Title: The Rising Son; or, the Antecedents and Advancement of the Colored Race

Author: William Wells Brown

Contributor: Alonzo D. Moore

Elijah W. Smith

Release date: March 31, 2021 [eBook #64971]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: hekula03, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

OR,

THE ANTECEDENTS AND ADVANCEMENT

OF THE COLORED RACE.

BY

WM. WELLS BROWN, M. D.

AUTHOR OF “SKETCHES OF PLACES AND PEOPLE ABROAD,” “THE

BLACK MAN,” “THE NEGRO IN THE REBELLION,”

“CLOTELLE,” ETC.

Thirteenth Thousand.

BOSTON:

A. G. BROWN & CO., PUBLISHERS.

1882.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873,

By A. G. BROWN

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

After availing himself of all the reliable information obtainable, the author is compelled to acknowledge the scantiness of materials for a history of the African race. He has throughout endeavored to give a faithful account of the people and their customs, without concealing their faults.

Several of the biographical sketches are necessarily brief, owing to the difficulty in getting correct information in regard to the subjects treated upon. Some have been omitted on account of the same cause.

WM. WELLS BROWN.

Cambridgeport, Mass.

Few works written upon the colored race have equaled in circulation “The Rising Son.”

In the past two years the sales have more than doubled in the Southern States, and the demand for the book is greatly on the increase. Twelve thousand copies have already been sold; and if this can be taken as an index to the future, we may look forward with hope that the colored citizens are beginning to appreciate their own authors.

BY ELIJAH W. SMITH.

| PAGE | |

| Memoir of the Author | 9 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Ethiopians and Egyptians | 36 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Carthaginians | 49 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Eastern Africa | 65 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Causes of Color | 78 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Causes of the Difference in Features | 84 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Civil and Religious Ceremonies | 90 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Abyssinians | 97 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Western and Central Africa | 101 |

| [Pg vi] | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Slave-Trade | 118 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Republic of Liberia | 129 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Progress in Civilization | 135 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Hayti | 140 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Success of Toussaint | 150 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Capture of Toussaint | 159 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Toussaint a Prisoner in France | 168 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Dessalines as Emperor of Hayti | 173 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| War between the Blacks and Mulattoes of Hayti | 185 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Christophe as King, and Pétion as President of Hayti | 201 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Peace in Hayti, and Death of Pétion | 209 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Boyer the Successor of Pétion in Hayti | 218 |

| [Pg vii] | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Insurrection, and Death of Christophe | 222 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Union of Hayti and Santo Domingo | 229 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Soulouque as Emperor of Hayti | 234 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Geffrard as President of Hayti | 236 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Salnave as President of Hayti | 241 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Jamaica | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| South America | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Cuba and Porto Rico | 258 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Santo Domingo | 262 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Introduction of Blacks into American Colonies | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Slaves in the Northern Colonies | 270 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Colored Insurrections in the Colonies | 276 |

| [Pg viii] | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Black Men in the Revolutionary War | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Blacks in the War of 1812 | 286 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| The Curse of Slavery | 291 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Discontent and Insurrection | 296 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Growing Opposition to Slavery | 319 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Mob Law Triumphant | 322 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Heroism at Sea | 325 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| The Iron Age | 329 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| Religious Struggles | 336 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry | 340 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| Loyalty and Bravery of the Blacks | 342 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| The Proclamation of Freedom | 347 |

| [Pg ix] | |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| Blacks enlisted, and in Battle | 352 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| Negro Hatred at the North | 382 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| Caste and Progress | 387 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| The Abolitionists | 393 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| The New Era | 413 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| Race Representatives. | |

| PAGE. | PAGE. | ||

| Attucks, C. | 418 | | Downing, G. T. | 474 |

| Aldridge, Ira. | 489 | | Dunn, O. J. | 491 |

| Banneker, B. | 425 | | Douglass, L. H. | 543 |

| Brown, I. M. | 449 | | Day, W. H. | 499 |

| Bell, P. A. | 470 | | Elliott, R. B. | 403 |

| Butler, W. F. | 525 | | Forten, C. L. | 475 |

| Banister, E. M. | 483 | | Freeman, J. J. | 551 |

| Bassett, E. D. | 497 | | Gaines, J. I. | 450 |

| Bell, J. M. | 504 | | Grimes, L. A. | 534 |

| Campbell, J. P. | 446 | | Garnett, H. H. | 457 |

| Clark, P. H. | 520 | | Greener, R. T. | 542 |

| Chester, T. M. | 526 | | Harper, F. E. | 524 |

| Clinton, J. J. | 528 | | Hayden, L. | 547 |

| Carey, M. S. | 539 | | Jackson, F. M. | 508 |

| Cardozo, T. W. | 495 | | Jones, S. T. | 531 |

| Cain, R. H. | 544 | | Jordan, E., Sir | 481 |

| Douglass, F. | 435 | | Lewis, E. | 465 |

| Delany, M. R. | 460 | | Langston, J. M. | 447 |

| [Pg x]De Mortie, L. | 496 | | Ransier, A. H. | 510 |

| Martin, J. S. | 535 | | Ruffin, G. L. | 540 |

| Nell, W. C. | 485 | | Still, W. | 520 |

| Purvis, C. B. | 549 | | Simpson, W. H. | 478 |

| Purvis, R. | 468 | | Smith, M’Cune | 453 |

| Pinchback, P. B. S. | 517 | | Smith, S. | 445 |

| Pennington, J. W. C. | 461 | | Smith, E. W. | 552 |

| Payne, D. A. | 454 | | Tanner, B. T. | 530 |

| Perry, R. L. | 533 | | Vashon, G. B. | 476 |

| Quinn, W. P. | 432 | | Wheatley, P. | 423 |

| Reason, C. L. | 442 | | Wayman, —— | 440 |

| Ray, C. B. | 472 | | Wilson, W. J. | 444 |

| Remond, C. L. | 459 | | Whipper, W. | 493 |

| Ruggles, D. | 434 | | Wears, I. C. | 512 |

| Reveles, H. R. | 500 | | Zuille, J. J. | 473 |

| Rainey, J. H. | 507 | |

BY ALONZO D. MOORE.

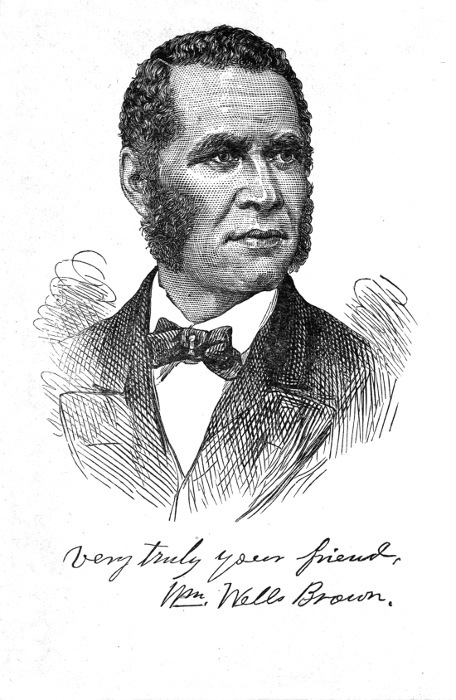

Thirty years ago, a young colored man came to my father’s house at Aurora, Erie County, New York, to deliver a lecture on the subject of American Slavery, and the following morning I sat upon his knee while he told me the story of his life and escape from the South. Although a boy of eight years, I still remember the main features of the narrative, and the impression it made upon my mind, and the talk the lecture of the previous night created in our little quiet town. That man was William Wells Brown, now so widely-known, both at home and abroad. It is therefore with no little hesitancy that I consent to pen this sketch of one whose name has for many years been a household word in our land.

William Wells Brown was born in Lexington, Ky., in the year 1816. His mother was a slave, his father a slaveholder. The boy was taken to the State of Missouri in infancy, and spent his boyhood in St. Louis. At the age of ten years he was hired out to a captain of a steamboat running between St. Louis and New Orleans, where he remained a year or two, and was then employed as office boy by Elijah P. Lovejoy, who was at that time editor of the St. Louis Times. Here William first began the groundwork of his education. After one year spent in the printing office, the object of our sketch was again let out to a captain of one of the steamboats plying on the river. In the year 1834 William made his escape from the boat, and came North.

He at once obtained a situation on a steamer on Lake Erie, where, in the position of steward, he was of great service to fugitive slaves making their way to Canada. In a single year he gave a free passage across the lake to sixty-five fugitives. Making his home in Buffalo, Mr. Brown organized a vigilance committee whose duties were to protect and aid slaves, while passing through that city on their way to the “Land of the free,” or to the eastern States. As chairman of that committee, Mr. Brown was of great assistance to the fleeing bondmen. The Association kept a fund on hand to employ counsel in case of capture of a fugitive, besides furnishing all with[Pg 11] clothing, shoes, and whatever was needed by those who were in want. Escaping from the South without education, the subject of our sketch spent the winter nights in an evening school and availed himself of private instructions to gain what had been denied him in his younger days.

In the autumn of 1843, he accepted an agency to lecture for the Anti-slavery Society, and continued his labors in connection with that movement until 1849; when he accepted an invitation to visit England. As soon as it was understood that the fugitive slave was going abroad, the American Peace Society elected him as a delegate to represent them at the Peace Congress at Paris.

Without any solicitation, the Executive Committee of the American Anti-slavery Society strongly recommended Mr. Brown to the friends of freedom in Great Britain. The President of the above Society gave him private letters to some of the leading men and women in Europe. In addition to these, the colored citizens of Boston held a meeting the evening previous to his departure, and gave Mr. Brown a public farewell, and passed resolutions commending him to the confidence and hospitality of all lovers of liberty in the mother-land.

Such was the auspices under which this self-educated man sailed for England on the 18th of July, 1849.

Mr. Brown arrived in Liverpool, and proceeded at[Pg 12] once to Dublin, where warm friends of the cause of freedom greeted him. The land of Burke, Sheridan, and O’Connell would not permit the American to leave without giving him a public welcome. A large and enthusiastic meeting held in the Rotunda, and presided over by James Haughton, Esq., gave Mr. Brown the first reception which he had in the Old World.

After a sojourn of twenty days in the Emerald Isle, the fugitive started for the Peace Congress which was to assemble at Paris. The Peace Congress, and especially the French who were in attendance at the great meeting, most of whom had never seen a colored person, were somewhat taken by surprise on the last day, when Mr. Brown made a speech. “His reception,” said La Presse, “was most flattering. He admirably sustained his reputation as a public speaker. His address produced a profound sensation. At its conclusion, the speaker was warmly greeted by Victor Hugo, President of the Congress, Richard Cobden, Esq., and other distinguished men on the platform. At the soirée given by M. de Tocqueville, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, the American slave was received with marked attention.”

Having spent a fortnight in Paris and vicinity, viewing the sights, he returned to London. George Thompson, Esq., was among the first to meet the fugitive on his arrival at the English metropolis. A few days after, a very large meeting, held in the [Pg 13]spacious Music Hall, Bedford Square, and presided over by Sir Francis Knowles, Bart., welcomed Mr. Brown to England. Many of Britain’s distinguished public speakers spoke on the occasion. George Thompson made one of his most brilliant efforts. This flattering reception gained for the fugitive pressing invitations from nearly all parts of the United Kingdom.

He narrates in his “Three Years in Europe,” many humorous incidents that occurred in his travels, and of which is the following:

“On a cold winter’s evening, I found myself seated before the fire, and alone, in the principal hotel in the ancient and beautiful town of Ludlow, and within a few minutes’ walk of the famous old castle from which the place derives its name. A long ride by coach had so completely chilled me, that I remained by the fire to a later hour than I otherwise would have.

“‘Did you ring, sir?’ asked the waiter, as the clock struck twelve.

“‘No,’ I replied; ‘but you may give me a light, and I will retire.’

“I was shown to my chamber, and was soon in bed. From the weight of the covering, I felt sure that the extra blanket which I had requested to be put on was there; yet I was shivering with cold. As the sheets began to get warm, I discovered, to my astonishment, that they were damp—indeed, wet. My first thought[Pg 14] was to ring the bell for the servant, and have them changed; but, after a moment’s consideration, I resolved to adopt a different course. I got out of bed, pulled the sheets off, rolled them up, raised the window, and threw them into the street. After disposing of the wet sheets, I returned to bed, and got in between the blankets, and lay there trembling with cold till Morpheus came to my relief.

“The next morning I said nothing about the sheets, feeling sure that the discovery of their loss would be made by the chambermaid in due time. Breakfast over, I visited the ruins of the old castle, and then returned to the hotel, to await the coach for Hereford. As the hour drew near for me to leave, I called the waiter, and ordered my bill. ‘Yes, sir, in a moment,’ he replied, and left in haste. Ten or fifteen minutes passed away, and the servant once more came in, walked to the window, pulled up the blinds, and then went out.

“I saw that something was afloat; and it occurred to me that they had discovered the loss of the sheets, at which I was pleased; for the London newspapers were, at that time, discussing the merits and the demerits of the hotel accommodations of the kingdom, and no letters found a more ready reception in their columns than one on that subject. I had, therefore, made up my mind to have the wet sheets put in the bill, pay for them, and send the bill to the Times.

“The waiter soon returned again, and, in rather an[Pg 15] agitated manner, said, ‘I beg your pardon, sir, but the landlady is in the hall, and would like to speak to you.’ Out I went, and found the finest specimen of an English landlady that I had seen for many a day. There she stood, nearly as thick as she was tall, with a red face garnished around with curls, that seemed to say, ‘I have just been oiled and brushed.’ A neat apron covered a black alpaca dress that swept the floor with modesty, and a bunch of keys hung at her side. O, that smile! such a smile as none but an adept could put on. However, I had studied human nature too successfully not to know that thunder and lightning were concealed under that smile, and I nerved myself for the occasion.

“‘I am sorry to have to name it, sir,’ said she; ‘but the sheets are missing off your bed.’

“‘O, yes,’ I replied; ‘I took them off last night.’

“‘Indeed!’ exclaimed she; ‘and what did you do with them?’

“‘I threw them out of the window,’ said I.

“‘What! into the street?’

“‘Yes; into the street,’ I said.

“‘What did you do that for?’

“‘They were wet; and I was afraid that if I left them in the room they would be put on at night, and give somebody else a cold.’

“‘Then, sir,’ said she, ‘you’ll have to pay for them.’

“‘Make out your bill, madam,’ I replied, ‘and put the price of the wet sheets in it, and I will send it to the Times, and let the public know how much you charge for wet sheets.’

“I turned upon my heel, and went back to the sitting-room. A moment more, and my bill was brought in; but nothing said about the sheets, and no charge made for them. The coach came to the door; and as I passed through the hall leaving the house, the landlady met me, but with a different smile.

“‘I hope, sir,’ said she, ‘that you will never mention the little incident about the sheets. I am very sorry for it. It would ruin my house if it were known.’ Thinking that she was punished enough in the loss of her property, I promised not to mention the name of the house, if I ever did the incident.

“The following week I returned to the hotel, when I learned the fact from the waiter that they had suspected that I had stolen the sheets, and that a police officer was concealed behind the hall door, on the day that I was talking with the landlady. When I retired to bed that night, I found two jugs of hot water in the bed, and the sheets thoroughly dried and aired.

“I visited the same hotel several times afterwards, and was invariably treated with the greatest deference, which no doubt was the result of my night with the wet sheets.”

In 1852, Mr. Brown gave to the public his “Three[Pg 17] Years in Europe,” a work which at once placed him high as an author, as will be seen by the following extracts from some of the English journals. The Eclectic Review, edited by the venerable Dr. Price, one of the best critics in the realm, said,—“Mr. Brown has produced a literary work not unworthy of a highly-cultivated gentleman.”

Rev. Dr. Campbell, in the British Banner, remarked: “We have read Mr. Brown’s book with an unusual measure of interest. Seldom, indeed, have we met with anything more captivating. A work more worthy of perusal has not, for a considerable time, come into our hands.”

“Mr. Brown writes with ease and ability,” said the Times, “and his intelligent observations upon the great question to which he has devoted and is devoting his life will command influence and respect.”

The Literary Gazette, an excellent authority, says of it, “The appearance of this book is too remarkable a literary event, to pass without a notice. At the moment when attention in this country is directed to the state of the colored people in America, the book appears with additional advantage; if nothing else were attained by its publication, it is well to have another proof of the capability of the negro intellect. Altogether, Mr. Brown has written a pleasing and amusing volume, and we are glad to bear this testimony to the literary merit of a work by a negro author.”

The Glasgow Citizen, in its review, remarked,—“W. Wells Brown is no ordinary man, or he could not have so remarkably surmounted the many difficulties and impediments of his training as a slave. By dint of resolution, self-culture, and force of character, he has rendered himself a popular lecturer to a British audience, and a vigorous expositor of the evils and atrocities of that system whose chains he has shaken off so triumphantly and forever. We may safely pronounce William Wells Brown a remarkable man, and a full refutation of the doctrine of the inferiority of the negro.”

The Glasgow Examiner said,—“This is a thrilling book, independent of adventitious circumstances, which will enhance its popularity. The author of it is not a man, in America, but a chattel,—a thing to be bought, and sold, and whipped; but in Europe, he is an author, and a successful one, too. He gives in this book an interesting and graphic description of a three years’ residence in Europe. The book will no doubt obtain, as it well deserves, a rapid and wide popularity.”

In the spring of 1853, the fugitive brought out his work, “Clotelle; or, the President’s Daughter,” a book of nearly three hundred pages, being a narrative of slave life in the Southern States. This work called forth new criticisms on the “Negro Author” and his literary efforts. The London Daily News pronounced it a book that would make a deep impression; while[Pg 19] The Leader, edited by the son of Leigh Hunt, thought many parts of it “equal to anything which had appeared on the slavery question.”

The above are only a few of the many encomiums bestowed upon our author. Besides writing his books, Mr. Brown was also a regular contributor to the columns of The London Daily News, The Liberator, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, and The National Anti-slavery Standard. When we add, that in addition to his literary labors, Mr. Brown was busily engaged in the study of the medical profession, it will be admitted that he is one of the most industrious of men. After remaining abroad nearly six years, and travelling extensively through Great Britain and on the continent, he returned to the United States in 1854, landing at Philadelphia, where he was welcomed in a large public meeting presided over by Robert Purvis, Esq.

On reaching Boston, a welcome meeting was held in Tremont Temple, with Francis Jackson, Esq., in the chair, and at which Wendell Phillips said,—“I rejoice that our friend Brown went abroad; I rejoice still more that he has returned. The years any thoughtful man spends abroad must enlarge his mind and store it richly. But such a visit is to a colored man more than merely intellectual education. He lives for the first time free from the blighting chill of prejudice. He sees no society, no institution, no place of resort or means of comfort from which his color debars him.

“We have to thank our friend for the fidelity with which he has, amid many temptations, stood by those whose good name religious prejudice is trying to undermine in Great Britain. That land is not all Paradise to the colored man. Too many of them allow themselves to be made tools of the most subtle of their race. We recognize, to-night, the clear-sightedness and fidelity of Mr. Brown’s course abroad, not only to thank him, but to assure our friends there that this is what the Abolitionists of Boston endorse.”

Mr. Phillips proceeded:—“I still more rejoice that Mr. Brown has returned. Returned to what? Not to what he can call his ‘country.’ The white man comes ‘home.’ When Milton heard, in Italy, the sound of arms from England, he hastened back—young, enthusiastic, and bathed in beautiful art as he was in Florence. ‘I would not be away,’ he said, ‘when a blow was struck for liberty.’ He came to a country where his manhood was recognized, to fight on equal footing.

“The black man comes home to no liberty but the liberty of suffering—to struggle in fetters for the welfare of his race. It is a magnanimous sympathy with his blood that brings such a man back. I honor it. We meet to do it honor. Franklin’s motto was, Ubi Libertas, ibi patria—Where liberty is, there is my country. Had our friend adopted that for his rule, he would have stayed in Europe. Liberty for him[Pg 21] is there. The colored man who returns, like our friend, to labor, crushed and despised, for his race, sails under a higher flag. His motto is,—‘Where my country is, there will I bring liberty!’”

Although Dr. Brown could have entered upon the practice of his profession, for which he was so well qualified, he nevertheless, with his accustomed zeal, continued with renewed vigor in the cause of the freedom of his race.

In travelling through the country and facing the prejudice that met the colored man at every step, he saw more plainly the vast difference between this country and Europe.

In giving an account of his passage on the little steamer that plies between Ithica and Cayuga Bridge, he says,—

“When the bell rang for breakfast, I went to the table, where I found some twenty or thirty persons. I had scarcely taken my seat, when a rather snobby-appearing man, of dark complexion, looking as if a South Carolina or Georgia sun had tanned him, began rubbing his hands, and, turning up his nose, called the steward, and said to him, ‘Is it the custom on this boat to put niggers at the table with white people?’

“The servant stood for a moment, as if uncertain what reply to make, when the passenger continued, ‘Go tell the captain that I want him.’ Away[Pg 22] went the steward. I had been too often insulted on account of my connection with the slave, not to know for what the captain was wanted. However, as I was hungry, I commenced helping myself to what I saw before me, yet keeping an eye to the door, through which the captain was soon to make his appearance. As the steward returned, and I heard the heavy boots of the commander on the stairs, a happy thought struck me; and I eagerly watched for the coming-in of the officer.

“A moment more, and a strong voice called out, ‘Who wants me?’

“I answered at once, ‘I, sir.’

“‘What do you wish?’ asked the captain.

“‘I want you to take this man from the table,’ said I.

“At this unexpected turn of the affair, the whole cabin broke out into roars of laughter; while my rival on the opposite side of the table seemed bursting with rage. The captain, who had joined in the merriment, said,—

“‘Why do you want him taken from the table?’

“‘Is it your custom, captain,’ said I, ‘to let niggers sit at table with white folks on your boat?’

“This question, together with the fact that the other passenger had sent for the officer, and that I had ‘stolen his thunder,’ appeared to please the company very much, who gave themselves up to laughter; while[Pg 23] the Southern-looking man left the cabin with the exclamation, ‘Damn fools!’”

In the autumn of 1854, Dr. Brown published his “Sketches of Places and People Abroad,” that met with a rapid sale, and which the New York Tribune said, was “well-written and intensely interesting.”

His drama, entitled “The Dough Face,” written shortly after, and read by him before lyceums, gave general satisfaction wherever it was heard.

Indeed, in this particular line the doctor seems to excel, and the press was unanimous in its praise of his efforts. The Boston Journal characterized the drama and its reading as “interesting in its composition, and admirably rendered.”

“The Escape; or, Leap for Freedom,” followed the “Dough Face,” and this drama gave an amusing picture of slave life, and was equally as favorably received by the public.

In 1863, Dr. Brown brought out “The Black Man,” a work which ran through ten editions in three years, and which was spoken of by the press in terms of the highest commendation, and of which Frederick Douglass wrote in his own paper,—

“Though Mr. Brown’s book may stand alone upon its own merits, and stand strong, yet while reading its interesting pages,—abounding in fact and argument, replete with eloquence, logic, and learning, clothed with simple yet eloquent language,—it is hard to repress[Pg 24] the inquiry, Whence has this man this knowledge? He seems to have read and remembered nearly everything which has been written and said respecting the ability of the negro, and has condensed and arranged the whole into an admirable argument, calculated both to interest and convince.”

William Lloyd Garrison said, in The Liberator, “This work has done good service, and proves its author to be a man of superior mind and cultivated ability.”

Hon. Gerritt Smith, in a letter to Dr. Brown, remarked,—“I thank you for writing such a book. It will greatly benefit the colored race. Send me five copies of it.”

Lewis Tappen, in his Cooper Institute speech, on the 5th of January, 1863, said,—“This is just the book for the hour; it will do more for the colored man’s elevation than any work yet published.”

The space allowed me for this sketch will not admit the many interesting extracts that might be given from the American press in Dr. Brown’s favor as a writer and a polished reader. However, I cannot here omit the valuable testimony of Professor Hollis Read, in his ably-written work, “The Negro Problem Solved.” On page 183, in writing of the intelligent colored men of the country, he says: “As a writer, I should in justice give the first place to Dr. William Wells Brown, author of ‘The Black Man.’”

“Clotelle,” written by Dr. Brown, a romance founded on fact, is one of the most thrilling stories that we remember to have read, and shows the great versatility of the cast of mind of our author.

The temperance cause in Massachusetts, and indeed, throughout New England, finds in Dr. Brown an able advocate.

The Grand Division of the Sons of Temperance of Massachusetts did itself the honor of electing him Grand Worthy Associate of that body, and thereby giving him a seat in the National Division of the Sons of Temperance of North America, where, at its meeting in Boston, 1871, his speech in behalf of the admission of the colored delegates from Maryland, will not soon be forgotten by those who were present.

The doctor is also a prominent member of the Good Templars of Massachusetts. His efforts, in connection with his estimable wife, for the spread of temperance among the colored people of Boston, deserve the highest commendation.

Some five years ago, our author, in company with others, organized “The National Association for the Spread of Temperance and Night-schools among the Freed People at the South,” of which he is now president. This society is accomplishing great good among the freedmen.

It was while in the discharge of his duties of visiting the South, in 1871, and during his travels through the[Pg 26] State of Kentucky, he became a victim of the Ku-Klux, and of which the following is the narrative:—

“I visited my native State in behalf of The National Association for the Spread of Temperance and Night-schools among the Freedmen, and had spoken to large numbers of them at Louisville, and other places, and was on my way to speak at Pleasureville, a place half-way between Louisville and Lexington. I arrived at Pleasureville dépôt a little after six in the evening, and was met by a colored man, who informed me that the meeting was to take place five miles in the country.

“After waiting some time for a team which was expected, we started on foot, thinking we would meet the vehicle. We walked on until dark overtook us, and seeing no team, I began to feel apprehensive that all was not right. The man with me, however, assured me that there was no danger, and went on. But we shortly after heard the trotting of horses, both in front and in the rear, and before I could determine what to do, we were surrounded by some eight or ten men, three of whom dismounted, bound my arms behind me with a cord, remounted their horses, and started on in the direction I had been travelling. The man who was with me disappeared while I was being tied. The men were not disguised, and talked freely among themselves.

“After going a mile or more they stopped, and consulted a moment or two, the purport of which I could[Pg 27] not hear, except one of them saying,—‘Lawrence don’t want a nigger hung so near his place.’ They started again; I was on foot, a rope had been attached to my arms, and the other end to one of the horses. I had to hasten my steps to keep from being dragged along by the animal. Soon they turned to the right, and followed up what appeared to be a cow-path.

“While on this road my hat fell off, and I called out to the man behind and said, ‘I’ve lost my hat.’

“‘You’ll need no hat in half an hour’s time,’ he replied. As we were passing a log house on this road, a man came out and said, in a trembling voice, ‘Jim’s dying!’ All the men now dismounted, and, with the exception of two, they went into the building. I distinctly heard the cries, groans, and ravings of the sick man, which satisfied me at once that it was an extreme case of delirium tremens; and as I treated the malady successfully by the hypodermic remedy, and having with me the little instrument, the thought flashed upon my mind that I might save my life by the trial. Consequently, I said to one of the men,—‘I know what’s the matter with that man, and I can relieve him in ten minutes.’

“One of the men went into the house, related what I had said, and the company came out. The leader, whom they all addressed as ‘Cap,’ began to question me with regard to my skill in such complaints. He soon became satisfied, untied me, and we entered the[Pg 28] sick man’s chamber. My hands were so numb from the tightness of the cord which bound my arms, that I walked up and down the room for some minutes, rubbing my hands, and contemplating the situation. The man lay upon a bed of straw, his arms and legs bound to the bedstead to keep him from injuring himself and others. He had, in his agony, bitten his tongue and lips, and his mouth was covered with bloody froth, while the glare of his eyes was fearful. His wife, the only woman in the house, sat near the bed with an infant upon her lap, her countenance pale and anxious, while the company of men seemed to be the most desperate set I had ever seen.

“I determined from the first to try to impress them with the idea that I had derived my power to relieve pain from some supernatural source. While I was thus thinking the matter over, ‘Cap’ was limping up and down the room, breathing an oath at nearly every step, and finally said to me,—‘Come, come, old boy, take hold lively; I want to get home, for this d—d old hip of mine is raising h—l with me.’ I said to them,—‘Now, gentlemen, I’ll give this man complete relief in less than ten minutes from the time I lay my hands on him; but I must be permitted to retire to a room alone, for I confess that I have dealings with the devil, and I must consult with him.’ Nothing so charms an ignorant people as something that has about it the appearance of superstition, and I did not[Pg 29] want these men to see the syringe, or to know of its existence. The woman at once lighted a tallow candle, handed it to ‘Cap,’ and pointed to a small room. The man led the way, set the light down, and left me alone. I now took out my case, adjusted the needle to the syringe, filled it with a solution of the acetate of morphia, put the little instrument into my vest pocket, and returned to the room.

“After waving my hands in the air, I said,—‘Gentlemen, I want your aid; give it to me, and I’ll perform a cure that you’ll never forget. All of you look upon that man till I say, “Hold!” Look him right in the eye.’ All eyes were immediately turned upon the invalid. Having already taken my stand at the foot of the bed, I took hold of the right leg near the calf, pinched up the skin, inserted the needle, withdrew it after discharging the contents, slipped the syringe into my pocket, and cried at the top of my voice, ‘Hold!’ The men now turned to me, alternately viewing me and the sick man. From the moment that the injection took place, the ravings began to cease, and in less than ten minutes he was in perfect ease. I continued to wave my hands, and to tell the devils ‘to depart and leave this man in peace.’ ‘Cap’ was the first to break the silence, and he did it in an emphatic manner, for he gazed steadily at me, then at the sick man, and exclaimed,—‘Big thing! big thing, boys, d—d if it ain’t!’

“Another said,—‘A conjurer, by h—ll! you heard him say he deals with the devil.’ I now thought it time to try ‘Cap,’ for, from his limping, groaning, and swearing about his hip, it seemed to me a clear case of sciatica, and I thus informed him, giving him a description of its manner of attack and progress, detailing to him the different stages of suffering.

“I had early learned from the deference paid to the man by his associates, that he was their leader, and I was anxious to get my hands on him, for I had resolved that if ever I got him under the influence of the drug, he should never have an opportunity of putting a rope around my neck. ‘Cap’ was so pleased with my diagnosis of his complaint, that he said,—‘Well, I’ll give you a trial, d—d if I don’t!’ I informed him that I must be with him alone. The woman remarked that we could go in the adjoining room. As we left the company, one of them said: ‘You aint agoin’ to kill “Cap,” is you?’ ‘Oh, no!’ I replied. I said, ‘Now, “Cap,” I’ll cure you, but I need your aid.’ ‘Sir,’ returned he, ‘I’ll do anything you tell me.’ I told him to lay on the bed, shut his eyes, and count one hundred. He obeyed at once, and while he was counting, I was filling the syringe with the morphia.

“When he had finished counting, I informed him that I would have to pinch him on the lame leg, so as to get the devil out of it. ‘Oh!’ replied he, ‘you may pinch as much as you d—d please, for I’ve seen[Pg 31] and felt h—ll with this old hip!’ I injected the morphia as I had done in the previous case, and began to sing a noted Methodist hymn as soon as I had finished. As the medicine took effect, the man went rapidly off into a slumber, from which he did not awake while I was there, for I had given him a double dose.

“I will here remark, that while the morphia will give most instant relief in sciatica, it seldom performs a perfect cure. But in both cases I knew it would serve my purpose. As soon as ‘Cap’ was safe, I called in his companions, who appeared still more amazed than at first. They held their faces to his to see that he breathed, and would shake their heads and go out. I told them that I should have to remain with the man five or six hours. At this announcement one of the company got furious, and said, ‘It’s all a trick to save his neck from the halter,’ and concluded by saying at the top of his voice, ‘Come to the tree, to the tree!’ The men all left the room, assembled in the yard, and had a consultation. It was now after eleven o’clock, and as they had a large flask of brandy with them they appeared to keep themselves well-filled, from the manner in which the room kept scented up. At this juncture one of the company, a tall, red-haired man, whose face was completely covered with beard, entered the room, took his seat at the table, drew out of his pocket a revolver, laid it on the table,[Pg 32] and began to fill his mouth with tobacco. The men outside mounted their horses and rode away, one of whom distinctly shouted, ‘Remember, four o’clock.’ I continued to visit one and then the other of the invalids, feeling their pulse, and otherwise showing my interest in their recovery.

“The brandy appeared to have as salutary effect on the man at the table as the morphia had on the sick, for he was fast asleep in a few minutes. The only impediment in the way of my escape now was a large dog, which it was difficult to keep from me when I first came to the house, and was now barking, snapping, and growling, as if he had been trained to it.

“Many modes of escape suggested themselves to me while the time was thus passing, the most favored of which was to seize the revolver, rush out of the house, and run my chance with the dog. However, before I could put any of these suggestions into practice, the woman went out, called ‘Lion, Lion,’ and returned, followed by the dog, which she made lie down by her as she reseated herself. In a low whisper, this woman, whose fate deserves to be a better one, said,—‘They are going to hang you at four o’clock; now is your time to go.’ The clock was just striking two when I arose, and with a grateful look, left the house. Taking the road that I had come, and following it down, I found my hat, and after walking some distance out of the way by mistake, I reached[Pg 33] the station, and took the morning train for Cincinnati.”

I cannot conclude this sketch of our author’s life without alluding to an incident which occurred at Aurora, my native town, on a visit to that place in the winter of 1844.

Dr. Brown was advertised to speak in the old church, which he found filled to overflowing, with an audience made up mostly of men who had previously determined that the meeting should not be held.

The time for opening the meeting had already arrived, and the speaker was introduced by my father, who acted as chairman.

The coughing, whistling, stamping of feet, and other noises made by the assemblage, showed the prejudice existing against the anti-slavery cause, the doctrines of which the speaker was there to advocate. This tumult lasted for half an hour or more, during which time unsalable eggs, peas, and other missiles were liberally thrown at the speaker.

One of the eggs took effect on the doctor’s face, spattering over his nicely-ironed shirt bosom, and giving him a somewhat ungainly appearance, which kept the audience in roars of laughter at the expense of our fugitive friend.

Becoming tired of this sort of fun, and getting his Southern blood fairly aroused, Dr. Brown, who, driven from the pulpit, was standing in front of the altar,[Pg 34] nerved himself up, assumed a highly dramatic air, and said: “I shall not attempt to address you; no, I would not speak to you if you wanted me to. However, let me tell you one thing, and that is, if you had been in the South a slave as I was, none of you would ever have had the courage to escape; none but cowards would do as you have done here to-night.”

Dr. Brown gradually proceeded into a narrative of his own life and escape from the South. The intense interest connected with the various incidents as he related them, chained the audience to their seats, and for an hour and a half he spoke, making one of the most eloquent appeals ever heard in that section in behalf of his race.

I have often heard my father speak of it as an effort worthy of our greatest statesmen. Before the commencement of the meeting, the mob had obtained a bag of flour, taking it up into the belfry of the church, directly over the entrance door, with the intention of throwing it over the speaker as he should pass out.

One of the mob had been sent in with orders to keep as close to the doctor as he could, and who was to give the signal for the throwing of the flour. So great was the influence of the speaker on this man, that his opinions were changed, and instead of giving the word, he warned the doctor of the impending danger, saying,—“When you hear the cry of ‘let it slide,’[Pg 35] look out for the flour.” The fugitive had no sooner learned these facts than he determined to have a little fun at the expense of others.

Pressing his way forward, and getting near a group of the most respectable of the company, including two clergymen, a physician, and a justice of the peace, he moved along with them, and as they passed under the belfry, the doctor cried out at the top of his voice, “Let it slide!” when down came the flour upon the heads of some of our best citizens, which created the wildest excitement, and caused the arrest of those engaged in the disturbance.

Everybody regarded Dr. Brown’s aptness in this matter as a splendid joke; and for many days after, the watchword of the boys was, “Let it Slide!”

Dr. Brown wrote “The Negro in the Rebellion,” in 1866, which had a rapid sale.

THE RISING SON.

The origin of the African race has provoked more criticism than any other of the various races of man on the globe. Speculation has exhausted itself in trying to account for the Negro’s color, features, and hair, that distinguish him in such a marked manner from the rest of the human family.

All reliable history, and all the facts which I have been able to gather upon this subject, show that the African race descended from the country of the Nile, and principally from Ethiopia.

The early history of Ethiopia is involved in great obscurity. When invaded by the Egyptians, it was found to contain a large population, consisting of savages, hunting and fishing tribes, wandering herdsmen, shepherds, and lastly, a civilized class, dwelling in houses and in large cities, possessing a [Pg 38]government and laws, acquainted with the use of hieroglyphics, the fame of whose progress in knowledge and the social arts had, in the remotest ages, spread over a considerable portion of the earth. Even at that early period, when all the nations were in their rude and savage state, Ethiopia was full of historical monuments, erected chiefly on the banks of the Nile.

The earliest reliable information we have of Ethiopia, is (B. C. 971) when the rulers of that country assisted Shishank in his war against Judea, “with very many chariots and horsemen.” Sixteen years later, we have an account of Judea being again invaded by an army of a million Ethiopians, unaccompanied by any Egyptian force.[1] The Ethiopian power gradually increased until its monarchs were enabled to conquer Egypt, where three of them reigned in succession, Sabbackon, Sevechus, and Tarakus, the Tirhakah of Scripture.[2]

Sevechus, called so in Scripture, was so powerful a monarch that Hoshed, king of Israel, revolted against the Assyrians, relying on his assistance,[3] but was not supported by his ally. This indeed, was the immediate cause of the captivity of the Ten Tribes; for “in the ninth year of Hoshed the king, the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria,” as a punishment for unsuccessful rebellion.

Tirhakah was a more war-like prince; he led an[Pg 39] army against Sennacherib,[4] king of Assyria, then besieging Jerusalem; and the Egyptian traditions, preserved in the age of Herodotus, give an accurate account of the providential interposition by which the pride of the Assyrians was humbled.

It is said that the kings of Ethiopia were always elected from the priestly caste; and there was a strange custom for the electors, when weary of their sovereign, to send him a courier with orders to die. Ergamenes was the first monarch who ventured to resist this absurd custom; he lived in the reign of the second Ptolemy, and was instructed in Grecian philosophy. So far from yielding, he marched against the fortress of the priests, massacred most of them, and instituted a new religion.

Queens frequently ruled in Ethiopia; one named Candace made war on Augustus Cæsar, about twenty years before the birth of Christ, and though not successful, obtained peace on very favorable conditions.

The pyramids of Ethiopia, though inferior in size to those in Egypt, are said to surpass them in architectural beauty, and the sepulchres evince the greatest purity of taste.

But the most important and striking proof of the progress of the Ethiopians in the art of building, is their knowledge and employment of the arch. Hoskins has stated that their pyramids are of superior antiquity to those of Egypt. The Ethiopian vases depicted on the monuments, though not richly ornamented, display a taste and elegance of form that has never been surpassed. In sculpture and coloring,[Pg 40] the edifices of Ethiopia, though not so profusely adorned, rival the choicest specimens of Egyptian art.

Meroe was the entrepot of trade between the North and the South, between the East and the West, while its fertile soil enabled the Ethiopians to purchase foreign luxuries with native productions. It does not appear that fabrics were woven in Ethiopia so extensively as in Egypt; but the manufacture of metal must have been at least as flourishing.

But Ethiopia owed its greatness less to the produce of its soil or its factories than to its position on the intersection of the leading caravan routes of ancient commerce.

The Ethiopians were among the first nations that organized a regular army, and thus laid the foundation of the whole system of ancient warfare. A brief account of their military affairs will therefore illustrate not only their history, but that of the great Asiatic monarchies, and of the Greeks during the heroic ages. The most important division of an Ethiopian army was the body of war-chariots, used instead of cavalry. These chariots were mounted on two wheels and made low; open behind, so that the warrior could easily step in and out; and without a seat.

They were drawn by two horses and generally contained two warriors, one of whom managed the steeds while the other fought. Nations were distinguished from each other by the shape and color of their chariots.

Great care was taken in the manufacturing of the chariots and also of the breeding of horses to draw them. Nothing in our time can equal the attention[Pg 41] paid by the ancients in the training of horses for the battle-field.

The harness which these animals wore was richly decorated; and a quiver and bow-case, decorated with extraordinary taste and skill, were securely fixed to the side of each chariot. The bow was the national weapon, employed by both cavalry and infantry. No nation of antiquity paid more attention to archery than the Ethiopians; their arrows better aimed than those of any other nation, the Egyptians perhaps excepted. The children of the warrior caste were trained from early infancy to the practice of archery.

The arms of the Ethiopians were a spear, a dagger, a short sword, a helmet, and a shield. Pole-axes and battle-axes were occasionally used. Coats of mail were used only by the principal officers, and some remarkable warriors, like Goliath, the champion of the Philistines. The light troops were armed with swords, battle-axes, maces, and clubs. Some idea of the manly forms, great strength, and military training of the Ethiopians, may be gathered from Herodotus, the father of ancient history.

After describing Arabia as “a land exhaling the most delicious fragrance,” he says,—“Ethiopia, which is the extremity of the habitable world, is contiguous to this country on the south-west. Its inhabitants are very remarkable for their size, their beauty, and their length of life.”[5]

In his third book he has a detailed description of a single tribe of this interesting people, called the Macrobian, or long-lived Ethiopians. Cambyses, the Persian[Pg 42] king, had made war upon Egypt, and subdued it. He is then seized with an ambition of extending his conquests still farther, and resolves to make war upon the Ethiopians. But before undertaking his expedition, he sends spies into the country disguised as friendly ambassadors, who carry costly presents from Cambyses. They arrive at the court of the Ethiopian prince, “a man superior to all others in the perfection of size and beauty,” who sees through their disguise, and takes down a bow of such enormous size that no Persian could bend it. “Give your king this bow, and in my name speak to him thus:—

“‘The king of Ethiopia sends this counsel to the king of Persia. When his subjects shall be able to bend this bow with the same ease that I do, then let him venture to attack the long-lived Ethiopians. Meanwhile, let him be thankful to the gods, that the Ethiopians have not been inspired with the same love of conquest as himself.’”[6]

Homer wrote at least eight hundred years before Christ, and his poems are well ascertained to be a most faithful mirror of the manners and customs of his times, and the knowledge of his age.

In the first book of the Iliad, Achilles is represented as imploring his goddess-mother to intercede with Jove in behalf of her aggrieved son. She grants his request, but tells him the intercession must be delayed for twelve days. The gods are absent. They have gone to the distant climes of Ethiopia to join in its festal rites. “Yesterday Jupiter went to the feast with the blameless Ethiopians, away upon the limits of the[Pg 43] ocean, and all the gods followed together.”[7] Homer never wastes an epithet. He often alludes to the Ethiopians elsewhere, and always in terms of admiration and praise, as being the most just of men; the favorites of the gods.[8]

The same allusion glimmers through the Greek mythology, and appears in the verses of almost all the Greek poets ere the countries of Italy and Sicily were even discovered. The Jewish Scripture and Jewish literature abound in allusion to this distinct and mysterious people; the annals of the Egyptian priests are full of them, uniformly the Ethiopians are there lauded as among the best, most religious, and most civilized of men.[9]

Let us pause here one moment, and follow the march of civilization into Europe. Wherever its light has once burned clearly, it has been diffused, but not extinguished. Every one knows that Rome got her civilization from Greece; that Greece again borrowed hers from Egypt, that thence she derived her earliest science and the forms of her beautiful mythology.

The mythology of Homer is evidently hieroglyphical in its origin, and has strong marks of family resemblance to the symbolical worship of Egypt.

It descended the Nile; it spread over the delta of that river, as it came down from Thebes, the wonderful city of a hundred gates. Thebes, as every scholar knows, is more ancient than the cities of the[Pg 44] delta. The ruins of the colossal architecture are covered over with hieroglyphics, and strewn with the monuments of Egyptian mythology. But whence came Thebes? It was built and settled by colonies from Ethiopia, or from cities which were themselves the settlements of that nation. The higher we ascend the Nile, the more ancient are the ruins on which we tread, till we come to the “hoary Meroe,” which Egypt acknowledged to be the cradle of her institutions.

But Meroe was the queenly city of Ethiopia, into which all Africa poured its caravans laden with ivory, frankincense, and gold. So it is that we trace the light of Ethiopian civilization first into Egypt, thence into Greece, and Rome, whence, gathering new splendor on its way, it hath been diffusing itself all the world over.[10]

We now come to a consideration of the color of the Ethiopians, that distinguish their descendants of the present time in such a marked manner from the rest of the human race.

Adam, the father of the human family, took his name from the color of the earth from which he was made.[11]

The Bible says but little with regard to the color of the various races of man, and absolutely nothing as to the time when or the reasons why these varieties were introduced. There are a few passages in which color is descriptive of the person or the dress. Job said, “My skin is black upon me.” Job had been sick for[Pg 45] a long time, and no doubt this brought about a change in his complexion. In Lamentations, it is said, “Their visage is blacker than a coal;” also, “our skin was blacker than an oven.” Both of these writers, in all probability, had reference to the change of color produced by the famine. Another writer says, “I am black, but comely.” This may have been a shepherd, and lying much in the sun might have caused the change.

However, we now have the testimony of one whom we clearly understand, and which is of the utmost importance in settling this question. Jeremiah asks, “Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?” This refers to a people whose color is peculiar, fixed, and unalterable. Indeed, Jeremiah seems to have been as well satisfied that the Ethiopian was colored, as he was that the leopard had spots; and that the one was as indelible as the other. The German translation of Luther has “Negro-land,” for Ethiopia, i. e., the country of the blacks.

All reliable history favors the belief that the Ethiopians descended from Cush, the eldest son of Ham, who settled first in Shina in Asia. Eusebius informs us that a colony of Asiatic Cushites settled in that part of Africa which has since been known as Ethiopia proper. Josephus asserts that these Ethiopians were descended from Cush, and that in his time they were still called Cushites by themselves and by the inhabitants of Asia. Homer divides the Ethiopians into two parts, and Strabo, the geographer, asserts that the dividing line to which he alluded was the Red Sea. The Cushites emigrated in part to the west of the Red Sea; these, remaining unmixed with other[Pg 46] races, engrossed the general name of Cushite, or Ethiopian, while the Asiatic Cushites became largely mingled with other nations, and are nearly or quite absorbed, or, as a distinct people well-nigh extinct. Hence, from the allusion of Jeremiah to the skin of the Ethiopian, confirmed and explained by such authorities as Homer, Strabo, Herodotus, Josephus, and Eusebius, we conclude that the Ethiopians were an African branch of the Cushites who settled first in Asia. Ethiop, in the Greek, means “sunburn,” and there is not the slightest doubt but that these people, in and around Meroe, took their color from the climate. This theory does not at all conflict with that of the common origin of man. Although the descendants of Cush were black, it does not follow that all the offspring of Ham were dark-skinned; but only those who settled in a climate that altered their color.

The word of God by his servant Paul has settled forever the question of the equal origin of the human races, and it will stand good against all scientific research. “God hath made of one blood all the nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

The Ethiopians are not constitutionally different from the rest of the human family, and therefore, we must insist upon unity, although we see and admit the variety.

Some writers have endeavored to account for this difference of color, by connecting it with the curse pronounced upon Cain. This theory, however, has no foundation; for if Cain was the progenitor of Noah, and if Cain’s new peculiarities were perpetuated, then, as Noah was the father of the world’s new population, the question would be, not how to account for[Pg 47] any of the human family being black, but how can we account for any being white? All this speculation as to the change of Cain’s color, as a theory for accounting for the variety peculiar to Cush and the Ethiopians, falls to the ground when we trace back the genealogy of Noah, and find that he descended not from Cain, but from Seth.

Of course Cain’s descendants, no matter what their color, became extinct at the flood. No miracle was needed in Ethiopia to bring about a change in the color of its inhabitants. The very fact that the nation derived its name from the climate should be enough to satisfy the most skeptical. What was true of the Ethiopians was also true of the Egyptians, with regard to color; for Herodotus tells us that the latter were colored and had curled hair.

The vast increase of the population of Ethiopia, and a wish of its rulers to possess more territory, induced them to send expeditions down the Nile, and towards the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Some of these adventurers, as early as B. C. 885, took up their abode on the Mediterranean coast, and founded the place which in later years became the great city of Carthage. Necho, king of Egypt, a man distinguished for his spirit of enterprise, sent an expedition (B. C. 616) around the African coast. He employed Phœnecian navigators. This fleet sailed down the Red Sea, passed the straits of Balel-Mandeb, and, coasting the African continent, discovered the passage around the Cape of Good Hope, two thousand years before its re-discovery by Dias and Vasco de Gama. This expedition was three years in its researches, and while gone, got out of food, landed, planted corn, and[Pg 48] waited for the crop. After harvesting the grain, they proceeded on their voyage. The fleet returned to Egypt through the Atlantic Ocean, the straits of Gibralter, and the Mediterranean.

The glowing accounts brought back by the returned navigators of the abundance of fruits, vegetables, and the splendor of the climate of the new country, kindled the fire of adventurous enthusiasm in the Ethiopians, and they soon followed the example set them by the Egyptians. Henceforward, streams of emigrants were passing over the Isthmus of Suez, that high road to Africa, who became permanent residents of the promised land.

[1] 2 Chron. xiv: 8-13.

[2] Hawkins, in his work on Meroe, identifies Tirhakah with the priest Sethos, upon ground, we think, not tenable.

[3] 2 Kings, xvii: 4.

[4] 2 Kings, xix: 9.

[5] Herod. iii: 114.

[6] Herod iii: 21.

[7] Iliad II: 423.

[8] Iliad XXIII.

[9] Chron. xiv: 9; xvi: 8; Isaiah xlv: 14; Jeremiah xlvi: 9; Josephus Aut. II; Heeren, vol I: p. 290.

[10] E. H. Sears, in the “Christian Examiner,” July, 1846.

[11] Josephus Ant., Vol. I: p. 8.

Although it is claimed in history that Carthage was settled by the Phœnecians, or emigrants from Tyre, it is by no means an established fact; for when Dido fled from her haughty and tyrannical brother, Pygmalion, ruler of Tyre, and sailing down the Nile, seeking a place of protection, she halted at Carthage, then an insignificant settlement on a peninsula in the interior of a large bay, now called the gulf of Tunis, on the northern shore of Africa (this was B. C. 880), the population was made up mainly of poor people, the larger portion of whom were from Ethiopia, and the surrounding country. Many outlaws, murderers, highwaymen, and pirates, had taken refuge in the new settlement. Made up of every conceivable shade of society, with but little character to lose, the Carthaginians gladly welcomed Dido, coming as she did from the royal house of Tyre, and they adopted her as the head of their government. The people became law-abiding, and the constitution which they adopted was considered by the ancients as a pattern of political wisdom. Aristotle highly praises it as a[Pg 50] model to other States. He informs us that during the space of five centuries, that is, from the foundation of the republic down to his own time, no tyrant had overturned the liberties of the State, and no demagogue had stirred up the people to rebellion. By the wisdom of its laws, Carthage had been able to avoid the opposite evils of aristocracy on the one hand, and democracy on the other. The nobles did not engross the whole of the power, as was the case in Sparta, Corinth, and Rome, and in more modern times, in Venice; nor did the people exhibit the factious spirit of an Athenian mob, or the ferocious cruelty of a Roman rabble.

After the tragical death of the Princess Dido, the head of the government consisted of the suffetes, two chief magistrates, somewhat resembling the consuls of Rome, who presided in the senate, and whose authority extended to military as well as civil affairs. These officers appeared to be entirely devoted to the good of the State and the welfare of the people.

The second was the senate itself, composed of illustrious men of the State. This body made the laws, declared war, negotiated peace, and appointed to all offices, civil and military. The third estate was still more popular. In the infancy and maturity of the republic, the people had taken no active part in the government; but, at a later period, influenced by wealth and prosperity, they advanced their claims to authority, and, before long, obtained nearly the whole power. They instituted a council, designed as a check upon the nobles and the senate. This council was at first very beneficial to the State, but afterwards became itself tyrannical.

The Carthaginians were an enterprising people, and in the course of time built ships, and with them explored all ports of the Mediterranean Sea, visiting the nations on the coast, purchasing their commodities, and selling them to others. Their navigators went to the coast of Guinea, and even advanced beyond the mouths of the Senegal and the Gambia. The Carthaginians carried their commerce into Spain, seized a portion of that country containing mines rich with gold, and built thereon a city which they called New Carthage, and which to the present day is known as Carthaginia.

The Mediterranean was soon covered with their fleets, and at a time when Rome could not boast of a single vessel, and her citizens were entirely ignorant of the form of a ship. The Carthaginians conquered Sardinia, and a great part of Sicily. Their powerful fleets and extensive conquests gave them the sovereign command of the seas.

While Carthage possessed the dominion of the seas, a rival State was growing up on the opposite side of the Mediterranean, distant about seven hundred miles, under whose arms she was destined to fall. This was Rome, the foundation of which was commenced one hundred years after that of Carthage. These two powerful nations engaged in wars against each other that lasted nearly two hundred years. In these conflicts the Carthaginians showed great bravery.

In the first Punic war, the defeat and capture of Regulus, the Roman general, by the Carthaginians, and their allies, the Greeks, humiliated the Romans, and for a time gave the former great advantage over the latter. The war, however, which lasted twenty-four [Pg 52]years, was concluded by some agreement, which after all, was favorable to the Romans. The conclusion of the first Punic war (B. C. 249) was not satisfactory to the more republican portion of the ruling spirits among the Carthaginians, and especially Hamilcar, the father of Hannibal, who, at that time occupied a very prominent position, both on account of his rank, wealth, and high family connections at Carthage; also on account of the great military energy which he displayed in the command of the armies abroad. Hamilcar had carried on the wars which the Carthaginians waged in Africa and Spain after the conclusion of the war with the Romans, and he was anxious to begin hostilities with the Romans again. On Hamilcar’s leaving Carthage the last time to join his army in Spain, he took his son Hannibal, then a boy of nine years, and made him swear on the altar of his country eternal hatred to the Romans, an oath that he kept to the day of his death.

When not yet twenty years of age, Hannibal was placed second in command of the army, then in Spain, where he at once attracted the attention and the admiration of all, by the plainness of his living, his abstinence from strong drink, and the gentlemanly treatment that he meted out to the soldiers, as well as his fellow-officers.

He slept in his military cloak on the ground, in the midst of his soldiers on guard; and in a battle he was always the last to leave the field after a fight, as he was foremost to press forward in every contest with the enemy. The death of Hasdrubal placed Hannibal in supreme command of the army, and inheriting his father’s hatred to Rome, he resolved to take[Pg 53] revenge upon his ancient enemy, and at once invaded the Roman possessions in Spain, and laid siege to the city of Saguntum, which, after heroic resistance, yielded to his victorious arms. Thus commenced the second Punic war, in which Hannibal was to show to the world his genius as a general.

Leaving a large force in Africa, and also in Spain, to defend these points, Hannibal set out in the spring of the year B. C. 218, with a large army to fulfill his project against Rome.

His course lay along the Mediterranean; the whole distance to Rome being about one thousand miles by the land route which he contemplated. When he had traversed Spain, he came to the Pyrenees, a range of mountains separating that country from Gaul, now France. He was here attacked by wild tribes of brave barbarians, but he easily drove them back. He crossed the Pyrenees, traversed Gaul, and came at last to the Alps, which threw up their frowning battlements, interposing a formidable obstacle between him and the object of his expedition.

No warrior had then crossed these snowy peaks with such an army; and none but a man of that degree of resolution and self-reliance which could not be baffled, would have hazarded the fearful enterprise. Indeed, we turn with amazement to Hannibal’s passage of the Alps; that great and daring feat surpasses in magnitude anything of the kind ever attempted by man. The pride of the French historians have often led them to compare Napoleon’s passage of the Great St. Bernard to Hannibal’s passage of the Alps; but without detracting from the well-earned fame of the French Emperor, it may safely be affirmed that his [Pg 54]achievements will bear no comparison whatever with the Carthaginian hero. When Napoleon began the ascent of the Alps from Martigny, on the shores of the Rhone, and above the Lake of Geneva, he found the passage of the mountains cleared by the incessant transit of two thousand years. The road, impracticable for carriages, was very good for horsemen and foot passengers, and was traversed by great numbers of both at every season of the year.

Comfortable villages on the ascent and descent afforded easy accommodation to the wearied soldiers by day and by night; the ample stores of the monks at the summit, and the provident foresight of the French generals had provided a meal for every man and horse that passed. No hostile troops opposed their passage; the guns were drawn up in sleds made of hollowed firs; and in four days from the time they began the ascent from the banks of the Rhone, the French troops, without losing a man, stood on the Doria Baltea, the increasing waters of which flowed towards the Po, amidst the gardens and vineyards, and under the sun of Italy. But the case was very different when Hannibal crossed from the shores of the Durance to the banks of the Po.

The mountain sides, which had not yet been cleared by centuries of laborious industry, presented a continual forest, furrowed at every hollow by headlong Alpine torrents. There were no bridges to cross the perpetually recurring obstacles; provisions, scanty at all times in those elevated solitudes, were then nowhere to be found, having been hidden away by the natives, and a powerful army of mountaineers occupied the entrance of the defiles, defended with desperate valor the[Pg 55] gates of their country, and when dispersed by the superior discipline and arms of Hannibal’s soldiers, still beset the ridges about their line of march, and harassed his troops with continual hostility. When the woody region was passed, and the vanguard emerged in the open mountain pastures, which led to the verge of perpetual snow, fresh difficulties awaited them.

The turf, from the gliding down of the newly-fallen snow on those steep declivities, was so slippery that it was often scarcely possible for the men to keep their feet; the beasts of burden lost their footing at every step, and rolled down in great numbers into the abyss beneath; the elephants became restive amidst privation and a climate to which they were totally unaccustomed; and the strength of the soldiers, worn out by incessant marching and fighting, began to sink before the continued toil of the ascent. Horrors formidable to all, but in an especial manner terrible to African soldiers, awaited them at the summit.

It was the end of October; winter in all its severity had already set in on those lofty solitudes; the mountain sides, silent and melancholy even at the height of summer, when enameled with flowers and dotted with flocks, presented then an unbroken sheet of snow; the lakes which were interspersed over the level valley at their feet, were frozen over and undistinguishable from the rest of the dreary expanse, and a boundless mass of snowy peaks arose at all sides, presenting an apparently impassable barrier to their further progress. But it was then that the genius of Hannibal shone forth in all its lustre.

“The great general,” says Arnold, “who felt that he now stood victorious on the ramparts of Italy, and that[Pg 56] the torrent which rolled before him was carrying its waters to the rich plains of cisalpine Gaul, endeavored to kindle his soldiers with his own spirit of hope. He called them together; he pointed out to them the valley beneath, to which the descent seemed but the work of a moment.

“That valley,” said he, “is Italy; it leads to the country of our friends, the Gauls, and yonder is our way to Rome.” His eyes were eagerly fixed on that part of the horizon, and as he gazed, the distance seemed to vanish, till he could almost fancy he was crossing the Tiber, and assailing the capital. Such were the difficulties of the passage and the descent on the other side, that Hannibal lost thirty-three thousand men from the time he entered the Pyrenees till he reached the plains of Northern Italy, and he arrived on the Po with only twelve thousand Africans, eight thousand Spanish infantry, and six thousand horse.

Then followed those splendid battles with the Romans, which carried consternation to their capital, and raised the great general to the highest pinnacle in the niche of military fame.

The defeat of Scipio, at the battle of Ticinus, the utter rout and defeat of Sempronius, the defeat of Flaminius, the defeat of Fabius, and the battle of Cannæ, in the last of which, the Romans had seventy-six thousand foot, eight thousand horse, and many chariots, and where Hannibal had only thirty thousand troops, all told, and where the defeat was so complete that bushels of gold rings were taken from the fingers of the dead Romans, and sent as trophies to Carthage, are matters of history, and will ever give to[Pg 57] Hannibal the highest position in the scale of ancient military men. Hannibal crossed the Alps two hundred and seventeen years before the Christian Era, and remained in Italy sixteen years. At last, Scipio, a Roman general of the same name of the one defeated by Hannibal at Ticinus, finished the war in Spain, transported his troops across the Mediterranean; thus “carrying the war into Africa,” and giving rise to an expression still in vogue, and significant of effective retaliation. By the aid of Masinissa, a powerful prince of Numidia, now Morocco, he gained two victories over the Carthaginians, who were obliged to recall Hannibal from Italy, to defend their own soil from the combined attacks of the Romans and Numidians.

He landed at Leptis, and advanced near Zama, five days’ journey to the west of Carthage. Here he met the Roman forces, and here, for the first time, he suffered a total defeat. The loss of the Carthaginians was immense, and they were compelled to sue for peace. This was granted by Scipio, but upon humiliating terms.

Hannibal would still have resisted, but he was compelled by his countrymen to submit. Thus ended the second Punic war (B. C. 200), having continued about eighteen years.

By this war with the Romans, the Carthaginians lost most of their colonies, and became in a measure, a Roman province. Notwithstanding his late reverses, Hannibal entered the Carthaginian senate, and continued at the head of the state, reforming abuses that had crept into the management of the finances, and the administration of justice. But these judicious reforms[Pg 58] provoked the enmity of the factious nobles who had hitherto been permitted to fatten on public plunder; they joined with the old rivals of the Barcan family, of which Hannibal was now the acknowledged head, and even degraded themselves so far as to act as spies for the Romans, who still dreaded the abilities of the great general.

In consequence of their machinations, the old hero was forced to fly from the country he had so long labored to serve; and after several vicissitudes, died of poison, to escape the mean and malignant persecution of the Romans whose hatred followed him in his exile, and compelled the king of Bithynia to refuse him protection. The mound which marks his last resting-place is still a remarkable object.

Hannibal, like the rest of the Carthaginians, though not as black as the present African population, was nevertheless, colored; not differing in complexion from the ancient Ethiopians, and with curly hair. We have but little account of this wonderful man except from his enemies, the Romans, and nothing from them but his public career. Prejudiced as are these sources of evidence, they still exhibit him as one of the most extraordinary men that have ever lived.

Many of the events of his life remind us of the career of Napoleon. Like him, he crossed the Alps with a great army; like him, he was repeatedly victorious over disciplined and powerful forces in Italy; like him, he was finally overwhelmed in a great battle; like him, he was a statesman, as well as a general; like him, he was the idol of the army; like him, he was finally driven from his country, and died in exile.[Pg 59][12] Yet, no one of Napoleon’s achievements was equal to that of Hannibal in crossing the Alps, if we consider the difficulties he had to encounter; nor has anything in generalship surpassed the ability he displayed in sustaining himself and his army for sixteen years in Italy, in the face of Rome, and without asking for assistance from his own country.

We now pass to the destruction of Carthage, and the dispersion of its inhabitants. Fifty years had intervened since Hannibal with his victorious legions stood at the gates of Rome; the Carthaginian territory had been greatly reduced, the army had witnessed many changes, Hannibal and his generals were dead, and a Roman army under Scipio, flushed with victory and anxious for booty, were at the gates of Carthage.

For half a century the Carthaginians had faithfully kept all their humiliating treaties with the Romans; borne patiently the insults and arrogance of Masinissa, king of Numidia, whose impositions on Carthage were always upheld by the strong arm of Rome; at last, however, a serious difficulty arose between Carthage and Numidia, for the settlement of which the Roman senate dispatched commissioners to visit the contending parties and report.

Unfortunately for the Carthaginians, one of these commissioners was Cato the elder, who had long entertained a determined hatred to Carthage. Indeed, he had, for the preceding twenty years, scarcely ever made a speech without closing with,—“Delenda est Carthago.”—Carthage must be destroyed. Animated by this spirit, it can easily be imagined that Cato would give the weight of his influence against the Carthaginians in everything touching their interest.

While inspecting the great city, Cato was struck with its magnificence and remaining wealth, which strengthened him in the opinion that the ultimate success of Rome depended upon the destruction of Carthage; and he labored to bring about that result.