Title: The Boy Aviators with the Air Raiders: A Story of the Great World War

Author: John Henry Goldfrap

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release date: May 23, 2014 [eBook #45727]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz, Roger Frank and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

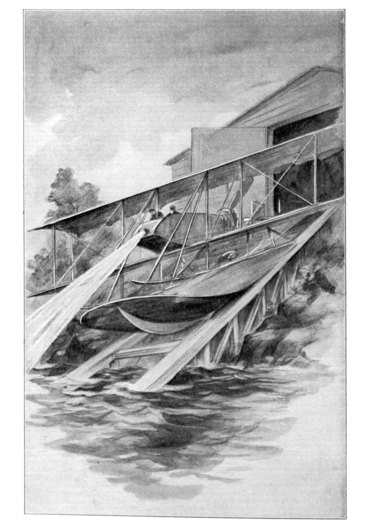

The plunging monster glided by.—Page 38.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Not Far from the Firing Line | 5 |

| II. | The Work of German Spies | 18 |

| III. | Saving the Great Seaplane | 29 |

| IV. | The Escape | 38 |

| V. | A Night on the Channel | 49 |

| VI. | Under Shrapnel Fire | 60 |

| VII. | The Sea Eagle on Parade | 72 |

| VIII. | A Safe Return | 83 |

| IX. | Thrilling News | 94 |

| X. | The Aëroplane Boys in Luck | 106 |

| XI. | The Man in the Locker | 117 |

| XII. | Frank Makes a Bargain | 129 |

| XIII. | Not Caught Napping | 142 |

| XIV. | The Peril in the Sky | 151 |

| XV. | On Guard | 162 |

| XVI. | The Coming of the Dawn | 173 |

| XVII. | News by Wireless | 185 |

| XVIII. | Off with the Air Raiders | 196 |

| XIX. | How Zeebrugge was Bombarded | 207 |

| XX. | Caught in a Snow Squall | 218 |

| XXI. | A Startling Discovery | 230 |

| XXII. | The Narrow Escape | 241 |

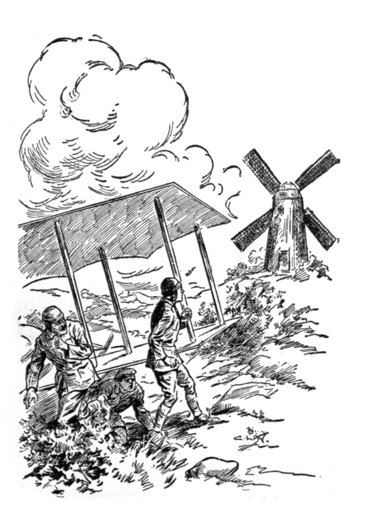

| XXIII. | The Windmill Fort | 252 |

| XXIV. | Friends in Need | 261 |

| XXV. | The Desperate Game of Tag | 275 |

| XXVI. | Headed Toward Home | 298 |

“It seems queer not to have Harry along with us on this trip to the war zone of Europe!”

“Just what Pudge, here, was saying last night, Billy. But you know my brother Harry has been ordered by Doctor Perkins to keep quiet for two whole months.”

“Frank, he was lucky to break only his arm and collar bone, when it might have been his neck, in that nasty fall. But why are you rubbing your eyes like that, I’d like to know, Pudge Perkins?”

“Pirates and parachutes, I’ll tell you why, Billy. Every little while I get to thinking I must be dreaming. So I pinch myself, and dig my knuckles in my eyes to make sure. But it’s the real thing, isn’t it, boys?”

6 “If you mean that the three of us, here, representing the Sea Eagle Company, Limited, of Brig Island, in Casco Bay, Maine, makers of up-to-date seaplanes, have come over to look up a sample shipment of our manufactures, and find ourselves being pestered by the French and British Governments to take a contract from them, why it certainly is the real thing.”

“It was lucky my father has that arrangement with the French Government to protect our property through thick and thin,” continued the boy called Pudge, who, as his name would signify, was very rotund in build, with a rosy face, and a good-natured twinkle in his eyes.

“Yes, only for that they would have commandeered the boxed seaplane long ago, and by now dozens of fleets made on the same model would be pouncing on the German bases along the Belgian coast,” remarked the boy whose name was Frank, and to whom the other two evidently looked up as though he might be their leader in the enterprise requiring skill and courage.

“But they’ve been mighty good to us since then,” went on Pudge. “They have allowed us to have a 7 substantial hangar built after our own peculiar pattern within reach of the water here at Dunkirk, though we are not so many miles away from where the Allies are fighting the Kaiser’s men who are in Belgian trenches.”

“Yes,” added Billy Barnes, who had once been a lively reporter, now a member of the aëroplane manufacturing company engaged in making the remarkable type of airships invented by Pudge’s scientific father, Doctor Perkins, “and during these weeks we’ve been able to get our machine together, so that right now it’s in prime condition for making a flight on the sea or in the air.”

“Whisper that next time, Billy,” cautioned Frank, casting a quick glance about him as the three boys continued to walk along the road leading out of Dunkirk, which in places even skirted the water’s edge.

“Why, what’s up, Frank?” exclaimed the talkative Billy. “Do you think these bushes and trees have ears?”

“No, but there might be some sharp German spy hanging around this place,” replied the other earnestly. “You know they do say they’re everywhere. I’ve 8 heard British soldiers in Calais and Dunkirk tell of mysterious strangers who disappeared when approached as if they were made of smoke. This spy system the Kaiser’s men have down to a fine point. It’s hard to keep anything from being carried to German Headquarters these days.”

“Still, there are a lot of things they haven’t learned before they happened,” declared Billy. “That first British army of some eighty thousand soldiers came over to France, and nobody knew a thing about it until they were on the firing line. But, Frank, do you reckon the Germans have been watching the three of us working here with our hangar and hydro-aëroplane?”

“I’m as sure of it as I am of my own name,” declared the other firmly. “Why, the very fact that our hangar differed so much from ordinary ones, being so much larger for one thing, would make them suspect. Then there has been a heap of talk going on about this wonderful airship of ours, which was carried, every word of it, to German Headquarters.”

“Batter and butterflies!” spluttered Pudge, who seemed addicted to strange exclamations, especially 9 when excited, “we’ll certainly have to watch out, then, now that our wonderful Sea Eagle is in working order.”

“Yes,” said Billy Barnes earnestly, “it would be a tough joke on the company to have some clever thieves get away with it, just when we are ready to show the French Government that it is away above ordinary seaplanes.”

“There’s the hangar, boys,” remarked Frank, with a vein of relief in his voice, as though grave fears may have been giving him more or less uneasiness. “Stir your stumps, Pudge, and we’ll soon be under our own roof. I may have a suggestion to make after we’ve looked around a bit that I hope both of you will agree with.”

While the three chums are advancing on the strangely elevated building that had been erected to accommodate their seaplane, we may take advantage of the opportunity to glance backward a bit, in order to see who and what they were. We do this for the benefit of those readers who may not have had the good fortune to peruse previous volumes in this series.

10 Two bright, inventive brothers, New York boys, who had actually built an aëroplane which they named the Golden Eagle, had shipped it to Central America when given a chance to save a plantation owned by their father, and threatened by the revolutionists in Nicaragua. This they had managed to accomplish, through the assistance of a young reporter friend named Billy Barnes. In this book, which was called The Boy Aviators in Nicaragua, were also related the thrilling adventures that befell the young air pilots when their craft was carried out to sea in an electrical storm; and also how they were rescued by means of a wireless apparatus through which they communicated with a steamer.

In the second volume, The Boy Aviators on Secret Service, the reader was taken to the mysterious Everglades region of Florida where the young inventors once more demonstrated their ability to grapple with emergencies. They proved that they were patriotic sons of Uncle Sam by discovering and putting out of commission a factory that was making dangerous explosives without the consent of the Washington Government.

11 It was a long jump from Florida to the depths of the Dark Continent, but the occasion arose necessitating their taking this trip to Africa. If you want to learn how theirs was virtually the first aëroplane to soar above the trackless heart of Africa, how they found the hidden hoard of priceless ivory secreted by slavers in the wonderful Moon Mountains, what strange things came about through their being hunted by the vindictive Arab slave trader, with many other interesting adventures, you can do so by procuring The Boy Aviators in Africa.

Through the coaxing of their warm chum, Billy Barnes, the boys were next induced to enter in a competitive race across the continent, and it can be easily understood that the pages of this book, The Boy Aviators in Record Flight, fairly teem with exciting incidents and thrilling adventures. Crossing the great Western cow country, they met with many difficulties from sand storms to treacherous cowboys and renegade Indians that threatened to end their game voyage. But the same indomitable spirit that had carried Frank and Harry through so many trials allowed 12 them to meet with the glorious success they so richly deserved.

From one series of adventures like this it was easy for the wide-awake young air pilots to engage in others. A story of an old Spanish galleon caught in the grip of that mysterious Sargasso Sea, where the circling tides have held vessels amidst the floating grass for centuries, fascinated them, and they set out to explore the dismal region that has been the graveyard for countless ships. Of course, the lure lay in the fact that a vast treasure was said to be aboard this old galleon; and the hunt for it, together with the opposition caused by a rival expedition, makes great reading for boys who have red blood in their veins. It is all set down in The Boy Aviators’ Treasure Quest, which has been voted one of the best of the entire series.

The Boy Aviators’ Polar Dash was possibly the most remarkable example of Young America’s nerve ever written. How the brothers came to plan the trip to the Antarctic region, and what amazing things happened to them while carrying it out, you will certainly appreciate when you read the book. The object of 13 the expedition was fairly covered, and they came back in safety; but only for the aëroplane the result could never have been attained, which proved how valuable an airship might be amidst the eternal ice of the frozen zones.

In the volume following this, the boys again found themselves caught in a swirl of exciting events. They had become engaged to Doctor Perkins, who was not only a scientific gentleman of note but particularly an aviator bent on startling the world through the agency of a monster seaplane which he had invented. He believed that a voyage across the ocean could easily be made in one of his safe aircraft, which combined many features not as yet in common use among the most advanced aviators. On Brig Island in Casco Bay, within sight of the Maine coast, they erected their factory, and manufactured various types of aëroplanes for the market. So far this wonderful seaplane had not been given to the world, for Doctor Perkins was shrewd enough to first get his patents in all foreign countries in order to protect his interests. In The Boy Aviators’ Flight for a Fortune have been related a series of remarkable adventures that befell 14 the young air pilots when trying out the first of these enormous hydro-aëroplanes, that would skim along the water or sail through the air with equal swiftness and safety.

One of these enormous seaplanes had been boxed in sections and shipped over to France, with the design of giving the Government officials an actual exhibition before they would agree to making a large contract with the firm.

Then the terrible world war had broken out, and for some months it was not known just what had become of the precious machine.

Finally word was received that it was safe at Havre, under the protection of the French Government, which would adhere strictly to the letter of the written agreement which they had entered into with the American company.

An urgent request was sent across the sea for some competent aviators to come over and put the several parts together, so that an actual test could be made. The French Government, if the trial proved convincing, stood ready to make almost any kind of contract with the company. This would be either in the way 15 of ordering a large number of seaplanes, providing they could be delivered without breaking the neutrality laws binding the United States, or else giving a royalty on each and every machine manufactured in France under the patents granted to the doctor.

This necessary but brief explanation puts the reader, who may not have previously known Frank and his chums, in possession of facts concerning their past. While Pudge Perkins, the doctor’s son, was not an experienced aviator, he had picked up more or less general knowledge in the factory, and had come abroad with Frank and Billy, as he was accustomed to say, just to “keep them from dying of the blues, in case the French Government kept putting them off from week to week, or if anything else disagreeable happened.”

Indeed, Pudge, with his abounding good nature, his love for fun, and great capacity for eating, might be looked upon as a pretty fine antidote for the dread disease known as the “blues.” No one could long remain depressed in mind when he was around. Besides, Pudge was really smarter than he looked; appearances in his case were apt to be deceptive; for 16 the boy had a fund of native sagacity back of his jolly ways.

Their hangar had been built in a rather lonely spot close to the water. This was done for several purposes, chief among which might be mentioned their desire to avoid publicity.

The obliging French authorities had even placed a guard at the point where the road passed the open spot now enclosed with a high fence; and so effectual had this proved that up to now the Americans had really not been annoyed to any extent.

Frank, however, had known for some time that all their movements were being watched from different elevated stations in the way of hilltops, or the roofs of houses, by men who carried field glasses. He had many times caught the glint of the sun on the lens when a movement was made.

As long as it went no further than that Frank had not cared, because these suspected spies could see next to nothing. But of late serious fears had begun to annoy him. The seaplane was ready for its first trip, and in a condition where it might be stolen, if 17 a band of daring men took it into their heads to make the attempt.

At one end of the hangar a long track with a gradual slope ran down to the water, so that the seaplane could be launched in that way if desired. A narrow stairway on the land side led up to the stout door which they always kept fastened with an odd padlock capable of resisting considerable pressure.

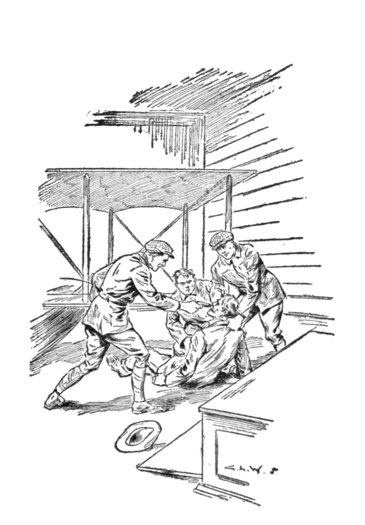

Each one of the three boys had a key for this lock, which they were very careful to keep fastened to a steel pocket chain. Pudge, having mounted the stair first, puffing from the exertion, was about to insert his key in the padlock when he was heard to utter an exclamation. The others saw him look closely, and then turn upon them with an expression of mingled alarm and consternation on his round face.

“As sure as you live, boys,” the stout boy gasped, “that’s a bit of wax sticking to our padlock! Someone’s been taking an impression so as to have a duplicate key made!”

When that astonishing declaration made by Pudge told the other two boys the nature of his discovery, they also glanced at the suspicious atom of wax sticking to the brass padlock.

“Sure enough, Frank; that it is,” gurgled Billy Barnes.

“There’s no question about it,” admitted Frank, as he took the fragment between his thumb and forefinger, and examined it.

“It wasn’t here when we came around this morning, I’d take my affidavy to that,” declared Billy.

“Dories and dingbats, not a bit of it!” exclaimed Pudge. “That padlock was as clean as a whistle, for I rubbed it with my sleeve to brighten it. There’s been some one snooping around here since then; and I guess they must mean to come back again to-night to steal the seaplane!”

“Open up, and let’s make sure things are all right 19 still,” demanded Frank. “We can settle on some sort of plan to upset their scheme by putting on a new lock, or something like that.”

Pudge, with a trembling hand, managed to insert his key, and upon the door being opened the three boys hurried inside the curious elevated hangar. It had been built with a metal roof, though whether this would really prove bombproof in case of a German air raid, such as had occurred several times, was a question.

“Thank goodness! everything seems to be O. K., boys!” cried Billy, after he had taken a swift survey of the interior, including the monster seaplane built on so advanced a model that there was certainly nothing like it known to aviators.

Frank, too, breathed more freely, for he had not known what to expect.

“Yes,” he went on to say earnestly, “and we ought to be mighty thankful that we’ve managed to get along up to now without having our whole outfit wrecked by a bomb, set on fire by a German spy, or raided some night by a party of unknown persons 20 who would have an interest in keeping the French Government from getting this sample seaplane.”

“My idea is this,” remarked Billy soberly. “They could have done the mischief at almost any time, but some one in authority thought it would be a brighter idea for them to wait until we had finished working on the plane, and then steal it, so that the Germans could copy our model for their army.”

“Gatling guns and grasshoppers, but I think you must be right, Billy,” exploded Pudge. “Haven’t we known that they kept a steady watch on us while we worked away here, even if they couldn’t see much? And many a time we disputed whether those chaps were German spies, or Frenchmen set on guard so as to make sure we didn’t take a notion to fly away some day to the enemy.”

Frank was looking unusually serious, and it could be plainly seen that he had a weight on his mind. The afternoon was near its close; and before long the shadows of a dark February night would be closing in around them.

“One thing sure, boys,” he finally said, “we must not leave our seaplane unguarded another night.”

21 “Do you think they mean to make away with it tonight, Frank?” demanded Billy.

“In some way they seem to know we’ve finished our work,” came the reply. “It puzzles me to guess how they learned it, when we only this noon notified the French authorities in secret that we were ready for any sort of long-distance test they might wish to order.”

“Must be a leak at Headquarters!” suggested Billy quickly.

“Tamales and terrapins, that would be a nice proposition, I should think!” ejaculated Pudge.

“Let’s step out and look around a little,” suggested Frank. “Perhaps we may find some trace of these unwelcome visitors who have managed to get up here to our door in spite of the soldier standing guard by the gate of our stockade.”

“They must have come from the water side, Frank,” Pudge was heard to say as he followed the others down the stairway that led to the ground.

“Be careful how you step around,” cautioned Frank. “Here, both of you plant a foot alongside mine, and in that way we’ll have a set of prints to 22 go by. Now notice just what they look like, and see if you can find any fresh marks that are different in some way from ours.”

It was an easy task he had set them, for almost immediately Billy sang out to the effect that he had made a discovery, and hardly had he ceased speaking when Pudge announced that he, too, wanted Frank’s opinion on a footprint that was much too large to have been made by any of them.

A further hunt revealed the fact that apparently three parties must have been at the foot of the steps leading up to their locked hangar. This important discovery was anything but pleasant to Frank Chester; it told him that a crisis was undoubtedly approaching their enterprise, which would seriously affect its success or failure.

What if, after all their earnest work, just when the wonderful seaplane had been made ready for a flight, those secret emissaries of the Germans managed to steal it away! Doubtless they had prepared for just such a stroke, and had an experienced air pilot hovering around so as to take charge of the hydro-aëroplane after it was successfully launched.

23 That would be the last the aëroplane boys would ever see of their valuable property. In time of war all devices are recognized as proper, and this theft of the American seaplane would be hailed as one of the most glorious feats of the German arms, as well as a serious blow at the air power of the Allies.

“There’s only one thing to be done,” said Frank, turning to the stout chum, “if you are game to tackle it, Pudge.”

The fat boy winced but set his teeth hard together.

“Rifles and rattlesnakes, just try me, Frank, that’s all!” he chortled, squaring his shoulders aggressively in a manner the others both knew meant that his fighting blood had been aroused.

“While Billy and I stay here to guard the machine, you must go back to town and get another kind of padlock, Pudge!” exclaimed Frank. “Pick out one that will hold as securely as this does. If we have to change it every day, we’ve got to make a sure thing of it.”

“Was it that you said you meant to speak about after we got inside the hangar, Frank?” inquired 24 Billy as Pudge prepared to start bravely away through the gathering shadows of evening.

“Well, it was something along the same lines,” explained Frank; “in fact, I meant to suggest that one of us stay here nights until we had word from Headquarters that the hour had come to make our test, and prove that the Sea Eagle could stand up against a gale when common seaplanes would go to smash, or have to stay at their moorings.”

“Mumps and mathematics, but I agree with you there, Frank!” cried Pudge. “And for one I’m in favor of camping out here right along. We could rig up a little stove, and cook our meals. It would be good fun at that, because then we’d have the real old-fashioned Yankee grub instead of this French fool stuff that never satisfies a healthy appetite.”

The others looked at Pudge and exchanged nods. They knew his failing, and could sympathize with the poor fellow. Pudge was patriotic enough to prefer the American style of cooking, which always spelled abundance according to his way of thinking.

“I’m off, fellows,” he now announced. “Look for me inside of an hour or so. Of course, it’ll be about 25 dark by then, but I know every stone on the road between here and town, I’ve traveled along the way so often. So long!”

With a genial wave of his hand, Pudge left them. The other pair looked after him with considerable solicitude; there was only one Pudge after all, according to their opinion, and he had a happy faculty for wrapping himself in the affections of his mates.

“You don’t think anything could happen to him going or coming, do you, Frank?” asked Billy Barnes, as they saw Pudge vanish through the partly open gate of the high stockade.

“Why, no; I hardly think so,” replied the other slowly. “Perhaps I should have gone for the padlock myself. If I had thought twice, I would have done that.”

“Too late—Pudge is on the way,” remarked Billy. “Let’s go up and take a peep around once more to see that everything is in apple-pie shape—each wire-stay keyed up to the right tune for efficiency, the motors ready to do business, the gas pump lubricated, and, in fact, our machine fit to toe the scratch as if there were a race on.”

26 Once they were inside the hangar, Frank fastened the door with a bar that had been arranged for just such a purpose. Then, turning on a flood of light from an acetylene gas battery, they examined every part of the big seaplane. It had something of the appearance of a gigantic sleeping bat as it lay there motionless, but with all the attributes of tremendous power for skimming along on the surface of the water or soaring among the clouds.

“In perfect condition, as far as I can make out!” remarked Frank, after they had completed this careful survey.

“Yes,” added the other, with a glow of excusable enthusiasm on his face, “and if there was any necessity for doing it we could be off with a minute’s notice.”

“I took pains to make sure that there was a clear and uninterrupted stretch of water in front of our hangar,” said Frank. “No vessels are allowed to anchor on this side of the harbor, though there are many transports from Great Britain across the way that have brought men and war material and stores over.”

27 “Oughtn’t Pudge be about due by now, Frank? It’s pitch dark outside, and I should think a full hour must have crept by since he left us?”

“I was thinking of that myself, Billy. Still, we must remember that our chum is a bit slow on his legs, compared with the way you and I get over the ground. Besides, he may have been delayed at the store where he expects to get the new padlock.”

“Yes, I hadn’t thought of that,” admitted Billy. “But we might use the ’phone we have installed, and find out if he’s started back. It would make our minds a little more easy, you know.”

“Just as you say, Billy. And suppose you call them up while I do something I want to alter here—nothing of consequence, of course, but the change would strike my eye better.”

“All right, Frank.” With which remark Billy turned to one end of the hangar close by, where a telephone apparatus could be seen attached to the wooden wall.

Frank went at his little task with his customary vim. It mattered nothing to him that the flight of the great seaplane would be neither hindered nor 28 assisted by its consummation. He simply liked to see things shipshape at all times.

“What’s the matter, Billy?” he called out presently, on hearing the other ring for the third time, and also muttering to himself as though annoyed.

“Why, Frank, I don’t seem able to get Central,” replied Billy, once more energetically working the handle of the apparatus.

Apparently Frank was enough interested to cross over so as to see for himself what was wrong. He sat down on the box Billy vacated and tried to get in touch with the operator at the central switchboard. After testing it in several ways, Frank replaced the receiver and looked up at his chum.

“Have they disconnected our wire at Central, do you think, Frank; or is the hello girl flirting with her beau, and not paying attention to business?” asked Billy.

“Neither,” answered the other soberly; “but I’m afraid somebody has cut our wire so as to keep us from calling for help if anything happens here to-night!”

“Gee whillikins! that sounds like a serious proposition, Frank!” exclaimed Billy Barnes, when he heard the opinion of his companion.

“It looks as though we’re up against something,” admitted the other grimly. “They’ve evidently set out to capture this seaplane, and mean to do it, no matter at what cost.”

“A compliment from the Kaiser to the ingenuity of Yankee inventors, I’d call it,” said Billy; “but all the same I don’t feel like throwing up my hands and letting them raid our shop here. It’s a good thing we made that discovery, thanks to Pudge and his sharp eyes.”

“Yes, and that you thought to use the wire, which showed us how somebody had been meddling so as to cut us off from the city,” Frank remarked.

“What if they come in force, knowing we’re here, Frank?”

30 “That door would not be able to stand much of an attack if they carried axes along with them, I’m afraid,” Billy was told.

“My stars! do you think they’d be apt to do that sort of thing?” demanded the astonished assistant, as he looked around for some sort of weapon with which he might defend the passage of the doorway, should it come to a question of fighting.

“If they want this plane as badly as we think they do,” said Frank, “there is little that desperate men might attempt that they would not try.”

“And still there’s no sign of poor Pudge!” ventured Billy, putting considerable emphasis on the adjective, as though he could almost imagine the happy-go-lucky Pudge lying on his back somewhere along the road, groaning in pain after having been struck down by a cowardly blow.

“I’m sorry to agree with you,” Frank admitted slowly, “but at the worst we’ll hope they’re only detaining our chum, and that he hasn’t been hurt.”

“How about my slipping out and trying to go for help, Frank? If they only knew at Headquarters about this, they would send a whole regiment of 31 British Tommies on the run to patrol our works here. Say the word and I’m off.”

Frank, however, shook his head as though the idea did not appeal to him.

“The chances are they would be on the lookout for something like that, Billy.”

“And lay for me, you mean, don’t you, Frank? Well, then, if it wasn’t so cold I’d propose slipping down to the water and doing a little swimming stunt. Too bad we didn’t think to have a boat of some kind with us.”

“I was just thinking,” ventured Frank, “that only on account of our being rushed for time we would have installed a wireless plant here, as we’ve often done before. Then we could send all the messages we wanted, and these spies wouldn’t be able to bother with them.”

“Yes, if we had only thought we’d run against a snag like this, Frank, we could have done that as easy as falling off a log. But it’s too late now to bother. The question is, what can we do about it?”

“There’s always one last resort that I know of, Billy.”

32 “Glad to know it, but please inform me as to its nature, won’t you, Frank? I would give half of my year’s salary just to be able to snap my fingers in the faces of these smart secret agents of the envious Germans who want to steal our thunder.”

Frank turned and pointed straight at the big seaplane.

“There’s the answer, Billy!” he said shortly.

At first the other simply stared as though unable to grasp the meaning of Frank’s words. Then a sudden gleam of gathering intelligence began to show itself in his eyes; he emphatically brought down his fist in the open palm of his other hand.

“Wow! that’s sure the ticket, Frank!” he burst out with, his enthusiasm spreading until his face was one solid grin. “We’ve got a way of escape right in our grip, and I was so blind as not to see it. Run off in the plane, of course, and leave the smarties to bite their fingernails. Great head, Frank! These German spies may think themselves wide-awake, but they’ll have to get up bright and early in the morning to catch two Yankee boys napping, believe me!”

“Listen, Billy!”

33 “Did you think you heard something then, Frank?”

“There’s someone at the door yonder; I saw it move, but the bar kept it from giving way,” Frank went on in a low tone. “Don’t act as though you suspected anything out of the way. They may be watching us through some peep-holes that have been bored in the walls. It would be foolish for us to give our plan away.”

“I understand what you are aiming at, Frank,” remarked the other, trying hard to appear perfectly natural, immediately adding under his breath: “There, I saw the door quiver again. They must wonder why it refuses to give way. That bar is our salvation, because like as not there’s a number of them out there who would flock in with all sorts of weapons, meaning to keep us quiet while their aviators examine the machine and get ready for a launching. Whee! then good-by to our bully Sea Eagle forever.”

“That’ll never happen as long as we can lift a hand to prevent it,” said Frank.

“Say, you don’t think that could be Pudge trying 34 the door?” suggested Billy, as though struck by a sudden bright idea.

“Not very likely,” came the reply; “but we can easily tell. If he hears me give our old signal, Pudge will answer on the dot. Listen and see if anything comes of it.”

The whistle Frank emitted was of a peculiar character. It was immediately imitated from without, and so exactly that one might think it an echo. Frank shook his head on hearing this.

“Pudge isn’t there,” he said decisively. “If he was, as you very well know, Billy, he would have sent back the other call, entirely different from the one I gave.”

“Then some fellow answered for Pudge, thinking we might open up, when they could rush the place and get possession—is that the way it stands, Frank?”

“As near as I can make out, it covers the ground,” the young air pilot replied. “Now I’m going to put out this light. We don’t really need it any longer, and if they are watching us through any peep-holes, it would give our plan away.”

“We ought to know every part of this coop, 35 Frank. As for the machine itself, I warrant you could find any stay or guy while it’s pitch dark. Let it go. There, they are trying the door again. Seems as if they can’t understand why it doesn’t give way. If it keeps on shutting them out, sooner or later they’ll try to batter it down. Oh! if I only had a gun here.”

“I intended having one with the seaplane, but thought I wouldn’t bother until we meant to start on a trip,” explained Frank, keen regret in his voice.

“Seems to me it’s always the unexpected that keeps cropping up with us,” complained Billy. “I can look back to lots of times when things happened just as suddenly and without warning as this has.”

“But they didn’t down us, you want to remember,” advised the other, in that confident way of his that always made his chums feel so much better.

“Now they’re starting to pry at the doors, Frank, which means business. Hadn’t we better be getting ready to make a start?”

“First of all I want you to stand by, and when I give the word fling both the large doors wide open,” Frank told him. “After that, as I switch on the 36 searchlight, so as to see what lies ahead, climb aboard to your regular place. And, Billy, please don’t have any hitch in the program if you can help it!”

“Depend on me, Frank,” said the other, slipping away in the darkness that now filled the interior of the big hangar.

Frank mounted to his seat. As no flight of consequence was intended, he did not bother donning the head shield he always carried with the machine, his gloves alone being deemed necessary for the occasion, though both of them had wisely secured their fleece-lined leather jackets. Just as Billy had said, Frank was so familiar with every lever and stay, as well as with the engine, that, with his eyes blindfolded, he could have manipulated the intricate working parts.

Quickly he adjusted things to his liking with a deftness that left nothing to be desired. The fact that those unseen parties on the other side of the door were becoming more insistent with every passing second did not seem to disturb Frank at all; for he knew very well they could not stop his departure now.

When, presently, he had finished his simple 37 preparations and everything was ready for the grand finale, he gave the signal that Billy was expectantly awaiting.

“Open up, Billy!”

Immediately both wide doors flew back, for the boys had arranged things so that it required but a simple movement to accomplish this. Then Billy hustled toward the seaplane, which no longer stood there like a black shadow; for Frank had, with the pressure of his finger, caused the powerful searchlight placed in the bow of the remarkable craft to flood the space in front of the hangar down to and out on the water of the harbor.

Billy swung himself aboard almost in the twinkling of an eye. Then a lever was manipulated and with a rush the monster seaplane started. Even as it left the shelter of the building, Billy, hanging on with nervous hands, could see several figures in the dazzling flood of white light spring wildly aside so as to avoid being crushed by the oncoming giant seaplane as it tore down the inclined track leading to the water.

Ahead of them lay that track of dazzling light. Every fragment of timber used in the construction of the inclined trestle upon which the seaplane was expected to reach the water was as plainly visible as at midday, with the sun shining above.

Billy fairly held his breath in fear lest the swift rush of the hydro-aëroplane should catch the two men on the slope unprepared, and hurl them into space. Just in the nick of time they threw themselves to one side, and the plunging monster glided by, so close that had he so willed, Billy could have thrust out a hand and touched one of the shrinking figures.

Then came a tremendous splash as they struck the water. Frank had made his calculations so carefully that there was not the slightest danger of a mishap. The boat was descending at such an angle that it instantly shot off the wheels that were underneath, and 39 skimmed along the surface of the water like a great duck.

Billy drew his breath again, for it seemed as though they had actually run the gauntlet in safety. He heard the familiar throb of the reliable motors beginning to take up their sweet song, which told that Frank had started the machinery at the proper second, so that they did not lose any of the impetus gained in that rush down the slope.

From up in the quarter where they knew the hangar must be, came loud cries of anger. Those who had planned to capture the seaplane when it was in prime condition for a flight to the German lines had evidently met with a most aggravating disappointment.

Suddenly the brilliant light vanished, shutting them in a pall of darkness that was all the more dense because of their having been staring into that illuminated avenue ahead, along which the seaplane was rushing at fair speed.

“It’s all clear in front, Billy,” Frank hastened to say, knowing that his companion must naturally think of the danger of a collision the first thing.

“Listen to ’em growl!” chuckled Billy, who had 40 evidently been greatly amused as well as interested in the remarkable dash of the Sea Eagle. “But, after all, that was what I’d call a close shave, Frank. Didn’t you hear the door being smashed in as we started?”

“I thought I did,” replied the other, “but I knew that nothing up there could give us any trouble. The only chance of our being wrecked was for those on the inclined plane to place some obstruction on the track that would throw the wheels of our carriage off, and dump us in a heap below.”

“They didn’t want to wreck the seaplane, which was what saved us from that smashup,” ventured Billy, and then quickly adding: “Hello! shut her off, did you, Frank?”

The musical hum of the twin motors and the whir of the revolving propellers had suddenly ceased, though the boat still continued to move along the top of the little waves coming in from the Channel.

“Yes, we have gone far enough for the present,” replied the pilot.

They sat there for a little while, listening to the various sounds that reached their ears from the shore. Not far away the lights of Dunkirk could be 41 seen, though these were by no means as brilliant as they might have been before the war broke out. This was on account of the fact that at any hour a raid from German aëroplanes might be expected in and around the encampment of the British troops.

“This is about the queerest situation we’ve ever found ourselves in, Frank,” ventured Billy presently, as he felt the boat moving up and down gently on the bosom of the sea. “It’s an experience we’ll never forget. I’m wondering what the next move on the program is going to be? How can we get ashore tonight in this terrible darkness?”

“We may make up our minds not to try it,” Frank told him quietly, as though he had some sort of plan in his mind, hatched on the spur of the moment.

“What’s the idea, Frank?” asked Billy eagerly. “No matter how you figure it I’m game to stand by you.”

“I’d never question that, Billy,” declared the other warmly. “You’ve proved your grit many a time in the past. But here’s the way the case stands. We could make an ascent from the water if we wanted, but on such a pitch-dark night that would mean trouble about coming down again. So what’s to hinder our 42 staying here until morning—lying on the water like a duck?”

“If the wind doesn’t come up with the change in the tide, we could do it as easy as anything,” assented Billy. “She rides like a duck, and could stand a lot more rough water than we’re getting now. Frank, let’s call it a go.”

“We will find it pretty cold, of course, you understand, Billy?”

“Shucks! haven’t we got on our leather jackets that are lined with fleece that have given us solid comfort many a time when we were six thousand feet and more up in the cold air? Why, Frank, we can strap ourselves to our seats, you know, and one of us can get a few winks of sleep while the other watches, ready to switch on the searchlight if anything threatens.”

“It’s plain to be seen that you’re set on trying a night of it,” said Frank, no doubt well pleased to have it so. “I’m worrying more about Pudge than of myself. Wish we knew he was all right.”

“The same here,” said Billy. “Frank, we must keep listening all through the night to catch his 43 signal, if ever he makes it. You know we’ve got that code for communicating by means of fish horns. If Pudge gets to the hangar and finds that we’re not around, the first thing he’ll think will be that the seaplane has been stolen.”

“Unless,” Frank hastily interrupted, “he happened to be near enough to hear something of the row, when he ought to be able to guess what really happened. In that case I expect that later on, when he thinks the coast may be clear, Pudge will try to communicate with us. As you say, we must keep on the alert. If you hear a sound that comes stealing from far away on the shore and resembles the bawl of a bull, answer it. Pudge will be in a stew about us, of course.”

They sat there for some time listening, and exchanging occasional remarks. Then, at Billy’s suggestion, they made use of the stout straps that were attached to each seat, intended to enable the navigators of the air to reduce to a minimum the risk of falling from a dizzy height.

“Take your choice, Frank, first watch or second,” was the next proposition advanced by the one-time 44 reporter. “I’m used to be up at all hours of the night—that was my busy time on the paper. So turn in, and I’ll take charge of the deck.”

“It’ll only be a cat nap then, Billy,” said the other, settling himself as comfortably as the conditions allowed, which was not saying much. “See that bright star over there in the west; it will drop behind the horizon in about an hour or so. Shake me then if I happen to be asleep.”

“All right, Frank. And if anything crops up in the meantime that bothers me, I’m going to disturb you in a hurry.”

“I hope you will, Billy; we can’t afford to take any chances, understand, for the sake of a little sleep. Listen for signs of Pudge. It would relieve me a whole lot if I knew that he was safe.”

After that Billy sat there and kept watch. The buoyant craft that had been so cleverly constructed so as to be equally at home on the water or in the air, rode the lazy billows that came rolling in from the Channel. The only sounds Billy could hear close by were the constant lapping of the waves against the side of the craft; though further off, toward the 45 city, there was a half subdued murmur, such as might accompany the gathering of thousands of men in camp.

The lights had almost wholly vanished by this time, showing the strict discipline that was in vogue in these stirring times. Frequently had daring German aviators appeared above Dunkirk to drop their bombs in the endeavor to damage the congested stores of the British troops, or strike a note of terror among the inhabitants of the Channel city.

Billy every little while twisted his head around and looked in different directions. But thick darkness lay about the floating seaplane, utterly concealing the shore as well as all vessels that lay further along in the harbor.

Possibly half an hour had passed in this way when Billy felt a sudden thrill. He started up, straining his hearing, as though to catch the repetition of some sound he believed he had heard.

Then, leaning over, he shook Frank.

“It’s Pudge signaling, Frank, or else I’m away off my base. Listen!” was what he told the other, in excited tones.

46 A minute later and they both caught the far-away sound of what seemed to be the winding blast of an Alpine hunter’s horn.

“Yes, it’s Pudge, all right, and he wants to hear from us if we’re within reach of the sound of his signal. Answer him, Billy!”

Already Billy had taken the horn from its fastenings, and no sooner had Frank given the order than he applied it to his lips. The sound that went forth, coming as it did from the blackness of the sea beyond, must have astonished any sailor on board the various steamers in the harbor.

Once, twice, three times did Billy give the peculiar note that Pudge knew so well. It must tell the absent chum that they were safe, and in the language of their secret code ask how things were going with him.

“There, he’s given us back the message word for word!” cried Billy, as they caught the faint but positive reply from the unseen shore, perhaps at the deserted hangar. “Frank, he’s all right! That takes a big load off our minds.”

“Yes, now I can rest easy!” declared the other. 47 “As that star isn’t close to the sea as yet, Billy, if you don’t mind, I think I’ll try for a few more winks of sleep. Pudge will go back to town and stay at our lodgings until we turn up, or send him a message. Everything is working finely.”

“For us,” added Billy, chuckling. “But think how mad those spies must be over losing the prize they thought was sure to fall into their hands. Why, I wouldn’t be surprised if they discounted the capture of our seaplane, and over in Belgium were ready to start to work making copies of the same as soon as the sample could be delivered.”

Billy appeared to be highly amused, for he chuckled to himself for several minutes while picturing the disappointment of the baffled plotters. Then once more he settled down to his task of serving as “officer of the watch.”

As the minutes crept on, Billy began to observe the gradual approach of the star to the vague region where sea and heavens merged in one. In fact, Billy was yawning quite frequently now. He found himself fairly comfortable, thanks to the warmth of that leather fleece-lined jacket, and the hood which he 48 had drawn partly over his head. Still, it was not very delightful, sitting there on the water; and perhaps the boy’s thoughts frequently turned toward the bed he was missing.

“I wonder which way we’re drifting now?” he suddenly asked himself; he immediately set to work trying to answer his question by observing the direction of the tide, as well as by the light current of air.

When next he thought to turn his head so as to glance backward, Billy received a bit of a shock. A sort of thin haze had settled down on the water by now, but through this he had discovered two moving lights. They looked very queer as seen in that foggy atmosphere; but Billy was smart enough to know what they stood for.

He immediately awoke Frank, whispering the astonishing news in his ear.

“They’re looking for us, and they’ve got lanterns, Frank!” was what the one on guard said in a low tone as he pulled his chum’s sleeve.

Frank was wide-awake instantly, and one quick glance showed him the approaching peril.

“Yes, you’re right about it, Billy,” he observed cautiously, and if there was a little quiver to his voice that was no more than might be expected under the exciting conditions by which they were surrounded.

“How queer the lights look swinging along close to the water, and in that fog, too. They are heading out this way, I’m afraid, Frank.”

“It seems so, Billy.”

“Hadn’t we better get under way, then?” continued the nervous one.

“No hurry,” Frank told him. “They may happen to swing around one way or the other and miss us. We’ll wait and find out. You know we can get 50 moving with a second’s warning. Now let’s watch and see what happens.”

Billy could be heard sighing every now and then. Doubtless, as he sat there with his head turned halfway around, observing the creeping movements of those two strange lights through the fog that hugged the surface of the water, he was thinking it the most exciting moment of his whole career.

Then a new idea seemed to have lodged in his brain, for again he whispered to his companion.

“There may be more than those two boats, Frank!”

“Possible but not probable,” Frank replied.

“What if, when we started off with a rush, one happened to get in the way?” pursued Billy.

“I’d be sorry for the men in that boat, that’s all, Billy!” was the laconic reply he received, and apparently it satisfied the other, for he did not pursue the subject any further.

Meanwhile it became apparent that the searching boats were gradually drawing nearer the floating seaplane. Unless they changed their course very soon those in the hostile craft would be likely to make a discovery that must fill them with delight.

51 “Are we headed right for a start, Frank?” asked Billy, a minute later.

Frank himself had been considering that very thing. The influence of the tide seemed to have swung the seaplane around a little more than he liked; but then this could be easily remedied, for they were prepared for such a possibility when on the water.

There was a little paddle within reach of Frank’s hand; all he had to do was to pull a couple of cords, and it was in his possession.

Softly he worked it through the water. Frank had spent many happy hours in a canoe when on his outing trips, and knew how to wield a paddle like an expert. He had even taken lessons from one of those old-time guides accustomed, in years gone by, to using a birch bark canoe in stealing up on deer when jacklight hunting was not banned by the law.

Consequently he now used his paddle without making the slightest noise; and under its magic influence the clumsy craft gradually veered until he had its spoon-shaped bow heading just where he wanted it. Then he handed the paddle to Billy to replace as best he might.

52 They could by this time vaguely make out the nearer boat, and also the indistinct figures of two men. One of these was rowing, while the other held up the lantern.

Of course, there was nothing to tell Frank who they might be. Perhaps, in these stirring times, the waters of the harbor had to be patrolled by guards on the watch for submarines or other perils. These protectors of shipping may have heard or seen enough that was suspicious to warrant a search of the adjacent waters.

He was more inclined to believe, however, that the German spies, rendered furious by the escape of the coveted American seaplane had, as a last resort, started out to scour the water nearby in hopes of locating it.

“Frank!” whispered Billy again, “I think he glimpses the seaplane through the fog!”

The actions of the man holding the lantern indicated this, for he was plainly much excited, turning to his companion at the oars as though urging him to make more haste.

“Then it’s high time we were off!” said Frank.

Again did Billy hold his breath as the possibility 53 of the motors failing them in this great emergency flashed through his mind. But he need not have allowed himself this mental anxiety, for no such calamity befell them.

A shrill whistle was heard, evidently a signal to those in the second boat to inform them that the object of their search had been discovered. Then came the cheery whirr of the motors, accompanied by the churn of the busy propellers, and like a giant, double-winged dragonfly, the seaplane started along the surface of the water, followed by another burst of angry shouts.

“Duck! they may be going to shoot!” exclaimed Frank, suiting his actions to his own words.

That was just what did happen, for a volley of shots sounded, and had the motors not been making so much noise the boys might have heard the whistle of the passing leaden messengers.

There was no harm done, for, unable to longer see the speeding seaplane, those who used their weapons with such reckless abandon had to fire at random. Skimming the water like an aquatic bird, with a 54 gradual but rapid increase to their speed, the seaplane soon began to rise.

Billy realized from that that Frank meant to make an ascension, possibly deeming it wise to get away from such a dangerous neighborhood as quickly as possible. And, as they anticipated, the reliable Sea Eagle was doing her prettiest when called upon to show her fine points.

Once free from the sea, they rose until Frank felt sure of his position. He had switched on the electric searchlight, and the storage battery was of sufficient power to send the ray of white light far ahead. It could be turned to any quarter of the compass.

“Well, here we are off on our trial trip sooner than we expected,” said Billy, meaning to draw the other out, for he was consumed by curiosity to know what was coming next.

“Two narrow squeaks on one night ought to be enough, don’t you think, Billy?” asked the pilot, as he started out into that avenue of light, and then glanced at the handy compass so as to fix their course on his mind.

“Well, we’ve been pretty lucky so far,” admitted the other. “It wouldn’t pay to keep up that sort of 55 racket. They say, you know, that the pitcher may go to the well just once too often. It might be three times and out for us.”

“And neither of us feels like accommodating those anxious German secret agents whose one business in Dunkirk is to steal our thunder, do we, Billy?”

“Not much,” replied the other boy with decided emphasis. “I’d sooner see the airship smashed to pieces than know it had fallen into the hands of the Kaiser’s men.”

“Hold on, Billy! You know we’re supposed to be neutral in this fighting business. We’ve got some mighty good friends who are of German blood, and we think a whole lot of them, too.”

“Oh! I’m not saying a word against Germans; they’re as fine a people as any in all the world; but, Frank, what we’ve met with in Northern France and in the little of Belgium we saw that day Major Nixon took us out in his motor car, somehow set me against the invaders. Anyway, we’ve been treated splendidly by the French here, and our business has been with them.”

“That’s understood, Billy, and I agree with you in 56 all you say. But let’s talk now about our chances of dropping down again to the water.”

“Oh! then you don’t mean to stay up here, Frank? Will it be safe to descend, do you think?” asked Billy, a new sense of anxiety gripping him.

“So far as the plane is concerned we can do almost anything with it,” Frank assured him. “Our light will tell us whether the sea is too rough for alighting. We’re heading downward as it is right now. Steady, Billy, and keep on the watch.”

Having taken his course, Frank knew that they must be out on the channel some miles from the harbor. On nine nights out of ten he would have hesitated about attempting such a risky proceeding as he now had in view; but the calmness that prevailed encouraged him to take the chances of a descent in the darkness.

“I can see the water all right, Frank!” exclaimed Billy a minute later, as the wonderful air and water craft continued to head downward, though with but a gradual descent.

“It looks good to me,” ventured the pilot, with confidence in his tone.

57 Presently they were so close to the surface of the water that both of the boys could see that it was fairly quiet. The long rollers were steadily moving toward the southeast, as though the night air influenced them, but then Frank had before now dropped down on the sea when it was much more boisterous.

“Here goes!” he remarked, as he deflected the rudder just a trifle more, and immediately they struck the water.

The Sea Eagle, being especially constructed for this sort of work, and having a spoon bow that would not allow her to dip deeply, started along on the surface, with the motors working at almost their lightest speed. Then Frank cut off all power.

“We did it handsomely, Frank!” exulted Billy Barnes, feeling quite relieved now that the seaplane had proven fit and right for the business it had been built to demonstrate.

“And here we are floating again,” said Frank, “but this time so far away from the harbor of Dunkirk that there’s no longer any danger from spies. Billy, since that star has dipped behind the horizon, suppose you take your little twenty winks of sleep.”

58 “You think it’s perfectly safe to lie here the rest of the night, do you, Frank?”

“Why not, when we can get away if the wind should come up, and the sea prove too rough for us? Make your mind easy on that score, Billy.”

“But how about steamers crossing from the other side of the channel?” asked Billy. “I think I heard that they generally take the night to make the trip these times, so as to keep the German aviators from learning how many transports loaded with troops come over. Besides, they avoid danger from submarines, and bombs dropped from Zeppelins that way.”

“Oh! the chances of our being run down are so small that we needn’t bother about them,” Frank assured the nervous chum. “I promise you that if I see a moving light, or hear the propeller of a steamer, I’ll wake you up, and we can stand by, ready to go aloft in case the worst threatens.”

That seemed to appease Billy, for he gave a satisfied grunt and proceeded to settle himself for a nap.

“This is being ‘rocked in the cradle of the deep,’ all right,” he remarked, as the floating seaplane rose 59 and fell on the swell. Frank made no reply, so that presently Billy relapsed into silence, his regular breathing telling the other he was sound asleep.

So the long night crept on. The boys managed to catch more or less sleep, for nothing arose to alarm them. Naturally, their position was far from a comfortable one, and therefore Frank, who happened to be on duty at the time, felt pleased more than words could tell when he eventually glimpsed a light in the eastern sky that proclaimed the coming of dawn.

“Have we anything to eat along with us, Frank?”

“Why, hello! are you awake, Billy? I was just thinking of calling you, or sending a bell hop up to pound on your door. It’s morning, you see.”

“Yes, I noticed that light over there in the east, and was thinking how the poor fellows in the trenches must feel when they see it creeping on, knowing as they do that it means another day of hard work and fighting. But how about my question, Frank? Did we think to fetch that pouch of ship-biscuit along with us?”

“Yes, it’s tied just back of you,” the other informed him with a laugh. “But I’m surprised to hear you so keen for a bite, Billy. If it had been Pudge, now, I wouldn’t have thought so much about it, because he’s always ready for six meals a day.”

“I don’t know what ails me,” acknowledged the other, as he reached for the little waterproof bag in 61 which Frank always tried to keep a pound or so of hardtack, with some cheese as well, to provide for any emergency like the present, “it may be this sea air, or perhaps it’s due to the excitement we’ve gone through; but I’m as hungry as a wolf in winter.”

“Perhaps I may take your appetite away then,” suggested Frank, with a chuckle.

“In what way?” demanded Billy, with a round ship biscuit halfway to his mouth.

“Oh! by making a stunning proposition I’ve been considering while I sat here, that’s all.”

“Gee! it takes you to think up things, Frank. Now, as for me, I’ve been badgering my poor brains about how we would astonish the people of Dunkirk when we came sailing into the harbor and made for our hangar. There’d be as much excitement as if a dozen of those little Taube aëroplanes of the Germans had hove in sight, just as they did on that day of the last air raid. Now tell me what the game is, please, Frank.”

“Suppose, then, we weren’t in such a big hurry to go back to our moorings?” said the other. “Suppose, that having broken away, we took that trial spin we’ve 62 always been promising ourselves when things were ready!”

Billy became so excited that he actually forgot to eat.

“Wow! that’s a brilliant scheme, Frank, let me tell you!” he exclaimed. “Say, for a wonder, all the conditions favor aëroplane work. The wind that has kept up during the last three days seems to have blown itself out, and we’re likely to have a quiet spell. They’ll be on the watch for another raid of those Taubes from up Antwerp way on such a calm day as this. Frank, shall we try it?”

“Wait for another half hour,” replied the other. “By then it will be broad daylight, and we can see what the signs promise. If things look good we’ll start up and take a run to the northeast.”

“Over the trenches, do you mean, and perhaps far into Belgium?” cried Billy, to whom the prospect of seeing something of the terrible fighting that was daily taking place in the lowlands along the canal appealed with irresistible force; for the old reporter spirit had never been killed when he gave up newspaper work for aëroplane building.

63 “We’ll see how the land lies,” was all Frank would say. Billy knew very well the other was bound to be just as keenly interested in the warlike scenes below them as he could be, hence he was willing to check his impatience, leaving everything to Frank.

Both of them munched away on the ship-biscuit and cheese. It was pretty dry fare, but then there was a bottle of water at hand if they felt choking at any time.

The half hour passed and they could see from the growing light in the eastern sky that the sun would soon be making its appearance. Around them there was nothing but an endless succession of rollers, upon which the buoyant seaplane rose and fell with a continual gurgling sound.

“If this low-hanging fog would only lift,” remarked Billy, as he put away the hardtack bags, “we could tell just where we were. As it is, there’s no such thing as seeing land, which must be over there to the east.”

“The sea fog is rising and will disappear as soon as the breeze comes,” Frank observed sagaciously. “By then we want to be several thousand feet up, 64 and taking a look through the glasses at the picture we’ll have spread out below us.”

“Let’s start now,” suggested Billy. “I’m wild to see what the country up across the border of Belgium looks like. To think of us being able to glimpse all the German defenses as we go sailing over so smoothly.”

Frank laughed.

“You are counting your chickens again before they’re hatched, Billy, an old failing of yours. It may not be the smooth sailing you think. Remember that the Germans are always ready-primed with their wonderful anti-aëroplane guns for hostile raiders. We may have a dozen Taubes, too, buzzing after us, or find ourselves chased into the clouds by a big Zeppelin.”

If Frank thought to alarm Billy by saying this, he immediately saw that he had failed to shake the other’s nerve.

“Gee! that would make it interesting, for a fact!” the other exclaimed, his face beaming with eagerness. “Frank, you can take my word for it, no Taube, or Zeppelin either, for that matter, can catch up with 65 our good old Sea Eagle, once you crack on all of her two thousand revolutions a minute with both motors. They haven’t got a thing over on this side of the big pond that is in the same class with Doctor Perkins’s invention.”

“I think you’re pretty near right there, Billy,” said the pilot, as he proceeded to press the button that would start things humming.

Immediately they were beginning to move along on the surface, the peculiar spoon-shaped bow preventing the water from coming aboard. Faster went the huge seaplane as Frank gave increased power, until when he tilted the ascending rudder they left the water just as a frightened duck does after attaining sufficient momentum.

“Hurrah!” exclaimed the delighted Billy, as soon as he realized, from the change in motion, that they no longer rested on the water, but were cleaving the air.

Mounting in spirals, as usual, the two boys soon began to have a splendid view, not only of the sea, but of the nearby land as well.

“Oh! look, Frank, over there in the west; those 66 must be the famous white chalk cliffs of Dover across the channel we see. To think that we are looking down at France, and even Belgium, and on England at the same time.”

“That’s about where the Kaiser is aiming to throw those monster shells from his big forty-two centimeter guns, after he has captured Calais, you know,” remarked Frank.

“I guess that dream’s been smashed by now, and there’s nothing in it,” Billy was saying. “Not that the Germans didn’t try mighty hard to get there, and tens of thousands of their brave fellows gave up their lives to carry out a whim of the commander, which might not have amounted to much, after all. Oh! Frank, with the glass here I can see our hangar as easy as anything.”

“That’s good, Billy. I was just going to ask you to look and see if those disappointed spies had done anything to it. I’m glad to hear you say it’s still there in good shape. I expect we’ll have more or less need of that shed from time to time.”

“Well, we don’t mean to spend many nights paddling around on the sea,” affirmed Billy, now 67 beginning to turn his glass upon the country they were approaching, and which lay to the north of Dunkirk.

Frank had changed their course so that they were now over the land. They could easily see the camps of the British troops, though they were so far above them that moving companies looked like marching ants. The tents could not be concealed, and there were besides numerous low sheds, which doubtless sheltered supplies of every description, needed by the army fighting in the trenches further north.

As Frank drew more upon the motors that were keeping up a noisy chorus, the huge seaplane rushed through the air and gave them a change of landscape every little while.

The sun was in plain sight, although just beginning to touch things below with golden fingers. Covering land and water, they could see over a radius that must have been far more than fifty miles.

Billy kept uttering exclamations, intended to express the rapture that filled his breast. In all his experience he had never gazed upon anything to compare with what he now saw spread out below him as though upon a monster checkerboard. African 68 wilds, Western deserts and Polar regions of eternal ice were all dwarfed in interest by this spectacle.

Again and again did he call the attention of his chum to certain features of the wonderful picture that especially appealed to him. Now it was the snakelike movements of what appeared to be a new army heading toward the front, accompanied by a long line of big guns that were drawn by traction engines. Then the irregular line of what he made out to be the opposing trenches riveted his attention. He was thrilled when he actually saw a rush made by an attacking party of Germans, to be met with volleys that must have sadly decimated their ranks, for as Billy gazed with bated breath he saw the remnant of the gallant band reel back and vanish amidst their own trenches.

“Am I awake, Frank, or asleep and dreaming all this?” Billy exclaimed, as he handed the glasses to his chum.

This Frank could readily do because they were running along as smoothly as velvet, and long habit had made him perfectly at home in handling the working parts of the seaplane.

69 “I wonder what they think of us?” wondered Billy. “You may be sure that every field glass and pair of binoculars they own is leveled at us right now. They must think the French or the British have sprung one on them, to beat out their old Zeppelins at the raiding business! Oh! wouldn’t I give something to be close enough to the commanding general to see the look on his face.”

Frank was looking for something else just then. Although they were flying at such a great height, he fancied that the present security would hardly last. The Germans were only waiting until they had gone on a certain distance; then probably a dozen of their hustling little Taube machines would spring upward and chase after the singular stranger like a swarm of hornets, seeking to cut off escape, and hoping by some lucky shot to bring it down.

The barograph was in plain sight from where Frank sat, and perhaps the quick glance he gave at its readings just then had some connection with this expectation of coming trouble.

Billy interpreted it otherwise. He was afraid Frank, thinking they had gone far enough, was 70 sweeping around to start back toward the British trench line.

“Just a little further, Frank,” pleaded Billy. “There’s a big move on over yonder, seems like, where that army is coming along; and I’d like to see enough to interest our good friend Major Nixon when we get back.”

“I don’t know whether I’ll let you say a single word, Billy,” the air pilot told him, as he relinquished the glasses to the eager one. “That wouldn’t be acting neutral, you know. Besides, there are plenty of the Allies’ machines able to fly, and those airmen like Graham-White ought to be able to pick up news of any big movement.”

They could see patches of snow in places, and much water in others where the low country had been inundated by the Belgians. This was done in hopes of hastening the retreat of the invaders, who despite all had stuck to their trenches and the unfinished canal for months, as though rooted there.

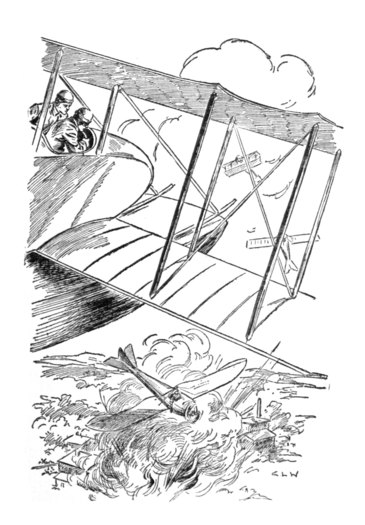

All at once there sounded a loud crash not far below the young air pilots, and a puff of white smoke told where a shrapnel shell had burst.

71 “Frank, they’re firing at us!” exclaimed Billy, who had made an involuntary ducking movement with his head as the sharp discharge burst upon his ears.

Even as he spoke another, and still a third crash told that the Germans had determined the time was at hand to try their anti-aëroplane guns on the strange seaplane that was soaring above the camps.

“That means we’ll have to climb higher, so that their guns can’t reach!” Frank immediately decided.

It was indeed getting rather warm around them, Billy thought. The shrapnel puffs seemed to be above, below, and on every side, and it was a wonder that neither of them received a wound.

“Only for the speed we’re hitting up, the story might be a whole lot different, according to my notion, Frank. They have a hard job to get our range, you see.”

“Yes, most of it bursts back of us, showing a faulty figuring,” the pilot explained, as he started a corkscrew movement of the seaplane calculated to cause the aircraft to bore upward in spirals.

The guns, far below, kept up a merry chorus. Billy could hear the faint noise made by the continuous discharges, and the puffs of smoke that seemed to rise in a score of places at the same time told him 73 how eagerly the German gunners were trying to strike that elevated mark.

Now the shrapnel ceased to worry Billy, for he saw that none of it seemed to be bursting around them as before. The limits or range of the anti-aircraft guns had apparently been reached.

“We’re safe from the iron rain up at this height, Frank. What does the barometer say?” he asked, with that spirit of curiosity that had made him a good reporter in the old days.

“That’s too bad,” replied Frank, as he bent forward to look.

“Don’t tell me that the only fragment of a shell that’s struck home ruined our fine barometer!” cried Billy.

“Just what happened,” he was told. “At any rate, it’s knocked to flinders; and I think I must have had a pretty close shave. But we can buy a new one when we get back to Dunkirk. As near as I can give a rough guess we must be between three and four thousand feet high.”

“I should say it was a lot more than that,” Billy declared. “But so long as they can’t reach us 74 any longer, why dispute over a few thousand feet?”

He thereupon once more started to make use of the glasses, and had hardly settled them to his eyes than he gave a startled cry.

“Frank, they’re coming up like a swarm of angry bees!” Billy exclaimed.

“Do you mean Taube aëroplanes, Billy?”

“Yes, I can see as many as six right now in different directions, and others are going to follow, if looks count for anything. The word must have been given to attack us.”

“I’m not worrying any,” Frank told him calmly. “In fact, I don’t believe they’ll try to tackle such a strange hybrid aircraft. They can see how differently constructed the Sea Eagle is from all other hydro-aëroplanes, and expect that we must mount at least one quick-firing gun.”

“Then what are they climbing for, Frank? I can hear the buzz of their propellers right now, and let me tell you it sounds like ‘strictly business’ to me!”

“They are meaning to get close enough to let the pilots see what kind of a queer contrivance it is that’s hanging over their camps,” Frank continued in a 75 reassuring manner. “When we choose to turn tail and clear out, there isn’t one in the lot that can tag on after us.”

“I know that, Frank, thanks to those wonderful motors, and the clever construction of Dr. Perkins’ model. But now here’s new trouble looming up ahead.”

“I can see what you mean, Billy. Yes, that is a Zeppelin moving along down there, one of the older type, I should say, without having used the glasses.”

“But surely it will make for us, Frank. A real Zeppelin wouldn’t think of sheering off from any sort of aëroplane.”

“Watch and see what happens,” Billy was told, as Frank changed their course so as to head straight for the great dirigible that was floating in space halfway between their present altitude and the earth that lay thousands of feet below.

The firing had stopped. Probably the German gunners, having realized the utter futility of trying to reach the Sea Eagle while it remained at such a dizzy height, were now watching to see what was about to take place. Many of them may have pinned great 76 faith in the ability of their aircraft to out-maneuver any similar fliers manipulated by the pilots of the Allies. They may even have expected to see a stern chase, with their air fleet in hot pursuit of this remarkable stranger.

If this were really the case, those same observers were doomed to meet with a bitter disappointment.

“Well, what does it look like now?” Frank asked presently, while his companion continued to keep the glasses glued to his eyes as though fairly fascinated by all he saw.

“The Zeppelin has put on full steam, I should say, Frank,” admitted Billy.

“Coming to attack us?” chuckled the other, though the motors were humming at such a lively rate that Billy barely caught the words.

“Gee whillikins, I should say not!” he cried exultantly. “Why, they’re on the run, Frank, and going like hot cakes. I bet you that Zeppelin never made faster time since the day it was launched. They act as though they thought we wanted to get above them so as to bombard the big dirigible with bombs.”

“And that’s just what they do fear,” said Frank 77 positively. “That’s the greatest weakness of those big dirigibles, they offer such a wide surface for being hit. While an ordinary shell might pass straight through, and only tear one of the many compartments, let a bomb be dropped from above, and explode on the gas bag, and the chances are the Zeppelin would go to the scrap-heap.”

“They’re dropping down in a hurry!” declared Billy. “There, I can see a great big shed off yonder, and it must be this that the dirigible is aiming to reach. We could, however, bombard the shed as easily, and destroy it together with its contents. Frank, it makes me think of an ostrich trying to hide its head in a little patch of grass or weeds, and because it can’t see anything, believes itself completely hidden.”

“Well, as we haven’t even a gun along with us the Zeppelin is pretty safe from our attack,” remarked Frank. “We’ve proved one thing by coming out to-day.”

“I guess you mean that we’ve given the Germans something to puzzle their wits over, eh, Frank? They know now that no matter what big yarns have been 78 told about the new Yankee seaplane they tried to steal, it’s all true, every single word of it.”

Billy seemed to be quite merry over it. The fact that the dangerous Zeppelin had fled in such wild haste, shunning an encounter, while the vicious little Taube aëroplanes darted about like angry hornets, yet always kept a respectable distance away from the majestic soaring Sea Eagle was enough to make anyone feel satisfied.

“I admit that at first I was kind of shaky about defying the whole lot, but I’ve changed my mind some, Frank,” he called out a minute later. “Yes, the shoe is on the other foot now. They’re afraid of us! Makes a fellow puff out with pride. There’s only one thing I feel sorry about.”

“What might that be?” asked the other.

“If only Harry could have been along to enjoy this wonderful triumph with us, or Dr. Perkins either. It would have completed our victory. But from here I can see that army on the move as plain as anything. They’re meaning to make one of their terrible drives somewhere along the Yser Canal, 79 perhaps when that air raid comes off that we heard so much quiet talk about.”

“Well, that raid may be held up a while,” Frank told him. “They must believe that French or British pilots are aboard the Sea Eagle right now; and for all they know there are half a dozen just such big aircraft waiting to engage their fleet if it hove in sight of Dunkirk or Calais.”

“Every time we make a sweep around you can see the nearest Taube scuttle off in a big hurry,” ventured Billy. “Why, Frank, some of those machines are carrying a quick-firer with them, but they’ve had orders not to take risks. What would you do if they actually started to close in on us?”

Frank laughed as though that did not worry him very much.

“Why, there are several things we could do, Billy. In the first place we can go higher with the Sea Eagle than any of those flimsy Taubes would dare to venture, though I’d hate to risk it in this bitter cold air.”

“Yes, that’s true, Frank, and like you I hope we will not have to climb any further. It isn’t so bad in the summer, but excuse me from doing it now. 80 We would need two more coats on top of the ones we’ve got, and another hood to keep our ears from being frozen stiff. What’s the other idea?”

“A straight run-away,” explained Frank. “If I really saw that any of them meant business, I could crack on all speed until we were making the entire two thousand revolutions per minute. That would leave them far behind.”