Title: The Maid of Orleans

Author: Friedrich Henning

Translator: George P. Upton

Release date: May 23, 2021 [eBook #65431]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: D A Alexander, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

“Oh, were I only a man!” she sighed (Page 25)

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Frederick Henning

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” etc.

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1904

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1904

Published October 1, 1904

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

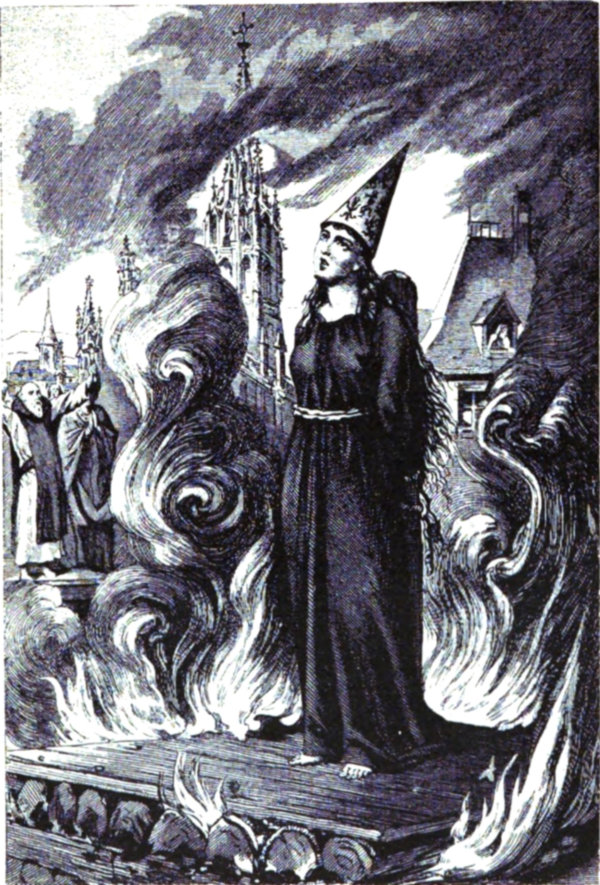

The life story of Joan of Arc, as told in this volume, closely follows the historical facts as well as the official records bearing upon her trial and burning for “heresy, relapse, apostasy, and idolatry.” It naturally divides into two parts. First, the simple pastoral life of the shepherd maiden of Domremy, which is charmingly portrayed; the visions of her favorite saints; the heavenly voices which commissioned her to raise the English siege of Orleans and crown the Dauphin; her touching farewell to her home; and, secondly, the part she played as the Maid of Orleans in the stirring events of the field; the victories which she achieved over the English and their Burgundian allies; the raising of the siege; the coronation of the ungrateful Dauphin at Rheims; her fatal mistake in remaining in his service after her mission was accomplished; her capture at Compiègne; her infamous sale to the English by Burgundy; her more infamous trial by the corrupt and execrable Cauchon; and her cruel martyrdom at the stake. Another story, the abduction of Marie of Chafleur, her rescue by Jean Renault, and their final happiness, is closely interwoven with the movement of the main story, and serves to lighten up the closing chapters. This episode is pure romance of an exciting nature; but the life of the Maid of Orleans is a remarkably faithful historical picture, which is all the more vivid because the characters are real. In this respect it resembles nearly all the volumes in the numerous German “libraries for youth.” They are stories of real lives, concisely, charmingly, and honestly told, and adhere so closely to fact that the reader forms something like an intimate personal acquaintance with the characters they introduce.

G. P. U.

Chicago, 1904.

As the traveller, descending the valley from Neufchâteau, approaches the village of Domremy,[1] he will observe at his right upon an eminence of the nearest range of hills a stately chestnut-tree, its lower branches hung with wreaths of flowers, some fresh, some fading. If he does not mind a little fatigue and climbs to this spot, he will be richly rewarded for his exertions. The tree in itself is a sufficient compensation for his efforts, for who does not contemplate with admiration such a work of nature? Who does not listen with rapture to the gentle rustle of its leaves and find rest in its cool shade? But this tree has a still stronger attraction for those who believe its story. Ofttimes in the twilight they see happy sprites dancing round it with joyous faces, and the soft rustling of its leaves they declare is celestial whispers, for it is given to them to understand heavenly speech.

This tree is the “Fairy Tree.”[2]

The outlook from this spot will still further repay the traveller. A beautiful valley spreads out before him, bounded on either side by the forest-crowned heights of Argonne and Ardennes, between which the Meuse[3] winds its silvery way. Numerous villages dot these heights and are sprinkled here and there along the lower pasture-land. North and south gleam the towers of Neufchâteau and Vaucouleurs.[4] The nearest, and at the same time most pleasant of these villages, is Domremy, whose cottages, embowered in greenery, cluster about the little church of Saint Margaret. Many herds of cattle and sheep are feeding in the pastures between fields luxuriant with growing crops. Looking back, the eye catches the dusky summits of the Bois de Chêne,[5] and at the crossroad leading thither stands the chapel of Saint Catherine.

Between the chapel and the Fairy Tree, and somewhat nearer the latter, sparkles a bubbling spring whose curative powers were believed in by those of pious faith in the olden times.

Thus the scene appears under pleasant skies. But when the temperature suddenly changes, and the cold air rushes down into the valley, its mists are driven and scattered among the mountainous defiles. At such times superstitious villagers believe they see the fairies dancing round the tree, and even the saints of heaven in the wavering shapes of the mist.

Among the mysterious spots which have invested the neighborhood of Domremy with such fame and sacredness Bois de Chêne is not the least famous. One cannot enter its dark recesses without that peculiar feeling of awe which inspires a solitary wanderer in the presence of nature’s grandeurs,—a feeling which inevitably fills the mind of a superstitious person with a bewildering array of supernatural fancies. It was from this very forest that Merlin the wizard predicted the deliverer of France would come.

Think of a child of susceptible and fanciful nature, fed upon nursery tales full of superstitions, a child passionately fond of solitary reveries and fervent appeals to the saints, growing up in such an environment! Is it remarkable that such a child should see marvels on the earth and in the air, and the saints themselves in bodily image, and that she should hear their voices and listen devoutly to angelic music in the celestial regions?

Just such a child as this sat under the Fairy Tree on a beautiful spring morning in the year 1424.[6] She was a maiden of twelve years, and was tending a little flock of sheep grazing on the hillside. Even the casual observer would have noticed her striking appearance, for while the other girls were frolicking in the meadow below her, she sat leaning against the tree, gazing fixedly into space, and evidently thinking of other things than dance, and sport, and herds. Looking more closely into her lovely oval face and observing its transparent tints and delicate features, the question would at once suggest itself—How did such a slight, ethereal creature happen among the children of peasants? Those wonderful eyes did not merely reveal the self-unconsciousness of the visionary and the rapture of supernatural contemplation. They were clear mirrors of the heart, reflecting its inmost recesses and depths. That heart was the heart of an angel, the heart of a child so innocent it was impossible not to love her and sympathize with her.

As she sat there, a flock of little birds flew to the tree, filling the air with the music of their songs. Apparently she did not notice them, for she neither moved nor changed the expression of her face. They fluttered down from the tree and hopped about the dreamer, approaching her more and more nearly, until at last some of them lit on her head and shoulder. Now for the first time she was conscious of her little guests.

“Ah!” she exclaimed in a soft melodious voice. “You are here and I did not know it.” She quickly opened a little basket standing near her, sprinkled some crumbs upon the ground, and watched with childish delight the liveliness of her tiny companions. Her pleasure, however, was soon marred by a saucy and envious fellow in the little crowd, who pecked his neighbor. Chirping sorrowfully, the victim flew to the maiden’s feet.

“Alas! alas! poor little bird!” she exclaimed, the tears coming into her eyes. She took the little fellow in her lap and caressed him. “Wait, now, thou envious ‘wolf,’” she said, addressing the offender. “Did I not scatter crumbs enough for you all? And did you not know I would have doubled the amount if that had not been sufficient? You deserve to be punished for your greediness. Now you shall see how finely this poor little fellow will fare at his own table.” Thereupon she filled her lap from the basket, and the little one ate with a relish, while the “wolf” was not allowed to come near the table, much as he wished to. Suddenly the flock rose and flew into the branches of the tree in manifest alarm. Her sheep, which had been feeding below her, rushed up the hill as fast as they could, and closely huddled together.

“What is the matter?” cried the maiden, as she cast a hasty glance at the flying herd. “What has driven you away from the meadow in such fright? Holy Catherine! the cruel wolf must be lurking on the edge of the wood.”

She quickly sprang up, seized her crook, and flew to the Bois de Chêne, where a wolf was really lying in wait. One who had seen her then would hardly have recognized the gentle maiden, the dreamer of a moment before, in this resolute heroine, her eyes flashing with courage. Wonderful to relate, the beast fled from her. For an instant it crouched, ready to spring upon her, and then slunk away into the forest. Thereupon the little heroine went to the neighboring chapel, knelt before the image of Saint Catherine, and poured out the thankfulness of her heart in long and fervent prayers. It was her childish belief that her patron saint had performed a miracle. She did not know that the beasts of the wood can be intimidated by the firmness and courage of a fearless person’s glance, and that even the lion himself will not attack such a person unless he is in a frenzy of rage.

As the little one left the chapel the spiritual illumination which irradiated her face when she sat dreaming under the Fairy Tree again shone in her beautiful eyes. Her route led her to the miraculous spring.[7] The fresh green of the bushes and turf allured her. She threw herself down, and soon was lulled by the gentle plashing of the water into sweet fancies. For a long time she failed to observe that she had companions who had come there to drink,—a doe and fawns, who fearlessly approached and drank the clear water undisturbed. After they had quenched their thirst, the fawns stood watching the dreamer with their intelligent little eyes as if they were awaiting friendly recognition from an old acquaintance. Not receiving it, they sported frolicsomely around her. Suddenly the charming scene was interrupted. The animals tossed up their heads, listened intently, and then, as if at a word of command, galloped away to the forest. A bevy of simple, joyous, sun-browned shepherdesses came running toward her from the meadow.

“Joan, Joan,” cried one, “where are you?”

The maiden rose.

“Aha!” said the one just speaking, “she has been listening again to the murmurs of the spring. Just see how wondrously her eyes glisten!”

At this all of them came up and gazed with a kind of awe at the strange maiden.

“Well, what do you wish?” said Joan, gently.

“We have made a wager,” replied the former speaker. “See this beautiful wreath, Joan. After we had woven it we decided it should go to the winner in a race to the Fairy Tree. Agnes boasted it would be hers. Margot was just as sure that she would win it. ‘Ah!’ said I; ‘if Joan were only here you would not talk this way!’ ‘And why not?’ said Agnes. ‘Because,’ said I, ‘Saint Catherine always helps her.’ ‘Oh,’ interposed Margot, ‘I will find Joan and she also shall race.’ Then I said, ‘We will all search for Joan.’ ‘Yes,’ all shouted, ‘let us find Joan!’ And here we are. Here is the wreath, and there is the Fairy Tree. Will you run?”

Joan made no reply. She stood absorbed in devotion, and prayed: “Holy Catherine, give me the victory, not for my sake, but for thy honor.”

“Joan, do you not hear us?”

“Yes, I am ready.”

Gleefully the maidens formed a line. “One, two, three,” a clear voice counted, and all ran up the hillside. In a few seconds the line was zig-zag, with Agnes, Margot, and Joan in the lead. Most of the others gave up the race and followed slowly on, watching the three in eager suspense. Soon, however, they noticed there was one in the lead, for the other two had perceptibly fallen back.

“Did I not tell you Joan would win?” said the one who had first spoken.

“But there is some witchcraft about it,” said her neighbor. “Look at her, look! Holy Margaret! Her feet do not touch the ground.”

“That is so,” all said, as they crossed themselves. “She is flying through the air.”

It really seemed as if Joan were flying. The mist, the fast-gathering twilight, and the distance created such an ocular illusion that any superstitious spectator would have sworn she was flying. All hurried to the tree, under whose branches the victor was not standing, but devoutly kneeling. The joyous crowd surrounded her, and no feeling of envy clouded their joy as they placed the wreath upon her fair head. As the night was now fast coming on, the girls went homewards with the flocks. They were all from the village of Domremy.

Joan found Jacques, her father, Pierre, her brother, and Duram Laxart, her uncle, engaged in earnest conversation with a stranger in the square in front of the church. A few words which she overheard aroused her curiosity, and she approached the group and listened.

“I bid you repent,” said the stranger, “lest the wrath of Heaven be visited upon you, for all the misfortunes of this land are divine punishments for the sins of the Court and the King’s kindred.”

“Oh, oh, holy father,” said one, “that would be very sad.”

“What do you mean by that, my son?”

“I mean it would be very sad for Heaven to punish poor people who have done no wrong, for the wrongdoings of the Court.”

“Go home, thou son of Belial who doubtest that which the Spirit reveals to thee through my lips. Shut thyself up in thy chamber, and three times repeat seven paternosters, that thy soul may be released from the bonds of doubt, for doubt is the work of the devil, who is already stretching out his claws to seize thee.”

“But, holy father—”

“Be quiet, Gamoche,” interposed another villager. “Do not interrupt the holy father. He will explain it all to us.”

“Yes, yes,” cried the others, “he will explain everything.”

“Well, then, listen to me, children,” resumed the stranger. “But, holy Mother of God, where shall I begin? The list of the sins of this Court is so long that if I should go back a century, even then it would not be the beginning. I will confine myself to the recent ones, which must be more or less familiar to you all. Have you heard about the last King, Charles the Sixth?”[8]

“Why should we not have heard? He died insane only two years ago.”

“Yes, insane. He had a few lucid moments after 1392, in which he recognized in some measure the profligacy of the administration. The whole royal family, with but few exceptions, acted as if they were insane. First of all, there was the Queen, the notorious Isabella of Bavaria, who was as much a stranger to the nobility of human nature as she was to the divine. Her every purpose and act had no higher motive than the gratification of her own desires and the discovery how to accomplish them. It would have mattered nothing to her if a sea of blood had been shed, if only her interests were advanced. There was the Duke Louis of Orleans,[9] brother of the insane King, who pandered to Isabella’s profligacy and lust of power, finally seized the reins of sovereignty, and plunged the state into direst confusion. There were the King’s uncles, the dukes of Bourbon, Berry, Burgundy, and Anjou, all alike avaricious and ambitious for power, who lashed the Duke of Orleans and the King with the scourge of war, murdered their subjects, and ravaged the country. Then came numerous factions which contended with one another, one for this, and one for that, and finally almost countless great and little lords, robber barons, who, pretending to espouse the cause of one party, harried the districts of others, leaving a trail of pillage and blood. To complete the burden of wretchedness, King Henry the Fifth sent his Englishmen, those hereditary enemies of France, across the Channel. In alliance with the turbulent dukes, particularly those of Burgundy and Brittany, they advanced victorious, captured one place after another, and at last even Rouen and Paris, so that few provinces were left to the unfortunate King. Frightful confusion followed when this King died in 1422. Henry the Fifth, to be sure, died in the same year, but his field marshal, the Duke of Bedford, guardian of young Henry the Sixth,[10] did not abandon the field. The infamous treaty of Troyes gave him the semblance of right.”

“How so, holy father?” interposed one of the villagers.

“Be quiet,” replied another. “You ought to have known that Queen Isabella, out of hate and revenge against her youngest son Charles, who, after the death of his brother the Dauphin, was crown prince, concluded that treaty with England whereby the French royal family was barred from the succession and the King of England was declared successor of Charles the Sixth.”

“Oh, the disgrace! Oh, the shame!” several exclaimed.

“And this poor Dauphin,” continued the former speaker, “spent a joyless youth, in which his unnatural mother often forced him as well as his father to suffer the pangs of hunger; and yet, poor, weak, and throneless as he is, he is still ready to struggle for that throne which is his birthright as Charles the Seventh. Is this not so, holy father?”

“Certainly, certainly, God’s pity,” replied the stranger. “He should rule by his own and by divine right. The treaty of Troyes cannot prevent it. But where is the hero who will lead him to coronation at Rheims? Alas, only miraculous interposition can save him from ruin.”

“Saint Catherine,” sighed a gentle voice.

“Joan!” exclaimed Jacques, as he recognized his daughter, “what are you doing here? Go home.”

“Not yet, father Jacques,” said the stranger. “Let her stay. Do you not know that the prayers from a pure child’s heart are heard by the dear saints? And,” he added, “I have never seen eyes so full of innocence and piety as hers.”

“Ah!” replied Jacques, “of what use are the prayers of a child when the whole country lies helpless?”

“Are you also an unbeliever?” replied the stranger. “Know you not that the great God can manifest Himself in a little child?”

These were the last words of the conversation which Joan heard. She suddenly disappeared, but she did not go home. She wended her way to the church, which was always open. Never had her heart been so troubled and full of strange longings, never had she been so powerfully moved to hold communion with her saint. It was not so much the desire to make a votive offering of her wreath as it was the unspeakable sorrow of the fatherland and the wretched plight of the poor Dauphin that urged her to this sacred spot. And was this strange? If her sympathetic nature made her shed tears over the slight suffering of a bird, how much more would it force her to weep over the story of universal misfortune which she had just heard! Why should not the courage with which she had defended her sheep from the wolf display itself now even more decidedly? And why should she not believe in her very soul that her favorite saint would perform a miracle of rescue?

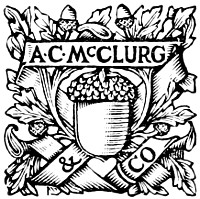

“Oh, were I only a man!” she sighed from the depth of her heart. “Oh that I could clothe my limbs in armor and wield the sword for the right! I would ask for nothing better in life. No sacrifice would be too great to accomplish it. Then, surely, the beloved saints would not refuse to help me.”

In such a spirit she entered the sacred house. It was empty. The shadows of evening, mingling with the clouds of incense smoke which still lingered in the church, were intensified by the feeble light of a small lamp. She thrilled with sacred awe as she advanced through the mysterious gloom. In her exalted mood it seemed to her that Saint Catherine smiled, as with trembling hand she placed the wreath upon her altar. In transports of sorrow and gratitude, of divine trust, and of overwhelming desire for action, she knelt at the altar, and her soul ascended to the celestial abodes. She knew no prayers except the Lord’s Prayer, the Credo, and the Ave Maria, but the more she repeated them the more completely was she spiritually absorbed.

Thus little by little she sank into that species of ecstasy in which the ordinary spiritual functions are suspended and there remain only the sacred feeling of heavenly contemplation and the free play of the fancy. It is a condition which differs from actual dreaming only in its danger, for there is danger that this ecstatic feeling once aroused may become real, and its possessor may behold illusive pictures of the fancy. The enthusiast may believe he sees real objects and hears actual voices. He may believe them to be messages from heaven, never asking himself whether such fancies will stand the test of reason. Because of ecstasies like these, deeds have been committed which have darkened the page of history with everlasting shame. But when these ecstasies arise from exalted moral ideas they may achieve results which are far beyond mere human strength and secure imperishable fame for the enthusiast.

Thus it was with this simple child praying at the altar. In her ecstatic fancy she saw the roof of the church open, and her favorite Saints Catherine and Margaret floating down through the clouds of incense. She heard them saying, “Keep thy heart unsullied, Joan, for Heaven has chosen thee as the champion of France.”

The vision disappeared. The dream was over. But in that instant the career of this child was determined. She was the subsequent Maid of Orleans.

By the storm of an April day in the year 1428, four years after the events related in the preceding chapter, a man was detained at home in the castle of Chinon.[11] His costume showed that he was of the highest rank, and the apartment also was furnished in a style of princely luxury. As it was apparent, however, that these luxurious surroundings were the survivals of an older period, evidently the present occupant of the castle either did not care to improve them or could not afford to do it. As a matter of fact the shabbiness of his own costume favored the latter inference. The morose expression of his face, which had but little that was attractive in it, deepened this impression. Nothing about it indicated any higher ambition than the gratification of his physical desires. His appearance gave the impression that he was at least thirty-five years of age, but in reality he was only twenty-six. This man was the Dauphin of France, afterwards King Charles the Seventh.

Before him stood a young and beautiful woman, whose face was in striking contrast with his. A dignified royal presence, eyes flashing with spirit and resolution, womanly gentleness and kindness,—such were the characteristics portrayed in her beautiful countenance. Some of its lines indicated troubles of the heart, but her present trouble was of another kind.

This lady was Marie of Anjou, the proud consort of the Dauphin. They were both standing, for in the excitement of their conversation they had evidently risen from their seats.

“Oh, this wretchedness!” she moaned. “Beautiful France desolate! The luxurious fields of the Loire laid waste! The poor people killed or fugitives in the forests! Townsmen in servitude or in continual fear of a victorious enemy! And you! What are you doing?”

“How, I? Who laments all this more than I? Who has to suffer from it more than I? Am I not growing poorer every day because of it? I am afraid I shall not have even an ordinary dinner to-day.”

He hastily rang a silver bell, and a servant entered. “Jacques, go to the cook and ask him what he has for dinner.”

Contempt and deep sorrow were pictured on Marie’s face, but she quickly mastered her anger. “Certainly, my husband, you have to suffer,” said she, “but what kind of a king would he be who did not feel the sufferings of his people a thousand-fold?”

“Pah! I feel my poverty above everything else.”

“But what necessity is there for your poverty? Do you not know that your poverty will disappear on the day when you overcome the enemy?”

“I overcome the enemy! God help me! I need what few mercenaries I have to forage for the kitchen. Raise fresh troops! How can I do it? What little gold there is in my treasury is already pledged. I overcome the enemy! Ha, ha, ha! they already hold nearly all of France. La Hire[12] told me to-day that Count Salisbury is before Orleans, and is besieging the city. When Orleans falls, I must fly from here. Then what? I shall end by being a beggar.”

“You will not if you pluck up courage and remember that when the necessity is the greatest, divine aid is nearest, and that it is more glorious and more worthy of a king to be vanquished in battle than to be ruined by inglorious indolence.”

“Pah! I will do neither the one nor the other. I will live and enjoy myself. That will compensate me for what I lacked in the hungry days of my youth. I will make terms with the English. They may have everything else if they will only leave me Languedoc.[13] I can live there in a manner that suits my income.”

“Shame! shame! what is this I hear?” exclaimed Marie. “Are you a Valois? Does royal blood flow in your veins? Do you not blush to utter such words? Oh, my husband, do whatever else you wish, but save France and me from such shame.”

“Well, well, all is not over yet at Orleans.”

“But even if it fall, and if all seem lost, even then do not make such a shameful agreement.”

With these words the noble lady retired. The moral indignation of her manner and her words appeared to make some impression upon the Dauphin. He buried his face in his hands, and was absorbed in thought—as far as he was capable of thinking.

While thus engaged, an arras door opened behind him, revealing the charming little curly head of a girl of eighteen or nineteen years. No one could have seen that exquisite figure moving along with such easy and consummate grace without confessing he had never before seen such exquisite beauty and fascinating manner. Her charm appeared not only in her beautiful figure, but also in the gracious expression which characterized her personality and radiated from her countenance.

This maiden was the famous Agnes Sorel,[14] the favorite of Charles the Seventh, who, as history relates, was conspicuous for her womanly tenderness, and who always used her influence over the King for noble purposes and never for personal ends.

The Dauphin was not aware of her presence until he felt the light touch of her hand upon his shoulder. The sight of her was magical in its effect. His face lightened up, and all traces of dejection disappeared.

“Is it you, Agnes? Now everything is all right.”

“What has been wrong?” she asked most tenderly.

“Marie has been here. She has made my head ache and has nearly ruined my appetite. But—”

“I know all about it,” interrupted Agnes.

“How? You know all about it? Who could have told you?”

“No one told me.”

“Oh, you have been eavesdropping. Ah, ha!”

“I had to. I could not go back, and of course I was not permitted to enter.”

“Hm! Never mind. It is all right, just the same.”

“Oh, no, Your Majesty.”

“How? What do you mean?”

“I share the anxiety and trouble of your proud consort.”

“Nonsense! You ought not to be troubled.”

“By all the saints, Your Majesty, I shall be inconsolable and unhappy if you do not abandon your decision. I should be ashamed to serve a prince who can so easily renounce his rights and his dignities.”

“Well, well, I will consider the matter. Will that satisfy you?”

“Oh, no, sire. You must promise me that you will not think again of that hateful scheme. Will you not for my sake?” Thereupon she triumphantly and gracefully pirouetted about the apartment.

“Agnes, I take back my word,” cried the Dauphin.

This made her all the happier, and she continued her dance, singing this accompaniment:—

“Eio, eio, eio, no,

He cannot be a King

Who does not keep his word!

Eio, eio, eio, O,

This one here—he is not such,

No, no, no, oh, no.”

With the last word she suddenly disappeared, for the heavy tramp of men’s feet was heard in the antechamber. The interruption displeased the Dauphin, and he was about to leave the room, but before he could do so the new-comers stood at the door. It only increased his displeasure that he was forced to remain. The two men, whom he regarded with a sinister expression, were rough and sturdy, men of the class who stand fast in battle and look death fearlessly in the eye, knights in the truest sense of the word.

“So quickly back, my brave La Hire?” said Charles to one of them.

“By Our Lady, Your Majesty, never was there greater need for quick and decisive action than now,” was his reply. “I have just heard that Count Salisbury has completely invested the city of Orleans. Not even a cat can get out of it, and in a few weeks it will be in the clutches of famine. If we do not help them you can easily see—”

“Help them!” interrupted the Dauphin, despondently. “My good knight, how much money do you suppose there is in my treasury? Ha! ha!”

“The people will see to it that the treasury of their legitimate King is filled if in turn they have the assurance that he will make a stand for the right, for his honor, and for the fatherland.”

“And until then I suppose I can keep on with my fasting cure to which my mother accustomed me. You will not believe it, my good La Hire, but it is the sad truth that my cook has notified me he has nothing to serve to-day but a pair of fowls and a hind-quarter of mutton. And you are to be invited as guests to such a banquet as that!”

“Well, sire, that is all right. To-day we will eat the fowls and the mutton; to-morrow we will drive the English out of their kitchens, and seat ourselves at their tables.”

“But how are we going to drive them out? It is impossible. Can I summon troops out of the ground?”

“Yes, sire, you can!”

The Dauphin looked at him with astonishment.

“Do you take me for a wizard? Or, do you mean I am in partnership with the devil?”

“Resolution and courage, sire, have often worked wonders. Inscribe them on your banner to-day, and to-morrow it will not flutter deserted. It will rally those around it who have fallen away discouraged as well as those who follow the profession of arms, and would gladly enlist under such a royal banner for the sake of the rich reward. There are men yet who are ready to stand by you with their good swords. See, here is my stanch friend Saintrailles,” pointing to his companion, “and he is not the only one who is ready.”

“You are welcome, brave knight,” said Charles. “It is a shame I can only invite you to sit down to two fowls and a leg of mutton.”

“Sire,” replied Saintrailles, who could hardly restrain his indignation, “I was not thinking of your table when I followed my friend here. I was thinking of your wretched plight and of the bleeding fatherland.”

“And do you believe it can be helped?”

“Certainly, sire, but he who would win must venture.”

“Yes, and in the meantime he may also lose. But, by my faith, I have not much more to lose.”

“But all the more to win. The brave soul thinks only of winning.”

“Oh, yes, you talk like La Hire, and La Hire talks like Marie, and Marie talks like—but if the English would let me have Languedoc as an independent dukedom, then—”

He did not finish the sentence, for through the side-door, which was partly open, he saw the warning finger of Agnes Sorel. Then he resumed:

“I am glad you have come, noble knights. We will meet at table and further consider this matter. But, alas! two fowls and a leg of mutton!”

On the evening of the same day, when La Hire reached his lodgings and was laying off his armor, a young man of about eighteen years entered. His strong, supple frame, handsome, noble face, piercing black eyes, lofty forehead beneath raven-black hair, as well as his resolute, self-confident bearing, impressed themselves upon the knight.

“Who are you, and what do you wish?” he said, at the same time regarding the young man with evident satisfaction.

“My name, noble knight, is probably unknown to you,” was his reply. “My father of blessed memory, however, left it to me unstained. I have come to honor that name under your banner in the service of the distressed King and the unhappy fatherland.”

“Well said, young man, and, by Our Lady, you look to me like one who can use his sword as well as his tongue. We will consider the matter.”

“Will you not accept my service, noble sir?”

“Gently, young man. Do you suppose that I confide the honor of my banner to every nameless fellow? Out with your name.”

“I am called Jean Renault.”

“Renault? Was your father that Thomas Renault who fell in the service of the Duke of Orleans, fighting against the English?”

“The same, noble sir.”

“Then a thousand times welcome. Your father was a brave knight and a noble gentleman. From to-day you shall serve under my banner, and you will have ample opportunities to earn your knightly spurs.” Thereupon he shook the young man’s hand heartily.

“I thank you for your confidence, noble sir,” replied the new adherent, with beaming eyes. “I will do my utmost to justify this confidence, but what I can do to earn my knightly spurs I do not yet know, partly because of my youth, and also, though it is no disgrace, partly because of my poverty.”

“Poverty! Your father had property.”

“Yes; but it was at Rouen, and it has fallen into the hands of the English.”

“Well, we will see that it is returned to you. But now tell me where you acquired your training.”

“Under my father, to whose retinue I was last attached.”

“Then you have also fought against the English?”

“Yes, I was in the battle in which my father fell and the Duke of Orleans was captured.”

“Then you are doubly welcome, my young friend,” warmly exclaimed the knight. “I well know I cannot take your father’s place, but I will do for you all that a man can.”

Overcome by such generosity, Jean pressed the knight’s proffered hand to his lips. His heart was too full for words. La Hire understood his silence, and admired him all the more. “You are from the neighborhood of Rouen, and are acquainted there?” he resumed.

“I know every village thereabouts, noble sir. Alas! they are nearly all ruined.”

“Yes! God and the saints pity them. But, further, do you know the Bishop of Beauvais?”

“Certainly I know him. It is his diocese.”

“That is fortunate. I have a message for the bishop, but no messenger who is acquainted with that region, or cunning enough to evade the English. I can trust you for both?”

“I am ready, noble sir, provided you do not wish me to act as a spy.”

“Do you suppose, my young friend, that I would choose you if I needed a spy? No, the mission you are to undertake has nothing to do with the war. However, I cannot conceal from you the danger involved in the undertaking. The Bishop of Beauvais has the reputation of loving money and leaning to both sides. Do you understand me?”

“Perfectly, noble sir. He is devoted, now to the Burgundians, now to the Lotharingians, now to the English, and now to the Duke of Orleans.”

“Listen. The English might easily regard a messenger to him as a spy, which, by Our Lady, would grieve me. But then again, even if they should hold you as a prisoner it would be uncomfortable, for money is so scarce in our treasury that you might have to wait a long time for your release.”

“I do not think, noble sir, that the English will catch me.”

“Then you will undertake the mission?”

“I await your commands.”

“Rest to-day and to-morrow. The day after to-morrow you shall have the letter for the Bishop.”

As the road to Rouen led directly through the English district it was practically impossible for a messenger to make the journey on horseback. Jean therefore decided to go on foot, disguised as a peasant. As the cities around Orleans were in possession of the English, he was continually forced to take divergent routes. He made a wide circuit around Paris, and at last approached Rouen from the east. While on this part of his journey he stopped in a forest one noon to rest and enjoy his simple meal. While thus engaged, he suddenly heard a female voice crying for help. He sprang up, and ran to the road whence the cry had come. Concealing himself behind some bushes, he watched and listened. He heard the distant rattle of a carriage and the clatter of armor toward the east. A heavy travelling carriage soon came lumbering along the rough road, accompanied by half a dozen men at arms.

“Has a shameful crime been committed, and did the cry come from that carriage?” said Jean to himself. “What! I think I know the arms on the carriage door. Why, certainly. They are the Duke of Luxemburg’s. But I must be sure of it.” With this he rushed from his hiding-place. “Halt!” he shouted, brandishing his knobbed stick.

The coachman and attendants were astonished. It seemed incredible that a single man, armed with such a weapon, should dare to order them to halt. While they prepared for resistance they watched, not so much the young man as the thickets, for they were suspicious that other peasants might make their appearance. During this brief waiting Jean discovered what he had feared, and what he was so anxious to ascertain. Scarcely had his “halt” died away when a girl’s face appeared at the carriage door.

“Help! help!” she cried, in terror. “Help! They are dragging me to a convent—”

A smothered exclamation of pain followed the last word. Some one inside the carriage had pulled her back and stifled her cries. Instead of the girl’s face there now appeared at the door the wrathful face of a knight.

“Seize the dog,” he shouted. “Do not kill him. I must have him alive.”

The men at arms prepared for action at once, but Jean did not stir. He stood immovable as a statue, staring at the door. The distress which he was powerless to relieve threatened his own undoing, but he remained as if glued to the spot, trying to identify the personality of the victim. He had only caught a fleeting glance of her, but that glance left an impression that could not be effaced. She was a girl of fifteen or sixteen years, and so radiantly beautiful that even her expression of poignant suffering and fear could not diminish her charm.

Meanwhile the men at arms were arranging their plan. They evidently intended to surround and overpower him, but their movements were too slow to suit the knight in the carriage. “Well,” he roared, “what are you waiting for? Seize him!”

The command brought Jean to his senses, and the first glance revealed his danger. With a quick rush he broke through the circle of his assailants and ran back into the thicket.

“Follow him, ride him down,” furiously cried the knight.

The men at arms rode after him, but before they could overtake him he had disappeared in the woods, where they could not follow him on horseback. To dismount and pursue him on foot would have been a rash undertaking, so they turned about only to receive violent reproaches and curses from their master, who was forced to resume his journey without his wished-for victim.

Jean did not go far, for he well knew they would not dare to follow him into the forest. Leaning against a tree, he watched the carriage, which took the road to Rouen. His first impulse was to follow it and keep it in sight, but, upon second thought, he remembered he was not at that moment his own master, but was in the service of another, and that under such circumstances he had no right to risk his liberty or his life. Accordingly he let the carriage go on several hours before he resumed his journey.

Making allowance for the precautions he must take, it would be three or four days before he could reach Rouen. On the way he made several inquiries as to the whereabouts of the carriage, so that when he entered that city on the evening of the fourth day, he knew it was there. At the inn where he put up he passed himself off as a fugitive peasant who desired an interview with the bishop, that he might tell him of the sufferings of himself and his fellow villagers. As his story was a probable one, he hoped there would be no opposition to his remaining there. He was told that the bishop arrived two days before in the company of the Duke of Luxemburg, and had brought a young novice to the convent of Saint Ursula. He had gone away again with the Duke, but only for a short time.

Whenever Jean ventured out of the inn, he took his way to the convent. He could see only its outer walls, and yet he was drawn to it over and over again. Near the convent stands the church of Saint Ursula. As its doors were always open there was nothing to prevent him from entering and praying fervently for the unhappy girl he had seen in the forest. One day he as usual selected a spot close to the wall between the church and the convent for his devotions. This wall must have been in frequent use, for there was a door in it opening upon a passage-way to the other buildings. While Jean was praying the church was empty, and in the gathering shades of evening the sacred room was quiet and restful. In the profound silence it seemed to him that he heard human sobs in the distance. He listened intently. There could be no doubt of it. He was not deceived. The sound seemed to come out of the wall. He placed his ear against the stone, and distinctly heard a woman’s painful ejaculations between alternate groans and gentle sobs. A cold sweat stood on his brow. He felt rooted to the spot. The longer he listened the fiercer grew the storm in his breast. At last he could endure it no longer. He rushed out into the air. His heart was almost bursting. “The captive lady!” he cried, “can it be she?”

His despair drew him again to the spot, and again he listened. His pulse beat so feverishly, and he was under such excitement, that it was impossible for him to judge calmly, but he fancied he recognized the voice.

During the remainder of his stay in Rouen Jean spent his time almost exclusively in trying to discover the fate of this unfortunate one, but it was in vain. He only found that he was drawing attention to himself, and this attention at last became so apparent that after delivering the letter to the Bishop he was forced to leave Rouen abruptly and make his way back.

Four leagues distant from Cambray[15] the towers of Beaurevoir Castle rise from forest-crowned heights. In selecting this spot the builders combined the useful and the beautiful, for the castle was famous both for its strength and for its attractive situation. The view from the upper windows and from the towers repaid the appreciative observer at any season of the year, but he would have lingered longest in admiration when park and gardens, wood and meadow, field and grove were decked in the beauty of early spring, when the thickly clustered villages, east, west, and north, smiled amid their luxuriant crops, or when on the southern heights the Argonne forest was clad in its most gorgeous greenery. How much more attractive the beauties of this spot must have been to a child whose greatest delight was to be among the flowers of the garden and meadow, the birds in the parks, and the varied scenery! How closely such a child must have been attached to such a spot! How strong its temptation to pass all its time with nature!

Just such a child as this had been allured to the park and gardens by the sunshine of an early April day in the year last named,—a girl blooming with color, vigorous with health. At a distance she appeared to be about eighteen years of age, but closer observation showed she could not have been much over fifteen. Of all the beautiful things in this beautiful scene she was the most attractive, as she frolicked and skipped about like a fawn, bounding over the flowery meadows for the first time. As she ran about in the sunshine she gave expression to her childish joy at each fresh manifestation of the marvellous work of spring, and broke out in most exultant exclamations when she discovered the first violets in the grass.

Two ladies slowly following her, and engaged in earnest conversation, were attracted by her outcries. “There now,” said one of them, a somewhat slender person with angular features and sharp eyes, “you see what an undisciplined creature she is. Is it proper for her to behave in such a manner? This comes of letting her have her own way. How often have I protested! But of what use is it? When you see that your talking is of no avail it is best to hold your tongue. If you do not, then they say, ‘Oh, yes, that’s the way envious old spinsters always talk.’”

The other lady, whose handsome face, beaming with good nature, was in striking contrast with that of her companion, cast an appealing glance at her. “Oh, dear Rosette, are you not mistaken? Who would dare to insult my husband’s sister by making such a remark?”

“Oh, well, you know people often think many things they do not say.”

“That is true. But even if they do, why should you conclude they are thinking things about you they do not venture to say?”

“I cannot give you any precise reason.”

“Then I must tell you it is not kind to think evil of others, especially of your own friends, unless you have sufficient cause to do so. But never mind. You were speaking of Marie. You are offended with the behavior of the poor child.”

“Child! A fine child she is,—ha! ha! You ought to have known some time ago that she is no longer a child. She is a grown-up girl.”

“Let us hope she may not discover it for a long time yet. How happy she would be if she could always preserve her childlike nature! Look at her, dear Rosette! Is it not a beautiful sight—such an innocent child, sporting in pure delight?”

The sister-in-law turned up her nose.

“But why is not her behavior proper?” continued the other. “Proper! What is proper? Are not many things proper which are called highly improper? Marie is in her own world here. She has grown up in it, is attached to it, and enjoys herself in it. You cannot imagine how delighted I am to see her thus. Poor little one! Orphaned at an early age, she has never known the comfort of a father’s or mother’s embraces, and shall I begrudge her her harmless pleasures?”

“It would be much better if she were to begin leading a more quiet and serious life right away, in preparation for her future.”

“What has the future in store for her?”

“Is she not intended for the convent?”

“Who says so? She is sole heir of Louis of Chafleur, who has left her a rich property. Why should she take the veil?”

“She will not take it voluntarily. I think it is the wish of your husband.”

“I think you are mistaken. At least, I do not know of any such plan. John simply said that a convent would be the safest retreat for Marie in case the tumult of war should invade the Argonne forest. To seek the shelter of a convent and to take the veil are two different things.”

Rosette’s eyes glistened with malicious triumph as she looked at Marie, who at that instant came bounding forward with a bunch of violets and put an end to the conversation; her look seemed to say, “I know some things better than you.”

While this was going on in the park, two men were standing at an upper window of the castle. They were considerably beyond middle age, and resembled one another in a certain cold, crafty, calculating expression of countenance. One of them wore the usual costume of a knight, the other the conventional dress of a high church dignitary. One was John of Luxemburg, lord of the castle; the other, Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais.

“The girl is really a handsome child,” said the Bishop, as he looked at Marie.

“Oh, yes,” slowly assented the lord of the castle. “But,” he added with a peculiar twinkle of the eye, “I know something that is more beautiful.”

The prelate understood. “Hm! I won’t dispute that. These are fine possessions. It would be a pity to have them pass into the hands of strangers.”

“You have echoed my very thought, your reverence. So I think we are agreed on the general point.”

“You mean that in these times of disturbance there is no place where Marie will be so secure as in the cell of a convent.”

“Exactly, and unless I am mistaken that is also what you mean.”

“In a general sense, yes; but we have not yet considered the most important point.”

“Let us come to it.”

“The question arises, How is the girl to be secured for the convent? and next, How is she to be taken there?”

“I will see that she is taken there. As to the rest of the business, I appeal to the experience of your reverence.”

“Hm! a difficult task when, as in this case, the novice has the utmost aversion to a convent.”

“It is not so difficult as appears at first sight. I know of similar cases where the task has been successfully accomplished.”

“Yes, but under peculiar circumstances.”

“The circumstances in our case are similar.”

The Bishop’s face wore a crafty expression. “That is truly quite another thing. Let us hear about it.”

“Of course Marie’s property remains in possession of her guardian until she reaches legal age, when it is at her disposal.”

“That is clear. But what will the Church get?”

“Patience, your reverence. If she should not reach that age—and that is not impossible—”

“Well?”

“I understand that in such a case the property is legally mine.”

“That is also clear. But what will the Church get?”

“In that case we can make an agreement as to how much the Church shall have.”

“We understand each other, noble knight. But supposing she reaches legal age?”

“Then the Church must see to it that the legal requirements are not binding. I say ‘legal requirements.’ You understand me, holy father?”

“Perfectly, my noble friend. Sometimes we have had to grant exemptions from requirements which afterwards were shown to have been void because of irregularities.”

“I am glad we understand each other so well.”

“Yes, but what will the Church get?”

“The same as in the other case, namely, a share of the property, only the Church will not come into actual possession until after the death of the testatrix.”

“Hm! It seems to me, my noble friend, that you not only propose to take the lion’s share, but the entire prize. The Church would have the first claim in case of death.”

“You haven’t let me finish, your reverence. Until the death of the heir I will secure you, as the representative of the Church, a yearly income of three hundred pounds.”

“Dear uncle, see these beautiful violets,” she cried

The Bishop’s eyes glistened. “And the security?” he said, stretching out his hand.

“My word, the word of a nobleman;” and they shook hands.

A pause ensued. Each of the men, in the stillness, seemed to be studying whether he might not find eventually that he had been overreached and had not received his proper share. The Bishop was the first to come to a decision, and asked, “When shall we begin our work, noble friend?”

“At once, if you are ready.” Thereupon he rang a bell, and ordered the servant who answered it to call Mademoiselle de Chafleur.

It was not long before Marie came running into the room, full of joyous exultation. “Dear uncle, see these beautiful violets,” she cried. “Oh, what delicious perfume!”

“Very beautiful indeed. They are messengers sent by Spring to the other flowers.”

“It must be so. Oh, you cannot imagine how beautiful the park is already! Tell me quickly what I am to do, so that I can return soon.”

“So you find it very pleasant in the park?”

“Oh, I could stay there always.”

“I am all the more sorry, then, that you will have to leave it soon.”

“What! Leave! Uncle, I do not understand you.”

“Yes, child. The tumult of war approaches nearer and nearer.”

“What of that? Is not the castle safe? Let the Englishmen come. We will send those long-nosed gentlemen home again. Yes, ‘we,’ I say, for you know I am a Chafleur.”

“I have the highest respect for your courage, my little Amazon, but the English will not be greatly scared by it. No, child, I must find a safer place for you.”

“And my aunts?”

“Oh, that is a different matter. My wife and sister must submit to the inevitable.”

“And I can also.”

“No, child. Your father sacredly intrusted you to me. I should not be keeping my word if I exposed you to the dangers of war.”

“But I say again, uncle, and you have said yourself, that the castle is safe enough.”

“Still it can be taken; but no enemy will dare to attack the sacred walls of a convent.”

“A convent! What do you mean? Do you intend to make me a nun? Me! A nun! Ha! ha! ha! I shall die a-laughing.”

“It is not always nuns who find shelter in a convent.”

“Nevertheless, uncle, and once for all, I say I will have nothing to do with a convent.”

“Then tell me what you will do, for you cannot stay here.”

“Are you in earnest, uncle?”

“Absolutely so.”

The tears came to the girl’s eyes. Sobbing, and throwing her arms around his neck, she exclaimed: “Uncle, you cannot send me away from you.”

“It is for your safety, my child.”

“But I do not wish any special safety. Where my aunts can stay, I can stay.”

“It is of no use. No use. My decision is final.”

The girl stood erect. She wiped the tears from her eyes and looked at the knight with a strange and distressed expression. Gradually her look became colder and more fixed, and at last he realized her undaunted determination.

“My decision is made too, uncle. I will not go to a convent. I would rather fall into the hands of the English. But the situation is not so desperate as that. I will let my kinsman La Hire know. He will protect me. Let me have a messenger, uncle. In an hour I will have a letter ready.” Thereupon she left the room.

“Well, what do you think now, noble knight?” began the Bishop.

“Pah!” he replied, “I will send her a messenger who will throw her letter into the first forest brook he comes to, and return without seeing La Hire.”

On the morning of the fourteenth day after this scene, a heavy travelling carriage stood in the castle yard with an escort of six armed men. Marie lay sobbing in the arms of Madame de Luxemburg. Still sobbing, she at last followed the impatient lord of the castle to the carriage. Nothing had been heard from La Hire, and when, as John of Luxemburg had said, an attack upon the castle was likely to be made, he told Marie he would accompany her to her kinsman. At the first inn they met the Bishop of Beauvais, apparently by accident. As he was journeying in the same direction he accepted the knight’s invitation to take a seat in the carriage.

Overcome with grief, and not expecting any trickery, Marie at first did not notice the road they were taking. After passing three or four inns, however, she saw that they were going west instead of south. Not even then did she suspect treachery. They easily satisfied her inquiries by pretending they must take a circuitous route to avoid encountering the English. When, however, they kept on in the same direction the next day, her suspicions were fully aroused.

“Uncle,” she said, “you cannot deceive me any longer; you are not taking me to Chinon. What are you going to do with me?”

“I will not deceive you, child,” replied the knight, for pretense was useless any longer. “I cannot carry out my plan to take you to Chinon. The whole district of the Loire is in the hands of the English. I cannot even get back to Beaurevoir, so nothing remains but—”

“But what?” she piteously exclaimed.

“The convent.”

She uttered a scream of terror.

“Be quiet,” said the knight, harshly. “If you scream again I will silence you in a way that may not be agreeable.”

They were in a forest where fugitive peasants might be in hiding. Even at a distance from it, he had been fearful lest the girl might attract some one’s attention. He wished to reach his destination without being observed, and was particularly anxious no one should even suspect where he was or what he was doing.

Marie was not frightened by his threat, but a quick glance showed her they were in a forest where no help of any kind could be expected. In despair she sank back into a corner of the carriage. Anger, desperation, and scorn raged by turns in her breast, until at last, overcome by exhaustion, she buried her face in her hands and wept.

The vigorous “halt” of a manly voice aroused her from her wretched condition. In an instant she was at the carriage door. Her first glance fell upon a handsome youth who was advancing courageously toward the carriage. The reader knows who he was.

“Help! help!” she involuntarily cried. “They are taking me to a convent.”

Her guardian pulled her back, and silenced her cries by holding his handkerchief over her mouth. She tried desperately to release herself,—but what availed her weakness against the strength of a trained knight? In her anguish the image of the brave youth rose before her, and her anxiety about his fate made her forget her own. She listened intently to all that was going on outside. She trembled when it seemed impossible for her to escape, but at last she exulted when she knew that he was safe.

It was late at night when the carriage came to a stop. Marie knew by the call of a watchman that they were either before a city or a castle. The Bishop gave his name, and the creaking gate opened. The carriage passed through several dark streets, and stopped at last before a large, gloomy building. Here also the Bishop’s name was an Open Sesame; the heavy bolts were pushed back, the carriage rolled over a paved yard, and with a hollow, fateful sound the gate was closed and locked.

Marie shook as in an ague fit. She realized that she was a prisoner, and perhaps was cut off from all the pleasures of life; but not a sound escaped her lips. Her mute sorrow alone reproached her persecutors. She did not know she was in the Ursuline Convent at Rouen, but she had no doubt it was some convent in the Bishop’s diocese. Evidently they were ready to receive an exalted guest, whom they had expected, in a manner befitting her station. The abbess, a lady of middle age, who, judging by her speech and manners, might have been of high rank, was awaiting her in the parlor. After the Bishop had exchanged a few words with her, the abbess turned to Marie and said: “May your entrance among us be blest, Mademoiselle de Chafleur. I hope these sacred walls will furnish you both the outward security which you need, and your heart that peace which the world cannot give.”

There was something so cordial, and withal so winning, in the tone with which she spoke these words, that Marie pressed her extended hand to her lips with the utmost sincerity, and covered it with kisses. She longed to throw herself into the arms of this gracious lady, and weep away her sorrow as she would on a mother’s breast. Her longing was so overpowering that she sank upon her knees and moistened the abbess’s hand with her tears.

“Save me, gracious lady, save me,” she implored. “I am the victim of a conspiracy. They have deceived me, brought me here by force, and torn me from all that is dear and sacred to me.”

The astonished abbess cast an inquiring glance at the Bishop. “The novice,” he said in reply to it, “is here because it is the wish of her guardian, a lord of Luxemburg, who alone has authority to act for her. Therefore it is idle to talk of force. To your—”

“I am not a novice,” cried Marie, rising. “I am Marie of Chafleur. My guardian has control of my property, but he has no right arbitrarily to dispose of my person.”

“I trust your ability,” resumed the Bishop, “to remove these worldly ideas, which are unbecoming within these sacred walls, and to implant in this perverse soul the spirit of quiet resignation and Christian humility. I authorize you to employ all the means which are at your command to produce this result, and I have no doubt of their efficacy.”

The last words were spoken with a peculiar intonation which was in the nature of a command to the abbess, but of the significance of which the poor child had not the most remote idea. The abbess, who understood well enough what was expected from her, made a quiet sign of assent, and the two men took their leave, firmly convinced that their work was completed successfully.

Marie was assigned to the usual cell and left alone. She first went to the grated window. It looked out only upon the yard. With a pitiful sob she threw herself upon the hard couch. Her tears flowed, and she gave vent to her anguish in melancholy ejaculations. At last she knelt before the crucifix and poured out her aching heart in long and fervent prayer. Again she quietly sought her couch. She was now able to think calmly over recent events. As she was ignorant of what was in store for her, she was still buoyant with the hopefulness of youth. She thought of La Hire, whom she had known as an honorable knight. The image of the young man also mingled pleasantly in her thoughts of the future. She decided she would write again to La Hire. He could not have deserted her. Thus consoling herself, she sank into kindly slumber. Poor child! Little she knew that her letters could not find their way into the outside world without first being read by the superior.

One day two nuns, commissioned to acquaint her with the rules of the Ursuline order, visited her. Her declaration that she did not wish to know them made no impression upon the sisters. They performed their duty, and then withdrew to make their report. Shortly afterwards another sister entered, and summoned the novice to prepare herself by prayer and fasting for the vow which she was shortly to take.

“What means this farce?” said Marie. “I am not a novice. I will not join your order. I will not take a vow.”

“Our wishes are useless within these walls,” replied the sister. “We must do what the superior, the abbess, and the rules of the order command.”

“What is that to me? I am not one of you.”

“You will do well, sister, to submit to the inevitable.”

“And what if I do not?”

“Then they will force you to submit.”

“Force me, Marie of Chafleur! I should like to hear how they propose to do it.”

“I can tell you, sister. They will lock you in your cell and let you go half starved.”

“Well, I would rather wholly starve than take the vow.”

“They will thrust you into a gloomy prison.”

“Go on.”

“They will come daily to your prison and punish you without mercy.”

Marie shrieked aloud. She clenched her fists. Her lips quivered. “Woman,” she at last exclaimed, “the devil has sent you to tempt me! Leave me. Go and report that I will suffer death rather than consent.”

“I must first do what I have been ordered, sister.” Thereupon the nun knelt before the crucifix and repeated aloud the prayers which were prescribed as a preparation for the vow. When she had finished she withdrew. What she had said came to pass. Marie first was locked in her cell and given only a scanty bit of bread. When that proved of no avail she was put into the prison. It was her loud laments which Jean had heard while praying in the church of Saint Ursula, for the prison was only separated from the church by a single wall.

News of the siege of the City of Orleans by the English at last reached the village of Domremy. No one was more deeply affected by it than Joan, for she believed from what her confessor had told the villagers that with the fall of Orleans the King’s cause would be lost, that there was no hope for the raising of the siege, and that the wretchedness of the fatherland would then be complete.

Scarcely had Joan heard the news before she left the village to meditate upon this new situation in some one of her favorite solitudes. She was at this time about seventeen years of age, blooming and beautiful in person, but unchanged in nature and habits. She longed to abandon herself to her thoughts and impressions in solitude as she used to do when tending her father’s flocks. Deep down in her heart she felt the sorrows of others now as she did then, and was moved by the same irresistible desire to help them. She longed to prostrate herself before her saints, to look into the clouds with supernatural vision and see their figures and hear their voices as she used to do. Her communion with the spiritual world at this time had become so intimate that she could question her saints and hear their instant replies. The Fairy Tree, under which she fed the birds, the miraculous spring where the fawns frisked about her, and the chapel at the cross-road near the oak forest, in which she had most of her visions, were her favorite resorts. In this chapel she knelt before the image of Saint Catherine, unconscious of the outside world. The burden of her fervent prayer was the necessities of the country, the rescue of the City of Orleans, and the coronation of the King.

“O that I were a man! O that I were a commander!” she sighed. “I would rush to the rescue. Perhaps it is not impossible. Does not the wolf fly from me when my saints are near? Can I not hide my maiden’s figure in the garb of the soldier? Are not these limbs strong enough to wear armor? What if the dear saints should commission me to rescue the fatherland!”

Absorbed in such thoughts and longings, she lost herself in communion with the celestial world, and in a vision she saw her favorite saints in the glowing clouds.

“Why do you tarry, Joan?” said the voices. “Cities and villages are being destroyed every day. Daily the blood of the people is being shed. Arise! Execute the decree of Heaven.”

“But,” said Joan, “how may I know it is Heaven which sends me?”

“The signs of your mission will not fail.”

“And what is my mission?”

“To raise the siege of the city of Orleans, and conduct the King to his coronation at Rheims.”

“How shall I begin?”

“Go to the King and offer yourself to him as commander of the army.”

“To whom shall I apply so that I may reach the King?”

“Go to the knight, Robert of Baudricourt.[16] He will help you.”

Joan returned home, and remained several days deeply absorbed in contemplating the mission to which she had been assigned. She would often steal away to her little chamber and weep bitterly; for although she felt exalted by the heavenly decree, still, it seemed impossible for her secretly to leave all the dear ones at home,—father, mother, brothers, and sister. And yet she must go secretly, for her father never would approve of her purpose or consent to her going, and no other way suggested itself. They had grown so accustomed to seeing her absorbed in silent and solitary meditations that they kept aloof from her at such times. It had been village gossip for years that she communicated with spirits and practised magic. In what other way indeed could her mastery of the wild beasts be explained? Her brother Pierre, however, who was devotedly attached to her, was an exception. He never pained her by suspicions. She had no secrets from him, and she came to him now in perfect confidence and wept upon his breast.

“It is not true, Pierre,” she said, looking up at him with her beautiful tearful eyes, “that you mock at me as the others do?”

“How can you think such a thing of me, little sister?”

“Oh, I do not think it, my brother.”

“And yet your question seems to imply that you do.”

“Not at all, Pierre. I know very well that you love me, but you must tell me so over and over again. I know very well you do not mock me, but even that does not satisfy me. I must have the assurance from your own lips.”

“I know very well, Joan, that you are a favorite with your saints, that they manifest themselves to you in the clouds, and that you talk with them as you talk with us.”

“Yes; you believe me when I tell you these things. But when I tell the others—”

“Oh, my sister, they do not know you as I do. I know that you never speak an untruth.”

“And yet my actions now must be deceitful. Alas! Pierre, that is what distresses me.”

“But remember, little sister, that you are obeying the celestial ones, that it is the fatherland which calls you.”

“And still it grieves me, my brother. I go about here just as usual. Father, mother, and all the others think that I shall always go on this way, and I let them think so, and purposely strengthen this belief while I am preparing to leave them secretly. Oh, Pierre, they will never forgive me.”

“Why should you distress yourself with such thoughts, my sister? You know that you must undertake this mission. And it is right you should, for the will of Heaven is superior to the human will. When father and mother and the others hear what Heaven has accomplished through you, do you not think they will forgive you?”

“Your words have done me good, my brother,” cried Joan, her clear, brilliant eyes shining with happiness. “Would that I could always have you by my side and hear your voice! If you were near I would fear no one whom I may encounter.”

“I will go with you, my sister.”

“No, Pierre, you cannot.”

“And why not?”

“Is it not enough for me to bring sorrow to our parents? Would you add to that sorrow by secretly going away also?”

“You are right. I ought not to go. You are obeying the decree of Heaven, but I cannot offer that plea. But I know of some one who might go with you.”

“Who?”

“Uncle Laxart. He also loves you, and he will not have to ask permission of any one.”

“But will he go?”

“I will speak to him about it.”

The next day (in the year 1429)—it was the day of the Three Holy Kings—Joan crossed the snow-covered valley to the Fairy Tree, sprinkled crumbs for the birds as usual, and listened to their grateful songs. Soon afterwards she was lost in deep reverie in the chapel at the cross-roads, and while in this state her enraptured eyes beheld her saints, Catherine and Margaret, in the clouds.

“The hour has come, Joan,” she heard them say. “Arise! the Queen of Heaven will be with you.”

“But I must go all alone,” she replied. “They will call me an adventuress.”

“Not so! Your protector is already at the door.”

As Joan arose she saw a man approaching the chapel. With joyous surprise she recognized her uncle, Duram Laxart.

“I know all, Joan,” he exclaimed. “I am ready to escort you as soon as you need my protection. I have already been to Vaucouleurs and have seen the knight Baudricourt. Start as soon as you can get ready. We will lodge with Wagner, whom you know.”

Before the astonished maiden could reply her uncle was off in the direction of Vaucouleurs.

The time for departure had come at last. Deeply agitated, she stood at the door of the chapel, and looked once more with tearful eyes out over the valley. Once more her gaze lingered upon the miraculous spring, the Fairy Tree, and her home at Domremy, and her soul was filled with tender and sacred associations.

“Farewell, O Wonder Tree, where I have spent so many happy hours,” she said between her sobs. “And you, little birds, farewell! Alas! Joan can never feed you again. In vain will you wait for her. Farewell, dear spring, whose music I have heard so often in my happy dreams. Tell the deer I cannot play with them again. Farewell, loved valleys and fields! How happy I was when I played here with the companions of my childhood! Alas! I shall never see you again! Farewell, my father! My beloved mother, farewell! And you, my Pierre, my good, dear brother. Oh, how hard it is to leave you! Alas! never again shall I look into your true eyes, never again hear words of love and sympathy from your lips. Farewell all, all farewell! Grieve not that I leave you. Be not angry. It cannot be otherwise. No! it must be so, for Heaven has decreed it, and the fatherland has called me. Away, Joan, away! The struggle is at hand.”

No one could have seen the simple peasant maiden at that moment, her eyes shining as the tears glistened on their lashes, no one could have realized her strength of will in giving up all that had filled her soul with sorrow as she thought of leaving it, no one could have watched her passing down the valley like a soldier defiant of danger, without the conviction that it was an event fraught with the highest significance for France.

Joan found her uncle at Wagner’s house in Vaucouleurs. He had already called upon Baudricourt, but was sent away with instructions to reprove his silly niece and take her back to her parents. Though not in the least discouraged, Joan spent the night in prayer, and in the morning went to see Baudricourt. She found him in the company of Jean de Nouillemport de Metz. Both laughed when they learned the nature of her errand, but she spoke with such sincere conviction of her celestial visions that Baudricourt at last dismissed her with a promise to give the matter serious consideration. Subsequently, when Joan prayed in the church, and the people came in crowds to see “the saint,” a priest approached her with a crucifix to see if she was possessed of the devil. Joan fell upon her knees and kissed the holy symbol, and the priest declared, “She may be mad but she is not possessed.” On her way out of the church she met the knight Nouillemport de Metz, to whom she thus appealed: “Alas! No one will believe me, and yet France can be saved only by me.” The words reminded him of the prophecy of Merlin. After observing her more closely, and recognizing her spiritual purity and her resolute determination of purpose, he expressed his willingness to take her to the Dauphin, and he had little difficulty in persuading Baudricourt to join him. A few days afterwards Joan was delighted to find herself on the way to Chinon with the knights and their men at arms. In her costume she looked like a slim, handsome page rather than a trooper. Chinon was more than one hundred and fifty leagues away, and for half that distance the country was occupied by the English. Hence they were obliged to make wide circuits, and frequently halt in the forests and ford rivers. After a fourteen days’ march they reached the city of Gien[17] on the Loire. The news spread like wildfire that the Maiden who, according to Merlin’s prophecy, was to rescue France, had come, and all hastened to extend her an enthusiastic welcome.

After leaving Gien there was little danger, and at last they safely reached Chinon and put up at an inn. Here, as at Gien, the news of Joan’s arrival spread rapidly, and attracted a great crowd. To satisfy the universal curiosity, she appeared on the balcony and was welcomed with enthusiastic shouts. Her knightly companions promptly waited upon the Dauphin; but they found him greatly discouraged and in a despondent mood because of the news that the Englishman, John Falstaff, had repulsed the French, who tried to prevent him from taking supplies of herring to his countrymen before Orleans. The Dauphin’s disappointment over the “herrings day” defeat, however, would have been short-lived had he not at the same time been overtaken by a calamity which seemed to him even worse, namely, his utter lack of money and the consequent emptiness of his kitchen and cellar. In such a mood Joan’s companions found him. At first he listened to them with indifference and a contemptuous smile, but when they told him the people had recognized the Maiden as a saint, and welcomed her as the rescuer of France, it occurred to him she might be instrumental in relieving his necessitous condition. At last he ordered that she should be admitted. To test the prophetic gift ascribed to her, he received her standing among the nobles of his court, while another person sat on the throne.

Joan recognized him at once, however, and advancing to him, knelt, and greeted him with these words: “God grant you a long and happy life, Dauphin.”[18]

“You are mistaken,” he replied. “Yonder is the King,” pointing to the person on the throne.

“Noble prince,” she answered, “you cannot deceive me. You are the Dauphin.” A murmur of astonishment ran through the hall.

“Sire,” she continued, “if we can be alone I will tell you something that will remove all doubt as to my mission.”[19]

The Dauphin conducted her to the adjacent oratory, and there, according to the tradition, she revealed things to him which he was certain none could know but God and himself. He was so sure of this that at the close of the interview he exclaimed: “I am convinced of your divine commission, but my councillors must also be convinced.”

“Very well, sire,” she replied. “Summon the three most learned and experienced to meet me in the morning, and I will give them a sign.” Her wish was gratified. The three selected were the Archbishop of Rheims, Charles of Bourbon, and De la Tremouille, the King’s minister. They first required her to give her history, and then they asked for the sign. Joan went back to the oratory. Then, according to tradition, the heavenly ones appeared, and with them an angel in long white raiment. The latter carried a brilliant crown and slowly advanced into the audience-room.

“Sire,” said the angel, “trust this maiden whom Heaven sends to you. Give her at once as many soldiers as you can raise. As a sign that you shall be crowned at Rheims, Heaven sends you this token.” Thereupon the angel handed the crown to the Archbishop, went out as he had entered, and disappeared through the ceiling of the oratory. So says the tradition.