Title: The Romance of Modern Sieges

Author: Edward Gilliat

Release date: October 16, 2015 [eBook #50231]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Shaun Pinder, Paul Clark and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including some inconsistent hyphenation. Some minor corrections of spelling and punctuation have been made.

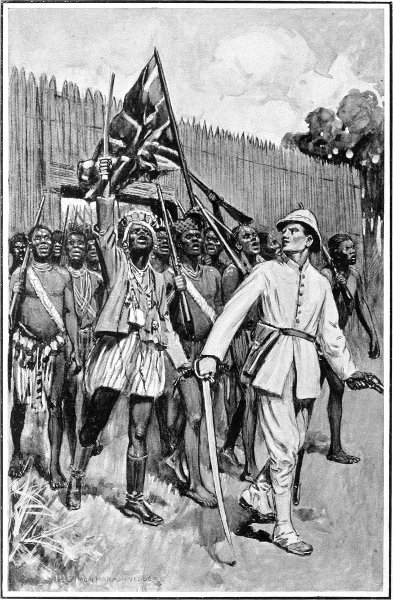

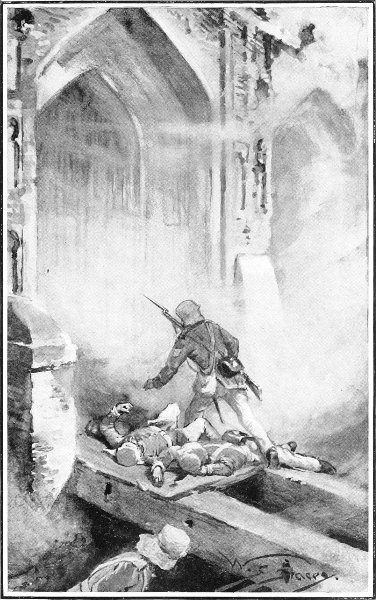

The Sally from the Fort at Kumassi

Led by Capt. Armitage, some two hundred loyal natives sallied forth. At their head marched the native chiefs, prominent amongst whom was the young king of Aguna. He was covered back and front with fetish charms, and on his feet were boots, and where these ended his black legs began.

THE ROMANCE OF

MODERN SIEGES

DESCRIBING THE PERSONAL ADVENTURES,

RESOURCE AND DARING OF BESIEGERS

AND BESIEGED IN ALL PARTS OF

THE WORLD

BY

EDWARD GILLIAT, M.A.

SOMETIME MASTER AT HARROW SCHOOL

AUTHOR OF “FOREST OUTLAWS,” “IN LINCOLN GREEN,” &c., &c.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

LONDON: SEELEY & CO. LIMITED

1908

These chapters are not histories of sieges, but narratives of such incidents as occur in beleaguered cities, and illustrate human nature in some of its strangest moods. That “facts are stranger than fiction” these stories go to prove: such unexpected issues, such improbable interpositions meet us in the pages of history. What writer of fiction would dare to throw down battlements and walls by an earthquake, and represent besiegers as paralysed by religious fear? These tales are full, indeed, of all the elements of romance, from the heroism and self-devotion of the brave and the patient suffering of the wounded, to the generosity of mortal foes and the kindliness and humour which gleam even on the battle-field and in the hospital. But the realities of war have not been kept out of sight; now and then the veil has been lifted, and the reader has been shown a glimpse of those awful scenes which haunt the memory of even the stoutest veteran.

We cannot realize fully the life that a soldier lives unless we see both sides of that life. We cannot feel the gratitude that we ought to feel unless we know the strain and suspense, the agony and endurance, that go[Pg viii] to make up victory or defeat. In time of war we are full of admiration for our soldiers and sailors, but in the past they have been too often forgotten or slighted when peace has ensued. Not to keep in memory the great deeds of our countrymen is mere ingratitude.

Hearty acknowledgments are due to the authors and publishers who have so kindly permitted quotation from their books. Every such permission is more particularly mentioned in its place. The writer has also had many a talk with men who have fought in the Crimea, in India, in France, and in South Africa, and is indebted to them for some little personal touches such as give life and colour to a narrative.

CHAPTER I |

PAGES |

| The position of the Rock—State of defence—Food-supply—Rodney brings relief—Fire-ships sent in—A convoy in a fog—Heavy guns bombard the town—Watching the cannon-ball—Catalina gets no gift—One against fourteen—Red-hot shot save the day—Lord Howe to the rescue | 17-27 |

CHAPTER II |

|

| Jaffa stormed by Napoleon—Sir Sidney Smith hurries to Acre—Takes a convoy—How the French procured cannon-balls—The Turks fear the mines—A noisy sortie—Fourteen assaults—A Damascus blade—Seventy shells explode—Napoleon nearly killed—The siege raised—A painful retreat | 28-36 |

CHAPTER III |

|

| Talavera between two fires—Captain Boothby wounded—Brought into Talavera—The fear of the citizens—The surgeons’ delay—Operations without chloroform—The English retire—French troops arrive—Plunder—French officers kind, and protect Boothby—A private bent on loot beats a hasty retreat | 37-52[Pg x] |

CHAPTER IV |

|

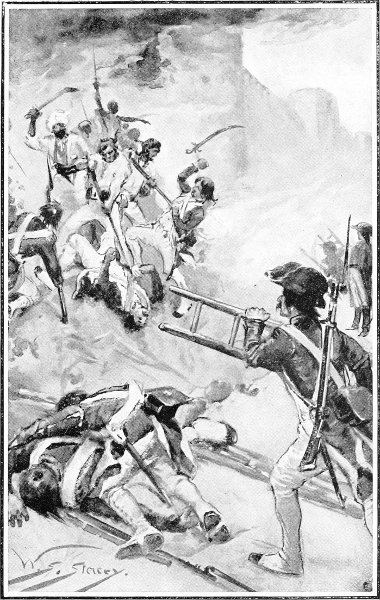

| A night march—Waiting for scaling-ladders—The assault—Ladders break—Shells and grenades—A magazine explodes—Street fighting—Drink brings disorder and plunder—Great spoil | 53-61 |

CHAPTER V |

|

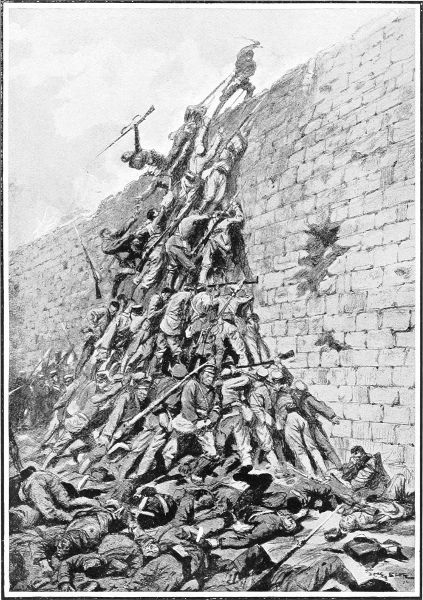

| Rescue of wounded men—A forlorn hope—Fire-balls light up the scene—A mine explodes—Partial failure of the English—Escalade of the castle—Pat’s humour and heroism—Saving a General—Wellington hears the news—The day after the storm | 62-75 |

CHAPTER VI |

|

| The coup de grâce—The hospital—A cruel order—An attempt at escape—Removed to the castle—The English at the breach—Many are wounded—French ladies sleep in the open—A vertical fire—English gunners shoot too well—A good sabre lightly won | 76-89 |

CHAPTER VII |

|

| Position of the town—Sale’s brigade rebuilds the defences—A sortie—Bad news—A queer noise—A ruse that did not succeed—The only survivor comes in—Story of a massacre—The earthquake—The walls are down—Are rebuilt—English magic—Pollock comes—Fight outside—The peril of Lady Sale | 90-109 |

CHAPTER VIII |

|

| The English land without tents—Mr. Kinglake shows off before Lord Raglan—The Alma—Strange escapes—Looted houses—[Pg xi]Fair plunder—Balaklava Bay—Horses lost at sea—A derelict worth having—Jack very helpful—The Heavy and Light Brigades—Spies—Fraternizing | 110-125 |

CHAPTER IX |

|

| Valiant deeds—Lord Raglan under fire—Tryon the best shot—A Prince’s button—A cold Christmas—Savage horses—The Mamelon redoubt—Corporal Quin—Colonel Zea | 126-136 |

CHAPTER X |

|

| The Mutiny begins—A warning from a sepoy—A near thing—A noble act of a native officer—In camp at Delhi with no kit—A plan that failed—Our first check—Wilson in command—Seaton wounded—Arrival of Nicholson—Captures guns—The assault—The fate of the Princes—Pandy in a box | 137-158 |

CHAPTER XI |

|

| Firing at close quarters—Adventures of fugitives—Death of Sir H. Lawrence—His character—Difficulty of sending letters—Mines and counter-mines—Fulton killed—Signs of the relief coming—A great welcome—Story of the escape from Cawnpore | 159-174 |

CHAPTER XII |

|

| The scene at Cawnpore—Fights before Lucknow—Nearly blown up—A hideous nightmare—Cheering a runaway—All safe out of the Residency—A quick march back—Who stole the biscuits?—Sir Colin’s own regiment | 175-190[Pg xii] |

CHAPTER XIII |

|

| North v. South—A new President hates slavery—Port Sumter is bombarded—Ladies on the house-top—Niggers don’t mind shells—A blockade-runner comes to Oxford—The Banshee strips for the race—Wilmington—High pay—Lights out—Cast the lead—A stern chase—The run home—Lying perdu—The Night-hawk saved by Irish humour—Southern need at the end of the war—Negro dignity waxes big | 191-201 |

CHAPTER XIV |

|

| Will they sink or swim?—Captain Ericsson, the Swede—The Merrimac raised and armoured—The Monitor built by private venture—Merrimac surprises Fort Monroe—The Cumberland attacked—The silent monster comes on—Her ram makes an impression—Morris refuses to strike his flag—The Cumberland goes down—The Congress is next for attention—On fire and forced to surrender—Blows up at midnight—The Minnesota aground shows she can bite—General panic—Was it Providence?—A light at sea—Only a cheese-box on a raft—Sunday’s fight between two monsters—The Merrimac finds she is deeply hurt, wounded to death—The four long hours—Worden and Buchanan both do their best—Signals for help—The fiery end of the Whitehall gunboat | 202-212 |

CHAPTER XV |

|

| New Orleans and its forts—Farragut despises craven counsel—The mortar-fleet in disguise—Fire-rafts rush down—A week of hot gun-fire—A dash through the defences—The Varuna’s last shot—Oscar, aged thirteen—Ranged before the city—Anger of mob—Summary justice—Soldiers insulted in the streets—General Butler in command—Porter nearly blown up in council—Fort Jackson in ruins—“The fuse is out” | 213-219[Pg xiii] |

CHAPTER XVI |

|

| Fair Oaks a drawn battle—Robert Lee succeeds Johnston—Reforms in the army—Humours of the sentinels—Chaffing the niggers—Their idea of liberty—The pickets chum together—Stuart’s raid—A duel between a Texan and a German—Effect of music on soldiers—A terrible retreat to James River—Malvern Hill battle-scenes—Three years after—General Grant before Richmond—Coloured troops enter the Southern capital in triumph—Lee surrenders—Friends once more | 220-230 |

CHAPTER XVII |

|

| The Germans invest Paris—Trochu’s sortie fails—The English ambulance welcomed—A Prince’s visit to the wounded—In the snow—Madame Simon—A brave Lieutenant—Piano and jam—The big guns begin—St. Denis—Old Jacob writes to the Crown Prince—A dramatic telegram—Spy fever—Journalists mobbed | 231-240 |

CHAPTER XVIII |

|

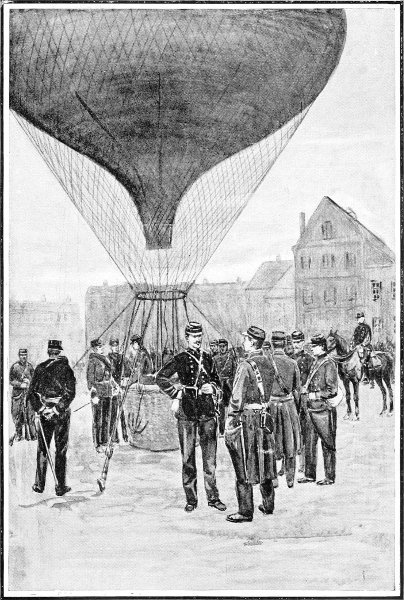

| Moods in Paris—The Empress escapes—Taking down Imperial flags—Playing dominoes under fire—Cowards branded—Balloon post—Return of the wounded—French numbed by cold—The lady and the dogs—The nurse who was mighty particular—Castor and Pollux pronounced tough—Stories of suffering | 241-250 |

CHAPTER XIX |

|

| Metz surrounded—Taken for a spy—Work with an ambulance—Fierce Prussians rob an old woman—Attempt to leave Metz[Pg xiv]—Refusing an honour—The cantinière’s horse—The grey pet of the regiment—Deserters abound—A village fired for punishment—Sad scenes at the end | 251-263 |

CHAPTER XX |

|

| An English boy as Turkish Lieutenant—A mêlée—Wounded by a horseman—Takes letter to Russian camp—The Czar watches the guns—Skobeleff’s charge—The great Todleben arrives—Skobeleff deals with cowards—Pasting labels—The last sortie—Osman surrenders—Prisoners in the snow—Bukarest ladies very kind | 264-279 |

CHAPTER XXI |

|

| Gordon invited to the Soudan—The Mahdi—Chinese Gordon—His religious feeling—Not supported by England—Arabs attack—Blacks as cowards—Pashas shot—The Abbas sent down with Stewart—Her fate—Relief coming—Provisions fail—A sick steamer—Bordein sent down to Shendy—Alone on the house-top—Sir Charles Wilson and Beresford steam up—The rapids and sand-bank—“Do you see the flag?”—“Turn and fly”—Gordon’s fate | 280-288 |

CHAPTER XXII |

|

| The Governor’s visit—Pageant of Kings—Evil omens—The Fetish Grove—The fort—Loyal natives locked out—A fight—King Aguna’s triumph—Relief at last—Their perils—Saved by a dog—Second relief—Governor retires—Wait for Colonel Willcocks—The flag still flying—Lady Hodgson’s adventures | 289-302[Pg xv] |

CHAPTER XXIII |

|

| Snyman begins to fire—A flag of trace—Midnight sortie—The dynamite trolley—Kaffirs careless—A cattle raid—Eloff nearly takes Mafeking—Is taken himself instead—The relief dribble in—At 2 a.m. come cannon with Mahon and Plumer | 303-317 |

CHAPTER XXIV |

|

| The diamond-mines—Cecil Rhodes comes in—Streets barricaded—Colonel Kekewich sends out the armoured train—Water got from the De Beers Company’s mines—A job lot of shells—De Beers can make shells too—Milner’s message—Beef or horse?—Long Cecil—Labram killed—Shelter down the mines—A capture of dainties—Major Rodger’s adventures—General French comes to the rescue—Outposts astonished to see Lancers and New Zealanders | 318-325 |

CHAPTER XXV |

|

| Ladysmith—Humours of the shell—The Lyre tries to be funny—Attack on Long Tom—A brave bugler—Practical jokes—The black postman—A big trek—Last shots—Some one comes—Saved at last | 326-340 |

CHAPTER XXVI |

|

| Port Arthur—Its hotel life—Stoessel not popular—Fleet surprised—Shelled at twelve miles—Japanese pickets make a mistake—Wounded cannot be brought in—Polite even under the knife—The etiquette of the bath—The unknown death—Kondrachenko, the real hero—The white flag at last—Nogi the modest—“Banzai!”—Effect of good news on the wounded—The fleet sink with alacrity | 341-352 |

The position of the Rock—State of defence—Food-supply—Rodney brings relief—Fire-ships sent in—A convoy in a fog—Heavy guns bombard the town—Watching the cannon-ball—Catalina gets no gift—One against fourteen—Red-hot shot save the day—Lord Howe to the rescue.

Gibraltar! What a thrill does the very name evoke to one who knows a little of English history and England’s heroes! But to those who have the good fortune to steam in a P. and O. liner down the coast of Portugal, and catch sight of the Rock on turning by Cabrita Point into the Bay of Algeciras the thrill of admiration is intensified. For the great Rock lies like a lion couched on the marge of the Mediterranean. It is one of the pillars of Hercules: it commands the entrance to the inner sea.

From 712 to the beginning of the fourteenth century Gibraltar was in the hands of the Saracens; then it fell into the hands of the Spaniards. In 1704, the year of Blenheim, a combined English and Dutch fleet under Sir George Rooke captured the Rock from the Marquis[Pg 18] de Salines, and Gibraltar has since then remained in the possession of the English, though several attempts have been made to wrest it from us. Before we follow Captain Drinkwater in some details of the great siege, a few words must be said about the Rock and its defences as they then were.

The Rock itself juts out like a promontory, rising to a height of 1,300 feet, and joined to the Spanish mainland by a low sandy isthmus, which is at the foot of the Rock about 2,700 feet broad. On a narrow ledge at the foot of the north-west slope lies the little town, huddled up beneath the frowning precipice and bristling batteries excavated out of the solid rock. At different heights, up to the very crest, batteries are planted, half or wholly concealed by the galleries. All along the sea-line were bastions, mounted with great guns and howitzers, and supplied with casemates for 1,000 men. In all the fortifications were armed with 663 pieces of artillery. Conspicuous among the buildings was an old Moorish castle on the north-west side of the hill: here was planted the Grand Battery, with the Governor’s residence at the upper corner of the walls. Many caves and hollows are found in the hill convenient both for powder magazines and also for hiding-places to the apes who colonize the Rock. The climate even at mid-winter is so mild and warm that cricket and tennis can be played on dry grass, wherever a lawn can be found in the neighbourhood, as the writer has experienced. But at Gibraltar itself all is stony ground and barren rock; only on the western slope a few palmettos grow, with lavender and Spanish broom, roses and asphodels.

In 1777 a good opportunity seemed to be offered for Spain to recover the Rock from England. The North American colonies had seceded, and the prestige of Britain had suffered a severe blow. The fleets of[Pg 19] France and Spain, sixty-six sail of the line, were opposed by Sir Charles Hardy’s thirty-eight, but with these he prevented the enemy from landing an invading army on the English shore. But Spain was intent on retaking Gibraltar, and had already planted batteries across the isthmus which connects the Rock with Spain.

General Elliot, the Governor of Gibraltar, had a garrison 5,382 strong, 428 artillerymen, and 106 engineers. Admiral Duff had brought his ships—a sixty-gun man-of-war, three frigates, and a sloop—alongside the New Mole. All preparations were made to resist a siege. Towards the middle of August the enemy succeeded in establishing a strict blockade with the object of reducing the garrison by famine. There were not more than forty head of cattle in the place, and supplies from Africa were intercepted by the Spanish cruisers. In November the effects of scarcity began to be felt, though many of the inhabitants had been sent away. Mutton was three shillings a pound, ducks fourteen shillings a couple; even fish and bread were very scarce. General Elliot set the example of abstemious living, and for eight days he lived on 4 ounces of rice a day. The inhabitants had for some time been put upon a daily ration of bread, delivered under the protection of sentries with fixed bayonets. But even with this safeguard for the week there was a scene of struggling daily. Many times the stronger got more than their share, the weaker came away empty-handed, and eked out a wretched existence on leeks and thistles. Even soldiers and their families were perilously near starvation. So that a listless apathy fell on the majority, and they looked seaward in vain for a help that did not arrive.

It was not until the 15th of January, 1780, that the joyful news went round the little town of a brig in the offing which bore the British flag.

“She cannot pass the batteries!”

“She is standing in for the Old Mole! Hurrah!”

That brig brought the tidings of approaching relief, and many a wet eye kindled with hope.

But the look-out on Signal Point could see the Spaniards in Algeciras Bay preparing for sea eleven men-of-war to cut off the convoy. Again the hopes of the garrison went down. They did not know, neither did the Spaniards, that Admiral Sir George Rodney, an old Harrow boy, was escorting the convoy with a powerful fleet of twenty-one sail of the line. He quickly drove the eleven Spaniards into headlong flight, but before rounding into the bay he fell in with fifteen Spanish merchant-men and six ships of war, which became his prize.

Then for a time the town and garrison enjoyed themselves frugally, and life became worth living. But on the departure of Rodney the Spaniards tried to destroy the British vessels in the bay with fire-ships.

It was on a June night that the fire spread, and the gleam shot across the water, lighting up Algeciras and the cork forests that clothe the mountain-side. Then the alarm was given. The Panther, a sixty-gun man-of-war, and the other armed ships opened fire on the assailants; officers and men sprang into their boats and grappled the blazing ships, making fast hawsers, and towing them under the great guns of the Rock, where they were promptly sunk.

Again the blight of ennui, sickness, and famine came on the little garrison; but in October a cargo of fruit came just in time to save them from scurvy. In March, 1781, the want of bread became serious: biscuit crumbs were selling for a shilling a pound. “How long?” was the anxious cry that was felt, if not expressed in words. Had England forgotten her brave men?

On the 12th of April, to the joyful surprise of all, a great convoy was signalled, escorted by a strong fleet. Every man, woman, and child who could walk came out upon the ramparts and gazed seawards with glistening eyes. At daybreak, says the historian of the siege, “Admiral Darby’s much-expected fleet was in sight from our signal-house, but was not discernible from below, being obscured by a thick mist in the Gut. As the sun rose, however, the fog rose too like the curtain of a vast theatre, discovering to the anxious garrison one of the most beautiful and pleasing scenes it is possible to conceive. The ecstasies of the inhabitants at this grand and exhilarating sight are not to be described; but, alas! they little dreamed of the tremendous blow that impended, which was to annihilate their property, and reduce many of them to indigence and beggary.”

For this second relief of the garrison stung the Spaniards into the adoption of a measure which inflicted a large amount of suffering on the citizens. They at once began to bombard the town with sixty-four heavy guns and fifty mortars. All amongst the crowds in the narrow, winding streets, through the frail roofs and windows, came shot and shell, so that one and all fled from their homes, seeking cover among the rocks. This was the time for thieves to operate, and many houses were rifled of their contents. Then it was discovered that many hucksters and liquor-dealers had been hoarding and hiding their stocks, and a fire having broken out in a wine-shop, the soldiers tasted and drank to excess. Then in a few days the discipline became relaxed; many of the garrison stole and took away to their quarters barrels of wine, which they proceeded to stow away, to their own peril and ruin. At length General Elliot was compelled to issue orders that any soldier found drunk or asleep at his post should be shot.

What surprises us in our days of long-distance firing is the strange fact that a man with sharp vision could see one of the cannon-balls as it came towards him. One day, we are told, an officer saw a ball coming his way, but he was so fascinated by it that he could not move out of the way. Another day a shot fell into a house in which nearly twenty people were gathered together: all escaped except one child. On another occasion a shot came through the embrasures of one of the British batteries, took off the legs of two men, one leg of another, and wounded a fourth man in both legs, so that “four men had seven legs taken off and wounded by one shot.” A boy who had been posted on the works, on account of his keenness of vision, to warn the men when a cannon-ball was coming their way, had only just been complaining that they did not heed his warnings, and while he turned to the men this shot which did all this hurt was fired by the enemy. A large cannon-ball in those days weighed 30 pounds, others much less. The author remembers Admiral Colomb telling the Harrow boys in a lecture that a Captain of those days could carry two or more cannon-balls in his coat-tail pocket; the balls of modern guns have to be moved by hydraulic machinery. Yet it is astonishing how much damage the old cannon-balls could inflict, lopping along like overgrown cricket-balls as they did.

Sometimes incidents happened of an amusing character.

One day a soldier was rummaging about among the ruins of a fallen house, and came upon a find of watches and jewels. He bethought him at once of a very pretty Spanish girl who had coquetted with him in the gardens of the Alameda.

“Now, let me see,” he murmured to himself, “how can I put this away safe? Little Catalina will laugh when she sees them there jewels, I’ll be bound! Humph![Pg 23] I can’t take this lot to quarters, that’s sartin! Them sergeants, as feel one all round on return from duty, will grab the lot.”

So he walked on, musing and pondering over his weighty affair.

As he was passing the King’s Bastion a happy thought struck him.

“By George, sir!” he said to himself, “it’s just the very thing. Who would think of looking for a watch inside a gun?” and he chuckled to himself.

It was high noon; the sentinel seemed half asleep. The soldier tied up his prize in his handkerchief, took out the wad of the gun, and slipped his treasure-trove into the bore of the cannon, replacing the wad carefully. That evening he met Catalina, and managed to inform her that he had a pleasant surprise for her, if she could come to the King’s Bastion.

Her dark eyes glanced mischievously.

“No, not in the evening, I thank you, Jacko. I will come to-morrow, an hour ofter sunrise.”

“Very well, Catalina; I see you do not trust me. To-morrow, then, you shall come with me to the King’s Bastion, and see with your own eyes how rich I can make you.”

Catalina understood enough English to laugh heartily at her lover’s grave and mysterious words.

“He has stolen a loaf and a bottle of wine,” she thought in her simplicity.

However, Catalina did not disappoint Jack, and together they paced towards the semi-circular platform of the King’s Bastion.

Jack was a very proud man as he tried to explain to his lady-love what a surprise was in store for her: he touched her wrists to show how the bracelets would fit, and her shapely neck to prove the existence of a splendid necklace, and Catalina began to believe her boy.

But as they came out upon the gun platform, Jack stopped suddenly, and uttered a fearful oath.

“O dios!” cried the maid, “what is there to hurt, Jacko?”

“Don’t you see? Oh, Catalina, the game is up! That devil of a gunner is wiping out the bore of his gun!”

Jack ran up, and, seizing the man by the arm, said: “I say, mate, if you have found a parcel in that gun, it’s mine! I put it in last night. I tell you it’s mine, mate! Don’t you try to make believe you have not seen it, ’cos I know you has.”

The gunner stared in open-mouthed astonishment at the speaker. At last he said, with a touch of sarcasm:

“What for do you think I am wiping out her mouth, you silly! You must have slept pretty sound not to know that them gun-boats crept up again last night.”

“The devil take them! Then, where’s that gold watch of mine and them jewels? I put ’em for safety in that fool of a gun.”

“Oh, then, you may depend upon it, my lad, that the watch-glass has got broke, for we fired a many rounds in the night.”

“What for you look so to cry?” asked little Catalina in wonder.

“Oh, come away, sweetheart. You’ll get no rich present this year; them Spaniards have collared ’em all. O Lord! O Lord!”

On the 7th of July the Spaniards at Cabrita Point were seen to be signalling the approach of an enemy. As the mists melted away, the garrison could see a ship becalmed out in the bay. Fourteen gunboats from Algeciras had put out to cut her off; on this, Captain Curtis, of the Brilliant, ordered three barges to row alongside, and receive any dispatches she might have on board. This was done just before the leading Spanish gunboat got within range;[Pg 25] then came a hideous storm of round and grape shot as the fourteen gunboats circled round the Helma.

But Captain Roberts, though he had only fourteen small guns, returned their fire gallantly. The English sloop was lying becalmed about a league from the Rock, and the garrison in Gibraltar could do nothing to help her. They looked every minute to see the Helma sink, but still she battled on against their 26-pounders.

Then, when hope seemed desperate, a westerly breeze sprang up; the waters darkened and rippled round the Helma, her canvas slowly filled out, and she came away with torn sails and rigging to the shelter of the Mole.

In September, 1782, a grand attack was made by the Spaniards with ten men-of-war, gunboats, mortar-boats, and floating batteries. They took up their position about 900 yards from the King’s Bastion. Four hundred pieces of the heaviest artillery were crashing and thundering, while all the air was thick with smoke. General Elliott had made his preparations: the round shot was being heated in portable furnaces all along the front, and as the furnaces were insufficient, huge fires were lit in the angles between buildings on which our “roast potatoes,” as the soldiers nicknamed the hot shot, were being baked.

But the enemy’s battering-ships seemed invulnerable. “Our heaviest shells often rebounded from their tops, whilst the 32-pound shot seemed incapable of making any visible impression upon their hulls. Frequently we flattered ourselves they were on fire, but no sooner did any smoke appear than, with admirable intrepidity, men were observed applying water from their engines within to those places whence the smoke issued. Even the artillery themselves at this period had their doubts of the effect of the red-hot shot, which began to be used about twelve, but were not general till between one and two o’clock.” After some hours’ incessant firing, the masts[Pg 26] of several Spanish ships were seen to be toppling over; the flag-ship and the Admiral’s second ship were on fire, and on board some others confusion was seen to be prevailing. Their fire slackened, while ours increased. Then, as night came on, the gleams spread across the troubled waters; the cannonade of the garrison increased in rapidity and power. At one in the morning two ships were blazing mast-high, and the others soon caught fire from the red-hot shot or from the flying sparks. The light and glow of this fearful conflagration brought out the weird features of the whole bay: the sombre Rock, the blood-red sea, the white houses of Algeciras five miles across, the dark cork forests, and the Spanish mountains—all stood out in strange perspective. Amid the roar of cannon were fitfully heard the hoarse murmurs of the crowds that lined the shore and the screams of burning men. Sometimes a deep gloom shrouded the background of earth and sea, while gigantic columns of curling, serpent flame shot up from the blazing hulls.

Brigadier Curtis, who was encamped at Europa Point, now took out his flotilla of twelve gunboats, each being armed with a 24-pounder in its bow, and took the floating batteries in flank, compelling the Spanish relieving boats to retire.

Daylight showed a sight never to be forgotten: the flames had paled before the sun, but the dark forms of the Spaniards moving amongst the fire and shrieking for help and compassion stirred all the feelings of humanity. Some were clinging to the sides of the burning ships, others were flinging themselves into the waves. Curtis led his boats up to the smoking hulks in order to rescue some of the victims. He and his men climbed on board the battering-ships at the risk of their lives, and helped down the Spaniards, who were profuse in their expressions of gratitude.

The Last Siege of Gibraltar by France and Spain

A floating battery may be seen to the extreme left beyond the heeling ship.

But as the English thus worked for the rescue of their enemies, the magazine of one of the Spanish ships blew up with a crash at about five o’clock, and a quarter of an hour after another exploded in the centre of the line. Burning splinters were hurled around in all directions, and involved the British gunboats in grave danger. In the Brigadier’s boat his coxswain was killed, his stroke wounded, and a hole was forced through the bottom of the boat. After landing 357 Spaniards, the English were compelled to retire under the cover of the Rock, leaving the remainder to their dreadful fate. Of the six ships still on fire, three blew up before eleven o’clock; the other three burned down to the water’s edge.

Thus ended the attempt to take the Rock by means of floating castles. The loss sustained by the Spaniards was about 2,000 killed, wounded, and taken prisoners; whereas the losses in the garrison were surprisingly small, considering how long a cannonade had been kept up upon the forts: 16 only were killed; 18 officers, sergeants, and rank and file were wounded. Yet the enemy had been firing more than 300 pieces of heavy ordnance, while the English garrison could bring to bear only 80 cannon, 7 mortars, and 9 howitzers; but even for these they expended 716 barrels of powder.

As Admiral Lord Howe was sailing with a powerful fleet to the help of Gibraltar, he heard the news of General Elliot’s splendid defence. On the night of the 18th of October, 1782, a great storm scattered the French and Spanish ships; and soon after the delighted garrison saw Lord Howe’s fleet and his convoy, containing fresh troops and provisions, approaching in order of battle. The blockade was now virtually at an end. The siege had lasted three years, seven months, and twelve days. Since then no attempt has been made to capture Gibraltar.

Jaffa stormed by Napoleon—Sir Sidney Smith hurries to Acre—Takes a convoy—How the French procured cannon-balls—The Turks fear the mines—A noisy sortie—Fourteen assaults—A Damascus blade—Seventy shells explode—Napoleon nearly killed—The siege raised—A painful retreat.

Napoleon Bonaparte had crushed all opposition in Central and Southern Europe, but there was one Power which foiled him—Great Britain.

The French Government compelled Spain and Holland to join in a naval war against England, but Jervis and Nelson broke and scattered the combined fleets.

Bonaparte had conceived a bitter hatred against the only Power which now defied the might of France, and was causing him “to miss his destiny.”

“I will conquer Egypt and India; then, attacking Turkey, I will take Europe in the rear.” So he wrote. In the spring of 1798 he set out for Egypt, reducing Malta on the way, and just eluding Nelson’s fleet.

He had got as far as Cairo when he heard of Nelson’s victory in Aboukir Bay, where his French fleet was destroyed.

But Bonaparte, undaunted, pressed on to attack Syria. He stormed Jaffa, and put the garrison to the sword. Not content with this cruelty, he marched the[Pg 29] townsfolk, to the number of 3,700, into the middle of a vast square, formed by the French troops. The poor wretches shed no tears, uttered no cries. Some who were wounded and could not march so fast as the rest were bayonetted on the way.

The others were halted near a pool of dirty, stagnant water, divided into small bodies, marched in different directions, and there shot down. When the French soldiers had exhausted their cartridges, the sword and bayonet finished the business. Sir Sidney Smith, a Captain commanding a few ships in the Levant, hearing of these atrocities, hurried with his ships to St. Jean d’Acre, which lies north of Jaffa, on the north end of the bay which is protected on the south by the chalk headland of Carmel, jutting out like our Beachy Head far into the sea.

Sir Sidney arrived in the Tigre at Acre only two days before Bonaparte appeared. On the 17th of March he sent the Tigre’s boats by night to the foot of Mount Carmel, and there they found the French advanced guard encamped close to the water’s edge. The boats opened with grape, and the French retired in a hurry up the side of the mount.

The main body of the army, hearing that the sea-road was exposed to gun-fire from British ships, went round by Nazareth and invested Acre to the east. A French corvette and nine sail of gun vessels coming round Mount Carmel, found themselves close to the English fleet, and seven of them were made prizes, manned from the ships, and employed to harass the enemy’s posts.

The French trenches were opened on the 20th of March with thirty-two cannon, but they were deficient in balls. The French General, Montholon, tells us how they made the English provide them with cannon-balls. It reminds us of our own plan at Jellalabad. He says that Napoleon[Pg 30] from time to time ordered a few waggons to be driven near the sea, on sight of which Sir Sidney would send in shore one of his ships and pour a rolling fire around the waggons. Presently the French troops would run to the spot, collect all the balls they could find and bring them in to the Director of Artillery, receiving five sous for each ball. This they did, while laughter resounded on every side. The French could afford to be merry. Under Bonaparte they had become the masters of the greater part of Europe. Nothing seemed impossible to them under that military genius. Here they were besieging a little trumpery Syrian town, which they calculated they could take in three days; “for,” said they, “it is not so strong as Jaffa. Its garrison only amounts to 2,000 or 3,000 men, whereas Jaffa had a garrison of 8,000 Turks.”

On the 25th of March the French had made a breach in the tower which was considered practicable. A young officer with fifteen sappers and twenty-five Grenadiers, was ordered to mount to the assault and clear the tower fort; but a counter-scarp 15 feet high stopped them. Many were wounded, and they hastily retired. On the 28th a mine was sprung, and they assaulted again; but “the Turks exerted themselves so far on this occasion,” writes Sir Sidney, “as to knock the assailants off their ladders into the ditch, where about forty of their bodies now lie.” Montholon writes: “The breach was found to be too high by several feet, and Mailly, an officer of the staff, and others were killed. When the Turks saw Adjutant Lusigier fixing the ladder, a panic seized them, and many fled to the port. Even Djezzar, the Governor, had embarked. It was very unfortunate. That was the day on which the town ought to have been taken.”

Early in April a sortie took place, in which the British[Pg 31] Marines were to force their way into the French mine, while the Turks attacked the trenches. The sally took place just before daylight, but the noise and shouting of the Turks rendered the attempt to surprise the enemy useless; but they succeeded in destroying part of the mine, at considerable loss. The Turks brought in above sixty heads, many muskets and entrenching tools. “We have taught the besiegers,” writes Sir Sidney, “to respect the enemy they have to deal with, so as to keep at a greater distance.” On the 1st of May the enemy, after many hours’ heavy cannonade from thirty pieces of artillery brought from Jaffa, made a fourth attempt to mount the breach, now much widened, but were repulsed with loss.

“The Tigre moored on one side and the Theseus on the other, flank the town walls, and the gunboats, launches, etc., flank the enemy’s trenches, to their great annoyance. Nothing but desperation can induce them to make the sort of attempts they do to mount the breach under such a fire as we pour in upon them; and it is impossible to see the lives, even of our enemies, thus sacrificed, and so much bravery misapplied, without regret. I must not omit to mention, to the credit of the Turks, that they fetch gabions, fascines, and other material which the garrison does not afford from the face of the enemy’s works.”

By the 9th of May the French had on nine several occasions attempted to storm, but had been beaten back with immense slaughter. On the fifty-first day of the siege the English had been reinforced by Hassan Bey with corvettes and transports; but this only made Bonaparte attack with more ferocity, having protected themselves with sand-bags and the bodies of their dead built in with them. It was a touch and go whether the French would not fight their way in. A group of Generals was assembled on Cœur-de-Lion’s Mount, among whom Napoleon was[Pg 32] distinguishable, as he raised his glasses and gesticulated. At this critical moment Sir Sidney landed his boats at the mole and took the crews up to the breach armed with pikes. The enthusiastic gratitude of the Turks—men, women, and children—at sight of such a reinforcement is not to be described. The few Turks who were standing their ground in the breach were flinging heavy stones down on the heads of the advancing foe, but many of the French mounted to the heap of ruins in the breach so close that the muzzles of their muskets touched and their spear-heads locked.

Djezzar Pasha, on hearing that so large a force of the English were fighting in the breach, left his seat, where, according to Turkish custom, he was sitting to distribute rewards to such as should bring him the heads of the enemy, and coming behind our men, the energetic old man pulled back his English friends with violence, saying, “If any harm happen to the English, all is lost.”

A sally made by the Turks in another quarter caused the French in the trenches to uncover themselves above their parapet, so that the fire from our boats brought down numbers of them. A little before sunset a massive column came up to the breach with solemn step. By the Pasha’s orders a good number of the French were let in, and they descended from the rampart into the Pasha’s garden, where in a very few minutes their bravest lay headless corpses, the sabre proving more than a match for the bayonet. The rest, seeing what was done, fled precipitately. The breach was now practicable for fifty men abreast. “We felt,” says Sir Sidney, “that we must defend it at all costs, for by this breach Bonaparte means to march to further conquest, and on the issue of this conflict depends the conduct of the thousands of spectators who sit on the surrounding hills, waiting to see which side they shall join.”

With regard to the cutting off of heads by the Turks, one day, when out riding, Sir Sidney questioned the superior metal of the Damascus blade, when Djezzar Pasha replied that such a blade would separate the head from the body of any animal without turning the edge.

“Look!” said the Pasha; “this one I carry about with me never fails. It has taken off some dozens of heads.”

“Very well, Pasha,” said Sir Sidney. “Could you not give me ocular proof of the merit of your Damascus, and at the same time of your own expertness, by slicing off, en passant, the head of one of the oxen we are now approaching?”

“Ah, q’oui, monsieur, c’est déjà fait;” and springing off at a gallop, he smote a poor ox as it was grazing close to the path, and the head immediately rolled on the ground. A Damascus sabre regards neither joints nor bones, but goes slicing through, and you cannot feel any dint on the edge thereof.

On the 14th of May Sir Sidney writes to his brother: “Our labour is excessive: many of us have died of fatigue. I am but half dead, and nearly blinded by sun and sand. Bonaparte brings fresh troops to the assault two or three times in the night, and so we are obliged to be always under arms. He has lost the flower of his army in these desperate attempts to storm, as appears by the certificates of former services which we find in their pockets. We have been now near two months constantly under fire and firing. We cannot guard the coast lower down than Mount Carmel, for the Pasha tells me, if we go away, the place will fall, so that the French get supplies from Jaffa to the south. I sent Captain Miller in the Theseus yesterday to chase three French frigates off Cæsarea; but, alas! seventy shells burst at the forepart of Captain Miller’s cabin, killing him and thirty-two men, including some who jumped overboard and were drowned.” The[Pg 34] ship got on fire in five places, but was saved. By the 16th of May Bonaparte had lost eight Generals and most of his artillerymen—in all upwards of 4,000 men. The Turks were becoming quite brave and confident. They boldly rushed in on the assaulting columns, sabre in hand, and cut them to pieces before they could fire twice. But they were struck with terror at the thought of the mines which they imagined might blow up at any time, and could not be forced to remain on the walls or in the tower. However, the knowledge which the garrison had of the massacre at Jaffa rendered them desperate in their personal defence.

In the fourteenth assault General Kleber led his victorious troops to the breach. It was a grand and terrific spectacle. The Grenadiers rushed forward under a shower of balls. Kleber, with the gait of a giant, with his thick head of hair and stentorian voice, had taken his post, sword in hand, on the bank of the breach. The noise of the cannon, the rage of the soldiers, the yells of the Turks, were all bewildering and awful.

General Bonaparte, standing on the battery of the breach, looking rather paler than usual, was following the progress of the assault through his glass, when a ball passed above his head; but he would not budge. In vain did Berthier ask him to quit this perilous post—he received no answer—and two or three officers were killed close to him; yet he made no sign of moving from the spot. All at once the column of the besiegers came to a standstill. Bonaparte went further forward, and then perceived that the ditch was vomiting out flames and smoke. It was impossible to go on. Kleber, in a great rage, struck his thigh with his sword and swore. But the General-in-Chief, judging the obstacle to be insurmountable, gave a gesture and ordered a retreat. After this failure the French Grenadiers absolutely refused to[Pg 35] mount the breach any more over the putrid bodies of their unburied companions. Bonaparte for once seems to have lost his judgment, first by sacrificing so many of his best men in trying to take a third-rate fort; and, secondly, because, even if he had succeeded in taking the town, the fire of the English ships must have driven him out again in a short time.

One last desperate throw was made for success by sending an Arab dervish with a letter to the Pasha proposing a cessation of arms for the purpose of burying the dead. During the conference of the English and Turkish Generals on this subject a volley of shot and shells on a sudden announced an assault; but the garrison was ready, and all they did was to increase the numbers of the slain, to the disgrace of the General who thus disloyally sacrificed them. The game was up after a siege of sixty days: in the night following the 20th of May the French army began to retreat. But as they could not carry their guns and wounded with them, these were hurried to sea without seamen to navigate the ships, in want of water and food. They steered straight for the English ships, and claimed and received succour. Their expressions of gratitude to Sir Sidney were mingled with execrations on their General for his cruel treatment of them. English boats rowed along the shore and harassed their march south. The whole track between Acre and Gaza was strewn with the dead bodies of those who had sunk under fatigue or from their wounds. At Gaza Bonaparte turned inland, but there he was much molested by the Arabs. The remnant of a mighty host went on, creeping towards Egypt in much confusion and disorder.

Sir Sidney Smith had thus defeated the great General of France, who grudgingly said: “This man has made me miss my destiny.” In the hour of victory Sir Sidney was generous and humane, for he had a good heart, good[Pg 36] humour, and much pity. Nor did he forget the Giver of all victory, as the following extract from a letter testifies:

“Nazareth, 1799.—I am just returned from the Cave of the Annunciation, where, secretly and alone, I have been returning thanks to the Almighty for our late wonderful success. Well may we exclaim, ‘the race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong.’—W. S. S.”

Talavera between two fires—Captain Boothby wounded—Brought into Talavera—The fear of the citizens—The surgeons’ delay—Operations without chloroform—The English retire—French troops arrive—Plunder—French officers kind, and protect Boothby—A private bent on loot beats a hasty retreat.

Captain Boothby, of the Royal Engineers, left behind him a diary of his experiences in Spain during part of the Peninsular War in 1809. It will help us to understand how much suffering war inflicts, and how much pain we have been saved by the inventions of modern science.

He tells us he had been provided with quarters in Talavera, at the house of Donna Pollonia di Monton, a venerable dame. She was the only person left in the house, the rest having fled to the mountains in fear lest the French should come and sack the city; for in the streets those who remained were shouting in their panic, “The French have taken the suburbs!” or “The British General is in full retreat!” or “O Dios! los Ingleses nos abandonan!” (“O God! the English are deserting us!”). The fact was that Wellesley was not sure if he could hold his ground at Talavera.

Captain Boothby went out one morning towards the enemy’s position; he was brought back in the evening on a bier by four men, his leg shattered by a musket-ball.[Pg 38] The old lady threw up her hands when she saw him return.

“What!” she exclaimed, while the tears ran down her cheeks. “Can this be the same? This he whose cheeks in the morning were glowing with health? Blessed Virgin, see how white they are now!”

She made haste to prepare a bed.

“Oh, what luxury to be laid upon it, after the hours of pain and anxiety, almost hopeless, I had undergone! The surgeon, Mr. Bell, cut off my boot, and having examined the wound, said:

“‘Sir, I fear there is no chance of saving your leg, and the amputation must be above the knee.’

“He said the operation could not be performed until the morning, and went back to the hospital.

“I passed a night of excruciating pain. My groans were faint, because my body was exhausted with the three hours’ stumbling about in the woods. Daylight was ushered in by a roar of cannon so loud, so continuous, that I hardly conceived the wars of all the earth could produce such a wild and illimitable din. Every shot seemed to shake the house with increasing violence, and poor Donna Pollonia rushed in crying:

“‘They are firing the town!’

“‘No, no,’ said I; ‘don’t be frightened. Why should they fire the town? Don’t you perceive that the firing is becoming more distant?’”

So the poor lady became less distraught, and watched by him with sympathizing sorrow. But at length, finding the day advancing, his pains unabating, and no signs of any medical help coming, he tore a leaf from his pocket-book, and with a pencil wrote a note to the chief surgeon, Mr. Higgins, saying that, as he had been informed no time was to be lost in the amputation, he was naturally anxious that his case should be attended to. The mes[Pg 39]senger returned, saying that the surgeon could not possibly leave the hospital. He sent a second note, and a third, and towards ten o’clock a.m. the harrassed surgeon made his appearance.

“Captain Boothby,” said he, “I am extremely sorry that I could not possibly come here before, still more sorry that I only come now to tell you I cannot serve you. There is but one case of instruments. This I cannot bring from the hospital while crowds of wounded, both officers and men, are pressing for assistance.”

“I did but wish to take my turn,” said the Captain.

“I hope,” he added, “that towards evening the crowd will decrease, and that I shall be able to bring Mr. Gunning with me to consult upon your case.”

“Will you examine my wound, sir,” said Boothby, “and tell me honestly whether you apprehend any danger from the delay?”

He examined the leg, and said:

“No, I see nothing in this case from which the danger would be increased by waiting five or six hours.”

There was nothing for it but patience.

“I taxed my mind to make an effort, but pain, far from loosening his fangs at the suggestion of reason, clung fast, and taught me that, in spite of mental pride, he is, and must be, dreadful to the human frame.”

Mr. Higgins came to him about three o’clock, bringing with him Mr. Gunning and Mr. Bell, and such instruments as they might have occasion for.

Mr. Gunning sat down by his bedside, and made a formal exhortation: explained that to save the life it was necessary to part with the limb, and he required of him an effort of mind and a manly resolution.

“Whatever is necessary, that I am ready to bear,” said the Captain.

Then the surgeons, having examined his wound, went[Pg 40] to another part of the room to consult, after which they withdrew—to bring the apparatus, as he imagined. Hours passed, and they did not return. His servant, Aaron, having sought Mr. Gunning, was told that he was too much occupied. This after having warned him that there was no time to be lost!

“Go, then,” said the Captain to Aaron—“go into the street, and bring me the first medical officer you happen to fall in with.”

He returned, bringing with him Mr. Grasset, surgeon of the 48th Regiment.

After examining the wound, Mr. Grasset declared that he was by no means convinced of the necessity of the amputation, and would not undertake the responsibility.

“But,” said the wounded man, “I suppose an attempt to save the leg will be attended with great danger.”

“So will the amputation,” he replied. “But we must hope for the best, and I see nothing to make your cure impossible. The bones, to be sure, are much shattered, and the leg is much mangled and swollen; but have you been bled, sir?”

“No,” said Captain Boothby.

Mr. Grasset conceived bleeding absolutely necessary, though he had already lost much, and at his request he bled him in the arm.

He guessed that Mr. Gunning’s departure proceeded from his conviction that a gangrene had already begun, and that it would be cruel to disturb his dying moments by a painful and fruitless operation.

As he had taken nothing but vinegar and water since his misfortune, his strength was exhausted, and the operation of bleeding was succeeded by an interval of unconsciousness. From this state he was roused by some one taking hold of his hand. It was his friend Dr. FitzPatrick.

“If I had you in London,” said he with a sigh, “I might attempt to save your limb; but amid the present circumstances it would be hopeless. I had been told that the amputation had been performed, else, ill as I could have been spared, I would have left the field and come to you.”

“Do you think you are come too late?” asked the Captain.

He said “No”; but he dissembled. At that time Boothby was under strong symptoms of lockjaw, which did not disappear until many hours after the operation. The doctor took a towel, and soaking it in vinegar and water, laid it on the wound, which gave much relief. He stayed with him till late, changing the lotion as often as needed. The operation was fixed for daylight on the morrow.

The patient passed another dismal night. At nine o’clock next morning FitzPatrick and Miller, Higgins and Bell, staff-surgeons, came to his bedside. They had put a table in the middle of the room, and placed on it a mattress. Then one of the surgeons came and exhorted him to summon his fortitude. Boothby told him he need not be afraid, and FitzPatrick said he could answer for him. They then carried him to the table and laid him on the mattress. Mr. Miller wished to place a handkerchief over his eyes, but he assured him that it was unnecessary; he would look another way.

“I saw that the knife was in FitzPatrick’s hand, which being as I wished, I averted my head.

“I will not shock the reader by describing the operation in detail, but as it is a common idea that the most painful part of an operation lies in sundering the bone, I may rectify an error by declaring that the only part of the process in which the pain comes up to the natural anticipation is the first incision round the limb, by which[Pg 42] the skin is divided, the sensation of which is as if a prodigious weight were impelling the severing edge. The sawing of the bone gives no uneasy sensation; or, if any, it is overpowered by others more violent.

“‘Is it off?’ said I, as I felt it separate.

“‘Yes,’ said FitzPatrick, ‘your sufferings are over.’

“‘Ah no! you have yet to take up the arteries.’

“‘It will give you no pain,’ he said kindly; and that was true—at least, after what I had undergone, the pain seemed nothing.

“I was carried back to my bed much exhausted. Soon hope returned to my breast; it was something to have preserved the possibility of yet being given back to happiness and friendship.”

For some time after the operation his stomach refused sustenance, and a constant hiccough was recognized by the surgeons as a fatal prognostic.

His faithful friend, Edmund Mulcaster, hardly ever left his bedside. General Sherbrooke came to see him often, and evinced the most earnest anxiety for his welfare. They wrote to his friends for him, and to his mother. This last he signed himself.

In the night of the 30th, by the perseverance of Mulcaster, he managed to retain some mulled wine, strongly spiced, and in the morning took two eggs from the same welcome hand. This was the “turn.” The unfavourable symptoms began to subside, and the flowing stream of life began to fill by degrees its almost deserted channels.

On the 2nd of August some officers, entering his room, said that information had been received of Soult’s arrival at Placentia, and that General Wellesley intended to head back and engage him.

“If the French come while we are away, Boothby,” said Goldfinch, “you must cry out, ‘Capitaine anglais,’ and you will be treated well.”

On the 3rd of August his friends all came to take leave of him. It was a blank, rugged moment. Mr. Higgins, the senior surgeon, was left behind to tend the wounded.

The mass of the people of England is hasty, and often unjust, in its judgment of military events. They will condemn a General as rash when he advances, or revile him as a coward when he retreats. News of the battle of Talavera had been announced by the trumpet of victory. The people of England expected the emancipation of Spain. Now were they cast down when told that the victors had been obliged to retire and leave their wounded to the mercy of a vanquished enemy.

If Lord Wellington knew the strength and condition of the force under Soult, it would be hard to justify his conduct in facing back. In Spain, however, it was impossible to get correct information. The Spaniards are deaf to bad news and idiotically credulous to all reports that flatter their hopes. Thus the rashness of Lord Wellington in placing himself between two armies, Soult and Ney, the least of whom was equal to himself, may be palliated.

The repulse and flight of the French after the Battle of Talavera restored confidence to the fugitive townsfolk. They left the mountains and re-entered Talavera. The house was again filled with old and young, who strove to wait on the Captain. But soon the evacuation of the town by the British awoke their fears; but with thankfulness let us record that a British officer, wounded and mutilated, was to the women of the house too sacred an object to be abandoned.

The citizens of Talavera had clung to the hope that at least their countrymen would stay and protect them; but on the 4th, seeing them also file under their windows in a long, receding array, they came to the Captain—those near his house—beating their breasts and tearing[Pg 44] their hair, and demanded of him if he knew what was to become of them.

Boothby sent Aaron to take a message to the Colonel left Commandant by General Wellesley, but he came back saying that the Colonel was gone, having given orders that those in the hospitals who were able to move should set off instantly for Oropesa, as the French were at hand. The sensation this notice produced is beyond all description. The Captain lay perfectly still; other wounded men had themselves placed across horses and mules, and fruitlessly attempted to escape. The road to Oropesa was covered with our poor wounded, limping, bloodless soldiers. On crutches or sticks they hobbled woefully along. For the moment panic terror lent them a new force, but many lay down on the road to take their last sleep.

Such were the tales that Aaron and others came to tell him. He tried to comfort them, and said the French were not so bad as they fancied. Still, his mind was far from being at ease. He thought it possible that some foraging party might plunder him and commit excesses in the house, or on the women, who would run to him for protection, however uselessly. The evening of the 4th, however, closed in quietness, and a visit from the senior medical officer, Mr. Higgins, gave him great comfort.

The 5th of August dawned still and lovely. A traveller might have supposed Talavera to be in profound peace until, gazing on her gory heights, he saw they were covered with heaps of ghastly slain. The tranquil interval was employed in laying in a stock of provisions. Pedro argued with him.

“But, signore, the Brencone asks a dollar a couple for his chickens!”

“Buy, buy, buy!” was all the answer he could get from the Captain.

Wine, eggs, and other provender were laid in at a rate[Pg 45] which provoked the rage and remonstrance of the little Italian servant.

About the middle of the day a violent running and crying under the windows announced an alarm. The women rushed into his room, exclaiming, “Los Franceses, los Franceses!” The assistant surgeon of artillery came in.

“Well, Mr. Steniland,” said the Captain, “are the French coming?”

“Yes,” he answered; “I believe so. Mr. Higgins is gone out to meet them.”

“That’s right,” said Boothby.

In about an hour Mr. Higgins entered, saying, “I have been out of town above two leagues and can see nothing of them. If they do come, they will have every reason to treat us with attention, for they will find their own wounded lying alongside of ours, provided with the same comforts and the same care.”

On the 6th, reports of the enemy’s approach were treated with total disregard. Between eight and nine o’clock the galloping of horses was heard in the street. The women ran to the windows and instantly shrank back, pale as death, with finger on lip.

“Los demonios!” they whispered, and then on tiptoe watched in breathless expectation of seeing some bloody scene.

“They have swords and pistols all ready,” cried Manoela, trembling.

“How’s this?” cried old Donna Pollonia. “Why, they pass the English soldiers. They go on talking and laughing. Jesus! Maria! What does it mean?”

Presently Mr. Higgins came in. He had ridden out to meet the French General, and had found that officer full of encomiums and good assurances.

“Your wounded are the most sacred trust to our[Pg 46] national generosity. As for you, medical gentlemen, who have been humane and manly enough not to desert your duty to your patients (many of whom are Frenchmen), stay amongst us as long as you please. You are as free as the air you breathe.”

The town owed much to Mr. Higgins!

To prepare for the approaching crisis, to ride forth and parley with the enemy and persuade him that he owes you respect, gratitude—this is to be an officer of the first class. Throughout Mr. Higgins displayed the character of no common man.

We should say something of the household among which the Captain was placed.

Servants and masters and mistresses in Spain associate very freely together, but the submissive docility of the servants keeps pace with the affability with which they are treated. First after Don Manoel and Donna Pollonia came Catalina—a tall, elegant woman of forty, a sort of housekeeper held in high estimation by the señora. Then come two old women, Tia Maria and Tia Pepa “tia” means “aunt”); then Manoela, a lively, simple lass, plain and hardy, capable of chastising with her fists any ill-mannered youth. Then the carpenter’s daughters, two pretty little girls, often came to play in his room—Martita, aged about ten, and Maria Dolores, perhaps fifteen, pensive, tender, full of feminine charm. These fair sisters used to play about him with the familiarity and gentleness of kittens, and lightened many an hour.

Well, it was not all plain sailing, for stories of pillage and plunder came to their ears. Three troopers had gone to the quarters of his wounded friend, Taylor, and began coolly to rifle his portmanteau.

Taylor stormed and said he was an English Captain.

“Major, ’tis very possible,” said they; “but your money, your watch, and your linen are never the worse[Pg 47] for that; no, nor your wine either!” and the ruthless savages swallowed the wine and the bread which had been portioned out as his sustenance and comfort for the day.

Feeling that such might be his case, Boothby put his money and watch in a little earthen vessel and sent it to be buried in the yard; then calling for his soup and a large glass of claret, he tossed it off defiantly, saying to himself, “You don’t get this, my boys!”

Next morning they heard that the French infantry were coming, and the town was to be given up to pillage, as so many of the citizens had deserted it.

The women came to him. “Shall we lock the street door, Don Carlos?” they said.

“By all means,” said he. “Make it as fast as you can, and don’t go near the windows.”

Soon they heard the bands playing, and the women rushed to the windows, as if to see a raree-show, forgetting all his injunctions.

Soon after thump! thump! thump! sounded at the door.

“Virgin of my soul!” cried old Pollonia, tottering to the window. “There they are!” But, peeping out cautiously, she added, “No, ’tis but a neighbour. Open, Pepa.”

“You had better not suffer your door to be opened at all,” said the Captain.

But Pepa pulled the string, and in came the neighbour, shrieking:

“Jesus! Maria! Dios Santissimo! The demons are breaking open every door and plundering every house; all the goods-chests—everything—dragged out into the street.”

“Maria di mi alma! Oh, señora!”

The crashing of doors, breaking of windows, loud[Pg 48] thumpings and clatterings, were now distinctly heard in all directions. All outside seemed to boil in turmoil.

Ere long, thump! thump! at their own door.

But it was only another neighbour. Pepa pulled the string, and in she came. Her head was piled up with mattresses, blankets, quilts, and pillows. Under one arm were gowns, caps, bonnets, and ribbons. Her other hand held a child’s chair. Add to all this that her figure was of a stunted and ludicrous character, and she came in puffing and crying under that cumbrous weight of furniture. They could not resist laughing.

“For the love of God, señora,” she whined, “let me put these things in your house.”

She was shown up into the garret. Others followed after her.

But soon there was a louder knocking, with a volley of French oaths. The house shook under the blows.

“Pedro, tell them in French that this is the quarter of an English Captain.”

Pedro cautiously peeped out of the window.

“Dios! there is but one,” said Pedro, “and he carries no arms. Hallo, sair! la maison for Inglis Captin! Go to hell!”

This strange language, and his abrupt, jabbering way of talking, forced a laugh out of his master.

“Ouvrez la porte, bête!” shouted the Frenchman. “I want some water.”

“Holy Virgin!” cried Pollonia. “We had better open the door.”

“No, no, no!” said Boothby. “Tell him, Pedro, that if he does not take himself off I shall report him to his General.”

Pedro had not got half through this message, when suddenly he ducked his head, and a great stone came in and struck the opposite wall.

“Il demonio!” groaned the women, as they, too, ducked their heads.

Then the fellow, who was drunk, just reeled off in search of some easier adventure.

Pedro had hardly finished boasting of his victory when the door was again assailed.

“Oh,” said Pollonia, “it’s only two officers’ servants;” and she shut the window.

“Well, what did they want?” asked the Captain.

“They wanted lodgings for their masters, but I told them we had no room.”

“And have you room, Donna Pollonia?”

“Yes; but I didn’t choose to say so.”

“Run, Pedro, run and tell those servants that there is plenty of room. Don’t you see, señora, that this is the best chance of preserving your house from pillage?”

They returned—one a Prussian lad who spoke French very ill. The Captain’s hope that these fellow-lodgers would prove gentlemen lent him a feeling of security.

Little Pedro was watching the motions of the two servants like a lynx.

“Signore,” said he, “those two diavoli are prying about into every hole and corner.”

On this Aaron was sent to dig up the watch and money and bring the wine upstairs.

Soon after in came Pedro, strutting with a most consequential air.

“The French Captain, signore,” said he.

There followed him a fine, military-looking figure, armed cap-à-pie, and covered with martial dust. He advanced to the bedside with a quick step.

“I have had the misfortune, sir, to lose a limb,” said Boothby, “and I claim your protection.”

“My protection!” he replied, putting out his hand. “Command my devoted services! The name of an[Pg 50] Englishman in distress is sufficient to call forth our tenderest attention.”

The Captain was a good deal affected by the kindness of his manner. Kindness can never be thoroughly felt unless it be greatly wanted.

He begged he would visit him sometimes, and he promised to bring a friend.

Señora Pollonia was charmed with M. de la Platière, who, with his young friend Captain Simon, often came in for a chat.

Alas! they had to go away after a few days’ stay, but de la Platière wrote his name in chalk on the door, in the hope that it might discourage any plunderers.

One day Boothby was suddenly aroused by the appearance in his room of an officer whom he had seen before, but did not much like.

“Eh, Capitaine, comment ça va-t-il? Ça va mieux! Ha! bon!”

Then he explained that the blade of his sword was broken. “As prisoner of war,” he said, “you will have no use for a sword. Give me yours, and, if you will, keep mine. Where is yours?”

“It stands,” said Boothby, “in yonder corner. Take it by all means.”

“Je vous laisserai la mienne,” he said, and hurried off.

Boothby wished his sword in the Frenchman’s gizzard, he was so rough and rude.

One afternoon Pedro rushed in, excited, and said: “The General himself is below, sir!”

“Bring him up, Pedro.”

Quickly he ushered in an officer of about the age of five-and-thirty. He was splendidly dressed, of an elegant person, his face beaming with good nature and intelligence.

He came up to the bed, and without waiting for the[Pg 51] form of salutation, seated himself in a chair close to the pillow, and laying his hand on Boothby’s arm, he said, in a mild and agreeable voice:

“Ne vous dérangez, mon ami! Solely I am here to see if I can possibly lighten a little the weight of your misfortune. Tell me, can I be useful to you? Have you everything you want?”

For all these kind inquiries the Captain expressed his gratitude, and added, “I have really nothing to ask for, unless you could send me to England.”

“Ah! if you were able to move, Captain, I could exchange you now; but by the time you will have gained strength to travel you will be at the disposal of the Major-General of the army.”

That visit gave much comfort and hope.

In the evening de la Platière and Simon returned with the news that Sir Arthur Wellesley had met with disasters.

“Taisez-vous, mon cher,” said Simon. “It may have a bad effect on his spirits.”

But he insisted on hearing all they knew, and while they were talking a French soldier walked calmly up into the room, and coming up to the foot of the bed, stood before his officers, astounded, petrified.

When, after sternly eyeing him a while, they sharply demanded his business, his faculties returned, and he stammered out:

“Mon Capitaine, I—I—I took it for a shop! I beg pardon.” And off he went in a hurry. But what would he have done if he had found the English officer alone?

On October 1 Captain Boothby was allowed to go out on crutches. He says: “The sense of attracting general observation hurried me. The French soldiers who met me expressed surprise at seeing the success of an amputation which in the hands of their field surgeons was nearly always fatal. The Spaniards were most sympathizing.[Pg 52] ‘What a pity!’ ‘So young, too!’ ‘Poor young Englishman!’ were pathetically passed along the street as he hobbled by.”

In July, 1810, Captain Boothby was exchanged with a French prisoner and returned to his father and mother in England.

This gives us the kindlier side of war; but there is another side.

In the prison of Toro were some French soldiers kept by the Spaniards. Nothing could be worse than the cruelty under which these Frenchmen suffered. In their prison was a cell, with a window strongly barred, and covered by an iron shutter pierced with small holes. The dungeon was about 10 feet square and 5 feet high. At the furthest end was a block of stone for a seat, with an iron collar for the neck, fixed by a short chain in the wall. Another chain was passed round the body. The poor wretches were chained in one position all day, which often hurried them to a miserable death. Their food was a little bread and water.

It is easy, however, to bear any amount of suffering when you know the time will soon come when you will be free.

It is not so easy to bear a whole lifelong penalty for having dared to fight for one’s country. One would think that a national gratitude would rescue our wounded soldiers from a life of beggary or the workhouse. Yet after every war how many one-armed and one-legged soldiers or sailors are pitifully begging along our streets and roads!

There is no animal so cruel as man. Corruptio optimi pessima.

From a “Prisoner of France,” by Captain Boothby. By kind permission of Messrs. A. and C. Black and Miss Boothby.

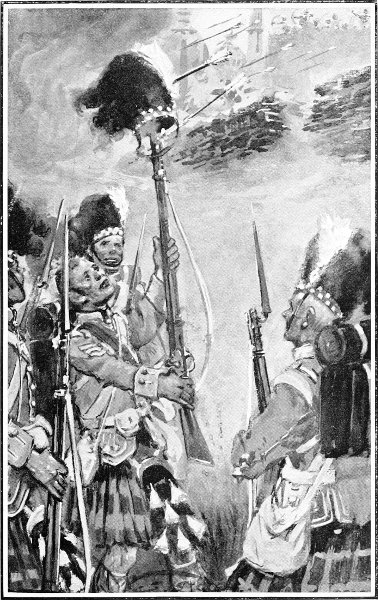

A night march—Waiting for scaling-ladders—The assault—Ladders break—Shells and grenades—A magazine explodes—Street fighting—Drink brings disorder and plunder—Great spoil.

After Talavera Sir Arthur Wellesley became Lord Wellington; he was opposed by Soult, Marmont, and Masséna. On the 1st of January Wellington crossed the Agueda, and advanced to the assault of Ciudad Rodrigo, which had to be hurried on because Marmont was advancing to its relief. Fortunately, we have descriptions from more than one eyewitness of the siege. Ciudad Rodrigo is built on rising ground, on the right bank of the Agueda. The inner wall, 32 feet high, is without flanks, and has weak parapets and narrow ramparts. Without the town, at the distance of 300 yards, the suburbs were enclosed by a weak earthen entrenchment, hastily thrown up.

It was six o’clock on the evening of the 19th of January. The firing on both sides had slackened, but not ceased. The chiefs were all bustle and mystery. They had had their instructions. Soon the 5th and 77th were ordered to fall in, and halted on the extreme right of the division. Whilst the men hammered at their flints the order was read to the troops. They were to take twelve axes in order to cut down the gate by which the ditch was entered.[Pg 54] The 5th Regiment were to have twelve scaling-ladders, 25 feet long, to scale the Fausse Brage, clear it of the enemy, throw over any guns, and wait for General M’Kinnon’s column in the main attack.

“Whilst waiting in the gloom for the return of the men sent for the ladders, we mingled in groups of officers, conversing and laughing together with that callous thoughtlessness which marks the old campaigner.

“I well remember how poor McDougall of the 5th was quizzed about his dandy moustaches. When next I saw him, in a few short hours, he was a lifeless and a naked corpse.

“Suddenly a horseman galloped heavily towards us. It was Picton. He made a brief and inspiriting speech to us—said he knew the 5th were men whom a severe fire would not daunt, and that he reposed equal confidence in the 77th. A few kind words to our commander and he bade us God-speed, pounding the sides of his hog-maned cob as he trotted off.”

Major Sturgeon and the ladders having arrived, the troops again moved off about half-past six. The night was rather dark, the stars lending but little light.

They were enjoined to observe the strictest silence. It was a time of thrilling excitement as they wound their way by the right, at first keeping a distance of 1,200 yards from the town, then bending in towards the convent of Santa Cruz and the river. The awful stillness of the hour was unbroken save by the soft, measured tread of the little columns as they passed over the green turf, or by the occasional report of a cannon from the walls, and the rush and whizz of its ball as it flew past, or striking short, bounded from the earth over their heads, receiving, perhaps, most respectful, though involuntary, salaams. Every two or three minutes a gun was fired at some suspicious quarter.

They had approached the convent and pushed on nearer the walls, which now loomed high and near. They reached the low glacis, through which was discovered a pass into the ditch, heavily palisaded with a gate in the centre. Through the palisades were visible the dark and lofty old Moorish walls, whilst high overhead was the great keep or citadel, a massive square tower, which looked like a giant frowning on the scene. The English still were undiscovered, though they could distinguish the arms of the men on the ramparts, as they fired in idle bluster over their heads.

Eagerly, though silently, they all pressed towards the palisades as the men with hatchets began to cut a way through them. The sound of the blows would not have been heard by the enemy, who were occupied by their own noises, had it not been for the enthusiasm, so characteristic of his country, which induced a newly-joined ensign, fresh from the wilds of Kerry, to utter a tremendous war-whoop as he saw the first paling fall before the axes. The cheer was at once taken up by the men, and, as they instantly got convincing proofs that they were discovered—the men on the walls began to pepper them soundly—they all rushed through the opening. In the ditch the assailants were heavily fired on from rampart and tower. The French tossed down lighted shells and hand-grenades, which spun about hissing and fizzing amongst their feet. Some of these smashed men’s heads as they fell, whilst others, exploding on the ground, tossed unlucky wretches into the air, tearing them asunder. Seldom could any men have passed three or four minutes more uncomfortably than the time which was consumed in bringing in and fixing the ladders against a wall, towards which they all crowded.

Amongst the first to mount was the gallant chieftain of the 5th, but the love they bore him caused so many of[Pg 56] the soldiers to follow on the same ladder that it broke in two, and they all fell, many being hurt by the bayonets of their own comrades round the foot of the ladder.

“I was not one of the last in ascending,” writes an officer of the 77th, “and as I raised my head to the level of the top of the wall, I beheld some of our fellows demolishing a picket which had been stationed at that spot, and had stood on the defensive.

“They had a good fire of wood to cheer themselves by, and on revisiting the place in the morning, I saw their dead bodies, stripped, strangely mingled with wounded English officers and men, who had lain round the fire all night, the fortune of war having made them acquainted with strange bed-fellows.

“Our ascent of the ladders placed us in the Fausse Brage—a broad, deep ditch—in which we were for the moment free from danger.

“When about 150 men had mounted, we moved forward at a rapid pace along this ditch, cowering close to the wall, whilst overhead we heard the shouts and cries of alarm. Our course was soon arrested by the massive fragments and ruins of the main breach made by our men, and here we were in extreme danger, for instead of falling into the rear of a column supposed to have already carried the breach, we stood alone at its base, exposed to a tremendous fire of grape and musketry from its defences.

“For a minute or two we seemed destined to be sacrificed to some mistake as to the hour of attack, but suddenly we heard a cheer from a body of men who flung down bags of heather to break their fall, and leaped on them into the ditch.

“It was the old Scots Brigade, which, like us, having been intended as a support, was true to its time, and was placed in the same predicament as we were.”

The Night Assault of Ciudad Rodrigo