Title: Lincoln's Love Story

Author: Eleanor Atkinson

Release date: February 11, 2015 [eBook #48233]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

LINCOLN’S

LOVE STORY

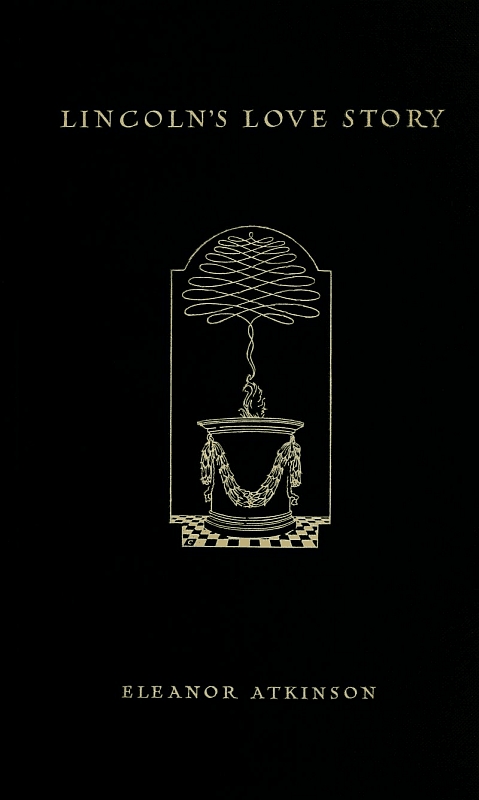

Drawing by Jay Hambidge.

“‘I cannot bear to think of her out there alone in the storm.’”

BY

ELEANOR ATKINSON

Author of “The Boyhood of Lincoln,”

and “Mamzelle Fifine”

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

MCMIX

Transcriber’s Notes:

Punctuation has been standardized.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table at the end of the text.

Transcriber Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are not identified in the text, but have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

PUBLISHED, JANUARY, 1909

NOTE

THIS STORY FIRST APPEARED IN THE “LADIES’ HOME JOURNAL” UNDER THE TITLE “THE LOVE STORY OF ANN RUTLEDGE.”

| “‘I cannot bear to think of her out there alone in the storm’” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Above the dam at New Salem | 6 |

| The grammar which Lincoln studied as a young man | 16 |

| New Salem, Ill., where Lincoln was postmaster | 20 |

| Squire Bowling Green’s cabin, near New Salem, Ill., as it is to-day | 32 |

| The top of the hill, New Salem | 36 |

| Gutzon Borglum’s conception of Lincoln | 46 |

| The grave of Ann Rutledge, Oakland Cemetery, Petersburg, Ill. | 56 |

In the sweet spring weather of 1835, Abraham Lincoln made a memorable journey. It was the beginning of his summer of love on the winding banks of the Sangamon. Only one historian has noted it as a happy interlude in a youth of struggle and unsatisfied longings, but the tender memory of Ann Rutledge, the girl who awaited him at the end of it, must have remained with him to the day of his martyrdom.

He was returning from Vandalia, Illinois, then the capital, and his first term in the state legislature, to the backwoods village of New Salem that had been his home for four years. The last twenty miles of the journey, from the town of Springfield, he made on a hired horse. The landscape through which he rode that April morning still holds its enchantment; the swift, bright river still winds in and out among the wooded hills, for the best farming lands lie back of the gravelly bluffs, on the black loam prairie. But three-quarters of a century ago central Illinois was an almost primeval world. Settlements were few and far apart. No locomotive awoke the echoes among the verdant ridges, no smoke darkened the silver ribbon of the river, no coal-mine gashed the green hillside. Here and there a wreath of blue marked the hearth-fire of a forest home, or beyond a gap in the bluff a log-cabin stood amid the warm brown furrows of a clearing; but for the most part the Sangamon River road was broken through a sylvan wilderness.

There were walnut groves then, as there are still oaks and maples. Among the darker boles the trunks of sycamores gleamed. In the bottoms the satin foliage of the cottonwood shimmered in the sun, and willows silvered in the breeze. Honey-locusts, hawthorn and wild crab-apple trees were in bloom, dogwood made pallid patches in the glades and red-bud blushed. Wild flowers of low growth carpeted every grassy slope. The earth exhaled all those mysterious fragrances with which the year renews its youth. In April the mating season would be over and the birds silent, a brooding stillness possess an efflorescent Eden.

It was a long enough ride for a young man to indulge in memories and dreams. A tall, ungainly youth of twenty-six was this rising backwoods politician. He wore a suit of blue jeans, the trousers stuffed in the tops of cowhide boots; a hat of rabbit-fur felt, with so long a nap that it looked not unlike the original pelt, was pushed back from his heavy black hair. But below primitive hat and unruly hair was a broad, high forehead, luminous gray eyes of keen intelligence, softened by sympathy and lit with humour, features of rugged strength, and a wide mouth, full and candid and sweet. His wardrobe was in his saddle-bags; his library of law books, most of them borrowed, in a portmanteau on his saddle-bow; a hundred dollars or so of his pay as a legislator in his belt, and many times that amount pledged to debtors. His present living was precarious; his only capital reputation, courage, self-confidence and a winning personality; his fortune still under his shabby hat.

But this morning he was not to be dismayed. Difficulties dissolved, under this fire of spring in his heart, as the snow had melted in the sugar groves. The sordid years fell away from him; debts no longer burdened his spirit. That sombre outlook upon life, his heritage from a wistful, ill-fated mother, was dissipated in the sun of love.

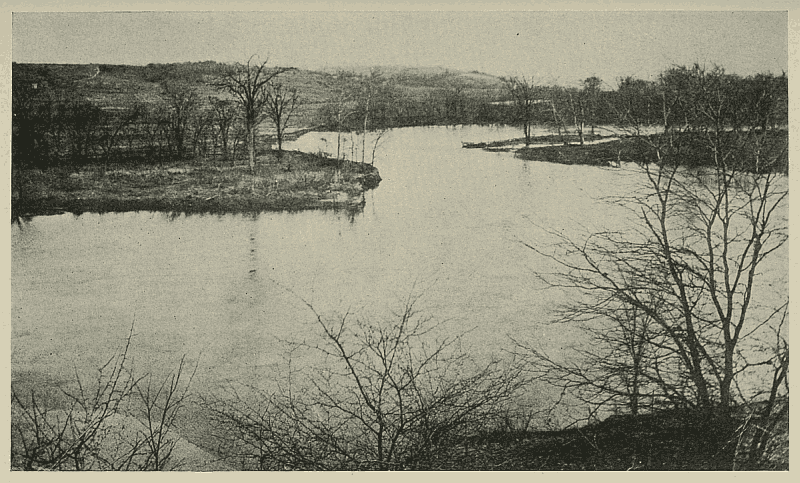

From Menard-Salem-Lincoln Album.

Above the dam at New Salem, Illinois.

It was on the bank of the Sangamon, near the dam, that Lincoln first saw Ann Rutledge.

It was on such an April morning as this, four years before, that he had first seen Ann Rutledge. She was in the crowd that had come down to the mill to cheer him when he got the flat-boat he was taking to New Orleans safely over New Salem dam. Ann was eighteen then, and she stood out from the villagers gathered on the bank by reason of a certain fineness of beauty and bearing. Her crown of hair was so pale a gold as to be almost flaxen. Besides always being noted as kind and happy, her eyes are described as a dark, violet-blue, with brown brows and lashes. Her colouring was now rose, now pearl, changing like the anemones that blow along the banks of the Sangamon.1

Hero of the day, the raw youth was taken up the bluff and over the ridge into the busy town of twenty log-houses and shops. He was feasted in the eight-room tavern of hewn logs owned by her father, James Rutledge, and for an hour entertained a crowd of farmers, emigrants, and shopkeepers with droll stories—stories that, unknown to him, would be repeated before nightfall over a radius of twenty miles. He was beginning to discover that men liked to hear him talk, and to wonder if this facility for making friends could be turned to practical use. But as a young man whose fancy had fed on a few books and many dreams, it may have meant more that this beautiful girl waited on the table, laughed at his jokes—too kind of heart, too gentle of breed, to laugh at his awkwardness—and praised his wit and cleverness and strength.

When he pushed his boat off, Ann waved her kerchief from the bank. He looked back at her outlined against the green bluff, to fix it in a memory none too well-furnished with such gracious pictures. He might never see her again. Poor, obscure, indifferently self-educated, unaware of his own powers, he saw before him, at that time, only the vagabond life of a river boatman, or the narrow opportunities of a farm labourer. But he displayed such qualities on that voyage as to win his employer. In July he returned to New Salem as a clerk in Denton Offutt’s store.

It is not probable that Lincoln was conscious of a pang when he heard that Ann Rutledge was engaged to marry John McNeill, proprietor of the best store in the town and of rich farming lands. Daughter of the mill and tavern owner, descended from a family of South Carolina planters that boasted a Signer of the Declaration, a Chief Justice of the Supreme Court under President Washington, and a leader in an early Congress, she was far above the penniless, undistinguished store-clerk. In the new West ability and worth could push itself to the front as nowhere else in the world, but pioneer society was not so democratic but that birth and wealth had their claims to consideration.

Most girls, at that time, were married at eighteen, but Ann was still studying under the Scotch schoolmaster, Mentor Graham. Lincoln met her often at the “spell-downs” with which the school closed the Friday afternoon sessions. When he returned from an inglorious Indian campaign the next year, he went to the Rutledge tavern to board. He had risen rapidly in public esteem, had captained a local company in the war, made a vigorous campaign for the legislature, and betrayed a wide and curious knowledge of books and public questions. A distinguished career was already predicted for him.

He and Ann were fast friends now, and for the next year and a half he saw her daily in her most endearing aspects of elder sister and daughter. It was a big, old-fashioned family of nine children, and Ann did the sewing and much of the spinning and weaving. At meal times she waited on the long tables, bringing platters of river fish, game, and pork from the kitchen fire-place, corn and wheat bread and hominy, milk and butter, honey and maple sugar, pots of coffee, and preserves made from wild berries and honey. Amid the crowds of rough men and the occasional fine gentleman, who could not but note her beauty and sweetness, Ann held an air of being more protected and sheltered in her father’s house than was often possible in a frontier tavern.

The meal over, she vanished into the family room. One chimney corner was hers for her low chair of hickory splints, her spinning wheel, and her sewing table, with its little drawer for thread and scissors. About her work in the morning she wore a scant-skirted tight-fitting gown of blue or brown linsey. But for winter evenings the natural cream-white of flax and wool was left undyed, or it was coloured with saffron, a dull orange that glorified her blond loveliness. She had wide, cape-like collars of home-made lace, pinned with a cameo or painted brooch, and a high comb of tortoise-shell behind the shining coil of her hair, that made her look like the picture of a court lady stepped out of its frame. Not an hour of privation or sorrow had touched her since the day she was born. On the women whom Lincoln had known and loved—his mother, his stepmother, and his sister—pioneer life had laid those pitiless burdens that filled so many early, forlorn graves. Ann’s fostered youth and unclouded eyes must have seemed to him a blessed miracle; filled him with determination so to cherish his own when love should crown his manhood.

The regular boarders at the tavern were a part of that patriarchal family—Ann’s lover McNeill, Lincoln, and others. The mother was at her wheel, the little girls had their knitting or patchwork, the boys their lessons. The young men played checkers or talked politics. James Rutledge smoked his pipe, read the latest weekly paper from St. Louis or Kaskaskia, and kept a fond eye on Ann.

The beautiful girl sat there in the firelight, knitting lace or sewing, her skilful fingers never idle; but smiling, listening to the talk, making a bright comment now and then, wearing somehow, in her busiest hour, an air of leisure, with all the time in the world for others, as a lady should. In the country parlance Ann was always spoken of as “good company.” Sweet-natured and helpful, the boys could always go to her with their lessons, or the little sisters with a dropped stitch or tangled thread. With the latest baby, she was a virginal madonna. Lincoln attended the fire, held Mrs. Rutledge’s yarn, rocked the cradle, and told his inimitable stories. When he had mastered Kirkham’s Grammar he began to teach Ann the mysteries of parsing and analysis.

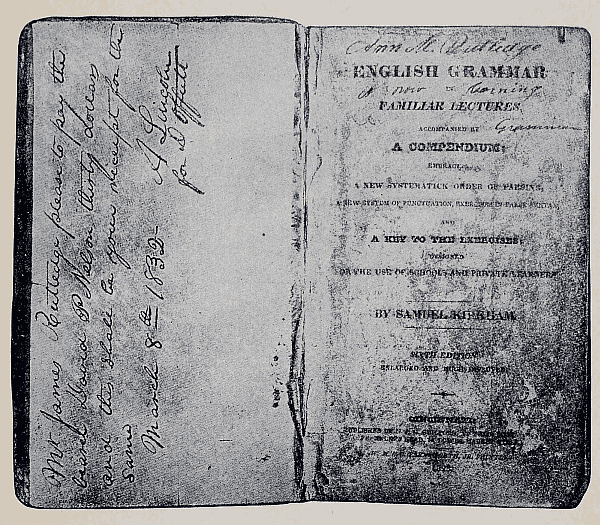

After the school debate one night a year before, Mentor Graham, one of those scholarly pedagogues who leavened the West with learning, had thrilled him with ambition by telling him he had a gift for public speaking, but that he needed to correct many inaccuracies and crudities of speech. Text books were scarce, but he knew of a grammar owned by a farmer who lived seven miles in the country. Lincoln got up at daylight, filled his pockets with corn dodgers, and went for that grammar. He must have bought it, paying for it in work, for he afterward gave it to Ann—his single gift to her, or at least the only one that is preserved. Her brother Robert’s descendants have to-day this little old text-book, inscribed on the title-page in Lincoln’s handwriting:

Ann M. Rutledge is now learning grammar.

The grammar which Lincoln studied as a young man.

It is said that Lincoln learned this grammar by heart, and it is the only gift which he is known to have given to Ann Rutledge.

How eloquent that battered, faded, yellow-leafed little old grammar is of the ambitions and attainments that set these two apart from the unrecorded lives in that backwoods community! Ann was betrothed, and her content and trust in her lover were something beautiful to see, but McNeill’s figure is vague. There is no description of him, few facts about him are remembered, except that he had prospered and won Ann Rutledge’s love. In the stories of the region, that have now taken on the legendary haze of cherished romance, Lincoln is the hero, long before he appears in the character of chivalrous suitor.

Oh, those long, intimate evenings! Twenty people were in the big, fire-lit family room, perhaps, storm outside and flames roaring merrily in the chimney. But they two, with a special candle on Ann’s little sewing-table, were outside the circle of murmurous talk and laughter, the pale gold head and the raven one close together over the hard-and-fast rules of the text book! Lincoln loved her then, unconsciously, must have loved her from the first, but he was incapable of a dishonourable thought, and Ann’s heart was all McNeill’s.

After Mr. Rutledge sold the mill and tavern in 1833 and moved to a farm, Lincoln lived much of the time at Squire Bowling Green’s, on a farm a half-mile north of the town, under the brow of the bluff. The jovial squire was a justice of the peace, a sort of local Solomon whose decisions were based on common sense and essential justice, rather than on the law or evidence. He had a copy of the Statutes of Illinois that Lincoln was going through. William G. Greene was there, too, much of the time, although he was in no way related to the Squire. This most intimate friend of Lincoln’s among the young men of New Salem was preparing to go to college. Aunt Nancy Green adored Lincoln, and said he paid his board twice over in human kindness and pure fun. Here he made his home most of the time until he went away to Springfield to practise law. It was while he was living at Squire Green’s, in the spring of 1834, that John McNeill suddenly sold his store and left for his old home, indefinitely “back East.” The event turned all Lincoln’s current of thought and purposes into new and deeper channels.

The reason McNeill gave was that he wanted to bring his old father and mother out West to care for them on his farm. When he returned he and Ann were to be married. It was a long journey, not without its perils—first across to Vincennes, Indiana, down the Wabash and up the Ohio to Pittsburg, then over the Alleghanies into New York State. It would be weeks between letters, a year at least before he could return. Many said openly that a man who was worth twelve thousand dollars, like John McNeill, could have his parents brought to him. What Ann thought no one ever knew. If she was hurt, she hid it in her loyal heart, not cherishing it against him, and James Rutledge did not object. Of a race in which honour and chivalry were traditions, it could not have occurred to him that any man lived so base as to break faith with his beloved daughter.

So Ann packed John McNeill’s saddle-bags, putting in every little comfort her loving heart could think of or her industrious fingers contrive, stepped up on the toe of her lover’s riding-boot to kiss him good-bye, then bade him God-speed and watched him ride away, not knowing that he was riding out of her life.

From a fresco painting in the State House, Springfield, Illinois.

Main Street of New Salem, Illinois.

Where Lincoln was postmaster, store clerk, politician and law-student.

Lincoln was the New Salem postmaster. In his journeys about the country—surveying, working in the harvest field, electioneering—he carried the mail of such farms as he passed in his hat or his saddle-bags. The pioneer postmaster was the confidant of those he served, in the absence of ministers and doctors. People read to him the letters they received, complained of neglect, demanded of him sympathy in their private joys and sorrows. And so it was he came close to the grief of Ann Rutledge.

Weeks went by, and there was no letter from the absent McNeill. Ann wrote often herself, tying the missives in wrapping paper with stout string, sealing them securely, and giving them to Lincoln to mail. Cheerful at first, her face grew wistful, her colour fled, her singing voice fell silent. Too loyal to suspect, too proud to complain, what fears possessed the lonely watches of the night, what hope awoke with each dawn, those who loved her best could only dimly guess. Her head held high in the pride of a faith unshaken, she asked for her letter only with a look, but such a look as one could scarce endure and the heart must ache to deny. Afterward she said she thought of her lover as dead. Steamboats often blew up in those days; there were swamps along the Wabash and the Ohio where men died of malarial fever; there were treacherous places in the mountains where a stumbling horse could end, in unrecorded tragedy, the sweetest human drama. In her heart she set up a shrine to a consecrated memory. For the one blow fate held for her she was unprepared.

In early summer there was a letter. Lincoln must have leaped on the nearest saddled horse and galloped out to the farm to give it to her. He slipped it into her hand unseen, saw the happy colour flood her face, and watched her speed away to the riverbank to read it. It was evening when she crept home again, in the radiance of the harvest moon, across the stubble of the wheat, like a dazed ghost.

It was not a letter that Ann could speak of to her father and mother with confidence and pride. McNeill had been ill on the journey—not so ill, however, that he could not have written. And his name was not McNeill, but McNamar. Family misfortunes had caused him to change his name out West so dependent relatives could not find him, thus giving the lie to his excuse for going back. He said nothing about returning, showed no remorse for his neglect, did not speak of her tender letters to him. Perhaps, in the old home, he had not cared to claim them under the name by which she knew him. It was a strange letter, heartless and without a spark of honour. But Ann had loved the man for four years, plighting her troth with him at seventeen. Although he had wounded her inrooted affections and faith, apparently deserted her without a pang, placed her in an intolerable position before a censorious world, she could not put him out of her mind and heart. She wrote to him again, with no reproaches, and she kept her own counsel.

Two more letters came at long intervals. Then they ceased altogether. In every sparsely settled community there is much curiosity about the unusual event, and some malice toward misfortune. Here offensive gossip ran about. It was reported that McNamar was a fugitive from justice—a thief, a murderer, that he already had a wife in the East. The talk enraged her father, and enveloped sweet Ann Rutledge in an atmosphere of blight. The truth—that he had tired of her—was surely not so bad as these rumours of criminal acts. With that element of the maternal that underlies the love of women for men, she came to the defence of his good name. She showed her father the letters, laying the sacrifice of her rejected self on the altar of a lost, unworthy love.

But it had the opposite effect she intended. In James Rutledge’s Southern code this was the blackest thing a man could do. A thousand miles of wilderness separated him from the scoundrel who had broken the heart of his daughter! Was John McNamar to go unpunished? Not an old man, he seemed to break up physically under the blow. Public sympathy was with him and with the deserted girl. Her father was her lover now, surrounding her with every attention and tender care. It was remarked in a day and place when family affection was not demonstrative. Again, in the country parlance, it was said: “James Rutledge is just wrapped up in Ann.”

A new element was added to this absorbing drama when Lincoln began to pay open court to Ann, publishing it far and wide that he would be proud to win what McNamar had not cared to keep. A wave of enthusiastic admiration swept over the country-side. Nothing else was talked of in the town and around the mill. His chivalrous love may well have played its part in his spectacular campaign for the legislature, and his triumphant election in August.

Ann gave no encouragement to his suit. To Lincoln, who was reading Jack Kelso’s precious copy of Shakespeare’s plays at the time, his love must have seemed another Ophelia, crushed by unkindness, bewildered by a world in which men could break faith. As she shrank from the blunt perception of curious neighbours she came to lean more and more on Lincoln’s devotion. It had in it, permeating its human quality, that divine compassion which, enlarged, was afterward to free a race. He wanted to free her spirit from bonds of the past. In the early days of his wooing his personal feeling and hopes were put in the background.

He persuaded Ann to study with him again. All that long autumn, while the walnuts turned to gold, the maples flamed across the world, and the oaks poured their cascades of red wine over the bluffs, they were together. Often the two were seen under a giant sycamore, on a hill below the town and overlooking the river, Ann puzzling over conjugations, Lincoln sprawled at her feet reading Blackstone’s Commentaries. It was such an extraordinary thing in that unlettered region that it was remarked ever after by those who saw it. It was an affair of public interest, and now of publicly expressed satisfaction at the happier turn of events. The world not only loves a lover, but it loves wedding bells at the end of the story. The first frost touched the forests with a magic wand, then Indian summer lay its bloomy haze over the landscape like the diaphanous veil that parts a waiting soul from Paradise. With the gales and snows of December Lincoln rode away for his winter of lawmaking at Vandalia.

Now, indeed, letters came for Ann across the white silence that lay in the valley of the Sangamon. Dated from the state capital they were, written with the quill pens and out of the cork inkstands the commonwealth provided. Not one of these letters is in existence to-day. They could not have been love-letters in the conventional sense, but eloquent of that large comradeship love holds for men and women of rare hearts and minds. For the first time he had come into contact with the men who were shaping the destinies of his state, measuring his capacities with theirs, and finding that he did not differ from them much in kind or degree. His ambition took definite shape. He saw a future of distinction and service such as he would be proud to ask Ann to share.

What pictures of men and the times he must have drawn for her! In those pioneer days only a few of the public men were backwoods lawyers like himself. Some, indeed, and many of the best, expressed the native genius and crude force that were transforming the wilderness. But there were old-world aristocrats, to whom the English language even was exotic, from Kaskaskia and the French mission towns, more than a century old, on the Mississippi. And there were Southern planters of wealth, whose fiery code always held for Lincoln an element of the absurd. Eastern men too, were there, with traditions of generations of learning and public service, and some “Yankees” with an over-developed shrewdness that the others agreed in detesting. Chicago was only an upstart village; northern Illinois just opened up to emigration from the East; southern Illinois was of the South, in population and sentiment, with the added grace of French manners. The capital was a tiny city, but it had high-bred society into which Ann would fit so well. There would be humorous anecdotes in those letters, too, to restore the gaiety of her heart, for, much as he loved men, their foibles and failings furnished him infinite amusement.

The lonely girl could not but be cheered by these letters and have her outlook on life enlarged by them, so that her own experience dwindled somewhat in the perspective. She wrote to him—girlish, grateful letters—saying nothing of McNamar, and showing how pathetically she leaned on him. On his homeward ride in the sweet spring weather his mind dwelt on her with a tenderness no longer forbidden, no longer hopeless of its reward.

Squire Green’s farm lay to the north of New Salem, so that, on this day of his return, he must have avoided the village, its clamorous welcome, its jesting surmises. In fancy he could imagine that lovable vagabond, Jack Kelso, fishing from the pier below the dam, catching sight of him out of the tail of a mischievous Irish eye, and announcing his arrival with a tender stanza from “Annie Laurie.” The sympathy of town and country-side was with him in his wooing, and it warmed his heart; but to-day was sacred to love.

He turned from the road into the ravine toward the big cabin of hewn logs that nestled under the brow of the bluff. We know that a grove of forest trees surrounded it and a young apple orchard, in blossom in April, concealed it from the highway and river. If it was after the noon hour the men would have gone back to their ploughing, and Aunt Nancy Green, in a gown of lilac print, be sitting with her patchwork in the orchard, where she could smell the bloom, keep an eye on strolling, downy broods, and watch the honey-bees fill her hives. The Squire was there, too, very likely, tilted back in his wide chair of hickory splints, asleep. He was a well-to-do man, and as he weighed two hundred and fifty pounds he took life easy, and was never far away from the slender shadow cast by busy “mother.”

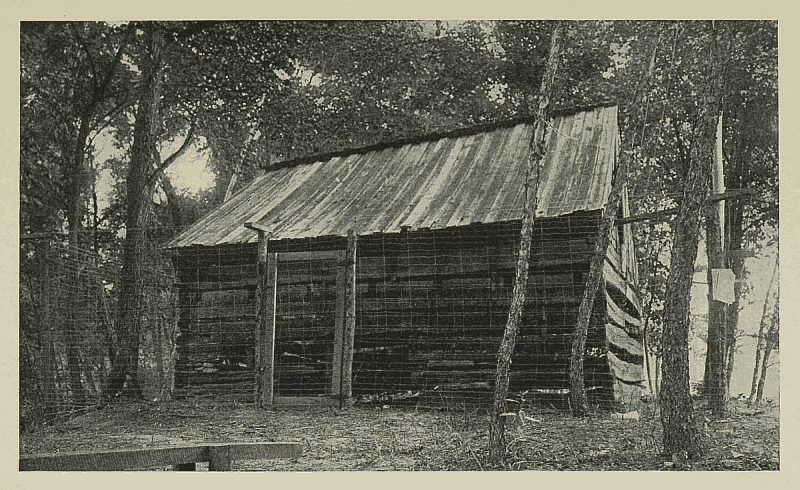

Photograph by C. U. Williams, Bloomington, Ill.

Lincoln’s Old Home.

Squire Bowling Green’s Cabin, near New Salem, Illinois, as it appears to-day.

Lincoln lived here from 1834 to 1837. It was in this cabin that he mourned the death of Ann Rutledge.

“Yes, Bill was some’ers ’round,” but lively Aunt Nancy ventured an affectionate joke, saying she “reckoned Abe wasn’t pinin’ to see Bill as much as he was someone else.” She was willing to get his dinner in the middle of the afternoon, but he had to pay for it with his best new stories. A visit with Aunt Nancy, his books arranged on the shelf he had built above his table in the chimney corner, a swim in a warm shallow pool in the Sangamon, then up the ladder-like stair to the loft chamber he often shared with the friend of his youth, to dress for Ann!

Lincoln is described, about this time, by Harvey Ross, who carried the mail over the star-route of central Illinois, as having a summer suit of brown nankeen, with a white waistcoat sprigged with coloured flowers. The wide, soft collar of his white shirt rolled back over a neck-cloth made of a black silk, fringed handkerchief. His hat was of brown buckeye splints, the pioneer’s substitute for straw. It was in this fashion he must have appeared as he walked back along the river and across the fields when he went to urge his love for Ann Rutledge.

In old patch-work quilts, cherished as the work of our great-grandmothers, we may see to-day bits of cotton print—white with coloured pin-dots, indigo blue and oil red, and violet and pink grounds powdered with tiny, conventional figures and flowers in white. They remind us of old-fashioned gardens of perennials where lilacs, damask roses, and flowering almonds bloomed. A young girl like Ann would have one such pink gown to wear on warm evenings; and a quilted and ruffled sun-bonnet of sheer muslin, not to wear seriously, but to hang distractingly by the strings around her white neck. There was little self-consciousness about her, and no coquetry at all. Ann never teased; she was just simple and sincere and sweet. But it would be instinctive with her to pick up the grammar as an excuse for the stroll along the bluff with her lover.

Of an oak or a maple, no matter how dense the foliage, one has a distinct image of the individual leaf; but of the sycamore—the American plane-tree—you may see thousands, and carry away only an impression of a silvery column and an enormous dome of green gossamer—a diaphanous mesh of vernal lace, whose pattern dissolves momently in the sun, and frays and ravels in the wind. When they came to where the sycamore was weaving its old faery weft in the sunset light, she laid the bonnet on the grass, and listened to his stories and comments on the new men and things he had seen, until he made her laugh, almost like the happy girl of old tavern days; for Lincoln was a wizard who could break the spell of bad dreams and revive dead faiths. A pause, a flutter of hearts as light as the leaf-shadows, and a hasty question to cover the embarrassment. There was a puzzling point in her grammar lesson—how can adverbs modify other adverbs?

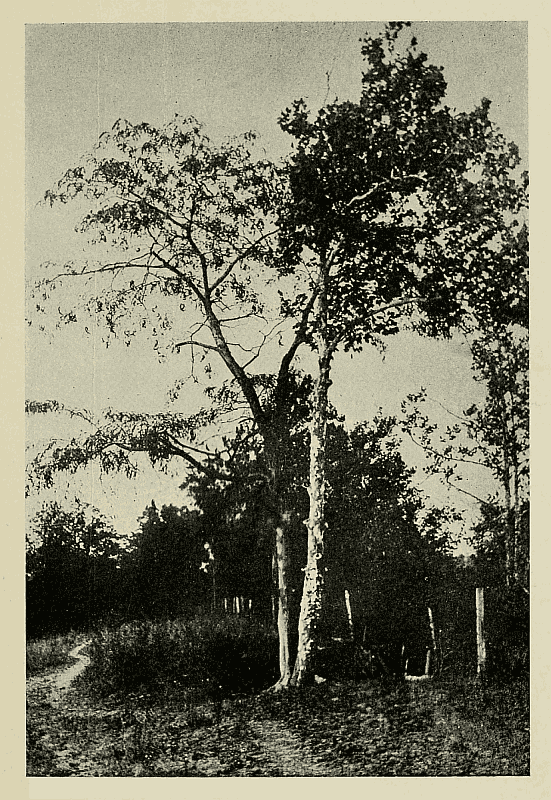

Photograph by C. U. Williams, Bloomington, Ill.

The top of the hill, New Salem, Illinois.

The honey locust and sycamore, growing together from a slight depression that marks the site of Denton Offutt’s store, are known as the “Lincoln Trees.”

Yes, he had been puzzled by that, too, and Mentor Graham had helped him with an illustration.

I love you very dearly!

Oh yes, she understood now! A burning blush, a gasping sigh at the shock of flooding memory! She still struggled to forget this blighting thing. But could she ever again listen to such words without pain or shame? She had the courage of a proud race. If her lips trembled, she could at least lift her eyes to meet that immemorial look of brooding tenderness, and she could ask timidly if he would hear her recite the conjugation of the regular verb to see if she had forgotten.

Why is it that these sober old grammars, full of hard-and-fast rules—and bewildering exceptions—strewing the path of learning with needless thorns and obstructions of every sort, still instinctively chose the one verb ardent youth conjugates with no teaching at all? First person, singular number, present tense, declarative mood—I love, transitive, requiring an object to complete its meaning, as life itself requires one—you.

No pause! The story neither begins there, nor ends. How tireless that confession; how thrilling that mutual self-analysis; what glamour over every aspect! Past, to the beginning of things, future to Eternity; the insistent, pleading interrogative, do you love; the absurd potential, as if there ever was any may or might about it; the inevitable, continuing state, loving; the infinitive to love—all the meaning and purpose of life; and the crown of immortality to have loved. Then that strange, introspective subjunctive, wild with vain regret, that youth ponders with disbelief that Fate could ever so defraud—that a few lonely souls have had to con in the sad evening of empty lives:

If we had loved!

O, sweet Ann Rutledge, could you endure to look back across such arid years and think of this lover denied? No! No matter what life yet held for them of joy or sorrow, the conjugation is to be finished with the first person plural, future-perfect, declarative. At the very worst—and best—and last, robbing even death of its sting, at least:

We shall have loved.

And so they sat there long, in the peaceful evening light, looking out across the river with the singing name, that purls and ripples over its gravelly bars and sings the story of their love, forever!

No one who saw the two together that summer ever forgot it. Pioneer life was too often a sordid, barren thing, where men and women starved on bread alone. So Lincoln’s mother had dwindled to an early grave, lacking nourishment for the spirit. Courtship, even, was elemental, robbed of its hours of irresponsible idleness, its faery realm of romance. To see anyone rise above the hard, external facts of life touched the imagination of the dullest. In his public aspect a large part of Lincoln’s power, at this time, was that he expressed visibly community aspirations that still lay dormant and unrecognized. Now, he and Ann expressed the capacities of love of the disinherited. To the wondering, wistful eyes that regarded them, they seemed to have escaped to a fairer environment of their own making—of books, of dreams, of ambitions, of unimagined compatibilities.

He borrowed Jack Kelso’s Burns and Shakespeare again, to read with Ann. Together they read of Mary, loved and lost; of Bonnie Doon, and Flow Gently, Sweet Afton, that plea to old mother-earth for tenderness for one gone beyond loving. With no prescience of disaster they read that old love tragedy of Verona.

The young and happy can read these laments without sadness. They sound the depths of passion and the heights of consecration. They sing not only of dead loves, but of deathless love, and they contract the heart of youth with no fear of bereavement. Young love is always secure, thrice ringed around with protecting spells and enchantment; death an alien thing in some distant star. The banks of the Sangamon bloomed fresh and fair that golden summer, the meadow-lark sang unreproached, the flowing of the river accompanied only dreams of fuller life.

They knew Italy for the first time, think of the wonder of it!—as something more than a pink peninsula in the geography—felt the soft air of moon-lit nights of love throb with the strain of the nightingale. There are no nightingales in America, but when he took the flat-boat down to New Orleans—Did she remember waving her kerchief from the bank? When the boat was tied up in a quiet Louisiana bayou one night, he heard the dropping-song of the mockingbird. That was like Juliet’s plea: “Oh love, remain!”

What memories! What discoveries! What searching self-revelations by which youth leads love back through an uncompanioned past, finding there old experiences, trivial and forgotten until love touches and transforms them. Life suddenly becomes spacious and richly furnished. Lincoln’s old ties of affection were Ann’s now, dear and familiar; his old griefs. In tender retrospect she shared that tragic mystery of his childhood, his mother’s early death. And, like all the other women who ever belonged to him, she divined his greatness—had a glimpse of the path of glory already broadening from his feet.

She set her own little feet in that path, determined that he should not outdistance her if she could keep up with his strides. They could not be married until he was admitted to the bar, so she took up her old plan of going to Jacksonville Academy. Her brother David was going to college there, and then was to study law with Lincoln. What endearing ties were beginning to bind him to her family! They spent long afternoons studying, and Lincoln made rapid progress, for his mind was clear and keen, freed from its old miasma of melancholy.

But they seemed curiously to have changed characters. Ann had been the one of placid temperament, dwelling on a happy level of faith in a kind world. Lincoln had, by turns, been hilarious and sunk in gloom. Privations and loss had darkened his youth; promise lured his young manhood only to mock; powers were given him only to be baffled. But now life was fair, the course open, the goal in sight, happiness secure! For Ann had the quiet ways, the steadfast love, and the sweet, sweet look, in which a man, jaded and goaded by the world of struggle, could find rest. Surely fate had played all her malicious tricks! It was enough for him, that summer, to lie at his lady’s feet, his elbows in the grass, his shock head in his hands, absorbed in Chitty’s “Pleadings.”

Ann studied fitfully, often looking off absently across field and river, starting from deep reverie when he spoke to her. Her mother noticed her long, grave silences, but thought of them as the pensive musings of a young girl in love. This impression was increased by her absorption in her lover. When with him, talking with him, a subtle excitement burned in her eye and pulsed in her cheek; but when he was gone the inner fire of her spirit seemed to turn to ashes. She clung desperately, visibly, to this new love—so infinitely more precious and satisfying than the old. She did not doubt its reality, but happiness, in the nature of things, was to her, now, evanescent and escaping.

People remembered afterward, as the days lengthened, how fragile Ann looked, as if withered by hot, sleepless nights—how vivid and tremulous. She had spells of wild gaiety, her laughter bubbling up like water from a spring, and she grew lovelier, day by day. And there were times, when Lincoln was away in the harvest-field or on surveying trips, that she sat pale and listless and brooding for hours, with hands that had always been so busy and helpful, clasped idly in her lap.

Like Juliet, she must often have cried in her secret heart, “Oh, love, remain!” Left alone, she became the prey of torturing thoughts. Life had dealt Ann Rutledge but one blow, but that had struck to the roots of her physical and spiritual life. Her world still tottered from the shock. If she had confessed all her first vague, foolish fears, her mind might have been freed of their poison. But she came of brave blood and tried to fight her battle alone.

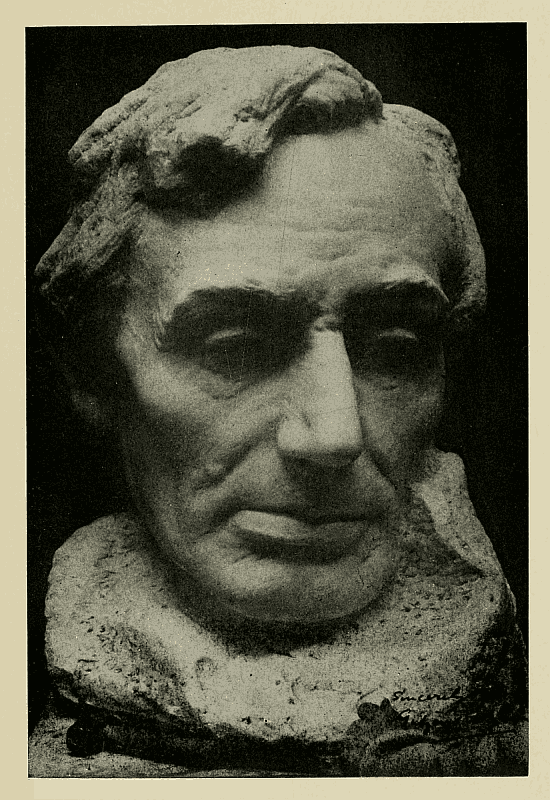

Copyright, 1907, by Gutzon Borglum.

Gutzon Borglum’s conception of Abraham Lincoln.

Considered the most inspired head of Lincoln ever modelled.

From the memorial head in the Capitol, Washington, D. C.

At last, worn out with mental and moral wrestlings, she turned to her father for help. Lincoln was working at high pressure and he had some perplexities of debts. She shrank from troubling him.

Her heart must have beat in slow, suffocating throbs when she crept to her father’s arms and confessed her fears:

What if McNamar should come back!

She need not trouble her golden head about that! The country would be too hot to hold him. Lincoln had thrashed the breath out of a man for swearing before women in his store.

But what if he still loved her, trusted her, was on his way back, confident and happy, to claim her? What if he could lift this veil of mystery and stand forth clear and manly?

McNamar would never appear in such guise, bless her innocent heart. He was a black-hearted scoundrel. In the old days, in South Carolina, men of the Rutledge breed would have killed such a hound. But he was alarmed now, surely, at this strange obsession, and questioned her. And then the whole piteous truth was out.

She was afraid he would come back—shuddering at the thought—come back to reproach her with pale face and stricken eyes. And she loved him no longer. She had been so happy this summer, and then it began to seem all wrong. Love forsaken was such pain and bewilderment. Could she endure happiness purchased at the price of another’s misery?

McNamar had come back, indeed, and love was impotent to defend this hapless innocence! She had never understood his behaviour. Incapable of such baseness herself, she had never comprehended his. Like a flower she had been blighted by the frost of his desertion, and had revived to brief, pale life in a new sun; but the blight had struck to the root.

But what beauty of soul was here revealed, adding poignancy to grief! No one had quite known her. Physically so perfect, no one had divined those exquisite subtleties of the heart that made her hold on life tenuous. Lincoln was sent for but he was not found at once, for his employments kept him roving far afield. Round and round, in constantly contracting circles, her inverted reason, goaded by an accusing conscience ran until, at last, her sick fancy pictured herself as the faithless one. The event was forgotten—she remembered only the agony of love forsaken. And so she slipped away into the delirium of brain fever.

Lincoln had one anguished hour with her in a brief return to consciousness. It was in the living-room of a pioneer log-cabin, untouched by grace or beauty; homely, useful things about them, the light on her face coming through a clapboard door open to the sun and wind of an unspoiled landscape. The houses of the wealthiest farmers were seldom more than two big rooms and a sleeping loft, and privacy the rarest, most difficult privilege. Her stricken family was in the kitchen, or out of doors, to give them this hour of parting alone. What was said between them is unrecorded. When she fell into a coma, Lincoln stumbled out of that death-chamber like a soul gone blind and groping. Two days later Ann Rutledge died.

As a pebble falling from a peak in the Alps may start an avalanche on its path of destruction, so one man’s unconsidered sin may devastate many lives. The tragedy shocked the country for twenty miles around. It had the elements and proportions of a classic tale, so that to-day, when it is three-quarters of a century gone by, the great-grandchildren of those who witnessed it speak of it with hushed voices. Lincoln’s mission and martyrdom imbued it with those fates that invest old Greek drama. James Rutledge died three months later, at the age of fifty-four, it was currently believed of a broken heart.2 The ambitious young brother David, who was to have been Lincoln’s partner, died soon after being admitted to the bar. The Rutledge farm was broken up, the family scattered. Lincoln came to the verge of madness.

A week after the funeral William G. Greene found him wandering in the woods along the river, muttering to himself. His mind was darkened, stunned by the blow. He sat for hours in a brooding melancholy that his friends feared would end in suicidal mania. Although some one always kept a watchful eye upon him, he sometimes succeeded in slipping away to the lonely country burying ground, seven miles distant. There he would be found with one arm across her grave, reading his little pocket Testament. This was the only book he opened for months.

All that long autumn he noticed nothing. He was entirely docile, pitifully like a child who waits to be told what to do. Aunt Nancy kept him busy about the house, cutting wood for her, picking apples, digging potatoes, even holding her yarn; the men took him off to the fields to shock and husk corn. All of them tried, by constant physical employment, to relieve the pressure on his clouded mind, love leading them to do instinctively what the wisest doctors do to-day. In the evenings he sat outside the family circle, sunk in a brown study from which it was difficult to rouse him. It was a long and terrible strain to those devoted friends who protected and loved him in that anxious, critical time. Not until the first storm of December was there any change.

It was such a night of wind and darkness and snow, as used to cause dwellers in pioneer cabins, isolated from neighbours at all times, but now swirled about, shut in, and cut off other from human life by the tempest, to pile the big fireplace with dry cord-wood, banking it up against the huge back-log, and draw close together around the hearth, to watch the flames roar up the chimney. There would be hot mulled cider to drink, comforting things to eat, and cheerful talk.

Lincoln was restless and uneasy in his shadowy corner. His eyes burned with excitement. When he got up and wandered about the room William followed him, fearing he might do himself harm. He went to the door, at last, threw it open and looked out into the wild night. Turning back suddenly, his hands clenched above his head, he cried out in utter desolation:

“I cannot bear to think of her out there alone, in the cold and darkness and storm.”

The ice of his frozen heart was unlocked at last, and his reason saved. But there were months of bitter grief and despair that wore him out physically. His fits of melancholy returned, a confirmed trait that he never lost. In time he went back to his old occupations, bearing himself simply, doing his duty as a man and a citizen. His intellect was keener, his humour kindlier; to his sympathy was added the element of compassion. And on his face—in his eyes and on his mouth—was fixed the expression that marks him as our man of sorrows deep and irremediable.

Until he went away to Springfield a year later to practise law, he disappeared at times. Everyone knew he was with Ann, sitting for hours by the grassy mound that covered her. Once he said to William G. Greene: “My heart is buried in the grave with that dear girl.”

The place was in a grove of forest trees on the prairie at that time, but afterward the trees were cut down or neglected, and it became choked with weeds and brambles—one of those forlorn country burying-grounds that marked the passing of many pioneer settlements. For in 1840 New Salem was abandoned. The year after Ann Rutledge died, Lincoln surveyed and platted the city of Petersburg, two miles farther north on the river. A steam mill built there drew all the country patronage. Most of the people of New Salem moved their houses and shops over to the new town, but the big tavern stood until it fell and the logs were hauled away for firewood. The dam was washed out by floods, the mill burned. To-day, the bluff on which the town stood has gone back to the wild, and the site is known as Old Salem on the Hill.

The Bowling Green farm passed into the possession of strangers. Many years ago the cabin of hewn logs was moved from under the brow of the bluff down to the bank of the river and turned into a stable. More than eighty years old now, this primitive structure that was Lincoln’s home for three years, still stands. Every spring it is threatened by freshets. You look across the flooded bottom land to where it stands among cottonwoods and willows, and think—and think—that this crumbling ruin, its squared logs worn and shrunken and parted, its clapboard roof curled, its crazy door sagging from the post, rang to that cry of desolation of our country’s hero-martyr. He lies under a towering marble monument at Springfield, twenty miles away. There is his crown of glory; here his Gethsemane.

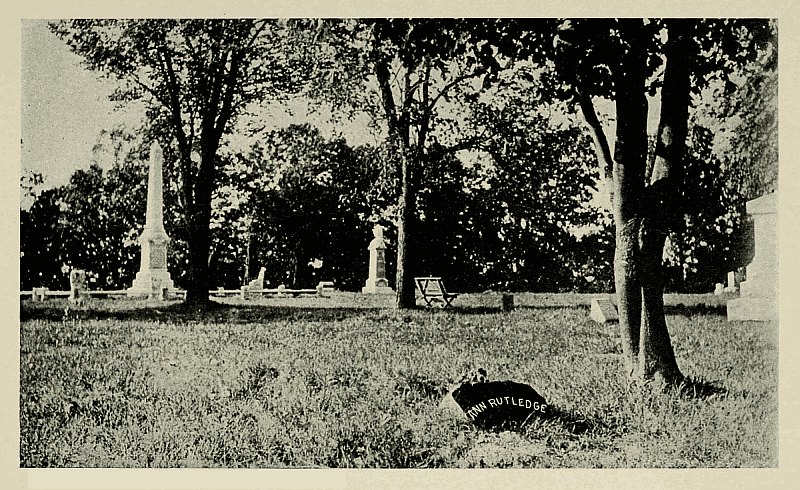

Photograph by C. U. Williams, Bloomington, Ill.

The grave of Ann Rutledge, Oakland Cemetery, Petersburg, Illinois.

Twenty years ago Ann Rutledge was brought in from the country burying-ground and laid in Oakland Cemetery, in Petersburg. Only a field boulder marks the mound to-day, but the young girls of the city and county, who claim her as their own, are to celebrate Lincoln’s centennial year by setting up a slender shaft of Carrara marble over the grave of Lincoln’s lost love. Around her, on that forest-clad bluff, lie Old Salem neighbours. It is a cheerful place, where gardeners mow the grass and sweep the gravelled roadways, where carriages drive in the park-like enclosure on Sunday afternoons and flowers are laid lavishly on new-made graves. Bird-haunted, robins chirp in the blue grass and woodpeckers drum on the tree-trunks; bluebirds, tanagers and orioles, those jewels of the air with souls, flash across the sunlit spaces, and the meadow-lark trills joyously from a near-by field of clover.

No longer is she far away and alone, in cold and darkness and storm, where he could not bear to think of her, but lying here among old friends, in dear familiar scenes, under enchantment of immortal youth and deathless love, on this sunny slope, asleep....

Flow gently, sweet Sangamon; disturb not her dream.

There are two descriptions of Ann Rutledge, one by W. H. Herndon. The other, not so well known, is by T. G. Onstot, son of Henry Onstot, the New Salem cooper, in his “Pioneers of Mason and Menard.” Mr. Onstot is still living, at the age of eighty in Mason City, Illinois, the sole survivor of the historic settlement on the Sangamon, and an unquestioned authority on the history of the region. He was six years old when Ann Rutledge died. He does not profess to remember her personally, but to have got her description from his father and mother. The families were next-door neighbours for a dozen years, and life-long friends. Herndon lived in Springfield. Mr. Onstot’s description is used here as, in all probability, the correct one, for this reason, and also because it is more in keeping with the character of Ann Rutledge, as revealed in her tragic story.

| The following corrections have been made in the text: | |

| 1 — |

‘yath’ replaced with ‘path’ (an avalanche on its path) |