Old Tavern Signs

by Fritz Endell

Title: Old Tavern Signs: An Excursion in the History of Hospitality

Author: Fritz August Gottfried Endell

Release date: January 18, 2013 [eBook #41869]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Chris Curnow, Matthew Wheaton, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Old Tavern Signs, by Fritz August Gottfried Endell

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/oldtavernsignsex00enderich |

Old Tavern Signs

by Fritz Endell

Old Tavern Signs

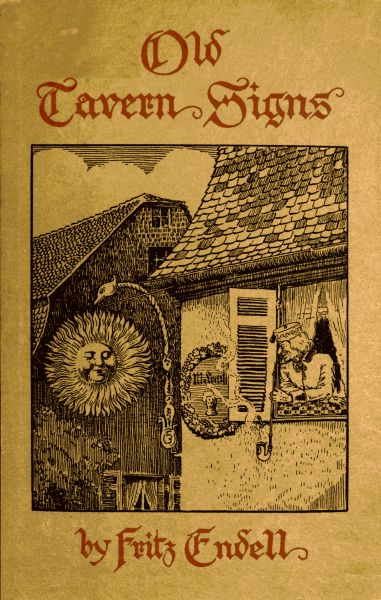

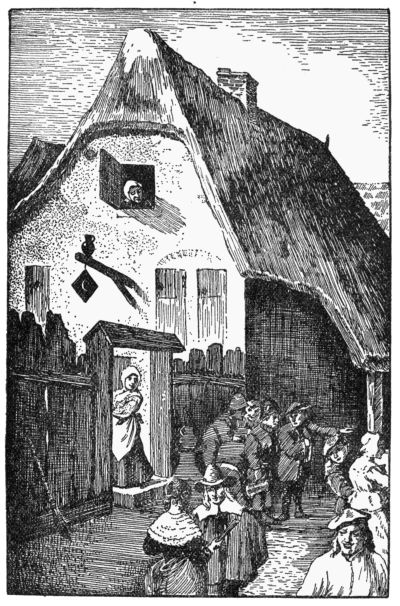

Old Dutch Signs

From a Painting by Gerrit and Job Berkheyden

With Illustrations by the Author

Published by Houghton Mifflin Company

Printed at The Riverside Press Cambridge

Mdccccxvi

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published November 1916

THIS EDITION, PRINTED AT THE RIVERSIDE PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, CONSISTS OF FIVE HUNDRED AND FIFTY NUMBERED COPIES, OF WHICH FIVE HUNDRED ARE FOR SALE. THIS IS NUMBER 5

For a sign! as indeed man, with his singular imaginative faculties, can do little or nothing without signs.

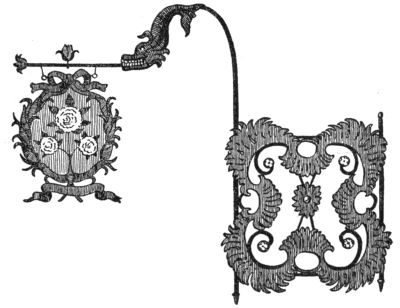

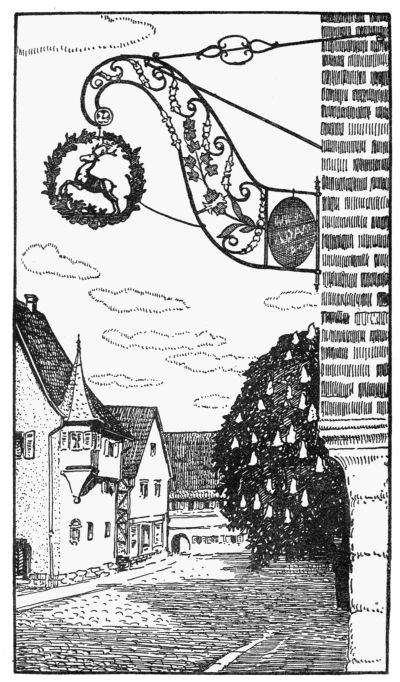

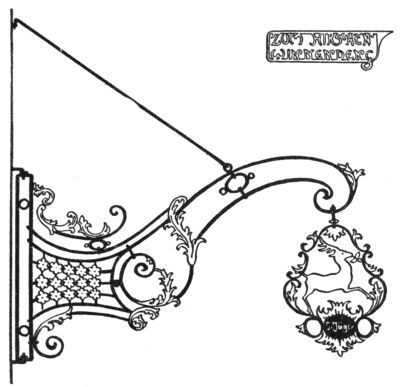

The author’s love of the subject is his only apology for his bold undertaking. First it was the filigree quality and the beauty of the delicate tracery of the wrought-iron signs in the picturesque villages of southern Germany that attracted his attention; then their deep symbolic significance exerted its influence more and more over his mind, and tempted him at last to follow their history back until he could discover its multifarious relations to the thought and feeling of earlier generations.

For the shaping of the English text the author is greatly indebted to his American friends Mr. D. S. Muzzey, Mr. Emil Heinrich Richter, and Mr. Carleton Noyes.

| I. | Hospitality and its Tokens | 1 |

| II. | Ancient Tavern Signs | 23 |

| III. | Ecclesiastical Hospitality and its Signs | 47 |

| IV. | Secular Hospitality: Knightly and Popular Signs | 75 |

| V. | Traveling with Shakespeare and Montaigne | 101 |

| VI. | Tavern Signs in Art—especially in Pictures by the Dutch Masters | 127 |

| VII. | Artists as Sign-Painters | 141 |

| VIII. | The Sign in Poetry | 167 |

| IX. | Political Signs | 187 |

| X. | Traveling with Goethe and Frederick the Great | 217 |

| XI. | The English Sign and its Peculiarities | 235 |

| XII. | The Enemies of the Sign and its End | 259 |

| Envoy: And the Moral? | 277 | |

| Bibliography | 291 | |

| Index | 297 |

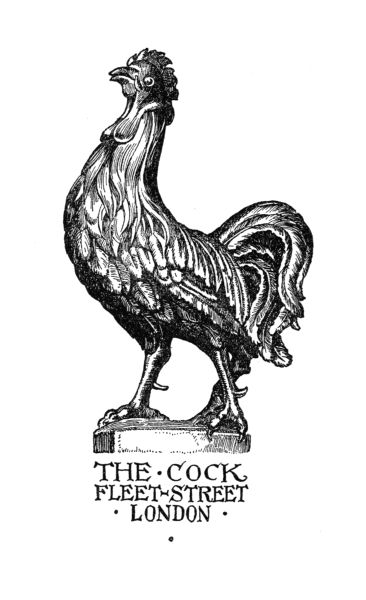

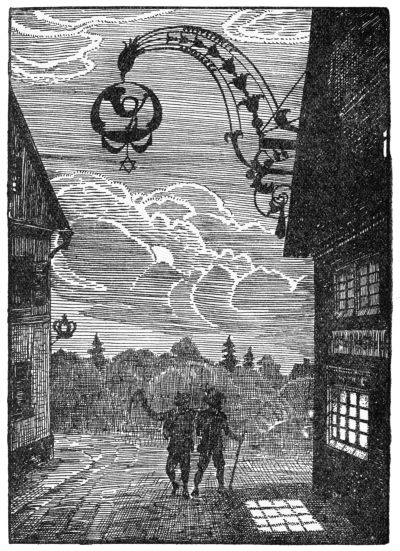

THE COCK FLEET-STREET LONDON

Without a question, the first journey that ever mortals made on this round earth was the unwilling flight of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden out into an empty world. Many of us who condemn this world as a vale of tears would gladly make the return journey into Paradise, picturing in bright colors the road that our first parents trod in bitterness and woe. Happy in a Paradise in which all the beauties of the first creation were spread before their eyes, where no enemies[Pg 4] lurked, and where even the wild beasts were faithful companions, Adam and Eve could not, with the least semblance of reason, plead as an excuse for traveling that constraint which springs from man’s inward unrest striving for the perfect haven of peace beyond the vicissitudes of his lot.

And as Adam and Eve went out, weak and friendless, into a strange world, so it was long before their poor descendants dared to leave their sheltering homes and fare forth into unknown and distant parts. Still, the bitter trials which the earliest travelers had to bear implanted in their hearts the seeds of a valor which has won the praise of all the spiritual leaders of men, from the Old Testament worthies, with their injunction “to care for the stranger within the gates,” to the divine words of the Nazarene: “I was a stranger, and ye took me in.... Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”

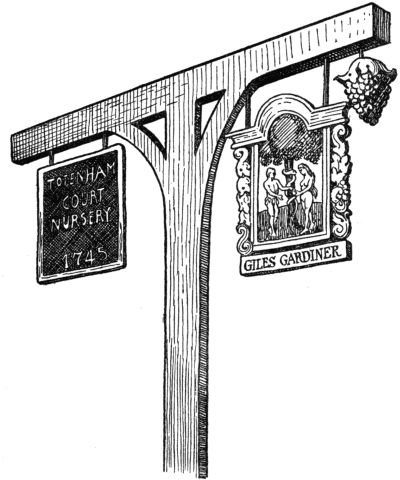

Our first parents, naturally, could not enjoy the blessings of hospitality. And still, in later ages, they have not infrequently been depicted on signs which hosts have hung[Pg 5] out to proclaim a hospitality not gratuitous but hearty. So in one of Hogarth’s drawings, of the year 1750, “The March of the Guards towards Scotland,” which the artist himself later etched, and dedicated to Frederick the Great, we see Adam and Eve figuring on a tavern sign. No visitor to London[Pg 6] should fail to see this work of the English painter-satirist. One may see a copy of it, with other distinguished pictures, in the large hall of a foundling asylum established in 1739, especially for the merciful purpose of caring for illegitimate children in the cruel early years of their life. This hall, which is filled with valuable mementos of great men, like Händel, is open to visitors after church services on Sundays. And we would advise the tourist who is not dismayed by the thought of an hour’s sermon to attend the service. If he finds it difficult to follow the preacher in his theological flights, he has but to sit quiet and raise his eyes to the gallery, where a circlet of fresh child faces surrounds the stately heads of the precentor and the organist. At the end of the service let him not forget to glance into the dining-hall, where all the little folks are seated at the long fairy tables, with a clear green leaf of lettuce in each tiny plate, and each rosy face buried in a mug of gleaming milk. This picture will be dearer to him in memory than many a canvas of noted masters in the National Gallery.

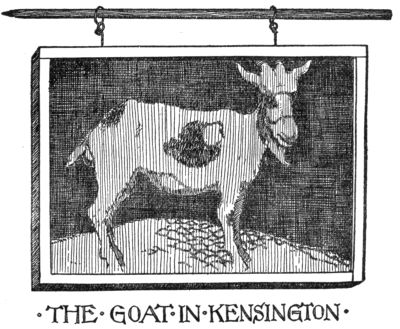

The present-day tourist who takes the bus[Pg 7] out Finchley Road to hunt up the old sign will be as sorely disappointed as if he expected to find the “Angel” shield in Islington or the quaint “Elephant and Castle” sign in South London. Almost all the old London signs have vanished out of the streets, and only a few of them have taken refuge in the dark sub-basement of the Guildhall Museum, where they lead a right pitiable existence, dreaming of the better days when they hung glistening in the happy sunshine. There were “Adam and Eve” taverns in London, in “Little Britain,” and in Kensington High Street. In other countries, France and Switzerland, for example, they were called “Paradise” signs. A last feeble echo of the old Paradise sign lingers in the inscription over a fashion shop in modern Paris, “Au Paradis des Dames,” the woman’s paradise, in which are sold, it must be said, only articles for which Eve in Paradise had no use.

ELEFANT·AND·CASTLE·LONDON·

Gavarni, who spoke the bitter phrase, “Partout Dieu n’est et n’a été que l’enseigne d’une boutique,” made bold in one of his lithographs of “Scènes de la vie intime” (1837) to inscribe over the gates of Paradise, from which the “tenants” were flying: “Au pommier sans pareil.” Schiller tells us that the world loves to smirch shining things and bring down the lofty to the dust. This need not deter us from reading in the old Paradise signs a reminder of the journey of our first parents, and to enjoy thankfully the blessings of ordered hospitality to-day.

Until this ordered hospitality prevailed, however, many centuries had to elapse, and for the long interval every man who ventured out into the hostile wilderness resembled Carlyle’s traveler, “overtaken by Night and its tempests and rain deluges, but refusing to pause; who is wetted to the bone, and does not care further for rain. A traveler grown familiar with howling solitudes, aware that the storm winds do not pity, that Darkness is the dead earth’s shadow.” Only the strong and bold could dare to defy wild nature, especially when there was need to cross desolate places, inhospitable[Pg 9] mountains like the Alps. So the ancients celebrated Hercules as a hero, because he was the pioneer who made a road through their rough mountain world.

A still longer time had to elapse ere the traveler could rejoice in the beauties of nature which surrounded him. The civilizing work of insuring safe highways had to be done before what Macaulay names “the sense of the wilder beauties of nature” could be developed. “It was not till roads had been cut out of the rocks, till bridges had been flung over the courses of the rivulets, till inns had succeeded to dens of robbers ... that strangers could be enchanted by the blue dimples of the lakes and by the rainbow which overhung the waterfalls, and could derive a solemn pleasure even from the clouds and tempests which lowered on the mountain-tops.”

No wonder, then, that the literature of olden times, when traveling was so dangerous an occupation, is filled with admonitions to hospitality. The finest example of it, perhaps, is preserved in the Bible story of the visit of the angels to Abraham, and later to Lot. This story deserves to be read again[Pg 10] and again as the typical account of hospitality. As is the custom to speak in the most modest terms of a meal to which one invites a guest, calling it “a bite” or “a cup of tea,” so Abraham spoke to the angels, “I will fetch a morsel of bread, and comfort ye your hearts.” Then Abraham told his wife to bake a great loaf, while he himself went out to kill a fatted calf and bring butter and milk. In like fashion Lot extends his hospitality, providing the strangers with water to refresh their tired feet, and in the night even risking his life against the attacking Sodomites, to protect the guests who have come for shelter beneath his roof.

The feeling that a guest might be a divine messenger, nay, even Deity itself, continued into the New Testament times, as St. Paul’s advice to the Hebrews shows: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” And did not the disciples, too, at times, receive their Master as a guest in their homes, the Son of Man, the Son of God? William Allen Knight has dwelt on this thought very beautifully in his little book called “Peter in the Firelight”: “The people of Capernaum slept[Pg 11] that night with glowings of peace lighting their dreams. But in no house where loved ones freed from pain were sleeping was there gladness like in Simon’s; for the Master himself was sleeping there.”

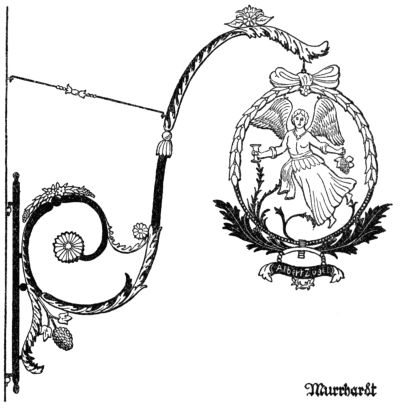

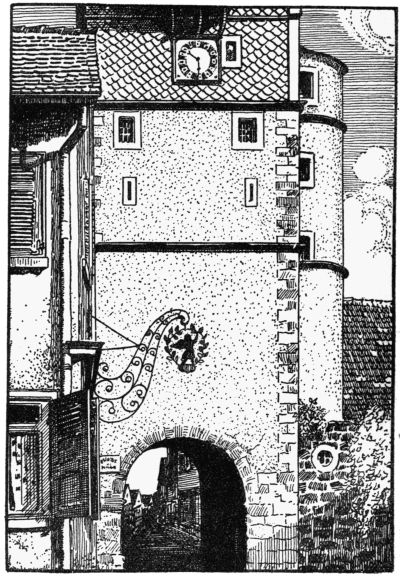

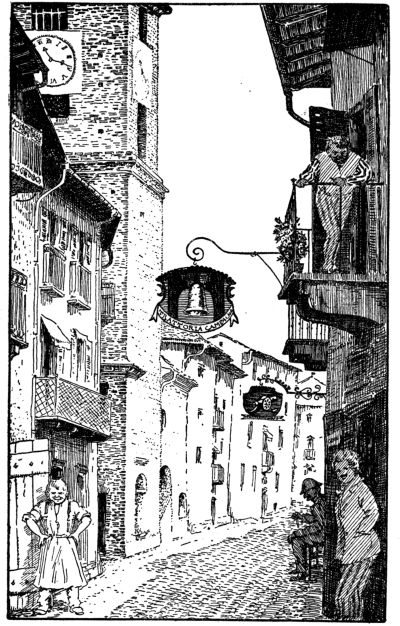

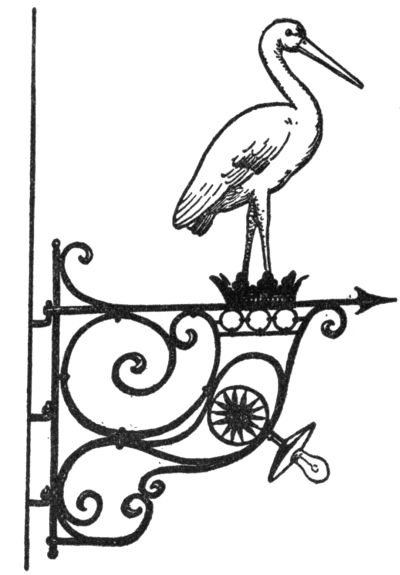

Murrhardt

A later type of legend pictures the angels, not as guests, but as benefactors, preparing a wonderful meal for starving monks who in their charity have given away all their possessions to the poor, and have no bread to[Pg 12] eat. The tourist, walking through the seemingly endless galleries of the Louvre, will pause a moment before the beautiful canvas on which Murillo has depicted this story. The French call it “la cuisine des anges.” It is a historical fact that many cloisters were reduced to poverty in the Middle Ages on account of their generous almsgiving. Not all of them could lay claim to the holy Diego of Murillo’s painting, who could pray with such perfect trust in Him who feeds the sparrows that angels came down from heaven into the cloister kitchen to prepare the meal. The widespread popularity of these Biblical stories and holy legends need cause no wonder that the angel was a favorite subject for tavern signs in the Middle Ages, and that even at this day he takes so many an old inn under the patronage of his benevolent wings. It has been asserted that the angel sign originated in the age of the Reformation, simply by leaving out the figure of the Virgin Mary from the portrayal of the scene of the Annunciation. But against this theory stands the fact that there were simple angel signs in the Middle Ages as well as Annunciation signs. We learn that the students of Paris in[Pg 13] the year 1380 assembled for their revels in the tavern “in angelo.” The records of these same Parisian students tell us how they lingered over their cups in the tavern “in duobus angelis,” in the year of grace 1449.

We may remark here in passing that the linen drapers’ guild in London had as its escutcheon the three angels of Abraham. One need only to recall the full, flowing garments of Botticelli’s angels to understand in what great respect the linen merchant would hold the angels as good customers of the drapery trade.

An angel in beggar’s form brought St. Julian the good news of the pardon of the sins of his youth. In a wild fit of anger the headstrong young Julian had killed his parents. As atonement for his dreadful crime he had done penance and built a refuge in which for many long years he freely cared for all travelers who came his way. At last the angel’s reward of hospitality was vouchsafed to him, and in memory of his good works tavern-keepers chose him as their patron saint.

The stern Consistory of Geneva had evidently forgotten all these beautiful legends[Pg 14] and their deep symbolical meaning, when in the year 1647 it forbade a tavern-keeper to hang out an angel sign, “ce qui est non accoutumé en cette ville et scandaleux.” Perhaps the grave city fathers of Geneva remembered their by-gone student days in Paris, and the handsome angel hostess in the city on the Seine, where a contemporary of Louis XIV celebrated in song:—

The most attractive angel tavern that the author has met in his travels is in the quiet little English town of Grantham, although he has to confess, in the words of the German song:—

It was a sharp autumn day. The wind that whistled about the lofty cathedral of Lincoln had searched us to the marrow, and we were well content after our ride from the station to find a kindly welcome at the “Angel.” The façade of the dignified tavern, which once belonged to the Knights’ Templars,[Pg 15] and which saw the royal guests, King John in 1213, and King Richard III in 1483, entertained within its walls, is one of the most splendid architectural monuments that we saw in England. As everywhere in this garden-land, the ivy winds its green arms around the stiffer forms of the English Gothic, which often lack the warm picturesqueness of architectural detail that makes the wonderful charm of the French and the South German Gothic.

Over the lintel of the door of the tavern the sculptured angel shone resplendent in his golden glory. A charming little balcony rested on his wings and his hands held out a crown of hospitable welcome to royal and common guests alike. All these winged messengers of hospitality seem to say in the words of the Old Testament: “The stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

The bitter experience of their own distress in a strange land planted in the hearts of the Israelitish people a kindly feeling toward the stranger. For all that, much was[Pg 16] permitted in dealing with a stranger which was forbidden in the case of a brother Israelite. The stranger might be made to pay interest, and it was no infraction of the Mosaic Law to make him and his children men-servants and maidservants.

While, then, the law of the exclusive Jews accorded certain rights to the stranger which the children of Israel were warned not to impair, the Græco-Roman world, on the other hand, recognized no claim of the stranger. “Il n’y a jamais de droit pour l’étranger,” says Fustel de Coulanges in “La Cité antique.” The same word in Latin means originally both enemy and stranger. “Hostilis facies” in Virgil, means the face of a stranger. To avoid all chance of encountering the sight of a stranger while performing his sacred office, the Pontifex performed the sacrifice with veiled face. In spite of this, the stranger met with favorable consideration both at Athens and at Rome, in case he was rich and distinguished. Commercial interests welcomed his arrival and bestowed on him the “jus commercii”—(the right to engage in trade). Yet he came wholly within the protection of the laws[Pg 17] only when he chose one of the citizens as his “patron.”

It seems as if it must have been embarrassing in those days to have shown one’s “hostilis facies” in foreign lands and cities in the course of a journey undertaken for pleasure or to seek the cures at the bathing resorts. Still we know that the Romans, in their enthusiasm for this kind of travel, built villas, theaters, temples, and baths at some of the most celebrated watering-places of modern days, like Nice and Wiesbaden.

The stiff and almost hostile attitude of classical antiquity toward the stranger was relieved by the hospitable custom which made the stranger almost a member of the family as soon as he had been received at the family hearth and had partaken of the family meal. This function was a sacred one among the ancients, for they believed that the gods were present at their table: “Et mensæ credere adesse deos,” says Ovid in the “Fastes.”

At especially festal meals it was the custom to crown the head with wreaths, as in the case of the public meals, where chosen delegates of the city, clad in white, met to partake of the food which was the symbol[Pg 18] of their common life of citizenship; or in the case of the bridal meals, where the maiden, veiled in white, pledged herself forever to the bridegroom. There was no rich wedding-cake, like those common in England and America, but a simple loaf, “panis farreus,” which after the common prayer they ate in common “under the eyes of the family gods.” “So,” says Plato, “the gods themselves lead the wife to the home of her husband.”

The custom of wearing a crown at solemn feasts was founded on the ancient belief that it was well pleasing to the gods. “If thou performest thy sacrifice [and the meal was a sacrifice] without the wreath upon thy head, the gods will turn from thee,” says a fragment from Sappho. The sense of the nearness of the gods at mealtime and the beautiful old custom of pouring out a bit of wine for the invisible holy guest, were preserved down to the time of the later Romans. We find the custom in vogue with such old sinners as Horace and Juvenal. We shall recall the significance of the wreath as a symbol when we meet the ivy wreath later as a tavern sign.

But even in classical antiquity the exercise of free hospitality demanded certain tokens to preserve it from abuse at the hands of fraudulent strangers. For example, the so-called “tessera hospitalis,” a tiny object in the shape of a ram’s head or a fish, was split in halves and shared by each party to the agreement of hospitality. By presenting his half of the “tessera” the stranger could always prove his identity and his claims to a hospitable reception by the family to which he came.

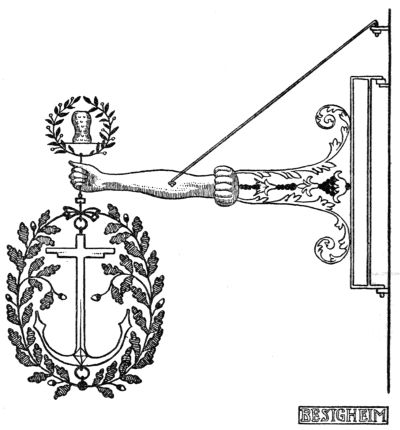

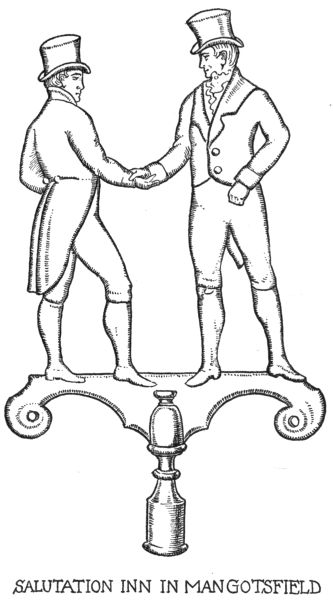

Other tokens were small ivory or metal hands carved with appropriate inscriptions. The latter were also sometimes exchanged on the negotiation of treaties between nations. In the medallion cabinet at Paris there is one of these treaty-hands in bronze, commemorating a treaty between the Gallic tribe of the Velavii and a Greek colony—probably Marseilles. This hand of hospitality, like the wreath, was a frequent motive in the development of the tavern sign. In fact, it was so frequent in the German lands that the people were accustomed to call the tavern, in figurative speech, the “place where the good God stretched out his hands.” If we recall[Pg 20] the deep symbolic meaning of such signs, we shall not find this naïve expression of the people shocking, like the Puritan Consistory at Geneva, whose narrow-minded prohibition of the angel sign we have already noticed.

BESIGHEIM

Now, before passing to the study of the origins of entertainment for pay, with its signs (which were really the first tavern signs) let us turn back to the old Germans, to note[Pg 21] their idea of hospitality. The German fathers, too, tell in a beautiful story of the reception of a divine guest in the cottage of a mortal, and of a reward like that which Abraham had for his spirit of friendly aid. In one of the religious songs of the “Edda,” which probably originated in the North-Scottish islands, we read how the god Heimdall, in the disguise of a humble traveler, visited the hut of an aged couple, and was honorably received by them:—

In the sayings of Hars (i.e., of Odin) the Lofty, the rule of hospitality is stated:—

So even the old Germans had felt the blessings of hospitality, and received the angel’s reward. An old poet expressed it in a simple phrase:—

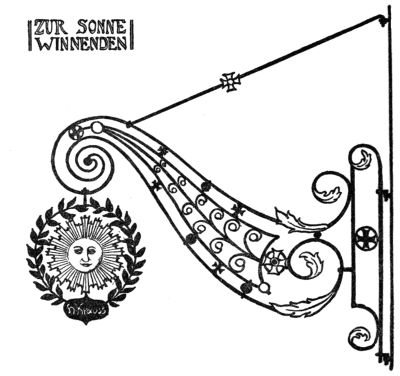

Engel Winnenden, Württemberg

We must now take leave of “holy hospitality” which is written in the hearts of men and truly needs no outward sign, and must follow Iago’s counsel: “Put money in thy purse!” For our journey is no longer from friend to friend, but from host to host and from sign to sign. Regret it as we may, a hospitality for profit’s sake had to succeed the old free hospitality of friends. The widening commerce of the Roman world-empire could hardly have existed without a well-regulated business of entertainment along those magnificent roads by which the empire was bound together. The traveler was more and more unlikely, with every extension of the area of his far journeyings, to find houses to which he was bound by the friendly ties of genuine hospitality; while he[Pg 26] who remained quietly by his own fireside (“qui sedet post fornacem”) would find the constantly increasing duties of the voluntary host growing to be so great a burden that he would be relieved to see the establishment of public inns. Indeed, he may himself, at first, have sought relief by charging his guests a nominal sum to defray their expense. At any rate, it would be very difficult to fix an exact line between these two forms of entertainment, which existed side by side for long ages of antiquity. Certain it is that at some moment, we know not just when, there appeared the Pompeian inscription over the tavern door: “Hospitium hic locatur.” (Hospitality for hire.) That was the birth-hour of the tavern sign.

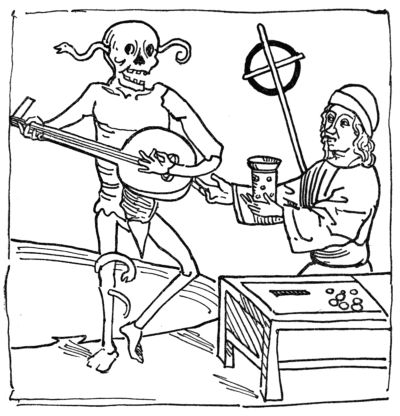

We cannot hide the fact that the beginnings of business hospitality were of a very unedifying character, under the plague of Mammon. In Jewish and Gentile society alike they must have been closely akin to that kind of hospitality against whose smooth speech and Egyptian luxury the wise old Solomon warned foolish youth in his Proverbs. Witness the identical word in Hebrew to denote a courtesan and a tavern hostess; witness[Pg 27] Plato’s exclusion of the tavern-keeper from his ideal republic; witness the reluctance of the respectable Greek and Roman to enter a tavern. In the Berlin collection of antiques there is a stone relief which has been pronounced an old Roman tavern sign. On it the “Quattuor sorores,” or four sisters, are represented as frivolous women. And there are charges entered on old Roman tavern bills which could not possibly appear on a hotel bill to-day. Both the rich and the poor were imbued with the spirit of Horace’s words:—

This spirit reveals itself in a dance of death, which decorated the beautiful silver tankards found in Boscoreale, a Pompeian suburb. And so we must not be surprised to see later, during the Middle Ages, even on tavern signs the grim figure of Death; as for example, on the French tavern, “La Mort qui trompe.”

The magnificent frescoes of the rich in Pompeian art show us a palatial feasting-hall[Pg 28] with the inscription, “Facite vobis suaviter” (Enjoy your life here); and at the same time the tavern guests for a few pennies woo the philosophy of “carpe diem”—the careless abandonment to pleasure that knows no concern for the morrow. Another inscription found in Pompeii makes the tavern Hebe say: “For an as [penny] I give you good wine; for a double as, still better wine; for four ases, the famed Falerian wine of song.” To be sure, the wine was often pretty bad in these greasy inns—Horace’s “uncta popina.” One guest relieved his mind of his complaint by writing on the chamber wall: “O mine host, you sell the doctored wine, but the undiluted you drink yourself.” On the same wall, which seems to have served as a kind of “guest-book” (“libro dei forestieri”) are the names of many guests, one of whom complains in touching phrase that he is sleeping far away from his beloved wife for whom he yearns: “urbanam suam desiderabat.”

In spite of the contempt which ancient writers all manifest for these wine-shops and inns, we remark that men of the senatorial order, like Cicero, did not scorn at times to[Pg 29] stop for a few hours on their summer journey at some country inn like the “Three Taverns,” in the neighborhood of Rome, to call for a letter or to write one. This was the same “Tres Tabernæ” to which the Roman Christians went out to meet the Apostle Paul, to welcome him with brotherly greetings after the trials of his Christian Odyssey. We read in the Acts of the Apostles how great his joy was when he saw them, and how “he thanked God and took courage.” He had no need, however, of the tavern. The hospitality of Christian fraternity, which he had praised so beautifully in his message to the Roman community, now received him with open arms.

The very name “tavern,” which in its Latin original means a small wooden house built of “tabulæ,” or blocks, indicates the very modest origins of professional hospitality. And we must distinguish, in the olden times as in the Middle Ages, between hospitality proper, which takes the guest in overnight, and the mere charity which refreshes him with food and drink and sends him on his way.

The original sign of the tavern-keeper is[Pg 30] the wreath of ivy with which Bacchus and his companions are crowned, and which twines around the Bacchante’s thyrsos staff. As the ivy is evergreen, so is Bacchus ever young (“juvenis semper”), Shakespeare’s “eternal boy.” As the ivy winds its closely clinging vine around all things, so Bacchus enmeshes the senses of men. Thus the custom grew of crowning the wine-jars with ivy, a custom which Matthias Claudius, in his famous Rhine wine song, has described thus:—

Now, whether a good wine really needed the recommendation of the wreath was a question on which experts were not agreed. In general, the ancients leaned to the opinion that “good wine needs no bush”—“Vino vendibili suspensa hedera non opus est.” The French later expressed the same idea in their proverb, “À bon vin point d’enseigne”; though La Fontaine seems to have been of a different mind when he said, “L’enseigne fait la chalandise.” And Shakespeare[Pg 31] enters the controversy in his epilogue to “As You Like It,” when he makes Rosalind say, “If it be true that good wine needs no bush, ’tis true that a good play needs no epilogue.” An English humorist, George Greenfield of Henfield (whoever he may be), is fully of the opinion that there is no need of the bush: “No, certainly not,” says he; “all that is wanted is a corkscrew and a clean glass or two.”

It is perfectly natural that gloomy and distrustful natures like Schopenhauer’s should have no confidence in the sign. He uses the word “sign” always as a synonym for deceit. He calls academic chairs “tavern signs of wisdom”; and illuminations, bands, processions, cheers, and the like, “tavern signs of joy”—“whereas real joy is generally absent, having declined to attend the feast.” Wieland shows the same mistrust in his verses of Amadis:—

On the other hand, happy optimistic natures like Fischart’s, the author of the famous “Ship of Fools” (“Narrenschiff”), and perhaps of its jolly woodcuts as well, give full[Pg 32] credence to a handsome sign. “How shall you think,” says he, “that poor wine can go with so brave a sign displayed, or that so neat an inn can harbor a slovenly host or guest?”

We can see what an important business the making of wreaths was in ancient times by the place which the Amorettes, who were engaged in this work, had in the favorite Pompeian wall frescoes, which portray Cupids in varied activities. We look into the workshop where a small winged figure is working industrially twining garlands; or into the sale-shop where a tiny Psyche is asking the price of a wreath. The winged saleslady answers her in the finger language which the Italians still use: “Since it is you, pretty maiden, only two ases.”

A very favorite tavern sign in the later times also dates from high

antiquity, namely, the pentagram, triangles intersecting so as to make

this figure

![]() .

The Pythagoreans held this as a

talisman of health and protection. The Northern myths called the sign

a footprint of a swan-footed animal. They called it the “Drudenfuss,”

and thought it would protect men against evil spirits like the[Pg 33]

“Trude,” a female devil-nixie which harassed sleepers. We see the sign

in the study-scene in the first part of “Faust”; and remark how evil

spirits and the devil himself could slip into human habitations if the

pentagram before the door was not fully closed at the apexes—but had

a hard time getting out again. The elfish verses are well known:—

.

The Pythagoreans held this as a

talisman of health and protection. The Northern myths called the sign

a footprint of a swan-footed animal. They called it the “Drudenfuss,”

and thought it would protect men against evil spirits like the[Pg 33]

“Trude,” a female devil-nixie which harassed sleepers. We see the sign

in the study-scene in the first part of “Faust”; and remark how evil

spirits and the devil himself could slip into human habitations if the

pentagram before the door was not fully closed at the apexes—but had

a hard time getting out again. The elfish verses are well known:—

“Mephistopheles: I must confess it! just a little thing Prevents my getting out beyond the threshold: That is the Drudenfuss before the door.

“Faust: Ah, then the pentagram is in thy way! So tell me then, abandoned son of Hell, If that can stop thee how thou camest in; Can such a spirit be so tricked and caught!

“Mephistopheles: Look closely! It is badly drawn: one angle, The one that’s pointing outward, is not closed.

“Faust: Ah, that’s a lucky fall of fortune then; It makes thee willy-nilly captive here.”

Besides wreath and pentagram, we find among the ancients a third customary sign of hospitality, namely, a chessboard, which invited the passer-by to a game of draughts along with a draught of wine. The game was not chess, for that came to Europe from the East in the post-classical age. Hogarth’s[Pg 34] engraving “Beerstreet” shows us that this sign prevailed in old England, for the characteristic signpost in front of the tavern door is painted in black and white checkered squares.

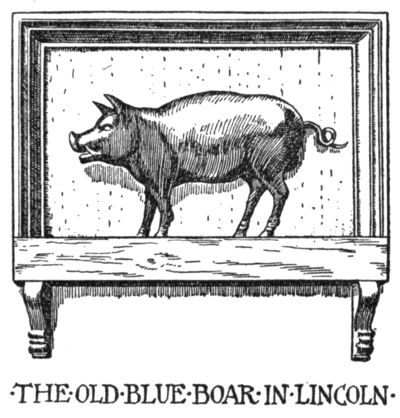

Painted and carved animal images also served as signs in Roman times. We have a few examples left, and the names of a great many more. In Pompeii there was a little inn called the “Elephant,” in which one could rent a dining-room with three couches and all modern comforts (“cum commodis omnibus”). The sign represents an elephant, around whose body a serpent is entwined, and to whose defense a dwarf is running. It was an animal scene on an old sign that inspired Phædron with his fable of the battle of the rats and the weasels; so the author tells us at the opening of his poem: “Historia quorum et in tabernis pingitur.” Perhaps the host of the “Elephant” had an ancestor in the African wars, and in his honor chose the African animal as a sign; just as the host of the “Cock,” in the Roman Forum, hung out for a sign a Cimbric shield captured in the old wars against Germania. On the shield he had painted a stately rooster[Pg 35] with the inscription: “Imago galli in scuto Cimbrico picta.” The choice of the elephant, however, might be due simply to the preference which tavern-keepers showed for strange and wonderful beasts. For the traveler would first stop and stare at the queer animal, and then, like as not, turn in at the door, half expecting that the wily host might be harboring the very beast in real life. There was a grand elephant sign on a Strassburg tavern, which invited to a hospitable table the young students of the town, especially the law students—among them a young man named Goethe. The elephant stood erect on his hind legs, and the toast of the students was: “à l’élève en droit” (à l’éléphant droit).

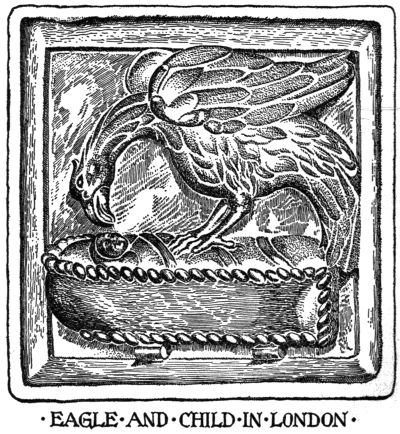

Among other figures of animals on Roman signs the eagle was a great favorite. The Romans bore the eagle on their standards, after having long accorded the honor to the she-wolf, the minotaur, and the wild boar. The Corinthians likewise carried a Pegasus, and the Athenians an owl, on their banners. The sign was closely related to the banner: it was a kind of rigid flag. We shall see later, in the Dutch pictures, how, at the jolly kermess,[Pg 36] flag and shield together invited the peasant to drink and dance. In mediæval France the tavern hosts hung out flags on which the sign was painted or woven in colors. The French word “enseigne” means originally a flag: “Le signe militaire sous lequel se rangent les soldats,” as the classic definition in Diderot’s famous Encyclopédie runs. A secondary definition is: “Le petit tableau pendu à une boutique.”

The Romans seldom had signs that hung free, such as the Cimbric shield described above. Generally their signs were paintings or reliefs on a wall. There were in the shops of Pompeii depressions in the wall made especially to receive these signs. So, too, the so-called “dealbator” whitewashed a place on the wall for the election bulletins. Sometimes the painter used wood or glass as the ground for his sign.

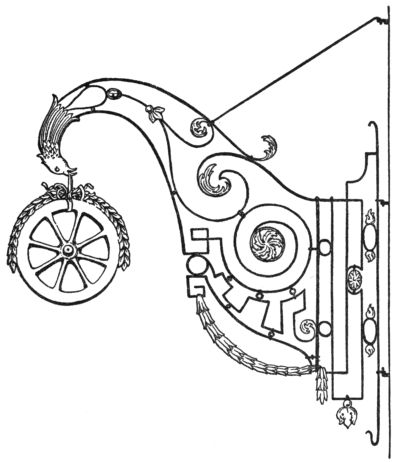

We find all the Roman animal signs—storks, bears, dragons, as well as the eagle, the cock, and the elephant—in the later Christian ages. It is not impossible that the eagle signs of later days are the direct descendants of the old Roman eagle; and they probably existed in most of the old towns[Pg 37] founded by the Romans—Mayence, Speyer, Worms, Basel, Constance. The names that have come down to us are chiefly of taverns in the African colonies. Here we find, curiously enough, the wheel (“ad rotam”), the symbol of St. Catherine, which we shall meet later in Christian lands; for example,[Pg 38] in a picturesque sign in the old town of Ravensburg in Württemberg.

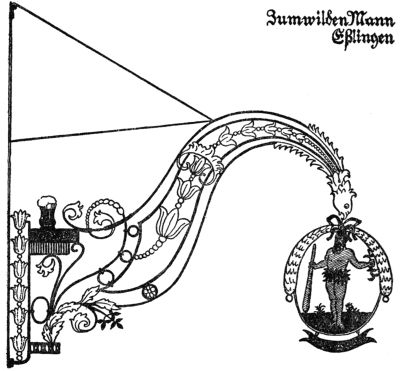

Zumwilden Mann Eßlingen

In Spain we find the Moor (“ad Maurum”) who kept his popularity for centuries. In Sardinia, Hercules, the pattern of the later hero with the “big stick,” as he appears in the German sign at Esslingen. Some of the inns had names of heathen divinities, like Diana, or Mercury, the god of commerce, or Apollo, whose emblem the sun shed its inviting rays from so many a tavern[Pg 39] portal in fair and foul weather alike. A tavern in Lyons was named “Ad Mercurium et Apollinem”: “Mercurius hic lucrum permittit, Apollo salutem” (“Here Mercury dispenses prosperity, and Apollo health”). It is possible that these taverns had gods as signs, just as in the Middle Ages the streets abounded in images of the Madonna and saints, which invited the traveler to turn in for profit or pleasure. Tertullian tells us that there was not a public bath or tavern without its image of a god: “balnea et stabula sine idolo non sunt.” After the victory of Christianity the images of the gods were cheap: tavern-keepers could buy them for a few obols. We can little doubt that among this “rubbish” was many a precious work of art which the museums of to-day would be proud to own.

It would be hard to say whether an unbroken tradition connects the signs of the Middle Ages with those of like name in classical antiquity. Many a sign may have been invented anew. But that we have learned much directly from the old Romans in the field of hospitality is proved by a curious fact. The Bavarian Knödel, which every[Pg 40] true Bajuware claims as an indigenous, national institution, are prepared to-day exactly like the old Roman “globuli,” after the recipes of Columella and Varro. Such, at least, is the assurance of Herr von Liebenau in his interesting book on Swiss hospitality.

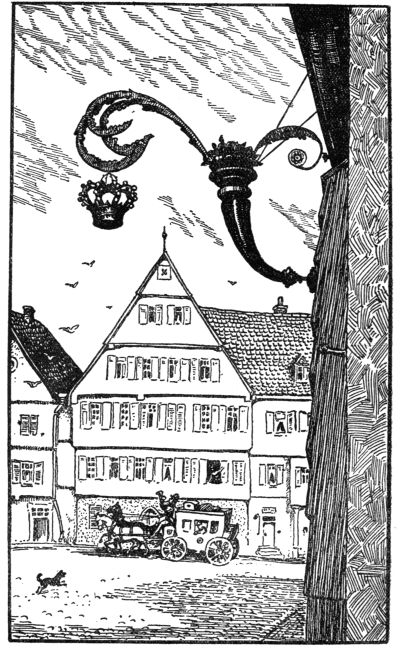

We remarked above that it was by their roads especially that the Romans extended their power over all the world. We must notice now briefly the Roman post-system, the “cursus publicus,” whose coaches probably carried travelers from tavern to tavern like the modern mail-coaches. We must, however, curb the imagination of the reader with a reminder that practically only the state officials used this service. Not every country bumpkin could mount with market-basket on his arm, to make a jolly journey over hill and dale to the sound of the echoing horn. Still the Emperor or his prefect could issue tickets to private persons; and furthermore, these persons could, under certain circumstances, get a sort of Cook’s ticket, called “diploma tractoria,” which included board and lodging as well as transportation. If the journey lay through a lonely region, where there were no private taverns to provide[Pg 41] shelter for the night, the traveler might put up at the state inn (“mansio”) which the province was obliged to maintain at public cost, with all the necessities and comforts to which respectable Roman travelers were accustomed. One can well understand how, as the empire disintegrated, the provincials were glad to throw off this hated compulsory tax for the support of the state inn. It was not till the time of Charlemagne that the institution was revived as a military-feudal service along the routes of the imperial army. Whether these Roman state inns displayed signs or not, we do not know. It is, however, very likely that they were distinguished by the sign of the Roman eagle, and so became the type of the later private eagle inns.

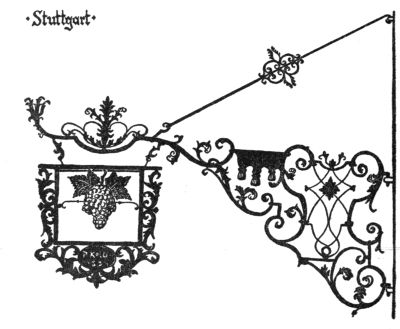

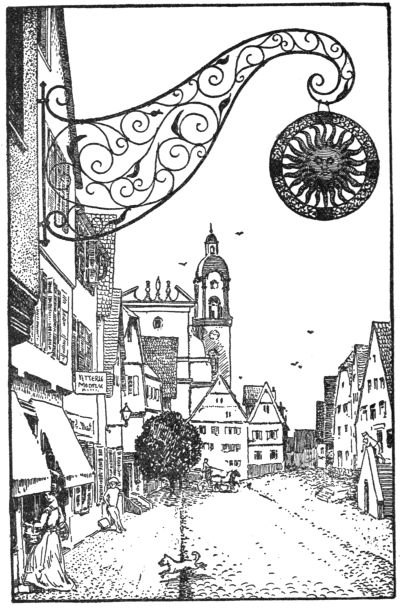

Here let us remark that the post-coaches of our own day, which seem to us an institution dating from the Deluge, are a comparatively late invention. The first so-called “land-coach” in Germany was established between Ulm and Heidelberg in the year 1683. Through all the Middle Ages and the Renaissance period, we depended on mounted messengers, traveling cloister brothers, university[Pg 42] students, and rare travelers to carry messages. In Württemberg, where we find to-day the most abundant reminders of the good old post-coach days, and consequently the finest old signs, bands of “noble post-boys” are found, including the distinguished names of Trotha and Hutten.

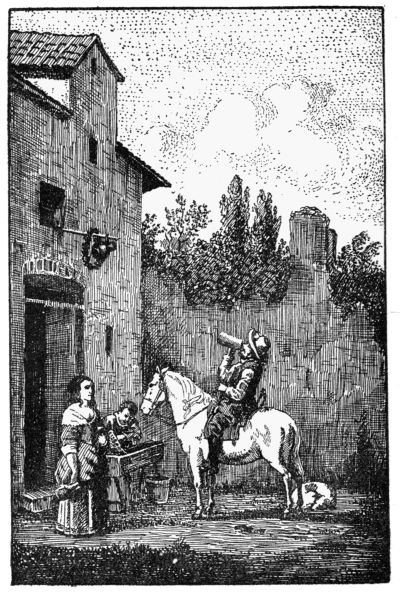

That the common workman, even in the Roman days, had to use “shank’s mare” when he went traveling goes without saying. But the well-to-do burgher or trader who had no license to ride in the state post-coach rode on his horse or his high mule. Horse and saddle remained for centuries the only method of travel after the Roman roads had fallen into that state of dilapidation from which they fully recovered only in the days of Napoleon. One needs only to look at the coaches of princes in past centuries to see for what bottomless mud-bogs these lumbering vehicles were built. Montaigne rode on horseback from his home in Bordeaux to the baths of southern France and Italy, although he seems, from the entries in his diary, to have been very much afflicted with “distempers.”

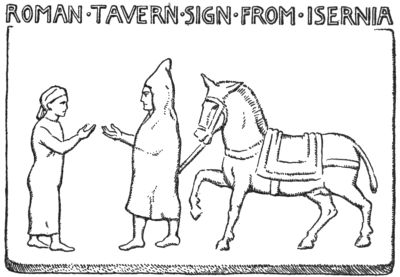

A late Roman relief found in Isernia (in[Pg 43] Samnium)—a kind of tavern sign—shows us a traveler holding his mule by the bridle as he takes leave of the hostess and pays his account. The traveler has on his cloak and hood. The hood, even up to Seume’s time (i.e., up to the end of the eighteenth century), was generally worn by travelers in Italy, and especially in Sicily: “My mule-driver showed a tender solicitude for me,” wrote Seume, “and gave me his hood. He could not understand how I dared to travel without one. This peculiar kind of dark-brown mantle with its pointed headgear is the standard dress in all Italy, and especially in Sicily. I took a great fancy to it, and if I may judge[Pg 44] from this night’s experience, I have a great inclination toward Capuchin vows, for I slept very well.”

ROMAN·TAVERN·SIGN·FROM·ISERNIA

We have had to confine ourselves in the treatment of ancient signs entirely to Roman examples, for we have very little knowledge of Greek signs. In fact, the tavern sign seems to have come late into Greece, through Roman influence. We hear of a tavern “The Camel” at the Piræus, also of a sailors’ inn having the sign in relief: a boiled calf’s head and four calf’s feet.

We shall later see what an important part signs played in directing travelers in a city through the Middle Ages and even in modern times. They took the place of house numbers and street names. In ancient Rome a whole quarter was often named after an inn, like the “Bear in the Cap” (“vicus ursi pileati”). This is the longest-lived bear in history: he lives even to-day. An excellent German tavern guide, Hans Barth, writes in his delightful little book “Osteria”: “On the quay of the Tiber was the famous old inn of the Bear, where Charlemagne lodged, because the Cafarelli Palace was not yet built; where Father Dante frolicked with the [Pg 45]pussy-cats; where Master Rabelais raised his famous bumpers of wine.” In Montaigne’s time the Bear was so frightfully stylish an inn, with its rooms hung with gilded leather, that the essayist stayed there only two days and then forthwith sought a private lodging.

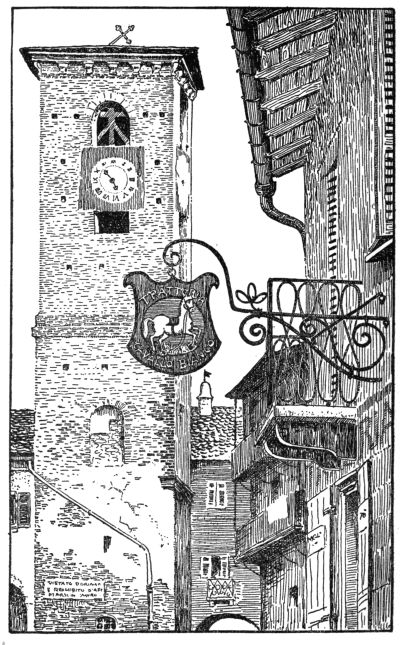

Campana and Canone d’Oro

Borgo San Dalmazzo, Italy

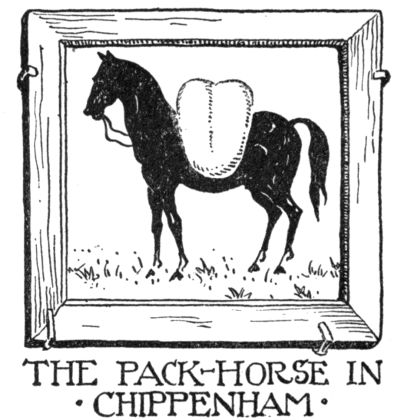

In modern Italy there are only a few interesting signs. The most delightful ones (the Golden Cannon, and the Bell) we found in the main street of the North Italian mountain town of Borgo San Dalmazzo. The “White Horse” (“cavallo bianco”) was a little off the main street. The form of these was probably influenced by the proximity of Switzerland—a country very rich in beautiful signs.

Seume, who had the finest opportunity for studying taverns and signs in his walking tour from Leipzig to Syracuse, often mentions the name of his inn; as, for instance, “Hell” in Imola, or the “Elephant” in Catania. But there was only one Italian town in which the signs impressed him: that was Lodi. “The people of Lodi,” he writes, “must be very imaginative if one can judge them from their signs. One of them, over a shoemaker’s shop, represents a Genius taking[Pg 46] a man’s measure—a motif which reminds one of Pompeii.”

Our excellent guide, who has an eye for everything picturesque, does not seem to have met much of interest from Verona to Capri. An exception was the “Osteria del Penello,” in Florence, on the Piazza San Martino, a tavern established about the year 1500 by Albertinelli, the friend of Raphael. On the sign over the door was the jolly curly head of the founder, who, when the envy of his colleagues poisoned the work of his brush, here established a tavern. An inscription read: “Once I painted flesh and blood, and earned only contempt; now I give flesh and blood, and all men praise my good wine.”

Barth also mentions, by the way, the characteristic wall-paintings of Italy that rest on the old Roman tradition and yet serve as tavern signs, like the “Three Madonnas” of the Porta Pincia in Rome: “A portal decorated with three pictures of the Mother of God leads into the green garden court.”

Lest the thought of a religious painting serving as a tavern sign should shock any of our readers, we hasten to turn to the study of religious hospitality and its emblems.

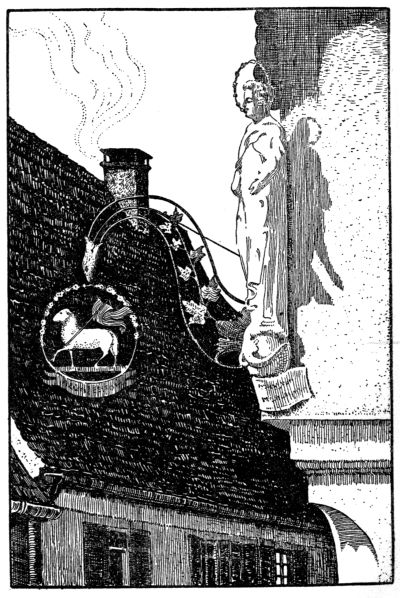

Lamm Erlenbach, Württemberg

Rome was to conquer the northern Germanic world once more, not with the sword as had been the case in the olden days of a pagan Rome, but with the cross and its exponent, the monk. The northward surging wave of Roman Cæsarism had been followed by the tidal wave, southward-roaring, of Germanic barbarians. The orderly life of one vast empire gave way to the restlessness and insecurity of the period of migration and a shattered empire. Not individuals but whole peoples go a-traveling with household goods and wife and children, whole towns and countries become their inns, the standard of the conquerors are their tavern signs. Then again flowing northward, progressing by insensible stages, comes the silent throng of monastic brotherhoods, the Benedictines in the van, who bring forth various orders from[Pg 50] their midst, the Cistercians among others, who dig and reclaim the soil with their spades and later, as builders, dedicate it to their God, unknown and now revealed, with high-soaring monuments of worship.

Undaunted by solitude, fearless of the wildness of desolate regions, they enter the forest primeval to clear it and establish quiet homesteads for themselves and their worship; their doors are open to all those who pass their way. For had not St. Benedict, mindful of repeated apostolic admonitions to the bishops, included hospitality in the rules of his order? Therefore ere long there lacked not in any convent certain rooms given over to the comfort of the wayfarer, be it a “hospitium,” a “hospitale,” or a “receptaculum.” Witness the Hospice of the Great St. Bernard in the Alps of the Vallais, named after the pious founder of that earliest of Occidental orders, part of the convent erected in the ninth century by the bishops of Lausanne, while the shelter on Mont Cenis is said to date back to a past equally remote. Beginning with the year 1000, convents likewise erect inns in the villages, outside of their immediate domains, leasing these[Pg 51] against rental, while in the towns pilgrim inns, poor men’s taverns, and “Seelhäuser” are endowed for the free housing of pilgrims and wayfarers, evolving later into town inns.

To the pilgrim, then, who wended his way to the tombs of saints, and, in the crusade times, to the holiest of graves in Jerusalem, mediæval hospitality is mainly devoted. The crusaders were agents of especial power in the development of hospitality, since on his lengthy journey the pilgrim stood in need, not only of food and shelter, but also of convoy along roads perilous everywhere. The Knights of St. John set themselves these two tasks, to care for the pilgrims and escort them in safety, which is implied by their name “fratres hospitales S. Johannis.” In the rule of their order (ca. 1118) the foremost duty of lay as well as clerical brothers was to serve the poor, “our lords.” With like intent of safeguarding pilgrims the Order of Knights Templars was instituted in 1119, especially for the care of German pilgrims. We may venture to assume from their name, “Order of the German House of our dear Lady in Jerusalem,” that a homelike[Pg 52] Madonna picture adorned their hospitable house as a pious welcome. Shakespeare has inimitably described the warlike duties of these orders, duties which went hand in hand with kindly care and hospitality, in the first part of “Henry IV”:—

These knightly orders, whose hospitable roofs originally sheltered the pious pilgrims bound for Jerusalem, also opened in welcome the gates of their proud houses at home, which still adorn more than one old German town. When Luther was summoned to Worms by the Emperor, in 1521, he stayed with the Knights of St. John. Here in this noble inn he exclaimed to his friends, after the ordeal, with upraised arms, and face shining with joy: “I am through, I am through.” Like an enduring rock he had stood his ground and had expressed his unalterable will to be a free Christian in those famous words: “Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders, Gott helfe mir! Amen.”

In like manner Luther had accepted ecclesiastical[Pg 53] hospitality on his journey Romeward, as a young monk, notably on the part of the Order of St. Augustine. From the pages of that Baedeker of the fifteenth century, the “Mirabilia Romæ,” we can realize how thoroughly a pilgrimage to Rome was viewed in those days as a pious journey to hallowed places, relics and tombs of the saints. The work referred to appeared first as a block-book, with pictures and text both printed from the same wood block. The youthful monk may well have carried such an early copy of the “Mirabilia” in his cowl when he entered the holy precincts of the Eternal City, which revealed itself to his great disillusionment as an ungodly spot and the seat of Anti-Christ. Occasionally we also see the great reformer descending at a lay tavern, such as the famous inn of the High Lily in Erfurt, which subsequently saw within its walls great warriors like Maurice of Saxony and Gustavus Adolphus.

To this day there is in England a hospital founded by the Knights of St. John, in which every wayfarer can obtain bread and ale upon request. This is the “Hospital of St. Cross without the walls of Winchester,” as it is[Pg 54] called in a document in the British Museum; ceded by the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem to Richard Toclive, Bishop of Winchester, in 1185, the bishop raising the number of poor there entertained from 113 to 213, of whom 200 were to be fed and 13 fed and clothed. Emerson once made a pilgrimage to the hospital, claimed and received the victuals, and triumphantly quoted the incident as a proof of the majestic stabilities of English institutions. In his wake numberless Americans yearly wend their way to the Hospital of the Holy Cross, and to the beautiful Minster of Winchester embedded in verdure. There they lodge either at the “George,” or, more cozily yet, in the ancient “God begot House” of a type found, perhaps, in England only.

Another American no less renowned, Mark Twain, the “New Pilgrim,” as he styled himself, has felt on his own physical self the blessings of clerical hospitality in Palestine, the land of ecclesiastic foundations, which he celebrates as follows in his “Innocents Abroad”: “I have been educated to enmity toward all that is Catholic, and sometimes, in consequence of this, I find[Pg 55] it much easier to discover Catholic faults than Catholic merits. But there is one thing I feel no disposition to overlook, and no disposition to forget: and that is, the honest gratitude I and all pilgrims owe to the Convent Fathers in Palestine. Their doors are always open, and there is always a welcome for any worthy man who comes, whether he comes in rags or clad in purple.... A pilgrim without money, whether he be a Protestant or a Catholic, can travel the length and breadth of Palestine, and in the midst of her desert wastes find wholesome food and a clean bed every night, in these buildings.... Our party, pilgrims and all, will always be ready and always willing to touch glasses and drink health, prosperity, and long life to the Convent Fathers in Palestine.”

We may well believe that private individuals then as now bid for the patronage of pilgrims. Shakespeare tells us of a case in point, in his “All’s Well that Ends Well” (Act iii, Sc. v). Helena appears in Florence in search of her husband gone to the wars, “clad in the dress of a pilgrim,” and inquires where the palmers lodge. A kindly widow tells her “at the Franciscans here[Pg 56] near the port”; but knows how to win the fair pilgrim by her words:—

If, on the other hand, we consider how pilgrims made their long journey more toilsome yet, as related by Helena herself,—

we shall appreciate how gratefully the proffer of the good widow must have been accepted. The hospitality of the monks was not always lavish; on the contrary, it proved scant and poor, as Germany’s greatest troubadour, Walter von der Vogelweide, to his sorrow experienced. Once he turned aside more than four miles from his road in order to visit the far-famed convent of Tegernsee. The learned monks, whose library forms to-day one of the treasures of the State Library in Munich, may have been too deeply engrossed in the transcription of a classic author, or in elaborate miniature paintings; at any rate, they did not realize what noble guest sat at their board and brought him—[Pg 57]not the choice vintage which the thirsty poet expected but simply water:—

If guests were thus given cause for complaints of their treatment by the convents, the monks on their side had no less ground for occasional displeasure at the abuse of their hospitality. Carlyle cites an instance of this kind in “Past and Present”; the excellent abbot, Simon of Edmundsbury, had forbidden tournaments within his domain. In spite of this prohibition twenty-four young nobles arranged a knightly joust under his very nose, so to speak. Not content with that, they rode gayly to the convent at its conclusion and demanded supper and a night’s lodging. “Here is modesty,” says Carlyle. “Our Lord Abbot, being instructed of it, orders the Gates to be closed; the whole party shut in. The morrow was the vigil of the Apostles Peter and Paul; no out-gate on the morrow. Giving their promise not to depart without permission, those four-and-twenty young bloods dieted all that day with the Lord Abbot waiting for trial on the[Pg 58] morrow.” And now Carlyle cites his own source the “Jocelini Chronica”: But “after dinner”—mark it, posterity!—“the Lord Abbot retiring into his Talamus, they all started up, and began carolling and singing; sending into the Town for wine; drinking and afterwards howling (ululantes);—totally depriving the Abbot and Convent of their afternoon’s nap; doing all this in derision of the Lord Abbot, and spending in such fashion the whole day till evening, nor would they desist at the Lord Abbot’s order! Night coming on, they broke the bolts of the Town-Gates, and went off by violence!”

Not only had convents to suffer from such exuberant guests; oftener far they were burdened by those who forgot to depart and continue their journey. The abbot, Herboldus Gutegotus of Murrhardt, the convent whose romantic church still ranks among the finest ecclesiastical monuments in Germany, used to tell such forgetful guests the following little story: “Do you know why our Lord remained but three days in his tomb?—Because during that time he was making a friendly visit to the patriarchs and prophets in Paradise. So in order not to[Pg 59] cause them inconvenience he took timely leave and resurrected upon the third day.” Evidently the refined abbot knew how to veil politely the old Germanic directness which finds such clear expression in the “Edda”:

In wild and inhospitable countries, the convents long remained, even till recent times, the only shelters for travelers. Hence, when Henry VIII of England began to confiscate monastic property on a grand scale, a significant revolt for their reinstallment flamed up in the north of England,—the so-called “Pilgrimage of Grace” of the year 1536, which was suppressed with deplorable sternness. The convents were very popular in those parts because the monks had been the only physicians and their doors were always open to all wayfarers.

Chaucer shows us in his “Canterbury Tales” that monks could be pleasant guests as well as good hosts, for there we read in regard to the friar: “He knew well the tavernes in every town”; and “What should he studie and make himself wood?”

Having thus pictured to ourselves the clerical hospitality of the Middle Ages, we shall not wonder that, in outward signs for the designation of the houses as inns, religious subjects and their pictorial presentation were adopted.

Among the saints particularly revered by the pious pilgrims St. Christopher stands foremost, since he had himself experienced so perilous a journey. In many mediæval pictures we see him leaning on his massive staff, carrying the Christ child across a river. The “Golden Legend” tells us that he was nearly drowned, so heavy was the burden of this child. “Had I carried the whole world,” he says, when finally reaching the shore, “my burden could have been no heavier”; whereupon the child of whose identity he was not yet aware: “for a sign that you have carried on your shoulders not only the world but the Creator, thrust this staff into the ground near your hut, and behold, it will blossom and bear fruit.” Hence the partiality for huge pictures of St. Christopher, visible afar, such as we find occasionally to this day in and upon certain churches; for instance, the spacious mural paintings in the church of[Pg 61] St. Alexander at Marbach, the birthplace of Schiller, close to the tracks on which the modern traveler thunders past; or the gigantic sculpture on the south side of the cathedral in Amiens, or the large fresco in the minster at Erfurt. They give us a conception of similar presentations on Poor Men’s Inns and ecclesiastical hospices. The belief in the efficacious protection by the saint, especially from sudden death, is expressed in the French mediæval saying: “Qui verra Saint Christophe le matin, rira le soir.” The tenacity of this belief among the people is well instanced by the fact that the jewelers of so worldly a city as Nice sell to owners of automobiles little silver plaques, with the picture of the saint and the inscription, “Regarde St. Christophe et puis va-t-en rassuré.” Let us hope, in the interest of the rest of mankind, that these motorists do not feel too reassured in consequence.

American readers might be interested to hear that in their own country a guest-house of St. Christopher gives refuge to the modern fraternity of tramps, charitably called the “Brother Christophers” by the Friars of the Atonement, who founded this house[Pg 62] at Gray Moor, near the beautiful residential district of Garrison, in the State of New York.

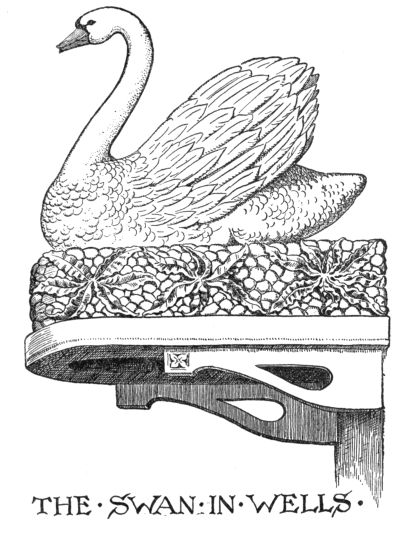

Another saint, deservedly in great favor, is St. George, who slew the dragon, a knightly patron who smooths the traveler’s path and makes it safe by brushing aside all its threatening dangers. Two of the finest hostelries still existing are named after him: the “Ritter” in Heidelberg, and the “George,” more ancient yet by a century, in the time-hallowed town of Glastonbury. Two miracles have drawn pilgrims to the latter place since olden times, the “Holy Thornbush,” which had blossomed forth from the staff of Joseph of Arimathea and bloomed every Christmas, and the “Holy Well,” in the garden of the cloister school, now deserted, whose waters were to heal the bodily ailments of the pious pilgrims. The throng of wayfarers to the convent, whose gigantic abbot’s kitchen is eloquent of hospitality on a large scale, made the establishment of a pilgrim’s inn outside the walls imperative. First they erected the “Abbot’s Inn,” and when this proved insufficient—at the end of the fifteenth century—the elegant Gothic structure was erected,[Pg 63] which bears to this day the ensign “Pilgrim’s Inn,” but is popularly known as “The George,” from a likeness of the saint which once adorned the handsome bracket so happily wedded to the architecture of the house. The tourist undaunted by fearsome reminiscences may ask to be given the choice apartment there, the so-called “abbot’s chamber,” where Henry VIII rested on the day when he ordered the last abbot hung on the town gate. The fine four-poster, it is true, has been sold to a fancier of antiquities and replaced by a new canopied bed, but despite this the room retains its mediæval appearance.

About a hundred years later, the delightful Renaissance structure, “Zum Ritter,” was erected in Heidelberg. Originally the house of a wealthy Frenchman, it was subsequently changed into a hostelry and took its name from the knight on the peak of the gable. Doubtless no one has ever sung the praise of this noble building more worthily than Victor Hugo, who visited Heidelberg in 1838, and passed by the house of St. George every morning, as he said, “pour faire déjeuner mon esprit.” Jokingly he[Pg 64] observes that the Latin inscription (Psalm 127, i) has protected the inn better than the little iron plate of the insurance firm. As a matter of fact neither the great conflagration of 1635, during the Thirty Years’ War, nor the fires started under Mélac and Maréchal de Lorges, in 1689 and 1693, could harm this inn, while “all the other houses built without the Lord were burnt to the ground.”

In England the good knight St. George was an especial favorite; even in the middle of the last century there were in London alone no less than sixty-six hostelries of that name. Truly, the pious meaning of old associated with the sign had long been forgotten by hosts and guests alike, so that as early as the seventeenth century these mocking lines were penned:—

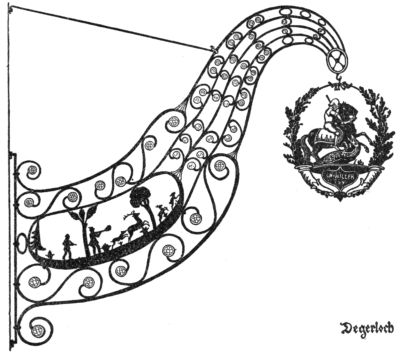

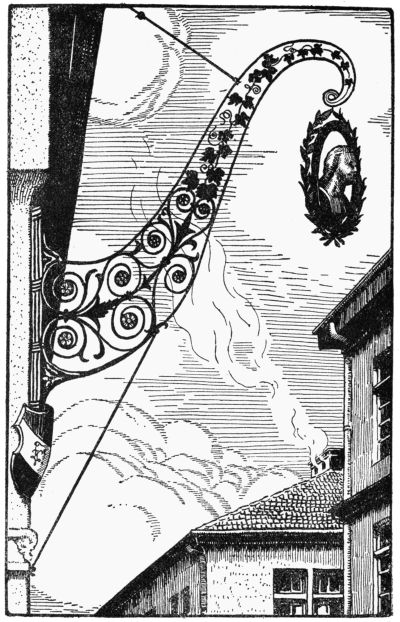

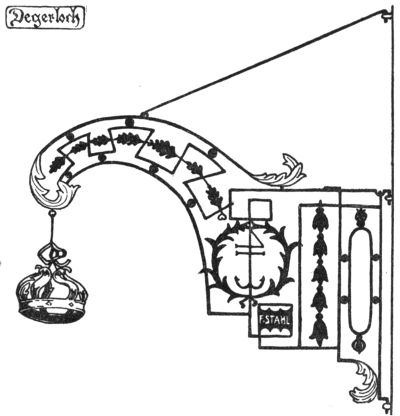

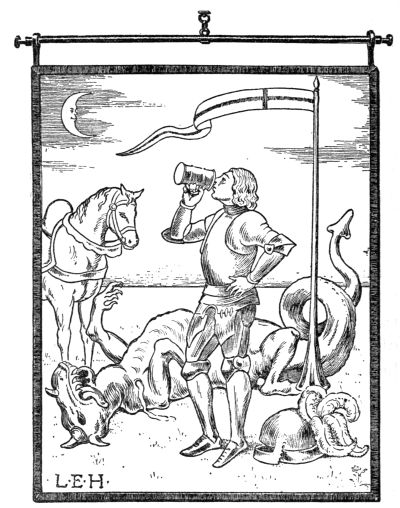

The pictures of the “valiant knight’s” mount were often so dubious that a connoisseur of horses like Field Marshal Moltke, writing from Kösen, Thuringia, construed it as the[Pg 65] picture of a mad dog. On the other hand, we have such charming conceptions of St. George as the sign here shown, from the hamlet of Degerloch, delightfully situated on the heights overlooking Stuttgart, a notable artistic achievement in wrought iron, interesting, moreover, for the associations of merry chase linked with the saint in the mind of the country folk.

Degerloch

Among other saints frequently chosen for tavern signs, St. Martin must be mentioned. At times he appears in like manner as does[Pg 66] St. Christopher; for instance, on the large reliefs decorating the façade of the minster in Basle: a friend of the needy, dividing his cloak with his sword, to share it with them; thus the pious saint lives on in the minds of the people. At the season of the new wine, the 21st of November, the Church commemorates his name: “A la saint Martin, faut goûter le vin,” is the French saying.

At the sign of St. Dominic too, whose meaning of religious hospitality had been utterly perverted in the course of time, stanch topers used to congregate for joyous orgies. Proudly they called themselves “Dominican”; and

is their interpretation of such strange affiliation, in a song of the seventeenth century.

St. Urban has likewise figured on many a tavern sign. Once upon a time he took refuge from his pursuers behind a grapevine, and for that reason he has become a patron saint of vintners and tavern hosts. “Alas,” exclaims the refined Erasmus of Rotterdam, “mine host is not always as ‘urbane’ as he should be to justify this patronage.”

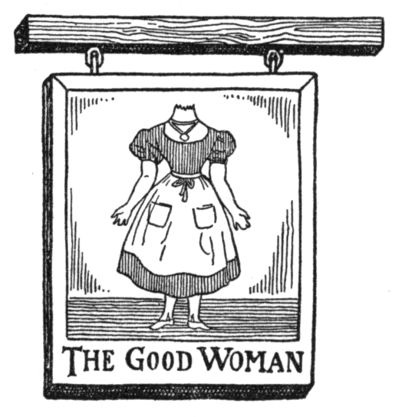

The Good Woman

There is one sign whose religious origin is not self-evident, namely, the “Femme sans tête.” Yet the figure has its origin, no doubt, in mediæval representations of saints after decapitation, sometimes shown with the head in the hands. Whoever has perused the illustrated “Lives of the Saints” with their many horrible mutilations of the martyrs depicted in woodcuts, must have realized that their moral influence on the popular imagination cannot have been of a beneficial nature. Even great artists did not hesitate to celebrate such awful scenes with the power of their genius. Among the drawings of Dürer we see the executioner with his great sword ready to behead St. Catherine. Nothing so disgusted Goethe in his Italian journey as all the painted atrocities perpetrated on the martyrs. The most peculiar[Pg 68] example of this form of art is probably that in the Tower of London. It is a set of horse armor presented, apparently without malice, by Emperor Maximilian to Henry VIII of England, embellished with the most gruesome scenes of martyrdom. In the Tower, where so much innocent blood has flowed, one feels doubly repulsed by such excrescences of so-called religious art: one is even tempted to accept the popular conception of these beheaded saints as comforting symbols of forgetfulness. In fact, the oil merchants chose the “woman without head” as their sign, as one of the foolish virgins of the parable who had neglected to provide themselves in good time with the necessary oil: a warning example to delaying, unwilling customers.

A coarser interpretation of the figure styles it as the “silent woman,” or as the “good woman,” who can no longer do mischief with her tongue. Moreover, one finds this most gallant of signs—which should be unmentionable in these days of woman’s emancipation—not only in outspoken Holland, with the words: “Goede vrouw een mannen plaag” but also in Italy; in Turin, for[Pg 69] instance, styled as “La buona moglie.” The most polite people on earth—I do not mean the Chinese, but the French—have named a street in Paris the “Rue de la Femme sans Tête” after a tavern of like appellation. Young Gavarni stayed awhile in the “Auberge de la Femme sans Tête” in Bayonne, as the Goncourts tell us, and waxed eloquent about the dainty charms of the “vierge du cabaret,” the tavern-keeper’s daughter.

Ben Jonson, who loved to discuss with Shakespeare in the Siren Club and to “anatomize the times deformity,” may have been stimulated to write his comedy “The Silent Woman” by the tavern sign of that name. In Jonson’s play, a Mr. Morose, an original old fellow, who holds all noise in detestation, weds a young lady, whose barely audible voice and scant replies have charmed him. When after the ceremony she reveals herself a loquacious scold and he gives vent to his disappointment, she replies with these endearing words: “Why, did you think you had married a statue, or a motion only? one of the French puppets, with the eyes turned with a wire? or some innocent out of the hospital that would stand with her hands[Pg 70] thus, and a plaise mouth, and look upon you?”

But to comfort the feminists we should speak of a host truly gallant, who had a great white sign made, with the inscription below, “The Good Man.” To the universal inquiry, “Where is the good man? I can’t see him,” he made answer, “Well, you see that is why I have left the blank space; if only I could find him.”

Since there is a saint for every day of the calendar, we must not be astonished to find names among those adopted for tavern signs which to us bear no relation to sanctity; such as St. Fiacre over a drivers’ bar, which seems rather the invention of some wag.

We must needs realize that all these religious signs have their origin in a time when popular imagination was mainly filled with the happenings of the Bible and the legends of the saints; when religion had not yet grown to be a Sunday occupation of a couple of hours, but was most intimately interwoven with the life of every day. Hence we find among subjects for signs not the saints only, whose human errors and sufferings have riveted a bond between them and the common[Pg 71] people, but also the Deity itself. “La Trinité” was one of the latter in mediæval France, as evidenced by this passage in the song of a pilgrim:—

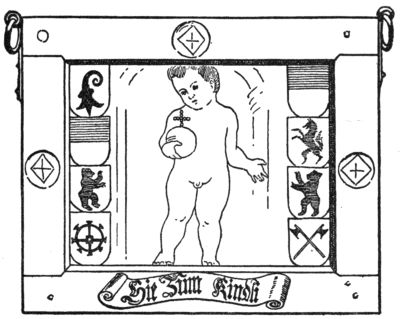

Hie Zum Kindli

Other pilgrim taverns styled themselves “A l’image du Christ.” We also meet with such inscriptions as “L’Humanité de Jesus Christ, notre sauveur divin”; the birth of Christ as a child, as in the charming old Swiss sign “Hie zum Christkindli”; the Madonna[Pg 72] and scenes of her life like the “Annunciation,” called Salutation in England. These and many other signs, such as “Purgatory,” “Hell,” and “Paradise,” which have been revived in modern Paris on fantastic cabarets, meet our eyes on tavern signs. An old enumeration of London bars of the seventeenth century begins with the words:—

And when the author tires of mentioning them all by name, he concludes with:—

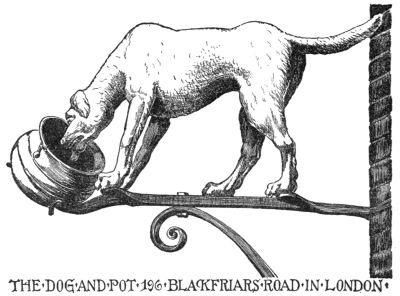

Finally, we must turn to those signs, not religious at first sight, which may well have their origin in attributes of the saints. Thus, we meet in Swiss towns, which have St. Gall as their local patron, with the sign of the “Bear”; “Crown” and “Star” are the symbols of the three magi who followed the star to the lowly tavern in Bethlehem; the “Wheel” reminds us of the martyrdom of St. Catherine; the “Stag” may be a reminder[Pg 73] of the legend of St. Hubert; while the “Bell,” once used by St. Anthony to drive away the demons by its sound, was fastened on the neck of animals to preserve them from epidemic diseases. We often see the bell, in old woodcuts, fastened round the neck of the little pig which accompanies the saint. The bell assumed a very worldly meaning, when it called the tipplers to their merry gatherings, which called forth in England the patriotic rhyme:—

The Tower of St. Barbara grew into an independent tavern sign, which, misunderstood, occasionally changed into a cage. Even the platter on which rested the head of the Baptist is deformed into the “Plat d’argent” over a tavern door. Hogarth does not refrain from introducing a sign in his engraving “Noon,” of 1738, showing the Baptist’s head on a charger, with the cynical inscription “Good Eating.” Whether such coarsenesses were actually perpetrated, even under the lax régime of Charles II[Pg 74] in England, when frivolity reigned after the fall of Cromwell, it is hard to decide. Possibly they may be set down as brutal outcroppings of the satirist’s truth-deforming brain. The fact is, that even in the sixteenth century the abuse of religious subjects for the most disreputable resorts roused the indignation of serious, thinking men. Thus a certain Artus Désiré indignantly laments, in a rhymed broadside, that the tavern-keepers dare place over houses where the great hell devil himself is lodged the images of God and the saints to advertise their vine:—

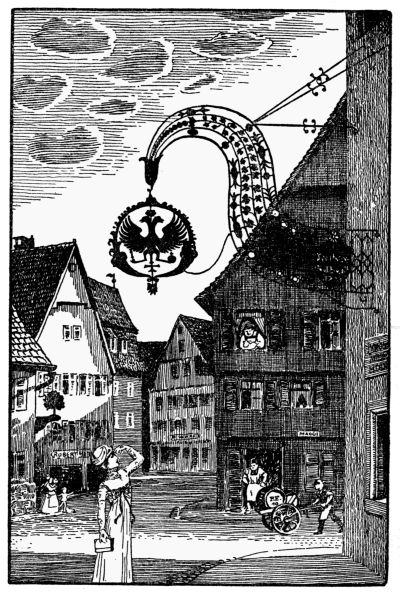

Adler Leonberg, Württemberg

The heavy castle gates in mediæval times were gladly opened to the minstrels who came to charm with their art the banquets of the noble lords and ladies—troubadours and minstrels, the ancestors of that vast and still thriving fraternity of poets whose blood runs too quickly through their veins to keep them content in the quiet monotony of a home. With the sailing clouds, with the migrating birds, and the rising sun they wander through woods and fields “to be like their mother the wandering world.” With Walt Whitman they love the open road and hate the confinement of the stuffy room:—

Never do they feel happier than when the long, long road lies before them, which now seems to dip down into the green sea of the forests and now to climb straight into the bright blue heaven. Jean Richepin, himself a “chemineau,” now well settled as an honorable member of the French Academy, has sung the open road’s praise. All poets feel deeply the words of Kleist, “Life is a journey.” And how bitter the journey often was in the days of the minstrels, how glad they were when the dark forests and unsafe roads lay behind them and the big hearth-fire of the castle hall brightened face and soul! Gratefully they praised the noble lord for his hospitable reception and his kindly welcome. Thus Walter von der Vogelweide, Germany’s greatest minstrel:—

Impoverished knights may have occasionally hung out an iron helmet over the castle door as a sign that they were willing to receive and to entertain paying guests: certainly[Pg 79] a more honorable method of gaining one’s livelihood than to plunder the passing merchant or even one’s own peasants, as was the noble fashion at the end of mediæval times. But it is more likely that such poor noblemen would first think of using their city houses for such commercial purposes and not their lonely and uninviting fortified castles. Here on one of their city houses, where they used to lodge in time of markets or city festivities, the first iron helmet perhaps appeared as a knightly sign. Certain it is that we find inns of such name in France as well as in Germany, the most famous one in Rothenburg on the Tauber, the best preserved mediæval city in existence, infinitely more charming than the much-talked-about Carcassonne, reconstructed by Viollet-le-Duc with such cold correctness. Here in the quaint hall of the “Eisenhut,” under the glittering arms of knights dead and gone, we will rest awhile and gladden our heart with the golden Tauber wine. Let the comfort-seeker go to the modern prosaic hotel outside the city wall!

The iron helmet is not the only martial tavern sign. Other names sounded equally[Pg 80] well to the soldier’s ear: in France “Le Haubert” (iron shirt), for instance, that might remind us of the old English inn, “The Tabard,” in which Chaucer gathered his joyous pilgrims for happy meals and amusing conversations; the sword, St. Peter’s attribute, was used as tavern sign in his holy city Rome in the sixteenth century (“alla spada”); the cannon was very popular as “canone d’oro” in northern Italy; and many others.

Like chicks under the wings of the hen, the little huts of the villagers cluster around the protecting mountain castle of the knightly lord. Most naturally the village innkeeper, therefore, chooses his master’s escutcheon as a tavern sign. And the landlord in the town feels equally honored when noble guests leave him, as parting presents, their coats of arms neatly painted on the panels or the windows of the dining-room as Montaigne informs us: “Les Alemans sont fort amoureux d’armoiries; car en tous les logis, il en est une miliasse que les passans jantilshomes du païs y laissent par les parois, et toutes leurs vitres en sont fournies.” Although a philosopher Montaigne himself was vain enough[Pg 81] to follow the pretty custom, and occasionally to dedicate his escutcheon to the innkeeper as a sign of his satisfaction; so in “The Angel” at Plombières, already a popular resort even in his day, and in Augsburg at “The Linde,” situated near the palace of the rich Fuggers. Like a good housekeeper, who daily writes his expenses down, he tells us that the painter, who did his work very well, received “deux escus” or two dollars, the carpenter “vint solds” or a whole quarter, for the screen on which the escutcheon was painted and which was placed before the big green stove.

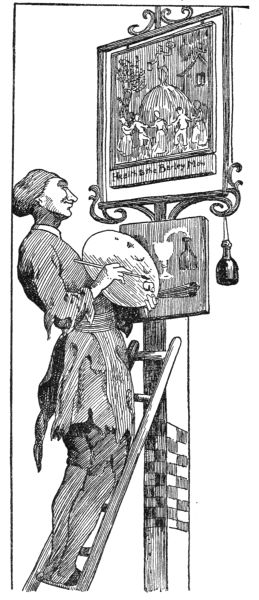

The painting of heraldic designs goes back to the time of the crusaders and soon became the principal source of income of the painters. In the Netherlands, which grew to be such a wonderful hotbed of art, the sign-painters were called “Schilderer,” for that same reason, a name which clings to them to the present day. Whoever has traveled in England knows that the same custom of the nobility, to give coats of arms to the landlords, prevailed there too. “Mol’s Coffee House” in Exeter, close to the beautiful cathedral, is a good example. Here Sir[Pg 82] Walter Raleigh used to sit in the paneled room on the second floor, drink a cup of the beverage then quite rare, and chat with his friends. All along the walls the escutcheons of the noble visitors of days gone by decorate the quaint old room and every modern visitor admires them duly, especially that of the valiant but unhappy seafarer.

To come back to the heraldic tavern signs, we find everywhere in German lands, where once the imperial House of Hapsburg ruled, their coat of arms, the double eagle, and in the domains of the House of Savoy and the Dukes of Lorraine, the cross. In France the escutcheon of the Bourbons, the fleur de lys, hangs over the tavern door, and in England the white horse of the royal House of Hanover. Long before the Georges, the white horse was a popular symbol in England. The giant horse, roughly hewn in the chalk of the “White Horse Hill,” near Faringdon, still reminds us of Alfred the Great’s victory over the Danes at Ashdown in 871. In our days the noble white horse has been degraded into an advertisement for Scotch whiskey—O quæ mutatio rerum!

The heraldic meaning of the signs was[Pg 83] just as quickly forgotten as was the pious significance of the religious signs. Only a few notable animals, such as lions, unicorns, and the like interested the tavern habitués.

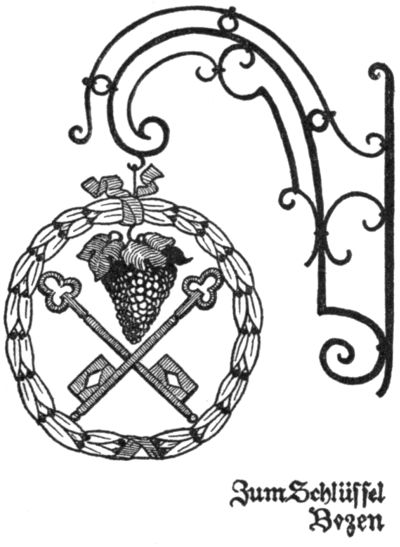

·Zum Rössle·

·Bozen·

More important than the hospitality under the protection of knights and sovereigns was the hospitality extended to the traveler behind big city walls. The city government provided not only lodgings for the poor pilgrims, tramps, and jobless people, but not[Pg 84] infrequently offered hospitality likewise to the merchant who came to display his wares in the open vaults of the city hall. In the famous “Rathskeller” every business transaction was duly celebrated by buyer and seller; the brotherly act of drinking a glass of wine together seemed to be the essential finishing-touch which clinched the business. These old cellars are still a great attraction of the town in many German places, such as Bremen, Lübeck, or Heilbronn, for instance, and all travelers are glad to refresh themselves in their quiet vaults.

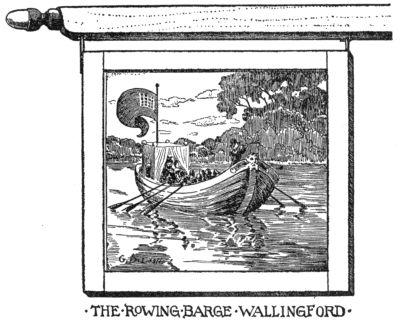

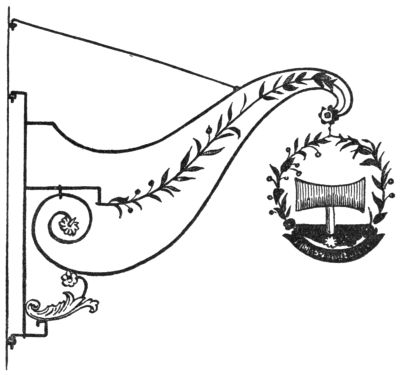

A hospitality of more intricate character was given by the guilds, in their houses, to all the members of the trade or craft. Most naturally they choose as signs symbols of the special work of each guild. The fisher and boatmen loved to see a fish, an anchor, or a ship over their tavern door; but they did not claim these signs as a special privilege, every “compleat angler,” to use Izaak Walton’s expression, as well as every incomplete one, could hang a fish out over his porch or on his house corner even if he did not keep a tavern. The house where Dr. Faustus treated his comrades in such miraculous[Pg 85] way was called “Zum Anker” and belonged to a nobleman in Erfurt if we believe the oldest popular reports of the event. Goethe transferred the scene to Auerbach’s Keller in Leipzig, which was familiar to him from his happy student-days. Old sea-captains and blue-jackets cannot resist the temptations of “The Anchor” even if the signboard does not invite them so charmingly as the one of “The Three Jolly Sailors” in Castleford:—

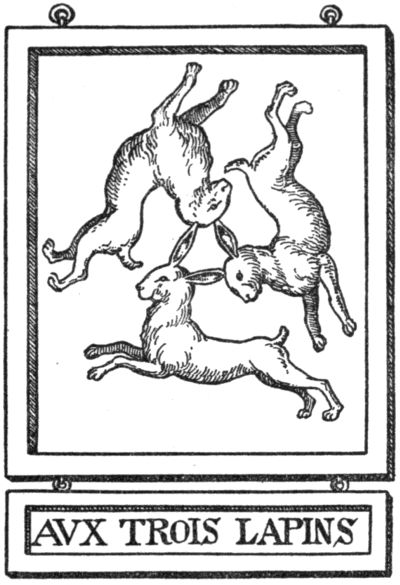

The shoemakers most naturally decorated their guild-house with a beautiful big boot, a word closely related to the old French “botte,” a large drinking cup, and its diminutive “bouteille,” the origin of the English “bottle.” The butchers seldom show the cruel axe, far oftener the poetical lamb, their oldest sign being the Pascal lamb holding the little flag of the resurrection. A patriotic English landlord in the neighborhood of Bath changed the flag into a Union Jack, forgetting all about the religious meaning of the sign as it still appears in a French relief “L’Agneau Pascal” in Caen, Rue de[Pg 86] Bayeux. The tavern “Zum guldin Schooffe” in Strassburg, “la vieille ville allemande” as Victor Hugo called the city quite frankly, is perhaps the oldest sign of this group. It dates back to the year 1311 at least. Another butcher sign is the ox or bull, most popular, of course, in the land of John Bull, where the bull appears in the most surprising combinations as “Bull and Bell,” “Bull and Magpie,” “Bull and Stirrup,” and the like.

The tavern signs of the bakers, “The Crown,” “The Sun,” or “The Star,” lead us back to old pagan times in which the cakes offered as sacrifice to the gods were shaped in the same curious forms which we observe to-day in our various breakfast rolls. Christian legends of the holy three kings and the star that stood over the stable in Bethlehem effaced these pagan souvenirs. On the day of Epiphany especially beautiful crowns were baked; in France the bakers still follow the old tradition and offer such a crown to each of their customers as a present, not without hiding a tiny porcelain shoe in the dough. The happy finder of this shoe becomes the king of the company. Dutch masters have represented the merry[Pg 87] family scene of the Epiphany dinner, none perhaps so convincingly as Jordaens in the famous picture, “The King Drinks,” in the great gallery of the Louvre.