Title: Our Little Persian Cousin

Author: E. Cutler Shedd

Illustrator: Diantha W. Horne

Release date: May 31, 2014 [eBook #45844]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Beth Baran and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Our Little Persian

|

||

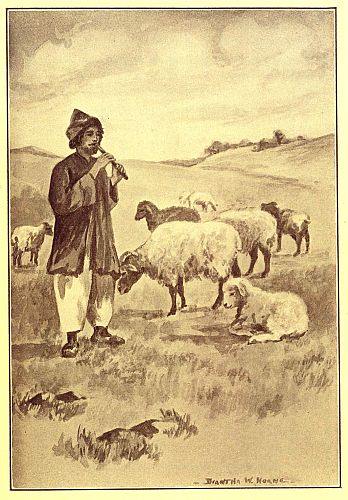

Persia is mostly a tableland, from which rise many high mountains. In the winter come storms of snow and rain; in the spring the ground is green with grass and bright with many flowers; but in the late summer and fall it is dry and hot. Over the mountains wander the Kurds, who live in tents, and drive with them the great flocks of goats and sheep whose milk gives them food and from whose wool they weave their clothing and rugs. In many of the valleys are villages. Here live the busy Persian peasants, who have brought the water in long channels from its bed in the valleys to water their fields and orchards. Where[vi] plenty of water is found there are towns and cities.

Over two thousand years ago the kings of the Persians were the most powerful in the world, and ruled all the country from India to Europe. Some of them helped the Jews, as is told in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Old Testament. Two of them tried to conquer Greece, but the brave Greeks defeated their armies in the famous battles of Marathon and Salamis. Many years later the Greeks themselves under Alexander the Great invaded Persia and won its empire. But the Persians afterwards regained the power, and for five centuries held their own against the armies of the Roman emperors.

Suddenly great armies of Arabs poured out from the wide desert land of Arabia, eager to conquer the world, and to bring others to accept the new religion taught by[vii] their prophet, Muhammad. Thousands of them entered Persia. They induced the Persians to forsake their own religion, called fire worship, and to become Muhammadans.

Six hundred years passed, when new and more terrible invaders spread over the land. These were armies of horsemen armed with bows, who came in thousands from the wide plains of Siberia. They were the ancestors of the Turks. They destroyed a great many villages and cities, and killed tens of thousands of the Persians. Even yet, after more than five hundred years, one may see in Persia ruins made by them. A great many Turks still live in northern Persia.

The Persians are now a weak and ignorant nation; but the most progressive of them are trying to secure good schools and to improve their country in other ways.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

| "He carried it home on his shoulder" (See page 92) | Frontispiece |

| "He was so fat that her back often ached" | 18 |

| "Here Karim sat all day" | 37 |

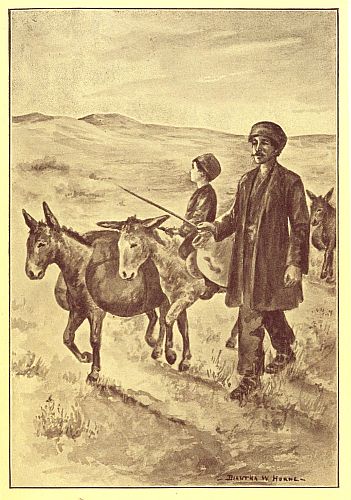

| "Dada and Karim started very early" | 49 |

| "The sun rose when they were half way over" | 50 |

| The Governor's Palace | 81 |

| "Putting the paper on his knee as he sat on the floor" | 118 |

| A Kurdish Shepherd | 130 |

| Sheikh Tahar and His Horsemen | 150 |

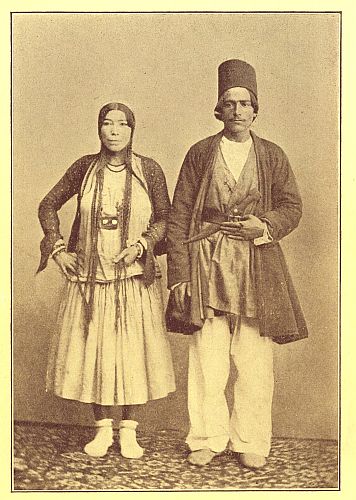

| Karim and His Bride | 164 |

Every one in the house of Abdullah was smiling on the day when a boy was born. Even Ashak the donkey, as he was bringing big bundles of wheat from the field, did not get half as many pokes as usual from the nail pointed stick that took the place of a whip, and was actually let alone for a whole afternoon to eat the dead grass and crisp thistles by the roadside.

Old Bajee, who was caring for the baby, ran as fast as she could to be the first to tell the news to Abdullah, calling out all the way, "Good news! a boy! a boy!"

"Praise be to God!" exclaimed Abdullah, and gave her a piece of silver money worth half a dollar. Laughing from joy she clutched this tight in her fist, and almost touched the ground with her forehead as she bowed to him. She had never owned half a dollar at one time except twice before in her life.

Abdullah hurried to the little shop around the corner and bought a loaf of sugar and some tea, and the tea urn, or samovar, was soon steaming. His neighbours—all men—came to congratulate him. Some brought raisins as a present, some melons. One brought another small loaf of sugar.

"May his foot be blessed!" they said. (They meant the baby's foot.) "This is light to your eyes!" "May you be the father of eight boys and no girls!"

Said Abdullah, "Praise be to God!"[3] and gave them all small tumblers of tea that was nearly boiling and as sweet as sugar could make it.

Meantime the women were coming to see the baby. Old Bajee had rubbed him all over with salt; then she had tied a dark handkerchief over his eyes and wrapped him up in strips of cotton cloth and a little quilt. He was now lying by his mother. She was thinking about the Evil Eye,—an evil spirit or fairy who was always trying to do bad things,—and looked anxiously at the baby's arm.

"Where is the charm, Bajee?" she asked.

"Yes," said a neighbour, "he needs a charm at once, for he is so very pretty."

"Oh, don't say that," exclaimed the mother; "the Evil Eye will hurt him if you do. Bring the charm."

Bajee brought a piece of paper on which[4] the mullah (or preacher) had written a prayer asking the angels to keep the Evil Eye away, and putting this in a tiny bag she tied it to the baby's right arm. "That prayer will frighten the Evil Eye," she said.

All this seemed very interesting to Almas. How delightful it was to have a baby brother. She wondered why her uncle Mashaddi had not seemed greatly pleased when a baby girl had come to his house two weeks before. No one had even called to congratulate him. But now her father was getting up a dinner party, and they were roasting a whole lamb for it, and cooking, oh! so many other delicious things. She could smell the onions even from the street, so she asked her grandmother for something good.

Grandmother laughed and said, "The front door cried for three days when you[5] were born. But God gave you to us, and we are not sorry."

Then she gave Almas a big piece of bread with rice and meat heaped upon it, and some omelet mixed with molasses.

Meantime mother was sleeping with baby by her side. Her last words had been, "Bajee, be sure to keep the light burning, so that the evil spirits will be afraid and not get the baby."

When baby was just a week old, the preacher, whom they called the mullah, came to give him a name. He brought the holy book which was their Bible, and which they called the Koran. No one in that village believed in Jesus Christ in the way in which Christians do, but were in religion what we call Muhammadans. The mullah stood over the baby and read out of this Koran in a loud, sing-song voice.

Baby was frightened, and cried.

The mullah did not stop, but next made a long prayer in words which no one else could understand, because he was speaking in Arabic, the holy language which Muhammad, the prophet who had composed the Koran, had spoken. Then he called out, "Your name is Karim!"

Almas thought it was quite a funny sight to see his long red beard wagging back and forth while he made such strange sounds, and so she broke into a laugh, at which her father turned and struck her. She went out crying softly. She did not like the mullah. Why had he come to frighten baby? He had not named her little cousin. Old Bajee had shouted in her ear, "Your name is Fatima!" and that was all.

After this Karim was laid in a very narrow cradle without any sides, and long strips of cloth were wrapped around and[7] around him and under the bottom of the cradle. His arms were tied down, and a calico curtain kept the light out. He lay in this dark little place nearly all the time for the first six months, generally asleep.

Although Abdullah was very proud of him, he hardly noticed him for over a month, because the evil spirits would wonder what he was looking at and come to see.

Once a day baby's mother would build the fire for cooking, and the room would fill with smoke, because there was no chimney, but only a hole in the middle of the ceiling. At first he cried every time, for the smoke made his eyes smart with pain. His mother put some medicine upon them when she saw how red they had become, and asked Bajee what the matter was.

"How can I tell?" said Bajee. "Babies always have sore eyes."

When the curtain was loose and it was not too dark the flies came to visit him. There seemed to be hundreds of them, and they walked all over his face and even into his mouth, but were especially fond of his red eyes and gathered in black rows around them. He winked and winked, but they did not care. Then he would begin to cry.

After a while mother would come to fix the curtain and rock the cradle, or perhaps—and this was the best of all—she would undo the wrappings and take him in her arms for a few minutes, singing, "My dear baby! my sweet baby! You are my father! and the father of my father!" She meant that she thought as much of him as of her grandfather, and every one always talked as if people cared more for a grandfather than for any one else.

One day Karim's mother, whom he was now learning to call "Nana," said to father Abdullah, "Master, your boy—may his eyes have light!—is now five months old, and ought to come out of his cradle. Buy some calico, and I will make another shirt for him. Do not buy red or any bright colour, so that the Evil Eye may not think him too pretty and so become jealous and strike him."

She made the shirt so short that his fat brown legs were bare to the knee.

When he could crawl around in the house sister Almas watched him. It was too dark for him to see much, for all the[10] light came from the door, when that was open, and from the hole, about a foot square, in the middle of the ceiling, where the smoke at last went out. The door was so low that Nana had to stoop every time she went through it. The walls were black from the smoke, which Karim now found poured out each morning from a hole in the floor about as big as a large barrel. Nana did the cooking with the fire which she kept burning in this hole.

One afternoon Karim looked down, and found that its bottom was all bright with light which came from glowing red lumps. It was the prettiest thing he had ever seen, and he grasped the edge and leaned away over to see still better. Just then Almas screamed and jerked him back by his foot so suddenly that the skin of his hands was scratched by the rough edge. Of course he cried.

Nana came running in, and snatching him up exclaimed between her sobs, "Awý! my precious! he might have fallen in!" Then she struck Almas, so that she, too, cried.

After this Karim had to be satisfied with the bright light shining in through the hole above his head, and with the two round trays which, leaning against the wall, shone like polished silver until at last the smoke darkened them. They remained so until the next year, when a man came from the city and polished them over again.

In the daytime there were large piles of bedclothes tightly rolled up near the cradle. A few rugs lay folded beside them. There were no tables or chairs or bedsteads, and the floor was simply the hard earth. In the corner were a few green bowls, and some wooden spoons and[12] copper plates. These were the dishes for the meals. Just across from the door stood a wooden chest, half as high as the room. This was where all the flour was put in the autumn, when Abdullah had packed it down carefully by stamping upon it with his bare feet. Near it was a door opening into darkness, through which Karim was afraid to crawl.

When he tired of these things, he looked at the chickens,—an old rooster dressed in red and black, but without any tail (he had never had any), and two or three clucking old biddies in sober gray, besides a half dozen others, hungry looking, half grown, with long legs. Like the flies, they came into the house whenever the door was open. If Nana left any food standing even for a minute she had to cover it. They came at meal time as regularly as if they had been invited, and fought with each[13] other for the scraps of bread or bits of gristle that Abdullah threw away. Several times the rooster snatched the piece of bread which Karim was eating right out of his hand; but when he laid the bread down to crow for the biddies, one of the half grown chickens caught it up and ran around the room with it, chased by all of his hungry brothers.

The family got up every morning when it was just beginning to become light. All but Karim were busy nearly the whole of the day. When the sun was two or three hours high—no one had a clock—Abdullah came in for breakfast.

At meal time Nana brought the large tray that took the place of a table, and Abdullah set it upon the floor and laid upon it two or three sheets of bread which looked a good deal like brown paper, and was as thick as heavy pasteboard. It[14] was made of whole wheat flour and tasted very good. Nana poured the soup out of a small kettle into one of the green bowls. Sometimes the soup was mixed with pieces of meat and onions, and was red with pepper; sometimes it was made of curded milk and greens. There were also onions and salted cheese and red peppers for side dishes, with cucumbers and melons and other fruits in summer.

Abdullah sat down on the floor upon his heels and ate alone, until Karim was old enough, when he always ate with "Dada," as he called his father, while Nana and Almas waited upon them. They never dreamed of eating with Dada, for that would have been very impolite, but when he had finished they sat down and ate what was left.

There were no knives and forks—what were fingers made for?—and no plates or[15] tumblers, for all ate out of the same bowl and drank from the same water jug.

Between meals Nana was very busy. First came the milking of the cow; then the bedclothes must be rolled up and the stable cleaned out, and there was sweeping and churning to be done. The water must be brought upon her back in a heavy jar from the spring. In winter the cotton and wool was spun into yarn and knit into bright coloured socks, and in summer she helped Abdullah gather the cotton or the tobacco, and worked in the orchard or wheat-field. In the fall she swept up the leaves which fell from the trees growing on the edges of the streams and carried them home on her back to be stored for kindling.

While Nana was working she usually went barefoot. She had large black eyes, and she made them bright by putting a[16] powder into them. She painted a black streak across her eyebrows to make them darker. Her black hair, hanging in long braids down her back, was banged in front, and was covered by a large handkerchief which she wore all the time. Very carefully, once a month, she dyed her hair and coloured with red the tips of her finger and toe nails.

Because she was careful about all these things and was somewhat fleshy and had red cheeks, her neighbours thought her beautiful; that is, the women thought so. The men hardly ever saw her face, because she always drew something over it whenever any man except Dada came near.

The men never asked him, "How is your wife and little girl?" which would have insulted him, but always said, "How is your boy?" and sometimes, perhaps, "How is the mother of your boy?"

Still Dada was really proud of her, but of course he was careful not to let her see it, "for," he said, "she is a woman, and must be kept under." He seldom called her by any sweet name, but when he wanted to praise her called her simply "the mother of Karim," and thought that, alone, was enough.

In pleasant weather Nana tied Karim upon Almas' back and sent her out of doors to carry him around. He was so fat that her back often ached, yet when a woman asked her if she was not tired she exclaimed, "Why, of course not! He is my brother." However, they were all so anxious to see him walking that he soon became bow-legged.

He now found what was to be seen out of doors. The yard was small, and there was no grass in it, nothing but the bare earth. When it rained the cattle tramped it into a deep black mud, which made a splendid place to sit in and play. Across[19] the yard was the door of the stable, where the donkey and the cow and two buffalos lived with a few goats. In front was a wall six feet high.

Just before the front door of the house was a small porch, where the big dog and the chickens spent the most of their time. The calves came there, too, and the dog, but he never dared to come into the house. Nana explained that he was "unclean," and the mullah said that it was a wicked thing to allow "unclean" animals to come into the living rooms. Karim liked to hit the dog, who always let him do just what he wanted.

One day when Nana was away, suddenly a fierce barking and snarling was heard, mixed with shouts. Almas ran out to find that a stranger had stepped into the yard, and that the dog had caught him by the ankle and would not let go, although[20] the man was hitting hard with his heavy walking stick. Almas was then only eight years old, but she put her foot on the dog's neck and raised her fist. The dog growled angrily before he obeyed her and slunk away. Some neighbours now came running in.

"Did you not know better than to enter a yard when no one was in sight?" said they to the stranger.

Then Mashaddi had Almas cut off some hairs from the shaggy neck of the dog. He took these hairs into the house and burned them, and brought the ashes to the stranger, who seemed very grateful.

"Thanks to you, if God will, the wound will heal very fast," he said, as he sprinkled the ashes on it and wrapped it around with an old piece of cloth. "Not even a doctor could give me better medicine than this."

The cat was allowed to come into the house, and was often there at dinner time with the chickens. Sometimes Almas petted her a little, and Nana threw her some food once in a while, but even they tried to hit her if she got in their way. She spent the most of the day hiding under the piles of fuel and in the dark stable in the hay. The dogs were anxious to chase her, and the boys were making bets as to who could hit her oftenest. Abbas was bragging because he had done it twice, for she was hard to hit, because she had practised dodging all of her life.

The door which opened into the dark from the family living room led to the store room. Karim often followed his mother when she went in, holding a lighted wax dip. There were no old trunks with newspapers and letters, because no one of the family had even seen[22] a newspaper and no one but Dada had ever learned to read. Instead, there were big wooden shovels, plows, sickles and a pickax. In the autumn grapes hung in long clusters from the ceiling.

The baskets and jars were carefully covered, but Nana used to open them for Karim if he cried hard enough, and let him feel and taste what was in them. Most of the baskets were full of raisins. Two held red peppers. Some jars held salted cheese, and some were filled with butter, which felt very cool and soft. The pickled cucumbers tasted good, and best of all was the molasses.

One day Nana had just taken the heavy cover off from the molasses jar, when she found that she had forgotten a dish. She went out to get it, and Karim was left alone. He pulled the molasses ladle out of the jar and tried to get its bowl to[23] his lips, all dripping as it was. It was half as long as he, and somehow hit him fairly in the eyes, filling them with molasses instead of his mouth. He screamed and ran through the door, dropping the ladle as he went.

Nana ran quickly to Karim. "My darling," she cried, "light of my eyes! Did the molasses hurt my darling? We shall beat the jug. See!" and she took the broom and started for the store room.

Just then Almas appeared in the door.

"Why did you not watch Karim?" Nana cried angrily. "We shall whip you, too! See"—she added to Karim—"shall we whip this naughty girl because she let the molasses hurt you?"

"No," said Karim, picking up a stick, "it was the jug. We shall whip it."

"Wonderful!" exclaimed Nana, "how kind he is to his sister."

Karim felt very much grown up as he thrashed the jug, while Nana laughed proudly because he showed so much spirit, and Almas looked on with smiles because it was the jug that was being whipped, and not herself. The jug was the only one that did not care.

Karim at this time happened to have only the shirt that he was wearing. He had never had more than two at one time, and one had dropped to pieces from age the week before. Nana had not found time as yet to finish a new one. The shirt was a dirty brown, although if one could have examined the seams he would have found that it had once been a dark red with black stripes. Now, with the molasses streaks, it looked fairly black.

Nana decided that it must be washed at once, for Dada might not like to see[26] his son looking so very dirty, so she took him with her to the pool when she went for water that morning. She washed the shirt thoroughly, while he stood beside her shivering in the cool breeze. When at last it looked somewhat cleaner she wrung the water from it as well as she could, and put it back upon him to dry. Karim fairly howled with cold as he trotted along by her side, and when they reached home, to comfort him, she gave him two cucumbers and some of the raisins that he liked so well.

That afternoon he began to cough severely, and his head was very hot. Nana pulled at her hair in her anxiety.

"The Evil Eye has struck him!" she exclaimed. "The charm fell off from his neck when I washed his shirt, and I did not notice it for some time. The[27] Evil Eye must have struck him then. Why did I not keep him dressed in Fatima's clothes, so that the Evil Eye would think him a girl, and not notice him? or rub his face with ashes, so that he would look ugly? Awý! What can I do?"

"Get up," said Grandmother, "run to the mullah, and have him write another charm; perhaps it will frighten the Evil Eye away."

Nana did so.

Said the mullah, as he gave her the roll of paper, "If there are twenty evil spirits in your son, they will all run away when you tie this prayer around his neck. It is worth fifty cents."

Nana began to cry. "What can I do, O holy man?" she said, "I have only twenty-seven cents, and my son will die."

"Take comfort, my daughter," replied the mullah, "I am God's servant, and He is merciful. The twenty-seven cents are enough."

But that night Karim nearly choked in his coughing. Dada looked very anxious. "Women are donkeys," he said, "and so are mullahs. I will go for the barber."

The barber looked grave. "See the black blood. I will take it out, and he will get well." He cut a vein with his razor, and caught the blood in a bowl, but Karim became worse. The next morning Dada hurried to the best doctor in the village. He looked at the boy a long time.

"Bring me this afternoon," he said, "fifty cents, and that hen with a white tail"—he pointed to the largest of the old biddies—"and with its blood and a[29] mouse's eye I will make a medicine which will cure him. If it does not, take back your money."

When he had gone Bajee and some other women came to see Nana.

"My uncle once was sick like this," said Bajee, "and an old woman told grandmother to take a rooster and cut it in two, and tie the warm, bleeding pieces upon his breast. That made him well."

"My brother," said an old woman, "was cured of a cough by lying in the oven for the whole of one morning."

So Karim spent the afternoon lying upon the warm ashes in the hole where the cooking was done, with the bleeding body of the old rooster pressed tightly against his chest, while the charms were still about his neck and the doctor's medicine at hand. That evening he was much better.

Nana insisted that he was cured because of the mullah's charm; Grandmother believed in the dead rooster, while Dada went to thank the doctor and give him a lamb for a present.

It was some days before Karim was himself again, and as he was fretful his grandmother amused him with stories.

Here is one of them. The others were very similar to this.

A fox started to travel to the city of Mashad, because he knew that he was a wicked fox, and such a good man was buried in that city that simply visiting his grave was enough to make one good. On the way he met a wolf, who asked him where he was going.

He replied, "I am a wicked fox and am going to Mashad to be made good."

The wolf said, "I am very bad, too, and ought to go there. Let me go with you."

They went on together, and after a while met a bear.

"Where are you going?" he asked, and when they had told him he wished to go with them.

As they made their journey they came to a country where there was nothing to eat. They all became very hungry; so hungry that the fox and the bear dropped behind, as the three were walking, and, suddenly jumping upon the wolf when he did not expect it, caught him with their teeth in the neck and killed him. Then they each took a part of the body and began to eat. The bear ate until nothing but bones was left, but the fox took some[32] of his meat while the bear was not looking and hid it in a dark corner of a cave near by.

After a while they both began to feel hungry again, for the wolf had been so lean that there was not much of a meal to be made off of him. The fox went into the corner of the cave where he had hidden the meat, and soon the bear heard him smacking his lips very loudly.

He was very much surprised, and asked, "What can you have found to eat?"

"O bear," said the fox, "I was so hungry that I have pulled out my left eye, and am eating it, and you cannot think how good it tastes."

"That is quite an idea!" said the bear, and he pulled out his own left eye, and ate it.

But he was soon very hungry again. Then he heard the fox in the corner[33] once more smacking his lips very loudly, and he exclaimed, "What on earth can you be eating now?"

"O bear," said the fox, "I was so hungry that I pulled out my other eye and am eating it."

"How smart the fox is to think of such things!" thought the bear, and he pulled out his own right eye and ate it.

Then the fox got a long pole, and taking hold of one end he told the bear that if he would take hold of the other end he would lead him (since he was blind) to a place where he would find plenty to eat. But he led him to the edge of a very high rock.

"O bear," he said, "there is a large, fat sheep right in front of you. Now jump!"

The bear jumped, and fell so hard upon the stones below that it killed him.[34] Then the fox ate the body of the bear, and it made him strong enough to go on and reach Mashad, where he visited the grave of the holy man and so was made good.

The village where Karim lived lay at the mouth of a little valley. Down this valley ran a stream of sparkling water that came out of the ground about a quarter of a mile above the village. This was not a spring, but a "kareez," for beyond it could be seen a long line of pits, joined at the bottom by an underground channel, through which the water ran. The road lay by their side, and in two places the path divided, a part passing on each side of a pit.

Once while Karim lay flat on the ground looking over the smooth sides at the water trickling across the bottom of[36] the pit, he asked, "Doesn't any one ever fall in?"

"Why should he?" replied Dada. "Can't you see the hole plainly enough?"

"But suppose it was dark?"

"At night honest men are in bed, and robbers know the roads. But if God wills that a man shall fall in, why, he will fall in, and cannot help himself. It is Fate."

The stream ran down the valley past an orchard of apricot and cherry trees. By its side were willow trees, with short, thick trunks, and a row of poplars, that seemed to Karim the tallest trees he could think of. Then it ran into the village pond. Twice a week all the water was let out of this pond, to be used in watering the fields, but it soon filled up again.

When Karim was seven years old Dada began to send him here with his cousin,[37] Ali, to wash the two big black Indian buffalos which he and Mashaddi used for plowing. It was hard to say who enjoyed it the most, the buffalos, who dearly loved the water, or the boys, who rode upon their broad backs, and splashed and swam about during the warm summer evenings as long as they pleased.

Dada soon gave Karim other work as well. He took him to the field and lifted him up upon the yoke between the buffalos. Here Karim sat all day, to keep the yoke by his weight from pressing against the throats of the buffalos as they slowly drew the plow back and forth across the field.

Next Dada sent him to watch the cows as they grazed in the open meadow in the lowland, or among the dried grasses on the hillside. Here he spent whole days with the other boys, going swimming[38] and playing "marbles." For marbles they used the bones from the joints of sheep's legs.

The next year, in early summer, Dada told him to keep the birds away from the cherries and apricots in the little orchard, by shouting and clapping two boards together. At first this was great fun, but he became very tired of it in a few days, and his voice grew hoarse and rough. Then came harvest time, and he went out to the hot field and carried water to the reapers, and rode upon the straw cutter or swept up the grain upon the smooth threshing floor until he was so tired that he could hardly stand.

About this time he fell sick again. His head ached and he was hot with fever. The doctor wrote a prayer with the blood of a lamb, and Nana burned the paper[39] and poured the ashes into a cup of water which she made Karim drink, but it did no good. He lay on the floor on a thin mattress dressed in his every-day, dirty clothes, and the flies kept settling on his eyes and mouth.

Nana and Grandmother were as kind as they knew how to be. They took great pains to get the tongue of a starling, for a woman said that this would cure him, but, instead, he became worse. At last he broke out with the smallpox.

"All have the smallpox," said Grandmother, when she saw this; "what can we do?"

Some of the neighbours brought their young children to see him. "They must all have this sickness," was their reason, "and it is best that they have it now, when they are young." In this way Fatima caught the disease, and died.

Hers was a dreary little funeral. The house was filled with the noise of the sobs and wailing of her mother, who was nearly frantic with grief, and with the cries of a few of her friends. No one thought of flowers, and there was no music. As the funeral was that of a girl, only three men walked behind the body when Mashaddi carried it to the grave. Of course no women went with him, for that was not the custom.

Soon after Karim got over the smallpox he began to go to school for a part of the year. He was proud of this, because a great many of the boys were too poor to go to school. As for the girls, of course people never sent them. What would be the use? "Teach a girl! You might as well try to teach a cat," they thought.

The teacher was the mullah. On the[41] first day of school he and his eight pupils came to Karim's home to welcome him. All were dressed better than usual. Karim looked very gay in a brand new coat of bright blue. Dada met the teacher with a present of three chickens. Then the boys marched to the school in a straggling line, the teacher at the head, the older boys chanting in a loud voice a song they had been taught, and the three youngest carrying the chickens dangling by the legs.

The school house was the mosque, or Muhammadan church. The room was large and bare. Straw mats covered the floor. There were no blackboards or maps or desks; indeed, most of the boys had never even seen a lead pencil. The mullah sat upon his heels on a rug by the window with a long stick in his hand. The boys sat upon the mats, facing him.

"You must come to school before breakfast," said the mullah. "If any one eats any food before coming to his lessons I shall pull out his ears."

If a boy was at all tardy he exclaimed, "You silly animal, hah! Have you been eating, and so are late?"

"Oh no, indeed I did not eat anything!"

"Put out your tongue!"

Once Karim's breath smelled of onions, and the mullah gave him so sharp a tap that he felt it for an hour.

They studied a little arithmetic, but spent most of the time learning to write the Persian language, and to read from the Koran. As the Koran was printed in the Arabic language, which none of the boys knew, at first they did not understand what it meant, although the mullah explained a great many things to them. It was very important to learn to recite a[43] good many chapters from this holy book, even if one could not understand what he recited. No one could pray to God in a way that was pleasing, the mullah said, unless he repeated in his prayer parts of these chapters, which the holy prophet Muhammad long ago had brought down from heaven.

Studying the Persian language was more interesting work. In a short time Karim was given stories to read which told of the wonderful deeds of King Solomon, who talked with the birds and made the spirits of the air obey him. He also read other interesting stories, very much like those to be found in the "Arabian Nights' Tales."

While they were studying the boys all swayed their bodies forwards and back and read from their books in a loud sing-song tone. If a boy became tired he did[44] not dare to stop. Karim did so once, but a stroke from the mullah's stick and his question, "Son of a dog, why are you not studying?" made him yell out with the loudest.

He soon learned not to ask questions. Once when there had been a slight earthquake shock he asked what it was that had made the earth shake.

"The ox," said the mullah, "which holds up the earth upon his twenty-one horns has become angry, and is shaking his horns."

"What is he angry at?" asked Karim.

"God knows, and He has not told us," said the mullah.

"I wonder what the ox stands upon," added Karim, after a minute.

"If it were right for us to know God would have told us," was the answer. "Such questions are irreverent, and fools[45] ask them. Pray to God to forgive you, and then begin your study again."

When Karim was eleven years old Almas was married. The friends of the bridegroom came to the house, and were given a good dinner. Almas was so bundled up that no one could recognize her. Then they put her on a horse, and in a noisy procession led her off to her new home. She now lived in a village ten miles away, and Karim saw her only two or three times a year. He missed his sister for a long time, because she had always waited upon him so carefully.

As the wedding occurred a little before the great festival of "Norooz," that helped him forget his loss. "Norooz," or the festival for the new year, came in the early spring, when everyone was glad that winter had gone. Mashaddi said that the world came to life then. A few[46] days before the festival Karim's head was shaved, and the nails of his fingers and toes were coloured red. He was given a new suit of clothes exactly like Dada's in cut, and when dressed in them looked like a little old man. "But then," said Nana, "he is almost grown up now, and ought to look so."

She arranged plates full of nuts, raisins, dried apricots, quinces, figs, dates and candy (there must be seven kinds of food, and their names must each begin with an S) and Karim took these as presents to the mullah and to a few other friends. Dada bought some sugar, tea, tobacco and candy, and all was ready.

The festival lasted for a week. On the first day Dada and Karim (now that he was old enough) sat upon their heels in the room to receive callers. Each caller, as he entered, bowed low and said, "Peace[47] be to you! May the festival be a happy one."

"May you be fortunate," replied Dada.

"How is your health?" asked the caller.

"Praise be to God, we are well."

Then, sitting down, they talked together, and took turns smoking from the water-pipe. After the third cup of tea had been served the caller rose and said good-bye.

The greatest fun was on Tuesday evening, when the roofs of the village were alight with blazing pin wheels, Roman candles, small volcanoes and rockets.

Children's Day was also a lively time. Several of the young men of the village dressed up as clowns. They had some musicians with cymbals with them, and went about saying and doing absurd things. Karim and his school mates[48] dressed themselves up like robbers, with beards made of cotton, and canes for spears, and went to the mullah's house.

"Give us some money, or we will rob you!" they shouted.

He laughed, and gave them enough to buy a plenty of candy.

One evening Dada said, "Shahbaz has just come from the city, and says that they are paying twenty-five shahis a batman for wheat. If God is willing, I and Karim will get Hussain's donkeys, and take in our wheat to sell to-morrow."

Early next morning each donkey was loaded with two of the black sacks of wheat, excepting one donkey, which was saddled and carried two empty jars, for Dada intended to buy some molasses in the city. To the saddle was fastened a jug of water and a red handkerchief filled with bread and cheese. None of the animals had on a bridle. Dada and Karim started[50] very early, going as fast as one could walk, and taking turns at riding the saddled donkey.

The road lay over a dry and sandy plain six miles wide, which it took nearly three hours to cross. The sun rose when they were half way over, and soon there was only the deep blue sky and blazing sun above, and the hot, parched ground, with bare, rugged mountains in the distance. The only green place in sight was that made by the trees around their own village, now looking like a dark band against the yellow hills.

Karim looked back later, and was astonished to see what appeared like a large lake, bordered by many trees, instead of the village and the plain. He called to Dada, who hardly looked around, but said, "The evil spirits do this to deceive you."

Then, for an hour more, they climbed a slope up the mountain-side. It was tiresome work, and Dada had to grunt "uh! uh!" at the donkeys harder than ever, and prod them with the nail pointed stick. A few stunted bushes were growing among the bare rocks and thirsty gullies. One small tree was passed, half covered by tattered bits of cloth tied to its branches.

Dada carefully tore off a faded strip from his ragged coat, and fastened it to a twig. "There is no water," he said, "and yet this tree is always green. It is a spirit who does this. Let us give him an offering of respect." Karim felt afraid, and did the same.

At last they went down a steep slope into a valley. Here was a spring of cold water. Around it were willow trees, and near by melon and cucumber patches, and[52] an orchard of mulberries and apricots. They unloaded the donkeys and for a shahi bought a melon from the man who was in charge. They then untied the handkerchief and sat down on the ground to eat. After the meal they stretched themselves at full length under the trees, and were lulled to sleep by the deep "boom, boom" of the bells that swung from the necks of some camels who had just passed with their heavy loads.

In an hour Dada waked Karim and they started again. Soon the road grew wider. All of the streams were now spanned by bridges, while on every side were vineyards and orchards. They met many people, and many droves of donkeys, and at last entered a long avenue bordered by willow trees. At its end was the gate of the city.

In front of the gate the road crossed a[53] ditch forty feet wide and in some places half full of water covered with a thick green scum, where the frogs were singing cheerily. Behind this was a wall, half in ruins, with broken down towers here and there. Inside the city gate the street was about fifteen feet wide, and one could not see anything on either side except high walls of dried earth, with here and there a gate or a narrow alley. There was a narrow sidewalk, but people did not seem to care much whether they used it or walked in the middle of the street.

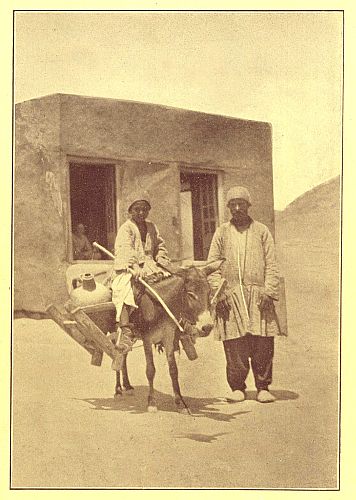

In a few minutes they had passed more donkeys than there were in the whole of their village. Some carried baskets of grapes, some looked like moving piles of yellow straw, and a few were loaded with dripping lumps of ice carried in black bags. Some were dragging poles whose ends were for ever getting under one's[54] feet. One had a dead sheep strapped to its back. These were small, mouse coloured, half starved donkeys, like the one on which Karim had been riding, without any ambition or pride, but jogging along because their drivers would prod them if they stopped. They passed a few larger donkeys as well, with handsome saddles, ridden by well dressed men in long brown robes and white turbans, who were mullahs, or by women who were so bundled up that one could not see even their eyes.

In a corner was a group of beggars sitting in the dirt, dressed in rags. Some of them were holding up the stumps of their arms, or pointing to their blinded eyes.

"Give me money for food!" was their cry. "May God bless your sons! For the Prophet's sake, give me a shahi!"

It was a pitiful sight, yet very few paid any attention to them.

At a turn of the crooked street Karim and Dada came upon three shops. The goods of one were spread upon a platform next to the sidewalk, and the shopkeeper sat upon his heels behind within reach of everything. Dead sheep were hung up by their legs before another shop, and a dead ox was lying upon the sidewalk upon its own hide, spread flat on the ground. At the third a blacksmith was shoeing a horse, and everyone had to dodge by with an eye upon the horse's heels.

Fifteen or twenty people were gathered around a man with long, uncombed hair and fierce, wild eyes who carried a small ax in his hand, and was waving it about and talking loudly in a singsong tone, while a boy was going around with a carved cocoanut shell, asking for shahis.[56] Dada said that he was a "darvish" or holy man who was telling stories about the saints.

Suddenly two horsemen appeared, shouting, "Khabardar! Khabardar!"

The blacksmith dropped the shoe and gave the horse a blow that sent him against the wall, and the holy man with his audience spread in a row along the side of the street. Dada in a great hurry crowded the donkeys down one of the alleys. They were none too soon, for almost at once a large crowd of blue coated horsemen armed with guns turned the corner. Their horses pranced and snorted, while the men cursed some of the people because they could not squeeze themselves flatter against the wall. One of them struck a man, who did not even say a word in return.

And now there came something more[57] wonderful than even Karim's grandfather had "seen in a dream," as he told Nana later. It was drawn by two spirited horses, which no one was riding, but a man held them back by long straps, and they went wherever he guided them. The thing itself was a great box of polished black colour, with a door, and with soft cushioned seats inside, upon which were sitting two splendidly dressed men. This box was carried on wheels that seemed much too light to support it, and which made no noise at all as they went around. The only wheels Karim had ever seen before had no spokes, and were each almost as heavy as a man, and creaked so that they could be heard a quarter of a mile away. He was so astonished that he did not notice that every one bowed low until he felt a sharp blow from behind, and a "Bow low, you fool!"

Then he bobbed so quickly that his hat rolled off into the road. No one moved to get it, and in silent misery he watched one of the horses crush it. It was a new hat, and Dada bought him only one new hat each year.

When the horsemen had all passed he picked the hat up. There was a hole in the soft crown, and it was stained with mud. As he was wiping it off Dada came up, so angry that he struck him with his stick. Some boys who saw this laughed at him. Dada did not comfort him at all, but exclaimed, "I have a fool for a son! Why do you stand gaping like a donkey at the wagon of the governor? If that man had not made you bow to the governor, and to the prince riding with him, some of the horsemen might have noticed it. Then we both would have been seized, and probably beaten. All my wheat[59] would have been taken from me, and perhaps I would have had to pay some money to keep from being put into prison."

Sometimes Karim went to the mosque with Dada in the early morning on Friday.

The mullah had told him, "The prophet Muhammad has advised that every one should bathe on Friday and then come on foot to the mosque to prayers, and be reverent during the service. God will give a great reward to the person who does this."

The mosque was a plain building, with one large room and a porch in front. The room was bare, except for a few mats and a small pulpit. When any one entered he took off his shoes as a mark of respect, but kept on his hat.

During the service those present repeated aloud with the mullah prayers and chapters from the Koran. Then the mullah preached a short sermon.

The mullah got up early every morning in the week and went upon the roof of the mosque. Here, as the day was breaking, in a very loud and musical voice he chanted the "Call to Prayer." This was in the Arabic language, so that Karim for a long time did not know what it meant, although he had heard it so often that he could repeat most of it by heart.

But at school he learned that it meant, "God is most great! God is most great! I declare that there is no God but God, and that Muhammad is the messenger of God. Come to prayer! Come to the refuge! God is most great! Prayer is better than sleep. God is most great!"

In school Karim had also been taught[62] the Creed, "I testify that there is no God but God. I testify that Muhammad is the prophet of God, and that Ali is the ruler appointed by God."

Although he had been taught these things, the mullah said that he was still a boy, and that boys were not expected to do all that God commanded. But when Karim was thirteen years old the mullah said, "You have reached the age when the Recording Angel begins to write down in his book whatever you do, whether it is good or bad, so you must begin carefully to perform good deeds, that they may help to save you from the evil deeds you will do, and thus permit you to enter heaven. I have taught you the prayers that you ought to say each day, and the way in which you must wash yourself before saying them."

Karim felt quite proud to be thought[63] so old, and began to copy Abdullah, who was more careful about his prayers than many of his neighbours. Abdullah bought for his son a little rug and a bit of dried clay that came from the holy city Mecca, where the prophet Muhammad had lived. Each morning, at the time of the Call, Karim repeated his prayers, standing, and kneeling just as Dada did, and touching his forehead to the bit of clay when he bowed.

Somewhat later came the month of Ramadan. During this month it was against the law for him to eat or drink anything, or even to smoke a pipe, from dawn until late in the evening. Of course it was very hard to obey this rule, but it was thought wicked to disobey it. What made it harder was that Karim had to work during the morning. In the afternoon he slept some, and longed for the[64] sun to set. As soon as he heard the crack of the gun that announced the time when it was right to take food he hurried into the house. Here was a good meal, all steaming hot, prepared by Nana. How they all did eat!

Dada always sent some of the food to Bajee, the poor widowed woman who lived down the street. Whenever a beggar appeared, he fed him, too.

"We must give alms," he said, "if we wish to enter heaven, for our holy prophet has so commanded."

At the close of the month came the great Week of Mourning, or Muharrem. When Karim was still a little boy Nana had taken him with her to the mosque each day during this week. They had sat outside in the street and listened to the mullah as he told the sacred story of the death of the holy Husain.

He explained how the rightful ruler had been Ali, after the death of the prophet Muhammad, long ago, because Ali was the prophet's son-in-law, having married his daughter Fatima. But wicked men had made Umar the ruler instead of Ali, and even yet the people of Turkey, and the Turkmans, and many who lived in India and Africa believed that Umar was a holy man. When Ali died his sons Hassan and Husain should have become rulers. Hassan soon died; the men of the city Kufa then promised to honour Husain if he should come to them. Husain believed them, and came from the city Mecca with his family, guarded only by a few warriors. But when he came near Kufa no one came to help him. Instead, the wicked governors of that city actually dared to come out with a great many soldiers and attack him, although he was the[66] grandson of the prophet Muhammad. The men with Husain were too few to conquer, yet he did not surrender, because he was the grandson of the prophet and the rightful ruler, and none of his warriors ran away, but together they died fighting bravely against their wicked enemies.

As the mullah told in his sermons how Husain was killed, first some women began to moan, and later all burst into loud sobs, while the tears streamed down their faces. The most devout caught these tears in little long necked bottles, to keep them for medicine.

"God is pleased with us because we weep for Husain," Nana explained, "and because of our tears for Husain He gives us all the good things that come to us during the year. And the mullah says that if we weep for our lord Husain the martyr God will take away all our sins."

"In the cities," added Dada, "they have processions in memory of our lord Husain."

"I saw the processions in the city last year," broke in Mashaddi. "They were wonderful. First came men bearing the two black banners of the mosque. Then followed others playing funeral music on drums and fifes. After them walked the mullahs and holy men. Then came a long line of men and boys, marching two by two. They were beating their breasts in time with the music, and chanting a dirge that was so strangely stirring and yet so full of tears that I can never forget it. Indeed, I found myself running out to join the marchers, while my eyes were blinded with weeping. There were two little girls and a woman on horseback, with straw on their heads and collars of wood on their necks. They represented,[68] you know, the wife and children of Husain, who were captured by his enemies when he had been killed. Boys walked alongside, throwing straw into the air. The woman's collar represented iron fetters, and the straw was a sign of grief.

"In some of the other processions there were men beating their breasts with chains, and crying out as they marched, 'Awý! Hassán! Awý! Husaín!' After them came some men with white cloths spread over their shoulders. They carried swords in their hands, and as they marched they cut their faces so that the blood ran down."

"Why did they cut themselves?" asked Karim.

"Because it is a very holy thing to do," replied Dada, "almost as holy as to visit the grave of our lord Husain at the city Kerbella."

"I saw a boy on horseback," continued Mashaddi, "with a dagger in his hand, and his face was bloody from the cuts he was giving himself. How they can do it I cannot see. God gives them the power to forget their pain. Sometimes friends walk alongside with sticks in their hands to dull the blows, and so keep them from injuring themselves too much. But they say that if a man dies from his cuts God takes him straight to heaven."

One evening Dada asked Karim, "How would you like to travel, as Mashaddi did, who was once a soldier of the Shah, and was blessed by a visit to the sacred shrine of the holy Imam Reza when the Shah sent his regiment to Mashad to frighten the Turkmans. Wouldn't you like to be called 'Mashaddi,' too?"

"It would be splendid," replied Karim. "Only yesterday Mashaddi was telling me about this shrine. The room inside is just covered with gold and silver and bright stones, and splendid rugs. The[71] blessings the Imam gives to those who visit it cannot be counted.

"But the mullah says that the tomb of the Imam's sister, Fatima, in the city Kum is almost as holy, and it is much nearer. The dome of its roof is covered with flashing gold, and inside is a silver gate, with tiles of such beautiful colours that he can't describe them. And Mashaddi has seen the palace of the Shah at Teheran, too. He says that he saw a throne covered over with carved gold, and everywhere in this gold are set flashing emeralds and rubies and other precious stones. Mashaddi called it the 'Peacock Throne,' and said that the great Nadir Shah brought it from India when he went to that country with an army to fight the Great Mogul!

"But I cannot travel,—the Shah isn't asking for soldiers now."

"That is so," said Dada. "But the mullah has taught you how to behave before khans (noblemen). Our agha (master) is coming here in a few weeks, and I am going to take you to call upon him."

"Our agha is a kind master," broke in Nana. "It happened the last time he came that he passed Abbas' field when he was tying up the sheaves. Of course Abbas hurried to put a sheaf in the road before him as a present. The agha threw two silver coins into the sheaf for Abbas! That is a good deal better than the copper shahis one usually gets."

"He is a just man," added Dada. "He doesn't eat up all that the poor have, like the master of Hissar. The people there can never pay all that man wants, especially since the poor harvest seven years ago. That man had his servants put some wheat in each house. Of course the people[73] cooked and ate it—poor things, they were hungry. Then he told them that because they had eaten up his wheat they owed him money for it. The interest they pay each year is one fifth of what they owe. But he cannot get it from most of them, although his ferashes (officers) have thrashed the men so that they went limping about for two weeks. Our agha takes only what is due, one tenth of the crop, and his servants don't take very much, either. Ahmad was the only man he had bastinadoed last year, and Ahmad was trying to cheat him. He said that he had no money, when really he did have some buried in a bowl in a corner of his house."

"They say that our agha may even become the governor," added Shahbaz, who had just come in. "I heard in the city last week that the Shah had given[74] him the title 'The Good Fortune of the State.'"

"May God so will!" said Dada. "He will be as good a governor as Rashid Khan, the 'Glory of the King's Court.' When he was governor a woman could walk safely from here to the city with a purse full of gold in her hand. I remember that once I saw the heads of two thieves stuck on the tops of poles before his house. He cut off the hands of a lot of rascals, too. But it isn't so now. Only last week some Kurds stole five cows from the herd of Hissar. The foolish boys had taken the animals up into the hills, where no men were near."

"Karim has learned to read our language, and to behave properly," said Grandmother. "Perhaps he will find grace in the eyes of the agha, so that he may want him as a servant."

"O Dada, do you think that could be?" cried Karim.

"I shall beg this of the agha," said Dada, "and the mullah has promised to help me. If God will, we shall find favour, and all our faces will be made white with joy."

On the next day a horseman arrived, to announce that the agha himself would come within a week. When the horseman reached the door of Abdullah's house, Abdullah met him with low bows, and said, "This is no longer my house, but yours. I am your servant."

The rider got off his horse and went into the house. Here Nana had ready as tasty a supper as she could cook.

The next day the "white beards" (old men who manage village affairs) came to call. They brought two large trays piled high with apples, grapes and pears,[76] with a coat of blue broadcloth, and one toman in money. Now for three days everyone was busy. The agha's house was swept, carpets were put down, and plenty of food made ready for cooking. Most important of all, the money tax was collected. This must be paid to the agha because he was the master of the village. Abdullah was the "kedkhoda" or village head.

Sometimes the taxes made him and the white beards very anxious, for all the money must be collected. But this year the harvest had been a good one, and only three men told Abdullah that they could not pay what was expected. The white beards were much displeased.

They said, "You will make our faces black before our agha. We shall have to tell him, 'These three men only did[77] not pay.' What he will do God knows. Our agha has many ferashes."

The three men cried, and their wives screamed and tore their hair. They offered to pay one half, or three quarters, but the white beards only replied,

"We must leave it to the agha."

Finally, on the day before the agha arrived, the last shahi due was paid to Abdullah.

The master looked very much pleased the next afternoon, when Abdullah and the white beards, with many bows, offered him the taxes in full, with a present of ten tomans and three large baskets of grapes besides.

"You have made my face white," he said. "And you, kedkhoda; in all of my villages I have no one better than you. You have made my eyes to shine;[78] speak, then, that I may make your face white. What wish have you?"

"O agha!" replied Abdullah, "what we have done is nothing, it is dirt, and we are as the dirt under your feet. And yet, since you have stooped to notice me, and have filled my mouth with sugar by your words, I have indeed a request, that I shall make, since you so command.

"I have a son. He is a worthless boy, indeed, and yet he has studied long with our mullah, and has read the holy Koran, and the books of the poets. If he could live with you, if only to sweep the straw for your horse's stall, why, then, indeed you would lift my head to the clouds and fill my mouth with laughing."

"Is he with you?" asked the agha. "Let him enter."

The man at the door called Karim, who was waiting outside, dressed in a[79] new blue broadcloth coat. As he entered he bowed low, and then stood at the end of the room, politely covering his hands in his coat-sleeves.

"What is your name?" asked the agha.

"Thanks to God, your servant's name is Karim."

"Which of our poets have you read?"

"A few of the pearls of wisdom of Sheikh Sa'adi have lodged in my skull, thanks to the thumpings of our mullah."

"Indeed," added Abdullah, proudly, "he is not stupid. If it please you, he can recite well."

"It is well," said the agha. "Let me hear you, my lad."

So Karim recited a poem, in a sing-song voice, as he had been trained by the mullah.

As he closed the agha rubbed his hands with pleasure. "This is wonderful![80] Who would have expected such knowledge in a village peasant? You say that the mullah taught you. He shall have a reward for such faithful service. And you," he added, turning to Abdullah, "your request is granted. Nasr'ullah, my groom, will find a place for your son with him."

When the agha went back to the city to become its governor Karim bade good-bye to his parents and went with him. He was one of the stable boys for Nasr'ullah the groom.

He now lived on the grounds of the governor's palace. One entered these grounds through large gates of wood. The gateway was faced with bright red brick arranged in pretty patterns.

Then came a large court yard, paved with stone, and surrounded with rooms for Nasr'ullah and those who helped him. In one of these Karim slept. A large doorway near by led to a long line of[82] stalls, where twenty riding horses were kept, with their saddles, saddle cloths and bridles hanging ready for use at a half hour's notice.

From this court yard a small gate way opened into another and larger yard. Here were broad walks paved with flat stones and bordered with little plots of green grass, rose bushes and small beds of bright yellow and red flowers. A few mulberry trees gave a pleasant shade. There were two great stone rimmed tanks full of water.

Around this court yard were many rooms. The reception room was large, with white walls and windows of stained glass. Its floor was covered with richly coloured carpets. The tea room had soft divans along the walls, with wide windows to catch the breeze. There were also rooms for the governor's son, Ardashir[83] Khan, and for the mirza (secretary) who taught him, and for the servants. Beyond were the kitchens, where the men in charge always kept tea and food ready, because no one could tell just when a visitor might come with his attendants.

In all about fifty men had work to do about the palace. All of them were given their meals, and many slept there.

Behind the great court yard was another yard, almost as large, into which Karim never entered, as it was reserved for the ladies of the governor's family, and for the women and girls who served them.

The court yard was shaded by tall chenars (a kind of sycamore), and had in it streams of water, plots of grass, rose bushes, flower beds, and a grape arbour.

In the branches of the chenars, thirty[84] feet above the ground, were two nests of the "Hajji Legleg," or stork. This bird was called "hajji," or "pilgrim," because storks fly away each fall and always return to their nests in the spring. They were never disturbed, because they were said to bring good luck. They reminded Karim of his own village, where two pairs of storks had made their nests for years. He had heard of one village where there were twenty or thirty nests, on the trees, walls, and even on the roofs of the houses.

He had often watched the parent storks, one at a time, brooding over the blue eggs or feeding their young. Father Stork used to feed the mother while she was sitting, dropping from his bill into hers such tidbits as live frogs or snakes captured from the little swamps near the river, and around the ponds. As soon as[85] the three or four young storks had hatched the father and mother took turns in their work. One stayed at home and guarded the children, while the other hunted for food. When the hunter came in sight of the nest he made a great noise clapping with his bill, for storks have no call, and his mate answered him. The young storks made a low sound something like a kitten's mews as they sat with their long bills wide open, waiting for breakfast to drop in; they spent much time, too, leaping up and down in their nests like Jacks-in-the-box, exercising their wings.

Karim's first work was to help take care of the horses. It was not always easy, for they were splendid animals, high spirited and vicious, and ready to break away, if possible, in order to get into a fierce fight with each other. After Karim learned to ride, he asked Nasr'ullah if he could not be one of the attendants of Ardashir Khan, the agha's son, on his horseback rides.

"I can let you have a horse," said Nasr'ullah, "but I have no good saddle to spare. The khan is very particular."

"May I go if I get a new saddle?" asked Karim, eagerly.

"If God will, I am willing," said Nasr'ullah.

So Karim got his money and started to the shops or "bazaars." He went down the narrow street and past the graveyard, with its rude slabs of untrimmed stone, and on to the bazaars. Here the street was roofed over by a row of little domes, with round openings above for light and air. It was crowded with people. There were women wrapped in shapeless masses of blue cloth, with faces carefully covered; long robed "sayids" with green turbans on to show that they were descendants of the prophet Muhammad; peasants passed in old and ragged coats; city men in blue broadcloth and tall black hats, and Kurds from the mountains, wearing bright coloured coats, baggy trousers, and wide red belts, in which were thrust big daggers.

Here, in a corner, sat a man roasting "kabobs," bits of meat which he deftly wrapped in flaps of bread and sold. The purchasers took them in their fingers and ate them at once. Here were shops where a dozen men were making a great noise hammering out brass vases, bowls and tea urns. Just beyond were the shops of the saddle makers. There Karim saw just the saddle he wanted. He stepped to the edge of the shop and looked at it. The shop keeper looked up from the strap he was cutting.

"Peace be to you," said Karim.

"Peace be to you," replied the shop keeper, eyeing Karim's good coat and new hat. "With God's blessing have you come. I can see by your looks that you are a good rider and know good saddles. Let me show you this one. It is fit for King Solomon himself."

"I am looking for a saddle," replied Karim, feeling pleased, "and it must be a good one, suited to an attendant of Ardashir Khan, the son of the governor. But I am not as rich as King Solomon, and cannot buy saddles fitted for him."

"Indeed, may I be your sacrifice!" cried the shop keeper. "This saddle is a very poor gift, but take it, for you are a servant of our good governor, whom I hope God will bless. It is a present. My eyes for it, just command me, and it's yours."

"O no," said Karim, "of course I could not rob you so. I shall buy it, and pay you good money. What's your price?"

"No!" insisted the shop keeper, "take it. It is yours, with God's blessing."

"I cannot," said Karim. "I will buy it. What is your price?"

The shop keeper looked disappointed. "If you won't take the saddle as a present," he said, "you must name your own price. I can sell nothing to the servant of our governor, whom I hope God will bless. Name a price, my soul; anything, and it is yours."

"Since you say I must name a price," said Karim, feeling rather at sea, "I will give one toman."

"What!" screamed the shop keeper, "only one toman for a saddle fit for the hero Rustem! What pack horse's saddle would cost so little? Ten tomans could not buy it."

"Fit for Rustem, indeed!" said Karim, scornfully. "My master's mule driver would be ashamed to ride on it. See how the leather is worn, here, and here, and here. One toman is too much, but my master is generous, and so[91] I must be. Take eleven krans, and thank God."

"This is the way you servants of the khans laugh at my beard, and grind the faces of us who are poor. The leather alone of this saddle cost more than eleven krans. If I sold it for seven tomans, I would be giving it away."

"Your beard indeed saves you," said Karim, "for it is long, and I must treat you with respect. For the sake of your beard I'll offer fifteen krans."

"It is plain you are a country bumpkin, and do not know what saddles are worth," said the shop keeper. "Ask any one of these merchants here, and he will tell you that if I sell the saddle for six tomans I shall lose money. But our governor, your master, is a good man. For his sake take it for five and a half."

In reply Karim offered two tomans.

The shop keeper came down to five.

They kept on disputing in this way until at last Karim bought the saddle for three tomans. He carried it home on his shoulder, and began to brag to the other servants about his bargain.

But the groom laughed at him.

"The shop keeper was right," he said, "you are a bumpkin. Why did you tell him you were a servant of the governor? They sell saddles like this in the bazaars every day for two tomans."

Nasr'ullah was true to his promise, for he saw that Karim was large for his age, and had already learned how to manage horses.

Ardashir Khan, the agha's son, was very fond of riding, and was often in the saddle. Sometimes there was simply a ride across country to the hills, made gay by feats of horsemanship. The young khan and his friends, with their servants, rode madly at full speed in small circles, or pretended to get into a fight and fired their guns when at full run. At other times there was a party to hunt quail or partridge with the aid of falcons and dogs.

But one of the pleasantest excursions[94] was to a garden-house, surrounded by tall trees and grassy lawns. Here the young khans, in a cool porch beside a pool of clear water, drank the tea prepared by their servants, and smoked the pipe, while they enjoyed each other's jokes and stories.

One story of which no one seemed to tire, if it was well told, was about the disappointments of the lovers Leila and Majnoun.

Leila was the beautiful daughter of a chieftain who camped with his followers in tents, and wandered over the country, going wherever he could find water and grass for his flocks of sheep. Once he stopped near a village where dwelt a noble young man, Majnoun. Leila lived a freer life than the women and girls who[95] were in the villages, and was allowed to wander over the hillsides with uncovered face; in this way she happened to meet Majnoun. They fell deeply in love with each other, and often met among the lonely hillside rocks. Leila's father did not know of this, or he would have been displeased, for Majnoun was not a chieftain, like himself.

One day Majnoun was astounded to find the place empty where the chief's tent had been. It seemed hopeless to find him, for no one knew in which direction he had gone, but Majnoun did not give up. He left his father's house and wandered through all the neighbouring region, searching for the encampment. Although his search was in vain, he loved Leila so that he could not give up, but wandered in all directions searching eagerly for her.

The weeks lengthened to months, and the months to years, but still he could not find her.

Meantime Leila was as much distressed as was Majnoun. But it was impossible for her to search, for she was a woman, and must remain at home. All she could do was to weep in secret and sing songs or compose little verses that told of her grief.

After a time the chief of another tribe, who had heard of Leila's beauty, came with many horsemen and splendid presents to ask her father if he might marry her. Her father was much pleased, but poor Leila was heart broken. When her father heard that she was unwilling to be married he became angry.

"My daughter is of age," he said, "and her suitor is wealthy and of high rank. What more can she want? She must be married to the chief."

So the wedding was celebrated with a great deal of expense, and every one was very happy except the bride.

There was now no hope for Leila, but she could not forget her lover. Long years passed, and she heard nothing of Majnoun. Yet she did not forget him. She used to wander alone over the mountain side near her husband's tents, singing of her disappointment.

One day she heard her song answered by a well remembered voice, singing, like her, of a long lost love. And so at last they had found each other. But it was a very sad meeting. Leila was too honourable to disgrace her husband and herself by running off with Majnoun, and he was too noble to wish her to do so. They could only express their grief in song, and then bid farewell to each other for ever.

After Karim had become well acquainted with the governor's servants he persuaded Musa, who had charge of such matters, to allow him to be one of the men who waited upon the agha when he had callers. Karim stood at the door with hands covered until it was time to bring in the tea or "kalian," or water pipe, in which the smoke was drawn first through water and then through a long tube to cool it. Karim brought it in and silently placed it before a guest, who took a few whiffs, and then passed it to the man next him. This man did the same, and in this way the pipe was passed along the whole line of guests, sitting against the walls on either side of the governor.

The tea was served in little tumblers. It was made with plenty of sugar, and was so hot that the guest made a noise when[99] drinking it, drawing in air to keep from scalding his mouth.

The governor usually treated his guests very politely, although he did not rise as they entered, because he was of higher rank than they.

When he wished to show very great honour to a caller he beckoned to him to come and sit by his side. He kissed him on both cheeks, and asked him quickly, "Is your health good? Is your appetite good? Are you healthy, and fat? Your coming is delightful. Your arrival is most pleasant. You have come on my eyes."

But he was not always so gracious. Once a very rich khan called, bringing a letter which he wished to present. It happened that he was very near-sighted, and usually wore glasses. But to wear glasses when calling on the governor[100] would have been impolite, so he took them off before entering. It was an amusing sight to see his eyes rolling as he walked up the carpet trying to pick out the governor from among the callers who were seated by him. To have given the letter to the wrong man would have been a great insult. Luckily, he made no mistake, and, bowing low, handed the governor the letter. The governor opened and read it, then tore it up and threw it out of the window, and began to converse again with the other callers. Meantime the khan stood patiently waiting, for to speak without being first spoken to was impolite, and to leave without permission an insult.

At last he said to the governor, "With your permission, may I be excused?"

"You were excused before you came," replied the governor.

So the khan managed to get away, backing all the way to the door (to turn around would be improper), and bowing again and again.

The governor's mirza (or secretary) was very friendly with Karim, and allowed him to read his books. He had a fine copy of the "Shah Nameh" or "Book of Kings," by the great poet Firdousi. It was very large, and full of stirring poetry describing the wonderful deeds of kings and heroes who lived long ago. The greatest of them was Rustem. At eight years of age he was as strong as any hero of that time. This is one of the famous stories that Karim most enjoyed.

Rustem once went on a hunting trip that led him to the boundaries of Persia.[103] Becoming tired after a long day's chase, he lay down to sleep, leaving his splendid horse Rakush to graze near by. Some Tartar robbers, creeping up, led away the horse. Rustem, when he awoke, followed the hoofprints until he arrived at the kingdom of Samengan. Its king came to meet the hero, and promised to give back his horse if he became his guest. While here Rustem met the king's daughter, the princess Tamineh. They fell in love and were married with great splendour.

It was not possible for Rustem to live long with his bride, because he was needed by his lord, the king of Persia. He was compelled to leave Tamineh before he could even see the baby that was born. But he sent them a splendid present.

The baby was a boy, and Tamineh[104] said to herself, "If Rustem hears that his child is a boy he will send for him, and leave me desolate." So she told the messenger who brought the present that the child was a girl. Tamineh named her son Sohrab. As he grew up he became very strong and brave. When he was ten years old she told him that his father was Rustem, but added, "If you let this be known Rustem's enemies will try to kill you, for he is hated by many warriors here, because he has beaten them in battle."

When Sohrab was fourteen years old he was as strong as the greatest warrior. He now declared that he intended to conquer Kaoos, the king of Persia, and to make Rustem king in his stead. King Afraysiab, who was a great enemy of the Persians, heard of this plan. He thought to himself, "Sohrab is the only hero[105] strong enough to meet Rustem. If I can keep him from recognizing Rustem perhaps he will kill him as a foe." So he sent word to Sohrab that he would join with him in the war. But secretly he told his generals, Human and Bahman, that they should not permit Sohrab to recognize Rustem, and that if they could they should bring the two together in battle.

When the armies met, these generals arranged with King Kaoos that two champions, one for each side, should meet in single combat. The king selected his greatest hero, Rustem, as the champion for the Persians. Sohrab, of course, was chosen by Afraysiab's generals to fight against him.

Sohrab suspected that his foe was Rustem, and when they met begged him to tell his name, but Rustem refused. Twice[106] they fought, and twice Sohrab conquered. But he was moved by a strange love for his foe, and, though victor, spared his life.

And now the third and last day of the struggle arrived.

As Sohrab was putting on his armour he looked at the Persian hero, and said to Human, "See how strong and brave my foe appears! just such a man as my mother said that Rustem is. He surely is Rustem."

"Not at all," replied Human, "I know Rustem's appearance well. That horse, it is true, looks like Rakush, but is less strong and beautiful."

The champions now approached each other.

Sohrab, again in doubt, spoke, "Let us sit here as friends, for my heart is drawn to you. Be as generous as I am,[107] and tell me who you are! Say, are you Rustem, whom I long to know?"

"Away with your excuses!" cried Rustem. "We meet to fight. I claim the struggle."

"Old man," said Sohrab, "you refuse to listen to me. Then take care for yourself!"

Each now tied his horse, tightened his belt, and rubbed his arms and wrists in angry excitement, for the struggle was to be by wrestling. And now the heroes meet and clasp; in the terrible strain they seem like raging elephants. The ground grows black with the blood and sweat that drops from their straining bodies. Sohrab threw himself forward with a sudden spring and seized his enemy around the belt. Rustem, feeling his strength give way, fell heavily to the ground. Sohrab leaned over to kill him,[108] but Rustem cried out, "Hold! Do you not know the law? It gives the beaten man a second chance."

This was a crafty lie. Sohrab believed it. He left his foe, and went proudly back to the cheering ranks of his friends. Careless he waited, and made no preparation for the next fight. But Rustem went to a stream, and bathed his limbs, and prayed for the strength that once had been his.