Title: The World's Best Poetry, Volume 03: Sorrow and Consolation

Editor: Bliss Carman

Commentator: Lyman Abbott

Release date: October 1, 2005 [eBook #16786]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charles Aldarondo, Victoria Woosley and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BLISS CARMAN

John Vance Cheney

Charles G.D. Roberts

Charles F. Richardson

Francis H. Stoddard

John R. Howard

J.D. Morris and Company

Philadelphia

COPYRIGHT, 1904, by

J.D. Morris & Company

American poems in this volume within the legal protection of copyright are used by the courteous permission of the owners,—either the publishers named in the following list or the authors or their representatives in the subsequent one,—who reserve all their rights. So far as practicable, permission has been secured also for poems out of copyright.

Publishers of THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY.

1904.

Messrs. D. Appleton & Co., New York.—W.C. Bryant: "Blessed are They that Mourn," "The Conqueror's Grave," "Thanatopsis."

Messrs. E.P. Dutton & Co., New York.—Mary W. Howland: "Rest."

The Funk & Wagnalls Company, New York.—John W. Palmer: "For Charlie's Sake."

Messrs. Harper & Brothers, New York.—Will Carleton: "Over the Hill to the Poor House."

Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Co., Boston.—Margaret Deland: "Love and Death;" John Hay: "A Woman's Love;" O.W. Holmes: "The Last Leaf," "The Voiceless;" Mary Clemmer A. Hudson: "Something Beyond;" H.W. Longfellow: "Death of Minnehaha," "Footsteps of Angels," "God's Acre," "The Rainy Day," "The Reaper and the Flowers," "Resignation;" J.R. Lowell: "Auf Wiedersehen," "First Snow Fall," "Palinode;" Harriet W. Preston: "Fidelity in Doubt;" Margaret E. Sangster: "Are the Children at Home?" E.R. Sill: "A Morning Thought;" Harriet E. Spofford: "The Nun and Harp;" Harriet B. Stowe: "Lines to the Memory of Annie." "Only a Year;" J.T. Trowbridge: "Dorothy in the Garret;" J.G. Whittier: "To Her Absent Sailor," "Angel of Patience," "Maud Muller."

Mr. John Lane, New York.—R. Le Gallienne: "Song," "What of the Darkness?"

Messrs. Little, Brown & Co., Boston.—J.W. Chadwick: "The Two Waitings;" Helen Hunt Jackson: "Habeas Corpus."

The Lothrop Publishing Company, Boston.—Paul H. Hayne: "In Harbor."

Messrs. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York.—Elaine Goodale Eastman: "Ashes of Roses;" R.C. Rogers: "The Shadow Rose."

Messrs. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.—R. Bridges (Droch): "The Unillumined Verge;" Mary Mapes Dodge: "The Two Mysteries;" Julia C.R. Dorr: "Hush" (Afterglow).

American poems in this volume by the authors whose names are given below are the copyrighted property of the authors, or of their representatives named in parenthesis, and may not be reprinted without their permission, which for the present work has been courteously granted.

Publishers of THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY.

1904.

W.R. Alger; Mrs. Amelia E. Barr; Henry A. Blood (Mrs. R.E. Whitman); Robert J. Burdette; John Burroughs; Mary A. De Vere; Nathan H. Dole; William C. Gannett; Dr. Silas W. Mitchell; Mrs. Sarah M. Piatt; Walt Whitman (H. Traubel, Literary Executor).

BY LYMAN ABBOTT.

Poetry, music, and painting are three correlated arts, connected not merely by an accidental classification, but by their intrinsic nature. For they all possess the same essential function, namely, to interpret the uninterpretable, to reveal the undiscoverable, to express the inexpressible. They all attempt, in different forms and through different languages, to translate the invisible and eternal into sensuous forms, and through sensuous forms to produce in other souls experiences akin to those in the soul of the translator, be he poet, musician, or painter. That they are three correlated arts, attempting, each in its own way and by its own language, to express the same essential life, is indicated by their co-operation in the musical drama. This is the principle which Wagner saw so clearly, and has used to such effective purpose in his so-called operas, whose resemblance to the Italian operas which preceded them is more superficial than real. In the drama Wagner wishes you to consider neither the music apart from the scenery, nor the scenery apart from the acting, nor the three apart from the poetry. Poetry, music, and art combine with the actor to interpret truths of life which transcend philosophic definition. Thus in the first act of "Parsifal," innocence born of ignorance, remorse born of the experience of temptation and sin, and reverence bred in an atmosphere not innocent yet free from the experience of great temptation, mingle in a drama which elevates all hearts, because in some one of these three phases it touches every heart. And yet certain of the clergy condemned the presentation as irreverent, because it expresses reverence in a symbolism to which they were unaccustomed.

But while it is true that these three arts are correlative and co-operative, they do not duplicate one another. Each not only speaks in a language of its own, but expresses in that language a life which the others cannot express. As color and fragrance combine to make the flower, but the color expresses what the fragrance cannot express, and the fragrance expresses what the color cannot express, so in the musical drama, music, poetry, and painting combine, not by duplicating but by supplementing each other. One may describe in language a symphony; but no description will produce the effect which the symphony produces. One may describe a painting; but no description will produce the effect which the painting will produce. So neither music, nor painting, nor both combined, can produce the same effect on the soul as poetry. The "Midsummer Night's Dream" enacted in pantomime, with Mendelssohn's music, would no more produce the same effect on the auditors which would be produced by the interpretation of the play in spoken words, than would the reading of the play at home produce the same effect as the enacting of the play with what are miscalled the accessories of music and scenery. The music and scenery are no more accessories to the words than the words are accessories to the music and scenery. The three combine in a triple language to express and produce one life, and it can be expressed and produced in no other way than by the combination of the three arts in harmonious action. This is the reason why no parlor readings can ever take the place of the theatre, and no concert performance can ever take the place of the opera. This is the reason why all attempts to suppress the theatre and opera are and always will be in vain. They are attempts to suppress the expression and awakening of a life which can neither be expressed nor awakened in any other way; and suppression of life, however successfully it may be accomplished for a time, is never permanently possible.

These arts do not truly create, they interpret. Man is not a creator, he is only a discoverer. The imagination is not creative, it is only reportorial. Ideals are realities; imagination is seeing. The musician, the artist, the poet, discover life which others have not discovered, and each with his own instrument interprets that life to those less sensitive than himself. Observe a musician composing. He writes; stops; hesitates; meditates; perhaps hums softly to himself; perhaps goes to the piano and strikes a chord or two. What is he doing? He is trying to express to himself a beauty which he has heard in the world of infinite phenomena, and to reproduce it as well as sensuous sounds can reproduce it, that those with duller hearing than himself may hear it also. Observe a painter before his easel. He paints; looks to see the effect; erases; adds; modifies; reexamines; and repeats this operation over and over again. What is he doing? He is copying a beauty which he has seen in the invisible world, and which he is attempting to bring out from its hiding so that the men who have no eyes except for the sensuous may also see it. In my library is an original sonnet by John G. Whittier. In almost every line are erasures and interlineations. In some cases the careful poet has written a new line and pasted it over the rejected one. What does this mean? It means that he has discovered a truth of moral beauty and is attempting to interpret his discovery to the world. His first interpretation of his vision did not suit him, nor his second, nor his third, and he has revised and re-revised in the attempt to make his verse a true interpretation of the truth which he had seen. He did not make the truth; it eternally was. Neither did the musician make the truth of harmony, nor the painter the truth of form and color. They also eternally were. Poet, musician, painter, have seen, heard, felt, realized in their own souls some experience of life, some potent reality which philosophy cannot formulate, nor creed contain, nor eloquence define; and each in his own way endeavors to give it to the world of men; each in his own way endeavors to lift the gauzy curtain, impenetrable to most souls, which hides the invisible, the inaudible, the eternal, the divine from men; and he gives them a glimpse of that of which he himself had but a glimpse.

In one sense and in one only can art be called creative: the artist, whether he be painter, musician, or poet, so interprets to other men the experience which has been created in him by his vision of the supersensible and eternal, that he evokes in them a similar experience. He is a creator only as he conveys to others the life which has been created in himself. As the electric wire creates light in the home; as the band creates the movement in the machinery; thus and only thus does the artist create life in those that wait upon him. He is in truth an interpreter and transmitter, not a creator. Nor can he interpret what he has not first received, nor transmit what he has not first experienced. The music, the painting, the poem are merely the instruments which he uses for that purpose. The life must first be in him or the so-called music, painting, poem are but dead simulacra; imitations of art, not real art. This is the reason why no mechanical device, be it never so skillfully contrived, can ever take the place of the living artist. The pianola can never rival the living performer; nor the orchestrion the orchestra; nor the chromo the painting. No mechanical device has yet been invented to produce poetry; even if some shrewd Yankee should invent a printing machine which would pick out rhymes as some printing machines seem to pick out letters, the result would not be a poem. This is the reason too why mere perfection of execution never really satisfies. "She sings like a bird." Yes! and that is exactly the difficulty with her. We want one who sings like a woman. The popular criticism of the mere musical expert that he has no soul, is profound and true. It is soul we want; for the piano, the organ, the violin, the orchestra, are only instruments for the transmission of soul. This is also the reason why the most flawless conductor is not always the best. He must have a soul capable of reading the soul of the composer; and the orchestra must receive the life of the composer as that is interpreted to them through the life of the conductor, or the performance will be a soulless performance.

Into each of these arts, therefore—music, painting, poetry—enter two elements: the inner and the outer, the truth and the language, the reality and the symbol, the life and the expression. Without the electric current the carbon is a mere blank thread; the electric current is not luminous if there be no carbon. The life and the form are alike essential. So the painter must have something to express, but he must also have skill to express it; the musician must have music in his soul, but he must also have a power of instrumentation; the poet must feel the truth, or he is no poet, but he must also have power to express what he feels in such forms as will create a similar feeling in his readers, or he is still no poet. Multitudes of women send to the newspapers poetical effusions which are not poems. The feeling of the writer is excellent, but the expression is bad. The writer has seen, but she cannot tell what she has seen; she has felt, but she cannot express her experience so as to enkindle a like experience in others. These poetical utterances of inarticulate poets are sometimes whimsical but oftener pathetic; sometimes they are like the prattle of little children who exercise their vocal organs before they have anything to say; but oftener they seem to me like the beseeching eyes of a dumb animal, full of affection and entreaty for which he has no vocal expression. It is just as essential that poetical feeling should have poetical expression in order to constitute poetry as it is that musical feeling should have musical expression in order to constitute music. And, on the other hand, as splashes of color without artistic feeling which they interpret are not art, as musical, sounds without musical feeling which they interpret are not music, so poetical forms without poetical feeling are not poetry. Poetical feeling in unpoetical forms may be poetical prose, but it is still prose. And on the other hand, rhymes, however musical they may be to the ear, are only rhymes, not poetry, unless they express a true poetical life.

But these two elements are separable only in thought, not in reality. Poetry is not common thought expressed in an uncommon manner; it is not an artificial phrasing of even the higher emotions. The higher emotions have a phrasing of their own; they fall naturally—whether as the result of instinct or of habit need not here be considered—into fitting forms. The form may be rhyme; it may be blank verse; it may be the old Hebrew parallelism; it may even be the indescribable form which Walt Whitman has adopted. What is noticeable is the fact that poetical thought, if it is at its best, always takes on, by a kind of necessity, some poetical form. To illustrate if not to demonstrate this, it is only necessary to select from literature any fine piece of poetical expression of a higher and nobler emotion, or of clear and inspiring vision, and attempt to put it into prose form. The reader will find, if he be dealing with the highest poetry, that translating it into prose impairs its power to express the feeling, and makes the expression not less but more artificial. If he doubt this statement, let him turn to any of the finer specimens of verse in this volume and see whether he can express the life in prose as truly, as naturally, as effectively, as it is there expressed in rhythmical form.

These various considerations may help to explain why in all ages of the world the arts have been the handmaidens of religion. Not to amplify too much, I have confined these considerations to the three arts of music, painting, and poetry; but they are also applicable to sculpture and architecture. All are attempts by men of vision to interpret to the men who are not equally endowed with vision, what the invisible world about us and within us has for the enrichment of our lives. This is exactly the function of religion: to enrich human lives by making them acquainted with the infinite. It is true that at times the arts have been sensualized, the emphasis has been put on the form of expression, not on the life expressed; and then reformers, like the Puritans and the Quakers, have endeavored to exclude the arts from religion, lest they should contaminate it. But the exclusion has been accomplished with difficulty, and to maintain it has been impossible. It is neither an accident, nor a sign of decadence, that painting and sculpture are creeping back into the Protestant churches, to combine with poetry and music in expressing the religious life of man. For the intellect alone is inadequate either to express that life as it exists, or to call it into existence where it does not exist. The tendency to ritual in our time is a tendency not to substitute æsthetic for spiritual life, though there is probably always a danger that such a substitution may be unconsciously made, but to express a religious life which cannot be expressed without the aid of æsthetic symbols. The work of the intellect is to analyze and define. But the infinite is in the nature of the case indefinable, and it is with the infinite religion has to do. All that theology can hope to accomplish is to define certain provinces in the illimitable realm of truth; to analyze certain experiences in a life which transcends all complete analysis. The Church must learn to regard not with disfavor or suspicion, but with eager acceptance, the co-operation of the arts in the interpretation of infinite truth and the expression of infinite life. Certainly we are not to turn our churches into concert rooms or picture and sculpture galleries, and imagine that æsthetic enjoyment is synonymous with piety. But as surely we are not to banish the arts from our churches, and think that we are religious because we are barren. All language, whether of painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry, or oratory, is legitimately used to express the divine life, as all the faculties, whether of painter, sculptor, architect, musician, poet, orator, and philosopher, are to be used in reaching after a more perfect knowledge of Him who always transcends and always will transcend our perfect knowing.

Thus the study of poetry is the study of life, because poetry is the interpretation of life. Poetry is not a mere instrument for promoting enjoyment; it does not merely dazzle the imagination and excite the emotions. Through the emotions and the imagination it both interprets life and ministers to life. When the critic attempts to express that truth, that is, to interpret the interpreter, which he can do only by translating the poetry into prose, and the language of imagination and emotion into that of philosophy, he destroys the poem in the process, much as the botanist destroys the flower in analyzing it, or the musical critic the composition in disentangling its interwoven melodies and explaining the mature of its harmonic structure. The analysis, whether of music, art, or poetry, must be followed by a synthesis, which, in the nature of the case, can be accomplished only by the hearer or reader for himself. All that I can do here is to illustrate this revelatory character of poetry by some references to the poems which this volume contains. I do not attempt to explain the meaning of these poems; that is a task quite impossible. I only attempt to show that they have a meaning, that beneath their beauty of form is a depth of truth which philosophical statement in prose cannot interpret, but the essence of which such statement may serve to suggest. I do not wish to expound the truth of life which is contained in the poet's verse; I only wish to show that the poet by his verse reveals a truth of life which the critic cannot express, and that it is for this reason pre-eminently that such a collection of poetry as this is deserving of the reader's study.

If for example the student turns to such a volume as Newman Smyth's "Christian Ethics," he will find there a careful though condensed discussion of the right and wrong of suicide. It is cool, deliberate, philosophical. But it gives no slightest hint of the real state of the man who is deliberating within himself whether he will commit suicide or no; no hint of the real arguments that pass in shadow through his mind:—the weariness of life which summons him to end all; the nameless, indefinable dread of the mystery and darkness and night into which death carries us, which makes him hesitate. If we would really understand the mind of the suicide, not merely the mind of the philosopher coolly debating suicide, we must turn to the poet.

"To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 't is a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin! Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourne

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action."

This first the poet does: he draws aside the veil which hides the working of men's hearts, and lets us see their hidden life. But he does more. Not merely does he afford us knowledge, he imparts life. For we know feeling only by participating in the feeling; and the poet has the art not merely to describe the experiences of men but so to describe them that for the moment we share them, and so truly know them by the only process by which they can be known. Who, for instance, can read Thomas Hood's "The Bridge of Sighs" and not, as he reads, stand by the despairing one as she waits a moment upon the bridge just ready to take her last leap out of the cruelty of this world into, let us hope, the mercy of a more merciful world beyond?

"Where the lamps quiver

So far in the river,

With many a light

From window and casement,

From garret to basement,

She stood, with amazement,

Homeless by night.

"The bleak wind of March

Made her tremble and shiver;

But not the dark arch,

Or the black flowing river:

Mad from life's history,

Glad to death's mystery

Swift to be hurled—

Anywhere, anywhere

Out of the world.

"In she plunged boldly—

No matter how coldly

The rough river ran,—

Over the brink of it!

Picture it—think of it,

Dissolute man!

Lave in it, drink of it,

Then, if you can.

"Take her up tenderly,

Lift her with care;

Fashioned so slenderly,

Young, and so fair!"

No analysis of philosophy can make us acquainted with the tragedy of this life as the poet can; no exhortation of preacher can so effectively arouse in us the spirit of a Christian charity for the despairing wanderer as the poet.

Would you know the tragedy of a careless and supercilious coquetry which plays with the heart as the fisherman plays with the salmon? Read "Clara Vere de Vere." Would you know the dull heartache of a loveless married life, growing at times into an intolerable anguish which no marital fidelity can do much to medicate? Read "Auld Robin Gray." Who but a poet can interpret the pain of a parting between loving hearts, with its remorseful recollections of the wholly innocent love's joys that are past?

"Had we never loved sae kindly,

Had we never loved sae blindly,

Never met—or never parted,

We had ne'er been broken hearted."

Who but a poet can depict the perils of an unconscious drifting apart, such as has destroyed many a friendship and wrecked many a married life, as Clough has depicted it in "Qua Cursum Ventus"? If you would know the life-long sorrow of the blind man at your side, would enter into his life and for a brief moment share his captivity, read Milton's interpretation of that sorrow in Samson's Lament. If you would find some message to cheer the blind man in his darkness and illumine his captivity, read the same poet's ode on his own blindness:

"God doth not need,

Either man's work, or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best: his state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed,

And post o'er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait."

No prison statistics, no police reports, no reformer's documents, no public discussions of the question, What to do with the tramp, will ever so make the student of life participant of the innermost experience of the tramp, his experience of dull despair, his loss of his grip on life, as Béranger's "The Old Vagabond." No expert in nervous diseases, no psychological student of mental states, normal and abnormal, can give the reader so clear an understanding of that deep and seemingly causeless dejection, which because it seems to be causeless seems also to be well-nigh incurable, as Percy Bysshe Shelley has given in his "Stanzas written near Naples." No critical expounder of the Stoical philosophy can interpret the stoical temper which interposes a sullen but dauntless pride to attacking sorrow as William Ernest Henley has done:

"Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

"In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed."

Nor can any preacher put in so vital a contrast to this despairing defiance with which pride challenges sorrow, the joyous victory which a trusting love wins over it by submitting to it, as John Greenleaf Whittier has done in "The Eternal Goodness":

"I know not what the future hath

Of marvel or surprise,

Assured alone that life and death

His mercy underlies.

"I know not where His islands lift

Their fronded palms in air:

I only know I cannot drift

Beyond His love and care."

No philosophical treatise can interpret bereavement as the great poets have interpreted it. The mystery of sorrow, the bewilderment it causes, the wonder whether there is any God or any good, the silence that is the only answer to our call for help, the tumult of emotion, the strange perplexity of mind, the dull despair, the inexplicable paralysis of feeling, intermingling in one wholly inconsistent and incongruous experience: where, in all the literature of Philosophy can we find such an exposition and echo and interpretation of this experience as in that great Hebrew epic—the Book of Job? And where in all the literature of Philosophy can we find such interpreters of the two great comforters of the soul, faith and hope, as one finds in the poets? They do not argue; they simply sing. And, as a note struck upon one of a chime of bells will set the neighboring bell vibrating, so the strong note of faith and hope sounded by the poet, sets a like note vibrating in the mourner's heart. The mystery is not solved, but the silence is broken. First we listen to the poet, then we listen to the same song sung in our own hearts,—the same, for it is God who has sung to him and who sings to us. And when the bereaved has found God, he has found light in his darkness, peace in his tempest, a ray in his night.

"As a child,

Whose song-bird seeks the wood forevermore,

Is sung to in its stead by mother's mouth;

Till, sinking on her breast, love-reconciled,

He sleep the faster that he wept before."

The visitor to the island of Catalina, off the coast of California, is invited to go out in a glass-bottomed boat upon the sea. If he accepts the invitation and looks about him with careless curiosity, he will enjoy the blue of the summer sky and ocean wave, and the architectural beauty of the island hills; but if he turns his gaze downward and looks through the glass bottom of the boat in which he is sailing, he will discover manifold phases of beauty in the life beneath the sea waves: in goldfish darting hither and thither, in umbrella-shaped jellyfish lazily swimming by, in starfish and anemones of infinite variety, in sea-urchins brilliant in color, and in an endless forest of water-weeds exquisitely delicate in their structure. Perhaps he will try to photograph them; but in vain: his camera will render him no report of the wealth of life which he has seen. So he who takes up such a volume of poetry as this will find ample repayment in the successive pictures which it presents to his imagination, and the transient emotions which it will excite in him. But besides this there is a secret life which the careless reader will fail to see, and which the critic cannot report, but which will be revealed to the thoughtful, patient, meditative student. In this power to reveal an otherwise unknown world, lies the true glory of poetry. He that hath ears to hear, let him hear what the poet has to say to him.

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW Frontispiece

Photogravure from photograph by Hanfstaengl after portrait by Kramer.

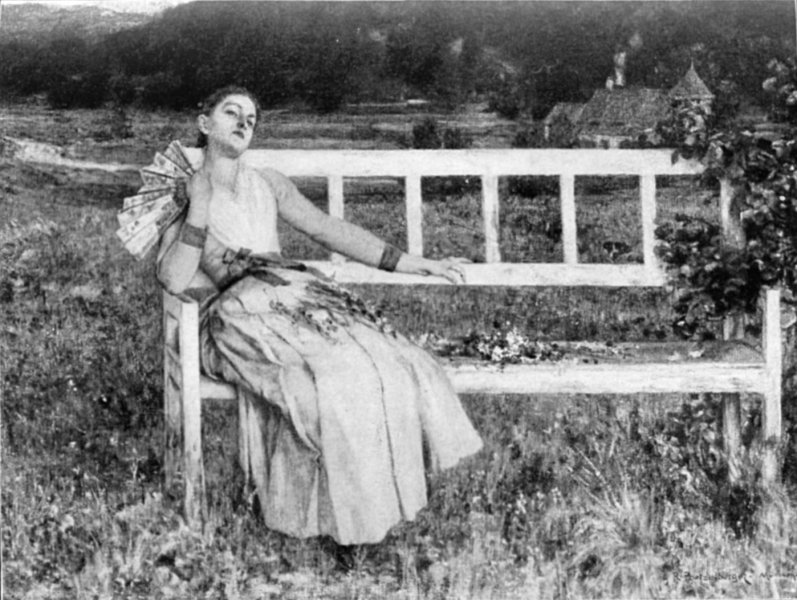

The patient grief and endurance of Absence: while the tapestry woven by day stands on the frame to be unravelled by night, as the

loyal wife puts off her suitors.

Painting by Rudolph von Deutsch.

"What shall I do with all the days and hours

That must be counted ere I see thy face?"

From a photograph by the Berlin Photographic Co., after a painting by R. Pötzelberger.

"Behold me, a god, what I endure from gods!

Behold, with throe on throe,

How, wasted by this woe,

I wrestle down the myriad years of Time!"

From photograph after a painting by G. Graeff.

From lithograph after a crayon-drawing by H. Alophe.

After an engraving from contemporary portrait.

After a photograph from life by Talfourd, London.

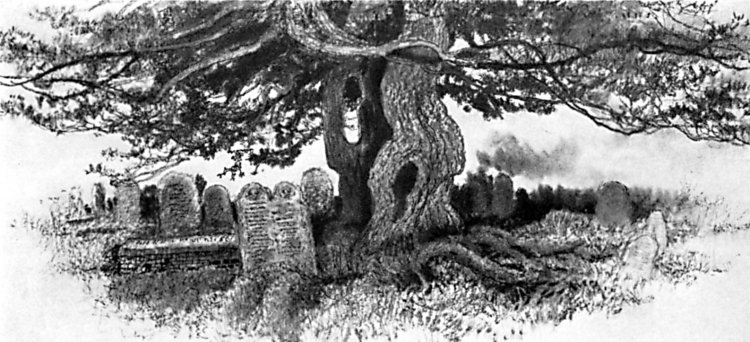

"Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a moldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell forever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep."

After an original drawing by Harry Fenn.

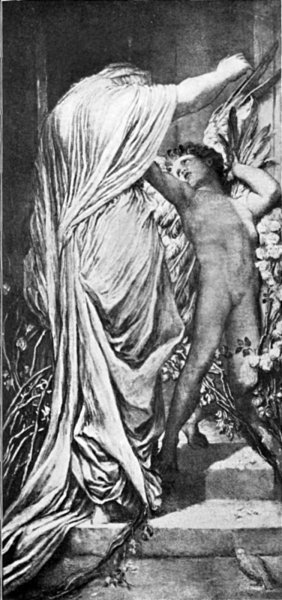

Death comes in,

Though Love, with outstretched arms and wings outspread,

Would bar the way."

From photogravure after the painting by George Fredeick Watts.

After a life-photograph by Rockwood, New York.

From an engraving after the drawing by George Richmond.

After a life-photograph by Elliott and Fry, London.

FROM "MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM," ACT I. SC. 1.

For aught that ever I could read,

Could ever hear by tale or history,

The course of true love never did run smooth:

But, either it was different in blood,

Or else misgraffèd in respect of years,

Or else it stood upon the choice of friends;

Or, if there were a sympathy in choice,

War, death, or sickness did lay siege to it,

Making it momentary as a sound,

Swift as a shadow, short as any dream;

Brief as the lightning in the collied night,

That, in a spleen, unfolds both heaven and earth,

And ere a man hath power to say,—Behold!

The jaws of darkness do devour it up:

So quick bright things come to confusion.

SHAKESPEARE.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

Of me you shall not win renown;

You thought to break a country heart

For pastime, ere you went to town.

At me you smiled, but unbeguiled

I saw the snare, and I retired:

The daughter of a hundred Earls,

You are not one to be desired.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

I know you proud to bear your name;

Your pride is yet no mate for mine,

Too proud to care from whence I came.

Nor would I break for your sweet sake

A heart that dotes on truer charms.

A simple maiden in her flower

Is worth a hundred coats-of-arms.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

Some meeker pupil you must find,

For were you queen of all that is,

I could not stoop to such a mind.

You sought to prove how I could love,

And my disdain is my reply.

The lion on your old stone gates

Is not more cold to you than I.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

You put strange memories in my head.

Not thrice your branching lines have blown

Since I beheld young Laurence dead.

O your sweet eyes, your low replies:

A great enchantress you may be;

But there was that across his throat

Which you had hardly cared to see.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

When thus he met his mother's view,

She had the passions of her kind,

She spake some certain truths of you.

Indeed I heard one bitter word

That scarce is fit for you to hear;

Her manners had not that repose

Which stamps the caste of Vere de Vere.

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

There stands a spectre in your hall:

The guilt of blood is at your door:

You changed a wholesome heart to gall.

You held your course without remorse,

To make him trust his modest worth,

And, last, you fixed a vacant stare,

And slew him with your noble birth.

Trust me, Clara Vere de Vere,

From yon blue heavens above us bent

The grand old gardener and his wife

Smile at the claims of long descent.

Howe'er it be, it seems to me,

'T is only noble to be good.

Kind hearts are more than coronets,

And simple faith than Norman blood.

I know you, Clara Vere de Vere:

You pine among your halls and towers:

The languid light of your proud eyes

Is wearied of the rolling hours.

In glowing health, with boundless wealth,

But sickening of a vague disease,

You know so ill to deal with time,

You needs must play such pranks as these.

Clara, Clara Vere de Vere,

If Time be heavy on your hands,

Are there no beggars at your gate.

Nor any poor about your lands?

Oh! teach the orphan-boy to read,

Or teach the orphan-girl to sew,

Pray Heaven for a human heart,

And let the foolish yeoman go.

ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON.

FROM "THE FIRE-WORSHIPPERS."

"How sweetly," said the trembling maid,

Of her own gentle voice afraid,

So long had they in silence stood,

Looking upon that moonlight flood,—

"How sweetly does the moonbeam smile

To-night upon yon leafy isle!

Oft in my fancy's wanderings,

I've wished that little isle had wings,

And we, within its fairy bowers,

Were wafted off to seas unknown,

Where not a pulse should beat but ours,

And we might live, love, die alone!

Far from the cruel and the cold,—

Where the bright eyes of angels only

Should come around us, to behold

A paradise so pure and lonely!

Would this be world enough for thee?"—

Playful she turned, that he might see

The passing smile her cheek put on;

But when she marked how mournfully

His eyes met hers, that smile was gone;

And, bursting into heartfelt tears,

"Yes, yes," she cried, "my hourly fears,

My dreams, have boded all too right,—

We part—forever part—to-night!

I knew, I knew it could not last,—

'T was bright, 't was heavenly, but 't is past!

O, ever thus, from childhood's hour,

I've seen my fondest hopes decay;

I never loved a tree or flower

But 't was the first to fade away.

I never nursed a dear gazelle,

To glad me with its soft black eye,

But when it came to know me well,

And love me, it was sure to die!

Now, too, the joy most like divine

Of all I ever dreamt or knew,

To see thee, hear thee, call thee mine,—

O misery! must I lose that too?"

THOMAS MOORE.

Love not, love not, ye hapless sons of clay!

Hope's gayest wreaths are made of earthly flowers,—

Things that are made to fade and fall away

Ere they have blossomed for a few short hours.

Love not!

Love not! the thing ye love may change;

The rosy lip may cease to smile on you,

The kindly-beaming eye grow cold and strange,

The heart still warmly beat, yet not be true.

Love not!

Love not! the thing you love may die,—

May perish from the gay and gladsome earth;

The silent stars, the blue and smiling sky,

Beam o'er its grave, as once upon its birth.

Love not!

Love not! O warning vainly said

In present hours as in years gone by!

Love flings a halo round the dear one's head,

Faultless, immortal, till they change or die.

Love not!

CAROLINE ELIZABETH SHERIDAN.(HON. MRS. NORTON.)

The Princess sat lone in her maiden bower,

The lad blew his horn at the foot of the tower.

"Why playest thou alway? Be silent, I pray,

It fetters my thoughts that would flee far away.

As the sun goes down."

In her maiden bower sat the Princess forlorn,

The lad had ceased to play on his horn.

"Oh, why art thou silent? I beg thee to play!

It gives wings to my thought that would flee far away,

As the sun goes down."

In her maiden bower sat the Princess forlorn,

Once more with delight played the lad on his horn.

She wept as the shadows grew long, and she sighed:

"Oh, tell me, my God, what my heart doth betide,

Now the sun has gone down."

From the Norwegian of BJÖRNSTJERNE BJÖRNSON.

Translation of NATHAN HASKELL DOLE.

FROM "TWELFTH NIGHT," ACT I. SC. 4.

VIOLA.—Ay, but I know,—

DUKE.—What dost thou know?

VIOLA.—Too well what love women to men may owe:

In faith, they are as true of heart as we.

My father had a daughter loved a man,

As it might be, perhaps, were I a woman,

I should your lordship.

DUKE.—And what's her history?

VIOLA.—A blank, my lord. She never told her love,

But let concealment, like a worm i' the bud,

Feed on her damask cheek; she pined in thought;

And, with a green and yellow melancholy,

She sat like Patience on a monument,

Smiling at grief. Was not this love, indeed?

We men may say more, swear more: but, indeed,

Our shows are more than will; for still we prove

Much in our vows, but little in our love.

SHAKESPEARE.

O saw ye not fair Ines? she's gone into the west,

To dazzle when the sun is down, and rob the world of rest;

She took our daylight with her, the smiles that we love best,

With morning blushes on her cheek, and pearls upon her breast.

O turn again, fair Ines, before the fall of night,

For fear the moon should shine alone, and stars unrivalled bright;

And blessèd will the lover be that walks beneath their light,

And breathes the love against thy cheek I dare not even write!

Would I had been, fair Ines, that gallant cavalier

Who rode so gayly by thy side and whispered thee so near!

Were there no bonny dames at home, or no true lovers here,

That he should cross the seas to win the dearest of the dear?

I saw thee, lovely Ines, descend along the shore,

With bands of noble gentlemen, and banners waved before;

And gentle youth and maidens gay, and snowy plumes they wore;—

It would have been a beauteous dream—if it had been no more!

Alas! alas! fair Ines! she went away with song,

With music waiting on her steps, and shoutings of the throng;

But some were sad, and felt no mirth, but only Music's wrong,

In sounds that sang Farewell, Farewell to her you've loved so long.

Farewell, farewell, fair Ines! that vessel never bore

So fair a lady on its deck, nor danced so light before—

Alas for pleasure on the sea, and sorrow on the shore!

The smile that blest one lover's heart has broken many more!

THOMAS HOOD.

Ye banks and braes o' bonnie Doon,

How can ye bloom sae fresh and fair?

How can ye chant, ye little birds,

And I sae weary, fu' o' care?

Thou'lt break my heart, thou warbling bird,

That wantons through the flowering thorn;

Thou minds me o' departed joys,

Departed—never to return.

Thou'lt break my heart, thou bonnie bird,

That sings beside thy mate;

For sae I sat, and sae I sang,

And wistna o' my fate.

Aft hae I roved by bonnie Doon,

To see the rose and woodbine twine;

And ilka bird sang o' its luve,

And, fondly, sae did I o' mine.

Wi' lightsome heart I pou'd a rose,

Fu' sweet upon its thorny tree;

And my fause luver stole my rose,

But ah! he left the thorn wi' me.

ROBERT BURNS.

FROM "ASTROPHEL AND STELLA."

With how sad steps, O Moon! thou climb'st the skies,

How silently, and with how wan a face!

What may it be, that even in heavenly place

That busy Archer his sharp arrows tries?

Sure, if that long-with-love-acquainted eyes

Can judge of love, thou feel'st a lover's case;

I read it in thy looks; thy languished grace

To me, that feel the like, thy state descries.

Then, even of fellowship, O Moon, tell me,

Is constant love deemed there but want of wit?

Are beauties there as proud as here they be?

Do they above love to be loved, and yet

Those lovers scorn whom that love doth possess?

Do they call virtue there ungratefulness?

SIR PHILIP SIDNEY.

AGATHA.

She wanders in the April woods,

That glisten with the fallen shower;

She leans her face against the buds,

She stops, she stoops, she plucks a flower.

She feels the ferment of the hour:

She broodeth when the ringdove broods;

The sun and flying clouds have power

Upon her cheek and changing moods.

She cannot think she is alone,

As over her senses warmly steal

Floods of unrest she fears to own

And almost dreads to feel.

Among the summer woodlands wide

Anew she roams, no more alone;

The joy she feared is at her side,

Spring's blushing secret now is known.

The primrose and its mates have flown,

The thrush's ringing note hath died;

But glancing eye and glowing tone

Fall on her from her god, her guide.

She knows not, asks not, what the goal,

She only feels she moves towards bliss,

And yields her pure unquestioning soul

To touch and fondling kiss.

And still she haunts those woodland ways,

Though all fond fancy finds there now

To mind of spring or summer days,

Are sodden trunk and songless bough.

The past sits widowed on her brow,

Homeward she wends with wintry gaze,

To walls that house a hollow vow,

To hearth where love hath ceased to blaze;

Watches the clammy twilight wane,

With grief too fixed for woe or tear;

And, with her forehead 'gainst the pane,

Envies the dying year.

ALFRED AUSTIN.

THE SUN-DIAL.

'T is an old dial, dark with many a stain;

In summer crowned with drifting orchard bloom,

Tricked in the autumn with the yellow rain,

And white in winter like a marble tomb.

And round about its gray, time-eaten brow

Lean letters speak,—a worn and shattered row:

I am a Shade; a Shadowe too art thou:

I marke the Time: saye, Gossip, dost thou soe?

Here would the ring-doves linger, head to head;

And here the snail a silver course would run,

Beating old Time; and here the peacock spread

His gold-green glory, shutting out the sun.

The tardy shade moved forward to the noon;

Betwixt the paths a dainty Beauty stept,

That swung a flower, and, smiling hummed a tune,—

Before whose feet a barking spaniel leapt.

O'er her blue dress an endless blossom strayed;

About her tendril-curls the sunlight shone;

And round her train the tiger-lilies swayed,

Like courtiers bowing till the queen be gone.

She leaned upon the slab a little while,

Then drew a jewelled pencil from her zone,

Scribbled a something with a frolic smile,

Folded, inscribed, and niched it in the stone.

The shade slipped on, no swifter than the snail;

There came a second lady to the place,

Dove-eyed, dove-robed, and something wan and pale,—

An inner beauty shining from her face.

She, as if listless with a lonely love,

Straying among the alleys with a book,—

Herrick or Herbert,—watched the circling dove,

And spied the tiny letter in the nook.

Then, like to one who confirmation found

Of some dread secret half-accounted true,—

Who knew what hearts and hands the letter bound,

And argued loving commerce 'twixt the two,—

She bent her fair young forehead on the stone;

The dark shade gloomed an instant on her head;

And 'twixt her taper fingers pearled and shone

The single tear that tear-worn eyes will shed.

The shade slipped onward to the falling gloom;

Then came a soldier gallant in her stead,

Swinging a beaver with a swaling plume,

A ribboned love-lock rippling from his head.

Blue-eyed, frank-faced, with clear and open brow,

Scar-seamed a little, as the women love;

So kindly fronted that you marvelled how

The frequent sword-hilt had so frayed his glove;

Who switched at Psyche plunging in the sun;

Uncrowned three lilies with a backward swinge;

And standing somewhat widely, like to one

More used to "Boot and Saddle" than to cringe

As courtiers do, but gentleman withal,

Took out the note;—held it as one who feared

The fragile thing he held would slip and fall;

Read and re-read, pulling his tawny beard;

Kissed it, I think, and hid it in his breast;

Laughed softly in a flattered, happy way,

Arranged the broidered baldrick on his crest,

And sauntered past, singing a roundelay.

· · · · · ·

The shade crept forward through the dying glow;

There came no more nor dame nor cavalier;

But for a little time the brass will show

A small gray spot,—the record of a tear.

AUSTIN DOBSON.

LOCKSLEY HALL.

Comrades, leave me here a little, while as yet 'tis early morn,—

Leave me here, and when you want me, sound upon the bugle horn.

'Tis the place, and all around it, as of old, the curlews call,

Dreary gleams about the moorland, flying over Locksley Hall:

Locksley Hall, that in the distance overlooks the sandy tracts,

And the hollow ocean-ridges roaring into cataracts.

Many a night from yonder ivied casement, ere I went to rest,

Did I look on great Orion sloping slowly to the west.

Many a night I saw the Pleiads, rising through the mellow shade,

Glitter like a swarm of fire-flies tangled in a silver braid.

Here about the beach I wandered, nourishing a youth sublime

With the fairy tales of science, and the long result of time;

When the centuries behind me like a fruitful land reposed;

When I clung to all the present for the promise that it closed;

When I dipt into the future far as human eye could see,—

Saw the vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be.

In the spring a fuller crimson comes upon the robin's breast;

In the spring the wanton lapwing gets himself another crest;

In the spring a livelier iris changes on the burnished dove;

In the spring a young man's fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love.

Then her cheek was pale and thinner than should be for one so young,

And her eyes on all my motions with a mute observance hung.

And I said, "My cousin Amy, speak, and speak the truth to me;

Trust me, cousin, all the current of my being sets to thee."

On her pallid cheek and forehead came a color and a light,

As I have seen the rosy red flushing in the northern night.

And she turned,—her bosom shaken with a sudden storm of sighs;

All the spirit deeply dawning in the dark of hazel eyes,—

Saying, "I have hid my feelings, fearing they should do me wrong;"

Saying, "Dost thou love me, cousin?" weeping, "I have loved thee long."

Love took up the glass of time, and turned it in his glowing hands;

Every moment, lightly shaken, ran itself in golden sands.

Love took up the harp of life, and smote on all the chords with might;

Smote the chord of self, that, trembling, passed in music out of sight.

Many a morning on the moorland did we hear the copses ring,

And her whisper thronged my pulses with the fulness of the spring.

Many an evening by the water did we watch the stately ships,

And our spirits rushed together at the touching of the lips.

O my cousin, shallow-hearted! O my Amy, mine no more!

O the dreary, dreary moorland! O the barren, barren shore!

Falser than all fancy fathoms, falser than all songs have sung,—

Puppet to a father's threat, and servile to a shrewish tongue!

Is it well to wish thee happy?—having known me; to decline

On a range of lower feelings and a narrower heart than mine!

Yet it shall be: thou shalt lower to his level day by day,

What is fine within thee growing coarse to sympathize with clay.

As the husband is, the wife is; thou art mated with a clown,

And the grossness of his nature will have weight to drag thee down.

He will hold thee, when his passion shall have spent its novel force,

Something better than his dog, a little dearer than his horse.

What is this? his eyes are heavy,—think not they are glazed with wine.

Go to him; it is thy duty,—kiss him; take his hand in thine.

It may be my lord is weary, that his brain is over wrought,—

Soothe him with thy finer fancies, touch him with thy lighter thought.

He will answer to the purpose, easy things to understand,—

Better thou wert dead before me, though I slew thee with my hand.

Better thou and I were lying, hidden from the heart's disgrace,

Rolled in one another's arms, and silent in a last embrace.

Cursed be the social wants that sin against the strength of youth!

Cursed be the social lies that warp us from the living truth!

Cursed be the sickly forms that err from honest nature's rule

Cursed be the gold that gilds the straitened forehead of the fool!

Well—'t is well that I should bluster!—Hadst thou less unworthy proved,

Would to God—for I had loved thee more than ever wife was loved.

Am I mad, that I should cherish that which bears but bitter fruit?

from my bosom, though my heart be at the root.

Never! though my mortal summers to such length of years should come

As the many-wintered crow that leads the clanging rookery home.

Where is comfort? in division of the records of the mind?

Can I part her from herself, and love her, as I knew her, kind?

I remember one that perished; sweetly did she speak and move;

Such a one do I remember, whom to look at was to love.

Can I think of her as dead, and love her for the love she bore?

No,—she never loved me truly; love is love forevermore.

Comfort? comfort scorned of devils; this is truth the poet sings,

That a sorrow's crown of sorrow is remembering happier things.

Drug thy memories, lest thou learn it, lest thy heart be put to proof,

In the dead, unhappy night, and when the rain is on the roof.

Like a dog, he hunts in dreams; and thou art staring at the wall,

Where the dying night-lamp flickers, and the shadows rise and fall.

Then a hand shall pass before thee, pointing to his drunken sleep,

To thy widowed marriage-pillows, to the tears that thou wilt weep.

Thou shalt hear the "Never, never," whispered by the phantom years,

And a song from out the distance in the ringing of thine ears;

And an eye shall vex thee, looking ancient kindness on thy pain.

Turn thee, turn thee on thy pillow; get thee to thy rest again.

Nay, but nature brings thee solace; for a tender voice will cry;

'Tis a purer life than thine, a lip to drain thy trouble dry.

Baby lips will laugh me down; my latest rival brings thee rest,—

Baby fingers, waxen touches, press me from the mother's breast.

O, the child too clothes the father with a dearness not his due.

Half is thine and half is his: it will be worthy of the two.

O, I see thee old and formal, fitted to thy petty part,

With a little hoard of maxims preaching down a daughter's heart.

"They were dangerous guides, the feelings—she herself was not exempt—

Truly, she herself had suffered"—Perish in thy self-contempt!

Overlive it—lower yet—be happy! wherefore should I care?

I myself must mix with action, lest I wither by despair.

What is that which I should turn to, lighting upon days like these?

Every door is barred with gold, and opens but to golden keys.

Every gate is thronged with suitors, all the markets overflow.

I have but an angry fancy: what is that which I should do?

I had been content to perish, falling on the foeman's ground,

When the ranks are rolled in vapor, and the winds are laid with sound.

But the jingling of the guinea helps the hurt that honor feels,

And the nations do but murmur, snarling at each other's heels.

Can I but relive in sadness? I will turn that earlier page.

Hide me from my deep emotion, O thou wondrous mother-age!

Make me feel the wild pulsation that I felt before the strife,

When I heard my days before me, and the tumult of my life;

Yearning for the large excitement that the coming years would yield,

Eager-hearted as a boy when first he leaves his father's field,

And at night along the dusky highway near and nearer drawn,

Sees in heaven the light of London flaring like a dreary dawn;

And his spirit leaps within him to be gone before him then,

Underneath the light he looks at, in among the throngs of men;

Men, my brothers, men the workers, ever reaping something new:

That which they have done but earnest of the things that they shall do:

For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see,

Saw the vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be;

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales;

Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rained a ghastly dew

From the nations' airy navies grappling in the central blue;

Far along the world-wide whisper of the south-wind rushing warm,

With the standards of the peoples plunging through the thunder-storm;

Till the war-drum throbbed no longer, and the battle flags were furled

In the parliament of man, the federation of the world.

There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe,

And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law.

So I triumphed ere my passion sweeping through me left me dry,

Left me with a palsied heart, and left me with the jaundiced eye;

Eye, to which all order festers, all things here are out of joint.

Science moves, but slowly, slowly, creeping on from point to point:

Slowly comes a hungry people, as a lion, creeping nigher,

Glares at one that nods and winks behind a slowly dying fire.

Yet I doubt not through the ages one increasing purpose runs,

And the thoughts of men are widened with the process of the suns.

What is that to him that reaps not harvest of his youthful joys,

Though the deep heart of existence beat forever like a boy's?

Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers; and I linger on the shore

And the individual withers, and the world is more and more.

Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers, and he bears a laden breast,

Full of sad experience moving toward the stillness of his rest.

Hark! my merry comrades call me, sounding on the bugle horn,—

They to whom my foolish passion were a target for their scorn;

Shall it not be scorn to me to harp on such a mouldered string?

I am shamed through all my nature to have loved so slight a thing.

Weakness to be wroth with weakness! woman's pleasure, woman's pain—

Nature made them blinder motions bounded in a shallower brain;

Woman is the lesser man, and all thy passions, matched with mine,

Are as moonlight unto sunlight, and as water unto wine—

Here at least, where nature sickens, nothing. Ah for some retreat

Deep in yonder shining Orient, where my life began to beat!

Where in wild Mahratta-battle fell my father, evil-starred;

I was left a trampled orphan, and a selfish uncle's ward.

Or to burst all links of habit,—there to wander far away,

On from island unto island at the gateways of the day,

Larger constellations burning, mellow moons and happy skies,

Breadths of tropic shade and palms in cluster, knots of Paradise.

Never comes the trader, never floats an European flag,—

Slides the bird o'er lustrous woodland, swings the trailer from the crag,—

Droops the heavy-blossomed bower, hangs the heavy-fruited tree,—

Summer isles of Eden lying in dark-purple spheres of sea.

There, methinks, would be enjoyment more than in this march of mind—

In the steamship, in the railway, in the thoughts that shake mankind.

There the passions, cramped no longer, shall have scope and breathing-space;

I will take some savage woman, she shall rear my dusky race.

Iron-jointed, supple-sinewed, they shall dive, and they shall run,

Catch the wild goat by the hair, and hurl their lances in the sun,

Whistle back the parrot's call, and leap the rainbows of the brooks,

Not with blinded eyesight poring over miserable books—

Fool, again the dream, the fancy! but I know my words are wild,

But I count the gray barbarian lower than the Christian child.

I, to herd with narrow foreheads vacant of our glorious gains,

Like a beast with lower pleasures, like a beast with lower pains!

Mated with a squalid savage,—what to me were sun or clime?

I, the heir of all the ages, in the foremost files of time,—

I, that rather held it better men should perish one by one,

Than that earth should stand at gaze like Joshua's moon in Ajalon!

Not in vain the distance beacons. Forward, forward let us range;

Let the great world spin forever down the ringing grooves of change.

Through the shadow of the globe we sweep into the younger day:

Better fifty years of Europe than a cycle of Cathay.

Mother-age, (for mine I knew not,) help me as when life begun,—

Rift the hills and roll the waters, flash the lightnings, weigh the sun,

O, I see the crescent promise of my spirit hath not set;

Ancient founts of inspiration well through all my fancy yet.

Howsoever these things be, a long farewell to Locksley Hall!

Now for me the woods may wither, now for me the roof-tree fall.

Comes a vapor from the margin, blackening over heath and holt,

Cramming all the blast before it, in its breast a thunderbolt.

Let it fall on Locksley Hall, with rain or hail, or fire or snow;

For the mighty wind arises, roaring seaward, and I go.

ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON.

"A weary lot is thine, fair maid,

A weary lot is thine!

To pull the thorn thy brow to braid,

And press the rue for wine!

A lightsome eye, a soldier's mien,

A feather of the blue,

A doublet of the Lincoln green—

No more of me you knew,

My love!

No more of me you knew.

"The morn is merry June, I trow—

The rose is budding fain;

But she shall bloom in winter snow

Ere we two meet again."

He turned his charger as he spake,

Upon the river shore;

He gave his bridle-rein a shake,

Said, "Adieu for evermore,

My love!

And adieu for evermore."

SIR WALTER SCOTT.

When the sheep are in the fauld and the kye a' at hame,

When a' the weary world to sleep are gane,

The waes o' my heart fa' in showers frae my e'e,

While my gudeman lies sound by me.

Young Jamie lo'ed me weel, and sought me for his bride;

But saving a crown, he had naething else beside.

To mak' the crown a pound, my Jamie gaed to sea;

And the crown and the pound, they were baith for me!

He hadna been awa' a week but only twa,

When my mither she fell sick, and the cow was stown awa;

My father brak his arm—my Jamie at the sea—

And Auld Robin Gray came a-courtin' me.

My father couldna work,—my mither couldna spin;

I toiled day and night, but their bread I couldna win;

And Rob maintained them baith, and, wi' tears in his e'e,

Said, "Jennie for their sakes, will you marry me?"

My heart it said na, for I looked for Jamie back;

But hard blew the winds, and his ship was a wrack;

His ship was a wrack! Why didna Jamie dee?

Or why was I spared to cry, Wae is me!

My father argued sair—my mither didna speak,

But she looked in my face till my heart was like to break;

They gied him my hand, but my heart was in the sea;

And so Auld Robin Gray, he was gudeman to me.

I hadna been his wife, a week but only four,

When, mournfu' as I sat on the stane at the door,

I saw my Jamie's ghaist—I couldna think it he,

Till he said, "I'm come hame, love, for to marry thee!"

O sair, sair did we greet, and mickle did we say:

Ae kiss we took—nae mair—I bad him gang away.

I wish that I were dead, but I 'm no like to dee,

And why do I live to say, Wae is me!

I gang like a ghaist, and I carena to spin;

I darena think o' Jamie, for that wad be a sin.

But I will do my best a gude wife aye to be,

For Auld Robin Gray, he is kind unto me.

LADY ANNE BARNARD.

A pensive photograph

Watches me from the shelf—

Ghost of old love, and half

Ghost of myself!

How the dear waiting eyes

Watch me and love me yet—

Sad home of memories,

Her waiting eyes!

Ghost of old love, wronged ghost,

Return: though all the pain

Of all once loved, long lost,

Come back again.

Forget not, but forgive!

Alas, too late I cry.

We are two ghosts that had their chance to live,

And lost it, she and I.

ARTHUR SYMONS.

Maud Muller, on a summer's day,

Raked the meadow sweet with hay.

Beneath her torn hat glowed the wealth

Of simple beauty and rustic health.

Singing, she wrought, and her merry glee

The mock-bird echoed from his tree.

But, when she glanced to the far-off town,

White from its hill-slope looking down,

The sweet song died, and a vague unrest

And a nameless longing filled her breast,—

A wish, that she hardly dared to own,

For something better than she had known.

The Judge rode slowly down the lane,

Smoothing his horse's chestnut mane.

He drew his bridle in the shade

Of the apple-trees, to greet the maid,

And ask a draught from the spring that flowed

Through the meadow, across the road.

She stooped where the cool spring bubbled up,

And filled for him her small tin cup,

And blushed as she gave it, looking down

On her feet so bare, and her tattered gown.

"Thanks!" said the Judge, "a sweeter draught

From a fairer hand was never quaffed."

He spoke of the grass and flowers and trees,

Of the singing birds and the humming bees;

Then talked of the haying, and wondered whether

The cloud in the west would bring foul weather.

And Maud forgot her brier-torn gown,

And her graceful ankles, bare and brown,

And listened, while a pleased surprise

Looked from her long-lashed hazel eyes.

At last, like one who for delay

Seeks a vain excuse, he rode away.

Maud Muller looked and sighed: "Ah me!

That I the Judge's bride might be!

"He would dress me up in silks so fine,

And praise and toast me at his wine.

"My father should wear a broadcloth coat,

My brother should sail a painted boat.

"I 'd dress my mother so grand and gay,

And the baby should have a new toy each day.

"And I'd feed the hungry and clothe the poor,

And all should bless me who left our door."

The Judge looked back as he climbed the hill,

And saw Maud Muller standing still:

"A form more fair, a face more sweet,

Ne'er hath it been my lot to meet.

"And her modest answer and graceful air

Show her wise and good as she is fair.

"Would she were mine, and I to-day,

Like her, a harvester of hay.

"No doubtful balance of rights and wrongs,

Nor weary lawyers with endless tongues,

"But low of cattle, and song of birds,

And health, and quiet, and loving words."

But he thought of his sister, proud and cold,

And his mother, vain of her rank and gold.

So, closing his heart, the Judge rode on,

And Maud was left in the field alone.

But the lawyers smiled that afternoon,

When he hummed in court an old love tune;

And the young girl mused beside the well,

Till the rain on the unraked clover fell.

He wedded a wife of richest dower,

Who lived for fashion, as he for power.

Yet oft, in his marble hearth's bright glow,

He watched a picture come and go;

And sweet Maud Muller's hazel eyes

Looked out in their innocent surprise.

Oft, when the wine in his glass was red,

He longed for the wayside well instead,

And closed his eyes on his garnished rooms,

To dream of meadows and clover blooms;

And the proud man sighed with a secret pain,

"Ah, that I were free again!

"Free as when I rode that day

Where the barefoot maiden raked the hay."

She wedded a man unlearned and poor,

And many children played round her door.

But care and sorrow, and child-birth pain,

Left their traces on heart and brain.

And oft, when the summer sun shone hot

On the new-mown hay in the meadow lot,

And she heard the little spring brook fall

Over the roadside, through the wall,

In the shade of the apple-tree again

She saw a rider draw his rein,

And, gazing down with a timid grace,

She felt his pleased eyes read her face.

Sometimes her narrow kitchen walls

Stretched away into stately halls;

The weary wheel to a spinnet turned,

The tallow candle an astral burned;

And for him who sat by the chimney lug,

Dozing and grumbling o'er pipe and mug,

A manly form at her side she saw,

And joy was duty and love was law.

Then she took up her burden of life again,

Saying only, "It might have been."

Alas for maiden, alas for judge,

For rich repiner and household drudge!

God pity them both! and pity us all,

Who vainly the dreams of youth recall;

For of all sad words of tongue or pen,

The saddest are these: "It might have been!"

Ah, well! for us all some sweet hope lies

Deeply buried from human eyes;

And, in the hereafter, angels may

Roll the stone from its grave away!

JOHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER.

Beneath an Indian palm a girl

Of other blood reposes;

Her cheek is clear and pale as pearl

Amid that wild of roses.

Beside a northern pine a boy

Is leaning fancy-bound.

Nor listens where with noisy joy

Awaits the impatient hound.

Cool grows the sick and feverish calm,

Relaxed the frosty twine.—

The pine-tree dreameth of the palm,

The palm-tree of the pine.

As soon shall nature interlace

Those dimly-visioned boughs,

As these young lovers face to face

Renew their early vows.

From the German of HEINRICH HEINE.

Translation of RICHARD MONCKTON MILNES, LORD HOUGHTON.

[SAID TO HAVE BEEN THE SUGGESTIVE ORIGIN OF SCOTT'S "KENILWORTH."]

The dews of summer night did fall;

The moon, sweet regent of the sky,

Silvered the walls of Cumnor Hall,

And many an oak that grew thereby.

Now naught was heard beneath the skies,

The sounds of busy life were still,

Save an unhappy lady's sighs,

That issued from that lonely pile.

"Leicester," she cried, "is this thy love

That thou so oft hast sworn to me,

To leave me in this lonely grove,

Immured in shameful privity?

"No more thou com'st with lover's speed,

Thy once belovèd bride to see;

But be she alive, or be she dead,

I fear, stern Earl, 's the same to thee.

"Not so the usage I received

When happy in my father's hall;

No faithless husband then me grieved,

No chilling fears did me appal.

"I rose up with the cheerful morn,

No lark more blithe, no flower more gay

And like the bird that haunts the thorn,

So merrily sung the livelong day.

"If that my beauty is but small,

Among court ladies all despised,

Why didst thou rend it from that hall,

Where, scornful Earl, it well was prized?

"And when you first to me made suit,

How fair I was, you oft would say!

And proud of conquest, plucked the fruit,

Then left the blossom to decay.

"Yes! now neglected and despised,

The rose is pale, the lily's dead;

But he, that once their charms so prized,

Is sure the cause those charms are fled.

"For know, when sick'ning grief doth prey,

And tender love's repaid with scorn,

The sweetest beauty will decay,—

What floweret can endure the storm?

"At court, I'm told, is beauty's throne,

Where every lady's passing rare,

That Eastern flowers, that shame the sun,

Are not so glowing, not so fair.

"Then, Earl, why didst thou leave the beds

Where roses and where lilies vie,

To seek a primrose, whose pale shades

Must sicken when those gauds are by?

"'Mong rural beauties I was one,

Among the fields wild flowers are fair;

Some country swain might me have won,

And thought my beauty passing rare.

"But, Leicester, (or I much am wrong,)

Or 't is not beauty lures thy vows;

Rather ambition's gilded crown

Makes thee forget thy humble spouse.

"Then, Leicester, why, again I plead,

(The injured surely may repine,)—

Why didst thou wed a country maid,

When some fair princess might be thine?

"Why didst thou praise my humble charms,

And, oh! then leave them to decay?

Why didst thou win me to thy arms,

Then leave to mourn the livelong day?

"The village maidens of the plain

Salute me lowly as they go;

Envious they mark my silken train,

Nor think a Countess can have woe.

"The simple nymphs! they little know

How far more happy 's their estate;

To smile for joy than sigh for woe

To be content—than to be great.

"How far less blest am I than them

Daily to pine and waste with care!

Like the poor plant, that, from its stem

Divided, feels the chilling air.

"Nor, cruel Earl! can I enjoy

The humble charms of solitude;

Your minions proud my peace destroy,

By sullen frowns or pratings rude.

"Last night, as sad I chanced to stray,

The village death-bell smote my ear;

They winked aside, and seemed to say,

'Countess, prepare, thy end is near.'

"And now, while happy peasants sleep,

Here I sit lonely and forlorn;

No one to soothe me as I weep,

Save Philomel on yonder thorn.

"My spirits flag—my hopes decay—

Still that dread death-bell smites my ear,

And many a boding seems to say,

'Countess, prepare, thy end is near!'"

Thus sore and sad that lady grieved,

In Cumnor Hall so lone and drear,

And many a heartfelt sigh she heaved,

And let fall many a bitter tear.

And ere the dawn of day appeared,

In Cumnor Hall, so lone and drear,

Full many a piercing scream was heard,

And many a cry of mortal fear.

The death-bell thrice was heard to ring,

An aerial voice was heard to call,

And thrice the raven flapped its wing

Around the towers of Cumnor Hall.

The mastiff bowled at village door,

The oaks were shattered on the green;

Woe was the hour, for nevermore

That hapless Countess e'er was seen.

And in that manor now no more

Is cheerful feast and sprightly ball;

For ever since that dreary hour

Have spirits haunted Cumnor Hall.

The village maids, with fearful glance,

Avoid the ancient moss-grown wall,

Nor ever lead the merry dance,

Among the groves of Cumnor Hall.

Full many a traveller oft hath sighed,

And pensive wept the Countess' fall,

As wandering onward they've espied

The haunted towers of Cumnor Hall.

WILLIAM JULIUS MICKLE.

O waly, waly, up the bank,

O waly, waly, doun the brae,

And waly, waly, yon burn-side,

Where I and my love were wont to gae!

I leaned my back unto an aik,

I thocht it was a trustie tree,

But first it bowed and syne it brak',—

Sae my true love did lichtlie me.

O waly, waly, but love be bonnie

A little time while it is new!

But when it's auld it waxeth cauld,

And fadeth awa' like the morning dew.

O wherefore should I busk my heid.

Or wherefore should I kame my hair?

For my true love has me forsook,

And says he'll never lo'e me mair.

Noo Arthur's Seat sall be my bed,

The sheets sall ne'er be pressed by me;

Saint Anton's well sall be my drink;

Since my true love's forsaken me.

Martinmas wind, when wilt thou blaw,

And shake the green leaves off the tree?

O gentle death, when wilt thou come?

For of my life I am wearie.

'Tis not the frost that freezes fell,

Nor blawing snaw's inclemencie,

'Tis not sic cauld that makes me cry;

But my love's heart grown cauld to me.

When we cam' in by Glasgow toun,

We were a comely sicht to see;

My love was clad in the black velvet,

An' I mysel' in cramasie.

But had I wist before I kissed

That love had been so ill to win,

I 'd locked my heart in a case o' goud,

And pinn'd it wi' a siller pin.

Oh, oh! if my young babe were born,

And set upon the nurse's knee;

And I mysel' were dead and gane,

And the green grass growing over me!

ANONYMOUS.

A SCOTTISH SONG.

Balow, my babe, ly stil and sleipe!

It grieves me sair to see thee weipe;

If thoust be silent, Ise be glad,

Thy maining maks my heart ful sad.

Balow, my boy, thy mither's joy!

Thy father breides me great annoy.

Balow, my 'babe, ly stil and sleipe!

It grieves me sair to see thee weipe.

When he began to court my luve,

And with his sugred words to muve,

His faynings fals and flattering cheire

To me that time did not appeire:

But now I see, most cruell hee,

Cares neither for my babe nor mee.

Balow, etc.

Ly stil, my darlinge, sleipe awhile,

And when thou wakest sweitly smile:

But smile not, as thy father did,

To cozen maids; nay, God forbid!

But yette I feire, thou wilt gae neire,

Thy fatheris hart and face to beire.

Balow, etc.

I cannae chuse, but ever will

Be luving to thy father stil:

Whaireir he gae, whaireir he ryde,

My luve with him maun stil abyde:

In weil or wae, whaireir he gae,

Mine hart can neir depart him frae.

Balow, etc.

But doe not, doe not, prettie mine,

To faynings fals thine hart incline;

Be loyal to thy luver trew,

And nevir change hir for a new;

If gude or faire, of hir have care,

For womens banning's wonderous sair.

Balow, etc.

Bairne, sin thy cruel father is gane,

Thy winsome smiles maun eise my paine;

My babe and I 'll together live,

He'll comfort me when cares doe grieve;

My babe and I right saft will ly,

And quite forgeit man's cruelty.

Balow, etc.

Fareweil, fareweil, thou falsest youth

That ever kist a woman's mouth!

I wish all maids be warned by mee,

Nevir to trust man's curtesy;

For if we doe but chance to bow,

They'll use us then they care not how.

Balow, my 'babe, ly stil and sleipe!

It grieves me sair to see thee weipe.

ANONYMOUS.

MY HEID IS LIKE TO REND, WILLIE.

My heid is like to rend, Willie,

My heart is like to break;

I'm wearin' aff my feet, Willie,

I'm dyin' for your sake!

O, say ye'll think on me, Willie,

Your hand on my briest-bane,—

O, say ye'll think of me, Willie,

When I am deid and gane!

It's vain to comfort me, Willie,

Sair grief maun ha'e its will;

But let me rest upon your briest

To sab and greet my fill.

Let me sit on your knee, Willie,

Let me shed by your hair,

And look into the face, Willie,

I never sall see mair!

I'm sittin' on your knee, Willie,

For the last time in my life,—

A puir heart-broken thing, Willie,

A mither, yet nae wife.

Ay, press your hand upon my heart,

And press it mair and mair,

Or it will burst the silken twine,

Sae strang is its despair.

O, wae's me for the hour, Willie,

When we thegither met,—

O, wae's me for the time, Willie,

That our first tryst was set!

O, wae's me for the loanin' green

Where we were wont to gae,—

And wae's me for the destinie

That gart me luve thee sae!

O, dinna mind my words, Willie,

I downa seek to blame;

But O, it's hard to live, Willie,

And dree a warld's shame!

Het tears are hailin' ower our cheek,

And hailin' ower your chin:

Why weep ye sae for worthlessness,

For sorrow, and for sin?

I'm weary o' this warld, Willie,

And sick wi' a' I see,

I canna live as I ha'e lived,

Or be as I should be.

But fauld unto your heart, Willie,

The heart that still is thine,