Title: Shakespeare the Boy

Author: W. J. Rolfe

Release date: February 11, 2017 [eBook #54151]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MWS, John Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Shakespeare the Boy, by W. J. (William James) Rolfe

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/shakespeareboy00rolf |

A detailed TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE can be found at the end of the book.

WITH SKETCHES OF

THE HOME AND SCHOOL LIFE

THE GAMES AND SPORTS, THE MANNERS, CUSTOMS

AND FOLK-LORE OF THE TIME

BY

WILLIAM JAMES ROLFE, Litt.D.

WITH FORTY-ONE ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1897

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Two years ago, at the request of the editors of the Youth's Companion, I wrote for that periodical a series of four familiar articles on the boyhood of Shakespeare. It was understood at the time that I might afterwards expand them into a book, and this plan is carried out in the present volume. The papers have been carefully revised and enlarged to thrice their original compass, and a new fifth chapter has been added.

The sources from which I have drawn my material are often mentioned in the text and the notes. I have been particularly indebted to Halliwell-Phillipps's Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare, Knight's Biography of Shakspere, Furnivall's Introduction to the "Leopold" edition of Shakespeare, his Babees Book, and his edition of Harrison's Description of England, Sidney Lee's Stratford-on-Avon, Strutt's Sports and Pastimes, Brand's Popular Antiquities, and Dyer's Folk-Lore of Shakespeare.

I hope that the book may serve to give the young folk some glimpses of rural life in England when Shakespeare was a boy, and also to help them—and possibly their elders—to a better understanding of many allusions in his works.

W. J. R.

Cambridge, June 10, 1896.

| PAGE | |

| PART I.—HIS NATIVE TOWN AND NEIGHBORHOOD | 1 |

| Warwickshire | 3 |

| Warwick Castle and Saint Mary's Church | 4 |

| Warwick in History | 8 |

| Guy of Warwick | 9 |

| Kenilworth Castle | 12 |

| Coventry | 14 |

| Charlecote Hall | 19 |

| Stratford-on-Avon | 24 |

| The Early History of Stratford | 27 |

| The Stratford Guild | 34 |

| The Stratford Corporation | 39 |

| The Topography of Stratford | 43 |

| PART II.—HIS HOME LIFE | 47 |

| The Dwelling-houses of the Time | 49 |

| The Household Furniture | 52 |

| Food and Drink | 57 |

| The Training of Children | 60 |

| Indoor Amusements | 67 |

| Popular Books | 71 |

| Story-telling | 73 |

| Christenings | 80 |

| Superstitions connected with Birth and Baptism | 84 |

| Charms and Amulets | 87 |

| PART III.—AT SCHOOL | 93 [vi] |

| The Stratford Grammar School | 95 |

| What Shakespeare Learnt at School | 99 |

| The Neglect of English | 106 |

| School Life in Shakespeare's Day | 110 |

| School Morals | 112 |

| School Discipline | 113 |

| When William Left School | 118 |

| PART IV.—GAMES AND SPORTS | 119 |

| Boyish Games | 121 |

| Swimming and Fishing | 130 |

| Bear-baiting | 132 |

| Cock-fighting and Cock-throwing | 136 |

| Other Cruel Sports | 139 |

| Archery | 142 |

| Hunting | 145 |

| Fowling | 151 |

| Hawking | 153 |

| Theatrical Entertainments | 160 |

| PART V.—HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, FAIRS, ETC. | 165 |

| Saint George's Day | 167 |

| Easter | 172 |

| The Perambulation of the Parish | 174 |

| May-day and the Morris-dance | 176 |

| Whitsuntide | 184 |

| Midsummer Eve | 186 |

| Christmas | 190 |

| Sheep-shearing | 193 |

| Harvest-home | 195 |

| Markets and Fairs | 198 |

| Rural Outings | 207 |

| NOTES | 213 |

| INDEX | 247 |

| SHAKESPEARE THE BOY | Frontispiece | |

| THE SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE, ABOUT 1820 | 3 | |

| WARWICK CASTLE | 5 | |

| GATE-HOUSE OF KENILWORTH CASTLE | 13 | |

| COVENTRY CHURCHES AND PAGEANT | Facing p. | 14 |

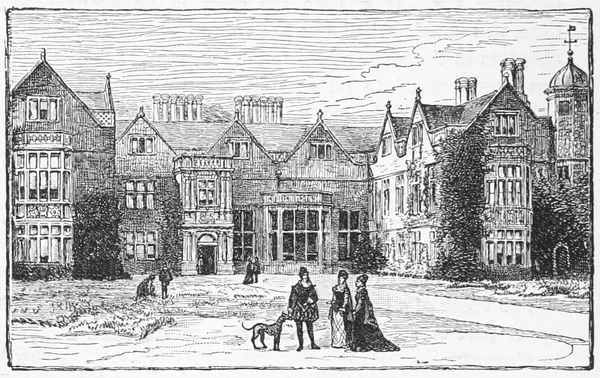

| CHARLECOTE HALL | 20 | |

| ENTRANCE TO CHARLECOTE HALL | 22 | |

| SIR THOMAS LUCY | 23 | |

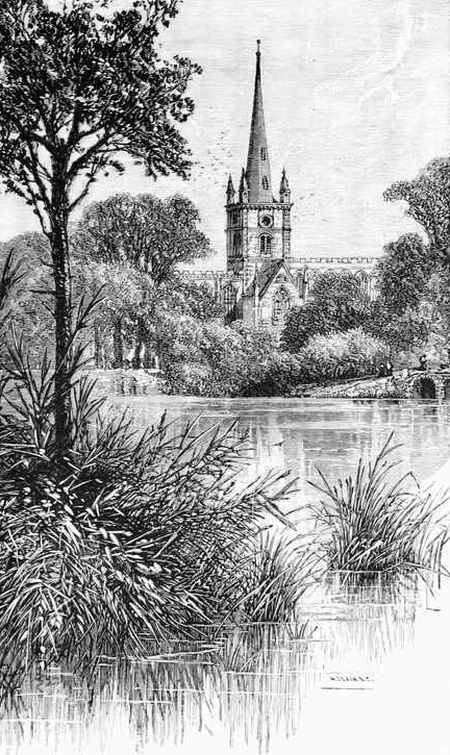

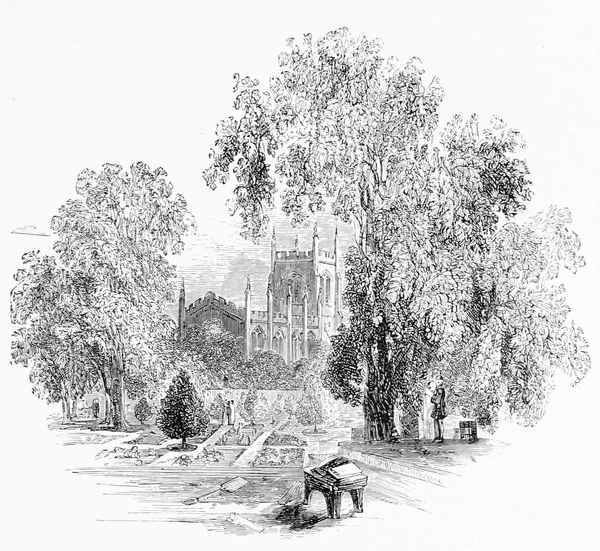

| STRATFORD CHURCH | Facing p. | 30 |

| STRATFORD CHURCH, WEST END | 32 | |

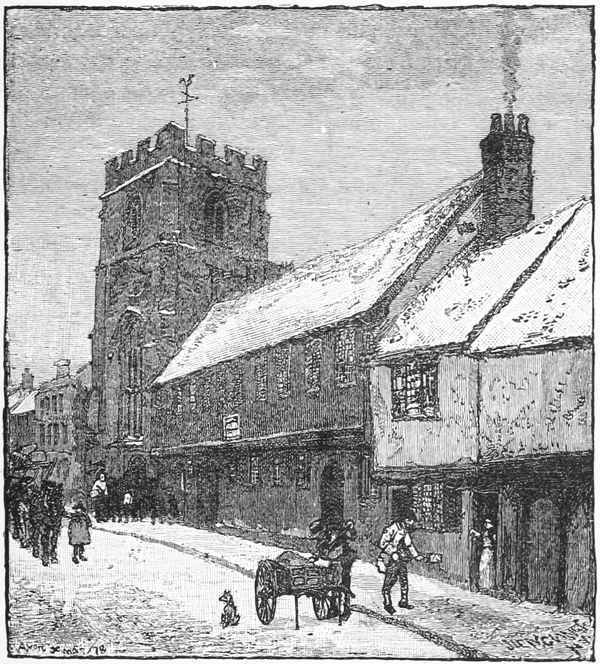

| THE GUILD CHAPEL AND GRAMMAR SCHOOL, STRATFORD | 35 | |

| MAP—PLAN OF STRATFORD | 42 | |

| SHAKESPEARE HOUSE, RESTORED | 49 | |

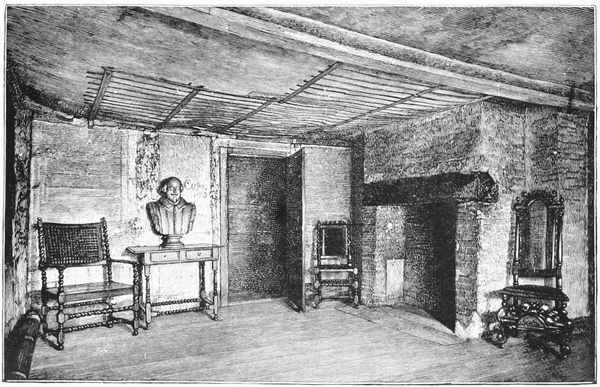

| ROOM IN WHICH SHAKESPEARE WAS BORN | Facing p. | 50 |

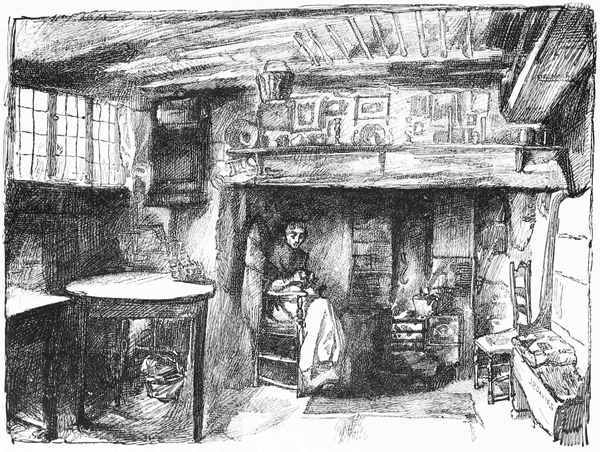

| INTERIOR OF ANNE HATHAWAY'S COTTAGE | " | 56 |

| OLD HOUSE IN HIGH STREET | 59 | |

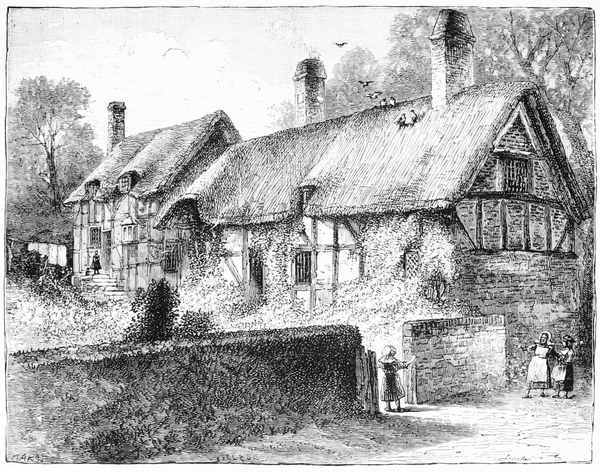

| ANNE HATHAWAY'S COTTAGE | Facing p. | 64 |

| SHILLING OF EDWARD VI. | 68 | |

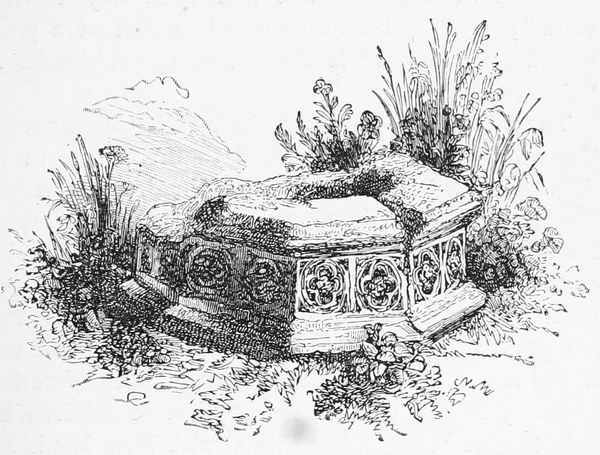

| ANCIENT FONT AT STRATFORD | 81 | |

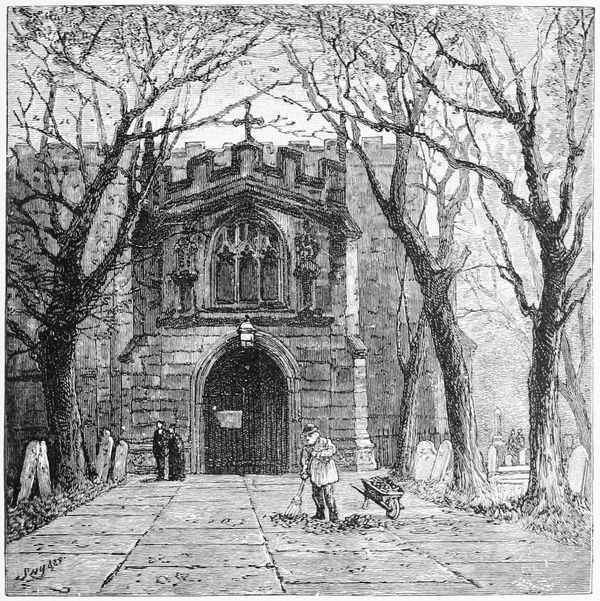

| PORCH, STRATFORD CHURCH | Facing p. | 88 |

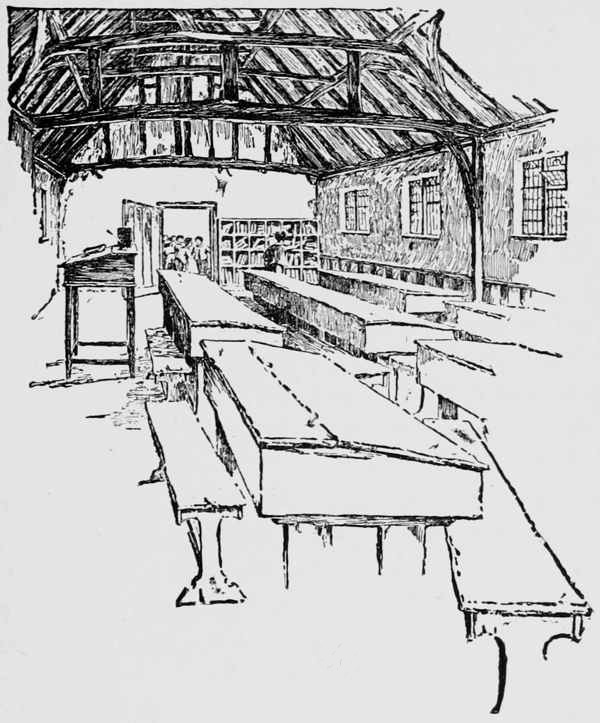

| INNER COURT, GRAMMAR SCHOOL | 95 | |

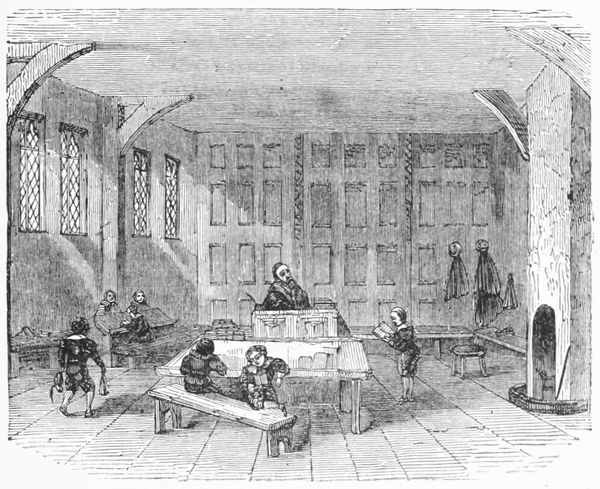

| THE SCHOOL-ROOM AS IT WAS | 97 [viii] | |

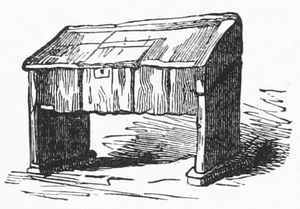

| DESK SAID TO BE SHAKESPEARE'S | 102 | |

| WALK ON THE BANKS OF THE AVON | Facing p. | 112 |

| HIDE-AND-SEEK | " | 122 |

| "MORRIS" BOARD | 130 | |

| FISHING IN THE AVON | Facing p. | 132 |

| THE BEAR GARDEN, LONDON | 133 | |

| GARDEN AT NEW PLACE | Facing p. | 146 |

| ELIZABETH HAWKING | 155 | |

| BOY WITH HAWK AND HOUNDS | 159 | |

| ITINERANT PLAYERS IN A COUNTRY HALL | Facing p. | 160 |

| WILLIAM KEMP DANCING THE MORRIS | 163 | |

| THE BOUNDARY ELM | 167 | |

| MORRIS-DANCE | Facing p. | 178 |

| CLOPTON HOUSE ON CHRISTMAS EVE | " | 190 |

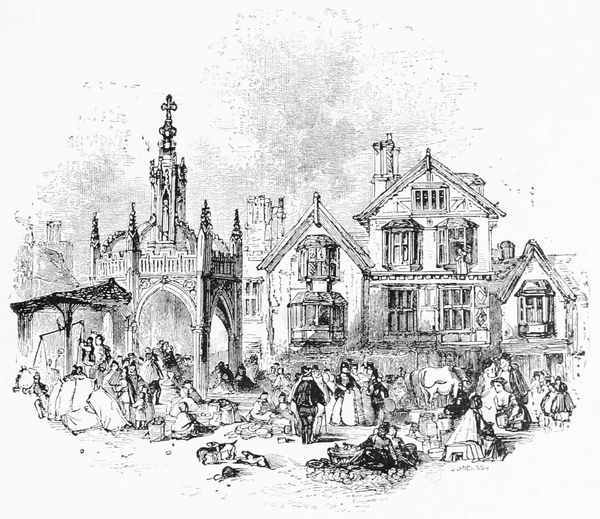

| THE FAIR | " | 200 |

| INTERIOR OF GRAMMAR SCHOOL, BEFORE THE RESTORATION | 225 | |

| CLOPTON MONUMENTS | Facing p. | 238 |

| THE BAR-GATE, SOUTHAMPTON | 242 | |

| ARMS OF JOHN SHAKESPEARE | 251 | |

SHAKESPEARE THE BOY

The county of Warwick was called the heart of England as long ago as the time of Shakespeare. Indeed, it was his friend, Michael Drayton, born the year before himself, who first called it so. In his Poly-Olbion (1613) Drayton refers to his native county as "That shire which we the heart of England well may call." The form of the expression seems to imply that it was original with him. It was doubtless suggested by the central situation of the county, about equidistant from the eastern, western, and southern shores of the island; but it is no less appropriate with reference to its historical, romantic, and poetical associations. Drayton, whose rhymed geography in the Poly-Olbion is rather[4] prosaic and tedious, attains a kind of genuine inspiration when, in his 13th book, he comes to describe

"Brave Warwick that abroad so long advanced her Bear,

By her illustrious Earls renowned everywhere;

Above her neighboring shires which always bore her head."

The verse catches something of the music of the throstle and the lark, of the woosel "with golden bill" and the nightingale with her tender strains, as he tells of these Warwickshire birds, and of the region with "flowery bosom brave" where they breed and warble; but in Shakespeare the same birds sing with a finer music—more like that to which we may still listen in the fields and woodlands along the lazy-winding Avon.

Warwickshire is the heart of England, and the country within ten miles or so of the town of Warwick may be called the heart of this heart. On one side of this circle are Stratford and Shottery and Wilmcote—the home of Shakespeare's mother—and on the other are Kenilworth and Coventry.

In Warwick itself is the famous castle of its Earls—"that fairest monument," as Scott calls it, "of ancient and chivalrous splendor which yet remains uninjured by time." The earlier description written by the veracious Dugdale almost two hundred and fifty years ago might be applied to it to-day. It is still "not only a place of great strength, but extraordinary delight; with most pleasant gardens, walls, and thickets such as this[5] part of England can hardly parallel; so that now it is the most princely seat that is within the midland parts of this realm."

The castle was old in Shakespeare's day. Cæsar's Tower, so called, though not built, as tradition alleged, by the mighty Julius, dated back to an unknown period; and Guy's Tower, named in honor of the redoubted Guy of Warwick, the hero of many legendary exploits, was built in 1394. No doubt the general appearance of the buildings was more ancient in the sixteenth century than it is to-day, for they had been allowed to become somewhat dilapidated; and it was not until the reign of James I. that they were repaired and embel[6]lished, at enormous expense, and made the stately fortress and mansion that Dugdale describes.

But the castle would be no less beautiful for situation, though it were fallen to ruin like the neighboring Kenilworth. The rock on which it stands, washed at its base by the Avon, would still be there, the park would still stretch its woods and glades along the river, and all the natural attractions of the noble estate would remain.

We cannot doubt that the youthful Shakespeare was familiar with the locality. Warwick and Kenilworth were probably the only baronial castles he had seen before he went to London; and, whatever others he may have seen later in life, these must have continued to be his ideal castles as in his boyhood.

It is not likely that he was ever in Scotland, and when he described the castle of Macbeth the picture in his mind's eye was doubtless Warwick or Kenilworth, and more likely the former than the latter; for

"This castle hath a pleasant seat; the air

Nimbly and sweetly recommends itself

Unto our gentle senses. This guest of summer,

The temple-haunting martlet, does approve,

By his loved mansionry, that the air

Smells wooingly here; no jutty, frieze,

Buttress, nor coign of vantage, but this bird

Hath made his pendent bed and procreant cradle.

Where they most breed and haunt I have observed

The air is delicate."

Saint Mary's church at Warwick was also standing then—the most interesting church in Warwickshire next to Holy Trinity at Stratford. It was burned in 1694,[7] but the beautiful choir and the magnificent lady chapel, or Beauchamp Chapel, fortunately escaped the flames, and we see them to-day as Shakespeare doubtless saw them, except for the monuments that have since been added. He saw in the choir the splendid tomb of Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, and in the adjacent chapel the grander tomb of Richard Beauchamp, unsurpassed in the kingdom except by that of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey. He looked, as we do, on the full-length figure of the Earl, recumbent in armor of gilded brass, under the herse of brass hoops also gilt; his hands elevated in prayer, the garter on his left knee, the swan at his head, the griffin and bear at his feet. He read, as we read, in the inscription on the cornice of the sepulchre, how this "most worshipful knight decessed full christenly the last day of April the year of oure Lord God 1439, he being at that time lieutenant general and governor of the realm of Fraunce," and how his body was brought to Warwick, and "laid with full solemn exequies in a fair chest made of stone in this church" on the 4th day of October—"honoured be God therefor." And the young Shakespeare looked up, as we do, at the exquisitely carved stone ceiling, and at the great east window, which still contains the original glass, now almost four and a half centuries old, with the portrait of Earl Richard kneeling in armor with upraised hands.

The tomb of "the noble Impe, Robert of Dudley," who died in 1584, with the lovely figure of a child seven or eight years old, may have been seen by Shakespeare when he returned to Stratford in his latter years, and also the splendid monument of the father of the "noble imp," Robert Dudley, the great Earl of Leicester, who[8] died in 1588; but in the poet's youth this famous nobleman was living in the height of his renown and prosperity at the castle of Kenilworth five miles away, which we will visit later.

Only brief reference can be made here to the important part that Warwick, or its famous Earl, Richard Neville, the "King-maker," played in the English history on which Shakespeare founded several dramas,—the three Parts of Henry VI. and Richard III. He is the most conspicuous personage of those troublous times. He had already distinguished himself by deeds of bravery in the Scottish wars, before his marriage with Anne, daughter and heiress of Richard Beauchamp, made him the most powerful nobleman in the kingdom. By this alliance he acquired the vast estates of the Warwick family, and became Earl of Warwick, with the right to hand down the title to his descendants. The immense revenues from his patrimony were augmented by the income he derived from his various high offices in the state; but his wealth was scattered with a royal liberality. It is said that he daily fed thirty thousand people at his numerous mansions.

The Lady Anne of Richard III., whom the hero of the play wooes in such novel fashion, was the youngest daughter of the King-maker, born at Warwick Castle in 1452. Richard says, in his soliloquy at the end of the first scene of the play:—

"I'll marry Warwick's youngest daughter.

What though I kill'd her husband and her father?"

Her husband was Edward, Prince of Wales, son of Henry VI., and was slain at the battle of Tewkesbury.

The Earl of Warwick who figures in 2 Henry IV. was the Richard Beauchamp already mentioned as the father of Anne who became the wife of the King-maker. He appears again in the play of Henry V., and also in the first scene of Henry VI., though he has nothing to say; and, as some believe, he (and not his son) is the Earl of Warwick in the rest of the play, in spite of certain historical difficulties which that theory involves. In 2 Henry IV. (iii. 1. 66) Shakespeare makes the mistake of calling him "Nevil" instead of Beauchamp.

The title of the Warwick earls became extinct with the death of the King-maker on the battle-field of Barnet. It was then bestowed on George, Duke of Clarence, who was drowned in the butt of wine by order of his loving brother Richard. It then passed to the young son of Clarence, who is another character in the play of Richard III. He, like his unfortunate father, was long imprisoned in the Tower, and ultimately murdered there after the farce of a trial on account of his alleged complicity in a plot against Henry VII. The subsequent vicissitudes of the earldom do not appear in the pages of Shakespeare, and we will not refer to them here.

The dramatist was evidently familiar with the legendary renown of Warwick as well as its authentic history. Doubtless he had heard the story of the famous Guy of Warwick in his boyhood; and later he probably visited "Guy's Cliff," on the edge of the town of Warwick, where the hero is said to have spent the closing years[10] of his life. Learned antiquarians, in these latter days, have proved that his adventures are mythical, but the common people believe in him as of old. There is his "cave" in the side of the "cliff" on the bank of the Avon, and his gigantic statue in the so-called chapel; and can we not see his sword, shield, and breastplate, his helmet and walking-staff, in the great hall of Warwick Castle? The breastplate alone weighs more than fifty pounds, and who but the mighty Guy could have worn it? There too is his porridge-pot of metal, holding more than a hundred gallons, and the flesh-fork to match. We may likewise see a rib and other remains of the famous "dun cow," which he slew after the beast had long been the terror of the country round about. Unbelieving scientists doubt the bovine origin of these interesting relics, to be sure, as they doubt the existence of the stalwart destroyer of the animal; but the vulgar faith in them is not to be shaken.

Of Guy's many exploits the most noted was his conflict with a gigantic Saracen, Colbrand by name, who was fighting with the Danes against Athelstan in the tenth century, and was slain by Guy, as the old ballad narrates. Subsequently Guy went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, leaving his wife in charge of his castle. Years passed, and he did not return. Meanwhile his lady lived an exemplary life, and from time to time bestowed her alms on a poor pilgrim who had made his appearance at a secluded cell by the Avon, not far from the castle. She may sometimes have talked with him about her husband, whom she now gave up as lost, assuming that he had perished by the fever of the East or the sword of the infidel. At last she received a summons to visit the aged pilgrim on his death-bed, when,[11] to her astonishment, he revealed himself as the long-lost Guy. In his early days, when he was wooing the lady, she had refused to give him her hand unless he performed certain deeds of prowess. These had not been accomplished without sins that weighed upon his conscience during his absence in Palestine; and he had made a vow to lead a monastic life after his return to his native land.

The legend, like others of the kind, was repeated in varied forms; and, according to one of these, when Guy came back to Warwick he begged alms at the gate of his castle. His wife did not recognize him, and he took this as a sign that the wrath of Heaven was not yet appeased. Thereupon he withdrew to the cell in the cliff, and did not make himself known to his wife until he was at the point of death.

Shakespeare refers to Guy in Henry VIII. (v. 4. 22), where a man exclaims, "I am not Samson, nor Sir Guy, nor Colbrand"; and Colbrand is mentioned again in King John (i. 1. 225) as "Colbrand the giant, that same mighty man."

The scene of Guy's legendary retreat on the bank of the Avon is a charming spot, and there was certainly a hermitage here at a very early period. Richard Beauchamp founded a chantry for two priests in 1422, and left directions in his will for rebuilding the chapel and setting up the statue of Guy in it. At the dissolution of the monasteries in the time of Henry VIII. the chapel and its possessions were bestowed upon a gentleman named Flammock, and the place has been a private residence ever since, though the present mansion was not built until the beginning of the eighteenth century. There is an ancient mill on the Avon not far from the[12] house, commanding a beautiful view of the river and the cliff. The celebrated actress, Mrs. Siddons, lived for some time at Guy's Cliff as waiting-maid to Lady Mary Greatheed, whose husband built the mansion.

But we must now go on to Kenilworth, though we cannot linger long within its dilapidated walls, majestic even in ruin. If, as Scott says, Warwick is the finest example of its kind yet uninjured by time and kept up as a noble residence, Kenilworth is the most stupendous of similar structures that have fallen to decay. It was ancient in Shakespeare's day, having been originally built at the end of the eleventh century. Two hundred years later, in 1266, it was held for six months by the rebellious barons against Henry III. After having passed through sundry hands and undergone divers vicissitudes of fortune, it was given by Elizabeth to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who spent, in enlarging and adorning it, the enormous sum of £60,000—three hundred thousand dollars, equivalent to at least two millions now. Scott, in his novel of Kenilworth, describes it, with no exaggeration of romance—for exaggeration would hardly be possible—as it was then. Its very gate-house, still standing complete, was, as Scott says, "equal in extent and superior in architecture to the baronial castle of many a northern chief"; but this was the mere portal of the majestic structure, enclosing seven acres with its walls, equally impregnable as a fortress and magnificent as a palace.

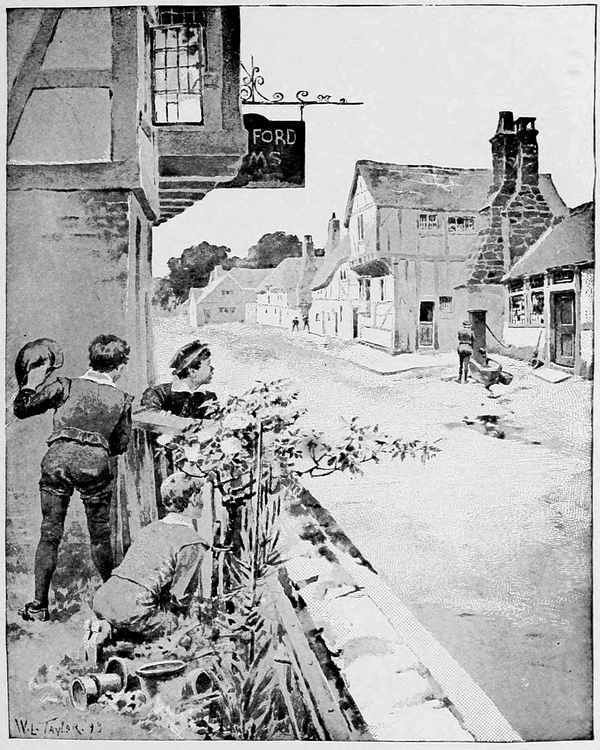

There were great doings at this castle of Kenilworth in 1575, when Shakespeare was eleven years old, and the[13] good people from all the country roundabout thronged to see them. Then it was that Queen Elizabeth was entertained by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and from July 9th to July 27th there was a succession of holiday pageants in the most sumptuous and elaborate style of the time. Master Robert Laneham, whose accuracy as a chronicler is not to be doubted, though he may have been, as Scott calls him, "as great a coxcomb as ever blotted paper," mentions, as a proof of the earl's hospitality, that "the clock bell rang not a note all the while her highness was there; the clock stood also still[14] withal; the hands stood firm and fast, always pointing at two o'clock," the hour of banquet! The quantity of beer drunk on the occasion was 320 hogsheads, and the total expense of the entertainments is said to have been £1000 ($5000) a day.

John Shakespeare, as a well-to-do citizen of Stratford, would be likely to see something of that stately show, and it is not improbable that he took his son William with him. The description in the Midsummer-Night's Dream (ii. 1. 150) of

"a mermaid on a dolphin's back

Uttering such dulcet and harmonious sounds

That the rude sea grew civil at her song,"

appears to be a reminiscence of certain features of the Kenilworth pageant. The minstrel Arion figured there, on a dolphin's back, singing of course; and Triton, in the likeness of a mermaid, commanded the waves to be still; and among the fireworks there were shooting-stars that fell into the water, like the stars that, as Oberon adds,

"shot madly from their spheres

To hear the sea-maid's music."

When Shakespeare was writing that early play, with its scenes in fairy-land, what more natural than that this youthful visit to what must then have seemed veritable fairy-land should recur to his memory and blend with the creations of his fancy?

The road from Warwick to Kenilworth is one of the loveliest in England; and that from Kenilworth five[15] miles further on to Coventry is acknowledged to be the most beautiful in the kingdom; yet it is only a different kind of beauty from the other, as that is from the beauty of the road between Warwick and Stratford.

Till you reach Kenilworth you have all the varieties of charming rural scenery—hill and dale, field and forest, river-bank and village, hall and castle and church, grouping themselves in ever-changing pictures of beauty and grandeur; and now you come to a straight road for nearly five miles, bordered on both sides by a double line of stately elms and sycamores, as impressive in its regularity as the preceding stretch had been in its kaleidoscopic mutations.

This magnificent avenue with its over-arching foliage brings us to Coventry, no mean city in our day, but retaining only a remnant of its ancient glory. In the time of Shakespeare it was the third city in the realm—the "Prince's Chamber," as it was called—unrivalled in the splendor of its monastic institutions, "full of associations of regal state and chivalry and high events."

In 1397 it had been the scene of the famous hostile meeting between Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Hereford (afterwards Henry IV.), and Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, which Shakespeare has immortalized in Richard II. Later Henry IV. held more than one parliament here; and the city was often visited and honored with many marks of favor by Henry VI. and his queen, as also by Richard III., Henry VII., Elizabeth, and James I.

Coventry, moreover, played an important part in the history of the English Drama. It was renowned for the religious plays performed by the Grey Friars of its great monastery, and kept up, though with diminished[16] pomp, even after the dissolution of their establishment. It was not until 1580 that these pageants were entirely suppressed; and Shakespeare, who was then sixteen years old, may have been an eye-witness of the latest of them. No doubt he heard stories of their attractions in former times, when, as we are told by Dugdale, they were "acted with mighty state and reverence by the friars of this house, had theatres for the several scenes, very large and high, placed upon wheels, and drawn to all the eminent parts of the city for the better advantage of spectators; and contained the story of the New Testament composed into old English rhyme." There were forty-three of these ancient plays, performed by the monks until, as Tennyson puts it,

"Bluff Harry broke into the spence,

And turned the cowls adrift."

When the boy Shakespeare saw them—if he did see them—they were played by the different guilds, or associations of tradespeople. Thus the Nativity and the Offering of the Magi, with the Flight into Egypt and the Slaughter of the Innocents, were rendered by the company of Shearmen and Tailors; the Smiths' pageant was the Crucifixion; that of the Cappers was the Resurrection; and so on. The account-books of the guilds are still extant, with charges for helmets for Herod and gear for his wife, for a beard for Judas and the rope to hang him, etc. In the accounts of the Drapers, whose pageant was the Last Judgment, we find outlays for a "link to set the world on fire," "the barrel for the earthquake," and kindred stage "properties."

In the books of the Smiths or Armorers, some of the charges are as follows:—

"Item, paid for v. schepskens for gods cote and for makyng, iiis.

Item, paid for mendyng of Herods hed and a myter and other thyngs, iis.

Item, paid for dressyng of the devells hede, viiid.

Item, paid for a pair of gloves for god, iid."

The most elaborate and costly of the properties was "Hell-Mouth," which was used in several plays, but specially in the representation of the Last Judgment. This was a huge and grotesque head of canvas, with vast gaping mouth armed with fangs and vomiting flames. The jaws were made to open and shut, and through them the Devil made his entrance and the lost souls their exit. The making and repairing of this was a constant expense, and frequent entries like the following occur in the books of the guilds:—

"Paide for making and painting hell mouth, xiid.

Paid for keping of fyer at hell mouthe, iiiid."

Many curious details of the actors' dresses have come down to us. The representative of Christ wore a coat of white leather, painted and gilded, and a gilt wig. King Herod wore a mask and a helmet, sometimes of iron, adorned with gold and silver foil, and bore a sword and a sceptre. He was a very important character, and the manner in which he blustered and raged about the stage became proverbial. In Hamlet (iii. 2. 16) we have the expression, "It out-herods Herod"; and in the Merry Wives of Windsor (ii. 1. 20), "What a Herod of Jewry is this!"

All the actors were paid for their services, the amount varying with the importance of the part. The same[18] actor, as in the theatres of Shakespeare's day, often played several parts. In addition to the payment of money, there was a plentiful supply of refreshments, especially of ale, for the actors. Pilate, who received the highest pay of the company, was moreover allowed wine instead of ale during the performance.

Reference has been made above to the "lost souls" in connection with Hell-Mouth. There were also "saved souls," who were dressed in white, as the lost were in black, or black and yellow. There is an allusion to the latter in Henry V. (ii. 3. 43), where the flea on Bardolph's rubicund nose is compared to "a black soul burning in hell-fire."

The Devil wore a dress of black leather, with a mask, and carried a club, with which he laid about him vigorously. His clothes were often covered with feathers or horsehair, to give him a shaggy appearance; and the traditional horns, tail, and cloven feet were sometimes added.

The regular time for these religious pageants was Corpus Christi Day, or the Thursday after Trinity Sunday, but they were occasionally performed on other days, especially at the time of a royal visit to Coventry, like that of Queen Margaret in 1455. Prince Edward was thus greeted in 1474, Prince Arthur in 1498, Henry VIII. in 1510, and Queen Elizabeth in 1565.

Shakespeare has other allusions to these old plays besides those here mentioned, showing that he knew them by report if he had not seen them.

Historical pageants, not Biblical in subject, were also familiar to the good people of Coventry a century at least before the dramatist was born. "The Nine Wor[19]thies," which he has burlesqued in Love's Labour's Lost, was acted there before Henry VI. and his queen in 1455. The original text of the play has been preserved, and portions of Shakespeare's travesty seem almost like a parody of it.

But we must not linger in the shadow of the "three tall spires" of Coventry, nor make more than a brief allusion to the legend of Godiva, the lady who rode naked through the town to save the people from a burdensome tax. It was an old story in Shakespeare's time, if, indeed, it had not been dramatized, like other chapters in the mythic annals of the venerable city. It has been proved to be without historical foundation, being mentioned by no writer before the fourteenth century, though the Earl who figures in the tale lived in the latter part of the eleventh century. The Benedictine Priory in Coventry, of which some fragments still remain, is said to have been founded by him in 1043. He died in 1057, and both he and his lady were buried in the porch of the monastery.

The effigy of "Peeping Tom" is still to be seen in the upper part of a house at the corner of Hertford Street in Coventry.

Shakespeare makes no reference to this story of Lady Godiva, though it was probably well known to him.

Returning to Warwick, and travelling eight miles on the other side of the town, we come to Stratford. By one of the two roads we may take we pass Charlecote Hall and Park, associated with the tradition of Shake[20]speare's deer-poaching—a fine old mansion, seen across a breadth of fields dotted with tall elms.

The winding Avon skirts the enclosure to the west. The house, which has been in the possession of the Lucy family ever since the days of Shakespeare, stands at the water's edge. It has been enlarged in recent times, but the original structure has undergone no material change. It was begun in 1558, the year when Elizabeth came to the throne, and was probably finished in 1559. It took the place of a much older mansion of which no trace remains, the ancestors of Sir Thomas Lucy having then held the estate for more than five centuries. The ground plan of the house is in the form of a capital letter E, being so arranged as a compliment to the Virgin Queen; and only one out of many such tributes paid her by noble builders of the time.[21] Over the main door are the royal arms, with the letters E. R., together with the initials of the owner, T. L.

Within there is little to remind one of the olden time, but some of the furniture of the library,—chairs, couch, and cabinet of coromandel-wood inlaid with ivory,—is said to have been presented by Elizabeth to Leicester in 1575, and to have been brought from Kenilworth in the seventeenth century. There is a modern bust of Shakespeare in the hall.

The tradition that the dramatist in his youth was guilty of deer-stealing in Sir Thomas's park is not improbable. Some critics have endeavored to prove that there was no deer-park at Charlecote at that time; but Lucy had other estates in the neighborhood, on some of which he employed game-keepers, and in March, 1585, about the date of the alleged poaching, he introduced a bill into Parliament for the better preservation of game.

The strongest argument in favor of the tradition is to be based on the evidence furnished by the plays that Shakespeare had a grudge against Sir Thomas, and caricatured him as Justice Shallow in Henry IV. and The Merry Wives of Windsor. The reference in the latter play to the "dozen white luces" on Shallow's coat of arms is palpably meant to suggest the three luces, or pikes, in the arms of the Lucys. The manner in which the dialogue dwells on the device indicates that some personal satire was intended.

It should be understood that poaching was then regarded, except by the victims of it, as a venial offence. Sir Philip Sidney's May Lady calls deer-stealing "a prettie service." The students at Oxford were the most notorious poachers in the kingdom, in spite of laws[22] making expulsion from the university the penalty of detection. Dr. Forman relates how two students in 1573 (one of whom afterwards became Bishop of Worcester) were more given to such pursuits than to study; and one good man lamented in later life that he had missed the advantages that others had derived from these exploits, which he believed to be an excellent kind of discipline for young men.

We must not assume that Sir Thomas was fairly represented in the character of Justice Shallow. On the contrary, he appears to have been an able man and magistrate, and very genial withal. The Stratford records bear frequent testimony to his judicial services; and his attendance on such occasions is generally[23] coupled with a charge for claret and sack or similar beverages. It is rather amusing that these entries occur even when he is sitting in judgment on tipplers. In the records for 1558 we read: "Paid for wine and sugar when Sir Thomas Lucy sat in commission for tipplers, xx d."

That he was a good husband we may infer from the long epitaph of his wife in Charlecote Church, which, after stating that she died in 1595, at the age of 63, goes on thus: "all the time of her life a true and faithful servant of her good God; never detected of any crime or vice; in religion most sound; in love to her husband most faithful and true; in friendship most constant; to what in trust was committed to her most secret; in wisdom excelling; in governing of her house and bringing up of youth in the fear of God that did converse with her, most rare and singular; a great maintainer of hospitality; greatly esteemed of her betters, misliked of none unless of the envious. When all is spoken that can be said, a woman so furnished and garnished with virtue as not to be bettered, and hardly to be equalled by any. As she lived most virtuously, so she died most godly. Set down by him that best did know what hath been written to be true, Thomas Lucy."

The author of this beautiful tribute may have been a severe magistrate, but he could not have been a Robert Shallow either in his official capacity or as a man.

Stratford lies on a gentle slope declining to the Avon, whose banks are here shaded by venerable willows, which the poet may have had in mind when he painted the scene of poor Ophelia's death:—

"There is a willow grows aslant a brook,

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream."

The description could have been written only by one who had observed the reflection of the white underside of the willow-leaves in the water over which they hung. And I cannot help believing that Shakespeare was mindful of the Avon when in far-away London he wrote that singularly musical simile of the river in one of his earliest plays, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, so aptly does it give the characteristics of the Warwickshire stream:

"The current that with gentle murmur glides,

Thou know'st, being stopp'd, impatiently doth rage;

But when his fair course is not hindered,

He makes sweet music with the enamell'd stones,

Giving a gentle kiss to every sedge

He overtaketh in his pilgrimage;

And so by many winding nooks he strays,

With willing sport, to the wild ocean.

Then let me go, and hinder not my course:

I'll be as patient as a gentle stream,

[25]And make a pastime of each weary step,

Till the last step have brought me to my love;

And there I'll rest, as, after much turmoil,

A blessed soul doth in Elysium."

The river cannot now be materially different from what it was three hundred years ago, but the town has changed a good deal. I fear that we might not have enjoyed a visit to it in that olden time as we do in these latter days.

It is not pleasant to learn that the poet's father was fined for maintaining a sterquinarium, which being translated from the Latin is dung-heap, in front of his house in Henley Street—now, like the other Stratford streets, kept as clean as any cottage-floor in the town—and we have ample evidence that the general sanitary condition of the place was very bad. John Shakespeare would probably not have been fined if his sterquinarium had been behind his house instead of before it.

Stratford, however, was no worse in this respect than other English towns. The terrible plagues that devastated the entire land in those "good old times" were the natural result of the unwholesome habits of life everywhere prevailing—everywhere, for the mansions of noblemen and the palaces of kings were as filthy as the hovels of peasants. The rushes with which royal presence-chamber and banquet-hall were strewn in place of carpets were not changed until they had become too unsavory for endurance. Meanwhile disagreeable odors were overcome by burning perfumes—of which practice we have a hint in Much Ado About Nothing in the reference to "smoking a musty room."

But away from these musty rooms of great men's houses, and the foul streets and lanes of towns, field and forest and river-bank were as clean and sweet as now. The banished Duke in As You Like It may have had other reasons than he gives for preferring life in the Forest of Arden to that of the court from which he had been driven; and Shakespeare's delight in out-of-door life may have been intensified by his experience of the house in Henley Street, with the reeking pile of filth at the front door.

His poetry is everywhere full of the beauty and fragrance of the flowers that bloom in and about Stratford; and the wonderful accuracy of his allusions to them—their colors, their habits, their time of blossoming, everything concerning them—shows how thoroughly at home he was with them, how intensely he loved and studied them.

Mr. J. R. Wise, in his Shakespeare, His Birthplace and its Neighbourhood, says: "Take up what play you will, and you will find glimpses of the scenery round Stratford. His maidens ever sing of 'blue-veined violets,' and 'daisies pied,' and 'pansies that are for thoughts,' and 'ladies'-smocks all silver-white,' that still stud the meadows of the Avon.... I do not think it is any exaggeration to say that nowhere are meadows so full of beauty as those round Stratford. I have seen them by the riverside in early spring burnished with gold; and then later, a little before hay-harvest, chased with orchises, and blue and white milkwort, and yellow rattle-grass, and tall moon-daisies: and I know nowhere woodlands so sweet as those round Stratford, filled with the soft green light made by the budding leaves, and paved with the golden ore of primroses, and their banks veined[27] with violets. All this, and the tenderness that such beauty gives, you find in the pages of Shakespeare; and it is not too much to say that he painted them because they were ever associated in his mind with all that he held precious and dear, both of the earliest and the latest scenes of his life."

Stratford is a very ancient town. Its name shows that it was situated at a ford on the Roman street, or highway, from London to Birmingham; but whether it was an inhabited place during the Roman occupation is uncertain. The earliest known reference to the town is in a charter dated A.D. 691, according to which Egwin, the Bishop of Worcester, obtained from Ethelred, King of Mercia, "the monastery of Stratford," with lands of about three thousand acres, in exchange for a religious house built by the bishop at Fladbury. It is not improbable that Stratford owes its foundation to this monastic settlement. Tradition says that the monastery stood where the church now is; and, as elsewhere in England, the first houses of the town were probably erected for its servants and dependants. These dwellings were doubtless near the river, in the street that has been known for centuries as "Old Town."

The district continued to be a manor of the Bishop of Worcester until after the Norman Conquest in 1066. According to the Domesday survey in 1085, its territory was "fourteen and a half hides," or about two thousand acres. It was of smaller extent than in 691, because the neighboring villages had become separate manors. The inhabitants were a priest, who doubtless[28] officiated in the chapel of the old monastery (of which we find no mention after the year 872), with twenty-one villeins and seven bordarii, or cottagers. The families of these residents would make up a population of about one hundred and fifty. "Every householder, whether villein or cottager, evidently possessed a plough. The community owned altogether thirty-one ploughs, of which three belonged to the bishop, the lord of the manor." The agricultural produce was chiefly wheat, barley, and oats. A water-mill stood by the river, probably where the old mill now is; and there the villagers were obliged to grind all their corn, paying a fee for the privilege. In 1085 the annual income from the mill was ten shillings, but the bishop was often willing to accept eels in payment of the fees, and a thousand eels were then sent yearly to Worcester by the people who used the mill.

During the 12th century Stratford appears to have made little progress. Alveston, now a small village on the other side of the Avon, seemed likely then to rival it in prosperity. The boundaries of the Alveston manor were gradually extended until they reached their present limit on the south side of the bridge at Stratford (at that time a rude wooden structure), and there a little colony was planted which was known until after the Elizabethan period as Bridgetown.

We get an idea of the life led by the majority of the inhabitants of Stratford and its vicinity in the 12th and 13th centuries from the ecclesiastical records of the various services and payments rendered as rent. Many of the large estates outside of the town had been let as "knight's fees," that is, on condition of certain military services to be performed by the holders. Some of the[29] villeins within the village had become "free tenants," or free from serfdom, and were permitted to cultivate their land as they pleased on payment of a fixed rental in money, with little or no labor service in addition. But most of the inhabitants were still villeins or cottagers, from whom labor service was regularly exacted. "Villeins who owned sixty acres had to supply two men for reaping the lord's fields, and cottagers with thirty acres supplied one. On a special day an additional reaping service was to be performed by villeins and cottagers with all their families except their wives and shepherds. Each of the free tenants had then also to find a reaper, and to direct the reaping himself.... The villein was to provide two carts for the conveyance of the corn to the barns, and every cottager who owned a horse provided one cart, for the use of which he was to receive a good morning meal of bread and cheese. One day's hoeing was expected of the villein and three days' ploughing, and if an additional day were called for, food was supplied free to the workers.... No villein nor cottager was allowed to bring up his child for the church without permission of the lord of the manor. A fee had to be paid when a daughter of a villein or cottager was married. On his death his best wagon was claimed by the steward in his lord's behalf, and a fine of money was exacted from his successor—if, as the record wisely adds, he could pay one. Any townsman who made beer for sale paid for the privilege."

In 1197 the inhabitants obtained for the town from Richard I. the privilege of a weekly market, to be holden on Thursdays, for which the citizens paid the bishop a yearly toll of sixteen shillings. The market was doubt[30]less held at first in the open space still known as the Rother Market, in the centre of which the Memorial Fountain, the gift of Mr. George W. Childs of Philadelphia, now stands. Rother is an old word, of Anglo-Saxon origin, applied to cattle, which must have been a staple commodity in the early Stratford market. The term was familiar to Shakespeare, who uses it in Timon of Athens (iv. 3. 12):—

"It is the pasture lards the rother's sides,

The want that makes him lean."

In the course of the 11th century Stratford was also endowed with a series of annual fairs, "the chief stimulants of trade in the middle ages." The earliest of these fairs was granted by the Bishop of Worcester in 1216, to begin "on the eve of the Holy Trinity, and to continue for the next two days ensuing." In 1224 a fair was established for the eve of St. Augustine (May 26th) "and on the day and morrow after"; in 1242, for the eve of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (September 14th), "the day, and two days following"; and in 1271, "for the eve of the Ascension of our Lord, commonly called Holy Thursday, and upon the day and morrow following." Early in the next century (1313) another fair was instituted, to begin on the eve of St. Peter and St. Paul (June 29th) and to be held for fifteen days.

Trinity Sunday was doubtless chosen for the opening of the first of these fairs because the parish church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, and a festival in commemoration of the dedication of the church was celebrated on that Sunday by a "wake," which attracted[31] many people from the neighboring villages. "There was nothing exceptional in a Sunday of specially sacred character being turned to commercial uses. In most medieval towns, moreover, traders exposed their wares at fair-time in the churchyard, and chaffering and bargaining were conducted in the church itself." Attempts were made by the ecclesiastical authorities to restrain these practices, but they continued until the Reformation.

At the close of the 13th century the prosperity of Stratford was assured. Alveston had then ceased to be a dangerous rival. The town was more and more profitable to the Bishops of Worcester, who interested themselves in promoting its welfare. It appears also that Bishop Gifford had a park here; for on the 3d of May, 1280, he sent his injunctions to the deans of Stratford and the adjacent towns "solemnly to excommunicate all those that had broke his park and stole his deer."

In the 14th century the condition of the Stratford folk materially improved. Villeinage gradually disappeared in the reign of Edward III. (1327–1377), and those who had been subject to it became free tenants, paying definite rents for house and land. Three natives of the town, who, after the fashion of the time, took their surnames from the place of their birth, rose to high positions in the Church, one becoming Archbishop of Canterbury, and the others respectively Bishops of London and Chichester. John of Stratford and Robert of Stratford were brothers, and Ralph of Stratford was their nephew. John and Robert were both for a time Chancellors of England, and there is no other instance of two brothers attaining that high office in succession.

All three had a great affection for their native town, and did much to promote its welfare. Robert, while holding the living of Stratford, took measures for the paving of some of the main streets. John enlarged the parish church, rebuilding portions of it, and founded a chantry with five priests to perform masses for the souls of the founder and his friends. Later he pur[33]chased the patronage of Stratford from the Bishop of Worcester, and gave it to his chantry priests, who thus came into full control of the parish church. Ralph, in 1351, built for the chantry priests "a house of square stone for the habitation of these priests, adjoining to the churchyard." This building, afterwards known as the College, remained in possession of the priests until 1546, when Henry VIII. included it in the dissolution of monastic establishments. After passing through various hands as a private residence, it was finally taken down in 1799.

Other inhabitants of Stratford followed the example set by John and Ralph in their benefactions to the church. Dr. Thomas Bursall, warden of the College in the time of Edward IV., added "a fair and beautiful choir, rebuilt from the ground at his own cost"—the choir which is still the most beautiful portion of the venerable edifice, and in which Shakespeare lies buried.

The only important alteration in the church since Shakespeare's day was the erection of the present spire in 1764, to replace a wooden one covered with lead and about forty feet high, which had been taken down a year before. The tower is the oldest part of the church as it now exists, and was probably built before the year 1200. It is eighty feet high, to which the spire adds eighty-three feet more.

The last of the early benefactors of Stratford was Sir Hugh Clopton, who came from the neighboring village of Clopton about 1480. A few years later he built "a pretty house of brick and timber wherein he lived in his latter days." This was the mansion afterwards known as New Place, which in 1597 became the property of William Shakespeare, and was his residence[34] after he returned to his native town about 1611 or 1612.

Sir Hugh also built "the great bridge upon the Avon, at the east end of the town," constructed of freestone, with fourteen arches, and a "long causeway" of stone, "well walled on each side." ... Before this time, as Leland the antiquarian wrote about 1530, "there was but a poor bridge of timber, and no causeway to come to it, whereby many poor folk either refused to come to Stratford when the river was up, or coming thither stood in jeopardy of life." This bridge, though often repaired, is to this day a monument to Sir Hugh's public spirit.

In the latter part of the 13th century an institution attained a position and influence in Stratford which were destined to deprive the Bishops of Worcester of their authority in the government of the town. This was the Guild of the Holy Cross, the Blessed Virgin, and St. John the Baptist, as it was then called. The triple name has suggested that it was formed by the union of three separate guilds, but of this no historical evidence has been discovered.

This guild, like other of these ancient societies, had a religious origin, being "collected for the love of God and our souls' need"; but relief of the poor and of its own indigent members was also a part of its functions.

The "craft-guilds," formed by people engaged in a single trade or occupation, were a different class of societies, though in many instances offshoots from the religious guilds, and often, as in London, surviving the decay of the parent institution.

Members of both sexes were admitted to the Stratford Guild, as to others of its class, on payment of a small annual fee. "This primarily secured for them the performance of certain religious rites, which were more valued than life itself. While the members lived, but more especially after their death, lighted tapers were duly distributed in their behalf, before the altars of[36] the Virgin and of their patron saints in the parish church. A poor man in the Middle Ages found it very difficult, without the intervention of the guilds, to keep this road to salvation always open. Gifts were frequently awarded to members anxious to make pilgrimages to Canterbury, and at times the spinster members received dowries from the association. The regulation which compelled the members to attend the funeral of any of their fellows united them among themselves in close bonds of intimacy."

The social spirit was fostered yet more by a great annual meeting, at which all members were expected to be present in special uniform. They marched with banners flying in procession to church, and afterwards sat down together to a generous feast.

Though of religious origin the guilds were strictly lay associations. In many towns priests were excluded from membership; if admitted, they had no more authority or influence than laymen. Priests were employed to perform the religious services of the guild, for which they were duly paid; but the fraternities were governed by their own elected officers—wardens, aldermen, beadles, and clerks—and a council of their representatives controlled their property and looked after their rights.

When the Stratford Guild was founded it is impossible to determine. "Its beginning," as its chief officers wrote in 1389, "was from time whereunto the memory of man reacheth not." Records preserved in the town prove that it was in existence early in the 13th century, and that bequests were then made to it. The Bishops of Worcester encouraged such gifts, and apparently managed that some of the revenues of the Guild[37] should be devoted to ecclesiastical purposes outside its own regular uses. Before the time of Edward I. the society was rich in houses and lands; and in 1353, as its records show, it owned a house in almost every street in Stratford.

In 1296 the elder Robert of Stratford, father of John and Robert (p. 31), laid the foundation of a special chapel for the Guild, and also of adjacent almshouses. These doubtless stood where the present chapel, Guildhall, and other fraternity buildings now are.

In 1332 Edward III. gave the Guild a charter confirming its right to all its property and to the full control of its own affairs. In 1389 Richard II. sent out commissioners to report upon the ordinances of the guilds throughout England, and the report for Stratford is still extant. It shows what a good work the society was doing for the relief of the poor and for the promotion of fraternal relations among its members. Regulations for the government of the Guild by two wardens or aldermen and six others indicate the progress of the town in the direction of self-government. An association which had come to include all the substantial householders naturally acquired much jurisdiction in civil affairs. Its members referred their disputes with one another to its council; and the aldermen gradually became the administrators of the municipal police. The College priests were very jealous of the Guild's increasing influence, and when the society resisted the payment of tithes they brought a lawsuit to compel the fulfilment of this ancient obligation; but in all other respects the Guild appears to have been independent of external control.

A curious feature of the conditions of membership in[38] the 15th century was that the souls of the dead could be admitted to its spiritual privileges on payment of the regular fees by the living. Early in the century six dead children of John Whittington of Stratford were allowed this benefit for the sum of ten shillings.

The fame of the institution in its palmy days spread far beyond the limits of Stratford, and attracted not a few men of the highest rank and reputation. George, Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV., and his wife, were enrolled among its members, with Edward Lord Warwick and Margaret, two of their children; and the distinguished judge, Sir Thomas Lyttleton, received the same honor. Few towns or villages of Warwickshire were without representation in it, and merchants joined it from places as far away as Bristol and Peterborough.

To us, however, the most remarkable fact in the history of the Guild is the establishment of the Grammar School for the children of its members. The date of its foundation has been usually given as 1453, but it is now known to have been in existence before that time. Attendance was free, and the master, who was paid ten pounds a year by the Guild, was forbidden to take anything from the pupils. In this school, as we shall see later, William Shakespeare was educated, and we shall become better acquainted with it when we follow the boy thither.

The Guild Chapel, with the exception of the chancel, which had been renovated about 1450, was taken down and rebuilt in the closing years of the century by Sir Hugh Clopton (see page 34 above), who was a prominent member of the fraternity. The work was not finished until after his death in September, 1496, but the expense of its completion was provided for in his will.

The Guild was dissolved by Henry VIII. in 1547, and its possessions remained as crown property until 1553. For seven years the town had been without any responsible government. Meanwhile the leading citizens—the old officers of the Guild—had petitioned Edward VI. to restore that society as a municipal corporation. He granted their prayer, and by a charter dated June 7, 1553, put the government of the town in the hands of its inhabitants. The estates, revenues, and chattels of the Guild were made over to the corporation, which, as the heir and successor of the venerable fraternity, adopted the main features of its organization. The names and functions of its chief officers were but slightly changed. The warden became the bailiff, and the proctors were called chamberlains, but aldermen, clerk, and beadle resumed their old titles. The common council continued to meet monthly in the Guildhall; but it now included, besides the bailiff and ten aldermen, the ten chief burgesses, and its authority covered the whole town. The fraternal sentiment of the ancient society survived; it being ordered "that none of the aldermen nor none of the capital burgesses, neither in the council chamber nor elsewhere, do revile one another, but brother-like live together, and that after they be entered into the council chamber, that they nor none of them depart not forth but in brotherly love, under the pains of every offender to forfeit and pay for every default, vjs. viijd." When any councillor or his wife died, all were to attend the funeral "in their honest apparel, and bring the corpse to the church, there to continue and abide devoutly until the corpse be buried."

The Grammar School and the chapel and almshouses of the Guild became public institutions. The bailiff became a magistrate who presided at a monthly court for the recovery of small debts, and at the higher semi-annual leets, or court-leets, to which all the inhabitants were summoned to revise and enforce the police regulations. Shakespeare alludes to these leets in The Taming of the Shrew (ind. 2. 89) where the servant tells Kit Sly that he has been talking in his sleep:—

"Yet would you say ye were beaten out of door,

And rail upon the mistress of the house,

And say you would present her at the leet

Because she brought stone jugs and no seal'd quarts."

And Iago (Othello, iii. 3. 140) refers to "leets and law-days." Prices of bread and beer were fixed by the council, and ale-tasters were annually appointed to see that the orders concerning the quality and price of malt liquors and bread were enforced. Shakespeare's father was an ale-taster in 1557, and about the same time was received into the corporation as a burgess. In 1561 he was elected as one of the two chamberlains; in 1565 he became an alderman; and in 1568 he was chosen bailiff, the highest official position in the town.

The rule of the council was of a very paternal character. "If a man lived immorally he was summoned to the Guildhall, and rigorously examined as to the truth of the rumors that had reached the bailiff's ear. If his guilt was proved, and he refused to make adequate reparation, he was invited to leave the town. Rude endeavors were made to sweeten the tempers of scolding wives. A substantial 'ducking-stool,' with iron[41] staples, lock, and hinges, was kept in good repair. The shrew was attached to it, and by means of ropes, planks, and wheels was plunged two or three times into the Avon whenever the municipal council believed her to stand in need of correction. Three days and three nights were invariably spent in the open stocks by any inhabitant who spoke disrespectfully to any town officer, or who disobeyed any minor municipal decree. No one might receive a stranger into his house without the bailiff's permission. No journeyman, apprentice, or servant might 'be forth of their or his master's house' after nine o'clock at night. Bowling-alleys and butts were provided by the council, but were only to be used at stated times. An alderman was fined on one occasion for going to bowls after a morning meeting of the council, and Henry Sydnall was fined twenty pence for keeping unlawful or unlicensed bowling in a back shed. Alehouse-keepers, of whom there were thirty in Shakespeare's time, were kept strictly under the council's control. They were not allowed to brew their own ale, or to encourage tippling, or to serve poor artificers except at stated hours of the day, on pain of fine and imprisonment. Dogs were not to go about the streets unmuzzled. Every inhabitant had to go to church at least once a month, and absences were liable to penalties of twenty pounds, which in the late years of Elizabeth's reign commissioners came from London to see that the local authorities enforced. Early in the 17th century swearing was rigorously prohibited. Laws as to dress were regularly enforced. In 1577 there were many fines exacted for failure to wear the plain statute woollen caps on Sundays, to which Rosaline makes allusion in Love's Labour's Lost (v. 2. 281); and the regulation[42] affected all inhabitants above six years of age. In 1604 'the greatest part' of the inhabitants were presented at a great leet, or law-day, 'for wearing their apparel contrary to the statute.' Nor would it be difficult to quote many other like proofs of the persistent strictness with which the new town council of Stratford, by the enforcement of its own order and the statutes of the realm, regulated the inhabitants' whole conduct of life."

No map of Stratford made before the middle of the 18th century is known to exist. The one here given in fac-simile was executed about the year 1768, and, as Mr. Halliwell-Phillipps tells us, "it clearly appears from the local records that there had then been no material alteration in either the form or the extent of the town since the days of Elizabeth. It may therefore be accepted as a reliable guide to the locality as it existed in the poet's own time, when the number of inhabited houses, exclusive of mere hovels, could not have much exceeded five hundred."

The following is a copy of the references which are appended to the original map: "1. Moor Town's End;—2. Henley Lane;—3. Rother Market;—4. Henley Street;—5. Meer Pool Lane;—6. Wood Street;—7. Ely Street or Swine Street;—8. Scholar's Lane alias Tinker's Lane;—9. Bull Lane;—10. Street call'd Old Town;—11. Church Street;—12. Chapel Street;—13. High Street;—14. Market Cross;—15. Town Hall;—16. Place where died Shakespeare;—17. Chapel, Public Schools, &c.;—18. House where was Shakespeare born;—19. Back Bridge Street;—20. Fore Bridge[44] Street;—21. Sheep Street;—22. Chapel Lane;—23. Buildings call'd Water Side;—24. Southam's Lane;—25. Dissenting Meeting;—26. White Lion."

Moor Town's End (1) is now Greenhill Street. The Town Hall (15) did not exist in Shakespeare's time, having been first erected in 1633, taken down in 1767, and rebuilt the following year. The "Place where died Shakespeare" (16) was New Place, the home of his later years. The "Dissenting Meeting" or Meeting-house (25) was built long after the poet's day. The "White Lion" (26) was also post-Shakespearian, the chief inns in the 16th century being the Swan, the Bear, and the Crown, all in Bridge Street. The Mill and Mill Bridge (built in 1590) are indicated on the river at the left-hand lower corner of the map; and the stone bridge, erected by Sir Hugh Clopton about 1500, is just outside the right-hand lower corner.

The only important change in the streets since the map was made is the removal of the row of small shops and stalls, known as Middle Row, between Fore Bridge Street (20); and Back Bridge Street (19); thus making the broad avenue now called Bridge Street.

The "Market Cross" (14) was "a stone monument covered by a low tiled shed, round which were benches for the accommodation of listeners to the sermons which, as at St. Paul's Cross in London, were sometimes preached there." Later a room was added above, and a clock above that. The open space about the Cross was the chief market-place of the town. Near by was a pump, at which housewives were frequently to be seen "washing of clothes" and hanging them on the cross to dry, and butchers sometimes hung meat there; but these practices were forbidden by the town[45] council in 1608. The stocks, pillory, and whipping-post were in the same locality.

There was also a stone cross in the Rother Market (3), and near the Guild Chapel (17) was a second pump, which was removed by order of the council in 1595. The field on the river, near the foot of Chapel Lane (22), was known as the Bank-croft, or Bancroft, where drovers and farmers of the town were allowed to take their cattle to pasture for an hour daily. "All horses, geldings, mares, swine, geese, ducks, and other cattle," according to the regulation established by the council, if found there in violation of this restriction, were put by the beadle into the "pinfold," or pound, which was not far off. This Bancroft, as it is still called, is now part of the beautiful little park on the river-bank, adjacent to the grounds of the Shakespeare Memorial.

Chapel Lane, which bounded one side of the New Place estate, was one of the filthiest thoroughfares of the town, the general sanitary condition of which (see page 25 above) was bad enough. A streamlet ran through it, the water of which turned a mill, alluded to in town records of that period. This water-course gradually became "a shallow fetid ditch, an open receptacle of sewage and filth." It continued to be a nuisance for at least two centuries more. A letter written in 1807, in connection with a lawsuit, gives some interesting reminiscences of it. "I very well remember," says the writer, "the ditch you mention forty-five years, as after my sister was married, which was in October, 1760, I was very often at Stratford, and was very well acquainted both with the ditch and the road in question;—the ditch went from the Chapel, and extended to Smith's house;—I well remember there was[46] a space of two or three feet from the wall in a descent to the ditch, and I do not think any part of the new wall was built on the ditch;—the ditch was the receptacle for all manner of filth that any person chose to put there, and was very obnoxious at times;—Mr. Hunt used to complain of it, and was determined to get it covered over, or he would do it at his own expense, and I do not know whether he did or not;—across, the road from the ditch to Shakespeare Garden was very hollow and always full of mud, which is now covered over, and in general there was only one wagon tract along the lane, which used to be very bad, in the winter particularly;—I do not know that the ditch was so deep as to overturn a carriage, and the road was very little used near it, unless it was to turn out for another, as there was always room enough." Thomas Cox, a carpenter, who lived in Chapel Lane from 1774, remembered that the open gutter from the Chapel to Smith's cottage "was a wide dirty ditch choked with mud, that all the filth of that part of the town ran into it, that it was four or five feet wide and more than a foot deep, and that the road sloped down to the ditch." According to other witnesses, the ditch extended to the end of the lane, where, between the roadway and the Bancroft, was a narrow creek or ditch through which the overflow from Chapel Lane no doubt found a way into the river.

Mr. Halliwell-Phillipps believes that the fever which proved fatal to Shakespeare was caused by the "wretched sanitary conditions surrounding his residence"—an explanation of it which would never have occurred even to medical men in that day.

The house in Henley Street in which William Shakespeare was probably born and spent his early years has undergone many changes; but, as carefully restored in recent years and reverently preserved for a national memorial of the poet, its appearance now is doubtless not materially different from what it was in the latter part of the 16th century.

There are a few houses of the same period and the same class still standing in Stratford and its vicinity,[50] which, according to the highest antiquarian authority, are almost unaltered from their original form and finish. Mr. Halliwell-Phillipps mentions one in particular in the Rother Market, "the main features of which are certainly in their original state," and the sketches of the interior given by him closely resemble those of the Shakespeare house.

These houses were usually of two stories, and were constructed of wooden beams, forming a framework, the spaces between the beams being filled with lath and plaster. The roofs were usually of thatch, with dormer windows and steep gables. The door was shaded by a porch or by a pentice, or penthouse, which was a narrow sloping roof often extending along the the front of the lower story over both door and windows, as in Shakespeare's birthplace on Henley Street.

In the Merchant of Venice (ii. 6. 1) Gratiano says:—

"This is the penthouse under which Lorenzo

Desired us to make stand."

In Much Ado About Nothing (iii. 3. 110) Borachio says to Conrade: "Stand thee close, then, under this penthouse, for it drizzles rain." We find a figurative allusion to the penthouse in Love's Labour's Lost (iii. 1. 17): "with your hat penthouse-like o'er the shop of your eyes"; and another in Macbeth (i. 3. 20):—

"Sleep shall neither night nor day

Hang upon his penthouse lid";

the projecting eyebrow being compared to this part of the Elizabethan dwelling.

The better houses, like New Place, were of timber and brick, instead of plaster, though sometimes entirely of stone. Shakespeare appears to have rebuilt the greater part of New Place with stone. The roofs of this class of dwellings were usually tiled, but occasionally thatched. We read of one Walter Roche, who in 1582 replaced the tiles of his house in Chapel Street with thatch. The wood-work in the front of some houses, as in a fine example still to be seen in the High Street (page 59 below), was elaborately carved with floral and other designs.

The gardens were bounded by walls constructed of clay or mud and usually thatched at the top. Fruit-trees were common in these gardens, and the orchard about the Guild buildings was noted for its plums and apples. When the mulberry-tree was first introduced into England, Shakespeare bought one and set it out in his grounds at New Place, where it grew to great size. It survived for nearly a century and a half after the death of the poet, but in 1758 was cut down by the Rev. Francis Gastrell, who had bought the estate in 1756.

There was little of what we should regard as comfort in those picturesque old English houses, with their great black beams chequering the outer walls into squares and triangles, their small many-paned windows, their low ceilings and rude interior wood-work, their poor and scanty furnishings.

Chimneys had but just come into general use in England, and, though John Shakespeare's house had one, the dwellings of many of his neighbors were still unprovided with them. In 1582, when William was eighteen years old, an order was passed by the town council[52] that "Walter Hill, dwelling in Rother Market, and all the other inhabitants of the borough, shall, before St. James's Day, 30th April, make sufficient chimneys," under pain of a fine of ten shillings.

This was intended as a precaution against fires, the frequent occurrence of which in former years had been mainly due to the absence of chimneys.

William Harrison, in 1577, referring to things in England that had been "marvellously changed within the memory of old people," includes among these "the multitude of chimneys lately erected, whereas in their young days there were not above two or three, if so many, in most uplandish towns of the realm (the religious houses and manor places of their lords always excepted), but each one made his fire against a reredos[1] in the hall, where he dined and dressed his meat."

In another chapter Harrison says: "Now have we many chimneys; and yet our tenderlings complain of rheums, catarrhs, and poses. Then had we none but reredosses; and our heads did never ache. For as the smoke in those days was supposed to be a sufficient hardening for the timber of the house, so it was reported a far better medicine to keep the goodman and his family from the quack or pose, wherewith, as then, very few were acquainted."

Of the furniture in these old houses we get an idea from inventories of the period that have come down to[53] us. We have, for instance, such a list of the household equipment of Richard Arden, Shakespeare's maternal grandfather, who was a wealthy farmer; and another of such property belonging to Henry Field, tanner, a neighbor of John Shakespeare, who was his chief executor.

From these and similar inventories we find that the only furniture in the hall, or main room of the house—often occupying the whole of the ground floor—and the parlor, or sitting-room, when there was one, consisted of two or three chairs, a few joint-stools—that is, stools made of wood jointed or fitted together, as distinguished from those more rudely made—a table of the plainest construction, and possibly one or more "painted cloths" hung on the walls.

These painted cloths were cheap substitutes for the tapestries with which great mansions were adorned, and they were often found in the cottages of the poor. The paintings were generally crude representations of Biblical stories, together with maxims or mottoes, which were sometimes on scrolls or "labels" proceeding from the mouths of the characters.

Shakespeare refers to these cloths several times; for instance, in As You Like It (iii. 2. 291), where Jaques says to Orlando: "You are full of pretty answers; have you not been acquainted with goldsmiths' wives and conned them out of rings?"—referring to the mottoes, or "posies," as they were called, often inscribed in finger-rings. Orlando replies: "Not so; but I answer you right painted cloth, from whence you have studied your questions." Falstaff (1 Henry IV. iv. 2. 28) says that his recruits are "ragged as Lazarus in the painted cloth."

In an anonymous play, No Whipping nor Tripping, printed in 1601, we find this passage:—

"Read what is written on the painted cloth:

Do no man wrong; be good unto the poor;

Beware the mouse, the maggot, and the moth,

And ever have an eye unto the door," etc.

When carpets are mentioned in these inventories, they are coverings for the tables, not for the floors, which, even in kings' palaces, were strewn with rushes. Grumio, in The Taming of the Shrew (iv. 1. 52) sees "the carpets laid" for supper on his master's return home. A Stratford inventory of 1590 mentions "a carpet for a table." Carpets were also used for window-seats, but were seldom placed on the floor except to kneel upon, or for other special purposes.

The bedroom furniture was equally rude and scanty, though better than it had been when the old folk of the time were young. Harrison says:—

"Our fathers and we ourselves have lien full oft upon straw pallets covered only with a sheet, under coverlets made of dagswain or hopharlots [coarse, rough cloths], and a good round log under their heads instead of a bolster. If it were that our fathers or the good man of the house had a mattress or flock-bed, and thereto a sack of chaff to rest his head upon, he thought himself to be as well lodged as the lord of the town, so well were they contented."

But feather beds had now come into use, with pillows, and "flaxen sheets," and other comfortable appliances. Henry Field had "one bed-covering of yellow and green" among his household goods.

Kitchen utensils and table-ware had likewise improved within the memory of the old inhabitant, though still rude and simple enough. Harrison notes "the exchange of treen [wooden] platters into pewter, and wooden spoons into silver or tin."

He adds: "So common were all sorts of treen stuff in old time that a man should hardly find four pieces of pewter (of which one was peradventure a salt) in a good farmer's house"; but now they had plenty of pewter, with perhaps a silver bowl and salt-cellar, and a dozen silver spoons.

The table-linen was hempen for common use, but flaxen for special occasions, and the napkins were of the same materials. These napkins, or towels, as they were sometimes called, were for wiping the hands after eating with the fingers, forks being as yet unknown in England except as a curiosity.

Elizabeth is the first royal personage in the country who is known to have had a fork, and it is doubtful whether she used it. It was not until the middle of the 17th century that forks were used even by the higher classes, and silver forks were not introduced until about 1814.

Thomas Coryat, in his Crudities, published in 1611, only five years before Shakespeare died, gives an account of the use of forks in Italy, where they appear to have been invented in the 15th century. He says:—

"The Italian and also most strangers do always at their meals use a little fork when they do cut their meat. For while with their knife, which they hold in one hand, they cut the meat out of the dish, they fasten the fork, which they hold in their other hand, upon the same dish; so that whosoever he be that, sitting in the[56] company of others at meals, should unadvisedly touch the dish of meat with his fingers, from which all the table do cut, he will give occasion of offence unto the company, as having transgressed the laws of good manners."

Coryat adds that he himself "thought good to imitate the Italian fashion by this forked cutting of meat," not only while he was in Italy, but after he came home to England, where, however, he was sometimes "quipped" for what his friends regarded as a foreign affectation.

The dramatists of the time also refer contemptuously to "your fork-carving traveller"; and one clergyman preached against the use of forks "as being an insult to Providence not to touch one's meat with one's fingers!"

Towels, except for table use, are rarely noticed in inventories of the period, and when mentioned are specified as "washing towels." Neither are wash-basins often referred to, except in lists of articles used by barbers.

Bullein, in his Government of Health, published about 1558, says: "Plain people in the country use seldom times to wash their hands, as appeareth by their filthiness, and as very few times comb their heads."