Title: The Diary of a Hunter from the Punjab to the Karakorum Mountains

Author: Augustus Henry Irby

Release date: May 9, 2013 [eBook #42674]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Paul Clark and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including some inconsistencies of hyphenation. Some changes have been made. They are listed at the end of the text.

THE

DIARY OF A HUNTER

FROM

THE PUNJAB

TO THE

KARAKORUM MOUNTAINS.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, GREEN, LONGMAN, AND ROBERTS;

NORWICH:

HENRY W. STACY, HAYMARKET.

M.DCCC.LXIII.

NORWICH:

PRINTED BY HENRY W. STACY,

HAYMARKET.

It is hoped that the circumstances under which this volume appears may be considered such as to excuse its imperfections. It is—with some omissions and completions of sentences but with hardly a verbal alteration—the copy of a journal, not written with a view to publication but simply as a private record, kept up from time to time as opportunity offered in the midst of the scenes which it describes. The hand that wrote it is now in the grave. And it is solely in compliance with the wishes of many relatives and friends who were anxious to obtain such a memorial of one whom they loved, that it is now committed to the press by a brother.

| PAGE. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | Preparations and Equipments | 1 |

| II. | To Sirinuggur | 7 |

| III. | Sirinuggur—to the Wurdwan | 28 |

| IV. | Shikar in the Wurdwan | 48 |

| V. | Ditto | 67 |

| VI. | Ditto | 89 |

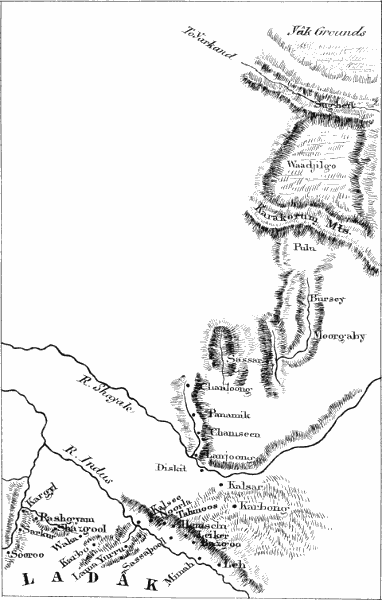

| VII. | Sooroo Pass to Ladâk | 109 |

| VIII. | Ladâk | 135 |

| IX. | Leh | 157 |

| X. | To the Shayak | 176 |

| XI. | To the Karakorum | 196 |

| XII. | Sugheit | 225 |

| XIII. | The Yâk | 249 |

| XIV. | The Return | 264 |

| XV. | Leh and Ladâk | 285 |

| XVI. | The Bara Sing | 302 |

| XVII. | Cashmere | 324 |

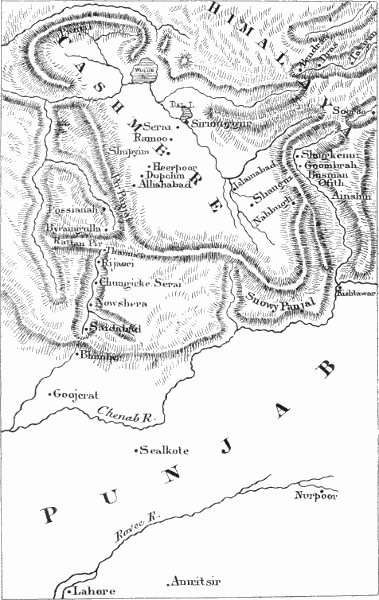

Browne. Lith. Norwich.

Possianah, Pir Panjal,

29th April, 1860.

An attempt at a Diary, with the intention of recording my adventures and experiences in an excursion contemplated in Cashmere and adjacent countries—that of Ladâk being a principal object—during six months' leave from my duties at Amritsir.

Several times in former days have I resolved to keep a journal, or jot down briefly the incidents and experiences of each passing day. But as often, after the lapse of a few days, have I failed to persist in the undertaking: whether from infirmity of purpose, or idleness, or from an utter contempt of the 'small beer' I had to chronicle, I do not myself know; and whether I shall be more successful in this present effort remains to be seen. Primary indications are not promising, as I have now been 'en route' from Amritsir, from the 16th to the 29th, thirteen days, and have excused myself, on one ground or other, from making a commencement until now.

To be in order, I must note my preparatory arrangements, detail my supplies—their quality and quantity—[Pg 2]the number and office of my attendants—the extent of my stud, and the amount and nature of my sporting equipments; especially this latter, as the chase, or, as it is called in India, 'shikar,' is with me a sort of mania, and all that appertains thereto is to me of very great importance. Therefore, as a guide for myself, or to advise others on some subsequent and similar occasion, I must minutely specify my shooting apparatus and fishing appointments, and, in the course of my diary, especially take note of efficiences and deficiences in this respect, as occasion may demand.

To commence with the most important part of my travelling establishment,—the servants,—there was, First in consideration, the khansamah, who unites the duties of caterer, cook, and director general of the ways and means. Secondly, the sirdar or bearer,—the individual who, in this land of the minutest division of labour, looks after the clothes, bedding, &c., and assists in dressing and washing. He was a new hand, hired for the occasion, as my regular sirdar had to remain behind in charge of my property. Thirdly, the bheestie, who, in addition to his ordinary duties of fetching water, undertook to assist in cooking, washing up dishes, &c., for the consideration of three rupees additional wages, which I thought preferable to hiring a mussulchee, as the fewer attendants one has on the road to Ladâk the better, considering that for some marches all provisions and food have to be carried for the whole party. Fourthly, the classee, in whose charge were the tents and their belongings, &c.—his duty to accompany and pitch them. Fifthly and sixthly, two syces, grooms, in whose charge were my two ponies: one of which was a stout animal from Yarkand, a famous animal for mountain travelling: the other a good-looking, good sort of pony from Cabul, which I bought at hazard,[Pg 3] taking him according to description in an advertisement, and he seems likely to justify fully the account given of him.

In addition to these attendants, I agreed, after consultation with my excellent friends, the missionaries of Amritsir, to attach to my party a native Catechist, who by birth claims to be a Cashmiri. He has been, however, brought up and educated in the Punjab; where, when serving as a khitmudgur or sirdar, he became a convert to Christianity, and has for some years been in the employment of the Amritsir Mission. He has been in Cashmere and Ladâk, and understands the language of the former country. The object of his accompanying me is to circulate the Gospel in Bibles, Testaments, and tracts, which I received for that purpose from the missionaries, having myself first suggested the possibility of my being able to promote the spread and knowledge of the Christian Faith and Hope, by means of these books, in the heathen lands to which I was going,—intending to distribute them personally should opportunities offer. But the co-operation of the Catechist was a sudden after-thought of one of my good friends, the missionaries; which, as it only had birth two days before I started, was rather embarrassing to mature and act upon. But after the project had almost lapsed, owing to some misunderstanding resulting from the excited and unsettled state of mind of Suleiman, the Catechist, consequent on so sudden a summons to start, with little or no preparation, on such an arduous journey, leaving, too, a wife and family—she in a delicate state—it was finally arranged that Suleiman should accompany me at my charges.

My retinue was again unexpectedly increased by engaging a Cashmiri who presented himself to me as I was returning home from breakfast at mess. He shewed me[Pg 4] a certificate of character, stating him to be an useful servant, capable of any personal attendance required by a traveller and hunter. He had the strong recommendation, too, of an intimate acquaintance with the country of Ladâk, and the routes north and east of Cashmere, together with the sporting localities, the haunts of the yâk (wild cattle), and the kyang (wild horse); so thinking him an acquisition I closed with him at twelve rupees per month, and directed him to proceed to the rendezvous at Bhimber.

Having thus enumerated my personal attendants, I must now mention my coolies, Cashmiries, twenty of whom I engaged at five rupees a month to convey my baggage to Sirinuggur, the capital of Cashmere.

My stores, and all articles that could be so disposed, were packed in long baskets, called kheltas, which the Cashmiries hoist on their backs, strapping them to their shoulders: and with them they carry a stout crutch about two feet high, on the cross-piece of which they rest their load when pausing on the road, and taking breath in ascending mountains—an excellent mode of relief as it does not cause them to shift or put down their load. They only straighten their backs, so that the khelta rests on the crutch; and when refreshed again bend to their burden and trudge on, often—too often for the early arrival of one's baggage—repeating this process.

This mode of hiring coolies answers admirably. They are returning to their homes in Cashmere from Amritsir, to which grand emporium for Cashmere goods they had brought loads of merchandise in the commencement of the cold season, and it is to them, of course, a piece of good luck getting return loads. They all appeared strong, sturdy, well-limbed men, and got away with my traps, my servants and horses in company, the whole under[Pg 5] charge of my khansamah, Abdoolah, on the evening of the 8th April.

I must not forget, in my catalogue of live stock, two little dogs, of no particular merit, but dear to me as affectionate companions after their kind.

I had made ample provision for my creature comforts, having been told by an experienced traveller, and having gleaned from books of travel, that the Ladâk country is sterile in the extreme, and consequently possesses little of what constitutes by habit the necessaries of an European.

I took 4 tins of bacon, 1 case of maccaroni, 1 ditto vermicelli, 2 ditto biscuits, 1 tin of cheese, 3 pots of jam, 7 bottles of pickles, 24 lbs. of tea in 3 tins, and 3 lbs. for immediate use, two 8-lb. boxes of China sugar, and some 5 or 6 lbs. I had by me, 3 bottles essence of coffee, 7 lbs. raw ditto, 2 bottles fish sauce, 4 various ditto, 3 bottles lime juice, 2 vinegar, 2 oil, 6 lbs. candles, besides which Clarke's patent lamp, and lots of candles, 6 bottles brandy, 12 sherry, 12 beer, to which I added, carrying with me, 6 bottles of hock and 6 claret—some of a batch arriving the day I left, which, having ordered expressly for the mess myself, I was anxious to taste. I took, by way of medicines, 12 drams of quinine, a box of Peake's pills, one phial chloridyne, some Holloway's ointment and sticking-plaister, with some odds and ends I do not remember. This was my stock.

Of fire arms, I took a double rifle by Blissett, 10 bore—one heavy double Enfield, ditto—one rifle, military pattern, by Whitworth—one double-barrelled Westley Richards for shot; 8 lbs. powder, good supply of bullets, shot No 3 and 6, caps, wads, &c.

These guns were taken from their cases and placed in a woollen case, then in a leathern case respectively, this being, I think, the most convenient way of carrying them,[Pg 6] four of my servants having charge, each of one. Two Colt's revolvers and ammunition, shikar knife and belts, knives for skinning, four boxes arsenical paste, from Peake and Allen, cleaning rods, bullet moulds, and all the paraphernalia of a sportsman.

Of fishing-tackle, a large salmon-rod, a common trout-rod, a gaff, two large winches, one small; stout plaited silk line, and hair for the small rod, a variety of flies, and a good supply of spinning tackle and hooks, on which, from past success, I principally depended. Being without good spinning gear, I had some hooks, or rather the spinning contrivance to which they were fitted, made by a 'maistry' in Amritsir, after a model I had given him; and very well he succeeded. The system of hooks was devised and fitted by a young brother officer, an ardent devotee of the gentle craft, and clever at all kinds of fishing gear.

Having the year previous killed some good fish in a fine stream 'en route' to Cashmere, I anticipated some sport this time.

My tents were, the one a small two-poled shikar tent made very light, about 12 ft. long by 7, which for the present trip I had covered so as to resemble, in some degree, what is called a Swiss cottage tent; the other was a small thing, just big enough to put a bed in, and carried altogether by one coolie: the bigger one takes four. I had also a folding wooden bed, and lots of bed clothes, &c.

I have now enumerated all I recollect of my equipment, a good stock of suitable clothes being understood.

I had hoped to have received intelligence of the Commander-in-Chief's sanction of my application for leave ere the 15th. I only heard from the Assistant Adjutant General at Lahore that it had been forwarded: so, being in command at Amritsir, I gave myself leave in anticipation, and, having some days previously arranged my 'palki dâk,' I entered it about 4.30 P.M. on Monday the 16th, and making up my mind for a grilling, it being extremely hot, off I started amid the farewell salaams of my deserted retainers. The heat was very great, but the prospect before me of, ere many days, plunging into the eternal snows rendered endurance easy.

I reached the Sealkote bungalow about twelve next day: bathed, breakfasted, made another meal at 4 P.M., after which I again jogged on along the dusty road, keeping down my disgust and refreshing my weary spirits, by conjuring up visions of snowy regions, and glorious sport as before. And thus I arrived at Goojerat, after crossing the Chenab at 5 A.M. on the morning of the 18th.

Here I halted, breakfasted, and dined. Pursuing my hot and dusty route at 4.30 P.M., I arrived at Bhimber about twelve midnight, received good accounts of my belongings from Abdoolah, was almost devoured by my two little pets, found Suleiman had arrived, but no tidings of the Cashmiri, Jamhal Khan. I turned into bed in my tent, feeling a delightful sensation at being really out of the scorching plains of the Punjab; though I could hardly be said to be so, for the following day,—

Thursday, 19th April, the heat was excessive, thermometer in the day 96°, and at 9 P.M. in my tent, 90°. This day was employed in arranging loads, and selecting such articles as I needed on the road. Jamhal Khan joined, and made salaam. Suleiman went into Bhimber, a large straggling town, and endeavoured to create a desire for the knowledge of the Gospel. He encountered opposition, and found none willing to receive books.

20th April. I made a good start before day had well dawned. It was a miserable day's march, having a river to be crossed about ten times, the bed of which, and indeed the road itself, is composed of boulders and stones innumerable. There is also a steep ascent to climb, which is no easy job, the path up it being merely indented in the naked rock by continual footsteps. I may as well remark here, that this road is the whole way abominable, nothing being ever done to improve it, although there is a large amount of traffic along it with the Punjab; and the Maharajah, with his usual avarice, takes good care to have heavy dues levied on all imports and exports—bad luck to him, for a horrid screw! The track is nothing more than a watercourse, and up and down the steep hills is really dangerous.

The path this day leads over the said hill, on which is a station of the rajah's in a narrow pass, where are[Pg 9] officials to examine passengers and take toll. The path thence descends roughly and irregularly to a small valley, in which is the halting place, the 'baraduri' being a repaired portion of one of the old 'serais,' built, I believe, by the Emperor Akbar. Many of them still exist, as also remnants of bridges, also the work of that mighty potentate.

This place is called Saidabad, and though, perhaps, as hot as the Punjab, being very confined, the pines and firs, the variety of foliage, green crops, and verdant grassy slopes, with hills around you, and mountains in the distance, tend much to lessen the sense of heat. There are officials and sepoys here, and supplies in moderation—tattoos, perhaps, coolies, fowls, &c. to be had.

21st April. I made a good start for Nowshera, sending on a coolie with a basket containing breakfast.

The first part of the road is rough and difficult, lying by the stream, interrupted by rocks; but it now opens into a pretty narrow valley, from which you ascend a stiff steep hill of rock, but well wooded, and, at this season, clothed with varieties of flowering shrubs and plants, dog-roses abounding, by which the air was pleasantly perfumed. On the summit of the hill is an old piece of solid masonry, now inhabited by an old couple who supply excellent milk and eggs to wayfarers.

There is a beautiful and very extensive view from this eminence of a fertile valley in which, on a small hill, is situate Nowshera, its white buildings conspicuous. But the object of interest is the snowy ridge of the Panjal range, and interposing itself midway, so as to exclude from sight all but the upper ridges of the Pir Panjal, lies the Rattan Panjal, its upper crests partially and thinly covered with snow. The whole scene is charming as viewed at early morning, ere the dews, ascending in misty[Pg 10] vapours—in themselves beautifying the landscape by their varied and many-tinted effects—are dissipated by the sun.

At the foot of the hill the path proceeds through ups and downs of a more or less stony character, until you descend into the valley of the Tooey, a fine rapid brawling stream, in some places one hundred yards wide, but averaging perhaps fifty: possessing some deep still pools, at the turbulent entrances to which an angler would wager good fish would be found, were there any in these waters. Nor would he be far wrong. There are fish, and huge ones, too, in those promising pools. Nor are they quite insensible to the wiles of the crafty angler, who may with moderate skill enjoy good sport along this river. But here, as elsewhere, fish have their moods and whims, their times and seasons, so that some practice and observation are requisite.

You cross this river, and some two hundred yards on the 'baraduri' is situated in the middle of a densely-planted garden. Not liking its appearance—thinking it would, at least, be prolific of insects and of fever—I went on through the town of Nowshera, and, descending again to the river, encamped under a 'tope' of mulberry trees, in a long grassy plain, lying between a range of hills of moderate height and the river. There is little to notice in Nowshera, a long street with the ordinary bazaar shops, and, on the right-hand, a castellated gateway, leading into an old serai, one of the series of Akbar, I suppose.

I tried fishing in the evening at a splendid looking pool, very deep, in which the rushing waters bury themselves, as it were, for a time, pausing ere they again pursue their onward troubled course. This pool lies under a precipitous cliff, just beneath the town; it is of considerable extent, and of unknown depth, and in its dark recesses[Pg 11] lurk mahseer of monstrous bulk, I am told. My fortunes were at their worst this evening, as far as catching a dish of fish went. I tried spinning, having been provided with most tempting minnow-like bait by some small boys, eager for 'backsheesh': and I tried 'atta' in a sticky lump on a large-sized salmon-hook—a bait of reputed irresistibility—but without effect. Numbers of fish, small and some evidently of goodly size, to set one longing, rose and actually floundered on the surface; but not a run could I get. A heavy thunderstorm, bursting in the distance, was rapidly approaching, which was, perhaps, the unlucky evil influence: so, tired of trying to get anything out of the water, I took a header in, and enjoyed a most refreshing and cooling swim.

22nd April. Sunday. Halted and passed the Sabbath in repose.

23rd April. To Chungir-ke-Serai—a long and tedious march, the path leading over rocks which hedge in the river, on turning an angle of which I overtook Abdoolah, who had preceded me with the breakfast things, standing gazing back in my direction. I told him it was not yet time for breakfast, supposing that to be his meaning, when he pointed upwards, and, suspended from the projecting limb of a tree, some little way up the hill shutting in the river, hung the still-mouldering body of a man, his lower limbs still in his clothes, the ghastly face denuded of flesh, yet with a matted felt of hair straggling here and there over the glistening bones, grinning horribly down upon us.

This wretch, it appeared, had in the most treacherous, barbarous, and cowardly manner murdered an old man and child, close to the spot where he expiated his crime. Being a sort of rural policeman in the employ of the Maharajah, he was armed with a sword, which, of course,[Pg 12] excited no suspicion in his victims, whom he joined on the road as they journeyed from Nowshera, and ascertaining that they possessed a few rupees' worth of property, the miserable caitiff, yielding to the suggestions of the Tempter, cut them down, and threw their bodies into the river. Suspicions followed their disappearance: other circumstances pointed to this man, who was arrested, and confessing his guilt was executed where the bloody deed was committed.

I left this gloomy spot full of reflections of the most depressing nature: but with that rapidly revolving mental process, which so soon exchanges our train of thought, I was soon almost as though the repulsive object had not been met with.

I soon afterwards arrived at a pool, where I proposed stopping to breakfast, and also to fish, having in this pool, when passing last year, whilst occupying a seat on a rock overhanging it, observed some monstrous great fish basking; for it was a scorching hot day, and the sun at high meridian at the time.

I tried the 'atta' bait—merely paste made very adhesive—but without more than one or two nibbles which came to nothing: so knocked off and comforted the inner man. While so employed, came by a 'gent' riding, whom I saluted. I knew him to be in my rear, proceeding to join the Trig. survey party which was before me some days: asked him to dinner, and he accepted.

Arrived at Chungir-ke-Serai, an old Akbar serai, on the top of a hill overhanging the river—a fine view of the snowy range—the features of the country rough, but picturesque. I tried fishing again without success: enjoyed a cool swim: returned and had to wait about three-quarters of an hour for my guest, although he was close at hand, and I sent to him two or three times. But, lo![Pg 13] he at length appeared, got up rather considerably, quite abashing me, who was sitting in a flannel shirt and corresponding nethers. We had a pleasant chat together. He informed me that he had never been out of India, was born in the country, and educated at Landour, whence he was appointed direct to the Survey department. I do not know his name.

24th April. Rijaori. I made an early start as usual, and had a rough scrambling march of it. The road following the trend of the river, here and there crosses steep stony hills, where the track is only a watercourse. We crossed the river just below Rijaori. This passage is at times very difficult and dangerous, and never very pleasant, as there is a great body of water, and strong current at all times, but after the rains a roaring flood.

The camp-ground of Rijaori is very pretty, in a garden, one of much note, there being remains of aqueducts and fountains, a summer-house on an eminence overlooking the river, and the town on the other side. In the garden are some magnificent plane trees, called 'chunar' in Cashmere, affording good and pleasant protection from the sun.

I found a young officer of the 24th encamped here, and asked him and my former guest to dinner.

I prepared my tackle, and was provided with small fish by youngsters who remembered me the year before, and started to fish, full of expectation, at 4.30 P.M.—the sun broiling. I tried the nearest pool under the temple, where last year a mighty fish had got off, breaking my line and robbing me of my best spinning tackle—no run, nothing stirring. I went down to another fine pool, where two streams blend their waters, situated under a lofty hill, steep and well-wooded down to the precipitous rocky bank of the river—a lovely piece of water; had an offer or[Pg 14] two, and hooked and landed an impudent little brat of 2-lb. weight; then had some little sport with a nice little chap of 5-lb. or so, when, having disturbed the pool, I went lower and fished two or three likely spots, without moving anything.

So I struggled back over the bothering boulders to my pet pool, where I strove long and ineffectually, and was actually on the point of leaving off, when—Whirr, whirr, whirr, whirr went the reel, the rod bent double, the line smoked again, and the still waters of the pool rose in swells, as the sogdollager I had hold of darted violently down the stream. Fifty yards were out in no time, when I butted him strongly, and turned him, only then getting an idea of his weight, and joyfully exclaimed he was a twenty-pounder. The young officer of the 24th was with me; he and the native attendants were greatly excited.

I was conscious of having work cut out for me, and intensely eager to secure the prize I knew to be at stake. The struggle was long and stout. At one time the fish turning up stream, made direct for the bank where 24th stood, about forty yards from me. A brawling cascade separated us, and I was over knees in water in another noisy rapid, so did not hear his remarks, but noticed his gesticulations, and judged from them, he was astonished at the monster I had hold of.

Well, after a rare game of pully-hauly, my scaly enemy took the bottom, and I could not move him. 'Oh! what a weight he must be,' thought I; 'hold on good tackle!' I shook the bait, so as to make his jaws rattle and his teeth ache, when at last he moved with a vengeance, making a violent effort, up and down and all sides, to break away. Then he shewed his massive golden side—glorious sight! I hauled him towards a round hand-net a handy lad held ready in the water—no gaff with me—[Pg 15]but too soon yet. Away he sped, bending the rod alarmingly, and making the winch talk loudly. I turned him again, and repeated the attempt to net him—away he rushed again. I then humoured him, and tired him with the rod and short line, until he was bagged, the lad going up to his middle, and when in the net he could not lift him out himself.

He was a regular monster in size, but beautiful to behold—a truly handsome fish, of lustrous golden hues. He was carried off in triumph, suspended from my mountain staff across the shoulders of two well-sized youths, who could but just keep his tail off the ground.

Great was the admiration in camp, and many and various the guesses at his weight. 24th and I each had a 24-lb. weighing hook: putting both together, a weight of 48 lb. was required to bring both indicators flush, which my captive did; so we rated him as a fifty-pounder.

I must not dismiss this sporting incident without recording the excellent qualities of this fish when brought to table. He had hung all night, disembowelled: in the morning was not scaled, but skinned, and being cut in lateral scallops was simply fried, and without any exaggeration was delicious, only inferior to a good salmon. It was firm and rich, of a brown colour, flaked with curd, and though I was prepared with anchovy sauce, that was scouted. I never myself eat any mahseer, or other Indian river fish, anything like it.

My two guests chatted away at dinner, a glass or two of ale being highly appropriate on the occasion of this huge success. We parted at nine, early hours being essential, they intending to proceed onwards at dawn, I to stop and try my luck again.

25th April. Rijaori. I tried the upper pool above the town, a beautiful and most promising-looking pool: but,[Pg 16] after trying every persuasive and seducing attitude, failed to move an admirer, and being chilled returned to camp and breakfast, when I regaled upon the morsel I have above described.

I passed the day reading, and anxious for the shades of evening to permit my further attempts on the fishes, but to cut short this evening's proceeding need only say that I fastened to another leviathan in the same pool, after many indecisive offers had been made; but, woe is me! he at once, after feeling himself fast and trying rod and line, bored straight down, and cutting my bottom-line over a stone got clear off with my set of spinning tackle. Let me draw a veil over my misery, nor again awake memory to the bitterness of my disappointment.

26th April. To Thanna. The road still running in company with the river, the courses only being reversed. This day's march was much pleasanter than any previous one, there being but little up and down comparatively, and the pathway in many places lying under shady wooded slopes, its sides fringed with numbers of sweet-smelling shrubs.

The approach to Thanna presents a lovely view of the Rattan Panjal range in front; and on the left-hand is a well-wooded range of hills, beneath which are undulating slopes, whereon is a good deal of cultivation which is in some parts carried in terraces to the tops of the hills. There is an old fort-like building, formerly the habitation of some ruffian of a rajah, I presume. The camp was pitched close to a small village on the road to the Rattan Pir. At this place Suleiman had an attentive audience of some ten or twelve respectable natives, who listened to his account of our religion with pleasure, and were glad to accept some Gospels and tracts, never having, they said, obtained any accurate idea before of what the Christian Faith consisted.

I have omitted to note the effect produced by Suleiman at the different stations, so will retrace my steps for that purpose.

At Rijaori, the first day, he was not only repulsed, but threatened. On the second day, however, he had listeners, and distributed some books.

At Nowshera, favourable results—being listened to calmly and attentively, some enquiries and discussions entered into, and some Gospels and tracts received. There was here a teacher in a school, who had been educated in the mission school of Lahore, and he it was whose influence operated favourably. He took some books for his school.

I forgot to mention an occurrence at Bhimber. I had noticed in the day a man lying near the 'baraduri,' who was apparently suffering, and continually uttered cries and moans from the same spot. I called Suleiman, and with a light proceeded to make enquiries; when it appeared that this unfortunate man had fallen from a mulberry tree close by, and had disabled himself so much that he could not proceed on his way home to Cashmere. So there he was left to shift for himself, dependent on the charity of passers by, wholly unable to raise himself from the ground. I sent for the havildar of the guard, and giving the disabled man five rupees, which I understood to be ample for the purpose, ordered him to be removed to a house, to be cared for, and sent to his home when recovered.

Thinking this a good opportunity, I called the attention of some thirty people, who were looking on, to the fact that the Christian religion thus enjoined its professors to obey their Lord's commands, and that the religion of Jesus Christ was love. Not being sufficiently fluent myself, I requested Suleiman to use this living text, and he ad[Pg 18]dressed the assemblage, who seemed much impressed, and expressed their entire concurrence in the sentiments and principles uttered. But this is often the case without any further consequences.

27th April. From Thanna across the Rattin Pir pass to Byramgullah.

This is a stiff pull, but not precipitous. The path winds about, taking advantage of the slopes of the mountain to gain the summit gradually. There is a faquir's establishment on the top, and the view on either side is very fine. That looking down over the plain past Rijaori and Nowshera—over the several wave-like lines of inferior hills into the plains of the Punjab of limitless extent, lost only in vapour and distance—is grand from its great extent, and beautiful in its varied features as in its colouring.

The other side presents the masses of the Pir Panjal, covered with snow. This range is of bold massive proportions, and affords the traveller a truly sublime picture of mountain scenery.

The descent to Byramgullah is steep and rugged, and altogether wearisome. But, when accomplished, one is amply compensated for one's toils. The road from the foot of the mountain crosses a bridge over a picturesque torrent, clear and rapid, rushing in roaring cascades below. There is here every component part of a beautiful landscape, but space. The valley is confined, there being but just room for the river and a small bit of level on an elevated bank. This is shut in by lofty hills, some entirely clothed with a rich mantle of foliage, others having intervals of grassy slopes. But the whole is singularly beautiful.

There is a fort on an isolated hill, of curious structure, only capable of defence against bows and arrows, I should[Pg 19] think; but it is a picturesque object, of a Swiss character as to architectural appearance.

28th April. Along the bed of the torrent to Possianah, crossing some thirty-five bridges (so called), very awkward for riding, but, on the whole, an easy march, the scenery of a romantic character.

Possianah is a singularly built village, on the precipitous side of a mountain which is the vis-a-vis of the redoubtable Pir Panjal; which here, lifting his snowy summit to the clouds, frowns down upon you in all his majesty and grandeur, looking by no means affable to approach, and promising an arduous struggle to get the better of.

The village is at this time more miserable than ever, its ordinary inhabitants having deserted it to escape the rigours of the winter; there remained or had returned only two or three. Many houses, being most inappropriately built with flat roofs, had fallen in, and altogether the place had anything but a cheerful aspect.

Here, however, I must pass two days, the 29th being Sunday. So I had the hovel, used as a baraduri, cleaned out, and there ensconced myself and traps, and had nothing whatever to complain of,—the most magnificent scenery around me, a delightful climate (the wind, perhaps, a little too chill here), and no scarcity of creature comforts.

29th April. Sunday. I halted at Possianah. When at Byramgullah, I heard the Pir was not passable for tattoos, so left mine there to await orders, intending to leave them to come on in a few days, when the road would probably be open. But from a near reconnoitre of the mountain as to snow, and from information acquired, I determined to run the risk, and sent for my ponies.

As I was at breakfast a saheb was announced, and a stout party made his appearance, a M. Olive, a French[Pg 20] merchant in the shawl trade, who passes the winter season at Amritsir, returning to Cashmere, when the passes open, for business.

The Maharajah does not permit Europeans to reside in the valley during the winter; perhaps, from jealousy of their becoming permanent residents, and finally annexing the country; perhaps, because the winter is the time for collecting his revenue, when, it is said, the most infamous oppression is practised, and complaints are rife and loud.

I had seen the new comer, but was not acquainted with him, and could do no less than invite him to share my homely fare, and after some polite demur he fell to. He spoke no English, and my French had been lying 'perdue' a couple of years or so; but I assayed to converse, and eking out my French with Hindostani managed to keep up the conversation without difficulty. The stout gent had been carried all the way from Amritsir in a jan-pan—a sort of covered chair on poles—which four or six men at a time carry on their shoulders. How he could ever get up the Pir Panjal, I could not imagine.

Another traveller had also arrived—one, by the bye, I should have previously noted as having arrived at Rijaori the day I halted there—an artillery Vet, who had been suffering from some affection of the head, and irritability of nerves. He dined with me at Rijaori, and highly approved the mahseer, which he pronounced equal to salmon, but far inferior in my opinion.

In the course of the day I found the unfortunate Vet had sent his pony round by the Poonah pass from Baramoolah, and he lamented having done so, groaning over the prospect of the morrow's arduous exertions. I, therefore, placed mine at his disposal, as I prefer footing it, especially when the path is difficult.

30th April. From Possianah to Dupchin. The road from Possianah descends to the torrent roaring at a considerable depth below, from which the ascent recommences, so that you have to descend from a considerable elevation, perhaps a quarter of the height of the Pir, and then again ascend on the other side; which loss of way is provoking. From Possianah to the foot of the Pir is, I imagine, two miles, the latter part of the road very rough and stony.

I started on this occasion without any refreshment, such as tea, thinking I should better husband my breath, and work my lungs more easily: and I think the idea a success, as I ascended with much more ease and comfort than on the former occasion, when I primed myself with tea, hard eggs, &c. It is, undoubtedly, a tremendous pull; and one meets with a provoking deception as to distance. For when about a quarter of the height has been ascended, the first flight, as it were, up to the snow drift, the traveller looking above him, puffing and panting with his violent efforts, sees above him what appears to be the summit close at hand, which is but the top of the lower ridge, from which runs a somewhat level path on the slope to the snow drift—an enormous mass of snow, some half-mile long, and, I suppose, from one to two hundred yards broad, and, I fancy, from fifty to a hundred feet deep, filling a gorge of the mountain which commences quite at the summit. Over this mass we struggled, a violent icy blast in our faces, to a point where the path turns off to the left, and climbs upwards by zigzags to the more gradual slope under the summit. Here I overtook a woman carrying a boy of, perhaps, five years old, who, poor little creature, was crying bitterly from cold, his teeth chattering, and presenting a forlorn appearance. The woman was sitting down disconsolate, unable to proceed. I tried to persuade her to put the lad down, and[Pg 22] lead him, to restore circulation, but she did not adopt my suggestion; so, leaving a man to help them on, I continued my ascent, and finally reached the top.

The height is, I believe, some 10,000 feet above the sea. The view, looking back, is magnificent—an endless succession of wave-like lines of hills terminating, as they gradually recede, in the hot vapours of the Punjab.

It was pleasant to look down the steep and rugged path we had won our way up, there beholding others still toiling and struggling upwards, the coolies with their loads in a long-drawn straggling line, here coming into view, and quickly disappearing behind some projection or in some bend of the road, but constantly to be seen resting on their crutches. I watched my ponies with some anxiety. They had been stripped in order to give them every freedom of limb, and several coolies had been told off to assist them. They were more than half-way up when I saw them: it was just at a difficult point, where the snow was deep and soft, and the path hung on the side of the mountain. The old Yarkandi broke through the snow, and was plunging and struggling violently, but after three or four desperate efforts got out of trouble. The other avoided this place. I find the former from his very caution apt to go off the good path, and get himself into difficulties. When the snow gives, he goes down on his knees and so hobbles on.

I did not wait longer, but strode away over the snowy plains, which descend in a very gentle incline to the Alliahabad Serai. The sensation was delightful after the troublesome ascent, and I enjoyed the change of play of muscles amazingly, as did my two little dogs to whom the snow was a novelty. They kept frisking and bounding about, rushing off to a distance, then occasionally taking a roll.

The landscape, as a winter scene, was perfect,—one glittering field of snow, lofty hills on either side also covered with snow, the sun shining cheerily, and the difficult entrance to the valley achieved. But after a time my eyes ached from the glare, and I was glad when a mile or two of descent brought us to patches of brown hillside. There were two very awkward watercourses to cross, the banks high, precipitous, and covered with snow, giving every chance of a tumble.

I got well over, and found the serai, where I had intended to halt, in such a state from snow, melted and unmelted, and the only place for camping in a similar condition that, shrinking from its chill uninviting aspect, I determined to push on; so after my usual breakfast of cold tea and hard eggs I again sped on my way—and a toilsome way it was. The sun was now very hot, and the path running over ridges and down gorges of rock on the slopes of the mountain, and encumbered with snow, in enormous drifts in some of the ravines, made this additional eight miles (I think it was) a formidable addition to the ascent of the Panjal.

I forgot to mention that on the top of the Pir is a faquir's hut, where last year we were supplied with the most delicious draught of milk we had ever tasted. But the faquir had not yet ventured to face the inclement climate, so no milk this time.

There is also a small watch tower of an octagonal form, of which there are several to be seen, here and there, along the route. This forms a very conspicuous object, being so distinctly seen at Possianah as to deceive one as to the distance; and I fancy that an European accustomed to the denser atmosphere of the mountain regions in that quarter of the globe would be astonished at the atmospheric effects here. Rarely, except in case of a thunder[Pg 24]storm, and in the rainy season which lasts about two months, is there any vapour to impede the vision, which roams over snowy peaks of various chains of mountains far on the other side of Cashmere.

The beauties of this scenery, in its magnificence and colossal proportions, its illimitable extent and brilliancy of colouring, is far beyond any description. All around you nature exhibits herself in her most attractive forms, presenting almost every variety of shape and colour, mountain and valley, rock and dell, forests of noble pines and individual giants waving their monstrous arms overhead as you pursue your path, with foaming torrents dashing at the bottom of the precipices below you, gushing rills of purest water trickling from the hills on whose slopes you move, and from the path to the torrent below you stretch undulating grassy slopes, here steep, there gently inclining, occasionally intercepted by a rough ravine through which tumbles a torrent, and the whole surface gay with many flowers which the while perfume the air—the 'tout ensemble' is such as to send the observant traveller, however much his limbs may be taxed, exhilarated and rejoicing on his way. It is a new existence to any one coming from the depressing monotony of the interminable plains of the Punjab.

I had a long time to wait at Dupchin before any of my followers arrived; so I took a snooze under a pine tree adjoining a fine stream, at which I had slaked my thirst. The whole of my effects did not arrive until about five o'clock. There was no village, no house here, it being simply used as a camp ground, for which it offered some facilities—a level surface, wood and water in abundance—food we had brought with us.

The night was bitterly cold, but my servants managed tolerably, four or five sleeping in my smaller tent, as many[Pg 25] as it would hold. Others and the coolies coiling themselves up in their warm blankets under a pine-clad bank, screening them from the wind, by the help of rousing fires of dry pine wood kept up through the night, if not perfectly comfortable, did not suffer: for they did not grumble—a good sign.

1st May. To Shupyim. The first part of the road is rough and difficult, through a pine forest. You then cross the river by a bridge, the scenery charming; emerge from the forest, and enter upon level grass lands. We halted at Heerpoor for breakfast, a small village where supplies are to be got: there is an old serai, one small room only habitable, but good ground for camping.

The road from Heerpoor to Shupyim is good, over level grassy elevated land, park-like scenery on either hand, the valley of Cashmere widening before you, and a glorious display of mountains beyond it.

One may consider oneself fairly in the valley here, having left the mountains behind; there remain only slight elevations between Shupyim and Sirinuggur.

2nd May. I followed the path to Sirinuggur which, although one of the principal roads to the capital, was but a bridle path, in some places difficult to find, and leading over rivers and streams, some of which, being without bridges, are awkward to cross.

We halted at a village called Serai, from there being the remains of one there. Ramoo is the usual station, but it does not divide the distance so equally, being too near Shupyim.

We had some difficulty in obtaining supplies, Jamhal Khan being compelled to resort to harsh measures, such as kicking and so forth, to bring the village official to a sense of his duties, and the importance of a 'burra saheb.' This discipline was that best adapted to his rude percep[Pg 26]tions: and after some vociferations, and making as though he would apply to me, who cruelly stopped the address with threats of further coercive measures, he roused himself, and set to work with activity to get what was required.

M. Olive came up: he had intended going right on to Sirinuggur, expecting horses out to meet him, with his city man of business. The latter did appear, and informed him that the ponies were sent the other road, it being understood he would enter the valley of Baramoolah. M. O. decided to remain, and readily accepted my invitation 'a gouter:' when with some biscuits and potted bloaters, washed down by a bottle of excellent hock, we contrived to open the sources of our eloquence, and sat out regardless of the sun which, though the air was pleasant and fresh, had a powerful tanning effect, as my face indicated on retiring to my tent. Previous to thus taking 'tiffin,' I proposed to M. Olive that we should unite our provisions and dine together, as I had some claret on which I wished to have his judgment pronounced. He readily assented, remarking that his khansamah should have orders to combine culinary operations with mine.

I strolled out, and went in the direction of Sirinuggur, looking to obtain a view of that city, but could only discern its site, indicated by the fort of Hari-Parbut, conspicuous on a solitary hill, and by the poplar trees, forming avenues round the city.

I returned and sat down to dinner with M. Olive, who, by the bye, added nothing to the repast, apologising as he had intended dining at Sirinuggur. However, I had abundance, and the claret was greatly admired, and fully appreciated, M. Olive declaring it to be 'une veritable acquisition': it had, however, considerable body, so we did not drink more than half the bottle—sufficient again to engage us in uninterrupted conversation.

M. Olive became quite eloquent, and getting on some pet topics connected with France and her glories, Louis Nap. and his genius and policy, he launched out and discussed these matters with great intelligence. He is a very agreeable companion, having all the politeness of manner of the well-educated Frenchman, and being a man of sense and observation I found all he enlarged upon, and his views and opinions, interesting and instructive.

3rd May. To the city of Sirinuggur—the immediate object and termination of the first part of my journey. The road was indifferent and uninteresting, running through a low level country with undulations, more or less elevated, and watercourses.

We passed some splendid chunar trees, and occasional stretches of verdant turf; and on either side, adjoining the road, were growing large patches of lilies, blue and white, scenting the air with the most delicate perfume. About a mile from the city one enters an avenue of poplars, leading on to a bridge crossing the river Jhelum which flows through the midst of the city; and from this bridge one obtains a general idea of the city itself. The impression is far from favourable, the houses appearing mean and in a state of ruin and neglect, the population squalid and dirty. Nor does a more intimate acquaintance remove this impression. The site of the city is beautiful, the surrounding scenery all that could be wished, but man, in himself and his works, has disfigured and defiled[Pg 29] as lovely a spot as could be anywhere selected in the universe.

I was conducted to a small house on the Jhelum, called Colonel Browne's house, from his frequently residing there. It is kept for the senior officer arriving, and I happen at this time to be that important individual. There was no noticeable difference between this and the eight or nine small residences on either side. They are paltry buildings, only calculated for roughing it 'en garçon.' They are, however, pleasantly situated on the right bank of the Jhelum, at considerable intervals, shady groves in rear, and well removed from the smells and sounds of the city and its multitude.

I was waited upon by the Maharajah's Vakeel, the Baboo, Mohur Chunder, a most intelligent, active, and obliging official, affording every information and every assistance possible in one's affairs. He is the 'factotum' as regards Europeans, being, I believe, retained on account of his tact in giving them satisfaction, and keeping things 'serene' between them and the residents. He provided me with a boat, partly thatched, and six men, to pull about and do the lions, the river being the highway.

I had written to the Baboo to engage two shikarries whom I named, and he had despatched a 'purwanah' for their attendance, but had not yet heard of them. This I did not regret, as I wished to look about me a bit before starting upon any fresh excursion.

In the afternoon I took boat, and descended the river, passing amid the city under some half-dozen bridges of, I think, four arches each, if arches they may be called, for the tops are flat. The piers are constructed of large rough timbers in the log, placed in layers transversely, and the roadway is formed of longitudinal and transverse[Pg 30] timbers its whole length. The 'tetes-de-pont' are nearly all of wood, with a rough stone pediment.

The Jhelum is very deep, and the stream strong, the water not clear. The city is, undoubtedly, interesting as viewed in this manner, and the buildings decidedly picturesque from the very irregularity of their dilapidations. They are built principally of timber, roofs slightly aslant covered with earth, on which is generally grass or other vegetation. Some buildings are of brick and wood; a few of stone, brick, and wood, the stone forming the foundation, and many of them bearing distinct signs of having been portions of other buildings of a by-gone age.

The banks of the river are high and steep, built up in some places by stone facings. Houses with balconies projecting are supported by wooden props sloping to the wall, and there resting in what appears a very precarious manner—just stayed on an irregular ledge of the stone facing at hazard, and any interstice to make up the measurement filled in with chips. There are a few houses of more pretension and better finish, exhibiting more taste and elegance in their decoration in carved wood. These belong to wealthy merchants, and they have some nondescript sort of glazed windows; but the houses generally have only lattices.

There are no buildings especially to notice, except the Rajah's residence, or fort, as they call it, a long, rambling string of buildings on the left bank, connected with which is the most conspicuous object in the city, a new Hindoo temple, with a gilt pyramido-conical cupola. This is new and glaring, and, therefore, quite out of harmony with the mass of buildings around it. There are also two or three old wooden 'musjeds,' constructed when the professors of Islam were in the ascendant, now in a state of rapid decay, as appears to be the race and religion they represent.

We pulled down beyond the city to the new houses building by the Maharajah for Europeans, an out of the way place, though affording a fine view of the fort of Hari-Parbut and the mountain ranges looking N.E., but too remote from the bazaar to suit most visitors.

I returned up the river, and enjoyed the trip much. The banks of the river and the houses overhanging are prettily diversified by trees, here and there. One sees some odd wooden buildings floating and attached to the shore, used for purposes of cleanliness, washing, &c.; yet is the city abominably dirty, beyond anything I ever saw.

4th May. I took my boat, and, on the representation of Jamhal Khan, gun and shot for wild fowl, and was pulled rapidly down stream. We turned up a canal, and passing under some beautiful trees, the air fresh and pure, lending a charm to everything, we entered a sort of sluice gate by which the waters of the Dal have exit, passing through this channel to the Jhelum.

In this Dal are the far-famed floating gardens, in which vegetables are cultivated. There are also beautiful isles forming groves and gardens, which in the palmy days of the Mahomedan conquerors were places of constant resort for the indulgence of luxury and pleasure, and still attract numerous parties of pleasure, European, of course, and native, the latter adopting quite the pic-nic style. The floating gardens are formed of the weeds dragged up from the bottom, with which the lake is covered, with the exception of large open spaces under the mountains to whose sides sloping downwards it carries its waters. This lake is partly artificial, as it is pent in by embankments with sluice gates, the system of which, however, I am unacquainted with. This piece of water is of great extent, and is one of the most important features of the neighbouring scenery.

I returned to the same outlet by a circuitous route among the weed islands and gardens: and when seated at breakfast in my upper-storied room, from which a beautifully diversified prospect was visible, I quite revelled in the delightful sensations of the delicious climate and surrounding loveliness of scenery.

I called upon the Government Agent, a resident—an anomalous appointment. The individual holding it is a civilian, and his duties are to maintain amiable relations between English visitors and the inhabitants, adjust any disputes, and check irregularities; a duty—from the peculiar position which gives no direct authority over officers—calling for much tact and judgment. Had a long conversation with the present incumbent, Mr. Forde.

I cruised down the river in the evening, and saw some decidedly pretty faces among the young girls washing or drawing water at the river side: but none appear to exhibit themselves but those of mature years and the very young. Probably the Hindoos adopt the custom of the Mahomedans in this respect. It is a mixed population, and it is reasonable to imagine such a fashion to prevail. I was disposed to reject the generally pronounced opinion that there is much female beauty among the Cashmiries, but I now consider it extremely probable there is. The features are of quite a distinct type from the Hindoos of the plains, as is the complexion which is a clear rich olive-brown—eyes dark and fine—mouths rather large, but teeth even and white. The hair, also, appears to be finer in fibre than that of the people of Hindostan. It is generally worn as far as I could see, in a number of small plaits, divided from the centre of the forehead, and falling regularly all round the head, their extremities being lengthened by some artificial hair or wool, which continues the plait. The centre plaits resting on the[Pg 33] middle of the back are longest, and extend to the swell: all the points are worked into a sort of finishing plait, from the centre of which depends a large tassel. The effect, were the hair but clean, would, I think, be charming. Of the figures I can say nothing, as they are enveloped in a hideous, shapeless, woollen smock, of no pretension to form or fashion. This appears to be the only article of dress the lower classes wear, and I have seen no other. I have been much struck with the decidedly Jewish caste of countenance repeatedly exhibited. Some faces, I have noticed, would be positively affirmed to belong to that remarkable race, if in Europe.

Another observation I made was, that the expression was quite different from other Asiatic races I am acquainted with, there being an open, frank, and agreeable intelligent look about the Cashmiries quite European, and such as you would expect to meet with only in a highly-civilized people. I should like to unravel the mystery of their origin, but that is lost in the mists of early traditions, not to be relied on: and their country has undergone so many changes of rulers, that the original race, though perhaps still retaining much of its own characteristics, has imbibed those of the races commingling with them.

5th May. I walked through the city to the Jumma Musjed, the principal place of Mahomedan worship, now much dilapidated and rapidly yielding to the desolating inroads of time, without any attempt, apparently, to check or repair its ravages. A complete panorama of the city is presented to the visitor from the top of the 'musjed.' The city, unworthy of the name, is only an irregular collection of wooden hovels, extending over some two hundred acres, its form undefined. The surrounding country is picturesque, presenting a pleasing variety of mountain and water, but deficient in timber. The beauty[Pg 34] of the valley consists in what is really out of the valley, in the glorious range of mountains forming it, with their never-ending variety of form and colour. The valley is a dead flat, with uplands also level which, in their remarkable resemblance to shores, with other corresponding features, have given rise to the theory entertained by scientific men, that the valley was once a lake. And there is a tradition generally prevalent and confidently believed by the Cashmiries, that their valley was a lake, and they have legends as numerous as the Irish about it: and connected with every fountain and spring, and almost every remarkable natural feature in the country, is some wondrous fable of goblin, sprite, or fairy.

The fort of Hari-Parbut overlooking the city is a fine object, and should form a part of every sketch of Sirinuggur and its environs. The famous Takt-i-Suleiman also claims especial notice. This is a very ancient Hindoo temple, crowning a hill of considerable height which bounds the eastern side of the Dal lake. I ascended to the Takt this afternoon, and enjoyed a beautiful and extensive panoramic view around, too lovely and varied for description. The ascent was steep, and the sun warm, but the air when on the summit, fresh and pure, soon refreshed me. I descended on the Jhelum side of the hill, and made for the boat which was to meet me, and so returned.

6th May. Sunday. I took a walk round the Jhelum side of the Takt-i-Suleiman to the Dal lake; and then made my way back by its shore.

It appears to me advisable that both a chaplain and a surgeon should be provided by Government during the leave season in Sirinuggur, as so large a number of officers resort there.

Suleiman has not succeeded in hiring a place in the city, as I had directed him; but has been stirring him[Pg 35]self, and was waited upon here by some Affghans, who wished to possess the Scriptures, of which they had heard.

7th May. I took boat, and went down the river, and selected a place to sketch—the sun very hot, and the boat constantly in motion. One of the boatmen caught a fish; it was handsome in form and colour, bearing a resemblance to a trout, but without spots. I had him for breakfast—very bony, and not particularly good in flavour.

I determined to make a start somewhere; heard nothing of my shikarries expected, so directed another to attend. I went down river, and got out to visit a shoemaker's shop, who was making some leather socks for me to wear with grass sandals, the best things for climbing slippery hills. They require socks to be divided to admit the great toe separately, as the bands of the sandal pass between that toe and the others; and as the grass thong is apt to chafe one unaccustomed to it, the protection of a leather over a thick worsted sock is desirable.

8th May. I employed the day in dividing my stock of stores, preparing clothes, &c.: had an interview with a shikarry, Subhan, who shewed good certificates from officers who had employed him. He recommended me to go to the Wurdwan, and I decided to do so.

Phuttoo, and another shikarry who was with me last year, arrived; so all goes well. I agreed with Jamhal Khan, who is unfit for mountain work from asthma, to give him his discharge. I take with me Abdoolah, Ali Bucks, the 'bheestie,' and assistant scullion, and Buddoo, 'classee,' who is likewise personal attendant. The bearer and Suleiman remain behind with my effects, as do my ponies and 'syces'; also little Fan, who is about to increase the canine race, and needs quiet and nursing.

I have engaged two large boats, which convey me and my staff and baggage as far as Islamabad, which will[Pg 36] take two days to reach by their mode of progression—one man tracking, hauling the boat with a tow-rope, another steering with a paddle. But I am told they keep it up day and night.

I made all arrangements with the invaluable Baboo, with reference to my servants and effects. I propose remaining in the Wurdwan valley above a month, and having my things sent on to meet me on the Ladâk road, to which I propose making my way by an outlet from the Wurdwan. The Wurdwan is reputed to be the best locality for shikar in Cashmere. Ibex are plentiful, bears also, and in the autumn, 'bara sing.'

I went down river, and sent to the shoemaker, who was reported to have gone up to my place: had a pleasant row, and took a farewell view of the beauties of the landscape: had everything packed and ready for an early start in the morning.

9th May. Embarked myself and belongings—servants, shikarries, and baggage in separate boat. My folding bed had just room for it under the thatch. The boats are long, narrow for their length, and flat-bottomed; they are floored, and, barring the necessity of constantly stooping, not incommodious.

We got off at last, after the usual delays, and made slowly up the stream, propelled by one-man power, a heavy prospect: but everything charming around, so I went in for pictorial enjoyment. After half an hour of this tedious confinement, I jumped ashore, and took my way by the river side, making short cuts at some of the bends and turns which are numerous; for, after toiling around them some six hours, we were within a quarter of a mile of the Takt-i-Suleiman, as the crow flies, though no doubt we had navigated twelve or fourteen miles. This did not look encouraging.

Having made good headway, I sat under a noble 'chunar' tree, awaiting the arrival of the boats, when I breakfasted, and embarked, and we pursued our watery way. Again I went ashore, and walked through the country until stopped by a creek, and, the sun being very hot, then took shelter under my thatch, and so on until dusk, when I halted or anchored for dinner, turned in about nine, and roused at daybreak,—

10th May. I went ashore, and walked from half-past five to half-past seven, and having cut off some tremendous 'detours,' as I thought, I sat down to await the boats. Nine o'clock, and no boats—saw two men hurrying: a sepoy, of whom two of the Maharajah's attend me, to assist in procuring supplies, &c., as is usual in this country, and Buddoo came up, and informed me that I had followed the wrong river. Here was a business. I ascertained the direction of the right one, got a boat, and crossing the deceptive stream, made across country to the boats, which we hit upon without difficulty; and without further adventure or mishap, but in dull and prosperous monotony, we punted our way to Islamabad, where we arrived about 4 P.M., and after some delay, procuring coolies, I was safely lodged in the 'baraduri' which Willis and I occupied last autumn.

Everything the same, but now familiar and less interesting; I think some of the larger fishes have been taken out of the tank—my old acquaintance the kotwal officiously civil as usual—the vizier, my friend Ahmet Shah, the kardar, absent in the neighbourhood. I made all arrangements to go on towards the Wurdwan in the morning, and sent on a sepoy to arrange for coolies and supplies—which have to be carried with us—at Shanguz, the village we are to halt at to-morrow.

May 11th. I got well away early, and had a pleasant[Pg 38] march over a level grassy tract of country, crossing a deep watercourse now and then, and, passing through a very pretty village, stopped in a delightful spot under some giant chunars on a bank overhanging a rivulet, a village close at hand. Then, having breakfasted, I came on here to Shanguz, also a prettily situated village, with its stream, its irregular garden plats, grassy slopes, and noble chunar trees: under one of which leafy monsters, my humble tent, a little thing just containing my bed, is pitched.

Ahmet Shah and the kotwal came all the way from Islamabad, the former to pay his respects and make his acknowledgments for a turban I sent him from the Punjab, as a recognition of his great civility and attention last year. He brought me a beautiful cock pheasant alive, one of the Meynahl: he had been caught about a month, so I hope he may live. I should like to take some of these birds home and naturalize them; they would be highly prized. They may be called a link between the pea-fowl and the pheasant. They have a delicate top knot, and their colour is the most brilliant deep blue, rifle-green, and bronze, of glossy and metallic sheen. The tail is plain buff; there he falls off in plumage. He is much larger than the English bird. He is to be put in a cage, and kept for me till I return to the Punjab.

There is a thunder-storm, and rain now falling—a bore for my retinue, who have but a leafy canopy over them: but they have lots of covering. I purchased my three servants each a warm Cashmere blanket yesterday, four rupees each, rather a heavy pull as I had, previous to leaving Amritsir, given each of them a warm suit. But, poor chaps, they will have to rough it in the Wurdwan snows, so some additional warm wrapper is necessary.

I am snug in my little canvas nutshell, though without room to turn round. I have now, to my surprise, brought[Pg 39] up my diary to this date, and feel as if I could stick to it. To-morrow is my birthday: what a crowd of thoughts arise and connect themselves with it!

12th May. Nah-bugh. We arrived here at a quarter to nine, having in the earlier portion of the journey passed through a beautiful country.

The path led along the slopes of some hills of moderate height, well-wooded and, here and there, opening out into smooth lawns; the woods were full of blossoms, a white clematis very plentiful and full of flower. The trees and shrubs, in their character and distribution, and indeed the whole scene, strongly resembled an extensive shrubbery or wilderness, intended to look wild and natural, such as we see in the domains of the wealthy in Old England. And to strengthen the resemblance, the well-remembered voice of the cuckoo resounded over hill and dale, and one remained perched on a tree near enough to be distinctly observed. Other birds were singing lustily: among them the blackbird's sweet melody was plainly distinguished. It is, I believe, the same bird, and sings the same notes as the English bird. The cuckoo, also, is precisely similar to our welcome spring visitor, and, curious enough, the Cashmiries also call him 'cuckoo.'

How pleasant it was to traverse these lovely glades, lifting the eyes from which, mountain ranges presented themselves, the more distant rugged and bleak, and covered with snow, those nearer displaying their many diverging slopes in multiplied ramifications, some open and grassy, others with nearly all the ridges covered with pine forests, with which other trees mingling agreeably contrasted their diverse colours.

I must not forget to note that this my birth-day was ushered in by a real May morning, much such in temperature as the finest and brightest in England would be;[Pg 40] and abundance of May, the thorn being in full blossom, adorned and perfumed the way side. There was also white clover, and a veritable bumble-bee, with the same portly person and drab coloured behind as the common English one. The banks, also, sported their violets, but, alas! without fragrance, and the wild strawberry was peeping out of the bushes and grass all around. Who could fail to exult in exuberance of spirits, thus surrounded by nature's choicest beauties? Certainly not I. Rejoicing, and buoyant with vigorous health, my mind undisturbed, having a long holiday before me, and feeling within me the ability and taste, fresh and capable as ever of old, to appreciate and enjoy the blessings of Providence so amply vouchsafed me, I felt my whole being full to overflowing of joy, admiration, gratitude, and praise. I gave myself up to reflections suitable to the day—

—Was interrupted by the shikarries rushing into my tent, to apprise me of the arrival of another saheb with shikarries and guns. They were in great excitement, in consequence of the probability of the new comer interfering with their plans for my shooting operations, by occupying the localities they desired to hunt. I had, as usual, given notice of my intention to rest here to-morrow, Sunday. The shikarries tried to shake this resolve by pointing out the advantages to be gained by pushing on, and getting first into the Wurdwan valley; but I was proof against such arguments.

The dreaded stranger proved to be an officer of the 79th from Lahore, on two months' leave. I asked him to dinner, and fortunately, in addition to my usual stew, had a rice pudding, to which I added guava jelly; a rich plumcake brought up the rear. These solids, with a glass or two of very fair sherry, was quite a feast in these wild regions, and my luxurious habits astonished my sporting[Pg 41] companion; to whom, to save my character, I revealed that it was my birthday, and repeated my friend D——'s quaint apology for an unusual extravagance, "Sure, and it isn't every day that Shamus kills a bullock."

My guest informed me that he had just missed two shots at bara sing near the village, the coolies having given him information of four or five of those animals having crossed their path. He intended going further to day, but I believe has halted for the night. He told me the spot in the Wurdwan he is making for, which my shikarries tell me is out of our beat; so all is serene, except the weather—a heavy thunder-shower, and more coming—the sky unsettled.

This is a charming bivouac, my camp by a village, on a level spot of turf shaded by walnut trees. Below, in a cultivated valley, runs an inconsiderable river, divided into many channels. The stream runs towards the South, the valley of its formation disappearing in the distance, as shut in gradually by a succession of hills, prolongations of the spurs of the mountains. But a considerable extent of the valley is visible, and forms a lovely landscape. I strolled out after dinner, and remained gazing over its charms, till dusk warned me to return. I then sat outside reading by the light of my lantern, an honest stable utensil, broken in upon by a consultation with my shikarries, who are in good spirits, and anticipate great sport.

An aspiration to heaven, a thought to home, and my birth-day, my forty-second is ended. What may not happen ere I see another—should such be the will of God!

13th May. Sunday. Nah-bugh. Rain continued to pour all day. I was visited, however, by the lumbadar of Eish Mackahm whose acquaintance I made last year, and the jolly, lusty-looking individual, hearing of my arrival at Islamabad, had come three days' journey to see[Pg 42] me, bringing as a propitiatory 'nuzzur,' some of his cakes of bread, which I had formerly commended, and two jars of delicious honey. My stout friend is by no means loquacious, and is blind of one eye; but with the other he steadily contemplated me, appearing to receive much inward satisfaction therefrom.

He brought with him, and introduced, a renowned shikarry, a fine-looking middle-aged man, who said he was desirous of an interview, as he had heard so much of my character as a hunter. It is true that in this country it needs but small exploits to win fame, so expansive is rumour, the inhabitants delighting in tattle, and magnifying their consequence by exalting the performances and success of the saheb they attend in the chase. But I suspect my sporting visitor had other views, more interested—perhaps, hoping for employment. I was really pleased to see the 'lumbadar,' who was most civil and obliging last year. He was detained by the continued rain, so I gave orders for the due entertainment of himself and followers, who found suitable accommodation in the village.

14th May. We moved on towards the Wurdwan, the path leading up the Nah-bugh valley, which gradually narrowed, cultivation appearing only at intervals, until it ceased altogether, as the valley became transformed into a wild, rugged ravine, shut in by steep and lofty hills, dotted with firs. We advanced to the foot of the pass, nearly to the snow, and there encamped.

I went out in the afternoon to look for game, and ascended some steep hills, very hard work; having traversed much ground without seeing anything, I sat down, peering from an eminence, down on the slopes below, like an eagle from his eyrie. One of the shikarries went a little further on, and shortly gave notice of game in view:[Pg 43] we rapidly closed with him, and learned that a bear with two cubs were in the adjoining ravine.

Away, in pursuit—we sighted the chase, who were moving quickly away, here and there grubbing, routing, and feeding, as is the wont of these creatures. Over very rough ground we climbed, and scrambled; and descended to the bed of the ravine. The Bruin family, still going ahead, were concealed by a projecting ledge of rock, to which we hurried; and from the fall of stones down the hill on the other side the rock, we knew that we were close on our game. We turned the angle, and saw B. junior peeping. He did not see us; but a step or two further and B. major's acute nasal perceptions indicated danger; so, giving office to the young uns, off scuttled the trio at a good round pace up the hill. There was no time to lose, so rapidly aiming at the old bear, I struck her hard somewhere in the back; but, after stumbling and uttering a fierce growl, she went on, but was again descried, when I fired the second barrel ineffectually, then loaded and pursued up hill. The chase was soon in view, labouring heavily. We got to the top of the hill, and a few paces down the declivity was B. major alone, standing. Hearing her pursuers, she shuffled on, when I fired and brought her down, finishing her with another barrel.

Leaving men to take the skin, we went after the Meynahl pheasants, some of which had been seen; and after trying in vain to get within shot of these beautiful birds, we descended the hill, and when near the bottom, the leading shikarry suddenly stopped, and directed me to prepare for action. I, supposing a Meynahl pheasant to be the object, took the double gun, but was told to change, and, following the direction of the shikarry, saw the great ugly head of a large bear, protruding from the bushes—only the head visible. I fired the single Whitworth, but[Pg 44] ineffectually. The animal was about fifty yards off only, and I found the sight at two hundred yards, which accounted for the ball passing over his head. He hastened rapidly out of danger. Then we returned to camp.

15th May. Up and away, to mount the pass leading into the Wurdwan. It was laborious climbing, but after some half-dozen pauses, I reached the summit—glorious scenery all around, and a magnificent backward and downward view into the valley of Cashmere, passing over which the eye rested on the Pir Panjal range, which formed a fitting background to so splendid a picture. There was an extensive tract of snow to traverse, leading with a slight downward slope into the Wurdwan, which soon was partly indicated, rather than revealed, by the system of snowy mountains.

I had two shots with the Whitworth at a small animal, the natives call 'drin,' which I suppose from its habits to be the marmot. It is of a dark red-brown, burrows, sits on a stone close to its hole, and chatters. The little animal was about one hundred and twenty yards from me: the first bullet passed about an inch over it. It soon took up the same position again, and the second missile struck the stone close under it; so that the fragments must have struck him. He made a precipitate dive, and we saw no more of him.

I halted to breakfast; then pushed on, the path a tolerable one, following the windings of the hills on whose sides it hung—the scenery wild, and romantic, and full of interest. We crossed many ravines and snowdrifts. We met two coolies who had accompanied my late guest of the 79th, returning: they informed the shikarries that the saheb had not gone down the valley, but up to the ground that we had hoped to secure. Wrath of shikarries excessive—unmeasured abuse heaped upon conflicting[Pg 45] party—all sorts of plans of retaliation suggested, and appeals made to me to exercise the authority of my superior rank and order the offender back. I took it all very quietly, and succeeded not only in calming the angry men, but put them in good humour by suggesting various problematical advantages to be derived from the presence of the other party.

We came at length—and really at length, for it was a long stretch—in view of the Wurdwan, the valley opening out many thousand feet below, two or three small villages with their clustering hovels and irregular patches of cultivation shewing themselves. A rapid stream, of dimensions and volume claiming, perhaps, to be styled a river, was brawling and fighting its way against innumerable obstacles and impediments down the vale. A very steep winding path brought us down to its banks, and instead of crossing over to the village of Ainshin, as we should have done, had it not been already in possession of a hostile party, we moved along the right bank upwards.