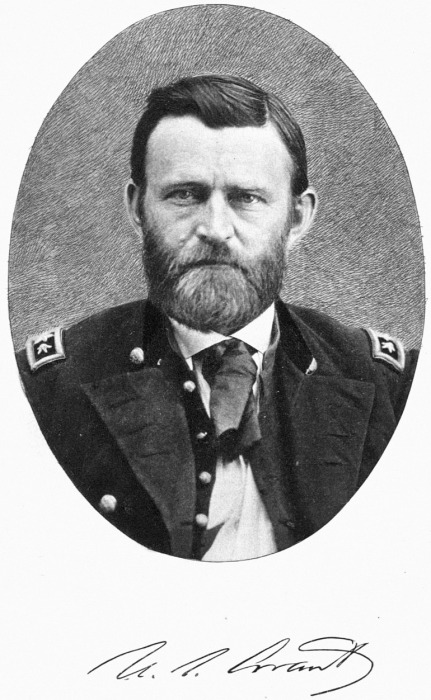

Title: Ulysses S. Grant

Author: Walter Allen

Release date: March 22, 2009 [eBook #28386]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Since the end of the civil war in the United States, whoever has occasion to name the three most distinguished representatives of our national greatness is apt to name Washington, Lincoln, and Grant. General Grant is now our national military hero. Of Washington it has often been said that he was "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen." When this eulogy was wholly just the nation had been engaged in no war on a grander scale than the war for independence. That war, in the numbers engaged, in the multitude and renown of its battles, in the territory over which its campaigns were extended, in its destruction of life and waste of property, in[Pg 2] the magnitude of the interests at stake (but not in the vital importance of the issue), was far inferior to the civil war. It happens quite naturally, as in so many other affairs in this world, that the comparative physical magnitude of the conflicts has much influence in moulding the popular estimate of the rank of the victorious commanders.

Those who think that in our civil war there were other officers in both armies who were Grant's superiors in some points of generalship will hardly dispute that, taking all in all, he was supreme among the generals on the side of the Union. He whom Sherman, Sheridan, Thomas, and Meade saw promoted to be their commander, not only without envy, but with high gratification, under whom they all served with cordial confidence and enthusiasm, cannot have been esteemed by them unfit for the distinction. If these great soldiers then and always acclaimed him worthy to be their leader, it is unbecoming for others, and especially for men who are not soldiers, to contradict their judgment.

Whether he was a greater soldier than General Robert E. Lee, the commander-in-chief of the army of the Confederate States, is a question on which there may always be two opinions. As time passes, and the passions of the war expire, it may be that wise students of military history, weighing the achievements of each under the conditions imposed, will decide that in some respects Lee was Grant's superior in mastery of the art of war. Whether or not this comes about, Lee can never supplant Grant as our national military hero. He fought to destroy the Union, not to save it, and in the end he was beaten by General Grant. However much men may praise the personal virtues and the desperate achievements of the great warrior of the revolt against the Union, they cannot conceal that he was the defeated leader of a lost cause, a cause which, in the chastened judgment of coming time, will appear to all men, as even now it does to most dispassionate patriots, well and fortunately lost.

In the story of Grant's life some things[Pg 4] must be told that are not at all heroic. Much as it might be wished that he had been what Carlyle says a hero should be, a hero at all points, he was not a worshipful hero. Like ourselves all, he was a combination of qualities good and not good. The lesson and encouragement of his life are that in spite of weaknesses which at one time seemed to have doomed him to failure and oblivion, he so mastered himself upon opportune occasion that he was able to prove his power to command great and intelligent armies fighting in a right cause, to obtain the confidence of Lincoln and of his loyal countrymen, and to secure a fame as noble and enduring as any that has been won with the sword.

This hero of ours was of an excellent ancestry. Until lately, most Americans have been careless of preserving their family records. That they were Americans and of a respectable line, if not a distinguished one, for two or three generations back, was as much of family history as interested them, and all they really knew. This was especially true of families which had emigrated from place to place as pioneers in the settlement of the country. Family records were left behind, and in the hard desperate work of life in a new country, where everything depended on individual qualities, and forefathers counted for little in the esteem of men as poor, as independent, and as aspiring as themselves, memories faded and traditions were forgotten. It was esteemed a condition of the equality which was the national boast[Pg 6] that no one should take credit to himself on account of distant ancestry. Not until Abraham Lincoln had honored his name by his own nobility did anybody think it worth while to inquire whether his blood was of the strain of the New England Lincolns.

All that was known of the Grants in Ohio was that Jesse, the father of Ulysses, came from Pennsylvania. Jesse himself knew that his father, who died when he was a boy, was Noah Grant, Jr., who came into Pennsylvania from Connecticut, and he had made some further exploration of his genealogical line. But this was more than his neighbors knew or cared to know about the family, until a son demonstrated possession of extraordinary qualities, which set the believers in heredity upon making investigation. The Grants are traced back through Pennsylvania to Connecticut, and from Connecticut to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where Matthew Grant lived in 1630. He is believed to have come from Scotland, where the Grant clan has been distinguished for centuries on account of its sturdy indomitable traits and[Pg 7] its prowess in war. The chiefs of the clan had armorial crests of which the conspicuous emblem was commonly a burning mountain, and the motto some expression of unyielding firmness. In one case it was, "Stand Fast, Craig Ellarchie!" in another, simply "Stand Fast;" in another, "Stand Sure." Sometimes Latin equivalents were used, as "Stabit" and "Immobile." It is said that, as late as the Sepoy rebellion in India, there was a squadron of British troops, composed almost entirely of Scotch Grants, who carried a banner with the motto: "Stand Fast, Craig Ellarchie!"

If it be true that our General Grant came from such stock, his most notable characteristics are no mystery. It was in his blood to be what he was. Ancestral traits reappeared in him with a vigor never excelled. But they had not been quite dormant during the intermediate period. His great-grandfather, Captain Noah Grant, of Windsor (now Tolland), Conn., commanded a company of colonial militia in the French and Indian war, and was killed in the battle of[Pg 8] White Plains in 1776. His grandfather Noah was a lieutenant in a company of the Connecticut militia which marched to the succor of Massachusetts in the beginning of the Revolution. He served, off and on, through the war.

Regarding the circumstances of the removal to Pennsylvania little is known. The home was in Westmoreland County, where Jesse R. Grant was born. Soon afterwards the family went to Ohio. When Jesse was sixteen he was sent to Maysville, Ky., and apprenticed to the tanner's trade, which he learned thoroughly, and made the chief occupation of his life. Soon after he reached his majority he started in business for himself in Ravenna, Portage County, Ohio. In a short time he removed to Point Pleasant, on the Ohio side of the Ohio River, about twenty miles above Cincinnati. Here he lived and prospered for many years, marrying, in 1821, Hannah Simpson, daughter of a farmer of the place in good circumstances. The Simpsons were also of Scotch ancestry, and of stout, self-reliant, [Pg 9]industrious, respectable character, like the Grants. Thus in the parents of General Grant were united strains of one of the strong races of the world,—sound in body, mind, and soul, and having in a remarkable degree vital energy, the spirit of independence, and the staying power which enables its possessors to work without tiring, to endure hardships with fortitude, and to accumulate a competence by patient thrift. This last ability General Grant lacked.

These parents, like those of the majority of Americans of the old stock, thought it no dishonor to toil for livelihood, cultivating their souls' health by performance of daily duty in fidelity to God, their country, and their home. Jesse R. Grant had slight opportunities of schooling, but he had no contempt for knowledge. Throughout his life he was a diligent reader of books and newspapers, and was rated a man of uncommon intelligence and of sound judgment in business. He was an entertaining talker, and a newspaper writer and public speaker of local celebrity. Through his early manhood,[Pg 10] while he lived in Ohio, he was a farmer, a trader, a contractor for buildings and roads, as well as a tanner. When he reached the age of sixty, having secured a comfortable competence, he retired from active business. In his declining years he removed to Covington, Ky., near Cincinnati. Mrs. Grant was a true helpmate, a woman of refinement of nature, of controlling religious faith, being from her youth an active member of the Methodist Church, of strong wifely and maternal instincts. Her life was centred in her home and family. Both these parents lived to rejoice in the high achievement and station of their son Ulysses.

Of such ancestry General Grant was born April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, and was named Hiram Ulysses Grant. A picture of the house in which he was born shows it to have been a small frame dwelling of primitive character. Its roof, sloping to the road in front, inclosed the two or three rooms that may have been above the ground floor. The principal door was in the middle of the front, and there was one small window on each side of it. Apparently there was a low extension in the rear. This manner of house immediately succeeded the primal log cabins of the Western States, and such houses have sufficed for the happy shelter of large families of strong boys and blooming girls, as sound in body and soul, if not so refined and variously accomplished, as are reared in mansions of more pretension. Love, virtue, [Pg 12]industry, and mutual helpfulness made true homes and bred useful citizens.

In the next year his parents removed to the village of Georgetown, Ohio, in Brown County, where the father continued his business of tanner. There young Grant lived until he became a cadet in the Military Academy at West Point. His life was that of other boys of like condition, with few uncommon incidents. Being the eldest of an increasing family, it naturally happened that he was required to perform a share of work for its support, and to bear responsibilities. In his early youth his employment was in the farm work, and this he always preferred. He had a native liking for the open air, and enjoyed the smell of furrows and pastures and woods more than that of reeking hides in their vats. He was fond of all animals, and especially delighted in horses, early demonstrating a surprising power in managing them. He was locally noted for his success in breaking colts, and as a trainer of horses to be pacers, those having this gait being esteemed more desirable for riding, at[Pg 13] a time when a large part of all traveling was done on horseback. As General Grant became famous at a comparatively early age, a large crop of stories of his early feats in the subjection and use of horses was cultivated by persons who knew him as a boy. Many of these, doubtless, are entirely credible; few of them are so extraordinary that they might not be true of any clever boy who loved horses and studied their disposition and powers.

He was a lad of self-reliance, fertile in resources, and of good judgment within certain limitations. Before he was fairly in his teens his father intrusted to him domestic and business affairs which required him to go to the city of Cincinnati alone, a two-days' trip. His own account of this period of his life is: "When I was seven or eight years of age I began hauling [driving the team] all the wood used in the house and shops.... When about eleven years old, I was strong enough to hold a plow. From that age until seventeen, I did all the work done with horses.... While still young, I[Pg 14] had visited Cincinnati, forty-five miles away, several times alone; also Maysville, Ky., often, and once Louisville.... I did not like to work; but I did as much of it while young as grown men can be hired to do in these days, and attended school at the same time.... The rod was freely used there, and I was not exempt from its influence."

But his knowledge of horses, of timber, and of land was better than his knowledge of men. He had no precocious "smartness," as the Yankees name the quality which enables one person to outwit another. His credulity was simple and unsuspecting, at least in some directions. This is illustrated by a story which he has told himself, one which he was never allowed to forget:—

"There was a Mr. Ralston, who owned a colt which I very much wanted. My father had offered twenty dollars for it, but Ralston wanted twenty-five. I was so anxious to have the colt that ... my father yielded, but said twenty dollars was all the horse was worth, and told me to offer that price. If it was not accepted, I was to offer [Pg 15]twenty-two and a half, and if that would not get him, to give the twenty-five. I at once mounted a horse and went for the colt. When I got to Mr. Ralston's house, I said to him: 'Papa says I may offer you twenty dollars for the colt, but, if you won't take that, I am to offer twenty-two and a half, and if you won't take that, to give you twenty-five.'" This naïve bargaining was done when he was eight years old. Some persons have thought it betokens a defect in business acumen which was never fully cured.

He learned his school tasks without great effort. His parents were alive to the advantages of education, and required him to attend all the subscription schools kept in the town. There were no free schools there during his youth. He was twice sent away from home to attend higher schools. It is not recorded that he especially liked study or disliked it. Probably he took it as a part of life, something that had to be done, and did it. He was most apt in mathematics. When he arrived at West Point he[Pg 16] was able to pass the not very severe entrance examination without trouble. He seems to have had good native powers of perception, reasoning, and memory. What he learned he kept, but he was never an ardent scholar. He had no enthusiasm for knowledge, nor, indeed, so far as appears, for anything else except horses. He used to fish occasionally, but never hunted. The sportsman's tastes were not his, nor were his social tastes demonstrative. Possibly they may have been restrained in some measure by his mother's strictness of religious principles. He was neither morose nor brooding,—not a dreamer of destiny. He yearned for no star. No instinct of his future achievements made him peculiar among his companions or caused him to hold himself aloof. He exhibited nothing of the young Napoleon's distemper of gnawing pride. He was just an ordinary American boy, with rather less boyishness and rather more sobriety than most, disposed to listen to the talk of his elders instead of that of persons of his own age, and fond of visiting strange places and riding[Pg 17] and driving about the country. His work had made him acquainted with the subjects in which grown men were interested. The family life was serious but not severe. Obedience and other domestic virtues were inculcated with fidelity; but he said that he was never scolded or punished at home.

When the boy was about seventeen years old he had made up his mind upon one matter,—he would not be a tanner for life. He told his father, possibly in response to some suggestion that it was time for him to quit his aimless occupations and begin his lifework, that he would work in the shop, if he must, until he was twenty-one, but not a day longer. His desire then was to be a farmer, or a trader, or to get an education; but he seems to have had no definite inclination except to escape from the disagreeable tannery. His father treated the matter judiciously, not being disposed to force the boy to learn a business that he would not follow. He was unable to set him up in farming. He had not much respect for the river traders, and may have had little confidence in the boy's ability to thrive in competitions of enterprise and greed.

Without consulting his son, he wrote to one of the United States Senators from Ohio, Hon. Thomas Morris, telling him that there was a vacancy in the district's representation in West Point, and asking that Ulysses might be appointed. He would not write to the congressman from the district, because, although neighbors and old friends, they belonged to different parties and had had a falling out. But the Senator turned the letter over to the Congressman, who procured the appointment, thus healing a breach of which both were ashamed. General Grant gives an account of what happened when this door to an education and a life service was opened before him. His father said to him one day: "'Ulysses, I believe you are going to receive the appointment.' 'What appointment?' I inquired. 'To West Point. I have applied for it.' 'But I won't go,' I said. He said he thought I would, and I thought so too, if he did." The italics are the general's. They make it plain that he did not think it prudent to make further objection when his father had reached a decision.

Little did Congressman Thomas L. Hamer imagine that in doing this favor for his friend, Jesse Grant, he was doing the one thing that would secure remembrance of his name by coming generations. It did not contribute to his immediate popularity among his constituents, for the general opinion was that many brighter and more deserving boys lived in the district, and one of them should have been preferred. Neighbors did not hesitate to shake their heads and express the opinion that the appointment was unwise. Not one of them had discerned any particular promise in the boy. Nor were they unreasonable. He was without other distinctions than of being a strong toiler, good-natured, and having a knack with horses. He had no aspiration for the career of a soldier, in fact never intended to stick to it. Even after entering West Point his hope, he has said, was to be able, by reason of his education, to get "a permanent position in some respectable college,"—to become Professor Grant, not General Grant.

In the course of making his appointment,[Pg 21] his name by an accident was permanently changed. When Congressman Hamer was asked for the full name of his protégé to be inserted in the warrant, he knew that his name was Ulysses, and was sure there was more of it. He knew that the maiden name of his friend's wife was Simpson. At a venture, he gave the boy's name as Ulysses Simpson Grant. Grant found it so recorded when he reached the school, and as he had no special fondness for the name Hiram, which was bestowed to gratify an aged relative, he thought it not worth while to go through a long red-tape process to correct the error. There was another Cadet Grant, and their comrades distinguished this one by sundry nicknames, of which "Uncle Sam" was one and "Useless" another.

When he arrived at West Point, in July, 1839, he was not a prepossessing figure of a young gentleman. The rusticity of his previous occupation and breeding was upon him. Seventeen years old, hardly more than five feet tall, but solid and muscular, with no particular charm of face or manner,[Pg 22] no special dignity of carriage, he was only a common sort of pleb, modest, good-natured, respectful, companionable but sober-minded, observant but undemonstrative, willing but not ardent, trusty but without high ambitions,—the kind of boy who might achieve commendable success in the academy, or might prove unequal to its requirements, without giving cause of surprise to his associates.

He had no difficulty in passing the examination at the end of his six months' probationary period, which enabled him to be enrolled in the army, and he was never really in danger of dismissal for deficient scholarship. He seems to have made no effort for superior excellence in scholarship, and in some studies his rank was low. Mathematics gave him no trouble, and he says that he rarely read over any of his lessons more than once, which is evidence that he had unusual power of concentrating his attention, the secret of quick work in study. This power and a faithful memory will enable any one to achieve high distinction if he is willing to toil for it. Grant was not[Pg 23] willing to toil for it. He gave time to other things, not in the routine prescribed. He pursued a generous course of reading in modern English fiction, including all the works then published of Scott, Bulwer, Marryat, Lever, Cooper, and Washington Irving, and much besides.

The thing for which he was especially distinguished was, as may be surmised, horsemanship. He was esteemed one of the best horsemen of his time at the academy. But this, too, was easy for him. He appears to have been on good terms with his fellows and well liked, but he was not a leader among them. He has said that while at home he did not like to work. It must be judged that his mind was affected by a certain indolence, that he was capable enough when he addressed himself to any particular task, but not self-disposed to exertion. He felt no constant, pricking incitement to do his best; but was content to do fairly well, as well as was necessary for the immediate occasion. One of his comrades in the academy said in later years that he remembered[Pg 24] him as "a very uncle-like sort of a youth.... He exhibited but little enthusiasm in anything."

He was graduated in 1843, at the age of 21 years, ranking 21 in a class of 39, a little below the middle station. He had grown 6 inches taller while at the academy, standing 5 feet 7 inches, but weighed no more than when he entered, 117 pounds. His physical condition had been somewhat reduced at the end of his term by the wearing effect of a threatening cough. It cannot be said that any one then expected him to do great things. The characteristics of his early youth that have been set forth were persistent. He was older, wiser, more accomplished, better balanced, but in fundamental traits he was still the Ulysses Grant of the farm—hardly changed at all. No more at school than at home was his life vitiated by vices. He was neither profane nor filthy. His temperament was cool and wholesome. He tried to learn to smoke, but was then unable. It is remembered that during the vacation in the middle of his[Pg 25] course, spent at home, he steadily declined all invitations to partake of intoxicants, the reason assigned being that he with others had pledged themselves not to drink at all, for the sake of example and help to one of their number whose good resolutions needed such propping. At his graduation he was a man and a soldier. Life, with all its attractions and opportunities, was before. Phlegmatic as he may have been, it cannot be supposed that the future was without beckoning voices and the rosy glamour of hope.

He had applied for an appointment in the dragoons, the designation of the one regiment of cavalry then a part of our army. His alternative selection was the Fourth Infantry. To this he was attached as a brevet second lieutenant, and after the expiration of the usual leave spent at home, he joined his regiment at Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis. Duties were not severe, and the officers entertained much company at the barracks and gave much time to society in the neighborhood. Grant had his saddle-horse, a gift of his father, and took his full share in the social life. A few miles away was the home of his classmate and chum during his last year at the academy, F. T. Dent. One of Dent's sisters was a young lady of seventeen, educated at a St. Louis boarding school. After she returned to her home in the late[Pg 27] winter young Grant found the Dent homestead more attractive than ever.

This was the time of the agitation regarding the annexation of Texas, a policy to which young Grant was strongly hostile. About May 1 of the next year, 1844, some of the troops at the barracks were ordered to New Orleans. Grant, thinking his own regiment might go soon, got a twenty-days leave to visit his home. He had hardly arrived when by a letter from a fellow officer he learned that the Fourth had started to follow the Third, and that his belongings had been forwarded. It was then that he became conscious of the real nature of his feeling for Julia Dent. His leave required him to report to Jefferson Barracks, and although he knew his regiment had gone, he construed the orders literally and returned there, staying only long enough to declare his love and learn that it was reciprocated. The secret was not made known to the parents of the young lady until the next year, when he returned on a furlough to see her. For three years longer they were separated, while he[Pg 28] was winning honor and promotion. After peace was declared, and the regiment had returned to the States, they were married. She shared all his vicissitudes of fortune until his death. Their life together was one in which wifely faith and duty failed not, nor did he fail to honor and esteem her above all women. Whatever his weaknesses, infidelity in domestic affection was not one of them. In all relations of a personal character he reciprocated trust with the whole tenacity of his nature.

In Louisiana the regiment encamped on high ground near the Sabine River, not far from the old town of Natchitoches. The camp was named Camp Salubrity. In Grant's case, certainly, the name was justified. There he got rid of the cough that had fastened upon him at West Point and had caused fears that he would early fall a victim to consumption. In Louisiana he was restored to perfect, lusty health, fit for any exertion or privation. He was regarded as a modest and amiable lieutenant of no great promise. The regiment was moved to [Pg 29]Corpus Christi, a trading and smuggling port. There the army of occupation (of Texas) was slowly collected, consisting of about three thousand men, commanded by General Zachary Taylor. Mexico still claimed this part of Texas, and it was expected that our forces would be attacked. But they were not, and, as the real purpose was to provoke attack, the army was moved to a point opposite Matamoras on the Rio Grande, where a new camp was established and fortified. Previous to leaving Corpus Christi, Grant had been promoted, September 30, 1845, from brevet second lieutenant to full second lieutenant. The advance was made in March, 1846. On the 8th of May the battle of Palo Alto was fought, on the hither side of the Rio Grande, in which Grant had an active part, acquitting himself with credit. On the next day was the battle of Resaca de la Palma, in which he was acting adjutant in place of the officer killed. One consequence of these victories was the evacuation of Matamoras. War with Mexico having been declared, General Taylor's army became an army of invasion.

Volunteers for the war now began coming from the States. In August the movement on Monterey began, and on the 19th of September, Taylor's army was encamped before the city. The battle of Monterey was begun on the 21st, and the desperately defended city was surrendered and evacuated on the 24th. Grant, although then doing quartermaster's duty, having his station with the baggage train, went to the front on the first day, and was a participant in the assault, incurring all its perils, and volunteering for the extremely hazardous duty of a messenger between different parts of the force.

When General Scott arrived at the mouth of the Rio Grande, Grant's regiment was detached from Taylor's army and joined Scott's. He was present and participated in the siege of Vera Cruz, the battle of Cerro Gordo, the assault on Churubusco, the storming of Chapultepec, for which he volunteered with a part of his company, and the battle of Molino del Rey. Colonel Garland, commander of the brigade, in his report of the[Pg 31] storming of Chapultepec, said: "Lieutenant Grant, 4th Infantry, acquitted himself most nobly upon several occasions under my own observation." After the battle of Molino del Rey he was appointed on the field a first lieutenant for his gallantry. For his conduct at Chapultepec he was later brevetted a captain, to date from that battle, September 13, 1847. He entered the city of Mexico a first lieutenant, after having been, as he says, in all the engagements of the war possible for any one man, in a regiment that lost more officers during the war than it ever had present in a single engagement.

Perhaps his most notable exploit was during the assault on the gate of San Cosme, under command of General Worth. While reconnoitring for position, Grant observed a church not far away, having a belfry. With another officer and a howitzer, and men to work it, he reached the church, and, by dismounting the gun, carried it to the belfry, where it was mounted again but a few hundred yards from San Cosme, and did excellent service. General Worth sent[Pg 32] Lieutenant Pemberton (the same who in the civil war defended Vicksburg) to bring Grant to him. The general complimented Lieutenant Grant on the execution his gun was doing, and ordered a captain of voltigeurs to report to him with another gun. "I could not tell the general," says Grant, "that there was not room enough in the steeple for another gun, because he probably would have looked upon such a statement as a contradiction from a second lieutenant. I took the captain with me, but did not use his gun."

The American army entered the city of Mexico, September 14, 1847, and this was his station until June, 1848, when the American army was withdrawn from Mexico, peace being established. There was no more fighting. Grant was occupied with his duties as quartermaster, and in making excursions about the country, in which and its people he conceived a warm interest that never changed. Upon returning to his own country he left his regiment on a furlough of four months. His first business was to[Pg 33] go to St. Louis and execute his promise to marry Miss Dent. The remainder of this honeymoon vacation was spent with his family and friends in Ohio.

Although he had done excellent service, demonstrating his courage, his good judgment, his resourcefulness, his ability in command, and in the staff duties of quartermaster and commissary, his experience did not kindle in him any new love for his profession, nor any ardor of military glory. He had not revealed the possession of extraordinary talent, nor any spark of genius. He accounted the period of great value to him in his later life, but his heart was never enlisted in the cause for which the war was made. His letters home declared this. When he came to write his memoirs, speaking of the annexation of Texas, he said: "For myself I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker[Pg 35] nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.... The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war.... We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times."

But the Mexican war changed Grant's plan of life. While he was at Jefferson Barracks he had applied for a place as instructor of mathematics at West Point, and had received such encouragement that he devoted much time to reviewing his studies and extending them, giving more attention to history than ever before. After the war the notion of becoming a college professor appears to have left him. He regarded himself as bound to the service for the rest of his days. It was not so much his choice as his lot, and he accepted it, not because he relished it, but because he discovered no way out of it. This illustrates a negative trait of his character remarked throughout his career. He was never a pushing man.[Pg 36] He had no self-seeking energy. The work that was assigned to him he did as well as he could; but he had little art to recommend himself in immodest ways. He had not the vanity to presume that he would certainly succeed in strange enterprises. He shrank from the personal hostilities of ambition.

Then followed a long period of uneventful routine service in garrisons at Detroit and at Sackett's Harbor, until in the summer of 1852 his regiment was sent to the Pacific coast via the Panama route. The crossing of the isthmus was a terrible experience, owing to the lack of proper provision for it and to an epidemic of cholera. The delay was of seven weeks' duration, and about one seventh of all who sailed on the steamer from New York died on the isthmus of disease or of hardships. Lieutenant Grant, however, had no illness, and exhibited a humane devotion to the necessities of the unfortunate, civilians as well as soldiers. His company was destined to Fort Vancouver, in Oregon Territory, where he remained nearly a year, until, in order, he[Pg 37] received promotion to a captaincy in a company stationed at Humboldt Bay in California. Here he remained until 1854, when he resigned from the army, because, as he says, he saw no prospect of being able to support his family on his pay, if he brought them—there were then two children—from St. Louis, where Mrs. Grant had remained with her family since he left New York. His resignation took effect, following a leave of absence, July 31, 1854.

There was another cause, as told in army circles, for his resignation. He had become so addicted to drink that his resignation was required by his commanders, who held it for a time to afford him an opportunity to retrieve his good fame if he would; but he was unable. Through what temptation he fell into such disgrace is not clearly known. But garrison posts are given to indulgences which have proved too much for many an officer, no worse than his fellows, but constitutionally unable to keep pace with men of different temperament. It might be thought that Grant was one unlikely to be easily[Pg 38] affected; but the testimony of his associates is that he was always a poor drinker, a small quantity of liquor overcoming him.

He was now thirty-two years old, a husband and father, discharged from the service for which he had been educated, and without means of livelihood. His wife fortunately owned a small farm near St. Louis, but it was without a dwelling house. He had no means to stock it. He built a humble house there by his own hard labor. He cut wood and drew it to St. Louis for a market. In this way he lived for four years, when he was incapacitated for such work by an attack of fever and ague lasting nearly a year. There is no doubt that the veteran and his family experienced the rigors of want in these years; no question that neither his necessities nor his duties saved him from being sometimes overcome by his baneful habit.

In the fall of 1858 the farm was sold. Grant embarked in the real estate agency business in St. Louis, and made sundry unsuccessful efforts to get a salaried place[Pg 39] under the city government. But his fortunes did not improve. Finally in desperation he went in 1860 to his father for assistance. His father had established two younger sons in a hide and leather business in Galena, Ill. Upon consultation they agreed to employ Ulysses as a clerk and helper, with the understanding that he should not draw more than $800 a year. But he had debts in St. Louis, and to cancel these almost as much more had to be supplied to him the first year. His father has told that the advance was repaid as soon as he began earning money in the civil war.

In Galena he was known to but few. Ambition for acquaintance seemed to have died in him. He was the victim of a great humiliation and was silent. He avoided publicity. He was destitute of presumption. What brighter hopes he cherished were due to his father's purpose to make him a partner with his brothers. He heard Lincoln and Douglas when they canvassed the State, and approved of the argument of the former rather than of the other. He had voted for[Pg 40] Buchanan in 1856, his only vote for a President before the war. In 1860 he had not acquired a right to vote in Illinois.

These thirteen quiet years of Grant's life are not of account in his public career, but they are a phase of experience that left its deep traces in the character of the man. He was changed, and ever afterwards there was a tinge of melancholy and a haunting shadow of dark days in his life that could not be escaped. Nor in the pride and power of his after success did he completely conquer the besetting weakness of his flesh. The years from twenty-six to thirty-nine in the lives of most men who ever amount to anything are years of steady development and acquisition, of high endeavor, of zealous, well-ordered upward progress, of growth in self-mastery and outward influence, of firm consolidation of character. These conditions are not obvious in the case of General Grant. Had he died before the summer of 1861, being nearly forty years of age, he would have filled an obscure grave, and those to whom[Pg 41] he was dearest could not have esteemed his life successful, even in its humble scope. He had not yet found his opportunity: he had not yet found himself.

The tide of patriotism that surged through the North after the fall of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, lifted many strong but discouraged men out of their plight of hard conditions and floated them on to better fortune. Grant was one of these. At last he found reason to be glad that he had the education and experience of a soldier.

On Monday, April 15, 1861, Galena learned that Sumter had fallen. The next day there was a town meeting, where indignation and devotion found utterance. Over that meeting Captain Grant was called to preside, although few knew him. Elihu B. Washburn, the representative of the district in Congress, and John A. Rawlins, a rude, self-educated lawyer, who had been a farmer and a charcoal burner, made passionate, fiery speeches on the duty of every man to stand[Pg 43] by the flag. At the close of that meeting Grant told his brothers that he felt that he must join the army, and he did no more work in the shop. How clearly he perceived the meaning of the conflict was shown in a letter to his father-in-law, wherein he wrote: "In all this I can see but the doom of slavery."

He was offered the captaincy of the company formed in Galena, and declined it, although he aided in organizing and drilling the men, and accompanied them to the state capital, Springfield. As he was about starting for home, he was asked by Governor Richard Yates to assist in the adjutant-general's office, and soon he was given charge of mustering in ten regiments that had been recruited in excess of the quota of the State, under the President's first call, in preparation for possible additional calls. His knowledge of army forms and methods was of great service to the inexperienced state officers.

Later, but without wholly severing his connection with the office, he returned home, and wrote a letter to the adjutant-general[Pg 44] of the regular army, at Washington, briefly setting forth his former service, and very respectfully tendering his service "until the close of the war in such capacity as may be offered," adding, that with his experience he felt that he was "competent to command a regiment, if the President should see fit to intrust one to him." The letter brought no reply. He went to Cincinnati and tried, unsuccessfully, to see General McClellan, whom he had known at West Point and in Mexico, hoping that he might be offered a place on his staff. While he was absent Governor Yates appointed him colonel of the Twenty-First Regiment of Illinois Infantry, then in camp near Springfield, his commission dating from June 15. It was a thirty-day regiment, but almost every member reënlisted for three years, under the President's second call. Thus, two months after the breaking out of the war, he was again a soldier with a much higher commission than he had ever held, higher than would have come to him in regular order had he remained in the army.

At Springfield he was in the centre of a great activity and a great enthusiasm. He met for the first time many leading men of the State, and became known to them. Their personality did not overwhelm him, famous and influential as many of them were, nor did he solicit from them any favor for himself. His desire was to be restored to the regular army rather than to take command of volunteers. When the sought-for opportunity did not appear, he accepted the place that was offered, a place in which he was needed; for the first colonel, selected by the regiment itself, had already by his conduct lost their confidence. They exchanged him for Grant with high satisfaction.

The regiment remained at the camp, near Springfield, until the 3d of July, being then in a good state of discipline, and officers and men having become acquainted with company drill. It was then ordered to Quincy, on the Mississippi River, and Colonel Grant, for reasons of instruction, decided to march his regiment instead of going by the railroad. So began his advance, which ended less than four years later at Appomattox, when he was the captain of all the victorious Union armies,—holding a military rank none had held since Washington,—and a sure fame with the great captains of the world's history. The details of this wonderful progress can only be sketched in this little volume. It was not without its periods of gloom, and doubt, and check; but, on the whole, it was steadily on and up.

His orders were changed at different times, until finally he was directed to proceed with all dispatch to the relief of an Illinois regiment, reported to be surrounded by rebels near Palmyra, Mo. Before the place was reached, the imperiled regiment had delivered itself by retreating. He next expected to give battle at a place near the little town of Florida, in Missouri. As the regiment toiled over the hill beyond which the enemy was supposed to be waiting for him, he "would have given anything to be back in Illinois." Never having had the responsibility of command in a fight, he really distrusted his untried ability. When the top of the hill was reached, only a deserted camp appeared in front. "It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him.... From that event to the close of the war," he says in his book, "I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had [to fear] his."

On August 7 he was appointed by the President a brigadier-general of volunteers, upon the unanimous recommendation of the congressmen from Illinois, most of whom were unknown to him. He had not won promotion by any fighting; but generals were at that time made with haste to meet exigent requirement, a proportional number being selected from each loyal State. Among those whom General Grant appointed on his staff was John A. Rawlins, the Galena lawyer, who was made adjutant-general, with the rank of captain, and who as long as he lived continued near Grant in some capacity, dying while serving as Secretary of War in the first term of Grant's presidency. He was an officer of high ability and personal loyalty. He alone had the audacity to interpose a resolute no, when his chief was disposed to over-indulgence in liquor. He did not always prevent him, but it is doubtful whether Grant would not have fallen by the way without the constant, imperative watchfulness of his faithful friend. There were times when both army and people were [Pg 49]impatient with him, not wholly without reason. Nothing saved him then but President Lincoln's confidence and charity. The reply to all complaints was: "This man fights; he cannot be spared."

In the last days of August, having been occupied, meantime, in reducing to order distracted and disaffected communities in Missouri, he was assigned to command of a military district embracing all southwestern Missouri and southern Illinois. He established his headquarters at Cairo, early in September, and from there he promptly led an expedition that forestalled the hostile intention of seizing Paducah, a strategical point at the mouth of the Tennessee River. This was his first important military movement, and it was begun upon his own initiative. His first battle was fought at Belmont, Mo., opposite Columbus, Ky., on the Mississippi River, on November 7, 1861. Grant, in command of a force of about 3000 men, was demonstrating against Columbus, held by the enemy. Learning that a force had been sent across the river to Belmont, he [Pg 50]disembarked his troops from their transports and attacked. The men were under fire for the first time, but they drove the enemy and captured the camp. They came near being cut off, however, through the inexperience and silly recklessness of subordinate officers. By dint of hard work and great personal risk on the part of their commander, they were got safely away. It was an all-day struggle, during which General Grant had a horse shot under him, and made several narrow escapes, being the last man to reëmbark. The Union losses were 485 killed, wounded, and missing. The loss of the enemy was officially reported as 632. This battle was criticised at the time as unnecessary; but General Grant always asserted the contrary. The enemy was prevented from detaching troops from Columbus, and the national forces acquired a confidence in themselves that was of great value ever afterwards. Grant's governing maxim was, to strike the enemy whenever possible, and keep doing it.

From the battle of Belmont until [Pg 51]February, 1862, there was no fighting by Grant's army. Troops were concentrated at Cairo for future operations—not yet decided upon. Major-General H. W. Halleck superseded General Fremont in command of the department of Missouri. Halleck was an able man, having a high reputation as theoretical master of the art of war, one of those who put a large part of all their energy into the business of preparing to do some great task, only to find frequently, when they are completely ready, that the occasion has gone by. When he was first approached with a proposition to capture Forts Henry and Donelson, the first on the Tennessee River, the other on the Cumberland River, where the rivers are only a few miles apart near the southern border of Kentucky, he thought that it would require an army of "not less than 60,000 effective men," which could not be collected at Cairo "before the middle or last of February."

Early in January General Grant went to St. Louis to explain his ideas of a campaign against these forts to Halleck, who told him[Pg 52] his scheme was "preposterous." On the 28th he ventured again to suggest to Halleck by telegraph that, if permitted, he could take and hold Fort Henry on the Tennessee. His application was seconded by flag officer Foote of the navy, who then had command of several gunboats at Cairo. On February 1, he received instructions to go ahead, and the expedition, all preparations having been made beforehand, started the next day, the gunboats and about 9000 men on transports going up the Ohio and the Tennessee to a point a few miles below Fort Henry. After the troops were disembarked the transports went back to Paducah for the remainder of the force of 17,000 constituting the expeditionary army. The attack was made on the 6th, but the garrison had evacuated, going toward Fort Donelson, to escape the fire of the gunboats. General Tilghman, commanding the fort, his staff, and about 120 men were captured, with many guns and a large quantity of stores. The principal loss on the Union side was the scalding of 29 men on the gunboat Essex by the [Pg 53]explosion of her boiler, pierced by a shell from the fort.

Grant had no instructions to attack Fort Donelson, but he had none forbidding him to do it. He straightway moved nearly his whole force over the eleven miles of dreadful roads, and on the 12th began investing the stronghold, an earthwork inclosing about 100 acres, with outworks on the land and water sides, and defended by more than 20,000 men commanded by General Floyd, who had been President Buchanan's Secretary of War. The investing force had its right near the river above the fort. The weather was alternately wet and freezing cold. The troops had no shelter, and suffered greatly. On the 14th, without serious opposition, the investment was completed. At three o'clock in the afternoon of the 14th, flag officer Foote began the attack, the fleet of gunboats steaming up the river and firing as rapidly as possible; but several were disabled by the enemy's fire, and all had to fall back before nightfall. The enemy telegraphed to Richmond that a great victory had been achieved.

On the next day, Grant, riding several miles to the river, met Foote on his gunboat, to which he was confined by a wound received the day before. Returning, he found that a large force from the fort had made a sortie upon a part of his line, but had been driven back after a severe contest. It was found that the haversacks of the Confederates left on the field contained three days' rations. Instantly, Grant reasoned that the intention was not so much to drive him away as to break through his line and escape. He ordered a division that had not been engaged to advance at once, and before night it had established a position within the outer lines of defense. Surrender or capture the next day was the fate of the Confederates.

During the night General Floyd and General Pillow, next in command, and General Forest made their escape with about 4000 men. Before light the next morning, General Grant received a note from General S. B. Buckner, who was left in command of the fort, suggesting the appointment of [Pg 55]commissioners to agree upon terms of capitulation, and meanwhile an armistice until noon. To this note General Grant sent the curt reply: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." General Buckner sent back word that he was compelled by circumstances "to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms" which had been proposed.

This victory electrified the whole North, then greatly in need of cheer. General Grant became the hero of the hour. His name was honored and his exploit lauded from one end of the country to the other. It was not yet a year since he had been an obscure citizen of an obscure town. Already many regarded him as the nation's hope. A phrase from his note to General Buckner was fitted to his initials, and he was everywhere hailed as "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

In this campaign he first revealed the peculiar traits of his military genius, clear discernment of possibilities, comprehension[Pg 56] of the requirements of the situation, strategical instinct, accurate estimate of the enemy's motive and plan, sagacious promptness of action in exigencies, staunch resolution, inspiring energy, invincible poise. For his achievement he was promoted to be a major-general of volunteers. He had found himself now.

On the 4th of March, sixteen days after his victory, he was in disgrace. General Halleck ordered him to turn over the command of the army to General C. F. Smith and to remain himself at Fort Henry. This action of Halleck was the consequence partly of accidents which had prevented communication between them and caused Halleck to think him insubordinate, partly of false reports to Halleck that Grant was drinking to excess, partly of Halleck's dislike of Grant,—a temperamental incapacity of appreciation. After Donelson he issued a general order of congratulation of Grant and Foote for the victory, but he sent no personal congratulations, and reported to Washington that the victory was due to General Smith, whose promotion, not Grant's, he recommended. As to the reports of Grant's[Pg 58] drinking, they were decisively contradicted by Rawlins, to whom the authorities in Washington applied for information. He asserted that Grant had drunk no liquor during the campaign except a little, by the surgeon's prescription, on one occasion when attacked by ague. The fault of failing to report his movements and to answer inquiries was later found to be due to a telegraph operator hostile to the Union cause, who did not forward Grant's reports to Halleck nor Halleck's orders to Grant.

Grant's mortification was intense. Since the fall of Donelson he had been full of activities. The enemy had fallen back, his first line being broken, and Grant was scheming to follow up his advantage by pushing on through Tennessee, driving the discouraged Confederate forces before him. He had visited Nashville to confer with General Buell, who had reached that city, and it was on his return that he received Halleck's dispatch of removal. For several days he was in dreadful distress of mind, and contemplated resigning his commission. It[Pg 59] seemed as if Fate had cut off his career just as it had gloriously begun. But he made no public complaint. He obeyed orders and waited at Fort Henry. To some of his friends he said that he would never wear a sword again. But on the 13th he was restored to command. Halleck became aware of the facts, and made a report vindicating Grant's conduct, of which he sent him a copy. It was not until after the war that Grant learned that Halleck's previous reports had caused his degradation.

His first battle after restoration to command was an unfortunate one in the beginning, but was turned into a victory. He was advancing on Corinth, Miss., a railroad centre of the Southwest, where a large Confederate army under General Albert Sidney Johnston was collecting. All the available Union forces in the West were gathering to meet it. Grant had selected Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River, twenty miles from Corinth, as the place for landing his forces, and Hamburg Landing, four miles up the river, as the starting point for Buell's[Pg 60] army in marching on Corinth. Buell was hastening to the rendezvous, coming through Tennessee with a large force. On the 4th of April Grant's horse fell while he was reconnoitring at night, and the general's leg was badly bruised but not broken.

Expecting to make an offensive campaign and meet the enemy at Corinth, he had not enjoined intrenchment of the temporary camp. So great was the confidence that Johnston would await attack that the enemy's proximity in force was discovered too late. Johnston led his whole army out of Corinth, and early on the morning of the 6th of April surprised Sherman's division encamped at Shiloh, three miles from Pittsburg Landing, attacking with a largely superior force. The battle raged all day, with heavy losses on both sides, the Union army being gradually forced back to Pittsburg Landing. Five divisions were engaged, three of them composed of raw troops, and many regiments were in a demoralized condition at night.

On the next day the Union army, reinforced by Buell's 20,000 men, advanced, [Pg 61]attacking the enemy early in the morning, with furious determination. The Confederate forces, although weakened, were determined not to lose the advantage gained, and fought with desperate stubbornness. But it was in vain. A necessity of vindicating their courage was felt by officers and men of the Union Army. They had fully recovered from the effects of the surprise, and pressed forward with zealous assurance. Before the day was done Grant had won the field and compelled a disorderly retreat. In this battle the commander of the Confederate army, General Albert Sidney Johnston, was killed in the first day's fighting, the command devolving on General G. T. Beauregard. On the first day the Union forces on the field numbered about 33,000 against the enemy's above 40,000. On the second day the Union forces were superior. The Union losses in the two days were 1754 killed, 8408 wounded, and 2885 missing; total 13,047. Beauregard reported a total loss of 10,694, of whom 1723 were killed. General Grant says that the Union army buried more of the[Pg 62] enemy's dead than is here reported in front of Sherman's and McClernand's divisions alone, and that the total number buried was estimated at 4000.

The battles of Shiloh and Pittsburg Landing together constitute one of the critical conflicts of the long war. Had the Confederate success of the first day been repeated and completed on the second day, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to prevent the enemy from possessing Tennessee and a large part of Kentucky.

After this battle General Halleck came to Pittsburg Landing and took command of all the armies in that department. Although General Grant was second in command, he was not in General Halleck's confidence, and was contemptuously disregarded in the direction of affairs. Halleck proceeded to make a safe campaign against Corinth by road-building and parallel intrenchments. He got there and captured it, indeed, having been a month on the way, but the rebel army, with all its equipments, guns, and stores, had escaped beforehand. Grant's [Pg 63]position was so embarrassing that during Halleck's advance he made several earnest applications to be relieved. Halleck would not let him go, apparently thinking that he needed to be instructed by an opportunity of observing how a great soldier made war. What Grant really learned was how not to make war.

After the fall of Corinth he was permitted to make his headquarters at Memphis, while Halleck proceeded to construct defensive works on an immense scale. But in July Halleck was appointed commander-in-chief of all the armies, with his headquarters in Washington, and Grant returned to Corinth. He was the ranking officer in the department, but was not formally assigned to the command until October. The intermediate time was spent, for the most part, in defensive operations in the enemy's country, the great army that entered Corinth having been scattered east, north, and west to various points. Two important battles were fought, by one of which an attempt to retake Corinth was defeated. The other was at[Pg 64] Iuka, in Mississippi, where a considerable Confederate force was defeated.

In this period the energy and resourcefulness of General Grant were conspicuous, although nothing that occurred added largely to his reputation. He was, however, gathering stores of useful experience while operating in the heart of the enemy's country, where every inhabitant, except the negroes, was hostile. Both of the battles mentioned above were nearly lost by failure of his subordinates to render expected service according to orders; but he suffered no defeat. The service was wearing, but he was equal to all demands made upon him.

Vicksburg had long been the hard military problem of the Southwest. The city, which had been made a fortress, was at the summit of a range of high bluffs, two hundred and fifty feet above the east bank of the Mississippi River, near the mouth of the Yazoo. It was provided with batteries along the river front and on the bank of the Yazoo to Haines's Bluff. A continuous line of fortifications surrounded the city on the crest of the hill. This hill, the slopes of which were cut by deep ravines, was difficult of ascent in any part in the face of hostile defenders. The back country was swampy bottom land, covered with a rank growth of timber, intersected with lagoons and almost impassable except by a few rude roads. The opposite side of the river was an extensive wooded morass.

In May, 1862, flag officer Farragut, coming up the Mississippi from New Orleans, had demanded the surrender of the city and been refused. In the latter part of June he returned with flag officer Porter's mortar flotilla and bombarded the city for four weeks without gaining his end. In November, 1862, General Grant started with an army from Grand Junction, intending to approach Vicksburg by the way of the Yazoo River and attack it in the rear. But General Van Dorn captured Holly Springs, his depot of supplies, and the project was abandoned.

The narration, with any approach to completeness, of the story of the campaign against Vicksburg would require a volume. It was a protracted, baffling, desperate undertaking to obtain possession of the fortifications that commanded the Mississippi River at that point. Grant was not unaware of the magnitude of the work, nor was he eager to attempt it under the conditions existing. He believed that, in order to their greatest efficiency, all the armies operating[Pg 67] between the Alleghanies and the Mississippi should be subject to one commander, and he made this suggestion to the War Department, at the same time testifying his disinterestedness by declining in advance to take the supreme command himself. His suggestion was not immediately adopted. On the 22d of December, 1862, General Grant, whose headquarters were then at Holly Springs, reorganized his army into four corps, the 13th, 15th, 16th, and 17th, commanded respectively by Major-Generals John A. McClernand, William T. Sherman, S. A. Hurlbut, and J. B. McPherson. Soon afterwards he established his headquarters at Memphis, and in January began the move on Vicksburg, which, after immense labors and various failures of plans, resulted in the surrender of that fortress on July 4, 1863.

He first sent Sherman, in whose enterprise and ability to take care of himself he had full confidence, giving him only general instructions. Sherman landed his army on the east side of the river, above Vicksburg, and made a direct assault, which[Pg 68] proved unsuccessful, and he was compelled to reëmbark his defeated troops. The impracticability of successful assault on the north side was then accepted. General McClernand's corps on the 11th of January, aided by the navy under Admiral Porter, captured Arkansas Post on the White River, taking 6000 prisoners, 17 guns, and a large amount of military stores.

On the 17th, Grant went to the front and had a conference with Sherman, McClernand, and Porter, the upshot of which was a direction to rendezvous on the west bank in the vicinity of Vicksburg. McClernand was disaffected, having sought at Washington the command of an expedition against Vicksburg and been led to expect it. He wrote a letter to Grant so insolent that the latter was advised to relieve him of all command and send him to the rear. Instead of doing so, he gave him every possible favor and opportunity; but months afterwards, in front of Vicksburg, McClernand was guilty of a breach of discipline which could not be overlooked, and he was deprived of his command.

Throughout the war Grant was notably considerate and charitable in respect of the mistakes and the temper of subordinates if he thought them to be patriotic and capable. His rapid rise excited the jealousy and personal hostility of many ambitious generals. Of this he was conscious, but he did not suffer himself to be affected by it so long as there was no failure in duty. The reply he made to those who asked him to remove McClernand revealed the principle of his action: "No. I cannot afford to quarrel with a man whom I have to command."

The Union army, having embarked at Memphis, was landed on the west bank of the Mississippi River, and the first work undertaken was the digging of a canal across a peninsula that would allow passage of the transports to the Mississippi below Vicksburg, where they could be used to ferry the army across the river, there being higher ground south of the city from which it could be approached more easily than from any other point. After weeks of labor, the scheme had to be abandoned as [Pg 70]impracticable. Then various devices for opening and connecting bayous were tried, none of them proving useful. The army not engaged in digging or in cutting through obstructing timbers was encamped along the narrow levee, the only dry land available in the season of flood. Thus three months were seemingly wasted without result. The aspect of affairs was gloomy and desperate.

The North became impatient and began grumbling against the general, doubting his ability, even clamoring for his removal. He made no reply, nor suffered his friends to defend him. He simply worked on in silence. Stories of his incapacity on account of drinking were rife, and it may have been the case that under the dreary circumstances and intense strain he did sometimes yield to this temptation. But he never yielded his aim, never relaxed his grim purpose. Vicksburg must fall. As soon as one plan failed of success another was put in operation. When every scheme of getting the vessels through the by-ways failed, one thing remained,—to send the gunboats and [Pg 71]transports past Vicksburg by the river, defying the frowning batteries and whatever impediments might be met. Six gunboats and several steamers ran by the batteries on the night of April 16th, under a tremendous fire, the river being lighted up by burning houses on the shore. Barges and flatboats followed on other nights. Then Grant's way to reach Vicksburg was found; but it was not an easy one, nor unopposed. A place of landing on the east side was to be sought. The navy failed to silence the Confederate batteries at Grand Gulf, twenty miles below Vicksburg, so that a landing could be effected there, and the fleet ran past it, as it had run by Vicksburg. Ten miles farther down the river a landing place was found at Bruinsburg. By daylight, on the 1st of May, McClernand's corps and part of McPherson's had been ferried across, leaving behind all impedimenta, even the officers' horses, and fighting had already begun in rear of Port Gibson, about eight miles from the landing. The enemy made a desperate stand, but was defeated with[Pg 72] heavy loss. Grand Gulf was evacuated that night, and the place became thenceforth a base of operations. Grant had defeated the enemy's calculation by the celerity with which he had transferred a large force. He slept on the ground with his soldiers, without a tent or even an overcoat for covering.

General Joseph E. Johnston had superseded General Beauregard in command of all the Confederate forces of the Southwest. His business was to succor General Pemberton and drive Grant back into the river. Sherman with his corps joined Grant on the 8th. Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, a Confederate railroad centre and depot of supplies, was captured on the 14th, the defense being made by Johnston himself. Then Pemberton's whole army from Vicksburg, 25,000 men, was encountered, defeated, and forced to retire into the fortress, after losing nearly 5000 men and 18 guns. On the 18th of May Grant's army reached Vicksburg and the actual siege began.

Since May 1, Grant had won five hard battles, killed and wounded 5200 of the[Pg 73] enemy, captured 40 field guns, nearly 5000 prisoners, and a fortified city, compelled the abandonment of Grand Gulf and Haines's Bluff, with their 20 heavy guns, destroyed all the railroads and bridges available by the enemy, separated their armies, which altogether numbered 60,000 men, while his own numbered but 45,000, and had completely invested Vicksburg. It was an astonishing exhibition of courage, energy, and military genius, calculated to confound his critics and reëstablish him in the confidence of the people. It has been said that there is nothing in history since Hannibal invaded Italy that is comparable with it.

The incidents of the siege, abounding in difficult and heroic action, including an early unsuccessful assault, must be passed over. Preparations had been made and directions given for a general assault on the works on the morning of July 5. But on the 3d General Pemberton sent out a flag of truce asking, as Buckner did at Donelson, for the appointment of commissioners to arrange terms of capitulation. Grant [Pg 74]declined to appoint commissioners or to accept any terms but unconditional surrender, with humane treatment of all prisoners of war. He, however, offered to meet Pemberton himself, who had been at West Point and in Mexico with him, and confer regarding details. This meeting was held, and on the 4th of July Grant took possession of the city. The Confederates surrendered about 30,000 men, 172 cannon, and 50,000 small arms, besides military stores; but there was little food left. Grant's losses during the whole campaign were 1415 killed, 7395 wounded, 453 missing. When the paroled prisoners were ready to march out, Grant ordered the Union soldiers "to be orderly and quiet as these prisoners pass," and "to make no offensive remarks."

This great victory was coincident with the repulse of Lee at Gettysburg, and the effect of the two events was a wonderfully inspiriting influence upon the country. President Lincoln wrote to General Grant a characteristic letter "as a grateful acknowledgment of the almost inestimable service[Pg 75] you have done the country." In it he said: "I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition and the like could succeed. When you got below and took Port Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join General Banks [besieging Port Hudson]; and when you turned northward, east of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make a personal acknowledgment that you were right and I was wrong."

Port Hudson surrendered to General Banks, to whom Grant sent reinforcements as soon as Vicksburg fell, on the 8th of July, with 10,000 more prisoners and 50 guns. This put the Union forces in possession of the Mississippi River all the way to the Gulf.

Grant now appeared to the nation as the foremost hero of the war. The disparagements and personal scandals so rife a few months before were silenced and forgotten. He was believed to be invincible. That he[Pg 76] never boasted, never publicly resented criticism, never courted applause, never quarreled with his superiors, but endured, toiled, and fought in calm fidelity, consulting chiefly with himself, never wholly baffled, and always triumphant in the end, had shown the nation a man of a kind the people had longed for and in whom they proudly rejoiced. The hopes to which Donelson had given birth were confirmed in the hero of Vicksburg, who was straightway made a major-general in the regular army, from which, when a first lieutenant, he had resigned nine years before.

Halleck, issuing orders from Washington, proceeded to disperse Grant's army hither and yon as he thought fractions of it to be needed. Grant wanted to move on Mobile from Lake Pontchartrain, but was not permitted to do it. Having gone to New Orleans in obedience to a necessity of conference with General Banks, he suffered a severe injury by the fall of a fractious horse, as he was returning from a review of Banks's army. For a long time he was unconscious. As soon as he could be moved he was taken on a bed to a steamer. For several days after reaching Vicksburg he was unable to leave his bed. Meantime he was repeatedly called upon to send reinforcements to Rosecrans, in Chattanooga, to which place the latter had retreated after the repulse of his army at Chickamauga,[Pg 78] September 19 and 20. On October 3, Grant was directed to go to Cairo and report by telegraph to the Secretary of War as soon as he was able to take the field. He started on the same day, ill as he still was. On arriving in Cairo he was ordered to proceed to Louisville. He was met at Indianapolis by Secretary Stanton, whom he had never before seen, and they proceeded together.

On the train Secretary Stanton handed him two orders, telling him to take his choice of them. Both created the military division of the Mississippi, including all the territory between the Alleghanies and the Mississippi River, north of General Banks's department, and assigning command of it to Grant. One order left the commanders of the three departments, the Ohio, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee, as they were, the other relieved General Rosecrans, commanding the Army of the Cumberland, and assigned Gen. George H. Thomas to his place. General Grant accepted the latter. This consolidation was a late compliance[Pg 79] with his earnest, unselfish counsel given before the Vicksburg campaign. Its wisdom had become apparent.

The centre of interest and anxiety now was Chattanooga, in East Tennessee, near the border of Georgia. The Confederates had been striving to retrieve the ground lost, since the fall of Fort Henry, by pushing northward in this direction. Halleck's dispersion of forces had sent Buell to this section, and Buell had been superseded by Rosecrans, a zealous and patriotic but unfortunate commander. The repulse at Chickamauga might have proved disastrous to his army but for the splendid behavior of the division under General Thomas, an officer not unlike Grant in the mould of his military talent, who there earned the sobriquet, "The Rock of Chickamauga."

The army of Rosecrans had been gathered again at Chattanooga, where it was confronted by Bragg, whose force surrounded it in an irregular semicircle from the Tennessee River to the river again, occupying Missionary Ridge on one flank and Lookout[Pg 80] Mountain on the other, with its centre where these two ridges come nearly together. Chattanooga was in the valley between, near the centre of which, behind the town, was an elevation, Orchard Knob, held by the enemy. Bragg commanded the river and the railroads. The route for supplies was circuitous, inadequate, and insecure, over mountain roads that had become horrible. Horses and mules had perished by thousands. The soldiers were on half rations. Word came to Grant in Louisville, that Rosecrans was contemplating a retreat. He at once issued an order assuming his new command, notified Rosecrans that he was relieved, and instructed Thomas to hold the place at all hazards until he reached the front.

Still so lame that he could not walk without crutches, and had to be carried in arms over places where it was not safe to go on horseback, he left Louisville on the 21st of October, and reached Chattanooga on the evening of the 23d. Then began a work of masterly activity and preparation, in which his genius again asserted its supreme [Pg 81]quality. Sherman with his army was ordered to join Grant. In five days the river road to Bridgeport was opened, the enemy being driven from the banks, two bridges were built, and Hooker's army added to his force. The enemy, having a much superior force, and assuming the surrender of the Army of the Cumberland to be only a question of time and famine, sent Longstreet with 15,000 men to reinforce the army of Johnston, holding Burnside in Knoxville, to the relief of whom the enemy supposed Sherman to be marching. Grant waited for Sherman, who was coming on between Longstreet and Bragg. All general orders for the battle were prepared in advance, except their dates. Sherman reached Chattanooga on the evening of the 15th, and with Grant inspected the field on the 16th. Sherman's army, holding the left, was to cross to the south side of the river and assail Missionary Ridge. Hooker, on the right, was to press through from Lookout valley into Chattanooga valley. Thomas, in the centre, was to press forward through the valley and strike the[Pg 82] enemy's centre while his wings were thus fully engaged, or as soon as Hooker's support was available.

The battle began on the afternoon of October 23. Orchard Knob, in the centre of the great amphitheatre, was attacked and captured, and became the Union headquarters. On the 24th Sherman crossed the river and established his army, on the north end of Missionary Ridge. On the morning of the same day Hooker assailed Lookout Mountain, and after a long climbing fight, lasting far into the night, secured his position; and the enemy, who had occupied the mountain, retreated across the valley at its upper end to Missionary Ridge. Grant's forces were now in touch from right to left. Everything so far had gone well.

Early on the next morning Sherman opened the attack. The ridge in his front was exceedingly favorable for defense, and during the whole night the enemy had been at work strengthening the position. Sherman's first assault failed, but he continued pressing the enemy with resolution, although making little[Pg 83] progress. From Grant's place on Orchard Knob he watched the struggle. At three o'clock he saw Sherman's right repulsed. Then he gave to Thomas, standing at his side, the order to advance. Six guns were fired as a signal, and the Army of the Cumberland moved forward in splendid array to avenge Chickamauga. The immediate purpose was to carry the rebel rifle pits at the foot of the Ridge. This done, the soldiers were subjected to a galling fire from the line 800 feet above them. As by inspiration, they rushed on, climbing as they could, by aid of rocks and bushes, and using their guns as staves. They reached the crest and swept it in a mighty fury. It was the decisive action. All the columns now converged on the distracted foe who fled before them. Grant galloped to the front with all speed, urging on the pursuit and exposing himself to every hazard of the fight.

So Chattanooga was added to Grant's lengthening score of brilliant victories; and again, as at Donelson and at Vicksburg, he had been the instrument of relieving a tense[Pg 84] oppression of anxiety that had settled upon the nation. Sherman, with two corps, was at once sent to the relief of Knoxville; but Longstreet, having heard of Bragg's defeat, made an unsuccessful assault and retreated into Virginia. By the administration in Washington, and by the people of the North, General Grant's preëminence was conceded. His star shone brightest of all. Congress voted a gold medal for him.