachee form with the intervening country a semicircular bay, in which an island and some sand-banks might lead a stranger to believe, that the ocean was yet distant. “Alexander sent two long galleys before the fleet, towards the ocean, to view a certain island, which they called Cillutas, where his pilots[11] told him he might go on shore before he entered the main ocean; and when they assured him that it was a large island, and had commodious harbours, besides plenty of fresh water, he commanded the rest of the fleet to put in there, while he himself passed out to sea.” The island, as it now exists, is scantily covered with herbage, and destitute of fresh water. In vain I sought an identity of name in the Indian dialect, for it was nameless; but it presented a safe place of anchorage; and, as I looked upon it, I could not but think it was that Cillutas where the hero of Macedon, “drawing up his fleet under a promontory, sacrificed to the gods, as he had received orders from Ammon.” Here it was, too, that Nearchus caused “a canal to be dug, of about five stadia in length, where the earth was easiest to remove; as soon as the tide began to rise they got their whole fleet safe through that passage into the ocean.” The Greek admiral only availed himself of the experience of the people; for it is yet customary among the natives of Sinde to dig shallow canals, and leave the tides or river to deepen them; and a distance of five stadia, or half a mile, would call for no great labour. It is not to be supposed that sand-banks will continue unaltered for centuries; but I may observe, that there was a large bank contiguous to the island,[12] between it and which a passage like that of Nearchus might have been dug with the greatest advantage. “Having sailed from the mouth of the Indus, Nearchus came to a sandy island, called Crocola, and proceeded on his voyage, having the mountain Irus on his right hand.” The topography is here more accurate: two sandy islands, called Andry, lie off Curachee, at a distance of eighteen miles from the Indus; and it is worthy of remark, that that portion of the Delta through which the Pittee runs, is yet denominated “Crocola” by the natives.

But the ebb and flow of the tides were an object of the greatest surprise to Alexander’s fleet, and we could soon discover the cause of their astonishment, for two of our boats stranded at a spot where, half an hour previously, there had been abundance of water. The tides inundate the country with great impetuosity, and recede as rapidly, so that if a vessel be not in the channel, she will be left on shore. Arrian observes, that “while they continued in that station, an accident happened which astonished them; namely, the ebbing and flowing of the waters, like as in the great ocean, inasmuch that the ships were left upon dry ground, which Alexander and his friends never having perceived before, were so much the more surprised. But what increased their astonish[13]ment was, that the tide returning a short while after began to heave the ships, so that * * * some of them were swept away by the fury of the tide, and dashed to pieces, and others driven against the bank, and destroyed.”[2]

A graphic and animated description of these disasters of the Greeks has been likewise given by Quintus Curtius, and is nowhere more remarkable than in the allusion to the “knolls” rising above the river like “little islands,” for at full tide the mangrove shrubs present exactly that appearance; but let the author speak in his own words:—

“About the third hour, the ocean, according to a regular alternation, began to flow in furiously, driving back the river. The river, at first, resisted; then impressed with a new force, rushed upwards with more impetuosity than torrents descend a precipitous channel. The mass on board, unacquainted with the nature of the tide, saw only prodigies and symbols of the wrath of the gods. Ever and anon the sea swelled; and on plains, recently dry, descended a diffused flood. The vessels lifted from their stations, and the whole fleet dispersed; those who had debarked, in terror and astonishment at the calamity, ran from all[14] quarters towards the ships. But tumultuous hurry is slow. * * * Vessels dash together, and oars are by turns snatched away, to impel other galleys. A spectator would not imagine a fleet carrying the same army; but hostile navies commencing a battle. * * * * Now the tide had inundated all the fields skirting the river, only tops of knolls rising above it like little islands; to these, from the evacuated ships, the majority swam in consternation. The dispersed fleet was partly riding in deep water, where the land was depressed into dells; and partly resting on shoals, where the tide had covered elevated ground; suddenly breaks on the Macedonians a new alarm more vivid than the former. The sea began to ebb; the deluge, with a violent drain, to retreat into the frith, disclosing tracts just before deeply buried. Unbayed, the ships pitched some upon their prows, others upon their sides. The fields were strewed with baggage, arms, loose planks, and fragments of oars. The soldiers scarcely believed what they suffered and witnessed. Shipwrecks on dry land, the sea in a river. Nor yet ended their unhappiness; for ignorant that the speedy return of the tide would set their ships afloat, they predicted to themselves famine and death. Terrifying monsters, too, left by the waves, were[15] gliding about at random.” Our little fleet did not encounter such calamity and alarm as that of Nearchus; for, in Q. Curtius’s words,—“by a gradual diffusion, the inundation began to raise the ships, presently flooding all the fields, set the fleet in motion.”

I shall not now dwell on these subjects, though eminently interesting; but, in the course of my narrative, I shall endeavour to identify the modern Indus with the features of remoter times. If successful in the enquiry, we shall add to our amusement, and the interest of the chronicles themselves. It is difficult to describe the enthusiasm one feels on first beholding the scenes which have exercised the genius of Alexander. That hero has reaped the immortality which he so much desired, and transmitted the history of his conquests, allied with his name, to posterity. A town or a river, which lies on his route, has acquired a celebrity that time serves only to increase; and, while we gaze on the Indus, we connect ourselves, at least in association, with the ages of distant glory. Nor can I pass over such feelings without observing, that they are productive of the most solid advantages to history and science. The Scamander has an immortality which the vast Mississippi itself can never eclipse, and the descent of the Indus by Alexander of Macedon is, perhaps, the[16] most authentic and best attested event of profane history.

The jealousy of the Sinde government had been often experienced, and it was therefore suggested that we should sail for the Indus, without giving any previous information. Immediately on anchoring, I despatched a communication to the agent of the Ameers at Darajee, signifying my plans; and, in the meanwhile, ascended the river with caution, anchoring in the fresh water on the second evening, thirty-five miles from the sea. Near the mouth of the river we passed a rock stretching across the stream, which is particularly mentioned by Nearchus, who calls it a “dangerous rock,” and is the more remarkable, since there is not even a stone below Tatta in any other part of the Indus. We passed many villages, and had much to enliven and excite our attention, had we not purposely avoided all intercourse with the people till made acquainted with the fate of our intimation to the authorities at Darajee. A day passed in anxious suspense; but, on the following morning, a body of armed men crowded round our boats, and the whole neighbourhood was in a state of the greatest excitement. The party stated themselves to be the soldiers of the Ameer, sent to number our party, and see the contents of all the boats, as well as every box[17] that they contained. I gave a ready and immediate assent; and we were instantly boarded by about fifty armed men, who wrenched open every thing, and prosecuted the most rigorous search for cannon and gunpowder. Mr. Leckie and myself stood by in amazement, till it was at length demanded that the box containing the large carriage should be opened; for they pretended to view it as the Greeks had looked on the wooden horse, and believed that it would carry destruction into Sinde. A sight of it disappointed their hopes; and we must be conjurors, it was asserted, to have come without arms and ammunition.

When the search had been completed, I entered into conversation with the head man of the party, and had hoped to establish, by his means, a friendly connection with the authorities; but after a short pause, this personage, who was a Reis of Lower Sinde, intimated, that a report of the day’s transactions would be forthwith transmitted to Hydrabad; and that, in the meanwhile, it was incumbent on us to await the decision of the Ameer, at the mouth of the river. The request appeared reasonable; and the more so, since the party agreed to furnish us with every supply while so situated. We therefore weighed anchor, and dropped down the[18] river; but here our civilities ended. By the way we were met by several “dingies” full of armed men, and at night were hailed by one of them, to know how many troops we had on board. We replied, that we had not even a musket. “The evil is done,” rejoined a rude Belooche soldier, “you have seen our country; but we have four thousand men ready for action!” To this vain-glorious observation succeeded torrents of abuse; and when we reached the mouth of the river, the party fired their matchlocks over us; but I dropped anchor, and resolved, if possible, to repel these insults by personal remonstrance. It was useless; we were surrounded by ignorant barbarians, who shouted out in reply to all I said, that they had been ordered to turn us out of the country. I protested against their conduct in the most forcible language; reminded them that I was the representative, however humble, of a great Government, charged with presents from Royalty; and added, that, without a written document from their master, I should decline quitting Sinde. Quit the country. An hour’s delay served to convince me that personal violence would ensue, if I persisted in such a resolution; and as it was not my object to risk the success of the enterprise by such collision, I sailed for the most eastern mouth of the Indus, from which I addressed the authorities[19] in Sinde, as well as Colonel Pottinger, the Resident in Cutch.

I was willing to believe that the soldiers had exceeded the authority which had been granted them; and was speedily put in possession of a letter from the Ameer, couched in friendly terms, but narrating, at great length, the difficulty and impossibility of navigating the Indus. “The boats are so small,” said his Highness, “that only four or five men can embark in one of them; their progress is likewise slow; they have neither masts not sails; and the depth of water in the Indus is likewise so variable as not to reach, in some places, the knee or waist of a man.” But this formidable enumeration of physical obstacles was coupled with no refusal from the Ruler himself; and it seemed expedient, therefore, to make a second attempt, after replying to his Highness’s letter.

On the 10th of February we again set sail for Sinde; but at midnight, on the 14th, were overtaken by a fearful tempest, which scattered our little fleet. Two of the vessels were dismasted; we lost our small boat, split our sails, sprung a leak; and, after being buffeted about for some days by the fury of the winds and waves, succeeded in getting an observation of the sun, which enabled us to steer our course, and finally conducted us in safety to Sinde. One of the[20] other four boats alone followed us. We now anchored in the Pieteanee mouth of the Indus, and I forthwith despatched the following document, by a trustworthy messenger, to the agents at Darajee.

1. “Let it be known to the Government agent at Darajee, that this is the memorandum of Mr. Burnes (sealed with his seal, and written in the Persian language in his own handwriting), the representative (vakeel) of the English to the Ameer of Sinde, and likewise the bearer of presents to Maharaja Runjeet Sing from the King of England.

2. “I came to the Indus a few days ago; and you searched my baggage, that you might report the contents thereof to your master. I have now returned, and await an answer.

3. “You may send any number of armed men that you please; my life is in your power; but remember that the Ameer will hold every one responsible who molests me. Remember, too, that I am a British officer, and have come without a musket or a soldier (as you well know); placing implicit reliance on the protection of the ruler of Sinde, to whose care my Government have committed me.

4. “I send this memorandum by two of my own servants, and look to you for their being protected.”

[21]

This remonstrance drew no reply from the agent at Darajee; for the individual who had held the situation on our first visit to Sinde, had been dismissed for permitting us to ascend the river; and our servants brought us notice that we should not be permitted to land, nor to receive either food or water. We observed, therefore, the greatest possible economy in the distribution of our provisions, and placed padlocks on the tanks, in the hope of reason yet guiding the councils of the Ameer. When our supply of water failed, I despatched a small boat up the river to procure some; but it was seized, and the party detained; which now rendered us hopeless of success, and only anxious to quit the inhospitable shores of Sinde.

On the 22d of February we weighed our anchor, at daylight; and when in the narrow mouth of the river, the wind suddenly changed. The tide, which ran with terrific violence, cast us on the breakers of the bar; the sea rolled over us, and we struck the ground at each succeeding wave. In despair, the anchor was dropped; and when we thought only of saving our lives, we found our vessel had rubbed over the breakers of the bank, and floated. I admired the zeal and bravery of our crew; and was much struck with their pious ejaculations to the tutelar saint of Cutch, Shah Peer, when they found themselves[22] beyond the reach of danger. “Oh! holy and generous saint,” shouted the whole crew, “you are truly good.” Frankincense was forthwith burned to his honour; and a sum of money was collected, and hallowed by its fragrance, as the property of the saint. The amount subscribed testified the sincerity of the poor men’s gratitude; and if I believed not the efficacy of the offering, I refused not, on that account, to join, by their request, in the manifestations of their duty and gratitude. Our other vessel, not so fortunate as ourselves, was cast on shore, though on a less dangerous bank. We rendered her assistance, and sailed for Cutch, and anchored in Mandivee roads after a surprising run of thirty-three hours.

It could not now be concealed that the conduct of the Ameer of Sinde was most unfriendly; but he yet betrayed no such feeling in his letters. He magnified the difficulties of navigating the Indus, and arrayed its rocks, quicksands, whirlpools, and shallows, in every communication; asserting that the voyage to Lahore had never been performed in the memory of man. It was evident that he viewed the expedition with the utmost distrust and alarm; and the native agent, who resides at Hydrabad on the part of the British Government, described, not without some degree of humour, the fear and dread of this[23] jealous potentate. In his estimation, we were the precursors of an army; and did he now desire to grant us a passage through Sinde, he was at a loss to escape from the falsehoods and contradictions which he had already stated in his epistles. One letter went on to say, that “the Ameer of Sinde avoids giving any reply, lest he should be involved in perplexity; and he has stopped his ears with the cotton of absurdity, and taken some silly notions into his head, that if Captain Burnes should now come, he will see thousands of boats on the Indus, and report the same to his Government, who will conclude that it is the custom of the Ameer of Sinde to deceive on all subjects, and that he has no sort of friendship.” At length, after a remonstrance from Colonel Pottinger, both he and myself received letters from Hydrabad, offering a road through Sinde by land. As this might be fairly deemed the first opening which had presented itself during the whole negotiation, with the advice of Colonel Pottinger I set out a third time for the Indus. That officer in the meanwhile intimated my departure to the Ameer, and pointed out the impossibility of my proceeding by land to Lahore. He also intimated, in no measured language, that the vacillating and unfriendly conduct of the Ameer of Sinde would not pass unnoticed;[24] the more particularly, since it concerned the passage of gifts, which had been sent by his most gracious Majesty the King of Great Britain.

On the 10th of March we once more set sail for the Indus; and reached the Hujamree, one of the central mouths of the river, after a prosperous voyage of seven days. We could hire no pilot to conduct us across the bar, and took the wrong and shallow mouth of the river, ploughing up the mud as we tacked in its narrow channel. The foremost vessel loosened her red ensign when she had fairly reached the deep water; and, with the others, we soon and joyfully anchored near her. We were now met by an officer of the Sinde Government, one of the favoured descendants of the Prophet, whose enormous corpulence bespoke his condition. This personage came to the mouth of the river; for we were yet refused all admittance to the fresh water. He produced a letter from the Ameer, and repeated the same refuted arguments of his master, which he seemed to think should receive credit from his high rank. It would be tiresome to follow the Sindians through the course of chicanery which they adopted, even in this stage of the proceedings. An embargo was laid on all the vessels in the Indus; and we ourselves were confined to our boats, on a dangerous shore, and even denied fresh water. The officer urged the[25] propriety of our taking a route by land; and, as a last resource, I offered to accompany him to the capital, and converse with the Ameer in person, having previously landed the horses. Land in Sinde. I made known this arrangement by a courier, which I despatched to the Court; and on the following morning quitted the boats, along with Syud Jeendul Shah, who had been appointed our Mihmandar.[3] No sooner had we reached Tatta, than the required sanction for the boats to ascend by the Indus was received, provided we ourselves took the land route; but I immediately declined to advance another step without my charge; and ultimately effected, by a week’s negotiation at Tatta, the desired end. At the expense of being somewhat tedious, I will give an abstract of these proceedings as a specimen of Sindian policy and reasoning.

A few hours after reaching Tatta, Syud Zoolfkar Shah, a man of rank, and engaging manners, waited on us on the part of the Ameer. He was accompanied by our Mihmandar, and met us very politely. He said that he had been sent by his Highness to escort us to Hydrabad; to which I laconically replied, that nothing would now induce me to go, since the Ameer had conceded the request which I had made of him. The Syud here marshalled all his eloquence; asked[26] me if I wished to ruin the Mihmandar, by making him out a liar, after I had promised to accompany him to the Court, and he had written so to the Ameer; if I had no regard for a promise; that the capital was close at hand, and I could reach it in two marches; that, if I did not now go, it could only be inferred that I had been practising delusion, from a desire to see Tatta; for I had even been allowed to choose the route by that city, contrary to orders; and that I was not, perhaps, aware of the high character of the Syud, who was a descendant of the holy Prophet, and honourable in this land; whose dignity, the Christians, who preserved even the relic of Jesus Christ’s nail, could well understand; and that it was not the part of a wise man to cavil like a moollah, since the Ameer had sanctioned the advance of the mission by water, if we embarked at Hydrabad, and would be answerable for the safety of the horses to that place; and, finally, that if I persisted in taking the route by water, he was desired to say that it was a violation of the treaty between the states.

I heard with attention the arguments of Zoolfkar Shah; nor did I forget that the praises and respect which he claimed for his friend, as a descendant of the Prophet, likewise included himself. I replied, that there had existed a long standing friendship between Sinde and the[27] British Government; that I had been despatched by a well frequented route, to deliver the presents of our gracious Sovereign to Runjeet Sing at Lahore; that, on reaching Sinde, I had been insulted, abused, starved, and twice turned out of the country by low persons, whom I named; that my Government, which was ever considerate, had attributed this unheard-of insolence, not to their friend, the Ameer of Sinde, but to the ignorance of mean individuals, and had despatched me a third time to Sinde: when I reached it, I found Syud Jeendul Shah ready to receive me; but although thoroughly satisfied that the presents of which I was in charge could never be forwarded by land, he offered me that route, and detained me on board ship for eleven days, till necessity had driven me to make a proposal of repairing in person to the presence of the Ameer, in hopes of persuading that personage. The case was now altered; the water route had been granted, which rendered my visit to Hydrabad unnecessary; and I could only view the present procedure in the light of jealousy, which it was unbecoming in a Government to entertain. I continued, that I had chosen the route by Tatta, because my bills were payable at that city; and the sooner the Syud got his master to meet my wishes, the better; for the floods of the Indus were at hand, the hot[28] season approached, and delay would increase the hazard; while no arguments but force would now induce me to visit the Court, or permit the horses to be moved without my presence. In fine, if it were not the intention of the Ameer to act a friendly part, he had only to say so, and I would forthwith quit the country when I received a letter to that effect; and finally, that he had formed a very erroneous opinion of the British character, if he considered that I had been sent here in breach of a treaty, for I had come to strengthen the bonds of union; and, what was further, that the promise of an officer was sacred.

An interview in the following morning, brought a repetition of the whole arguments; and as we could not convince each other, we both agreed to address his Highness. After the style of Asiatic diplomacy, I informed the Ameer, “that he had acted the part of a friend, in first pointing out the difficulties of navigating the Indus, and now assisting me through them by giving his sanction to the water route; but since I was so thoroughly acquainted, through his Highness’s kindness, with the dangers of the river, I dared not trust such royal rarities, as the gifts of the King of Great Britain, to the care of any servant.” Success. In three days I received a full and unqualified sanction to advance by water from the mouth of the Indus. I gladly quit the[29] detail of occurrences which have left few pleasing reflections behind, except that success ultimately attended our endeavours, and that they elicited the approbation of Government. The Ameer of Sinde had sought to keep us in ignorance of the Indus; but his treatment had led to another and opposite effect; since we had entered, in the course of out several voyages, all the mouths of the river, and a map of them, as well as of the land route to Tatta, now lay before me. Our dangers on the banks and shoals had been imminent; but we looked back upon them with the pleasing thought, that our experience might guide others through them.

[30]

A week’s stay was agreeably spent in examining Tatta and the objects of curiosity which surround it. The city stands at a distance of three miles from the Indus. It is celebrated in the history of the East. Its commercial prosperity passed away with the empire of Delhi, and its ruin has been completed since it fell under the iron despotism of the present rulers of Sinde. It does not contain a population of 15,000 souls; and of the houses scattered about its ruins, one half are destitute of inhabitants. It is said, that the dissentions between the last and present dynasties, which led to Sinde being overrun by the Afghans, terrified the merchants of the city, who fled the country at that time, and have had no encouragement to return. Of the weavers of “loongees” (a kind of silk and cotton manufacture), for which this place was once so famous, but 125 families remain. There are not forty merchants[4] in the city. Twenty money-changers transact all the business of Tatta; and[31] its limited population is now supplied with animal food by five butchers. Such has been the gradual decay of that mighty city, so populous in the early part of last century, in the days of Nadir Shah. The country in its vicinity lies neglected, and but a small portion of it is brought under tillage.

The antiquity of Tatta is unquestioned. The Pattala of the Greeks has been sought for in its position, and, I believe, with good reason; for the Indus here divides into two great branches; and these are the words of the historian:—“Near Pattala, the river Indus divides itself into two vast branches.”[5] Both Robertson and Vincent appear to have entertained the opinion of its identity with Tatta. The Hindoo Rajas named it Sameenuggur, before the Mahommedan invasion; which I believe to be the Minagur of the Periplus. There is a ruined city, called Kullancote, to be yet seen, four miles S.W. of Tatta. It was also named Brahminabad, and ruled by one brother, while another held Hydrabad, then called Nerancote; the Arabs called it Dewul Sindy. Nuggur Tatta (by which it is now familiarly known) is a more modern name. Till the Talpoors secured their present footing in Sinde, it was always the capital of the country. It is an open town, built on a rising ground in a[32] low valley. In several wells I found bricks imbedded in earth, at a depth of twenty feet from the surface; but there are no remains of a prior date to the tombs, on a remarkable ridge westward of the town, which are about 200 years old. The houses are formed of wood and wicker-work, plastered over with earth; they are lofty, with flat roofs, but very confined, and resemble square towers; their colour, which is of a greyish murky hue, gives an appearance of solidity to the frail materials of which they are constructed. Some of the better sort have a base of brickwork; but stone has only been used in the foundations of one or two mosques, though it may be had in abundance. There is little in modern Tatta to remind one of its former greatness. A spacious brick mosque, built by Shah Jehan, still remains, but is crumbling to decay.

Tatta stands on the high road from India to Hinglaj, in Mekran, a place of pilgrimage and great celebrity, situated under the barren mountains of Hala (the Irus of the ancients), and marked only by a spring of fresh water, without house or temple. The spot is believed to have been visited by Ramchunder, the Hindoo demi-god, himself; an event which is chronicled on the rock, with figures of the sun and moon engraven as further testimony! The distance from Tatta exceeds 200 miles; and the road[33] passes by Curachee, Soumeeanee, and the province of Lus, the country of the Noomrees, a portion of the route of Alexander the Great. A journey to Hinglaj purifies the pilgrim from his sins; a cocoa-nut, cast into a cistern, exhibits the nature of his career: if the water bubbles up, his life has been, and will continue, pure; but if still and silent, the Hindoo must undergo further penance, to appease the deity. The tribe of Goseins, who are a kind of religious mendicants, though frequently merchants and most wealthy, frequent this sequestered place, and often extend their journey to an island called Seetadeep, not far from Bunder Abbass, in Persia. They travel in caravans of an hundred, or even more, under an “agwa,” or spiritual guide. At Tatta they are furnished by the high-priest with a rod, which is supposed to partake of his own virtues, and to conduct the cortège to its destination. In exchange for its talismanic powers, each pilgrim pays three rupees and a half, and faithfully promises to restore the rod on his return; for no one dares to reside in so holy and solitary a spot. The “agwa” receives with it his reward; and many a Hindoo expends in this pilgrimage the hard-earned wealth of a whole life. On his arrival at Tatta from Hinglaj, he is invested with a string of white beads, peculiar to that city, and only found on the rocky ridge near it[34]. They resemble the grains of pulse or juwaree; and the pilgrim has the satisfaction of believing that they are the petrified grain of the Creator, left on earth to remind him of his creation. They now form a monopoly and source of profit to the priests of Tatta.

We quitted Tatta on the morning of the 10th of April, and retraced our steps to Meerpoor; a distance of twenty-four miles, over roads nearly impassable from rain. I observe, in Hamilton’s “India,” that there is frequently a dearth of it here for three years at a time; but we had very heavy showers and a severe fall of hail, though the thermometer stood at 86°. The dews and mists about Tatta make it a disagreeable residence at this season; and the dust is described as intolerable in June and July.

Our road lay through a desert country along the “Buggaur;” one of the two large branches of the Indus, which separate below Tatta. It has its name from the destructive velocity with which it runs, tearing up trees in its course. It has been forsaken for a few years past, and had only a width of 200 yards where we crossed it, below Meerpoor. The Indus itself, before this division takes place, is a noble river; and we beheld it at Tatta with high gratification. The water is foul and muddy; but it is 2000 feet wide, two fathoms and a half deep, from shore to shore. When I[35] first saw it, the surface was agitated by a violent wind, which had raised up waves, that raged with great fury; and I no longer felt wonder at the natives designating so vast a river by the name of “durya,” or the Sea of Sinde.

On our return, we saw much of the people, who were disposed from the first to treat us more kindly than the government. Their notions regarding us were strange: some asked us why we allowed dogs to clean our hands after a meal, and if we indiscriminately ate cats and mice, as well as pigs. They complained much of their rulers, and the ruinous and oppressive system of taxation to which they were subjected, as it deterred them from cultivating any considerable portion of land. Immense tracts of the richest soil lie in a state of nature, between Tatta and the sea, overgrown with tamarisk shrubs, which attain, in some places, the height of twenty feet, and, threading into one another, form impervious thickets. At other places, we passed extensive plains of hard-caked clay, with remains of ditches and aqueducts, now neglected. We reached the sea in two days.

Arrian informs us, that, after Alexander returned from viewing the right branch of the Indus, he again set out from Pattala, and descended the other branch of the river, which conducted him to a “certain lake, joined either[36] by the river spreading wide over a flat country, or by additional streams flowing into it from the adjacent parts, and making it appear like a bay in the sea.” There, too, he commanded another haven to be built, named Xylenopolis. The professed object of this second voyage to the sea was to seek for bays and creeks on the sea-coast, and to explore which of the two branches would afford the greatest facilities for the passage of his fleet; for Arrian says, “he had a vast ambition of sailing all through the sea, from India to Persia, to prove that the Indian Gulf had a communication with the Persian.” In this bay Alexander landed, with a party of horse, and travelled along the coast, to try if he could find bays and creeks to secure his fleets from storms; “causing wells to be dug, to supply his navy with water.” I look upon it, therefore, as conclusive that Alexander the Great descended by the Buggaur and Sata, the two great branches below Tatta, and never entered Cutch, as has been surmised, but that his three days’ journey, after descending the eastern branch, was westward, and between the two mouths, in the direction his fleet was to sail.

On the 12th of April, we embarked in the flat-bottomed boats, or “doondees,” of Sinde, and commenced our voyage on the Indus, with no small degree of satisfaction. Our fleet con[37]sisted of six of these flat-bottomed vessels, and a small English-built pinnace, which we had brought from Cutch. The boats of the Indus are not unlike China junks, very capacious, but most unwieldy. They are floating houses; and with ourselves we transported the boatmen, their wives and families, kids and fowls. When there is no wind, they are pulled up against the stream, by ropes attached to the mast-head, at the rate of a mile and a half an hour; but with a breeze, they set a large square-sail, and advance double the distance. We halted at Vikkur, which is the first port; a place of considerable export for grain, that had then fifty “doondees,” besides sea-vessels, lying near it.

On the 13th, we threaded many small creeks for a distance of eight miles, and then entered the Wanyanee, or principal branch of the Indus, which is a fine river, 500 yards broad and 24 feet deep. Its banks were alternately steep and flat, the course very crooked, and the different turnings were often marked by branches running from this trunk to other arms of the delta. We had nothing but tamarisk on either bank, and the reed huts of a few fishermen, alone indicated that we were in a peopled country.

As we ascended the river, the inhabitants came for miles around to see us. A Syud stood on the water’s edge, and gazed with astonish[38]ment. He turned to his companion as we passed, and, in the hearing of one of our party, said, “Alas! Sinde is now gone, since the English have seen the river, which is the road to its conquest.” If such an event do happen, I am certain that the body of the people will hail the happy day; but it will be an evil one for the Syuds, the descendants of Mahommed, who are the only people, besides the rulers, that derive precedence and profit from the existing order of things.

Nothing more arrests the notice of a stranger, on entering Sinde, than the severe attention of the people to the forms of religion, as enjoined by the Prophet of Arabia. In all places, the meanest and poorest of mankind may be seen, at the appointed hours, turned towards Mecca, offering up their prayers. I have observed a boatman quit the laborious duty of dragging the vessel against the stream, and retire to the shore, wet and covered with mud, to perform his genuflexions. In the smallest villages, the sound of the “mowuzzun,” or crier, summoning true believers to prayers, may be heard, and the Mahommedans within reach of the sonorous sound suspend, for the moment, their employment, that they may add their “Amen” to the solemn sentence when concluded. The effect is pleasing and impressive; but, as has often happened in[39] other countries at a like stage of civilisation, the moral qualities of the people do not keep pace with this fervency of devotion.

On the evening of the 15th, we anchored at Tatta, after a prosperous voyage, that afforded a good insight into the navigation of the Indus; which, in the Delta, is both dangerous and difficult. The water runs with impetuosity from one bank to another, and undermines them so, that they often fall in masses which would crush a vessel. During night they may be heard tumbling with a terrific crash and a noise as loud as artillery. In one place, the sweep of the river was so sudden that it had formed a kind of whirlpool, and all our vessels heeled round, on passing it, from the rapidity of the current. We had every where six fathoms of water, and in these eddies the depth was sometimes threefold; but our vessels avoided the strength of the current, and shifted from side to side, to choose the shallows.

We ascended the Indus in the season of the “pulla,” a fish of the carp species, as large as the mackerel, and fully equalling the flavour of salmon. It is only found in the four months that precede the swell of the river from January to April, and never higher than the fortress of Bukkur. The natives superstitiously believe the fish to proceed there on account of Khaju[40] Khizr, a saint of celebrity, who is interred there, from whence they are said to return without ever turning their tails on the sanctified spot,—an assertion which the muddy colour of the Indus will prevent being contradicted. The mode of catching this fish is ingenious, and peculiar, I believe, to the Indus. Each fisherman is provided with a large earthen jar, open at the top, and somewhat flat. On this he places himself, and, lying on it horizontally, launches into the stream, swimming or pushing forward like a frog, and guiding himself with his hands. When he has reached the middle of the river, where the current is strongest, he darts his net directly under him, and sails down with the stream. The net consists of a pouch attached to a pole, which he shuts on meeting his game; he then draws it up, spears it, and, putting it into the vessel on which he floats, prosecutes his occupation. There are some vessels of small dimensions, without any orifice, and on these the fishermen sail down, in a sitting posture. Hundreds of people, old and young, may be seen engaged in catching pulla, and the season is hailed with joy by the people, as furnishing a wholesome food while it lasts, and an abundant supply of dry fish for the remaining part of the year, as well as for exportation to the neighbouring countries.

[41]

On the morning of the 18th, we moored opposite Hydrabad, which is five miles inland, having had a strong and favourable breeze from Tatta, that brought us against the stream, at the rate of three miles an hour. The dust was intolerable every where, and a village might always be discovered by the dense clouds which hovered over it. This part of Sinde is well known: the country is devoted to sterility by the Ameers, to feed their passion for the chase. The banks are enclosed to the water’s edge, and the interior of these hunting-thickets is overgrown with furze, brushwood, and stunted babool trees, which always retain a verdant hue, from the richness of the soil. One or two solitary camels were to be seen raising water to fill the pools of these preserves, as the Ameer and his relatives had announced a hunting excursion, and the deer[6] would be drawn by thirst to drink at the only fountain, and shot by an Ameer from a place of concealment. It is thus that the chiefs sport with their game and their subjects.

Immediately on our arrival, four different deputations waited on us, to convey the congratulations of Meer Moorad Ali Khan, and his family, at our having reached the capital of[42] Sinde, and at the same time to tender the strongest professions of friendship and respect for the British government; to all of which I returned suitable answers. In the evening we were conducted to Hydrabad, and alighted at the house, or “tanda,” of Nawab Wulee Mahommed Khan, the Vizier of Sinde, whose son, in the father’s absence, was appointed our mihmandar. Tents were pitched, and provisions of every description sent to us; and it would, indeed, have been difficult to discover that we were the individuals who had so long lingered about the shores of Sinde, now the honoured guests of its jealous master. Great and small were in attendance on us: khans and Syuds, servants and chobdars brought messages and enquiries, till the night was far spent; and it may not be amiss to mention, as a specimen of conducting business in Sinde, that the barber, the water-cooler, and the prime minister were sent indiscriminately with errands on the same subject.

The ceremonial of our reception was soon adjusted, but not without some exhibition of Sindian character. After the time had been mutually fixed for the following afternoon, our mihmandar made his appearance at daybreak, to request that we would then accompany him to the palace. I spoke of the arrangements that had[43] been made; but he treated all explanation with indifference, and eulogised, in extravagant language, the great condescension of his master in giving us an interview so early, while the Vakeels, or representatives of other states, often waited for weeks. I informed the Khan that I entertained very different sentiments regarding his master’s giving us so early a reception, and assured him that I viewed it as no sort of favour, and was satisfied that the Ameer himself was proud in receiving, at any time, any agent of the British Government. The reply silenced him, and he shortly afterwards withdrew, and sent an apology for this importunity, which, he stated, had originated in a mistake. The pride of the Sindian must be met by the same weapons; and, however disagreeable the line of conduct, it will be found, in all matters of negotiation, to carry along with it its own reward: altercations that have passed will be succeeded by civility and politeness, and a shade of oblivion will be cast over all that is unpleasant.

In the evening we were presented to the Ameer of Sinde by his son, Nusseer Khan, who had previously received us in his own apartments, to inform us of his attachment to the British Government, and the state secret of his having been the means of procuring for us a passage through Sinde. We found the Ameer[44] seated in the middle of a room, attended by his various relatives: they all rose on our entrance, and were studiously polite. His Highness addressed me by name; said I was his friend, both on public and private grounds; for my brother (Dr. Burnes) had cured him of a dangerous disease. At the same time he caused me to be seated along with him on the cushion which he occupied: he begged that I would forget the difficulties and dangers encountered, and consider him as the ally of the British Government, and my own friend. The long detention which had occurred in our advance, he continued, had arisen from his ignorance of political concerns, as he considered it involved a breach of the treaty between the states; for he was a soldier, and knew little of such matters, and was employed in commanding the three hundred thousand Beloochees, over whom God had appointed him to rule! We had now, however, arrived at his capital, and he assured us that we were welcome: his own state barge should convey us to his frontier; his subjects should drag our vessels against the stream. Elephants and palanqueens were at our disposal, if we would accept them; and he would vie in exertion with ourselves, to forward, in safety, the presents of his Most Gracious Majesty the King of Great Britain, and had nominated the son of[45] his Vizier to accompany us to the limits of his territories. I did not deem it necessary to enter into any explanation with his Highness, nor to give him in return the muster-roll of our mighty army. I thanked him for his marks of attention to the Government and ourselves, and said, that I was glad to find that the friendship between the states, which had led to my taking the route through his dominions, had not been underrated; for it would be worse than folly in an unprotected individual to attempt a passage by the Indus without his cordial concurrence. With regard to the dangers and difficulties which had been already encountered, I assured his Highness, that the prevailing good fortune of the British Government had predominated; and though it was not in the power of man to avert calamities by sea, we had by the favour of God happily escaped them all, and I doubted not that the authorities I served would derive as much satisfaction from the manner in which he had now received us as I myself did. The interview here terminated; his Highness previously fixing the following morning for a second meeting, when I would communicate some matters of a political nature with which I had been charged by the Government.

I shall not enter on a description of the Court[46] of Sinde, as it may be found in Lieut. Col. Pottinger’s work, and in a narrative lately published by my brother.[7] Its splendour must have faded, for though the Ameer and his family certainly wore some superb jewels, there was not much to attract our notice in their palace or durbar: they met in a dirty hall without a carpet; they sat in a room which was filled by a rabble of greasy soldiery, and the noise and dust were hardly to be endured. The orders of the Ameer himself to procure silence, though repeated several times, were ineffectual, and some of the conversation was inaudible on that account. We were, however, informed that the crowd had been collected to display the legions of Sinde; and they certainly contrived to fill the alleys and passages every where, not could we pass out of the fort without some exertion on the part of the nobles, who were our conductors.

I followed up the interview by sending the government presents which I had brought for his Highness: they consisted of various articles of European manufacture,—a gun, a brace of pistols, a gold watch, two telescopes, a clock, some English shawls and cloths, with two pair of elegant cut glass candlesticks and shades. Some Persian works beautifully lithographed in[47] Bombay, and a map of the World and Hindoostan, in Persian characters, completed the gift. The principal Ameer had previously sent two messages, begging that I would not give the articles to any person but himself; and the possessor of fifteen millions sterling portioned, with a partial hand, among the members of his family, the gifts that did not exceed the value of a few hundred pounds. Sindian meanness. His meanness may be imagined, when he privately deputed his Vizier to beg that I would exchange the clock and candlesticks for some articles among the presents, which I doubtless had for other chiefs, as they formed no part of the furniture of a Sindian palace. I told the Vizier that the presents which I had brought were intended to display the manufactures of Europe, and it was not customary to give the property of one person to another. This denial produced a second message; and, as a similar occurrence happened, in 1809, to a mission at this court, we gather from the coincidence how little spirit and feeling actuate the cabinet of Hydrabad. Some score of trays, loaded with fruit and sweetmeats adorned with gold-leaf, and sent by the different members of the family, closed the day.

Early in the morning, we were conducted to the durbar by Meer Ismaeel Shah, one of the Viziers, and our mihmandar: on the road the[48] Vizier took occasion to assure me how much I would please the Ameer by changing the clock! There was more order and regularity in our second interview, which was altogether very satisfactory; for the Ameer gave a ready assent to the wishes of Government when they were communicated to him. The conversation which ensued was of the most friendly description. His Highness asked particularly for my brother, looked attentively at our dress, and was much amused with the shape and feather of the cocked hat I wore. Before bidding him adieu, he repeated, in even stronger language, all his yesterday’s professions; and, however questionable his sincerity, I took my departure with much satisfaction at what had passed, since it seemed he would no longer interrupt our advance to Lahore. Meer Nusseer Khan, the son of the Ameer, presented me with a handsome Damascus sword, which had a scabbard of red velvet ornamented with gold; his father sent me a purse of fifteen hundred rupees, with an apology, that he had not a blade mounted as he desired, and begged I would accept the value of one. After all the inconvenience to which we had been subjected, we hardly expected such a reception at Hydrabad. Next morning we left the city, and encamped on the banks of the Indus near our boats.

[49]

The scenery near the capital of Sinde is varied and beautiful: the sides of the river are lined with lofty trees; and there is a background of hill to relieve the eye from the monotony which presents itself in the dusty arid plains of the Delta. The Indus is larger, too, than in most places lower down, being about 830 yards wide; there is a sand-bank in the middle, but it is hidden by the stream. The island on which Hydrabad stands is barren, from the rocky and hilly nature of the soil, but even the arable parts are poorly cultivated.

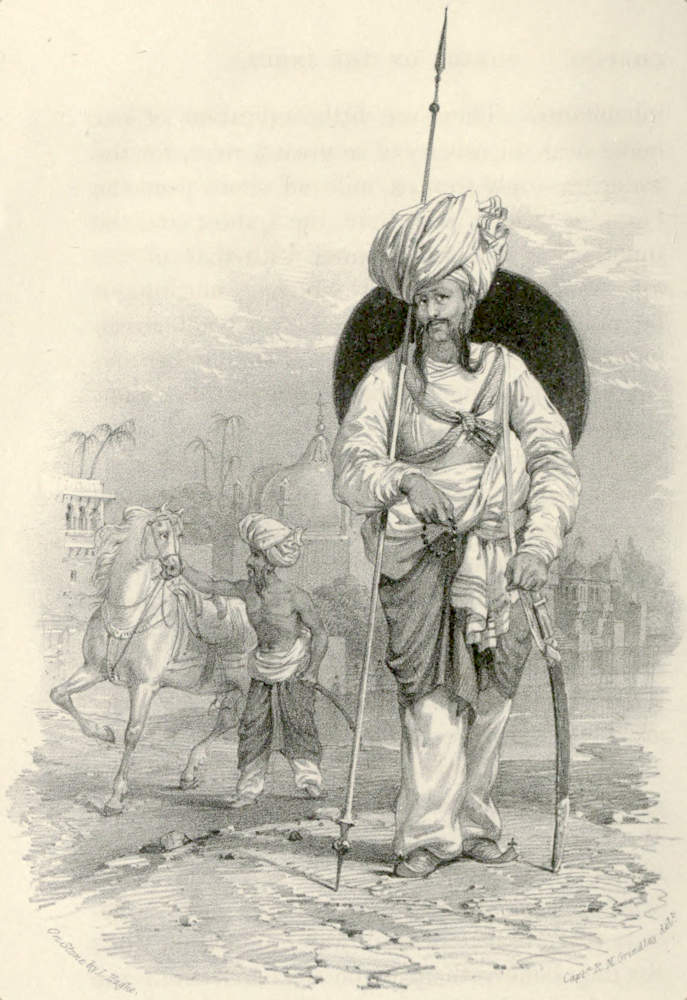

On the capital itself, I can add little to the accounts which are already on record. It does not contain a population of twenty thousand souls, who live in houses, or rather huts, built of mud. The residence of the chief himself is a comfortless miserable dwelling. The fort, as well as the town, stands on a rocky hillock; and the former is a mere shell, partly surrounded by a ditch, about ten feet wide and eight deep, over which there is a wooden bridge. The walls are about twenty-five feet high, built of brick, and fast going to decay. Hydrabad is a place of no strength, and might readily be captured by escalade. In the centre of the fort there is a massive tower, unconnected with the works, which overlooks the surrounding country. Here are deposited a great portion of the riches of[50] Sinde. The Fulailee river insulates the ground on which Hydrabad stands; but, though a considerable stream during the swell, it was quite dry when we visited this city in April. The view of Hydrabad, prefixed to this volume, and for which I am indebted to Captain M. Grindlay, faithfully represents that capital and the country which surrounds it.

[51]

On the morning of the 23d of April, we embarked in the state barge of the Ameer, which is called a “jumtee” by the natives of the country. They are very commodious vessels, of the same build as the other flat-bottomed boats of the Indus, and sadly gainsayed the beggarly account which his Highness had, in his correspondence, so often given of the craft in the river. It was about sixty feet long, and had three masts, on which we hoisted as many sails, made of alternate stripes of red and white cloth. There were two cabins, connected with each other by a deck; but, contrary to the custom in other countries, the one at the bows is the post of honour. It was of a pavilion shape, covered with scarlet cloth, and the eyes of intruders were excluded on all sides by silken screens. The jumtee was further decorated by variegated flags and pendants, some of which were forty feet long. We hoisted the British ensign at the stern of our pinnace, the first time, I suppose, it had ever been unfurled on the Indus; and the little vessel which bore it out-sailed[52] all the fleet. I hope the omen was auspicious, and that the commerce of Britain may soon follow her flag. We moved merrily through the water, generally with a fair wind, anchoring always at night, and pitching our camp on the shore, pleased to find ourselves beyond the portals of Hydrabad.

We reached Sehwun on the 1st of May, a distance of 100 miles, in eight days. There was little to interest us on the banks of the river, which are thinly peopled, and destitute of trees or variety to diversify the scene. The Lukkee mountains, a high range, came in sight on the third day, running in upon the Indus at Sehwun. The stream itself, though grand and magnificent, was often divided by sand-banks, and moved sluggishly along at the rate of two miles and a half an hour. One of our boats had nearly sunk from coming in contact with a protruding stump; an accident of frequent occurrence on the Indus, as well as on the American rivers, and sometimes attended with fatal results, particularly to vessels descending the stream. Our escape from calamity gave the Sindians a topic for congratulation, and we daily heard the greatness of our fortune proclaimed. Every trivial incident, a slight breeze or any such occurrence, they did not hesitate to ascribe to our destiny.

[53]

Our crew consisted of sixteen men; and a happy set of beings they were: they waded through the water all day, and swam and sported about, as they passed along, with joyous hearts, returning occasionally to the boat to indulge in the hooka, and the intoxicating “bang,” or hemp, to which they are much addicted. They prepare this drug by straining the juice from the seeds and stalks through a cloth: when ready for use, it resembles green putrid water. It must be very pernicious. I do not know if I can class their pipes among the movables of the ship; for their stands were formed of a huge piece of earthenware, too heavy to be lifted, which remains at the stern, where the individuals retire to inhale the weed, made doubly noxious by its being mixed with opium. The sailors of Sinde are Mahommedans. They are very superstitious, the sight of a crocodile below Hydrabad is an evil omen which would never be forgotten; and in that part of the Indus these monsters certainly confined themselves to the deep.

In the songs and chorus which the Sindians use in pulling their ropes and sails, we discover their reverence for saints. Seafaring people are, I believe, musical in all countries; and, though in a strange dialect, there is simplicity and beauty in some of the following rhymes:—

[54]

Original.

Translation.

Another specimen runs thus:—

Translation.

[55]

As we discovered the mosques of Sehwun, the boatmen in their joy beat a drum, and chanted many of these verses, which had a pleasing sound on passing the base of the Lukkee mountains, that present a rocky buttress to the Indus on approaching Sehwun.