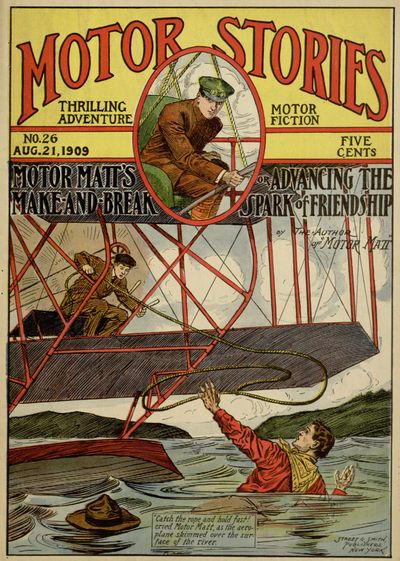

Title: Motor Matt's Make-and-Break; or, Advancing the Spark of Friendship

Author: Stanley R. Matthews

Release date: May 9, 2016 [eBook #52025]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Demian Katz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 26 AUG. 21, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S MAKE-AND-BREAK |

or ADVANCING THE SPARK of FRIENDSHIP |

|

by The Author of "Motor Matt" | |

|

Street & Smith, Publishers, New York. |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-80 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 26. | NEW YORK, August 21, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

Motor Matt's "Make and Break"

OR,

ADVANCING THE SPARK OF FRIENDSHIP.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. THE SKELETON IN THE CLOSET.

CHAPTER II. WHAT NEXT?

CHAPTER III. BRINGING THE SKELETON OUT.

CHAPTER IV. MARKING OUT A COURSE.

CHAPTER V. THE START.

CHAPTER VI. A SHOT ACROSS THE BOWS.

CHAPTER VII. THE MAN HUNTERS.

CHAPTER VIII. FOOLING THE COWBOYS.

CHAPTER IX. THE TRAILING ROPE.

CHAPTER X. A BOLT FROM THE BLUE.

CHAPTER XI. "ADVANCING THE SPARK."

CHAPTER XII. THE TRAIL TO THE RIVER.

CHAPTER XIII. UNWELCOME CALLERS.

CHAPTER XIV. AN UNEXPECTED TURN.

CHAPTER XV. A RISKY VENTURE.

CHAPTER XVI. CONCLUSION.

MOSE HOWARD'S FISH TRAP.

PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN IN DANGEROUS PLACES.

COSTLY FISHES.

Matt King, otherwise Motor Matt.

Joe McGlory, a young cowboy who proves himself a lad of worth and character, and whose eccentricities are all on the humorous side. A good chum to tie to—a point Motor Matt is quick to perceive.

Ping Pong, a Chinese boy who insists on working for Motor Matt, and who contrives to make himself valuable, perhaps invaluable.

Amos Murgatroyd, the unscrupulous broker whose fight against the Traquairs and Motor Matt finally results in complete disaster to himself.

Prebbles, Murgatroyd's old clerk, who resurrects the skeleton from the family closet, fights a good fight, and, with the help of the king of the motor boys, finally banishes the skeleton altogether.

Newt Prebbles, for whom Motor Matt undertakes to advance the spark of friendship; a youth who has erred, but who comes to a turning point and takes the right path.

Lieutenant Cameron, an officer in the Signal Corps, U. S. A., who proves to be the cousin of an old friend of Matt, and who nearly loses his life when the aëroplane is tested.

Jed Spearman, "Slim," "Hen," and three others, cowboys belonging with the Tin Cup outfit, who make some mistakes and are finally set right by the sheriff.

Roscoe, sheriff of Burleigh County, who plays a small but very important part.

THE SKELETON IN THE CLOSET.

"Where's the old man, Prebbles?"

"Don't ask me, Jim. I haven't a notion."

"Well, there's a letter for him."

The postman dropped a letter on the desk in front of the little old man on the high stool, and the door slammed. Prebbles picked up the letter and blinked at it. For a while he sat staring like a person in a dream, then a gasp escaped his lips, and he slipped from the stool and carried the letter closer to the window.

It was almost sunset, and a neighboring building shut off the light, but there, close to the dusty window pane, the light was good enough. The letter dropped from Prebbles' shaking hand, and he fell back against the wall.

"It's from him," the old man mumbled; "it's—it's——"

The words died on his lips, and a choking gurgle arose in his throat. Trembling like a man with the palsy, Prebbles pulled himself together and staggered to the water cooler. He drew himself a glass, and the tumbler rattled against his teeth as he drank.

"This won't do," he said to himself, drawing a hand across his forehead in a dazed and bewildered way. "I've got to brace up, that's what I have. But what's Newt writing to him for? I—I can't understand that."

Prebbles went back and picked up the letter. He was still greatly shaken, although he was getting firmer hold of himself by swift degrees.

It was a very ordinary appearing letter to have aroused such an extraordinary state of mind in the old man. The address, in a peculiar backhand, was to "Mr. Amos Murgatroyd, Loan Broker, Jamestown, North Dakota."

Prebbles was Murgatroyd's clerk, and the only clerk in the loan office. For several weeks Murgatroyd had not been in Jamestown, and the work of the office—what little there was—fell to Prebbles.

During those weeks of absence, the broker had been doing unlawful things. Prebbles, knowing his employer well, expected nothing better of him; but just what Murgatroyd had been doing, the old clerk did not know.

Strange men, who might be detectives in disguise, were watching the office night and day. Prebbles had been keen enough to discover that.

It was the peculiar handwriting of the letter that had had such a powerful effect upon the old clerk. Not one man in a thousand, perhaps in ten thousand, used a pen as the writer of that letter to the broker had used it. Prebbles felt sure that he could not be mistaken—that there was not the least possibility of a mistake. He knew who the writer of the letter was, and for weeks the old man's dream by day and night was that he could discover the whereabouts of the man.

The envelope was postmarked at Steele, N. D. The writer might be there, or he might not be there. After setting hand to the letter, it was more than possible he had mailed the letter at Steele and then gone to some other place.

There was one way to make sure—and only one: In order to find out positively where the writer of the letter was, Prebbles would have to open it and read it. Although a clerk in the office, his position did not give him the right to open his employer's personal mail; in fact, Murgatroyd had expressly forbidden this.

The letters received during Murgatroyd's absence—and they were but few—had been placed in the office safe. A week before, the collected letters had mysteriously vanished during the night, and in their place was left this scribbled line:

"Dropped in and got my mail. Say nothing to any one about my having been here.

A. M."

That was all, absolutely all, Prebbles had learned of his employer since he had left Jamestown several weeks before. Only two or three letters had collected in the safe since the others had been taken, and now this one from Steele must be added to them, unless——

Prebbles caught up a pair of scissors. Before he could snip off the end of the envelope, he paused. To deliberately open a letter addressed to some one else is a crime which, if brought to the attention of the postal authorities, is heavily punished. Prebbles was not afraid of the punishment, for he believed that Murgatroyd himself was a fugitive; still, it was well to be wary.

Laying down the scissors, he ran the end of a pen-holder under the flap. But again he paused, realizing, with a tremor, that he belonged to the army, the Salvation Army. As a soldier in the ranks, had he the right to take this advantage of his employer? On the streets, Prebbles, because of his earnestness in the army work, he was known as "Old Hallelujah." Poor business, this, for Old Hallelujah to rifle his employer's mail!

With a groan, Prebbles pushed the letter aside and dropped his face in his hands. While he was thus humped over his desk, a picture of distress and misery, the door opened and a boy came in with a telegram. The message was for Prebbles, and he signed the receipt. As soon as the boy had left, he tore the message open.

"Forward mail at once to George Hobbes, Bismarck.

"Hobbes."

This was from Murgatroyd, and it was not the first time he had used the name of "George Hobbes."

Was Prebbles to send that letter on without first seeing what was inside it? Duty to his employer and duty to himself warred in his soul.

That last letter received for Murgatroyd might have been taken to the police. They could secure authority from Washington to open it. But, if the letter came from the person Prebbles suspected, he did not want the police to see it.

The six o'clock whistle blew, but Prebbles paid no attention. He was fighting with his Salvation Army principles, and the stake was the contents of that letter to Murgatroyd.

At seven o'clock, the haggard old man, the battle still going on in his breast, pushed the letter into his pocket and left the office, locking the door behind him. He did not go to the cheap eating house where he usually took his meals—there was no supper for him that night—but he proceeded directly to the "barracks," got into his dingy blue cap and coat, and took his cymbals. By eight, a dozen of the "faithful" were in the street, their torches flaring smokily, and the bass drum, the snare drum, the cymbals, and the tambourine whanging and clashing and rattling a quickstep.

Back and forth they marched, then rounded up on a corner and sang one of their army songs.

Old Hallelujah was particularly earnest, that night. His voice was loudest in the singing, and his exhorting was done with a fine fervor. His thin, crooked body straightened, and his eyes gleamed, and he struck the cymbals with unusual vigor.

"Ole Halleluyer is gittin' young ag'in," ran the comment of more than one bystander.

"If he's so pious," observed some one, "it's a wonder he don't break away from that ole thief, Murgatroyd."

It was a wonder, and no mistake. But the wonder was soon to cease.

At ten o'clock Prebbles and the rest were back in the barracks; and at ten-thirty Prebbles was in his five-by-ten little hall bedroom, calmly steaming open the letter to Murgatroyd. He had finished the fight, and had nerved himself for his first false step. But was it a false step? He had come to the conclusion that the end justified the means.

The letter, carefully written, jumped immediately into the business the writer of it had in mind.

"I must have more money or I shall tell all I know about you and the accident to Traquair and his aëroplane. I can't live on promises, and I'm not going to make a fugitive out of myself any longer just to shield you. You're a fugitive yourself, now, but I reckon you can dig up enough money for both of us. I have dropped down the line of the Northern Pacific to mail this letter; as soon as it is in the office, I'm going back to my headquarters at the mouth of Burnt Creek, on the Missouri, ten miles above Bismarck. You'd better meet me there at once, as it's the safest place you can find. I suppose you've made arrangements to have your mail forwarded, so I'm sending this to your office. Bring plenty of money.

Newt Prebbles."

For many a weary hour the old man paced the narrow confines of his room, reading the letter again and again and turning the contents over and over in his mind.

"The boy don't care for me, he's mad at me," muttered Prebbles wearily, "but if I can make up with him, maybe he can be saved. What's this about the accident to Traquair? What does Newt know about Murgatroyd? No matter what happens, I've got to get the boy out of Murgatroyd's clutches. If Newt stays with him, he'll be as bad as he is."

It was after midnight when Prebbles dropped weakly into a chair.

"Motor Matt will help me," he muttered.

The thought had come to him like a flash of inspiration. And another inspiration had come to him, as well. He made a copy of the letter, then placed the original in its envelope, carefully resealed it, and went to the broker's office. To take the collected letters from the safe, place them and the one from Steele in a large envelope and address the envelope to "Mr. George Hobbes, General Delivery, Bismarck, N. D.," consumed only a few minutes.

"Motor Matt will know how to do the rest of it," thought the old clerk. "He's a clever lad, and he helps people. He helped Mrs. Traquair and he'll help Prebbles. I'm done with this office for good, and I'm glad of it."

He looked around the room with a grim laugh.

"I never thought I'd be pulling the pin on myself," he said aloud. "Maybe it's the poorhouse for mine, but I'll be glad to starve if I can make up with Newt and save him from that robber, Murgatroyd."

He turned off the light and closed and locked the office door. An hour later he had dropped the long envelope into a letter box and was back in his room. At seven in the morning he had boarded the northbound train for Minnewaukon and Devil's Lake. Motor Matt was at Fort Totten, on the south shore of the lake, and Prebbles would be at the fort in the afternoon.

The king of the motor boys was the old man's hope. Prebbles knew Matt, and had abundant faith in his ability to accomplish seemingly impossible things.

"He'll help me," murmured Prebbles, leaning back in one corner of the seat; "he helped Mrs. Traquair, and he'll help me."

WHAT NEXT?

"An elegant day—for ducks," said Joe McGlory, turning from the window against which a torrent of rain was splashing. "I'd about got my nerve screwed up to the place where I was going to take a fly with you in the Comet, pard."

"Well," laughed Matt, "perhaps it will be a clear, still day to-morrow, Joe."

"The day may be all right, but whether I have the necessary amount of nerve is a question. It takes sand to sit on a couple of wings and let a gasoline engine push you through the clouds. Sufferin' jack rabbits! Why, Ping, that little, slant-eyed chink, has got more sand than me when it comes to slidin' around through the firmament on a couple o' squares of canvas. I'm disgusted with myself, and that's honest."

"It's as easy as falling off a log," remarked Lieutenant Cameron, of the Signal Corps. "I've been up with Matt, and I know. He does all the work, McGlory. You won't have to do anything but sit tight and hang on."

"'Sit tight and hang on!'" echoed the cowboy. "Sounds easy, don't it? At the same time, Cameron, you know that if your hair ain't parted in the middle, the overweight on one side is liable to make the Comet turn turtle."

"Hardly as bad as that," grinned Matt.

The three—Lieutenant Cameron, Motor Matt, and Joe McGlory—were in Cameron's quarters in officers' row at the post.

One window of the room overlooked the parade ground and, if the weather had not been so thick, would have given a view of the old barracks, beyond. Another window commanded a prospect of the lake, just now surging high and lashing its waters against the foot of the bluff on which the fort stood.

The post was practically abandoned, and no more than a handful of soldiers were in possession. Most of these comprised a detail of the Signal Corps sent there for the try-out of the Traquair aëroplane with which Matt had acquitted himself so creditably.

It was about three o'clock in the afternoon, and all day long Matt and McGlory had been housed up at the post on account of the storm.

Ping Pong, the Chinese boy, was watching the aëroplane, which was in a big shelter tent not far from the post trader's store.

The cowboy, grumbling over the cheerless prospect from each window of the room, finally returned to his rocking-chair and sat down.

"What next, Matt?" inquired Cameron. "You don't remain long in any one place, and I've been wondering when you'd leave here and where you'd go."

"We're liable to break out in any old place on the map," said McGlory. "That's what I like about trailing around with Pard Matt. You never know, from one week to the next, whether you're going to hang up your hat in Alaska or Panama. It's the uncertainty and the vast possibilities that hooked me."

"I haven't laid any plans," remarked the king of the motor boys. "The failure of the government to buy that aëroplane, after Joe and I had put up a lot of money and time building it, leaves me with the machine on my hands. It's something of a white elephant."

"It needn't be a white elephant," returned Cameron. "You can crate the Comet and leave it here at the post until you find a use for it. The other aëroplane which you and Mrs. Traquair sold the war department is going to prove such a success that I am sure the government will be after this one. It will take a little time. There's a certain amount of red tape connected with the matter, you know."

"I'm hoping the government will buy the machine, but I don't feel like leaving it in storage while we're waiting for the war department to make up its mind."

"Why don't you go hunting for Murgatroyd?" inquired Cameron. "The government has offered a reward of one thousand dollars for his capture."

Murgatroyd had not only tried to wreck the first Traquair aëroplane at the time of the government trials at Fort Totten, but he had also resorted to crime in an attempt to secure, from Mrs. Traquair, a quarter section of land in Wells County, which, for some mysterious reason of his own, he was eager to get hold of. A deserter from the army, Cant Phillips by name, had assisted Murgatroyd in his nefarious work; and, for that, Phillips was now on his way to Fort Leavenworth to serve out a long sentence in a government prison, and Amos Murgatroyd was a fugitive.

Matt and his friends had been drawn into these lawless plots of the broker's, and Cameron supposed that, apart from the reward offered for the broker's capture, the young motorist would be eager to see him brought to book.

"I've lost interest in Murgatroyd," said Matt. "He's a scoundrel, and the government is dealing with him. What I want to do is to put the aëroplane to some profitable use. It was damaged considerably, when Murgatroyd brought it down with that rifle shot, and Joe and I have had to put up about three hundred more good dollars for repairs. Now that it's all shipshape and ready to fly once more, I feel as though we ought to make it earn something for us, instead of leaving it here at Fort Totten in storage."

"Aëroplanes are built to sell, aren't they?" asked the lieutenant quizzically. "How can you make any profit off them if you don't sell them?"

"Well, for one thing," replied Matt, "aëro clubs, in different parts of the world, are offering prizes for flights in flying machines. This machine of Traquair's, as you know, Cameron, is the best one yet invented. It can go farther and do more than any other aëroplane on the market."

"I guess that's right," agreed Cameron.

"However, I'm not thinking of flying for a prize. We'd have to go to Europe in order to get busy with a project of that sort, and I don't want to leave the United States—at least, not for a while yet."

"I wouldn't go out of the country, Matt," said Cameron earnestly. "You're under contract, you know, not to dispose of any of the Traquair patents to foreign governments."

"I wasn't thinking of such a thing as that, Cameron. What I was thinking of is this: Yesterday I received a letter from a show—— one of these 'tented aggregations,' as they're called in the bills—offering five hundred dollars a week if we would travel with the outfit and give two short flights each day from the show grounds——"

McGlory was on his feet in an instant, waving his hand above his head and hurrahing.

"That hits me plump!" he cried. "I've always wanted to do something in a show. Whoop-ya! Matt, you old sphinx, why didn't you say something about this before?"

"I've been turning the proposition over in my mind," answered Matt. "Frankly, I don't like the idea of traveling with a show so much as I do the prospect of earning five hundred a week. I'll have to find out, too, whether the manager of the show is good for the money before I'll talk with him."

"Are we going to St. Paul for an interview?"

"No, to Fargo. The show will make that town in about a week, and I wired the manager that we would meet him there. The Comet will carry two light-weight passengers in addition to the operator, so you and Ping, Joe, will have to fly with me to Fargo. We can save railroad fare by going in the aëroplane, and that's why I want to get you accustomed to being in the air with the machine."

Cameron listened to Matt with an air that showed plainly his disapproval.

"You won't like the show business, Matt," he declared.

"I understand that," was the response, "but it's the salary that appeals to me."

"Furthermore," continued Cameron, "the manager of the show will probably dock your salary every time you fail to pull off a flight. You know how hard it is to bank on the weather. At least half of each week, I should say at a guess, you will find it too windy to go up."

"We'll have to have an understanding with the manager about that. It will have to be a pretty stiff wind, though, to keep me from flying. I've got the knack of handling the aëroplane, now, and a moderate breeze won't bother me at all."

"The show's the thing!" jubilated McGlory. "Speak to me about that, will you? The king of the motor boys and the Comet will be top-liners. And draw? Well, I should say! Why, they'll draw the people like a house afire."

The first Traquair aëroplane—the one sold to the government after the Fort Totten trials had been christened the June Bug by McGlory; but this one, built by Matt after the Traquair model, he had himself named the Comet. This name was to perpetuate the memory of a motorcycle which Matt had owned and had used with telling effect in far-away Arizona.

"I'm sure I wish you all the luck in the world, Matt," said Cameron heartily, "although I tell you flat that this show project of yours doesn't commend itself to me worth a cent. However, you know your own business best. You have demonstrated, beyond all doubt, that the Traquair aëroplane can travel across country equally as well as around a prescribed course. This makes it possible for you to take your friends aboard and fly to Fargo, or to New York, if you want to—providing the wind isn't too strong and nothing goes wrong with the machinery, but——"

Cameron did not finish. Just at that moment a rap fell on the door, and he turned in his chair to ask who was outside.

"O'Hara, sor," came the response from the hall.

"What is it, O'Hara?"

"There's a little old man wid me, sor, who has just rained in from Minnewaukon. He's as damp as a fish and about all in, sor, an' he's afther wantin' t' spake wid Motor Matt."

"Bring him in, at once."

The door opened and Sergeant O'Hara entered the room, half dragging and half carrying a water-soaked individual who dropped feebly into a chair.

"Prebbles!" exclaimed the king of the motor boys, starting back in amazement.

BRINGING THE SKELETON OUT.

The old clerk was so wrought up over the business he had in hand that he had given scant consideration to himself. All his life—ever since he had been cast adrift to make his own way in the world—he had been a clerk. The only outdoor exercise he had ever taken consisted in walking from his sleeping quarters to his boarding place, and thence to the office, back to the boarding place for lunch, then back once more for supper and to his lodgings for sleep. During the last few months, since joining the "army," he had had evening exercise of a strenuous nature, but it came at a time of life when it merely ran down the physical organism instead of building it up.

It was a bedraggled and shattered Prebbles that completed the trip by wagon from Minnewaukon to the post. This lap of the journey was through a driving rain, the old man being insufficiently protected by a thin horse[Pg 5] blanket. His whole body was shaking, as he sat dripping in the chair, and his teeth clattered and rattled.

Several times Prebbles tried to speak to Motor Matt, but the chill splintered his words into indistinguishable sounds.

O'Hara peered into the clerk's gray face, and then turned a significant look at his superior officer.

"Sor," said he, "th' ould chap ain't built t' shtand a couple av hours in th' rain."

"Get him something hot from the kitchen, sergeant," ordered Cameron. Then, when O'Hara had left, the lieutenant turned to Matt. "Bring him into my bedroom, Matt you and McGlory. I've some clothes he can put on. They'll be a mile too big for him, but they'll be dry."

"Don't try to talk now, Prebbles," admonished Matt, as he and the cowboy supported him into the next room. "You'll feel better in a little while and then you can talk all you please."

O'Hara came with a pitcher of hot milk, in which the post doctor had mixed a stimulant of some kind, and he was left in the bedroom to help Prebbles out of his wet clothes and into the dry ones.

"Who is he?" inquired Cameron, when he and the boys were once more back in the sitting room.

"Murgatroyd's clerk," replied Matt. "I saw him once, when I first reached Jamestown and called on the broker to make inquiries about Traquair's aëroplane."

"Then, if he works for a scoundrel like Murgatroyd, he must be of the same calibre. Like master, like man, you know."

"That old saw don't apply to this case, Cameron," said Matt earnestly. "Prebbles is a good deal of a man. He belongs to the Salvation Army and tries to be square with everybody. Why, the very first time I called on Murgatroyd, Prebbles warned me to beware of the broker."

"The old boy is the clear quill," said McGlory, "you take it from me. But what's he doing here? Sufferin' horned toads! Say, do you think he's come to tell us something about Murg?"

"By Jove," muttered Cameron, with suppressed excitement, "I'll bet that's what brought him!"

"Perhaps," said Matt. "We'll know all about it, in a little while."

In less than half an hour the old clerk emerged from the room, in a comfortable condition outside and in. The only thing about him that was at all damp was a sheet of folded paper which he carried in his hand.

"We had to swim, just about, from Minnewaukon over here," muttered Prebbles, as he lowered himself into a chair. "You're mighty good to an old man, Motor Matt, you and your friends."

"When did you leave Jamestown?" asked Matt.

"This morning."

"Then it was raining hard when you got off the train at Minnewaukon!"

"Raining pitchforks!"

"Why didn't you wait in the town until the rain was over?"

"There wasn't time," and the shake in Prebbles' high-pitched voice told of his growing excitement. "I just had to get here, that's all. What I've got to say, Motor Matt," he added, with an anxious look at Cameron and McGlory, "is—is mighty important."

"Perhaps we'd better go, then," said Cameron, with a look at the cowboy.

"Wait a minute," interposed Matt. "Has what you've got to say anything to do with Murgatroyd?"

"He's a robber," barked Prebbles: "he's worse'n a robber. Yes, Murg's mainly concerned in what I've got to say."

"Then it will be well for Cameron to stay and hear it. He represents the government, and the government is after Murgatroyd. As for McGlory, here, he's my pard, and I have few secrets from him."

"All right, then," returned Prebbles. "It ain't a pleasant story I'm goin' to tell—leastways not for me. I've got to dig a few old bones out of my past life, and I know you won't think hard of me, seeing as how I belong to the army. It's a great thing to belong," and the old man seemed to forget what he was about to say, for a few moments, and fell to musing.

The young motorist, the cowboy, and the lieutenant waited patiently for Prebbles to pull himself together and proceed. The old clerk's haggard face proved that he had suffered much, and his three auditors had only kindness and consideration for him.

"It's like this," went on the old man suddenly, pulling himself together and drawing a hand over his eyes. "I was married, a long while ago—so long it seems as though it must have been in another world. I reckon I was happy, then, but it didn't last long. My wife died in two years and left me with a boy to raise. I wonder if you know how hard it is for a man like me to bring up a boy without a good woman to help? The job was too much for Prebbles. I did the best I knew how, on only thirty-five dollars a month, givin' the lad an education—or trying to, rather, for he never took much to books and schooling. He ran away from me when he was fifteen, an' I didn't see him again until last spring, when he was twenty-one.

"Six years had made a big difference in that boy, friends. He had gone his way, and it wasn't a good way, either. He was in Jimtown just a month, gamblin' and carryin' on, and then him and me had a quarrel. They were bitter words we passed, me accusin' him of dishonoring his dead mother and his father, by his ways, and him twitting me of bein' a failure in life just because I didn't have the nerve to be dishonest and go to grafting. I must have said things that were awful—I can't remember—but all I do know is that Newt hit me. He knocked me down, right in Murgatroyd's office. Murg was out, at the time, and Newt and me was alone there together. When I came to, Newt was gone."

Again was there a silence, the old clerk fingering a scar on the side of his cheek.

"How like a serpent's tooth is an ungrateful son," went on Prebbles. "And yet, Newt wasn't all to blame. I wasn't the right sort to bring up a high-spirited boy. I wasn't able to do my duty. He left four hundred in gamblin' debts, when he went away. Murgatroyd showed me the I O U's with Newt's name to 'em. That's why I kept right on workin' for Murg, when I knew he was a robber, and after I had joined the army. I've been taking up those I O U's. Three of 'em's been paid, and there's one more left; and here I've pulled the pin on myself before takin' up the other. I don't know what I'm going to do for a job," and a pathetic helplessness crept into the old clerk's voice, "but," and the voice strengthened grimly, "I started out on this thing and I'm going to see it through. What I want, is to make up with Newt. Lawsy, how that quarrel has worried me! I[Pg 6] don't care about the way he hit me—he had the right, I guess—but I want to make up with him an' get him back."

The old man dropped his face in his hands. The other three looked at him sympathetically, and then exchanged significant glances.

"It isn't so hard, Prebbles," remarked Matt gently, "to advance the spark of friendship, and it ought to be more than easy in the case of you and your son."

Prebbles lifted his head and his forlorn face brightened.

"I knew you'd help me, Matt," and he put out his thin, clawlike hand to grip Matt's; "you help everybody that wants you to, and I knew sure you'd see me through this business. I did what I could for you—remember that? Mebby what I done didn't amount to such a terrible sight, but I put you next to Murgatroyd the first time you ever came into his office."

"Of course I'll do what I can to help you, Prebbles," said Matt reassuringly.

"It's make or break with me, this time," shivered Prebbles. "I'm pretty well along to stand such a row as I had with Newt."

"Where is Newt now?" inquired Matt.

"That's the point!" murmured Prebbles, trying to brace up in his chair. "Somehow, he's got under the thumb of Murgatroyd, or Murg's got under his thumb, I can't just understand which."

Prebbles smoothed out the damp sheet of folded paper on his knee.

"I belong to the army," he quavered, "and I don't feel that what I've done's wrong. A letter came to Murgatroyd, at the office, last night. It was addressed in Newt's handwriting. I opened that letter and made a copy of it; then I sent the letter on, with some others, to George Hobbes, Bismarck. That's the name Murg uses when he pretends he's lendin' money for some one else. He can gouge and strip a man, while sayin' he's actin' for Hobbes, see?"

Every one of the three who had listened to Prebbles was deeply interested. The bringing in of Murgatroyd seemed to offer a chance for capturing the rascal.

"Here's the letter, Motor Matt," said Prebbles. "Read it out loud, and then you'll all understand. There's a way to get Newt, and advance the spark of friendship, as you call it. By doin' that, the boy can be saved from the influence of Murgatroyd—and that's what I want."

Matt took the copy of the letter from the clerk's nerveless hand and read it aloud. Just as he finished, Prebbles slumped slowly forward out of his chair and fell in a senseless heap on the floor.

MARKING OUT A COURSE.

"Poor old codger!" exclaimed McGlory, as he and Matt lifted the clerk and carried him to the bed in the other room. "He's had more trouble than he could dodge, pard."

"He didn't try to dodge it, Joe," answered Matt quietly, "and that's to his credit. He's worn out. I'll bet that, while he was scrimping in order to take up his son's I O U's, he has hardly eaten enough to keep himself alive. His constitution is broken down, and this trip in the rain from Minnewaukon has topped off his endurance. It's only a faint, that's all, but it proves the old man has got to be looked after."

Matt and McGlory had revived Prebbles before Cameron came with the doctor. The latter, after listening to as much of the matter as the boys could tell him, felt the old man's pulse and shook his head gravely.

"We'll have to keep him in bed for a day or two, I think," he said.

"Don't say that!" begged Prebbles. "I got work to do, doctor! Besides, this isn't my bed—it belongs to Motor Matt's friend, Cameron, and——"

"Motor Matt's friend," put in the lieutenant, "is only too glad to give you his bed, Prebbles. I can sleep on the couch in the next room, and you can stay here until you're well enough to leave."

"But I can't stay here," cried Prebbles querulously. "Didn't you hear me say I had work to do? I've got to help Motor Matt—all of you know why."

"Anyhow, Prebbles," said Matt, "nothing can be done until morning. You stay here and keep quiet until then. Meanwhile, Cameron, McGlory, and I will mark out a course, and we'll tell you all about it before we begin following it. If you're able, you can go with us. If you're not able, you can stay here and feel sure that I'll carry out this make-and-break affair of yours just as though it was my own. You can trust me to advance the spark of friendship, can't you?"

"There ain't any one else I'd trust but you, Motor Matt," declared Prebbles. "But I'm going with you, in the morning. I haven't any money——"

"You don't need any," interrupted Cameron. "You're welcome to stay here as long as you please, at the government's expense. You have brought a clue which may lead to the capture of Murgatroyd, and the government has offered a reward of one thousand dollars for him."

"If he can be captured, Prebbles," added Matt, "the money will go to you."

"It'll come in handy, but—but it's Newt I want."

At a nod from the doctor, Matt, McGlory, and Cameron went into the other room and closed the door.

"Prebbles will never be able to leave here to-morrow morning," averred Cameron.

"It's up to McGlory and me," said Matt, "to do what we can."

"Give me a share in the work," begged Cameron. "Perhaps I can do something. If necessary, I'll get a furlough."

Matt was thoughtful for a few moments. Stepping to the window overlooking the parade ground, he peered out at the weather. The rain continued to come down in torrents, but there was a hint, overhead, that the storm would not last out the night.

"We have a good clue to Murgatroyd's whereabouts," said Matt presently, coming back and taking a chair facing his friends, "but there are several points to be considered. Prebbles sent on the original of his son's letter last night. That means that some time to-day Murgatroyd got the letter in Bismarck. If it is raining as hard, over on the Missouri, as it is here, it is unlikely that Murgatroyd went up the river to Burnt Creek to-day. With clearing weather, he'll probably go up to-morrow."

"Then," said Cameron, "it's our business to take a train for Jamestown at once, connect with a west-bound train there for Bismarck, and then take a team and drive from Bismarck to Burnt Creek."

"The afternoon train has left Minnewaukon," answered Matt, who seemed to have considered every phase of the matter, "and there is no other train south until to-morrow morning. That train, I think, connects with one on the main line for Bismarck, but we could hardly reach the town before late to-morrow afternoon, and it would be night before we could get to Burnt Creek. While we were losing all this time, what will Murgatroyd be doing?"

"Why not get an automobile from Devil's Lake City," suggested Cameron, "and reach Jamestown in time to connect with an earlier train?"

"How will the roads be after this rain?" inquired Matt.

"That's so!" exclaimed Cameron, with a gloomy look from one of the windows. "These North Dakota roads are fine in dry weather, but they're little more than bogs after a rain like this. We can't use the automobile, that's sure, and Murgatroyd is likely to reach Burnt Creek before we can possibly get there. Will he and young Prebbles stay at Burnt Creek until we arrive? That's the point."

"It's so uncertain a point," said Matt, "that we can't take chances with it."

"We've got to take chances, pard," put in McGlory, "unless we charter an engine for the run to Jamestown."

"There's another way," asserted Matt.

"What other way is there?" asked Cameron.

"Well, first off, we can send a message at once to Bismarck, to the chief of police——"

"Sufferin' blockheads!" grunted McGlory. "I never thought of that."

"How are the police going to locate Murgatroyd?" went on Cameron. "The scoundrel is there under an assumed name."

"Why," said Matt, "tell the police, in the message, to arrest any man who calls at the post office and asks for mail for 'George Hobbes.'"

"Easy enough," muttered Cameron.

"No," proceeded Matt, "not so easy as you think, for it may be that Murgatroyd has already received the letter. But shoot the message through at once, Cameron, and let's do all we can, and as quick as we can."

The message was written out and sent to the telegraph office by O'Hara.

"Now," said Cameron, "assuming that that does the trick for Murgatroyd, there is still young Prebbles to think about. He'll wait at Burnt Creek, I take it, for Murgatroyd, and if Murgatroyd is captured, and isn't able to leave Bismarck, we can reach Burnt Creek in time to find our man and advance that 'spark of friendship'—which, to be perfectly candid, I haven't much faith in."

"I believe," said Matt, "that the greatest scoundrel that ever lived has an affection for his parents, somewhere deep down in his heart. If I'm any judge of human nature, that cowardly blow Newt gave his father has bothered the young fellow quite as much as it has that old man, in there," and Matt nodded toward the door of the bedroom. "Leaving out sentiment altogether, though, and our ability to reach Newt on Prebbles' behalf, there's something else in his letter that makes the biggest kind of a hit with me."

"What's that?" came from both Cameron and McGlory.

"Well, young Prebbles is asking Murgatroyd for money, and hinting at something he knows about the accident to Harry Traquair. You remember that Mrs. Traquair's husband lost his life, in Jamestown, by a fall with his aëroplane. It is possible that young Prebbles knows more about that accident than Murgatroyd wants him to know."

"Speak to me about that!" muttered the wide-eyed McGlory. "Matt, you old gilt-edged wonder, you're the best guesser that ever came down the pike! Give him the barest line on any old thing, Cameron, and this pard of mine will give you, offhand, all the dips, angles, and formations."

"This is plain enough, Joe," protested Matt.

"I can see it now," said Cameron, "but I couldn't before. There are big things to come out of this business, friends! I feel it in my bones."

"And the biggest thing," declared Matt, with feeling, "is making Newt Prebbles' peace with his father."

"Then," said Cameron, with sudden animation, "I'm to get leave and go with you by train, to-morrow morning, to Bismarck, on our way to Burnt Creek?"

Matt shook his head.

"That depends, Cameron," he answered, dropping a friendly hand on the lieutenant's knee.

"Depends on what?"

"Why, on whether it's a clear, still day or a stormy one."

Both Cameron and McGlory were puzzled.

"I can't see where that comes in," said the lieutenant.

"If it's a fine day, Joe and I will go to Burnt Creek with the Comet."

McGlory jumped in his chair.

"That's another time I missed the high jump!" he exclaimed. "Never once thought of the Comet."

"All roads are the same," went on Matt, "when you travel through the air. Apart from that, we can cut across lots, in the Comet, and do our forty to sixty miles an hour between here and the Missouri and Burnt Creek."

Cameron was dashed. He was eager to take part in the work of bagging Murgatroyd, and in finding Newt Prebbles.

"Suppose an accident happens to the flying machine," said he, "and you are dropped on the open prairie, fifty miles from anywhere? You wouldn't be gaining much time over the trip by train."

"We won't go by air ship," replied Matt, "unless we are very sure the conditions are right. Give me the proper conditions, and I'll guarantee no accident will happen to the Comet."

"But McGlory is scared of his life to fly in the machine," went on Cameron. "Why not leave him here and let me go with you?"

"Not in a thousand years!" clamored McGlory. "I'm going to ride in the Comet. That's flat."

"Well, the machine will carry three," proceeded Cameron. "Why not leave the Chinaman behind and take me?"

"The Comet will carry three light weights," laughed Matt. "You're too heavy, Cameron."

"That lets me out," deplored Cameron, "so far as the Comet is concerned, but I'll go by train. Maybe I'll arrive in time to be of some help."

"We may all have to go by train, lieutenant," returned Matt; "we won't know about that until to-morrow morning. For the present, though, the course is as I've marked it out."

"Well, let's go and eat," said Cameron, getting up as the notes of a bugle came to his ears. "There goes supper[Pg 8] call. I'll hope for the best, but I'm for Burnt Creek, Matt, whether I go in the Comet or by train."

Prebbles, they found, was asleep. O'Hara was brought in to sit with him while they were at supper, and all three left the room.

THE START.

The following morning dawned clear, and bright, and still. It was a day made to order, so far as aëroplane flying was concerned.

Matt and his cowboy chum spent the night at the post. Before turning in, Matt got into sou'wester, slicker, and rubber boots and churned his way down to the aëroplane tent to see how Ping and the machine were getting along.

Everything was all right, and the heavy, water-proofed canvas was turning the rain nicely. Ping was in love with the Comet, and could be counted on to guard it as the apple of his eye.

"As fine a morning for your start as one could wish for," observed Cameron, with a note of regret in his voice, as he, and Matt, and McGlory came out of the mess hall and started along the board walk that edged the parade ground.

"I'm sorry, old chap, we can't take you with us," said Matt, "but the Comet is hardly a passenger craft, you know."

"What will you do with Prebbles, if he's well enough to go?"

"We'll let Ping come with you by train. Prebbles doesn't weigh much more than the Chinaman."

"Suppose Prebbles doesn't care to risk his neck in the machine?"

"I don't think he'll make any objection. However, we'll go to your quarters and make sure of that, right now. How did he pass the night?"

"Slept well, so O'Hara said. He was still sleeping when a private relieved the sergeant. McGlory," and here the lieutenant turned to the cowboy, "do you feel as much like flying, this morning, as you did last night?"

"Not half so much, Cameron," answered McGlory, with a tightening of his jaws, "but you couldn't keep me out of that flyin' machine with a shotgun. If we join a circus as air navigators, I've got to get used to flying, and I might as well begin right now."

"All right," answered the disappointed lieutenant, "I'll go by train."

The doctor was with Prebbles when Cameron and the boys reached the lieutenant's quarters. What is more, the doctor's face was graver than it had been the preceding afternoon. The old man was throwing himself around on the bed and muttering incoherently.

"Delirious," said the doctor, examining a temperature thermometer; "temperature a hundred and three, and he's as wild as a loon. Newt, Newt, Newt—that's the trend of his talk. You can't understand him, now, but he was talking plain enough when I got here."

"Is the sickness serious?" asked Matt.

"Pneumonia. Know what that is, don't you, Matt? It's hard enough on a person with a good constitution, but in a case like this, where the powers of resistance are almost exhausted, the end is pretty nearly a foregone conclusion. However, we're taking the trouble right at the beginning, and there's a chance I may break it up."

"Get a good nurse for him," said Matt, "and see that he gets all the care possible. The poor old chap was a good friend of mine, once, and I'll bear all the expense."

"Never mind that, Matt," spoke up Cameron. "If Murgatroyd is caught, because of the tip he gave us, the government will be owing Prebbles a lot of money."

Suddenly the old man sat up in bed, his eyes wide and staring vacantly, his arms stretched out in front of him and his hands beating together. His voice grew clear and distinct, echoing through the room with weird shrillness.

One verse was all. Spent with the effort, Prebbles dropped back on the pillow and continued his whispered muttering.

"It's one of those Salvation Army songs," observed the doctor.

"He thought he was marching and playing the cymbals," said Matt, in a low tone.

"Too bad!" exclaimed McGlory, shaking his head.

"Do all you can for him, doctor," urged Matt.

"I will, of course," was the answer, "but you may be able to do more for him than any one else, Matt."

"How so?"

"Why, by bringing back that scalawag son of his. That's the one thing the old man needs. If we can show Prebbles the boy, and make him realize that he's here, and sorry for the past, it will do a world of good."

"I'll bring him!" declared Matt, his voice vibrant with feeling. "Prebbles said this business would make or break him; and, as the work is on my shoulders now, it's make or break for me. Come on, Joe!"

He turned from the room, followed by McGlory and Cameron. Out of the post went the three, and down the hill and past the post trader's store, the king of the motor boys saying not a word; but, when the shelter tent was in sight, he turned to his companions.

"It's mighty odd," said he, "how chances to do a little good in the world will sometimes come a fellow's way. Through that rascal, Murgatroyd, I was led into giving a helping hand to Mrs. Traquair; and here, through the same man, I've a chance to help Prebbles."

"And you can bet your moccasins we'll help him," declared McGlory, "even though we lose that circus contract. Hey, pard?"

"We will!" answered Matt.

Ping had cooked himself a mess of rice on a camp stove near the shelter tent. He was just finishing his rations when the boys and the lieutenant came up.

"We're going out in the aëroplane to-day, Ping," announced Matt.

"Allee light," said the Chinaman, wiping off his chop sticks and slipping them into his blouse.

"You and McGlory are going with me," went on Matt.

The yellow face glowed, and the slant eyes sparkled.

"Hoop-a-la!" exulted Ping. "By Klismus, my likee sail in Cloud Joss!"

"I wish I had that heathen's nerve," muttered the cowboy. "It's plumb scandalous the way the joy bubbles out of him. All his life he's been glued to terra firma, same as me, but, from the way he acts, you'd think he'd spent[Pg 9] most of his time on the wing. But mebby he's only running in a rhinecaboo, and will dive into his wannegan as soon as we're ready to take a running start and climb into the air. We'll see."

"Pump up the bicycle tires, Joe," said Matt. "Get them good and hard. Ping," and Matt pointed to the haversack of provender McGlory had brought from the post, "stow that back of the seat on the lower wing. We may be gone two or three days."

"And mebby we'll be cut off in our youth and bloom and never come back," observed McGlory, grabbing the air pump. "This is Matt's make and break," he grinned grewsomely; "we make an ascent and break our bloomin' necks. But who cares? We're helping a neighbor."

Ping crooned happily as he set about securing the haversack. He'd have jumped on a streak of chain lightning, if Matt had been going along with him to make the streak behave.

The Comet had two gasoline tanks, and both of these were full. The oil cups were also brimming, and there was a reserve supply to be drawn on in case of need.

Matt went over the machine carefully, as he always did before a flight, making sure that everything was tight and shipshape, and in perfect running order.

Even if anything went wrong with the motor, and the propeller ceased to drive the aëroplane ahead, there would have been no accident. The broad wings, or planes, would have glided down the air like twin parachutes and landed the flyers safely.

Cameron, having manfully smothered his disappointment, lent his hearty aid in getting the boys ready for the start. The machine, at the beginning of the flight, had to be driven forward on the bicycle wheels until the air under the wings offered sufficient resistance to lift the craft. A speed of thirty miles an hour was sufficient to carry the flying machine off the ground and launch it skyward.

But there was disappointment in store for the boys. The three, seated on the lower plane, Matt at the levers, tried again and again to send the machine fast enough along the muddy road to give it the required impetus to lift it. But the road was too heavy.

The trick of fortune caused Ping to gabble and jabber furiously, but McGlory watched and waited with passive willingness to accept whatever was to come.

"I guess you'll have to give up, Matt," said Cameron. "The road's too soft and you can't get a start."

Matt looked at the prairie alongside the road. The grass was short, and the springy turf seemed to offer some chance for a getaway.

"We'll try it there," said he, pointing to the trailside. "Give us a boost off the road, Cameron, and then start us."

The lieutenant assisted the laboring bicycle wheels to gain the roadside, and then pushed the machine straight off across the prairie. Matt threw every ounce of power into the wheels.

Usually the air ship took to wing in less than a hundred yards, but now the distance consumed by the start was three times that. For two hundred feet Cameron kept up and pushed; then the Comet went away from him at a steadily increasing pace. Finally the wheels lifted.

Quick as thought, Matt shifted the power to the propeller. The Comet dropped a little, then caught herself just as the wheels were brushing the grass and forged upward.

"Hoop-a-la!" cried Ping.

McGlory said nothing. His face was set, his eyes gleaming, and he was hanging to his seat with both hands.

A SHOT ACROSS THE BOWS.

The sensation of gliding through the air, entirely cut adrift from solid ground, is as novel as it is pleasant. The body seems suddenly to have acquired an indescribable lightness, and the spirits become equally buoyant. Dizziness, or vertigo, is unheard of among aëronauts. While on the ground a man may not be able to climb a ladder for a distance of ten feet without losing his head and falling, the same man can look downward for thousands of feet from a balloon with his nerves unruffled.

Joe McGlory, now for the first time leaping into the air with a flying machine, was holding his breath and hanging on desperately to keep himself from being shaken off his seat, but, to his astonishment, his fears were rapidly dying away within him.

The cowboy was a lad of pluck and daring; nevertheless, he had viewed his projected flight in a mood akin to panic. Although passionately fond of boats, yet the roll of a launch in a seaway always made him sick; in the same manner, perhaps, he was in love with flying machines, although it had taken a lot of strenuous work to get him to promise to go aloft.

The necessity, on account of wet ground, of juggling for a start, had thrown something of a wet blanket over McGlory's ardor. Once in the air, however, his enthusiasm arose as his fears went down.

Matt sat on the left side of the broad seat, firmly planted with his feet on the footrest and his body bent forward, one hand on the mechanism that expanded or contracted the great wings, and the other manipulating the rudder that gave the craft a vertical course.

On Matt's quickness of judgment and lightning-like celerity in shifting the levers, the lives of all three of the boys depended. Every change in the centre of air pressure—and this was shifting every second—had to be met with an expansion or contraction of the wings in order to make the centre of air pressure and the centre of gravity coincide at all times.

Upon Matt, therefore, fell all the labor and responsibility. He had no time to give to the scenery passing below, and what talking he indulged in was mechanical and of secondary importance to his work. But this is not to say that he missed all the pleasures of flying. A greater delight than that offered by the zest of danger and responsibility in the air would be hard to imagine. Every second his nerves were strung to tightest tension.

Ping sat between Matt and McGlory, his yellow hands clutching the rim of the seat between his knees. He was purring with happiness, like some overgrown cat, while a grin of heavenly joy parted his face as his eyes marked the muddy roads over which they were passing without hindrance.

Up and up Matt forced the machine until they reached a height of five hundred feet. Here the air was crisp and cool, and much steadier than the currents closer to the surface.

"Great!" shouted the cowboy. "I haven't the least fear that we're going to drop, and I'd just as lieve go out on the end of one of the wings and stand on my head."

"Don't do it," laughed Matt, keeping his eyes straight ahead, while his hand trawled constantly back and forth with the lever controlling the wing ends.

"Him plenty fine!" cooed Ping.

"Fine ain't the name for it," said McGlory. "I'm so plumb tickled I can't sit still. And to think that I shied and side-stepped, when I might have been having this fun right along! Well, we can't be so wise all the time as we are just some of the time, and that's a fact. How far do you make it, Matt, to where we're going?"

"A little over a hundred miles, as the crow flies."

"As the Comet flies, you mean. How fast are we going?"

"Fifty miles an hour."

"That clip will drop us near Burnt Creek in two hours. Whoop-ya!"

The cowboy let out a yell from pure exhilaration. Not a thought regarding possible accident ran through his head. The engine was working as sweetly as any motor had ever worked, the propeller was whirling at a speed that made it look like a solid disk, and the great wings were plunging through the air with the steady, swooping motion of a hawk in full flight.

A huddle of houses rushed toward the Comet, far below, and vanished behind.

"What was that, pard?" cried the cowboy.

"Minnewaukon," answered Matt.

At that moment the young motorist shifted the rudder behind, which was the one giving the craft her right and left course, and they made a half turn. As the Comet came around and pointed her nose toward the southwest, she careened, throwing the right-hand wings sharply upward.

McGlory gave vent to a hair-raising yell. He was hurled against Ping, and Ping, in turn, was thrown against Matt.

"Right yourselves, pards," called Matt. "That was nothing. When we swing around a turn we're bound to roll a little. You can't expect more of an air ship, you know, than you can of a boat in the water. You keep track of the time, Ping. Joe, follow our course on the map. You can hang on with one hand and hold the map open with the other. We can't sail without a chart."

Matt had secured his open-face watch to a bracket directly above Ping's head. The boy could see the time-piece without shifting his position.

The map McGlory had in his pocket. Removing the map from his coat with one hand, the cowboy opened it upon his knee.

With a ruler, Matt had drawn a line from Minnewaukon straight to the point where Burnt Creek emptied into the Missouri. This line ran directly southwest, crossing four lines of railroad, and as many towns.

"How are we going to know we're keeping the course, pard?" inquired McGlory. "We ought to have a compass."

"A compass wouldn't have been a bad thing to bring along," returned Matt, "but we'll be able to keep the course, all right, by watching for the towns we're due to pass. The first town is Flora, on the branch road running northwest from Oberon. If I'm not mistaken, there it is to the right of us. Hang on, both of you! I'm going to drop down close, Joe, while you hail one of the citizens and ask him if I've got the name of the place right."

There was plenty of excitement in the little prairie village. Men, women, and children could be seen rushing out of their houses and gazing upward at the strange monster in the sky. Everybody in that section had heard of Motor Matt and his aëroplanes, so the curiosity and surprise were tempered with a certain amount of knowledge.

"Hello, neighbor!" roared McGlory, as the air ship swept downward to within fifty feet of the ground, "what town is this?"

"Flora," came the reply. "Light, strangers, an' roost in our front yard. Ma and the children would like to get a good look at your machine, and——"

The voice faded to rearward, and "ma and the children" had to be disappointed.

Having assured himself that he was right, Matt headed the aëroplane toward the skies, once more.

Settlers' shacks, and more pretentious farmhouses, raced along under them, and in every place where there were any human beings, intense excitement was manifested as the Comet winged its way onward.

In less than fifteen minutes after passing Flora, they caught sight of another railroad track and another huddle of buildings. It was the "Soo" road, and the town was Manfred.

"How long have we been in the air, Ping?" asked Matt.

"Fitty-fi' minutes," replied the Chinaman.

"Manfred ain't many miles from Sykestown, pard," said Joe, "and we must be within gunshot of that place where we had our troubles, a few days back."

"I'm glad we're giving the spot a wide berth," returned Matt, with a wry face. "We've got to make better time," he added, opening the throttle; "we're not doing as well as I thought."

The Comet hurled herself onward at faster speed. The air of their flight whistled and sang in the boys' ears, and hills underneath leaped at them and then vanished rearward with dizzying swiftness.

"I'd like to travel in an aëroplane all the time," remarked McGlory. "Sufferin' skyrockets! What's the use of hoofin' it, or ridin' in railroad cars, when you can pick up a pair of wings and a motor and go gallywhooping through the air?"

The machine was well over the coteaus, now, and the rough country would hold, with only now and then an occasional break, clear to the Missouri.

Another railroad, and a cluster of dwellings known as "Goodrich," were passed, and the aëroplane slid along over the corner of McLean County and into Burleigh.

They were drawing close to Burnt Creek, and everything was going swimmingly. Matt, notwithstanding the severe strain upon him, was not in the least tired. In a little less than two hours after leaving Fort Totten they crossed their last railroad—a branch running northward from Bismarck. The town, near where they winged over the steel rails, was down on the map as "Arnold."

"Speak to me about this!" cried McGlory. "There's a creek under us, Matt, and I'll bet it's the one we're looking for."

"We're finding something else we were not looking for," answered the king of the motor boys grimly.

"What's that?" queried McGlory.

"Look straight ahead at the top of the next hill."

McGlory turned his eyes in the direction indicated. A number of rough-looking horsemen, evidently cowboys, were scattered over the hill. They were armed with rifles, and were spurring back and forth in an apparent desire to get directly in front of the Comet.

"Why, pard," shouted McGlory, "they're punchers, same as me. Punchers are a friendly lot, and that outfit wouldn't no more think of cutting up rough with us than——"

The words were taken out of the cowboy's mouth by the sharp crack of a rifle. One of the horsemen had fired, his bullet singing through the air in front of the Comet.

"That's across our bows," said Matt, "and it's an invitation to come down."

The "invitation" was seconded by a yell the import of which there was no mistaking.

"Hit the airth, you, up thar, or we'll bring ye down wrong-side up!"

"Nice outfit they are!" grunted McGlory. "Get into the sky a couple of miles, Matt, and—— Sufferin' terrors! What are you about?"

Motor Matt had pointed the air ship earthward, and was gliding toward the hilltop.

"No use, Joe," Matt answered. "They could hit us with their bullets and wreck us before we got out of range. They want to talk with us, and we might as well humor them."

"Mighty peculiar way for a lot of cowboys to act," muttered McGlory.

"No likee," said Ping.

THE MAN HUNTERS.

Motor Matt was not anticipating any serious trouble with the cowboys. The worst that could possibly happen, he believed, was a slight delay while the curiosity of the horsemen regarding the aëroplane was satisfied.

Armed cattlemen are proverbially reckless. A refusal to alight would certainly have made the Comet a target for half a dozen guns, and it was a foregone conclusion that not all the bullets would have gone wild.

The cowboys, of course, knew nothing about aëroplanes. They wanted Matt to come down, no matter whether the landing was made in a spot from which the aëroplane could take a fresh start, or in a place where a start would be impossible.

The hill on which the horsemen were posted was a high one, and had smooth, treeless slopes on all sides. It was, in fact, a veritable turf-covered coteau.

Matt was planning to alight on the very crest of the hill. When he and his pards were ready to take wing again, he thought they could dash down the hill slope, and be in the air before the foot of the hill was reached.

The horses of the men below were frightened by the aëroplane, and began to kick and plunge. The trained riders, however, held them steady with one hand while gripping rifles with the other.

The flying machine circled obediently in answer to her steering apparatus, and landed on the crest of the hill with hardly a jar. As the craft rested there, the boys got out to stretch their cramped legs and inquire what the cowboys wanted. The latter had spurred their restive animals close, and were grouped in a circle about the Comet.

"Well, I'll be gosh-hanged!" muttered one, staring at the machine with jaws agape.

"Me, too!" murmured another. "Gee, man, but this here's hard ter believe."

"Hustlin' around through the air," put in another, "same as I go slashin' over the range on a bronk."

The fourth man gave less heed to his amazement than he did to the business immediately in hand.

"Ain't either one o' 'em George Hobbes?" he averred, looking Matt, McGlory, and Ping over with some disappointment.

That name, falling from the cowboy's lips, caused Matt and McGlory to exchange wondering glances.

"What did you stop us for?" asked Matt.

"Me an' Slim, thar, thought ye mout hev Hobbes aboard that thing-um-bob," went on the last speaker. "We're from the Tin Cup Ranch, us fellers are. I'm Jed Spearman, the foreman. Whar d'ye hail from?"

"From Fort Totten."

"When d'ye leave thar?"

"About two hours ago."

"Come off! Toten's a good hunnerd an' twenty miles from here."

"Well," laughed Matt, "we can travel sixty miles an hour, when we let ourselves out, and bad roads can't stop us. But tell us about this man, Hobbes. Who is he?"

"He's a tinhorn, that's what. He blowed inter the Tin Cup bunkhouse, last night, an' cleaned us all out in a leetle game o' one-call-two."

"If you're foolish enough to gamble," said Matt, "you ought to have the nerve to take the consequences."

"Gad-hook it all," spoke up the man referred to as "Slim," "I ain't puttin' up no holler when I loses fair, but this Hobbes person is that rank with his cold decks, his table hold outs, an' his extra aces, that I blushes ter think o' how we was all roped in."

"He cheated you?"

"Cheat?" echoed Jed Spearman, "waal, no. From the way we sized it up when we got tergether this mornin', it was jest plain rob'ry. Hobbes headed this way, an' we slid inter our saddles an' follered. But we've lost the trail, an' was jest communin' with ourselves ter find out what jump ter make next, when this thing"—he waved his hand toward the aëroplane—"swung inter sight agin' the sky. We seen you three aboard the thing, an' got the fool notion that mebby Hebbes was one o' ye."

"Didn't you find out last night that you had been cheated?" asked Matt.

"Nary. If we had, pilgrim, ye kin gamble a stack we'd have took arter this Hobbes person right then. It was only this mornin' when Slim diskivered the deck o' keerds belongin' ter the feller, which same he had left behind most unaccountable, that we sensed how bad we'd been done. The' was an extry set o' aces with that pack, the backs was all readers, an' the hull lay-out was that peculiar we wasn't more'n a brace o' shakes makin' up our minds what ter do."

"What sort of a looking man was this Hobbes?"

"Dead ringer fer a cattleman, neighbor. Blue eyes, well set up, an' youngish."

Matt was surprised. He was expecting to receive a description of Murgatroyd, but the specifications did[Pg 12] not fit the broker. Murgatroyd was a large, lean man with black, gimlet-like eyes.

"What's yer bizness in these parts?" demanded Jed Spearman. "Jest takin' a leetle fly fer the fun o' the thing?"

"Well," answered Matt, "not exactly."

"Ain't in no rush, are ye?"

"Yes. Now that you know the man Hobbes isn't with us, we'll get aboard and resume our flight."

Matt stepped toward the aëroplane, with the intention of taking his place at the driving levers. But Jed Spearman stayed him with a grip of the arm.

"I got er notion," said Jed, "that I'd like ter take a ride in that thing myself." The other cowboys gave a roar of wild appreciation and approval. "Ye say ye kin do sixty miles an hour," proceeded Jed. "I'm goin' back ter the Tin Cup Ranch ter see if the other party that went out arter Hobbes had any success. It's thirty miles ter the Tin Cup, an' ye ort ter git me thar an' back inside o' an hour—onless ye was puttin' up a summer breeze when ye told how fast this here dufunny machine could travel. Hey? How does it hit ye?"

Motor Matt was taken all aback. An hour's delay might spell ruin so far as meeting Newt Prebbles at the mouth of Burnt Creek was concerned.

"We're in too much of a hurry," said Matt, "and we can't spare the time. I'd like to oblige you, Spearman, but it's out of the question."

"No more it ain't out o' the question," growled Spearman. "I'm pinin' ter take a ride in that thar machine, an' ye kin help us in our hunt fer Hobbes if ye'll only take me back ter the ranch. I reckon yore bizness ain't any more important than what ours is."

"Make him take ye, Jed!" howled the other punchers. "If he won't, we'll make kindlin' wood out er the ole buzzard."

The temper of the cowboys was such that Matt was in a quandary. While he was turning the situation over in his mind, McGlory stepped forward and took part in the talk.

"Say, you," he cried angrily, "what you putting up this kind of a deal on us for? You can't make us toe the mark by putting the bud to us, and if you try it, we'll pull till the latigoes snap."

"Don't git sassy," said Jed, in a patronizing tone. "We're too many fer ye, kid. Ridin' in that thing'll be more fun fer me than a three-ring circus, say nothin' o' the help it'll be fer us ter find out whether the other bunch o' man hunters struck 'signs' er not. Step back, an' sing small. Here, Slim, you take charge o' my hoss."

The foreman passed his bridle reins to Slim, dismounted, and laid his gun on the ground.

"We'll have to wait here till ye git back, won't we?" asked Slim.

"Sure," replied Jed. "We've lost the trail, an' thar ain't no manner o' use ter keep on ontil we find out somethin'."

"Then I'm goin' ter git down," said Slim. "We kin bunch up the critters an' smoke a little."

McGlory's temper was rapidly growing. The cool way in which Jed Spearman was planning to appropriate the Comet was more than McGlory could stand.

"You're a lot of tinhorns!" he cried. "This lad here," he waved his hand toward the king of the motor boys, "is Motor Matt, and he's making this flight on government business, mainly. You keep hands off, or you'll get into trouble."

"That's me!" whooped Spearman. "Trouble! I live on that. Get ready that flyin' machine, kase I'm hungry ter do my sixty miles an hour on the way back ter headquarters."

An idea suddenly popped into McGlory's head.

"This way, Matt," said he, stepping off to one side and beckoning Matt to follow.

The cowboys were a little suspicious, but their curiosity prompted them to inspect the Comet and leave Matt and McGlory to their own devices.

"What do you think, pard?" asked McGlory, when he and Matt were by themselves.

"I think it won't do to have any delay," replied Matt, "but I don't just see how we're going to avoid it. If it wasn't for those rifles——" He cast a look at the cowboys and shrugged his shoulders.

"I've got a notion we can fool the punchers," said McGlory, "but Ping and I will have to be left behind, if we do it. You'll be going it alone, from here on. Think you can manage it?"

"I'll try anything," answered Matt. "All I want is to get away. Who this gambler the cowboys call George Hobbes is, I haven't the least idea. Their description of the fellow doesn't tally with the description of Murgatroyd, and the whole affair is beginning to have a queer look. I don't think there's any time to be lost."

"No more there isn't," replied McGlory. "Ping and I can wander on to the mouth of Burnt Creek on foot as soon as we can shake the punchers, and you can look for us there. What I'm plannin' is this."

Thereupon McGlory hastily sketched his swiftly formed plan. It had rather a venturesome look, to Matt, and might, or might not, win out. There was nothing to do, however, but to try it.

"What you shorthorns gassin' about?" yelled Jed Spearman. "I'm all ready ter fly, an' time's skurse."

Matt and McGlory, having finished their brief talk, walked back to the cowboys.

FOOLING THE COWBOYS.

"If you're bound to make Motor Matt take you to the ranch, Spearman," said McGlory, "that means that the chink and me'll have to wait here till you get back."

"Which is what I was expectin'," answered Spearman. "I don't want ter feel cramped in that thar machine."

"The rest of you will have to give the machine a start down the hill," went on McGlory innocently. "When the craft gets a start, and is in the air, you'll have to watch your chance, Spearman, and jump aboard."

"Jump on when she's goin' sixty miles an hour?" howled Spearman. "Say, what d'ye think my scalp's wuth?"

"It won't be going sixty miles an hour," parried McGlory.

Matt had already taken his seat in the Comet.

"Why kain't I git in thar with him," asked Spearman, "an' travel with the machine right from the start?"

"Sufferin' centipedes!" exclaimed McGlory, in well-feigned[Pg 13] disgust. "Say, I reckon you don't savvy a whole lot about flyin' machines. She's got to have a runnin' start, as light as possible; then, when she begins to skyhoot, you climb aboard. I guess you don't want to take a trip aloft."

"Guess again," cried Spearman. "I kin jump some, if it comes ter that, only"—and here he turned to Matt, who was quietly waiting—"fly low an' slow."

"All of you have got to help," proceeded Matt's cowboy pard briskly. "Lay your guns away, somewhere, so you can give both hands to your work."

None of the cowboys had six-shooters, but all were armed with rifles. This was rather odd, but, nevertheless, a fact. When they started out after George Hobbes, the Tin Cup men had been counting on target practice at long range.

The horses had already been bunched with their heads together. Four of the cowboys, who were still holding their rifles, stepped hilariously over to where Slim and Spearman had deposited their guns, and dropped their weapons.

McGlory gave Ping a significant look. The young Chinaman stared blankly for a moment, and then a complacent grin settled over his yellow face. He was as sharp as a steel trap when it came to understanding guileful things. Ping knew what was expected of him, and he was ready.

The Comet was headed down the western slope of the hill. Four of the cowboys placed themselves at the lower wings, two on each side, ready to run with the machine when they received the word. Spearman, in his shirt sleeves, was tying one end of a riata to the timber which passengers in the aëroplane used as a footrest.

"What are you doing that for?" demanded Matt.

Spearman straightened up with a wink.

"Waal, it's fer two things, pilgrim," he answered jocosely. "Fust off, by hangin' ter the rope, Slim an' me kin pull while the rest o' the boys push. Then, ag'in, if ye've got any little trick up yer sleeve, I'll have a line on yer ole sky sailer an' ye kain't leave me behind, not noways."

That rope troubled Matt, but he could voice no reasonable objection to it. Already McGlory had played on the credulity of the punchers to the limit, and it was not safe to go much farther.

"I'm goin' ter have yer job, Jed," rallied one of the cowboys, "if ye fall outen the machine an' bust yer neck."

"Don't ye take my job till I'm planted, Hen, that's all," grinned the foreman. "I been wantin' a new sensation fer quite a spell, an' I guess here's the place whar I connect with it."

If the plans of Matt and his friends worked out successfully, Jed Spearman was to "connect with a sensation" vastly different from what he was expecting. McGlory was chuckling to himself over the prospect.

The cowboys, in their uproarious mood, did not seem to notice that neither McGlory nor Ping were helping to give the aëroplane a running start down the hill.

"Ye'll be a reg'lar human skyrocket, Jed," remarked Slim, "if ye travel at the rate o' sixty miles an hour."

"I'll be goin' some, an' that's shore," answered the foreman. "Wonder what folks'll invent next? Say, thar! If ye're ready, let's start."

Matt started the motor. This evidence of power rather awed the cowboys, and their grins faded as they watched and listened.

"Now," instructed Matt, "the minute I turn the power into the bicycle wheels, you fellows begin to run the machine downhill."

"Let 'er go!" came the whooping chorus.

Jed Spearman and Slim, tailed on to a forty-foot riata, were some twenty feet ahead of the aëroplane.

"Now!" cried Matt.

The bicycle wheels began to take the push, and the Comet started down the slope, the two cowboys ahead pulling, and the four at the wings pushing.

Naturally, the descent aided the motor. There had not been as much rain, in that part of the State, as there had been in the Devil's Lake country, and the turf was fairly dry and afforded tolerably good wheeling.

The cowboys roared with delight as they ran awkwardly in their tight, high-heeled boots. What happened was only natural, in the circumstances, although quite unexpected to the ignorant cattlemen.

In less than fifty feet the aëroplane was going too fast for the runners. The four at the wings had to let go; and the two at the rope, finding themselves in imminent danger of being run over, dropped the rope and leaped to one side.

All six of the cowboys watched while the Comet, catching the air under her outspread pinions, mounted gracefully—and then continued to mount, the riata trailing beneath.

"He ain't comin' back fer ye, Jed!" howled Slim.

"Here, you!" bellowed the foreman. "Whar ye goin'? What kinder way is that ter treat a feller? Come back, or I'll send a bullet arter ye!"

Matt paid no attention. He was following, to the very letter, the plan McGlory had formed, and was rushing at speed in the direction of the Missouri and the mouth of Burnt Creek.

"Git yer guns!" cried the wrathful Spearman. "Shoot him up!"

It is doubtful whether the cowboys would have been able to retrace their way up the hill and secure their guns before Matt had got out of range. But they had not a chance to put their purpose to the test, for the contingency had been guarded against.

When the cowboys reached the top of the hill, Ping was at the foot of it on the eastern side, traveling as fast as his legs could carry him; and clasped in his arms were the six rifles!

"Blazes ter blazes an' all hands round!" fumed the enraged Jed. "The chink's runnin' off with the guns so'st we kain't shoot. Hosses, boys! Capter the little heathen!"

And here, again, were the cowboys doomed to disappointment. Well beyond the foot of the hill, on the south side, was McGlory. He was riding one horse and leading the other five bronchos.

"Done!" gasped Slim, pulling off his Stetson and slamming it on the ground, "done ter a turn! Who'd 'a' thort it possible?"