The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Flags of the World, by F. Edward Hulme

|

Transcriber's note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

are listed at the end of the text, after the plates.

For convenience of viewing, each coloured plate has been positioned alongside its respective index.

|

THE FLAGS OF THE WORLD:

THEIR HISTORY,

BLAZONRY, AND ASSOCIATIONS.

THE

Flags of The World:

THEIR HISTORY,

BLAZONRY, AND ASSOCIATIONS.

FROM THE

BANNER OF THE CRUSADER TO THE BURGEE OF THE YACHTSMAN;

FLAGS NATIONAL, COLONIAL, PERSONAL;

THE ENSIGNS OF MIGHTY EMPIRES;

THE SYMBOLS OF LOST CAUSES.

BY

F. EDWARD HULME, F.L.S., F.S.A.,

Author of

"Familiar Wild Flowers," "History, Principles and Practice of Heraldry,"

"Birth and Development of Ornament," &c., &c.

LONDON:

FREDERICK WARNE & CO.,

AND NEW YORK

[All rights reserved.]

{iii}

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. |

| The necessity of some special Sign to distinguish Individuals, Tribes,

and Nations—the Standards of Antiquity—Egyptian, Assyrian,

Persian, Greek, and Roman—the Vexillum—the Labarum of

Constantine—Invocation of Religion—the Flags of the Enemy—Early

Flags of Religious Character—Flags of Saints at Funeral

Obsequies—Company and Guild Flags of the Mediæval Period—Political

Colours—Various kinds of Flags—the Banner—Rolls

of Arms—Roll of Karlaverok—The Flag called the Royal Standard

is really the Royal Banner—Main-sail Banners—Trumpet

Banners—Ladies embroidering Banners for the Cause—Knights'

Banneret—Form of Investiture—the Standard—the Percy Badges

and Motto—Arctic Sledge-flags—the Rank governing the size

of the Standard—Standards at State Funerals—the Pennon—Knights'

Pennonciers—the Pennoncelle—Mr. Rolt as Chief

Mourner—Lord Mayor's Show—the Pennant—the Streamer—Tudor

Badges—Livery Colours—the Guidon—Bunting—Flag

Devising a Branch of Heraldry—Colours chiefly used in Flags—Flags

bearing Inscriptions—Significance of the Red Flag—of the

Yellow—of the White—of the Black—Dipping the Flag—the

Sovereignty of the Sea—Right of Salute insisted on—Political

changes rendering Flags

obsolete | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| The Royal Standard—the Three Lions of England—the Lion

Rampant of Scotland—Scottish sensitiveness as to precedence—the

Scottish Tressure—the Harp of Ireland—Early Irish

Flags—Brian Boru—the Royal Standards from Richard I.

to Victoria—Claim to the Fleurs-de-lys of France—Quartering

Hanover—the Union Flag—St. George for England—War

Cry—Observance of St. George's Day—the Cross of St.

George—Early Naval Flags—the London Trained Bands—the

Cross of St. Andrew—the "Blue Blanket"—Flags of the

Covenanters—Relics of St. Andrew—Union of England and

Scotland—the First Union Flag—Importance of accuracy in

representations of it—the Union Jack—Flags of the Commonwealth

and Protectorate—Union of Great Britain and

{iv}

Ireland—the Cross of St. Patrick—Labours of St. Patrick in Ireland—Proclamation

of George III. as to Flags, etc.—the Second

Union Flag—Heraldic Difficulties in its Construction—Suggestions

by Critics—Regulations as to Fortress Flags—the White

Ensign of the Royal Navy—Saluting the Flag—the Navy the

Safeguard of Britain—the Blue Ensign—the Royal Naval Reserve—the

Red Ensign of the Mercantile Marine—Value of

Flag-lore | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| Army Flags—the Queen's Colour—the Regimental Colour—the

Honours and Devices—the Flag of the 24th Regiment—Facings—Flag

of the King's Own Borderers—What the Flag Symbolises—Colours

of the Guards—the Assaye Flag—Cavalry Flags—Presentation

of Colours—Chelsea College Chapel—Flags of the

Buffs in Canterbury Cathedral—Flags of the Scottish Regiments

in St. Giles's Cathedral—Burning of Rebel Flags by the Hangman—Special

Flags for various Official Personages—Special

Flags for different Government Departments—the Lord High

Admiral—the Mail Flag—White Ensign of the Royal Yacht

Squadron—Yacht Ensigns and Burgees—House or Company

Flags—How to express Colours with Lines—the Allan Tricolor—Port

Flags—the British Empire—the Colonial Blue Ensign

and Pendant—the Colonial Defence Act—Colonial Mercantile

Flag—Admiralty Warrant—Flag of the Governor of a Colony—the

Green Garland—the Arms of the Dominion of Canada—Badges

of the various Colonies—Daniel Webster on the Might

of England—Bacon on the Command of the

Ocean | 61 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

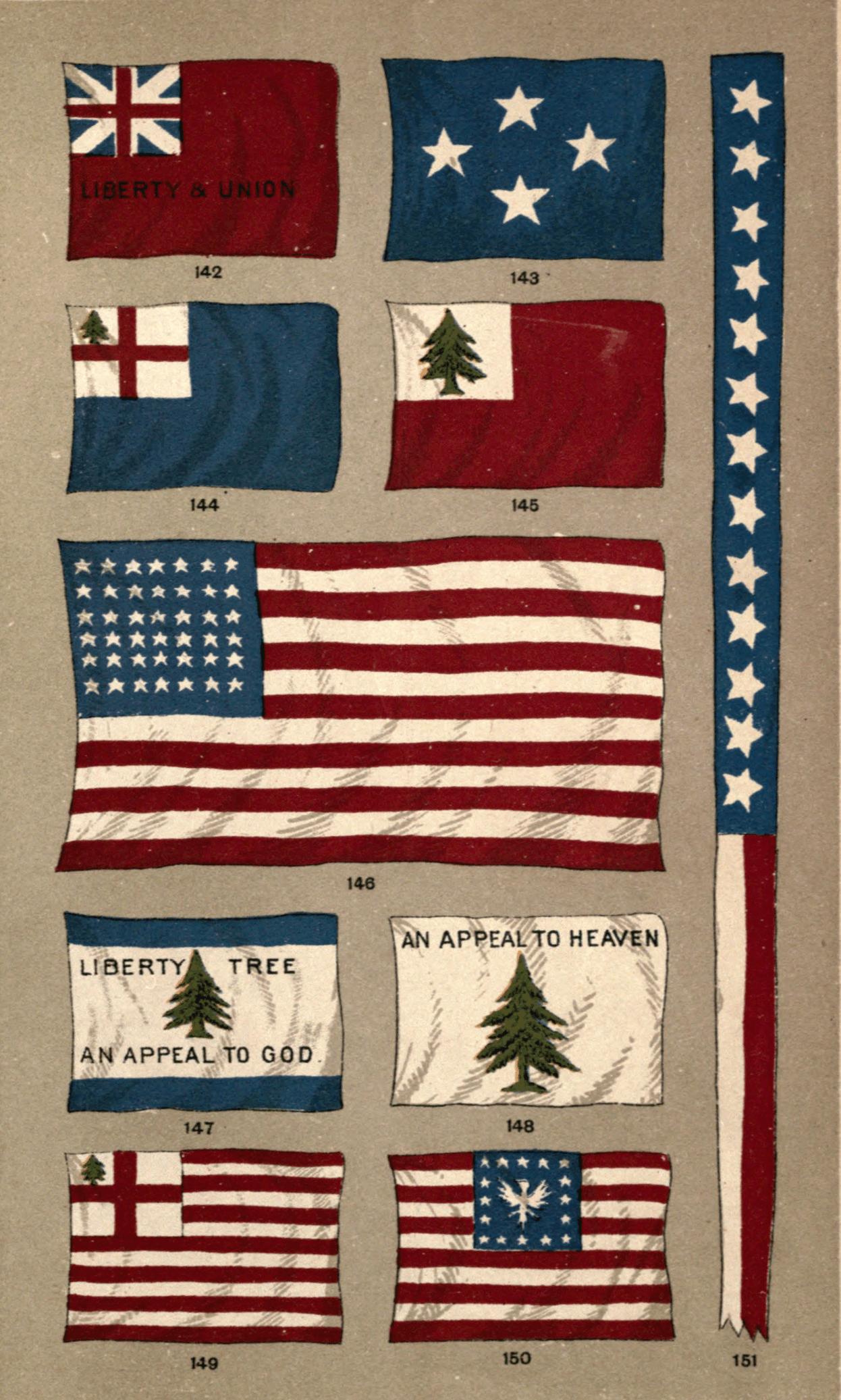

| The Flag of Columbus—Early Settlements in North America—the

Birth of the United States—Early Revolutionary and State

Flags—the Pine-tree Flag—the Rattle-snake Flag—the Stars

and Stripes—Early Variations of it—the Arms of Washington—Entry

of New States into the Union—the Eagle—the Flag of

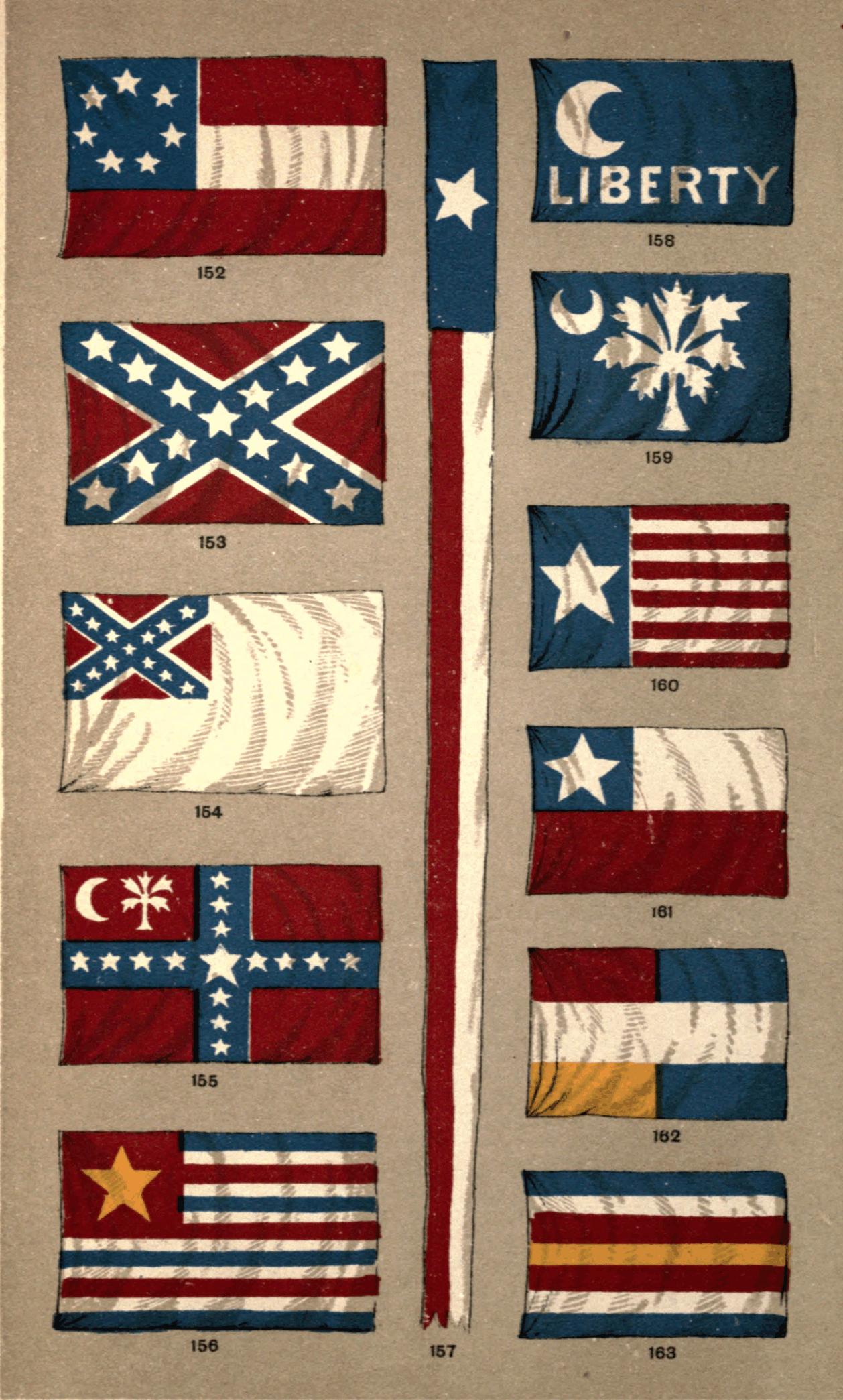

the President—Secession of the Southern States—State Flags

again—the Stars and Bars—the Southern Cross—the Birth of

the German Empire—the Influence of War Songs—Flags of the

Empire—Flags of the smaller German States—the Austro-Hungary

Monarchy—the Flags of Russia—the Crosses of St.

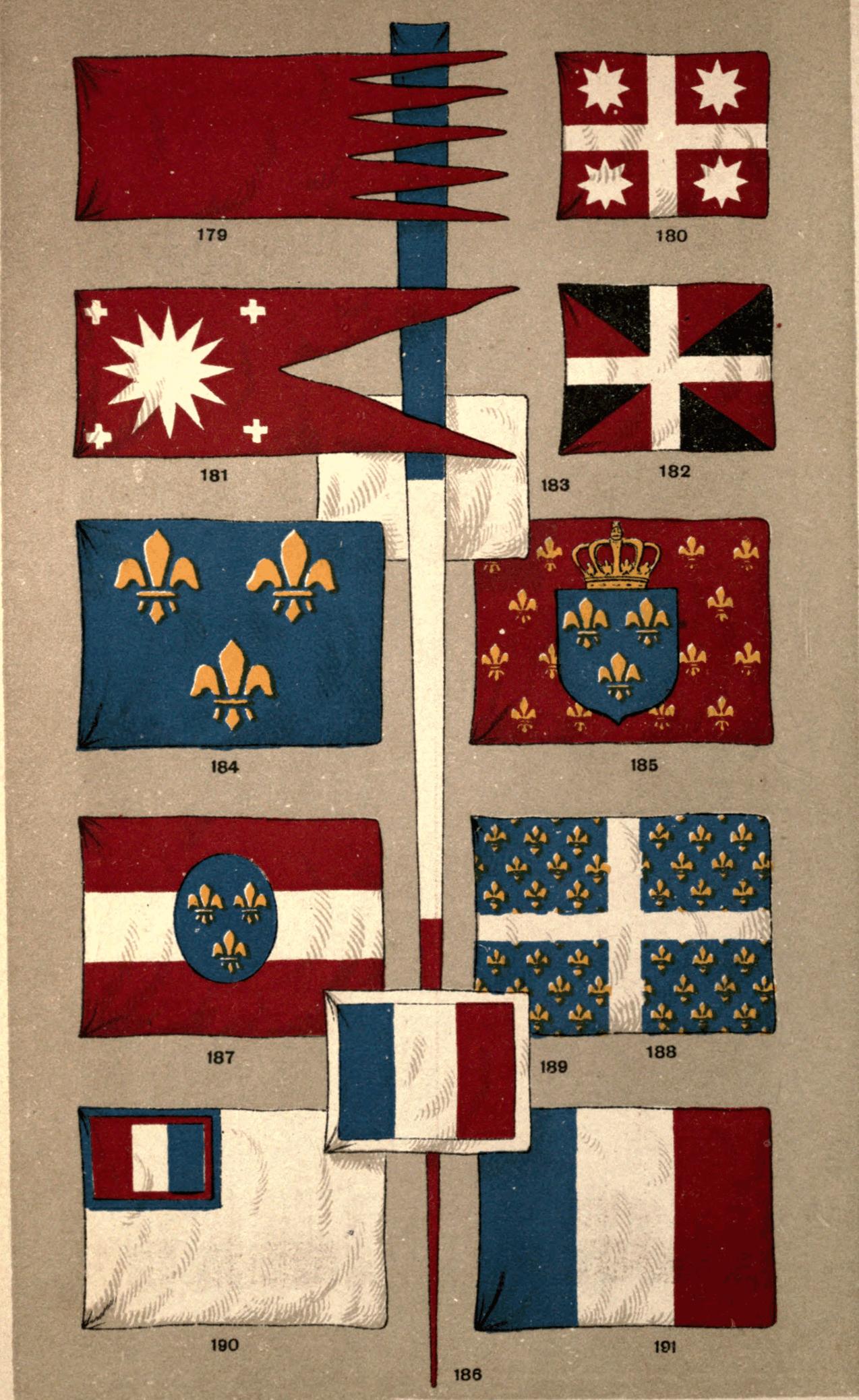

Andrew and St. George again—the Flags of France—St. Martin—the

Oriflamme—the Fleurs-de-lys—Their Origin—the White

Cross—the White Flag of the Bourbons—the Tricolor—the Red

{v}

Flag—the Flags of Spain—of Portugal—the Consummation of

Italian Unity—the Arms of Savoy—the Flags of Italy—of the

Temporal Power of the Papacy—the Flag of Denmark—its

Celestial Origin—the Flags of Norway and Sweden—of Switzerland—Cantonal

Colours—the Geneva Convention—the Flags of

Holland—of Belgium—of Greece—the Crescent of Turkey—the

Tughra—the Flags of Roumania, Servia, and Bulgaria—Flags

of Mexico, and of the States of Southern and Central

America—of Japan—the Rising Sun—the Chrysanthemum—the

Flags of China, Siam and Corea—of Sarawak—of the Orange

Free State, Liberia, Congo State, and the Transvaal

Republic | 86 |

| CHAPTER V. |

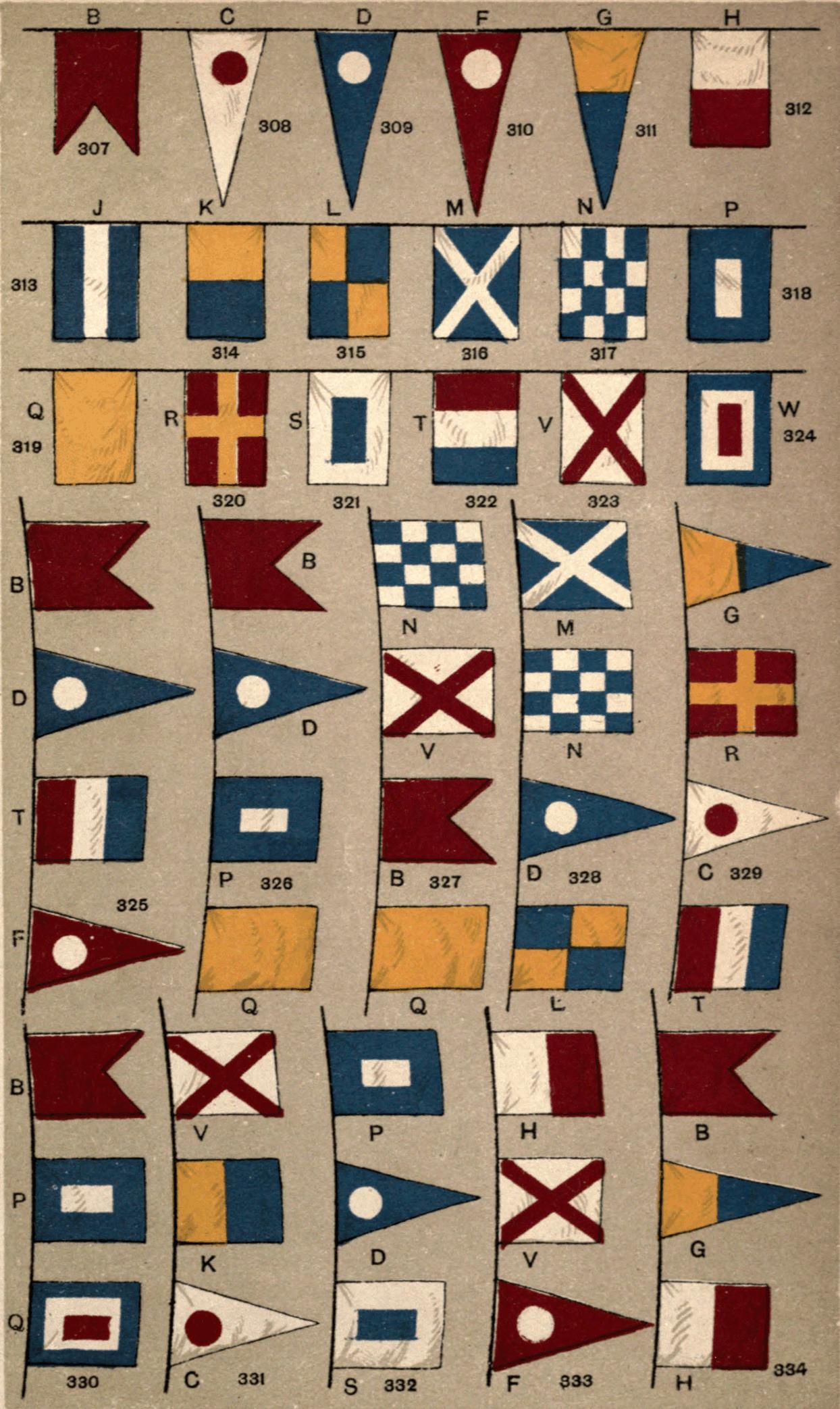

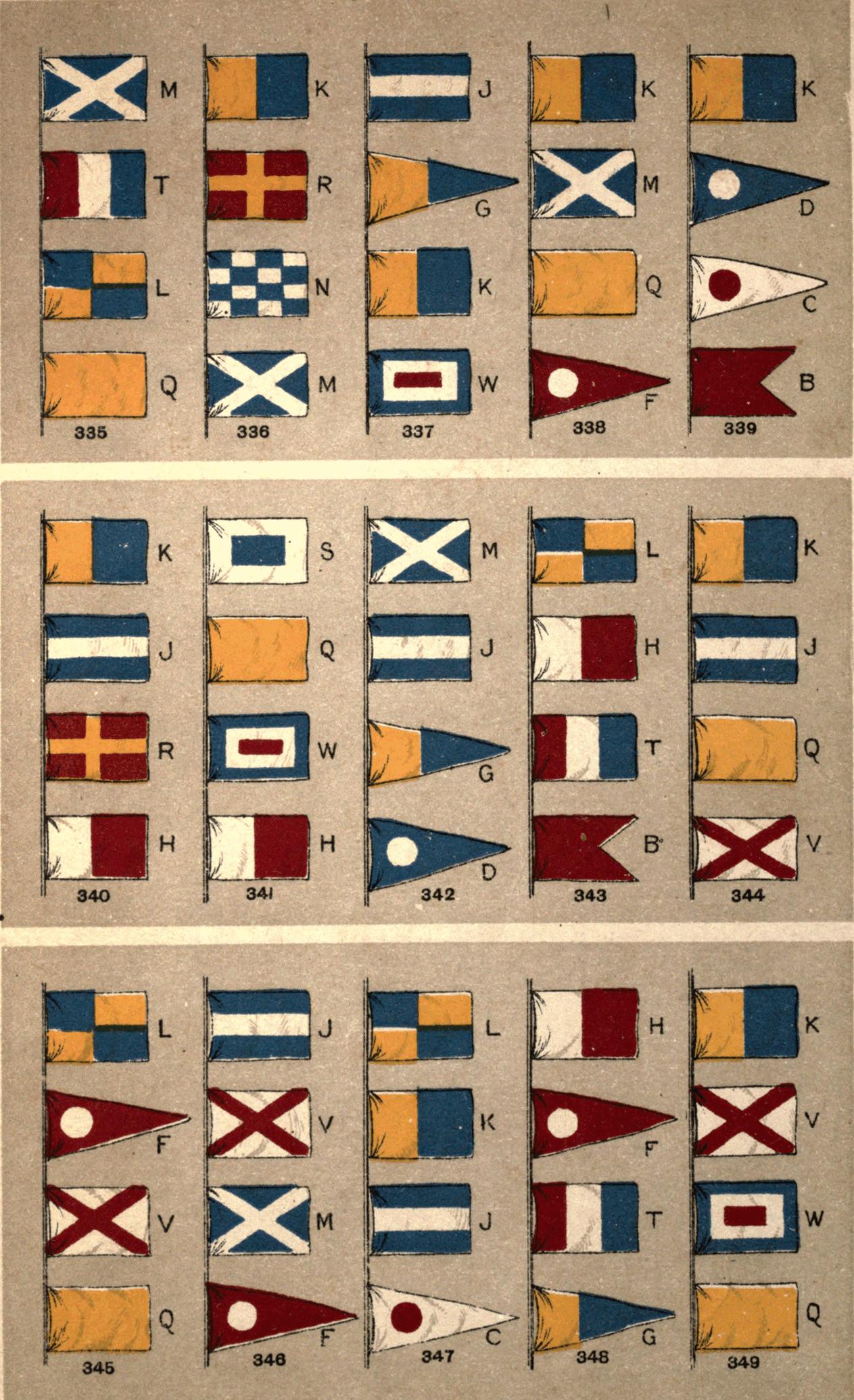

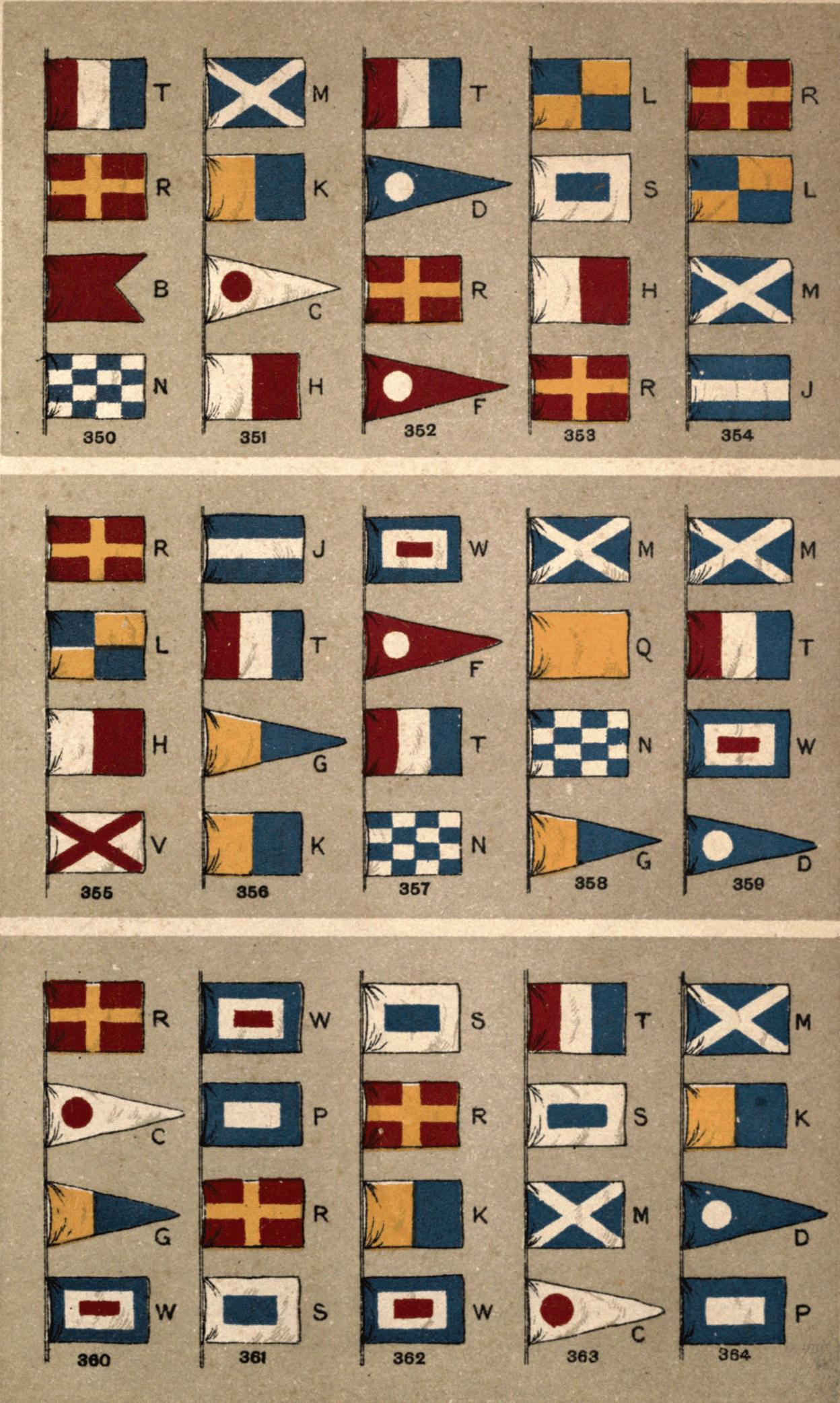

| Flags as a Means of Signalling—Army Signalling—the Morse

Alphabet—Navy Signalling—First Attempts at Sea Signals—Old

Signal Books in Library of Royal United Service Institution—"England

expects that every man will do his duty"—Sinking

Signal Codes on defeat—Present System of Signalling in

Royal Navy—Pilot Signals—Weather Signalling by Flags—the

International Signal Code—First Published in 1857—Seventy-eight

Thousand Different Signals possible—Why no

Vowels used—Lloyd's Signal

Stations | 127 |

| Alphabetical Index to Text | 141 |

| Coloured Plates | 149 |

{1}

THE FLAGS OF THE WORLD.

CHAPTER I.

The necessity of some special Sign to distinguish Individuals, Tribes,

and Nations—the Standards of Antiquity—Egyptian, Assyrian,

Persian, Greek, and Roman—the Vexillum—The Labarum of

Constantine—Invocation of Religion—the Flags of the

Enemy—Early Flags of Religious Character—Flags of Saints at

Funeral Obsequies—Company and Guild Flags of the Mediæval

Period—Political Colours—Various kinds of Flags—the

Banner—Rolls of Arms—Roll of Karlaverok—The Flag called

the Royal Standard is really the Royal Banner—Mainsail

Banners—Trumpet Banners—Ladies embroidering Banners for the

Cause—Knights' Banneret—Form of Investiture—the

Standard—the Percy Badges and Motto—Arctic

Sledge-flags—the Rank governing the size of the

Standard—Standards at State Funerals—the

Pennon—Knights-Pennonciers—the Pennoncelle—Mr. Rolt as

Chief Mourner—Lord Mayor's Show—the Pennant—the

Streamer—Tudor Badges—Livery Colours—the

Guidon—Bunting—Flag Devising a Branch of

Heraldry—Colours chiefly used in Flags—Flags bearing

Inscriptions—Significance of the Red Flag—of the

Yellow—of the White—of the Black—Dipping the

Flag—the Sovereignty of the Sea—Right of Salute insisted

on—Political Changes rendering Flags obsolete.

So soon as man passes from the lowest stage of barbarism the necessity

for some special sign, distinguishing man from man, tribe from tribe,

nation from nation, makes itself felt; and this prime necessity once met,

around the symbol chosen spirit-stirring memories quickly gather that

endear it, and make it the emblem of the power and dignity of those by

whom it is borne. The painted semblance of grizzly bear, or beaver, or

rattlesnake on the canvas walls of the tepi of the prairie Brave, the

special chequering of colours that compose the tartan[1] of the Highland clansman, are examples of

this; and as we pass from individual or local tribe to mighty nations,

the same influence is still at work, and the distinctive Union Flag of

Britain, the tricolor of France, the gold and scarlet bars of the flag of

Spain, all alike appeal with irresistible force to the patriotism of

those born beneath their folds, and speak to them of the glories and

greatness of the historic past, the duties of the present, and the hopes

of the future—inspiring those who gaze upon their proud blazonry

with the determination to be no unworthy sons of their fathers, but to

live, and if need be to die, for the dear home-land of which these are

the symbol. {2}

The standards used by the nations of antiquity differed in nature from

the flags that in mediæval and modern days have taken their place. These

earlier symbols were ordinary devices wrought in metal, and carried at

the head of poles or spears. Thus the hosts of Egypt marched to war

beneath the shadow of the various sacred animals that typified their

deities, or the fan-like arrangement of feathers that symbolised the

majesty of Pharoah, while the Assyrian standards, to be readily seen

represented on the slabs from the palaces of Khorsabad and Kyonjik, in

the British Museum and elsewhere, were circular disks of metal containing

various distinctive devices. Both these and the Egyptian standards often

have in addition a small flag-like streamer attached to the staff

immediately below the device. The Greeks in like manner employed the Owl

of Athene, and such-like religious and patriotic symbols of the

protection of the deities, though Homer, it will be remembered, makes

Agamemnon use a piece of purple cloth as a rallying point for his

followers. The sculptures of Persepolis show us that the Persians adopted

the figure of the Sun, the eagle, and the like. In Rome a hand erect, or

the figures of the horse, wolf, and other animals were used, but at a

later period the eagle alone was employed. Pliny tells us that "Caius

Marius in his second consulship ordained that the Roman legions should

only have the Eagle for their standard. For before that time the Eagle

marched foremost with four others, wolves, minatours, horses, and

bears—each one in its proper order. Not many years past the Eagle

alone began to be advanced in battle, and the rest were left behind in

the camp. But Marius rejected them altogether, and since this it is

observed that scarcely is there a camp of a Legion wintered at any time

without having a pair of Eagles." The eagle, we need scarcely stay to

point out, obtained this pre-eminence as being the bird of Jove. The

Vexillum, or cavalry flag, was, according to Livy, a square piece of

cloth fixed to a cross bar at the end of a spear; this was often richly

fringed, and was either plain or bore certain devices upon it, and was

strictly and properly a flag. The ensigns which distinguished the allied

forces from the legions of the Romans were also of this character.

Examples of these vexilla may be seen on the sculptured columns of Trajan

and Antoninus, the arch of Titus, and upon various coins and medals of

ancient Rome.

The Imperial Standard or Labarum carried before Constantine and his

successors resembled the cavalry Vexillum.[2] It was of purple silk, richly embroidered

with gold, and though ordinarily {3}suspended from a horizontal cross-bar, was

occasionally displayed in accordance with our modern usage by attachment

by one of its sides to the staff.

The Roman standards were guarded with religious veneration in the

temples of the metropolis and of the chief cities of the Empire, and

modern practice has followed herein the ancient precedent. As in classic

days the protection of Jove was invoked, so in later days the blessing of

Jehovah, the Lord of Hosts, has been sought. At the presentation of

colours to a regiment a solemn service of prayer and praise is held, and

when these colours return in honour, shot-rent from victorious conflict,

they are reverently placed in stately abbey, venerable cathedral, or

parish church, never more to issue from the peace and rest of the home of

God until by lapse of years they crumble into indistinguishable dust.

The Israelites carried the sacred standard of the Maccabees, with the

initial letters of the Hebrew text, "Who is like unto Thee, O God,

amongst the gods?" The Emperor Constantine caused the sacred monogram of

Christ to be placed on the Labarum, and when the armies of Christendom

went forth to rescue the Holy Land from the infidel they received their

cross-embroidered standards from the foot of the altar. Pope Alexander

II. sent a consecrated white banner to Duke William previous to his

expedition against Harold, and we read in the "Beehive of the Romish

Church," published in 1580, how "the Spaniardes christen, conjure, and

hallow their Ensignes, naming one Barbara, another Katherine," after the

names of saints whose aid they invoked in the stress of battle. We may

see this invocation again very well in Figs. 147,

148: flags borne by the colonists of Massachusetts

when they arrayed themselves against the mercenaries of King George, and

appealed to the God of Battles in behalf of the freedom and justice

denied by those who bore rule over them.

This recognition of the King of kings has led also to the captured

banners of the enemy being solemnly suspended in gratitude and

thanksgiving in the house of God. Thus Speed tells us that on the

dispersal and defeat of the Armada, Queen Elizabeth commanded solemn

thanksgiving to be celebrated at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul's, in

her chief city of London, which accordingly was done upon Sunday, the 8th

of September, when eleven of the Spanish ensigns were hung, to the great

joy of the beholders, as "psalmes of praise" for England's deliverance

from sore peril. Very appropriately, too, in the Chapel of the Royal

College at Chelsea, the home of the old soldiers who helped to win them,

hang the flags taken at Barrosa, Martinique, Bhurtpore, Seringapatam,

Salamanca, Waterloo, and many another hard-fought struggle; {4}and thus, in like manner, is the tomb of

Napoleon I., in Paris, surrounded by trophies of captured flags. On March

30th, 1814, the evening before the entry of the Allies into Paris, about

1,500 flags—the victorious trophies of Napoleon—were burnt in

the Court of the Eglise des Invalides, to prevent their falling into the

hands of the enemy.

Early flags were almost purely of a religious character.[3] The first notice of banners

in England is in Bede's description of the interview between the heathen

King Ethelbert and Augustine, the missionary from Rome, where the

followers of the latter are described as bearing banners on which were

displayed silver crosses; and we need scarcely pause to point out that in

Roman Catholic countries, where the ritual is emotional and sensuous,

banners of this type are still largely employed to add to the pomp of

religious processions. Heraldic and political devices upon flags are of

later date, and even when these came freely into use their presence did

not supplant the ecclesiastical symbols. The national banner of England

for centuries—the ruddy cross of her patron Saint George (Fig. 91)—was a religious one, and, whatever other

banners were carried, this was ever foremost in the field. The Royal

banner of Great Britain and Ireland that we see in Fig. 44, in its rich blazonry of the lions of England and

Scotland and the Irish harp, is a good example of the heraldic flag,

while our Union flag (Fig. 90), equally symbolizes

the three nations of the United Kingdom, but this time by the allied

crosses of the three patron saints, St. George, St. Andrew, and St.

Patrick, and it is therefore a lineal descendant and exemplar of the

religious influence that was once all-powerful.

The ecclesiastical flags were often purely pictorial in character,

being actual representations of the Persons of the Trinity, of the Virgin

Mother, or of divers saints. At other times the monasteries and other

religious houses bore banners of heraldic character; as the leading

ecclesiastics were both lords temporal and lords spiritual, taking their

places in the ranks of fighting men and leading on the field the body of

dependants and retainers that they were required to maintain in aid of

the national defence. In such case {5}the distinguishing banner of the

contingent conformed in character to the heraldic cognisances of the

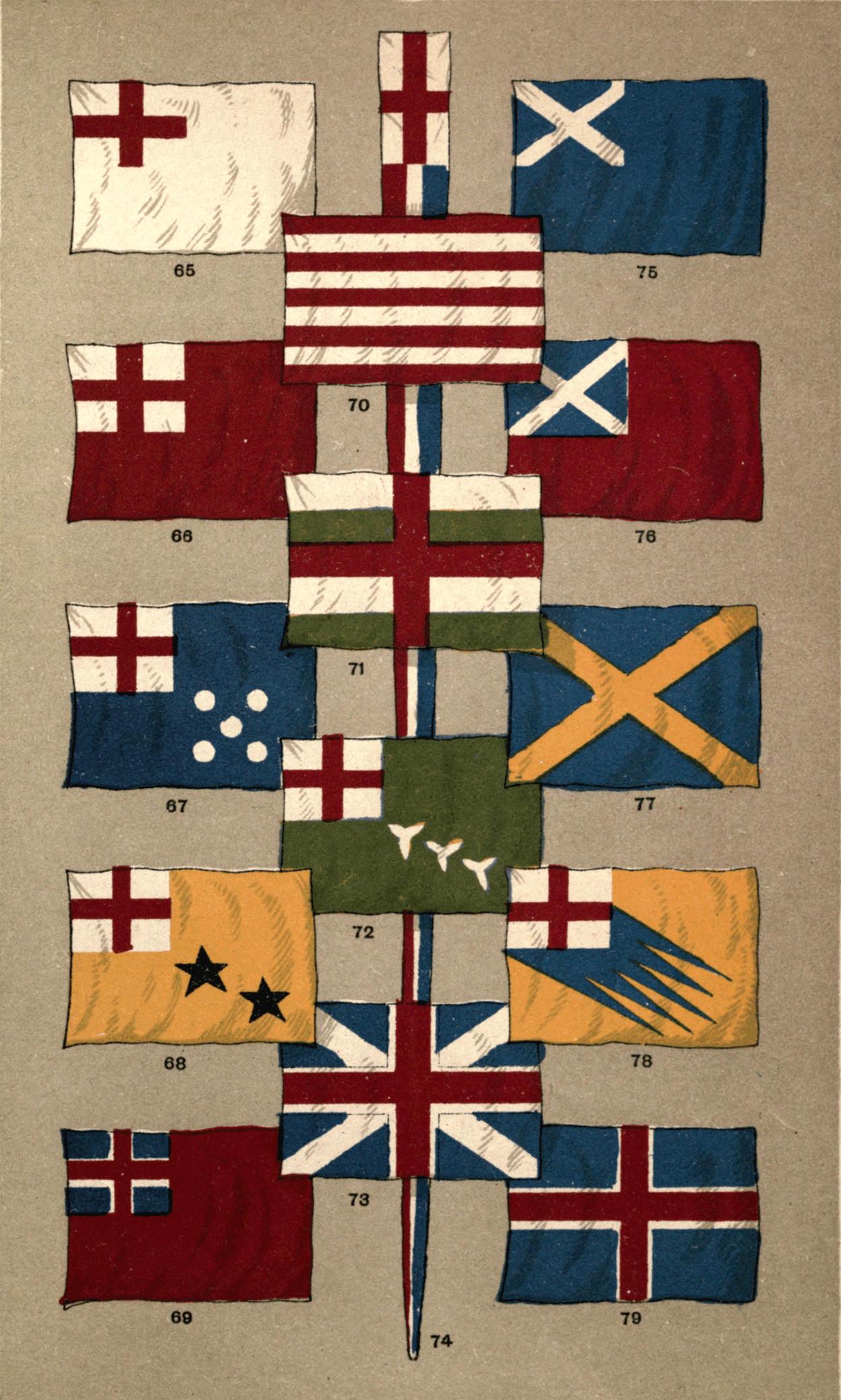

other nobles in the host. Fig. 77, for instance, was

the banner of St. Alban's Abbey. In a poem on the capture of Rouen by the

English, in the year 1418, written by an eye-witness of the scenes

described, we read how the English commander—

"To the Castelle firste he rode

And sythen the citie all abrode,

Lengthe and brede he it mette

And riche baneres up he sette

Upon the Porte Seint Hillare

A Baner of the Trynyte;

And at Porte Kaux he sette evene

A Baner of the Quene of Heven;

And at Porte Martvile he upplyt

Of Seint George a Baner breight."

and not until this recognition of Divine and saintly aid was made

did

"He sette upon the Castelle to stonde

The armys of Fraunce and Englond."

Henry V., at Agincourt, in like manner displayed at his headquarters

on the field not only his own arms, but, in place of special honour and

prominence, the banners of the Trinity, of St. George, and of St. Edward.

These banners of religious significance were often borne from the

monasteries to the field of battle, while monks and priests in attendance

on them invoked the aid of Heaven during the strife. In an old statement

of accounts, still existing, we read that Edward I. made a payment of

8½d. a day to a priest of Beverley for carrying throughout one of his

campaigns a banner bearing the figure of St. John. St. Wilfred's banner

from Ripon, together with this banner of St. John from Beverley, were

brought on to the field at Northallerton; the flag of St. Denis was

carried in the armies of St. Louis and of Philip le Bel, and the banner

of St. Cuthbert of Durham was borrowed by the Earl of Surrey in his

expedition against Scotland in the reign of Henry VIII. This banner had

the valuable reputation of securing victory to those who fought under it.

It was suspended from a horizontal bar below a spear head, and was a yard

or so in breadth and a little more than this in depth; the bottom edge

had five deep indentations. The banner was of red velvet sumptuously

enriched with gold embroidery, and in the centre was a piece of white

velvet, half a yard square, having a cross of red velvet upon it. This

central portion covered and protected a relic of the saint. The victory

of Neville's Cross, October 17th, 1346, was held to be largely {6}due to the presence of this sacred banner, and

the triumph at Flodden was also ascribed to it.

During the prevalence of Roman Catholicism in England, we find that

banners of religious type entered largely into the funeral obsequies of

persons of distinction: thus at the burial of Arthur, Prince of Wales,

the eldest son of Henry VII., we find a banner of the Trinity, another

with the cross and instruments of the Passion depicted upon it; another

of the Virgin Mary, and yet another with a representation of St. George.

Such banners, as in the present instance, were ordinarily four in number,

and carried immediately round the body at the four corners of the bier.

Thus we read in the diary of an old chronicler, Machyn, who lived in the

reigns of Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, that at the burial of the

Countess of Arundel, October 27th, 1557, "cam iiij herroldes in ther

cotes of armes, and bare iiij baners of emages at the iiij corners."

Again, on "Aprell xxix, 1554, was bered my Lady Dudley in Saint Margarett

in Westminster, with iiij baners of emages." Another item deals with the

funeral of the Duchess of Northumberland, and here again "the iiij baners

of ymages" again recur. Anyone having the old records, church

inventories, and the like before them, would find it easy enough, as easy

as needless, to multiply illustrations of this funeral use of pictured

banners. These "emages" or "ymages" of old Machyn are of course not

images in the sense of sculptured or carved things, but are painted and

embroidered representations of various saints. Machyn, as a greatly

interested looker-on at all the spectacles of his day, is most

entertaining, but his spelling, according to the severer notions of the

present day, is a little weak, as, for instance, in the following words

that we have culled at random from his pages:—prossessyon,

gaffelyns, fezyssyoun, dysquyet, neckclygens, gorgyusle, berehyng, wypyd,

pelere, artelere, and dyssys of spyssys. The context ordinarily makes the

meaning clear, but as our readers have not that advantage, we give the

same words according to modern orthography—procession, javelins,

physician, disquiet, negligence, gorgeously, burying, whipped, pillory,

artillery, dishes of spices.

The various companies and guilds of the mediæval period had their

special flags that came out, as do those of their successors of the

present day, on the various occasions of civic pageantry; and in many

cases, as may be seen in the illuminated MSS. in the British Museum and

elsewhere, they were carried to battle as the insignia of the companies

of men provided at the expense of those corporations. Thus in one example

that has come under our notice we see a banner bearing a chevron between

hammer, trowels, and builder's square; in another between an axe and two

pairs of compasses, while a third on its azure field bears a pair of

golden {7}shears. In the representation of a battle

between Philip d'Artevelde and the Flemings against the French, many of

the flags therein introduced bear the most extraordinary devices, boots

and shoes, drinking-vessels, anvils, and the like, that owe their

presence there to the fact that various trade guilds sent their

contingents of men to the fight. In a French work on mediæval guilds we

find the candle-makers of Bayeux marching beneath a black banner with

three white candles on it, the locksmiths of La Rochelle having a scarlet

flag with four golden keys on it. The lawyers of Loudoun had a flag with

a large eye on it (a single eye to business being, we presume,

understood), while those of Laval had a blue banner with three golden

mouths thereon. In like manner the metal-workers of Laval carried a black

flag with a silver hammer and files depicted on it, those of Niort had a

red flag with a silver cup and a fork and spoon in gold on either side.

The metal-workers of Ypres also carried a red flag, and on this was

represented a golden flagon and two buckles of gold. Should some national

stress this year or next lead our City Companies, the Fishmongers, the

Carpenters, the Vintners, and others to contribute contingents to the

defence of the country, and to send them forth beneath the banners of the

guilds, history would but repeat itself.

In matters political the two great opposing parties have their

distinctive colours, and these have ordinarily been buff and blue, though

the association of buff with the Liberal party and "true blue" with the

Conservatives has been by no means so entirely a matter of course as

persons who have not looked into the matter might be disposed to imagine.

The local colours are often those that were once the livery colours of

the principal family in the district, and were assumed by its adherents

for the family's sake quite independently of its political creed. The

notion of livery is now an unpleasant one, but in mediæval days the

colours of the great houses were worn by the whole country-side, and the

wearing carried with it no suggestion either of toadyism or servitude. As

this influence was hereditary and at one time all-powerful, the colour of

the Castle, or Abbey, or Great House, became stereotyped in that district

as the symbol of the party of which these princely establishments were

the local centre and visible evidence, and the colour still often

survives locally, though the political and social system that originated

it has passed away in these days of democratic independence.

It would clearly be a great political gain if one colour were all over

Great Britain the definite emblem of one side, as many illiterate voters

are greatly influenced by the colours worn by the candidates for their

suffrages, and have sufficient sense of consistency of principle to vote

always for the flag that first claimed {8}their

allegiance, though it may very possibly be that if they move to another

county it is the emblem of a totally distinct party, and typifies

opinions to which the voter has always been opposed. At a late election a

Yorkshire Conservative, who had acquired a vote for Bournemouth, was told

that he must "vote pink," but this he very steadily refused to do. He

declared that he would "never vote owt else but th' old true blue," so

the Liberal party secured his vote; and this sort of thing at a General

Election is going on all over the country. The town of Royston, for

instance, stands partly in Hertfordshire and partly in Cambridgeshire,

and in the former county the Conservatives and in the latter the Liberals

are the blue party; hence the significance of the colour in one street of

the little town is entirely different to that it bears in another. At

Horsham in Sussex we have observed that the Conservative colour is pale

pink, while in Richmond in Surrey it is a deep orange. The orange was

adopted by the Whigs out of compliment to William III., who was Prince of

Orange.

In the old chronicles and ballads reference is made to many forms of

flags now obsolete. The term flag is a generic one, and covers all the

specific kinds. It is suggested that the word is derived from the

Anglo-Saxon verb fleogan, to fly or float in the wind, or from the old

German flackern, to flutter. Ensign is an alternative word formed on the

idea of the display of insignia, badges, or devices, and was formerly

much used where we should now employ the word colours. The company

officers in a regiment who were until late years termed ensigns were at a

still earlier period more correctly termed ensign-bearers. Milton, it

will be recalled, describes a "Bannered host under spread ensigns

marching." Sir Walter Scott greatly enlarges our vocabulary when he

writes in "Marmion" of where

"A thousand streamers flaunted fair,

Various in shape, device, and hue,

Green, sanguine, purple, red, and blue,

Broad, narrow, swallow-tailed, and square,

Scroll, pennon, pensil, bandrol, there

O'er the pavilions flew,"

while Milton again writes of

"Ten thousand thousand ensigns high advanced

Standards and gonfalons 'twixt van and rear

Stream in the air, and for distinction serve

Of hierarchies, orders, and degrees."

We have seen that the pomp of funeral display led to the use of

pictorial flags of religious type, and with these were associated others

that dealt with the mundane rank and position of the {9}deceased.

Thus we find Edmonson, in his book on Heraldry, writing as

follows:—"The armorial ensigns, as fixed by the officers of arms,

and through long and continued usage established as proper to be carried

in funeral processions, are pennons, guidons, cornets, standards,

banners, and banner-rolls, having thereon depicted the arms, quarterings,

badges, crests, supporters, and devices of the defunct: together with all

such other trophies of honour as in his lifetime he was entitled to

display, carry, or wear in the field; banners charged with the armorial

ensigns of such dignities, titles, offices, civil and military, as were

possessed or enjoyed by the defunct at the time of his decease, and

banner-rolls of his own matches and lineal descent both on the paternal

and maternal side. In case the defunct was an Archbishop, banner-rolls of

the arms and insignia of the sees to which he had been elected and

translated, and if he was a merchant or eminent trader pennons of the

particular city, corporation, guild, fraternity, craft, or company

whereof he had been a member." However true the beautiful stanza of

Gray—

"The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth ere gave,

Await at last the inevitable hour,

The paths of glory lead but to the grave"—

the survivors of the deceased most naturally and most justly bore to

their rest those to whom honour was due with the full respect to which

their career on earth entitled them.

The names bestowed upon the different kinds of flags have varied from

time to time, the various authorities of mediæval and modern days not

being quite of one mind sometimes, so that while the more salient forms

are easily identifiable, some little element of doubt creeps in when we

would endeavour to bestow with absolute precision a name to a certain

less common form before us, or a definite form to a name that we

encounter in some old writer. Whatever looseness of nomenclature,

however, may be encountered on the fringe of our subject, the bestowal of

the leading terms is sufficiently definite, and it is to these we now

turn our attention, reflecting for our comfort that it is of far greater

value to us to know all about a form that is of frequent recurrence, and

to which abundant reference is made, than to be able to quite

satisfactorily decide what special name some abnormal form should carry,

or what special form is meant by a name that perhaps only occurs once or

twice in the whole range of literature, and even that perhaps by some

poet or romance writer who has thought more of the general effect of his

description than of the technical accuracy of the terms in which he has

clothed it. {10}

The Banner first engages our attention. This was ordinarily, in the

earlier days of chivalry, a square flag, though in later examples it may

be found somewhat greater in length than in depth, and in some early

examples it is considerably greater in depth than in its degree of

projection outwards from the lance. In the technical language of the

subject, the part of a flag nearest the pole is called the hoist, and the

outer part the fly. Fig. 37 is a good illustration

of this elongated form. It has been suggested that the shortness of the

fly in such cases was in order that the greater fluttering in the wind

that such a form as Fig. 30 would produce might be

prevented, as this constant tugging at the lance-head would be

disagreeable to the holder, while it might, in the rush of the charge,

prevent that accuracy of aim that one would desire to give one's

adversary the full benefit of at such a crisis in his career. Pretty as

this may be as a theory, there is probably not much in it, or the form in

those warlike days of chivalry would have been more generally adopted.

According to an ancient authority the banner of an emperor should be six

feet square; of a king, five; of a prince or duke, four; and of an earl,

marquis, viscount, or baron three feet square. When we consider that the

great function of the banner was to bear upon its surface the

coat-of-arms of its owner, and that this coat was emblazoned upon it and

filled up its entire surface in just the same way that we find these

charges represented upon his shield, it is evident that no form that

departed far either in length or breadth from the square would be

suitable for their display. Though heraldically it is allowable to

compress or extend any form from its normal proportions when the

exigencies of space demand it,[4] it is clearly better to escape this when

possible.[5] The arms

depicted in Fig. 37 are certainly not the better for

the elongation to which they have been subjected, while per contra

the bearings on any of the banners in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, or 11, have had no despite done them, the square form

being clearly well-adapted for their due display.

The Rolls of Arms prepared on various occasions by the mediæval and

later heralds form an admirable storehouse of examples. Some of these

have been reproduced in facsimile, and are, therefore, more or less

readily accessible. We have before us as we write the roll of the arms of

the Sovereign and of the {11}spiritual and temporal peers who sat in

Parliament in the year 1515, and another excellent example that has been

reproduced is the roll of Karlaverok. This Karlaverok was a fortress on

the north side of Solway Frith, which it was necessary for Edward I. to

reduce on his invasion of Scotland in the year 1300, and this investiture

and all the details of the siege are minutely described by a contemporary

writer, who gives the arms and names of all the nobles there engaged. As

soon as the castle fell into Edward's hands he caused his banner and that

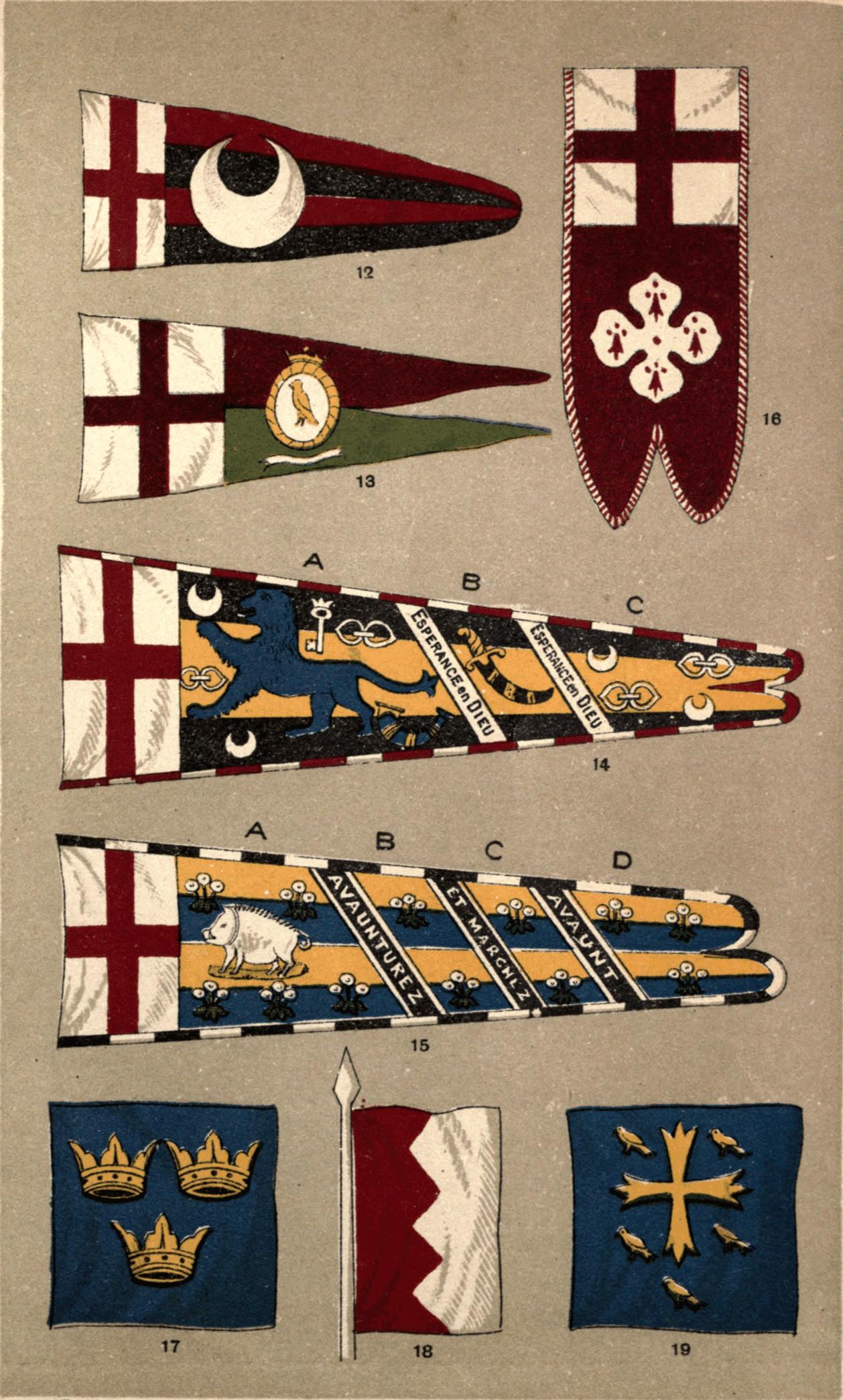

of St. Edmund (Fig. 17), and St. Edward (Fig. 19), to be displayed upon its battlements. The roll is

written in Norman French, of which the following passage may be given as

an example:—

"La ont meinte riche garnement

Brode sur cendeaus et samis

Meint beau penon en lance mis

Meint baniere desploie."

That is to say, there were—in modern English wording—many

rich devices embroidered on silk and satin, many a beautiful pennon fixed

on lance, many a banner displayed. The writer says:—"First, I will

tell you of the names and arms, especially of the banners, if you will

listen how." Of these numerous banners we give some few examples: Fig. 1 belongs to him "who with a light heart, doing good to

all, bore a yellow banner and pennon with a black saltire engrailed, and

is called John Botetourte." Fig. 2 is the banner of

Sire Ralph de Monthermer; Fig. 3 the devices of

Touches, "a knight of good-fame"; while Fig. 4, "the

blue with crescents of brilliant gold," was the flag of William de Ridre.

"Sire John de Holderton, who at all times appears well and promptly in

arms," bore No. 6, the fretted silver on the scarlet field; while Fig. 5 is the cognisance of "Hugh Bardolph, a man of good

appearance, rich, valiant, and courteous." Fig. 7 is

the well-known lion of the Percys, and is here the banner of Henri de

Percy; we meet with it again in Fig. 14. Fig. 8 is "the banner of good Hugh de Courtenay," while Fig.

9 is that of the valiant Aymer de Valence. Fig. 10 bears the barbels of John de Bar, while the last

example we need give (Fig. 11) is the banner of Sire

William de Grandison. Of whom gallant, courteous Englishmen as they were,

we can now but say that "they are dust, their swords are rust," and deny

them not the pious hope "their souls are with the saints, we trust."

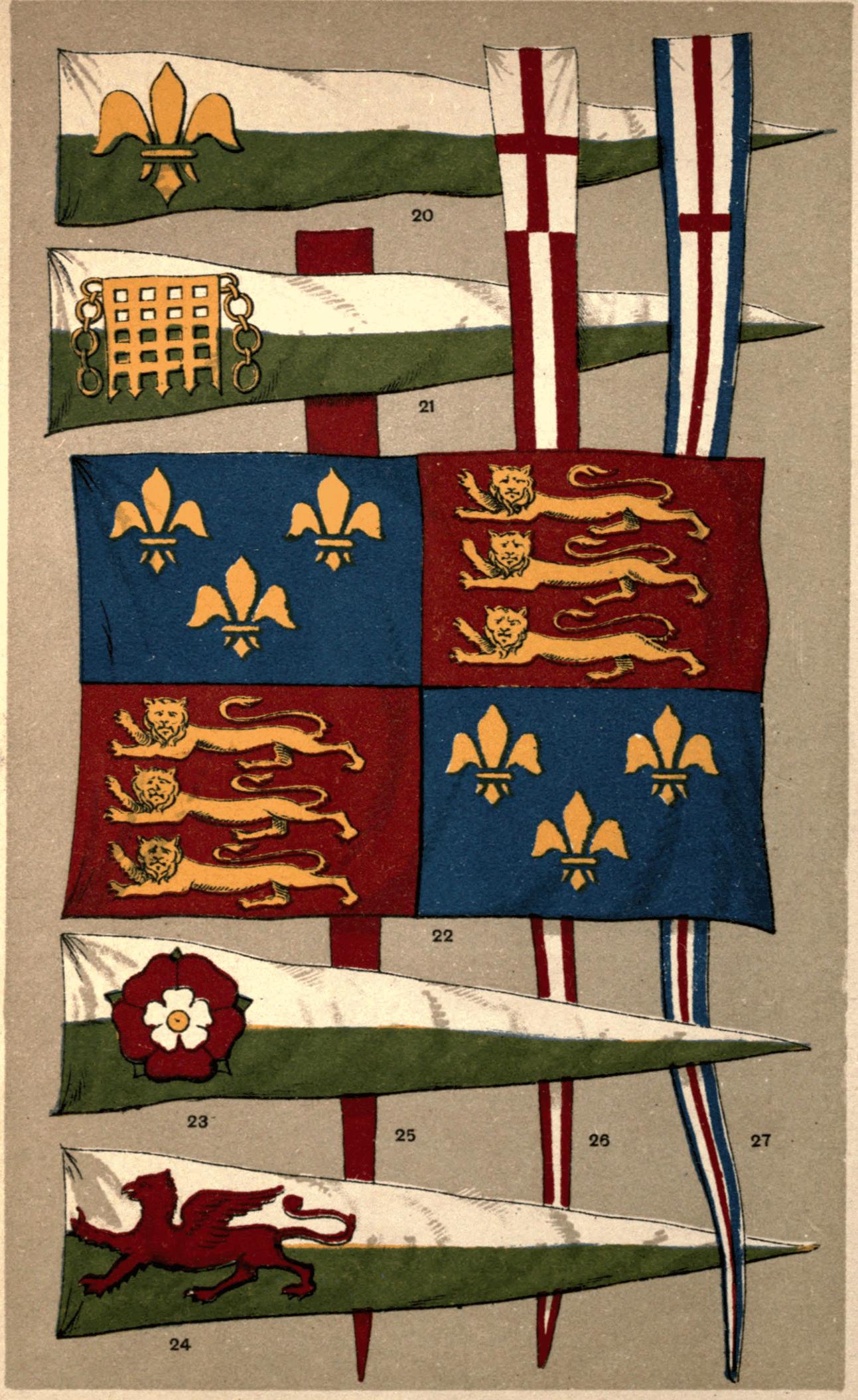

The well-known flag (Fig. 44), that everyone

recognises as the Royal Standard, is nevertheless misnamed, as it should

undoubtedly be called the Royal Banner, since it bears the arms of the

Sovereign in precisely the same way that any of our preceding {12}examples bear the arms of the knights with

whom they were associated. A standard, as we shall see presently, is an

entirely different kind of flag; nevertheless, the term Royal Standard is

so firmly established that it is hopeless now to think of altering it,

and as it would be but pedantry to ignore it, and substitute in its

place, whenever we have occasion to refer to it, its proper

title—the Royal Banner—we must, having once made our protest,

be content to let the matter stand. Figs. 22, 43, 44, 194,

226, and 245 are all royal or

imperial banners, but popular usage insists that we shall call them royal

or imperial "standards," so, henceforth, rightly or wrongly, through our

pages standards they must be.

The banners of the Knights of the Garter, richly emblazoned with their

armorial bearings, are suspended over their stalls in St. George's

Chapel, Windsor, while those of the Knights of the Bath are similarly

displayed in the Chapel of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey.

The whole of the great mainsail of a mediæval ship was often

emblazoned with arms, and formed one large banner. This usage may be very

well seen in the illuminations, seals, etc., of that period. As early as

the year 1247 we find Otho, Count of Gueldres, represented as bearing on

his seal a square banner charged with his arms, a lion rampant; and in a

window in the Cathedral of Our Lady, at Chartres, is a figure of Simon de

Montfort, Earl of Leicester from 1236 to 1265. He is depicted as bearing

in his right hand a banner of red and white, as shown in Fig. 18.

References in the old writers to the banner are very numerous. Thus in

the "Story of Thebes" we read of "the fell beastes," that were "wrought

and bete upon their bannres displaied brode" when men went forth to war.

Lydgate, in the "Battle of Agincourt," writes:—

"By myn baner sleyn will y be

Or y will turne my backe or me yelde."

The same writer declares that at the siege of Harfleur by Henry V., in

September, 1415, the king—

"Mustred his meyne faire before the town,

And many other lordes, I dar will say,

With baners bryghte and many penoun."

The trumpeters of the Life Guards and Horse Guards have the Royal

Banner attached to their instruments, a survival that recalls the lines

of Chaucer:—

"On every trump hanging a brode bannere

Of fine tartarium, full richly bete."

{13}

An interesting reference is found in a letter of Queen Katharine of

Arragon to Thomas Wolsey, dated Richmond, August 13th, 1513, while King

Henry VIII. was in France. Speaking of war with the Scots, her Majesty

says: "My hert is veray good to it, and I am horrible besy with making

standards, banners, and bagies."[6]

While the men are buckling on their armour for the coming strife,

wives, sisters, sweethearts, daughters, with proud hearts, give their

aid, and with busy fingers—despite the tear that will sometimes

blur the vision of the gay embroidery—swiftly and deftly labour

with loving care on the devices that will nerve the warriors to living

steel in the shock of battle. The Queen of England, so zealously busy in

her task of love, is but a type and exemplar of thousands of her sex

before and since. The raven standard of the Danish invaders of

Northumbria was worked by the daughters of Regnar Lodbrok, and in the

great rebellion in the West of England many a gentlewoman suffered sorely

in the foul and Bloody Assize for her zealous share in providing the

insurgents with the standards around which they rallied. The Covenanters

of Scotland, the soldiers of Garibaldi freeing Italy from the Bourbons,

the levies of Kossuth in Hungary, the Poles in the deadly grip of Russia,

the armies of the Confederate States in America, the Volunteers who would

fain free Greece from the yoke of the Turk,[7] all fought to the death beneath the

banners that fair sympathisers with them, and with their cause, placed in

their hands. When two great nations, such as France and Germany, fall to

blows, the whole armament, weapons, flags, and whatever else may be

necessary, is supplied from the government stores according to regulation

pattern, but in the case of insurgents against authority

struggling—rightly or wrongly—to be free, the weapons may be

scythe blades or whatever else comes first to hand, while the standards

borne to the field will bear the most extraordinary devices upon them,

devices that appeal powerfully at the time to those fighting beneath

their folds, but which give a shudder to the purist in heraldic blazonry,

as for instance, to quote but one example, the rattle-snake flag with its

motto "Beware how you tread on me," adopted by the North American

colonists in their struggle against the troops of George III.

When a knight had performed on the field of battle some especially

valiant or meritorious act, it was open to the Sovereign to {14}mark his sense of it by making him a

knight-banneret. Thus, in the reign of Edward III., John de Copeland was

made a banneret for his service in taking prisoner David Bruce, the King

of Scotland, at the battle of Durham; Colonel John Smith, having rescued

the royal banner from the Parliamentarians at Edgehill, was in like

manner made a knight-banneret by Charles I. The title does not seem to

have been in existence before the reign of Edward I., and after this

bestowal by Charles I. we hear no more of it till 1743, when the title

was conferred upon several English officers by the king, George II., upon

the field of Dettingen. It was an essential condition that the rank

should be bestowed by the Sovereign on the actual field of battle and

beneath the royal banner. General Sir William Erskine was given this rank

by George III. on his return from the Continent in 1764, after the battle

of Emsdorff; but as the investiture took place beneath the standard of

the 15th Light Dragoons and in Hyde Park, it was deemed hopelessly

irregular, and, the royal will and action notwithstanding, his rank was

not generally recognised.

The ceremony of investiture was in the earlier days a very simple one.

The flag of the ordinary knight was of the form known as the

pennon—a small, swallow-tailed flag like that borne by our lancer

regiments, of which Fig. 30 is an illustration. On

being summoned to the royal presence, the king took from him his lance,

and either cut or tore away the points of his flag, until he had reduced

it roughly to banner form, and then returned it to him with such words of

commendation as the occasion called for. What the ceremony employed at so

late a period as Dettingen was we have not been able to trace. As the

officers there honoured were lanceless and pennonless, it is evident that

the formula which served in the Middle Ages was quite inapplicable, but

it is equally evident that in the thronging duties and responsibilities

of the field of battle the ceremony must always have been a very short

and simple one.

The term Standard is appropriately applied to any flag of noble size

that answers in the main to the following conditions—that it should

always have the Cross of St. George placed next to the staff, that the

rest of the flag should be divided horizontally into two or more stripes

of colours, these being the prevailing colours in the arms of the bearers

or their livery colours, the edge of the standard richly fringed or

bordered, the motto and badges of the owner introduced, the length

considerably in excess of the breadth, the ends split and rounded off. We

find such standards in use chiefly during the fifteenth century, though

some characteristic examples of both earlier and later dates may be

encountered. Figs. 14 and 15

are very good typical illustrations. The {15}first of

these (Fig. 14) is the Percy standard. The blue

lion, the crescent, and the fetterlock there seen are all badges of the

family, while the silver key betokens matrimonial alliance with the

Poynings,[8] the bugle-horn

with the Bryans,[9] and the

falchion with the family of Fitzpayne. The ancient badge of the Percys

was the white lion statant. Our readers will doubtless be familiar with

the lines—

"Who, in field or foray slack,

Saw the blanch lion e'er give back?"

but Henry Percy, the fifth earl, 1489 to 1577, turned it into a blue

one. The silver crescent is the only badge of the family that has

remained in active and continuous use, and we find frequent references to

it in the old ballads—so full of interesting heraldic

allusions—as, for instance, in "The Rising of the North"—

"Erle Percy there his ancyent spred,

The halfe-moon shining all soe faire,"

and in Claxton's "Lament"—

"Now the Percy's crescent is set in blood."

The motto is ordinarily a very important part of the standard, though

it is occasionally missing. Its less or greater length or its possible

repetition may cut up the surface of the flag into a varying number of

spaces. The first space after the cross is always occupied by the most

important badge, and in a few cases the spaces beyond are empty.

The motto of the Percys is of great historic interest. It is referred

to by Shakespeare, "Now Esperance! Percy! and set on," and we find in

Drayton the line, "As still the people cried, A Percy, Esperance!" In the

"Mirror for Magistrates" (1574) we read, "Add therefore this to

Esperance, my word, who causeth bloodshed shall not 'scape the sword." It

was originally the war-cry of the Percys, but it has undergone several

modifications, and these of a rather curious and interesting nature,

since we see in the sequence a steady advance from blatant egotism to an

admission of a higher power even than that of Percy. The war-cry of the

first Earl was originally, "Percy! Percy!" but he later substituted for

it, "Esperance, Percy." The second and third Earls took merely

"Esperance," the fourth took "Esperance, ma comfort," and, {16}later on, "Esperance en Dieu ma comfort,"

and the fifth and succeeding Earls took the "Esperance en Dieu."[10]

Fig. 15 is the standard of Sir Thomas de

Swynnerton. The swine is an example of the punning allusion to the

bearer's name that is so often seen in the charges of mediæval

heraldry.

Figs. 14 and 15 are typical

standards, having the cross of St. George, the striping of colours, the

oblique lines of motto, the elongated tapering form, and all the other

features that we have already quoted as belonging to the ideal standard,

though one or two of these may at times be absent. Thus, though

exceptions are rare, a standard is not necessarily particoloured for

example, and, as we have seen, the motto in other examples may be

missing. The Harleian MS. No. 2,358 lays down the rule that "every

Standard or guydhome is to hang in the Chiefe the Crosse of St. George,

to be slitte at the ende, and to conteyne the crest or supporter, with

the poesy, worde, and devise of the owner." That the Cross of St. George,

the national badge, must always be present and in the most honourable

position is full of significance, as it means that whatever else of rank

or family the bearer might be, he was first and foremost an

Englishman.

Figs. 13 and 16 are

interesting modern examples of the Standard. They are from a series of

sledge-flags used during the Arctic Expedition of 1875-6, the devices

upon them being those of the officers in charge of each detachment.

When in earlier days a man raised a regiment for national defence, he

not only commanded it, but its flag often bore his arms or device. Thus

the standard of the dragoons raised by Henry, Lord Cardross, in 1689 was

of red silk, on which was represented the Colonel's crest, a hand holding

a dagger, and the motto "Fortitudine," while in the upper corner next the

staff was the thistle of Scotland, surmounted by the crown.

Our readers should now have no difficulty in sketching out for

themselves as an exercise the following: The standard of Henry V., white

and blue, a white antelope standing between four red roses; the motto

"Dieu et mon droit," and in the interspaces more red {17}roses. The standard of Richard II., white

and green, a white hart couchant between four golden suns, the motto

"Dieu et mon droit," in the next space two golden suns, and in the next,

four. As further exercises, we may give the standard of Sir John Awdeley,

of gold and scarlet, having a Moor's head and three white butterflies,

the motto "Je le tiens," then two butterflies, then four; and the

standard of Frogmorton, of four stripes of red and white, having an

elephant's head in black, surrounded by golden crescents. While no one,

either monarch or noble, could have more than one banner, since this was

composed of his heraldic arms, a thing fixed and unchangeable, the same

individual might have two or three standards, since these were mainly

made up of badges that he could multiply at discretion, and a motto or

poesy that he might change every day if he chose. Hence, for instance,

the standards of Henry VII. were mostly green and white, since these were

the Tudor livery colours; but in one was "a red firye dragon," and in

another "was peinted a donne kowe," while yet another had a silver

greyhound between red roses. Stowe and other authorities tell us that the

two first of these were borne at Bosworth Field, and that after his

victory there over Richard III. these were borne by him in solemn state

to St. Paul's Cathedral, and there deposited on his triumphal entry into

the metropolis.

The difference between the standard and the banner is very clearly

seen in the description of the flags borne at the funeral obsequies of

Queen Elizabeth—"the great embroidered banner of England" (Fig. 22), the banners of Wales, Ireland, Chester, and

Cornwall, and the standards of the dragon, greyhound, and falcon. In like

manner Stowe tells us that when King Henry VII. took the field in 1513,

he had with him the standard with the red dragon and the banner of the

arms of England, and Machyn tells that at the funeral of Edward VI.,

"furst of all whent a grett company of chylderyn in ther surples and

clarkes syngyng and then ij harolds, and then a standard with a dragon,

and then a grett nombur of ye servants in blake, and then anoder standard

with a whyt greyhound." Later on in the procession came "ye grett baner

of armes in brodery and with dyvers odere baners."

Standards varied in size according to the rank of the person entitled

to them. A MS. of the time of Henry VII. gives the following

dimensions:—For that of the king, a length of eight yards; for a

duke, seven; for an earl, six; a marquis, six and a half; a viscount,

five and a half; a baron, five; a knight banneret, four and a half; and

for a knight, four yards. In view of these figures one can easily realise

the derivation of the word standard—a thing that is meant to stand;

to be rather fastened in the ground as a rallying point than carried,

like a banner, about the field of action. {18}

At the funeral of Nelson we find his banner of arms and standard borne

in the procession, while around his coffin are the bannerolls, square

banner-like flags bearing the various arms of his family lineage. We see

these latter again in an old print of the funeral procession of General

Monk, in 1670, and in a still older print of the burial of Sir Philip

Sydney, four of his near kindred carrying by the coffin these indications

of his descent. At the funeral of Queen Elizabeth we find six bannerolls

of alliances on the paternal side and six on the maternal. The standard

of Nelson bears his motto, "Palmam qui meruit ferat," but instead

of the Cross of St. George it has the union of the crosses of St. George,

St. Andrew, and St. Patrick, since in 1806, the year of his funeral, the

England of mediæval days had expanded into the Kingdom of Great Britain

and Ireland. In the imposing funeral procession of the great Duke of

Wellington we find again amongst the flags not only the national flag,

regimental colours, and other insignia, but the ten bannerolls of the

Duke's pedigree and descent, and his personal banner and standard.

Richard, Earl of Salisbury, in the year 1458, ordered that at his

interment "there be banners, standards, and other accoutrements,

according as was usual for a person of his degree" and what was then held

fitting, remains, in the case of State funerals, equally so at the

present day.

The Pennon is a small, narrow flag, forked or swallow-tailed at its

extremity. This was carried on the lance. Our readers will recall the

knight in "Marmion," who

"On high his forky pennon bore,

Like swallow's tail in shape and hue."

We read in the Roll of Karlaverok, as early as the year 1300, of

"Many a beautiful pennon fixed to a lance,

And many a banner displayed;"

and of the knight in Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales," we hear that

"By hys bannere borne is hys pennon

Of golde full riche."

The pennon bore the arms of the knight, and they were in the earlier

days of chivalry so emblazoned upon it as to appear in their proper

position not when the lance was held erect but when held horizontally for

the charge. The earliest brass now extant, that of Sir John Daubernoun,

at Stoke d'Abernon Church, in Surrey, represents the knight as bearing a

lance with pennon. Its date is 1277, and the device is a golden chevron

on a field of azure. In {19}this example the pennon, instead of

being forked, comes to a single point.

The pennon was the ensign of those knights who were not bannerets, and

the bearers of it were therefore sometimes called pennonciers; the term

is derived from the Latin word for a feather, penna, from the

narrow, elongated form. The pennons of our lancer regiments (Fig. 30) give one a good idea of the form, size, and general

effect of the ancient knightly pennon, though they do not bear

distinctive charges upon them, and thus fail in one notable essential to

recall to our minds the brilliant blazonry and variety of device that

must have been so marked and effective a feature when the knights of old

took the field. In a drawing of the year 1813, of the Royal Horse

Artillery, we find the men armed with lances, and these with pennons of

blue and white, as we see in Fig. 31.[11]

Of the thirty-seven pennons borne on lances by various knights

represented in the Bayeux tapestry, twenty-eight have triple points,

while others have two, four, or five. The devices upon these pennons are

very various and distinctive, though the date is before the period of the

definite establishment of heraldry. Examples of these may be seen in

Figs. 39, 40, 41, 42.

The pennoncelle, or pencel, is a diminutive of the pennon, small as

that itself is. Such flags were often supplied in large quantities at any

special time of rejoicing or of mourning. At the burial in the year 1554

of "the nobull Duke of Norffok," we note amongst other items "a dosen of

banerolles of ys progene," a standard, a "baner of damaske, and xij dosen

penselles." At the burial of Sir William Goring we find "ther was viij

dosen of penselles," while at the Lord Mayor's procession in 1555 we read

that there were "ij goodly pennes [State barges] deckt with flages and

stremers and a m penselles." This "m," or thousand, we can perhaps

scarcely take literally, though in another instance we find "the cordes

were hanged with innumerable pencelles."[12]

The statement of the cost of the funeral of Oliver Cromwell is

interesting, as we see therein the divers kinds of flags that graced the

ceremony. The total cost of the affair was over £28,000, and the unhappy

undertaker, a Mr. Rolt, was paid very little, if any, of his bill. The

items include "six gret banners wrought on rich taffaty in oil, and gilt

with fine gold," at £6 each. Five large standards, similarly wrought, at

a cost of £10 each; six dozen {20}pennons, a yard long, at a sovereign

each; forty trumpet banners, at forty shillings apiece; thirty dozen of

pennoncelles, a foot long, at twenty shillings a dozen; and twenty dozen

ditto at twelve shillings the dozen. Poor Rolt!

In "the accompte and reckonyng" for the Lord Mayor's Show of 1617 we

find "payde to Jacob Challoner, painter, for a greate square banner, the

Prince's Armes, the somme of seven pounds." We also find, "More to him

for the new payntyng and guyldyng of ten trumpet banners, for payntyng

and guyldyng of two long pennons of the Lord Maior's armes on callicoe,"

and many other items that we need not set down, the total cost of the

flag department being £67 15s. 10d., while for the Lord

Mayor's Show of the year 1685 we find that the charge for this item was

the handsome sum of £140.

The Pennant, or pendant, is a long narrow flag with pointed end, and

derives its name from the Latin word signifying to hang. Examples of it

may be seen in Figs. 20, 21, 23, 24, 36,

38, 100, 101, 102, and 103, and some of the flags employed in ship-signalling

are also of pennant form. It was in Tudor times called the streamer.

Though such a flag may at times be found pressed into the service of city

pageantry, it is more especially adapted for use at sea, since the lofty

mast, the open space far removed from telegraph-wires, chimney-pots, and

such-like hindrances to its free course, and the crisp sea-breeze to

boldly extend it to its full length, are all essential to its due

display. When we once begin to extend in length, it is evident that

almost anything is possible: the pendant of a modern man-of-war is some

twenty yards long, while its breadth is barely six inches, and it is

evident that such a flag as that would scarcely get a fair chance in the

general "survival of the fittest" in Cheapside. It is charged at the head

with the Cross of St. George. Figs. 26, 27, 74 are Tudor examples of such

pendants, while Fig. 140 is a portion at least of

the pendant flown by colonial vessels on war service, while under the

same necessarily abbreviated conditions may be seen in Fig. 151 the pendant of the United States Navy, in 157 that of Chili, and in 173

that of Brazil.

In mediæval days many devices were introduced, the streamer being made

of sufficient width to allow of their display. Thus Dugdale gives an

account of the fitting up of the ship in which Beauchamp, fifth Earl of

Warwick, during the reign of Henry VI., went over to France. The original

bill between this nobleman and William Seburgh, "citizen and payntour of

London," is still extant, and we see from it that amongst other things

provided was "the grete stremour for the shippe xl yardes in length and

viij yardes in brede." These noble dimensions gave ample room for {21}display of the badge of the Warwicks,[13] so we find it at the head

adorned with "a grete bere holding a ragged staffe," and the rest of its

length "powdrid full of raggid staves,"

"A stately ship,

With all her bravery on, and tackle trim,

Sails filled, and streamers waving."

Machyn tells us in his diary for August 3rd, 1553, how "The Queen came

riding to London, and so on to the Tower, makyng her entry at Aldgate,

and a grett nombur of stremars hanging about the sayd gate, and all the

strett unto Leydenhalle and unto the Tower were layd with graffel, and

all the crafts of London stood with their banars and stremars hangyd over

their heds." In the picture by Volpe in the collection at Hampton Court

of the Embarkation of Henry VIII. from Dover in the year 1520, to meet

Francis I. at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, we find, very naturally, a

great variety and display of flags of all kinds. Figs. 20, 21, 23

are streamers therein depicted, the portcullis, Tudor rose, and

fleur-de-lys being devices of the English king, while the particular

ground upon which they are displayed is in each case made up of green and

white, the Tudor livery colours. We may see these again in Fig. 71, where the national flag of the Cross of St. George

has its white field barred with the Tudor green. In the year 1554 even

the naval uniform of England was white and green, both for officers and

mariners, and the City trained bands had white coats welted with green.

Queen Elizabeth, though of the Tudor race, took scarlet and black as her

livery colours; the House of Plantaganet white and red; of York, murrey

and blue; of Lancaster, white and blue; of Stuart, red and yellow. The

great nobles each also had their special liveries; thus in a grand review

of troops on Blackheath, on May 16th, 1552, we find that "the Yerle of

Pembroke and ys men of armes" had "cotes blake bordered with whyt," while

the retainers of the Lord Chamberlain were in red and white, those of the

Earl of Huntingdon in blue, and so forth.

In the description of one of the City pageants in honour of Henry VII.

we find among the "baggs" (i.e., badges), "a rede rose and a wyght

in his mydell, golde floures de luces, and portcullis also in golde," the

"wallys" of the Pavilion whereon these were displayed being "chekkyrs of

whyte and grene."

The only other flag form to which we need make any very definite

reference is the Guidon. The word is derived from the {22}French guide-homme, but in the lax

spelling of mediæval days it undergoes many perversions, such as

guydhome, guydon, gytton, geton, and such-like more or less barbarous

renderings. Guidon is the regulation name now applied to the small

standards borne by the squadrons of some of our cavalry regiments. The

Queen's guidon is borne by the first squadron; this is always of crimson

silk; the others are the colour of the regimental facings. The modern

cavalry guidon is square in form, and richly embroidered, fringed, and

tasselled. A mediæval writer on the subject lays down the law that "a

guydhome must be two and a half yardes or three yardes longe, and therein

shall be no armes putt, but only the man's crest, cognizance, and device,

and from that, from his standard or streamer a man may flee; but not from

his banner or pennon bearinge his armes." The guidon is largely employed

at State or ceremonious funeral processions; we see it borne, for

instance, in the illustrations of the funeral of Monk in 1670, of Nelson

in 1806, of Wellington in 1852. In all these cases it is rounded in form,

as in Fig. 28. Like the standard, the guidon bears

motto and device, but it is smaller, and has not the elongated form, nor

does it bear the Cross of St. George.

In divers countries and periods very diverse forms may be encountered,

and to these various names have been assigned, but it is needless to

pursue their investigation at any length, as in some cases the forms are

quite obsolete; in other cases, while its form is known to us its name is

lost, while in yet other instances we have various old names of flags

mentioned by the chroniclers and poets to which we are unable now to

assign any very definite notion of their form. In some cases, again, the

form we encounter may be of some eccentric individuality that no man ever

saw before, or ever wants to see again, or, as in Fig. 33, so slightly divergent from ordinary type as to

scarcely need a distinctive name. One of the flags represented in the

Bayeux tapestry is semi-circular. Fig. 32 defies

classification, unless we regard it as a pennon that, by snipping, has

travelled three-quarters of the way towards being a banner. Fig. 35, sketched from a MS. of the early part of the

fourteenth century, in the British Museum, is of somewhat curious and

abnormal form. It is of religious type, and bears the Agnus Dei. The

original is in a letter of Philippe de Mezières, pleading for peace and

friendship between Charles VI. of France and Richard II. of England.

Flags are nowadays ordinarily made of bunting, a woollen fabric which,

from the nature of its texture and its great toughness and durability, is

particularly fitted to stand wear and tear. It comes from the Yorkshire

mills in pieces of forty yards in length, while the width varies from

four to thirty-six inches. Flags are {23}only

printed when of small size, and when a sufficient number will be required

to justify the expense of cutting the blocks. Silk is also used, but only

for special purposes.

Flag-devising is really a branch of heraldry, and should be in

accordance with its laws, both in the forms and the colours introduced.

Yellow in blazonry is the equivalent of gold, and white of silver, and it

is one of the requirements of heraldry that colour should not be placed

upon colour, nor metal on metal. Hence the red and blue in the French

tricolour (Fig. 191) are separated by white; the

black and red of Belgium (Fig. 236) by yellow. Such

unfortunate combinations as the yellow, blue, red, of Venezuela (Fig. 170); the yellow, red, green of Bolivia (Fig. 171); the red and blue of Hayti (Fig. 178); the white

and yellow of Guatemala (Fig. 162), are violations

of the rule in countries far removed from the influence of heraldic law.

This latter instance is a peculiarly interesting one; it is the flag of

Guatemala in 1851, while in 1858 this was changed to that represented in

Fig. 163. In the first case the red and the blue

are in contact, and the white and the yellow; while in the second the

same colours are introduced, but with due regard to heraldic law, and

certainly with far more pleasing effect.

One sees the same obedience to this rule in the special flags used for

signalling, where great clearness of definition at considerable distances

is an essential. Such combinations as blue and black, red and blue,

yellow and white, carry their own condemnation with them, as anyone may

test by actual experiment; stripes of red and blue, for instance, at a

little distance blending into purple, while white and yellow are too much

alike in strength, and when the yellow has become a little faded and the

white a little dingy they appear almost identical. We have this latter

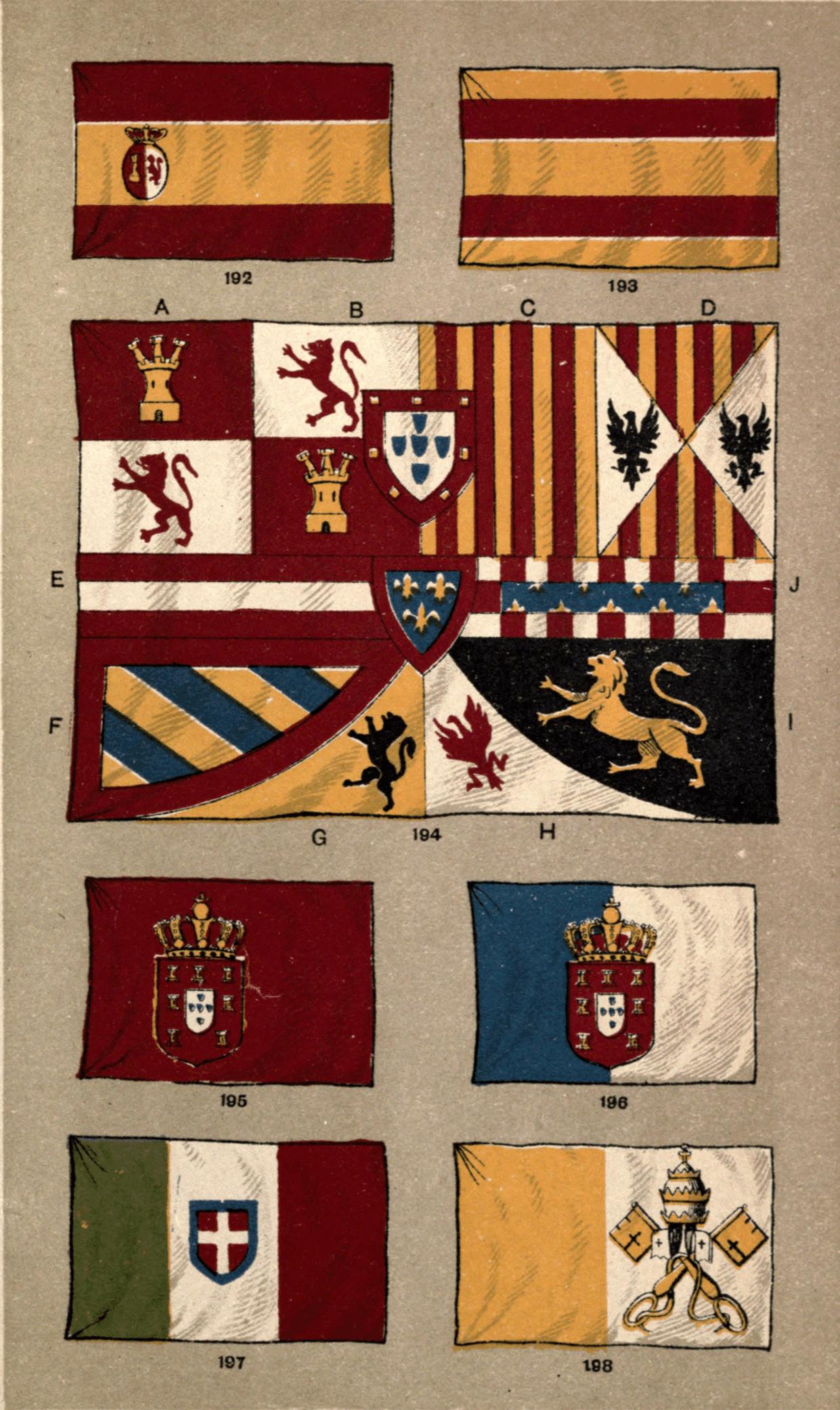

combination in Fig. 198, the flag of the now

vanished Papal States. It is a very uncommon juxtaposition, and only

occurs in this case from a special religious symbolism into which we need

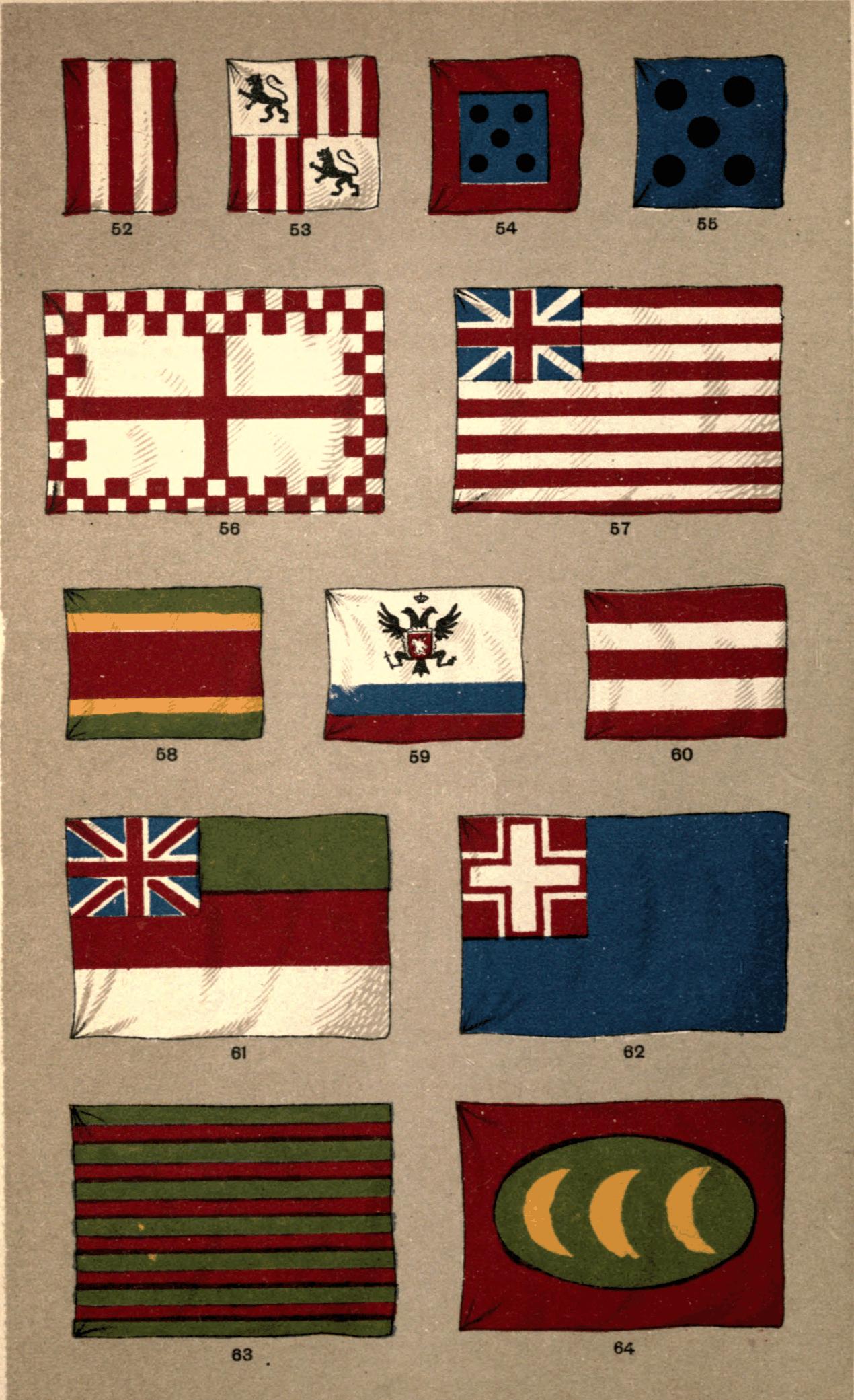

not here enter. The alternate red and green stripes in Fig. 63 are another violation of the rule, and have a very

confusing effect.[14]

The colours of by far the greatest frequency of occurrence are red,

white, and blue; yellow also is not uncommon; orange is only found once,

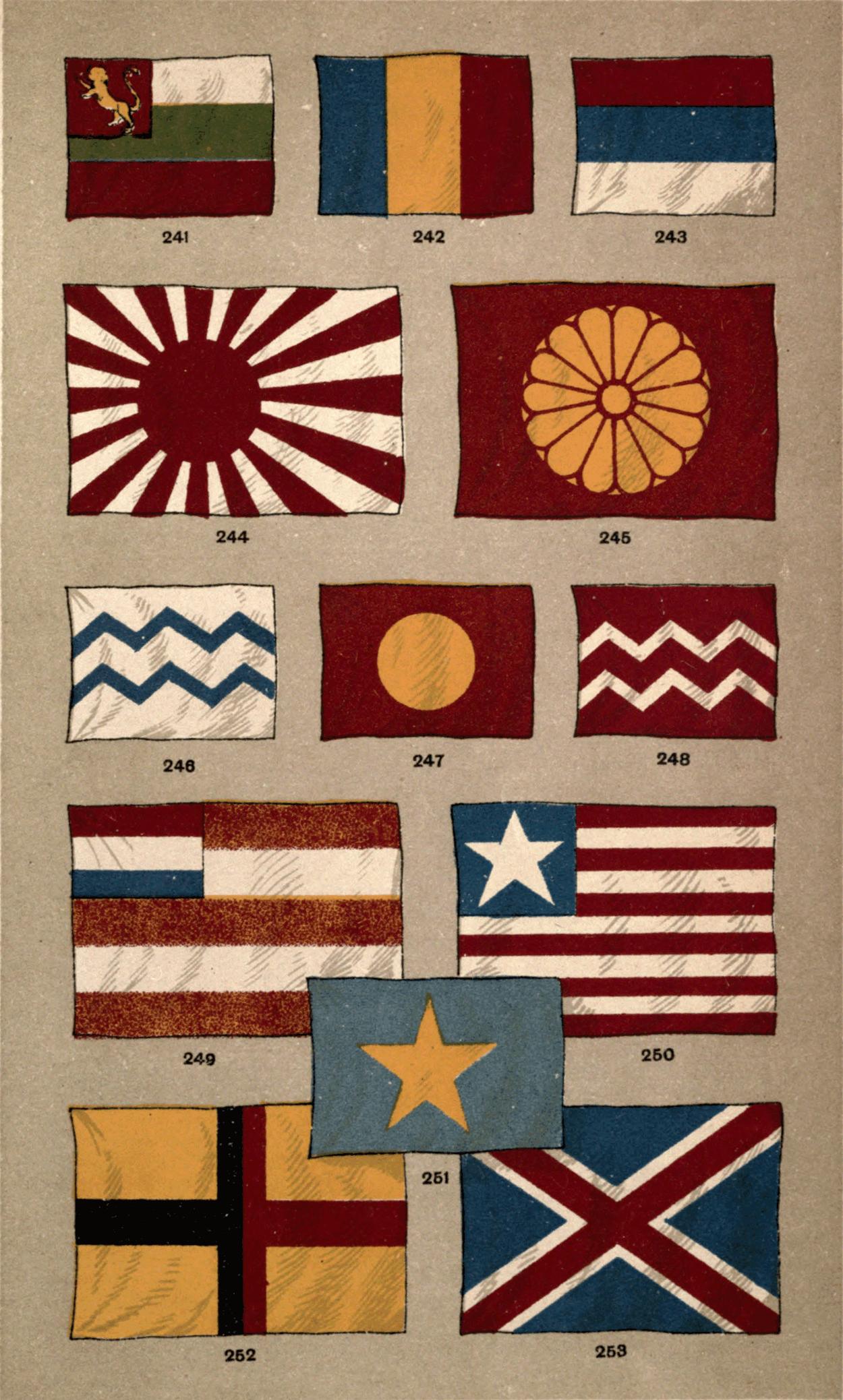

in Fig. 249, where it has a special significance,

since this is the flag of the Orange Free State. Green occurs sparingly.

Italy (Fig. 197) is perhaps the best known example.

We also find it in the Brazilian flag (Fig. 169),

the Mexican (Fig. 172), in the Hungarian tricolor

(Fig. 214), and in Figs. 199,

201, 209, the flags {24}of smaller German States, but it is more

especially associated with Mohammedan States, as in Figs. 58, 63, 64,

235. Black is found but seldom, but as heraldic

requirements necessitate that it should be combined either with white or

yellow, it is, when seen, exceptionally brilliant and effective. We see

it, for example, in the Royal Standard of Spain, (Fig. 194), in Figs. 207 and 208, flags of the German Empire, in Fig. 226, the Imperial Standard of Russia, and in Fig. 236, the brilliant tricolor of the Belgians.[15]

In orthodox flags anything of the nature of an inscription is very

seldom seen. We find a reference to order and progress on the Brazilian

flag (Fig. 169), while the Turkish Imperial

Standard (Fig. 238) bears on its scarlet folds the

monogram of the Sultan; but these exceptions are rare.[16] We have seen that, on the contrary, on

the flags of insurgents and malcontents the inscription often counts for

much. On the alteration of the style in the year 1752 this necessary

change was made the subject of much ignorant reproach of the government

of the day, and was used as a weapon of party warfare. An amusing

instance of this feeling occurs in the first plate of Hogarth's election

series, where a malcontent, or perhaps only a man anxious to earn a

shilling, carries a big flag inscribed, "Give us back our eleven days."

The flags of the Covenanters often bore mottoes or texts. Fig. 34 is a curious example: the flag hoisted by the crew

of H.M.S. Niger when they opposed the mutineers in 1797 at

Sheerness. It is preserved in the Royal United Service Museum. It is, as

we have seen, ordinarily the insubordinate and rebellious who break out

into inscriptions of more or less piety or pungency, but we may conclude

that the loyal sailors fighting under the royal flag adopted this device

in addition as one means the more of fighting the rebels with their own

weapons.

During the Civil War between the Royalists and Parliamentarians, we

find a great use made of flags inscribed with mottoes. Thus, on one we

see five hands stretching at a crown defended by an armed hand issuing

from a cloud, and the motto, "Reddite Cæsari." In another we see an angel

with a flaming sword treading a dragon underfoot, and the motto, "Quis ut

Deus," while yet another is inscribed, "Courage pour la Cause." On a

fourth we find an ermine, and the motto, "Malo mori quam

fœdari"—"It is better to die than {25}to be

sullied," in allusion to the old belief that the ermine would die rather

than soil its fur. Hence it is the emblem of purity and stainless

honour.

The blood-red flag is the symbol of mutiny and of revolution. As a

sign of disaffection it was twice, at the end of last century, displayed

in the Royal Navy. A mutiny broke out at Portsmouth in April, 1797, for

an advance of pay; an Act of Parliament was passed to sanction the

increase of expenditure, and all who were concerned in it received the

royal pardon, but in June of the same year, at Sheerness, the spirit of

disaffection broke out afresh, and on its suppression the ringleaders

were executed. It is characteristic that, aggrieved as these seamen were

against the authorities, when the King's birthday came round, on June

4th, though the mutiny was then at its height, the red flags were

lowered, the vessels gaily dressed in the regulation bunting, and a royal

salute was fired. Having thus demonstrated their real loyalty to their

sovereign, the red flags were re-hoisted, and the dispute with the

Admiralty resumed in all its bitterness.

The white flag is the symbol of amity and of good will; of truce

amidst strife, and of surrender when the cause is lost. The yellow flag

betokens infectious illness, and is displayed when there is cholera,

yellow fever, or such like dangerous malady on board ship, and it is also

hoisted on quarantine stations. The black flag signifies mourning and

death; one of its best known uses in these later days is to serve as an

indication after an execution that the requirements of the law have been

duly carried out.

Honour and respect are expressed by "dipping" the flag. At any parade

of troops before the sovereign the regimental flags are lowered as they

pass the saluting point, and at sea the colours are dipped by hauling

them smartly down from the mast-head and then promptly replacing them.

They must not be suffered to remain at all stationary when lowered, as a

flag flying half-mast high is a sign of mourning for death, for defeat,

or for some other national loss, and it is scarcely a mark of honour or

respect to imply that the arrival of the distinguished person is a cause

of grief or matter for regret.

In time of peace it is an insult to hoist the flag of one friendly

nation above another, so that each flag must be flown from its own

staff.

Even as early as the reign of Alfred England claimed the sovereignty

of the seas. Edward III. is more identified with our early naval glories

than any other English king; he was styled "King of the Seas," a name of

which he appears to have been very proud, and in his coinage of gold

nobles he represented himself with shield and sword, and standing in a

ship "full royally {26}apparelled." He fought on the seas under

many disadvantages of numbers and ships: in one instance until his ship

sank under him, and at all times as a gallant Englishman.

If any commander of an English vessel met the ship of a foreigner, and

the latter refused to salute the English flag, it was enacted that such

ship, if taken, was the lawful prize of the captain. A very notable

example of this punctilious insistance on the respect to the flag arose

in May, 1554, when a Spanish fleet of one hundred and sixty sail,

escorting the King on his way to England to his marriage with Queen Mary,

fell in with the English fleet under the command of Lord Howard, Lord

High Admiral. Philip would have passed the English fleet without paying

the customary honours, but the signal was at once made by Howard for his

twenty-eight ships to prepare for action, and a round shot crashed into

the side of the vessel of the Spanish Admiral. The hint was promptly

taken, and the whole Spanish fleet struck their colours as homage to the

English flag.

In the year 1635 the combined fleets of France and Holland determined

to dispute this claim of Great Britain, but on announcing their intention

of doing so an English fleet was at once dispatched, whereupon they

returned to their ports and decided that discretion was preferable even

to valour. In 1654, on the conclusion of peace between England and

Holland, the Dutch consented to acknowledge the English supremacy of the

seas, the article in the treaty declaring that "the ships of the

Dutch—as well ships of war as others—meeting any of the ships

of war of the English, in the British seas, shall strike their flags and

lower their topsails in such manner as hath ever been at any time

heretofore practised." After another period of conflict it was again

formally yielded by the Dutch in 1673.

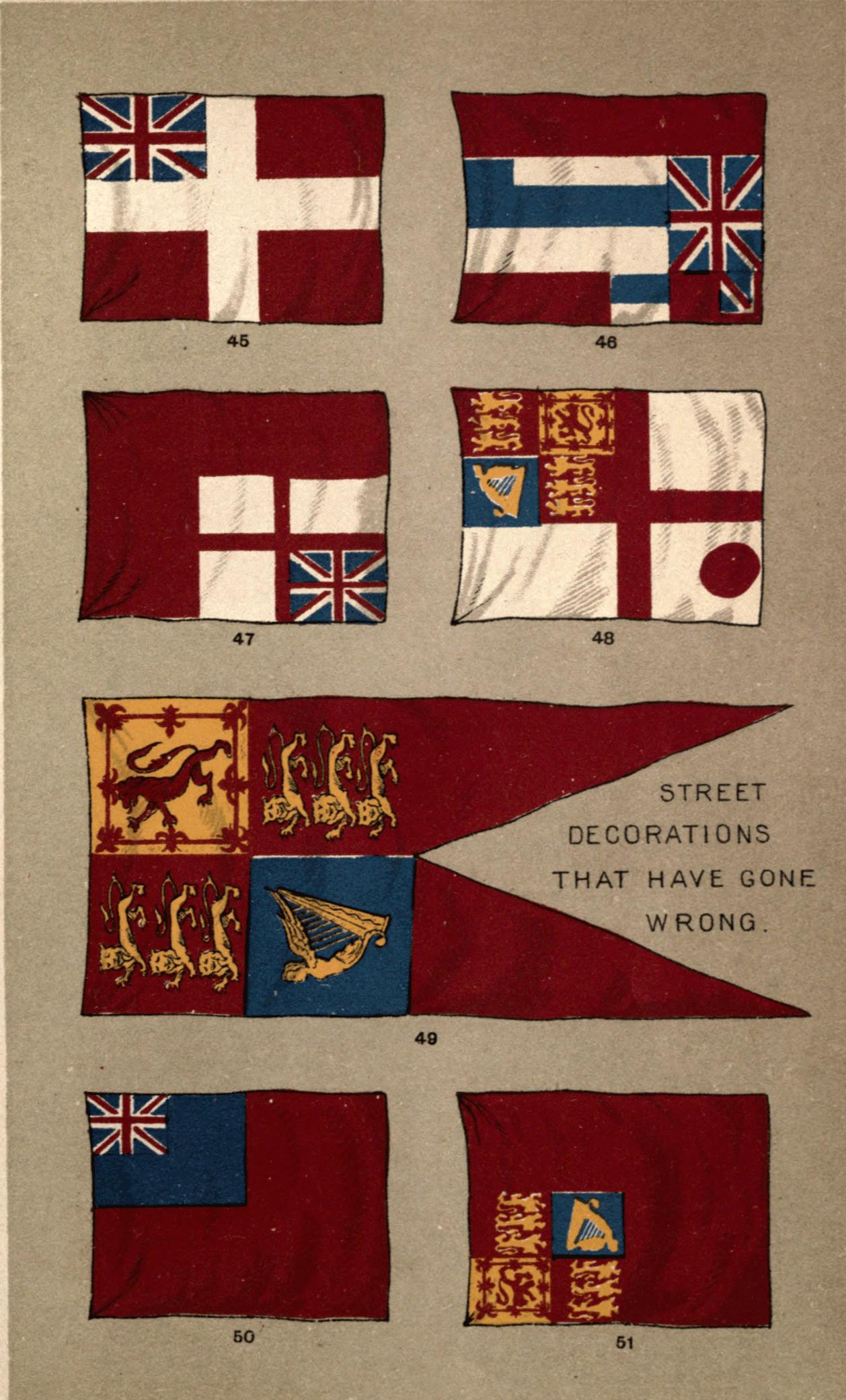

Political changes are responsible for many variations in flags, and

the wear and tear of Time soon renders many of the devices obsolete. On

turning, for instance, to Nories' "Maritime Flags of all Nations," a

little book published in 1848, many of the flags are at once seen to be

now out of date. The particular year was one of exceptional political

agitation, and the author evidently felt that his work was almost

old-fashioned even on its issue. "The accompanying illustrations," he

says, "having been completed prior to the recent revolutionary movements

on the Continent of Europe, it has been deemed expedient to issue the

plate in its present state, rather than adopt the various tri-coloured

flags, which cannot be regarded as permanently established in the present

unsettled state of political affairs." The Russian American Company's

flag, Fig. 59, that of the States of the Church, of