C.R. Coleridge

"Maud Florence Nellie"

"Don't care"

Chapter One.

Maud Florence Nellie.

Maud Florence Nellie Whittaker was standing before her little looking-glass, getting ready for her afternoon Sunday school. She was a fine tall girl of fifteen, rather stoutly made, with quantities of light brown hair, which fell on her shoulders and surrounded her plump rosy face with a perfect halo of fringe and friz. She had hazel eyes, which were rather bold and rather stupid, a cocked up nose, and full red lips, which could look sulky; but which were now curved in smiling satisfaction at the new summer hat, all creamy lace and ribbons, which she was fixing at exactly the right angle above her curly hair. She had on a very fashionable cream-coloured costume to match the hat, and altogether she was justified in considering herself as one of the best dressed girls in her class, and one whose good looks were not at all likely to pass unnoticed as she took her way along the sunshiny road that led into the large country town of Rapley. Her fine frock, her big girlish form, and her abundant hair seemed to fill up the little bedroom in which she stood; which had a sloping roof and small latticed windows, though it was comfortably furnished and had no more appearance of poverty than its inhabitant. Florrie Whittaker lived in the lodge at the gate of the great suburban cemetery, which had replaced all the disused churchyards of Rapley. Her father was the gatekeeper and caretaker, and as the cemetery was a very large one the post was important and the salary good. Florrie and her brothers and sisters had run up and down the rows of tomb-stones and played in the unoccupied spaces for as long as most of them could recollect. They saw many funerals everyday, and heard the murmur of the funeral service and the toll of the funeral bell whenever they went out, but it never occurred to them to think that tomb-stones were dismal or funerals impressive; they looked with cheerful living eyes at their natural surroundings, and never thought a bit more of the end of their own lives because they so constantly saw the end of other people’s. Florrie finished herself up with a red rosebud, found her hymn-book and a pair of new kid gloves, and then with a bounce and a clatter ran down the narrow stairs into the family sitting-room below; where the din of voices betokened the father’s absence, and the bustle attendant on starting for school on the part of a boy and two girls younger than herself.

“You’ll all be late, children, and get bad marks from your teachers,” cried Florence, in a loud gay voice.

“And what’ll you be?” was the not unnatural retort of the next sister, Sybil.

“It ain’t the same thing in my class,” returned Florrie. “Teacher knows that girls of my age can’t be punctual like little ones. They’ve to clear away, and mind the children, and all sorts of things to do.”

“And what have you been clearing away?”

“And who have you been minding of?”

“And what have you had to do but put your fine hat on?” rose in a chorus from the indignant children; while another voice put in—

“When I went to school the elders came punctual for the sake of an example.”

“Oh my! Aunt Lizzie, I didn’t see you,” said Florrie. “How d’ye do? There’s plenty of examples nowadays if one wanted them, which I don’t.”

“I’m sure, Aunt Lizzie,” put in the eldest sister, a tall young woman of nineteen or so, “there isn’t harder work in the world than in trying to set an example to Florrie.”

“You don’t set a nice one,” said Florrie.

“It would be a deal better for you, Florence,” said her aunt, “if you did take example by some one. You’re getting a big girl, and that hat and frock are a deal too smart to run about the roads in. When I was a girl, I had a nice brown mushroom hat and a neat black silk jacket, and pleased enough I was with them as a new thing.”

“And did your aunts wear mushroom hats and black silk jackets?” said Florrie.

“My aunts? no, indeed! Whatever are you thinking of, Florence? My aunts were most respectable women, and wore bonnets, when bonnets was bonnets. Hats, indeed!”

“Your hat was in the fashion then, and mine’s in the fashion now,” said Florence saucily; but Aunt Lizzie, refusing to perceive that her niece had made a point, continued, “Aunt Eliza Brown was married to a man in the grocery way, and Aunt Warren, as you very well know, was housekeeper to Mr Cunningham at Ashcroft Hall, and married the head keeper, which her son has the situation to this day.”

“I do tell Florrie,” said the elder sister again, “that she’d look a deal more like a real lady if she dressed a bit quieter than she does.”

“I don’t want to look like a lady. I want to have my fun,” said Florrie. “Come on, Ethel, if you’re coming; I want to catch up with Carrie and Ada. Good-bye, aunt; I like lessons best in school.”

And off dashed Florrie through the summer sunshine, between the avenue of monuments, her hair flying, her skirts swinging, and her loud lively voice sounding behind and before her as she scurried along.

“Well!” said Aunt Lizzie, “she be a one, surely. That girl wants a tight hand over her, Martha Jane, if ever a girl die yet.”

Aunt Lizzie—otherwise Mrs Stroud—was an excellent person, and had “kept her brother’s family together,” as she expressed it, ever since their mother’s death; but she was not invariably pleasant, and her eldest niece disliked being called Martha Jane much more than Florence disliked being scolded for her finery. When all the younger ones had such beautiful names—Maud Florence Nellie, Ethel Rosamond, and Sybil Eva Constance—it was hard upon her that she had been born before her mother’s love of reading, and perhaps her undeveloped love of the beautiful things of life, had overcome the family traditions. “Martha” was bad enough, and she did not know that the children’s use of “Matty” was a fashionable variation of it. But “Martha Jane!”

She was not, however, saucy like Florence, so she only sighed a little and said:

“I do my best, indeed, aunt; but won’t you lay off your mantle and sit down comfortably? Father won’t be in yet. He likes to be round, when so many friends come to visit the graves and put flowers, in case of mischief, and the children won’t be back for near two hours.”

Mrs Stroud was a stout comfortable woman, not very unlike what her niece Florence might be after five and thirty more years in a workaday world had marked and subdued her beaming countenance. She was glad to sit down after the hot walk, take off her cloth mantle, which, though an eminently dignified and respectable garment, was rather a heavy one for a June day, and fan herself with her pocket-handkerchief, while she inquired into the well-being of her nieces and nephews. Martha Jane was of a different type—dark and slim, with pretty, rather dreamy grey eyes, and a pale refined face. She was a good girl, and tried to do her duty by her young brothers and sisters; but she had not very strong health or spirits, and in many ways she wished that her life was different from what fate had made it.

“That there Florrie,” said Mrs Stroud, “ain’t the sort of girl to be allowed to stravage about the roads by herself for two hours.”

“Why, aunt, she must go to her Bible class,” said Martha meekly.

“Well,” said Mrs Stroud, “there’s girls that aren’t calculated for Bible classes, in my opinion. Does she come in punctual from her work on weekdays?”

“Oh, yes, aunt, and it’s supposed that George meets her. Not that he always does; but she has to look out for him. And Mrs Lee keeps her very strict at the shop. She don’t have her hair flying about on weekdays, nor dress fine, and she’s a good girl for her work and very civil, Mrs Lee says. You wouldn’t know Florrie when she’s behaving.”

“Pity she don’t behave always then,” said Mrs Stroud.

“That’s just the thing,” said Martha, “I tell her, aunt, constant. I tell her to read the tales out of the library, and see what the young ladies are like that are written about in them. And she says a tale may be a tale, but she ain’t in a book, and she don’t want to be. Florrie’s always got an answer ready.”

“Well, Martha Jane, I don’t hold much with wasting time over tales and novels myself. You read a deal too many, and where’s the good?”

“I should waste my time more than I do but for some talcs I’ve read,” said Martha, colouring.

“Well, ‘Waste not, want not.’ Read your Bible, I say.”

“That’s not in the Bible, Aunt Lizzie.”

“It might be,” said Mrs Stroud; “there’s a deal of truth in it. But, bless you, Martha, it ain’t talcs nor nonsense of that kind that signifies. Florrie must be held in. She’s that saucy, and that bouncing and set on her own way, that there’s only one in the family she’s like, Martha Jane, and that’s ’Enery himself.”

“Harry! Oh, Aunt Lizzie! But she’s a girl.”

“Well, Martha Jane, and if she is? There’s plenty of ways for girls to trouble their families. You wasn’t more than eleven or so when ’Enery went; but surely you can recollect him, ramping round. Why, when he come to sit with his family he was like an engine with the steam up for starting off again! And he went about that audacious!”

“I can remember his jumping me off the tomb-stones,” said Martha.

“Ah! He jumped off tomb-stones once too often. It all came of ramping about and reading, so there’s lessons in it for you and Florence both. Well, I promised a call on Mrs Taylor at the upper lodge, so I’ll stroll up quietly and meet your father, and come back for a cup of tea.”

Martha made no objection to this proposal; for though she never “answered back,” nor asserted herself against her elders, she strongly resented the connection between ramping about and reading, and between herself and the troublesome Florence, and was very glad to get rid of her aunt for the present.

She sat still when Mrs Stroud, having assumed her mantle and opened her parasol, walked up the cemetery to meet her brother. She really wished to be a good elder sister; but what could she do with a girl only three years younger than herself, and with more “go” in her little finger than poor Martha had in her whole body?

Surely Florence was not going to be like poor Harry! Martha called him “poor Harry” in her thoughts—it is an epithet often applied half in kindness and half in contempt to the family ne’er-do-weel; but she had not a very pleasant recollection of this absent brother. If Florrie was rude, inconsiderate, and bouncing, she was nothing to Harry at fifteen. Martha recollected his utterly unscrupulous teasing and bullying alternating with rough good-nature, which had made her hopelessly afraid of him. He got situations, and lost them by practical jokes. He was started in a good place at a large printing establishment in Rapley, and, after sundry smaller feats, had sent the rector of the parish a packet of playbills announcing the performance that night of “The Corsican Brothers” and “Cut off with a Shilling;” while the manager of the theatre received the rector’s notices of a missionary meeting, also being got up in a hurry on some special occasion. Neither the rector nor the manager spared the printer, and as Harry Whittaker had been heard sniggering with a companion over the exchange, it could not pass as a mistake, so that situation came to an end. Then he had to content himself with being errand-boy at a linen-draper’s. There somehow the ball dresses which should have been delivered to Lady Temple in time for the county ball floated down the river instead, and were landed the next afternoon mashed up in their cardboard boxes.

And worst of all, a dreadful night, which Matty never did forget, when some poor people, coming in the dusk to one of those sad hurried evening funerals which terrible infection sometimes necessitates, had been frightened—how she did not know, but cruelly and unfeelingly by Harry’s means. Martha remembered her father’s just annoyance and anger. Harry had been sent away to his Uncle Warren’s, where something else happened—Martha never knew what—and that was the last she heard of her eldest brother.

A little while before, mother had died, and father grew severe and strict, and Aunt Lizzie bustled them about till a year ago, when, late in life, she married a well-to-do ironmonger, and turned her energies on to her step-children.

Since then Martha Jane had done her best for her three sisters, for the brother, George, who had a good post as clerk on the railway, and for Johnnie and Arthur, the youngest of the family, who still attended the day school. The Whittaker girls had never been sent to a national school, but had got, or were getting, their education at one of the many “Establishments for Young Ladies” which prevailed at Rapley. It was supposed that in this way they would be less likely to “make acquaintances;” but acquaintances are very easily made by sociable people, and Mrs Stroud had always thought it the proper thing to send them all to Sunday school. Martha, however, had had very little of this. She was a good girl, with a turn for church-going, and the interest of most well-disposed girls of her day in varieties of church services, church music, and church decorations; but she had no personal tie to the church which the Whittakers attended, and she had not found the connection between these tastes and the duties of life.

She was rather imaginative, and she read every story book she could lay her hands on—religious domestic tales from the parochial library, novels from that provided for the servants of the railway company, which her brother brought home, and quantities of penny serial fiction. Very little of it was absolutely bad. Martha would not have read it if she had known it to be so, but a great deal of it was extremely unreal, silly, and frivolous. Martha’s taste and critical powers were so uncultivated that she hardly knew that one book was of a higher tone than another, any more than she knew that it was better written. There were fine sentiments which she admired in all of them about love and constancy and self-devotion, and perhaps Martha was not to blame if she thought that people usually died in carrying out these virtues. Still, the character of the books did make a difference to her; for she was not one to whom a tale was nothing but a tale, and if she learnt from some that ladies wore wonderful and ever-varying costumes, and spent their time in what she would have called “talking about the gentlemen,” she learnt from others that they studied hard, and devoted themselves much to the good of their fellow-creatures and the comfort of their families.

Martha, when she might have been attending to the comfort of hers, was sometimes lost in imagining herself reading to a mothers’ meeting in “a tightly fitting costume of the richest velvet,” etc, etc; but, confused as were her notions, she had ideas and aspirations, and was ready for a guiding hand if only she could have found one.

Chapter Two.

A Sunday Walk.

Florrie was troubled with no aspirations and with very few ideas. She was just like a young animal, and enjoyed her life much in the same way and with as little regard to consequences. When she and her little sisters came out of the great cemetery gates into a broad, cheerful, suburban road, the children ran on, afraid of being late. Florrie caught up, as she had expressed it, with Carrie Jones and Ada Price, also in the full glory of their new summer things, and both eagerly looking out for her. For Florrie was bigger, smarter, and more daring than any of them; she was the ringleader in their jokes, and bore the brunt of the scrapes consequent upon them; she was therefore a favourite companion. The three girls hurried along the sunny road, chattering and laughing, with their heads full of their new clothes, their friends, and themselves, so that there was not an atom of room left for the Bible lesson which they were about to receive. They came with a rush and a bounce into the parish room, where their class was held, just as the door was unfastened after the opening hymn, found their places with a scuffle and a titter, pulled some Bibles towards them, and looked all round to greet their special acquaintances, as the teacher began her lesson.

Florrie Whittaker did not behave worse than several others of the young, noisy, irrepressible creatures who sat round the table; but there was so much of her in every way that the teacher never lost the sense of her existence through the whole lesson. Miss Mordaunt was a clever, sensible lady, not very young, nor with any irresistible power of commanding attention, but quite capable of keeping her class together, and of repressing inordinately bad conduct. Sometimes her lessons were interesting and impressive, and, as she was human, sometimes they were rather dull; but the girls liked her as well as they liked anyone, and if they had been aware that they wanted a friend would have expected her to prove a kind one. But they were mostly young and well-to-do, with life in every limb and every feeling; and the Bible class was a very trifling incident to them.

Florrie felt quite good-naturedly towards her, but she did like to make the other girls laugh, and to know that she could upset nearly all of them if she liked. She was not clever enough to care with her mind for the history of Saint Paul, and she was no more open to any spiritual impression than the table at which she sat, new gloves to button and new hats to compare effectually occupying her attention. She jumped up when her class was over, a little more full of spirits for the slight restraint, and rushed out in a hurry with Carrie and Ada, that they might be round on the other side when the boys’ class came out, and see who was there.

It was general curiosity on Florrie’s part, and the desire to do what was disapproved of; her family were above the class who were likely to “walk with” anyone at fifteen, and she only hurried along giggling and whispering towards the riverside.

A pretty, sleepy, flat-country river ran through the meadows that lay round about Rapley, and the towing-path beside it was a favourite Sunday walk, and in its quieter regions was the resort of engaged couples, and of quiet families walking out with their babies in their perambulators. But the stretch of river between the suburban region where the cemetery lay and the church of Saint Jude, in the district of which it was included, was near the lower parts of the town, and on Sundays was full of roughs, and idle lads on the way to become roughs. No girls who were careful of their conduct and wished to keep out of noisy company would have gone there in the afternoon. Florrie Whittaker and her two friends knew quite well that they had no business to be in that direction; but a feint of pursuit from some of the lads as they hung about the classroom door sent them scurrying and looking behind them down the street, and they soon found themselves, in all their conspicuous finery, walking along the towing-path by the river. It was a shabby region; new and yet dirty little houses bordered it, their back yards and back gardens, each one less ornamental than the last, stretching down to the path, between which and the river were a few pollard willows. On the other side spread out a low-lying marshy region, which was generally flooded in the winter. A small public-house ended the row of houses where a swing gate led into the fields beyond.

“I say,” said Carrie, “we didn’t ought to have come down here. Mother ’ll give it me when I get back.”

“No more we’d ought,” said Ada. “If Miss Simpson were to hear of it, she’d say I was letting down the school. Come through the gate and across the fields, Florrie; this ain’t nice at all.”

“I don’t care,” said Florrie, stimulated by sundry remarks caught in passing; “we can take care on ourselves. I ain’t a-going to speak to anyone; but I’ll walk here as long as I like. Oh my! what fun it’d be if your governess did catch you, Ada!”

“You wouldn’t think it fun if Mrs Lee was to catch you,” said Ada.

“Oh my! shouldn’t I though?” said Florrie, with her beaming face all in a twinkle. “I’d like to see her coming through the gate. There’s a boat on the river; let’s stop and see it go by.”

“Don’t, Florrie Whittaker,” said Carrie. “There’s Liza Mason and Polly Grant, and I ain’t a-going to be seen with they.”

“Well, I am then,” said Florrie, delighted at teasing her friends, and quite indifferent to the fact that the two girls who joined them were of a much rougher, lower stamp than themselves—girls whose Sunday finery consisted of an artificial flower to enliven their weekday dirt, and who, poor things, were little general drudges in places which no respectable girl would take. Liza and Polly were nothing loth, when Florrie chose to acknowledge an old Sunday school fellowship in mischief by stopping to speak. Liza was saucy, and called out loudly that she thought they’d all be too proud to take any notice.

“Not I,” said Florrie. “I don’t care for no one. You come into our shop, Liza, any day, and I’ll show you all the best things in it.”

“That you won’t,” said one of a group of the Sunday school lads who had followed. “I’d dare you to do that—you’d be afraid.”

“I dare,” said Florrie. “You come in with an errand and see. I dare do anything I’ve a mind to; I don’t care for no one!”

“Florence Whittaker,” said Ada Price, the pupil-teacher getting the better of the mischievous, idle girl in her, “I’ll never walk with you again, you’re too bad—and—oh my, come on, for there is your Mrs Lee coming through the gate. Florrie, Florrie! She’ll see you in another minute!”

Ada and Carrie were indifferently behaved and common-minded girls, but they were not without some sense. A moderate amount of misbehaviour at, and on the road to and from their Sunday class was their way of enjoying their rather scanty bit of freedom; but risking their weekday occupation and their means of earning their living was another thing altogether. They pulled away from Florence, held up their heads, and walked on.

But Florence Whittaker was daring with a different degree of folly from that of most silly girls. The sense of when to stop was lacking in her, as it had been woefully lacking in her eldest brother, and the sense of how delightful her employer’s face of horror would be kept her standing in the midst of the group of rough lads and girls, and tempted her to raise her voice and call out again, “You see if I don’t!”

Mrs Lee, a most respectable-looking tradeswoman, walking through the fields with a friend, stopped short at sight of the “young lady” who served in her fancy shop thus surrounded. “Miss Whittaker!” she said in a voice of blank amazement.

“Good afternoon, Mrs Lee,” said Florence pertly. “Isn’t it a nice afternoon?”

“Miss Whittaker, I am surprised.”

“Are you, Mrs Lee? Our class is just over.” Mrs Lee looked her up and down, and walked on in silence. This was no place for an altercation.

“Go on, Florence Whittaker,” said one of the bigger lads. “The old lady’s right enough, and this ain’t the place for young ladies—”

“’Twas all along of you we came,” said Florence. “Well, good-bye, Liza; don’t you forget.”

She ran off after her companions, who were now walking soberly enough across the field path which led back into the high road. But Florrie’s spirits were quite unchecked. She laughed at the thought of Mrs Lee’s amazement, she laughed at Carrie and Ada’s fright, she repeated with more laughing the various vulgar jokes which had passed with the lads and with Polly and Liza.

“I never thought,” said Ada indignantly, “that you’d join company, Florence Whittaker, with such as them. It’s as much as I’d do to pass the time of day with them.”

“Now then,” said Florrie, “didn’t Miss Mordaunt say last Sunday as it was very stuck up and improper to object to Maria Wilson coming to the class because she’s a general? and she said I was a kind girl to let her look over my Bible, so there!”

“Maria Wilson do behave herself,” said Carrie.

“Well, Carrie Jones, don’t you talk about behaviour! Do Miss Mullins always behave herself? Don’t she walk out at the back with the young men in the shop, and wait outside the church for them? And you’re glad enough to walk with her. I don’t care how people behave so long as I can have my fun, and I don’t care who they are neither.”

Ada and Carrie, brought face to face with one of the practical puzzles of life for girls of their standing, the difficulty of “keeping oneself up” in a right and not in a wrong way, were far too conscious of inconsistency to have anything to say, and Ada changed the subject.

“Well, anyway, I wouldn’t be you to-morrow morning, Florrie,” she said.

“I like to get a rise out of Mrs Lee,” said Florrie, “and I don’t care a bit for her. I shall just enjoy it.”

Carrie and Ada did not believe her, but, worse luck for Florence, it was perfectly true. She did not care. The power of calculating consequences was either absent from her nature or entirely undeveloped in it. She was not a bit put out by her companions’ annoyance, and laughed at them as she parted from them at the upper gate of the cemetery. The sun was still shining brightly on the clean gravel walks, the white marble crosses and columns, and on the many flowers planted beneath them. Apart from its associations, Rapley cemetery was a cheerful, pleasant place, and Florence, as she noted a new-made grave, heaped up with white flowers, only thought that there was an extra number of pretty wreaths there, without a care as to the grief which they represented.

Mr Whittaker was very proud of the good taste and good order of his cemetery, and took a great deal of trouble to have everything kept as it should be.

Even Martha, in whose favourite literature lonely churchyards and silent tombs were often to be met with, never thought of connecting the sentiment which they evoked with the nice tidy rows of modern monuments among which she lived. Aunt Lizzie occasionally pointed a moral by hoping her nieces would remember that they might soon be lying beneath them; but they never regarded the remark as anything more than a flower of speech.

Florence got in just in time for tea, to find her father giving Mrs Stroud the history of some transactions he had lately had with the “Board,” in which he had brought over all the gentlemen to see that he was right as regarded certain by-laws.

Mr Whittaker was a round-faced, rosy man, like his younger children. He was a very respectable, hard-working man, and a kind father; but he thought a good deal of his own importance and of the importance of his situation, and a good deal of his conversation consisted in impressing his own good management on his hearers. He would have been almost as much put out with Martha for wanting what she had not got as he had been with the one of his children who had brought him into disrepute. Florrie’s misdemeanours had never come across him, and she did not know what his displeasure would be like. She knew quite well what that of her brother George could be, and enjoyed provoking it. George was an irreproachable youth, and aimed at being a gentleman. He was of the dark and slender type, like Martha, and cultivated a quiet style of dress and manner. He sang in the choir of another church in the town, and was friendly with the clergy and church officials. It was a new line of departure for the Whittakers, and an excellent one; but somehow George rather liked to keep it to himself, and did not encourage his sisters to attend his church, or follow his example in religious matters.

Florrie came in, and as soon as tea was over, and her father and aunt were out of hearing, she amused herself with scandalising George and Martha by boasting of how she had shocked Carrie and Ada through stopping to talk to Liza and Polly. She omitted to mention either Mrs Lee or the cause of the walk by the river. There were limits to the home endurance, and even Florence, when not worked up to delightful defiance, was aware of their existence.

Chapter Three.

Don’t Care!

Mrs Lee was a widow. She kept a small, but very superior, ‘Fancy Repository’ in a good street in Rapley. Her daughter helped her to manage the business, and Florence Whittaker was being trained up as an assistant. Idleness was not one of Florrie’s failings, and, as she was quick, neat-handed, and willing, she gave tolerable satisfaction, though Mrs Lee considered her lively, free and easy manners to pleasant customers, and her short replies to troublesome ones, as decidedly “inferior,” and not what was to be expected in such an establishment as hers. Florence, however, was gradually acquiring a professional manner, which she kept for business hours, as too many girls do, apparently regarding refinement and gentleness as out of place when she was off duty.

She presented herself as usual on Monday morning, in a nice dark frock and hat, and with her flying hair tied in a neat tail, and began cheerfully to set about her duties, which were not at all distasteful to her. But she wondered all the time what Mrs Lee was going to say. Perhaps, if that lady had been a keen student of human nature, she would have disappointed the saucy girl by saying little or nothing. But she knew that most girls disliked being found fault with, and had not discovered that Florrie Whittaker rather enjoyed it. She believed, too, in the impressiveness of her own manner, and presently, summoning Florence into the parlour, said majestically:

“Miss Whittaker, it is not my intention to say much of what I witnessed yesterday, except that it was altogether unworthy of any young lady in my employment. Should it occur again I shall be obliged to take other measures.”

“I’m very sorry, ma’am, I’m sure,” said Florence meekly, and hanging down her head.

“No one can say more. I will not detain you from your duties.”

“Thank you, ma’am. I’ll remember,” said Florrie, retreating, and leaving Mrs Lee much pleased with the result of her admonitions. Miss Lee, who caught sight of the young lady’s face as she passed behind the counter, did not feel quite so well satisfied.

There was, however, very little fault to be found with Florence in business hours; and all went well till about twelve o’clock, when, there being several customers in the shop, Miss Lee became aware of an unusual bustle at one end of it, and beheld Florence opening boxes, spreading out fine pieces of needlework, and showing off plush and silk, with the greatest civility and a perfectly unmoved countenance, to a shabby little girl in an old hat and a dirty apron, while a boy with a basket on his arm stood just inside the door, open-mouthed with rapturous admiration.

“What are you doing, Florence Whittaker?” whispered Miss Lee in an undertone.

“Waiting on this young lady, Miss Lee. This peacock plush, miss, worked with gold thread is very much the fashion; but some ladies prefer the olive—”

“What do you want here?” said Miss Lee to the customer, as her mother, suddenly perceiving what was going on, paused with a ball of knitting silk in her hand and unutterable things in her face. “Have you a message?”

But Polly fled at the first sound of her voice, and was out of sight in a moment, while the errand-boy’s loud laugh sounded as he ran after her.

“Put those things up, Miss Whittaker,” said Mrs Lee, turning blandly to her customer. “Some mistake, ma’am.”

“Why, Miss Lee,” said Florence, “I thought I was to be civil just the same to everyone, and show as many articles as the customers wish.”

“You had better not be impertinent,” said Miss Lee. “Wait till my mother is at leisure.”

In the almost vacant hour at one o’clock Mrs Lee turned round to her assistant, and demanded what she meant by her extraordinary behaviour.

Florrie looked at her. She did feel a little frightened, but the intense delight of carrying the sensation a stage farther mastered her, and she said:

“The boy there, yesterday, when you saw us down by the river, dared me to show Polly the fine things in the shop, or to notice her up here. So I said, ‘Let her come and try.’ And she came just now, so I kept my word. There ain’t no harm done.”

It was the absolute truth, but telling the truth under the circumstances, with never a blush or an excuse, was hardly a virtue.

“Do you mean to say you have dared to play a practical joke on me and my establishment—that you have been that audacious?” exclaimed Mrs Lee.

“I didn’t know it was a joke,” said Florrie. “You didn’t laugh.”

“No, Florence Whittaker, I did not. I am much more likely to cry. I have a regard for your father, but there have been too many practical jokes in your family. It is your brother Harry over again, and I could not—could not continue to employ you if that kind of spirit is to be displayed.”

“There’s other occupations,” said Florrie. “I ain’t so fond of fancy work.”

“Oh, Florrie, don’t be such a silly girl,” said Miss Lee. “Ask mother’s pardon, and have done with it. Then maybe she’ll overlook it this time, as you’ve never done such a thing before.”

“I don’t know what I’ve done now,” said Florrie. “I only showed the articles to a customer.”

Mrs Lee looked at her. If she had appeared tearful or sulky she would have sent her away to think the matter over. But Florrie looked quite cool, and as if she rather enjoyed the situation.

“Well,” said Mrs Lee, “I must speak to your father.”

“I don’t care if you do,” said Florence.

“Then, Florence Whittaker, I shall,” said Mrs Lee with severe emphasis. “Go back now and attend to your business.”

Florence revenged herself by doing nothing but what she was told.

“Why didn’t you show the Berlin wools to that lady?”

“I didn’t know as I might, Miss Lee.”

Towards the end of the afternoon Mrs Lee went out, and her daughter was so quiet a person that Florrie had very little opportunity of being saucy to her.

She came up as the girl was putting on her hat to go home.

“Florence,” she said, in a rather hesitating voice, “tell mother you’re sorry. She’ll not be hard on you. Don’t be like your poor brother, and throw all your chances away. You are like him, but there’s no need to follow in his steps.”

“If Harry was like me he must have been a deal nicer than George,” said Florrie, who knew nothing about her eldest brother’s history.

“I don’t care,” she said to herself as she walked home. “I ain’t done nothing, and I won’t stay to be put upon. If she’ve gone to father!”

The guess was too true. When Florence opened the parlour door, there sat Mrs Lee, her father, and Martha, all looking disturbed and worried.

“Oh,” said Florence, “if you please, father, I was just coming home to tell you as how I’d rather leave Mrs Lee’s shop, as she ain’t satisfied with me, and I ain’t done nothing at all.”

“You’ve taken a great liberty, Florence, as I understand,” said her father, “and you will certainly not leave if Mrs Lee is good enough to give you another trial.”

“If Florence will express herself sorry,” said Mrs Lee.

“I ain’t sorry,” said Florence coolly.

“And I shall put a stop to your Bible class at once, and forbid you to go out without your sister if I hear of such behaviour as yours on Sunday afternoon.”

“Martha’d have a time of it,” said Florence. “Well, Mr Whittaker,” said Mrs Lee, rising, “I know what girls’ tempers are, and if Florence has come to a better mind by to-morrow, and will come down and tell me so, I will overlook it this once, but no more.”

“Bless me, Florrie,” said little Ethel, as her father took Mrs Lee out, “what a piece of work to make! It ain’t much to say you’re sorry and have done with it.”

“I ain’t sorry, and I mean to have done with it. I’m tired of the shop, and I’m tired of the Lees. Mrs Lee’s an old cat and Miss Lee’s a young one! She ain’t so very young neither.”

“Oh my, Florrie!” repeated Ethel. “What a deal you’ll have to say you’re sorry for before you’ve done! For you’ll have to say it first or last.”

“Why?” said Florence.

“Why, one always has to.”

“You’ll see.”

Florence remained stubborn. She did not look passionate or sulky, but say she was sorry she would not. She was tired of the business, and she didn’t care for losing her situation. She didn’t care at all.

“Don’t care came to a bad end,” said Matty angrily.

“Don’t care if he did,” said Florence.

George had come back from his walk by this time, and had added his voice to the family conclave. Now he gave an odd, half-startled look at his father, and to the supreme astonishment of the naughty girl her sally was received in silence. Nobody spoke.

Back on Martha’s mind came an evening long ago, and the sound of a sharp, aggravating, provoking whistle, a boy’s face, too like Florrie’s, peeping in first at the door and then at the window, and a voice repeating, “Don’t care—don’t care—don’t care!” in more and more saucy accents, as the speaker ran off across the forbidden turf of the cemetery, jumping over the graves as he came to them. That night had brought the explosion of mischief which had resulted in Harry’s departure from home and in his final banishment. Where was that saucy lad now? And had he learnt to care out in the wide world by himself? But Florence was a girl and if she said “Don’t care” once too often her father could not say to her, “Obey me, or you shall do for yourself in future.”

And she had no sense of responsibility sufficient to give her a good reason for conquering herself. She had a child’s confidence in the care she was childishly defying. People so proud and so respectable as the Whittakers could not even send their girl to a rough place where she would “learn the difference” between Mrs Lee’s “fancy shop” and general service. Poor Martha felt that to have Florence at home, doing nothing but give trouble, would be nearly intolerable; while what she would do if Mrs Stroud’s suggestion was adopted, and she was sent to stay with her, passed the wildest imagination to conceive.

“You’ll be very sorry, Florrie,” she said, “when it’s too late.”

“No, I shan’t,” said Florence; “I like a change. I’m tired of serving in the shop. Dear me! there’s a many situations in the world. I’ll get a new one some time.”

Florence got her way, and though she was supposed to be in disgrace, she declined to recognise the fact. She fell back into the position of an idle child at home, worried Matty, set her little sisters a very poor example, and enjoyed as much half-stolen, half-defiant freedom as she could. When she found that Carrie and Ada had been forbidden by their respective mothers to “go with her,” as they expressed it, she made it her delight to tease and trap them into enduring her company, and finally, after about a fortnight, walked coolly down to see Mrs Lee and ask how she got on with the new assistant!

Chapter Four.

Ashcroft.

Some twenty miles away from Rapley, in a less flat and dull and more richly wooded landscape, was the little village of Ashcroft, where Mr Whittaker’s cousin, Charles Warren, was head keeper to Mr Cunningham, of Ashcroft Hall.

The keeper’s lodge was a large, substantial cottage, with a thatched roof and whitewashed walls, standing all alone in a wide clearing in the midst of the woods that surrounded the Hall. It was nearly a mile from the great house, and had no other cottages very near it, being situated in what was sometimes grandly called “the Forest”—a piece of unenclosed woodland, where the great ash-trees that gave their name to the place grew up, tall and magnificent, with hardly any copse or brushwood at their feet—only ferns, brambles, and short green turf! Right out on this turf the keeper’s cottage lay, with never a bit of garden ground about it, the idea being that, as the rabbits and hares could not be kept out of the way of temptation, temptation had better be kept out of the way of the rabbits and hares.

There were no flowers, except in the sitting-room window, but there were tribes of young live things instead—broods of little pheasants, rare varieties of game and poultry, and puppies of different kinds under training. The barking, twittering, and active movements of all these little creatures made the place cheerful, and took off from the lonely solemnity of the great woodland glades, stretching out from the clearing as far as eye could reach.

It was a very beautiful place, but “it weren’t over populated,” as Mrs Stroud remarked one fine July evening, as she sat at the door looking out at the wood, having come to spend a couple of nights with her cousins.

“We don’t find it lonesome,” said Mrs Warren. “It’s not above half a mile down that path to the village, and there’s a good many of us scattered about in the lodges and gardens to make company for each other.”

Mrs Warren was a pleasant-looking woman, well spoken, with a refined accent and manner, being indeed the daughter of a former gardener at Ashcroft Hall.

“Well,” said Mrs Stroud, “there’s something about them glades as I should find depressing. With a street, if you don’t see the end of it, at least you know there’s fellow-creatures there, if you did see it; but there’s no saying what may be down among those green alleys. To say nothing that one does associate overhanging trees with damp.”

“Well, we have to keep good fires, but, you see, there’s plenty of fuel close by. And how did you leave your brother and his young family? I’ve often thought I’d like to renew the acquaintance.”

“Well, they have their health,” said Mrs Stroud. “But there, Charlotte, young people are always an anxiety, and them girls do want a mother’s eye.”

“No doubt they do, poor things. Why, the eldest must be quite a young woman.”

“I don’t know that there’s much to be said against Martha Jane,” said Mrs Stroud. “She’s a good girl enough in her way, though too much set on her book, and keeps herself to herself too much, to my thinking. If that girl ever settles in life, she’ll take the crooked stick at last, mark my word for it.”

“Has she any prospects?” asked Mrs Warren.

“She might,” said Mrs Stroud with emphasis. “Undertaking is an excellent trade, and she sees young Mr Clements frequent at funerals—or might if she looked his way, as I’m certain sure he looks hers.”

“Well, girls will have their feelings,” said Mrs Warren. “And isn’t the next one growing up too?”

“Ah,” said Mrs Stroud, with a profound sigh.

“There’s worse faults than being too backward after all, and that there Florence is indeed a trial. I tell my brother that good service is the only chance for her, and that I should consult you about it.”

“I thought she was in a shop.”

“She were. But she’ve thrown up an excellent chance.”

Here Mrs Stroud entered on a long account of Florence’s appearance, character, and recent history, ending with: “So, Charlotte, seeing that she’s that flouncy and that flighty that she’ll come to no good as she is, I thought if you could get her under the housekeeper here for a bit it would be a real kindness to my poor brother.”

“But Mrs Hay would never look at a girl that was flighty and flouncy. The servants are kept as strict and old-fashioned as possible—plain straw bonnets on Sunday, and as little liberty as can be. No doubt they learn their business well, but I do think if there was a lady at the head she might see her way to making things a bit pleasanter for young people. ’Tis a dull house, even for Miss Geraldine herself, and has been ever since the time you know of.”

“Ay,” said Mrs Stroud mysteriously, “and it’s that there unlucky Harry that Florence takes after—more’s the pity. Well, tell me about your young folk.”

“Well, Ned, you know, is under his father—his wife is a very nice steady girl—and Bessie’s got the Roseberry school; she got a first-class certificate, and is doing well. And Wyn—we’re rather unsettled in our minds about Wyn. He don’t seem quite the build, the father thinks, for a keeper, and he don’t do much but lead about poor Mr Edgar’s pony chaise and attend to his birds and beasts for him. Mr Edgar seems to fancy him, and we’re glad to do anything for the poor young gentleman. But Bessie, she says that it’s all very well for the present, but it leads to nothing. Wyn declares he’ll be Mr Edgar’s servant when he grows up. But there, poor young gentleman! there’s no counting on that—but of course Wyn might take to that line in the end, and be a gentleman’s valet.”

“And Mr Alwyn, that Wyn was named after, haven’t never come home?”

“Never—nor never will, to my thinking. The place is like to come to Miss Geraldine, unless Mr Cunningham leaves it to Mr James, his nephew.” Mrs Warren was only relating well-known facts, as she delivered herself of this piece of dignified gossip with some pride even in the misfortunes of the great family under whose shadow she lived, and Mrs Stroud sighed and looked impressed.

“Well,” she said, “small and great have their troubles, and Mr Alwyn were no better than Harry, and where one is the other’s likely to be.”

“I’ve always felt a regret,” said Mrs Warren, “that we couldn’t take better care of Harry when he was sent to us here. And I’ve been thinking, Elizabeth, that if John Whittaker would trust us with Florence I should be glad to have her here for a time, and see if I could make anything of her. It would be a change, and if she’s got with idle girls, it would separate her from them.”

“Well, there’d be no streets here for her to run in,” said Mrs Stroud. “You’re very kind, Charlotte, but I doubt you don’t know what a handful that there girl is!”

“I’ve seen a good many girls in my time,” said Mrs Warren, smiling, “though my Bessie is a quiet one; and if she finds herself a bit dull at first, it’s no more than she deserves, by your account of her, poor thing!”

“I believe my brother ’ll send her off straight,” said Mrs Stroud. “It’s downright friendly of you, Charlotte, and Florrie shall come, if I have to bring her myself.”

Mrs Warren was a kind and conscientious woman; but she would hardly have proposed to burden herself with such a maiden as Florence was described to be but for circumstances which had always dwelt on her mind with a sense of regret and responsibility. When Harry Whittaker had, as his aunt put it, made Rapley too hot to hold him, he had been sent to Ashcroft to try if his cousin could make him fit for an under-keeper’s place, alongside of his own son Ned. Harry’s spirit of adventure and active disposition were not unfitted for such work, and the plan looked hopeful.

At that time Ashcroft Hall had been a gayer place than it was now. Mr Cunningham was still a young man, taking his full share in society, and his two sons were active, high-spirited youths of sixteen and twenty, devoted to sport and to amusements of all kinds. Alwyn, the eldest, was at home at the time when Harry Whittaker was sent to Ashcroft. He had the sort of grace and good-nature which wins an easy pardon, at any rate among old friends and dependents, for a character for idleness and extravagance, and naturally he and his brother were intimate and companionable with the young keepers, side by side with whom they had grown up. It was quite new to Harry Whittaker to spend long days in a gentleman’s company, fishing and shooting, joining in conversation, and often sharing meals together; but he contrived, with tact, to adapt himself to the mixture of freedom and deference with which his cousin treated the young squires.

It was a happy relation, and one which is often productive of much good to both parties; but neither Alwyn Cunningham nor Harry Whittaker was good company for the other. Alwyn took a fancy to the saucy, sharp lad, and encouraged him in talcs of mischievous daring, and Harry was quick to perceive that, as he put it, “the young gentleman was not so mighty particular after all.”

A good deal went on that was not for the good of any of the lads, and at last came a great crash, the particulars of which no one except those actually involved ever knew.

There was an old house near Ashcroft Hall called Ravenshurst, which had the reputation of being haunted. It belonged to a Mr and Mrs Fletcher, who came there occasionally with their one daughter and entertained the neighbourhood. At last, on the occasion of a great ball, there was an alarm of the Ravenshurst ghost, a pursuit, and, it was said, a discovery that Alwyn Cunningham, assisted by Harry Whittaker, had played a trick. The affair was hushed up, and no one ever knew exactly what had happened; but a little girl had been frightened into serious illness, and at the same time some valuable jewels belonging to Mrs Fletcher had disappeared.

All that was known to the Ashcroft public was that Harry Whittaker was brought before Mr Cunningham and other magistrates the next morning on the charge of having stolen the jewels, but that the case was dismissed from absolute want of evidence, and also on Alwyn Cunningham declaring on oath that Harry Whittaker had never been near the place from which the jewels had disappeared. Ned Warren was out of the scrape, having been with his father all night. All that he could or would say of the matter was that he had told Harry that “it wasn’t their place to frighten the gentlefolk, whatever Mr Alwyn might say,” and had so kept out of the affair.

But the lost jewels were never found, and the exact mode of their disappearance was never clearly known outside the families of those concerned, and the magistrates who had refused to commit Harry Whittaker. But after that interview neither Alwyn Cunningham nor Harry Whittaker had ever been seen in Ashcroft again. It was known that the young gentleman and his father had had a desperate quarrel, and that Mr Cunningham never intended to forgive him.

In spite of Alwyn’s oath and the magistrates’ decision, the loss of the jewels hung over the memory of the two foolish youths with a cloud of suspicion. Most of the Ashcroft people thought that young Whittaker had stolen them, and had been screened by Alwyn Cunningham.

Mr Fletcher, the owner of the jewels, soon after died, and the family in the natural course of things left Ravenshurst at the end of their tenancy.

Whether Edgar Cunningham had had any share in the practical joke or knew anything of the fate of its authors no one could tell, for shortly after his health had failed from an unexplained accident in which his spine had been injured, and he had been an invalid ever since.

Since those events Ashcroft Hall had been a very dull and dreary place.

Mr Cunningham went very little into society, and only entertained a few old friends in the shooting season. Mr Edgar found what interests he could for himself, when his health allowed him to pursue any interests at all; and the girl, Geraldine, lived entirely apart from her father and brother, under charge of a governess who had been with her for many years.

Mr Cunningham was not popular or intimately known. The vicar of Ashcroft was a stranger, who had come to the place since the break-up at the Hall, and was only on terms of distant courtesy with its inhabitants, excepting with little Geraldine, who was brought up by her governess to the ordinary village interests of a squire’s daughter.

Chapter Five.

A New Experience.

Mrs Stroud and Mrs Warren before they parted arranged the details of Florence’s proposed visit. She was to come for three months, during which time her father was to pay a small sum for her board, and put her entirely in the hands of her cousin, Mrs Warren. If the latter thought fit, she would send her to learn “the dressmaking” in the village, and if she did not choose to trust her out of her sight, she could teach her dairy-work, and employ her as seemed best. At the end of three months, if Florence behaved herself, and appeared likely to be of any use, a situation in a superior line of service should be found for her, and if she proved incurably troublesome it was always possible to send her home.

“Well, Charlotte,” said Mrs Stroud, “’tis a work of charity, and I hope you won’t repent undertaking of it.”

“I’d be sorry to think that another of those young things was to be thrown away,” said Mrs Warren. “There was a deal to like in poor Harry. Maybe he’s doing well in foreign parts, and has pushed himself up again; but that’s what a girl never can do, once she lets herself go. I’ll try my best for Florence.”

If anything could have set Florence against any scheme, it would have been the fact that it was proposed for her benefit by her Aunt Stroud; but she dearly loved novelty, and, being of an active temper, was getting very tired of hanging about at home with nothing to do, and with a general sense of being in disgrace; so when Mrs Stroud arrived full of the idea, so far from opposing it, she rushed upstairs at once, and began to turn over her things to see if they were fit for her visit.

“I’m sure, Aunt Lizzie,” said Matty gratefully, “it’s a real kindness of anyone to take Florrie. I couldn’t say how tiresome she is, with nothing to do. I know she isn’t growing up the sort of girl she ought to be, and yet I don’t see how to help it.”

“Well, she’s got a chance now, Martha Jane. No one can say I don’t do my duty by my nieces. I always have, and I always shall, until I see you all comfortably settled in life, which it is every girl’s duty to look to.”

“I don’t think it’s a girl’s duty to think of anything of the sort,” said Martha colouring angrily.

“It ain’t her duty to be forward and peacocky, Martha Jane,” said Mrs Stroud impressively, “far from it; but when a good chance offers itself, and a respectable young man comes forward, she should turn him over in her mind.”

“He don’t want any turning,” said Matty, with a toss of the head. “What you’re alluding to, aunt, wouldn’t be to my taste at all.”

“Hoity-toity, your taste indeed! You’re nearly as perverse in your way as Florrie, Martha Jane. Young Mr Clements is a very steady young man, and a very good match for you, and looks at you constant whenever he has the chance. It’s your duty to let him say his say, and turn the thing over—”

“No, no! Aunt Lizzie,” said Martha, in tears. “I don’t want him to say anything—I don’t want him to say anything at all—it quite upsets me!”

“Upsets you, indeed! No, Martha Jane, there’s no one more against flirty ways than I am; but a young woman should be able to receive proper attentions without being shook to the foundations either! A good offer is to her credit, and she can say yes or no, civil and lady-like. But in my opinion, Martha Jane, this is a case for saying yes.” Matty offered no explanation, but if she had had Florence’s tongue at that minute she might have surprised Mrs Stroud. Perhaps if she had not had a sneaking kindness for the attentive Mr Clements, his striking dissimilarity to every hero who ever adorned the pages of fiction would not have struck her so forcibly, nor would his attentions have been so upsetting.

Love of novelty was a strong element in Florence’s adventurous nature, and she started off for Ashcroft in very good spirits, and enjoyed the short journey by rail from Rapley to Ashdown Junction exceedingly. She had never been away from home before. The mere sitting in the railway carnage and watching her fellow-travellers was a delight; her round, rosy face beamed with satisfaction, and she had nursed a crying baby, and put it to sleep, and screamed out of window to ask questions of the porter for a nervous old lady before she arrived at her destination, and jumped out on the platform at Ashdown, where she was to be met.

There was a little bustle of arrival. A gentleman got out, and the porters ran for his luggage, and presently one came up to Florence, saying:

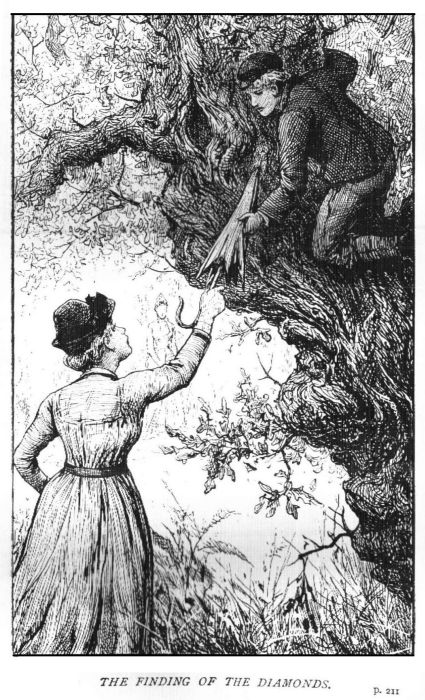

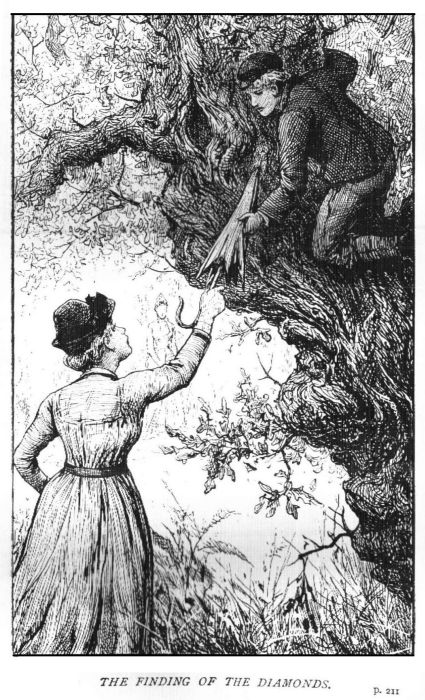

“Young woman for the keeper’s lodge at Ashcroft? You’re to go back in the trap that fetched Mr James’s luggage. He’s riding himself.”

“And who’s Mr James?” said Florence cheerfully, as her box was found and she was conducted out of the station.

“Mr James Cunningham for the Hall,” said the porter, evidently surprised at any explanation being needed.

The trap was driven by a stolid-looking lad, and spinning along behind the big horse was the newest sensation Florence had ever experienced. She was fairly silenced, and next door to frightened, as they passed along the narrow woodland roads, where the branches brushed her hat, and trees—trees—seemed to go on for ever.

She had had no sort of image in her mind of the place she was going to, or of the sort of people she was likely to see, and when they came out into the open clearing, and stopped in front of the roomy, low-lying cottage, she echoed unconsciously her Aunt Stroud’s sentiments, by saying to herself:

“Well! It’s a queer spot.”

“So here you are, my dear,” said a pleasant voice, as Mrs Warren came out of the house. “The master and Ned couldn’t come to meet you, so we were glad of the chance of the trap for the luggage.”

Florence jumped down and received Mrs Warren’s kiss, looking about her curiously. She was bigger and more grown-up looking than her cousin had expected; but her cheerful face with its look of pert good-nature was very familiar, and it was at least evident that she had arrived with the intention of being good-humoured.

“I hope you won’t find yourself dull, my dear,” said Mrs Warren, as she offered tea and a new-laid egg to her visitor. “It’s quiet here, no doubt, but we shall have Bessie home come harvest, and Gracie Elton, the gardener’s daughter, is a nice girl that you could go with now and then.”

“Oh, I ain’t the sort that gets dull,” said Florence; “leastways, not when things are new. Most things are dull you have to do every day constant.”

“I dare say,” said Mrs Warren, “that your own home may be a little gloomy sometimes for young folks.”

“Oh, it’s very cheerful in the cemetery,” said Florence, “and there’s a deal going on with funerals and folks coming to walk there on Sundays; but I was getting tired of staying at home. I think I’d have gone back to Mrs Lee if she’d have took me.”

She spoke in a voice of complete unconcern, and presently asked if she might go and look round outside.

Mrs Warren agreed, and Florence stepped out on to the short smooth turf and looked about her.

The sun was getting low, and threw long golden shafts of light under the trees across the grass; above the waving branches the sky was blue and still.

Florence was an observant girl, who walked the world with her eyes open, and she was aware that she had never seen anything so pretty as this before.

“’Tis like a picture,” she said to herself. Presently a pony chair came up one of the green alleys, drawn by a little grey pony and led by a pretty fair-haired boy, younger and smaller than herself. A young man was lying back in the chair, and Florence stood staring in much curiosity as the boy led the pony up to the cottage and Mrs Warren came out curtseying.

“Here’s Mr Edgar,” she whispered. “You were best to go in, Florence.”

Florence retreated a few steps under the shadow of the porch, but watched eagerly as the little boy said:

“Mother, I’m going to fetch the puppies for Mr Edgar to see.”

“Very well, Wyn; bring them round directly. Good evening, Mr Edgar. How are you, sir, to-night?”

“Oh, pretty well, Mrs Warren, thank you. Wyn’s had a long tramp with the pony, but he wants me to see how much the little dachshunds have grown. I want to give one to Miss Geraldine for herself.”

“They’re too wrigglesome for my taste, sir,” said Mrs Warren, smiling, “but Warren, he says they’re all the fashion.”

Mr Edgar laughed, and raised himself a little as Wyn Warren returned with a couple of struggling tan-coloured puppies in his arms.

“They’re nearly as slippery as ferrets, sir,” he said, “but they’re very handsome. They’ve no legs at all to speak of—and their paws are as crooked as can be.”

Mr Edgar turned over the puppies and discussed their merits with evident interest, finally fixing, as Wyn said, on the “wriggliest” to give his sister.

Florence had been far too curious to keep in the background, and had not the manners not to stare at the young gentleman’s helpless attitude and white delicate face. Wyn, being engaged with his master, had not thought it an occasion to notice anyone else; but Mr Edgar caught sight of her as he handed the puppies back, and gave a slight start as he looked. Mrs Warren coloured up and looked disturbed.

“My cousin, sir,” she said, “come to pay me a visit, and to learn the dairy-work.”

“Ah!” said Mr Edgar, with rather a marked intonation. “Good evening, Mrs Warren. Come along, Wyn—if you’ve got rid of the puppies.”

Mrs Warren looked after the pony chair as it passed out of sight.

“My master did say I was in too great a hurry—but there, they’ll never see anything of her. But she do take after poor Harry!”

“You should have made the gentleman a curtsey, Florence, when he saw you, and I had to name you,” she said repressively, for she was annoyed at Florence’s bad manners in coming out and staring.

“Law!” said Florence good-humouredly, but quite coolly, “should I? I never seen it done.”

Chapter Six.

Mr Edgar.

On the morning after Florence’s arrival at Ashcroft little Wyn Warren stood on the terrace of a pretty piece of walled garden on the south side of the great house, with the wrigglesome puppy in his arms, waiting for his master to come out and give him his orders for the day. Wyn was devoted to Mr Edgar, and to all the birds and beasts and flowers, which were the chief diversion of a very dull life. Edgar Cunningham was not naturally given to intellectual pursuits. He had been fond of sport and athletic exercises of all kinds, and there was a good deal of unconscious courage in the way in which he amused himself as much as possible, especially as there was no one but Wyn to care much about his various hobbies. Winter was a bad time for the poor young fellow, but in the summer, he was often well enough to get about in his pony chair, and visit the water-fowl or the farm, or hunt about in the woods for lichens, ferns, and mosses; sometimes, if he was able to sit up against his cushions, stopping to sketch a little, not very successfully in any eyes but Wyn’s perhaps, but greatly to his own pleasure. Wyn managed to lead that pony into very wonderful places, and he and his master liked best to take these expeditions by themselves; for when the grave and careful Mr Robertson, who waited on Mr Edgar, went with them, they were obliged to keep to smooth ground, as he did not approve of Mr Edgar being tired and shaken, and when they had once got stuck in a bog it was difficult to say whether master or boy felt the most in disgrace for such imprudence. But Wyn secretly thought that an occasional jolt—and really he was so careful that it very seldom happened—was not half so bad for Mr Edgar as lying all alone on his sofa, with no one to speak to but the grave father, who always looked at him as if his helpless state was such a dreadful disappointment and trouble that he could not bear to see more of him than could be helped. Mr Edgar’s tastes opened a good deal of desultory information to Wyn, and though the young gentleman was not of the sort to think much about teaching and educating the boy, the study of botany and natural history seemed to come naturally, books of travels interested them both, and Wyn got more knowledge than he was aware of. Edgar was scrupulously careful not to interfere with the boy’s church-going and Sunday school, so that he did well enough, and had a very happy life into the bargain. The garden in which he stood was arranged according to Mr Edgar’s special fancies, and contained many more or less successful attempts to domesticate wild flowers, and Wyn was noticing the not very flourishing condition of a purple vetch when Mr Edgar came out from the open window of his sitting-room, and, leaning on his servant’s arm, walked slowly to a long folding-chair at the end of the terrace, on which he lay down, then, spying Wyn, called him up at once.

“Ha, Wyn, so you’ve got the puppy? Miss Geraldine will be out directly. What a jolly little chap he is! Put him down on my knee. No—no, sir, you don’t eat the newspaper! Anything else new, Wyn?”

“Yes, sir, the wild duck’s eggs are hatched, and there are seven of them on the lower pond. Should you like to go and see them, sir?”

“Yes, I should. Get the pony round in half an hour. It’s a lovely day.”

As he spoke a tall girl of about fourteen, in a blue linen frock made sailor fashion and a sailor hat stuck on the back of her long dark hair, came running up the broad walk in the middle of the garden, sprang up the shallow steps that led to the terrace with one bound, and pounced on the puppy.

“Oh! what a little darling! What a perfect pet! Oh, how jolly of you to get him for me, Edgar! I’ll teach him to walk on his hind legs and to die—and to bark when I ask him if he loves me—”

“Have you got Miss Hardman’s leave to keep him?” said her brother.

“No, not yet. I thought I’d put him in the cupboard in my room, and introduce him gradually.”

“He’ll howl continually, Miss Geraldine, if you shut him up,” said Wyn.

“Nonsense,” said Edgar; “go and ask her if you may have him as a present from me.”

“Oh, must I? It would be such fun to have him in a secret chamber, and visit him at night and save the schoolroom tea for him as if he was a Jacobite,” said Geraldine.

“More fun for you than for the puppy, I should say,” said Edgar.

“Well, I think a secret prisoner would be delightful—like the ‘Pigeon Pie.’ Edgar, didn’t you ever read the ‘Pigeon Pie’?”

“No,” said Edgar, “I haven’t had that pleasure.”

“Please, ma’am,” said Wyn with a smile, “I have. My sister Bessie brought it me out of her school library.”

“I’m sure,” said Geraldine, “it’s a very nice book for you to read, Wyn. But what shall I call the puppy?”

“Please, ma’am, we calls them Wriggle and Wruggle.”

“Rigoletto?” suggested Edgar.

“No,” said Geraldine, “it ought to be Star or Sunshine, or something like that, for I’m sure he’ll be a light in a dark place. I know—Apollo. I shall call him Apollo. Well, I’ll take him and fall on my knees to Miss Hardman, and beg her and pray her. And oh, Edgar! it’s holidays—mayn’t I come back and go with you to see the creatures?”

Edgar nodded, and Geraldine flew off, but was stopped in her career by her cousin James, who came out of the house as she passed, and detained her to shake hands and look at the puppy. He came up to Edgar’s chair as Wyn went off to fetch the pony.

“Good morning, Edgar,” he said; “pretty well to-day? I see you are teaching Geraldine to be as fond of pets as you are yourself.”

“Poor little girl! she has a dull life,” said Edgar. “I wish she had more companions.”

“She is beginning to grow up.”

“She is. She ought soon to be brought more forward, I suppose. But we never see anyone, or do anything. I don’t see much of Geraldine—often—and she is kept very tight at her lessons.”

“It’s dull for you, too,” said his cousin compassionately.

“Oh, I don’t care when I get out and about a bit.”

“My uncle doesn’t look well, I think?”

“Doesn’t he?” said Edgar quickly. “Ah, I haven’t much opportunity of judging.”

There was a touch of bitterness in his voice, and a look that was not quite pleasant in the bright hazel eyes, that were usually wonderfully cheery, considering how much their owner had to suffer, and keen as a hawk’s into the bargain.

“I say, Edgar,” said James Cunningham, sitting down on the wall near him, and speaking low, “people do get into the way of going on and taking things for granted. It’s a long time since the subject was mentioned, but do you really think my uncle doesn’t know where poor Alwyn is?”

“I don’t know,” said Edgar, flushing. “I’ve no reason to think he does.”

“It has always seemed to me,” said James, with some hesitation, “that if not, some one ought to find out.”

“Do you think I should rest without knowing if I could help it?” said Edgar, starting up so suddenly, that the pain of the movement forced him to drop back again on his cushions and go on speaking with difficulty. “I did ask my father once, and he forbade me to mention him again. Don’t talk of him.”

James Cunningham was silenced. The situation was an awkward one. The estate had always gone in the male line, and he would have liked to know what had become of the next heir, after whom only a life as fragile as Edgar’s stood between himself and the great estates of Ashcroft. He did not even know how deep in the eyes of father and brother was the disgrace that rested on the exile. But Edgar did not look approachable, and any attempt at further conversation was checked by the appearance of Mr Cunningham himself, a tall, pale, grey-haired gentleman, with dark eyes and long features, like his son and daughter.

He spoke to Edgar, rather distantly, but with a careful inquiry after his health, and Edgar answered shortly, and with a manner that was remarkably repellent of any sympathy his father might be inclined to offer. Geraldine came rushing back with Apollo clasped tenderly in her arms, but she stopped and walked demurely down the terrace at sight of her father.

“Miss Hardman says I may have him, Edgar,” she said, “if I don’t let him distract my attention at lesson-time.”

“That’s all right then,” said Edgar, “and here is Wyn with the pony, so we had better come and see the wild duck.”

The servant came out, Edgar was helped into the pony chair, on which rather pitiful process Mr Cunningham turned his back and walked away, discussing the morning news with his nephew; and presently they started off, Wyn leading the pony along the broad walk with Geraldine and Apollo frisking beside it. They turned down a shrubbery, stopping at intervals to admire the gold and silver pheasants, the doves and pigeons, and rare varieties of foreign poultry, which all had their separate establishments in what Geraldine called the Zoological Gardens. Wyn hunted them into sight, fed them, and discussed their growth, plumage, and general well-being; while Geraldine smothered the puppy in the carriage rug to keep him from frightening them with his barking and yapping.

Then they came out into an open space, where the pea-hens had their nursery—several of the ordinary coloured sort, and one rarer white one, whose two little white chicks were watched with much anxiety; while, to Geraldine’s delight, the great white peacock himself appeared with his wide tail, with its faintly marked eyes like shadows in the whiteness, spread in the sun.

Then round towards the back of the farm-buildings, where, in a little square court, lived a yellow French fox, tied up with a long chain—a savage and unhappy little beast, which “might as well have been back in France for all the pleasure he gave himself or anyone else,” as Geraldine said.

“Who’s to take him?” said Edgar. “He was funny when he was a little cub. Being tied up isn’t soothing to the temper.”

A family of hedgehogs, fenced round into their own little domain, amused Geraldine mightily, as she watched the smallest curl himself up into a ball at the approach of Apollo, who thought him a delightful plaything till the prickles touched his tender tan nose, and he fled howling.

There was no time to-day to visit all the varieties of poultry, and the horses were in another direction, and formed another object for Edgar’s drives; for though he could never mount one of them, the love of horseflesh was in his nature, and he liked to have them led out for his inspection, and had always plenty to say about their condition and management. To-day the little party crossed over the open turf of the park to a large pond, where Edgar cultivated varieties of aquatic birds. He was very proud of the black swans and the beautiful Muscovy ducks, the teal and the widgeon, which he had induced to breed among the reeds, rushes, and tangled grass that clothed its banks. Geraldine stood at the pony’s head, while Wyn plunged into the rushes, waded and scrambled till he had driven the little flock of tiny dark ducklings into his master’s range of vision.

Edgar was pleased; but his attention was less free than usual, and presently he said abruptly to Wyn:

“So you’ve got a cousin come to stay with you?”

“Yes, sir. Mother’s got her to see what she’s made of, and get her suited with a place.”

“What’s her name? Where does she come from?”

“Florence Whittaker—leastways, she says it’s Maud Florence Nellie, which is a many names, sir, for one girl, don’t you think?”

“Will she come to the Sunday school?” asked Geraldine.

“I don’t know, ma’am. Shall I say as you desire her to come, Miss Geraldine?”

“Yes, do. There are never any new girls in Ashcroft. She isn’t too old, is she?”

“She’s only going in her fifteen, ma’am, but she’s very big.”

“Oh, well, Bessie Lee and Grace Elton are sixteen, quite. Yes, tell her to come.”

“Thank you, ma’am, I will,” said Wyn. “Do you want to go home, sir?”

“Yes, I’m tired this morning. Go straight back. I don’t want to go round the wood.”

He fell into silence. Geraldine played with her puppy, and Wyn trudged cheerily at the pony’s head, thinking of an expedition he wanted to propose some day when Mr Edgar was very well and fresh, and there was no one to interfere with them. Mr Edgar had been so weak all the spring, and had had so many headaches and fits of palpitation—once he had even fainted after an attempt to walk a few steps farther than usual—so that he and Wyn had not been trusted to make long excursions alone together.

But now that he was better again, and the weather was so fine, Wyn longed to take Dobbles to a certain spot recently laid open to his approach. He had been thoroughly imbued with his young master’s tastes, knew the haunts of every bird and beast in the wood, every hollow in the old ash-trees where owls or squirrels could nest and haunt. He watched the growth of all the wild flowers, and at the autumn cottage show intended to win the first prize for a collection of them—a new idea in Ashcroft which had been recently suggested by a lady whose husband, Sir Philip Carleton, had just taken Ravenshurst for the shooting.

Chapter Seven.

Sunday School.

Entirely unfamiliar surroundings will exercise a subduing effect on the most daring nature; and Florence Whittaker for the first few days of her stay at Ashcroft felt quite meek and bewildered. She really had nothing to say. She was quite unused to so small and quiet a family. The eldest son, Ned Warren, had recently married, and did not live at home, Bessie was away at her school until the harvest holidays, and Wyn was busy all day and had lessons to do in the evening. She had never seen so civil and well-mannered a little boy; while Mr Warren was a great big man over six feet high, with an immense red beard, very silent and grave, and good manners gained from the gentlemen with whom he associated. Her Aunt Charlotte, as she was directed to call Mrs Warren, was very kind to her, and never aggravated her, a fact which upset Florence’s previous ideas of aunts. There really was no opportunity of distinguishing herself by “answering back,” for Mrs Warren never said anything that gave her a chance. As she was neither idle nor unhandy, she acquitted herself well in all the little tasks her aunt set her; but she was dull enough to look favourably on the idea of the Sunday school.

“Miss Geraldine’s been inquiring about you, Florence,” said Wyn when he came in to dinner.

“She says she wishes you to come down to Sunday school with Gracie Elton.”

“I don’t mind if I do,” said Florence, “but I attend a Bible class at home.”

“The girls in the first class here are quite as old as you,” said Mrs Warren, “but I dare say you are accustomed to a much larger number.”

“Oh, I don’t mind,” said Florence, with cheerful condescension. “Our teacher says we ought not to be stuck up, so, though we’re nearly all business young ladies, we ain’t exclusive. There’s two generals attend the class, and I think it’s a shame to make them sit by themselves, don’t you?”

“I think it would be very ill-mannered,” said Mrs Warren quietly, “if you did. I dare say you are very fond of the lady who teaches you?”

“Oh, she’s as good as another—better than some. She knows us, you see, and don’t expect too much of us. But there, last spring, when she went away and Miss Bates took us, we weren’t going to go to her. Why, she gave us bad marks for talking, when she’d only just come. She hadn’t any call to find fault with us; she were just there to keep us together till teacher came back.”

“Well, I suppose, as she was kind enough to teach you, you were careful not to give any trouble to a stranger,” said Mrs Warren, “because that would have been rude.”

“We ain’t so rude as the Saint Jude’s girls,” said Florence virtuously. “They locked the door and kept their teacher waiting, and pretended they’d lost the key. That’s going too far, I say. If ever I’m a teacher I’ll not put up with such as that.”

“Could you be a teacher?” said Wyn, who had listened open-mouthed.

“Well,” said Florence, “they’ll always give little ones to the Bible class if we apply, and I’d keep ’em strict if I had ’em. But I don’t think as I’m religious enough.”

“Yes,” said Mrs Warren, “my Bessie says that we never feel our own defects so much as when we come to think of teaching others.”

“I ain’t confirmed yet,” said Florence, “but I mean to go up next spring. I say our church is good enough for anyone but George; he don’t think nothing of us. His place is a deal higher; he says we’re as old-fashioned as old-fashioned can be.”

Here Florence entered on a lively description of the ritual practised at the different churches of Rapley, showing considerable acquaintance with their external distinctions, while Wyn, who had never thought the Church services concerned him in any way except to behave properly at them, stared in amazement. Neither he nor his young master knew much about Church matters outside of Ashcroft.

Mrs Warren listened and pondered, and for the time being said nothing. Silence was a weapon with which Florrie’s chatter had never yet been encountered.