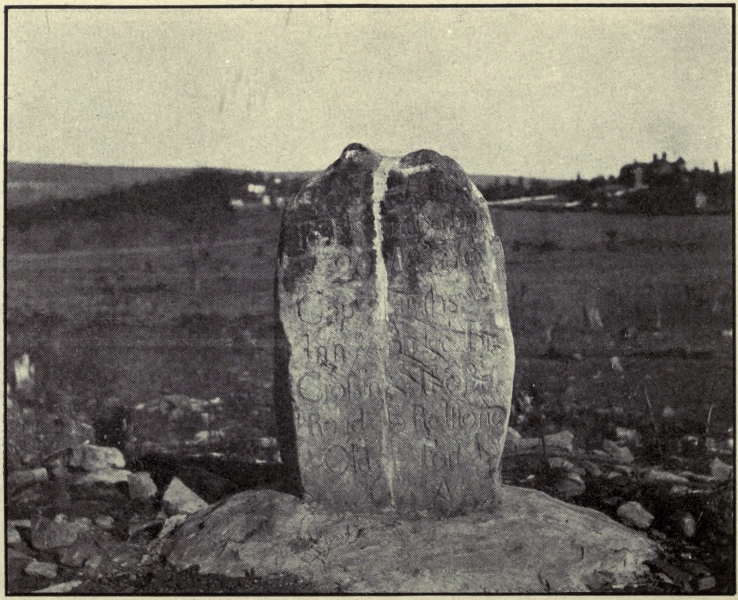

A Milestone on Braddock’s Road

A Milestone on Braddock’s Road

[See page 105, note 19]

Title: Pioneer Roads and Experiences of Travelers (Volume 1)

Author: Archer Butler Hulbert

Release date: October 15, 2012 [eBook #41067]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note: Obvious errors in spelling and punctuation have been corrected. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the text body. Also images have been moved from the middle of a paragraph to the closest paragraph break, causing missing page numbers for those image pages and blank pages in this ebook.

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

CLEVELAND, OHIO

1904

COPYRIGHT, 1904

BY

The Arthur H. Clark Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 11 | |

| I. | The Evolution of Highways: from Indian Trail to Turnpike | 15 |

| II. | A Pilgrim on the Pennsylvania Road | 106 |

| III. | Zane’s Trace and the Maysville Pike | 151 |

| IV. | Pioneer Travel in Kentucky | 175 |

| I. | A Milestone on Braddock’s Road | Frontispiece |

| II. | Indian Travail | 19 |

| III. | Old Conestoga Freighter | 50 |

| IV. | Earliest Style of Log Tavern | 87 |

| V. | Widow McMurran’s Tavern (Scrub Ridge, Pennsylvania Road) | 134 |

| VI. | Bridge on which Zane’s Trace Crossed the Muskingum River at Zanesville, Ohio | 162 |

| VII. | Pioneer View of Houses at Fort Cumberland, Maryland | 191 |

The first chapter of this volume presents an introduction to the two volumes of this series devoted to Pioneer Roads and Experiences of Travelers. The evolution of American highways from Indian trail to macadamized road is described; the Lancaster Turnpike, the first macadamized road in the United States, being taken as typical of roads of the latter sort.

An experience of a noted traveler, Francis Baily, the eminent British astronomer, is presented in chapter two.

The third chapter is devoted to the story of Zane’s Trace from Virginia to Kentucky across Ohio, and its terminal, the famous Maysville Pike. It was this highway which precipitated President Jackson’s veto of the Internal Improvement Bill of 1830, one of the epoch-making vetoes in our economic history.

The last chapter is the vivid picture of Kentucky travel drawn by Judge James Hall in his description of “The Emigrants,” in Legends of the West.

The illustrations in this volume have been selected to show styles of pioneer architecture and means of locomotion, including types of earliest taverns, bridges, and vehicles.

A. B. H.

Marietta, Ohio, December 30, 1903.

We have considered in this series of monographs the opening of a number of Historic Roads and the part they played in the development of the most important phases of early American history. But our attitude has been that of one asking, Why?—we have not at proper length considered all that would be contained in the question, How? It will be greatly to our purpose now to inquire into the methods of road-making, and outline, briefly, the evolution of the first trodden paths to the great highways of civilization.

From one aspect, and an instructive one, the question is one of width; few, if any, of our roads are longer than those old “threads of soil”—as Holland called the Indian trails; Braddock’s Road was not [Pg 16]longer than the trail he followed; even the Cumberland Road could probably have been followed its entire length by a parallel Indian path or a buffalo trace. But Braddock’s Road was, in its day, a huge, broad track, twelve feet wide; and the Cumberland Road exceeded it in breadth nearly fifty feet. So our study may be pursued from the interesting standpoint of a widening vista; the belt of blue above our heads grows broader as we study the widening of the trail of the Indian.

To one who has not followed the trails of the West or the Northland, the experience is always delightful. It is much the same delight as that felt in traversing a winding woodland road, intensified many fold. The incessant change of scenery, the continued surprises, the objects passed unseen yet not unguessed, those half-seen through a leafy vista amid the shimmering green; the pathway just in front very plain, but twenty feet beyond as absolutely hidden from your eyes as though it were a thousand miles away—such is the romance of following a trail. One’s mind keeps as active as when looking at Niagara, and it[Pg 17] is lulled by the lapsing of those leaves as if by the roar of that cataract.

Yet the old trail, unlike our most modern roads, kept to the high ground; even in low places it seemed to attempt a double-bow knot in keeping to the points of highest altitude. But when once on the hills, the vista presented varied only with the altitude, save where hidden by the foliage. We do not choose the old “ridge roads” today for the view to be obtained, and we look continually up while the old-time traveler so often looked down. As we have hinted, elsewhere, many of our pioneer battles—those old battles of the trails—will be better understood when the position of the attacking armies is understood to have been on lower levels, the rifles shooting upward, the enemy often silhouetted against the very sky-line.

But the one characteristic to which, ordinarily, there was no exception, was the narrowness of these ancient routes. The Indian did not travel in single file because there was advantage in that formation; it was because his only routes were trails which he never widened or improved;[Pg 18] and these would, ordinarily, admit only of one such person as broke them open. True, the Indians did have broader trails; but they were very local in character and led to maple-sugar orchards or salt wells. From such points to the Indian villages there ran what seemed not unlike our “ribbon roads”—the two tracks made by the “travail”—the two poles with crossbar that dragged on the ground behind the Indian ponies, upon which a little freight could be loaded. In certain instances such roads as these were to be found running between Indian villages and between villages and hunting grounds. They were the roads of times of peace. The war-time trails were always narrow and usually hard—the times of peace came few and far between. As we have stated, so narrow was the trail, that the traveler was drenched with water from the bushes on either hand. And so “blind”—to use a common pioneer word—were trails when overgrown, that they were difficult to find and more difficult to follow. Though an individual Indian frequently marked his way through the forest, for the benefit of others who were to follow [Pg 21] him or for his own guidance in returning, the Indian trails in native state were never blazed. Thus, very narrow, exceedingly crooked, often overgrown, worn a foot or more into the ground, lay the routes on which white men built roads which have become historic. Let us note the first steps toward road-building, chronologically.

The first phase of road-making (if it be dignified by such a title) was the broadening of the Indian path by the mere passing of wider loads over it. The beginning of the pack-horse era was announced by the need of greater quantities of merchandise and provisions in the West to which these paths led. The heavier the freight tied on either side of the pack-horse, the more were the bushes bruised and worn away, and the more the bed of the trail was tracked and trampled. The increasing of the fur-trade with the East at the beginning of the last half of the eighteenth century necessitated heavier loads for the trading ponies both “going in” and “coming out”—as the pioneers were wont to say. Up to this time, so far as the present[Pg 22] writer’s knowledge goes, the Indian never lifted a finger to make his paths better in any one respect; it seems probable that, oftentimes, when a stream was to be crossed, which could not be forded, the Indian bent his steps to the first fallen tree whose trunk made a natural bridge across the water. That an Indian never felled such a tree, it is impossible to say; but no such incident has come within my reading. It seems that this must have happened and perhaps was of frequent occurrence.

Our first picture, then, of a “blind” trail is succeeded by one of a trail made rougher and a little wider merely by use; a trail over which perhaps the agents of a Croghan or a Gist pushed westward with more and more heavily-loaded pack-horses than had been customarily seen on the trails thither. Of course such trails as began now to have some appearance of roads were very few. As was true of the local paths in Massachusetts and Connecticut and Virginia, so of the long trails into the interior of the continent, very few answered all purposes. Probably by 1750[Pg 23] three routes, running through southwestern Pennsylvania, central Pennsylvania, and central New York, were worn deep and broad. By broad of course we mean that, in many places, pack-horses could meet and pass without serious danger to their loads. But there were, probably, only these three which at this time answered this description. And the wider and the harder they became, the narrower and the softer grew scores of lesser trails which heretofore had been somewhat traversed. It is not surprising that we find the daring missionary Zeisberger going to the Allegheny River like a beast on all fours through overgrown trails, or that Washington, floundering in the fall of 1784 along the upper Monongahela and Cheat Rivers, was compelled to give up returning to the South Branch (of the Potomac) by way of the ancient path from Dunkards Bottom. “As the path it is said is very blind & exceedingly grown up with briers,” wrote Washington, September 25, 1784, in his Journal, “I resolved to try the other Rout, along the New Road to Sandy Creek; ...” This offers a signal instance in which an[Pg 24] ancient route had become obsolete. Yet the one Washington pursued was not an Appian Way: “... we started at dawning of day, and passing along a small path much enclosed with weeds and bushes, loaded with Water from the overnights rain & the showers which were continually falling, we had an uncomfortable travel....”[1] Such was the “New Road.”

The two great roads opened westward by the armies of Washington, Braddock, and Forbes, whose history has been dealt with at length in this series, were opened along the line of trails partially widened by the pack-horses of the Ohio Company’s agents (this course having been first marked out by Thomas Cresap) and those of the Pennsylvania traders. Another route led up the Mohawk, along the wide Iroquois Trail, and down the Onondaga to the present Oswego; this was a waterway route primarily, the two rivers (with the portage at Rome) offering more or less facilities for shipping the heavy baggage by batteaus. It was a portage path from[Pg 25] the Hudson to Lake Ontario; the old landward trail to Niagara not being opened by an army.[2]

Yet Braddock’s Road, cut in 1755, was quite filled up with undergrowth in 1758 as we have noted. It was “a brush wood, by the sprouts from the old stumps.”[3] In those primeval forests a road narrowed very fast, and quickly became impassable if not constantly cared for. The storms of a single fall or spring month and the heavy clouds of snow on the trees in winter kept the ground beneath well littered with broken limbs and branches. Here and there great trees were thrown by the winds across the traveled ways. And so a military road over which thousands may have passed would become, if left untouched, quite as impassable as the blindest trail in a short time.

Other Indian trails which armies never traversed became slightly widened by agents of land companies, as in the case of Boone blazing his way through Cumber[Pg 26]land Gap for Richard Henderson. For a considerable distance the path was widened, either by Boone or Martin himself, to Captain Joseph Martin’s “station” in Powell’s Valley. Thousands of traces were widened by early explorers and settlers who branched off from main traveled ways, or pushed ahead on an old buffalo trail; the path just mentioned, which Washington followed, was a buffalo trail, but had received the name of an early pioneer and was known as “McCulloch’s Path.”

But our second picture holds good through many years—that trail, even though armies had passed over it, was still but a widened trail far down into the early pioneer days. Though wagons went westward with Braddock and Forbes, they were not seen again in the Alleghenies for more than twenty-five years. These were the days of the widened trails, the days of the long strings of jingling ponies bearing patiently westward salt and powder, bars of bended iron, and even mill-stones, and bringing back to the East furs and ginseng. Of this pack-saddle era—this age of the widened trail—very little has been writ[Pg 27]ten, and it cannot be passed here without a brief description. In Doddridge’s Notes we read: “The acquisition of the indispensable articles of salt, iron, steel and castings presented great difficulties to the first settlers of the western country. They had no stores of any kind, no salt, iron, nor iron works; nor had they money to make purchases where these articles could be obtained. Peltry and furs were their only resources before they had time to raise cattle and horses for sale in the Atlantic states. Every family collected what peltry and fur they could obtain throughout the year for the purpose of sending them over the mountains for barter. In the fall of the year, after seeding time, every family formed an association with some of their neighbors, for starting the little caravan. A master driver was to be selected from among them, who was to be assisted by one or more young men and sometimes a boy or two. The horses were fitted out with pack-saddles, to the latter part of which was fastened a pair of hobbles made of hickory withes—a bell and collar ornamented their necks. The bags provided[Pg 28] for the conveyance of the salt were filled with feed for the horses; on the journey a part of this feed was left at convenient stages on the way down, to support the return of the caravan. Large wallets well filled with bread, jerk, boiled ham, and cheese furnished provision for the drivers. At night, after feeding, the horses, whether put in pasture or turned out into the woods, were hobbled and the bells were opened [unstuffed].... Each horse carried [back] two bushels of alum salt, weighing eighty-four pounds to the bushel.” Another writer adds: “The caravan route from the Ohio river to Frederick [Maryland] crossed the stupendous ranges of the ... mountains.... The path, scarcely two feet wide, and travelled by horses in single file, roamed over hill and dale, through mountain defile, over craggy steeps, beneath impending rocks, and around points of dizzy heights, where one false step might hurl horse and rider into the abyss below. To prevent such accidents, the bulky baggage was removed in passing the dangerous defiles, to secure the horse from being thrown from his[Pg 29] scanty foothold.... The horses, with their packs, were marched along in single file, the foremost led by the leader of the caravan, while each successive horse was tethered to the pack-saddle of the horse before him. A driver followed behind, to keep an eye upon the proper adjustment of the packs.” The Pennsylvania historian Rupp informs us that in the Revolutionary period “five hundred pack-horses had been at one time in Carlisle [Pennsylvania], going thence to Shippensburg, Fort Loudon, and further westward, loaded with merchandise, also salt, iron, &c. The pack-horses used to carry bars of iron on their backs, crooked over and around their bodies; barrels or kegs were hung on each side of these. Colonel Snyder, of Chambersburg, in a conversation with the writer in August, 1845, said that he cleared many a day from $6 to $8 in crooking or bending iron and shoeing horses for western carriers at the time he was carrying on a blacksmith shop in the town of Chambersburg. The pack-horses were generally led in divisions of 12 or 15 horses, carrying about two hundred weight each ...; when the[Pg 30] bridle road passed along declivities or over hills, the path was in some places washed out so deep that the packs or burdens came in contact with the ground or other impending obstacles, and were frequently displaced.”

Though we have been specifically noticing the Alleghenies we have at the same time described typical conditions that apply everywhere. The widened trail was the same in New England as in Kentucky or Pennsylvania—in fact the same, at one time, in old England as in New England. Travelers between Glasgow and London as late as 1739 found no turnpike till within a hundred miles of the metropolis. Elsewhere they traversed narrow causeways with an unmade, soft road on each side. Strings of pack-horses were occasionally passed, thirty or forty in a train. The foremost horse carried a bell so that travelers in advance would be warned to step aside and make room. The widened pack-horse routes were the main traveled ways of Scotland until a comparatively recent period. “When Lord Herward was sent, in 1760, from Ayrshire to the college at[Pg 31] Edinburgh, the road was in such a state that servants were frequently sent forward with poles to sound the depths of the mosses and bogs which lay in their way. The mail was regularly dispatched between Edinburgh and London, on horseback, and went in the course of five or six days.” In the sixteenth century carts without springs could not be taken into the country from London; it took Queen Henrietta four days to traverse Watling Street to Dover. Of one of Queen Elizabeth’s journeys it is said: “It was marvelous for ease and expedition, for such is the perfect evenness of the new highway that Her Majesty left the coach only once, while the hinds and the folk of baser sort lifted it on their poles!” A traveler in an English coach of 1663 said: “This travel hath soe indisposed mee, yt I am resolved never to ride up againe in ye coatch.”

Thus the widened trail or bridle-path, as it was commonly known in some parts, was the universal predecessor of the highway. It needs to be observed, however, that winter travel in regions where much snow fell greatly influenced land travel. The[Pg 32] buffalo and Indian did not travel in the winter, but white men in early days found it perhaps easier to make a journey on sleds in the snow than at any other time. In such seasons the bridle-paths were, of course, largely followed, especially in the forests; yet in the open, with the snow a foot and more in depth, many short cuts were made along the zig-zag paths and in numerous instances these short cuts became the regular routes thereafter for all time. An interesting instance is found in the “Narrative of Andrew J. Vieau, Sr.:” “This path between Green Bay [Wisconsin] and Milwaukee was originally an Indian trail, and very crooked; but the whites would straighten it by cutting across lots each winter with their jumpers [rude boxes on runners], wearing bare streaks through the thin covering [of snow], to be followed in the summer by foot and horseback travel along the shortened path.”[4]

This form of traveling was, of course, unknown save only where snow fell and remained upon the ground for a considerable time. Throughout New York State[Pg 33] travel on snow was common and in the central portion of the state, where there was much wet ground in the olden time, it was easier to move heavy freight in the winter than in summer when the soft ground was treacherous. Even as late as the building of the Erie Canal in the second and third decades of the nineteenth century—long after the building of the Genesee Road—freight was hauled in the winter in preference to summer. In the annual report of the comissioners of the Erie Canal, dated January 25, 1819, we read that the roads were so wretched between Utica and Syracuse in the summer season that contractors who needed to lay up a supply of tools, provisions, etc., for their men, at interior points, purchased them in the winter before and sent the loads onward to their destinations in sleighs.[5] One of the reasons given by the Erie Canal commissioners for delays and increased expenses in the work on the canal in 1819, in their report delivered to the legislature February 18, 1820, was that[Pg 34] the absence of snow in central New York in the winter of 1818-19 prevented the handling of heavy freight on solid roads; “no hard snow path could be found.”[6] The soft roads of the summer time were useless so far as heavy loads of lumber, stone, lime, and tools were concerned. No winter picture of early America is so vivid as that presented by the eccentric Evans of New Hampshire, who, dressed in his Esquimau suit, made a midwinter pilgrimage throughout the country lying south of the Great Lakes from Albany to Detroit in 1818.[7] His experiences in moving across the Middle West with the blinding storms, the mountainous drifts of snow, the great icy cascades, the hurrying rivers, buried out of sight in their banks of ice and snow, and the far scattered little settlements lost to the world, helps one realize what traveling in winter meant in the days of the pioneer.

The real work of opening roads in America began, of course, on the bridle-paths in the Atlantic slope. In 1639 a measure was passed in the Massachusetts[Pg 35] Bay Colony reading: “Whereas the highways in this jurisdiction have not been laid out with such conveniency for travellers as were fit, nor as was intended by this court, but that in some places they are felt too straight, and in other places travelers are forced to go far about, it is therefore, ordered, that all highways shall be laid out before the next general court, so as may be with most ease and safety for travelers; and for this end every town shall choose two or three men, who shall join with two or three of the next town, and these shall have power to lay out the highways in each town where they may be most convenient; and those which are so deputed shall have power to lay out the highways where they may be most convenient, notwithstanding any man’s propriety, or any corne ground, so as it occasion not the pulling down of any man’s house, or laying open any garden or orchard; and in common [public] grounds, or where the soil is wet or miry, they shall lay out the ways the wider, as six, or eight, or ten rods, or more in common grounds.” With the establishment of the government in the province of New[Pg 36] York in 1664 the following regulation for road-making was established, which also obtained in Pennsylvania until William Penn’s reign began: “In all public works for the safety and defence of the government, or the necessary conveniencies of bridges, highways, and common passengers, the governor or deputy governor and council shall send warrents to any justice, and the justices to the constable of the next town, or any other town within that jurisdiction, to send so many laborers and artificers as the warrent shall direct, which the constable and two others or more of the overseers shall forthwith execute, and the constable and overseers shall have power to give such wages as they shall judge the work to deserve, provided that no ordinary laborer shall be compelled to work from home above one week together. No man shall be compelled to do any public work or service unless the press [impressment] be grounded upon some known law of this government, or an act of the governor and council signifying the necessity thereof, in both which cases a reasonable allowance shall be made.” A later amendment indi[Pg 37]cates the rudeness of these early roads: “The highways to be cleared as followeth, viz., the way to be made clear of standing and lying trees, at least ten feet broad; all stumps and shrubs to be cut close by the ground. The trees marked yearly on both sides—sufficient bridges to be made and kept over all marshy, swampy, and difficult dirty places, and whatever else shall be thought more necessary about the highways aforesaid.”

In Pennsylvania, under Penn, the grand jury laid out the roads, and the courts appointed overseers and fence-viewers, but in 1692 the townships were given the control of the roads. Eight years later the county roads were put in the hands of the county justices, and king’s highways in the hands of the governor and his council. Each county was ordered to erect railed bridges at its expense over rivers, and to appoint its own overseers and fence-viewers.

Even the slightest mention of these laws and regulations misrepresents the exact situation. Up to the time of the Revolutionary War it can almost be said that nothing had been done toward what we today[Pg 38] know as road-building. Many routes were cleared of “standing and lying trees” and “stumps and shrubs” were cut “close by the ground”—but this only widened the path of the Indian and was only a faint beginning in road-building. The skiff, batteau, and horse attached to a sleigh or sled in winter, were the only, common means of conveying freight or passengers in the colonies at this period. We have spoken of the path across the Alleghenies in 1750 as being but a winding trace; save for the roughness of the territory traversed it was a fair road for its day, seek where the traveler might. In this case, as in so many others, the history of the postal service in the United States affords us most accurate and reliable information concerning our economic development. In the year mentioned, 1750, the mail between New York and Philadelphia was carried only once a week in summer and twice a month in winter. Forty years later there were only eighteen hundred odd miles of post roads in the whole United States. At that time (1790) only five mails a week passed between New York and Philadelphia.[Pg 39]

It may be said, loosely, that the widened trail became a road when wheeled vehicles began to pass over it. Carts and wagons were common in the Atlantic seaboard states as early and earlier than the Revolution. It was at the close of that war that wagons began to cross the Alleghenies into the Mississippi Basin. This first road was a road in “the state of nature.” Nothing had been done to it but clearing it of trees and stumps.

Yet what a tremendous piece of work was this. It is more or less difficult for us to realize just how densely wooded a country this was from the crest of the Alleghenies to the seaboard on the east, and from the mountains to central Indiana and Kentucky on the west. The pioneers fought their way westward through wood, like a bullet crushing through a board. Every step was retarded by a live, a dying, or a dead branch. The very trees, as if dreading the savage attack of the white man on the splendid forests of the interior, held out their bony arms and fingers, catching here a jacket and there a foot, in the attempt to stay the invasion of their[Pg 40] silent haunts. These forests were very heavy overhead. The boughs were closely matted, in a life-and-death struggle for light and air. The forest vines bound them yet more inextricably together, until it was almost impossible to fell a tree with out first severing the huge arms which were bound fast to its neighbors. This dense overgrowth had an important influence over the pioneer traveler. It made the space beneath dark; the gloom of a real forest is never forgotten by the “tenderfoot” lumberman. The dense covering overhead made the forests extremely hot in the dog days of summer; no one can appreciate what “hot weather” means in a forest where the wind cannot descend through the trees save those who know our oldest forests. What made the forests hot in summer, on the other hand, tended to protect them from winter winds in cold weather. Yet, as a rule, there was little pioneer traveling in the Allegheny forests in winter. From May until November came the months of heaviest traffic on the first widened trails through these gloomy, heated forest aisles.[Pg 41]

It can be believed there was little tree-cutting on these first pioneer roads. Save in the laurel regions of the Allegheny and Cumberland Mountains, where the forest trees were supplanted by these smaller growths, there was little undergrowth; the absence of sunlight occasioned this, and rendered the old forest more easily traversed than one would suppose after reading many accounts of pioneer life. The principal interruption of travelers on the old trails was in the form of fallen trees and dead wood which had been brought to the ground by the storms. With the exception of the live trees which were blown over, these forms of impediment to travel were not especially menacing; the dead branches crumbled before an ax. The trees which were broken down or uprooted by the winds, however, were obstructions difficult to remove, and tended to make pioneer roads crooked, as often perhaps as standing trees. We can form some practical notion of the dangerous nature of falling trees by studying certain of the great improvements which were early projected in these woods. The Allegheny Portage Railway over the[Pg 42] mountains of Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, and the Erie Canal in central New York, both offer illustrations to the point. The portage track was sent through an unbroken, uninhabited forest wilderness from Hollidaysburg to Johnstown in the twenties. In order to render the inclines safe from falling trees and breaking branches, a swath through the woods was cut one hundred and twenty feet wide.[8] The narrow trellis of the inclines scaled the mountain in the center of this avenue; wide as it was, a tree fifty feet long could have swept it away like paper. The Erie Canal was to be forty feet in width; a clean sixty foot aisle was opened through the forests before the digging could begin.

Of course nothing like this could be done for pioneer highways; when the states began to appropriate money for state roads, then the pioneer routes were straightened by cutting some trees. It was all the scattered communities could do before this period to keep the falling trees and branches from blocking the old roads. Travelers wound in and out on one of the[Pg 43] many tracks, stumbling, slipping, grinding on the roots, going around great trees that had not been removed, and keeping to the high ground when possible, for there the forest growth was less dense.

The question immediately arises, What sort of vehicle could weather such roads? First in the van came the great clumsy cart, having immensely high and solid wooden wheels. These were obtained either by taking a thin slice from the butt of the greatest log that could be found in good condition, or by being built piecemeal by rude carpenters. These great wheels would go safely wherever oxen could draw them, many of their hubs being three feet from the ground. Thus the body of the cart would clear any ordinary brook and river at any ford which horses or oxen could cross. No rocks could severely injure such a massy vehicle, at the rate it usually moved, and no mere rut could disturb its stolid dignity. Like the oxen attached to it, the pioneer cart went on its lumbering way despising everything but bogs, great tree boles and precipices. These creaking carts could proceed, therefore, nearly on the[Pg 44] ancient bridle-path of the pack-horse age. On the greater routes westward the introduction of wheeled vehicles necessitated some changes; now and then the deep-worn passage-way was impassable, and detours were made which, at a later day, became the main course. Here, where the widened trail climbed a steeper “hog-back” than usual, the cart-drivers made a roundabout road which was used in dry weather. There, where the old trail wound about a marshy piece of ground in all weathers, the cart-drivers would push on in a straight line during dry seasons.

Thus the typical pioneer road even before the day of wagons was a many-track road and should most frequently be called a route—a word we have so frequently used in this series of monographs. Each of the few great historic roads was a route which could have been turned into a three, four, and five track course in very much the same way as railways become double-tracked by uniting a vast number of side-tracks. The most important reason for variation of routes was the wet and dry seasons; in the wet season advantage had[Pg 45] to be taken of every practicable altitude. The Indian or foot traveler could easily gain the highest eminence at hand; the pack-horse could reach many but not all; the “travail” and cart could reach many, while the later wagon could climb only a few. In dry weather the low ground offered the easiest and quickest route. As a consequence every great route had what might almost be called its “wet” and “dry” roadways. In one of the early laws quoted we have seen that in wet or miry ground the roads should be laid out “six, eight, or ten rods [wide],” though elsewhere ten or twelve feet was considered a fair width for an early road. As a consequence, even before the day of wagons, the old routes of travel were often very wide, especially in wet places; in wet weather they were broader here than ever. But until the day of wagons the track-beds were not so frequently ruined. Of this it is now time to speak.

By 1785 we may believe the great freight traffic by means of wagons had fully begun across the Alleghenies at many points. It is doubtful if anywhere else in the United[Pg 46] States did “wagoning” and “wagoners” become so common or do such a thriving trade as on three or four trans-Allegheny routes between 1785 and 1850. The Atlantic Ocean and the rivers had been the arteries of trade between the colonies from the earliest times. The freight traffic by land in the seaboard states had amounted to little save in local cases, compared with the great industry of “freighting” which, about 1785, arose in Baltimore and Philadelphia and concerned the then Central West. This study, like that of our postal history, throws great light on the subject in hand. Road-building, in the abstract, began at the centers of population and spread slowly with the growth of population. For instance, in Revolutionary days Philadelphia was, as it were, a hub and from it a number of important roads, like spokes, struck out in all directions. Comparatively, these were few in number and exceedingly poor, yet they were enough and sufficiently easy to traverse to give Washington a deal of trouble in trying to prevent the avaricious country people from treacherously feeding the British invaders.[Pg 47]

These roads out from Philadelphia, for instance, were used by wagons longer distances each year. Beginning back at the middle of the eighteenth century it may be said that the wagon roads grew longer and the pack-horse routes or bridle-paths grew shorter each year. The freight was brought from the seaboard cities in wagons to the end of the wagon roads and there transferred to the pack-saddles. Referring to this era we have already quoted a passage in which it is said that five hundred pack-horses have been seen at one time at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. For a longer period than was perhaps true elsewhere, Carlisle was the end of the wagon road westward. A dozen bridle-paths converged here. Here all freight was transferred to the strings of patient ponies. Loudon, Pennsylvania, was another peculiar borderland depot later on. It will be remembered that when Richard Henderson and party advanced to Kentucky in 1775 they were able to use wagons as far as Captain Joseph Martin’s “station” in Powell’s Valley. At that point all freight had to be transferred to the backs of ponies for the climb[Pg 48] over the Cumberlands. In the days of Marcus Whitman, who opened the first road across the Rocky Mountains, Fort Laramie, Wyoming, was the terminus of wagon travel in the far West. Thus pioneer roads unfolded, as it were, joint by joint, the rapidity depending on the volume of traffic, increase of population, and topography.

The first improvement on these greater routes, after the necessary widening, was to enable wagons to avoid high ground. Here and there wagons pushed on beyond the established limit, and, finding the way not more desperate than much of the preceding “road,” had gone on and on, until at last wagons came down the western slopes of the Alleghenies, and wagon traffic began to be considered possible—much to the chagrin of the cursing pack-horse men. No sooner was this fact accomplished than some attention was paid to the road. The wagons could not go everywhere the ponies or even the heavy carts had gone. They could not climb the steep knolls and remain on the rocky ridges. The lower grounds were, therefore, pursued and the wet grounds were made passable [Pg 51] by “corduroying”—laying logs closely together to form a solid roadbed. So far as I can learn this work was done by everybody in particular and nobody in general. Those who were in charge of wagons were, of course, the most interested in keeping them from sinking out of sight in the mud-holes. When possible, such places were skirted; when high or impassable ground prevented this, the way was “corduroyed.”

We have spoken of the width of old-time bridle-paths; with the advent of the heavy freighter these wide routes were doubled and trebled in width. And, so long as the roadbeds remained in a “state of nature,” the heavier the wagon traffic, the wider the roads became. We have described certain great tracks, like that of Braddock’s Road, which can be followed today even in the open by the lasting marks those plunging freighters made in the soft ground. They suggest in their deep outline what the old wagon roads must have been; yet it must be remembered that only what we may call the main road is visible today—the innumerable side-tracks being obliterated because not so deeply worn. In a number[Pg 52] of instances on Braddock’s Road plain evidence remains of these side-tracks. Judging then from this evidence, and from accounts which have come down to us, the introduction of the freighter with its heavier loads and narrower wheels turned the wide, deeply worn bridle-paths and cart tracks into far wider and far deeper courses. The corduroy road had a tendency to contract the route, but even here, where the ground was softest, it became desperate traveling. Where one wagon had gone, leaving great black ruts behind it, another wagon would pass with greater difficulty leaving behind it yet deeper and yet more treacherous tracks. Heavy rains would fill each cavity with water, making the road nothing less than what in Illinois was known as a “sloo.” The next wagoner would, therefore, push his unwilling horses into a veritable slough, perhaps having explored it with a pole to see if there was a bottom to be found there. In some instances the bottoms “fell out,” and many a reckless driver has lost his load in pushing heedlessly into a bottomless pit. In case a bottom could be found the driver[Pg 53] pushes on; if not, he finds a way about; if this is not possible he throws logs into the hole and makes an artificial bottom over which he proceeds.

We can hardly imagine what it meant to get stalled on one of the old “hog wallow” roads on the frontier. True, many of our country roads today offer bogs quite as wide and deep as any ever known in western Virginia or Pennsylvania; and it is equally true that roads were but little better in the pioneer era on the outskirts of Philadelphia and Baltimore than far away in the mountains. It remains yet for the present writer to find a sufficiently barbarous incident to parallel one which occurred on the Old York (New York) Road just out of Philadelphia, in which half a horse’s head was pulled off in attempting to haul a wagon from a hole in the road. “Jonathan Tyson, a farmer of 68 years of age [in 1844], of Abington, saw, at 16 years of age, much difficulty in going to the city [Philadelphia on York Road]: a dreadful mire of blackish mud rested near the present Rising Sun village.... He saw there the team of Mr. Nickum, of[Pg 54] Chestnut hill, stalled; and in endeavoring to draw out the forehorse with an iron chain to his head, it slipped and tore off the lower jaw, and the horse died on the spot. There was a very bad piece of road nearer to the city, along the front of the Norris estate. It was frequent to see there horses struggling in mire to their knees. Mr. Tyson has seen thirteen lime wagons at a time stopped on the York road, near Logan’s hill, to give one another assistance to draw through the mire; and the drivers could be seen with their trowsers rolled up, and joining team to team to draw out; at other times they set up a stake in the middle of the road to warn off wagons from the quicksand pits. Sometimes they tore down fences, and made new roads through the fields.”[9]

If such was the case almost within the city limits of Philadelphia, it is not difficult to realize what must have been the conditions which obtained far out on the continental routes. It became a serious problem to get stalled in the mountains late in the day; assistance was not always[Pg 55] at hand—indeed the settlements were many miles apart in the early days. Many a driver, however, has been compelled to wade in, unhitch his horses, and spend the night by the bog into which his freight was settling lower and lower each hour. Fortunate he was if early day brought assistance. Sometimes it was necessary to unload wholly or in part, before a heavy wagon, once fairly “set,” could be hauled out. Around such treacherous places ran a vast number of routes some of which were as dangerous—because used once too often—as the central track. In some places detours of miles in length could be made. A pilot was needed by every inexperienced person, and many blundering wiseacres lost their entire stock of worldly possessions in the old bogs and “sloos” and swamps of the “West.”

A town in Indiana was “very appropriately” named Mudholes, a name that would have been the most common in the country a century ago if only descriptive names had been allowed.[10] The condition[Pg 56] of pioneer roads did, undoubtedly, influence the beginnings of towns and cities. On the longer routes it will be found that the steep hills almost invariably became the sites of villages because of physical conditions. “Long-a-coming,” a New Jersey village, bore a very appropriate name.[11]

The girls of Sussex, England, were said to be exceedingly long-limbed, and a facetious wag affirmed the reason to be that the Sussex mud was so deep and sticky that in drawing out the foot “by the strength of the ancle” the muscles, and then the bones, of the leg were lengthened! In 1708 when Prince George of Denmark went to meet Charles the Seventh of Spain traveling by coach, he traveled at the rate of nine miles in six hours—a tribute to the strength of Sussex mud. Charles Augustus Murray, in his Travels in North America, leaves us a humorous account of the mud-holes in the road from the Potomac to Fredericksburg, Maryland, and his experience upon it:

“On the 27th of March I quitted Wash[Pg 57]ington, to make a short tour in the districts of Virginia adjacent to the James River; comprising Richmond, the present capital, Williamsburgh, the former seat of colonial government, Norfolk, and other towns.

“The first part of the journey is by steam-boat, descending the Potomac about sixty miles. The banks of this river, after passing Mount Vernon, are uninteresting, and I did not regret the speed of the Champion, which performed that distance in somewhat less than five hours; but this rate of travelling was amply neutralized by the movement of the stage which conveyed me from the landing-place to Fredericsburgh. I was informed that the distance was only twelve miles, and I was weak enough (in spite of my previous experience) to imagine that two hours would bring me thither, especially as the stage was drawn by six good nags, and driven by a lively cheerful fellow; but the road bade defiance to all these advantages—it was, indeed, such as to compel me to laugh out-right, notwithstanding the constant and severe bumping to which it subjected both the intellectual and sedentary parts of my person.[Pg 58]

“I had before tasted the sweets of mud-holes, huge stones, and remnants of pine-trees standing and cut down; but here was something new, namely, a bed of reddish-coloured clay, from one to two feet deep, so adhesive that the wheels were at times literally not visible in any one spot from the box to the tire, and the poor horses’ feet sounded, when they drew them out (as a fellow-traveller observed), like the report of a pistol. I am sorry that I was not sufficiently acquainted with chemistry or mineralogy to analyze that wonderful clay and state its constituent parts; but if I were now called upon to give a receipt for a mess most nearly resembling it, I would write, ‘Recipe—(nay, I must write the ingredients in English, for fear of taxing my Latin learning too severely)—

| Ordinary clay | 1 lb. |

| Do. Pitch | 1 lb. |

| Bird-lime | 6 oz. |

| Putty | 6 oz. |

| Glue | 1 lb. |

| Red lead, or colouring matter | 6 oz. |

| Fiat haustus—ægrot. terq. quaterq. quatiend.’ | |

“Whether the foregoing, with a proper admixture of hills, holes, stumps, and rocks, made a satisfactory draught or not, I will refer to the unfortunate team—I, alas! can answer for the effectual application of the second part of the prescription, according to the Joe Miller version of ‘When taken, to be well shaken!’

“I arrived, however, without accident or serious bodily injury, at Fredericsburgh, having been only three hours and a half in getting over the said twelve miles; and, in justice to the driver, I must say that I very much doubt whether any crack London whip could have driven those horses over that ground in the same time: there is not a sound that can emanate from human lungs, nor an argument of persuasion that can touch the feelings of a horse, that he did not employ, with a perseverance and success which commanded my admiration.”

Fancy these wild, rough routes which, combined, often covered half an acre, and sometimes spread out to a mile in total width, in freezing weather when every hub and tuft was as solid as ice. How many an anxious wagoner has pushed his[Pg 60] horses to the bitter edge of exhaustion to gain his destination ere a freeze would stall him as completely as if his wagon-bed lay on the surface of a “quicksand pit.” A heavy load could not be sent over a frozen pioneer road without wrecking the vehicle. Yet in some parts the freight traffic had to go on in the winter, as the hauling of cotton to market in the southern states. Such was the frightful condition of the old roads that four and five yoke of oxen conveyed only a ton of cotton so slowly that motion was almost imperceptible; and in the winter and spring, it has been said, with perhaps some tinge of truthfulness, that one could walk on dead oxen from Jackson to Vicksburg. The Bull-skin Road of pioneer days leading from the Pickaway Plains in Ohio to Detroit was so named from the large number of cattle which died on the long, rough route, their hides, to exaggerate again, lining the way.

In our study of the Ohio River as a highway it was possible to emphasize the fact that the evolution of river craft indicated with great significance the evolution of social conditions in the region under[Pg 61] review; the keel-boat meant more than canoe or pirogue, the barge or flat-boat more than the keel-boat, the brig and schooner more than the barge, and the steamboat far more than all preceding species. We affirmed that the change of craft on our rivers was more rapid than on land, because of the earlier adaptation of steam to vessels than to vehicles. But it is in point here to observe that, slow as were the changes on land, they were equally significant. The day of the freighter and the corduroy road was a brighter day for the expanding nation than that of the pack-horse and the bridle-path. The cost of shipping freight by pack-horses was tremendous. In 1794, during the Whiskey Insurrection in western Pennsylvania, the cost of shipping goods to Pittsburg by wagon ranged from five to ten dollars per hundred pounds; salt sold for five dollars a bushel, and iron and steel from fifteen to twenty cents per pound in Pittsburg. What must have been the price when one horse carried only from one hundred and fifty to two hundred and fifty pounds? The freighter represented a[Pg 62] growing population and the growing needs of the new empire in the West.

The advent of the stagecoach marked a new era as much in advance of the old as was the day of the steamboat in advance of that of the barge and brig of early days.

The social disturbance caused by the introduction of coaches on the pioneer roads of America gives us a glimpse of road conditions at this distant day to be gained no other way. A score of local histories give incidents showing the anger of those who had established the more important pack-horse lines across the continent at the coming of the stage. Coaches were overturned and passengers were maltreated; horses were injured, drivers were chastised and personal property ruined. Even while the Cumberland Road was being built the early coaches were in danger of assault by the workmen building the road, incited, no doubt, by the angry pack-horse men whose profession had been eclipsed. It is interesting in this connection to look again back to the mother-country and note the unrest which was occasioned by the introduction of stagecoaches on the bridle-paths of[Pg 63] England. Early coaching there was described as destructive to trade, prejudicial to landed interests, destructive to the breed of horses,[11*] and as an interference with public resources. It was urged that travelers in coaches got listless, “not being able to endure frost, snow or rain, or to lodge in the fields!” Riding in coaches injured trade since “most gentlemen, before they travelled in coaches, used to ride with swords, belts, pistols, holsters, portmanteaus, and hat-cases, which, in these coaches, they have little or no occasion for: for, when they rode on horseback, they rode in one suit and carried another to wear when they came to their journey’s end, or lay by the way; but in coaches a silk suit and an Indian gown, with a sash, silk stockings, and beaver hats, men ride in and carry no other with them, because they escape the wet and dirt, which on horseback they cannot avoid; whereas in[Pg 64] two or three journeys on horseback, these clothes and hats were wont to be spoiled; which done, they were forced to have new very often, and that increased the consumption of the manufacturers; which travelling in coaches doth in no way do.” If the pack-horse man’s side of the question was not advocated with equally marvelous arguments in America we can be sure there was no lack of debate on the question whether the stagecoach was a sign of advancement or of deterioration. For instance, the mails could not be carried so rapidly by coach as by a horseman; and when messages were of importance in later days they were always sent by an express rider. The advent of the wagon and coach promised to throw hundreds of men out of employment. Business was vastly facilitated when the freighter and coach entered the field, but fewer “hands” were necessary. Again, the horses which formerly carried the freight of America on their backs were not of proper build and strength to draw heavy loads on either coach or wagon. They were ponies; they could carry a few score pounds with great skill over blind and[Pg 65] ragged paths, but they could not draw the heavy wagons. Accordingly hundreds of owners of pack-horses were doomed to see an alarming deterioration in the value of their property when great, fine coach horses were shipped from distant parts to carry the freight and passenger loads of the stagecoach day.

The change in form of American vehicles was small but their numbers increased within a few years prodigiously. Nominally this era must be termed that of the macadamized road, or roads made of layers of broken stone like the Cumberland Road. These roads were wider than any single track of any of the routes they followed, though thirty feet was the average maximum breadth. To a greater degree than would be surmised, the courses of the old roads were followed. It has been said that the Cumberland Road, though paralleling Braddock’s Road from Cumberland to Laurel Hill, was not built on its bed more than a mile in the aggregate. After studying the ground I believe this is more or less incorrect; for what we should call Braddock’s route was composed of many[Pg 66] roads and tracks. One of these was a central road; the Cumberland Road may have been built on the bed of this central track only a short distance, but on one of the almost innumerable side-tracks, detours, and cut-offs, for many miles. At Great Meadows, for instance, it would seem that the Cumberland Road was separated from Braddock’s by the width of the valley; yet as you move westward you cross the central track of Braddock’s Road just before reaching Braddock’s Grave. May not an old route have led from Great Meadows thither on the same hillside where we find the Cumberland Road today? The crookedness of these first stable roads, like many of the older streets in our cities,[12] indicates that the old corduroy road served in part as a guide for the later road-makers. It is a common thing in the mountains, either on the Cumberland or Pennsylvania state roads, to hear people say that had the older routes been even more strictly adhered to[Pg 67] better grades would have been the result. A remarkable and truthful instance of this (for there cannot, in truth, be many) is the splendid way Braddock’s old road sweeps to the top of Laurel Hill by gaining that strategic ridge which divides the heads of certain branches of the Youghiogheny on the one hand and Cheat River on the other near Washington’s Rock. The Cumberland Road in the valley gains the same height (Laurel Hill) by a longer and far more difficult route.

The stagecoach heralded the new age of road-building, but these new macadamized roads were few and far between; many roadways were widened and graded by states or counties, but they remained dirt roads; a few plank roads were built. The vast number of roads of better grade were built by one of the host of road and turnpike companies which sprang up in the first half of the nineteenth century. Specific mention of certain of these will be made later.

Confining our view here to general conditions, we now see the Indian trail at its broadest. While the roads, in number,[Pg 68] kept up with the vast increase of population, in quality they remained, as a rule, unchanged. Traveling by stage, except on the half dozen good roads then in existence, was, in 1825, far more uncomfortable than on the bridle-path on horseback half a century previous. It would be the same today if we could find a vehicle as inconvenient as an old-time stagecoach. In our “Experiences of Travelers” we shall give pictures of actual life on these pioneer roads of early days. A glimpse or two at these roads will not be out of place here.

The route from Philadelphia to Baltimore is thus described by the American Annual Register for 1796: “The roads from Philadelphia to Baltimore exhibit, for the greater part of the way, an aspect of savage desolation. Chasms to the depth of six, eight, or ten feet occur at numerous intervals. A stagecoach which left Philadelphia on the 5th of February, 1796, took five days to go to Baltimore. [Twenty miles a day]. The weather for the first four days was good. The roads are in a fearful condition. Coaches are overturned, passengers killed, and horses destroyed by[Pg 69] the overwork put upon them. In winter sometimes no stage sets out for two weeks.” Little wonder that in 1800, when President and Mrs. Adams tried to get to Washington from Baltimore, they got lost in the Maryland woods! Harriet Martineau, with her usual cleverness, thus touches upon our early roads: “... corduroy roads appear to have made a deep impression on the imaginations of the English, who seem to suppose that American roads are all corduroy. I can assure them that there is a large variety in American roads. There are the excellent limestone roads ... from Nashville, Tennessee, and some like them in Kentucky.... There is quite another sort of limestone road in Virginia, in traversing which the stage is dragged up from shelf [catch-water] to shelf, some of the shelves sloping so as to throw the passengers on one another, on either side alternately. Then there are the rich mud roads of Ohio, through whose deep red sloughs the stage goes slowly sousing after rain, and gently upsetting when the rut on one or the other side proves to be of a greater depth than was anticipated.[Pg 70] Then there are the sandy roads of the pine barrens ... the ridge road, running parallel with a part of Lake Ontario.... Lastly there is the corduroy road, happily of rare occurrence, where, if the driver is merciful to his passengers, he drives them so as to give them the association of being on the way to a funeral, their involuntary sobs on each jolt helping the resemblance; or, if he be in a hurry, he shakes them like pills in a pill-box. I was never upset in a stage but once ...; and the worse the roads were, the more I was amused at the variety of devices by which we got on, through difficulties which appeared insurmountable, and the more I was edified at the gentleness with which our drivers treated female fears and fretfulness.”[13]

Perhaps it was of the Virginian roads here mentioned that Thomas Moore wrote:

“Dear George! though every bone is aching,

After the shaking

I’ve had this week, over ruts and ridges,

And bridges,

Made of a few uneasy planks,

In open ranks

[Pg 71]

Over rivers of mud, whose names alone

Would make the knees of stoutest man knock.”[14]

David Stevenson, an English civil engineer, leaves this record of a corduroy road from Lake Erie to Pittsburg: “On the road leading from Pittsburg on the Ohio to the town of Erie on the lake of that name, I saw all the varieties of forest[Pg 72] road-making in great perfection. Sometimes our way lay for miles through extensive marshes, which we crossed by corduroy roads, ...; at others the coach stuck fast in the mud, from which it could be extricated only by the combined efforts of the coachman and passengers; and at one place we travelled for upwards of a quarter of a mile through a forest flooded with water, which stood to the height of several feet on many of the trees, and occasionally covered the naves of the coach-wheels. The distance of the route from Pittsburg to Erie is 128 miles, which was accomplished in forty-six hours ... although the conveyance ... carried the mail, and stopped only for breakfast, dinner, and tea, but there was considerable delay caused by the coach being once upset and several times mired.”[15]

“The horrible corduroy roads again made their appearance,” records Captain Basil Hall, “in a more formidable shape, by the addition of deep, inky holes, which almost swallowed up the fore wheels of the wagon[Pg 73] and bathed its hinder axle-tree. The jogging and plunging to which we were now exposed, and occasionally the bang when the vehicle reached the bottom of one of these abysses, were so new and remarkable that we tried to make a good joke of them.... I shall not compare this evening’s drive to trotting up or down a pair of stairs, for, in that case, there would be some kind of regularity in the development of the bumps, but with us there was no wavering, no pause, and when we least expected a jolt, down we went, smack! dash! crash! forging, like a ship in a head-sea, right into a hole half a yard deep. At other times, when an ominous break in the road seemed to indicate the coming mischief, and we clung, grinning like grim death, to the railing at the sides of the wagon, expecting a concussion which in the next instant was to dislocate half the joints in our bodies, down we sank into a bed of mud, as softly as if the bottom and sides had been padded for our express accommodation.”

The first and most interesting macadam[Pg 74]ized road in the United States was the old Lancaster Turnpike, running from Philadelphia to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Its position among American roads is such that it deserves more than a mere mention. It has had several historians, as it well deserves, to whose accounts we are largely indebted for much of our information.[16]

The charter name of this road was “The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road Company;” it was granted April 9, 1792, and the work of building immediately began. The road was completed in 1794 at a cost of four hundred and sixty-five thousand dollars. When the subscription books were opened there was a tremendous rush to take the stock. The money raised for constructing and equipping this ancient highway with toll houses and bridges, as well as grading and macadamizing it, was by this sale of stock. In the Lancaster Journal of Friday, February 5, 1796, the following notice appeared:[Pg 75]

“That agreeable to a by-law of stockholders, subscriptions will be opened at the Company’s office in Philadelphia on Wednesday, the tenth of February next, for one hundred additional shares of capital stock in said company. The sum to be demanded for each share will be $300, with interest at six per cent. on the different instalments from the time they are severally called for, to be paid by original stockholders; one hundred dollars thereof to be paid at time of subscribing, and the remainder in three equal payments, at 30, 60 and 90 days, no person to be admitted to subscribe more than one share on the same day.

By order of the Board.

William Govett,

Secretary.”

“When location was fully determined upon,” writes Mr. Witmer, “as you will observe, today, a more direct line could scarcely have been selected. Many of the curves which are found at the present time did not exist at that day, for it has been crowded and twisted by various improvements along its borders so that the original[Pg 76] constructors are not responsible. So straight, indeed, was it from initial to terminal point that it was remarked by one of the engineers of the state railroad, constructed in 1834 (and now known as the Pennsylvania Railroad), that it was with the greatest difficulty that they kept their line off of the turnpike, and the subsequent experiences of the engineers of the same company verify the fact, as you will see. Today there is a tendency, wherever the line is straightened, to draw nearer to this old highway, paralleling it in many places for quite a distance, and as it approaches the city of Philadelphia, in one or two instances they have occupied the old road bed entirely, quietly crowding its old rival to a side, and crossing and recrossing it in many places.

“You will often wonder as you pass over this highway, remembering the often-stated fact by some ancient wagoner or stage-driver (who today is scarcely to be found, most of them having thrown down the reins and put up for the night), that at that time there were almost continuous lines of Conestoga wagons, with their[Pg 77] feed troughs suspended at the rear and the tar can swinging underneath, toiling up the long hills (for you will observe there was very little grading done when that roadway was constructed), and you wonder how it was possible to accommodate so much traffic as there was, in addition to stagecoaches and private conveyances, winding in and out among these long lines of wagons. But you must bear in mind that the roadway was very different then from what it is at the present time.

“The narrow, macadamized surface, with its long grassy slope (the delight of the tramp and itinerant merchant, especially when a neighboring tree casts a cooling shadow over its surface), which same slope becomes a menace to belated and unfamiliar travelers on a dark night, threatening them with an overturn into what of more recent times is known as the Summer road, did not exist at that time, but the road had a regular slope from side ditch to center, as all good roads should have, and conveyances could pass anywhere from side to side. The macadam was carefully broken and no stone was allowed to be placed on[Pg 78] the road that would not pass through a two-inch ring. A test was made which can be seen today about six miles east of Lancaster, where the roadway was regularly paved for a distance of one hundred feet from side to side, with a view of constructing the entire line in that way. But it proved too expensive, and was abandoned. Day, in his history, published in 1843,[17] makes mention of the whole roadway having been so constructed, but I think that must have been an error, as this is the only point where there is any appearance of this having been attempted, and can be seen at the present time when the upper surface has been worn off by the passing and repassing over it.”

The placing of tollgates on the Lancaster Pike is thus announced in the Lancaster Journal, previously mentioned, where the following notice appears:

“The public are hereby informed that the President and Managers of the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road having perfected the very arduous and import[Pg 79]ant work entrusted by the stockholders to their direction, have established toll gates at the following places on said road, and have appointed a toll gatherer at each gate, and that the rates of toll to be collected at the several gates are by resolution of the Board and agreeable to Act of Assembly fixed and established as below. The total distance from Lancaster to Philadelphia is 62 miles.

| Gate No. 1—2 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 3 miles |

| Gate No. 2—5 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 5 miles |

| Gate No. 3—10 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 7 miles |

| Gate No. 4—20 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 10 miles |

| Gate No. 5—29½ | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 10 miles |

| Gate No. 6—40 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 10 miles |

| Gate No. 7—49½ | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 10 miles |

| Gate No. 8—581⁄8 | miles W from Schuylkill, collect | 5 miles |

| Gate No. 9—Witmer’s Bridge, collect 61 miles.” | ||

There is also in the same journal, bearing date January 22, 1796, the following notice:

“Sec. 13. And be it further enacted, by authority of aforesaid, that no wagon or other carriage with wheels the breadth of whose wheels shall not be four inches, shall be driven along said road between the first day of December and the first day of May following in any year or years, with[Pg 80] a greater weight thereon than two and a half tons, or with more than three tons during the rest of the year; that no such carriage, the breadth of whose wheels shall not be seven inches, or being six inches or more shall roll at least ten inches, shall be drawn along said road between the said day of December and May with more than five tons, or with more than five and a half tons during the rest of the year; that no carriage or cart with two wheels, the breadth of whose wheels shall not be four inches, shall be drawn along said road with a greater weight thereon than one and a quarter tons between the said first days of December and May, or with more than one and a half tons during the rest of the year; no such carriage, whose wheels shall be of the breadth of seven inches shall be driven along the said road with more than two and one half tons between the first days of December and May, or more than three tons during the rest of the year; that no such carriage whose wheels shall not be ten inches in width shall be drawn along the said road between the first days of Decem[Pg 81]ber and May with more than three and a half tons, or with more than four tons the rest of the year; that no cart, wagon or carriage of burden whatever, whose wheels shall not be the breadth of nine inches at least, shall be drawn or pass in or over the said road or any part thereof with more than six horses, nor shall more than eight horses be attached to any carriage whatsoever used on said road, and if any wagon or other carriage shall be drawn along said road by a greater number of horses or with a greater weight than is hereby permitted, one of the horses attached thereto shall be forfeited to the use of said company, to be seized and taken by any of their officers or servants, who shall have the privilege to choose which of the said horses they may think proper, excepting the shaft or wheel horse or horses, provided always that it shall and may be lawful for said company by their by-laws to alter any and all of the regulations here contained respecting burdens or carriages to be drawn over the said road and substituting other regulations, if on experience such alterations should be found conducive of public good.[Pg 82]”

There were regular warehouses or freight stations in the various towns through which the Lancaster Pike passed, Mr. Witmer leaves record, where experienced loaders or packers were to be found who attended to filling these great curving wagons, which were elevated at each end and depressed in the centre; and it was quite an art to be able to so pack them with the various kinds of merchandise that they would carry safely, and at the same time to economize all the room necessary; and when fully loaded and ready for the journey it was no unusual case for the driver to be appealed to by some one who wished to follow Horace Greeley’s advice and “go west,” for permission to accompany him and earn a seat on the load, as well as share his mattress on the barroom floor at night by tending the lock or brake. Mr. Witmer was told by one of the largest and wealthiest iron masters of Pittsburg that his first advent to the Smoky City was on a load of salt in that capacity.

“In regard to the freight or transportation companies,” continues the annalist, “the Line Wagon Company was the most[Pg 83] prominent. Stationed along this highway at designated points were drivers and horses, and it was their duty to be ready as soon as a wagon was delivered at the beginning of their section to use all despatch in forwarding it to the next one, thereby losing no time required to rest horses and driver, which would be required when the same driver and horses took charge of it all the way through. But, like many similar schemes, what appeared practical in theory did not work well in practice. Soon the wagons were neglected, each section caring only to deliver it to the one succeeding, caring little as to its condition, and soon the roadside was encumbered with wrecks and breakdowns and the driver and horses passed to and fro without any wagon or freight from terminal points of their sections, leaving the wagons and freight to be cared for by others more anxious for its removal than those directly in charge. So it was deemed best to return to the old system of making each driver responsible for his own wagon and outfit.

“A wagoner, next to a stagecoach-driver, was a man of immense importance,[Pg 84] and they were inclined to be clannish. They would not hesitate to unite against landlord, stage-driver or coachman who might cross their path, as in a case when a wedding party was on its way to Philadelphia, which consisted of several gigs. These were two-wheeled conveyances, very similar to our road-carts of the present day, except that they were much higher and had large loop springs in the rear just back of the seat; they were the fashionable conveyance of that day. When one of the gentlemen drivers, the foremost one (possibly the groom), was paying more attention to his fair companion than his horses, he drove against the leaders of one of the numerous wagons that were passing on in the same direction. It was an unpardonable offense and nothing short of an encounter in the stable yard or in front of the hotel could atone for such a breach of highway ethics. At a point where the party stopped to rest before continuing their journey the wagoners overtook them and they immediately called on the gentleman for redress. But seeing a friend in the party they claimed they would excuse the[Pg 85] culprit on his friend’s account; the offending party would not have it so, and said no friend of his should excuse him from getting a beating if he deserved it, and I have no doubt he prided himself on his muscular abilities also. However it was peaceably arranged and each pursued his way without any blood being shed or bones broken. That was one of the many similar occurrences which happened daily, many not ending so harmlessly.

“The stage lines were not only the means of conveying the mails and passengers, but of also disseminating the news of great events along the line as they passed. The writer remembers hearing it stated that the stage came through from Philadelphia with a wide band of white muslin bound around the top, and in large letters was the announcement that peace had been declared, which was the closing of the second war with Great Britain, known as the War of 1812. What rejoicing it caused along the way as it passed!”

The taverns of this old turnpike were typical. Of them Mr. Moore writes:

“Independent of the heavy freighting,[Pg 86] numerous stage lines were organized for carrying passengers. As a result of this immense traffic, hotels sprung up all along the road, where relays of horses were kept, and where passengers were supplied with meals. Here, too, the teamsters found lodging and their animals were housed and cared for over night. The names of these hotels were characteristic of the times. Many were called after men who had borne conspicuous parts in the Revolutionary War that had just closed—such as Washington, Warren, Lafayette, and Wayne, while others represented the White and Black Horse, the Lion, Swan, Cross Keys, Ship, etc. They became favorite resorts for citizens of their respective neighborhoods, who wished at times to escape from the drudge and ennui of their rural homes and gaze upon the world as represented by the dashing stages and long lines of Conestoga wagons. Here neighbor met neighbor—it was the little sphere in which they all moved, lived and had their being. They sipped their whisky toddies together, which were dispensed at the rate of three cents a single glass, or for a finer quality, [Pg 89] five for a Spanish quarter, with the landlord in, was asked; smoked cigars that were retailed four for a cent—discussed their home affairs, including politics, religion and other questions of the day, and came just as near settling them, as the present generation of men, that are filling their places, required large supplies and made convenient home markets for the sale of butter, eggs, and whatever else the farmers had to dispose of.”

In our history of the Cumberland Road the difference between a wagonhouse and a tavern was emphasized. Mr. Witmer gives an incident on the Lancaster Turnpike which presents vividly the social position of these two houses of entertainment: “It was considered a lasting disgrace for one of the stage taverns to entertain a wagoner and it was sure to lose the patronage of the better class of travel, should this become known. The following instance will show how carefully the line was drawn. In the writer’s native village, about ten miles east of this city [Lancaster], when the traffic was unusually heavy and all the wagon taverns were full, a[Pg 90] wagoner applied to the proprietor of the stage hotel for shelter and refreshment, and after a great deal of consideration on his part and persuasion on the part of the wagoner he consented, provided the guest would take his departure early in the morning, before there was any likelihood of any aristocratic arrivals, or the time for the stage to arrive at this point. As soon as he had taken his departure the hostlers and stable boys were put to work to clean up every vestige of straw or litter in front of the hotel that would be an indication of having entertained a wagoner over night!”

The later history of the turnpike has been sketched by Mr. Moore as follows:

“The turnpike company had enjoyed an uninterrupted era of prosperity for more than twenty-five years. During this time the dividends paid had been liberal—sometimes, it is said, exceeding fifteen per cent of the capital invested. But at the end of that time the parasite that destroys was gradually being developed. Another, and altogether new system of transportation had been invented—a railroad—and which had already achieved partial success in[Pg 91] some places in Europe. It was about the year 1820 that this new method of transportation began to claim the serious attention of the progressive business men throughout the state. The feeling that some better system than the one in use must be found was fed and intensified by the fact that New York State was then constructing a canal from Albany to the lakes; that when completed it would give the business men of New York City an unbroken water route to the west....

“With the completion of the entire Pennsylvania canal system to Pittsburg, in 1834, the occupation of the famous old Conestoga teams was gone.[18] The same may also be said of the numerous lines of the stages that daily wended their way over the turnpike. The changes wrought were almost magical. Everyone who rode patronized the cars; and the freight was also forwarded by rail. The farmers, however, were not ruined as they had maintained they would be. Their horses, as well as[Pg 92] drivers, were at once taken into the railway service and employed in drawing cars from one place to another. It was simply a change of vocation, and there still remained a market for grain, hay, straw and other produce of the farm.

“The loss sustained by the holders of turnpike stock, however, was immeasurable. In a comparative sense, travel over the turnpike road was suspended. Receipts from tolls became very light and the dividends, when paid, were not only quite diminutive, but very far between.