THE PLEASURES OF THE TABLE

Title: The Pleasures of the Table

Author: George H. Ellwanger

Release date: June 8, 2020 [eBook #62354]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Karin Spence, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE PLEASURES OF THE TABLE

BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

"The Garden's Story, or Pleasures and Trials of an Amateur Gardener." Illustrated by Louis Rhead.

"The Story of My House." With a frontispiece by Sidney L. Smith.

"In Gold and Silver." Illustrated by A. B. Wenzell and W. Hamilton Gibson.

"The Rose." By H. B. Ellwanger. Revised edition, with an Introduction by George H. Ellwanger.

"Idyllists of the Country Side." With a title-page by George Wharton Edwards.

"Love's Demesne: A Garland of Contemporary Love Poems Gathered from Many Sources."

"Meditations on Gout, with a Consideration of its Cure through the Use of Wine." With a frontispiece and title-page by George Wharton Edwards.

"A SA TOUTE-PUISSANCE!"

From the painting by Gabriel Metzu, 1664

AN ACCOUNT OF GASTRONOMY

FROM ANCIENT DAYS TO

PRESENT TIMES.

WITH A HISTORY OF ITS LITERATURE,

SCHOOLS, AND MOST DISTINGUISHED ARTISTS;

TOGETHER WITH SOME SPECIAL RECIPES,

AND VIEWS CONCERNING

THE AESTHETICS OF DINNERS

AND DINNER-GIVING.

BY

GEORGE H. ELLWANGER, M.A.

NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY PAGE AND CO.

1902

Copyright, 1902, by

Doubleday, Page & Co.

FANTAISIE CULINAIRE: LE

POISSON PRÉVOYANT

By A. Thierry

TO HER,

TRUE COMRADE, WHOSE

VERSANT TOUCH AND ARTFUL

HAND HAVE KEENED MY

ZEST FOR GASTRONOMIC LORE,

THIS VOLUME IS DEVOTEDLY

INSCRIBED.

"Gasteria is the Tenth Muse; she presides over the enjoyments of Taste."

Brillat-Savarin.

"The History of Gastronomy is that of manners, if not of morals; and the learned are aware that its literature is both instructive and amusing; for it is replete with curious traits of character and comparative views of society at different periods, as well as with striking anecdotes of remarkable men and women whose destinies have been strangely influenced by their epicurean tastes and habits."

Abraham Hayward.

It is far from the purpose or desire of the author to add another to the innumerable volumes having practical cookery as their theme—the published works of the past decade alone being too numerous to digest.

The following chapters, therefore, though touching upon the practical part of the art, will be found more closely concerned with the history, literature, and æsthetics of the table than with its purely utilitarian side. Indeed, a complete manual of practical cookery is one of the impossibilities, for no person would have the patience to compile it; and even were such a work achievable, few readers could find sufficient time for its perusal. A glance at the portly "Bibliographie Gastronomique" of Georges Vicaire, in which English contributions to the subject are so meagrely represented, will suffice to show the difficulties such a task would impose. To classify properly the multitudinous dishes which, virtually identical, figure under so many different names, would of itself require years of severe application and laborious research. It may be observed, notwithstanding, that the world stands much less in need of additional inventions as regards the utilisation and preparation of foods than of an expert anthologist to garner the most worthy among recipes already existing in such bewildering profusion.

In the succeeding pages the writer has drawn from many sources, both ancient and modern—wherever an anecdote which is not too familiar has been found amusing, or an observation has been deemed pertinent or instructive. An occasional recipe has been given, and the sweet tooth of femininity has not been neglected. The hygiene of the table has likewise been considered, and some pernicious customs in connection with dining have been plainly dealt with. There are also some allusions to wines with respect to their complementary dishes, although wine is so important a subject as to call for a volume by itself.

It has not been deemed advisable to pass the cookery of the entire globe under review, even in a cursory manner. To devote separate chapters to Scandinavian, South American, and Oriental dishes, or even to purely Spanish, Mexican, and Russian food preparations, were both needless and cumbersome. The best have been embodied in the cosmopolitan kitchen; and the rest, for the most part, require the atmosphere of their native surroundings to be appraised at their proper value. It is with the French that the annalist of the table has chiefly to deal.

Necessarily, in treating of what Thomas Walker has termed "one of the most important of our temporal concerns," many gastronomic expressions and names of dishes, and not a few observations relating to the table, which would lose their piquancy or precise colouring on translation, have been retained in the language in which they originally appear. "Les quenelles de levraut saucées d'une espagnolle au fumet," "les amourettes de bœuf marinées frites," "l'épaule[xi] de veau en musette champêtre," "un coq vièrge en petit deuil," for example, while natural and comprehensible in French, would sound somewhat bizarre as "Forcemeat balls of leverets sauced with a racy Spanish woman," "the love-affairs of soused beef fried," "a shoulder of veal in rural bagpipes," and "a virgin rooster in half-mourning." And surely, in reviewing the aide-de-camp of the cook, it becomes obligatory to employ a French term upon occasion, and equally seemly to address him now and then in the classic tongue of the kitchen.

The principal meal has chiefly been considered, as through this to the greatest extent depend the health and frame of mind that determine the actions of man from day to day. It will, accordingly, be an entrée compounded of numerous flavourings, or a braise with its "bouquet garni" that has simmered gently over the smothered charcoal, rather than a familiar pièce de résistance which the reader is invited to partake of and discuss at his leisure.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| Introductory | ix | |

| I | Cookery among the Ancients | 3 |

| II | With Lucullus and Apicius | 24 |

| III | The Renaissance of Cookery | 49 |

| IV | Old English Dishes | 80 |

| V | L'Almanach des Gourmands | 112 |

| VI | A German Speisekarte | 145 |

| VII | The School of Savarin | 175 |

| VIII | From Carême to Dumas | 199 |

| IX | The Cook's Confrère | 229 |

| X | American vs. English Cookery | 248 |

| XI | At Table with the Clergy | 280 |

| XII | Sundry Guides to Good Cheer | 315 |

| XIII | Of Sauces | 344 |

| XIV | The Spoils of the Cover | 354 |

| XV | Two Esculents Par Excellence | 383 |

| XVI | Sallets and Salads | 409 |

| XVII | Sweets to the Sweet | 428 |

| Bibliography | 447 | |

| Index | 469 |

| "A Sa Toute-Puissance!" | Frontispiece |

| From the painting by Gabriel Metzu, 1664 | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Fantaisie culinaire: le poisson prévoyant | iv |

| By A. Thierry | |

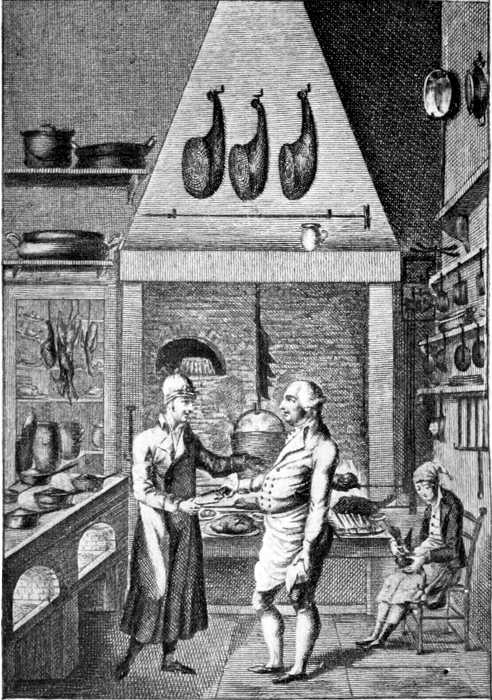

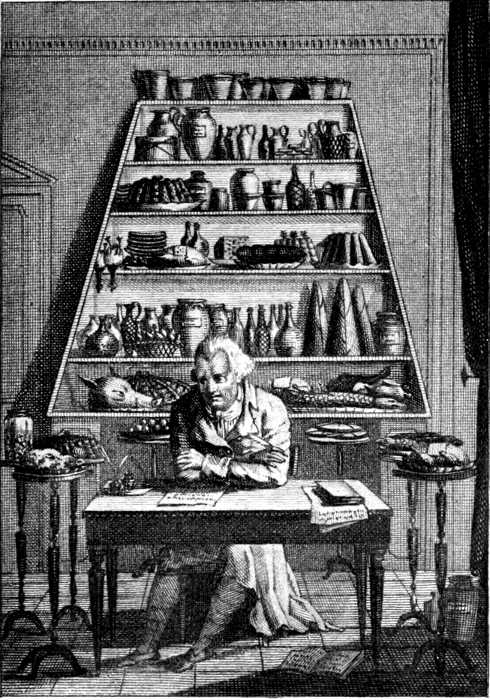

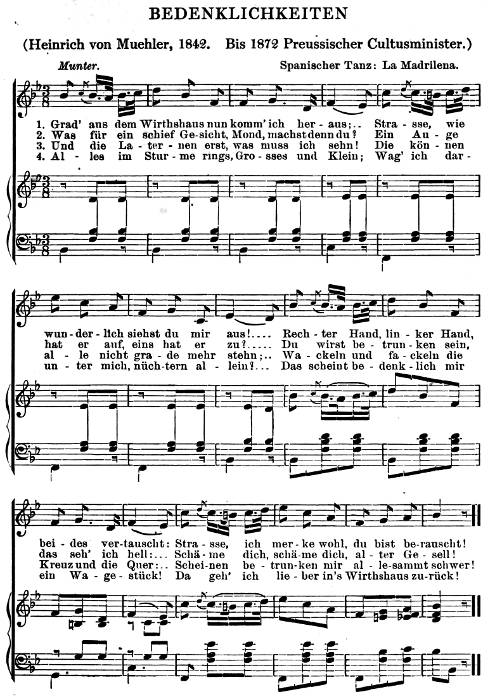

| Le Cuisinier | xi |

| After the engraving by Mariette | |

| FACING PAGE | |

| A Bacchante | 3 |

| From the stipple engraving in colours by Bartolozzi, after Cipriani | |

| Portrait du Gourmand | 24 |

| After Carle Vernet | |

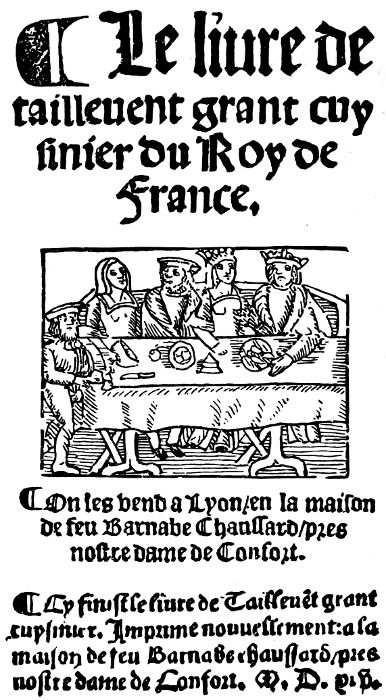

| Le Livre de Taillevent | 49 |

| Facsimile of title-page of the edition of 1545 | |

| The Cries of Paris: "Old clothes, old laces!" | 69 |

| Facsimile of an old French plate | |

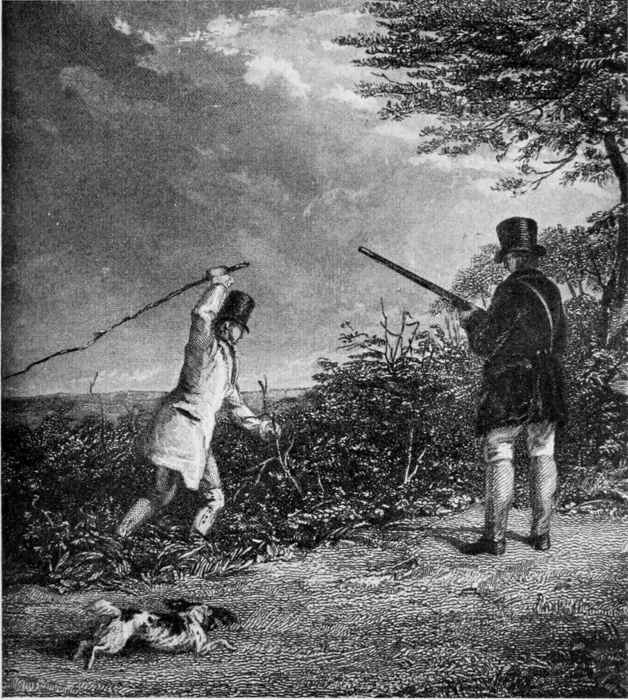

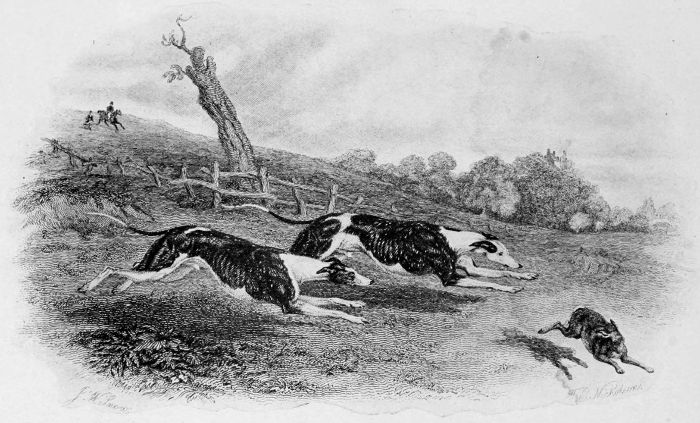

| First of September | 80 |

| From the engraving after A. Cooper, R.A. | |

| The English Housewife | 94 |

| Facsimile of title-page of the edition of 1675 | |

| "Un Viel Amateur" | 112 |

| A. B. L. Grimod de la Reynière, né à Paris le 20 9bre, 1756. From an old print | |

| Le Premier Devoir d'un Amphitryon | 121 |

| Frontispiece of the fifth year of the "Almanach des Gourmands" | |

| Les Méditations d'un Gourmand | 132 |

| Frontispiece of the fourth year of the "Almanach des Gourmands" | |

| The Chef | 145 |

| From a print after an old Dutch master | |

| The Bird of St. Michael | 160 |

| From the etching by Birket-Foster, R.A. | |

| Promenade Nutritive | 175 |

| Frontispiece of "Le Gastronome Français" (1828) | |

| "Pour voir de bons refrains éclore, Buvons encore!" | 186 |

| Frontispiece of "Le Caveau Moderne" (1807) | |

| Alexandre Dumas | 199 |

| From the etching by Rajon | |

| "L'Art du Cuisinier" (Beauvilliers') | 213 |

| Facsimile of title-page, 1824, Vol. II | |

| Day's Closing Hour | 229 |

| From the etching by Charles Jacque | |

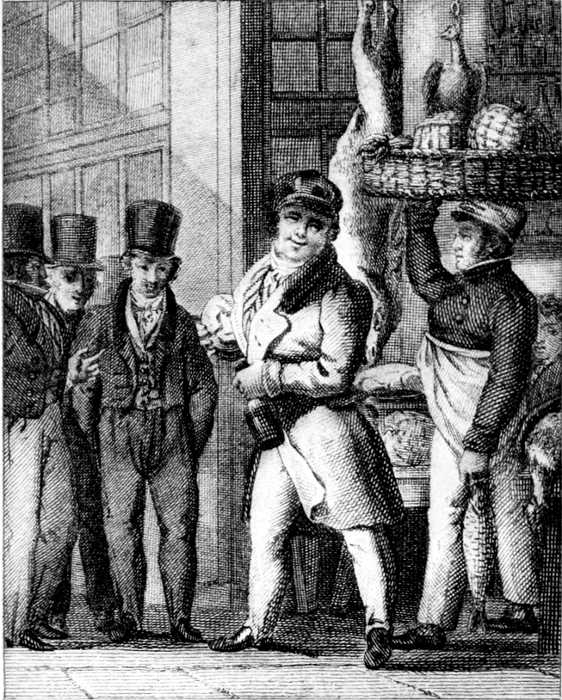

| "First Catch Your Hare!" | 248 |

| From the engraving by J. W. Snow | |

| "Rôti-Cochon" | 261 |

| Facsimile page from volume, 1696 | |

| Non in Solo Pane Vivit Homo | 280 |

| From the original oil-painting by Klein | |

| La Contenance de la Table | 296 |

| Facsimile of title-page (early part of sixteenth century) |

| Promenade du Gourmand | 315 |

| Frontispiece of "Le Manuel du Gastronome ou Nouvel Almanach des Gourmands" (1830) | |

| La Table | 331 |

| Frontispiece of the Second Canto of "La Conversation" of the Abbé Délille, 1822 | |

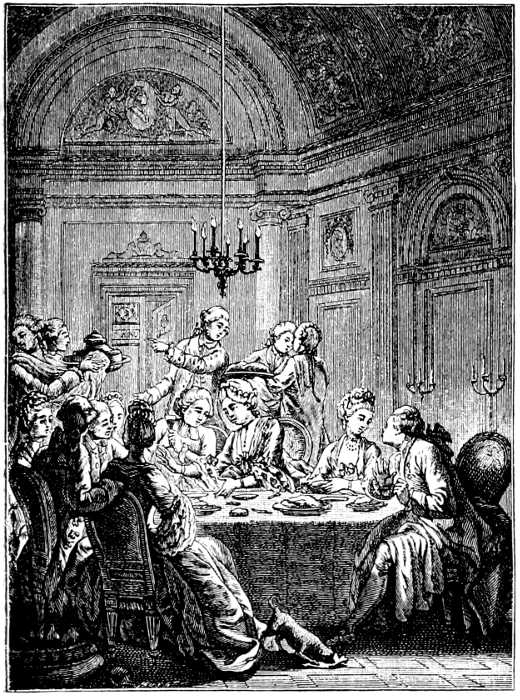

| A Supper in the Eighteenth Century | 344 |

| From the engraving after Masquelier | |

| The Spanish Pointer | 354 |

| From the engraving by Woollett, after the painting by Stubbs, 1768 | |

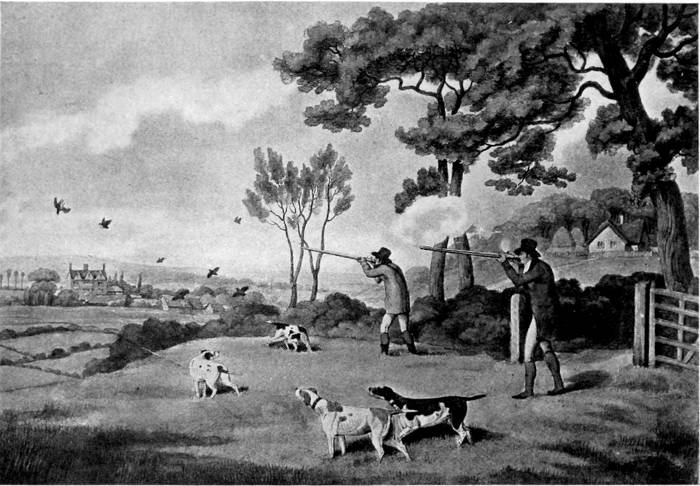

| Partridge Shooting. I. La Chasse aux Perdrix | 364 |

| From the coloured print after Howitt, 1807 | |

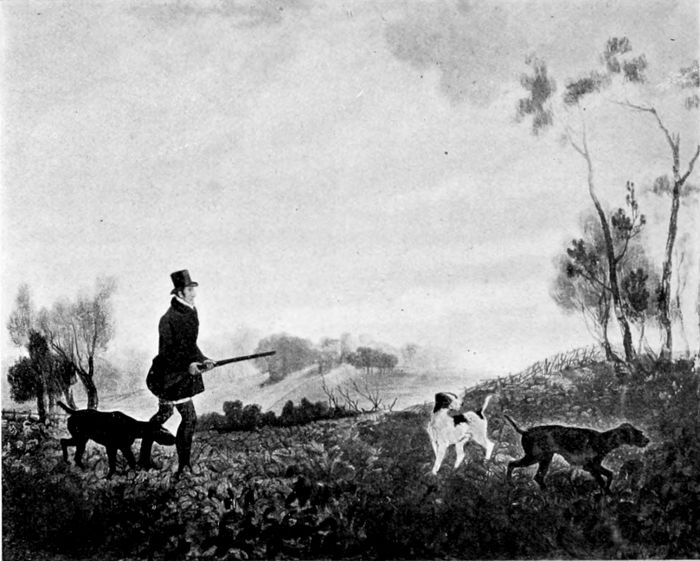

| Partridge Shooting—September | 375 |

| From the coloured engraving by Reeve, after the painting by R. B. Davis, 1836 | |

| Truffle-hunting in the Dauphiné | 383 |

| From the Salon picture after Paul Vayson | |

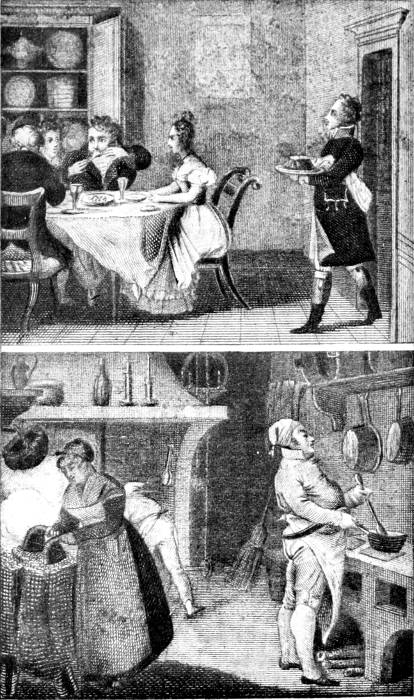

| "Nouvel Manuel Complet du Cuisinier et de la Cuisinière" | 397 |

| Facsimile of frontispiece, 1822 | |

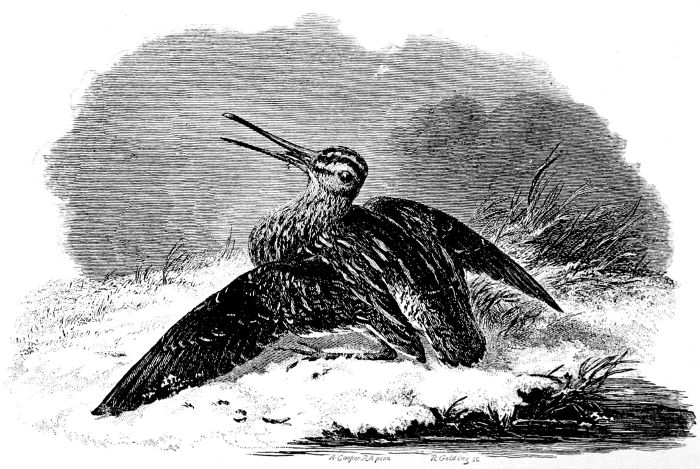

| The Wounded Snipe | 409 |

| From the engraving after A. Cooper, R.A. | |

| "Après Bon Vin" | 428 |

| From the engraving by Eisen in the Fermiers-Généreaux edition of the "Contes et Nouvelles" (1762) | |

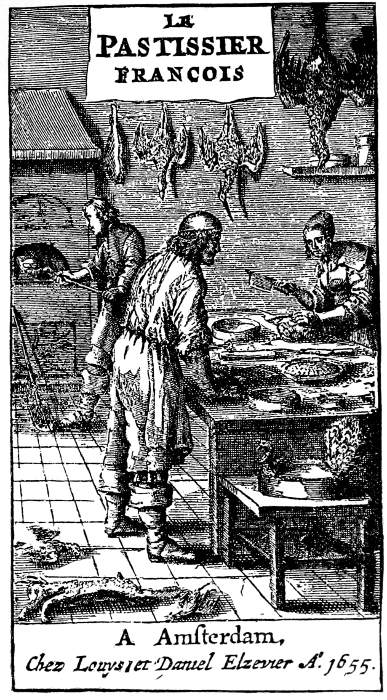

| Le Pâtissier Français | 442 |

| Facsimile of title-page of the edition of 1655 |

LE CUISINIER

After the engraving by Mariette

THE PLEASURES OF THE TABLE

"L'art qui contient toutes les élégances, toutes les courtoisies, sans lesquelles toutes les autres sont inutiles et perdus; l'art hospitalier par excellence qui emploie avec un égal succès tous les produits les plus excellents de l'air, des eaux, de la terre."—Fayot.

Cookery is naturally the most ancient of the arts, as of all arts it is the most important. Whether one should live to eat, is a question concerning which the epicure and the ascetic will hold widely varying opinions; but that one must eat to live, will scarcely admit of controversy. The man who is wise in his generation will be inclined to choose a happy medium. Or perchance the French axiom that we only eat to live when we do not understand how to live to eat, may somewhat simplify the matter. As it is largely through food and drink that man[4] derives his highest mental efficiency and physical well-being, as equally through improper diet accrue countless bodily disorders, it would appear that the proper choice and preparation of aliments and the selection of beverages should receive the profound consideration of every one.

In few of the arts has progress been more apparent during modern times. The mechanic has improved its accessories until the utmost perfection would seem to have been attained, medicine and chemistry have endeavoured to determine what elements of our daily dietary are injurious to certain individuals or to all, volume after volume has been written upon the subject, while the grand army of cooks has been busy in inventing new combinations or in resurrecting forgotten recipes.

And yet the digestive ills of humanity have continued to multiply, even though there are over six-score ways presented by a single author of serving the rabbit, and a competent priest of the range can utilise the egg in hundreds of different forms. Is it that with greater variety in our aliments, a greater number of ailments is a necessary sequence, and that as mankind increases in culinary knowledge digestion decreases in power? It is an olden adage that too many cooks spoil the broth; and it may be worthy of consideration whether a superfluity of dishes is not responsible to a considerable degree for the furtherance of various stomachic maladies. Or, on the other hand, is it that with the trebled facilities of locomotion supplied by modern science, and the closer confinement of indoor pursuits, the cause may [5]be largely ascribed to lack of exercise and insufficient oxygenation?

A BACCHANTE

From the stipple engraving in colours by Bartolozzi, after Cipriani

However this may be, the art of cookery is far less generally understood than its great hygienic importance demands, while the art of dining is understood only by the relatively few. As M. Fayot observed to Jules Janin, "Without doubt, Monsieur, as you have often said, it is difficult to write well, but it is a hundred times more difficult to know how to dine well." Or, as Dumas has expressed it, "To eat understandingly and to drink understandingly are two arts that may not be learned from the day to the morrow." He himself was a striking example of the accomplished bon vivant, and his marked intellectual superiority over his son may be readily attributed to his greater knowledge of dining.

Where, indeed, more than at the well-appointed dinner-table may one echo the sentiment of Seneca, "When shall we live if not now?" "An empty stomach produces an empty brain," observes the author of the "Comédie Humaine"; "our mind, independent as it may appear to be, respects the laws of digestion, and we may say with as much justice as did La Rochefoucauld of the heart, that good thoughts proceed from the stomach." It is, however, a source whence our joys and sorrows both may spring. Neglect and indifference may impair its action to destruction; but, humoured kindly, it ever guides us in paths of peace. In a healthy and a hungry state, it yearns for special gifts which gustatory edicts demand, and rarely will confusion attend them when their bestowal is flavoured with prudence. It is a faithful minister and[6] discriminating guardian, which rebels only when its functions are imposed upon; but when they are, its resentment is thorough and relentless. Worthy then, most certainly, of solicitous regard is the nourishment of an organ which may shape our ends for weal or woe.

"Cookery," said Yuan Mei, the Savarin of China and author of a scholarly cook-book during the eighteenth century, "is like matrimony—two things served together should match. Clear should go with clear, hard with hard, and soft with soft.... Into no department of life should indifference be allowed to creep—into none less than into the domain of cookery."

Concerning the art itself, it may be remarked that the French have been to cookery what the Dutch and Flemish schools have been to painting—cookery with the one and painting with the other having attained their highest excellence. Rubens, Rembrandt, Teniers, Jordaens, Ruysdael, Snyders, Berghem, and Cuyp may be paralleled in another branch of art by Carême, Vatel, Beauvilliers, Robert, Laguipière, Véry, Francatelli, and Ude. But, as in painting during its earlier stages Flanders and the Netherlands owed much to the Roman and Venetian schools, so in cookery the French are vastly indebted to their predecessors and former masters the Italians, who, if less distinguished colourists, were not to be despised as draughtsmen, and who if by instinct not as skilled in the chiaroscuro of sauces, were most dexterous in creating breadstuffs and pastry. Montaigne's reference to an Italian cook of the period will be remembered in this[7] connection—one of the artists who had been employed by Cardinal Caraffa who discoursed upon the subject in such rich, magnificent words, well-couched phrases, oratoric figures, and pathetical metaphors as learned men use and employ in speaking of the government of an empire.

It is a long stone's throw from the first apple eaten in the Garden of Eden—and this was a wild fruit, and not a Spitzenberg or a Northern Spy—to a Chartreuse à la bellevue or that triumph of the ovens of Alsace—the pâté de foie gras. The first dish of which any record exists is the red pottage of lentils for which Esau sold his birthright—a form of food still very common in Germany and France. The first direct mention of breadstuffs in the Bible occurs in Genesis, where Abraham tenders the angel a morsel of bread, and bids Sarah make ready quickly three measures of fine meal, knead it, and make cakes upon the hearth.

The primitive tribes and nations were content of necessity with the spoils of the chase and the then more limited products of the vegetable world; and long before John the Baptist's time the Hebrews lived to no small extent upon locusts and kindred insects. In his enumeration of the animal food which they might eat without rendering themselves unclean, Moses specifies four insects of the locust family (Lev. x, 22). Some species of the Locusta are yet esteemed a delicacy in the East, these being cooked with oil, roasted upon wooden spits, baked in ovens, or broiled. The Bedouins, who are ever on the march, pack them with salt in close masses, carrying them in their[8] leathern sacks. By the Athenians they were usually roasted; and mention is made by Athenæus of an archimagirus, or master cook, who, in his tour around the ovens and stock-pots, enjoins one of his subalterns to take the utmost precaution with them and see that they obtain only a light golden hue.

Eggs, milk, rice, and honey, onions, succory, leeks, and garlic, the leaves of the vine, radishes, and carrots, with other growths of the garden, formed the staple articles of diet among ancient peoples. Vegetable food was more common than animal, the latter being served principally in the case of entertainments and special occasions of hospitality (Gen. xviii, 7, 8). Instead of lard and butter, olive oil was employed, and is still almost entirely employed by the Orientals. Fish constituted an important article of diet, together with game, lambs, and kids. Though not common, the flesh of young bullocks and stall-fed oxen was highly prized (Prov. xv, 17; Matt. xxii, 4), the shoulder being considered the choicest part. The master of the house was the matador, and upon the mistress devolved the preparation of the food. Among primitive cooks, Rebekah proved herself a performer of no mean ability, as instanced by her dressing the flesh of a young kid after the manner of venison, in order to obtain a father's blessing for her favourite son. Roots, berries, fruits, and the quarry of the bow and harpoon composed the fare of aboriginal man, and proved all-sufficient. When the struggle for physical existence called for strong exercise in procuring necessary food, little variety in nutriment sufficed, at no loss of brawn and sinew.

With many savage races, bread-fruit, nuts, the plantain, the cocoa-palm—known as the "tree of life"—with numerous other food-yielding palms, served as a principal means of subsistence. The first fruit-tree cultivated by man is said by all the most ancient writers to be the fig, the vine being next in order. The almond and pomegranate were cultivated at an early date in Canaan, and the fig, grape, pomegranate, and melon were known to Egypt from time immemorial. In Solon's law's, the olive, the fig, and the vine are enumerated, as also the cabbage, crambe, or sea-kale, pulse of various kinds, and onions. Cabbage and asparagus were known to the Greeks from the earliest ages, and by them the chestnut, largely utilised for food, was termed the "Oak of Jupiter." The original home of wheat and barley is supposed to be Mesopotamia and the fertile plains of the Euphrates, whence, after a period of cultivation, they spread eastward to China and westward to Syria and thence to Europe. Among other food-stuffs of the inhabitants were onions, vetches, kidney-beans, egg-plants, pumpkins, lentils, cucumbers, chick-peas, and beans—with such fruits as the apple, fig, apricot, pistachio, almond, walnut, and the product of the palm and vine.

Coffee, of very remote use in Abyssinia, was unknown to the early Greeks and Romans; they were, however, familiar with the cucumber, cultivated in India for at least three thousand years. The cucumber was also known to Moses and the Israelites, the patriarch referring to fish and cucumbers, melons and leeks, as among the delicacies that were freely eaten[10] in Egypt (Numbers xi, 5). Various kinds of Cichorium, or chicory, were familiar to antiquity, while Lactuca, or lettuce, was extensively grown as a salad. The onion was a favourite with the ancient Egyptians, garlic likewise being made much use of—a plant denounced by their priests as unclean.[1]

Baking in ovens is of great antiquity, the ovens of old Egypt being frequently represented in contemporary paintings. The table appointments of Egypt are similarly portrayed in her paintings—the guests of both sexes seated in gala attire, with jewelled fingers holding the lily of the Nile or sacred lotus, while slaves, naked except for necklace and girdle, served them with viands and wines. Differing from the Egyptians, the Greeks and Romans excluded women from their feasts, agreeing with the sentiment of Fulbert Dumonteil that for a true gourmand there exist no blue eyes, white teeth, or rosy lips that may take the place of a black truffle. The only exception related to the cup-bearers—fair youths and tender maids—who were enjoined to refuse nothing to the guests, and the richly and gorgeously arrayed hetæræ, the voluptuous Aspasias, Barinés, and Phrynes of the period, who made their appearance at the conclusion of the repast.

With a corps of twelve stewards to provide for his table, eleven of whom were constantly travelling in search of viands and wines, it is reasonable to assume[11] that Solomon, of whose menus so little record exists, scarcely confined himself to coarse dishes prepared from the flesh of "bullocks, sheep, harts, and roebucks," but that he, with his thousand wives and concubines, observed a sufficient variety and luxury in his kitchen to correspond with the magnificent table appointments and sumptuous surroundings chronicled in the book of Kings. For ruthless extravagance, Cleopatra's dish of a melted pearl, weighing seventy-four carats and valued at six million sesterces, probably exceeds that of any single plate of the Egyptian rulers or prodigal Roman potentates. Horace, in the third satire of the Second Book, makes mention of the spendthrift son of Æsopus as also dissolving a pearl in vinegar—his mistress's earring—

Boiling was another primitive mode of cooking; and the method even yet practised by barbarians is to utilise the hide of the slaughtered animal for a bag, placing the meat in this receptacle with water, and dropping in stones heated to a white heat until the flesh is cooked. Laving the meat on hot stones and covering it with ashes, or hanging it upon a tripod of sticks over the flames, was the mode of roasting and broiling of the aborigines, with whom utensils of pottery and metal were unknown—a method often resorted to by woodsmen at the present time.

The Persians were first to set an example of luxurious cookery, at least as it was understood in an[12]cient times—the favourable climate and fertility of their products, as well as their natural inclination to ease, all tending to foster a love for the pleasures of the table. The oldest books of which we have any knowledge refer to their pomp in banqueting, and portray the brilliant revels of the Oriental kings.

Thousands of years before Henrion de Pensey pronounced his famous aphorism, a novel culinary preparation was regarded as of vaster importance than a new celestial visitant. The saturnalia of Darius and Xerxes, the powerful Persian despots, are notorious in history, as are also the feasts of Nebuchadnezzar, King of Chaldea, and those of Belshazzar, the final ruler of corrupt Babylon who fêted and feasted a thousand of his lords, his wives, and his concubines. Anticipating the munificence of the Roman emperors, Sardanapalus, last of the Assyrian kings, offered a guerdon of a thousand pieces of gold to him who would produce a new dish. "Eat, drink, amuse thyself: all else is vanity," was his maxim, and the precept he desired to have engraven on his tomb.

The book of Esther records the magnificent royal feast at Shushan given in the third year of his reign by the Persian king Ahasuerus: a carnival which lasted an hundred and fourscore days—where the beds were of gold and silver upon a pavement of red and blue and white and black marble; where were white, green, and blue hangings, fastened with cords of fine linen and purple to silver rings and pillars of marble; and where the people were given to drink, in vessels of gold, of royal wine in abundance, according to the state of the king. From the land of Zoroaster,[13] therefore, the Greeks received their first lessons in gastronomy.

Simplicity in their habits was a characteristic of the early Greeks, this simplicity extending in a marked degree to their cookery, when the famous Spartan black broth, composed of pork-broth, vinegar, and salt, became a national dish. But this epoch of abstention was of comparatively short duration. The spiritual sense was overcome by the carnal, and, imitating the Arians, they soon converted a natural craving into a hypersensuous pleasure.

The dinner or supper developed into an elaborate banquet, partaken of on reclining couches, accompanied by wines of Corinth, Samos, Chios, and Tenedos, the fumes of incense, the strains of music, and the singing of pages and beautiful maids. The couches on which they partook of their repasts and offered their generous libations to the gods were ornamented with tortoise-shell, ivory, and bronze, some being inlaid with pearls and precious stones; the mattresses were of purple embroidered with gold. Then Archestratus, the Syracusan, who had travelled far and wide in quest of alimentary dainties of different lands, was the Carême of the Attic cuisine. His much-lauded poem on "Gastronomy" is unfortunately lost to posterity, and thus it may not be compared with that of Berchoux, composed twenty centuries later. This poem Athenæus has termed a treasure of light, every verse of which was a precept, and from which numerous cooks drew the principles of an art that rendered them illustrious. The cook in the "Thesmophorus" of Dionysius, however, denounces Archestratus, his rules,[14] and his maxims. But cooks are notoriously jealous and prone to asperse their rivals, just as a jealous woman will decry another member of her sex whom men admire. His aspersions, therefore, are not to be weighed against the avalanche of encomiums that Archestratus has received. It was to the select few who appreciated the delicacies and importance of his art that his poem was addressed. He spoke with authority, and not as the scribes. Witness his stately opening stanza, one of the few surviving fragments of his epic:

Mithæcus, another famous Hellenic guide to epicurean delights, wrote a book entitled "The Sicilian Cook," which has been mentioned by Plato; but this was written in prose, and was the product of a former native of Sicily, whence Greece was largely accustomed to draw her supply of culinary masters. Among the most distinguished of Sicilian craftsmen was Trimalchio, whose cunning is said to have been so great that when he could not procure scarce and much coveted fish he could counterfeit their form and flavour so deftly as to deceive even Neptune himself.

The cook of Nicomedes, King of the Babylonians, was accustomed to serve him with anchovies, made in imitation of the real fish, at such times as his majesty expressed a desire for anchovies on a sea voyage. A[15] turnip, disguised by oil, salt, poppy-seed, and other seasonings, was the basis of the plat, the king, as Euphron, the comic writer, records, smacking his lips over the dish and saying that cooks were equally as useful as poets, and even more skilful. That, with the aid of olives, salt pork, onion, parsley, condiments, and stuffing, with veal as the medium, an accomplished cook can prepare a fair semblance to an overdone quail is proverbial. But how a turnip can be made to counterfeit anchovies is not so apparent. The celebrated repasts of Socrates, at which the guests were seated on chairs, were an exception to the luxury of the times; these entertainments were extremely frugal, the cheer being of an intellectual more than a corporeal nature—a mere collation,

Epicurus, the Athenian who flourished three hundred years before the Christian era, is wrongly supposed by many to have been one of the dediti ventri—a slave to appetite and living only for epicurean pleasure: a supposition that his name naturally implies. But it should be recollected that in proposing pleasure or happiness as the supreme good, he qualified this doctrine by the maxim that temperance is necessary in order to enjoy the noble and durable pleasures which are proper to human nature.

However varied the fare and splendid the appointments, the position of the ancients at table—resting on their left elbows and reclining on couches as the[16] gnomon and clepsydra noiselessly marked the lapse of the hours—must have been not only irksome, but one greatly furthering stomachic maladies. Besides, it must be borne in mind that the ancients ate with their fingers, while the use of emetics, first in vogue among the Egyptians, and later on among the Romans in order to forefend satiety and enable them to prolong their saturnalia, was extremely common. The ten books of Athenæus give us a complete manual of olden Greek cookery, and Herodotus, Plutarch, and other authors, if not as exhaustive, are most fertile in references to the subject. Plato, who denounced epicureanism and preferred olives to all other kinds of food, often making his meal from them alone, nevertheless praises Attic pastry, and extols the baker Thearion, who was noted for the perfection of his bread.

Besides beef and mutton, kids, the domestic swine, fowls, the wild boar, the roebuck, hares, rabbits, and numerous game and song birds, the Greeks were especially fond of the peacock, served in all his panoply of plumage.

As the Romans considered the mullet the king of fish, so the Greeks regarded the sole as the piscis nobilis. They were served then, as now, fried, when their size admitted, and likewise were prepared with a savoury sauce under the name of citharus,—

Suckling pig was considered a signal delicacy, its charms no doubt having been set forth in melodious measures in the lost poem of Archestratus. Indeed, who knows but that the sportive grace of the "Dissertation upon Roast Pig" may, after all, be Grecian rather than Anglo-Saxon in essence, and be merely an inspiration caught from some forgotten Attic author? The sea, on its part, yielded its infinite treasures, including the oyster, the earth contributing its varied fruits and esculents. Strong and sweet wine was a common beverage, both mixed, unmixed, spiced, and scented.

After fish and game, pork was the most esteemed food set upon the salvers of ancient Greece and Rome—a food in which epicures believed themselves to have discovered fifty different flavours, or fifty parts, each possessing an individual taste. At large entertainments, and even where the guests were only equal in number to the Muses, it was customary to serve pigs roasted whole, stuffed with sausages and bursting with boudins, or "black pudding." The pig was salted by the ancients in order to preserve it; but Apicius recommended, for keeping purposes, that medium-sized pieces of pork be chosen and covered with a paste composed of salt, vinegar, and honey, and be stored in carefully closed vessels.

Of ancient recipes, Apicius and Athenæus present a vast array. Soyer also, in his aspiring, cumbersome, and learned "Pantropheon," affords convenient access to the mysteries of the Greek and Roman kitchens. But the only way to pass intelligently upon the cookery of the ancients would be to try it. It is[18] true that we do not possess their marvellous digestive powers ere their vigour became impaired by centuries of unbridled luxury. To young and vigorous stomachs it is possible that, if accompanied by the appropriate wines, some of their dishes, executed by a skilful chef who would exercise extreme caution as regards the use of cummin, rue, coriander, and boiled grapes, might prove an agreeable surprise party at a dinner à la Grecque or à la Romaine. So light a touch and so discriminating a palate, however, are necessary in employing certain herbs and spices; so much, moreover, depends upon knowing the precise moment when an entrée or a ragout has received its just caress from the flames, that only an artist of the foremost rank would be able to reproduce some of these dishes with success.

Two especially prized dishes were those termed myma and mattya—the one composed of all kinds of finely minced viands and fowls, seasoned with vinegar, cheese, onions, honey, raisins, and various spices; the other a fowl boiled with a great variety of herbs. "Boil a fat hen and some young cocks just beginning to crow, with some vinegar added to the water, and in summer with sour grapes in place of the vinegar, then remove the herbs from the vessel in which they are cooked and serve portions of the fowls on the herbs, if you wish to make a dish worthy to be eaten with your wine," enjoins Artimidor in his treatise of cooking. Finally, Athenæus, in the "Banquet of the Learned," has the scholarly host Laurentius give his recipe for what he terms the "Dish of Roses," prepared, he states, in such a way that you may not only[19] have the ornament of a garland on your head, but also in yourself.

"'Having pounded a quantity of the most fragrant roses in a mortar,' says Laurentius, 'I put in the brains of birds and pigs boiled and thoroughly cleansed of all the sinews, and also the yolks of eggs, and with them oil, and pickle-juice, and pepper and wine. And having pounded all these things carefully together, I put them into a new dish, applying a gentle and steady fire to them.' And while saying this he uncovered the dish, and diffused such a sweet perfume over the whole party that one of the guests present said with great truth:

'The winds perfumed, the balmy gale, conveyThrough heav'n, through earth, and all the aërial way'—so excessive was the fragrance which was diffused from the roses."

Truly a noble pot-pourri—meet for the gods of high Olympus. The pickle-juice, the pepper, and the wine denote the address of a master in disguising any possible taint of the pen, while the yolks of eggs and the oil would necessarily blend and assimilate with the attar of the rose-leaves. Thus does a great architect plan the construction of a cathedral, or a wizard of the brush adjust his pigments upon a canvas that is destined to become immortal.

The early Greeks had four meals daily—the breakfast, or acratisma; the dinner, ariston or deipnon; the relish, hesperisma; and the supper, dorpe. As luxury and cookery advanced, luncheon took the place of the midday dinner, the latter, among the wealthier classes, gradually being postponed to a later hour. At all[20] great feasts and dinners of ceremony, which it was customary to hold in the evening, the bill of fare was presented to the guests, and huge chalices were offered them to quaff from.

The frequent and detailed references by the old Greek dramatists, poets and writers to eating, drinking and banqueting, and to the various products employed as food, make it apparent to what an extent gratification of appetite and feasting prevailed.

The reader who would penetrate further into the mysteries of Grecian cookery may be referred with advantage to Homer's repast of Ulysses at the home of Eumæus, Athenæus's "Marriage of Caranus," and Barthélemy's "Feast of Dinias." But Homer's fare which he allowed his heroes was, with few exceptions, extremely simple. Although he mentions many kinds of wine, he praises moderation, and never represents either fish or game as being put upon the table, but "viands of simple kind and wholesome sort," such as were calculated to render man vigorous in body and mind, the meat being all roasted and chiefly beef.

Athenæus, in particular, presents the Greek and Oriental kitchens in all their aspects, and, with his marvellous erudition, proves himself a very Burton of gastronomy—the most accomplished Master of Feasts that antiquity has produced. To turn the pages of the "Deipnosophists, or Banquet of the Learned" is to enter a larder of which he only holds the key. Thus he introduces Damoxenus, the old Greek comic writer, who picturesquely portrays a master cook of the period, superintending his saucepans and directing the preparation of the feast:

The ideal cook is depicted with equal picturesqueness in a lengthy tribute by Dionysius wherein he thus sums up his qualifications,—

Cratinus, in his play of the "Giants," extols the merits of Sicilian cookery:

And Hegesander, in his "Brothers," presents an archimagirus, proud as Lucifer, who sings his own praises in the following grandiloquent strain:

Philemon, in turn, the witty Athenian bard, represents a cook as pluming himself upon his cunning, and saying:

Anthippus, too, presents a graduate of the range who was no less proficient in the resources of his art,[23] and who devised his dishes according to the age of those who were to partake of them,—

Nor does Athenæus fail to depict a glutton of the period, transcribed from Pherecrates:

Milo of Crotona, Titormus the Ætolian, and Astydamas the Milesian were still more celebrated; and even Ulysses in his old age is represented by Homer as eating "endless dishes" and quaffing "unceasing cups of wine." Gargantua and Pantagruel evidently existed long before the days of Rabelais, and time will run back to fetch the age of gluttony, as well as that of gold.

"Whether woodcock or partridge, what does it signify, if the taste is the same? But the partridge is dearer, and therefore thought preferable."—Martial, Epigrams, xiii. 76.

Passing from Greece to Italy, we find frugality to have been a prominent trait of the early Romans, and porridge to have been the national dish until wheaten bread was introduced from Athens. Like the Greeks, who received their initial lessons from the Persians, the Romans derived their knowledge of cookery from Attica, whence they imported their first masters. The Romans proved apt scholars, and soon outrivalled their instructors in the pleasures of the table, where the pomp, luxury, and licentiousness of the times were carried to their furthest limit. It is indeed well nigh impossible to conceive the splendour, prodigality, and sensuality [25]that prevailed during the Republic and the Empire, when fabulous revenues were squandered at a single feast, and gluttony and intemperance were the gods of the hour.

PORTRAIT DU GOURMAND

After Carle Vernet

It was towards the decline of the Republic, during the period of Pompey the Great, Cæsar, and Lucullus, that, dispensing with the culinary preceptors of Greece, the Roman cuisine attained its greatest celebrity.

For it was at this period that the great ravagers of the world, who were to carry the name and arms of Rome into distant lands, brought their cooks with them, who vied with one another in contributing the most appetising dishes of various countries. It was then when Antony, intoxicated with the spoils of conquest and more than usually pleased with the artist of his kitchen, sent for him at the dessert and presented him with a city of thirty-five thousand inhabitants—an example followed in a minor way by Henry VIII of England, who rewarded his cook for having composed a pudding of especial merit by the gift of a manor. It was then that the Sybarites bestowed public recompense and marks of distinction upon those who gave the most magnificent banquets, and especially upon those who invented new dishes.[2] It was then that the practised epicure professed to distinguish by the taste from what locality of Italy a[26] wild boar had been procured, or whether a pike had been caught in the lower or upper Tiber. Thus Horace, in one of the "Satires":

It was then that the rich Romans had at their villas magnificent piscinæ filled with fresh-and salt-water fishes that might be netted at a moment's notice to set before their guests. In his ode "On the Prevailing Luxury," the Venusian bard also alludes to these vivaria and the inordinate fondness for fish of the Romans:

The mansions of the wealthy were likewise provided with splendid aviaries filled with thrushes that were fed with millet and crushed figs mixed with wheaten flour. Cygnets and snow-white geese were held in great repute, and when fattened upon green figs their livers were highly prized.

Hortensius the consul was among the first to maintain salt-water ponds stocked with his favourite fish,[27] the red mullet of the Mediterranean. He was also the introducer of the peacock served in its feathers, a dish extremely popular during the Republic. Horace proved a better judge than his many moneyed hosts, and chose the chicken in preference, asserting that it was the costliness of the bird of Juno and the glory of his glittering train more than the quality of the flesh that were prized. Artificial oyster-beds, according to Pliny, were first formed at Baiæ by Sergius Orata, a contemporary of Crassus the orator, not for the gratification of gluttony, but as a speculation from which he derived a large income. He too was the first to adjudge the preëminence for delicacy of flavour to the oysters of Lake Lucrinus. Preserves were subsequently formed by others for murenæ, sea-snails, and numerous saline delicacies.

Like the Hellenes, the Romans had three meals—the breakfast (jentaculum), the luncheon (prandium), and the dinner (cena). Originally, as has been the case with all peoples, the dinner was held in the morning, but with the progress of luxury and owing to the greater convenience to men of affairs, it became gradually deferred to late afternoon or evening. Nine was the favourite number of guests at the cena. It was a custom borrowed from the Greeks to appoint a king or dictator of the feast, who prescribed its laws, which the guests were bound, under penalties, to obey. By him the quantity of the cups to be drunk was decided, ten bumpers being the usual allowance—nine in honour of the Muses, and one to Apollo. Similar to the Grecian custom, every man who had a mistress was compelled to toast her when[28] called upon. To this a penalty was sometimes attached, in which case the challenger was obliged to empty a cup to each letter of the lady's name. When the gallant had reasons for secrecy, he merely announced the number of cups which had to be drunk.

The place of tobacco was taken by perfumes at feasts, a practice carried by the Romans to great excess. Nard and other perfumes in use being extremely costly, Horace insists upon Virgil contributing them when he comes to dine in the vale of Ustica. Catullus, also, who asks his friend Fabullus to dinner, agrees to supply the perfumes, providing Fabullus bring with him all the other requisites. The spiciness of the essences doubtless spurred the appetite, and tended to produce a pleasant languor.[5]

Very numerous plants and herbs were employed as flavourings in the kitchens of the ancients, such as dill, anise-seed, hyssop, thyme, pennyroyal, rue, cummin, poppy-seed, shallots, and, naturally, onions, garlic, and leeks—savoury then taking the place of parsley, which, though known, was used more as a decoration and worn by guests as an adornment. Cummin was largely utilised for seasoning. Sorrel was cultivated by the Romans to increase its size, and, according to Apicius, was eaten stewed with mustard and seasoned with oil and vinegar. The carrot was stewed, boiled with cummin and a little oil, and eaten as a salad, with salt, oil, and vinegar.

Brocoli was an especial favourite with Apicius, the most tender parts being boiled, with the addition of pepper, chopped onions, cummin and coriander seed bruised together, and a little oil and sun-made wine. Turnips were boiled and seasoned with rue, cummin, and benzoin, pounded in a mortar, adding afterwards honey, vinegar, gravy, boiled grapes, and oil. Asparagus, which Lamb says inspires gentle thoughts, was cultivated with notable care. The finest heads were dried, and when wanted were placed in hot water and boiled. Lucullus and Apicius ate only those that were grown in the environs of Nesis, a city of Campania. Beets, mallows, artichokes, and cucumbers were greatly relished and elaborately prepared, and garlic, extolled by Virgil and decried by Horace, was generously used.

Apicius, in his treatise "De re Culinaria," gives numerous recipes for cooking the cabbage—the silken-leaved, curled, and hard white varieties. From these recipes we at once may judge of his resources, and obtain an idea of a master vegetable-cook of the period:

"1. Take only the most delicate and tender part of the cabbage, which boil, and then pour off the water; season it with cummin seed, salt, old wine, oil, pepper, alisander, mint, rue, coriander seed, gravy, and oil.

"2. Prepare the cabbage in the manner just mentioned, and make a seasoning of coriander seed, onion, cummin seed, pepper, a small quantity of oil, and wine made of sun raisins.

"3. When you have boiled the cabbages in water put them into a saucepan and stew them with gravy, oil, wine, cummin seed, pepper, leeks, and green coriander.

"4. Add to the preceding ingredients flour of almonds, and raisins dried in the sun.

"5. Prepare them again in the above manner, and cook them with green olives."

To what an extent strange condiments, herbs, and other seasonings were employed, as well as to what a task the human stomach was subjected, will be apparent from a recipe, given by the same authority, for a thick sauce for a boiled chicken: "Put the following ingredients into a mortar: anise-seed, dried mint, and lazer-root (similar to asafœtida); cover them with vinegar; add dates; pour in garum, oil, and a small quantity of mustard-seeds; reduce all to a proper thickness with red wine warmed; and then pour this same over your chicken, which should previously be boiled in anise-seed water."

With regard to the olden wines, let us be duly grateful for the progress of viniculture, and thankful that we may read of them, rather than have to partake of them, to rue the Katzenjammer of the following morning. For if one must have a headache on rare occasions as the penalty of dining, it were assuredly less to be deplored if obtained through a grand vintage of the Marne or the Médoc than from a wine mixed with sea-water or spices, or old Falernian cloyed with honey from Mount Hymettus. By all means, if we must drink an excessively sweet wine, let it be, at most, a glass of Hermitage paille or Muscat Rivesaltes, iced to snow!

The tables, the plate, and the dinner-service corresponded with the rarity of the viands and beverages.[31] Cicero's table of lemon-wood cost him two hundred thousand sesterces, or over seven thousand dollars. Besides being made of the most precious foreign woods, veined and spotted to imitate the tiger's and the leopard's skin, they were also wrought of ivory, silver, bronze, and tortoise-shell.

The drinking-cups of gold and glass, the nimbus and ampulla—crystal chalices, ewers, and flagons in which the luxurious were wont to mix myrrh, spikenard, and other perfumes with their wine—were equally costly. Martial extols a jewelled cup: "See how the gold, begemmed with Scythian emeralds, glistens! How many fingers does it deprive of jewels!" His lovely description of an exquisitely chased wine-cup of gold, received from Instantius Rufus, will also be recalled. Again, he praises a gold dinner-service: "Do not dishonour such large gold dishes with an insignificant mullet; it ought at least to weigh two pounds." "I see," says Seneca, "the shell of the tortoise bought for immense sums and ornamented with the most elaborate care; I see tables and pieces of wood valued at the price of a senator's estate, which are all the more precious the more knots the tree has been twisted into by disease. I see murrhine-cups, for luxury would be too cheap if men did not drink to one another out of hollow gems the wine to be afterwards thrown up again." In vain Pompey the Great and Licinius Crassus strove to cheek the riotous table extravagance, which continued despite previous and subsequent sumptuary laws for its suppression.

"To-day," says Pliny, "a cook costs as much as a[32] triumph, a fish as much as a cook, and no mortal costs more than the slave who knows best how to ruin his master." Fabulous prices were paid for fish, notably for the famed red mullet or sea-barbel. Tiberius, who was an exception, and was not partial to this fish, on being presented with an unusually large specimen, weighing four and a half pounds, sent it to the market to be sold. "I will be greatly surprised," he observed, "if the mullet is not purchased by Apicius or Octavius." It was borne off in triumph by Octavius, who became celebrated for having paid two hundred dollars for a fish sold by the emperor and that Apicius himself had not secured.

Seneca also states that the mullet was looked upon as tainted unless it expired in the hands of the guests, who were provided with glass vessels in which to put their fish, in order the better to perceive their changes and motions in the last agony betwixt life and death. "Look how it reddens!" cries one; "there is no vermilion like it; look at those lateral veins, see how the grey brightens upon its head, and now it is at its last gasp, it pales and its inanimate body fades to a single hue." "The mullet of the ocean is certainly a meritorious fish," observes Baron Brisse, "but how greatly superior is that of the Mediterranean!"

This greatly valued fish was the European Mullus barbatus, one of the forty or more different species of the red mullet, found chiefly in the subtropical parts of the Indo-Pacific Ocean. By far the most abundant in the Mediterranean, it is nevertheless not uncommon to the coasts of England and Ireland, though nowhere does it attain so delicate a flavour as[33] in the Mediterranean. The name is said to have reference to the scarlet colour of the sandal or shoe worn by the Roman consuls, and in later times by the emperors, which was called mullus.

Like the ruby, the mullet increased rapidly in price when it exceeded the usual size—the largest weighing scarcely three or four pounds. Suetonius is authority for the statement that this fish was so esteemed in his time that three large specimens were sold for thirty thousand sesterces, or more than a thousand dollars, which caused Tiberius to enact sumptuary laws and tax the provisions brought to market. The red mullet, although much less highly thought of than in olden days, is still in request by the modern French epicure. Francatelli cautions that it should never be drawn; it is sufficient to remove the gills only, as the liver and trail are considered the best part—an opinion held by the Romans. It is possible that, owing to this circumstance, it has been termed the "sea-woodcock."

The mullet was served by the Romans with a seasoning of pepper, rue, onions, dates, and mustard, to which was added the flesh of the sea-hedgehog reduced to a pulp and oil. When the priceless liver alone was to be eaten by an emperor or a senator, it was cooked and then seasoned with pepper, salt, or a little garum, some oil was added, and hare's or fowl's liver, and oil poured over the whole.

The turbot was another favourite supplied by the sea, and one will remember Martial's panegyric concerning it: "However great the dish that holds the turbot, the turbot is still greater than the dish."[34] From the foam-fleeced flocks of Proteus many other fish with strange names were transferred by the wealthy Romans to their vast aquaria—the sargus, the harp-fish, the hyca, the synodon, the hespidus, the chromis, the callichithys,

The huge tunny and sturgeon, the tiny anchovy, and, in fact, nearly every denizen of the ocean appeared upon the Roman tables in some form. The dolphin was a sacred fish, and was left unmolested to pilot Triton's car. Even the polypus, sea-urchin, and cuttlefish were held in great esteem. The scaurus or char, a species unknown to us, and the murex, an edible purple mussel of which the finest flavoured came from Baiæ were highly prized. Fatted eels were considered a great delicacy, and among fresh-water species the tench, carp, and pike were the most employed. Piscis was the Phryne of the Roman feasts, and dolphins, whales, and mermaids appear to be the only species that were not consumed.

According to Juvenal, who relates the story at great length, the members of Domitian's cabinet were one day suddenly summoned to the Alban Villa, where they were obliged to remain in waiting while the emperor gave audience to a fisherman who had brought him an unusually large Rhombus, and when they were finally admitted they found they had nothing to debate about except whether the fish was to be minced or cooked in a special dish, there being none[35] of sufficient size in the imperial kitchens. After mature deliberation, a special receptacle was decided upon, when the audience was dismissed. The turbot was served with a sauce piquante.

Nor were the affluent nobles and business men far behind the triumvirs, consuls, and emperors in their ruinous manner of living. Autocracy set the pace, and her wealthy vassals were not slow to follow. Trimalchio, the moneyed landholder, was accustomed to serve a wild boar whole, with a number of live fieldfares inside, ready to fly out as soon as they were given their liberty by Carpus, his professional carver. These, as they fluttered about the room, were caught by fowlers with reeds tipped with bird-lime.

The minute account of one of Trimalchio's dinners, given by the licentious Latin classicist Petronius Arbiter, descriptive of the viands, beverages, service, and table customs of the day, may be advantageously consulted by those whose powers of digestion are strong enough to enable them to consider a representative feast during the reign of Nero at the home of this ostentatious host. The elaborate first course is described as terminating with the appearance of a servant bearing a silver skeleton so artfully constructed that its joints and backbone turned in all directions; when, having cast it several times upon the table and causing it to assume various postures, Trimalchio cried out, "Of such are we—let us live while we may!" The first course finished, the second was presented in the form of a large circular tray with the twelve signs of the zodiac surrounding it, upon each of which the arranger had placed an appropriate dish—on[36] Aries, ram's-head pies; on Taurus, a piece of roasted beef; on Gemini, kidneys and lamb's fry; on Cancer, a crown; on Leo, African figs; on Virgo, a young sow's haslet; on Libra, a pair of scales, in one of which were tarts, in the other cheese-cakes; on Scorpio, a little sea-fish of the same name; on Sagittarius, a hare; on Capricorn, a lobster; on Aquarius, a goose; on Piscis, two mullets, while in the centre spread a green turf on which lay a honeycomb. It will be readily apparent that the modern French chef does not stand alone in his skill of producing a pièce-montée. Meanwhile, an Egyptian slave carried bread in a silver portable oven, singing a song in praise of wine flavoured with laserpitium. Whereupon four attendants came dancing in to the sound of music, and, removing the upper part of the tray, there was revealed on a second tray beneath stuffed fowls, a sow's paps, and in the middle a hare fitted with wings to resemble Pegasus. At the several corners stood four figures of Marsyas spouting a highly seasoned sauce on a school of fish.

At the third course a very large hog was brought in, much larger even than the wild boar that had been previously served. This was followed by a young calf, boiled whole, with more wine, perfumes, fruits, and sweetmeats—thrushes in pastry, stuffed with nuts and raisins, and quinces stuck over with prickles to resemble sea-urchins. "Only command him," exclaimed the host, "and my cook will make you a fish out of a pig's chitterlings, a wood-pigeon out of the lard, a turtle-dove out of the gammon, and a hen out of the shoulder!"

Apparently, the artist of Trimalchio was no less fertile in resources and liberal ideas of expenditure than the chef of the Prince of Soubise, who, on being taken to task by his employer for including fifty hams for a single supper, replied:

"Only one will appear upon the table, monseigneur; the rest are not the less necessary for my espagnole, my blonds, my garnitures, my—"

"Bertrand, you are plundering me."

"Oh, monseigneur," replied the conjurer, "you do not understand our resources; say the word, and these fifty hams which confound you—I will put them all into a glass bottle no bigger than your thumb!"

To be sure, the accounts given by Petronius Arbiter, Juvenal, Martial, and other satirists must be taken with some limitation. Yet, making all due allowance for exaggeration, it is hardly to be wondered at that many of the olden rulers and opulent personages, armed with unbounded power and possessed of unlimited riches, should have yielded so abjectly to luxury and vice as to have fully warranted the stricture of Juvenal:

These accounts, moreover, attested as they are by serious annalists, may not be dismissed as largely imaginative or grossly exaggerated. The strictures on the besetting vices that occur in the contemporary works of historians, moralists, philosophers, and poets[38] are far too vehement and voluminous to leave any doubt of the inordinate abuse of the table among the ancients, particularly among the Romans, when their wealthy capital, as Propertius records, "was beset all round in its own victories." It was the period of insatiable voracity and the peacock's plume. Even Martial was careful to state that it was vices, not personages, to which his scourge was applied. His caustic and highly seasoned epigrams deal largely with the dinner-table, and from these one may derive a most realistic idea of the bill of fare of his contemporaries, as well as of the varied and luxurious character of the presents made to the guests at feasts. The excesses of eating and drinking are roundly denounced by him at every turn, while his picture of the crapulous Santra in the Seventh Book is only equalled by the "Portrait of a Gourmand" of Carle Vernet, or Spenser's etching of "Gluttony" in the "Faerie Queene."

Horace in particular, a scholar, poet, and man of the world, the friend of Mæcenas, and an onlooker and frequenter of society, may be accepted as a competent authority on the table manners and customs of the times. No one more than he was aware of the gross extravagance and intemperance of the age. Nor has any writer depicted his own and the everyday life of the Romans more vividly. To peruse him attentively in the "Satires," "Epistles," "Epodes," and "Odes," is to take part in the feasts, be admitted to the inner circle of the optimates, knock at the door of Lydia, and join in the pageant of the Sacra Via. The table of Mæcenas, the rich voluptuary and dilet[39]tante, who had a palace on the Esquiline Hill, where Horace was often a guest, was widely celebrated. As the poet was a visitor also at the palace of Augustus, and numbered among his friends the most eminent men of Rome, he had unusual opportunities to become acquainted both with the vie intime and haute cuisine of his day. While not a gastronomer, he was far from averse to good living, though, from his digestion not being of the soundest, he had frequent cause to rue the sumptuous banquets, borrowed from the Asiatic Greeks, which were in vogue at the time. And while he was a frequent attendant at the entertainments of the wealthy, we nevertheless find him constantly censuring their intemperance and extravagance at table. For himself, he would have "simple dinners, richly dressed," and "let the strong toil give relish to the feast." Rare old Cæcuban, Falernian, and Massic, Mæcenas might pour out at home from his well-filled amphoræ into chased crystal cups and vessels of gold—at the Sabine farm the common Sabine wine in modest goblets would alone be tendered him.

If we may regard the elaborate repast of Nasidienus as a typical one, we may readily conceive the nightmares that must have ensued from such a plenitude of viands and wines and such copious libations. The student of Horace will remember the menu. First a Lucanian boar, surrounded by excitants to the appetite—

Fish and wild fowl, lampreys and shrimps, succeeded, washed down with brimmers of Cæcuban, Alban, Falernian, and vintages of Greece; and finally, as the feast and the night wore on,

That Nasidienus was proverbially penurious, was guilty of purchasing tainted game in order to save expense, and would have been chary of his wines had it not been for Servilius, who cried loudly for "larger goblets," leads one to conclude that even his repast was far below those of the pampered upper classes in its prodigality.

Apicius, who is referred to by Pliny, Seneca, Juvenal, and Martial, is said to have squandered nearly four million dollars in riotous living, when, looking over his accounts, he found he had only about a tenth of that amount remaining, and, unwilling to starve[41] on such a pittance, he poisoned himself. Of the three persons bearing the name of Apicius, one of whom lived in the times of Sulla, another during the reign of Tiberius, and the third under Trajan, none is supposed to be the author of "De re Culinaria," since published in so many different editions, a work now ascribed to Cœlius, who, in admiration of the renowned Marcus Gabius, termed himself Apicius. The latter, the richest of the three who bore the name by right, vied with royalty in his regal tastes. He is reported as having voyaged to Africa expressly to ascertain whether the crawfish there were superior to those he was accustomed to have at Minturnæ; but finding them inferior, he returned immediately, without setting foot to land. "Look at Nomentanus and Apicius," says Seneca, "who digest all the good things, as they call them, of the sea and the land, and review upon their tables the whole animal kingdom. Look at them as they lie on beds of roses, gloating over their banquet and delighting their ears with music, their eyes with exhibitions, their palates with flavours."

Where the deliciously scented cyclamen carpets the shore of the Mediterranean in myriads at Baiæ, Apicius repaired to savour shell-fish—"the manna of the sea"—and from the self-same sea that laves the isle of Capri and rolls its azure wave into the famed blue grotto, Tiberius sent turbots to him that Apicius was not rich enough to buy himself.

Yet far exceeding Apicius, who was almost deified for discovering how to maintain oysters fresh and alive during long journeys, was his predecessor Lu[42]cullus, the wealthy general, a great patron of learning and the arts, as well as the king of epicures. Juvenal has etched his portrait in four lines:

The Monte Cristo of Naples, he pierced a mountain to place two of his country villas in closer communication and to conduct the sea-water to one of them, where he had constructed a huge aquarium for sea-fish. His carvers were paid at the rate of four thousand a year. The various dining-rooms at his Neapolitan palace were designed according to the costliness of the repasts which were given in them, the saloon of Apollo being the most sumptuous. Cicero and Pompey, resolving one day to surprise him, presented themselves unceremoniously, and, upon being pressed to remain to dinner, assented on condition that he would go to no extra trouble. Summoning his major-domo, he dismissed him with the simple command:

"Place two more covers in the saloon of Apollo"—the cost of the dinner in this apartment being fixed at a thousand dollars per plate.

No review of the Roman table, however brief, would be complete without retelling the story of Lucullus as his own host. On this occasion, when, through some misunderstanding, he was without guests for dinner, his cook appeared as usual to receive his orders.

"I am alone," said Lucullus; whereupon his servitor, thinking that a five-hundred-dollar dinner would suffice, acted accordingly. At the conclusion of his repast, his face flushed with the juices of Falernian, Lucullus sent for his minister of the interior and took him severely to task. There were no fig-peckers, and the prized spawn of the sea-lamprey was missing. The cook was profuse in his apologies.

"But, seigneur, you were alone—"

"It is precisely when I happen to be alone that you require to pay especial attention to the dinner; at such times you must remember that Lucullus dines with Lucullus."

The great dining-room of Claudius, termed "Mercury," was constructed on an equally magnificent scale. But this was eclipsed by Nero's marvellous Domus aurea, which, through a circular movement of its sides and ceiling, counterfeited the changes of the skies and represented the different seasons of the year, while at intervals during the repast flowers and essences were showered down upon the guests.

The gluttonous feasts of Verres, Claudius, Nero, Vitellius, Domitian, and the rest of the Roman potentates are familiar to the student of ancient history. Claudius, who had usually six hundred guests at his feasts, died of an indigestion of mushrooms, facilitated, it is said, by a poisoned feather applied to his throat. Tiberius is also said to have met his death through an asphyxia of poisonous mushrooms, seconded by suffocation on the part of his favourite Macro, who in turn was put to death by Caligula. Caligula was noted for the fabulous sums spent upon[44] his suppers, while Cæsar is credited with a four months' supper bill of more than five millions sterling. The present of this monarch, during one of his table debauches, of a sum equivalent to eighty thousand dollars to his charioteer Eutychus is the largest table present recorded of the Romans. Seneca states that one of his suppers cost nearly half a million, and he also it was who gave his charger Incitatus barley mixed with wine in a vase of gold. Vitellius spent not less than fifteen thousand dollars for each of his repasts, the composition of his favourite dishes requiring that vessels should constantly ply between the Gulf of Venice and the Straits of Cadiz. The flocks of flamingos placidly feeding in the Pontine marshes dreaded his fowlers—he had dishes made of their tongues. Later on, their haunts were invaded by Heliogabalus, who preferred their brains.[7] The life and reign of Vitellius were a continuous orgy, and his name was bequeathed to a multitude of dishes. According to Suetonius, Tiberius, who was inordinately fond of fig-peckers and mushrooms, presented Sabinus the author with eight thousand dollars for having composed a dialogue in which the fig-pecker, mushroom, oyster, and thrush were the dramatis personæ. As the author and the poet are proverbially scantily remunerated, it is easy to imagine the wealth that a competent chef could command in the days when the haughty mistress of the world, sated with conquest and exultant with victory, lapsed into luxury and sensuality, while a constant stream of riches[45] flowed into her treasury from tributary rulers and oppressed and spoliated nations.

The truffle and the snail were well known to the ancients. The speckled trout, of which there appears to be no mention by the recorders, seems to have been a neglected dainty. How Lucullus would have rejoiced at the sight of the pompano—that ruby of the salt-sea wave—and Apicius have been transported at the apparition of a puff-paste pâté of oyster-crabs! The brilliant iridescent hues of the rainbow-trout would have held a Roman epicure spellbound, while a dish of terrapin or a celery-fed Chesapeake canvasback might have decided the destinies of an empire. What a burst of applause a platter of roast ruffed-grouse would have commanded from a senate! Were the soft-shell crab a denizen of Baiæ, or the whitefish, as he attains supreme perfection in Lake Ontario, a habitant of an Italian tarn, one can fancy how a feast of Heliogabalus would have been prolonged. That there are still as good fish in the sea as ever were caught seems an anomaly, in view of the voracity of the old Latins for this form of food.

History has recorded less of the excesses of the table during the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus, and even during the dissolute monarchies of Commodus and Caracalla. It would be wrong, however, to assume that these excesses were renounced, even where the rulers did not themselves set the example, or that they did not continue in a flagrant form. The unbridled lust and gluttony of Commodus were scarcely equalled save by Heliogabalus. Septimius Severus, unable to en[46]dure the tortures he experienced in all his members, especially in his feet, in place of the poison that was refused him eagerly devoured a quantity of rich viands and died of indigestion. Gout and kindred maladies were notoriously common with both men and women, and upon this subject Seneca has descanted at length: "Is it necessary to enumerate the multitude of maladies that are the punishment of our luxury? The multiplicity of viands has produced a multiplicity of maladies. The greatest of physicians, the founder of medicine, has said that women do not become bald or subject to gout. Now they are both bald and gouty. Woman has not changed since in her nature, but in her mode of life, and, imitating man in his excesses, she shares his infirmities. Where is the lake, the sea, the forest, the spot of land that is not ransacked to gratify our palates? Our infirmities are the price of the pleasures to which we have abandoned ourselves beyond all measure and restraint. Are you astounded at the innumerable diseases?—count the number of our cooks!"

The favourite garum of the old Romans of itself were enough to have invited all the diseases that indigestion is heir to. This was a liquid, and was thus prepared: The insides of large fish and a variety of smaller fish were placed in a vessel and well salted, and then exposed to the sun till they became putrid. In a short time a liquor was produced, which, being strained off, was the garum or liquamen.

With the advent of Heliogabalus upon the throne, gluttony and extravagance reigned supreme. By this youthful monarch, during his brief reign of four[47] years, the tyranny of Nero, and Caligula, the lust of Claudius and Commodus, the prodigality of Vitellius, the saturnalia and riotous living of Verres and Domitian were trebly exceeded. Entering Rome from Syria in a chariot drawn by naked women, surrounded with eunuchs, courtesans, and buffoons, wearing the tiara of the priests of the sun-god, dressed as a female in stuffs of silk and gold, and accompanied by a historiographer whose sole function it was to describe his orgies, he at once eclipsed all his predecessors. The Sardanapalus of Rome, his daily feasts are said to have consisted of over twoscore courses, and to have cost not less than ten thousand dollars each.

As related by Lampridius, his table-couches were stuffed with hares' down or partridges' feathers, his beds adorned with coverlets of gold, and in his kitchens none but richly chased utensils of silver were employed. The invention of a new sauce was royally rewarded by him, but if it was not relished the inventor was confined, to partake of nothing else until he had produced another more agreeable to the imperial palate. The liver of the priceless mullet seeming too paltry to Heliogabalus, he was served with large dishes completely filled with the gills. He brought the soft roe of the rare sea-eel into disrepute by maintaining a fleet of fishing craft for their capture, and ordering that the peasants of the Mediterranean should be gorged with them. Resides countless dishes, each of which was worth the price of a king's ransom, he was the inventor of coloured decorations at table. "In the summer," says Lampridius, "Helio[48]gabalus gave feasts at which the service was composed of different colours, constantly varied throughout the season." The brains of partridges and ostriches were among his favourite dainties. Frequently the brains of six hundred ostriches were served at a single repast, as well as the heads of innumerable parrots, pheasants, and peacocks. He had cockscombs served in pâtés, and was therefore the inventor of vol au vent à la financière. The tongues of nightingales and thrushes he had likewise served in pâtés, and hearing that a strange bird, the phœnix, existed in Lydia, he offered two hundred pieces of gold to him who would procure it. In the course of his reign of four years he had depleted the treasury of an empire largely through gluttony, and died, anticipating the assassination of his soldiers, by his own hand.

It were superfluous to follow the subject to the decadence of the Empire, when, with wars and contentions and invasions of conquering hordes, came the decline of cookery, literature, and the arts. Nor does history record a resumption of gastronomy until towards the Renaissance—when Dante and Petrarch had touched their lyres, and Donatello and Robbia wrought their bassi-rilievi; when the Medici and the Este became the patrons of art; when Leonardo, Raffaello, Titian, and Guido stamped their genius upon the canvas; when Michelangelo created his "David," and Cellini his "Perseus"; when Giorgio fashioned his gorgeous lustres, and Orazio his glorious vasques.

Or, rather, with the revival of cookery we find the revival of literature and the arts, and mark the Muses resume their sway.

LE LIVRE DE TAILLEVENT

Facsimile of the title-page of the edition of 1545

"Le malheur de toutes les cuisines excepté de la cuisine française, c'est d'avoir l'air d'une cuisine de hasard. La cuisine française est seule raisonnée, savante, chimique."—Alexandre Dumas: Le Caucase.

It is not unnatural that cookery as an art should finally have been resumed in the land where it had once attained its greatest development. First among Italian treatises on the subject was the volume of Bartolomeo Platina, "De Honesta Voluptate et Valitudine," which was written in Latin and printed at Venice in 1474, a year or two after the introduction of printing into that city. Many editions of this appeared subsequently, as also translations in French and German. Other Italian treatises of the sixteenth century were Rosselli's "Opera Nova chiamata Epulario" (Venice, 1516); a work by Christoforo di Messisbugo, chef to the Cardinal of Ferrara[50] (Ferrara, 1549); a manual by Bartolomeo Scappi, privy cook to Pope Pius V (Venice, 1570); and works by Vincenzo Cervio, Domenico Romoli, and Gio. Battista Rossetti—Cervio and Romoli having been respectively carver and cook to Cardinal Farnese. The two most important Italian culinary publications of the seventeenth century were those of Vittorio Lancioletti (Rome, 1627) and Antonio Frugoli (Rome, 1632). In addition to these was the old Roman treatise "De re Culinaria" of Cœlius Apicius, published in 1498, as well as many works relating to wines and the hygiene of gastronomy.

Glancing for a moment across the Mediterranean, from Italy to Spain, we find record of but one Spanish cook-book of any note during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries—that of Ruberto de Nola (Toledo, 1525). While Spanish cookery is far from meriting a place among the fine arts, one must yet thank Spain for at least two things—the dulcet Spanish onion and the poignant Spanish omelette—as one should be grateful to Mexico for the tamale and to Russia for its caviare. But the Spaniard boils his partridge (perdrix à l'Espagnol), as the Hollander boils his chicken, with rice or vermicelli. The Spanish "olla podrida"—the Alhambra of the national cuisine, wherein garlic, onion, and red peppers are by no means forgotten—is well known to all travellers beyond the Pyrenees; but, on account of the many native ingredients it contains, it is difficult to be obtained in perfection outside its original country. Its best form is the olla en grande, which requires two pots to brew it in—the rich olla that Don Quixote[51] says is eaten only by canons and presidents of colleges. With virgin oil and a pianissimo touch, so far as the garlic is concerned, the aristocratic guisado is both an excellent and accommodating dish, inasmuch as a fowl, pheasant, rabbit, or hare may serve as its base; and for those who wish to try a dish with a Spanish name, prepared somewhat on the order of the French civet of hare, the recipe may be given: "Dress and prepare a fowl, pheasant, rabbit, or hare—whichever is most easily obtainable—taking care to preserve the liver, giblets, and blood. Cut it up in pieces and dry, without washing, on a cloth. Brown a few slices of onion in a gill of boiling fat, turn them with the pieces of meat into an earthenware pan, add a seasoning of herbs, garlic, onions, a few chillies, salt and pepper, put in also a few slices of bacon, and pour over all sufficient red wine and rich stock in equal proportions to moisten. Place the pan over the fire and bring the liquor slowly to the boiling-point, skim and stir frequently, and let it simmer until the meat is quite tender. About half an hour before serving, put in the liver, giblets, and blood. When ready, turn the whole into a hot dish and serve quickly."