Title: Geofroy Tory

Author: Auguste Bernard

Translator: George Burnham Ives

Release date: October 21, 2019 [eBook #60542]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Jane Robins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

PAINTER AND ENGRAVER: FIRST ROYAL PRINTER: REFORMER OF ORTHOGRAPHY AND TYPOGRAPHY UNDER FRANÇOIS I.

AN ACCOUNT OF HIS LIFE AND WORKS, BY AUGUSTE BERNARD, TRANSLATED BY GEORGE B. IVES.

THE RIVERSIDE PRESS: MDCCCCIX

ERNARD'S monograph on Tory was first

published in 1857, when M. Bernard was

already a recognized authority on the history

of typography. In 1865, after an interval

devoted largely to a search for further

information concerning Tory, and for probable

examples of his work as an artist, a

second edition of the book appeared, enlarged

by more than one-half, arranged more systematically,

and embellished with several

additional engravings of designs which are, in the author's opinion, attributable

to Tory. The Iconography, which forms the third part of this

revised edition, did not appear as such in the first edition, although a

small part of the material it contains may be found scattered through

that edition. It now occupies more space than the Biography and Bibliography

combined. The new arrangement necessitated more or less repetition

where, as in many instances, the same book is referred to by M.

Bernard in more than one section of his work; and this repetition sometimes

reveals discrepancies between the different descriptions. Where

such discrepancies have been discovered by him the translator has endeavoured

to correct them, generally, in the absence of an opportunity

to inspect the volume in question, assuming that the description in the

bibliographical section is more likely to be trustworthy; in a number of

cases, however, inspection of title-pages themselves, or of reproductions

thereof, has enabled him to correct numerous minor errors in transcription.

ERNARD'S monograph on Tory was first

published in 1857, when M. Bernard was

already a recognized authority on the history

of typography. In 1865, after an interval

devoted largely to a search for further

information concerning Tory, and for probable

examples of his work as an artist, a

second edition of the book appeared, enlarged

by more than one-half, arranged more systematically,

and embellished with several

additional engravings of designs which are, in the author's opinion, attributable

to Tory. The Iconography, which forms the third part of this

revised edition, did not appear as such in the first edition, although a

small part of the material it contains may be found scattered through

that edition. It now occupies more space than the Biography and Bibliography

combined. The new arrangement necessitated more or less repetition

where, as in many instances, the same book is referred to by M.

Bernard in more than one section of his work; and this repetition sometimes

reveals discrepancies between the different descriptions. Where

such discrepancies have been discovered by him the translator has endeavoured

to correct them, generally, in the absence of an opportunity

to inspect the volume in question, assuming that the description in the

bibliographical section is more likely to be trustworthy; in a number of

cases, however, inspection of title-pages themselves, or of reproductions

thereof, has enabled him to correct numerous minor errors in transcription.

The kindness of the late Mr. Amor L. Hollingsworth, in lending his fine copy of the first edition of 'Champ fleury,' made it possible to collate therewith M. Bernard's numerous extracts from that rare and interesting book, and to ensure entire accuracy with respect to them.

As M. Bernard writes certain printers' names in different ways, the translator has assumed that the names are printed differently in different books, and has not attempted to make them uniform. Such names are Dubois (Du Bois), Lecoq (Le Coq), Galliot (Galiot). The few notes supplied by the translator are inserted in square brackets.

The translations of Tory's various Latin effusions, including the complete text of the little brochure called forth by the death of his daughter Agnes, were made by Mr. J. W. H. Walden of Cambridge. The Latin originals will be found at the end of the book, in Appendix X.

Since such authorities as M. Bernard and M. Renouvier differ as to the ascription to Tory of many of the designs mentioned in this work, it seemed the wiser course to choose for illustration only such subjects as are described by the author, without questioning the soundness of his reasoning or the infallibility of his deductions. The only exception is the beautiful design reproduced on the first page of the Index. This is taken from Robert Estienne's folio New Testament (in Greek) of 1550, where, with two other similar decorations, it occurs in conjunction with the friezes and floriated Greek letters reproduced elsewhere in this volume. They are unsigned, but all are indubitably from the same hand. Although they are not mentioned by M. Bernard, it seems incredible that he should never have seen them.

The printer of this volume has had more than ordinary good fortune in literally stumbling upon most of the designs here reproduced. The pressure of other work has prohibited systematic research, and the originals of these illustrations were nearly all discovered while he was engaged upon other matters. Many were found in the Harvard Library, some in the reference library of the Riverside Press, some in auction rooms, and some in booksellers' catalogues. The only exception is the series of borders from the Hours of 1524-25, which were expressly photographed from the copy in the library of the British Museum.

That so much has come to hand in so haphazard a way is but an additional proof of Tory's industry and versatility. There seems to be almost no limit to the work which may fairly be credited to him, and M. Bernard hardly exaggerated when he said that there was scarcely an illustrated volume of any importance issued in Paris during the first half of the XVI th century in which the artist of the Lorraine cross did not have a hand. Hours and Classics, Bibles and Testaments, Mathematical and Medical works—all bear evidence to his prolific pen and graver, and were time disregarded, the preparation of this volume might be almost indefinitely prolonged. Incomplete as it is, however, it is hoped that it will measurably fulfill the desire expressed by Mr. A. W. Pollard nearly fifteen years ago, in the first issue of 'Bibliographica.' Speaking of Bernard's monograph, he said, 'It would be pleasant if some French publisher would bring out a new edition worthily illustrated, for in 1865 the modern processes of reproduction were not yet invented, and the few and poor woodcuts in M. Bernard's book give no just idea of the artistic powers of Tory, whose illustrated editions are so difficult to meet with that M. Bernard's admirable commentary loses half its value for lack of a proper accompaniment of text.'

A word regarding the method of reproduction of these illustrations may not be out of place here. More was aimed at than mere photographic copies, which are in many ways inadequate. It was thought desirable to make the decorations an integral part of the typographic treatment of the volume and to preserve when practicable their original relations to the type. To attain this end, more perfect printing plates were necessary than could be obtained directly from the old editions. The designs, therefore, were all redrawn with the greatest care over photographs of the originals, and from these drawings photo-engravings made, which were afterward perfected by hand when the forms were on the press.

Notwithstanding some inevitable slight divergences of line, this method preserves with far greater faithfulness the spirit and effect of the original prints, and the result is more truly a facsimile than a direct photographic copy would have been. Both drawing and engraving of Tory's designs were exquisite, and as a rule they were beautifully printed, especially by Colines and Robert Estienne. Some of them, however, suffered at the hands of inferior printers. Imperfections and irregularities due to the carelessness or unskilfullness of the printer are readily discernible, and in the reproductions in this volume have been eliminated. The preservation, by this treatment, of more of the beauty and interest of the originals is sufficient justification for departing to this extent from the usual methods of facsimile reproduction.

Following the French fashion, the Table of Contents and List of Illustrations are printed at the end of the volume.

G. B. I.

B. R.

January, 1909.

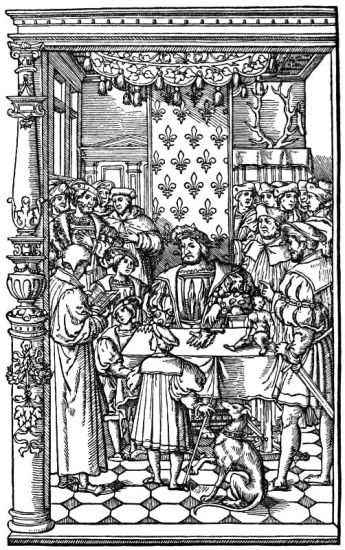

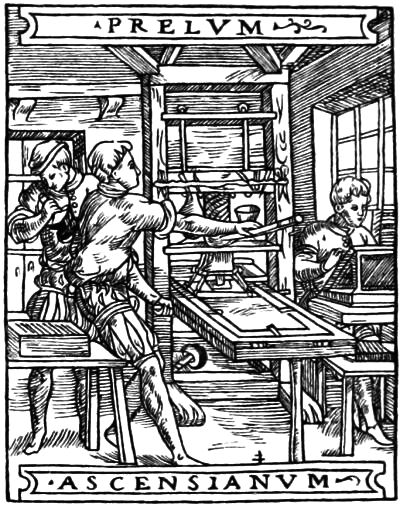

HE first half of the

sixteenth century was

with respect to printing

(as with respect to

the other arts) a period

of renovation, not in

the matter of processes

of execution, which remained about the

same as in the fifteenth century, but in the

matter of the make-up of books, which was

entirely revolutionized. Typographical arrangement,

appearance of the letters and

ornaments, everything, even to the cover,

was changed almost at the same time, or, at

all events, within a very few years. At that

time printing gave over the servile copying

of manuscripts, which had at first served it

as models, and adopted special rules, better

adapted to its method of execution. For instance,

it relegated notes to the foot of the

pages, calling attention to them by marks of

reference, instead of placing them at the

side of the text, as had previously been the

custom, at the cost of an enormous amount

of labour, without benefit to the reader. It

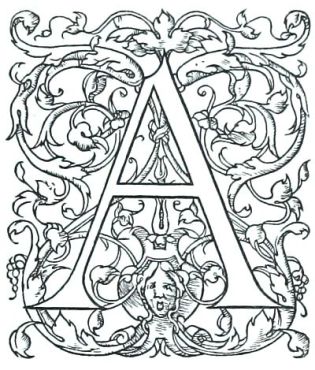

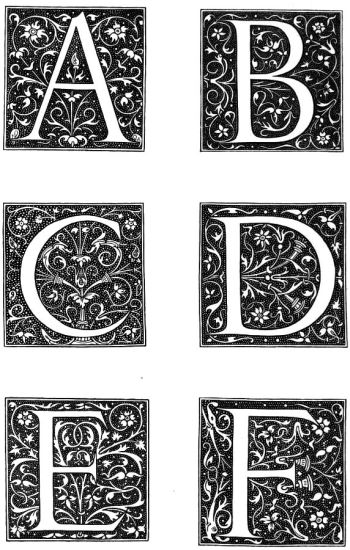

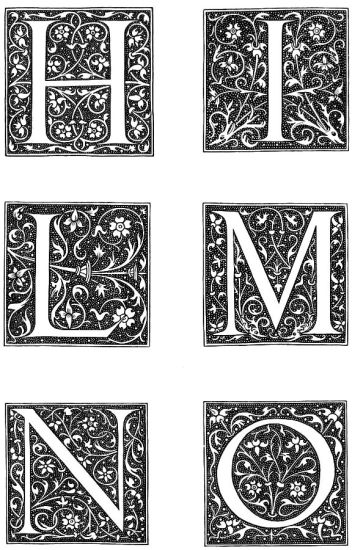

also abandoned the use of red capitals,[1]

which, by increasing the labour twofold,

made books expensive, and replaced them

by floriated letters, which were quite as distinctive,

but were set up and printed with

the text. This style of ornament, so favourable

to artistic results, developed rapidly,

and soon extended from the letters to the

illustrations, which began to be introduced

in books in constantly increasing numbers.

Under the general impulsion of the Renaissance,

engraving was transformed: instead

of the coarse woodcuts, of the so-called criblé

style, in which the background was black

sprinkled with white dots,[2] and the design

stamped in white, as with a punch, engraving in relief came into

vogue, just as we have it to-day, identical in

form, although the processes have been perfected. A similar revolution

took place in the matter of letters: the gothic or semi-gothic characters,

which had hitherto been used, were replaced by roman characters of a novel

shape, borrowed from the monuments of antiquity (then studied with great

ardour), which continued in use until the Revolution. Lastly, the covers

of books also underwent a transformation brought about by the force of

events: the parchment rolls used by the ancients had been succeeded,

during the Middle Ages, by bound volumes, of a shape more convenient

for reading; these volumes, of which those who were fortunate enough to

own any never owned more than a very small number, being intended to be

arranged on the library shelves in such wise as to present one side to

the visitor's eye, were adorned with numerous ornaments of various sorts

on that side, so that they could easily be distinguished.

Later, these ornaments were omitted and the title of the book substituted,

in huge black or gauffered letters. But the invention of printing soon

caused that device to be abandoned. As the increasing numbers of books

made it impossible to give up so much space to them, they were arranged

side by side on the shelves, care being taken to print the title in gold

letters (so that it might be more legible) on the back of the book, which

was the only part of it in sight. This innovation compelled the doing away

with raised decorations, especially those in precious stones or in metal,

which would have torn the books that stood next them. Thereafter leather

binding came into general use; the gauffering on the sides was continued

for some time; but in the sixteenth century this in turn was replaced by

gold tooling 'à filet,' and the transformation was complete.

HE first half of the

sixteenth century was

with respect to printing

(as with respect to

the other arts) a period

of renovation, not in

the matter of processes

of execution, which remained about the

same as in the fifteenth century, but in the

matter of the make-up of books, which was

entirely revolutionized. Typographical arrangement,

appearance of the letters and

ornaments, everything, even to the cover,

was changed almost at the same time, or, at

all events, within a very few years. At that

time printing gave over the servile copying

of manuscripts, which had at first served it

as models, and adopted special rules, better

adapted to its method of execution. For instance,

it relegated notes to the foot of the

pages, calling attention to them by marks of

reference, instead of placing them at the

side of the text, as had previously been the

custom, at the cost of an enormous amount

of labour, without benefit to the reader. It

also abandoned the use of red capitals,[1]

which, by increasing the labour twofold,

made books expensive, and replaced them

by floriated letters, which were quite as distinctive,

but were set up and printed with

the text. This style of ornament, so favourable

to artistic results, developed rapidly,

and soon extended from the letters to the

illustrations, which began to be introduced

in books in constantly increasing numbers.

Under the general impulsion of the Renaissance,

engraving was transformed: instead

of the coarse woodcuts, of the so-called criblé

style, in which the background was black

sprinkled with white dots,[2] and the design

stamped in white, as with a punch, engraving in relief came into

vogue, just as we have it to-day, identical in

form, although the processes have been perfected. A similar revolution

took place in the matter of letters: the gothic or semi-gothic characters,

which had hitherto been used, were replaced by roman characters of a novel

shape, borrowed from the monuments of antiquity (then studied with great

ardour), which continued in use until the Revolution. Lastly, the covers

of books also underwent a transformation brought about by the force of

events: the parchment rolls used by the ancients had been succeeded,

during the Middle Ages, by bound volumes, of a shape more convenient

for reading; these volumes, of which those who were fortunate enough to

own any never owned more than a very small number, being intended to be

arranged on the library shelves in such wise as to present one side to

the visitor's eye, were adorned with numerous ornaments of various sorts

on that side, so that they could easily be distinguished.

Later, these ornaments were omitted and the title of the book substituted,

in huge black or gauffered letters. But the invention of printing soon

caused that device to be abandoned. As the increasing numbers of books

made it impossible to give up so much space to them, they were arranged

side by side on the shelves, care being taken to print the title in gold

letters (so that it might be more legible) on the back of the book, which

was the only part of it in sight. This innovation compelled the doing away

with raised decorations, especially those in precious stones or in metal,

which would have torn the books that stood next them. Thereafter leather

binding came into general use; the gauffering on the sides was continued

for some time; but in the sixteenth century this in turn was replaced by

gold tooling 'à filet,' and the transformation was complete.

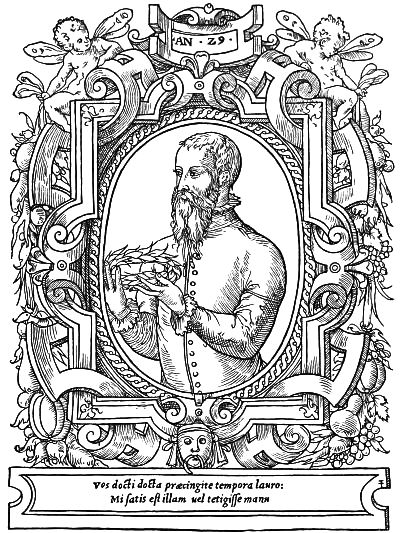

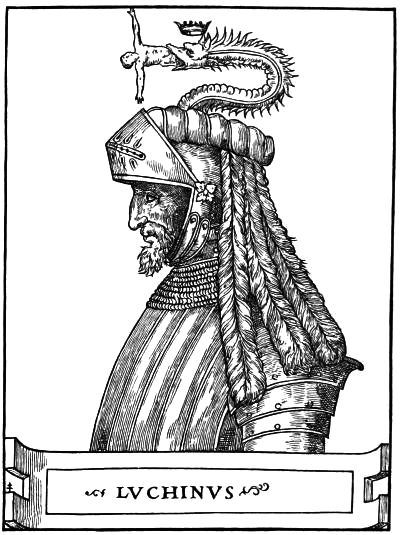

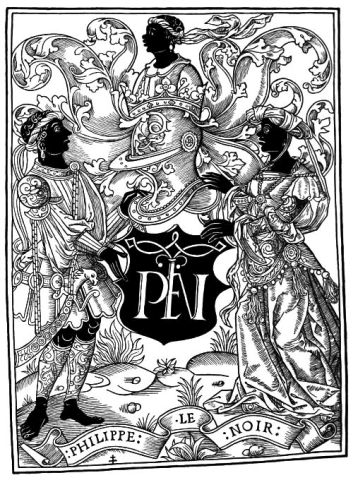

THE man who contributed most largely to the threefold evolution I have described was Geofroy Tory, a man who is hardly known to-day,[3] despite all his talents, although he received in 1530, as reward of his labours, the title of king's printer, which François I had never before bestowed upon any one. I say that Tory is hardly known to-day; in truth, it is, in his case, equivalent to being unknown, to be known, as he is, only as a publisher. Some few scholars, to be sure, are aware that he was a printer; but the fact is so little known that his biographer has denied it.[4] As for his noblest title to fame, that of engraver, nobody is aware of it; and yet we owe to Tory the resuscitation of engraving in France. As the historian of typography,[5] I have thought that it was for me to describe with special care one of the fairest jewels in his crown. Such is the purpose of the work here presented, wherein will also be found, in connection with the honour paid to Tory by François I, some information concerning the first royal printers, and a list of those officers from the beginning down to the extinction of the office in 1830, three centuries, year for year, after its creation. François I is, in truth, entitled to be considered the creator of the office of king's printer, for prior to his reign we find but one typographer who bore that title, while, from François I down, the series of king's printers was not again interrupted. The appointment of Pierre le Rouge, on whom the title was bestowed in 1488,[6] may be creditable to Charles VIII, but it was without result. The honour of having made of the eminently literary post of king's printer a permanent office reverts of right and naturally to the prince who has been called the Father of Letters. In truth that prince, as we shall see hereafter, was not content with a single printer; he had several at once, with distinct functions, and appointed successors without loss of time to such as retired or died during his lifetime.

But, I repeat, the principal purpose of my work is to make Tory known as one of the most skilful engravers we have ever had. Of course I cannot forget that he was the learned editor of the 'Cosmographie du Pape Pie II,' the 'Itinéraire Antonin,' etc.; the publisher, of rare taste, who put forth the Hours of 1525, 1527, etc.; the accomplished printer of the 'Sacre de la Reine Eléonore,' and the distinguished philologist of 'Champ fleury,' to whom, as we shall see, we owe the invention of the orthographic forms peculiar to the French language.[7] But what has especially attracted me in Tory is his work as an engraver. In that rôle he was without predecessor or rival, for those persons who may be represented as such may have been his pupils, nothing more. Jean Duvet alone might quarrel with this limitation; but, although he was Tory's contemporary, he was not his teacher; for Tory had gone for his schooling in the art to the very fountain-head, to Italy, before Duvet produced anything. As for Jean Cousin, de Laulne, du Cerceau, Léonard Gauthier, and the rest, they did not come until after Tory. The honour of revivifying the art of engraving in France belongs to Tory alone, bestriding two centuries, the fifteenth and sixteenth; indeed, some of his productions are pure gothic. This I propose to demonstrate in the third part of my book, after I have, in the first part, narrated the general facts of our artist's life, in which we may observe also the development of a revolution in the matter of philology; for Tory was a devoted partisan of the classic tongues before he became one of the sturdiest champions of the French language.

In order to emphasize the importance of the orthographic reform achieved by Tory, I have usually followed the orthography of the time in my quotations from ancient works. It is an anachronism, to be sure, but it is of no consequence when the reader is forewarned. I have also felt at liberty to correct now and then, without calling attention to them, the typographical errors found in the texts quoted.

I will not conclude without thanking publicly those persons who have kindly assisted me in my researches concerning Tory. I have had occasion to mention their names in the course of my work, but that is not enough: I beg them to accept in this place the assurance of my gratitude. There are two to whom I am especially grateful, for they have considerably augmented my store of documents: they are MM. Achille Devéria[8] and Olivier Barbier, of the Bibliothèque Impériale: it is owing to their kind communications to me that the list of Tory's artistic works will be found not far from complete.

PAINTER AND ENGRAVER: FIRST ROYAL PRINTER: REFORMER OF ORTHOGRAPHY AND TYPOGRAPHY UNDER FRANÇOIS I.

PART I. BIOGRAPHY.

ESS than twenty years after the introduction

of printing at Paris, there was born

at Bourges a child of the people, destined

to impart to French typography a vigorous

artistic impulsion, or, to speak more

accurately, to work therein a genuine

revolution. Geofroy Tory[9] was born in the

capital of Berry, about 1480, of obscure,

middle-class parents, as he himself tells

us.[10] Everything seems to indicate that he

first saw the light of day in the faubourg of Saint-Privé, to this day the

abode of humble vine-dressers. How, in that most lowly condition of

life, he succeeded in acquiring the degree of education which he afterward

exhibited, it is hard to say. However, it is proper to remember that

Bourges was at that time a metropolitan and university city, where there

were several schools, both ecclesiastic and lay. We may well believe

that, having, at an early age, aroused the interest of some patron by

virtue of his fortunate natural endowments and his intelligence, he was

admitted to the schools attached to the chapter, where he learned the

first elements of grammar. We shall soon find him dedicating the first

fruits of his labours to a canon of the metropolitan church of Bourges,

who seems to have been, at that time, his Mæcenas.

ESS than twenty years after the introduction

of printing at Paris, there was born

at Bourges a child of the people, destined

to impart to French typography a vigorous

artistic impulsion, or, to speak more

accurately, to work therein a genuine

revolution. Geofroy Tory[9] was born in the

capital of Berry, about 1480, of obscure,

middle-class parents, as he himself tells

us.[10] Everything seems to indicate that he

first saw the light of day in the faubourg of Saint-Privé, to this day the

abode of humble vine-dressers. How, in that most lowly condition of

life, he succeeded in acquiring the degree of education which he afterward

exhibited, it is hard to say. However, it is proper to remember that

Bourges was at that time a metropolitan and university city, where there

were several schools, both ecclesiastic and lay. We may well believe

that, having, at an early age, aroused the interest of some patron by

virtue of his fortunate natural endowments and his intelligence, he was

admitted to the schools attached to the chapter, where he learned the

first elements of grammar. We shall soon find him dedicating the first

fruits of his labours to a canon of the metropolitan church of Bourges,

who seems to have been, at that time, his Mæcenas.

Once master of the first rudiments of grammar, Tory perfected himself by following the curriculum of the university, where, as we learn from himself, he had for his teacher a Fleming named Guillaume de [2]Ricke, otherwise called 'le Riche' in French and 'Dives' in Latin; and for a fellow disciple under this Ghent-born master, a certain Herverus de Berna, from Saint-Amand, who afterward wrote a panegyric of the Comtes de Nevers.[11]

Tory then went, to finish his literary education, to Italy, whither he betook himself early in the sixteenth century. He sojourned principally in Rome, where he attended most frequently the famous college called La Sapienza,[12] and in Bologna, where he attended the lectures of the celebrated Filippo Beroaldo, who died in 1505.[13] Tory returned to France a little before that event, and established his domicile in Paris, which he always loved henceforward as one loves one's native city,[14] and where he began his literary career.

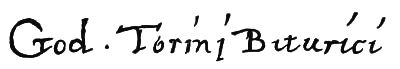

The first work of his of which we have any knowledge is an edition of Pomponius Mela, which he prepared for the bookseller Jean Petit; it was printed by Gilles de Gourmont because it required the use of some Greek type.[15] This book was dedicated by Tory to his compatriot Philibert Babou, at that time valet de chambre to the king. The dedicatory epistle is dated Paris, the VI[16] of the Nones of December, 1507; but the printing of the book was not completed until January 10, 1508 (new style).[17] Several articles in this volume, which were written by Tory, are signed by the word CIVIS, which he had adopted for his device. That patriotic designation was well suited to a descendant of those Bituriges who strove vainly at Avaricum[18] to defend the autonomy of Gaul against Cæsar. In any event it is interesting to find, three hundred years before Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a man, justly proud of his learning, which he owed entirely to himself, clothing himself in that title of citizen, which was formerly held in such honour in the provincial cities, and especially in Bourges, whose name Tory never fails to append to his own: 'Geofroy Tory de Bourges.'

This erudite production and the patronage of Philibert Babou were perhaps responsible for Tory's appointment to the office of regent, otherwise[3] called professor, of the College of Plessis, where we find him installed in 1509. It was there that he edited for the first Henri Estienne the 'Cosmographie du pape Pie II.'[19]

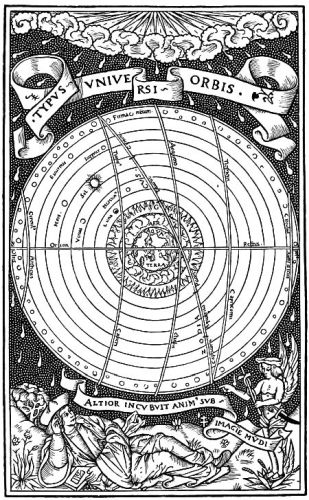

The dedication of this book, addressed by Tory to Germain de Gannay, canon of the metropolitan church of Bourges, and recently appointed Bishop of Cahors by King Louis XII,[20] was dated at the College of Plessis, on the VI of the Nones of October,[21] 1509. Tory's edition (the third according to him) contains forty-one quarto sheets of text, and is accompanied by a map of the old world. The 'avis au lecteur,' also written by Tory, is signed, according to his custom, with the word CIVIS. In the following year, in collaboration with a compatriot and fellow pupil, Herverus de Berna, Tory published a short Latin poem on the Passion, written by his former teacher, Guillaume de Ricke. In this wise he acquitted his debt of gratitude.[22] Shortly after, Tory published for the Marnef brothers an edition of Berosus, who was then much in vogue, thanks to the fabrications of Annius of Viterbo. This book, the preface of which is dated May 9, 1510, went to no less than three editions, to say nothing of those issued by other publishers.[23]

In the same year Tory published for the same booksellers a small volume of miscellanies, under this title: 'Valerii Probi grammatici de interpretandis Romanorum literis opusculum, cum aliis quibusdam scitu dignissimis.' It was probably printed by Gilles de Gourmont, for we find in it his unaccented Greek type.[24] This volume, which contains twelve octavo sheets, has two engravings on wood—the mark of the booksellers on the title-page, and a Roman portico a little farther on. There are also a few small cuts engraved on metal in one of the articles. The dedicatory epistle, dated at the College of Plessis the VI of the Ides of May (May 10), 1510, and addressed by Tory to two compatriots, who had probably been his fellow pupils, is signed by his device, the word CIVIS. The dedication begins thus: 'Godofredus Torinus Bituricus ornatissimos Philibertum Baboum et Ioannem Alemanum Iuniorem, cives Bituricos,[4] pari inter se amicitia conjunctissimos, salutat.' Babou and Lallemant were at this time two important personages in Bourges: the former was secretary and silversmith to the king, the other, mayor of the city. We see that Tory had acquired valuable connections in his native place, despite his modest origin. Among the extracts from ancient authors in this book he interspersed several pieces of verse of his own composition.[25]

Finally, in the same year, Tory issued an edition of Quintilian's 'Institutiones,' carefully collated by him with several manuscripts. This work was undertaken at the request of Jean Rousselet, Seigneur de La Part-Dieu, near Lyon, and an ancestor of Château-Regnaud, Maréchal de France. This Rousselet, who died in 1520, belonged to one of the wealthy Lombard families which had settled at Lyon long before; they made, as we see, a noble use of their wealth. His real name was Ruccelli. He had married a young gentlewoman of Bourges, Jeanne Lallemant, daughter of Jean Lallemant, Seigneur de Marmagne, a school friend of Tory, whom I have already had occasion to mention. Doubtless it was this connection which brought Tory into relations with Rousselet. The text is preceded by the following dedicatory letter:

Geofroy Tory of Bourges to Jean Rousselet, devoted lover of letters, long life and happiness.

Never, I think, most illustrious Jean, will you omit or cease to have the aspiration of nobly justifying, both by your character and by your good deeds, the great hopes which your relatives and your country have of you. That you might benefit the State by your counsel also, you made it your interest that I should emend Quintilian and have him printed as handsomely as might be. After carefully collating a large number of manuscripts, I industriously set to work and, by eliminating almost countless errors, I made a single manuscript of considerable accuracy. This, in accordance with your orders, I sent from Paris to Lyon. I only hope that the printers will not introduce other, new, errors. Farewell, and love me.

Paris, at the College of Plessis, the third of the Calends of March.[26]

This book, which forms a large octavo volume, unpaged, printed in italic type, and in which we find some most attractive Greek type, with accents, was finished on the VII of the Calends of July (that is to say, June 25), 1510. The printer's name does not anywhere appear, and the place of printing (Lyon) is mentioned only in Tory's letter.[27]

I know of nothing of Tory's dated in 1511[28]; but that does not prove that he produced nothing in that year, for it is certain that about that time he published several works which have not come down to us. In fact, he tells us in his 'Champ fleury'[29] that he has 'caused to be printed and put before the eyes of worthy scholars divers little works in Latin, both in verse and in prose.' Now we know of nothing of his in verse prior to 1524, except what we find at the end of the 'Valerius Probus' of 1510, and of Guillaume de Ricke's 'Passion.' Moreover, the absence of any publication by Tory in 1511 may be explained by the confusion incident to his retirement from the College of Plessis and his installation at the College Coqueret, which seems to have taken place in that year, but concerning which I have no other information than the imprint on two books published by him in the following year.

The first work edited by Tory in 1512 was an architectural treatise entitled: 'Leonis Baptistæ Alberti Florentini.—Libri de re ædificatoria decem,' etc.; a quarto volume of 14 preliminary leaves and 174 leaves of text. This book was printed by Berthold Rembolt (whose mark it bears on the first page), at the joint expense of that printer and the bookseller Louis Hornken, whose mark is at the end of the book. The dedication, which is addressed to Philibert Babou, and dated at the College Coqueret on the XV of the Calends of September (August 18), 1512, informs us that Tory received the manuscript of the book from his friend Robert Dure,[30] principal of the College of Plessis, who gave it to him four years earlier, when Tory himself was professor at the same college. As always, this dedication is signed CIVIS. A note on the last page but one informs us that the printing was finished on August 23, 1512.[31]

The second work put forth by Tory in 1512 was the 'Itinerarium Antonini.' It was the second book that he prepared for Henri Estienne, in whose establishment it has been said[32] (erroneously, I think) that he filled the post of corrector of the press. However that may be, the dedication, addressed by Tory to Philibert Babou, is dated at the College Coqueret [6]the XIV of the Calends of September (August 19), 1512. Tory says to Babou that he had dispatched a copy of the manuscript of this book to him at Tours four years before (that is to say, in 1508), but that the person to whom it was entrusted for delivery to him had given it, in his own name, to somebody else. This time, in order not to be defrauded of the fruits of his labours, he had caused the work to be printed from his own copy, having carefully collated it with a manuscript lent him by Christophe de Longueil.[33] The volume is a sexto-decimo, remarkable for the beauty of its execution. The copy in vellum which I have seen at the Bibliothèque Nationale is still redolent of the fifteenth century. We find in it certain verses of the Burgundian Gérard de Vercel in honour of Tory, which prove that the latter was even then in some repute as a scholar, and as a printer, too; for the author contrasts him with the wretched printers of the day. The preliminary matter, by Geofroy Tory, is signed by the word CIVIS, printed in red. At the end of the volume the same word reappears in a very curious monogram composed of the letters CIVS so arranged that we can read the word CIVIS in all directions. Therein we may detect thus early Tory's taste for ciphers and devices, a taste to which he afterward gave free rein, in his 'Champ fleury.'

At this epoch occurs a momentous event in Geofroy Tory's life. On August 26, 1512, he became the father of a daughter, who was christened Agnes. I do not know the date of his marriage, but it was at least as early as 1511. A document of much later date, to which we shall have occasion to refer hereafter, informs us that his child's mother was named Perrette le Hullin. There is reason to believe that she, like her husband, was of Bourges, as the name of Hullin was common there at that time. Soon after the birth of Agnes, perhaps just at the opening of the term of 1512, Tory entered the College of Bourgogne as regent, or professor of philosophy. His lectures, which were continued for several years, were attended by a large number of hearers, if we may believe a poetical epitaph composed in laudation of him and published by La Caille.[34] Tory [7]himself seems to refer to this professorship in his 'Champ fleury,'[35] but I have been unable to find any record of it, because, presumably, the new direction in which he was then turning his faculties required a certain time of preparation.

This is what happened: Tory, whose activity was very great, did not confine himself to his professorship,[36] but set about learning drawing (probably under the instruction of Jean Perreal, of whom I shall have occasion to speak again), and also engraving, for which he had a special bent. This apprenticeship, with the duties of his professor's chair,—for Tory drove art and philosophy side by side, as the epitaph just quoted has it ('philosophiam simulque artem exercuit typographicam'),[37]—engrossed him completely for three or four years; but at the end of that time, being far from content with his attempts at printing and engraving, or too enthusiastic to be satisfied with a partial result, he determined to study classic forms and outlines in Italy itself, of which country he had retained such agreeable memories that he speaks of it constantly. Consequently he abandoned his professorship and started south again. It was on this journey that he visited the Coliseum 'more than a thousand times,'[38] that he saw the theatre of Orange,[39] and the ancient monuments of Languedoc[40] and of other places in France and Italy,[41] which he cites as his authorities on every page of his 'Champ fleury.'

Tory does not give the precise date of this artistic journey; but it is established by a passage in his book, where he informs us that he saw the 'Epitaphs of Ancient Rome' printed in that city.[42] Now this book of Epitaphs can be no other than the collection published by the celebrated printer Mazochi, under the title: 'Epigrammata sive inscriptiones antiquæ urbis,' folio, dated 1516, but preceded by a license from the Pope, of 1517.[43] This hint of Tory's is doubly valuable to us, for it not[8] only tells us the date of our artist's second journey to Italy, but reveals his predilection for typography. As we see, he was already studying the printing art with interest.

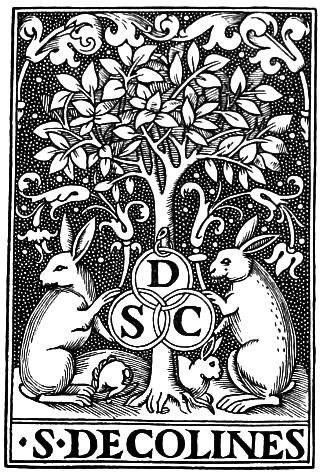

On his return to Paris, about 1518, Tory, who was not a wealthy man, was obliged to think about turning his talents to account, in order to earn his living. His principal resource seems to have been the painting of manuscripts, otherwise called miniature; but, whether because he did not find sufficient work of that sort, or because he considered another branch of art more useful, he soon gave his entire attention to engraving on wood, in which he speedily acquired considerable celebrity. About the same time, Tory also joined the fraternity of booksellers, following a custom then quite general among engravers,—a custom which their predecessors, the miniaturists, had handed down to them, and which was continued down to the eighteenth century.[44] In truth, it was not unnatural that those who decorated books should sell them, or, if you prefer, that those who sold them should decorate them. It was one way of earning more money. Desiring to signalize his début in the career of a bibliopole in a noteworthy way, Tory undertook to engrave for himself a series of borders 'à l'antique,' which he intended for a book of Hours,—a sort of book that was very profitable at that time, because of the great amount of work which it required; but the task was a long one, and he was obliged to work for different printers in the mean time. One of the first who employed him was Simon de Colines. Colines, who became a printer in 1520, as a result of his marriage to Henri Estienne's widow, commissioned Tory to design marks, floriated letters, and borders for the books that he published in his own name; he also entrusted him, I think, with the engraving of his italic type, which he soon began to use in conjunction with the roman type that he had from his predecessor.

But Tory's active mind could not be content with a single occupation. He was a patriot first of all, as his device proves. And so, far from allowing himself to be engrossed by his memories of the literary and artistic[9] treasures of Italy, he began to study with ardour the monuments of his mother tongue, not only in those books printed in French—very few as yet—which he had at hand in his shop, but also, and especially, in divers fine manuscripts on parchment confided to him by 'his good friend and brother, René Massé, of Vendôme, chronicler to the king,' whose merits, entirely forgotten in our day,[45] he warmly extols.[46]

Now, while studying that same French tongue, so decried by the scholars of his time, Tory discovered therein beauties which required only a little cultivation to make of it the finest language in the world. From that moment our Berrichon, hitherto a partisan of the classics, shook off entirely the yoke of Greek and Latin, and thought only of the means of making French take precedence everywhere.

'I see,' he says, 'some who choose to write in Greek and in Latin, and yet cannot speak French well.... To me it seems, with submission, that it would better beseem a Frenchman to write in French than in another tongue, as well for the profit of his said French tongue, as to adorn his nation and enrich his native language, which is as fair and fine [belle et bonne] as another when it is well set down in writing.... When I see a Frenchman write in Greek or in Latin, I seem to see a mason clad in philosopher's or king's garb, who would fain recite a mask on the stage of La Baroche[47] or in the confraternity of La Trinité, and cannot pronounce well enough, as having too thick a tongue; cannot bear himself well, nor walk fittingly, insomuch as his legs and feet are unwonted to the gait of philosopher or king. Who should see a Frenchman clad in the native dress of a Lombard, which is most often long and scant, of blue linen or of buckram, methinks that Frenchman would scarce jest at his ease without soon slashing it and taking from it its true form as a Lombard dress, which is but very rarely slashed, for Lombards do not often work havoc with their belongings. However, I leave all this to the wise guidance of learned men, and will not burden myself with Greek or Latin save to cite them in due time and place, or to talk with such as cannot speak French.'[48]

Tory had found his vocation at last. He resolved to establish the superiority of his mother tongue in a special book, illustrated by engravings by his own hand, and intended particularly for printers and booksellers, who were in a position to distribute it so rapidly with the aid of their connections.

But while he was engaged in his studies, a terrible catastrophe fell upon him without warning, and caused him to forget his new projects for some time. His daughter Agnes, of whom he had conceived the most brilliant hopes, was taken from him on August 25, 1522, at the age of nine years eleven months and thirty days, that is to say, ten years less one day. Entirely absorbed by his grief, Tory wrote a short Latin poem upon the sad event. This poem, dedicated, like most of his other books, to Philibert Babou, was not published until February 15, 1523 (1524, new style). In this little work, consisting of two quarto sheets, are contained some most interesting details of Tory's life. We learn here, for example, that he had grounded his daughter Agnes, young as she was, in Latin and the fine arts.

'Desiring to instruct me in the Ausonian tongue, and also to render me accomplished in the polite arts, he, like a most affectionate father, teaching me night and day, himself laid the foundations, sweet and ample, for my life.'[49]

Farther on, he makes his daughter speak thus, from the depths of the urn in which she is supposed to repose:—

MONITOR

Who made for you this urn set with brilliant gems?

AGNES

Who? My father, famed in this art.

MONITOR

Your father is certainly an excellent potter.

AGNES

He practises industriously every day the liberal arts.

MONITOR

Does he also write melodies and poems?

AGNES

He does. He also blesses with sweet words this lot of mine.

MONITOR

Yes, the skill of the man is wonderful.

AGNES

Hardly has any land produced so famous a man.[50]

We learn from this that Tory was not only a scholar, which we already knew, but an artist of great merit. Who knows? it may be that we had in him the making of a Benvenuto Cellini. What more was necessary that he [11]should reveal himself as such? Very little—perhaps the falling in with a wealthy Mæcenas. In fact, we find these lines in another piece of verse in the same collection:—

WAYFARER

He is certainly well deserving of some Mæcenas.

GENIUS

Few are the Mæcenases who live in the French world. No one to-day either encourages the liberal arts by appropriate gifts or undertakes to encourage them in any way. Uprightness and fair virtue are in no esteem. So powerful is the sway of unhappy Avarice. Treachery, deceit, and vice are in the ascendant. Virtues are put in the background, and every form of wretched evil creeps abroad.

WAYFARER

What, therefore, does he who is trained by the charming Muses?

GENIUS

He takes pleasure in being able to live in his own house.

WAYFARER

He ought to go with hurried step to the courts of kings.

GENIUS

He does not care to, because he has a free heart. Your potentates sometimes take pleasure in looking at songs, but what then? They requite them with nods. Golden songs, drawn from the high heavens, they should reward with jewels and with pure gold. But, frivolous as they are, they instead foolishly give their grand gifts to fools, spendthrifts, and rogues.[51]

Alas! this depiction of the vices of society is not peculiar to the sixteenth century. The world is very old, and it changes little. If Tory were living in our day, it may be that he would use even darker colours; for, after all, he was appreciated in his own time, and perhaps he would die of hunger to-day. As we see, he was not fond of cooling his heels in the antechambers of the great, and lived peacefully in his own house; but honour came there to seek him. Unluckily it was a little late, as will appear hereafter.

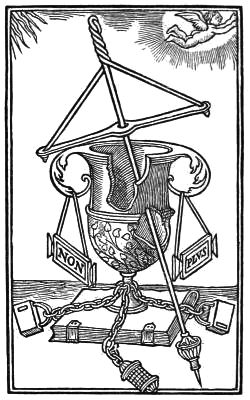

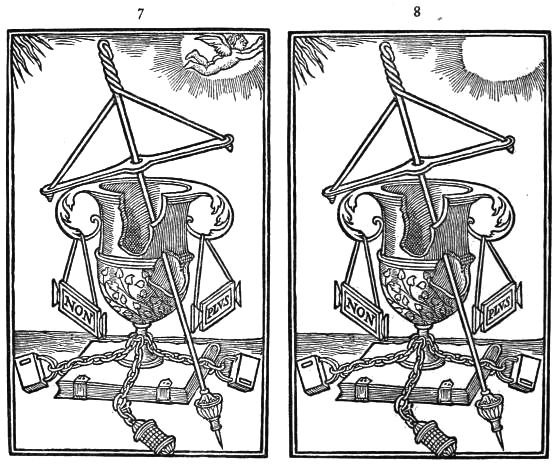

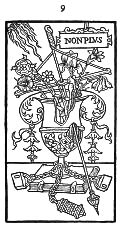

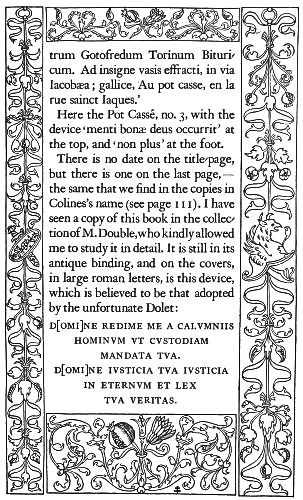

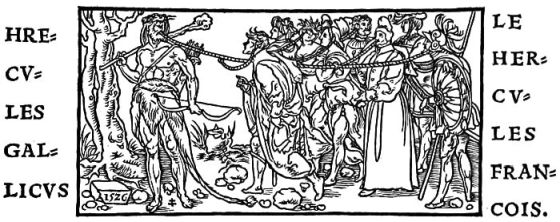

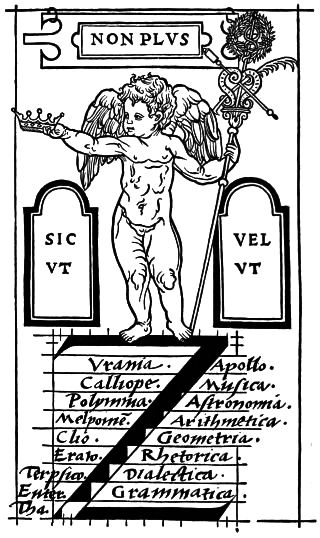

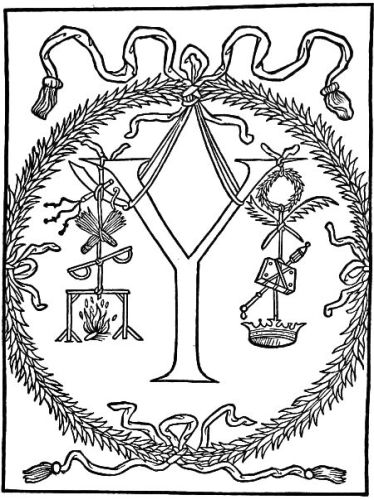

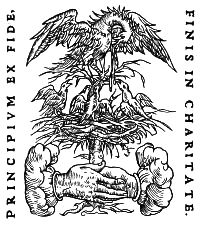

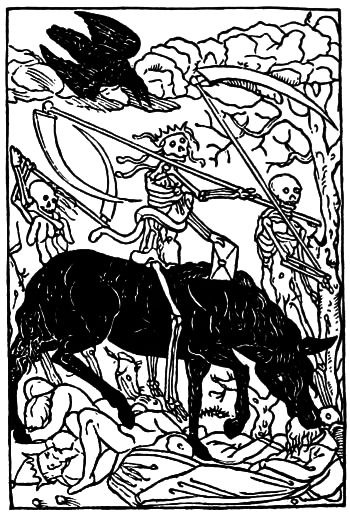

At the end of the poem is the design reproduced on the next page, wherein we see for the first time the famous 'Pot Cassé' [broken jar] which Tory adopted thenceforth as the mark of his bookshop; together with the device 'non plus,' which he used thereafter instead of the word 'civis.'

Tory subsequently offered, in his 'Champ fleury,' a very confused explanation of his Pot Cassé, doing his utmost to connect it with the ordinary events of life; but everything tends to prove that it owes its origin to the death of Agnes. This shattered antique vessel represents Tory's daughter, whose career was shattered by destiny at the age of ten. The book secured by padlocks suggests Agnes's literary studies; the little winged figure among the clouds is her soul flying up to heaven. The device 'non plus' suggests the desperate grief of Tory, who seems to say: 'I no longer [non plus] care for anything'; or, more laconically: 'There is nothing more for me'; after the example of Valentine of Milan when he found himself in a similar situation.[52]

Luckily, time, which deadens all sorrows, even those which seem likely to endure for ever, assuaged Tory's grief. Before his funeral poem saw the light, he had returned to his beloved studies, and they had restored tranquillity to his mind. This is proved by the following passage from his 'Champ fleury,' in which he tells us how, on January 6, 1523 (or 1524, according to our method of computing time), that is to say, eighteen months after he lost his daughter, the idea of that curious book came to his mind. We are glad to recognize once more therein the patriotic Berrichon who had taken for his device the word 'civis.'

'In the morning of the day of the feast of Kings,'[53] he says, '... which was reckoned M. D. XXIII, the fancy came to me to muse in my bed, and to move the wheel of my memory, thinking on a thousand petty conceits, both serious and merry, whereamong I bethought me of a letter of ancient form, which I not long since made for the house of my lord the treasurer of the wars, Maistre Jehan Groslier, counsellor and secretary to the king our sire, lover of goodly letters and of all learned persons, of whom also he is greatly beloved and esteemed, as well on this[13] side as the other of the mountains. And while thinking of that said antique letter there came of a sudden to my memory a pithy sentence of the first book and eighth chapter of Cicero's "Offices," where it is written: "Non nobis solum nati sumus, ortusque nostri partem patria vendicat, partem amici."[54] Which is to say, in substance, that we are not born into this world for ourselves alone, but to do service and pleasure to our friends and our country.'[55]

Such was the origin of 'Champ fleury.' Here follows the composition of that work, as the author himself gives it to us, in the form of a table of contents, at the beginning:[56]—

'This whole work is divided into three books.

'In the first book is contained the exhortation to establish and ordain the French language by fixed rule, and to speak elegantly, in good and soundest French.

'In the second is treated the invention of antique letters, and the proportionate coincidence thereof with the natural body and face of the perfect man. With several happy inventions and reflections upon the said antique letters.

'In the third and last book all the said antique letters, in their alphabetical order, are drawn and proportioned in height and width according to their proper formation and required articulation, both Latin and French, as well in the ancient as in the modern fashion.

'In two sheets at the end are added thirteen different sorts of letters, to-wit: Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French,—and these latter in four sorts, which are: "cadeaulx," "forme," "bastarde," and "torneure." Then follow the Persian, Arabic, African, Turkish, and Tartar letters, which have, all five, one and the same type of alphabet. After these are the Chaldaic, the "goffes," which are otherwise called "impériales et bullatiques," the "phantastiques" letters, the utopian letters, which one may call "voluntaires," and, lastly, the floriated letters.[57] With instructions for making[14] ciphers of letters for golden rings, for tapestries, stained-glass windows, paintings, and other things, as may seem best.'

I will say nothing here of the first book, the excellence of which has recently been pointed out by M. Génin,[58] who is much better versed in the subject than I, and who has at the same stroke exculpated the French from the charge that has been brought against them of having allowed themselves to be anticipated by foreigners in the careful study of their language. I will simply call attention to the fact that Tory wrote shortly before Rabelais, who did not hesitate to borrow from him his criticism of the 'skimmers of Latin,'[59] who were then changing the French language on the pretext of perfecting it. The harangue of the Limousin orator, which is found in the sixth chapter of the second book of 'Pantagruel,' is copied verbatim from Tory's epistle to the reader.[60] Rabelais has simply added to it some obscene reflections which did not enter our author's mind. Tory ends with a pathetic appeal to those who are interested in the mother tongue, whose excellence he is never tired of extolling. 'O ye devoted lovers of goodly letters!' he cries, 'God grant that some noble heart may give itself to the task of establishing and ordering our French tongue according to rule! By that means would many thousands of men set themselves to using often goodly words. If it is not established and ordered, we shall find that the French tongue will be in great part changed and ruined every fifty years.'[61] This patriotic prayer was soon granted. As we know, the sixteenth century did not lack great geniuses,[15] who set the French language in order and brought it to a great degree of perfection. Indeed, some most expressive words, the disuse of which Tory deplored,[63] reappeared. For instance, 'affaissé' and 'tourbillonner,' which in his time had been replaced by periphrases, returned into use; many others deserve the same honour and perhaps will receive it some day.

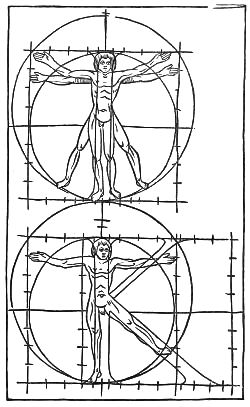

The second book of 'Champ fleury' is, I apprehend, only a paradox; but that paradox is maintained by arguments so ingenious, that one lacks courage to condemn it. Tory holds that the shapes of all the roman capital letters are derived from the different parts of the human body, which he looks upon as the type of the beautiful; and he makes a most admirable use of wood engraving to explain his idea. Moreover, if Tory was mistaken, we must acknowledge that he did not fall into the error inconsiderately. Indeed, I believe that he had for confederate his friend Perreal, to whom we may attribute the greater number of the designs on wood in the second book, judging from those in the third, which are directly attributed to him by Tory, as we shall see hereafter. However that may be, Tory seems to have studied his subject for a long time, not only on ancient monuments, but on modern ones as well, and in the works of contemporary authors who had turned their attention to the shapes of letters. His judgement of these latter is as follows:—

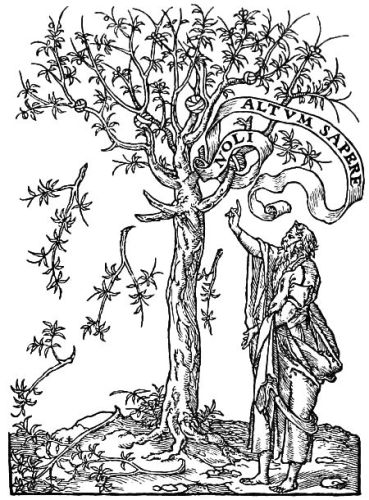

'Frère Lucas Paciol, of Bourg Saint Sepulchre, of the order of Frères Mineurs, and a theologian, who has written in popular Italian a book called "Divina proportione,"[64] and who has essayed to represent the said antique letters, does not give a true account of them nor explain them; and I am not surprised thereat, for I have heard from certain Italians that he stole his said letters and took them from the late Messere Leonard Vince [Leonardo da Vinci], who has of late died at Amboise, and was a most excellent philosopher and admirable painter, and as it were another Archimedes. This said Frère Lucas has caused his antique letters to be printed as his own. In sooth they may well be his, for he has not drawn them in their due proportions, as I shall show when I speak of said letters. Nor does Sigismunde Fante, a noble of Ferrara, who teaches how to write many kinds of letters, speak truly thereof.[65] Nor does Messere[16] Ludovico Vincentino.[66] I know not whether Albert Dürer writes justly thereof,[67] but none the less he goes astray in the due proportion of the figures of many letters, in his book on "Perspective."[68]... I see no man who makes them or understands them better than Maistre Simon Hayeneufve, otherwise called Maistre Simon du Mans. He makes them so well and in proper proportions, that he satisfies the eye as well and better than any Italian master on this side or the other of the mountains. He is most excellent in the restoration of ancient architecture, as one may see in a thousand excellent designs and portraits that he has made in the noble city of Mans and in many a foreign city. He is worthy to be held in honoured memory, as well for his upright life as for his noble learning. And to this end, let us not fail to consecrate and dedicate his name to immortality, naming him a second Vitruvius, a holy man and good Christian. I write this with good will because of the virtues and great praise "which I have heard said of him" by many great and humble good men and true lovers of all goodly and honest things.'[69]

The eulogistic tone in which Tory speaks here and elsewhere[70] of Simon Haieneuve leads M. Renouvier to think[71] that our artist may have learned the art of drawing letters from the Mans architect; but it is a mistaken supposition; the phrase in quotation marks proves that they had never met. Moreover Tory, a little further on, claims most reasonably the honour of having been his own master in this matter: 'I know no Greek, Latin nor French author who gives the explanation of such letters as I have described, wherefore I may hold it for my own, saying that I have excogitated and found it rather by divine inspiration than by anything written or heard. If there be any one who has seen it written, let him say so, and he will give me pleasure.'[72]

We see that Tory does not beat about the bush concerning his theory,[17] which, although it was different from those of his predecessors, was not on that account better than theirs.[73] However, let his opinion concerning the original design of the roman letters be what it may, it is, in my judgement, simply a sort of preface which we may pass over without inconvenience. The real substance of his work is in the third book. But he does not leave the second without returning once more to the charge in favour of his mother tongue.

'I know,' he says, 'that there are many goodly minds who would willingly write many excellent things if they thought they could write them well in Greek or Latin; and yet they abstain for fear of making solecisms or some other fault that they dread; or they choose not to write in French, thinking the French tongue not good nor elegant enough. With all respect to them, it is one of the most beauteous and graceful of all human tongues, as I have shown in the first book by the authority of noble and ancient authors, poets and orators, as well Latin as Greek.'[74]

To be accurate, I will say that this idea of the 'preëxcellence of the French tongue,' which, a little later, was the subject of another special work on the part of another famous printer, the second Henri Estienne, was neither new nor original with Tory. No less than three hundred years before, it had been set forth in honest French by an author who cannot be taxed with patriotic illusions, for he was an Italian. This is what Brunetto Latini wrote at the beginning of a sort of encyclopædia which he prepared in the thirteenth century, under the name of 'Trésor':—

'Et se aucuns demandoit por quoi cist livres est escriz en romans selonc le langage des François, puisque nos somes Ytaliens, je diroie que ce est por deux raisons: lune, car nos somes en France, et lautre, porce que la parleure est plus delitable et plus commune a toutes gens.'[75]

As I have said, the third book is the important part of Tory's work. Laying theory aside, he there gives us the exact design of the letters of the alphabet and the method of executing them. He does not overlook, moreover, this essential fact—that the designer of letters and the printer ought before all else to be grammarians in the ancient meaning of the[18] word[76]; and at the same time that he gives us the shape of a letter, he instructs us as to its value and pronunciation. It is at this point that Tory's book becomes especially interesting to us: he passes in review the pronunciation in vogue in each of the French provinces, or nations, as they were called then. One after another they appear before us, with their special idioms, which have become mere myths to-day,—Flemings, Burgundians, Lyonnaises, Forésiens, Manseaux, Berrichons, Normans, Bretons, Lorrainers, Gascons, Picards, and even Italians, Germans, English, Scotch, etc. His observations do not stop at the somewhat mixed idioms of the men,[77] but extend to the more individual language of the women. For instance, he informs us that 'the ladies of Lyon often gracefully pronounce A for E, as when they say, "Choma vous choma chat effeta,"[78] and a thousand other like expressions'; whereas, on the contrary, 'the ladies of Paris very often pronounce E instead of A, as when they say: "Mon mery est a la porte de Peris, ou il se faict peier"; instead of saying, "Mon mary est a la porte de Paris, ou il se faict paier."'[79]

It will be noticed that in this particular the 'ladies of Paris' succeeded in perpetuating their pronunciation in part, for we do not now say 'paier.' They had equal success in many other cases. For example, it seems to be due to them that the final S of the plural is not pronounced except under exceptional circumstances[80]: as, for instance, when it is followed by a word beginning with a vowel; for, speaking of the cases in which that letter is elided in Latin, Tory expresses himself thus: 'The ladies of Paris for the most part observe this poetic figure of speech, dropping the final S in many words, as when, instead of saying: "Nous avons disne en ung iardin, & y avons menge des prunes blanches et noires, des amendes doulces & ameres, des figues molles, des pomes, des poires & des gruselles," they say and pronounce: "Nous avon disne en ung iardin, & y avon menge des prune blanche & noire, des amende doulce & amere, des figue molle, des pome, des poyre & des gruselle."' The thing that seems especially offensive to Tory is that they make the men join them[19] in this faulty pronunciation. 'This fault,' he says, 'would be pardonable in them, were it not that it passes from woman to man, and that there is entire absence of perfect pronunciation in speaking.'[81]

Moreover, if we are to credit Tory, the provincials have also, in certain cases, succeeded in establishing their pronunciation, as we may conclude from the following passage, relative to the letter T: 'The Italians pronounce it so full and resonant that it seems that they add an E thereto, as when, for and instead of saying: "Caput vertigine laborat," they pronounce: "Capute vertigine laborate." I have seen and heard it pronounced so in Rome at the schools called La Sapienza, and in many another noble place in Italy. Which pronunciation is no wise held or used by the Lionnois, who drop the said T, and do not pronounce it any wise at the end of the third person plural of verbs active and neuter, saying "Amaverun" and "Araverun," for "Amaverunt" and "Araverunt." In like manner some Picards drop this T at the end of some words in French, as when they would say: "Comant cela, comant? monsieur, c'est une jument," they pronounce: "Coman chela, coman? monsieur, chest une jumen."'[82] We see that the Picard pronunciation has prevailed in this instance, for we no longer pronounce the final T at the end of the words 'comment,' 'jument,' and the like.

Tory did not content himself with setting forth the state of things existent in his day: he suggested improvements, almost all of which have been sanctioned by usage. For instance, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the pronunciation was very difficult to grasp for lack of accents; he proposed to supply them. 'In our French language,' he says, 'we have no symbol of accent in writing, and it is on account of this lack that our language is not yet established nor submitted to fixed rules, like the Hebrew, Greek and Latin. I would like that it should be, as might well be done.... In French,' he says farther on, 'as I have said, we do not write the accent over O vocative, but pronounce it full, as when we say:

'In this lack of accent we have an imperfection, which we ought to remedy by purifying and subjecting to fixed rule and art our language,[20] which is the most graceful language known.'[83] Elsewhere he suggests replacing elided letters by an apostrophe, which had not then been done in French. 'I say and allege these things in this place to the end that if it should happen that one had to write in antique letters verses where the S must disappear, one may write them honestly and purposely without using the said letter, ... and place a hooked point over the place where it should be.'[84] In another place he emphasizes the necessity of the cedilla, which we find in French manuscripts from the thirteenth century, but which typography had not as yet adopted. 'C before O,' he says, 'in French pronunciation and language, is sometimes hard, as in saying "coquin," "coq," "coquillard"; sometimes it is soft, as in saying "garcon," "macon," "françois," and other like words.'[85]

Tory could hardly overlook the matter of punctuation, that most essential, and even in our day so sadly neglected, branch of orthography; but as he had only 'antique' letters to deal with, he presented only three sorts of punctuation marks, without going into details as to their use, which, in truth, if we may judge by his own book, was not as yet fully settled. The comma, for instance, which has so much to do with the clearness of the sentence, is frequently there inserted in a far from rational way.

I have said above that Tory had adopted about 1523, for the mark of his bookshop, the Pot Cassé represented in the engraving placed at the end of his poem on his daughter's death. To make it more appropriate for that purpose, he subjected it to various modifications. At first we find it alone, as in the accompanying cut, on the cover,[86] or on the back,[87] of a number of octavo books bound at his establishment. Other bindings, in quarto, exhibit the broken jar with the drill (toret).[88]

Afterward, Tory placed the jar on a closed book, and still later he modified the design by the introduction of other additions.[89]

Finally, we have Geofroy Tory's device, or mark, definitively constituted in his 'Champ fleury,' thus:[90]—

'Behold,' he says, 'my declared device and mark, drawn as I have cogitated and conceived it, imparting moral meaning thereto, to give friendly admonition to the printers and booksellers beyond the mountains[91] to practise and employ themselves in goodly inventions and delectable execution, to show that their wits have not been always useless, but eager to serve the public weal by labouring to that end and living uprightly.'

Then follows his explanation of this mark,[92]—an explanation which does not invalidate that suggested above.[93] In truth, all that Tory says here in general terms may be applied to his daughter Agnes.

'In the first place, there is herein an ancient jar, which is broken, through which is passed a toret. This said broken jar signifies our body, which is an earthen jar. The toret signifies Fate, which pierces and passes through weak and strong. Beneath this broken jar there is a book secured by three chains and padlocks, which signifies that after our body is broken by death, its life is closed by the three fatal goddesses.[94] This book is so firmly closed that there is no man who may come to see anything therein, except he know the secret of the padlocks, and above all of the round padlock, which is locked and signed by letters. Even so, after the book of our life is closed, there is no man who may in any wise open it, except it be he who knows the secrets, and he is God, who alone knows, before and after our death, what has been, what is, and what will be our fate. The foliage and flowers in the said jar signify the virtues which our body may have in itself during its life. The sun-rays which are above and beside the toret and the jar signify the inspiration that God gives us by impelling us to[22] virtue and worthy acts. Near the said broken jar it is written: "Non plvs," which are two monosyllabic words, as well in French as in Latin, signifying that which Pittacus said long since in Greek: ΜΗΔΕΝΑΓΑΝ,[95] "nihil nimis." Let us not say, let us not do aught beyond measure or beyond reason, except it be in the last necessity: "aduersus quā nec Dij quidē pugnant."[96] But let us say and let us do "Sic. vt. vel. vt." That is to say, as we ought, or as little wrongly as we may. If we seek to do well, God will aid us, and therefore have I written above: "Menti bonæ Deus occurrit," that is to say, God goes out to meet the desire to do good, and gives it aid.'

I believe that we should see in the toret an 'enseigne parlante,' alluding at once to Tory's name and to his various professions. The way in which the name of the instrument was pronounced, its shape, resembling that of a T, and, lastly, its use by the engravers, were doubtless the considerations that led Tory to adopt it. But let us not subtilize too far.

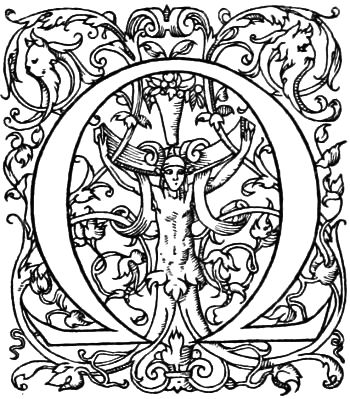

Tory was not content with giving us his symbol in 'Champ fleury': he engraved on the first page of that book, that is to say, in the place of honour, what would be called to-day the blazonry of his artistic acquirements,—in other words, a collection of all the tools that he used. Unfortunately, he did not feel called upon, as in the case of his mark, to supply an explanation, deeming the matter clear enough; whereas, in our day it has become rather difficult, because of the changes that have taken place in the customs of artists, to state the exact use of some of the tools. The order in which they are arranged, however, may assist us, to a certain extent, in identifying them. An exact reproduction of this engraving, the initial letter of the first page of the text of 'Champ fleury,' is given at the beginning of this section.[97]

The first series of tools, suspended in the first arabesque, embraces a pair of compasses, a rule, and a square: these are the fundamental instruments of art and of geometry. In the second arabesque, if I am not mistaken, we find an 'échoppe' and a burin, engravers' tools; in the third, a writing-case (or 'galimart'), a pencil, and a knife, above a book; these are the tools of the writer and the draughtsman. In the fourth, we find an object which I take to be a small box of colours, hanging from a case of brushes; these appertain to the painter. Tory was, in fact, draughtsman, painter and engraver.

I have already said that Tory was probably instructed in the art of drawing by the famous Jean Perreal. He was on terms of the closest friendship with that artist, who drew several of the vignettes in 'Champ fleury,' if we may judge by the one positively attributed to him, which is printed on the verso of folio 46. Geofroy informs us that this plate, insignificant in itself (it represents two circles in which are the letters I and K, modelled on the human body), was engraved from the design of a friend of his, 'from that which a noble lord and good friend of mine, Jehan Perreal, who is otherwise called Jehan de Paris, valet de chambre and excellent painter to King Charles VIII, Louis XII, and François, first of the name, made known and gave to me, most excellently drawn by his hand.' Now this engraving is in all respects similar to those to be found in the second book of 'Champ fleury.' Both in form and subject, it is altogether different from those in the third book, in which Tory printed it. Probably Perreal died while the work was on the press, and Tory, who had not thought of naming him while he was alive, in connection with his first drawings, did so after his death, by publishing the last souvenir of this sort which he possessed from the hand of his friend, although it did not fit perfectly with the subject; he laid, as it were, a flower on the dead man's grave.[98]

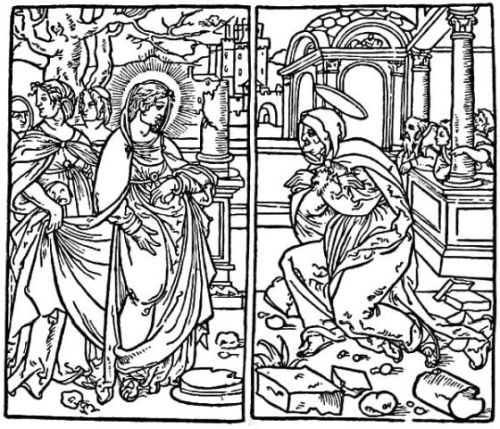

We give this drawing also, as the only work which can be with certainty attributed to Jean Perreal, and as a specimen of the engravings which serve as a foundation for the reformation of the roman letters proposed by Tory in the second book of his 'Champ fleury.'

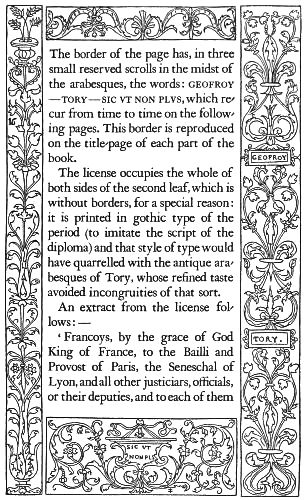

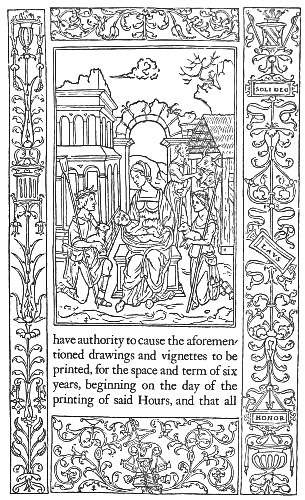

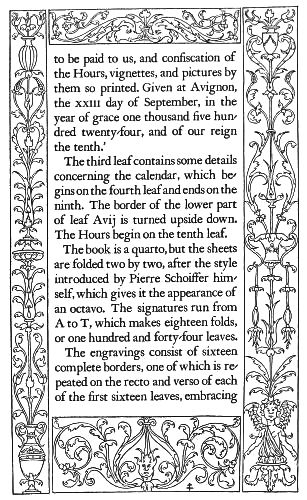

From what I have said it will be seen that Tory's book required several years of labour. Nor is one surprised thereat when one considers the great number of engravings which it contains. But even without the engravings, it will readily be understood that a work which necessitated so much observation required a vast expenditure of time. Begun, as we have seen, in 1523 (1524, new style), it was not finally completed until 1529, that is to say, after six years of toil. However, Tory did not propose that those years should be lost for art. Desirous to preach by example rather than by precept, he determined to publish, in the interim, other books wherein he might give utterance to his artistic taste. And he did in fact print books of Hours, admirably executed, which, although in different form, may fitly be compared to the Hours of Simon Vostre, who had acquired so great a reputation in that typographical specialty. Tory received from François I a 'privilége' (license) for this work, to run six years, dated at Avignon, September 23, 1524.[99] This license to print[100] informs us that Tory had 'made and caused to be made[101] certain illustrations [histoires] and vignettes "a lantique" and likewise some "a la moderne," in order to have the same printed, and to serve a plusieurs usages dheures,' and that to that end he had 'expended an exceeding long time and incurred divers great expenses and outlays.'

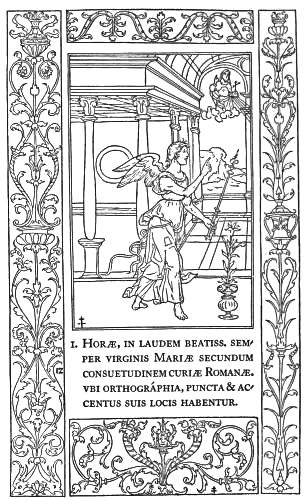

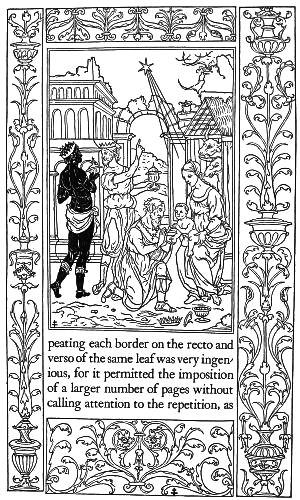

The first book of this sort which he published, so far as I have learned, is an edition in quarto of the Hours of the Virgin, according to the Roman use, in Latin. It is a superb volume, printed by Simon de Colines, with borders and illustrations 'à l'antique,' perfect in taste and execution.

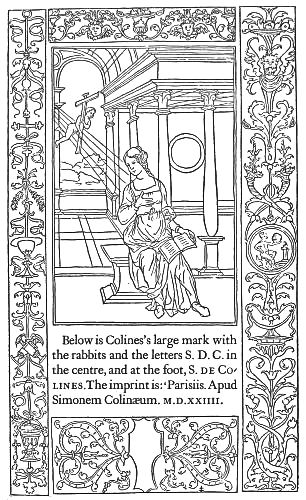

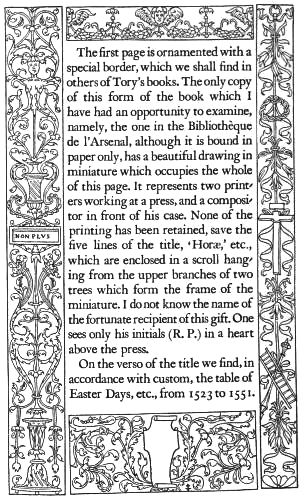

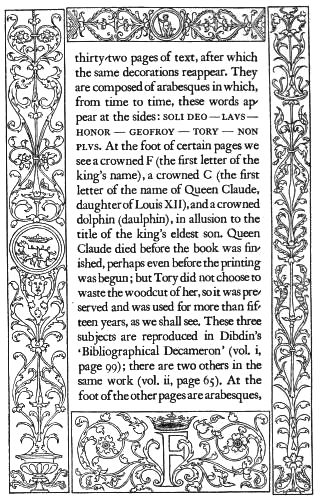

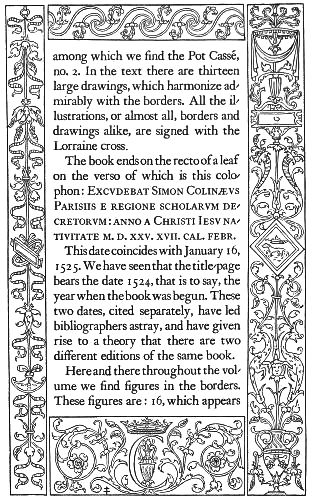

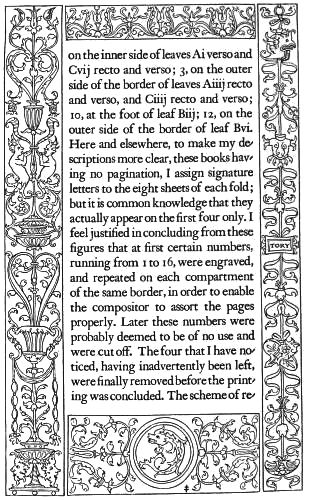

The book was undoubtedly printed by Colines as a joint venture with Tory, for there are copies in existence in the name of each. Those in the name of Colines bear on the title-page the date 1524, and, at the end, that of the 17th of the Calends of February (January 16), 1525; those in the name of Tory (there are two varieties of these) bear but one date, 1525, and that at the end. I shall speak of this book later, in detail.[102]

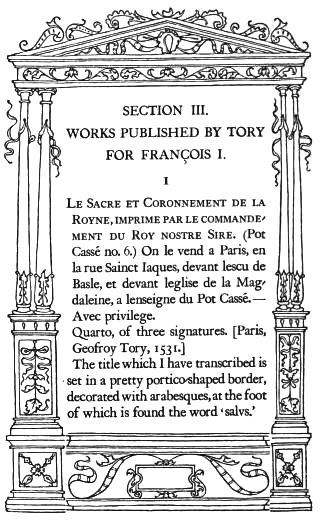

Two years later Tory published a new edition of the same Hours, in a small octavo volume, also printed by Simon de Colines, in roman type, with borders and illustrations of the same kind but much smaller.[103] The printing was finished October 21, 1527. It is preceded by a new license from François I, extending Tory's rights for ten years, not for this book alone, but for the earlier one as well, 'for certain illustrations and vignettes "a lantique" by him heretofore printed,' and in consideration of the great outlay which his engravings had caused him to make. This license is dated at Chenonceaux, September 5, 1526, and includes 'Champ fleury,' the printing of which had begun, but which had not yet received its poetic title, for it was still referred to as 'Lart et science de la deue et vraye proportion des lettres.' In the same year Tory published an edition in quarto of these same Hours, according to the use of Paris, printed by Simon Dubois (Silvius). This book, in which we find again the license of 1526, is printed in gothic type, with borders and illustrations of a special style, called 'à la moderne.' The borders are arabesques formed of plants, insects, birds, animals, etc. At the foot we see the F, crowned, of François I, and the salamander; the L, crowned, of Louise of Savoy, the king's mother; and the impaled shield of France and Savoy, etc. Of this book also I shall speak in detail hereafter.[104] Finally, a little later, at a time which I am unable to fix precisely, but prior to 1531, Tory caused to be printed another book of Hours of the same description, that is to say, with borders of plants, insects, birds, etc., but in a smaller format—small octavo. I shall describe it in its place.[105]

These publications did not prevent our artist from giving his attention to literature. While he was overlooking the impression of his Hours and his 'Champ fleury,' he was preparing various works to which we shall have occasion to refer hereafter. Generally speaking, they are translations intended to enrich the French tongue; for Tory did not lose sight of his patriotic purpose. All of these works were printed subsequently, save one, perhaps—a translation of the hieroglyphs of Orus Apollo,[26] which he gave to a 'noble lord and good friend of his.'[106] It is not known whether this translation was ever printed. There are many editions of Orus in existence, but no one of them bears the name of Tory.

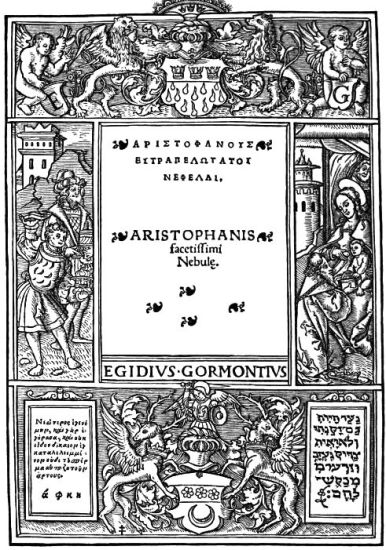

'Champ fleury' appeared at last in 1529. We have seen that this book was conceived on 'the day of the feast of Kings, which was reckoned M. D. XXIII,' that is to say, January 6, 1524, new style. The printing was not completed until 'the XXVIII day of the month of April one thousand five hundred XXIX,'[107] as we learn from the subscription at the end; that is to say, it cost nearly six years of toil. The following is an exact copy of the title-page as it appears in the first edition:—

CHAMP FLEVRY. Au quel est contenu Lart & Science de la deue & vraye Proportiõ des Lettres Attiques, quõ dit autremēt Lettres Antiques, & vulgairement Lettres Romaines, proportionnees selon le Corps & Visage humain.—Ce Liure est Priuilegie pour Dix Ans Par Le Roy nostre Sire, & est a vendre a Paris sus Petit Pont a Lenseigne du Pot Casse par Maistre Geofroy Tory de Bourges/Libraire, & Autheur du dict Liure. Et par Giles Gourmont aussi Libraire demourant en la Rue sainct Iaques a Lenseigne des Trois Coronnes.

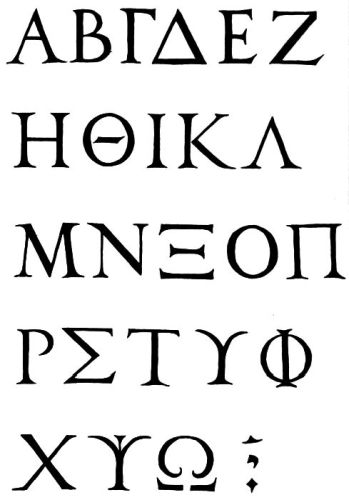

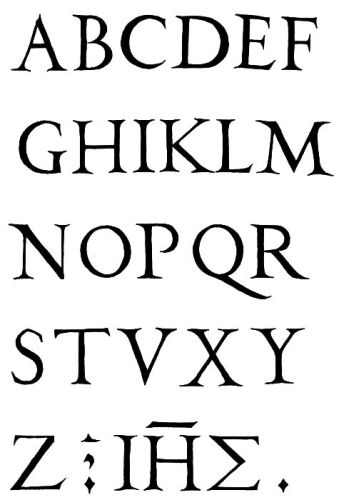

It is gratifying to see here the name of the first printer in Greek type in Paris. It was Gourmont himself who printed this learned book, wherein we find some very interesting details concerning the Hebrew, Greek and Latin letters, of which he exhibits models which have not changed since that time.[108] The workshop of Gilles de Gourmont was on rue Saint-Jean-de-Latran; but we see that in 1529 he had a bookshop on rue Saint-Jacques, at the sign of the Trois Couronnes,—an allusion doubtless to the three roses which adorned the chief, or top, of his shield. This shop adjoined the church of Saint-Benoît on the north.[109] As for Tory, he seems to have lived at this time on the Petit-Pont, 'next to Hostel-Dieu.' It was there that he wrote his book, for he dates his epistle to the reader thus: 'En Paris ce. XXVIII. Jour Dapvril sus Petit Pont, a Lenseigne du Pot Casse.' He had, however, another abode on rue Saint-Jacques, opposite the 'Écu de Bâle,' the sign of Chrétien Wechel.

At the beginning of 'Champ fleury' is printed the license of September 5, 1526, already published in the two editions of the Hours of 1527, which granted to Tory a ten years' right, not only for the Hours, but also for 'Champ fleury,' which was then being printed, but, as I have already said, had not then received that graceful title. This license makes it clear that as early as 1526 Tory was thinking of joining the brotherhood of printers. He became a printer in fact soon after the publication of his book, and proceeded to print several works of his own composition. I give here a list of these various publications, in the order of their dates.

I. La Table de lancien philosophe Cebes ... Avec trente Dialogues moraulx de Lucian ... translate de latin en vulgaire françois par maistre Geofroy Tory de Bourges...[110]

The license is of September 18, 1529, for ten years. The printing was finished October 5, 1529. It is a small octavo volume, in two parts, with roughly executed borders on each page. There are twelve preliminary leaves, containing a long list of errata, and two series of signatures, the first running from A to T, the second from a to v. The book was for sale at the translator's shop, 'rue Sainct Iaques, devant lescu de Basle,[111] a lenseigne du Pot Casse,' and at Jean Petit's on 'rue Sainct Iaques, a lenseigne de la Fleur de lys.' There is nothing to indicate where the book was printed; but as it is set in the type used for the 'Epitaphs' of Louise of Savoy, I am inclined to think that it came from Tory's workshop. In that case it was the first book that he printed.[112] The long list of errata would seem, in truth, to suggest a novice, and would explain why no printer's name is given.