Title: The Transgression of Andrew Vane: A Novel

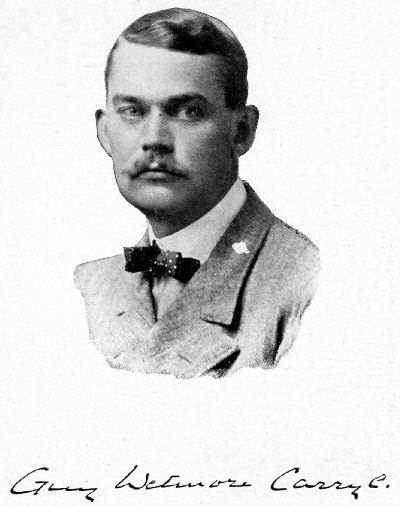

Author: Guy Wetmore Carryl

Release date: November 15, 2011 [eBook #38020]

Most recently updated: November 27, 2015

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Rory OConor, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BOOKS BY GUY WETMORE CARRYL

| PUBLISHED BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY | |

| THE TRANSGRESSION OF ANDREW VANE | $1.50 |

| PUBLISHED BY HARPER AND BROTHERS | |

| FABLES FOR THE FRIVOLOUS | $1.50 |

| MOTHER GOOSE FOR GROWN-UPS | $1.50 |

| PUBLISHED BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO. | |

| GRIMM TALES MADE GAY | $1.50 |

| THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR | $1.50 |

| ZUT, AND OTHER PARISIANS | $1.50 |

A NOVEL

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1904

| PAGE | |

| Prologue | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Mr. Carnby Receives a Letter | 22 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| New Friends and Old | 36 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Girl in Red | 51 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Mother and Daughter | 71 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Good and Faithful Servant | 89 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Revolt Suppressed | 106 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| A Pledge of Friendship | 117 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| A Parley and a Prayer | 130 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Woman in the Case | 143 |

| CHAPTER X.[viii] | |

| The Fairy Godmother | 159 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Some After-dinner Conversation | 175 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Reaction | 192 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Rhapsodie Hongroise, No. 2 | 204 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Fate is Hard—Cash! | 218 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| "As it was in the Beginning, is now, and ever shall be." | 237 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A Declaration of Independence | 256 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| A Dog and His Master | 268 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Fair Exchange is No Robbery | 283 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Redemption | 297 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Shadow | 311 |

For months past, she had felt that she was weakening, that the crescent wretchedness of five long years—an uninterrupted descent from level to level, on each of which the thorns of disillusion caught at, and tore from her, some shred of hope or self-respect—had done its work at last. Her courage and her faith, inherited, the one from the mental, the other from the moral, vigour of a rigid and uncompromising Puritan ancestry, were slipping from her. What the end was to be, she did not dare to ask; but it lay there ahead, grim and ominous, gradually taking form, through the mist of the immediate future. Its very suggestion of divergence from all that was familiar to her, of being even a degree more monstrous than what she had already suffered, sickened and appalled her, who had never known a dread of mere death, but drew back with unspeakable fear before the looming of this unknown, ultimate degradation.

John Vane had wooed his wife with the easy confidence born of adequate position, adequate means,[2] and more than adequate ability. Four years of Harvard had taught him to believe life in the little Western town which had been his birthplace, to be, for a man of literary bent, a practical impossibility; and when he stepped easily from the halls of his Alma Mater into the offices of a Boston magazine, it was a practical renunciation of his early environment, and an expression of his resolve to follow in the actual as well as the metaphorical footprints of some of the greatest figures in American literature.

Six months later, he announced his engagement to Helen Sterling, the only daughter of a pioneer in copper, whose character had long since built him up a reputation, to which, later, the five figures of his income lent an added lustre. From first to last, from the occasion of the young collegian's presentation to the reigning belle of her season to the moment when she said, "I, Helen, do take thee, John"—and the rest of it—there was, by way of proving the rule, never a stumbling-block in the exceptionally smooth course of their love. They were made for each other, people said, and no one subscribed more confidently to this opinion than themselves.

But—and does ever a honeymoon pass without the uneasy awakening of that latent 'But'?—Helen was not a month older before she was forced to the unwilling conclusion that there was a singular, intangible something lacking in her husband's character. It was not that he was not gifted; for that, his most casual acquaintance knew him to be;—or in[3] love with her; for of that he gave evidence almost as conclusive as would have been furnished by the ceaseless reiteration of that spoken devotion which a woman craves, without hope of receiving, from the man she loves. But things had come to him so easily, so independent of any effort of his own, that he was become the chief of optimists, imbued with the serene and confident laisser aller of the clan; and, now that association was making her intimate with his methods of work, she found them to be wholly haphazard, inspired merely by the whim of the moment, unregulated by any remotest evidence of system. His performances were the meaningless flashes and snaps of Chinese crackers, not the steady and purposeful, if less imposing, fire of a skilfully laid fuse, leading on to great results. His confidence in his own ability, in the certainty of his ultimate triumph, was so absolute that he was content with the minimum of endeavor, oblivious to the fact that only statues can remain thus passive with the assurance that laurel wreaths will be laid before them. He did not realize that the living must pluck their laurels for themselves.

Lacking the initiative which is its indispensable ally, Vane nevertheless possessed all the impatience of restraint or routine characteristic of the creative faculty. A year of editorial work was sufficient to convince him that it was not possible for such a temperament as his to be trammelled by fixed hours, and strait-jacketed by observance of detail. He[4] resigned his position, on the plea of devoting himself entirely to writing, and there ensued a period during which he sunned himself in society's favour, and received his share of flattery in return for several trifles contributed to the magazines, but created nothing worthy even of the infinitesimal effort which he made. A man had to think, to arrange, to compose, he told his wife. Rome was not built in a day, and the mere manual act of transferring his thoughts to paper was a trifle, when contrasted with the process of incubation. So month after month dragged by, and little by little, as his novelty wore off, John Vane dropped out of society's consideration as a literary potentiality, and came to be regarded as nothing more than one of many good-looking, agreeable men-about-town, to whom, in the matter of his wife and his worldly weal, the Fates had been generous beyond the ordinary.

One of the first unmistakable signs of degeneration was his now constant complaint that he was unappreciated. The average man's share of applause is in strict proportion to his deserts. In Vane's case the allowance had been appreciably in excess of his due, but it was exhausted at last; and flattery is a drug which, with indulgence, becomes, a necessity. Deprived of it, he grew fretful and impatient, made occasional abortive efforts at performance of the great things formerly expected of him, and talked savagely of prejudice when his manuscripts came back from the editors, accompanied by polite notes[5] wherein the pill of non-availability was sugar-coated with reference to the pleasure of examining his work, and the regret with which it was returned.

For a time he had his wife's most loyal support and sympathy. She liked to believe that what he said was true, that literary excellence counted for nothing in a commercial age, and that a man who would not conform to silly superficial standards had no chance of recognition. But Helen was a woman to whom a goose was a goose, and a swan a swan, at all times, and regardless of ownership. Moreover, she had been a lover of the best in literature since first she had been given the run of her father's library, and sat for entire afternoons curled into a big arm-chair, skipping the long words of Thackeray or Charles Lamb. Her critical sense, thus perfected, was now too alert to allow of any treachery to standard. Intensely loyal she was, but intensely just, as well; and all her eagerness to believe her husband what he claimed to be could not blind her to the mediocrity, often the utter worthlessness, of his later work. With revelation arose, naturally, an ardent desire to aid him, and strict sincerity, which was her most admirable quality, pointed to candour as the only adequate means. With his resentment of her counsel came her first disheartening insight into the shallowness and perversity of his nature. That he could accuse her of attempting to belittle him, rank her as at one with those who misunderstood him, hurt her more keenly than if he had turned[6] and cursed her. It was the parting of their ways, the first decisive step on the road which she was to follow wearily for five years of discouragement and disillusion.

With the waning of his popularity Vane renounced Boston, as he had renounced his birthplace, and they moved to New York. Here, for a time, he contributed listlessly to the humorous weeklies and the less pretentious magazines; but reputation of the kind he sought was not to be won by mere facility in rhyming or in writing around a dozen illustrations; and, presently, he reverted to his old complaint of prejudice and non-appreciation. Then a chance acquaintance led him into speculation. Where abler men failed, John Vane was swept into complete disaster. In a transient panic, he was caught long of a big line of stocks, tried to average too soon, and was finally forced to let go his holdings at about the bottom of the market.

It was ruin, absolute and utter; but Helen almost welcomed it, in the belief that the spur of a necessity he had never known before would goad him to the achievement of better things. But the character of John Vane was not the stuff whereof is made the moral phœnix. He shrivelled before the fire of defeat, and sank hopelessly into the ashes of surrender.

They moved from their luxurious apartment to a cheap hotel, thence to a cheaper one, thence to a boarding-house. The backward path was strewn[7] with unsettled bills, and loans never to be repaid. Vane wrote spasmodically for the daily papers, and for such of the magazines as would still accept his work, and, on the pittance thus earned, and the generosity of Helen's father, they contrived to exist, in a fashion, for something over two years.

But, given the temperament of John Vane, the next development was inevitable. At first Helen sturdily refused to believe that a new demon had entered the hell which he was making of her life. She met him, at night, with an attempt at a smile, deliberately ignoring his unsteady gait, his sodden face, his hot, rank breath. But the evidence was plain, constant, incontestable. Drink had gripped him, and she knew too well that whatever of weakness laid hand upon her husband never relinquished hold.

So another year went by, the gulf between them widening and widening. Finally, he struck her—and then, or the first time, that final degradation, that ominous, unknowable end of hope and self-respect, loomed, hideous and shadowy, through the fog before her. Unable to interpret its significance, she told herself, nevertheless, that it was very near.

They were living in Kingsbridge, in a little frame house into which a man who had known her husband in his Wall Street days had come, in settlement of a bad debt, and which he had offered them, for charity's sake, at a paltry annual rental. The same Samaritan had given Vane a small position in his office, and the[8] latter now went to and fro, between the city and its gruesome little neighbour on the Harlem, taking leave of his wife with a curt, contemptuous nod, and returning, bloated and foul-breathed, to pass the evenings in a semi-stupor.

The chance had been too good to be disregarded, but life under such conditions was no better than sheer existence. The cottage was one of a squat, ill-favoured row on a side street, within a stone's throw of the railway station. They had found it equipped, in a way, with cheap, yellowish furniture, worn and faded carpets, and kitchen utensils distinguished by the grime of many meals and the musty inheritance of insufficient washings. About the house there was a stale, moist smell of plaster, and the plot of turf in the little front yard was dry and discoloured, like the mats of imitation grass in the establishment of a country photographer. Helen had striven to redeem the desolation of the tiny living-room with the few pictures and articles of furniture which she had contrived to save from the wreck of their former fortunes; but the attempt was not successful. The rare prints were out of place against the tawdry wall-paper, and the few pieces of Sheraton and Chippendale to which she had clung took on, in such surroundings, the shabbiness of what was already there.

She was obliged to do her own marketing and cooking and housework, since a servant, in their straitened circumstances, was out of the question: and not the least part of her martyrdom was the purchase[9] of scrawny yellow fowls, and vegetables of a freshness past, and their preparation in the dingy little kitchen, which left an odour of frying lard on the very clothes she wore.

Vane had left her, an hour before, on his way to the city; and now, as the weight of depression became intolerable, she took her hat, locked the door behind her, and started for a long walk over the hill-roads back of the town. This had lately come to be her habit. It was something to escape, even for half a day, from the dispirited little suburb, with its sallow frame houses, its patched fences, and its cinder-strewn roadways, along which lean cats slunk guiltily, and dishevelled fowls picked their way in search of food. Up on the hills, the air of late November was keen and chill, and grayed with a drifting smoke-mist from distant fires of dried leaves. The brown grass was veiled here and there with thin patches of snow, stippled with faint shadows, cast by the filial oak-leaves, which cling longer than any other to the maternal bough. As Helen passed, squirrels darted nimbly away to a safe distance, and then sat up to watch her, with their fore paws held coquettishly against their breasts. It was all very sane and healthy, all in wonderful contrast to her morbid life in the shadow of John Vane's personality.

There had been no children—a fact which, in happier hours, she had deplored, but for which she was now profoundly grateful. There are things which it is easier to bear alone. To share with another[10]—and that other her child—the humiliation of her ill-starred association with her husband, would but have been to double the burden's weight. In her own case the period of martyrdom was well-nigh done. For his son and hers it would simply be at its beginning, tragic in its boundless possibilities of shame.

As the thought came of the motherhood thus denied her, she wondered why she had been faithful to John Vane. Once she had believed in him, and so strong had been this faith that some shreds of it yet remained, to bind her to him through all the unspeakably humiliating days of his gradual but inevitable degradation. Nor was her fidelity of the negative, meaningless kind which is strong simply because unassailed. As a woman of the world, she had, more than once, been brought into contact with men lax in their scrupulosity, but scrupulous in their laxity. She had had her temptations, her chances of escape; and the price to be paid was not exorbitant, in view of the relief to be obtained. But upon these she had resolutely turned her back, hoping against hope for the miracle which never came. Even now, her father's door stood wide to her, and every instinct of reason impelled her to a separation. But Vane had not only killed her love for him; he had destroyed her very taste for life itself, under any circumstances whatever. She clung to him now, not because she loved him, not because it was impossible to do without him, but because he[11] had sapped her youth, her faith, her craving for anything short of oblivion.

She stood for a long time, motionless, at a point where a little stream tinkled pleasantly over the stones beneath its first thin sheathing of ice. The trees, saving only the oaks, were bare, and stood stiffly, in close proximity, in the weird, white brilliance of contre-lumière; and for a few moments the barren tranquillity of the scene was indescribably restful. Then the light changed, as a slow cloud crept across the sun, and, with the coming of the resultant shadow, Helen, always exquisitely sensible to the moods of nature, returned suddenly to a consciousness of her extremity. It was not real, then, this negative beauty, this serene simplicity of nun-like, early winter; it was not real, her own unwonted calm! What was actual, material, inevitable, was the personality of the man who dominated her life like an evil spirit, using her as his chattel, abusing her as his slave. Abruptly, the whole course of their association spread itself before her, up to her last glimpse of him, that morning, shambling on his way to the miserable daily duty to which he had sunk. And this was the life which she had been so eager to share with him, the life which, in those early days, his promises had made to seem so fair! Together, they were to have seen the world—the wonderful, great world, that had shone in the distance, like a Promised Land, from the Pisgah of her girlish imaginings: London, Paris, Rome, the Nile, Greece, India, and Japan.[12] They were to have seen them all—drunk, in company, of the wine of beauty and inspiration, doubling their individual pleasures with the magic wand of mutual comprehension, as he should turn the treasures found along their enchanted way into such words as men preserve to praise, and she stand at his side, the first to read and reverence. And now? For the first time, the full splendour of the dream, the full squalor of the reality, swept down upon her. She saw him, diverted from his own ideals, and ignorant of hers, taking the initial step upon his downward way, no foot of which was ever to be retraced: drunken, debauched, impotent to write one worthy word, skulking, shamefaced and sodden, through a world of sunlight and manly endeavour, like some noisome prowler of the night, surprised, far from its lair, by the dawn of sweet young day. She was no more than a girl, and already it was too late. The blitheness of life was gone, never to return. For a moment she stood with her worn hands crushed against her face, and then she stretched her arms upward to their full length, and cried aloud, "Ah, God! Ah, God!" to the chill, clear sky of the November day.

A voice at her side aroused her before she realized that she was not alone. At the sound she turned guiltily, and found herself face to face with a man she had never seen. He stood quite near, hat in hand, surveying her with cool, steel-blue eyes. In that first instant, with a perception sharpened by[13] her mental anguish, she became suddenly as familiar with every detail of his appearance as if they had been intimates for years. He was tall and slender, and unmistakably young; and, in singular contrast to his pallid complexion, his lips, under the thin mustache, were full and red, with a strange, sensual crookedness that was half a smile and half a sneer. There was about him a curious, compellant air of mastery and self-possession, as of one sure of himself, and accustomed to control; and his first words, under their veneer of polite solicitude, were, in their total lack of surprise or idle curiosity, significant of the trained man of the world, while the quaint, foreign flavour of the title by which he addressed her was equally suggestive of the cosmopolite.

"You are in distress, madame?"

Helen paused before replying. With the instinctive delicacy of her sex, she realized that in the approach of a stranger who had surprised her in a betrayal of extreme emotion there was something which she would do well to resent; and yet she was come to one of those crises which every woman knows; when the need of sympathy, even the most casual, was imperative—when, albeit at the sacrifice of conventionality, she was fain to seek support, to grasp a firm hand, to hear a friendly, though an unknown, voice. Pride, her stanch ally through all the bitter hours of her despair, had weakened at this the most crucial point, and, like a frightened[14] child, she would have run for reassurance into the arms of the veriest passer-by.

"Perhaps," she answered presently. "But, believe me, the expression of my feeling was purely involuntary. I thought myself alone. There are, ordinarily, few passers by this road."

He had replaced his hat now, and was no longer looking at her, but down across the shelving slope of hillside, spiked with slender trees, as close-set as the bristles of a giant brush. When he spoke again, his tone had curiously assumed the existence of a relation between them, as if, instead of total strangers, they had been old acquaintances, come together at this spot, and exchanging impressions of the scene before them.

"Strange," he said slowly, "that you should be in distress, when Nature, which always seems to me the most sympathetic of companions, is wrapped in so great repose. In my dealings with humanity, I've frequently met with misunderstanding; but never, in the attitude of Nature, a lack of what I felt to be completest comprehension of my mood. She always seems to divine our difficulties, and to have some little helpful hint, some small parable, which, if we read it aright, will point out the solution of our problem, or at least serve to soothe the momentary pang. This little stream at our feet, for example: how it preaches the lesson that while we must meet with days that are cold, unsympathetic, drear, it's not only possible, but best, to preserve, under the ice[15] in which adversity wraps our hearts, the life and laughter which friendlier suns have taught us! I wonder if that is not the secret of all human contentment—to resign oneself to the chilling touch of the wintry days of life, secure in the knowledge that summer will return, the compensation be made manifest, and the wrong turned to right."

The rebuff which was on Helen's lips an instant before was never spoken. It was one of those moments when the intuitive assertion of dignity and self-reliance lays down its arms before the need of comfort and companionship. She did not look at him, but in her silence there was that which encouraged him to continue.

"You don't resent my speaking to you in this way?" he asked. "After all, why should you? You are a bubble on this strange, erratic stream of life, and I another. Bubble does not ask bubble the reason of their meeting, at some predestined spot between source and sea. Instead, they touch, perhaps to drift apart again after a moment; perhaps, as one often sees them, to unite in one larger, better, brighter bubble than either had been before. Neither cares a tittle for its chance companion's previous history, or for what the other bubbles say. Curiosity as to another's past is the prerogative of small-spirited man, as is also the dread of adverse criticism. Now the commingling bubbles are one of Nature's little parables, and my conception of ideal sympathy."

His eyes were upon her now, and, strangely impelled, her own came round to meet them.

"I'm not wholly sure that I get your meaning," she said, feeling that he exacted a reply. "Is it that association and sympathy are merely the result of chance?"

"Chance is only a word that we use to express the workings of a force beyond our understanding." He stooped and picked up a little stone, weighed it momentarily in his palm, and then, reversing his hand, let it fall. "One would hardly be apt to call it chance," he added, "that, after leaving my hand, that pebble reached the ground. If we understood destiny as we understand gravitation, we should not say that our present meeting was due to chance, but rather that it was the logical outcome of a natural law."

There was a long pause, during which he glanced at her more than once, with the seemingly careless but actually keenly observant air of a skilled physician studying a nervous patient. She was a little frightened, she confessed to herself, as she gathered her wits, staring at the bit of river which was visible from where they stood, and the slopes beyond. For weeks she had been prey to an apathy which was only broken, at intervals, by an outburst of passionate revolt. Now, in some inexplicable fashion, the burden seemed to have slipped from her shoulders, and the feeling of depression was replaced by one of uplifting, of unreasonable exhilaration. The[17] sensation was vaguely familiar to her, and, groping for a clue, she found its parallel in the preliminary action of ether, which she had taken a year or so before. Through the growing, not unpleasurable, dizziness which came upon her thus, the man's voice made its way.

"Let me try to explain myself more clearly," he was saying. "Something—God, or chance, or destiny, or whatever you choose to call it—led me around that last turn of the road at a moment when, if I'm not mistaken, a fellow being came to the snapping-point of self-control. I can't think our meeting without significance. I believe I was sent to help you. The question is, whether you're broad and generous and courageous enough to take for granted a formal introduction, and the gradual evolution of acquaintance into intimacy, up to the moment when you would naturally turn to me, as your most loyal friend, for sympathy. And I think you will do that."

Once more Helen looked at him. Her mind was curiously clouded, but the sensation gave her no uneasiness. Instead, she felt that she was smiling.

"I think you will do it," he repeated.

He was holding out his hand with the confidence of one who knows it will be accepted, and, after a moment, she laid her own within it. His fingers closed firmly on hers, and, of a sudden, the world drew in about her, graying, as under the touch of fog. Her last perception was of his eyes fixed[18] full on hers with an expression of quiet amusement.

"I'm faint," she murmured, "I am—faint—"

When she came to herself, his eyes still held her.

"In the strange, unknowable book of Fate," he said, "it was written, from the beginning of time, that you and I should meet upon a dull hillside in late November, and—and that all that has been should be!"

Before she had time to answer, he had left her.

Briefly she stood, dizzy and perplexed, and then, after one great leap, her heart seemed to shudder and stand still. She was in the sordid little living-room of the Kingsbridge cottage, and outside the day was glooming into twilight!

Without power to move, she watched from the window the man who had just gone, pass down the path and through the gate, and, turning, wave a farewell, before he hurried away in the direction of the station. Then she was fully aroused by the entrance of the postman, and went slowly to meet him at the door. There was only one letter, but this was directed in her husband's unsteady hand, and, as she opened it, the contents leapt at her like a blow:

"Helen:"

"Let me be as brief as you will think me brutal. When this reaches you I shall already be far at sea—with another woman. I have seen how you despised [19]me, and I think that you know this, and that I hate you for it. I shall not ask you to forgive me, for I, too, have many things to forgive. If you had understood me, much that has happened might never have been. But what is past is past. Let us bury it and have done."

"John."

For minutes, which seemed an eternity, Helen stood, fingering the wretched sheet, and gazing straight before her with blank, unwinking eyes. Then, with a rush, came remembrance, and with it a great wave of relief. Before she fully comprehended her intention, she was at the gate of the cottage. But there she halted, with a nameless sense of loss and desperation. From the distance had come the yelp of a signalled locomotive, and then a dozen short, choking pants, as it dragged the reluctant train into motion. He had gone!

"But he will come back!" she murmured, "and, that he may come sooner, I will write."

It was only towards the end of her black, sleepless night that she remembered that she did not even know his name.

Late autumn slid gloomily into winter, and winter into spring, before she realized that he would never come. To her father she had written nothing of Vane's desertion. For a year past, his name had not been mentioned in their letters, so the omission was no longer noted, and Mr. Sterling's remittances[20] enabled her to live in material comfort. She clung to the forlorn little cottage with a vague feeling that by it alone could she be traced when He should come back for her; but took a servant, a slovenly little wench, who moved in a circumambient odour of carbolic acid, and amassed dust under beds and sofas as a miser hoards his gold.

Helen herself saw nothing, heeded nothing. Save in the impulse which followed her reading of Vane's letter, her mind was never wholly clear from the shadow which had descended upon it at the moment of that hand-grip on the hillside. Hour after hour, day after day, week after week, she sat at the window, motionless, listening for the creak of the gate, the crunch of footsteps on the gravel path, which would tell her that He had returned.

With spring the disillusion came, and she crept back to the shelter of her father's house, but to no change, save slow and listless surrender to the inevitable. Sometimes they heard her whispering to herself, as she sat, with some book which they had brought her, unopened on her knee—odd scraps of sentences, and broken phrases, without apparent relevancy or connection. The family physician, a friend from boyhood of Andrew Sterling, tapped his forehead significantly at such times as these, and the hands of the two men would meet in a grasp of mutual understanding.

One night in late August her child was born, and the west wind that brought a new soul to the Sterling[21] door, pausing an instant in its passing, gathered up, and in its kind arms bore away, on its pathless flight into the Great Unknown, the tired spirit of Helen Vane.

Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy Carnby furnished to the reflective observer a striking illustration of the circumstance that extremes not only meet, but, not infrequently, marry. Mrs. Carnby confessed to fifty, and was in reality forty-seven. As, in any event, incredulity answers "Never!" when a woman makes mention of her age, she preferred that the adverb should be voiced with flattering emphasis and in her presence, rather than sarcastically and behind her back. She was nothing if not original.

Mrs. Carnby was distinctly plain, a fact which five minutes of her company effectually deprived of all significance: her power of attraction being as forceful as that of a magnet, and similar to a magnet's in its absence of outward evidence. She was a woman of temperate but kaleidoscopic enthusiasms, who had retained enough of the atmosphere of each to render her interesting to a variety of persons. Prolonged experience of the world had invested her with an admirable broad-mindedness, which caused her to tread the notoriously dangerous paths of the[23] American Colony, in which she was a constant and conspicuous figure, with the assurance of an Indian fakir walking on broken glass—pleasurably appreciative of the risk, that is, while assured by consummate savoir faire against cutting her feet. Her fort was tact. She had at one and the same time a faculty for forgetting confidences which commended her to women, and a knack of remembering them which endeared her to men. It was with the latter that she was preëminently successful. What might have been termed her masculine method was based on the broad, general principle that the adult male is most interested in the persons most interested in him, and it never failed, in its many modifications, of effect. Men told her of their love-affairs, for example, with the same unquestioning assurance wherewith they intrusted their funds to a reputable banker; and were apt to remember the manner in which their confidences were received, longer than the details of the confidences themselves. And when you can listen for an hour, with every evidence of extreme interest, to a man's rhapsodies about another woman, and, at the end, send him away with a distinct recollection of the gown you wore, or the perfume on the handkerchief he picked up for you, then, dear lady, there is nothing more to be said.

Mr. Jeremy Carnby infrequently accompanied his wife to a reception or a musicale, somewhat as Chinese idols and emperors are occasionally produced[24] in public—as an assurance of good faith, that is, and in proof of actual existence. As it is not good form to flaunt one's marriage certificate in the faces of society, an undeniable, flesh-and-blood husband is, perhaps, the next best thing—when exhibited, of course, with that golden mean of frequency which lies between a hint of henpeck on the one side and a suggestion of neglect upon the other. Mrs. Carnby blazed in the social firmament of the American Colony with the unwavering fixity of the Polar Star: Jeremy appeared rarely, but with extreme regularity, like a comet of wide orbit, as evidence that the marital solar system was working smoothly and well.

Mrs. Carnby was, and not unreasonably, proud of Jeremy. They had lived twenty-five years in Paris, and, to the best of her knowledge and belief, he was as yet unaware, at least in a sentimental sense, that other women so much as existed. Since one cannot own the Obélisque or the Vénus de Milo, it is assuredly something to have a husband who never turns his head on the Avenue du Bois, or finds a use for an opera-glass at the Folies-Bergère. Jeremy was not amusing, still less brilliant, least of all popular; but he was preëminently loyal and unfeignedly affectionate—qualities sufficiently rare in the world in which Mrs. Carnby lived, and moved, and had the greater portion of her being, to recommend themselves strongly to her shrewd, uncompromising mind. In her somewhat over-furnished life he[25] occupied a distinct niche, which one else could have filled; and in this, to her way of thinking, he was unique—as a husband. After foie gras and champagne, Mrs. Carnby always breakfasted on American hominy, a mealy red apple, and a glass of milk. She was equally careful, however, to take the meal in company with Jeremy. He was part of the treatment.

The Carnby hôtel was one of the number in the Villa Dupont. One turned in through a narrow gateway, from the sordid dinginess of the Rue Pergolèse, and, at a stone's throw from the latter's pungent cheese and butter shops, and grimy charbonneries, came delightfully into the shade of chestnuts greener than those exposed to the dust of the great avenues, and to the sound of fountains plashing into basins buried in fresh turf. It was very quiet, like some charming little back street at St. Germain or Versailles, and the houses, with their white walls and green shutters and glass-enclosed porticos, were more like country villas than Parisian hôtels. The gay stir of the boulevards and the Avenue du Bois might, to all seeming, have been a hundred kilometres distant, so still and simple was this little corner of the capital. Jeremy frankly adored it. He had a great office looking out upon the Place de l'Opéra, and when he rose from his desk, his head aching with the reports and accounts of the mighty insurance company of which he was the European manager, and went to the window in[26] search of distraction, it was only to have his eyes met by a dizzier hodge-podge than that of the figures he had left—the moil of camions, omnibuses, and cabs, threading in and out at the intersection of the six wide driveways, first up and down, and then across, as the brigadier in charge regulated the traffic with sharp trills of his whistle, which jerked up the right arms of the policemen at the crossings, as if some one had pulled the strings of so many marionettes with white batons in their hands. All this was not irritating, or even displeasing, to Jeremy. He was too thorough an American, despite his long residence in Paris, and too keen a business man, notwithstanding his wife's fortune, not to derive satisfaction from every evidence of human energy. The Place de l'Opéra appealed to the same instincts in his temperament that would have been gratified by the sight of a stop-cylinder printing-machine in action. But, not the less for that, his heart was domiciled in the hôtel in the Villa Dupont.

On a certain evening in mid-April, Jeremy had elaborated his customary half-hour walk homeward with a detour by way of the Boulevard Malesherbes, the Parc Monceau, and the Avenue Hoche, and it was close upon six when he let himself in at his front door, and laid his derby among the shining top-hats of his wife's callers, on the table in the antichambre. Through the half-parted curtains at the salon door came scraps of conversation, both in French and English, and the pleasant tinkle of cups[27] and saucers; and, as he passed, he had a glimpse of several well-groomed men, in white waistcoats and gaiters, sitting on the extreme edges of their chairs, with their toes turned in, their elbows on their knees, and tea-cups in their hands; and smartly-dressed women, with big hats, and their veils tucked up across their noses, nibbling at petits fours. He turned into his study with a feeling of satisfaction. It was incomprehensible to his mind, this seemingly universal passion for tea and sweet cakes; but if the institution was to exist under his roof at all, it was gratifying to know that, albeit the tea was the finest Indian overland, and the sweet cakes from the Maison Gagé, it was not for these reasons alone that the 16th Arrondissement was eager, and the 7th not loath, to be received at the hôtel in the Villa Dupont. Jeremy knew that his wife was the most popular woman in the Colony, as to him she was the best and most beautiful in the world. Before he touched the Temps or the half-dozen letters which lay upon his table, he leaned forward, with his elbows on the silver-mounted blotter, and his temples in his hands, and looked long at her photograph smiling at him out of its Russian enamel frame. If the world, which laughed at him for his prim black neckties and his common-sense shoes, even while it respected him for his business ability, had seen him thus, it would have shared his wife's knowledge that Jeremy Carnby was an uncommonly good sort.

He opened his letters carefully, slitting the envelopes[28] with a slender paper-knife, and endorsing each one methodically with the date of receipt before passing on to the next. All were private and personal, his voluminous business mail being handled at his office by a secretary and two stenographers. With characteristic loyalty, Jeremy wrote regularly to a score of old acquaintances and poor relations in the States, most of whom he had seen but once or twice in the twenty-five years of his exile, and read their replies with interest, often with emotion: and his own left hand knew not how many cheques had been signed, and cheering words written, by his unassuming right, in reply to the plaints and appeals of his intimates of former years. For the steady, white light of Jeremy Carnby's kindliness let never a glint of its brightness pass through the closely-woven bushel of his modesty.

He hesitated with the last letter in his hand, reread it slowly, and then lit a cigar and sat looking fixedly at his inkstand, blowing out thin coils of smoke. So Mrs. Carnby found him, as she swept in, dropped into a big red-leather arm-chair, and slid smoothly into an especial variety of small talk, wherewith she was wont to smooth the business wrinkles from his forehead, and bring him into a frame of mind proper to an appreciation of the efforts of their chef.

"If it isn't smoking a cigar at fifteen minutes before the dinner-hour!" she began, with an assumption of indignation. "Really, Jeremy, you're getting[29] quite revolutionary in your ways. I think I shall tell Armand that hereafter we shall begin dinner with coffee, have salad with the Rüdesheimer, and take our soup in the conservatory."

Mr. Carnby laid down his cigar.

"I lit it absent-mindedly," he answered. "Have they gone?"

"No, of course not, stupid!" retorted his wife. "They're all out there. I told them to wait until we'd finished dinner. Now, Jeremy! why will you ask such questions?"

"It was stupid of me," he admitted.

"And to punish you, I shall tell you who they were," announced Mrs. Carnby. "I might do worse and tell you all they said. You're so—so comfortable, Jeremy. When I'm on the point of boiling over because of the inanities of society I can always come in here and open my safety-valve, and you don't care a particle, do you, if I fill your study full of conversational steam?"

Jeremy smiled pleasantly.

"You nice person!" added his wife. "Well, here goes. First, there was that stupid Mrs. Maitland. She told me all about her portrait. It seems Benjamin-Constant is painting it—and I thought the others would never come. Finally, however, they did—the Villemot girls and Mrs. Sidney Kane, and a few men—Daulas and De Bousac and Gerald Kennedy and that insufferable little Lister man. Then Madame Palffy. It makes me furious every time I[30] hear her called 'madame.' The creature was born in Worcester—and do you know, Jeremy, I'm positive she buys her gowns at an upholsterer's? No mere dressmaker could lend her that striking resemblance to a sofa, which is growing stronger every day! Her French is too impossible. She was telling Daulas about something that never happened to her on her way out to their country place, and I heard her say 'compartiment de dames soûles' quite distinctly. I can't imagine how she contrives to know so many things that aren't so. One would suppose she'd stumble over a real, live fact now and again, if only by accident. And her husband's no better. Trying to find the truth in one of his stories severely taxes one's aptitude in long division. I saw him at the Hatzfeldts' musicale night before last. Pazzini was playing, and Palffy was sound asleep in a corner, after three glasses of punch. I really felt sorry that a man with such a wife should be missing something attractive, and I was going to poke him surreptitiously with my fan, but Tom Radwalader said, 'Better let the lying dog sleep!' He positively is amusing, that Radwalader man!"

Mrs. Carnby looked up at her husband for the admiring smile which was the usual guarantee that she had amused him, but only to find Jeremy's eyes once more riveted upon the inkstand, and the cigar between his thin lips again.

"My dear Jeremy," she said, "I'm convinced[31] that you've not heard one syllable of my carefully prepared discourse."

"My dear Louisa," responded Mr. Carnby with unwonted readiness, "I'm convinced that I have not. The truth of the matter is," he added apologetically, "that I've received an unusual letter."

"It must indeed be unusual if it can cause you to ignore my conversation," said Louisa Carnby.

"That is perfectly true," said Jeremy with conviction.

His wife rose, came over to his side, and kissed him on the tip of his nose.

"Good my lord," she said, "I think I like your tranquil endorsement of the compliments I make for myself better than those which other men invent out of their own silly heads! Am I to know what is in your unusual letter?"

"Why not?" asked Jeremy seriously.

"Why not, indeed?" said Mrs. Carnby. "I have taken you for better or worse. There's so little 'worse' about the contract, Jeremy, that I stand ready to accept such as there is in a willing spirit, even when it comes in the form of a dull letter."

Jeremy looked up at her with his familiar smile.

"Louisa," he said, "if I were twenty years of age, I should ask nothing better than the chance to marry you again."

"Man! but thou'rt the cozener!" exclaimed Mrs. Carnby. "Thou'dst fair turn the head of a[32] puir lassis. There—that'll do. Go on with your letter!"

"It's from Andrew Sterling," said Jeremy. "You'll remember him, I think, in Boston. He was a friend of my father's, and kept a friendly eye on me after the old gentleman's death. We've always corresponded, more or less regularly, and now he writes to say—but perhaps I'd best read you that part of his letter."

"Undoubtedly," put in his wife. "That is, if you can. People write so badly, nowadays."

"Um—um—" mumbled Jeremy, skipping the introductory sentences. "Ah! Here we have it. Mr. Sterling says: 'Now for the main purpose of this letter. My poor daughter's only son, Andrew Sterling Vane, is sailing to-day on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. He has been obliged to leave Harvard, as his health is not robust, and I have thought that perhaps the sea-voyage and some months in Paris might put him in shape—'"

"Good Lord!" broke in Mrs. Carnby. "Imagine some months in Paris by way of rest-cure!"

"'And so,'" continued Jeremy, "'I'm sending him over, in hopes that the change may be of benefit. He is a singular lad—sensitive in the extreme, and utterly inexperienced—and I am going to ask if, "for auld lang syne," you will be so good as to make him welcome. I don't mean, of course, that I expect you to exercise any sort of supervision. The boy must take care of himself, like all of us, but I would[33] like to feel that, in a strange city, there is one place where he may find a hint of home."

Jeremy paused.

"Go on!" observed Mrs. Carnby.

"There is really nothing more of importance," said her husband, "except that I've also received a note from young Vane. He's at the Ritz."

"Of course!" ejaculated Mrs. Carnby. "Paying two louis per diem for his room, and making semi-daily trips to Morgan, Harjes'. They're wonderful, these tourist bank-accounts. Their progress from a respectable amount to absolute zero is as inevitable as the recession of the sea from high-water mark to dead low tide—a steady withdrawal from the bank, my dear Jeremy! How old might the young gentlemen be?"

Mr. Carnby made a mental calculation.

"His mother was about my own age," he said presently. "I know she and I used to go to dancing-school together. And she died in childbirth, if I remember rightly. Her husband was a scamp—ran off with another woman. I never saw him. That would make the boy about twenty or twenty-one."

"He will be rather good-looking," said Mrs. Carnby reflectively, "with a general suggestion of soap and cold water about him. He will wear preposterously heavy boots with the soles projecting all around like little piazzas, and a straw hat, and dog-skin gloves with seams like small hedges, and turned[34] back at the wrists. They're all exactly alike, the young Americans one sees over here. One would think they came by the dozen, in a box. And when he is sitting down he will be hitching at his trousers all the time, so that the only thing one remembers about him afterwards is the pattern of his stockings."

"We ought to invite him to dinner," suggested Jeremy.

"Without doubt," agreed his wife; "but to breakfast first, I think—and on Sunday. One can judge a man's character so well by the way he behaves at Sunday breakfast. If he fidgets, and drinks quantities of water, then he's dissipated! I don't know why Saturday night is always fatal to dissipated men, but it is. If his top hat looks as if it had been brushed the wrong way, then he's religious, and has been to church. I shall go out and inspect it while you're smoking. If he does all the talking, he's an ass; and if I do it all, he's a fool."

"You're a difficult critic, my dear," said Jeremy. "You must remember he is only twenty or so."

"To be twenty or so in appearance is a man's misfortune," replied Mrs. Carnby. "To be twenty or so in behaviour is his fault. I'll write to him to-night, and ask him to breakfast on Sunday, tout à fait en famille, and we'll try him on a—you don't mind my calling you a dog, Jeremy?"

"Not in the least," said Mr. Carnby.

"Eh bien!" said his wife. "We'll have him to breakfast on Sunday, and try him on a dog! If[35] he's presentable and amusing, I shall make him my exclusive property. If he's dull, I shall tell him Madame Palffy is a woman he should cultivate assiduously. I send her all the people who don't pass muster at my dinners. She has them next day, like warmed-over vol-au-vents. My funeral baked meats do coldly furnish forth her breakfast-table."

"When you wish to appear most unmerciful, my dear," said Jeremy, "you always pick out Madame Palffy; and whenever you do, I spoil the effect of what you say by thinking of—"

"Margery?" put in Mrs. Carnby. "Yes, of course, that's my soft spot, Jeremy. There's only one thing which Margery Palffy ought to be that she isn't, and that's—ahem!—an orphan."

In ordinary, Mrs. Carnby was one of the rare mortals who succeed in disposing as well as in proposing, but there were times when there was not even a family resemblance between her plans and her performances. She had fully intended that young Vane should be the only guest at her Sunday breakfast, but as she came out of church that morning into the brilliant sunlight of the Avenue de l'Alma, she found herself face to face with the Ratchetts, newly returned from Monte Carlo, and promptly bundled the pair of them into her victoria. Furthermore, as the carriage swung round the Arc, and into the Avenue du Bois, she suddenly espied Mr. Thomas Radwalader, lounging, with an air of infinite boredom, down the plage.

"There's that Radwalader, thinking about himself again!" she exclaimed, digging her coachman in the small of his ample back with the point of her tulle parasol. "Positively, it would be cruelty to animals not to rescue him. Arretez, Benoit!"

Radwalader came up languidly as the carriage stopped.

"Where are you going?" demanded Mrs. Carnby, after greetings had been exchanged.

"Home," answered Radwalader. "I met Madame Palffy back there a bit, and couldn't get away for ten minutes. You know, it's shocking on the nerves, that kind of thing, so I thought I'd drop in at my quarters for a pick-me-up."

"Well, if I'm not a pick-you-up, I'm sure I don't know what is," said Mrs. Carnby. "You're to come to breakfast. You'll have to walk, though. We're three already, you see, and I don't want people to take my carriage for a panier à salade. I hadn't the most remote intention of asking you; but when a man tells me he's been talking for ten minutes to that Palffy, I always take him in and give him a good square meal."

"You're very kind," said Radwalader. "Are you going to play bridge afterwards? If so, I must go home for more money."

"Nothing of the sort!" said Mrs. Carnby emphatically. "There's a protégé of Jeremy's coming to breakfast—a Bostonian, twenty years young, and over here for his health. You must all go, directly after coffee. I'm going to spend the afternoon feeding him with sweet spirits of nitre out of a spoon, and teaching him his catechism. Perhaps you'd like to stay and learn yours?"

"I think I know it," laughed Radwalader.

"If you do, it's one of your own fabrication, then—with just a single question and answer. 'What is[38] my duty toward myself? My duty toward myself is, under all circumstances, to do exactly as I dee please.'"

"If that were the case, my good woman, I should live up to my profession of faith, not only by accepting your invitation, as I mean to do, but by staying the entire afternoon."

"That's very nicely said indeed," answered Mrs. Carnby. "Allez, Benoit!"

Twenty minutes later the whole party were assembled in her salon. Carnby, caught by his wife as he was scuttling into his study, was now doing his visibly inadequate best to entertain Philip Ratchett, who stood gloomily before him, with his legs far apart, his hands in his pockets, and his eyes on the top button of his host's waistcoat. He was a typical Englishman, of the variety which leans against door-jambs in the pages of Punch, and makes unfortunate remarks beginning with "I say—" about the relatives of the stranger addressed. Society bored him to the verge of extinction, but it is only fair to say that he repaid the debt with interest. He was tolerated—as many a man before and after him has been—for the sake of his wife.

Mrs. Ratchett patronized, with equal ardour, a sewing-class which fabricated unmentionable garments of red flannel for supposedly grateful heathen, and a society for psychical research which boasted of liberal-mindedness because it was willing to admit[39] that, at the dawn of the twentieth century, the causes of certain natural phenomena yet remained unexplained. Her entire conception of life underwent a radical change whenever she read a new book, which she did at fortnightly intervals. She was thirty, clever, and frankly beautiful, hence a factor in the Colony.

The fifth member of the company in Mrs. Carnby's salon, Mr. Thomas Radwalader, enjoyed the truly Parisian distinction of being an impecunious bachelor who did not accept all the invitations he received. He might have been thirty-five or forty-five or fifty-five. His smooth-shaven, impassive face offered no indication whatever of his age. He was already quite gray, but, in contrast to this, his speech was tinged with a frivolity, rather pleasant than otherwise, which hinted at youth. Mrs. Carnby had once described him as being "dappled with knowledge," and this, in common with the majority of Mrs. Carnby's estimates, came admirably near to being exact. Radwalader's actual fund of information was far less ample than was indicated by the facility with which he talked on any and every subject, but he was master of the science of selection. He judged others—and rightly—by himself, and went upon the often-proven theory that a polished brilliant attracts more attention than an uncut Koh-i-nur. He made the superficial things of life his own, and on the rare occasions when the trend of conversation led him out of his depth, he caught at the life-belt[40] of epigram, and had found his feet again before men better informed had finished floundering. He lived in a tiny apartment, on the safe side of nothing a year, and kept up appearances with a skill that was little short of genius. Gossip passed him by, a circumstance for which he was devoutly grateful, though it was due less to chance than to management.

Such was the company into which Mr. Andrew Sterling had despatched his grandson—in hopes that the change might be of benefit. As he came through the portières, young Vane proved to tally, in the main essentials of appearance, with Mrs. Carnby's prophetic estimate. He was somewhat more than rather good-looking, and essentially American, with the soap-and-cold-water suggestion strongly to the fore. Mrs. Carnby always noted three things about a man before she spoke to him—his hands, his linen, and his eyes. In the first two Andrew Vane qualified immediately; in the third his hostess was forced to confess herself at a loss. In singular contrast to a complexion dark almost to swarthiness, his eyes were large and of an intense steel-blue. He met those of another squarely, not alone with the frankness characteristic of youth, but with the strange calm of confidence typical of men accustomed to the command of a battle-ship or an army corps. Mrs. Carnby, in ordinary the most self-possessed of women, gave, almost guiltily, before the keen, clear eyes of Andrew Vane.

"He has no business whatever to have eyes like[41] that, at his age," she told herself, almost angrily. "They ought to grow in a man's head, after he has seen everything there is to be seen."

The thought was involuntary, but it recalled to her memory where she had seen their like before.

"Radwalader has them," she added mentally. "Good Lord! Radwalader! And this child hasn't even graduated!"

During the brief interval between the general introduction and the announcement of breakfast, she studied her new guest with unwonted interest. He was of the satisfactory medium height at which a man is neither contemptible nor clumsy, slight in build, but straight as an arrow, with narrow hips and a square backward fling of shoulder which spoke of resolution.

"He has 'No Compromise' written all over his back," said Mrs. Carnby to herself. "I should believe everything he told me, and not be afraid of what I told him."

Then she noted that he was eminently at ease. There is something out of the common about twenty that keeps its hands hanging at its sides, and its feet firmly planted, without suggesting a tailor's dummy. Andrew was talking to Mr. Carnby about his grandfather and Boston, and from the first to the last word of the short colloquy he did not once shift his position. As he stood thus, in some curious fashion consideration of his years was completely eliminated from one's thought of him. He was[42] deferential, but in the negative manner of guest to host, rather than in the positive of youth to age; and, at the same time, he was assertive, but with the force of personality, not the conspicuity of awkwardness. He fitted into his surroundings instantly, like a wisely placed bibelot, but he dominated them as well.

"That Palffy," was Mrs. Carnby's final resolve, "shall get him only over my dead body."

And so, unconsciously, Andrew scored his first Parisian triumph.

For the first ten minutes of breakfast, Mrs. Carnby, at whose left he sat, let him designedly alone. It was her belief that men, like saddle-horses, should be given their heads in strange territory, and left to find themselves—this in contrast to the policy of her social rival, Madame Palffy, who boasted of being able to draw out the best there was in a new acquaintance in the first quarter-hour of conversation. In this she was probably correct, though in a sense which she did not perceive—for few good qualities survived the strain of that initial quarter-hour.

But if Mrs. Carnby's attention appeared to be engrossed by Radwalader on her right, and Mrs. Ratchett beyond Radwalader, she kept, nevertheless, a weather eye on Andrew; and when, presently, his spoon tinkled on his bouillon saucer, she turned to him.

"I've been watching you," she began, "to see how you would take to French oysters. It's a test I[43] always apply to newcomers from America. If they eat only one Marennes verte, I know at once that they approve of forty-story buildings, and are going to talk about 'getting back to God's country'; if they eat all six, I know I may venture to hint that there are advantages about living in Paris, without having my head bitten off for being an expatriate."

"It would seem your head is quite safe, so far as I am concerned," laughed Andrew, "for I finished off my half-dozen, and thought them very good."

"Then you have the soul of a Parisian in the body of a Bostonian," affirmed Mrs. Carnby. "A liking for Marennes vertes is a survival of a previous state of existence. Here's Mr. Radwalader, for instance, who can't abide them, even after Heaven knows how many years in Paris."

"They taste so much like two-sou pieces that, whenever I eat them, they make me feel like a frog savings-bank," said Radwalader.

"There you are!" cried Mrs. Carnby triumphantly. "That would never have arisen as an objection in the mind of any one who had known what it is to be a Parisian."

"Or a frog savings-bank," said Radwalader. "No, I suppose not. I can't seem to live down the fact that I was born in the shadow of Independence Hall. But I'm doing so much to make up for the bad beginnings of my present incarnation, that I shall undoubtedly be a Parisian in my next. Have you been here long, Mr. Vane?"

"Three days."

"Do you speak French?" put in Mrs. Carnby. "No? What a pity! You've no idea what a difference it makes."

"I've only such a smattering as one gets in school and college," said Andrew. "Of course I didn't know I was coming over here. But, after all, one seems to get on very well with English."

"That's just the trouble, Mr. Vane," volunteered Mrs. Ratchett. "So many Americans are content just to 'get on' over here. That isn't the cue to Paris at all! It only means that you and she are on terms of bowing acquaintance. You'll never get to know her till you can talk to her in her own tongue."

"Or listen to her talk to you," observed Radwalader. "So long as we're using the feminine gender—"

"Oh!" interrupted Mrs. Carnby. "A remark like that does come with extreme grace from you, I must say. Here," she added, turning to Mrs. Ratchett, and indicating Radwalader with her fish-fork, "here's a man, my dear, who spent two solid hours of last Monday telling me the story of his life. And it reminded me precisely of a peacock—one long, stuck-up tale with a hundred I's in it. Radwalader, you're a brute!"

Carnby, with his eyes fixed vacantly upon a spot midway between a pepper-mill and a little dish of salted almonds, appeared to be revolving some complicated business problem in his mind;[45] and, as his wife caught sight of him, her fish-fork swung round a quarter-circle in her fingers, like a silver weathercock, until, instead of Radwalader, it indicated the point of her husband's nose.

"That person," she said to Andrew, "is either in Trieste or Buda. His company has an incapable agent in both cities, and whenever he glares at vacancy, like a hairdresser's image, I know he is in either one town or the other. With practice, I shall come to detect the shade of difference in his expression which will tell me which it is. Mr. Ratchett—some more of the éperlans?"

Ratchett was deeply engaged in dressing morsels of smelts in little overcoats of sauce tartare, assisting them carefully with his knife to scramble aboard his fork, and, having braced them there firmly with cubes of creamed potato, conveying the whole arrangement to his mouth, where he instantly secured it from escape by popping in a piece of bread upon its very heels. He looked up, as Mrs. Carnby spoke to him, murmured "'k you," and immediately returned to the business in hand. Radwalader and Mrs. Ratchett had fallen foul of each other over a chance remark of his, and were now just disappearing into a fog of art discussion, from which, in his voice, an abrupt "Besnard" popped, at intervals, as indignantly as a ball from a Roman candle, or, in hers, the word "Whistler" rolled forth with an inflection which suggested the name of a cathedral.

"Tell me a little about yourself," said Mrs. Carnby, turning again to Andrew.

"If it's to be about myself," he answered, "I think it's apt to be little indeed. I've been in college almost three years, but I've been kept back, more or less, by a touch of fever I picked up on a trip to Cuba. It crops out every now and again, and knocks me into good-for-nothingness for a while. I'm not sure that I shall go back to Harvard. You see, I want to do something."

"What?" demanded Mrs. Carnby.

"I'm not sure. I'm over here in search of a hint."

"And a very excellent idea, too!" said his hostess. "Because, if you will keep your eyes open in the American Colony, you'll see about everything which a man ought not to do; and after that it should be comparatively easy to make a choice among the few things that remain."

"You're not very flattering to the American Colony," said Andrew.

"That's because I belong to it," replied Mrs. Carnby, "and you'll find I'm about the only woman in it, able to speak French, who will make that admission. I belong to it, and I love it—for its name. It's about as much like America as a cold veal cutlet with its gravy coagulated—if you've ever seen that!—is like the same thing fresh off the grill. But I don't allow any one but myself to say so!"

"You're patriotic," suggested Andrew.

"Only passively. I'm extremely doubtful as to[47] the exact location of 'God's country,' and, even if you were to prove to my satisfaction that it lies between Seattle and Tampa, I'm not sure I should want to live there. America's a kind of conservatory on my estate. I don't care to sit in it continually, but, at the same time, I don't like to have other people throwing stones through the roof. But about what you want to do?"

"I really haven't the most remote idea. I want it to be something worth while—something which will attract attention."

"Nothing does, nowadays," said Mrs. Carnby, "except air-ships and remarriage within two hours of divorce."

"What are you talking about?" asked Mrs. Ratchett, suddenly abandoning the argument in which it was evident that she was coming out second best.

"My choice of a profession," replied Andrew. "I don't want to make a mistake. But everything seems to be overcrowded."

"Exactly," observed Radwalader. "It isn't so much a question of selecting what's right as of getting what's left. Haven't you a special talent?"

"I'm afraid not," said Andrew.

"And if you had, it wouldn't do you much good in the States," commented Mrs. Carnby. "Nothing counts over there but money and social position. It's the only country on earth where it's less blessed to be gifted than received."

"I had thought of civil engineering," said Andrew.

"Civil engineering?" repeated Mrs. Carnby. "But, my dear Mr. Vane, that's not a profession. It's only a synonym for getting on in society. We're all of us civil engineers!"

She pushed back her chair as she spoke.

"We'll wait for you in the salon," she added, "and, meanwhile, Mrs. Ratchett and I will think up a profession for Mr. Vane. Jeremy, you're to give them the shortest cigars you have."

"I was once in the same quandary," said Radwalader to Andrew, when the men were left alone, "and concluded to let Time answer the question for me. You may have noticed that Time is prone to reticence. So far, he has not committed himself one way or another."

"I'm afraid I haven't the patience for that," said Andrew. "Besides, it's different in America. One has to do something over there. It's almost against the law to be idle."

"Of course. The only remedy for that is to live in Paris. You might do that. It's a profession all by itself—of faith, if nothing else. Only one has need of the golden means."

"I think I am a homeopathist, so far as Europe is concerned," said Andrew. "I'm already a little homesick for the Common."

"It's a bad pun," answered Radwalader, "but is there anything in America but—the common?"

"You can't expect me to agree with you there."

"I don't. I never expect any one to agree with[49] me. It takes all the charm out of conversation. You may remember that Mark Twain once said that it's a difference of opinion which makes horse-races. He should have made it human races. That would have been truer, and so, more original. But a homeopathist is only a man who has never tried allopathy. You must let me convert you by showing you something of Paris. If I've any profession at all, it's that of guide."

"You're very kind," said Andrew, "but you mustn't let your courtesy put you to inconvenience on my account. There must be a penalty attached to knowing Paris well, in the form of fellow country-men who want to be shown about."

"'Never a rose but has its thorn,'" quoted Radwalader. "If you know Paris well, you're overrun; and if you don't, you're run over. Of the two, the former is the less objectionable. When we leave here, perhaps you'd like to go out to the races for a while? If you haven't been, Auteuil is well worth seeing of a Sunday afternoon."

"I should be very glad," said Andrew.

"Then we'll consider it agreed. I see Carnby is getting to his feet. He is about to make his regular postprandial speech. It is one to be commended for its brevity."

"The ladies?" suggested Jeremy interrogatively.

"By all means!" said Radwalader, as his cigarette sizzled into the remainder of his coffee. "It's a toast to which we all respond."

"By the way," said Ratchett, as they moved toward the portières, "I was going to ask you chaps about membership in the Volney."

The three men gathered in a group, and Andrew, seeing that they were about to speak of something in which he had no concern, passed into the salon. Here he was surprised to find three women instead of two—still more surprised when the newcomer wheeled suddenly, and came toward him with both hands outstretched.

"How do you do?" she said. "What a charming surprise! Mrs. Carnby was just speaking of you, and I've been telling her what jolly times we used to have last summer at Beverly. How delightful to find you here! Mrs. Carnby's my dearest friend, you must know, Mr. Vane."

"Miss Palffy is one of the few people to whom I always feel equal," observed Mrs. Carnby.

"I can say the same, I'm sure," agreed Andrew.

"That means that you and I are to be friends as well, then," answered Mrs. Carnby, "because things that are equal to the same thing are bound to be equal to each other. Are you going out with Jeremy, Margery?"

"Yes—our usual Sunday spree, you know. He's a dear!"

She bent over as she spoke and buried her nose in one of the big roses on the table.

"Lord, girl, but I'm glad to see you again!" said the inner voice of Andrew Vane.

The saddling-bell was whirring for the third race as Andrew and Radwalader slipped in at the main entrance of Auteuil, and made their way rapidly through the throng behind the tribunes, in the direction of the betting-booths beyond.

"We'll just have time to place our bets," said Radwalader, as he scanned the bulletins. "Numbers two, five, six, and eleven are out. Scratch them off your programme and we'll take our pick of the rest."

"You'll have to advise me," answered Andrew. "One couldn't very well be more ignorant of the horses than I am."

"I never give advice," said Radwalader, with an air of seriousness. "I used to, long ago. I went about vaccinating my friends, as it were, with counsel, but none of it ever took, or was taken—whichever way you choose to put it—so I gave it up. Besides, a French race-horse is like the girl one elects to marry. The choice is purely a matter of luck, and there's no depending upon the record[52] of previous performances. I've always thought that if I had to choose a wife, I'd prefer to do it in the course of a game of blind-man's buff. The one I caught I'd keep. Then the choice would at least be unprejudiced. Shut your eyes, my dear Vane, and stick your pencil-point through your programme. Then open them and bet on the horse nearest the puncture." And he went through this little performance himself with the utmost solemnity. "It's Vivandière," he added. "I shall stake a louis on Vivandière."

"And I, for originality's sake, shall choose Mathias, with my eyes open," said Andrew, laughing, as they took their places in line before the booth.

"Well, you couldn't do better," observed his companion. "He's a willing little beast, and not unlikely to romp home in the lead. I'd bet on him myself, except that I'm so damnably unlucky that it really wouldn't be fair to you, Vane. I never back a horse but what he falls. I had ten louis up, last Sunday, on a steeplechase, and the water-jump was so full of the horses I'd chosen that, upon my soul, you couldn't see the water! It was for all the world like the sunken road at Waterloo after the charge of the cuirassiers."

When they had purchased their tickets, Radwalader led the way to the front of the tribunes, and, mounting upon the bench along the rail, turned his back upon the course, and began to survey the throng in the tiers of seats above.

"This is my favourite way of introducing a newcomer to Paris," he said presently. "She never appears to better advantage than when she is togged out in her Sunday-go-to-race-meeting-best."

With his stick he began to point out people here and there, until, from a narrow gateway to their right, the horses filed out upon the track, and they turned, resting their elbows on the railing, to watch them go by.

"That's Vivandière," said Radwalader. "Poor animal! She runs the best possible chance of breaking her neck. If the jockey so much as suspected that I'd her number in my pocket, he'd probably have taken out a policy on his life. There's Mathias—the little chestnut. He looks in rattling good form. I suspect you haven't thrown away that louis."

"It wouldn't be a very ruinous loss, in any event," said Andrew.

Radwalder was choosing a cigarette from his case.

"I wonder," he answered, rolling it between his fingers, "if you'd mind my asking you if you mean that? To some people it would be a consideration; to others, none whatever. It isn't conventional, or even good form, to pry into a man's finances, but we shall probably be going about together, more or less, during your stay, and in such a case I always like to know how a man stands in regard to expenses. I don't want to embarrass you by proposing things you don't feel you can afford, still less to be a clog[54] upon you when you wish to go beyond my means."

He looked up, smiling frankly.

"Don't misunderstand me," he added. "It's not in the least an idle curiosity. I'm an old friend of Mrs. Carnby's, and it would be a great pleasure to do anything to make your visit a success. But, if you'll trust me, I'd be glad to know how you propose to live. You don't think me impertinent?"

"Not in the least," said Andrew. "I understand perfectly. It's a very sensible point of view. And I'll say candidly that my grandfather, Mr. Sterling, has been very generous; so that, unless I'm totally reckless, there's no reason why I shouldn't have the best of everything." He paused for a moment, and then added: "My letter of credit is for thirty thousand francs."

"Thank you," said Radwalader. "It makes things easier. I'd forgotten for the moment your relationship to Mr. Sterling, or I shouldn't have needed to take the liberty of speaking as I did. I met him once in Boston, I think. Isn't he called the 'Copper Czar'?"

"I believe he is," replied Andrew. "But there's not much in nicknames, you know."

"No, of course not," agreed his companion. "There goes the bell. For once, it's a fair start."

Far away, beyond the thickly-peopled stretch of the pelouse, a group of gaily-coloured dots went rocking rapidly to the left, vanished for an instant[55] at the turn, and then flashed into view again in the form of jockeys standing stiffly in their stirrups, as the horses swept down the transverse stretch. People were shouting all about them, and in Andrew's unaccustomed ears the blood surged and hammered madly. He was at the age when there is nothing more inspiring than such a play of life and action, under the open sky and over the close-cropped turf. The ripple of lithe muscles along the sleek flanks of the horses; the set, smooth-shaven faces of the rigid jockeys; the gleam of sunlight and colour; and the deep, crescendo voice of the multitude, swelling to thunder as the racers flew past—all these set his pulses tingling, until he, too, cried out impulsively in his excitement. It was his first horse-race, and his first glimpse of Paris into the bargain. There is more than enough in the combination to set young blood aglow.

"Houp! Houp! Houp!" With sharp, staccato cries of encouragement, the jockeys were raising their mounts at the water-jump, over which they sailed gallantly, one after another, like great brown birds, until the very last. There was a lisp of grazed twigs, a long "A-ah!" from pelouse and pesage alike, a dull splash which sent the spray flying high in silver beads and then a jockey in a crimson blouse rolled heavily forward on the turf, arose, stamped his foot, and swore profusely in picturesque cockney at his mare, who had regained her feet and, with dangling rein and saddle all askew, stood looking[56] back at him, as if uncertain whether to stop and inquire after his injuries or go on alone. Abruptly deciding upon the latter as the wiser course, she set off at a leisurely gallop, to the accompaniment of shrill, sarcastic comments from the crowd, and an additional exposition of the jockey's astonishing wealth of vocabulary.

"Voilà!" sighed Radwalader. "That was Vivandière! What did I tell you? It's absolutely inhuman of me to bet on a horse. And look at Mathias! He's twenty metres ahead of the rest, and going better every minute. You've hit it this time, Vane. There's one comfort. You'll win back my louis, at all events. It's something to know that the money's not going out of the family."

The crowd was already shouting "Mathias! C'est Mathias qui gagne!" as Andrew bent forward to see the horses wheel again into the transverse cut. Mathias was far in the lead, and seemed to gain yet more at the hurdle. The race was practically over, a thousand yards from the finish, and, as Mathias flashed past the post, a winner by twenty lengths, and Vivandière came ambling complacently in, at the end of the procession, with the stirrups bouncing grotesquely up and down, Radwalader replaced his field-glass with a deep sigh of resignation, and the two men went back toward the bulletins to see the posting of the payments.

It appeared, when the figures snapped into place, that Mathias returned one hundred and ten francs,[57] which meant a clear gain of ten louis. Andrew had "hit it" in good earnest.

"I think I shall adopt horse-racing as my profession," he laughed, as they cashed the ticket at the caisse. "Let's see: forty dollars a race, six races a day, seven days to the week—two-forty— twenty-eight—fourteen—sixteen—sixteen hundred and eighty dollars a week. By Jove! That's not bad, by way of a start!"

"The start's the easiest part of it," observed Radwalader. "Even Vivandière can manage that. It's the finish that counts, and the finish of horse-racing is commonly the penitentiary. It's the only profession where the hard labor comes at the end instead of at the beginning."