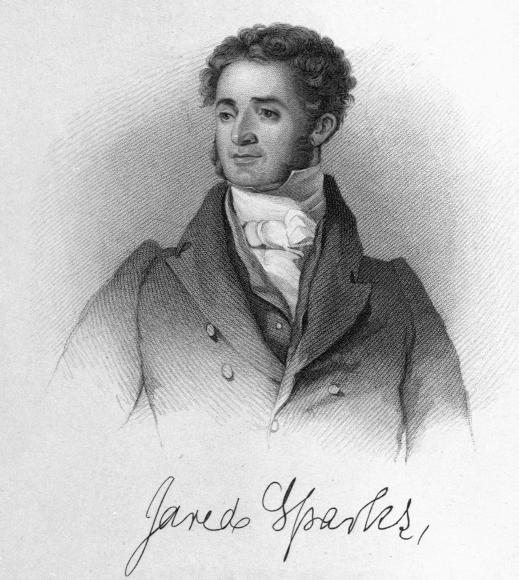

Jared Sparks

Jared SparksAnno Ætatis XL.

Title: Memoir of Jared Sparks, LL.D.

Author: Brantz Mayer

Release date: April 22, 2010 [eBook #32089]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Julia Miller, Diane Monico, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/americana)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/memoirofjaredspa00mayeiala |

Jared Sparks

Jared Sparks

Anno Ætatis XL.

By BRANTZ MAYER.

President of the Maryland Historical Society:

PREPARED AT THE REQUEST OF THE SOCIETY,

And read before its Annual Meeting,

On Thursday Evening, February 7, 1867.

Printed for the Maryland Historical Society,

By JOHN MURPHY.

Baltimore, 1867.

IT has been a sad but not entirely unpleasant duty to prepare, at the request of the Maryland Historical Society, a brief memoir of one of our earliest and most distinguished Honorary Members, the late Jared Sparks, LL.D. The duty, though sad, is not without a pleasant recompense, for the eulogium which a long-continued friendship and intercourse demand can be bestowed with cordial truth.

Mr. Sparks was what we call, in America, a self-made man. Although his life is a fair illustration of what an industrious person of talent and common sense may compass by decision of character and a high aim, my object in these observations is not to draw from his biography what has been aptly called "ostentatious precepts and impertinent lessons." By a self-made man I do not mean to class Mr. Sparks with that large and influential body of citizens whose portraits adorn the illustrated newspapers, and whose memoirs disclose the opinion[Pg 4] that the making of a great deal of money is the making of a very exemplary man. When I speak of Mr. Sparks as a self-made man I use the phrase in a sense of intellectual progress and success, founded on self-relying discipline,—of mental culture and mental fruit, bringing him up to honorable fame from low obscurity,—making him a lasting power in our nation, nay, throughout the world, in our best society, in our literature, in our institutions of learning; and, finally, bestowing on him the just pecuniary rewards always due, yet seldom obtained in America, by intellectual pursuits alone.

Jared Sparks, the son of Joseph and Eleanor Orcutt Sparks, was born in Willington, Connecticut, on the 10th of May, 1789. The dawn of his life was overshadowed by poverty. I do not know the character or pursuits of his parents, but certainly they were very poor; nor have I found any record of their early care over the child, or, that his youth was comforted by the love and society of a brother or sister. The most reliable account I have received of his infancy shows that he went, with the childless sister of his mother, and her wayward husband, to Washington county, New York, and that the eager boy obtained the scant elements of education at the public schools of those days; working, at the same time, on a farm for his livelihood, and sometimes serving a dilapidated saw-mill,[Pg 5] (his uncle's last resource,) whose slow movements afforded him broken hours to pour over a copy of Guthrie's Geography, which he always spoke of as a "real treasure."

Thus, there were no external influences to bring forth whatever powers were inborn in his character. Probably, it was in spite of those influences that he became a man of mark. His aunt, kind at all times, is chiefly remembered for her gentleness and beauty; his mother, for her devotion to reading, and mainly to the constant study of Josephus; while the grandmother of these ladies, Bethiah Parker, is mentioned as a singular enthusiast, who left to her posterity a manuscript volume of poems and letters peculiar only from the fact that, while they are vehicles of religious fervor, they are also autobiographical sketches, in which she discloses (in 1757) her prophetic visions of the "terrible times that are to come among the nations." There may have been some inheritance by the youth from his mother of a fondness for books, for he always spoke of her with great respect as a superior woman; but the probability is that the intellectual turn of his mind originated within itself, and was cherished by the affection he felt, and everywhere inspired as a boy, and the personal interest with which such a disposition is always repaid. His impressible mind was, doubtless, affected by the grand or beautiful scenery amid which his[Pg 6] early life was passed. He was a bright pupil of all his teachers. One of them he so soon excelled in acquirements that the honest pedagogue frankly advised him to seek an abler instructor. But that boon was not to be at once or easily obtained, for Jared was too poor to follow the master's advice; and, becoming apprenticed to a carpenter, he wrought at his trade for two years, still employing his spare time in study. He borrowed and mastered a common sailor's book on navigation. He taught himself the names and positions of the stars, and how to calculate the simpler problems of astronomy, the higher mysteries of which he also strove to unravel. For this purpose, he bought a large wooden ball, on which he marked the stars and traced the course of a celebrated comet; and finally he succeeded in calculating an eclipse. At sixteen, he seems to have lost entirely the care of his aunt and uncle, so that he was adrift in the world from that early period. But, his gentle and intellectual character had made him friends. His conduct was observed in that New England neighborhood, where such indications of worth are not only praised but protected. His employer, seeing the tendency of his mind and appreciating his talent, voluntarily released him from indenture, and his first impulse upon emancipation was to become, himself, a schoolmaster. He applied, at once, to the local authorities. The[Pg 7] school-committee examined and passed him; and being thus pronounced able to instruct, he taught in a small district on the outskirts of Tolland, until the scholars ceased coming during the summer, when Jared, for lack of means, was obliged to return for support to his saw and chisel.

Fortunately, however, he was not detained long at the work-bench. The story of a carpenter-boy studying Euclid and solving algebraic problems, made a stir in the village of Willington, where he then lived. Nor could the eager youth any longer study alone. Sparks became restless under the double goad of his ambition and his disadvantages, and plucking up courage, one day marched bravely into the presence of the Rev. Hubbell Loomis, an intelligent and cultivated clergyman, requesting his counsel and instruction. Mr. Loomis examined him carefully, and, taking him as an inmate of his house, taught him mathematics gratuitously, and induced him to commence the study of Greek and Latin, encouraging the spirit of independence—which was very lively in Sparks—by allowing him to shingle his barn as partial compensation for board and tuition.

Hitherto, the life of a schoolmaster had been his utmost ambition, and the trials he made satisfied him that, with his love of knowledge and desire to impart it, he would ultimately be able to succeed. The prospect of a college course had not yet dawned[Pg 8] on him. But, from his patron Loomis to others of greater influence the carpenter's merit spread wider and wider, until the Rev. Abiel Abbott, then a clergyman at Coventry, Connecticut, procured for him a scholarship at Phillips Exeter Academy, upon a benevolent foundation, to which meritorious pupils of limited means were admitted without charge for board and instruction. On the 4th of September, 1809, he left Tolland, Connecticut, and walked the one hundred and twenty miles to Exeter, New Hampshire, becoming a scholar of the Academy for two years. Here he first met, as fellow pupils, his life-long friends, Palfrey and Bancroft. He studied diligently, and made rapid progress; yet, anxious to preserve his independence, and to obtain what was necessary for his personal comfort without further tax on friends or obligation to strangers, he taught, during one winter of these two years, a school at Rochester in New Hampshire. In one of his memorandums he sums up his tuition thus: "the whole amount of my schooling was about forty months, which was the length of time I attended school before I was twenty years old."

But the great hope of his heart—a hope that had been gradually kindled—was at last to be realized, and, in 1811, at the age of twenty-two, through the active interest of President Kirkland, Sparks entered Harvard University, on a Pennoyer scholarship.[Pg 9] Yet, the res angusta domi pursued him still. It is said, that, "in consequence partly of ill health and partly of poverty," he was unable to pass more than two entire years, of his four, at Cambridge. To eke out a slender but necessary income, he obtained leave of absence during parts of his Freshman and Sophomore years, and spent the time as a private teacher in the family of Mr. Mark Pringle, at Havre de Grace, Maryland. He was there when the British, under Admiral Cockburn, plundered and partly destroyed the village; and here, probably, he enjoyed the only military experience of his life, by serving, as a private, in the Maryland militia, called out to guard the neighborhood. The inhabitants, it is related, generally fled to the woods, and but few, among whom was Sparks, remained to witness the barbarous behaviour of the enemy. Fifteen months of this leave of absence were, thus, spent in our State, in the bosom of an excellent and refined family, by whose members he was warmly esteemed; and, at length, he received his degree of Bachelor of Arts, at Harvard, with the class of 1815.

His college course, notwithstanding its interruptions, was successful. President Kirkland used to say, in his quaint way, "Sparks is not only a man, but a man and a-half." He graduated with high honors. In his senior year he gained the Bowdoin prize for an essay on the physical discoveries of[Pg 10] Sir Isaac Newton, an essay which is remembered in the traditions of the University as "a masterpiece of analytic exposition, philosophical method, lucid and exact statement."

This successful essay was, perhaps, the key of his life and character, for his mind was emphatically clear, exact, analytic, mathematical; and throughout his career, the same qualities were distinct in whatever he investigated or wrote. It has, indeed, been said that his merits were already recognized by the rival University of Yale, and that offers for his removal thither had been made during one of his years at Harvard; but the friendly influence of Dr. Kirkland prevailed over those allurements, and he remained constant to his patron and college.

The years 1816 and 1817 were passed by the graduate in teaching a private school at Lancaster, Massachusetts. He finished his college course at the advanced age of twenty-six, and had now added two years more to the score. At Lancaster he cultivated those habits of methodical industry which always characterized him afterwards. Soon after undertaking the school, he wrote: "I board at Major Carter's, a mile and a quarter from my school, to and from which I walk twice a day. I rose this morning an hour before sunrise, and rode five or six miles before breakfast, an exercise which I shall continue regularly. My school[Pg 11] occupies six hours, and I have resolved to devote, and thus far, have devoted, six hours of the twenty-four to study." Before this, he has a memorandum of walking from Cambridge to Bolton, twenty-six miles; setting out at half-past one, and arriving at Bolton at eight in the evening.

In 1817, at the age of twenty-eight, and two years after graduation, his alma mater recognizing the tendency of his mind towards the exact sciences, as well as the extent of his acquirements, chose him tutor in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Harvard. There also, very soon afterwards, chiefly under the instruction of the Rev. Dr. Ware, who was then the Hollis Professor, he commenced the study of divinity, pursuing it zealously during two years, being, at the same time, the "working editor" of the North American Review. Its numbers from May, 1817, to March, 1819, inclusive, were edited by him. In May, of the latter year, at the age of thirty, he was called to Baltimore and ordained in this city as the first pastor of the Unitarian church which had just been erected. On this memorable occasion, the Rev. Dr. William Ellery Channing preached that discourse in exposition of the Unitarian faith, which has been so widely celebrated, published, and read in America and Europe: a discourse which is said to have "caused more[Pg 12] remark on its theological views, while more controversy grew out of the statement of doctrines therein declared, than any single religious discourse in this country ever occasioned."

As clergyman of this congregation, Mr. Sparks remained a resident of our city for four years. He is well remembered in the families of his own church and of other religious societies, among whose members his firm but genial manners always made the studious and estimable gentleman a welcome guest. He was a steadfast laborer among his congregation; but the ultimate literary drift of his life was already beginning to develop itself, having probably received an impetus from his editorial task on the North American Review. In addition to his clerical duty in Baltimore, he did a great deal of work in editing the Unitarian Miscellany, in publishing his well-known Letters on the Comparative Moral tendency of the Unitarian and Trinitarian Doctrines, which drew on him the controversial notice of that renowned champion, Dr. Miller, of Princeton, and produced a discussion, which, instead of estranging the combatants, strengthened their personal relations, and increased their mutual confidence and respect. In after years, when Mr. Sparks required a Life of Jonathan Edwards for his American Biography, he selected Dr. Miller to write it, and, in the truly liberal spirit that[Pg 13] always governed his editorial labors, and, indeed, his whole literary life, published the memoir of the great Calvanist "without the alteration of a single word." It was here, too, in Baltimore, in consequence of a sermon against Unitarianism by the late Rev. Dr. Wm. E. Wyatt, of St. Paul's, that Mr. Sparks published his volume of Letters on the Ministry, Ritual, and Doctrines of the Protestant Episcopal Church. It was in Baltimore, in 1822, that he arranged and began the republication of Essays and Tracts in Theology by Wm. Penn, Bishop Hoadley, Newton, Whitby, Evelyn, Locke, and others. It was in Baltimore, also, during his religious ministry, that he received the flattering tribute from Congress of being elected its Chaplain. This was a great honor, won in ten years, by the Harvard student of 1811; and although his election alarmed the clergy and laity of other Christian denominations, and a member of Congress declared they had "voted Christ out of the House," still, in time, Congress learned to know him better, to admit the tolerance of his catholic spirit, and to honor him with increased confidence. But, in 1823, after four years of labor in our city, Mr. Sparks's health became so much impaired that he resolved to retire from the Church entirely, and devote himself exclusively to literature. Yet, he always loved Baltimore; he always met the people with[Pg 14] warmth, and recurred joyfully to the happy years he spent in Maryland as teacher and minister. At the beginning of the late rebellion he wrote to me concerning an address published by one of our patriotic citizens: "I could not," said he, "but approve most highly its candor and independent tone, and the enlightened and just views it presented of our public affairs. It furnished a demonstration that there were brave spirits and true in your city, notwithstanding the misgivings which many, in this quarter, had, at that time, begun to indulge. Most heartily do I wish prosperity, good fortune, and success to Baltimore. With no place have I more deeply cherished associations. May peace, quiet, and brotherly sympathies prevail within her borders." And again, at a later day, he wrote in the same strain of affectionate memory of our city and its people: "I take a lively interest in all that concerns Maryland both present and past. I have not forgotten that my home was once there. I have many and deeply cherished recollections of Baltimore, which will remain in my heart and mind while the power of memory continues to act. The order of Providence and strange events have produced changes, but it is Baltimore, still." Such were the sentiments of this excellent man towards our state, and city, and people. They continued to be cherished by him[Pg 15] to the last hour of his life, and were warmly repeated to me in one of the last letters he ever wrote, received but a day or two before his death. He left Baltimore reluctantly; his congregation parted with him painfully, and its farewell letter, written and signed by the late Chancellor of our state, Theodorick Bland, bears the most honorable testimony to the success of his pastoral labors.

Yet, probably, it was not ill health alone that determined Mr. Sparks's removal to Boston. I think he had already set his heart on the great themes of National History, and resolved, if possible, to pursue the work faithfully by the acquisition of the vast and scattered materials it needed. Upon his arrival in Massachusetts in 1823, he purchased the North American Review, and became its sole editor from January, 1824, to April, 1830. In these seven years his industrious pen contributed no less than fifty articles, many of profound study, and all adding to the solid critical literature of America. It was in 1828 that he made his first elaborate biographical essay in the attractive Life of John Ledyard, the American Traveller. About this time, too, good fruits were borne to him by his previous residence in Baltimore and the acquaintance he had made with the illustrious men who, in those days, were found every winter[Pg 16] in Washington. In that city his worth had been recognized by the descendants of prominent revolutionary personages, by leading legislators and public functionaries from the several States, and, particularly, by such persons as Chief Justice Marshall, the biographer of Washington, and his nephew Bushrod Washington and Mr. Justice Story, both, at that time, Associate Judges of the Supreme Court. Thenceforward, the idea that had taken possession of his mind on the temporary failure of his health at Baltimore—"the city of noble souls, of large-hearted men," as he was wont to call it—became the ruling purpose of his life. He was to run the career of a man of letters, and in a country hardly ripe for literary production. American history was to be his occupation; all things else became subservient to this great purpose. He had conceived the project of collecting the correspondence of Washington, and of gathering all the accessible documents in this country and Europe necessary for an authentic life of the great chief. On his first application for the Washington manuscripts, which Mr. Justice Bushrod Washington had intended to edit, Mr. Sparks was told, much as he was respected, he could by no means have them. Yet, his journal of that date has no complaining, despondent mention of the rebuff, for, on that very day he set forth from the city of Washington on[Pg 17] his journey to the South, in quest of other materials; and, with a light, confident, indefatigable spirit, went on patiently collecting them from public and private sources, everywhere finding profitable work, and, with marvellous keenness and sagacity, choosing and appropriating whatever he should want for the great task which it was his destiny to accomplish. Our archives at Annapolis, scant and neglected as they unfortunately are, still bear marks of his diligence; and, years after his task was completed in our State House, I have found, among our documents, the frequent traces of his minute and accurate labors. This, I am told, was a life-long trait of his preparation, for he always provided himself with every species of preliminary information which could lead to what he did not possess, in case, at some future day, it might become useful or necessary. His memorandums, therefore, were copious and explicit. Indeed, he became so familiar with the archives of the several States, that from his study in Massachusetts, he could readily, without a fresh journey, command the desired documents, and always indicate the department, and, generally, the shelf, book, or bundle in which the coveted manuscript was to be found by his correspondents. And, so he went on cheerily from state to state and family to family, increasing his[Pg 18] national treasures, until, at last, the richest of the American collections was yielded to him by the Washington family and the government. The manuscripts at Mount Vernon—the entire correspondence of Washington and his papers—arranged by him in more than two hundred folio volumes; the state papers of the "old thirteen," and the private papers of many of the civil and military leaders of the Revolution, were opened to his inspection, and some of them actually placed in his possession for ten years, while engaged in the composition of his great work.

This would have been anxious labor even for a man of leisure, robust health, and a fortune that secured him from all care for present support or comfort. But Sparks was still poor, and, while engaged in this expensive preliminary task of mere accumulation—a task that might produce profitable results after many years—he was also obliged to provide for the needs of the passing day. His ready talent and economical habits enabled him to do it.[1] Nor did he rest satisfied with what he found in the United States or could gain by correspondence from abroad. He went to Europe to complete his researches; and the national[Pg 19] and private archives of France and England, which had hitherto been closed to American students, were soon unlocked for him through the personal solicitations in his favor of Sir James Mackintosh, Mr. Lockhart, Mr. Hamilton, Lord Landsdowne, and Lord Holland, in Great Britain, and of General Lafayette, Monsieur Guizot, and Monsieur de Marbois in France;—another proud achievement by the charity student of 1811. I may add here, at once, that Mr. Sparks paid a second visit to Europe in 1840, in order to examine its archives; on that occasion, discovering, in the French cabinet, the original letter of Franklin and the famous map with our North-eastern boundary delineated by a "red line," which were so much discussed in the subsequent negotiations with Great Britain in regard to our limits in that quarter.

The first fruits of these domestic and foreign studies was Mr. Sparks's valuable publication, in 1829-30, of the Diplomatic Correspondence of the Revolution; followed, after two years, by the Life of Gouverneur Morris, with selections from his correspondence and miscellaneous papers. In 1830, he originated and edited that excellent annual, so long a favorite in our country, known as the American Almanac; and, about the same time, he began his Library of American Biography, extending, in two series, to twenty-five volumes, for which[Pg 20] he composed the charming biographies of La Salle, Ribault, Pulaski, Benedict Arnold, Father Marquette, Charles Lee, and Ethan Allen.

Meanwhile, his attention to the great work—the Life and Writings of Washington—never flagged. Of course, the labor of careful selection, arrangement, and illustration was immense. His apartment in Ashburton Place, Boston, was covered from floor to ceiling with volumes and packages; nor did he ever leave it until his completed task of ten or twelve hours' work, freed him, after night, for a healthful walk and a refreshing visit to friends. Ten of these busy years were thus spent in the preparation, printing, and publication of the Life and Writings of Washington, which was finally given to the world, volume by volume, between 1834 and 1837, in twelve stout octavos, at a cost, I understand, of about one hundred thousand dollars. In 1840, appeared his other great national book, the Life and Works of Franklin, in ten massive octavos, comprizing, among other valuable papers discovered by him, no less than two hundred and fifty-three letters of the philosopher, never before printed, and one hundred and fifty-four not included in any previous edition. To this superb collection he added the "Life" as far as it had been written by Franklin himself, and continued it, from his own materials, to the patriot's death.[Pg 21]

In seventeen years, and at the age of fifty-one, he had won the highest honors of literature, and the right to have his name linked forever, throughout the world, with the names of Franklin and Washington. Nor were these honors less dear to him when he reflected that he had reached the mature age of thirty-four before he had a real purpose in life, and that, in spite of adverse fortune, he had accomplished his designs by the force of character, by self-denial and indomitable industry.

In 1852-3, occurred the singular controversy between Lord Mahon, Mr. W. B. Reed, and Mr. Sparks, in regard to the manner in which the latter had edited Washington's Writings. It was conducted by our late colleague with good temper and success. He vindicated his facts and plan from all assaults, foreign and domestic, and was, doubtless, vastly aided by the exact method with which his letters, documents, and references had been arranged for his great work. For, preparation was, at once, his task and his strength. He always wrote rapidly and alone, without the aid of an amanuensis, as soon as he was prepared to compose. He then worked with great perfection and ease to himself, because the materials were not only at hand but thoroughly digested. When asked how long a time would be required by him to make an abridgement of his Life of Washington, while he was still busy with his Franklin, his[Pg 22] reply was, "No time!" and the printer never waited for him a moment, so keen and clear were his decision and sense of proportion.

In 1854, he published the Correspondence of the American Revolution, in letters from eminent men to General Washington from the time of his taking command of the army to the end of his Presidency. This valuable addition to his historical series was prepared from the original MSS., and terminated Mr. Sparks's important contributions to our national stores. It has been said that he contemplated a History of the Foreign Diplomacy of the Revolution, and it is quite certain that he intended to write a History of the Revolution, itself, preceding it, probably, by several volumes on our Colonial history. As I heard Mr. Irving once say that the biography of Washington was not a task to his liking, for "he had no private life" to give it the personal interest essential to secure the reader's sympathy; so it may truly be said, from the constant publicity of the Chief's career, that his life, during most of it, was the life of his country. Nevertheless, Mr. Sparks felt that it was, in truth, biography and not history, and he sought a more extended field, for which he considered his powers to be, as doubtless they were, entirely equal. His collection of materials for this purpose was rich, completed, and bound in volumes;[Pg 23] but his noble intention was, unfortunately, frustrated, and with it perished his most cherished hope. He always regretted his inability to go on with this work. All his other publications, valuable as they were, in his estimation had been but preparatory. In 1850 he broke his right arm, which was already weakened by a neuralgic affection contracted by long years of labor at the desk. This, ever afterwards, made the use of a pen extremely irksome. Under the weight of these mixed evils of nervous malady and fractured limb, his task was procrastinated; yet, his patient hope was profound. The conflict between the desire to achieve and the disability was so painful, that the subject of his projected History became a sacred one among all who were familiar with him, and, even in his family, it was passed over in silence. At times, he would look at these accumulations of years in his library, with the simple ejaculation, "sad, sad!" When others alluded to them, he had some light reply: "you are a younger man; do you work?" It was his great grief that the mine of golden ore was at hand, but that he could work no more. Yet, he never ceased to be prepared, by adding constantly to his materials; and, even in the last year of his life, he exclaimed, at times, "I think I may soon go on!" He never ceased to look forward to the time[Pg 24] when his infirmity would allow him to march once more in pursuit of what had become the "Evangeline" of his life, the only work worthy of his mature powers:

The rich collection he had amassed for this History of the American Revolution, carefully arranged and bound in volumes, was bequeathed to his son, ultimately to pass to the Library of Harvard University. I understand his heir has already discharged the trust by depositing these treasures in the institution where their collector designed they should be permanently preserved.

Although the life of Mr. Sparks as an author may be said to have terminated with his last original publications, he, nevertheless, did not withhold himself from an active interest in the cause of letters. He had been appointed McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History at Cambridge, in 1839; and for the ten following years, in the midst of other work, performed the duties of that chair, until, on the resignation of President Edward Everett, his alma mater bestowed her highest honor by electing him President of Harvard. This was the finale of a career of successful labor extending through thirty-eight years. His Presidency was[Pg 25] acceptable as well as popular; especially commanding the confidence and affectionate respect of the pupils. He was no martinet, but fostered the manhood of the generation entrusted to his government. A friend who was present in Cambridge, and well acquainted with Mr. Sparks's administration of the Presidency, tells me that its peculiarity was the parental character of his intercourse with the under-graduates. After the stateliness of some of his predecessors, this bland demeanor of the new President alarmed by its supposed relaxation of a discipline which the over-nice are accustomed to enforce by a stern preservation of cold formality; yet, even the critics who considered him a little slack, did not fail to see that he won the love of all, while many a poor fellow in disgrace felt quite inclined to bless a rod which fell in such sweet mercy.[2]

For three years, the successor of Kirkland, Quincy, and Everett held the responsible Presidency; nor, in all that period of watchfulness, did he ever forget or neglect the striving, indigent students, who required a helping hand in the days of their adversity. His works had made him independent in fortune, so that, wherever assistance was needed, his was an open but judicious hand. "In the days of his prosperity," it is said by one who knew him well, "he returned to his original benefactors not only the money he had received from them, but more than the interest." On resigning the Presidency of Harvard he retired to the property he owned in Cambridge, where, in the enjoyment of society, of favorite studies, and of a large correspondence and intercourse with friends and distinguished strangers, he passed the remaining years of a tranquil life, which ended, after a short and painless malady, on the 14th of March, 1866, in the seventy-seventh year of his age. The summons to eternity was sudden; but the faith and the life of the veteran sustained him to the close. As he was consciously approaching it, "I think," said he, feebly, "I shall not recover,[Pg 27] but I am happy." And when asked whether he was rightly understood as saying he was "happy," his answer was, "certainly!"

Mr. Sparks was twice married; first, in 1832, to Frances Anne Allen, of Hyde Park, New York, who died in 1835; and again, in 1839, to Mary C. Silsbee, daughter of Nathaniel Silsbee, a wealthy and honored merchant of Salem, for many years a Senator of the United States from Massachusetts, as colleague of Daniel Webster. Four children, a son and three daughters, all the offspring of the second marriage, survive, with their mother, to rejoice in the memory of their illustrious father.

The amount of Mr. Sparks's literary labor and its popular estimation, maybe judged from the fact that more than six hundred thousand volumes of his various publications have been published and disposed of.

In personal appearance Mr. Sparks had a noble presence, a firm, bold, massive head, which, as age crept on, sometimes seemed careworn and impassive; but never lost its intellectual power. His portraits show that in his prime his face was remarkable for dignified, manly beauty. His manners were winning; and, though undemonstrative and rather reticent among strangers, with friends, he was always cheerful and hearty. He was never dogmatic, patronizing or repulsive, by that self-assertion into which superior men are too often[Pg 28] petted by the subservient deference of society. He had large social resources, but, withal, was modest without being shy. His character was, indeed, a perfect balance of charming qualities. Though moderate in the announcement of opinions, and too patriotic to degenerate into a partizan, he gave no timid, lukewarm support to the nation in its hour of trial. His knowledge of the world was ample; but that excellent lore did not always save him from the overreaching, so that, at one time, he lost much of the hard-earned avails of his labors, and though not impoverished, was uncomfortably straitened. Yet, he loved to be trustful and serviceable; and, what he knew, he gave cordially to friends, correspondents, and respectful strangers who approached him properly. He desired to stimulate the young by truthful approbation, and, from his recognized eminence, to bestow the "nutritious praise of veteran talent." He was never spoken of lightly. Large and active as was his mind, "his heart," unlike Fontenelle's, was not "made of his brains." He was as pure, affectionate, and charitable a man in all his relations, as he was eminent in the literature he created and consecrated to his country.

An author's life is commonly a catalogue of his works. The career of a scholar is generally uneventful, seldom possessing those stirring traits which give dramatic interest to public characters[Pg 29] of less quiet pursuits. Mr. Sparks was not an exception to this rule. His life is in his works; for, as long as he could work well he was a worker for his country.

The few and simple facts I have told of this gentle student's struggles and success, show that his labors were mostly in the field of History. But, the field of History is large and sub-divided. It comprehends Annals, Chronicles, Memoirs, Biography; and these—the essence of the past—become the elements from which an artist endowed with disciplined judgment and combining imagination, shapes the master-pieces which are properly called by the generic name, History.

It has been usual to associate the name of Mr. Sparks with those of Bancroft, Prescott, Motley, and Irving; yet, the qualities of these writers, as well as the tasks they set themselves, seem to me quite different from those of our late associate.

If History may be properly defined, as I think it should be—a narrative of national life, claiming the utmost comprehension of fact, date, description, biography, annals, and chronicle, woven together with brilliant analysis and wholesome philosophy,—I hope I may not be considered unjust in the opinion that, as yet, our country has but one writer who will be classed with Hume and Gibbon. This is certainly no disparagement of others, for it is,[Pg 30] probably, the result of extent of aim rather than of quality or power. No American, of acknowledged superiority, has yet equalled George Bancroft in the breadth of his theme, the extent of time and place covered, the variety of character, circumstance, and nationality concerned, the corresponding research, the sparkling story, and the philosophic analysis of his National History.

Prescott, the prince of scholars and gentlemen, matchless in the department he chose, was rather a biographer than a historian. He selected stirring epochs and their prominent men, the pivots of certain times, upon whom the affairs of two worlds turned at critical periods,—the great warders who stood at the portals of America and Europe in the sixteenth century. Thus, Ferdinand and Isabella, Cortez, Pizarro, Charles V., and Philip II., wonderfully as they revive in the books of Prescott, exquisite in accuracy, harmonious style, and enamelled finish, are but beautiful cabinet-pictures of the princes and heroes of the age. The Life of a Nation requires a taller and wider canvas, a bolder and broader brush. And, so it is with the historical labors of Irving and Motley, though the latter has closely approached the true grandeur of History in his narrative of the Rise of the Dutch Republic. Yet, it must ever remain as the highest praise of our late colleague, that, in the field of[Pg 31] national biographies, national in all their elements, he stands beside the masters on the platform of acknowledged success. He was the real pioneer in the unexplored wilderness of our historical literature. "Indeed," says one familiar with his works, "it requires considerable knowledge on the part of a reader, a knowledge of the state of things, of the obstacles and perplexities, in the way of effort, and of the hard conditions of success, at the time when Mr. Sparks gave himself to his large and costly enterprise, in order that his eminent devotion and success may be, even in degree, appreciated." But he brought together the dispersed fragments of colonial and revolutionary days, and made the writing of history untroublesome for authors who, in "slippered ease" and comfortable libraries, availed themselves of his labor, and patronizingly patted him on the head. These are the silk-worms of literature, whose glory is spun from the digested leaves of other men's culture. It was his habit, when allusions were made to such appropriations, to find sufficient reward in his own diligence, and to comfort himself for this "way of the world" by a patient shrug and a pinch of snuff.[3] Irving, in his advanced life,[Pg 32] could never have written his Washington, had not Sparks organized his twelve volumes of materials, and analysed them in the biography. That work must be studied, in order to be appreciated in relation to Mr. Sparks's literary merit: it is a mine of editorial tact and industry, displaying the mathematical spirit of the author in its method and organization, in its lucid statements, and in his sagacious perception of the value of what was retained and the worthlessness of what was rejected, so that Washington is self-shown to the hereafter by what he thought, and wrote, and did. The commendation bestowed on Mr. Sparks, in the masterly eulogium of Mr. Haven before the American Antiquarian Society, may be taken as a wise and exact definition of his labors in the field of History: "Not that Mr. Sparks," said he, "limited himself to the preparation and preservation of history in bulk; for he was equally able in narrative, in criticism, and in controversy,—he was an essayist as well as a compiler; but the last was his forte, his peculiar field of usefulness and eminence, where, it may be said, he reigns supreme."

This estimate of Mr. Sparks by his friend does not classify him with the annalist and chronicler who build up a fleshless skeleton of facts and dates. Nothing could be less just to the subject or the[Pg 33] commentator. Imagination was not a predominant quality of Mr. Sparks's mind. Its cool precision so curbed the exercise of the ideal faculty that it was unjustly subdued if not absolutely stifled; and thus we do not always discern in him that creative power, so rarely found combined with sagacity in gathering and marshalling details, which, while it apprehends the true relation of men and circumstances, masses the historic groups with picturesque effect, delineates character with intuitive insight, gives soul to the moving drama of national life, and vividly realizes the scenes and personages of the past. But, if he was not so brilliant in description as others, or in the majestic and harmonious march of his story, or in keen scrutiny of character, he unquestionably excelled in ample, direct, and truthful statement, so that his narrative was not only transparent in the fulness of detail, but the detail itself disclosed its philosophic lesson. No man can charge him with hasty or capricious censure. He was always the careful protector of human reputation, dealing with the unresisting and undefending dead as their advocate as well as righteous judge; reluctant to condemn by argument or inference, and never unless the proved facts were irresistible. He studiously discarded all that might either attract or detract by fancy or elaborate discussion; in a[Pg 34] word, he shunned ambitious rhetoric, so perilous to solid judgments, and so often giving false color to historical portraits, for he knew the risk of losing the reliable in the brilliant. In his style, he was an artless artist, if there is truth in Thackeray's observation, that the "true artist makes you think of a great deal more than the objects before you." His extreme calmness may have, sometimes, made him cold; yet, by conforming himself to plain forms of language, he always aimed to convey the absolute truth, which he regarded as the coveted prize of history. For history, to his mind, was a serious thing, not a melodramatic tale, and he wrote it as he would have delivered testimony in the presence of God. His desire was that the fact and not the form should fascinate and teach; because the fact was permanent and independent, the form flexible and voluntary. No one knew better or more dreaded the risk of biasing opinion by over or under-statements concerning the conspicuous persons of whom he wrote. If his theme was not so large as Mr. Bancroft's, he still felt that both addressed the American nation in words that were to last, concerning the founders of our political system and the Chief who presided at the foundation. What he recorded was to form the opinions of posterity, and thus, not merely to influence but virtually to become a principle of[Pg 35] action for his countrymen in relation to the great things that concern patriots. Enthusiastic, yet, never excited; patient, and devoid of partizanship; he had the rare faculty of writing so fairly of men of a near period that his books were satisfactory to every one, save Lord Mahon. He never wrote a sentence that was not in the interest of his whole country. He was so calmly judicial in temper, that he found it easy to convert himself into what Madame de Stael so happily called "contemporaneous posterity."

His life demonstrates that cultivated talents, independent self-respect, and industry in intellectual pursuits, not only secure reputation but fortune. It is a plea for wholesome literature in our land. Literature, though never a speculation in his hands, was, as he conducted it, a successful enterprise. His career was charmingly rounded by honor, prosperity, and the love of mankind. In all respects it was a requited life. Be it said, with reverence, that, considering the difference of their fields, there is a singular concord between the virtues and common sense of Washington and Sparks, and hence the sympathetic veneration of the Author for the Hero. If I attempted to characterize him briefly, I might say that he attained all the ends of an ambitious life without being, at any time, ambitious. He was certainly not devoid[Pg 36] of a love of approbation, but it was not the selfish end for which he wrought; for, with him, approbation bestowed was only a recognition of the fact that his endeavor to be a good and useful man had been successful.

"Dignum laude virum Musa vetat mori."

[1] He good-humoredly described himself as "dependent on his wits and daily exertions for a living; and this, too, with small abilities for making, and still less for keeping, money."

[2] The Rev. James Freeman Clark relates a characteristic anecdote of Dr. Sparks's demeanor to the Harvard scholars, which is worthy of repetition: One of the pupils, as he left the recitation-room, made a noise derisive of a tutor. The tutor stated the fact to the faculty, with the names of several, who, if not guilty, might know the real offender. They were summoned before the faculty, and President Sparks was desired to ask them, one by one, "if they made the noise, or, knew who made it?" Dr. Sparks had previously said to the faculty that they could not expect to get the information thus, or suppose the boys would inform on their fellows; the invitation to falsehood was too great. When they came before him, Dr. S. addressed them to the following effect: "I have been requested by the faculty to ask you if you made, or, know who made, the disturbance at the close of your recitation. I state to you their request; but, if you know who made the noise, I do not intend to ask you to tell." The answers were various; till, at length, one said: "I did it. I know I ought not to have done it, and am sorry. I hardly know why I did it; yes, I should say it was because I did not like the tutor, who, I thought, had not used me fairly in some of my recitations." Having told the truth, and acknowledged his fault, Dr. Sparks thought the youth should be commended instead of punished; but the tutors outvoted the others, and he was suspended. The President, however, wrote a note to his father, saying he considered it no dishonor, as young men did not often have such opportunities to show themselves frank and noble. (Memoir of Sparks, Hist. Mag., vol. x., p. 153.)

[3] No candid student in lauding Mr. Sparks, should fail to acknowledge our debt of gratitude to Peter Force, for his vast and successful labors in recovering and rendering accessible the large stores of materials for American history and biography contained in the "American Archives."