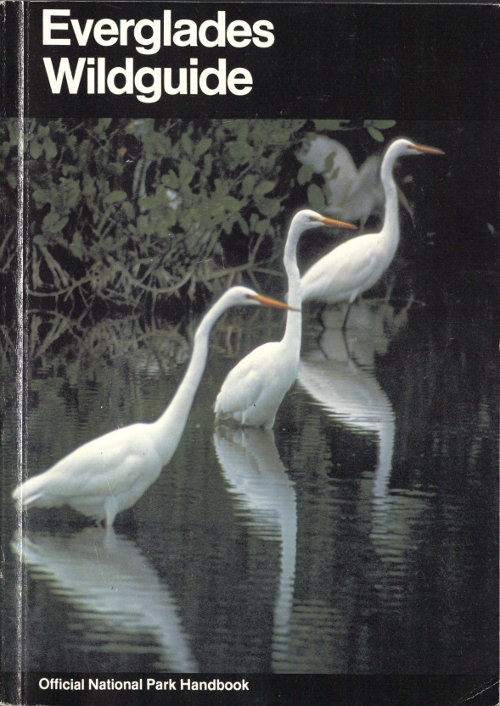

Title: Everglades Wildguide

Author: Jean Craighead George

Illustrator: Betty Fraser

Release date: June 24, 2017 [eBook #54970]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, MFR and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Handbook 143

by Jean Craighead George

Illustrations by Betty Fraser

The Natural History of Everglades National Park, Florida

Produced by the

Division of Publications

National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior

Washington, D.C. 1988

Here is the story of the plants and animals of the Everglades, this country’s subtropical kingdom. Plants and animals found nowhere else in the 50 states are found here in abundance, though in an increasingly perilous state. In this handbook, first published in 1972, author and researcher Jean Craighead George brings to the telling of this story long years of study and understanding. Checklists and glossaries at the back buttress her account of the natural history of this national park.

National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the great natural and historic places administered by the National Park Service, are published to support the National Park Service’s management programs at the parks and to promote understanding and enjoyment of the parks. Each is intended to be informative reading and a useful guide before, during, and after a park visit. More than 100 titles are in print. This is Handbook 143. You may purchase the handbooks through the mail by writing to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402.

★GPO: 1987—181-917/60504

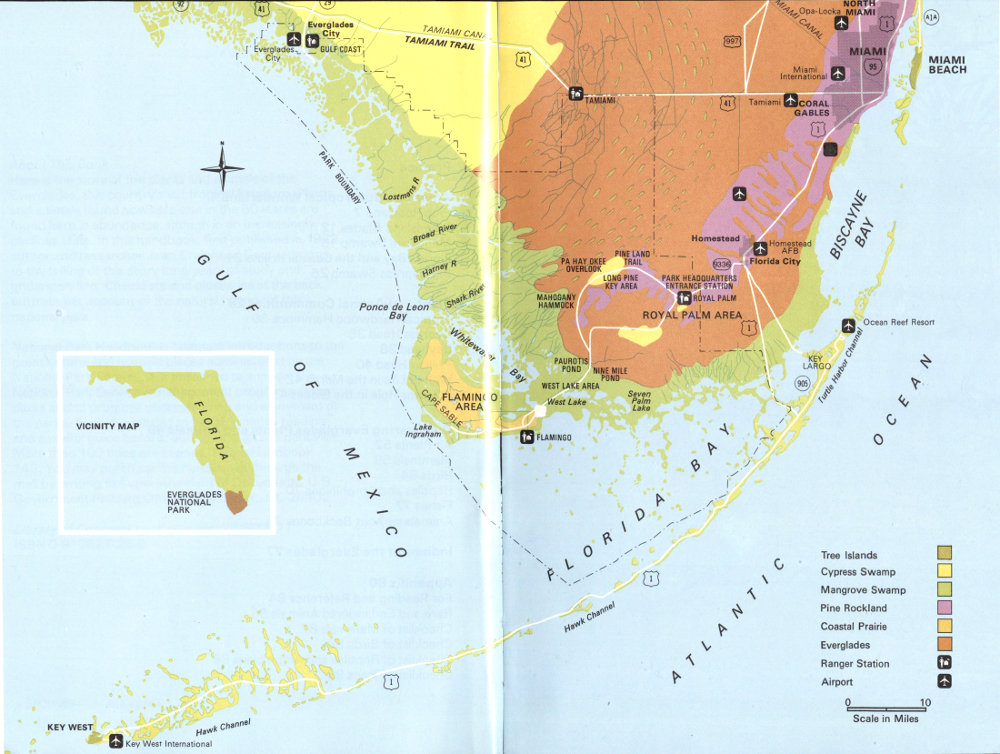

EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK

High-resolution Map

The shimmering waters of the everglades creep silently down the tip of Florida under warm subtropical skies. In a vast, shallow sheet this lazy river idles through tall grasses and shadowy forests, easing over alligator holes and under bird rookeries, finally mingling with the salty waters of Florida Bay and the Gulf of Mexico in the mangrove swamps. From source to sea, all across the shallow breadth of this watery landscape, life abounds.

Everglades National Park is to most Americans an Eden where birds, mammals, reptiles, and orchids find sanctuary. Sunshine sparkles on sloughs teeming with fish, and on marshes where wildflowers bloom the year around; it shines on tree islands where birds roost and deer bed down. In this semitropical garden of plant-and-animal communities, every breeze-touched glade, every cluster of trees is a separate world in which are tucked yet smaller worlds of such complexity that even ecologists have not learned all their intricate relationships.

This book has been written to help you see how the many pieces of this ecological puzzle fit together to form a complex, ever-changing, closely woven web of plants, animals, rock, soil, sun, water, and air.

Everglades may not be our largest national park (that honor belongs to Wrangell-St. Elias in Alaska), but it is certainly the wettest. During and after the rainy season, when not only the mangrove swamp but also the sawgrass prairie is under water, most of the park abounds in fish and other water life, and even the white-tailed deer leads a semi-aquatic existence.

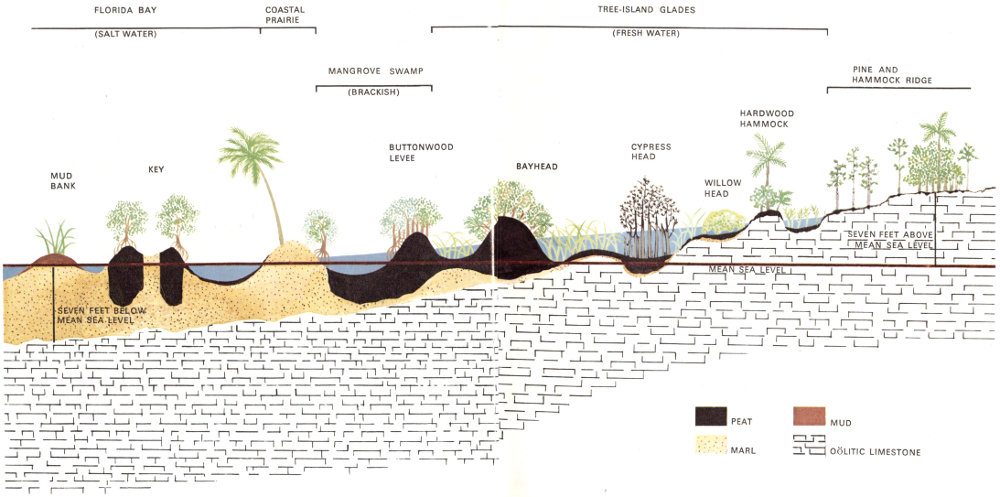

Despite the fact that it is low, flat, and largely under water, Everglades is a park of many environments: shallow, key-dotted Florida Bay; the coastal prairie; the vast mangrove forest and its mysterious waterways; cypress swamps; the true everglades—an extensive freshwater marsh dotted with tree islands and occasional ponds; and the driest zone, the pine-and-hammock rockland.

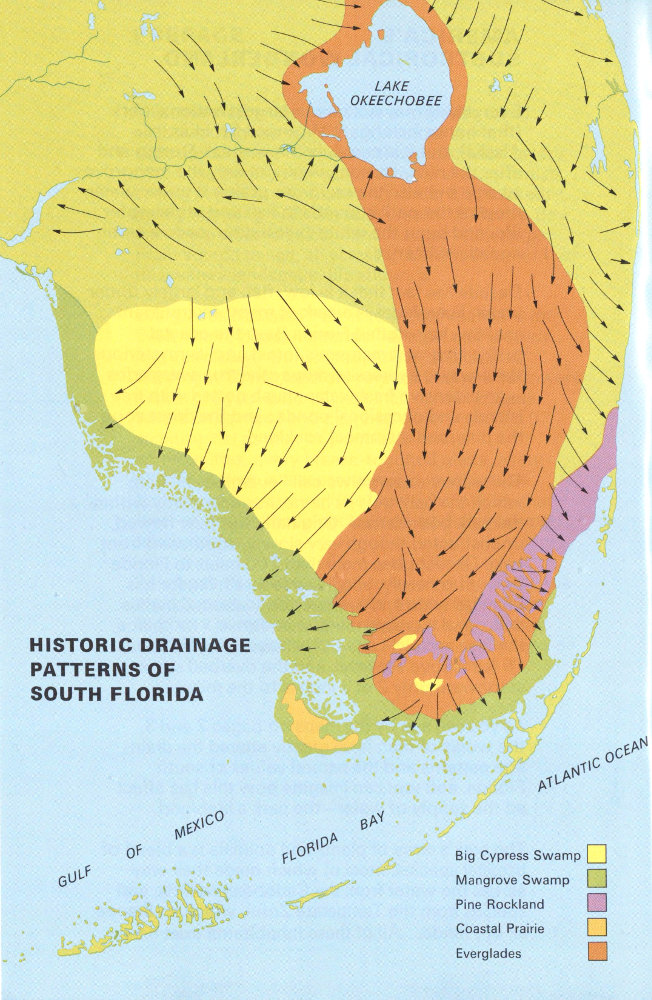

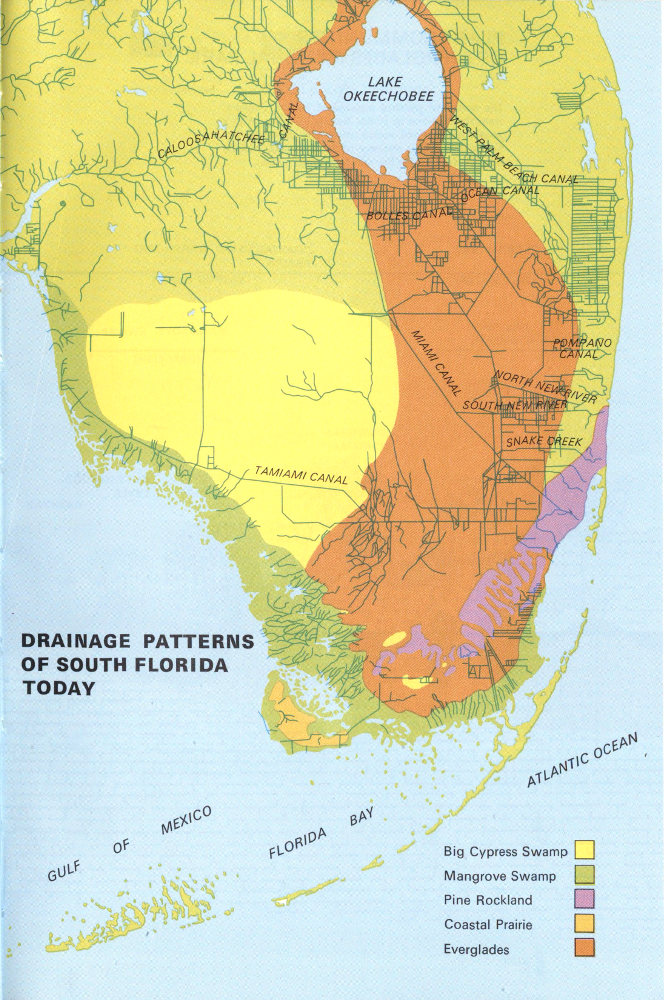

The watery expanse we call “everglades,” from which the park gets its name, lies only partly within the park boundaries. Originally this river flowed, unobstructed though very slowly, southward from Lake Okeechobee more than 100 miles to Florida Bay. It is hardly recognizable as a river, for it is 50 miles wide and averages only about 6 inches deep, and it creeps rather than flows. Its source, the area around Lake Okeechobee, is only about 15 feet above sea level, and the riverbed slopes southward only 2 or 3 inches to the mile.

As you can see by the maps on pages 2 and 3, the works of man have greatly altered the drainage patterns and the natural values of south Florida, and you can imagine how this has affected the supply of water—the park’s lifeblood.

The park’s array of plants and animals is a blend of tropical species, most of which made their way across the water from the Caribbean islands, and species from the Temperate Zone, which embraces all of Florida. All of these inhabitants exist here through adaptation to the region’s peculiar cycles of flood, drought, and fire and by virtue of subtle variations in temperature, altitude, and soil.

HISTORIC DRAINAGE PATTERNS OF SOUTH FLORIDA

DRAINAGE PATTERNS OF SOUTH FLORIDA TODAY

PLANT COMMUNITIES OF EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK

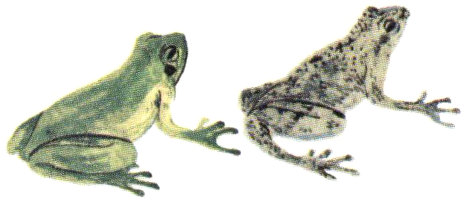

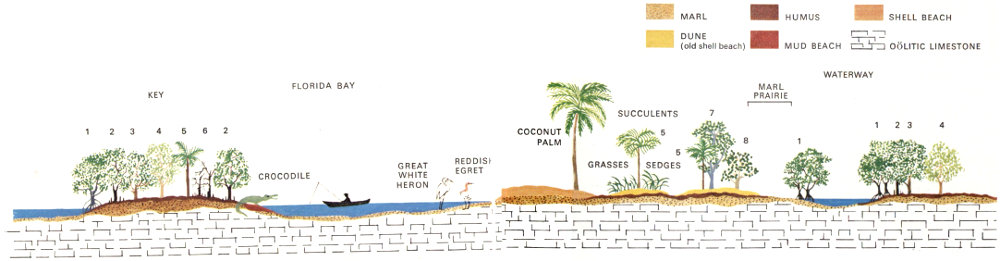

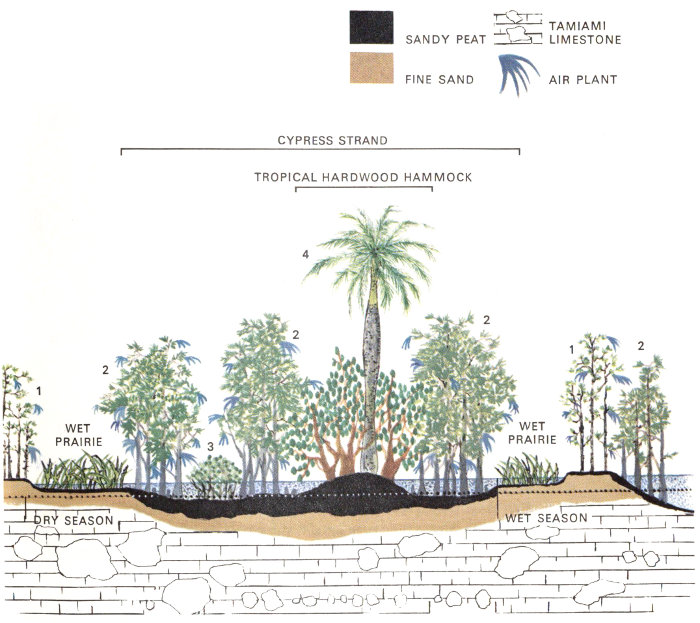

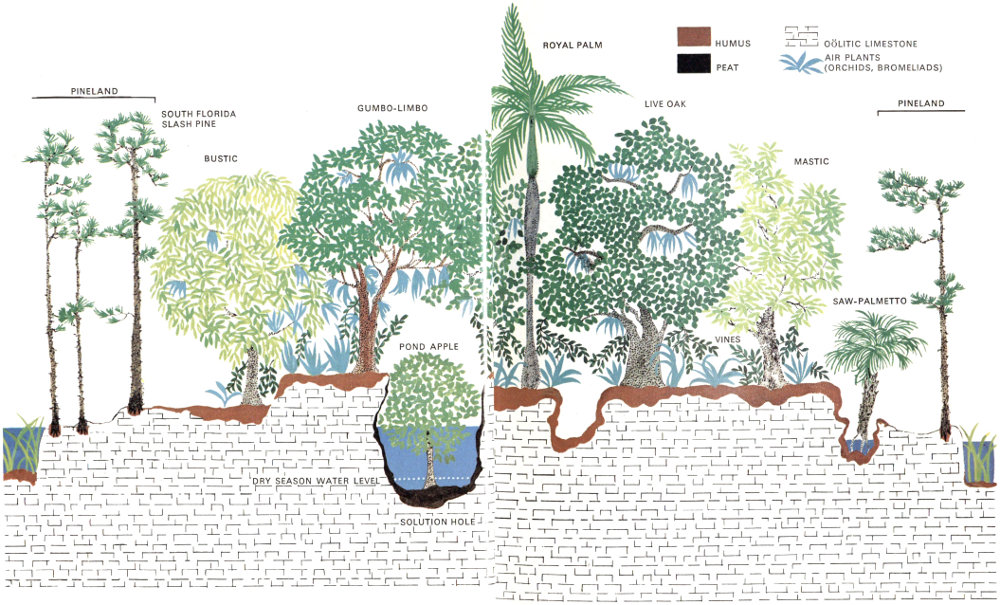

The horizontal distance represented on this diagram, from the Pineland to Florida Bay, is 15 miles. With a greatly exaggerated vertical scale, the difference between the greatest elevation of the pine ridge and the bottom of the Florida Bay marl bed is only 14 feet.

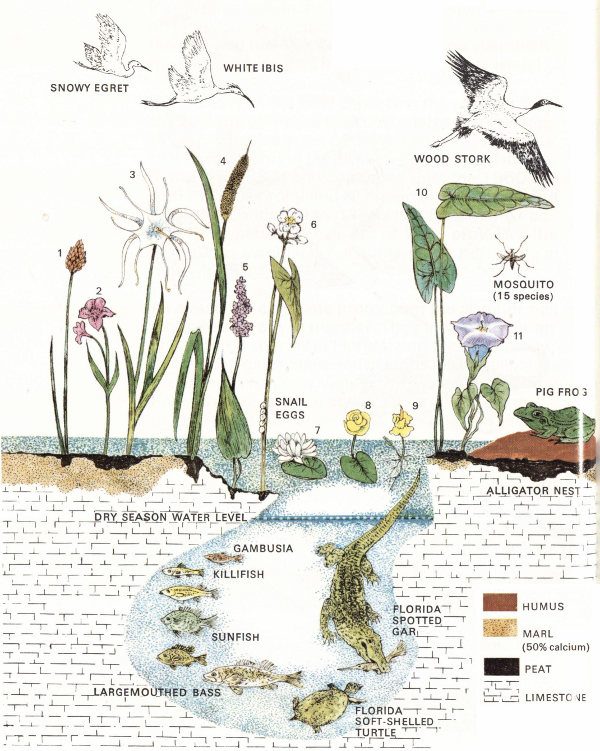

Underlying the entire park is porous limestone (see glossary), which was deposited ages ago in warm seas that covered the southern part of today’s Florida peninsula. Over this limestone only a thin mantle of marl and peat provides soil for rooting plants.

Some of the park’s ecosystems (see glossary) are extremely complex. For example, a single jungle hammock of a dozen acres may contain, along with giant live oaks and other plants from the Temperate Zone, many kinds of tropical hardwood trees; a profusion of vines, mosses, ferns, orchids, and air plants; and a great variety of vertebrate and invertebrate animals, from tree snails to the white-tailed deer.

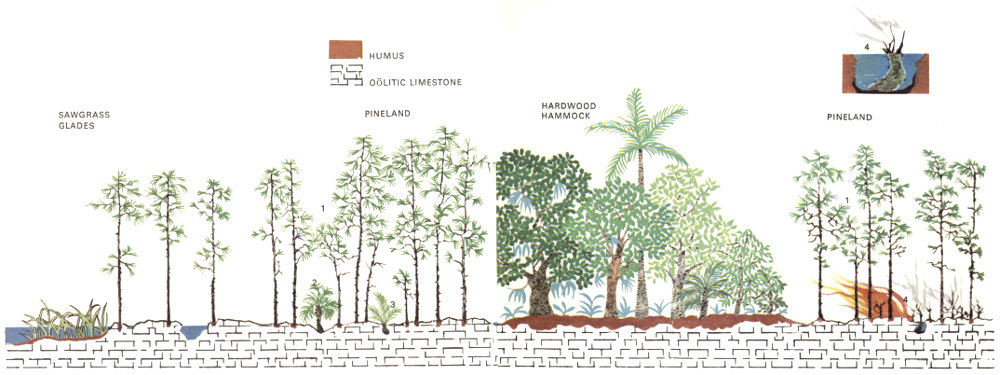

Entering the park from the northeast, you are on a road traversing the pineland-and-hammock “ridge.” This elevated part of the South Florida limestone bedrock, which at the park entrance is about 6 feet above sea level, is the driest zone in the park. Pine trees, which will grow only on ground that remains above water most of the year, thrive on this rockland.

There is another condition essential to the survival of the pine forest in this region—fire. We usually think of fire as the enemy of forest vegetation; but that is not true here. The pines that grow in this part of Florida have a natural resistance to fire. Their thick, corky bark insulates their trunks from the flames. And strangely enough the fire actually seems to help with pine reproduction; it destroys competing vegetation and exposes the mineral soil seedlings need. If there has been a good cone crop, you will find an abundant growth of pine seedlings after a fire in the pinelands.

What would happen if the pinelands were protected from fire? Examine a pine forest where there have been no recent fires. You will note that there are many small hardwood (broadleaved) trees growing in the shade of the pines. These hardwoods would eventually shade out the light-demanding pine seedlings, and take over as the old pines died off. But under normal conditions, lightning-caused fires sweep at fairly frequent intervals through the pineland. Since the hardwoods have little resistance to fire, they are pruned back.

Before this century, fires burned vast areas. The only barriers were natural waterways—sloughs, lakes and ponds, and estuaries—which retained some water during the rainless season when the rest of the glades and pinelands dried up. Old-timers say that sometimes a fire would travel all the way from Lake Okeechobee to the coastal prairie of Cape Sable (see page 2). In the pine forest, any 8 area bypassed by these fires for a lengthy period developed into a junglelike island of hardwoods. We call such stands “hammocks,” whether they develop in the pine forest or in the open glades. On the limestone ridge, the hammocks support a community of plants and animals strikingly different from the surrounding pine forests.

PINE AND HAMMOCK RIDGE

(elevation: 3 to 7 feet above sea level)

With the opening up of south Florida for farming and industry, man’s works—particularly roads and canals—soon crisscrossed the region, forming barriers to the spread of the fires. Suppression of fire by farmers, lumbermen, and park managers also lessened their effect. Thus the hardwoods, which previously had been held back by fire, tended to replace the pines. And although the park was established to preserve a patch of primitive subtropical America as it was in earlier centuries, the landscape began to change.

Continued protection of the park from fire would in time eliminate the pineland—a plant community that has little chance to survive elsewhere. So, in Everglades National Park, Smokey Bear must take a back seat: park rangers deliberately set fires to help nature maintain the natural scene. Thus, as you drive down the road to Flamingo, do not be shocked to discover park rangers burning the vegetation. The fires are controlled, of course, and the existing hammocks are not destroyed.

When you visit the park take a close look at the pinelands community. Notice, as you walk on the manmade trail through the pine forest, that the ground on either side of you is extremely rough. The limestone bedrock is visible everywhere; what soil there is has accumulated in the pits and potholes that riddle the bedrock. The trees, shrubs, grasses, and other plants are rooted in these pockets of soil.

The limestone looks rather hazardous to walk on—and it is. You must be careful not to break through a thin shell of rock covering a cavity. This pitted, honeycombed condition is due to the fact that the limestone is easily dissolved by acids. Decaying pine needles, palmetto leaves, and other dead plant materials produce weak acids that continually eat away at the rock.

If a fire has passed through the pineland recently, you may notice that while most of the low-growing plants have been killed, some, such as the saw-palmetto, are sending up new green shoots. The thick, stubby stem of the palmetto lies in a pothole, with its roots in the soil that has accumulated there; even in the dry season the pocket in the limestone remains damp, for water is never very far below the surface in this region. When fire kills the top of the plant, the stem and roots survive, and the palmetto, like the pine, remains a part of the plant community.

A number of other plants of the south Florida pinelands have adapted to the conditions of periodic burning. Coontie (a cycad, from the underground stems of which the Indians made flour) and moon vine (a morningglory) are among many you will see surviving pineland fires severe enough to result in the death or stunting of the hardwood seedlings and saplings.

Sometimes we forget that fire—like water, wind, and sunlight—is a natural force that operates with the others to influence the evolution of plants as well as to shape the landscape.

The pineland, like other plant communities, has its own community of animals. Some of its residents, such as the cotton mouse, opossum, and raccoon, are found in other communities of the park, too.

Some of the pineland animals, however—pine warbler, reef gecko, and five-lined skink, for example—are particularly adapted to this environment. These lovers of sunlight are dependent, like the pine forest, on the occasional natural or manmade fires 11 that hold back the hardwood trees.

The pine rockland is quite different from the other plant-and-animal communities you will see as you drive through the park: it is the only ecosystem you can explore on foot in any season. Other parts of the park are largely flooded during the wet season. Elevated boardwalks have been provided in some of these areas to enable you to penetrate them a short distance from the road.

As you will see, fire plays an important role in some of the other Everglades communities, too.

PIG FROG

one-third life size

GREEN TREEFROG

one-third life size

SQUIRREL TREEFROG

color variation

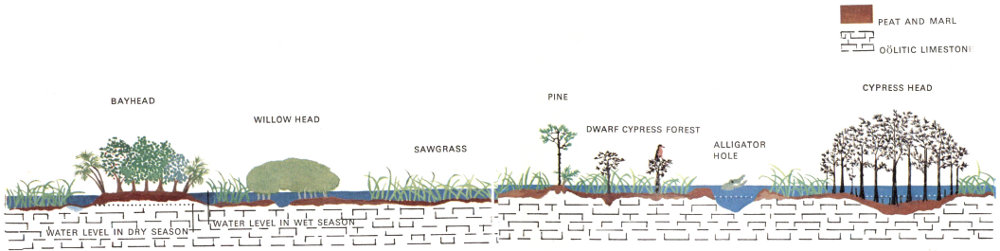

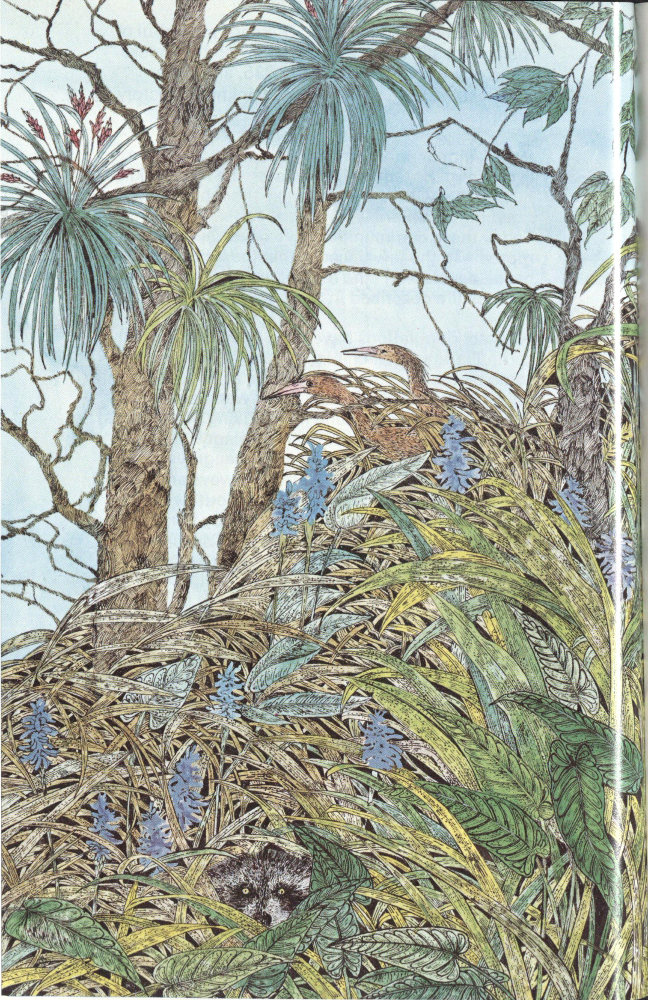

Beyond the pinelands the road, having descended some 2 feet from the park entrance, brings you into the true everglades—the river of grass, or, as the Seminoles call it, Pa-Hay-Okee (grassy waters). To the eye, the glades look like a very flat, grassy prairie broken by scattered clumps of trees. During the dry season (winter) it is in fact a prairie—and sometimes burns fiercely. The dominant everglades plant is sawgrass (actually not a grass but a sedge). The tree islands develop in both high and low spots of the glades terrain. In this unbelievably flat country, small differences in elevation—measured in inches rather than feet—cause major differences in the plantlife: tropical hardwoods on the “mesas,” and swamp trees in the potholes.

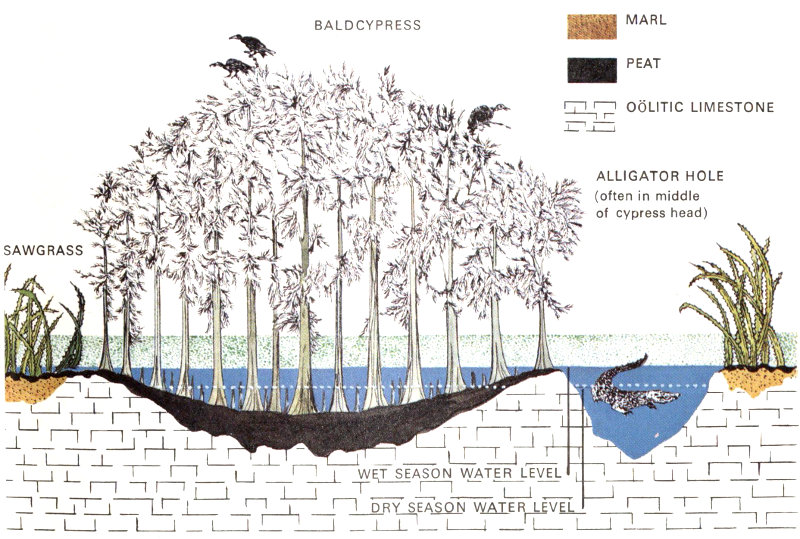

A spot in the glades where the limestone base is elevated just 2 feet will be occupied by a small forest of tropical hardwoods and palms—a 14 “hammock” much like those of the pinelands. A low spot—just a few inches below the general level of the limestone base—will remain wet even in the relatively rainless winter when the sawgrass becomes tinder dry. This sloughlike depression will support a stand of baldcypress, called a “cypress head.” Other tree islands, called bayheads and willow heads, develop in many places where soil and peat accumulate.

Step from the sawgrass glades into one of these hammocks or heads; you will find yourself in another world. You cannot know the park until you have investigated these plant-and-animal communities so distinct from the surrounding marsh yet so much a part of it. As you drive through the park, look for the trails provided to give you easy access into the interior of the tree islands.

Also characteristic of the glades are the sloughs—channels where the glades water, generally a thin, seemingly motionless sheet, is deeper and has a noticeable current. The sloughs support a rich plantlife and attract a variety of animals, particularly during the dry season when the water level drops below the shallow glades bottom. Animals that live in the glades when they are under water must migrate or estivate (see glossary) if they are to survive the rainless months. Many migrate to the sloughs, the best known of which is Taylor Slough, where the elevated Anhinga Trail enables you to walk over the water and observe the wildlife.

Fire is an important factor in the ecology of the tree-island glades, just as it is in the pineland. Here, too, artificial barriers such as canals and roads have hindered the spread of natural fires. There is some evidence that tree islands were scattered more thinly over the sawgrass prairie a half-century ago, when a single fire might wipe out scores of them and destroy much of the bed of peat that provided a foothold for them. A bird’s-eye view of the glades region today shows many tree islands that have been established in recent decades. But park rangers are now utilizing 15 controlled fires in the glades as well as in the pineland. This tends to prevent new tree islands from taking hold, and thus helps maintain the natural everglades landscape.

Driving over the glades toward Florida Bay, you come to a sign reading “Rock Reef Pass—Elevation 3 Feet.” The road then traverses the so-called dwarf cypress forest. The forest is an open area of scattered, stunted baldcypress growing where marl (which, unlike peat, does not burn) has accumulated in small potholes dissolved in the limestone. These marl potholes provide a foothold for the dwarf cypresses in an area that is spotted with cypress heads containing much larger trees. Many of the dwarf cypresses are more than 100 years old, while tall cypresses in the heads may be less than 50 years old. These anomalies can be attributed to varying soil depths and water levels and to the effects of fire.

Before you reach the limit of the fresh-water marsh you will come to a side road leading to Mahogany Hammock. (A good foot trail makes it easy to explore this hardwood jungle island.) Just beyond, you will notice the first red mangroves. Small and scattered in this zone, they are a signal that you are approaching a strikingly different plant-and-animal community, the mangrove swamp.

PRAIRIE SEDGES

BONEFISH Comes in with the tide to feed on crabs and mollusks in shallow water

FLORIDA HORN SHELL Lives in shallow water and feeds upon algae and other aquatic plants

’COON OYSTER A small (1½″) oyster that lives attached to the roots of mangroves

The southward-creeping waters of the glades eventually meet and mingle with the salty waters of the tidal estuaries. In this transition zone and along the gulf and Florida Bay coasts a group of trees that are tolerant of salty conditions, called “mangroves,” form a vast, watery wilderness. Impenetrable except by boat, it occupies hundreds of square miles, embracing both the shifting zone of brackish water and the saltier coastal waters.

Several kinds of trees are loosely called “mangroves.” The water-tolerant red mangrove grows well out into the mudflats and is easily recognized by its arching stiltlike roots. Black-mangrove typically grows at levels covered by high tide but exposed at low tide, and it is characterized by the root projections called pneumatophores that stick up out of the mud like so many stalks of asparagus growing 18 in the shade of the tree. White-mangrove has no peculiar root structure and grows, generally, farther from the water, behind the other trees. Sometimes all three are found in mixed stands.

This mangrove wilderness, laced by thousands of miles of estuarine channels (called “rivers” and “creeks”) and broken by numerous bays and sounds, is extremely productive biologically. The brackish zone is particularly valuable as a nursery ground for shrimp. The larvae and young of these marine crustaceans and of other marine animals remain in this relatively protected environment until they are large enough to venture into the open waters beyond the mangroves.

The shrimp represent a multi-million-dollar industry, and the sports-fishing business of the area is said to exceed that by far. Both would suffer if any damage 19 occurred to this ecosystem. The greatest danger is the alteration in the flow of fresh waters from the glades and cypress swamps that occurs when new canals are built and land is drained for cultivation or development. The flow carries with it into the estuaries organic materials from the rich glades ecosystem; these supplement the vast quantities of organic matter derived from the decay of red mangrove leaves. Thus, a reduction in the amount of nutrient-laden fresh water flowing into the mangrove region will affect the welfare of the ecosystem, and indirectly the livelihood or recreation of many persons.

The productive zone of brackish water varies in breadth according to the flow of fresh water. In the wet summer it moves seaward as the flow of fresh water from the glades pushes the tides back. In the drier winter the bay and gulf waters move inland and the brackish zone is quite narrow. The drainage and canal-building operations in south Florida can be extremely disruptive here, since too little, or too much, fresh water flowing into the estuaries can interfere with their productivity.

Natural disasters such as hurricanes can also bring about great changes in the mangrove ecosystem. Yet biologists do not necessarily view the destruction of mangroves by hurricanes as catastrophic. The hurricanes have been occurring as long as the mangroves have grown here and are part of the complex of natural forces making the region what it is.

Fire does not seem to be a problem in the mangrove wilderness. The trees themselves are not especially fire-resistant, but it is not uncommon to see a glades fire burn to the edge of the mangroves and stop when it runs out of fine fuel.

The mangrove wilderness is a mecca for many park visitors. Sportsmen take their motorboats into the bays and rivers to challenge the fighting tarpon. Bird lovers seek the roosts and rookeries of herons 20 and wood storks. Canoeists, the only ones able to explore the secret depths, are drawn by the spell of labyrinthine channels under arching mangrove branches. Here, in a wilderness still thwarting man’s efforts at destruction, one experiences a feeling of utter isolation from the machine world.

But the relentlessly rising sea of the past 10,000 years has belittled drought, fire, hurricane, and frost as it slowly inundated this land 3 inches each hundred years. In compensation, the mangrove forest adds peat and rises with the sea. The sawgrass marshes retreat, and the mangrove ecosystem prevails essentially unchanged.

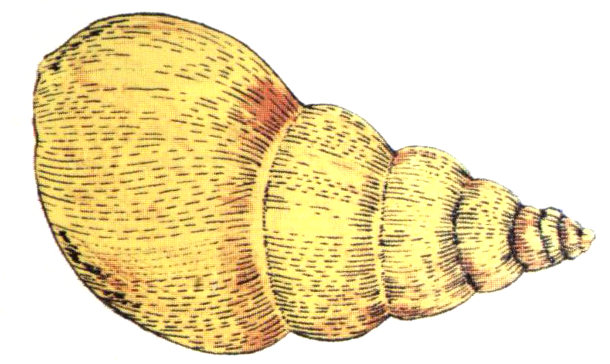

APPLE MUREX

A carnivorous mollusk that feeds on oysters.

When you reach Flamingo, a former fishing village and now a center for visitor services and accommodations, you will be on the shore of Florida Bay. Here is an environment rich in variety of animal life, where porpoises play, the American crocodile makes its last stand, and the great white heron, once feared doomed to extinction, holds its own. The abundance of game fish in the bay has given it a reputation as one of the best sport-fishing grounds on the east coast.

The bay’s approximately 100 keys (low-lying islets) were built up by mangroves and provide foothold for other plants hardy enough to withstand the salty environment and the sometimes violent winds. The keys are also a breeding ground for water birds, ospreys, and bald eagles.

Florida Bay, larger than some of our States, is so shallow that at low tide some of it is out of water; its greatest depth is about 9 feet. The shallows and mudflats attract great numbers of wading birds, which feed upon the abundant life sheltered in the seaweeds—a plant-and-animal community nourished by nutrients carried in the waters flowing from the glades and mangroves.

To the west beyond Flamingo is Cape Sable. This near-island includes the finest of the park’s beaches and much of the coastal prairie ecosystem. A fringe of coconut palms along the beach could be the remnants of early attempts at a plantation on the cape that did not survive the hurricanes; or it could be the result of the sprouting of coconuts carried by currents from Caribbean plantations and washed up on the cape. For a time, casuarina trees (called “Australian pines”), which became established on Cape Sable after Hurricane Donna, seemed to threaten the ecology of the beach. But these invaders were mostly removed in 1971, and now appear to be under control.

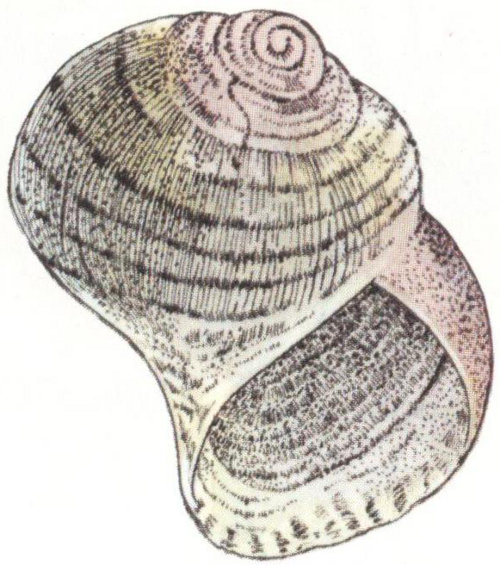

Examine the “sand” of this beach. You will discover that it is not quartz grains—but mostly minute shell fragments. Entire shells of the warm-water molluscs that live offshore also wash up on the beach. There are also artifacts that speak of Indian activity in this area in past centuries, curled centers of conch shells from which the pre-Columbian Indians fashioned tools, and numerous pieces of pottery (potsherds). Both shells and potsherds tempt the collector. Shelling—that is, the collecting of dead shells, for noncommercial purposes—is permitted. But Federal law prohibits the removal of even a fragment of pottery—for these are invaluable Indian relics, essential to continuing scientific investigation of the human history of the region.

FLORIDA BAY AND THE COASTAL PRAIRIE

(elevation: sea level to 2 feet above sea level)

Back from the narrow beach is a drier zone of grasses and other low-growing vegetation. Some of the plants of this zone, such as the railroad vine, 23 are so salt-tolerant that in places they grow almost to the water’s edge. (No plant that is extremely sensitive to salty soil could survive on Cape Sable.) Beyond the grassy zone is a zone of hardwoods (buttonwood, gumbo-limbo, Jamaica dogwood), cactuses, yucca, and other plants forming a transition from beach to coastal prairie.

Birds provide much of the visual excitement of the beach community, just as they do in other parts of the park. Sandpipers, pelicans, gulls, egrets, ospreys, and bald eagles use it and the bordering waters for feeding, nesting, and resting. Mammals, notably raccoons, stalk the beach in search of food. And the big loggerhead turtle depends on it for nesting. In late spring and early summer the female loggerhead hauls herself up on the beach and digs a hole above hightide mark. There she deposits about 100 ping-pong balls—which should hatch 24 out into baby loggerheads. Unfortunately for this marine reptile, however, most of them meet another fate. Hardly has the female turtle covered the eggs with sand and started back toward the water, than they are dug up and devoured by raccoons and other predators. These conditions created such high mortality of the turtles that the National Park Service has adopted special protective measures—removing some of the raccoons and erecting wire barriers around turtle nests. These measures have been effective, but continued surveillance is required if the loggerhead is not to disappear from Florida.

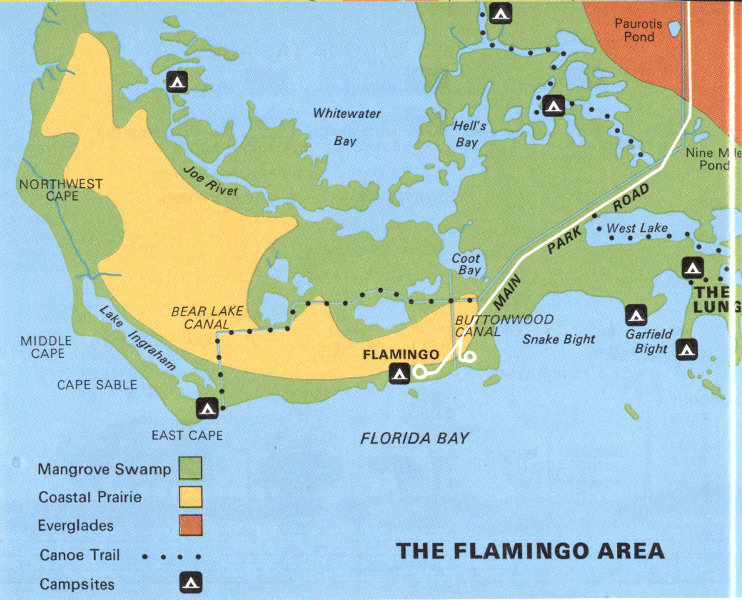

THE FLAMINGO AREA

An abundance of raccoons and other predators is not the only threat to survival of the loggerhead turtle. A major factor in its decline is the serious depletion of its nesting habitat. Park visitors are prohibited from interfering with these reptiles. 25 Cape Sable beach is today virtually the only wild beach in South Florida, thanks to its inclusion in Everglades National Park. At present, visitors can reach it only by boat. But it would be foolhardy to take it for granted that the beach will remain unspoiled. Its potential as an attraction is such that someone not ecologically aware might believe that access for motorists would be an improvement. Roads, however, would bring increased pressure on the ecosystem by large numbers of visitors, and demands for further development, for lodging, meals, and other services seem always to go with automobiles. With continued protection from such encroachments, Cape Sable Beach will remain a unique wilderness resource and will not become just another recreational facility.

Merging with the beach is the coastal prairie, an ecosystem supporting red and black mangroves, grasses, and other plants tolerant of the very salty environment. Hardwood hammocks have developed here on Indian shell mounds, but the trees are stunted by the saline soils. Though there is no lack of water on the cape, much of the region appears arid because hurricane-lashed tides have deposited soils of marl and debris so salt-laden that only sparse vegetation develops.

To the west of the great fresh-water marsh called the everglades, lying almost entirely outside the park, is an ecosystem vitally linked to the park. Big Cypress Swamp is a vast, shallow basin that includes practically all of Collier County. It is commonly called “The Big Cypress”—not because of the size of its trees, but because of its extent. Most of the baldcypresses (which are not true cypresses) are small trees, growing in open to dense stands throughout the area. The swamp is watered by about 50 inches of annual rainfall, the runoff from which flows as a sheet and in sloughs south and west to meet the coastal strip of mangroves and low sand dunes.

Big Cypress is speckled with low limestone outcrops, cut with shallow sloughs 1 to 2 feet deep, and dotted with ponds and wet prairies. As in the everglades, fire and water maintain the character of the plantlife in this swampy realm of sunlight and shadow. Also as in the everglades, a difference of a few inches in elevation creates different communities. Tropical hardwood hammocks grow on rocky outcrops. In the depressions arise bayheads and clumps of pond apple, pop ash, and willow. The larger baldcypress trees grow in shallow sloughs, which are usually surrounded by prairies of sawgrass and maiden cane growing on slightly higher land. Although the several different plant communities resemble those in the glades, they support slightly different plants, because of the sandy soil (there being more quartz in the limestone under Big Cypress than in the park).

These baldcypresses, many measuring 3 to 6 feet in diameter, were heavily lumbered from 1930 to 1950. Today, few giant trees survive, but a sizable stand exists on the Norris Tract—so named for its conservation-minded donor—which forms the nucleus of Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary. Here, protected by the National Audubon Society, are baldcypresses 130 feet tall; some have a girth 27 of 25 feet! A boardwalk more than one-half mile long enables you to enjoy the beauty of this wild preserve without getting your feet wet.

CYPRESS STRAND

Large stands of baldcypress, called “strands,” support small communities such as ponds, prairies, and tropical hammocks. One such hammock is famous for the finest stand of royal palms remaining in south Florida. The largest cypress strand—the Fakahatchee—extends some 23 miles north and south a few miles east of Naples.

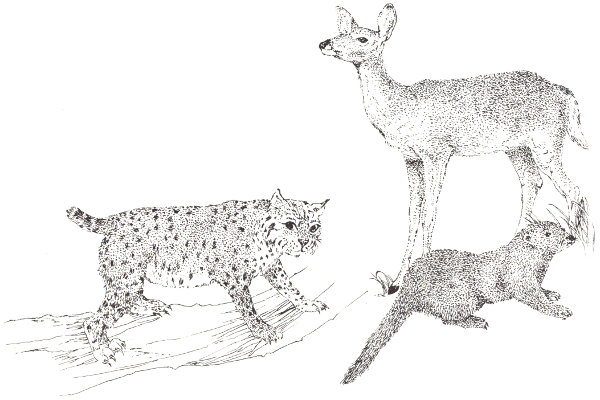

Big Cypress Swamp is the home of wild turkey, bobcat, deer, and an occasional Florida panther. The 28 fish-eating otter plays in its waterways. Most of the birds found in the everglades also are found in the trees and waterways of Big Cypress, because the swamp has an abundance of food. The area is so rich in wildlife and edible plants that the Seminole Indians formerly lived entirely off its products.

BOBCAT WHITE-TAILED DEER OTTER

The eastern edge of the big swamp and its importance to Everglades National Park came to worldwide attention in 1969 when it was selected as the site for the proposed Miami International Jetport. According to plans, this was to be the biggest airport in the world, covering 39 square miles and handling 65 million passengers a year. Millions of persons were expected to make their home in and around the jetport. Such a threat to the national park, into which the waters of Big Cypress partly drain, provoked protest letters from all over the world. Most writers objected on the grounds that Everglades belongs to all and that a jetport here would seal the doom of the park. Congress acted in 1974 by establishing Big Cypress National Preserve to help protect the water supply to Everglades National Park.

To know Everglades, you must become acquainted with some of its diverse communities. The physical conditions determining the existence of a particular community may seem subtle—just a few inches difference in elevation, or an accumulation of peat in a depression in the limestone bedrock, for example. But often, the change in your surroundings as you step from one community to another is startling—for it is abrupt and complete. In Everglades, the dividing line between two habitats may separate an almost entirely different association of plants and animals.

Use the trails that have been laid out to help you see the communities. They make access easy for you; the rest is up to you. Be observant: notice the stemlike root of a saw-palmetto in a damp pothole of the pineland; look closely at the periphyton that plays such an important role in the glades food chain. Note the difference in feeding methods of wading birds; each species has its own niche in the habitat. Most of all, get into the habit of thinking of each animal, each plant, as a member of the closely woven web of life that makes up an integrated community.

Generally, in south Florida, hardwood hammocks develop only in areas protected from fire, flood, and saline waters. The land must be high enough (1 to 3 feet above surrounding levels) to stand above the water that covers the glades much of the year. The roots of the trees must be out of the water and must have adequate aeration. In the park, these conditions prevail on the limestone “ridge” (elevation of which ranges from 3 to 7 feet above sea level) and some spots in the glades region. On the limestone ridge, in areas bypassed by fires for a long period, hammocks have developed. Pines grow in the surrounding areas, where repeated fires have held back the hardwoods.

The moats that tend to form around glades hammocks, as acids from decaying plant materials dissolve the limestone, hold water even during the dry season; the moats thus act as barriers protecting the hammock vegetation from glades fires.

When the white man took over southern Florida, these hammocks were luxuriant jungle islands dominated by towering tropical hardwoods and palms. Stumps and logs on the floors of some of the remaining hammocks, attesting to the enormous size of some of the earlier trees, are sad reminders of the former grandeur of the hammocks. While most of south Florida’s hammocks have been destroyed, you can still see some fine ones protected in the park. At Royal Palm Hammock, near park headquarters, Gumbo Limbo Trail winds through a dim, dense forest with welcome coolness on a hot day.

Stepping into a jungle hammock from either the sunbathed glades or the open pine forest is a sudden, dramatic change. The contrast when you enter Gumbo Limbo Trail immediately after walking the Anhinga Trail is striking. While the watery world of Anhinga is dominated by a noisy profusion of wildlife, the environment of Gumbo Limbo will 31 seem to be a mere tangle of vegetation. But the jungle hammock, too, has its community of animals—even though you may notice none but mosquitoes. Many of its denizens are nocturnal in their habits, but if you remain alert you will observe birds, invertebrates, and perhaps a lizard.

TREE SNAILS

There are 52 color forms of Liguus fasciatus found in south Florida.

Liguus fasciatus pseudopictus

Liguus fasciatus pictus

Liguus fasciatus ornatus

The trees that envelop you as you walk on Gumbo Limbo Trail are mostly tropical species; of the dominant trees, only the live oak (which grows as far north as Virginia) can be considered non-tropical. Under oaks and tropical bustics, poisonwood, mastics, and gumbo-limbos grow small trees such as tetrazygia, rough-leaf velvetseed, and wild coffee, a multitude of mosses and ferns, and only a few species of shade-tolerant flowering plants. Orchids and air plants burst like sun stars from limbs, trunks, and fallen logs. Twining among them all, the woody vines called lianas enhance the jungle atmosphere. Adding a final touch are the royal palms that here and there tower over the hardwood canopy—occasionally reaching 125 feet.

TROPICAL HARDWOOD HAMMOCK

The limestone rock that underlies the entire park is porous and soluble; consequently the floor of the hammock is pitted with solution holes dissolved by the acid from decaying vegetation. Soil and peat accumulating in the water-filled bottom of one of these holes supports a plant community of its own: perhaps a pond apple, surrounded by ferns and mosses (including some varieties that seem to be limited to this pothole environment).

A dead, decaying log on the ground may support another miniature plant community—a carpet of mosses, ferns, and other small plants that thrive in such moist situations.

Strangest of the hammock plants is the strangler fig, which first gets a foothold in the rough bark of a live oak, cabbage palm, or other tree. It then sends roots down to the ground, entwining about the host tree as it grows, and eventually killing it. On the Gumbo Limbo Trail you will see a strangler fig that grew in this manner and was enmeshed by another strangler fig—which now is threatened by a third fig that already has gained a foothold in its branches.

Best known of the glades hammocks is Mahogany Hammock. A boardwalk trail in this lush, junglelike tree island leads past the giant mahogany tree for which the hammock was named—now, because of Hurricane Donna, a dismembered giant. This fine tree island was explored only after the park was established.

An array of large and small vertebrate animals, mostly representative of the Temperate Zone, populates these tropical hardwood jungles: raccoons and opossums, many varieties of birds, snakes and lizards, tree frogs, even bobcats and the rare Florida panther, or cougar. Not surprisingly, invertebrates—including insects and snails—abound in this luxuriant plant community. The tropical influence is evident in the presence of invertebrates such as tree snails of the genus Liguus, known outside of Florida only in Hispaniola and Cuba.

Standing out conspicuously on the glades landscape are tall, domelike tree islands of baldcypress. Unlike hammocks, which occupy elevations, cypress heads, or domes, occupy depressions in the limestone bedrock—areas that remain as ponds or wet places during seasons when the glades dry up. Water-loving cypresses need only a thin accumulation of peat and soil to begin their growth in these depressions or in smaller solution holes in the limestone.

TURKEY VULTURE

Though most conifers retain their needles all year, baldcypresses shed their foliage in winter. The fallen needles decay, forming acids that dissolve the limestone further; thus these trees tend to enlarge their own ponds. Since the pond is deeper in the middle, and the accumulation of peat is greater there, the taller trees grow in the center of the head, with the smaller ones toward the edge. Hence the characteristic dome-shaped profile.

Usually when fire sweeps the glades, the baldcypresses, occupying low, wet spots, are not injured. But with extended drought, the water disappears and the peat may burn for months, killing all the baldcypresses.

The cypress heads sometimes serve as alligator holes, where the big reptiles and other aquatic animals are able to survive dry periods. As you drive along the park road, stop and examine these tree islands through your binoculars; they are favored haunts of many of the park’s larger wading 37 birds. Look for herons, egrets, wood storks, and white ibis, which visit these swampy habitats to feed on the abundant aquatic life.

Bald eagles find the tops of the tallest cypresses advantageous perches from which to scan the marsh. And at night certain of the cypress heads are “buzzard roosts”—resting areas for gatherings of hundreds of turkey vultures.

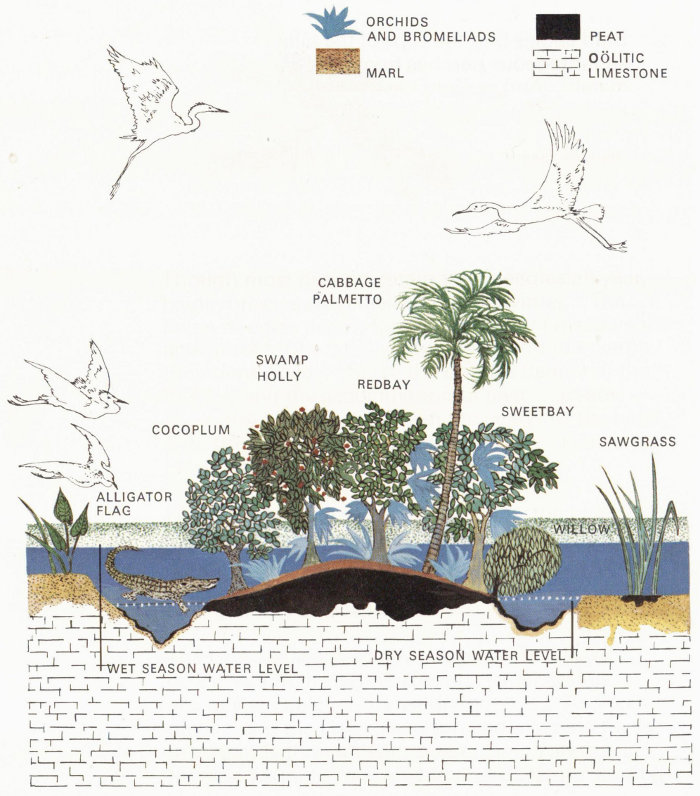

Bayhead

Many of the tree islands in the fresh-water glades are of the type called bayhead. Growing in depressions in the limestone or from beds of peat built up on the bedrock, these plant communities contain a variety of trees, including swamp holly, redbay, sweetbay, wax myrtle, and cocoplum. Some of them, on the fringes of the brackish zone, are marked by clumps of graceful paurotis palms growing at their edges.

Like the hardwood hammocks in the pinelands, bayheads are prevented from taking over the entire glades ecosystem by the dry-season fires that sweep the region at irregular intervals. The fires do not always affect the bayheads. A moat, formed by the dissolving action of acids from decaying plant materials on the limestone, may surround the tree island, providing some protection from fire. Wildlife concentrates in these moats during the dry season. Birds congregate here to harvest the fish, snails, and other aquatic life—and occasionally themselves fall prey to lurking alligators.

Willows pioneer new territories and create an environment that enables other plants to gain a foothold. Their windblown seeds usually root in sunny land opened by fire and agriculture. Since these trees require a great quantity of water, the solution holes in the glades are favorable sites. Seedlings grow, leaves fall, and stems and twigs die and drop—contributing to the formation of peat. When this builds up close to or above the surface of the water, it provides a habitat for other trees such as sweet bay and cocoplum; with enough of these the willow head changes character and becomes a bayhead.

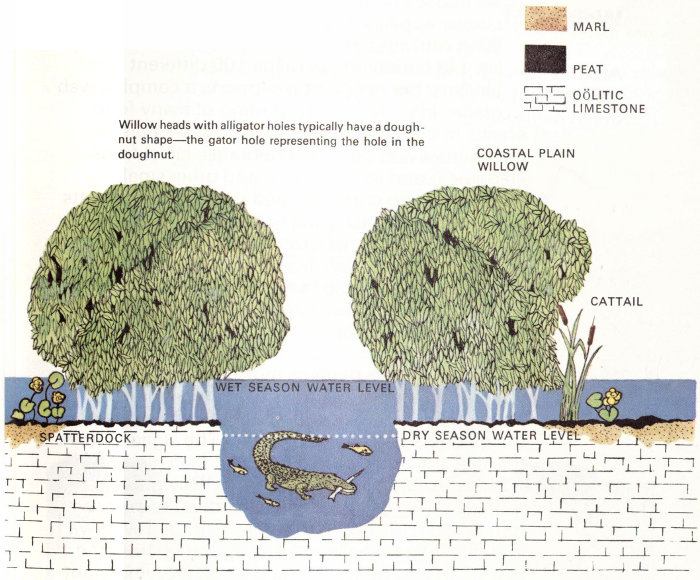

Years ago, when alligators were plentiful, they weeded the willow-bordered solution holes, keeping them open. Consequently, the willow heads were typically donut-shaped. Today, however, alligators are scarce and many of the willow heads have no ’gators. The solution holes fill with muck and peat; relatively tall willows rise out of the deep, peat-filled centers, with increasingly smaller ones toward the less fertile edges, and the willow heads take on the characteristic dome-shaped profile but not nearly the height of the cypress domes. They have a clumpy, brushy appearance, seeming to grow right out of the marsh without trunks.

POMACEA SNAIL—The sole food of the everglade kite

EVERGLADE KITE

Willow heads with alligator holes typically have a doughnut shape—the gator hole representing the hole in the doughnut.

Willow heads that do have alligator holes have a seasonal concentration of aquatic animals and the birds and mammals that prey upon them. They rarely support orchids or bromeliads, for the bark of the southern willow is too smooth to provide anchorage for the seedlings of these plants.

During drought periods willow heads, like bayheads, are vulnerable to the fires that sometimes burn over the glades.

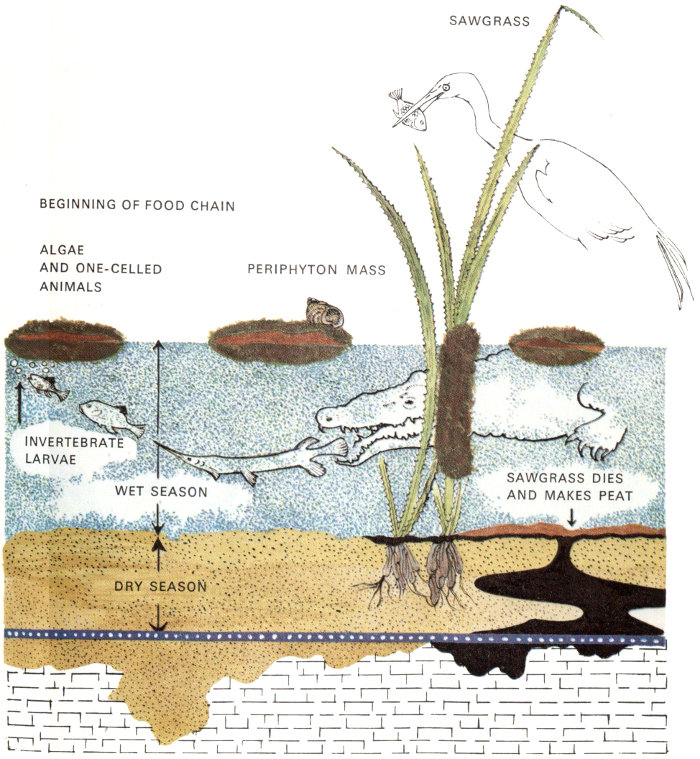

Around the stems and other underwater parts of the glades plants are cylindrical masses of yellowish-green periphyton. So incredibly abundant are these masses of living material that in late summer the water appears as though clogged with mossy-looking sausages and floating pancakes. Largely algae, but containing perhaps 100 different organisms, the periphyton supports a complex web of glades life. It is the beginning of many food chains in the fresh-water marsh. The larvae of mosquitoes and other invertebrates, larval frogs (tadpoles) and salamanders, and other small, free-swimming creatures feed upon the tiny plants and minute animals living in the masses of periphyton. These periphyton feeders are in turn fed upon by small fish, frogs, and other vertebrates, which are food for big fish, birds, mammals, and reptiles; most of these larger creatures are preyed upon by the alligator.

The periphyton is perhaps most important for its role in maintaining the physical environment of the marsh. The water flowing over the limestone of the glades is hard with calcium. The algae remove this calcium and convert it to marl (see glossary), which precipitates to the bottom. Sawgrass is rooted in this marl; accumulated dead sawgrass forms peat; other marsh plants, including willows and the trees of the bayheads, spring up from the peat. Acid from the peat and from decaying plant matter of the tree islands dissolves some of the marl and underlying bedrock—and the cycle is complete.

Every plant, every animal, every physical element is involved in this web of life—as soil builder, predator, plant-eater, scavenger, agent of decay, or converter of energy and raw materials into food. Damage to or removal of any of these components—pollution of the water, lowering of the water table, elimination of a predator, or any interference in the energy cycle—could destroy the glades as we know them.

BEGINNING OF FOOD CHAIN

Every other plant-and-animal community in the park—hammock, mangrove swamp, pineland, etc.—is an association of large and small organisms sharing a physical environment. It is impossible to understand either the park as a whole or the life of a single creature without being aware of these interrelationships.

Out in the sunny glades the broad leaves of the alligator flag mark the location of an alligator hole. This is the most incredible ecosystem of all the worlds within the world of the park; for in a sense the alligator is the keeper of the everglades.

With feet and snout these reptiles clear out the vegetation and muck from the larger holes in the limestone. In the dry season, when the floor of the glades checks in the sun, these holes are oases. Then large numbers of fish, turtles, snails, and other fresh-water animals take refuge in the holes, moving right in with the alligators. Enough of these water-dependent creatures thus survive the drought to repopulate the glades when the rains return. Birds and mammals join the migration of the everglades animal kingdom to the alligator holes, feed upon the concentrated life in them—and in turn occasionally become food for their alligator hosts.

ALLIGATOR FLAG

Lily pads float on the surface. Around the edges arrowleaf, cattails, and other emergent plants grow. Behind them on higher muckland, much of which is created by the alligators as they pile up plant debris, stand ferns, wildflowers, and swamp trees. Algae thrive in the water. The rooted water plants might become so dense as to hinder the movement 46 and growth of the fish, were it not for the weeding activities of the alligators. With the old reptiles keeping the pool open, the fish thrive, and alligator and guests live well.

Plants piled beside the hole by the alligator decay and form soil with mud and marl. Ferns, wildflowers, and tree seedlings take root, and eventually the alligator hole may be the center of a tree island.

So, it’s easy to see how important the alligator is to the ecology of the park. Unfortunately for this reptile, many people in the past believed only in the value of its hide. Hunting for alligators became profitable in the mid-1880’s and continued until the 1960’s. In 1961 Florida prohibited all hunting of alligators, but poaching continued to take its toll. Finally, the Federal Endangered Species Act of 1969 protected the alligator by eliminating all hunting and trafficking in hides.

As a result of complete protection, the alligator has increased greatly in number. They are no longer an endangered species in Florida, and they can easily be found in gator holes and sloughs. Today alligators are eagerly sought by visitors to Everglades National Park who are anxious to see and photograph this unique creature. Once again, the alligator is the keeper of the everglades.

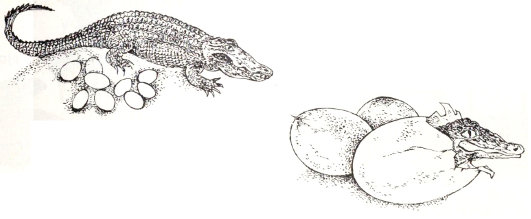

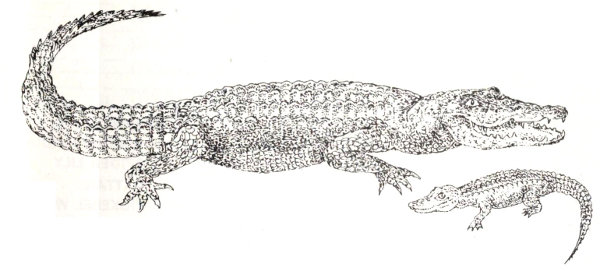

ACTUAL SIZE AT HATCHING (8″ to 10″)

40 TO 60 EGGS LAID IN NEST OF HUMUS IN MAY OR JUNE

MOTHER TENDS YOUNG 1 TO 2 YEARS

1 YEAR OLD: ABOUT 2′ LONG

ALLIGATOR HOLE IN THE GLADES

Everglades National Park, with its array of plant communities—ranging from the pines and palmettos rooted in the pitted limestone bedrock of the park’s dry uplands, through the periphyton-based marsh community and the brackish mangrove swamp, to the highly saline waters of Florida Bay—is an amateur botanist’s paradise. Many of the park’s plants are found nowhere else in the United States. Only here at the southern tip of the Florida peninsula do tropical trees and orchids mingle with oaks and pines.

This book is not intended to be a manual for identification of the Everglades plants. You will need to arm yourself with appropriate field guides to ferns, orchids, aquatic plants, trees, or whatever your special interest may be. The reading list in the appendix suggests a few.

While the park is a mecca for students of plantlife, you must keep one thing in mind: your collecting will be limited to photographs (and, if you’re an artist, drawings). No specimens may be removed or disturbed. Fortunately, with today’s versatile cameras and high-quality color films you can take home a complete and accurate record of your plant discoveries.

Much of our present knowledge of Everglades plantlife has been garnered by amateurs. Much more needs to be accumulated before an environmental management program for the park can be perfected, and serious students of botany are invited to make their data available to the park staff.

As for wild animals, one hardly needs to look for them in this park! Most visitors come here, at least partly, for that reason. And even those not seeking wildlife should be alert to avoid stepping on or running down the slower or less wary creatures. But animal watching is a great pastime, and it pays to learn to do it right. A few suggestions may help you make the most of your experience in Everglades.

BIRDS AND REPTILES

A notebook in which to record your observations will help you discover that this park is not just a landscape of grass, water, and trees where a lot of animals happen to live—but a complex, subtropical world of plant-and-animal communities, each distinct and yet dependent upon the others. To gain real understanding of this world you will need certain skills and some good habits. Ability to identify what you see—with the help of good field guides (see reading list) and quite a bit of practice—will make things easier and much more enjoyable.

Knowing where to look for the animals helps; this book and the field guides are useful for this. You’ll find that some species are seen only in certain parts of the park, while others roam far and wide. Don’t look for the crocodile in the fresh-water glades—nor for the round-tailed muskrat in the mangroves. On the other hand, don’t be surprised to see the raccoon or its tracks in almost any part of the park.

Keep in mind that all species in the national parks are protected by law. Most wild animals are harmless as long as they are not molested. If you encounter an animal you aren’t sure about, simply keep out of its way; don’t try to harm it or drive it off. Always remember that each animal is part of the Everglades community; you cannot disturb it without affecting everything else.

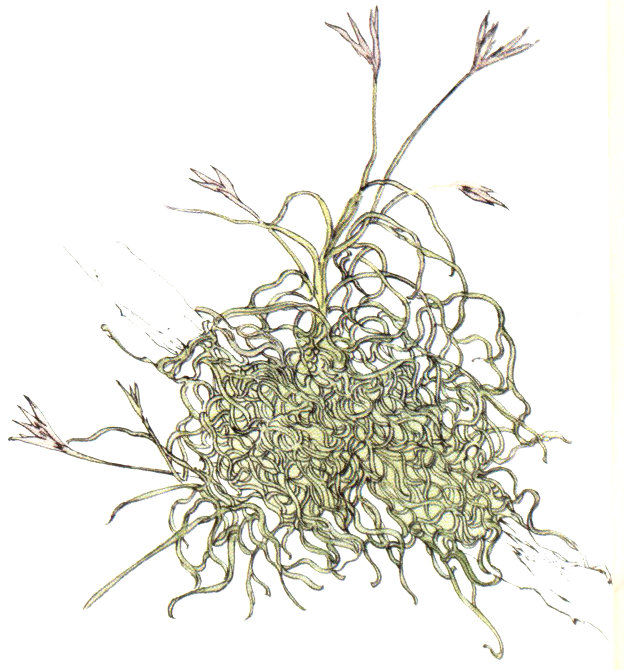

Long before you have learned to distinguish the major plant communities, you will be aware of the air plants—or epiphytes—that grow so profusely in Everglades. Epiphytes are non-parasitic plants that grow on other plants, getting their nourishment from the air. Best known is Spanish moss, which festoons the trees of the coastal South from Virginia to Texas; this plant is used by the swallow-tailed kite in constructing its beautiful nest. Despite its name, Spanish moss is actually a member of the pineapple family—the bromeliads. Bromeliads are the most conspicuous of the park’s air plants. The epiphytic orchids, though less common, are celebrated for their beauty; their fame, unfortunately, has led to their widespread destruction. There are also epiphytic ferns, trees, and vines; and one cactus, the mistletoe cactus, has taken to the air.

Air plants are highly specialized for making a living under crowded conditions; there are more than 2,000 species of plants competing for sun and water in southern Florida. The epiphytes have adapted to the problem of space by growing on other plants. Their roots, although they absorb some water and minerals, are primarily anchors. Living in an atmosphere that fluctuates between drought and humidity, they have evolved several water-conserving tricks. Some have a reduced number of leaves; others have tough skins that resist loss of water through transpiration; still others have thick stems, called pseudobulbs, that store moisture. The bromeliads are particularly ingenious: many have leaves shaped in such a way that they hold rainwater in vaselike reservoirs at their bases. Mosquitoes and tree frogs breed in these tiny reservoirs, and in dry periods many arboreal animals seek the dew that collects here.

Most of the orchids and bromeliads grow in the dimly lit tropical hardwood hammocks and cypress sloughs. A few species, however, having adapted to the sunlight, live on dwarf mangroves and the scattered buttonwoods, pond apples, willows, and cocoplums of the glades. The butterfly and cowhorn orchids are sun lovers, as are the twisted, banded, and stiff-leaved bromeliads. All have adapted to the sun with dew-condensing mechanisms or vases at the bottom of the clustered leaves.

COMMON BROMELIADS

STIFF-LEAVED WILDPINE

NEEDLE-LEAVED AIR PLANT

SMALL CATOPSIS

REFLEXED WILDPINE

TWISTED AIR PLANT

SOFT-LEAVED WILDPINE

SPANISH MOSS

BANDED WILDPINE

BALL-MOSS

One tree, the strangler fig, starts as an epiphytic seedling on the branches of other trees. Eventually, however, it drops long aerial roots directly to the ground or entwines them about the trunk of the host tree—which in time dies, leaving a large fig tree in its place.

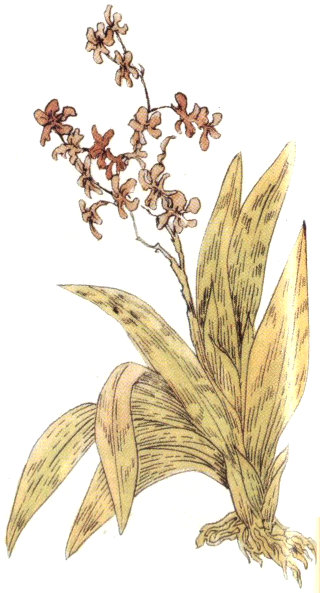

Of all Everglades plants, the epiphytic orchids are most fascinating to man—a fact which largely explains their decline. Of some 50,000 species around the world (the orchids being one of the largest of plant families), the park has only a few. Fire, loss of habitat due to agriculture and construction, and poaching by both commercial and amateur collectors have brought about the extermination of some and have made others exceedingly rare. Some are rare because of special life requirements. For example, a few must live in association with a certain fungus that coats their roots and provides specific nutrients.

The largest orchid in the park is the cowhorn, some specimens of which weigh as much as 75 pounds. Unfortunately, this orchid has been a popular item for orchid growers and collectors and is becoming rare in Florida. Poachers have practically eliminated it from the park. In the late 1960s Boy Scout friends of Everglades salvaged many orchids from hammocks about to be bulldozed for the jetport. By laboriously tying them to trees in the park, they assured the survival of the plants.

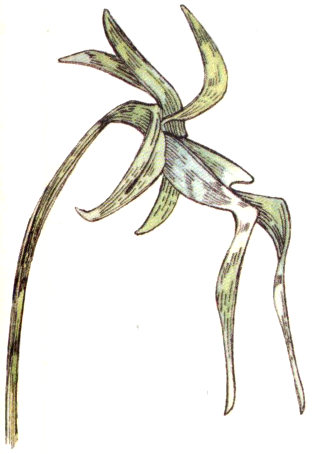

The night-blooming epidendrum is perhaps the most beautiful of the park’s orchids. It is widespread and fairly common in Everglades, occurring in all ecosystems. Flowering throughout the year, it bears its white, spiderlike blossoms, 2 inches across, one at a time. It is especially fragrant at night—hence its name.

SHOWY ORCHIDS OF THE HAMMOCKS AND TREE ISLANDS

BROWN EPIDENDRUM

DOLLAR ORCHID

NIGHT BLOOMING EPIDENDRUM

SPREAD-EAGLE ORCHID

BUTTERFLY ORCHID

FLORIDA ONCIDIUM

MULE-EAR ORCHID

OBLONG-LEAVED VANILLA

GHOST ORCHID

SPIDER ORCHID

CLAMSHELL ORCHID

WORM-VINE ORCHID

COWHORN ORCHID

TRINIDAD MACRADENIA

Epiphytic orchids have the smallest seeds of any flowering plants. Dustlike, they travel far and wide on the air; it is believed that over eons all species of Florida orchids arrived on the wind from South America and the West Indies.

The giant wildpine is a spectacular bromeliad that grows on the sturdy limbs of buttonwoods, spreading to 48 inches and developing a flower stalk 6 feet long.

Of the approximately 20 species of epiphytic ferns in the park, the most common is the curious resurrection fern. Sometimes called the poor man’s barometer, it has leaves that in dry weather curl under and turn brown but with the coming of rain quickly unfold and turn bright green, making instant gardens of the logs, limbs, and branches on which they grow.

Watch for the air plants (as well as the trees and other wildflowers) that have been labeled along the trails and boardwalks. You will be able to examine some of them closely—but leave them unharmed for future visitors!

In the drowned habitats of Everglades it is not surprising to find water-bound mammals such as the porpoise; or fish-eating amphibious mammals such as the otter; or even land mammals, such as the raccoon, that characteristically feed upon aquatic life. But to see mammals that one ordinarily does not associate with water behaving as though they were born to it is another matter. The white-tailed deer is an example. It is so much a part of this watery environment that you will most likely observe it far out in the glades, feeding upon aquatic plants or bounding over the marsh. Very probably the deer you see was born on one of the tree islands, and has never been out of sight of the sawgrass river.

Many other mammals of Everglades are adapted to a semi-aquatic existence. The park’s only representative of the hare-and-rabbit clan is the marsh rabbit; smaller than its close relative, the familiar cottontail of fields and woodlands, it is as comfortable in this wet world as if it had webbed feet. So don’t be startled if you see a rabbit swimming here! The park’s rodents include the marsh rice rat and round-tailed muskrat, also at home in a watery environment.

The playful otter, though it may travel long distances overland, is a famous water-lover. Lucky is the visitor who sees a family of these large relatives of the weasel! The otter’s smaller cousin, the everglades mink, is also a denizen of the marsh and a predator in the food web; but you are not likely to see this wary animal.

Raccoons and opossums, adaptable creatures that they are, live in all the park’s environments—except in the air and under water. Their diets are as wide-ranging as their habitat. The raccoon, though it has a taste for aquatic animals such as fish, frogs, and crayfish, also consumes small land vertebrates and various plant foods. The opossum eats virtually anything in the animal kingdom that it can find and subdue, as well as a wide variety of plant materials.

| SPECIES | PINE ROCKLAND | HARDWOOD HAMMOCK | GLADES | MANGROVE SWAMP | FRESHWATER SWAMPS | FLORIDA BAY and KEYS | COASTAL PRAIRIE | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opossum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Short-tailed Shrew | X | |||||||

| Least Shrew | X | |||||||

| Marsh Rabbit | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Fox Squirrel | X | ? | ||||||

| Rice Rat | X | X | ||||||

| Cotton Mouse | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Hispid Cotton Rat | X | |||||||

| Florida Water Rat | X | X | ||||||

| Raccoon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Abundant |

| Black Bear | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Very rare | |

| Mink | X | X | ||||||

| River Otter | X | X | ||||||

| Gray Fox | [1]X | |||||||

| Bobcat | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Florida panther | X | X | X | X | Rare | |||

| White-tailed Deer | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Bottle-nosed Dolphin | X | |||||||

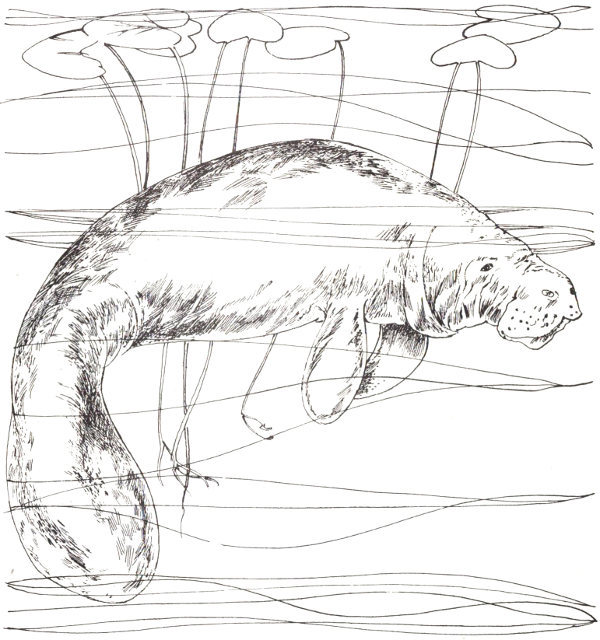

| Manatee | [2]X | X |

South Florida is the last known refuge in the world for a sub-species of cougar known as the Florida panther. This large, beautiful cat is on the endangered species list. Today many groups and individuals are working to keep this predator a part of the environment. Their efforts have resulted in methods to assist panther recovery: lower speed limits and highway culverts and bridges, to mention only two. With continued assistance, the panther may remain a part of the Everglades for years to come.

Because it is much more numerous and much less secretive in its habits, the bobcat is more likely to be encountered by park visitors than is the cougar. Keep your eyes alert for this wild feline—particularly in the Flamingo area—and you may have a chance to observe it closely and at some length (even by daylight!). Such boldness and such unconcern for humans are not typical of this species, but seem to be peculiarities of the bobcats living in the park. Although bobcats are not known as water lovers, they are found in all the Everglades environments. Their apparent liking for life in the park may be due to an abundance of food and to freedom from persecution by man and his dogs. Bobcats in Everglades, if their food habits elsewhere are any guide, probably live on rodents, marsh rabbits, and birds, with possibly an occasional fawn.

In Florida Bay and the estuaries, look for the porpoise, or bottlenosed dolphin, a small member of the whale order that has endeared itself to Americans through its antics at marine aquariums and on television. Watch for it when you are on a boat trip in the park’s marine environment.

Much less commonly seen, and much less familiar, is the timid and very rare manatee. It’s probably the “most” animal of the park—the largest (sometimes over 15 feet long and weighing nearly 1 ton), the shyest, the strangest, and the homeliest; and it is probably also the most delicate, for a drop in water temperatures may kill it. The estuaries of 63 Everglades National Park are almost the northern limits of its normal range. But manatees are often found well north of the park on both coasts in cold weather, when they swim up rivers to seek the constant-temperature water discharged by electric power plants. Despite its size, the manatee is a harmless creature, being a grazer—a sort of underwater cow that is exceptionally vulnerable to motorboats because of its gentle nature and languid movement.

MANATEE

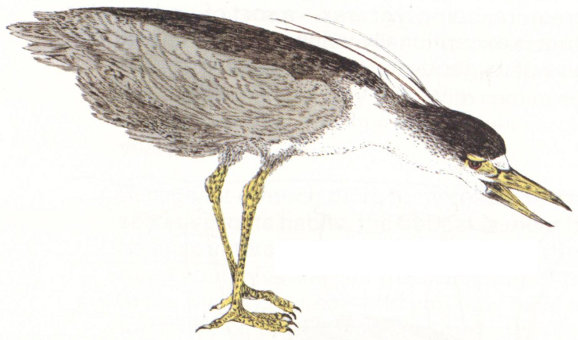

BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT HERON

LOUISIANA HERON

GREEN HERON

YELLOW-CROWNED NIGHT HERON

From the pelican—whose mouth can hold more than its belly can—to the tiny hummingbird, the birds of Everglades National Park add beauty, amusement, excitement, and drama to the daily scene. Much more conspicuous than the park’s other animals, they can be enjoyed with no special effort. But a pair of binoculars and a field guide will make bird watching a more rewarding pastime for you.

Many of the park’s birds are large and colorful, and so tolerant of man’s presence that you can observe them closely without the aid of binoculars. The Anhinga Trail and other sites on or near the main park road provide ready access to activity by herons and egrets, cormorants, gallinules, and other species that feed upon the fish, frogs, and lesser life of the waters.

The anhinga, after whom the park’s most popular trail is named, is a favorite with visitors. It is also called water-turkey, probably because of its large size and long, white-tipped tail feathers. A third name, snake bird, derives from the anhinga’s habit of swimming almost totally submerged with its long, snaky neck above the surface. The anhinga is a skilled fisherman, seeking out its quarry by swimming underwater. It spears a fish with its beak, surfaces, tosses the fish into the air, catches it, and gulps it down head first. During this activity, the anhinga has gotten soaked to the skin, for, unlike ducks and many other water birds, it is not well supplied with oil to keep its plumage dry. So, following a plunge, the anhinga struggles to the branch of a shrub or tree, and, spreading its wings, hangs its feathers out to dry.

The snail kite, one of America’s rarest birds, flies low over the fresh-water marshes, its head pointed downward, searching for its sole food—the Pomacea snail. A sharply hooked beak enables it to remove the snail from its shell. More striking in appearance is its cousin, the swallow-tailed kite, aerial acrobat of the hawk family—a migrant that nests in the park in spring and spends the winter in South America. On long, pointed wings this handsome bird eats in the air while holding itself in one place on the wind. In the mangroves, it hunts in an unusual way: skimming over the trees, it snatches lizards and other small animals from the topmost branches. Red-shouldered hawks, often seen perching on the treetops beside the park road, feed upon snakes and other small animals. The fish-eating osprey is another conspicuous resident of the park, and its bulky nests will be seen when you take a boat trip into Florida Bay or the mangrove wilderness. The bald eagle, which, sadly, is no longer common in North America and may soon be exterminated because of pesticide pollution of its fishing waters, is still holding out in the Everglades region, where 50 or so breeding pairs seem to be reproducing successfully.

LITTLE BLUE HERON

GREAT BLUE HERON

REDDISH EGRET

WHITE PHASE

WOOD STORK

GLOSSY IBIS

WHITE IBIS

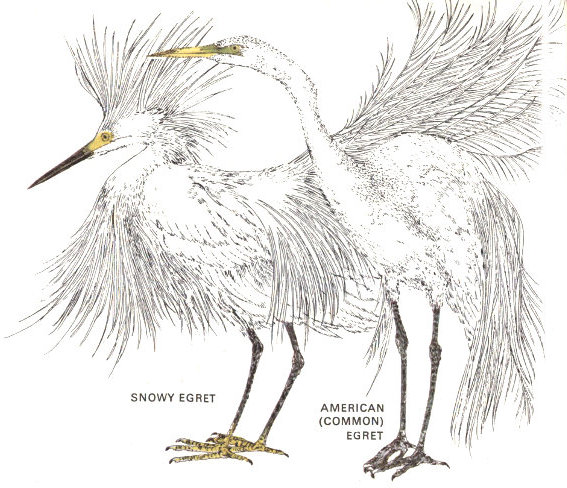

AMERICAN (COMMON) EGRET

SNOWY EGRET

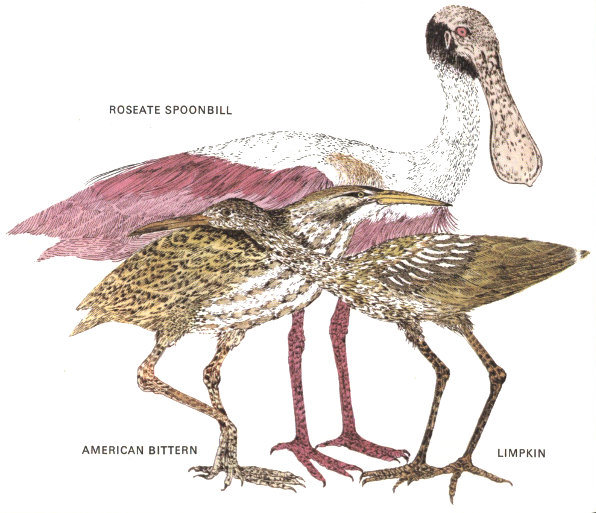

LIMPKIN

AMERICAN BITTERN

ROSEATE SPOONBILL

The long-legged wading birds of the heron family are so numerous and so much alike in appearance that you will need your bird guide for sure identification. The waders are interesting to watch, because of the variety of feeding methods. Particularly amusing are the antics of the reddish egret as it hunts small animals in the shallows of Florida Bay at low tide. It is much unlike other herons in its manner of hunting: it lurches through the shallows, dashing to left and right as if drunk, in pursuit of its prey. This clownish survivor of the old plume-hunting days exists in Florida in very limited numbers.

Since about 300 species of birds have been recorded in the park, this sampling barely suggests the pleasures awaiting you if you plan to spend some time playing the Everglades bird-watching game.

Everglades’ most famous citizen—the alligator—is looked for by all visitors to the park, who may, however, be unaware that many other kinds of reptiles and a dozen species of amphibians dwell here.

The American crocodile, less common than the alligator and restricted to the Florida Bay region, is a shy and secretive animal seen by few visitors. Similar in size and appearance to the alligator, it is distinguished by a narrower snout and a lighter color. Its habitat overlaps that of the alligator, which prefers fresh or brackish water.

The turtles of the park include terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine species. Box turtles are often seen along the roads. The softshell and snapping turtles live in the fresh-water areas and are often eaten by alligators. Loggerhead turtles nest on Cape Sable beaches, otherwise they rarely come ashore. Their eggs are often discovered and devoured by the abundant raccoons. But man has been largely responsible for the loggerhead’s increasing rarity.

Although the park has about two dozen species of snakes, you may not encounter any of them. Most are harmless—several species of snakes frequent the waterways, and it is a mistake to assume that any water snake you see is a moccasin. Two worth watching for are the everglades rat snake and the indigo snake, both handsome and entirely harmless to man. The former is a constrictor, feeding mostly on rodents. The indigo is one of our longest snakes—sometimes reaching more than 100 inches—and now in danger of extinction.

Ordinary caution and alertness when walking on trails is advisable; but keep in mind that the snakes are not aggressive, and that as part of the web of life in the park they are given protection just as are birds and mammals.

Of those close relatives of snakes, the lizards, the 71 Florida anole is most commonly seen. This is the little reptile sold at circuses as a “chameleon”; it is quite unlike the true chameleon of the Old World. The so-called “glass snake”—which got its name from its defensive maneuver of dropping off its tail (which is longer than the rest of its body) and from its snakelike appearance—is actually a legless lizard. The lizards, like the smaller snakes, are primarily insectivorous.

The park’s amphibians, too, are quite inconspicuous. The voices of frogs and toads during the breeding season, however, are part of the Everglades atmosphere. You will enjoy the nocturnal serenade at egg-laying time—and it is quite possible to learn to identify species by their songs, which are as distinctive as those of birds.

The green treefrog, with its bell-like, repeated “queenk-queenk-queenk” call, is abundant, and can be seen and heard easily during the breeding season, particularly at Royal Palm Hammock and on the Anhinga Trail.

The cold-blooded vertebrates, including fish, amphibians, and reptiles, play a significant role in the balance of life in the park, feeding upon each other and upon lesser animals and in turn being food for larger predators such as herons, hawks, raccoons, and otters.

“Fishing Reserved for the Birds,” says the sign at the beginning of the Anhinga Trail. Actually, the catching of fish in the fresh waters of the park is an important activity not only for herons, anhingas, grebes, and ospreys, but also for raccoons, mink, turtles, alligators ... and bigger fish. Not surprisingly in the drowned habitats of Everglades, even the smallest fish are important in the web of life.

One tiny species, the gambusia, is of special interest to us. This 2-inch fish is credited with helping keep down the numbers of mosquitoes by feeding upon their aquatic larvae. This accounts for its other name—mosquito fish—and for its popularity with humans. But its services to us are not the measure of the gambusia’s importance, for it is a link in many food chains in the park’s brackish and fresh-water habitats. Beginning with algae, we can trace one such chain through mosquito larvae, sunfish, and bass, to end with the alligator. We can only guess at the extent of the ecological effects of the loss of a single species such as the little gambusia.

The larger fish of Everglades are the most sought after. Sport fishermen want to know where to find and how to recognize the many varieties of game fish, especially largemouth bass and such famed salt-water and brackish zone species as tarpon, snook, mangrove snapper, and barracuda. Because of its cycles of flood and drought, and the shifting brackish zones, however, the distribution and the numbers of fish fluctuate greatly in the glades and mangrove regions. At times of drought, the fish concentrations are particularly evident. In mid- or late winter, sloughs that are no longer deep enough to flow, pools, and other standing bodies of water will have a myriad of gambusia, killifish, and minnows. Larger fish seek the sanctuary of the headwaters of the Harney, Shark, and Broad Rivers. At such times concentrations of bass may be so great that the angler may catch his 73 daily limit in a few hours. (There are no legal limits for the herons and ’gators!)

As water levels continue to fall, salt water intrudes farther inland; such species as snook and tarpon move up the now brackish rivers, and may be seen in the same waters as bluegills and largemouth bass.

In some years water levels drop so severely that concentrations of fish are too great for the habitat to support. As the surface water shrinks, the fish use up the available free oxygen and begin to die. The largest expire first; the smaller fish seem less vulnerable to depleted oxygen supply. Even though many tons of fish may perish in such a die-off, a few small specimens of each variety survive to restock the glades when the rains return.

With no cold season when fish must remain dormant, and with a year-round food supply, bass and sunfish grow rapidly and reach breeding size before the next drought.

These fish kills are associated with drought conditions that occur in the ordinary course of events, and thus are natural phenomena not to be considered ecological disasters. But man’s violent upsetting of the drainage patterns of south Florida, through airport, canal, and highway construction and other developments, can bring about such drastic shortages (or even surpluses) of water that irreparable damage could be done to the ecology of Everglades aquatic communities.

While fish watching may not be the exciting sport that bird watching is, you are the loser if you ignore this part of the life of Everglades. Fish are so abundant in the park that no one has to haul them in on a line to discover them. You can hardly miss spotting the larger fresh-water forms if you take the trouble to look down into the sloughs, ponds, and alligator holes.

Identifying the species of fish, however, is more difficult. The voracious-looking Florida spotted gar 74 is an exception. This important predator on smaller fishes, which is in turn a major item in the diet of the alligator, is quite easily recognized. Experienced anglers will spot the largemouthed bass and the bluegill sunfish. You’ll see these and others as you walk on the Anhinga Trail boardwalk.

As you watch alligators and other native Everglades predators, you may get an inkling of how important in the web of life are the prolific fish populations of the sloughs, marshes, swamps, and offshore waters of the park.

Insects are the most noticeable of the park’s invertebrates. (At times you may find your can of repellent as important as your shoes!) In all the fresh-water and brackish environments, insects and their larvae are important links in the food chains—at the beginning as primary consumers of algae and other plant material, and farther along as predators, mostly on other insects. Some insects are parasites on the park’s warmblooded animals (including you).

The invertebrates most sought by visitors are molluscs—or rather, their shells. You may find a few on the beach at Cape Sable, but don’t expect to find the park a productive shelling area. Stick to marine shells—dead ones. You cannot collect the fresh-water molluscs. Also protected are the tree snails of jungle hammocks. Famed for their beauty, these snails of the genus Liguus, which grow to as much as 2½ inches in diameter, feed upon the lichens growing on certain hammock trees. Look for them—but leave them undisturbed, for they are a part of the community, protected just as are the park’s royal palms and its alligators.

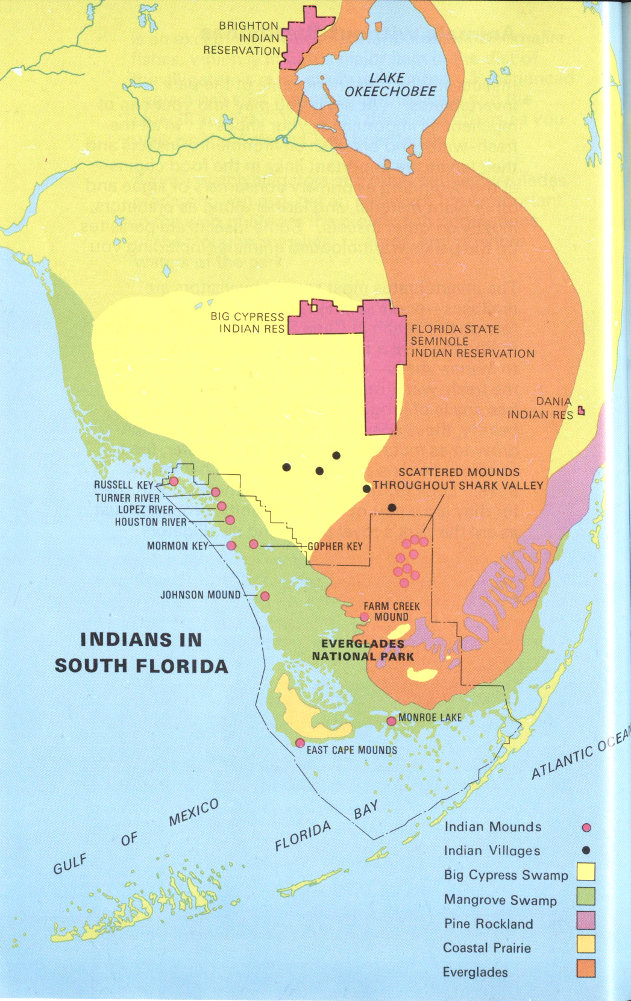

INDIANS IN SOUTH FLORIDA

Your first awareness of the south Florida Indians will probably come during a trip along the Tamiami Trail (U.S. 41, the cross-State highway just north of the park). You will notice clusters of Indian homes close to the road. Some are built on stilts, are thatched with palm fronds, and are open-sided so that no walls hamper the flow of cooling breezes. Many of the glades Indians prefer to live as their ancestors did some 150 years ago when they were newcomers to the everglades. Others have adopted the white man’s dwellings (as well as his occupations).

The Indians of south Florida—Miccosukees, sometimes called “Trail Indians”; and Muskogees, the “Cow Creek Seminoles”—are separate tribes, not sharing a common language. Today no Indians live inside the park boundaries.

The Indians arrived in Spanish Florida after the American Revolution. Many Creeks of Georgia and Alabama, crowded by the aggressive white man, fled south to the peninsula. They first settled in north Florida; when Florida became a State in 1845 they had to retreat farther south. Driven into the interior during the Seminole War of 1835, they eventually settled in the everglades, where deer, fish, and fruit were available. Though their territory is now much more limited, they still retain much of their independent spirit, and have never signed a peace treaty with the U.S. Government.

Many earn their living operating air boats, as proprietors and employees of roadside businesses, and in a variety of jobs on farms and in cities. The women create distinctive handicraft items, which find a ready market with tourists.

No one is certain when the first Indians—the Calusas and Tequestas—appeared in south Florida; it may have been more than 2,000 years ago. Even more 78 than today’s glades Indians, these coastal Indians lived with the rhythm of river and tides, rain and drought. Hunting, fishing, and gathering of shellfish were their means of existence. We have learned this much of their life from artifacts unearthed from the many Indian mounds or washed up along the beaches. They lived on huge shell mounds, made pottery, used sharks’ teeth to make saws, and fashioned other tools from conch shells. They even built impoundments for fish—a few remains of these can be seen today. They were ingenious hunters. (Ponce de León and his Spanish explorer-marauders were said to have been turned back from the everglades by the deadly arrows these Indians fashioned from rushes.)

Following the arrival of the Spanish, these early Indians disappeared from the scene. They were apparently wiped out, destroyed by the white man’s diseases as much as by his aggression; but some 79 may have escaped to Cuba. Perhaps a handful of them were still in the everglades when the Creeks came down from the north in 1835, and were absorbed into the new tribe. Their known history ends here.

Proud, independent, and ingenious in wresting a living from the land and the water, the Indians knew how to live with nature. Unlike the white man, they fitted into the plant-and-animal communities. Today these communities have been severely disrupted. In the few decades that the white man has been “developing” the region, he has broken every chain of life described in this book.

Alligator populations have been much reduced in south Florida; their chief prey, the garfish, has in some places become so numerous as to constitute a nuisance (most of all to the fresh-water anglers, some of whom had a hand in the killing of alligators). The pattern of waterflow over the glades, through the cypress swamps, and into the mangrove wilderness has been altered by highways and canals. Much of the habitat has been wiped out by construction of homes and factories and by farming operations. An increasingly alarming development is the pollution of glades waters by agricultural chemicals.

Only through complete understanding of this fragile, unique subtropical world can man reverse the destructive trend. Only through carefully applied protective and management practices can we make progress toward restoring to the Everglades some of its lost splendor.

ALGAE: (pronounced “AL-jee”) A group of plants (singular: ALGA, pronounced “AL-ga”), one-celled or many-celled, having chlorophyll, without roots, and living in damp places or in water.

BRACKISH WATER: Mixed fresh and salt water. Many species of plants and animals of marine and fresh-water habitats are adapted to life in estuaries and coastal swamps and marshes, where the water varies greatly in degree of salinity. Some animal species can be found in all three habitats.

BROMELIAD: A plant of the pineapple family. Many bromeliads are air plants, growing (not parasitically) on the trunks and branches of other plants, or even, as in the case of “Spanish moss,” on telephone wires.

COMMUNITY: The living part of the ecosystem; an assemblage of plants and animals living in a particular area or physical habitat. It can be as small as a decaying log, with its variety of mosses, insect larvae, burrowing beetles, ants, etc.; or as large as a forest of hundreds of square miles.

DECIDUOUS TREES: Trees that shed their leaves annually. Most hardwood trees are deciduous; some conifers, such as larches and baldcypresses, are deciduous.

ECOLOGY: The study of the relationship of living things to one another and to their physical environment.

ENDANGERED: A species of plant or animal that, throughout all or a significant portion of its range, is in danger of extinction.

ENVIRONMENT: All the external conditions, such as soil, water, air, and organisms, surrounding a living thing.

ESTIVATION: A prolonged dormant or sleeplike state that enables an animal to survive the summer in a hot climate. As in hibernation, breathing and heartbeat slow down, and the animal neither eats nor drinks.

ESTUARY: The portion of a river or coastal wetland affected by the rise and fall of the tide, containing a graded mixture of fresh and salt water.

EVERGLADE: A tract of marshy land covered in places with tall grasses. (In this book, “the everglades” refers to the river of grass; “Everglades” refers to the park, which contains other habitats besides everglades.)

EXOTIC: A foreign plant or animal that has been introduced, intentionally or unintentionally, into a new area.