Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

List of Illustrations

(In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the illustration.)

will bring up a larger version of the illustration.)

Contents.

Chapter I.,

II.,

III.,

IV.,

V.,

VI.,

VII.,

VIII.,

IX.,

X.,

XI.,

XII.,

XIII.,

XIV.,

XV.,

XVI.,

XVII.,

XVIII.,

XIX.,

XX.,

XXI.,

XXII.,

XXIII.,

XXIV.,

XXV.,

XXVI.,

XXVII.,

XXVIII.,

XXIX.,

XXX.,

XXXI.,

XXXII.,

XXXIII.,

XXXIV.,

XXXV.,

XXXVI.,

XXXVII.

(etext transcriber's note) |

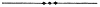

JULIAN HAWTHORNE.

JULIAN HAWTHORNE.

“OUR CONTINENT” LIBRARY.

D U S T:

A NOVEL

BY

Julian Hawthorne,

Author of “Bressant,” “Sebastian Strome,” “Idolatry,”

“Garth,” etc.

NEW YORK:

FORDS, HOWARD, & HULBERT

1883

COPYRIGHT, 1882,

By Julian Hawthorne.

All rights reserved.

|

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Julian Hawthorne (Portrait), | Frontispiece. |

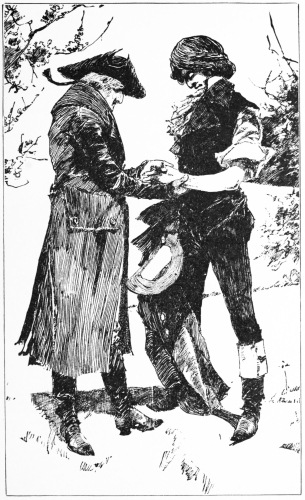

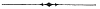

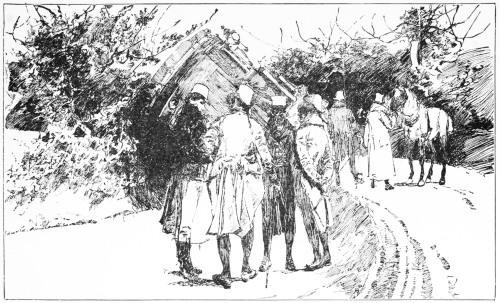

| “I am a Bit of a Surgeon; Let me Look

at Your Arm,” | 14 |

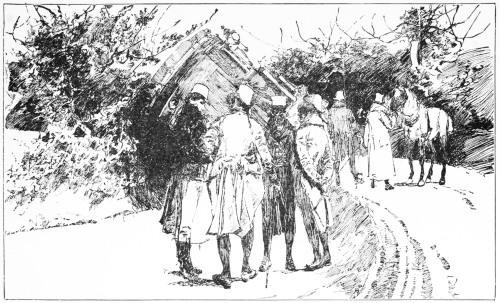

| “Pulling Themselves Together and Discussing

the Magnitude of Their

Disaster,” | 86 |

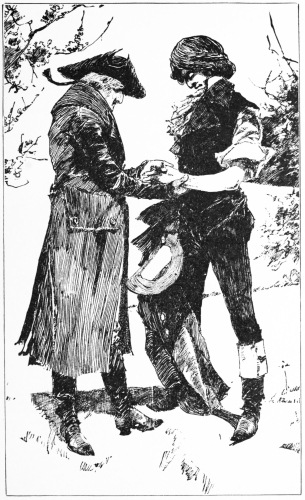

| “I Tied the Card to the Gate Myself.

Nobody can Fail to See it,” | 134 |

“Only the Actions of the Just

Smell Sweet and Blossom in the Dust.”

DUST.

CHAPTER I.

THE time at which this story begins was a time of many beginnings and

many endings. The Eighteenth Century had expired the better part of a

score of years before, and everything was in confusion.

Youth—tumultuous, hearty, reckless, showy, slangy, insolent, kindly,

savage—was the genius of the hour. The Iron Duke had thrashed the

Corsican Ogre, England was the Queen of nations, and Englishmen thought

so much of themselves and of one another that society, for all its

caste, became well-nigh republican. Gentlemen were bruisers and bruisers

were gentlemen. At Ranelagh and Vauxhall fine ladies rubbed shoulders

with actresses, magistrates foregathered with jockeys and sharpers, and

the guardians of public order had more to fear from young bloods and

sprigs of nobility than from professional thieves and blacklegs.

Costumes were grotesque and irrational, but were worn with a dash and

effrontery that made them becoming. There were cocked hats and

steeple-crowned hats; yards of neck-cloth and mountains of coat-collar;

green coats and blue coats, claret coats and white coats; four or five

great coats, one on top of another; small clothes and tight breeches,

corduroys, hessians and pumps. Beards were shaved smooth, and hair grew

long. Young ladies wore drab josephs and flat-crowned beaver bonnets,

and rode to balls on pillions with their ball clothes in bandboxes. The

lowest of necks were compensated by the shortest of waists; and the

gleam of garter-buckles showed through the filmy skirts that scarcely

reached to the ankle. Coral necklaces were the fashion, and silvery

twilled silks and lace tuckers; and these fine things were laid up in

lavender and rose leaves. Hair was cropped short behind and dressed with

flat curls in front. Mob-caps and top-knotted caps, skull-caps and

fronts, turbans and muslin kerchiefs, and puffed yellow satins—these

things were a trifle antiquated, and belonged to the elder generation.

Gentlemen said “Dammy, sir!” “Doosid,” “Egad,” “Stifle me!” “Monstrous

fine,” “Faith!” and “S’blood!” The ladies said, “Thank God!” “God

A’mighty!” and “Law!” and everybody said “Genteel.” Stage-coaches and

post-horses occupied the place of railways and telegraphs, and driving

was a fine art, and five hours from Brighton to London was monstrous

slow going. Stage-coachmen were among the potentates of the day; they

could do but one thing, but that they did perfectly; they were clannish

among themselves, bullies to the poor, comrades to gentlemen,

lickspittles to lords, and the high-priests of horse-flesh, which was at

that epoch one of the most influential religions in England; pugilism

being another, caste a third, and drunkenness the fourth. A snuff-box

was still the universal wear, blue-pill was the specific for liver

complaint, shopping was done in Cheape and Cornhill; fashionable bloods

lodged in High Holborn, lounged at Bennet’s and the Piazza Coffee-House,

made calls in Grosvenor Square, looked in at a dog-fight, or to see

Kemble, Siddons or Kean in the evening, and finished the night over

rack-punch and cards at the club. Literature was not much in vogue,

though most people had read “Birron” and the “Monk,” and many were

familiar with the “Dialogues of Devils,” the “Arabian Nights,” and

“Zadkiel’s Prophetic Almanac;” while the “Dairyman’s Daughter” either

had been written or soon was to be. Royalty and nobility showed

themselves much more freely than they do now. George the Third was still

King of England, and George, his son, was still the first gentleman and

foremost blackguard of Europe; and everything, in short, was outwardly

very different from what it is at the present day. Nevertheless,

underneath all appearances, flowed then, as now, the mighty current of

human nature. Then, as now, mothers groaned that infants might be born;

poverty and wealth were married in every human soul, so that beggars

were rich in some things and princes poor in others; young men and women

fell in love, and either fell out again, or wedded, or took the law into

their own hands, or jilted one another, just as they do now. Men in

power were tyrannous or just, pompous or simple, wise or foolish, and

men in subjection were faithful or dishonest, servile or

self-respectful, scheming or contented, then as now. Then, no less than

now, some men broke one Commandment, some another, and some broke all;

and the young looked forward to a good time coming and the old

prophesied misfortune. At that epoch, as in this, Death plied his trade

after his well-known fashion, which seems so cruel and arbitrary, and is

so merciful and wise. And finally—to make an end of this summary—the

human race was predestined to good, and the individual human being was

free to choose either good or evil, the same then as now and always.

And—to leave generalities and begin upon particulars—it was at this

time that Mrs. Lockhart (who, seven-and-forty years ago, as lovely Fanny

Pell, had cherished a passing ideal passion for Handsome Tom Grantley,

and had got over it and married honest young Lieutenant Lockhart)—that

Mrs. Lockhart, we say, having lost her beloved Major at Waterloo, and

finding herself in somewhat narrow circumstances, had made up her mind

to a new departure in life, and had, in accordance with this

determination, caused her daughter Marion to write “Lodgings to Let” on

a card, and to hang the same up in the window of the front drawing-room.

This event occurred on the morning of the third of May, Eighteen hundred

and sixteen.

CHAPTER II.

THAT same day the Brighton coach was bowling along the road to London at

the rate of something over five minutes to the mile, a burly, much

be-caped Jehu on the box and a couple of passengers on the seat on

either side of him. The four horses, on whose glistening coats the

sunshine shifted pleasantly, seemed dwarfed by the blundering structure

which trundled at their heels, and which occasionally swayed top-heavily

from side to side like a vessel riding the seas. Jehu had for the time

being surrendered the reins to the young gentleman who sat beside him.

The youth in question was fashionably dressed, so far as could be judged

from the glimpses of his attire that showed beneath the layers of

benjamins in which his rather diminutive person was enveloped. His

narrow face wore a rakish but supercilious expression, which was

enhanced by his manner of wearing a hat shaped like a truncated cone

with a curled brim. He sat erect and square, with an exaggerated

dignity, as if the importance of the whole coach-and-four were

concentrated in himself.

“You can do it, Mr. Bendibow—you can do it, sir,” remarked Jehu, in a

tone half-way between subservience and patronage. “You’ve got it in you,

sir, and do you know why?”

“Well, to be sure, I’ve had some practice,” said Mr. Bendibow, conscious

of his worth and pleased to have it commended, but with the modesty of

true genius, forbearing to admit himself miraculous.

Jehu shook his head solemnly. “Practice be damned, sir! What’s

practice, I ask, to a man what hadn’t got it in him beforehand? It was

in your blood, Mr. Bendibow, afore ever you was out of your cradle, sir.

Because why? Because your father, Sir Francis, as fine a gen’lman and as

open-handed as ever sat on a box, was as good a whip as might be this

side o’ London, and I makes no doubt but what he is so to this day.

That’s what I say, and if any says different why I’m ready to back it.”

In uttering this challenge Jehu stared about him with a hectoring air,

but without meeting any one’s eye, as if defying things in general but

no one in particular.

“Is Sir Francis Bendibow living still? Pardon me the question; I

formerly had some slight acquaintance with the gentleman, but for a good

many years past I have lived out of the country.”

These were the first words that the speaker of them had uttered. He was

a meagre, elderly man, rather shabbily dressed, and sat second from the

coachman on the left. While speaking he leaned forward, allowing his

visage to emerge from the bulwark of coat collar that rose on either

side of it. It was a remarkable face, though at first sight not

altogether a winning one. The nose was an abrupt aquiline, thin at the

bridge, but with distended nostrils; the mouth was straight, the lips

seeming thin, rather from a constant habit of pressing them together

than from natural conformation. The bony chin slanted forward

aggressively, increasing the uncompromising aspect of the entire

countenance. The eyebrows, of a pale auburn hue, were sharply arched,

and the eyes beneath were so widely opened that the whole circle of the

iris was visible. The complexion of this person, judging from the color

of the hair, should have been blonde; but either owing to exposure to

the air or from some other cause it was of a deep reddish-brown tint.

His voice was his most attractive feature, being well modulated and of

an agreeable though penetrating quality, and to some ears it might have

been a guarantee of the speaker’s gentility strong enough to outweigh

the indications of his somewhat threadbare costume.

“My father is in good health, to the best of my knowledge,” said young

Mr. Bendibow, glancing at the other and speaking curtly. Then he added:

“You have the advantage of me, sir.”

“I call myself Grant,” returned the elderly man.

“Never heard my father mention the name,” said Mr. Bendibow loftily.

“I dare say not,” replied Mr. Grant, relapsing into his coat collar.

“Some folks,” observed Jehu in a meditative tone, yet loud enough to be

heard by all—“some folks thinks to gain credit by speaking the names of

those superior to them in station. Other folks thinks that fine names

don’t mend ragged breeches. I speaks my opinion, because why? Because I

backs it.”

“You’d better mind your horses,” said the gentleman who sat between the

coachman and Mr. Grant. “There!—catch hold of my arm, sir!”

The last words were spoken to Mr. Grant just as the coach lurched

heavily to one side and toppled over. The off leader had shied at a tall

white mile-stone that stood conspicuous at a corner of the road, and

before Mr. Bendibow could gather up his reins the right wheels of the

vehicle had entered the ditch and the whole machine was hurled off its

balance into the hedge-row. The outside passengers, with the exception

of one or two who clung to their seats, were projected into the field

beyond, together with a number of boxes and portmanteaux. The wheelers

lost their footing and floundered in the ditch, while the leaders,

struggling furiously, snapped their harness and careered down the road.

From within the coach meanwhile proceeded the sound of feminine screams

and lamentation.

The first thing clearly perceptible amidst the confusion was the

tremendous oath of which the coachman delivered himself, as he upreared

his ponderous bulk from the half-inanimate figure of young Mr. Bendibow,

upon whom he had fallen, having himself received at the same time a

smart blow on the ear from a flying carpet-bag. The next person to arise

was Mr. Grant, who appeared to have escaped unhurt, and after a moment

the gentleman who, by interposing himself between the other and danger,

had broken his fall, also got to his feet, looking a trifle pale about

the lips.

“I much fear, sir,” said the elder man, with an accent of grave concern

in his voice, “that I have been the occasion of your doing yourself an

injury. You have saved my bones at the cost of your own. I am a bit of a

surgeon; let me look at your arm.”

“Not much harm done, I fancy,” returned the other, forcing a smile.

“There’s something awkward here, though,” he added the next moment. “A

joint out of kilter, perhaps.”

“I apprehend as much,” said Mr. Grant. He passed his hand underneath the

young man’s coat. “Ay, there’s a dislocation here,” he continued; “but

if you can bear a minute’s pain I can put it right again. We must get

your coat off, and then—”

“Better get the ladies out of their cage first; that’s not so much

courtesy on my part as that I wish to put off the painful minute you

speak of as long as may be. I’m a damnable coward—should sit down and

cry if I were alone. Ladies first, for my sake!”

“You laugh, sir; but if that shoulder is not in place immediately it may

prove no laughing matter. The ladies are doing very well—they have

found a rescuer already. Your coat off, if you please. What fools

“I AM A BIT OF A SURGEON; LET ME LOOK AT YOUR ARM.”

“I AM A BIT OF A SURGEON; LET ME LOOK AT YOUR ARM.”

fashion makes of men! Where I come from none wear coats save Englishmen,

and even they are satisfied with one. Ah! that was a twinge; it were

best to cut the sleeve perhaps?”

“In the name of decency, no! To avoid trouble, I have long carried my

wardrobe on my back, and ’twould never do to enter London with a shirt

only. Better a broken bone than a wounded coat sleeve—ha! well, this is

for my sins, I suppose. I wish Providence would keep the punishment till

all the sins are done—this piecemeal retribution is the devil. Well,

now for it! Sir, I wish you were less humane—my flesh and bones cry out

against your humanity. Dryden was wrong, confound him! Pity is akin

to—to—whew!—to the Inquisition. God Apollo! shall I ever write poetry

after this? And ’tis only a left arm, after all!—not to be left alone,

however—ah!... A thousand thanks, sir; but you leave me ten years older

than you found me. Our acquaintance has been a long and (candor compels

me to say) a confoundedly painful one. To be serious, I am heartily

indebted to you.”

“Take a pull at this flask, young gentleman; ’tis good cognac that I got

as I came through France. I recollect to have read, when I was a boy in

school, that Nero fiddled whilst Rome was burning: you seem to have a

measure of his humor, since you can jest while the framework of your

mortal dwelling-place is in jeopardy. As for your indebtedness—my neck

may be worth much or little, but, such as it is, you saved it. The

balance is still against me.”

“Leave balances to bankers: otherwise we might have to express our

obligations to Mr. Bendibow, there, for introducing us to each other.

Does no one here, besides myself, need your skill?”

“It appears not, to judge by the noise they make,” replied the old

gentleman dryly. “That blackguard of a coachman should lose his place

for this. The manners of these fellows have changed for the worse since

I saw England last. How do you find yourself, Mr.—— I beg your

pardon?”

“Lancaster is my name; and I feel very much like myself again,” returned

the other, getting up from the bank against which he had been reclining

while the shoulder-setting operation had been going on, and stretching

out his arms tentatively.

As he stood there, Mr. Grant looked at him with the eye of a man

accustomed to judge of men. With his costume reduced to shirt,

small-clothes and hessians, young Lancaster showed to advantage. He was

above the medium height, and strongly made, deep in the chest and

elastic in the loins. A tall and massive white throat supported a head

that seemed small, but was of remarkably fine proportions and character.

The contours of the face were, in some places, so refined as to appear

feminine, yet the expression of the principal features was eminently

masculine and almost bold. Large black eyes answered to the movements of

a sensitive and rather sensuous mouth; the chin was round and resolute.

The young man’s hair was black and wavy, and of a length that, in our

day, would be called effeminate; it fell apart at the temple in a way to

show the unusual height and fineness of the forehead. The different

parts of the face were fitted together compactly and smoothly, without

creases, as if all had been moulded from one motive and idea—not as if

composed of a number of inharmonious ancestral prototypes: yet the range

of expression was large and vivid. The general aspect in repose

indicated gravity and reticence; but as soon as a smile began, then

appeared gleams and curves of a humorous gayety. And there was a

brilliance and concentration in the whole presence of the man which was

within and distinct from his physical conformation, and which rendered

him conspicuous and memorable.

“Lancaster—the name is not unknown to me,” remarked Mr. Grant, but in

an indrawn tone, characteristic of a man accustomed to communing with

himself.

During this episode, the other travelers had been noisily and confusedly

engaged in pulling themselves together and discussing the magnitude of

their disaster. Some laborers, whom the accident had attracted from a

neighboring field, were pressed into service to help in setting matters

to rights. One was sent after the escaped horses; others lent their

hands and shoulders to the task of getting the coach out of the ditch

and replacing the luggage upon it. Mr. Bendibow, seated upon his

portmanteau, his fashionable attire much outraged by the clayey soil

into which he had fallen, maintained a demeanor of sullen indignation;

being apparently of the opinion that the whole catastrophe was the

result of a conspiracy between the rest of the passengers against his

own person. The coachman, in a semi-apoplectic condition from the

combined effects of dismay, suppressed profanity, and a bloody jaw, was

striving with hasty and shaking fingers to mend the broken harness; the

ladies were grouped together in the roadway in a shrill-complaining and

hysteric cluster, protesting by turns that nothing should induce them

ever to enter the vehicle again, and that unless it started at once

their prospects of reaching London before dark would be at an end.

Lancaster glanced at his companion with an arch smile.

“My human sympathies can’t keep abreast of so much distress,” said he.

“I shall take myself off. Hammersmith cannot be more than three or four

miles distant, and my legs will be all the better for a little

stretching. If you put up at the ‘Plough and Harrow’ to-night, we may

meet again in an hour or two; meantime I will bid you good-day; and,

once more, many thanks for your surgery.”

He held out his hand, into which Mr. Grant put his own. “A brisk walk

will perhaps be the best thing for you,” he remarked. “Guard against a

sudden check of perspiration when you arrive; and bathe the shoulder

with a lotion ... by-the-by, would you object to a fellow-pedestrian? I

was held to be a fair walker in my younger days, and I have not

altogether lost the habit of it.”

“It will give me much pleasure,” returned the other, cordially.

“Then I am with you,” rejoined the elder man.

They gave directions that their luggage should be put down at the

“Plough and Harrow,” and set off together along the road without more

ado.

CHAPTER III.

THEY had not made more than a quarter of a mile, when the tramp of hoofs

and trundle of wheels caused them to turn round with an exclamation of

surprise that the coach should so speedily have recovered itself. A

first glance showed them, however, that the vehicle advancing toward

them was a private carriage. Two of the horses carried postilions; the

carriage was painted red and black; and as it drew near a coat of arms

was seen emblazoned on the door-panel. The turn-out evidently belonged

to a person of quality, and there was something in its aspect which

suggested a foreign nationality. The two gentlemen stood on one side to

let it pass. As it did so, Mr. Grant said, “The lady looked at you as if

she knew you.”

“Me! a lady?” returned Lancaster, who had been so occupied in watching

the fine action of one of the leaders, as to have had no eyes for the

occupants of the carriage.

As he spoke the carriage stopped a few rods beyond them, and a lady, who

was neither young nor beautiful, put her head out of the window and

motioned to Lancaster with her lifted finger. Muttering an apology to

his companion, the young man strode forward, wondering what new

adventure might be in store for him. But on reaching the carriage-door

his wonder came to an end. There were two ladies inside, and only one of

them was unbeautiful. The other was young and in every way attractive.

Her appearance and manner were those of a personage of distinction, but

her fair visage was alive with a subtle luminousness and mobility of

expression which made formality in her seem a playful grace rather than

an artificial habit. The margin of her face was swathed in the soft

folds of a silken hood, but a strand of reddish hair curled across her

white forehead, and a pair of dark, swift-moving and very penetrating

eyes met with a laughing sparkle the eyes of Lancaster. He doffed his

hat.

“Madame la Marquise! In England! Where is Monsieur?—”

“Hush! You are the same as ever—you meet me after six months, and

instead of saying you are glad to see me, you ask where is the Marquis!

Ma foi! don’t know where he is.”

“Surely Madame la Marquise does not need to be told how glad I am—”

“Pshaw! Don’t ‘Madame la Marquise’ me, Philip Lancaster! Are we not old

friends—old enough, eh? Tell me what you were doing walking along this

road with that shabby old man?”

“Old gentleman, Madame la Marquise. The coach was upset—”

“What! You were on that coach that we passed just now in the ditch? You

were not hurt?”

“If it had not been for this shabby old gentleman I might have been a

cripple for life.”

“Oh! I beg his pardon. Where do you go, then? To London?”

“Not so far. I shall look for lodgings in Hammersmith.”

“Nonsense! Hammersmith? I never heard of such a place. What should you

do there? You will live in London—near me—n’est-ce pas?”

“I have work to do. I must keep out of society for the present. You—”

“Listen! For the present, I keep out of society also. I am incognito. No

one knows I am here; no one will know till the time comes. We shall

keep each other’s secrets. But we cannot converse here. Get in here

beside me, and on the way I will tell you ... something! Come.”

“You are very kind, but I have made my arrangements; and, besides, I am

engaged to walk with this gentleman. If you will tell me where I may pay

my respects to you and Monsieur le Marquis—”

“You are very stupid! I shall tell you nothing unless you come into the

carriage. Monsieur le Marquis is not here—he never will be here. I am

... well you need not stare so. What do you suppose I am, then?”

“You are very mysterious.”

“I am nothing of the sort. I am ... a widow. There!”

Philip Lancaster lifted his eyebrows and bowed.

“What does that mean?” demanded the Marquise sharply; “that you

congratulate me?”

“By no means, Madame.”

She drew herself up haughtily, and eyed him for a moment. “It appears

that your coach has upset you in more ways than one. I apologize for

interrupting you in your walk. Beyond doubt, your friend there is very

charming. You are impatient to say farewell to me.”

“Nothing more than ‘au revoir,’ I hope.”

She let her haughtiness slip from her like a garment, and, leaning

forward, she touched with her soft fingers his hand which rested upon

the carriage door.

“You will come here and sit beside me, Philip? Yes?” Her eyes dwelt upon

his with an expectation that was almost a command.

“You force me to seem discourteous,” he said, biting his lips, “but—”

“There! do not distress yourself,” she exclaimed with a laugh, and

leaning back in her seat. “Adieu! I do not recognize you in England: in

Paris you were not so much an Englishman. If we meet in Paris perhaps

we shall know each other again. Madame Cabot, have the goodness to tell

the coachman to drive on.” These words were spoken in French.

Madame Cabot, the elderly and unbeautiful lady already alluded to, who

had sat during this colloquy with a face as unmoved as if English were

to her the same as Choctaw, gave the order desired, the horses started,

and Philip Lancaster, left alone by the roadside, put on his hat, with a

curve of his lip that was not either a smile or a sneer.

Mr. Grant, meanwhile, had strolled onward, and was now some distance

down the road. He waited for Lancaster to rejoin him, holding his open

snuff-box in his hand; and when the young man came up, he offered him a

pinch, which the latter declined. The two walked on together for several

minutes in silence, Lancaster only having said, “I am sorry to have kept

you waiting—an acquaintance whom I met abroad;” to which Mr. Grant had

replied by a mere nod of the head. By-and-by, however, he said, in

resumption of the conversation which had been going on previous to the

Marquise’s interruption:

“Is it many years then since you left England?”

“Seven or eight—long enough for a man of my age. But you have been

absent even longer?”

“Yes; much has been changed since my time. It has been a period of

changes. Now that Bonaparte is gone, we may hope for repose. England

needs repose: so do I—though my vicissitudes have not been involved in

hers. I have lived apart from the political imbroglio. But you must have

been in the midst of it. Did you see Waterloo?”

“Only the remains of it: I was a non-combatant. Major Lockhart—a

gentleman I met in Paris about three years ago, a fine fellow and a good

soldier—we ran across each other again in Brussels, a few days before

the battle. Lockhart was killed. He was a man of over sixty; was

married, and had a grown-up daughter, I believe. He had been living at

home with his family since ’13, and had hoped to see no more fighting.

When he did not come back with his regiment, I rode out to look for him,

and found his body. That’s all I know of Waterloo.”

“You never bore arms yourself?”

“No. My father was a clergyman; not that that would make much

difference; besides, he was not of the bookworm sort, and didn’t object

to a little fox-hunting and sparring. But I have never believed in

anything enough to fight for it. I am like the Duke in ‘Measure for

Measure’—a looker-on at life.”

“Ah! I can conceive that such an occupation may be not less arduous than

any. But do you confine yourself to that? Do you never record your

impressions?—cultivate literature, for example?”

Lancaster’s face flushed a little, and he turned his head toward his

companion with a quick, inquiring look. “How came you to think of that?”

he asked.

The old gentleman passed his hand down over his mouth and chin, as if to

correct an impulse to smile. “It was but a chance word of your own,

while I was at work upon your shoulder-joint,” he replied. “You let fall

some word implying that you had written poetry. I am very slightly

acquainted with modern English literature, and could not speak from

personal knowledge of your works were you the most renowned poet of the

day. Pardon me the liberty.”

Lancaster looked annoyed for a moment; but the next moment he laughed.

“You cannot do me a better service than to show me that I’m a fool,” he

said. “I’m apt to forget it. In theory, I care not a penny whether what

I write is read or not; but I do care all the same. I pretend to be a

looker-on at life from philosophical motives; but, in fact, it’s

nothing but laziness. I try to justify myself by scribbling poetry, and

am pleased when I find that any one has discovered my justification. But

if I were really satisfied with myself, I should leave justification to

whom it might concern.”

“My existence has been passed in what are called practical affairs,” Mr.

Grant returned; “but I am not ready to say that, considered in

themselves, they have as much real life in them as a single verse of

true poetry. Poetry and music are things beyond my power to achieve, but

not to enjoy. The experience of life which cannot be translated into

poetry or music is a lifeless and profitless experience.” He checked

himself, and added in his usual tone: “I mean to say that, man of

business though I am, I am not unacquainted with the writings of poets,

and I take great delight in them. The wisest thing a man can do is, I

apprehend, to augment the enjoyment of other men. Commerce and politics

aim to develop our own wealth and power at the cost of others; but

poetry, like love, gives to all, and asks for nothing except to be

received.”

“Have a care, or you will undo the service I have just thanked you for.

Besides, as a matter of fact, poetry in our days not only asks to be

received, but to be received by publishers, and paid for!”

Something in the young man’s manner of saying this, rather than the

saying itself, seemed to strike Mr. Grant, for he glanced at the other

with a momentary keenness of scrutiny, and presently said:

“Your father, I think you mentioned, was a clergyman?”

“He was Herbert Lancaster.”

Mr. Grant halted for a moment in his walk to extract his snuff-box from

his pocket. After having taken a pinch, he again gave a sharp look at

his companion, and observed as he walked on:

“My prolonged absence from my native land has made my recollection of

such matters a little rusty, but am I mistaken in supposing there is a

title in the family?”

“My uncle is Lord Croftus—the fifth baron.”

“Ah! precisely; yes, yes. Then was it not your father who married a

daughter of the Earl of Seabridge? or am I confounding him with

another?”

“You are quite right. He married the youngest daughter, Alice; and I am

their only child, for lack of a better.”

“Ah! Very singular,” returned Mr. Grant; but he did not explain in what

the singularity consisted.

CHAPTER IV.

MRS. LOCKHART’S house at Hammersmith had been considered a good house in

its day, and was still decent and comfortable. It stood on a small side

street which branched off from the main road in the direction of the

river, and was built of dark red brick, with plain white-sashed windows.

It occupied the centre of an oblong plot of ground about half an acre in

extent, with a high brick wall all round it, except in front, where

space was left for a wrought-iron gate, hung between two posts, with an

heraldic animal of ambiguous species sitting upright on each of them.

The straight path which led from this gate to the front door of the

house was paved with broad square flagstones, kept very clean. In the

midst of the grass-plot on the left, as you entered, was a dark-hued

cedar of Lebanon, whose flattened layers of foliage looked out of

keeping with the English climate and the character of English trees. At

the back of the house was an orchard, comprising three ancient

apple-trees and the lifeless stump of the fourth; some sunflowers and

hollyhocks, alternating with gooseberry bushes, were planted along the

walls, which, for the most part, were draped in ivy. The interior of the

building showed a wide hall, giving access to a staircase, which, after

attaining a broad landing, used as a sort of an open sitting-room, and

looking out through a window upon the back garden, mounted to the region

of bed-rooms. The ground floor was divided into three rooms and a

kitchen, all of comfortable dimensions, and containing sober and

presentable furniture. In the drawing-room, moreover, hung a portrait,

taken in 1805, of the deceased master of the establishment; and a

miniature of the same gentleman, in a gold-rimmed oval frame, reposed

upon Mrs. Lockhart’s work-table. The sideboard in the dining-room

supported a salver and some other articles of plate which had belonged

to Mrs. Lockhart’s family, and which, when she surrendered her maiden

name of Fanny Pell, had been included in her modest dowry. For the rest,

there was a small collection of books, ranged on some shelves sunk into

the wall on either side of the drawing-room mantel-piece; and fastened

against the walls were sundry spoils of war, such as swords, helmets and

flint-lock muskets, which the Major had brought home from his campaigns.

Their stern and battle-worn aspect contrasted markedly with the gentle

and quiet demeanor of the dignified old lady who sat at the little table

by the window, with her sewing in her hands.

Mrs. Lockhart, as has been already intimated, had been a very lovely

girl, and, allowing for the modifications wrought by age, she had not,

at sixty-six, lost the essential charm which had distinguished her at

sixteen. Her social success had, during four London seasons, been

especially brilliant; and, although her fortune was at no time great,

she had received many highly eligible offers of marriage; and his Royal

Highness the Prince of Wales had declared her to be “a doosid sweet

little creature.” She had kept the citadel of her heart through many

sieges, and, save on one occasion, it had never known the throb of

passion up to the period of her marriage with Lieutenant Lockhart. But,

two years previous to that event, being then in her eighteenth year, she

had crossed the path of the famous Tom Grantley, who, at four-and-thirty

years of age, had not yet passed the meridian of his renown. He was of

Irish family and birth, daring, fascinating, generous and dangerous with

both men and women; accounted one of the handsomest men in Europe, a

fatal duelist, a reckless yet fortunate gambler, a well-nigh

irresistible wooer in love, and in political debate an orator of

impetuous and captivating eloquence. His presence and bearing were lofty

and superb; and he was one of those whose fiat in manners of fashion was

law. When only twenty-one years old, he had astonished society by

eloping with Edith, the eldest daughter of the Earl of Seabridge, a girl

not less remarkable for beauty than for a spirit and courage which were

a match for Tom Grantley’s own. The Earl had never forgiven this wild

marriage, and Tom having already seriously diminished his patrimony by

extravagance, the young couple were fain to make a more than passing

acquaintance with the seamy side of life. But loss of fortune did not,

for them, mean loss either of heart or of mutual love, and during five

years of their wedded existence there was nowhere to be found a more

devoted husband than Tom Grantley, or a wife more affectionate and loyal

than Lady Edith. And when she died, leaving him an only child, it was

for some time a question whether Tom would not actually break his heart.

He survived his loss, however, and, having inherited a fresh fortune

from a relative, he entered the world again and dazzled it once more.

But he was never quite the same man as previously; there was a sternness

and bitterness underlying his character which had not formerly been

perceptible. During the ensuing ten years he was engaged in no fewer

than thirteen duels, in which it was generally understood that the honor

of some unlucky lady or other was at stake, and in most of these

encounters he either wounded or killed his man. In his thirteenth affair

he was himself severely wounded, the rapier of his antagonist

penetrating the right lung; the wound healed badly, and probably

shortened his life by many years, though he did not die until after

reaching the age of forty. At the time of his meeting with Fanny Pell

he was moving about London, a magnificent wreck of a man, with great

melancholy blue eyes, a voice sonorously musical, a manner and address

of grave and exquisite courtesy. Gazing upon that face, whose noble

beauty was only deepened by the traces it bore of passion and pain,

Fanny Pell needed not the stimulus of his ominous reputation to yield

him first her awed homage, and afterwards her heart. But Tom, on this

occasion, acted in a manner which, we may suppose, did something toward

wiping away the stains of his many sins. He had been attracted by the

gentle charm of the girl, and for a while he made no scruple about

attracting her in turn. There was a maidenly dignity and

straightforwardness about Fanny Pell, however, which, while it won upon

Grantley far more than did the deliberate and self-conscious

fascinations of other women, inspired at the same time an unwonted

relenting in his heart. Feeling that here was one who might afford him

something vastly deeper and more valuable than the idle pride of

conquest and possession with which he was only too familiar, he

bethought himself to show his recognition of the worth of that gift in

the only way that was open to him—by rejecting it. So, one day, looking

down from his majestic height into her lovely girlish face, he said with

great gentleness, “My dear Miss Fanny, it has been very kind of you to

show so much goodness to a broken-down old scamp like myself, who’s old

enough to be your father; and faith! I feel like a father to ye, too!

Why, if I’d had a little girl instead of a boy, she might have had just

such a sweet face as yours, my dear. So you’ll not take it ill of

me—will ye now!—if I just give you a kiss on the forehead before I go

away. Many a woman have I seen and forgotten, who’ll maybe not forget me

in a hurry; but your fair eyes and tender voice I never will forget, for

they’ve done more for me than ever a father confessor of ’em all!

Good-by, dear child; and if ever any man would do ye wrong—though,

sure, no man that has as much heart as a fish would do that—tell him to

’ware Tom Grantley! and as true as there’s a God in heaven, and a Tom

Grantley on earth, I’ll put my bullet through the false skull of him.

That’s all, my child: only, when ye come to marry some fine honest chap,

as soon ye will, don’t forget to send for your old friend Tom to come

and dance at your wedding.”

Poor Fanny felt as if her heart were being taken out of her innocent

bosom; but she was by nature so quiet in all her ways that all she did

was to stand with her glistening eyes uplifted toward the splendid

gentleman, her lips tremulous, and her little hands hanging folded

before her. And Tom, who was but human after all, and had begun to fear

that he had undertaken at least as much as he was capable of performing,

kissed her, not on her forehead, but on her mouth, and therewith took

his leave hurriedly, and without much ceremony. And Fanny never saw him

again; but she never forgot him, nor he her; though two years afterwards

she married Lieutenant Lockhart, and was a faithful and loving wife to

him for five-and-forty years. The honest soldier never thought of asking

why she named their first child Tom; and when the child died, and Mrs.

Lockhart put on mourning, it never occurred to him that Tom Grantley’s

having died in the same month of the same year had deepened the folds of

his wife’s crape. But so it is that the best of us have our secrets, and

those who are nearest to us suspect it not.

For the rest, Mrs. Lockhart’s life was a sufficiently adventurous and

diversified one. War was a busy and a glorious profession in those days;

and the sweet-faced lady accompanied her husband on several of his

campaigns, cheerfully enduring any hardships; or awaited his return at

home, amidst the more trying hardships of suspense and fear. During

that time when the nations paused for a moment to watch France cut off

her own head as a preliminary to entering upon a new life, Captain

Lockhart (as he was then) and his wife happened to be on that side of

the Channel, and saw many terrible historical sights; and the Captain,

who was no friend to revolution in any shape, improved an opportunity

for doing a vital service for a distinguished French nobleman, bringing

the latter safely to England at some risk to his own life. A year or two

later Mrs. Lockhart’s second child was born, this time a daughter; and

then followed a few summers and winters of comparative calm, the

monotony of which was only partially relieved by such domestic events as

the trial of Warren Hastings, the acting of Kemble and the classic

buffoonery of Grimaldi. Then the star of Nelson began to kindle, and

Captain Lockhart, reading the news, kindled also, and secretly glanced

at his honorable sword hanging upon the wall; yet not so secretly but

that his wife detected and interpreted the glance, and kissed her little

daughter with a sigh. And it was not long before Arthur Wellesley went

to Spain, and Captain Lockhart, along with many thousand other loyal

Englishmen, followed him thither; and Mrs. Lockhart and little Marion

stayed behind and waited for news. The news that chiefly interested her

was that her husband was promoted to be Major for gallant conduct on the

field of battle; then that he was wounded; and, finally, that he was

coming home. Home he came, accordingly, a glorious invalid; but even

this was not to be the end of trouble and glory. England still had need

of her best men, and Major Lockhart was among those who were responsible

for the imprisonment of the Corsican Ogre in St. Helena. It was between

this period and the sudden storm that culminated at Waterloo, that the

happiest time of all the married life of the Lockharts was passed. He

had saved a fair sum of money, with part of which he bought the house

in Hammersmith; and upon the interest of the remainder, in addition to

his half-pay, he was able to carry on existence with comfort and

respectability. Marion was no longer the odd little creature in short

skirts that she had been when the Major kissed her good-by on his

departure for the Peninsular War, but a well-grown and high-spirited

young lady, with the features of her father, and a character of her own.

She was passionately devoted to the gray-haired veteran, and was never

tired of listening to his famous histories; of cooking his favorite

dishes; of cutting tobacco for his pipe; of sitting on the arm of his

chair, with her arm about his neck, and her cheek against his. “Marion

has the stuff of a soldier in her,” the Major used to declare; whereupon

the mother would silently thank Providence that Marion was not a boy. It

had only been within the last five or six years that Marion had really

believed that she was not, or might not become, a boy after all; a not

uncommon hallucination with those who are destined to become more than

ordinarily womanly.

When the event occurred which widowed France of her Emperor and Mrs.

Lockhart of her husband (much the worst catastrophe of the two, in that

lady’s opinion), the prospects of the household in Hammersmith seemed in

no respect bright. The Major’s half-pay ceased with the Major, and the

widow’s pension was easier to get in theory than in practice. The

interest of the small capital was not sufficient by itself to meet the

current expenses, though these were conducted upon the most economical

scale; and Marion, upon whose shoulders all domestic cares devolved, was

presently at her wit’s end how to get on. She did all the cooking

herself, and much of the washing, though Mrs. Lockhart strongly

protested against the latter, because Marion’s hands were of remarkably

fine shape and texture, being, in fact, her chief beauty from the

conventional point of view, and washing would make them red and ugly.

Marion affirmed, with more sincerity than is commonly predicable of such

sayings, that her hands were made to use, and that she did not care

about them except as they were useful; and she went on with her washing

in spite of protestations. But even this did not cover deficiencies; and

then there was the wardrobe question. Marion, however, pointed out that,

in the first place, she had enough clothes on hand to last her for a

long time, especially as she had done growing; and, secondly, that she

could easily manage all necessary repairs and additions herself. To this

Mrs. Lockhart replied that young ladies must be dressed like young

ladies; that good clothes were a necessary tribute to good society; and

that in order to be happily and genteelly married, a girl must make the

most of her good points, and subdue her bad ones, by the adornments of

costume. This was, no doubt, very true; but marriage was a thing which

Marion never could hear proposed, even by her own mother, with any

patience; and, as a consequence, to use marriage as an argument in

support of dress, was to insure the rejection of the argument. Marriage,

said Marion, was, to begin with, a thing to which her whole character

and temperament were utterly opposed. She was herself too much like a

man ever to care for a man, or not to despise him. In the next place, if

a girl had not enough in her to win an honest man’s love, in spite of

any external disadvantages, then the best thing for her would be not to

be loved at all. Love, this young dissenter would go on to observe, is

something sacred, if it is anything; and so pure and sensitive, that it

were infinitely better to forego it altogether than to run the least

risk of getting it mixed up with any temporal or expedient

considerations. And since, she would add, it seems to be impossible

nowadays ever to get love in that unsullied and virginal condition, she

for her part intended to give it a wide berth if ever it came in her

way—which she was quite sure it never would; because it takes two to

make a bargain, and not only would she never be one of the two, but, if

she were to be so, she thanked God that she had so ugly a face and so

unconciliating a temper that no man would venture to put up with her;

unless, perhaps, she were possessed of five or ten thousand a year; from

which misfortune it was manifestly the beneficent purpose of Providence

to secure her. The upshot of this diatribe was that she did not care how

shabby and ungenteel her clothes were, so long as they were clean and

covered her; and that even if she could afford to hire a dressmaker, she

would still prefer to do her making and mending herself; because no one

so well as herself could comprehend what she wanted.

“You should not call yourself ugly, Marion,” her mother would reply: “at

any rate, you should not think yourself ugly. A girl generally appears

to others like what she is in the habit of thinking herself to be. Half

the women who are called beauties are not really beautiful; but they

have persuaded themselves that they are so, and then other people

believe it. People in this world so seldom take the pains to think or to

judge for themselves; they take what is given to them. Besides, to think

a thing, really does a great deal toward making it come true. If you

think you are pretty, you will grow prettier every day. And if you keep

on talking about being ugly.... You have a very striking, intelligent

face, my dear, and your smile is very charming indeed.”

Marion laughed scornfully. “Believing a lie is not the way to invent

truth,” she said. “All the imagination in England won’t make me

different from what I am. Whether I am ugly or not, I’m not a fool, and

I shan’t give anybody the right to call me one by behaving as if I

fancied I were somebody else. I am very well as I am,” she continued,

wringing out a towel and spreading it out on the clothes-horse to dry.

“I should be too jealous and suspicious to make a man happy, and I don’t

mean to try it. You don’t understand that; but you were made to be

married, and I wasn’t, and that’s the reason.”

Nevertheless, the income continued to be insufficient, and inroads

continued to be made on the capital, much to the friendly distress of

Sir Francis Bendibow, the head of the great banking-house of Bendibow

Brothers, to whose care the funds of the late Major Lockhart had been

intrusted “The first guinea you withdraw from your capital, my dear

madam,” he had assured Mrs. Lockhart, with his usual manner of

impressive courtesy, “represents your first step on the road that leads

to bankruptcy.” The widow admitted the truth of the maxim; but

misfortunes are not always curable in proportion as they are undeniable;

though that seemed to be Sir Francis’ assumption. Mrs. Lockhart began to

suffer from her anxieties. Marion saw this, and was in despair. “What a

good-for-nothing thing a woman is!” she exclaimed bitterly. “If I were a

man I would earn our living.” She understood something of music, and

sang and played with great refinement and expression: but her talent in

this direction was natural, not acquired, and she was not sufficiently

grounded in the science of the accomplishment to have any chance of

succeeding as a teacher. What was to be done?

“What do you say to selling the house and grounds, and going into

lodgings?” she said one day.

“It would help us for a time, but not for always,” the mother replied.

“Lodgings are so expensive.”

“The house is a great deal bigger than we need,” said Marion.

“We should be no better off if it were smaller,” said Mrs. Lockhart.

There was a long pause. Suddenly Marion jumped to her feet, while the

light of inspiration brightened over her face. “Why, mother, what is to

prevent us letting our spare rooms to lodgers?” she cried out.

“Oh, that would be impossible!” returned the mother in dismay. “The

rooms that your dear father used to live in!”

“That is what we must do,” answered Marion firmly; and in the end, as we

have seen, that was what they did.

CHAPTER V.

THE third of May passed away, and, beyond the hanging up in the window

of the card with “Lodgings to Let” written on it, nothing new had

happened in the house at Hammersmith. But the exhibition of that card

had been to Mrs. Lockhart an event of such momentous and tragic

importance, that she did not know whether she were most astonished,

relieved, or disappointed that it had produced no perceptible effect

upon the outer universe.

“It seems to be of no use,” she said to her daughter, while the latter

was assisting her in her morning toilet. “Had we not better take down

the card, and try to think of something else. Couldn’t we keep

half-a-dozen fowls, and sell the eggs?”

“How faint-hearted you are, mother!”

“Besides, even if somebody were to pass here who wanted lodgings, they

could never think of looking through the gate; and if they did, I doubt

whether they could see the card.”

“I have thought of that; and when I got up this morning I tied the card

to the gate itself. Nobody can fail to see it there.”

“Oh, Marion! It is almost as if we were setting up a shop.”

“Everybody is more or less a shopkeeper,” replied Marion

philosophically. “Some people sell rank, others beauty, others

cleverness, others their souls to the devil: we might do worse than sell

house-room to those who want it.”

“Oh, my dear!”

“Bless your dear heart! you’ll think nothing of it, once the lodgers are

in the house,” rejoined the girl, kissing her mother’s cheek.

They went down to breakfast: it was a pleasant morning; the sky was a

tender blue, and the eastern sunshine shot through the dark limbs of the

cedar of Lebanon, and fell in cheerful patches on the floor of the

dining-room, and sent a golden shaft across the white breakfast cloth,

and sparkled on the silver teapot—the same teapot in which Fanny Pell

had once made tea for handsome Tom Grantley in the year 1768. Marion was

in high spirits: at all events, she adopted a lightsome tone, in

contrast to her usual somewhat grave preoccupation. She was determined

to make her mother smile.

“This is our last solitary breakfast,” she declared. “To-morrow morning

we shall sit down four to table. There will be a fine old gentleman for

me, and a handsome young man for you; for anybody would take you to be

the younger of us two. The old gentleman will be impressed with my

masculine understanding and knowledge of the world; we shall talk

philosophy, and history, and politics; he will finally confess to a more

than friendly interest in me; but I shall stop him there, and remind him

that, for persons of our age, it is most prudent not to marry. He will

allow himself to be persuaded on that point; but he has a vast fortune,

and he will secretly make his will in my favor. Your young gentleman

will be of gentle blood, a sentimentalist and an artist; his father will

have been in love with you; the son will have the good taste to inherit

the passion; he will entreat you to let him paint your portrait; but, if

he becomes too pressing in his attentions, I shall feel it my duty to

take him aside, and admonish him like a mother. He will be so mortally

afraid of me, that I shall have no difficulty in managing him. In the

course of a year or two—”

“Is not that somebody? I’m sure I heard—”

“La, mother, don’t look so scared!” cried Marion, laughing, but coloring

vividly: “it can’t be anything worse than an executioner with a warrant

for our arrest.” She turned in her chair, and looked through the window

and across the grass-plot to the gate.

“There is somebody—two gentlemen—just as I said: one old and the other

young.”

“Are you serious, Marion?” said the widow, interlacing her fingers

across her breast, while her lips trembled.

“They are reading the card: the old one is holding a pair of gold-rimmed

eye-glasses across his nose. Now they are looking through the gate at

the house: the young one is saying something, and the other is smiling

and taking snuff. The young one has a small head, but his eyes are big,

and he has broad shoulders: he looks like an artist, just as I said. The

old one stoops a little and is ugly; but I like his face—it’s honest.

He doesn’t seem to be very rich, though; his coat is very old-fashioned.

Oh, they are going away!”

“Oh, I am so glad!” exclaimed Mrs. Lockhart fervently.

“No, they are coming back—they are coming in: the young one is opening

the gate. Here they come: that young fellow is certainly very handsome.

There!”

A double knock sounded through the house.

“Say we are not at home—oh, they must not come in! Tell them to call

another day. Perhaps they may not have called about the lodgings,”

faltered the widow, in agitation.

Marion said nothing; being, to tell the truth, engaged in screwing her

own courage to the sticking-point. After a pause of a few moments she

marched to the door, with a step so measured and deliberate as to

suggest stern desperation rather than easy indifference. Passing into

the hall, and closing the door behind her, she threw open the outer door

and faced the two intruders.

The elder gentleman stood forward as spokesman. “Good morning to you,”

he said, glancing observantly at the young woman’s erect figure. “You

have lodgings to let, I believe?”

“Yes.”

“This gentleman and I are in search of lodgings. Is the accommodation

sufficient for two? We should require separate apartments.”

“You can come in and see.” She made way for them to enter, and conducted

them into the sitting-room on the left.

“You had better speak to your mistress, my dear, or to your master, if

he is at home, and say we would like to speak to him.” This was said by

the younger man.

Marion looked at him with a certain glow of fierceness. “My father is

not living,” she said. “There is no need to disturb my mother. I can

show you over the house myself.”

“I ask your pardon sincerely. It has always been my foible to speak

before I look. I took it for granted—”

“I don’t suppose you intended any harm, sir,” said Marion coldly. “If we

could have afforded a servant to attend the door, we should not have

been forced to take lodgers.” She turned to the elder man and added: “We

have three vacant rooms on the floor above, and a smaller room on the

top story. You might divide the accommodation to suit yourselves. You

can come up stairs, if you like, and see whether they would suit you.”

The gentlemen assented, and followed Marion over the upper part of the

house. The elder man examined the rooms and the furniture with care; but

the younger kept his regards fixed rather upon the guide than upon what

she showed them. Her gait, the movement of her arms, the carriage of her

head, her tone and manner of speaking, all were subjected to his

scrutiny. He said little, but took care that what he did say should be

of a courteous and conciliatory nature. The elder man asked questions

pleasantly, and seemed pleased with the answers Marion gave him. Within

a short time the crudity and harshness of the first part of the

interview began to vanish, and the relations of the three became more

genial and humane. There was here and there a smile, and once, at least,

a laugh. Marion, who was always quick to recognize the humorous aspect

of a situation, already foresaw herself making her mother merry with an

account of this adventure, when the heroes of it should have gone away.

The party returned to the sitting-room in a very good humor with one

another, therefore.

“For my part, I am more than satisfied,” remarked the elder gentleman,

taking out his snuff-box. “Do you agree with me, Mr. Lancaster?”

Lancaster did not reply. He was gazing with great interest at the oil

portrait that hung on the wall. At length he turned to Marion and said:

“Is that—may I ask who that is?”

“My father.”

“Was he a major in the 97th regiment?”

“Did you know him?”

“I knew Major Lockhart; He—of course you know—fell at Waterloo.”

“We know that he was killed there, but we have no particulars,” said

Marion, her voice faltering, and her eyes full of painful eagerness.

“And you are Miss Lockhart—the Marion he spoke of?”

“Wait a moment,” she said, in a thick voice, and turning pale. She

walked to the window, and pressed her forehead against the glass.

Presently she turned round and said, “I will call my mother, sir. She

must hear what you have to tell us,” and left the room.

“A strange chance this!” remarked the elder man thoughtfully.

“She’s a fine girl, and looks like her father,” said Lancaster.

In a few moments Marion re-entered with her mother. Mrs. Lockhart looked

from one to the other of the two men with wide-open eyes and flushed

cheeks: a slight tremor pervaded the hand with which she mechanically

smoothed the thick braids of gray hair that covered her graceful head.

She moved with an uncertain step to a chair, and said in a voice

scarcely audible, “Will you be seated, gentlemen? My daughter tells me

that you—one of you—”

“The honor belongs to me, madam,” said Lancaster, with deep respect and

with some evidence of emotion, “of having seen your husband the day

before his death. He mentioned both of you; he said no man in the army

had had so happy a life as he—such a wife and such a daughter. I shall

remember other things that he said, by-and-by; but this meeting has come

upon me by surprise, and.... The day after the battle I rode out to the

field and found him. He had fallen most gallantly—I need not tell you

that—at a moment such as all brave soldiers would wish to meet death

in. He was wounded through the heart, and must have died instantly. I

assumed the privilege of bringing his body to Brussels, and of seeing it

buried there.” Here he paused, for both the women were crying, and, in

sympathy with them, his own voice was getting husky. The elder man sat

with his face downcast, and his hands folded between his knees.

“Is the grave marked?” he suddenly asked, looking up at Lancaster.

“Yes; the name, and the regiment, and the date. I brought something from

him,” he went on, addressing Marion, as being the stronger of the two

women; “it was fastened by a gold chain round his neck, and he wore it

underneath his coat. You would have received it long ago if I had known

where to find you.” He held out to her, as he spoke, a small locket with

its chain. Marion took it, and held it pressed between her hands, not

saying anything. After a moment, the two gentlemen exchanged a glance,

and got up. The elder gentleman approached Marion with great gentleness

of manner; and, when she arose and attempted to speak, he put his hand

kindly on her shoulder.

“I had a little girl once, who loved me,” he said. “You must let me go

without ceremony now; to-morrow I shall ask leave to come back and

complete our arrangements. God bless you, my child! Are you going with

me, Mr. Lancaster?”

“Shall you come back to-morrow, too?” said Marion to the latter.

“Indeed I will.”

“Then I won’t try to thank you now,” she replied. But their eyes met for

a moment, and Lancaster did not feel that the recognition of his service

had been postponed.

They were going out without attempting to take leave of Mrs. Lockhart;

but she rose up from her chair and courtseyed to them with a grace and

dignity worthy of Fanny Pell. And then, yielding to an impulse that was

better than the best high breeding, the gentle widow stepped quickly up

to Lancaster, and put her arms about his neck, and kissed him.

CHAPTER VI.

THE great banking-house of Bendibow Brothers, like many other great

things, had a modest beginning. At the beginning of the eighteenth

century there was a certain Mr. Abraham Bendibow in London, who kept a

goldsmith’s shop in the neighborhood of Whitechapel, and supplemented

the profits of that business by lending money at remunerative interest,

on the security of certain kinds of personal property. To his customers

and casual acquaintances he was merely a commonplace, keen, cautious,

hard-headed and hard-hearted man of business; and, perhaps, till as

lately as the second decade of the century, this might have fairly

represented his own opinion of himself. Nevertheless, there lurked in

his character, in addition to the qualities above mentioned, two others

which are by no means commonplace, namely, imagination and enterprise.

They might have lurked there unsuspected till the day of his death, but

for the intervention of circumstances—to make use of a convenient word

of which nobody has ever explained the real meaning. But, in 1711, that

ingenious nobleman, the Earl of Oxford, being animated by a praiseworthy

desire to relieve a nightmare of a half-score million sterling or so of

indebtedness which was then oppressing the government, hit upon that

famous scheme which has since entered into history under the name of the

South Sea Bubble. The scheme attracted Bendibow’s attention, and he

studied it for some time in his usual undemonstrative but thoroughgoing

manner. Whenever occasion offered he discussed it, in an accidental and

indifferent way, with all kinds of people. At the end of two or three

years he probably understood more about the affair than any other man in

London. Whether he believed that it was a substance or a bubble will

never be known to any one except himself. All that can be affirmed is

that he minded his own business, and imparted his opinion to no one. The

opinion gradually gained ground that he shared the views of Sir Robert

Walpole, who, in the House of Commons, was almost the only opposer of

the South Sea scheme. So matters went on until the year 1720.

It was at this period that the excitement and convulsion began. The

stock had risen to 330. Abraham Bendibow sat in his shop, and preserved

an unruffled demeanor. The stock fell to below 300; but Abraham kept his

strong box locked, and went about his business as usual. Stock mounted

again to 340; but nobody perceived any change in Mr. Bendibow. For all

any one could see, he might never have heard of the South Sea scheme in

his life. And yet a great fortune was even then in his grasp, had he

chosen to stretch out his hand to take it.

Weeks and months passed away, and the stock kept on rising. Often it

would tremble and fall, but after each descent it climbed higher than

before. It became the one absorbing topic of conversation with everybody

except Abraham Bendibow, who composedly preferred to have no concern in

the matter: it was not for small tradesmen like him to meddle with such

large enterprises. And, meanwhile, the stock rose and rose, and rose

higher still, until men lost their heads, and other men made colossal

fortunes, and everybody expected to secure at least ten thousand a year.

One day the stock touched 890, and then people held their breath and

turned pale, and the most sanguine said in their hearts that this was

supernatural and could not last.

On that day Abraham Bendibow went into his private room, and locked the

door; and taking pen and paper he made a calculation. After having made

it he sat for a long time gazing at the little array of figures in

seeming abstraction. Then he leaned back in his chair, with one hand in

the pocket of his small-clothes, while with the other he slowly rubbed

his chin at intervals. By degrees he began to breathe more quickly, and

his eyes became restless. He arose from his chair and paced up and down

the room. “Eight hundred and ninety,” he kept muttering to himself, over

and over again. The strong box stood in the corner of the room, and

toward this Mr. Bendibow often looked. Once he approached it, and laid

his hand upon the lid; then he turned away from it with an abrupt

movement, compressing his lips and shaking his head. He resumed his

pacing up and down the room, his head bent down in deep and troubled

thought. At last an idea seemed to strike him. He unlocked and opened

the door of the room, and called in a harsh, peremptory tone:

“Jacob!”

A young man appeared, about twenty years of age. In features he

resembled the other, but his face was not so broad, nor was his air so

commanding. Mr. Bendibow motioned to him with his head to enter. He then

seated himself in his chair, and eyed Jacob for a while in silence.

Jacob stood with his head stretched forward, and slowly chafing the back

of one hand with the palm of the other, while his countenance wore an

expression of deferential inquiry.

“Jacob,” said the elder, “what is doing out-doors to-day—eh?”

“The same as usual, father,” answered Jacob, tentatively, as being in

some doubt what the question might portend. “There is plenty of

excitement: same as usual.”

“Excitement; on what account?”

“Well, sir, the stocks: terrible speculation: madness—nothing less.

There was a fellow, sir, this very morning, got out a prospectus of a

company for prosecuting a certain undertaking not at present to be

revealed: capital one million, in ten thousand shares of one hundred

each: deposit two pounds, entitling to one hundred per annum, per share:

particulars next week, and balance of subscription week after next.

Frightful, upon my soul, sir!”

“Has anybody bitten?”

“A good many have been bitten,” returned Jacob, with a dry giggle.

“Three thousand pounds were subscribed in three hours; and then the

fellow decamped. Madness, upon my life!”

“You would not advise having anything to do with such speculations, eh,

Jacob?”

“Me? Bless my soul, not I indeed!” exclaimed Jacob with energy.

“Why not?”

“In the first place, because you have expressed disapproval of it,

father,” replied the virtuous Jacob. “And I may flatter myself I have

inherited something of your sound judgment.”

“So you have never speculated at all—eh, Jacob? Never at all, eh? Never

bought a shilling’s worth of stock of any kind in your life—eh? The

truth, Jacob!”

The last words were pronounced in so stern a tone that Jacob changed

color, turning his eyes first to one side of his father’s point-blank

gaze, and then to the other. At last, however, their glances met, and

then Jacob said:

“I might not be able to swear to a shilling or so, neither—”

“Nor to a guinea: nor to ten, nor to fifty—eh, Jacob?”

“Not more than fifty; upon my soul, sir,” said Jacob, laying his hands

upon his heart in earnest deprecation. “Not a penny, sir, upon my word

of honor!”

“What of the fifty then—eh?”

“It was in South Sea: I bought at 400,” said Jacob.

“At 400? And what is it to-day?”

“Eight hundred and ninety it was this morning,” said Jacob.

“Was this morning? Do you mean it has fallen since?”

“It has indeed, sir. They’ve all been selling like demons; and it’s

below eight hundred at this moment.”

“What have you done—eh?”

“Sold out the first thing, sir, at four hundred and ninety per cent,

clear profit,” replied Jacob, something of complacency mingling with the

anxious deference of his tone.

“Therefore, instead of fifty pounds, you now have three hundred or so?”

“Two hundred, ninety and five, sir,” said the youth modestly.

“Jacob, you are a fool!”

“Sir?”

“You have thrown your money away. You are a fool! You are timid! You

have neither the genius, the steadiness, nor the daring to manage and to

multiply a great fortune. Were you like myself, Jacob, you or your

children might have a hand in controlling the destinies of England, and

thus of the world. You have behaved like a pettifogger and a coward,

Jacob. I do not ask you to be honest. No man is honest when he is sure

that dishonesty will enrich him. But, whatever you are, I ask you to be

that thing with all your soul. Be great, or be nothing! Only fools and

cowards patter about morality! I tell you that success is the only

morality.” Here Mr. Bendibow, who had spoken with calmness, though by no

means without emphasis, checked himself, and putting his hand in his

pocket drew forth a key which he handed to his son. “Open the strong

box,” he said, “and take out the papers you will find in it.”

Jacob did as he was bid. But his first glance at the papers made him

start and stare in a bewildered manner at the unmoved countenance of his

father. He then reverted to the papers; but, after a close inspection of

them, he seemed only more bewildered than before.

“This is South Sea stock, sir,” he said at length.

“Well, Jacob?” said Mr. Bendibow, composedly.

“Nigh on fifteen thousand pounds’ worth at par, sir.”

“Yes, Jacob.”

“I see how it is; you have been buying for some one!” broke out Jacob,

energetically.

“Evidently, Jacob.”

There was a pause. “On commission, of course?” hazarded Jacob.

“No commission at all, Jacob.”

Jacob’s jaws relaxed. “No commission? Whom did you buy for, sir?”

“For myself, Jacob.”

Jacob dropped the papers on the table, and leaned against it dizzily;

his breath forsook him. Finally, Mr. Bendibow said: “Jacob, you are even

more a fool than I took you for.”

“But how.... When did you buy, sir?” faltered Jacob.

“Eight or nine years ago,” Mr. Bendibow replied.

“Then ... why, then you must have got it at under two hundred?”

“Eighty to a hundred and twenty,” said Mr. Bendibow, curtly.

There was another pause. Jacob moistened his lips and passed his hand

over his forehead. Suddenly he screamed out, “But you haven’t sold,

sir!”

“Well, Jacob?”

“If you’d sold this morning you’d have been worth a hundred and

thirty-five thousand sterling—one hundred and thirty-five thousand!”

“Very nearly, Jacob.”

“And stock is falling: you’ve lost fifteen thousand since ten o’clock!”

shouted Jacob, now quite beside himself. He seized the papers again, and

made for the door. There he was stopped by an iron grasp on his arm, and

Mr. Bendibow said, in a voice as uncompromising as his grasp, “Stay

where you are!”

“But it’s not too late, sir; we’ll clear a hundred thousand yet,”

pleaded Jacob, in agony.

“Be silent, and hear what I say to you. When I bought this stock, and

paid fifteen thousand pounds for it, I made up my mind either to lose

all or to win ten times my stake. I made up my mind that my fortune

should be either one hundred and fifty thousand sterling, or nothing.

Through nine years I have held to my purpose. Until this hour no one has

known that I have risked a penny. Men have made fortunes—I have seen

it, and held to my purpose, and held my tongue. Men have gone mad with

success or failure; I am the same to-day that I was ten years ago. This

morning stock reached eight hundred and ninety; a thousand fools like

you sold, and now it is falling, and will fall yet more. But it is my

belief that it will rise again. It will rise to one thousand. When it

touches one thousand, I sell; not before, and not afterward. I shall win

one hundred and fifty thousand pounds. With that money I shall found a

banking-house. It will be known as the banking-house of Bendibow and

Son. If you and your children were men like myself, the house of

Bendibow and Son would become one of the great Powers of Europe. Where

now we have ten thousand, in a century we should have a million. But you

are not such a man as I am. Your children and your great-grandchildren

will not be such men as I am. But I have done what I could. I have

written down in a book the rules which you are to obey—you, and all

your descendants. If you disobey them, my curse will be upon you, and