[1]

CAPITALS OF THE NORTHLANDS

THREE DEGREES FROM THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

TRONDHJEM CATHEDRAL

[Frontispiece

[2]

[3]

CAPITALS OF

THE NORTHLANDS

TALES OF TEN CITIES

BY

IAN C. HANNAH, M.A.

AUTHOR OF "EASTERN ASIA: A HISTORY," "THE SUSSEX COAST,"

"THE BERWICK AND LOTHIAN COASTS," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY EDITH BRAND HANNAH

HEATH CRANTON & OUSELEY, LTD.

FLEET LANE, LONDON, E.C.

[4]

TO

THE LOVED MEMORY

OF THE BEST OF MOTHERS

WITH WHOM I ONCE MADE A PILGRIMAGE

TO THE SHRINE OF ST. OLAF

[5]

PREFACE

Many excellent things have been written about the

cities of the South, but little, comparatively speaking,

about the cities of the North. True, indeed, they have

not moulded kingdoms and shaped the culture of a

continent, but England, like Scandinavia, is not a

country city-built; she was formed by the dwellers

on the land. Yet the less prominent part that they

have played does not make our cities less noteworthy

than those of the South.

Few and peculiarly interesting are the cities of the

North. And, with the exception, perhaps, of St.

Petersburg, those spoken of in this book have all the

charm that comes because they were built by country-loving

folk, to whom deep woods and open fields were

lovelier than monumental streets and squares.

I shall not have written in vain if the perusal of this

small book leads any one to study larger works on the

Northlands, and particularly the matchless sagas,

many of them so skilfully Englished by the joint

labour of an Englishman and an Icelander, William

Morris and Eirîkr Magnússon. In them we may read

of all these ten towns, save that Copenhagen and[6]

St. Petersburg have risen in Saga Lands after the

sagas were penned.

After accuracy I have striven hard, but if any

reader should detect any error I should be grateful to

have it pointed out for correction in a later edition.

I. C. H.

Fernroyd,

Forest Row.

[7]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER |

|

|

PAGE |

| I. |

|

Thorshavn, Capital of the Faroe Islands |

11 |

| II. |

Reykjavik, Capital of Iceland |

28 |

| III. |

Trondhjem, Old Capital of Norway |

66 |

| IV. |

Christiania, Capital of Norway |

93 |

| V. |

Roskilde, Old Capital of Denmark |

111 |

| VI. |

Copenhagen, Capital of Denmark |

127 |

| VII. |

Visby, Capital of Gothland |

150 |

| VIII. |

Upsala, Old Capital of Sweden |

176 |

| IX. |

Stockholm, Capital of Sweden |

199 |

| X. |

St. Petersburg, Capital of Russia |

226 |

| |

Index |

261 |

[8]

[9]

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Gol Stavekirke |

Title Page |

| Trondhjem Cathedral |

Frontispiece |

| |

PAGE |

| Thorshavn |

11 |

| Reykjavik Harbour |

28 |

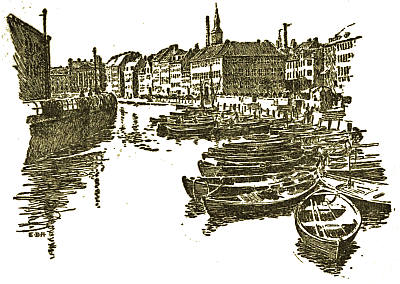

| Boats at Trondhjem |

66 |

| Stabbur at Bygdö, Christiania |

93 |

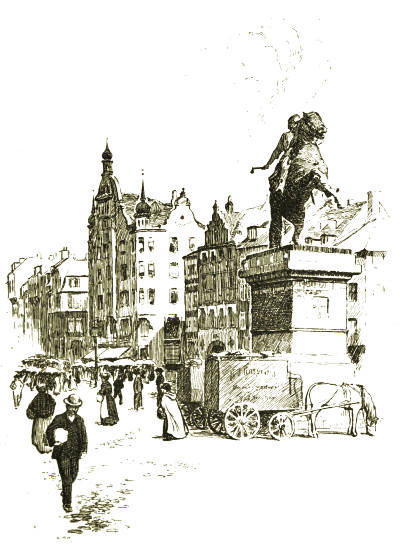

| Market Place at Roskilde |

111 |

| Canal at Copenhagen |

127 |

| East Wells at Visby |

150 |

| Castle and Cathedral, Upsala |

176 |

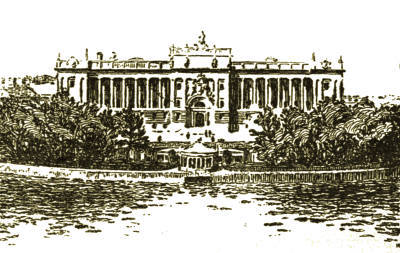

| Houses of Parliament, Stockholm |

199 |

| Cathedral of St. Isaac, St. Petersburg |

226 |

| |

FACE PAGE |

| Thorshavn Fishermen |

22 |

| Hot Springs near Reykjavik |

60 |

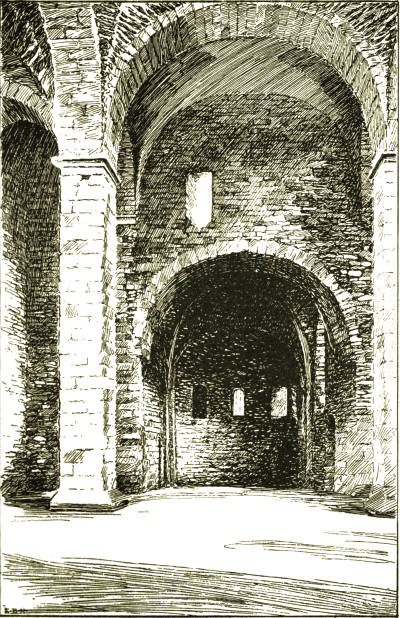

| Corona of Trondhjem Cathedral (interior) |

86 |

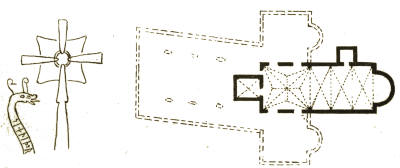

| Gamla Upsala, Church and Runic Stone (plan) |

99 |

| Greensted Church[10] |

108 |

| Roskilde Cathedral (plan) |

118 |

| Roskilde Cathedral |

122 |

| Hojbroplads, Copenhagen |

134 |

| Town of Visby, with Drawing of a Saddle Tower (plan) |

158 |

| Interior of St. Lars, Visby |

166 |

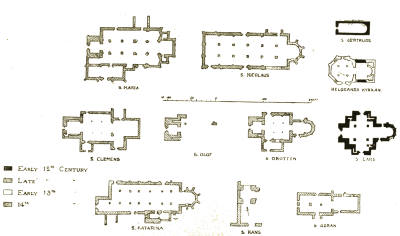

| Churches of Visby (plan) |

172 |

| Gamla Upsala |

180 |

| General View of Stockholm |

206 |

| Trondhjem Cathedral (plan) |

246 |

| St. Isaac's Cathedral, St. Petersburg (plan) |

246 |

| Church of the Resurrection, St. Petersburg |

254 |

[11]

CHAPTER I

THORSHAVN

Loud in Harfur's echoing bay,

Heard ye the din of battle bray,

'Twixt Kiotvi rich, and Harald bold?

Eastward sail the ships of war;

The graven bucklers gleam afar,

And dragon heads adorn the prows of gold.

Glittering shields of purest white,

And swords, and Celtic falchions bright,

And Western chiefs the vessels bring:

Loudly roar the wolfish rout,

And maddening Champions wildly shout,

And long and loud the twisted hauberks ring.

Firm in fight they proudly vie

With him whose might will make them fly,

Of Eastmen kings the warlike head.

Forth his gallant fleet he drew,

Soon as the hope of battle grew,

But many a buckler brake ere Long-chin bled.

[12]

Fled the lusty Kiotvi then

Before the Shock-head king of men,

And bade the islands shield his flight.

Warriors wounded in the fray,

Beneath the thwarts all gasping lay,

Where head-long cast they mourned the loss of light.

So does an Icelandic skald describe the most important

battle in the annals of the Norse.[1] Harald

Shock-head had exalted himself, and said "I will

be king" over the whole of Norway. He desired

to wed the daughter of the kinglet of Hordaland.

She was a maiden exceeding fair and withal somewhat

high-minded.

To Harald's messengers she answered in this wise:

"I will not waste my maidenhood for the taking to

husband of a king who has no more realm to rule

over than a few folks. Marvellous it seems to me

that there is no king minded to make Norway his

own, and be sole lord thereof in such wise as Gorm

of Denmark or Eric of Upsala have done."

The messengers came back in wrath and told the

king that Gyda (for so the maiden was called)

was witless and overbold, but Harald answered

that the maid had spoken nought of ill, and done

nought worthy of evil reward. Rather he bade her

much thank for her word; "For she has brought

to my mind that matter which it now seems to[13]

me wondrous I have not had in my mind heretofore."

And, moreover, he said: "This oath I make fast,

and swear before that god who made me and rules

over all things, that never more will I cut my hair

nor comb it, till I have gotten to me all Norway,

with the scat thereof and the dues, and all rule

thereover, or else will I die rather."

And so for ten winters his hair was neither cut nor

combed, but during all those days the kinglets were

being warred down, and at last, in 872, as monarch of

all Norway, Harald took a bath and let his hair be

combed. Jarl Rognvald sheared his locks and called

him Harald Fairhair; the name by which he is known

in history to-day.[2]

Thus he wedded the fair Gyda, but unhappily he

also took to wife more other maidens than one may

count with ease. Their very numerous sons were

soon waxen riotous men in the land and were not at

one among themselves. The good work of their father

they came near to undoing.

For good work to Norway it very truly was: national

unity is a priceless thing. One king was better than a

score of kinglets from the nation's point of view.

But otherwise thought the jarls (or earls) and the[14]

stoutest opponents of Harald embarked on their ships

and sailed away. Some turned their prows to the

northward and settled in the Faroes or Iceland, or on

the more distant American shore. These were, perhaps,

the more peaceably disposed; they found lands

waiting for settlement that became at once their own.

Their descendants are Norsemen to-day, and among

the most cultured of mankind. Others fared to the

British Isles or the Continent of Europe or to the

more distant Mediterranean Sea. These found lands

that were richer, but to be gained only at the point

of the sword. These set up powerful kingdoms, but

none of them are Norse to-day.

The classic sagas of Iceland have disappointingly

little to tell us about the Faroe Islands. There are

plenty of references to them indeed, but they are

exiguous and dull. The Faereyinga Saga is distinctly

less vigorous and vivid than the elder sagas of heroic

days. It was compiled in Iceland not long after

the beginning of the thirteenth century, but older

materials were used.

It commences with a somewhat scrappy description

of the first settlement of the islands. "There

was a man named Grim Camban. He first settled

the Faroes in the days of Harald Fairhair. For

before the king's overbearing many men fled in those

days. Some settled in the Faroes and began to dwell

there, and some sought to other waste lands."

[15]

Gladly would we have more details of the first

settler in the islands with his Irish-sounding name,

but they are lost in the abyss of years. With great

probability, however, Professor York Powell, who

Englished the Faereyinga Saga, supposes that the first

place occupied was the present capital, the Harbour

of Thor. There at any rate was the chief seat of

the Thing or Moot for the Islands, certainly till the

thirteenth century.

At Thorshavn, too, was played the first half of the

delightfully simple 2-Act drama which changed the

faith of the archipelago. The renowned King Olaf

Tryggvison of Norway (p. 72) had treated Sigmund

with high regard and caused him to trow in the faith

of the White Christ.

"When the spring was coming in, the king fell

on a day to talk with Sigmund, and said that he was

minded to send him out to the Faroes to christen the

folk that dwelt there. Sigmund said that he would

rather not do that errand, but at last said he would do

the king's will. Then the king made him lord over

all the islands, and gave him wise men to baptize the

folk and teach them the needful lore. Sigmund sailed

when he was bound, and sped well on his way. When

he came to the Faroes he summoned the franklins to

a Thing in Stromo,[3] and much folk came. And when

the Thing was set, Sigmund stood up and set forth his[16]

business at length, telling all that had happened since

he had gone eastward to Norway to see King Olaf

Tryggvison. Moreover, he said that the king had

laid all the island under his lordship, and most of the

franklins took this very well. Then Sigmund said on,

'I would likewise have you know that I have taken

another faith, and am become a Christian man. I

have also this errand and bidding from the king, to

turn all folk in the island to the true faith.' Thrond

answered this speech and said that it was right the

franklins should talk over this hard matter among

themselves. The franklins said this was well spoken.

Then they went to the other side of the Thing-field,

and Thrond told the franklins that the right thing

clearly was to refuse to fulfil this command, and he

brought things so far by his fair speeches that they

were all of one mind thereon. But when Sigmund

saw that all the folk had crowded over to Thrond's

side, so that there was none stood by him save his

own men who were christened, he said, 'Too much

might have I given Thrond to-day.' And now men

began to crowd back to where Sigmund was sitting;

they bore their weapons aloft and carried themselves

in no peaceful wise. Sigmund and his men sprang

up to meet them. Then spake Thrond, 'Let men

sit down and carry themselves more quietly. Now I

have this to tell thee, kinsman Sigmund; we franklins

are all of one mind on this errand thou hast done,[17]

namely that we will by no means change our faith,

and we will set on here in the Thing and slay thee,

unless thou give it up and bind thyself fast never

more to carry this bidding to the islands.' And when

Sigmund saw that he could not then bring this matter

of the faith about, and was not strong enough to deal

with all the folk that was come together there by the

strong hand, it ended in his bidding himself to what

they wished with witnesses and hand-plight. And

with that the Thing broke up.

"Sigmund sat at home that winter, and was right

ill-pleased that the franklins had cowed him, although

he did not let his mind be known."

"One day in the spring, what time the races ran

faster and men thought no ship could live on the main

or between the islands, Sigmund set out from home

with thirty men and two ships, saying that he would

run the risk and carry out the king's errand or else

die. They ran for Ostero and made the island; they

got there at nightfall without being seen, made a

ring round the homestead at Gate, drove a trunk of

wood at the door of the house where Thrond slept,

and broke it down, then laid hands on Thrond and led

him out. Then said Sigmund, 'It happens now, as

it often does, Thrond, that things go by turns. Thou

didst cow me last harvest-tide, and gave me two hard

things to choose between; and now I will give thee

two very unlike things to choose between: the one[18]

is good—that thou take the true faith and let thyself

be baptized, or else thou shalt be slain here on the

spot; and that is a bad choice for thee to make, for

thereby thou shalt swiftly lose thy wealth and earthly

bliss in this world, and get instead woe and the everlasting

torments of hell in the other world.' But

Thrond said, 'I will not fail my old friends.' Then

Sigmund sent a man to kill Thrond, and put a great

axe in his hand; but as he went up to Thrond with his

axe on high, Thrond looked at him and said, 'Strike

me not so quickly. I have something to say first.

Where is thy kinsman Sigmund?' 'Here am I,'

said he. 'Thou alone shalt settle between me and

thee, and I will take thy faith as thou wilt.' Then

said Thore, 'Hew at him, man.' But Sigmund said,

'He shall not be cut down this time.' 'It will be

thy bane and thy friends' as well if Thrond get off

to-day,' said Thore. But Sigmund said that he would

risk that. Then Thrond was baptized of the priest

and all his household. Sigmund made Thrond come

with him when he was baptized. And then he went

through all the Faroes and stayed not till the whole

people was christened."[4]

King Olaf, called the Thick in life and the Holy in

death—with whom we shall be much concerned later

on—also sought to make his influence felt in the

Faroe Islands. Thither he sent to look after the[19]

royal interests Karl o' Mere, who had been a viking

and the greatest of lifters, but "was a man of great

kin, a man of mickle stir, a man of prowess and

doughty in many matters." Him King Olaf took

"into his peace, and thereafter into his good love, and

let array his journey in the best wise. Nigh twenty

men they were on board the ship. The king made

word to his friends in the Faroes, and sent Karl for

trust and troth to Leif, son of Ozur, and Gilli the

Speaker-at-law, and to that end he sent his tokens.

Karl fared forthwith when he was ready, and a fair

wind they had, and came to Faroe, and hove into

Thorshavn in Stream-isle. Then a Thing was summoned

there, and folk came thronging thereto.

Thither came Thrand o' Gate with a mickle flock, and

thereto came Leif and Gilli, and had with them a

multitude of people. Now when they set up their

tilts and dight them their booths there, they went to

see Karl o' Mere, and the greetings there were good."

It need hardly be said that one object the king

had at heart was to collect his scat (or taxes) from the

islands, and when the subject was mentioned to

Thrand he amiably replied that "it was due and

welcome that he should give that much furtherance

to the king's errand."

When the time came round for the next Thing,

Thrand duly fared to Thorshavn and, because he

had pains in the eyes and other ailments besides, he[20]

let hang the inner part of his tent with black cloth so

that the daylight might be less dazzling. Here the

purse containing the scat was duly delivered to Leif,

who "bore it further out into the booth, where it

was light, and poured the silver down upon his shield,

and stirred it about with his hand, and said that Karl

should look at the silver.

"They looked on it for awhile, and Karl asked

Leif how the silver seemed to him. He answered:

'Methinks that every bad penny to be found in the

North isles is here come together.' Thrand heard this

and said: 'Seemeth the silver nought well to thee,

Leif?' 'Even so,' says he. Said Thrand: 'Forsooth,

those my kinsmen are no middling dastards,

whereas one may trust them in nought. I sent them

in the spring north into the islands to gather up the

scat, because last spring I was good for nothing

myself; but they will have taken bribes of the bonders

to take this false coin which is not deemed fit to pass.

Thou hadst better, Leif, look at this silver wherewith

my rents have been paid.'

"So Leif took back to him that silver, and took

from him another purse, and bore it to Karl, and they

ransacked it, and Karl asked what Leif thought of

this money. He said he deemed it bad, but not so

bad as that it might not be taken in payment for

debts carelessly bespoken,'but on behalf of the king

I will have nought of this money.'"

[21]

At last Thrand "bade Leif hand him that silver

back: 'And take thou here this purse which my

tenants have fetched me home last spring, and dim

of sight though I be, still, 'Self hand the safest

hand.'"

"Leif took the purse and once more bore it to Karl,

and they looked at the money, and Leif spoke:

'No need to look long at this silver; every penny

here is better than the other, and this money will we

have.'"

The payment of taxes has seldom proved the most

soothing thing for doubtful tempers. While the

money was being weighed there appeared on the

scene a man "with a cudgel in his hand and a slouch-hat

on his head, and a green cloak; barefoot, in linen

breeches strait-laced to the bone." There followed a

scrimmage, in the course of which Karl got an axe-hammer

in his brain, nor was his the only death.

"But it came never to pass that King Olaf might

avenge this on Thrand or his kinsmen, because of the

unpeace which now befell in Norway.... And hereby

leaves the tale to tell of the tidings which sprung out

of King Olaf's claiming scat of the Faroes. Yet

later on strifes arose in the Faroes out of the slaying

of Karl o'Mere, and the kinsmen of Thrand o' Gate

and Leif, the son of Ozur, had to do herein, and great

tales are told thereof."[5]

[22]

The haven of Thor is a little rocky bay; a small

island, called Nolsö, protects its broad mouth.

Streams trickle into it over the volcanic rocks, intersecting

the town and justifying the name of the island

upon whose shore it stands. One stream is fairly

large, the rest are very small. The well-kept gardens

are bright with flowers and stocked with currant

bushes; a few are shaded by plane trees of the most

diminutive size. The wooden houses, mostly Stockholm-tarred,

some painted different shades, rest on

rude foundations of boulders; some buildings are

wholly of rough stone. Most of the roofs are covered

with grass—amidst which wild flowers grow—so

green that they are not to be distinguished from the

hill-sides just behind, and the first impression is

almost that of a ruined, roofless town.

A few houses are creeper-covered: almost all have

fish hanging out to dry and the passer-by is more

conscious of their presence than of that of the flowers.

Through the grassy roofs rise chimneys which in many

cases are of wood. The main streets are wide and

breezy, the byways are but three feet broad; the

pavement for the most part is living rock. A mere

fishing village indeed is Thorshavn, but there is

much of the character of the capital of a little state.

The culture of Scandinavia is displayed in the existence

of a library, well used.

Face page 22

[23]

The Amtmand, or Governor, dwells in a quite

imposing house of stone; school, church and Lagthinghuus

are merely framed of wood. Of the Mother

of Parliaments Cowper once wrote, and some are

making much the same remark to-day,

Where flails of oratory thresh the floor,

That yields them chaff and dust and nothing more.

But of the legislature that meets in the Lagthinghuus

no man can say anything so rude. However barren

of other results the deliberations of the assembly

may be, the community is at least benefited by the

value of the hay that grows upon the roof. It may

be the sluggard that lets the grass grow under his

feet, but no stigma can attach to the man who lets

it grow over his head. Besides possessing this

venerable local Thing, the islanders send their own

representatives to the Rigsdag, or Diet, at Copenhagen,

for which qualified voters must have reached

their thirtieth year. The Danish dominions have

not yet followed Norway and Sweden in granting

votes to women, but this will shortly come to pass.

The mediæval bishop for the Faroes had his stool

at Kirkebö, on the same island as Thorshavn but a

few miles further south. There was a house of Benedictine

monks, the ruins of which still remain. In[24]

the haven named from Thor the church[6] of the White

Christ is conspicuous, though modern of date and

unbeautiful of form. An ancient coffin-slab, however,

is incised with an ornate and flowery cross,

that shows a mediæval structure occupied the site.

The tower vane bears the date 1788, pierced in

the Scandinavian way. The effect within is rather

quaint. On the altar two great candles stand;

hanging from the roof are a large ship-model and

some chandeliers of brass, one dated 1682, adorned

with metal flowers; on the walls a picture of the

Last Supper that was painted on wood in 1647, and

several monuments in timber and stone to the dead

who passed from earth two hundred years ago.

On a promontory overlooking the town and the

rocks covered with shells and pink and dark green

sea-weed, there frowns a picturesque old fort; more

interesting to the antiquary than formidable to the

soldier. What higher praise than that could any place

of strength deserve? The two lines of defence are

each formed of boulders and earth. Though Thorshavn

in the past has known unpeace, many an empire

has risen to high power or crumbled to decay since

these grass-grown ramparts were stained with human

gore.

The stony country round the town is partly enclosed[25]

by strange frail transparent dykes, which, though as

in Scotland mortarless, display surprisingly wide

openings between the stones. Hay grown on the

rocky soil is much the commonest crop; ragged

robin, white clover, and, in swampy parts, marsh

marigolds, diversify the grass. Men capped and

stockinged, women shawled, also tend the tiniest

patches of oats and potatoes: here and there peat is

cut. The older cottages are frequently half floored

above, half open to the ridge, and most conspicuous

still are the sooty rafters of which the sagas so often

tell. Some faint breath from the atmosphere that

filled such dwellings long ago is wafted to us by the

complaint of Cetil to his son in the Vatzdaela Saga,

that, when he was a boy, men yearned to do some

daring deed, "But now young men have become

stay-at-homes, sitting over the baking fires, and

stuffing their bellies with mead and ale, and all

manhood and hardihood is waning away." Gone

to museums are the ancient looms weighted with

stones from the beach, but old carved chests and

solid furniture of wood worked in the northern way

are still by no means rare.

Men of great mark, by no means few, have had

the Faroe Isles for home. In this remote and quiet

capital there was born in 1860 Dr. N. R. Finsen, one

of the great benefactors of mankind, widely known

in medical circles from his study of the laws of[26]

light-rays, and the foundation of the Medical Light

Institute at Copenhagen. A monument in the streets

of the Danish metropolis bears his name, and it is

possible that to the next generation he may be as

well known as he would have been to his own, had

he only invented some potent engine of destruction,

instead of mere antidotes to wasting disease.

A little like the Scottish highlands here and there,

with mountain tarn and trickling stream and rock

hill-side and distant sea, a little, yet not very like,

for the most striking feature of this delightful group

of islands is its lack of resemblance to any other part

of earth. Vast mountains rising from the very sea,

and never destitute of whitest clouds, fold upon fold

of country devoid of trees and yet so fertile and kept

so moist by shower and mist that the grass grows over

house-top as well as ground, the close proximity of

fjord and hay-field and fish and flowers, give a

combined impression so individual that the widest

wanderer will but faintly be reminded of any other

part of the world.

The surpassing stateliness of much of the coast

declines to be expressed in ink or paint. Even the

Naerofjord of Norway, most justly famed throughout

the earth, is distanced in wild and rugged grandeur

by some of the lonely channels among the north isles

of the group, restricted in extent though they be.

The largest steamer seems like a little toy between the[27]

towering mountains that rise on either side, carved

into cliffs here and there, worn into caves now and

then. The mountain sides are marked by waterfalls,

like little silver threads. Wherever there is grass on

the steep volcanic rocks, appearing like insects, there

climb about white sheep and black; such gave the

archipelago its name—far, the Norse word for

sheep.[7] Everywhere hang white mists, clinging to

the summits of the hills or streaming away like

pennons in sharpest contrast with the coal-black

sea of the sagas.

[28]

CHAPTER II

REYKJAVIK

Hail, Isle! with mist and snow-storms girt around,

Where fire and earthquake rend the shattered ground,—

Here once o'er furthest ocean's icy path

The Northmen fled a tyrant monarch's wrath:

Here, cheered by song and story, dwelt they free,

And held unscathed their laws and liberty.

Robert Lowe.

A faint idea of Icelandic scenery may perhaps be

gained by taking a journey on the moon by the aid

of a good telescope. Nowhere else is to be found

the same weird impression of vastness and of

magnificent desolation!

Not infrequently, particularly in a land of hills,

do the works of man seem puny beside the works of[29]

God, but as in Iceland nowhere else. Only rarely,

here and there, are signs of cultivation, and that is

on the tiniest scale. Wild stretches of jagged lava

and volcanic rock spread into space like "the ruins

of an elder world." The great rugged mountains,

capped by snow, and the numerous hot springs suggest

the eternal battle-ground of elements, and give to

the landscape a weird, almost unearthly effect.

As Gudbrand Thorlac (Bishop of Holar, quoted by

Hakluyt) expresses it: "There be in this Iland

mountaines lift up to the skies, whose tops being white

with perpetuall snowe, their roots boile with everlasting

fire." The prevailing colours, including every

shade of brown and yellow, are relieved only where

appears the deep blue-black of the sea; save that

here and there a tiny waterfall by stunted trees and

a carpet of wild flowers, such as heather or grass of

Parnassus, rather faintly suggest the glories of more

southern lands.

The Great Pyramid and the Chinese Wall themselves

would be lost, St. Peter's would appear a mere

pebble, amid those gigantic stretches of lonely mountain.

And during the very darkest days of early

mediæval times a small handful of men in these

remote solitudes were to play a part in history that

is perfectly unique, to endow humanity with something

it could ill afford to put away.

Here, on the dark winter nights of a region only[30]

just without the Arctic Circle, were written and

enjoyed those sagas that are true history and very

human, while nothing but dry chronicles were being

composed in all Europe besides. Far less we should

know of the early story of the British Isles and of

North America had the Icelanders been dumb.

Worthily appears the name of their Republic among

those of other famous Commonwealths of earth in

the hub of the universe, the State House at Boston,

Massachusetts!

Interest in Iceland and her sagas has been greatly

revived of recent years. In these days it seems

strange to read what P. H. Mallet (p. 152) wrote about

1755: "Such was the constitution of a republic,

which is at present quite forgotten in the North, and

utterly unknown through the rest of Europe even to

men of much reading, notwithstanding the great

number of poets and historians which that republic

produced."

The stories of the early settlers, as related in the

sagas, slightly recall the conditions that even to-day

exist in such places as Rhodesia and newly-opened

districts of the Western States. The details are as

different as they could well be, but there is something

of the same overflowing youthful vitality, the same

grim sort of humour and vigorous enjoyment of life.

This tale, for instance, from the Liosvetninga Saga,

shows a rather indirect and possibly somewhat modern[31]

method of leading up to an extremely simple point:

"When the table was set there Ufey put his fist

on the board, and spake, 'How big dost think that

fist is, Gudmund?' He spake, 'Very big!' Ufey

spake, 'Thou wouldst think that there would be

strength in it.' Gudmund spake, 'Indeed I would.'

Ufey answers, 'A heavy blow thou wouldst think it

would give?' Gudmund spake, 'Mighty heavy.'

Ufey spake, 'What harm wouldst think it would

do?' Gudmund spake, 'Breaking of bones or death.'

Ufey spake, 'How wouldst like that way of death?'

Gudmund spake, 'Very ill, and I should not wish it

to happen to me.' Ufey spake, 'Then do not thou

sit in my seat.'"

The settlement of Iceland was part of the happy

movement that first carried Norsemen to the Faroe

Islands and far beyond. There was a man named

Gard-here, a Swede, and he journeyed to Sodor, or

the Southern Islands[8] on the very common quest

of getting in the inheritance of his wife's father, who

had died. A gale broke his moorings. He was

driven westward into the sea, and the eventual result

was that he reached the island with which we are

concerned. He praised the land much, and desired

that it should be called by his own name.

But he did not discover the island. That glory

belongs to dreamy mystics of the ancient Irish Church[32]

in the days when her rays lit up the whole of Western

Europe, and her missionaries went out into all

lands.[9] Where he heard no other sound than the

thud of the storm waves on the lonely rocks, and the

shrill cry of the sea-gulls, quite alone with his God,

there the Celtic monk could best say his prayers.

And the Libellus Islandorum expressly says of the first

days of settlement: "There were then here Christian

men, whom the Northmen call 'papa.' But soon

they went away because they could not dwell with

pagan hordes, and they left behind them Irish books

and bells and crooks." A little cross of theirs is in

the Museum at Reykjavik to-day.

Again there were certain men who needed to

journey out of Norway to the Faroes, some say that

Naddodh was of their number, and they also were

driven to the same country, which they named

Snowland. They walked up a high mountain in the

East-friths, and looked far and wide to see if they

could discover any smoke or other token of the presence

of mankind, but they saw none. They went

back to the Faroes at harvest-time and they praised

the new country very much.

The third party of Norsemen that reached Iceland

had decorously made a great sacrifice before setting

forth, and three ravens had been hallowed. In the[33]

Faroe Islands, Floki, their leader, got his daughter

very satisfactorily married, and then he sailed out

into the sea and let loose the three ravens. The first

feebly flew to the bows of the vessel; the second

with little more adventure soared into the air and

then came back to the ship; but the third flew forth

from the bows and led the way to the island. And

when they sailed past Reek-ness, or Smoky Cape, and

entered the great mountain-walled fjord, Faxe said,

"This must be a big country which we have found;

here are great rivers." And, though his surmise as

to the rivers was mistaken, the inlet received his

name; as Faxefjoth men know it to this day. The

whole frith was full of fish, including seals and whales,

and the party became so absorbed in catching them

that they imprudently took no heed to make hay—with

the result that they lost all their stock in the

winter. As to the climate there were many different

views, but Thorwolf said that butter dripped out of

every blade of grass in the country that they had

found. Wherefore he was called Thorwolf Butter.

It was nevertheless so cold that the party originated

the unfortunate designation of Iceland, a name

that has probably done more than anything else to

spread through the world undoubtedly exaggerated

notions as to the coldness of the island. Sometimes

for weeks together Reykjavik has been warmer than

London. The famous Icelandic explorer, Eric the[34]

Red, seems to have realised that a mistake had been

made, and with much discretion he gave another

land "a name, and called it Greenland, and said that

men would be ready to go thither if the land had a

good name."[10]

The Icelanders are as sensitive as the Canadians

about the climate of their country, and as early as the

sixteenth century we find the Bishop of Holar, already

mentioned (p. 29), whose observations are quoted by

Hakluyt, growling thus about one whose strictures on

the island did not however stop with criticisms of the

climate. "There came to light about the yeare of

Christ 1561, a very deformed impe, begotten by a

certain Pedlar of Germany; namely, a booke of

German rimes, of al that ever were read the most

filthy and most slanderous against the nation of

Island. Neither did it suffice the base printer once

to send abroad that base brat, but he must publish

it also thrise or foure times over; that he might

thereby, what lay in him, more deepely disgrace our

innocent nation among the Germans, and Danes,

and other neighbour countries, with shamefull, and

everlasting ignomine. So great was the malice of

this printer, and his desire so greedy to get lucre, by

a thing unlawfull. And this he did without controlment,

even in that citie, which these many yeares

hath trafficked with Island to the great gaine, and[35]

commodity of the citizens. His name is Ioachimus

Leo, a man worthy to become lion's foode."

As late as 1846 "Sylvanus" (p. 202) wrote, "Iceland,

a dreary, storm-beaten isle, nearly deprived of all

communication with its fatherland. It is the abode

of all but ceaseless winter, in which the sun, rarely

for more than a few months out of the twelve, is

ever seen."

It is possible to suffer very much from heat in

Iceland, but there seems to be good ground for believing

that the climate has changed for the severer in

the course of a thousand years. Forests are frequently

mentioned in the earlier sagas—the Libellus

Islandorum expressly says that in the first days of

settlement the country "was grown with wood

between fell and foreshore." But to-day there is

nothing much bigger than a Japanese dwarf tree.

The first permanent settler was Ingwolf Arnerson

(or Erneson) and he was told to go thither by an

oracle while he sacrificed. And at that time Harald

of the Fairhair had for twelve years been king in

Norway, and since the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus

Christ 874 winters had passed away. He sailed to

Iceland with Heor-leif, his sworn brother and the

husband of his sister; a man who refused to sacrifice.

They kept company till they saw Iceland and then

they parted. And as soon as Ingwolf noticed the

land he pitched his porch-pillars overboard to get[36]

an omen. For it was the pious custom of those days

to let the site for a new settlement be fixed, not by

the caprice of man, but by the decision of the gods,

who made it known by causing the currents of ocean

to cast up the porch-pillars on the shore where they

would have the dwelling to be.

Before their emigration to Iceland Leif and Ingwolf

had made a foray in Ireland. There they had gained

riches and thralls, and Leif was called Heor, or Sword,

from an encounter with an Irishman, from whom he

gained such a weapon. Driven westward off the

land, Leif and his men ran short of water, and the

thralls, with the readiness that ever marks their race,

took to the plan of kneading meal and butter together,

and they declared that this was a thirst-slake. But

as soon as it was ready there fell a great rain and

water was caught in the awnings.

Eventually they reached land in safety, and there

was only one ox, so the thralls had to drag the plow.

And they plotted together to kill the ox, and to say

that a bear had devoured it; then while Leif and his

Norsemen were seeking to punish the non-existent

bear, and were scattered through the shaw, the thralls

should slay every one his man, and so should murder

them all. And everything fell out just as the Irish

had plotted.

The dead body of Heor-leif was found by Ingwolf's

thralls, who had been sent to search for the porch-pillars,[37]

and when they told their master he was very

angry. And when he saw his brother dead he said,

"It was a pitiful death for a brave man that thralls

should slay him, but I see how it goes with those

who will never perform sacrifice."

"Then Ingwolf went up to the headland and saw

islands lying in the sea to the south-west. It came

into his mind that the thralls must have run away

thither, for the boat had disappeared. So he and his

men went to seek the thralls, and found them there

at a place called Eith (the Tarbet) in the islands.

They were sitting at their meat when Ingwolf fell

upon them. They became fearful, and every man

of them ran off his own way. Ingwolf slew them

all. The place is called Duf-thac's Scaur, where he

lost his life. Many of them leaped over the rock,

which was afterwards called by their name. The

islands were afterwards called the Westmen Isles

whereon they were slain, for they were Westmen"

(or Irish).

Heimaey (or Home Isle), the largest of these

Westmen Isles, consists of two great jagged masses

of igneous rock, presenting wild cliffs to the ocean

and a wild fretted outline to the sky. Between

the two mountains is a rolling stretch of grass-land,

and upon it stands the scattered little town of Kaupstadr.

The cliffs are covered with sea-birds' nests,

most of them filthy fulmars. And some of the other[38]

islands of the group, among which modern cruising

steamers thread their way, are sea-worn into caves

and caverns by the much contorted rocks along the

shore.

At last, in the third winter, Ingwolf's thralls,

Weevil and Carle, found the porch-pillars, and at the

spot where they came to land he made for himself

a homestead. He dwelt in Reek-wick, and the Land-nama-bok,

or Icelandic Domesday, from which nearly

all the above facts are taken,[11] says that the pillars are

still to be seen in his fire-house, or temple.

In the Eyrbyggja Saga we read of the building of

another temple that stood on the north side of Faxefjoth.

Somewhat similar, no doubt, was the shrine

that incorporated the porch-pillars at Reykjavik.

"There he let build a temple, and a mighty house

it was. There was a door in the side-wall, and nearer

to one end thereof. Within the door stood the porch-pillars

and nails were therein; they were called the

Gods' nails. There within was a great frith-place.

But of the inmost house was there another house, of

the fashion whereof now is the quire of a church,

and there stood a stall in the midst of the floor in the

fashion of an altar, and thereon lay a ring without

a join that weighed twenty ounces, and on that must[39]

men swear all oaths; and that ring must the chief

have on his arm at all man-motes."

A gold ring that Olaf Tryggvison took from the

Temple of Lade (p. 69), and presented to a lady whom

he admired, turned out to be only plated copper,

and much trouble resulted from that gift. The gods

had in all probability never discovered the fraud, for,

like the Chinese to-day, the pagan Norse had a most

mean opinion of the intelligence of the objects of

their worship (p. 106). Some of the temples of Iceland

were of considerable dimensions: in the Vatzdaela

Saga we read of one at Thordisholt a hundred feet

in length.

Ingwolf, the founder of Reykjavik, was the most

famous of all the fathers of Iceland, for he came to a

desolate country, and was the first to build a house

and to cultivate the ground. His son "was Thorstan,

who let set the Thing at Keel-ness, before the

Allthing was established. His son was Thor-kell

Moon, the Law-speaker, who was one of the best

conversation of any heathen men in Iceland, of those

whom men have records of. He had himself carried

out into the rays of the sun in his death-sickness,

and commended himself to that God which had made

the sun. Moreover, he had lived as cleanly as those

Christian men who were of the best conversation or

way of life." (Landnama-bok.)

A fair broad bay, an arm of the Faxefjoth, rocky[40]

islands rising from the water and low hills all around,

the heights of Esja straight in front of the ship that

sails in, was the site chosen by the pagan gods.

The city of Reykjavik stands on low hills at whose

foot the porch-pillars were found. At the head of

the little reeking bay is the white steam of the hot

springs; away to the north, just visible across the

choppy waves of Faxefjoth, towers, four thousand

seven hundred feet above the sea, the huge volcanic

mass of Snaefells Jökull.

Thus Reykjavik, the present capital of Iceland,

bordered landward by a little lake, is more than a

thousand years old, yet it does not look fifteen!

No new settlement in the American West has a rawer

or more recent appearance. The building materials

are wood, brick, cement, felt and galvanized iron.

There are a few fair gardens with very stunted trees,

and in the rough grass square is a metal statue to

Thorwaldsen (p. 138). For ugly commonplaceness

the broad and dusty streets are hardly rivalled even

on the North American continent, and that is saying

a good deal. Yet the glorious views of wild mountain

and ever-changing sea, with air as fresh and pure as

in mid-ocean, make it attractive in spite of all.

The Norse settlement of the island, having prosperously

begun on the grassy plains at the edge of

which the city stands, soon spread all round the shore.

At wide intervals were built, or dug, the half underground[41]

turf-covered dwellings where men sat under

their smoky rafters by the fire, drinking wine or mead,

telling or hearing the saga tales. Old buildings that

still remain, including a few in the vicinity of Reykjavik,

give a fair idea of what these primitive dwellings

were like; sometimes they were partly excavated in

the side of a hill. Their interiors are much more

cosy and homelike than would be suspected from

their desolate-looking outsides. Hangings round the

walls must have greatly improved the appearance as

a rule, though the Laxdaela Saga says that the hall

which Thurid Olaf built in Herd-holt, whose sides and

roof were lined with noble histories carved on wainscotting,

looked better when the hangings were down.

Each large householder was chief and priest, lord of

all within sight of his dwelling.

The same (Laxdaela) saga describes one of them,

in fact the husband of this same Olaf's daughter.

"Garmund was generally a reserved man, and surly

to most folks, and he was always dressed the same;

he used to wear a red-scarlet kirtle and a grey cloak

over it, and a bear-skin hood on his head, a sword in

his hand that was a great and good weapon with

hilt of walrus-tooth, and there was no silver inlaid

on it, but the blade was sharp and no rust to be

found on it. This sword he called Leg-biter, and

he never let it pass out of his hand." This man

contrived to win Thurid, the daughter of Olaf, only[42]

by "giving no small sum of money" to her mamma.

As not infrequently happens in such cases, husband

and wife "did not get on very well, and this was

felt by both of them." So Garmund sailed away from

Iceland, and, to the great displeasure of his wife and

mother-in-law, he left no chattels behind him. However

Olaf's daughter pursued and, finding her husband

asleep in his vessel, she took away the sword Leg-biter

and left the baby in its place! As soon as the disgusted

father awoke from its crying and discovered

the unwelcome exchange, he sent a boat in pursuit of

wife and sword. Thurid had, however, foreseen that

manœuvre and the boat, being riddled with holes,

had in haste to put back to the ship. "Then Garmund

called to Thurid and bade her turn back and

give him the sword Leg-biter, and take the girl back,

'and as much money or chattels with her as thou

wilt.' Thurid says, 'Dost think it better to get

back the sword or not?' Garmund answered her,

'I would sooner lose great monies than lose the sword.'

She spake, 'Then thou shalt never get it; thou hast

in many ways treated me unjustly, and we will now

part.'"

Even less careful of his personal appearance than

Garmund must have been Anlaf of Black-fen, whose

deeds are recorded in the Havardz Saga (II., 1). Men

say that he had bear's warmth, for "there never was

frost or cold so great that Anlaf would not go about[43]

in no more clothes than his breeches and a shirt

tucked into the breeches. And he never went abroad

off the farm with more clothes on him than these."

He was, however, a good man, and somewhat before

midwinter he walked over the hill pasture and all

over the fell seeking men's sheep, and he found many

and drove them home, and brought every man his

own, so that every one wished him well.

Iceland is perhaps the least mixed nation to be

found on the surface of the globe. Among the

fathers of her settlement there were indeed a few of

other than Norse blood, particularly ubiquitous

Irish, some of whom were men very well thought of,

but all except a few individuals here and there were

of pure Scandinavian stock. The Landnama-bok

expressly tells us: "Men of knowledge say that the

country was wholly settled and taken up in sixty

winters, so that it hath never after been settled

any more."

As the community grew older it became apparent

that something more than local chiefs and Things

were imperatively needed if any sort of peace was to

be preserved and some kind of order to be established.

And thus there was called into being in a.d. 930 the

most famous parliament of the North—the Allthing,

that assembled every year under the clear sky, by

the banks of a little stream where the horizon was

formed by the wild rocky hills of Thingvellir. From[44]

all over the island men came for practically every

purpose for which human beings can gainfully meet.

Laws were made and declared, law cases were decided;

tales were recited and much was bought and sold.

But the only official of the Republic was the Speaker

of the Law, the jurisdiction was purely moral.

Administrative machinery, civil service, navy or

army there were none. He who refused to obey

could but be outlawed.[12]

No doubt this essentially Teutonic reform brought

vast improvement on the lawless violence of earlier

days, but the respect entertained for law still left very

much to be desired. The famous Saga of the Burnt

Njal gives a truly Homeric account of proceedings at

the Allthing itself.

Flosi and certain others who were on trial for

arson and manslaughter were on the point of getting

off by the kind of legal quibble in which Dickens was

interested so much. Gizur, one of the plaintiffs,

said, "What counsel shall we now take, kinsman

Asgrim?" Then Asgrim said, "Now will we send

a man to my son Thorhall, and know what counsel

he will give us."

"Now the messenger comes to Thorhall, Asgrim's

son, and tells him how things stood, and how Mord

Volgard's son and his friends would all be made[45]

outlaws, and the suits for manslaughter be brought

to nought.

"But when he heard that, he was so shocked at it

that he could not utter a word. He jumped up then

from his bed, and clutched with both hands his spear,

Skarphedinn's gift, and drove it through his foot....

Now he went out of the booth unhalting and walked

so hard that the messenger could not keep up with

him, and so he goes until he came to the Fifth Court.

There he met Grim the Red, Flosi's kinsman, and as

soon as they were met, Thorhall thrust at him with

the spear, and smote him on the shield and clove it

in twain, but the spear passed right through him,

so that the point came out between his shoulders.

Then there was a mighty cry all over the host, and

then they shouted their war-cries.

"Flosi and his friends then turned against their

foes, and both sides egged on their men fast.

"Kari Solmund's son turned now thither where

Arni (Kol's son) and Hallbjorn the Strong were in

front, and as soon as ever Hallbjorn saw Kari, he made

a blow at him, and aimed at his leg, but Kari leaped

up into the air, and Hallbjorn missed him. Kari

turned on Arni (Kol's son) and cut at him, and smote

him on the shoulder, and cut asunder the shoulder

blade and collar bone, and the blow went right down

into his breast, and Arni (Kol's son) fell down dead at

once to earth.

[46]

"After that he hewed at Hallbjorn and caught him

on the shield, and the blow passed through the shield,

and so down and cut off his great toe. Holmstein

hurled a spear at Kari, but he caught it in the air,

and sent it back, and it was a man's death in Flosi's

band....

"Then there was a little lull in the battle, and

Snorri the priest came up with his band, and Skapti

was there in his company, and they ran in between

them, and so they could not get at one another to

fight.... So a truce was set, and was to be kept

throughout the Thing, and then the bodies were laid

out and borne to the church, and the wounds of those

men were bound up who were hurt."

The day after men went to the Hill of Laws. A

skald opportunely sang some verses with the result

that now men burst out in great fits of laughter.

And eventually "in this way the atonement came

about, and then hands were shaken on it, and twelve

men were to utter the award, and Snorri the priest

was the chief man in this award, and others with

him. Then the manslaughters were set off the one

against the other, and those men who were over and

above were paid for in fines. They also made an

award in the suit about the Burning."[13]

The Allthing still meets, but no longer amid

mountain wilds. A very substantial stone structure,[47]

two storeys and an attic high, faces the square at

Reykjavik; it bears date 1881. Below is a library;

above the chamber, from a gallery in the attic, the

public may look on. It is impossible to visit this

humble structure without emotion, for it is the seat

of one of the ancientest moots upon the earth. Had

it only a continuous history from its first institution

it would be older by, at any rate, a century or two

than the very Mother of Parliaments, for the French-named

body that sits at St. Stephen's can hardly

claim historic continuity with the Saxon Witanagemot.

But the well-fitted Althinghuus is an unromantic

substitute for the vast and desolate wildness

of the Thingvellir. It is with a shock, too, that one

notices on the walls great pictures of Egypt and of

Greece. Are not Ellidaar and Hvita, salmon rivers

of Iceland, to this assembly at any rate better than

all the waters of Nile and Cephissus?[14]

The Cathedral of Reykjavik, next to the Althinghuus,

is a small whitewashed structure with saddle

roof tower, whose vane is dated 1847. It is entirely

destitute of the slightest interest, save for the lovely

font by Thorwaldsen (p. 138), a cube of white marble.

Round the top is a garland of flowers to support

the metal bowl; on the four sides are bas-reliefs[48]

representing the Baptism of Christ, a mother and her

children, cherubs, and Christ blessing the children.

The Bishop, or Lutheran superintendent, has charge

of the whole island, which in the middle ages formed

two dioceses.

The Christianising of Iceland was a less violent

process than that of the other northern lands. The

building of the earliest church was owing to the gentle

influence of the great Scottish apostle of Ireland.

"Aur-lyg was the name of a son of Hrapp, the son

of Beorn Buna. He was in fosterage with Bishop

Patrec, the saint in the Southreys. A yearning came

upon him to go to Iceland, and prayed Bishop

Patrec that he would give him an outfit. The bishop

gave him timber for a church and asked him to take

it with him, and a plenarium, and an iron church-bell,

and a gold penny, and consecrated earth to lay

under the corner-posts instead of hallowing the

church, and prelates to dedicate the church to Columcella."[15]

And the church was built at Esia-rock,

looking out over the ocean. Close by in the sea-weed

the iron bell had been found, for it was cast into the

sea that, like the heathen porch-pillars, it might

point out the exact site that was the best.

The passing from the old faith to the new was

on the whole remarkably destitute of bigotry. One,

Helge, for example, "put his trust in Christ, and[49]

named his homestead after him, but yet would he

pray to Thor on sea voyage and in hard stress, and

in all those things that he deemed really of most

account."[16] While the Landnama-bok itself ends

with the remark: "Some held their Christendom

well till their death-day, but it did not often go on in

the family, because that of their sons, some reared

temples and sacrificed, and the land was heathen

nearly a hundred and twenty winters."

Then at a notable Allthing, about the year 1000,

one Thor-gar spoke to the people at the Rock of the

Laws. He told them a story about two kings who

formerly ruled in Norway and Denmark respectively.

"They had long kept up strife between them, till at

last the people of both countries took the matter into

their own hands, and made peace between them,

although they themselves did not wish it; but this

plan was so successful that the kings after a few

winters' space were sending gifts to each other, and

their friendship endured as long as they both did

live. 'And this seems to me the best not to let them

have their will that are most out and out on each side,

but let us so umpire the matter between them that

each side may gain somewhat of his case, but let us

all have one law and one faith. For this saying shall

be proved true, If the Constitution be broken the peace

will be broken.'

[50]

"Thor-gar ended his speech in such a way that

each side agreed to hold those laws which he should

think best to declare.

"This was the declaration of Thor-gar, that all

men in Iceland should be baptized and believe in one

God, but as to the exposure of children, and the eating

of horse-flesh, the old law should hold; men might

sacrifice in secret if they would, but should fall under

the lesser outlawry if witnesses came forward against

them. This heathendom was taken away some years

later."[17]

The final establishment of the faith was chiefly

owing to Bishop Gizor, who was, we are told, "better

beloved by all the people of the land than any other

man whom we know to have been on the land."[18]

Such, indeed, was the devotion men felt for him, so

much did they appreciate his speeches, that the

Icelanders voluntarily agreed to a complete valuation

of all that they possessed in order that they might

have the privilege of paying tithes! Greater proof

of love than that no people ever showed! It would

stagger humanity indeed were anything of the sort

to be recorded to-day. Gizor it was who fixed the

seat of the Bishopric at Skalholt, for before it was

nowhere; he, too, set up the northern Bishop's stool

at Holar, giving more than the fourth part of his

income to endow it. This Gizor was surnamed the[51]

White, and he kept such peace in the land that there

were no great feuds between the chiefs, and the carrying

of arms was almost laid aside. And he sent his

son Islaf to school in Saxland; he also became

a Bishop and took to wife Dalla, the daughter of

Thorwald.

So the faith in Iceland grew, not by bigotry but

by conciliation, and men were apt to prefer prime-signing

to baptism, for so could they have full intercourse

with Christian men and with heathen too,

and they could hold to the faith of their liking.[19]

But good arguments had a very-powerful effect,

and "this made men very eager in church-building,

which was promised by the clergy, that a man should

have room in the Kingdom of Heaven for as many as

could stand in the church that he had built."[20]

Things being thus comfortably and happily settled

by the Icelanders, it was not to be expected that

the sledge-hammer methods of the mainland would

find much favour among them. St. Olaf (p. 79) sent

a priest, one Thangbrand, to hasten the triumph of

the faith in Iceland, but he soon made that cool

country a great deal too hot to hold him. And, as

the Cristne Saga puts it: "At that very time Thangbrand

the priest came to the king from Iceland, and

told him what enmity men had shown him there,

and said there was no hope of Christendom being[52]

received there. Then the king was so angry that

he had many of the Icelanders taken prisoners and

set in irons. Some he ordered to be slain, and some

maimed, and some were plundered, for he said that

he would pay them for the unworthy way their fathers

had received his message in Iceland. But Sholto

and Gizor spoke for them, saying that the king had

promised that no man should have done such ill,

but that he would give them his peace if they would

be baptized.... Moreover Gizor said that he

thought there was hope that Christendom would

succeed in Iceland if it were wisely forwarded. 'But

Thangbrand hath carried himself there, as he did

here, rather lawlessly in slaying certain men there,

and men thought it hard to brook such behaviour

in a stranger.'"

Longfellow (The Saga of King Olaf) sums up this

troublesome missionary in the following verse:—

He was quarrelsome and loud,

And impatient of control,

Boisterous in the market crowd,

Boisterous at the wassail-bowl,

Everywhere

Would drink and swear,

Swaggering Thangbrand, Olaf's Priest.

So firm a hold did Christianity take on the land

that the sagas of early Christian days are largely

concerned with bishops' lives. The Church was as

powerful as in Italy, and the two prelates were much

honoured in the land. Thus we read in the book[53]

called Hungrvaca, or Hunger-Waker, because many

uninformed men, wise though they be, that have

gone through it have wished to know much more

concerning those notable persons of whom it speaks.

"Bishop Cetil was now well seventy years of age;

he went to the Allthing and commended himself to

the prayers of all the clerks in the synod of priests.

And then Bishop Magnus asked him to come home

with him to Skalholt to keep the dedication feast

of the church and a bridal that was to be there. The

feast was so very splendid that it was a pattern after

in Iceland; there was much mead mixed, and all

other stores of the best that might be. But the

Friday evening both bishops went to bathe at Bathridge

after supper. And then it came to pass that

Bishop Cetil died there, and men thought this great

news (July 6, 1145). There was great grief at this

feast among many of the guests till the bishop was

buried and service done for him. But by the comforting

speeches of Bishop Magnus and the noble

drink that was provided, men got their sorrow the

sooner out of mind than they would otherwise have

done."

The bathing of the bishops was in Iceland by no

means exceptional. While in the rest of Europe

personal cleanliness was inconspicuous between the

destruction of the buildings of Rome and comparatively

recent days, in Iceland, even during the[54]

tenth century, men could not get on without washing.

One householder is specially distinguished in the

Landnama-bok as Leot the Unwashed. Thus the

Eyrbyggja Saga describes a bath: "Stir let build a

hot bath at his house at Lava, and it was dug down in

the ground, and there was a window over the furnace,

so that it might be fed from without, and wondrous

hot was that place." Many such are mentioned

in the sagas, and one of the few mediæval ruins in

Iceland is that of the bath-house of Snorri Sturluson,

author of the Heimskringla, one who adorned history

by his writings, but not by his actions; for the discreditable

collapse of the Republic and the annexation

of Iceland to Norway was largely owing to him.

On his own estate and by his own son-in-law he was

murdered in 1241.

Two Icelandic bishops were placed among the Saints.

Bishop Thorlak of Skalholt "never spoke a word that

did not tend to some good purpose when he was

asked anything. He was so wary of his words that

he never blamed the weather as many do, or any of

those things that are not blameworthy, but which

he perceived went according to God's will. He did

not look forward to any day above the rest." And

most deservedly he was called that precious friend of

God, the Beam and Gem of Saints, both in Iceland

and other lands.[21]

[55]

A still greater reputation was, however, gained by

the other Icelandic saint, the holy bishop, John of

Holar, widely famed for the beauty of his voice. His

peculiar holiness very early in his life attracted the

attention of the devout. "When John was yet a

child his father and mother broke up housekeeping

and went abroad together. They came to Denmark

and went to King Swein, and the king received

them worshipfully, and Thorgerd (John's mother)

was made to sit by the queen herself, the mother of

King Swein. Thorgerd had her son, the holy John,

at the table with her, and when many kinds of

precious dainties with good drink came to the king's

table, then it happened with the boy John, as is ever

the way with children, that he stretched out his

hands to the things he wished to have. But his

mother would have chidden him, and smote his hands.

But when Queen Estrith saw this, she spake to

Thorgerd, 'Not so, not so, Thorgerd mine; do not

strike those hands, for they are bishop's hands!"[22]

John not only survived this spoiling, but fulfilled

the prophecy of the kindly queen. In due course,

bearing a letter from Bishop Gizor, he sailed to Denmark

for his consecration; "the Archbishop was at

church at evensong, and when John, the holy bishop-elect,[56]

got to the church (presumably the Cathedral

at Lund), evensong was well-nigh over. He took

his place outside the quire, and began to sing evensong

with his clerks. The Archbishop had forbidden all

his clerks, old and young alike, to look out of the

quire while the hours were being sung, and he set a

penalty to be taken if his command were broken.

But as soon as the Archbishop heard the chanting

of the holy John, he looked out down the church,

trying to see who the man was that had such a voice.

But when evensong was over, the Archbishop's

clerks said to him, 'How now, my lord bishop, have

ye not yourself broken the rules ye made?' The

Archbishop answered, 'I confess that it is true as

ye say, but yet I have not done it for nought, for a

voice was borne into my ears such as I have never

heard before, and it may rather be likened to the

voice of an angel than of a man.'"[23]

The Primate perceived that his very dear brother

had all the qualities desirable in a bishop, and so favourable

was the impression made that the canonical

difficulty to the consecration—that John had been

twice married—was surmounted with little trouble.[24]

Well did the new bishop regulate the affairs of the[57]

church on his arrival at Holar, where he rebuilt the

Cathedral, and at the bishopstead, west of the church

door, set up a school. A master he chose from Gothland

and he paid him a great wage, both to teach

the priestlings and to give such support to holy

Christendom along with the bishop himself as he

could manage in his teachings and addresses. By

this time the days of transition in Iceland were

over, and John felt strong enough not only to destroy

the material relics of paganism, but also to anticipate

George Fox in objecting to pagan names for

the days of the week. "He also forbade all omens,

which the men of old had been wont to take from

the coming of the moon and observance of days, and

dedicating days to heathen men or gods—as it is

when they are called Tew's day, Woden's day, or

Thor's, and so of all the week-days; but he bade

men to keep the reckoning which the holy fathers

have set in the Scriptures, and call them the Second

Day of the week, and the Third Day, and so on—and

all other things beside, which he thought sprung

from ill roots."[25] At last, in 1121, on April 23, he

departed out of this world into everlasting bliss.

As might perhaps be expected, by far the most

interesting object in Reykjavik is the National

Museum, into which is gathered, Scandinavian fashion,

much choice carved work from many an Icelandic[58]

church. For their inability to raise great fabrics

like those of southern lands, the disciples of the

White Christ in Iceland, much as in Ireland, resolved

as far as possible to atone by wealth of detail. Here

accordingly are quaint or beautiful works of art

whose composition beguiled many a long winter

night of old. Even Mallet (p. 151) most patronisingly

remarks: "Nor is this sculpture so bad as might

be expected." The sagas here and there refer to the

use of timber from the Icelandic forests for purposes

of building, but soft drift-wood is by far the commonest

material used for carving figures of saints,

many of which are extremely crude and some grotesque.

The ornate "Kirkjustodir" are rather like

the totem poles of North American Indians. Many

things there are of post-Reformation date, as pulpits,

bas-reliefs and fonts. Runic inscriptions survive

into the eighteenth century. The finest feature is

the magnificent retable in alabaster and wood, representing

scenes from the Passion, that came from

Holar Cathedral.[26] Carving of similar kind, though

much earlier in date, for Skalholt Cathedral is described

in the Pols Saga.[27] Margaret was the most

cunning carver of all folk in Iceland, and she was

surnamed the Skilful. "Bishop Paul had put in

hand, and had her begin a tabula for the altar before[59]

he died, and had meant to spend on it much money,

both gold and silver, and Margaret carved it most

nobly out of tusk-ivory, and this would have been

the greatest jewel or masterpiece if, according to his

plan, both Thorstan the shrine-maker and Margaret

had wrought it out with their craft. But his death

was a big black blow, and such things had to be put

off for the sake of many other things that had to be

done."

Some objects illustrate things other than ecclesiastical,

but, comparatively speaking, they are few.

Among them are old Icelandic chair-saddles with huge

and unwieldy stirrups, and guns of wood with iron

rings.

The country surrounding the city seems dreary

enough until the intense fascination of the wildly

desolate land and the extreme purity of the air grows

more and more upon the mind. The jagged rock-hills

all round are never quite free from snow, but

they were thrown up by the earth fires too late to be

planed down by ice. The well-known little ponies

of Iceland in considerable numbers wander at will over

the rough rolling pasture land, save that some are

ridden by tourists from the south, and some by radiant

Icelandic girls. These come jogging in from the

country on their curious flat side-saddles, both feet

resting on a wide hanging step. They wear their

hair in four plaits, the ends of which are looped up[60]

under a little flat cap of black cloth. From the

centre of the cap there hangs through a little silver

cylinder a long black tassel which reaches to the

shoulder.

The ground is largely dug into hummocks so as to

increase the area available for grass. A good road,

fringed by telegraph poles each side and patronised by

a fair number of cyclists, leads out of the town, and

after a mile or two crosses the Ellidaar, which has

cut a broad winding channel through the hard volcanic

rock, and is famous for fishing.

Nearer the sea are the hot springs whose waters

send up steam that is visible from far, and gave

the capital its name. The ponies are kept from burning

their noses by stretches of barbed wire. In water

heated by the fires that burn far down, beyond the

reach of man, the people of Reykjavik have long

been wont to wash their linen and their clothes. A

constant procession of women bear soiled things to

the spring and clean things to the town.

Many Icelanders speak English, and they are often

surprisingly well-informed, both concerning their

own history and the affairs of foreign lands. Still

read are the sagas in the land of their birth, and they

were Englished largely by Icelandic minds. There

are very good secondary schools in the towns, and a

College at Reykjavik itself. Though no elementary

schools exist, almost every one can read and write

from the excellent teaching in the homes. Reykjavik,

Akureyri and Isafjordr are fair-sized towns,

the former has a population of about ten thousand

souls, but the loneliness of life in many parts is evident

from the fact that the rest of the nation, about fifty or

sixty thousand in number, tending cattle and ponies,

and fishing for whale and cod, is thinly sprinkled

through some two hundred and eighty parishes.

HOT SPRINGS NEAR REYKJAVIK

[Face page 60

[61]

Of the rocky islands in Reykjavik Harbour by far

the most interesting is Videy, the resort to-day of

ptarmigan and eider duck, in past years the seat of

one of the chief religious houses of Iceland, a Priory

of the Benedictine order. The founder and the first

Prior (1226-35) was one Thorvald, son of a Speaker

of the Law, who was fifth in descent from Gizor the

White. He was succeeded by Styrmir, surnamed

hinn fródi or the Wise, who was one of the editors

of the Landnama-bok, and died in 1245. The chapel

in which he worshipped still exists, a rude early

thirteenth century structure, plain oblong with

gables, built roughly of volcanic stone. The sole

original features are the very plainest of windows

under segmental arches. It is still used for service,

and has plain eighteenth century fittings with tall

screen, and pulpit rising behind the altar, all painted

green and blue and red. Three bells are dated 1735,

1752 and 1785. In the loft under the roof is a

collection of old spinning wheels. The absence of[62]

surnames, which is still a characteristic of the unchanged

Norse tradition of Iceland, appears on a

gravestone of 1820, to Viefus Scheving and his

wife, Aunnu Stephansdóttur.

This little chapel appears to have been almost the

only stone church in mediæval Iceland; even the

famous Cathedral at Skalholt, which was in every

way glorious above any other building in Iceland, the

finest and most precious in the island, was merely a

structure of wood.

From the highest point of the island of Videy

there is a really superb view over the plantless

mountains and the steepleless city across a few

miles of blue-black, white-crested sea. The island

pastures support fifty head of cattle and slope right

down to the shore, where the waves have carved

arches and caverns in the yielding rocks. The farmhouse

by the chapel is a long stone building, whose

weathering by the storms of some two hundred

winters is concealed by a coat of whitewash, while