Title: Uncle Rutherford's Nieces: A Story for Girls

Author: Joanna H. Mathews

Release date: June 3, 2007 [eBook #21666]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

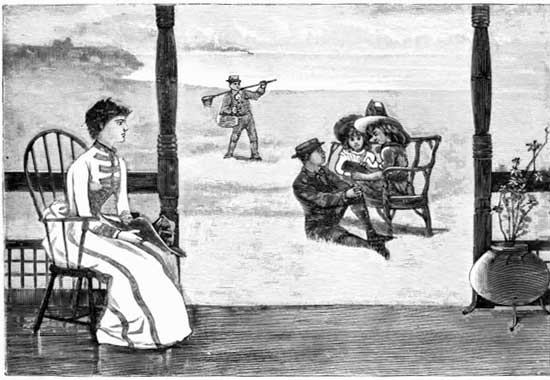

"SUCH WAS THE PICTURE THAT PRESENTED ITSELF TO MY VIEW."—Page 10.

"For ruling wisely I should have small skill,

Were I not lord of simple Dara still."

DEDICATED TO

HERBERT HUNT,

WITH LOVING AND BEST WISHES FOR HIS FUTURE YEARS,

ON HIS BIRTHDAY,

August 6, 1888.

CONTENTS.

page

CHAPTER I.

AN ARITHMETICAL PUZZLE.

A sunny and a dark head, both bent over a much-befigured, much-besmeared slate, the small brows beneath the curls puckered,—the one in perplexity, the other with sympathy; opposite these two a third head whose carrotty hue betrayed it to be Jim's, although the face appertaining thereto was hidden from my view, as its owner, upon his hands and knees, also peered with interest at the slate. Wanderer, familiarly known as "Wand,"—the household dog, and the inseparable companion of my little sisters,—lay at their feet, as they sat upon a low rustic seat, manufactured for their special behoof by the devoted Jim; its chief characteristic being a tendency to upset, unless the occupant or occupants maintained the most exact balance, a seat not to be depended upon by the unwary or uninitiated, under penalty of a disagreeable surprise. To Allie and Daisy, however, it was a work of art, and left nothing to be desired, they having become accustomed to its vagaries.

Such was the picture which presented itself to my view as I came out on the piazza of our summer-home by the sea, and from that point of vantage looked down upon the little group on the lawn below.

But the problem upon which all three were intent had evidently proved too much for the juvenile arithmeticians; and, as I looked, Allie pushed the slate impatiently from her, saying,—

"I can't make it out, Jim: it's too hard. You are too mixed up."

"Now, Miss Allie! an' you with lessons every day," said Jim reproachfully. "Should think you might make it out."

"I'm not so very grown up, Jim," answered the little girl; "and I've not gone so very far in the 'rithmetic; and I'm sure this kind of a sum must be in the very back part of the book."

"Here comes Bill," said Jim, as a boy of his own age and social standing appeared around the corner of the house, a tin pail in one hand, a shrimp-net in the other. "Maybe he'll know. Mr. Edward's taught him lots of figgerin'. Come on, Bill, an' help me an' Miss Allie make out this sum. You ought to know it, bein' a Wall-street man."

Allie said nothing; but I saw a slight elevation of her little head and a pursing of her rosy lips, which told me that she did not altogether relish the idea that a servant-boy might possess superior knowledge to herself, although he might be nearly double her age. Allie's sense of class distinctions was strong.

Having faith in his own attainments, however, the "Wall-street man"—this was the liberal interpretation put by Jim upon his position as office-boy to brother Edward—deposited his pail and net upon the ground, and himself in a like humble position beside his fellow-servant and chum. He might be learned, but he was not proud by reason thereof.

"Now le's see, Miss Allie," he said; "what is it you're tryin' to figger out?"

"It's Jim's sum; and I can't see a bit of sense in it, even when it's down on the slate," answered Allie, still in a somewhat aggrieved tone. "He's as mixed up as a—as a—any thing," she concluded hastily, at a loss for a simile of sufficient force.

"As a Rhode-Island clam-bake when they puts fish an' clams an' sweet-potatoes an' corn all in to once," said Jim.

"At once, not to once; and they put, not they puts," corrected Allie, who, remarkably choice herself in the matter of language, never lost sight of a slip in grammar on the part of our protégés.

"Seems funny, Miss Allie, that you, that's so clever in the right ways of talkin', can't do a sum," said Jim.

Allie's self-complacency was somewhat restored by the compliment; but she still answered, rather resentfully,—

"Well, I can, a decent sum! I had five lines yesterday, and added it all right, too; but a sum like that—I b'lieve even brother Ned couldn't do it!"

That which brother Ned could not do was not to be compassed by man, in the opinion of the children. And, as if this settled the matter, Allie rose from her seat, forgetting for the moment the necessity for keeping an exact equilibrium, and that both its occupants must rise simultaneously, unless dire results were to follow to the one left behind. The usual catastrophe took place: the vacant end went up, and Daisy was thrown upon the ground, the seat fortunately being so low that her fall was from no great height; but the rickety contrivance turned over upon the child, and she received quite a severe blow upon her head. This called for soothing and ministration from an older source, and, for the time, put all thought of arithmetical puzzles to flight; but after I had quieted her, and she rested, with little arnica-bound head against my shoulder, Jim returned to the charge.

"Miss Amy," he said, a little doubtfully, as not being quite sure of my powers, "bein' almost growed up, you're good at doin' up sums, I s'pose."

Now, arithmetic was not altogether my strong point, nevertheless I believed myself quite equal to any problem of that nature which Jim was likely to propound; and I answered vain-gloriously, and with a view to divert the attention of the still-sobbing Daisy from her own woes,—

"Of course, Jim. What do you want to know? No," declining the soiled slate which he proffered for my use, "I'll just do it in my head."

"You're awful smart then, Miss Amy," said Bill, admiringly.

But the question set before me by Jim proved so inextricably involved, so hopelessly "mixed up," as poor little Allie had said, that, even with the aid of the rejected slate, it would, I believe, have lain beyond the powers of the most accomplished arithmetician to solve. No wonder that it had puzzled Allie's infantile brains. To recall and set it down here, at this length of time, would be quite impossible; nor would the reader care to have it inflicted upon him. Days, weeks, and years, peanuts, pence, and dollars, were involved in the statement he made, or attempted to make, for me to work out the solution thereof; but it was hopeless to try to tell what the boy would be at; and, indeed, his own ideas on the subject were more than hazy, and, to his great disappointment, I was obliged to own myself vanquished.

"What are you at, Jim?" I asked. "What object have you in all this"—rigmarole, I was about to say, but regard for his feelings changed it into "troublesome sum?"

Jim looked sheepish.

"Now, Miss Amy," broke in Bill, "he's got peanuts on his mind; how much he could make on settin' up some one in the peanut-business, an' gettin' his own profits off it. But now, Miss, did you ever hear of a peanut-man gettin' to be President of the United States, an' settin' in the White House?"

"I believe I never heard of any peanut-man coming to that, Bill," I answered, laughing; "but I have heard of men whose early occupations were quite as lowly, becoming President in their later years."

"An' I ain't goin' to be any peanut-man," said Jim. "I'm just goin' to stick to this place, an' Miss Milly an' her folks, till I get eddication enough to be a lawyer. I find it's mostly lawyers or sojers that gets to be Presidents; lawyers like Mr. Edward. Miss Amy," with a sudden air of apprehension, "you don't think Mr. Edward would try to cut me out, do you? He might, you know; an', bein' older an' with more learnin', he would have the start of me."

"I do not think that Mr. Edward has any ambition to be President, Jim," I answered, reassuringly. "You need have no fear of him."

For to no less a height than this did Jim's ambition soar, and he had full faith that he should in time attain thereto. In his opinion, the day would surely come when,—

"The Father of his country's shoes

No feet would fit but his'n."

And it was with a single eye to this that his rules of life were conformed. The reforms which he intended to institute, mostly in the interest of boys of his own age and social standing, when he should have attained to that dignity, were marvellous and startling. No autocrat of all the Russias, no sultan, was ever endowed with the irresponsible powers which Jim believed to appertain to the position he coveted; but, to his credit be it said, these were to be exercised by him more for the benefit of others than for himself.

But he repudiated, now, the idea that the peanut venture upon which his mind was dwelling had any thing to do with his future honors.

"Brother Edward would not be so mean to you, Jim," quoth Allie, who was standing by my knee. "You spoke first to be President, and he would never do such a thing as to take it from you."

"And Jim is not thinking about that when he tries to find out that sum," said Daisy, raising her little bandaged head from my shoulder; "he is quite nice and pious, sister Amy, and wants to do a very right thing."

"'Tain't for pious, neither, Miss Daisy," said Jim, who rather resented the imputation of being influenced by motives of that nature. "'Tain't none of your doin' good to folks, nor any of that kind of thing; it's on'y to animals, cause I'm sorry for 'em."

"O Jim, what grammar!" sighed Allie. For Jim, when excited or specially interested, was apt to lapse into the vernacular against which he and his friends were striving; Allie in particular setting her face against it, and constituting herself his instructress and monitress in grammar and style.

"Can't help it, Miss Allie," said Jim. "Can't keep grammar an' 'rithmetic into my head both to once; leastways, not when the 'rithmetic's such a hard one as this."

The excuse was accepted as valid; and Jim and the matter which was now agitating his mind, both being at present in high favor and held in great interest, any further lapses were suffered to pass without correction or remark.

Jim's love for and sympathy with all animals, especially such as were feeble or disabled in any way, was a well-known trait. A maimed or otherwise afflicted dog, horse, cat, or bird was sure to meet with more favor in his eyes than the most beautiful and perfect of its kind; and he had a horror of shooting birds or other game, which was quite remarkable in a boy of his antecedents. He even questioned the right and expediency of killing animals for food, although he never objected to partaking thereof when it was set before him. Fish, only, seemed to him legitimate prey in the way of sport; and for all noxious insects, snakes, or vermin of any description, he had a perfect hatred, setting at naught the principles of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty, and really taking a most reprehensible delight in tormenting them, altogether at variance with his feeling for other creatures.

"Bill," I said, turning to that youth as the most practical and clear-headed of the group, "tell me if you know what it is that Jim desires to find out, and the rest of you keep silence, and do not interrupt."

"Well, Miss Amy," answered Bill, "it's just this. Jim was readin' in the newspaper about a' old lady, how she left all her money—an' she'd worked hard for it too, makin' a show of herself on account of bein' so fat—to keep a hospital for all sorts of hurt an' sick animals an' birds; an' Jim, he's just about as much took up with animals an' natur an' things of that kind as she must ha' been, even if he ain't so fat; an' he's got it on his mind to set up his own hospital, an' let Tony Blair an' his sister Matty keep it an' take care of the animals. Tony's lame, you know, and Matty's hunchbacked, an' can't work; so it's kind of beginnin' on the two-legged animals—at least, Tony's only one legged, but he has a right to be two, an' it's a help to them, too."

Poor Tony Blair, with his deformed sister, had formerly been associates and chums of Bill and Jim, in the days when these last had themselves been young vagabonds, waifs, and strays, buffetting with a hard world; and that sentiment in Jim, which was "took up with animals an' natur," had led him to befriend the helpless creatures, and to do them such kind turns as fell in his way. Overwhelming modesty, or a desire to hide his light under a bushel, were not distinguishing characteristics of Jim; but Bill also had borne ample testimony to the fact, that many a time in the old days Jim had deprived himself of a meal—Milly come by, it might be—to give it to the little cripples, poorly provided for by a drunken father and ill-tempered mother to whom they were naught but a burden. Many a faded and limp bouquet, discarded by some happier child of fortune, did Jim rescue from the ash-heap and bring to Matty, who had a passionate love for flowers; and not seldom during the spring and summer months would he take a long trudge into the suburbs, and gather wild blossoms to gratify the craving of the little hunchback. On one of these occasions he stole a little, fluffy chicken, which had wandered from its mother's guardianship beyond the garden palings of a small cottage, and, hastily buttoning it beneath his worn jacket, made off as fast as his feet would carry him to bestow his prize upon Matty, who had expressed a longing desire for a bird. But the stolen gift brought naught but distress to Matty's tender heart; for, when the ragged jacket was unbuttoned, the little yellow ball fell lifeless into Jim's hand.

"I'm sure I thought he'd got lots of air to breathe," said Jim, wofully gazing at his victim, while Matty's tears bedewed it; "there's holes enough in my jacket to make it as ventilatin' as a' ash-sifter, an' it was awful mean in him to up an' die on me that way. An', Matty, I wish I hadn't brought him, for him to go an' disappint you like this. Never mind, some day I'll buy you a parrot an' a monkey."

Tearful Matty declined the monkey, but the parrot had long since gladdened her weary hours; for a gorgeous specimen, given to much screaming, even more than is the usual manner of his kind, had been purchased by Jim for her behoof out of his little savings, soon after he and Bill had fallen into good hands, namely, those of my sister Millicent and brother Edward.

This occurred not long after the chicken episode. Milly had become interested in the boys, whom she had encountered at one of the Moody and Sankey meetings, whither they had come, not for purposes of edification to themselves or others, but drawn, partly by their love of music, and partly by the desire to make themselves obnoxious to more decently disposed worshippers. But Milly, by her gentle tact, had disarmed them,—they being our near neighbors at the service,—and, profiting by this love of sweet sounds, had brought them within her influence; nor ceased her missionary efforts on their behalf until, with the aid of brother Edward, and the consent and co-operation of our parents, she had established them both as servants in the family, where they had opportunity and encouragement to fit themselves for decent and useful lives.

But their rise in life had not caused Bill and Jim to forget their less fortunate little friends and protégés,—for Bill, too, had in his way been good to Tony and Matty, though he was not nearly so generous and self-sacrificing as Jim,—and they made them sharers in their improved circumstances so far as they were able. Jim had proposed that they also should be taken into our household, and nursed and cared for; but, as father and mother objected to having the house turned into a wholesale reformatory and hospital, his modest plan was not carried out. Some help, however, had been extended to the two cripples, who could have been provided with good homes in some beneficent institution, could the wretched mother have been induced to give them up; but, thinking probably that they excited sympathy by which she could profit, she refused to do so.

Ever since Jim had fallen upon happier times, it seemed that the boy's whole nature had expanded, and he was constantly on the lookout, to use his own language, "for a chance to do a make-up for all the good done to me an' Bill." A certain ambitious and not unpraiseworthy pride, too, and a strong sense of gratitude and obligation to those who were befriending and helping them, particularly strong in Jim, were causing both boys to make the most of the opportunities offered to them.

And now, it would seem, Jim was actuated by schemes of wholesale benevolence for one, two, and four legged animals.

He had proved himself quite a hero during the last summer; had, through the force of circumstances and appearances, fallen under unjust suspicion, but had been absolutely and triumphantly cleared (the story of which may be found in "Uncle Rutherford's Attic"); and had made himself an object of considerable interest, not only to the members of our own family, to whom he had shown great loyalty and fidelity under severe temptation and trial, but also to outsiders who had known of the story of his adventures. Hence, he had been made the recipient of various tokens of this interest and appreciation, mostly of a pecuniary nature, and he now felt himself to be quite a moneyed man.

With the generosity which was one of his characteristics,—perhaps the most distinguishing one,—he scouted the idea of retaining the whole of his small fortune for his own benefit, pressing a share of it upon Bill, presenting our children and his fellow-servants with tokens of his regard, mostly of a tawdry, seaside-bazaar nature, but beautiful in their eyes and his own; conveying, with an eye to the future, another portion to the care of brother Edward, to be used for "'lection expenses" when the time should come for him to run for that dignity to which he aspired; and now it appeared that he had other ends, of a philanthropic nature, in view.

Old Captain Yorke, a veteran sailor, now retired from active service, was our purveyor-general, going each morning in boat or wagon to the nearest town, whence he brought for us and other families such supplies as we ordered; the Point affording no facilities for marketing or daily household needs. He was a great friend and crony of our two young servant-lads, and to him as well as to Bill had Jim confided his plans; but the three heads had proved unequal to the settlement of the arithmetical difficulties which presented themselves, and Jim had applied to Allie, as being possessed of greater educational advantages. This had not proved equal to the situation, however, as has been seen; the knowledge of eight years not being able to cope with this mathematical problem.

Divested of Jim's complications, Bill's discursive remarks upon other subjects, and put into rather more choice English than that in which the latter delivered it, the plan amounted to this:—

Captain Yorke, heartily admiring, and willingly co-operating, was to bring from the town a large quantity of peanuts, which Mrs. Yorke, also full of sympathy, had promised to roast. The amount of peanuts purchased was to be determined by the price per bag, but Jim's ideas were of a wholesale nature; for my young brothers Norman and Douglas, who both had a weakness for this vegetable, had also greatly encouraged him in his undertaking, giving him not only hopes of great results from the home-market, but promises that they would interest "the other fellows," and induce them also to become customers. He was not to be salesman himself, of course, his daily avocations not permitting of this; but, for the rest of our stay at the seashore, he purposed obtaining the services of an acquaintance who belonged in the place, and who was in the habit of peddling about papers, periodicals, an assortment of very inferior confectionery, and other small wares. The proceeds of these sales made here at the seaside, deducting a commission for the boy-vender, Jim hoped would suffice to start his larger and more ambitious enterprise when we should return to the city. This was to set up Tony and Matty Blair in business.

So far all was plain sailing, in anticipation; but now came the more complicated part of the arrangement.

A stand was to be secured, a roaster, a fresh supply of peanuts, and other necessary appliances purchased; and "our ladies," to wit, mother, Milly, and myself, asked to provide the crippled young merchants with warm clothing sufficient to protect them against exposure to the elements.

There were so many "shares" to be provided for, shares of divers proportions, and Jim's arithmetic was of such a very elementary nature, that he soon found himself lost in a hopeless labyrinth of calculations. With peanuts at so much by the wholesale, and so much at retail, running-expenses, and so forth, on the one hand; what would be the various amounts to be allowed from the proceeds, on the other, for a "share" for Tony and Matty, another for return profits to Jim's own pocket, and the third and larger for the establishment of the hospital for crippled animals, the main object of the undertaking?

Now, if peanuts were so much per bag, and other needful appurtenances so much more, how much profit might be realized, and what would be the respective shares? Hardly had I solved this complicated problem to Jim's satisfaction, and my own relief,—for, as I have said, numbers were a weariness to my flesh, and the rule of three a burden to my spirit,—when the boy remembered other claimants upon the fund.

"Miss Amy," he said, "didn't I forget. There's Rosie ought to have a share for savin' me out the Smuggler's Hole; she must have a share, for sure; an' there's Captain Yorke, he ought to have some, too. Please do it all over again, Miss Amy, takin' out their shares."

This was too much, however, and despite Jim's reproachful appeals to my superior learning, I flatly refused to "do up" any more sums on his behalf.

And now, happily, a diversion in my favor was effected, by the appearance upon the scene of old Captain Yorke himself, who was seen coming up the carriage-way, guiding before him a donkey-cart filled with fish, while upon his arm he bore a basket of fruit, vegetables, and so forth.

He was a character, this old, retired sea-captain,—a firm friend and ally to all pertaining to the names of Livingstone, or Rutherford, or to any belonging to those families, our factotum and standby; and, moreover, an endless source of amusement to the mature part of the household, and of unbounded admiration to the more juvenile portion. In the eyes of our little girls, and indeed in those of my two younger brothers, Norman and Douglas, and above all, in those of Jim and Bill, he was a veritable hero, for his had been a hard and venturesome life, full of thrilling adventure and hairbreadth escapes; and the children never tired of listening to the narration of them. Nor, I am bound to believe, did the old man depart from the ways of truth, or draw upon his imagination, in narrating them. But I will let the garrulous old veteran speak for himself, a thing which he was never loth to do.

CHAPTER II.

A CABLEGRAM.

"Mornin', boys; mornin', little ones; mornin', Miss Amy," said the captain, regardless alike of my seniority to the rest of the group, and of any claims of social position over the servants. "Where's pa?" This to me.

"Mr. Livingstone is out driving," I answered, with what I intended to be crushing dignity; for, much as I liked Captain Yorke, it always vexed me to have my father and mother spoken of thus familiarly.

"Ma in, then?" he asked, quite unabashed; and indeed, quite unconscious of any reproof.

"No; Mrs. Livingstone is with Mr. Livingstone," I answered again.

"Wal," drawled the captain, "that's likely enough. If ye see one on 'em drivin' or walkin' roun', you're like enough to see t'other, for they're lover-like yet, if they has got a big fam'ly part grown up. I declar', yer pa an' ma is as like me an' Mis' Yorke as two peas is like two more peas, allus kind of hankerin' to be together, jes' as if we was all young folks yet, an' doin' our courtin'. Not that pa an' ma is sech old folks as me an' Mis' Yorke, but they'll get to it bimeby if they lives long enough."

I passed over the compliment to my parents without comment, merely asking,—

"Can you leave your message with me, captain?"

"'Twill keep," he answered; "an' I've got a bit of business with Jim here. Yer projeck ain't no secret, be it, Jim?"

"No," replied Jim. "I was just tellin' Miss Amy, an' askin' her to do up the sums about it; but"—lowering his voice, and ignorant of the laws of acoustics, by virtue of which I heard every word from my position—"she ain't none too smart at sums if she has had such a lot of schoolin', an' she didn't make it out real nice and clear like. But you can speak out. She knows, an' is agreeble, an' says she'll help. She's awful generous, like the rest of 'em, Miss Amy is."

With this little salve to the wounds which my filial pride and personal vanity had received, he raised his voice once more, quite unnecessarily, and continued,—

"Miss Amy, Captain Yorke's got somethin' to say' bout what we was just talkin' of. Go on, captain; Miss Amy don't mind."

"I was jes' goin' to tell you what I been an' done," drawled the old man, raising his hat with one hand, and rubbing up his grizzled locks with the other, as was his wont when he was talking at length,—he generally did talk at length when he talked at all. "You've jes' about made up yer mind to do that undertakin', haven't yeou? That peanut-undertakin', I mean."

Jim gave a prompt and decided assent.

"All right. So far so good, an' better too," said the captain, rather illogically; "for if you hadn't, maybe I'd a been a little too forehanded, as it were; but it was my opinions you'd made up yer mind for it, so I acted accordin' an' brought 'em along."

"Brought who along?" asked Jim impatiently.

"I'm jes' goin' to tell ye," continued the old man. "Don't yeou be in too great a hurry. Things takes time to tell when there's any thin' in 'em worth tellin'; not that I'm no great hand on a long story, for I allers was a man of few words; an' Mis' Yorke she can allers tell a story more to the pint than me, or than any one I know on—bless her heart."—Certainly the old man's loyalty to, and affection for, his dear motherly wife was beautiful to see and hear.—"But she ain't here to tell, an', what's more, she don't know nothin' 'bout it to tell. She ain't the kind to go on talkin', talkin' 'bout things she don't know nothin' 'bout; or, s'pose she does know somethin' 'bout 'em, to go yarnin', yarnin' on forever an' a day, an' never gettin' to the pint, like to Mis' Clay,—ye've seen Mis' Clay, ain't ye? She's Mis' Yorke's cousin, comes over from Millville now an' then, an' the powerfullest han' to talk, an' never comin' to the pint, an' never givin' anybody else the chance."

Mrs. Clay was the captain's pet grievance, and almost the only person of whom we ever heard him speak disparagingly; his objection to her probably being founded on the ground that she never gave him "a chance."

"Such a tongue," rambled on the captain, "an' so fast an' confused like she's wuss than the Tower of Babel itself, an' jes' as like to scatter the folks what's livin' around her. But if ye've got a thing to tell that's got a pint, folks mostly likes to hear the ins an' outs of it, 'thout the trouble of askin' no questions, an' I'd as lieve tell 'em to 'em. So I'll tell ye all about it, Jim, an' all of ye."

"Well, if it's any thin' about my business, would you mind havin' it out right quick, Cap?" said Jim.

"An' ain't I a doin' it?" responded the captain. "Don't be in sech a hurry, boy. I got to get my breath to talk, after walkin' up the hill for to rest Sanky Pansy a bit, for the cart was powerful full this mornin', an' he did have a load, an' he's gettin' old an' has to be eased off a bit like myself, an' I felt kind of blowed an' puffy-like. Soon's I can talk good, I will. Young folks is allers got to be impatient. There's my darter, Matildy Jane, she ain't none too patient, you know—leastways, not onless it's with you, Jim,"—here a wink of the eye at Jim made evident the playful irony of the exception, for Jim was Matilda's bête noir, and a chronic warfare waged between the two,—"an' she says to me this mornin', says she, 'Pa,' says she,—an' ye might think I hadn't never learned her the Ten Comman'ments, leastways the one about honorin' her father an' mother; but young folks is different behaved from what they was in my day—at least them's my opinions. I was jest a tellin' her an' Mis' Yorke how Peter Slade got his boat capsized last night; an' 'Pa,' says she, 'it's time my bread was took out of the oven, an' if you've got any thin' to say'—I declar', Miss Amy, if she didn't give me a message about yer clothes; how when the wind riz up last night, some of 'em was carried off the lines into the sand, an' she had 'em to wash over again, an' wouldn't have 'em home jes' up to time. Now, where was I, Jim?"

"Out on the sands, an' upset in Slade's boat, an' talkin' to Matilda Jane; an' where you're goin' to is more than me or any one else can tell, Cap," answered Jim, saucily. "You started to tell us something about my peanut-business, I believe; but you've got considerable off the line."

"To-o be sure, to-o be sure," said the old man, no whit offended or displeased by the boy's pertness; for the spirit of bon camaraderie which existed between them was not easily disturbed. "Well, now, I'm jes' comin' to it right spang off. Well, ye see, I been over to Millville this mornin' in the boat, accordin' to custom, when the water ain't too rough, an' bein' off extry early, too, for I'd more 'n common to market for,—Mis' Douglas she told me to bring her cowcumbers for picklin'; an' Mis' Stewart she wanted some chany dishes an' some glasses outer the crockery store,—an' that's considerable way from the dock, you know; an' Mis' Yorke she gimme some bit of flannen she wanted matched,—an' such like arrands takes time. So I says, says I, I'll jes' run over to the station an' see what's doin' there, more by token, as it was near time for the express, an' it kind of livens ye up a bit to see them express-trains come in,—they're nice an' bustlin' like, with a sort of go in 'em; an' after she come in, there was a freight-train come, an' there was lots of freight put off, an'—guess what I see, Jim, among it."

"Peanuts, I suppose," answered Jim, "an' I guess I'll get at the whole story jest as quick by guessing it out myself, as by waitin' for you, Cap."

The captain gave Jim a friendly nod, still no whit disturbed by the freedom of his criticisms, and rambled on again,—

"Yes, peanuts, bags of 'em, half a dozen or more, I reckon, though I didn't take the trouble to count 'em; an' the way I foun' out—how do ye s'pose I knew what was in them bags?"

"Smelled 'em," said Jim; "Sampled 'em," said Bill, in a breath.

"How was I to sample 'em when they was—I mean, if they was fastened up in the bags?" continued the captain; "nor it wasn't no smell, either. There ain't much smell outer peanuts 'thout they're cookin'. Mis' Yorke, she's a master hand to roast peanuts, does 'em jes' to a turn, an' then ye can smell 'em clear down to the beach, an' fustrate it is, too. I'd rather smell 'em than all the fine parfumery things they puts up in bottles."

"What about the peanuts?" urged Jim. "Then how did you know, an' what did you do? Hurry up."

"There was a feller—one of the freight-hands—a pitchin' of the things outer the cars; an' one of them bags hit against a barrow stood there, an' got cut right through, the bag did,—an' what do you s'pose come a pourin' outer that bag, Jim?"

"Think I can guess that riddle. Peanuts," answered Jim.

"Yes, peanuts," said the captain; "an' it was a lucky thing for Sam Bates, to who they was consigned, that there wasn't a raft of youngsters roun' that freight-house as there is most times of the day. There's a Sunday-school clam-bake comin' off up to the Pint to-day, an' I reckon most of the Millville boys was gettin' ready for to go to that, so they wasn't on hand. Sam himself was there, though, an' it beat all, the takin' he was in over them peanuts; an', to be sure, it was enough to make any creetur' mad, to see them good peanuts go rollin' an' hoppin' over the platform, an' Sam he in a' awful hurry to load up an' go home, for he's a darter gettin' married this arternoon. Ye didn't never hear about Sam Bates' darter, an' her city young man, did ye? Well, ye see, Sam Bates' darter, her that is called——"

"But the peanuts; tell us what became of the peanuts first, Cap," interrupted Jim, determined to check the old sailor's wanderings, and keep him to the "pint."

"Why, ye see," meandered on the captain, "when I see them peanuts a-rollin' round, an' Sam in that takin', I says to myself, Sam ain't got no time to lose a-pickin' up of them peanuts, an' maybe he'd be glad to get rid of 'em for what he give for 'em an' no profits, an' let Jim have the profits, an' no freight to pay on 'em but me to get 'em picked up. 'Sam,' says I, as he was fussin' round, 'the Scriptur' says,'—Sam's a deacon in the church, an' I thought mebbe a little Scriptur' would fetch him, and keep the price down,—'the Scriptur' says, Whatever a man can get, therewith let him be content; an' I take it the moral of that is, make the best of a bad bargain. An' there's another teks that says, Don't ye fret over spilt milk; an', bein' a pillar of the church, I reckon you'd like to practise 'em, an' let your light shine afore men.' Now if there's one thing more'n another that Sam prides himself on, its bein' a deacon, an' livin' up to it; an' my speakin' Scriptur' to him was jest a word in season, for he quiets down an' falls to reckonin'. 'Give 'em to me for what you give by the lot, an' throw in the freight,' says I, seein' he meant to make on 'em, 'an' I'll take 'em an' see to the pickin' 'em up, an' you can load up the cart an' start off home.' He jes' took to it at once, for, with the lot he had, one bag didn't make so much differ out half a dozen—he buys 'em that way mostly, for ye know he keeps a' eatin' house; temperance strict it is, up to Stony Beach, where there's lots of clambakes an' picnics holdin' all the time, an' the folks eats heaps of peanuts. So Sam came to my terms, an' I made thirty cents on the bag of nuts, an' the freight throwed in for ye, Jim; an' me an' Taylor an' Shepherd picked up all the nuts, an' I brought 'em along in a basket Taylor lent me."

Jim turned expectant eyes towards the donkey-cart.

"No," said Captain Yorke, seeing the direction of his glance, "they bean't here in the cart, nor nowheres here; they're down into the lighthouse. Perry was comin' over in his boat 'thout no load; an', as I was pretty well filled up, he brought 'em over, an' he's took 'em to his own landin'. Soon's I'm rid of my load I'll go after 'em. Hello!" as a blue-coated, brass-buttoned boy from the chief hotel of the place came running into our grounds, and up to the house. "Hello, here's a telegraph for some on ye! Hope 'tain't no bad news. I don't like them telegraphs; ill news comes fast enough of its own accord, an' good news is jes' as good for a little keepin', an' ain't goin' to spile. Mis' Yorke she says——"

But Mrs. Yorke's sayings, valuable though they might be, were lost upon me as I took the yellow-covered message from the hand of the messenger. Telegrams were matters of such almost daily occurrence in our family that the sight of one rarely excited any apprehension; and, as all of our immediate household were at present here at our seaside home, I knew that the message could bring no ill news of any one of them. But my heart sank as I saw that this was a cablegram, for a dearly loved uncle and aunt were over the sea, and my fears were at once excited for them.

But fear was quickly changed to joy when, opening the cablegram in the absence of my parents, to whom it was addressed, I read these words,—

"We take 'Scythia' to-morrow for home, direct to you at the Point. All well."

As we had not expected the dear absentees for at least six weeks or perhaps two months, this news was not only a relief, but a joyful surprise, and I gave a little shriek of delight, which called forth eager inquiries from the children, while Captain Yorke and Bill and Jim were alert to catch my answer.

"Uncle Rutherford and aunt Emily are coming home, now, right away; they will be here in a week or so, and they are coming to us, here to this house!" I exclaimed, waving aloft the paper, in the exuberance of my joy.

Daisy forgot her downfall, and her bandaged head, as she and Allie seized one another by the hands, and went capering up and down the piazza in an improvised dance; and Captain Yorke's face beamed, as he said,—

"That's the best news I've heered this summer, leastways next to hearin' Jim was likely to get well that time, for the Pint ain't the Pint when the Governor and the Madam ain't on to it. But, Miss Amy, I wouldn't be for turnin' your folks out afore ye'd go to the city anyhow; for, take ye for all in all, ye're a pretty likely set, an' I'd miss Jim an' Bill a heap."

There was no fear of that: we were tenants for the season in the dear old seaside homestead, where we had been guests for more or less of every previous summer; and the beloved uncle and aunt whose home-coming from a European trip we were now rejoicing over, would, in their turn, be now our much prized and welcome visitors. It would not be for long, however; for, to the great regret of the whole household, our summer sojourn by the sea would in a few weeks come to a close. I said the whole household; but there was one exception, for father had privately sighed all summer for our own country home, where he had his fancy farm, extensive and beautifully cultivated grounds, and superb old trees in which his soul delighted. We told him that a branch of one of these last was, in his eyes, worth the whole broad ocean, in which his family so revelled; and he did not deny the soft impeachment. But his patience was not to be much longer tried, for we were to spend a couple of months at Oaklands after leaving the seashore, and before we settled down for the winter in our city home. Nevertheless, absence from his beloved Oaklands had been more than compensated for by the roses which the invigorating sea-breezes had brought to the cheeks of the two youngest of the household, Allie and Daisy, who had been brought here pale, feeble, and drooping, from the effects of the scarlet-fever, but who were now more robust than they had been before the dreadful scourge had laid its hand upon them.

Nor had the summer been one of unmixed enjoyment, even to those members of the family who gloried in the sea and the seashore; for circumstances had arisen which had been productive, not only of great anxiety and trouble to us all, but which had involved bodily injury, and all but fatal consequences, to poor Jim. And although his name and character had come out scatheless from the trying ordeal of doubt and suspicion which had fallen upon them at that time, it had been otherwise with those of one who had been received as no other than a favored friend and guest in our household; and a young girl whose advantages had outweighed a thousand-fold those of the once neglected waif rescued by our Milly from a life of evil, had gone forth from among us with a record of shame and wrong-doing which had forfeited, not only her own good name, but also the respect and liking of all who had become cognizant of the shameful tale.

To those who have read "Uncle Rutherford's Attic," these circumstances will be familiar; to those who have not, a few words will suffice for explanation.

In the early part of the summer, my aunt, Mrs. Rutherford, had sent to me a pair of very valuable diamond earrings, old family jewels, and an heirloom. They came to me by virtue of my baptismal name, Amy Rutherford, which I had inherited from several successive grandmothers on my mother's side; the young cousin to whom they would have descended, the only daughter of aunt and uncle Rutherford, having died some years since, when a very little girl. She was exactly of my own age; and this, with the fact that she too was an Amy, had caused me to be regarded by my uncle and aunt, especially the latter, with a peculiar tenderness; and they seemed to feel that to me, the only living representative of the family name once borne by their lost darling, belonged all the rights and privileges which would have fallen to their own Amy Rutherford. It may be imagined how I had prized a gift precious, not only for its own intrinsic value, but for the many associations which clustered about it.

Scarcely, however, had the earrings become my personal property, than there followed in their train such a course of sin, sorrow, and tribulation, that my pleasure in them was quite destroyed; and, for a long time, the very sight of them became hateful to me.

Ella Raymond, a ward of my father's, and a girl somewhat older than myself, had come to make us a visit just about the time that the beautiful jewels came into my hands. Incited by vanity, and an inordinate love of dress, this unhappy girl had recklessly allowed herself to become heavily involved in debt,—debt from which she saw no means of escape, and which she was resolved not to confess to her guardians. The sight of my diamonds aroused within her the desire to possess herself of them, not for her own personal adornment, but that she might dispose of the jewels, replacing them with counterfeit stones, and so obtaining the means to satisfy her creditors.

Unrestrained by principle, honor, or the laws of hospitality, the wish became but the precursor to the actual carrying-out of the evil thought. Thanks to my heedlessness, and the careless way in which I had guarded the earrings, she obtained them with little trouble; and after an amount of duplicity and deceit, terrible and shameful to contemplate in a woman so young, had contrived to carry out her purpose, to have the stones changed, and then to convey the earrings back to my possession, without drawing suspicion upon herself.

Nor, was this the worst; for when, by a most unfortunate series of events, suspicion was forcibly directed toward Jim, she failed to exonerate him by acknowledging her own guilt; and but for the merest accident, which brought about the proverbial "Murder will out" and fixed the crime without a shadow of doubt upon her, would have suffered the innocent boy to bear all the penalties and disgrace which by right belonged to her.

So it will be seen that the summer, spite of its many pleasures and much happiness, had not been without a large share of care and perplexity.

That all this was over, and that our fears for Jim's moral and physical well-being had come to an end, we were most thankful; and the most of us still clung lovingly to the grand old ocean, and our summer-home on its shore.

But autumn gales would, ere many weeks, be sweeping over this exposed coast; and already the summer-guests were flitting from the large hotels, although the cottagers would probably hold their ground for some little time longer. But what would it matter to us if we should be left the very last of the summer-residents upon the Point, so long as dear aunt and uncle Rutherford were to be with us? They were a host in themselves, especially the latter, who always seemed to pervade the whole house with his jovial, hearty presence, and who was the first of favorites with all the young people of the family.

There would be much for them to hear, too: all the sad story related above in brief, to be told, with all its minor particulars; for it had been kept from them hitherto, as I had been very sensitive on the subject, my own carelessness having been partially in fault, and I had preferred that they should hear nothing of it until their return. Aunt Emily would not have been severe with me, I knew; but I had wished that the face and the voice, which she always associated with her own lost Amy, should speak and plead for my shortcomings in the matter, when it should come to her knowledge. And oh! was I not thankful beyond measure, for her sake, even more than for my own, that the jewels had been recovered, and were once more safe in my own possession, before she learned of the perils they had passed through. If I felt somewhat shamefaced and repentant, as it was, what would it have been if they had been lost beyond recovery!

The joy at the unexpected return of the absentees was not confined to their own family or circle, for the "Governor"—uncle Rutherford had years since held that dignity in the State, and was still "the Governor" to all the denizens of the Point—was greatly beloved by all who knew him well; and the old residents of the place, which had for so many years been his summer-home, considered themselves to be his intimate acquaintances. He was an authority and a law to each one among them. What "the Governor" did, was invariably right in their eyes; from what "the Governor" said, there was no appeal. He would, indeed, have been a daring man who should question the right or wisdom of uncle Rutherford's words or deeds in the presence of any of these stanch adherents.

And dear aunt Emily was not less beloved in her way, for the simple people of the Point all but adored her,—true, wise friend that she had proved to them; and among them none were more ardent in their devotion and admiration than Captain and Mrs. Yorke.

So it was no wonder that the captain's face beamed with delight, nor that, being somewhat after the manner of the Athenians of old, who delighted in some new thing to tell or to hear, he should now be in haste to despatch his daily business, and take his departure to spread the news about the Point. Indeed, he would scarcely wait until I—who regained my senses before it was too late—furnished him with the list for the next day's supplies, which mother had confided to my keeping. In fact, in the midst of the excitement and pleasant anticipations which uncle Rutherford's cablegram had called forth, Jim's "peanut-undertakin'" was for the present entirely lost sight of, unless it was by the lad himself and his faithful chum and ally, Bill.

No need to give here the reasons which had influenced uncle Rutherford's unexpected return; they were purely of a business nature, and would interest no one else.

CHAPTER III.

AN ARRIVAL.

I had made my confession,—for a confession I had felt it was,—involving for my own share no small amount of carelessness, and some little pride and self-will; all of which "little foxes" had opened the way to the commission of actual crime in another.

It was the day after that on which my uncle and aunt had arrived at the Point,—mild, soft, and sunny; only the September haze upon sea and sky to tell that the lingering summer was near its end.

We sat upon the piazza,—these two dear newcomers, my sister Milly, and I. Father off upon some business; mother in the house attending to Norman, who had come home with a sprained wrist; the children at play upon the beach with Mammy, and their faithful pages, Bill and Jim, in attendance. I had stipulated, with a fanciful idea that I was making some righteous atonement, that I should be the one to relate the sad story of my diamond earrings; and hence no one had until now mentioned the subject in the hearing of my uncle and aunt.

The opportunity was propitious, the audience lenient and sympathetic; and seated on the piazza-step, with my head resting against aunt Emily's knee, and, as the tale proceeded, her dear hand tenderly stroking my hair and cheek, I had told the story to its minutest particular, taking, as the sober sight of after days has shown me, more than the necessary amount of blame upon myself.

So my uncle and aunt now said; and, while inexpressibly shocked at such heartless wickedness in one so young as the guilty girl, they would not allow that their "own Amy" was at all blameworthy in the matter, and only congratulated themselves and me upon the recovery of the earrings. My name, and the likeness I bore to the Amy Rutherford in heaven, would have pleaded for and won me absolution in a far worse case than this; and they at once set themselves to work to demolish my almost morbid fancies in connection with the theft of the jewels. The very fact that I had now told them all was a relief, and my elastic spirits at once began to rise from the weight which had burdened them during the last few weeks.

"So that is the hero of your tale?" said uncle Rutherford, looking thoughtfully down upon the beach where the little ones were enjoying themselves to the utmost, and having matters all their own way, as usual. Jim was lying prone upon the beach, while Allie and Daisy were industriously covering him with sand; Bill assisting by filling their pails for them. This was a daily amusement, and never palled.

"So that is your hero?" he repeated. "And what do you mean to do with him, Milly?" he asked, turning to my sister. "Such a fellow should have a chance in life."

"He thinks he has it since he has been here," answered Milly; "since he has been among respectable people and surroundings, provided and cared for, and taught. He and Bill both talk as if they needed no greater advantages than those they possess already. As to what I mean to do with him, dear uncle,—well, it is less what I mean to do with him, than what he means to do with himself. His own ambitions are soaring, and quite beyond any plans that I could form for him; his aim being the head of the government of our country, with the powers of an autocrat, and no responsibility to any one. Nor is his mind disturbed with any doubts that he will be able to achieve this dignity, provided that he continues to 'have his chance.' At present he is content with learning his duties as a house and table servant, believing those to be but stepping-stones towards his goal."

"To say nothing of his ambitious views regarding Milly herself," I interrupted. But my remark was ignored as unworthy of the gravity of the subject.

"But he should have some schooling, a boy such as he is,—do not you think so?" asked uncle Rutherford; adding, "Whatever his aims and ambitions may be, he can achieve nothing without some education."

Milly hesitated for a moment, unwilling to make mention of all that she was doing for Jim and his confrère; and I spoke for her.

"Milly is spending a goodly portion of her worldly substance in that way," I said. "The boys go to a teacher for two hours every evening, and are both making quite remarkable progress in the three R's; and Bill had singing-lessons all last winter, and I believe Milly intends that he shall continue them when we go back to the city."

"H'm'm," said uncle Rutherford. "Very good, so far as it goes; but I mean something more thorough and far-reaching than this." And Milly's eyes lighted, for she knew that uncle was already planning some means of substantial advancement for her protégé.

"If you are going to give him any further 'chance,'" I said, "Columbia itself will not bound his ambition. He, too, will sigh because there is but one world for him to conquer."

"H'm'm," said uncle Rutherford again, with his eyes still fixed thoughtfully upon the incipient candidate for presidential honors, who, having shaken himself free from the sand, and risen to his feet, was now tumbling rapidly over in a series of "cart-wheels;" another performance in which the souls of our children delighted, and in which he was an expert. But he—uncle Rutherford—said nothing more at present; and we were all left in ignorance as to what benevolent plan tending Jim-wise he might be pondering.

For a man otherwise so charming and considerate, uncle Rutherford had the most exasperating way of exciting one's curiosity and interest to the verge of distraction, and then calmly ignoring them.

But now I suddenly bethought myself of Jim's "peanut plan," which, truth to tell, had passed entirely from my mind since the day I had first heard of it; and, with an eye to further prepossessing uncle Rutherford in the boy's favor, I forthwith unfolded his scheme for the benefit of the helpless young Blairs. My uncle was amused, but, as I could see, was pleased, too, with Jim's gratitude and appreciation of the good which had fallen to his own lot.

"Amy," said uncle Rutherford presently,—apropos of some further allusion which was made to my tale, and to Captain Yorke's share in it,—"Amy, I am going to invite Captain and Mrs. Yorke to visit New York this winter, and," with a twinkle in his eye, "shall depend upon you and Milly to escort them hither and thither to see the city lions."

"Invite them to your house?" I inquired, in not altogether approving surprise, for the idea of Captain and Mrs. Yorke as visitors in uncle Rutherford's house was somewhat incongruous; while the vision of Milly and myself escorting them about was not attractive in my eyes, fond though I was, in a certain way, of the old man and his dear motherly wife.

"Not to my own house, no," answered uncle Rutherford, with an assumption of gravity which by no means imposed upon me, "for I do not expect to have any house of my own this coming winter,—or, I should say, not to occupy my own house; for, Amy, as my boys will pass the winter abroad, and your aunt and I would feel lonely without them, we have been persuaded by some kind friends, with a whole houseful of troublesome young people, to make our home with them, and help to keep their flock in order. So Captain Yorke and——"

But he was interrupted, as I fell upon him in an ecstasy of delight,—worthy of Allie or Daisy,—enchanted to learn that we were to have the inexpressible pleasure of having him and aunt Emily to spend the winter with us; a pleasure which I would willingly have earned by any amount of ciceroneship to the old sailor and his wife. The subject had not been mooted before the younger portion of the family, but had been discussed and settled in private conclave among our elders; so it was a most agreeable surprise to each one and all of us.

"But about Captain and Mrs. Yorke?" I said, at length, when my transports had somewhat subsided, and calmness was once more restored. "You do not really mean that you are going to bring them to the city, and—to our house?"

And all manner of domestic and social complications presented themselves to my mind's eye, in view of such an arrangement. For uncle Rutherford, in his far-reaching desire to benefit and make others happy, was given to ways and plans which, at times, were too much even for his ever-charitable, generous wife; and which now and then would sorely try the souls of those less interested, but who, nolens volens, became the victims of his benevolent schemes.

No one was better aware of uncle Rutherford's proclivities in this way, or more in dread of them, than my young brother Norman, who had just joined our circle, fresh from mother's surgery, and with his arm in a sling. For Norman's bump of benevolence was not as large as that of some other members of the family, and he was inclined to look askance upon uncle Rutherford's demands upon his heart and his purse. These, to tell the truth, were not infrequent; for our uncle, believing that young people should be led to the exercise of active and unselfish charity, and seeing that Norman was inclined to shirk such claims, was constantly presenting them to the boy, with a view to training him in the way he should go in such matters.

"Uncle Rutherford gives with one hand, and takes away with the other," Norman had said, grumblingly, only this same morning, in my hearing.

"You had better say he takes with one hand, and gives seven-fold with the other," said Douglas, resentfully; for he inherited, to the fullest extent, the family generosity. "Nor, I saw the skins of your flints hanging out to dry this morning."

Whereupon Douglas dodged a book aimed at his head, and left his shot to work what execution it might.

Norman had caught my last words, and taken in their meaning, and his delight at the prospect of a visit from Captain Yorke was almost as great as Milly's and mine in view of the stay of our uncle and aunt at our home; being incited, probably, by the thought of the "jolly fun" which he and Douglas could extract from the old man while piloting him about the city.

"I certainly do not intend to bring the old people to your house, Amy," said uncle Rutherford; "but your aunt is anxious that Mrs. Yorke should see some good physician, who may be able to relieve her from her lameness before she is entirely crippled; and we shall therefore propose that they come to the city after we are fairly settled there, when we will provide comfortable quarters for them, and put Mrs. Yorke under proper treatment. There is a fitness to all things, my child; and Captain and Mrs. Yorke would probably feel as much embarrassed as your guests, as we should be in having them with us."

"I was only thinking——" I began, then stopped.

"You were only thinking that your quixotic old uncle was about to inflict a somewhat trying experience upon you," said uncle Rutherford, in answer to the unspoken thought. "But he has a modicum of sense left yet, Amy."

Truth would not allow me to enter a disclaimer, for this had been my very thought. Any slight embarrassment which I might have felt, however, was relieved by a little diversion in my favor, as uncle Rutherford said,—

"Here is Fred Winston coming over from the hotel."

"Yes, he is generally coming over, and never going back," said Norman, with what I chose to consider a saucy glance in my direction; but I ignored both speech and glance, as I welcomed the new-comer.

Now be it understood, that this young man was neither a gossip nor news-monger; but, being at present a resident of the largest hotel in the place, he was, from the force of circumstances, apt to be the hearer of various items of interest, and these, for reasons which seemed good to himself, he usually considered it necessary to bring over to the homestead as soon as possible after they came to his knowledge. Indeed, our boys basely slandered him, by crediting him with the invention of sundry small fictions as an excuse for coming over to our house. Nevertheless, he was always a welcome guest with each one and all of the family, and with none more than with these saucy boys.

"Mr. Rutherford," he said now, when he had settled himself in such comfort as he might upon the next lowest step to that on which I was seated, and addressing himself to my uncle, who, by virtue of his interest in, and proprietorship of, a great portion of the Point, was regarded by most people as a sort of lord of the manor,—"Mr. Rutherford, have you heard what has befallen Captain Yorke?"

"I have heard nothing," answered uncle Rutherford. "No misfortune, I hope."

Mr. Winston slightly raised his eyebrows, as he answered, laughingly, "I do not know whether he considers it in the light of a misfortune or a blessing; but I know very well how I should feel had such an affliction fallen to my lot,—that it was an unmitigated calamity; while Miss Milly, again, would probably consider it as the choicest of blessings. It seems that the old man had a reprobate son, who, many years since, went off to parts unknown; and his parents have heard nothing of him since,—that is, until to-day, when a woman, claiming to be his widow, appeared with five children. She had his "marriage lines," as she called them, a letter from the prodigal himself to his father, and other papers, which appear to substantiate her claim; and the old couple have admitted it, and received the whole crowd. 'Matildy Jane' is sceptical, derisive, and not amiable. Nor can one be surprised that she is not pleased at this addition to her household cares and labors, for I have not told the worst. The woman is apparently in the last stages of consumption; one of the children is blind; another has hip-disease; and a third looks as if it would go the way its mother is going. There is a sturdy boy of fourteen or so, the eldest of the family, and another chubby, healthy rogue, in the lot; but they really looked like a hospital turned loose. Brayton and I had gone down for bait, and were talking to the captain, when they arrived."

"Don't, don't, Mr. Winston!" exclaimed Norman. "Milly will adopt the crowd, and have them here amongst us. That is her way, you know."

"And what did the captain say?" I asked, fully agreeing with Mr. Winston, that this must be, for the old seaman, an appalling misfortune. "Imagine, if the thing is true, and these people dependent upon him, the utter up-turning of the even tenor of his way,—of all their ways. I sympathize with 'Matildy Jane.' What did the captain say?"

"He asked me to read his son's letter to him,—for he is not apt, it would appear, in deciphering writing; and, indeed, it was more or less hieroglyphical,—then gazed for a few moments at the dilapidated crew,—dilapidated as to health, I mean; for they are clean and decent, and fairly respectable looking,—and said, 'Well, ye do all seem to be enj'yin' a powerful lot of poor health among ye.' Then he turned into the house, saying that he must 'see what mother said,' giving neither word of welcome nor refusal to admit the claim of the strangers; and presently Mrs. Yorke appeared, in a state of overwhelming excitement, and, nothing doubting, straightway fell upon the new arrivals with an attempt to take the whole quintette into her ample embrace. No need of proofs for her; and, seeing this, the captain's doubts were dispersed, and he began a vigorous hand-shaking with each and every one of those present, including Brayton and myself, and repeating the process, until Brayton and I, feeling ourselves to be intruders in the midst of this family scene, made good our escape. Not, however, before 'Matildy Jane' had appeared, with tone, look, and manner, which you who know 'Matildy Jane' do not need to have described, denouncing the woman and children as 'ampostors,' and bidding them begone."

"And you do not think that the woman is a fraud?" asked aunt Emily.

"I do not, Mrs. Rutherford; and neither did Brayton," answered Fred Winston. "And, besides the letter and marriage certificate which were in her possession, making good her pretensions, she had an honest face, and appeared respectable,—far too much so for the wife of such a scallywag as old Yorke's son is said to have been."

"If the Yorkes allow her claim, and take in this numerous family, it will interfere with your plans for Mrs. Yorke, uncle," I said.

"Not at all," said uncle Rutherford, who, when he had once made up his mind to a thing, would move heaven and earth to carry it out, and who often insisted upon benefiting people against their will. "Not at all. The new family can be left here to keep Matilda Jane company while her father and mother are away. There is all the more reason now that Mrs. Yorke should be cured of her lameness; and I believe that it can be done."

Blessed with the most sanguine of dispositions, as well as with the kindest and most generous of hearts, he always believed, until it was proved otherwise, that the thing he wished could be done.

"Milly," said aunt Emily, suddenly turning to my sister, "will you come down to the Yorkes' with me?"

Milly assented readily; and the two kindred spirits set forth together.

"The blessed creatures!" said Fred Winston. "What unlimited possibilities the arrival of this infirmary opens up to them. I knew that they would be off at once to inquire into the condition of the sick and wounded."

"And to find out how many candidates there may be for the hospital cottage and other refuges," I added.

But the two good Samaritans, as they afterwards reported, were not so appalled by the state of things at the Yorkes' cottage, as Mr. Winston's tale had prepared them to be. Perhaps matters had improved since he had left two hours since, or the stricken family had at once accommodated themselves to the change in their circumstances. Certain it is that aunt Emily and Milly found peace and serenity reigning: Mrs. Yorke with the little cripple in her capacious lap, coddling and petting her as the good soul well knew how to do; the captain piloting the blind child about the house and garden, familiarizing him with different objects, by which he might learn his own way about by his acute sense of touch; the youngest—a teething, not consumptive, baby—fast asleep; and even the recalcitrant "Matildy Jane" tolerably pleasant and good-natured beneath the fascinations of a handsome, sturdy urchin four years old, who, undaunted by her hard face and snappish voice, insisted upon following her around, and "helping" her in her manifold occupations. He was a boy who did not know how to be snubbed, and had fairly won his way with his ungracious aunt, by sheer persistence in his unwelcome attentions. To all her hospitable intimations that he and his family had brought an immense addition to her cares and labors,—which certainly was true,—he opposed smiles and caresses, and assurances that so long as he was there he would share and lighten all these; appearing to think that she complained and scolded only to draw forth his sympathy and aid.

Who could stand out against such a fellow? Not even "Matildy Jane." And she had succumbed; at least, so far as he was concerned.

The mother of the helpless group, pale, feeble, and careworn though she was, had already shown herself eager to lessen, so far as possible, the burden she had brought upon the family of her husband, and sat peeling potatoes from a huge basket on the one side, while a pan of apples, duly pared and quartered, stood awaiting the oven upon the other. Plainly Matilda Jane had had no scruples of delicacy in availing herself of the services of her newly arrived sister-in-law.

"What are you going to do with them all, Captain Yorke?" asked Milly, pityingly, as she stood beside the old sailor in the porch, while aunt Emily interviewed Mrs. Yorke and the widow. "This is such a care for you."

"Do with 'em?" repeated the veteran, apparently quite undismayed by the prospect before him. "Waal, I reckon we've got to be eyes an' backs an' lungs to 'em, for they've run mighty short of them conveniences. Let alone Theodore, an' that feller over there,"—nodding towards the kitchen-door, within which Matilda Jane was to be seen mixing biscuit, with the boy beside her, his round, fat arms up to the elbows in the dough, with which he was bedaubing himself and every thing about him, unrestrained by his subdued aunt,—"let alone that feller over there, there ain't the makin' of a hull one among 'em. I guess they've got to be took care of; an', if the Almighty hadn't a meant us to do it, he wouldn't a sent 'em here. Them's my opinions, an' me an' Mis' Yorke we ain't the ones to throw back his orderin's an' purposin's in his face. They do seem a bit like a hospital full, though, don't they?" he added, unconsciously expressing Mr. Winston's view of the situation. "Me an' Mis' Yorke, we foun' out the truth of the Scriptur' sayin', how sharper than an achin' tooth it is to have a thankless child, an' Tom,—I don't min' sayin' it to you,—he was thankless enough, though he's dead an' gone, an' his old father ain't the one to cast stones at him now. But me an' Mis' Yorke, we don't want to make out the truth of that other Scriptur', that the sins of the father shall be visited on the children,—leastways, not Tom's children; they ain't to blame for his short-comin's; an', meanin' no disrespec' nor onbelief, that Scriptur' do always seem to me a little hard on the children. Maybe—who knows—them youngsters will ha' brought a blessin' with 'em; an' my opinions is they has, when I see Mis' Yorke a cuddlin' an' croonin' over that little hunchback. Now she's awful contented an' easy-minded like to have somethin' to pet, for she's allers a hankerin' after babies an' them sort of critters. We was kinder took aback, for sartain, when Maria,—her name's Maria, Tom's widder's is,—when she come right in with the hull crowd followin', an' John Waters' wagon, what they come from the station in, standin' at the gate, an' all the luggage in it; an' them gentlemen was here gettin' bait an' askin' about the fishin', an' Matildy Jane she kinder flew out, an' one of the little ones was hollerin',—an' it was all kinder Bedlamy. But it's all come right now; an' Maria, she's a willin' soul, an' if Jabez," the old man's son-in-law, and a power in the household, "if Jabez an' Charlotte don't be grumpy over it, we'll all get along as pretty as a psalm-book. Jabez, he an' Charlotte has gone to Millville for the day, an' all this is unbeknownst to them."

Clearly, the captain was somewhat in dread of Jabez and Jabez's opinions; but Milly had no fear that the strangers would be sent adrift in deference to these.

But something must be done to help the old people with the burden which had so suddenly fallen upon them. The gray-haired seaman was comparatively vigorous still, but his sea-faring days were over; and while he had put by a sum sufficient to keep him, his good wife, and "Matildy Jane" in comfort, this unlooked for addition to the family, helpless and crippled as the grandchildren were, would be too great a drain upon his little fund. As this had been placed in father's hands for investment, we knew to a fraction what he had to depend upon, and that it was not enough to provide for all. The sturdy independence of the captain would no doubt revolt against the idea of receiving any actual pecuniary assistance, as would that of his wife; but some way must be contrived of lessening their responsibilities and cares. Jabez Strong and his wife must share these, although he might and probably would be "grumpy;" but even then it would be hard to meet all demands, without depriving the old couple of their accustomed comforts. The cheerful, it-will-all-come-right spirit in which they had received the intruders,—I could not look upon them in any other light,—made us all the more anxious to do this; and, before night, Milly and I were exercising our brains with all manner of expedients for accomplishing it without hurting their pride and their feelings.

Meanwhile, our elders, with less of enthusiasm perhaps, but in a more practical spirit, were considering the same matter; and the little ones, our Allie and Daisy, having also heard of the influx of children at the Yorkes' cottage, had laden themselves with toys and picture-books, and persuaded mammy to escort them thither. Our little sisters had so burdened themselves, that they needed assistance to transport all these gifts to Captain Yorke's house; and they could not look for any great amount of this from mammy, who had all she could do to convey her own portly person, and the enormous umbrella without which she never stirred, as a possibly needed protection against sun or rain, as the case might be. So they begged that Bill and Jim might act as carriers, coaxing Thomas to spare them from pantry duty,—a matter not attended with much difficulty, as the old butler was only too willing to indulge them on all occasions, even to the length of taking double work on his own shoulders.

They all set forth on their errand of charity in high glee; but Jim returned from the expedition with a face and air of such portentous gravity, so different from his usual happy-go-lucky bearing, that Milly was moved to ask if any thing unpleasant had occurred.

"Captain Yorke nor his folks didn't do nothin', Miss Milly," answered Jim.

"Who, then?" asked Milly.

"Well, no one, Miss Milly," he replied. "I was on'y thinkin' what a lot of 'em there was, an' it bothers me."

"So many Yorkes, do you mean?" queried Milly, rather wondering at his evident perturbation.

"Such a many blind an' hunchback an' sick folks," he said; "an' how are they all goin' to be done for. The more you try to do for some of 'em, the more of 'em seem to come up. There's Matty and Tony Blair, who me an Bill has took into our keepin' soon as we get to the city; an' now here comes a Yorke hunchback, an' a Yorke blind, an' a Yorke sick baby, all sudden like; an' I say that's pretty hard on the ole captain. I like the captain firstrate, I do, Miss Milly; an' I don't like to see him put upon that way. Some of us ought to see to 'em for him, but you can't do for all."

"No, Jim," Milly said, soothingly, to the young philanthropist, "we cannot do for all who need; but, if each one does his or her mite, we can among us greatly lighten the load of human suffering; and that is what we must all try to do, without making ourselves unhappy over that which is beyond our reach or means."

"You did a mighty big mite, when you did for Bill an' me, Miss Milly," said her pupil and protégé, looking gratefully at her. "There ain't no halfway 'bout you, Miss Milly. But I would like to help Captain Yorke, if I could; an' I was thinkin', could I do up them sums again 'bout the peanuts, an' get out a share for the Yorkes."

Milly laughed, for she had heard of Jim's plans, and of the various objects which were to be benefited by the "peanut-undertaking;" and, as frequent new claims and claimants appeared to share in the profits, she argued that the proportion of each would be small.

"Jim," she said, "I think I would not undertake to help the Yorkes as well as all the other people you have upon your list. They shall not be allowed to suffer, you may be sure; Mr. Rutherford and Mr. Livingstone will see to that."

"Miss Milly," he answered, reproachfully, "I on'y didn't reckon up Captain Yorke an' his folks before, 'cause they hadn't need of it. Now they will, with all that raft of broke-up children on 'em; an' do you think I'd go to passin' 'em over when they was so good to me? No, that I wouldn't; I ain't never goin' to forget how Mis' Yorke nussed me, an' made much of me, when I was sick there in her house; an' they were good to me, too, when I was a little chap, an' got shipwrecked on to the shore. Miss Milly, do you know,"—hesitatingly,—"I'd liever take some out of the 'lection expenses share, than to pass over the Yorkes. I would, really, Miss Milly."

Truly, our Milly was reaping a rich fruit of generosity, loyalty, and earnest endeavor, from the seed of self-sacrifice and charity which she herself had shown in faith and hope. And this, too, in ground which the on-lookers had judged to be so hardened and stony that no harvest was to be gathered therefrom. Oh, my Milly, sweet soul,

"Great feelings hath she of her own,

Which lesser souls may never know."

CHAPTER IV.

"FOOD FOR THE GODS."

Behold our household now settled in our city home,—our summer by the sea, with all its many pleasures, and its measure of perplexities and anxieties, a thing of the past; our stay at Oaklands, where papa had enjoyed himself to his heart's content, all the more for his enforced absence of the previous months, also over; and the different members of the family, according to his or her individual taste, occupied with divers plans and projects for the winter's duties and diversions.

In view of certain contingencies which were likely to arise in the future,—father and mother said in the far future; and, indeed, although it was pleasant to contemplate them from a distant standpoint, I was in no haste to leave my dearly beloved home,—in view of these, and with the comfort and well-being of a certain young man before my eyes, to say nothing of my own pride in my housekeeping capabilities, I had chosen to enlist myself as a member of a "cooking-class." Said cooking-class was to meet once a week, in the afternoon, at the house of each member, in turn, when we were to try our maiden hands on the composition of any such dishes as we might choose; after which, certain martyrs—namely, the aforesaid young man, and sundry of his friends and associates—were to be allowed to join us, and, in case they were not too fearful of consequences, to test the results of our efforts. Milly, who had a regular engagement for the afternoon appointed, was not able to aid in the culinary efforts, but pleaded, that, as she contributed a sister, she might be allowed to join the later entertainment of the evening. And the plea was considered all sufficient, for who would not choose Milly when she might be had? So said Bessie Sandford, our inseparable friend and intimate; and there was no dissenting voice among the gay circle of girls.

She did not intend, however, to be without her share in the flesh-pots which were to furnish the more substantial part of the entertainment; and having a natural gift for cooking,—a faculty in which I was altogether wanting,—she promised to prepare some dainty dish beforehand, and send it as her share in the feast.

My last essay in that line had been in the shape of some gingerbread, of which article of diet father was very fond, and I had exerted my energies on his behalf. When it was presented at the Sunday-evening tea-table, the family, excepting papa, contented themselves with viewing it respectfully from a distance; even old Thomas, as he passed the plate, regarding it doubtfully and askance.

Father heroically endeavored to taste it; but mother, whose regard for his physical well-being outweighed even her consideration for my feelings, protested; and, with an air of relief, he obeyed the suggestion.

"What did you say it is? Ginger bricks?" asked Douglas.

I took no notice of this, but later bade Thomas take all the gingerbread down-stairs.

"Yes, Miss," he answered, with an "I wouldn't care if I were you" sort of an air; and the gingerbread disappeared. The next morning, however, as I went to the store-room to execute some small order for mother, our old cook confronted me.

"Miss Amy," she said, "whatever will I do with that gingerbread? There isn't one in the kitchen will touch it, not even them b'ys; an' all's mostly grist that comes to their mills."

"Oh, give it away to any one that comes," I answered indifferently, and concealing, as I best might, my chagrin at this added mortification.

But later in the day, Allie and Daisy, returning from their walk with mammy, rushed into the house in a state of frantic indignation.