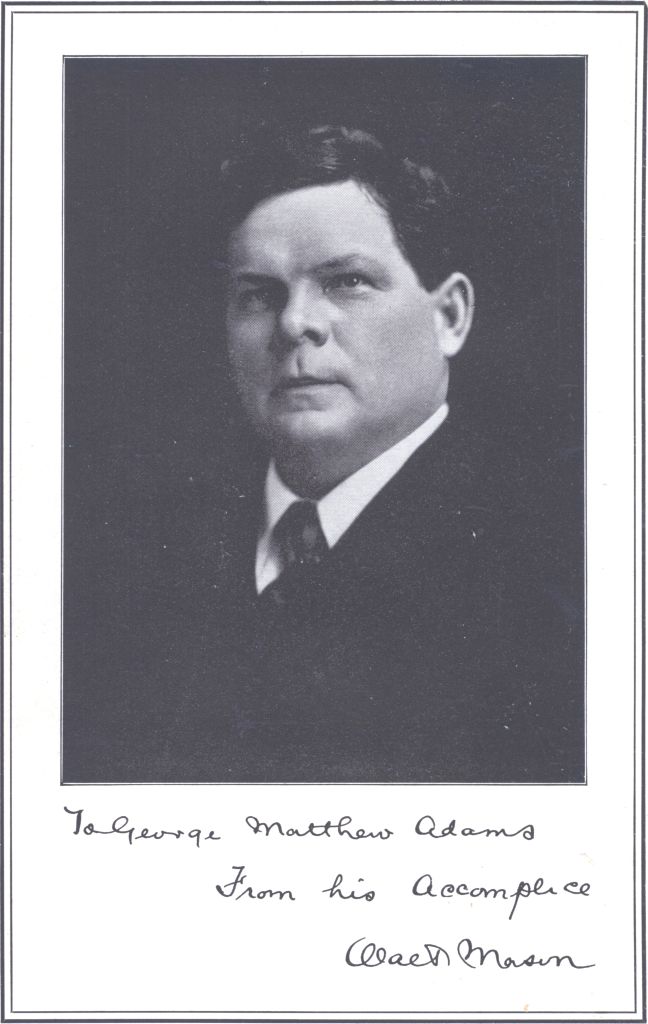

Title: Uncle Walt [Walt Mason], the Poet Philosopher

Author: Walt Mason

Release date: November 18, 2012 [eBook #41397]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by D Alexander and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (http://archive.org/details/toronto)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Uncle Walt [Walt Mason], by Walt Mason

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/unclewaltwaltma00maso |

Uncle Walt

The Poet Philosopher

Chicago

George Matthew Adams

1910

Copyright, 1910, by George Matthew Adams.

Registered in Canada in accordance with

the copyright law. Entered at Stationers'

Hall, London. All rights reserved.

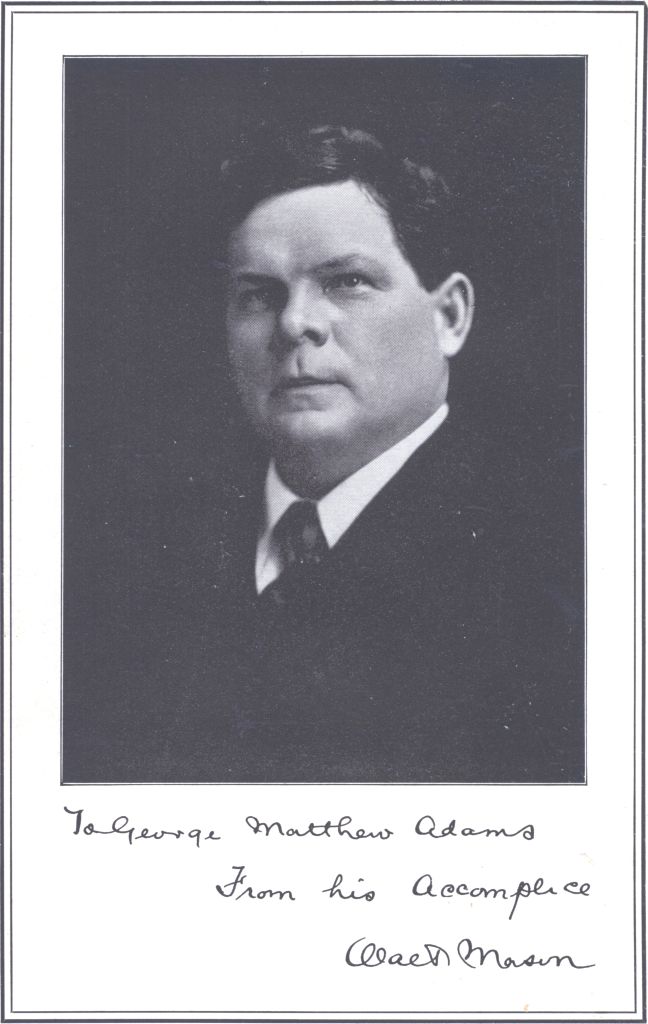

| A Glance at History | 17 |

| Longfellow | 18 |

| In Politics | 19 |

| The Human Head | 20 |

| The Universal Help | 21 |

| Little Sunbeam | 22 |

| The Flag | 23 |

| Doc Jonnesco | 24 |

| Little Girl | 25 |

| The Landlady | 26 |

| Twilight Reveries | 27 |

| King and Kid | 28 |

| Little Green Tents | 29 |

| Geronimo Aloft | 31 |

| The Venerable Excuse | 32 |

| Silver Threads | 33 |

| The Poet Balks | 34 |

| The Penny Saved | 35 |

| Home Life | 36 |

| Eagles and Hens | 37 |

| The Sunday Paper | 38 |

| The Nation's Hope | 39 |

| Football | 40 |

| Health Food | 41 |

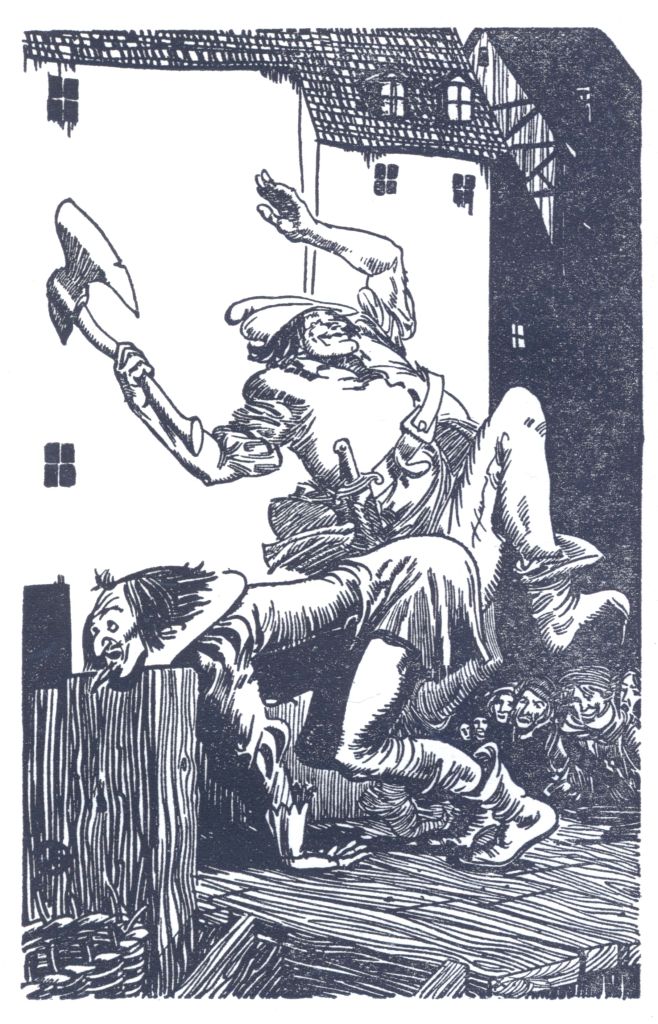

| Physical Culture | 43 |

| The Nine Kings | 44 |

| The Eyes of Lincoln | 45 |

| The Better Land | 46 |

| Knowledge Is Power | 47 |

| The Pie Eaters | 48 |

| The Sexton's Inn | 49 |

| He Who Forgets | 50 |

| Poor Father | 51 |

| The Idle Question | 52 |

| Politeness | 53 |

| Little Pilgrims | 55 |

| The Wooden Indian | 56 |

| Home and Mother | 57 |

| E. Phillips Oppenheim | 58 |

| Better than Boodle | 59 |

| The Famous Four | 60 |

| [Pg 8]Niagara | 61 |

| A Rainy Night | 62 |

| The Wireless | 63 |

| Helpful Mr. Bok | 64 |

| Beryl's Boudoir | 65 |

| Post-Mortem Honors | 67 |

| After A While | 68 |

| Pretty Good Schemes | 69 |

| Knowledge by Mail | 70 |

| Duke and Plumber | 71 |

| Human Hands | 72 |

| The Lost Pipe | 73 |

| Thanksgiving | 74 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh | 75 |

| The Country Editor | 76 |

| Useless Griefs | 77 |

| Fairbanks' Whiskers | 78 |

| Letting It Alone | 79 |

| The End of the Road | 80 |

| The Dying Fisherman | 81 |

| George Meredith | 82 |

| The Smart Children | 83 |

| The Journey | 85 |

| Times Have Changed | 86 |

| My Little Dog "Dot" | 87 |

| Harry Thurston Peck | 88 |

| Tired Man's Sleep | 89 |

| Tomorrow | 90 |

| Toothache | 91 |

| Auf Wiedersehen | 92 |

| After the Game | 93 |

| Nero's Fiddle | 94 |

| The Real Terror | 95 |

| The Talksmiths | 96 |

| Woman's Progress | 97 |

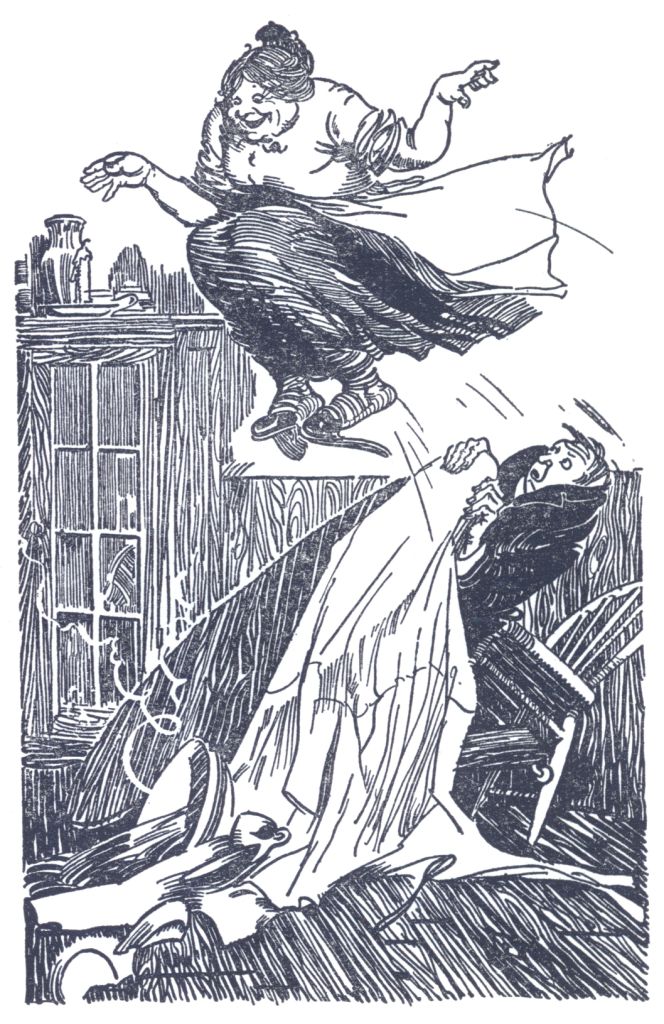

| The Magic Mirror | 99 |

| The Misfit Face | 100 |

| A Dog Story | 101 |

| The Pitcher | 102 |

| Lions and Ants | 103 |

| The Nameless Dead | 104 |

| [Pg 9]Ambition | 105 |

| Night's Illusions | 106 |

| Before and After | 107 |

| Luther Burbank | 108 |

| Governed Too Much | 109 |

| Success in Life | 110 |

| The Hookworm Victim | 111 |

| Alfred Austin | 112 |

| Weary Old Age | 113 |

| Lullaby | 114 |

| The School Marm | 115 |

| Poe | 116 |

| Gay Parents | 117 |

| Dad | 118 |

| John Bunyan | 119 |

| A Near Anthem | 121 |

| The Yellow Cord | 122 |

| The Important Man | 123 |

| Toddling Home | 124 |

| Trifling Things | 125 |

| Trusty Dobbin | 126 |

| The High Prices | 127 |

| Omar Khayyam | 128 |

| The Grouch | 129 |

| The Pole | 130 |

| Wilhelmina | 131 |

| Wilbur Wright | 132 |

| The Broncho | 133 |

| Schubert's Serenade | 135 |

| Mazeppa | 136 |

| Fashion's Devotee | 137 |

| Christmas | 138 |

| The Tightwad | 139 |

| Blue Blood | 140 |

| The Cave Man | 141 |

| Rudyard Kipling | 142 |

| In Indiana | 143 |

| The Colonel at Home | 144 |

| The June Bride | 145 |

| At The Theatre | 146 |

| Club Day Dirge | 147 |

| [Pg 10]Washington | 149 |

| Hours and Ponies | 150 |

| The Optimist | 151 |

| A Few Remarks | 152 |

| Little Things | 153 |

| The Umpire | 154 |

| Sherlock Holmes | 155 |

| The Sanctuary | 156 |

| The Newspaper Graveyard | 157 |

| My Lady's Hair | 158 |

| The Sick Minstrel | 159 |

| The Beggar | 160 |

| Looking Forward | 161 |

| The Depot Loafers. | 162 |

| The Foolish Husband | 163 |

| Halloween | 165 |

| Rienzi To The Romans | 166 |

| The Sorrel Colt | 167 |

| Plutocrat and Poet | 168 |

| Mail Order Clothes | 169 |

| Evening | 170 |

| They All Come Back | 171 |

| The Cussing Habit | 172 |

| John Bull | 173 |

| An Oversight | 174 |

| The Traveler | 175 |

| Saturday Night | 176 |

| Lady Nicotine | 177 |

| Up-To-Date Serenade | 179 |

| The Consumer | 180 |

| Advice To A Damsel | 181 |

| The New Year Vow | 182 |

| The Stricken Toiler. | 183 |

| The Law Books | 184 |

| Sleuths of Fiction | 185 |

| Put It On Ice | 186 |

| The Philanthropist | 187 |

| Other Days | 188 |

| The Passing Year | 189 |

| Page | |

| Frontispiece | 12 |

| "A Glance at History" | 16 |

| "Geronimo Aloft" | 30 |

| "Physical Culture" | 42 |

| "Little Pilgrims" | 54 |

| "Post-Mortem Honors" | 66 |

| "The Journey" | 84 |

| "The Magic Mirror" | 98 |

| "A Near Anthem" | 120 |

| "Schubert's Serenade" | 134 |

| "Washington" | 148 |

| "Halloween" | 164 |

| "Up-to-Date Serenade" | 178 |

Walt Mason's Prose Rhymes are read daily by approximately ten million readers.

A newspaper service sells these rhymes to two hundred newspapers with a combined daily circulation of nearly five million, and assuming that five people read each newspaper—which is the number agreed upon by publicity experts—it may be called a fair guess to say that two out of every five readers of newspapers read Mr. Mason's poems.

So the ten million daily readers is a reasonably accurate estimate. No other American verse-maker has such a daily audience.

Walt Mason is, therefore, the Poet Laureate of the American Democracy. He is the voice of the people.

Put to a vote, Walt would be elected to the Laureate's job, if he got a vote for each reader. And, generally speaking, men would vote as they read.

The reason Walt Mason has such a large number of readers is because he says what the average man is thinking so that the average man can understand it.

The philosophy of Walt Mason is the philosophy of America. Briefly it is this: The fiddler must be paid; if you don't care to pay, don't dance. In the meantime—grin and bear it, because you've got to bear it, and you might as well grin. But don't try to lie out of it. The Lord hates a cheerful liar.

This is what the American likes to hear. For that is the American idea about the way the world is put together. So he reads Walt Mason night and morning and smiles and takes his knife and cuts out the piece and carries it in his vest pocket, or her handbag.

It will interest the ten million readers of Walt Mason's rhymes to know that they are written in Emporia, Kansas, in the office of the Emporia Gazette, after Mr. Mason has done a day's work as editorial writer and telegraph editor of an afternoon paper. The rhymes are written on a typewriter as rapidly as he would write if he were turning out prose.

Day after day, year after year, the fountain flows. There is no poison in it. And sometimes real poetry comes welling up from this Pierian spring at 517 Merchant street, Emporia, Kansas, U. S. A.

In the meantime we do not claim its medicinal properties will cure everything. But it is good for sore eyes; it cures the blues; it sweetens the temper, cleanses the head, and aids the digestion. In cases of heart trouble it has been known to unite torn ligaments and encourage large families.

And a gentleman over there takes a bottle! Step up quickly; remember we are merely introducing this great natural remedy. Our supply is limited. In a moment the music will begin.

Charles the First, with stately walk, made the journey to the block. As he paced the street along, silence fell upon the throng; from that throng there burst a sigh, for a king was come to die! Charles upon the scaffold stood, in his veins no craven blood; calm, serene, he viewed the crowd, while the headsman said, aloud: "Cheer up, Charlie! Smile and sing! Death's a most delightful thing! I will cure your hacking cough, when I chop your headpiece off! Headache, toothache—they're a bore! You will never have them more! Cheer up, Charlie, dance and yell! Here's the axe, and all is well! I, though but a humble dub, represent the Sunshine Club, and our motto is worth while: 'Do Not Worry—Sing and Smile!' Therefore let us both be gay, as we do our stunt today; I to swing the shining axe, you to take a few swift whacks. Lumpty-doodle, lumpty-ding, do not worry, smile and sing!"

Singer of the kindly song, minstrel of the gentle lay, when the night is dark and long, and beset with thorns the way—in the poignant hour of pain, in this weary worldly war, there is comfort in thy strain, courage in "Excelsior." When the city bends us down, with its weight of bricks and tiles, lead us, poet, from the town, to the fragrant forest aisles, where the hemlocks ever moan, like old Druids clad in green, as they sighed, when all alone, wandered sad Evangeline. Writer of the cleanly page, teacher of the golden truth; still I love thee in my age, as I loved thee in my youth. In some breasts a fiercer fire flamed, than ever thou hast known; but no mortal minstrel's lyre ever gave a purer tone. Singer of the kindly song, minstrel of the gentle lay, time is swift and art is long, and thy fame will last alway.

His days were joyous and serene, his life was pure, his record clean; folks named their children after him, and he was in the social swim; ambitious lads would say: "I plan to be just such a worthy man!" But in the fullness of his years, the tempter whispered in his ears, and begged that he would make the race for county judge, or some such place. And so he yielded to his fate, and came forth as a candidate. The night before election day they found him lying, cold and gray, the deadest man in all the land, this message in his icy hand: "The papers that opposed my race have brought me into deep disgrace; I find that I'm a fiend unloosed; I robbed a widow's chicken roost, and stole an orphan's Easter egg, and swiped a soldier's wooden leg. I bilked a heathen of his joss, and later kidnapped Charlie Ross; I learn, with something like alarm, that I designed the Gunness farm, and also, with excessive grief, that Black Hand cohorts call me chief. I thought myself a decent man, whose record all the world might scan; but now, alas, too late! I see that all the depths of infamy have soiled me with their reeking shame, and so it's time to quit the game."

The greatest gift the gods bestowed on mortal was his dome of thought; it sometimes seems a useless load, when one is tired, and worn and hot; it sometimes seems a trifling thing, less useful than one's lungs or slats; a mere excuse, it seems, to bring us duns from men who deal in hats. Some men appreciate their heads, and use them wisely every day, and every passing minute sheds new splendor on their upward way; while some regard their heads as junk, mere idle knobs upon their necks; such men are nearly always sunk in failure, and are gloomy wrecks. I know a clerk who's served his time in one old store for twenty-years; he's marked his fellows climb, and climb—and marked with jealousy and tears; he's labored there since he was young; he'll labor there till he is dead; he never rose a single rung, because he never used his head. I know a poorhouse in the vale, where fifty-seven paupers stay; they paw the air and weep and wail, and cuss each other all the day; and there they'll loll while life endures, and there they'll die in pauper beds; their chances were as good as yours—but then they never used their heads. O human head! Majestic box! O wondrous can, from labels free! If man is craving fame or rocks, he'll get them if he uses thee!

My cow's gone dry, my hens won't lay, my horse has got the croup; the hot winds spoiled my budding hay, and I am in the soup. And while my life is sad and sore, and earthly joys are few, I'll write a note to Theodore; he'll tell me what to do. I wasn't home when Fortune called, my feet had strayed afar; I fear that I am going bald, and I have got catarrh. The wolf is howling at my door, I've naught to smoke or chew; but I shall write to Theodore—he'll tell me what to do. My Sunday suit is old and sere, I'm wearing last year's lids; my aunt is coming for a year, to visit, with her kids. They will not trust me at the store, and I am feeling blue, so I shall write to Theodore—he'll tell me what to do. When we are weary and distraught, from worldly strife and care, and we're denied the balm we sought, and given black despair, ah, then, my friends, there is one chore devolves on me and you; we'll simply write to Theodore—he'll tell us what to do.

She was sweet and soft and clinging, and he always found her singing, when he came home from his labors as the night was closing in; she was languishing and slender, and her eyes were deep and tender, and he simply couldn't tell her that her coffee was a sin. Golden hair her head was crowning; she was fond of quoting Browning, and she knew a hundred legends of the olden, golden time; and her heart was full of yearning for the Rosicrucian learning, and he simply couldn't tell her that the beefsteak was a crime. She was posted on Pendennis, and she knew the songs of Venice, and he listened to her prattle with an effort to look pleased; and she liked the wit of Weller—and he simply couldn't tell her that the eggs he had for breakfast had been laid by hens diseased. So she filled his home with beauty, and she did her wifely duty, did it as she understood it, and her conscience didn't hurt, when dyspepsia boldly sought him, and the sexton came and got him, and his tortured frame was buried 'neath a wagon-load of dirt. O, those marriageable misses, thinking life all love and kisses, mist and moonshine, glint and glamour, stardust borrowed from the skies! Man's a gross and sordid lummix—men are largely made of stomachs, and the songs of all the sirens will not take the place of pies!

Bright-hued and beautiful, it floats upon the summer air; and every thread of it denotes the love that's woven there; the love of veterans whose tread has sounded on the fields of red; and women old, who mourn their dead, but mourn without despair. Bright-hued and beautiful, it courts caresses of the breeze; and, straining at its staff it sports, in flaunting ecstasies; and other flags, that once were gay, long, long ago were laid away, and many men, whose heads are gray, are thinking now of these. Serene and beautiful it waves, the flag our fathers knew; in Freedom's sunny air it laves, and gains a brighter hue; and may it still the symbol be of all that makes a nation free; still may we cherish Liberty, and to our God be true.

"O Doc," I cried, "I humbly beg, that you will amputate my leg." The doctor cheerfully complied, and shot some dope into my hide, and made his bucksaw fairly sail, until it struck a rusty nail. "Hoot, mon!" he said, quite undismayed, "I'll have to finish with a spade." And as he dug and toiled away, we talked about the price of hay, the recent frightful rise in pork, the sugar grafters in New York, the things we found in Christmas socks, the flurry in Rock Island stocks, the hookworm and the hangman's noose, the bright career of Captain Loose. I felt no pain or ache or shock; it pleased me much to watch the doc; and when the job was done, I said: "Now that you're here, cut off my head." With skillful hands he wrought and wrought, and soon cut off my dome of thought, and when I asked him for his bill: "There is no charge, already, still; I work for Science, not for scads, so keep the dollars of your dads; to banish pain is my desire; to nothing more do I aspire; if I may win that goal, you bet, I'll be so happy, always, yet!" Is there a more heroic game? Could any man have nobler aim? One poet, old, and bald and fat, to this great man takes off his hat!

Little girl, so glad and jolly, playing with your home-made dolly, built of rags and straw, fill the sunny air with laughter, heedless of the sorrow after—that is childhood's law! Let no sad and sordid vision cheat you of the joy Elysian that to youth belongs; let no prophecy of sorrow scheduled for a sad tomorrow still your joyous songs! Soon enough will come the worry, and the labors, and the hurry, soon you'll cook and scrub; soon with milliners and drapers you will fuss, and read long papers, at the Culture Club. Lithe your form, but soon you'll force it in a torture-chamber corset that will make you bawl; and those little feet, that twinkle, you will squeeze, until they wrinkle, into shoes too small. And those sunny locks so tangled will be tortured and kedangled into waves and curls; and you'll buy complexion powder, and your bonnets will be louder than the other girl's. Little girl, with home-made dolly, cut out woe and melancholy, jump and sing and play! Fill the rippling air with laughter! Tears and corns will follow after! This is childhood's day!

I run a hash bazaar, just up the street; there all my boarders are yelling for meat; boarders carniverous, boarders herbiverous; Allah deliver us! just watch them eat! Boarders are ravenous, all the world o'er; "feed till you spavin us," thus they implore; boarders are gluttonous, roastbeef and muttonous; "come and unbutton us, so we'll eat more!" Little they pay me for chicken and rice; yet they waylay me for dainties of price; "bring us canary birds"—these are their very words, bawling like hairy Kurds—"bring them on ice!" I give them tea and toast, jelly and jam, some kind of stew or roast, codfish or ham; their words are Chaucerous: "Dame Cup-and-Saucerous, bring us rhinoceros, boiled with a yam!" I run a boarding booth, as I have said; there Age and Smiling Youth, raise the Old Ned; maybe the clamoring, knocking and hammering bunch will be stammering, when I am dead!

At that hour supremely quiet, when the dusk and darkness blend, and the sordid strife and riot of the day are at an end; when the bawling and the screaming of the mart have died away, then I like to lie a-dreaming of my castles in Cathay. I would roam in flowery spaces watered by the fabled streams, I would travel starry spaces on the winged feet of dreams; I would float across the ages to a more heroic time, when inspired were all ages, and the warriors sublime. At that hour supremely pleasing, dreams are all knocked galley west, by the phonograph that's wheezing: "Birdie, Dear, I Love You Best."

The king sat up on his jeweled throne, and he heaved a sigh that was like a groan, for his crown was hard, and it bruised his head, and his scepter weighed like a pig of lead; the ladies smirked as they came to beg; the knights were pulling the royal leg. The king exclaimed: "If I had my wish, I would cut this out, and I'd go and fish. For what is pomp to a weary soul that yearns and yearns for the fishing hole; the throne's a bore and the crown a gawd, and I'd swap the lot for a bamboo rod, and a can of worms and a piece of string—but there's no such luck for a poor old king!" And a boy who passed by the palace high, to fish for trout in the streamlet nigh, looked up in awe at the massive walls, and caught a glimpse of the marble halls, and he said to himself: "Oh, hully chee! Wisht I was the king, and the king was me! To reign all day with your crown on straight is a whole lot better'n diggin' bait, and fishin' round when the fish won't bite, and gettin' licked for your luck at night!"

The little green tents where the soldiers sleep, and the sunbeams play and the women weep, are covered with flowers today; and between the tents walk the weary few, who were young and stalwart in 'sixty-two, when they went to the war away. The little green tents are built of sod, and they are not long, and they are not broad, but the soldiers have lots of room; and the sod is part of the land they saved, when the flag of the enemy darkly waved, the symbol of dole and doom. The little green tent is a thing divine; the little green tent is a country's shrine, where patriots kneel and pray; and the brave men left, so old, so few, were young and stalwart in 'sixty-two, when they went to the war away!

The sod is o'er the dauntless head, the fierce old eyes are dim and dead, the martial heart is dust; they say he died in sanctity, and his wild soul, of fetters free, went forth to join the just. But will the joys of Paradise, as we imagine them, suffice to hold Geronimo? Will joyous song and endless calm to that bold spirit be a balm, while silent eons flow? But Heaven is a region fair, and there may be long reaches there, to give the savage space to ride his steed o'er field and fell and raise his fierce, defiant yell, in foray and in race. The Judge who knows the hearts of men may find a desert or a glen for souls that love the wild; and through the gates perchance may jog the hunter's pinto and his dog, his painted squaw and child.

You say your grandma's dead, my lad, and you, bowed down with woe, to see her laid beneath the mold believe you ought to go; and so you ask a half day off, and you may have that same; alas, that grannies always die when there's a baseball game! Last spring, if I remember right, three grandmas died for you, and you bewailed the passing, then, of souls so warm and true; and then another grandma died—a tall and stately dame; the day they buried her there was a fourteen-inning game. And when the balmy breeze of June among the willows sighed, another grandma closed her eyes and crossed the Great Divide; they laid her gently to her rest beside the churchyard wall, the day we lammed the stuffing from the Rubes from Minnepaul. Go forth, my son, and mourn your dead, and shed the scalding tear, and lay a simple wreath upon your eighteenth grandma's bier; while you perform this solemn task I'll to the grandstand go, and watch our pennant-winning team make soupbones of the foe.

Sing a song of long ago, now the weary day is done, and the breeze is sighing low dirges for the vanished sun; sing a song of other days, ere our hearts were tired and old; sing the sweetest of old lays: "Silver Threads Among the Gold." We who feebly hold the track in the gloaming of life's day, love the songs that take us back to life's springtime, far away, when our hope had airy wing, and our hearts were strong and bold, and at eve we used to sing "Silver Threads Among the Gold." Then our hair no silver knew, and these eyes, that shrunken seem, were the brightest brown or blue, and old age was but a dream; but the years have taken flight, and life's evening bells are tolled; so, my children, sing tonight, "Silver Threads Among the Gold."

If old Jim Riley came to town, to read a bundle of his rhyme, I guess you couldn't hold me down—I'd want to hear him every time. I wouldn't heed the tempest's shriek; I'd walk ten miles and not complain, to hear Jim Hoosier Riley speak. But I would not go round a block to see a statesman saw the air, to hear a hired spellbinder talk, like a faker at the county fair. For statesmen are as thick as fleas, and poets, they are far between; one song that lingers on the breeze is worth a million yawps, I ween. If John McCutcheon came to town, to make some pictures on the wall, I'd tear the whole blamed doorway down to be the first one in the hall; you couldn't keep me in my bed if I was dying there of croup; the push would find me at the head of the procession, with a whoop. But I won't push my fat old frame across a dozen yards of bricks, to list to men whose only fame is based on pull and politics.

It is wise to save the pennies when the pennies come your way, for you're more than apt to need them when arrives the rainy day; and when Famine comes a-whooping with the cross-bones on her vest, then the fellow with the bundle has the edge on all the rest. I admire the man who's saving, if he doesn't save too hard, if he doesn't think a dollar bigger than the courthouse yard; and I like to see him salting down the riches that he's struck, if he always has a quarter for the guy that's out of luck. When the winter comes upon us, yelling like a baseball fan, then it's nice to have some boodle in an old tomato can; when there's sickness in the wigwam, and we have to call the doc, then it's nice to have a package hidden in the eight-day clock; when Old Age, the hoary rascal, comes a-butting in at last, then it's nice to have some rubles that you cornered in the past; and the man who saves the pennies is a dandy and a duck—if he always has a quarter for the guy that's out of luck.

Now the nights are growing longer, and the frost is in the air, and it's nice to hug the fireside in your trusty rocking chair, with the good wife there beside you, feeding cookies to the cat, while the energetic children play the dickens with your hat. O, it's nice to look around you, and to feel that you're a king, that your coming home at evening makes your joyous subjects sing! So you read some twenty chapters of old Gibbon's dope on Rome, and you know what human bliss is in your humble little home! There is really nothing better in the way of earthly bliss, than to toddle home at evening, and to get a welcome kiss, and to know the kids who greet you at the pea-green garden gate, have been wailing, broken-hearted, that you were two minutes late! There is nothing much more soothing than a loving woman's smile, when she sees your bow-legs climbing o'er the bargain counter stile! If you don't appreciate it, then the bats are in your dome, for the greatest king a-living is the monarch of a home!

The eagle ought to have a place among the false alarms; we place its picture on our coins, and on our coat of arms; but what did eagles ever do but frolic in the sun? They'd be in jail for larceny if justice should be done. They are not half so good to eat as mallard duck or grouse; they'd surely cause a panic in a section boarding house; and never in this weary world was farmer seen to go, to trade a pail of eagle eggs for nails or calico. The humble hen, on t'other hand, still helps the world along; she lifts the farmer's mortgage as she trills her morning song; she yields the fragrant omelet, and when reduced to pie, she makes the boarder feel that he at last is fit to die. The eagle does not stir the souls of earnest, thoughtful men; and so let's take him from the shield and substitute the hen.

I spent five cents for the Sunday "Dart," and hauled it home in a two-wheeled cart; I piled the sections upon the floor, till they reached as high as the kitchen door; I hung the chromos upon the wall, though there wasn't room to hang them all, and the yard was littered some ten feet deep with "comic sections" that made me weep; and there were sections of pink and green, a woman's section and magazine, and sheets of music the which if played would quickly make an audience fade; and there were patterns for women's gowns and also for gentlemen's hand-me-downs; and a false mustache and a rubber doll, and a deck of cards and a parasol. Now men are busy with dray and cart, a-hauling away the Sunday "Dart."

The nation's sliding down the path that leads to Ruin's lair, and all of Ruin's dogs of wrath will chew its vitals there; each day we deeper plunge in grief; we'll soon have reached the worst; why don't we turn, then, for relief, to William Randolph Hurst? It seems we haven't any sense, that we these ills endure; he's told us oft, in confidence, that he alone is pure; he is the bulwark of our hope—our last shield and our first; then let's rely upon the dope of William Randolph Hurst. He offers us the helping hand, he fain would be our guide; and still we wreck this blooming land, and let all virtue slide; of all that is the country's best we're making wienerwurst; O let us lean upon the breast of William Randolph Hurst! He stands and waits, serene, sublime, he beckons and he sings! He wears a halo all the time, and he is growing wings! So let us quit the course that harms, forsake the things accurst, and rest, like children, in the arms of William Randolph Hurst!

The game was ended, and the noise, at last had died away, and now they gathered up the boys where they in pieces lay. And one was hammered in the ground by many a jolt and jar; some fragments never have been found, they flew away so far. They found a stack of tawny hair, some fourteen cubits high; it was the half-back, lying there, where he had crawled to die. They placed the pieces on a door, and from the crimson field, that hero then they gently bore, like soldier on his shield. The surgeon toiled the livelong night above the gory wreck; he got the ribs adjusted right, the wishbone and the neck. He soldered on the ears and toes, and got the spine in place, and fixed a gutta-percha nose upon the mangled face. And then he washed his hands and said: "I'm glad that task is done!" The half-back raised his fractured head, and cried: "I call this fun!"

The doctor is sure that my health is poor, he says that I waste away; so bring me a can of the shredded bran, and a bale of the toasted hay; O feed me on rice and denatured ice, and the oats that the horses chew, and a peck of slaw and a load of straw and a turnip and squash or two. The doctor cries that it won't be wise to eat of the things I like; if I make a break at a sirloin steak, my stomach is sure to strike; I dare not reach for the luscious peach, or stab at the lemon pie; if I make a pass at the stew, alas! I'm sure to curl up and die. If a thing looks good, it must be eschewed, if bad, I may eat it down; so bring me a jar of the rich pine tar from the Health Food works up town; and bring me a bag of your basic slag, and a sack of your bolted prunes, and a bowl of slop from the doctor's shop, and ladle it in with spoons! I will have to feed on the jimson weed, and the grass that the cows may leave, for the doctor's sure that my health is poor, and I know that he'd not deceive.

My grandmother suffered and languished in pain, till she read in a magazine ad, that a woman should put on a sweater and train, and help the Delsartean fad. And now when I go to my midday repast, no meal is made ready for me; my grandmother's climbing a forty-foot mast or shinning up into a tree. The house has a stairway that she will not use she always slides down on the rail; she's spoiled all the floors with her spiked sprinting shoes, and she laughs when I put up a wail. O, it may be all right for a woman so old, to leap o'er the table and chairs, while I try to fill up on the grub that is cold, with the dishes all piled on the stairs. Today I protested with many a tear, made a moan like a maundering dunce; and she kicked all the lights from the brass chandelier, and turned forty handsprings at once. I told her I never could prosper and thrive, on victuals unfit for a man; she offered to throw me three falls out of five, Graeco-Roman or catch-as-catch-can.

Nine monarchs followed in the gloom when Edward journeyed to the tomb; nine monarchs walked, as in a dream—enough to make a baseball team—and cast upon King Edward's bier the futile tribute of a tear. And at his task the sexton sings (the man who digs the graves for kings): "Nine monarchs, in their brave array, are bending over Edward's clay; and does the silent sovereign care, or does he know that they are there? And can the tears of monarchs nine make those dim eyes of Edward's shine? And if they give their nine commands, can they bring life to those cold hands? Can all their armies and their ships bring laughter to those dead white lips? Can their nine crowns and sceptres nine, bring to the dead the life divine? Nine paupers at a pauper's grave, who claw their rags and weep and rave, can do as much to help the dead, as those nine kings at Edward's bed."

Sad eyes, that were patient and tender, sad eyes, that were steadfast and true, and warm with the unchanging splendor of courage no ills could subdue! Eyes dark with the dread of the morrow, and woe for the day that was gone, the sleepless companions of sorrow, the watchers that witnessed the dawn. Eyes tired from the clamor and goading, and dim from the stress of the years, and hollowed by pain and foreboding, and strained by repression of tears. Sad eyes that were wearied and blighted, by visions of sieges and wars, now watch o'er a country united from the luminous slopes of the stars!

There is a better world, they say, where tears and woe are done away; there shining hosts in fields sublime are playing baseball all the time, and there (where no one ever sins) the home team nearly always wins. Upon that bright and sunny shore, we'll never need to sorrow more; no umpires on the field are slain, no games are called because of rain. So let us live that we may fly, on snowy pinions, when we die, to where the pitcher never falls, or gives a man first base on balls; where goose-eggs don't adorn the score, and shortstops fumble never more.

One day a farmer found a bone; he thought at first it was a stone, and threw it at a passing snake ere he discovered his mistake. But when he knew it was a bone, and not a diamond or a stone, he took it to an ancient sage, who said: "In prehistoric age, this was the shin-bone of a Thor-dineriomegantosaur-megopium-permastodon-letheriumsohelpmejohn." The farmer cried: "Dad bing my eyes! Was ever man so wondrous wise? He gazes on a piece of bone, that I supposed to be a stone, and, with a confidence sublime, he looks across the void of time, and gives this fossil bone a name, the fragment of some creature's frame! To have such knowledge, sir, as thine, I'd give those fertile farms of mine." "Don't envy me," the sage replied, and shook his weary head, and sighed, "Your life to me seems full and sweet—you always have enough to eat!"

A sport in New Jersey, whose name is mislaid, has issued a challenge, serene, undismayed. He claims he can shovel more pies in his hold than any man living, and puts up the gold to back up his challenge, so here is a chance for pie eating experts their fame to advance. Now here is a sport that I like to indorse; a man can eat pies and not work like a horse; no heart-breaking training for wearisome weeks; no sparring or wrestling with subsidized freaks; no rubbing or grooming or skipping the rope, no toning your nerves with some horse doctor's dope; no bones dislocated, or face pounded sore, no wearing gum boots in a whirlpool of gore. The pie eater's training no anguish implies; he starves till his stomach is howling for pies; he loosens his belt to the uttermost hole, and says to the umpire: "All right! Let her roll!" There's gold for the winner, and honor and fame, and even the loser's ahead of the game.

Only a little longer, and the journey is done, my friend! Only a little further, and the road will have an end! The shadows begin to lengthen, the evening soon will close, and it's ho for the Inn of the Sexton, the inn where we'll all repose. The inn has no Bridal Chamber, no suites for the famed or great; the guests, when they go to slumber, are all of the same estate; the chambers are small and narrow, the couches are hard and cold, and the grinning, fleshless landlord is not to be bribed with gold. A sheet for the proud and haughty, a sheet for the beggar guest; a sheet for the blooming maiden—a sheet for us all, and rest! No bells at the dawn of morning, no rap at the chamber door, but silence is there, and slumber, for ever and ever more. Then ho for the Inn of the Sexton, the inn where we all must sleep, when our hands are done with their toiling, and our eyes have ceased to weep!

The merchant said, in caustic tones: "James Henry Charles Augustus Jones, please get your pay and leave the store; I will not need you any more. Important chores you seem to shun; you're always leaving work undone; and when I ask the reason why, you heave a sad and soulful sigh, and idly scratch your dome of thought, and feebly say: "Oh, I forgot!" James Henry Charles Augustus Jones, this world's a poor resort for drones, for men with heads so badly set that their long suit is to forget. No man will ever write his name upon the shining wall of fame, or soar aloft on glowing wings because he can't remember things. I've noticed that such chaps as you remember when your pay is due; and when the noontime whistles throb, your memory is on the job; and when a holiday's at hand, your recollection isn't canned. The failures on life's busy way, the paupers, friendless, wan and gray, throughout their bootless days, like you, forgot the things they ought to do. So take your coat, and draw your bones, James Henry Charles Augustus Jones!"

Children, hush! for father's resting; he is sitting, tired and sore, with his feet upon the table and his hat upon the floor. He is wearied and exhausted by the labors of the day; he has talked about the tariff since the dawn was cold and gray; he has lost eight games of checkers, for his luck today was mean, and that luck was still against him when he bucked the slot machine; so his nerves are under tension, and his brow is dark with care, and the burdens laid upon him seem too great for him to bear. Stop the clock, for it annoys him; throttle that canary bird; take the baby to the cellar, where its howling won't be heard; you must speak in whispers, children, for your father's tired and sore, and he seems to think the ceiling is some kind of cuspidor. Oh, he's broken down and beaten by the long and busy day; he's been sitting in the feedstore on a bale of prairie hay, telling how the hungry grafters have the country by the throat, how the tariff on dried apples robs the poor man of his coat, how this nasty polar rumpus might be settled once for all—and his feet are on the table, and his back's against the wall; let him find his home a quiet and a heart-consoling nest, for the father's worn and weary, and his spirit longs for rest.

I'm tired of the bootless questions that rise in my vagrant mind; I gaze at the stars and wonder how many may be behind; a myriad worlds are whirling, concealed by the nearer spheres; and there they have coursed their orbits a million million years. I gaze at the spangled spaces, the bed of a billion stars, from the luminous veil of Venus, to the militant glare of Mars, and wonder, when all is ended, as ended all things must be, if the Captain will then remember a poor little soul like me. I'm tired of the endless questions that come, and will not begone, when I face to the East and witness the miracle of the dawn; the march of the shining coursers o'er forest and sea and land; the splendor of gorgeous colors applied by the Captain's hand; the parting of crimson curtains afar in the azure steep; the hush of a world-wide wonder, when even the zephyrs sleep. And I look on the birth of morning as millions have gazed before, and question the wave that questions the rocks and the sandy shore. "When all of these things are ended, as ended these things must be, will the Captain of all remember a poor little soul like me?"

In my youth I knew an aleck who was most exceeding smart, and his flippant way of talking often broke the hearer's heart. He was working for a grocer in a little corner store, taking down the wooden shutters, sweeping up the greasy floor, and he always answered pertly, and he had a sassy eye, and the people often asked him if he wouldn't kindly die. Oh, the festive years skedaddled, and the children of that day, now are bent beneath life's burdens, and their hair is turning gray; and the flippant one is toiling in the same old corner store, taking down the ancient shutters, sweeping up the greasy floor. In the same old sleepy village lived a springald so polite that to hear him answer questions was a genuine delight; he was working in a foundry where they dealt in eggs and cheese, and the work was hard and tiresome, but he always tried to please. And today he's boss of thousands, and his salary's sky high—and his manner's just as pleasant as it was in days gone by. It's an idle, trifling story, and you doubtless think it flat, but its moral might be pasted with some profit in your hat.

We are weary little pilgrims, straying in a world of gloom; just behind us is the cradle, just before us is the tomb; there is nothing much to guide us, or the proper path to mark, as we toddle on our journey, little pilgrims in the dark. And we jostle, and we struggle, in our feeble, futile wrath, always striving, always reaching to push others from the path; and the wrangling and the jangling of our peevish voices rise, to the seraphim that watch us through the starholes in the skies; and they say: "The foolish pilgrims! Watch them as they push and shove! They might have a pleasant ramble, if their hearts were full of love, if they'd help and cheer each other from the hour that they embark—but they're only blind and erring little pilgrims in the dark!"

A poor old Wooden Indian, all battered by the years, was seated on a pile of junk, and shedding briny tears. "What hurts you?" asked the Teddy Bear, "why are you thus distressed? Why do you tear your willow hair, and smite your basswood breast?" "Alas, my occupation's gone," the Indian replied; "cigar men now refuse to keep red warriors outside; I used to stand in pomp and pride before a stogie store; but times have changed, and those glad days will come to me no more. I'm waiting here among the junk in mournful solitude, till some one breaks me into chunks to use for kindling wood." "Cheer up!" exclaimed the Teddy Bear, "don't break your heart, old sport! You yet may have a chance to serve as juryman, in court."

"What is Home Without a Mother?" There's the motto on the wall, hanging in a place obtrusive, where it may be seen by all; and the question's never answered—we can't know what home would be, if its gentle guardian angel in her place no more we'd see. Mother washes all the dishes and she's sweeping up the floors, while the girls are in the parlor doing Paderewski chores; mother's breaking up some kindling at the woodpile by the gate, while the boys are in the garden with their shovels, digging bait; mother's on her knees a-scrubbing, where the careless footprints are, while the father sits in comfort, toiling at a bad cigar. Mother sits with weary fingers, and with bent and aching head, sewing, darning, for the children while they're all asleep in bed; mother's up before the sunrise, up to labor and to moil, thinking ever of the others, in the weary round of toil. What is home without a mother? That we'll never realize till the light of life has faded from the kind and patient eyes; when the implements of labor fall unheeded from her hand, and the loving voice is silent—then, at last, we'll understand.

I have read your latest book, Oppenheim; it involves a swarthy crook, Oppenheim; and a maid with languid eyes, and a diplomat who lies, and a dowager who sighs, Oppenheim, Oppenheim, and your glory never dies, Oppenheim. Oh, your formula is great, Oppenheim! Write your novels by the crate, Oppenheim! When we buy your latest book we are sure to find the crook, and the diplomat and dook, Oppenheim, Oppenheim, and the countess and the cook, Oppenheim! You are surely baling hay, Oppenheim, for you write a book a day, Oppenheim; from your fertile brain the rot comes a-pouring, smoking hot, and you use the same old plot, Oppenheim, Oppenheim, but it seems to hit the spot, Oppenheim! You're in all the magazines, Oppenheim; same old figures, same old scenes, Oppenheim; same old counts and diplomats, dime musee aristocrats, same old cozy corner chats, Oppenheim, Oppenheim, and we cry the same old "Rats!" Oppenheim. If you'd only rest a day, Oppenheim! If you'd throw your pen away, Oppenheim! If there'd only come a time when we'd see no yarn or rhyme 'neath the name of Oppenheim, Oppenheim, Oppenheim, it would truly be sublime, Oppenheim!

If you help a busted pilgrim, who's been out of luck a while, if you stake him with a dollar and a stogie and a smile, and you see his haggard features light up with a glow of joy, and you hear him try to murmur that you are a bully boy, then you'll get a lot of pleasure from the life you're leading here; there are better things than boodle in this little whirling sphere. If you write a friendly letter to some fellow far away, who's so weary and so homesick that his hair is turning gray, he will feel a whole lot better, and the cheer-up smile will come, and he'll sail into his duties in a way to make things hum; then you've done a thing to help you when St. Peter calls your name; there are better things than boodle in this little human game. If you see a man a-struggling to regain some ground he's lost, some one who's been up against it, knocked about and tempest tossed, and you turn around and help him to his place with other men, crying shame upon the knockers who would drag him down again, then you've shown that you're a critter of a princely strain of blood; there are better things than boodle on this little ball of mud.

John and Peter, and Robert and Paul, what in the world has become of them all? How are they stacking, and where are they gone—Paul and Robert and Peter and John? Paul was a poet, and labored and wrought over his harp, and he kept its strings hot; haunting and sad was his music, though sweet—bards can't be glad when they've nothing to eat. Peter made pictures and painted them well; 'twasn't his fault that they never would sell; 'twasn't his fault that he took a brief ride out to the poorhouse, where later he died. Robert taught school till he died of old age; hard were his labors and scanty his wage; we laid him to rest in a grave on the hill; the county was called on to settle the bill. John was a pitcher, whose curves were immense; he was the pet of the bleachers, and hence he was the owner of riches untold; diamonds and rubies and sapphires and gold. John and Peter and Robert and Paul! Through the long years we've kept cases on all!

I gazed upon that mighty flood, that writhed as though in pain or woe, and fell with dull and sick'ning thud, into the chasm far below. If there's a man with soul so dead that he unmoved can view that scene, he surely has a basswood head, and had it carved when it was green. O noble falls! Stupendous sight! Dame Nature's most emphatic fact! The gods were on their job all right when they designed that cataract. All other wonders are a dream, a foolish, feeble phantasy! The pauper falls of Europe seem absurd when they're compared with thee! Had I but seen thee in thy prime, when this proud nation had its dawn, in that fair, distant, golden time, before they strapped thy harness on, then I'd have written thee an ode, to make thy waters pause a while; but go and drag along thy load, since beasts of burden are in style. Alas, that two such handsome falls, that should be kicking up their heels, come forth like horses from their stalls, to turn a million greasy wheels! To grind up glue, make lightning rods, and furnish cheap electric light—no wonder that the nine great gods look down in anger at the sight!

I hear the plashing of the rain upon the roof, upon the pane, it murmurs at the door; it patters forth a futile boast; it whispers like a timid ghost; it streams upon the floor. And as I sit me here alone, and listen to its monotone, strange fancies come and go; I seem to see, distinct and plain dim faces drawn upon the pane, of friends I used to know. Soft voices whisper in the rain, and friends I ne'er shall see again, are crying bitterly; the raindrops seem to be their tears, and o'er the misty void of years, they're calling, calling me. O shadows from a starless shore, begone, and torture me no more, and leave me here alone! I fear the voices in the rain, the voices vibrant with their pain—I fear the spectres that complain, in weary monotone! But still they chide me at the door, and whisper there for evermore, and murmur in their woe; I hear them in the tempest's swell, I hear them sigh, I hear them yell: "Where is that old green umberell, you swiped two years ago?"

Every day we read the story of some vessel tempest-tossed, which sends forth a wireless message and would otherwise be lost. It would join the ghostly squadrons in the realm beneath the wave, were it not for modern science, which can rob the ocean grave. Vainly of such mighty marvels—all in vain the poet sings! They would need another Homer and a harp with cast-iron strings! We can only pause in wonder, as we read these thrilling tales of the mystic spark that carries news of shipwreck through the gales. We can only take our lids off to the noble master mind that achieved this latest triumph over fog and wave and wind. Yet, to show appreciation, we might buy some shares of stock in the Wireless Corporation office, just around the block. With each share we'll get a picture of a Hero—maybe twins—and, in time, in every parlor there will hang a Johnnie Binns; there will be so many Binnses, coming from the rescued ships, that they'll form a secret order, with its passwords, signs and grips.

I owe so much to Mr. Bok that language fails me when I try about his kindnesses to talk, and briny tears bedim my eye. I owe it to that gifted man that I can take ten yards of string, and decorate a frying pan until it is a beauteous thing. He taught me how to paint a brick and hang it on the parlor wall, which made the blamed room look so slick that callers cry: "It does beat all!" 'Twas Mr. Bok who taught me how to tie pink ribbons on my corns, and when I bought a muley cow, he showed me how to gild her horns. I made a cupboard from a trunk, directed by his kindly charts; a cart-load of hand-painted junk to my poor home a charm imparts. When Arctic stories stirred the soul, his enterprise was just immense; he showed me how to make a pole complete for ninety-seven cents. And when B. Tumbo sailed away, among the roaring beasts to rush, Bok pictured, in his L. H. J., a jungle made of yellow plush. And when I face the tyrant Death, may Bok be with me in the gloom, to decorate my final breath, with tassels and an ostrich plume.

She is a vain and foolish lass; she stands before her looking-glass, and fusses with her pins and rats, and tries on half a dozen hats, and fixes doodads in her hair, and tints her cheeks, already fair. And when she's fooled three hours away, and she appears, in glad array, she isn't half as nice and neat, she isn't half as slick and sweet as she appeared, four hours ago, when she was wearing calico. If she would take the time she fools away with paints and curling tools, and read some books, of prose or rhyme, she'd get some value for her time. She pads her head outside with rats, machine made hair and monster hats; and gladness might with her abide, if she would pad her head inside. For beauty is a transient thing; the hurried years are on the wing; the dazzling maiden of today will soon be haggard, worn and gray; and in life's winter, when she sits beside her lonely hearth and knits, it will not lessen her despair, to think of rats she used to wear. But if her mind is stored with gold from books the sages wrote of old, with ancient lore or modern song, the days will not seem drear and long; life's twilight will be calm and fair, and loneliness will not be there.

When you are dead, my weary friend—and some day you must die—the crowds will stand along the curb to see the hearse go by; and at the church the folks will stand and raise a mournful din, and pile a lot of roses on the box that you are in. And people then will shake their heads and say it is a shame, that such a honeybird as you should have to quit the game; and when beneath the sod you rest in your mail order gown, you'll have a big fat monument that's sure to hold you down. But little will it all avail, for you'll be sleeping sound, and honors do not count for much with people underground. You'd rather have some kindness while you tread this vale of tears, than have your dust lamented o'er for fifty million years.

The mother, tired, with aching head, from sweeping floors and baking bread, called to her daughter: "Susan, dear, I wish you'd help a little here." Fair Susan, in the parlor dim, was playing o'er a tender hymn; methinks it was "The Maiden's Prayer"—a melody beyond compare. She cried, while playing on, in style: "I'll help you in a little while." Her lover blew in unawares—a fine young man with princely airs. His heart was free from sordid stains; his head was full of high-class brains; most any girl would give her eyes to gather in so big a prize. He heard the mother's weary cry; he heard the damsel's flip reply. His bosom swelled with noble ire! His tawny eyes flashed streaks of fire! He cried: "Miss Susan Sarah Brown, it's up to me to turn you down! While groundhogs live and comets shine, you'll be no blushing bride of mine! The healthy girl who doesn't jump, and on her system get a hump, when mother calls, I do not want; so get thee hence! Aroint! Avaunt! I'll hunt me up a damsel fair who passes up 'The Maiden's Prayer' when she has got a chance to chase the troubles from her mother's face!"

It's a pretty good scheme to be cheery, and sing as you follow the road, for a good many pilgrims are weary, and hopelessly carry the load; their hearts from the journey are breaking, and a rod seems to them like a mile; and it may be the noise you are making will hearten them up for a while. It's a pretty good scheme in your joking, to cut out the jest that's unkind, for the barbed kind of fun you are poking, some fellow may carry in mind; and a good many hearts have been broken, a good many hearts fond and true, by words that were carelessly spoken by alecky fellows like you. It's a pretty good scheme to be doing some choring around while you can; for the gods with their gifts are pursuing the earnest industrious man; and those gods, in their own El Dorado, are laying up wrath for the one who loafs all the day in the shadow, while others toil, out in the sun.

When I was young and fresh and ruddy, and full of snap and vim, my parents used to make me study until my head would swim. I sat upon the schoolhouse bleachers, with pencil, book and slate, while sundry bald and weary teachers drilled knowledge through my pate. For some quick method I was yearning, some easy path to tread; "there is no royal road to learning," the bald old teachers said; "stick closely to the printed pages, all idleness eschew, and then, perhaps, in future ages, you'll know a thing or two." And when I left the school and college, to climb life's toilsome hill, I found my little store of knowledge would barely fill the bill. But nowadays the world moves quicker than in the long ago; old-fashioned methods make us snicker, they were so crude and slow. By sending seven wooden dollars to Messrs. Freaks and Freaks, they'll make our children finished scholars, and do it in three weeks. So let us close the schools and leave 'em to ruin and decay, and take the books and maps and heave 'em a million miles away; for now the kids take erudition in three-grain capsule form; the teacher loses the position that he so long kept warm.

Samantha Arabella Luke has gone abroad and caught a duke—a nobleman of gilded ease, who has a standard blood disease. She'll build again his stately halls, and pay for papering the walls; she'll straighten up his park and grounds, and buy him nags to ride to hounds; she'll tear the checks from out her book, to pay the butler and the cook, whose wages have been in arrears for maybe twenty-seven years. In fifty ways she'll spend the scads, the good old rocks that were her dad's; and all the nobles in the land will greet her with the arctic hand, and snub her in her husband's lair, and pass her up with stony stare. And ere a year has run its course, the duke will hustle for divorce, and Arabella's tears will drop upon the marble floors, kerflop! Samantha's cousin, Mary Ann, has hooked up with the plumber man, a gent of industry and peace, whose face is often black with grease. They dwell together in a cot surrounded by a garden plot, and there she raises beans and tripe, while he is fixing valve and pipe. He takes his money, like a man, and hands it o'er to Mary Ann, and she is salting down his wage where it will help them in old age. O reader, who has made a fluke? Samantha with her pallid duke, or fat and sassy Mary Ann, who gathered in the plumber man?

There's the man whose hand is clammy as a fish that lately died, and to grasp it sends a shudder percolating through your hide, and you feel its cold impression in your muscles and your glands, and you wish he'd wear an oven on his blamed antarctic hands. There's the man with hands so horny that they feel like chunks of slate, and when he is shaking with you, you can feel them grind and grate; and he nearly breaks your fingers, and you mutter through your hat: "I would run them through a smelter if my hands were hard as that!" There's the man whose hands are always pawing, pawing while he talks; they are fussing with your whiskers, they are reaching for your socks; they are patting on your bosom, they are clawing on your arm, and you'd like to meet their owner on the Mrs. Gunness farm. There's the man whose hands are always sliding down into his jeans, to relieve some broken pilgrims of their miseries and pains; and such hands, that in their giving, never falter, never tire, in the golden time a-coming will be twanging at a lyre!

Upon the joyous New Year's day I threw my briar pipe away. I said, with conscious rectitude: "The smoking habit's base and lewd; it taints the breath and soils the teeth, and often stains the chin beneath; the smoker's tongue is badly seared, and he has clinkers in his beard; of nicotine he is so full no self-respecting cannibull would eat him raw, well done or rare; and e'en his neckties and his hair, his hat, his breath, and trouserloons, suggest plug-cut and cuspitoons. And so I throw my pipe away, upon this gladsome New Year's day; my friends no more will have to choke and wheeze in my tobacco smoke." Since then the days drag slowly on; it seems as though ten years have gone; I walk the floor the long night through, and, jealous, watch the kitchen flue—for it can smoke and hold carouse, and not bust forty-seven vows; the cookstove makes my vitals gripe, for it can use its trusty pipe. Thus far I've kept the vow I swore, but do not tempt me any more; don't talk of cabbage on the place, or flaunt alfalfa in my face!

This one day let us forget all the little things that fret, all the little griefs and cares which are bringing us gray hairs; let's forget the evil thought, and the ill that others wrought; thinking only of the hand that has led us through a land smiling with a richer store than fair Canaan knew of yore. Let's forget to jeer and rail at the men who fight and fail; let's forget to criticise motes within our neighbors' eyes; thinking only of the hand that has led us through a land where the toiler gets reward; where no grasping overlord harries men with lash or chain, robbing them of brawn and brain. Let's forget malicious things; better is the heart that sings than the one that harbors hate, which is aye a killing weight. Let's forget the scowling brow; it's the time for gladness now! It's the time for well-stuffed birds, kindly smiles and cheerful words; it's a time to try to rise somewhat nearer to the skies, thinking only of a hand that will lead us to a land in the distances above, where the countersign is love.

Sir Walter Raleigh sat in jail, removed from strife and flurry; the light was dim, his bread was stale, and yet he didn't worry. He knew the headsman, grim and dour, with sleeves up-rolled and frock off, might come to him at any hour, and cut his blooming block off. He knew that he would evermore with dismal chains be laden, till he had traveled through the door that opens into Aidenn. To have his name wiped off the map King James was in a hurry; and yet—he was a dauntless chap!—he still refused to worry. Serenely he pursued his work, and wrote his lustrous pages, serenely as a smiling clerk who writes for weekly wages. And when the headsman came and said: "I hate the job, Sir Walter, but I must ask you for your head," the great man did not falter. "Gadzooks," quoth he, "and eke odsfish! Thou art a courteous shaver! Take off my head! I only wish I might return the favor!" And so the headsman swung the axe, beneath the sky of Surrey; Sir Walter died beneath his whacks, but still refused to worry!

"O Come," I said, to the Printer Man, who edits the Weekly Swish, "a rest will do you a lot of good—so come to the creek and fish." "If you'll wait a while," said the Printer Man, "I'll toddle along, I think; but first I must write up some local dope, and open a can of ink, and carry in coal for the office stove, and mix up a lot of paste, and clean the grease from the printing press with a bushel of cotton waste, and set up an ad for the auctioneer, and throw in a lot of type, and hunt up a plumber and have him see what's clogging the waterpipe, and call on the doctor to have him soak the swellings upon my head, for I had it punched but an hour ago, for something the paper said—" "I fear," I said to the Printer Man, "if I wait till your chore list fails, the minnows that frolic along the creek will all be as large as whales!"

A hundred years ago and more, men wrung their hands, and walked the floor, and worried over this or that, and thought their cares would squash them flat. Where are those worried beings now? The bearded goat and festive cow eat grass above their mouldered bones, and jay birds call, in strident tones. And where the ills they worried o'er? Forgotten all, for ever more. Gone all the sorrow and the woe, that lived a hundred years ago! The grief that makes you scream today, like other griefs, will pass away; and when you've cashed your little string, and jay birds o'er your bosom sing, the stranger pausing there to view the marble works that cover you, will think upon the uselessness of human worry and distress. So let the worry business slide; live while you live, and when you've died, the folks will say, around your bier: "He made a hit while he was here!"

Well may a startled nation mourn, with wailings greet the dawn, for Charlie's whiskers have been shorn—another landmark gone! No more, no more will robins nest within their lilac shade, for they are folded now and pressed, and with the mothballs laid. The zephyrs that have sobbed and sighed athwart that hangdown bunch, through other whiskers now must glide; they'll doubtless take the hunch. Vain world! This life's an empty boast, and gods have feet of clay; the things we love and honor most, are first to pass away. The world seems new at every dawn, seems new and queer, and strange; and we can scarce keep tab upon the ringing grooves of change. The changing sea, the changing land, are speaking of decay; "but Charlie's whiskers still will stand," we used to fondly say; "long may they dodge the glinting shears, and shining snickersnees, and may they brave a thousand years, the battle and the breeze! With Charlie's whiskers in the van, we'll fight and conquer yet, and show the world that there's one man, who's not a suffragette!" Vain dreams! Vain hopes! We now repine, and snort, and sweat, and swear; for Charlie's sluggers are in brine, and Charlie's chin is bare.

He used to take a flowing bowl perhaps three times a day; he needed it to brace his nerves, or drive the blues away, but as for chaps who drank too much, they simply made him tired; "a drink," he said, "when feeling tough, is much to be desired; some men will never quit the game while they can raise a bone, but I can drink the old red booze, or let the stuff alone." He toddled on the downward path, and seedy grew his clothes, and like a beacon in the night flamed forth his bulbous nose; he lived on slaw and sweitzer cheese, the free lunch brand of fruits, and when he sought his downy couch he always wore his boots; "some day I'll cut it out," he said; "my will is still my own, and I can hit the old red booze, or let the stuff alone." One night a prison surgeon sat by this poor pilgrim's side, and told him that his time had come to cross the great divide. "I've known you since you were a lad," the stern physician said, "and I have watched you as you tried to paint the whole world red, and if you wish, I'll have engraved upon your churchyard stone: 'He, dying, proved that he could let the old red booze alone.'"

Some day this heart will cease to beat; some day these worn and weary feet will tread the road no more; some day this hand will drop the pen, and never never write again those rhymes which are a bore. And sometimes, when the stars swing low, and mystic breezes come and go, with music in their breath, I think of Destiny and Fate, and try to calmly contemplate this bogie men call Death. Such thinking does not raise my hair; my cheerful heart declines to scare or thump against my vest; for Death, when all is said and done, is but the dusk, at set of sun, the interval of rest. But lines of sorrow mark my brow when I consider that my frau, when I have ceased to wink, will have to face a crowd of gents who're selling cheap tin monuments, and headstones made of zinc. And crayon portrait sharks will come, and make the house with language hum, and ply their deadly game; they will enlarge my photograph, attach a hand-made epitaph, and put it in a frame. They'll hang that horror on the wall, and then, when neighbors come to call, they'll view my crayon head, and wipe sad tears from either eye, and lean against the chairs, and cry: "How fortunate he's dead!"

Once a fisherman was dying in his humble, lowly cot, and the pastor sat beside him saying things that hit the spot, so that all his futile terrors left the dying sinner's heart, and he said: "The journey's lonely, but I'm ready for the start. There is just one little matter that is fretting me," he sighed, "and perhaps I'd better tell it ere I cross the Great Divide. I have got a string of stories that I've told from day to day; stories of the fish I've captured, and the ones that got away, and I fear that when I tell them they are apt to stretch a mile; and I wonder when I'm wafted to that land that's free from guile, if they'll let me tell my stories if I try to tell them straight, or will angels lose their tempers then, and chase me through the gate?" Then the pastor sat and pondered, for the question vexed him sore; never such a weird conundrum had been sprung on him before. Yet the courage of conviction moved him soon to a reply, and he wished to fill the fisher with fair visions of the sky: "You can doubtless tell fish stories," said the clergyman, aloud, "but I'd stretch them very little if old Jonah's in the crowd."

He wrote good books, and wrote in vain, and writing, wore out heart and brain. The few would buy his latest tome, and, filled with gladness, take it home, and read it through, from end to end, and lend it to some high-browed friend. The few would say it was a shame that George was scarcely in the game; that grocers, butlers, clerks and cooks would never read his helpful books, but blew themselves for "Deadwood Dick," and "Howling Hank from Bitter Creek," "The Bandit That Nick Carter Caught," and Laura Libbey's tommyrot. Alas! It is a bitter thing! We'd rather have a Zenda king, or hold, with Sinclair, coarse carouse, in some Chicago packing house, or wade, with Weyman, to our knees, in yarns of swords and snickersnees, or trek with Haggard to the veldt, where Zulus seek each other's pelt, than buy a volume, learned and deep, and o'er it yawn ourselves to sleep!

The other night I took a walk, and called on Jinx, across the block. The home of Jinx was full of boys and girls and forty kinds of noise. Dad Jinx was good, and kind, and straight; he let the children go their gait; he never spoke a sentence cross, he never showed that he was boss, and so his home, as neighbors know, was like the Ringling wild beast show. We tried to talk about the crops; the children raised their fiendish yawps; they hunted up a Thomas cat, and placed it in my stovepipe hat; they jarred me with a carpet tack, and poured ice water down my back; my long coat tails they set afire, and this aroused my slumb'ring ire. I rose, majestic in my wrath, and through those children mowed a path, I smote them sorely, hip and thigh, and piled them in the woodshed nigh; I threw their father in the well, and fired his cottage, with a yell. Some rigid moralists, I hear, have said my course was too severe, but their rebukes can not affright—my conscience tells me I was right.

A little work, a little sweating, a few brief, flying years; a little joy, a little fretting, some smiles and then some tears; a little resting in the shadow, a struggle to the height, a futile search for El Dorado, and then we say Good Night. Some moiling in the strife and clangor, some years of doubt and debt, some words we spoke in foolish anger that we would fain forget; some cheery words we said unthinking, that made a sad heart light; the banquet, with its feast and drinking—and then we say Good Night. Some questioning of creeds and theories, and judgment of the dead, while God, who never sleeps or wearies, is watching overhead; some little laughing and some sighing, some sorrow, some delight; a little music for the dying, and then we say Good Night.

The maiden lingered in her bower, within her fathers stately tower—it was four hundred years ago—her lover came, o'er cliff and scar, and twanged the strings of his guitar, and sang his love songs, soft and low. He said her breath was like the breeze that wandered over flowery leas, her cheeks were lovely as the rose; her eyes were stars, from heaven torn, and she was guiltless of a corn upon her sweet angelic toes. For hours and hours his songs were sung, until a puncture spoiled a lung, and then of course he had to quit; but Arabella from her room would shoot a smile that lit the gloom, and gave him a conniption fit. Then homeward would the lover hie, as happy as an August fly upon a bald man's shining head; and Arabella's heart would swell with happiness too great to tell; ah me, those good old times are dead! Just let a modern lover scheme to win the damsel of his dream by punching tunes from his guitar! In silver tones she'd jeer and scoff; she'd call to him: "Come off! come off! where is your blooming motor car?"

My little dog dot is a sassy pup, and I scold him in savage tones, for he keeps the garden all littered up with feathers and rags and bones. He drags dead cats for a half a mile, and sometimes a long-dead hen; and when I have carted away the pile, he builds it all up again. He howls for hours at the beaming moon, and thinks it a Melba chore; and neighbors who list to his throbbing tune, rear up in the air and roar. And often I hand down this stern decree: "This critter will have to die." And he puts his paws on my old fat knee, and turns up a loving eye; and he wags his tail, and he seems to say: "You're almost too fat to walk, and your knees are sprung and your whiskers gray, and your picture would stop a clock; some other doggies might turn you down—some dogs that are proud and grand, but you are the best old boss in town; I love you to beat the band!" And he bats his eye and he wags his tail, conveying this kindly thought; and I'd rather live out my days in jail, than injure that derned dog Dot!

He's so familiar with the great, this Harry Thurston Peck, that every man of high estate has wept upon his neck. The poet Browning pondered deep the things that Harry said; Lord Tennyson was wont to sleep in Harry's cattle-shed. When Ibsen wrote, he wildly cried: "My life will be a wreck, if this, my drama, is denied, the praise of Thurston Peck!" Said Kipling, in his better days: "What use is my renown, since Harry scans my blooming lays, and blights them with a frown?" The poet, when his end draws near, cries: "Death brings no alarms, if I, in that grim hour of fear, may die in Harry's arms." And, being dead, his spirit knows no shade of doubt or gloom, if Harry plants a little rose upon his humble tomb. Poor Shakespeare and those elder bards, who haunt the blessed isles, were born too soon for such rewards as Harry Thurston's smiles. But joy will lighten their despair, and flood the realms of space, for Harry Peck will join them there—they'll see him face to face!

Now the long, long day is fading, and the hush of dusk is here, and the stars begin parading, each one in its distant sphere; and the city's strident voices dwindle to a gentle hum, and the heart of man rejoices that the hour of rest has come. Thrown away is labor's fetter, when the day has reached its close; nothing in the world is better than a weary man's repose. Nothing in the world is sweeter than the sleep the toiler finds, while the ravening moskeeter fusses at the window blinds. Nothing 'neath the moon can wake him, short of cannon cracker's roar; if you'd rouse him you must shake him till you dump him on the floor. Idle people seek their couches, seek their beds to toss and weep, for a demon on them crouches, driving from their eyes the sleep. And the weary hours they number, and they cry, in tones distraught: "For a little wad of slumber, I would give a house and lot!" When the long, long day is dying, and you watch the twinkling stars, knowing that you'll soon be lying, sleeping like a train of cars, be, then, thankful, without measure; be as thankful as you can; you have nailed as great a treasure as the gods have given man!

"Tomorrow," said the languid man, "I'll have my life insured, I guess; I know it is the safest plan, to save my children from distress." And when the morrow came around, they placed him gently in a box; at break of morning he was found as dead as Julius Caesar's ox. His widow now is scrubbing floors, and washing shirts, and splitting wood, and doing fifty other chores, that she may rear her wailing brood. "Tomorrow," said the careless jay, "I'll take an hour, and make my will; and then if I should pass away, the wife and kids will know no ill." The morrow came, serene and nice, the weather mild, with signs of rain; the careless jay was placed on ice, embalming fluid in his brain. Alas, alas, poor careless jay! The lawyers got his pile of cash; his wife is toiling night and day, to keep the kids in clothes and hash. Tomorrow is the ambushed walk avoided by the circumspect. Tomorrow is the fatal rock on which a million ships are wrecked.

Now my weary heart is breaking, for my left hand tooth is aching, with a harsh, persistent rumble that is keeping folks awake; hollowed out by long erosion, it, with spasm and explosion, seems resolved to show the public how a dog-gone tooth can ache. Now it's quivering or quaking; now it's doing fancy aching, then it shoots some Roman candles which go whizzing through my brain; now it does some lofty tumbling, then again it's merely grumbling; and anon it's showing samples of spring novelties in pain. All the time my woe increases; I have kicked a chair to pieces, but it didn't seem to soothe me or to bring my soul relief; I have stormed around the shanty till my wife and maiden auntie said they'd pull their freight and leave me full enjoyment of my grief. I have made myself so pleasant that I'm quarantined at present, and the neighbors say they'll shoot me if I venture from my door; now a voice cries: "If thou'd wentest in the first place, to a dentist—" it is strange that inspiration never came to me before!

"Farewell," I said, to the friend I loved, and my eyes were filled with tears; "I know you'll come to my heart again, in a few brief, hurried years!" Ah, many come up the garden path, and knock at my cottage door, but the friend I loved when my heart was young, comes back to that heart no more. "Farewell!" I cried to the gentle bird, whose music had filled the dawn; "you fly away, but you'll sing again, when the winter's snows are gone." Ah, the bright birds sway on the apple-boughs, and sing as they sang before; but the bird I loved, with the golden voice, shall sing to my heart no more! "Farewell!" I said to the Thomas Cat, I threw in the gurgling creek, all weighted down with a smoothing iron, and a hundredweight of brick. "You'll not come back, if I know myself, from the silent, sunless shore!" Then I journeyed home, and that blamed old cat was there by the kitchen door!

When I cash in, and this poor race is run, my chores performed, and all my errands done, I know that folks who mock my efforts here, will weeping bend above my lowly bier, and bring large garlands, worth three bucks a throw, and paw the ground in ecstasy of woe. And friends will wear crape bow-knots on their tiles, while I look down (or up) a million miles, and wonder why those people never knew how smooth I was until my spirit flew. When I cash in I will not care a yen for all the praise that's heaped upon me then; serene and silent, in my handsome box, I shall not heed the laudatory talks, and all the pomp and all the vain display, will just be pomp and feathers thrown away. So tell me now, while I am on the earth, your estimate of my surprising worth; O tell me what a looloo-bird I am, and fill me full of taffy and of jam!