Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 1024, August 12, 1899

Author: Various

Editor: active 1880-1907 Charles Peters

Release date: July 10, 2021 [eBook #65816]

Language: English

Credits: Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

{721}

Vol. XX.—No. 1024.]

[Price One Penny.

AUGUST 12, 1899.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

SHEILA’S COUSIN EFFIE.

THE PLEASURES OF BEE-KEEPING.

CHRONICLES OF AN ANGLO-CALIFORNIAN RANCH.

VARIETIES.

FOLDING-UP WORK CASE.

HOW WE MANAGED WITHOUT SERVANTS.

HOUSEHOLD HINTS.

MAN AND THE MOUNTAIN.

LETTERS FROM A LAWYER.

“I NEED SOME MUSIC.”

THE HOUSE WITH THE VERANDAH.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

A STORY FOR GIRLS.

By EVELYN EVERETT-GREEN, Author of “Greyfriars,” “Half-a-dozen Sisters,” etc.

AT THE EDGE OF THE PLATEAU.

All rights reserved.]

CAMACHA.

Up, up, up, ceaselessly up. Would the paved road never merge into something more like an English mountain track? Sheila wondered, as her brave little horse pushed steadily and boldly onward, eager as it seemed to breast the long, steep ascents, never asking to pause for a breather, although the riders of their own accord would stop from time to time for the sake of their horses, and of the grooms on foot, who seemed as untiring as the steeds themselves.

“Poor fellows, we will give them a drink here,” said Ronald, as they reached a little plateau where there was one of the numerous drinking bars of the island. “It must be jolly hot work keeping up with these plucky little horses. Let us rest a moment whilst they refresh themselves.”

“And let the others come up,” answered Sheila looking backwards and downwards. “We have quite left them behind.”

“Oh, they’ll come up all in good time,” answered Ronald carelessly. “One can’t ride in a cavalcade in these narrow roads.”

For the peculiarity of Madeira is that for miles and miles the roads run between walls, with houses or cultivated ground behind them. It is only as the heights are reached that these walls are left behind, and more open country reached. Often the road is so narrow that two horses can barely ride abreast.

“What does tabaco habilitado mean?” asked Sheila, “that you see written on almost every tenth house.”

“I believe it means licensed to sell tobacco,” answered Ronald,{722} “and I expect they have to pay pretty high too for the licence. The imposts here are iniquitous. I wish we had the place. We’d make a different country of it. Just look at these barbarous roads cut straight up the sides of the mountains! It’s ridiculous. It might be beautiful if they had only zig-zagged them as they do in other places. But let us ride on now. We shall get beyond the region of walls soon; up yonder I believe the country is very pretty. They say it is like a hot spring day in England when you get to Camacha.”

“Shall we not wait for the others?” asked Sheila.

“I don’t see why. They will come on all right. Our horses are bound to get ahead anyway. One must let them take their own natural pace. We shall all meet at the rendezvous. The horses soon get fidgety standing still. Come along, I believe it gets very pretty a little farther on.”

Sheila looked back, but there was no sign of the rest of the party, and she followed Ronald perforce. She had a vaguely uneasy feeling that her aunt was not pleased with her, and she would rather have avoided all cause of offence, and she thought this might possibly be one. Since that New Year’s Eve night something had been creeping into Sheila’s life which she did not altogether understand—something that made her happy, yet pensive, restless sometimes, and sometimes half afraid of her own thoughts and dreams. She strove to banish the thoughts and feelings which she did not understand, but they would not be altogether banished, though she often managed to forget them or push them out of sight. She had been a child so long that she did not know what it meant—this waking of her womanhood within her.

Yet some instinct had made her keep very close to Lady Dumaresq and little Guy at starting, whilst Ronald had ridden beside Effie’s hammock through the town, wherever the streets were wide enough, amusing her with his gay talk, and pointing out things which he thought might interest her as they went along.

But with the ascent through the narrow lanes, and up the very steep places, this order had been broken. The horses took matters into their own hands. The fast animals gradually distanced bullocks, hammock bearers, and the pony which little Guy bestrode, and beside which his mother walked her horse, and Sheila found herself riding with Ronald some considerable distance in advance of the rest.

She did not know why she had a feeling that her aunt would be displeased, and gradually in Ronald’s merry talk she forgot her misgiving. It was so delightful leaving behind the region of walls and houses, and getting out into the open country—seeing leafless trees again, just like England—although other things were not much like, for oranges and lemons grew freely, and the scent of orange blossom was heavy sometimes in the air, and arum lilies growing wild evoked rapturous exclamations from the girl.

“Isn’t it delicious?” she cried. “I do like to see bare trees again! I don’t think it is very pretty when the old leaves hang on through the winter. It gives them such a shabby look. The air up here feels just like England on an April day, doesn’t it? Dear old England! We always grumble at its weather, but there’s something about it that makes us always want to go back.”

“Do you want to go back already?” asked Ronald.

“Oh, no!” she answered quickly. “Not a bit—not now. But you know what I mean—the sort of feeling that it is home.”

And then she suddenly stopped, and the shadow swept over her face. Ronald had learnt to know that face so well that he was able to read it like a book. He knew just what she was thinking. He would like to have put out a hand and taken hers, but he was afraid of startling her. Yet he spoke what he knew would be an answer to her unspoken thought.

“Never mind, Sheila, some day you will have a real home of your own again—a home that will be happier even than the one you have lost.”

She lifted her eyes to his with a glance half startled and wholly sweet. It thrilled him through and through, and words trembled on his lips that he was yet half afraid to utter. If he spoke too soon he might lose all. He hoped—he believed—that he might win her for his own. But she was such a child still. He must have patience. There was time—plenty of time. Little by little he would teach her to understand what she was to him. Before they went back to England he hoped to have won her promise to be his—and go back to make for her that home which in his fancy he was already building.

“You are always so kind to me,” she said softly, “you always understand.”

The slight emphasis upon the pronoun made him ask, smiling—

“And who is it that does not understand?”

“Oh, my aunt—and Effie; they think that their house is home, and can’t understand what I mean. Of course, I am grateful to them. I have been quite happy there often. But it cannot be the same, and they do not seem to understand.”

“You must come and see us when we get back to England,” said Ronald cheerfully. “We shall expect you on a long visit. Little Guy will see to that if nobody else does. Would you like that, Sheila? I beg your pardon, I ought not to call you that. It comes through hearing you always spoken of by that soft name.”

“I like you to call me Sheila,” said the girl shyly, and with a soft blush. “I have never been called anything else by friends—till quite lately.”

“Well, when we are by ourselves I should like to,” said Ronald, “and you must do the same by me. I think it is much nicer when people are real friends to drop ceremonious titles.”

After that the ride seemed all sunshine to both of them. Ronald thought he had sufficiently advanced his cause, and abstained from any more direct overtures; but he talked in a fashion that was delightful to his companion, and the exhilarating freshness of the air and the beauty of everything about them seemed a fit setting for their happiness, as they rode along together side by side in the clear soft sunshine.

“Here we are!” cried Ronald at length, as they reached the green plateau at the summit of the hill. “There is the clock-tower that the doctor built. Do you know that before they had that, the people here had no means of knowing the time—and that on market days, or when they wanted to get down early in Funchal, they used often to get up in the middle of the night, and sit up watching for the dawn, afraid to go to sleep again lest they should not awake in time.”

From the edge of the plateau there were beautiful views of the sea, and away to the left the long jagged line of the reef running out to the east from the most easterly portion of the island. The sea seemed sleeping and dreaming away below them. It looked more like the blue Mediterranean than the storm-tossed Atlantic.

They had dismounted and left the men to take care of the horses. They wandered happily about together from place to place, finding new beauties at every turn. They were recalled to the present by the familiar cry of the “bully-boy.” Sheila exclaimed—

“Oh, here come the rest! The carro must be coming! Can you make the noise the boys do? I have tried so often, but I can’t quite get it right.”

Ronald made attempts more or less successful to imitate the wild peculiar cries by which the boys and men encourage and guide the bullocks, and Sheila stood laughing and praising.

“I think it is so sweet of the bullies not to go unless the boy goes in front. They really won’t. I thought it was a make up when I heard it first. But one day after a cricket match our boy was missing for a little while, and nothing would induce the bullies to start, not all the prodding and yelling of the man. But the moment the boy came and walked in front they went like lambs!”

The bullock carro with its four bullocks, and Mr. and Mrs. Cossart as passengers, was the vanguard of the main party. Lady Dumaresq and her little boy were immediately behind, and the hammock bearers came up very shortly with Effie, Miss Adene, and Sir Guy. He, however, had left his hammock and was on foot by this time.

“I begin to feel it ignominious to be carried in that fashion, but the fellows are quite hurt in their minds if you ask to be let out! I couldn’t induce them to put me down till we had got to the more level stretches, and then they made quite a favour of it!”

“We’ve had a jolly ride!” cried Ronald, whose face was full of brightness, and whose spirits were so high that his brother glanced at him more than once with a look of quiet scrutiny, and said in an undertone to his wife as they stood apart—

“Do you think?”—and then he gave{723} an expressive glance that travelled from Ronald to Sheila.

Sheila was engrossed by little Guy who had claimed her instantly. Ronald by this time was beside Effie, whom he had helped from her hammock, and who was a little stiff from the long journey in one posture, and was glad to take a turn up and down leaning on his arm.

“I think not,” answered Lady Dumaresq. “I think he understands not to be too precipitate—not to frighten the child. But that it is coming I do not doubt. I am so pleased about it both for his sake and hers. They are rather a pair of babies still. But they will grow out of that, and they seem just made for each other.”

The luncheon was spread in a sheltered spot, where a bank gave fairly comfortable sitting accommodation to the elders of the party. Miss Adene seemed to see the cloud resting upon Mrs. Cossart’s face, and set herself to dissipate it. Her pleasant talk had a somewhat softening effect; but had anybody chanced to note it, they might have observed how very little that lady spoke, and that the glances she threw from time to time towards the place where Sheila sat between Ronald and little Guy, were of a very hostile description.

She never addressed the girl once the whole day, but Sheila did not notice it. She had given herself over to the enjoyment of the little festivity, and she was too happy to be very observant.

Little Guy wanted to play hide-and-seek amongst the bushes. Of course Ronald was pressed into the service. Effie offered herself, but for some reason or other Guy had taken rather a dislike to her. It might have been her eye-glasses or the occasional sharpness of her voice, but it was noticeable that he only accepted her overtures with great reservation, and to-day he replied firmly though politely—

“No, sank you, you might get tired. Mozzer will come, and Uncle Ronald and Sheila. Sat will be quite enough. You had better rest yourself.”

When the afternoon light began to grow mellow, the party got into train again for the descent. It was a two hours’ ride up, but the descent was generally rather quicker.

Again they started sociably in a cavalcade, but again by degrees the horses distanced the bullocks and bearers, and once more as they reached the region of the narrow roads Ronald and Sheila found themselves some distance in advance of the rest of the party.

It seemed too natural for her to oppose the arrangement. It did not occur to her that anybody would make any serious to-do because they happened to have faster horses than Lady Dumaresq and her little son. It had been such a perfectly happy day that Sheila was in no mood to think of anything unpleasant, and she had not even noted the cold regards and marked silence of her aunt.

Down and down they rode, the soft sunlight making everything look even more beautiful than its wont. The curtains of flowers hanging over the walls seemed to blaze with a kind of glory, and the rainbows shining over the sea were more than ordinarily beautiful.

“I never saw such a place for rainbows!” cried Sheila. “Miss Adene told me about them, but I never could have believed without seeing. Why, first thing in the morning as I lie in bed I can see them hanging over the hills. Oh, you don’t know what the sunrises are like—I mean the reflected light upon the hills, all red and lovely every morning, and to be able to watch it as you lie in bed! I shall never forget it as long as I live! I wonder if I shall ever see Madeira again?”

“You shall if you want to,” said Ronald so softly that he did not think she heard.

“Let us come down the steps and watch the sea,” said Ronald when they reached the hotel, “the rest won’t be back just yet. I love to go down the steps and get right to its level.”

Sheila loved it too, and wished that she could bathe there in the mornings, as the young men did. It was something of a scramble, but she delighted in making it. The surf always broke grandly at the base of the rocks, however calm the sea looked from above. They stood watching it a long time, and they talked of many things, till suddenly the quickly coming darkness warned them that it was time to go back and dress for dinner.

“I shall never forget our day at Camacha all my life,” said Ronald, holding her hands to help her up the rough boulders.

She looked back at him, and her face flushed softly.

“I am sure I never shall,” she answered.

(To be continued.)

By F. W. L. SLADEN.

The hive generally fills rapidly with honey during July. When the super is full it may be removed from the hive, and, if honey is still coming in in fair quantity, another one substituted for it.

When honey—or, strictly speaking, nectar—is first gathered from the flowers, its consistency is thin, almost like water, and if it remained in this state it would soon ferment and go sour. But by means of the high temperature which the bees always maintain inside the hive the excess of moisture is evaporated out, and the nectar is changed into thick ripe honey. As each cell in the honey-comb gets filled with this honey, the bees seal it over with a thin capping of wax, to preserve the contents from any outside contamination, just as we tie the vegetable parchment over our pots of jam. In this condition the honey will keep good any length of time.

The combs in the middle of the super are always finished first, the work extending from the centre outwards, so that if, by lifting a corner of the quilts we see that the outside combs are sealed over, we may be sure that all the combs in the super are finished in like manner, and that the super is ready for removal.

I will now describe the operation of removing a full rack of sections from off the hive. The bees, of course, must first have timely warning that something is about to be done by our giving them a few light puffs of smoke under the quilt. After leaving them for a minute, the rack of sections may be prized up underneath, at the back, with a screw-driver, and a few more puffs of smoke blown into the opening thus formed. The rack of sections may now be lifted right off the hive and taken away. If another rack is not to be put on, the sheet of queen-excluding zinc must also be removed, and the quilts must be taken from off the rack of sections to cover the frames in the stock-box. The hive may then be closed up.

But the operation by no means concludes here; the super is full of bees, and our work now will be to get rid of these. The quickest and simplest way of doing this is to take each section out of the rack and shake the bees off it on to the alighting-board of the hive; in doing this a goose-wing or bottle-brush will be found useful to brush off any bees that may not be detached by a few gentle shakes. The sections must be handled carefully, as they are rather fragile, and the comb is easily cracked and bruised.

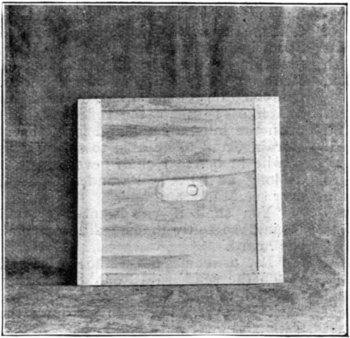

A far better way of ridding the super of bees is to use a super-clearer, which consists of a board with a thick frame round the edge, and having a hole in the centre in which is inserted a little tin appliance with springs, which will allow the bees to pass through it only in a downward direction, so that they cannot go back again into the super.

The super-clearer is placed between the super and the stock-box. If the weather is warm it will be found that in about twenty-four hours’ time not a bee will be left in the super, and it may then be removed and{724} brought indoors. In colder weather the super-clearer may take two days or more to do its work. It should not be left on the hive after the super has been taken away, but must be removed with a little smoke, its place over the frames being taken by the quilts.

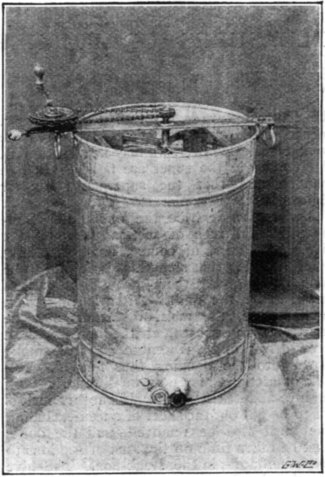

SUPER-CLEARER.

One word of caution is necessary before we leave the subject of removing the super.

Combs containing honey, or drops of honey, must never be left out-of-doors, or anywhere within reach of the bees. Their scent for all sweets of this kind is very keen, especially if there is not much to be obtained in the fields, and they will soon discover and steal them, even fighting over the ill-gotten booty, so that many thousands of workers are sometimes killed by their greedy companions. Frequently the mischief does not end here, for when the robbers have finished their spoil they may, in their thirst for more, attack and force a passage into the hive of some weak neighbouring colony, which is incapable of defending its stores against such an overwhelming army of marauders, and this will often result in the annihilation of the luckless colony—“cleared out,” as the bee-keeper, who has not been careful to prevent the mischief in the beginning, exclaims with surprise, when in going the round of his hives a few days later, he discovers too late the sad state of affairs.

Sections of honey-comb should be stored in a warm and dry place. For home use they may be left in the section-rack, but if they are to be offered for sale they must be separated, and the particles of wax and propolis scraped off the sides and edges of the wood of each section, care being taken in so doing not to bruise or crack the combs.

Sections for sale are rendered more attractive if placed in neat cardboard boxes, with or without glass on one side. These boxes can be obtained from any of the dealers in bee-appliances. 1s. to 1s. 3d. ought to be readily obtained for a section of good honey done up in this way; but the price of honey varies in different seasons and districts.

In removing a super containing shallow frames, proceed in the same way as with the rack of sections. The honey must be extracted from these frames in the honey-extractor.

The extracting should be done immediately after the frames are taken from off the hive, while the combs are still warm.

Before placing the comb in the extractor, the cappings must be pared off both sides of the comb with a long, sharp knife, which does the work much better if it is warm. It will be convenient to have two knives in a dish of hot water close at hand for the purpose. Uncapping is an operation the beginner cannot expect to excel at the first time. Plenty of mess and stickiness will most likely be the order of the day during the first few occasions, so it will be advisable to have the clothes well protected by a good apron.

Two combs having been uncapped, they will be placed in the cages of the extractor, and the handle turned so as to make them revolve. This must be done slowly at first. A few turns of the extractor will bring the centrifugal force into play by which the honey will be thrown out in countless drops, which will settle on the inside walls of the extractor, and coalescing, will trickle down to the receptacle in the bottom of the machine in which the clear amber fluid will quickly gather. There is a danger, in turning the handle too fast, of the honey not getting extracted on the inside of the comb, pressing on the midrib, and breaking through it, especially in warm weather when the wax is soft. This danger is reduced by the use of “wired” combs. In from five to ten minutes’ time the honey will cease to flow from the combs. The turning must then be stopped, the combs lifted out and replaced in the extractor with the reverse side outward, the revolving process being then repeated to extract the honey from the second side of the comb. When the combs are again lifted out they will be emptied, and the extractor will be ready to take another pair of uncapped combs. The emptied combs should be given back to the bees, either to be filled again with honey, or to be licked clean preparatory to their being put away for the winter for use next year.

The honey which has gathered in the bottom of the extractor should be strained through flannel to get rid of the small particles of wax and other impurities it is likely to contain. After this, it may be run into jars or bottles, which should be tied over with parchment to exclude the air.

HONEY-EXTRACTOR.

The wax cappings should also be strained in a warm room to separate the honey. They may then be melted down in a pan of water over a slow fire. When they are quite melted, the pan should be removed and stood in a cool place. In a few hours’ time the beeswax will be found to have set in a solid cake, floating on the surface of the water. The impurities which have collected on the under side of the cake can be scraped off. If desired, the wax can again be melted and cast in convenient-sized blocks in moulds which have previously been well smeared with sweet oil to prevent the wax sticking to them. An appliance called a wax-extractor will be useful for rendering larger quantities of wax from old combs.

Beeswax comes in very useful for a variety of purposes in the home. Mixed with spirits of turpentine, it forms a valuable furniture polish. A lump is handy in the work-basket for waxing sewing-threads. It is also useful for securing foundation in frames and sections. A compound of beeswax with mutton fat, with the addition of a little lamp-black, sweet oil, turpentine, and lard, makes an excellent dubbing for children’s boots in the winter, keeping the leather soft and dry.

Carrying out the details of harvesting their crop of honey in the manner described above is a pleasant enough occupation with most bee-keepers, but it is one that I fear a good many of my readers may not have the pleasure of experiencing in this their first season.

Perhaps the swarm has not been strong enough to do any work in the super at all, and the sad prospect of no honey this season is rather a damper to your ardour. Never mind, the bees may have been able to gather more than enough for themselves in the stock-box. If, however, the colony is very weak, the bees not nearly filling the stock-box, they will now require a little looking after to bring them up quickly to the requisite strength, to ensure successful wintering, followed by a profitable yield of honey, or perhaps a swarm or two, next year. If the weather keeps unfavourable, they may require feeding. Such feeding should be kept up regularly two or three times a week, and only a small quantity of syrup given at each time. It will then have the effect of encouraging breeding.

Another good way to stimulate a weak colony is to give it a comb containing brood from another stronger hive that can well afford to spare it. The bees on the comb must be shaken back into the hive from which they came before it is put into the hive we want to strengthen, and care must be taken to see that the queen, should she chance to be on this particular comb, is returned to her hive in safety. Bees from different hives will not agree if put together, unless special means are taken to make them do so, and these will be explained later on when we consider “uniting.”

Those who have been fortunate enough to secure a crop of honey may sometimes be disappointed to find that it is inferior in quality, with a more or less disagreeable flavour. This is a trouble which it is beyond the power of the bee-keeper to remedy, as it depends on the flora of the neighbourhood. The best honey, barring heather honey, is very pale in colour, and comes chiefly from the Dutch clover, sainfoin, mustard and lime-tree blossoms. Inferior kinds are darker; the blackberry and sunflower are among the flowers to which credit is given for producing them, and probably most honey obtained from mixed bloom, whether in the garden or on the wayside, is not so good as that which is gathered from flowers of the clover group. But what most spoils a sample of honey, making it dark and unpalatable, is leaf honey or honey-dew. This substance is not really honey, being secreted by the leaves of certain trees, especially the lime-tree, oak, and sycamore, and in some years much more than in others. The bees feed on it with relish, but it is not wholesome for them.

(To be continued.)

{725}

By MARGARET INNES.

ON THE RANCH—THE ANIMALS.

would be difficult for anyone who has never had the work to do, to realise how puzzling it is to take an up-and-down hilly piece of land, all covered with shrub and brush, and plan it out so that all shall be placed conveniently, and also look at its best.

In our great hurry, we had certainly chosen the wrong place for our barn, and, moreover, it was much too small. We saw now perfectly well which was the right place. So as soon as the last piece of furniture had been lifted into the house, the carpenters set to work to take the barn to pieces, and carry it down the hill to the new site upon which we had settled.

It is a wonderful and rather a fearful thing to see how they can move large and small buildings about in this land of ingenuity. One feels quite embarrassed the first time one meets a house walking down the middle of a street. No doubt it is a great convenience to be able to keep your own house, and yet change your neighbourhood!

An acquaintance of ours, having some money to invest, put up a neat row of small detached houses on a piece of land which he had bought during a boom in those parts. The boom, alas! departed, leaving, as usual, disaster and emptiness behind, and these poor little houses stood all by themselves, never a single tenant or purchaser offering for them. Finally, however, someone of enterprise was found, who chose one for himself, and having a “lot” in an attractive part of San Miguel, had his new cottage driven over and rearranged in its new setting.

This answered so well, that it seemed to break the spell of ill-luck for the others also, and soon we were much amused to meet another and yet another of Jim Baxter’s houses driving with stately slowness up and down the different streets of San Miguel, till the desolate little row, planted quite four miles away in an empty waste, had all been absorbed into friendly comfortable corners of the town.

Our present barn has very little resemblance to the original one, which was, however, all absorbed into it. With all the additions which have grown as they were felt to be needed, it is now about four times the size of the little wooden box we lived in during those four hot, dusty months.

There is a large, cool, lemon-curing room in the centre, over which is the hay-loft, holding twenty-five tons. At one side is a convenient workshop, with joiner’s bench, and all necessary arrangements for the many different kinds of jobs one has to do for oneself here, such as harness mending, soldering, etc. A nice little room for the ranchman is built over this. At the other side is a waggon-shed, and good-sized buggy-house, large enough to hold four vehicles. There are stalls for six horses and the cow, with one loose box, and a shed extending over one part of the corral, to give shade from the fierce sun. This, with hen-houses, etc., is quite a little settlement.

We have a comfortable bench down there, where I often sit in the evening, during “chore” time, while the animals are being made comfortable for the night; the cow milked, with the barn cat in close attendance, waiting for her accustomed share; the horses each in turn brought to the trough for a drink; the hens, too, after much fuss and hysterical chatter, fed and shut up, lest the coyotes, whose mocking yelp sounds often so very near in the night, should “carry off one to his den, oh!”

We soon realised in our ranch life how very much the animals added to our pleasure and interest. They are so very happy on a ranch, both dogs and horses, that one catches many a wave of the infection from them. They are so interested in each other and in us, showing such friendliness and affection, and also so much individuality. When the horses are not needed on the ranch, they are put into the corral, where they go through an impromptu circus performance of their own. After a good roll over in a spot carefully selected by much snuffing and pawing, they will stand on their hind legs in front of each other, pawing the air, and looking huge, then chase each other round and round the corral at such a speed, that one wonders they escape hurting themselves against the enclosing fence.

Poee, who is very exclusive, and resents the slightest intrusion on the part of any of the horses, lady or gentleman, has a stall close to the corral. As there is a window in her box, it is one of their mischievous pleasures to go softly up to it and look in, so as to hear Poee’s angry shrill squeal, followed by a few hard kicks, when they scamper off, just as pleased as any wicked schoolboy who brings out an angry servant in answer to a runaway ring at the bell.

Jennie, the only other lady among them, though very nervous and high-strung, is much more amiable; in fact, she is quite ready to flirt and coquette with Rex. Like other flirts, she has more than one string to her bow, and though she does not really approve of Ben, she will tempt him to pay her attentions, which she receives with a virtuous and indignant squeal. They are all accustomed to being talked to, and look for occasional mouthfuls of something dainty from friends.

The dogs take a more intimate part still in our lives, and, indeed, we miss them greatly if for any reason they have to be left out of any expedition or undertaking. Whatever the spirit of the moment, they understand, and take the cue. If it is a pleasure drive, off for the day, with baskets of eatables and drinkables, then there is such excitement among them that they can hardly wait till we are ready, but make little false starts by themselves, to rush back, jumping up at the horses’ noses again and again, bumping up against each other, and smiling at us. Or, if the business in hand is serious, like any work on the ranch, or hauling firewood from the Silvero Valley, they take part with quite a different air; every line of head and tail shows grave responsibility, and I am sure they are convinced that things could not be carried on without their help.

It is quite pathetic to see old Sport doing his ranch duties. He is a brown setter, and was getting well on in years when given to Larry, and is now showing many signs of real old age; but when the little grey team are being hitched up to the cultivation, or Ben is waiting, staid and obedient, to be harnessed to the plough, Sport will lift himself rather stiffly from his favourite seat, which is on the top of the rain-water cistern, from which high perch he can keep a ready look-out all over the ranch, and after a grave shake he trudges down the hill, and stands waiting quietly till all is ready, and will follow the plough up and down the ranch till his tired old legs can do no more, when he limps up to the house, and rests in a cosy corner with the air of one who has done his duty, and can look any man, or any dog, in the face.

Between him and Bullie there is an undying rivalry, kept in abeyance generally by the truly gentlemanly spirit of both dogs, but breaking out now and again into a savage fight, when everyone flies to the rescue, lest poor old Sport should have his little remnant of pleasant life shaken out of him.

Bullie is a very “low down” dog, mongrel to the tips of his big, clumsy toes; but he is Tip’s dearly-loved friend, and, indeed, we all take part in him.

Skibi, the bull terrier, is a perfect darling. She is so bright, and loving, and quick, so anxious to please, so brave, that she would fain fly at all the dogs three times her own size, bristling her whole back, and looking terribly dangerous. It is no wonder that Bullie and Sport look hatred and murder at each other for her sake. Both Skibi and Bullie adore the horses. Bullie will stand perfectly rigid in front of Dick and Rex, waiting anxiously for a little notice. If they lean down and sniff at him, he seems to hold his very breath, and when they lay hold of him, by his thick, loose skin, and lift him off his legs, as they do sometimes (though he weighs sixty pounds), then the very height of his pride and ambition is reached.

The greetings which the dogs give one, either in the mornings, or when one returns after any absence, is so full of true love and friendship, that we would feel quite bereft without our faithful comrades in this lonely life.

(To be continued.)

Drifting.—No waste of time is so lavish as that which is the result of drifting, and there is no way in which people squander it more. Thousands of good intentions are daily swamped and destroyed, simply by allowing the time to slip away unconsciously until it is too late.

Usefulness.—Our duty is to be useful, not according to our desires, but according to our powers.

The Deepest Secret.—We shall have read the deepest secret of nature when we have read our own hearts.

“The object of education is the carrying out of God’s will for the individual; but the purpose of His will is hidden from us. The direction, only, in which we are to work is pointed out by the peculiar endowments of temper and of intellect in the child.”—Mrs. Sewell.

{726}

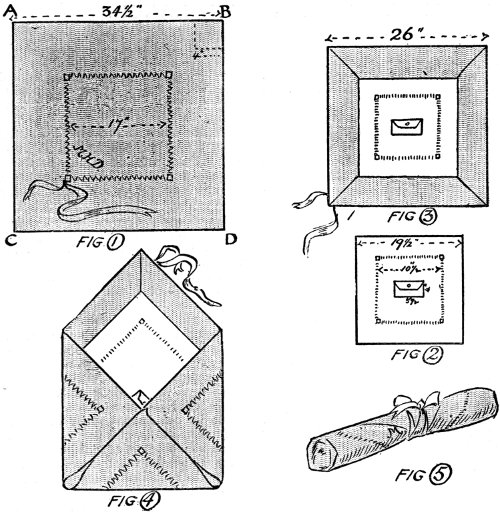

To those of our “girls” who can do “hemstitching,” we commend this pattern, which was most kindly sent to us the other day from Glasgow. Fig. 1 represents a piece of pink (or any other colour) linen, 34½ inches square. In the centre may be worked, in white linen thread, a conventional design, or, better still, the initials or name of the friend for whom it is intended; a border of hemstitching is then added, any nice open pattern of half an inch wide. The corners A, B, C, D, are then cut out four inches, turned over the other side and mitred down as in Fig. 3. Fig. 2 represents a small square of white linen with a narrower inner border of hemstitching, and a small pocket, feather-stitched all round, in the centre. This white linen is placed in the middle of the pink as seen in Fig. 2, and the edges of the latter are carefully hemmed down over it. A yard of strong white ribbon, an inch and a half wide, is then sewn on the outside near the initials as shown in Fig. 1. Be careful to notice that one end is long and the other short. When in use this case is spread out, like an apron, on the lap, and the method of folding is shown in Fig. 4. All the work materials are inside, and the little pocket contains thimble, scissors, etc. Roll it up from the lower edge, pass the long end of ribbon round it twice, tie in a bow, and behold! everything is compact and neat.

“Cousin Lil.”

By Mrs. FRANK W. W. TOPHAM, Author of “The Alibi,” “The Fateful Number,” etc.

That very afternoon we set to work, moved our belongings into mother’s room, and dragged up the carpet in our own room. Ann washed the boards for us, while we went off to the stores for the stain. We had to wait till the next morning before we could begin our staining, but it did not take us very long to finish. Ann advised us to let her rub it over with boiled oil, and it certainly looked far better afterwards. That good-natured girl spent her afternoon in unpicking our old carpet to find the brightest pieces to turn into mats.

“Don’t you go down on your knees, miss, to dust these boards,” she impressed upon us more than once. “Where I lived last they had a deal of stained floors, and we always put our soft brooms into a bag of linen and dusted them with that.”

The servants worked very hard, as we did also, so that by the time cook was ready for her new place we had “spring-cleaned” the house all through, staining the floors of the three bedrooms we were using, and putting away all superfluous glass and china, as well as some ornaments and nicknacks.

By cook’s advice we decided to arrange the work as nearly as possible as she and Ann had worked. I, who had all my mornings free, was to be the cook, while Cecilly, who had her music lessons to give, called herself “house-parlour-maid.” Of course, we were always ready to help each other in every detail, and I feel sure that servants would find their work much lighter and pleasanter if only they would work together. The variety even would make it pleasanter, at least, so Cecilly and I found.

It was rather an effort to turn out of bed at half-past six the first morning we were alone. I ran down in my dressing-gown and set light to the stove before I took my bath, so that when we were dressed the kettle was boiling, and we could have a cup of tea and some bread and butter before we began our duties. I stayed in the kitchen to prepare breakfast, while Cecilly went into the dining-room to sweep. I heard her making a great deal of noise, and when I was ready to help her, I could not help laughing at her preparations and efforts. She was scarlet and breathless with exertion, as she swept the carpet as if it were never to be swept again. She had moved every piece of furniture from its place that she could move, and would not believe that the heavy pieces were only moved out once a week on “turning out” days.

I took the broom from her and sent her for wood to light the fire, for the mornings were still chilly. Then we found the wood was damp, but we quickly dried it in the oven of the gas stove, and never afterwards did we forget to dry our wood directly we took it in.

We were just ready to ring the breakfast-bell when from upstairs came such a shouting from the boys, mingled with Jack’s voice, angry and stern, that we both ran out to see what was wrong, and to our dismay found water pouring down the staircase into the hall. We at last learnt that Phil and Bob, who had their bath in their bedroom, had, in order to be helpful, tried to carry it to the bath-room to empty, the result being they had overturned it on the landing. They were so sorry, and had been acting from kindness, not mischief, that we stopped Jack’s scoldings, and very soon we had sopped up the worst of the damage. Jack, however, insisted on their getting up as soon as we were down, so they could take their bath in the bath-room before he was ready for his.

Poor Jack! he did so hate our doing the work of the house, but Aunt Jane had taken him in hand and made him reasonable, and it was she who wrote to mother, telling her of our plan, and begging her to consent to our giving it a fair trial.

I cleared away the breakfast, while Cecilly ran up to air the bedrooms and beddings. Then together we washed up, and afterwards made the beds and tidied the bedrooms. Our house is a bright sunny one in West Hampstead, and the kitchen arrangements are all on the same floor as the living-rooms, which saved us many steps. One of Aunt Jane’s orders was, “Always have something hot for the boys’ dinner,” and she gave me a list of dishes I could prepare in the morning, and leave them to “cook for themselves.” The list was as follows.

Stewed Steak.—Put into your stew-pan a piece of dripping, two or three onions cut up, two or three carrots (according to size), lay your steak on the top of these, till all is a nice brown. Take all from the stew-pan and place in a brown jar (previously heated), add a few peppercorns, a pinch of spice, ginger, and three cloves, add sufficient hot water or stock to cover the meat, cover tightly, and leave in a cool oven for two or three hours. Before serving, strain off the gravy, thicken it with flour, heat to boiling in a saucepan. Put steak on dish and pour the gravy over. In preparing this dish our mistakes were—once we allowed it to cook too quickly, so that it was too hard; another time we cooked it too slowly, so that it was not done enough. We learnt that with all stews they must come to nearly boiling point, then put back just far enough to keep them from boiling.

Haricot Mutton.—Cook as above.

Steak Pudding, Steak Pie.—Beef steak answers perfectly for all these.

Canadian Steak Puddings.—Cut up two{727} pounds of steak into a pie-dish; pepper and salt freely. Pour on water just to cover steak. Take two ounces of suet, shred very fine; the crumb of a small loaf rubbed through a sieve. Mix together, moisten with milk, add two eggs well beaten, pour over the steak, and bake for two or three hours. This was a great favourite.

Curries.—Aitch-bone of beef stewed in the same manner as the steak, but not removed from the pan it is first put into. This requires stewing from four to five hours. When possible use weak stock instead of water, as it makes nicer soup for the following day.

But I must go back to our first day’s experience. We had just finished tidying the house when the door bell rang, and when I ran to open the door, there stood dear Aunt Jane with a lovely bunch of flowers “to help poor Jack enjoy his first dinner without a waitress.” She readily accepted my invitation into the kitchen, and it was certainly by her kind advice we were able to manage as well as we have. “Do you work regularly and methodically,” was one of her maxims we endeavoured to follow, which has smoothed our way considerably. We made a plan of the daily work, turning out a room each day. On the first day Cecilly turned out our room while I prepared the dinner. In the afternoon I was due at my old lady’s, to whom I read for two hours, and to amuse her I told her of our plan. I saw she was greatly shocked, and I never was able to convince her we had succeeded satisfactorily. As I was hurrying home I overtook the two boys, one carrying a brown paper parcel, the other what looked like a broom-stick.

They refused to satisfy my curiosity concerning their packages until we reached home and Cecilly had joined us. Then they disclosed to our view a carpet-sweeper, and on our exclaiming our delight and demanding to know how they had managed to get such a treasure, it came out that the dear old things had parted with their most cherished possession, having sold their stamp collection to a schoolfellow.

“Now Cecilly needn’t get so hot, need she?” asked Phil, but, on Cecilly rushing to hug them, they both fled to their own room, refusing to listen to our thanks.

“Mother is right,” I said to Cecilly. “Hard times have their bright sides. We should never have known how sweet the boys really were if there had been no necessity for their sacrifice.”

Our chief saving has been in the preparation of our food and in doing away with the early dinner. Luckily we have both such very good appetites that, eating heartily as we did at breakfast and dinner, there was no need for us to prepare a midday meal. Our luncheon consisted of anything we had to spare from the larder, sometimes of bread and cheese only, although we always indulged in a cup of hot cocoa afterwards. In the days when cook was in charge of the cooking I had to give her a special order for breakfast, either sausages, bacon, or fish. But now that I was cooking we learned (of course from Aunt Jane as well as by experience) to make out of scraps plenty of suitable dishes. We found the following most liked by the boys:—

Breakfast Pies.—Mince through the machine any scraps the larder affords (ham, cold bacon, cold steak, pieces left in meat-pies—in fact, anything that is quite sweet and wholesome). Boil a cupful of Quaker Oats. Mix all together, add flavouring of Tarragon vinegar, pepper, and salt. Line patty-pans with pastry, fill with mixture, cover with pastry.

Beef Brawn.—Mince any pieces of cold meat, season well with pepper and salt. Boil some weak stock, with an onion, one or two cloves, and spice if liked. While boiling pour over gelatine (previously soaked). Mix all together and pour into a mould. To be eaten cold. Half an ounce of gelatine to a pint of water. Sufficient minced meat to nearly fill a pint measure.

Mulligatawny Pâté.—Mince or cut any pieces of cold meat very fine. Add equal quantity of boiled rice (boiled in stock when possible), add a teaspoonful of curry-powder. Line pie-dish with pastry. Put in mixture, cover with boiled rice, and bake.

Macaroni and Tomatoes.—Boil macaroni in stock, add any scraps of meat, two or three tomatoes cut in slices. Can be eaten hot, baked in pie-dish, or poured into a mould to be eaten cold. All these dishes can be prepared the day before, and only require heating up in the oven.

We always had stock by us, boiling down at once any bones that were in the house, and keeping all liquor that meat had been boiled in. Not being fat eaters we melted down for dripping all we did not consume, and I have often cut off the fat from a joint before cooking it to use as suet for puddings. If we had to buy suet, we bought Hugon’s; it is cheaper and saves much labour in chopping than ordinary suet. But my advice to every housekeeper is, never throw away any fat, for every piece can be utilised.

Unfortunately none of us are fond of what the boys call “pap” puddings, and we had some difficulty in getting rid of our stale bread till Aunt Jane advised us to dip the pieces into milk and crisp them in the oven for the cheese course. The ones that were not eaten at dinner we broke up, ground through the coffee mill, and kept in a tin for when we were cooking fish, rissole, or anything that requires breadcrumbs or raspings. We also used our stale bread in fruit puddings. Fill a pudding-basin, previously well greased, with pieces of bread. Boil any fruit, such as currants, blackberries, etc., and while hot pour over the bread till the basin is quite full. Place a saucer or small plate on the top, stand a heavy weight on it, and leave till the following day. To be turned out and eaten cold.

Half-pay Pudding.—¼ lb. suet, ¼ lb. currants, ¼ lb. raisins, ¼ lb. flour, ¼ lb. breadcrumbs, 2 tablespoonfuls dark treacle, ½ pint milk. Boil for three or four hours. The longer this pudding boils the better it is. Apple charlotte, rhubarb charlotte, and Manchester pudding also used up our stale bread. It had always been a difficulty when cook was with us to choose a pudding the boys would not call “pappy;” and now that every egg represented a penny to us the difficulty was greater, till it occurred to Cecilly that we might substitute cakes for ordinary puddings, and the result was most satisfactory. We could use dripping, of course; and after a friend told us of “Paisley Flour,” there seemed no end to a variety of nice and inexpensive sorts.

The boys delighted in Ginger-bread.—1½ lb. flour, 6 oz. dripping, 1 teaspoonful carbonate of soda, 2 tablespoonfuls “Paisley Flour,” ½ lb. dark treacle (or more), ¼ lb. dark sugar, 2 teaspoonfuls ginger and ground spice, 2 tablespoonfuls vinegar, ½ pint milk. Dissolve the soda in a little milk, mix dry ingredients together, add treacle slightly warmed. Then pour in the soda, add the vinegar to the rest of the milk, stir all thoroughly, and bake immediately.

Vinegar Cake.—6 oz. dripping, ½ lb. currants or sultanas, ½ lb. moist sugar, 1 teaspoonful carbonate of soda dissolved in milk, 1¼ lb. flour, 2 tablespoonfuls “Paisley Flour,” 2 tablespoonfuls vinegar to about ½ pint milk. To be mixed in the same way as the ginger-bread.

Scones with raisins, plain scones, cheese biscuits, were all favourites; but as these recipes can all be made from the recipe for scones given with each packet of “Paisley Flour,” I need not write them. In one of the books that had so annoyed poor Cecilly in her search for advice how to manage without servants the lady had found her greatest difficulty in the door-answering; but that, I can assure you, never troubled us. Our friends came as often to see us as when Ann, in her flying white streamers, answered their knocking—in fact, they came more frequently, for it was no unusual occurrence for us to have three or four willing helpers in the morning to assist us through our work, Cynthia Marriott being our most regular assistant. Never was there a merrier, more laughing set of servants than we were, nor were there more elaborately decorated pies and tarts ever made than those made for Jack’s dinner by the fairest hands in the kingdom. Sometimes I think we might have bored the boys by our domestic interests, had it not been for Aunt Jane impressing on us constantly the importance of making their home-life a social one. It was often a trouble to leave the kitchen just before serving up the dinner to change into an evening blouse; but we always did so for fear the boys would grow careless in their dress, and constantly our helpers in the morning would run in after dinner to help make the evenings as merry as when we had servants to answer the door. But the work was work, although we could play over it at times. There were many backaches and weary feet, many hot, depressing days when even the gas stove suffocated us with the heat as we stirred a saucepan or opened the oven door; but we bore it all bravely, as who would not, when she felt she was, at least, trying to give back health to a father, and such a father as ours?

(To be concluded.)

It is now authoritatively declared by medical opinion that it is dangerous to moisten many postage stamps with the tongue. It may lead to cancer of the tongue and other serious complaints in the mouth or stomach; and the stamp margin paper should never be used to put over an open wound.

Meat baked in the oven is the cause of much indigestion.

Nothing makes a room look more untidy than blinds drawn up crooked, and faded flowers on the table. Cultivate a spirit of neatness in all the rooms, but especially those in which you receive your friends.

Loose sofa covers and spare blankets should be constantly inspected in summer, and periodically shaken, to prevent moths fastening on them.

Beds should never be placed against a wall except just at the top. If the side of a bed is against a wall, it cannot be properly made, nor can there be sufficient air moving around it for health.

It is well that one member of a family should keep a diary to record family and other events. These diaries prove valuable for reference in after years.

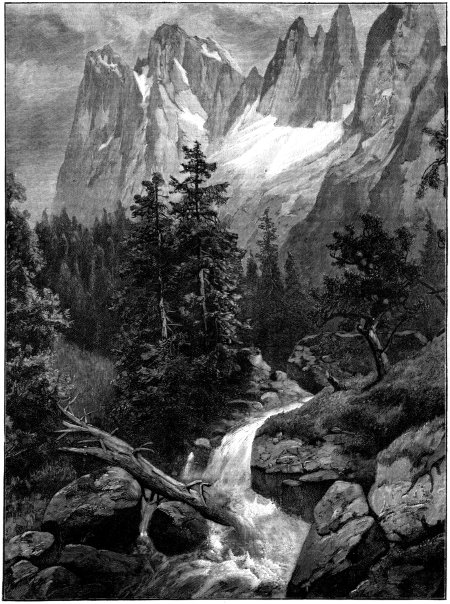

“THE HEARTS OF THESE OLD MOUNTAINS.”

{729}

By WILLIAM T. SAWARD.

The Temple.

My dear Dorothy,—I was very sorry to hear that your holiday had commenced in such a disastrous manner; but you were quite justified in leaving the furnished house which you had taken for a month at the end of the first week, when you found that the drainage was in a defective condition.

It is all very well for the landlord to threaten Gerald with proceedings to recover his rent for the three weeks which you did not stay at his house. There is an implied condition in the letting of a furnished house that it shall be reasonably fit for habitation; if it is not fit, the tenant may leave without notice.

No one could possibly assert that a house whose drainage was out of order was fit for habitation; so that, if your landlord is ill-advised enough to bring an action against you, you need have no fear of the result. But I fancy that he is only trying it on, and will abandon his claim when he finds that you are determined to resist it.

It was fortunate for him that you did not stay on in his house and contract typhoid fever, or something of the kind. If one of you had done so, you might have taken action against the landlord for damages and compensation.

What I have just written only applies to the hire of a furnished house. The law on the letting of furnished lodgings is quite different. There is no implied warranty that the lodgings shall continue fit for habitation during the term.

I know of a case where a friend of mine took lodgings at the seaside for his wife and family, and while they were staying there one of the landlady’s children became ill with scarlet fever; but, as she did not wish to lose her lodgers, the landlady concealed the fact of her child’s having the fever from my friend. The consequence was that my friend’s wife and child also became stricken with the fever, and he was put to a lot of expense for medical attendance, nursing, etc. But he was unsuccessful in an action which he brought to recover such expenses as damages, because the jury found that the house was healthy at the time of the letting. And the judges of the Appeal Court laid down the axiom that there is no implied agreement in the letting of furnished lodgings that they shall continue fit for habitation.

If a landlady were to let out lodgings knowing that one of the inmates of her house was suffering from an infectious disease, I have no doubt that she would render herself liable to a claim for damages if one were subsequently brought against her; and it may give you, my dear Dorothy, some satisfaction to learn that she would certainly be liable to a criminal prosecution involving a heavy fine or imprisonment.

“Trespassers will be prosecuted” is a notice which one frequently sees in the country; but it is an empty threat. Provided you are careful to do no damage to the grass, you may trespass as much as you please. Very often you will find such notices stuck up in fields over which there is a right of way. In such cases the notice simply means that you should keep to the footpath and not trample down the grass. It has been said that it is no offence to take mushrooms, blackberries, primroses, or wild plants of any kind or to trespass to find them.

Of course this only applies to mushrooms which are growing wild; but it still applies even when such mushrooms may be a source of profit to the owner of the field, provided they are growing wild and not in a state of cultivation.

At the same time I ought to warn you that the farmers do not regard things in a purely legal light, and they generally manage to make themselves exceedingly unpleasant to the people whom they find trespassing over their lands. I am bound to say that personally I sympathise with the farmer to a certain extent.

The law does not regard professors of palmistry with a favourable eye; on the contrary, it is inclined to class them as “rogues and vagabonds,” although it is true that a prosecution of two professors of the art in Yorkshire was not upheld on appeal and the conviction was quashed. I do not think, however, that the followers of the art have much cause to congratulate themselves on this decision as, at any rate, the London magistrates have a very summary method of disposing of those who are brought before them charged with practising “certain subtle crafts, means and devices by way of palmistry, and imposing upon Her Majesty’s subjects.”

Your affectionate cousin,

Bob Briefless.

{730}

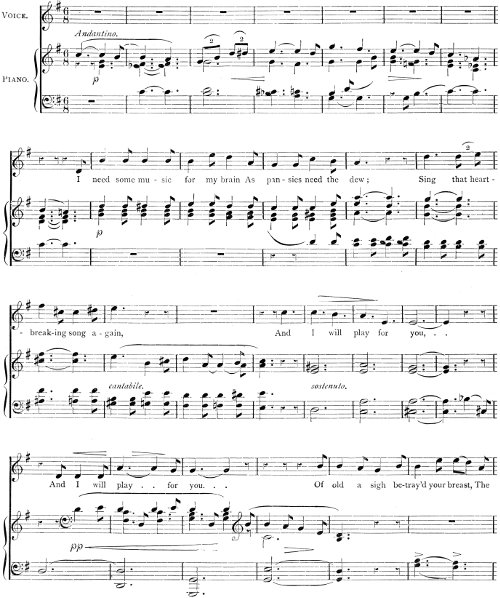

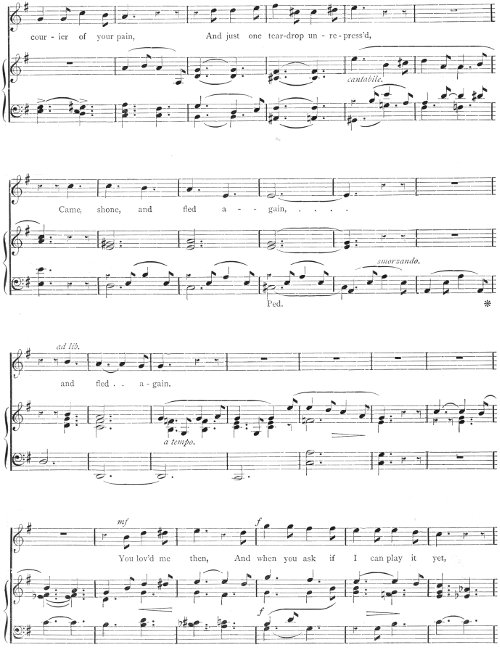

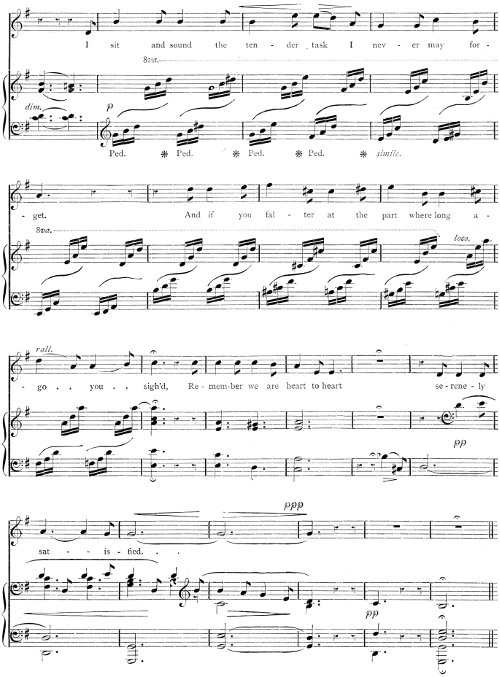

(Song, Introducing Theme of Chopin’s Nocturne in G Major.)

Words by Norman R. Gale. Music by Thomas Ely, Mus. Bac., F.R.C.O., London.

{733}

By ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO, Author of “Other People’s Stairs,” “Her Object in Life,” etc.

THE MANNERS OF A MISTRESS.

he little excitement in the street centred round the Marvels’ house. Two policemen were standing at its door, and an inspector with his note-book was just inside talking to somebody out of sight.

“I wonder if it is anything wrong about Jane Smith,” remarked Lucy.

“Perhaps the tipsy young carpenter has turned up there at last,” said Tom. While they watched, Lucy and Miss Latimer told Mr. Somerset the story of their midnight alarm.

“They’re all looking across here! They are coming over,” cried Hugh. He was right. In a moment a heavy official knock sounded on the hall door.

“I shall answer it myself,” said Lucy. “Clementina is busy, and, besides, the sight of all these legal functionaries would terrify her out of her wits.”

The others all followed in her train, Hugh clinging to his mother’s skirts.

“There has been something wrong over at Number 14, ma’am,” the policeman explained. “Their servant has run away with some property. We understand she was in your service before she entered Mrs. Marvel’s, and we want you to kindly answer a few questions about her—if you can.”

“I will tell you all I can,” returned Lucy.

“Thank you, ma’am. Was the girl Jane Smith long in your service?”

Lucy considered. “Only for about five months,” she said, “a little more I think.”

He made a note in his book.

“Where did you get her from, ma’am? Excuse me.”

“I got her through a registry office,” Lucy replied, naming it.

“Took her in a hurry, without any references perhaps, ma’am,” observed the inspector.

“Certainly not,” answered Lucy. “I went to her last employer,” and Lucy furnished her name and address. The man wrote them down.

“Character good then, I suppose?” was the next remark.

“The character was satisfactory, or I should not have taken her,” said Lucy.

“Can you be sure you got the girl whose character you received?” he asked. “You know there is such a thing as personation; and the name is a common one.”

“There is no mistake on that score,” Lucy replied. “Jane Smith herself opened the door to me when I went to inquire for her character.”

The man was writing again. “And may I ask why you parted from her?” he went on.

“She gave me notice herself because she knew she had displeased me. I had allowed her to receive a weekly visit from the young man to whom she was engaged, and then, without the least interval, or any intimation given to me, the man was changed!” Lucy was almost startled by the unshrinking directness of her words.

There was a little movement between the two policemen on the doorstep, and a sort of ejaculation from Tom in the rear. Lucy, looking aside from her questioner, recognised in one of his subordinates the policeman who had found Jane’s discarded lover in her area. He made a smiling salute, and said something in a low tone to his superior.

“I understand one of these men has since been found in your area in the night?” the inspector inquired.

“Yes,” said Lucy, “your man found him and removed him.”

“Have you any reason to think he was there for any nefarious purpose?” asked the inspector.

“No; he was quite tipsy,” said Lucy. “He did not know what he was doing. I thought it was only a mistake.”

“Are you sure he was quite tipsy?” urged the inspector.

“Your man and my friend said so, and I could see he could scarcely walk,” Lucy answered. “It was at my request only that your man did not take him in charge. I thought he was in trouble through being deserted by this girl.”

“There’s often more than meets the eye at the bottom of these here love affairs and troubles,” said the unromantic inspector; “it might have done that youth and other folks too some good to have had it all out in court. But there’s no saying. Even there such things can’t be always looked into as deep as they should be.”

He wrote in his book. His next question was—

“Did you tell Mrs. Marvel why you had been dissatisfied with this girl?”

“She never asked me,” answered Lucy. “She sought no character from me.”

The inspector half smiled and gave his head a knowing little wag. He closed his book. “Thank you, ma’am. That’s all we need ask now. If any other point arises on which we think you may throw light, you’ll excuse our coming to you. We’re sorry to have had to disturb you, especially to-day.”

“You are only doing your duty,” said Lucy. “Good morning.” As she turned back into her little hall—Clementina’s rueful countenance, gleaming pale in the background—Lucy thought that this was for her a very mild disturbance indeed, as compared with the wreckage of last Christmas Day. It might indeed be otherwise with the Marvels? Yet Lucy could not avoid the reflection that they had, in a manner, brought this trouble on themselves.

The little dinner-party passed off very pleasantly. Clementina had done her part admirably, and everybody was resolutely talkative and bright. Even Lucy brought herself to say that perhaps it might be better still if Charlie arrived for New Year’s Day, since that would be an inauguration of a new order of things, while, socially considered, Christmas is rather a festival of the past.

After dinner in the little drawing-room, Hugh was the centre of all attention, as children always are at Christmas time. Games of the kind in which he could take largest share were the order of the day. In one of these Tom Black was dismissed from the apartment to wait outside till those within should summon him to rack his brains to discover “what their thought was like.” When they shut him out, they left him planted on a little table, which stood on the only half-lit landing. But when they opened the door to call him, he was not there!

“I believe he is so honest that he feared he might catch what we were saying, and he has gone down to his own room,” said Lucy. “Tom!” she cried. But as she did so she heard a sound of voices in the hall. Tom was there and Clementina was talking to him.

He answered, “Coming, coming!” and came running up. He dashed into the game with great spirit, but nevertheless seemed a little absent-minded, and proved so dense that he had to be told what he ought to have guessed, which was very unusual with Tom. After that, Lucy suggested that they would not begin another game till they had had tea, which was just coming in. The little service stood in readiness. Clementina had only to carry up the kettle and the tea-cakes. In this interval, Tom suddenly proposed to Mr. Somerset that they should take a few minutes’ turn in the street. “For a breath of fresh air,” he said.

The gentlemen did not stay out for quite half an hour. Hugh peeping from the window announced that he saw them walking up and down, talking. They nodded up to him, and they came in a few minutes afterwards. Lucy served them with cups of tea, and then all again went merrily till it was time for Lucy to take Hugh off to bed. She did not require to apologise to these friends for leaving them together while she discharged her happy maternal duty.

Mr. Somerset stood on the middle of the rug with his back to the fire. Miss Latimer settled herself in the easy-chair to resume the knitting which she had thrown down during the games.

“Miss Latimer,” said Mr. Somerset rather abruptly, “I don’t think you are a nervous woman.”

{734}

The old lady laughed, deftly shifting her needles.

“I don’t think so,” she answered.

“Because if we are to believe what Clementina says, some evil attention is being directed to this house, which can have no other aim but to annoy and terrify, perhaps with hope of robbery at last,” he explained.

Miss Latimer was all interest.

“The servant says,” pursued Mr. Somerset, “that every morning, early, for more than a week past there have been heavy blows on the area door. They have always been struck while she was out of sight in the back kitchen. She has hastened to respond to them, but by the time she reached the door nobody was there. She says that for the first day or two, she thought that whoever had knocked must have hurried away, though she could not understand how they could get up the area steps so quickly. Afterwards she says she lingered longer in the front kitchen, so as to be there when the knocks came. But they never came while she was there—only at the moment when she turned her back. Next she ran to the window so quickly that she is sure there was no time for anybody to get away. Yet nobody was there.”

“Ran to the window!” echoed Miss Latimer. “Why didn’t she go to the door?”

“She says she was frightened,” answered Mr. Somerset.

“Does the window command every corner of the area?” asked the old lady. “Possibly some mischievous boy gave the knock and then stood back against the wall.”

“That’s what I said,” remarked Tom Black, “but Clementina made me go down into the kitchen and put my head where she said she had put hers, pressed against the window, and certainly nobody—not even a cat—could have been in the area without my seeing them.”

“Why didn’t Clementina tell us about this before?” asked Miss Latimer. “Why did she keep it back to tell us to-day?”

“She says she didn’t want to worry her mistress,” said Tom. “But after hearing what has gone wrong at Mr. Marvel’s house, and seeing the policemen come here making inquiries, she thought it might be best for some of us to know it at once. So when she saw me standing on the staircase, she took the opportunity of calling me downstairs and telling me the whole thing.”

“Very considerate indeed,” observed Miss Latimer. “So many servants take delight in rushing forward with bad news or worries. I was afraid the policemen’s visit alone would prove too much for Clementina. I do hope she won’t get flurried into leaving—for she seems a treasure in so many ways. Was she much disturbed?”

“No,” said Tom reflectively. “No, she took it quite sensibly.”

“Perhaps, as you say she is a superstitious woman, she accepts the mysterious as a natural factor in ordinary existence,” observed Mr. Somerset.

Tom was still meditative.

“Now I come to think of it,” he said, “there was something funny happened two or three weeks ago, though we didn’t think much of it at the time. Do you remember the blank letter, Miss Latimer?”

“Yes, indeed,” cried the old lady. “Mrs. Challoner received a very ill-written envelope, which we thought must contain a bill due to a bricklayer who had been lately employed. But there was nothing in the envelope save a sheet of blank paper. Still we thought the man must have put this in by mistake, till he presented his bill in person a few days afterwards, and then Lucy asked him if he had sent it in before, and he said no, he had made it up only that morning.”

“Is Mrs. Challoner to hear about these knocks?” asked Tom.

“Why not?” said Miss Latimer. “It was good of Clementina to keep silence about what she thought might annoy her mistress. But Lucy would not feel any worry over such a thing as this.”

“You see,” said Tom speaking with bated breath, “Clementina said now this had come out about the Marvels’ servant, it might be to do with them. But at first she had thought that it might be a sign that—that—something had happened to Mr. Challoner, and that was why she wouldn’t speak!”

“Oh, nonsense,” returned Miss Latimer. “We must not let her suggest this idea to Lucy—not till Charlie is here safe and sound. But we won’t have any mysteries or keepings back. A sensitive nature suffers more from those than from the sternest revelation. Even when there’s real trouble in question and somebody thinks to hide it out of kindness, he has to hide his true self at the same time, and that generally gives greater pain than anything else could.”

“We’ll tell Mrs. Challoner all about it the minute she comes back,” decided Mr. Somerset.

“That’s right,” said Miss Latimer. “If one’s bothers reach one through friendly hands two-thirds of their poison is drained off.”

“I say,” remarked Tom, “I don’t believe the dining-room waste-paper basket has been emptied lately. This morning I noticed it was very full. I shouldn’t wonder if the envelope in which that blank sheet came is still there. I’ll go down and look for it.”

Tom was still prosecuting this search when Lucy came back to the drawing-room. She heard the story of the knocks with interest rather than with alarm, and was rather inclined to think they might be due to Clementina’s “nerves.” When Tom appeared with the torn envelope they all discussed it quite cheerily, speculating whether the handwriting was that of a man or a woman. Lucy thought it was that of a man—possibly a man accustomed to use clumsier tools than a pen. She clung to her original suspicion of the tipsy young carpenter. Miss Latimer declared that one or two of the characters looked of feminine construction, while Mr. Somerset remarked that some of them seemed to him to be far too well formed to be in natural keeping with the wild distortion of the rest.

This envelope having been thus accidentally preserved, it was now decided, in view of the later developments, that it should be kept for a while longer. It was given into Tom’s charge, and he locked it away in his desk. Mr. Somerset advised that if the inspector should pay Mrs. Challoner another visit over the Jane-Smith-and-Marvel matter, she might do well to mention to him this strange blank missive and the mysterious knocks.

Also, before he went away, he and Mrs. Challoner together had a little conference with Clementina. They told her that there was nothing to be alarmed about, and while thanking her for her original consideration in the matter of the uncanny knocks, they urged her henceforth to tell promptly of any happening which might strike her as peculiar.

“It’s well I’m not a silly girl,” was Clementina’s remark. “I don’t like to be mixed up in strange ongoings, nor to see policemen coming to the door of the house where one lives. But what one’s born to, that one must go through. We all have our enemies, and if they don’t hurt us in one way, they will in another. I reckon those knocks ain’t meant to call for Clementina Gillespie.” There she paused, but glancing at Mr. Somerset, she read warning in his eye, and said no more.

The next morning brought two events. The first was an intimation by post of Mr. Bray’s death at Bath. The second was a call from Mrs. Marvel, who sent up her card, with an apology for intruding on her neighbour at an unconventionally early hour.

“Those who won’t make inquiries at the right season, naturally make them at last at the wrong time!” observed Tom.

“Yes,” said Miss Latimer, “as Goethe says—

Lucy knew Mrs. Marvel by sight, prim and stately. But this morning she was a very perturbed and dishevelled lady. She had called to thank Lucy for having been interviewed on her behalf by the policemen.

“So kind of you, Mrs. Challoner. After I had sent them across, it occurred to me how rude and selfish it was—on Christmas Day too! But really you will pardon me, considering the state I was in. Imagine our coming home from church to find the house not only deserted, but with all the silver I had put out for the Christmas feast carried off, with a salver which Mr. Marvel got as a testimonial, and the very brooches which we had left sticking in our pin-cushions! After that, what did it matter that not only was no dinner prepared, but the turkey itself was taken away. And we had friends coming, among them the gentleman who is engaged to our youngest daughter.”

“It was very trying indeed,” said{735} Lucy gently. “I have never suffered quite so bitterly, but I have suffered enough to know how it must have felt.”

“I suppose you can’t give us any other clues about the wretched girl,” panted Mrs. Marvel. “The police have already been to her former mistress’s house, and it is empty. It is said the people are gone abroad. You didn’t know anything of this girl’s family, did you?”

“She said she came from the country. She said her father had been a blacksmith. She named the village to me, but I own it escapes my mind just now,” Lucy admitted.

“Of course, one can’t be expected to burden one’s mind with such things,” said Mrs. Marvel.

“If she had stayed with me, I meant to have given her a summer holiday to visit her friends, and then I should have heard more about them,” Lucy remarked. “It is not easy to press questions without grounds. One has to rest satisfied at first with getting a character.” She paused rather abruptly, seeing that her remarks seemed to reflect on her visitor. But Mrs. Marvel was undisturbed by them.

“You didn’t detect her in any dishonesty while she was with you?” she asked.

“No, not the slightest,” said Lucy.

Mrs. Marvel looked compassionately at her hostess. “Ah, poor dear,” she said, “you are young—and—and busy. I daresay she plucked you a little without your noticing it.”

“She may have done so,” said Lucy quietly; “I do not claim notability as a housewife. But I have my household lists, and when I went over them before she left, everything was right.”

“We hear that it is true she did dismiss herself,” Mrs. Marvel went on. “Did you really feel enough dissatisfaction and distrust to have dismissed her if she had not done so?”

“Certainly,” Lucy answered, “unless she could have given a full and satisfactory explanation—which I cannot imagine—of how, when I had given her permission to receive her sweetheart, I was left to find out that another man had suddenly appeared in his stead.”

“I doubt if it’s wise to let these girls’ sweethearts come near one’s house,” remarked Mrs. Marvel. “I never allow it. I never permit any visits but from relations.”

“I saw Jane Smith’s second lover go down your area steps many times,” said Lucy.

“I know he did. She told us he was her uncle, lately widowed, and that he came every week to bring and take away the mending she did for him.”

Lucy could not wholly restrain a smile as she thought of the shouts of laughter which announced this bereaved “relative’s” earliest appearances in her own kitchen.

“Now, my dear Mrs. Challoner,” said Mrs. Marvel, in her most unctuous manner, “don’t think I want to reproach you in the least; but when you felt this girl to be so untrustworthy, and when you saw her in a neighbour’s service, don’t you think you would have shown a neighbourly and Christian spirit if you had dropped us a word of warning about her?”

This was a little too much! Lucy rose and towered over her seated visitor.

“No, Mrs. Marvel,” she said, “certainly not. Any such interference of mine would have been most gratuitous and uncharitable. I should have deserved the soundest snub you could have given me. I had been the girl’s employer, and you had not chosen to use the proper method of communicating with me about her. That meant either that you did not value my opinion in the least, or that you had some other reason for your action. You might, for all I knew, have received a full confession from Jane Smith, and so have determined to give her another chance. Even then, of course, it would have been right and best for you to communicate with me. If I had retained her in my service after I distrusted her, and had sent her to your house on messages, and then she had robbed you, you might have good reason to complain. But certainty not now. You knew she had left my service and you never cared to inquire why or how!”

“She said she had dismissed herself, and you own that was true,” said Mrs. Marvel, also rising, and allowing the vinegar of her nature to overcome the oil in her tones. “And she said she had done so because she wanted to live where the mistress did not have to go out to work, but was able to pay proper attention to her housekeeping. That seemed reasonable enough. She said she wanted to get on, and girls can’t get on under such circumstances.”

Lucy walked to the door and opened it. Before her eyes, in that brief journey, there floated a phantasmagoria of the Marvel women daily starting for their afternoon calls, of the perpetual evening outings of the whole family, of their bed-chamber curtains often undrawn till near noon! And yet these women had their stone ready to fling at her, because in the power of all the womanliness in her, her duties had swerved aside from the narrower groove. But she commanded herself to perfection!

“I think I have told you all I can,” she said. “If the inspector finds any other questions, I will do my best to answer them. This is my holiday time, and from what you say, Mrs. Marvel, I am sure you realise how much I must appreciate holidays. Good morning.”

She had rebuked the vulgar woman without losing either dignity or temper. Yet she went back pale and trembling to Miss Latimer. Every glimpse of the world’s falseness and cruelty is itself cruel!

(To be continued.)

French Canadian.—A year’s board at Leipsic and tuition at the Leipsic Conservatorium will cost you, with due economy, from 1350 to 1800 marks (£67 10s. to £90). If you write “An das Directorium des Königl; Conservatoriums der Musik, Leipsic, Germany,” you will receive a small pamphlet in English, containing the most explicit details.

Gertrude A. Simpson.—November 21st, 1881, was a Monday. Many thanks for your kind letter of praise. We insert your request.