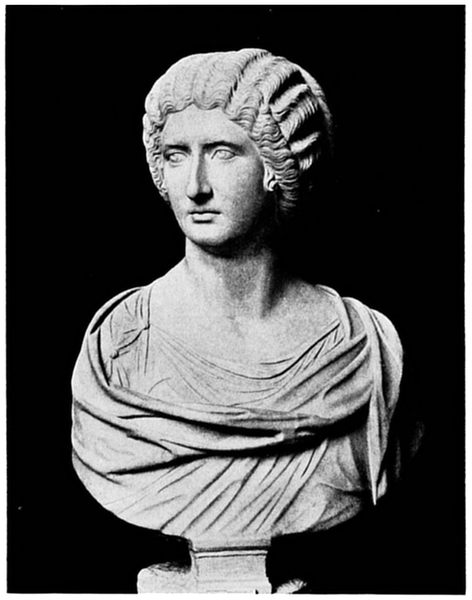

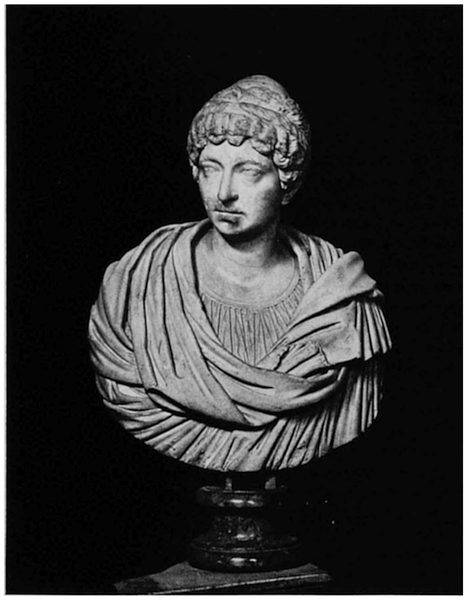

CRISPINA

BUST IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM

Title: The Empresses of Rome

Author: Joseph McCabe

Release date: December 15, 2019 [eBook #60933]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Empresses of Rome, by Joseph McCabe

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924028299075 |

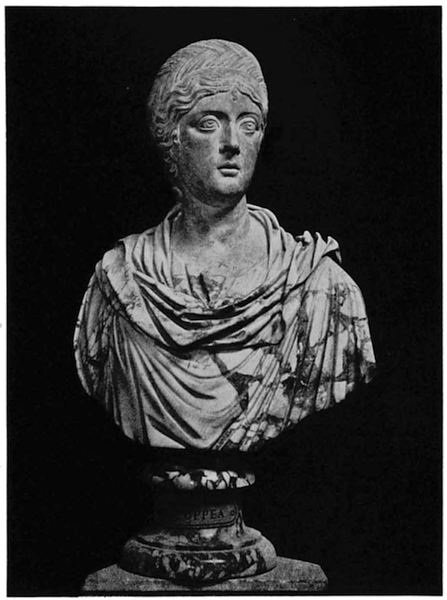

CRISPINA

BUST IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM

THE

EMPRESSES OF ROME

BY

JOSEPH McCABE

AUTHOR OF “THE DECAY OF THE CHURCH OF ROME”

WITH TWENTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1911

v

The period embraced by this work extends to the fall of the Western Empire, or to the middle of the fifth century. It was felt that a more extensive range would involve either an inconveniently large work or an inadequate treatment. While, therefore, the Empresses of the East have been included down to the fall of Rome, it seemed that the collapse of the Empire in Rome and the West indicated a quite natural term for the present study. The restriction has enabled the author to tell all that is known of the Empresses of Rome within that period, to enlarge the interest of the study by framing the Imperial characters in occasional sketches of their surroundings, and to weave the threads of biography into a continuous story.

vii

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 1 | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | THE MAKING OF AN EMPRESS | 7 |

| II. | THE END OF THE GOLDEN AGE | 23 |

| III. | THE WIVES OF CALIGULA | 46 |

| IV. | VALERIA MESSALINA | 60 |

| V. | THE MOTHER OF NERO | 79 |

| VI. | THE WIVES OF NERO | 105 |

| VII. | THE EMPRESSES OF THE TRANSITION | 122 |

| VIII. | PLOTINA | 136 |

| IX. | SABINA, THE WIFE OF HADRIAN | 149 |

| X. | THE WIVES OF THE STOICS | 163 |

| XI. | THE WIVES OF THE SYBARITES | 179 |

| XII. | JULIA DOMNA | 194 |

| XIII. | IN THE DAYS OF ELAGABALUS | 210 |

| XIV. | ANOTHER SYRIAN EMPRESS | 222 |

| XV. | ZENOBIA AND VICTORIA | 233 |

| XVI. | THE WIFE AND DAUGHTER OF DIOCLETIAN | 250viii |

| XVII. | THE FIRST CHRISTIAN EMPRESSES | 265 |

| XVIII. | THE WIVES OF CONSTANTIUS AND JULIAN | 286 |

| XIX. | JUSTINA | 306 |

| XX. | THE ROMANCE OF EUDOXIA AND EUDOCIA | 322 |

| XXI. | THE LAST EMPRESSES OF THE WEST | 340 |

| INDEX | 351 | |

ix

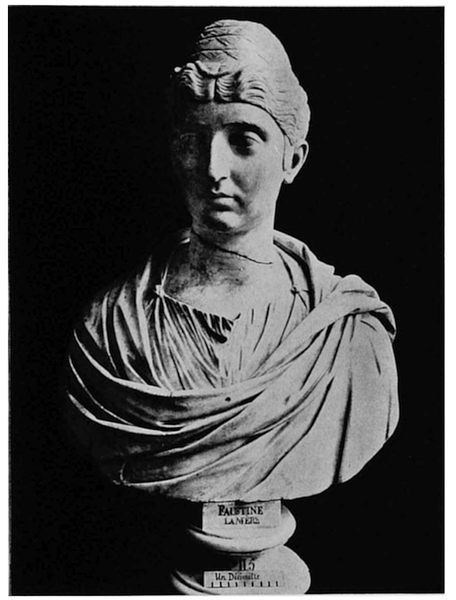

| Crispina. Bust in the British Museum From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

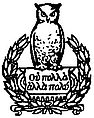

| Livia as Ceres. Statue in the Louvre | 20 | |

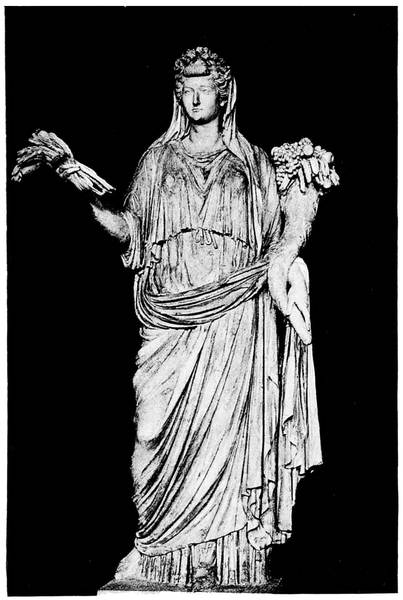

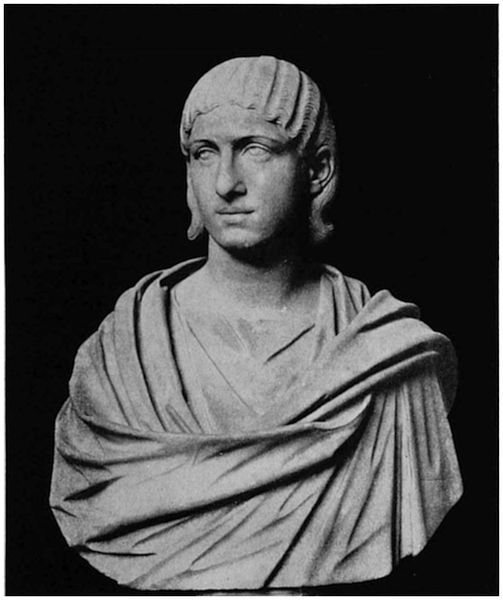

| Julia. Bust in the Museum Chiaramonti | 28 | |

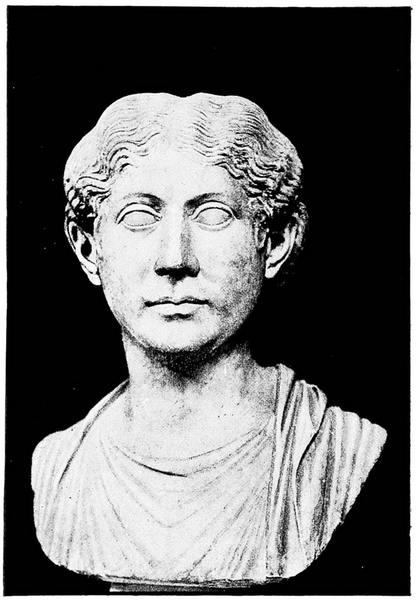

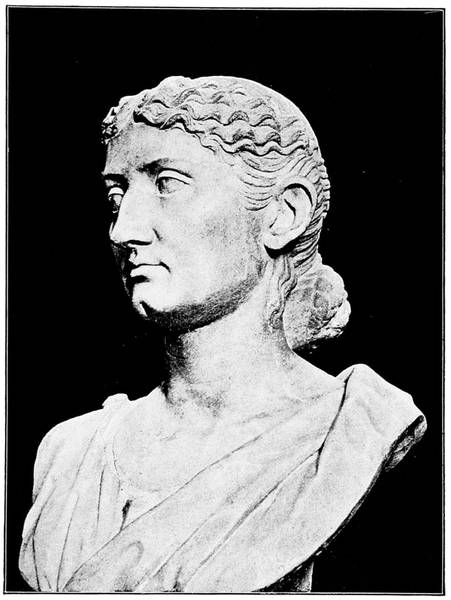

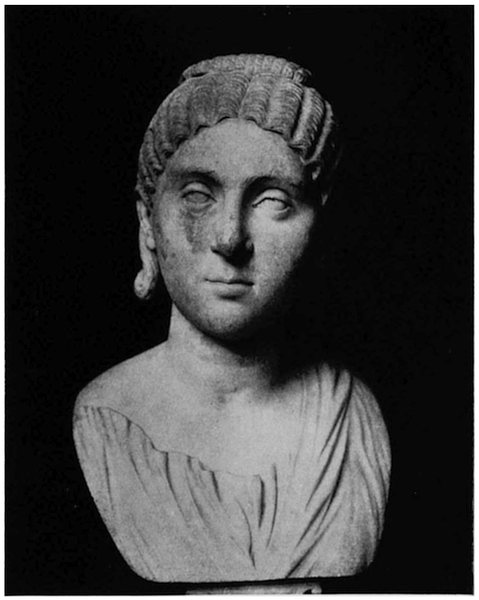

| Agrippina the Elder. Bust in the Museum Chiaramonti | 46 | |

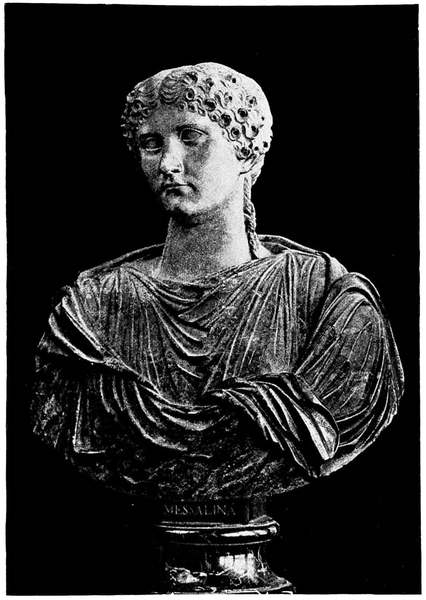

| Messalina. Bust in the Uffizi Palace, Florence | 70 | |

| Agrippina the Younger. Bust in Museo Nazionale, Florence | 82 | |

| Octavia. Porphyry Bust in the Louvre | 112 | |

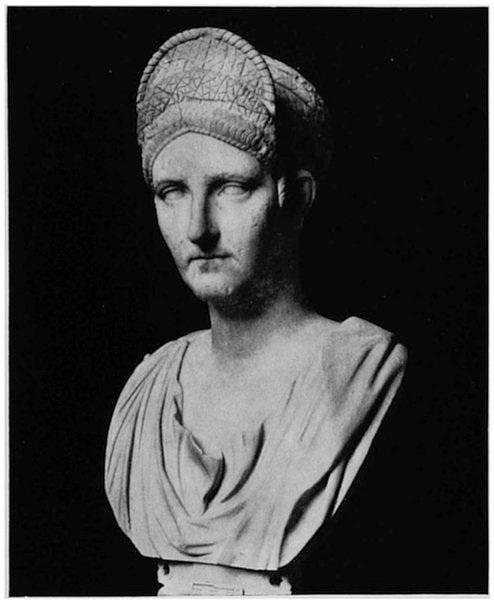

| Poppæa. Bust in the Capitoline Museum, Rome From a photograph by Anderson. |

118 | |

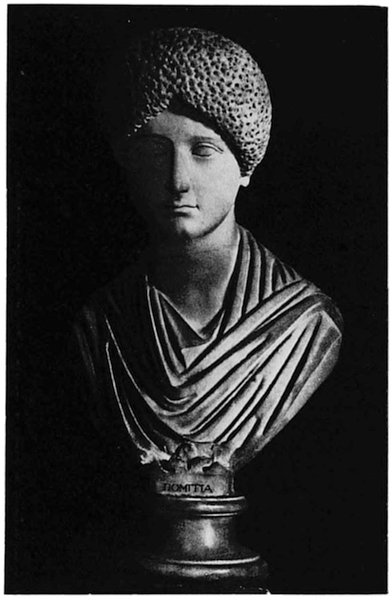

| Domitia. Bust in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence | 130 | |

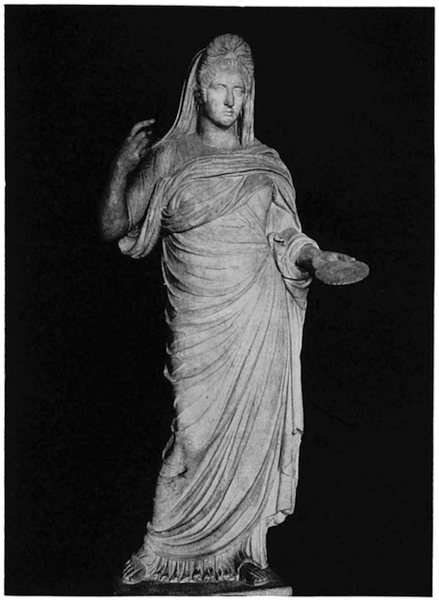

| Plotina. Statue in the Louvre From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

142 | |

| Sabina. Bust in the British Museum From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

154 | |

| Faustina the Elder. Bust in the Louvre From a photograph by A. Giraudon. |

164 | |

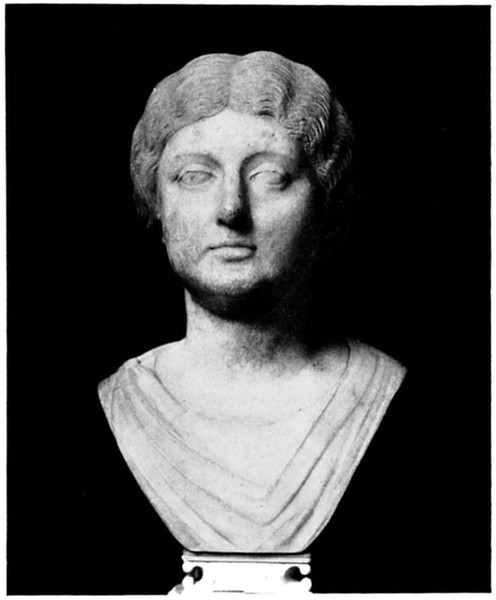

| Faustina the Younger. Bust (reputed) in the British Museum From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

172 | |

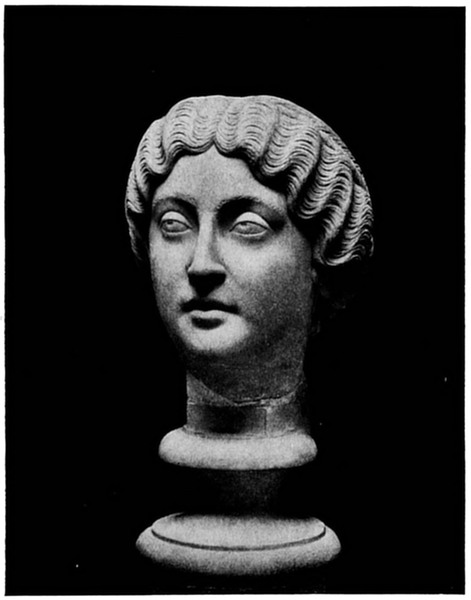

| Lucilla. Bust in the National Museum, Rome From a photograph by Anderson. |

184 | |

| Julia Domna. Bust in the Vatican Museum From a photograph by Anderson. |

202 | |

| Julia Mæsa. Bust in the Capitoline Museum, Rome From a photograph by Anderson. |

214 | |

| Julia Mamæa. Bust in the British Museum From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

226 | |

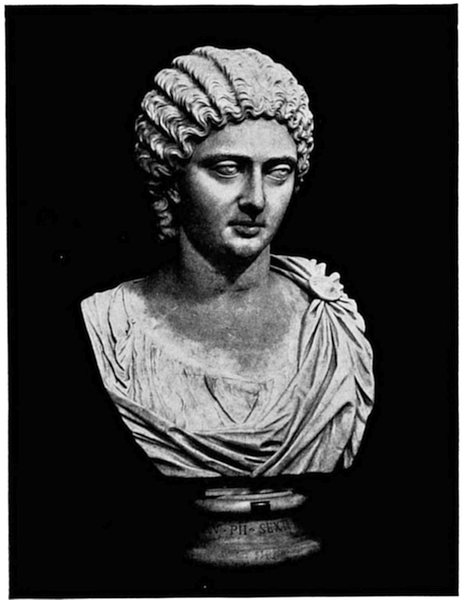

| Marcia Otacilia Severa From a photograph by W. A. Mansell & Co. |

236x | |

| Zenobia Enlarged from coin in the Berlin Museum. |

248 | |

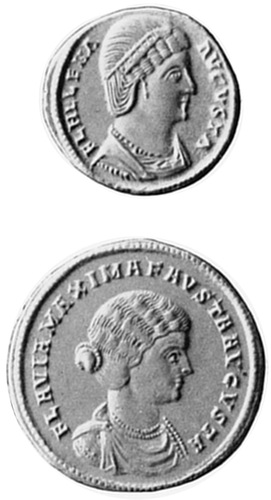

| Salonina and Valeria Enlarged from coins in the British Museum. |

262 | |

| Fausta and Flavia Helena Enlarged from coins in the British Museum. |

280 | |

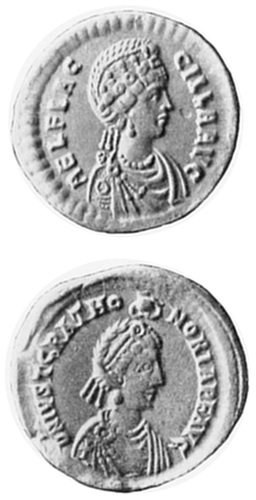

| Ælia Flaccilla and Honoria Enlarged from coins in the British Museum. |

316 | |

| Eudoxia and Pulcheria Enlarged from coins in the British Museum. |

330 | |

| Placidia and Euphemia Enlarged from coins in the British Museum. |

342 | |

1

The story of Imperial Rome has been told frequently and impressively in our literature, and few chapters in the long chronicle of man’s deeds and failures have a more dramatic quality. Seven centuries before our era opens, when the greater part of Europe is still hidden under virgin forests or repellent swamps, and the decaying civilizations of the East cast, as they die, their seed upon the soil of Greece, we see, in the grey mist of the legendary period, a meagre people settling on one of the seven hills by the Tiber. As it grows its enemies are driven back, and it spreads confidently over the neighbouring hills and down the connecting valleys. It gradually extends its rule over other Italian peoples, bracing its arm and improving its art in the long struggle. It grows conscious of its larger power, and sends its legions eastward, over the blue sea, to gather the wealth and culture of Egypt, Assyria, Persia, and Greece; and westward and northward, over the white Alps, to sow the seed in Germany, Gaul, Britain, and Spain. A hundred years before the opening of the present era the tiny settlement on the Palatine has become the mistress of the world. Its eagles cross the waters of the Danube and the Rhine, and glitter in the sun of Asia and Africa. But, with the wealth of the dying East, it has inherited the germs of a deadly malady. Rome, the heart of the giant frame, loses its vigour. The strong2 bronze limbs look pale and thin; the clear cold brain is overcast with the fumes of wine and heated with the thrills of sense; and Rome passes, decrepit and dishonoured, from the stage on which it has played so useful and fateful a part.

The fresh aspect of this familiar story which I propose to consider is the study of the women who moulded or marred the succeeding Emperors in their failure to arrest, if not their guilt in accelerating, the progress of Rome’s disease. Woman had her part in the making, as well as the unmaking, of Rome. In the earlier days, when her work was confined within the walls of the home, no consul ever guided the momentous fortune of Rome, no soldier ever bore its eagles to the bounds of the world, but some woman had taught his lips to frame the syllables of his national creed. However, long before the commencement of our era, the thought and the power of the Roman woman went out into the larger world of public life; and when the Empire is founded, when the control of the State’s mighty resources is entrusted to the hands of a single ruler, the wife of the monarch may share his power, and assuredly shares his interest for us. Even as mere women of Rome, as single figures and types rising to the luminous height of the throne out of the dark and indistinguishable crowd, they deserve to be passed in review.

Some such review we have, no doubt, in the two great works which spread the panorama of Imperial Rome before the eyes of English readers. In the graceful and restrained chapters of Merivale we find the earlier Empresses delineated with no less charm than learning. In the more genial and voluptuous narrative of Gibbon we may, at intervals, follow the fortunes and appreciate the character of the later Empresses. But, no matter how nice a skill in grouping the historian may have, his stage is too crowded either for us to pick out the single character with proper distinctness, or for him to appraise it with entire accuracy. The fleeting glimpses of the Empresses which we catch, as the splendid panorama passes before us, must3 be blended in a fuller and steadier picture. The tramp and shock of armies, the wiles of statesmen, the social revolutions, which absorb the historian, must fall into the background, that the single figure may be seen in full contour. When this is done it will be found that there are many judgments on the Empresses, both in Merivale and Gibbon, which the biographer will venture to question.

For the study of the earlier Empresses the English reader will find much aid in Mr. Baring-Gould’s “Tragedy of the Cæsars” (1892). Here again, however, though the Empresses are drawn with discriminating freshness and full knowledge, they are constantly merging in the great crowd of characters. The aim of the present work is to place them in the full foreground, and to continue the survey far beyond the limits of Mr. Baring-Gould’s work. It differs also in this latter respect from Stahr’s brilliant “Kaiser-Frauen,” which is, in fact, now almost unobtainable; and especially from V. Silvagni’s recent work, of unhappy title, “L’Impero e le Donne dei Cesari,” which merely includes slight and familiar sketches of four Empresses in a general study of the period.

The work differs in quite another way from the learned and entertaining book of the old French writer Roergas de Serviez, of which an early English translation has recently been republished under the title “The Roman Empresses, or the History of the Lives and Secret Intrigues of the Wives of the Twelve Cæsars”—an improper title, because the work is far from confined to the wives of the Cæsars. The work is an industrious compilation of original references to the Empresses, interwoven with considerable art, so as to construct harmonious pictures, and adorned with much charm and piquancy of phrase, if some hollowness of sentiment. But it is so intent upon entertaining us that it frequently sacrifices accuracy to that admirable aim. Serviez has not invented any substantial episode, but he has encircled the facts with the most charming imaginative haloes, and where the authorities differ, as they frequently do, he has not hesitated to grant his verdict to the writer4 who most picturesquely impeaches the virtue of one of his Empresses. Roergas de Serviez was a gentleman of Languedoc in the days of the “grand monarque.” His Empresses and princesses reflect too faithfully the frail character of the ladies at the Court of Louis XIV. For him the most reliable writer is the one who betrays least inclination to seek virtue in courtly ladies.

It need hardly be said that the present writer is indebted to these authors, to the learned Tillemont, and to others who will be named in the course of the work. But this study is based on a careful examination of all the references to the Empresses in the Latin and Greek authorities, with such further aid as is afforded by coins, statues, inscriptions, and the incidental research of commentators. We shall consider, as we proceed, the varying authority of these writers. We shall find in them defects which impose a heavy responsibility on the writer whose aim it is to restore those faded and delicate portraits of the Empresses, over which later artists have spread their sharper and more crudely coloured figures. One may, however, say at once that it is not contemplated to urge any very revolutionary change in the current estimate of the character of most of them. If a few romantic adventures must be honestly discarded, we shall find Messalina still flaunting her vices in the palace, Agrippina still pursuing her more masculine ambition, Poppæa still representing the gaily-decked puppet of that luxurious world, and Zenobia, in glittering helmet, still giving resonant commands to her troops.

But it will be well, before we introduce the first, and one of the best and greatest of the Empresses, to glance at the development of Roman life which prepared the way for woman to so exalted a dignity. The condition of woman in early Rome has often been restored. We see the female infant, her fate trembling in the hand of man from the moment when her eyes open to the light, brought before the despotic father for the decision of her fate. With a glance at the little white frame he will say whether5 she shall be cast out, to be gathered by the merchants in human flesh, or suffered to breed the next generation of citizens. We follow her through her guarded girlhood, as she learns to spin and weave, and see her passing from the tyranny of father to the tyranny of husband at an age when the modern girl has hardly begun to glance nervously at marriage as a remote and mystic experience. We then find her, not indeed so narrowly confined as her Greek sister, yet little more than the servant of her husband. Public feeling, it is true, mitigated the harsher features, and forbade the graver consequences, of this ancient tradition. For many centuries divorce was unknown at Rome. Yet woman’s horizon was limited to her home, while her husband boasted of his share in controlling the Commonwealth’s increasing life.

In the second century before Christ we find symptoms of revolt. The wealthier women of Rome resent the curtailing of their finery by the Oppian Law, now that the war is over (195 B.C.). Old-fashioned Senators are dismayed to find them holding a public meeting, besetting all the approaches to the Senate, demanding their votes, and even invading the houses of the Tribunes and coercing them to withdraw their opposition. The truth is that Rome has changed, and the women feel the pervading change. The passage of the victorious Roman through the cities of the East had corrupted the patriarchal virtues. Roman officers could not gaze unmoved on the surviving memorials of the culture of Athens, or make festival in the drowsy chambers of Corinthian courtesans or the licentious groves of Daphne, without altering their ideal of life. The splendour of Eastern wisdom and vice made pale the old standard of Roman virtus. The vast wealth extorted from the subdued provinces swelled the pride of patrician families until they disdainfully burst the narrow walls of their fathers’ homes. The hills of Rome began to shine with marble mansions, framed in shady and spacious gardens, from which contemptuous patrician eyes looked down on the sordid and idle crowds in the valleys of the6 Subura and the Velabrum. Rome aspired to have its art and its letters.

Roman women were not content to be secluded from the new culture, and could not escape the stimulation of their new world. The Roman husband must be kept away from the accomplished courtesans of Greece and the voluptuous sirens of Asia by finding no lesser attractions in his wife. So the near horizon of woman’s mind rolled outward. An inscription found at Lanuvium, where the Empress Livia had a villa, shows that the little provincial town had a curia mulierum, a women’s debating club. The walls of Pompeii, when the shroud of lava had been removed from its scorched face, bore election-addresses signed by women. The world was mirrored in Rome, and few minds could retain their primitive simplicity as they contemplated that seductive picture.

By the beginning of the first century of the older era the women of Rome had ample opportunity for culture and for political influence. In the great conflicts of the time their names are chronicled as the inspirers of many of the chief actors. They rise and fall with the cause of the Senate or the cause of the People. They unite culture with character, public interest with beauty and motherhood. At last the conflicting parties disappear one by one, and a young commander, Octavian, the great-nephew of Julius Cæsar, gathers up the power they relinquish. A youth of delicate and singularly graceful features, of refined and thoughtful, rather than assertive, appearance, he hears that Cæsar has made him heir to his wealth and his opportunities; he goes boldly to Rome, adroitly uses its forces to destroy those who had slain Cæsar, forces Mark Antony to share the rule of the world with him and Lepidus, and then destroys Lepidus and Mark Antony. It is at this point, when he returns to Rome from his last victories, when the whole world wonders whether he will keep the power he has gathered or meekly place it in the hands of the Senate, that the story opens.

7

On an August morning of the year 29 B.C. the million citizens of Rome lined the route which was taken by triumphal processions, to greet the man who brought them the unfamiliar blessing of peace. From the Triumphal Gate to the Capitol, past the Great Circus and through the dense quarter of the Velabrum, with its narrow streets and high tenements, the chattering crowd was drawn out in two restless lines, on either side of the road, ready to fling back the resonant “Io Triumphe” of the bronzed soldiers, bubbling with discussion of the war-blackened stretch of the past and the more pleasant prospect of the future. The hedges of spectators were thicker, and the debate was livelier, under the cliff of the Palatine Hill and in the Forum, through which ran the Sacred Way to the white Temple of Jupiter, towering above them and crowning the Capitol at the end of the Forum. There the conqueror would offer sacrifice, before he sank back into the common rank of citizens of the Republic. Would the young Octavian really lay down his power, and become a citizen among many, now that he was master of the Roman world?

Possibly one woman, who looked out on the seething Forum and the glistening temple of Jupiter from a modest mansion on the Palatine Hill, knew the answer to the eager question. Possibly it was unknown to Octavian himself, her husband. She heard the blasts of the leading trumpeters, and saw the sleek white oxen,8 with their gilded horns and their green garlands, advance along the Sacred Way and mount the Capitol. She saw the people rock and quiver with excitement as painted scenes of the remote Dalmatian forests, where her husband’s latest victories had been won, and the gold and silver of despoiled Egypt, and the very children of the witch Cleopatra, were driven before the conqueror. She saw the red-robed lictors slowly pass, their fasces wreathed in laurel; she saw the band of dancers and musicians tossing joyful music in his path; and she saw at last the four white horses drawing a triumphal chariot, in which her husband and her two children received the frenzied ovation of the people.

Octavian was then in his thirty-fourth year. Fifteen years of struggle had drawn a manly gravity over the handsome boyish face, though the curly golden hair still seemed a strange bed for the chaplet of laurel that crowned it. His full impassive lips, steady watchful eyes, and broad smooth forehead gave a singular impression of detachment—as if he were a disinterested spectator of the day’s events and the whole national drama, instead of being the central figure. The busts which portray him about this period seem to me, in profile, to recall David’s Napoleon, without the slumbering fire and the hard egoism. Men would remind each other how, when he was a mere boy, fifteen years before, he had found his way through a maze of intrigue with remarkable dexterity. Now, Mark Antony was dead, Brutus and Cassius were dead, Lepidus was dead, and the followers of Pompey were scattered. It was natural to assume that dreams of further power were hidden behind that mask of strong repose.

Behind Octavian went the body of Senators, with purple-striped togas, and silver crescents on their sandals. The lines of spectators broke into gossiping groups when the tail of the procession had passed on. The white oxen fell before the altar of Jupiter. Octavian gave the customary address to the Senate, and joined Livia in the small9 mansion on the Palatine. But for many a day afterward Rome bubbled in praise of him. Not for years had such combats reddened the sands of the amphitheatre, such clowns and conjurors and actors filled the stage of the theatre, such sports fired the 300,000 citizens at the circus. Never before had the uncouth form of the rhinoceros or hippopotamus been seen at Rome. Not since the beginning of the civil wars had so much money flowed through the shops of the Velabrum and the taverns of the Subura. Such wealth had been added to the public store by the despoiling of Egypt that the bankers had to reduce the rate of interest. To a people grown parasitic the temptation to make a king was overpowering; and it was easy to point out, to those who clung to the strict democratic forms, that Octavian was extraordinarily modest for a man who had reached so brilliant and resourceful a position. So within a few months Octavian was Imperator, and Livia became, in modern phrase, the Empress of Rome.1

Livia, unhappily for Rome, gave Octavian no direct heir to the purple, and we may therefore speak briefly of her extraction. She came of the Claudii, one of the oldest and proudest families of the Republic, one that numbered twenty-eight consuls and five dictators in its line. A strong, haughty race, more useful than brilliant, religiously devoted to the old Republic, they had helped much to make Rome the mistress of the world. Livia’s father, Livius Drusus Claudianus, had taken arms against Octavian and Antony, and had killed himself, with Roman dignity, when Brutus and Cassius fell, and he saw the shadow of despotism coming over the city.

Livia was then in her sixteenth year,2 and had early experience of the storms of Roman political life. Her10 husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero, had been promoted more than once by Julius Cæsar, but, after the assassination of Cæsar, he had passed into what he regarded as the more favourable current. He seems to have steered his course with some skill until the year 41 B.C., when, like many other small schemers, he came under the influence of Mark Antony’s wife, Fulvia. Antony was caught at the time in the silken net with which Cleopatra prevented him from carrying out the ambition of Rome at the expense of her country. Fulvia, a virile and passionate woman, tried to draw Antony from her arms by provoking a revolt against Octavian. She induced her brother-in-law and other nobles to rebel, and Nero, who was then prefect of a small town in Campania, joined the movement.

Octavian swung his legions southward, and scattered the thin ranks of the insurgents. With her infant—the future Emperor Tiberius—in her arms the girl-wife fled to the coast with her husband, and endured all the horrors of civil warfare. So close were the soldiers of Octavian on their heels that at one point the cry of the baby nearly destroyed them. Octavian had little mercy on rebellious nobles before he married Livia. At last they reached the coast, where the galleys of Sextus Pompeius hovered to receive fugitives, and sailed for Sicily. They were cordially received there by the Pompeians, but went on to Greece, and were again hunted by the troops. Long afterwards in Rome they used to tell how the delicate girl, the descendant of all the Claudii, fled through a burning forest by night before Roman soldiers, and singed her hair and garments as she rushed onward with her baby in her arms. The troubled history of Rome for a hundred years was stamped on her mind by a personal experience that she could never forget. With worn feet and aching heart, she and her husband at last found shelter, until the feud between Antony and Octavian had been composed.

From the straits of exile they returned to their pretty home on the Palatine Hill, and the story of her adventures ran, and gathered substance, in Roman society. If the11 experts be right in assigning to Livia a small mansion which has been uncovered on the hill, we find that she was, in the year 38 B.C., living only a short distance from the house of Octavian. Among the palatial buildings which now whitened the slopes of the Roman hills, Nero’s house—later, Livia’s house—was poor, but its mural paintings are amongst the most delicate that have been discovered under the overlying centuries of mediæval rubbish. A small portico gave shelter from the summer sun, and the small, cool atrium (hall) led only to some half dozen modest rooms. But Livia was happy in her husband, and sober in her tastes. She was then in her nineteenth year, a young woman of regular and pleasing, though scarcely beautiful, features and rounded form, one of those who happily united the old matronly virtue to the new love of society and gaiety. All Rome discussed her adventures, and the generous feeling which her romance engendered made people give her an exceptional beauty and wit—qualities which neither her marble image nor her recorded career permits us to accept in any large measure. There was no whisper of slander against her until the days of her power. From this peaceful and happy little world she was now to be suddenly removed.

Octavian, who mingled very freely with his fellows, and often supped with the literary men who were now multiplying at Rome, heard the gossip about the youthful Livia, and sought her. He was already married, and a word may be said about the impératrices manquées before we unite him to Livia.

In early youth he had been affianced to the girlish daughter of Publius Servilius Isauricus, but a mere betrothal had little strength at a time when even the marriage bond was so frail. When he came to face Mark Antony, with many grim legions at his command, and a fresh civil war was threatened, peacemakers suggested that the storm might be turned from the fields of Italy by a matrimonial alliance. The soldiers, weary of slaying each other, acclaimed the proposal. Servilia was sacrificed, and12 Octavian was married to the young and hardly marriageable daughter of Fulvia. As we saw, there was a fresh rupture with Antony in the year 41, and Octavian sent back the maiden, as he described her, to her infuriated mother. Some of our authorities declare that Fulvia had tried to draw Antony from the arms of Cleopatra by making love to his handsome rival, but one can only suppose that Antony would smile if he were told that his unpleasant spouse—the woman who is said to have gloated over the bloody head of Cicero, and thrust her hair-pin through his tongue—was offering her heart to Octavian. We cannot, therefore, accept the rumour that, when Octavian sent back her daughter to Fulvia, he maliciously explained that he was anxious to spare Fulvia the mortification of thinking that he had preferred the pretty insipidity of Clodia to her own more assertive qualities.

The marriage with Clodia had been frankly political, and it naturally broke down in the new political dissolution. The second marriage had the same origin, and the same welcome termination. He had married Scribonia, a woman older than himself, during the rupture with Antony, because her brother was one of the chief members of the Pompeian faction. The leader of this party, Sextus Pompeius, held Sicily, and not only welcomed fugitives from Octavian’s anger, but commanded the sea-route to Rome. Through his devoted friend Mæcenas, the famous patron of letters, Octavian proposed a marriage with Scribonia. It would not be unnatural for a woman in her thirties, who had already outlived two husbands, eagerly to espouse, and probably love, so graceful, ambitious, and advancing a youth as Octavian; but to him the alliance was only one more move in the great game he was playing. He could bear the strain of a diplomatic marriage with ease, since there is no reason to reject the statement of Dio and Suetonius that he found affection among the wives of his nobler friends.

It has been commonly held that Octavian masked a tense13 and unwavering ambition with an affectation of simple joviality, and his irregularities have been excused on the ground that he used them as means to detect political whispers in Roman society. But this view of Octavian’s character may be confidently questioned. His tastes, we shall see, remained extremely simple when he might safely have indulged any feeling for luxury, when every rival had been removed. That he was ambitious it would be foolish to question; but his ambition must not be measured by his success. There are few other cases in history in which fortune so wantonly smoothed the path and drew onward an easy and vacillating ambition. Octavian could well believe the assurances of the Chaldæan astrologers that he was born to power.

With all his simplicity, however, Octavian had some sense of luxury in love-matters, and his imagination wandered. Scribonia’s solid virtue was unrelieved by any of the graces of the new womanhood of Rome, her sparing charms had already faded under the pitiless sun of Italy, and she had a sharp tongue. Moreover, his marriage with her had proved a superfluous sacrifice. Fulvia’s stormy career had come to a close shortly after the return of her daughter, and Antony and Octavian had divided the Roman world between them. Antony married his colleague’s sister, but the pale virtue of Octavia had no avail against the burning caresses, if not the calculated patriotism, of Cleopatra. At the second rupture between Antony and Octavian she was driven from Antony’s palace at Rome, where she was patiently enduring his distant infidelity, and sent back to her brother. In the meantime Octavian had discovered a pleasanter way of obtaining peace with the Pompeians than by the endurance of Scribonia’s jarring laments of his infidelity. He found, or alleged, that Sextus Pompeius did not curb the pirates of the Mediterranean as he ought, and he determined to wrest from him the rich appointments that he held. He was in this mood when, in the year 38 B.C., the young Livia came to Rome, and the exaggerated story of her adventures and her14 beauty began to circulate among the mansions of the Palatine.

Some of the authorities describe Octavian as hovering about her for some time, and say that the splendour with which he celebrated his barbatoria, or first shave of the beard, was due to the generosity of his new passion. It is more probable that he at once informed Nero of his resolution to marry Livia. Tacitus expressly says that it is unknown whether Livia consented or not to the change of husband. Great as was the liberty then enjoyed by Roman women, they were rarely consulted on such matters. Scribonia received a letter of divorce, in which it was suggested that the perversity of her character made her an unsuitable spouse for so roving a husband. She had given birth to a daughter a few days before, and we shall find the later chapters of this chronicle lit up more than once by the lurid hatred which was begotten of this despotic dismissal. For the moment I need only point out that later Roman writers borrowed their estimate of the character of Livia from Scribonia’s great-grandchild, the Empress Agrippina, and we must be wary in accepting their statements. Scribonia herself, who came so near to being an Empress, we must now dismiss, save that we shall catch one more glimpse of her when she follows her dissolute daughter into exile.

Roman law imposed a fitting delay on the divorced wife before she could marry again, but Octavian was impatient. He consulted the sacred augurs, and, if the legend is correct, the diviners gave admirable proof of their art. They gravely reported that the omens were auspicious for an immediate marriage if the petitioner had ground to believe that it would be fruitful. The verdict entertained Rome, because Livia was well known to be far advanced in pregnancy, and Octavian was widely regarded as the father. Whether that be true or no, Octavian intimated to Nero that he must divorce Livia, and we cannot think that she felt much pain at being invited to share the mansion in the Palatine to which all Roman eyes were now directed. An15 anecdote of the time lightly illustrates the ease with which such matrimonial transfers were accomplished at Rome. Dio says that, during the festive meal, one of those bejewelled boys who then formed part of a Roman noble’s household, and whose vicious services were rewarded with an extraordinary license, said to Livia, as she reclined at table with Octavian: “What do you here, mistress? Your husband is yonder.” The pert youngster pointed to Nero at another table. He had given away the bride, and was cheerfully taking part in the banquet.

Livia’s second son, Drusus Nero, was born three months after her marriage, and was sent by Octavian to Nero’s house. Nero died soon afterwards, and made Octavian the guardian of his sons, so that they returned to the care of their mother. The extreme fondness of Octavian for the younger boy lends no colour to the rumour that Drusus was his own son. The probability is that Octavian, in his impetuous way, married Livia as soon as his fancy rested on her. The accepted busts of Drusus do not give any support to the calumny that Octavian was his father. He loved both the boys, and assisted in educating them, in their early youth. It is only when his daughter Julia brings her handsome children into the household that we detect a beginning of an estrangement between him and his successor, Tiberius.

The household in which these first seeds of tragedy slowly germinated was, in the year 38 B.C., one of great simplicity and sobriety. They lived in the comparatively small house in which Octavian had been born, and Livia adopted his plain ways with ease and dignity. In that age of deadly luxury, when the veins of Rome were swollen with the first flush of parasitic wealth, Octavian and Livia were content with a prudent adaptation of the old Roman ideal to the new age. The noble guests whom Octavian brought to his table found that his simple taste shrank, not only from the peacocks’ brains and nightingales’ tongues which were served in their own more sumptuous banquets, but even from the pheasant, the boar, and the other16 ordinary luxuries of a patrician dinner. Rough bread, cream cheese, fish, and common fruit composed his customary meal. Often was he seen, as he came home in his litter from some fatiguing public business, such as the administration of justice, to munch a little bread and fruit, like some humble countryman. Of wine he drank little, and he never adopted the enervating nightly carousal which was draining away the strength of Rome. While wealthy senators and knights prolonged the hours of entertainment after the evening meal, and hired sinuous Syrian dancing girls and nude bejewelled boys and salacious mimes to fire the dull eyes of their guests, as they lay back, sated, on the couches of silk and roses, under fine showers of perfume from the roof, sipping choice wine cooled with the snow of the Atlas or the Alps, Octavian withdrew to his study, after a frugal supper, to write his diary, dictate his generous correspondence, and enjoy the poets who were inaugurating the golden age of Latin letters. When there were guests, he provided fitting dishes and music for them, but often retired to his study when the meal was over. After seven hours’ sleep in the most modest of chambers he was ready to resume his daily round.

Since Octavian retained these sober habits to the end of his life, years after they could have had any diplomatic aim, it is remarkable that so many writers have regarded them as an artful screen of his ambition. Nor can we think differently of Livia. If Octavian presents a healthy contrast to the sordid sensuality of some of his successors, his wife contrasts no less luminously with later Empresses, and is no less unjustly accused of cunning. How far she developed ambition in later years we shall consider later. In the fullness of his manhood, at least, she was content to be the wife of Octavian. With her own hands she helped to spin, weave, and sew his everyday garments. She carefully reared her two boys, tended the somewhat delicate health of Octavian, and cultivated that nice degree of affability which kept her husband affectionate and the husbands of other noble dames respectful. Dio would have17 us believe that her most useful quality was her willingness to overlook the genial irregularities of Octavian; but Dio betrays an excessive eagerness to detect frailties in his heroes and heroines. We have no serious evidence that Octavian continued the loose ways of his youth after he married Livia. The plainest and soundest reading of the chronicle is that they lived happily, and retained a great affection for each other, even when fate began to rain its blows on their ill-starred house.

But before we reach those tragic days, we have to consider briefly the years in which Octavian established his power. His first step after his marriage with Livia was to destroy the power of the Pompeians. Livia followed the struggle anxiously from her country villa a few miles from Rome. Sextus Pompeius was experienced in naval warfare, and, as repeated messages came of blunder and defeat on the part of Octavian’s forces, she trembled with alarm. Her confidence was restored by one of the abundant miracles of the time. An eagle one day swooped down on a chicken which had just picked up a sprig of laurel in the farm-yard. The eagle clumsily dropped the chicken, with the laurel, near Livia, and so plain an omen could not be misinterpreted. Rumour soon had it that the eagle had laid the laurel-bearing chick gently at Livia’s feet. As in all such cases, the sceptic of a later generation was silenced with material proof. The chicken became the mother of a brood which for many years spread the repute of the village through southern Italy; the sprig of laurel became a tree, and in time furnished the auspicious twigs of which the crowns of triumphing generals were woven.

Whether it was by the will of Jupiter, or by the reinforcement of a hundred and fifty ships which he received from Antony, Octavian did eventually win, and, to the delight of Rome, cleared the route by which the corn-ships came from Africa. Only two men now remained between Octavian and supreme power—the two who formed with him the Triumvirate which ruled the Republic. The first, Lepidus, was soon convicted of maladministration in his18 African province, and was transferred to the innocent duties of the pontificate, under Octavian’s eyes, at Rome. Octavian added the province of Africa to his half of the Roman world, and found himself in command of forty-five legions and six hundred vessels. Fresh honours were awarded him by the Senate, in which his devoted friend Mæcenas, who foresaw the advantage to Rome of his rule, was working for him.

Then Octavian entered on his final conflict with Mark Antony. I have already protested against the plausible view that Octavian was pursuing a definite ambition under all his appearance of simplicity. Circumstances conspired first to give him power, and then to give him the appearance of a thirst for it. He really did not destroy Antony, however: Antony destroyed himself. The apology that has been made for Cleopatra in recent times only enhances Antony’s guilt. It is said that she used all that elusive fascination of her person, of which ancient writers find it difficult to convey an impression, all her wealth and her wit, only to benumb the hand that Rome stretched out to seize her beloved land. The theory is not in the least inconsistent with the facts, and it is more pleasant to believe that the last representative of the great free womanhood of ancient Egypt sacrificed her person and her wealth on the altar of patriotism than that her dalliance with Antony was but a languorous and selfish indulgence in an hour of national peril. But if it be true that Cleopatra was the last Egyptian patriot, Antony was all the more clearly a traitor to Rome. The quarrel does not concern us. Octavian induced the Senate to make war on Egypt; and we can well believe that when, in a herald’s garb, he read the declaration of war at the door of the temple of Bellona, the thought of his despised sister added warmth to his phrases. The pale, patient face and outraged virtue of Octavia daily branded Antony afresh in the eyes of Rome.

Livia and Antonia followed the swift course of the last struggle from Rome. They heard of the meeting of the19 fleets off Actium, the victorious swoop of Octavian, the flight of Antony and Cleopatra. What followed would hardly be known to Livia. It is said that Cleopatra offered to betray Antony to Octavian, and such an offer is in entire harmony with the patriotic theory of her conduct. While his able but ill-regulated rival, deserted by his forces, drew near the edge of the abyss, Octavian visited Cleopatra in her palace. Her seductive form was displayed on a silken couch, and from the slit-like eyes the dangerous fire caressed the young conqueror. Cleopatra probably relied on Octavian’s weakness, but his sensuous impulses were held in check by a harder thought. He felt that he must have this glorious creature to adorn his triumph at Rome. Cleopatra saw that she had failed, and she went sadly, with a last dignity, before the throne of Osiris. Octavian returned to Rome with the immense treasures of Egypt, to enjoy the triumph I have already described and to await the purple.

The domestic life of Livia and Octavian lost none of its plainness after the attainment of supreme power. Some time after the Senate had (27 B.C.) strengthened his position by inventing for him the title of “Augustus”—a title by which he is generally, but improperly, described in history after that date3—he removed from the small house which his father had left him to a larger mansion, built by the orator Hortensius, on the Palatine. This was burned down in the year 6 B.C., and the citizens built a new palace for Livia and Octavian by public subscription. At the Emperor’s command the contribution of each was limited to one denarius. If we may trust the archæologists, it was modest in size, but of admirable taste, especially in the marble lining of its interior. On one side it looked down, over the steep slope of the hill, on the colonnaded space, the Forum, in which the life of Rome centred. On the other side it faced a group of public20 buildings, raised by Octavian, which impressed the citizens with his liberality in the public service. The splendid temple of Apollo, the public library and other buildings, adorned with the most exquisite works of art that his provincial expeditions had brought to Rome, stood in fine contrast to his own plain mansion, of which the proudest decoration was the faded wreath over the door—the Victoria Cross of the Roman world—which bore witness that he had saved the life of a citizen.

In this modest palace Livia reared her two children in the finer traditions of the old Republic, while Octavian made the long journeys into the provinces which filled many years after his attainment of power. Livia was no narrow conservative. She took her full share in the decent distractions of patrician life, and, like many other noble women of the period, she built temples and other edifices of more obvious usefulness to the public. A provincial town took the name Liviada in her honour. We have many proofs that she was consulted on public affairs by Octavian, and exercised a discreet and beneficent influence on him. One of the anecdotes collected by later writers tells that she one day met a group of naked men on the road. It is likely that they were innocent workers or soldiers in the heat, and not the “band of lascivious nobles” which prurient writers have made them out to be. However, Octavian impetuously demanded their heads when she told him, and Livia saved them with the remark that, “in the eyes of a decent woman they were no more offensive than a group of statues.” On another occasion she dissuaded Octavian from executing a young noble for conspiracy. At her suggestion the noble was brought to the Emperor’s private room. When, instead of the merited sentence of death, Cinna received only a kindly admonition, an offer of Octavian’s friendship, and further promotion, he was completely disarmed and won. We shall see further proof that the wise and humane counsels of Livia contributed not a little to the peace and prosperity which Rome enjoyed in its golden age.

LIVIA AS CERES

STATUE IN THE LOUVRE

21 For it was in truth an age of gold in comparison with the previous hundred years and the centuries to come. The flames of civil war had scorched the Republic time after time. The best soldiers of Rome were dying out; the best leaders were perishing in an ignoble contest of ambitions. Corruption spread, like a cancerous growth, through all ranks of the citizens of Rome, and far into the provinces. The white-robed (candidati) seekers of office in the city now relied on the purchase of votes by expert and recognized agents. Hundreds of thousands of the citizens lived parasitically on the State, or on the wealthy men to whom they sold their votes, and from whom they had free food and free entertainments. The loathsome spectacle was seen of vast crowds of strong idle men, boasting of their dignity as citizens of Rome, pressing to the appointed steps for their daily doles of corn. Large numbers of them could hardly earn an occasional coin to buy a cup of wine, a game of dice, or a visit to the lupanaria in the Subura. By means of other agents the wealthy refilled their coffers by extortion in the provinces, and paraded at Rome a luxury that was often as puerile as it was criminal. Rome, once so sober and virile, now shone on the face of the earth like some parasitic flower, of deadly beauty, on the face of a forest.

No man, perhaps, could have saved Rome from destruction, but Octavian did much to clear its veins of the poison, and its chronicle would have run very differently if he had not been succeeded by a Caligula, a Claudius, and a Nero. He chastised injustice in the provinces, purified the administration of justice at Rome, fought against the growing practices of artificial sterility and artificial vice, and genially pressed on the senators his own ideal of sober public service. From his mansion on the Palatine he looked down without remorse on the idle chatterers in the Forum, from whom he had withdrawn the power, of which they still boasted, of ruling their spreading empire. Nor were there many, amongst those who looked up to his unpretentious palace on the edge of the cliff, who did not feel22 that they had gained by the sale of their tarnished democracy. There was more than literal truth in Octavian’s boast that he had found Rome a city of brick, and had left it a city of marble.

Yet all the augurs and soothsayers of Rome failed to see the swift and terrible issue that would come of this seemingly happy change. Corrupt and repellent as democracy had become, monarchy was presently to exhibit spectacles which would surpass all the horrors of its civil wars, and outshame the sordid reaches of its avarice. The new race of rulers was to descend so low as to use its imperial power to shatter what remained of old Roman virtue, and to embellish vice with its richest awards. From the sobriety and public spirit of Octavian we pass quickly to the sombre melancholy of Tiberius, the wanton brutality of Caligula, the impotent sensuality of Claudius, the mincing folly of Nero, and the alternating gluttony and cruelty of Domitian, before we come to the second honest effort to avert the fate of Rome. From the genial virtue of Livia we are led to contemplate the dissolute gaieties of Julia, the cold ambition of Agrippina, the robust vulgarity of Cæsonia, the infectious vice of Messalina, and the insipid frippery of Poppæa. Had there been one syllable of truth in the divine messages which augurs and Chaldæans saw in every movement of nature, not even the beneficent rule of Octavian would have lured men to sacrifice even the effigy of power that remained to them, and that they had lightly sold for a measure of corn and the bloody orgies of the amphitheatre.

23

In tracing the further career of Livia we enter upon the opening acts of the tragedy of the Cæsars, and we have to consider carefully if there be any truth in the charge that Livia herself initiated the long series of murders that now make a trail of blood over the annals of Rome. With the coming of the Empire we more rarely find legion pitted against legion in the horrors of civil war, but we have nerveless ambition stooping to the despicable aid of the poisoner, autocracy paralysing the best of the nobility with its murderous suspicions, and folly growing more foolish with the increasing splendour of the imperial house. We already know that the germs of this disease were found in the quiet home of Livia and Octavian on the Palatine. Scribonia had received her letter of divorce a few days after the birth of her daughter Julia. As Livia bore no direct heir to the Emperor, while Julia became the mother of many children, we have at once the promise of a dramatic struggle for the succession. When we further learn that the strain of Imperial blood, which takes its rise in Julia, is thickly tainted with disease, we are prepared for a bloody and unscrupulous conflict. And when we reflect that on this unstable pivot the vast Empire will turn for many generations, we begin to understand the larger tragedy of the fall of Rome.

Let us first glance at the interior of the modest household on the Palatine. Besides Livia and Octavian, with24 whom we are now familiar, there is Octavia, sister of the Emperor and divorced wife of Mark Antony, a gentle lady with the matronly virtues of the time when a Roman could slay his wife or daughter for irregular conduct. With her were her children, Marcellus and Marcella, of whom we shall hear much. Then there were Livia’s two sons—the elder, Tiberius, a tall, silent, moody youth, with little care to please; the younger, Drusus, a handsome, buoyant, fair-headed boy, threatening the elder’s birthright. Octavian closely watched the education of the boys. He taught them to write on the wax-faced tablets in the fine script on which he prided himself, kept them beside him at table, and drove them in his chariot about public business.

But the most interesting and fateful figure in the group was Julia. Octavian had removed her at an early age from the care of Scribonia, and adopted her in the palace. She learned to spin and weave, and helped to make the garments of the family, under the severe eyes of Livia and Octavia. The Emperor was charmed with the pretty and lively girl, and would make a second Livia of her. Knowing well, if only from his own youth, the vice and folly that abounded in those mansions on the hills of Rome, and roared in its dimly-lighted valleys by night, he kept her apart. None of the young fops who drove their chariots madly out by the Flaminian Gate, and sipped their wine after supper to the prurient jokes of mimes, were suffered to approach her. And, not for the first or last time in history, the veiling of the young eyes had an effect quite contrary to that intended. A Roman girl became a woman at fourteen, a mother at fifteen. At that early age, in the year 25 B.C., Julia was married to her cousin Marcellus, who was then seventeen. Marcellus was so clearly a possible successor to the throne that courtiers hung about him, and taught him the art of princely living. The doors of the hidden world were opened, and the tender eyes of Julia were dazed.

The authorities are careless in chronology, and we25 may decline to believe that Julia at once entered on the riotous ways which led her to the abyss. Her marriage concerns us in a very different respect. All the writers who adopt the view that Livia was a hard and unscrupulous woman—a view that Tacitus must have taken from the memoirs of her rival’s granddaughter, the Empress Agrippina, which were made public in his time—consider that this marriage of Julia and Marcellus marks the beginning of her career of crime. She is supposed to have been alarmed at the marriage of two direct descendants of Cæsar, seeing that she herself had no child by Octavian. Most certainly she was ambitious for her elder son. The boy whom she had clasped to her breast, when she fled along the roads of Campania and through the burning forests of Greece, was now a clever and studious youth, and she wished Octavian to adopt him. Unfortunately, Tiberius was of a moody and solitary nature, and was easily displaced in Octavian’s affection by the handsome and popular Marcellus and the beautiful and witty Julia.

The first cloud appeared in the year 23 B.C. Octavian fell seriously ill, and Livia’s hope of securing the succession for her son was troubled by two formidable competitors. One was Marcellus, the other was Octavian’s friend and ablest general, M. V. Agrippa. He was of poor origin, but of commanding ability and character, and was suspected of entertaining a design to restore the Republic. He was married to Marcella, and had some contempt for the spoiled boy, her brother Marcellus—a contempt which Marcellus repaid with petulance and rancour. Octavian recovered, sent Agrippa on an important errand to the East, and made Marcellus Ædile of the city. Marcellus was winning, the eager observers thought, when suddenly he fell seriously ill and died. The death was so opportune for Tiberius that we cannot wonder that a faint whisper of poison went through Rome when his ashes were laid in the lofty marble tower that Octavian had built in the meadows by the Tiber. But we need not linger over this first charge against Livia.26 Even Dio, who is no sceptic in regard to rumours which defame Empresses, hesitates to press on us so airy and improbable a myth. It was a hot and pestilential summer, and Marcellus seems to have contracted fever by remaining too long at his post, before going to Baiæ on the coast.

The death of Marcellus, far from promoting the cause of Tiberius, brought a more formidable obstacle in his way. Octavian sent for Agrippa, and directed him to divorce Marcella and wed Julia. The general, who was in his forty-second year, thought it immaterial which of the two young princesses shared his bed, and Octavia consented to the divorce of her daughter—as some conjecture, to thwart Livia’s design. To the delight of Octavian the union of robust manhood and amorous young womanhood was fruitful. During the ten years of their marriage Julia gave birth to three sons and two daughters. Happily unconscious of the tragedies which were to close the careers of these children in his own lifetime, Octavian welcomed them with great enthusiasm. During his whole reign he was engaged in a futile effort to induce or compel the better families of Rome to take a larger share in the peopling of the Empire. When he penalized celibacy, they defeated him by contracting marriages with the intention of seeking an immediate divorce. When he made adultery a public crime, there were noblewomen—few in number, it is true; the facts are often exaggerated—who enrolled themselves on the list of shame, and noblemen who took on the degrading rank of gladiators, in order to escape the penalties. He created a guild of honour for the mothers of at least three children; but the distinction seemed to the ladies of Rome to be an inadequate reward for so onerous an accomplishment, and they scoffed when Livia was enrolled in the guild, though the only child she had conceived of Octavian had never seen the light.

Far greater, however, was the amusement of Rome when Octavian held up Julia as a model of maternity,27 and ostentatiously fondled her babies in public. A coarse and witty reply that she is said to have made, when some one asked her how it was that all her children so closely resembled her husband, was then circulated in Roman society, and is preserved in Macrobius.4 Beautiful, lively, and cultivated, the young girl had exchanged with delight the dull homeliness of her father’s mansion for the rose-crowned banquets of her new world. Her marriage with Agrippa restrained her gaiety for a time, but her husband was often summoned to distant provinces, and she was left to her dissolute friends. Octavian was curiously blind to her conduct, but when Agrippa was compelled to undertake a lengthy mission in the East, he ordered Julia to accompany him. The journey would not improbably foster her vicious tendencies. There is truth in the old adage that all light came to Europe from the East, but it is hardly less true that darkness came to Rome from the East. Julia would not be ignorant how the ancient Roman puritanism had been corrupted by the introduction of Eastern habits and types—the poisoner, the Chaldæan astrologer, the Syrian dancer, the eunuch, the cultivated Greek slave, the priests of orgiastic Eastern cults. A mind like hers would seek to penetrate the depths from which these types had emerged. In Greece she would find the remains of its perfumed vices lingering at the foot of its decaying monuments. In Antioch there would not be wanting freedwomen to gratify her curiosity in regard to its unnatural excesses and the world-famed license of its groves. In Judæa she was long and splendidly entertained at the court of Herod, a monarch with ten wives and concubines innumerable.

They returned to Rome in the year 13, and in the following year Agrippa died of gout, and Julia was free. One of the most surprising features of her wild career—one that would make us hesitate to admit the charges against her, if hesitation were possible—is that Livia was either ignorant of her more serious28 misdeeds, or unable to convince Octavian of them. Livia would hardly spare her, as Julia was inflaming Octavian’s dislike for Tiberius. Refined, sensitive, and studious, the young man avoided the boisterous amusements in which other young patricians spent their ample leisure, and his cold melancholy made him distasteful to them. One of the Roman writers would have us believe that Julia made love to him during the life of Agrippa, and that she incited Octavian against him in revenge for his rejection of her advances. The story is improbable. We need only suppose that Julia, in speaking of Tiberius, used the disdainful language which was common to her friends. Neither Livia nor Tiberius seems to have attempted to open the Emperor’s eyes to Julia’s conduct. Octavian disliked her luxurious ways, but was blind to her vices, though the names of her lovers were on the lips of all. One day Octavian scolded her for having a crowd of fast young nobles about her, and commended to her the staid example of Livia. She disarmed him with the laughing reply that, when she was old, her companions would be as old as those of the Empress. One writer says that Octavian compelled her to give up a too sumptuous palace which she occupied. One is more disposed to believe the story that, when he remonstrated with her for her luxurious ways, she replied “My father may forget that he is Cæsar, but I cannot forget that I am Cæsar’s daughter.”

In spite of their mutual aversion Octavian now ordered Tiberius to marry her. He was already married to Vipsania, the virtuous and affectionate daughter of Agrippa, and this enforced separation from one whom he loved with an ardour that was fading from Roman marriage, and union with one who contrasted with Vipsania as the wild flaming poppy contrasts with the lily, further soured and embittered him. We may dismiss in a very few words his relations with the woman who ought to have been the second Empress of Rome. After a few years spent, as a rule, in distant frontier wars, he returned to29 Rome in the year 6 B.C., to find that his wife had passed the last bounds of decency and Octavian was as blind as ever. In intense disgust, and in spite of his mother’s entreaties, he begged the Emperor’s permission to spend some years in literary and scientific studies at Rhodes. Not daring to open the eyes of Octavian to the true character of his daughter, he had to bow to his anger and disdain, and seek consolation in the calm mysteries of the planets and the fine sentiments of Greek tragedians.

JULIA

BUST IN THE MUSEUM CHIARAMONTI

Julia now cast aside the last traces of restraint. A half-dozen of the young nobles of Rome are associated with her in the chronicles, and, gossipy and unreliable as the records are, in this case the issue of the story disposes us to believe the charges. Round such a repute as hers legends were bound to grow, and the conscientious biographer must be reserved in giving details. Dio tells us, for instance, that she expected her lovers to put crowns, for each success she permitted them to attain, at the foot of the statue of Marsyas—a public statue, at the feet of which Roman lawyers were wont to place a crown when they had won a case. However that may be, it is certain that in the nightly dissipation of Rome, when plebeian offenders sought the darkness of the Milvian Bridge, or wantoned in the taverns and brothels of the Subura, Julia’s party was one of the boldest and most conspicuous. Not content with the riotous supper, which it was now the fashion to prolong by lamp-light, in perfumed chambers, until late hours of the night, Julia and her friends went out into the streets, and caroused in the very tribunal in the Forum—the Rostra, a platform decorated with the prows of captured vessels—from which her father made known his Imperial decisions.5

30 The thunder of the Imperial anger scattered this licentious band some time in the second year before Christ. In the earlier part of the year Octavian had entertained Rome with one of the thrilling spectacles which he often provided. To celebrate the dedication of a new temple of Mars, which he had built, he had the Flaminian Circus flooded, gave the people a mock naval battle, and had thirteen crocodiles slain by the gladiators. Julia had hoodwinked the Emperor so long that she and her friends seem to have abandoned all restraint, and their adventures came to the knowledge of the Emperor.

The charges against Julia must have been beyond cavil, since Octavian, who loved her deeply, at once yielded her to the course of justice. A charge of conspiracy was made out against her companions. One of the young nobles killed himself, and the rest were banished. Julia was convicted of adultery—the evil that her father had fought for ten years—and from the glitter of Rome she was roughly conducted to the barren rock-island of Pandateria (Ponza), in the Gulf of Gæta. In that narrow and depressing jail, with no female attendants, no wine and no finery, accompanied only by her unhappy mother, the fascinating young princess spent five years, looking with anguish over the blue water toward the faint outline of the hills of Italy, or southward toward those rose-strewn waters of Baiæ, where she had dreamed away so many brilliant summers. Rome, touched with pity for the stricken woman, implored Octavian to forgive her; and when he swore that fire and water should meet before he pardoned her, the people naively flung burning torches into the Tiber. Hearing, after a few years, that there was a plot to release her, Octavian had her removed to a more secure prison in Calabria. There she dragged out her miserable life until her father died, and Tiberius came to the throne. When he in turn refused to release her, she sank slowly into the peace of death.

There is no charge against Livia in connexion with this tragic fate of Julia, but another possible rival of31 Tiberius had disappeared during these years, and there is the usual vague accusation that the Empress assisted the action of nature. Drusus, her younger son, died in the year 9 B.C., and Livia is charged with sacrificing him to her affection for her elder son. The charge is preposterous. Drusus had, it is true, been much more popular than Tiberius at Rome. His genial and engaging manner gave him a great advantage over the retiring and almost sullen Tiberius. But the brothers loved each other deeply, and when Tiberius, who was making a tour in the north of Gaul, heard that Drusus was dangerously ill in Germany, he at once rode four hundred miles on horseback, and held Drusus in his arms in his last hour. Livia was at Ticinum, in the north of Italy, with Octavian when the news reached them. That either Livia or Tiberius—for both are accused—should have in any way promoted the death of Drusus is a frivolous suggestion. The epitomist of Livy, Tacitus, and Suetonius, describe the death as natural. Drusus was thrown and injured by a frantic horse. The libel that his death was in some mysterious way accelerated may have been set afoot by his partisans. It was generally believed that he favoured a restoration of the Republic, and the corrupt officials who, at his death, lost their faint hope of returning to the days of peculation and bribery, may have begun the charge. No evidence is offered for it. Livia and Octavian accompanied the remains to Rome with great sorrow. Seneca says that the Empress was so distressed that she summoned one of the Stoic philosophers to console her.

The next charge against Livia requires a more careful examination. By the beginning of the present era, when the poor health of Octavian gave occasion for many speculations as to the succession, there were only two rivals to the chances of Tiberius. These were the elder sons of Julia, and Livia must have reflected gloomily on their fortune. While Tiberius remained in retirement at Rhodes the young princes were idolized by Octavian and by the people. Tiberius had proposed to return to Rome after the banishment32 of Julia, but Octavian peevishly told him to remain in Greece. Every astrologer in Rome must have read in the planets that either Caius or Lucius was born to the purple. They were spoiled by Octavian, enriched with premature honours, and, glittering in silver trappings, appeared in the spectacles as “Princes of the youth of Rome.” Let those youths be removed from the scene by any accident, and so prurient a city as Rome will be bound to discover some insidious action on the part of Livia; and later writers, brooding over a chronicle in which ambition leads freely to the most brutal murders, will be disposed to believe her guilty.

It is somewhat surprising to find more recent writers caught by the fallacy. We are not puzzled when the scandal-loving Serviez opens his chapter on Livia with a glowing enumeration of her virtues, adopts nearly every libel against her as he proceeds, and closes with a very dark estimate of her character; but we are entitled to expect more discrimination in Merivale. Even Mr. Tarver, in his recent “Tiberius the Tyrant” (1902), does much injustice to the mother in vindicating the son. He speaks of her as “hard, avaricious, and a lover of power,” and, without the least evidence—indeed, against all probability—suggests that it was Livia who urged Octavian to keep Tiberius in retirement at Rhodes. He makes Livia hostile to Tiberius in favour of Julia’s sons, on the ground that she would find them more pliant than Tiberius. Every other writer suggests precisely the contrary. They make her murder Julia’s sons in the interest of Tiberius.

The death of the younger son, Lucius, is obscure. He was sent on a mission to Spain in the year 2 A.D., and died at Marseilles on the way. Since the only ground for the rumour that he was poisoned is the indubitable fact that he died, we need not delay in considering it. Octavian then sent the elder brother Caius on a mission into Syria under the care of his old tutor Lollius. His counsellor unhappily died in the East, and the young prince was left to the vicious companions who regarded him as the future dispenser of33 Imperial favours. He fell into Oriental ways, and was at length (A.D. 3) treacherously wounded by a Syrian patriot. Instead of returning to Rome, he remained in the unhealthy atmosphere of the East, indulged in its habits of languor and vice, and died eighteen months after the death of his brother. There is no obscurity about his death. It is beyond question that he was severely wounded by a Syrian. But the deaths of the two brothers happened so opportunely for Tiberius that one cannot wonder at the suspicion, in certain minds, that Livia had had the youths poisoned. Nothing more than this vague rumour is given us by Tacitus, Dio, Suetonius, or Pliny; and it is from a sheer pruriency of romance that later writers, like Serviez, have accepted and emphasized the suspicion recorded in the Roman historians. Not on such slender grounds can we be asked to sacrifice the conception of Livia’s character which is forced on us by the plainer facts of her career. The youths were delicate; Caius, at least, had undermined his frail constitution by luxury, if not by vice; and the Roman world harboured death in a hundred forms.

If we still hesitate to choose between the artifice of Livia and the unaided action of natural causes in this removal of the obstacles to the advancement of Tiberius, we have only to glance at the fate of the rest of Julia’s children. The third son, Agrippa, was as robust in body as his brothers were weak, but he was defective in mind and devoid of moral control. His boorish conduct as a boy gave great pain to Livia and Octavia, and his great physical strength broke out in uncontrollable gusts of passion. In his adolescence he readily adopted the worst vices that Rome could teach him, and Octavian was obliged to condemn him to imprisonment and exile. There remained the two daughters, Julia and Agrippina. The younger, the sanest of Julia’s children, lived to intrigue for power, and greatly to embarrass Livia’s later years; though we shall find the same tragic fate befalling her after the death of the Empress, who protected her. The elder, Julia, was banished34 (A.D. 9) for incest, and, like her mother, lacking the courage or virtue to end her shame as the nobler Romans did, she protracted her miserable life for twenty years, her hard lot only alleviated by the charity of Livia.

Fate had removed every possible competitor to the succession of Tiberius. He returned to Rome, and his judicious and sedulous activity removed the last traces of the Emperor’s resentment. Peace returned, after many years of storm, to the mansion on the Palatine. But Octavian had suffered profoundly from those terrible and persistent storms. The Rome of his manhood was gone. All his friends and counsellors had disappeared, and the future of his people filled him with apprehension. The patrician stock was decaying from luxury and vice; the ordinary citizens clamoured for free food and free entertainment with a blind disregard of the laws of national health. He shrank from the public gaze, and leaned affectionately on Livia and Tiberius.

In the year 14 he remained at Rome in the early heat of the summer, and became seriously ill. Livia and Tiberius went down with him to the coast, where he rallied, and some pleasant days were spent on the island of Capreæ (Capri), which he had bought. They passed to the mainland, where Tiberius left them, but he was soon recalled by a message from his mother that the Emperor was sinking. On the last morning of his life Octavian dressed with unaccustomed care, and summoned his friends to his bedside. Was Rome tranquil on receiving the news of his dangerous condition? Did they approve of his conduct and accomplishments? They gave him the assurance he desired, and were dismissed. Could they have foreseen the line of rulers who were to stain the purple robe with blood, and load it with shame, for so many decades to come, they would have wept. The last moments were for Livia. He died kissing her, and murmuring: “Be mindful of our marriage, Livia. Farewell.” So ended, peacefully, a union that had lasted fifty-two years in a city where divorce was as lightly esteemed as marriage. There35 can be little serious doubt about the character of the first Empress of Rome.

Livia probably concealed the death of Octavian until Tiberius arrived from Dalmatia. A report was given out that Tiberius arrived in time to receive the last injunctions of the Emperor. This may be doubted without any serious reflection on her character; if, indeed, it was she, and not Tiberius, who spread the report. There were grave fears—well-founded fears, as we shall see—that a plot, in the interest of corruption, had been framed to prevent the succession of Tiberius. In the coolness of the night, so as to avoid the intense heat of August, they bore the remains with great pomp to the capital. There, on a bed of ivory and purple, preceded by wax effigies of Octavian and of earlier rulers of Rome, the body was carried to the temple of Julius, where Tiberius read a funeral oration. The cortège went on to the Field of Mars, by the Tiber, through lines of black-draped citizens. The pile was fired, and zealous eyes saw the soul of Octavian mount toward heaven in the outward form of an eagle.

Livia, on approved custom, remained by the sacred ashes for five days, and then returned to face the new life which opened for her. With the especially wild suggestion that she had accelerated the death of her husband we may disdain to concern ourselves. It was owing to her devoted care that the ailing and delicate Octavian had lived to old age. But a second libel in connexion with the death of Octavian must be briefly considered.

The apprehension, or the secret information, of the dying Emperor was correct. No sooner was his death announced than a servant of the imprisoned son of Julia hurried to the coast, and set sail for the island of Planasia, with the intention of bringing Agrippa to Rome as a candidate for the purple. He arrived only to find a bleeding corpse. The centurion in charge had dispatched Agrippa as soon as the Emperor’s death was made known to him.

Who gave the order for this execution? One cannot36 call it murder, for Agrippa was unfit to be restored to society, and any attempt to raise him to the throne would have been disastrous to Rome. The authorities, as usual, merely give us the rumours that circulated at the time, and leave us to choose between Octavian, Livia, and Tiberius. We can have little difficulty in choosing. It would be so natural for either Octavian or Tiberius to crush the conspiracy by executing Agrippa that the introduction of Livia is superfluous. Most probably Octavian had left directions with Agrippa’s custodian. There is a curious story, in several contradictory versions, but credible in substance, that Octavian in his later years paid a secret visit to Planasia, to see personally what Agrippa’s real condition was. Quite the most plausible theory is that, after personal verification of his madness, Octavian felt it best for Rome, and not inhuman to Agrippa, to have him put to death as soon as the question of succession was opened.

We come to the last phase of Livia’s career. Tiberius was now a tall, handsome man, though slightly disfigured, with long fair hair and features strangely delicate for one of his exceptional physical strength. A better soldier than his predecessor, and not an inept statesman, he was well enough fitted to wield the power which Octavian had virtually bequeathed to him. But a retiring disposition, an unhappy youth, and long years of study, had made him shrink from the society of any but scholars, and he long hesitated to ascend the throne to which the Senate invited him. We have not good ground to regard this reluctance as feigned. At last he consented, and the critics of Livia would have it that her ambition now passed such bounds as had been set to it by the ability of Octavian. We may freely admit that she looked forward to being closely associated in power with the son whose career she had followed with such devotion and helpfulness. On the other hand, we shall see how advantageous to the State her influence was; the evils that at once begin to darken the life of Rome when Tiberius rejects her counsels37 will plainly show this. Nor is there any evidence that she sought power from any other motive than the good of the State. She might take pride in what she did, and even exaggerate it, but such a pride is not inconsistent with the view that she was ever gentle, humane, and generous.

The first searching test of her character occurs a few years after the accession of Tiberius. As the news of the death of Octavian slowly travelled over the Empire, there were mutinous movements among the legions in many provinces. In Lower Germany, especially, the troops considered that their commander, Germanicus, the nephew of Tiberius, was entitled to the purple, and they asked him to lead them to Rome. He was a handsome, engaging young general, of imperial blood, with moderate ability and much conceit, and had won the regard of the soldiers by visiting the sick and wounded, advancing their pay out of his own purse, and other popular acts. He was married to Julia’s daughter, Agrippina, who lived in camp with him. They dressed their little son Caius in soldier’s costume, and his quaint appearance in miniature military boots won for him the pet-name Caligula (“Little-boots”) by which he is known to history. The legionaries thought that they had with them a model Imperial family, and promised to wrest the throne from Tiberius. Germanicus weakly composed the mutiny—mainly by forging a letter in the name of Tiberius and then treacherously executing the leaders—and endeavoured to cover his blunders by vigorous and rather aimless attacks upon the Germans. Tiberius recalled him to Rome to enjoy a “triumph,” and to keep him out of further mischief.

Merivale acknowledges that his conquests were “wholly visionary,” but Germanicus had inherited the charm and popularity of his father, Drusus, and Rome was easily won for him. People streamed out from the gates to meet him, and gazed with awe on his gigantic blue-eyed captives and on the large highly-coloured paintings of his victories in Germany. It was a new source of concern for38 Livia and Tiberius, and, to the satisfaction of Livia’s critics, the danger ended like all the others.

Germanicus and Agrippina were sent on a mission to the East. Tiberius seems to have had some disdain for his spoiled and conceited nephew, and he was well aware of the interested aims of those who affected to see in him a restorer of the old republican liberty. He chose an older statesman, Cn. Calpurnius Piso, to go out as Governor of Syria, to watch and prudently direct the movements of Germanicus. With Piso was his wife Plancina, an intimate friend of Livia. From these Tiberius and Livia shortly heard exasperating accounts of the progress of Germanicus and Agrippina. Piso found, on calling at Athens, that Germanicus had been flattering the Greeks for their ancient culture, instead of pressing the dominion of Rome. He made free comments on the young general’s conduct, pushed past his galleys, as they dallied in Greek waters, and was hard at work in Syria when Germanicus arrived. The wives conducted the quarrel with more asperity than their husbands.