The Clog—a Perpetual Almanack.

Explained in the Preface.

Title: The Every-day Book and Table Book. v. 2 (of 3)

Author: William Hone

Release date: October 14, 2016 [eBook #53276]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Harry Lamé, Google Books for

some images. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes

at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this e-text and is placed in the public domain.

Enlarged illustration (400 kB).

BY WILLIAM HONE.

Herrick.

WITH FOUR HUNDRED AND THIRTY-SIX ENGRAVINGS.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THOMAS TEGG,

73, CHEAPSIDE.

LONDON:

J. HADDON, PRINTER, CASTLE STREET, FINSBURY.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE EARL OF DARLINGTON,

LORD LIEUTENANT AND VICE-ADMIRAL OF THE COUNTY

PALATINE OF DURHAM, &c. &c. &c.

My Lord,

To your Lordship—as an encourager of the old country sports and usages chiefly treated of in my book, and as a maintainer of the ancient hospitality so closely connected with them, which associated the Peasantry of this land with its Nobles, in bonds which degraded neither—

I RESPECTFULLY DEDICATE THIS VOLUME;

not unmindful of your Lordship’s peculiar kindness to me under difficulties, and not unmoved by the pride which I shall have in subscribing myself,

MY LORD,

YOUR LORDSHIP’S HIGHLY HONOURED,

MOST OBEDIENT,

AND VERY HUMBLE SERVANT,

WILLIAM HONE.

February 27, 1827.

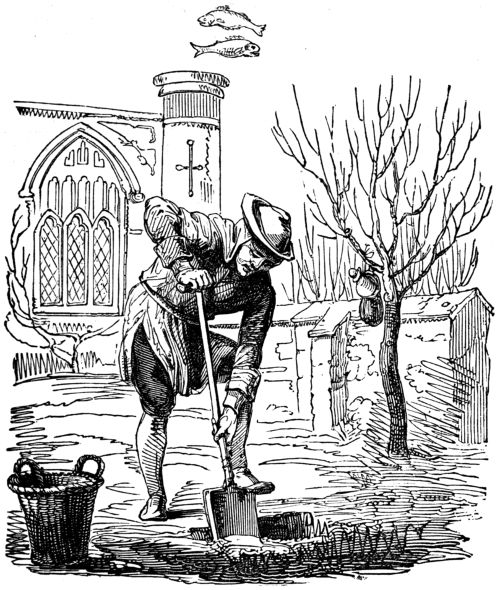

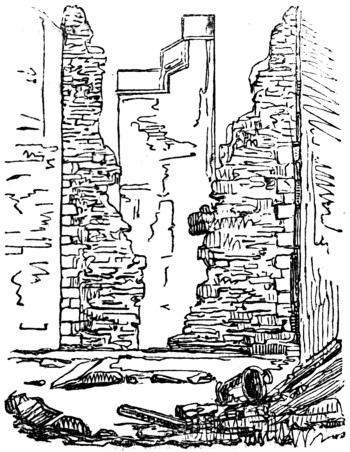

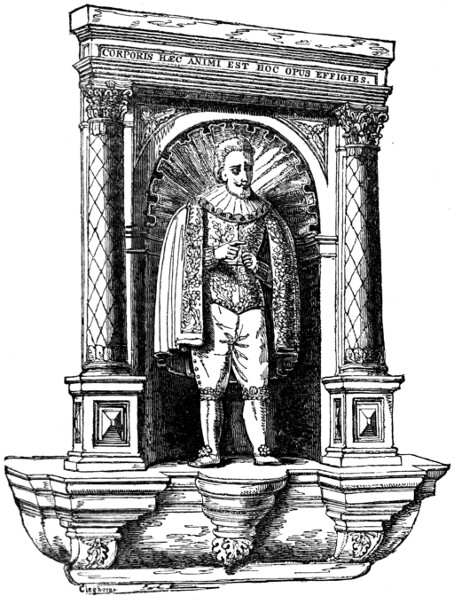

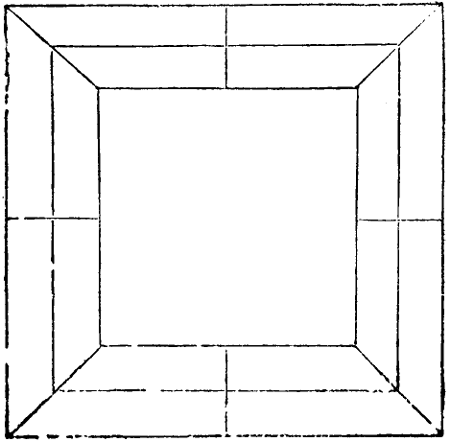

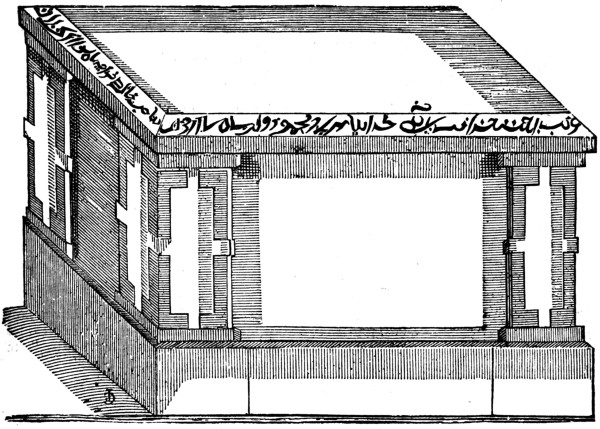

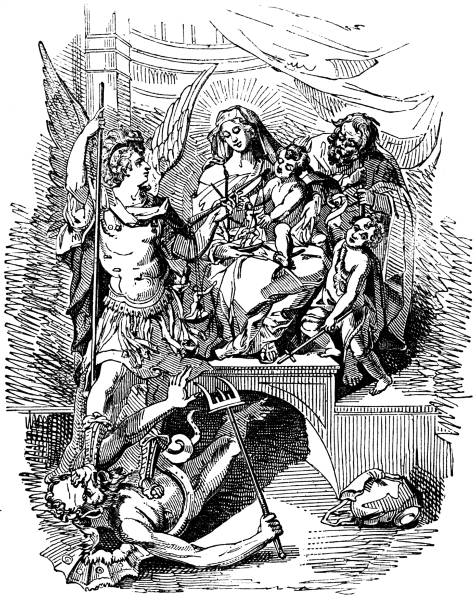

Before remarking on the work terminating with this volume, some notice should be taken of its Frontispiece.

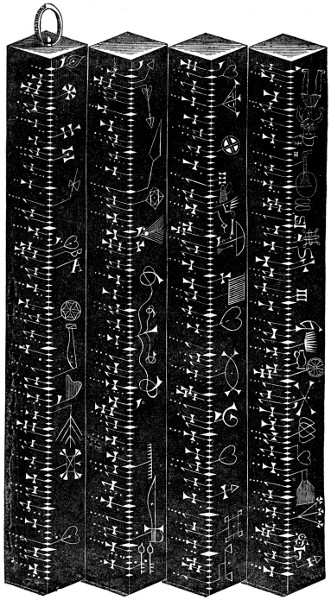

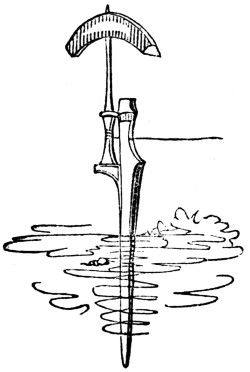

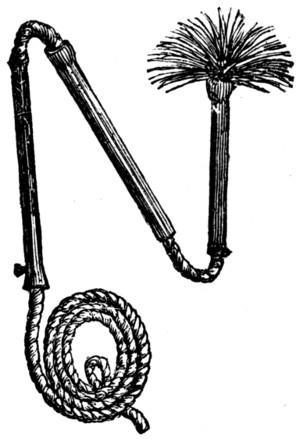

I. The “Clog” or “Perpetual Almanack” having been in common use with our ancient ancestors, a representation and explanation of it seemed requisite among the various accounts of manners and customs related in the order of the calendar.

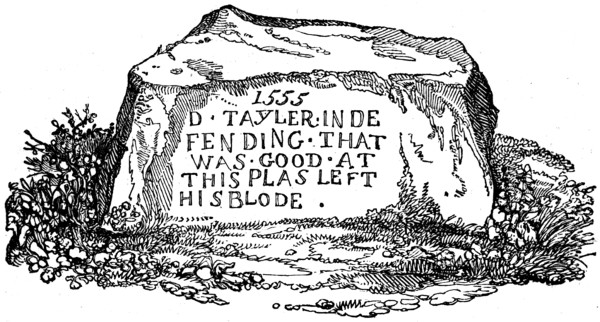

Of the word “clog,” there is no satisfactory etymology in the sense here used, which signifies an almanack made upon a square stick. Dr. Robert Plot, who published the “History of Staffordshire,” in 1686, instances a variety of these old almanacks then in use in that county. Some he calls “public,” because they were of a large size, and commonly hung at one end of the mantle-tree of the chimney; others he calls “private,” because they were smaller, and carried in the pocket. For the better understanding of the figures on these clogs, he caused a family clog “to be represented in plano, each angle of the square stick, with the moiety of each of the flat sides belonging to it, being expressed apart.” From this clog, so represented in Dr. Plot’s history, the engraving is taken which forms the frontispiece now, on his authority, about to be described.

There are 3 months contained upon each of the four edges; the number of the days in them are represented by the notches; that which begins each month has a short spreading stroke turned up from it; every seventh notch is of a larger size, and stands for Sunday, (or rather, perhaps, for the first day of each successive natural week in the year.)

Against many of the notches there are placed on the left hand several marks or symbols denoting the golden number or cycle of the Moon, which number if under 5, is represented by so many points, or dots; but if 5, a line is drawn from the notch, or day, it belongs to, with a hook returned back against the course of the line, which, if cut off at due distance, may be taken for a V, the numeral signifying 5. If the golden number be above 5, and under 10, it is then marked out by the hooked line, which is 5; and with one point, which makes 6; or two, which makes 7; or three, for 8; or four, for 9; the said line being crossed with a broad stroke spreading at each end, which represents an X, when the golden number for the day, over against which it is put, is 10; points being added (as above over the hook for 5,) till the number arises to 15, when a hook is placed again at the end of the line above the X, to show us that number.

The figures issuing from the notches, towards the right hand, are symbols or hieroglyphics, of either, 1st, the offices, or endowments of the saints, before whose festivals they are placed; or 2dly, the manner of their martyrdoms; or 3dly, their actions, or the work or sport, in fashion about the time when their feasts are kept.

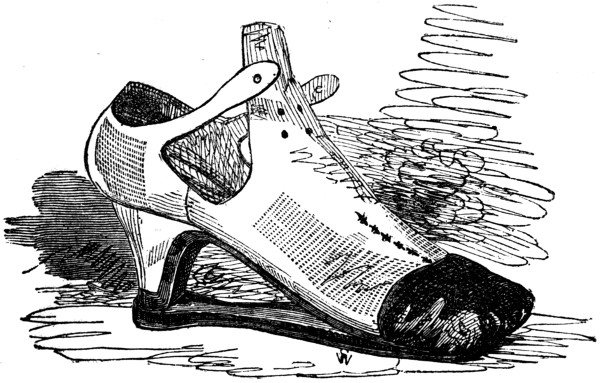

For instance: 1. from the notch which represents January 13th, on the feast of St. Hilary, issues a cross or badge of a bishop, as St. Hilary was; from March 1st, a harp, showing the feast of St. David, by that instrument; from June 29th, the keys for St. Peter, reputed the Janitor of heaven; from October 25th, a pair of shoes for St. Crispin, the patron of shoe-makers. Of class 2, are the axe against January 25th, the feast of St. Paul, who was beheaded with an axe; the sword against June 24th, [viii] the feast of St. John Baptist, who was beheaded; the gridiron against August 10th, the feast of St. Lawrence, who suffered martyrdom on one; a wheel on the 25th of November, for St. Catherine, and a decussated cross on the last of that month, for St. Andrew, who are said also to have suffered death by such instruments. Of the 3d kind, are the star on the 6th of January, to denote the Epiphany; a true lover’s knot against the 14th of February, for Valentine’s-day; a bough against the 2d of March, for St. Ceadda, who lived a Hermit’s life in the woods near Litchfield; a bough on the 1st of May, for the May-bush, then usually set up with great solemnity; and a rake on the 11th of June, St. Barnabas’-day, importing that then it is hay-harvest. So, a pot is set against the 23d of November, for the feast of St. Clement, from the ancient custom of going about that night to beg drink to make merry with: for the purification, annunciation, and all other feasts of our lady, there is always the figure of a heart: and lastly, for December 25th, or Christmas-day, a horn, the ancient vessel in which the Danes use to wassail, or drink healths; signifying to us, that this is the time we ought to rejoice and make merry.

II. Respecting this second volume of the Every-Day Book, it is scarcely necessary to say more than that it has been conducted with the same desire and design as the preceding volume; and that it contains a much greater variety of original information concerning manners and customs. I had so devoted myself to this main object, as to find no lack of materials for carrying it further; nor were my correspondents, who had largely increased, less communicative: but there were some readers who thought the work ought to have been finished in one volume, and others, who were not inclined to follow beyond a second; and their apprehensions that it could not, or their wishes that it should not be carried further, constrained me to close it. As an “Everlasting Calendar” of amusements, sports, and pastimes, incident to the year, the Every-Day Book is complete; and I venture, without fear of disproof, to affirm, that there is not such a copious collection of pleasant facts and illustrations, “for daily use and diversion,” in the language; nor are any other volumes so abundantly stored with original designs, or with curious and interesting subjects so meritoriously engraven.

III. Every thing that I wished to bring into the Every-Day Book, but was compelled to omit from its pages, in order to conclude it within what the public would deem a reasonable size, I purpose to introduce in my Table Book. In that publication, I have the satisfaction to find myself aided by many of my “Every-Day” correspondents, to whom I tender respectful acknowledgments and hearty thanks. This is the more due to them here, because I frankly confess that to most I owe letters; I trust that those who have not been noticed as they expected, will impute the neglect to any thing rather than insensibility of my obligations to them, for their valuable favours.

Although I confess myself to have been highly satisfied by the general reception of the Every-Day Book, and am proud of the honour it has derived from individuals of high literary reputation, yet there is one class whose approbation I value most especially. The “mothers of England” have been pleased to entertain it as an every-day assistant in their families; and instructors of youth, of both sexes, have placed it in school-libraries:—this ample testimonial, that, while engaged in exemplifying “manners,” I have religiously adhered to “morals,” is the most gratifying reward I could hope to receive.

February, 1827.

W. HONE

THE

EVERY-DAY BOOK.

Spenser

Laus Deo!—was the first entry by merchants and tradesmen of our forefathers’ days, in beginning their new account-books with the new year. Laus Deo! then, be the opening of this volume of the Every-Day Book, wherein we take further “note of time,” and make entries to the days, and months, and seasons, in “every varied posture, place, and hour.”

January, besides the names already mentioned,[1] was called by the Anglo-Saxons [3, 4] Giuli aftera, signifying the second Giul, or Yule, or, as we should say, the second Christmas.[2] Of Yule itself much will be observed, when it can be better said.

To this month there is an ode with a verse beautifully descriptive of the Roman symbol of the year:[3]

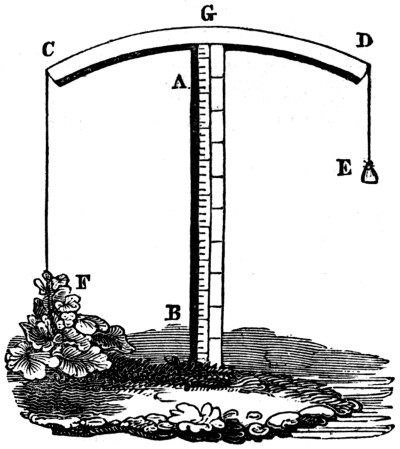

Mr. Luke Howard is the author of a highly useful work, entitled “The Climate of London, deduced from Meteorological Observations, made at different places in the neighbourhood of the Metropolis: London, 1818.” 2 vols. 8vo. Out of this magazine of fact it is proposed to extract, from time to time, certain results which may acquaint general readers with useful knowledge concerning the weather of our latitude, and induce the inquisitive to resort to Mr. Howard’s book, as a careful guide of high authority in conducting their researches. That gentleman, it is hoped, will not deem this an improper use of his labours: it is meant to be, as far as regards himself, a humble tribute to his talents and diligence. With these views, under each month will be given a state of the weather, in Mr. Howard’s own words: and thus we begin.

The Sun in the middle of this month continues about 8 h. 20 m. above the horizon. The Temperature rises in the day, on an average of twenty years, to 40·28° and falls in the night, in the open country to 31·36°—the difference, 8·92°, representing the mean effect of the sun’s rays for the month, may be termed the solar variation of the temperature.

The Mean Temperature of the month, if the observations in this city be included, is 36·34°. But this mean has a range, in ten years, of about 10·25°, which may be termed the lunar variation of the temperature. It holds equally in the decade, beginning with 1797, observed in London, and in that beginning with 1807, in the country. In the former decade, the month was coldest in 1802, and warmest in 1812, and coldest in 1814. I have likewise shown, that there was a tendency in the daily variation of temperature through this month, to proceed, in these respective periods of years, in opposite directions. The prevalence of different classes of winds, in the different periods, is the most obvious cause of these periodical variations of the mean temperature.

The Barometer in this month rises, on an average of ten years, to 30·40 in., and falls to 28·97 in.: the mean range is therefore 1·43 in.; but the extreme range in ten years is 2·38 in. The mean height for the month is about 29·79 inches.

The prevailing Winds are the class from west to north. The northerly predominate, by a fourth of their amount, over the southerly winds.

The average Evaporation (on a total of 30·50 inches for the year) is 0·832 in., and the mean of De Luc’s hydrometer 80.

The mean Rain, at the surface of the earth, is 1·959 in.; and the number of days on which snow or rain falls, in this month, averages 14,4.

A majority of the Nights in this month have constantly the temperature at or below the foregoing point.[4]

Grahame

[1] In vol. i. p. 2.

[2] Sayers.

[3] See vol. i. p. 1.

[4] Howard on Climate.

[5] The first visitant who enters a house on New-year’s day is called the first-foot.

The Saints of the Roman calendars and martyrologies.

So far as the rev. Alban Butler, in his every-day biography of Roman catholic saints, has written their memoirs, their names have been given, together with notices of some, and especially of those retained in the calendar of the church of England from the Romish calendar. Similar notices of others will be offered in continuation; but, on this high festival in the calendar of nature, particular or further remark on the saints’ festivals would interrupt due attention to the season, and therefore we break from them to observe that day which all enjoy in common,

Referring for the “New-year’s gifts,” the “Candlemas-bull,” and various observances of our ancestors and ourselves, to the first volume of this work, wherein they are set forth “in lively pourtraieture,” we stop a moment to peep into the “Mirror of the Months,” and inquire “Who can see a new year open upon him, without being better for the prospect—without making sundry wise reflections (for any reflections on this subject must be comparatively wise ones) on the step he is about to take towards the goal of his being? Every first of January that we arrive at, is an imaginary mile-stone on the turnpike track of human life; at once a resting place for thought and meditation, and a starting point for fresh exertion in the performance of our journey. The man who does not at least propose to himself to be better this year than he was last, must be either very good, or very bad indeed! And only to propose to be better, is something; if nothing else, it is an acknowledgment of our need to be so, which is the first step towards amendment. But, in fact, to propose to oneself to do well, is in some sort to do well, positively; for there is no such thing as a stationary point in human endeavours; he who is not worse to-day than he was yesterday, is better; and he who is not better, is worse.”

It is written, “Improve your time,” in the text-hand set of copies put before us when we were better taught to write than to understand what we wrote. How often these three words recurred at that period without their meaning being discovered! How often and how serviceably they have recurred since to some who have obeyed the injunction! How painful has reflection been to others, who recollecting it, preferred to suffer rather than to do!

The author of the paragraph quoted above, expresses forcible remembrance of his youthful pleasures on the coming in of the new year.—“Hail! to thee, January!—all hail! cold and wintry as thou art, if it be but in virtue of thy first day. The day, as the French call it, par excellence, ‘Le jour de l’an.’ Come about me, all ye little schoolboys that have escaped from the unnatural thraldom of your taskwork—come crowding about me, with your untamed hearts shouting in your unmodulated voices, and your happy spirits dancing an untaught measure in your eyes! Come, and help me to speak the praises of new-year’s day!—your day—one of the three which have, of late, become yours almost exclusively, and which have bettered you, and have been bettered themselves, by the change. [7, 8] Christmay-day, which was; New-year’s-day, which is; and Twelfth-day, which is to be; let us compel them all three into our presence—with a whisk of our imaginative wand convert them into one, as the conjurer does his three glittering balls—and then enjoy them all together,—with their dressings, and coachings, and visitings, and greetings, and gifts, and “many happy returns”—with their plum-puddings, and mince-pies, and twelfth-cakes, and neguses—with their forfeits, and fortune-tellings, and blindman’s-buffs, and sittings up to supper—with their pantomimes, and panoramas, and new penknives, and pastrycooks’ shops—in short, with their endless round of ever new nothings, the absence of a relish for which is but ill supplied, in after life, by that feverish lingering and thirsting after excitement, which usurp without filling its place. Oh! that I might enjoy those nothings once again in fact, as I can in fancy! But I fear the wish is worse than an idle one; for it not only may not be, but it ought not to be. “We cannot have our cake and eat it too,” as the vulgar somewhat vulgarly, but not less shrewdly, express it. And this is as it should be; for if we could, it would neither be worth the eating nor the having.”[6]

The Wassail Bowl.

Now, on New-year’s-day as on the previous eve, the wassail bowl is carried from door to door, with singing and merriment. In Devonshire,

Polwhele.

Mr. Brand says, “It appears from Thomas de la Moore,[7] and old Havillan,[8] that was-haile and drinc-heil were the usual ancient phrases of quaffing among the English, and synonymous with the ‘Come, here’s to you,’ and ‘I’ll pledge you,’ of the present day.”

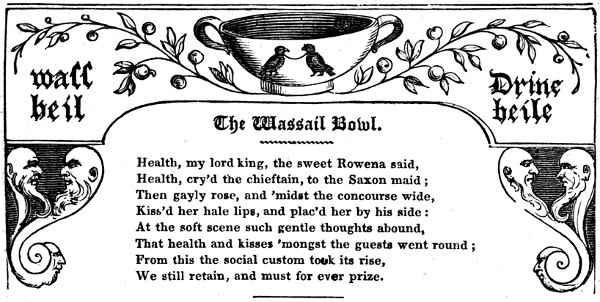

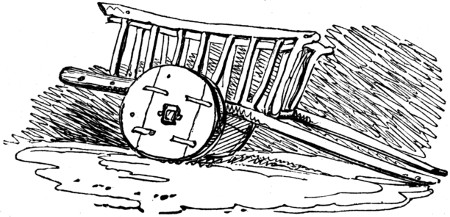

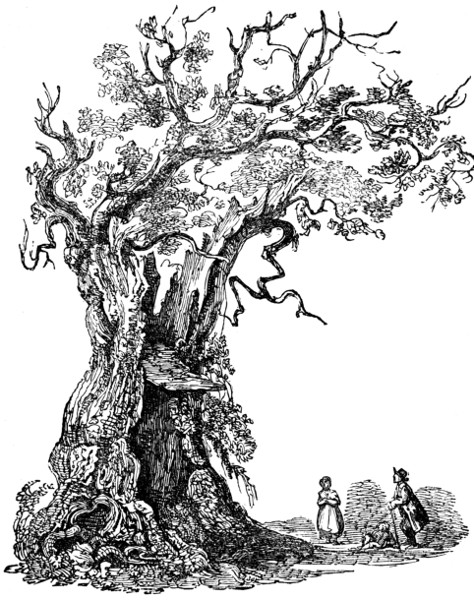

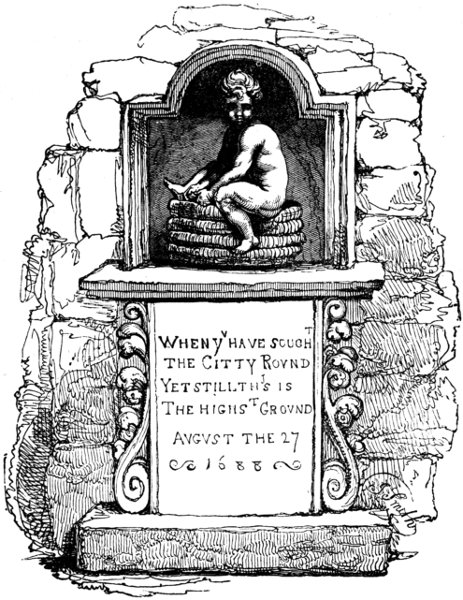

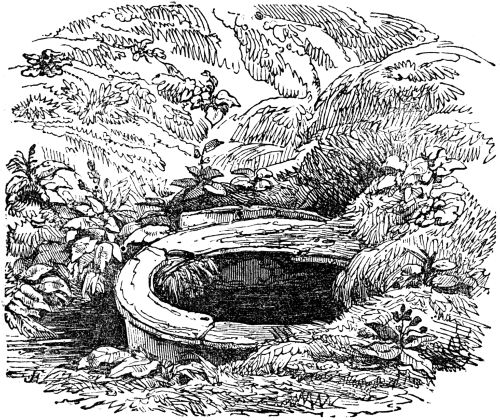

In the “Antiquarian Repertory,” a large assemblage of curious communications, published by Mr. Jeffery, of Pall-mall, in 4 vols. 4to. there is the following paper relating to an ancient carving represented in that work, from whence the above engraving is taken. The verses beneath it are a version of the old lines in Robert of Gloucester’s chronicle, by Mr. Jeffery’s correspondent.

In the parish of Berlen, near Snodland, in the county of Kent, are the vestiges of a very old mansion, known by the name of Groves. Being on the spot before the workmen began to pull down the front, I had the curiosity to examine its interior remains, when, amongst other things well worth observation, appeared in the large oak beam that supported the chimney-piece, a curious piece of carved work, of which the preceding is an exact copy. Its singularity induced me to set about an investigation, which, to my satisfaction, was not long without success. The large bowl in the middle is the figure of the old wassell-bowl, so much the delight of our hardy ancestors, who, on the vigil of the new year, never failed (says my author) to assemble round the glowing hearth with their cheerful neighbours, and then in the spicy wassell-bowl (which testifies the goodness of their hearts) drowned every former animosity—an example worthy modern imitation. Wassell, was the word; Wassell, every guest returned as he took the circling goblet from his friend, whilst song and civil mirth brought in the infant year. This annual custom, says Geoffrey of Monmouth, had its rise from Rouix, or Rowen, or as some will have it, Rowena, daughter of the Saxon Hengist; she, at the command of her father, who had invited the British king Voltigern to a banquet, came in the presence with a bowl of wine, and welcomed him in these words, Louerd king wass-heil; he in return, by the help of an interpreter, answered, Drinc heile; and, if we may credit Robert of Gloster,

Thomas De Le Moor, in his “Life of Edward the Second,” says partly the same as Robert of Gloster, and only adds, that Wass-haile and Drinc-hail were the usual phrases of quaffing amongst the earliest civilized inhabitants of this island.

The two birds upon the bowl did for some time put me to a stand, till meeting with a communicative person at Hobarrow, he assured me they were two hawks, as I soon plainly perceived by their bills and beaks, and were a rebus of the builder’s name. There was a string from the neck of one bird to the other, which, it is reasonable to conjecture, was to note that they must be joined together to show their signification; admitting this, they were to be red hawks. Upon inquiry, I found a Mr. Henry Hawks, the owner of a farm adjoining to Groves; he assured me, his father kept Grove farm about forty years since, and that it was built by one of their name, and had been in his family upwards of four hundred years, as appeared by an old lease in his possession.

The apple branches on each side of the bowl, I think, means no more than that they drank good cider at their Wassells. Saxon words at the extremities of the beam are already explained; and the mask carved brackets beneath correspond with such sort of work before the fourteenth century.

T. N.

The following pleasant old song, inserted by Mr. Brand, from Ritson’s collection of “Antient Songs,” was met with by the Editor of the Every-day Book, in 1819, at the printing-office of Mr. Rann, at Dudley, printed by him for the Wassailers of Staffordshire and Warwickshire. It went formerly to the tune of “Gallants come away.”

A CARROLL FOR A WASSELL-BOWL.

From the “Wassail” we derive, perhaps, a feature by which we are distinguished. An Englishman eats no more than a Frenchman; but he makes yule-tide of all the year. In virtue of his forefathers, he is given to “strong drink.” He is a beer-drinker, an enjoyer of “fat ale;” a lover of the best London porter and double XX, and discontented unless he can get “stout.” He is a sitter withal. Put an Englishman “behind a pipe” and a full pot, and he will sit till he cannot stand. At first he is silent; but as his liquor gets towards the bottom, he inclines towards conversation; as he replenishes, his coldness thaws, and he is conversational; the oftener he calls to “fill again,” the more talkative he becomes; and when thoroughly liquefied, his loquacity is deluging. He is thus in public-house parlours: he is in parties somewhat higher, much the same. The business of dinner draws on the greater business of drinking, and the potations are strong and fiery; full-bodied port, hot sherry, and ardent spirits. This occupation consumes five or six hours, and sometimes more, after dining. There is no rising from it, but to toss off the glass, and huzza after the “hip! hip! hip!” of the toast giver. A calculation of the number who customarily “dine out” in this manner half the week, would be very amusing, if it were illustrated by portraits of some of the indulgers. It might be further, and more usefully, though not so agreeably illustrated, by the reports of physicians, wives, and nurses, and the bills of apothecaries. Habitual sitting to drink is the “besetting sin” of Englishmen—the creator of their gout and palsy, the embitterer of their enjoyments, the impoverisher of their property, the widow-maker of their wives.

By continuing the “wassail” of our ancestors, we attempt to cultivate the body as they did; but we are other beings, cultivated in other ways, with faculties and powers of mind that would have astonished their generations, more than their robust frames, if they could appear, would astonish ours. Their employment was in hunting their forests for food, or battling in armour with risk of life and limb. They had no counting-houses, no ledgers, no commerce, no Christmas bills, no letter-writing, no printing, no engraving, no bending over the desk, no “wasting of the midnight oil” and the brain together, no financing, not a hundredth part of the relationships in society, nor of the cares that we have, who “wassail” as they did, and wonder we are not so strong as they were. There were no Popes nor Addisons in the days of Nimrod.

The most perfect fragment of the “wassail” exists in the usage of certain corporation festivals. The person presiding stands up at the close of dinner, and drinks from a flaggon usually of silver having a handle on each side, by which he holds it with each hand, and the toast-master announces him as drinking “the health of his brethren out of the ‘loving cup.’” The loving cup, which is the ancient wassail-bowl, is then passed to the guest on his left hand, and by him to his left-hand neighbour, and as it finds its way round the room to each guest in his [13, 14] turn, so each stands up and drinks to the president “out of the loving cup.”

The subsequent song is sung in Gloucestershire on New-year’s eve:—

Of this usage in Scotland, commencing on New-year’s eve, there was not room in the last sheet of the former volume, to include the following interesting communication. It is, here, not out of place, because, in fact, the usage runs into the morning of the New Year.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

The annexed account contains, I believe, the first notice of the acting in our Daft Days. I have put it hurriedly together, but, if of use, it is at your service.

I am, Sir, &c.

John Wood Reddock.

Falkirk, December, 1825.

During the early ages of christianity, when its promulgation among the barbarous Celts and Gauls had to contend with the many obstacles which their ignorance and superstition presented, it is very probable that the clergy, when they were unable entirely to abolish pagan rites, would endeavour, as far as possible, to twist them into something of a christian cast; and of the turn which many heathen ceremonies thus received, abundant instances are afforded in the Romish church.

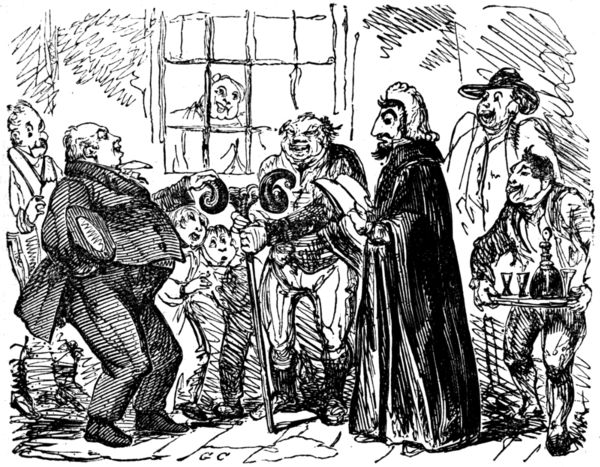

The performance of religious MYSTERIES, which continued for a long period, seems to have been accompanied with much licentiousness, and undoubtedly was grafted upon the stock of pagan observances.—It was discovered, however, that the purity of the christian religion could not tolerate them, and they were succeeded by the MORALITIES, the subjects of which were either historical, or some existing abuse, that it was wished [15, 16] to aim a blow at. Of this we have an interesting instance in an account given by sir William Eure, the envoy of Henry the Eighth to James the Fifth, in a letter to the lord privy seal of England, dated 26th of January 1540, on the performance of a play, or morality, written by the celebrated sir David Lindsay. It was entitled The Satire of the Three Estates, and was performed at Linlithgow, “before the king, queene, and the whole counsaill, spirituall and temporall,” on the feast of Epiphany. It gives a singular proof of the liberty then allowed, by king James and his court witnessing the exhibition of a piece, in which the corruptions of the existing government and religion were treated with the most satirical severity.

The principal dramatis personæ were a king, a bushop, a burges man, “armed in harness, with a swerde drawn in his hande,” a poor man, and Experience, “clede like ane doctor.” The poor man (who seems to have represented the people) “looked at the king, and said he was not king in Scotland, for there was another king in Scotland that hanged Johne Armstrong with his fellows, Sym the laird, and mony other mae.” He then makes “a long narracione of the oppression of the poor by the taking of the corse-presaunte beits, and of the herrying of poor men by the consistorye lawe, and of mony other abusions of the spiritualitie and church. Then the bushop raised and rebuked him, and defended himself. Then the man of arms alleged the contrarie, and commanded the poor man to go on. The poor man proceeds with a long list of the bushop’s evil practices, the vices of cloisters, &c. This is proved by EXPERIENCE, who, from a New Testament, showes the office of a bishop. The man of arms and burges approve of all that was said against the clergy, and allege the expediency of a reform, with the consent of parliament. The bushop dissents. The man of arms and burges said they were two and he but one, wherefore their voice should have the most effect. Thereafter the king in the play ratified, approved, and confirmed all that was rehearsed.”

None of the ancient religious observances, which have escaped, through the riot of time and barbarism, to our day, have occasioned more difficulty than that which forms the subject of these remarks. It is remarkable, that in all disputed etymological investigations, a number of words got as explanatory, are so provokingly improbable, that decision is rendered extremely difficult. With no term is this more the case, than HOGMENAY. So wide is the field of conjecture, as to the signification of this word, that we shall not occupy much space in attempting to settle which of the various etymologies is the most correct.

Many complaints were made to the Gallic synods of the great excesses committed on the last night of the year and first of January, by companies of both sexes dressed in fantastic habits, who ran about with their Christmas boxes, calling tire lire, and begging for the lady in the straw both money and wassels. The chief of these strollers was called Rollet Follet. They came into the churches during the vigils, and disturbed the devotions. A stop was put to this in 1598, at the representation of the bishop of Angres; but debarred from coming to the churches, they only became more licentious, and went about the country frightening the people in their houses, so that the legislature having interfered, an end was put to the practice in 1668.

The period during the continuance of these festivities corresponded exactly with the present daft days, which, indeed, is nearly a translation of their French name fêtes de fous. The cry used by the bachelettes during the sixteenth century has also a striking resemblance to the still common cry “hogmenay trololay—gi’ us your white bread and nane o’ your grey,” it being “au gui menez, Rollet Follet, au gui menez, tiré liré, mainte du blanc et point du bis.”

The word Rollet is, perhaps, a corruption of the ancient Norman invocation of their hero, Rollo. Gui, however, seems to refer to the druidical custom of cutting branches from the mistletoe at the close of the year, which were deposited in the temples and houses with great ceremony.

A supposition has been founded upon the reference of this cry to the birth of our Saviour, and the arrival of the wise men from the east; of whom the general belief in the church of Rome is, that they were three in number. Thus the language, as borrowed from the French may be “homme est né, trois rois allois!” A man is born, three kings are come!

Others, fond of referring to the dark period of the Goths, imagine that this name had its origin there. Thus, minne was one of the cups drunk at the feast of Yule, as celebrated in the times of heathenism, [17, 18] and oel is the general term for festival. The night before Yule was called hoggin-nott, or hogenat, signifying the slaughter night, and may have originated from the number of cattle slaughtered on that night, either as sacrifices, or in preparation for the feast on the following day. They worshipped the sun under the name Thor. Hence, the call for the celebration of their sacrifices would be “Hogg-minne! Thor! oel! oel!” Remember your sacrifices, the feast of Thor! the feast!

That the truth lies among these various explanations, there appears no doubt; we however turn to hogmenay among ourselves, and although the mutilated legend which we have to notice remains but as a few scraps, it gives an idea of the existence of a custom which has many points of resemblance to that of France during the fêtes du fous. It has hitherto escaped the attention of Scottish antiquaries.

Every person knows the tenacious adherence of the Scottish peasantry to the tales and observances of auld lang syne. Towards the close of the year many superstitions are to this day strictly kept up among the country people, chiefly as connected with their cattle and crops. Their social feelings now get scope, and while one may rejoice that he has escaped difficulties and dangers during the past year, another looks forward with bright anticipation for better fortune in the year to come. The bannock of the oaten cake gave place a little to the currant loaf and bun, and the amories of every cottager have goodly store of dainties, invariably including a due proportion of Scotch drink. The countenances of all seem to say

Ferguson’s Daft Days.

It is deemed lucky to see the new moon with some money (silver) in the pocket. A similar idea is perhaps connected with the desire to enter the new year rife o’ roughness. The grand affair among the boys in the town is to provide themselves with fausse faces, or masks; and those with crooked horns and beards are in greatest demand. A high paper cap, with one of their great grandfather’s antique coats, then equips them as a guisard—they thus go about the shops seeking their hogmenay. In the carses and moor lands, however, parties of guisards have long kept up the practice in great style. Fantastically dressed, and each having his character allotted him, they go through the farm houses, and unless denied entrance by being told that the OLD STYLE is kept, perform what must once have been a connected dramatic piece. We have heard various editions of this, but the substance of it is something like the following:—

One enters first to speak the prologue in the style of the Chester mysteries, called the Whitsun plays, and which appear to have been performed during the mayoralty of John Arneway, who filled that office in Chester from 1268 to 1276. It is usually in these words at present—

One with a sword, who corresponds with the Rollet, now enters and says:

If national partiality does not deceive us, we think this speech points out the origin of the story to be the Roman invasion under Agricola, and the name of Galgacus (although Galacheus and Saint Lawrence [19, 20] are sometimes substituted, but most probably as corruptions) makes the famous struggle for freedom by the Scots under that leader, in the battle fought at the foot of the Grampians, the subject of this historical drama.

Enter Galgacus.

They close in a sword fight, and in the “hash smash” the chief is victorious. He says:

Enter Doctor (saying)

Here comes in the best doctor that ever Scotland bred.

Chief. What can you cure?

The doctor then relates his skill in surgery.

Chief. What will ye tak to cure this man?

Doctor. Ten pound and a bottle of wine.

Chief. Will six not do?

Doctor. No, you must go higher.

Chief. Seven?

Doctor. That will not put on the pot, &c.

A bargain however is struck, and the Doctor says to Jack, start to your feet and stand!

Jack. Oh hon, my back, I’m sairly wounded.

Doctor. What ails your back?

Jack. There’s a hole in’t you may turn your tongue ten times round it!

Doctor. How did you get it?

Jack. Fighting for our land.

Doctor. How mony did you kill?

Jack. I killed a’ the loons save ane, but he ran, he wad na stand.

Here, most unfortunately, there is a “hole i’ the ballad,” a hiatus which irreparably closes the door upon our keenest prying. During the late war with France Jack was made to say he had been “fighting the French,” and that the loon who took leg bail was no less a personage than Nap. le grand! Whether we are to regard this as a dark prophetic anticipation of what did actually take place, seems really problematical. The strange eventful history however is wound up by the entrance of Judas with the bag. He says:

This character in the piece seems to mark its ecclesiastical origin, being of course taken from the office of the betrayer in the New Testament; whom, by the way, he resembles in another point; as extreme jealousy exists among the party, this personage appropriates to himself the contents of the bag. The money and wassel, which usually consists of farles of short bread, or cakes and pieces of cheese, are therefore frequently counted out before the whole.

One of the guisards who has the best voice, generally concludes the exhibition by singing an “auld Scottish sang.” The most ancient melodies only are considered appropriate for this occasion, and many very fine ones are often sung that have not found their way into collections: or the group join in a reel, lightly tripping it, although encumbered with buskins of straw wisps, to the merry sound of the fiddle, which used to form a part of the establishment of these itinerants. They anciently however appear to have been accompanied with a musician, who played the kythels, or stock-and-horn, a musical instrument made of the thigh bone of a sheep and the horn of a bullock.

The above practice, like many customs of the olden time, is now quickly falling into disuse, and the revolution of a few years may witness the total extinction of this seasonable doing. That there does still exist in other places of Scotland the remnants of plays performed upon similar occasions, and which may contain many interesting allusions, is very likely. That [21, 22] noticed above, however, is the first which we remember of seeing noticed in a particular manner.

The kirk of Scotland appears formerly to have viewed these festivities exactly as the Roman church in France did in the sixteenth century; and, as a proof of this, and of the style in which the sport was anciently conducted in the parish of Falkirk, we have a remarkable instance so late as the year 1702. A great number of farmers’ sons and farm servants from the “East Carse” were publicly rebuked before the session, or ecclesiastical court, for going about in disguise upon the last night of December that year, “acting things unseemly;” and having professed their sorrow for the sinfulness of the deed, were certified if they should be found guilty of the like in time coming, they would be proceeded against after another manner. Indeed the scandalized kirk might have been compelled to put the cutty stool in requisition, as a consequence of such promiscuous midnight meetings.

The observance of the old custom of “first fits” upon New-year’s day is kept up at Falkirk with as much spirit as any where else. Both Old and New Style have their “keepers,” although many of the lower classes keep them in rather a “disorderly style.” Soon as the steeple clock strikes the ominous twelve, all is running, and bustle, and noise; hot-pints in clear scoured copper kettles are seen in all directions, and a good noggin to the well-known toast, “A gude new year, and a merry han’sel Monday,” is exchanged among the people in the streets, as well as friends in the houses. On han’sel Monday O. S. the numerous colliers in the neighbourhood of the town have a grand main of cocks; but there is nothing in these customs peculiar to the season.

Falkirk, 1825.

J. W. R.

The following are recorded particulars of a whimsical custom in Yorkshire, by which a right of sheep-walk is held by the tenants of a manor:—

Hutton Conyers, Com. York.

Near this town, which lies a few miles from Ripon, there is a large common, called Hutton Conyers Moor, whereof William Aislabie, esq. of Studley Royal, (lord of the manor of Hutton Conyers,) is lord of the soil, and on which there is a large coney-warren belonging to the lord. The occupiers of messuages and cottages within the several towns of Hutton Conyers, Baldersby, Rainton, Dishforth, and Hewick, have right of estray for their sheep to certain limited boundaries on the common, and each township has a shepherd.

The lord’s shepherd has a preeminence of tending his sheep on every part of the common; and wherever he herds the lord’s sheep, the several other shepherds are to give way to him, and give up their hoofing-place, so long as he pleases to depasture the lord’s sheep thereon. The lord holds his court the first day in the year, to entitle those several townships to such right of estray; the shepherd of each township attends the court, and does fealty, by bringing to the court a large apple-pie, and a twopenny sweetcake, (except the shepherd of Hewick, who compounds by paying sixteen pence for ale, which is drank as after mentioned,) and a wooden spoon; each pie is cut in two, and divided by the bailiff, one half between the steward, bailiff, and the tenant of the coney-warren before mentioned, and the other half into six parts, and divided amongst the six shepherds of the above mentioned six townships. In the pie brought by the shepherd of Rainton an inner one is made, filled with prunes. The cakes are divided in the same manner. The bailiff of the manor provides furmety and mustard, and delivers to each shepherd a slice of cheese and a penny roll. The furmety, well mixed with mustard, is put into an earthen pot, and placed in a hole in the ground, in a garth belonging to the bailiff’s house; to which place the steward of the court, with the bailiff, tenant of the warren, and six shepherds, adjourn with their respective wooden spoons. The bailiff provides spoons for the stewards, the tenant of the warren, and himself. The steward first pays respect to the furmety, by taking a large spoonful, the bailiff has the next honour, the tenant of the warren next, then the shepherd of Hutton Conyers, and afterwards the other shepherds by regular turns; then each person is served with a glass of ale, (paid for by the sixteen pence brought by the Hewick shepherd,) and the health of the lord of the manor is drank; then they adjourn back to the bailiff’s house, and the further business of the court is proceeded in.

Each pie contains about a peck of flour, is about sixteen or eighteen inches [23, 24] diameter, and as large as will go into the mouth of an ordinary oven. The bailiff of the manor measures them with a rule, and takes the diameter; and if they are not of a sufficient capacity, he threatens to return them, and fine the town. If they are large enough, he divides them with a rule and compasses into four equal parts; of which the steward claims one, the warrener another, and the remainder is divided amongst the shepherds. In respect to the furmety, the top of the dish in which it is put is placed level with the surface of the ground; all persons present are invited to eat of it, and those who do not, are not deemed loyal to the lord. Every shepherd is obliged to eat of it, and for that purpose is to take a spoon in his pocket to the court; for if any of them neglect to carry a spoon with him, he is to lay him down upon his belly, and sup the furmety with his face to the pot or dish, at which time it is usual, by way of sport, for some of the bystanders to dip his face into the furmety; and sometimes a shepherd, for the sake of diversion, will purposely leave his spoon at home.[13]

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

A practice which well deserves to be known and imitated is established at Maresfield-park, Sussex, the seat of sir John Shelley, bart. M. P. Rewards are annually given on New-year’s day to such of the industrious poor in the neighbourhood as have not received parish relief, and have most distinguished themselves by their good behaviour and industry, the neatness of their cottages and gardens, and their constant attendance at church, &c. The distribution is made by lady Shelley, assisted by other ladies; and it is gratifying to observe the happy effects upon the character and disposition of the poor people with which this benevolent practice has been attended during the few years it has been established. Though the highest reward does not exceed two guineas, yet it has excited a wonderful spirit of emulation, and many a strenuous effort to avoid receiving money from the parish. Immediately as the rewards are given, all the children belonging to the Sunday-school and national-school lately established in the parish, are set down to a plentiful dinner in the servants’ hall; and after dinner they also receive prizes for their good conduct as teachers, and their diligence as scholars.

I am, &c.

J.S.

ODE TO THE NEW YEAR.

BY

A Gentleman of Literary Habits

and Means.

For the Every-day Book.

We are truly and agreeably informed by the “Mirror of the Months,” that “Now periodical works put on their best attire; the old ones expressing their determination to become new, and the new [25, 26] ones to become old; and each makes a point of putting forth the first of some pleasant series (such as this, for example!), which cannot fail to fix the most fugitive of readers, and make him her own for another twelve months at least.”

Under this head it is proposed to place the “Mean temperature of every day in the Year for London and its environs, on an average of Twenty Years,” as deduced by Mr. Howard, from observations commencing with the year 1797, and ending with 1816.

For the first three years, Mr. Howard’s observations were conducted at Plaistow, a village about three miles and a half N. N. E. of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, four miles E. of the edge of London, with the Thames a mile and a half to the S., and an open level country, for the most part well-drained land, around it. The thermometer was attached to a post set in the ground, under a Portugal laurel, and from the lowness of this tree, the whole instrument was within three feet of the turf; it had the house and offices, buildings of ordinary height, to the S. and S. E. distant about twenty yards, but was in other respects freely exposed.

For the next three years, the observations were made partly at Plaistow and partly at Mr. Howard’s laboratory at Stratford, a mile and a half to the N. W., on ground nearly of the same elevation. The thermometer had an open N. W. exposure, at six feet from the ground, close to the river Lea.

The latter observations were made at Tottenham-green, four miles N. of London, which situation, as the country to the N. W. especially is somewhat hilly and more wooded, Mr. Howard considers more sheltered than the former site; the elevation of the ground is a trifle greater, and the thermometer was about ten feet from the general level of the garden before it, with a very good exposure N., but not quite enough detached from the house, having been affixed to the outer door-case, in a frame which gave it a little projection, and admitted the air behind it.

On this day, then, the average of these twenty years’ observations gives

Mean Temperature 36·57.

It is, further, proposed to notice certain astronomical and meteorological phenomena; the migration and singing of birds; the appearance of insects; the leafing and flowering of plants; and other particulars peculiar to animal, vegetable, and celestial existences. These observations will only be given from sources thoroughly authentic, and the authorities will be subjoined. Communications for this department will be gladly received.

[6] Mirror of the Months.

[7] Vita Edw. II.

[8] In Architren. lib. 2.

[9] The name of some horse.

[10] The name of another horse.

[11] The name of a cow.

[12] The author of Waverly, in a note to the Abbot, mentions three Moralities played during the time of the reformation—The Abbot of Unreason, The Boy Bishop, and the Pepe o’ Fools—may not pack o’ fools be a corruption of this last?

[13] Blount’s Plug. Antiq. by Beckwith.

Is said, by his English biographer Butler, to have been a sub-deacon in a desert, martyred at Spoletto, about the year 178; whereto the same biographer adds, “In the Roman Martyrology his name occurs on the first, in some others on the second of January.” The infallible Roman church, to end the discord, rejects the authority of the “Roman Martyrology” and keeps the festival of Concord on the second of January.

Mean Temperature 35·92.

There is a father with twice six sons; these sons have thirty daughters a-piece, party-coloured, having one cheek white and the other black, who never see each other’s face, nor live above twenty-four hours.

Cleobulus, to whom this riddle is attributed, was one of the seven wise men of Greece, who lived about 570 years before the birth of Christ.

Riddles are of the highest antiquity; the oldest on record is in the book of Judges xiv. 14-18. We are told by Plutarch, that the girls of his times worked at netting or sewing, and the most ingenious “made riddles.”

Mean Temperature 35·60.

The “Mirror of the Months,” a reflector of “The Months” by Mr. Leigh Hunt, enlarged to include other objects, adopts, “Above all other proverbs, that which says, ‘There’s nothing like the time present,’—partly because ‘the time present’ is but a periphrasis for Now!” The series of delightful things which Mr. Hunt links together by the word Now in his “Indicator,” is well remembered, and his pleasant disciple tells us, “Now, then, the cloudy canopy of sea-coal smoke that hangs over London, and crowns her queen of capitals, floats thick and threefold; for fires and feastings are rife, and every body is either ‘out’ or ‘at home’ every night. Now, if a frosty day or two does happen to pay us a flying visit, on its way to the North Pole, how the little boys make slides on the pathways, for lack of ponds, and, it may be, trip up an occasional housekeeper just as he steps out of his own door; who forthwith vows vengeance, in the shape of ashes, on all the slides in his neighbourhood, not, doubtless, out of vexation at his own mishap, and revenge against the petty perpetrators of it, but purely to avert the like from others!—Now the bloom-buds of the fruit-trees, which the late leaves of autumn had concealed from the view, stand confessed, upon the otherwise bare branches, and, dressed in their patent wind-and-waterproof coats, brave the utmost severity of the season,—their hard, unpromising outsides, compared with the forms of beauty which they contain, reminding us of their friends the butterflies, when in the chrysalis state.—Now the labour of the husbandman is, for once in the year, at a stand; and he haunts the alehouse fire, or lolls listlessly over the half-door of the village smithy, and watches the progress of the labour which he unconsciously envies; tasting for once in his life (without knowing it) the bitterness of that ennui which he begrudges to his betters.—Now, melancholy-looking men wander ‘by twos and threes’ through market-towns, with their faces as blue as the aprons that are twisted round their waists; their ineffectual rakes resting on their shoulders, and a withered cabbage hoisted upon a pole; and sing out their doleful petition of ‘Pray remember the poor gardeners, who can get no work!’”

Now, however, not to conclude mournfully, let us remember that the officers and some of the principal inhabitants of most parishes in London, preceded by their beadle in the full majesty of a full great coat and gold laced hat, with his walking staff of state higher than himself, and headed by a goodly polished silver globe, go forth from the vestry room, and call on every chief parishioner for a voluntary contribution towards a provision for cheering the abode of the needy at this cheerful season:—and now the unfeeling and mercenary urge “false pretences” upon “public grounds,” with the vain hope of concealing their private reasons for refusing “public charity:”—and now, the upright and kind-hearted welcome the annual call, and dispense bountifully. Their prosperity is a blessing. Each scattereth and yet increaseth; their pillows are pillows of peace; and at the appointed time, they lie down with their fathers, and sleep the sleep of just men made perfect, in everlasting rest.

Mean Temperature 36·42.

In the parish of Pauntley, a village on the borders of the county of Gloucester, next Worcestershire, and in the neighbourhood, “a custom, intended to prevent the smut in wheat, in some respect resembling the Scotch Beltein, prevails.” “On the eve of Twelfth-day all the servants of every farmer assemble together in one of the fields that has been sown with wheat. At the end of twelve lands, they make twelve fires in a row with straw; around one of which, made larger than the rest, they drink a cheerful glass of cyder to their master’s health, and success to the future harvest; then, returning home, they feast on cakes made of caraways, &c. soaked in cyder, which they claim as a reward for their past labours in sowing the grain.”[14]

In the beginning of the year 1825, the flimsiest bubbles of the most bungling [29, 30] projectors obtained the public confidence; at the close of the year that confidence was refused to firms and establishments of unquestionable security. Just before Christmas, from sudden demands greatly beyond the amounts which were ready for ordinary supply, bankers in London of known respectability stopped payment; the panic became general throughout the kingdom, and numerous country banks failed, the funds fell, Exchequer bills were at a heavy discount, and public securities of every description suffered material depression. This exigency rendered prudence still more circumspect, and materially retarded the operations of legitimate business, to the injury of all persons engaged in trade. In several manufacturing districts, transactions of every kind were suspended, and manufactories wholly ceased from work.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

As just at this time it may be interesting to many of your readers, to know the origin of Exchequer bills, I send you the following account.

In the years 1696 and 1697, the silver currency of the kingdom being, by clipping, washing, grinding, filing, &c. reduced to about half its nominal value, acts of parliament were passed for its being called in, and re-coined; but whilst the re-coinage was going on exchequer bills were first issued, to supply the demands of trade. The quantity of silver re-coined, according to D’Avenant, from the old hammered money, amounted to 5,725,933l. It is worthy of remark, that through the difficulties experienced by the Bank of England (which had been established only three years,) during the re-coinage, they having taken the clipped silver at its nominal value, and guineas at an advanced price, bank notes were in 1697 at a discount of from 15 to 20 per cent. “During the re-coinage,” says D’Avenant, “all great dealings were transacted by tallies, bank-bills, and goldsmiths’ notes. Paper credit did not only supply the place of running cash, but greatly multiplied the kingdom’s stock; for tallies and bank-bills did to many uses serve as well, and to some better than gold and silver; and this artificial wealth which necessity had introduced, did make us less feel the want of that real treasure, which the war and our losses at sea had drawn out of the nation.”

I am, &c.

J. G.

THE CHRISTMAS DAYS.

A Family Sketch.

December 30, 1825.

Mean Temperature 37·47.

“The King drinks!”

*

[14] Rudge’s Gloucester.

Epiphany.—Old Christmas-day.

Holiday at the Public-offices.

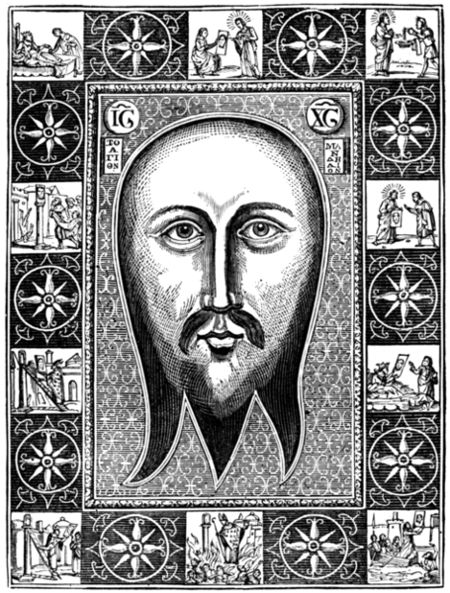

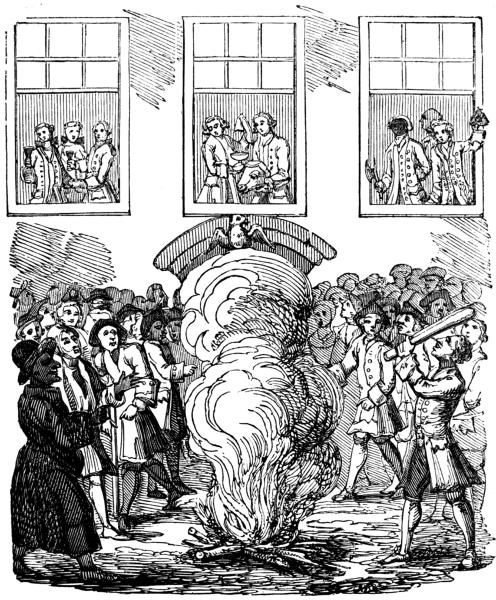

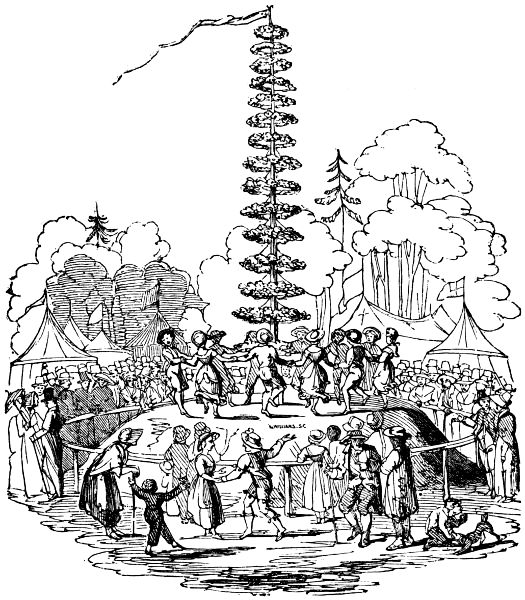

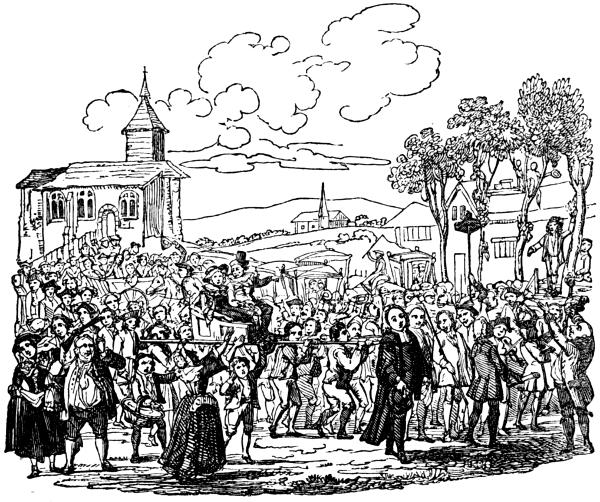

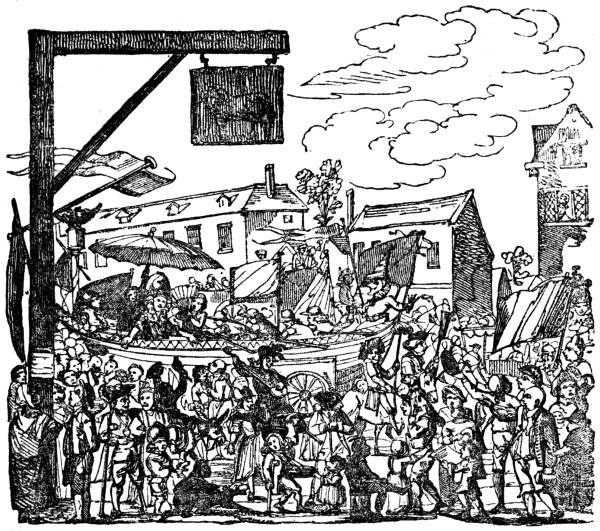

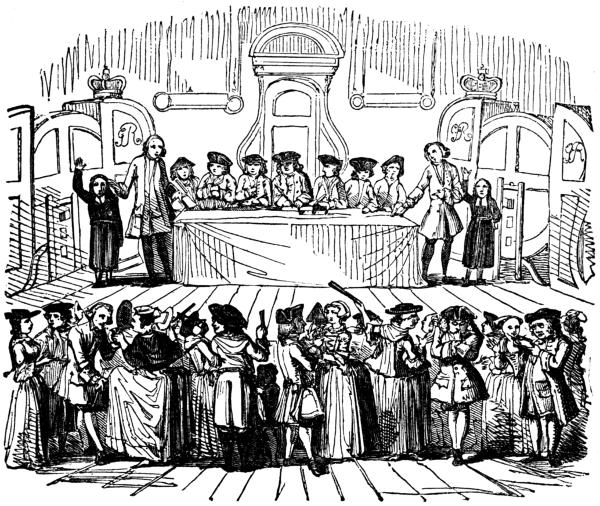

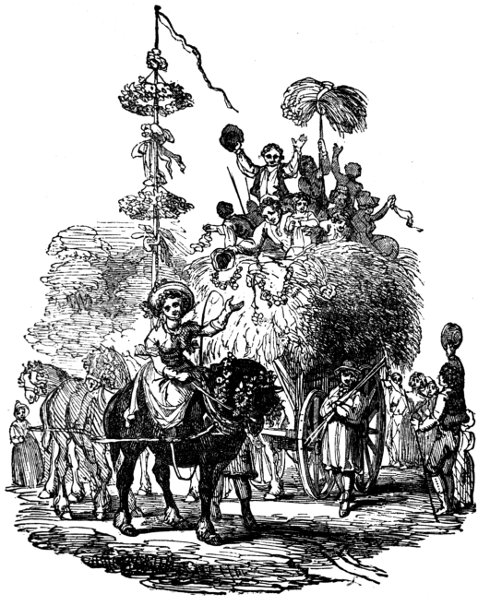

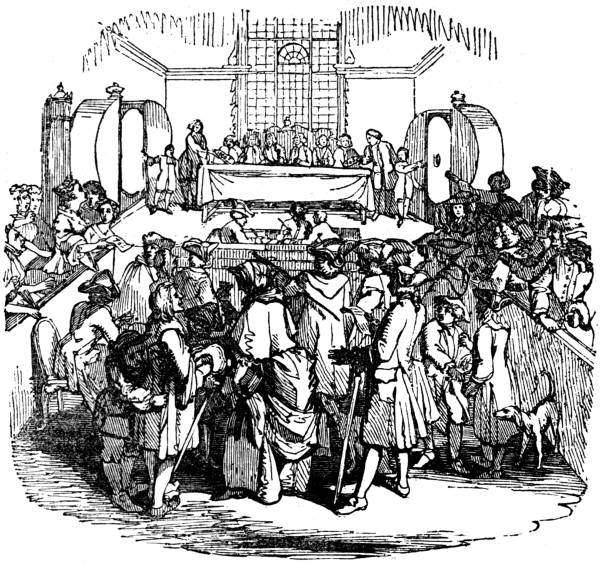

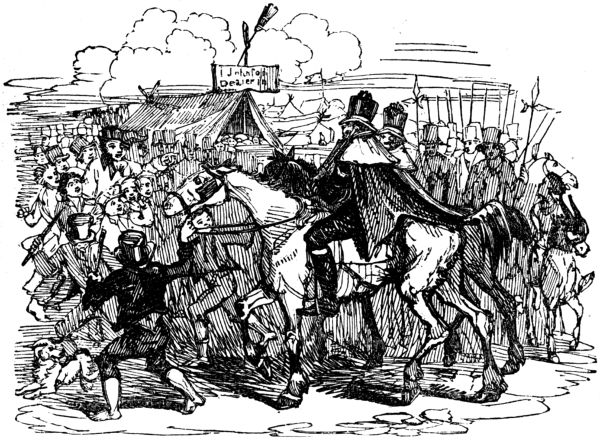

It is only in certain rural parts of France that the merriments represented above still prevail. The engraving is from an old print, “I. Marriette ex.” inscribed as in the next column.

“L’Hiver.

Les Divertissements du Roi-boit.

This print may be regarded a faithful picture of the almost obsolete usage.

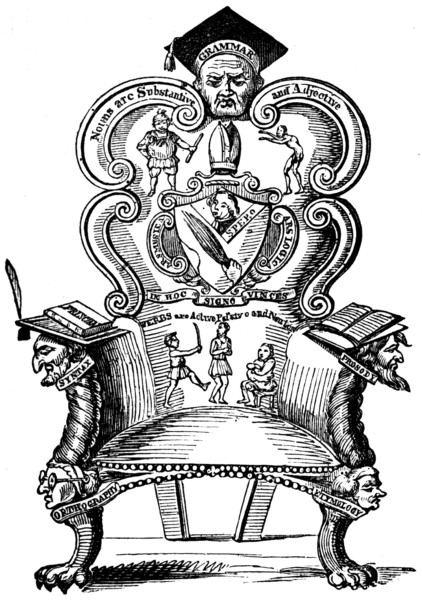

During the holidays, and especially on Twelfth-night, school-boys dismiss “the cares and the fears” of academic rule; or they are regarded but as a passing cloud, intercepting only for an instant the sunshine of joy wherewith their sports are brightened. Gerund-grinding and parsing are usually prepared for at the last moment, until when “the master’s chair” is only “remembered to be forgotten.” There is entire suspension of the authority of that class, by whom the name of “Busby” is venerated, till “Black Monday” arrives, and chaises and stages convey the young Christmas-keepers to the “seat of government.”

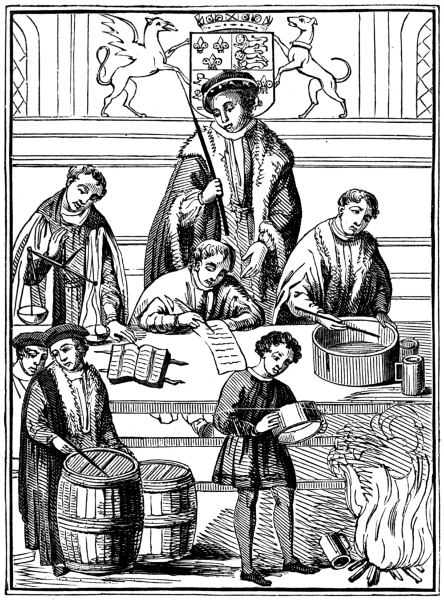

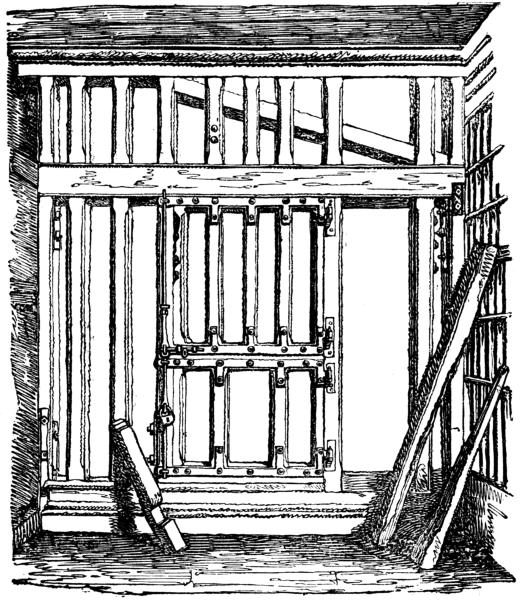

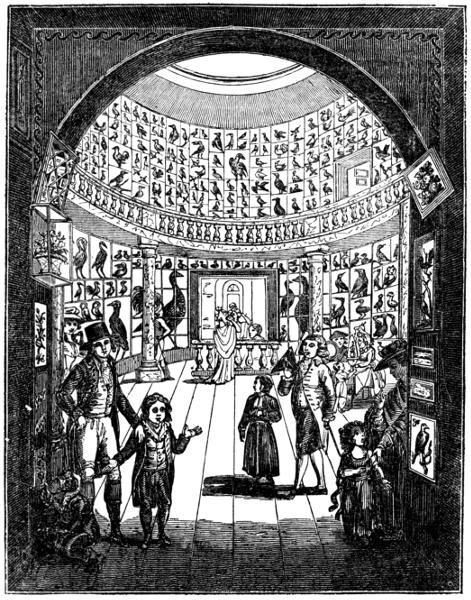

Dr. Busby’s Chair.

The name of Busby!—not the musical doctor, but a late magisterial doctor of Westminster school—celebrated for severe discipline, is a “word of fear” to all living who know his fame! It is perpetuated by an engraved representation of his chair, said to have been designed by sir Peter Lily, and presented by that artist to king Charles II. The arms, and each arm, are appalling; and the import of the other devices are, or ought to be, known by every tyro. Every prudent person lays in stores before they are wanted, and Dr. Busby’s chair may as well be “in the house” on Twelfth-day as on any other; not as a mirth-spoiler, but as a subject which we know to-day that we have “by us,” whereon to inquire and discuss at a more convenient season. Dr. Busby was a severe, but not an ill-natured man. It is related of him and one of his scholars, that during the doctor’s absence from his study, the boy found some plums in it, and being moved by lickerishness, began to eat some; first, however, he waggishly cried out, “I publish the banns of matrimony between my mouth and these plums; if any here present know just cause or impediment why they should not be united, you are to declare it, or hereafter hold your peace;” and then he ate. But the doctor had overheard the proclamation, and said nothing till the next morning, when causing the boy to be “brought up,” and disposed for punishment, he grasped the well-known instrument, and said, “I publish the banns of matrimony between this rod and this boy: if any of you know just cause or impediment why they should not be united, you are to declare it.”—The boy himself called out, “I forbid the banns!” “For what cause?” inquired the doctor. “Because,” said the boy, “the parties are not agreed!” The doctor enjoyed the validity of the objection urged by the boy’s wit, and the ceremony was not performed. This is an instance of Dr. Busby’s admiration of talent: and let us hope, in behalf of its seasonableness here, that it was at Christmas time.

We recur once more to this subject, for the sake of remarking that there is an account of a certain curate, “who having taken his preparations over evening, when all men cry (as the manner is) The king drinketh, chanting his masse the next morning, fell asleep in his memento; and when he awoke, added, with a loud voice, The king drinketh.” This mal-apropos exclamation must have proceeded from a foreign ecclesiastic: we have no account of the ceremony to which it refers having prevailed in merry England.

An excellent pen-and-ink picture of “Merry England”[15] represents honest old Froissart, the French chronicler, as saying of some English in his time, that “they amused themselves sadly after the fashion of their country;” whereon the portrayer of Merry England observes, “They have indeed a way of their own. Their mirth is a relaxation from gravity, a challenge to ‘Dull Care’ to ‘be gone;’ and one is not always clear at first, whether the appeal is successful. The cloud may still hang on the brow; the ice may not thaw at once. To help them out in their new character is an act of charity. Any thing short of hanging or drowning is something to begin with. They do not enter into their amusements the less doggedly because they may plague others. They like a thing the better for hitting them a rap on the knuckles, for making their blood tingle. They do not dance or sing, but they make good cheer—‘eat, drink, and are merry.’ No people are fonder of field-sports, Christmas gambols, or practical jests. Blindman’s-buff, hunt-the-slipper, hot-cockles, and snap-dragon, are all approved English games, full of laughable surprises and ‘hair-breadth ’scapes,’ and serve to amuse the winter fireside after the roast beef and plum-pudding, the spiced ale and roasted crab, thrown (hissing-hot) into the foaming tankard. Punch (not the liquor, but the puppet) is not, I fear, of English origin; but there is no place, I take it, where he finds himself more at home or meets a more joyous welcome, where he collects greater crowds at the corners of streets, where he opens the eyes or distends the cheeks wider, or where the bangs and blows, the uncouth gestures, ridiculous anger and screaming voice of the chief performer excite more boundless merriment or louder bursts of laughter among all ranks and sorts of people. An English theatre is the very throne of pantomime; nor do I believe that the gallery and boxes of Drury-lane or Covent-garden [37, 38] filled on the proper occasions with holiday folks (big or little) yield the palm for undisguised, tumultuous, inextinguishable laughter to any spot in Europe. I do not speak of the refinement of the mirth (this is no fastidious speculation) but of its cordiality, on the return of these long-looked-for and licensed periods; and I may add here, by way of illustration, that the English common people are a sort of grown children, spoiled and sulky, perhaps, but full of glee and merriment, when their attention is drawn off by some sudden and striking object.

“The comfort, on which the English lay so much stress, arises from the same source as their mirth. Both exist by contrast and a sort of contradiction. The English are certainly the most uncomfortable of all people in themselves, and therefore it is that they stand in need of every kind of comfort and accommodation. The least thing puts them out of their way, and therefore every thing must be in its place. They are mightily offended at disagreeable tastes and smells, and therefore they exact the utmost neatness and nicety. They are sensible of heat and cold, and therefore they cannot exist, unless every thing is snug and warm, or else open and airy, where they are. They must have ‘all appliances and means to boot.’ They are afraid of interruption and intrusion, and therefore they shut themselves up in in-door enjoyments and by their own firesides. It is not that they require luxuries (for that implies a high degree of epicurean indulgence and gratification,) but they cannot do without their comforts; that is, whatever tends to supply their physical wants, and ward off physical pain and annoyance. As they have not a fund of animal spirits and enjoyments in themselves, they cling to external objects for support, and derive solid satisfaction from the ideas of order, cleanliness, plenty, property, and domestic quiet, as they seek for diversion from odd accidents and grotesque surprises, and have the highest possible relish not of voluptuous softness, but of hard knocks and dry blows, as one means of ascertaining their personal identity.”

Twelfth-day, in the times of chivalry, was observed at the court of England by grand entertainments and tournaments. The justings were continued till a period little favourable to such sports.

In the reign of James I., when his son prince Henry was in the 16th year of his age, and therefore arrived to the period for claiming the principality of Wales and the duchy of Cornwall, it was granted to him by the king and the high court of parliament, and the 4th of June following appointed for his investiture: “the Christmas before which,” sir Charles Cornwallis says, “his highnesse, not onely for his owne recreation, but also that the world might know what a brave prince they were likely to enjoy, under the name of Meliades, lord of the isles, (an ancient title due to the first-borne of Scotland,) did, in his name, by some appointed for the same purpose, strangely attired, accompanied with drummes and trumpets, in the presence, before the king and queene, and in the presence of the whole court, deliver a challenge to all knights of Great Britaine.” The challenge was to this effect, “That Meliades, their noble master, burning with an earnest desire to trie the valour of his young yeares in foraigne countryes, and to know where vertue triumphed most, had sent them abroad to espy the same, who, after their long travailes in all countreyes, and returne,” had nowhere discovered it, “save in the fortunate isle of Great Britaine: which ministring matter of exceeding joy to their young Meliades, who (as they said) could lineally derive his pedegree from the famous knights of this isle, was the cause that he had now sent to present the first fruits of his chivalrie at his majesties’ feete; then after returning with a short speech to her majestie, next to the earles, lords, and knights, excusing their lord in this their so sudden and short warning, and lastly, to the ladies; they, after humble delivery of their chartle concerning time, place, conditions, number of weapons and assailants, tooke their leave, departing solemnly as they entered.”

Then preparations began to be made for this great fight, and each was happy who found himself admitted for a defendant, much more an assailant. “At last to encounter his highness, six assailants, and fifty-eight defendants, consisting of earles, barons, knights, and esquires, were appointed and chosen; eight defendants to one assailant, every assailant being to fight by turnes eight severall times fighting, two every time with push and pike of sword, twelve strokes at a time; after which, the barre for separation was to be let downe until a fresh onset.” The summons ran in these words:

“To our verie loving good ffreind sir Gilbert Houghton, knight, geave theis with speed:

“After our hartie commendacions unto you. The prince, his highnes, hath comanded us to signifie to you that whereas he doth intend to make a challenge in his owne person at the Barriers, with sixe other assistants, to bee performed some tyme this Christmas; and that he hath made choice of you for one of the defendants (whereof wee have comandement to give you knowledge), that theruppon you may so repaire hither to prepare yourselfe, as you may bee fitt to attend him. Hereunto expecting your speedie answer wee rest, from Whitehall this 25th of December, 1609. Your very loving freindes,

Notingham. | T. Suffolke. | E. Worcester.”

On New-year’s Day, 1610, or the day after, the prince’s challenge was proclaimed at court, and “his highnesse, in his own lodging, in the Christmas, did feast the earles, barons, and knights, assailants and defendants, untill the great Twelfth appointed night, on which this great fight was to be performed.”

On the 6th of January, in the evening, “the barriers” were held at the palace of Whitehall, in the presence of the king and queen, the ambassadors of Spain and Venice, and the peers and ladies of the land, with a multitude of others assembled in the banqueting-house: at the upper end whereof was the king’s chair of state, and on the right hand a sumptuous pavilion for the prince and his associates, from whence, “with great bravery and ingenious devices, they descended into the middell of the roome, and there the prince performed his first feats of armes, that is to say, at Barriers, against all commers, being assisted onlie with six others, viz. the duke of Lenox, the earle of Arundell, the earle of Southampton, the lord Hay, sir Thomas Somerset, and sir Richard Preston, who was shortly after created lord Dingwell.”

To answer these challengers came fifty-six earles, barons, knights, and esquiers. They were at the lower end of the roome, where was erected “a very delicat and pleasant place, where in privat manner they and their traine remained, which was so very great that no man imagined that the place could have concealed halfe so many.” From thence they issued, in comely order, to the middell of the roome, where sate the king and the queene, and the court, “to behold the barriers, with the several showes and devices of each combatant.” Every challenger fought with eight several defendants two several combats at two several weapons, viz. at push of pike, and with single sword. “The prince performed this challenge with wonderous skill and courage, to the great joy and admiration of the beholders,” he “not being full sixteene yeeres of age untill the 19th of February.” These feats, and other “triumphant shewes,” began before ten o’clock at night, and continued until three o’clock the next morning, “being Sonday.” The speeches at “the barriers” were written by Ben Jonson. The next day (Sunday) the prince rode in great pomp to convoy the king to St James’, whither he had invited him and all the court to supper, whereof the queen alone was absent; and then the prince bestowed prizes to the three combatants best deserving; namely, the earl of Montgomery, sir Thomas Darey (son to lord Darey), and sir Robert Gourdon.[16] In this way the court spent Twelfth-night in 1610.

On Twelfth-night, 1753, George II. played at hazard for the benefit of the groom porter. All the royal family who played were winners, particularly the duke of York, who won 3000l. The most considerable losers were the duke of Grafton, the marquis of Hartington, the earl of Holderness, earl of Ashburnham, and the earl of Hertford. The prince of Wales (father of George III.) with prince Edward and a select company, danced in the little drawing room till eleven o’clock, and then withdrew.[17]

According to the alteration of the style, OLD Christmas-day falls on Twelfth-day, and in distant parts is even kept in our time as the festival of the nativity. In 1753, Old Christmas-day was observed in the neighbourhood of Worcester by the Anti-Gregorians, full as sociably, if not so religiously, as formerly. In several villages, the parishioners so strongly insisted upon having an Old-style nativity sermon, as they term it, that their ministers could not well avoid preaching to them: and, at some towns, where the markets are held on Friday, not a butter basket, nor even a Goose, was to be seen in the market-place the whole day.[18]

To heighten the festivities of Christmas, 1825, the good folks of “London and its environs” were invited to Sadler’s Wells, by the following whimsical notice, printed and distributed as a handbill:

“SOVEREIGNS WILL BE TAKEN, during the Christmas holidays, and as long as any body will bring them to SADLER’S WELLS; nay so little fastidious are the Proprietors of that delectable fascinating snuggery, that, however incredible it may appear, they, in some cases, have actually had the liberality to prefer Gold to Paper. Without attempting to investigate their motives for such extraordinary conduct, we shall do them the justice to say, they certainly give an amazing quantum of amusement, All in One Night, at the HOUSE ON THE HEATH, where, besides the THREE CRUMPIES, AND THE BARON AND HIS BROTHERS, an immense number of fashionables are expected on MERLIN’S MOUNT, and some of the first Cambrian families will countenance HARLEQUIN CYMRAEG, in hopes to partake of the Living Leek, which being served up the last thing before supper, will constitute a most excellent Christmas carminative, preventing the effects of night air on the crowds who will adorn this darling little edifice. In addition to a most effective LIGHT COMPANY engaged here, a very respectably sized Moon will be in attendance to light home a greater number of Patrons than ever this popular petted Palace of Pantomime is likely to produce. We say nothing of warmth and comfort, acquired by recent improvements, because these matters will soon be subjects of common conversation, and omit noticing the happiness of Half-price, and the cheering qualities of the Wine-room, fearful of wounding in the bosom of the Manager that innate modesty which is ever the concomitant of merit; we shall therefore conclude, by way of invitation to the dubious, in the language of an elegant writer, by asserting that the Proof of the Pudding is in—VERBUM SAT.”

Mean Temperature 37·12.

[15] In the New Monthly Magazine, Dec. 1825

[16] Mr. Nichols’s Progresses of James I.

[17] Gentleman’s Magazine.

[18] Ibid.

1826. Distaff’s Day.[19]

STANZAS ON THE NEW YEAR.

L. E. L.[20]

Mean Temperature 35·85.

1826. First Sunday after Epiphany.

On the 8th of January, 1753, died sir Thomas Burnet, one of the judges of the court of Common Pleas, of the gout in his stomach, at his house in Lincoln’s-inn fields. He was the eldest son of the celebrated Dr. Gilbert Burnet, bishop of Salisbury; was several years consul at Lisbon; and in November, 1741, made one of the judges of the Common Pleas, in room of judge Fortescue, who was appointed master of the rolls. On November 23, 1745, when the lord chancellor, judges, and association of the gentlemen of the law, waited on his majesty with their address, on occasion of the rebellion, he was knighted. He was an able and upright judge, and a great benefactor to the poor.[21]

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

Encouraged by your various expressions of willingness to receive notices of customs not already “imprinted” in your first volume, I take the liberty of presenting the first of several which I have not yet seen in print.

I am, sir,

Your constant reader,

J. O. W.

Chelsea.

Gentle reader,

If thou art not over-much prejudiced by the advances of modernization, (I like a long new-coined word,) so that, even in these “latter days,” thou dost not hesitate to place explicit reliance on ancient, yet infallible “sayings and doings,” (ancient enough, since they have been handed down to us by our grandmothers—and who would doubt the weight and authority of so many years?—and infallible enough, since they themselves absolutely believed in their “quite-correctness,”) I will tell thee a secret well worth knowing, if that can be called a secret which arises out of a well-known and almost universal custom, at least, in “days of yore.” It is neither more nor less than the possession throughout “the rolling year” of a pocket never without money. Is not this indeed a secret well worth knowing? Yet the means of its accomplishment are exceedingly simple (as all difficult things are when once known.) On the first day of the first new moon of the new year, or so soon afterwards as you observe it, all that you have to do is this:—on the first glance you take at “pale Luna’s silvery crest” in the western sky, put your hand in your pocket, shut your eyes, and turn the smallest piece of silver coin you possess upside down in your said pocket. This will ensure you (if you will but trust its infallibility!) throughout the whole year that “summum bonum” of earthly wishes, a pocket never empty. If, however, you neglect, on the first appearance of the moon, your case is hopeless; nevertheless and notwithstanding, at a future new moon you may pursue the same course, and it will be sure to hold good during the then current month, but not a “whit” longer.

This mention of the new moon and its crest brings to mind a few verses I wrote some time ago, and having searched my scrap-book, (undoubtedly not such a one as Geoffery Crayon’s,) I copied them from thence, and they are here under. Although written in the “merry merry month of May,” they may be read in the “dreary dark December,” for every new moon presents the same beautiful phenomenon.

A Simile.

Here it may not be out of place to endeavour to describe, as familiarly as possible, the cause of the lunar appearance. Hold a piece of looking-glass in a ray of sunshine, and then move a small ball through the reflected ray: it is easy to conceive that both sides will be illumined; that side towards the sun by the direct sunbeam, and the side towards the mirror, though less powerfully, by the reflected sunbeam. In a somewhat similar manner, the earth supplies the place of the mirror, and as at every new moon, and for several days after the moon is in that part of her orbit between the earth and the sun, the rays of the sun are reflected from the earth to the dark side of the moon, and consequently to the inhabitants of that part of the moon, (if any such there be, and query why should there not be such?) the earth must present the curious appearance of a full moon of many times the diameter which ours presents.

J. O. W.

Mean Temperature 36·05.

[21] Gentleman’s Magazine.

1826. Plough Monday.

The first Monday after Twelfth day.[22]

On the 9th of January, 1752, William Stroud was tried before the bench of justices at Westminster-hall, for personating various characters and names, and defrauding numbers of people, in order to support his extravagance. It appeared by the evidence, that he had cheated a tailor of a suit of velvet clothes, trimmed with gold; a jeweller of upwards of 100l. in rings and watches, which he pawned; a coachmaker of a chaise; a carver and cabinet-maker of household goods; a hosier, hatter, and shoemaker, and, in short, some of almost every other business, to the amount of a large sum. He sometimes appeared like a gentleman attended with livery servants; sometimes as a nobleman’s steward; and, in the summer time, he travelled the west of England, in the character of Doctor Rock; and, at the same time, wrote to London for goods, in the names of the Rev. Laroche, and the Rev. Thomas Strickland. The evidence was full against him; notwithstanding which, he made a long speech in his own defence. He was sentenced to six months’ hard labour in Bridewell, and, within that time, to be six times publicly whipped.

Such offences are familiar to tradesmen of the present times, through many perpetrators of the like stamp; but all of them are not of the same audacity as Stroud, who, in the month following his conviction, wrote and published his life, wherein he gives a very extraordinary account of his adventures, but passes slightly over, or palliates his blackest crimes. He was bred a haberdasher of small wares in Fleet-street, married his mistress’s sister [47, 48] before his apprenticeship determined, set up in the Poultry, became a bankrupt, in three months got his certificate signed, and again set up in Holborn, where he lived but a little while before he was thrown into the King’s Bench for debt, and there got acquainted with one Playstowe, who gradually led him into scenes of fraud, which he afterwards imitated. Playstowe being a handsome man, usually passed for a gentleman, and Stroud for his steward; at last the former, after many adventures, married a girl with 4000l., flew to France, and left Stroud in the lurch, who then retired to Yorkshire, and lived some time with his aunt, pretending his wife was dead, and he was just on the brink of marrying advantageously, when his real character was traced. He then went to Ireland, passed for a man of fashion, hired an equipage, made the most of that country, and escaped to London. His next grand expedition was to the west of England, where he still personated the man of fortune, got acquainted with a young lady, and pursued her to London, where justice overtook him; and, instead of wedlock, bound him in the fetters of Bridewell.

On the 24th of June, 1752, Stroud received “his last and severest whipping, from the White Bear to St. James’s church Piccadilly.”[23]

Mean Temperature 36·12.