Title: Our Little Dutch Cousin

Author: Blanche McManus

Release date: February 26, 2013 [eBook #42203]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Dianna Adair and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

| Our Little African Cousin |

| Our Little Alaskan Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Arabian Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Armenian Cousin |

| Our Little Australian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Brazilian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Brown Cousin |

| Our Little Canadian Cousin |

| By Elizabeth R. MacDonald |

| Our Little Chinese Cousin |

| By Isaac Taylor Headland |

| Our Little Cuban Cousin |

| Our Little Dutch Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Egyptian Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little English Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Eskimo Cousin |

| Our Little French Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little German Cousin |

| Our Little Greek Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Hawaiian Cousin |

| Our Little Hindu Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Indian Cousin |

| Our Little Irish Cousin |

| Our Little Italian Cousin |

| Our Little Japanese Cousin |

| Our Little Jewish Cousin |

| Our Little Korean Cousin |

| By H. Lee M. Pike |

| Our Little Mexican Cousin |

| By Edward C. Butler |

| Our Little Norwegian Cousin |

| Our Little Panama Cousin |

| By H. Lee M. Pike |

| Our Little Philippine Cousin |

| Our Little Porto Rican Cousin |

| Our Little Russian Cousin |

| Our Little Scotch Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Siamese Cousin |

| Our Little Spanish Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Swedish Cousin |

| By Claire M. Coburn |

| Our Little Swiss Cousin |

| Our Little Turkish Cousin |

Our Little Dutch

|

||

Our little Dutch cousins have much in common with little American cousins, not so much perhaps with respect to present-day institutions and manners and customs, as with the survivals and traditions of other days, when the Dutch played so important a part in the founding of the new America.

It was from Holland, too, from the little port of Delfshaven, that the Pilgrim Fathers first set sail for the New World, and by this fact alone Holland and America are bound together by another very strong link, though this time it was of English forging.

No European country, save England, has the interest for the American reader or traveller[vi] that has "the little land of dikes and windmills," and there are many young Americans already familiar with the ways of their cousins from over the seas from the very fact that so many of them come to Holland to visit its fine picture-galleries, its famous and historic buildings, its tulip-gardens, and its picturesque streets and canals, which make it a paradise for artists.

Our little Dutch cousins mingle gladly with their little American cousins, and the ties that bind make a bond which is, and always has been, inseverable.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Pieter and Wilhelmina | 1 |

| II. | The American Cousin | 23 |

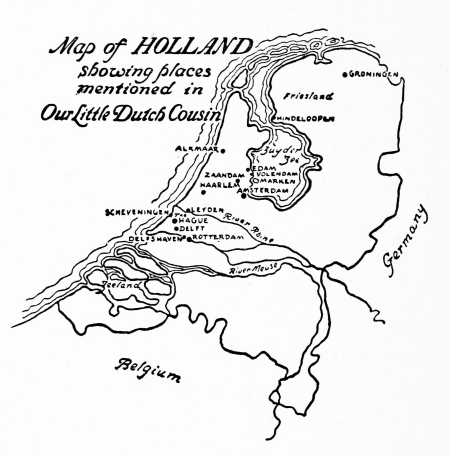

| III. | The Land of Dikes and Windmills | 34 |

| IV. | The Kermis | 53 |

| V. | The Bicycle Ride | 63 |

| VI. | Where the Cheeses Come from | 81 |

| PAGE | |

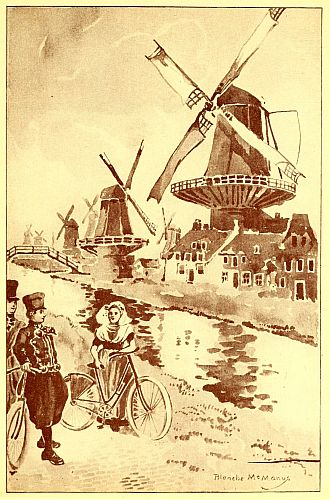

| Pieter and Wilhelmina | Frontispiece |

| "'How old is Cousin Theodore, mother?' asked Wilhelmina" | 27 |

| "'I'm going to snap-shot one of them with my camera'" | 48 |

| At the Kermis | 61 |

| On the Road to Delfshaven | 66 |

| "The children stood in the bows" | 98 |

What do you think of a country where you can pick up sugar-plums along the road? Well, this was just what Pieter and Wilhelmina were going to do as, hand in hand, they flew up the road as fast as their little wooden shoes would let them, to meet a carriage which was rapidly approaching. Behind the carriage ran a crowd of children, laughing and tumbling over each other.

"Oh! they are throwing the 'suikers' now; run faster, Wilhelmina," panted Pieter; and, sure enough, as the carriage went by, a shower[2] of candies fell all about them. One piece dropped right in Wilhelmina's mouth, which of course was open, because she had been running so hard. But there was no time to laugh, as the children were all scrambling hard to pick up the sweets. Then they tried to catch up with the carriage again, but it was nearly out of sight by this time, and so one by one the young folk stopped to count up their gains, and compare them with one another.

This was a wedding-party returning from church. In the carriage sat the bride and groom. The carriage sat high up on its two great wheels, and was gaudily painted and gaily decked with flowers and ribbons.

Pieter and Wilhelmina had been on the lookout for this bridal party with more than usual interest, for two relatives of the bride had come to their mother a few days before to invite her to the wedding ceremony, and the children thought these young men had looked[3] very fine in their best clothes, with flowers stuck in the sides of their caps.

The bride had her arms full of candies, and, as was the custom, she threw them out to the children as they drove along. The little Dutch children call these candies "suikers." As you may imagine, this is a great treat for them, and accordingly the children of Holland take more of an interest in weddings than do the children of other countries.

"Put all the 'suikers' in my apron, Pieter," said Wilhelmina, "and let us go and show them to the mother," and the children quickly ran back home.

Wilhelmina and Pieter were twins, so it does not matter whether we say Wilhelmina or Pieter first, and they looked so much alike that when they stood together in the high grass by the side of the canal which ran in front of their home, it was hard to tell one from the other if it had not been for Pieter's cap.

They both had round, rosy faces, and round, blue eyes, and yellow hair, only you would not know that Wilhelmina had any hair at all, for it was completely hidden by her cap. They both wore little wooden shoes, and it was a marvel how fast they could run in them, for they seem to be on the point of dropping off most of the time, but, strange to say, they never do.

Holland is the dearest little wee country in the world. Uncle Sam could put it in his vest pocket. It looks like a country just made to play in. Its houses are so small and trim, all set about with neat little gardens and trees, which look as if they had been cut out of wood, like the trees in the "Noah's arks." There are little canals and little bridges everywhere, and little towns scattered here and there all over the broad, flat country. You could go to all of the principal cities of this little land in one day, and you can stand in one of the[5] church towers and see over half the country at a glance. The only things that look big are the windmills.

What do you think of a garden gate without any fence? But this is just the sort of a gate that the twins entered when they arrived home. Instead of a fence there was a small canal which divided the garden from the road, and of course the gate was in the middle of a small bridge, otherwise how could they have got across the canal?

At the front door they both left their shoes on the steps outside, for Dutch people never think of bringing their dirty shoes into the house. Then they opened only half of the front door and went in. Many Dutch doors are made in two parts, the upper half remaining open most of the time, like a window, while the lower half is closed like an ordinary door.

"Oh, mamma, see what a lot of 'suikers' the bride threw to us," said Wilhelmina, running[6] up to Mevrouw Joost, who was bustling about the china cupboard in the living-room.

"And she was such a pretty bride, too, with a lovely dress; and there were flowers twined all about the carriage, and a wreath on the horse's head, and long streamers of white ribbon wound around the whip," she continued breathlessly.

"And we got more 'suikers' than any one else," put in Pieter.

"Yes, it was a gay party. I saw them pass by the house," said Mevrouw Joost, smilingly, as she ate a "suiker."

"Baby Jan must have one too," said Wilhelmina, as she went over to play with the baby who was kicking and crowing in his great carved cradle near the window. Jan was the household pet, and there had been a great celebration when he was a week old.

All the friends of the Joost family were invited to come and see the baby, a red pincushion[7] having been hung out beside the front door to let everybody know that there was a new baby boy within. When the guests arrived, they were given rusks to eat, a kind of sweet bread, covered with aniseed and sugar, called "muisjes," which really means "mice." Before, when the friends had come to pay their respects to Wilhelmina and Pieter, there had been two kinds of "muisjes." One had a sort of smooth white icing on the top, and that was Wilhelmina's, while Pieter's rusks had lumps of sugar sticking up all over them.

The Dutch are the neatest people in the world. They are always washing and rubbing and dusting things, and one could no more find a spider's web in Mevrouw Joost's home than they could a white elephant.

The floor of the living-room was made of tiny red bricks, waxed and polished until they shone like glass. There was much heavy oak furniture, beautifully carved; a big round table[8] stood in the centre, and on one side was a great dresser or sideboard. The chairs were solid and big, with high backs and straw seats, and some of them were painted dark green, with curious little pictures and decorations also painted on them.

One end of the square room was filled by what looked like two big cupboards with heavy green curtains hanging in front of them, but one of the curtains was drawn partly back and one could see that they were two great beds instead, built into the wall just like cupboards. These were the "show-beds," and were not for constant use, but mostly for ornament.

Mevrouw Joost was very proud of these beds and kept them always made up with her very finest linen, trimmed with rich lace, and her most brilliantly coloured embroidered coverlids, the whole being piled so high that the beds nearly reached the ceiling. There was barely enough room on top for the two enormous[9] eider-down pillows, with gay covers and lace ruffles, which lay on each of the beds and completed their furnishings.

Some Dutch houses have a separate room for these "show-beds," which we should call a parlour, but Mevrouw Joost had her "show-beds" where she could enjoy their magnificence every day.

She had her "show-room," too, but kept it most beautifully and tightly closed up, so that not a ray of light or a speck of dirt could come in, for it was only used on some great occasion.

Another side of the living-room was nearly filled by the huge fireplace, covered with square, blue Delft tiles, on each of which was a picture which told a story from the Bible. The ceiling was crossed with great beams of wood, and a wainscoting of wood went all around the room.

On the sideboard, on the shelves above the beds, and over the mantel were fine pieces of[10] rare old Delft china, which is a beautiful deep blue. It is very rare now, and much prized by the Dutch Mevrouws. There was also a quantity of copper and brass jugs and pewter platters, while by the fireplace hung a big brass warming-pan, which is a great pan with a cover and a long handle. On a cold and damp winter's night Mevrouw Joost filled it with red-hot coals, and warmed the household beds by slipping it in and out between the sheets.

There were spotless white curtains at the tiny windows, and everything shone under the housewife's brisk rubbings.

Back of the sitting-room was the kitchen, with another big fireplace, in which was set the cooking-stove. Around the walls were many bright copper pans and pots of all kinds.

There were big brass jugs to hold milk, and kegs with brass hoops in which they stow[11] away their butter. The Dutch are so fond of polishing things that they put brass on everything, it would seem, just for the joy of rubbing it afterward.

Many of the commoner things were made beautiful as well. The knife-handles were carved, and on many of the brass bowls and platters were graceful patterns. One would see a little cow carved on the big wooden butter-spoon, or a tiny windmill on the handle of a fork, while the great churn that stood in the corner of the kitchen had gay pictures painted upon it. From this you may judge what a pleasant and attractive room Mevrouw Joost's kitchen was.

"Why are you putting out all the best china and the pretty silver spoons, mother?" asked Wilhelmina.

"The father is showing a visitor through the tulip-gardens. It is the great merchant, Mynheer Van der Veer, from Amsterdam.[12] He has come to buy some of the choice plants, for he says truly there are no tulips in all Holland as fine as ours," and the good lady drew herself up with a pardonable pride, as she polished the big silver coffee-pot, which already shone so Wilhelmina might see her face in it like a mirror.

"Can I help you, mother?" asked Wilhelmina. She would have liked nothing better than to handle the dainty cups and saucers, but she knew well that her mother would not trust this rare old china to any hands but her own, for these cups and saucers had been handed down through many generations of her family, as had the quaint silver spoons with the long twisted handles, at the end of which were little windmills, ships, lions, and the like, all in silver.

"No, no, little one, you are only in the way; go out into the garden and tell your father not to delay too long or our guest will[13] drink cold coffee," said Mevrouw, bustling about more than ever.

Wilhelmina was eager enough to see the great Mynheer, so she joined Pieter, who had already slipped out, and together they went toward the bulb-gardens, where Mynheer and their father were looking over the wonderful tulips.

Pieter and Wilhelmina lived in a quaint little house of one story only, built of very small red brick, with a roof of bright red tiles. The window-frames were painted white, and the window-blinds a bright blue, while the front door was bright green. There was a little garden in front, and the paths all followed tiny canals, which were spanned here and there by small bridges. In one corner was a pond, on which floated little toy ducks and fish, and it was great fun for the children to wind up the clockwork inside of these curious toys, and watch them move about as if they[14] were alive. But on this afternoon the twins were thinking of other things, and kept on to the bulb-gardens. Here was a lovely sight,—acres and acres of nothing but tulips of all colours, and hyacinths, and other bulbs which Mynheer Joost grew to send to the big flower markets of Holland and other countries as well; for, as Mevrouw Joost had said, their tulips were famous the world over. Mynheer Joost took great pains with his bulbs, and was able to grow many varieties which could not be obtained elsewhere.

The tulip is really the national flower of Holland, so the Dutch (as the people of Holland are called) are very fond of them, and you see more beautiful varieties here than anywhere else. Every Dutchman plants tulips in his garden, and there is a great rivalry between neighbours as to who can produce the most startling varieties in size and colour.

Pieter and Wilhelmina were never tired of[15] hearing their father tell of the time all Holland went almost crazy over tulips. This was nearly three hundred years ago, after the tulip had just been brought to Holland, and was a much rarer flower than it is to-day. It got to be the fashion for every one to raise tulips, and they sold for large sums of money. Several thousands of "guldens" (a "gulden" is the chief Dutch coin) were paid for a single bulb. People sold their houses and lands to buy tulips, which they were able to sell again at a great profit. Everybody went wild over these beautiful flowers, rich and poor alike, men, women, and children. Everybody bought and sold tulips, and nobody thought or talked about anything but the price of tulips. At last the Dutch government put a stop to this nonsense, and down tumbled the prices of tulips.

In spite of this, the Dutch love for the flower still continued, and to-day one may see[16] these great fields of tulips and hyacinths and other bulb-plants covering miles and miles of the surface of Holland, just as do wheat-fields in other lands.

There is a large and continually growing trade in these plants going on all over Holland, and Mynheer Joost was always able to sell his plants for as big a price as any others in the market. The principal tulip-gardens are in the vicinities of the cities of Leyden and Haarlem, and from where Wilhelmina and Pieter now stood, in the midst of their father's tulip-beds, they could see the tower of the Groote Kerk, or Great Church, of Haarlem.

Mynheer Joost sold a very rare variety, which only he knew how to grow, and which was named the "Joost;" it was almost pure black, with only a tiny red tip on each petal. It was the pride of his heart, and he often told the children that he hoped some day to be able to turn it into a pure black one;[17] and then what a fortune it would bring them all! So Pieter and Wilhelmina watched its growth almost as carefully as did their father.

"There is Mynheer and the father now, looking at the 'great tulip,'" said Pieter. This was the way they always spoke of this wonderful plant.

But Wilhelmina suddenly grew shy at the sight of the great man. "Come, let us hide," she said, and she tried to draw Pieter behind one of the large glass houses, in which were kept many of the rarer plants. But Pieter wanted to see Mynheer Van der Veer, the well-known merchant who owned so many big warehouses in Amsterdam, and also a tall, fine house on one of the "grachten" of that city, which is the name given to the canals.

Mynheer was a portly old gentleman, and was dressed much as would be a merchant in any great city; in a black suit and a silk hat, for the wealthy people of the big cities of[18] Holland do not wear to-day the picturesque costumes of the country people. It is only in the country and small towns that one sees the quaint dress which often has changed but little from what it was hundreds of years ago. But the Joost family, like many another in the country, were very proud of their old-time dress, and would not have changed it for a modern costume for anything, and though Mynheer Joost was also a wealthy man, he was dressed in the same kind of clothes as those worn by his father and grandfather before him. He had on big, baggy trousers of dark blue velvet, coming only to the knee, and fastened at the waist with a great silver buckle; a tight-fitting vest or coat, with two rows of big silver buttons down the front, and around his neck was a gay-coloured handkerchief. On his head was a curious high cap, and on his feet the big wooden shoes, nicely whitened.

Each of the men were smoking big cigars, for the Dutch are great smokers, and are never without a pipe or cigar.

Mynheer Van der Veer had finished selecting his tulips, and now caught sight of the twins, who were standing shyly together, holding hands as usual, behind a mass of crimson and yellow tulips.

"Aha! these are your two young ones, my friend; they, too, are sturdy young plants.

"You look like one of your father's finest pink tulips, little one," he continued, patting Wilhelmina's pink cheeks.

You might not think it was a compliment to be called a tulip, but you must not forget what a high regard the Dutch have for these flowers. So Wilhelmina knew that she was receiving a great compliment, and grew pinker than ever, and entirely forgot the message which her mother had given her.

"And, Pieter, some day I suppose that you[20] will be growing rare tulips like your father," said Mynheer, peering at the lad over the rims of his glasses.

"Pieter helps me greatly now, out of school hours, and Wilhelmina can pack blossoms for the market as well as our oldest gardener," said Mynheer Joost, who thought that there were no children in Holland the equal of his twins. "But you must let the Vrouw give you some of her cakes and coffee before you leave, Mynheer," he continued as he led the way back to the house.

The Dutch are very hospitable, and are never so happy as when they are giving their visitors nice things to eat and drink, and it would be considered very rude to refuse any of these good things; but then nobody wants to.

Mynheer Van der Veer was soon seated at the big oak table, which was covered with a linen cloth finely embroidered, and edged with[21] a deep ruffle of lace. On it were the plates of Delftware filled with many kinds of cakes and sweet biscuits, which the Dutch call "koejes;" besides, there were delicious sweet rusks, which Mevrouw Joost brought hot from the oven. Then she poured the hot water on to the coffee from a copper kettle which stood on a high copper stand by the side of the table. The silver coffee-pot itself stood on a porcelain stand at one end of the table, and under this stand was a tiny flame burning from an alcohol-lamp in order to keep the coffee warm.

There was no better coffee to be had in all Holland than Mevrouw Joost's, and how good it tasted, to be sure, out of the dainty china cups,—real china, for they had been brought from the Far East by a great-uncle of the Joosts who had engaged in the trade with China at the time when there were nothing but sailing ships on the seas. After the coffee came brandied cherries, served in little glasses.

"When the young people come to Amsterdam again, Mynheer Joost, you must bring them to see me," said the merchant, "and perhaps the young man will want to leave even his tulips when he sees what is in the big warehouses."

The twins' eyes shone and they pinched each other with delight at the mere thought of a visit to the wonderful city house of the great merchant in wealthy Amsterdam, the largest city in their country.

Any one who saw the twins on their way to school one morning soon after the visit of Mynheer Van der Veer would know that something unusual had happened, for they were both talking away at once, in a most excited manner. Little Dutch children are usually very quiet, when compared to the children of most other countries, though they are full of fun, in a quiet sort of a way, when they want to be.

"Oh, Pieter," Wilhelmina was saying, "to think that we have a cousin coming to see us from across the seas!"

"I wonder if he can talk Dutch; if he can't we will have to speak English, so you had[24] better see to it that you have a better English lesson than you did yesterday," said Pieter, who was rather vain of his own English.

There is nothing strange in hearing little Dutch children speak English, French, or German, for they are taught all three languages in their schools; and even very little children can say some words of English or German.

"It is well for you to talk," said Wilhelmina, feeling hurt. "English is not hard for you to learn; as for me, I can learn my German lesson in half the time that you can."

"Ah well! the German is more like our own Dutch language," said Pieter, soothingly, for the twins were never "at outs" for long at a time. "You will soon learn English from our new cousin from America. Listen! there is the school-bell ringing now," and away they clattered in their wooden shoes to the schoolhouse.

Yesterday there had been a solemn meeting[25] in the Joost home. You must know that it was an important occasion, because they all met in the "show-room." The "domine" (as the Dutch call their clergymen) had been invited, and the schoolmaster, too, and they all sat around and sipped brandied cherries and coffee, the men puffing away on their long pipes, while Mynheer Joost read aloud to them a letter. It was from a distant relative of the Joost family who lived in New York City.

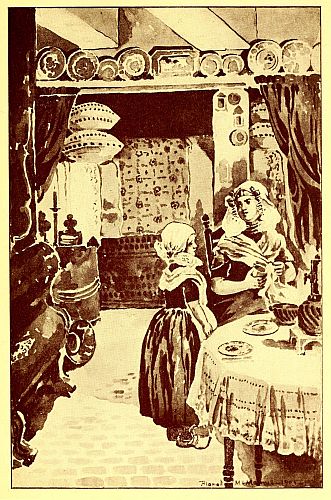

"'HOW OLD IS COUSIN THEODORE, MOTHER?' ASKED

WILHELMINA"

"'HOW OLD IS COUSIN THEODORE, MOTHER?' ASKED

WILHELMINA"

You know, of course, that the Dutch were among the first to settle in America, and in the present great city of New York. In those early days a great-great-grand-uncle of Mynheer Joost had gone to the island of Manhattan, and made his home, and now one of his descendants, a Mr. Sturteveldt, who was a merchant in New York City, was anxious to learn something about his family in Holland. He had heard of Mynheer Joost through a friend of his who was fond of flowers, and who had[26] once come to Holland to buy some of Mynheer Joost's beautiful tulips.

So Mr. Sturteveldt had written Mynheer Joost many letters and Mynheer Joost had written him many letters. Finally Mr. Sturteveldt wrote and said he very much wished his only son Theodore to see Holland, and to become acquainted with his Dutch relatives. Upon this, Mynheer Joost had invited Theodore to come and spend some time with them, and this letter that he was now reading said that Theodore was to sail in a few days in one of the big steamers that sail between New York and Rotterdam, under the care of the captain, and requested that Mynheer Joost would make arrangements to have him met at Rotterdam.

No wonder they all had to talk it over between many sips of coffee and puffs from the long pipes. It was a great event for the Joost family. As for Pieter and Wilhelmina, they could talk and think of nothing else, and Wilhelmina[27] went about all the time murmuring to herself, "How do you do?" and "I am very pleased to see you," and "I hope you had a pleasant voyage," so as to be sure to say it correctly when her American cousin should arrive.

"How old is Cousin Theodore, mother?" asked Wilhelmina, as she was helping to give the "show-room" its weekly cleaning. "Just twelve, I believe," said her mother.

"And coming all by himself! I should be frightened nearly to death," said Wilhelmina, who was polishing the arm of a chair so hard that the little gold ornaments on her cap bobbed up and down.

Wilhelmina was short and chubby, and her short blue dress, gathered in as full around her waist as could be, made her look chubbier still. Over her tight, short-sleeved bodice was crossed a gaily flowered silk handkerchief, and around her head, like a coronet, was a gold[28] band from which hung on either side a gold ornament, which looked something like a small corkscrew curl of gold. On top of all this she wore a pretty little lace cap; and what was really funny, her earrings were hung in her cap instead of in her ears! To-day she had on a big cotton working-apron, instead of the fine silk one which she usually wore.

Wilhelmina and her mother were dressed just alike, only Mevrouw's dress was even more bunchy, for she had on about five heavy woollen skirts. This is a Dutch fashion, and one wonders how the women are able to move around so lively.

"Oh, mother, you are putting away another roll of linen!" and Wilhelmina even forgot the coming of her new cousin for the moment, so interested was she as she saw the mother open the great linen-press. This linen-press was the pride of Mevrouw Joost's heart, for piled high on its shelves were rolls and rolls[29] of linen, much of it made from the flax which grew upon their place. Mevrouw Joost herself had spun the thread on her spinning-wheel which stood in one corner of the room, and then it had been woven into cloth.

Some of these rolls of linen were more than a hundred years old, for they had been handed down like the china and silver. The linen of a Dutch household is reckoned a very valuable belonging indeed, and Wilhelmina watched her mother smooth the big rolls which were all neatly tied up with coloured ribbons, with a feeling of awe, for she knew that they were a part of their wealth, and that some day, when she had a house of her own, some of this old family linen would be given her, and then she, too, would have a big linen-press of which to be proud.

Just as Mevrouw Joost closed up the big "show-room" there came a cry from the road of "Eggs, eggs, who'll give us eggs?" "There[30] come the children begging for Easter eggs," said Wilhelmina as she ran to the door.

At the gate were three little children waving long poles on which were fastened evergreen and flowers, and singing a queer Dutch song about Easter eggs.

"May I give them some, mother?"

"Yes, one each, though I think their pockets are stuffed out with eggs, now," answered Mevrouw.

But if they already did have their pockets stuffed, the children were delighted to get the three that Wilhelmina brought out to them, and went on up the road, still singing, to see how many they could get at the next house.

The Dutch children amuse themselves for some days before Easter by begging for eggs in this way, which they take to their own homes and dye different colours and then exhibit to their friends. On Easter Day there is more fun, for they all gather in the meadows[31] and roll the eggs on the grass, each trying to hit and break those of his neighbours.

At last the day came when Pieter and Wilhelmina were to see their new cousin for the first time. Their father had gone to Rotterdam to meet the steamship and bring Theodore back with him.

The twins hurried from school, and hurried through dinner, and in fact hurried with everything they did. Then they put on their holiday clothes and kept running up the road to see if their father and Theodore were coming, although they knew that it would be hours before they would reach home. But of course, just when they were not looking for them, in walked the father and said: "Here is your Cousin Theodore, children; make him welcome." And there stood a tall lad, much taller than Pieter, though they were the same age, holding out his hand and talking English so fast that it made their heads swim.

Pieter managed to say "How do you do? I am glad you have come," but poor Wilhelmina—every word of her English flew out of her head, and all she could think to say was, "Ik dank u, mijnheer,"—"Thank you, sir."

Then suddenly the children all grew as shy as could be, but after they had eaten of Mevrouw's good supper, they grew sociable and Theodore told them all about his voyage over, and Pieter found that he could understand him better than at first. Even Wilhelmina got in a few English words, and when Pieter and Theodore went to sleep together, in what Theodore called a "big box," anybody would have thought they had known each other all their lives.

The three young cousins were soon the best of friends; and as for Theodore, everything was so new and strange to him that he said it was like a big surprise party all the time. He said, too, that he was going to be a real Dutchman[33] while he was with them, and nothing would do but that he must have a suit of clothes just like Pieter's, and a tall cap. How they all laughed the first time he tried to walk in the big wooden shoes! But it wasn't long before he could run in them as fast as the twins.

Theodore wanted to learn to speak Dutch, and so every morning, after they had eaten their breakfast of coffee, rye bread, and butter, with either herrings or cheese, away he went with the twins across the meadows to the schoolhouse in the centre of the village.

After dinner Theodore and Pieter helped about in the tulip-gardens, while Wilhelmina and Mevrouw polished and dusted and rubbed things, and made butter in the great wooden and china churn.

On the weekly holiday the three children would take long walks, or perhaps a ride on the steam street-cars, or trams, which puffed through the village; or they would ride their[35] bicycles, for this is a favourite pastime with the Dutch, whose flat straight roads are always so excellently kept.

"Where shall we go to-day?" asked Pieter, as they started out for a walk one afternoon.

"Theodore has not seen Haarlem yet," said Wilhelmina. "Let's walk there and come back on the steam-tram."

"That makes me feel as if I were at home. We have a Harlem, too, which is a part of New York City. I suppose it was named after your city. Let's go by all means, and I will take some pictures," said Theodore, slinging his camera over his shoulder, and away they went in high spirits.

The children were soon walking along a shady road by the side of the canal. As far as they could see, in any direction, stretched the bulb-gardens blazing with colour of all kinds. Dotted everywhere about were windmills of all sizes, their sails gleaming[36] white in the sunlight as they went round and round.

On either side of the road were neat little villas, with trim gardens before them. As Pieter told them, these were the summer homes of the well-to-do people who live in the cities. Everybody who can, has one of these villas, where they can come during the hot weather, and they especially like to have one near Haarlem, because the beautiful gardens roundabout make the country seem so gay and bright.

"This is the one which belongs to Mynheer Van der Veer," said Wilhelmina. "I think it is the most beautiful of them all." And so it was, according to Dutch taste. The young people stopped to look at it admiringly.

For a Dutch home it was very large, because it had two stories. The entire front was painted in half a dozen different colours to[37] represent as many different coloured stones, all arranged in a fanciful pattern.

The window-blinds were a bright pea-green, and the framework a delicate pink. The door was a dark green with a fine brass knocker in the centre, and a brass railing, shining like gold, ran down on either side of the white steps. The roof was of bright red tiles, which glistened in the sun, and what do you think was on the highest point of the gable? A china cat, coloured like life, and standing with its back up, just as though it were ready to spring upon another cat! Over the doorway was painted the motto: "Buiten Zorg," which means "Without a Care."

What really amused the party most were the queer figures which stood around in the garden.

"See that funny old fellow over by the pond, shaking his head; you might think he was alive," said Theodore. "He looks like a Turk with a big turban."

"That," said Pieter, "is an automaton, which can be wound up so as to nod his head. And look, there is another figure near him,—a funny old woman, who keeps turning around, as if she got tired of seeing the gentleman with the turban. Those ducks swimming about on the pond are made to move in the same way."

The summer villa gardens are usually filled with these queer mechanical contrivances. I suppose it amuses the rich old burghers to watch them as they sit smoking their long pipes and taking their ease in their little summer-houses on the hot days. Mynheer Van der Veer was very proud of his collection and took great care of them. When a shower came up he would put an open umbrella over each one, which made them look funnier still, and when it rained very hard, he would pick them up bodily and carry them into the house; then when the sun shone again, out would come the funny little figures too.

"Why is the little summer-house in the corner of the garden built over the canal?" asked Theodore.

"I really don't know," said Pieter; "they always are, and no villa is complete in its appointments without one. There is where Mynheer and Mevrouw sit in the afternoon and have their coffee and 'koejes.' Mynheer sits and smokes and dozes and Mevrouw does embroidery."

The flower-beds were all arranged in regular shapes; the walks were made of several kinds of coloured sands which were arranged to form regular patterns. The trees were not allowed to grow as they pleased. Dear me, no! They were trimmed in shapes and forms too, and some of the tree-trunks were even painted. But all was very clean and proper, and every leaf looked as though it was frequently dusted and washed.

"Well, I should not dare to move about in[40] that garden for fear I should put something out of order," said Theodore. "It wouldn't do for American children to play in, with those fine patterns in the sand and all the rest. They would certainly disappear in a short time."

"So they would here, as well," laughed Pieter. "But they are kept up only for show, and everybody uses a side-entrance except on grand occasions."

"Oh, there is a family of storks on that house!" called out Wilhelmina; "look, Pieter, aren't they lucky people who live there?"

Sure enough, on the top of the chimney was a mass of straw, and in the midst of it stood two tall storks. This was their nest, and Papa and Mamma Stork were waiting for the young Stork family to come out of their shells. Papa Stork stood on one leg and cocked his head down to the children as much as to say: "Don't you wish that we were living at your house?"; for storks must know as well as anybody how[41] much they are thought of in Holland. The good people of that country build little platforms over their chimneys just so that a stork couple that are looking for a place to begin housekeeping will see it and say to themselves: "Here's a nice flat place on which to build our nest."

It is considered very lucky indeed for a stork family to come to live on one's chimney-top.

"We thought one was coming to live at our house last year," said Wilhelmina, "but they must have made up their minds to go elsewhere, and I was so sorry."

"And they build on churches, too," cried Theodore. "Look, there's a nest on the roof of that church. I had been thinking that it was a bundle of sticks, and wondering how it got up there."

"The storks have built there for many years, and they seem to like the highest places they can find," said Pieter. "There is a law[42] to protect the storks, and to forbid any injury being done to them, so you see they can have a better time than most birds."

"Look, Pieter, there are big ships over there in the middle of that green meadow; how ever did they get there? Bless my stars!" said Theodore, "I do believe they are sailing over the grass."

"Oh, Theodore, you are so funny!" laughed Wilhelmina; "of course they are on the water; there is a canal over there where you are looking."

"Well, I can't see it," persisted Theodore, who thought his eyes were playing him tricks.

"That's because our canals are higher than the land about them," said Pieter. "You must know that we are very economical with our dry land; there is nothing we prize so much, because we have so little of it; and there is no people in the world who have worked so hard for theirs as the Dutch, not[43] only to get it in the first place, but to keep it afterward.

"Once all this country about here was either a marsh or covered by water. The land could not be allowed to go to waste like that, and so great walls of mud and stone, called dikes, were built. Canals were run here, there, and everywhere, and the waters which covered the lowlands were pumped into these canals and so drained off. The new land was practically a new area added to the small territory of Holland, and where once was nothing but salt marsh and water-flooded meadows are now cities and towns and houses and lovely gardens.

"As one walks along many of the canal banks in Holland, one is often overlooking the roof-tops of the houses below."

"Why," said Theodore, "if we tried, we might look right down that man's chimney, and see what they are cooking for dinner; the road is on a level with the roof."

"Yes, our roads, too, are often built on dikes; this keeps them hard and dry," said Pieter. "You may judge as to how wide some of these dikes are, for on this particular one there is not only a road, but a row of trees on either side of it as well. Some are so broad that there are houses, and even villages, on top of them. The reclaimed lands lying between the dikes are called 'polders,' and thousands of acres of the richest part of Holland have been made in this way. Some day, too, it is planned that the whole of the Zuyder Zee will be planted and built over with gardens and houses."

"That is just like finding a country," said Theodore, "but hasn't it all cost a lot of money?"

"Yes, indeed," answered Pieter, "and not only that, but millions of 'gulden' have still to be spent every year to fight the waters back again."

Pieter also told Theodore that many of the great windmills which he saw were used to pump off the surplus water which drained through from the canals. So many of these canals are there in Holland that the country is cut up by them like a checker-board. They are of all sizes, from a tiny ditch to others big enough for large ships to sail upon.

There are not only these inland dikes, which protect the canals and the lands lying between, but there are great sea-walls of sand and rock to keep the sea itself in place, otherwise it would come rushing over the lowlands and drown half the country. Even that is not the end of the matter. Thousands and thousands of men have to watch these dikes day and night, for one little leak might be the means of flooding miles of country, and washing away many homes and lives. When the cry is heard, "The dike is breaking!" every man, woman, and child must go and help[46] do their share toward fighting back the water.

"Well, I am proud of my Dutch blood," said Theodore; "they are a splendid little people to work as they do, and they have had a hard fight to keep their heads above water. I wonder if that saying didn't first come from a Dutchman!"

"Perhaps that is the reason that we Dutch people talk so little," said Pieter; "we have to think and work so hard all the time to keep what we have."

"Well," said Theodore, "Holland is a wonderful country; it is wholly unlike any other place."

"Tell the story, Pieter," said Wilhelmina, "of the time when the people cut the dikes and let in the water to save themselves from the enemy."

"That's a long story, and we must save it for another time," said Pieter, "until after[47] Theodore has seen Leyden, for it was there that it happened."

This talk on Dutch history came to a sudden stop as Pieter called out: "Look out, Theodore, or you will get drenched," and the children had only time to dodge a big bucket of water that a fat Vrouw was tossing up on her windows. "You have not yet learned, Theodore, that a Dutch woman will not stop her washing and cleaning for any one," laughed Pieter, as they left the angry Vrouw shaking her mop at them.

"I have seen Vrouw Huytens, our neighbour," said Pieter, "scrubbing her house-front in a heavy rain, holding an umbrella over herself at the same time."

I suppose the idea of cleanliness comes from the fact that the Dutch have so much water handy; they say that when a Dutch Vrouw cannot find anything else to do, she says, "Let's wash something."

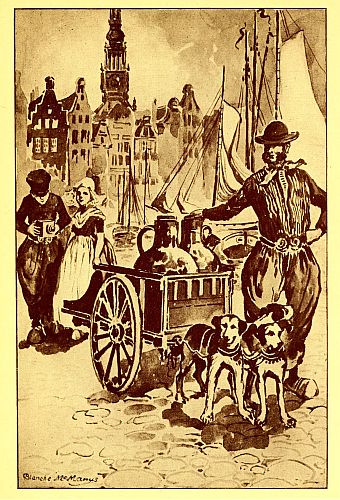

"'I'M GOING TO SNAP-SHOT ONE OF THEM WITH MY

CAMERA'"

"'I'M GOING TO SNAP-SHOT ONE OF THEM WITH MY

CAMERA'"

It was Saturday, the great cleaning day, and the housewives were washing down the doors and blinds and the sides of the houses with big mops, until everything shone brilliantly in the sunlight; the white door-steps, and even the tree-trunks and the red brick walks were not forgotten. They would dip up the water from the canals and dash it over the pavements with a reckless disregard for passers-by.

As the children entered the town matters grew worse. Everywhere were happy Dutch folk of all ages, swashing clean water about over everything, until Theodore finally said: "The next time I come out on cleaning-up day I shall wear a waterproof. I wonder the Dutch people don't grow web-footed, like ducks.

"You don't know how strange it looks to me to see carts drawn by dogs," he continued. "I'm going to snap-shot one of them with my camera."[49]

All along the road rattled the little carts drawn by dogs, for dogs are used a great deal in both Holland and Belgium in place of horses.

"Don't you have them in America?" asked Wilhelmina, in curious wonderment.

"No, indeed," said Theodore. "How people would stare to see the baker deliver his bread in one of our cites or towns from a little cart drawn by dogs."

"Most of the vegetables from the farms roundabout are brought into town in this way," said Pieter.

"And there is a man and a dog pulling side by side; what would they say to that at home, I wonder," said Theodore.

"Yes, some of our poor 'boers,' or farmers, have only one dog, and he must be helped. But there is a vegetable-cart with three fine dogs harnessed to it. Often there are four or five dogs to a cart," said Pieter, "and they can[50] draw big loads, too, I can tell you; and they are as intelligent as human beings.

"You see that big black dog knows that the brown one is not doing his share of the work, so he keeps his eye on him and gives him a sharp bite every once and again to keep him up to the mark."

"Is that a milk-cart?" asked Theodore, as he sighted a sort of a chariot with three great polished brass cans in it, all shining, like everything else that is Dutch. "See, while the master is serving his customer, the dog just lies down in his harness and rests; that is where he is better off than a pony would be under the same circumstances. Think of a pony lying down every time he stopped."

At this speech of Theodore's, Wilhelmina was much amused.

"A pony could not shield himself from the sun by crawling under the cart, either," said Pieter. "See, there is one who has crawled[51] under his cart while he is waiting, and is taking a comfortable nap. You may be sure, however, if any stranger attempted to take anything from his cart, he would become very wide awake, and that person would be very sorry for it, for the dogs guard their master's property faithfully."

By this time our party was well into town. They saw the "Groote Markt," or big market-place, and the Groote Kerk. Every Dutch town has a great market-place, and generally the Groote Kerk, or big church, stands in it, as well as the town hall. It is here, too, that the principal business of the town is transacted.

The children walked along the canals, which are the main streets in Dutch towns and cities, and Theodore never grew tired of looking at the queer houses, always with their gable ends to the street.

"What on earth does that mean?" said Theodore, stopping to read a sign on the[52] cellar-door of a small house,—"Water and Fire to Sell."

"Oh," said Pieter, "that is where the poor people can go and buy for a tiny sum some boiling water and a piece of red-hot peat, with which to cook their dinner. It is really cheaper for them than to keep a fire all the day in their own houses. Peat is generally sold for this purpose instead of coal or wood, for it is not so costly."

By this time the young cousins were quite ready to take the steam-tram home, and were hungry enough for the good supper which they knew Mevrouw Joost had prepared for them.

"Isn't it nice that Theodore has come in time for the Kermis?" said Wilhelmina, as the cousins were packing the flowers into the big baskets for the market, early one morning.

"What is a Kermis?" asked Theodore, all curiosity at once.

"It is a great fair, and generally lasts a week," said Pieter.

These fairs are held in many of the Dutch towns and cities. Booths are put up in the Groote Markt and on the streets, where the sale of all kinds of things is carried on. There are games and merrymakings, and dances, and singing, and fancy costumes, and much more[54] to make them novel to even the Dutch themselves.

"There is to be a Kermis at Rotterdam shortly," said Pieter, "and the father has promised to take us all."

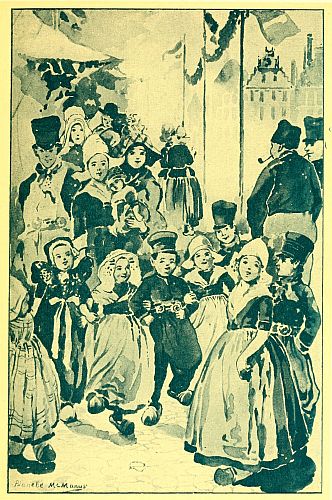

For a time the children talked about nothing but the Kermis, until at last the great day came, and they all found themselves on the train which was taking them to Rotterdam.

As they drew near the city it was easy to see that everybody was going to the Kermis, and was thinking of nothing else. The roads were crowded with all kinds of queer vehicles and gay costumes. There were the big country wagons, of strange shapes, and painted in bright colours. In them were piled the whole family,—grandparents, mother, father, aunts, uncles, and cousins. There were the dogs, too, drawing their little carts, and trying to keep up with the big wagons, panting bravely along with their tongues hanging out, as much[55] as to say, "We are not going to let the horses get there first, just because we are little."

There were men and women on bicycles,—the women with their caps and streamers flapping in the wind like white wings, and their half-dozen skirts filling out like a balloon, as they pedalled rapidly along.

It was just twelve o'clock as our party left the station, and the bells were ringing gaily, which was the signal for the opening of the Kermis.

"My, but isn't this a jam!" gasped Theodore, who found himself wedged in between the market-baskets of two fat Vrouws.

"It is, indeed," said Mynheer Joost, "and we must not lose sight of one another. Now, Wilhelmina, you keep between Theodore and Pieter, while the mother and I will go ahead to open the way."

There was no use trying to hurry,—Dutch folk do not hurry, even to a Kermis,—so our[56] party just let themselves be pushed slowly along until they reached the Groote Markt.

Here things were really getting lively. All around the great square were booths or stalls, where one could buy almost anything they were likely to want. Flags were flying everywhere, and from booth to booth were stretched garlands of flowers and streamers of ribbons. In the centre of the market-square a band of music was playing, and couples were trying to dance in spite of the rough cobblestone pavement and the jostling of the crowd which was watching them.

"You can see now, Theodore, just how your Dutch cousins really look, for there are folk here from all over the country, and all in their best holiday dress," said Mynheer Joost. "That group of little girls, with those high sleeves that come nearly to the tops of their heads, and with extra large skirts, are from Zealand."

"I see a woman with two or three caps on her head, and a big, black straw hat on top of them," said Theodore.

"She is from Hindeloopen; and there, too, are a number of fisherwomen, wearing huge straw hats, which look like big baskets."

There were other women wearing beautiful flowered silk shawls, and the sun glistened on the gold ornaments which dangled from their white caps as their owners danced up and down between the long lines of booths, holding each other's hands.

People were already crowding around the booths, buying their favourite dainties to eat, which at once reminded the young people that they, too, were hungry.

"What will you have, Theodore, 'poffertjes' or 'oliebollen'?" asked Pieter.

"Oh, what names!" laughed Theodore. "How can I tell? Show them to me first."

"Of course Theodore must eat the 'poffertjes,'[58] for that is the real Kermis cake," said Mynheer Joost, and led the way to a booth where a woman with a big, flapping cap and short sleeves was standing, dipping ladlefuls of batter from a big wooden bowl, and dropping them into hollowed-out places in a big pan, which was placed on an open fire before her.

As soon as they were cooked, another woman piled them nicely up, one on top of another, with butter and sugar between, and, with a smile, set a big plateful before the children, who made them disappear in short order.

"Why, they are buckwheat cakes, just like ours at home!" said Theodore, in the midst of his first mouthful; "and they are fine, too. Now let us try the other thing with the funny name," he continued.

"There they are, in that box," said Pieter, as he pointed to some fritters, made in the shape of little round balls.

"Oh, 'oliebollen' aren't half so nice as waffles; let us have them instead," said Wilhelmina.

"I think I agree with Wilhelmina," said Theodore; "the 'oliebollen' seem to be taking a bath in oil," he continued, shaking his head doubtfully.

"Oh, try one, anyhow," said Pieter. "You must not miss any of the Kermis cakes."

"Well, they taste better than they look," said Theodore, as he swallowed one of the greasy little balls.

"How would you like a raw herring, now, to give you an appetite for your dinner?" asked Pieter, as they passed the fish-stalls, which were decorated with festoons of fish that looked, at a little distance, like strings of white flags waving in the breeze.

"Not for me, thank you," answered his cousin, "but just look at all those people eating them as if they enjoyed them; and dried fish[60] and smoked fish, too, and all without any bread."

AT THE KERMIS

AT THE KERMIS

After the waffles had been found and eaten, the young people became much interested in watching a group of men trying to break a cake. The cake was placed over a hollowed-out place in a large log of wood, and whoever could break the cake in halves with a blow of his stick won the cake, or what was left of it. The thing sounds easy, but it proved more difficult than would have seemed possible.

"Let us eat an 'ellekoek' together, Pieter; there they are," and Wilhelmina pointed to what looked like yards and yards of ribbon hanging from one of the booths. The children forthwith bought a length, which was measured off for them just as if it really were ribbon, and Wilhelmina put one end in her mouth and Pieter the other end in his. The idea is to eat this ribbon cake without touching it with the hands or without its breaking. This Wilhelmina[61] and Pieter managed to do in spite of much laughter, and gave each other a hearty kiss when they got to the middle of it.

"Well," said Theodore, "I should think that a Kermis was for the purpose of eating cakes."

The market-place became gayer and gayer. A crowd of people would lock arms and form a long line, and then go skipping and dancing along between the booths, singing and trying to capture other merrymakers in order to make them join their band.

"Look out, Theodore, or this line will catch you," laughed Pieter, who jumped out of the way, pulling Wilhelmina after him.

The first thing Theodore knew, a gay crowd had circled around him and made him a prisoner, calling out to him to come and keep Kermis with them. But Theodore was not to be captured so easily; he had not become proficient in gymnastics for nothing, so he simply[62] ran up to a short little fellow, and putting his hands on his shoulders, vaulted clean over him, to the amazement of the crowd and the delight of the twins.

The fun lasted long into the night, but Mynheer Joost took his little party to their hotel early in the evening, for the fun was growing somewhat boisterous; besides, they had a long day ahead of them for the morrow.

Mevrouw and Jan were going back by the train, but Mynheer and the children had brought their bicycles with them, and were going to cycle back a part of the way. The children were looking forward to this with as much pleasure as they had to any feature of the Kermis. And so they went to bed and dreamed of cakes, miles long, that wiggled about like long snakes.

"Be up bright and early," Mynheer Joost had said the night before, and it was a little after seven when the young people finished breakfast. A Dutch breakfast is a big thing; besides nice coffee, there was rye bread and and white bread, rolls and rusks, half a dozen kinds of cheeses, as well as many kinds of cold sausages cut into thin slices.

After seeing Mevrouw and Jan off on the train, the children mounted their wheels, and, in company with Mynheer, went bumping over the big round cobblestones with which Rotterdam is paved.

"Our city streets are not as good as our country roads, but we will soon be out in the[64] open country," said Mynheer, as they turned into the "Boompjes."

"Do you remember, Theodore," he continued, "your steamer landed you just at that dock opposite."

The "Boompjes" is a great quay alongside of which are to be seen all manner of steamships, from those which trade with the ports of Great Britain and Germany, to the little craft which ply up and down the rivers and canals of Holland, and the long barges and canal-boats with their brown sails.

Our bicycle party crossed many bridges over little and big canals. By the side of many of these canals the great tall houses seemed to grow right up out of the water, queer old houses with gables all twists and curves. At last they passed through the "Delftsche Poort," one of the old gateways of Rotterdam, and then out on to the smooth country road, still running by the side of the canal.

"Ah, this is better," said Pieter, as he gave a sigh of relief.

"No wonder cycling is popular in Holland; you have such fine, flat roads," said Theodore. "Just look at this one all paved with tiny bricks; why, it's like riding on a table-top."

"They are called 'klinkers,' and many of our roads are paved this way; but do you see that town just to the left, Theodore?" said Mynheer Joost, as he pointed to a jumble of houses, windmills, and masts of ships not far away. "That is Delfshaven; you know what happened there once long ago, do you not?"

"Oh, it was from there that the Pilgrim Fathers sailed for America," cried Theodore.

"But I thought they sailed from Plymouth, England," said Pieter.

"They did put into Plymouth, on account of a storm, but their first start was from Delfshaven. Can't we go and see the place where[66] they went on board ship, Cousin Joost?" said Theodore, who nearly tumbled off his wheel in his effort to see the town.

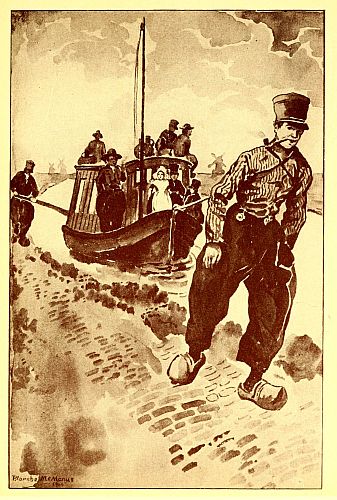

ON THE ROAD TO DELFSHAVEN

ON THE ROAD TO DELFSHAVEN

"I am afraid the spot could not be found now," smiled Mynheer. "Delfshaven has grown to be a big town since then; but you can see the church where they worshipped before they set sail."

So they turned on to the road into the town. The old church seemed plain and bare to Theodore, as he stood in it and looked at its simple white walls, and it was hard for him to realize that the history of New England began here.

"I must write Henry all about Delfshaven; he'd give a lot to be in my shoes, now," said Theodore, as they rode away again.

"Who is Henry?" asked Wilhelmina.

"He is a chum of mine and lives in Boston. You see his people came over with the Pilgrims, just as mine came over later from[67] Holland, and he is always talking a lot about the Mayflower and all that.

"But just see that woman pulling that big boat, and the two children helping her—think of it!" and Theodore forgot all about the Pilgrims in the strange sight before him.

"Those are barge-people; let us stop and rest awhile, and you can see them better," said Mynheer, who set the example by jumping off his wheel.

It did look like hard work, too, as the woman came slowly along, panting and straining at one end of a long rope. There was a loop in the rope which passed over her chest, and the other end was made fast to the prow of the barge, or "tjalk." Behind her were a little girl and a boy, not more than ten or twelve years old, each of them, like the mother, tugging away at the heavy load.

"Think of those little children helping to[68] move that great heavy boat! I don't see how they do it," said Wilhelmina.

"It must be hard work, but they don't seem to mind it," said her father.

It looked as if the children did not, for they were plump and round, and as they passed, they smiled shyly and said "Good morning," and kept looking back with grins of amusement.

"The father is the one who has the easy time," said Pieter; "see, he sits comfortably beside the big tiller, to which he only gives a slight turn once and again, for the canals are so straight that the 'tjalk' does not require much steering. He is quite content to let the Vrouw and the little ones tow the 'tjalk' while he smokes and dozes on deck."

"Well, it grows 'curiouser and curiouser,' as Alice in Wonderland said. Your roads are of water, and your wagons are boats, and your[69] people do the work of horses. Why don't they use horses?" demanded Theodore.

"Well the 'tjalks' really depend upon the wind to carry them along," said Mynheer. "You see this one has a big sail, and it is only when there is no wind that they have to tow the boats. Once they used dogs for the towing, but now the people who live on board do the work, and if it is slow, why, nobody seems to mind."

The barge was painted red and blue, and in the great rounded bow there were two round openings through which the anchor-chains passed, and which looked like big staring eyes, particularly at night, when a ray of light often shot through them.

"Of course some one is washing things, as usual," said Theodore; "even the barges don't escape a continual 'spring cleaning.' And sure enough, there was another woman splashing pailfuls of water over everything, even over[70] the drowsy Mynheer at the tiller. He was probably used to this, however, for he didn't take the slightest notice.

"Yes, indeed, the 'tjalk' owners take a great pride in the spick and span appearance of their boats," said Mynheer Joost. "You must remember that the 'tjalk' is their home. They are born on it, and often live and die there, as did their fathers and grandfathers before them, for many of these boats are very old. The little cabin on the poop is all the house they ever have, and they are just as proud of it as if it were a fine villa like that of Mynheer Van der Veer.

"You see," he continued, "they have their little garden, too. There are tulips planted in a box before the door, and a tiny path outlined with shells."

"And a little garden-gate, too," cried Wilhelmina; "isn't it funny?"

"Yes," said her father, "they like to think[71] that they have everything that goes with a house on land."

"There is a cage of birds, also," said Wilhelmina again, "and a little china dog sitting by the side of the tulip-bed, who seems to be watching them."

"I suppose if there were room enough in the garden there would be a summer-house, too," said Pieter.

There is no doubt but what the "bargees" enjoy their lives, and nothing would make them so unhappy as to have to live on dry land. There are thousands and thousands of these "tjalks" in Holland, and most of the merchandise of all kinds which is transported about the country is carried by them.

"Time to be on the road," said Mynheer to his young party; and before long they were all riding into the old town of Delft.

"Listen to those bells," cried Theodore,[72] "they are playing one of our popular American marches. Where are they?"

"Those are the chimes you hear ringing in the belfry," said Pieter. "They must be playing the march in your honour, Theodore."

Each town in Holland has its chime of bells, usually hung in the tower of the principal church. The chimes are played by means of a wonderful mechanical keyboard, and the Dutch are very fond of hearing them ring out the popular tunes of the day.

"It was in this place that long ago the famous blue and white Delftware was made, like that the mother has at home," said Mynheer. "There is Delftware made now, but it is not prized like the old kind.

"But we must not linger, children, if we are to reach The Hague for dinner," and he marshalled the young people again upon the road.

Soon they were skimming over the smooth, flat roadway, and came almost at once on to[73] fine boulevards lined with handsome houses, so they knew they were at The Hague itself.

The twins were as interested as their American cousin in the sights of their capital city, and Wilhelmina wanted to know at once if there would be a chance of their seeing the queen. You see she was named after Queen Wilhelmina, so she felt as if she had a right to see her, even more than other little Dutch girls, though indeed they are all fond of their young ruler, who not so very long ago was a young girl like Wilhelmina herself.

Wilhelmina had among her treasures at home a picture of Queen Wilhelmina, taken when she was a little girl, and dressed in the pretty Frisian costume, one of the prettiest of the national costumes of Holland.

"I can't say," smiled her father, in answer to Wilhelmina's question, "but we can go out to the 'Huis ten Bosch,' and maybe we shall[74] be fortunate enough to meet her out driving in the park."

After our friends had done justice to a good dinner at one of the famous hotels of The Hague, they left their bicycles at the hotel, and took the steam-tram to the "Huis ten Bosch," which is Dutch for "House in the Wood." It is one of the royal palaces of Holland and is situated in the midst of a beautiful wood. The forests of Holland are very much prized because there are so few of them, and so this "House in the Wood" is one of the favourite royal residences.

Though Wilhelmina did not see her queen, she saw the next best thing, for they went through the state apartments of the palace, and saw the beautiful Chinese Room and the Japanese Room, each of them entirely filled with beautiful things from the Orient.

"Now shall we go to Scheveningen, or are you too tired?" asked Mynheer.

"Tired!" The children laughed at the idea. They were out for a holiday, and were going to see as much as possible; and away they went again on another steam-tram to a fishing-town a few miles from The Hague, called Scheveningen, which is a big mouthful of a word, isn't it? This is where the fisherfolk live who go out in their stubby boats, called "pinken," to fish in the North Sea.

"I don't see the ocean," said Pieter, looking about him as they walked through the town, with its rows and rows of neat little houses of brick where the fishermen live.

"Climb up to the top of those sand-dunes and you will," said his father. "These dunes or banks of sand have been blown up by the wind and sea until they form a high wall or breakwater. There are many such all along the coast of Holland, and to keep the wind from blowing the loose sand back inland, over the fields and gardens, these banks of sand, or[76] dunes, are planted over in many places with grasses and shrubs, which bind the sand together and keep it in place."

"There is a fish auction going on over there: let's go down and see it," called out Pieter.

A boat-load of fish had just been landed on the beach, and a crowd of fishermen and women were standing around it. The women had big basket-shaped hats over their white caps, and the men wore baggy trousers and tall caps.

The fish were being auctioned off in the Dutch fashion, which is just the reverse of the usual auctioneering methods. A market price is put upon the fish, and the purchaser bidding the nearest thereto takes them.

"What are those things on the sands over there that look like big mushrooms, Cousin Joost?" asked Theodore, pointing to a spot half a mile or so farther on.

"They do look something like mushrooms, Theodore," said his uncle, "and they come and go about as quickly. They are the straw chairs and shelters in which visitors sit when they are taking the fresh air on the sands."

These chairs are closed in on all sides but one, and have a sort of roof over them, so as to protect the occupant from the wind and rain. Scheveningen, besides being one of the largest fishing-towns in Holland, is the great seaside resort of the Dutch people. Here the well-to-do burghers and merchants come with their Vrouws and sit in the big basket-chairs, while the children dig miniature canals and build toy dikes in the sand, modelled after those which surround their homes.

When our tourists got back to The Hague they walked around and looked at the fine houses of the city. They saw, too, the storks in the market-place, around which were many[78] fisherwomen with their wares spread out for sale. The storks are well fed, and are kept here at the expense of the city, for good luck, perhaps.

The children thought they had cycled quite enough for one day, so they put their wheels and themselves in the train for Leyden, and were soon tooting into one of the oldest cities of Holland.

"Are we there already?" asked Theodore, amazed at the shortness of the journey.

"Yes, everything is close together in our little Holland," said Mynheer.

The Dutch are very proud of Leyden for many reasons, but especially for the brave defence the city made against the Spaniards at the time when the sturdy Dutch were fighting to free themselves from the rule of Spain. The city was besieged for nearly a year, but the plucky burghers never gave in. The city was finally saved by cutting the dikes, and[79] letting in the waters, so that the Dutch fleet could sail right up to the city walls and thus drive off the enemy. It is said that to reward the people of Leyden for their bravery and courage, the government afterward offered to either free them forever from all taxes, or to give them a university. They wisely chose the latter, and this same University of Leyden has always ranked among the great institutions of learning throughout the world, and many great men have studied within its walls.

"Your friend Henry would like to see Leyden, also," said Mynheer. "It was here that the Pilgrim Fathers lived for many years before they finally set sail for the New World. The city gave them a safe shelter, when they were persecuted and driven from other lands, and for this reason alone Leyden should always be remembered by our American cousins."

"Don't you feel as if you had been up two[80] whole days?" asked Theodore of Pieter, as he gave a big yawn; but Pieter and Wilhelmina were already fast asleep as the train whirled them on toward Haarlem.

None of the children talked much either while they ate the hot supper Mevrouw Joost had ready for them, and soon they were tucked away in their beds. But the next day you should have heard the three tongues wag, and Mevrouw and Baby Jan had to hear all the adventures over again many times.

"What a jumble of ships and houses! I shouldn't think you would know whether you were going into a house or aboard ship, when you open the front door," said Theodore, one fine summer's day, when the cousins were strolling about Amsterdam, on their way to pay the promised visit to Mynheer Van der Veer.

Others besides Theodore might think the same thing, for Amsterdam really grew up out of the water. The houses are, for the most part, built on wooden piles; and there are as many canals as there are streets, and big ships move about between the buildings in the most wonderful manner.

They found Mynheer Van der Veer smoking his meerschaum pipe at his warehouse on one of the principal canals. He was glad indeed to see his little friends of the tulip-garden, as he called them, and showed them all around the big establishment. They saw the big ships that were anchored right at his door, and the bales and boxes being loaded into their holds from the very windows of the warehouse itself. He showed them the coffees and sugars and spices which other ships had brought from the Dutch East Indies, which as you all know are around on the other side of the world. Holland owns some of the richest islands in the world, many of them larger than Holland itself. One of these islands is Java, where the fine Java coffee comes from, and this is one of the reasons why the Dutch always have such good coffee, and drink so much of it.

Mynheer gave them all nice spices to taste,[83] and was amused at the faces they made at some hot peppery things they were eager to try.

After this he took them to his fine, tall house that faced on another canal, where there were long rows of other tall houses, all built of tiny bricks and as neat as pins. All of them were as much alike, in their outside appearance at least, as a row of pins, too. Here the children met the portly Mevrouw Van der Veer in her rustling silk dress, who gave them a warm welcome.

She had just come in from a walk, and on the top of her beautiful lace cap with its gold ornaments she wore a very fashionable modern hat.

"Oh," thought Wilhelmina, "why does she spoil her fine cap like that?" But you see many Dutch ladies who combine the old and the new styles in just that way.

They all sat in Mevrouw's fine parlour, with[84] its shining waxed floor, which was filled with beautiful things from all parts of the world. There was furniture of teak-wood from India, wonderfully carved, and rare china and porcelain from China and Japan. Exquisite silk curtains hung at the windows, and embroidered screens cut off any possible draughts.

These rare things had been brought from time to time in Mynheer's ships, as they were homeward bound from these far-off countries.

Mevrouw sat before a little table laden with silver and fine china, and poured coffee for them from a big silver coffee-pot, and gave them many kinds of nice Dutch cakes to eat; and when she said good-bye she promised Mynheer Joost that she would come some day and see his tulip-garden herself.

"Why was that small looking-glass fastened outside of one of the upper windows?" asked Theodore, as they left Mynheer Van der Veer's house.

"Many of these Dutch houses have these little mirrors fastened before the windows at such an angle that by merely looking in it from the inside, one may see who is at the front door," said his cousin; "and then, too, the ladies can sit by the window, sewing or reading, and can amuse themselves by watching what is going on in the street below, without troubling to look out of the window."

"I should hate to have to wear a dress like that," said Wilhelmina, looking at two young girls who were passing by. It did look strange, for one half of their dress was red and the other half black.

"They are the girls from the orphanage, and this is the uniform that they all must wear," said Mynheer Joost.

"Now Theodore must see some of the pictures of our great painters," he continued, as he led the young folks toward the splendid picture-gallery, where they strolled through what[86] seemed to them miles of rooms and corridors, all hung with beautiful and valuable pictures, for little Holland has had some of the greatest artists the world has ever known, and some day, if you care about pictures,—and you certainly should,—you will want to go there and see them for yourself.

After this they did a great deal more sight-seeing, and Mynheer showed them the "Exchange," where the business of the city is carried on, and told them that there was one week in the year when the boys of Amsterdam were allowed to use the "Exchange" for a playground.

This was a reward for the good deed of some brave boys of long ago, when the Spaniards were plotting to capture the city. The boys, it seems, first discovered the secret, and went and informed the authorities, who were thus able to defend their city from attack.

"This," said Mynheer, "was the case when[87] I was young, and I suppose the boys are still allowed the same privilege."

Our little folk were glad enough to take their seats on the deck of the little steamboat which was to take them to Alkmaar, the centre of the cheese-trade of North Holland.

"Whew! but we have done a lot of tramping about to-day; oh, my poor feet!" said Pieter, as he stretched himself out on a bench.

"Father, haven't you got something for us to eat in your pocket?" asked Wilhelmina, coaxingly.

Mynheer smiled, and from away down in the depths of his pocket, he drew forth a big loaf of gingerbread. The children munched away at this favourite Dutch delicacy, and amused themselves by watching the people who were making the journey with them.

There were two fat old women, sitting side by side and knitting away as if for their lives. They nodded their heads every time they[88] spoke, which made their long gold corkscrew ornaments in their caps bob up and down, and each had her feet on a little foot-stove as if it were midwinter. There were two little girls with their father, who looked like little dolls, in short red dresses, with dark green waists and short sleeves, and pretty aprons embroidered in many coloured silks, and many gold chains, and earrings reaching nearly down to their shoulders. They had a solid gold head-piece under their caps. The man had on velvet knickerbockers, nearly as broad as they were long, and two great silver rosettes fastened in his belt. There were big silver buttons on his jacket, and his cap must have been over a foot high.

The little girls were very shy, but when Wilhelmina offered them some of her gingerbread they soon made friends, and the three were soon chatting away like old acquaintances.

"Aren't they gorgeous?" whispered Pieter. "They are from the little island of Marken, near here, in the Zuyder Zee, and have on all their holiday clothes."

The island of Marken is like a big bowl, Mynheer told them, for all of it but the rim is lower than the waters which surround it. The rim is a high stone wall which was built to keep the water out. Everybody who lives there keeps a boat tied to their gate or door in order that they may have some means of escape if the wall should ever break.

"Just think of it! I should never sleep nights, if I lived there, for fear of waking up and finding myself floating about in the water. I should think the Dutch would be the most nervous people in the world, instead of the most placid," said Theodore.

"That danger does not often happen," said Mynheer. "But look how beautifully carved their shoes are. The men do it themselves[90] during the long winter evenings, and take great pride in their work."

The little steamer puffed along the North Sea Canal, by which the big ships come right up to Amsterdam. All kinds of queer tublike boats, with big brown sails, tanned to preserve them from the damp, passed them, and soon they turned into the river Zaan.

"There is Zaandam," said Mynheer; "they say that most of the people who live there are millionaires. It is a wealthy little town."