Nestleton Magna

Rev. Jackson Wray

Title: Nestleton Magna: A Story of Yorkshire Methodism

Author: J. Jackson Wray

Release date: January 26, 2013 [eBook #41916]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Lindy Walsh, Matthew Wheaton and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Nestleton Magna

Rev. Jackson Wray

NESTLETON MAGNA.

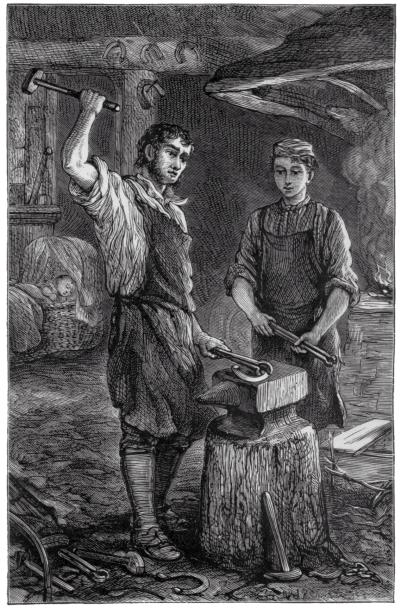

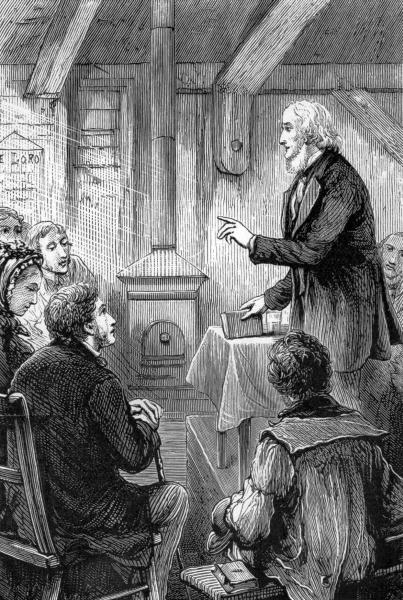

NATHAN AT WORK.—Page 294.

Thirtieth Thousand.

LONDON:

JAMES NISBET & CO., 21 BERNERS STREET.

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co

At the Ballantyne Press

TO THE

METHODIST CHURCHES

THROUGHOUT

THE WORLD,

NUMBERING SOME FIFTEEN MILLIONS OF ADHERENTS,

This Book is respectfully Dedicated,

IN HEARTY ADMIRATION OF THEIR NOBLE LABOURS IN

THE HIGHEST INTERESTS OF HUMANITY,

AND IN THE EXTENSION OF THE REDEEMER’S KINGDOM;

WITH THE EARNEST HOPE THAT,

UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DIVINE PROVIDENCE, THEY WILL

SPEEDILY BE ABLE TO

ADOPT SOME PRINCIPLE OF CONFEDERACY,

BY MEANS OF WHICH THEY MAY PRESENT

A UNITED AND RESISTLESS FRONT AGAINST EVERY FORM OF

ANTI-CHRIST, AND

IN LOVING CO-OPERATION WITH OTHER CHRISTIAN CHURCHES,

MAY SOON

“WIN THE WORLD FOR CHRIST.”

In this book I have sought to present a faithful picture of village Methodism—a picture which I do not hesitate to say is being reproduced to-day, as far as Church work and beneficent piety is concerned, in many a village in this country. I have had, for more years than I care to count, an intimate knowledge of Methodist rural life. Nathan Blyth, Old Adam Olliver and his wife Judith, and some other characters in the book, not excepting Balaam, have, unconsciously, stood for their portraits; and I dare to say that those parts of the story which have to do with Methodist operations and influences, will not be considered as overdrawn by those who are most conversant with the inner life of the Methodist people. If it be asked why I have presented my pictures in fictitious frames, my answer is, that I was bound to follow my natural bent, and to allow my pen to pursue the lines most congenial to the hand that wielded it; that, of all kinds of literature, fiction is the most attractive, and as it is utterly useless to try to prevent its perusal, wisdom and religion, too, suggest that it should be provided of so pure a quality, and with so definitely a moral and religious bias, that it may not only do no harm but some good to the reader, who would otherwise go further and fare worse. I have honestly endeavoured so to write as to be able to quote dear Old Bunyan, and say,—

The rapid sale of the former editions of “Nestleton Magna,” and the numerous criticisms to which it has been subjected, have given me a welcome and unexpectedly early opportunity of giving it a careful revision, especially in the rendering of the East Yorkshire dialect. It is now presented to the public in a new and much improved form, and at a price which will bring it within the reach of all classes. The liberal and spontaneous patronage, and the highly-favourable reviews which this my first venture has received, merit my hearty thanks, and encourage me to a new trial of skill in the same direction. According to the unanimous and emphatic testimony of a large jury of reviewers, “Aud Adam Olliver” is fully worthy of the esteem I have sought to win for him; I cannot, therefore, do better than quote the words of the godly old patriarch, in acknowledgment of their verdict and the popular approval, “Ah’s varry mitch obliged te yo’.”

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Nestleton Magna | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| “Blithe Natty,” the Harmonious Blacksmith | 5 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| “Master Philip” | 11 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| “Aud Adam Olliver” | 16 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| “Black Morris” | 22 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Philip’s Visit to the Forge; or, Love’s Young Dream | 28 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Kesterton Circuit and the “Rounders” | 33 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Adam Olliver Begins to Prophesy | 40 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Progress of Master Philip’s Wooing | 47 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Black Morris is More Free than Welcome | 53 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Both Philip and Lucy Make a Clean Breast of it | 59 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Adam Olliver in the “Methodist Confessional” | 66 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Squire Fuller Pays a Visit to the Forge | 76 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Aud Adam Olliver “Sees About It” | 83 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Nathan Blyth is the Victim of a Gunpowder Plot | 89 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Squire Fuller Receives a Deputation | 98 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Dr. Jephson Gives an Unprofessional Opinion | 106 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Philip Fuller Makes a Discovery | 112 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Black Morris is Taken by Surprise | 119 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Kasper Crabtree Falls Among Thieves | 126 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Squire Fuller Hears Unwelcome News | 133 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Lucy Blyth Makes a Conquest | 140 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Dark Deed In Thurston Wood | 150 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| “Balaam” is Taken into Consultation | 157 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Nathan Blyth is in a Quandary | 163 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Dr. Jephson’s Prescription Works Wonders | 170 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Hannah Olliver’s “Young Man” | 177 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Bill Buckley Sees an Apparition | 183 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| The Story of the Dead-Alive | 191 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Midden Harbour has a New Sensation | 198 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| “Balaam” Declares Himself a “Spiritualist” | 206 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Piggy Morris Hears “A Knock at the Door” | 212 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Squire Fuller Introduces an Innovation | 221 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Lucy Blyth has an Eye on Landed Property | 230 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Aud Adam Olliver to the Rescue | 239 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Sister Agatha’s Ghost | 247 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Philip Fuller Boldly Meets his Fate | 257 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Black Morris “Wants that Brickbat Again” | 267 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Nestleton Puts on Holiday Attire | 276 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| An Episode in a Methodist Love-feast | 285 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| The Revolution in Midden Harbour | 292 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| Aud Adam Olliver’s “Nunc Dimittis” | 299 |

![]() NESTLETON MAGNA is as “canny” a little village as can be found in any

portion of the Three Kingdoms; and that is saying a good deal, for

there are rural gems within British borders which are quite unequalled

for cosiness and beauty by anything you can find within the four

quarters of the globe, even if you take “all the isles of the ocean”

into the bargain. Situated in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and

nestling like a brooding bird in the[Pg 2] fertile valley of Waverdale, at

the foot of the Yorkshire Wolds, it possesses rare and quiet charms,

which elicit the spontaneous admiration of those not numerous

tourists, who prefer to explore the rich resources of English inland

scenery, rather than fag through the hurry-skurry and unsatisfactory

whirl of Continental travel. There is many a jaded man of business,

many a brain-worn student, who foolishly squanders the precious hours

of his brief holiday in rushing insanely over weary miles, through hot

and dusty cities, among tiresome hills and rugged mountains—returning

home again weary and worn—who would have found real rest and health,

and equally varied and charming landscapes, within the borders of his

motherland.

NESTLETON MAGNA is as “canny” a little village as can be found in any

portion of the Three Kingdoms; and that is saying a good deal, for

there are rural gems within British borders which are quite unequalled

for cosiness and beauty by anything you can find within the four

quarters of the globe, even if you take “all the isles of the ocean”

into the bargain. Situated in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and

nestling like a brooding bird in the[Pg 2] fertile valley of Waverdale, at

the foot of the Yorkshire Wolds, it possesses rare and quiet charms,

which elicit the spontaneous admiration of those not numerous

tourists, who prefer to explore the rich resources of English inland

scenery, rather than fag through the hurry-skurry and unsatisfactory

whirl of Continental travel. There is many a jaded man of business,

many a brain-worn student, who foolishly squanders the precious hours

of his brief holiday in rushing insanely over weary miles, through hot

and dusty cities, among tiresome hills and rugged mountains—returning

home again weary and worn—who would have found real rest and health,

and equally varied and charming landscapes, within the borders of his

motherland.

Nestleton Magna is surrounded by emerald hills, which slope gently down to the valley in which the hamlet lies, displaying a varied surface of wood and glade, of cornland and pasture-ground, and surmounted by a stretch of moorland, whereon the sheep crop the scantier herbage, and the morning mists hang like silver curtains until the “rosy fingers of the sun” draw them aside, and then purple heath and golden gorse gleam and glitter on them like a royal crown. Most of the cottages are thatched and white-washed, and not a few are embowered in honeysuckle and jasmine. Here and there a more pretentious dwelling lifts its head, and these with their red bricks and tiles give piquant variety to the picture. Through the village there flows a babbling brook, in whose clear, transparent waters the speckled trout may be seen poising themselves with waving fin, or darting like an arrow above the gravelly bed, while sticklebacks and minnows disport themselves in their crystal paradise. Along its borders are two rows of unshorn willows, and here and there a poplar lifts its stately head. On either side, in and out among the cosy cottages, are little patches of garden ground, small tree-shaded paddocks, and orchards which in sunny spring-time are flush with the manifold blossoms of[Pg 3] apple, plum, pear, and cherry-trees, which add a peculiar charm to the attractive scene.

The quaint old church stands on rising ground in the centre of the village, and its short, square Norman tower, ivy-clad and pinnacled, is almost overtopped by the gables of the ancient rectory which stands close by. The church, the rectory grounds, and the pretty little churchyard are enclosed and shadowed by a circle of fine old elms, in which a colony of rooks have been established from time immemorial, and their monotonous and familiar cawing gives a sylvan finish to the scene. Near the little wych gate of the churchyard a spacious and open green affords a pleasant playground for the chubby children, of whom Nestleton Magna provides quite a notable supply, a gossipping place for the village rustics in the evening hours, and pasturage for two or three cows, a donkey or two, and, last not least, a flock of geese, whose solemn-looking gander oft disputes possession of the field with the aforesaid chubby children, who flee motherward before it in undisguised alarm.

Neither is Nestleton Magna without its lions, and of these the Nestletonians are justly proud. In Gregory Houston’s “Home-close,” on the Abbey Farm, there are the veritable ruins of the ancient cloisters wherein, in darker times, the Waverdale nuns led ignoble and wasted lives. The crumbling walls and tottering archways, and grass-grown heaps of stone, are all covered with ivy bush, bramble, and briar; but if tradition is to be believed, there are underground passages to the parish church on the one hand, and reaching even to Cowley Priory on the other, where, in “the good old times,” a fraternity of Franciscan friars ruled the roast and played[Pg 4] queer pranks in Waverdale, according to the manner of their tribe. Nestleton Abbey, for by that name are the ruins known, is reputed to be haunted. It is said that long, long ago, a certain nun called Agatha, having been placed under penance, did in wicked revenge stab her offending Lady Superior to the heart, and then, in bitter remorse, did plunge the fatal knife into her own. From that day to this she has never rested quiet in her unhallowed grave, but ever and anon “revisits the glimpses of the moon,” attired in a white robe with a crimson stain upon the breast, and flits among the ruins with uplifted hands, wailing out the unavailing plaints of her unshriven soul. Surely it is given to few villages to possess so veritable and renowned a wonder as “Sister Agatha’s ghost.” Then there is St. Madge’s Well, in Widow Appleton’s croft—once a far-famed shrine, to which devout pilgrimages were made from far and near, and which is credited to this day with certain healing virtues second only to those of Bethesda’s sacred pool. Pure, bright, cold and crystalline, its waters strongly impregnated with iron, it bubbles up unceasingly in the cool grot, overshadowed by flowering hawthorn, fragrant elder, and purple beech, and no visitor to Waverdale could ever think of neglecting to visit this charming nook, or drinking from the iron cup chained to its stone brink, a refreshing draught from its crystal spring. At least, if he did, Widow Appleton’s money-box would be defrauded, and that brisk and cheery old dame in neat black gown and frilled white cap, would wish to know the reason why.

Time would fail to tell all the beauties of Nestleton Magna, and of that lovely valley of Waverdale, of which it is the loveliest gem. For the present, Waverdale Park, Thurston Wood, Cowley Priory, and a host of minor marvels must be content with passing mention—content to wait their several occasions in the development of this simple and veracious story of Yorkshire village life.

![]() NEARLY at the eastern end of Nestleton stood the village forge, a

spacious low-roofed building, in which Nathan Blyth, the blacksmith,

and his father before him, had wielded the hammer by the ringing

anvil, fashioning horse-shoes, forging plough-shares, and otherwise

following the arts and mysteries of their grimy craft. Close to the

smithy stood Nathan’s cottage, though that is almost too humble a name

to give to the neat and roomy dwelling which owned the stalwart

blacksmith for its lord and master.[Pg 6] True it was thatched and

white-washed like its humbler neighbours, but it boasted of two good

stories, and had a latticed porch, which, as well as the walls, was

covered with roses, jasmine, and other floral adornments. At the gable

end was a tall and fruitful jargonelle pear-tree, which not only

reached to the very peak of the gable, but like Joseph’s vine, its

branches ran over the wall, and were neatly tacked with loops of cloth

behind the house, and almost as far as the lowlier porch which

screened the kitchen entrance thereto. Both “fore and aft,” as the

sailors say, was a spacious and well-managed garden, whose fruits,

flowers, and vegetables, trim walks and tasteful beds, testified to

the fact that their owner was as skilful with the spade and the rake

as he was with the hammer, the chisel, and the file.

NEARLY at the eastern end of Nestleton stood the village forge, a

spacious low-roofed building, in which Nathan Blyth, the blacksmith,

and his father before him, had wielded the hammer by the ringing

anvil, fashioning horse-shoes, forging plough-shares, and otherwise

following the arts and mysteries of their grimy craft. Close to the

smithy stood Nathan’s cottage, though that is almost too humble a name

to give to the neat and roomy dwelling which owned the stalwart

blacksmith for its lord and master.[Pg 6] True it was thatched and

white-washed like its humbler neighbours, but it boasted of two good

stories, and had a latticed porch, which, as well as the walls, was

covered with roses, jasmine, and other floral adornments. At the gable

end was a tall and fruitful jargonelle pear-tree, which not only

reached to the very peak of the gable, but like Joseph’s vine, its

branches ran over the wall, and were neatly tacked with loops of cloth

behind the house, and almost as far as the lowlier porch which

screened the kitchen entrance thereto. Both “fore and aft,” as the

sailors say, was a spacious and well-managed garden, whose fruits,

flowers, and vegetables, trim walks and tasteful beds, testified to

the fact that their owner was as skilful with the spade and the rake

as he was with the hammer, the chisel, and the file.

And that is saying much, for Nathan Blyth had a wonderful repute as the deftest master of his handicraft within twenty miles of Waverdale. You could not find his equal in the matter of coulters and plough-shares. Farmer Houston used to say that his horses went faster and showed better mettle for his magic fit in the way of shoes; and as for millers’ chisels, with which the millstones are roughened to make them “bite,” they were sent to him from thirty miles the other side of Kesterton market town to be tempered and sharpened as only Nathan Blyth could. Then, too, he was handy in all things belonging to the whitesmith’s trade. He could doctor the smallest locks, and understood the secrets of every kind of catch and latch; the farm-lads of the village would even bring their big turnip watches to him, and the way in which he could fix a mainspring or put to rights a balance-wheel was wonderful to see.

Natty Blyth was a fine specimen of humanity from a physical point of view. He stood five feet eleven in his stockings, and at five-and-forty years of age had thews and sinews of Samsonian calibre and power. A bright, honest, open face, had Nathan; a pair of thick eye-brows, well[Pg 7] arched, surmounted by a bold, high forehead, and quite a wealth of dark brown hair. His happy temper, his merry face, and his constant habit of singing at his toil, had got him the name of “Blithe Natty,” and justly so, for a blither soul than he you could not find from John-o’-Groats to Land’s End, with the Orkneys and the Scilly Isles to increase your chances. Whenever he stood by his smithy hearth, his clear tenor voice would roll out its mirthful minstrelsy, while the hot iron flung out its sparks beneath his hammer, defying the ring of the anvil either to drown his voice or spoil his tune.

One fine spring morning, Blithe Natty was busy at his work, and, as usual, his voice and his anvil were keeping time, when old Kasper Crabtree, a miserly old bachelor, who farmed Kesterton Grange, stole on him unobserved. Natty was singing away—

“Aye, that’s right,” said Kasper Crabtree. “Honest duty, as you say, is the right sort of thing. I only wish my lazy fellows did a little more on ’t.”

“A little more” was Kasper Crabtree’s creed in a word.

“Why, you see,” said Blithe Natty, “its often ‘like master like man’; pipe i’t parlour, dance i’t kitchen; an’ maybe if you were to do your duty to them a little better they would do better by you. ‘Give a pint an’ gain a peck; give a noggin’ an’ get nowt.’”

Kasper Crabtree did not relish this salutary home-thrust, and made haste to change the subject.

“What a glorious morning it is!” said he, “it’s grand weather for t’ young corn.”

“Aye,” said Natty, “I passed by your forty-acre field yesterday, and your wheat looked splendid. The rows of bright fresh green looked very bonny, and the soil was as clean as a new pin.”

“Hey, hey,” said old Crabtree, for he was proud of his farming, and boasted that his management was without equal in the Riding, “I’ll warrant there isn’t much in the way of weeds, though it’s a parlous job to keep ’em under. It beats me to know why weeds should grow so much faster than corn, and so much more plentiful.”

“Why, you see, Farmer Crabtree, weeds are nat’ral. The soil is their mother, an’ you know it’s only stepmother to the corn, or you wouldn’t have to sow it; and stepmothers’ bairns don’t often thrive well. However, I’m pretty sure that you are a match for all the weeds that grow—in the fields, at any rate.”

“Hey, or anywhere else,” said the boastful farmer.

“Why, I don’t know so much about that,” said Natty. “There’s a pesky lot o’ rubbish i’ the heart, Maister Crabtree, an’ like wicks an’ couch grass there’s no getting to the bottom on em. The love of money, now, is the root of”——

But Kasper Crabtree was off like a shot, for Blithe Natty’s metaphor was coming uncomfortably close to a personal application, and his hearer knew of old that Nathan was in the habit of striking as hard with his tongue as he did with his hammer, so he rapidly beat a retreat. Natty’s face[Pg 9] broadened into a smile as he pulled amain at the handle of his bellows, and then drawing from the fire the red-hot coulter he was shaping, he began thumping away amid a shower of fiery spray, singing, as his wont was—

The coulter was again thrust into the fire, and once again the long lever of the blacksmith’s bellows, with a cow’s horn by way of handle, was gripped to raise another “heat,” when a second visitor crossed the smithy threshold, as different from the grim, gaunt, wrinkled and forbidding form and features of old Kasper Crabtree as a briar-rose differs from a hedgestake, an icicle from a sunbeam, or a polar bear from a summer fawn.

Gathering her skirts of neat-patterned printed calico around her to keep them from the surrounding grime, the new-comer stole noiselessly behind the unconscious smith, laid her dainty hands on his brawny shoulders, and springing high enough to catch a kiss from his swarthy cheek, landed again on terra firma, and, with a ripple of laughter which sounded like a strain of music, stood with merry, upturned face to greet Blithe Natty’s startled gaze.

“Give me that back again, you unconscionable thief!” said Nathan, laying his big hand on her dainty little wrist. “It’s flat felony, and I’ll prosecute you with the utmost rigour of the law.”

“Can’t do it, sir. You’ve no witnesses, and the offence isn’t actionable;” and the doughty little damsel took another from the same place with impunity.

There was a wondrous light in the eyes of Nathan Blyth, as he looked in the fair face of the beautiful girl, the light of a love surpassing the love of women, for was she not his only child, and the very image of the wife and mother, now a saint in heaven, and still loved by him with a tender fidelity that seemed to deepen and strengthen with the lapse of time? No deeper, truer, more concentrated affection ever glowed in the breast of man, than that which filled the heart of Nathan Blyth for his peerless Lucy, and sure I am that none was ever more richly merited.

![]() THE brief spring day had faded into night. Nathan Blyth raked out his

smithy fire, laid aside his leather apron, locked up the forge, and

after an extensive and enjoyable ablution, was seated by the little

round table in the cosy kitchen, discussing the tea and muffins which

Lucy had prepared for their joint repast. That young lady presented a

very piquant and attractive picture. In what her winsomeness consisted

it would be difficult to say: certainly, she was possessed of unusual

charms of face and form, but it is equally certain that these

constituted only a minor element in the glamour of a beauty which

commanded unstinted admiration. With much wisdom and at much[Pg 12]

self-sacrifice, Nathan Blyth had sent his daughter to a distant and

noted school for several years, and thanks to this and her own clear

intellect and singular diligence, she had obtained an education

altogether in advance of most girls of her age in a much higher rank

of social life. Her pleasant manners and maidenly behaviour made her

justly popular among the villagers, and many a farmer’s son in and

around Nestleton would have gone far and given much for a preferential

glance from her lustrous hazel eyes, and for the reward of a smile and

a word from lips which had no parallels amid the budding beauties of

Waverdale.

THE brief spring day had faded into night. Nathan Blyth raked out his

smithy fire, laid aside his leather apron, locked up the forge, and

after an extensive and enjoyable ablution, was seated by the little

round table in the cosy kitchen, discussing the tea and muffins which

Lucy had prepared for their joint repast. That young lady presented a

very piquant and attractive picture. In what her winsomeness consisted

it would be difficult to say: certainly, she was possessed of unusual

charms of face and form, but it is equally certain that these

constituted only a minor element in the glamour of a beauty which

commanded unstinted admiration. With much wisdom and at much[Pg 12]

self-sacrifice, Nathan Blyth had sent his daughter to a distant and

noted school for several years, and thanks to this and her own clear

intellect and singular diligence, she had obtained an education

altogether in advance of most girls of her age in a much higher rank

of social life. Her pleasant manners and maidenly behaviour made her

justly popular among the villagers, and many a farmer’s son in and

around Nestleton would have gone far and given much for a preferential

glance from her lustrous hazel eyes, and for the reward of a smile and

a word from lips which had no parallels amid the budding beauties of

Waverdale.

Lucy’s mother, a quiet, unpretentious woman, whose solid qualities and amiable disposition her daughter had inherited, had died some five years before the opening of my story; but the well-kept grave, the perpetual succession of flowers planted there, and the fresh-cut grave-stone at its head, gave proof enough that the widower and orphan kept her memory green.

For a long time after his wife’s death Nathan Blyth had lived a lonely and a shadowed life. His anvil rang as loudly, because his hammer was wielded as lustily as before, but his grand, clear, tenor voice was seldom lifted in cheerful song. Time, however, that merciful healer of sore hearts, had gradually extracted the sting of his bereavement, and loving memories, sweet and tender, took the place of the aching vacuum which had been so hard to bear. In his blooming daughter, lately returned from school in all the fair promise of beautiful womanhood, Nathan saw the express image of his sainted wife. So now again his home was lighted up with gladness, and from the hearthstone, long gloomy in its solitude, the shadows flitted: for as Lucy tripped around, performing her domestic duties with pleasant smile and cheery song, Nathan waxed content and happy, and no words can describe the joy the sweet girl felt as she heard the old anvil-music ringing at the forge and saw the olden[Pg 13] brightness beaming on his face. And so it should ever be:—

“Father,” said Lucy, as the pleasant meal proceeded, “What has become of Master Philip? Before I went to school he used to come riding up to the forge on his little white pony nearly every day. You and he were great friends, I remember, and I have never seen him since I came back.”

“Why, little lassie,” said Nathan, “you and he were quite as good friends as we were. Indeed, I’m pretty sure that his visits were quite as much for your sake as mine. At any rate, Master Philip would never turn his pony’s head towards Waverdale Park until he had seen ‘his little sweetheart,’ as he called you, and I’m bound to say, Miss Lucy, that you were quite as well pleased to see his handsome face and to hear the ring of his merry voice as ever I was—though I did not mean to make you blush by saying so.”

The concluding words only served to deepen and prolong the ingenuous blush which now dyed the face of Lucy with a rosy red.

“Well, father,” said Lucy, laughing, “I own I liked the bright open-hearted boy, who brought me flowers from his papa’s conservatory, and gave me many a ride on his long-maned pony, but I was only a little girl then”——

“And now you are a big woman, and as old as Methusaleh, you withered little witch,” said Blithe Natty, as he drew his heart’s idol to his side, and planted a kiss upon her brow. “Well, Master Philip went to college soon after you went to school, and his visits to Nestleton have been few and far between. He has grown into a fine young man now, and they tell me that he has borne off all the honours of the university. The old squire is as proud of his son as a hen with one chick, and small blame to him for that. He has just returned home for good; but,” said he, in a tone so serious as to surprise the unconscious maiden, “my little lassie must not expect any more pony rides or accept hothouse flowers from his hands again.”

“Of course not,” said my lady, arching her neck and fixing her dark eyes on her father in innocent amaze, “I don’t think Lucy Blyth is likely to forget herself or bring a cloud on ‘daddy’s’ face.”

“Neither do I, my darling,” said Nathan, as another and still another osculatory process proclaimed a perfect understanding between the doting father and his motherless girl.

Master Philip, the subject of the foregoing conversation, was the only son and heir of Ainsley Fuller, Esq., of Waverdale Park, who owned nearly all the village of Nestleton, many a farm round, and half the town of Kesterton into the bargain. The squire, as he was called, was rich in worldly wealth, but poor in human sympathies and the more enduring treasures of the heart. In early life[Pg 15] he had essayed to run a political career; but his first constituency turned their backs upon him, and on the second he turned his back, disgusted at the pressure brought to bear upon him by a predominant radicalism. Unfortunate in his wooing, his first and only true love was taken from him by death, and a lady to whom he was subsequently betrothed was stolen from him by a successful rival on the eve of the bridal day. After living to middle age, and developing a disposition half cynical and accepting a creed half sceptical, he had suddenly and unwisely married a youthful wife, whose tastes and habits of life were altogether foreign to his own. A brief span of unhappy married life was closed by the death of that lady, leaving the new-born babe to the sole guardianship of the seemingly cold and irascible father, whose whole affection, small in store apparently, was fixed on the infant squire—the Master Philip of this story.

Those, however, who depreciated the measure of Squire Fuller’s love for his only son were much mistaken. His immobile features and piercing eyes, peering from beneath the bushy brows of silver grey, told nothing of the mighty love that lurked within. Nor did Philip himself, for a long time, at all discern, beneath his father’s cold exterior, how the old man really doted on his boy. That remained to a great extent a secret, until a strangely potent key was inserted among the hidden wards of the parental heart, and a rude wrench flung wide the flood-gates, and set free the imprisoned stream.

![]() THE nearest neighbour to Nathan Blyth was an old farm labourer called

Adam Olliver, who for forty years and more, as man and boy, had toiled

and moiled on Gregory Houston’s farm. He had now reached an age at

which he was unequal to prolonged and heavy labour, and so he spent

his time in cutting and trimming the farmer’s hedges—his thoughtful

master giving him to understand that though his wages were to be

continued as usual, he was at full liberty to work when it pleased

him, and to rest when he chose. The old man used to ride to and from

his labour on a meek and mild old donkey, which rejoiced in the name

of Balaam, and which was never known to travel at any other pace than

a slow jog-trot, or to carry any other rider[Pg 17] than his master. No

sooner did old Balaam become conscious that he was bestridden by any

unfamiliar biped, than he curved his neck downwards, placed his head

between his knees, elevated his hinder quarters suddenly into mid-air,

and ejected the unwelcome tenant of the saddle, and with so brief a

notice to quit, that he had generally completed an involuntary

somersault, and was landed on Mother Earth, before he knew the nature

of the indignity to which he had been subjected.

THE nearest neighbour to Nathan Blyth was an old farm labourer called

Adam Olliver, who for forty years and more, as man and boy, had toiled

and moiled on Gregory Houston’s farm. He had now reached an age at

which he was unequal to prolonged and heavy labour, and so he spent

his time in cutting and trimming the farmer’s hedges—his thoughtful

master giving him to understand that though his wages were to be

continued as usual, he was at full liberty to work when it pleased

him, and to rest when he chose. The old man used to ride to and from

his labour on a meek and mild old donkey, which rejoiced in the name

of Balaam, and which was never known to travel at any other pace than

a slow jog-trot, or to carry any other rider[Pg 17] than his master. No

sooner did old Balaam become conscious that he was bestridden by any

unfamiliar biped, than he curved his neck downwards, placed his head

between his knees, elevated his hinder quarters suddenly into mid-air,

and ejected the unwelcome tenant of the saddle, and with so brief a

notice to quit, that he had generally completed an involuntary

somersault, and was landed on Mother Earth, before he knew the nature

of the indignity to which he had been subjected.

Adam was somewhat short in stature, thick-set in form and frame; his hair was short and grizzly, and his thick iron-grey eyebrows overarched a pair of twinkling blue eyes, full of keen insight and kindly humour. His fustian coat and battered “Jim Crow,” like his wrinkled and sun-browned features, were “weather-tanned, a duffil grey,” and, like his own bending frame, were a good deal worse for wear. A pair of old corduroy nether garments, buttoned at the knees, with gaiters of the same material, affording a peep at the warm, coarse-ribbed, blue worsted stockings underneath, with hobnailed boots armed with heel and toe-plates, all helped to make up a very quaint and favourable picture of his class—a class common enough upon the Yorkshire farms.

Adam Olliver’s talk was the very broadest Doric of the broadest dialect to be found amid all the phonetic fantasies of England, and his responses to the inquiries of tourists and others, not “to the manner born,” who asked the old hedge-cutter the way, say to Kesterton or Hazelby, were given in what was, to all intents and purposes, high Dutch to the bewildered listeners. They would have been left in glorious uncertainty as to his meaning, but that Old Adam’s energetic and oratorical action generally sufficed to speed the querist in the right direction. He was an honest, upright, intelligent Christian, was Adam, and an old-standing member of the little Methodist society, which had managed to hold its own in the village of Nestleton, and which, for[Pg 18] want of a chapel, held its meetings in Farmer Houston’s kitchen. All the villagers held the old man in respect, and few there were who did not enjoy “a crack o’ talk” with the old hedger. His odd humour, sound piety, and practical common sense, were expressed in short, sharp, nuggety sentences, which hit the nail on the head with a thump that drove it home without the need of a second blow. But I hope to give Adam Olliver abundant opportunity to speak for himself, and will say no more than that his “Aud Woman,” as he called his good wife Judith, or Judy in Yorkshire parlance, had been the partner of his joys and sorrows for nearly forty years, and was still a buxom body for her age; that of his three children, Jake the eldest, was Farmer Houston’s foreman; Pete, the second, was seeking his fortune in America; and Hannah, a strapping good-looking lass of nineteen, was under-housemaid at Waverdale Hall, and that all of them will ever and anon appear in the true and impartial village annals I am here recording.

On the evening of a fine spring day, Old Adam, having made Balaam snug and comfortable in a little thatched, half-tumble-down outhouse which did duty for a stable, and having despatched his frugal evening meal, was seated on a small wooden bench outside his cottage door, enjoying the fragrance of some tobacco which Pete had sent him, using for that purpose a short black pipe of small dimensions, strong flavour, and indefinite age.

“Hallo! Adam; then you are burning your idol again,” said Blithe Natty, who had sauntered round for a little gossip.

“Hey,” said Adam, “you see he’s like a good monny idols ov another sooat. He tak’s a plaguey deal o’ manishin’. He’s a reg’lar salimander. Ah’ve been at him off an’ on for weel nigh fotty year, an’ he’s a teeaf ’un; bud,” said he, with a twinkle in his eye, “Ah’ll tak’ good care ’at he ends i’ smook.”

“Ha! ha! ha!” laughed Natty, as he leaned his arms on the little garden gate, and swung it to and fro. “I can’t tell how it is you enjoy it so. It would soon do my business for me.”

“Why, ‘there’s neea accoontin’ for teeast,’ as t’ aud woman said when she kissed ’er coo, bud ah reckon you’ve tried it, if t’ truth wer’ knoan; an’ y’ see, it isn’t ivverybody,” with another twinkle, “’at ez eeather talents or passevearance te mak’ a smooker. Like monny other clever things, its nobbut sum ’at ez t’ gift te deea ’em. There’s Jim Raspin, noo; he’s been scrapin’ away on a fiddle for a twelvemonth, an’ when he’s deean ’is best, he can nobbut mak’ a grumplin’ noise like a pig iv a fit. Ah can’t deea mitch, but ah can clip a hedge an’ smook a pipe, an’ that’s better then being a Jack ov all trayds an’ maister o’ neean.”

Here the old man blew out a long cloud of curling smoke, and laying down his short pipe by the side of him, he gave a low chuckle of satisfaction at having come out triumphant from an attack on the only weakness of which he could be convicted.

“Ah see,” said he, “’at you’ve getten Lucy yam ageean, an’ a feyn smart wench she is. They say ‘feyn feathers mak’s feyn bods,’ but she’s a bonny bod i’ grey roosset, an’ depends for her prattiness mair on ’er feeace an’ manners then on ’er cleease.”

“Yes,” said Natty, well pleased with this genuine compliment on his darling; “Lucy is a fine lass and a good ’un, and makes the old house, which has been gloomy enough, as bright as sunshine.”

“God bless ’er,” said the old man, warmly; “an’ if she gets t’ grace o’ God she’ll be prattier still. There’s neea beauty like religion, Natty, an’ t’ robe o’ righteousness sets off a cotton goon as mitch as silk an’ velvet.”

“Hey, that’s true enough,” said Nathan Blyth; “an’ Lucy’s all right on that point. She isn’t a stranger to religion. She[Pg 20] loves her Bible and her Saviour, and her conduct is all that heart can wish.”

“Ah’s waint an’ glad to hear it,” said Adam. “Meeast o’ d’ young lasses noo-a-days seeam to me te mind nowt but falderals an’ ribbins. They cover their backs wi’ tinsel an’ fill their brains wi’ caff till they leeak like moontebanks, an’ their heeads is as soft as a feather bed.

“Who’s going to marry Matt, the miller, I wonder, Adam Olliver?” said Lucy Blyth, suddenly peeping over her father’s shoulder by the garden gate.

“Odd’s bobs,” said the startled hedger; “‘you come all at yance,’ as t’ man said when t’ sack o’ floor dropt on his nob. Why, Lucy, me’ lass, is it you? Ah’s waint an’ glad to see yer’ bonny feeace ageean. Come in a minnit. Judy! Judy! Here’s somebody come ’at it’ll deea your and een good te leeak at.”

Out came Judith Olliver, in her brown stuff gown and checked apron, a small three-cornered plaid shawl across her shoulders, and with her white hair neatly gathered beneath a cap of white muslin, double frilled and tied beneath the dimpled chin—as comely and motherly an old cottager as you could wish to see.

“Dear heart,” said Mrs. Olliver, as Lucy kissed her cheek, looking on the bright girl in unconstrained admiration, “Can this be little Lucy Blyth?”

At that moment a fine, tall, gentlemanly youth of some two-and-twenty summers, paused as he passed the garden gate. Turning his open handsome face toward the speaker, his eyes fell on the radiant beauty of the blacksmith’s daughter; he recognised the features of his childish “sweetheart” with a thrill of something more than wonder, and, resuming his walk, “Master Philip” repeated again and again Judith Olliver’s inquiry, “Can this be little Lucy Blyth?”

AT the opposite end of the village to that where Nathan Blyth resided,

there was a cluster of small tumble-down cottages, whose ragged

thatch, patched windows, and generally forlorn appearance denoted the

unthrifty and “unchancy” character of their occupants. This

disreputable addendum to the charming village of Nestleton was known

as Midden Harbour, a very apt description in itself of the unsavoury

character of its surroundings, and the unpleasant manners and customs

of most of the denizens of that locality. Squire Fuller had often

tried to purchase this unpleasant blotch, which lay in the centre of

his own trim and well-managed estate. Its owner, however, old Kasper

Crabtree, a waspish dog-in-the-manger kind of fellow, could not be

induced to sell it. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that

“Crabby,” as the villagers fitly[Pg 23] called him, found sincere

gratification in the fact that the property and its possessors were a

universal nuisance, for Crabby was one of that numerous family of

social Ishmaelites whose hand was against every man, and so every

man’s hand and tongue were against him.

AT the opposite end of the village to that where Nathan Blyth resided,

there was a cluster of small tumble-down cottages, whose ragged

thatch, patched windows, and generally forlorn appearance denoted the

unthrifty and “unchancy” character of their occupants. This

disreputable addendum to the charming village of Nestleton was known

as Midden Harbour, a very apt description in itself of the unsavoury

character of its surroundings, and the unpleasant manners and customs

of most of the denizens of that locality. Squire Fuller had often

tried to purchase this unpleasant blotch, which lay in the centre of

his own trim and well-managed estate. Its owner, however, old Kasper

Crabtree, a waspish dog-in-the-manger kind of fellow, could not be

induced to sell it. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that

“Crabby,” as the villagers fitly[Pg 23] called him, found sincere

gratification in the fact that the property and its possessors were a

universal nuisance, for Crabby was one of that numerous family of

social Ishmaelites whose hand was against every man, and so every

man’s hand and tongue were against him.

Of the colony of Midden Harbour, one family was engaged in the sale of crockery-ware, which was hawked around the country in a cart, accompanied by both man and woman kind. The former were clad in velveteen coat and waistcoat and corduroy breeches, all notable for extent of pocket and an outbreak of white buttons, with which they were almost as thickly studded as a May pasture is with daisies. The latter were clad in cotton prints notable for brevity of skirt, revealing substantial ankles, graced with high laced-up boots which would have well served a ploughboy. A second family were besom-makers, whose trade materials were surreptitiously gathered on Kesterton Moor and from the woods of Waverdale; the “ling” of the one and the “saplings” of the other sufficing to supply both heads and handles. A third family was of the tinker persuasion, travelling about the country with utensils of tin. They were great in the repair of such pots and pans as required the use of solder, which was melted by the aid of an itinerant fire carried in an iron grate. Midden Harbour also boasted a rag-and-bone merchant on a small scale, a scissors-grinder, who united umbrella-mending with his primal trade, and a pedlar also had pitched his tent within its boundaries; altogether, its limited population was about as queer a medley as could well be found. Most of the Harbourites had the character of being more or less, chiefly more, given to making nocturnal excursions in quest of game, and Squire Fuller, Sir Harry Everett, and other large land-owners in the neighbourhood were being perpetually “requisitioned” by clever and successful poachers, who either defied or bribed all the gamekeeperdom of the country side.

Just behind Midden Harbour was a much larger and somewhat more respectable house, though discredited by being in such an unrespectable locality. It stood in what might by courtesy be called a garden, but, like that which dear old Isaac Watts stood to look at, and which belonged to a neighbour of his who was late o’ mornings, you might see “the wild briar, the thorn and the thistle grow higher and higher.” The garden-gate was hung by one hinge, and was generally so much aslant that one might imagine, that, like its owner, it was given to beer. The garden wall, the house, the outbuildings were all first cousins to Tennyson’s Moated Grange.

In this house lived a man, well known for many a mile round as “Piggy” Morris, so called by reason of his pig-jobbing proclivities, though he varied his calling in that direction by dealing in calves, sheep, dogs, old horses—in fact, he was quite ready to buy or sell anything by which he could gain a profit, or, as he put it, “finger the rhino.”

Piggy Morris was once a respectable farmer, a tenant of Squire Fuller’s, but his drinking habits had been his ruin. His farm deteriorated so much that his landlord gave him notice to quit, and had threatened to prosecute him for damages into the bargain. From the day he was expelled from Eastthorpe to the time of which I am writing Piggy Morris had nursed and cherished a deadly hatred to Squire Fuller, and though some years had now elapsed, he still thirsted for vengeance on the man who had “been his ruin.”

The victims of intemperance are marvellously skilful in laying the blame of their downfall on men and circumstances, and Piggy Morris attributed all his melancholy change of fortune to a hard landlord and bad times.

After the loss of his farm, Morris had taken his present house because of a malt-kiln which was on the premises, and he hoped to gain a trade and position as maltster, which would equal if not surpass the opportunity he had lost. But alas! the ball was rolling down the hill, and neither malt-kiln nor brewery could stop it; indeed, as was most probable, they gave it an additional impetus, and poor Morris was fast descending to the low level of Midden Harbour. He was a keen, clever, long-headed fellow, and could always make money in his huckstering fashion, but he was sullen, sour, ill-tempered; at war with his better self, he seemed to be at war with everybody else, which is perhaps one of the most miserable and worriting states of mind into which sane men can fall. His wife, poor soul, an amiable and thoroughly respectable woman, was cowed and broken-spirited, and lived an ailing and depressed life, sighing in chronic sorrow over the happiness and comfort of other days.

This misfitting pair had four children. The eldest, a fine stalwart fellow of twenty-four, had made some proficiency in the art and science of farriery. He had received no special training to equip him as a veterinary surgeon, but in practical farriery he was accounted very clever, and might have done well in that particular line. But the sins of the fathers are often visited upon their children. Young Morris was sadly too frequent a guest at the Red Lion, and in spite of his education and native talents, was only a sort of ne’er-do-weel, very popular in the taproom and similar centres of sociality; “nobody’s enemy but his own,” but, withal, slowly and surely gravitating towards ruin, “going to the dogs.” He had an intimate acquaintance with dogs and guns, snares and springs, and was oft suspected of carrying on a contraband trade in[Pg 26] fish, flesh, and fowl, captured in flood and field. His coal-black hair and beard, and his swarthy though handsome features, had gained for him the soubriquet of Black Morris; and though he did not much relish the cognomen, it speedily became fixed, and there is no doubt that his wild and reckless conduct made the name, in some degree at least, appropriate. His two brothers, Bob and Dick, were in the employ of Kasper Crabtree, and his sister Mary, a quick and amiable girl of eighteen, was the loving helper, nurse, and companion of her ailing mother.

Since Lucy Blyth’s return home, Black Morris, who had seen her oft, on his visits to her father’s forge and in other parts of the village, had ventured at length to accost her, receiving, as her wont was, a pleasant smile and a courteous reply. Black Morris was made of very inflammable material, and speedily fell over head and ears in love with the blacksmith’s daughter. With his usual impetuosity of character, he swore that he and no other would capture the charming village belle, and took his steps accordingly. To carry out his purpose, his visits to the forge increased in number, his conduct was thoroughly proper and obliging, and his manners at their best, which is saying much, for when Black Morris chose he could be a gentleman. He often wielded the big hammer for Blithe Natty with muscle and skill, and that shrewd knight of the anvil was more than half inclined to change his opinion of his voluntary helper, and come to the conclusion that he was a “better fellow than he took him for.”

One evening, after Black Morris had been rendering useful and unbought aid in this way, Nathan Blyth felt constrained to thank him with unusual heartiness, and with his usual plainness of speech, he blurted out,—

“Morris, there’s the makings of a good fellow i’ you. What a pity it is that you don’t settle steadily down to some honest work, and give up loafing about after other[Pg 27] folks’ property! ‘A rolling stone gathers no moss,’ and ‘a scone o’ your own baking is better than a loaf begged, borrowed, or taken.’”

Black Morris’s swarthy features flushed up to the roots of his hair, his old temper leaped at once to the tip of his tongue, and his hand was involuntarily closed, for “a word and a blow” was his mode of argument. The remembrance that the speaker was Lucy’s father restrained him, and he replied,—

“Look here, Nathan Blyth, when you say I loaf about other folk’s property, you say more than you know; an’ as for settling down, give me your daughter Lucy for a wife, and I’ll be the steadiest fellow in Nestleton, aye, and in all Waverdale besides!”

“Marry Lucy!” exclaimed Natty, shocked at the idea of entrusting his darling to the keeping of such a reckless ne’er-do-weel, “I’d rather see her dead and in her grave! and so, good-night!”

Turning on his heel, Nathan Blyth went indoors, and Black Morris stood with lowering brow and flashing eyes. Shaking his fist at the closed door, he thundered out an oath, and said,—

“Mine or nobody’s, you ——, if I swing for it;” and strode homeward in a towering rage.

O Nathan Blyth! Nathan Blyth! Your hasty and ill-considered words have sown dragon’s teeth to-night! The time is coming, coming on wings as black as Erebus, when you will wish your tongue had cleaved to the roof of your mouth before you uttered them. You have beaten a ploughshare to-night which shall score as deep a furrow through your soul as ever did coulter from the ringing anvil by your smithy hearth.

“CAN this be little Lucy Blyth?” said Philip Fuller to himself, as he

wended his way to Waverdale Park. His memories were very pleasant, of

the bright and piquant child, whom as a boy he had known and romped

with in that freedom from restraint, which his youth, the lack of a

mother’s care, and the pre-occupied and studious habits of his father

rendered possible. The attractive little girl and the merry geniality

of Blithe Natty had induced him when he was barely in his teens to

take his rides almost constantly in the direction of the Forge, and

fruits and flowers and pony rides, as far as Lucy was concerned, were

the order of the day. Who can say that love’s subtle magic did not

weave its unseen[Pg 29] but potent spell around those two young hearts in

those early days of mirthful childhood? At any rate, Philip’s heart

responded at once to the sound of Lucy’s name, and now her superadded

charms of face and feature fairly took him captive. Whether there be

any truth or not in the poet’s idea of

“CAN this be little Lucy Blyth?” said Philip Fuller to himself, as he

wended his way to Waverdale Park. His memories were very pleasant, of

the bright and piquant child, whom as a boy he had known and romped

with in that freedom from restraint, which his youth, the lack of a

mother’s care, and the pre-occupied and studious habits of his father

rendered possible. The attractive little girl and the merry geniality

of Blithe Natty had induced him when he was barely in his teens to

take his rides almost constantly in the direction of the Forge, and

fruits and flowers and pony rides, as far as Lucy was concerned, were

the order of the day. Who can say that love’s subtle magic did not

weave its unseen[Pg 29] but potent spell around those two young hearts in

those early days of mirthful childhood? At any rate, Philip’s heart

responded at once to the sound of Lucy’s name, and now her superadded

charms of face and feature fairly took him captive. Whether there be

any truth or not in the poet’s idea of

it cannot be denied that Philip there and then knew that he loved Lucy Blyth, knew, moreover, that it was a love that would be all-absorbing, a love that time would not lessen, that trial would not weaken, that death would not destroy. No other idea could get in edgewise during that memorable walk. The radiant vision floated before his eyes, and thrilled him to the heart: the very trees seemed to whisper “Lucy” as they trembled in the breeze, and Philip Fuller knew from that hour that he had “found his fate.”

Difference of rank, social barriers, his father’s exaggerated family pride, Nathan Blyth’s sturdy independence, Lucy’s possible denial, and kindred prosy considerations, did not occur to the smitten youth; or if they did they were wondrously minified by love’s inverted telescope into microscopic proportions, and through them all he held the juvenilian creed that “love can find out the way.” In his dreams that night, he re-enacted all the scene at Adam Olliver’s garden gate; saw again the sweetest face in the world or out of it to his glamour-flooded eyes; heard again the question, “Can this be little Lucy Blyth?” Men live rapidly in dreams, time flies like a flash. Difficulties do not count in dreams, they are ignored, and so it was that Philip answered the question in a veni-vidi-vici kind of spirit, and shouted in dreamland over the garden gate, “Yes it can, and will be Lucy Fuller, by-and-bye!” Then, as John Bunyan says, he “awoke, and behold it was a dream.” Ah! Master Philip, Jason did not win the golden fleece without sore travail and fight; Hercules did not win the golden apple of[Pg 30] Hesperides without dire conflict with its dragon guard, and if you imagine that this dainty prize is going to fall into your lap for wishing for, you will find it is indeed a dream from which a veritable thunderclap shall wake you. Will the lightning scathe you? Who may lift the curtain of the future? I would not if I could—better far, as honest Natty sings, to

The next morning Master Philip left the breakfast-table to go out on a voyage of discovery. Bestriding a handsome bay horse, his father’s latest gift, he rode down to Nestleton Forge, and arrived just in time to hear the final strophes of Blithe Natty’s latest anvil song. That vivacious son of Vulcan was engaged in sharpening and tempering millers’ chisels, and as the labour was not hard, and the blows required were light and rapid, Natty’s song dovetailed with the accompaniment:—

“Good morning, Mr. Blyth,” said Philip; “I’m glad to have the chance of hearing your merry voice again. I’ve been intending to ride round ever since my return from college, but my father has managed to keep me pretty much by his side.”

“I’m heartily glad to see you, sir,” said Nathan, “and mighty pleased to see that college honours and gay company have not led you to forget your poorer neighbours. You know the old proverb, ‘When the sun’s in the eyes people don’t see midges.’”

“Why, as for that,” said Philip, with a laugh, “I am not aware that the sun is in my eyes. At any rate I can see you, and you are no midge by any means. ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot?’ As for gay company, that is not at all in my line. By-the-bye, what’s become of your little daughter? I hope I may have the pleasure of seeing her, too. I suppose she has grown altogether too womanly to accept a ride on Harlequin, the pony, even if I brought him. Is she at home?”

Now, I am quite sure that Nathan Blyth would much rather have preferred that Master Philip should not resume his acquaintance with Lucy. On the other hand, he had the most unbounded confidence in her, while he had no shadow of reason for suspecting Philip of any ulterior motive; hence he could scarcely avoid calling his daughter to speak with the young squire. That young lady soon appeared in graceful morning garb, and the impressible heart of the youthful lover was bound in chains for evermore. There was neither guile nor reserve in his greeting. The light that beamed in his eye and the tone that rung in his voice, could scarcely fail to betray to far less observant eyes and ears the unmeasured satisfaction with which he renewed his acquaintance with the charming girl. Lucy, however, seemed to have retired into herself; her words were few, constrained, and inconsequent, but the tell-tale blush was on her cheek,[Pg 32] and there was a singular flutter at her heart, as she saw the ardent admiration which shone in the eyes of her quondam friend. It was with a profound sense of relief that she was able to plead the pressure of domestic duties as a reason for shortening the interview and retiring from the scene. After a brief conversation with Nathan on trivial matters, Philip mounted his horse and rode homewards, in that frame of mind so admirably depicted by Otway:—

Such were the emotions Philip Fuller felt as he turned away from the Forge of Nathan Blyth. Rounding the corner in the direction of Waverdale Hall, he was suddenly confronted by the scowling face and suspicious eyes of Black Morris.

METHODISM was introduced into Kesterton in the days of John Wesley

himself, and in the plain, square, old-fashioned chapel, with its

arched windows, brick walls, and hip roof, red tiled and high peaked,

you might see the very pulpit in which the grand old apostle of the

eighteenth century preached more than a hundred years ago. The chapel

stood back from the main street, and to get at it you had to go

through a narrow passage, for the fathers of the Methodist Church,

unlike their more self-assertive successors, seem to have courted a

very modest retirement for the Bethels which they built for God.

Behind the chapel there is a small burial-ground, in which are the

honoured graves of those to whom Kesterton Methodism owes its origin,

and who did its work and bore its fortunes[Pg 34] in its earlier struggles

for existence. On the other side of an intervening wall, in the midst

of a little garden, capable of much improvement in the matter of

tidiness and cultivation, stands the “preacher’s house.” It is not by

any means an imposing structure, and taxes to the utmost the

contrivance of its itinerant tenants to find sleeping accommodation

for the “quiver full” of youngsters with which they are commonly

favoured in an unusual degree. In the matter of furniture the less

said the better; suffice it to say that it could not be regarded as

extravagant in quality or burdensome in quantity. Indeed, it was open

to serious imputations in both those directions; at least so thought

the Rev. Theophilus Clayton, who had latterly become located there,

and seemed likely to go through the maximum term of three years, to

the high satisfaction of the people, and with a moderate measure of

contentment to himself.

METHODISM was introduced into Kesterton in the days of John Wesley

himself, and in the plain, square, old-fashioned chapel, with its

arched windows, brick walls, and hip roof, red tiled and high peaked,

you might see the very pulpit in which the grand old apostle of the

eighteenth century preached more than a hundred years ago. The chapel

stood back from the main street, and to get at it you had to go

through a narrow passage, for the fathers of the Methodist Church,

unlike their more self-assertive successors, seem to have courted a

very modest retirement for the Bethels which they built for God.

Behind the chapel there is a small burial-ground, in which are the

honoured graves of those to whom Kesterton Methodism owes its origin,

and who did its work and bore its fortunes[Pg 34] in its earlier struggles

for existence. On the other side of an intervening wall, in the midst

of a little garden, capable of much improvement in the matter of

tidiness and cultivation, stands the “preacher’s house.” It is not by

any means an imposing structure, and taxes to the utmost the

contrivance of its itinerant tenants to find sleeping accommodation

for the “quiver full” of youngsters with which they are commonly

favoured in an unusual degree. In the matter of furniture the less

said the better; suffice it to say that it could not be regarded as

extravagant in quality or burdensome in quantity. Indeed, it was open

to serious imputations in both those directions; at least so thought

the Rev. Theophilus Clayton, who had latterly become located there,

and seemed likely to go through the maximum term of three years, to

the high satisfaction of the people, and with a moderate measure of

contentment to himself.

Kesterton rejoiced in the dignity of being a circuit town, and at the time to which these annals refer, the circuit extended from Meriton in the east to Amworth Marsh in the west; and from Chessleby on the north to Bexton on the south, an area of nineteen miles by twenty-one. There was a circuit horse and gig provided for the longer journeys, but as the “better days” which both of them had seen smacked of the mediæval age, the gig was as little remarkable for polish or paint as the horse was either for beauty or speed.

The Rev. Theophilus Clayton was an admirable specimen of an old-fashioned Methodist preacher. He was of middle-height and somewhat portly figure; had an intelligent and pleasant face, a broad forehead, a pair of piercing black eyes surmounted by dark thick eyebrows and hair fast whitening, but more with toil than age. His whole appearance was calculated to win attention and respect, and his piety and force of character were almost certain to retain them after they had been won. He was “in labours more abundant,”[Pg 35] and in addition to being an effective preacher, he was a capital business man, one under whose management a circuit is pretty sure to thrive.

His colleague, the Rev. Matthew Mitchell, was young in years, and not yet out of his probation. Though he was not equal to his superintendent in pulpit ability, he largely made up for it by his diligent pastoral visitation, and the earnest and vigorous way in which he went about his high and holy calling. It is not given to all men to possess high intellectual abilities and oratoric strength, but it is given to every man to be able, as the Americans say, “to do his level best,” and that by the blessing of God may be mighty in pulling down the strongholds of Satan and the lifting up of the Church to a higher altitude of spirituality and a broader gauge of moral force. Of an enthusiastic temperament and with strong revivalistic proclivities, the Rev. Matthew Mitchell was remarkably successful, especially among the village populations, in winning souls for Christ. He was a young fellow, of somewhat prepossessing appearance, lithe, agile, and strong as an athlete. As both these worthy men will have to play an important part in this history, nothing further need to be said at present; I am much mistaken, however, if the reader does not find that they were both of them made of sterling stuff.

The small society of Methodists in Nestleton, numbering some five-and-twenty members, owed its origin to the love and labours of Old Adam Olliver. Many long years before, when the quaint old hedger was foreman on old George Houston’s farm, Adam, with two or three fellow-servants, used to walk to Kesterton to the Sunday preaching. Through the ministry of a grand old Boanerges of the early age they had found peace through believing, and for some time used to attend a class-meeting held after the afternoon service for such outlying members as could not attend during the busy week days. One Sunday, after the quarterly tickets had[Pg 36] been renewed by the superintendent minister, Adam plucked up courage to address him,—

“Ah wop you’ll excuse ma, sor,” said he, “bud we’re desp’rate fain te get ya’ te cum te Nestleton. Meeast o’ t’ fooaks is nowt bud a parcel o’ heeathens. There’s neea spot for ’em te gan teea bud t’ chotch, an’ t’ parson drauns it oot like a bummle bee; summut at neeabody can mak’ neeather heead nor tayl on, an’ t’ Gospel nivver gets preeach’d frae yah yeear end te d’ t’ other.

“Well, but have you a place to preach in, Adam?” quoth the minister; “is there anybody who will take us in?”

“Why, there’s d’ green,” said Adam, “neeabody’ll molest uz there, unless it be t’ oad gander, an’ ah wop yo’ weeant tohn tayl at him. An’ i’ mucky weather yoo can hae mah hoose. Ah’ve axed Judy, an’ sha’ sez ’at you can hev it an’ welcome. It isn’t mitch ov a spot, but it’s az good az a lahtle fishin’ booat, an’ oor Sayviour preeached upo’ that monny a tahme; ah reckon ’at best sarmon ’at ivver was preeached was up ov a hill-sahd, an’ the Lord gay another te nobbut yah woman fre’ t’ steean wall ov a well. It isn’t wheear yo’ stand, bud what yo’ say ’at ’ll wakken Nestleton up, and gi’d folks a teeaste o’ t’ Gospel trumpet. When will yo’ cum?”

Adam Olliver gained the day, and services were held on Nestleton Green and in Adam’s cottage. Eventually the village was placed upon the plan, the local preachers were appointed on the Sunday evenings, Adam Olliver was made a leader of the class, and from that day Methodism had kept a foothold in Nestleton. Nay, more than that, for Adam’s cottage grew too small for the congregation, and the large kitchen of Gregory Houston was placed at their disposal. At the time of which we write, that good farmer and his family were all in church communion, and he, Adam Olliver, and Nathan Blyth, who was a popular and successful local preacher, were the props and pillars of the Nestleton Society.

It was a very inviting nest of rural piety. In their lowly services there was felt full often the presence and the power of God, and their mean and homely sanctuary was the palace of the King of Kings! Such little patches of evangelic life are happily common in Methodism. Her village triumphs have been amongst her greatest glories, and it is to be hoped that this Church, so remarkably owned of God in the rural districts, will never forget or neglect the rustic few, among whom its brightest trophies have been won, and from whom its noblest agents have been obtained.

One Sunday, Philip Fuller was walking from the Rectory, whither he had been to dinner after the morning and only service at the parish church. The evening was calm and fine, so he prolonged his walk by making a detour round the highest part of the village, and was passing Farmer Houston’s gate just at the time that the little Methodist congregation had assembled for worship. Philip, who was not aware of this arrangement, heard the hearty singing of a hundred voices, and in pure curiosity drew near the open door, for the weather was of the warmest, and listened to the strain,—

Philip was greatly struck, alike with the warmth and energy[Pg 38] of the singers and the directly evangelical character of the hymn. During his residence at Oxford he had, at first, been half inclined to accept the almost infidel views which at that time were tacitly held by not a few of the tutors and even the clerics of that famous university. A candid perusal of the Scriptures, however, for he was a genuine seeker after truth, and an attendance on the ministry of a godly and effective clergyman, who had rallied round him the evangelical element of the various colleges, rendered Philip utterly dissatisfied with the loose tenets he had been accustomed to hear. When he left college he was the subject of unavowed but strong conviction as to the importance and necessity of experimental religion, but as yet was very much at sea as to the Gospel plan of salvation. Philip noiselessly entered the kitchen, and took an unnoticed place among the rural worshippers.

Much to his surprise, he saw Nathan Blyth standing in the moveable pulpit, and, in obedience to his solemn invitation, “Let us pray!” Philip knelt with the rest, while Natty, who knew from happy and long experience how to talk with God, led their devotions in an extempore prayer, the like of which he had never heard before. Nathan’s sermon that night was founded on the text that stirred the heart and baffled the mind of the Ethiopian eunuch: “He was led as a sheep to the slaughter: and like a lamb dumb before his shearer, so opened he not his mouth:” and included the sable nobleman’s inquiry, “Of whom speaketh the prophet this? of himself, or of some other man?”

Of that “Other Man” Natty spoke as one who knew Him. He placed the atonement in a light so clear, and the love of the Atoner in a manner so impressive, that Philip found himself listening with a beating heart and a swimming eye. In plain, but powerful language, the speaker urged his hearers to accept the proffered gift of God. The congregation joined in singing that stirring hymn,—

Nathan Blyth called on “Brother Olliver” to engage in prayer. At the first Philip was inclined to be amused at the rude and rugged language in which the old man poured out his soul to God, but as he proceeded, bearing with him the subtle power and sympathy of a praying people, the listener was moved to wonder and to awe, and felt with Jacob, “Surely God is in this place and I knew it not.” “Thoo knoas, Lord,” said Adam Olliver, “’at we’re all poor helpless sinners; but Thoo’s a great Saviour, an’ sum on uz ez felt Thi’ pooer te seeave.

Lord! There’s them here to-neet’ at’s strangers te d’ blood ’at bowt ther pardon up o’ d’ tree. Thoo loves ’em. Thoo pities ’em. Thoo dee’d for ’em. Oppen ther hearts, Lord. Melt their consciences an’ mak’ ’em pray, ‘God be massiful te me a sinner.’ Seeave ’em, Lord! Rich or poor, young or aud. Put d’ poor wand’ring sheep o’ Thi’ shoother an’ lead ’em inte d’ foad o’ Thi’ infannit luv.” No sooner was the benediction pronounced than Philip stole silently away. As he trod the shady lanes and crossed the park his mind was full of serious thought. During the entire evening, he was silent and abstracted, and as he laid his head upon his pillow the plaintive appeal still rung in his ears,—

![]() GREGORY HOUSTON, Adam Olliver’s master, and, as far as means and

position were concerned, principal member of the little Methodist

society in Nestleton, was crossing his farmyard one summer’s day, when

his aged serving-man was engaged in getting together a few “toppers.”

These are long screeds of thinly-sawn larch fir, to be nailed[Pg 41] on the

top of stakes driven into weak places in the hedgerows to strengthen

them, and to secure the continuity of the fence.

GREGORY HOUSTON, Adam Olliver’s master, and, as far as means and

position were concerned, principal member of the little Methodist

society in Nestleton, was crossing his farmyard one summer’s day, when

his aged serving-man was engaged in getting together a few “toppers.”

These are long screeds of thinly-sawn larch fir, to be nailed[Pg 41] on the

top of stakes driven into weak places in the hedgerows to strengthen

them, and to secure the continuity of the fence.

“Well, Adam,” said the genial farmer, “how are you getting on?”

“Why, ah’s getting en all reet. It’s rayther ower yat for wark; but while it’s ower yat for me, it’s grand for t’ wheeat, an’ seea ah moan’t grummle. It’s varry weel there isn’t mitch te deea at t’ hedges, or ah’s flaid ’at ah sud be deead beeat.”

“Oh, they’re all right, I’ve no doubt,” said Mr. Houston; “I didn’t mean that. I was thinking of better matters.”

“Oh, as te that, bless the Lord, ah’ve niwer nowt te grummle at i’ that respect, but me aun want o’ faith an’ luv. T’ Maister’s allus good, an’ ah’s meeastlin’s ’appy. Neeabody sarves the Lord for nowt, an’ mah wayges is altegither oot of all measure wi’ me’ addlings, beeath frae you an’ Him.”

“How did you like Nathan’s sermon last night, Adam?”

Adam picked up one of the larch strips, and handing it to his master, he said, “It was just like that.”

“Like that?” said the farmer—“In what way?”

“Why,” quoth Adam, “Nathan Blyth’s sarmon was a reg’lar ‘topper.’ He’d a good tahme, an’ seea ’ad ah. T’ way he browt oot hoo Jesus was t’ Lamb o’ God, ‘armless an’ innocent, an’ willin’ te dee, was feyn, an’ ah felt i’ my sowl ’at if it was wanted ah wer’ willin’ te dee for Him. Bud wasn’t t’ kitchen crammed! Ah deean’t knoa what we’r gannin te deea wi’ t’ fooaks if they keep cummin’ i’ this oathers. Ah’ve aboot meead up me’ mind ’at we mun hev a chapel i’ Nestleton.”

“A chapel!” said Mr. Houston; “no such luck. I should like to see it, Adam; but there’s no chance of that, you may depend on’t.”

“Why, noo, maister, ah’s surprahsed at yo.’ What i’ the wolld are yo’ talkin’ aboot? ‘Luck’ and ‘chance’ hae neea[Pg 42] mair te deea wiv it then t’ ’osspond hez te deea wi’ t’ kitchen fire. ‘Them ’at trusts te luck may tummle i’ t’ muck;’ an’ ‘him ’at waits upo’ chances gets less then he fancies.’ For mah payt, ah’d rayther put mi’ trust i’ God, put mi’ shoother te d’ wheel, an’ wopp for t’ best.”

“Yes, that’s true,” said Mr. Houston, somewhat rebuked. “Still, you know, it isn’t likely.”

“Noa, ah deean’t say ’at it is; bud what o’ that? It wahn’t varry likely ’at watter sud brust oot ov a rock at t’ slap of a stick, or ’at t’ axe heead sud swim like a duck, or ’at a viper sud loss its vemmun; bud they were all deean for all that, an’ fifty thoosand wundherful things besahde. It altegither depends wheea undertak’s em.”

“But where is the money to come from? And if we had the money how are we to get the land?”

“That’s nowt te deea wiv it,” said Adam. “T’ queshun is, de wa’ need it? An’ is it right to ax God for it? T’ silver an’ gold’s all His, an’ He can tonn it intiv oor hands as eeasy as Miller Moss can oppen t’ sluice of his mill-dam. As for t’ land, it were God’s afoore it were Squire Fuller’s, an’ it’ll be His when Squire Fuller’s deead, an’ He can deea as He likes wiv it while Squire Fuller’s livin’. Ah reckon nowt aboot that. Next Sunday, t’ congregation ’ll hae te tonn oot inte d’ foadgarth, an’ ah want te knoa whither that isn’t a sign that the Lord speeaks tiv us te gan forrad.”

“Oh, there’s no doubt that a chapel is wanted, and if it was four times as big as the kitchen it would soon be full. I would give anything if we could manage it.”

“There you gooa, y’ see,” said Adam, laughing. “There’s payt o’ t’ silver an’ gowld riddy at yance. Ah sall set te wark an’ pray for ’t, an’ seea mun wa’ all. It’ll be gran’ day for Nestleton,” said Adam, rubbing his hands in fond anticipation, for he never dreamed of questioning the “mighty power of faithful prayer.”

Farmer Houston shook his head as he turned away[Pg 43] saying, “It’s too good to be true, Adam. It’s too good to be true.”

“What’s too good to be true?” said Mrs. Houston, who now appeared on the scene. A large and shady bonnet for “home service,” of printed calico, protected her from the sun. In her hand was a milk-can, containing the mid-day meal of certain calves she was rearing, for Mrs. Houston was a thrifty, bustling body, who not only saw that all the woman folk of the establishment did their duty, but was herself the first to show the way. Crossing the farmyard just at that moment she overheard the words, and hence her inquiry, “What’s too good to be true?”

“Why,” said Adam Olliver, “t’ maister’s gotten it intiv ’is heead that if the divvil an’ Squire Fuller says we aren’t te hev a Methodist chapel i’ Nestleton, t’ Almighty’s gotten te knock under an’ leave His bairns withoot a spot te put their heeads in.”

“Nay, nay,” said Farmer Houston, deprecatingly, “I was only saying that there was small hope of our getting a chapel at all.”

“An’ ah was sayin’,” persisted Adam, “’at we mun pray for it, an’ ah weean’t beleeave ’at prayer’s onny waiker then it was when Peter was i’ prison, or when t’ heavens was brass for t’ speeace o’ three years an’ six months. It oppen’d t’ iron yatt for Peter an’ t’ brass yatt for t’ rain, an’ it’ll oppen d’ gold an’ silver yatt for uz. Missis, we’re gannin’ te hev a Methodist chapel!”

“Well done, Adam! I think you’re in the right. I don’t see how it’s going to be done, but if the way is open, you may depend on it I’ll do my best.”