Title: Youth, Vol. I, No. 6, August 1902

Author: Various

Editor: Herbert Leonard Coggins

Release date: June 7, 2021 [eBook #65540]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: hekula03, Mike Stember, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 6

1902

AUGUST

An ILLUSTRATED MONTHLY JOURNAL for BOYS & GIRLS

The Penn Publishing Company Philadelphia

| FRONTISPIECE (Polly’s Letter) | Ida Waugh | PAGE |

| A BATTLE WITH A WINDMILL | Frank H. Coleburn | 197 |

| WITH WASHINGTON AT VALLEY FORGE (Serial) | W. Bert Foster | 201 |

| Illustrated by F. A. Carter | ||

| MARY LANE’S HIGHER EDUCATION | Marguerite Stables | 210 |

| Illustrated by Ida Waugh | ||

| LITTLE POLLY PRENTISS (Serial) | Elizabeth Lincoln Gould | 214 |

| A NOVEL WEAPON | 220 | |

| HOW PLANTS LIVE | Julia McNair Wright | 221 |

| Illustrated by Nina G. Barlow | ||

| A DAUGHTER OF THE FOREST (Serial) | Evelyn Raymond | 223 |

| WOOD-FOLK TALK | J. Allison Atwood | 230 |

| THE OLDEST COLLEGES | 231 | |

| WITH THE EDITOR | 232 | |

| EVENT AND COMMENT | 233 | |

| OUT OF DOORS | 234 | |

| THE OLD TRUNK (Puzzles) | 235 | |

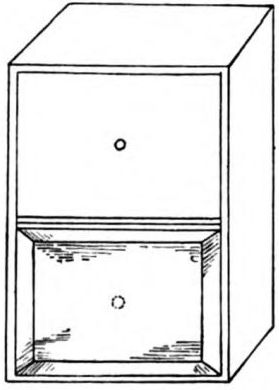

| IN-DOORS (Parlor Magic, Paper VI) | Ellis Stanyon | 236 |

| WITH THE PUBLISHER | 237 |

An Illustrated

Monthly Journal for Boys and Girls

SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION $1.00

Sent postpaid to any address Subscriptions

can begin at any time and must be paid in advance

Remittances may be made in the way most convenient to the sender,

and should be sent to

The Penn Publishing Company

923 ARCH STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA.

Copyright 1902 by The Penn Publishing Company

VOL. I August 1902 No. 6

By Frank H. Coleburn

SHORTLY after I left college, my father died, leaving me, his only son, so well-nigh penniless that I was very glad, indeed, to accept the position which Mr. Eller, an old friend of the family, offered me in his vineyard.

My benefactor’s home was in southern California, a region where the people’s livelihood depends upon grapes and wine-making.

One day, not long after my arrival, the big windmill, which supplied the whole winery with water, got out of order and refused to pump. Mr. Eller examined it carefully, but was unable to learn where the difficulty lay. He came down from the tank much disturbed, for water was a great necessity in that dry country.

“Harry,” he said to me, “you’re something of a mechanic, aren’t you?”

“I did pay a little attention to the study at one time,” I answered, modestly.

“Well, I wish you would try what you can do in the way of fixing that windmill.”

I promised that I would, and Mr. Eller left me.

After supper that night I secured a hammer and a chisel and started for the windmill. I had need to make haste if I expected to accomplish anything that evening, for the days were shortening and already darkness was falling.

The windmill stood some two or three hundred yards from the house directly behind the wine cellar. It was about seventy-five feet high—from the base to the top of the wheel—but in that deceptive twilight it looked like some giant finger reaching to the sky.

I stuck my tools in my coat pocket and began to climb the long ladder which stretched to the top of the tank. From thence it would be easy to reach and manipulate the wheel.

I made the ascent in safety, and after a little stood on top of the rough boards with which the tank was covered. For some time I stood, admiring the splendid view and wondering at the extent of country that came under my gaze, until warned by the ever-increasing gloom that I was out on business, not pleasure.

I forget just what was the matter with the wheel. Some simple disarrangement of the machinery which took me but little time to ascertain and less to remedy. Feeling certain that the mill would now perform its duty as well as before, I turned to retrace my way. In doing so I stepped upon a half-concealed trap-door, intended to be used as a means of ingress into the tank in case of repairs being needed. This door was old and rotten; its hinges were broken and it rested very insecurely upon its foundation. Consequently, it was unable to retain my weight and tilted suddenly. I fell with a prodigious splash into the water beneath.

There were about two feet of water in the tank. I gurgled and sputtered and struggled as though there were twenty. However, I quickly regained my feet, dripping and shivering, and very much confused from my sudden immersion, but uninjured. I was a prisoner, however.

The tank was about ten feet in height. The sides were perfectly smooth and afforded no foothold. There was no ladder or other means by which I could clamber out. I vowed that if ever I built a tank I would provide in some way for such an emergency as the present.

About three and a half feet above my head was the supply pipe. It extended a little ways into the tank. If I could only manage to reach that I might possibly pull myself up and escape. I knew perfectly well I could not reach it, but hope, like love, is blind to all obstacles, and I jumped desperately for it. I failed, of course. I didn’t come within a foot of it. However, after I had continued my effort for some time I began to feel a comfortable warmth creep over that portion of my body which was above water. Therefore, in lieu of anything better to do, I kept on jumping.

By and by my teeth stopped chattering—somewhat—and I stopped leaping altogether.

“Here’s a pretty mess,” I said to myself. “I wonder how long I’m to be penned up in this place. Goodness knows my legs are tired enough already without having to stand on them all night; and I can’t very well sit down in two feet of water.”

It suddenly occurred to me that I possessed a voice of tolerable strength and clearness, and that I might make good use of it upon the present occasion. Accordingly, I gave utterance to a few of the most startling shouts that probably ever assailed the ears of a mortal. But they were unsuccessful so far as escape was concerned.

After I had shouted myself hoarse, I waited with patience for the arrival of a relief party. At the end of five minutes it hadn’t come; at the end of half an hour I didn’t believe it would come.

“Surely,” I thought, “they must have heard those war-whoops at the house. At any rate it’s about time Eller started out to hunt me up. He certainly don’t think it’s going to take me forever to fix his plaguey windmill.”

I was becoming worried. The prospect of having to remain cooped up in my present narrow quarters all night was by no means pleasant. The expectation of having to stand for the next ten hours in two feet of cold water was not pleasing to a person of my tastes. It might have done for one of those old-time monks, who were always imposing penances upon themselves for sins committed, but it was not suited to my constitution. Most cheerfully would I have resigned my position to any one expressing a wish for it.

It was now pitch-dark in the tank. The only light I obtained was the feeble glow of the stars shining through the trap-door. I stood under this, gazing up wistfully into the heaven so high above me. After a time my eyes grew heavy, my head fell forward onto my breast, and, strange as it may appear, I dropped off into a gentle doze. I was awakened by a slight breeze fanning my cheek.

I opened my eyes dreamily. Overhead I could hear a deep, rumbling, grating sound; something going up and down, up and down, as it were a monstrous churn in motion.

“What can that be?” was my ejaculation. I was not left long in suspense. A perfect deluge of the coldest kind of water came pouring down over me, drenching me to the skin; giving me, in fact, a regular shower-bath.

The stream continued without abatement, and I soon recovered sufficiently from my momentary astonishment and confusion to move out of the way. No one should say that I did not know enough to come in when it rained.

As yet I was hardly awake. I stood to one side, getting splashed, and stupidly staring at the supply pipe, which was belching forth water. Then the solution of the problem flashed through my brain. The windmill was pumping.

I was too startled at first to realize my peril. But gradually it dawned upon me that the water was rising fast, and that if I did not escape or relief did not come, in the course of a few hours I would be drowned like a rat in a trap.

I thrust my hand into my trousers pocket and pulled out my knife. The large blade was open in a second, and I was at work with all my might trying to dig a hole through the side of the tank. I quickly saw that my task was hopeless. The wood was soft, but the planks were very thick, and it would be hours before I could produce the smallest opening.

I must have something to occupy my attention, else I would go wild. So I dug on till I broke my blade off short.

I dropped the useless knife into the water. It sunk with a dull splash. I stood feeling the water slowly creep its way upwards. I calculated that I had about an hour and a half of life left to me.

The water reached my waist. I threw myself against the walls of my prison, shouting for help. But none came. The sound of my voice echoed again and again into my own ears—it reached no others. I thought the reverberations would never cease. It seemed to me as though the whole world must have heard that despairing cry.

I listened—every nerve strained to catch some echoing shout. But the only sound that broke the stillness was the steady, incessant splash, splash, splash of falling water; and the heavy noise of that great pump working overhead. I called and listened again. Still no answer.

My past life came up before me like a dream. I could see my mother—my good mother—as plainly with my mind’s eye, as I had ever seen her with the flush of life upon her cheek. I remembered the long confidential talks we had together and the many times she told me to be good and true and noble, and that was all she would ever ask. Then I recalled many of the things I had said to her, and, strange to tell, there dwelt in my recollection not the kisses I had given nor the love I had bestowed upon her: I could call back only my unkind, cruel remarks, and the heartbreaks I had caused her. I thought what a wretch I had been, and did not believe that we could ever meet in heaven.

The water was up to my shoulders now, but I hardly noticed it.

My thoughts turned upon my father—so recently deceased. I remembered his kind face, his noble brow, those premature wrinkles, and that iron-gray hair. His failure, which had been the cause of his death, was more the result of a lack of business instinct than anything else. His tastes—like mine—had been wholly literary.

The water was up to my neck. Ugh! how icy-cold it was—right from the bowels of the earth. It seemed to freeze my blood. Ah, how stealthily it crept up, little by little, inch by inch. It knew it had a victim in its grasp, and had no fear of being cheated of its prey. In another moment it would be at my mouth; another instant and it would be all that I could do to breathe on tiptoe; another short minute and—I turned and furiously beat again upon my prison wall with both my fists. What madness! my eyes were almost starting from their sockets; I imagined that they had the strange, hunted look of a poor rat when cornered. I could understand the feelings of the little creature now.

My hands fell nerveless to my side. They struck upon something hard in either pocket of my coat. I thrust them in—almost unconsciously, and drew forth—the hammer and the chisel.

I uttered a cry of delight, and in another moment I was chiseling away for dear life under water. In no time I had hacked out two rude steps. I formed another just above the surface of the water, another still higher, and another as high as I could reach.

The water was to my nose. I dropped my tools and by the aid of nail and hand and foot managed to draw myself up step by step, until I could grasp the edge of the trap-door. Thus much accomplished, it was an easy matter to lift myself out. I fell, panting and trembling in every nerve, upon the rough board covering of the tank.

Mr. Eller had not heard my shouts for the simple reason that he had been called by business into Fresno. The men slept in a house too far distant from the windmill for my cries to reach. Thus it was that I had been allowed nearly to yell my voice away without attracting attention.

I had had a pretty good scare it must be confessed; so good, indeed, that I have forever ceased to emulate Don Quixote in any more adventures with a windmill.

By W. Bert Foster

The story opens in the year 1777, during one of the most critical periods of the Revolution. Hadley Morris, our hero, is in the employ of Jonas Benson, the host of the Three Oaks, a well-known inn on the road between Philadelphia and New York. Like most of his neighbors, Hadley is an ardent sympathizer with the American cause. When, therefore, he is intrusted with a message to be forwarded to the American headquarters, the boy gives up, for the time, his duties at the Three Oaks and sets out for the army. Here he remains until after the fateful Battle of Brandywine. On the return journey he discovers a party of Tories who have concealed themselves in a woods in the neighborhood of his home. By approaching cautiously to the group around the fire, Hadley overhears their plan to attack his uncle for the sake of the gold which he is supposed to have concealed in his house. With the assistance of Colonel Knowles, who, although a British officer, seems to have taken a liking to Hadley, our hero successfully thwarts the Tory raid. No sooner is the uncle rescued, however, than he ungratefully shuts the door upon his nephew. Thereupon Hadley immediately returns to the American army and joins the forces under that dashing officer, “Mad Anthony” Wayne. In the disastrous night engagement at Paoli our hero is left upon the battlefield wounded.

THE sun shining warmly upon his face through the rapidly-drying bushes which during the night had partly sheltered him, was Hadley’s first conscious feeling. Then he felt the dull pain in his leg where the spent ball had become imbedded, and he rolled over with a groan. The wood lay as peaceful and quiet under the rising sun as though such a thing as war did not exist. Here and there a branch had been splintered by a musket ball, or a bush had been trampled by the retreating Americans. But the rain had washed away all the brown spots from the grass and twigs, and the birds twittered gayly in the treetops, forgetting the disturbing conflict of the night.

The boy found, when he tried to rise, that his whole leg was numb and he could only drag it as he hobbled through the wood. To cover the few rods which lay between the place where he had slept and the road, occupied some minutes. The wound had bled freely, and now the blood was caked over it, and every movement of the limb caused much pain.

Where had his companions gone? When the company rolls were called that morning there would be no inquiry for him, for he was not a regularly recruited man. He had been but a hanger-on of the brigade which was so disastrously attacked during the night, and they would all forget him. Captain Prentice was far away, and Hadley had known nobody else well among Wayne’s troops. The fact of his loneliness, together with his wound and his hunger, fairly brought the tears to his eyes, great boy that he was. But many a soldier who has fought all day with his face to the enemy has wept childish tears when left at night, wounded and alone, on the battlefield.

However, one could not really despair on such a bright morning as this, and Hadley soon plucked up courage. He got out his pocket knife, found a sapling with a crotched top, cut it off the proper length, and used it for a crutch. With this, and dragging his useless musket behind him, he hobbled up the road in a direction which he knew must bring him to the American lines, and eventually to Philadelphia. But such traveling was slow and toilsome work, and he was trembling all the time for fear he would fall in with the British.

He had not been many minutes on the way, however, when a man stepped out of the brush beside the road and barred his way. Hadley was frightened at first; then he recognized the man and shouted with delight.

“Lafe Holdness! How ever did you come here?”

“Jefers-pelters!” exclaimed the Yankee scout. “I reckon I might better ask yeou that question, Had. An’ wounded, too! Was yeou with that brigade last night that got bamfoozled?”

“The British attacked us unexpectedly. Oh, Lafe! they charged right through our lines and bayonetted the men awful.”

“I reckon. It’s war, boy—you ain’t playin’.” Meanwhile the man had assisted Hadley to a seat on the bank and with his own knife calmly ripped up the leg of Hadley’s trousers. “Why, boy, you’ve got a ball in there—as sure as ye live!”

“It hurts pretty bad, Lafe,” Hadley admitted, wincing when the scout touched the leg which was now inflamed about the wound.

There was a rill nearby, and to this the scout hurried and brought water back in his cap. With the boy’s handkerchief he washed the dry blood away and then, by skilful pressure of his fingers, found the exact location of the imbedded bullet. “Oh, this ain’t so bad,” he said, cheerfully. “We’ll fix it all right in no time. But ye musn’t do much walking for some days to come. Yeou can ride, though, and I’ve got a hoss nearby. First of all, I must git the ball aout and wash the hole. Ye see, Had, the ball lies right under the skin on the back of the leg—so. D’ye see?”

“I can feel it all right,” groaned Hadley.

“Well, it’s a pity it didn’t go way through. Howsomever, if you’ll keep a stiff upper lip for a minute, I’ll get the critter aout. ’Twon’t hurt much ter speak of. Swabbin’ aout the hole, though, ’ll likely make ye jump.”

He opened the knife again and, before Hadley could object, had made a quick incision over the ball and the lead pellet dropped out into his hand. The boy did not have a chance to cry out, it was done so quickly. “So much for so much,” said Lafe, in a business-like tone. “Nothin’ like sarvin’ yer ’prenticeship ter all sorts of trades. I ain’t no slouch of a surgeon, I calkerlate. Now, lemme git an alder twig.”

He obtained the twig in question, brought more water, and then proceeded, after having removed the pith from the heart of the twig, to blow the cool water into the wound. Hadley cried out at this and begged him to desist, but Lafe said: “Come, Had, yeou can stand a little pain now for the sake of being all right by and by, can’t yeou? It’s better to be sure than sorry. P’r’aps there warn’t no cloth nor nothin’ got inter that wound, but ye can’t tell. One thing, there warn’t no artery cut or ye’d bled ter death lyin’ under them bushes all night. I ’spect many a poor chap did die in yander after the retreat. Anthony Wayne’ll have ter answer for that. They say he’s goin’ ter be court-martialed.”

Having cleaned the wound, Holdness bound it up tightly with strips torn from the boy’s cotton shirt, and then brought up the horse which he had hidden hard by. He helped the boy into the saddle and walked beside him until they were through the American picket lines. The wounded had been sent on to Philadelphia, for there were few conveniences for field hospitals. “Yeou take that hoss and ride inter Philadelphy, Had,” said Holdness. “Leave it at the Queen and take yourself to this house”—he gave the wounded lad a brief note scrawled on a bit of dirty paper—“and the folks there’ll look out for ye till the laig’s well. I’ll git another hoss somewhere else that’ll do jest as well. Yeou can’t go clean back to Jarsey with your laig in that shape.”

It was a hard journey for the wounded youth, and before he crossed the Schuylkill and followed Chestnut Street down into the heart of the town, he was well-nigh spent. He fairly fell off the horse in front of the Indian Queen Tavern, and the hostler had to help him to the address which Holdness had given him. Here the good man and his wife—Quaker folk were they, who greatly abhorred the bloodshed of the war, yet were stanch supporters of the American cause—took the boy in and cared for him as though he was their own son. For a night and a day he kept to his bed; but he could not stand it any longer than that. The surgeon who was called to attend him declared the wound had been treated very well indeed by the scout, and that it was healing nicely; so what does Master Hadley do but hobble downstairs to the breakfast table on the second morning, determined no longer to cause the good Quakeress, Mistress Pye, the extra trouble of sending his breakfast up to him.

He was anxious to learn the news, too. Affairs were moving swiftly these days in Philadelphia. The uncertainty of what the next day might bring forth forced shops to close and almost all business to cease. The Whigs were leaving by hundreds; even the men who held authoritative places in the council of the town had departed, fearful of what might happen when the redcoats marched in. And that Washington could keep them out for long, after the several reverses the American troops had sustained, was not to be believed.

A sense of portending calamity hung over the city like an invisible cloud. A third of the houses were shut and empty. Many of the others were occupied solely by servants or slaves, the families having flown to the eastward. Hadley did not get outside the door of the Pye house that day, for he was watched too closely. But early on the morning of the 26th the whole street was aroused by the swift dash of a horseman over the cobbles; and a cry followed the flying messenger:

“The British are coming!”

The people ran out of their houses, never waiting for their breakfasts. Was the news true? Had the redcoats eluded the thin line of Americans that so long had stayed their advance upon the town? Soon the truth was confirmed. Congress had adjourned to Lancaster. Howe had made a feint of marching on Reading, and when the Americans were thrown forward to protect that town the British had turned aside and were now within sight. They had surprised and overpowered a small detachment left to guard the approach to Philadelphia, and—the city was lost! His Excellency was then at Skippack Creek with the bulk of his army, and the city could hope for no help from him.

Hadley, hobbling on a crutch, but too anxious and excited to remain longer indoors, soon reached Second Street. From Callowhill to Chestnut it was filled with old men and children. Scarcely a youth of his own age was to be seen, for the young men had gone into the army. It was a quiet, but a terribly anxious crowd, and questions which went unanswered were whispered from man to man. Will the redcoats really march in to-day? Will the helpless folk left in the city be treated as a conquered people? Why had Congress, spurred on by hot-heads, sanctioned this war at all? Many who had been enthusiastic in the cause were lukewarm now. The occupation of the town might mean the loss of their homes and the scattering of those whom they loved.

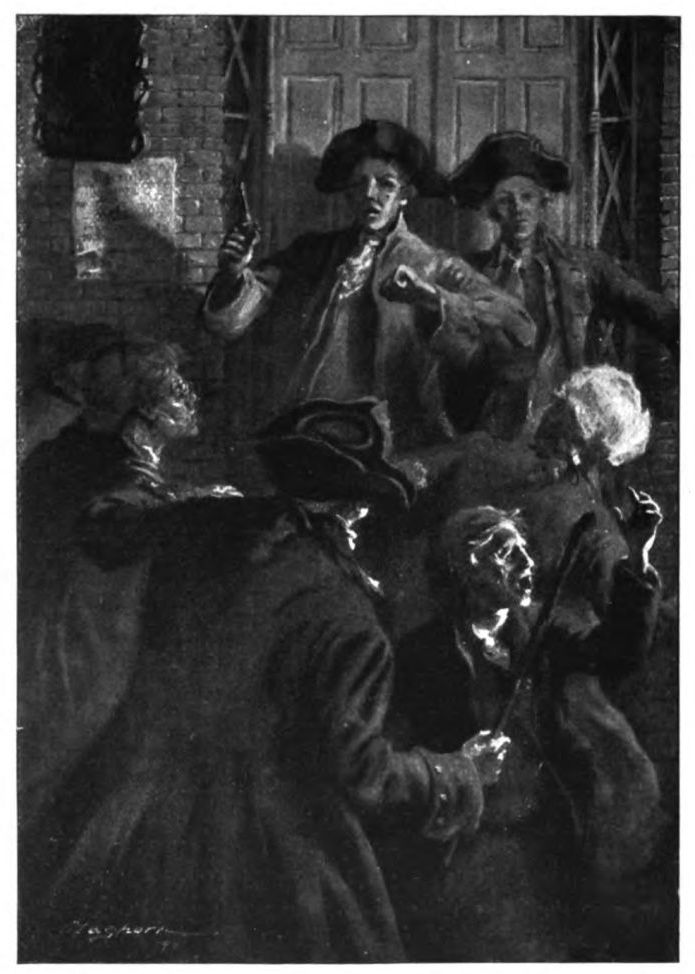

Here and there a Tory strutted, unable to hide his delight at the turn affairs had taken. Several times little disturbances, occasioned by the overbearing manners of this gentry arose, but as a whole the crowds were solemn and gloomy. At eleven o’clock a squadron of dragoons appeared and galloped along the street, scattering the crowd to right and left; but it closed in again as soon as they were through, for far down the thoroughfare sounded the first strains of martial music. Then something glittered in the sunshine, and the people murmured and stepped out into the roadway the better to see the head of the approaching army of their conquerors.

A wave of red—steadily advancing—and tipped with a line of flashing steel bayonets was finally descried. In perfect unison the famous grenadiers came into view, their pointed red caps, fronted with silver, their white leather leggings, and short scarlet coats, trimmed with blue, making an impressive display. Hadley, who had seen the nondescript farmer soldiery of the American army, sighed at this parade. How could General Washington expect to beat such men as these? And then the boy remembered how he had seen the same farmers standing off the trained British hosts at Brandywine, and later at the Warren Tavern, and he took heart. Training and dress, and food, and good looks were not everything. Every man on the American side was fighting for his hearth, for his wife, for his children, and for everything he loved best on earth.

Behind the grenadiers rode a group of officers, the first a stout man, with gray hair and a pleasant countenance, despite the squint in his eye. A whisper went through the silent crowd and reached Hadley’s ear: “’Tis Lord Cornwallis!” Then there was a louder murmur—in some cases threatening in tone. Behind the officers rode a party of Tories hated by every patriot in Philadelphia—the two Allens, Tench Coxe, Enoch Story, Joe Galloway. Never would they have dared return but under the protection of British muskets.

Then followed the Fourth, Fortieth and Fifty-fifth regiments—all in scarlet. Then Hadley saw a uniform he knew well—would never forget, indeed. He saw it when Wayne held the tide of Knyphausen’s ranks back at Chadd’s Ford. Breeches of yellow leather, leggings of black, dark blue coats, and tall, pointed hats of brass completed the uniform of the hireling soldiery which, against their own desires and the desires of their countrymen, had been sent across the ocean by their prince to fight for the English king. A faint hiss rose from the crowd of spectators as the Hessians, with their fierce mustaches and scowling looks marched by.

Then there were more grenadiers, cavalry, artillery, and wagons containing provisions and the officers’ tents. The windows rattled to the rumbling wheels and the women cowered behind the drawn blinds, peering out upon the ranks that, at the command of a ruler across the sea who cared nothing for these colonies but what could be made out of them, had come to shoot down and to enslave their own flesh and blood.

Hadley could not get around very briskly; but he learned where some of the various regiments were quartered. The artillery was in the State House yard. Those wounded Continentals, who had lain in the long banqueting hall on the second floor of the State House, and who could not get away or be moved by their friends, would now learn what a British prison pen was like. Hadley shuddered to think how he had so nearly escaped a like fate, and was fearful still that something might happen to reveal to the enemy that he, too, had taken up arms against the king. The Forty-second Highlanders were drawn up in Chestnut Street below Third; the Fifteenth regiment was on High Street. When ranks were broken in the afternoon the streets all over town were full of red or blue-coated figures.

Hadley hobbled back to the shelter of the Pye homestead and learned from the good Quaker where some of the officers had been quartered. Cornwallis was just around the corner on Second Street at Neighbor Reeves’s house; Knyphausen was at Henry Lisle’s, while the younger officers, including Lord Rawden, were scattered among the better houses of the town. A young Captain André (later Major André) was quartered in Dr. Franklin’s old house. The British had really come into the hot-bed of the “rebels” and had made themselves much at home.

THE army of occupation brought in its train plenty of Tories and hangers-on besides the men named, though none who had been quite so prominent in affairs or were so greatly detested. It now behooved the good folk of pronounced Whig tendencies to walk circumspectly, for enemies lay in wait at every corner to hale them before the British commander and accuse them of traitorous conduct. Hadley Morris, therefore, although he did not expect to be recognized by anybody in the town, resolved to get away as soon as his wound would allow.

He could not resist, however, going out at sunset to observe the evening parade of the conquerors. There was something very fascinating for him in the long lines of brilliant uniforms and the glittering accoutrements. The British looked as though they had been simply marching through the country on a continual dress parade. How much different was the condition of even the uniformed Continentals!

To the strains of martial music the sun sank to rest, and as the streets grew dark the boisterous mirth of the soldiery disturbed those of the inhabitants who, fearful still of some untoward act upon the part of the invaders, had retired behind the barred doors of their homes. In High Street and on the commons camp fires were burning, and Hadley wandered among them, watching the soldiers cooking their evening meal. Most of the houses he passed were shut; but here and there was one wide open and brilliantly lighted. These were the domiciles where the officers were quartered, or else, being the abode of “faithful” Tories, the proprietors were celebrating the coming of the king’s troops. Laughter and music came from these, and the Old Coffee House and the Indian Queen were riotous with parties of congratulation upon the occupation by the redcoats.

As Hadley hobbled back to Master Pye’s past the tavern, he suddenly observed a familiar face in the crowd. A number of country bumpkins were mixing with the soldiery before the entrance to the Indian Queen, and Hadley was positive he saw Lon Alwood. Whether the Tory youth had observed him or not, Hadley did not know; but the fact of Lon’s presence in the city caused him no little anxiety and he hurried on to the Quaker’s abode. He wondered what had brought Lon up to Philadelphia—and just at this time of all others?

“The best thing I can do is to get out of town as quick as circumstances will permit,” thought Hadley, and upon reaching Friend Pye’s he told the old Quaker how he had seen somebody who knew him in the city—a person who would leave no stone unturned to injure him if possible.

“We must send thee away, then, Hadley,” declared the Quaker. “Where wilt thou go with thy wounded leg?”

“I’ll go home. There isn’t anything for a wounded man to do about here, I reckon. But the leg won’t hobble me for long.”

“Nay, I hope not. I will see what can be done for thee in the morning.”

Friend Jothan Pye was considered, even by his Tory neighbors, to be too close a man and too sharp a trader to have any real interest in the patriot cause. He had even borne patiently from the Whigs much calumny that he might, by so doing, be the better able to help the colonies. Now that the British occupied the town, he might work secretly for the betterment of the Americans and none be the wiser. He had already gone to the British officers and obtained a contract for the cartage of grain into the city for the army, and in two days it was arranged that Hadley should go out of town in one of Friend Pye’s empty wagons, and he did so safely, hidden under a great heap of empty grain sacks. In this way he traveled beyond Germantown and outside the British lines altogether.

Then he found another teamster going across the river, and with him he journeyed until he was at the Mills, only six miles from the Three Oaks Inn. Those last six miles he managed to hobble with only the assistance of his crutch, arriving at the hostelry just at evening. Jonas Benson had returned from Trenton and the boy was warmly welcomed by him. Indeed, that night in the public room, Hadley was the most important person present. The neighbors flocked in to hear him tell of the Paoli attack and of the occupation of Philadelphia, and he felt like a veteran.

But he could not help seeing that Mistress Benson was much put out with him. As time passed the innkeeper’s wife grew more and more bitter against the colonists. She had been born in England, and the presence of Colonel Knowles and his daughter at the inn seemed to have fired her smoldering belief in the “divine right,” and had particularly stirred her bile against the Americans.

“I’m sleepin’ in the garret, myself, Had,” groaned Jonas, in an aside to the boy. “I can’t stand her tongue when she gets abed o’ nights. I’m hopin’ this war’ll end before long, for it’s a severin’ man and wife—an’ sp’ilin’ business, into the bargain. She’s complainin’ about me keepin’ your place for ye, Had, so I’ve got Anson Driggs for stable boy. And, of course, she won’t let me pay Miser Morris your wage no more. I didn’t know but she’d come down from her high hosses when them Knowlses went away, but she’s worse ’n ever!”

“Have the Colonel and Mistress Lillian gone?”

“They have, indeed—bad luck to them!—though I’ve no fault to find with the girl: she was prettily spoken enough. But the Colonel had been recalled to his command, I understand. His business with your uncle came to naught, I reckon. D’ye know what it was, Had?”

Hadley shook his head gloomily. “No. Uncle would tell me nothing. But the Colonel seemed very bitter against him.”

“And what d’ye think of doing?”

“I’m not fit for anything until this wound heals completely. I can’t walk much for some time yet. But I’ll go over and see Uncle in the morning.”

“Ride Molly over. There’s no need o’ your walking about here. And come back here to sleep. Likely Miser Morris will be none too glad to see ye. Your bed’s in the loft same’s us’al. Anson goes home at night. The place is dead, anyway. If this war doesn’t end soon I might as well burn the old house down—there’s no money to be got by keeping it open.”

On the morrow Hadley climbed upon Black Molly and rode over to the Morris homestead. Most of the farmers in the neighborhood had harvested their grain by this time. The corn was shocked and the pumpkins gleamed in golden contrast to the brown earth and stubble. In some fields he saw women and children at work, the men being away with the army. The sight was an encouraging one. Despite the misfortunes and reverses of General Washington’s army, this showed that the common people were still faithful to the cause of liberty.

News, too, of an encouraging nature had come from the north. The battle of Bennington and the first battle of Stillwater had been fought. The army of Burgoyne, which was supposed to be unconquerable, had been halted and, even with the aid of Indians and Tories, the British commander could not have got past General Gates. News traveled slowly in those days, but a pretty correct account had dribbled through the country sections; and there was still some hope of Washington striking a decisive blow himself before winter set in.

The signs of plenty in the fields as he rode on encouraged Hadley Morris, who had seen, of late, so many things to discourage his hope in the ultimate success of the American arms. When he reached his uncle’s grain fields he found that they, too, had been reaped, and so clean that there was not a beggar’s gleaning left among the stubble. He rode on to the house, thinking how much good the store of grain Ephraim Morris had gathered might do the patriot troops, were Uncle Ephraim only of his way of thinking.

As he approached the house the watch dog began barking violently, and not until he had laboriously dismounted before the stable door did the brute recognize him. Then it ran up to the boy whining and licked his hand; but as Uncle Ephraim appeared the dog backed off and began to bark again as though it were not, after all, quite sure whether to greet the boy as a friend or an enemy. Evidently the old farmer had been in like quandary, for he bore a long squirrel rifle in the hollow of his arm, and his brows met in a black scowl when his gaze rested on his nephew’s face.

“Well, what want ye here?” he demanded.

“Why, Uncle, I have come to see you—”

“I’m no uncle of yours—ye runaway rebel!” exclaimed the old man, harshly. “What’s this I hear from Jonas Benson? He says ye are not at his inn and that he’ll no longer pay me the wages he promised. If that doesn’t make you out a runaway ’prentice, then what does it mean?”

“Why, you know, Mistress Benson is very violent for the king just now—”

“Ha!” exclaimed the farmer. “I didn’t know she had the sense to be. It’s too bad she doesn’t get a little of it into Jonas.”

“Well, she doesn’t want me around. And Jonas can’t pay two of us.”

“She wouldn’t have turned ye off if ye’d stayed where ye belonged, Hadley Morris. Oh, I know ye—and I know what ye’ve been doing of late,” cried the farmer. “Ha! lame air ye? What’s that from?”

“I got a ball in my leg—”

“I warrant. Crippling yourself, too. Been fighting with the ‘ragamuffin reg’lars,’ hey? An’ sarve ye right—sarve ye right, I say!” The old man scowled still more fiercely. “And now that you’ve got licked, ye come back home like a cur with its tail ’twixt its legs, arskin’ ter be taken in—hey? I know your breed.”

“If you don’t want me here I can go away again,” Hadley said, quietly.

“What would I want ye for? You’re a lazy, good-for-nothing—that’s what ye air! There’s naught for ye to do about the farm this time o’ year—an’ crippled, too. Ye’d never come back to me if that ball hadn’t hit ye. Ye’d stayed on with that Mr. Washington ye’re so fond of talking about. Ha! I’m done with ye! Ye’ve been naught but an expense and a trouble since your mother brought ye here—and she was an expense, too. I’m a poor man; I can’t have folks hangin’ ter the tail o’ my coat. Your mother—”

“Suppose we let that drop, sir,” interrupted Hadley, firmly, and his eyes flashed. “Everybody in this neighborhood knows what my mother was. They know that she worked herself into her grave in this house. And if she hadn’t begged me to stay here as long as I could be of any use to you, I’d never stood your ill treatment as long as I did. And now,” cried the youth, growing angrier as he thought of the slurring tone his uncle had used in speaking of the dead woman, “it lies with you whether you break with your last relative on earth or not. I will stand abuse myself, and hard work; but you shan’t speak one word against mother!”

“Hoity, toity!” exclaimed the old man. “The young cock is crowing, heh? Who are you that tells me what I should do, or shouldn’t do?” Hadley was silent. He was sorry now that he had spoken so warmly. “Seems to me, Master Hadley, for a beggar, ye talk pretty uppishly—that’s it, uppishly! And you are a beggar—ye’ve got nothing and ye never will have anything. I’ll find some other disposal to make of my farm here—”

“I’m not looking for dead men’s shoes!” flashed out the boy again. “You’ve had my time, and you’ve a right to it for three years longer. If you want to hire me out as soon as my wound is well, you can do so. I haven’t refused to work for you.”

“Yah!” snarled the old man. “Who wants to hire a boy at this time of the year? The country’s ruined as it is—jest ruined. There’s no business. I tell you that you’re an expense, and I’d ruther have your room than your company.”

Hadley turned swiftly. He had clung to Black Molly’s bridle. Now he climbed upon the horse block and, in spite of his wound, fairly flung himself into the saddle. “You’ve told me to go, Uncle Ephraim!” he exclaimed, with flaming cheeks. “You don’t have to tell me twice,” and, pounding his heels into the mare’s sides, he set off at a gallop along the path, and in a moment was out of sight of the angry farmer.

There was bitterness in the boy’s heart and angry tears in his eyes as Black Molly fled across the pastures and out upon the highway. Hadley Morris did not really love his uncle. There was nothing lovable about Miser Morris. The boy had been misjudged and his mother spoken ill of—and that fact he could not forget. He had tried for a year and a half to keep from a final disagreement with Uncle Ephraim; but to no avail. The old man did not consider Hadley old enough to judge for himself, or to have any opinions of his own. The times were such that children grew to youth and young men to manhood very rapidly. When the fathers went to the war the sons became the providers and defenders of the household; if the fathers did not go, the sons were in the ranks themselves. Questions were not asked regarding age by the recruiting officers, providing a youth looked hearty and was able to carry a musket. And Hadley felt himself a man grown in experience, if not in years, after the exciting incidents of the past few weeks.

“I am able to judge for myself in some things,” he told himself, pulling Molly down to a walk, so as to ease his leg. “If Uncle would accept the fact that I have a right to my own opinion, as he has a right to his, we never would have quarreled. I’d never gone over to the Three Oaks to work. And then I’d never seen any active service, I s’pose. He’s got only himself to thank for it, if he did not want me to join the army.

“But now, I reckon, there isn’t anything left for me to do but that. Jonas can’t have me and keep peace in the family; and I wouldn’t stay after the way Mistress Benson talked last night—no, indeed. I’ll go to some of the neighbors. They’ll give me a bite to eat and a place to sleep till my leg gets well enough for me to walk. Then I’ll go back to the army.”

He so decided; but when Jonas heard his plan he vetoed it at once. “What, Had!” cried the old innkeeper, “d’ye think I’ll let a nagging woman drive you away from here to the neighbors? Nay, nay! I’m master here yet, and she is not really so bad, Had. She doesn’t begrudge ye the bite and sup. Stay till your leg is well.”

“But I shall not feel comfortable as long as I stay, Jonas,” declared the boy.

“And how long will that be? Your leg is mending famously. If you could but ride ye’d be fit to go into battle again now. Ah, lad, I’m proud of you—and glad that it was part through me ye went to the wars. I can’t go myself; but I can give of what I have, and if the mistress does not like it she can scold—’twill make her feel better, I vum.” Then he looked at Hadley curiously. “You’re anxious to get back to General Washington again, eh, lad?”

“I wish I had hunted up Captain Prentice, or Colonel Cadwalader, when I got out of Philadelphia, instead of coming over here,” admitted the youth.

“Then start back now,” Jonas said. “Ride Molly—she knows ye, and ye’ll get back in time to be of some use, mayhap, for I heard this morning that there’s a chance of another battle in a day or two.”

“Take Molly, sir?” cried the astonished boy.

“Yes. Most of my horses have already gone to the cause. I’ve got a packet of scrip, as they call it, for ’em, but it’s little worth the stuff is now, and perhaps it will never be redeemed. But I’m a poor sort of a fellow if I mind that. You take Molly. I know if you both live you’ll come back here. And if she is killed—”

The innkeeper stopped, for his voice had broken. He was looking hard at the boy’s flushed face, and now he reached up and gripped Hadley’s hand with sudden warmth. The youth knew that it was not the thought of the possible loss of Black Molly that had choked the worthy innkeeper, but the fear that, perhaps, her rider would never come back again.

“I’ll take her, Jonas—and thank you. I’ll be happier—better content, at least—away from here. Uncle doesn’t want me, nor does he need me; and certainly Mistress Benson doesn’t wish me about the inn. So I’ll take Molly, and if all comes well you shall have her back safe and sound.”

“That’s all right—that’s all right, Had!” exclaimed the other, quickly. “Look out when them army smiths shoe her. She’s got just the suspicion of a corn on that nigh fore foot, ye know. And take care of yourself, Had.”

He wrung Hadley’s hand again and the boy pulled the little mare around. There was nothing more to be said; there was nothing to keep him back. So Hadley Morris rode away to join Washington’s forces, which then lay idle near the beleaguered city.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

By Marguerite Stables

MRS. LANE dropped down on the door-step and fanned herself with her apron. “It does beat all,” she said, aloud to herself, “how trifling these heathens are. Here I am paying seven dollars a week to this miserable Chinaman to do nothing but the cooking, and now if he doesn’t slip off without a word and leave me to do all the work.”

“Don’t bother about it, mamma,” answered Mary Lane, with an abstracted air, “pingo, irregular, we can eat, pingere, anything. It’s too hot to worry, pinxi, pinctum.”

Mary meant to be kind, but as she hunched her shoulders over her book again, her mother’s trials were entirely out of her mind. But for once in her life the overworked woman’s patience forsook her. “I’ve got to bother,” she said, wearily, “what with a houseful of city boarders, and this being quarterly conference and the ministers coming here to dinner, and that heathen away. I can’t let it go, I’ve got to bother.” Then she arose and walked away quickly so her plaints should not disturb her daughter’s studying.

A few moments later a gentle knock was heard at the door, and—“Mamma says she would like to have screens put into her windows, Mrs. Lane,” said a crisp-looking young girl who put her head into the door, “and the water won’t run upstairs, and we need more—why, what in the world is the matter?” she finished abruptly, for poor Mrs. Lane had put down her pitcher, looking as if this was the last straw.

“Everything is the matter,” the tired woman answered, and motioned the girl into the hall to explain that all her troubles seemed to have culminated that morning and that the ministers were to be there for dinner.

“Can’t you get any one to help you?” the girl asked, looking inquiringly through the door at Mary.

“No, she’s too busy studying; I wouldn’t have her stop preparing for her Latin examination for anything; she is going to have a higher education, you know,” she added, with a touch of pride.

The youthful summer boarder looked down at the tired little woman with a bright smile. “Oh, Mrs. Lane, I’m coming right in to help you, myself,” she said; “I just love to do things in the kitchen, honestly I do,” commencing to take off her rings and rolling up her sleeves, as she saw Mrs. Lane had not fully grasped what she had said.

“No, you must not stay in this hot place,” the woman said, noticing the stiff collar and freshly starched duck skirt; “and, besides,” she continued, to herself, as she remembered how some of her boarders, last summer, had tried to have a candy-pull and had set the house on fire, “I can’t be bothered now showing her. I know how these city girls work.”

But by this time the “city girl,” unconscious of Mrs. Lane’s thoughts, had one of the latter’s big kitchen aprons tied around her waist and was waving a wooden spoon by way of punctuating her orders.

“Now, Mrs. Lane, I’m the new hired girl, Blanche is my name, and although I have no recommendation from my last place to give you, I assure you I am honest and willing. You don’t know how I just love to get a chance to fuss around a kitchen; it is such a change from the grind of—” Here the potatoes boiled over and she flew to take off the lid.

The morning wore away much more peacefully for Mrs. Lane than it had begun. Many steps were saved her by the “new girl’s” watchfulness, and there were even several bursts of merry laughter from the buttery, which dispelled more clouds than the real assistance did.

“I may not be so skilled in making bread and doing the useful things,” Blanche apologized, “for I have taken only the ‘classical course’ in cookery. Nettie and I spent last summer down at Aunt Cornelia’s while the rest of the family were in Europe, and she told us we could do whatever we pleased, and what do you suppose we chose? I chose puttering around the kitchen, and Nettie took to hoeing the weeds out of the vegetable garden. And it was such fun!”

The ministers came earlier than they were expected, and Mrs. Lane was hurried out of the kitchen to put on her good dress, with a pledge to secrecy as to the force in the culinary department.

By dinner-time, the Chinaman, having unexpectedly put in his appearance, was waiting on the table as if nothing had happened, but Mrs. Lane was too nervous and apprehensive at first even to notice how different the table looked. There were roses everywhere, a gorgeous American Beauty at each place, and the fish globe in the centre of the table was full of them; but they were all of one variety. Mrs. Lane thought secretly that when the larkspurs and hollyhocks were so fine it did seem a pity not to mix a few in just to give it a little style. She had grave doubts as to the salad when she saw it brought on, although she was bound to admit the yellow-green lettuce looked very pretty, garnished with the bright red petals; but when she tasted it she was reassured. She could not make out what it was made of, but she only hoped it seemed as palatable to every one else as it did to her.

The boarders were all delighted with this new departure, and attributed it to the presence of the ministers, consequently they warmed toward them with a friendliness born of gratitude, and the ministers in their turn did their utmost to return the graciousness and courtesy of the boarders, till the board might have been surrounded by a picked number of congenial friends, so beautifully did everything progress. “Brother” Mason eyed the array of forks and spoons at his plate somewhat suspiciously, wondering if he had them all and was expected to pass them along, but Blanche clattered hers so ostentatiously that he noticed she had the same number and was satisfied.

The success of the next course was due to Mrs. Lane, for the “new girl” explained to the mistress that meats and vegetables did not come in the “classical course.” “Brother” Hicks talked so volubly about foreign missions that Mary did not notice that even the currant jelly was made to do its part in developing the color scheme of the table and that it matched the roses as exactly as if it had been made after a sample. But when the cake was brought in and set before her to be cut she thought at the first glance it was another flower piece, but she saw the quick, approving glance shot from her mother to Miss Blanche, and suspected the new boarder might have suggested its design. It was set on the large, round wooden tray used to mash the sugar in. Even the frosting was tinted an American Beauty pink, and around its base a garland of the same glowing roses. Through the jumble of irregular verbs and the rules for indirect discourse the secret suddenly dawned upon her. It was the city girl who walked with her head so high and wore such beautiful dresses who had made the dinner such a success, while she—but that was different, she was preparing for college.

Mrs. Lane was complacent and happy the remainder of the evening and less tired than she had been for many days, and when the ministers took their leave of her the Presiding Elder said, “I shall remember this evening and the beautiful repast you have given us for a long time to come, Sister Lane.”

Blanche’s bright eyes sparkled with fun, and Mary, although she could not have told why, felt just a bit uncomfortable. “Isn’t it interesting to know that our English words transfer and translate come from the same root?” she said, presently, in her own mind trying to vindicate herself for not helping her mother.

“Oh, don’t,” broke in Blanche, laughingly, “talk about the dirty old roots under ground when we have these glorious flowers that grow on top.”

It had grown too dark for any one to see the pity in Mary’s smile for this frivolous city-bred girl who wasted her time on amusements and learning a little chafing-dish cooking, and didn’t even know what a Latin root was.

Blanche’s mother was kept in her room the next day with a headache, so Blanche’s time was divided between taking care of her invalid and lending a hand to Mrs. Lane till she could get another cook. Mrs. Lane had never expected Mary to help her; knowing how hard her own life had been, she was trying to fit her for a teacher, but as she watched Blanche flying about the house, setting the table, rolling out her cheese straws, running up and down to her mother’s room with a patch of flour on her curly hair, and singing gayly about her work, her tired eyes followed the young girl wistfully. It would be worth a great deal, she admitted, to have a daughter like that, even if she had not a word of Latin in her head. But, of course, the higher education could not be interfered with by the old-fashioned way of bringing up a daughter, and Mary took to books.

“I am going to college this fall if I pass the entrance examinations,” Mary announced at the lunch table, with just a touch of superiority in her tone. She could not have explained just why she felt so resentful toward the city girl.

“Are you going East, or will you stay out here on the coast?” Blanche asked, as if it were the most every-day thing to go to college.

“I have not decided yet, for I shall be the only girl anywhere around here who has gone to college,” she answered, nibbling one of Blanche’s cheese straws with an evident relish.

“Have another,” Blanche interrupted, passing her the plate with a hand that showed two burns and a slight scald. “We used to serve them with tamales when our friends came down from town to the trial foot-ball games.”

“Why, I thought you lived in San Francisco?” Mary said, looking up in surprise.

“I do,” Blanche answered, “but I’ve been down at Stanford the last four years, and have just finished this last semester.”

Mary’s eyes almost popped out of her head. “Why,” she began, incredulously, “I thought you—you—” She did not like to say she had thought that the sunny-faced girl before her had no appreciation of education because she liked to do useful, domestic things, too.

“You thought I could do nothing but cook?” Blanche finished, laughingly.

But Mary did not answer. Blanche Hallsey was certainly not much older than she, and yet, with all her college education, she had been in the kitchen all that hot morning, kneading bread and scouring silver for Mrs. Lane.

“If you decide to go to Stanford, I can write to some of the girls to look out for you,” Blanche went on, for she had not noticed Mary’s attitude of superiority the last few days.

“Oh, would you, please?” Mary Lane pleaded, in a tone that would have greatly surprised her mother had she heard it, for not even she guessed how the fear of going among strangers for the first time in her life had been haunting her diffident little girl.

It was several days, however, before Mary, with her forehead puckered into knots over the “ablative absolute,” could bring herself to knock at Miss Hallsey’s door, and ask for a little assistance.

But that was the beginning of the end of Mary Lane’s priggishness, and the first step toward a higher education in the true sense of the word. She passed her entrance examinations with honors, due, perhaps, to the patient coaching she received during the rest of the summer from Blanche Hallsey. She learned, too, besides irregular verbs, a great many other things fully as useful, topping off with what the college girl called “a classical course in cookery.”

BY ELIZABETH LINCOLN GOULD

Polly Prentiss is an orphan who, for the greater part of her life, has lived with a distant relative, Mrs. Manser, the mistress of Manser Farm. Miss Hetty Pomeroy, a maiden lady of middle age, has, ever since the death of her favorite niece, been on the lookout for a little girl whom she might adopt. She is attracted by Polly’s appearance and quaint manners, and finally decides to take her home and keep her for a month’s trial. In the foregoing chapters, Polly has arrived at her new home, and the great difference between the way of living at Pomeroy Oaks and her past life affords her much food for wonderment. In the meantime Miss Pomeroy has inwardly decided that she will keep Polly with her, but as yet she has not spoken to the little girl of her intention.

ARCTURA’S prediction came true, for the first sound Polly heard when she woke the next morning was a soft, steady patter on her window-pane; the trunk of the elm tree was wet and black as if it had been raining all night. Polly was reminded of that stormy afternoon not quite two weeks ago when she had sat close to Uncle Blodgett in the old shed at Manser Farm and heard him tell about his brave young nephew who had gone to the war and died for his country.

“I wonder if they miss me?” thought the little girl at Pomeroy Oaks. “Maybe they do, because they used to say I made all the noise there was in the house. It seems a pretty long time till next winter, but if I get real well acquainted with Miss Pomeroy so I can tell her that my loving the Manser Farm folks won’t make me stop wanting to be like Eleanor, maybe she’ll let me go to see them by Thanksgiving. I wonder how my rag dollie likes it up in the garret in that tight box where Mrs. Manser put her. I expect she’s lonesome, poor dolly! And Ebenezer—I don’t persume anybody gets down on the floor to play with him, because they’ve all got rheumatism except Mrs. Manser, and she has pains in her head.”

There was no trip to the village for Miss Pomeroy and Polly that morning. Toward noon Hiram drove off in the light wagon, holding a large umbrella over his head, and returned well splashed with mud an hour or so later.

Polly spent part of the morning in the library with Miss Pomeroy, darning some stockings and a rent in the old red frock. Miss Pomeroy had a book in her hands, but almost every time the little girl looked up from her work she found the keen, gray eyes fixed on her face, and it made her uneasy. She thought there must be something unsatisfactory about her appearance, for her kind friend looked grave and troubled. Polly decided to speak.

“My hair isn’t quite as flat as it is sometimes,” she ventured, after a long silence. “Mrs. Manser used to say that she believed Satan got into it when the weather was damp, and perhaps he does. I suppose the nicest folks all have straight hair, don’t they, Miss Pomeroy?”

The only answer was a smile and a stroke of the brown curls, and Polly was instantly confirmed in her opinion, while Miss Hetty’s mind was far away.

“But, perhaps, as I get more and more like Eleanor, my hair will change just as my cheeks are changing,” she thought, hopefully. “And I think I’m stretching out a little bit, too, practicing the way Ebenezer did.”

The library was a delightful room, but the hour with Arctura before the kitchen fire in the afternoon had a different sort of charm for Polly.

“You’re so comfortable, Miss Arctura,” she said, confidingly, to Miss Green, when they were fairly settled with their work. Polly’s task was an iron-holder, and that of her hostess the flaming sock designed for Hiram’s ample foot. Miss Pomeroy was in her room, writing letters; she had many correspondents in the world outside the little town, and they kept her busy. Besides that, she had a purpose in leaving Polly with the faithful Arctura a good deal of the time.

“The child is happier with you, and I want her to be happy,” she said, with perfect frankness. “She’s a little afraid of me for some reason, and though it hurts my vanity, I don’t want to hurry her confidence. I believe I shall win it in time.”

“Of course, you will,” said Arctura, stoutly. “I can’t quite make her out sometimes. She’ll seem real gay for a few minutes and then sober down all of a sudden, as if she remembered something. She’s just as anxious to please you as ever a child could be. Do you suppose that Manser woman could have scared her any way? Told her you were set on having her act any particular way, or anything?”

Miss Pomeroy’s life had been singularly apart from the current of village gossip; she stared blankly at this suggestion and then shook her head.

“It wouldn’t be possible,” she said, decidedly. “Mrs. Manser never spoke to me until I waylaid her after church that Sunday, three or four weeks ago. And there is nobody to tell her anything of me or my ways of living. She simply knows that I took a fancy to Mary, and—since yesterday—that I wish to adopt her.”

“M-m,” said Arctura, softly, as Miss Pomeroy turned away. “I shouldn’t want to be too sure what folks know and what they don’t, in any place where there’s a post-office, two meat-men, and a baker’s cart.”

“I’ve written my letter to go with the candy to-morrow morning,” said Polly, as she basted a strip of turkey-red binding around a square of ticking after Miss Green’s instructions. “It took me ’most an hour and a half by the big clock, and I made four blots and had to look in the dictionary three times, and now I expect it’s just full of mistakes. I carried it to Miss Pomeroy, but she said she wanted Aunty Peebles to have the first reading of it, and she helped me seal it with a great splotch of red sealing-wax, and marked it with her big stamp.”

“Won’t it mix ’em all up to see a ‘P’ on the letter?” inquired Arctura. “Why, no; what am I thinking of? ‘P’ stands for Prentiss just as well as Pomeroy.”

“Yes, and for—for other names, too,” said Polly, remembering just in time. “Polly Perkins—that’s in your song—it stands for both of her names.”

“To be sure it does,” said Arctura. Then the chairs rocked in silence for a few minutes. Arctura stole a glance at the face so near hers. The little mouth was shut firmly, but there was a downward droop at the corners, and it certainly appeared to Arctura that something glistened in the long lashes that hid the great brown eyes.

“H-m—it’s a kind of a dull day for little folks and big folks, too,” she said, poking vigorously at the ashes in the grate with her back to Polly. “I don’t know as there’ll ever come a better time for me to tell you about the Square and me when I was your age.”

When she turned around the brown eyes were shining to match the eager voice, and Arctura smiled with satisfaction.

“This occurred forty-five years ago,” she began, briskly. “I might as well break it to you that I’m all but fifty-five. I suppose you’ve met folks as old as that, haven’t you?”

“Why, everybody at Manser Farm is ever and ever so much older, except Mrs. Manser and Father Manser, and Bob Rust,” said Polly, earnestly. “They’re all traveling on toward their end, Uncle Blodgett says, and he doesn’t care how soon he gets his marching orders for the heavenly land, but I care,” and the brown curls danced, “for I just love Uncle Blodgett.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” said Arctura, heartily. “Well now, about the Square and me. You see, my mother—‘marm,’ we all called her—was a notable cook. I don’t approach her on pie crust nor muffins, and there was a sort of rye drop cake,” said Miss Green, lowering her voice, “that nobody but her could ever make. And she was a great one to invent cake receipts, and then invite folks in to take a dish of tea in the afternoon and test the new cake.

“The Square’s wife was a good deal younger than he—she’d only be seventy if she was alive to-day, while he was eighty-five when he died—and she’d often accept marm’s invitations, and come to our old house—’twas burned years ago—and spend the best part of an afternoon just as friendly as you please. Not that ’twas any great come down, either,” said Arctura, with proper pride, “for my marm was of excellent stock, and I’m the first woman in the family records to work for pay.

“But that’s nothing to do with the story. One morning when John and I were starting off for school—Hiram was only a baby—marm gave us each an errand to do on the way. I can remember I stood barefoot in the grass—what did you say?” as Polly made a sound.

“Nothing but ‘oh!’” said Polly, quickly. “I didn’t mean to interrupt, Miss Arctura.”

“Never mind, I’m glad to have you take an interest,” said the story-teller. “I can remember standing there in the grass waiting for John, and saying over and over to myself, ‘Please, Mrs. Pomeroy, marm sends her compliments and would like to have—no, that isn’t right—please, Mrs. Pomeroy, marm sends her compliments and would be happy to have you take tea with her this afternoon.’

“Pretty soon John came running out, and we took hold of hands and started for school. John said marm had told him to get an ounce of camphor at the store, and he was wishing she’d said a pound instead of such a stingy little mite, and I had to set forth to him how much an ounce of camphor could do before he was anyways reconciled.

“We had nearly two miles to go to school, and that morning when we got to the fork in the woods I ran across lots to get there quicker, and John went on down to the store. It was way out at the corners, not where the Burcham block is now,” explained Arctura. “Folks expected the village would grow this way, but it went the other.

“I ran to the front door, as marm had charged me to, and reached up for the knocker and gave it a good bang. And what should I see but the Square, instead of Mrs. Pomeroy that I was prepared for. He was tall and stern looking, and my ideas just fled away when I saw him, but I managed to remember my manners. I dropped a courtesy and said, ‘Please, marm wants Mrs. Pomeroy’s tea, and she’d be happy to have her compliments this afternoon.’”

“Then it came over me what I’d said, and with being scared and all I began to cry. And the Square just reached down and took my hand and led me into the house, and Mrs. Pomeroy understood the message right off, and said she’d be most happy to come. The Square kept hold of my hand all the time, and when the message was straightened out he said, ‘May I walk with you as far as our ways lie together, my little maid?’”

“Oh, wasn’t that beautiful!” cried Polly. “‘May I walk with you as far as our ways lie together, my little maid?’ That’s something like Mr. Shakespeare’s works that Uncle Blodgett has.”

“’Twas pretty fine talk, I think myself,” said Miss Green, “and ’twas followed up by finer, though I can’t recall anything else word for word. But we kept together hand in hand, he taking long strides and I running alongside, as you might say, till we reached a house where the Square had to stop. He took off his hat to me when he said good-bye and shook my hand, and said, ‘I beg you to accept this trifling remembrance, my little maid,’ and when I came to, there was a shining gold-piece in my hand.”

“‘I beg you to accept this trifling remembrance, my little maid,’” repeated Polly. “I think that’s even beautifuller than what he said at first. I guess Uncle Blodgett and Grandma Manser, too, would like to hear that. They love beautiful language.”

“When I got to school,” continued Arctura, after an appreciative smile at Polly, “John was in the middle of a group of children on the green. He’d taken off his coat and was showing ’em his first pair of ‘galluses’—bright red, they were, about the shade of this very yarn. One of the children ran up to me and said, ‘I suppose your brother John thinks he’s a man now, for he says his suspenders are just like your father’s.’”

“I never answered her, but I just opened out my palm to let her see the gold-piece, and I said, ‘The Square walked with me ’way to Mrs. Brown’s, and gave me this.’”

“John had considerable interest for the boys that day, but the girls were all taken up with me, and for weeks afterward when we got tired playing, somebody’d say, ‘Arctura, now you tell about your marm’s message, and the Square walking part way to school with you.’”

“Oh, I think it was ever so much more interesting than John’s suspenders,” said Polly, breathlessly. “I never heard anything so wonderful that happened to a little girl, Miss Arctura.”

Miss Green loosened the ruffle at her neck and slowly drew up a slender chain on the end of which something dangled.

“Suspenders wear out, even the best of ’em,” she said, softly leaning toward her little guest. “You look at that. My father bored a hole in it, and marm gave me this chain that was her marm’s, and I’ve worn it from that day to this.”

“And mind you,” said Miss Green, as Polly looked with awe at the little gold-piece, kept shining by Arctura’s loving care, “whenever the Square was a mite cross or unreasonable those last years, from his mind getting tangled, I’d put my hand over this little dangling thing, and I’d say to myself, ‘Arctura Green, who gave you the proudest day you ever knew as a little girl?’ and ’twould warm my heart up in a minute. There’s some that forgets, but, with all my faults, I ain’t one of the number.”

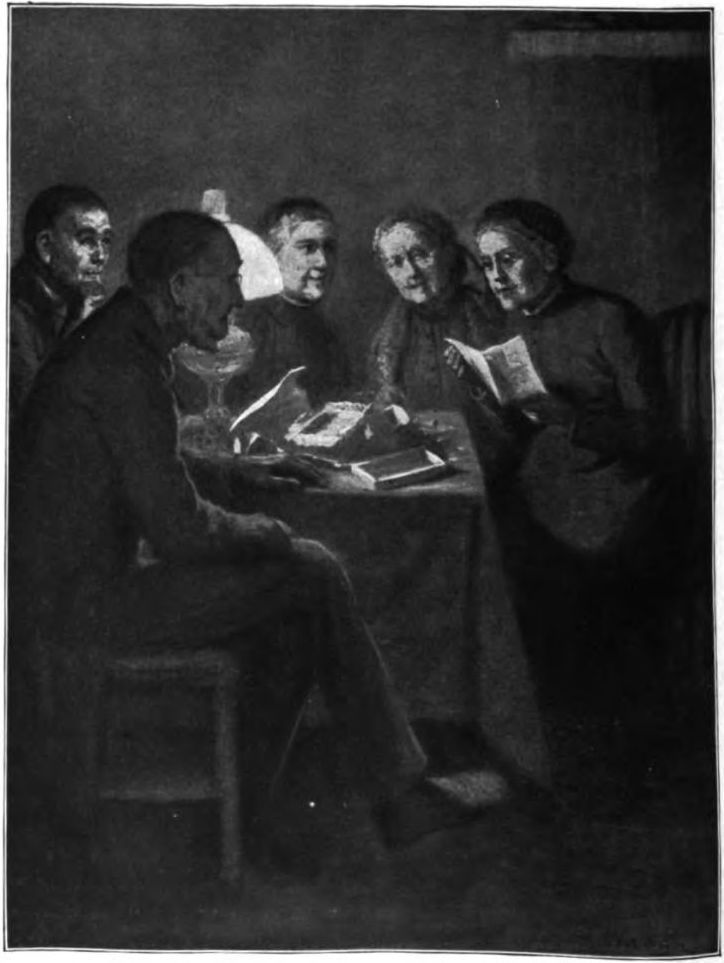

WHEN Father Manser returned from his trip to the post-office the next evening he found the residents at Manser Farm, with the exception of his melancholy spouse, gathered in the kitchen. Mrs. Manser had gone to bed with a headache, but her absence failed to cast a gloom over the company. It was the most cheerful evening that had been known since Polly left them, for Uncle Blodgett had not only read the weekly “Sentinel” in so clear a tone that even Grandma Manser, near whom he sat, could hear, but he had, after urging, recited several poems.

“I admire to hear battle-pieces,” said Aunty Peebles, just as the door swung open to admit Father Manser. “When you spoke that ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ it gave me chills all along my spine, and made me feel as if I could step right forth to war.”

“I expect you wouldn’t be a very murderous character, though, come to get you on the field of battle,” said Uncle Blodgett, good-naturedly. “Now, there’s Mis’ Ramsdell, I reckon she’d make a good fighter if she was put to it.”

“I come of war stock,” said Mrs. Ramsdell, her black eyes snapping, and nostrils dilating as she acknowledged the compliment. “My father and his three brothers were in the war of 1812, and back of that their parents and uncles were in the thick of ’76, and led wherever they were.”

“Ain’t you kind of reckless, speaking of ‘parents’ that way?” inquired Uncle Blodgett. “Did your grandmarm conduct a regiment, or what was her part in the proceedings?”

Mrs. Ramsdell directed a look of withering scorn at her old friend, but her eye caught sight of a package in Father Manser’s hand and she was suddenly alert.

“What you got there?” she demanded, and at once all the old heads turned toward the new-comer.

Usually they took no special note of Father Manser’s return, as there were scarcely ever any letters, and they well knew the paper must be Mrs. Manser’s spoil for the evening.

“It’s a box,” said Father Manser, turning the package over and over in his hand.

“We can all see that,” said Mrs. Ramsdell, sharply.

“And it seems to be directed to Miss Anne Peebles,” proceeded Father Manser, taking no offence.

Aunty Peebles began to tremble with excitement as the box was handed to her, and a flush rose in the other old faces as the group closed in around the table, so that the lamp might shed its light on this surprising package.

“If you could wait till I’ve taken the paper in to Mrs. Manser, I’ve got a sharp knife that would cut those fastenings,” said Father Manser, wistfully. “Her door’s closed, and I won’t be but a minute. I won’t speak of the package, and I’ll mention that the fire needs more wood, for I see it does.”

“I’ll wait,” said Aunty Peebles, and spurred by a “Hurry up, then, for goodness’ sake!” from Mrs. Ramsdell, Father Manser sped off with the paper.

“It’s Polly’s writing,” said Uncle Blodgett, after a long squint at the address on the brown paper covering of the box. “I’ve got one of her exercises that the teacher said she might keep—one of that last batch, if I haven’t lost it.”

Uncle Blodgett drew from his coat pocket a long, flat wallet, and took out of it a piece of paper carefully creased and bearing evidences of frequent handling. He spread it out close to the box, so that all might see.

“You mark that cross on the T,” he said, triumphantly. “She begins it with a kind of a hook, different from most that you’d see. I—I noticed it the day she made me a gift of the paper,” said Uncle Blodgett, as he replaced his treasure in the wallet.

“The box is from Polly Prentiss,” cried Mrs. Ramsdell in Grandma Manser’s ear. “I guess your daughter-in-law’s made a mistake about her forgetting us, after all.” Then the old lady put her arm through Grandma Manser’s and pressed her fiercely as if to make amends for this reference to the doubting one. “’Taint as if she was your daughter, dear heart,” she said, remorsefully.

When the string had at last given way—Father Manser had slashed it recklessly in half a dozen places in his haste—and the box cover was lifted, there lay the letter on which Polly had spent so much time and thought, with seven chocolate drops on it. Aunty Peebles passed the box around and each of the company took a piece of candy; even Bob Rust had his portion, which he carried to his favorite seat near the door into the shed, and handled as if it were something rare and wonderful, as, indeed, it was to him.

Father Manser set his wife’s piece carefully aside. Nobody failed for a moment to understand little Polly’s loving thought for them all. Below the letter lay row after row of the chocolates, but they could wait.

“Now we’ve—ahem!—eaten part of the message,” said Uncle Blodgett, gruffly, “suppose you read us the rest of it, Mis’ Peebles. Seems to be some time since we’ve heard direct from the child.”

Aunty Peebles’s voice quavered many times during the reading, and there was a frank use of handkerchiefs at some points, but the interest in Polly’s letter never flagged.

“Dear folks at Manser Farm,” read Aunty Peebles, “this is a beautiful place and every one is very kind to me. How do you all do, and is Ebyneezer well and the other Animals? The minister came to dinner Sunday, that was why I was so late and you had gone, but I heard the Wagon up the hill. This is a beautiful place, with big trees, and in the house there are books and books and Cabbynets with kurous Shells and other things. And there is silver that shines, and my bed and chairs are white with a pink Strype. Mrs. Manser, I am being careful of my Close and I allways wear an apron. There are two little kittens here. Their names are Snip and Snap.

“When folks have such a beautiful place I guess they do not care much about going out-doors, but there is a Pyaza and I walk on that a great deal, beside I have been to walk down the road most every day with Miss Pomeroy and she is just as good to me! And once I have been in the Woods with Miss Arctura, and she said ‘next time,’ so that means we are going again. Mr. Hiram that is her brother can resite pieces and he is teaching me On Linden when the Sun was Low, Uncle Blodgett do you know that piece? He says he would give all his boot buttons to hear you resite Mr. Shakespeer’s Works. I do not think I have spelled that name right. Perhaps I can see you all before Christmas, but perhaps I cannot, for I am going to be adopted. Do you miss me, Grandma Manser and Mrs. Ramsdell? Do you miss me, Uncle Blodgett? and Aunty Peebles do you miss me? This is a beautiful place, and I read and sew and play with the kittens and Miss Pomeroy says I am a quiet little girl, Mrs. Manser. Father Manser do you remember giving me Pepermints? I hope you will all like this Candy. I have been to the Village once with Miss Pomeroy, but I did not see any folks I knew.

“I hope Grandma Manser will have her ear Trumpet pretty soon. Aunty Peebles I love that Cushion I look at it very many times, and Uncle Blodgett Mr. Hiram will have that knife fixed for a Present he says. Now I must say Goodbye with heaps and heaps of love. I put Aunty Peebles’ name on this because she admires to get things through the Post Office.

“Mary Prentiss.”

“Miss Pomeroy is not going to look at this. I am trying to be just like Ellynor, but I expect I am not. Will you please call me Polly to yourselves? Nobody here knows it ever was my name.”

The last few lines were evidently written in great haste. Polly had run upstairs to add them when she found the letter would not be inspected. There was a short silence when the last word had been read. Mrs. Ramsdell fidgeted in her chair.

“She seems to be real contented and happy, don’t she?” said Father Manser, looking from one to another for confirmation of his views. “I guess they’re mighty kind to her.”

“Kind! who wouldn’t be kind to that darling little thing, I’d like to know?” snapped Mrs. Ramsdell. “But she’s grieving for all the folks she’s been used to, and trying not to let anybody know it. It isn’t that we’re such remarkable folks, but it’s because she’s such a loving little thing; that’s the reason of it.”

“What do they mean by keeping her housed up so?” demanded Uncle Blodgett, sternly. “They’ll have her sick of a fever next thing we know. Out-doors has been the breath of her living and her joy. I guess what those folks need is somebody to make a few points clear to ’em. What was this Eleanor the child talks of, that she should be set up for a pattern? Wa’n’t she mortal like all the rest of us?”

“Mrs. Manser says Miss Pomeroy thought she was perfection,” ventured Father Manser, as nobody else seemed prepared with an answer. “She used to talk with Polly about her, every day before she went, advising her what she’d better do—Mrs. Manser did.”

“I’ll warrant she did,” said Uncle Blodgett, bitterly. “That’s the whole root of the trouble. Now, you mark my words, all of you women folks”—Uncle Blodgett evidently included poor Father Manser in his summing up—“I’m going to have speech with that Pomeroy woman before many more days have gone over my head, and I’m going to set a few things straight. As for having that child carry the weight of this whole establishment, leaks, ear-trumpets, shingles, and all on her mind, and try to live up to nobody knows what—I won’t stand it!”

“What do you plan?” asked Mrs. Ramsdell, with unwonted respect.

“I shall fare down to the village with Father here,” said Uncle Blodgett, indicating the object of his choice with a careless nod, “and if she doesn’t happen to drive in that morning, I shall foot it to Pomeroy Oaks. My legs are good for a little matter of three miles or so.”

“It’s a good four miles, as I remember it,” muttered Mrs. Ramsdell.