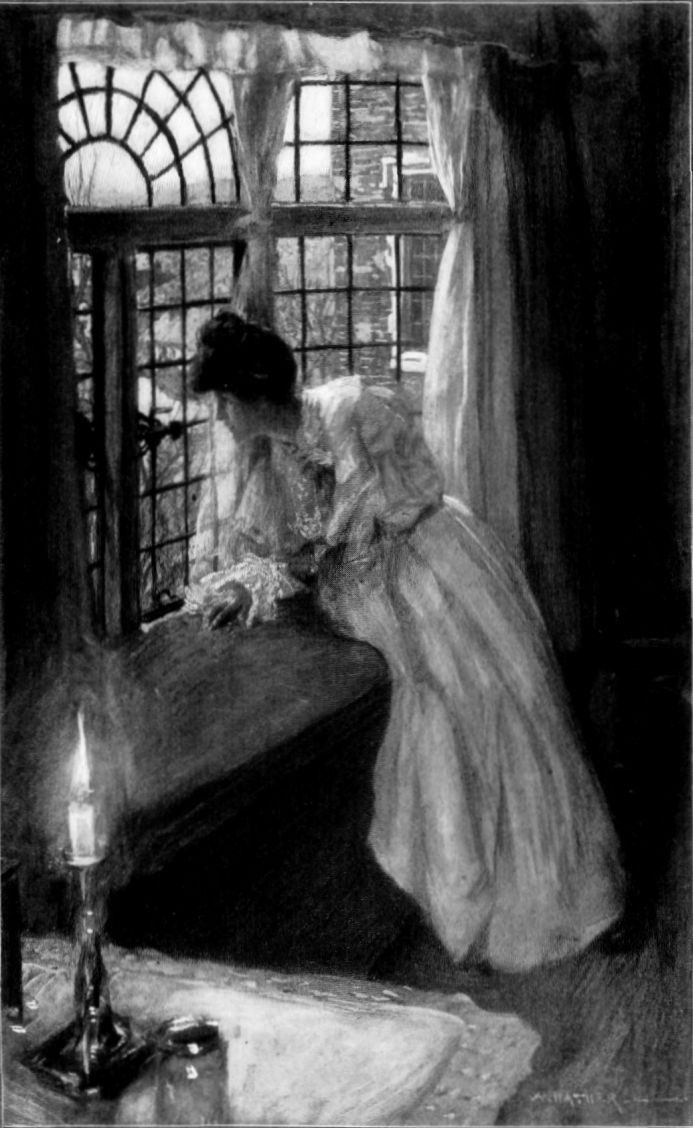

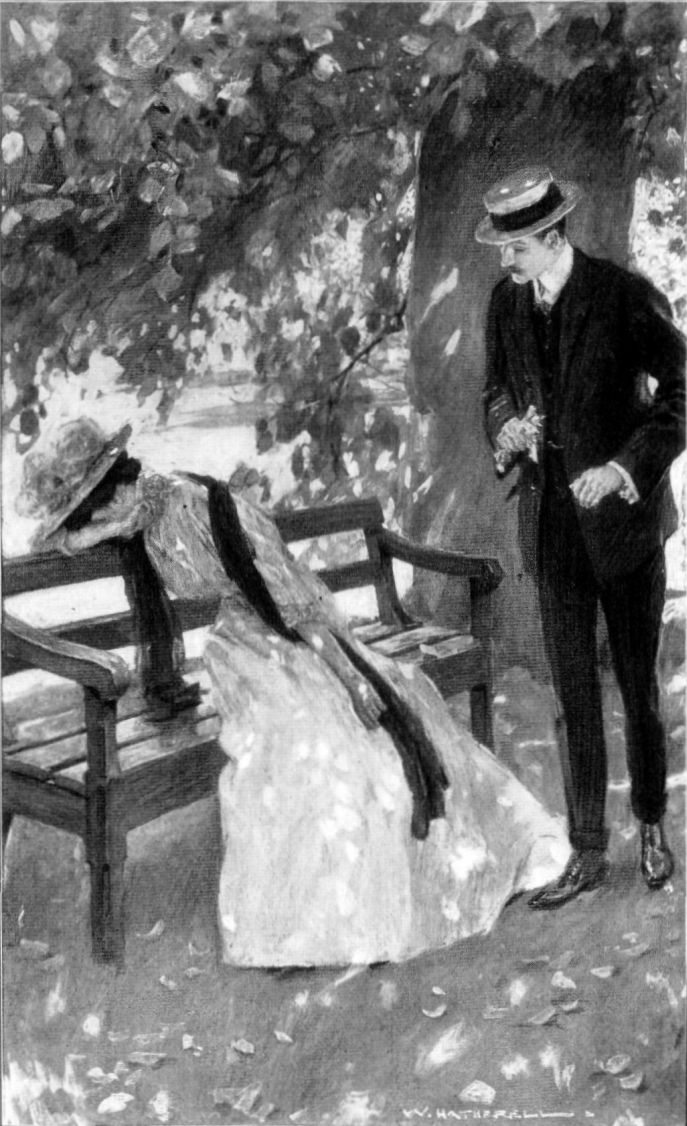

"There she waited while the dawn stole upon the night"

Title: The Testing of Diana Mallory

Author: Mrs. Humphry Ward

Illustrator: William Hatherell

Release date: September 14, 2004 [eBook #13453]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Kirschner, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Testing of Diana Mallory, by Mrs. Humphry Ward, Illustrated by W. Hatherell

"There she waited while the dawn stole upon the night"

| BOOKS BY | ||

|---|---|---|

| MRS. HUMPHRY WARD | ||

| THE TESTING OF DIANA MALLORY. Ill'd | $1.50 | |

| LADY ROSE'S DAUGHTER. Illustrated | 1.50 | |

| Two volume edition | 3.00 | |

| THE MARRIAGE OF WILLIAM ASHE. Ill'd | 1.50 | |

| Two volume Autograph edition | net | 4.00 |

| FENWICK'S CAREER. Illustrated | 1.50 | |

| De Luxe edition, two volumes | net | 5.00 |

| ELEANOR | 1.50 | |

| LIFE OF W.T. ARNOLD | net | 1.50 |

| "THERE SHE WAITED WHILE THE DAWN STOLE UPON THE NIGHT" | Frontispiece | |

| "THE MAN'S PULSES LEAPED ANEW" | 98 | |

| "YOU NEEDN'T BE CROSS WITH ME, DIANA" | 174 | |

| "'DEAR LADY,' HE SAID, GENTLY, 'I THINK YOU OUGHT TO GIVE WAY!'" | 256 | |

| "ALICIA, UPRIGHT IN HER CORNER--OLIVER, DEEP IN HIS ARMCHAIR" | 332 | |

| "SIR JAMES PLAYED DIANA'S GAME WITH PERFECT DISCRETION" | 462 | |

| "SIR JAMES MADE HIMSELF DELIGHTFUL TO THEM" | 492 | |

| "ROUGHSEDGE STOOD NEAR, RELUCTANTLY WAITING" | 514 |

"Action is transitory--a step, a blow,

The motion of a muscle--this way or that--

'Tis done, and in the after-vacancy

We wonder at ourselves like men betrayed:

Suffering is permanent, obscure, and dark,

And shares the nature of infinity."

--THE BORDERERS.

The clock in the tower of the village church had just struck the quarter. In the southeast a pale dawn light was beginning to show above the curving hollow of the down wherein the village lay enfolded; but the face of the down itself was still in darkness. Farther to the south, in a stretch of clear night sky hardly touched by the mounting dawn, Venus shone enthroned, so large and brilliant, so near to earth and the spectator, that she held, she pervaded the whole dusky scene, the shadowed fields and wintry woods, as though she were their very soul and voice.

"The Star of Bethlehem!--and Christmas Day!"

Diana Mallory had just drawn back the curtain of her bedroom. Her voice, as she murmured the words, was full of a joyous delight; eagerness and yearning expressed themselves in her bending attitude, her parted lips and eyes intent upon the star.

The panelled room behind her was dimly lit by a solitary candle, just kindled. The faint dawn in front, the flickering candle-light behind, illumined Diana's tall figure, wrapped in a white dressing-gown, her small head and slender neck, the tumbling masses of her dark hair, and the hand holding the curtain. It was a kind and poetic light; but her youth and grace needed no softening.

After the striking of the quarter, the church bell began to ring, with a gentle, yet insistent note which gradually filled the hollows of the village, and echoed along the side of the down. Once or twice the sound was effaced by the rush and roar of a distant train; and once the call of an owl from a wood, a call melancholy and prolonged, was raised as though in rivalry. But the bell held Diana's strained ear throughout its course, till its mild clangor passed into the deeper note of the clock striking the hour, and then all sounds alike died into a profound yet listening silence.

"Eight o'clock! That was for early service," she thought; and there flashed into her mind an image of the old parish church, dimly lit for the Christmas Eucharist, its walls and pillars decorated with ivy and holly, yet austere and cold through all its adornings, with its bare walls and pale windows. She shivered a little, for her youth had been accustomed to churches all color and lights and furnishings--churches of another type and faith. But instantly some warm leaping instinct met the shrinking, and overpowered it. She smote her hands together.

"England!--England!--my own, own country!"

She dropped upon the window-seat half laughing, yet the tears in her eyes. And there, with her face pressed against the glass, she waited while the dawn stole upon the night, while in the park the trees emerged upon the grass white with rime, while on the face of the down thickets and paths became slowly visible, while the first wreaths of smoke began to curl and hover in the frosty air.

Suddenly, on a path which climbed the hill-side till it was lost in the beech wood which crowned the summit, she saw a flock of sheep, and behind them a shepherd boy running from side to side. At the sight, her eyes kindled again. "Nothing changes," she thought, "in this country life!" On the morning of Charles I.'s execution--in the winters and springs when Elizabeth was Queen--while Becket lay dead on Canterbury steps--when Harold was on his way to Senlac--that hill, that path were there--sheep were climbing it, and shepherds were herding them. "It has been so since England began--it will be so when I am dead. We are only shadows that pass. But England lives always--always--and shall live!"

And still, in a trance of feeling, she feasted her eyes on the quiet country scene.

The old house which Diana Mallory had just begun to inhabit stood upon an upland, but it was an upland so surrounded by hills to north and east and south that it seemed rather a close-girt valley, leaned over and sheltered by the downs. Pastures studded with trees sloped away from the house on all sides; the village was hidden from it by boundary woods; only the church tower emerged. From the deep oriel window where she sat Diana could see a projecting wing of the house itself, its mellowed red brick, its Jacobean windows and roof. She could see also a corner of the moat with its running stream, a moat much older than the building it encircled, and beneath her eyes lay a small formal garden planned in the days of John Evelyn--with its fountain and its sundial, and its beds in arabesque. The cold light of December lay upon it all; there was no special beauty in the landscape, and no magnificence in the house or its surroundings. But every detail of what she saw pleased the girl's taste, and satisfied her heart. All the while she was comparing it with other scenes and another landscape, amid which she had lived till now--a monotonous blue sea, mountains scorched and crumbled by the sun, dry palms in hot gardens, roads choked with dust and tormented with a plague of motor-cars, white villas crowded among high walls, a wilderness of hotels, and everywhere a chattering unlovely crowd.

"Thank goodness!--that's done with," she thought--only to fall into a sudden remorse. "Papa--papa!--if you were only here too!"

She pressed her hands to her eyes, which were moist with sudden tears. But the happiness in her heart overcame the pang, sharp and real as it was. Oh! how blessed to have done with the Riviera, and its hybrid empty life, for good and all!--how blessed even, to have done with the Alps and Italy!--how blessed, above all, to have come home!--home into the heart of this English land--warm mother-heart, into which she, stranger and orphan, might creep and be at rest.

The eloquence of her own thoughts possessed her. They flowed on in a warm, mute rhetoric, till suddenly the Comic Spirit was there, and patriotic rapture began to see itself. She, the wanderer, the exile, what did she know of England--or England of her? What did she know of this village even, this valley in which she had pitched her tent? She had taken an old house, because it had pleased her fancy, because it had Tudor gables, pretty panelling, and a sundial. But what natural link had she with it, or with these peasants and countrymen? She had no true roots here. What she had done was mere whim and caprice. She was an alien, like anybody else--like the new men and prowling millionaires, who bought old English properties, moved thereto by a feeling which was none the less snobbish because it was also sentimental.

She drew herself up--rebelling hotly--yet not seeing how to disentangle herself from these associates. And she was still struggling to put herself back in the romantic mood, and to see herself and her experiment anew in the romantic light, when her maid knocked at the door, and distraction entered with letters, and a cup of tea.

An hour later Miss Mallory left her room behind her, and went tripping down the broad oak staircase of Beechcote Manor.

By this time romance was uppermost again, and self-congratulation. She was young--just twenty-two; she was--she knew it--agreeable to look upon; she had as much money as any reasonable woman need want; she had already seen a great deal of the world outside England; and she had fallen headlong in love with this charming old house, and had now, in spite of various difficulties, managed to possess herself of it, and plant her life in it. Full of ghosts it might be; but she was its living mistress henceforth; nor was it either ridiculous or snobbish that she should love it and exult in it--quite the contrary. And she paused on the slippery stairs, to admire the old panelled hall below, the play of wintry sunlight on the oaken surfaces she herself had rescued from desecrating paint, and the effect of some old Persian rugs, which had only arrived from London the night before, on the dark polished boards. For Diana, there were two joys connected with the old house: the joy of entering in, a stranger and conqueror, on its guarded and matured beauty, and the joy of adding to that beauty by a deft modernness. Very deft, and tender, and skilful it must be. But no one could say that time-worn Persian rugs, with their iridescent blue and greens and rose reds--or old Italian damask and cut-velvet from Genoa, or Florence, or Venice--were out of harmony with the charming Jacobean rooms. It was the horrible furniture of the Vavasours, the ancestral possessors of the place, which had been an offence and a disfigurement. In moving it out and replacing it, Diana felt that she had become the spiritual child of the old house, in spite of her alien blood. There is a kinship not of the flesh; and it thrilled all through her.

But just as her pause of daily homage to the place in which she found herself was over, and she was about to run down the remaining stairs to the dining-room, a new thought delayed her for a moment by the staircase window--the thought of a lady who would no doubt be waiting for her at the breakfast-table.

Mrs. Colwood, Miss Mallory's new chaperon and companion, had arrived the night before, on Christmas Eve. She had appeared just in time for dinner, and the two ladies had spent the evening together. Diana's first impressions had been pleasant--yes, certainly, pleasant; though Mrs. Colwood had been shy, and Diana still more so. There could be no question but that Mrs. Colwood was refined, intelligent, and attractive. Her gentle, almost childish looks appealed for her. So did her deep black, and the story which explained it. Diana had heard of her from a friend in Rome, where Mrs. Colwood's husband, a young Indian Civil servant, had died of fever and lung mischief, on his way to England for a long sick leave and where the little widow had touched the hearts of all who came in contact with her.

Diana thought, with one of her ready compunctions, that she had not been expansive enough the night before. She ran down-stairs, determined to make Mrs. Colwood feel at home at once.

When she entered the dining-room the new companion was standing beside the window looking out upon the formal garden and the lawn beyond it. Her attitude was a little drooping, and as she turned to greet her hostess and employer, Diana's quick eyes seemed to perceive a trace of recent tears on the small face. The girl was deeply touched, though she made no sign. Poor little thing! A widow, and childless, in a strange place.

Mrs. Colwood, however, showed no further melancholy. She was full of admiration for the beauty of the frosty morning, the trees touched with rime, the browns and purples of the distant woods. She spoke shyly, but winningly, of the comfort of her room, and the thoughtfulness with which Miss Mallory had arranged it; she could not say enough of the picturesqueness of the house. Yet there was nothing fulsome in her praise. She had the gift which makes the saying of sweet and flattering things appear the merest simplicity. They escaped her whether she would or no--that at least was the impression; and Diana found it agreeable. So agreeable that before they had been ten minutes at table Miss Mallory, in response, was conscious on her own part of an unusually strong wish to please her new companion--to make a good effect. Diana, indeed, was naturally governed by the wish to please. She desired above all things to be liked--that is, if she could not be loved. Mrs. Colwood brought with her a warm and favoring atmosphere. Diana unfolded.

In the course of this first exploratory conversation, it appeared that the two ladies had many experiences in common. Mrs. Colwood had been two years, her two short years of married life, in India; Diana had travelled there with her father. Also, as a girl, Mrs. Colwood had spent a winter at Cannes, and another at Santa Margherita. Diana expressed with vehemence her weariness of the Riviera; but the fact that Mrs. Colwood differed from her led to all the more conversation.

"My father would never come home," sighed Diana. "He hated the English climate, even in summer. Every year I used to beg him to let us go to England. But he never would. We lived abroad, first, I suppose, for his health, and then--I can't explain it. Perhaps he thought he had been so long away he would find no old friends left. And indeed so many of them had died. But whenever I talked of it he began to look old and ill. So I never could press it--never!"

The girl's voice fell to a lower note--musical, and full of memory. Mrs. Colwood noticed the quality of it.

"Of course if my mother had lived," said Diana, in the same tone, "it would have been different."

"But she died when you were a child?"

"Eighteen years ago. I can just remember it. We were in London then. Afterwards father took me abroad, and we never came back. Oh! the waste of all those years!"

"Waste?" Mrs. Colwood probed the phrase a little. Diana insisted, first with warmth, and then with an eloquence that startled her companion, that for an Englishwoman to be brought up outside England, away from country and countrymen, was to waste and forego a hundred precious things that might have been gathered up. "I used to be ashamed when I talked to English people. Not that we saw many. We lived for years and years at a little villa near Rapallo, and in the summer we used to go up into the mountains, away from everybody. But after we came back from a long tour, we lived for a time at a hotel in Mentone--our own little house was let--and I used to talk to people there--though papa never liked making friends. And I made ridiculous mistakes about English things--and they'd laugh. But one can't know--unless one has lived--has breathed in a country, from one's birth. That's what I've lost."

Mrs. Colwood demurred.

"Think of the people who wish they had grown up without ever reading or hearing about the Bible, so that they might read it for the first time, when they could really understand it. You feel England all the more intensely now because you come fresh to her."

Diana sprang up, with a change of face--half laugh, half frown.

"Yes, I feel her! Above all, I feel her enemies!"

She let in her dog, a fine collie, who was scratching at the door. As she stood before the fire, holding up a biscuit for him to jump at, she turned a red and conscious face towards her companion. The fire in the eyes, the smile on the lip seemed to say:

"There!--now we have come to it. This is my passion--my hobby--this is me!"

"Her enemies! You are political?"

"Desperately!"

"A Tory?"

"Fanatical. But that's only part of it, 'What should they know of England, that only England know!'"

Miss Mallory threw back her head with a gesture that became it.

"Ah, I see--an Imperialist?"

Diana nodded, smiling. She had seated herself in a chair by the fireside. Her dog's head was on her knees, and one of her slender hands rested on the black and tan. Mrs. Colwood admired the picture. Miss Mallory's sloping shoulders and long waist were well shown by her simple dress of black and closely fitting serge. Her head crowned and piled with curly black hair, carried itself with an amazing self-possession and pride, which was yet all feminine. This young woman might talk politics, thought her new friend; no male man would call her prater, while she bore herself with that air. Her eyes--the chaperon noticed it for the first time--owed some of their remarkable intensity, no doubt, to short sight. They were large, finely colored and thickly fringed, but their slightly veiled concentration suggested an habitual, though quite unconscious struggle to see--with that clearness which the mind behind demanded of them. The complexion was a clear brunette, the cheeks rosy; the nose was slightly tilted, the mouth fresh and beautiful though large; and the face of a lovely oval. Altogether, an aspect of rich and glowing youth: no perfect beauty; but something arresting, ardent--charged, perhaps over-charged, with personality. Mrs. Colwood said to herself that life at Beechcote would be no stagnant pool.

While they lingered in the drawing-room before church, she kept Diana talking. It seemed that Miss Mallory had seen Egypt, India, and Canada, in the course of her last two years of life with her father. Their travels had spread over more than a year; and Diana had brought Mr. Mallory back to the Riviera, only, it appeared, to die, after some eight months of illness. But in securing to her that year of travel, her father had bestowed his last and best gift upon her. Aided by his affection, and stimulated by his knowledge, her mind and character had rapidly developed. And, as through a natural outlet, all her starved devotion for the England she had never known, had spent itself upon the Englands she found beyond the seas; upon the hard-worked soldiers and civilians in lonely Indian stations, upon the captains of English ships, upon the pioneers of Canadian fields and railways; upon England, in fact, as the arbiter of oriental faiths--the wrestler with the desert--the mother and maker of new states. A passion for the work of her race beyond these narrow seas--a passion of sympathy, which was also a passion of antagonism, since every phase of that work, according to Miss Mallory, had been dogged by the hate and calumny of base minds--expressed itself through her charming mouth, with a quite astonishing fluency. Mrs. Colwood's mind moved uneasily. She had expected an orphan girl, ignorant of the world, whom she might mother, and perhaps mould. She found a young Egeria, talking politics with raised color and a throbbing voice, as other girls might talk of lovers or chiffons. Egeria's companion secretly and with some alarm reviewed her own equipment in these directions. Miss Mallory discoursed of India. Mrs. Colwood had lived in it. But her husband had entered the Indian Civil Service, simply in order that he might have money enough to marry her. And during their short time together, they had probably been more keenly alive to the depreciation of the rupee than to ideas of England's imperial mission. But Herbert had done his duty, of course he had. Once or twice as Miss Mallory talked the little widow's eyes filled with tears again unseen. The Indian names Diana threw so proudly into air were, for her companion, symbols of heart-break and death. But she played her part; and her comments and interjections were all that was necessary to keep the talk flowing.

In the midst of it voices were suddenly heard outside. Diana started.

"Carols!" she said, with flushing cheeks. "The first time I have heard them in England itself!"

She flew to the hall, and threw the door open. A handful of children appeared shouting "Good King Wenceslas" in a hideous variety of keys. Miss Mallory heard them with enthusiasm; then turned to the butler behind her.

"Give them a shilling, please, Brown."

A quick change passed over the countenance of the man addressed.

"Lady Emily, ma'am, never gave more than three-pence."

This stately person had formerly served the Vavasours, and was much inclined to let his present mistress know it.

Diana looked disappointed, but submissive.

"Oh, very well, Brown--I don't want to alter any of the old ways. But I hear the choir will come up to-night. Now they must have five shillings--and supper, please, Brown."

Brown drew himself up a little more stiffly.

"Lady Emily always gave 'em supper, ma'am, but, begging your pardon, she didn't hold at all with giving 'em money."

"Oh, I don't care!" said Miss Mallory, hastily. "I'm sure they'll like it, Brown! Five shillings, please."

Brown withdrew, and Diana, with a laughing face and her hands over her ears, to mitigate the farewell bawling of the children, turned to Mrs. Colwood, with an invitation to dress for church.

"The first time for me," she explained. "I have been coming up and down, for a month or more, two or three days at a time, to see to the furnishing. But now I am at home!"

The Christmas service in the parish church was agreeable enough. The Beechcote pew was at the back of the church, and as the new mistress of the old house entered and walked down the aisle, she drew the eyes of a large congregation of rustics and small shopkeepers. Diana moved in a kind of happy absorption, glancing gently from side to side. This gathering of villagers was to her representative of a spiritual and national fellowship to which she came now to be joined. The old church, wreathed in ivy and holly; the tombs in the southern aisle; the loaves standing near the porch for distribution after service, in accordance with an old benefaction; the fragments of fifteenth-century glass in the windows; the school-children to her left; the singing, the prayers, the sermon--found her in a welcoming, a child-like mood. She knelt, she sang, she listened, like one undergoing initiation, with a tender aspiring light in her eyes, and an eager mobility of expression.

Mrs. Colwood was more critical. The clergyman who preached the sermon did not, in fact, please her at all. He was a thin High Churchman, with an oblong face and head, narrow shoulders, and a spare frame. He wore spectacles, and his voice was disagreeably pitched. His sermon was nevertheless remarkable. A bare yet penetrating style; a stern view of life; the voice of a prophet, and apparently the views of a socialist--all these he possessed. None of them, it might have been thought, were especially fitted to capture either the female or the rustic mind. Yet it could not be denied that the congregation was unusually good for a village church; and by the involuntary sigh which Miss Mallory gave as the sermon ended, Mrs. Colwood was able to gauge the profound and docile attention with which one at least had listened to it.

After church there was much lingering in the churchyard for the exchange of Christmas greetings. Mrs. Colwood found herself introduced to the Vicar, Mr. Lavery; to a couple of maiden ladies of the name of Bertram, who seemed to have a good deal to do with the Vicar, and with the Church affairs of the village; and to an elderly couple, Dr. and Mrs. Roughsedge, white-haired, courteous, and kind, who were accompanied by a soldier son, in whom it was evident they took a boundless pride. The young man, of a handsome and open countenance, looked at Miss Mallory as much as good manners allowed. She, however, had eyes for no one but the Vicar, with whom she started, tête-à-tête, in the direction of the Vicarage.

Mrs. Colwood followed, shyly making acquaintance with the Roughsedges, and the elder Miss Bertram. That lady was tall, fair, and faded; she had a sharp, handsome nose, and a high forehead; and her eyes, which hardly ever met those of the person with whom she talked, gave the impression of a soul preoccupied, with few or none of the ordinary human curiosities.

Mrs. Roughsedge, on the other hand, was most human, motherly, and inquisitive. She wore two curls on either side of her face held by small combs, a large bonnet, and an ample cloak. It was clear that whatever adoration she could spare from her husband was lavished on her son. But there was still enough good temper and good will left to overflow upon the rest of mankind. She perceived in a moment that Mrs. Colwood was the new "companion" to the heiress, that she was a widow, and sad--in spite of her cheerfulness.

"Now I hope Miss Mallory is going to like us!" she said, with a touch of confidential good-humor, as she drew Mrs. Colwood a little behind the others. "We are all in love with her already. But she must be patient with us. We're very humdrum folk!"

Mrs. Colwood could only say that Miss Mallory seemed to be in love with everything--the house, the church, the village, and the neighbors. Mrs. Roughsedge shook her gray curls, smiling, as she replied that this was no doubt partly due to novelty. After her long residence abroad, Miss Mallory was--it was very evident--glad to come home. Poor thing--she must have known a great deal of trouble--an only child, and no mother! "Well, I'm sure if there's anything we can do--"

Mrs. Roughsedge nodded cheerfully towards her husband and son in front. The gesture awakened a certain natural reserve in Mrs. Colwood, followed by a quick feeling of amusement with herself that she should so soon have developed the instinct of the watch-dog. But it was not to be denied that the new mistress of Beechcote was well endowed, as single women go. Fond mothers with marriageable sons might require some handling.

But Mrs. Roughsedge's simple kindness soon baffled distrust. And Mrs. Colwood was beginning to talk freely, when suddenly the Vicar and Miss Mallory in front came to a stop. The way to the Vicarage lay along a side road. The Roughsedges also, who had walked so far for sociability's sake, must return to the village and early dinner. The party broke up. Miss Mallory, as she made her good-byes, appeared a little flushed and discomposed. But the unconscious fire in her glance, and the vigor of her carriage, did but add to her good looks. Captain Roughsedge, as he touched her hand, asked whether he should find her at home that afternoon if he called, and Diana absently said yes.

"What a strange impracticable man!" cried Miss Mallory hotly, as the ladies turned into the Beechcote drive. "It is really a misfortune to find a man of such opinions in this place."

"The Vicar?" said Mrs. Colwood, bewildered

"A Little Englander!--a socialist! And so rude too! I asked him to let me help him with, his poor--and he threw back my offers in my face. What they wanted, he said, was not charity, but justice. And justice apparently means cutting up the property of the rich, and giving it to the poor. Is it my fault if the Vavasours neglected their cottages? I just mentioned emigration, and he foamed! I am sure he would give away the Colonies for a pinch of soap, and abolish the Army and Navy to-morrow."

Diana's face glowed with indignation--with wounded feeling besides. Mrs. Colwood endeavored to soothe her, but she remained grave and rather silent for some time. The flow of Christmas feeling and romantic pleasure had been arrested, and the memory of a harsh personality haunted the day. In the afternoon, however, in the unpacking of various pretty knick-knacks, and in the putting away of books and papers, Diana recovered herself. She flitted about the house, arranging her favorite books, hanging pictures, and disposing embroideries. The old walls glowed afresh under her hand, and from the combination of their antique beauty with her young taste, a home began to emerge, stamped with a woman's character and reflecting her enthusiasms. As she assisted in the task, Mrs. Colwood learned many things. She gathered that Miss Mallory read two or three languages, that she was passionately fond of French memoirs and the French classics, that her father had taught her Latin and German, and guided every phase of her education. Traces indeed of his poetic and scholarly temper were visible throughout his daughter's possessions--so plainly, that at last as they came nearly to the end of the books, Diana's gayety once more disappeared. She moved soberly and dreamily, as though the past returned upon her; and once or twice Mrs. Colwood came upon her standing motionless, her finger in an open book, her eyes wandering absently through the casement windows to the distant wall of hill. Sometimes, as she bent over the books and packets she would say little things, or quote stories of her father, which seemed to show a pretty wish on her part to make the lady who was now to be her companion understand something of the feelings and memories on which her life was based. But there was dignity in it all, and, besides, a fundamental awe and reserve. Mrs. Colwood seemed to see that there were remembrances connected with her father far too poignant to be touched in speech.

At tea-time Captain Roughsedge appeared. Mrs. Colwood's first impression of his good manners and good looks was confirmed. But his conversation could not be said to flow: and in endeavoring to entertain him the two ladies fought a rather uphill fight. Then Diana discovered that he belonged to the Sixtieth Rifles, whereupon the young lady disclosed a knowledge of the British Army, and its organization, which struck her visitor as nothing short of astounding. He listened to her open-mouthed while she rattled on, mainly to fill up the gaps in his own remarks; and when she paused, he bluntly complimented her on her information. "Oh, that was papa!" said Diana, with a smile and a sigh. "He taught me all he could about the Army, though he himself had only been a Volunteer. There was an old History of the British Army I was brought up on. It was useful when we went to India--because I knew so much about the regiments we came across."

This accomplishment of hers proved indeed a god-send; the young man found his tongue; and the visit ended much better than it began.

As he said good-bye, he looked, round the drawing-room in wonderment.

"How you've altered it! The Vavasours made it hideous. But I've only been in this room twice before, though my people have lived here thirty years. We were never smart enough for Lady Emily."

He colored as he spoke, and Diana suspected in him a memory of small past humiliations. Evidently he was sensitive as well as shy.

"Hard work--dear young man!" she said, with a smile, and a stretch, as the door closed upon him. "But after all--'que j'aime le militaire'! Now, shall we go back to work?"

There were still some books to unpack. Presently Mrs. Colwood found herself helping to carry a small but heavy box of papers to the sitting-room which Diana had arranged for herself next to her bedroom. Mrs. Colwood noticed that before Diana asked her assistance she dismissed her new maid, who had been till then actively engaged in the unpacking. Miss Mallory herself unlocked the trunk in which the despatch-box had arrived, and took it out. The box had an old green baize covering which was much frayed and worn. Diana placed it on the floor of her bedroom, where Mrs. Colwood had been helping her in various unpackings, and went away for a minute to clear a space for it in the locked wall-cupboard to which it was to be consigned. Her companion, left alone, happened to see that an old mended tear in the green baize had given way in Diana's handling of the box, and quite involuntarily her eyes caught a brass plate on the morocco lid, which bore the words, "Sparling papers." Diana came back at the moment, and perceived the uncovered label. She flushed a little, hesitated, and then said, looking first at the label and then at Mrs. Colwood: "I think I should like you to know--my name was not always Mallory. We were Sparlings--but my father took the name of Mallory after my mother's death. It was his mother's name, and there was an old Mallory uncle who left him a property. I believe he was glad to change his name. He never spoke to me of any Sparling relations. He was an only child, and I always suppose his father must have been very unkind to him--and that they quarrelled. At any rate, he quite dropped the name, and never would let me speak of it. My mother had hardly any relations either--only one sister who married and went to Barbadoes. So our old name was very soon forgotten. And please"--she looked up appealingly--"now that I have told you, will you forget it too? It always seemed to hurt papa to hear it, and I never could bear to do--or say--anything that gave him pain."

She spoke with a sweet seriousness. Mrs. Colwood, who had been conscious of a slight shock of puzzled recollection, gave an answer which evidently pleased Diana, for the girl held out her hand and pressed that of her companion; then they carried the box to its place, and were leaving the room, when suddenly Diana, with a joyous exclamation, pounced on a book which was lying on the floor, tumbled among a dozen others recently unpacked.

"Mr. Marsham's Rossetti! I am glad. Now I can face him!"

She looked up all smiles.

"Do you know that I am going to take you to a party next week?--to the Marshams? They live near here--at Tallyn Hall. They have asked us for two nights--Thursday to Saturday. I hope you won't mind."

"Have I got a dress?" said Mrs. Colwood, anxiously.

"Oh, that doesn't matter!--not at the Marshams. I am glad!" repeated Diana, fondling the book--"If I really had lost it, it would have given him a horrid advantage!"

"Who is Mr. Marsham?"

"A gentleman we got to know at Rapallo," said Diana, still smiling to herself. "He and his mother were there last winter. Father and I quarrelled with him all day long. He is the worst Radical I ever met, but--"

"But?--but agreeable?"

"Oh yes," said Diana, uncertainly, and Mrs. Colwood thought she colored--"oh yes--agreeable!"

"And he lives near here?"

"He is the member for the division. Such a crew as we shall meet there!" Diana laughed out. "I had better warn you. But they have been very kind. They called directly they knew I had taken the house. 'They' means Mr. Oliver Marsham and his mother. I am glad I've found his book!" She went off embracing it.

Mrs. Colwood was left with two impressions--one sharp, the other vague. One was that Mr. Oliver Marsham might easily become a personage in the story of which she had just, as it were, turned the first leaf. The other was connected with the name on the despatch-box. Why did it haunt her? It had produced a kind of indistinguishable echo in the brain, to which she could put no words--which was none the less dreary; like a voice of wailing from a far-off past.

During the days immediately following her arrival at Beechcote, Mrs. Colwood applied herself to a study of Miss Mallory and her surroundings--none the less penetrating because the student was modest and her method unperceived. She divined a nature unworldly, impulsive, steeped, moreover, for all its spiritual and intellectual force, which was considerable, in a kind of sensuous romance--much connected with concrete things and symbols, places, persons, emblems, or relics, any contact with which might at any time bring the color to the girl's cheeks and the tears to her eyes. Honor--personal or national--the word was to Diana like a spark to dry leaves. Her whole nature flamed to it, and there were moments when she walked visibly transfigured in the glow of it. Her mind was rich, moreover, in the delicate, inchoate lovers, the half-poetic, half-intellectual passions, the mystical yearnings and aspirations, which haunt a pure expanding youth. Such human beings, Mrs. Colwood reflected, are not generally made for happiness. But there were also in Diana signs both of practical ability and of a rare common-sense. Would this last avail to protect her from her enthusiasms? Mrs. Colwood remembered a famous Frenchwoman of whom it was said: "Her judgment is infallible--her conduct one long mistake!" The little companion was already sufficiently attached to Miss Mallory to hope that in this case a natural tact and balance might not be thrown away.

As to suitors and falling in love, the natural accompaniments of such a charming youth, Mrs. Colwood came across no traces of anything of the sort. During her journey with her father to India, Japan, and America, Miss Mallory had indeed for the first time seen something of society. But in the villa beside the Mediterranean it was evident that her life with her father had been one of complete seclusion. She and he had lived for each other. Books, sketching, long walks, a friendly interest in their peasant neighbors--these had filled their time.

It took, indeed, but a short time to discover in Miss Mallory a hunger for society which seemed to be the natural result of long starvation. With her neighbors the Roughsedges she was already on the friendliest terms. To Dr. Roughsedge, who was infirm, and often a prisoner to his library, she paid many small attentions which soon won the heart of an old student. She was in love with Mrs. Roughsedge's gray curls and motherly ways; and would consult her about servants and tradesmen with an eager humility. She liked the son, it seemed, for the parents' sake, nor was it long before he was allowed--at his own pressing request--to help in hanging pictures and arranging books at Beechcote. A girl's manner with young men is always a matter of interest to older women. Mrs. Colwood thought that Diana's manner to the young soldier could not have been easily bettered. It was frank and gay--with just that tinge of old-fashioned reserve which might be thought natural in a girl of gentle breeding, brought up alone by a fastidious father. With all her impetuosity, indeed, there was about her something markedly virginal and remote, which is commoner, perhaps, in Irish than English women. Mrs. Colwood watched the effect of it on Captain Roughsedge. After her third day of acquaintance with him, she said to herself: "He will fall in love with her!" But she said it with compassion, and without troubling to speculate on the lady. Whereas, with regard to the Marsham visit, she already--she could hardly have told why--found herself full of curiosity.

Meanwhile, in the few days which elapsed before that visit was due, Diana was much called on by the country-side. The girl restrained her restlessness, and sat at home, receiving everybody with a friendliness which might have been insipid but for its grace and spontaneity. She disliked no one, was bored by no one. The joy of her home-coming seemed to halo them all. Even the sour Miss Bertrams could not annoy her; she thought them sensible and clever; even the tiresome Mrs. Minchin of Minchin Hall, the "gusher" of the county, who "adored" all mankind and ill-treated her step-daughter, even she was dubbed "very kind," till Mrs. Roughsedge, next day, kindled a passion in the girl's eyes by some tales of the step-daughter. Mrs. Colwood wondered whether, indeed, she could be bored, as Mrs. Minchin had not achieved it. Those who talk easily and well, like Diana, are less keenly aware, she thought, of the platitudes of their neighbors. They are not defenceless, like the shy and the silent.

Nevertheless, it was clear that if Diana welcomed the neighbors with pleasure she often saw them go with relief. As soon as the house was clear of them, she would stand pensively by the fire, looking down into the blaze like one on whom a dream suddenly descends--then would often call her dog, and go out alone, into the winter twilight. From these rambles she would return grave--sometimes with reddened eyes. But at all times, as Mrs. Colwood soon began to realize, there was but a thin line of division between her gayety and some inexplicable sadness, some unspoken grief, which seemed to rise upon her and overshadow her, like a cloud tangled in the woods of spring. Mrs. Colwood could only suppose that these times of silence and eclipse were connected in some way with her father and her loss of him. But whenever they occurred, Mrs. Colwood found her own mind invincibly recalled to that name on the box of papers, which still haunted her, still brought with it a vague sense of something painful and harrowing--a breath of desolation, in strange harmony, it often seemed, with certain looks and moods of Diana. But Mrs. Colwood searched her memory in vain. And, indeed, after a little while, some imperious instinct even forbade her the search--so rapid and strong was the growth of sympathy with the young life which had called her to its aid.

The day of the Marsham visit arrived--a January afternoon clear and frosty. In the morning before they were to start, Diana seemed to be often closeted with her maid, and once in passing Miss Mallory's open door, her companion could not help seeing a consultation going on, and a snowy white dress, with black ribbons, lying on the bed. Heretofore Diana had only appeared in black, the strict black which French dressmakers understand, for it was little more than a year since her father's death. The thought of seeing her in white stirred Mrs. Colwood's expectations.

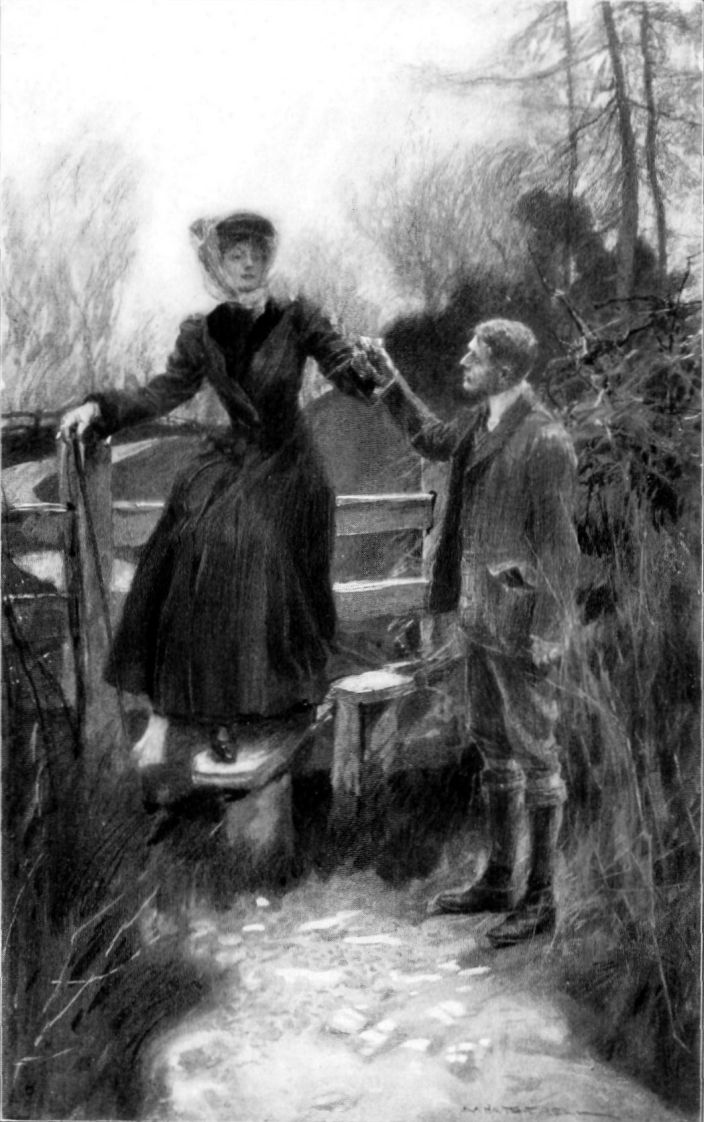

Tallyn Hall was eight miles from Beechcote. The ladies were to drive, but in order to show Mrs. Colwood something of the country, Diana decreed that they should walk up to the downs by a field path, meeting the carriage which bore their luggage at a convenient point on the main road.

The day was a day of beauty--the trees and grass lightly rimed, the air sparkling and translucent. Nature was held in the rest of winter; but beneath the outward stillness, one caught as it were the strong heart-beat of the mighty mother. Diana climbed the steep down without a pause, save when she turned round from time to time to help her companion. Her slight firm frame, the graceful decision of her movements, the absence of all stress and effort showed a creature accustomed to exercise and open air; Mrs. Colwood, the frail Anglo-Indian to whom walking was a task, tried to rival her in vain; and Diana was soon full of apologies and remorse for having tempted her to the climb.

"Please!--please!"--the little lady panted, as they reached the top--"wasn't this worth it?"

For they stood in one of the famous wood and common lands of Southern England--great beeches towering overhead--glades opening to right and left--ferny paths over green turf-tracks, and avenues of immemorial age, the highways of a vanished life--old earth-works, overgrown--lanes deep-sunk in the chalk where the pack-horses once made their way--gnarled thorns, bent with years, yet still white-mantled in the spring: a wild, enchanted no-man's country, owned it seemed by rabbits and birds, solitary, lovely, and barren--yet from its furthest edge, the high spectator, looking eastward, on a clear night, might see on the horizon the dim flare of London.

Diana's habitual joy broke out, as she stood gazing at the village below, the walls and woods of Beechcote, the church, the plough-lands, and the far-western plain, drawn in pale grays and purples under the declining sun.

"Isn't it heavenly!--the browns--the blues--the soberness, the delicacy of it all? Oh, so much better than any tiresome Mediterranean--any stupid Riviera!--Ah!" She stopped and turned, checked by a sound behind her.

Captain Roughsedge appeared, carrying his gun, his spaniel beside him. He greeted the ladies with what seemed to Mrs. Colwood a very evident start of pleasure, and turned to walk with them.

"You have been shooting?" said Diana.

He admitted it.

"That's what you enjoy?"

He flushed.

"More than anything in the world."

But he looked at his questioner a little askance, as though uncertain how she might take so gross a confession.

Diana laughed, and hoped he got as much as he desired. Then he was not like his father--who cared so much for books?

"Oh, books!" He shrugged his shoulders. "Well, the fact is, I--I don't often read if I can help it. But of course they make you do a lot of it--with these beastly examinations. They've about spoiled the army with them."

"You wouldn't do it for pleasure?"

"What--reading?" He shook his head decidedly. "Not while I could be doing anything else."

"Not history or poetry?"

He looked at her again nervously. But the girl's face was gay, and he ventured on the truth.

"Well, no, I can't say I do. My father reads a deal of poetry aloud."

"And it bores you?"

"Well, I don't understand it," he said, slowly and candidly.

"Don't you even read the papers?" asked Diana, wondering.

He started.

"Why, I should think I do!" he cried. "I should rather think I do! That's another thing altogether--that's not books."

"Then perhaps you read the debate last night?" She looked at him with a kindling eye.

"Of course I did--every word of it! Do you know what those Radical fellows are up to now? They'll never rest until we've lost the Khaibar--and then the Lord only knows what'll happen."

Diana flew into discussion--quick breath, red cheeks! Mrs. Colwood looked on amazed.

Presently both appealed to her, the Anglo-Indian. But she smiled and stammered--declining the challenge. Beside their eagerness, their passion, she felt herself tongue-tied. Captain Roughsedge had seen two years' service on the Northwest Frontier; Diana had ridden through the Khaibar with her father and a Lieutenant-Governor. In both the sense of England's historic task as the guardian of a teeming India against onslaught from the north, had sunk deep, not into brain merely. Figures of living men, acts of heroism and endurance, the thought of English soldiers ambushed in mountain defiles, or holding out against Afridi hordes in lonely forts, dying and battling, not for themselves, but that the great mountain barrier might hold against the savagery of the north, and English honor and English power maintain themselves unscathed--these had mingled, in both, with the chivalry and the red blood of youth. The eyes of both had seen; the hearts of both had felt.

And now, in the English House of Commons, there were men who doubted and sneered about these things--who held an Afridi life dearer than an English one--who cared nothing for the historic task, who would let India go to-morrow without a pang!

Misguided recreants! But Mrs. Colwood, looking on, could only feel that had they never played their impish part, the winter afternoon for these two companions of hers would have been infinitely less agreeable.

For certainly denunication and argument became Diana--all the more that she was no "female franzy" who must have all the best of the talk; she listened--she evoked--she drew on, and drew out. Mrs. Colwood was secretly sure that this very modest and ordinarily stupid young man had never talked so well before, that his mother would have been astonished could she have beheld him. What had come to the young women of this generation! Their grandmothers cared for politics only so far as they advanced the fortunes of their lords--otherwise what was Hecuba to them, or they to Hecuba? But these women have minds for the impersonal. Diana was not talking to make an effect on Captain Roughsedge--that was the strange part of it. Hundreds of women can make politics serve the primitive woman's game; the "come hither in the ee" can use that weapon as well as any other. But here was an intellectual, a patriotic passion, veritable, genuine, not feigned.

Well!--the spectator admitted it--unwillingly--so long as the debater, the orator, were still desirable, still lovely. She stole a glance at Captain Roughsedge. Was he, too, so unconscious of sex, of opportunity? Ah! that she doubted! The young man played his part stoutly; flung back the ball without a break; but there were glances, and movements and expressions, which to this shrewd feminine eye appeared to betray what no scrutiny could detect in Diana--a pleasure within a pleasure, and thoughts behind thoughts. At any rate, he prolonged the walk as long as it could be prolonged; he accompanied them to the very door of their carriage, and would have delayed them there but that Diana looked at her watch in dismay.

"You'll hear plenty of that sort of stuff to-night!" he said, as he helped them to their wraps. "'Perish India!' and all the rest of it. All they'll mind at Tallyn will be that the Afridis haven't killed a few more Britishers."

Diana gave him a rather grave smile and bow as the carriage drove on. Mrs. Colwood wondered whether the Captain's last remark had somehow offended her companion. But Miss Mallory made no reference to it. Instead, she began to give her companion some preliminary information as to the party they were likely to find at Tallyn.

As Mrs. Colwood already knew, Mr. Oliver Marsham, member for the Western division of Brookshire, was young and unmarried. He lived with his mother, Lady Lucy Marsham, the owner of Tallyn Hall; and his widowed sister, Mrs. Fotheringham, was also a constant inmate of the house. Mrs. Fotheringham was if possible more extreme in opinions than her brother, frequented platforms, had quarrelled with all her Conservative relations, including a family of stepsons, and supported Women's Suffrage. It was evident that Diana was steeling herself to some endurance in this quarter. As to the other guests whom they might expect, Diana knew little. She had heard that Mr. Ferrier was to be there--ex-Home Secretary, and now leader of the Opposition--and old Lady Niton. Diana retailed what gossip she knew of this rather famous personage, whom three-fourths of the world found insolent and the rest witty. "They say, anyway, that she can snub Mrs. Fotheringham," said Diana, laughing.

"You met them abroad?"

"Only Mr. Marsham and Lady Lucy. Papa and I were walking over the hills at Portofino. We fell in with him, and he asked us the way to San Fruttuoso. We were going there, so we showed him. Papa liked him, and he came to see us afterwards--several times. Lady Lucy came once."

"She is nice?"

"Oh yes," said Diana, vaguely, "she is quite beautiful for her age. You never saw such lovely hands. And so fastidious--so dainty! I remember feeling uncomfortable all the time, because I knew I had a tear in my dress, and my hair was untidy--and I was certain she noticed."

"It's all rather alarming," said Mrs. Colwood, smiling.

"No, no!"--Diana turned upon her eagerly. "They're very kind--very, very kind!"

The winter day was nearly gone when they reached their destination. But there was just light enough, as they stepped out of the carriage, to show a large modern building, built of red brick, with many gables and bow-windows, and a generally restless effect. As they followed the butler through the outer hall, a babel of voices made itself heard, and when he threw open the door into the inner hall, they found themselves ushered into a large party.

There was a pleased exclamation from a tall fair man standing near the fire, who came forward at once to meet them.

"So glad to see you! But we hoped for you earlier! Mother, here is Miss Mallory."

Lady Lucy, a woman of sixty, still slender and stately, greeted them kindly, Mrs. Colwood was introduced, and room was made for the new-comers in the circle round the tea-table, which was presided over by a lady with red hair and an eye-glass, who gave a hand to Diana, and a bow, or more precisely a nod, to Mrs. Colwood.

"I'm Oliver's sister--my name's Fotheringham. That's my cousin--Madeleine Varley. Madeleine, find me some cups! This is Mr. Ferrier--Mr. Ferrier, Miss Mallory.--expect you know Lady Niton.--Sir James Chide, Miss Mallory.--Perhaps that'll do to begin with!" said Mrs. Fotheringham, carelessly, glancing at a further group of people. "Now I'll give you some tea."

Diana sat down, very shy, and a little flushed. Mr. Marsham hovered about her, inducing her to loosen her furs, bringing her tea, and asking questions about her settlement at Beechcote. He showed also a marked courtesy to Mrs. Colwood, and the little widow, susceptible to every breath of kindness, formed the prompt opinion that he was both handsome and agreeable.

Oliver Marsham, indeed, was not a person to be overlooked. His height was about six foot three; and his long slender limbs and spare frame had earned him, as a lad, among the men of his father's works, the description of "two yards o' pump-waater, straight oop an' down." But in his thin lengthiness there was nothing awkward--rather a graceful readiness and vigor. And the head which surmounted this lightly built body gave to the whole personality the force and weight it might otherwise have missed. The hair was very thick and very fair, though already slightly grizzled. It lay in heavy curly masses across a broad head, defining a strong brow above deeply set small eyes of a pale conspicuous blue. The nose, aquiline and large; the mouth large also, but thin-lipped and flexible; slight hollows in the cheeks, and a long, lantern jaw. The whole figure made an impression of ease, power, and self-confidence.

"So you like your old house?" he said, presently, to Diana, sitting down beside her, and dropping his voice a little.

"It suits me perfectly."

"I am certain the moat is rheumatic! But you will never admit it."

"I would, if it were true," she said, smiling.

"No!--you are much too romantic. You see, I remember our conversations."

"Did I never admit the truth?"

"You would never admit it was the truth. And my difficulty was to find an arbiter between us."

Diana's face changed a little. He perceived it instantly.

"Your father was sometimes arbiter," he said, in a still lower tone--"but naturally he took your side. I shall always rejoice I had that chance of meeting him."

Diana said nothing, but her dark eyes turned on him with a soft friendly look. His own smiled in response, and he resumed:

"I suppose you don't know many of these people here?"

"Not any."

"I'm sure you'll like Mr. Ferrier. He is our very old friend--almost my guardian. Of course--on politics--you won't agree!"

"I didn't expect to agree with anybody here," said Diana, slyly.

He laughed.

"I might offer you Lady Niton--but I refrain. To-morrow I have reason to believe that two Tories are coming to dinner."

"Which am I to admire?--your liberality, or their courage?"

"I have matched them by two socialists. Which will you sit next?"

"Oh, I am proof!" said Diana. "'Come one, come all.'"

He looked at her smilingly.

"Is it always the same? Are you still in love with all the dear old abuses?"

"And do you still hate everything that wasn't made last week?"

"Oh no! We only hate what cheats or oppresses the people."

"The people?" echoed Diana, with an involuntary lift of the eyebrows, and she looked round the immense hall, with its costly furniture, its glaring electric lights, and the band of bad fresco which ran round its lower walls.

Oliver Marsham reddened a little; then said:

"I see my cousin Miss Drake. May I introduce her?--Alicia!"

A young lady had entered, from a curtained archway dividing the hall from a passage beyond. She paused a moment examining the company. The dark curtain behind her made an effective background for the brilliance of her hair, dress, and complexion, of which fact--such at least was Diana's instant impression--she was most composedly aware. At least she lingered a few leisurely seconds, till everybody in the hall had had the opportunity of marking her entrance. Then beckoned by Oliver Marsham, she moved toward Diana.

"How do you do? I suppose you've had a long drive? Don't you hate driving?"

And without waiting for an answer, she turned affectedly away, and took a place at the tea-table where room had been made for her by two young men. Reaching out a white hand, she chose a cake, and began to nibble it slowly, her elbows resting on the table, the ruffles of white lace falling back from her bare and rounded arms. Her look meanwhile, half absent, half audacious, seemed to wander round the persons near, as though she saw them, without taking any real account of them.

"What have you been doing, Alicia, all this time?" said Marsham, as he handed her a cup of tea.

"Dressing."

An incredulous shout from the table.

"Since lunch!"

Miss Drake nodded. Lady Lucy put in an explanatory remark about a "dressmaker from town," but was not heard. The table was engaged in watching the new-comer.

"May we congratulate you on the result?" said Mr. Ferrier, putting up his eye-glass.

"If you like," said Miss Drake, indifferently, still gently munching at her cake. Then suddenly she smiled--a glittering infectious smile, to which unconsciously all the faces near her responded. "I have been reading the book you lent me!" she said, addressing Mr. Ferrier.

"Well?"

"I'm too stupid--I can't understand it."

Mr. Ferrier laughed.

"I'm afraid that excuse won't do, Miss Alicia. You must find another."

She was silent a moment, finished her cake, then took some grapes, and began to play with them in the same conscious provocative way--till at last she turned upon her immediate neighbor, a young barrister with a broad boyish face.

"Well, I wonder whether you'd mind?"

"Mind what?"

"If your father had done something shocking--forged--or murdered--or done something of that kind--supposing, of course, he were dead."

"Do you mean--if I suddenly found out?"

She nodded assent.

"Well!" he reflected; "it would be disagreeable!"

"Yes--but would it make you give up all the things you like?--golfing--and cards--and parties--and the girl you were engaged to--and take to slumming, and that kind of thing?"

The slight inflection of the last words drew smiles. Mr. Ferrier held up a finger.

"Miss Alicia, I shall lend you no more books."

"Why? Because I can't appreciate them?"

Mr. Ferrier laughed.

"I maintain that book is a book to melt the heart of a stone."

"Well, I tried to cry," said the girl, putting another grape into her mouth, and quietly nodding at her interlocutor--"I did--honor bright. But--really--what does it matter what your father did?"

"My dear!" said Lady Lucy, softly. Her singularly white and finely wrinkled face, framed in a delicate capote of old lace, looked coldly at the speaker.

"By-the-way," said Mr. Ferrier, "does not the question rather concern you in this neighborhood? I hear young Brenner has just come to live at West Hill. I don't now what sort of a youth he is, but if he's a decent fellow, I don't imagine anybody will boycott him on account of his father's misdoings."

He referred to one of the worst financial scandals of the preceding generation. Lady Lucy made no answer, but any one closely observing her might have noticed a sudden and sharp stiffening of the lips, which was in truth her reply.

"Oh, you can always ask a man like that to garden-parties!" said a shrill, distant voice. The group round the table turned. The remark was made by old Lady Niton, who sat enthroned in an arm-chair near the fire, sometimes knitting, and sometimes observing her neighbors with a malicious eye.

"Anything's good enough, isn't it, for garden-parties?" said Mrs. Fotheringham, with a little sneer.

Lady Niton's face kindled. "Let us be Radicals, my dear," she said, briskly, "but not hypocrites. Garden-parties are invaluable--for people you can't ask into the house. By-the-way, wasn't it you, Oliver, who scolded me last night, because I said somebody wasn't 'in Society'?"

"You said it of a particular hero of mine," laughed Marsham. "I naturally pitied Society."

"What is Society? Where is it?" said Sir James Chide, contemptuously. "I suppose Lady Palmerston knew."

The famous lawyer sat a little apart from the rest. Diana, who had only caught his name, and knew nothing else of him, looked with sudden interest at the man's great brow and haughty look. Lady Niton shook her head emphatically.

"We know quite as well as she did. Society is just as strong and just as exclusive as it ever was. But it is clever enough now to hide the fact from outsiders."

"I am afraid we must agree that standards have been much relaxed," said Lady Lucy.

"Not at all--not at all!" cried Lady Niton. "There were black sheep then; and there are black sheep now."

Lady Lucy held her own.

"I am sure that people take less care in their invitations," she said, with soft obstinacy. "I have often heard my mother speak of society in her young days,--how the dear Queen's example purified it--and how much less people bowed down to money then than now."

"Ah, that was before the Americans and the Jews," said Sir James Chide.

"People forget their responsibility," said Lady Lucy, turning to Diana, and speaking so as not to be heard by the whole table. "In old days it was birth; but now--now when we are all democratic--it should be character.--Don't you agree with me?"

"Other people's character?" asked Diana.

"Oh, we mustn't be unkind, of course. But when a thing is notorious. Take this young Brenner. His father's frauds ruined hundreds of poor people. How can I receive him here, as if nothing had happened? It ought not to be forgotten. He himself ought to wish to live quietly!"

Diana gave a hesitating assent, adding: "But I'm sorry for Mr. Brenner!"

Mr. Ferrier, as she spoke, leaned slightly across the tea-table as though to listen to what she said. Lady Lucy moved away, and Mr. Ferrier, after spending a moment of quiet scrutiny on the young mistress of Beechcote, came to sit beside her.

Mrs. Fotheringham threw herself back in her chair with a little yawn. "Mamma is more difficult than the Almighty!" she said, in a loud aside to Sir James Chide. "One sin--or even somebody else's sin--and you are done for."

Sir James, who was a Catholic, and scrupulous in speech, pursed his lips slightly, drummed on the table with his fingers, and finally rose without reply, and betook himself to the Times. Miss Drake meanwhile had been carried off to play billiards at the farther end of the hall by the young men of the party. It might have been noticed that, before she went, she had spent a few minutes of close though masked observation of her cousin Oliver's new friend. Also, that she tried to carry Oliver Marsham with her, but unsuccessfully. He had returned to Diana's neighborhood, and stood leaning over a chair beside her, listening to her conversation with Mr. Ferrier.

His sister, Mrs. Fotheringham, was not content to listen. Diana's impressions of the country-side, which presently caught her ear, evidently roused her pugnacity. She threw herself on all the girl's rose-colored appreciations with a scorn hardly disguised. All the "locals," according to her, were stupid or snobbish--bores, in fact, of the first water. And to Diana's discomfort and amazement, Oliver Marsham joined in. He showed himself possessed of a sharper and more caustic tongue than Diana had yet suspected. His sister's sallies only amused him, and sometimes he improved on them, with epithets or comments, shrewder than hers indeed, but quite as biting.

"His neighbors and constituents!" thought Diana, in a young astonishment. "The people who send him to Parliament!"

Mr. Ferrier seemed to become aware of her surprise and disapproval, for he once or twice threw in a satirical word or two, at the expense, not of the criticised, but of the critics. The well-known Leader of the Opposition was a stout man of middle height, with a round head and face, at first sight wholly undistinguished, an ample figure, and smooth, straight hair. But there was so much honesty and acuteness in the eyes, so much humor in the mouth, and so much kindness in the general aspect, that Diana felt herself at once attracted; and when the master of the house was summoned by his head gamekeeper to give directions for the shooting-party of the following day, and Mrs. Fotheringham had gone off to attend what seemed to be a vast correspondence, the politician and the young girl fell into a conversation which soon became agreeable and even absorbing to both. Mrs. Colwood, sitting on the other side of the hall, timidly discussing fancy work with the Miss Varleys, Lady Lucy's young nieces, saw that Diana was making a conquest; and it seemed to her, moreover, that Mr. Ferrier's scrutiny of his companion was somewhat more attentive and more close than was quite explained by the mere casual encounter of a man of middle-age with a young and charming girl. Was he--like herself--aware that matters of moment might be here at their beginning?

Meanwhile, if Mr. Ferrier was making discoveries, so was Diana. A man, it appeared, could be not only one of the busiest and most powerful politicians in England, but also a philosopher, and a reader, one whose secret tastes were as unworldly and romantic as her own. Books, music, art--he could handle these subjects no less skilfully than others political or personal. And, throughout, his deference to a young and pretty woman was never at fault. Diana was encouraged to talk, and then, without a word of flattery, given to understand that her talk pleased. Under this stimulus, her soft dark beauty was soon glowing at its best; innocence, intelligence, and youth, spread as it were their tendrils to the sun.

Meanwhile, Sir James Chide, a few yards off, was apparently absorbed partly in the Times, partly in the endeavor to make Lady Lucy's fox terrier go through its tricks.

Once Mr. Ferrier drew Diana's attention to her neighbor.

"You know him?"

"I never saw him before."

"You know who he is?"

"Ought I?--I am so sorry!"

"He is perhaps the greatest criminal advocate we have. And a very distinguished politician too.--Whenever our party comes in, he will be in the Cabinet.--You must make him talk this evening."

"I?" said Diana, laughing and blushing.

"You can!" smiled Mr. Ferrier. "Witness how you have been making me chatter! But I think I read you right? You do not mind if one chatters?--if one gives you information?"

"Mind!--How could I be anything but grateful? It puzzles me so--this--" she hesitated.

"This English life?--especially the political life? Well!--let me be your guide. I have been in it for a long while."

Diana thanked him, and rose.

"You want your room?" he asked her, kindly.--"Mrs. Fotheringham, I think, is in the drawing-room. Let me take you to her. But, first, look at two or three of these pictures as you go."

"These--pictures?" faltered Diana, looking round her, her tone changing.

"Oh, not those horrible frescos! Those were perpetrated by Marsham's father. They represent, as you see, the different processes of the Iron Trade. Old Henry Marsham liked them, because, as he said, they explained him, and the house. Oliver would like to whitewash them--but for filial piety. People might suppose him ashamed of his origin. No, no!--I mean those two or three old pictures at the end of the room. Come and look at them--they are on our way."

He led her to inspect them. They proved to be two Gainsboroughs and a Raeburn, representing ancestors on Lady Lucy's side. Mr. Ferrier's talk of them showed his intimate knowledge both of Varleys and Marshams, the knowledge rather of a kinsman than a friend. Diana perceived, indeed, how great must be the affection, the intimacy, between him and them.

Meanwhile, as the man of fifty and the slender girl in black passed before him, on their way to examine the pictures, Sir James Chide, casually looking up, was apparently struck by some rapid and powerful impression. It arrested the hand playing with the dog; it held and transformed the whole man. His eyes, open as though in astonishment or pain, followed every movement of Diana, scrutinized every look and gesture. His face had flushed slightly--his lips were parted. He had the aspect of one trying eagerly, passionately, to follow up some clew that would not unwind itself; and every now and then he bent forward--listening--trying to catch her voice.

Presently the inspection was over. Diana turned and beckoned to Mrs. Colwood. The two ladies went toward the drawing-room, Mr. Ferrier showing the way.

When he returned to the hall, Sir James Chide, its sole occupant, was walking up and down.

"Who was that young lady?" said Sir James, turning abruptly.

"Isn't she charming? Her name is Mallory--and she has just settled at Beechcote, near here. That small fair lady was her companion. Oliver tells me she is an orphan--well off--with no kith or kin. She has just come to England, it seems, for the first time. Her father brought her up abroad away from everybody. She will have a success! But of all the little Jingoes!"

Mr. Ferrier's face expressed an amused recollection of some of Diana's speeches.

"Mallory?" said Sir James, under his breath--"Mallory?" He walked to the window, and stood looking out, his hands in his pockets.

Mr. Ferrier went up-stairs to write letters. In a few minutes the man at the window came slowly back toward the fire, staring at the ground.

"The look in the eyes!" he said to himself--"the mouth!--the voice!"

He stood by the vast and pompous fireplace--hanging over the blaze--the prey of some profound agitation, some flooding onset of memory. Servants passed and repassed through the hall; sounds loud and merry came from the drawing-room. Sir James neither saw nor heard.

Alicia Drake--a vision of pale pink--had just appeared in the long gallery at Tallyn, on her way to dinner. Her dress, her jewels, and all her minor appointments were of that quality and perfection to which only much thought and plentiful money can attain. She had not, in fact, been romancing in that account of her afternoon which has been already quoted. Dress was her weapon and her stock in trade; it was, she said, necessary to her "career." And on this plea she steadily exacted in its support a proportion of the family income which left but small pickings for the schooling of her younger brothers and the allowances of her two younger sisters. But so great were the indulgence and the pride of her parents--small Devonshire land-owners living on an impoverished estate--that Alicia's demands were conceded without a murmur. They themselves were insignificant folk, who had, in their own opinion, failed in life; and most of their children seemed to them to possess the same ineffective qualities--or the same absence of qualities--as themselves. But Alicia represented their one chance of something brilliant and interesting, something to lift them above their neighbors and break up the monotony of their later lives. Their devotion was a strange mixture of love and selfishness; at any rate, Alicia could always feel, and did always feel, that she was playing her family's game as well as her own.

Her own game, of course, came first. She was not a beauty, in the sense in which Diana Mallory was a beauty; and of that fact she had been perfectly aware after her first apparently careless glance at the new-comer of the afternoon. But she had points that never failed to attract notice: a free and rather insolent carriage, audaciously beautiful eyes, a general roundness and softness, and a grace--unfailing, deliberate, and provocative, even in actions, morally, the most graceless--that would have alone secured her the "career" on which she was bent.

Of her mental qualities, one of the most profitable was a very shrewd power of observation. As she swept slowly along the corridor, which overlooked the hall at Tallyn, none of the details of the house were lost upon her. Tallyn was vast, ugly--above all, rich. Henry Marsham, the deceased husband of Lady Lucy and father of Oliver and Mrs. Fotheringham, had made an enormous fortune in the Iron Trade of the north, retiring at sixty that he might enjoy some of those pleasures of life for which business had left him too little time. One of these pleasures was building. Henry Marsham had spent ten years in building Tallyn, and at the end of that time, feeling it impossible to live in the huge incoherent place he had created, he hired a small villa at Nice and went to die there in privacy and peace. Nevertheless, his will laid strict injunctions upon his widow to inhabit and keep up Tallyn; injunctions backed by considerable sanctions of a financial kind. His will, indeed, had been altogether a document of some eccentricity; though as eight years had now elapsed since his death, the knowledge of its provisions possessed by outsiders had had time to grow vague. Still, there were strong general impressions abroad, and as Alicia Drake surveyed the house which the old man had built to be the incubus of his descendants, some of them teased her mind. It was said, for instance, that Oliver Marsham and his sister only possessed pittances of about a thousand a year apiece, while Tallyn, together with the vast bulk of Henry Marsham's fortune, had been willed to Lady Lucy, and lay, moreover, at her absolute disposal. Was this so, or no? Miss Drake's curiosity, for some time past, would have been glad to be informed.

Meanwhile, here was the house--about which there was no mystery--least of all, as to its cost. Interminable broad corridors, carpeted with ugly Brussels and suggesting a railway hotel, branched out before Miss Drake's eyes in various directions; upon them opened not bedrooms but "suites," as Mr. Marsham père had loved to call them, of which the number was legion, while the bachelors' wing alone would have lodged a regiment. Every bedroom was like every other, except for such variations as Tottenham Court Road, rioting at will, could suggest. Copies in marble or bronze of well-known statues ranged along the corridors--a forlorn troupe of nude and shivering divinities. The immense hall below, with its violent frescos and its brand-new Turkey carpets, was panelled in oak, from which some device of stain or varnish had managed to abstract every particle of charm. A whole oak wood, indeed, had been lavished on the swathing and sheathing of the house, With the only result that the spectator beheld it steeped in a repellent yellow-brown from top to toe, against which no ornament, no piece of china, no picture, even did they possess some individual beauty, could possibly make it prevail.

And the drawing-room! As Alicia Drake advanced alone into its empty and blazing magnificence she could only laugh in its face--so eager and restless was the effort which it made, and so hopeless the defeat. Enormous mirrors, spread on white and gold walls; large copies from Italian pictures, collected by Henry Marsham in Rome; more facile statues holding innumerable lights; great pieces of modern china painted with realistic roses and poppies; crimson carpets, gilt furniture, and flaring cabinets--Miss Drake frowned as she looked at it. "What could be done with it?" she said to herself, walking slowly up and down, and glancing from side to side--"What could be done with it?"

A rustle in the hall announced another guest. Mrs. Fotheringham entered. Marsham's sister dressed with severity; and as she approached her cousin she put up her eye-glass for what was evidently a hostile inspection of the dazzling effect presented by the young lady. But Alicia was not afraid of Mrs. Fotheringham.

"How early we are!" she said, still quietly looking at the reflection of herself in the mirror over the mantel-piece and warming a slender foot at the fire. "Haven't some more people arrived, Cousin Isabel? I thought I heard a carriage while I was dressing."

"Yes; Miss Vincent and three men came by the late train."

"All Labor members?" asked Alicia, with a laugh.

Mrs. Fotheringham explained, with some tartness, that only one of the three was a Labor member--Mr. Barton. Of the other two, one was Edgar Frobisher, the other Mr. McEwart, a Liberal M.P., who had just won a hotly contested bye-election. At the name of Edgar Frobisher, Miss Drake's countenance showed some animation. She inquired if he had been doing anything madder than usual. Mrs. Fotheringham replied, without enthusiasm, that she knew nothing about his recent doings--nor about Mr. McEwart, who was said, however, to be of the right stuff. Mr. Barton, on the other hand, "is a great friend of mine--and a most remarkable man. Oliver has been very lucky to get him."

Alicia inquired whether he was likely to appear in dress clothes.

"Certainly not. He never does anything out of keeping with his class--and he knows that we lay no stress on that kind of thing." This, with another glance at the elegant Paris frock which adorned the person of Alicia--a frock, in Mrs. Fotheringham's opinion, far too expensive for the girl's circumstances. Alicia received the glance without flinching. It was one of her good points that she was never meek with the people who disliked her. She merely threw out another inquiry as to "Miss Vincent."

"One of mamma's acquaintances. She was a private secretary to some one mamma knows, and she is going to do some work for Oliver when the session begins.

"Didn't Oliver tell me she is a Socialist?"

Mrs. Fotheringham believed it might be said.

"How Miss Mallory will enjoy herself!" said Alicia, with a little laugh.

"Have you been talking to Oliver about her?" Mrs. Fotheringham stared rather hard at her cousin.

"Of course. Oliver likes her."

"Oliver likes a good many people."

"Oh no, Cousin Isabel! Oliver likes very few people--very, very few," said Miss Drake, decidedly, looking down into the fire.

"I don't know why you give Oliver such an unamiable character! In my opinion, he is often not so much on his guard as I should like to see him."

"Oh, well, we can't all be as critical as you, dear Cousin Isabel! But, anyway, Oliver admires Miss Mallory extremely. We can all see that."

The girl turned a steady face on her companion. Mrs. Fotheringham was conscious of a certain secret admiration. But her own point of view had nothing to do with Miss Drake's.